User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

Use of complimentary and alternative medicine common in diabetes patients

An updated worldwide estimate of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among individuals with diabetes found widespread use, though it varied greatly by region and is sometimes hard to define.

The report is the first literature review of the subject since 2007. The researchers looked at CAM use by region, as well as by patient categories such as those with advanced diabetes and by length of time since diagnosis. The most commonly reported CAMs in use were herbal medicine, acupuncture, homeopathy, and spiritual healing.

Only about one-third of patients disclosed their CAM use to their physician or health care provider. “We suggest that health care professionals should carefully anticipate the likelihood of their [patients’] diabetic CAM use in order to enhance treatment optimization and promote medication adherence, as well as to provide a fully informed consultation,” said first author Abdulaziz S. Alzahrani, a PhD student at the University of Birmingham (England). The study was published March 8, 2021, in the European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

Patients also have a responsibility, said Gregory Rhee, PhD, assistant professor of public health sciences at the University of Connecticut, Farmington. He was the lead author of a 2018 survey of CAM use in adults aged 65 years and older with diabetes in the United States using data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey, and found that 25% had used CAM in some form in the prior year. “They need to be more up front, more proactive talking about CAM use with their doctors, and the second part is the physician. They also should be better educated in terms of CAM use. Traditionally, the physician in Western societies have pretty much ignored CAM use. But they are getting aware of CAM use and also we know that people are coming from multiple cultural backgrounds. The physicians and other health care providers should be better informed about CAM, and they should be better educated about it to provide patients better practice,” said Dr. Rhee.

He also distinguished between approaches like yoga or Tai Chi, which are physically oriented and not particularly controversial, and herbal medicines or dietary supplements. “Those can be controversial because we do not have strong scientific evidence to support those modalities for effectiveness on diabetes management,” Dr. Rhee added.

Mr. Alzahrani and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 38 studies, which included data from 25 countries. The included studies varied in their approach. For example, 16 studies focused exclusively on herbal and nutritional supplements. The most commonly mentioned CAMs were acupuncture and mind-body therapies (each named in six studies), religious and spiritual healing (five studies), and homeopathy (four studies). Among 31 studies focusing on herbal and nutritional supplements, the most common herbs mentioned were cinnamon and fenugreek (mentioned in 18 studies), garlic (17 studies), aloe vera (14 studies), and black seed (12 studies).

Prevalence of CAM use varied widely, ranging from 17% in Jordan to 89% in India and in a separate study in Jordan. The pooled prevalence of CAM use was 51% (95% confidence interval, 43%-59%). Subgroup analyses found the highest rate of CAM use in Europe (76%) and Africa (55%), and the lowest in North America (45%).

When the researchers examined patient characteristics, they found no significant relationship between CAM use and established ethnicity groups, or between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The prevalence ratio was lower among men (PR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.81-0.91). PRs for CAM use were lower among those with diabetic complications (PR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.66-0.99). Individuals with diabetes of at least 5 years’ duration were more likely to use CAM than those with shorter duration of illness (PR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.04-1.32).

Most (78%) CAM users employed it as an addition to their treatment regimen (95% CI, 56-94%), while 21% used it as an alternative to prescribed medicine (95% CI, 12-31%). More than two-thirds (67%) of individuals did not disclose CAM use to health care professionals (95% CI, 58-76%).

Although CAM use can be a source of friction between patients and physicians, Dr. Rhee also sees it as an opportunity. Patients from diverse backgrounds may be using CAM, often as a result of different cultural backgrounds. He cited the belief in some Asian countries that the balance of Yin and Yang is key to health, which many patients believe can be addressed through CAM. “If we want to promote cultural diversity, if we really care about patient diversity, I think CAM is one of the potential sources where the doctors should know [more about] the issue,” said Dr. Rhee.

The study was funded by the University of Birmingham. Dr. Rhee and Mr. Alzahrani have no relevant financial disclosures.

An updated worldwide estimate of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among individuals with diabetes found widespread use, though it varied greatly by region and is sometimes hard to define.

The report is the first literature review of the subject since 2007. The researchers looked at CAM use by region, as well as by patient categories such as those with advanced diabetes and by length of time since diagnosis. The most commonly reported CAMs in use were herbal medicine, acupuncture, homeopathy, and spiritual healing.

Only about one-third of patients disclosed their CAM use to their physician or health care provider. “We suggest that health care professionals should carefully anticipate the likelihood of their [patients’] diabetic CAM use in order to enhance treatment optimization and promote medication adherence, as well as to provide a fully informed consultation,” said first author Abdulaziz S. Alzahrani, a PhD student at the University of Birmingham (England). The study was published March 8, 2021, in the European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

Patients also have a responsibility, said Gregory Rhee, PhD, assistant professor of public health sciences at the University of Connecticut, Farmington. He was the lead author of a 2018 survey of CAM use in adults aged 65 years and older with diabetes in the United States using data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey, and found that 25% had used CAM in some form in the prior year. “They need to be more up front, more proactive talking about CAM use with their doctors, and the second part is the physician. They also should be better educated in terms of CAM use. Traditionally, the physician in Western societies have pretty much ignored CAM use. But they are getting aware of CAM use and also we know that people are coming from multiple cultural backgrounds. The physicians and other health care providers should be better informed about CAM, and they should be better educated about it to provide patients better practice,” said Dr. Rhee.

He also distinguished between approaches like yoga or Tai Chi, which are physically oriented and not particularly controversial, and herbal medicines or dietary supplements. “Those can be controversial because we do not have strong scientific evidence to support those modalities for effectiveness on diabetes management,” Dr. Rhee added.

Mr. Alzahrani and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 38 studies, which included data from 25 countries. The included studies varied in their approach. For example, 16 studies focused exclusively on herbal and nutritional supplements. The most commonly mentioned CAMs were acupuncture and mind-body therapies (each named in six studies), religious and spiritual healing (five studies), and homeopathy (four studies). Among 31 studies focusing on herbal and nutritional supplements, the most common herbs mentioned were cinnamon and fenugreek (mentioned in 18 studies), garlic (17 studies), aloe vera (14 studies), and black seed (12 studies).

Prevalence of CAM use varied widely, ranging from 17% in Jordan to 89% in India and in a separate study in Jordan. The pooled prevalence of CAM use was 51% (95% confidence interval, 43%-59%). Subgroup analyses found the highest rate of CAM use in Europe (76%) and Africa (55%), and the lowest in North America (45%).

When the researchers examined patient characteristics, they found no significant relationship between CAM use and established ethnicity groups, or between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The prevalence ratio was lower among men (PR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.81-0.91). PRs for CAM use were lower among those with diabetic complications (PR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.66-0.99). Individuals with diabetes of at least 5 years’ duration were more likely to use CAM than those with shorter duration of illness (PR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.04-1.32).

Most (78%) CAM users employed it as an addition to their treatment regimen (95% CI, 56-94%), while 21% used it as an alternative to prescribed medicine (95% CI, 12-31%). More than two-thirds (67%) of individuals did not disclose CAM use to health care professionals (95% CI, 58-76%).

Although CAM use can be a source of friction between patients and physicians, Dr. Rhee also sees it as an opportunity. Patients from diverse backgrounds may be using CAM, often as a result of different cultural backgrounds. He cited the belief in some Asian countries that the balance of Yin and Yang is key to health, which many patients believe can be addressed through CAM. “If we want to promote cultural diversity, if we really care about patient diversity, I think CAM is one of the potential sources where the doctors should know [more about] the issue,” said Dr. Rhee.

The study was funded by the University of Birmingham. Dr. Rhee and Mr. Alzahrani have no relevant financial disclosures.

An updated worldwide estimate of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among individuals with diabetes found widespread use, though it varied greatly by region and is sometimes hard to define.

The report is the first literature review of the subject since 2007. The researchers looked at CAM use by region, as well as by patient categories such as those with advanced diabetes and by length of time since diagnosis. The most commonly reported CAMs in use were herbal medicine, acupuncture, homeopathy, and spiritual healing.

Only about one-third of patients disclosed their CAM use to their physician or health care provider. “We suggest that health care professionals should carefully anticipate the likelihood of their [patients’] diabetic CAM use in order to enhance treatment optimization and promote medication adherence, as well as to provide a fully informed consultation,” said first author Abdulaziz S. Alzahrani, a PhD student at the University of Birmingham (England). The study was published March 8, 2021, in the European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology.

Patients also have a responsibility, said Gregory Rhee, PhD, assistant professor of public health sciences at the University of Connecticut, Farmington. He was the lead author of a 2018 survey of CAM use in adults aged 65 years and older with diabetes in the United States using data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey, and found that 25% had used CAM in some form in the prior year. “They need to be more up front, more proactive talking about CAM use with their doctors, and the second part is the physician. They also should be better educated in terms of CAM use. Traditionally, the physician in Western societies have pretty much ignored CAM use. But they are getting aware of CAM use and also we know that people are coming from multiple cultural backgrounds. The physicians and other health care providers should be better informed about CAM, and they should be better educated about it to provide patients better practice,” said Dr. Rhee.

He also distinguished between approaches like yoga or Tai Chi, which are physically oriented and not particularly controversial, and herbal medicines or dietary supplements. “Those can be controversial because we do not have strong scientific evidence to support those modalities for effectiveness on diabetes management,” Dr. Rhee added.

Mr. Alzahrani and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of 38 studies, which included data from 25 countries. The included studies varied in their approach. For example, 16 studies focused exclusively on herbal and nutritional supplements. The most commonly mentioned CAMs were acupuncture and mind-body therapies (each named in six studies), religious and spiritual healing (five studies), and homeopathy (four studies). Among 31 studies focusing on herbal and nutritional supplements, the most common herbs mentioned were cinnamon and fenugreek (mentioned in 18 studies), garlic (17 studies), aloe vera (14 studies), and black seed (12 studies).

Prevalence of CAM use varied widely, ranging from 17% in Jordan to 89% in India and in a separate study in Jordan. The pooled prevalence of CAM use was 51% (95% confidence interval, 43%-59%). Subgroup analyses found the highest rate of CAM use in Europe (76%) and Africa (55%), and the lowest in North America (45%).

When the researchers examined patient characteristics, they found no significant relationship between CAM use and established ethnicity groups, or between type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The prevalence ratio was lower among men (PR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.81-0.91). PRs for CAM use were lower among those with diabetic complications (PR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.66-0.99). Individuals with diabetes of at least 5 years’ duration were more likely to use CAM than those with shorter duration of illness (PR, 1.71; 95% CI, 1.04-1.32).

Most (78%) CAM users employed it as an addition to their treatment regimen (95% CI, 56-94%), while 21% used it as an alternative to prescribed medicine (95% CI, 12-31%). More than two-thirds (67%) of individuals did not disclose CAM use to health care professionals (95% CI, 58-76%).

Although CAM use can be a source of friction between patients and physicians, Dr. Rhee also sees it as an opportunity. Patients from diverse backgrounds may be using CAM, often as a result of different cultural backgrounds. He cited the belief in some Asian countries that the balance of Yin and Yang is key to health, which many patients believe can be addressed through CAM. “If we want to promote cultural diversity, if we really care about patient diversity, I think CAM is one of the potential sources where the doctors should know [more about] the issue,” said Dr. Rhee.

The study was funded by the University of Birmingham. Dr. Rhee and Mr. Alzahrani have no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY

The best exercises for BP control? European statement sorts it out

Recommendations for prescribing exercise to control high blood pressure have been put forward by various medical organizations and expert panels, but finding the bandwidth to craft personalized exercise training for their patients poses a challenge for clinicians.

Now, European cardiology societies have issued a consensus statement that offers an algorithm of sorts for developing personalized exercise programs as part of overall management approach for patients with or at risk of high BP.

The statement, published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology and issued by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology Council on Hypertension, claims to be the first document to focus on personalized exercise for BP.

The statement draws on a systematic review, including meta-analyses, to produce guidance on how to lower BP in three specific types of patients: Those with hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg), high-normal blood pressure (130-139/85-89 mm Hg), and normal blood pressure (<130/84 mm Hg).

By making recommendations for these three specific groups, along with providing guidance for combined exercise – that is, blending aerobic exercise with resistance training (RT) – the consensus statement goes one step further than recommendations other organizations have issued, Matthew W. Martinez, MD, said in an interview.

“What it adds is an algorithmic approach, if you will,” said Dr. Martinez, a sports medicine cardiologist at Morristown (N.J.) Medical Center. “There are some recommendations to help the clinicians to decide what they’re going to offer individuals, but what’s a challenge for us when seeing patients is finding the time to deliver the message and explain how valuable nutrition and exercise are.”

Guidelines, updates, and statements that include the role of exercise in BP control have been issued by the European Society of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and American College of Sports Medicine (Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2019;51:1314-23).

The European consensus statement includes the expected range of BP lowering for each activity. For example, aerobic exercise for patients with hypertension should lead to a reduction from –4.9 to –12 mm Hg systolic and –3.4 to –5.8 mm Hg diastolic.

The consensus statement recommends the following exercise priorities based on a patient’s blood pressure:

- Hypertension: Aerobic training (AT) as a first-line exercise therapy; and low- to moderate-intensity RT – equally using dynamic and isometric RT – as second-line therapy. In non-White patients, dynamic RT should be considered as a first-line therapy. RT can be combined with aerobic exercise on an individual basis if the clinician determines either form of RT would provide a metabolic benefit.

- High-to-normal BP: Dynamic RT as a first-line exercise, which the systematic review determined led to greater BP reduction than that of aerobic training. “Isometric RT is likely to elicit similar if not superior BP-lowering effects as [dynamic RT], but the level of evidence is low and the available data are scarce,” wrote first author Henner Hanssen, MD, of the University of Basel, Switzerland, and coauthors. Combining dynamic resistance training with aerobic training “may be preferable” to dynamic RT alone in patients with a combination of cardiovascular risk factors.

- Normal BP: Isometric RT may be indicated as a first-line intervention in individuals with a family or gestational history or obese or overweight people currently with normal BP. This advice includes a caveat: “The number of studies is limited and the 95% confidence intervals are large,” Dr. Hanssen and coauthors noted. AT is also an option in these patients, with more high-quality meta-analyses than the recommendation for isometric RT. “Hence, the BP-lowering effects of [isometric RT] as compared to AT may be overestimated and both exercise modalities may have similar BP-lowering effects in individuals with normotension,” wrote the consensus statement authors.

They note that more research is needed to validate the BP-lowering effects of combined exercise.

The statement acknowledges the difficulty clinicians face in managing patients with high blood pressure. “From a socioeconomic health perspective, it is a major challenge to develop, promote, and implement individually tailored exercise programs for patients with hypertension under consideration of sustainable costs,” wrote Dr. Hanssen and coauthors.

Dr. Martinez noted that one strength of the consensus statement is that it addresses the impact exercise can have on vascular health and metabolic function. And, it points out existing knowledge gaps.

“Are we going to see greater applicability of this as we use IT health technology?” he asked. “Are wearables and telehealth going to help deliver this message more easily, more frequently? Is there work to be done in terms of differences in gender? Do men and women respond differently, and is there a different exercise prescription based on that as well as ethnicity? We well know there’s a different treatment for African Americans compared to other ethnic groups.”

The statement also raises the stakes for using exercise as part of a multifaceted, integrated approach to hypertension management, he said.

“It’s not enough to talk just about exercise or nutrition, or to just give an antihypertension medicine,” Dr. Martinez said. “Perhaps the sweet spot is in integrating an approach that includes all three.”

Consensus statement coauthor Antonio Coca, MD, reported financial relationships with Abbott, Berlin-Chemie, Biolab, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ferrer, Menarini, Merck, Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Coauthor Maria Simonenko, MD, reported financial relationships with Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Linda Pescatello, PhD, is lead author of the American College of Sports Medicine 2019 statement. Dr. Hanssen and all other authors have no disclosures. Dr. Martinez has no relevant relationships to disclose.

Recommendations for prescribing exercise to control high blood pressure have been put forward by various medical organizations and expert panels, but finding the bandwidth to craft personalized exercise training for their patients poses a challenge for clinicians.

Now, European cardiology societies have issued a consensus statement that offers an algorithm of sorts for developing personalized exercise programs as part of overall management approach for patients with or at risk of high BP.

The statement, published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology and issued by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology Council on Hypertension, claims to be the first document to focus on personalized exercise for BP.

The statement draws on a systematic review, including meta-analyses, to produce guidance on how to lower BP in three specific types of patients: Those with hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg), high-normal blood pressure (130-139/85-89 mm Hg), and normal blood pressure (<130/84 mm Hg).

By making recommendations for these three specific groups, along with providing guidance for combined exercise – that is, blending aerobic exercise with resistance training (RT) – the consensus statement goes one step further than recommendations other organizations have issued, Matthew W. Martinez, MD, said in an interview.

“What it adds is an algorithmic approach, if you will,” said Dr. Martinez, a sports medicine cardiologist at Morristown (N.J.) Medical Center. “There are some recommendations to help the clinicians to decide what they’re going to offer individuals, but what’s a challenge for us when seeing patients is finding the time to deliver the message and explain how valuable nutrition and exercise are.”

Guidelines, updates, and statements that include the role of exercise in BP control have been issued by the European Society of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and American College of Sports Medicine (Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2019;51:1314-23).

The European consensus statement includes the expected range of BP lowering for each activity. For example, aerobic exercise for patients with hypertension should lead to a reduction from –4.9 to –12 mm Hg systolic and –3.4 to –5.8 mm Hg diastolic.

The consensus statement recommends the following exercise priorities based on a patient’s blood pressure:

- Hypertension: Aerobic training (AT) as a first-line exercise therapy; and low- to moderate-intensity RT – equally using dynamic and isometric RT – as second-line therapy. In non-White patients, dynamic RT should be considered as a first-line therapy. RT can be combined with aerobic exercise on an individual basis if the clinician determines either form of RT would provide a metabolic benefit.

- High-to-normal BP: Dynamic RT as a first-line exercise, which the systematic review determined led to greater BP reduction than that of aerobic training. “Isometric RT is likely to elicit similar if not superior BP-lowering effects as [dynamic RT], but the level of evidence is low and the available data are scarce,” wrote first author Henner Hanssen, MD, of the University of Basel, Switzerland, and coauthors. Combining dynamic resistance training with aerobic training “may be preferable” to dynamic RT alone in patients with a combination of cardiovascular risk factors.

- Normal BP: Isometric RT may be indicated as a first-line intervention in individuals with a family or gestational history or obese or overweight people currently with normal BP. This advice includes a caveat: “The number of studies is limited and the 95% confidence intervals are large,” Dr. Hanssen and coauthors noted. AT is also an option in these patients, with more high-quality meta-analyses than the recommendation for isometric RT. “Hence, the BP-lowering effects of [isometric RT] as compared to AT may be overestimated and both exercise modalities may have similar BP-lowering effects in individuals with normotension,” wrote the consensus statement authors.

They note that more research is needed to validate the BP-lowering effects of combined exercise.

The statement acknowledges the difficulty clinicians face in managing patients with high blood pressure. “From a socioeconomic health perspective, it is a major challenge to develop, promote, and implement individually tailored exercise programs for patients with hypertension under consideration of sustainable costs,” wrote Dr. Hanssen and coauthors.

Dr. Martinez noted that one strength of the consensus statement is that it addresses the impact exercise can have on vascular health and metabolic function. And, it points out existing knowledge gaps.

“Are we going to see greater applicability of this as we use IT health technology?” he asked. “Are wearables and telehealth going to help deliver this message more easily, more frequently? Is there work to be done in terms of differences in gender? Do men and women respond differently, and is there a different exercise prescription based on that as well as ethnicity? We well know there’s a different treatment for African Americans compared to other ethnic groups.”

The statement also raises the stakes for using exercise as part of a multifaceted, integrated approach to hypertension management, he said.

“It’s not enough to talk just about exercise or nutrition, or to just give an antihypertension medicine,” Dr. Martinez said. “Perhaps the sweet spot is in integrating an approach that includes all three.”

Consensus statement coauthor Antonio Coca, MD, reported financial relationships with Abbott, Berlin-Chemie, Biolab, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ferrer, Menarini, Merck, Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Coauthor Maria Simonenko, MD, reported financial relationships with Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Linda Pescatello, PhD, is lead author of the American College of Sports Medicine 2019 statement. Dr. Hanssen and all other authors have no disclosures. Dr. Martinez has no relevant relationships to disclose.

Recommendations for prescribing exercise to control high blood pressure have been put forward by various medical organizations and expert panels, but finding the bandwidth to craft personalized exercise training for their patients poses a challenge for clinicians.

Now, European cardiology societies have issued a consensus statement that offers an algorithm of sorts for developing personalized exercise programs as part of overall management approach for patients with or at risk of high BP.

The statement, published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology and issued by the European Association of Preventive Cardiology and the European Society of Cardiology Council on Hypertension, claims to be the first document to focus on personalized exercise for BP.

The statement draws on a systematic review, including meta-analyses, to produce guidance on how to lower BP in three specific types of patients: Those with hypertension (>140/90 mm Hg), high-normal blood pressure (130-139/85-89 mm Hg), and normal blood pressure (<130/84 mm Hg).

By making recommendations for these three specific groups, along with providing guidance for combined exercise – that is, blending aerobic exercise with resistance training (RT) – the consensus statement goes one step further than recommendations other organizations have issued, Matthew W. Martinez, MD, said in an interview.

“What it adds is an algorithmic approach, if you will,” said Dr. Martinez, a sports medicine cardiologist at Morristown (N.J.) Medical Center. “There are some recommendations to help the clinicians to decide what they’re going to offer individuals, but what’s a challenge for us when seeing patients is finding the time to deliver the message and explain how valuable nutrition and exercise are.”

Guidelines, updates, and statements that include the role of exercise in BP control have been issued by the European Society of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and American College of Sports Medicine (Med Sci Sports Exercise. 2019;51:1314-23).

The European consensus statement includes the expected range of BP lowering for each activity. For example, aerobic exercise for patients with hypertension should lead to a reduction from –4.9 to –12 mm Hg systolic and –3.4 to –5.8 mm Hg diastolic.

The consensus statement recommends the following exercise priorities based on a patient’s blood pressure:

- Hypertension: Aerobic training (AT) as a first-line exercise therapy; and low- to moderate-intensity RT – equally using dynamic and isometric RT – as second-line therapy. In non-White patients, dynamic RT should be considered as a first-line therapy. RT can be combined with aerobic exercise on an individual basis if the clinician determines either form of RT would provide a metabolic benefit.

- High-to-normal BP: Dynamic RT as a first-line exercise, which the systematic review determined led to greater BP reduction than that of aerobic training. “Isometric RT is likely to elicit similar if not superior BP-lowering effects as [dynamic RT], but the level of evidence is low and the available data are scarce,” wrote first author Henner Hanssen, MD, of the University of Basel, Switzerland, and coauthors. Combining dynamic resistance training with aerobic training “may be preferable” to dynamic RT alone in patients with a combination of cardiovascular risk factors.

- Normal BP: Isometric RT may be indicated as a first-line intervention in individuals with a family or gestational history or obese or overweight people currently with normal BP. This advice includes a caveat: “The number of studies is limited and the 95% confidence intervals are large,” Dr. Hanssen and coauthors noted. AT is also an option in these patients, with more high-quality meta-analyses than the recommendation for isometric RT. “Hence, the BP-lowering effects of [isometric RT] as compared to AT may be overestimated and both exercise modalities may have similar BP-lowering effects in individuals with normotension,” wrote the consensus statement authors.

They note that more research is needed to validate the BP-lowering effects of combined exercise.

The statement acknowledges the difficulty clinicians face in managing patients with high blood pressure. “From a socioeconomic health perspective, it is a major challenge to develop, promote, and implement individually tailored exercise programs for patients with hypertension under consideration of sustainable costs,” wrote Dr. Hanssen and coauthors.

Dr. Martinez noted that one strength of the consensus statement is that it addresses the impact exercise can have on vascular health and metabolic function. And, it points out existing knowledge gaps.

“Are we going to see greater applicability of this as we use IT health technology?” he asked. “Are wearables and telehealth going to help deliver this message more easily, more frequently? Is there work to be done in terms of differences in gender? Do men and women respond differently, and is there a different exercise prescription based on that as well as ethnicity? We well know there’s a different treatment for African Americans compared to other ethnic groups.”

The statement also raises the stakes for using exercise as part of a multifaceted, integrated approach to hypertension management, he said.

“It’s not enough to talk just about exercise or nutrition, or to just give an antihypertension medicine,” Dr. Martinez said. “Perhaps the sweet spot is in integrating an approach that includes all three.”

Consensus statement coauthor Antonio Coca, MD, reported financial relationships with Abbott, Berlin-Chemie, Biolab, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Ferrer, Menarini, Merck, Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Coauthor Maria Simonenko, MD, reported financial relationships with Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis. Linda Pescatello, PhD, is lead author of the American College of Sports Medicine 2019 statement. Dr. Hanssen and all other authors have no disclosures. Dr. Martinez has no relevant relationships to disclose.

FROM THE EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF PREVENTIVE CARDIOLOGY

Long-haul COVID-19 brings welcome attention to POTS

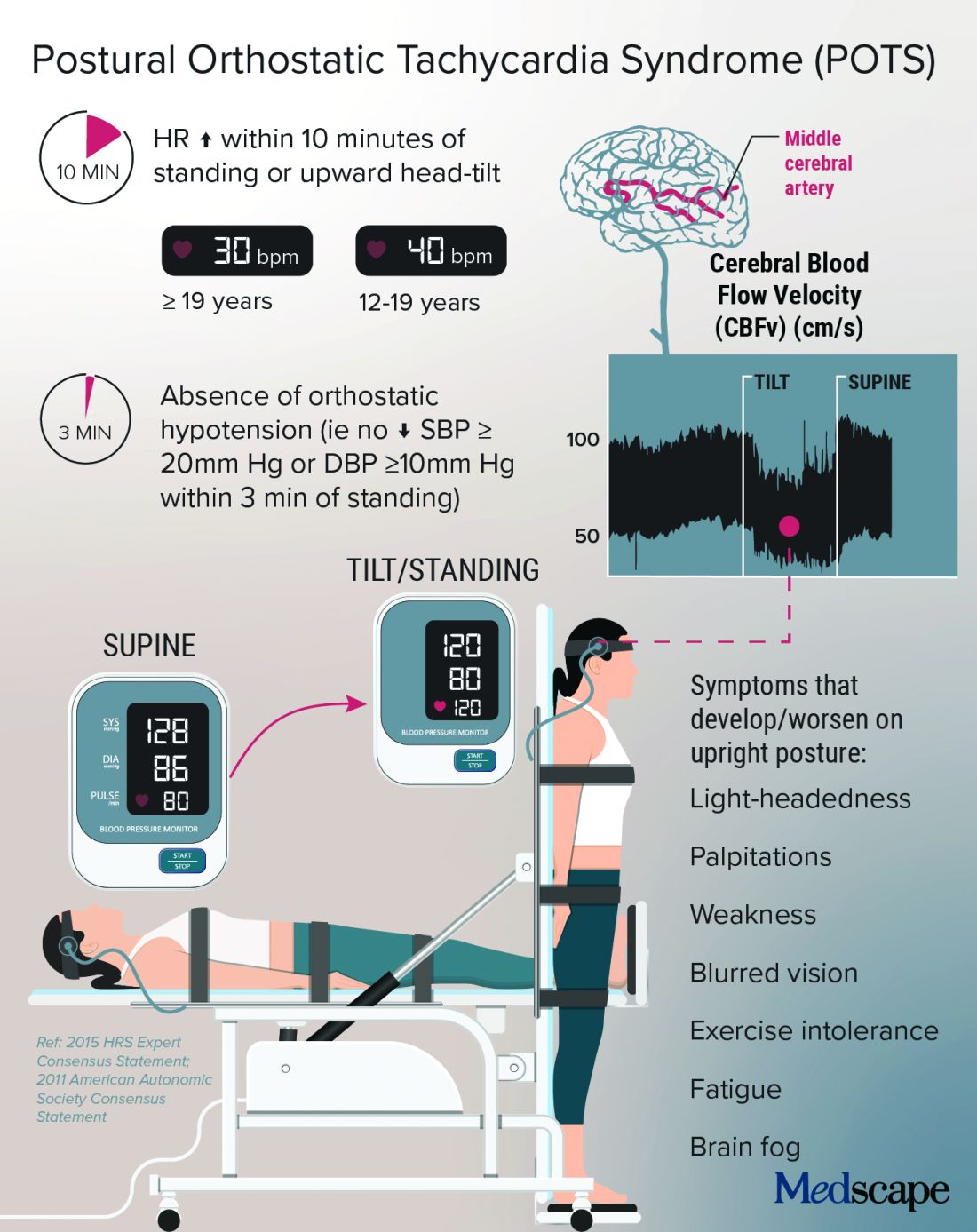

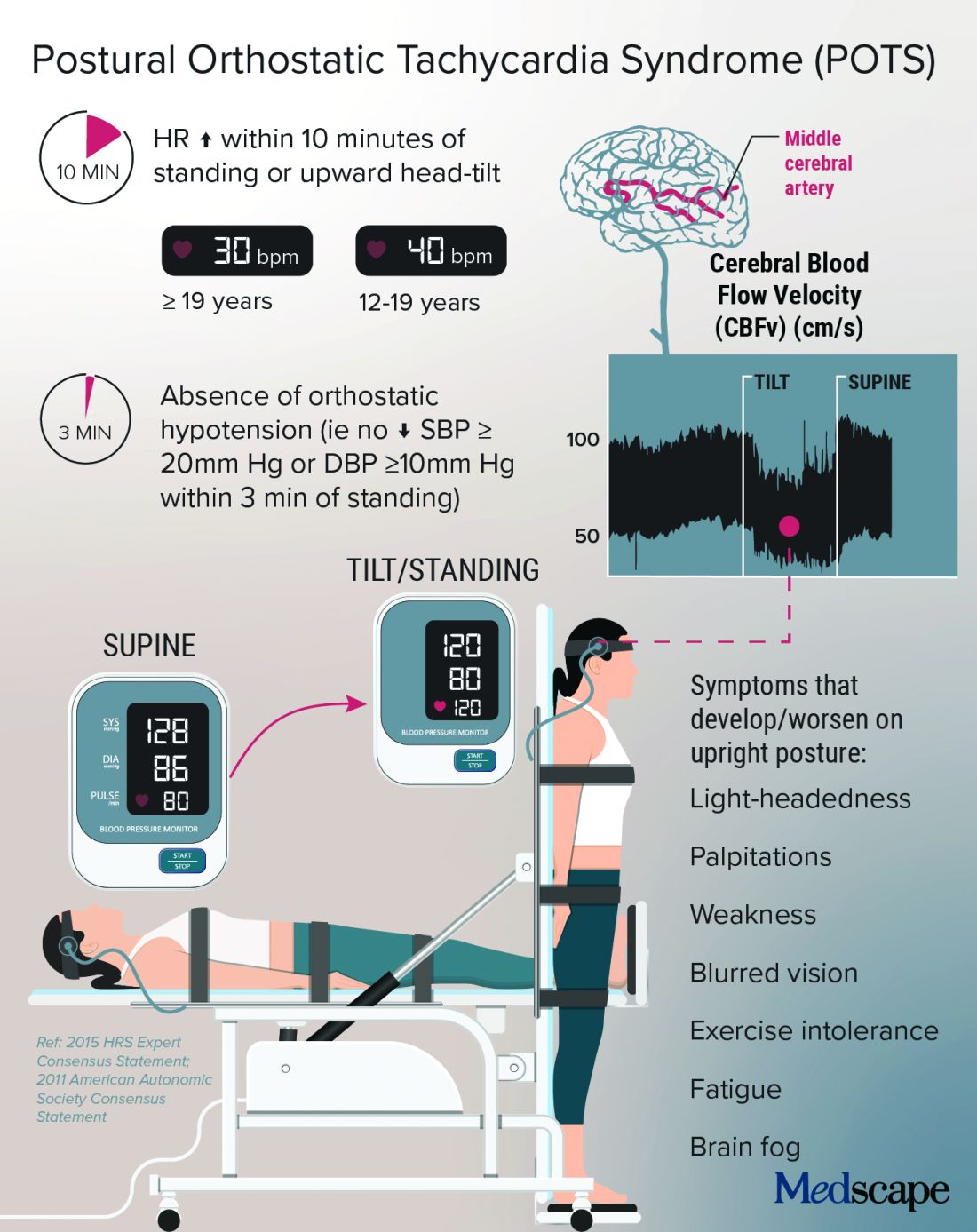

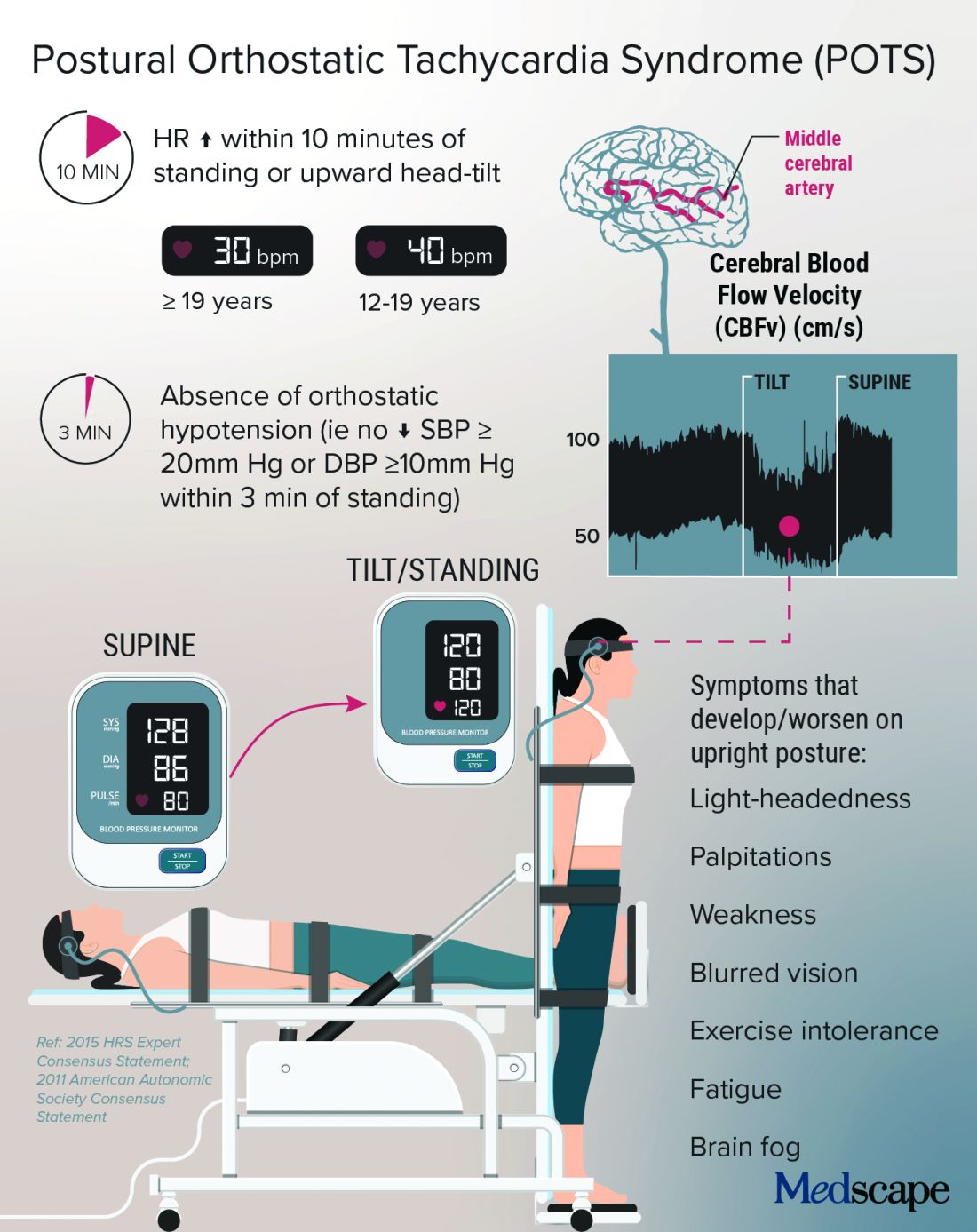

Before COVID-19, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) was one of those diseases that many people, including physicians, dismissed.

“They thought it was just anxious, crazy young women,” said Pam R. Taub, MD, who runs the cardiac rehabilitation program at the University of California, San Diego.

The cryptic autonomic condition was estimated to affect 1-3 million Americans before the pandemic hit. Now case reports confirm that it is a manifestation of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), or so-called long-haul COVID-19.

“I’m excited that this condition that has been so often the ugly stepchild of both cardiology and neurology is getting some attention,” said Dr. Taub. She said she is hopeful that the National Institutes of Health’s commitment to PASC research will benefit patients affected by the cardiovascular dysautonomia characterized by orthostatic intolerance in the absence of orthostatic hypotension.

Postinfection POTS is not exclusive to SARS-CoV-2. It has been reported after Lyme disease and Epstein-Barr virus infections, for example. One theory is that some of the antibodies generated against the virus cross react and damage the autonomic nervous system, which regulates heart rate and blood pressure, Dr. Taub explained.

It is not known whether COVID-19 is more likely to trigger POTS than are other infections or whether the rise in cases merely reflects the fact that more than 115 million people worldwide have been infected with the novel coronavirus.

Low blood volume, dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, and autoimmunity may all play a role in POTS, perhaps leading to distinct subtypes, according to a State of the Science document from the NIH; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

In Dr. Taub’s experience, “The truth is that patients actually have a mix of the subtypes.”

Kamal Shouman, MD, an autonomic neurologist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in an interview that he has seen patients present with post–COVID-19 POTS in “all flavors,” including “neuropathic POTS, which is thought of as the classic postinfectious phenomenon.”

Why does it mostly affect athletic women?

The condition, which can be the result of dehydration or prolonged bed rest, leading to deconditioning, affects women disproportionately.

According to Manesh Patel, MD, if a patient with POTS who is not a young woman is presented on medical rounds, the response is, “Tell me again why you think this patient has POTS.”

Dr. Patel, chief of the division of cardiology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., has a theory for why many of the women who have POTS are athletes or are highly active: They likely have an underlying predisposition, compounded by a smaller body volume, leaving less margin for error. “If they decondition and lose 500 cc’s, it makes a bigger difference to them than, say, a 300-pound offensive lineman,” Dr. Patel explained.

That hypothesis makes sense to Dr. Taub, who added, “There are just some people metabolically that are more hyperadrenergic,” and it may be that “all their activity really helps tone down that sympathetic output,” but the infection affects these regulatory processes, and deconditioning disrupts things further.

Women also have more autoimmune disorders than do men. The driving force of the dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system is thought to be “immune mediated; we think it’s triggered by a response to a virus,” she said.

Dr. Shouman said the underlying susceptibility may predispose toward orthostatic intolerance. For example, patients will tell him, “Well, many years ago, I was prone to fainting.” He emphasized that POTS is not exclusive to women – he sees men with POTS, and one of the three recent case reports of post–COVID-19 POTS involved a 37-year-old man. So far, the male POTS patients that Dr. Patel has encountered have been deconditioned athletes.

Poor (wo)man’s tilt test and treatment options

POTS is typically diagnosed with a tilt test and transcranial Doppler. Dr. Taub described her “poor man’s tilt test” of asking the patient to lie down for 5-10 minutes and then having the patient stand up.

She likes the fact that transcranial Doppler helps validate the brain fog that patients report, which can be dismissed as “just your excuse for not wanting to work.” If blood perfusion to the brain is cut by 40%-50%, “how are you going to think clearly?” she said.

Dr. Shouman noted that overall volume expansion with salt water, compression garments, and a graduated exercise program play a major role in the rehabilitation of all POTS patients.

He likes to tailor treatments to the most likely underlying cause. But patients should first undergo a medical assessment by their internists to make sure there isn’t a primary lung or heart problem.

“Once the decision is made for them to be evaluated in the autonomic practice and [a] POTS diagnosis is made, I think it is very useful to determine what type of POTS,” he said.

With hyperadrenergic POTS, “you are looking at a standing norepinephrine level of over 600 pg/mL or so.” For these patients, drugs such as ivabradine or beta-blockers can help, he noted.

Dr. Taub recently conducted a small study that showed a benefit with the selective If channel blocker ivabradine for patients with hyperadrenergic POTS unrelated to COVID-19. She tends to favor ivabradine over beta-blockers because it lowers heart rate but not blood pressure. In addition, beta-blockers can exacerbate fatigue and brain fog.

A small crossover study will compare propranolol and ivabradine in POTS. For someone who is very hypovolemic, “you might try a salt tablet or a prescription drug like fludrocortisone,” Dr. Taub explained.

Another problem that patients with POTS experience is an inability to exercise because of orthostatic intolerance. Recumbent exercise targets deconditioning and can tamp down the hyperadrenergic effect. Dr. Shouman’s approach is to start gradually with swimming or the use of a recumbent bike or a rowing machine.

Dr. Taub recommends wearables to patients because POTS is “a very dynamic condition” that is easy to overmedicate or undermedicate. If it’s a good day, the patients are well hydrated, and the standing heart rate is only 80 bpm, she tells them they could titrate down their second dose of ivabradine, for example. The feedback from wearables also helps patients manage their exercise response.

For Dr. Shouman, wearables are not always as accurate as he would like. He tells his patients that it’s okay to use one as long as it doesn’t become a source of anxiety such that they’re constantly checking it.

POTS hope: A COVID-19 silver lining?

With increasing attention being paid to long-haul COVID-19, are there any concerns that POTS will get lost among the myriad symptoms connected to PASC?

Dr. Shouman cautioned, “Not all long COVID is POTS,” and said that clinicians at long-haul clinics should be able to recognize the different conditions “when POTS is suspected. I think it is useful for those providers to make the appropriate referral for POTS clinic autonomic assessment.”

He and his colleagues at Mayo have seen quite a few patients who have post–COVID-19 autonomic dysfunction, such as vasodepressor syncope, not just POTS. They plan to write about this soon.

“Of all the things I treat in cardiology, this is the most complex, because there’s so many different systems involved,” said Dr. Taub, who has seen patients recover fully from POTS. “There’s a spectrum, and there’s people that are definitely on one end of the spectrum where they have very severe diseases.”

For her, the important message is, “No matter where you are on the spectrum, there are things we can do to make your symptoms better.” And with grant funding for PASC research, “hopefully we will address the mechanisms of disease, and we’ll be able to cure this,” she said.

Dr. Patel has served as a consultant for Bayer, Janssen, AstraZeneca, and Heartflow and has received research grants from Bayer, Janssen, AstraZeneca, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Shouman reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Homeland Security/FEMA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Before COVID-19, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) was one of those diseases that many people, including physicians, dismissed.

“They thought it was just anxious, crazy young women,” said Pam R. Taub, MD, who runs the cardiac rehabilitation program at the University of California, San Diego.

The cryptic autonomic condition was estimated to affect 1-3 million Americans before the pandemic hit. Now case reports confirm that it is a manifestation of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), or so-called long-haul COVID-19.

“I’m excited that this condition that has been so often the ugly stepchild of both cardiology and neurology is getting some attention,” said Dr. Taub. She said she is hopeful that the National Institutes of Health’s commitment to PASC research will benefit patients affected by the cardiovascular dysautonomia characterized by orthostatic intolerance in the absence of orthostatic hypotension.

Postinfection POTS is not exclusive to SARS-CoV-2. It has been reported after Lyme disease and Epstein-Barr virus infections, for example. One theory is that some of the antibodies generated against the virus cross react and damage the autonomic nervous system, which regulates heart rate and blood pressure, Dr. Taub explained.

It is not known whether COVID-19 is more likely to trigger POTS than are other infections or whether the rise in cases merely reflects the fact that more than 115 million people worldwide have been infected with the novel coronavirus.

Low blood volume, dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, and autoimmunity may all play a role in POTS, perhaps leading to distinct subtypes, according to a State of the Science document from the NIH; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

In Dr. Taub’s experience, “The truth is that patients actually have a mix of the subtypes.”

Kamal Shouman, MD, an autonomic neurologist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in an interview that he has seen patients present with post–COVID-19 POTS in “all flavors,” including “neuropathic POTS, which is thought of as the classic postinfectious phenomenon.”

Why does it mostly affect athletic women?

The condition, which can be the result of dehydration or prolonged bed rest, leading to deconditioning, affects women disproportionately.

According to Manesh Patel, MD, if a patient with POTS who is not a young woman is presented on medical rounds, the response is, “Tell me again why you think this patient has POTS.”

Dr. Patel, chief of the division of cardiology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., has a theory for why many of the women who have POTS are athletes or are highly active: They likely have an underlying predisposition, compounded by a smaller body volume, leaving less margin for error. “If they decondition and lose 500 cc’s, it makes a bigger difference to them than, say, a 300-pound offensive lineman,” Dr. Patel explained.

That hypothesis makes sense to Dr. Taub, who added, “There are just some people metabolically that are more hyperadrenergic,” and it may be that “all their activity really helps tone down that sympathetic output,” but the infection affects these regulatory processes, and deconditioning disrupts things further.

Women also have more autoimmune disorders than do men. The driving force of the dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system is thought to be “immune mediated; we think it’s triggered by a response to a virus,” she said.

Dr. Shouman said the underlying susceptibility may predispose toward orthostatic intolerance. For example, patients will tell him, “Well, many years ago, I was prone to fainting.” He emphasized that POTS is not exclusive to women – he sees men with POTS, and one of the three recent case reports of post–COVID-19 POTS involved a 37-year-old man. So far, the male POTS patients that Dr. Patel has encountered have been deconditioned athletes.

Poor (wo)man’s tilt test and treatment options

POTS is typically diagnosed with a tilt test and transcranial Doppler. Dr. Taub described her “poor man’s tilt test” of asking the patient to lie down for 5-10 minutes and then having the patient stand up.

She likes the fact that transcranial Doppler helps validate the brain fog that patients report, which can be dismissed as “just your excuse for not wanting to work.” If blood perfusion to the brain is cut by 40%-50%, “how are you going to think clearly?” she said.

Dr. Shouman noted that overall volume expansion with salt water, compression garments, and a graduated exercise program play a major role in the rehabilitation of all POTS patients.

He likes to tailor treatments to the most likely underlying cause. But patients should first undergo a medical assessment by their internists to make sure there isn’t a primary lung or heart problem.

“Once the decision is made for them to be evaluated in the autonomic practice and [a] POTS diagnosis is made, I think it is very useful to determine what type of POTS,” he said.

With hyperadrenergic POTS, “you are looking at a standing norepinephrine level of over 600 pg/mL or so.” For these patients, drugs such as ivabradine or beta-blockers can help, he noted.

Dr. Taub recently conducted a small study that showed a benefit with the selective If channel blocker ivabradine for patients with hyperadrenergic POTS unrelated to COVID-19. She tends to favor ivabradine over beta-blockers because it lowers heart rate but not blood pressure. In addition, beta-blockers can exacerbate fatigue and brain fog.

A small crossover study will compare propranolol and ivabradine in POTS. For someone who is very hypovolemic, “you might try a salt tablet or a prescription drug like fludrocortisone,” Dr. Taub explained.

Another problem that patients with POTS experience is an inability to exercise because of orthostatic intolerance. Recumbent exercise targets deconditioning and can tamp down the hyperadrenergic effect. Dr. Shouman’s approach is to start gradually with swimming or the use of a recumbent bike or a rowing machine.

Dr. Taub recommends wearables to patients because POTS is “a very dynamic condition” that is easy to overmedicate or undermedicate. If it’s a good day, the patients are well hydrated, and the standing heart rate is only 80 bpm, she tells them they could titrate down their second dose of ivabradine, for example. The feedback from wearables also helps patients manage their exercise response.

For Dr. Shouman, wearables are not always as accurate as he would like. He tells his patients that it’s okay to use one as long as it doesn’t become a source of anxiety such that they’re constantly checking it.

POTS hope: A COVID-19 silver lining?

With increasing attention being paid to long-haul COVID-19, are there any concerns that POTS will get lost among the myriad symptoms connected to PASC?

Dr. Shouman cautioned, “Not all long COVID is POTS,” and said that clinicians at long-haul clinics should be able to recognize the different conditions “when POTS is suspected. I think it is useful for those providers to make the appropriate referral for POTS clinic autonomic assessment.”

He and his colleagues at Mayo have seen quite a few patients who have post–COVID-19 autonomic dysfunction, such as vasodepressor syncope, not just POTS. They plan to write about this soon.

“Of all the things I treat in cardiology, this is the most complex, because there’s so many different systems involved,” said Dr. Taub, who has seen patients recover fully from POTS. “There’s a spectrum, and there’s people that are definitely on one end of the spectrum where they have very severe diseases.”

For her, the important message is, “No matter where you are on the spectrum, there are things we can do to make your symptoms better.” And with grant funding for PASC research, “hopefully we will address the mechanisms of disease, and we’ll be able to cure this,” she said.

Dr. Patel has served as a consultant for Bayer, Janssen, AstraZeneca, and Heartflow and has received research grants from Bayer, Janssen, AstraZeneca, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Shouman reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Homeland Security/FEMA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Before COVID-19, postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) was one of those diseases that many people, including physicians, dismissed.

“They thought it was just anxious, crazy young women,” said Pam R. Taub, MD, who runs the cardiac rehabilitation program at the University of California, San Diego.

The cryptic autonomic condition was estimated to affect 1-3 million Americans before the pandemic hit. Now case reports confirm that it is a manifestation of postacute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC), or so-called long-haul COVID-19.

“I’m excited that this condition that has been so often the ugly stepchild of both cardiology and neurology is getting some attention,” said Dr. Taub. She said she is hopeful that the National Institutes of Health’s commitment to PASC research will benefit patients affected by the cardiovascular dysautonomia characterized by orthostatic intolerance in the absence of orthostatic hypotension.

Postinfection POTS is not exclusive to SARS-CoV-2. It has been reported after Lyme disease and Epstein-Barr virus infections, for example. One theory is that some of the antibodies generated against the virus cross react and damage the autonomic nervous system, which regulates heart rate and blood pressure, Dr. Taub explained.

It is not known whether COVID-19 is more likely to trigger POTS than are other infections or whether the rise in cases merely reflects the fact that more than 115 million people worldwide have been infected with the novel coronavirus.

Low blood volume, dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system, and autoimmunity may all play a role in POTS, perhaps leading to distinct subtypes, according to a State of the Science document from the NIH; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

In Dr. Taub’s experience, “The truth is that patients actually have a mix of the subtypes.”

Kamal Shouman, MD, an autonomic neurologist at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn., said in an interview that he has seen patients present with post–COVID-19 POTS in “all flavors,” including “neuropathic POTS, which is thought of as the classic postinfectious phenomenon.”

Why does it mostly affect athletic women?

The condition, which can be the result of dehydration or prolonged bed rest, leading to deconditioning, affects women disproportionately.

According to Manesh Patel, MD, if a patient with POTS who is not a young woman is presented on medical rounds, the response is, “Tell me again why you think this patient has POTS.”

Dr. Patel, chief of the division of cardiology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., has a theory for why many of the women who have POTS are athletes or are highly active: They likely have an underlying predisposition, compounded by a smaller body volume, leaving less margin for error. “If they decondition and lose 500 cc’s, it makes a bigger difference to them than, say, a 300-pound offensive lineman,” Dr. Patel explained.

That hypothesis makes sense to Dr. Taub, who added, “There are just some people metabolically that are more hyperadrenergic,” and it may be that “all their activity really helps tone down that sympathetic output,” but the infection affects these regulatory processes, and deconditioning disrupts things further.

Women also have more autoimmune disorders than do men. The driving force of the dysregulation of the autonomic nervous system is thought to be “immune mediated; we think it’s triggered by a response to a virus,” she said.

Dr. Shouman said the underlying susceptibility may predispose toward orthostatic intolerance. For example, patients will tell him, “Well, many years ago, I was prone to fainting.” He emphasized that POTS is not exclusive to women – he sees men with POTS, and one of the three recent case reports of post–COVID-19 POTS involved a 37-year-old man. So far, the male POTS patients that Dr. Patel has encountered have been deconditioned athletes.

Poor (wo)man’s tilt test and treatment options

POTS is typically diagnosed with a tilt test and transcranial Doppler. Dr. Taub described her “poor man’s tilt test” of asking the patient to lie down for 5-10 minutes and then having the patient stand up.

She likes the fact that transcranial Doppler helps validate the brain fog that patients report, which can be dismissed as “just your excuse for not wanting to work.” If blood perfusion to the brain is cut by 40%-50%, “how are you going to think clearly?” she said.

Dr. Shouman noted that overall volume expansion with salt water, compression garments, and a graduated exercise program play a major role in the rehabilitation of all POTS patients.

He likes to tailor treatments to the most likely underlying cause. But patients should first undergo a medical assessment by their internists to make sure there isn’t a primary lung or heart problem.

“Once the decision is made for them to be evaluated in the autonomic practice and [a] POTS diagnosis is made, I think it is very useful to determine what type of POTS,” he said.

With hyperadrenergic POTS, “you are looking at a standing norepinephrine level of over 600 pg/mL or so.” For these patients, drugs such as ivabradine or beta-blockers can help, he noted.

Dr. Taub recently conducted a small study that showed a benefit with the selective If channel blocker ivabradine for patients with hyperadrenergic POTS unrelated to COVID-19. She tends to favor ivabradine over beta-blockers because it lowers heart rate but not blood pressure. In addition, beta-blockers can exacerbate fatigue and brain fog.

A small crossover study will compare propranolol and ivabradine in POTS. For someone who is very hypovolemic, “you might try a salt tablet or a prescription drug like fludrocortisone,” Dr. Taub explained.

Another problem that patients with POTS experience is an inability to exercise because of orthostatic intolerance. Recumbent exercise targets deconditioning and can tamp down the hyperadrenergic effect. Dr. Shouman’s approach is to start gradually with swimming or the use of a recumbent bike or a rowing machine.

Dr. Taub recommends wearables to patients because POTS is “a very dynamic condition” that is easy to overmedicate or undermedicate. If it’s a good day, the patients are well hydrated, and the standing heart rate is only 80 bpm, she tells them they could titrate down their second dose of ivabradine, for example. The feedback from wearables also helps patients manage their exercise response.

For Dr. Shouman, wearables are not always as accurate as he would like. He tells his patients that it’s okay to use one as long as it doesn’t become a source of anxiety such that they’re constantly checking it.

POTS hope: A COVID-19 silver lining?

With increasing attention being paid to long-haul COVID-19, are there any concerns that POTS will get lost among the myriad symptoms connected to PASC?

Dr. Shouman cautioned, “Not all long COVID is POTS,” and said that clinicians at long-haul clinics should be able to recognize the different conditions “when POTS is suspected. I think it is useful for those providers to make the appropriate referral for POTS clinic autonomic assessment.”

He and his colleagues at Mayo have seen quite a few patients who have post–COVID-19 autonomic dysfunction, such as vasodepressor syncope, not just POTS. They plan to write about this soon.

“Of all the things I treat in cardiology, this is the most complex, because there’s so many different systems involved,” said Dr. Taub, who has seen patients recover fully from POTS. “There’s a spectrum, and there’s people that are definitely on one end of the spectrum where they have very severe diseases.”

For her, the important message is, “No matter where you are on the spectrum, there are things we can do to make your symptoms better.” And with grant funding for PASC research, “hopefully we will address the mechanisms of disease, and we’ll be able to cure this,” she said.

Dr. Patel has served as a consultant for Bayer, Janssen, AstraZeneca, and Heartflow and has received research grants from Bayer, Janssen, AstraZeneca, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Shouman reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Taub has served as a consultant for Amgen, Bayer, Esperion, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; is a shareholder in Epirium Bio; and has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, and the Department of Homeland Security/FEMA.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Febuxostat, allopurinol real-world cardiovascular risk appears equal

Febuxostat (Uloric) was not associated with increased cardiovascular risk in patients with gout when compared to those who used allopurinol, in an analysis of new users of the drugs in Medicare fee-for-service claims data from the period of 2008-2016.

The findings, published March 25 in the Journal of the American Heart Association, update and echo the results from a similar previous study by the same Brigham and Women’s Hospital research group that covered 2008-2013 Medicare claims data. That original claims data study from 2018 sought to confirm the findings of the postmarketing surveillance CARES (Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat and Allopurinol in Patients With Gout and Cardiovascular Morbidities) trial that led to a boxed warning for increased risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality vs. allopurinol. The trial, however, did not show a higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) overall with febuxostat.

The recency of the new data with more febuxostat-exposed patients overall provides greater reassurance on the safety of the drug, corresponding author Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “We also were able to get data on cause of death, which we did not have before when we conducted our first paper.”

Dr. Kim said she was not surprised by any of the findings, which were consistent with the results of her earlier work. “Our result on CV death also was consistent and reassuring,” she noted.

The newest Medicare claims study also corroborates results from FAST (Febuxostat Versus Allopurinol Streamlined Trial), a separate postmarketing surveillance study that was ordered by the European Medicines Agency after febuxostat’s approval in 2009. It showed that the two drugs were noninferior to each other for the risk of all-cause mortality or a composite cardiovascular outcome (hospitalization for nonfatal myocardial infarction, biomarker-positive acute coronary syndrome, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death).

“While CARES showed higher CV death and all-cause death rates in febuxostat compared to allopurinol, FAST did not,” Dr. Kim noted. “Our study of more than 111,000 older gout patients treated with either febuxostat or allopurinol in real-world settings also did not find a difference in the risk of MACE, CV mortality, or all-cause mortality,” she added. “Taking these data all together, I think we can be more certain about the CV safety of febuxostat when its use is clinically indicated or needed,” she said.

Study details

Dr. Kim, first author Ajinkya Pawar, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s, and colleagues identified 467,461 people with gout aged 65 years and older who had been enrolled in Medicare for at least a year. They then used propensity-score matching to compare 27,881 first-time users of febuxostat with 83,643 first-time users of allopurinol on the primary outcome of the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as the first occurrence of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular mortality.

In the updated study, the mean follow‐up periods for febuxostat and allopurinol were 284 days and 339 days, respectively. Overall, febuxostat was noninferior to allopurinol with regard to MACE (hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.05), and the results were consistent among patients with baseline CVD (HR, 0.94). In addition, rates of secondary outcomes of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality were not significantly different between febuxostat and allopurinol patients, except for all-cause mortality (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.87-0.98).

The study findings were limited mainly by the potential bias caused by nonadherence to medications, and potential for residual confounding and misclassification bias, the researchers noted.

However, the study was strengthened by its incident new-user design that allowed only patients with no use of either medication for a year before the first dispensing and its active comparator design, and the data are generalizable to the greater population of older gout patients, they said.

Consequently, the data from this large, real-world study support the safety of febuxostat with regard to cardiovascular risk in gout patients, including those with baseline cardiovascular disease, they concluded.

The study was supported by the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Kim disclosed research grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Roche, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb for unrelated studies. Another author reported serving as the principal investigator with research grants from Vertex, Bayer, and Novartis to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for unrelated projects.

Febuxostat (Uloric) was not associated with increased cardiovascular risk in patients with gout when compared to those who used allopurinol, in an analysis of new users of the drugs in Medicare fee-for-service claims data from the period of 2008-2016.

The findings, published March 25 in the Journal of the American Heart Association, update and echo the results from a similar previous study by the same Brigham and Women’s Hospital research group that covered 2008-2013 Medicare claims data. That original claims data study from 2018 sought to confirm the findings of the postmarketing surveillance CARES (Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat and Allopurinol in Patients With Gout and Cardiovascular Morbidities) trial that led to a boxed warning for increased risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality vs. allopurinol. The trial, however, did not show a higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) overall with febuxostat.

The recency of the new data with more febuxostat-exposed patients overall provides greater reassurance on the safety of the drug, corresponding author Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “We also were able to get data on cause of death, which we did not have before when we conducted our first paper.”

Dr. Kim said she was not surprised by any of the findings, which were consistent with the results of her earlier work. “Our result on CV death also was consistent and reassuring,” she noted.

The newest Medicare claims study also corroborates results from FAST (Febuxostat Versus Allopurinol Streamlined Trial), a separate postmarketing surveillance study that was ordered by the European Medicines Agency after febuxostat’s approval in 2009. It showed that the two drugs were noninferior to each other for the risk of all-cause mortality or a composite cardiovascular outcome (hospitalization for nonfatal myocardial infarction, biomarker-positive acute coronary syndrome, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death).

“While CARES showed higher CV death and all-cause death rates in febuxostat compared to allopurinol, FAST did not,” Dr. Kim noted. “Our study of more than 111,000 older gout patients treated with either febuxostat or allopurinol in real-world settings also did not find a difference in the risk of MACE, CV mortality, or all-cause mortality,” she added. “Taking these data all together, I think we can be more certain about the CV safety of febuxostat when its use is clinically indicated or needed,” she said.

Study details

Dr. Kim, first author Ajinkya Pawar, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s, and colleagues identified 467,461 people with gout aged 65 years and older who had been enrolled in Medicare for at least a year. They then used propensity-score matching to compare 27,881 first-time users of febuxostat with 83,643 first-time users of allopurinol on the primary outcome of the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as the first occurrence of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular mortality.

In the updated study, the mean follow‐up periods for febuxostat and allopurinol were 284 days and 339 days, respectively. Overall, febuxostat was noninferior to allopurinol with regard to MACE (hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.05), and the results were consistent among patients with baseline CVD (HR, 0.94). In addition, rates of secondary outcomes of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality were not significantly different between febuxostat and allopurinol patients, except for all-cause mortality (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.87-0.98).

The study findings were limited mainly by the potential bias caused by nonadherence to medications, and potential for residual confounding and misclassification bias, the researchers noted.

However, the study was strengthened by its incident new-user design that allowed only patients with no use of either medication for a year before the first dispensing and its active comparator design, and the data are generalizable to the greater population of older gout patients, they said.

Consequently, the data from this large, real-world study support the safety of febuxostat with regard to cardiovascular risk in gout patients, including those with baseline cardiovascular disease, they concluded.

The study was supported by the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Kim disclosed research grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Roche, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb for unrelated studies. Another author reported serving as the principal investigator with research grants from Vertex, Bayer, and Novartis to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for unrelated projects.

Febuxostat (Uloric) was not associated with increased cardiovascular risk in patients with gout when compared to those who used allopurinol, in an analysis of new users of the drugs in Medicare fee-for-service claims data from the period of 2008-2016.

The findings, published March 25 in the Journal of the American Heart Association, update and echo the results from a similar previous study by the same Brigham and Women’s Hospital research group that covered 2008-2013 Medicare claims data. That original claims data study from 2018 sought to confirm the findings of the postmarketing surveillance CARES (Cardiovascular Safety of Febuxostat and Allopurinol in Patients With Gout and Cardiovascular Morbidities) trial that led to a boxed warning for increased risk of cardiovascular and all-cause mortality vs. allopurinol. The trial, however, did not show a higher rate of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) overall with febuxostat.

The recency of the new data with more febuxostat-exposed patients overall provides greater reassurance on the safety of the drug, corresponding author Seoyoung C. Kim, MD, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an interview. “We also were able to get data on cause of death, which we did not have before when we conducted our first paper.”

Dr. Kim said she was not surprised by any of the findings, which were consistent with the results of her earlier work. “Our result on CV death also was consistent and reassuring,” she noted.

The newest Medicare claims study also corroborates results from FAST (Febuxostat Versus Allopurinol Streamlined Trial), a separate postmarketing surveillance study that was ordered by the European Medicines Agency after febuxostat’s approval in 2009. It showed that the two drugs were noninferior to each other for the risk of all-cause mortality or a composite cardiovascular outcome (hospitalization for nonfatal myocardial infarction, biomarker-positive acute coronary syndrome, nonfatal stroke, or cardiovascular death).

“While CARES showed higher CV death and all-cause death rates in febuxostat compared to allopurinol, FAST did not,” Dr. Kim noted. “Our study of more than 111,000 older gout patients treated with either febuxostat or allopurinol in real-world settings also did not find a difference in the risk of MACE, CV mortality, or all-cause mortality,” she added. “Taking these data all together, I think we can be more certain about the CV safety of febuxostat when its use is clinically indicated or needed,” she said.

Study details

Dr. Kim, first author Ajinkya Pawar, PhD, of Brigham and Women’s, and colleagues identified 467,461 people with gout aged 65 years and older who had been enrolled in Medicare for at least a year. They then used propensity-score matching to compare 27,881 first-time users of febuxostat with 83,643 first-time users of allopurinol on the primary outcome of the incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), defined as the first occurrence of myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular mortality.

In the updated study, the mean follow‐up periods for febuxostat and allopurinol were 284 days and 339 days, respectively. Overall, febuxostat was noninferior to allopurinol with regard to MACE (hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% confidence interval, 0.93-1.05), and the results were consistent among patients with baseline CVD (HR, 0.94). In addition, rates of secondary outcomes of MI, stroke, and cardiovascular mortality were not significantly different between febuxostat and allopurinol patients, except for all-cause mortality (HR, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.87-0.98).

The study findings were limited mainly by the potential bias caused by nonadherence to medications, and potential for residual confounding and misclassification bias, the researchers noted.

However, the study was strengthened by its incident new-user design that allowed only patients with no use of either medication for a year before the first dispensing and its active comparator design, and the data are generalizable to the greater population of older gout patients, they said.

Consequently, the data from this large, real-world study support the safety of febuxostat with regard to cardiovascular risk in gout patients, including those with baseline cardiovascular disease, they concluded.

The study was supported by the division of pharmacoepidemiology and pharmacoeconomics at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Dr. Kim disclosed research grants to Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Roche, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Bristol‐Myers Squibb for unrelated studies. Another author reported serving as the principal investigator with research grants from Vertex, Bayer, and Novartis to Brigham and Women’s Hospital for unrelated projects.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HEART ASSOCIATION

Cardiologist forks out $2M to resolve unnecessary testing claims

Michigan cardiologist Dinesh M. Shah, MD, has paid the United States $2 million to resolve claims he violated the False Claims Act by knowingly billing federal health care programs for diagnostic tests that were unnecessary or not performed, the Department of Justice announced.

The settlement resolves allegations that, from 2006 to 2017, Dr. Shah and his practice, Michigan Physicians Group (MPG), of which he is sole owner, billed Medicare, Medicaid, and TRICARE for unnecessary diagnostic tests, including ankle brachial index and toe brachial index tests that were routinely performed on patients without first being ordered by a physician and without regard to medical necessity.

The prosecutors also alleged that Dr. Shah was routinely ordering, and MPG was providing, unnecessary nuclear stress tests to some patients.

“Subjecting patients to unnecessary testing in order to fill one’s pockets with taxpayer funds will not be tolerated. Such practices are particularly concerning because overuse of some tests can be harmful to patients,” acting U.S. Attorney Saima Mohsin said in the news release. “With these lawsuits and the accompanying resolution, Dr. Shah and Michigan Physicians Group are being held to account for these exploitative and improper past practices.”

In addition to the settlement, Dr. Shah and MPG entered into an Integrity Agreement with the Office of Inspector General for the Department of Health & Human Services, which will provide oversight of Dr. Shah and MPG’s billing practices for a 3-year period.

There was “no determination of liability” with the settlement, according to the Department of Justice. Dr. Shah’s case was sparked by two whistleblower lawsuits filed by Arlene Klinke and Khrystyna Malva, both former MPG employees.

The settlement comes after a years-long investigation by the HHS acting on behalf of TRICARE, a health care program for active and retired military members. Allegations that William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Mich., paid eight physicians excessive compensation to increase patient referrals led to an $84.5 million settlement in 2018.

Dr. Shah was one of three private practice cardiologists who denied involvement in the scheme but were named in the settlement, according to Crain’s Detroit Business.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Michigan cardiologist Dinesh M. Shah, MD, has paid the United States $2 million to resolve claims he violated the False Claims Act by knowingly billing federal health care programs for diagnostic tests that were unnecessary or not performed, the Department of Justice announced.

The settlement resolves allegations that, from 2006 to 2017, Dr. Shah and his practice, Michigan Physicians Group (MPG), of which he is sole owner, billed Medicare, Medicaid, and TRICARE for unnecessary diagnostic tests, including ankle brachial index and toe brachial index tests that were routinely performed on patients without first being ordered by a physician and without regard to medical necessity.

The prosecutors also alleged that Dr. Shah was routinely ordering, and MPG was providing, unnecessary nuclear stress tests to some patients.

“Subjecting patients to unnecessary testing in order to fill one’s pockets with taxpayer funds will not be tolerated. Such practices are particularly concerning because overuse of some tests can be harmful to patients,” acting U.S. Attorney Saima Mohsin said in the news release. “With these lawsuits and the accompanying resolution, Dr. Shah and Michigan Physicians Group are being held to account for these exploitative and improper past practices.”

In addition to the settlement, Dr. Shah and MPG entered into an Integrity Agreement with the Office of Inspector General for the Department of Health & Human Services, which will provide oversight of Dr. Shah and MPG’s billing practices for a 3-year period.

There was “no determination of liability” with the settlement, according to the Department of Justice. Dr. Shah’s case was sparked by two whistleblower lawsuits filed by Arlene Klinke and Khrystyna Malva, both former MPG employees.

The settlement comes after a years-long investigation by the HHS acting on behalf of TRICARE, a health care program for active and retired military members. Allegations that William Beaumont Hospital in Royal Oak, Mich., paid eight physicians excessive compensation to increase patient referrals led to an $84.5 million settlement in 2018.

Dr. Shah was one of three private practice cardiologists who denied involvement in the scheme but were named in the settlement, according to Crain’s Detroit Business.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Michigan cardiologist Dinesh M. Shah, MD, has paid the United States $2 million to resolve claims he violated the False Claims Act by knowingly billing federal health care programs for diagnostic tests that were unnecessary or not performed, the Department of Justice announced.