User login

Perceived Benefits of a Research Fellowship for Dermatology Residency Applicants: Outcomes of a Faculty-Reported Survey

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

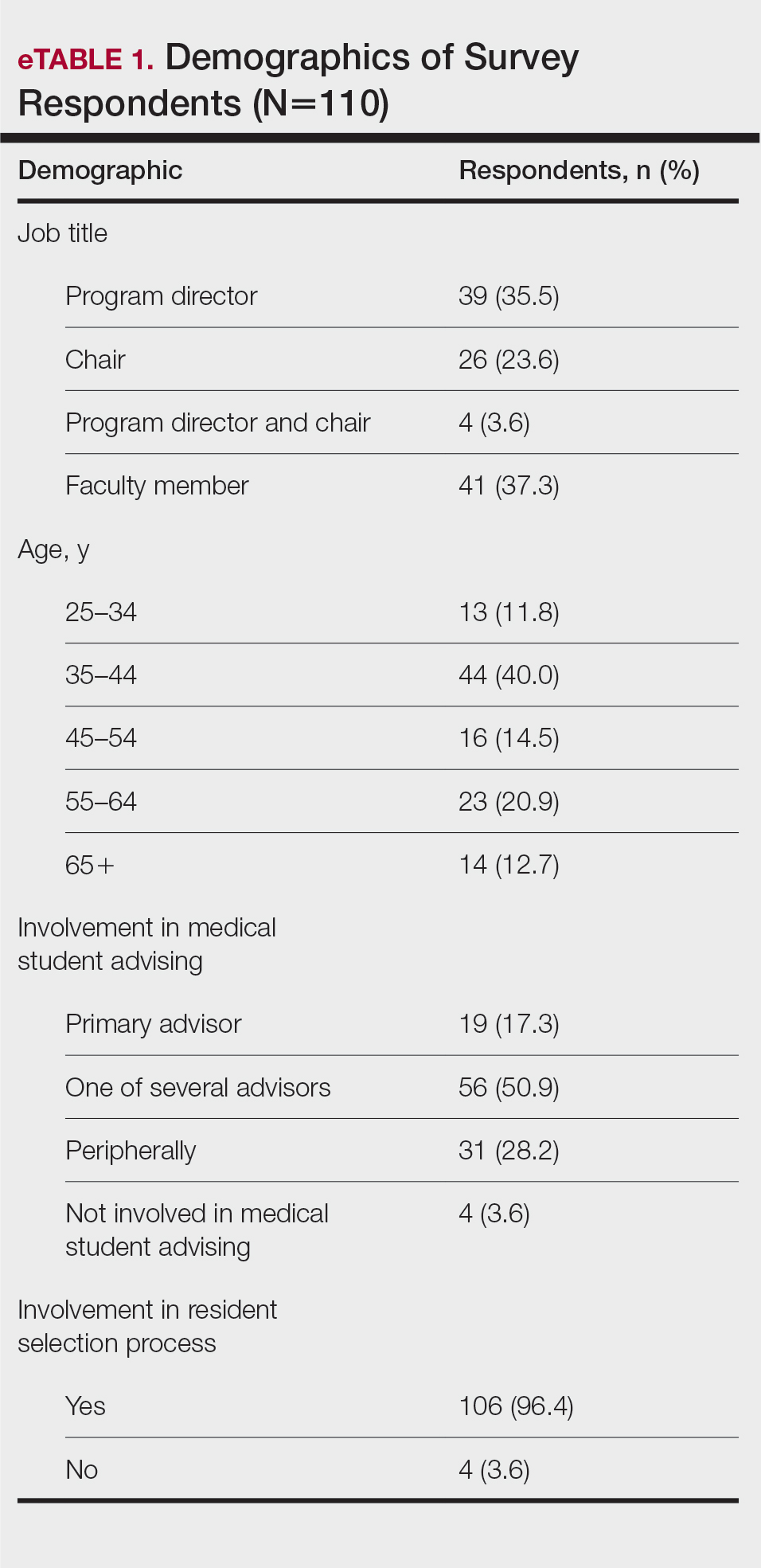

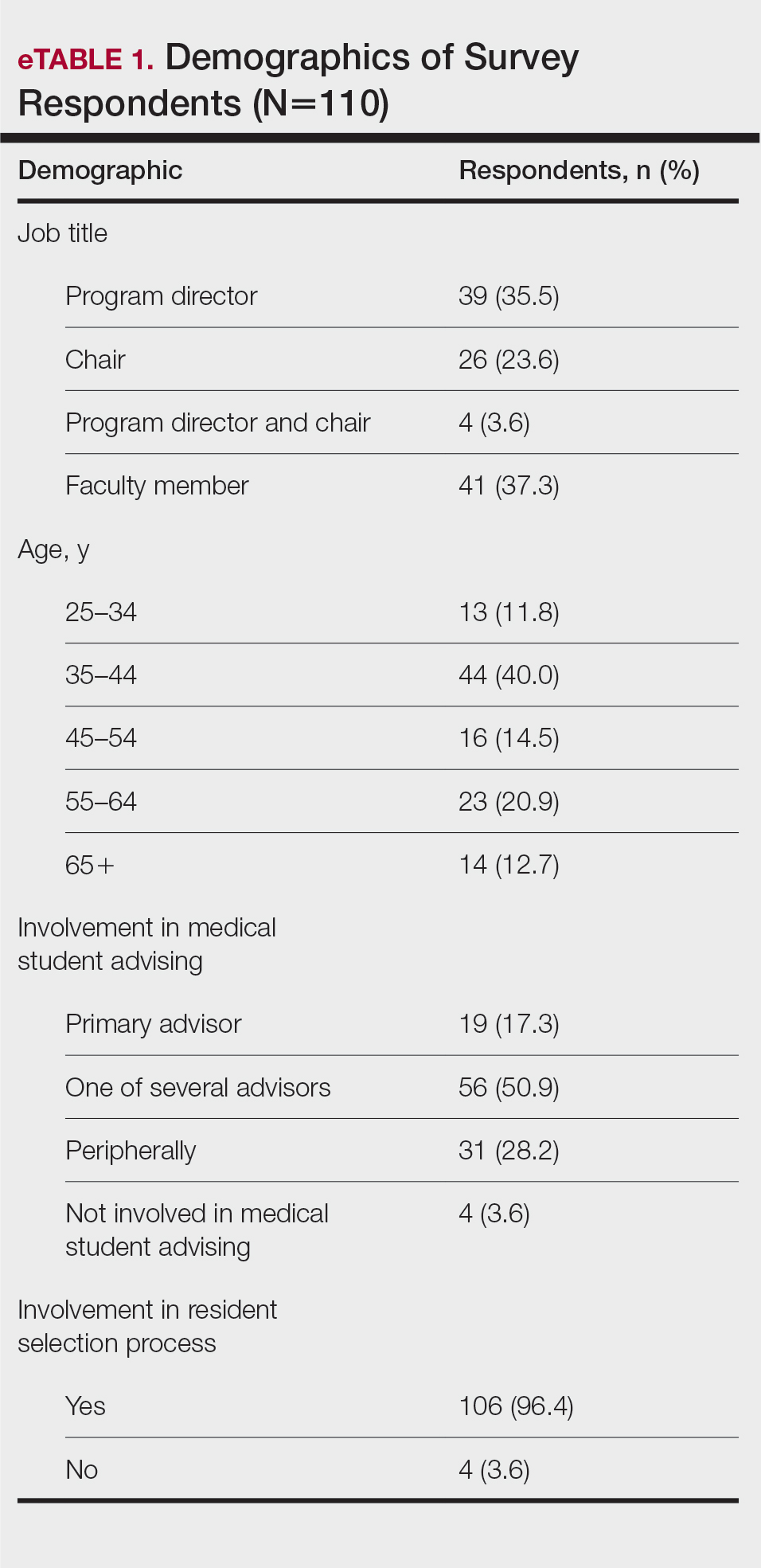

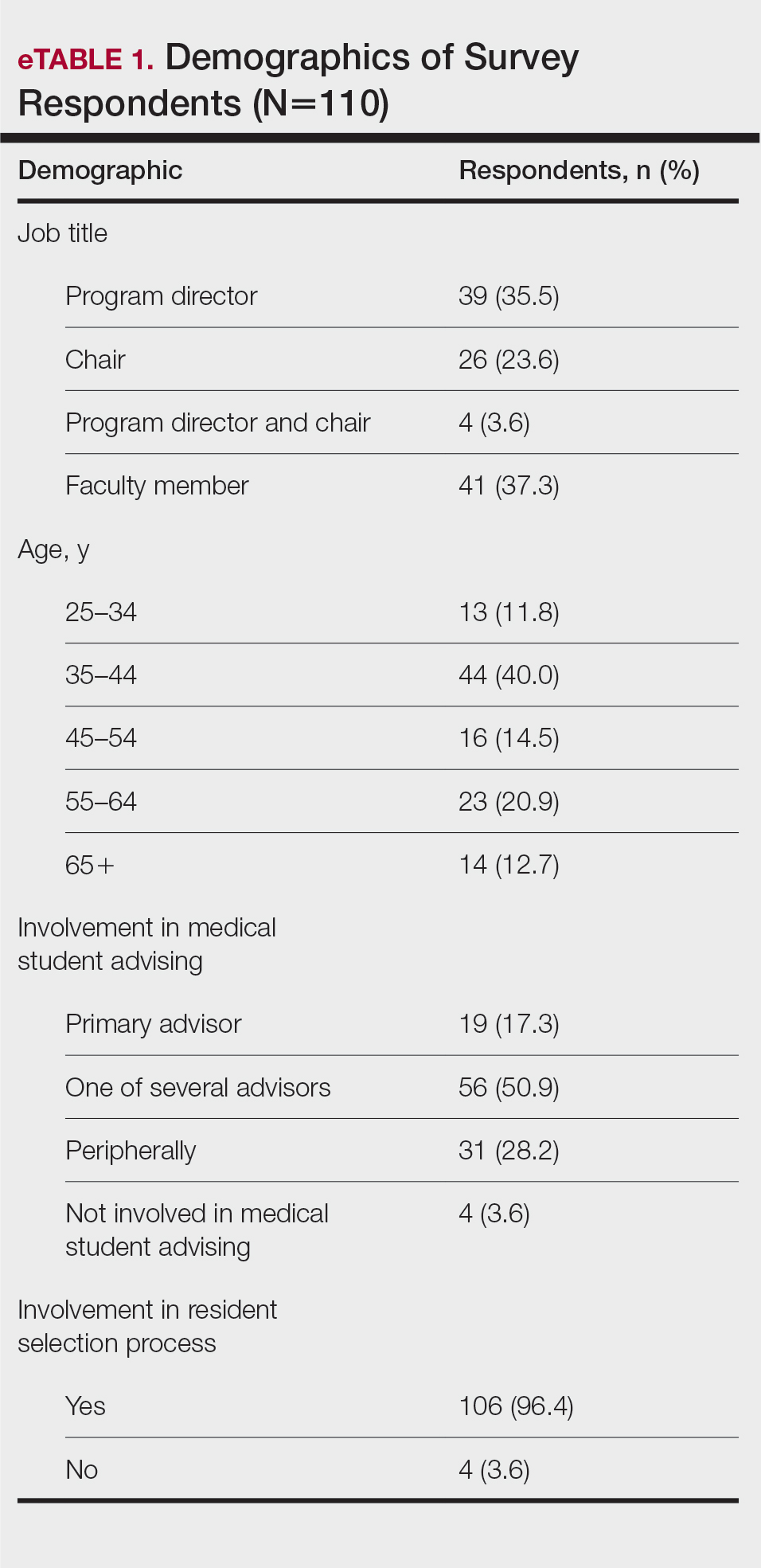

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

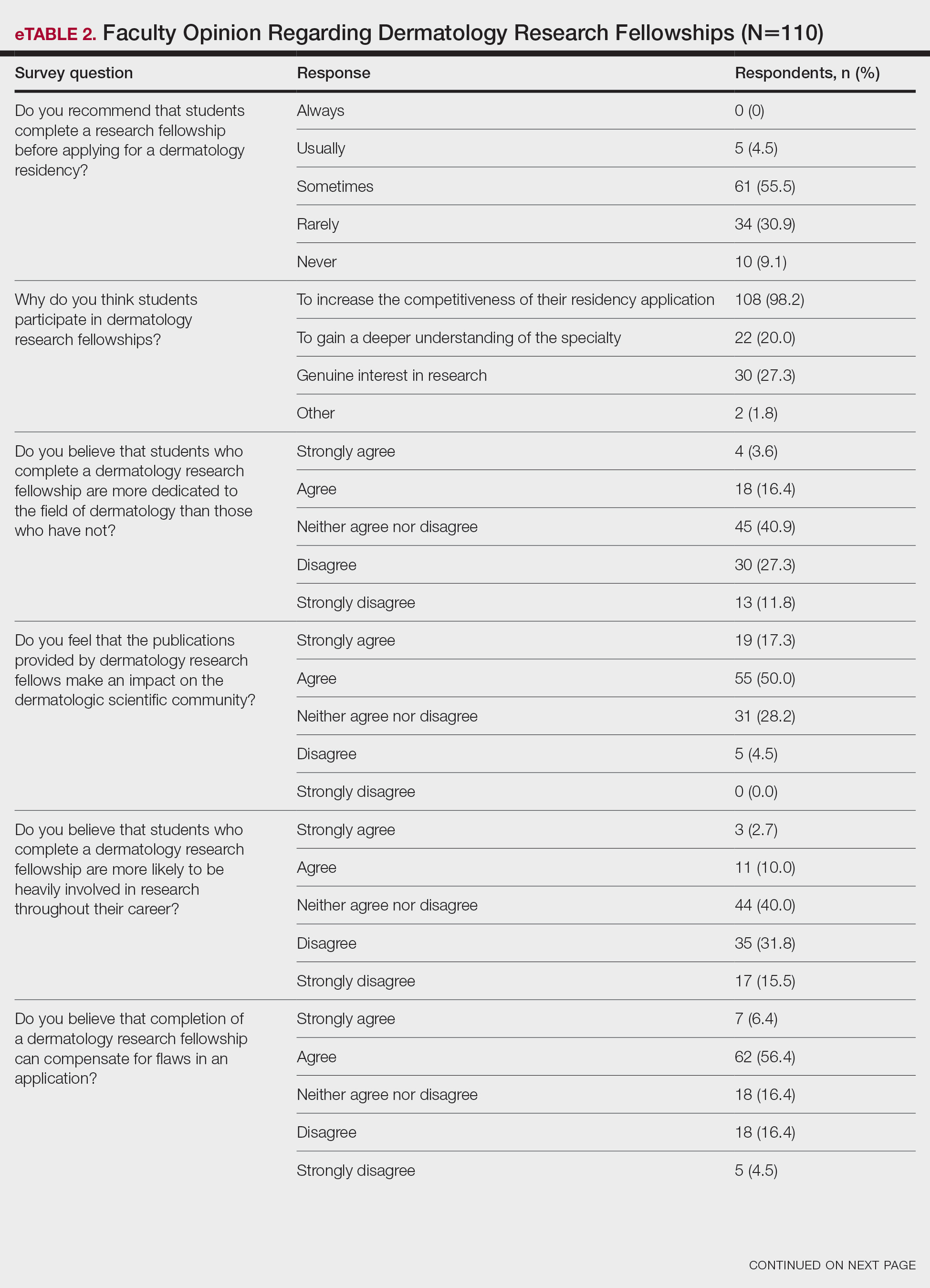

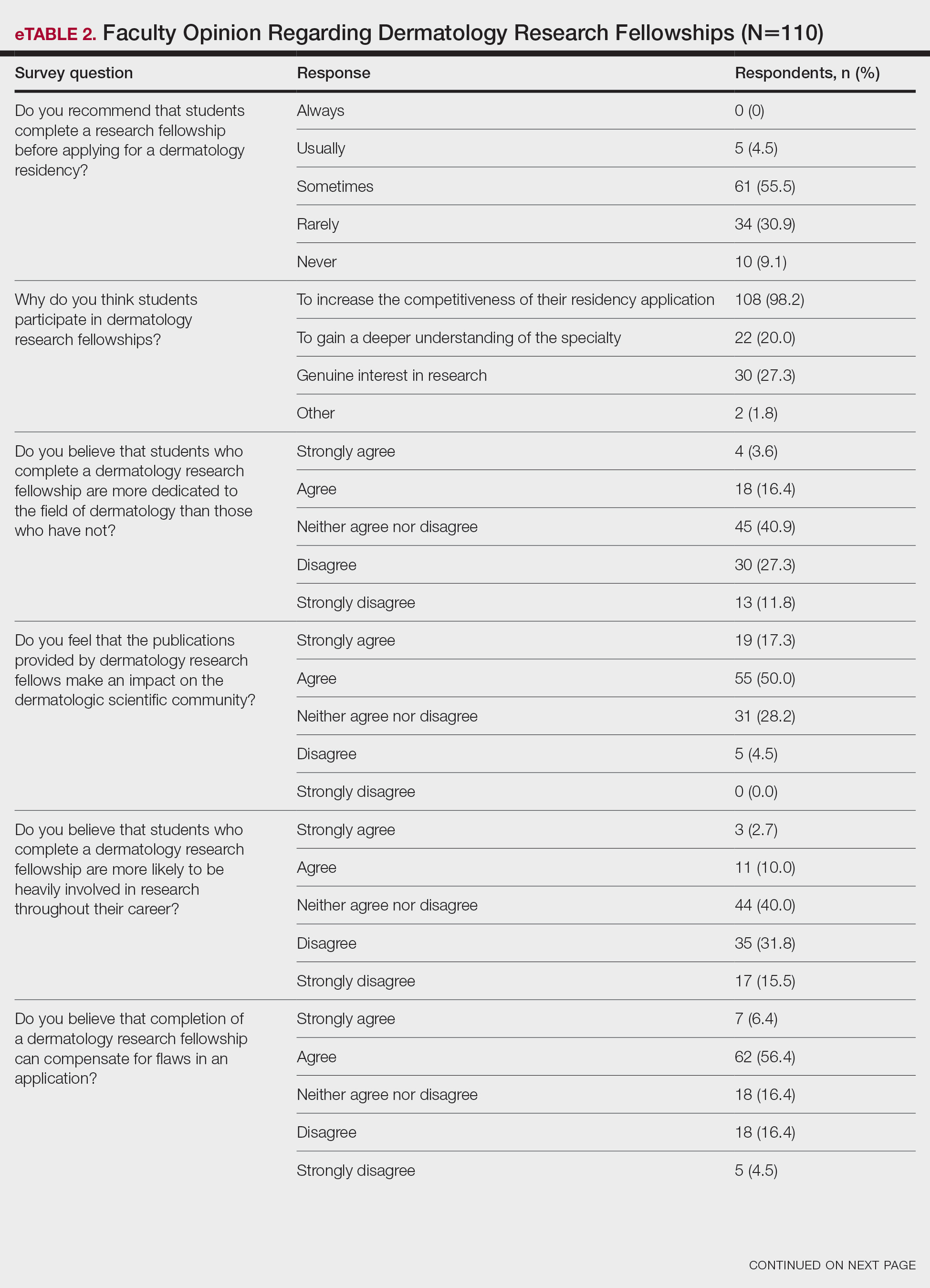

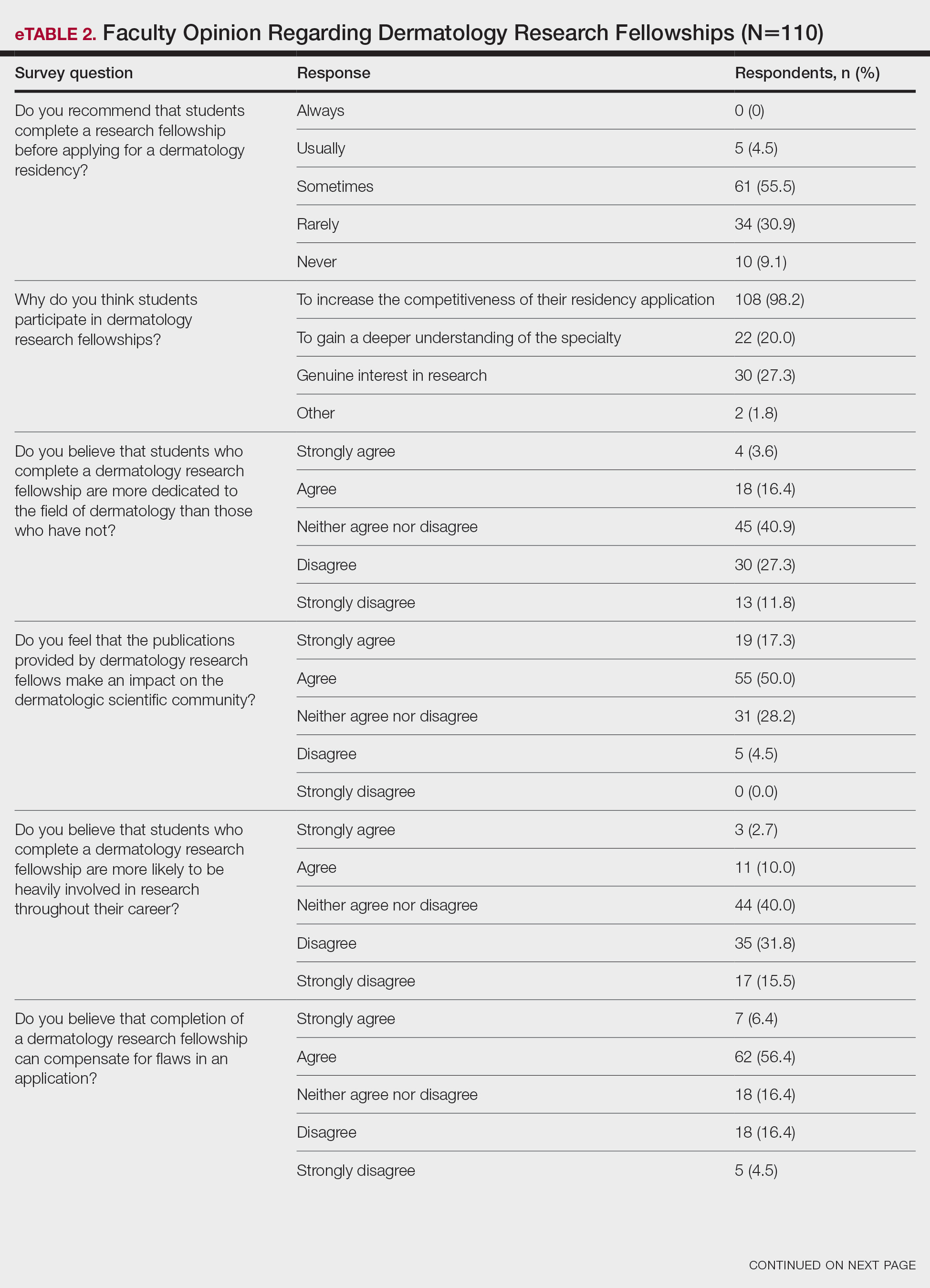

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

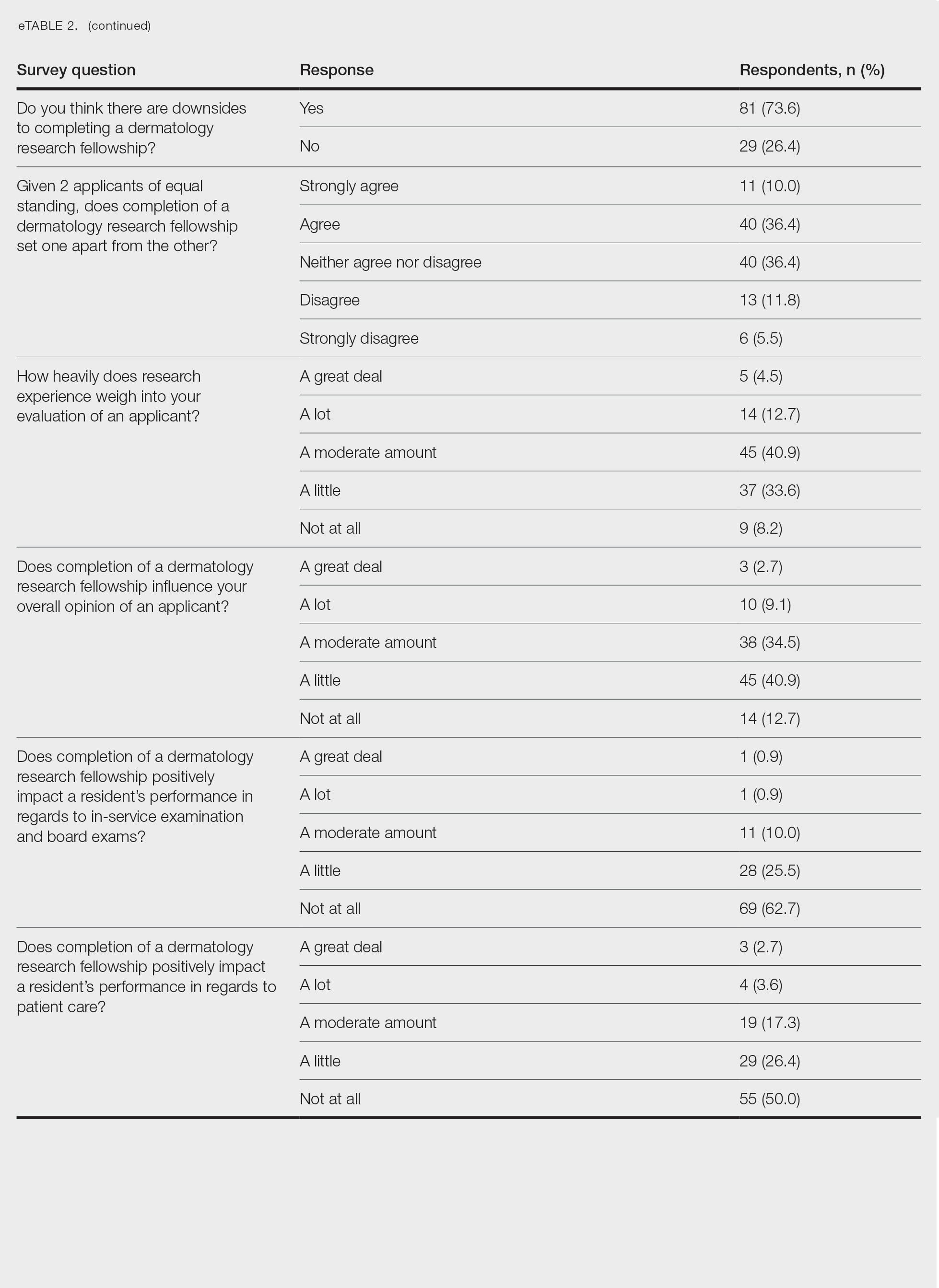

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

Dermatology residency positions continue to be highly coveted among applicants in the match. In 2019, dermatology proved to be the most competitive specialty, with 36.3% of US medical school seniors and independent applicants going unmatched.1 Prior to the transition to a pass/fail system, the mean US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score for matched applicants increased from 247 in 2014 to 251 in 2019. The growing number of scholarly activities reported by applicants has contributed to the competitiveness of the specialty. In 2018, the mean number of abstracts, presentations, and publications reported by matched applicants was 14.71, which was higher than other competitive specialties, including orthopedic surgery and otolaryngology (11.5 and 10.4, respectively). Dermatology applicants who did not match in 2018 reported a mean of 8.6 abstracts, presentations, and publications, which was on par with successful applicants in many other specialties.1 In 2011, Stratman and Ness2 found that publishing manuscripts and listing research experience were factors strongly associated with matching into dermatology for reapplicants. These trends in reported research have added pressure for applicants to increase their publications.

Given that many students do not choose a career in dermatology until later in medical school, some students choose to take a gap year between their third and fourth years of medical school to pursue a research fellowship (RF) and produce publications, in theory to increase the chances of matching in dermatology. A survey of dermatology applicants conducted by Costello et al3 in 2021 found that, of the students who completed a gap year (n=90; 31.25%), 78.7% (n=71) of them completed an RF, and those who completed RFs were more likely to match at top dermatology residency programs (P<.01). The authors also reported that there was no significant difference in overall match rates between gap-year and non–gap-year applicants.3 Another survey of 328 medical students found that the most common reason students take years off for research during medical school is to increase competitiveness for residency application.4 Although it is clear that students completing an RF often find success in the match, there are limited published data on how those involved in selecting dermatology residents view this additional year. We surveyed faculty members participating in the resident selection process to assess their viewpoints on how RFs factored into an applicant’s odds of matching into dermatology residency and performance as a resident.

Materials and Methods

An institutional review board application was submitted through the Geisinger Health System (Danville, Pennsylvania), and an exemption to complete the survey was granted. The survey consisted of 16 questions via REDCap electronic data capture and was sent to a listserve of dermatology program directors who were asked to distribute the survey to program chairs and faculty members within their department. Survey questions evaluated the participants’ involvement in medical student advising and the residency selection process. Questions relating to the respondents’ opinions were based on a 5-point Likert scale on level of agreement (1=strongly agree; 5=strongly disagree) or importance (1=a great deal; 5=not at all). All responses were collected anonymously. Data points were compiled and analyzed using REDCap. Statistical analysis via χ2 tests were conducted when appropriate.

Results

The survey was sent to 142 individuals and distributed to faculty members within those departments between August 16, 2019, and September 24, 2019. The survey elicited a total of 110 respondents. Demographic information is shown in eTable 1. Of these respondents, 35.5% were program directors, 23.6% were program chairs, 3.6% were both program director and program chair, and 37.3% were core faculty members. Although respondents’ roles were varied, 96.4% indicated that they were involved in both advising medical students and in selecting residents.

None of the respondents indicated that they always recommend that students complete an RF, and only 4.5% indicated that they usually recommend it; 40% of respondents rarely or never recommend an RF, while 55.5% sometimes recommend it. Although there was a variety of responses to how frequently faculty members recommend an RF, almost all respondents (98.2%) agreed that the reason medical students pursued an RF prior to residency application was to increase the competitiveness of their residency application. However, 20% of respondents believed that students in this cohort were seeking to gain a deeper understanding of the specialty, and 27.3% thought that this cohort had genuine interest in research. Interestingly, despite the medical students’ intentions of choosing an RF, most respondents (67.3%) agreed or strongly agreed that the publications produced by fellows make an impact on the dermatologic scientific community.

Although some respondents indicated that completion of an RF positively impacts resident performance with regard to patient care, most indicated that the impact was a little (26.4%) or not at all (50%). Additionally, a minority of respondents (11.8%) believed that RFs positively impact resident performance on in-service and board examinations at least a moderate amount, with 62.7% indicating no positive impact at all. Only 12.7% of participants agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF led to increased applicant involvement in research throughout their career, and most (73.6%) believed there were downsides to completing an RF. Finally, only 20% agreed or strongly agreed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology (eTable 2).

Further evaluation of the data indicated that the perceived utility of RFs did not affect respondents’ recommendation on whether to pursue an RF or not. For example, of the 4.5% of respondents who indicated that they always or usually recommended RFs, only 1 respondent believed that students who completed an RF were more dedicated to the field of dermatology than those who did not. Although 55.5% of respondents answered that they sometimes recommended completion of an RF, less than a quarter of this group believed that students who completed an RF were more likely to be heavily involved in research throughout their career (P=.99).

Overall, 11.8% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF influenced the evaluation of an applicant a great deal or a lot, while 53.6% of respondents indicated a little or no influence at all. Most respondents (62.8%) agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF can compensate for flaws in a residency application. Furthermore, when asked if completion of an RF could set 2 otherwise equivocal applicants apart from one another, 46.4% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, while only 17.3% disagreed or strongly disagreed (eTable 2).

Comment

This study characterized how completion of an RF is viewed by those involved in advising medical students and selecting dermatology residents. The growing pressure for applicants to increase the number of publications combined with the competitiveness of applying for a dermatology residency position has led to increased participation in RFs. However, studies have found that students who completed an RF often did so despite a lack of interest.4 Nonetheless, little is known about how this is perceived by those involved in choosing residents.

We found that few respondents always or usually advised applicants to complete an RF, but the majority sometimes recommended them, demonstrating the complexity of this issue. Completion of an RF impacted 11.8% of respondents’ overall opinion of an applicant a lot or a great deal, while most respondents (53.6%) were influenced a little or not at all. However, 46.4% of respondents indicated that completion of a dermatology RF would set apart 2 applicants of otherwise equal standing, and 62.8% agreed or strongly agreed that completion of an RF would compensate for flaws in an application. These responses align with the findings of a study conducted by Kaffenberger et al,5 who surveyed members of the Association of Professors of Dermatology and found that 74.5% (73/98) of mentors almost always or sometimes recommended a research gap year for reasons that included low grades, low USMLE Step scores, and little research. These data suggest that completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants despite most advisors acknowledging that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their careers, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

Given the complexity of this issue, respondents may not have been able to accurately answer the question about how much an RF influenced their overall opinion of an applicant because of subconscious bias. Furthermore, respondents likely tailored their recommendations to complete an RF based on individual applicant strengths and weaknesses, and the specific reasons why one may recommend an RF need to be further investigated.

Although there may be other perceived advantages to RFs that were not captured by our survey, completion of a dermatology RF is not without disadvantages. Fellowships often are unfunded and offered in cities with high costs of living. Additionally, students are forced to delay graduation from medical school by a year at minimum and continue to accrue interest on medical school loans during this time. The financial burdens of completing an RF may exclude students of lower socioeconomic status and contribute to a decrease in diversity within the field. Dermatology has been found to be the second least diverse specialty, behind orthopedics.6 Soliman et al7 found that racial minorities and low-income students were more likely to cite socioeconomic barriers as factors involved in their decision not to pursue a career in dermatology. This notion was supported by Rinderknecht et al,8 who found that Black and Latinx dermatology applicants were more likely to come from disadvantaged backgrounds, and Black applicants were more likely to indicate financial concerns as their primary reason for not pursuing an RF. The impact of accumulated student debt and decreased access should be carefully weighed against the potential benefits of an RF. However, as the USMLE transitions their Step 1 score reporting from numerical to a pass/fail system, it also is possible that dermatology programs will place more emphasis on research productivity when evaluating applications for residency. Overall, the decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic, as indicated by the results of this study.

Limitations—Our survey-based study is limited by response rate and response bias. Despite the large number of responses, the overall response rate cannot be determined because it is unknown how many total faculty members actually received the survey. Moreover, data collected from current dermatology residents who have completed RFs vs those who have not as they pertain to resident performance and preparedness for the rigors of a dermatology residency would be useful.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

- National Resident Matching Program. Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program; 2019. Accessed September 13, 2023. https://www.nrmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/NRMP-Results-and-Data-2019_04112019_final.pdf

- Stratman EJ, Ness RM. Factors associated with successful matching to dermatology residency programs by reapplicants and other applicants who previously graduated from medical school. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:196-202.

- Costello CM, Harvey JA, Besch-Stokes JG, et al. The role research gap-years play in a successful dermatology match. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:AB22.

- Pathipati AS, Taleghani N. Research in medical school: a survey evaluating why medical students take research years. Cureus. 2016;8:E741.

- Kaffenberger J, Lee B, Ahmed AM. How to advise medical students interested in dermatology: a survey of academic dermatology mentors. Cutis. 2023;111:124-127.

- Pandya AG, Alexis AF, Berger TG, et al. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:584-587.

- Soliman YS, Rzepecki AK, Guzman AK, et al. Understanding perceived barriers of minority medical students pursuing a career in dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:252-254.

- Rinderknecht FA, Brumfiel CM, Jefferson IS, et al. Differences in underrepresented in medicine applicant backgrounds and outcomes in the 2020-2021 dermatology residency match. Cutis. 2022;110:76-79.

PRACTICE POINTS

- Many medical students seeking to match into a dermatology residency program complete a research fellowship (RF).

- Completion of an RF can give a competitive advantage to applicants even though most advisors acknowledge that these applicants are not likely to be involved in research throughout their career, perform better on standardized examinations, or provide better patient care.

- The decision to recommend an RF represents an extremely complex topic and should be tailored to each individual applicant.

Nevus Lipomatosis Deemed Suspicious by Airport Security

To the Editor:

A 47-year-old man presented at the dermatology clinic with a growing lesion on the left medial thigh.

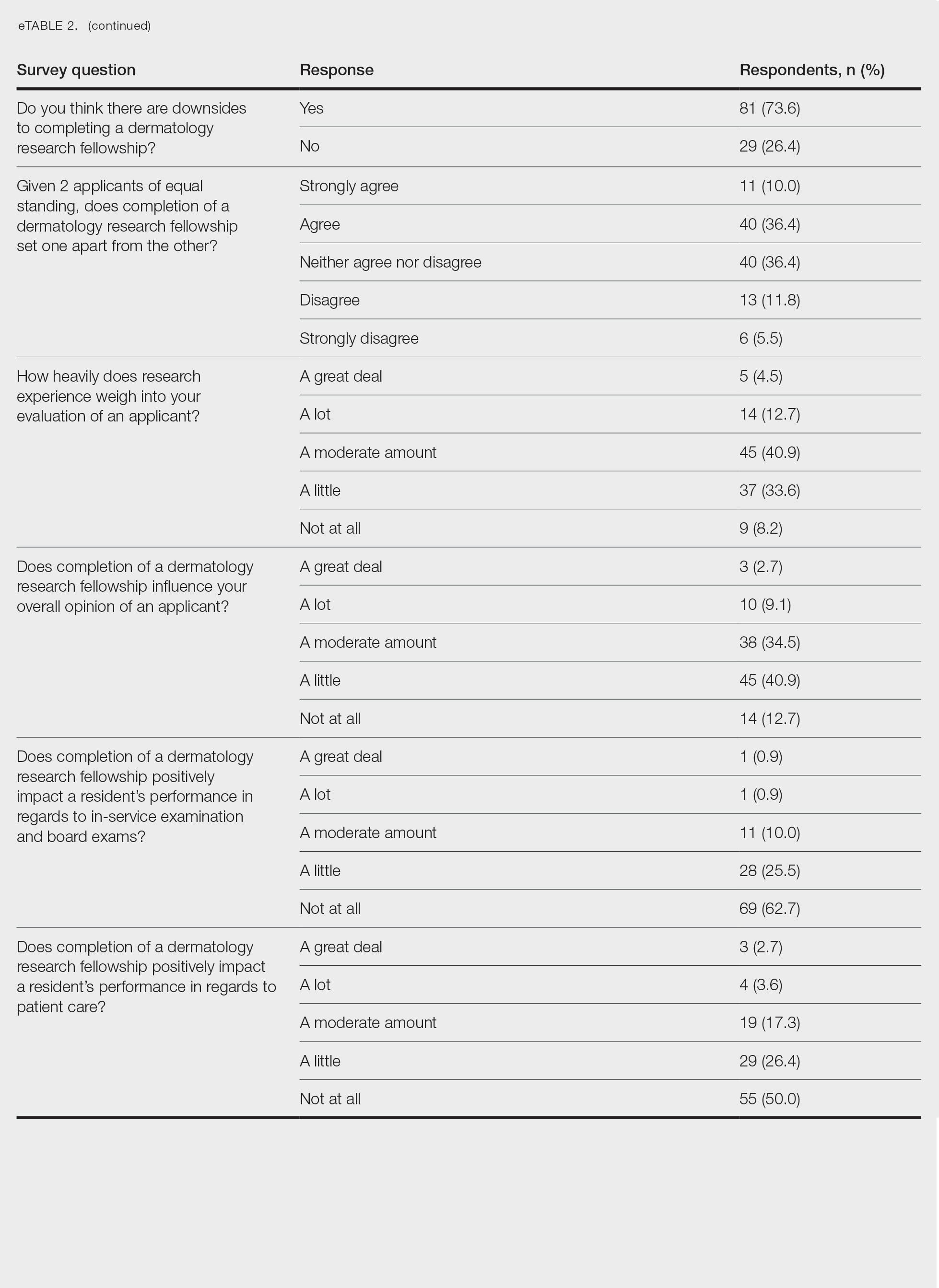

Physical examination revealed a 5-cm, pedunculated, fatty nodule on the left medial thigh that was clinically consistent with nevus lipomatosis (NL)(Figure). Although benign, trouble traveling through airport security prompted the patient to request shave removal, which subsequently was performed. Histology showed a large pedunculated nodule with prominent adipose tissue, consistent with NL. At 3-month follow-up, the patient reported getting through airport security multiple times without incident.

Nevus lipomatosis is a benign fatty lesion most commonly found on the medial thighs or trunk of adults. The lesion usually is asymptomatic but can become irritated by rubbing or catching on clothing. Our patient had symptomatic NL that caused delays getting through airport security; he experienced full resolution after simple shave removal. In rare instances, both benign and malignant skin conditions have been seen on airport scanning devices since the introduction of increased security measures following September 11, 2001. In 2016, Heymann1 reported a man with a 1.5-cm epidermal inclusion cyst detected by airport security scanners, prompting the traveler to request and carry a medically explanatory letter used to get through security. In 2015 Mayer and Adams2 described a case of nodular melanoma that was detected 20 times over a period of 2 months by airport scanners, and in 2016, Caine et al3 reported a case of desmoplastic melanoma that was detected by airport security, but after its removal was not identified by security for the next 40 flights. Noncutaneous pathology also can be detected by airport scanners. In 2013, Naraynsingh et al4 reported a man with a large left reducible inguinal hernia who was stopped by airport security and subjected to an invasive physical examination of the area. These instances demonstrate the breadth of conditions that can be cumbersome when individuals are traveling by airplane in our current security climate.

Our patient had to go through the trouble of having the benign NL lesion removed to avoid the hassle of repeatedly being stopped by airport security. The patient had the lesion removed and is doing well, but the procedure could have been avoided if systems existed to help patients with dermatologic and medical conditions at airport security. Our patient likely will never be stopped again for the suspicious lump on the left inner thigh, but many others will be stopped for similar reasons.

- Heymann WR. A cyst misinterpreted on airport scan as security threat. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3329

- Mayer JE, Adams BB. Nodular melanoma serendipitously detected by airport full body scanners. Dermatology. 2015;230:16-17. doi:10.1159/000368045

- Caine P, Javed MU, Karoo ROS. A desmoplastic melanoma detected by an airport security scanner. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2016.02.022

- Naraynsingh V, Cawich SO, Maharaj R, et al. Inguinal hernia and airport scanners: an emerging indication for repair? 2013;2013:952835. Case Rep Med. doi:10.1155/2013/952835

To the Editor:

A 47-year-old man presented at the dermatology clinic with a growing lesion on the left medial thigh.

Physical examination revealed a 5-cm, pedunculated, fatty nodule on the left medial thigh that was clinically consistent with nevus lipomatosis (NL)(Figure). Although benign, trouble traveling through airport security prompted the patient to request shave removal, which subsequently was performed. Histology showed a large pedunculated nodule with prominent adipose tissue, consistent with NL. At 3-month follow-up, the patient reported getting through airport security multiple times without incident.

Nevus lipomatosis is a benign fatty lesion most commonly found on the medial thighs or trunk of adults. The lesion usually is asymptomatic but can become irritated by rubbing or catching on clothing. Our patient had symptomatic NL that caused delays getting through airport security; he experienced full resolution after simple shave removal. In rare instances, both benign and malignant skin conditions have been seen on airport scanning devices since the introduction of increased security measures following September 11, 2001. In 2016, Heymann1 reported a man with a 1.5-cm epidermal inclusion cyst detected by airport security scanners, prompting the traveler to request and carry a medically explanatory letter used to get through security. In 2015 Mayer and Adams2 described a case of nodular melanoma that was detected 20 times over a period of 2 months by airport scanners, and in 2016, Caine et al3 reported a case of desmoplastic melanoma that was detected by airport security, but after its removal was not identified by security for the next 40 flights. Noncutaneous pathology also can be detected by airport scanners. In 2013, Naraynsingh et al4 reported a man with a large left reducible inguinal hernia who was stopped by airport security and subjected to an invasive physical examination of the area. These instances demonstrate the breadth of conditions that can be cumbersome when individuals are traveling by airplane in our current security climate.

Our patient had to go through the trouble of having the benign NL lesion removed to avoid the hassle of repeatedly being stopped by airport security. The patient had the lesion removed and is doing well, but the procedure could have been avoided if systems existed to help patients with dermatologic and medical conditions at airport security. Our patient likely will never be stopped again for the suspicious lump on the left inner thigh, but many others will be stopped for similar reasons.

To the Editor:

A 47-year-old man presented at the dermatology clinic with a growing lesion on the left medial thigh.

Physical examination revealed a 5-cm, pedunculated, fatty nodule on the left medial thigh that was clinically consistent with nevus lipomatosis (NL)(Figure). Although benign, trouble traveling through airport security prompted the patient to request shave removal, which subsequently was performed. Histology showed a large pedunculated nodule with prominent adipose tissue, consistent with NL. At 3-month follow-up, the patient reported getting through airport security multiple times without incident.

Nevus lipomatosis is a benign fatty lesion most commonly found on the medial thighs or trunk of adults. The lesion usually is asymptomatic but can become irritated by rubbing or catching on clothing. Our patient had symptomatic NL that caused delays getting through airport security; he experienced full resolution after simple shave removal. In rare instances, both benign and malignant skin conditions have been seen on airport scanning devices since the introduction of increased security measures following September 11, 2001. In 2016, Heymann1 reported a man with a 1.5-cm epidermal inclusion cyst detected by airport security scanners, prompting the traveler to request and carry a medically explanatory letter used to get through security. In 2015 Mayer and Adams2 described a case of nodular melanoma that was detected 20 times over a period of 2 months by airport scanners, and in 2016, Caine et al3 reported a case of desmoplastic melanoma that was detected by airport security, but after its removal was not identified by security for the next 40 flights. Noncutaneous pathology also can be detected by airport scanners. In 2013, Naraynsingh et al4 reported a man with a large left reducible inguinal hernia who was stopped by airport security and subjected to an invasive physical examination of the area. These instances demonstrate the breadth of conditions that can be cumbersome when individuals are traveling by airplane in our current security climate.

Our patient had to go through the trouble of having the benign NL lesion removed to avoid the hassle of repeatedly being stopped by airport security. The patient had the lesion removed and is doing well, but the procedure could have been avoided if systems existed to help patients with dermatologic and medical conditions at airport security. Our patient likely will never be stopped again for the suspicious lump on the left inner thigh, but many others will be stopped for similar reasons.

- Heymann WR. A cyst misinterpreted on airport scan as security threat. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3329

- Mayer JE, Adams BB. Nodular melanoma serendipitously detected by airport full body scanners. Dermatology. 2015;230:16-17. doi:10.1159/000368045

- Caine P, Javed MU, Karoo ROS. A desmoplastic melanoma detected by an airport security scanner. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2016.02.022

- Naraynsingh V, Cawich SO, Maharaj R, et al. Inguinal hernia and airport scanners: an emerging indication for repair? 2013;2013:952835. Case Rep Med. doi:10.1155/2013/952835

- Heymann WR. A cyst misinterpreted on airport scan as security threat. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1388. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.3329

- Mayer JE, Adams BB. Nodular melanoma serendipitously detected by airport full body scanners. Dermatology. 2015;230:16-17. doi:10.1159/000368045

- Caine P, Javed MU, Karoo ROS. A desmoplastic melanoma detected by an airport security scanner. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:874-876. doi:10.1016/j.bjps.2016.02.022

- Naraynsingh V, Cawich SO, Maharaj R, et al. Inguinal hernia and airport scanners: an emerging indication for repair? 2013;2013:952835. Case Rep Med. doi:10.1155/2013/952835

Practice Points

- Nevus lipomatosis is a benign fatty lesion that most commonly is found on the medial thighs or trunk of adults.

- Both benign and malignant skin conditions have been detected on airport scanning devices.

- At times, patients must go through the hassle of having the benign lesions removed to avoid repeated problems at airport security.

Dermatopathology Etiquette 101

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established core competencies to serve as a foundation for the training received in a dermatology residency program.1 Although programs are required to have the same concentrations—patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice—no specific guidelines are in place regarding how each of these competencies should be reached within a training period.2 Instead, it remains the responsibility of each program to formulate an individualized curriculum to facilitate proficiency in the multiple areas encompassed by a residency.

In many dermatology residency programs, dermatopathology is a substantial component of educational objectives and the curriculum.1 Residents may spend as much as 25% of their training on dermatopathology. However, there is great variability among programs in methods of teaching dermatopathology. When Hinshaw3 surveyed 52 of 109 dermatology residency programs, they identified differences in dermatopathology teaching that included, but was not limited to, utilization of problem-based learning (in 40.4% of programs), integration of journal reviews (53.8%), and computer-based learning (19.2%). In addition, differences were identified in the recommended primary textbook and the makeup of faculty who taught dermatopathology.3

Although residency programs vary in their methods of teaching this important component of dermatology, most use a multiheaded microscope in some capacity for didactics or sign-out. For most trainees, the dermatopathology laboratory is a new environment compared to the clinical space that medical students and residents become accustomed to throughout their education, thus creating a knowledge gap for trainees on proper dermatopathology etiquette and universal guidelines.

With medical students, residents, and fellows in mind, we have prepared a basic “dermatopathology etiquette” reference for trainees. Just as there are universal rules in the operating room for surgery (eg, sterile technique), we want to establish a code of conduct at the microscope. We hope that these 10 tips will, first, be useful to those who are unsure how to approach their first experience with dermatopathology and, second, serve as a guideline to aid development of appropriate communication skills and functioning within this novel setting. This list also can serve as a resource for dermatopathology attendings to provide to rotating residents and students.

1. New to pathology? It’s okay to ask. Do not hesitate to ask upper-year residents, fellows, and attendings for instructions on such matters as how to adjust your eyepiece to get the best resolution.

2. If a slide drops on the floor, do not move! Your first instinct might be to move your chair to look for the dropped slide, but you might roll over it and break it.

3. When the attending is looking through the scope, you look through the scope. Dermatopathology is a visual exercise. Getting in your “optic mileage” is best done under the guidance of an experienced dermatopathologist.

4. Rules regarding food and drink at the microscope vary by pathologist. It’s best to ask what each attending prefers. Safe advice is to avoid foods that make noise, such as chewing gum and chips, and food that has a strong odor, such as microwaved leftovers.

5. Limit use of a laptop, cell phone, and smartwatch. If you think that using any of these is necessary, it generally is best to announce that you are looking up something related to the case and then share your findings (but not the most recent post on your Facebook News Feed).

6. If you notice that something needs correcting on the report, speak up! We are all human; we all make typos. Do not hesitate to mention this as soon as possible, especially before the case is signed out. You will likely be thanked by your attending because it is harder to rectify once the report has been signed out.

7. Small talk often is welcome during large excisions. This is a great time to ask what others are doing next weekend or what happened in clinic earlier that day, or just to tell a good (clean) joke that is making the rounds. Conversely, if the case is complex, it often is best to wait until it is completed before asking questions.

8. When participating in a roundtable diagnosis, you are welcome to directly state the diagnosis for bread-and-butter cases, such as basal cell carcinomas and seborrheic keratoses. It is appropriate to be more descriptive and methodical in more complex cases. When evaluating a rash, give the general inflammatory pattern first. For example, is it spongiotic? Psoriasiform? Interface? Or a mixed pattern?

9. Extra points for identifying special sites! These include mucosal, genital, and acral sites. You might even get bonus points if you can determine something about the patient (child or adult) based on the pathologic features, such as variation in collagen patterns.

10. Whenever you are in doubt, just describe what you see. You can use the traditional top-down approach or start with stating the most evident finding, then proceed to a top-down description. If it is a neoplasm, describe the overall architecture; then, what you see at a cellular level will get you some points as well.

We acknowledge that this list of 10 tips is not comprehensive and might vary by attending and each institution’s distinctive training format. We are hopeful, however, that these 10 points of etiquette can serve as a guideline.

- Hinshaw M, Hsu P, Lee L-Y, et al. The current state of dermatopathology education: a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:620-628. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01128.x

- Hinshaw MA, Stratman EJ. Core competencies in dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:160-165. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00442.x

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826. doi:10.1016/j.det.2012.06.003

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established core competencies to serve as a foundation for the training received in a dermatology residency program.1 Although programs are required to have the same concentrations—patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice—no specific guidelines are in place regarding how each of these competencies should be reached within a training period.2 Instead, it remains the responsibility of each program to formulate an individualized curriculum to facilitate proficiency in the multiple areas encompassed by a residency.

In many dermatology residency programs, dermatopathology is a substantial component of educational objectives and the curriculum.1 Residents may spend as much as 25% of their training on dermatopathology. However, there is great variability among programs in methods of teaching dermatopathology. When Hinshaw3 surveyed 52 of 109 dermatology residency programs, they identified differences in dermatopathology teaching that included, but was not limited to, utilization of problem-based learning (in 40.4% of programs), integration of journal reviews (53.8%), and computer-based learning (19.2%). In addition, differences were identified in the recommended primary textbook and the makeup of faculty who taught dermatopathology.3

Although residency programs vary in their methods of teaching this important component of dermatology, most use a multiheaded microscope in some capacity for didactics or sign-out. For most trainees, the dermatopathology laboratory is a new environment compared to the clinical space that medical students and residents become accustomed to throughout their education, thus creating a knowledge gap for trainees on proper dermatopathology etiquette and universal guidelines.

With medical students, residents, and fellows in mind, we have prepared a basic “dermatopathology etiquette” reference for trainees. Just as there are universal rules in the operating room for surgery (eg, sterile technique), we want to establish a code of conduct at the microscope. We hope that these 10 tips will, first, be useful to those who are unsure how to approach their first experience with dermatopathology and, second, serve as a guideline to aid development of appropriate communication skills and functioning within this novel setting. This list also can serve as a resource for dermatopathology attendings to provide to rotating residents and students.

1. New to pathology? It’s okay to ask. Do not hesitate to ask upper-year residents, fellows, and attendings for instructions on such matters as how to adjust your eyepiece to get the best resolution.

2. If a slide drops on the floor, do not move! Your first instinct might be to move your chair to look for the dropped slide, but you might roll over it and break it.

3. When the attending is looking through the scope, you look through the scope. Dermatopathology is a visual exercise. Getting in your “optic mileage” is best done under the guidance of an experienced dermatopathologist.

4. Rules regarding food and drink at the microscope vary by pathologist. It’s best to ask what each attending prefers. Safe advice is to avoid foods that make noise, such as chewing gum and chips, and food that has a strong odor, such as microwaved leftovers.

5. Limit use of a laptop, cell phone, and smartwatch. If you think that using any of these is necessary, it generally is best to announce that you are looking up something related to the case and then share your findings (but not the most recent post on your Facebook News Feed).

6. If you notice that something needs correcting on the report, speak up! We are all human; we all make typos. Do not hesitate to mention this as soon as possible, especially before the case is signed out. You will likely be thanked by your attending because it is harder to rectify once the report has been signed out.

7. Small talk often is welcome during large excisions. This is a great time to ask what others are doing next weekend or what happened in clinic earlier that day, or just to tell a good (clean) joke that is making the rounds. Conversely, if the case is complex, it often is best to wait until it is completed before asking questions.

8. When participating in a roundtable diagnosis, you are welcome to directly state the diagnosis for bread-and-butter cases, such as basal cell carcinomas and seborrheic keratoses. It is appropriate to be more descriptive and methodical in more complex cases. When evaluating a rash, give the general inflammatory pattern first. For example, is it spongiotic? Psoriasiform? Interface? Or a mixed pattern?

9. Extra points for identifying special sites! These include mucosal, genital, and acral sites. You might even get bonus points if you can determine something about the patient (child or adult) based on the pathologic features, such as variation in collagen patterns.

10. Whenever you are in doubt, just describe what you see. You can use the traditional top-down approach or start with stating the most evident finding, then proceed to a top-down description. If it is a neoplasm, describe the overall architecture; then, what you see at a cellular level will get you some points as well.

We acknowledge that this list of 10 tips is not comprehensive and might vary by attending and each institution’s distinctive training format. We are hopeful, however, that these 10 points of etiquette can serve as a guideline.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education has established core competencies to serve as a foundation for the training received in a dermatology residency program.1 Although programs are required to have the same concentrations—patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism, and systems-based practice—no specific guidelines are in place regarding how each of these competencies should be reached within a training period.2 Instead, it remains the responsibility of each program to formulate an individualized curriculum to facilitate proficiency in the multiple areas encompassed by a residency.

In many dermatology residency programs, dermatopathology is a substantial component of educational objectives and the curriculum.1 Residents may spend as much as 25% of their training on dermatopathology. However, there is great variability among programs in methods of teaching dermatopathology. When Hinshaw3 surveyed 52 of 109 dermatology residency programs, they identified differences in dermatopathology teaching that included, but was not limited to, utilization of problem-based learning (in 40.4% of programs), integration of journal reviews (53.8%), and computer-based learning (19.2%). In addition, differences were identified in the recommended primary textbook and the makeup of faculty who taught dermatopathology.3

Although residency programs vary in their methods of teaching this important component of dermatology, most use a multiheaded microscope in some capacity for didactics or sign-out. For most trainees, the dermatopathology laboratory is a new environment compared to the clinical space that medical students and residents become accustomed to throughout their education, thus creating a knowledge gap for trainees on proper dermatopathology etiquette and universal guidelines.

With medical students, residents, and fellows in mind, we have prepared a basic “dermatopathology etiquette” reference for trainees. Just as there are universal rules in the operating room for surgery (eg, sterile technique), we want to establish a code of conduct at the microscope. We hope that these 10 tips will, first, be useful to those who are unsure how to approach their first experience with dermatopathology and, second, serve as a guideline to aid development of appropriate communication skills and functioning within this novel setting. This list also can serve as a resource for dermatopathology attendings to provide to rotating residents and students.

1. New to pathology? It’s okay to ask. Do not hesitate to ask upper-year residents, fellows, and attendings for instructions on such matters as how to adjust your eyepiece to get the best resolution.

2. If a slide drops on the floor, do not move! Your first instinct might be to move your chair to look for the dropped slide, but you might roll over it and break it.

3. When the attending is looking through the scope, you look through the scope. Dermatopathology is a visual exercise. Getting in your “optic mileage” is best done under the guidance of an experienced dermatopathologist.

4. Rules regarding food and drink at the microscope vary by pathologist. It’s best to ask what each attending prefers. Safe advice is to avoid foods that make noise, such as chewing gum and chips, and food that has a strong odor, such as microwaved leftovers.

5. Limit use of a laptop, cell phone, and smartwatch. If you think that using any of these is necessary, it generally is best to announce that you are looking up something related to the case and then share your findings (but not the most recent post on your Facebook News Feed).

6. If you notice that something needs correcting on the report, speak up! We are all human; we all make typos. Do not hesitate to mention this as soon as possible, especially before the case is signed out. You will likely be thanked by your attending because it is harder to rectify once the report has been signed out.

7. Small talk often is welcome during large excisions. This is a great time to ask what others are doing next weekend or what happened in clinic earlier that day, or just to tell a good (clean) joke that is making the rounds. Conversely, if the case is complex, it often is best to wait until it is completed before asking questions.

8. When participating in a roundtable diagnosis, you are welcome to directly state the diagnosis for bread-and-butter cases, such as basal cell carcinomas and seborrheic keratoses. It is appropriate to be more descriptive and methodical in more complex cases. When evaluating a rash, give the general inflammatory pattern first. For example, is it spongiotic? Psoriasiform? Interface? Or a mixed pattern?

9. Extra points for identifying special sites! These include mucosal, genital, and acral sites. You might even get bonus points if you can determine something about the patient (child or adult) based on the pathologic features, such as variation in collagen patterns.

10. Whenever you are in doubt, just describe what you see. You can use the traditional top-down approach or start with stating the most evident finding, then proceed to a top-down description. If it is a neoplasm, describe the overall architecture; then, what you see at a cellular level will get you some points as well.

We acknowledge that this list of 10 tips is not comprehensive and might vary by attending and each institution’s distinctive training format. We are hopeful, however, that these 10 points of etiquette can serve as a guideline.

- Hinshaw M, Hsu P, Lee L-Y, et al. The current state of dermatopathology education: a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:620-628. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01128.x

- Hinshaw MA, Stratman EJ. Core competencies in dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:160-165. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00442.x

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826. doi:10.1016/j.det.2012.06.003

- Hinshaw M, Hsu P, Lee L-Y, et al. The current state of dermatopathology education: a survey of the Association of Professors of Dermatology. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:620-628. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2008.01128.x

- Hinshaw MA, Stratman EJ. Core competencies in dermatopathology. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:160-165. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2006.00442.x

- Hinshaw MA. Dermatopathology education: an update. Dermatol Clin. 2012;30:815-826. doi:10.1016/j.det.2012.06.003

Keratotic Papule on the Abdomen

The Diagnosis: Hypergranulotic Dyscornification

Hypergranulotic dyscornification (HD) is a rarely reported reaction pattern present in benign solitary keratoses with only few reports to date. It may be an underrecognized reaction pattern based on the paucity of reported cases as well as the histologic similarities to other entities. It has been hypothesized that this pattern reflects an underlying keratin mutation or disorder of keratinization.1

Clinically, HD most commonly presents as a waxy, tan-colored, solitary keratosis generally found on the lower limbs, trunk, or back in individuals aged 20 to 60 years.1,2 Histopathology shows marked hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and clumped basophilic keratohyalin granules within the corneocytes with digitated epidermal hyperplasia. There is abnormal cornification across the entire lesion with papillomatosis and marked hypergranulosis.3 There often are homogeneous orthokeratotic mounds of large, dull, eosinophilic-staining anucleate keratinocytes that are sharply demarcated from the thickened granular layer.1,2 Within the spinous, granular, and corneal layers, there is a pale, gray-staining, basophilic, cytoplasmic substance intercellularly.1

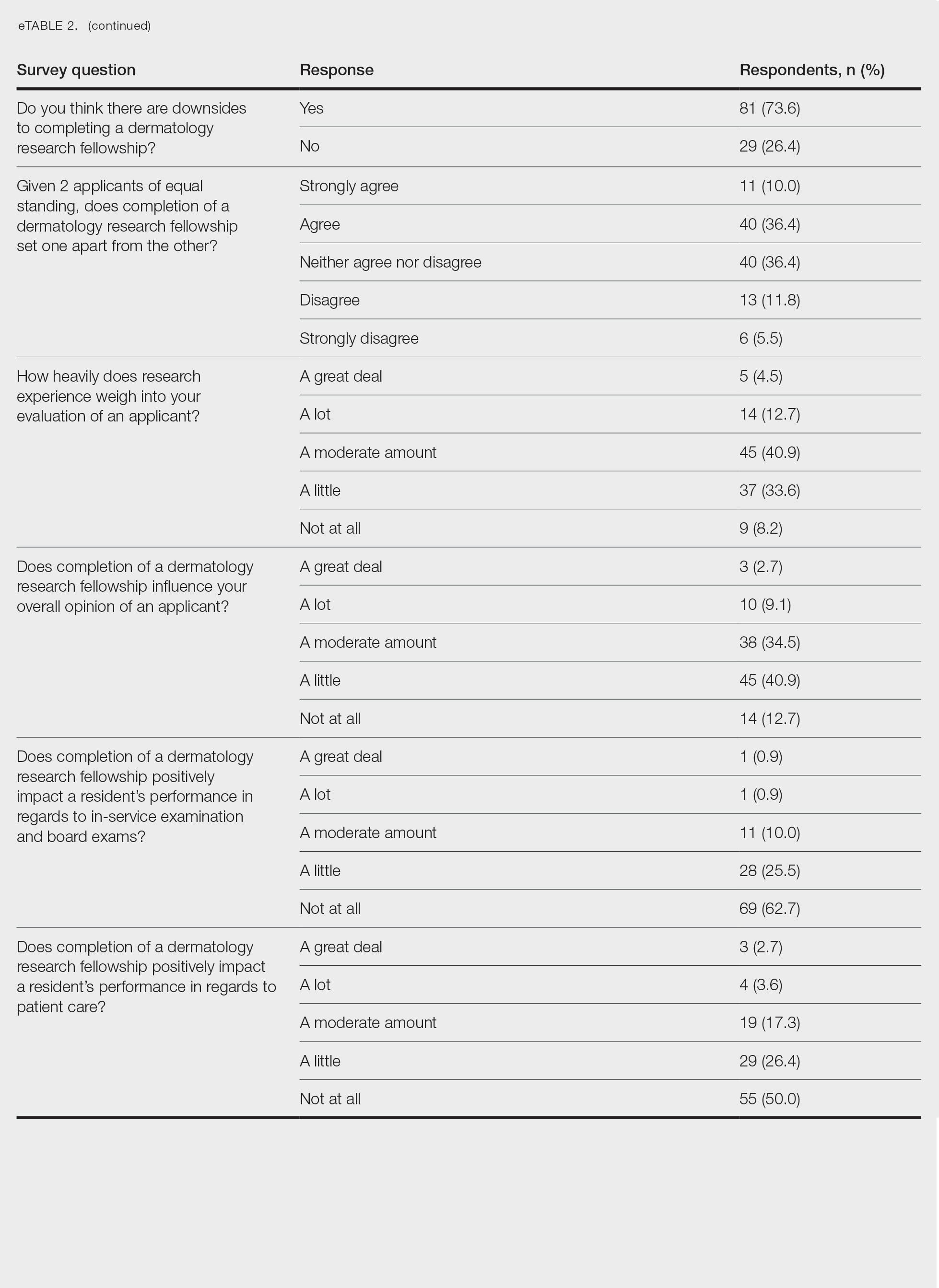

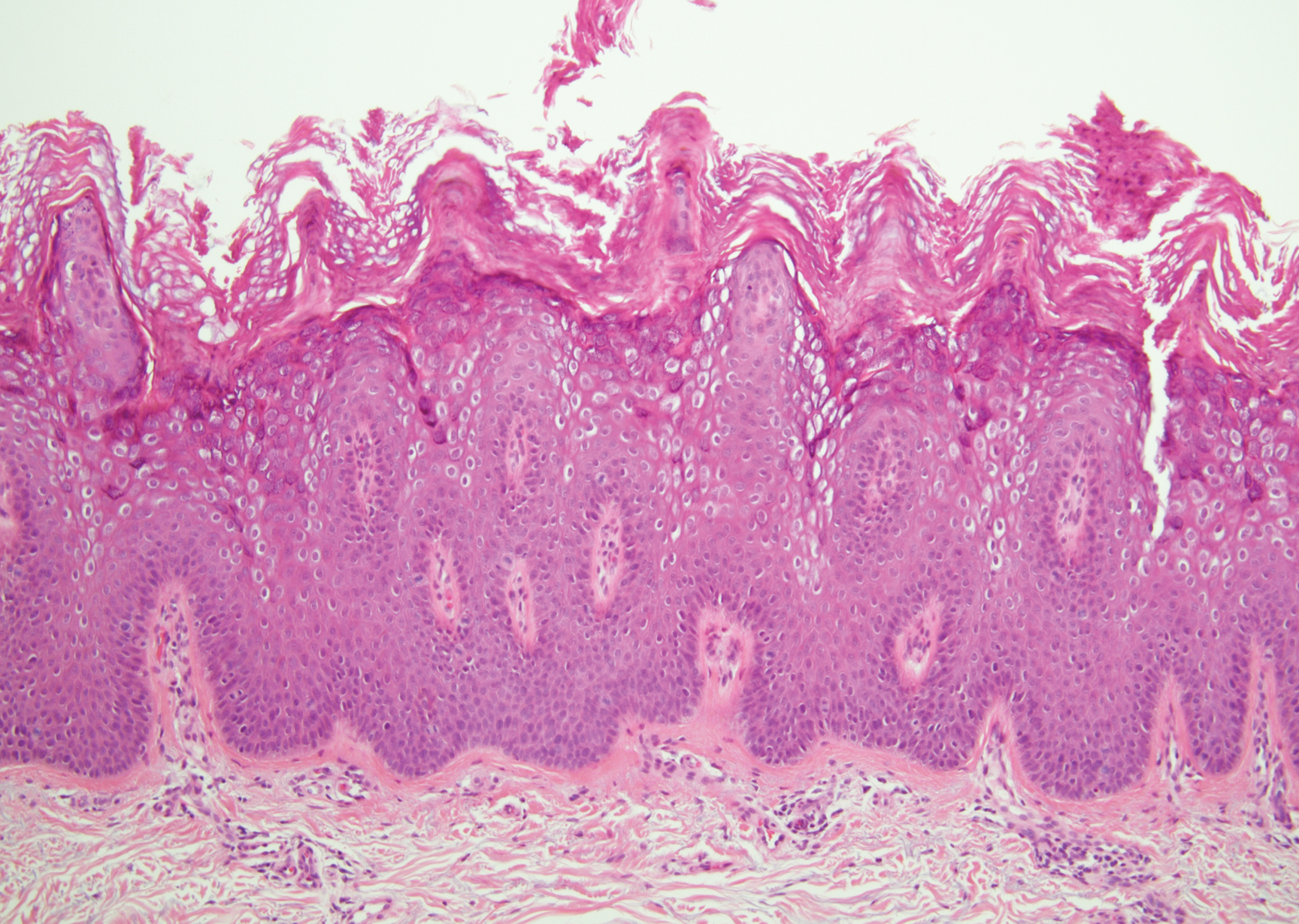

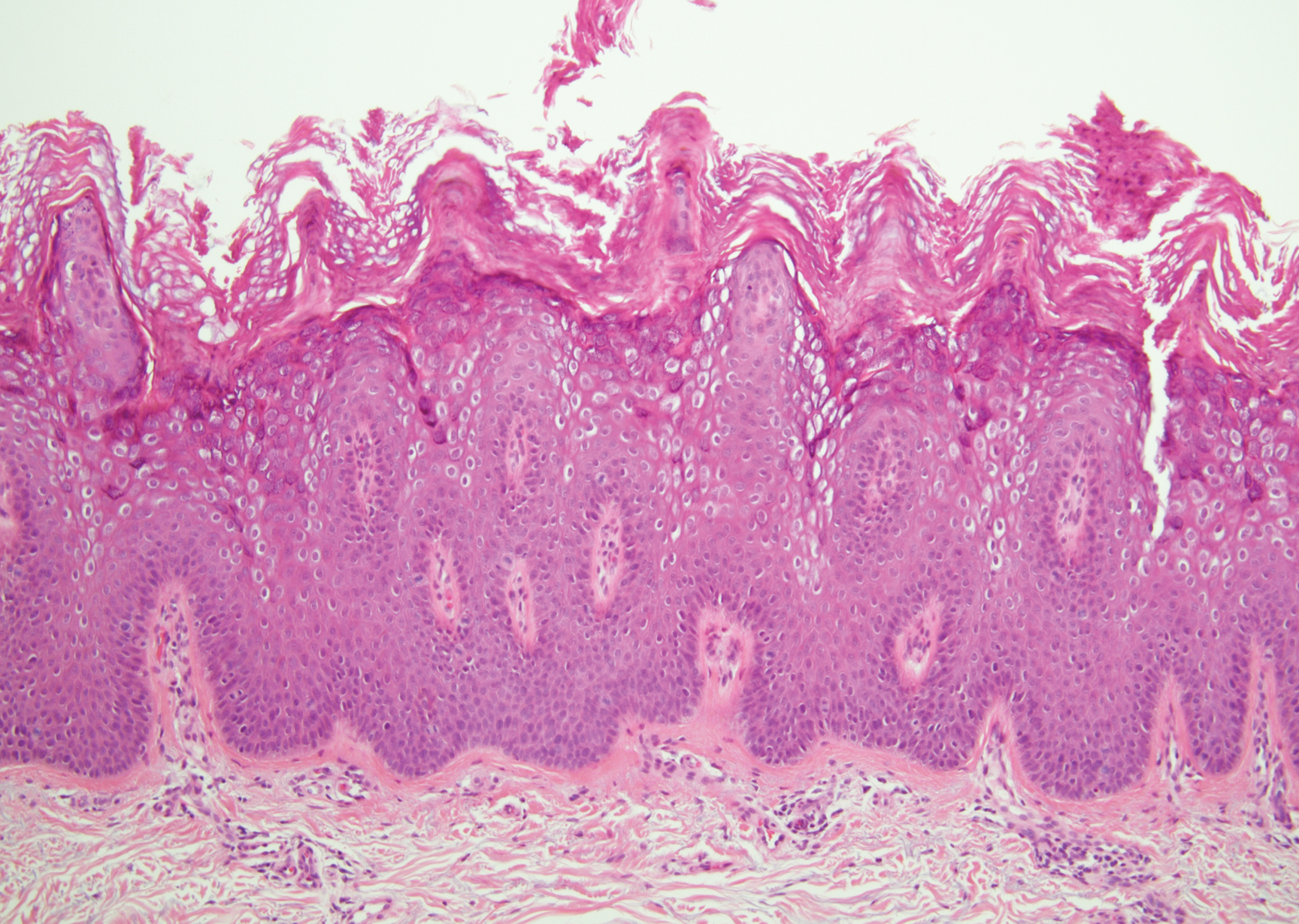

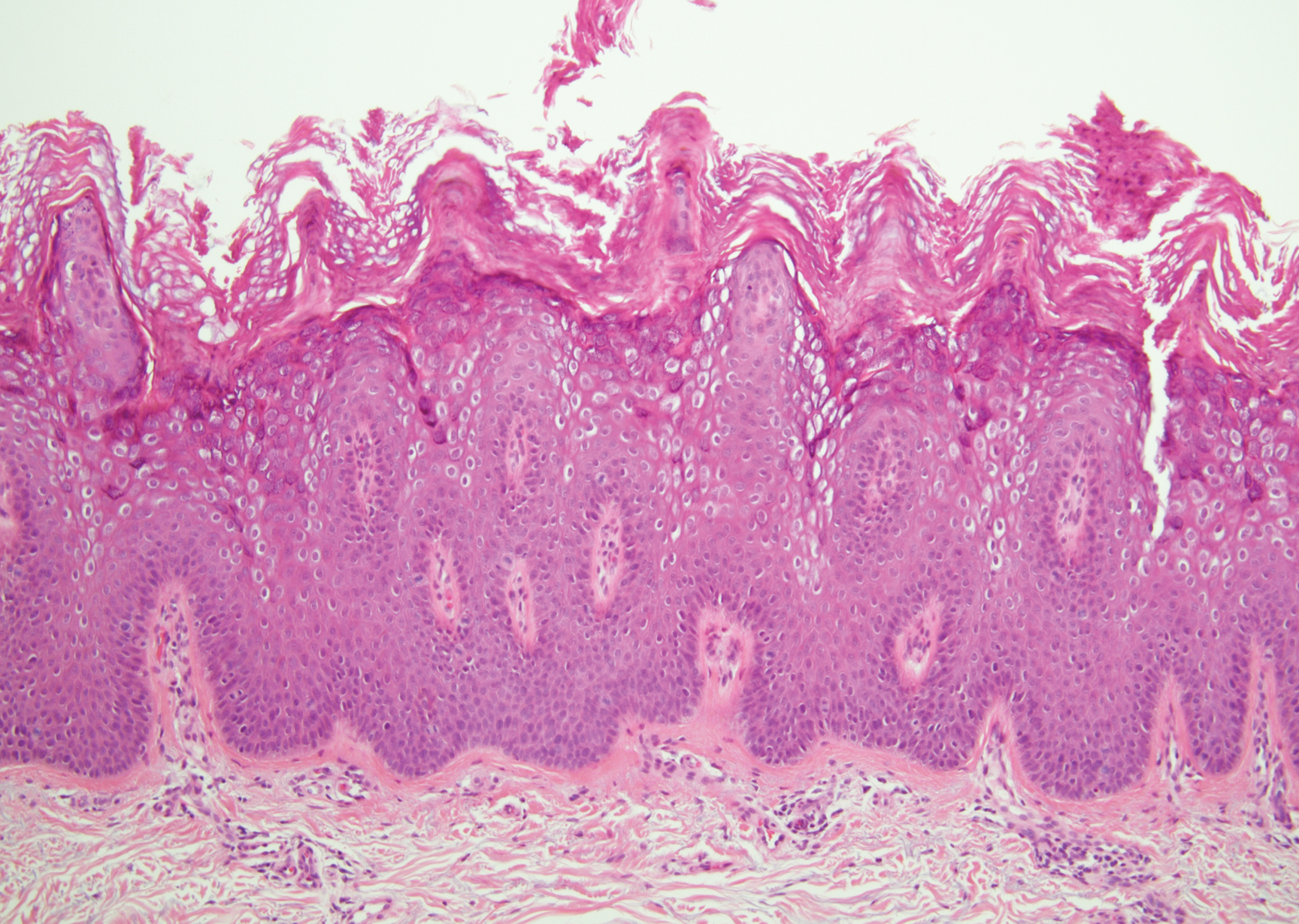

Histopathologically, HD may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant.1 Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis can be a genetic disorder, an incidental finding in a variety of skin conditions, or an isolated lesion.4 The genetic syndrome, caused by mutation in keratins 1 or 10, clinically presents with hyperkeratosis, erosions, blisters, and thickening of the epidermis, often with a corrugated appearance. Epidermal nevi findings often are seen in conjunction with histologic changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis caused by mutation. Solitary lesions also can resemble seborrheic keratosis or verruca. In all examples of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, the histopathologic findings are identical.4 The granular layer is thickened, and coarse keratohyalin granules aggregate in the suprabasal cells.5 There is acantholysis with perinuclear vacuolization in the spinous and granular layers with characteristic pale cytoplasmic areas devoid of keratin filaments (Figure 1). The basal layer may be hyperproliferative.5

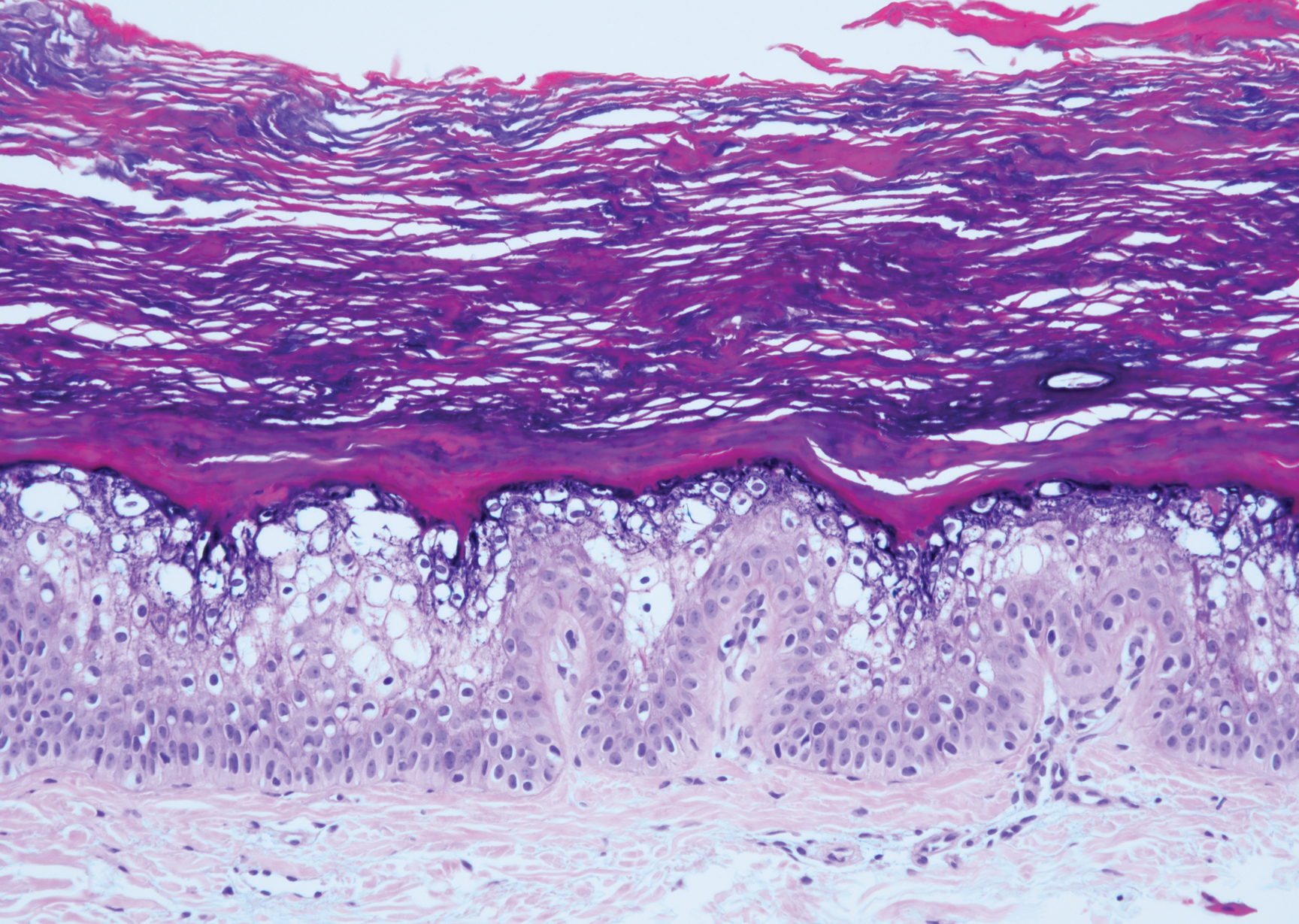

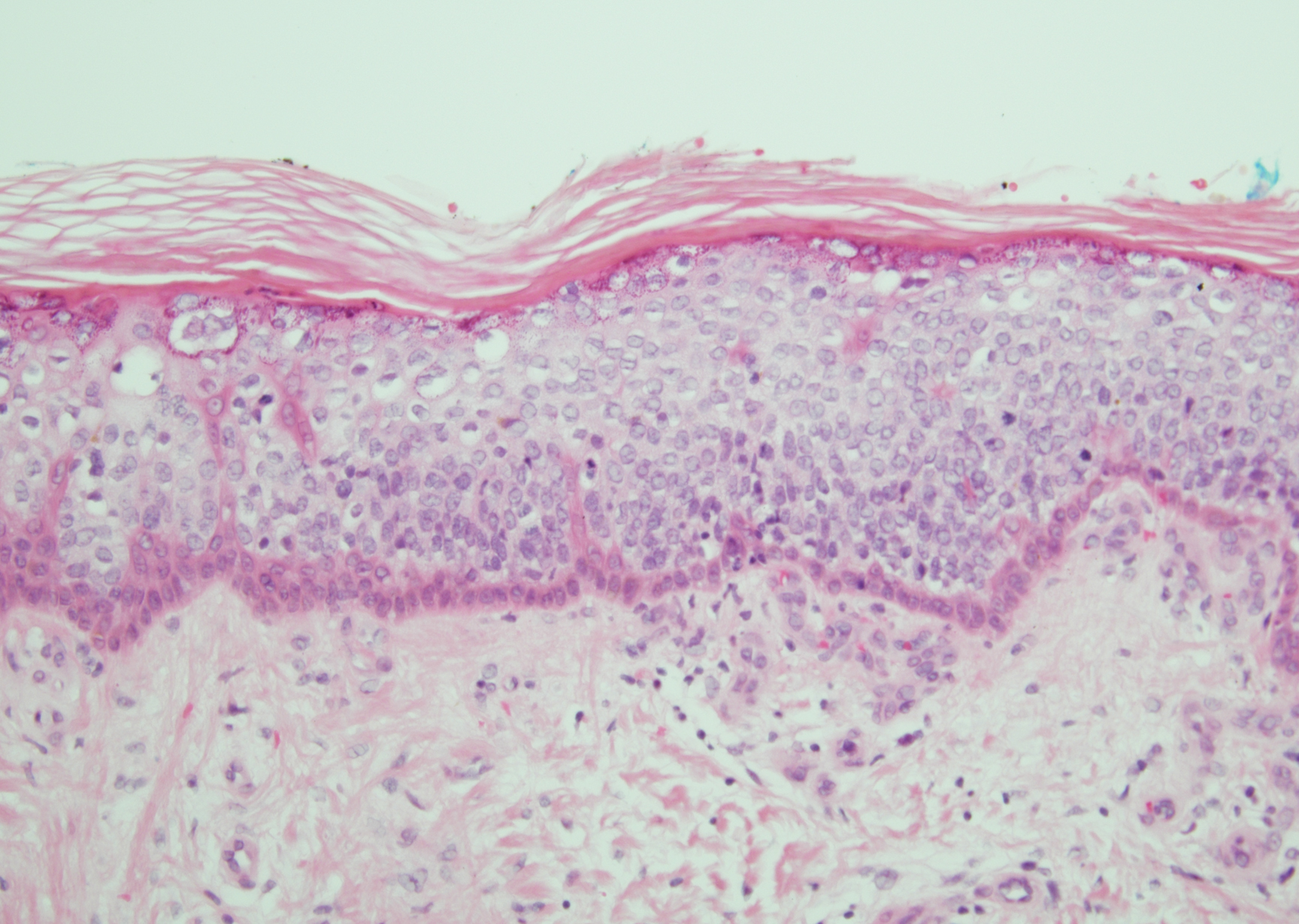

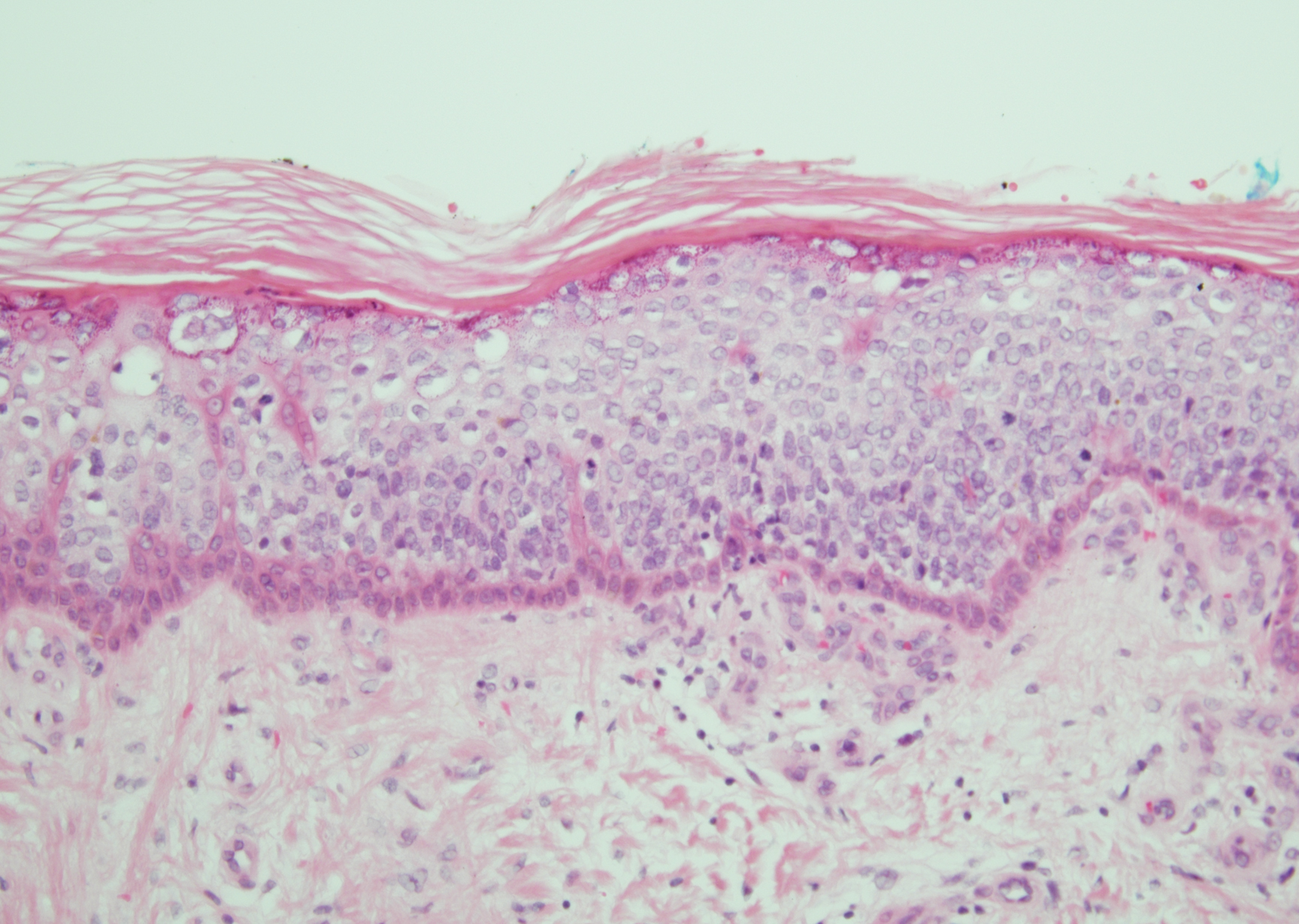

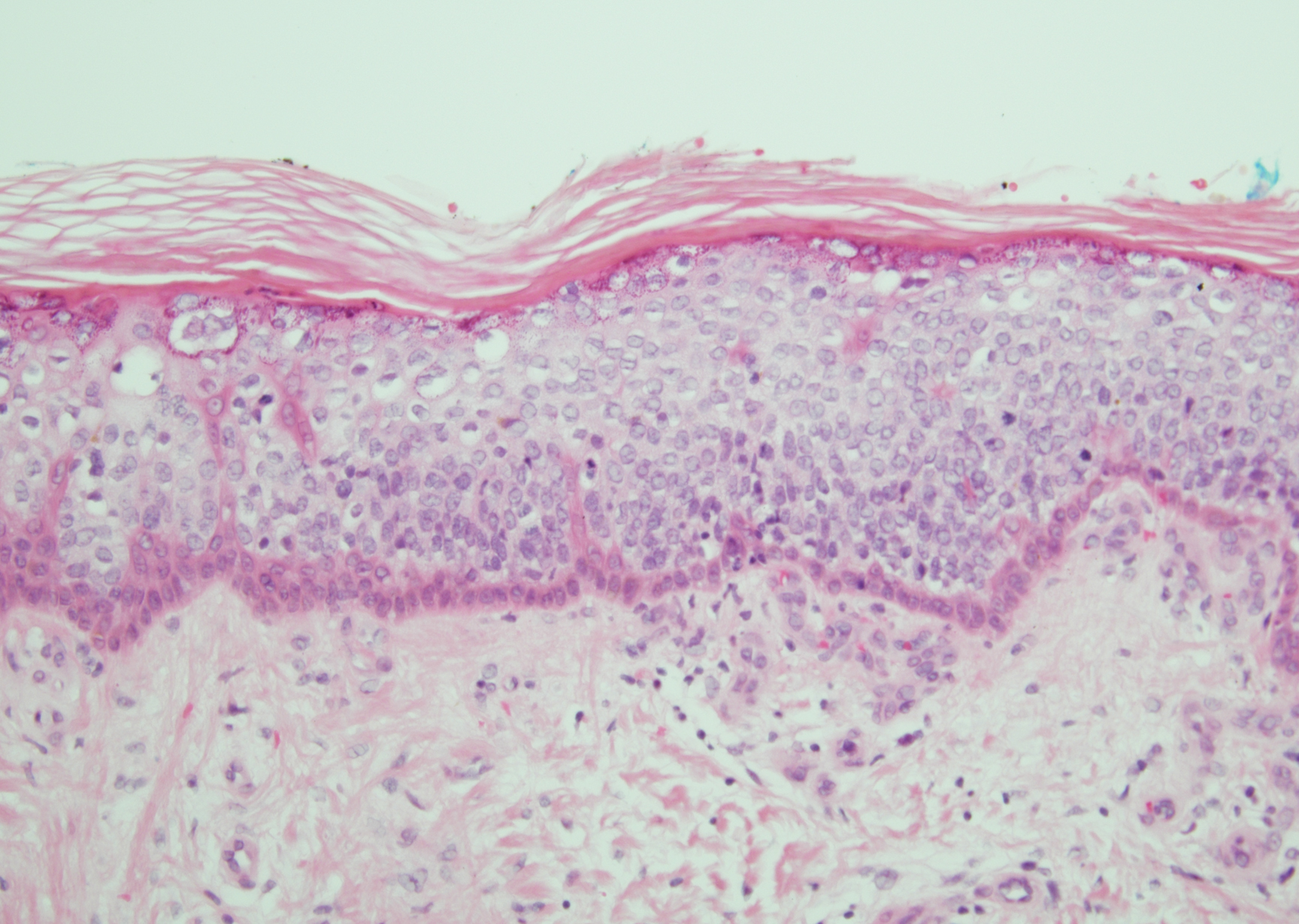

Irritated seborrheic keratosis presents as an exophytic, waxy, dark, sharply demarcated plaque with a stuck-on appearance.6 There is visible keratinization with comedolike openings, fissures and ridges, and scale; it also can contain milialike cysts. Histopathologically there is papillomatosis with prominent rete ridges, often including keratin pseudohorn cysts and squamous eddies. Enlarged capillaries can be seen in the dermal papillae. There is normal cytology with benign sheets of basaloid cells (Figure 2).7 Activating mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 leads to the growth and thickness of the epidermis that has been identified in these benign lesions.8

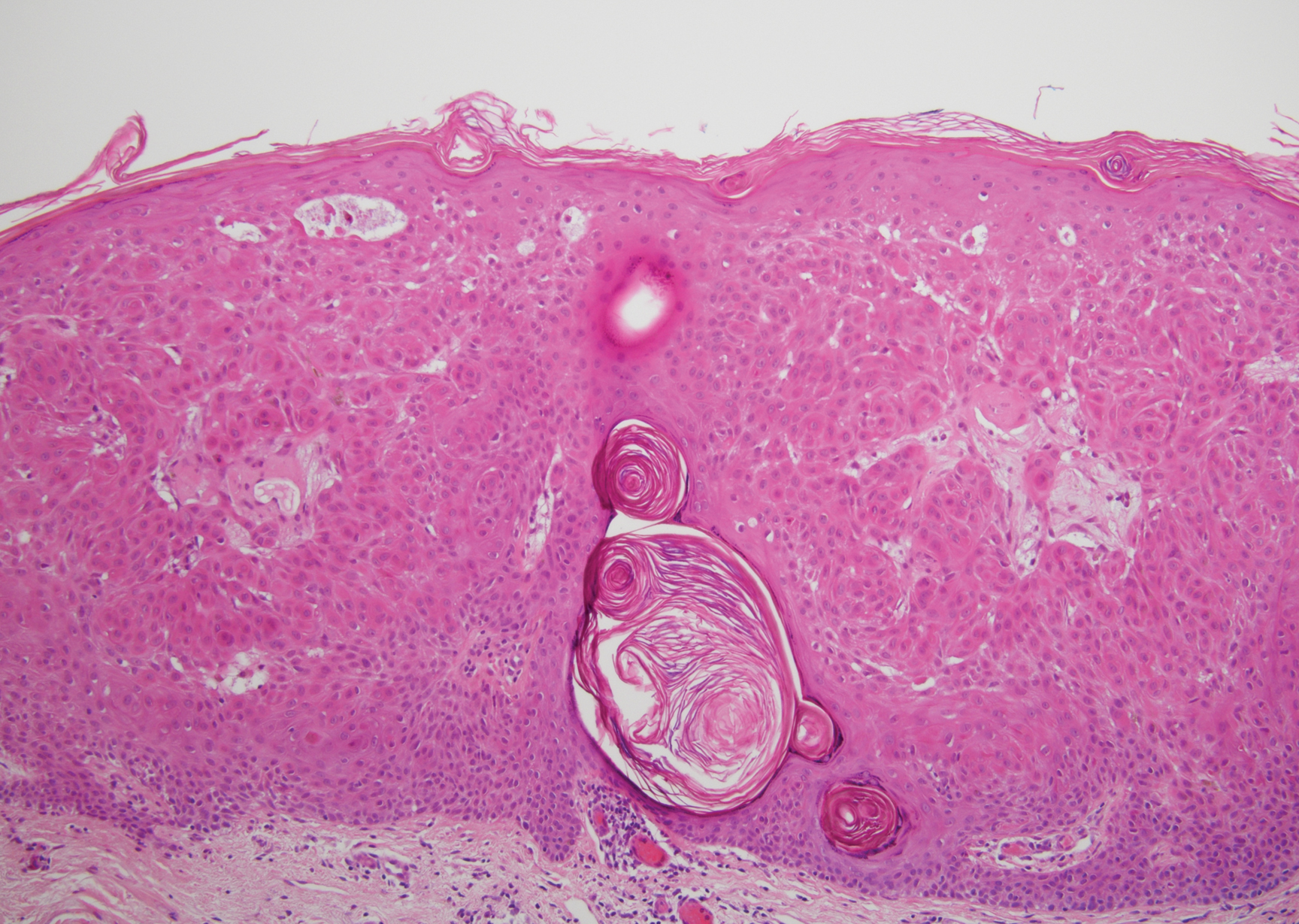

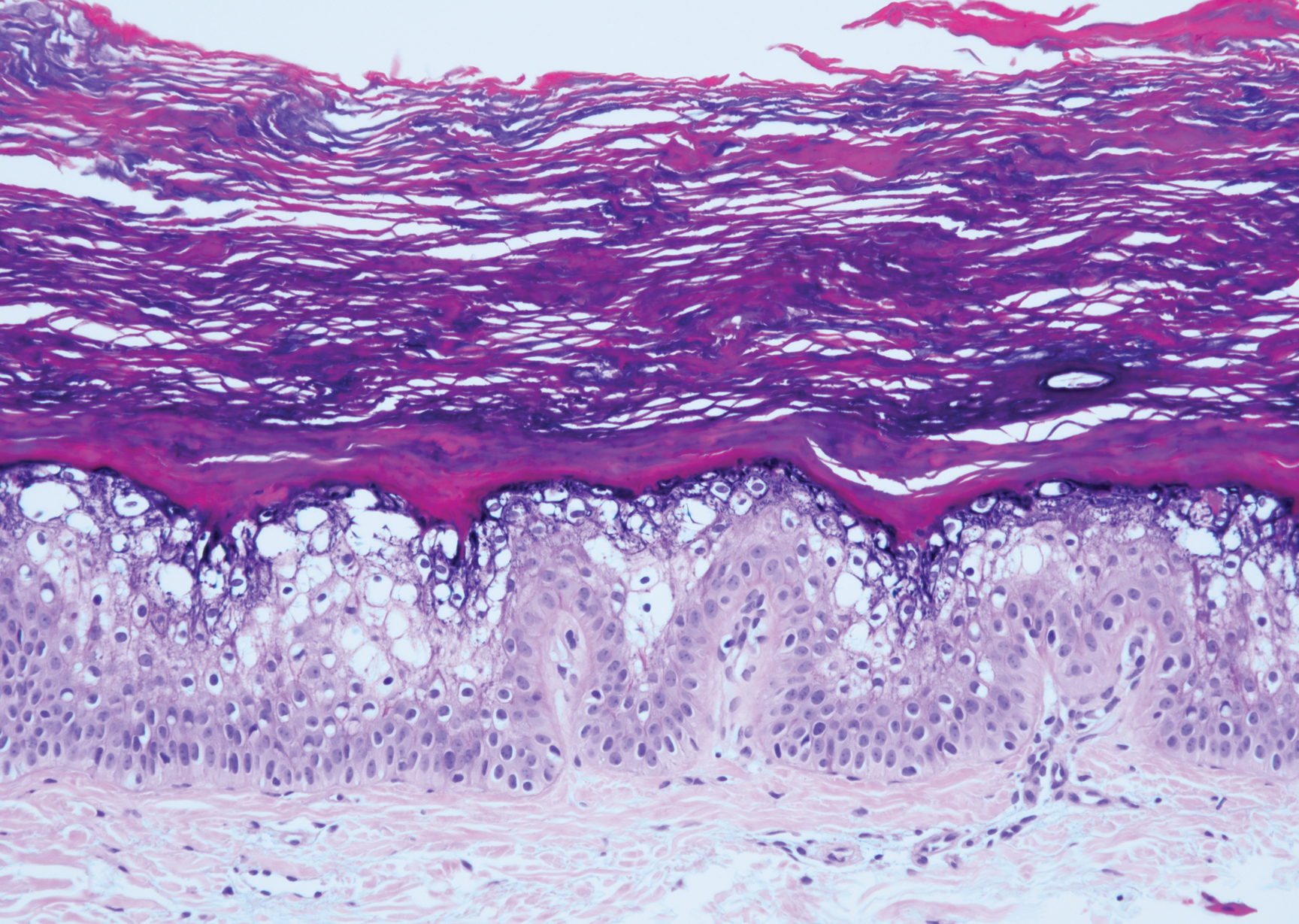

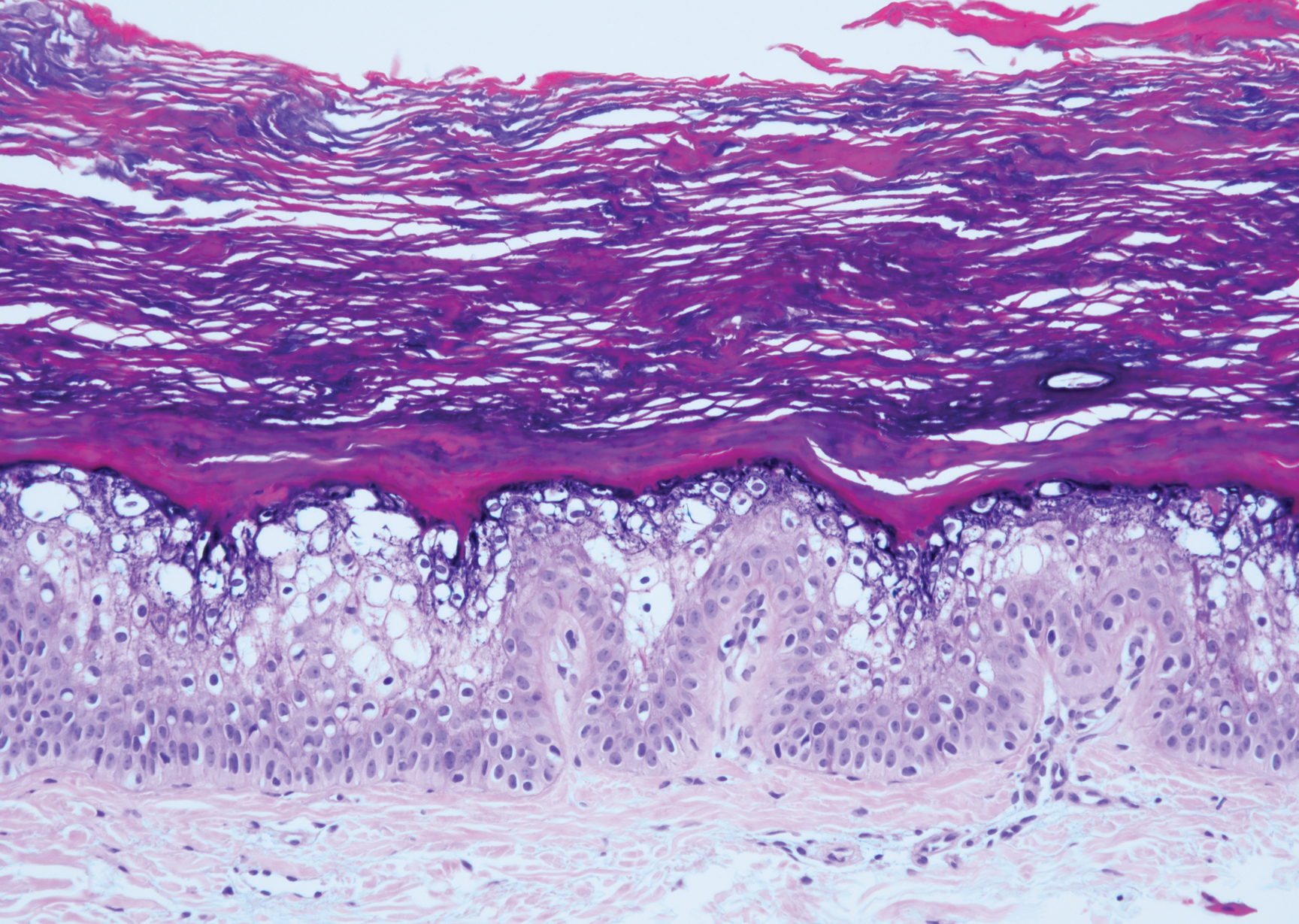

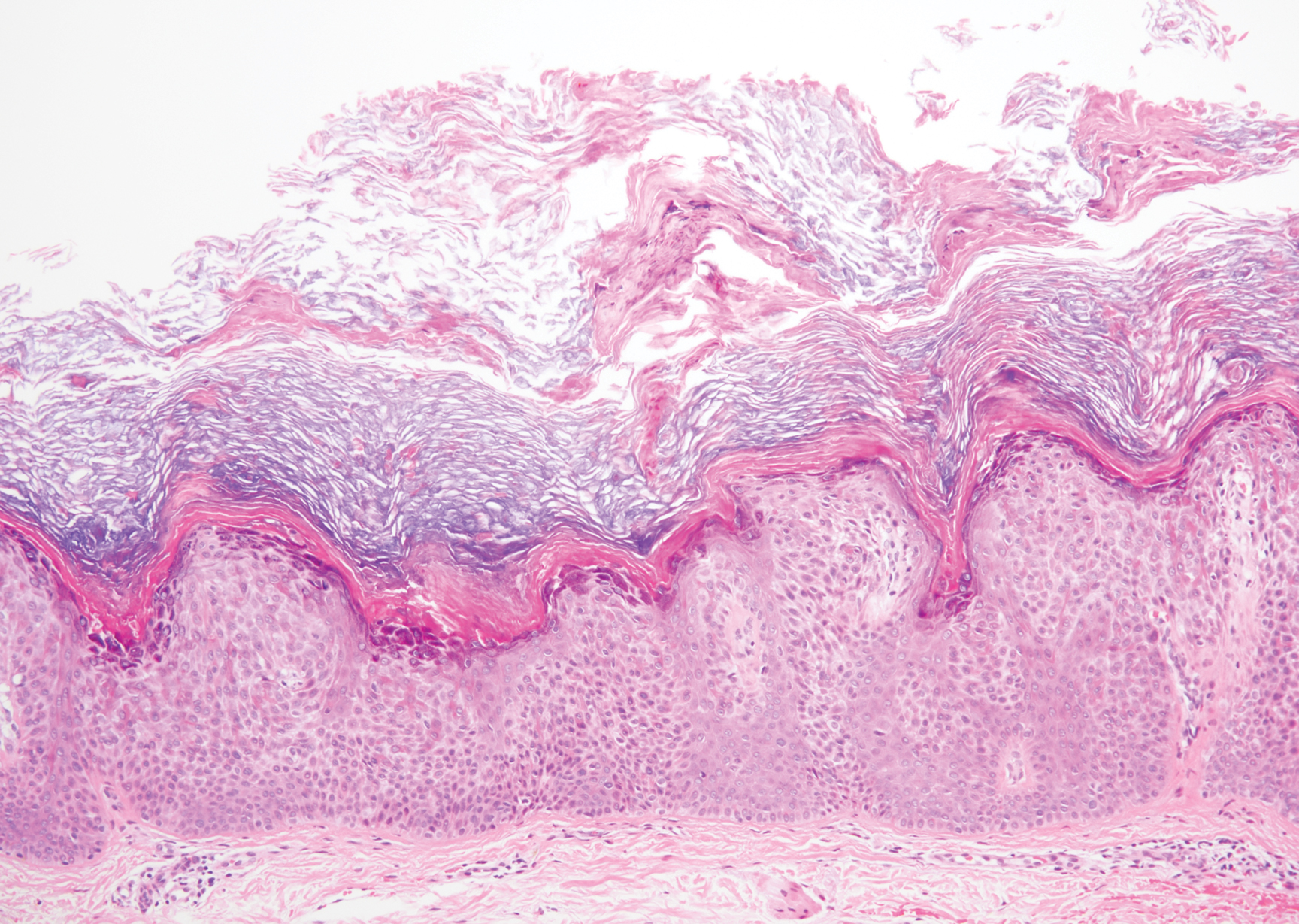

Verruca plana appears as a flesh-colored or reddish, warty, flat-topped papule that often forms clusters. Histopathologically it shows prominent hypergranulosis, thickened stratum spinosum, and vacuolized keratinocytes.9 The nuclei demonstrate a characteristic cytopathic effect of the virion, blurring the nuclear chromatin due to viral particle accumulation, known as koilocytes (Figure 3). The cause is the double-stranded DNA human papillomavirus types 2, 3, and 10.10

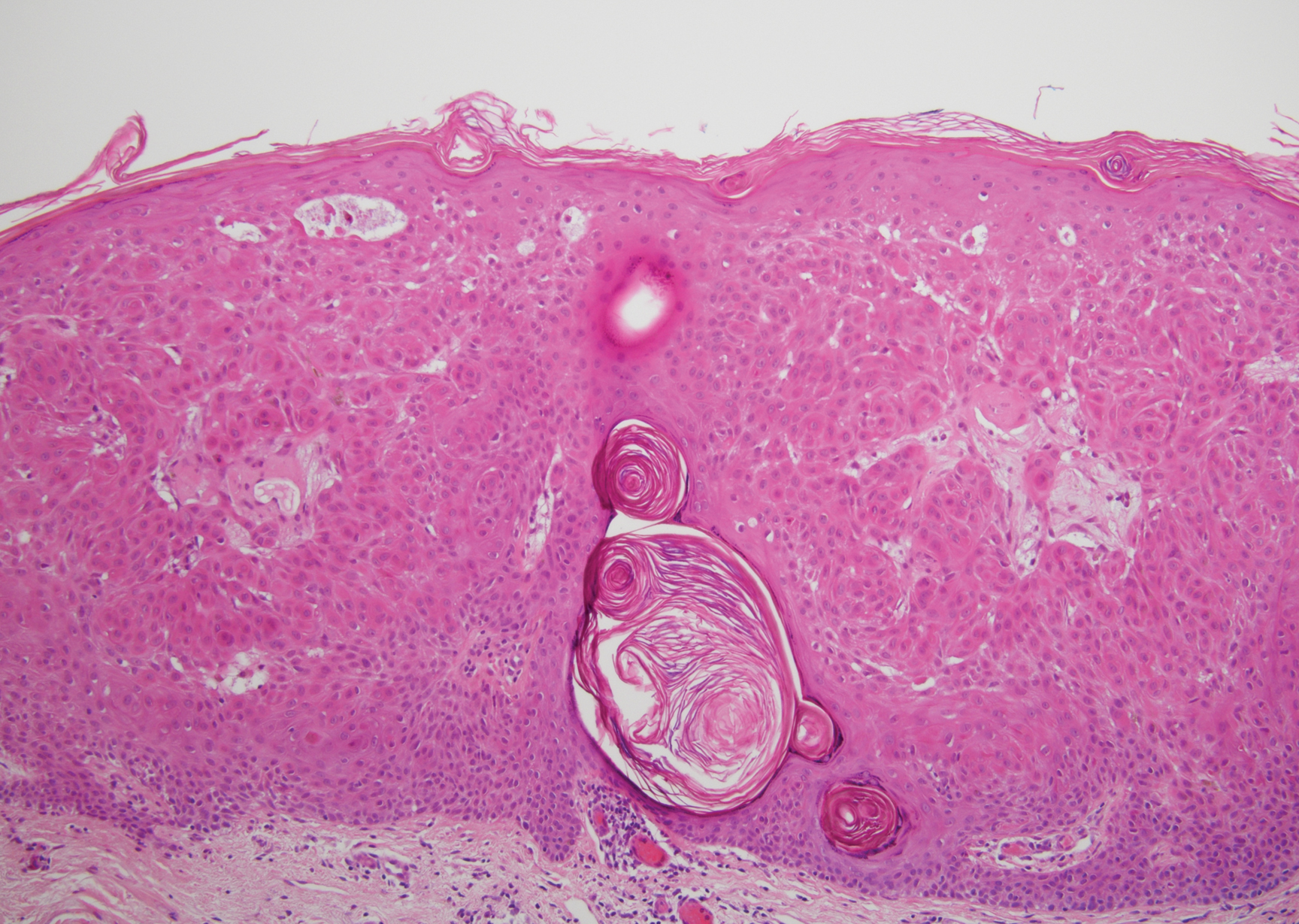

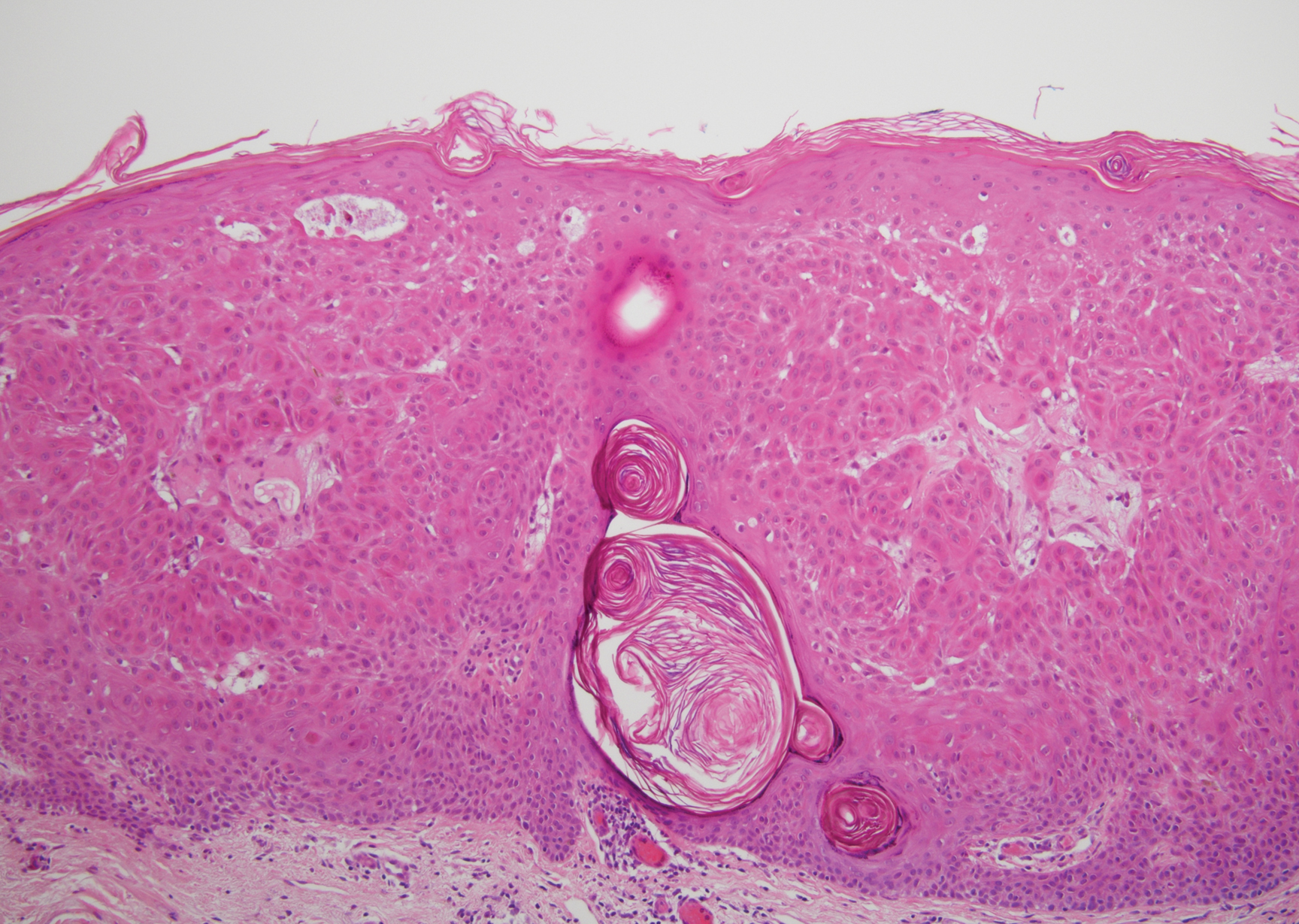

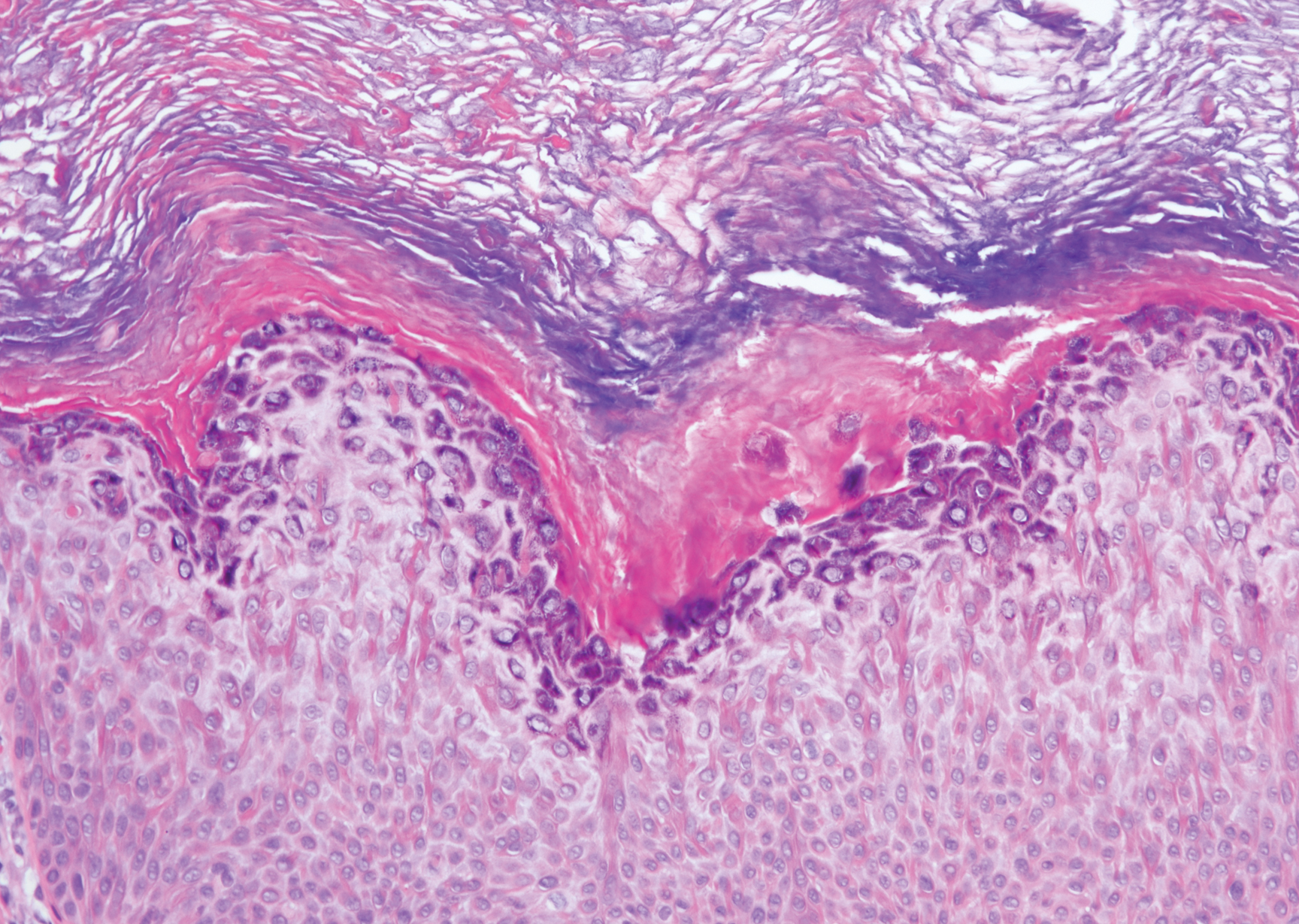

Bowen disease is a form of squamous cell carcinoma in situ characterized by an enlarging, well-demarcated, erythematous plaque with an irregular border and crusting or scaling. Histopathology reveals pleomorphic epidermal keratinization that becomes incorporated in the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei. There is acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, and disorganized keratinocytes with atypia.11 The granular and spinous layers show an atypical honeycomb pattern with atypical cellular morphology (Figure 4).12 Bowen disease is a malignant lesion commonly found in older adults on sun-exposed skin that can evolve into invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

- Roy SF, Ko CJ, Moeckel GW, et al. Hypergranulotic dyscornification: 30 cases of a striking epithelial reaction pattern. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:742-747.

- Dohse L, Elston D, Lountzis N, et al. Benign hypergranulotic keratosis with dyscornification. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:AB52.

- Reichel M. Hypergranulotic dyscornification. Am J Dermatopathol. 1999;21:21-24.

- Kumar P, Kumar R, Kumar Mandal RK, et al. Systematized linear epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:21248.

- Peter Rout D, Nair A, Gupta A, et al. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis: clinical update. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2019;12:333-344.

- Ingraffea A. Benign skin neoplasms. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21:21-32.

- Braun R. Dermoscopy of pigmented seborrheic keratosis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1556.

- Duperret EK, Oh SJ, McNeal A, et al. Activating FGFR3 mutations cause mild hyperplasia in human skin, but are insufficient to drive benign or malignant skin tumors. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:1551-1559.

- Liu H, Chen S, Zhang F, et al. Seborrheic keratosis or verruca plana? a pilot study with confocal laser scanning microscopy. Skin Res Technol. 2010;16:408-412.

- Prieto-Granada CN, Lobo AZC, Mihm MC. Skin infections. In: Kradin RL, ed. Diagnostic Pathology of Infectious Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2010:519-616.

- DeCoste R, Moss P, Boutilier R, et al. Bowen disease with invasive mucin-secreting sweat gland differentiation: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:425-430.

- Ulrich M, Kanitakis J, González S, et al. Evaluation of Bowen disease by in vivo reflectance confocal microscopy. Br J Dermatol. 2011;166:451-453.

The Diagnosis: Hypergranulotic Dyscornification

Hypergranulotic dyscornification (HD) is a rarely reported reaction pattern present in benign solitary keratoses with only few reports to date. It may be an underrecognized reaction pattern based on the paucity of reported cases as well as the histologic similarities to other entities. It has been hypothesized that this pattern reflects an underlying keratin mutation or disorder of keratinization.1

Clinically, HD most commonly presents as a waxy, tan-colored, solitary keratosis generally found on the lower limbs, trunk, or back in individuals aged 20 to 60 years.1,2 Histopathology shows marked hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and clumped basophilic keratohyalin granules within the corneocytes with digitated epidermal hyperplasia. There is abnormal cornification across the entire lesion with papillomatosis and marked hypergranulosis.3 There often are homogeneous orthokeratotic mounds of large, dull, eosinophilic-staining anucleate keratinocytes that are sharply demarcated from the thickened granular layer.1,2 Within the spinous, granular, and corneal layers, there is a pale, gray-staining, basophilic, cytoplasmic substance intercellularly.1

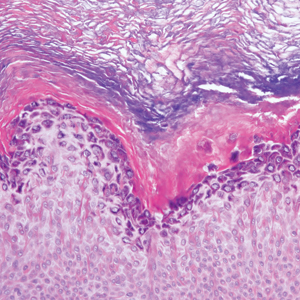

Histopathologically, HD may be mistaken for several other entities both benign and malignant.1 Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis can be a genetic disorder, an incidental finding in a variety of skin conditions, or an isolated lesion.4 The genetic syndrome, caused by mutation in keratins 1 or 10, clinically presents with hyperkeratosis, erosions, blisters, and thickening of the epidermis, often with a corrugated appearance. Epidermal nevi findings often are seen in conjunction with histologic changes of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis caused by mutation. Solitary lesions also can resemble seborrheic keratosis or verruca. In all examples of epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, the histopathologic findings are identical.4 The granular layer is thickened, and coarse keratohyalin granules aggregate in the suprabasal cells.5 There is acantholysis with perinuclear vacuolization in the spinous and granular layers with characteristic pale cytoplasmic areas devoid of keratin filaments (Figure 1). The basal layer may be hyperproliferative.5

Irritated seborrheic keratosis presents as an exophytic, waxy, dark, sharply demarcated plaque with a stuck-on appearance.6 There is visible keratinization with comedolike openings, fissures and ridges, and scale; it also can contain milialike cysts. Histopathologically there is papillomatosis with prominent rete ridges, often including keratin pseudohorn cysts and squamous eddies. Enlarged capillaries can be seen in the dermal papillae. There is normal cytology with benign sheets of basaloid cells (Figure 2).7 Activating mutation in fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 leads to the growth and thickness of the epidermis that has been identified in these benign lesions.8

Verruca plana appears as a flesh-colored or reddish, warty, flat-topped papule that often forms clusters. Histopathologically it shows prominent hypergranulosis, thickened stratum spinosum, and vacuolized keratinocytes.9 The nuclei demonstrate a characteristic cytopathic effect of the virion, blurring the nuclear chromatin due to viral particle accumulation, known as koilocytes (Figure 3). The cause is the double-stranded DNA human papillomavirus types 2, 3, and 10.10

Bowen disease is a form of squamous cell carcinoma in situ characterized by an enlarging, well-demarcated, erythematous plaque with an irregular border and crusting or scaling. Histopathology reveals pleomorphic epidermal keratinization that becomes incorporated in the stratum corneum as parakeratotic nuclei. There is acanthosis, elongation of the rete ridges, and disorganized keratinocytes with atypia.11 The granular and spinous layers show an atypical honeycomb pattern with atypical cellular morphology (Figure 4).12 Bowen disease is a malignant lesion commonly found in older adults on sun-exposed skin that can evolve into invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

The Diagnosis: Hypergranulotic Dyscornification

Hypergranulotic dyscornification (HD) is a rarely reported reaction pattern present in benign solitary keratoses with only few reports to date. It may be an underrecognized reaction pattern based on the paucity of reported cases as well as the histologic similarities to other entities. It has been hypothesized that this pattern reflects an underlying keratin mutation or disorder of keratinization.1

Clinically, HD most commonly presents as a waxy, tan-colored, solitary keratosis generally found on the lower limbs, trunk, or back in individuals aged 20 to 60 years.1,2 Histopathology shows marked hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and clumped basophilic keratohyalin granules within the corneocytes with digitated epidermal hyperplasia. There is abnormal cornification across the entire lesion with papillomatosis and marked hypergranulosis.3 There often are homogeneous orthokeratotic mounds of large, dull, eosinophilic-staining anucleate keratinocytes that are sharply demarcated from the thickened granular layer.1,2 Within the spinous, granular, and corneal layers, there is a pale, gray-staining, basophilic, cytoplasmic substance intercellularly.1