User login

Soft Nodule on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Schwannoma

Schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, is a benign encapsulated neoplasm of the peripheral nerve sheath that presents as a subcutaneous nodule.1 It also may present in the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, and viscera (eg, gastrointestinal tract, bone, upper respiratory tract, lymph nodes). It may occur as multiple lesions when associated with certain syndromes. It usually is an asymptomatic indolent tumor with neurologic symptoms, such as pain and tenderness, in the lesions that are deeper, larger, or closer in proximity to nearby structures.2,3

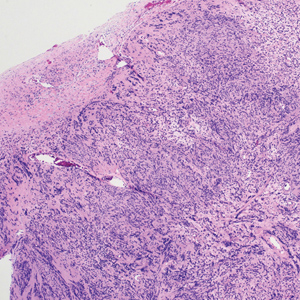

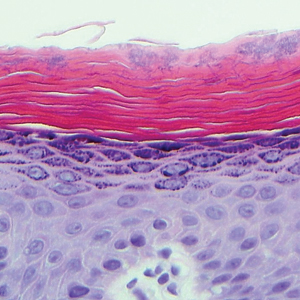

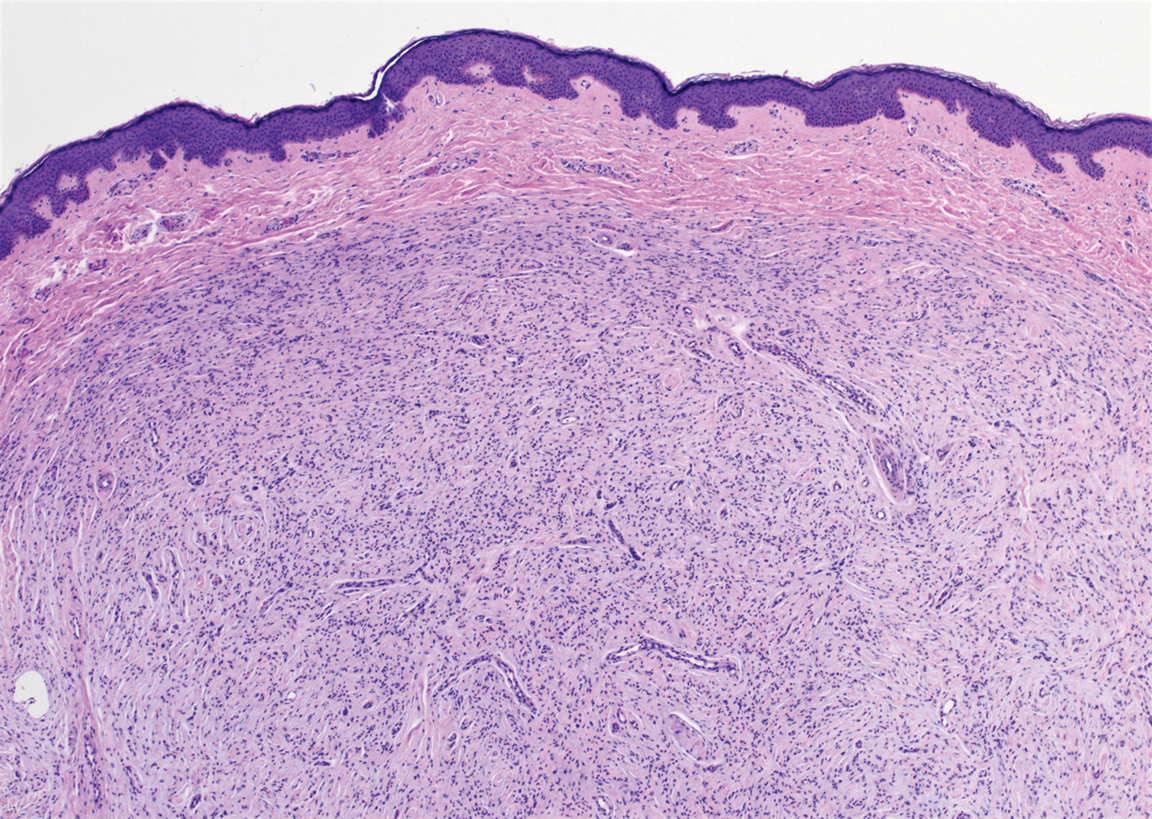

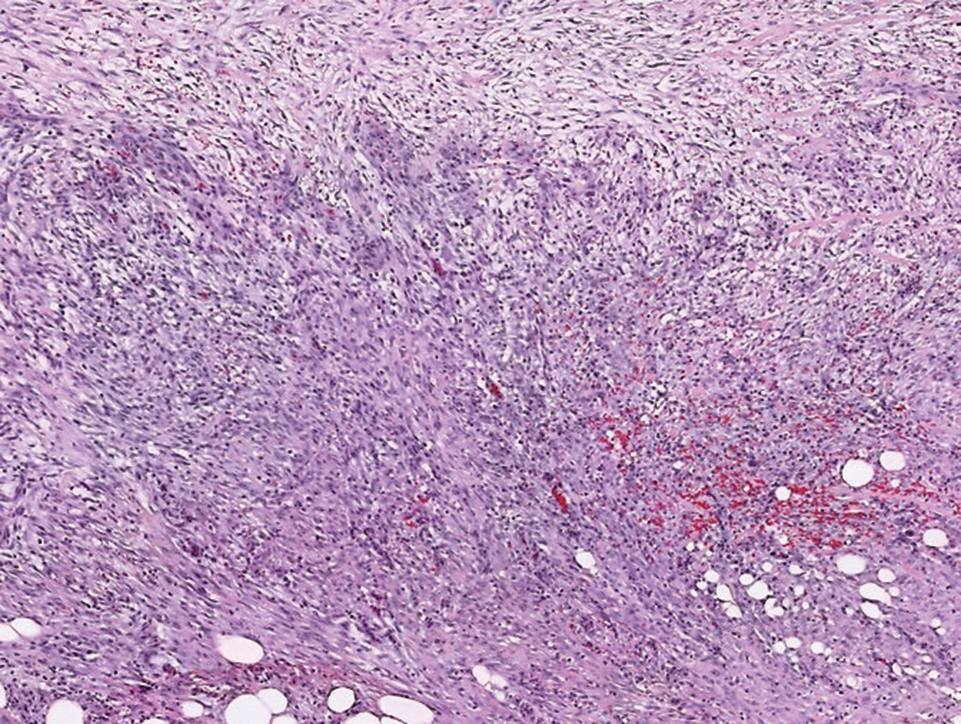

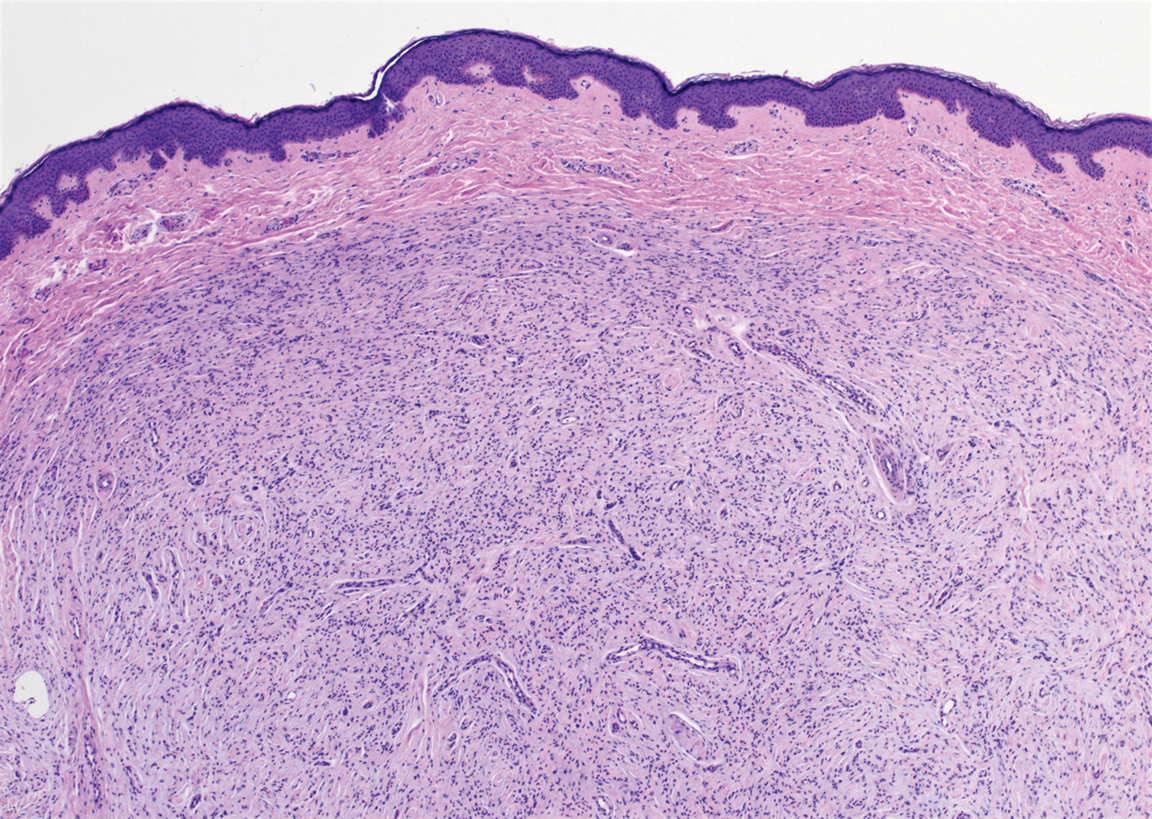

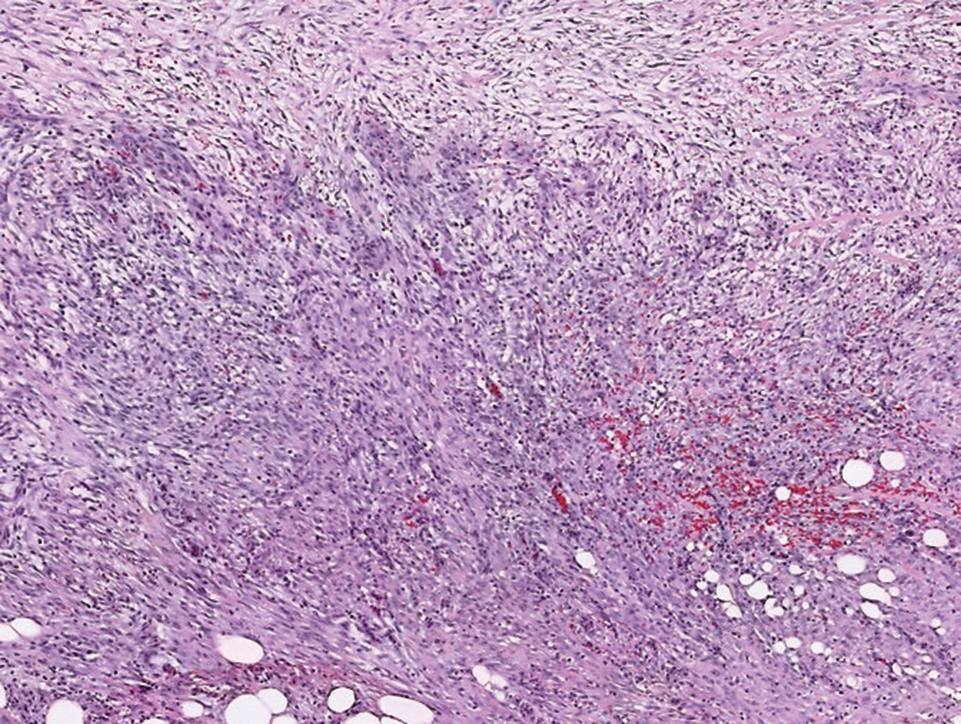

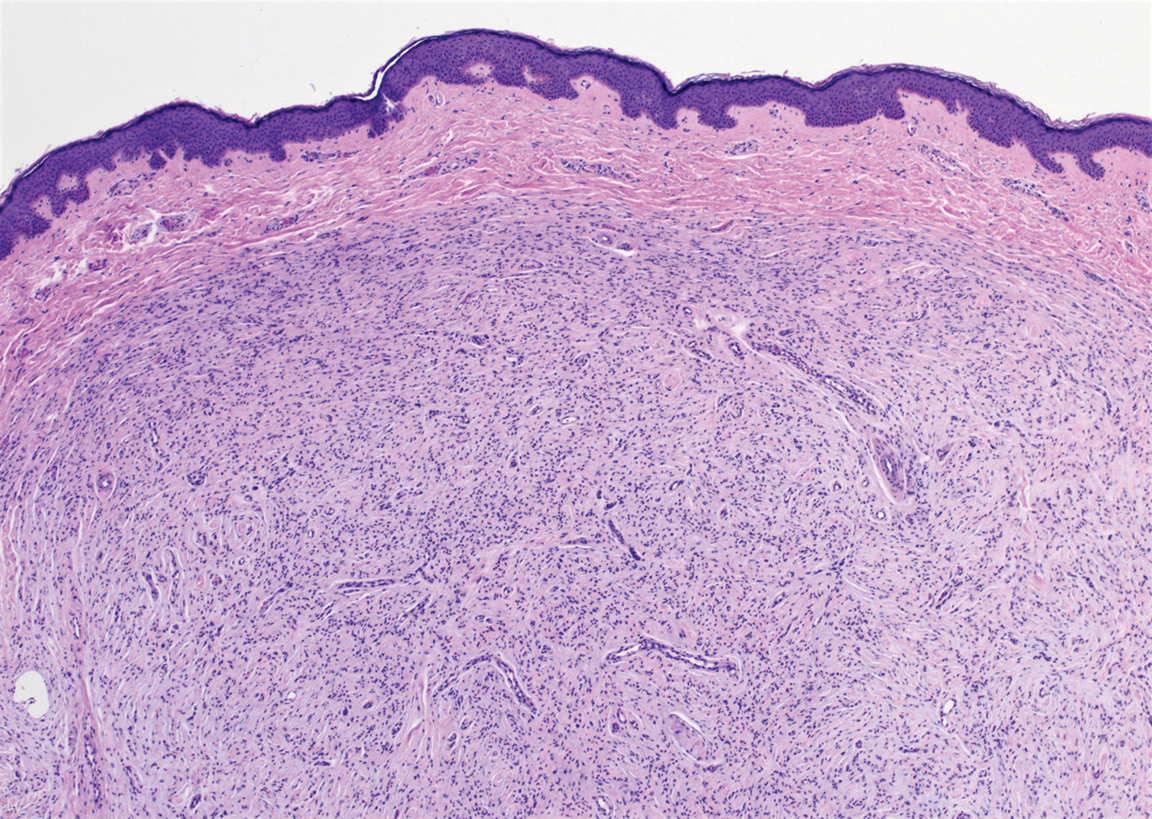

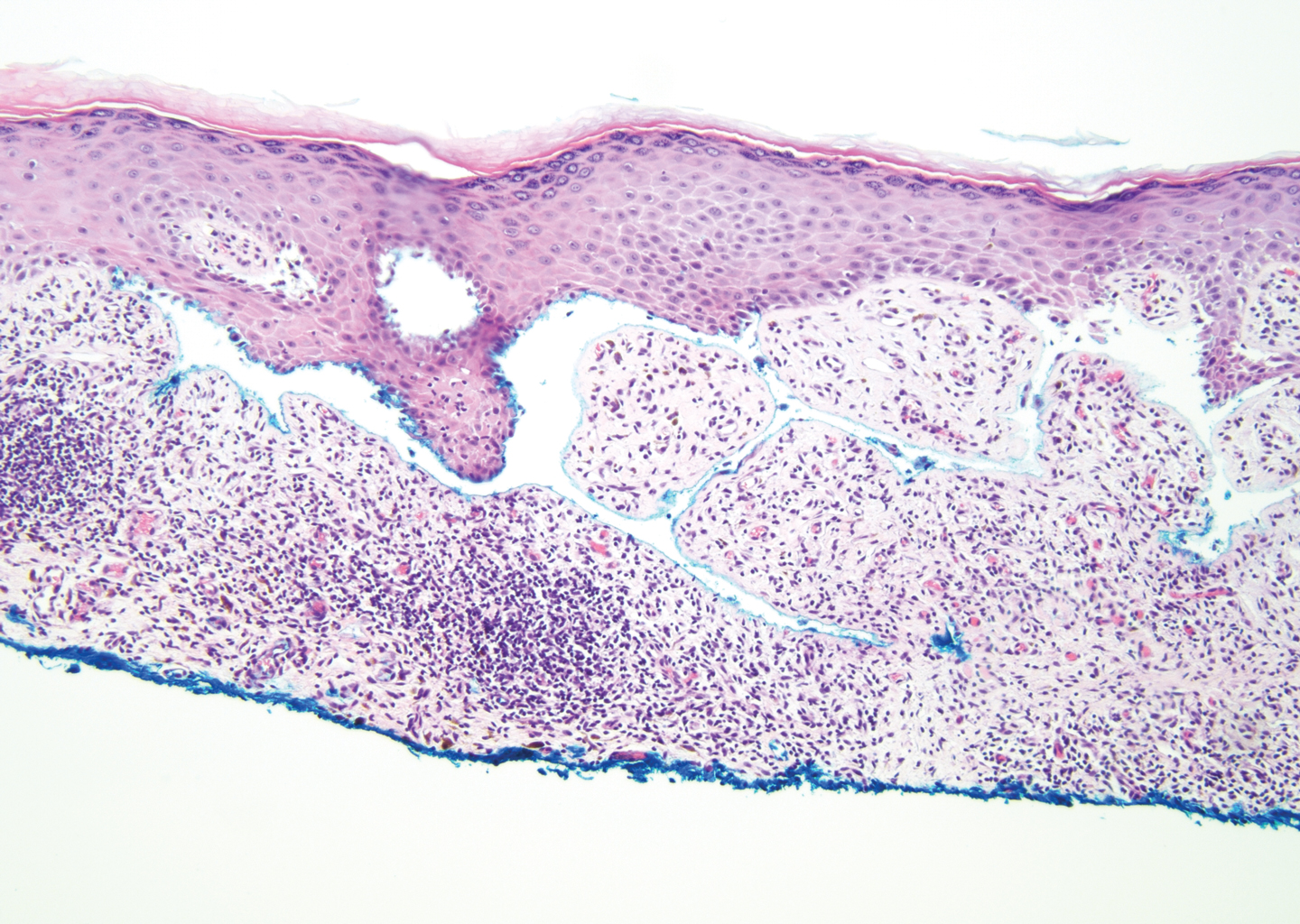

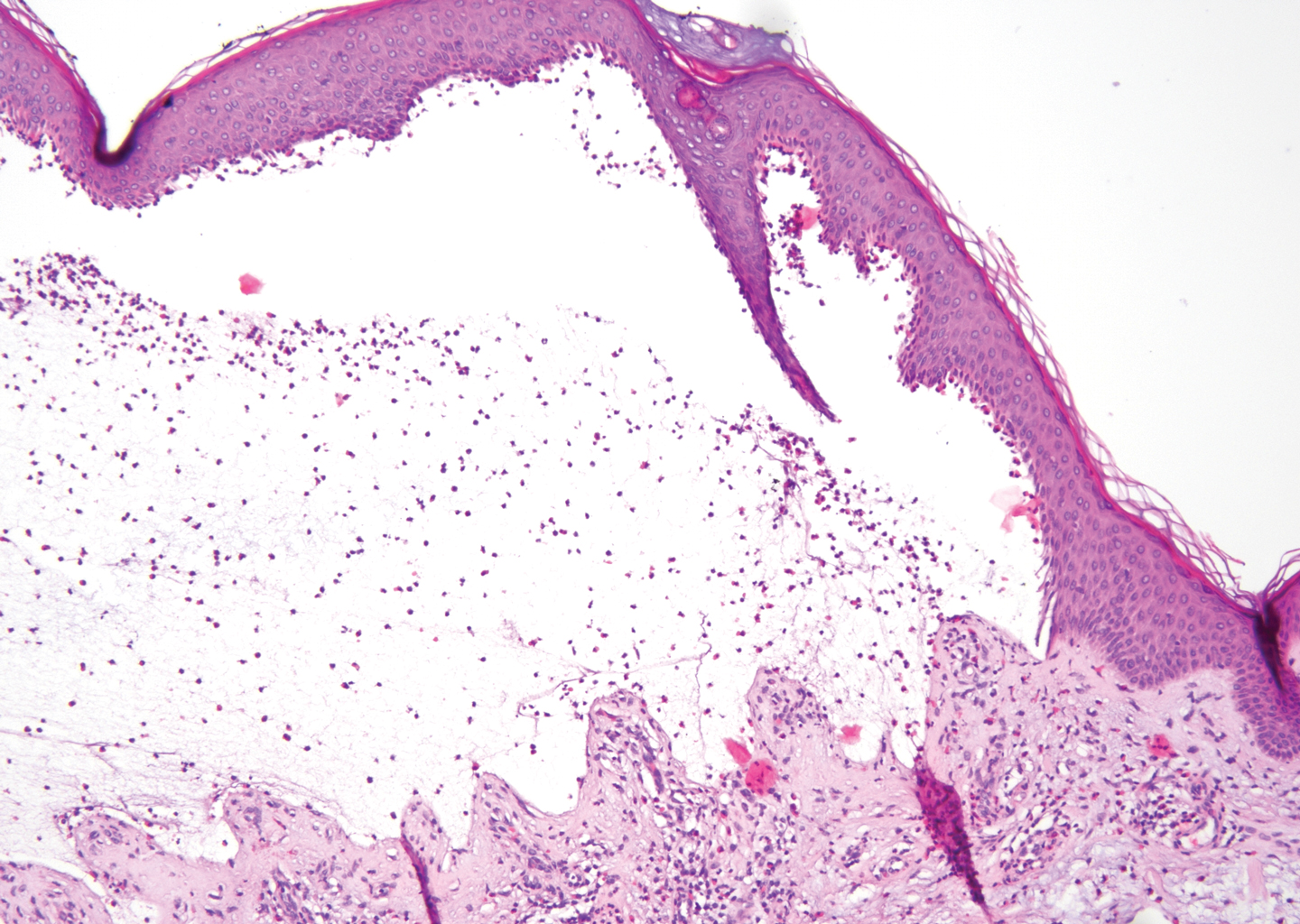

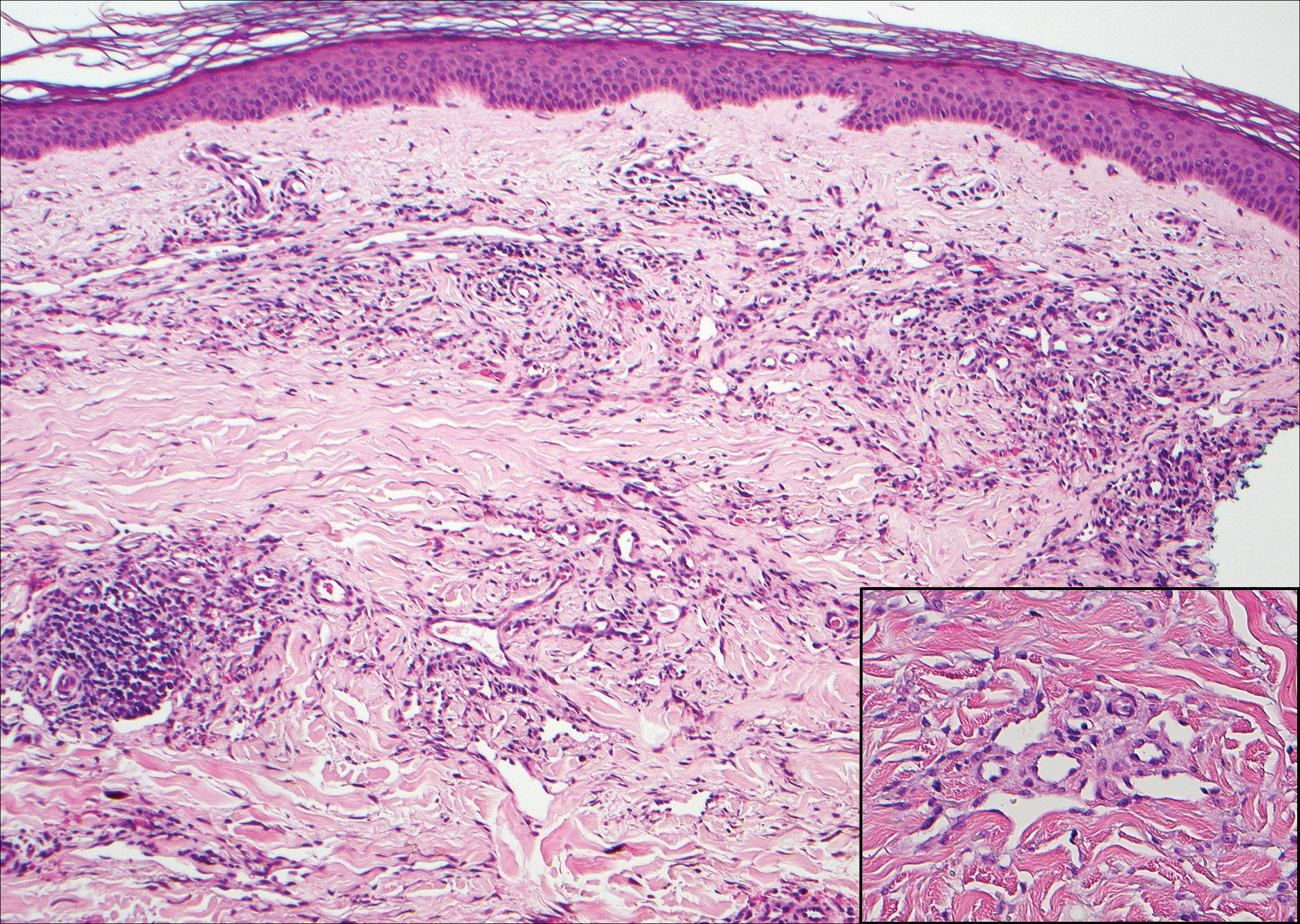

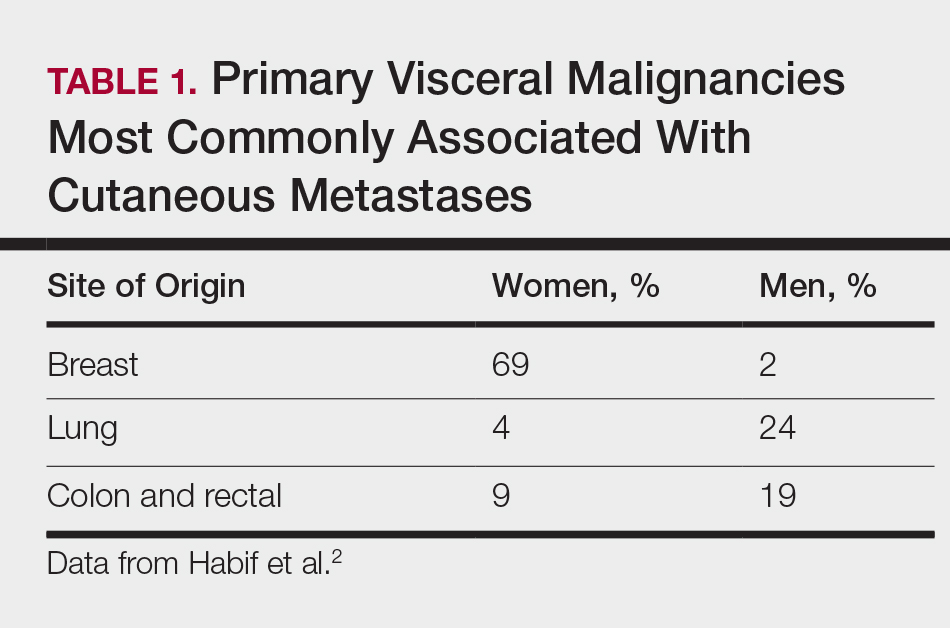

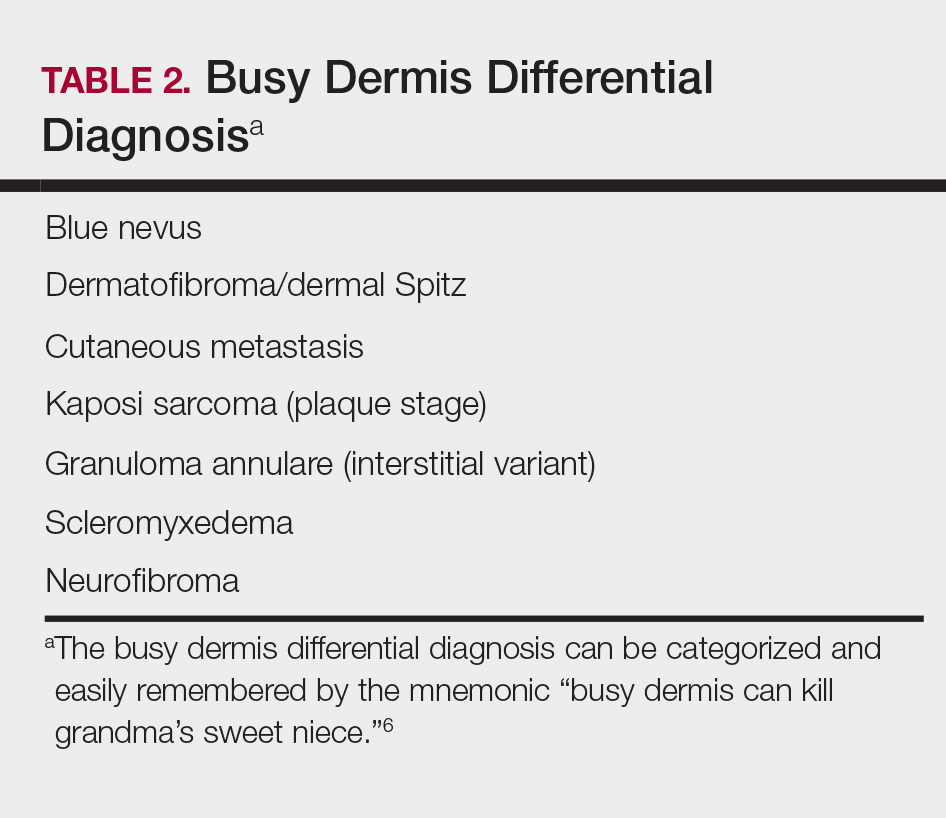

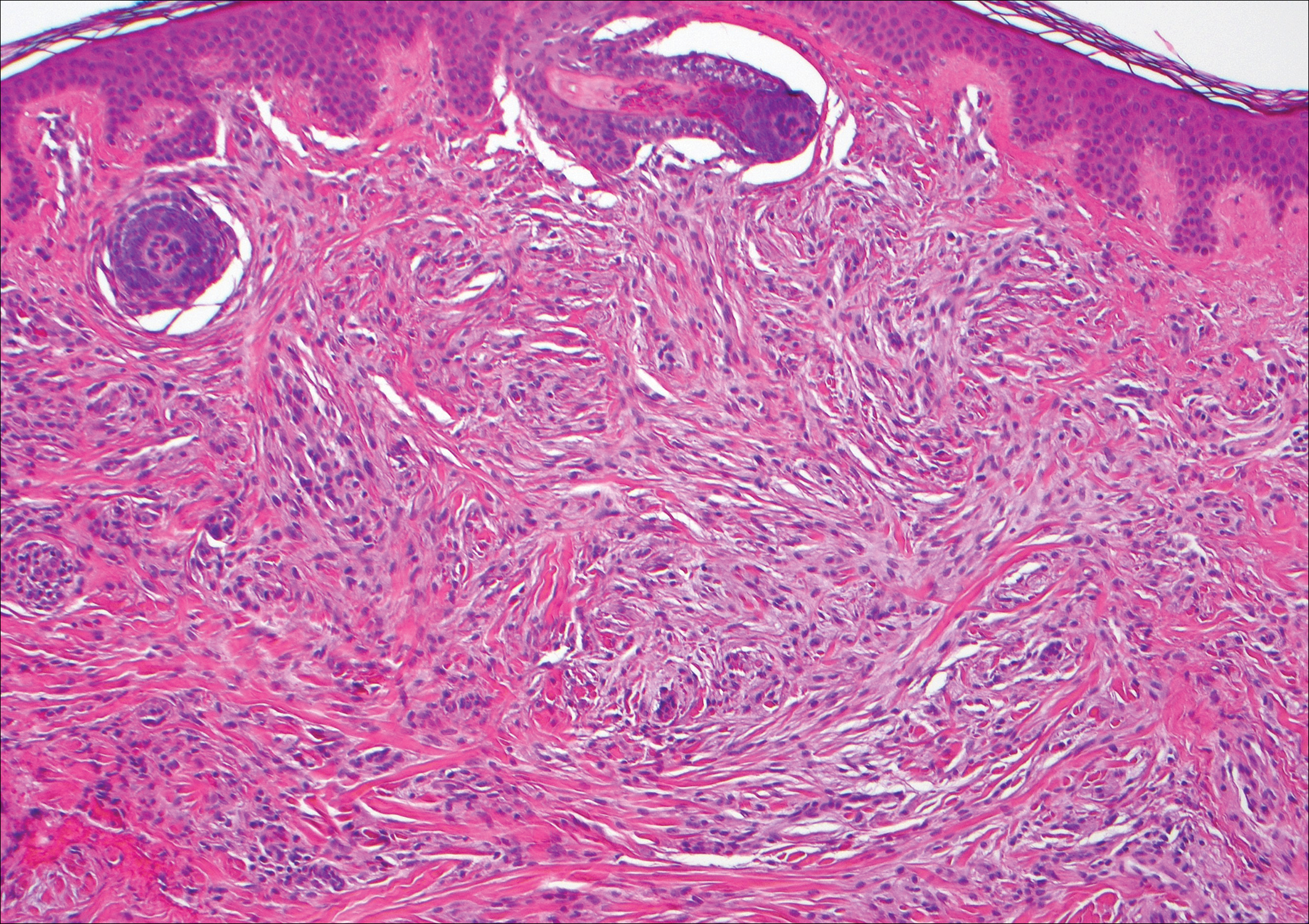

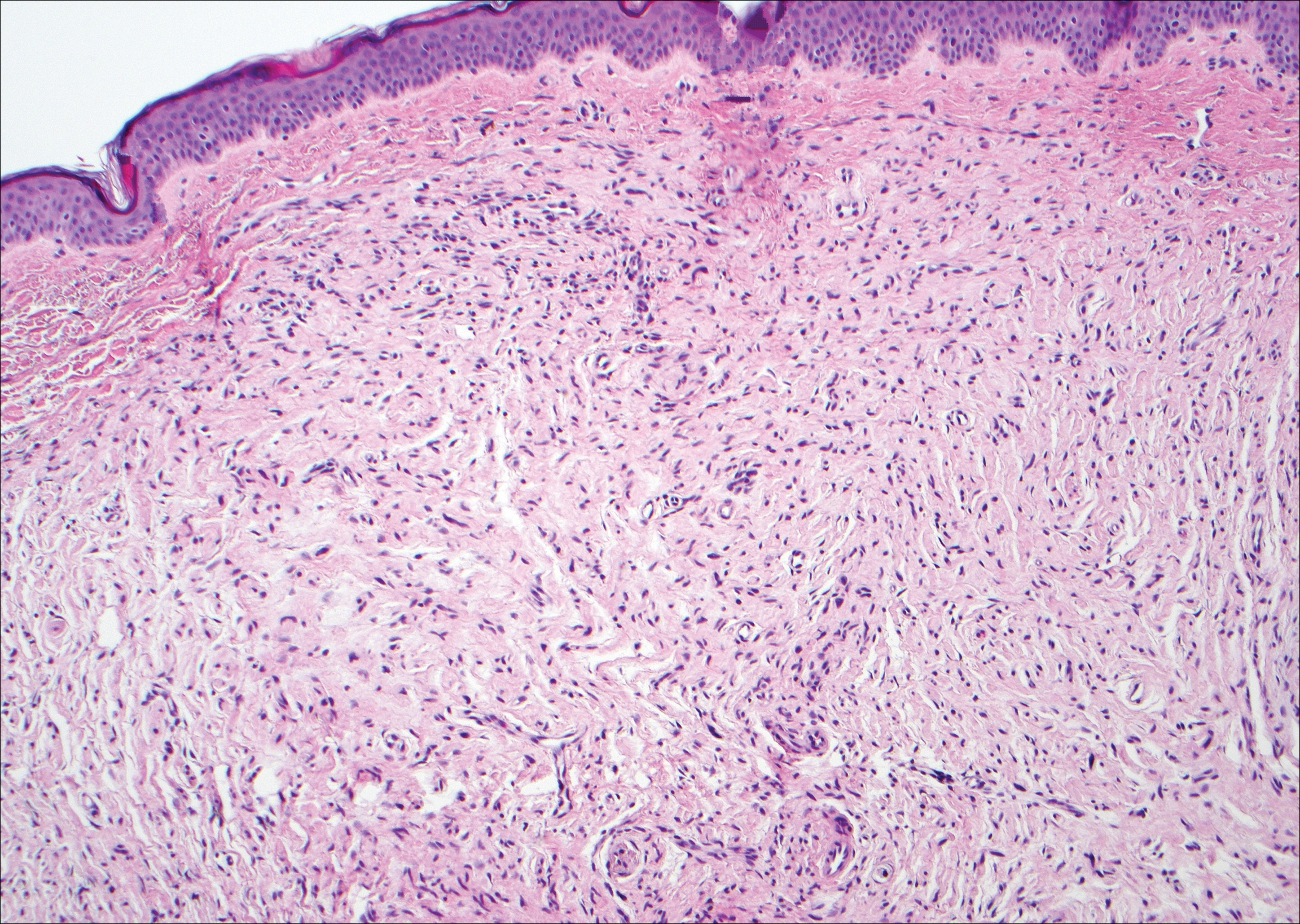

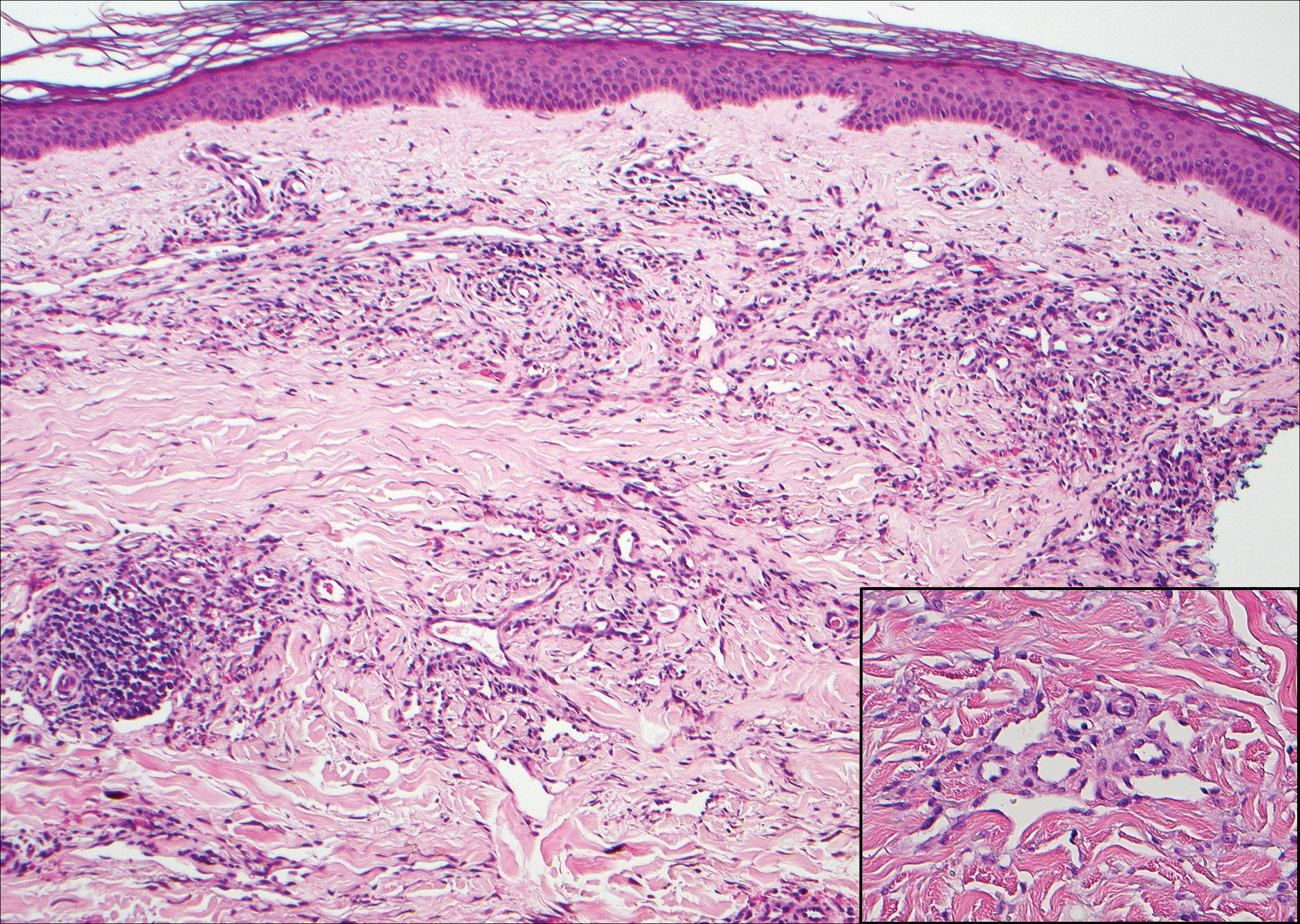

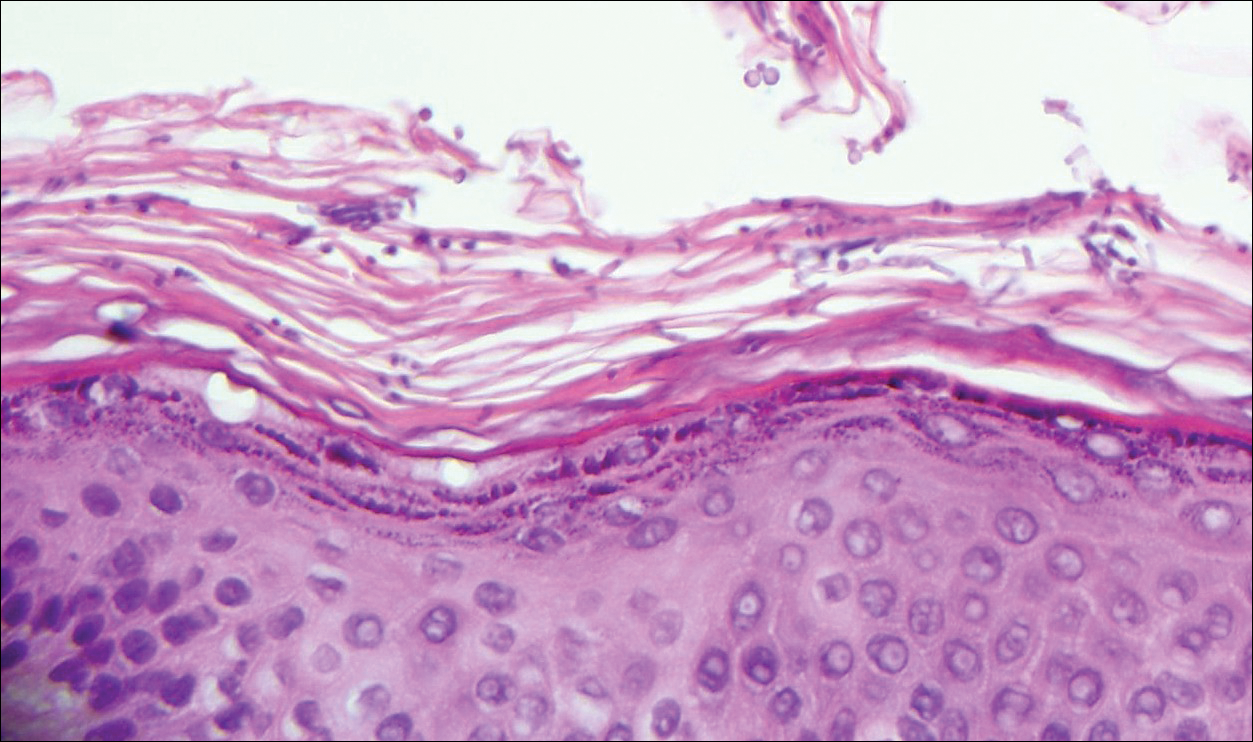

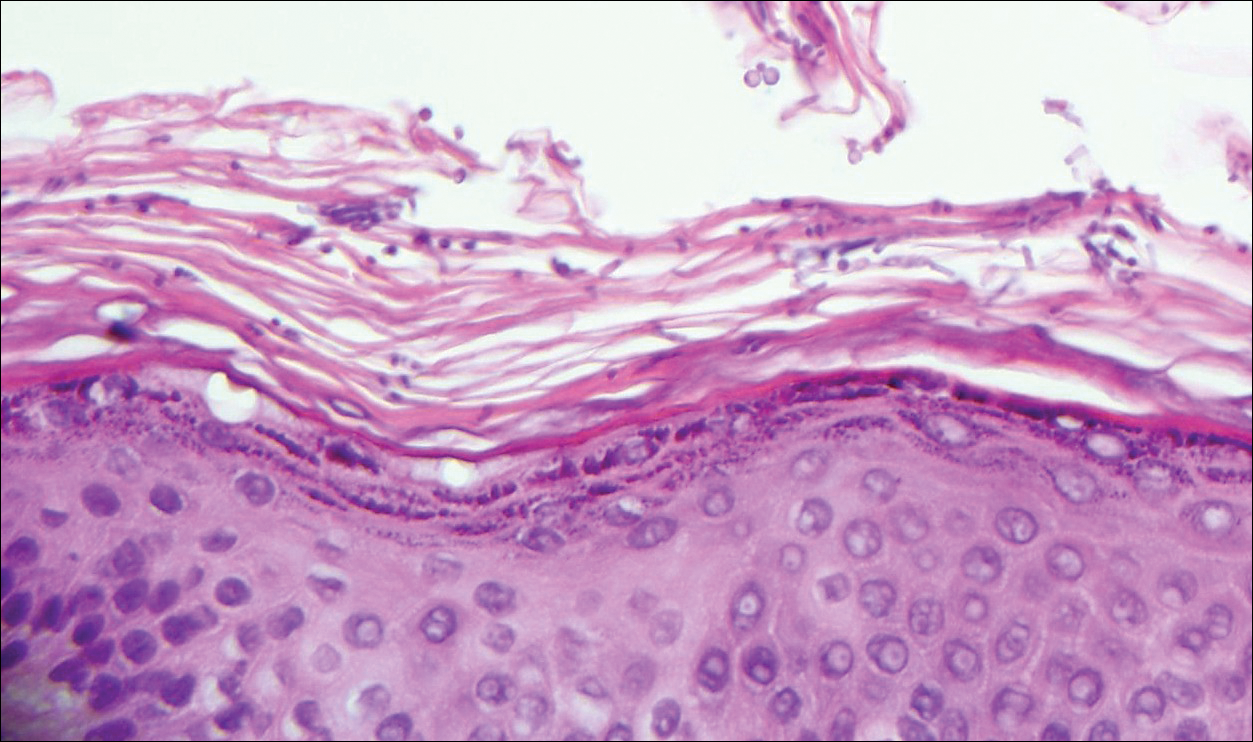

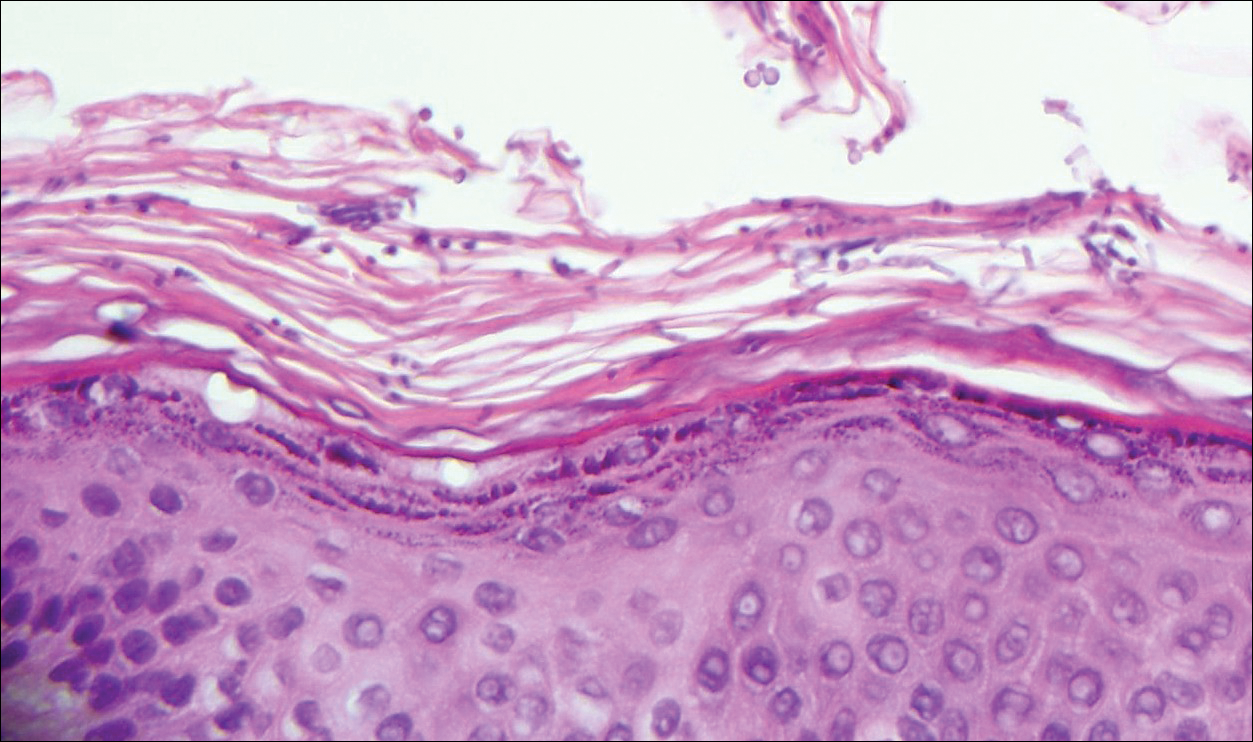

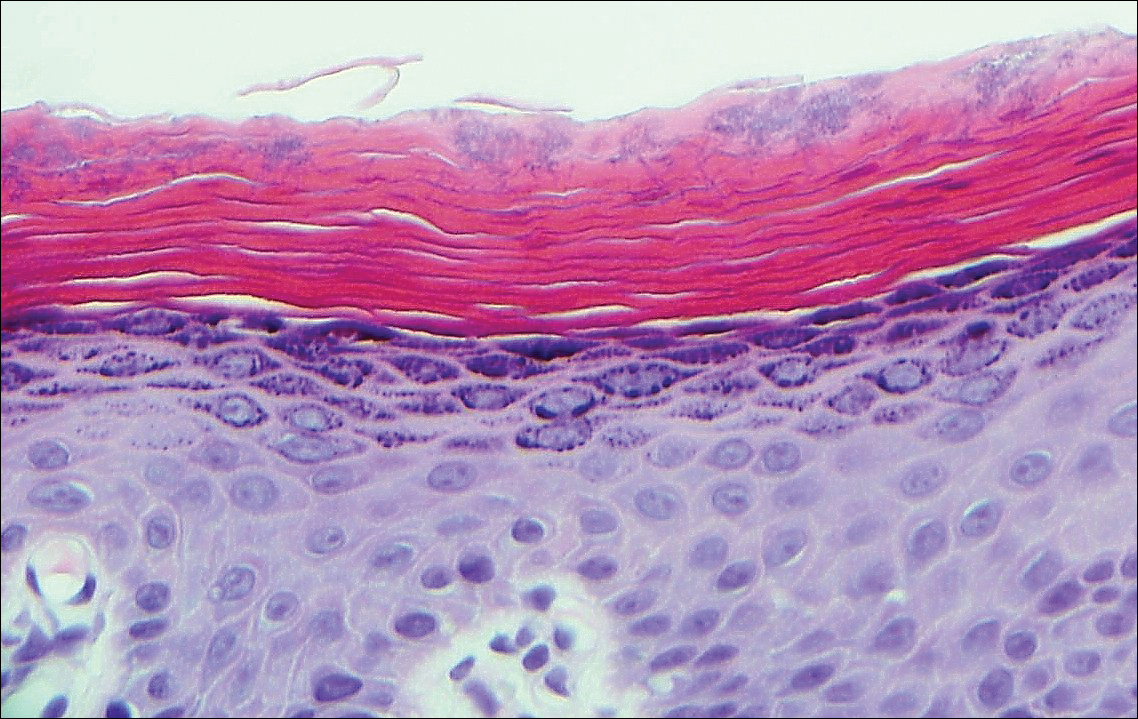

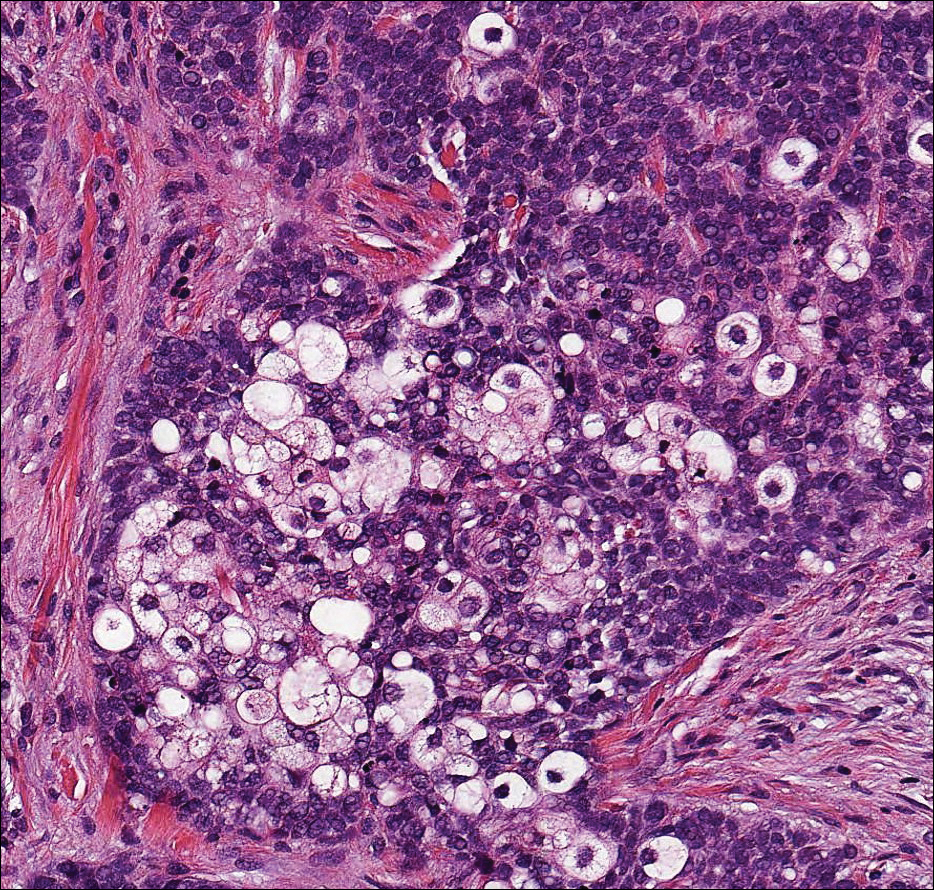

Histologically, a schwannoma is encapsulated by the perineurium of the nerve bundle from which it originates (quiz image [top]). The tumor consists of hypercellular (Antoni type A) and hypocellular (Antoni type B) areas. Antoni type A areas consist of tightly packed, spindleshaped cells with elongated wavy nuclei and indistinct cytoplasmic borders. These nuclei tend to align into parallel rows with intervening anuclear zones forming Verocay bodies (quiz image [bottom]).4 Verocay bodies are not seen in all schwannomas, and similar formations may be seen in other tumors as well. Solitary circumscribed neuromas also have Verocay bodies, whereas dermatofibromas and leiomyomas have Verocay-like bodies. Antoni type B areas have scattered spindled or ovoid cells in an edematous or myxoid matrix interspersed with inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and histiocytes. Vessels with thick hyalinized walls are a helpful feature in diagnosis.2 Schwann cells of a schwannoma stain diffusely positive with S-100 protein. The capsule stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen due to the presence of perineurial cells.2

The morphologic variants of this entity include conventional (common, solitary), cellular, plexiform, ancient, melanotic, epithelioid, pseudoglandular, neuroblastomalike, and microcystic/reticular schwannomas. There are additional variants that are associated with genetic syndromes, such as multiple cutaneous plexiform schwannomas linked with neurofibromatosis type 2, psammomatous melanotic schwannoma presenting in Carney complex, schwannomatosis, and segmental schwannomatosis (a distinct form of neurofibromatosis characterized by multiple schwannomas localized to one limb). Either presentation may have alteration or deletion of the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene, NF2, on chromosome 22.2,5

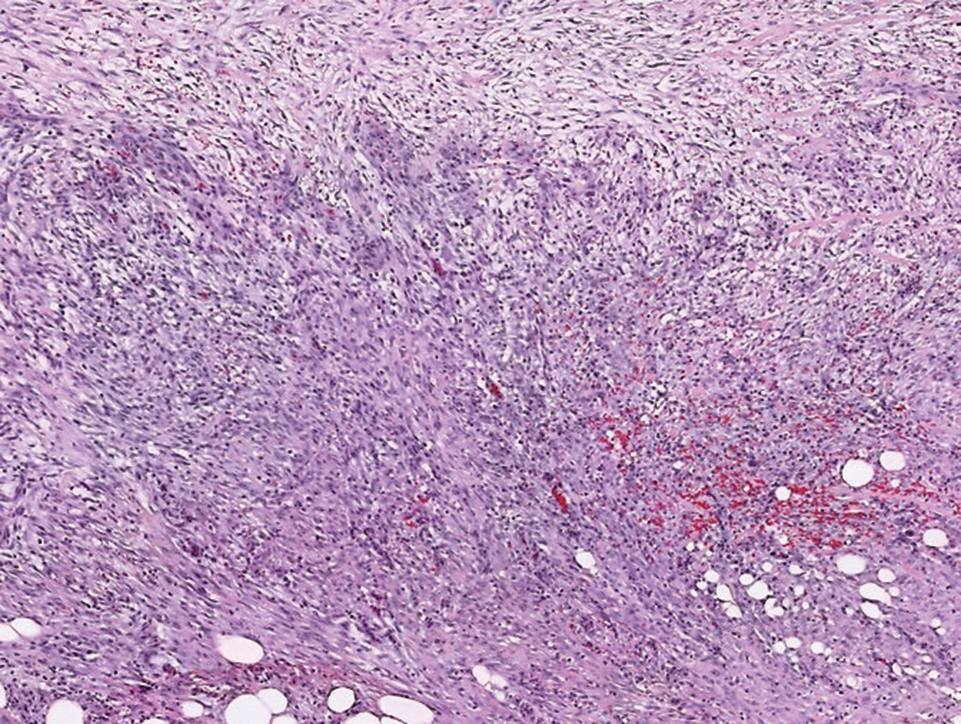

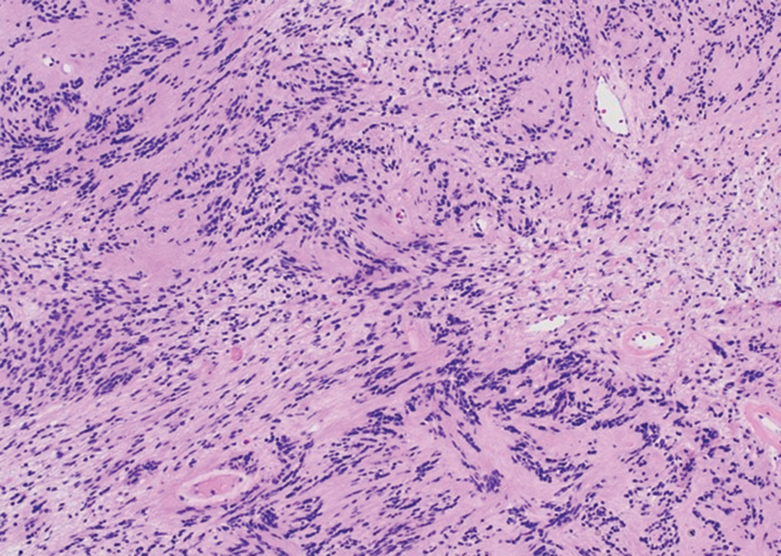

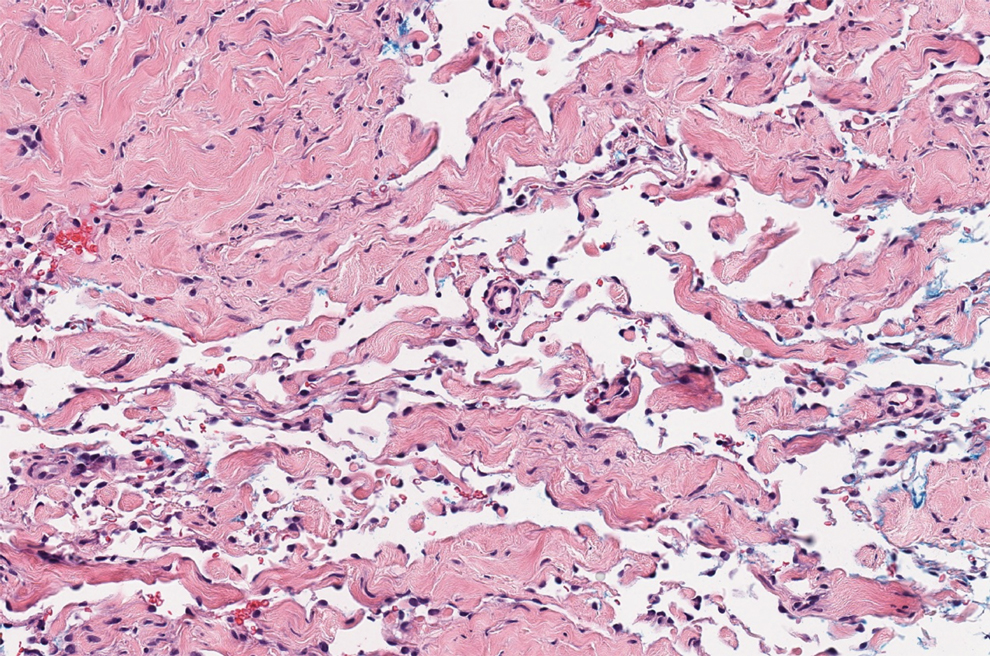

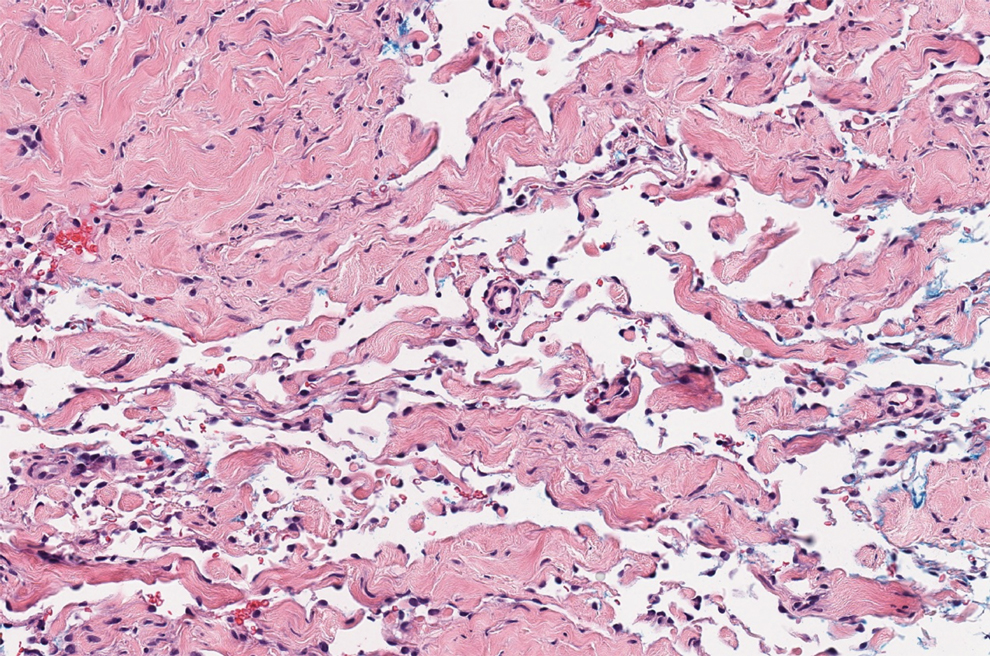

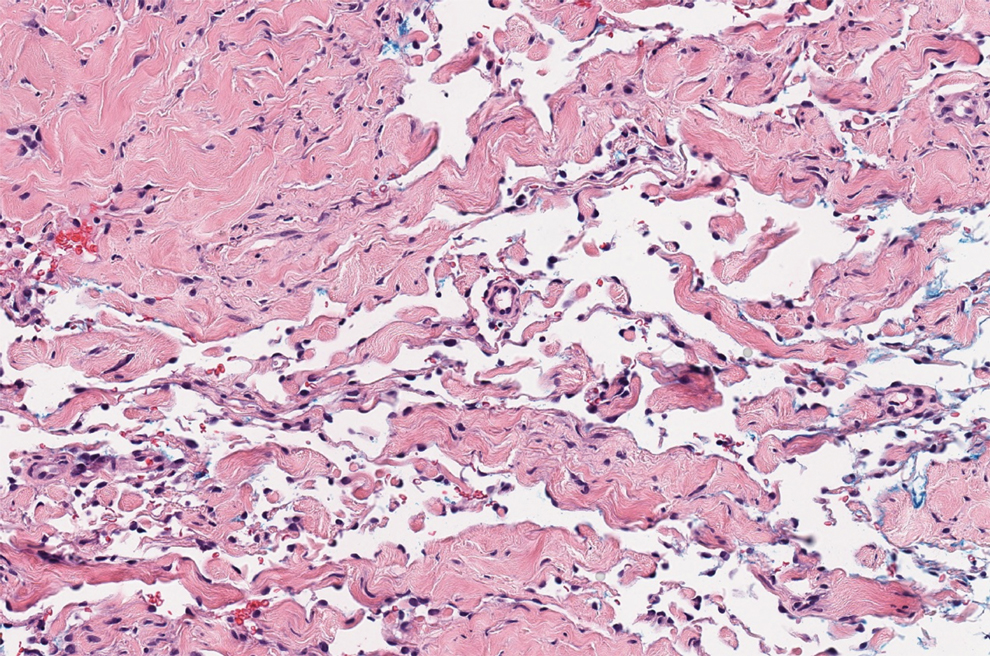

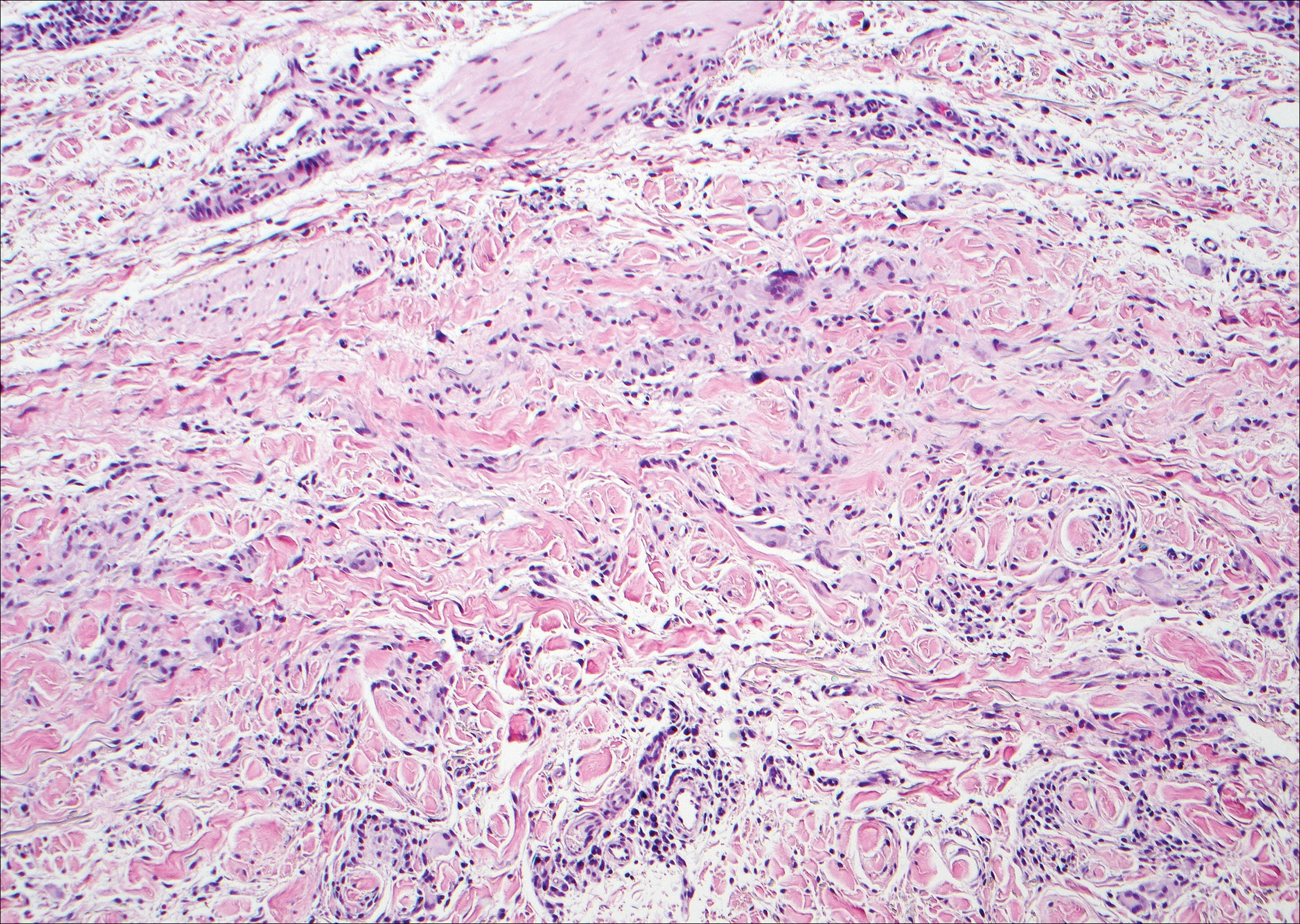

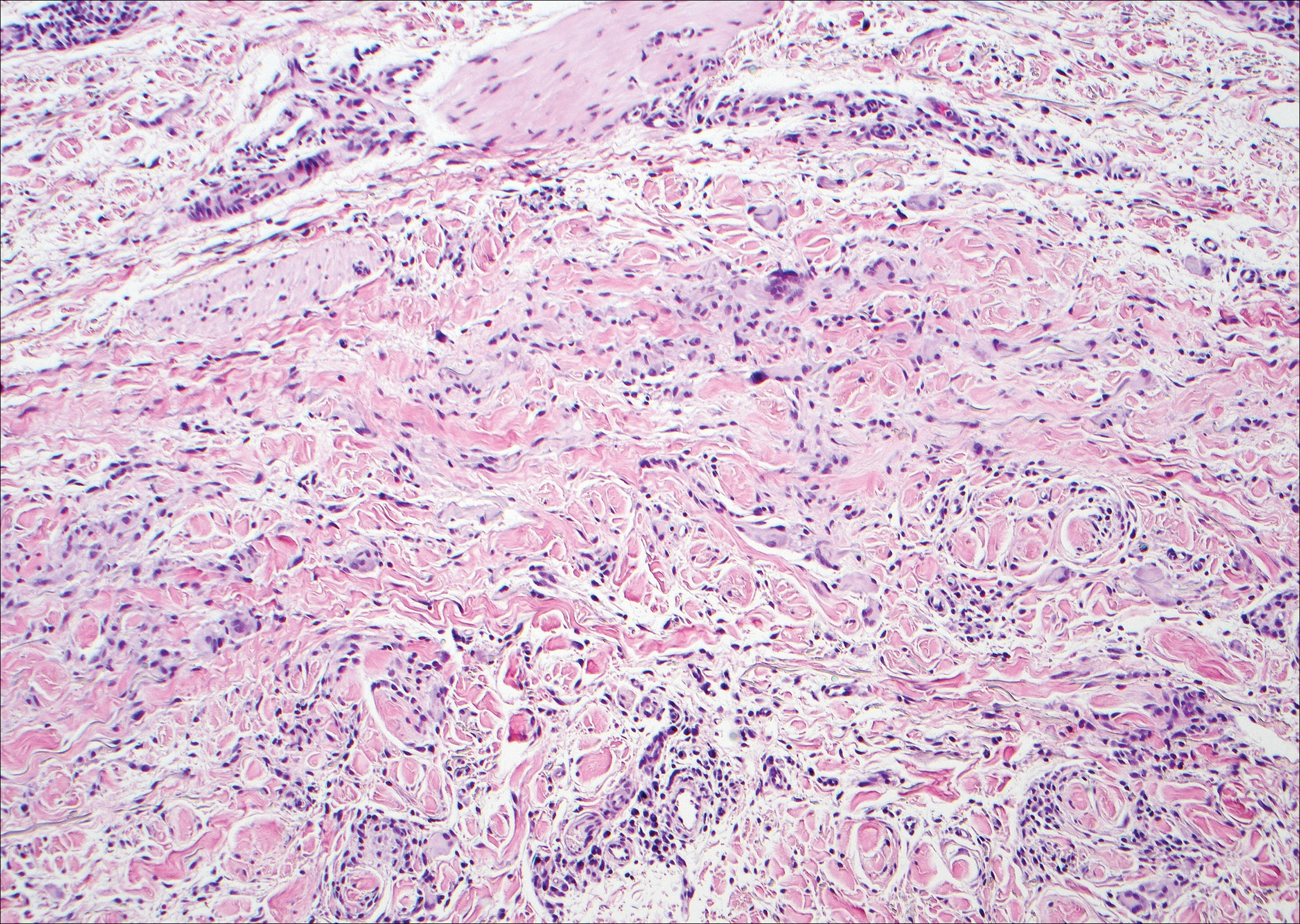

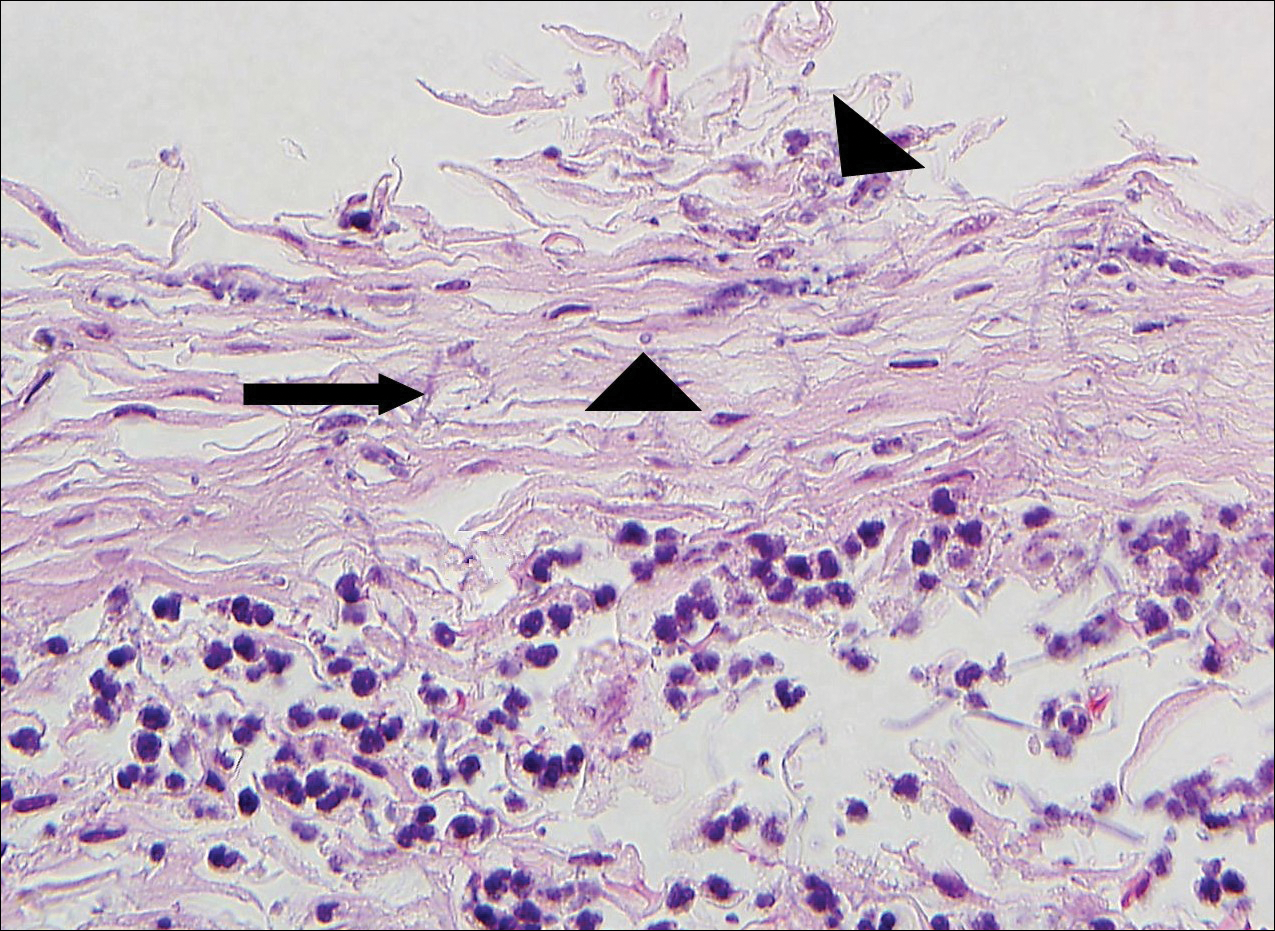

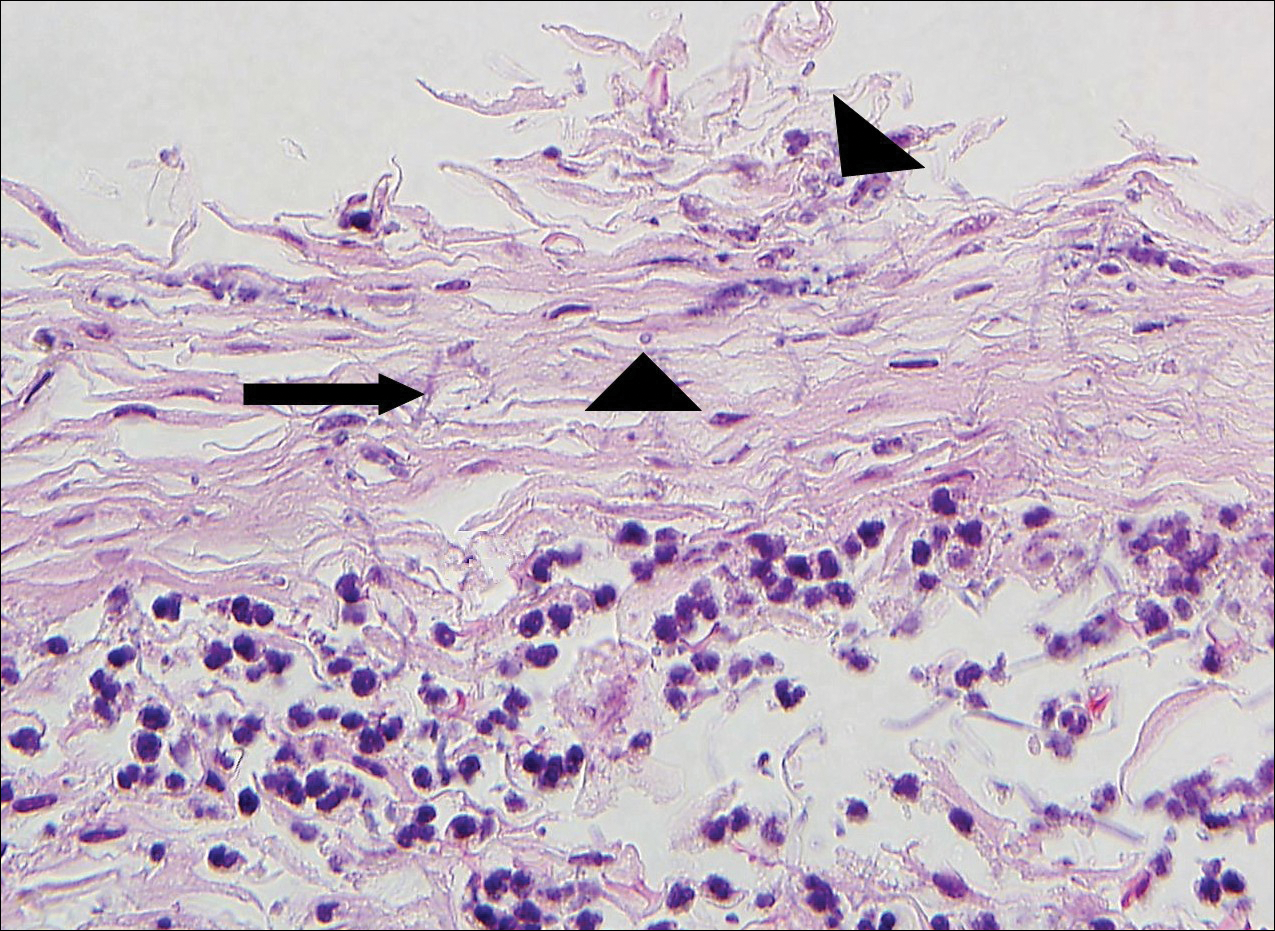

Nodular fasciitis is a benign tumor of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that usually arises in the subcutaneous tissues. It most commonly occurs in the upper extremities, trunk, head, and neck. It presents as a single, often painful, rapidly growing, subcutaneous nodule. Histologically, lesions mostly are well circumscribed yet unencapsulated, in contrast to schwannomas. They may be hypocellular or hypercellular and are composed of uniform spindle cells with a feathery or fascicular (tissue culture–like) appearance in a loose, myxoid to collagenous stroma. There may be foci of hemorrhage and conspicuous mitoses but not atypical figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemically, the cells stain positively for smooth muscle actin and negatively for S-100 protein, which sets it apart from a schwannoma. Most cases contain fusion genes, with myosin heavy chain 9 ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, being the most common fusion product.6

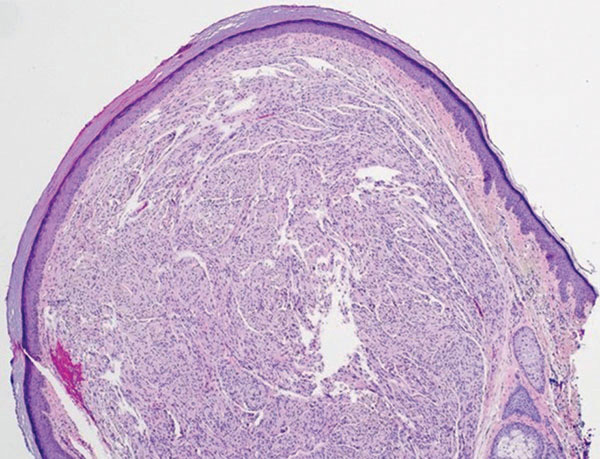

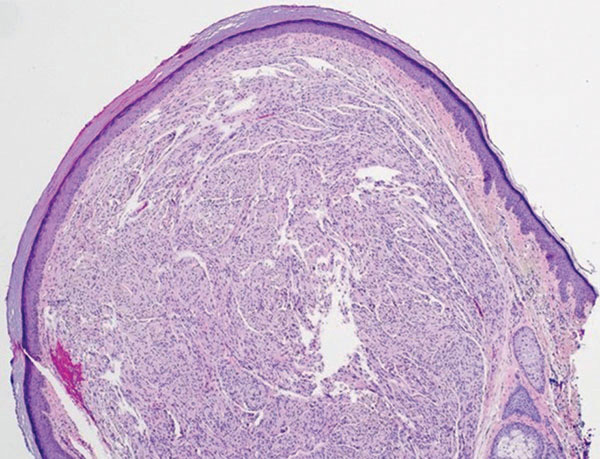

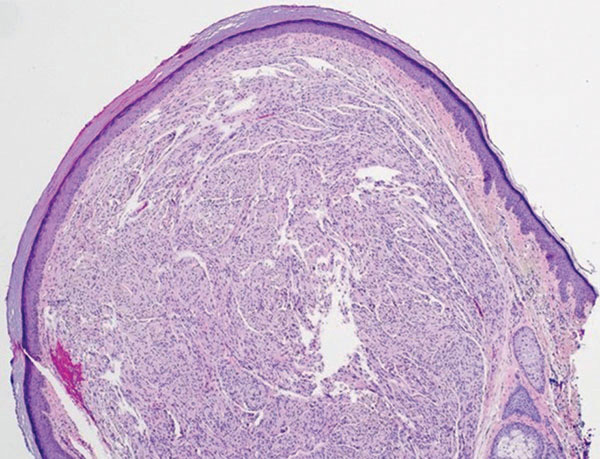

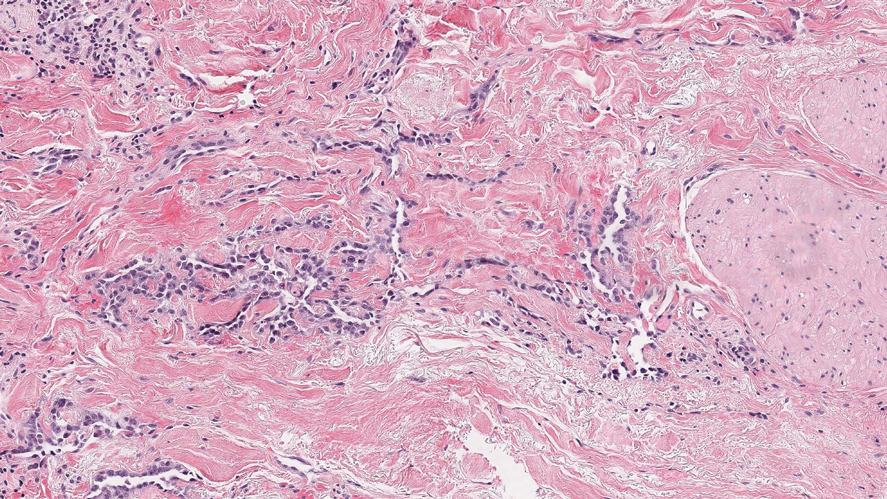

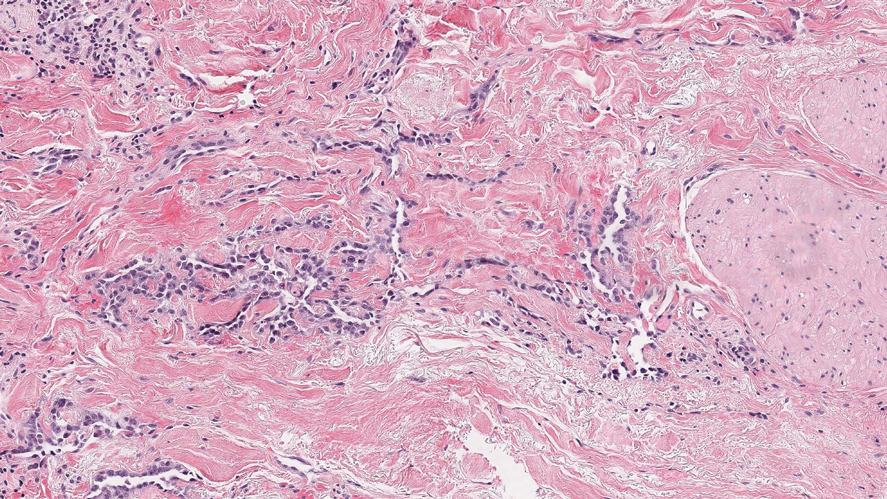

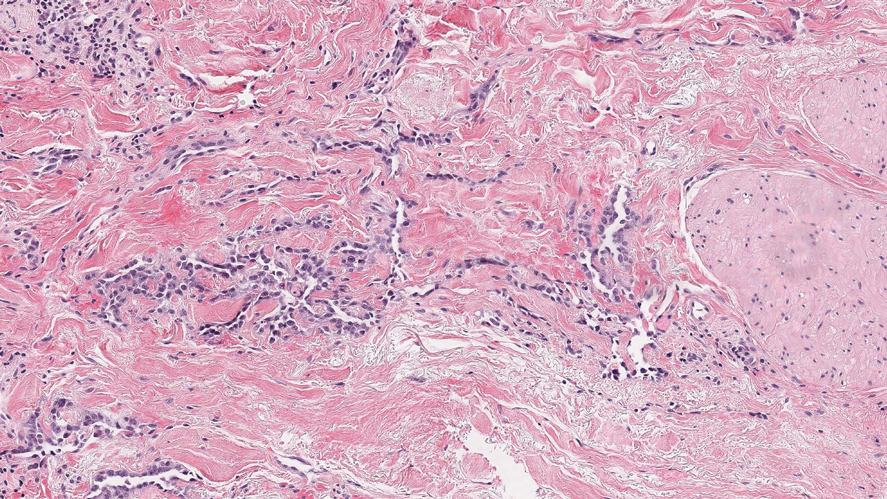

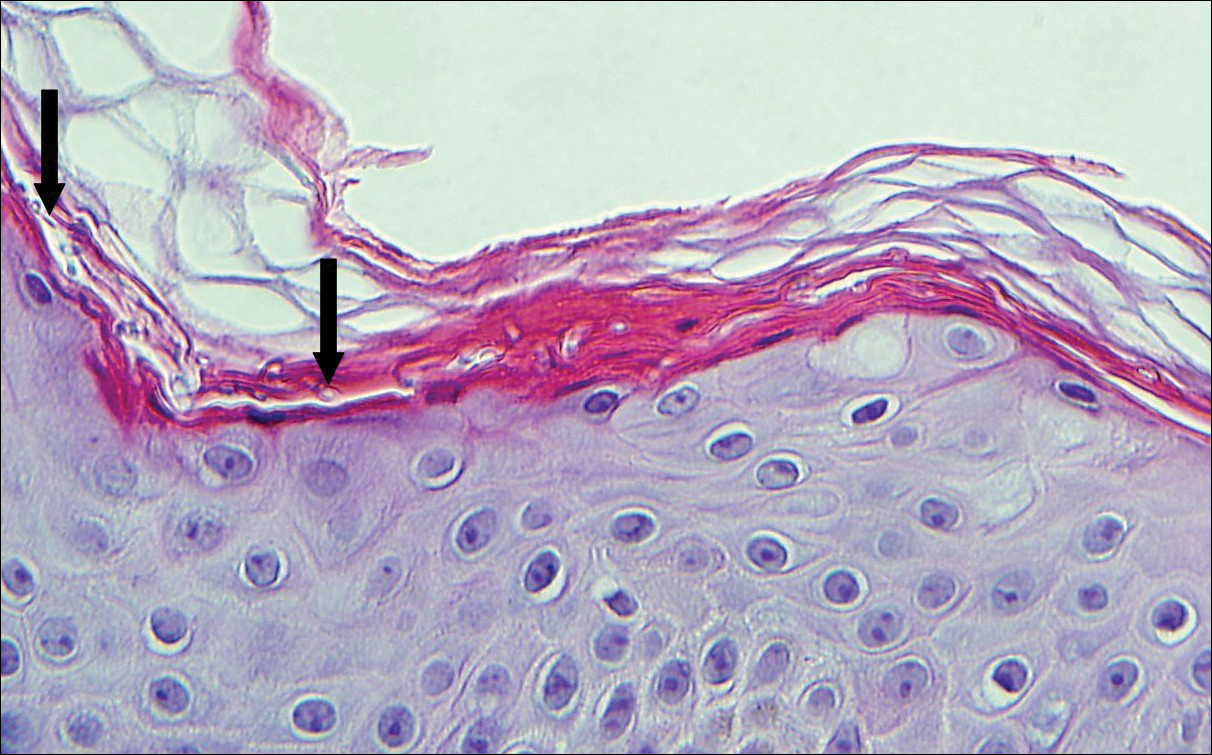

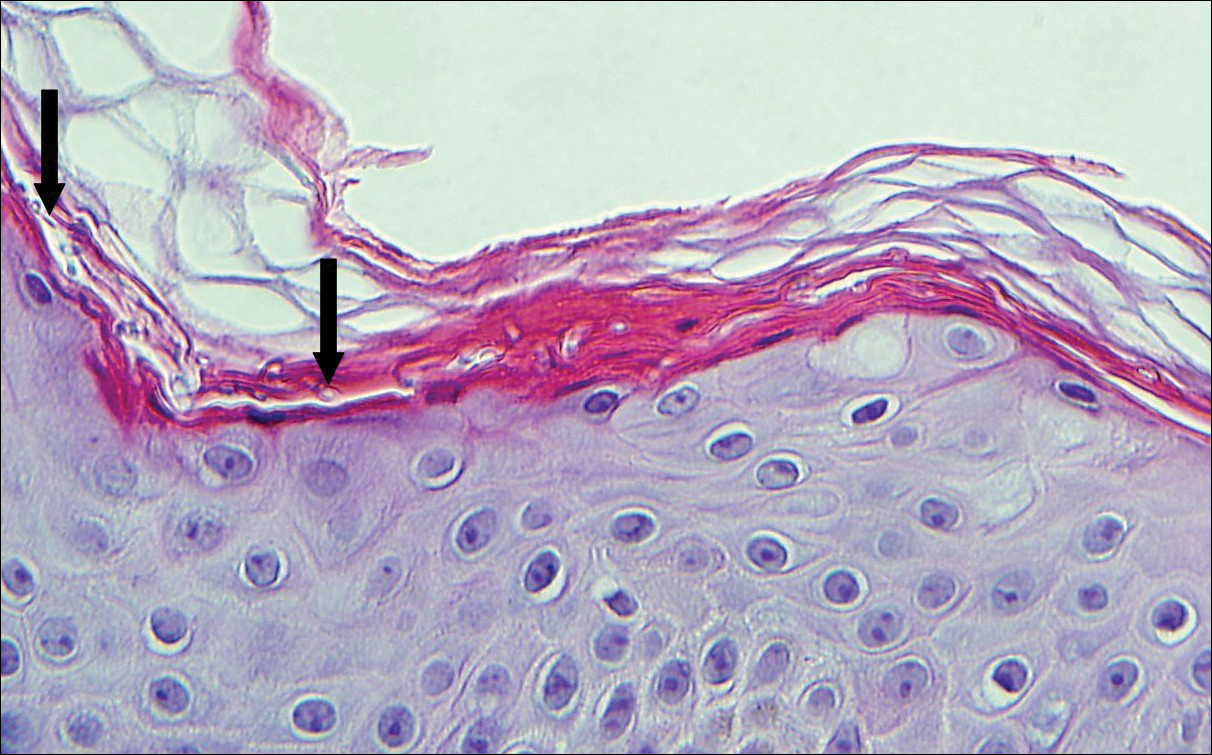

Solitary circumscribed neuroma (palisaded encapsulated neuroma) is a benign, usually solitary dermal lesion. It most commonly occurs in middle-aged to elderly adults as a small (<1 cm), firm, flesh-colored to pink papule on the face (ie, cheeks, nose, nasolabial folds) and less commonly in the oral and acral regions and on the eyelids and penis. The lesion usually is unilobular; however, other growth patterns such as plexiform, multilobular, and fungating variants have been identified. Histologically, it is a well-circumscribed nodule with a thin capsule of perineurium that is composed of interlacing bundles of Schwann cells with a characteristic clefting artifact (Figure 2). Cells have wavy dark nuclei with scant cytoplasm that occasionally form palisades or Verocay bodies causing these lesions to be confused with schwannomas. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positively with S-100 protein, and the perineurium stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, and Glut-1. Neurofilament protein stains axons throughout neuromas, whereas in schwannoma, the expression often is limited to entrapped axons at the periphery of the tumor.7

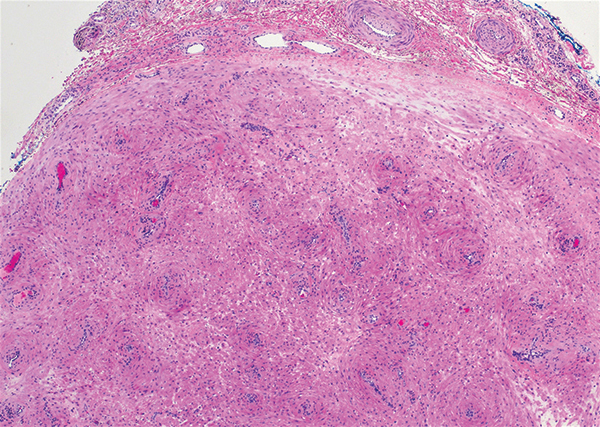

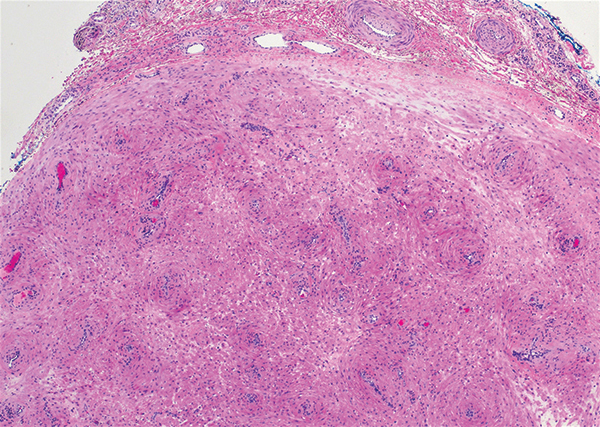

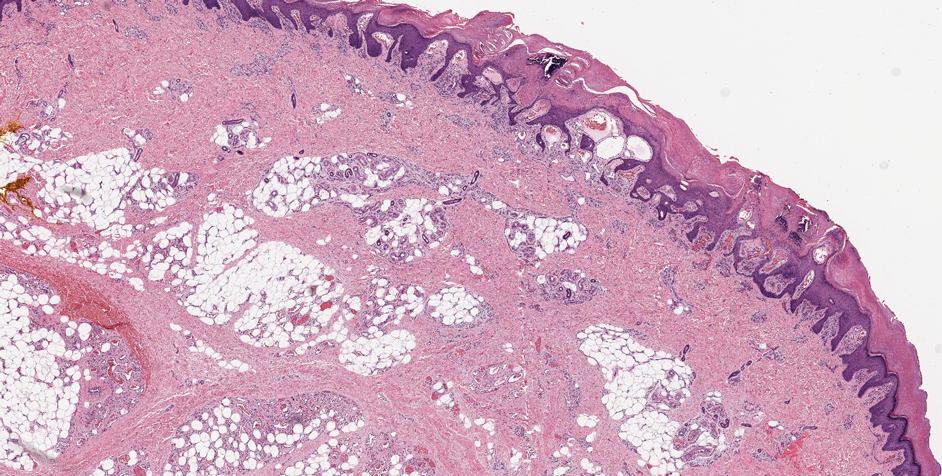

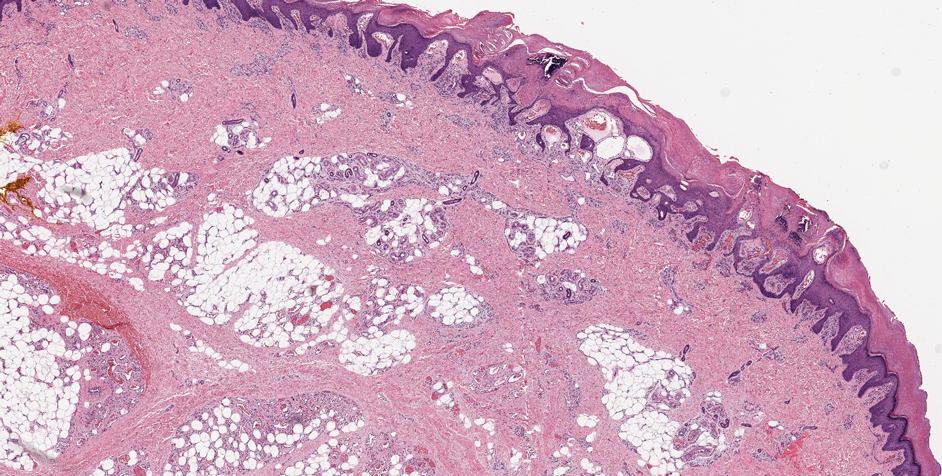

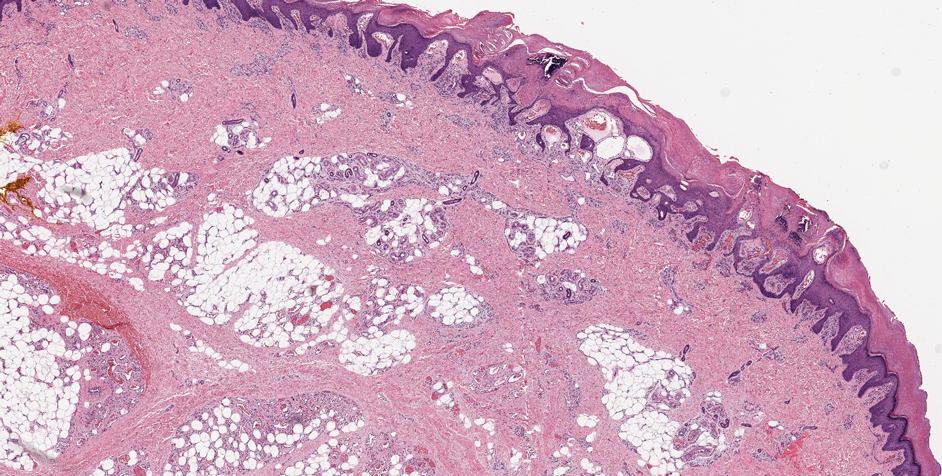

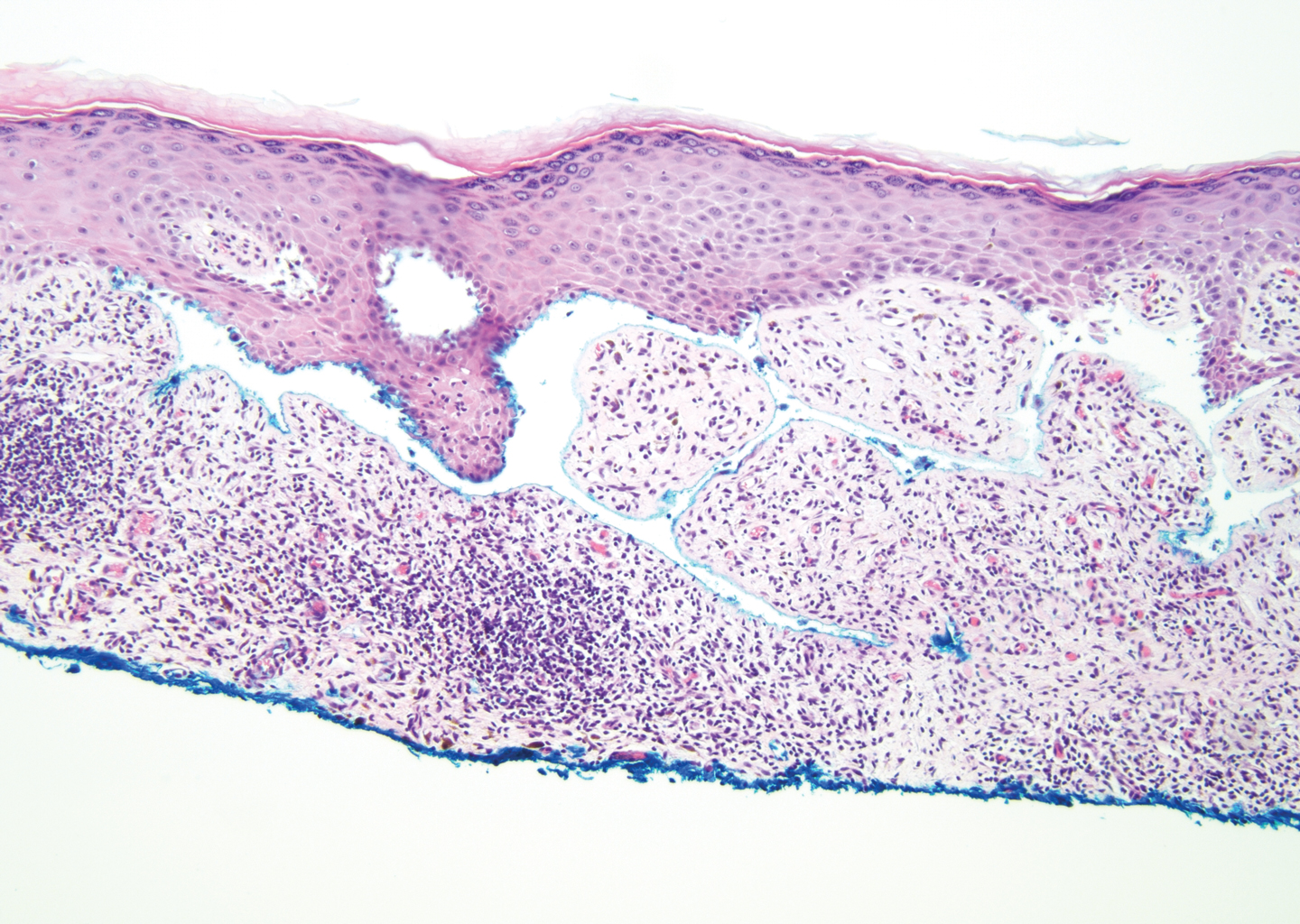

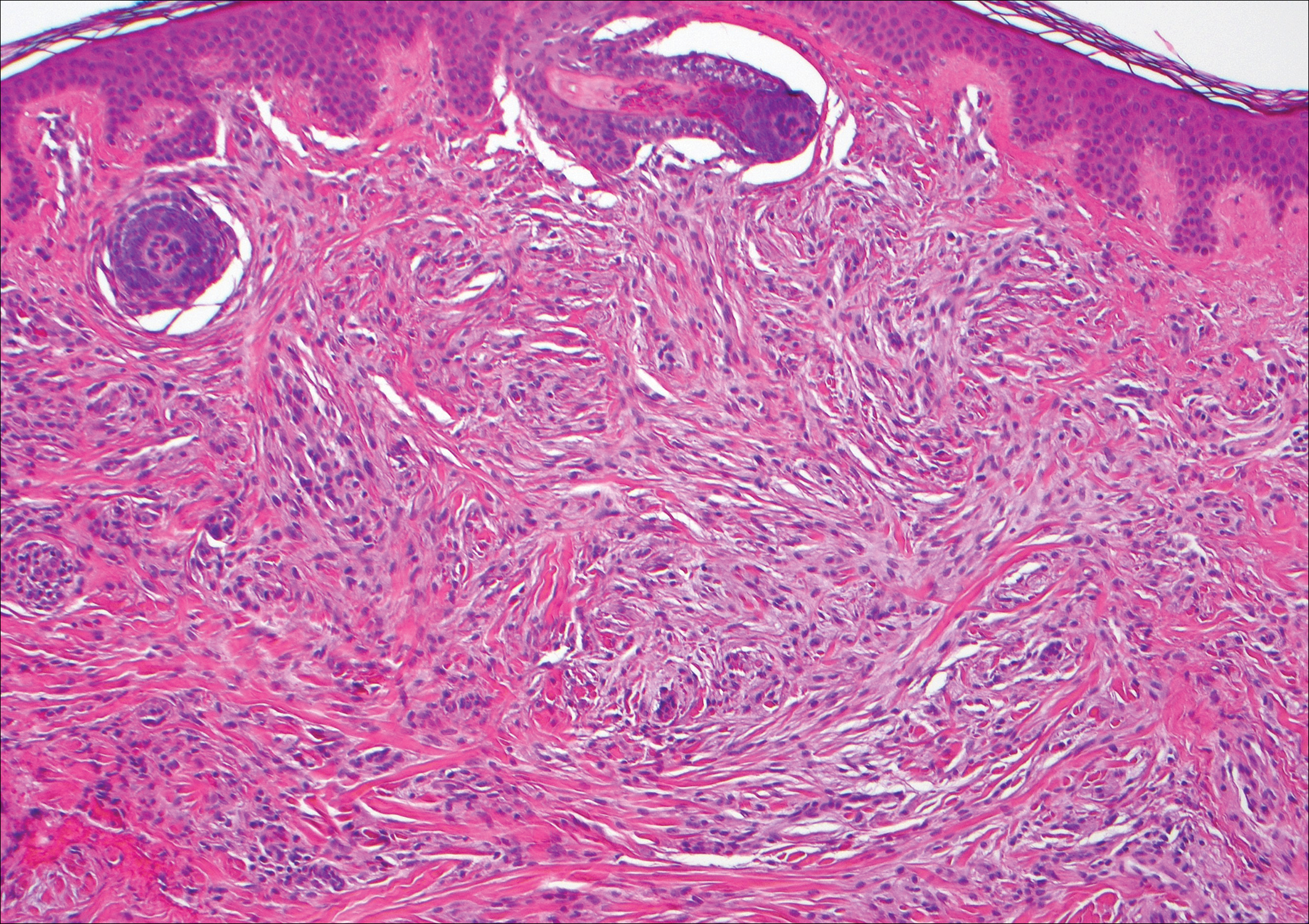

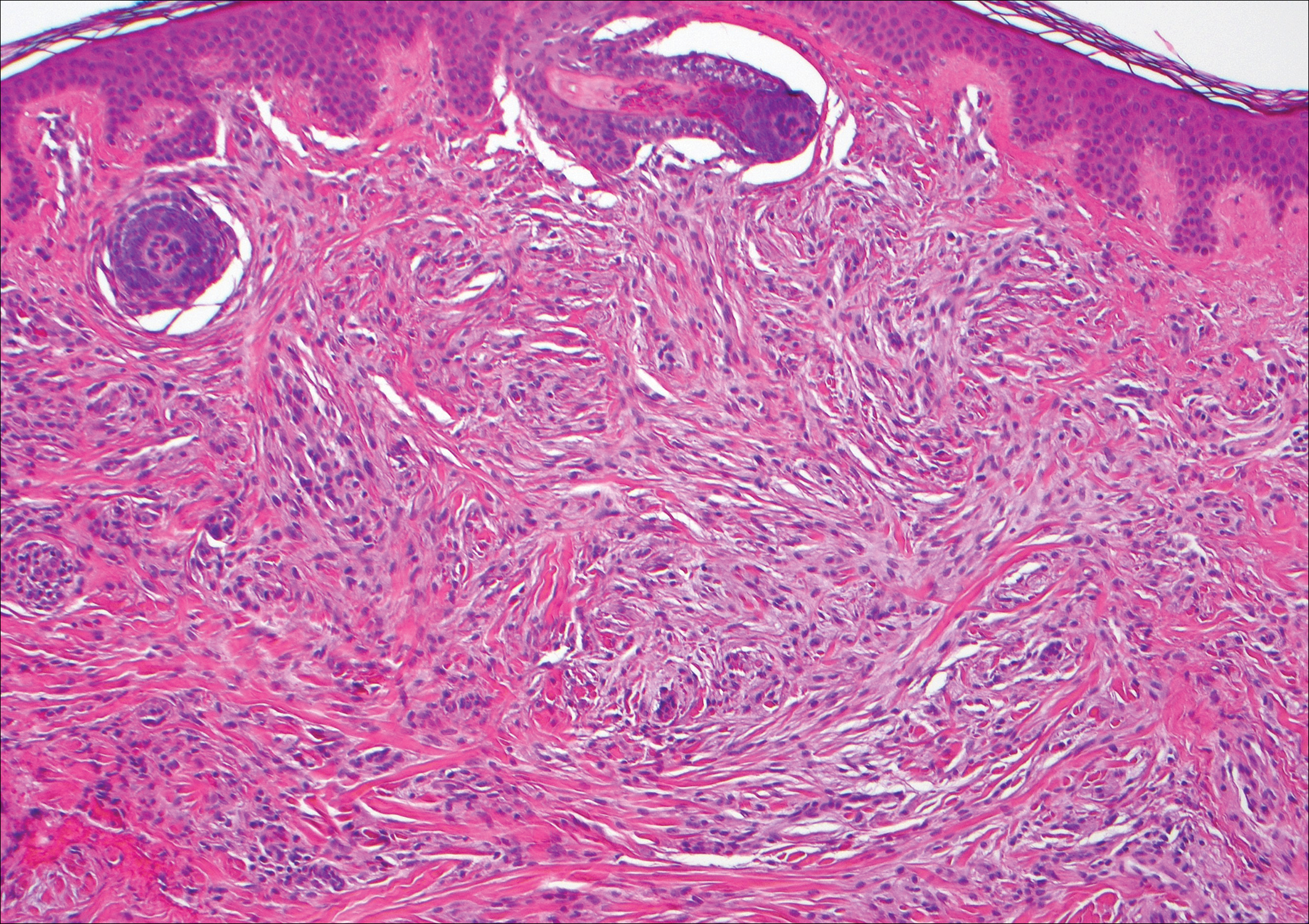

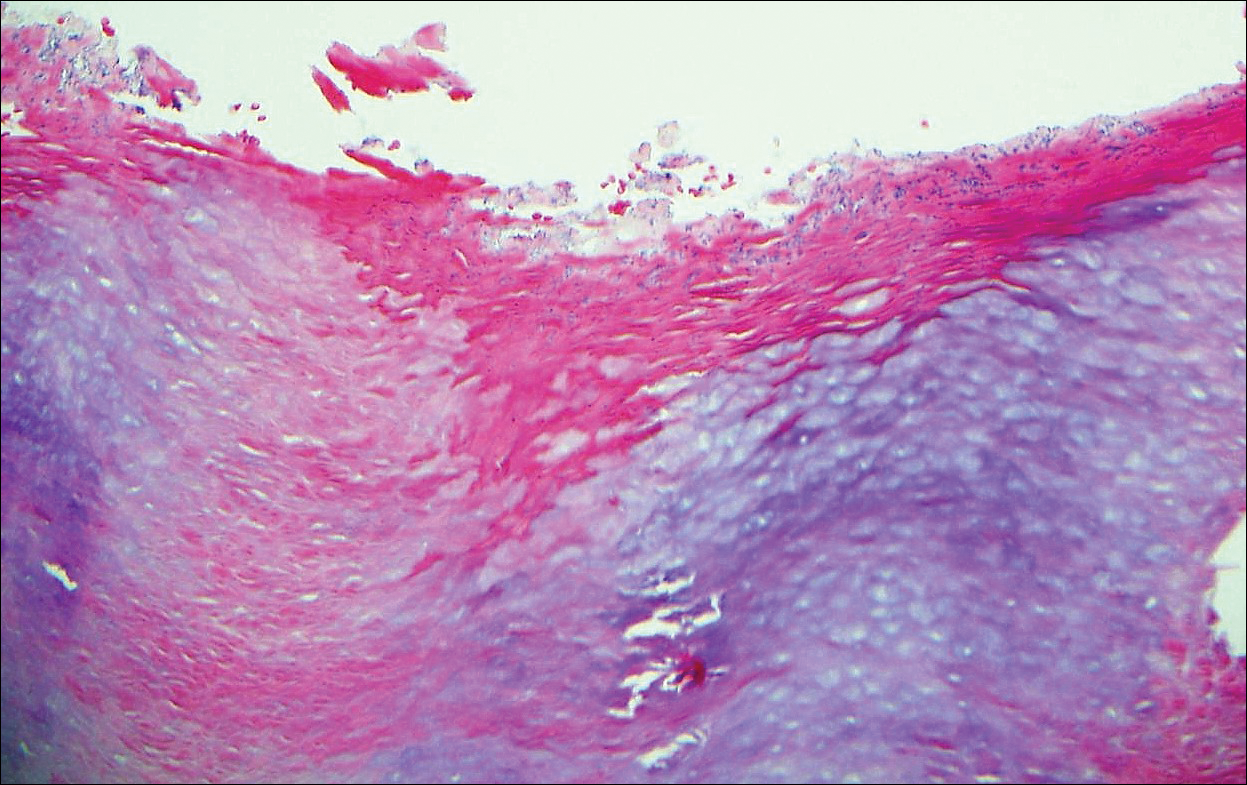

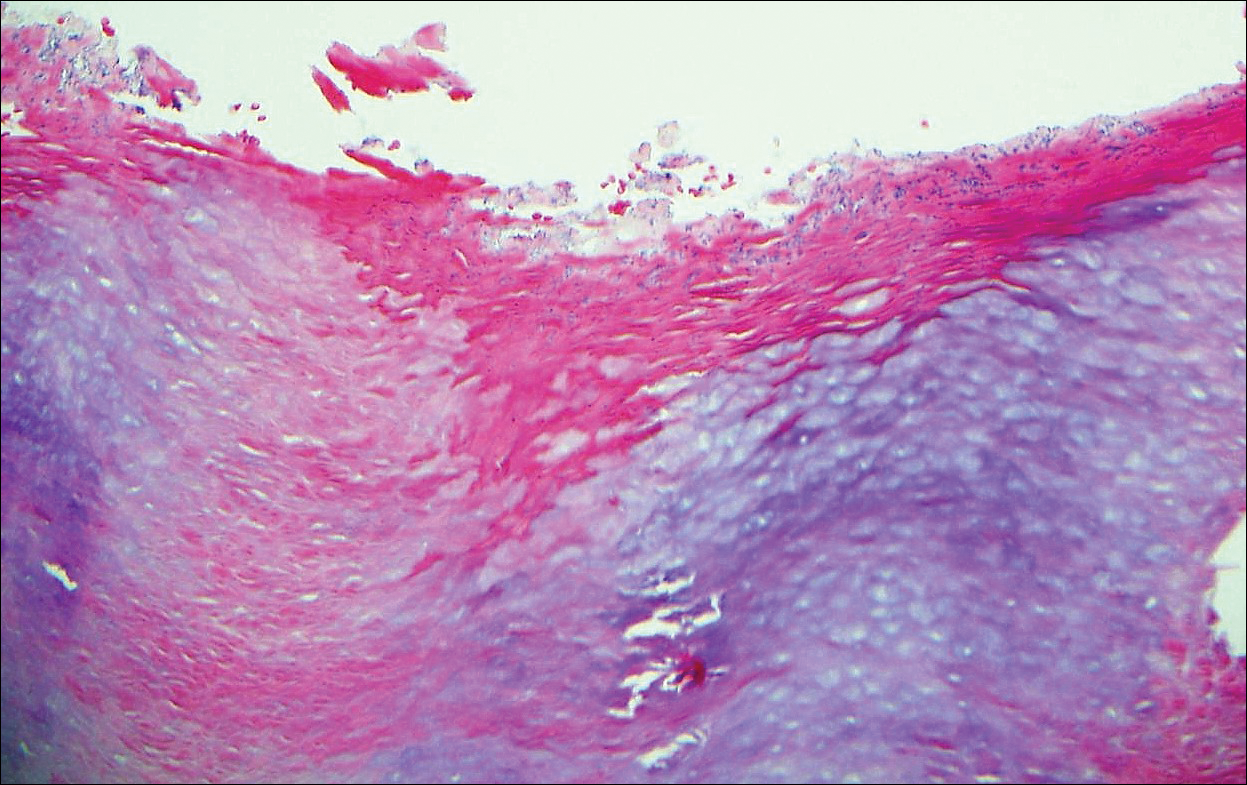

Angioleiomyoma is an uncommon, benign, smooth muscle neoplasm of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that originates from vascular smooth muscle. It most commonly presents in adult females aged 30 to 60 years, with a predilection for the lower limbs. These tumors typically are solitary, slow growing, and less than 2 cm in diameter and may be painful upon compression. Similar to schwannoma, angioleiomyoma is an encapsulated lesion composed of interlacing, uniform, smooth muscle bundles distributed around vessels (Figure 3). Smooth muscle cells have oval- or cigar-shaped nuclei with a small perinuclear vacuole of glycogen. Immunohistochemically, there is strong diffuse staining for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon. Recurrence after excision is rare.2,8

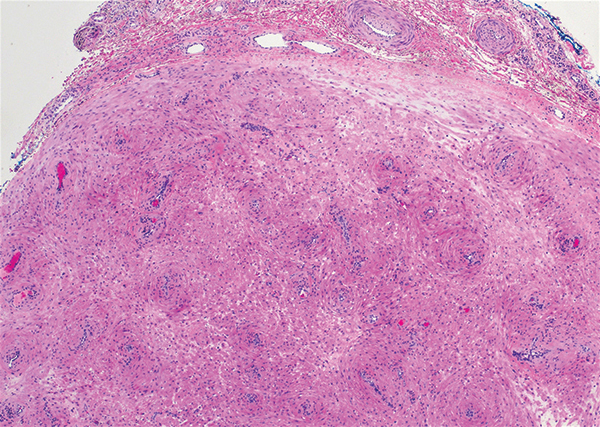

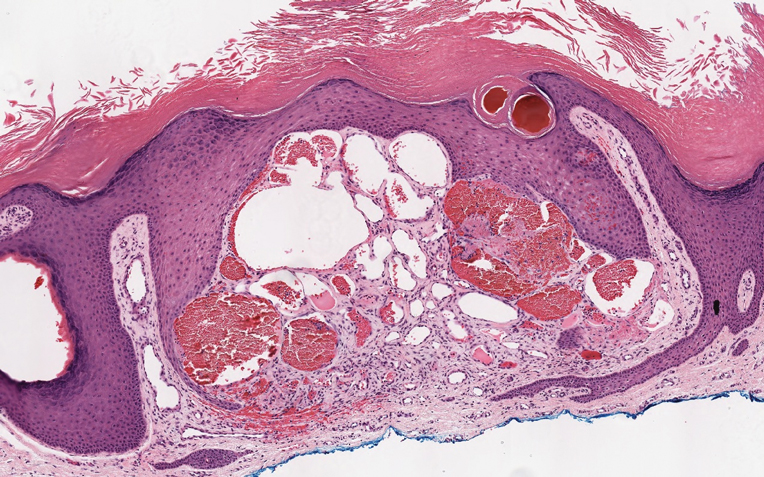

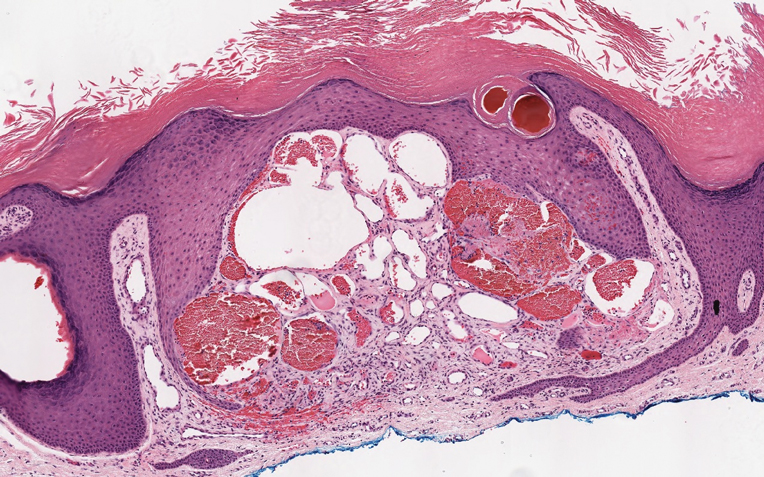

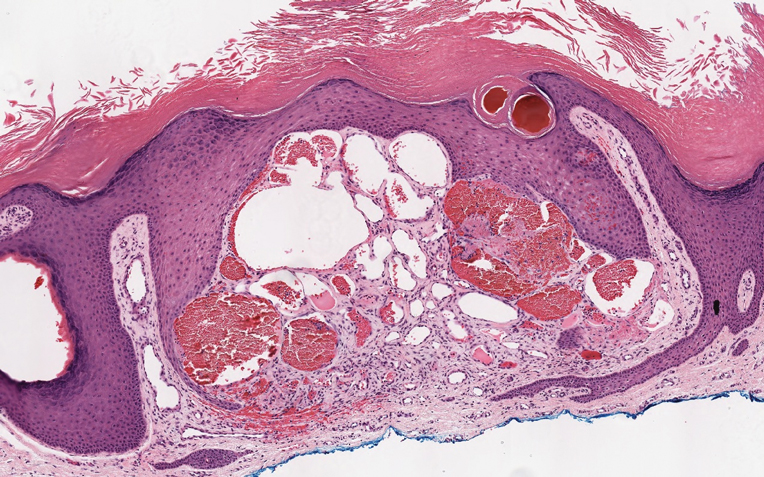

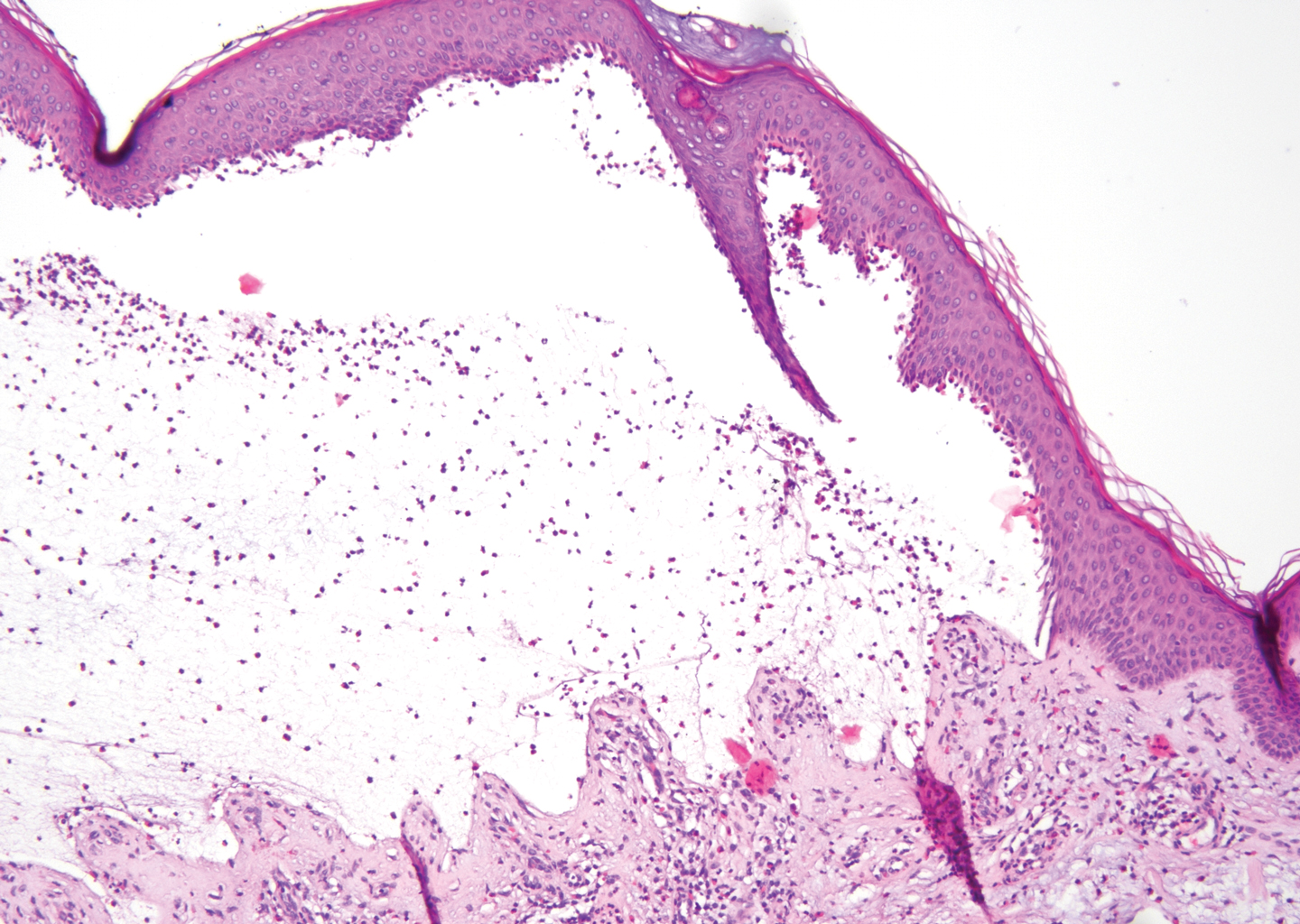

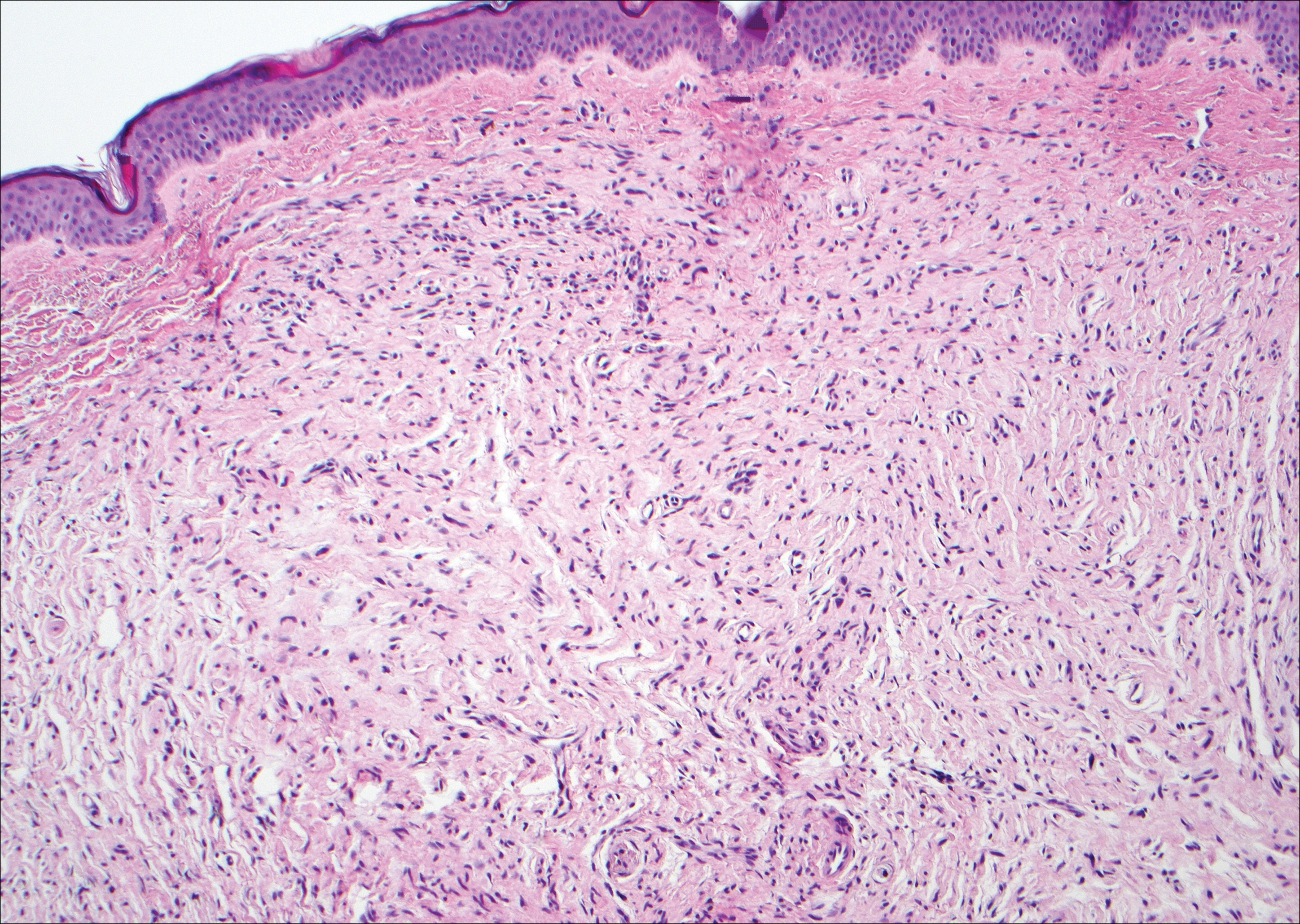

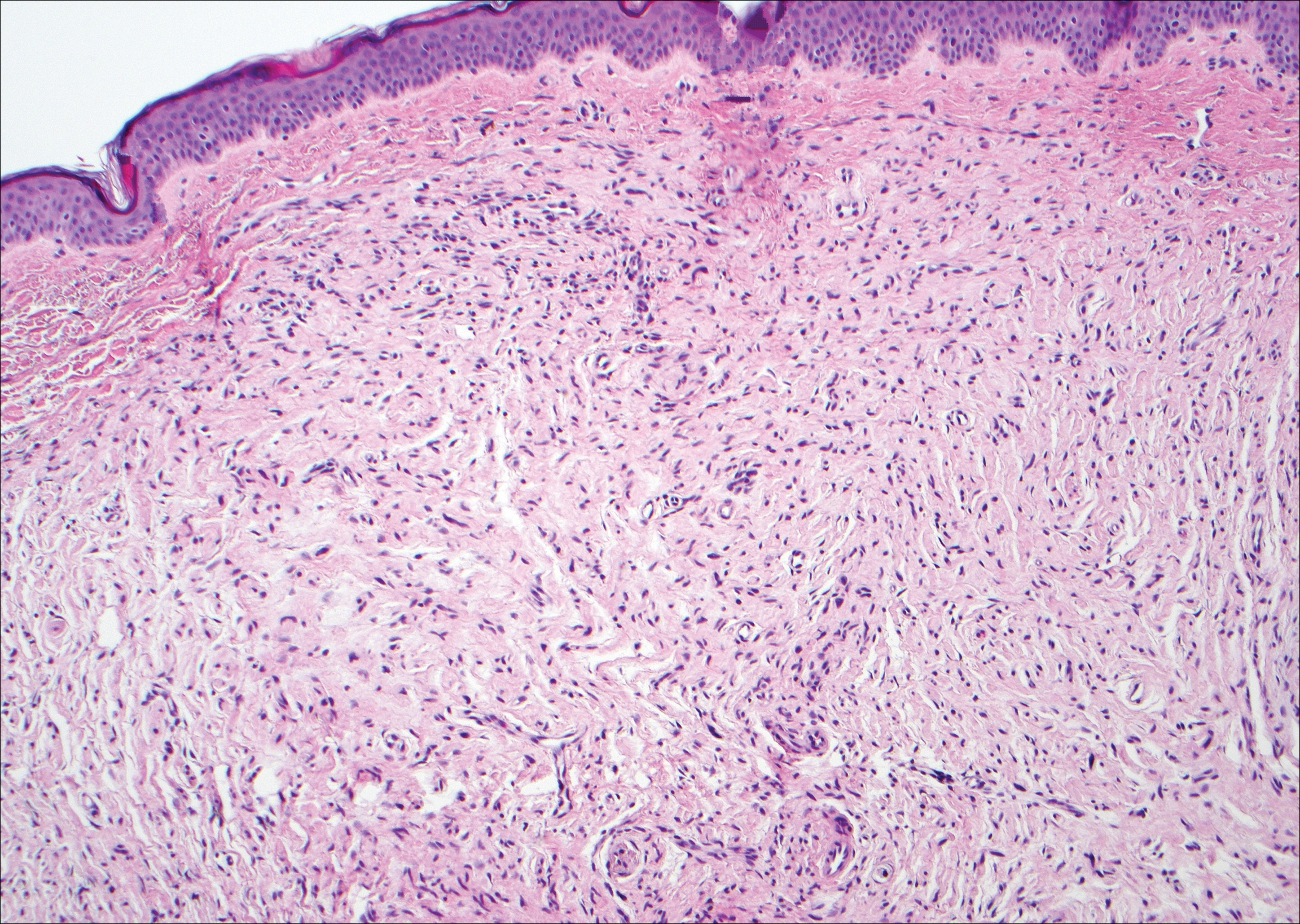

Neurofibroma is a common, mostly sporadic, benign tumor of nerve sheath origin. The solitary type may be localized (well circumscribed, unencapsulated) or diffuse. The presence of multiple, deep, and plexiform lesions is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) that is caused by germline mutations in the NF1 gene. Histologically, the tumor is composed of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineurial cells, and nerve axons within an extracellular myxoid to collagenous matrix (Figure 4). The diffuse type is an ill-defined proliferation that entraps adnexal structures. The plexiform type is defined by multinodular serpentine fascicles. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positive for S-100 protein and SOX10 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 10). Epithelial membrane antigen stains admixed perineurial cells. Neurofilament protein highlights intratumoral axons, which generally are not found throughout schwannomas. Transformation to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor occurs in up to 10% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, usually in plexiform neurofibromas, and is characterized by increased cellularity, atypia, mitotic activity, and necrosis.9

- Ritter SE, Elston DM. Cutaneous schwannoma of the foot. Cutis. 2001;67:127-129.

- Calonje E, Damaskou V, Lazar AJ. Connective tissue tumors. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier Saunders; 2020:1698-1894.

- Knight DM, Birch R, Pringle J. Benign solitary schwannomas: a review of 234 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:382-387.

- Lespi PJ, Smit R. Verocay body—prominent cutaneous leiomyoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:110-111.

- Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Scheithauer B, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:925-934.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Leblebici C, Savli TC, Yeni B, et al. Palisaded encapsulated (solitary circumscribed) neuroma: a review of 30 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:506-514.

- Yeung CM, Moore L, Lans J, et al. Angioleiomyoma of the hand: a case series and review of the literature. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020; 8:373-377.

- Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2004;15:157-166.

The Diagnosis: Schwannoma

Schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, is a benign encapsulated neoplasm of the peripheral nerve sheath that presents as a subcutaneous nodule.1 It also may present in the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, and viscera (eg, gastrointestinal tract, bone, upper respiratory tract, lymph nodes). It may occur as multiple lesions when associated with certain syndromes. It usually is an asymptomatic indolent tumor with neurologic symptoms, such as pain and tenderness, in the lesions that are deeper, larger, or closer in proximity to nearby structures.2,3

Histologically, a schwannoma is encapsulated by the perineurium of the nerve bundle from which it originates (quiz image [top]). The tumor consists of hypercellular (Antoni type A) and hypocellular (Antoni type B) areas. Antoni type A areas consist of tightly packed, spindleshaped cells with elongated wavy nuclei and indistinct cytoplasmic borders. These nuclei tend to align into parallel rows with intervening anuclear zones forming Verocay bodies (quiz image [bottom]).4 Verocay bodies are not seen in all schwannomas, and similar formations may be seen in other tumors as well. Solitary circumscribed neuromas also have Verocay bodies, whereas dermatofibromas and leiomyomas have Verocay-like bodies. Antoni type B areas have scattered spindled or ovoid cells in an edematous or myxoid matrix interspersed with inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and histiocytes. Vessels with thick hyalinized walls are a helpful feature in diagnosis.2 Schwann cells of a schwannoma stain diffusely positive with S-100 protein. The capsule stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen due to the presence of perineurial cells.2

The morphologic variants of this entity include conventional (common, solitary), cellular, plexiform, ancient, melanotic, epithelioid, pseudoglandular, neuroblastomalike, and microcystic/reticular schwannomas. There are additional variants that are associated with genetic syndromes, such as multiple cutaneous plexiform schwannomas linked with neurofibromatosis type 2, psammomatous melanotic schwannoma presenting in Carney complex, schwannomatosis, and segmental schwannomatosis (a distinct form of neurofibromatosis characterized by multiple schwannomas localized to one limb). Either presentation may have alteration or deletion of the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene, NF2, on chromosome 22.2,5

Nodular fasciitis is a benign tumor of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that usually arises in the subcutaneous tissues. It most commonly occurs in the upper extremities, trunk, head, and neck. It presents as a single, often painful, rapidly growing, subcutaneous nodule. Histologically, lesions mostly are well circumscribed yet unencapsulated, in contrast to schwannomas. They may be hypocellular or hypercellular and are composed of uniform spindle cells with a feathery or fascicular (tissue culture–like) appearance in a loose, myxoid to collagenous stroma. There may be foci of hemorrhage and conspicuous mitoses but not atypical figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemically, the cells stain positively for smooth muscle actin and negatively for S-100 protein, which sets it apart from a schwannoma. Most cases contain fusion genes, with myosin heavy chain 9 ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, being the most common fusion product.6

Solitary circumscribed neuroma (palisaded encapsulated neuroma) is a benign, usually solitary dermal lesion. It most commonly occurs in middle-aged to elderly adults as a small (<1 cm), firm, flesh-colored to pink papule on the face (ie, cheeks, nose, nasolabial folds) and less commonly in the oral and acral regions and on the eyelids and penis. The lesion usually is unilobular; however, other growth patterns such as plexiform, multilobular, and fungating variants have been identified. Histologically, it is a well-circumscribed nodule with a thin capsule of perineurium that is composed of interlacing bundles of Schwann cells with a characteristic clefting artifact (Figure 2). Cells have wavy dark nuclei with scant cytoplasm that occasionally form palisades or Verocay bodies causing these lesions to be confused with schwannomas. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positively with S-100 protein, and the perineurium stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, and Glut-1. Neurofilament protein stains axons throughout neuromas, whereas in schwannoma, the expression often is limited to entrapped axons at the periphery of the tumor.7

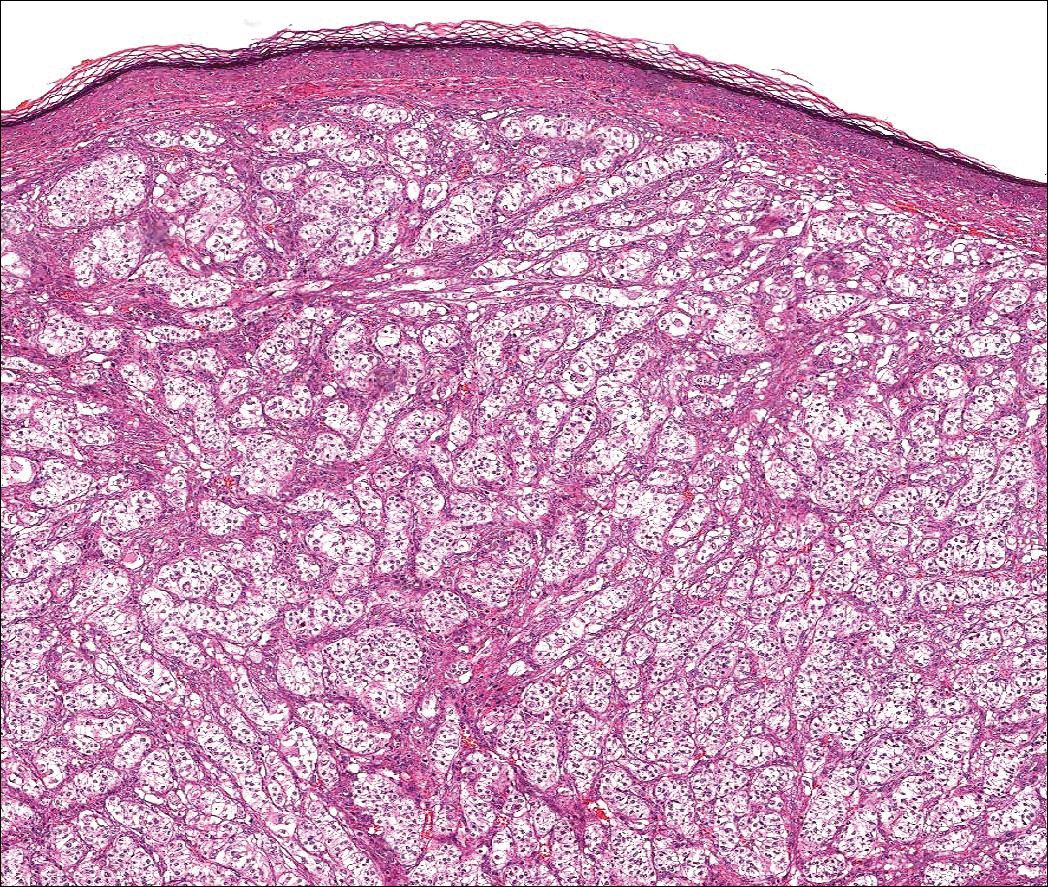

Angioleiomyoma is an uncommon, benign, smooth muscle neoplasm of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that originates from vascular smooth muscle. It most commonly presents in adult females aged 30 to 60 years, with a predilection for the lower limbs. These tumors typically are solitary, slow growing, and less than 2 cm in diameter and may be painful upon compression. Similar to schwannoma, angioleiomyoma is an encapsulated lesion composed of interlacing, uniform, smooth muscle bundles distributed around vessels (Figure 3). Smooth muscle cells have oval- or cigar-shaped nuclei with a small perinuclear vacuole of glycogen. Immunohistochemically, there is strong diffuse staining for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon. Recurrence after excision is rare.2,8

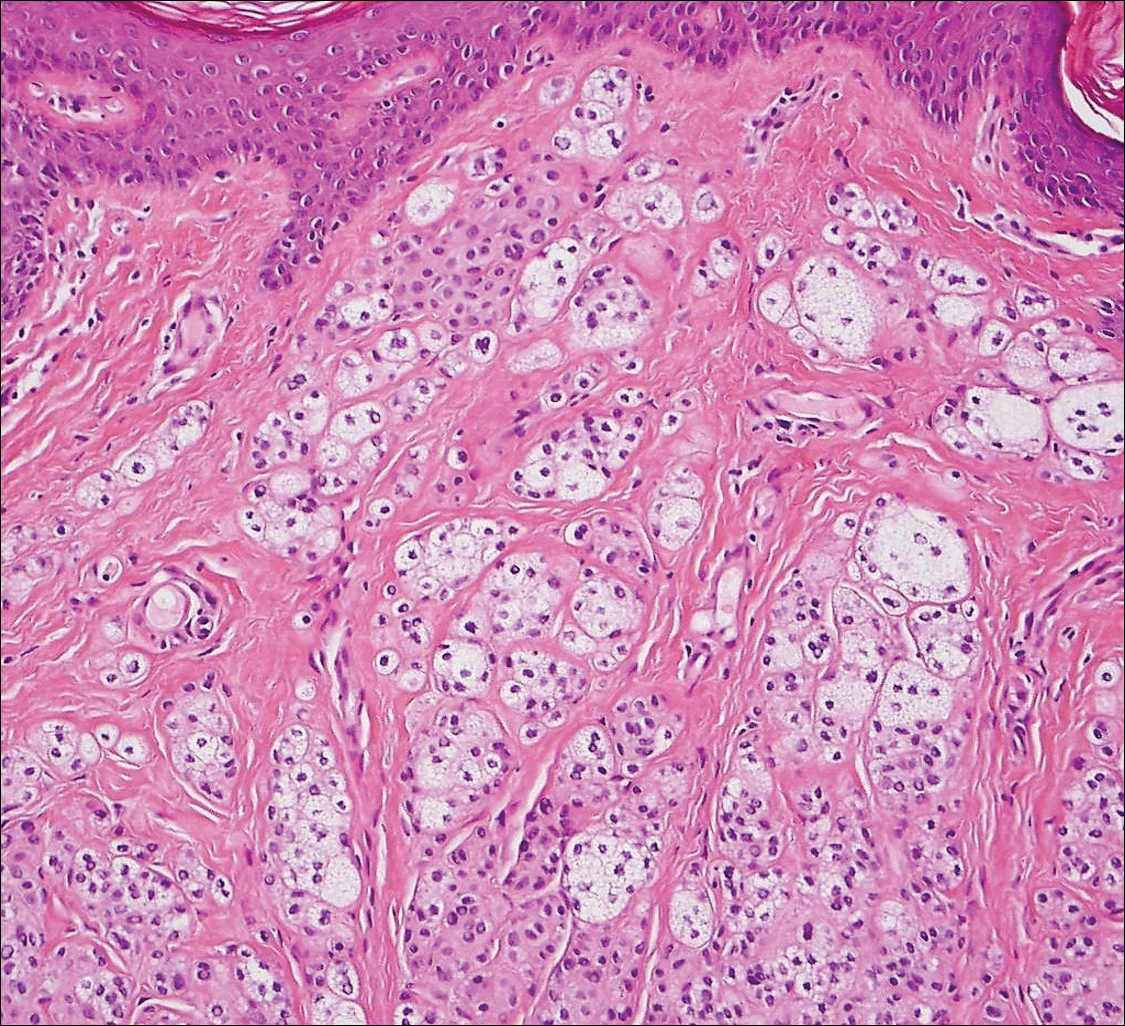

Neurofibroma is a common, mostly sporadic, benign tumor of nerve sheath origin. The solitary type may be localized (well circumscribed, unencapsulated) or diffuse. The presence of multiple, deep, and plexiform lesions is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) that is caused by germline mutations in the NF1 gene. Histologically, the tumor is composed of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineurial cells, and nerve axons within an extracellular myxoid to collagenous matrix (Figure 4). The diffuse type is an ill-defined proliferation that entraps adnexal structures. The plexiform type is defined by multinodular serpentine fascicles. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positive for S-100 protein and SOX10 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 10). Epithelial membrane antigen stains admixed perineurial cells. Neurofilament protein highlights intratumoral axons, which generally are not found throughout schwannomas. Transformation to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor occurs in up to 10% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, usually in plexiform neurofibromas, and is characterized by increased cellularity, atypia, mitotic activity, and necrosis.9

The Diagnosis: Schwannoma

Schwannoma, also known as neurilemmoma, is a benign encapsulated neoplasm of the peripheral nerve sheath that presents as a subcutaneous nodule.1 It also may present in the retroperitoneum, mediastinum, and viscera (eg, gastrointestinal tract, bone, upper respiratory tract, lymph nodes). It may occur as multiple lesions when associated with certain syndromes. It usually is an asymptomatic indolent tumor with neurologic symptoms, such as pain and tenderness, in the lesions that are deeper, larger, or closer in proximity to nearby structures.2,3

Histologically, a schwannoma is encapsulated by the perineurium of the nerve bundle from which it originates (quiz image [top]). The tumor consists of hypercellular (Antoni type A) and hypocellular (Antoni type B) areas. Antoni type A areas consist of tightly packed, spindleshaped cells with elongated wavy nuclei and indistinct cytoplasmic borders. These nuclei tend to align into parallel rows with intervening anuclear zones forming Verocay bodies (quiz image [bottom]).4 Verocay bodies are not seen in all schwannomas, and similar formations may be seen in other tumors as well. Solitary circumscribed neuromas also have Verocay bodies, whereas dermatofibromas and leiomyomas have Verocay-like bodies. Antoni type B areas have scattered spindled or ovoid cells in an edematous or myxoid matrix interspersed with inflammatory cells such as lymphocytes and histiocytes. Vessels with thick hyalinized walls are a helpful feature in diagnosis.2 Schwann cells of a schwannoma stain diffusely positive with S-100 protein. The capsule stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen due to the presence of perineurial cells.2

The morphologic variants of this entity include conventional (common, solitary), cellular, plexiform, ancient, melanotic, epithelioid, pseudoglandular, neuroblastomalike, and microcystic/reticular schwannomas. There are additional variants that are associated with genetic syndromes, such as multiple cutaneous plexiform schwannomas linked with neurofibromatosis type 2, psammomatous melanotic schwannoma presenting in Carney complex, schwannomatosis, and segmental schwannomatosis (a distinct form of neurofibromatosis characterized by multiple schwannomas localized to one limb). Either presentation may have alteration or deletion of the neurofibromatosis type 2 gene, NF2, on chromosome 22.2,5

Nodular fasciitis is a benign tumor of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts that usually arises in the subcutaneous tissues. It most commonly occurs in the upper extremities, trunk, head, and neck. It presents as a single, often painful, rapidly growing, subcutaneous nodule. Histologically, lesions mostly are well circumscribed yet unencapsulated, in contrast to schwannomas. They may be hypocellular or hypercellular and are composed of uniform spindle cells with a feathery or fascicular (tissue culture–like) appearance in a loose, myxoid to collagenous stroma. There may be foci of hemorrhage and conspicuous mitoses but not atypical figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemically, the cells stain positively for smooth muscle actin and negatively for S-100 protein, which sets it apart from a schwannoma. Most cases contain fusion genes, with myosin heavy chain 9 ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6, MYH9-USP6, being the most common fusion product.6

Solitary circumscribed neuroma (palisaded encapsulated neuroma) is a benign, usually solitary dermal lesion. It most commonly occurs in middle-aged to elderly adults as a small (<1 cm), firm, flesh-colored to pink papule on the face (ie, cheeks, nose, nasolabial folds) and less commonly in the oral and acral regions and on the eyelids and penis. The lesion usually is unilobular; however, other growth patterns such as plexiform, multilobular, and fungating variants have been identified. Histologically, it is a well-circumscribed nodule with a thin capsule of perineurium that is composed of interlacing bundles of Schwann cells with a characteristic clefting artifact (Figure 2). Cells have wavy dark nuclei with scant cytoplasm that occasionally form palisades or Verocay bodies causing these lesions to be confused with schwannomas. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positively with S-100 protein, and the perineurium stains positively with epithelial membrane antigen, Claudin-1, and Glut-1. Neurofilament protein stains axons throughout neuromas, whereas in schwannoma, the expression often is limited to entrapped axons at the periphery of the tumor.7

Angioleiomyoma is an uncommon, benign, smooth muscle neoplasm of the skin and subcutaneous tissue that originates from vascular smooth muscle. It most commonly presents in adult females aged 30 to 60 years, with a predilection for the lower limbs. These tumors typically are solitary, slow growing, and less than 2 cm in diameter and may be painful upon compression. Similar to schwannoma, angioleiomyoma is an encapsulated lesion composed of interlacing, uniform, smooth muscle bundles distributed around vessels (Figure 3). Smooth muscle cells have oval- or cigar-shaped nuclei with a small perinuclear vacuole of glycogen. Immunohistochemically, there is strong diffuse staining for smooth muscle actin and h-caldesmon. Recurrence after excision is rare.2,8

Neurofibroma is a common, mostly sporadic, benign tumor of nerve sheath origin. The solitary type may be localized (well circumscribed, unencapsulated) or diffuse. The presence of multiple, deep, and plexiform lesions is associated with neurofibromatosis type 1 (von Recklinghausen disease) that is caused by germline mutations in the NF1 gene. Histologically, the tumor is composed of Schwann cells, fibroblasts, perineurial cells, and nerve axons within an extracellular myxoid to collagenous matrix (Figure 4). The diffuse type is an ill-defined proliferation that entraps adnexal structures. The plexiform type is defined by multinodular serpentine fascicles. Immunohistochemically, the Schwann cells stain positive for S-100 protein and SOX10 (SRY-Box Transcription Factor 10). Epithelial membrane antigen stains admixed perineurial cells. Neurofilament protein highlights intratumoral axons, which generally are not found throughout schwannomas. Transformation to a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor occurs in up to 10% of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1, usually in plexiform neurofibromas, and is characterized by increased cellularity, atypia, mitotic activity, and necrosis.9

- Ritter SE, Elston DM. Cutaneous schwannoma of the foot. Cutis. 2001;67:127-129.

- Calonje E, Damaskou V, Lazar AJ. Connective tissue tumors. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier Saunders; 2020:1698-1894.

- Knight DM, Birch R, Pringle J. Benign solitary schwannomas: a review of 234 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:382-387.

- Lespi PJ, Smit R. Verocay body—prominent cutaneous leiomyoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:110-111.

- Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Scheithauer B, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:925-934.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Leblebici C, Savli TC, Yeni B, et al. Palisaded encapsulated (solitary circumscribed) neuroma: a review of 30 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:506-514.

- Yeung CM, Moore L, Lans J, et al. Angioleiomyoma of the hand: a case series and review of the literature. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020; 8:373-377.

- Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2004;15:157-166.

- Ritter SE, Elston DM. Cutaneous schwannoma of the foot. Cutis. 2001;67:127-129.

- Calonje E, Damaskou V, Lazar AJ. Connective tissue tumors. In: Calonje E, Brenn T, Lazar AJ, et al, eds. McKee’s Pathology of the Skin. 5th ed. Vol 2. Elsevier Saunders; 2020:1698-1894.

- Knight DM, Birch R, Pringle J. Benign solitary schwannomas: a review of 234 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89:382-387.

- Lespi PJ, Smit R. Verocay body—prominent cutaneous leiomyoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:110-111.

- Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Scheithauer B, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18:925-934.

- Erickson-Johnson MR, Chou MM, Evers BR, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433.

- Leblebici C, Savli TC, Yeni B, et al. Palisaded encapsulated (solitary circumscribed) neuroma: a review of 30 cases. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:506-514.

- Yeung CM, Moore L, Lans J, et al. Angioleiomyoma of the hand: a case series and review of the literature. Arch Bone Jt Surg. 2020; 8:373-377.

- Skovronsky DM, Oberholtzer JC. Pathologic classification of peripheral nerve tumors. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 2004;15:157-166.

A 54-year-old woman presented with an enlarging mass on the right volar forearm. Physical examination revealed a 1-cm, soft, mobile, subcutaneous nodule. Excision revealed tan-pink, indurated, fibrous, nodular tissue.

Dermatopathology Etiquette 101

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established core competencies to serve as a foundation for the training received in a dermatology residency program.1 Although programs are required to have the same concentrations—patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice—no specific guidelines are in place regarding how each of these competencies should be reached within a training period.2 Instead, it remains the responsibility of each program to formulate an individualized curriculum to facilitate proficiency in the multiple areas encompassed by a residency.

In many dermatology residency programs, dermatopathology is a substantial component of educational objectives and the curriculum.1 Residents may spend as much as 25% of their training on dermatopathology. However, there is great variability among programs in methods of teaching dermatopathology. When Hinshaw3 surveyed 52 of 109 dermatology residency programs, they identified differences in dermatopathology teaching that included, but was not limited to, utilization of problem-based learning (in 40.4% of programs), integration of journal reviews (53.8%), and computer-based learning (19.2%). In addition, differences were identified in the recommended primary textbook and the makeup of faculty who taught dermatopathology.3

Although residency programs vary in their methods of teaching this important component of dermatology, most use a multiheaded microscope in some capacity for didactics or sign-out. For most trainees, the dermatopathology laboratory is a new environment compared to the clinical space that medical students and residents become accustomed to throughout their education, thus creating a knowledge gap for trainees on proper dermatopathology etiquette and universal guidelines.

With medical students, residents, and fellows in mind, we have prepared a basic “dermatopathology etiquette” reference for trainees. Just as there are universal rules in the operating room for surgery (eg, sterile technique), we want to establish a code of conduct at the microscope. We hope that these 10 tips will, first, be useful to those who are unsure how to approach their first experience with dermatopathology and, second, serve as a guideline to aid development of appropriate communication skills and functioning within this novel setting. This list also can serve as a resource for dermatopathology attendings to provide to rotating residents and students.

1. New to pathology? It’s okay to ask. Do not hesitate to ask upper-year residents, fellows, and attendings for instructions on such matters as how to adjust your eyepiece to get the best resolution.

2. If a slide drops on the floor, do not move! Your first instinct might be to move your chair to look for the dropped slide, but you might roll over it and break it.

3. When the attending is looking through the scope, you look through the scope. Dermatopathology is a visual exercise. Getting in your “optic mileage” is best done under the guidance of an experienced dermatopathologist.

4. Rules regarding food and drink at the microscope vary by pathologist. It’s best to ask what each attending prefers. Safe advice is to avoid foods that make noise, such as chewing gum and chips, and food that has a strong odor, such as microwaved leftovers.

5. Limit use of a laptop, cell phone, and smartwatch. If you think that using any of these is necessary, it generally is best to announce that you are looking up something related to the case and then share your findings (but not the most recent post on your Facebook News Feed).

6. If you notice that something needs correcting on the report, speak up! We are all human; we all make typos. Do not hesitate to mention this as soon as possible, especially before the case is signed out. You will likely be thanked by your attending because it is harder to rectify once the report has been signed out.

7. Small talk often is welcome during large excisions. This is a great time to ask what others are doing next weekend or what happened in clinic earlier that day, or just to tell a good (clean) joke that is making the rounds. Conversely, if the case is complex, it often is best to wait until it is completed before asking questions.

8. When participating in a roundtable diagnosis, you are welcome to directly state the diagnosis for bread-and-butter cases, such as basal cell carcinomas and seborrheic keratoses. It is appropriate to be more descriptive and methodical in more complex cases. When evaluating a rash, give the general inflammatory pattern first. For example, is it spongiotic? Psoriasiform? Interface? Or a mixed pattern?

9. Extra points for identifying special sites! These include mucosal, genital, and acral sites. You might even get bonus points if you can determine something about the patient (child or adult) based on the pathologic features, such as variation in collagen patterns.

10. Whenever you are in doubt, just describe what you see. You can use the traditional top-down approach or start with stating the most evident finding, then proceed to a top-down description. If it is a neoplasm, describe the overall architecture; then, what you see at a cellular level will get you some points as well.

We acknowledge that this list of 10 tips is not comprehensive and might vary by attending and each institution’s distinctive training format. We are hopeful, however, that these 10 points of etiquette can serve as a guideline.

- Hinshaw M, Hsu P, Lee L-Y, et al. The current state of dermatopathology education: a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:620-628. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01128.x

- Hinshaw MA, Stratman EJ. Core competencies in dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:160-165. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00442.x

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826. doi:10.1016/j.det.2012.06.003

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established core competencies to serve as a foundation for the training received in a dermatology residency program.1 Although programs are required to have the same concentrations—patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice—no specific guidelines are in place regarding how each of these competencies should be reached within a training period.2 Instead, it remains the responsibility of each program to formulate an individualized curriculum to facilitate proficiency in the multiple areas encompassed by a residency.

In many dermatology residency programs, dermatopathology is a substantial component of educational objectives and the curriculum.1 Residents may spend as much as 25% of their training on dermatopathology. However, there is great variability among programs in methods of teaching dermatopathology. When Hinshaw3 surveyed 52 of 109 dermatology residency programs, they identified differences in dermatopathology teaching that included, but was not limited to, utilization of problem-based learning (in 40.4% of programs), integration of journal reviews (53.8%), and computer-based learning (19.2%). In addition, differences were identified in the recommended primary textbook and the makeup of faculty who taught dermatopathology.3

Although residency programs vary in their methods of teaching this important component of dermatology, most use a multiheaded microscope in some capacity for didactics or sign-out. For most trainees, the dermatopathology laboratory is a new environment compared to the clinical space that medical students and residents become accustomed to throughout their education, thus creating a knowledge gap for trainees on proper dermatopathology etiquette and universal guidelines.

With medical students, residents, and fellows in mind, we have prepared a basic “dermatopathology etiquette” reference for trainees. Just as there are universal rules in the operating room for surgery (eg, sterile technique), we want to establish a code of conduct at the microscope. We hope that these 10 tips will, first, be useful to those who are unsure how to approach their first experience with dermatopathology and, second, serve as a guideline to aid development of appropriate communication skills and functioning within this novel setting. This list also can serve as a resource for dermatopathology attendings to provide to rotating residents and students.

1. New to pathology? It’s okay to ask. Do not hesitate to ask upper-year residents, fellows, and attendings for instructions on such matters as how to adjust your eyepiece to get the best resolution.

2. If a slide drops on the floor, do not move! Your first instinct might be to move your chair to look for the dropped slide, but you might roll over it and break it.

3. When the attending is looking through the scope, you look through the scope. Dermatopathology is a visual exercise. Getting in your “optic mileage” is best done under the guidance of an experienced dermatopathologist.

4. Rules regarding food and drink at the microscope vary by pathologist. It’s best to ask what each attending prefers. Safe advice is to avoid foods that make noise, such as chewing gum and chips, and food that has a strong odor, such as microwaved leftovers.

5. Limit use of a laptop, cell phone, and smartwatch. If you think that using any of these is necessary, it generally is best to announce that you are looking up something related to the case and then share your findings (but not the most recent post on your Facebook News Feed).

6. If you notice that something needs correcting on the report, speak up! We are all human; we all make typos. Do not hesitate to mention this as soon as possible, especially before the case is signed out. You will likely be thanked by your attending because it is harder to rectify once the report has been signed out.

7. Small talk often is welcome during large excisions. This is a great time to ask what others are doing next weekend or what happened in clinic earlier that day, or just to tell a good (clean) joke that is making the rounds. Conversely, if the case is complex, it often is best to wait until it is completed before asking questions.

8. When participating in a roundtable diagnosis, you are welcome to directly state the diagnosis for bread-and-butter cases, such as basal cell carcinomas and seborrheic keratoses. It is appropriate to be more descriptive and methodical in more complex cases. When evaluating a rash, give the general inflammatory pattern first. For example, is it spongiotic? Psoriasiform? Interface? Or a mixed pattern?

9. Extra points for identifying special sites! These include mucosal, genital, and acral sites. You might even get bonus points if you can determine something about the patient (child or adult) based on the pathologic features, such as variation in collagen patterns.

10. Whenever you are in doubt, just describe what you see. You can use the traditional top-down approach or start with stating the most evident finding, then proceed to a top-down description. If it is a neoplasm, describe the overall architecture; then, what you see at a cellular level will get you some points as well.

We acknowledge that this list of 10 tips is not comprehensive and might vary by attending and each institution’s distinctive training format. We are hopeful, however, that these 10 points of etiquette can serve as a guideline.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established core competencies to serve as a foundation for the training received in a dermatology residency program.1 Although programs are required to have the same concentrations—patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice—no specific guidelines are in place regarding how each of these competencies should be reached within a training period.2 Instead, it remains the responsibility of each program to formulate an individualized curriculum to facilitate proficiency in the multiple areas encompassed by a residency.

In many dermatology residency programs, dermatopathology is a substantial component of educational objectives and the curriculum.1 Residents may spend as much as 25% of their training on dermatopathology. However, there is great variability among programs in methods of teaching dermatopathology. When Hinshaw3 surveyed 52 of 109 dermatology residency programs, they identified differences in dermatopathology teaching that included, but was not limited to, utilization of problem-based learning (in 40.4% of programs), integration of journal reviews (53.8%), and computer-based learning (19.2%). In addition, differences were identified in the recommended primary textbook and the makeup of faculty who taught dermatopathology.3

Although residency programs vary in their methods of teaching this important component of dermatology, most use a multiheaded microscope in some capacity for didactics or sign-out. For most trainees, the dermatopathology laboratory is a new environment compared to the clinical space that medical students and residents become accustomed to throughout their education, thus creating a knowledge gap for trainees on proper dermatopathology etiquette and universal guidelines.

With medical students, residents, and fellows in mind, we have prepared a basic “dermatopathology etiquette” reference for trainees. Just as there are universal rules in the operating room for surgery (eg, sterile technique), we want to establish a code of conduct at the microscope. We hope that these 10 tips will, first, be useful to those who are unsure how to approach their first experience with dermatopathology and, second, serve as a guideline to aid development of appropriate communication skills and functioning within this novel setting. This list also can serve as a resource for dermatopathology attendings to provide to rotating residents and students.

1. New to pathology? It’s okay to ask. Do not hesitate to ask upper-year residents, fellows, and attendings for instructions on such matters as how to adjust your eyepiece to get the best resolution.

2. If a slide drops on the floor, do not move! Your first instinct might be to move your chair to look for the dropped slide, but you might roll over it and break it.

3. When the attending is looking through the scope, you look through the scope. Dermatopathology is a visual exercise. Getting in your “optic mileage” is best done under the guidance of an experienced dermatopathologist.

4. Rules regarding food and drink at the microscope vary by pathologist. It’s best to ask what each attending prefers. Safe advice is to avoid foods that make noise, such as chewing gum and chips, and food that has a strong odor, such as microwaved leftovers.

5. Limit use of a laptop, cell phone, and smartwatch. If you think that using any of these is necessary, it generally is best to announce that you are looking up something related to the case and then share your findings (but not the most recent post on your Facebook News Feed).

6. If you notice that something needs correcting on the report, speak up! We are all human; we all make typos. Do not hesitate to mention this as soon as possible, especially before the case is signed out. You will likely be thanked by your attending because it is harder to rectify once the report has been signed out.

7. Small talk often is welcome during large excisions. This is a great time to ask what others are doing next weekend or what happened in clinic earlier that day, or just to tell a good (clean) joke that is making the rounds. Conversely, if the case is complex, it often is best to wait until it is completed before asking questions.

8. When participating in a roundtable diagnosis, you are welcome to directly state the diagnosis for bread-and-butter cases, such as basal cell carcinomas and seborrheic keratoses. It is appropriate to be more descriptive and methodical in more complex cases. When evaluating a rash, give the general inflammatory pattern first. For example, is it spongiotic? Psoriasiform? Interface? Or a mixed pattern?

9. Extra points for identifying special sites! These include mucosal, genital, and acral sites. You might even get bonus points if you can determine something about the patient (child or adult) based on the pathologic features, such as variation in collagen patterns.

10. Whenever you are in doubt, just describe what you see. You can use the traditional top-down approach or start with stating the most evident finding, then proceed to a top-down description. If it is a neoplasm, describe the overall architecture; then, what you see at a cellular level will get you some points as well.

We acknowledge that this list of 10 tips is not comprehensive and might vary by attending and each institution’s distinctive training format. We are hopeful, however, that these 10 points of etiquette can serve as a guideline.

- Hinshaw M, Hsu P, Lee L-Y, et al. The current state of dermatopathology education: a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:620-628. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01128.x

- Hinshaw MA, Stratman EJ. Core competencies in dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:160-165. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00442.x

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826. doi:10.1016/j.det.2012.06.003

- Hinshaw M, Hsu P, Lee L-Y, et al. The current state of dermatopathology education: a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:620-628. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01128.x

- Hinshaw MA, Stratman EJ. Core competencies in dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:160-165. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00442.x

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826. doi:10.1016/j.det.2012.06.003

Violaceous Papule With an Erythematous Rim

The Diagnosis: Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma

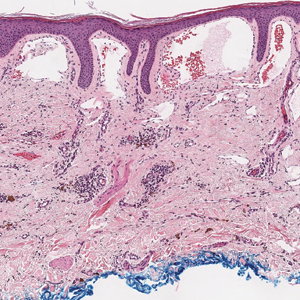

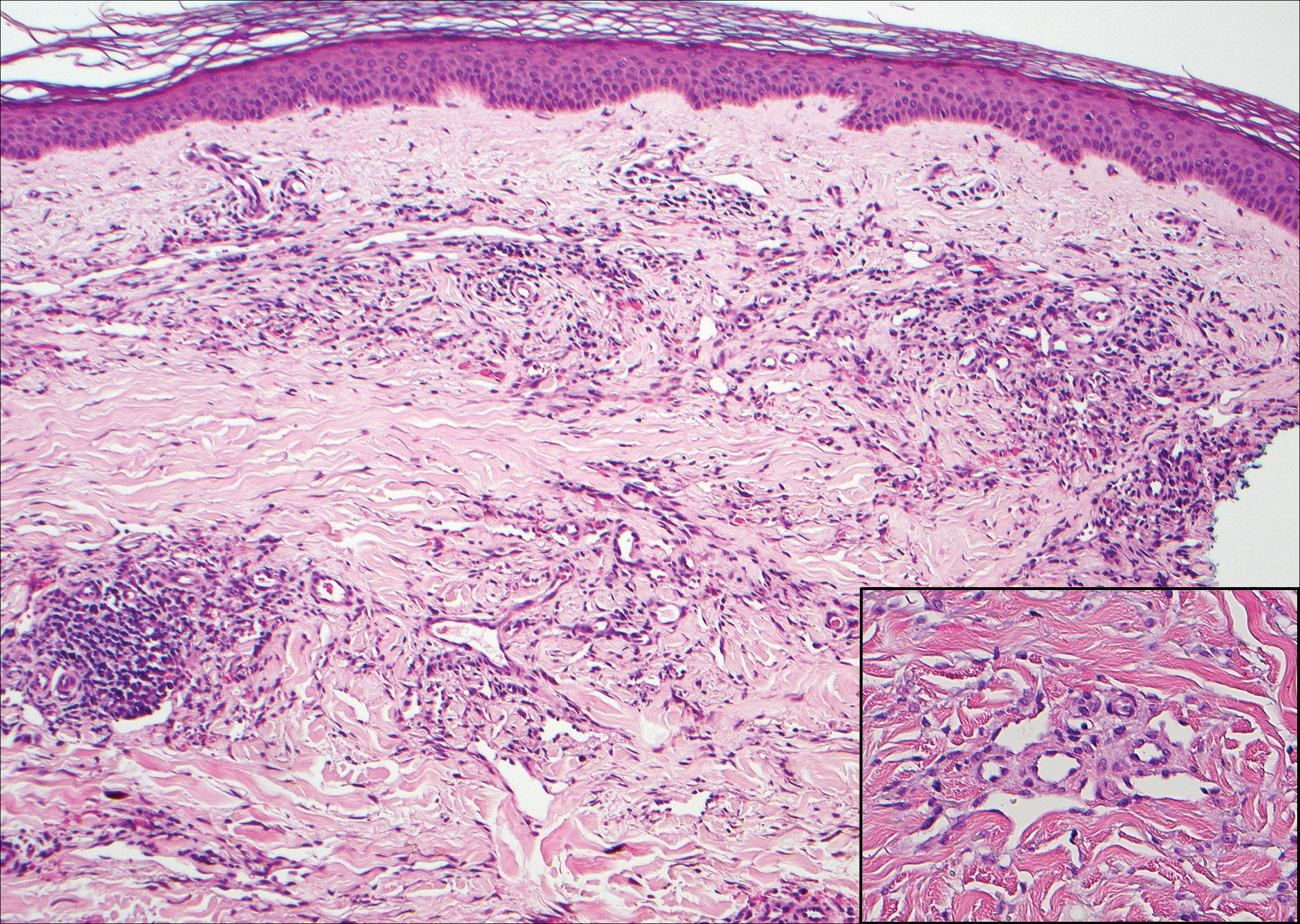

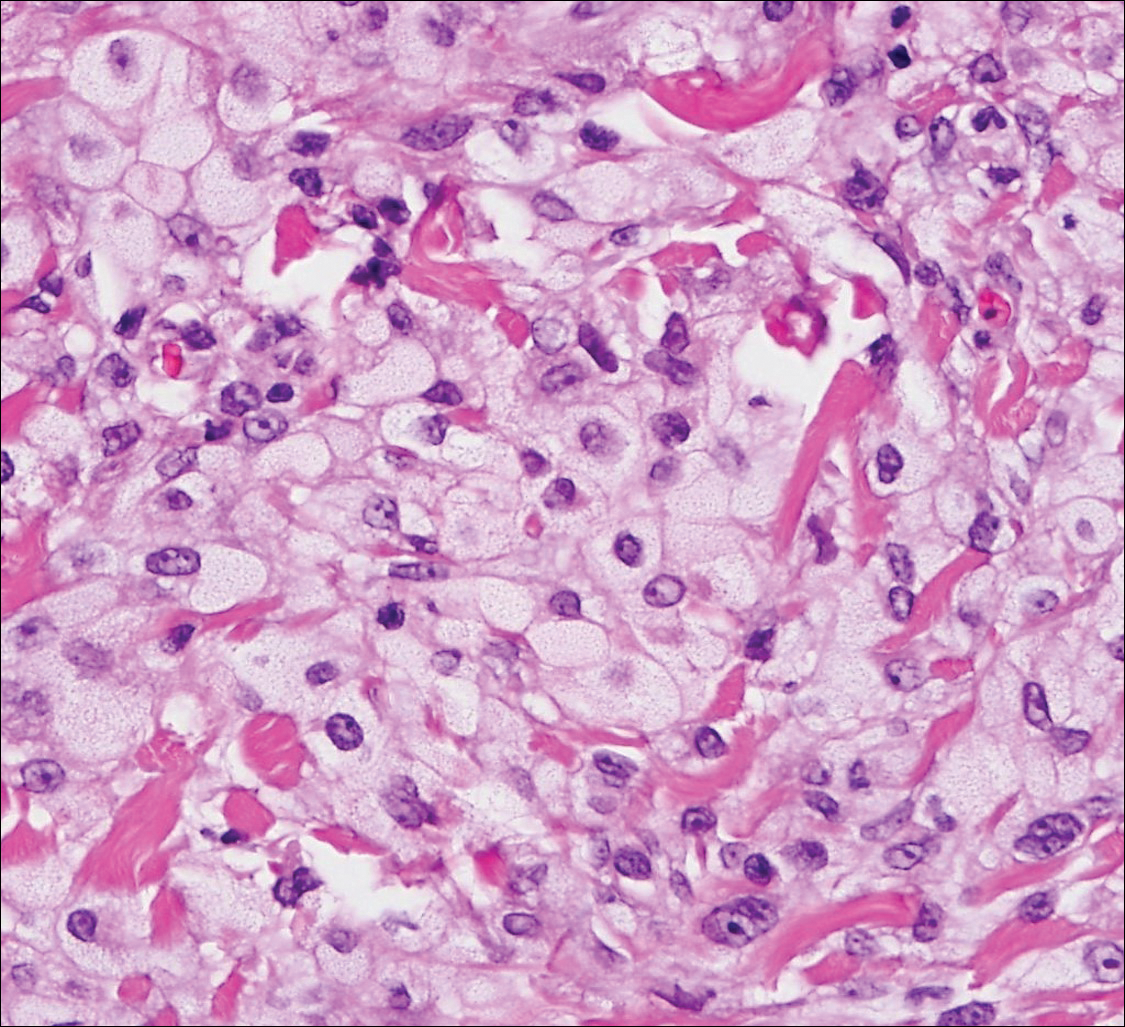

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma (THH), also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular tumor that usually occurs in young or middle-aged adults. It most commonly presents on the extremities or trunk as an isolated red-brown plaque or papule.1,2 Histologically, THH is characterized by superficial dilated ectatic vessels with underlying proliferating vascular channels lined by plump hobnail endothelial cells.1 Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma typically involves the dermis and spares the subcutis. The vascular channels may contain erythrocytes as well as pale eosinophilic lymph, as seen in our patient (quiz image). The deeper dermis contains vascular spaces that are more angulated and smaller and appear to be dissecting through the collagen bundles or collapsed.1,3 A variable amount of hemosiderin deposition and extravasated erythrocytes are seen.2,3 Histologic features evolve with the age of the lesion. Increasing amounts of hemosiderin deposition and erythrocyte extravasation may correspond histologically to the recent clinical color change reported by the patient.

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular abnormality that is characterized by dilated vessels in the papillary dermis along with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and irregular papillomatosis, as seen in angiokeratoma.4 However, the vascular proliferation composed of variably sized, thin-walled capillaries extends into the deep dermis as well as the subcutis (Figure 1). Verrucous hemangioma most commonly is reported on the legs and generally starts as a violaceous patch that progresses into a hyperkeratotic verrucous plaque or nodule.5,6

Angiokeratoma is characterized by superficial vascular ectasia of the papillary dermis in association with overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and rete elongation.7 The dilated vascular spaces appear encircled by the epidermis (Figure 2). Intravascular thrombosis can be seen within the ectatic vessels.7 In contrast to verrucous hemangioma, angiokeratoma is limited to the papillary dermis. Therefore, obtaining a biopsy of sufficient depth is necessary for differentiation.8 There are 5 clinical presentations of angiokeratoma: sporadic, angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry disease). Angiokeratomas may present on the lower extremities, tongue, trunk, and scrotum as hyperkeratotic, dark red to purple or black papules.7

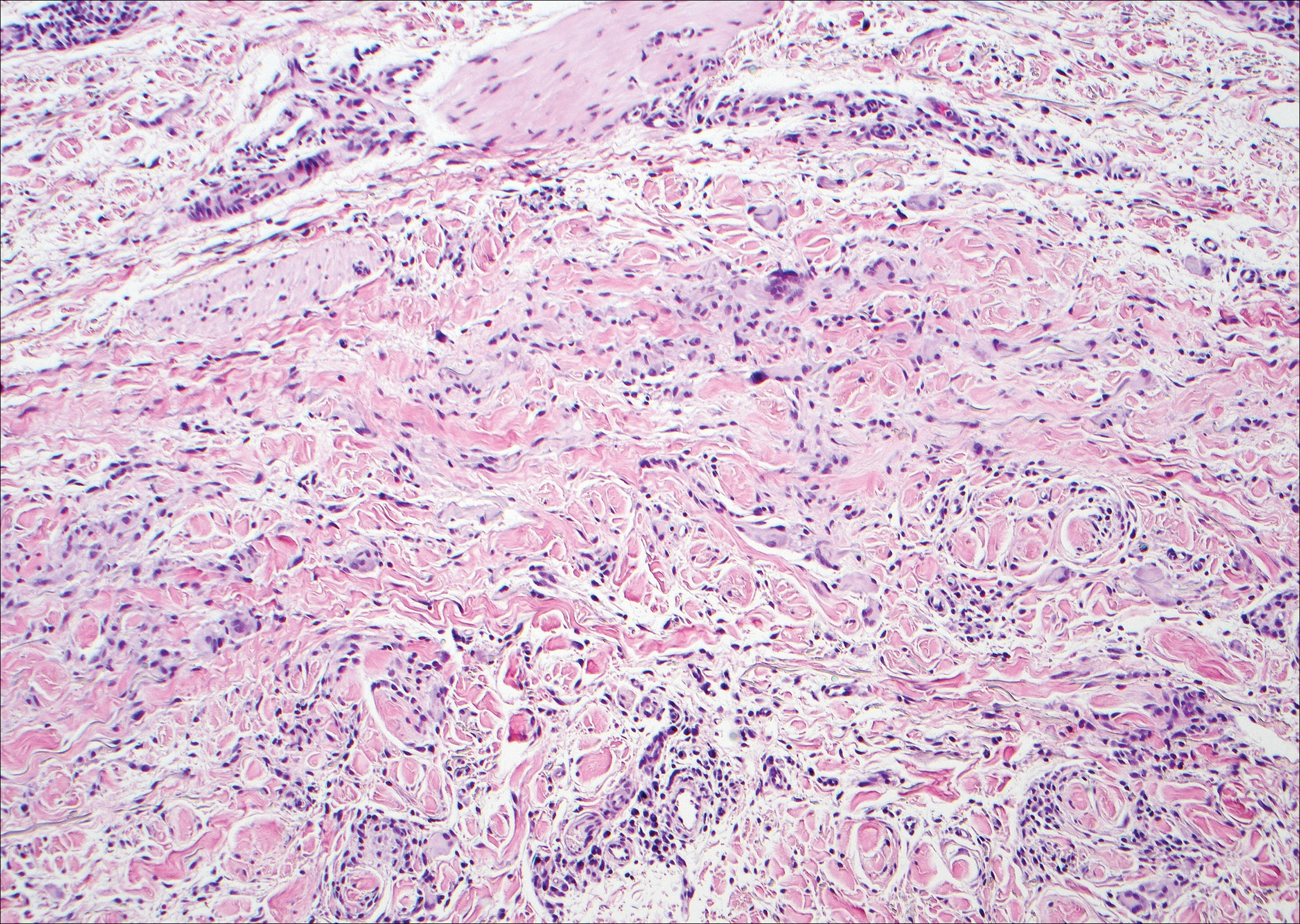

There are 3 clinical stages of Kaposi sarcoma: patch, plaque, and nodular stages. The patch stage is characterized histologically by vascular channels that dissect through the dermis and extend around native vessels (the promontory sign)(Figure 3).9,10 These features can show histologic overlap with THH. The plaque stage shows a more diffuse dermal vascular proliferation, increased cellularity of spindle cells, and possible extension into the subcutis.9,10 Focal plasma cells, hemosiderin, and extravasated red blood cells can be seen. The nodular stage is characterized by a proliferation of spindle cells with red blood cells squeezed between slitlike vascular spaces, hyaline globules, and scattered mitotic figures, but not atypical forms.10 In this stage, plasma cells and hemosiderin are more readily identifiable. A biopsy from the nodular stage is unlikely to enter the histologic differential diagnosis with THH. Clinically, there are 4 variants of Kaposi sarcoma: the classic or sporadic form, an endemic form, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated. Overall, it is more common in males and can occur at any age.10 Human herpesvirus 8 is seen in all forms, and infected cells can be highlighted by the immunohistochemical stain for latent nuclear antigen 1.9,10

Angiosarcoma is a malignant endothelial tumor of soft tissue, skin, bone, and visceral organs.11,12 Clinically, cutaneous angiosarcoma can present in a variety of ways, including single or multiple bluish red lesions that can ulcerate or bleed; violaceous nodules or plaques; and hematomalike lesions that can mimic epithelial neoplasms including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.11,13,14 The cutaneous lesions most commonly occur on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the face and scalp.12 Other clinical variants that are important to recognize are postradiation angiosarcoma, characterized by MYC gene amplification, and lymphedema-associated angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome). Angiosarcoma can have a variety of morphologic features, ranging from well to poorly differentiated. Classically, angiosarcoma is characterized by infiltrating vascular spaces lined by atypical endothelial cells (Figure 4). Poorly differentiated angiosarcoma can demonstrate spindle, epithelioid, or polygonal cells with increased mitotic activity, pleomorphism, and irregular vascular spaces.11 Endothelial markers such as ERG (erythroblast transformation specific-related gene)(nuclear) and CD31 (membranous) can be used to aid in the diagnosis of a poorly differentiated lesion. Epithelioid angiosarcoma also occasionally stains with cytokeratins.13,14

- Joyce JC, Keith PJ, Szabo S, et al. Superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation (hobnail hemangioma): a report of six cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:281-285.

- Sahin MT, Demir MA, Gunduz K, et al. Targetoid haemosiderotic haemangioma: dermoscopic monitoring of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:672-676.

- Kakizaki P, Valente NY, Paiva DL, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959.

- Oppermann K, Boff AL, Bonamigo RR. Verrucous hemangioma and histopathological differential diagnosis with angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:712-715.

- Boccara, O, Ariche-Maman, S, Hadj-Rabia, S, et al. Verrucous hemangioma (also known as verrucous venous malformation): a vascular anomaly frequently misdiagnosed as a lymphatic malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E378-E381.

- Mestre T, Amaro C, Freitas I. Verrucous haemangioma: a diagnosis to consider [published online June 4, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204612

- Ivy H, Julian CA. Angiokeratoma circumscriptum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549769/

- Shetty S, Geetha V, Rao R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: importance of a deeper biopsy. Indian J Dermatopathol Diagn Dermatol. 2014;1:99-100.

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Cancer, Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Papke DJ Jr, Hornick JL. What is new in endothelial neoplasia? Virchows Arch. 2020;476:17-28.

- Ambujam S, Audhya M, Reddy A, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head, neck, and face of the elderly in type 5 skin. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:45-47.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

The Diagnosis: Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma (THH), also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular tumor that usually occurs in young or middle-aged adults. It most commonly presents on the extremities or trunk as an isolated red-brown plaque or papule.1,2 Histologically, THH is characterized by superficial dilated ectatic vessels with underlying proliferating vascular channels lined by plump hobnail endothelial cells.1 Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma typically involves the dermis and spares the subcutis. The vascular channels may contain erythrocytes as well as pale eosinophilic lymph, as seen in our patient (quiz image). The deeper dermis contains vascular spaces that are more angulated and smaller and appear to be dissecting through the collagen bundles or collapsed.1,3 A variable amount of hemosiderin deposition and extravasated erythrocytes are seen.2,3 Histologic features evolve with the age of the lesion. Increasing amounts of hemosiderin deposition and erythrocyte extravasation may correspond histologically to the recent clinical color change reported by the patient.

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular abnormality that is characterized by dilated vessels in the papillary dermis along with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and irregular papillomatosis, as seen in angiokeratoma.4 However, the vascular proliferation composed of variably sized, thin-walled capillaries extends into the deep dermis as well as the subcutis (Figure 1). Verrucous hemangioma most commonly is reported on the legs and generally starts as a violaceous patch that progresses into a hyperkeratotic verrucous plaque or nodule.5,6

Angiokeratoma is characterized by superficial vascular ectasia of the papillary dermis in association with overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and rete elongation.7 The dilated vascular spaces appear encircled by the epidermis (Figure 2). Intravascular thrombosis can be seen within the ectatic vessels.7 In contrast to verrucous hemangioma, angiokeratoma is limited to the papillary dermis. Therefore, obtaining a biopsy of sufficient depth is necessary for differentiation.8 There are 5 clinical presentations of angiokeratoma: sporadic, angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry disease). Angiokeratomas may present on the lower extremities, tongue, trunk, and scrotum as hyperkeratotic, dark red to purple or black papules.7

There are 3 clinical stages of Kaposi sarcoma: patch, plaque, and nodular stages. The patch stage is characterized histologically by vascular channels that dissect through the dermis and extend around native vessels (the promontory sign)(Figure 3).9,10 These features can show histologic overlap with THH. The plaque stage shows a more diffuse dermal vascular proliferation, increased cellularity of spindle cells, and possible extension into the subcutis.9,10 Focal plasma cells, hemosiderin, and extravasated red blood cells can be seen. The nodular stage is characterized by a proliferation of spindle cells with red blood cells squeezed between slitlike vascular spaces, hyaline globules, and scattered mitotic figures, but not atypical forms.10 In this stage, plasma cells and hemosiderin are more readily identifiable. A biopsy from the nodular stage is unlikely to enter the histologic differential diagnosis with THH. Clinically, there are 4 variants of Kaposi sarcoma: the classic or sporadic form, an endemic form, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated. Overall, it is more common in males and can occur at any age.10 Human herpesvirus 8 is seen in all forms, and infected cells can be highlighted by the immunohistochemical stain for latent nuclear antigen 1.9,10

Angiosarcoma is a malignant endothelial tumor of soft tissue, skin, bone, and visceral organs.11,12 Clinically, cutaneous angiosarcoma can present in a variety of ways, including single or multiple bluish red lesions that can ulcerate or bleed; violaceous nodules or plaques; and hematomalike lesions that can mimic epithelial neoplasms including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.11,13,14 The cutaneous lesions most commonly occur on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the face and scalp.12 Other clinical variants that are important to recognize are postradiation angiosarcoma, characterized by MYC gene amplification, and lymphedema-associated angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome). Angiosarcoma can have a variety of morphologic features, ranging from well to poorly differentiated. Classically, angiosarcoma is characterized by infiltrating vascular spaces lined by atypical endothelial cells (Figure 4). Poorly differentiated angiosarcoma can demonstrate spindle, epithelioid, or polygonal cells with increased mitotic activity, pleomorphism, and irregular vascular spaces.11 Endothelial markers such as ERG (erythroblast transformation specific-related gene)(nuclear) and CD31 (membranous) can be used to aid in the diagnosis of a poorly differentiated lesion. Epithelioid angiosarcoma also occasionally stains with cytokeratins.13,14

The Diagnosis: Targetoid Hemosiderotic Hemangioma

Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma (THH), also known as hobnail hemangioma, is a benign vascular tumor that usually occurs in young or middle-aged adults. It most commonly presents on the extremities or trunk as an isolated red-brown plaque or papule.1,2 Histologically, THH is characterized by superficial dilated ectatic vessels with underlying proliferating vascular channels lined by plump hobnail endothelial cells.1 Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma typically involves the dermis and spares the subcutis. The vascular channels may contain erythrocytes as well as pale eosinophilic lymph, as seen in our patient (quiz image). The deeper dermis contains vascular spaces that are more angulated and smaller and appear to be dissecting through the collagen bundles or collapsed.1,3 A variable amount of hemosiderin deposition and extravasated erythrocytes are seen.2,3 Histologic features evolve with the age of the lesion. Increasing amounts of hemosiderin deposition and erythrocyte extravasation may correspond histologically to the recent clinical color change reported by the patient.

Verrucous hemangioma is a rare congenital vascular abnormality that is characterized by dilated vessels in the papillary dermis along with acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and irregular papillomatosis, as seen in angiokeratoma.4 However, the vascular proliferation composed of variably sized, thin-walled capillaries extends into the deep dermis as well as the subcutis (Figure 1). Verrucous hemangioma most commonly is reported on the legs and generally starts as a violaceous patch that progresses into a hyperkeratotic verrucous plaque or nodule.5,6

Angiokeratoma is characterized by superficial vascular ectasia of the papillary dermis in association with overlying acanthosis, hyperkeratosis, and rete elongation.7 The dilated vascular spaces appear encircled by the epidermis (Figure 2). Intravascular thrombosis can be seen within the ectatic vessels.7 In contrast to verrucous hemangioma, angiokeratoma is limited to the papillary dermis. Therefore, obtaining a biopsy of sufficient depth is necessary for differentiation.8 There are 5 clinical presentations of angiokeratoma: sporadic, angiokeratoma of Mibelli, angiokeratoma of Fordyce, angiokeratoma circumscriptum, and angiokeratoma corporis diffusum (Fabry disease). Angiokeratomas may present on the lower extremities, tongue, trunk, and scrotum as hyperkeratotic, dark red to purple or black papules.7

There are 3 clinical stages of Kaposi sarcoma: patch, plaque, and nodular stages. The patch stage is characterized histologically by vascular channels that dissect through the dermis and extend around native vessels (the promontory sign)(Figure 3).9,10 These features can show histologic overlap with THH. The plaque stage shows a more diffuse dermal vascular proliferation, increased cellularity of spindle cells, and possible extension into the subcutis.9,10 Focal plasma cells, hemosiderin, and extravasated red blood cells can be seen. The nodular stage is characterized by a proliferation of spindle cells with red blood cells squeezed between slitlike vascular spaces, hyaline globules, and scattered mitotic figures, but not atypical forms.10 In this stage, plasma cells and hemosiderin are more readily identifiable. A biopsy from the nodular stage is unlikely to enter the histologic differential diagnosis with THH. Clinically, there are 4 variants of Kaposi sarcoma: the classic or sporadic form, an endemic form, iatrogenic, and AIDS associated. Overall, it is more common in males and can occur at any age.10 Human herpesvirus 8 is seen in all forms, and infected cells can be highlighted by the immunohistochemical stain for latent nuclear antigen 1.9,10

Angiosarcoma is a malignant endothelial tumor of soft tissue, skin, bone, and visceral organs.11,12 Clinically, cutaneous angiosarcoma can present in a variety of ways, including single or multiple bluish red lesions that can ulcerate or bleed; violaceous nodules or plaques; and hematomalike lesions that can mimic epithelial neoplasms including squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, and malignant melanoma.11,13,14 The cutaneous lesions most commonly occur on sun-exposed skin, particularly on the face and scalp.12 Other clinical variants that are important to recognize are postradiation angiosarcoma, characterized by MYC gene amplification, and lymphedema-associated angiosarcoma (Stewart-Treves syndrome). Angiosarcoma can have a variety of morphologic features, ranging from well to poorly differentiated. Classically, angiosarcoma is characterized by infiltrating vascular spaces lined by atypical endothelial cells (Figure 4). Poorly differentiated angiosarcoma can demonstrate spindle, epithelioid, or polygonal cells with increased mitotic activity, pleomorphism, and irregular vascular spaces.11 Endothelial markers such as ERG (erythroblast transformation specific-related gene)(nuclear) and CD31 (membranous) can be used to aid in the diagnosis of a poorly differentiated lesion. Epithelioid angiosarcoma also occasionally stains with cytokeratins.13,14

- Joyce JC, Keith PJ, Szabo S, et al. Superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation (hobnail hemangioma): a report of six cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:281-285.

- Sahin MT, Demir MA, Gunduz K, et al. Targetoid haemosiderotic haemangioma: dermoscopic monitoring of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:672-676.

- Kakizaki P, Valente NY, Paiva DL, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959.

- Oppermann K, Boff AL, Bonamigo RR. Verrucous hemangioma and histopathological differential diagnosis with angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:712-715.

- Boccara, O, Ariche-Maman, S, Hadj-Rabia, S, et al. Verrucous hemangioma (also known as verrucous venous malformation): a vascular anomaly frequently misdiagnosed as a lymphatic malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E378-E381.

- Mestre T, Amaro C, Freitas I. Verrucous haemangioma: a diagnosis to consider [published online June 4, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204612

- Ivy H, Julian CA. Angiokeratoma circumscriptum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549769/

- Shetty S, Geetha V, Rao R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: importance of a deeper biopsy. Indian J Dermatopathol Diagn Dermatol. 2014;1:99-100.

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Cancer, Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Papke DJ Jr, Hornick JL. What is new in endothelial neoplasia? Virchows Arch. 2020;476:17-28.

- Ambujam S, Audhya M, Reddy A, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head, neck, and face of the elderly in type 5 skin. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:45-47.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

- Joyce JC, Keith PJ, Szabo S, et al. Superficial hemosiderotic lymphovascular malformation (hobnail hemangioma): a report of six cases. Pediatr Dermatol. 2014;31:281-285.

- Sahin MT, Demir MA, Gunduz K, et al. Targetoid haemosiderotic haemangioma: dermoscopic monitoring of three cases and review of the literature. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:672-676.

- Kakizaki P, Valente NY, Paiva DL, et al. Targetoid hemosiderotic hemangioma--case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2014;89:956-959.

- Oppermann K, Boff AL, Bonamigo RR. Verrucous hemangioma and histopathological differential diagnosis with angiokeratoma circumscriptum neviforme. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:712-715.

- Boccara, O, Ariche-Maman, S, Hadj-Rabia, S, et al. Verrucous hemangioma (also known as verrucous venous malformation): a vascular anomaly frequently misdiagnosed as a lymphatic malformation. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:E378-E381.

- Mestre T, Amaro C, Freitas I. Verrucous haemangioma: a diagnosis to consider [published online June 4, 2014]. BMJ Case Rep. doi:10.1136/bcr-2014-204612

- Ivy H, Julian CA. Angiokeratoma circumscriptum. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549769/

- Shetty S, Geetha V, Rao R, et al. Verrucous hemangioma: importance of a deeper biopsy. Indian J Dermatopathol Diagn Dermatol. 2014;1:99-100.

- Bishop BN, Lynch DT. Cancer, Kaposi sarcoma. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2019. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534839/

- Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

- Cao J, Wang J, He C, et al. Angiosarcoma: a review of diagnosis and current treatment. Am J Cancer Res. 2019;9:2303-2313.

- Papke DJ Jr, Hornick JL. What is new in endothelial neoplasia? Virchows Arch. 2020;476:17-28.

- Ambujam S, Audhya M, Reddy A, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma of the head, neck, and face of the elderly in type 5 skin. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2013;6:45-47.

- Shustef E, Kazlouskaya V, Prieto VG, et al. Cutaneous angiosarcoma: a current update. J Clin Pathol. 2017;70:917-925.

A 35-year-old man presented with a reddish brown papule on the left upper chest of 1 year’s duration that had changed color to reddish purple. Physical examination revealed a 6-mm violaceous papule with an erythematous rim.

Distinct Violaceous Plaques in Conjunction With Blisters

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6

The pathogenesis of LPP is not fully understood but likely represents a distinct entity rather than a subtype of BP or the simultaneous occurrence of LP and BP. Lichen planus pemphigoides generally has an earlier onset and better treatment response compared to BP.7 Further, autoantibodies in patients with LPP react to a novel epitope within the C-terminal portion of the BP-180 NC16A domain. Accordingly, it has been postulated that an inflammatory cutaneous process resulting from infection, phototherapy, or LP itself leads to damage of the epidermis and triggers a secondary blistering autoimmune dermatosis mediated by antibody formation against basement membrane (BM) antigens, such as BP-180.7

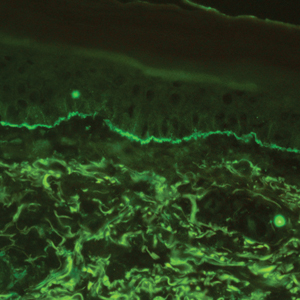

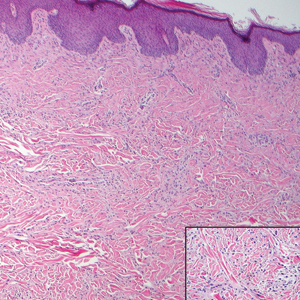

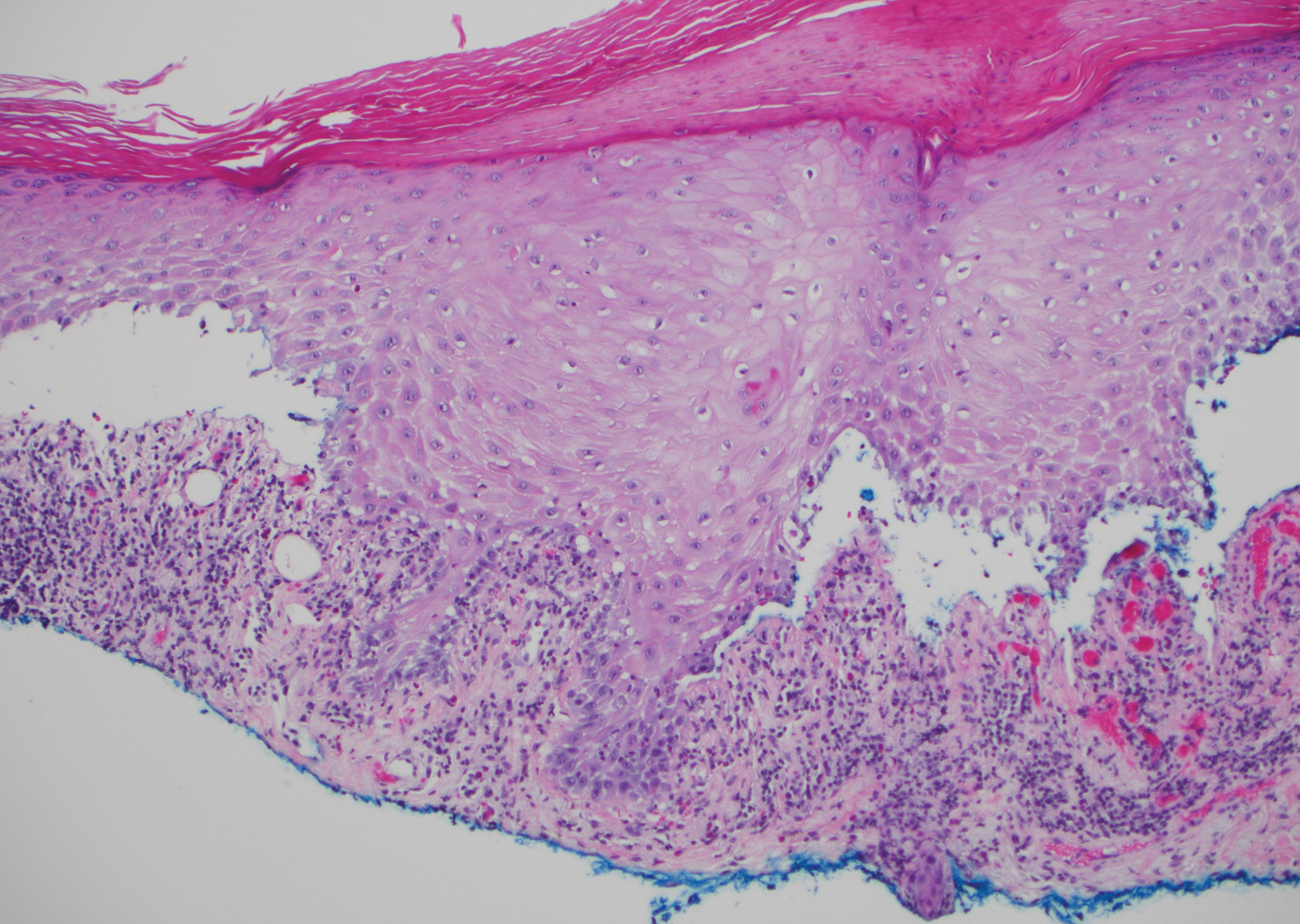

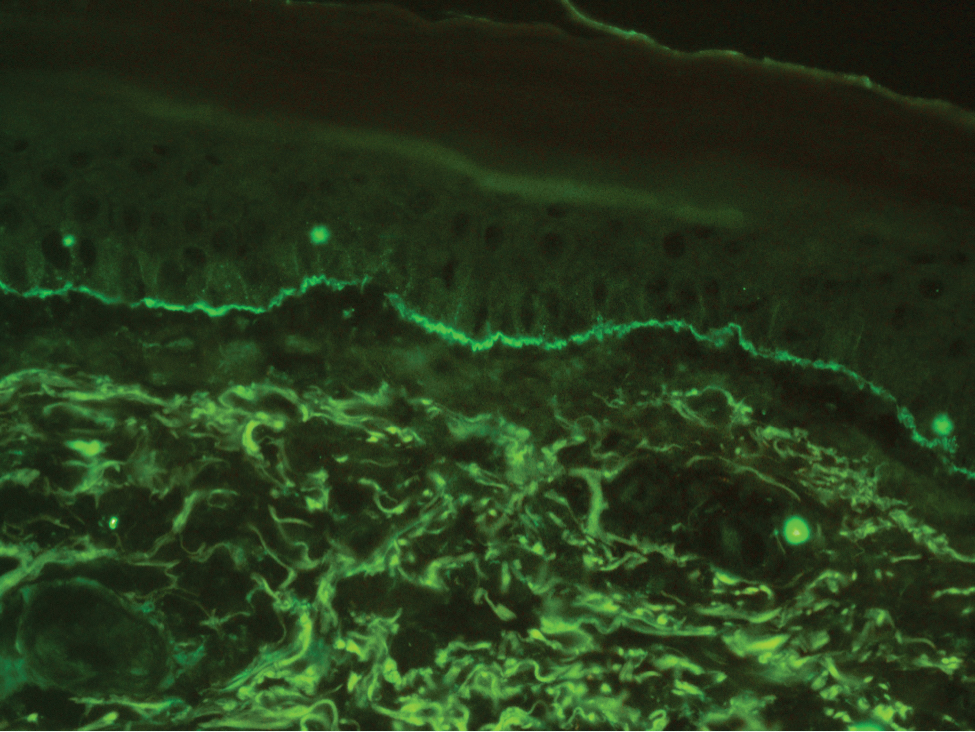

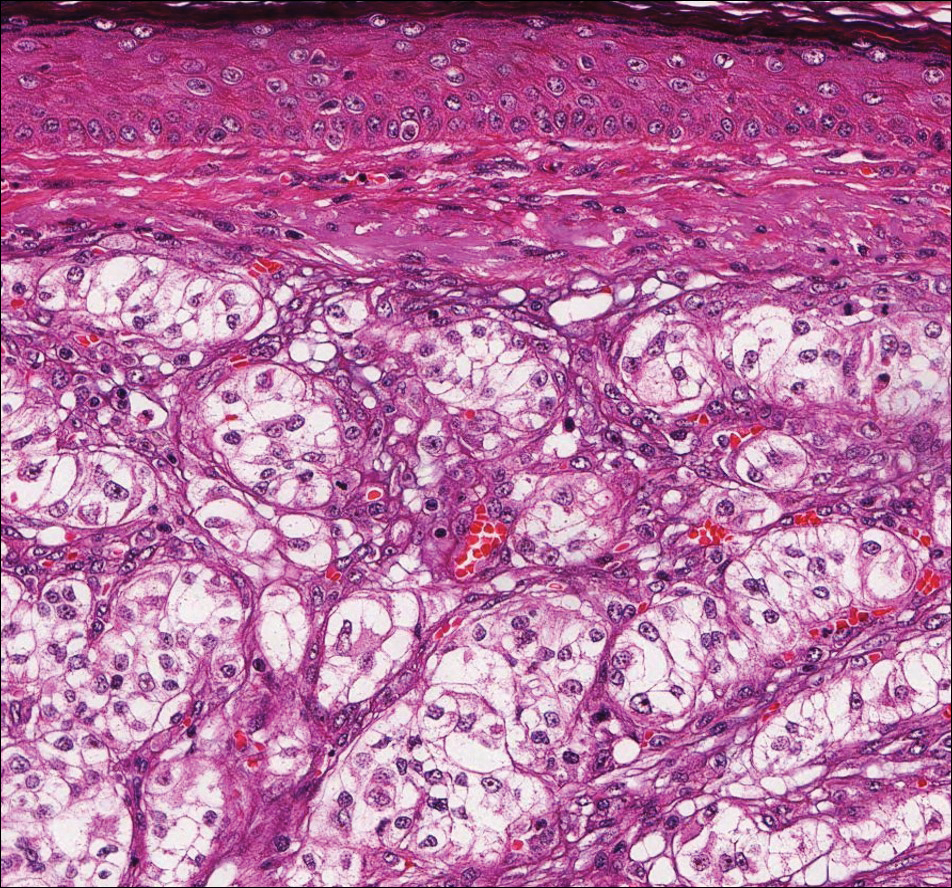

The diagnosis of LPP ultimately is confirmed with immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of LPP shows findings consistent with both LP and BP (quiz image [top]). In the lichenoid portion, biopsy reveals orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis; a bandlike infiltrate consisting primarily of lymphocytes in the upper dermis; and apoptotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).1 Biopsy of bullae reveals eosinophilic spongiosis, a subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils, and a mixed superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or C3 at the DEJ (quiz image [bottom]).1 Measurement of anti-BM antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230 can be useful in suspected cases, as 50% to 60% of patients have circulating antibodies against these antigens.6 Remission usually is achieved with topical and systemic corticosteroids and/or steroid-sparing agents, with rare recurrence following lesion resolution.1 More recently, successful treatment with biologics such as ustekinumab has been reported.8

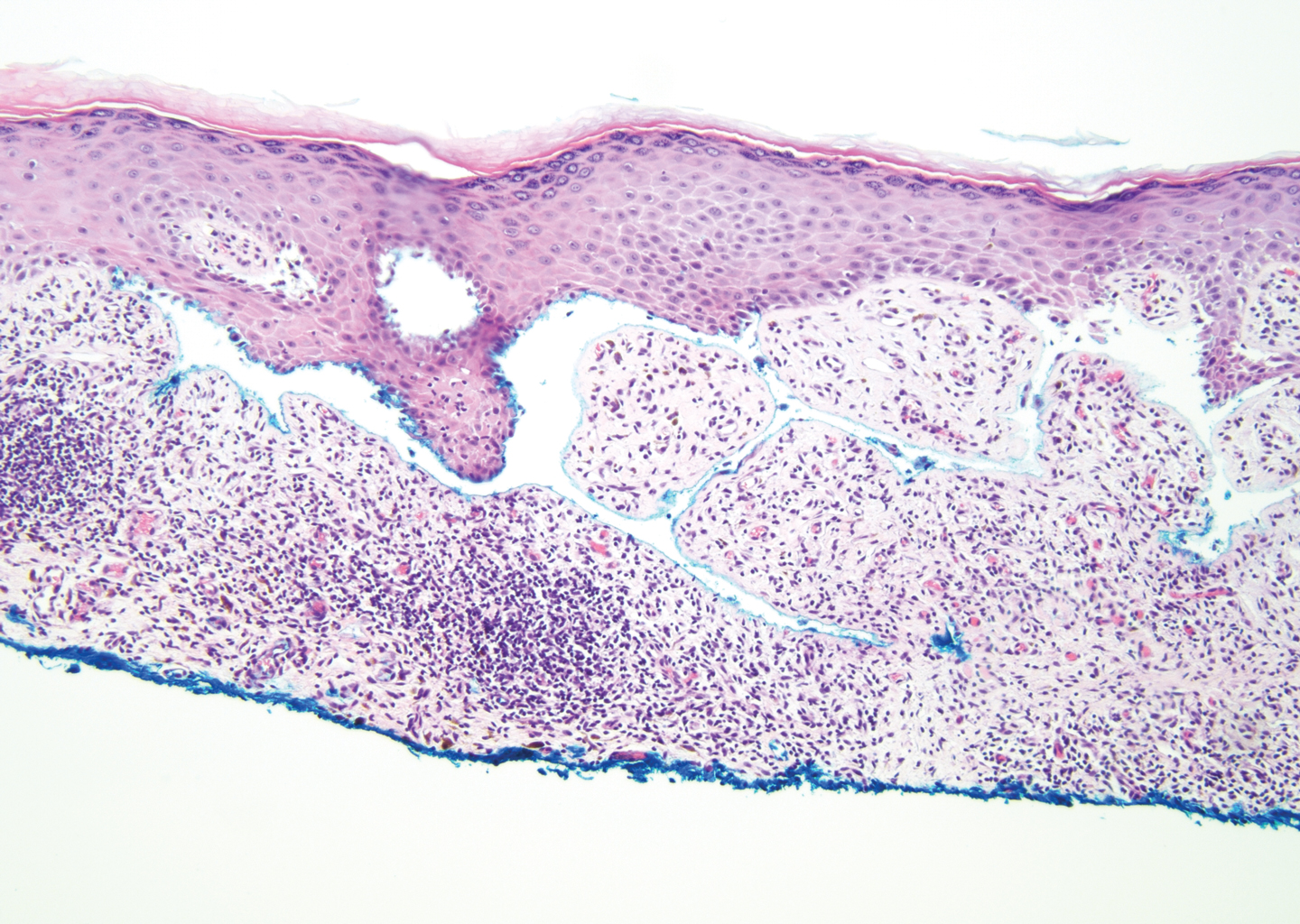

The predominant differential diagnosis for LPP is bullous LP, a variant of LP in which vesiculobullous disease occurs exclusively on preexisting LP lesions, commonly on the legs due to severe vacuolar degeneration at the DEJ. On histopathology, the characteristic features of LP (eg, orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies) along with subepidermal clefting will be seen. However, in bullous LP (Figure 1) there is an absence of linear IgG and/or C3 deposition at the DEJ on direct immunofluorescence. Furthermore, patients lack circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230.9

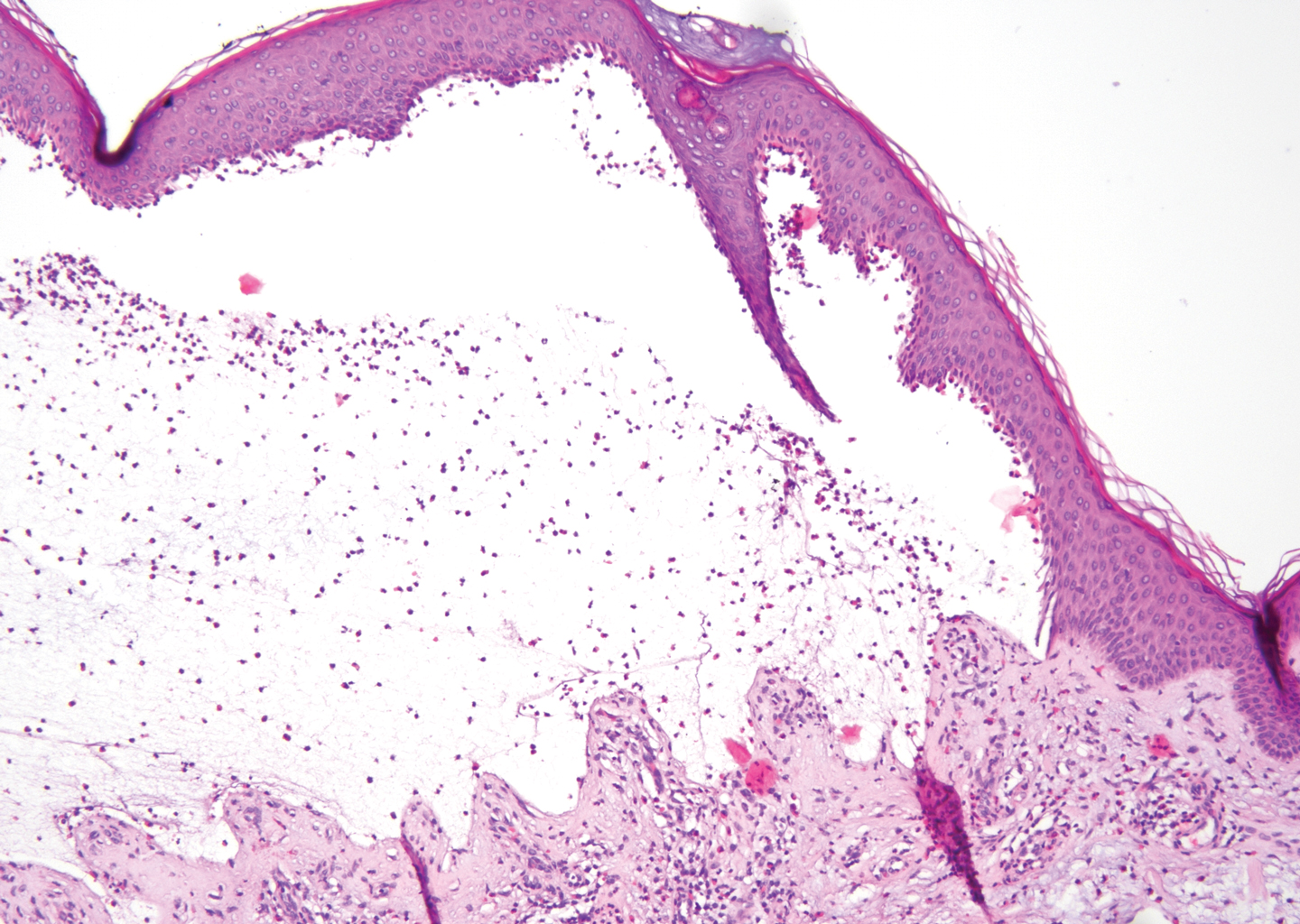

Lichen planus pemphigoides also can be confused with BP. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disorder; typically arises in older adults; and is caused by autoantibody formation against hemidesmosomal proteins, particularly BP-180 and BP-230. Patients classically present with tense bullae and erosions on an erythematous, urticarial, or normal base. These lesions often are pruritic and concentrated on the trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and extremity flexures. Histopathologic examination of a bulla edge reveals the classic findings seen in BP (eg, eosinophilic spongiosis, subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils)(Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin reveals linear IgG and/or C3 deposition along the DEJ. A large subset of patients also has circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230. In contrast to LPP, however, patients with BP do not develop lichenoid lesions clinically or a lichenoid tissue reaction histopathologically.10

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a rare cutaneous manifestation of SLE, typically arises in young women of African descent and is due to autoantibody formation against type VII collagen and other BM-zone antigens. Patients generally present with acute onset of tense vesiculobullae on a normal or erythematous base, which often are transient and heal without milia or scarring. Common sites of involvement include the trunk, arms, neck, face, and vermilion border, as well as the oral mucosa. The diagnosis of bullous SLE requires that patients fulfill the criteria for SLE and is confirmed by immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of a bulla edge reveals a subepidermal blister containing neutrophils and increased mucin within the reticular dermis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin most commonly reveals linear and/or granular deposition of IgG, IgA, C3, and IgM at the DEJ.11

Bullous tinea is a manifestation of cutaneous dermatophytosis that usually occurs in the setting of tinea pedis. Common causative dermatophytes include Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungal hyphae on potassium hydroxide preparation of the blister roof, biopsy with periodic acid-Schiff stain, or fungal culture. If routine histopathologic analysis is performed, epidermal spongiosis with varying degrees of papillary dermal edema is seen, along with abundant fungal elements in the stratum corneum (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin usually is negative, but C3 deposition in a linear and/or granular pattern along the DEJ has been reported.12

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare disease entity and often presents a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. The differential for LPP includes bullous LP as well as other bullous disorders. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed through immunohistologic analysis. Timely diagnosis of LPP is crucial, as most patients can achieve long-term remission with appropriate treatment.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Mohanarao TS, Kumar GA, Chennamsetty K, et al. Childhood lichen planus pemphigoides triggered by chickenpox. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:S98-S100.

- Onprasert W, Chanprapaph K. Lichen planus pemphigoides induced by enalapril: a case report and a review of literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:217-224.

- Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, et al. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509-512.

- Shimada H, Shono T, Sakai T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides concomitant with rectal adenocarcinoma: fortuitous or a true association? Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:501-503.

- Matos-Pires E, Campos S, Lencastre A, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:335-337.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Wagner G, Rose C, Sachse MM. Clinical variants of lichen planus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:309-319.

- Bagci IS, Horvath ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445-455.

- Contestable JJ, Edhegard KD, Meyerle JH. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:517-524.

- Miller DD, Bhawan J. Bullous tinea pedis with direct immunofluorescence positivity: when is a positive result not autoimmune bullous disease? Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:587-594.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6

The pathogenesis of LPP is not fully understood but likely represents a distinct entity rather than a subtype of BP or the simultaneous occurrence of LP and BP. Lichen planus pemphigoides generally has an earlier onset and better treatment response compared to BP.7 Further, autoantibodies in patients with LPP react to a novel epitope within the C-terminal portion of the BP-180 NC16A domain. Accordingly, it has been postulated that an inflammatory cutaneous process resulting from infection, phototherapy, or LP itself leads to damage of the epidermis and triggers a secondary blistering autoimmune dermatosis mediated by antibody formation against basement membrane (BM) antigens, such as BP-180.7

The diagnosis of LPP ultimately is confirmed with immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of LPP shows findings consistent with both LP and BP (quiz image [top]). In the lichenoid portion, biopsy reveals orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis; a bandlike infiltrate consisting primarily of lymphocytes in the upper dermis; and apoptotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).1 Biopsy of bullae reveals eosinophilic spongiosis, a subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils, and a mixed superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or C3 at the DEJ (quiz image [bottom]).1 Measurement of anti-BM antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230 can be useful in suspected cases, as 50% to 60% of patients have circulating antibodies against these antigens.6 Remission usually is achieved with topical and systemic corticosteroids and/or steroid-sparing agents, with rare recurrence following lesion resolution.1 More recently, successful treatment with biologics such as ustekinumab has been reported.8

The predominant differential diagnosis for LPP is bullous LP, a variant of LP in which vesiculobullous disease occurs exclusively on preexisting LP lesions, commonly on the legs due to severe vacuolar degeneration at the DEJ. On histopathology, the characteristic features of LP (eg, orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies) along with subepidermal clefting will be seen. However, in bullous LP (Figure 1) there is an absence of linear IgG and/or C3 deposition at the DEJ on direct immunofluorescence. Furthermore, patients lack circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230.9

Lichen planus pemphigoides also can be confused with BP. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disorder; typically arises in older adults; and is caused by autoantibody formation against hemidesmosomal proteins, particularly BP-180 and BP-230. Patients classically present with tense bullae and erosions on an erythematous, urticarial, or normal base. These lesions often are pruritic and concentrated on the trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and extremity flexures. Histopathologic examination of a bulla edge reveals the classic findings seen in BP (eg, eosinophilic spongiosis, subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils)(Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin reveals linear IgG and/or C3 deposition along the DEJ. A large subset of patients also has circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230. In contrast to LPP, however, patients with BP do not develop lichenoid lesions clinically or a lichenoid tissue reaction histopathologically.10

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a rare cutaneous manifestation of SLE, typically arises in young women of African descent and is due to autoantibody formation against type VII collagen and other BM-zone antigens. Patients generally present with acute onset of tense vesiculobullae on a normal or erythematous base, which often are transient and heal without milia or scarring. Common sites of involvement include the trunk, arms, neck, face, and vermilion border, as well as the oral mucosa. The diagnosis of bullous SLE requires that patients fulfill the criteria for SLE and is confirmed by immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of a bulla edge reveals a subepidermal blister containing neutrophils and increased mucin within the reticular dermis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin most commonly reveals linear and/or granular deposition of IgG, IgA, C3, and IgM at the DEJ.11

Bullous tinea is a manifestation of cutaneous dermatophytosis that usually occurs in the setting of tinea pedis. Common causative dermatophytes include Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungal hyphae on potassium hydroxide preparation of the blister roof, biopsy with periodic acid-Schiff stain, or fungal culture. If routine histopathologic analysis is performed, epidermal spongiosis with varying degrees of papillary dermal edema is seen, along with abundant fungal elements in the stratum corneum (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin usually is negative, but C3 deposition in a linear and/or granular pattern along the DEJ has been reported.12

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare disease entity and often presents a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. The differential for LPP includes bullous LP as well as other bullous disorders. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed through immunohistologic analysis. Timely diagnosis of LPP is crucial, as most patients can achieve long-term remission with appropriate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6