User login

Study: Quality of care may not determine pneumonia readmissions

Lower quality of care was not associated with pneumonia readmissions, according to a study using a commercially available software program to examine possibly preventable readmissions.

Rates of hospital readmission are now being used to demonstrate hospital performance and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services may even penalize hospitals with high rates of readmissions. As a result, it has become increasingly important to recognize clinical situations that may lead to a potentially preventable readmission.

The Potentially Preventable Readmission (PPRs) software was developed by 3M Health Information Systems to identify such cases and is being adopted by some state Medicaid programs for hospital payment and reporting. Dr. Ann M. Borzecki of the Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research in Bedford, Mass., and her colleagues sought to understand if patients with pneumonia flagged by the PPR software as preventable readmissions were associated with failures in the process of care.

The investigators conducted a cross-sectional retrospective observational study with Veterans Affairs electronic medical record (EMR) data from October 2005 to September 2010. Patients with diagnoses of pneumonia and a 30-day readmission were identified and then flagged as PPR-yes (for example, readmissions associated with quality of care problems) vs. PPR-no, using the 3M PPR software. A tool to measure quality of care was applied to 100 random readmissions abstracted for full review. The study was published online Sept. 14 in BMJ Quality and Safety. (http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-003911).

Of all the pneumonia readmission cases, 72% were PPR-yes vs.77% of the 100 abstracted cases. There were no significant differences between the groups other than a trend toward more comorbidity in the PPR-yes group.

After researchers adjusted for comorbidities and demographics, they noted no significant difference in quality of care between the PPR-yes and PPR-no groups. Interestingly, the PPR-yes group had slightly higher quality scores than did the PPR-no group (total scores, 71.2 vs. 65.8 respectively, P = .14).

The authors write, “Among veterans readmitted after a pneumonia discharge, we found no significant difference in quality of care, as measured by processes of care received during the index admission and after discharge, between cases flagged as PPRs and nonflagged cases. Indeed, contrary to our hypothesis, quality scores were slightly higher among PPR-flagged cases.”

The authors emphasized that causes of readmissions are multifaceted and many aspects may be out of the control of the hospital. However, they noted a concern for a lack of postdischarge documentation and emphasized the need for thorough documentation at all levels of care.

The authors report no competing interest. The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Service Research and Development Service.

Even with potentially preventable readmissions having a slightly higher, although not significant, quality score, the question remains: Do the flagged cases actually represent avoidable readmissions? The results bring up further questions on including preventable readmissions in quality measures.

Rates of readmission may reflect several aspects of care including the patient’s financial, environmental, and psychosocial factors. Furthermore, failure to address patient factors that contribute to readmission rates may abate hospital interventions to prevent those readmissions.

Dr. Christine Soong is affiliated with Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004484). No competing interests were declared.

Even with potentially preventable readmissions having a slightly higher, although not significant, quality score, the question remains: Do the flagged cases actually represent avoidable readmissions? The results bring up further questions on including preventable readmissions in quality measures.

Rates of readmission may reflect several aspects of care including the patient’s financial, environmental, and psychosocial factors. Furthermore, failure to address patient factors that contribute to readmission rates may abate hospital interventions to prevent those readmissions.

Dr. Christine Soong is affiliated with Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004484). No competing interests were declared.

Even with potentially preventable readmissions having a slightly higher, although not significant, quality score, the question remains: Do the flagged cases actually represent avoidable readmissions? The results bring up further questions on including preventable readmissions in quality measures.

Rates of readmission may reflect several aspects of care including the patient’s financial, environmental, and psychosocial factors. Furthermore, failure to address patient factors that contribute to readmission rates may abate hospital interventions to prevent those readmissions.

Dr. Christine Soong is affiliated with Mount Sinai Hospital in Toronto. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004484). No competing interests were declared.

Lower quality of care was not associated with pneumonia readmissions, according to a study using a commercially available software program to examine possibly preventable readmissions.

Rates of hospital readmission are now being used to demonstrate hospital performance and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services may even penalize hospitals with high rates of readmissions. As a result, it has become increasingly important to recognize clinical situations that may lead to a potentially preventable readmission.

The Potentially Preventable Readmission (PPRs) software was developed by 3M Health Information Systems to identify such cases and is being adopted by some state Medicaid programs for hospital payment and reporting. Dr. Ann M. Borzecki of the Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research in Bedford, Mass., and her colleagues sought to understand if patients with pneumonia flagged by the PPR software as preventable readmissions were associated with failures in the process of care.

The investigators conducted a cross-sectional retrospective observational study with Veterans Affairs electronic medical record (EMR) data from October 2005 to September 2010. Patients with diagnoses of pneumonia and a 30-day readmission were identified and then flagged as PPR-yes (for example, readmissions associated with quality of care problems) vs. PPR-no, using the 3M PPR software. A tool to measure quality of care was applied to 100 random readmissions abstracted for full review. The study was published online Sept. 14 in BMJ Quality and Safety. (http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-003911).

Of all the pneumonia readmission cases, 72% were PPR-yes vs.77% of the 100 abstracted cases. There were no significant differences between the groups other than a trend toward more comorbidity in the PPR-yes group.

After researchers adjusted for comorbidities and demographics, they noted no significant difference in quality of care between the PPR-yes and PPR-no groups. Interestingly, the PPR-yes group had slightly higher quality scores than did the PPR-no group (total scores, 71.2 vs. 65.8 respectively, P = .14).

The authors write, “Among veterans readmitted after a pneumonia discharge, we found no significant difference in quality of care, as measured by processes of care received during the index admission and after discharge, between cases flagged as PPRs and nonflagged cases. Indeed, contrary to our hypothesis, quality scores were slightly higher among PPR-flagged cases.”

The authors emphasized that causes of readmissions are multifaceted and many aspects may be out of the control of the hospital. However, they noted a concern for a lack of postdischarge documentation and emphasized the need for thorough documentation at all levels of care.

The authors report no competing interest. The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Service Research and Development Service.

Lower quality of care was not associated with pneumonia readmissions, according to a study using a commercially available software program to examine possibly preventable readmissions.

Rates of hospital readmission are now being used to demonstrate hospital performance and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services may even penalize hospitals with high rates of readmissions. As a result, it has become increasingly important to recognize clinical situations that may lead to a potentially preventable readmission.

The Potentially Preventable Readmission (PPRs) software was developed by 3M Health Information Systems to identify such cases and is being adopted by some state Medicaid programs for hospital payment and reporting. Dr. Ann M. Borzecki of the Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research in Bedford, Mass., and her colleagues sought to understand if patients with pneumonia flagged by the PPR software as preventable readmissions were associated with failures in the process of care.

The investigators conducted a cross-sectional retrospective observational study with Veterans Affairs electronic medical record (EMR) data from October 2005 to September 2010. Patients with diagnoses of pneumonia and a 30-day readmission were identified and then flagged as PPR-yes (for example, readmissions associated with quality of care problems) vs. PPR-no, using the 3M PPR software. A tool to measure quality of care was applied to 100 random readmissions abstracted for full review. The study was published online Sept. 14 in BMJ Quality and Safety. (http://qualitysafety.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-003911).

Of all the pneumonia readmission cases, 72% were PPR-yes vs.77% of the 100 abstracted cases. There were no significant differences between the groups other than a trend toward more comorbidity in the PPR-yes group.

After researchers adjusted for comorbidities and demographics, they noted no significant difference in quality of care between the PPR-yes and PPR-no groups. Interestingly, the PPR-yes group had slightly higher quality scores than did the PPR-no group (total scores, 71.2 vs. 65.8 respectively, P = .14).

The authors write, “Among veterans readmitted after a pneumonia discharge, we found no significant difference in quality of care, as measured by processes of care received during the index admission and after discharge, between cases flagged as PPRs and nonflagged cases. Indeed, contrary to our hypothesis, quality scores were slightly higher among PPR-flagged cases.”

The authors emphasized that causes of readmissions are multifaceted and many aspects may be out of the control of the hospital. However, they noted a concern for a lack of postdischarge documentation and emphasized the need for thorough documentation at all levels of care.

The authors report no competing interest. The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Service Research and Development Service.

BMJ QUALITY AND SAFETY

Key clinical point: A commercially available software program used to highlight possible preventable readmissions did not indicate cases with a lower quality of care in pneumonia readmissions.

Major finding: There was no significant difference in quality of care between groups of cases flagged by the software (PPR-yes) and groups not flagged (PPR-no), and the PPR-yes group actually had a slightly higher quality scores (total scores, 71.2 vs. 65.8 respectively, P = .14).

Data source: A cross-sectional retrospective observational study with Veterans Health Administration EMR data from October 2005 to September 2010.

Disclosures: The authors report no competing interest. The study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Service Research and Development Service.

HbA1c aids prediction of atherosclerotic CVD

When combined with conventional risk factors, hemoglobin A1c modestly aids in prediction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, according to a retrospective analysis published online Sept. 8 in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

Conventional risk factors for CVD such as sex, age, blood pressure, smoking, or lipid level are important tools used to aid in clinical decision making. However, there is current debate about whether to include hemoglobin A1c in the algorithms, despite the clear association of CVD with glucose levels, said Jamie A. Jarmul of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, and colleagues.

They used data from the 2011-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to analyze CVD risk factors and HbA1c in 2,000 individuals aged 40-79 years without a history of diabetes or CVD. Utilizing a regression model, the distribution of HbA1c based on patient characteristics was predicted. The impact of the predicted HbA1c on the 10-year atherosclerotic CVD risk was calculated with the use of example clinical scenarios.

Factors considered significant predictors of HbA1c were HDL-cholesterol, total cholesterol, current smoking, sex, age, race/ethnicity, and systolic blood pressure. Further, individuals who were of black, Asian, or Hispanic race/ethnicity were associated with prediction of higher HbA1c.

The investigators noted that by using the final model, they found a modest effect of HbA1c on post-test atherosclerotic CVD risk in participants with intermediate risk. In the example clinical scenarios, an HbA1c of more than 6.5% was associated with increase in posttest atherosclerotic CVD risk by 1.0%-2.5% points. An HbA1c less than 5.7% was associated with a lowering of posttest atherosclerotic CVD risk by 0.4%-2.0% points (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015 Sep 8. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.001639). The authors note the posttest atherosclerotic CVD risk of having an elevated HbA1c (greater than 6.5%) is similar to being 5 years older.

“The results we have presented here represent a necessary intermediate step before conducting these more comprehensive analyses assessing the utility of HbA1c testing in ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] primary prevention and the larger question of universal screening for abnormal blood glucose levels,” the authors noted.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study. Dr. Pignone reports being a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

With the modest effects of HbA1c on risk classification combined with its low cost, wide availability, and low risk, even a small improvement in cardiovascular disease risk prediction may add value to the current models.

However, utilizing biomarkers to create personalized risk prediction models has not seemed to return great results for CVD risk reclassification. Therefore, it may be time to consider alternative methods based on expert consensus.

Furthermore, it may be reasonable to move away from markers of the disease to detection with methods such as coronary artery calcium by noncontrast CT scan to detect the presence or, perhaps just as importantly, the absence of atherosclerosis.

Dr. Khurram Nasir is director of the Center for Healthcare Advancement and Outcomes in Coral Gables, Fla. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015 Sep 8. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002207). Dr. Nasir reported consulting for Regeneron and being on the advisory board for Quest Diagnostic.

With the modest effects of HbA1c on risk classification combined with its low cost, wide availability, and low risk, even a small improvement in cardiovascular disease risk prediction may add value to the current models.

However, utilizing biomarkers to create personalized risk prediction models has not seemed to return great results for CVD risk reclassification. Therefore, it may be time to consider alternative methods based on expert consensus.

Furthermore, it may be reasonable to move away from markers of the disease to detection with methods such as coronary artery calcium by noncontrast CT scan to detect the presence or, perhaps just as importantly, the absence of atherosclerosis.

Dr. Khurram Nasir is director of the Center for Healthcare Advancement and Outcomes in Coral Gables, Fla. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015 Sep 8. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002207). Dr. Nasir reported consulting for Regeneron and being on the advisory board for Quest Diagnostic.

With the modest effects of HbA1c on risk classification combined with its low cost, wide availability, and low risk, even a small improvement in cardiovascular disease risk prediction may add value to the current models.

However, utilizing biomarkers to create personalized risk prediction models has not seemed to return great results for CVD risk reclassification. Therefore, it may be time to consider alternative methods based on expert consensus.

Furthermore, it may be reasonable to move away from markers of the disease to detection with methods such as coronary artery calcium by noncontrast CT scan to detect the presence or, perhaps just as importantly, the absence of atherosclerosis.

Dr. Khurram Nasir is director of the Center for Healthcare Advancement and Outcomes in Coral Gables, Fla. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015 Sep 8. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002207). Dr. Nasir reported consulting for Regeneron and being on the advisory board for Quest Diagnostic.

When combined with conventional risk factors, hemoglobin A1c modestly aids in prediction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, according to a retrospective analysis published online Sept. 8 in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

Conventional risk factors for CVD such as sex, age, blood pressure, smoking, or lipid level are important tools used to aid in clinical decision making. However, there is current debate about whether to include hemoglobin A1c in the algorithms, despite the clear association of CVD with glucose levels, said Jamie A. Jarmul of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, and colleagues.

They used data from the 2011-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to analyze CVD risk factors and HbA1c in 2,000 individuals aged 40-79 years without a history of diabetes or CVD. Utilizing a regression model, the distribution of HbA1c based on patient characteristics was predicted. The impact of the predicted HbA1c on the 10-year atherosclerotic CVD risk was calculated with the use of example clinical scenarios.

Factors considered significant predictors of HbA1c were HDL-cholesterol, total cholesterol, current smoking, sex, age, race/ethnicity, and systolic blood pressure. Further, individuals who were of black, Asian, or Hispanic race/ethnicity were associated with prediction of higher HbA1c.

The investigators noted that by using the final model, they found a modest effect of HbA1c on post-test atherosclerotic CVD risk in participants with intermediate risk. In the example clinical scenarios, an HbA1c of more than 6.5% was associated with increase in posttest atherosclerotic CVD risk by 1.0%-2.5% points. An HbA1c less than 5.7% was associated with a lowering of posttest atherosclerotic CVD risk by 0.4%-2.0% points (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015 Sep 8. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.001639). The authors note the posttest atherosclerotic CVD risk of having an elevated HbA1c (greater than 6.5%) is similar to being 5 years older.

“The results we have presented here represent a necessary intermediate step before conducting these more comprehensive analyses assessing the utility of HbA1c testing in ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] primary prevention and the larger question of universal screening for abnormal blood glucose levels,” the authors noted.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study. Dr. Pignone reports being a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

When combined with conventional risk factors, hemoglobin A1c modestly aids in prediction of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk, according to a retrospective analysis published online Sept. 8 in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes.

Conventional risk factors for CVD such as sex, age, blood pressure, smoking, or lipid level are important tools used to aid in clinical decision making. However, there is current debate about whether to include hemoglobin A1c in the algorithms, despite the clear association of CVD with glucose levels, said Jamie A. Jarmul of the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, and colleagues.

They used data from the 2011-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to analyze CVD risk factors and HbA1c in 2,000 individuals aged 40-79 years without a history of diabetes or CVD. Utilizing a regression model, the distribution of HbA1c based on patient characteristics was predicted. The impact of the predicted HbA1c on the 10-year atherosclerotic CVD risk was calculated with the use of example clinical scenarios.

Factors considered significant predictors of HbA1c were HDL-cholesterol, total cholesterol, current smoking, sex, age, race/ethnicity, and systolic blood pressure. Further, individuals who were of black, Asian, or Hispanic race/ethnicity were associated with prediction of higher HbA1c.

The investigators noted that by using the final model, they found a modest effect of HbA1c on post-test atherosclerotic CVD risk in participants with intermediate risk. In the example clinical scenarios, an HbA1c of more than 6.5% was associated with increase in posttest atherosclerotic CVD risk by 1.0%-2.5% points. An HbA1c less than 5.7% was associated with a lowering of posttest atherosclerotic CVD risk by 0.4%-2.0% points (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2015 Sep 8. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.001639). The authors note the posttest atherosclerotic CVD risk of having an elevated HbA1c (greater than 6.5%) is similar to being 5 years older.

“The results we have presented here represent a necessary intermediate step before conducting these more comprehensive analyses assessing the utility of HbA1c testing in ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] primary prevention and the larger question of universal screening for abnormal blood glucose levels,” the authors noted.

The National Institutes of Health supported the study. Dr. Pignone reports being a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

FROM CIRCULATION: CARDIOVASCULAR QUALITY AND OUTCOMES

Key clinical point: Hemoglobin A1c modestly aids in prediction of atherosclerotic CVD.

Major finding: In the example clinical scenarios, an HbA1c of greater than 6.5% was associated with increase in post-test atherosclerotic CVD risk by 1.0%-2.5% points and an HbA1c less than 5.7% was associated with a lowering of posttest atherosclerotic CVD risk by 0.4%-2.0% points.

Data source: The 2011-2012 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health funded the study. Dr. Pignone reports being a member of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

Diabetes Prevalence Rising, Especially in Black, Asian, and Hispanic Populations

The prevalence of diabetes in the United States was 12% to 14% in 2011-2012 with higher rates in black, Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Over the past decade, the prevalence of diabetes has increased, placing it as a major cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States.

Andy Menke, Ph.D., of Social & Scientific Systems, a biotechnology company in Silver Spring, Md., and his colleagues sought to estimate the U.S. trends and prevalence of prediabetes, total diabetes, diagnosed diabetes, and undiagnosed diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Their results were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association online Sept. 8.

NHANES is a cross-sectional survey, conducted from 1988 to 1994 and 1999 to 2012. To estimate the most recent prevalence, the investigators sampled 2,781 adults from the 2011-2012 data and included 23,634 adults to estimate the trends from 1988 to 2010.

The prevalence of diabetes was determined based on a diagnosis of diabetes or evidence of based on fasting plasma glucose greater than 126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c of 6.5% or more, or 2-hour post prandial glucose greater than 200 mg/dL. Prediabetes was noted to be based on 2-hour post prandial glucose of 140-199 mg/dL, fasting plasma glucose of 100-125 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1c of 5.7%-6.4%.

During 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes based on 2-hour post prandial glucose, fasting plasma glucose, or hemoglobin A1c was 14.3% for total diabetes (diagnosed and undiagnosed). Furthermore, the prevalence was 9.1% for diagnosed, 5.2% for undiagnosed, and 38% for prediabetes.

When compared to white individuals (11.3%), the age-standardized prevalence of diabetes was higher in Hispanic (22.6%, P less than .001), Asian (20.6%, P = .007), and black (21.8%, P less than .001) individuals. Likewise, Hispanics (29.7%, P = .003) and blacks (30.8%, P less than .001) tended to have higher BMIs compared to whites (28.4%). Asians tended to have lower BMIs (24.6%, P less than .001).

The age-standardized prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was higher in Hispanic (49%, P = .02) and Asian (50.9%, P = .004) individuals than in other groups. However, the age-standardized prevalence of prediabetes was higher in blacks (39.6%) than in Asians (32.2%, P = .05).

When defining diabetes based on hemoglobin A1c or fasting plasma glucose alone, the authors found fewer people with undiagnosed diabetes. For example, the prevalence was 12.3% for total diabetes with 3.1% undiagnosed and 9.2% diagnosed. Furthermore, 36.5% of the study subjects qualified as prediabetic based on these definitions.

The age-standardized prevalance of diabetes increased from 9.8% to 12.4% during the 1988-1994 and 2011-2012 periods (P less than .001 trend). However, there was not much change in prevalence from 2007-2008 to 2011-2012 (12.5% to 12.4%).

The prevalence of diabetes significantly increased during the study time period in both sexes, all racial groups, education levels, incomes, and ages.

The amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed decreased in most groups, including sex, racial groups, and most age groups. However, in Mexican American subjects the rate of undiagnosed diabetes actually increased over the study period (5.6% to 5.9%, P = .01). The increased prevalence of diabetes was due to increases in the amount of diagnosed diabetes, the authors wrote.

Finally, the age-standardized prevalence of total diabetes for subjects aged 40-74 years was 15.9%, 18.1%, and 18% during 1988-1994, 2005-2006, and 2011-2012, respectively (P = .01 for trend).

“Between 1988-1994 and 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes increased significantly among the overall population and among each age group, both sexes, every racial/ethnic group, every education level, and every income level, with a particularly rapid increase among non-Hispanic black and Mexican American participants. The proportion of people who had undiagnosed diabetes significantly decreased,” the authors noted.

The authors further clarified that the lower rates of undiagnosed diabetes over time may be secondary to improved survival in patients with diabetes and better screening.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases supported the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

The decrease in amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed may suggest that initiatives to encourage behavior changes in physical activity and diet may have started to impact the prevalence of obesity and secondarily the prevalence of diabetes.

|

Dr. William H. Herman |

Although the higher prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes in Asian Americans, younger patients, and Hispanic patients highlights disparities that exist, efforts to promote screening, identification of at-risk people, development of prevention programs, encouraging behavior change, and these data provide some hope.

The prevalence of total diabetes remained stable from 2008 to 2012. What explains the recent change in the upward trend? Perhaps it is this: “Providing insurance coverage for intensive behavioral therapies for obesity and using behavioral economic approaches to encourage their uptake are further removing barriers to patient engagement and are providing strong incentives for individual behavioral change.”

Dr. William H. Herman is affiliated with the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial. Dr. Herman reported receiving personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, and Profil Institute for Clinical Research.

The decrease in amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed may suggest that initiatives to encourage behavior changes in physical activity and diet may have started to impact the prevalence of obesity and secondarily the prevalence of diabetes.

|

Dr. William H. Herman |

Although the higher prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes in Asian Americans, younger patients, and Hispanic patients highlights disparities that exist, efforts to promote screening, identification of at-risk people, development of prevention programs, encouraging behavior change, and these data provide some hope.

The prevalence of total diabetes remained stable from 2008 to 2012. What explains the recent change in the upward trend? Perhaps it is this: “Providing insurance coverage for intensive behavioral therapies for obesity and using behavioral economic approaches to encourage their uptake are further removing barriers to patient engagement and are providing strong incentives for individual behavioral change.”

Dr. William H. Herman is affiliated with the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial. Dr. Herman reported receiving personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, and Profil Institute for Clinical Research.

The decrease in amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed may suggest that initiatives to encourage behavior changes in physical activity and diet may have started to impact the prevalence of obesity and secondarily the prevalence of diabetes.

|

Dr. William H. Herman |

Although the higher prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes in Asian Americans, younger patients, and Hispanic patients highlights disparities that exist, efforts to promote screening, identification of at-risk people, development of prevention programs, encouraging behavior change, and these data provide some hope.

The prevalence of total diabetes remained stable from 2008 to 2012. What explains the recent change in the upward trend? Perhaps it is this: “Providing insurance coverage for intensive behavioral therapies for obesity and using behavioral economic approaches to encourage their uptake are further removing barriers to patient engagement and are providing strong incentives for individual behavioral change.”

Dr. William H. Herman is affiliated with the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial. Dr. Herman reported receiving personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, and Profil Institute for Clinical Research.

The prevalence of diabetes in the United States was 12% to 14% in 2011-2012 with higher rates in black, Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Over the past decade, the prevalence of diabetes has increased, placing it as a major cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States.

Andy Menke, Ph.D., of Social & Scientific Systems, a biotechnology company in Silver Spring, Md., and his colleagues sought to estimate the U.S. trends and prevalence of prediabetes, total diabetes, diagnosed diabetes, and undiagnosed diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Their results were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association online Sept. 8.

NHANES is a cross-sectional survey, conducted from 1988 to 1994 and 1999 to 2012. To estimate the most recent prevalence, the investigators sampled 2,781 adults from the 2011-2012 data and included 23,634 adults to estimate the trends from 1988 to 2010.

The prevalence of diabetes was determined based on a diagnosis of diabetes or evidence of based on fasting plasma glucose greater than 126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c of 6.5% or more, or 2-hour post prandial glucose greater than 200 mg/dL. Prediabetes was noted to be based on 2-hour post prandial glucose of 140-199 mg/dL, fasting plasma glucose of 100-125 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1c of 5.7%-6.4%.

During 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes based on 2-hour post prandial glucose, fasting plasma glucose, or hemoglobin A1c was 14.3% for total diabetes (diagnosed and undiagnosed). Furthermore, the prevalence was 9.1% for diagnosed, 5.2% for undiagnosed, and 38% for prediabetes.

When compared to white individuals (11.3%), the age-standardized prevalence of diabetes was higher in Hispanic (22.6%, P less than .001), Asian (20.6%, P = .007), and black (21.8%, P less than .001) individuals. Likewise, Hispanics (29.7%, P = .003) and blacks (30.8%, P less than .001) tended to have higher BMIs compared to whites (28.4%). Asians tended to have lower BMIs (24.6%, P less than .001).

The age-standardized prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was higher in Hispanic (49%, P = .02) and Asian (50.9%, P = .004) individuals than in other groups. However, the age-standardized prevalence of prediabetes was higher in blacks (39.6%) than in Asians (32.2%, P = .05).

When defining diabetes based on hemoglobin A1c or fasting plasma glucose alone, the authors found fewer people with undiagnosed diabetes. For example, the prevalence was 12.3% for total diabetes with 3.1% undiagnosed and 9.2% diagnosed. Furthermore, 36.5% of the study subjects qualified as prediabetic based on these definitions.

The age-standardized prevalance of diabetes increased from 9.8% to 12.4% during the 1988-1994 and 2011-2012 periods (P less than .001 trend). However, there was not much change in prevalence from 2007-2008 to 2011-2012 (12.5% to 12.4%).

The prevalence of diabetes significantly increased during the study time period in both sexes, all racial groups, education levels, incomes, and ages.

The amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed decreased in most groups, including sex, racial groups, and most age groups. However, in Mexican American subjects the rate of undiagnosed diabetes actually increased over the study period (5.6% to 5.9%, P = .01). The increased prevalence of diabetes was due to increases in the amount of diagnosed diabetes, the authors wrote.

Finally, the age-standardized prevalence of total diabetes for subjects aged 40-74 years was 15.9%, 18.1%, and 18% during 1988-1994, 2005-2006, and 2011-2012, respectively (P = .01 for trend).

“Between 1988-1994 and 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes increased significantly among the overall population and among each age group, both sexes, every racial/ethnic group, every education level, and every income level, with a particularly rapid increase among non-Hispanic black and Mexican American participants. The proportion of people who had undiagnosed diabetes significantly decreased,” the authors noted.

The authors further clarified that the lower rates of undiagnosed diabetes over time may be secondary to improved survival in patients with diabetes and better screening.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases supported the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

The prevalence of diabetes in the United States was 12% to 14% in 2011-2012 with higher rates in black, Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Over the past decade, the prevalence of diabetes has increased, placing it as a major cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States.

Andy Menke, Ph.D., of Social & Scientific Systems, a biotechnology company in Silver Spring, Md., and his colleagues sought to estimate the U.S. trends and prevalence of prediabetes, total diabetes, diagnosed diabetes, and undiagnosed diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Their results were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association online Sept. 8.

NHANES is a cross-sectional survey, conducted from 1988 to 1994 and 1999 to 2012. To estimate the most recent prevalence, the investigators sampled 2,781 adults from the 2011-2012 data and included 23,634 adults to estimate the trends from 1988 to 2010.

The prevalence of diabetes was determined based on a diagnosis of diabetes or evidence of based on fasting plasma glucose greater than 126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c of 6.5% or more, or 2-hour post prandial glucose greater than 200 mg/dL. Prediabetes was noted to be based on 2-hour post prandial glucose of 140-199 mg/dL, fasting plasma glucose of 100-125 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1c of 5.7%-6.4%.

During 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes based on 2-hour post prandial glucose, fasting plasma glucose, or hemoglobin A1c was 14.3% for total diabetes (diagnosed and undiagnosed). Furthermore, the prevalence was 9.1% for diagnosed, 5.2% for undiagnosed, and 38% for prediabetes.

When compared to white individuals (11.3%), the age-standardized prevalence of diabetes was higher in Hispanic (22.6%, P less than .001), Asian (20.6%, P = .007), and black (21.8%, P less than .001) individuals. Likewise, Hispanics (29.7%, P = .003) and blacks (30.8%, P less than .001) tended to have higher BMIs compared to whites (28.4%). Asians tended to have lower BMIs (24.6%, P less than .001).

The age-standardized prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was higher in Hispanic (49%, P = .02) and Asian (50.9%, P = .004) individuals than in other groups. However, the age-standardized prevalence of prediabetes was higher in blacks (39.6%) than in Asians (32.2%, P = .05).

When defining diabetes based on hemoglobin A1c or fasting plasma glucose alone, the authors found fewer people with undiagnosed diabetes. For example, the prevalence was 12.3% for total diabetes with 3.1% undiagnosed and 9.2% diagnosed. Furthermore, 36.5% of the study subjects qualified as prediabetic based on these definitions.

The age-standardized prevalance of diabetes increased from 9.8% to 12.4% during the 1988-1994 and 2011-2012 periods (P less than .001 trend). However, there was not much change in prevalence from 2007-2008 to 2011-2012 (12.5% to 12.4%).

The prevalence of diabetes significantly increased during the study time period in both sexes, all racial groups, education levels, incomes, and ages.

The amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed decreased in most groups, including sex, racial groups, and most age groups. However, in Mexican American subjects the rate of undiagnosed diabetes actually increased over the study period (5.6% to 5.9%, P = .01). The increased prevalence of diabetes was due to increases in the amount of diagnosed diabetes, the authors wrote.

Finally, the age-standardized prevalence of total diabetes for subjects aged 40-74 years was 15.9%, 18.1%, and 18% during 1988-1994, 2005-2006, and 2011-2012, respectively (P = .01 for trend).

“Between 1988-1994 and 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes increased significantly among the overall population and among each age group, both sexes, every racial/ethnic group, every education level, and every income level, with a particularly rapid increase among non-Hispanic black and Mexican American participants. The proportion of people who had undiagnosed diabetes significantly decreased,” the authors noted.

The authors further clarified that the lower rates of undiagnosed diabetes over time may be secondary to improved survival in patients with diabetes and better screening.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases supported the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

FROM JAMA

Diabetes prevalence rising, especially in black, Asian, and Hispanic populations

The prevalence of diabetes in the United States was 12% to 14% in 2011-2012 with higher rates in black, Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Over the past decade, the prevalence of diabetes has increased, placing it as a major cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States.

Andy Menke, Ph.D., of Social & Scientific Systems, a biotechnology company in Silver Spring, Md., and his colleagues sought to estimate the U.S. trends and prevalence of prediabetes, total diabetes, diagnosed diabetes, and undiagnosed diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Their results were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association online Sept. 8.

NHANES is a cross-sectional survey, conducted from 1988 to 1994 and 1999 to 2012. To estimate the most recent prevalence, the investigators sampled 2,781 adults from the 2011-2012 data and included 23,634 adults to estimate the trends from 1988 to 2010.

The prevalence of diabetes was determined based on a diagnosis of diabetes or evidence of based on fasting plasma glucose greater than 126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c of 6.5% or more, or 2-hour post prandial glucose greater than 200 mg/dL. Prediabetes was noted to be based on 2-hour post prandial glucose of 140-199 mg/dL, fasting plasma glucose of 100-125 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1c of 5.7%-6.4%.

During 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes based on 2-hour post prandial glucose, fasting plasma glucose, or hemoglobin A1c was 14.3% for total diabetes (diagnosed and undiagnosed). Furthermore, the prevalence was 9.1% for diagnosed, 5.2% for undiagnosed, and 38% for prediabetes.

When compared to white individuals (11.3%), the age-standardized prevalence of diabetes was higher in Hispanic (22.6%, P less than .001), Asian (20.6%, P = .007), and black (21.8%, P less than .001) individuals. Likewise, Hispanics (29.7%, P = .003) and blacks (30.8%, P less than .001) tended to have higher BMIs compared to whites (28.4%). Asians tended to have lower BMIs (24.6%, P less than .001).

The age-standardized prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was higher in Hispanic (49%, P = .02) and Asian (50.9%, P = .004) individuals than in other groups. However, the age-standardized prevalence of prediabetes was higher in blacks (39.6%) than in Asians (32.2%, P = .05).

When defining diabetes based on hemoglobin A1c or fasting plasma glucose alone, the authors found fewer people with undiagnosed diabetes. For example, the prevalence was 12.3% for total diabetes with 3.1% undiagnosed and 9.2% diagnosed. Furthermore, 36.5% of the study subjects qualified as prediabetic based on these definitions.

The age-standardized prevalance of diabetes increased from 9.8% to 12.4% during the 1988-1994 and 2011-2012 periods (P less than .001 trend). However, there was not much change in prevalence from 2007-2008 to 2011-2012 (12.5% to 12.4%).

The prevalence of diabetes significantly increased during the study time period in both sexes, all racial groups, education levels, incomes, and ages.

The amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed decreased in most groups, including sex, racial groups, and most age groups. However, in Mexican American subjects the rate of undiagnosed diabetes actually increased over the study period (5.6% to 5.9%, P = .01). The increased prevalence of diabetes was due to increases in the amount of diagnosed diabetes, the authors wrote.

Finally, the age-standardized prevalence of total diabetes for subjects aged 40-74 years was 15.9%, 18.1%, and 18% during 1988-1994, 2005-2006, and 2011-2012, respectively (P = .01 for trend).

“Between 1988-1994 and 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes increased significantly among the overall population and among each age group, both sexes, every racial/ethnic group, every education level, and every income level, with a particularly rapid increase among non-Hispanic black and Mexican American participants. The proportion of people who had undiagnosed diabetes significantly decreased,” the authors noted.

The authors further clarified that the lower rates of undiagnosed diabetes over time may be secondary to improved survival in patients with diabetes and better screening.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases supported the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

The decrease in amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed may suggest that initiatives to encourage behavior changes in physical activity and diet may have started to impact the prevalence of obesity and secondarily the prevalence of diabetes.

|

Dr. William H. Herman |

Although the higher prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes in Asian Americans, younger patients, and Hispanic patients highlights disparities that exist, efforts to promote screening, identification of at-risk people, development of prevention programs, encouraging behavior change, and these data provide some hope.

The prevalence of total diabetes remained stable from 2008 to 2012. What explains the recent change in the upward trend? Perhaps it is this: “Providing insurance coverage for intensive behavioral therapies for obesity and using behavioral economic approaches to encourage their uptake are further removing barriers to patient engagement and are providing strong incentives for individual behavioral change.”

Dr. William H. Herman is affiliated with the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial. Dr. Herman reported receiving personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, and Profil Institute for Clinical Research.

The decrease in amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed may suggest that initiatives to encourage behavior changes in physical activity and diet may have started to impact the prevalence of obesity and secondarily the prevalence of diabetes.

|

Dr. William H. Herman |

Although the higher prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes in Asian Americans, younger patients, and Hispanic patients highlights disparities that exist, efforts to promote screening, identification of at-risk people, development of prevention programs, encouraging behavior change, and these data provide some hope.

The prevalence of total diabetes remained stable from 2008 to 2012. What explains the recent change in the upward trend? Perhaps it is this: “Providing insurance coverage for intensive behavioral therapies for obesity and using behavioral economic approaches to encourage their uptake are further removing barriers to patient engagement and are providing strong incentives for individual behavioral change.”

Dr. William H. Herman is affiliated with the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial. Dr. Herman reported receiving personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, and Profil Institute for Clinical Research.

The decrease in amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed may suggest that initiatives to encourage behavior changes in physical activity and diet may have started to impact the prevalence of obesity and secondarily the prevalence of diabetes.

|

Dr. William H. Herman |

Although the higher prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes in Asian Americans, younger patients, and Hispanic patients highlights disparities that exist, efforts to promote screening, identification of at-risk people, development of prevention programs, encouraging behavior change, and these data provide some hope.

The prevalence of total diabetes remained stable from 2008 to 2012. What explains the recent change in the upward trend? Perhaps it is this: “Providing insurance coverage for intensive behavioral therapies for obesity and using behavioral economic approaches to encourage their uptake are further removing barriers to patient engagement and are providing strong incentives for individual behavioral change.”

Dr. William H. Herman is affiliated with the department of internal medicine at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial. Dr. Herman reported receiving personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, and Profil Institute for Clinical Research.

The prevalence of diabetes in the United States was 12% to 14% in 2011-2012 with higher rates in black, Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Over the past decade, the prevalence of diabetes has increased, placing it as a major cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States.

Andy Menke, Ph.D., of Social & Scientific Systems, a biotechnology company in Silver Spring, Md., and his colleagues sought to estimate the U.S. trends and prevalence of prediabetes, total diabetes, diagnosed diabetes, and undiagnosed diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Their results were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association online Sept. 8.

NHANES is a cross-sectional survey, conducted from 1988 to 1994 and 1999 to 2012. To estimate the most recent prevalence, the investigators sampled 2,781 adults from the 2011-2012 data and included 23,634 adults to estimate the trends from 1988 to 2010.

The prevalence of diabetes was determined based on a diagnosis of diabetes or evidence of based on fasting plasma glucose greater than 126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c of 6.5% or more, or 2-hour post prandial glucose greater than 200 mg/dL. Prediabetes was noted to be based on 2-hour post prandial glucose of 140-199 mg/dL, fasting plasma glucose of 100-125 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1c of 5.7%-6.4%.

During 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes based on 2-hour post prandial glucose, fasting plasma glucose, or hemoglobin A1c was 14.3% for total diabetes (diagnosed and undiagnosed). Furthermore, the prevalence was 9.1% for diagnosed, 5.2% for undiagnosed, and 38% for prediabetes.

When compared to white individuals (11.3%), the age-standardized prevalence of diabetes was higher in Hispanic (22.6%, P less than .001), Asian (20.6%, P = .007), and black (21.8%, P less than .001) individuals. Likewise, Hispanics (29.7%, P = .003) and blacks (30.8%, P less than .001) tended to have higher BMIs compared to whites (28.4%). Asians tended to have lower BMIs (24.6%, P less than .001).

The age-standardized prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was higher in Hispanic (49%, P = .02) and Asian (50.9%, P = .004) individuals than in other groups. However, the age-standardized prevalence of prediabetes was higher in blacks (39.6%) than in Asians (32.2%, P = .05).

When defining diabetes based on hemoglobin A1c or fasting plasma glucose alone, the authors found fewer people with undiagnosed diabetes. For example, the prevalence was 12.3% for total diabetes with 3.1% undiagnosed and 9.2% diagnosed. Furthermore, 36.5% of the study subjects qualified as prediabetic based on these definitions.

The age-standardized prevalance of diabetes increased from 9.8% to 12.4% during the 1988-1994 and 2011-2012 periods (P less than .001 trend). However, there was not much change in prevalence from 2007-2008 to 2011-2012 (12.5% to 12.4%).

The prevalence of diabetes significantly increased during the study time period in both sexes, all racial groups, education levels, incomes, and ages.

The amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed decreased in most groups, including sex, racial groups, and most age groups. However, in Mexican American subjects the rate of undiagnosed diabetes actually increased over the study period (5.6% to 5.9%, P = .01). The increased prevalence of diabetes was due to increases in the amount of diagnosed diabetes, the authors wrote.

Finally, the age-standardized prevalence of total diabetes for subjects aged 40-74 years was 15.9%, 18.1%, and 18% during 1988-1994, 2005-2006, and 2011-2012, respectively (P = .01 for trend).

“Between 1988-1994 and 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes increased significantly among the overall population and among each age group, both sexes, every racial/ethnic group, every education level, and every income level, with a particularly rapid increase among non-Hispanic black and Mexican American participants. The proportion of people who had undiagnosed diabetes significantly decreased,” the authors noted.

The authors further clarified that the lower rates of undiagnosed diabetes over time may be secondary to improved survival in patients with diabetes and better screening.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases supported the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

The prevalence of diabetes in the United States was 12% to 14% in 2011-2012 with higher rates in black, Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Over the past decade, the prevalence of diabetes has increased, placing it as a major cause of mortality and morbidity in the United States.

Andy Menke, Ph.D., of Social & Scientific Systems, a biotechnology company in Silver Spring, Md., and his colleagues sought to estimate the U.S. trends and prevalence of prediabetes, total diabetes, diagnosed diabetes, and undiagnosed diabetes using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES). Their results were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association online Sept. 8.

NHANES is a cross-sectional survey, conducted from 1988 to 1994 and 1999 to 2012. To estimate the most recent prevalence, the investigators sampled 2,781 adults from the 2011-2012 data and included 23,634 adults to estimate the trends from 1988 to 2010.

The prevalence of diabetes was determined based on a diagnosis of diabetes or evidence of based on fasting plasma glucose greater than 126 mg/dL, hemoglobin A1c of 6.5% or more, or 2-hour post prandial glucose greater than 200 mg/dL. Prediabetes was noted to be based on 2-hour post prandial glucose of 140-199 mg/dL, fasting plasma glucose of 100-125 mg/dL, or hemoglobin A1c of 5.7%-6.4%.

During 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes based on 2-hour post prandial glucose, fasting plasma glucose, or hemoglobin A1c was 14.3% for total diabetes (diagnosed and undiagnosed). Furthermore, the prevalence was 9.1% for diagnosed, 5.2% for undiagnosed, and 38% for prediabetes.

When compared to white individuals (11.3%), the age-standardized prevalence of diabetes was higher in Hispanic (22.6%, P less than .001), Asian (20.6%, P = .007), and black (21.8%, P less than .001) individuals. Likewise, Hispanics (29.7%, P = .003) and blacks (30.8%, P less than .001) tended to have higher BMIs compared to whites (28.4%). Asians tended to have lower BMIs (24.6%, P less than .001).

The age-standardized prevalence of undiagnosed diabetes was higher in Hispanic (49%, P = .02) and Asian (50.9%, P = .004) individuals than in other groups. However, the age-standardized prevalence of prediabetes was higher in blacks (39.6%) than in Asians (32.2%, P = .05).

When defining diabetes based on hemoglobin A1c or fasting plasma glucose alone, the authors found fewer people with undiagnosed diabetes. For example, the prevalence was 12.3% for total diabetes with 3.1% undiagnosed and 9.2% diagnosed. Furthermore, 36.5% of the study subjects qualified as prediabetic based on these definitions.

The age-standardized prevalance of diabetes increased from 9.8% to 12.4% during the 1988-1994 and 2011-2012 periods (P less than .001 trend). However, there was not much change in prevalence from 2007-2008 to 2011-2012 (12.5% to 12.4%).

The prevalence of diabetes significantly increased during the study time period in both sexes, all racial groups, education levels, incomes, and ages.

The amount of total diabetes that was undiagnosed decreased in most groups, including sex, racial groups, and most age groups. However, in Mexican American subjects the rate of undiagnosed diabetes actually increased over the study period (5.6% to 5.9%, P = .01). The increased prevalence of diabetes was due to increases in the amount of diagnosed diabetes, the authors wrote.

Finally, the age-standardized prevalence of total diabetes for subjects aged 40-74 years was 15.9%, 18.1%, and 18% during 1988-1994, 2005-2006, and 2011-2012, respectively (P = .01 for trend).

“Between 1988-1994 and 2011-2012, the prevalence of diabetes increased significantly among the overall population and among each age group, both sexes, every racial/ethnic group, every education level, and every income level, with a particularly rapid increase among non-Hispanic black and Mexican American participants. The proportion of people who had undiagnosed diabetes significantly decreased,” the authors noted.

The authors further clarified that the lower rates of undiagnosed diabetes over time may be secondary to improved survival in patients with diabetes and better screening.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases supported the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: The prevalence of diabetes is rising, especially among black, Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Major finding: The prevalence of diabetes was between 12% and 14% during 2011-2012 with higher rates in black, Asian, and Hispanic populations.

Data source: A cross-sectional survey with data from NHANES from 1988 to 1994 and 1999 to 2012.

Disclosures: The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases funded the study. The authors reported no conflicts of interests.

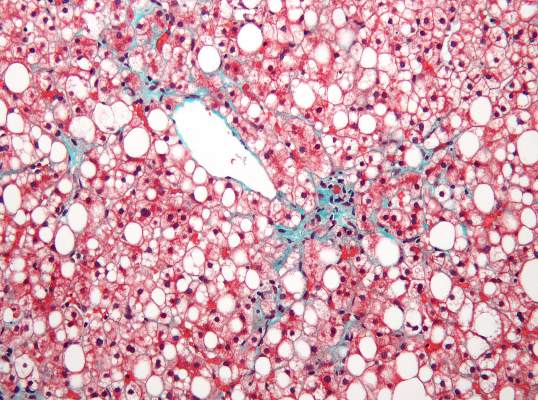

Subclinical Heart Dysfunction, Fatty Liver Linked

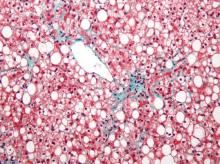

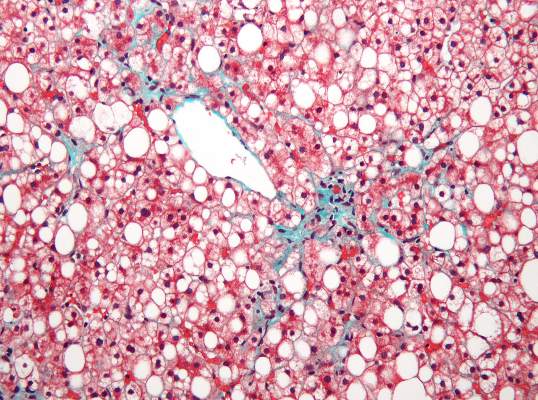

Researchers found an association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and myocardial dysfunction and remodeling, according to a new study published in Hepatology.

“Both NAFLD and heart failure (particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction) are obesity-related conditions that have reached epidemic proportions. We know from epidemiologic studies that persons with NAFLD are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than from liver-related death. This risk seems to be proportional to the amount of fat in the liver and is independent of the presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). There have been numerous studies that have focused on the relationship between NAFLD and coronary artery disease, but very little work has been done to determine relationships with heart failure,” Dr. Lisa B. VanWagner of Northwestern University in Chicago noted. She continued, “There are several well-established major risk factors for the development of clinical heart failure, including coronary artery disease, diabetes, and hypertension, all of which are also closely associated with NAFLD. However, whether NAFLD is independently associated with subclinical myocardial remodeling or dysfunction that may lead to the development of clinical heart failure is unknown.”

NAFLD and heart failure are both associated with obesity. Likewise, there is evidence that NAFLD may also be related to endothelial dysfunction, coronary plaques, coronary artery calcifications, as well as being an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. VanWagner and her colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of 2,713 patients from the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study to understand any associations between NAFLD and abnormalities in left ventricular (LV) function and structure. Study participants completed CT quantification of liver fat and echocardiography with Doppler during the 25-year follow-up to the initial study (Hepatology 2015;62:773-83 [doi:10.1002/hep.27869]). Participants were excluded from analysis if they had missing or incomplete imaging, pregnancy, a history of MI or heart failure, cirrhosis, hepatitis, or chronic liver disease risk factors, or if they weighed more than 450 pounds,

Of the 2,713 subjects included in analysis, 48% were black and 58.8% were female. NAFLD was detected in 10% (n = 271) of participants. Those with NAFLD were more likely to be white males with metabolic syndrome and who were obese and had higher CT-measured levels of visceral adipose tissue, and an increased waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Insulin resistance markers such as elevated fasting glucose, elevated C-reactive protein, and hypertriglyceridemia were more common in the participants with NAFLD.

Study participants with NAFLD had signs of myocardial remodeling such as more left ventricular wall thickness, LV end-diastolic volume, left aortic volume index, and LV mass index. Likewise, NAFLD was associated with more circumferential strain and global longitudinal strain but no differences in ejection fraction.

Subclinical systolic dysfunction (P less than .001 for the trend), subclinical diastolic dysfunction with impaired left ventricular relaxation (34.6% vs. 23.6%; P less than .0001), and elevated LV filling pressures (33.3% vs. 23.7%; P less than .001) was more common in NAFLD participants, compared with non-NAFLD subjects.

After researchers adjusted for health behaviors and demographic factors, evidence of NAFLD was associated with worse GLS (P less than .0001). Finally, NAFLD was associated with subclinical cardiac remodeling and dysfunction even after adjustment for body mass index and heart failure risk factors (P less than .01).

Dr. VanWagner summarized, “NAFLD may not necessarily be a ‘benign condition’ as previously thought. In our study, we determined liver fat by CT scan, which admittedly detects fat at a higher level (typically greater than 30%) than for example on MRI, which can detect fat as low as 5%. A fatty liver detected on CT or even on [ultrasound], which has similar sensitivity as CT for detecting liver fat should prompt evaluation for additional cardiovascular risk factors and treatment of identified abnormalities to reduce [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] and [heart failure] risk. Currently, our study only shows associations between liver fat and subclinical changes in the myocardium and causality cannot be determined. [On the basis] of our data, we cannot recommend screening for HF [heart failure] in this population, but future studies are needed to determine if NAFLD in fact lies in the casual pathway for the development of clinical HF.”

The investigators reported multiple supporting sources, including the National Institutes of Health, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Dr. Lewis reported receiving grants from Novo Nordisk.

Researchers found an association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and myocardial dysfunction and remodeling, according to a new study published in Hepatology.

“Both NAFLD and heart failure (particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction) are obesity-related conditions that have reached epidemic proportions. We know from epidemiologic studies that persons with NAFLD are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than from liver-related death. This risk seems to be proportional to the amount of fat in the liver and is independent of the presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). There have been numerous studies that have focused on the relationship between NAFLD and coronary artery disease, but very little work has been done to determine relationships with heart failure,” Dr. Lisa B. VanWagner of Northwestern University in Chicago noted. She continued, “There are several well-established major risk factors for the development of clinical heart failure, including coronary artery disease, diabetes, and hypertension, all of which are also closely associated with NAFLD. However, whether NAFLD is independently associated with subclinical myocardial remodeling or dysfunction that may lead to the development of clinical heart failure is unknown.”

NAFLD and heart failure are both associated with obesity. Likewise, there is evidence that NAFLD may also be related to endothelial dysfunction, coronary plaques, coronary artery calcifications, as well as being an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. VanWagner and her colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of 2,713 patients from the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study to understand any associations between NAFLD and abnormalities in left ventricular (LV) function and structure. Study participants completed CT quantification of liver fat and echocardiography with Doppler during the 25-year follow-up to the initial study (Hepatology 2015;62:773-83 [doi:10.1002/hep.27869]). Participants were excluded from analysis if they had missing or incomplete imaging, pregnancy, a history of MI or heart failure, cirrhosis, hepatitis, or chronic liver disease risk factors, or if they weighed more than 450 pounds,

Of the 2,713 subjects included in analysis, 48% were black and 58.8% were female. NAFLD was detected in 10% (n = 271) of participants. Those with NAFLD were more likely to be white males with metabolic syndrome and who were obese and had higher CT-measured levels of visceral adipose tissue, and an increased waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Insulin resistance markers such as elevated fasting glucose, elevated C-reactive protein, and hypertriglyceridemia were more common in the participants with NAFLD.

Study participants with NAFLD had signs of myocardial remodeling such as more left ventricular wall thickness, LV end-diastolic volume, left aortic volume index, and LV mass index. Likewise, NAFLD was associated with more circumferential strain and global longitudinal strain but no differences in ejection fraction.

Subclinical systolic dysfunction (P less than .001 for the trend), subclinical diastolic dysfunction with impaired left ventricular relaxation (34.6% vs. 23.6%; P less than .0001), and elevated LV filling pressures (33.3% vs. 23.7%; P less than .001) was more common in NAFLD participants, compared with non-NAFLD subjects.

After researchers adjusted for health behaviors and demographic factors, evidence of NAFLD was associated with worse GLS (P less than .0001). Finally, NAFLD was associated with subclinical cardiac remodeling and dysfunction even after adjustment for body mass index and heart failure risk factors (P less than .01).

Dr. VanWagner summarized, “NAFLD may not necessarily be a ‘benign condition’ as previously thought. In our study, we determined liver fat by CT scan, which admittedly detects fat at a higher level (typically greater than 30%) than for example on MRI, which can detect fat as low as 5%. A fatty liver detected on CT or even on [ultrasound], which has similar sensitivity as CT for detecting liver fat should prompt evaluation for additional cardiovascular risk factors and treatment of identified abnormalities to reduce [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] and [heart failure] risk. Currently, our study only shows associations between liver fat and subclinical changes in the myocardium and causality cannot be determined. [On the basis] of our data, we cannot recommend screening for HF [heart failure] in this population, but future studies are needed to determine if NAFLD in fact lies in the casual pathway for the development of clinical HF.”

The investigators reported multiple supporting sources, including the National Institutes of Health, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Dr. Lewis reported receiving grants from Novo Nordisk.

Researchers found an association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and myocardial dysfunction and remodeling, according to a new study published in Hepatology.

“Both NAFLD and heart failure (particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction) are obesity-related conditions that have reached epidemic proportions. We know from epidemiologic studies that persons with NAFLD are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than from liver-related death. This risk seems to be proportional to the amount of fat in the liver and is independent of the presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). There have been numerous studies that have focused on the relationship between NAFLD and coronary artery disease, but very little work has been done to determine relationships with heart failure,” Dr. Lisa B. VanWagner of Northwestern University in Chicago noted. She continued, “There are several well-established major risk factors for the development of clinical heart failure, including coronary artery disease, diabetes, and hypertension, all of which are also closely associated with NAFLD. However, whether NAFLD is independently associated with subclinical myocardial remodeling or dysfunction that may lead to the development of clinical heart failure is unknown.”

NAFLD and heart failure are both associated with obesity. Likewise, there is evidence that NAFLD may also be related to endothelial dysfunction, coronary plaques, coronary artery calcifications, as well as being an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. VanWagner and her colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of 2,713 patients from the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study to understand any associations between NAFLD and abnormalities in left ventricular (LV) function and structure. Study participants completed CT quantification of liver fat and echocardiography with Doppler during the 25-year follow-up to the initial study (Hepatology 2015;62:773-83 [doi:10.1002/hep.27869]). Participants were excluded from analysis if they had missing or incomplete imaging, pregnancy, a history of MI or heart failure, cirrhosis, hepatitis, or chronic liver disease risk factors, or if they weighed more than 450 pounds,

Of the 2,713 subjects included in analysis, 48% were black and 58.8% were female. NAFLD was detected in 10% (n = 271) of participants. Those with NAFLD were more likely to be white males with metabolic syndrome and who were obese and had higher CT-measured levels of visceral adipose tissue, and an increased waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Insulin resistance markers such as elevated fasting glucose, elevated C-reactive protein, and hypertriglyceridemia were more common in the participants with NAFLD.

Study participants with NAFLD had signs of myocardial remodeling such as more left ventricular wall thickness, LV end-diastolic volume, left aortic volume index, and LV mass index. Likewise, NAFLD was associated with more circumferential strain and global longitudinal strain but no differences in ejection fraction.

Subclinical systolic dysfunction (P less than .001 for the trend), subclinical diastolic dysfunction with impaired left ventricular relaxation (34.6% vs. 23.6%; P less than .0001), and elevated LV filling pressures (33.3% vs. 23.7%; P less than .001) was more common in NAFLD participants, compared with non-NAFLD subjects.

After researchers adjusted for health behaviors and demographic factors, evidence of NAFLD was associated with worse GLS (P less than .0001). Finally, NAFLD was associated with subclinical cardiac remodeling and dysfunction even after adjustment for body mass index and heart failure risk factors (P less than .01).

Dr. VanWagner summarized, “NAFLD may not necessarily be a ‘benign condition’ as previously thought. In our study, we determined liver fat by CT scan, which admittedly detects fat at a higher level (typically greater than 30%) than for example on MRI, which can detect fat as low as 5%. A fatty liver detected on CT or even on [ultrasound], which has similar sensitivity as CT for detecting liver fat should prompt evaluation for additional cardiovascular risk factors and treatment of identified abnormalities to reduce [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] and [heart failure] risk. Currently, our study only shows associations between liver fat and subclinical changes in the myocardium and causality cannot be determined. [On the basis] of our data, we cannot recommend screening for HF [heart failure] in this population, but future studies are needed to determine if NAFLD in fact lies in the casual pathway for the development of clinical HF.”

The investigators reported multiple supporting sources, including the National Institutes of Health, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Dr. Lewis reported receiving grants from Novo Nordisk.

FROM HEPATOLOGY

Subclinical heart dysfunction, fatty liver linked

Researchers found an association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and myocardial dysfunction and remodeling, according to a new study published in Hepatology.

“Both NAFLD and heart failure (particularly heart failure with preserved ejection fraction) are obesity-related conditions that have reached epidemic proportions. We know from epidemiologic studies that persons with NAFLD are more likely to die from cardiovascular disease than from liver-related death. This risk seems to be proportional to the amount of fat in the liver and is independent of the presence of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). There have been numerous studies that have focused on the relationship between NAFLD and coronary artery disease, but very little work has been done to determine relationships with heart failure,” Dr. Lisa B. VanWagner of Northwestern University in Chicago noted. She continued, “There are several well-established major risk factors for the development of clinical heart failure, including coronary artery disease, diabetes, and hypertension, all of which are also closely associated with NAFLD. However, whether NAFLD is independently associated with subclinical myocardial remodeling or dysfunction that may lead to the development of clinical heart failure is unknown.”

NAFLD and heart failure are both associated with obesity. Likewise, there is evidence that NAFLD may also be related to endothelial dysfunction, coronary plaques, coronary artery calcifications, as well as being an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Dr. VanWagner and her colleagues conducted a cross-sectional study of 2,713 patients from the CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study to understand any associations between NAFLD and abnormalities in left ventricular (LV) function and structure. Study participants completed CT quantification of liver fat and echocardiography with Doppler during the 25-year follow-up to the initial study (Hepatology 2015;62:773-83 [doi:10.1002/hep.27869]). Participants were excluded from analysis if they had missing or incomplete imaging, pregnancy, a history of MI or heart failure, cirrhosis, hepatitis, or chronic liver disease risk factors, or if they weighed more than 450 pounds,

Of the 2,713 subjects included in analysis, 48% were black and 58.8% were female. NAFLD was detected in 10% (n = 271) of participants. Those with NAFLD were more likely to be white males with metabolic syndrome and who were obese and had higher CT-measured levels of visceral adipose tissue, and an increased waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio. Insulin resistance markers such as elevated fasting glucose, elevated C-reactive protein, and hypertriglyceridemia were more common in the participants with NAFLD.

Study participants with NAFLD had signs of myocardial remodeling such as more left ventricular wall thickness, LV end-diastolic volume, left aortic volume index, and LV mass index. Likewise, NAFLD was associated with more circumferential strain and global longitudinal strain but no differences in ejection fraction.

Subclinical systolic dysfunction (P less than .001 for the trend), subclinical diastolic dysfunction with impaired left ventricular relaxation (34.6% vs. 23.6%; P less than .0001), and elevated LV filling pressures (33.3% vs. 23.7%; P less than .001) was more common in NAFLD participants, compared with non-NAFLD subjects.

After researchers adjusted for health behaviors and demographic factors, evidence of NAFLD was associated with worse GLS (P less than .0001). Finally, NAFLD was associated with subclinical cardiac remodeling and dysfunction even after adjustment for body mass index and heart failure risk factors (P less than .01).

Dr. VanWagner summarized, “NAFLD may not necessarily be a ‘benign condition’ as previously thought. In our study, we determined liver fat by CT scan, which admittedly detects fat at a higher level (typically greater than 30%) than for example on MRI, which can detect fat as low as 5%. A fatty liver detected on CT or even on [ultrasound], which has similar sensitivity as CT for detecting liver fat should prompt evaluation for additional cardiovascular risk factors and treatment of identified abnormalities to reduce [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] and [heart failure] risk. Currently, our study only shows associations between liver fat and subclinical changes in the myocardium and causality cannot be determined. [On the basis] of our data, we cannot recommend screening for HF [heart failure] in this population, but future studies are needed to determine if NAFLD in fact lies in the casual pathway for the development of clinical HF.”

The investigators reported multiple supporting sources, including the National Institutes of Health, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease Foundation, and the American Heart Association. Dr. Lewis reported receiving grants from Novo Nordisk.

Researchers found an association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and myocardial dysfunction and remodeling, according to a new study published in Hepatology.