User login

Cancer Screening for Dermatomyositis: A Survey of Indirect Costs, Burden, and Patient Willingness to Pay

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an uncommon idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) characterized by muscle inflammation; proximal muscle weakness; and dermatologic findings, such as the heliotrope eruption and Gottron papules.1-3 Dermatomyositis is associated with an increased malignancy risk compared to other IIMs, with a 13% to 42% lifetime risk for malignancy development.4,5 The incidence for malignancy peaks during the first year following diagnosis and falls gradually over 5 years but remains increased compared to the general population.6-11 Adenocarcinoma represents the majority of cancers associated with DM, particularly of the ovaries, lungs, breasts, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, bladder, and prostate. The lymphatic system (non-Hodgkin lymphoma) also is overrepresented among cancers in DM.12

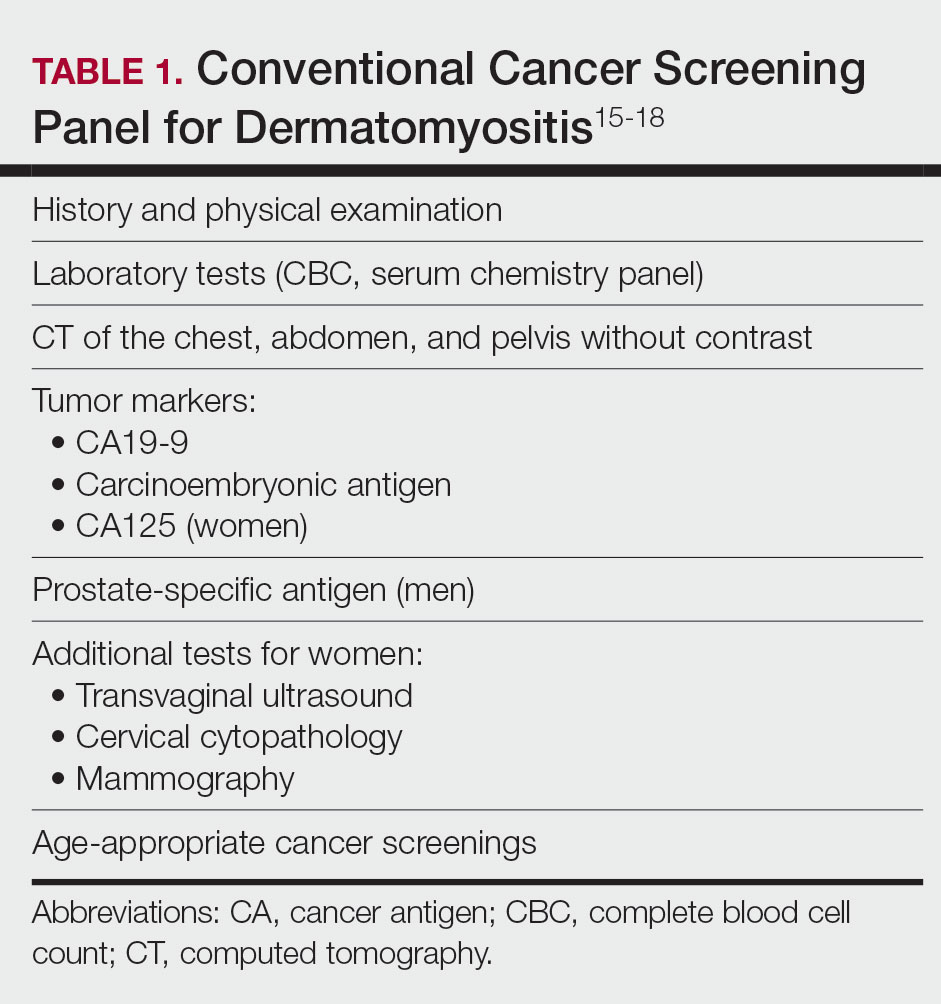

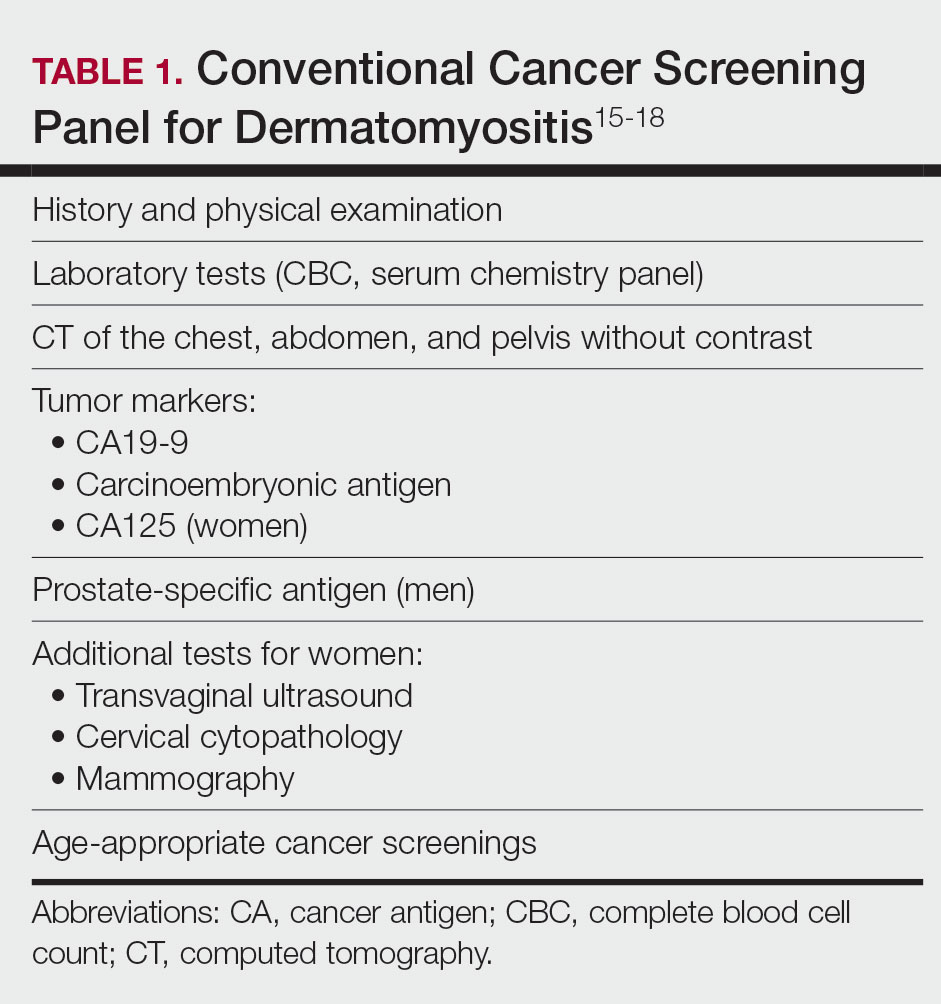

Because of the increased malignancy risk and cancer-related mortality in patients with DM, cancer screening generally is recommended following diagnosis.13,14 However, consensus guidelines for screening modalities and frequency currently do not exist, resulting in widely varying practice patterns.15 Some experts advocate for a conventional cancer screening panel (CSP), as summarized in Table 1.15-18 These tests may be repeated annually for 3 to 5 years following the diagnosis of DM. Although the use of myositis-specific antibodies (MSAs) recently has helped to risk-stratify DM patients, up to half of patients are MSA negative,19 and broad malignancy screening remains essential. Individualized discussions with patients about their risk factors, screening options, and risks and benefits of screening also are strongly encouraged.19-22 Studies of the direct costs and effectiveness of streamlined screening with positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) compared with a CSP have shown similar efficacy and lower out-of-pocket costs for patients receiving PET/CT imaging.16-18

The goal of our study was to further characterize patients’ perspectives and experience of cancer screening in DM as well as indirect costs, both of which must be taken into consideration when developing consensus guidelines for DM malignancy screening. Inclusion of patient voice is essential given the similar efficacy of both screening methods. We assessed the indirect costs (eg, travel, lost work or wages, childcare) of a CSP in patients with DM. We theorized that the large quantity of tests involved in a CSP, which are performed at various locations on multiple days over the course of several years, may have substantial costs to patients beyond the co-pay and deductible. We also sought to measure patients’ perception of the burden associated with an annual CSP, which we defined to participants as the inconvenience or unpleasantness experienced by the patient, compared with an annual whole-body PET/CT. Finally, we examined the relative value of these screening methods to patients using a willingness-to-pay (WTP) analysis.

Materials and Methods

Patient Eligibility—Our study included Penn State Health (Hershey, Pennsylvania) patients 18 years or older with a recent diagnosis of DM—International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code 710.3 or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes M33.10 or M33.90—who were undergoing or had recently completed a CSP. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a concurrent or preceding diagnosis of malignancy (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancers) or had another IIM. The institutional review board at Penn State Health College of Medicine approved the study. Data for all patients were prospectively obtained.

Survey Design—A survey was generated to assess the burden and indirect costs associated with a CSP, which was modified from work done by Tchuenche et al23 and Teni et al.24 Focus groups were held in 2018 and 2019 with patients who met our inclusion criteria with the purpose of refining the survey instrument based on patient input. A summary explanation of research was provided to all participants, and informed consent was obtained. Patients were compensated for their time for focus groups. Audio of each focus group was then transcribed and analyzed for common themes. Following focus group feedback, a finalized survey was generated for assessing burden and indirect costs (survey instrument provided in the Supplementary Information). REDCap (Vanderbilt University), a secure web application, was used to construct the finalized survey and to collect and manage data.25

Patients who fit our inclusion criteria were identified and recruited in multiple ways. Patients with appointments at the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Department of Dermatology were presented with the opportunity to participate, Penn State Health records with the appropriate billing codes were collected and patients were contacted, and an advertisement for the study was posted on StudyFinder. Surveys constructed on REDCap were then sent electronically to patients who agreed to participate in the study. A second summary explanation of research was included on the first page of the survey to describe the process.

The survey had 3 main sections. The first section collected demographic information. In the second section, we surveyed patients regarding the various aspects of a CSP that focus groups identified as burdensome. In addition, patients were asked to compare their feelings regarding an annual CSP vs whole-body PET/CT for a 3-year period utilizing a rating scale of strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, and strongly agree. This section also included a willingness-to-pay (WTP) analysis for each modality. We defined WTP as the maximum out-of-pocket cost that the patient would be willing to pay to receive testing, which was measured in a hypothetical scenario where neither whole-body PET/CT nor CSP was covered by insurance.26 Although WTP may be influenced by external factors such as patient income, it can serve as a numerical measure of how much the patient values each service. Furthermore, these external factors become less relevant when comparing the relative value of 2 separate tests, as such factors apply equally in both scenarios. In the third section of the survey, patients were queried regarding various indirect costs associated with a CSP. Descriptions for a CSP and whole-body PET/CT, including risks and benefits, were provided to allow patients to make informed decisions.

Statistical Analysis—Because of the rarity of DM and the subsequently limited sample size, summary and descriptive statistics were utilized to characterize the sample and identify patterns in the results. Continuous variables are presented with means and standard deviations, and proportions are presented with frequencies and percentages. All analyses were done using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

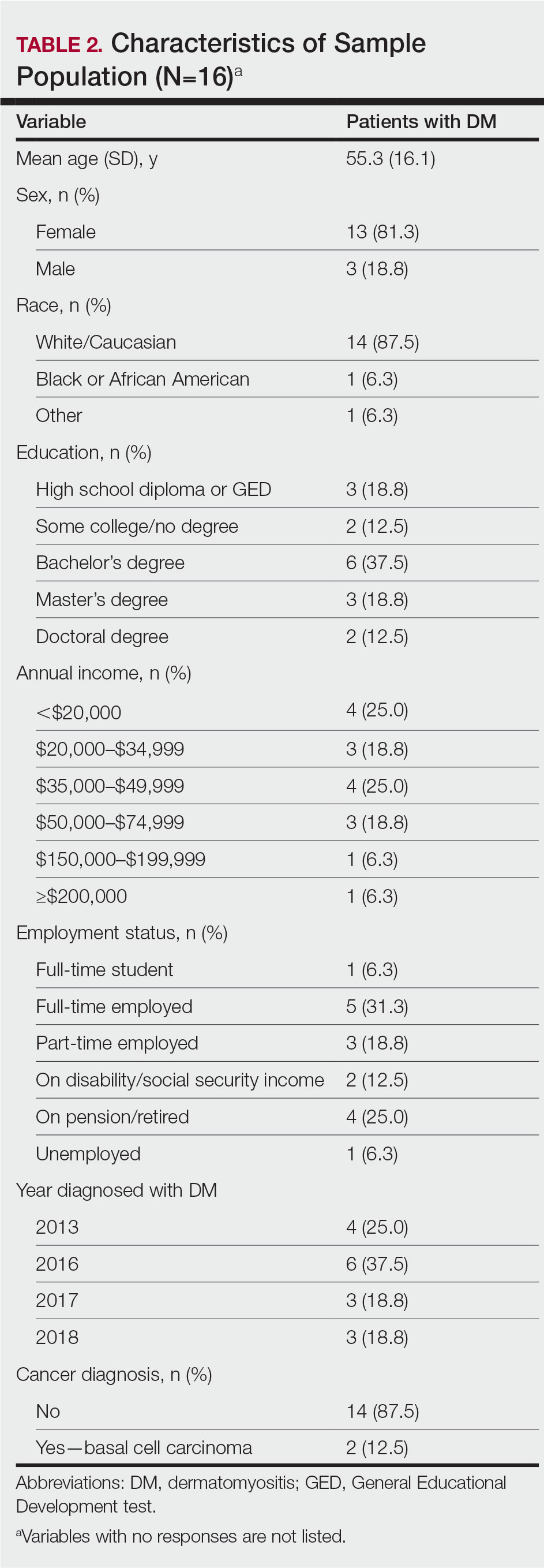

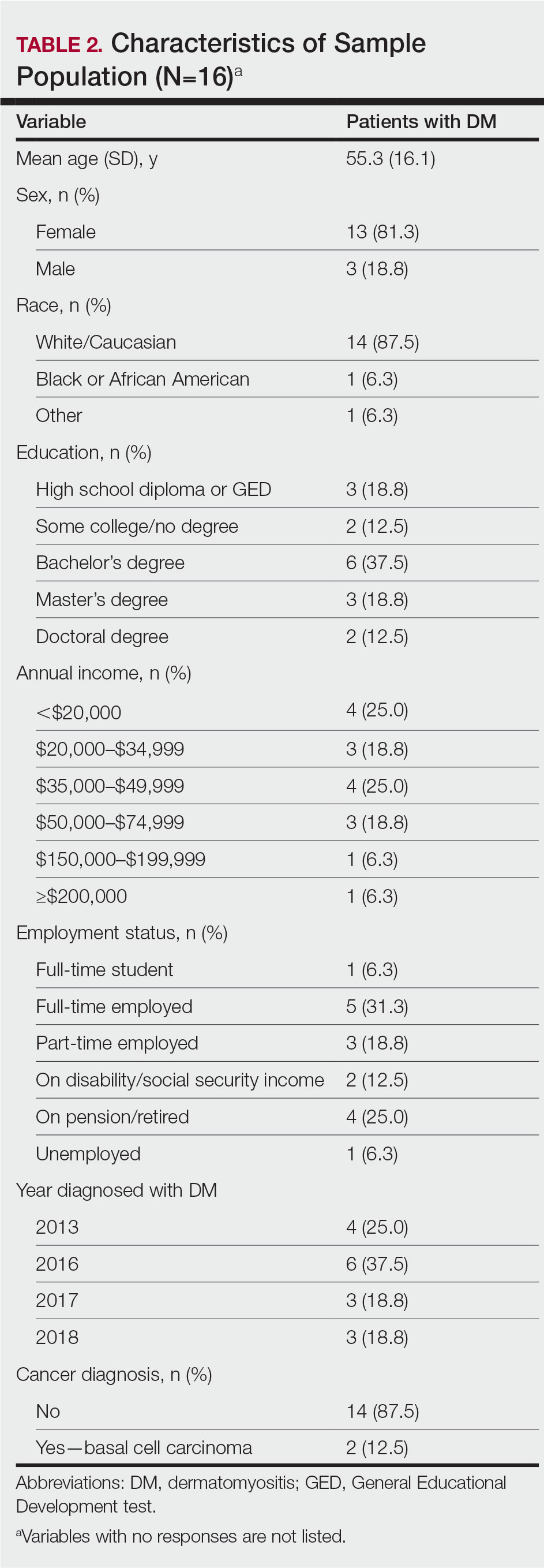

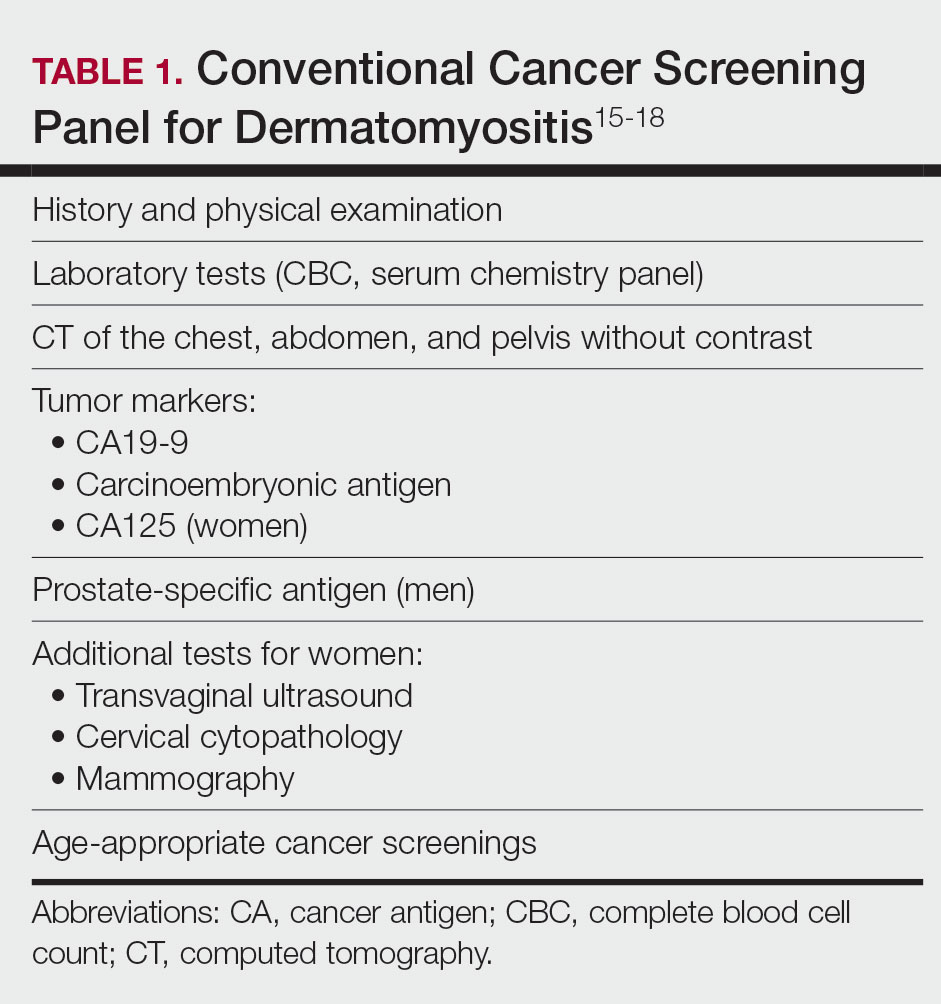

Patient Demographics—Fifty-four patients were identified using StudyFinder, physician referral, and search of the electronic health record. Nine patients agreed to take part in the focus groups, and 27 offered email addresses to be contacted for the survey. Of those 27 patients, 16 (59.3%) fit our inclusion criteria and completed the survey. Patient demographics are detailed in Table 2. The mean age was 55 years, and most patients were White (88% [14/16]), female (81% [13/16]), and had at least a bachelor’s degree (69% [11/16]). Most patients (69% [11/16]) had an annual income of less than $50,000, and half (50% [8/16]) were employed. All patients had been diagnosed with DM in or after 2013. Two patients were diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma during or after cancer screening.

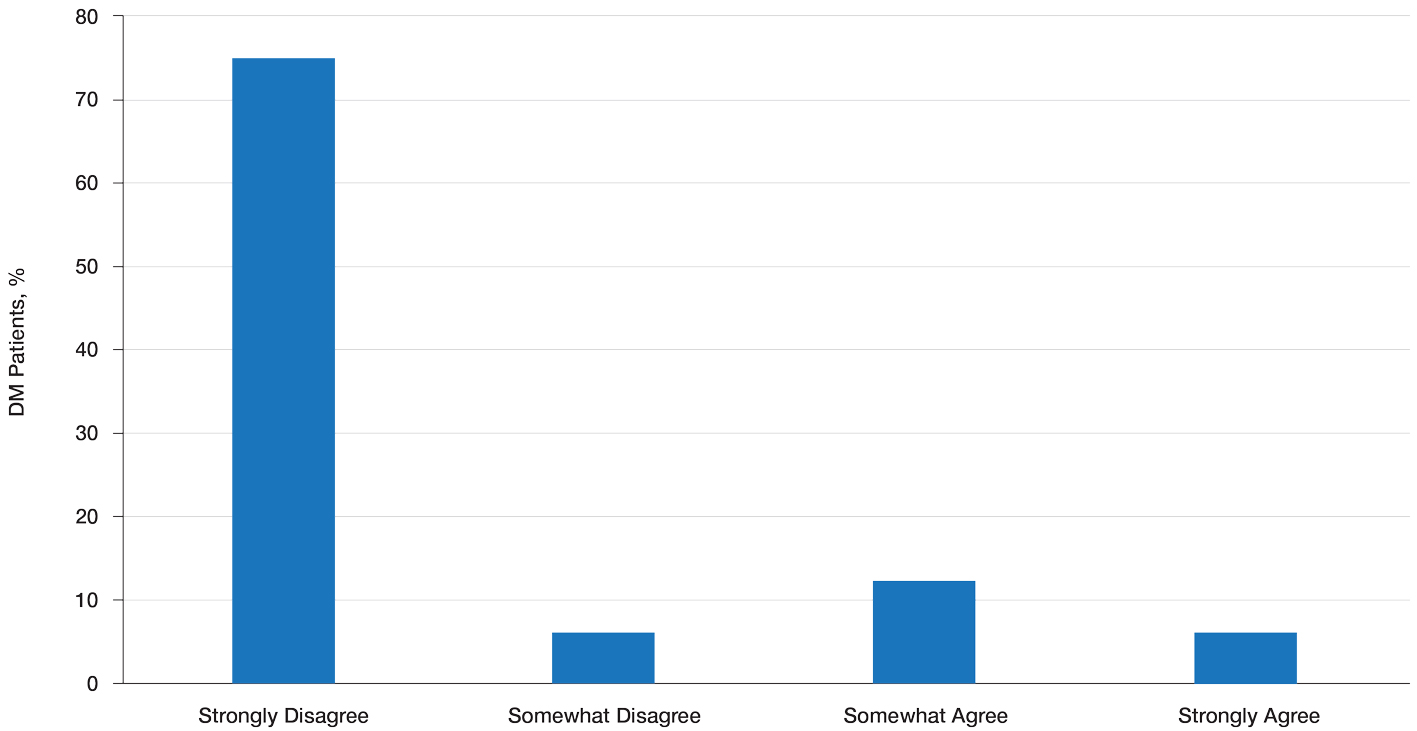

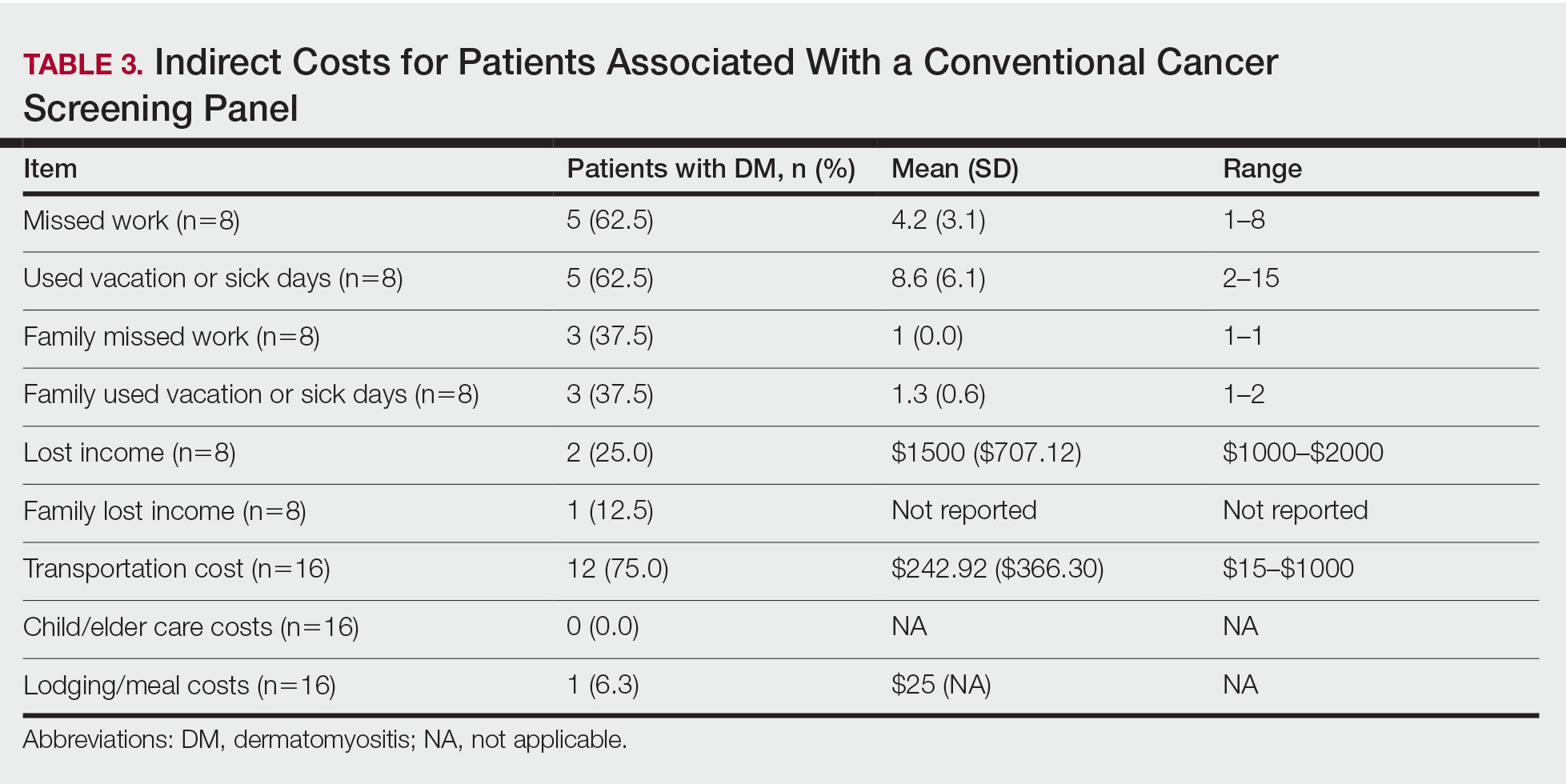

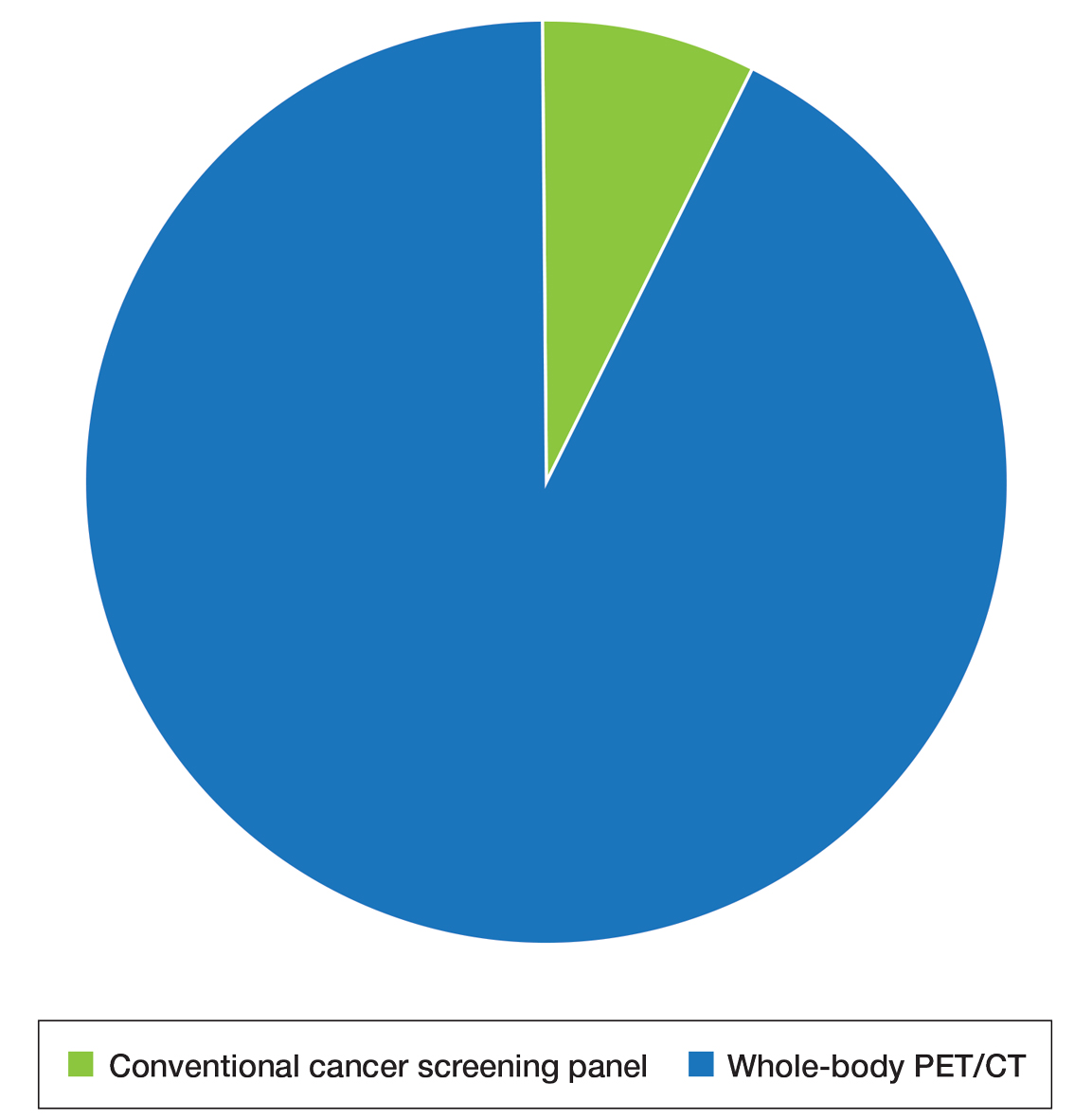

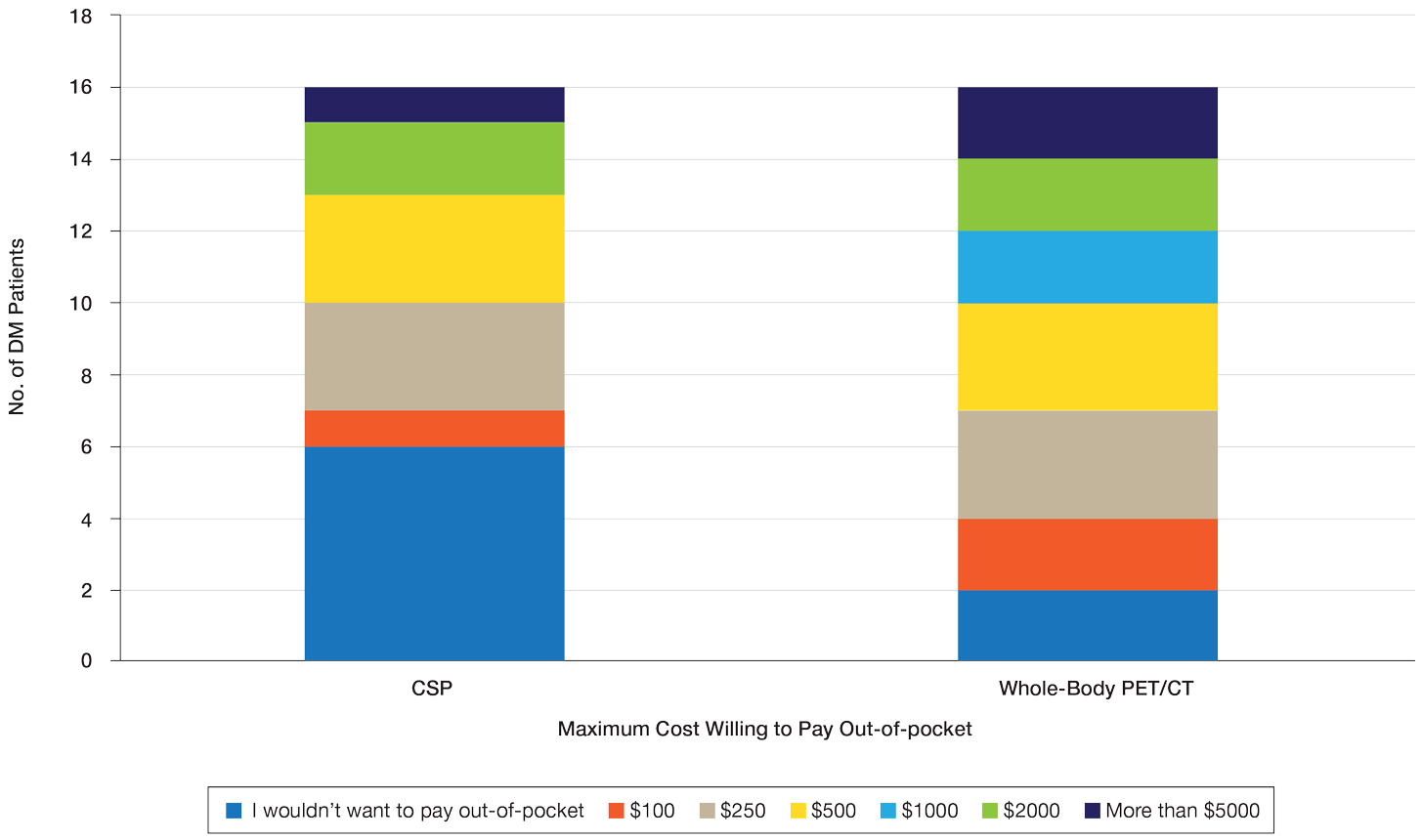

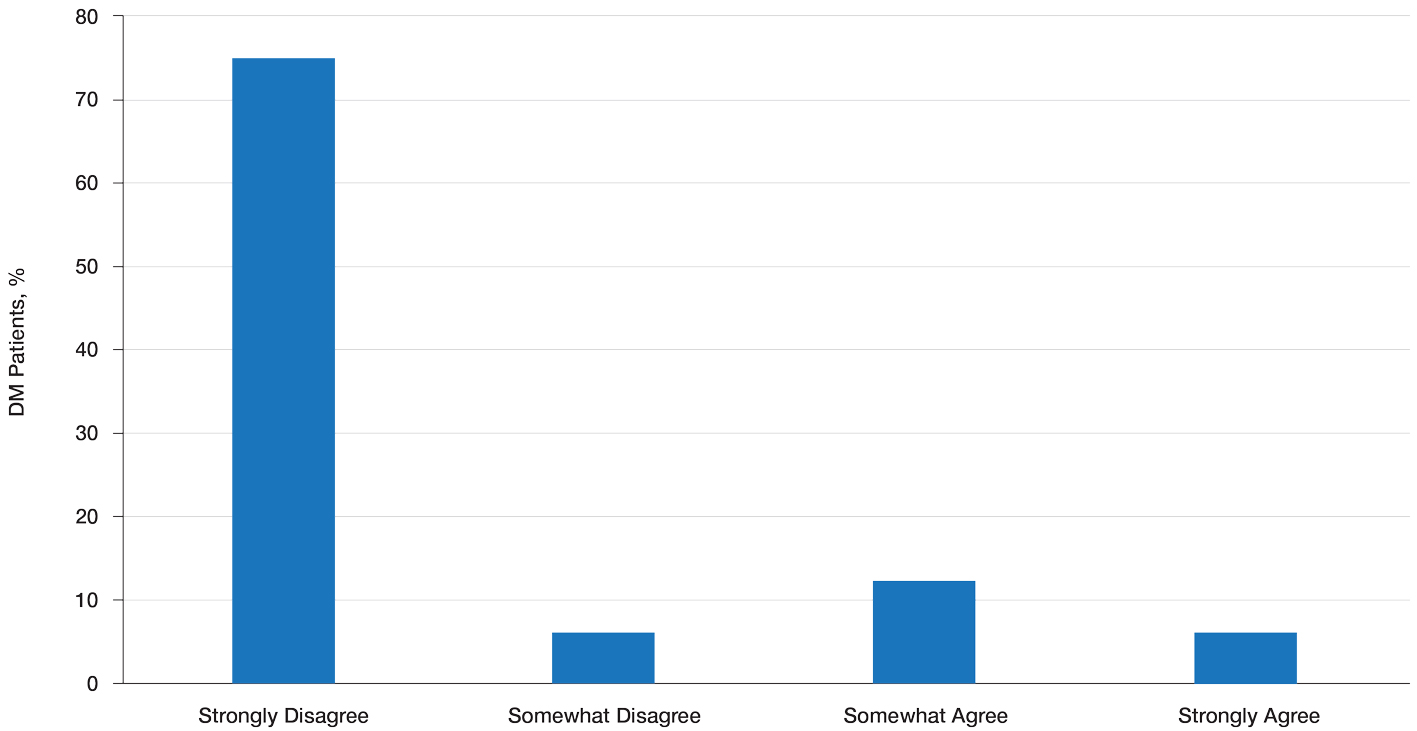

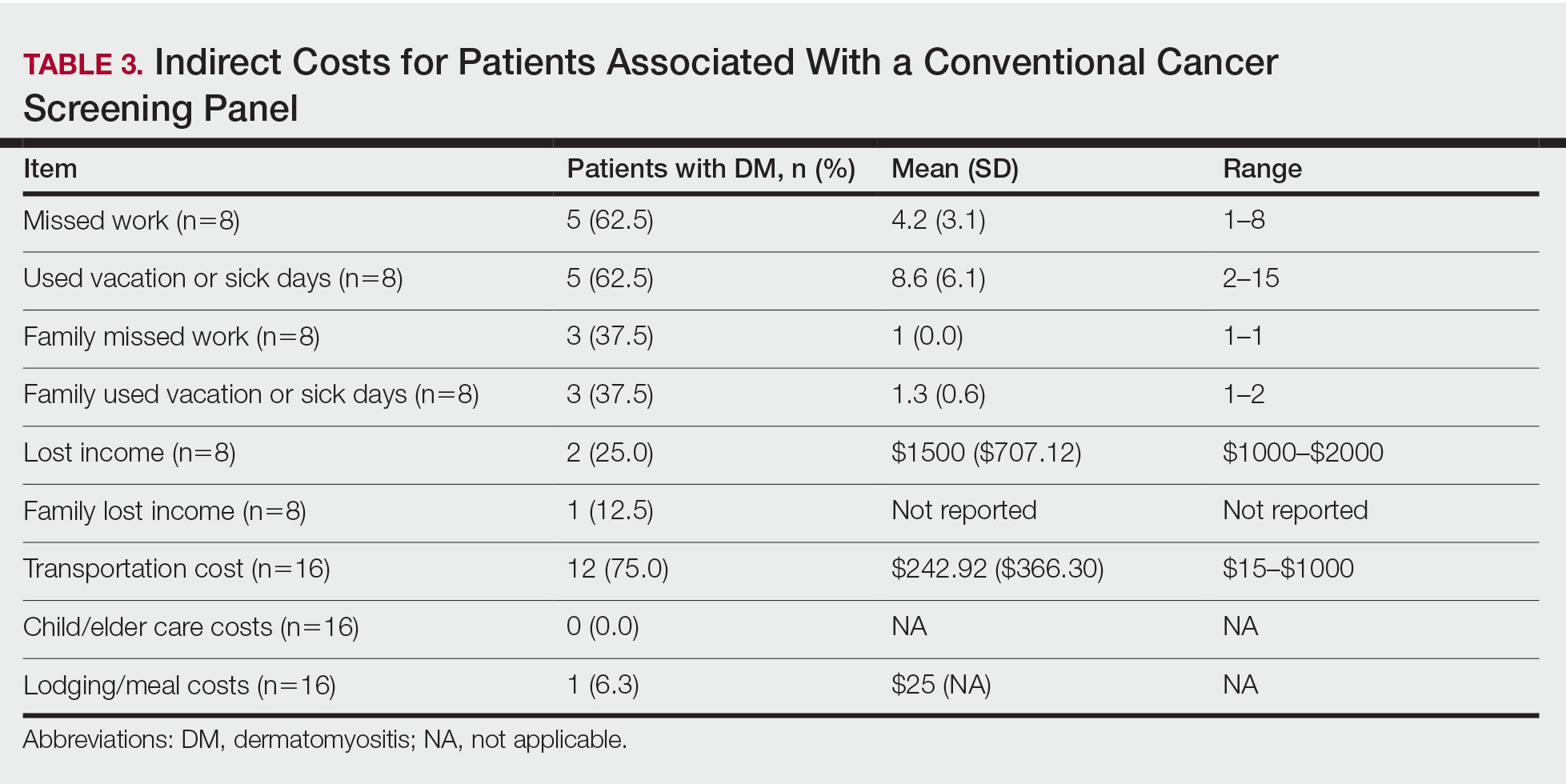

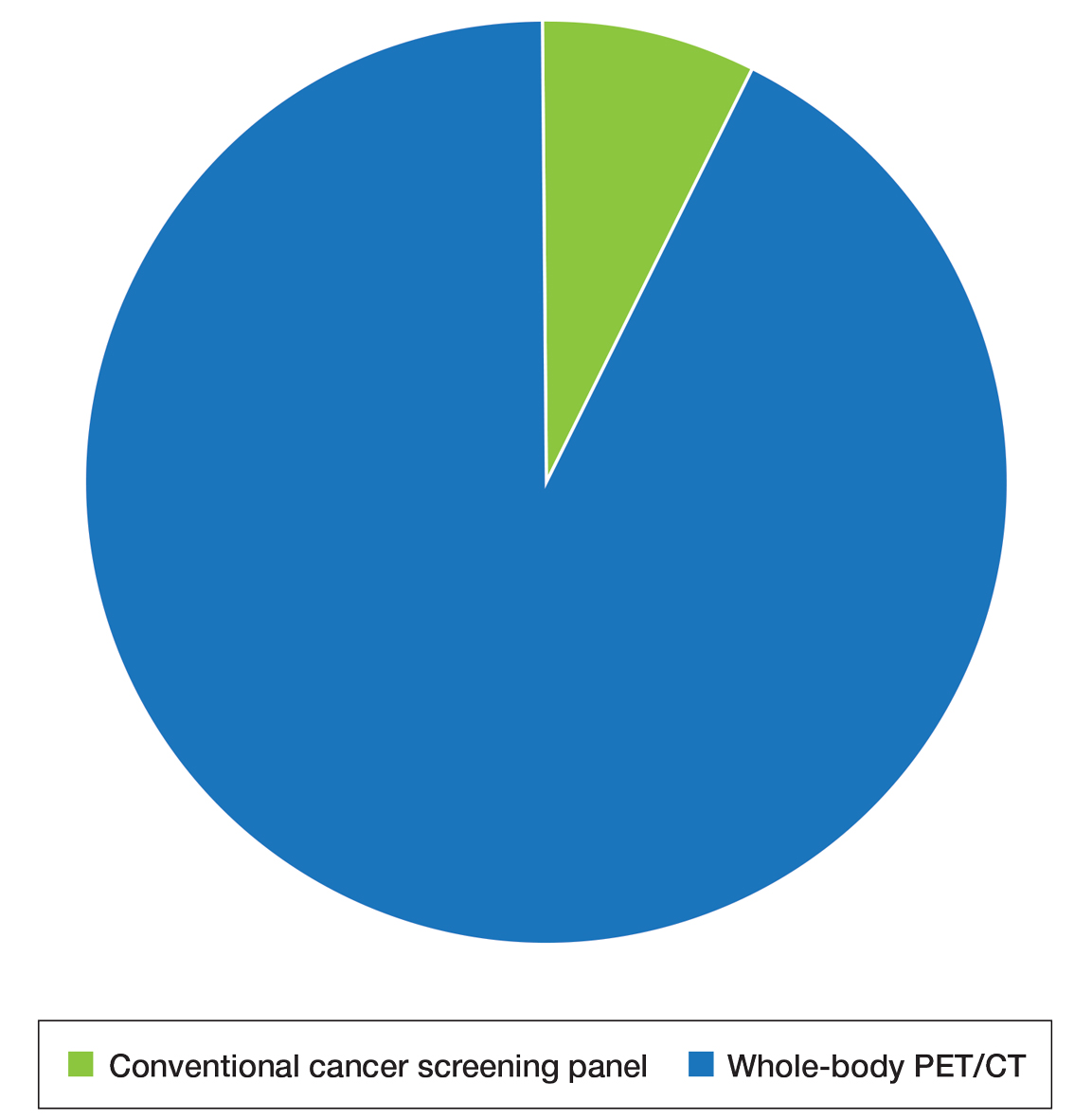

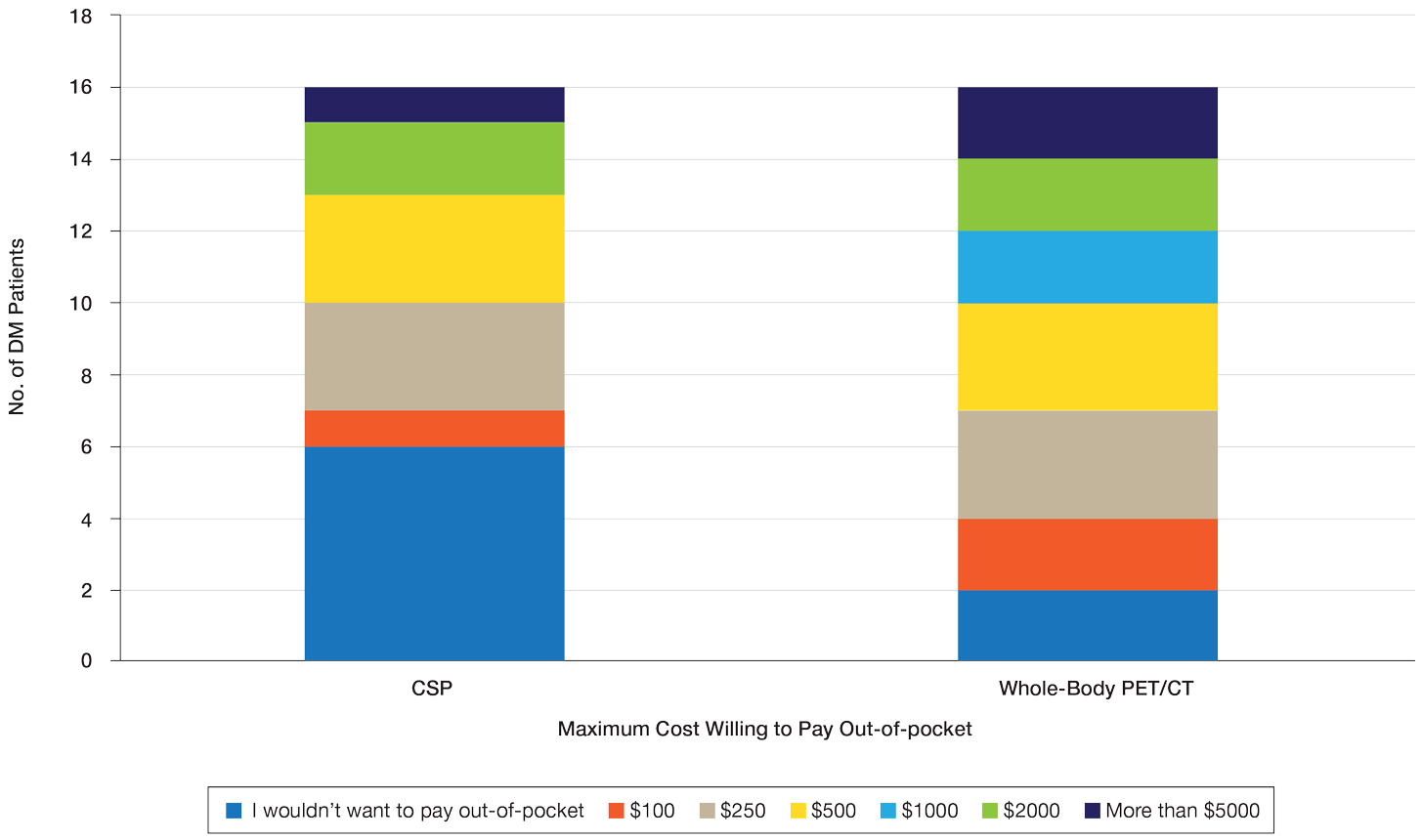

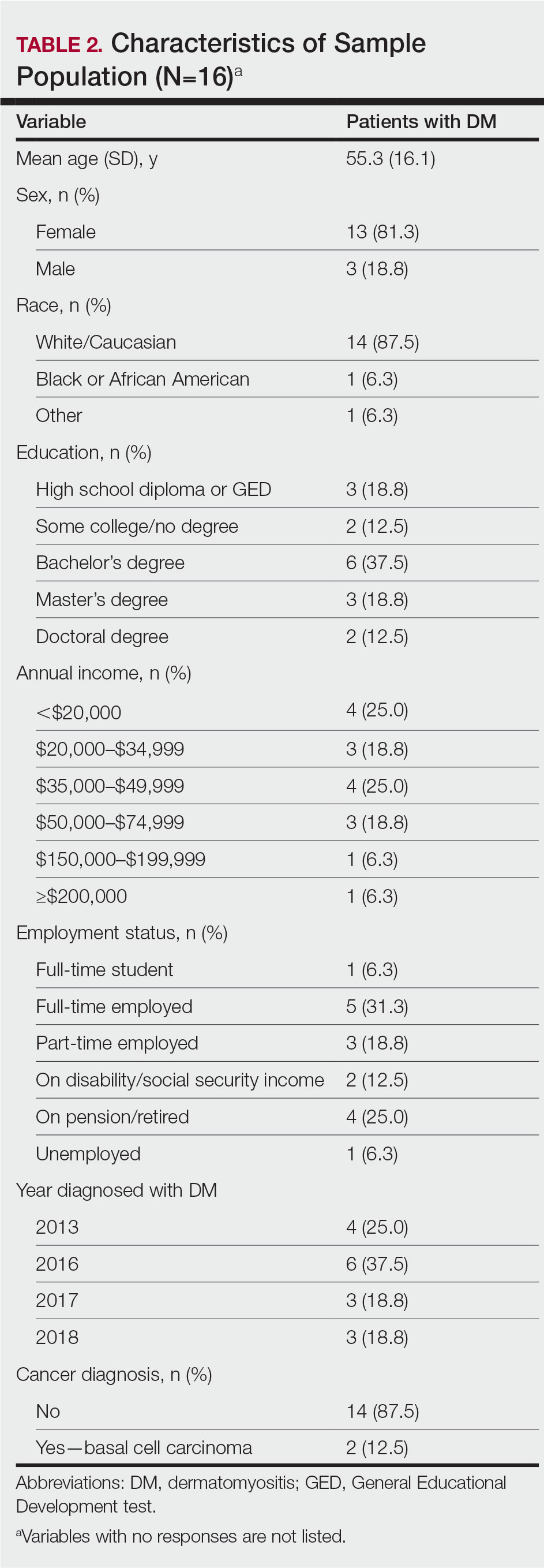

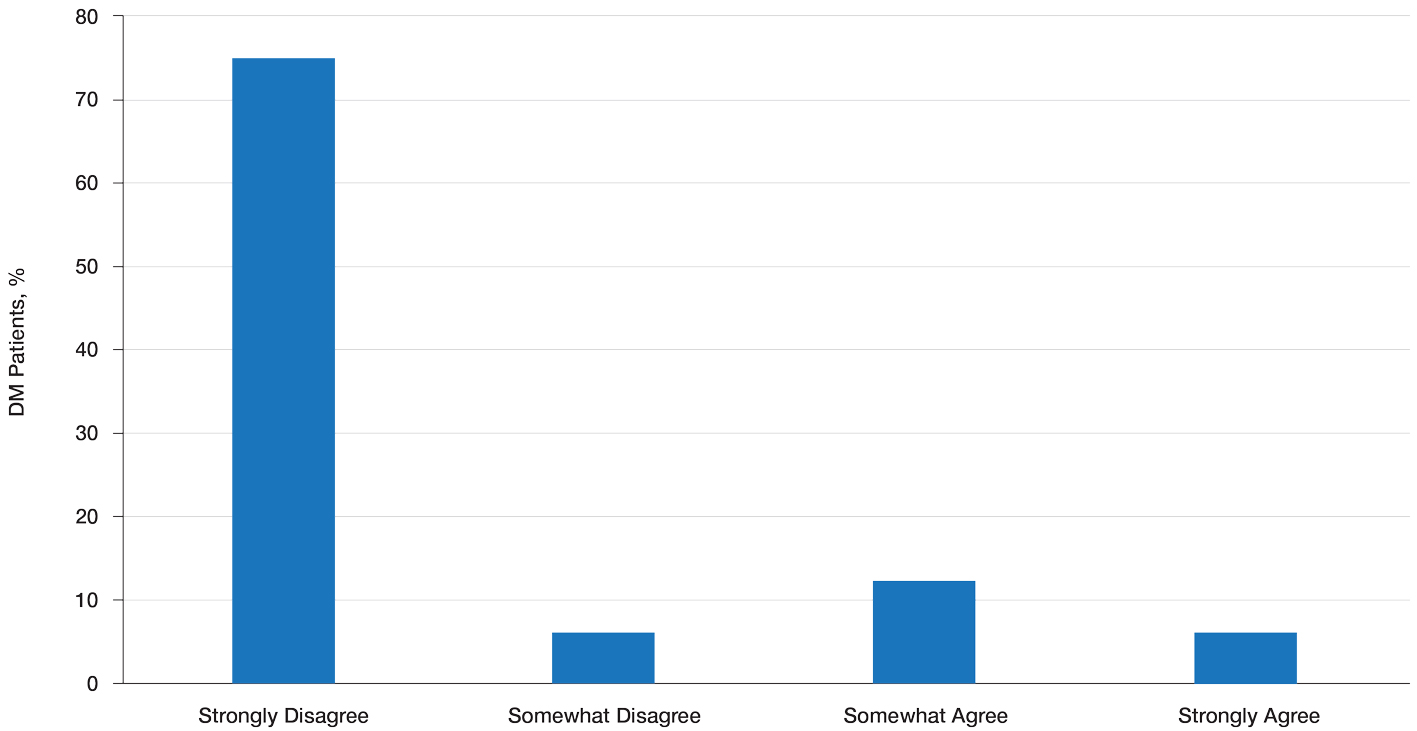

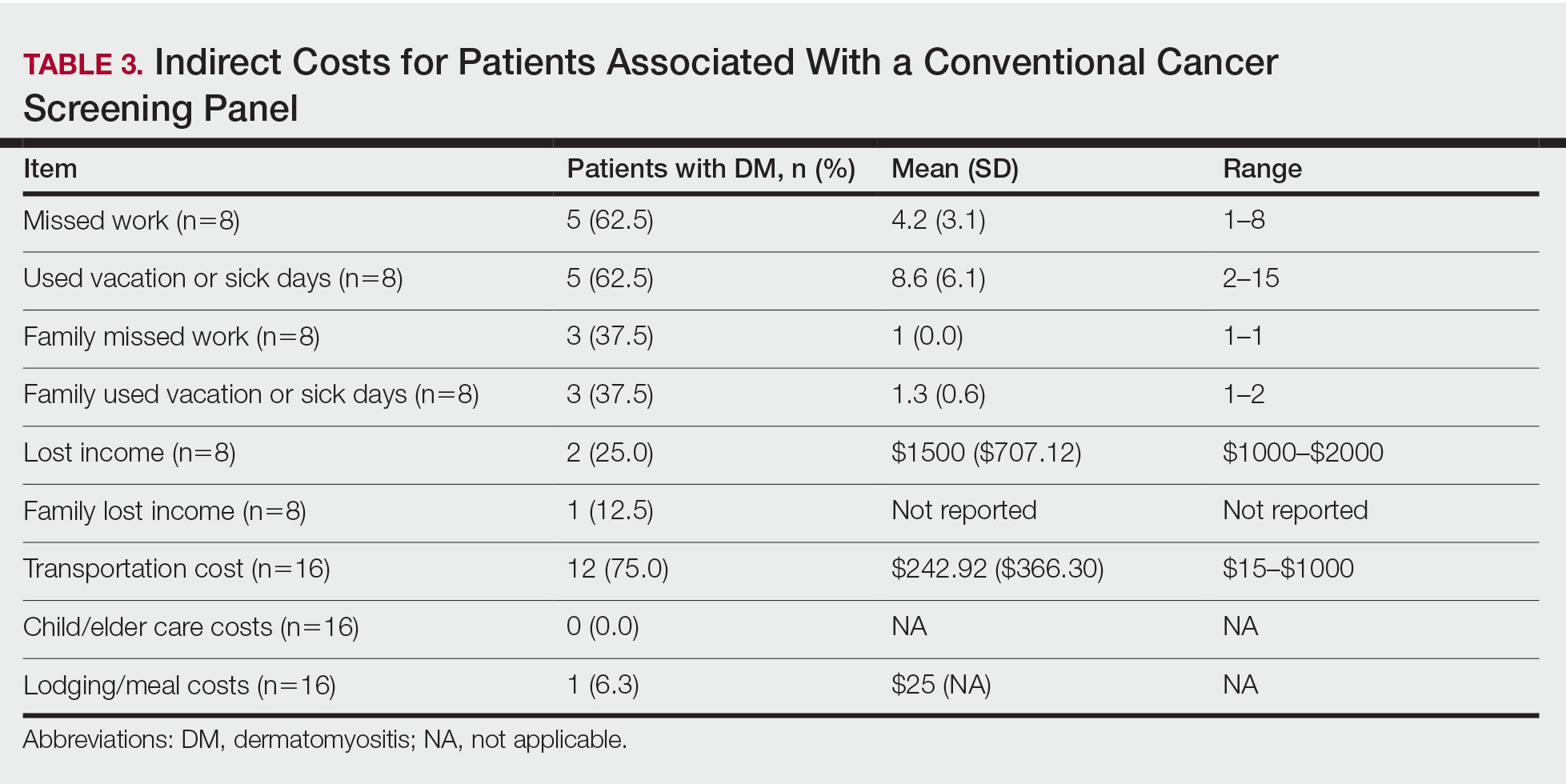

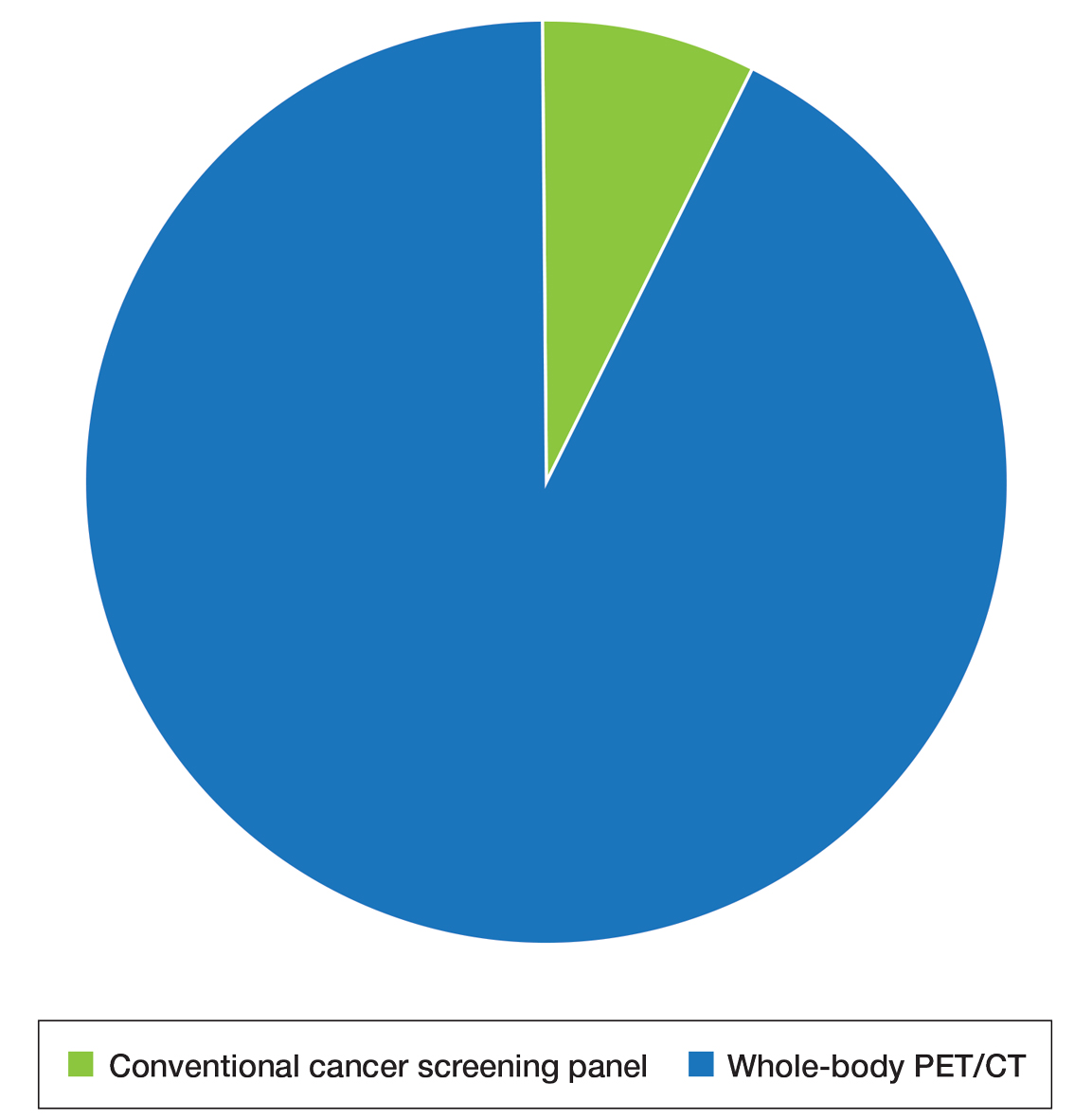

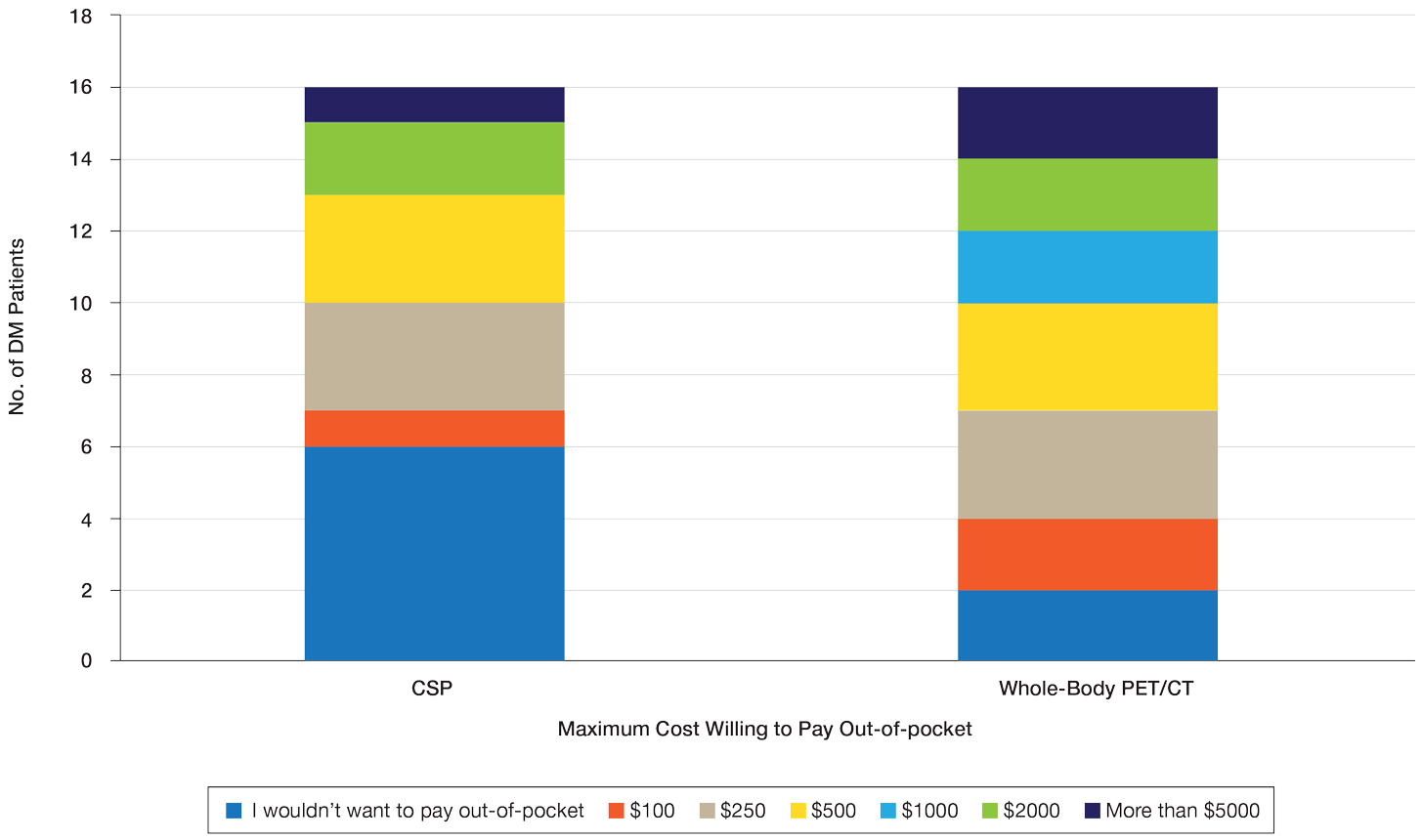

Patient Preference for Screening and WTP—A majority (81% [13/16]) of patients desired some form of screening for occult malignancy following the diagnosis of DM, even in the hypothetical situation in which screening did not provide survival benefit (Figure 1). Twenty-five percent (4/16) of patients expressed that a CSP was burdensome, and 12.5% of patients (2/16) missed a CSP appointment; all of these patients rescheduled or were planning to reschedule. Assuming that both screening methods had similar predictive value in detecting malignancy, all 16 patients felt annual whole-body PET/CT for a 3-year period would be less burdensome than a CSP, and most (73% [11/15]) felt that it would decrease the likelihood of missed appointments. Overall, 93% (13/14) of patients preferred whole-body PET/CT over a CSP when given the choice between the 2 options (Figure 2). This preference was consistent with the patients’ WTP for these tests; patients reliably reported that they would pay more for annual whole-body PET/CT than for a CSP (Figure 3). Specifically, 75% (12/16) and 38% (6/16) of patients were willing to spend $250 or more and $1000 or more for annual whole-body PET/CT, respectively, compared with 56% (9/16) and 19% (3/16), respectively, for an annual CSP. Many patients (38% [6/16]) reported that they would not be willing to pay any out-of-pocket cost for a CSP compared with 13% (2/16) for PET/CT.Indirect Costs of Screening for Patients—Indirect costs incurred by patients undergoing a CSP are summarized in Table 3. Specifically, a large percentage of employed patients missed work (63% [5/8]) or had family miss work (38% [3/8]), necessitating the use of vacation and/or sick days to attend CSP appointments. A subset (25% [2/8]) lost income (average, $1500), and 1 patient reported that a family member lost income due to attending a CSP appointment. Most (75% [12/16]) patients also incurred substantial transportation costs (average, $243), with 1 patient spending $1000. No patients incurred child or elder care costs. One patient paid a small sum for lodging/meals while traveling to attend a CSP appointment.

Comment

Patients with DM have an increased incidence of malignancy, thus cancer screening serves a crucial role in the detection of occult disease.13 Up to half of DM patients are MSA negative, and most cancers in these patients are found with blind screening. Whole-body PET/CT has emerged as an alternative to a CSP. Evidence suggests that it has similar efficacy in detecting malignancy and may be particularly useful for identifying malignancies not routinely screened for in a CSP. In a prospective study of patients diagnosed with DM and polymyositis (N=55), whole-body PET/CT had a positive predictive value of 85.7% and negative predictive value for detecting occult malignancy of 93.8% compared with 77.8% and 95.7%, respectively, for a CSP.17

The results of our study showed that cancer screening is important to patients diagnosed with DM and that most of these patients desire some form of cancer screening. This finding held true even when patients were presented with a hypothetical situation in which screening was proven to have no survival benefit. Based on focus group data, this desire was likely driven by the fear generated by not knowing whether cancer is present, as reported by the following DM patients:

“I mean [cancer screening] is peace of mind. It is ultimately worth it. You know, better than . . . not doing the screenings and finding 3 years down the road that you have, you know, a serious problem . . . you had the cancer, and you didn’t have the screenings.” (DM patient 1)

“I would rather know than not know, even if it is bad news, just tell me. The sooner the better, and give me the whole spiel . . . maybe all the screenings don’t need to be done, done so much, so often afterwards if the initial ones are ok, but I think too, for peace of mind, I would rather know it all up front.” (DM patient 2)

Further, when presented with the hypothetical situation that insurance would not cover screenings, a few patients remarked they would relocate to obtain them:

“I would find a place where the screenings were done. I’d move.” (DM patient 4)

“If it was just sky high and [insurance companies] weren’t willing to negotiate, I would consider moving.” (DM patient 3).

Sentiments such as these emphasize the importance and value that DM patients place on being screened for cancer and also may explain why only 25% of patients felt a CSP was burdensome and only 13% reported missing appointments, all of whom planned on making them up at a later time.

When presented with the choice of a CSP or annual whole-body PET/CT for a 3-year period following the diagnosis of DM, all patients expressed that whole-body PET/CT would be less burdensome. Most preferred annual whole-body PET/CT despite the slightly increased radiation exposure associated and thought that it would limit missed appointments. Accordingly, more patients responded that they would pay more money out-of-pocket for annual whole-body PET/CT. Given that WTP can function as a numerical measure of value, our results showed that patients placed a higher value on whole-body PET/CT compared with a CSP. The indirect costs associated with a CSP also were substantial, particularly regarding missed work, use of vacation and/or sick days, and travel expenses, which is particularly important because most patients reported an annual income less than $50,000.

The direct costs of a CSP and whole-body PET/CT have been studied. Specifically, Kundrick et al18 found that whole-body PET/CT was less expensive for patients (by approximately $111) out-of-pocket compared with a CSP, though cost to insurance companies was slightly greater. The present study adds to these findings by better illustrating the burden and indirect costs that patients experience while undergoing a CSP and by characterizing the patient’s perception and preference of these 2 screening methods.

Limitations of our study include a small sample size willing to complete the survey. There also was a predominance of White and female participants, partially attributed to the greater number of female patients who develop DM compared to male patients. However, this still may limit applicability of this study to males and patients of other races. Another limitation includes recall bias on survey responses, particularly regarding indirect costs incurred with a CSP. A final limitation was that only patients with a recent diagnosis of DM who were actively undergoing screening or had recently completed malignancy screening were included in the study. Given that these patients were receiving (or had completed) exclusively a CSP, patients were comparing their personal experience with a described experience. In addition, only 2 patients were diagnosed with cancer—both with basal cell carcinoma diagnosed on physical examination—which may have influenced their perception of a CSP, given that nothing was found on an extensive number of tests. However, these patients still greatly valued their screening, as evidenced in the survey.

Conclusion

- Dalakas MC, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362:971-982. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14368-1

- Schmidt J. Current classification and management of inflammatory myopathies. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2018;5:109-129. doi:10.3233/JND-180308

- Lazarou IN, Guerne PA. Classification, diagnosis, and management of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. J Rheumatol. 201;40:550-564. doi:10.3899/jrheum.120682

- Wang J, Guo G, Chen G, et al. Meta-analysis of the association of dermatomyositis and polymyositis with cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:838-847. doi:10.1111/bjd.12564

- Zampieri S, Valente M, Adami N, et al. Polymyositis, dermatomyositis and malignancy: a further intriguing link. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:449-453. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2009.12.005

- Sigurgeirsson B, Lindelöf B, Edhag O, et al. Risk of cancer in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis. a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:363-367. doi:10.1056/nejm199202063260602

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Huang YL, et al. Cancer risks of dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R70. doi:10.1186/ar2987

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL. Predicting factors of malignancy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:825-831. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04140.x

- Targoff IN, Mamyrova G, Trieu EP, et al. A novel autoantibody to a 155-kd protein is associated with dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3682-3689. doi:10.1002/art.22164

- Chow WH, Gridley G, Mellemkjær L, et al. Cancer risk following polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Cancer Causes Control. 1995;6:9-13. doi:10.1007/BF00051675

- Buchbinder R, Forbes A, Hall S, et al. Incidence of malignant disease in biopsy-proven inflammatory myopathy: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1087-1095. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00008

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03540-6

- Leatham H, Schadt C, Chisolm S, et al. Evidence supports blind screening for internal malignancy in dermatomyositis: data from 2 large US dermatology cohorts. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E9639. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000009639

- Sparsa A, Liozon E, Herrmann F, et al. Routine vs extensive malignancy search for adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a study of 40 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:885-890.

- Dutton K, Soden M. Malignancy screening in autoimmune myositis among Australian rheumatologists. Intern Med J. 2017;47:1367-1375. doi:10.1111/imj.13556

- Selva-O’Callaghan A, Martinez-Gómez X, Trallero-Araguás E, et al. The diagnostic work-up of cancer-associated myositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30:630-636. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000535

- Selva-O’Callaghan A, Grau JM, Gámez-Cenzano C, et al. Conventional cancer screening versus PET/CT in dermatomyositis/polymyositis. Am J Med. 2010;123:558-562. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.012

- Kundrick A, Kirby J, Ba D, et al. Positron emission tomography costs less to patients than conventional screening for malignancy in dermatomyositis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49:140-144. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.10.021

- Satoh M, Tanaka S, Ceribelli A, et al. A comprehensive overview on myositis-specific antibodies: new and old biomarkers in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;52:1-19. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8510-y

- Vaughan H, Rugo HS, Haemel A. Risk-based screening for cancer in patients with dermatomyositis: toward a more individualized approach. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:244-247. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5841

- Khanna U, Galimberti F, Li Y, et al. Dermatomyositis and malignancy: should all patients with dermatomyositis undergo malignancy screening? Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:432. doi:10.21037/atm-20-5215

- Oldroyd AGS, Allard AB, Callen JP, et al. Corrigendum to: A systematic review and meta-analysis to inform cancer screening guidelines in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:5483. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keab616

- Tchuenche M, Haté V, McPherson D, et al. Estimating client out-of-pocket costs for accessing voluntary medical male circumcision in South Africa. PLoS One. 2016;11:E0164147. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164147

- Teni FS, Gebresillassie BM, Birru EM, et al. Costs incurred by outpatients at a university hospital in northwestern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:842. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3628-2

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Bala MV, Mauskopf JA, Wood LL. Willingness to pay as a measure of health benefits. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15:9-18. doi:10.2165/00019053-199915010-00002

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an uncommon idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) characterized by muscle inflammation; proximal muscle weakness; and dermatologic findings, such as the heliotrope eruption and Gottron papules.1-3 Dermatomyositis is associated with an increased malignancy risk compared to other IIMs, with a 13% to 42% lifetime risk for malignancy development.4,5 The incidence for malignancy peaks during the first year following diagnosis and falls gradually over 5 years but remains increased compared to the general population.6-11 Adenocarcinoma represents the majority of cancers associated with DM, particularly of the ovaries, lungs, breasts, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, bladder, and prostate. The lymphatic system (non-Hodgkin lymphoma) also is overrepresented among cancers in DM.12

Because of the increased malignancy risk and cancer-related mortality in patients with DM, cancer screening generally is recommended following diagnosis.13,14 However, consensus guidelines for screening modalities and frequency currently do not exist, resulting in widely varying practice patterns.15 Some experts advocate for a conventional cancer screening panel (CSP), as summarized in Table 1.15-18 These tests may be repeated annually for 3 to 5 years following the diagnosis of DM. Although the use of myositis-specific antibodies (MSAs) recently has helped to risk-stratify DM patients, up to half of patients are MSA negative,19 and broad malignancy screening remains essential. Individualized discussions with patients about their risk factors, screening options, and risks and benefits of screening also are strongly encouraged.19-22 Studies of the direct costs and effectiveness of streamlined screening with positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) compared with a CSP have shown similar efficacy and lower out-of-pocket costs for patients receiving PET/CT imaging.16-18

The goal of our study was to further characterize patients’ perspectives and experience of cancer screening in DM as well as indirect costs, both of which must be taken into consideration when developing consensus guidelines for DM malignancy screening. Inclusion of patient voice is essential given the similar efficacy of both screening methods. We assessed the indirect costs (eg, travel, lost work or wages, childcare) of a CSP in patients with DM. We theorized that the large quantity of tests involved in a CSP, which are performed at various locations on multiple days over the course of several years, may have substantial costs to patients beyond the co-pay and deductible. We also sought to measure patients’ perception of the burden associated with an annual CSP, which we defined to participants as the inconvenience or unpleasantness experienced by the patient, compared with an annual whole-body PET/CT. Finally, we examined the relative value of these screening methods to patients using a willingness-to-pay (WTP) analysis.

Materials and Methods

Patient Eligibility—Our study included Penn State Health (Hershey, Pennsylvania) patients 18 years or older with a recent diagnosis of DM—International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code 710.3 or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes M33.10 or M33.90—who were undergoing or had recently completed a CSP. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a concurrent or preceding diagnosis of malignancy (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancers) or had another IIM. The institutional review board at Penn State Health College of Medicine approved the study. Data for all patients were prospectively obtained.

Survey Design—A survey was generated to assess the burden and indirect costs associated with a CSP, which was modified from work done by Tchuenche et al23 and Teni et al.24 Focus groups were held in 2018 and 2019 with patients who met our inclusion criteria with the purpose of refining the survey instrument based on patient input. A summary explanation of research was provided to all participants, and informed consent was obtained. Patients were compensated for their time for focus groups. Audio of each focus group was then transcribed and analyzed for common themes. Following focus group feedback, a finalized survey was generated for assessing burden and indirect costs (survey instrument provided in the Supplementary Information). REDCap (Vanderbilt University), a secure web application, was used to construct the finalized survey and to collect and manage data.25

Patients who fit our inclusion criteria were identified and recruited in multiple ways. Patients with appointments at the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Department of Dermatology were presented with the opportunity to participate, Penn State Health records with the appropriate billing codes were collected and patients were contacted, and an advertisement for the study was posted on StudyFinder. Surveys constructed on REDCap were then sent electronically to patients who agreed to participate in the study. A second summary explanation of research was included on the first page of the survey to describe the process.

The survey had 3 main sections. The first section collected demographic information. In the second section, we surveyed patients regarding the various aspects of a CSP that focus groups identified as burdensome. In addition, patients were asked to compare their feelings regarding an annual CSP vs whole-body PET/CT for a 3-year period utilizing a rating scale of strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, and strongly agree. This section also included a willingness-to-pay (WTP) analysis for each modality. We defined WTP as the maximum out-of-pocket cost that the patient would be willing to pay to receive testing, which was measured in a hypothetical scenario where neither whole-body PET/CT nor CSP was covered by insurance.26 Although WTP may be influenced by external factors such as patient income, it can serve as a numerical measure of how much the patient values each service. Furthermore, these external factors become less relevant when comparing the relative value of 2 separate tests, as such factors apply equally in both scenarios. In the third section of the survey, patients were queried regarding various indirect costs associated with a CSP. Descriptions for a CSP and whole-body PET/CT, including risks and benefits, were provided to allow patients to make informed decisions.

Statistical Analysis—Because of the rarity of DM and the subsequently limited sample size, summary and descriptive statistics were utilized to characterize the sample and identify patterns in the results. Continuous variables are presented with means and standard deviations, and proportions are presented with frequencies and percentages. All analyses were done using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Patient Demographics—Fifty-four patients were identified using StudyFinder, physician referral, and search of the electronic health record. Nine patients agreed to take part in the focus groups, and 27 offered email addresses to be contacted for the survey. Of those 27 patients, 16 (59.3%) fit our inclusion criteria and completed the survey. Patient demographics are detailed in Table 2. The mean age was 55 years, and most patients were White (88% [14/16]), female (81% [13/16]), and had at least a bachelor’s degree (69% [11/16]). Most patients (69% [11/16]) had an annual income of less than $50,000, and half (50% [8/16]) were employed. All patients had been diagnosed with DM in or after 2013. Two patients were diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma during or after cancer screening.

Patient Preference for Screening and WTP—A majority (81% [13/16]) of patients desired some form of screening for occult malignancy following the diagnosis of DM, even in the hypothetical situation in which screening did not provide survival benefit (Figure 1). Twenty-five percent (4/16) of patients expressed that a CSP was burdensome, and 12.5% of patients (2/16) missed a CSP appointment; all of these patients rescheduled or were planning to reschedule. Assuming that both screening methods had similar predictive value in detecting malignancy, all 16 patients felt annual whole-body PET/CT for a 3-year period would be less burdensome than a CSP, and most (73% [11/15]) felt that it would decrease the likelihood of missed appointments. Overall, 93% (13/14) of patients preferred whole-body PET/CT over a CSP when given the choice between the 2 options (Figure 2). This preference was consistent with the patients’ WTP for these tests; patients reliably reported that they would pay more for annual whole-body PET/CT than for a CSP (Figure 3). Specifically, 75% (12/16) and 38% (6/16) of patients were willing to spend $250 or more and $1000 or more for annual whole-body PET/CT, respectively, compared with 56% (9/16) and 19% (3/16), respectively, for an annual CSP. Many patients (38% [6/16]) reported that they would not be willing to pay any out-of-pocket cost for a CSP compared with 13% (2/16) for PET/CT.Indirect Costs of Screening for Patients—Indirect costs incurred by patients undergoing a CSP are summarized in Table 3. Specifically, a large percentage of employed patients missed work (63% [5/8]) or had family miss work (38% [3/8]), necessitating the use of vacation and/or sick days to attend CSP appointments. A subset (25% [2/8]) lost income (average, $1500), and 1 patient reported that a family member lost income due to attending a CSP appointment. Most (75% [12/16]) patients also incurred substantial transportation costs (average, $243), with 1 patient spending $1000. No patients incurred child or elder care costs. One patient paid a small sum for lodging/meals while traveling to attend a CSP appointment.

Comment

Patients with DM have an increased incidence of malignancy, thus cancer screening serves a crucial role in the detection of occult disease.13 Up to half of DM patients are MSA negative, and most cancers in these patients are found with blind screening. Whole-body PET/CT has emerged as an alternative to a CSP. Evidence suggests that it has similar efficacy in detecting malignancy and may be particularly useful for identifying malignancies not routinely screened for in a CSP. In a prospective study of patients diagnosed with DM and polymyositis (N=55), whole-body PET/CT had a positive predictive value of 85.7% and negative predictive value for detecting occult malignancy of 93.8% compared with 77.8% and 95.7%, respectively, for a CSP.17

The results of our study showed that cancer screening is important to patients diagnosed with DM and that most of these patients desire some form of cancer screening. This finding held true even when patients were presented with a hypothetical situation in which screening was proven to have no survival benefit. Based on focus group data, this desire was likely driven by the fear generated by not knowing whether cancer is present, as reported by the following DM patients:

“I mean [cancer screening] is peace of mind. It is ultimately worth it. You know, better than . . . not doing the screenings and finding 3 years down the road that you have, you know, a serious problem . . . you had the cancer, and you didn’t have the screenings.” (DM patient 1)

“I would rather know than not know, even if it is bad news, just tell me. The sooner the better, and give me the whole spiel . . . maybe all the screenings don’t need to be done, done so much, so often afterwards if the initial ones are ok, but I think too, for peace of mind, I would rather know it all up front.” (DM patient 2)

Further, when presented with the hypothetical situation that insurance would not cover screenings, a few patients remarked they would relocate to obtain them:

“I would find a place where the screenings were done. I’d move.” (DM patient 4)

“If it was just sky high and [insurance companies] weren’t willing to negotiate, I would consider moving.” (DM patient 3).

Sentiments such as these emphasize the importance and value that DM patients place on being screened for cancer and also may explain why only 25% of patients felt a CSP was burdensome and only 13% reported missing appointments, all of whom planned on making them up at a later time.

When presented with the choice of a CSP or annual whole-body PET/CT for a 3-year period following the diagnosis of DM, all patients expressed that whole-body PET/CT would be less burdensome. Most preferred annual whole-body PET/CT despite the slightly increased radiation exposure associated and thought that it would limit missed appointments. Accordingly, more patients responded that they would pay more money out-of-pocket for annual whole-body PET/CT. Given that WTP can function as a numerical measure of value, our results showed that patients placed a higher value on whole-body PET/CT compared with a CSP. The indirect costs associated with a CSP also were substantial, particularly regarding missed work, use of vacation and/or sick days, and travel expenses, which is particularly important because most patients reported an annual income less than $50,000.

The direct costs of a CSP and whole-body PET/CT have been studied. Specifically, Kundrick et al18 found that whole-body PET/CT was less expensive for patients (by approximately $111) out-of-pocket compared with a CSP, though cost to insurance companies was slightly greater. The present study adds to these findings by better illustrating the burden and indirect costs that patients experience while undergoing a CSP and by characterizing the patient’s perception and preference of these 2 screening methods.

Limitations of our study include a small sample size willing to complete the survey. There also was a predominance of White and female participants, partially attributed to the greater number of female patients who develop DM compared to male patients. However, this still may limit applicability of this study to males and patients of other races. Another limitation includes recall bias on survey responses, particularly regarding indirect costs incurred with a CSP. A final limitation was that only patients with a recent diagnosis of DM who were actively undergoing screening or had recently completed malignancy screening were included in the study. Given that these patients were receiving (or had completed) exclusively a CSP, patients were comparing their personal experience with a described experience. In addition, only 2 patients were diagnosed with cancer—both with basal cell carcinoma diagnosed on physical examination—which may have influenced their perception of a CSP, given that nothing was found on an extensive number of tests. However, these patients still greatly valued their screening, as evidenced in the survey.

Conclusion

Dermatomyositis (DM) is an uncommon idiopathic inflammatory myopathy (IIM) characterized by muscle inflammation; proximal muscle weakness; and dermatologic findings, such as the heliotrope eruption and Gottron papules.1-3 Dermatomyositis is associated with an increased malignancy risk compared to other IIMs, with a 13% to 42% lifetime risk for malignancy development.4,5 The incidence for malignancy peaks during the first year following diagnosis and falls gradually over 5 years but remains increased compared to the general population.6-11 Adenocarcinoma represents the majority of cancers associated with DM, particularly of the ovaries, lungs, breasts, gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, bladder, and prostate. The lymphatic system (non-Hodgkin lymphoma) also is overrepresented among cancers in DM.12

Because of the increased malignancy risk and cancer-related mortality in patients with DM, cancer screening generally is recommended following diagnosis.13,14 However, consensus guidelines for screening modalities and frequency currently do not exist, resulting in widely varying practice patterns.15 Some experts advocate for a conventional cancer screening panel (CSP), as summarized in Table 1.15-18 These tests may be repeated annually for 3 to 5 years following the diagnosis of DM. Although the use of myositis-specific antibodies (MSAs) recently has helped to risk-stratify DM patients, up to half of patients are MSA negative,19 and broad malignancy screening remains essential. Individualized discussions with patients about their risk factors, screening options, and risks and benefits of screening also are strongly encouraged.19-22 Studies of the direct costs and effectiveness of streamlined screening with positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) compared with a CSP have shown similar efficacy and lower out-of-pocket costs for patients receiving PET/CT imaging.16-18

The goal of our study was to further characterize patients’ perspectives and experience of cancer screening in DM as well as indirect costs, both of which must be taken into consideration when developing consensus guidelines for DM malignancy screening. Inclusion of patient voice is essential given the similar efficacy of both screening methods. We assessed the indirect costs (eg, travel, lost work or wages, childcare) of a CSP in patients with DM. We theorized that the large quantity of tests involved in a CSP, which are performed at various locations on multiple days over the course of several years, may have substantial costs to patients beyond the co-pay and deductible. We also sought to measure patients’ perception of the burden associated with an annual CSP, which we defined to participants as the inconvenience or unpleasantness experienced by the patient, compared with an annual whole-body PET/CT. Finally, we examined the relative value of these screening methods to patients using a willingness-to-pay (WTP) analysis.

Materials and Methods

Patient Eligibility—Our study included Penn State Health (Hershey, Pennsylvania) patients 18 years or older with a recent diagnosis of DM—International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision code 710.3 or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes M33.10 or M33.90—who were undergoing or had recently completed a CSP. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a concurrent or preceding diagnosis of malignancy (excluding nonmelanoma skin cancers) or had another IIM. The institutional review board at Penn State Health College of Medicine approved the study. Data for all patients were prospectively obtained.

Survey Design—A survey was generated to assess the burden and indirect costs associated with a CSP, which was modified from work done by Tchuenche et al23 and Teni et al.24 Focus groups were held in 2018 and 2019 with patients who met our inclusion criteria with the purpose of refining the survey instrument based on patient input. A summary explanation of research was provided to all participants, and informed consent was obtained. Patients were compensated for their time for focus groups. Audio of each focus group was then transcribed and analyzed for common themes. Following focus group feedback, a finalized survey was generated for assessing burden and indirect costs (survey instrument provided in the Supplementary Information). REDCap (Vanderbilt University), a secure web application, was used to construct the finalized survey and to collect and manage data.25

Patients who fit our inclusion criteria were identified and recruited in multiple ways. Patients with appointments at the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center Department of Dermatology were presented with the opportunity to participate, Penn State Health records with the appropriate billing codes were collected and patients were contacted, and an advertisement for the study was posted on StudyFinder. Surveys constructed on REDCap were then sent electronically to patients who agreed to participate in the study. A second summary explanation of research was included on the first page of the survey to describe the process.

The survey had 3 main sections. The first section collected demographic information. In the second section, we surveyed patients regarding the various aspects of a CSP that focus groups identified as burdensome. In addition, patients were asked to compare their feelings regarding an annual CSP vs whole-body PET/CT for a 3-year period utilizing a rating scale of strongly disagree, somewhat disagree, somewhat agree, and strongly agree. This section also included a willingness-to-pay (WTP) analysis for each modality. We defined WTP as the maximum out-of-pocket cost that the patient would be willing to pay to receive testing, which was measured in a hypothetical scenario where neither whole-body PET/CT nor CSP was covered by insurance.26 Although WTP may be influenced by external factors such as patient income, it can serve as a numerical measure of how much the patient values each service. Furthermore, these external factors become less relevant when comparing the relative value of 2 separate tests, as such factors apply equally in both scenarios. In the third section of the survey, patients were queried regarding various indirect costs associated with a CSP. Descriptions for a CSP and whole-body PET/CT, including risks and benefits, were provided to allow patients to make informed decisions.

Statistical Analysis—Because of the rarity of DM and the subsequently limited sample size, summary and descriptive statistics were utilized to characterize the sample and identify patterns in the results. Continuous variables are presented with means and standard deviations, and proportions are presented with frequencies and percentages. All analyses were done using SAS Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Patient Demographics—Fifty-four patients were identified using StudyFinder, physician referral, and search of the electronic health record. Nine patients agreed to take part in the focus groups, and 27 offered email addresses to be contacted for the survey. Of those 27 patients, 16 (59.3%) fit our inclusion criteria and completed the survey. Patient demographics are detailed in Table 2. The mean age was 55 years, and most patients were White (88% [14/16]), female (81% [13/16]), and had at least a bachelor’s degree (69% [11/16]). Most patients (69% [11/16]) had an annual income of less than $50,000, and half (50% [8/16]) were employed. All patients had been diagnosed with DM in or after 2013. Two patients were diagnosed with basal cell carcinoma during or after cancer screening.

Patient Preference for Screening and WTP—A majority (81% [13/16]) of patients desired some form of screening for occult malignancy following the diagnosis of DM, even in the hypothetical situation in which screening did not provide survival benefit (Figure 1). Twenty-five percent (4/16) of patients expressed that a CSP was burdensome, and 12.5% of patients (2/16) missed a CSP appointment; all of these patients rescheduled or were planning to reschedule. Assuming that both screening methods had similar predictive value in detecting malignancy, all 16 patients felt annual whole-body PET/CT for a 3-year period would be less burdensome than a CSP, and most (73% [11/15]) felt that it would decrease the likelihood of missed appointments. Overall, 93% (13/14) of patients preferred whole-body PET/CT over a CSP when given the choice between the 2 options (Figure 2). This preference was consistent with the patients’ WTP for these tests; patients reliably reported that they would pay more for annual whole-body PET/CT than for a CSP (Figure 3). Specifically, 75% (12/16) and 38% (6/16) of patients were willing to spend $250 or more and $1000 or more for annual whole-body PET/CT, respectively, compared with 56% (9/16) and 19% (3/16), respectively, for an annual CSP. Many patients (38% [6/16]) reported that they would not be willing to pay any out-of-pocket cost for a CSP compared with 13% (2/16) for PET/CT.Indirect Costs of Screening for Patients—Indirect costs incurred by patients undergoing a CSP are summarized in Table 3. Specifically, a large percentage of employed patients missed work (63% [5/8]) or had family miss work (38% [3/8]), necessitating the use of vacation and/or sick days to attend CSP appointments. A subset (25% [2/8]) lost income (average, $1500), and 1 patient reported that a family member lost income due to attending a CSP appointment. Most (75% [12/16]) patients also incurred substantial transportation costs (average, $243), with 1 patient spending $1000. No patients incurred child or elder care costs. One patient paid a small sum for lodging/meals while traveling to attend a CSP appointment.

Comment

Patients with DM have an increased incidence of malignancy, thus cancer screening serves a crucial role in the detection of occult disease.13 Up to half of DM patients are MSA negative, and most cancers in these patients are found with blind screening. Whole-body PET/CT has emerged as an alternative to a CSP. Evidence suggests that it has similar efficacy in detecting malignancy and may be particularly useful for identifying malignancies not routinely screened for in a CSP. In a prospective study of patients diagnosed with DM and polymyositis (N=55), whole-body PET/CT had a positive predictive value of 85.7% and negative predictive value for detecting occult malignancy of 93.8% compared with 77.8% and 95.7%, respectively, for a CSP.17

The results of our study showed that cancer screening is important to patients diagnosed with DM and that most of these patients desire some form of cancer screening. This finding held true even when patients were presented with a hypothetical situation in which screening was proven to have no survival benefit. Based on focus group data, this desire was likely driven by the fear generated by not knowing whether cancer is present, as reported by the following DM patients:

“I mean [cancer screening] is peace of mind. It is ultimately worth it. You know, better than . . . not doing the screenings and finding 3 years down the road that you have, you know, a serious problem . . . you had the cancer, and you didn’t have the screenings.” (DM patient 1)

“I would rather know than not know, even if it is bad news, just tell me. The sooner the better, and give me the whole spiel . . . maybe all the screenings don’t need to be done, done so much, so often afterwards if the initial ones are ok, but I think too, for peace of mind, I would rather know it all up front.” (DM patient 2)

Further, when presented with the hypothetical situation that insurance would not cover screenings, a few patients remarked they would relocate to obtain them:

“I would find a place where the screenings were done. I’d move.” (DM patient 4)

“If it was just sky high and [insurance companies] weren’t willing to negotiate, I would consider moving.” (DM patient 3).

Sentiments such as these emphasize the importance and value that DM patients place on being screened for cancer and also may explain why only 25% of patients felt a CSP was burdensome and only 13% reported missing appointments, all of whom planned on making them up at a later time.

When presented with the choice of a CSP or annual whole-body PET/CT for a 3-year period following the diagnosis of DM, all patients expressed that whole-body PET/CT would be less burdensome. Most preferred annual whole-body PET/CT despite the slightly increased radiation exposure associated and thought that it would limit missed appointments. Accordingly, more patients responded that they would pay more money out-of-pocket for annual whole-body PET/CT. Given that WTP can function as a numerical measure of value, our results showed that patients placed a higher value on whole-body PET/CT compared with a CSP. The indirect costs associated with a CSP also were substantial, particularly regarding missed work, use of vacation and/or sick days, and travel expenses, which is particularly important because most patients reported an annual income less than $50,000.

The direct costs of a CSP and whole-body PET/CT have been studied. Specifically, Kundrick et al18 found that whole-body PET/CT was less expensive for patients (by approximately $111) out-of-pocket compared with a CSP, though cost to insurance companies was slightly greater. The present study adds to these findings by better illustrating the burden and indirect costs that patients experience while undergoing a CSP and by characterizing the patient’s perception and preference of these 2 screening methods.

Limitations of our study include a small sample size willing to complete the survey. There also was a predominance of White and female participants, partially attributed to the greater number of female patients who develop DM compared to male patients. However, this still may limit applicability of this study to males and patients of other races. Another limitation includes recall bias on survey responses, particularly regarding indirect costs incurred with a CSP. A final limitation was that only patients with a recent diagnosis of DM who were actively undergoing screening or had recently completed malignancy screening were included in the study. Given that these patients were receiving (or had completed) exclusively a CSP, patients were comparing their personal experience with a described experience. In addition, only 2 patients were diagnosed with cancer—both with basal cell carcinoma diagnosed on physical examination—which may have influenced their perception of a CSP, given that nothing was found on an extensive number of tests. However, these patients still greatly valued their screening, as evidenced in the survey.

Conclusion

- Dalakas MC, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362:971-982. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14368-1

- Schmidt J. Current classification and management of inflammatory myopathies. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2018;5:109-129. doi:10.3233/JND-180308

- Lazarou IN, Guerne PA. Classification, diagnosis, and management of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. J Rheumatol. 201;40:550-564. doi:10.3899/jrheum.120682

- Wang J, Guo G, Chen G, et al. Meta-analysis of the association of dermatomyositis and polymyositis with cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:838-847. doi:10.1111/bjd.12564

- Zampieri S, Valente M, Adami N, et al. Polymyositis, dermatomyositis and malignancy: a further intriguing link. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:449-453. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2009.12.005

- Sigurgeirsson B, Lindelöf B, Edhag O, et al. Risk of cancer in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis. a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:363-367. doi:10.1056/nejm199202063260602

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Huang YL, et al. Cancer risks of dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R70. doi:10.1186/ar2987

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL. Predicting factors of malignancy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:825-831. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04140.x

- Targoff IN, Mamyrova G, Trieu EP, et al. A novel autoantibody to a 155-kd protein is associated with dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3682-3689. doi:10.1002/art.22164

- Chow WH, Gridley G, Mellemkjær L, et al. Cancer risk following polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Cancer Causes Control. 1995;6:9-13. doi:10.1007/BF00051675

- Buchbinder R, Forbes A, Hall S, et al. Incidence of malignant disease in biopsy-proven inflammatory myopathy: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1087-1095. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00008

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03540-6

- Leatham H, Schadt C, Chisolm S, et al. Evidence supports blind screening for internal malignancy in dermatomyositis: data from 2 large US dermatology cohorts. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E9639. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000009639

- Sparsa A, Liozon E, Herrmann F, et al. Routine vs extensive malignancy search for adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a study of 40 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:885-890.

- Dutton K, Soden M. Malignancy screening in autoimmune myositis among Australian rheumatologists. Intern Med J. 2017;47:1367-1375. doi:10.1111/imj.13556

- Selva-O’Callaghan A, Martinez-Gómez X, Trallero-Araguás E, et al. The diagnostic work-up of cancer-associated myositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30:630-636. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000535

- Selva-O’Callaghan A, Grau JM, Gámez-Cenzano C, et al. Conventional cancer screening versus PET/CT in dermatomyositis/polymyositis. Am J Med. 2010;123:558-562. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.012

- Kundrick A, Kirby J, Ba D, et al. Positron emission tomography costs less to patients than conventional screening for malignancy in dermatomyositis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49:140-144. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.10.021

- Satoh M, Tanaka S, Ceribelli A, et al. A comprehensive overview on myositis-specific antibodies: new and old biomarkers in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;52:1-19. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8510-y

- Vaughan H, Rugo HS, Haemel A. Risk-based screening for cancer in patients with dermatomyositis: toward a more individualized approach. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:244-247. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5841

- Khanna U, Galimberti F, Li Y, et al. Dermatomyositis and malignancy: should all patients with dermatomyositis undergo malignancy screening? Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:432. doi:10.21037/atm-20-5215

- Oldroyd AGS, Allard AB, Callen JP, et al. Corrigendum to: A systematic review and meta-analysis to inform cancer screening guidelines in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:5483. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keab616

- Tchuenche M, Haté V, McPherson D, et al. Estimating client out-of-pocket costs for accessing voluntary medical male circumcision in South Africa. PLoS One. 2016;11:E0164147. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164147

- Teni FS, Gebresillassie BM, Birru EM, et al. Costs incurred by outpatients at a university hospital in northwestern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:842. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3628-2

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Bala MV, Mauskopf JA, Wood LL. Willingness to pay as a measure of health benefits. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15:9-18. doi:10.2165/00019053-199915010-00002

- Dalakas MC, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362:971-982. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14368-1

- Schmidt J. Current classification and management of inflammatory myopathies. J Neuromuscul Dis. 2018;5:109-129. doi:10.3233/JND-180308

- Lazarou IN, Guerne PA. Classification, diagnosis, and management of idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. J Rheumatol. 201;40:550-564. doi:10.3899/jrheum.120682

- Wang J, Guo G, Chen G, et al. Meta-analysis of the association of dermatomyositis and polymyositis with cancer. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:838-847. doi:10.1111/bjd.12564

- Zampieri S, Valente M, Adami N, et al. Polymyositis, dermatomyositis and malignancy: a further intriguing link. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:449-453. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2009.12.005

- Sigurgeirsson B, Lindelöf B, Edhag O, et al. Risk of cancer in patients with dermatomyositis or polymyositis. a population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:363-367. doi:10.1056/nejm199202063260602

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Huang YL, et al. Cancer risks of dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a nationwide cohort study in Taiwan. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R70. doi:10.1186/ar2987

- Chen YJ, Wu CY, Shen JL. Predicting factors of malignancy in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a case-control study. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:825-831. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04140.x

- Targoff IN, Mamyrova G, Trieu EP, et al. A novel autoantibody to a 155-kd protein is associated with dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:3682-3689. doi:10.1002/art.22164

- Chow WH, Gridley G, Mellemkjær L, et al. Cancer risk following polymyositis and dermatomyositis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Cancer Causes Control. 1995;6:9-13. doi:10.1007/BF00051675

- Buchbinder R, Forbes A, Hall S, et al. Incidence of malignant disease in biopsy-proven inflammatory myopathy: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1087-1095. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00008

- Hill CL, Zhang Y, Sigurgeirsson B, et al. Frequency of specific cancer types in dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a population-based study. Lancet. 2001;357:96-100. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03540-6

- Leatham H, Schadt C, Chisolm S, et al. Evidence supports blind screening for internal malignancy in dermatomyositis: data from 2 large US dermatology cohorts. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:E9639. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000009639

- Sparsa A, Liozon E, Herrmann F, et al. Routine vs extensive malignancy search for adult dermatomyositis and polymyositis: a study of 40 patients. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:885-890.

- Dutton K, Soden M. Malignancy screening in autoimmune myositis among Australian rheumatologists. Intern Med J. 2017;47:1367-1375. doi:10.1111/imj.13556

- Selva-O’Callaghan A, Martinez-Gómez X, Trallero-Araguás E, et al. The diagnostic work-up of cancer-associated myositis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2018;30:630-636. doi:10.1097/BOR.0000000000000535

- Selva-O’Callaghan A, Grau JM, Gámez-Cenzano C, et al. Conventional cancer screening versus PET/CT in dermatomyositis/polymyositis. Am J Med. 2010;123:558-562. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2009.11.012

- Kundrick A, Kirby J, Ba D, et al. Positron emission tomography costs less to patients than conventional screening for malignancy in dermatomyositis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2019;49:140-144. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2018.10.021

- Satoh M, Tanaka S, Ceribelli A, et al. A comprehensive overview on myositis-specific antibodies: new and old biomarkers in idiopathic inflammatory myopathy. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;52:1-19. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8510-y

- Vaughan H, Rugo HS, Haemel A. Risk-based screening for cancer in patients with dermatomyositis: toward a more individualized approach. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:244-247. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.5841

- Khanna U, Galimberti F, Li Y, et al. Dermatomyositis and malignancy: should all patients with dermatomyositis undergo malignancy screening? Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:432. doi:10.21037/atm-20-5215

- Oldroyd AGS, Allard AB, Callen JP, et al. Corrigendum to: A systematic review and meta-analysis to inform cancer screening guidelines in idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:5483. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keab616

- Tchuenche M, Haté V, McPherson D, et al. Estimating client out-of-pocket costs for accessing voluntary medical male circumcision in South Africa. PLoS One. 2016;11:E0164147. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0164147

- Teni FS, Gebresillassie BM, Birru EM, et al. Costs incurred by outpatients at a university hospital in northwestern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:842. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3628-2

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381. doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010

- Bala MV, Mauskopf JA, Wood LL. Willingness to pay as a measure of health benefits. Pharmacoeconomics. 1999;15:9-18. doi:10.2165/00019053-199915010-00002

Practice Points

- Dermatomyositis (DM) is associated with an increased risk for malignancy. Patient perspective needs to be considered in developing cancer screening guidelines for patients with DM, particularly given the similar efficacy of available screening modalities.

- Current modalities for cancer screening in DM include whole-body positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) and a conventional cancer screening panel (CSP), which includes a battery of tests typically requiring multiple visits. Patients may find the simplicity of PET/CT more preferrable than the more complex CSP.

- Indirect costs of cancer screening include missed work, travel and childcare expenses, and lost wages. Conventional cancer screening has greater indirect costs than PET/CT.

Distinct Violaceous Plaques in Conjunction With Blisters

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6

The pathogenesis of LPP is not fully understood but likely represents a distinct entity rather than a subtype of BP or the simultaneous occurrence of LP and BP. Lichen planus pemphigoides generally has an earlier onset and better treatment response compared to BP.7 Further, autoantibodies in patients with LPP react to a novel epitope within the C-terminal portion of the BP-180 NC16A domain. Accordingly, it has been postulated that an inflammatory cutaneous process resulting from infection, phototherapy, or LP itself leads to damage of the epidermis and triggers a secondary blistering autoimmune dermatosis mediated by antibody formation against basement membrane (BM) antigens, such as BP-180.7

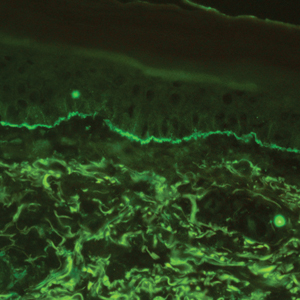

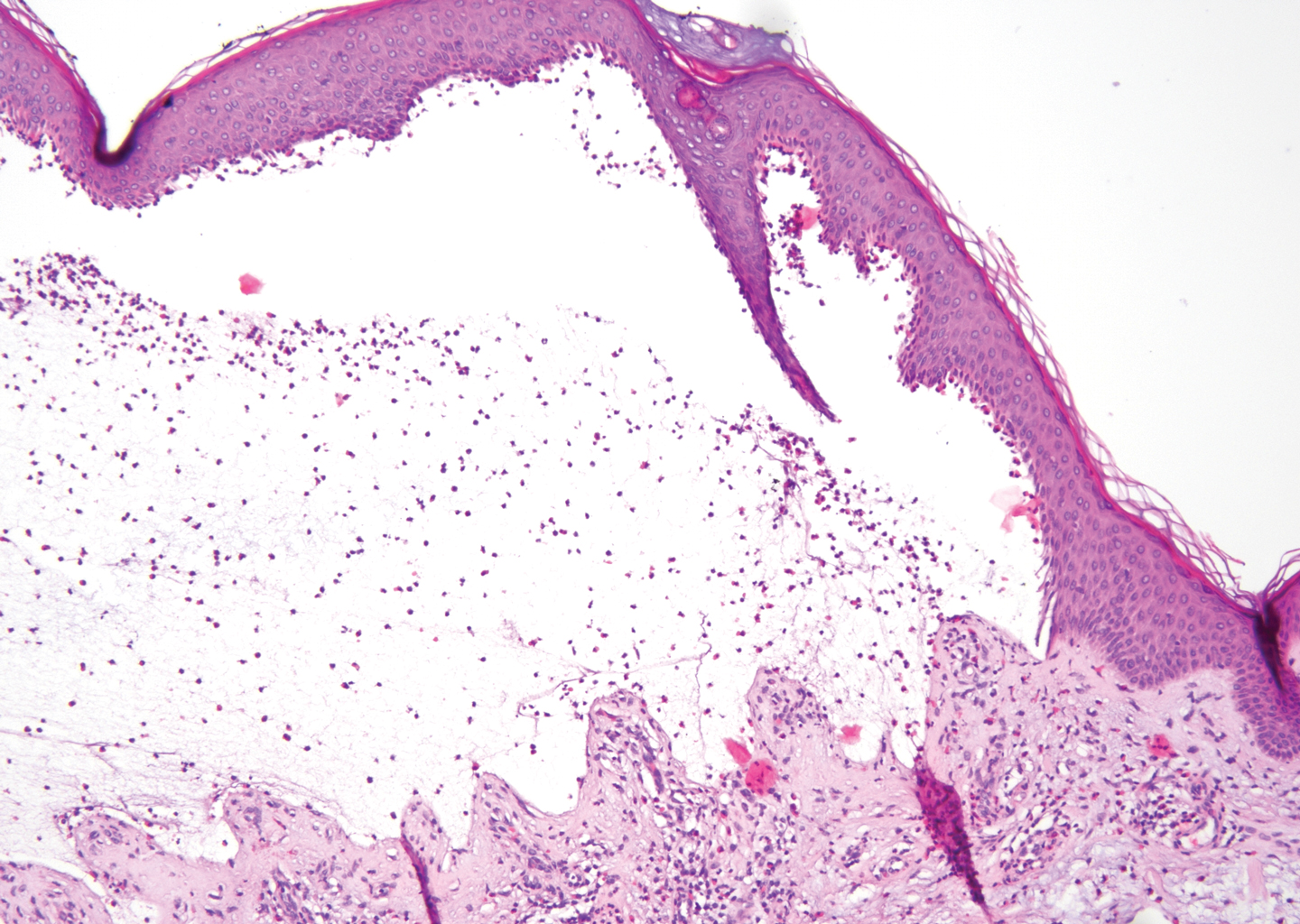

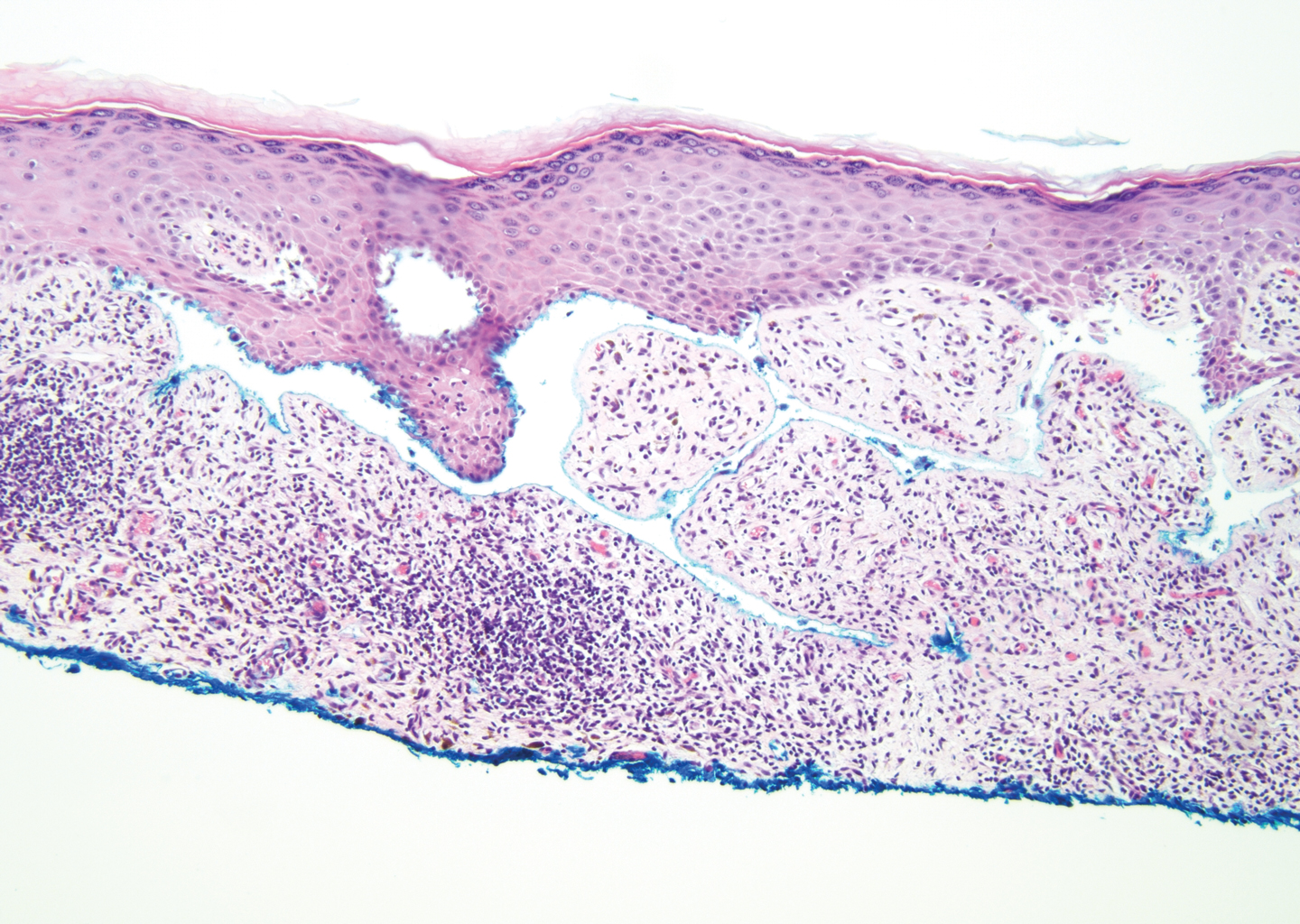

The diagnosis of LPP ultimately is confirmed with immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of LPP shows findings consistent with both LP and BP (quiz image [top]). In the lichenoid portion, biopsy reveals orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis; a bandlike infiltrate consisting primarily of lymphocytes in the upper dermis; and apoptotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).1 Biopsy of bullae reveals eosinophilic spongiosis, a subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils, and a mixed superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or C3 at the DEJ (quiz image [bottom]).1 Measurement of anti-BM antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230 can be useful in suspected cases, as 50% to 60% of patients have circulating antibodies against these antigens.6 Remission usually is achieved with topical and systemic corticosteroids and/or steroid-sparing agents, with rare recurrence following lesion resolution.1 More recently, successful treatment with biologics such as ustekinumab has been reported.8

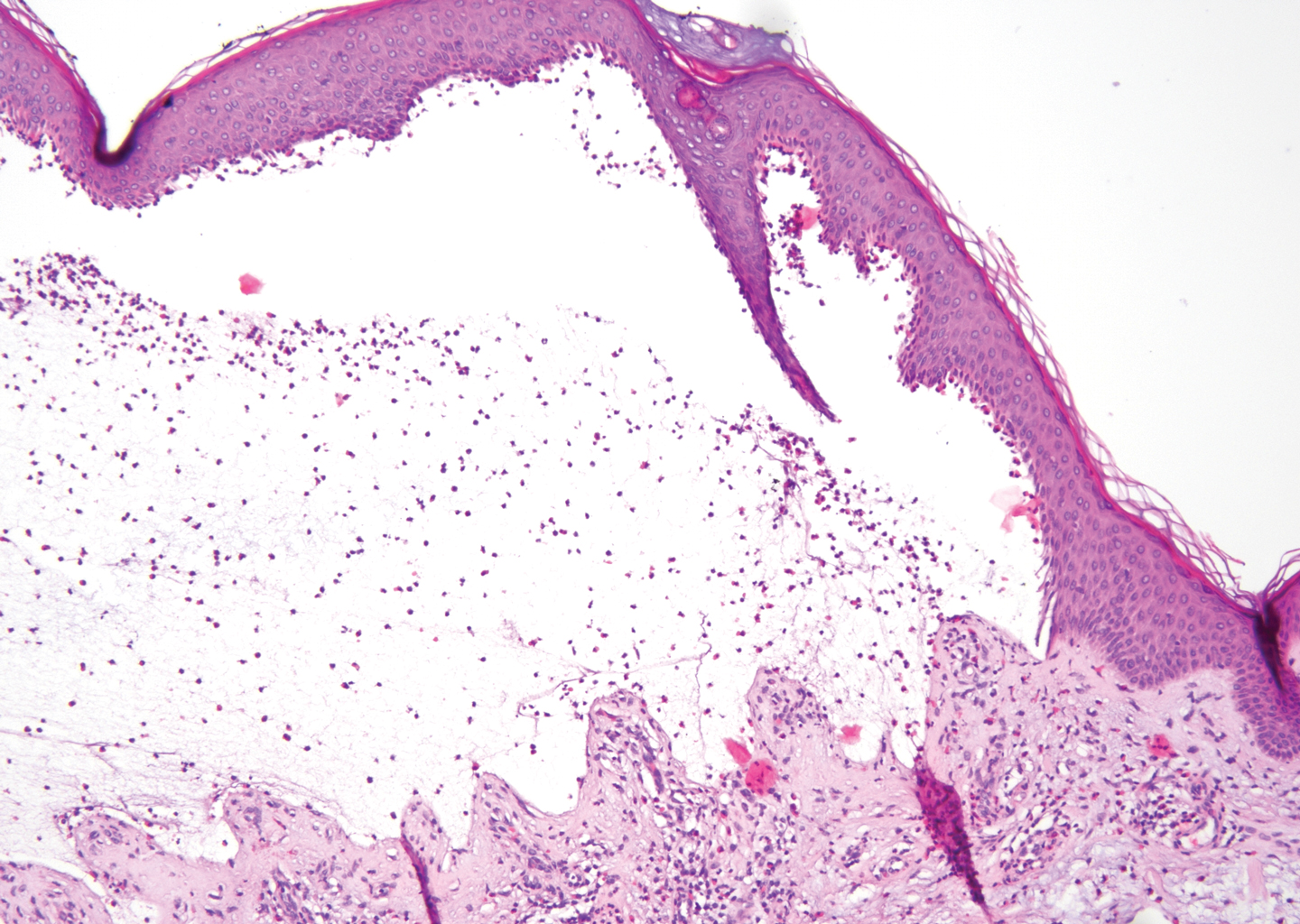

The predominant differential diagnosis for LPP is bullous LP, a variant of LP in which vesiculobullous disease occurs exclusively on preexisting LP lesions, commonly on the legs due to severe vacuolar degeneration at the DEJ. On histopathology, the characteristic features of LP (eg, orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies) along with subepidermal clefting will be seen. However, in bullous LP (Figure 1) there is an absence of linear IgG and/or C3 deposition at the DEJ on direct immunofluorescence. Furthermore, patients lack circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230.9

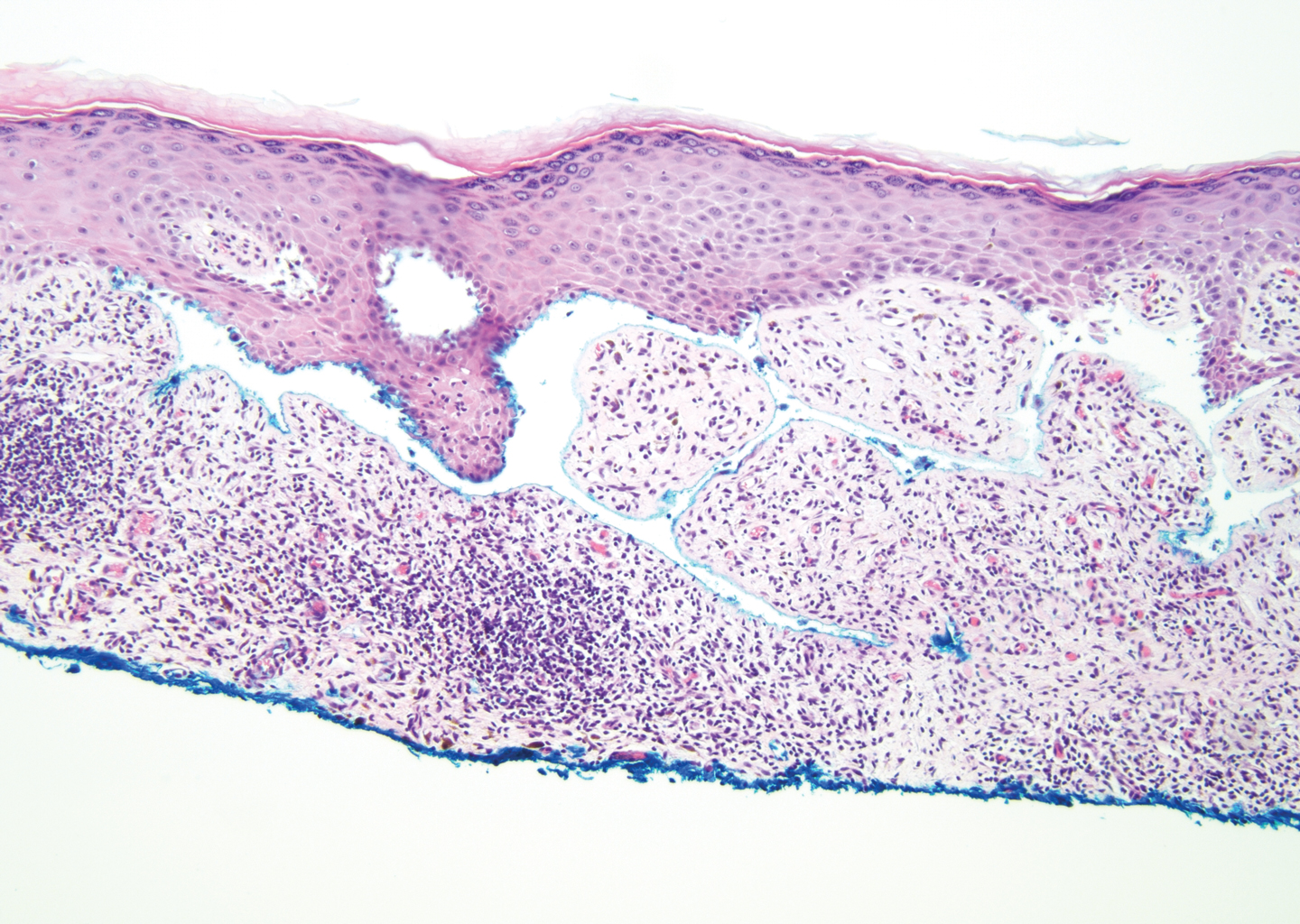

Lichen planus pemphigoides also can be confused with BP. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disorder; typically arises in older adults; and is caused by autoantibody formation against hemidesmosomal proteins, particularly BP-180 and BP-230. Patients classically present with tense bullae and erosions on an erythematous, urticarial, or normal base. These lesions often are pruritic and concentrated on the trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and extremity flexures. Histopathologic examination of a bulla edge reveals the classic findings seen in BP (eg, eosinophilic spongiosis, subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils)(Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin reveals linear IgG and/or C3 deposition along the DEJ. A large subset of patients also has circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230. In contrast to LPP, however, patients with BP do not develop lichenoid lesions clinically or a lichenoid tissue reaction histopathologically.10

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a rare cutaneous manifestation of SLE, typically arises in young women of African descent and is due to autoantibody formation against type VII collagen and other BM-zone antigens. Patients generally present with acute onset of tense vesiculobullae on a normal or erythematous base, which often are transient and heal without milia or scarring. Common sites of involvement include the trunk, arms, neck, face, and vermilion border, as well as the oral mucosa. The diagnosis of bullous SLE requires that patients fulfill the criteria for SLE and is confirmed by immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of a bulla edge reveals a subepidermal blister containing neutrophils and increased mucin within the reticular dermis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin most commonly reveals linear and/or granular deposition of IgG, IgA, C3, and IgM at the DEJ.11

Bullous tinea is a manifestation of cutaneous dermatophytosis that usually occurs in the setting of tinea pedis. Common causative dermatophytes include Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungal hyphae on potassium hydroxide preparation of the blister roof, biopsy with periodic acid-Schiff stain, or fungal culture. If routine histopathologic analysis is performed, epidermal spongiosis with varying degrees of papillary dermal edema is seen, along with abundant fungal elements in the stratum corneum (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin usually is negative, but C3 deposition in a linear and/or granular pattern along the DEJ has been reported.12

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare disease entity and often presents a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. The differential for LPP includes bullous LP as well as other bullous disorders. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed through immunohistologic analysis. Timely diagnosis of LPP is crucial, as most patients can achieve long-term remission with appropriate treatment.

- Zaraa I, Mahfoudh A, Sellami MK, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides: four new cases and a review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:406-412.

- Mohanarao TS, Kumar GA, Chennamsetty K, et al. Childhood lichen planus pemphigoides triggered by chickenpox. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:S98-S100.

- Onprasert W, Chanprapaph K. Lichen planus pemphigoides induced by enalapril: a case report and a review of literature. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:217-224.

- Kuramoto N, Kishimoto S, Shibagaki R, et al. PUVA-induced lichen planus pemphigoides. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:509-512.

- Shimada H, Shono T, Sakai T, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides concomitant with rectal adenocarcinoma: fortuitous or a true association? Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:501-503.

- Matos-Pires E, Campos S, Lencastre A, et al. Lichen planus pemphigoides. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:335-337.

- Zillikens D, Caux F, Mascaro JM, et al. Autoantibodies in lichen planus pemphigoides react with a novel epitope within the C-terminal NC16A domain of BP180. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:117-121.

- Knisley RR, Petropolis AA, Mackey VT. Lichen planus pemphigoides treated with ustekinumab. Cutis. 2017;100:415-418.

- Wagner G, Rose C, Sachse MM. Clinical variants of lichen planus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:309-319.

- Bagci IS, Horvath ON, Ruzicka T, et al. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445-455.

- Contestable JJ, Edhegard KD, Meyerle JH. Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus: a review and update to diagnosis and treatment. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:517-524.

- Miller DD, Bhawan J. Bullous tinea pedis with direct immunofluorescence positivity: when is a positive result not autoimmune bullous disease? Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:587-594.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6

The pathogenesis of LPP is not fully understood but likely represents a distinct entity rather than a subtype of BP or the simultaneous occurrence of LP and BP. Lichen planus pemphigoides generally has an earlier onset and better treatment response compared to BP.7 Further, autoantibodies in patients with LPP react to a novel epitope within the C-terminal portion of the BP-180 NC16A domain. Accordingly, it has been postulated that an inflammatory cutaneous process resulting from infection, phototherapy, or LP itself leads to damage of the epidermis and triggers a secondary blistering autoimmune dermatosis mediated by antibody formation against basement membrane (BM) antigens, such as BP-180.7

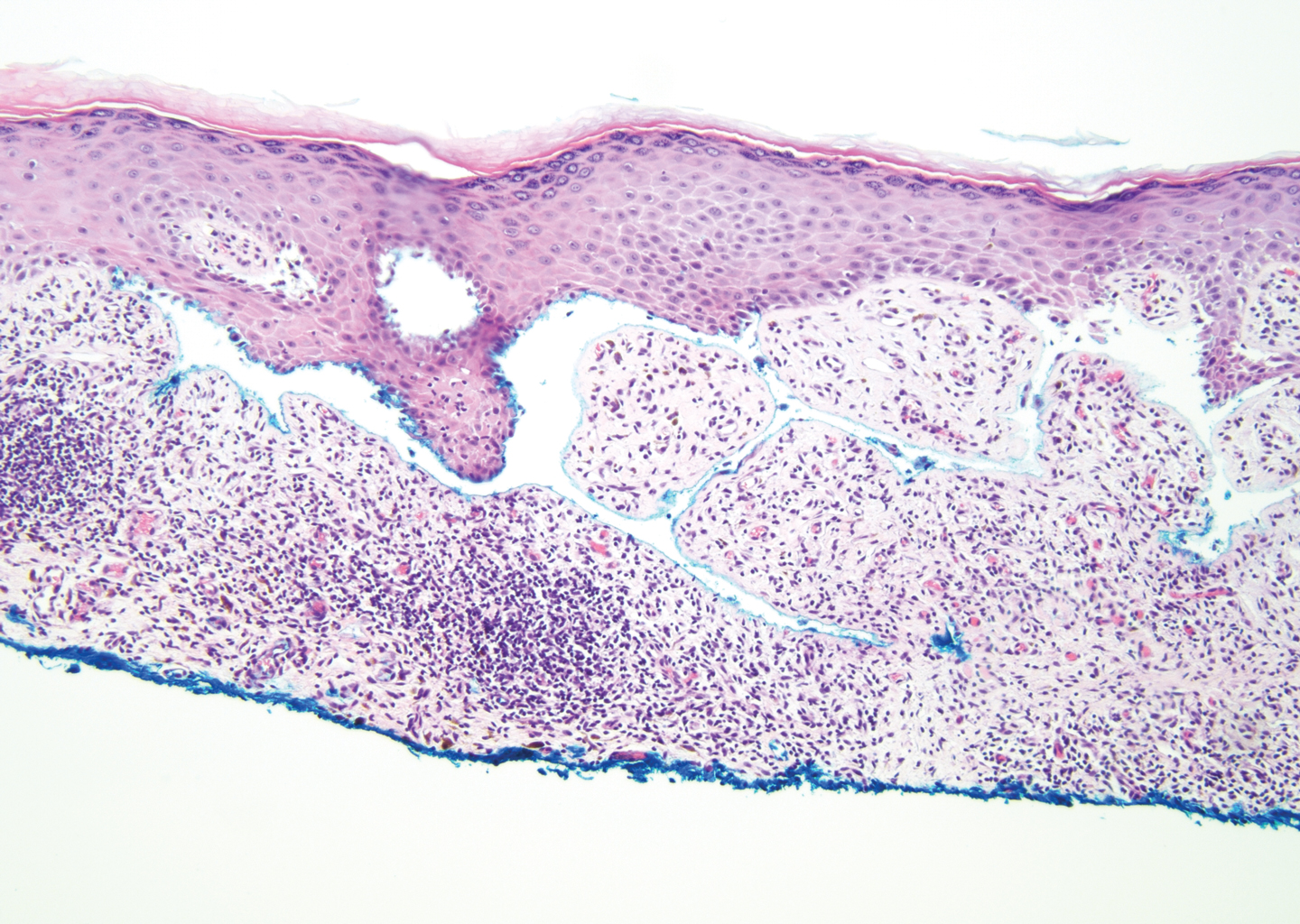

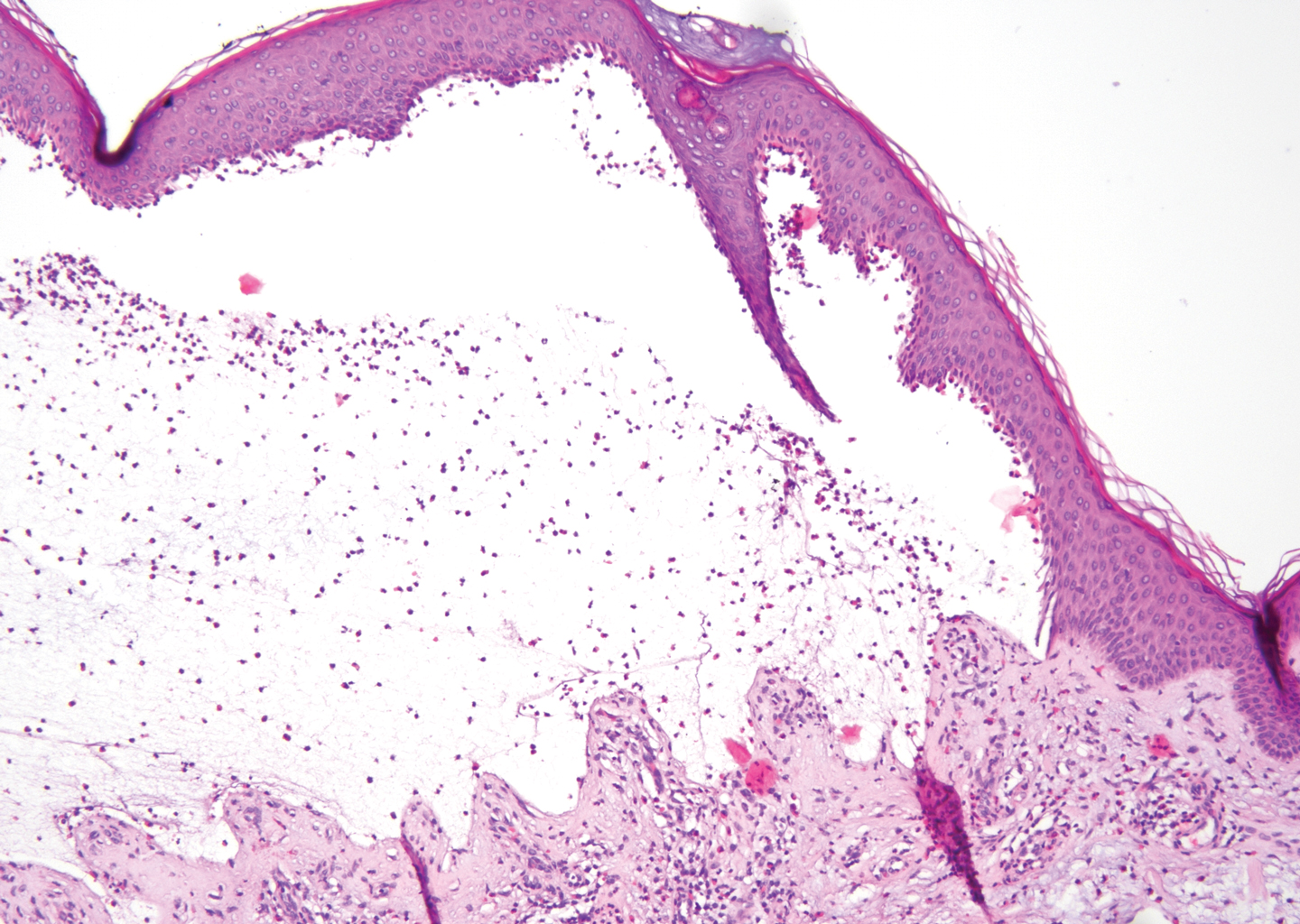

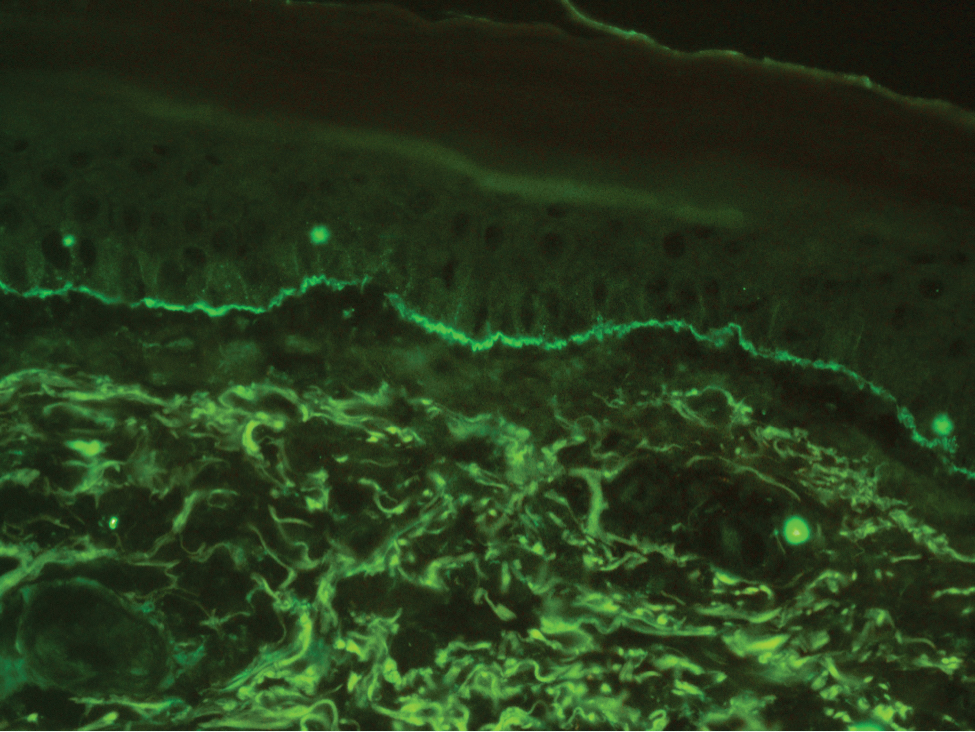

The diagnosis of LPP ultimately is confirmed with immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of LPP shows findings consistent with both LP and BP (quiz image [top]). In the lichenoid portion, biopsy reveals orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis; a bandlike infiltrate consisting primarily of lymphocytes in the upper dermis; and apoptotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).1 Biopsy of bullae reveals eosinophilic spongiosis, a subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils, and a mixed superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or C3 at the DEJ (quiz image [bottom]).1 Measurement of anti-BM antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230 can be useful in suspected cases, as 50% to 60% of patients have circulating antibodies against these antigens.6 Remission usually is achieved with topical and systemic corticosteroids and/or steroid-sparing agents, with rare recurrence following lesion resolution.1 More recently, successful treatment with biologics such as ustekinumab has been reported.8

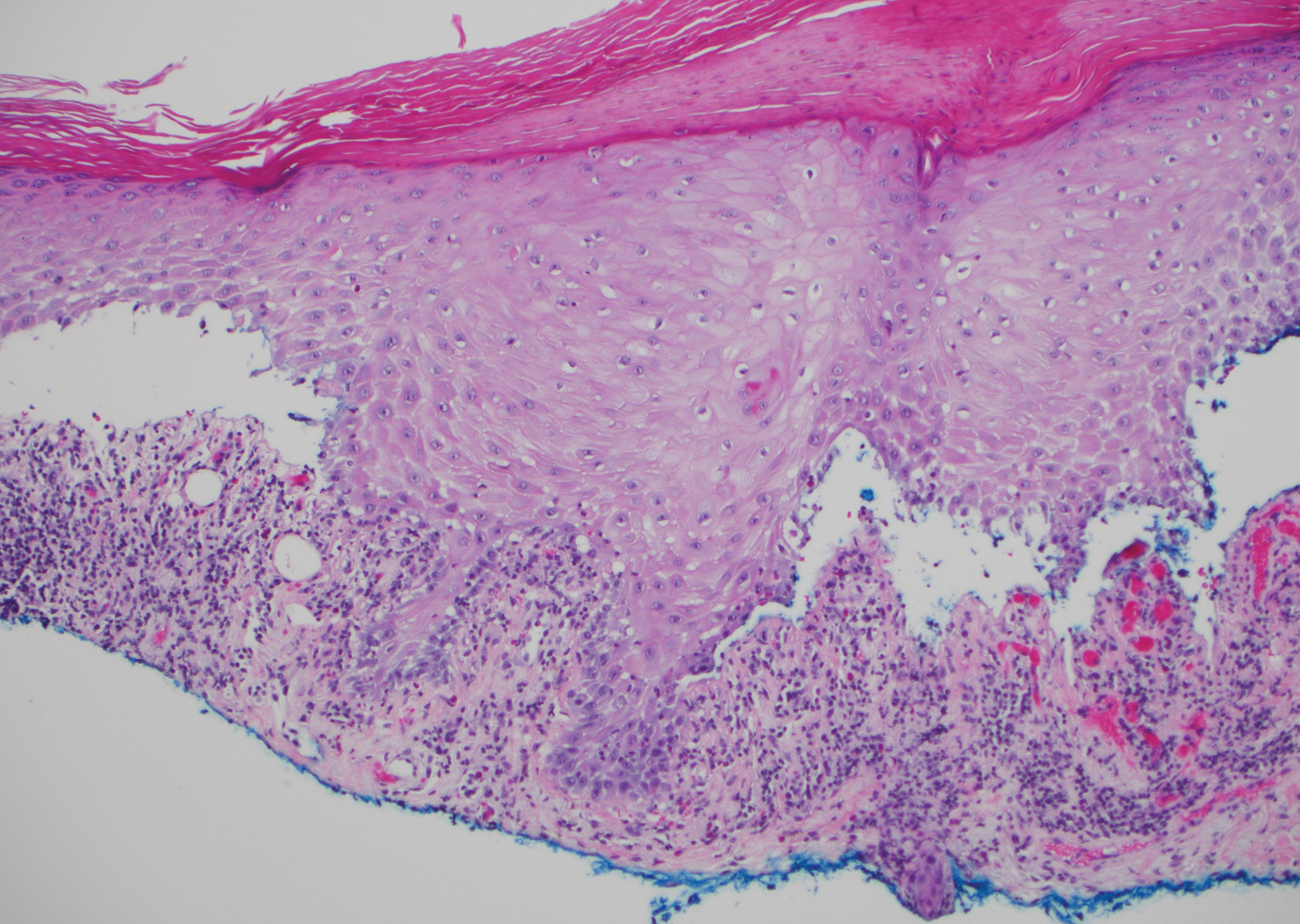

The predominant differential diagnosis for LPP is bullous LP, a variant of LP in which vesiculobullous disease occurs exclusively on preexisting LP lesions, commonly on the legs due to severe vacuolar degeneration at the DEJ. On histopathology, the characteristic features of LP (eg, orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies) along with subepidermal clefting will be seen. However, in bullous LP (Figure 1) there is an absence of linear IgG and/or C3 deposition at the DEJ on direct immunofluorescence. Furthermore, patients lack circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230.9

Lichen planus pemphigoides also can be confused with BP. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disorder; typically arises in older adults; and is caused by autoantibody formation against hemidesmosomal proteins, particularly BP-180 and BP-230. Patients classically present with tense bullae and erosions on an erythematous, urticarial, or normal base. These lesions often are pruritic and concentrated on the trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and extremity flexures. Histopathologic examination of a bulla edge reveals the classic findings seen in BP (eg, eosinophilic spongiosis, subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils)(Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin reveals linear IgG and/or C3 deposition along the DEJ. A large subset of patients also has circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230. In contrast to LPP, however, patients with BP do not develop lichenoid lesions clinically or a lichenoid tissue reaction histopathologically.10

Bullous systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a rare cutaneous manifestation of SLE, typically arises in young women of African descent and is due to autoantibody formation against type VII collagen and other BM-zone antigens. Patients generally present with acute onset of tense vesiculobullae on a normal or erythematous base, which often are transient and heal without milia or scarring. Common sites of involvement include the trunk, arms, neck, face, and vermilion border, as well as the oral mucosa. The diagnosis of bullous SLE requires that patients fulfill the criteria for SLE and is confirmed by immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of a bulla edge reveals a subepidermal blister containing neutrophils and increased mucin within the reticular dermis (Figure 3). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin most commonly reveals linear and/or granular deposition of IgG, IgA, C3, and IgM at the DEJ.11

Bullous tinea is a manifestation of cutaneous dermatophytosis that usually occurs in the setting of tinea pedis. Common causative dermatophytes include Trichophyton mentagrophytes, Trichophyton rubrum, and Epidermophyton floccosum. Diagnosis is made by demonstration of fungal hyphae on potassium hydroxide preparation of the blister roof, biopsy with periodic acid-Schiff stain, or fungal culture. If routine histopathologic analysis is performed, epidermal spongiosis with varying degrees of papillary dermal edema is seen, along with abundant fungal elements in the stratum corneum (Figure 4). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin usually is negative, but C3 deposition in a linear and/or granular pattern along the DEJ has been reported.12

Lichen planus pemphigoides is a rare disease entity and often presents a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. The differential for LPP includes bullous LP as well as other bullous disorders. Ultimately, the diagnosis is confirmed through immunohistologic analysis. Timely diagnosis of LPP is crucial, as most patients can achieve long-term remission with appropriate treatment.

The Diagnosis: Lichen Planus Pemphigoides

Lichen planus pemphigoides (LPP) is a rare autoimmune subepithelial blistering disorder with clinical, pathologic, and immunologic features of lichen planus (LP) and bullous pemphigoid (BP).1 It mainly arises in adults and usually is idiopathic but has been associated with certain infections,2 drugs such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors,3 phototherapy,4 and malignancy.5 Patients classically present with lichenoid lesions, tense vesiculobullae, and erosions.6 Vesiculobullae formation usually follows the development of lichenoid lesions, occurs on both lichenoid lesions and unaffected skin, and predominantly involves the lower extremities, as in our patient.1,6

The pathogenesis of LPP is not fully understood but likely represents a distinct entity rather than a subtype of BP or the simultaneous occurrence of LP and BP. Lichen planus pemphigoides generally has an earlier onset and better treatment response compared to BP.7 Further, autoantibodies in patients with LPP react to a novel epitope within the C-terminal portion of the BP-180 NC16A domain. Accordingly, it has been postulated that an inflammatory cutaneous process resulting from infection, phototherapy, or LP itself leads to damage of the epidermis and triggers a secondary blistering autoimmune dermatosis mediated by antibody formation against basement membrane (BM) antigens, such as BP-180.7

The diagnosis of LPP ultimately is confirmed with immunohistologic analysis. Biopsy of LPP shows findings consistent with both LP and BP (quiz image [top]). In the lichenoid portion, biopsy reveals orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, and acanthosis of the epidermis; a bandlike infiltrate consisting primarily of lymphocytes in the upper dermis; and apoptotic keratinocytes (colloid bodies) and vacuolar degeneration at the dermoepidermal junction (DEJ).1 Biopsy of bullae reveals eosinophilic spongiosis, a subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils, and a mixed superficial inflammatory cell infiltrate. Direct immunofluorescence from perilesional skin reveals linear deposition of IgG and/or C3 at the DEJ (quiz image [bottom]).1 Measurement of anti-BM antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230 can be useful in suspected cases, as 50% to 60% of patients have circulating antibodies against these antigens.6 Remission usually is achieved with topical and systemic corticosteroids and/or steroid-sparing agents, with rare recurrence following lesion resolution.1 More recently, successful treatment with biologics such as ustekinumab has been reported.8

The predominant differential diagnosis for LPP is bullous LP, a variant of LP in which vesiculobullous disease occurs exclusively on preexisting LP lesions, commonly on the legs due to severe vacuolar degeneration at the DEJ. On histopathology, the characteristic features of LP (eg, orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate, colloid bodies) along with subepidermal clefting will be seen. However, in bullous LP (Figure 1) there is an absence of linear IgG and/or C3 deposition at the DEJ on direct immunofluorescence. Furthermore, patients lack circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230.9

Lichen planus pemphigoides also can be confused with BP. Bullous pemphigoid is the most common autoimmune blistering disorder; typically arises in older adults; and is caused by autoantibody formation against hemidesmosomal proteins, particularly BP-180 and BP-230. Patients classically present with tense bullae and erosions on an erythematous, urticarial, or normal base. These lesions often are pruritic and concentrated on the trunk, axillary and inguinal folds, and extremity flexures. Histopathologic examination of a bulla edge reveals the classic findings seen in BP (eg, eosinophilic spongiosis, subepithelial blister plane with eosinophils)(Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence of perilesional skin reveals linear IgG and/or C3 deposition along the DEJ. A large subset of patients also has circulating antibodies against BP-180 and BP-230. In contrast to LPP, however, patients with BP do not develop lichenoid lesions clinically or a lichenoid tissue reaction histopathologically.10