User login

Erythematous Papule on the Nasal Ala

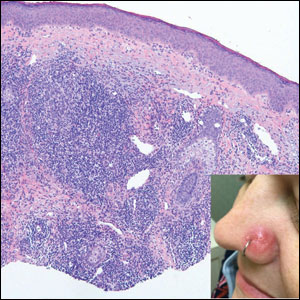

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Lymphoid Hyperplasia

Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (CLH)(also known as pseudolymphoma or lymphocytoma cutis) is a benign inflammatory condition that typically presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous or violaceous papule or nodule on the head or neck. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia may arise in response to an antigenic stimulus, such as an insect bite, infectious agent (eg, Borrelia species), medication, or foreign body (eg, tattoos and piercings).1,2 Given the benign nature and potential for spontaneous resolution, treatment is conservative; however, high-potency topical steroids, cryosurgery, surgical excision, or local radiotherapy may lead to improvement.3 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% and topical tacrolimus 0.1%. After 3 months of use, she reported lesion improvement, but a new lesion appeared on the nose superior to the original. She was offered a steroid injection and liquid nitrogen freezing but was lost to follow-up.

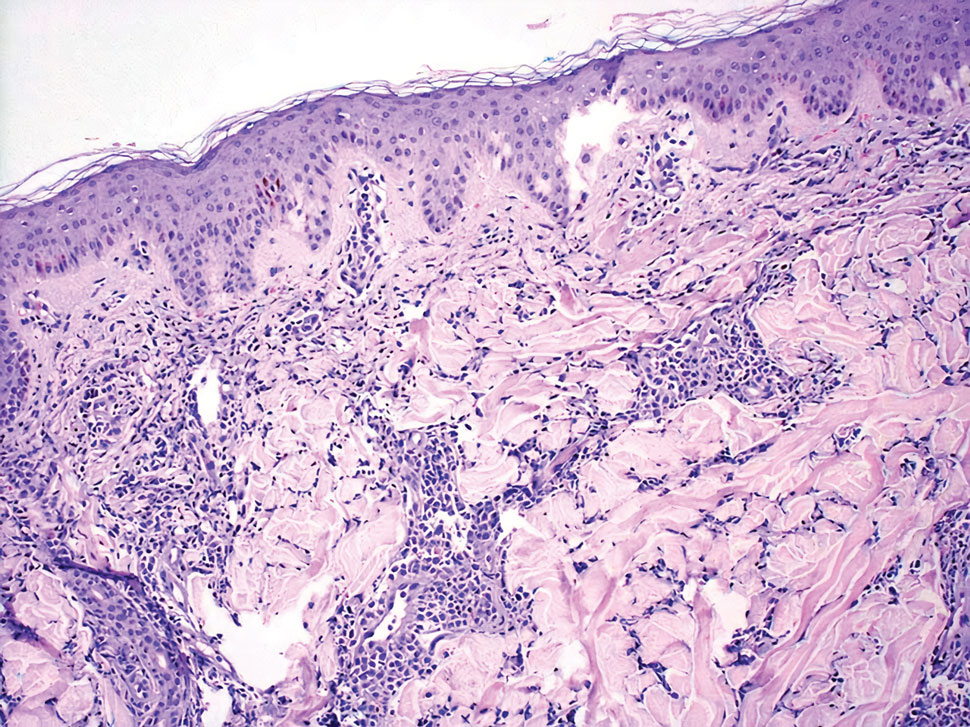

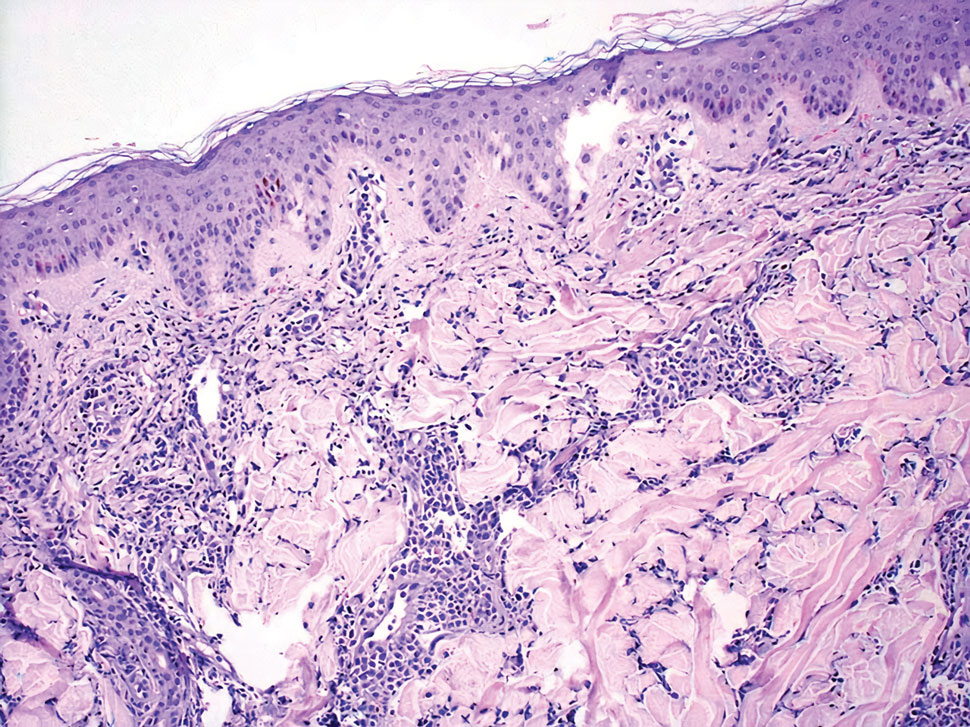

The histopathologic features of CLH are variable and can resemble a cutaneous B- or T-cell lymphoma (quiz images). If there is B-cell predominance, histopathology typically shows a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes admixed with sparse histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Multiple germinal-center phenotype lymphoid follicles also may be seen.4 Histopathology of T-cell–predominant CLH commonly shows CD4+ T helper lymphocytes admixed with CD8+ T cells within the dermis with possible papillary dermal edema and red cell extravasation.5 Immunohistochemical stains for CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD20 usually are positive. Most lymphocytes are CD3+ T cells. Admixed clusters of CD20+ B cells may be present.

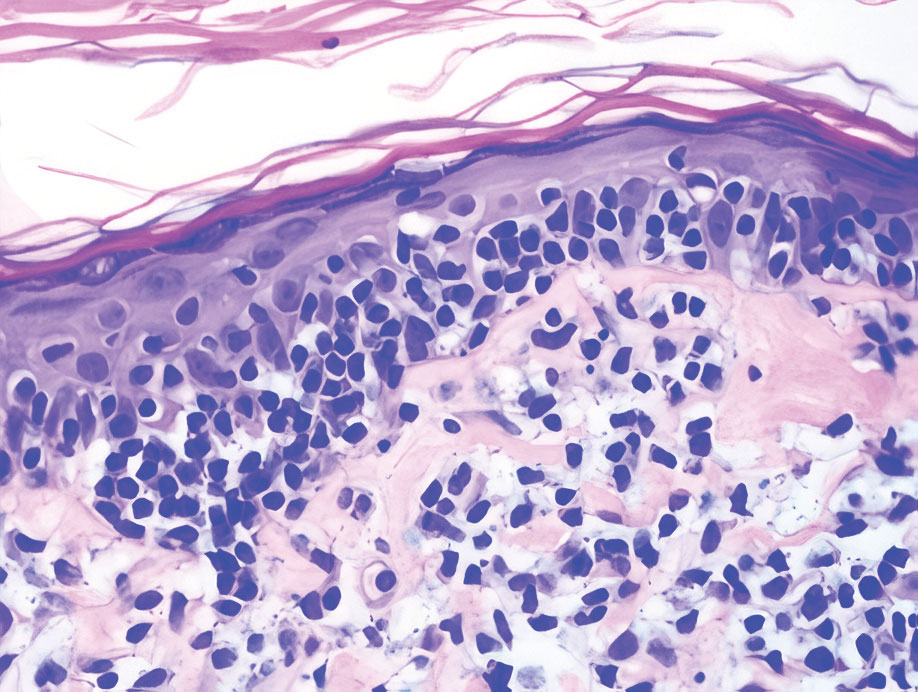

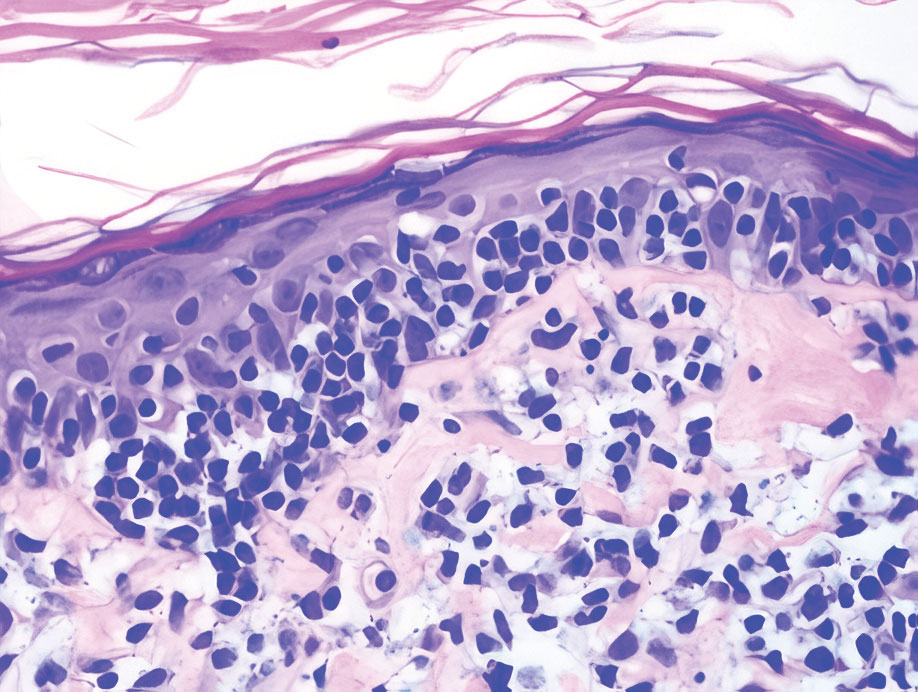

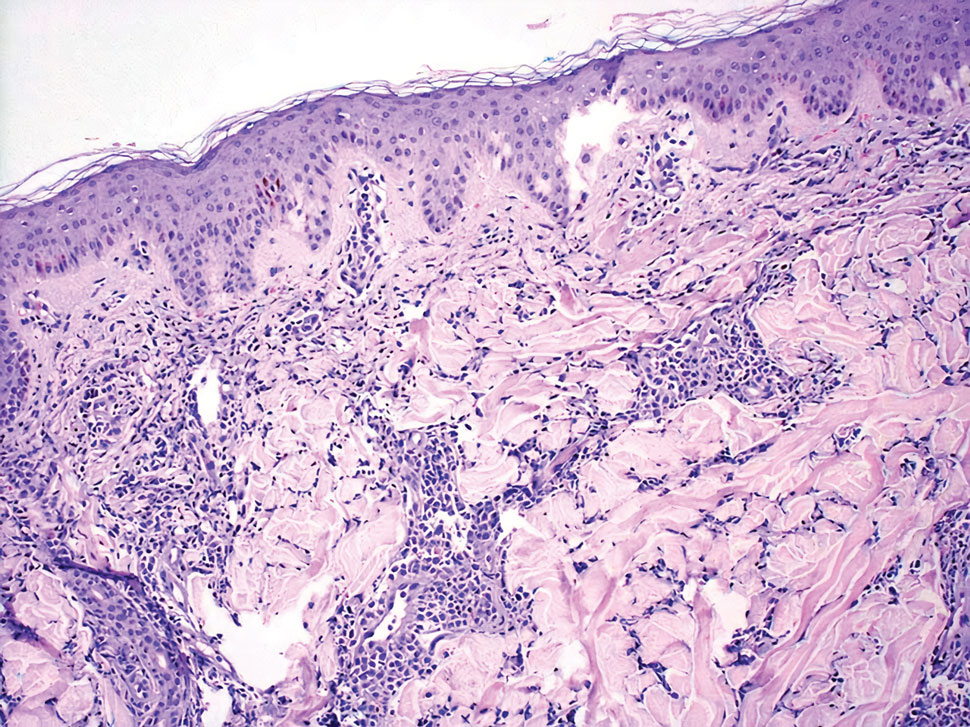

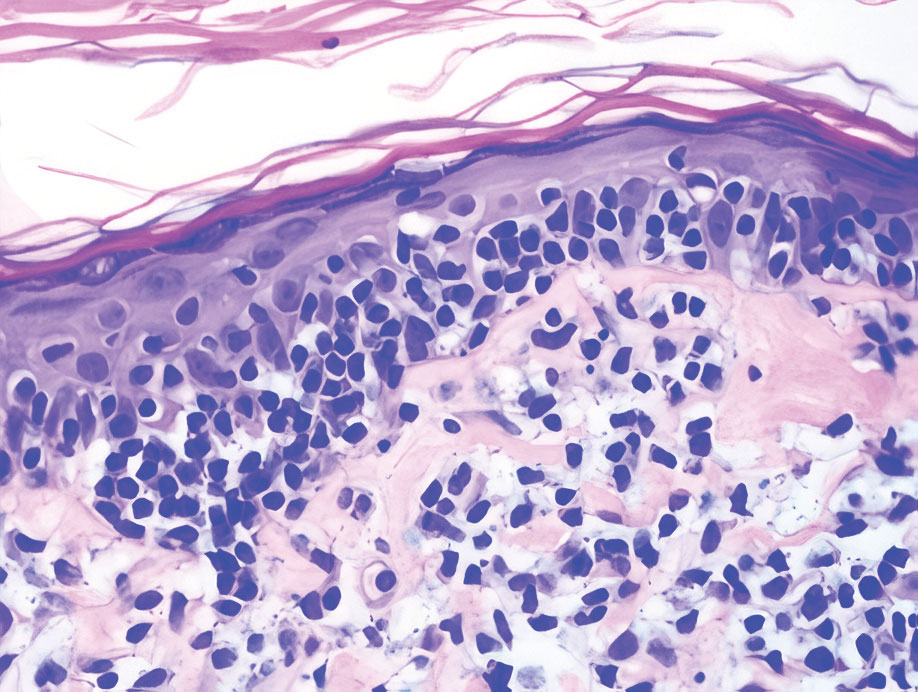

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia is a vascular tumor of the skin composed of endothelial cells and inflammatory cells.6,7 The condition presents as single or multiple flesh-colored to purple papules most commonly on the face, scalp, and ears.8 Histologically, lesions appear as well-circumscribed collections of blood vessels composed of plump endothelial cells and an inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 1A). Endothelial cells also may have an epithelioid appearance.7 Apparent fenestrations—holes within endothelial cells—may be present (Figure 1B). Surgical excision is the preferred treatment of angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Success with laser and cryosurgery also has been reported.

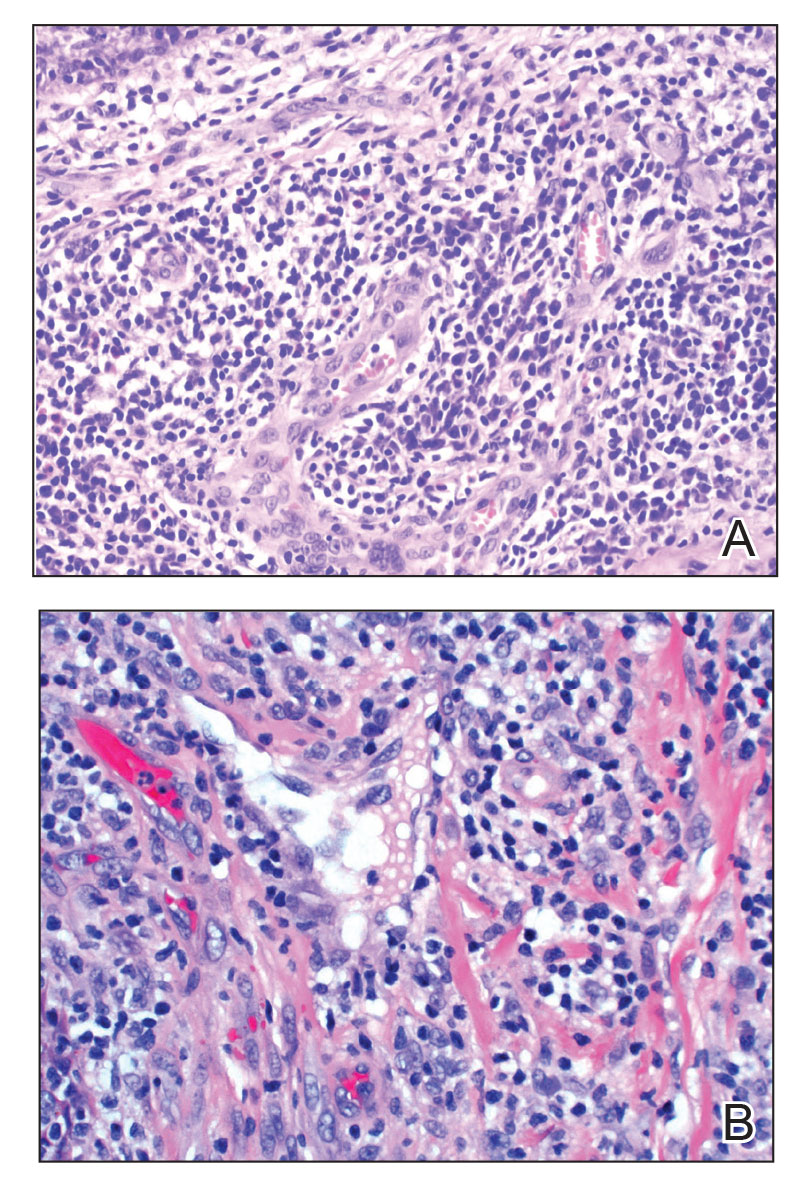

Granuloma faciale typically presents as a solitary redbrown papule or plaque on the face. Linear arborizing vessels and dilated follicular openings with brown globules frequently are seen on dermoscopy.9 Although it may resemble CLH clinically, the histopathology of granuloma faciale is characterized by a perivascular and interstitial dermal infiltrate of numerous eosinophils admixed with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils underneath a grenz zone (Figure 2).10 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may be seen in early lesions, and lesions can show variable angiocentric fibrosis.11 Treatment options include intralesional triamcinolone, topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors, topical psoralen plus UVA, surgical excision, and laser therapy, but outcomes are variable.12

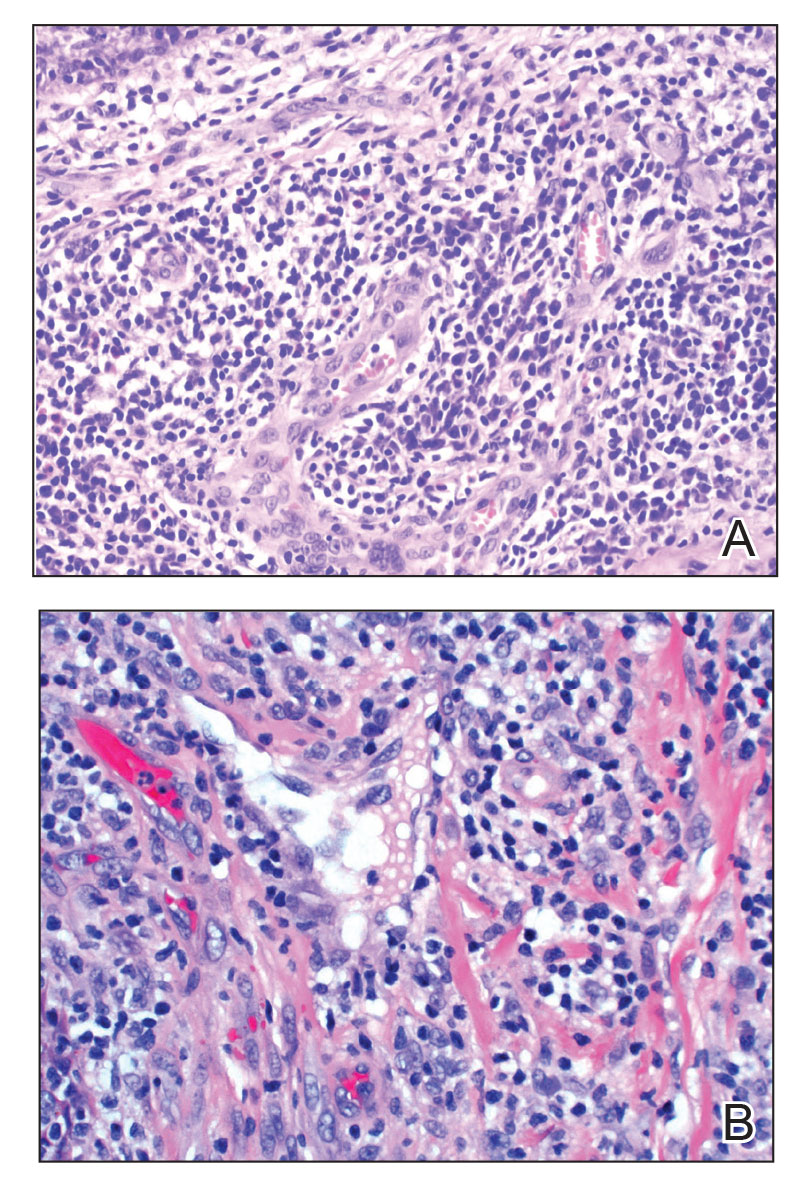

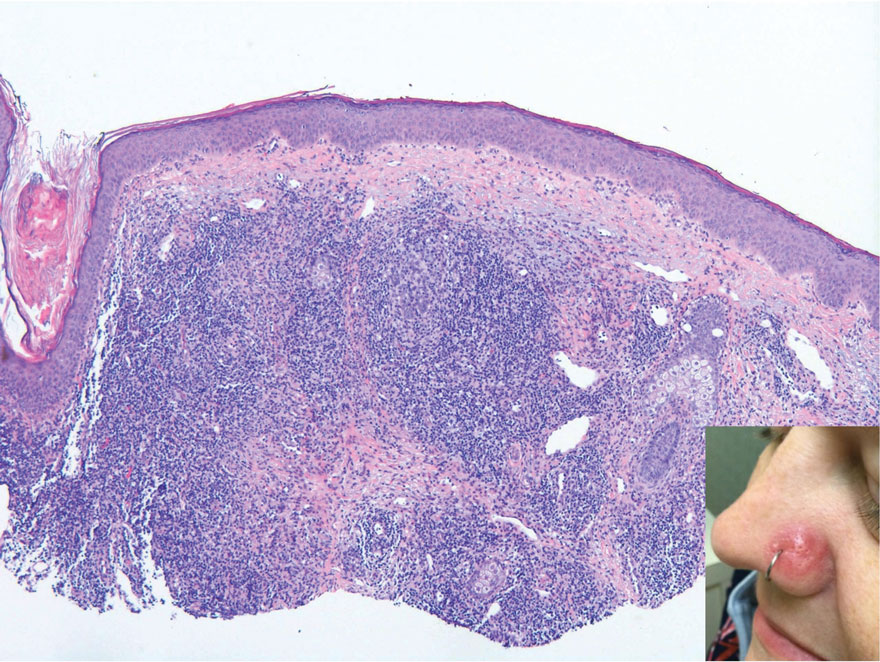

Leukemia cutis is a malignant hematopoietic skin infiltration that presents as multiple pink to red-brown, firm, hemorrhagic papules most frequently involving the head, neck, and trunk.13 Rarely, lesions of leukemia cutis may present as ulcers or bullae. Most lesions occur at presentation of systemic leukemia or in the setting of established leukemia. The cutaneous involvement portends a poor prognosis, strongly correlating with additional extramedullary leukemic involvement.14 Histologic features vary based on the specific type of leukemia (eg, acute myelogenous leukemia). Generally, neoplastic infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in a nodular, diffuse, perivascular, or interstitial pattern is seen (Figure 3).15 Leukemia cutis typically resolves after successful treatment of the underlying leukemia.

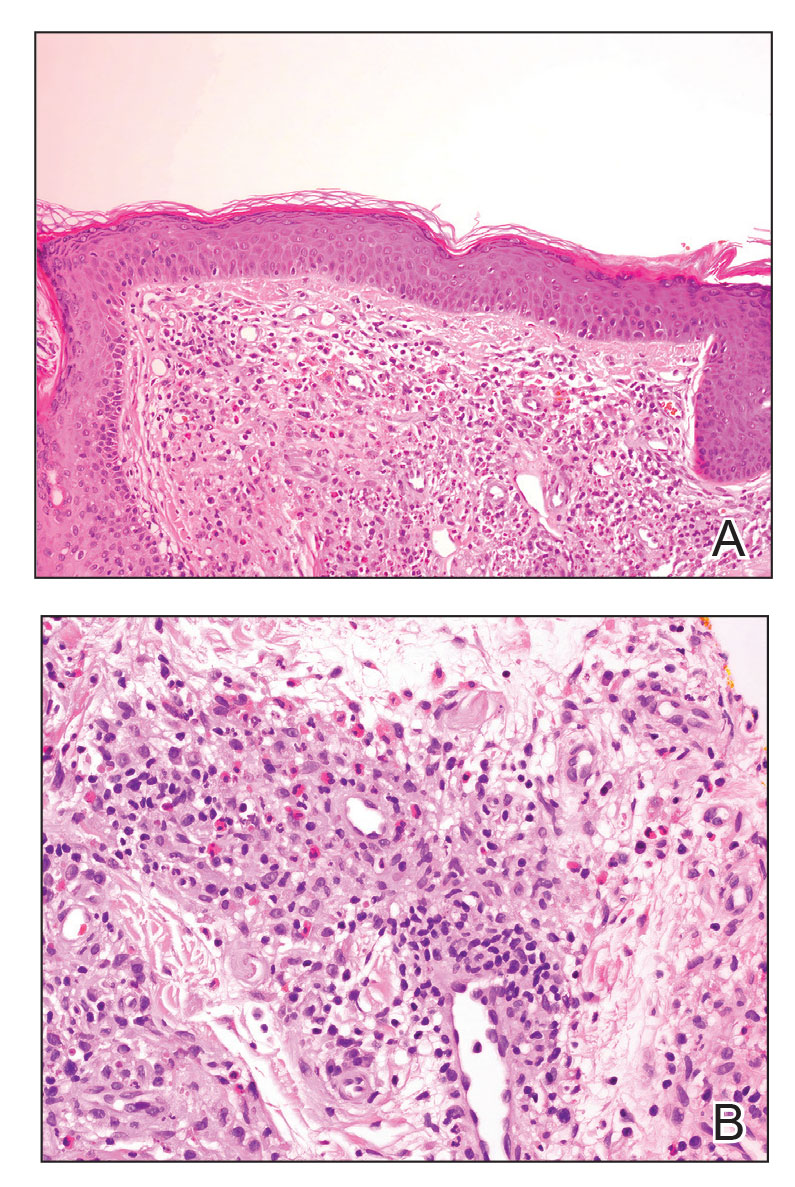

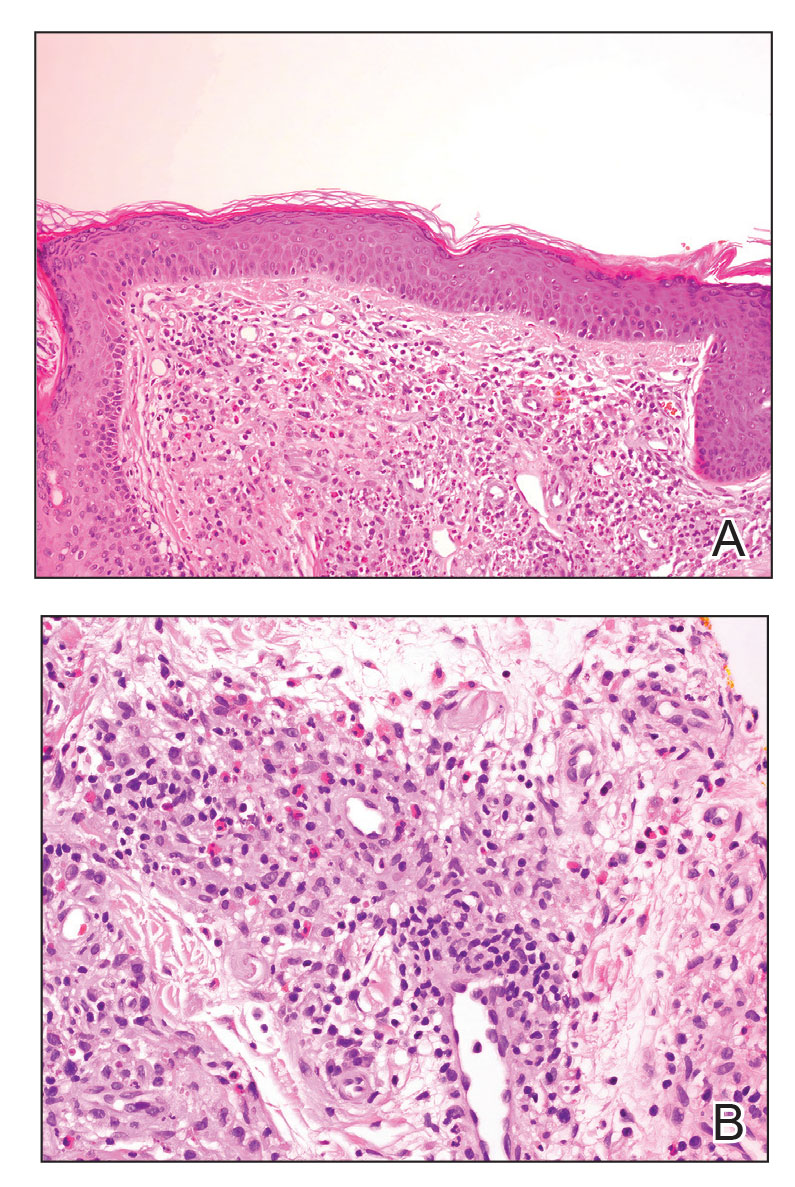

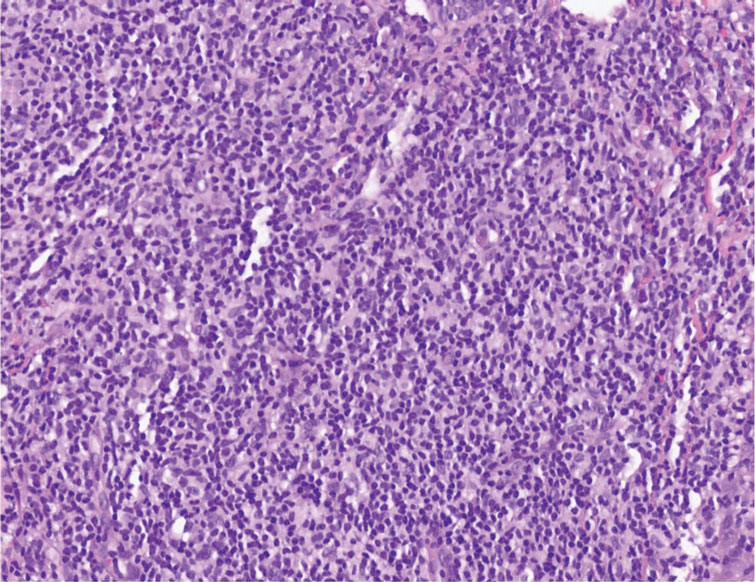

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In its early stages, MF presents as erythematous, brown, scaly patches and plaques. With progression to the tumor stage of disease, clonal expansion of CD4+ T cells leads to the development of purple papules and nodules.16 Microscopic findings of MF are dependent on the stage of disease. Early patch lesions show superficial or lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration of the epidermal basal layer.17 In the plaque stage, dermal infiltrates and epidermotropism become more pronounced, with increased atypical lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and interspersed inflammatory cells (Figure 4). In the tumor stage, lymphocytic infiltrates may involve the entirety of the dermis or extend into the subcutaneous tissue, and malignant cells become larger in size.17 Mycosis fungoides lesions typically stain positive for helper T-cell markers with a minority staining positive for CD8.

- Zhou LL, Mistry N. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma). CMAJ. 2018;190:E398.

- Lackey JN, Xia Y, Cho S, et al. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia: a case report and brief review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;79:445-448.

- Albrecht J, Fine LA, Piette W. Drug-associated lymphoma and pseudolymphoma: recognition and management. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:233-244, vii.

- Arai E, Shimizu M, Hirose T. A review of 55 cases of cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia: reassessment of the histopathologic findings leading to reclassification of 4 lesions as cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma and 19 as pseudolymphomatous folliculitis. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:505-511.

- Bergman R, Khamaysi Z, Sahar D, et al. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia presenting as a solitary facial nodule: clinical, histopathological, immunophenotypical, and molecular studies. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1561-1566.

- Wells GC, Whimster IW. Subcutaneous angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:1-14.

- Guo R, Gavino AC. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:683-686.

- Olsen TG, Helwig EB. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. a clinicopathologic study of 116 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:781-796.

- Lallas A, Sidiropoulos T, Lefaki I, et al. Photo letter to the editor: dermoscopy of granuloma faciale. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:59-60.

- Oliveira CC, Ianhez PE, Marques SA, et al. Granuloma faciale: clinical, morphological and immunohistochemical aspects in a series of 10 patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:803-807.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Lindhaus C, Elsner P. Granuloma faciale treatment: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:14-18.

- Haidari W, Strowd LC. Clinical characterization of leukemia cutis presentation. Cutis. 2019;104:326-330; E3.

- Rao AG, Danturty I. Leukemia cutis. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:504.

- Desch JK, Smoller BR. The spectrum of cutaneous disease in leukemias. J Cutan Pathol. 1993;20:407-410.

- Yamashita T, Abbade LP, Marques ME, et al. Mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical review and update. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:817-828; quiz 829-830.

- Smoller BR, Bishop K, Glusac E, et al. Reassessment of histologic parameters in the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1423-1430.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Lymphoid Hyperplasia

Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (CLH)(also known as pseudolymphoma or lymphocytoma cutis) is a benign inflammatory condition that typically presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous or violaceous papule or nodule on the head or neck. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia may arise in response to an antigenic stimulus, such as an insect bite, infectious agent (eg, Borrelia species), medication, or foreign body (eg, tattoos and piercings).1,2 Given the benign nature and potential for spontaneous resolution, treatment is conservative; however, high-potency topical steroids, cryosurgery, surgical excision, or local radiotherapy may lead to improvement.3 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% and topical tacrolimus 0.1%. After 3 months of use, she reported lesion improvement, but a new lesion appeared on the nose superior to the original. She was offered a steroid injection and liquid nitrogen freezing but was lost to follow-up.

The histopathologic features of CLH are variable and can resemble a cutaneous B- or T-cell lymphoma (quiz images). If there is B-cell predominance, histopathology typically shows a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes admixed with sparse histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Multiple germinal-center phenotype lymphoid follicles also may be seen.4 Histopathology of T-cell–predominant CLH commonly shows CD4+ T helper lymphocytes admixed with CD8+ T cells within the dermis with possible papillary dermal edema and red cell extravasation.5 Immunohistochemical stains for CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD20 usually are positive. Most lymphocytes are CD3+ T cells. Admixed clusters of CD20+ B cells may be present.

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia is a vascular tumor of the skin composed of endothelial cells and inflammatory cells.6,7 The condition presents as single or multiple flesh-colored to purple papules most commonly on the face, scalp, and ears.8 Histologically, lesions appear as well-circumscribed collections of blood vessels composed of plump endothelial cells and an inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 1A). Endothelial cells also may have an epithelioid appearance.7 Apparent fenestrations—holes within endothelial cells—may be present (Figure 1B). Surgical excision is the preferred treatment of angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Success with laser and cryosurgery also has been reported.

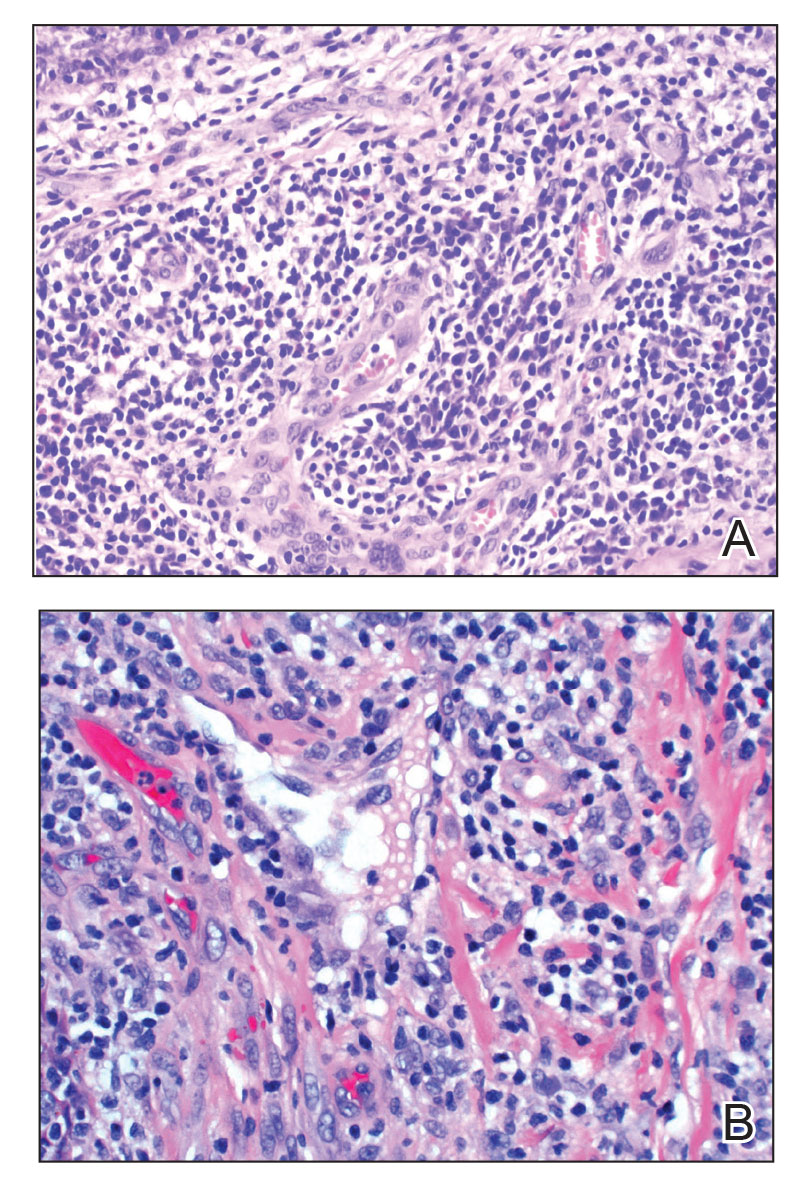

Granuloma faciale typically presents as a solitary redbrown papule or plaque on the face. Linear arborizing vessels and dilated follicular openings with brown globules frequently are seen on dermoscopy.9 Although it may resemble CLH clinically, the histopathology of granuloma faciale is characterized by a perivascular and interstitial dermal infiltrate of numerous eosinophils admixed with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils underneath a grenz zone (Figure 2).10 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may be seen in early lesions, and lesions can show variable angiocentric fibrosis.11 Treatment options include intralesional triamcinolone, topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors, topical psoralen plus UVA, surgical excision, and laser therapy, but outcomes are variable.12

Leukemia cutis is a malignant hematopoietic skin infiltration that presents as multiple pink to red-brown, firm, hemorrhagic papules most frequently involving the head, neck, and trunk.13 Rarely, lesions of leukemia cutis may present as ulcers or bullae. Most lesions occur at presentation of systemic leukemia or in the setting of established leukemia. The cutaneous involvement portends a poor prognosis, strongly correlating with additional extramedullary leukemic involvement.14 Histologic features vary based on the specific type of leukemia (eg, acute myelogenous leukemia). Generally, neoplastic infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in a nodular, diffuse, perivascular, or interstitial pattern is seen (Figure 3).15 Leukemia cutis typically resolves after successful treatment of the underlying leukemia.

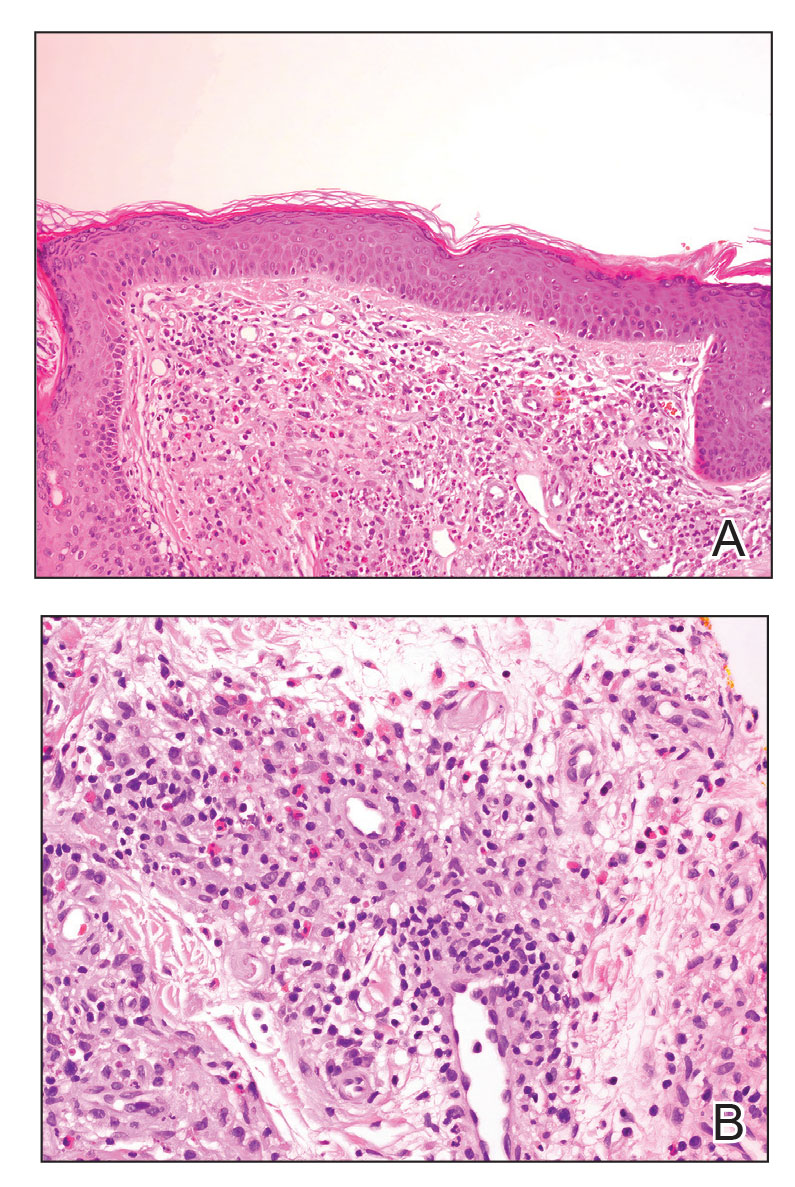

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In its early stages, MF presents as erythematous, brown, scaly patches and plaques. With progression to the tumor stage of disease, clonal expansion of CD4+ T cells leads to the development of purple papules and nodules.16 Microscopic findings of MF are dependent on the stage of disease. Early patch lesions show superficial or lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration of the epidermal basal layer.17 In the plaque stage, dermal infiltrates and epidermotropism become more pronounced, with increased atypical lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and interspersed inflammatory cells (Figure 4). In the tumor stage, lymphocytic infiltrates may involve the entirety of the dermis or extend into the subcutaneous tissue, and malignant cells become larger in size.17 Mycosis fungoides lesions typically stain positive for helper T-cell markers with a minority staining positive for CD8.

The Diagnosis: Cutaneous Lymphoid Hyperplasia

Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (CLH)(also known as pseudolymphoma or lymphocytoma cutis) is a benign inflammatory condition that typically presents as a flesh-colored to erythematous or violaceous papule or nodule on the head or neck. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia may arise in response to an antigenic stimulus, such as an insect bite, infectious agent (eg, Borrelia species), medication, or foreign body (eg, tattoos and piercings).1,2 Given the benign nature and potential for spontaneous resolution, treatment is conservative; however, high-potency topical steroids, cryosurgery, surgical excision, or local radiotherapy may lead to improvement.3 Our patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% and topical tacrolimus 0.1%. After 3 months of use, she reported lesion improvement, but a new lesion appeared on the nose superior to the original. She was offered a steroid injection and liquid nitrogen freezing but was lost to follow-up.

The histopathologic features of CLH are variable and can resemble a cutaneous B- or T-cell lymphoma (quiz images). If there is B-cell predominance, histopathology typically shows a dense dermal infiltrate of lymphocytes admixed with sparse histiocytes, eosinophils, and plasma cells. Multiple germinal-center phenotype lymphoid follicles also may be seen.4 Histopathology of T-cell–predominant CLH commonly shows CD4+ T helper lymphocytes admixed with CD8+ T cells within the dermis with possible papillary dermal edema and red cell extravasation.5 Immunohistochemical stains for CD3, CD4, CD8, and CD20 usually are positive. Most lymphocytes are CD3+ T cells. Admixed clusters of CD20+ B cells may be present.

Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia is a vascular tumor of the skin composed of endothelial cells and inflammatory cells.6,7 The condition presents as single or multiple flesh-colored to purple papules most commonly on the face, scalp, and ears.8 Histologically, lesions appear as well-circumscribed collections of blood vessels composed of plump endothelial cells and an inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and eosinophils (Figure 1A). Endothelial cells also may have an epithelioid appearance.7 Apparent fenestrations—holes within endothelial cells—may be present (Figure 1B). Surgical excision is the preferred treatment of angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Success with laser and cryosurgery also has been reported.

Granuloma faciale typically presents as a solitary redbrown papule or plaque on the face. Linear arborizing vessels and dilated follicular openings with brown globules frequently are seen on dermoscopy.9 Although it may resemble CLH clinically, the histopathology of granuloma faciale is characterized by a perivascular and interstitial dermal infiltrate of numerous eosinophils admixed with lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils underneath a grenz zone (Figure 2).10 Leukocytoclastic vasculitis may be seen in early lesions, and lesions can show variable angiocentric fibrosis.11 Treatment options include intralesional triamcinolone, topical steroids or calcineurin inhibitors, topical psoralen plus UVA, surgical excision, and laser therapy, but outcomes are variable.12

Leukemia cutis is a malignant hematopoietic skin infiltration that presents as multiple pink to red-brown, firm, hemorrhagic papules most frequently involving the head, neck, and trunk.13 Rarely, lesions of leukemia cutis may present as ulcers or bullae. Most lesions occur at presentation of systemic leukemia or in the setting of established leukemia. The cutaneous involvement portends a poor prognosis, strongly correlating with additional extramedullary leukemic involvement.14 Histologic features vary based on the specific type of leukemia (eg, acute myelogenous leukemia). Generally, neoplastic infiltration of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in a nodular, diffuse, perivascular, or interstitial pattern is seen (Figure 3).15 Leukemia cutis typically resolves after successful treatment of the underlying leukemia.

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. In its early stages, MF presents as erythematous, brown, scaly patches and plaques. With progression to the tumor stage of disease, clonal expansion of CD4+ T cells leads to the development of purple papules and nodules.16 Microscopic findings of MF are dependent on the stage of disease. Early patch lesions show superficial or lichenoid lymphocytic infiltration of the epidermal basal layer.17 In the plaque stage, dermal infiltrates and epidermotropism become more pronounced, with increased atypical lymphocytes with cerebriform nuclei and interspersed inflammatory cells (Figure 4). In the tumor stage, lymphocytic infiltrates may involve the entirety of the dermis or extend into the subcutaneous tissue, and malignant cells become larger in size.17 Mycosis fungoides lesions typically stain positive for helper T-cell markers with a minority staining positive for CD8.

- Zhou LL, Mistry N. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma). CMAJ. 2018;190:E398.

- Lackey JN, Xia Y, Cho S, et al. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia: a case report and brief review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;79:445-448.

- Albrecht J, Fine LA, Piette W. Drug-associated lymphoma and pseudolymphoma: recognition and management. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:233-244, vii.

- Arai E, Shimizu M, Hirose T. A review of 55 cases of cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia: reassessment of the histopathologic findings leading to reclassification of 4 lesions as cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma and 19 as pseudolymphomatous folliculitis. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:505-511.

- Bergman R, Khamaysi Z, Sahar D, et al. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia presenting as a solitary facial nodule: clinical, histopathological, immunophenotypical, and molecular studies. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1561-1566.

- Wells GC, Whimster IW. Subcutaneous angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:1-14.

- Guo R, Gavino AC. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:683-686.

- Olsen TG, Helwig EB. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. a clinicopathologic study of 116 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:781-796.

- Lallas A, Sidiropoulos T, Lefaki I, et al. Photo letter to the editor: dermoscopy of granuloma faciale. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:59-60.

- Oliveira CC, Ianhez PE, Marques SA, et al. Granuloma faciale: clinical, morphological and immunohistochemical aspects in a series of 10 patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:803-807.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Lindhaus C, Elsner P. Granuloma faciale treatment: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:14-18.

- Haidari W, Strowd LC. Clinical characterization of leukemia cutis presentation. Cutis. 2019;104:326-330; E3.

- Rao AG, Danturty I. Leukemia cutis. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:504.

- Desch JK, Smoller BR. The spectrum of cutaneous disease in leukemias. J Cutan Pathol. 1993;20:407-410.

- Yamashita T, Abbade LP, Marques ME, et al. Mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical review and update. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:817-828; quiz 829-830.

- Smoller BR, Bishop K, Glusac E, et al. Reassessment of histologic parameters in the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1423-1430.

- Zhou LL, Mistry N. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia (pseudolymphoma). CMAJ. 2018;190:E398.

- Lackey JN, Xia Y, Cho S, et al. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia: a case report and brief review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;79:445-448.

- Albrecht J, Fine LA, Piette W. Drug-associated lymphoma and pseudolymphoma: recognition and management. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:233-244, vii.

- Arai E, Shimizu M, Hirose T. A review of 55 cases of cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia: reassessment of the histopathologic findings leading to reclassification of 4 lesions as cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma and 19 as pseudolymphomatous folliculitis. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:505-511.

- Bergman R, Khamaysi Z, Sahar D, et al. Cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia presenting as a solitary facial nodule: clinical, histopathological, immunophenotypical, and molecular studies. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1561-1566.

- Wells GC, Whimster IW. Subcutaneous angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:1-14.

- Guo R, Gavino AC. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2015;139:683-686.

- Olsen TG, Helwig EB. Angiolymphoid hyperplasia with eosinophilia. a clinicopathologic study of 116 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;12:781-796.

- Lallas A, Sidiropoulos T, Lefaki I, et al. Photo letter to the editor: dermoscopy of granuloma faciale. J Dermatol Case Rep. 2012;6:59-60.

- Oliveira CC, Ianhez PE, Marques SA, et al. Granuloma faciale: clinical, morphological and immunohistochemical aspects in a series of 10 patients. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91:803-807.

- Marcoval J, Moreno A, Peyr J. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:269-273.

- Lindhaus C, Elsner P. Granuloma faciale treatment: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:14-18.

- Haidari W, Strowd LC. Clinical characterization of leukemia cutis presentation. Cutis. 2019;104:326-330; E3.

- Rao AG, Danturty I. Leukemia cutis. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:504.

- Desch JK, Smoller BR. The spectrum of cutaneous disease in leukemias. J Cutan Pathol. 1993;20:407-410.

- Yamashita T, Abbade LP, Marques ME, et al. Mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical review and update. An Bras Dermatol. 2012;87:817-828; quiz 829-830.

- Smoller BR, Bishop K, Glusac E, et al. Reassessment of histologic parameters in the diagnosis of mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1423-1430.

A 35-year-old woman presented with a slowly growing, smooth, erythematous papule of 2 months’ duration on the left nasal ala surrounding a piercing (top, inset) that had been performed 4 years prior. A tangential biopsy was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.

Firm Exophytic Tumor on the Shin

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

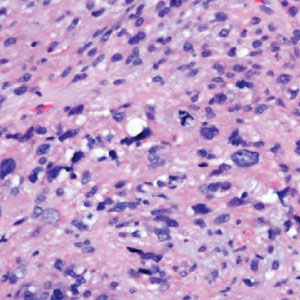

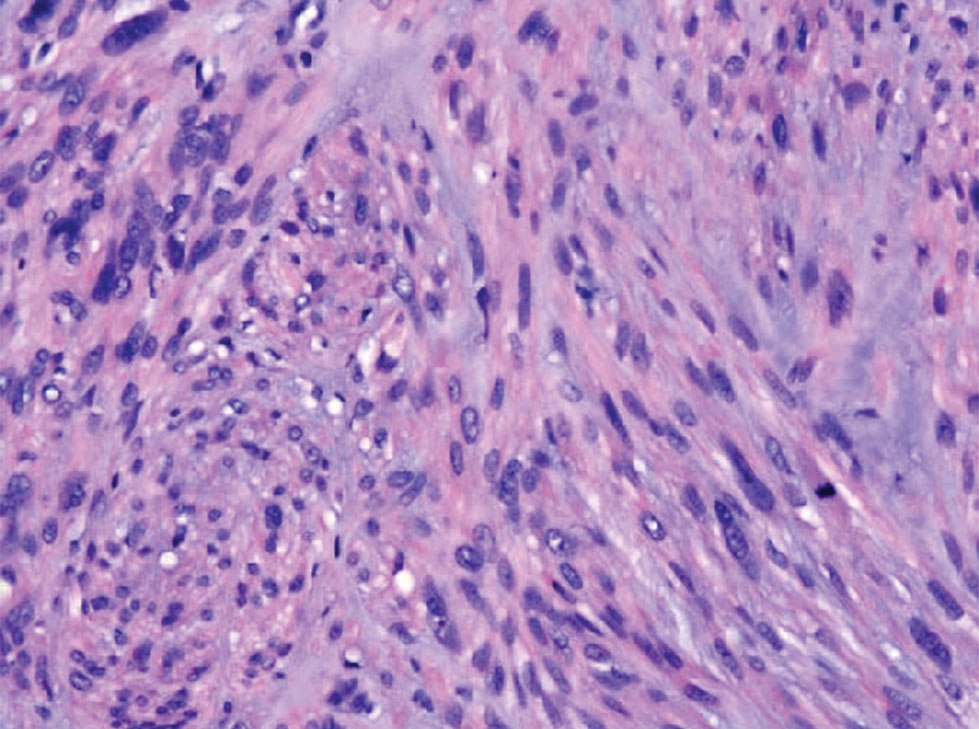

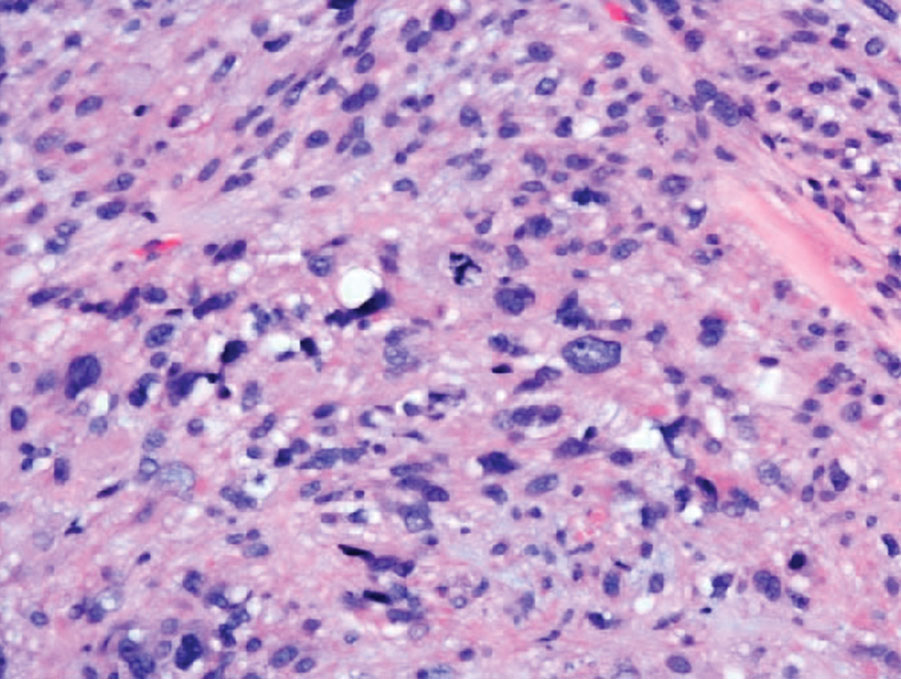

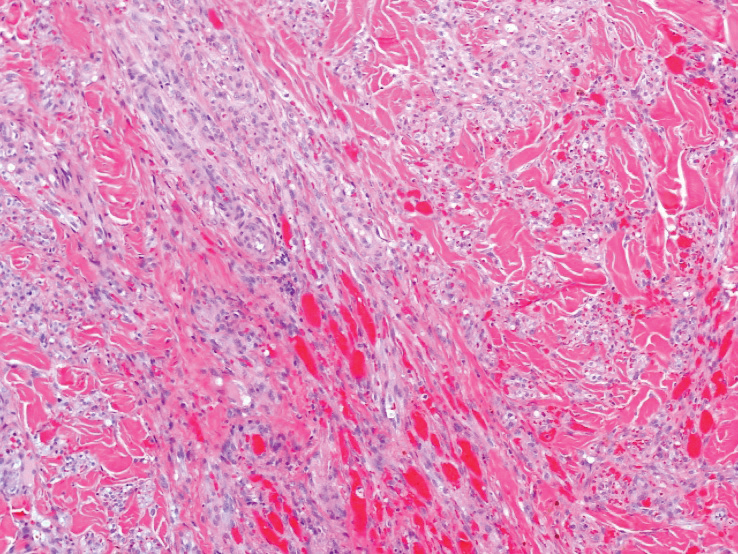

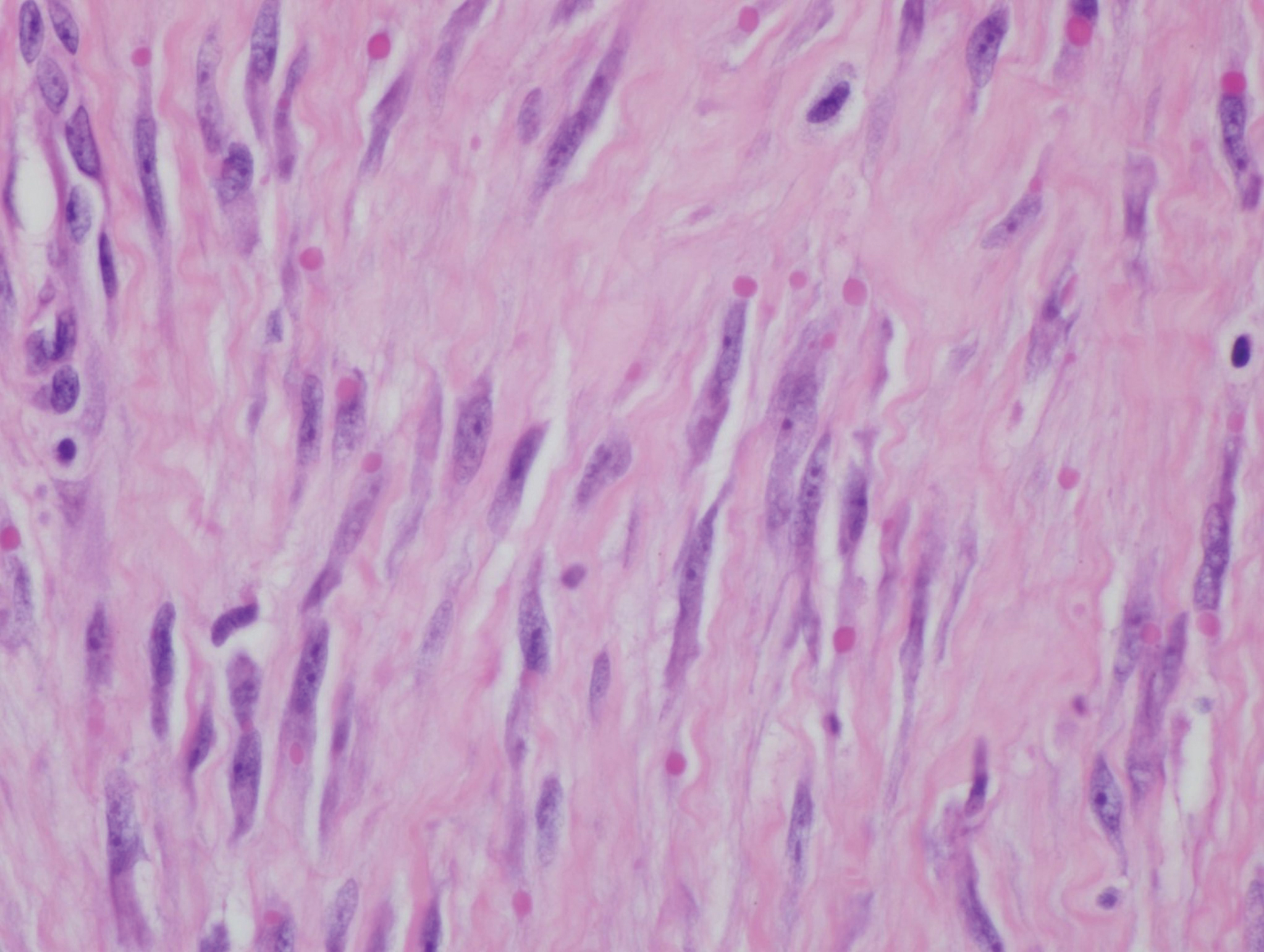

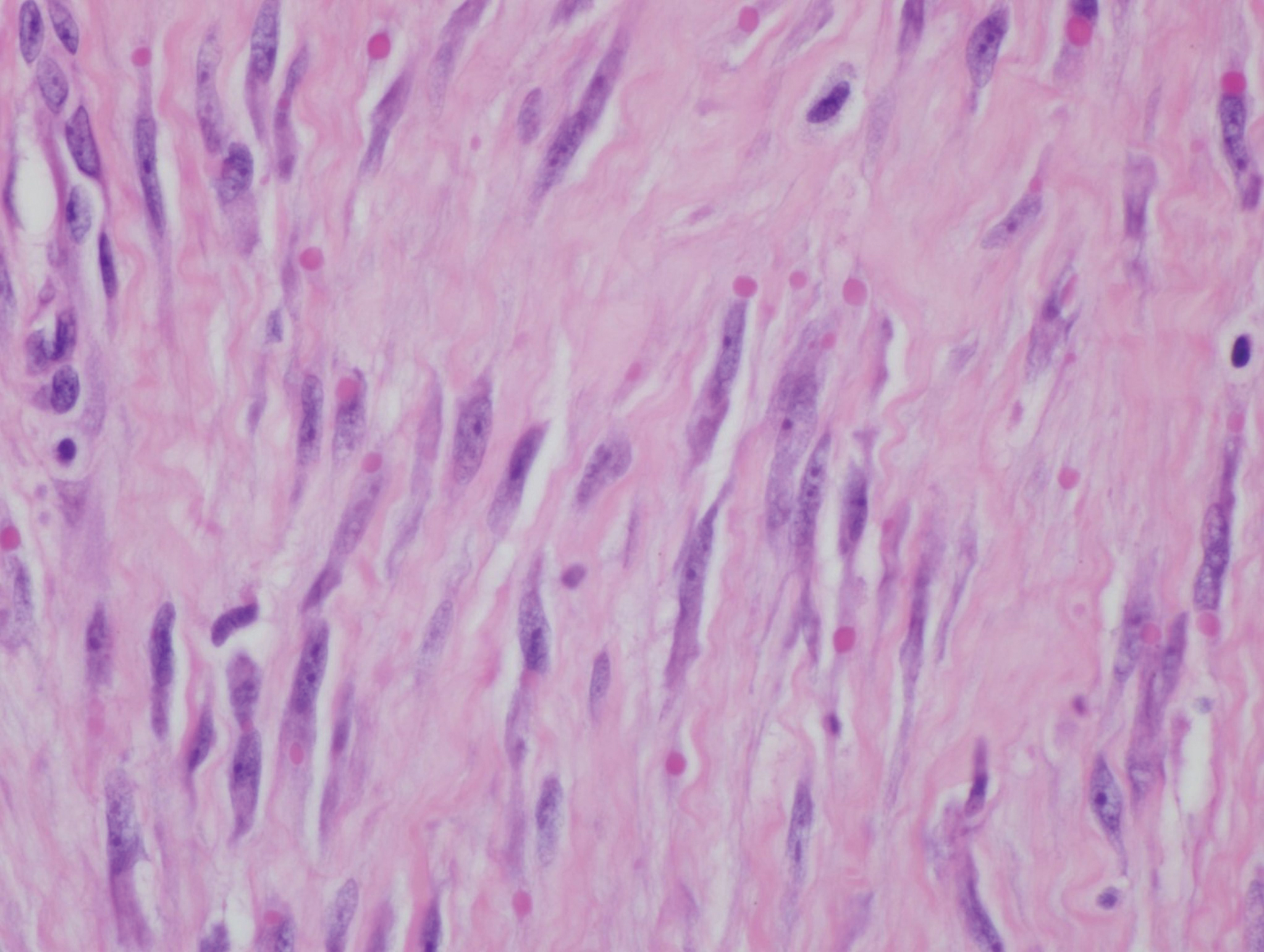

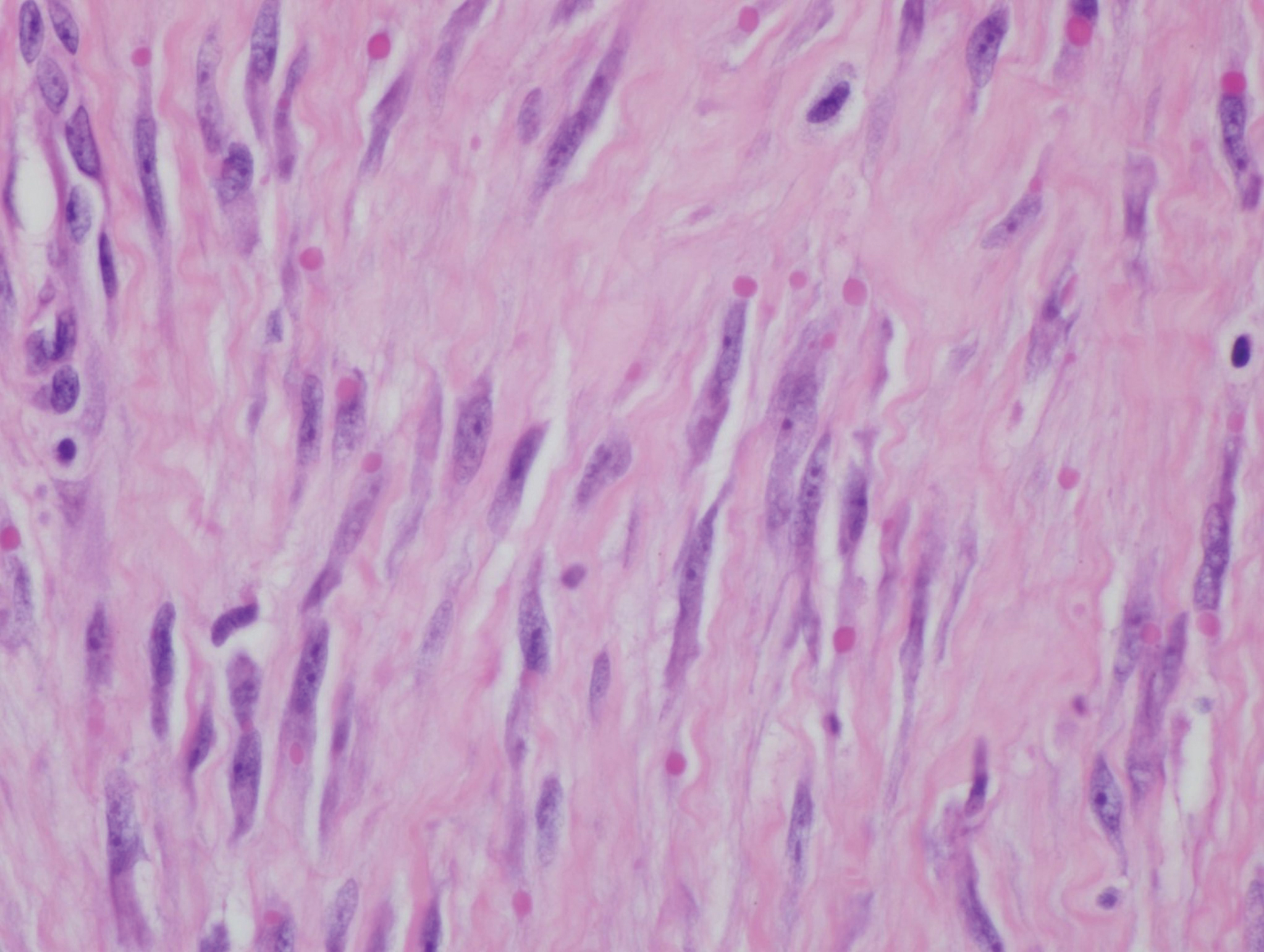

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

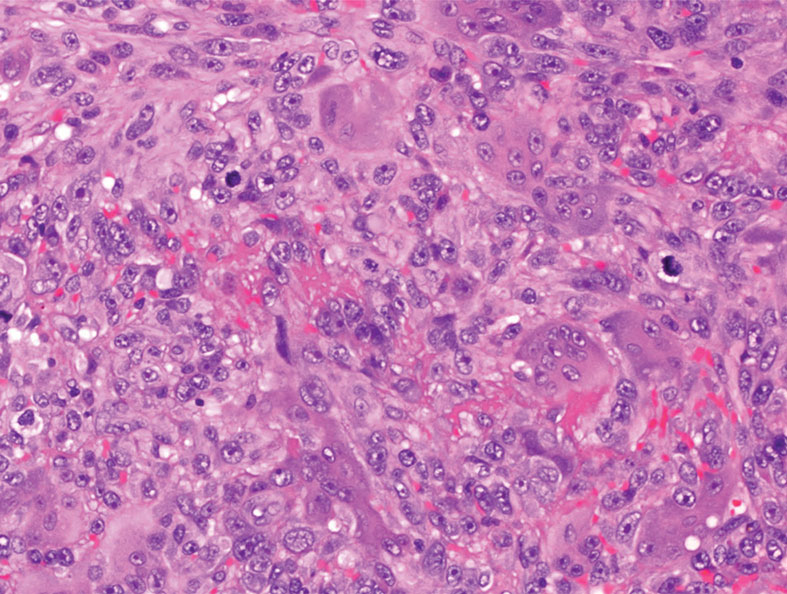

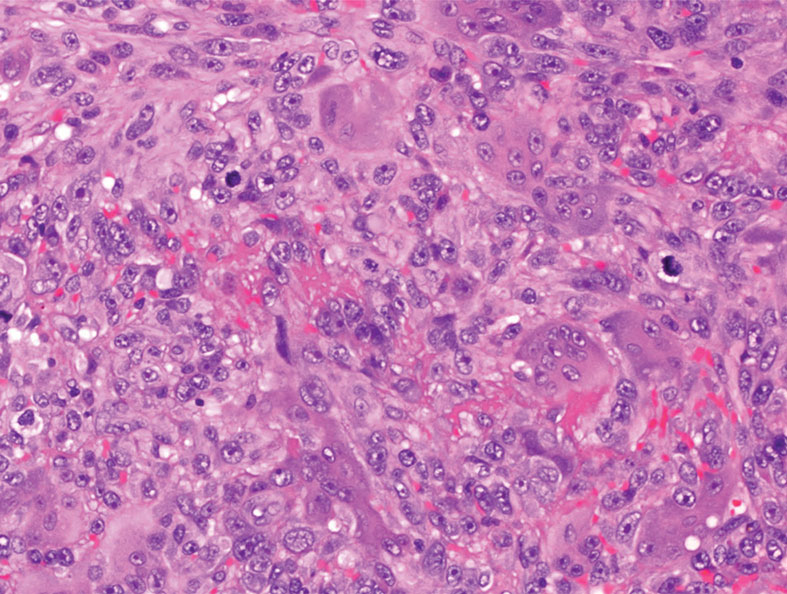

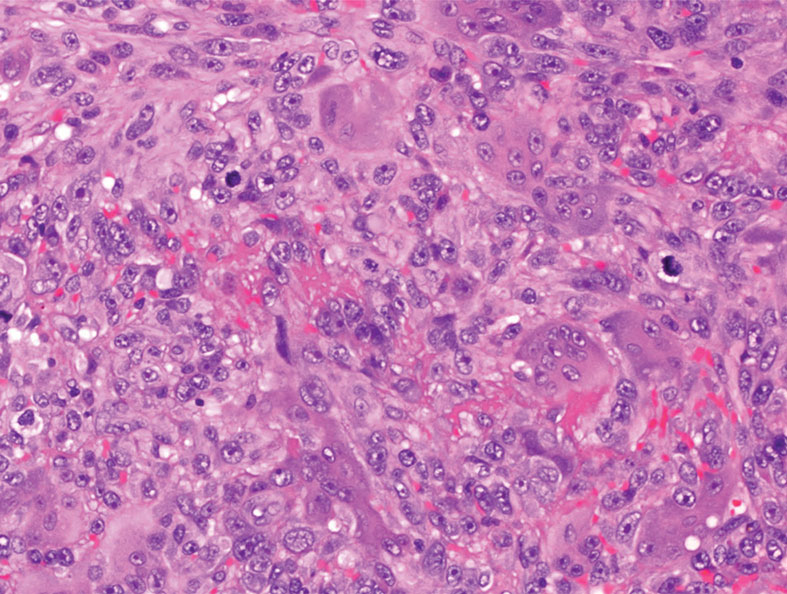

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

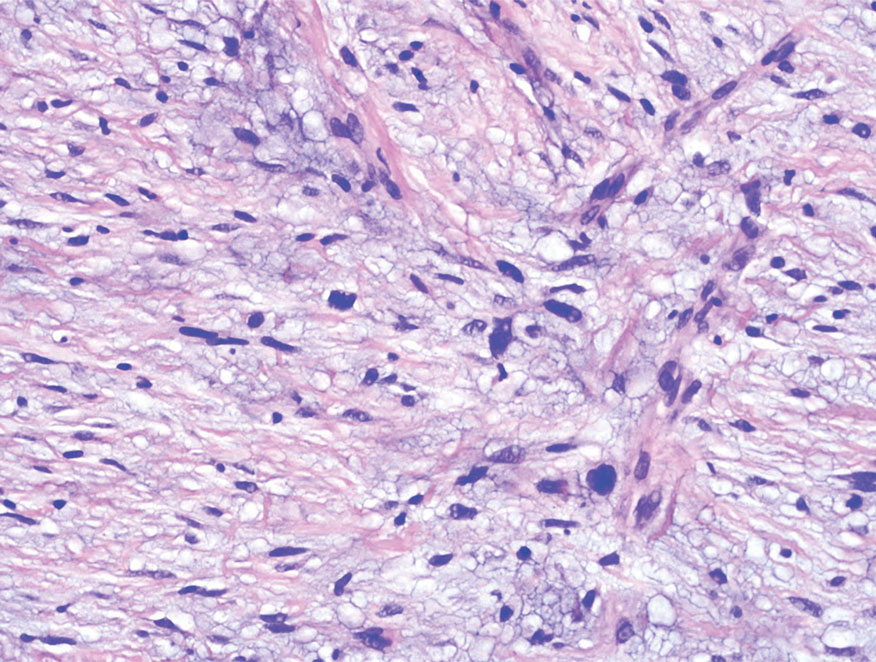

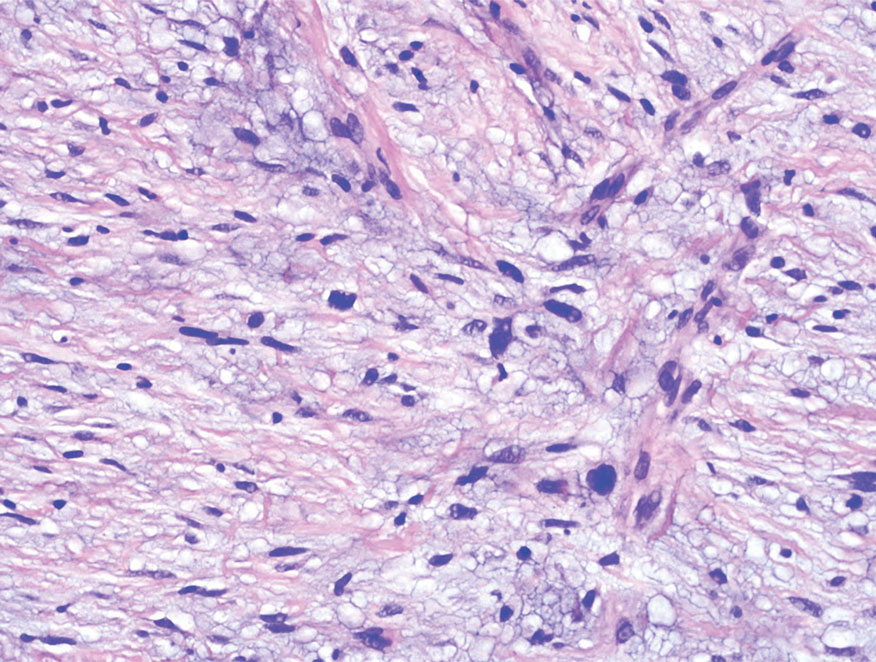

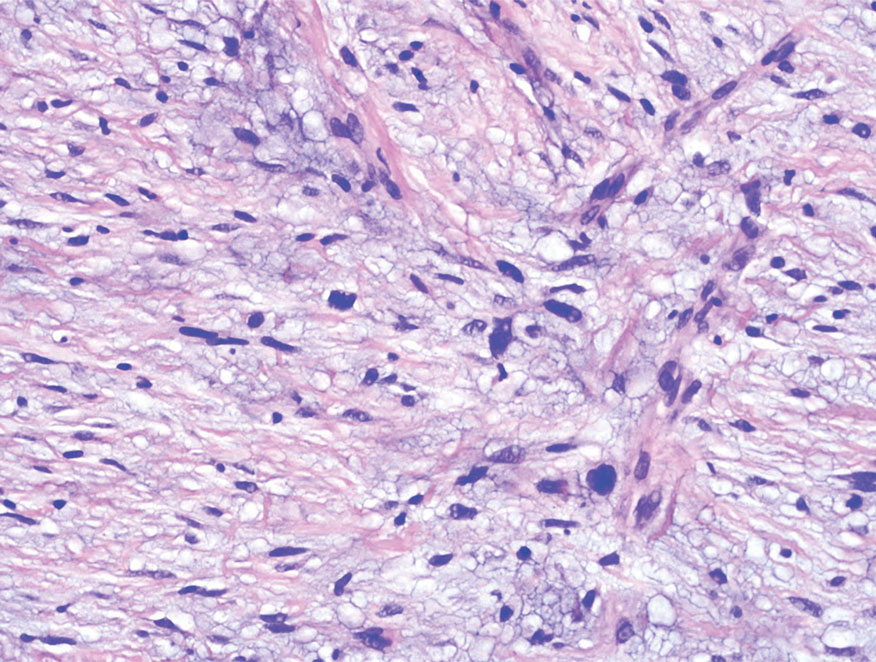

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

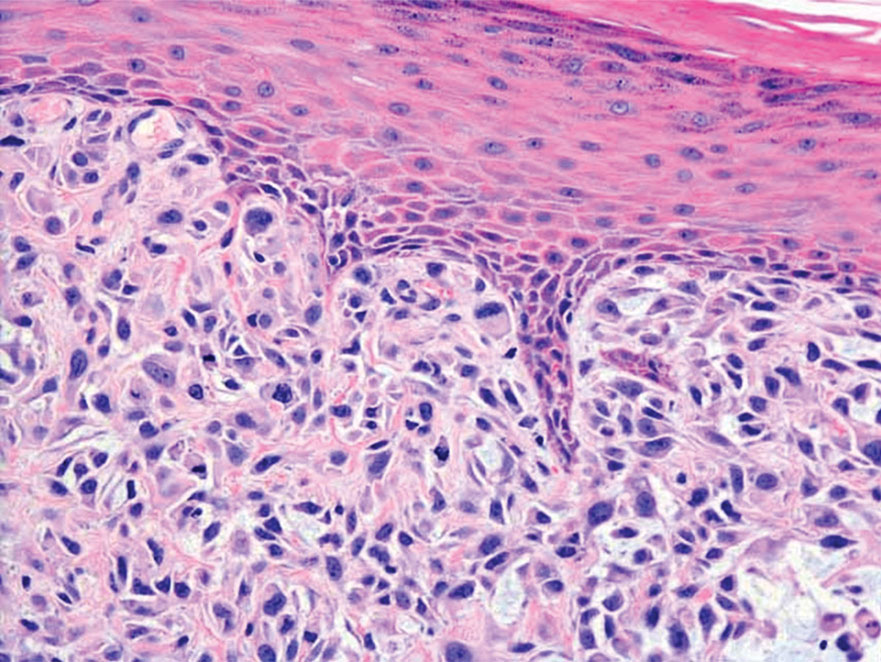

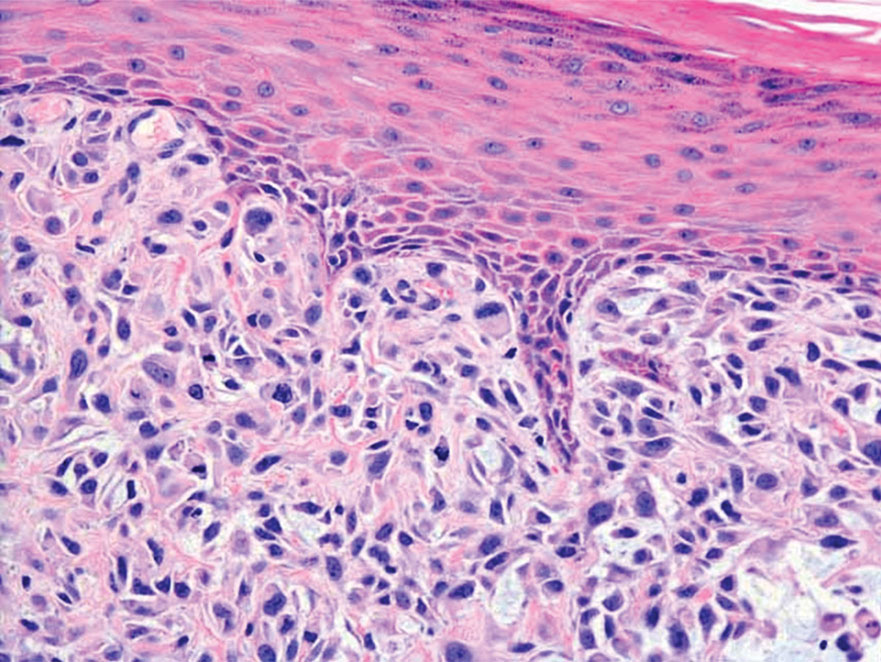

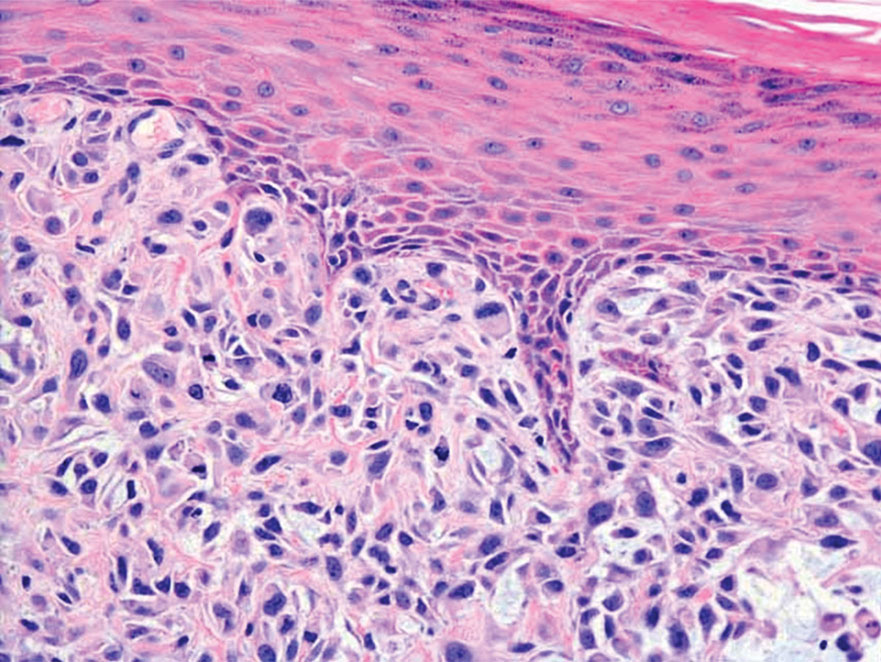

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

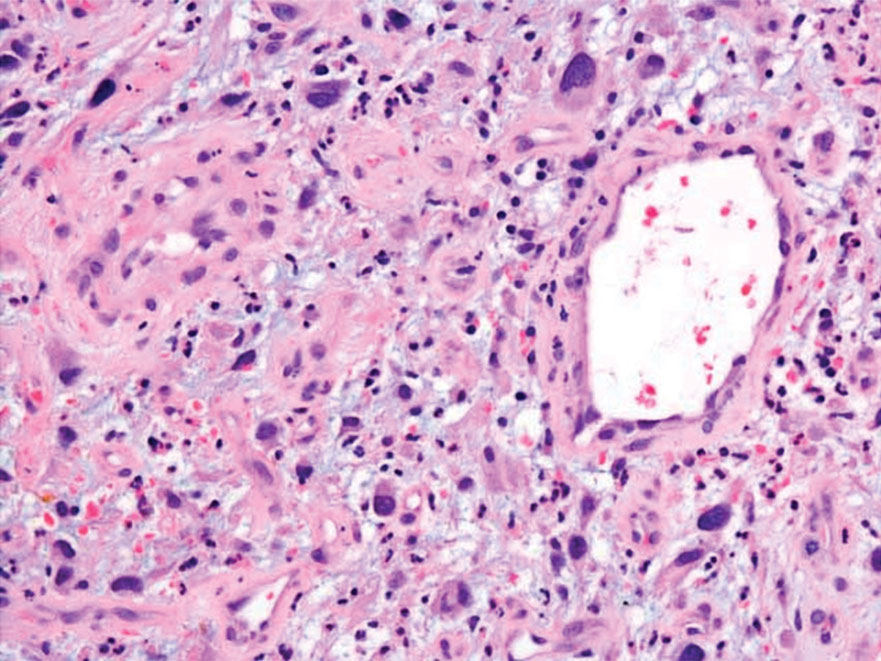

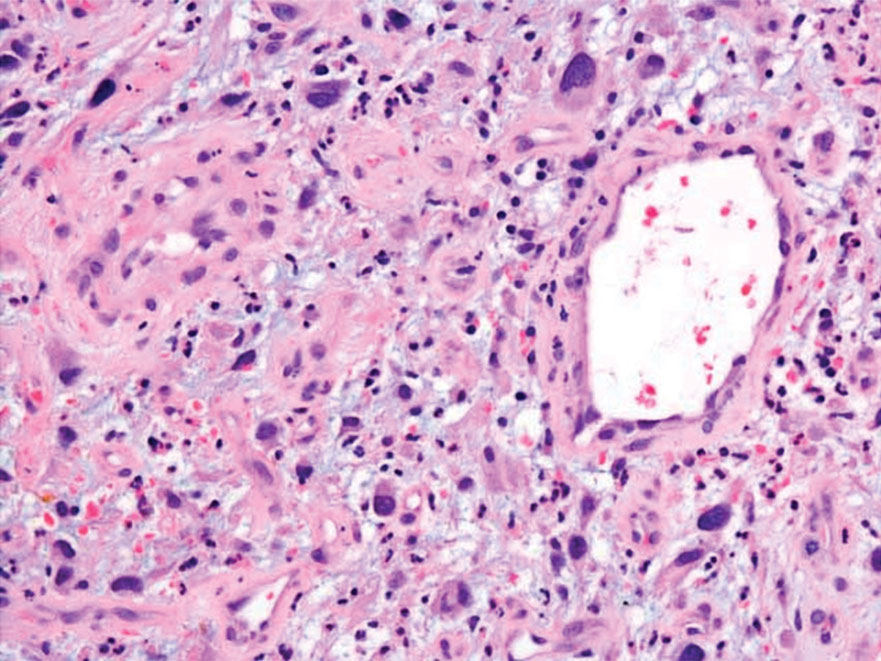

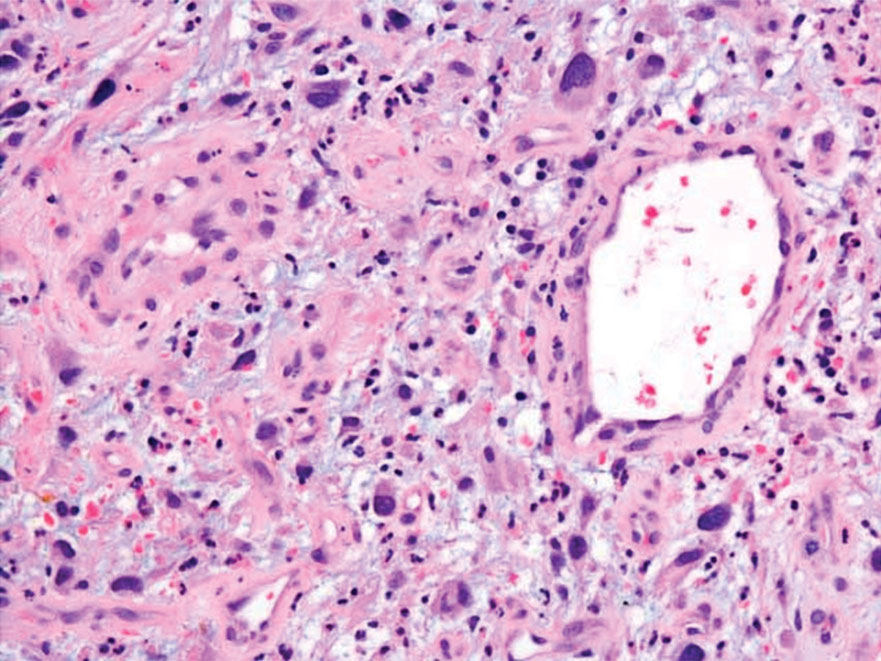

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

The Diagnosis: Leiomyosarcoma

Cutaneous leiomyosarcomas are relatively rare neoplasms that favor the head, neck, and extremities of older adults.1 Dermal leiomyosarcomas originate from arrector pili and are locally aggressive, whereas subcutaneous leiomyosarcomas arise from vascular smooth muscle and metastasize in 30% to 60% of cases.2 Clinically, leiomyosarcomas present as solitary, firm, well-circumscribed nodules with possible ulceration and crusting.3 Histopathology of leiomyosarcoma shows fascicles of atypical spindle cells with blunt-ended nuclei and perinuclear glycogen vacuoles, variable atypia, and mitotic figures (quiz images). Definitive diagnosis is based on positive immunohistochemical staining for desmin and smooth muscle actin.4 Treatment entails complete removal via wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.5

Atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX) is a malignant fibrohistiocytic neoplasm that arises in the dermis and preferentially affects the head and neck in older individuals.3 Atypical fibroxanthoma presents as a nonspecific, pinkred, sometimes ulcerated papule on sun-damaged skin that may clinically resemble a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) or basal cell carcinoma.6 Histopathology shows pleomorphic spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei and abundant cytoplasm mixed with multinucleated giant cells and scattered mitotic figures (Figure 1). Immunohistochemistry is essential for distinguishing AFX from other spindle cell neoplasms. Atypical fibroxanthoma stains positively for vimentin, procollagen-1, CD10, and CD68 but is negative for S-100, human melanoma black 45, Melan-A, desmin, cytokeratin, p40, and p63.6 Treatment includes wide local excision or Mohs micrographic surgery.

Melanoma is an aggressive cancer with the propensity to metastasize. Both desmoplastic and spindle cell variants demonstrate atypical spindled melanocytes on histology, and desmoplasia is seen in the desmoplastic variant (Figure 2). In some cases, evaluation of the epidermis for melanoma in situ may aid in diagnosis.7 Clinical and prognostic features differ between the 2 variants. Desmoplastic melanomas usually present on the head and neck as scarlike nodules with a low rate of nodal involvement, while spindle cell melanomas can occur anywhere on the body, often are amelanotic, and are associated with widespread metastatic disease at the time of presentation.8 SOX10 (SRY-box transcription factor 10) and S-100 may be the only markers that are positive in desmoplastic melanoma.9,10 Treatment depends on the thickness of the lesion.11

Spindle cell SCC is a histologic variant of SCC characterized by spindled epithelial cells. Spindle cell SCC typically presents as an ulcerated or exophytic mass in sun-exposed areas or areas exposed to ionizing radiation, or in immunocompromised individuals. Histopathology shows spindled pleomorphic keratinocytes with elongated nuclei infiltrating the dermis and minimal keratinization (Figure 3).12 Immunohistochemistry is necessary to distinguish spindle cell SCC from other spindle cell tumors such as spindle cell melanoma, AFX, and leiomyosarcoma. Spindle cell SCC is positive for high-molecular-weight cytokeratin, p40, and p63. Mohs micrographic surgery provides the highest cure rate, and radiation therapy may be considered when clear surgical margins cannot be obtained.6

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) (formerly known as malignant fibrous histiocytoma) describes tumors that resemble AFX but are more invasive. They commonly involve the soft tissue with a higher risk for both recurrence and metastasis than AFX.13 Histopathology shows marked cytologic pleomorphism, bizarre cellular forms, atypical mitoses, and ulceration (Figure 4).14 Diagnosis of UPS is by exclusion and is dependent on immunohistochemical studies. In contrast to AFX, UPS is more likely to be positive for LN-2 (CD74).6 Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma has been treated with surgical excision in combination with chemical and radiation therapy, but due to limited data, optimal management is less clear compared to AFX.15 There is a substantial risk for local recurrence and metastasis, and the lungs are the most common sites of distant metastasis.13 In a study of 23 individuals with high-grade UPS, 5-year metastasis-free survival and local recurrence-free survival were 26% and 16%, respectively.10

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

- Massi D, Franchi A, Alos L, et al. Primary cutaneous leiomyosarcoma: clinicopathological analysis of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2010;56: 251-262. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03471.x

- Ciurea ME, Georgescu CV, Radu CC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma—case report [published online June 25, 2014]. J Med Life. 2014;7:270-273.

- Fleury LFF, Sanches JA. Primary cutaneous sarcomas. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:207-221. doi:10.1590/s0365-05962006000300002

- Murback NDN, de Castro BC, Takita LC, et al. Cutaneous leiomyosarcoma on the face. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:262-264. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186715

- Winchester DS, Hocker TL, Brewer JD, et al. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin: clinical, histopathologic, and prognostic factors that influence outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:919-925. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2014.07.020

- Hollmig ST, Sachdev R, Cockerell CJ, et al. Spindle cell neoplasms encountered in dermatologic surgery: a review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:825-850. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02296.x

- De Almeida LS, Requena L, Rütten A, et al. Desmoplastic malignant melanoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 113 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:207-215. doi:10.1097/DAD.0B013E3181716E6B

- Weissinger SE, Keil P, Silvers DN, et al. A diagnostic algorithm to distinguish desmoplastic from spindle cell melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:524-534. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2013.162

- Ohsie SJ, Sarantopoulos GP, Cochran AJ, et al. Immunohistochemical characteristics of melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35:433-444. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00891.x

- Delisca GO, Mesko NW, Alamanda VK, et al. MFH and highgrade undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma—what’s in a name? [published online September 12, 2014]. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111:173-177. doi:10.1002/jso.23787

- Baron PL, Nguyen CL. Malignant of melanoma. In: Holzheimer RG, Mannick JA, eds. Surgical Treatment: Evidence-Based and Problem- Oriented. Zuckschwerdt; 2001. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books /NBK6877

- Wernheden E, Trøstrup H, Pedersen Pilt A. Unusual presentation of cutaneous spindle cell squamous cell carcinoma: a case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2020;12:70-75. doi:10.1159/000507358

- Ramsey JK, Chen JL, Schoenfield L, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma metastatic to the orbit. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;34:E193-E195. doi:10.1097/IOP.0000000000001240

- Winchester D, Lehman J, Tello T, et al. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: factors predictive of adverse outcomes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:853-859. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.05.022

- Soleymani T, Tyler Hollmig S. Conception and management of a poorly understood spectrum of dermatologic neoplasms: atypical fibroxanthoma, pleomorphic dermal sarcoma, and undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18:50. doi:10.1007 /s11864-017-0489-6

A 62-year-old man presented with a firm, exophytic, 2.8×1.5-cm tumor on the left shin of 6 to 7 years’ duration. An excisional biopsy was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.

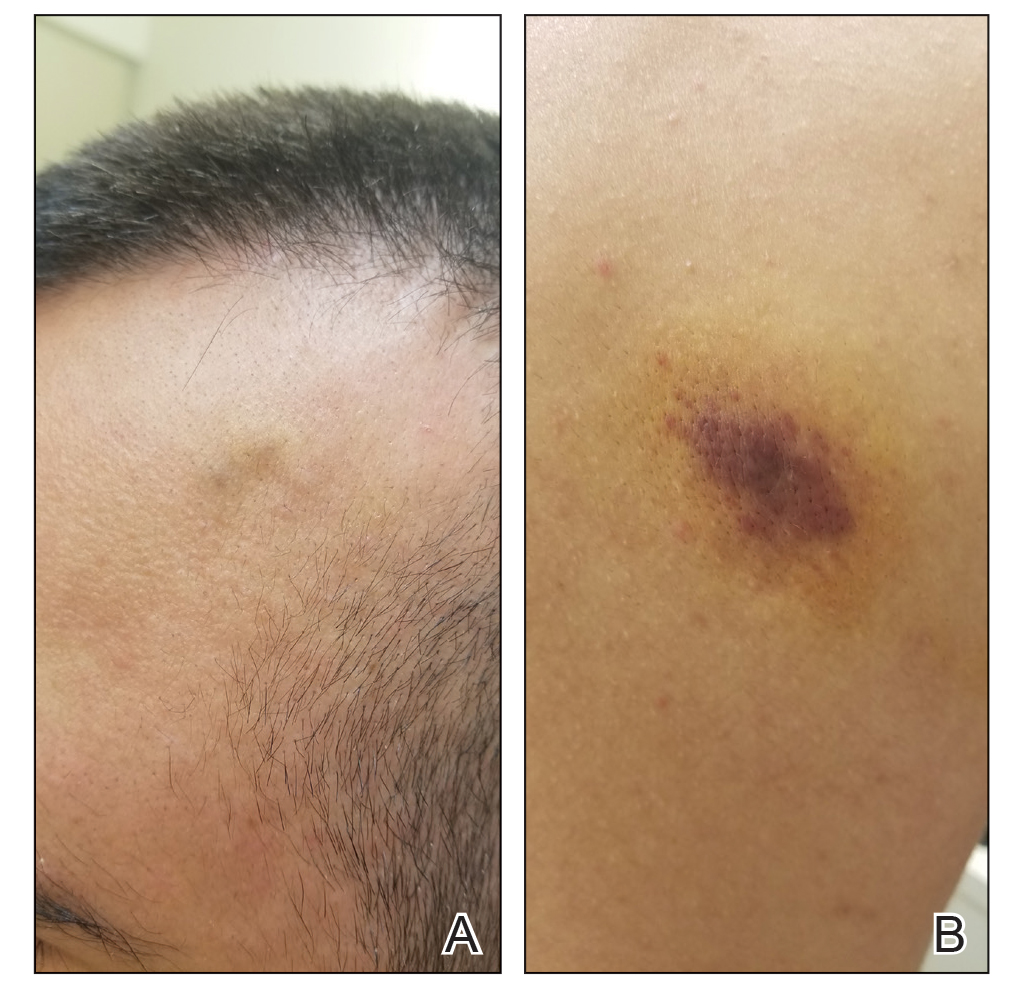

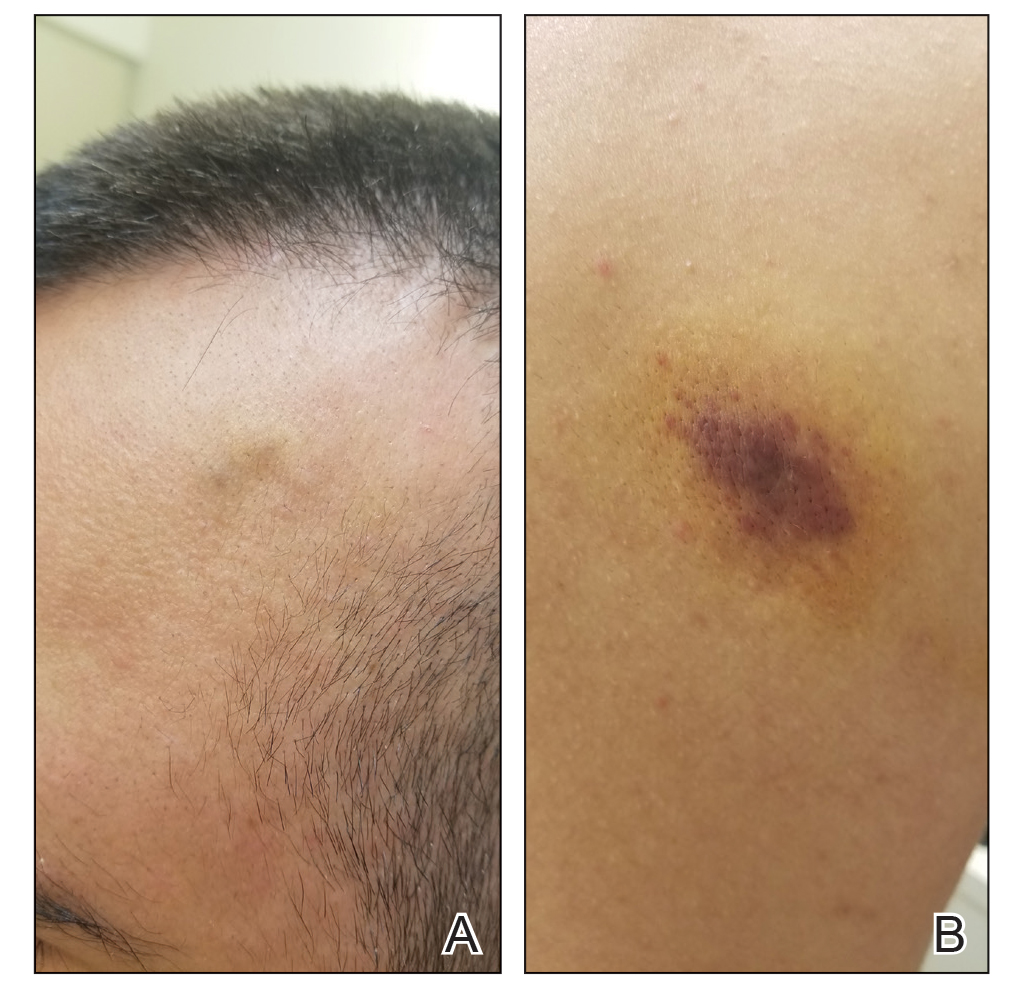

Indurated Violaceous Lesions on the Face, Trunk, and Legs

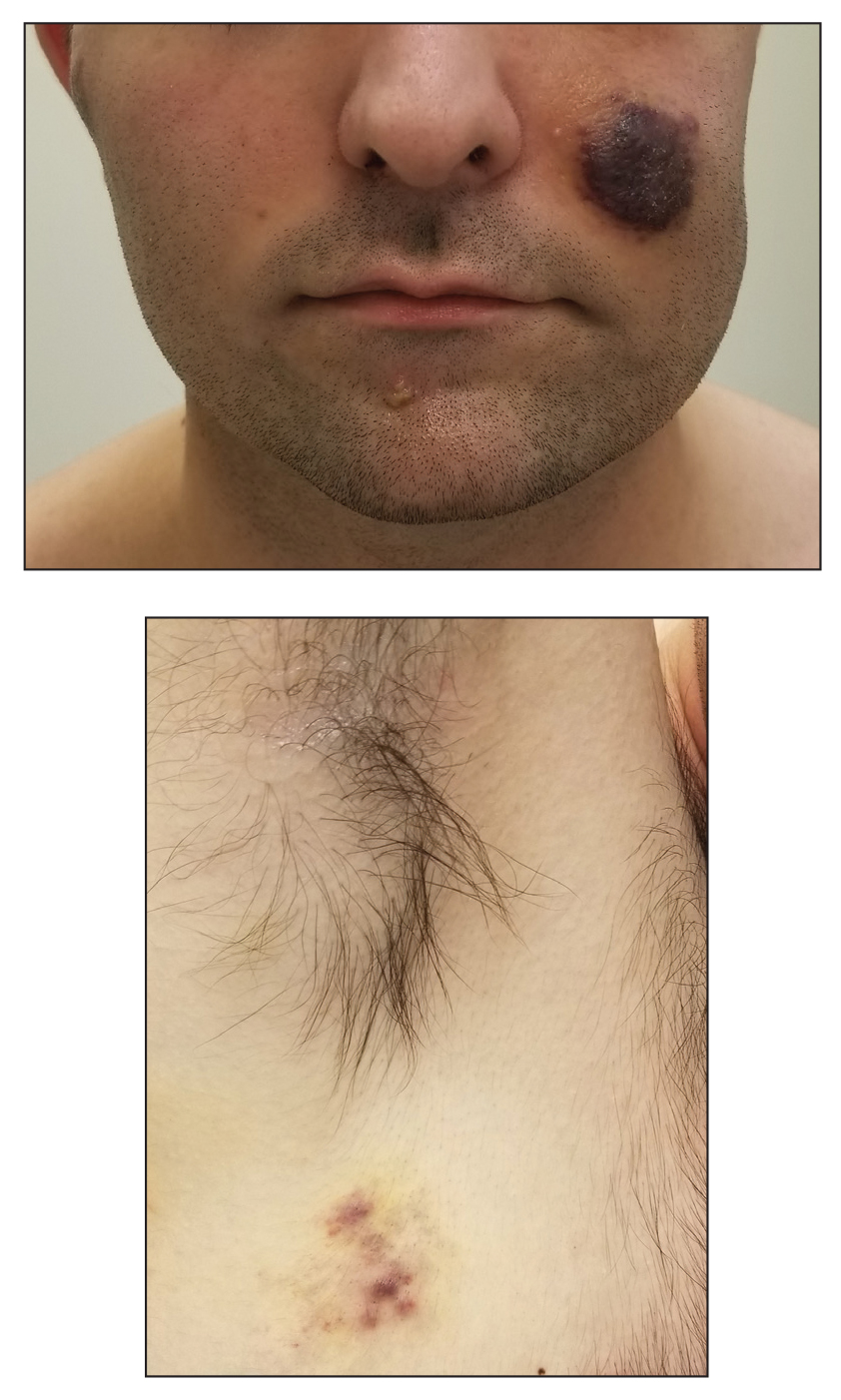

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

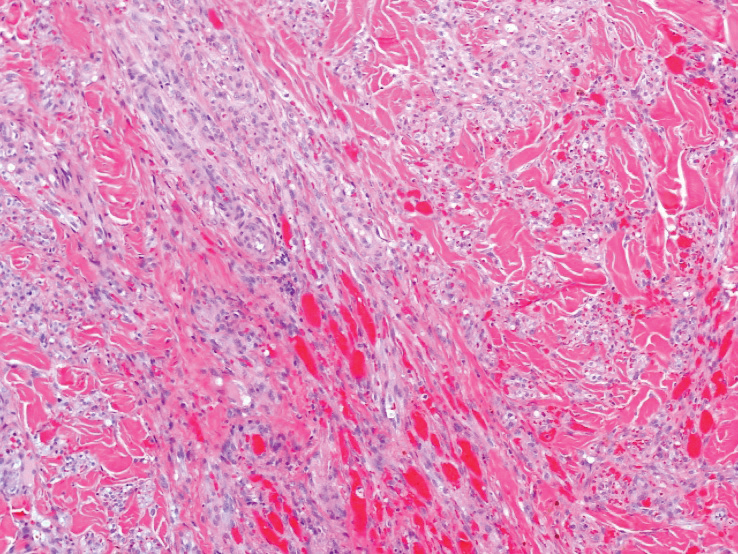

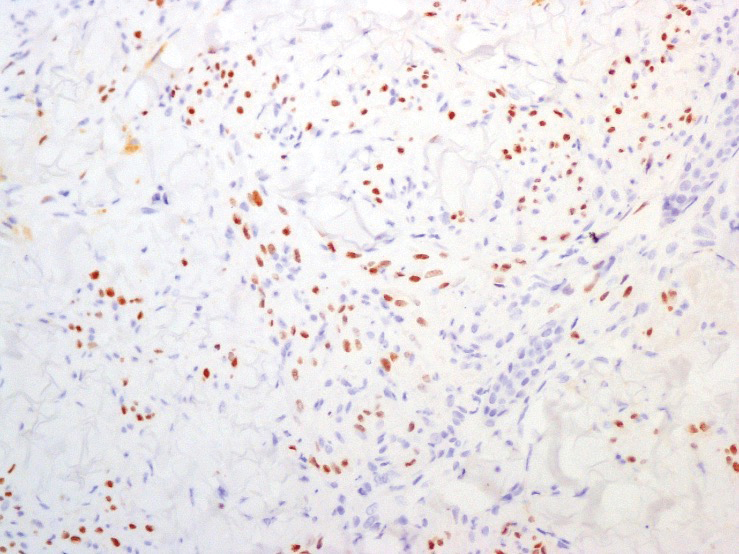

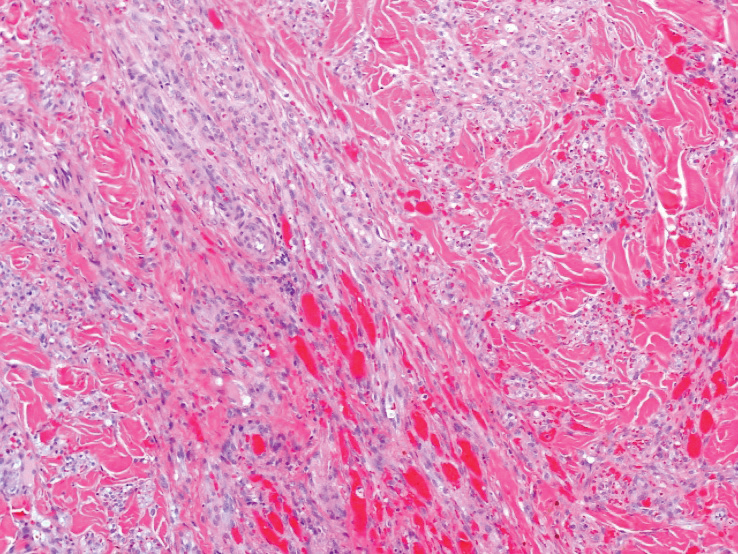

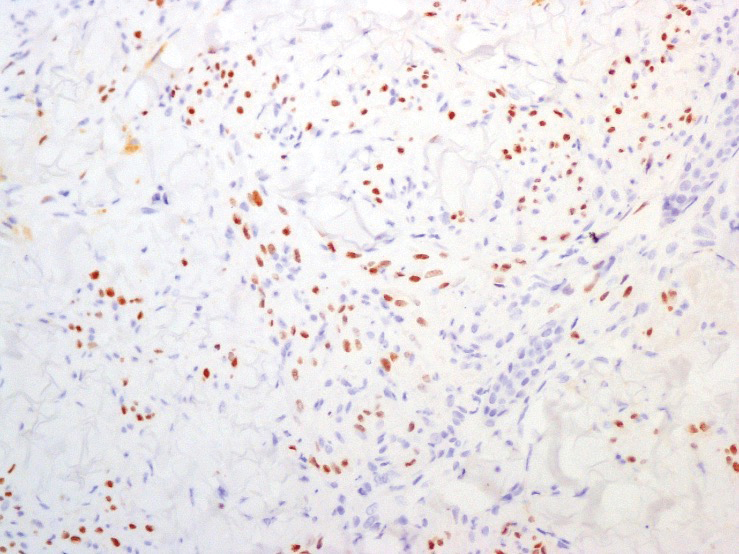

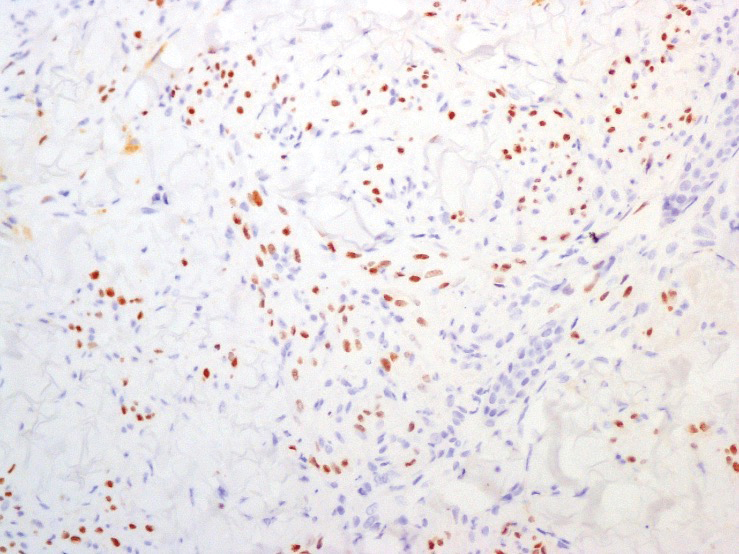

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative, AIDSdefining disease associated with HHV-8. There are 4 types of KS as defined by the populations they affect. AIDS-associated KS occurs in individuals with HIV, as seen in our patient. It often is accompanied by extensive mucocutaneous and visceral lesions, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and diarrhea.1 Classic KS is a variant that presents in older men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and South American descent. Cutaneous lesions typically are distributed on the lower extremities.2,3 Endemic (African) KS is seen in HIV-negative children and young adults in equatorial Africa. It most commonly affects the lower extremities or lymph nodes and usually follows a more aggressive course.2 Lastly, iatrogenic KS is associated with immunosuppressive medications or conditions, such as organ transplantation, chemotherapy, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4

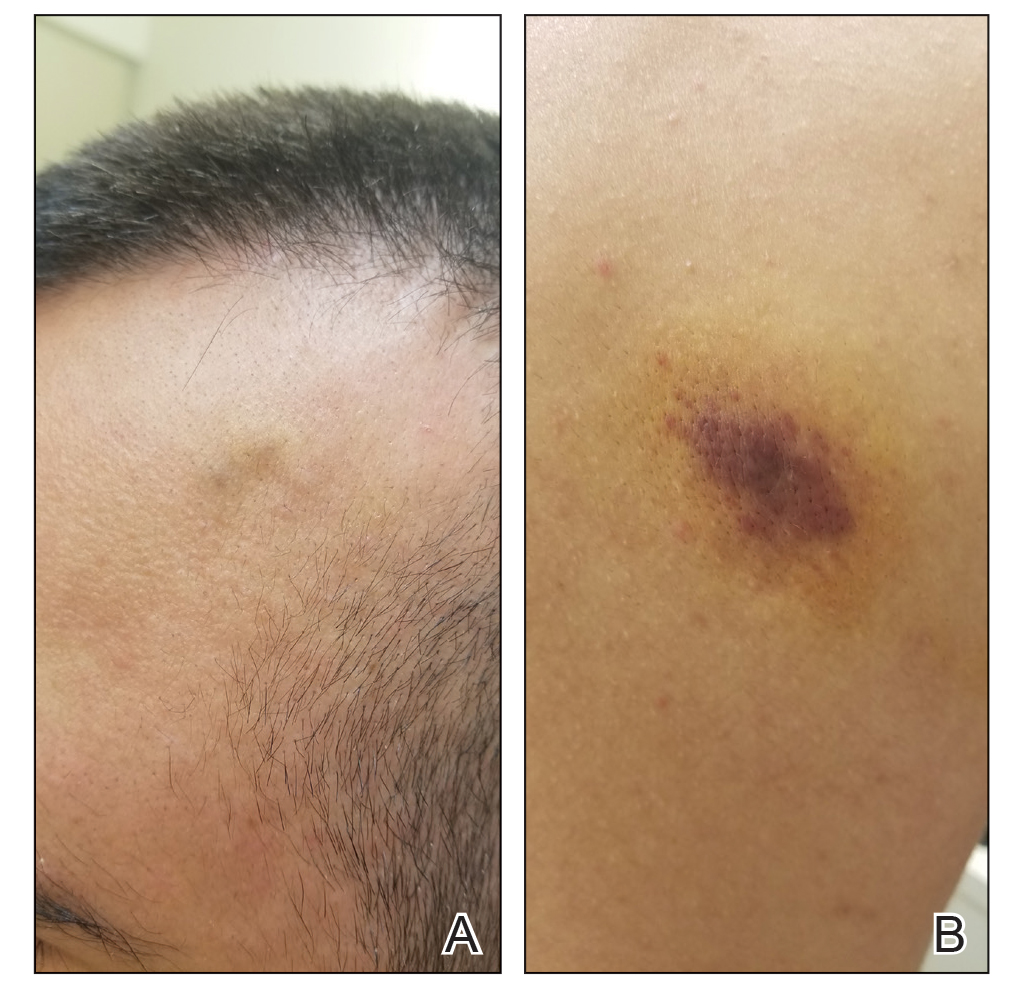

Kaposi sarcoma commonly presents as violaceous or dark red macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules on various parts of the body (Figure 3). Lesions typically begin as macules and progress into plaques or nodules. Our patient presented as a deceptively healthy young man with lesions at various stages of development. In addition to the skin and oral mucosa, the lungs, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract commonly are involved in AIDS-associated KS.5 Patients may experience symptoms of internal involvement, including bleeding, hematochezia, odynophagia, or dyspnea.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that can mimic KS, including bacillary angiomatosis, angioinvasive fungal disease, sarcoid, and other malignancies. A skin biopsy is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of KS. Histopathology shows a vascular proliferation in the dermis and spindle cell proliferation.6 Kaposi sarcoma stains positively for factor VIII–related antigen, CD31, and CD34.2 Additionally, staining for HHV-8 gene products, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen 1, is helpful in differentiating KS from other conditions.7

In HIV-associated KS, the mainstay of treatment is initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Typically, as the CD4 count rises with treatment, the tumor burden classic KS, effective treatment options include recurrent cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutics, such as vincristine, for localized lesions; for widespread disease, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or radiation have been found to be effective options. Lastly, for patients with iatrogenic KS, reducing immunosuppressive medications is a reasonable first step in management. If this does not yield adequate improvement, transitioning from calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine) to proliferation signal inhibitors (eg, sirolimus) may lead to resolution.7

- Friedman-Kien AE, Saltzman BR. Clinical manifestations of classical, endemic African, and epidemic AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1237-1250.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542.

- Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy. a 5‐year material of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Norway. Cancer. 1978;42:2626-2630.

- Lemlich G, Schwam L, Lebwohl M. Kaposi’s sarcoma and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: postmortem findings in twenty-four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:319-325.

- Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:10.

- Curtiss P, Strazzulla LC, Friedman-Kien AE. An update on Kaposi’s sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:465-470.

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative, AIDSdefining disease associated with HHV-8. There are 4 types of KS as defined by the populations they affect. AIDS-associated KS occurs in individuals with HIV, as seen in our patient. It often is accompanied by extensive mucocutaneous and visceral lesions, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and diarrhea.1 Classic KS is a variant that presents in older men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and South American descent. Cutaneous lesions typically are distributed on the lower extremities.2,3 Endemic (African) KS is seen in HIV-negative children and young adults in equatorial Africa. It most commonly affects the lower extremities or lymph nodes and usually follows a more aggressive course.2 Lastly, iatrogenic KS is associated with immunosuppressive medications or conditions, such as organ transplantation, chemotherapy, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4

Kaposi sarcoma commonly presents as violaceous or dark red macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules on various parts of the body (Figure 3). Lesions typically begin as macules and progress into plaques or nodules. Our patient presented as a deceptively healthy young man with lesions at various stages of development. In addition to the skin and oral mucosa, the lungs, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract commonly are involved in AIDS-associated KS.5 Patients may experience symptoms of internal involvement, including bleeding, hematochezia, odynophagia, or dyspnea.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that can mimic KS, including bacillary angiomatosis, angioinvasive fungal disease, sarcoid, and other malignancies. A skin biopsy is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of KS. Histopathology shows a vascular proliferation in the dermis and spindle cell proliferation.6 Kaposi sarcoma stains positively for factor VIII–related antigen, CD31, and CD34.2 Additionally, staining for HHV-8 gene products, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen 1, is helpful in differentiating KS from other conditions.7

In HIV-associated KS, the mainstay of treatment is initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Typically, as the CD4 count rises with treatment, the tumor burden classic KS, effective treatment options include recurrent cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutics, such as vincristine, for localized lesions; for widespread disease, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or radiation have been found to be effective options. Lastly, for patients with iatrogenic KS, reducing immunosuppressive medications is a reasonable first step in management. If this does not yield adequate improvement, transitioning from calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine) to proliferation signal inhibitors (eg, sirolimus) may lead to resolution.7

The Diagnosis: Kaposi Sarcoma

A punch biopsy of a lesion on the right side of the back revealed a diffuse, poorly circumscribed, spindle cell neoplasm of the papillary and reticular dermis with associated vascular and pseudovascular spaces distended by erythrocytes (Figure 1). Immunostaining was positive for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8)(Figure 2), ETS-related gene, CD31, and CD34 and negative for pan cytokeratin, confirming the diagnosis of Kaposi sarcoma (KS). Bacterial, fungal, and mycobacterial tissue cultures were negative. The patient was tested for HIV and referred to infectious disease and oncology. He subsequently was found to have HIV with a viral load greater than 1 million copies. He was started on antiretroviral therapy and Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia prophylaxis. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed bilateral, multifocal, perihilar, flame-shaped consolidations suggestive of KS. The patient later disclosed having an intermittent dry cough of more than a year’s duration with occasional bright red blood per rectum after bowel movements. After workup, the patient was found to have cytomegalovirus esophagitis/gastritis and candidal esophagitis that were treated with valganciclovir and fluconazole, respectively.

Kaposi sarcoma is an angioproliferative, AIDSdefining disease associated with HHV-8. There are 4 types of KS as defined by the populations they affect. AIDS-associated KS occurs in individuals with HIV, as seen in our patient. It often is accompanied by extensive mucocutaneous and visceral lesions, as well as systemic symptoms such as fever, weight loss, and diarrhea.1 Classic KS is a variant that presents in older men of Mediterranean, Eastern European, and South American descent. Cutaneous lesions typically are distributed on the lower extremities.2,3 Endemic (African) KS is seen in HIV-negative children and young adults in equatorial Africa. It most commonly affects the lower extremities or lymph nodes and usually follows a more aggressive course.2 Lastly, iatrogenic KS is associated with immunosuppressive medications or conditions, such as organ transplantation, chemotherapy, and rheumatologic disorders.3,4

Kaposi sarcoma commonly presents as violaceous or dark red macules, patches, papules, plaques, and nodules on various parts of the body (Figure 3). Lesions typically begin as macules and progress into plaques or nodules. Our patient presented as a deceptively healthy young man with lesions at various stages of development. In addition to the skin and oral mucosa, the lungs, lymph nodes, and gastrointestinal tract commonly are involved in AIDS-associated KS.5 Patients may experience symptoms of internal involvement, including bleeding, hematochezia, odynophagia, or dyspnea.

The differential diagnosis includes conditions that can mimic KS, including bacillary angiomatosis, angioinvasive fungal disease, sarcoid, and other malignancies. A skin biopsy is the gold standard for definitive diagnosis of KS. Histopathology shows a vascular proliferation in the dermis and spindle cell proliferation.6 Kaposi sarcoma stains positively for factor VIII–related antigen, CD31, and CD34.2 Additionally, staining for HHV-8 gene products, such as latency-associated nuclear antigen 1, is helpful in differentiating KS from other conditions.7

In HIV-associated KS, the mainstay of treatment is initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. Typically, as the CD4 count rises with treatment, the tumor burden classic KS, effective treatment options include recurrent cryotherapy or intralesional chemotherapeutics, such as vincristine, for localized lesions; for widespread disease, pegylated liposomal doxorubicin or radiation have been found to be effective options. Lastly, for patients with iatrogenic KS, reducing immunosuppressive medications is a reasonable first step in management. If this does not yield adequate improvement, transitioning from calcineurin inhibitors (eg, cyclosporine) to proliferation signal inhibitors (eg, sirolimus) may lead to resolution.7

- Friedman-Kien AE, Saltzman BR. Clinical manifestations of classical, endemic African, and epidemic AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1237-1250.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542.

- Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy. a 5‐year material of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Norway. Cancer. 1978;42:2626-2630.

- Lemlich G, Schwam L, Lebwohl M. Kaposi’s sarcoma and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: postmortem findings in twenty-four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:319-325.

- Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:10.

- Curtiss P, Strazzulla LC, Friedman-Kien AE. An update on Kaposi’s sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:465-470.

- Friedman-Kien AE, Saltzman BR. Clinical manifestations of classical, endemic African, and epidemic AIDS-associated Kaposi’s sarcoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:1237-1250.

- Radu O, Pantanowitz L. Kaposi sarcoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:289-294.

- Vangipuram R, Tyring SK. Epidemiology of Kaposi sarcoma: review and description of the nonepidemic variant. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:538-542.

- Klepp O, Dahl O, Stenwig JT. Association of Kaposi’s sarcoma and prior immunosuppressive therapy. a 5‐year material of Kaposi’s sarcoma in Norway. Cancer. 1978;42:2626-2630.

- Lemlich G, Schwam L, Lebwohl M. Kaposi’s sarcoma and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: postmortem findings in twenty-four cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;16:319-325.

- Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:10.

- Curtiss P, Strazzulla LC, Friedman-Kien AE. An update on Kaposi’s sarcoma: epidemiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2016;6:465-470.

A 25-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to the dermatology clinic with growing selfdescribed cysts on the face, trunk, and legs of 6 months’ duration. The lesions started as bruiselike discolorations and progressed to become firm nodules and inflamed masses. Some were minimally itchy and sensitive to touch, but there was no history of bleeding or drainage. The patient denied any new or recent environmental or animal exposures, use of illicit drugs, or travel correlating with the rash onset. He denied any prior treatments. He reported being in his normal state of health and was not taking any medications. Physical examination revealed indurated, violaceous, purpuric subcutaneous nodules, plaques, and masses on the forehead, cheek (top), jaw, flank, axillae (bottom), and back.

Firm Tumor Encasing the Left Second Toe of an Infant

The Diagnosis: Infantile Digital Fibromatosis

Infantile digital fibromatosis (IDF), or recurring digital fibrous tumor of childhood, is a benign juvenile myofibromatosis that presents as a firm, flesh-colored or slightly erythematous, dome-shaped papule or nodule on the dorsolateral aspects of the digits, usually sparing the thumbs and great toes.1 The tumor appears most commonly at birth and in infants younger than 1 year. It grows slowly over the first month, then rapidly over the next 10 to 14 months.1,2

Although lesions usually regress spontaneously within a few years, excision may be necessary when functional impairment and joint deformity occur. Tumors, however, may recur locally.1,2

Histologically, IDFs are composed of spindled myofibroblasts with characteristic round eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, which represent actin and vimentin filaments.1 In our case, histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of fibrous spindle cells with pathognomonic eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions consistent with IDF (Figure).

Fibrosarcomas are high-grade and low-grade soft-tissue neoplasms comprised of atypical spindle cells in a herringbone pattern with mitotic figures on pathology.3 They typically present as a slowly growing subcutaneous tumor on the lower extremities of young to middle-aged adults that may progress to become a palpable tender nodule. Infantile hemangiomas, the most common benign soft-tissue tumors of childhood, are vascular proliferations more commonly seen in low-birth-weight female white infants of multiple gestation pregnancies. Superficial hemangiomas present as bright red and lobular nodules or plaques. Deep hemangiomas present as ill-defined, blue-violaceous nodules with no overlying skin changes. Mixed hemangiomas present with features of both superficial and deep hemangiomas. Infantile hemangiomas experience a proliferative phase until 9 to 12 months of age, followed by a gradual involutional phase ending with possible residual telangiectases or fibrofatty change. Unlike IDFs, infantile hemangiomas favor the head and neck over other areas of the body. Keloids are firm, smooth, variably colored papules or plaques of haphazardly arranged thick dermal collagen bundles. They usually develop within a year of skin injury and extend beyond the original injury margin into normal tissue. Supernumerary digits present as small fleshy papules or larger nodules with a vestigial nail, most commonly on the ulnar side of the fifth finger or the radial side of the thumb. Histologically, they are composed of fascicles of nerve fibers.3

Treatment in our patient included partial amputation of the left second toe and excision with local tissue rearrangement by a plastic surgeon. His postoperative course was complicated by a minor wound infection, which resolved with a 7-day course of cephalexin. Since then, the patient has healed well, with gradual toe tissue and nail growth. No recurrence was reported 11 months after surgery.

- Heymann WR. Infantile digital fibromatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:122-123.

- Niamba P, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Further documentation of spontaneous regression of infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:280-284.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2018.

The Diagnosis: Infantile Digital Fibromatosis

Infantile digital fibromatosis (IDF), or recurring digital fibrous tumor of childhood, is a benign juvenile myofibromatosis that presents as a firm, flesh-colored or slightly erythematous, dome-shaped papule or nodule on the dorsolateral aspects of the digits, usually sparing the thumbs and great toes.1 The tumor appears most commonly at birth and in infants younger than 1 year. It grows slowly over the first month, then rapidly over the next 10 to 14 months.1,2

Although lesions usually regress spontaneously within a few years, excision may be necessary when functional impairment and joint deformity occur. Tumors, however, may recur locally.1,2

Histologically, IDFs are composed of spindled myofibroblasts with characteristic round eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, which represent actin and vimentin filaments.1 In our case, histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of fibrous spindle cells with pathognomonic eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions consistent with IDF (Figure).

Fibrosarcomas are high-grade and low-grade soft-tissue neoplasms comprised of atypical spindle cells in a herringbone pattern with mitotic figures on pathology.3 They typically present as a slowly growing subcutaneous tumor on the lower extremities of young to middle-aged adults that may progress to become a palpable tender nodule. Infantile hemangiomas, the most common benign soft-tissue tumors of childhood, are vascular proliferations more commonly seen in low-birth-weight female white infants of multiple gestation pregnancies. Superficial hemangiomas present as bright red and lobular nodules or plaques. Deep hemangiomas present as ill-defined, blue-violaceous nodules with no overlying skin changes. Mixed hemangiomas present with features of both superficial and deep hemangiomas. Infantile hemangiomas experience a proliferative phase until 9 to 12 months of age, followed by a gradual involutional phase ending with possible residual telangiectases or fibrofatty change. Unlike IDFs, infantile hemangiomas favor the head and neck over other areas of the body. Keloids are firm, smooth, variably colored papules or plaques of haphazardly arranged thick dermal collagen bundles. They usually develop within a year of skin injury and extend beyond the original injury margin into normal tissue. Supernumerary digits present as small fleshy papules or larger nodules with a vestigial nail, most commonly on the ulnar side of the fifth finger or the radial side of the thumb. Histologically, they are composed of fascicles of nerve fibers.3

Treatment in our patient included partial amputation of the left second toe and excision with local tissue rearrangement by a plastic surgeon. His postoperative course was complicated by a minor wound infection, which resolved with a 7-day course of cephalexin. Since then, the patient has healed well, with gradual toe tissue and nail growth. No recurrence was reported 11 months after surgery.

The Diagnosis: Infantile Digital Fibromatosis

Infantile digital fibromatosis (IDF), or recurring digital fibrous tumor of childhood, is a benign juvenile myofibromatosis that presents as a firm, flesh-colored or slightly erythematous, dome-shaped papule or nodule on the dorsolateral aspects of the digits, usually sparing the thumbs and great toes.1 The tumor appears most commonly at birth and in infants younger than 1 year. It grows slowly over the first month, then rapidly over the next 10 to 14 months.1,2

Although lesions usually regress spontaneously within a few years, excision may be necessary when functional impairment and joint deformity occur. Tumors, however, may recur locally.1,2

Histologically, IDFs are composed of spindled myofibroblasts with characteristic round eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies, which represent actin and vimentin filaments.1 In our case, histopathologic evaluation showed a proliferation of fibrous spindle cells with pathognomonic eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions consistent with IDF (Figure).

Fibrosarcomas are high-grade and low-grade soft-tissue neoplasms comprised of atypical spindle cells in a herringbone pattern with mitotic figures on pathology.3 They typically present as a slowly growing subcutaneous tumor on the lower extremities of young to middle-aged adults that may progress to become a palpable tender nodule. Infantile hemangiomas, the most common benign soft-tissue tumors of childhood, are vascular proliferations more commonly seen in low-birth-weight female white infants of multiple gestation pregnancies. Superficial hemangiomas present as bright red and lobular nodules or plaques. Deep hemangiomas present as ill-defined, blue-violaceous nodules with no overlying skin changes. Mixed hemangiomas present with features of both superficial and deep hemangiomas. Infantile hemangiomas experience a proliferative phase until 9 to 12 months of age, followed by a gradual involutional phase ending with possible residual telangiectases or fibrofatty change. Unlike IDFs, infantile hemangiomas favor the head and neck over other areas of the body. Keloids are firm, smooth, variably colored papules or plaques of haphazardly arranged thick dermal collagen bundles. They usually develop within a year of skin injury and extend beyond the original injury margin into normal tissue. Supernumerary digits present as small fleshy papules or larger nodules with a vestigial nail, most commonly on the ulnar side of the fifth finger or the radial side of the thumb. Histologically, they are composed of fascicles of nerve fibers.3

Treatment in our patient included partial amputation of the left second toe and excision with local tissue rearrangement by a plastic surgeon. His postoperative course was complicated by a minor wound infection, which resolved with a 7-day course of cephalexin. Since then, the patient has healed well, with gradual toe tissue and nail growth. No recurrence was reported 11 months after surgery.

- Heymann WR. Infantile digital fibromatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:122-123.

- Niamba P, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Further documentation of spontaneous regression of infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:280-284.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2018.

- Heymann WR. Infantile digital fibromatosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:122-123.

- Niamba P, Léauté-Labrèze C, Boralevi F, et al. Further documentation of spontaneous regression of infantile digital fibromatosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2007;24:280-284.

- Bolognia JL, Schaffer JV, Cerroni L, eds. Dermatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Limited; 2018.

A 10-month-old infant boy presented to the dermatology clinic with a firm, nonpainful, 5.5.×5.6-cm tumor encasing the left second toe, with associated skin breakdown, gait impairment, and lateral displacement of the third toe. The lesion began as a small bump under the toenail at 2 months of age; it then grew rapidly without bleeding or ulceration. It was diagnosed as a hemangioma at 4 months of age, and oral propranolol was initiated for 3 months, without suppression of tumor growth. The patient was referred to the pediatric dermatology department where a clinical diagnosis was made, and the patient was subsequently referred to plastic surgery for excision.