User login

Trial immunosuppressive therapy benefits outweigh long-term lymphoma risks in IBD

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – The benefits of short-term trial immunosuppressive therapy outweigh the risks in inflammatory bowel disease, but certain patient populations require more vigilance than others, Dr. James D. Lewis said at the 2013 Advances in IBD meeting.

"We can probably all agree that thiopurines increase the risk of lymphoma," said Dr. Lewis, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, at the conference on inflammatory bowel diseases. "But I’ve gone from ‘probably’ to ‘possibly’ when it comes to using anti-TNF [anti–tumor necrosis factor] therapy. I believe that a short trial of biologics therapy can really inform the risk-benefit balance, moving the conversation from ‘it might make a patient better’ to either it did or it didn’t."

In young males and the elderly, the benefit of combination therapy might not prove worth the risks of the treatment, said Dr. Lewis, "but in the middle ground, I think we have a sweet spot."

Overall, unless ineffective treatment is justifiable for other reasons such as the prevention of antibody formation, it should be discontinued, he said.

Results from the CESAME study, published in 2009, reinforce previously published data, indicating the risk of lymphoma is up to five times higher in IBD patients exposed to thiopurines than in the general population (Lancet 2009;374:1617-25).

"The most important data from CESAME, however, was that patients who discontinued thiopurines had a lymphoma incidence rate that went back to that of the general population," Dr. Lewis said at the meeting, sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America.

The link between lymphoma and anti-TNF treatment is harder to establish in IBD patients, because many in this cohort also have been exposed to thiopurines as part of combination therapies, he said.

Combination therapy is possibly associated with a higher risk of lymphoma than thiopurine monotherapy, and it has been shown to lead to a higher incidence rate than biologics monotherapy, said Dr. Lewis.

If you counsel patients that there is a 1 in 2,000 risk of lymphoma per year, he said, but it takes only a quarter of a year to figure out if the drugs are going to work, then the short-term risk is 1.25 per 10,000 that an additional lymphoma would develop because of that 3-month treatment. "And if you stop the treatment, presumably that risk goes away."

The risk-to-benefit ratio would therefore be favorable for most patients who took thiopurines versus those who did not, he said. "The caveat being, the older you get, the more marginal that risk-benefit balance becomes, probably because as you age, your baseline risk for lymphoma is going up."

Regarding the risk of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in patients exposed to immunosuppressive therapy, Dr. Lewis said that when he pooled the risk in person-years from two studies, he "did some back-of-the-envelope calculations and found that in males, the risk might be on the order of 11 in 100,000 person-years of thiopurine exposure."

That means the number needed to harm is about 9,000 patients, which when combined with the possible risk of developing other lymphomas, the number needed to harm is about 6,000 young males for 1 lymphoma death per year, according to Dr. Lewis.

"But I want to caution you that I am almost sure this is an overestimate of the risk, because if this is true, then it means in young males treated with thiopurines who get lymphoma, a third of them would be hepatosplenic lymphomas, and that seems unlikely," he said.

The ultimate magnitude of risk for adding thiopurine therapy for patients, particularly young males, is on par with that of the risk of death from annual use of automobiles, which Dr. Lewis said was approximately 1 in 9,090.

Since "a substantial proportion" of lymphomas associated with immunosuppression are related to the Epstein-Barr virus, according to Dr. Lewis, aside from minimizing unnecessary treatment, which can be hard to define, clinicians might consider discontinuing just thiopurine therapy, or all therapy in the setting of long-term remission. "I’m not endorsing that," he said. "I am saying that is a question for you to consider."

Other considerations include determining the minimum dose of thiopurine or methotrexate necessary to augment the effectiveness of anti-TNF treatment, as well as whether methotrexate is as effective as thiopurines without having an increased lymphoma risk, although only "indirect evidence" currently exists. "It would be nice to see a head-to-head comparison of those," he said.

As for using Epstein-Barr virus serology to help stratify risk, Dr. Lewis said that currently there are no guidelines for it in IBD, and he does not have a set rule to recommend it.

Dr. Lewis disclosed that he consults for AbbVie, Janssen, Prometheus, and Millennium and has received research funding from Centocor and Takeda.

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – The benefits of short-term trial immunosuppressive therapy outweigh the risks in inflammatory bowel disease, but certain patient populations require more vigilance than others, Dr. James D. Lewis said at the 2013 Advances in IBD meeting.

"We can probably all agree that thiopurines increase the risk of lymphoma," said Dr. Lewis, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, at the conference on inflammatory bowel diseases. "But I’ve gone from ‘probably’ to ‘possibly’ when it comes to using anti-TNF [anti–tumor necrosis factor] therapy. I believe that a short trial of biologics therapy can really inform the risk-benefit balance, moving the conversation from ‘it might make a patient better’ to either it did or it didn’t."

In young males and the elderly, the benefit of combination therapy might not prove worth the risks of the treatment, said Dr. Lewis, "but in the middle ground, I think we have a sweet spot."

Overall, unless ineffective treatment is justifiable for other reasons such as the prevention of antibody formation, it should be discontinued, he said.

Results from the CESAME study, published in 2009, reinforce previously published data, indicating the risk of lymphoma is up to five times higher in IBD patients exposed to thiopurines than in the general population (Lancet 2009;374:1617-25).

"The most important data from CESAME, however, was that patients who discontinued thiopurines had a lymphoma incidence rate that went back to that of the general population," Dr. Lewis said at the meeting, sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America.

The link between lymphoma and anti-TNF treatment is harder to establish in IBD patients, because many in this cohort also have been exposed to thiopurines as part of combination therapies, he said.

Combination therapy is possibly associated with a higher risk of lymphoma than thiopurine monotherapy, and it has been shown to lead to a higher incidence rate than biologics monotherapy, said Dr. Lewis.

If you counsel patients that there is a 1 in 2,000 risk of lymphoma per year, he said, but it takes only a quarter of a year to figure out if the drugs are going to work, then the short-term risk is 1.25 per 10,000 that an additional lymphoma would develop because of that 3-month treatment. "And if you stop the treatment, presumably that risk goes away."

The risk-to-benefit ratio would therefore be favorable for most patients who took thiopurines versus those who did not, he said. "The caveat being, the older you get, the more marginal that risk-benefit balance becomes, probably because as you age, your baseline risk for lymphoma is going up."

Regarding the risk of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in patients exposed to immunosuppressive therapy, Dr. Lewis said that when he pooled the risk in person-years from two studies, he "did some back-of-the-envelope calculations and found that in males, the risk might be on the order of 11 in 100,000 person-years of thiopurine exposure."

That means the number needed to harm is about 9,000 patients, which when combined with the possible risk of developing other lymphomas, the number needed to harm is about 6,000 young males for 1 lymphoma death per year, according to Dr. Lewis.

"But I want to caution you that I am almost sure this is an overestimate of the risk, because if this is true, then it means in young males treated with thiopurines who get lymphoma, a third of them would be hepatosplenic lymphomas, and that seems unlikely," he said.

The ultimate magnitude of risk for adding thiopurine therapy for patients, particularly young males, is on par with that of the risk of death from annual use of automobiles, which Dr. Lewis said was approximately 1 in 9,090.

Since "a substantial proportion" of lymphomas associated with immunosuppression are related to the Epstein-Barr virus, according to Dr. Lewis, aside from minimizing unnecessary treatment, which can be hard to define, clinicians might consider discontinuing just thiopurine therapy, or all therapy in the setting of long-term remission. "I’m not endorsing that," he said. "I am saying that is a question for you to consider."

Other considerations include determining the minimum dose of thiopurine or methotrexate necessary to augment the effectiveness of anti-TNF treatment, as well as whether methotrexate is as effective as thiopurines without having an increased lymphoma risk, although only "indirect evidence" currently exists. "It would be nice to see a head-to-head comparison of those," he said.

As for using Epstein-Barr virus serology to help stratify risk, Dr. Lewis said that currently there are no guidelines for it in IBD, and he does not have a set rule to recommend it.

Dr. Lewis disclosed that he consults for AbbVie, Janssen, Prometheus, and Millennium and has received research funding from Centocor and Takeda.

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – The benefits of short-term trial immunosuppressive therapy outweigh the risks in inflammatory bowel disease, but certain patient populations require more vigilance than others, Dr. James D. Lewis said at the 2013 Advances in IBD meeting.

"We can probably all agree that thiopurines increase the risk of lymphoma," said Dr. Lewis, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, at the conference on inflammatory bowel diseases. "But I’ve gone from ‘probably’ to ‘possibly’ when it comes to using anti-TNF [anti–tumor necrosis factor] therapy. I believe that a short trial of biologics therapy can really inform the risk-benefit balance, moving the conversation from ‘it might make a patient better’ to either it did or it didn’t."

In young males and the elderly, the benefit of combination therapy might not prove worth the risks of the treatment, said Dr. Lewis, "but in the middle ground, I think we have a sweet spot."

Overall, unless ineffective treatment is justifiable for other reasons such as the prevention of antibody formation, it should be discontinued, he said.

Results from the CESAME study, published in 2009, reinforce previously published data, indicating the risk of lymphoma is up to five times higher in IBD patients exposed to thiopurines than in the general population (Lancet 2009;374:1617-25).

"The most important data from CESAME, however, was that patients who discontinued thiopurines had a lymphoma incidence rate that went back to that of the general population," Dr. Lewis said at the meeting, sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America.

The link between lymphoma and anti-TNF treatment is harder to establish in IBD patients, because many in this cohort also have been exposed to thiopurines as part of combination therapies, he said.

Combination therapy is possibly associated with a higher risk of lymphoma than thiopurine monotherapy, and it has been shown to lead to a higher incidence rate than biologics monotherapy, said Dr. Lewis.

If you counsel patients that there is a 1 in 2,000 risk of lymphoma per year, he said, but it takes only a quarter of a year to figure out if the drugs are going to work, then the short-term risk is 1.25 per 10,000 that an additional lymphoma would develop because of that 3-month treatment. "And if you stop the treatment, presumably that risk goes away."

The risk-to-benefit ratio would therefore be favorable for most patients who took thiopurines versus those who did not, he said. "The caveat being, the older you get, the more marginal that risk-benefit balance becomes, probably because as you age, your baseline risk for lymphoma is going up."

Regarding the risk of hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in patients exposed to immunosuppressive therapy, Dr. Lewis said that when he pooled the risk in person-years from two studies, he "did some back-of-the-envelope calculations and found that in males, the risk might be on the order of 11 in 100,000 person-years of thiopurine exposure."

That means the number needed to harm is about 9,000 patients, which when combined with the possible risk of developing other lymphomas, the number needed to harm is about 6,000 young males for 1 lymphoma death per year, according to Dr. Lewis.

"But I want to caution you that I am almost sure this is an overestimate of the risk, because if this is true, then it means in young males treated with thiopurines who get lymphoma, a third of them would be hepatosplenic lymphomas, and that seems unlikely," he said.

The ultimate magnitude of risk for adding thiopurine therapy for patients, particularly young males, is on par with that of the risk of death from annual use of automobiles, which Dr. Lewis said was approximately 1 in 9,090.

Since "a substantial proportion" of lymphomas associated with immunosuppression are related to the Epstein-Barr virus, according to Dr. Lewis, aside from minimizing unnecessary treatment, which can be hard to define, clinicians might consider discontinuing just thiopurine therapy, or all therapy in the setting of long-term remission. "I’m not endorsing that," he said. "I am saying that is a question for you to consider."

Other considerations include determining the minimum dose of thiopurine or methotrexate necessary to augment the effectiveness of anti-TNF treatment, as well as whether methotrexate is as effective as thiopurines without having an increased lymphoma risk, although only "indirect evidence" currently exists. "It would be nice to see a head-to-head comparison of those," he said.

As for using Epstein-Barr virus serology to help stratify risk, Dr. Lewis said that currently there are no guidelines for it in IBD, and he does not have a set rule to recommend it.

Dr. Lewis disclosed that he consults for AbbVie, Janssen, Prometheus, and Millennium and has received research funding from Centocor and Takeda.

EXPERT ANALYSIS AT 2013 ADVANCES IN IBD

DVT risk higher in cardiac and vascular surgery

WASHINGTON - Cardiac and vascular surgery patients are at higher risk for deep vein thrombosis than are general surgery patients, according to data presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

In a retrospective analysis of 2,669,772 patients with a median age of 64 years, 43% of whom were males, in the ACS-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) during 2005-2009, Dr. Faisal Aziz of Penn State Hershey (Pa.) Heart and Vascular Institute and his colleagues sought to determine the actual rate of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during revascularization procedures, compared with general surgery.

The researchers sorted patients according to DVT risk factors such as age, gender, body mass index over 40 kg/m2, and whether the surgery was acute. They then assessed intraoperative factors such as total time to completion and the American Society of Anesthesiology score. They then considered the postoperative factors associated with DVT, such as blood transfusions, return to the operating room, deep wound infection, cardiac arrest, and mortality.

There were 18,512 incidences of DVT, equaling 0.69% of all patients studied. Of those, 0.66% occurred during general surgery, 2.08% occurred during cardiac surgery, and 1% occurred during vascular surgery.

"The implications of our study are that, contrary to popular belief, the incidence of postop DVT is actually higher after cardiac surgery and vascular surgery procedures," he said.

The cardiac surgery procedures associated with the highest DVT incidence rate were tricuspid valve replacement (8%), thoracic endovascular aortic repair (5%), thoracic aortic graft replacement (4%), and pericardial window (4%).

In a comparison of cardiac procedures, tricuspid valve replacement vs. aortic valve replacement had a risk ratio of 3.5 (P < .001). In tricuspid valve replacement vs. coronary artery bypass, the former had a risk ratio of 11.24 (P < .001).

Vascular surgeries with the highest DVT incidence rates were peripheral bypass (1%), amputation (trans-metatarsal, 0.75%; below knee, 1%; above the knee, 1%), and ruptured aortic aneurysms (3.5%).

Comparatively, in ruptured endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) vs. elective EVAR, the risk ratio was 3.55 (P < .001). In abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair, ruptured vs. elective surgeries had a risk ratio of 2.37 (P < .001).

Compared with 80% of general surgery patients, 74% of cardiac surgery patients were 70 years or older (relative risk, 1.12; P = .13); 86% of vascular surgery patients were 70 years or older (RR, 1.1; P < .05).

Male gender was an associated risk factor in 49% of general surgery patients, compared with 70% for cardiac patients (RR, 1.4; P < .001) and 51% for vascular patients (RR, 1.1; P < .001).

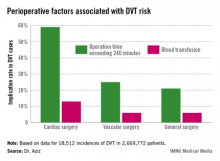

Intra- and postoperative factors associated with DVT risk included operation times exceeding 240 minutes and previous DVT. Compared with 21% of general surgery patients, operation time was implicated in 59% of cardiac surgery patients (relative risk, 2.72; P < .001) and 25% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.14; P <.001). Blood transfusions affected 13% of cardiac surgery patients (RR, 2.3; P < .001), 6% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001), and 6% of general surgery patients.

Compared with 24% for general surgery patients, returning to the operating room was implicated in 27% of cardiac patients (RR, 1.4; P = .27) and 32% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001).

"Procedures and perioperative factors associated with high risk of postoperative DVT should be identified, and adequate DVT prophylaxis should be ensured for these patients," Dr. Aziz concluded.

He had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON - Cardiac and vascular surgery patients are at higher risk for deep vein thrombosis than are general surgery patients, according to data presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

In a retrospective analysis of 2,669,772 patients with a median age of 64 years, 43% of whom were males, in the ACS-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) during 2005-2009, Dr. Faisal Aziz of Penn State Hershey (Pa.) Heart and Vascular Institute and his colleagues sought to determine the actual rate of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during revascularization procedures, compared with general surgery.

The researchers sorted patients according to DVT risk factors such as age, gender, body mass index over 40 kg/m2, and whether the surgery was acute. They then assessed intraoperative factors such as total time to completion and the American Society of Anesthesiology score. They then considered the postoperative factors associated with DVT, such as blood transfusions, return to the operating room, deep wound infection, cardiac arrest, and mortality.

There were 18,512 incidences of DVT, equaling 0.69% of all patients studied. Of those, 0.66% occurred during general surgery, 2.08% occurred during cardiac surgery, and 1% occurred during vascular surgery.

"The implications of our study are that, contrary to popular belief, the incidence of postop DVT is actually higher after cardiac surgery and vascular surgery procedures," he said.

The cardiac surgery procedures associated with the highest DVT incidence rate were tricuspid valve replacement (8%), thoracic endovascular aortic repair (5%), thoracic aortic graft replacement (4%), and pericardial window (4%).

In a comparison of cardiac procedures, tricuspid valve replacement vs. aortic valve replacement had a risk ratio of 3.5 (P < .001). In tricuspid valve replacement vs. coronary artery bypass, the former had a risk ratio of 11.24 (P < .001).

Vascular surgeries with the highest DVT incidence rates were peripheral bypass (1%), amputation (trans-metatarsal, 0.75%; below knee, 1%; above the knee, 1%), and ruptured aortic aneurysms (3.5%).

Comparatively, in ruptured endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) vs. elective EVAR, the risk ratio was 3.55 (P < .001). In abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair, ruptured vs. elective surgeries had a risk ratio of 2.37 (P < .001).

Compared with 80% of general surgery patients, 74% of cardiac surgery patients were 70 years or older (relative risk, 1.12; P = .13); 86% of vascular surgery patients were 70 years or older (RR, 1.1; P < .05).

Male gender was an associated risk factor in 49% of general surgery patients, compared with 70% for cardiac patients (RR, 1.4; P < .001) and 51% for vascular patients (RR, 1.1; P < .001).

Intra- and postoperative factors associated with DVT risk included operation times exceeding 240 minutes and previous DVT. Compared with 21% of general surgery patients, operation time was implicated in 59% of cardiac surgery patients (relative risk, 2.72; P < .001) and 25% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.14; P <.001). Blood transfusions affected 13% of cardiac surgery patients (RR, 2.3; P < .001), 6% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001), and 6% of general surgery patients.

Compared with 24% for general surgery patients, returning to the operating room was implicated in 27% of cardiac patients (RR, 1.4; P = .27) and 32% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001).

"Procedures and perioperative factors associated with high risk of postoperative DVT should be identified, and adequate DVT prophylaxis should be ensured for these patients," Dr. Aziz concluded.

He had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON - Cardiac and vascular surgery patients are at higher risk for deep vein thrombosis than are general surgery patients, according to data presented at the annual clinical congress of the American College of Surgeons.

In a retrospective analysis of 2,669,772 patients with a median age of 64 years, 43% of whom were males, in the ACS-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) during 2005-2009, Dr. Faisal Aziz of Penn State Hershey (Pa.) Heart and Vascular Institute and his colleagues sought to determine the actual rate of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) during revascularization procedures, compared with general surgery.

The researchers sorted patients according to DVT risk factors such as age, gender, body mass index over 40 kg/m2, and whether the surgery was acute. They then assessed intraoperative factors such as total time to completion and the American Society of Anesthesiology score. They then considered the postoperative factors associated with DVT, such as blood transfusions, return to the operating room, deep wound infection, cardiac arrest, and mortality.

There were 18,512 incidences of DVT, equaling 0.69% of all patients studied. Of those, 0.66% occurred during general surgery, 2.08% occurred during cardiac surgery, and 1% occurred during vascular surgery.

"The implications of our study are that, contrary to popular belief, the incidence of postop DVT is actually higher after cardiac surgery and vascular surgery procedures," he said.

The cardiac surgery procedures associated with the highest DVT incidence rate were tricuspid valve replacement (8%), thoracic endovascular aortic repair (5%), thoracic aortic graft replacement (4%), and pericardial window (4%).

In a comparison of cardiac procedures, tricuspid valve replacement vs. aortic valve replacement had a risk ratio of 3.5 (P < .001). In tricuspid valve replacement vs. coronary artery bypass, the former had a risk ratio of 11.24 (P < .001).

Vascular surgeries with the highest DVT incidence rates were peripheral bypass (1%), amputation (trans-metatarsal, 0.75%; below knee, 1%; above the knee, 1%), and ruptured aortic aneurysms (3.5%).

Comparatively, in ruptured endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) vs. elective EVAR, the risk ratio was 3.55 (P < .001). In abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair, ruptured vs. elective surgeries had a risk ratio of 2.37 (P < .001).

Compared with 80% of general surgery patients, 74% of cardiac surgery patients were 70 years or older (relative risk, 1.12; P = .13); 86% of vascular surgery patients were 70 years or older (RR, 1.1; P < .05).

Male gender was an associated risk factor in 49% of general surgery patients, compared with 70% for cardiac patients (RR, 1.4; P < .001) and 51% for vascular patients (RR, 1.1; P < .001).

Intra- and postoperative factors associated with DVT risk included operation times exceeding 240 minutes and previous DVT. Compared with 21% of general surgery patients, operation time was implicated in 59% of cardiac surgery patients (relative risk, 2.72; P < .001) and 25% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.14; P <.001). Blood transfusions affected 13% of cardiac surgery patients (RR, 2.3; P < .001), 6% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001), and 6% of general surgery patients.

Compared with 24% for general surgery patients, returning to the operating room was implicated in 27% of cardiac patients (RR, 1.4; P = .27) and 32% of vascular surgery patients (RR, 1.3; P < .001).

"Procedures and perioperative factors associated with high risk of postoperative DVT should be identified, and adequate DVT prophylaxis should be ensured for these patients," Dr. Aziz concluded.

He had no disclosures.

OSHA launches hospital worker safety initiative

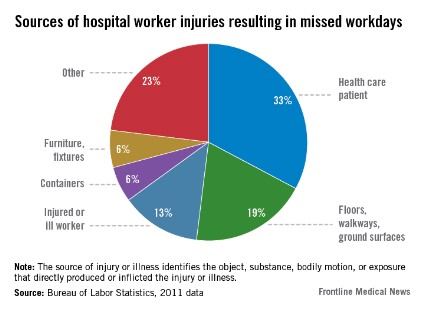

Improving hospital worker safety will result in improved patient safety, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which has unveiled a hospital worker safety online resource center.

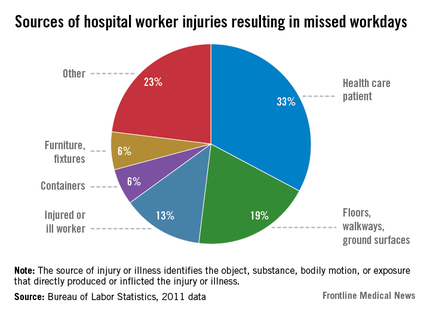

Worker Safety in Hospitals: Caring for our Caregivers, OSHA's new website aimed at curbing hospital worker injury rates, was introduced during a media teleconference Jan. 16. According to OSHA, injuries occur at a rate of 158 times per 10,000 workers, making hospitals more hazardous work environments than either construction or manufacturing sites.

National workers’ compensation losses from hospital workers total $2 billion annually, said OSHA assistant secretary Dr. David Michaels.

Musculoskeletal injuries, primarily from lifting and shifting patients, are the single biggest worker injury in hospitals, he said. According to OSHA, 16,680 hospital workers missed work because of a musculoskeletal injury sustained while handling a patient.

"Other hazards facing hospital workers include workplace violence, slips and falls, exposure to chemicals including hazardous drugs, exposure to infectious diseases, and needle sticks," said Dr. Michaels.

As part of a joint effort to promote the website, also on the conference call were Dr. John Howard, director of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and Dr. Erin DuPree, chief medical officer and vice president of the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, and Dr. Lucian Leape, chairman of the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation.

The OSHA website offers educational materials on avoiding injury when handling patients, as well as on workplace safety needs and the implementation of safety and health management systems.

The materials were culled from best practices employed at hospitals around the country deemed by OSHA to be "high-reliability organizations," and include tips such as having a daily "safety huddle" that includes a discussion of "great catches" and "near misses" that occurred during daily operations.

"One of the major barriers in making progress in patient safety is that when people report that they’ve made a mistake, they often get punished for it," said Dr. Leape. "What we’ve been trying to get people to understand is that mistakes happen because of bad systems, not bad people. You have to create an environment where you really believe that, and make it safe for people to talk about their errors so you can understand what you need to fix."

Dr. DuPree said the OSHA resources align with Joint Commission requirements such as those for hospitals to have a written plan for managing environmental safety for patients and all persons in hospitals. The Joint Commission expects that all individuals who work in the hospital should not fear retribution for speaking up about their safety concerns, Dr. DuPree said. "Leaders need to value and empower their workers. They need to understand that fear of reprisal and failure to share knowledge can compromise an organization’s ability to improve safety for all," he said.

As part of its efforts to advise hospital administrators on how to create safer work environments for their employees, the U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration has created a list of attributes of what it calls "high-reliability organizations."

Self-assessment tools, tip sheets, and other materials intended to help hospitals become high-reliability organizations (HROs) are available at OSHA's new website, Worker Safety in Hospitals: Caring for our Caregivers.

"The heart of these new materials are real life lessons from high-performing hospitals [that] have implemented best practices to reduce workplace injuries while also improving patient safety," said OSHA assistant secretary Dr. David Michaels in a press briefing.

The website emphasizes principles endorsed by the Joint Commission, particularly the promotion of a "no-blame" culture to destigmatize safety interventions. Operational strategies derived from the distillation of these best practices and endorsed by OSHA include the following:

• Sensitivity to operations. That means hospital workers should know what the standard procedures are, and follow them.

• Reluctance to simplify. This tenet calls upon hospital administrators to explore the larger context in which safety failures occur.

• Preoccupation with failure. OSHA warns administrators to "never let success breed complacency" and impels hospital leaders to "focus unceasingly on ways the system can fail" and to encourage staff to "listen to their ‘inner voice’ of concern."

• Deference to expertise. Pulling rank rather than going to the one who has the most direct experience in a situation is discouraged by OSHA.

• Resilience. Basically, know there will be failures, but hopefully only small ones; learn from them and rebound.

Dr. Michaels, Dr. Howard, Dr. DuPree, and Dr. Leape did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

*This article has been updated 1/16/2014.

Improving hospital worker safety will result in improved patient safety, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which has unveiled a hospital worker safety online resource center.

Worker Safety in Hospitals: Caring for our Caregivers, OSHA's new website aimed at curbing hospital worker injury rates, was introduced during a media teleconference Jan. 16. According to OSHA, injuries occur at a rate of 158 times per 10,000 workers, making hospitals more hazardous work environments than either construction or manufacturing sites.

National workers’ compensation losses from hospital workers total $2 billion annually, said OSHA assistant secretary Dr. David Michaels.

Musculoskeletal injuries, primarily from lifting and shifting patients, are the single biggest worker injury in hospitals, he said. According to OSHA, 16,680 hospital workers missed work because of a musculoskeletal injury sustained while handling a patient.

"Other hazards facing hospital workers include workplace violence, slips and falls, exposure to chemicals including hazardous drugs, exposure to infectious diseases, and needle sticks," said Dr. Michaels.

As part of a joint effort to promote the website, also on the conference call were Dr. John Howard, director of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and Dr. Erin DuPree, chief medical officer and vice president of the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, and Dr. Lucian Leape, chairman of the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation.

The OSHA website offers educational materials on avoiding injury when handling patients, as well as on workplace safety needs and the implementation of safety and health management systems.

The materials were culled from best practices employed at hospitals around the country deemed by OSHA to be "high-reliability organizations," and include tips such as having a daily "safety huddle" that includes a discussion of "great catches" and "near misses" that occurred during daily operations.

"One of the major barriers in making progress in patient safety is that when people report that they’ve made a mistake, they often get punished for it," said Dr. Leape. "What we’ve been trying to get people to understand is that mistakes happen because of bad systems, not bad people. You have to create an environment where you really believe that, and make it safe for people to talk about their errors so you can understand what you need to fix."

Dr. DuPree said the OSHA resources align with Joint Commission requirements such as those for hospitals to have a written plan for managing environmental safety for patients and all persons in hospitals. The Joint Commission expects that all individuals who work in the hospital should not fear retribution for speaking up about their safety concerns, Dr. DuPree said. "Leaders need to value and empower their workers. They need to understand that fear of reprisal and failure to share knowledge can compromise an organization’s ability to improve safety for all," he said.

As part of its efforts to advise hospital administrators on how to create safer work environments for their employees, the U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration has created a list of attributes of what it calls "high-reliability organizations."

Self-assessment tools, tip sheets, and other materials intended to help hospitals become high-reliability organizations (HROs) are available at OSHA's new website, Worker Safety in Hospitals: Caring for our Caregivers.

"The heart of these new materials are real life lessons from high-performing hospitals [that] have implemented best practices to reduce workplace injuries while also improving patient safety," said OSHA assistant secretary Dr. David Michaels in a press briefing.

The website emphasizes principles endorsed by the Joint Commission, particularly the promotion of a "no-blame" culture to destigmatize safety interventions. Operational strategies derived from the distillation of these best practices and endorsed by OSHA include the following:

• Sensitivity to operations. That means hospital workers should know what the standard procedures are, and follow them.

• Reluctance to simplify. This tenet calls upon hospital administrators to explore the larger context in which safety failures occur.

• Preoccupation with failure. OSHA warns administrators to "never let success breed complacency" and impels hospital leaders to "focus unceasingly on ways the system can fail" and to encourage staff to "listen to their ‘inner voice’ of concern."

• Deference to expertise. Pulling rank rather than going to the one who has the most direct experience in a situation is discouraged by OSHA.

• Resilience. Basically, know there will be failures, but hopefully only small ones; learn from them and rebound.

Dr. Michaels, Dr. Howard, Dr. DuPree, and Dr. Leape did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

*This article has been updated 1/16/2014.

Improving hospital worker safety will result in improved patient safety, according to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which has unveiled a hospital worker safety online resource center.

Worker Safety in Hospitals: Caring for our Caregivers, OSHA's new website aimed at curbing hospital worker injury rates, was introduced during a media teleconference Jan. 16. According to OSHA, injuries occur at a rate of 158 times per 10,000 workers, making hospitals more hazardous work environments than either construction or manufacturing sites.

National workers’ compensation losses from hospital workers total $2 billion annually, said OSHA assistant secretary Dr. David Michaels.

Musculoskeletal injuries, primarily from lifting and shifting patients, are the single biggest worker injury in hospitals, he said. According to OSHA, 16,680 hospital workers missed work because of a musculoskeletal injury sustained while handling a patient.

"Other hazards facing hospital workers include workplace violence, slips and falls, exposure to chemicals including hazardous drugs, exposure to infectious diseases, and needle sticks," said Dr. Michaels.

As part of a joint effort to promote the website, also on the conference call were Dr. John Howard, director of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, and Dr. Erin DuPree, chief medical officer and vice president of the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare, and Dr. Lucian Leape, chairman of the Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation.

The OSHA website offers educational materials on avoiding injury when handling patients, as well as on workplace safety needs and the implementation of safety and health management systems.

The materials were culled from best practices employed at hospitals around the country deemed by OSHA to be "high-reliability organizations," and include tips such as having a daily "safety huddle" that includes a discussion of "great catches" and "near misses" that occurred during daily operations.

"One of the major barriers in making progress in patient safety is that when people report that they’ve made a mistake, they often get punished for it," said Dr. Leape. "What we’ve been trying to get people to understand is that mistakes happen because of bad systems, not bad people. You have to create an environment where you really believe that, and make it safe for people to talk about their errors so you can understand what you need to fix."

Dr. DuPree said the OSHA resources align with Joint Commission requirements such as those for hospitals to have a written plan for managing environmental safety for patients and all persons in hospitals. The Joint Commission expects that all individuals who work in the hospital should not fear retribution for speaking up about their safety concerns, Dr. DuPree said. "Leaders need to value and empower their workers. They need to understand that fear of reprisal and failure to share knowledge can compromise an organization’s ability to improve safety for all," he said.

As part of its efforts to advise hospital administrators on how to create safer work environments for their employees, the U.S. Department of Labor Occupational Safety and Health Administration has created a list of attributes of what it calls "high-reliability organizations."

Self-assessment tools, tip sheets, and other materials intended to help hospitals become high-reliability organizations (HROs) are available at OSHA's new website, Worker Safety in Hospitals: Caring for our Caregivers.

"The heart of these new materials are real life lessons from high-performing hospitals [that] have implemented best practices to reduce workplace injuries while also improving patient safety," said OSHA assistant secretary Dr. David Michaels in a press briefing.

The website emphasizes principles endorsed by the Joint Commission, particularly the promotion of a "no-blame" culture to destigmatize safety interventions. Operational strategies derived from the distillation of these best practices and endorsed by OSHA include the following:

• Sensitivity to operations. That means hospital workers should know what the standard procedures are, and follow them.

• Reluctance to simplify. This tenet calls upon hospital administrators to explore the larger context in which safety failures occur.

• Preoccupation with failure. OSHA warns administrators to "never let success breed complacency" and impels hospital leaders to "focus unceasingly on ways the system can fail" and to encourage staff to "listen to their ‘inner voice’ of concern."

• Deference to expertise. Pulling rank rather than going to the one who has the most direct experience in a situation is discouraged by OSHA.

• Resilience. Basically, know there will be failures, but hopefully only small ones; learn from them and rebound.

Dr. Michaels, Dr. Howard, Dr. DuPree, and Dr. Leape did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

*This article has been updated 1/16/2014.

Olmesartan associated with some enteropathies

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – Patients on angiotensin-receptor blocking therapy who present with severe gastrointestinal symptoms may be experiencing drug-induced enteropathy, Dr. Joseph A. Murray said at the 2013 Advances in IBD meeting.

He discovered the connection in a retrospective analysis of patients after treating two women with collagenous celiac disease whose patient history included olmesartan therapy. "Until a few years ago, I’d never heard of such a thing," he said. "But for a condition like collagenous sprue, which is exceptionally rare, that really got my attention."

Olmesartan was implicated in 14 out of 32 cases of refractory idiopathic sprue treated by Dr. Murray at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., between 2008 and 2011. "It’s very much less common for other ARBs [angiotensin-receptor blockers] such as valsartan and irbesartan to have a spruelike effect on patients," Dr. Murray said of his clinical experience.

Since he noted the connection, he has successfully treated 22 additional such cases: When all patients were taken off the ARB, their symptoms – particularly their severe diarrhea – resolved, and the patients required no further therapy. They also were all able to return to a diet that contained gluten.

Autoimmune- vs. drug-induced enteropathy

Drug- and autoimmune-induced enteropathy have similar presentations, including severe chronic diarrhea; villous atrophy and collagen deposition with or without intraepithelial lymphocytes; and negative tissue transglutaminase antibodies and endomysial antibodies.

In drug-induced enteropathy, however, laboratory findings will always be seronegative for celiac disease and there will be no response to a gluten-free diet.

Patients taking olmesartan who previously were diagnosed with celiac disease should be retested, as should patients not currently taking olmesertan but who were on the drug at the time they were diagnosed.

In patients with severe diarrhea, olmesartan should be suspected, Dr. Murray said. Diarrhea in drug-induced cases is severe and protracted, with patients experiencing as many as 42 bowel movements a day. Acute renal failure and the need for parenteral nutrition are also possible with this condition, he said.

Clinical presentation

Of the 22 patients (median age, 70 years) treated for drug-induced enteropathy, 13 were women and 21 were non-Hispanic white. Twelve had one or more multiple electrolyte abnormalities, 14 had normocytic normochromic anemia, and 10 were severely hypoalbuminemic.

The amount of ARB prescribed to patients varied from 10 to 40 mg. "Patients had been on olmesartan for at least a year, and even as long as 3 years, before the symptoms started, which often did so abruptly, without explanation."

Prior treatments that had failed in these patients included a gluten-free diet, systemic steroids or budesonide, antidiarrheal agents, pancreatic enzymes, bile acid sequestrants, metronidazole, azathioprine, and octreotide.

In all of the 17 patients who had follow-up biopsies, the villi recovered. Anecdotal reports of four patients who were rechallenged with olmesartan included a full return of the illness, regardless of the period of time that had elapsed.

Possible mechanisms

"We think it’s a cell-mediated immune response, not the classic, ‘I take medication, I get hypersensistivity’ response," Dr. Murray said.

ARBs inhibit transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta, and TGF-beta "is key for regulating the immune response in the gut," he said. However, because TGF-beta also drives collagen formation, that there would be a high number of collagenous sprue cases casts doubt on this as a clear mechanism, he said.

Another possibility Dr. Murray and his associates tested, but rejected, is that a bioactivating hydrolase enzyme activates olmesartan given as a prodrug, in the epithelial tissue of the intestine and liver, creating polymorphisms.

The role of angiotensin receptors in the gut and on lymphocytes has not yet been explained, although there is some similarity to celiac disease where "lots of regulatory T cells in patients "simply don’t work," Dr. Murray said. "We know that these are CD8-positive T cells, so they are cytotoxic, and there are plenty of FOXP3 cells present, and they don’t change when you take them off the drug."

The conference was sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America. Dr. Murray had no relevant disclosures.

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – Patients on angiotensin-receptor blocking therapy who present with severe gastrointestinal symptoms may be experiencing drug-induced enteropathy, Dr. Joseph A. Murray said at the 2013 Advances in IBD meeting.

He discovered the connection in a retrospective analysis of patients after treating two women with collagenous celiac disease whose patient history included olmesartan therapy. "Until a few years ago, I’d never heard of such a thing," he said. "But for a condition like collagenous sprue, which is exceptionally rare, that really got my attention."

Olmesartan was implicated in 14 out of 32 cases of refractory idiopathic sprue treated by Dr. Murray at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., between 2008 and 2011. "It’s very much less common for other ARBs [angiotensin-receptor blockers] such as valsartan and irbesartan to have a spruelike effect on patients," Dr. Murray said of his clinical experience.

Since he noted the connection, he has successfully treated 22 additional such cases: When all patients were taken off the ARB, their symptoms – particularly their severe diarrhea – resolved, and the patients required no further therapy. They also were all able to return to a diet that contained gluten.

Autoimmune- vs. drug-induced enteropathy

Drug- and autoimmune-induced enteropathy have similar presentations, including severe chronic diarrhea; villous atrophy and collagen deposition with or without intraepithelial lymphocytes; and negative tissue transglutaminase antibodies and endomysial antibodies.

In drug-induced enteropathy, however, laboratory findings will always be seronegative for celiac disease and there will be no response to a gluten-free diet.

Patients taking olmesartan who previously were diagnosed with celiac disease should be retested, as should patients not currently taking olmesertan but who were on the drug at the time they were diagnosed.

In patients with severe diarrhea, olmesartan should be suspected, Dr. Murray said. Diarrhea in drug-induced cases is severe and protracted, with patients experiencing as many as 42 bowel movements a day. Acute renal failure and the need for parenteral nutrition are also possible with this condition, he said.

Clinical presentation

Of the 22 patients (median age, 70 years) treated for drug-induced enteropathy, 13 were women and 21 were non-Hispanic white. Twelve had one or more multiple electrolyte abnormalities, 14 had normocytic normochromic anemia, and 10 were severely hypoalbuminemic.

The amount of ARB prescribed to patients varied from 10 to 40 mg. "Patients had been on olmesartan for at least a year, and even as long as 3 years, before the symptoms started, which often did so abruptly, without explanation."

Prior treatments that had failed in these patients included a gluten-free diet, systemic steroids or budesonide, antidiarrheal agents, pancreatic enzymes, bile acid sequestrants, metronidazole, azathioprine, and octreotide.

In all of the 17 patients who had follow-up biopsies, the villi recovered. Anecdotal reports of four patients who were rechallenged with olmesartan included a full return of the illness, regardless of the period of time that had elapsed.

Possible mechanisms

"We think it’s a cell-mediated immune response, not the classic, ‘I take medication, I get hypersensistivity’ response," Dr. Murray said.

ARBs inhibit transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta, and TGF-beta "is key for regulating the immune response in the gut," he said. However, because TGF-beta also drives collagen formation, that there would be a high number of collagenous sprue cases casts doubt on this as a clear mechanism, he said.

Another possibility Dr. Murray and his associates tested, but rejected, is that a bioactivating hydrolase enzyme activates olmesartan given as a prodrug, in the epithelial tissue of the intestine and liver, creating polymorphisms.

The role of angiotensin receptors in the gut and on lymphocytes has not yet been explained, although there is some similarity to celiac disease where "lots of regulatory T cells in patients "simply don’t work," Dr. Murray said. "We know that these are CD8-positive T cells, so they are cytotoxic, and there are plenty of FOXP3 cells present, and they don’t change when you take them off the drug."

The conference was sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America. Dr. Murray had no relevant disclosures.

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – Patients on angiotensin-receptor blocking therapy who present with severe gastrointestinal symptoms may be experiencing drug-induced enteropathy, Dr. Joseph A. Murray said at the 2013 Advances in IBD meeting.

He discovered the connection in a retrospective analysis of patients after treating two women with collagenous celiac disease whose patient history included olmesartan therapy. "Until a few years ago, I’d never heard of such a thing," he said. "But for a condition like collagenous sprue, which is exceptionally rare, that really got my attention."

Olmesartan was implicated in 14 out of 32 cases of refractory idiopathic sprue treated by Dr. Murray at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., between 2008 and 2011. "It’s very much less common for other ARBs [angiotensin-receptor blockers] such as valsartan and irbesartan to have a spruelike effect on patients," Dr. Murray said of his clinical experience.

Since he noted the connection, he has successfully treated 22 additional such cases: When all patients were taken off the ARB, their symptoms – particularly their severe diarrhea – resolved, and the patients required no further therapy. They also were all able to return to a diet that contained gluten.

Autoimmune- vs. drug-induced enteropathy

Drug- and autoimmune-induced enteropathy have similar presentations, including severe chronic diarrhea; villous atrophy and collagen deposition with or without intraepithelial lymphocytes; and negative tissue transglutaminase antibodies and endomysial antibodies.

In drug-induced enteropathy, however, laboratory findings will always be seronegative for celiac disease and there will be no response to a gluten-free diet.

Patients taking olmesartan who previously were diagnosed with celiac disease should be retested, as should patients not currently taking olmesertan but who were on the drug at the time they were diagnosed.

In patients with severe diarrhea, olmesartan should be suspected, Dr. Murray said. Diarrhea in drug-induced cases is severe and protracted, with patients experiencing as many as 42 bowel movements a day. Acute renal failure and the need for parenteral nutrition are also possible with this condition, he said.

Clinical presentation

Of the 22 patients (median age, 70 years) treated for drug-induced enteropathy, 13 were women and 21 were non-Hispanic white. Twelve had one or more multiple electrolyte abnormalities, 14 had normocytic normochromic anemia, and 10 were severely hypoalbuminemic.

The amount of ARB prescribed to patients varied from 10 to 40 mg. "Patients had been on olmesartan for at least a year, and even as long as 3 years, before the symptoms started, which often did so abruptly, without explanation."

Prior treatments that had failed in these patients included a gluten-free diet, systemic steroids or budesonide, antidiarrheal agents, pancreatic enzymes, bile acid sequestrants, metronidazole, azathioprine, and octreotide.

In all of the 17 patients who had follow-up biopsies, the villi recovered. Anecdotal reports of four patients who were rechallenged with olmesartan included a full return of the illness, regardless of the period of time that had elapsed.

Possible mechanisms

"We think it’s a cell-mediated immune response, not the classic, ‘I take medication, I get hypersensistivity’ response," Dr. Murray said.

ARBs inhibit transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta, and TGF-beta "is key for regulating the immune response in the gut," he said. However, because TGF-beta also drives collagen formation, that there would be a high number of collagenous sprue cases casts doubt on this as a clear mechanism, he said.

Another possibility Dr. Murray and his associates tested, but rejected, is that a bioactivating hydrolase enzyme activates olmesartan given as a prodrug, in the epithelial tissue of the intestine and liver, creating polymorphisms.

The role of angiotensin receptors in the gut and on lymphocytes has not yet been explained, although there is some similarity to celiac disease where "lots of regulatory T cells in patients "simply don’t work," Dr. Murray said. "We know that these are CD8-positive T cells, so they are cytotoxic, and there are plenty of FOXP3 cells present, and they don’t change when you take them off the drug."

The conference was sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America. Dr. Murray had no relevant disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM 2013 ADVANCES IN IBD

Major finding: Olmesartan was implicated in 14 out of 32 cases of refractory idiopathic sprue treated at the Mayo Clinic between 2008 and 2011.

Data source: Retrospective case series analysis.

Disclosures: Dr. Murray had no relevant disclosures.

Metronidazole linked to increased risk for inflammatory bowel disease

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – Exposure to antibiotics other than penicillins, in particular metronidazole and quinolones, was associated with new-onset Crohn’s disease, based on a meta-analysis of observational and case-control studies presented by Dr. Ryan Ungaro at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases.

"Exposure to antibiotics may somehow contribute to alterations in the microbiome and result in dysbiosis, which is known to be part of the pathogenesis that leads to IBD," said Dr. Ungaro, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Alternatively, antibiotic exposures might just be surrogate markers for an infectious trigger that is actually associated with IBD. The analysis did not detect a link between antibiotic exposure and ulcerative colitis.

Dr. Ungaro and his colleagues performed a meta-analysis of 11 studies that included the records of 7,208 patients who had been newly diagnosed with IBD after antibiotic exposure; 3,937 had Crohn’s disease, 3,207 had ulcerative colitis, and 64 had unclassified IBD. Nine of the studies accounted for the potential confounding of diagnostic delay, with a range of 4 months to 4 years.

All classes of antibiotics except penicillin were implicated in new-onset IBD, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.55 for the overall risk of new-onset IBD after antibiotic exposure. Three studies provided data on the use of metronidazole, which proved to have the highest associated risk for new cases of IBD with a pooled OR of 5.01 (P = .005). Quinolones were accounted for in three of the studies and carried the next-highest associated risk, an OR of 1.79 (P = .040).

When stratified by age, the OR for new IBD diagnosis in adults was 1.43 and in children was 1.89. The OR for a new diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was 1.56 in adults and 2.7 in children.

The conference was sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America.

Dr. Ungaro did not have any relevant disclosures.

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – Exposure to antibiotics other than penicillins, in particular metronidazole and quinolones, was associated with new-onset Crohn’s disease, based on a meta-analysis of observational and case-control studies presented by Dr. Ryan Ungaro at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases.

"Exposure to antibiotics may somehow contribute to alterations in the microbiome and result in dysbiosis, which is known to be part of the pathogenesis that leads to IBD," said Dr. Ungaro, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Alternatively, antibiotic exposures might just be surrogate markers for an infectious trigger that is actually associated with IBD. The analysis did not detect a link between antibiotic exposure and ulcerative colitis.

Dr. Ungaro and his colleagues performed a meta-analysis of 11 studies that included the records of 7,208 patients who had been newly diagnosed with IBD after antibiotic exposure; 3,937 had Crohn’s disease, 3,207 had ulcerative colitis, and 64 had unclassified IBD. Nine of the studies accounted for the potential confounding of diagnostic delay, with a range of 4 months to 4 years.

All classes of antibiotics except penicillin were implicated in new-onset IBD, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.55 for the overall risk of new-onset IBD after antibiotic exposure. Three studies provided data on the use of metronidazole, which proved to have the highest associated risk for new cases of IBD with a pooled OR of 5.01 (P = .005). Quinolones were accounted for in three of the studies and carried the next-highest associated risk, an OR of 1.79 (P = .040).

When stratified by age, the OR for new IBD diagnosis in adults was 1.43 and in children was 1.89. The OR for a new diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was 1.56 in adults and 2.7 in children.

The conference was sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America.

Dr. Ungaro did not have any relevant disclosures.

HOLLYWOOD, FLA. – Exposure to antibiotics other than penicillins, in particular metronidazole and quinolones, was associated with new-onset Crohn’s disease, based on a meta-analysis of observational and case-control studies presented by Dr. Ryan Ungaro at a conference on inflammatory bowel diseases.

"Exposure to antibiotics may somehow contribute to alterations in the microbiome and result in dysbiosis, which is known to be part of the pathogenesis that leads to IBD," said Dr. Ungaro, of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York. Alternatively, antibiotic exposures might just be surrogate markers for an infectious trigger that is actually associated with IBD. The analysis did not detect a link between antibiotic exposure and ulcerative colitis.

Dr. Ungaro and his colleagues performed a meta-analysis of 11 studies that included the records of 7,208 patients who had been newly diagnosed with IBD after antibiotic exposure; 3,937 had Crohn’s disease, 3,207 had ulcerative colitis, and 64 had unclassified IBD. Nine of the studies accounted for the potential confounding of diagnostic delay, with a range of 4 months to 4 years.

All classes of antibiotics except penicillin were implicated in new-onset IBD, with an odds ratio (OR) of 1.55 for the overall risk of new-onset IBD after antibiotic exposure. Three studies provided data on the use of metronidazole, which proved to have the highest associated risk for new cases of IBD with a pooled OR of 5.01 (P = .005). Quinolones were accounted for in three of the studies and carried the next-highest associated risk, an OR of 1.79 (P = .040).

When stratified by age, the OR for new IBD diagnosis in adults was 1.43 and in children was 1.89. The OR for a new diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was 1.56 in adults and 2.7 in children.

The conference was sponsored by the Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation of America.

Dr. Ungaro did not have any relevant disclosures.

FROM 2013 ADVANCES IN IBD

Major finding: Three studies provided data on use of metronidazole, which proved to have the highest associated risk for new cases of IBD with a pooled odds ratio of 5.01 (P = .005).

Data source: A meta-analysis of 7,208 patients in 11 observational studies with antibiotic exposure prior to IBD diagnosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Ungaro did not have any relevant disclosures.

USPSTF gives final recommendation on lung cancer screening

Low-dose computed tomography screening of those at high risk for lung cancer has received a grade B recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Initially available for public comment in July 2013, the Task Force’s recommendations are now final and published.

The action allows the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid to mandate this service be provided without charging a copay or deductible. Widespread availability of screening raises concerns about inappropriate use of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) and the associated costs of the procedure, physician experts noted in editorials and interviews.

More than a third of Americans are current or former smokers. Increasing age and cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke are the leading risk factors for lung cancer.

The USPSTF defines those at high-risk patients as heavy smokers who are aged 55-80 years and have a 30-pack-year or more habit, and former heavy smokers who have quit in the past 15 years. Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years.

Patients also can be selected for screening based on risk factors other than tobacco use, including occupational exposures, radon exposure, family history, and incidence of pulmonary fibrosis or chronic obstructive lung disease.

Because of the potential for patients to experience "net harm, no net benefit, or at least substantially less benefit" from screening, the USPSTF stated it may be inappropriate to screen patients who have comorbidities that limit life expectancy, or who would be either unwilling or unable to have curative lung surgery.

Other forms of screening, including chest x-rays and sputum cytology, are not recommended because of their "inadequate sensitivity or specificity."

The USPSTF’s recommendations are based largely on a systematic review of several randomized, controlled trials published between 2000 and 2013, including the National Lung Screening Trial. That study of more than 50,000 asymptomatic adults, aged 55-74 years, showed a 16% reduction in lung cancer mortality and a 6.7% reduction in all-cause mortality when patients were screened using LDCT. One cancer death was averted for every 320 patients screened, and one death from all-causes was prevented in every 219 patients screened.

"Lung cancer causes as many deaths in the United States as the next three leading types of cancers combined, all of which already have screening interventions," wrote Dr. Frank C. Detterbeck of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., and Dr. Michael Unger of the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia in an editorial accompanying the report.

And while the use of LDCT is part of a structured screening process, not just a scan, the USPSTF report does not address many of the practical aspects of implementing lung cancer screening, they said.

Many patients who are not necessarily high risk will present to their physicians with anxiety about developing lung cancer. "These people have reasons for their concerns; turning them away because they do not meet the criteria does not provide them the reassurance they seek," the editorialists wrote. An educated discussion usually eases the patient’s fear, but "this requires specialized knowledge and time. It is easier to give in and screen an anxious patient who does not meet the criteria."

As noted by the USPSTF, the potential harms of LDCT screening include false-negative and false-positive results, including the potential for incidental findings, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure. "In a high-quality screening program, further imaging can resolve most false-positive results; however, some patients may require invasive procedures," the recommendations state.

Dr. Detterbeck and Dr. Unger wrote that effective screening hinges on reaching high-risk individuals, yet this is the population least likely to seek screening despite recognizing they are at risk. Further, chest CT is not a simple way to provide reassurance to anxious, lower-risk individuals. It is questionable whether primary care physicians will have the time and skill to advise patients on lung cancer screening and whether the "health care system is willing to support what the USPSTF is recommending."

Dr. Peter B. Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, authored a second editorial that accompanied the recommendations.

In an interview, he noted that issues of cost and counseling "matter a lot now that the Affordable Care Act links these recommendations to mandatory insurance benefits, which will then lead to automatic increases in health insurance premiums," according to Dr. Bach.

What is needed, he said, is more granular level of recommendations with more clinical utility.

"The expected degree of net benefit or level of certainty about the evidence is rarely uniform, even for selected populations," he wrote in his editorial. There are subgroups in which we have a lot of insight that screening is quite a bit more likely to help than harm, and the findings from the NLST should drive the approach.

Across the quintiles of lung cancer risk studied in the NLST, those considered to have experienced a probable benefit from screening varied from 5,276 in the lowest-risk group to 161 in the highest-risk group. Similarly, when considering the NLST’s benefit-to-harm ratio across the quintiles from lowest to highest, the number of false-positive results per lung cancer–related death prevented varied from 1,648 false-positive results per prevented death to 65, respectively, he said.

Screening protocols for patients in the low-risk group should receive a grade C from the USPSTF, which means the service should be offered selectively only, according to Dr. Bach.

"Screening should not be mandated for insurance coverage in the low-risk population. Neither should doctors and patients be told that it is definitely a good idea for everyone, nor should it become a quality standard for doctors, hospitals, and insurance plans, which are all things that could happen with this "B" recommendation," Dr. Bach said in an interview.

Dr. Bach was the lead author of practice guidelines issued jointly in 2013 by the American College of Chest Physicians and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Those guidelines, which are based mostly on the NLST, state that individuals aged 55-74 years who have at least a 30 pack-year smoking history should be screened with LDCT. The American Cancer Society has also endorsed lung cancer screening recommendations based on the same protocols as the ACCP and ASCO (CA Cancer J. Clin. 2013;63:107-17).

"I support the task force’s role in the crafting of essential health benefits absolutely," Dr. Bach said. "But I think their power now to create mandates means they should up their game."

Low-dose computed tomography screening of those at high risk for lung cancer has received a grade B recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Initially available for public comment in July 2013, the Task Force’s recommendations are now final and published.

The action allows the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid to mandate this service be provided without charging a copay or deductible. Widespread availability of screening raises concerns about inappropriate use of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) and the associated costs of the procedure, physician experts noted in editorials and interviews.

More than a third of Americans are current or former smokers. Increasing age and cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke are the leading risk factors for lung cancer.

The USPSTF defines those at high-risk patients as heavy smokers who are aged 55-80 years and have a 30-pack-year or more habit, and former heavy smokers who have quit in the past 15 years. Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years.

Patients also can be selected for screening based on risk factors other than tobacco use, including occupational exposures, radon exposure, family history, and incidence of pulmonary fibrosis or chronic obstructive lung disease.

Because of the potential for patients to experience "net harm, no net benefit, or at least substantially less benefit" from screening, the USPSTF stated it may be inappropriate to screen patients who have comorbidities that limit life expectancy, or who would be either unwilling or unable to have curative lung surgery.

Other forms of screening, including chest x-rays and sputum cytology, are not recommended because of their "inadequate sensitivity or specificity."

The USPSTF’s recommendations are based largely on a systematic review of several randomized, controlled trials published between 2000 and 2013, including the National Lung Screening Trial. That study of more than 50,000 asymptomatic adults, aged 55-74 years, showed a 16% reduction in lung cancer mortality and a 6.7% reduction in all-cause mortality when patients were screened using LDCT. One cancer death was averted for every 320 patients screened, and one death from all-causes was prevented in every 219 patients screened.

"Lung cancer causes as many deaths in the United States as the next three leading types of cancers combined, all of which already have screening interventions," wrote Dr. Frank C. Detterbeck of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., and Dr. Michael Unger of the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia in an editorial accompanying the report.

And while the use of LDCT is part of a structured screening process, not just a scan, the USPSTF report does not address many of the practical aspects of implementing lung cancer screening, they said.

Many patients who are not necessarily high risk will present to their physicians with anxiety about developing lung cancer. "These people have reasons for their concerns; turning them away because they do not meet the criteria does not provide them the reassurance they seek," the editorialists wrote. An educated discussion usually eases the patient’s fear, but "this requires specialized knowledge and time. It is easier to give in and screen an anxious patient who does not meet the criteria."

As noted by the USPSTF, the potential harms of LDCT screening include false-negative and false-positive results, including the potential for incidental findings, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure. "In a high-quality screening program, further imaging can resolve most false-positive results; however, some patients may require invasive procedures," the recommendations state.

Dr. Detterbeck and Dr. Unger wrote that effective screening hinges on reaching high-risk individuals, yet this is the population least likely to seek screening despite recognizing they are at risk. Further, chest CT is not a simple way to provide reassurance to anxious, lower-risk individuals. It is questionable whether primary care physicians will have the time and skill to advise patients on lung cancer screening and whether the "health care system is willing to support what the USPSTF is recommending."

Dr. Peter B. Bach, director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, authored a second editorial that accompanied the recommendations.

In an interview, he noted that issues of cost and counseling "matter a lot now that the Affordable Care Act links these recommendations to mandatory insurance benefits, which will then lead to automatic increases in health insurance premiums," according to Dr. Bach.

What is needed, he said, is more granular level of recommendations with more clinical utility.

"The expected degree of net benefit or level of certainty about the evidence is rarely uniform, even for selected populations," he wrote in his editorial. There are subgroups in which we have a lot of insight that screening is quite a bit more likely to help than harm, and the findings from the NLST should drive the approach.

Across the quintiles of lung cancer risk studied in the NLST, those considered to have experienced a probable benefit from screening varied from 5,276 in the lowest-risk group to 161 in the highest-risk group. Similarly, when considering the NLST’s benefit-to-harm ratio across the quintiles from lowest to highest, the number of false-positive results per lung cancer–related death prevented varied from 1,648 false-positive results per prevented death to 65, respectively, he said.

Screening protocols for patients in the low-risk group should receive a grade C from the USPSTF, which means the service should be offered selectively only, according to Dr. Bach.

"Screening should not be mandated for insurance coverage in the low-risk population. Neither should doctors and patients be told that it is definitely a good idea for everyone, nor should it become a quality standard for doctors, hospitals, and insurance plans, which are all things that could happen with this "B" recommendation," Dr. Bach said in an interview.

Dr. Bach was the lead author of practice guidelines issued jointly in 2013 by the American College of Chest Physicians and the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Those guidelines, which are based mostly on the NLST, state that individuals aged 55-74 years who have at least a 30 pack-year smoking history should be screened with LDCT. The American Cancer Society has also endorsed lung cancer screening recommendations based on the same protocols as the ACCP and ASCO (CA Cancer J. Clin. 2013;63:107-17).

"I support the task force’s role in the crafting of essential health benefits absolutely," Dr. Bach said. "But I think their power now to create mandates means they should up their game."

Low-dose computed tomography screening of those at high risk for lung cancer has received a grade B recommendation from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Initially available for public comment in July 2013, the Task Force’s recommendations are now final and published.

The action allows the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid to mandate this service be provided without charging a copay or deductible. Widespread availability of screening raises concerns about inappropriate use of low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) and the associated costs of the procedure, physician experts noted in editorials and interviews.

More than a third of Americans are current or former smokers. Increasing age and cumulative exposure to tobacco smoke are the leading risk factors for lung cancer.

The USPSTF defines those at high-risk patients as heavy smokers who are aged 55-80 years and have a 30-pack-year or more habit, and former heavy smokers who have quit in the past 15 years. Screening should be discontinued once a person has not smoked for 15 years.

Patients also can be selected for screening based on risk factors other than tobacco use, including occupational exposures, radon exposure, family history, and incidence of pulmonary fibrosis or chronic obstructive lung disease.

Because of the potential for patients to experience "net harm, no net benefit, or at least substantially less benefit" from screening, the USPSTF stated it may be inappropriate to screen patients who have comorbidities that limit life expectancy, or who would be either unwilling or unable to have curative lung surgery.

Other forms of screening, including chest x-rays and sputum cytology, are not recommended because of their "inadequate sensitivity or specificity."

The USPSTF’s recommendations are based largely on a systematic review of several randomized, controlled trials published between 2000 and 2013, including the National Lung Screening Trial. That study of more than 50,000 asymptomatic adults, aged 55-74 years, showed a 16% reduction in lung cancer mortality and a 6.7% reduction in all-cause mortality when patients were screened using LDCT. One cancer death was averted for every 320 patients screened, and one death from all-causes was prevented in every 219 patients screened.

"Lung cancer causes as many deaths in the United States as the next three leading types of cancers combined, all of which already have screening interventions," wrote Dr. Frank C. Detterbeck of Yale University in New Haven, Conn., and Dr. Michael Unger of the Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia in an editorial accompanying the report.

And while the use of LDCT is part of a structured screening process, not just a scan, the USPSTF report does not address many of the practical aspects of implementing lung cancer screening, they said.

Many patients who are not necessarily high risk will present to their physicians with anxiety about developing lung cancer. "These people have reasons for their concerns; turning them away because they do not meet the criteria does not provide them the reassurance they seek," the editorialists wrote. An educated discussion usually eases the patient’s fear, but "this requires specialized knowledge and time. It is easier to give in and screen an anxious patient who does not meet the criteria."

As noted by the USPSTF, the potential harms of LDCT screening include false-negative and false-positive results, including the potential for incidental findings, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure. "In a high-quality screening program, further imaging can resolve most false-positive results; however, some patients may require invasive procedures," the recommendations state.