User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

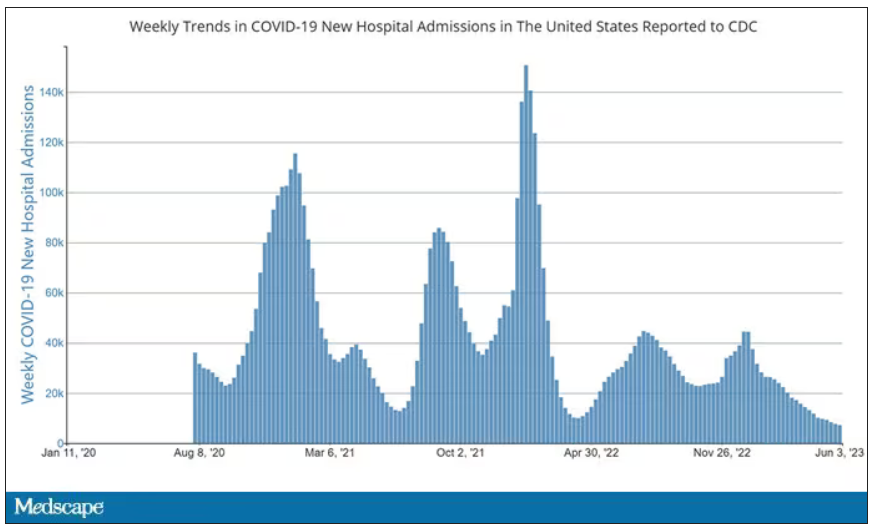

Millions who had COVID-19 still don’t have sense of smell, taste

Almost 36 million people were diagnosed in 2021, and 60% of them reported accompanying losses in smell or taste, according to the study by Mass Eye and Ear, which is affiliated with Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published in The Laryngoscope.

Most people fully regained the senses, but about 24% didn’t get smell back completely, and more than 3% had no recovery, the researchers reported. The numbers were similar among those who lost the sense of taste, they added.

“Many people never fully recovered,” Neil Bhattacharyya, MD, professor of otolaryngology and one of the study’s authors, told Fortune, estimating that up to 6 million people still have lingering symptoms. “If you lost your sense of smell, did you get it back? There’s about a one in four chance you didn’t. That’s terrible.”

Researchers looked at the records of 30,000 adults who had COVID-19 in 2021. They reported that patients who suffered more severe cases were less likely to regain some or all their senses.

Some patients said they lost appetite because they couldn’t smell food. There’s concern, too, about losing the ability to smell gas and smoke, spoiled food, and dirty diapers.

People with symptoms should see their doctors, Dr. Bhattacharyya said. The symptoms might be caused by something other than lingering COVID-19 effects and might be treatable.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Almost 36 million people were diagnosed in 2021, and 60% of them reported accompanying losses in smell or taste, according to the study by Mass Eye and Ear, which is affiliated with Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published in The Laryngoscope.

Most people fully regained the senses, but about 24% didn’t get smell back completely, and more than 3% had no recovery, the researchers reported. The numbers were similar among those who lost the sense of taste, they added.

“Many people never fully recovered,” Neil Bhattacharyya, MD, professor of otolaryngology and one of the study’s authors, told Fortune, estimating that up to 6 million people still have lingering symptoms. “If you lost your sense of smell, did you get it back? There’s about a one in four chance you didn’t. That’s terrible.”

Researchers looked at the records of 30,000 adults who had COVID-19 in 2021. They reported that patients who suffered more severe cases were less likely to regain some or all their senses.

Some patients said they lost appetite because they couldn’t smell food. There’s concern, too, about losing the ability to smell gas and smoke, spoiled food, and dirty diapers.

People with symptoms should see their doctors, Dr. Bhattacharyya said. The symptoms might be caused by something other than lingering COVID-19 effects and might be treatable.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Almost 36 million people were diagnosed in 2021, and 60% of them reported accompanying losses in smell or taste, according to the study by Mass Eye and Ear, which is affiliated with Harvard Medical School, Boston. The study was published in The Laryngoscope.

Most people fully regained the senses, but about 24% didn’t get smell back completely, and more than 3% had no recovery, the researchers reported. The numbers were similar among those who lost the sense of taste, they added.

“Many people never fully recovered,” Neil Bhattacharyya, MD, professor of otolaryngology and one of the study’s authors, told Fortune, estimating that up to 6 million people still have lingering symptoms. “If you lost your sense of smell, did you get it back? There’s about a one in four chance you didn’t. That’s terrible.”

Researchers looked at the records of 30,000 adults who had COVID-19 in 2021. They reported that patients who suffered more severe cases were less likely to regain some or all their senses.

Some patients said they lost appetite because they couldn’t smell food. There’s concern, too, about losing the ability to smell gas and smoke, spoiled food, and dirty diapers.

People with symptoms should see their doctors, Dr. Bhattacharyya said. The symptoms might be caused by something other than lingering COVID-19 effects and might be treatable.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM THE LARYNGOSCOPE

Alcohol may curb stress signaling in brain to protect heart

The study shows that light to moderate drinking was associated with lower major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and this was partly mediated by decreased stress signaling in the brain.

In addition, the benefit of light to moderate drinking with respect to MACE was most pronounced among people with a history of anxiety, a condition known to be associated with higher stress signaling in the brain.

However, the apparent CVD benefits of light to moderate drinking were counterbalanced by an increased risk of cancer.

“There is no safe level of alcohol consumption,” senior author and cardiologist Ahmed Tawakol, MD, codirector of the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“We see cancer risk even at the level that we see some protection from heart disease. And higher amounts of alcohol clearly increase heart disease risk,” Dr. Tawakol said.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Clear mechanistic link

Chronic stress is associated with MACE via stress-related neural network activity (SNA). Light to moderate alcohol consumption has been linked to lower MACE risk, but the mechanisms behind this connection remain unclear.

“We know that when the neural centers of stress are activated, they trigger downstream changes that result in heart disease. And we’ve long appreciated that alcohol in the short term reduces stress, so we hypothesized that maybe alcohol impacts those stress systems chronically and that might explain its cardiovascular effects,” Dr. Tawakol explained.

The study included roughly 53,000 adults (mean age, 60 years; 60% women) from the Mass General Brigham Biobank. The researchers first evaluated the relationship between light to moderate alcohol consumption and MACE after adjusting for a range of genetic, clinical, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors.

During mean follow-up of 3.4 years, 1,914 individuals experienced MACE. Light to moderate alcohol consumption (compared to none/minimal) was associated with lower MACE risk (hazard ratio [HR], 0.786; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.717-0.862; P < .0001) after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors.

The researchers then studied a subset of 713 individuals who had undergone previous PET/CT brain imaging (primarily for cancer surveillance) to determine the effect of light to moderate alcohol consumption on resting SNA.

They found that light to moderate alcohol consumption correlated with decreased SNA (standardized beta, –0.192; 95% CI, –0.338 to 0.046; P = .01). Lower SNA partially mediated the beneficial effect of light to moderate alcohol intake on MACE risk (odds ratio [OR], –0.040; 95% CI, –0.097 to –0.003; P < .05).

Light to moderate alcohol consumption was associated with larger decreases in MACE risk among individuals with a history of anxiety (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50-0.72, vs. HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 0.73-0.80; P = .003).

The coauthors of an editorial say the discovery of a “new possible mechanism of action” for why light to moderate alcohol consumption might protect the heart “deserves closer attention in future investigations.”

However, Giovanni de Gaetano, MD, PhD, department of epidemiology and prevention, IRCCS NEUROMED, Pozzilli, Italy, one of the authors, emphasized that individuals who consume alcohol should not “exceed the recommended daily dose limits suggested in many countries and that no abstainer should start to drink, even in moderation, solely for the purpose of improving his/her health outcomes.”

Dr. Tawakol and colleagues said that, given alcohol’s adverse health effects, such as heightened cancer risk, new interventions that have positive effects on the neurobiology of stress but without the harmful effects of alcohol are needed.

To that end, they are studying the effect of exercise, stress-reduction interventions such as meditation, and pharmacologic therapies on stress-associated neural networks, and how they might induce CV benefits.

Dr. Tawakol said in an interview that one “additional important message is that anxiety and other related conditions like depression have really substantial health consequences, including increased MACE. Safer interventions that reduce anxiety may yet prove to reduce the risk of heart disease very nicely.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Tawakol and Dr. de Gaetano have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The study shows that light to moderate drinking was associated with lower major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and this was partly mediated by decreased stress signaling in the brain.

In addition, the benefit of light to moderate drinking with respect to MACE was most pronounced among people with a history of anxiety, a condition known to be associated with higher stress signaling in the brain.

However, the apparent CVD benefits of light to moderate drinking were counterbalanced by an increased risk of cancer.

“There is no safe level of alcohol consumption,” senior author and cardiologist Ahmed Tawakol, MD, codirector of the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“We see cancer risk even at the level that we see some protection from heart disease. And higher amounts of alcohol clearly increase heart disease risk,” Dr. Tawakol said.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Clear mechanistic link

Chronic stress is associated with MACE via stress-related neural network activity (SNA). Light to moderate alcohol consumption has been linked to lower MACE risk, but the mechanisms behind this connection remain unclear.

“We know that when the neural centers of stress are activated, they trigger downstream changes that result in heart disease. And we’ve long appreciated that alcohol in the short term reduces stress, so we hypothesized that maybe alcohol impacts those stress systems chronically and that might explain its cardiovascular effects,” Dr. Tawakol explained.

The study included roughly 53,000 adults (mean age, 60 years; 60% women) from the Mass General Brigham Biobank. The researchers first evaluated the relationship between light to moderate alcohol consumption and MACE after adjusting for a range of genetic, clinical, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors.

During mean follow-up of 3.4 years, 1,914 individuals experienced MACE. Light to moderate alcohol consumption (compared to none/minimal) was associated with lower MACE risk (hazard ratio [HR], 0.786; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.717-0.862; P < .0001) after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors.

The researchers then studied a subset of 713 individuals who had undergone previous PET/CT brain imaging (primarily for cancer surveillance) to determine the effect of light to moderate alcohol consumption on resting SNA.

They found that light to moderate alcohol consumption correlated with decreased SNA (standardized beta, –0.192; 95% CI, –0.338 to 0.046; P = .01). Lower SNA partially mediated the beneficial effect of light to moderate alcohol intake on MACE risk (odds ratio [OR], –0.040; 95% CI, –0.097 to –0.003; P < .05).

Light to moderate alcohol consumption was associated with larger decreases in MACE risk among individuals with a history of anxiety (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50-0.72, vs. HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 0.73-0.80; P = .003).

The coauthors of an editorial say the discovery of a “new possible mechanism of action” for why light to moderate alcohol consumption might protect the heart “deserves closer attention in future investigations.”

However, Giovanni de Gaetano, MD, PhD, department of epidemiology and prevention, IRCCS NEUROMED, Pozzilli, Italy, one of the authors, emphasized that individuals who consume alcohol should not “exceed the recommended daily dose limits suggested in many countries and that no abstainer should start to drink, even in moderation, solely for the purpose of improving his/her health outcomes.”

Dr. Tawakol and colleagues said that, given alcohol’s adverse health effects, such as heightened cancer risk, new interventions that have positive effects on the neurobiology of stress but without the harmful effects of alcohol are needed.

To that end, they are studying the effect of exercise, stress-reduction interventions such as meditation, and pharmacologic therapies on stress-associated neural networks, and how they might induce CV benefits.

Dr. Tawakol said in an interview that one “additional important message is that anxiety and other related conditions like depression have really substantial health consequences, including increased MACE. Safer interventions that reduce anxiety may yet prove to reduce the risk of heart disease very nicely.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Tawakol and Dr. de Gaetano have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The study shows that light to moderate drinking was associated with lower major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and this was partly mediated by decreased stress signaling in the brain.

In addition, the benefit of light to moderate drinking with respect to MACE was most pronounced among people with a history of anxiety, a condition known to be associated with higher stress signaling in the brain.

However, the apparent CVD benefits of light to moderate drinking were counterbalanced by an increased risk of cancer.

“There is no safe level of alcohol consumption,” senior author and cardiologist Ahmed Tawakol, MD, codirector of the Cardiovascular Imaging Research Center at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, said in an interview.

“We see cancer risk even at the level that we see some protection from heart disease. And higher amounts of alcohol clearly increase heart disease risk,” Dr. Tawakol said.

The study was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

Clear mechanistic link

Chronic stress is associated with MACE via stress-related neural network activity (SNA). Light to moderate alcohol consumption has been linked to lower MACE risk, but the mechanisms behind this connection remain unclear.

“We know that when the neural centers of stress are activated, they trigger downstream changes that result in heart disease. And we’ve long appreciated that alcohol in the short term reduces stress, so we hypothesized that maybe alcohol impacts those stress systems chronically and that might explain its cardiovascular effects,” Dr. Tawakol explained.

The study included roughly 53,000 adults (mean age, 60 years; 60% women) from the Mass General Brigham Biobank. The researchers first evaluated the relationship between light to moderate alcohol consumption and MACE after adjusting for a range of genetic, clinical, lifestyle, and socioeconomic factors.

During mean follow-up of 3.4 years, 1,914 individuals experienced MACE. Light to moderate alcohol consumption (compared to none/minimal) was associated with lower MACE risk (hazard ratio [HR], 0.786; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.717-0.862; P < .0001) after adjustment for cardiovascular risk factors.

The researchers then studied a subset of 713 individuals who had undergone previous PET/CT brain imaging (primarily for cancer surveillance) to determine the effect of light to moderate alcohol consumption on resting SNA.

They found that light to moderate alcohol consumption correlated with decreased SNA (standardized beta, –0.192; 95% CI, –0.338 to 0.046; P = .01). Lower SNA partially mediated the beneficial effect of light to moderate alcohol intake on MACE risk (odds ratio [OR], –0.040; 95% CI, –0.097 to –0.003; P < .05).

Light to moderate alcohol consumption was associated with larger decreases in MACE risk among individuals with a history of anxiety (HR, 0.60; 95% CI, 0.50-0.72, vs. HR, 1.78; 95% CI, 0.73-0.80; P = .003).

The coauthors of an editorial say the discovery of a “new possible mechanism of action” for why light to moderate alcohol consumption might protect the heart “deserves closer attention in future investigations.”

However, Giovanni de Gaetano, MD, PhD, department of epidemiology and prevention, IRCCS NEUROMED, Pozzilli, Italy, one of the authors, emphasized that individuals who consume alcohol should not “exceed the recommended daily dose limits suggested in many countries and that no abstainer should start to drink, even in moderation, solely for the purpose of improving his/her health outcomes.”

Dr. Tawakol and colleagues said that, given alcohol’s adverse health effects, such as heightened cancer risk, new interventions that have positive effects on the neurobiology of stress but without the harmful effects of alcohol are needed.

To that end, they are studying the effect of exercise, stress-reduction interventions such as meditation, and pharmacologic therapies on stress-associated neural networks, and how they might induce CV benefits.

Dr. Tawakol said in an interview that one “additional important message is that anxiety and other related conditions like depression have really substantial health consequences, including increased MACE. Safer interventions that reduce anxiety may yet prove to reduce the risk of heart disease very nicely.”

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Tawakol and Dr. de Gaetano have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

The cardiopulmonary effects of mask wearing

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

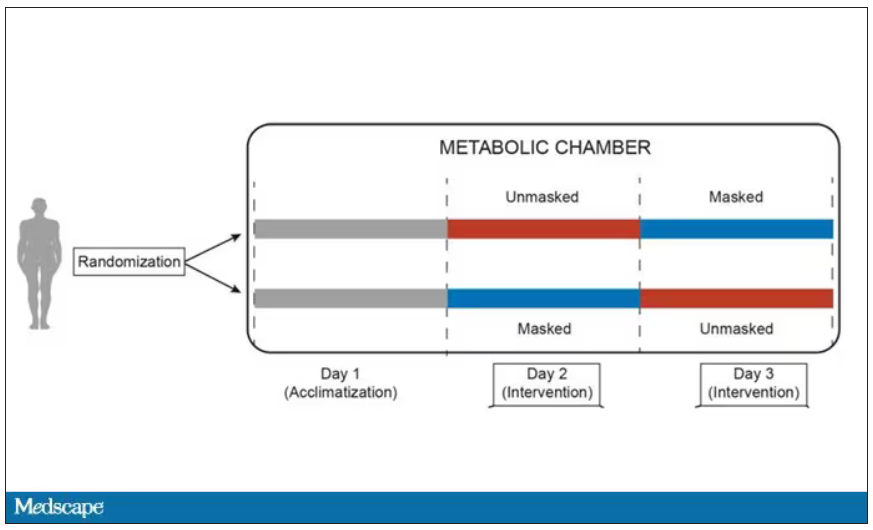

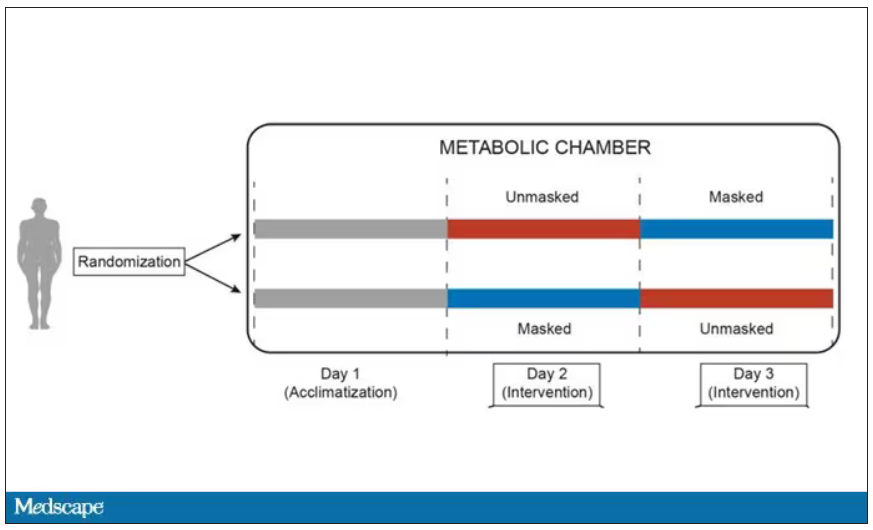

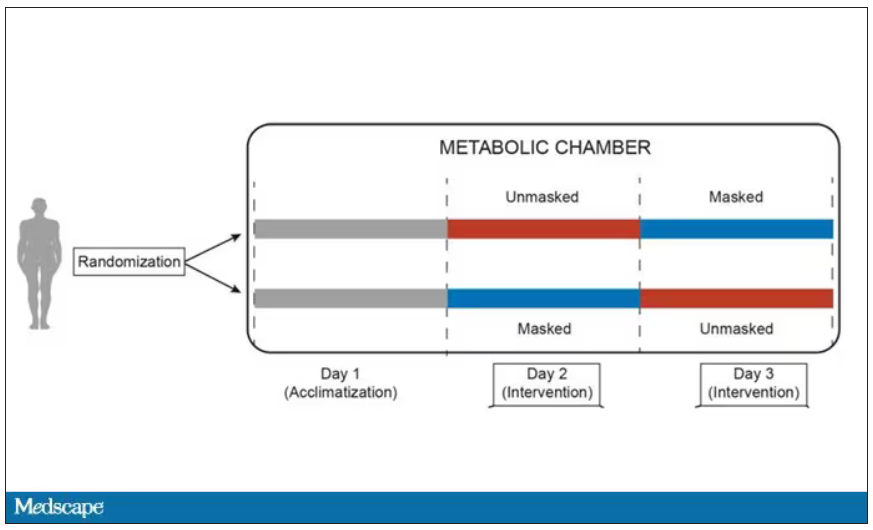

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

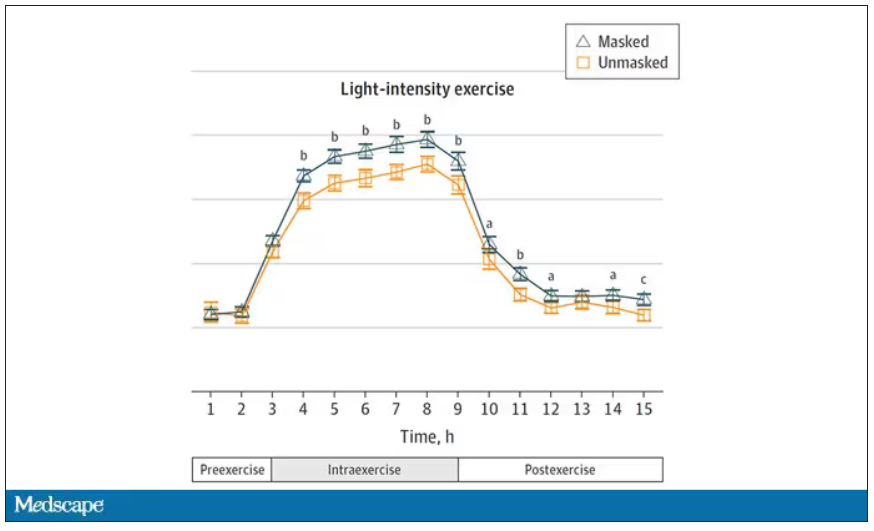

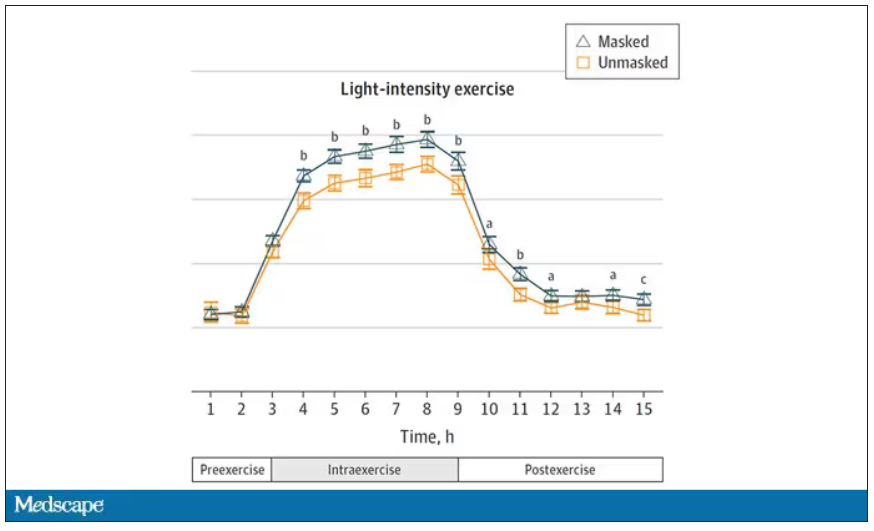

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

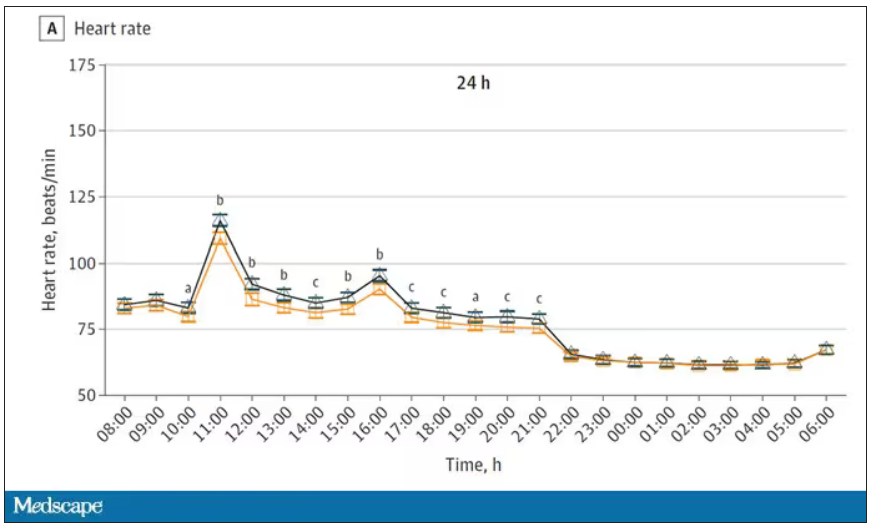

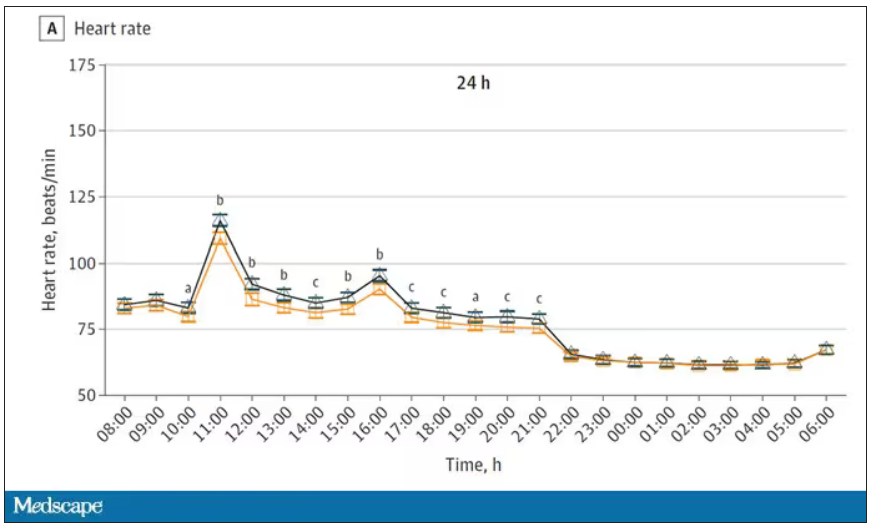

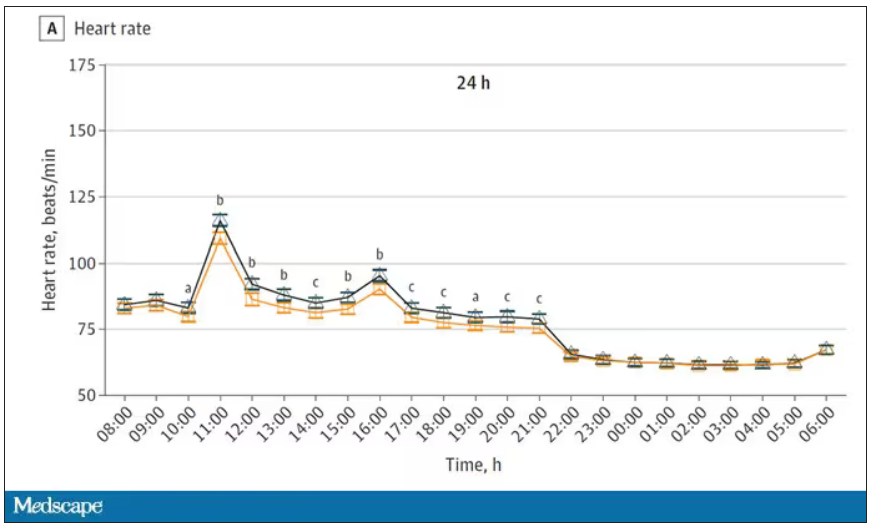

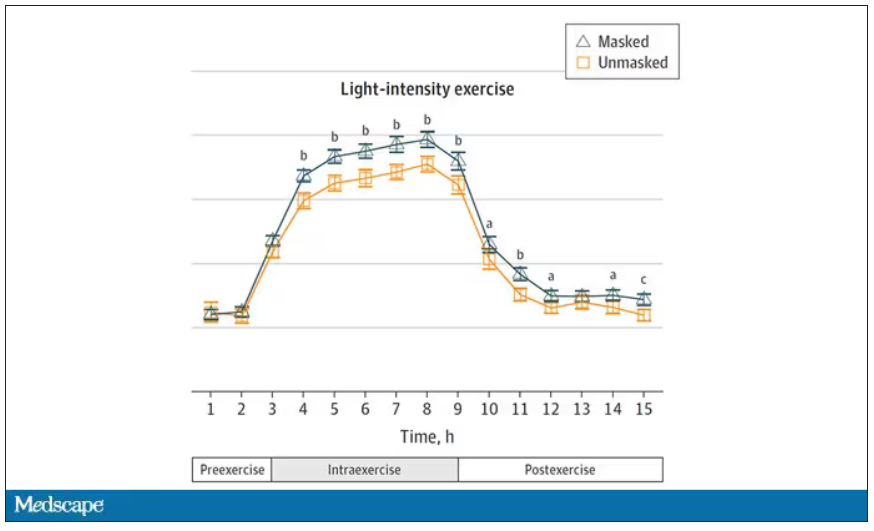

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr. F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

There was a time when I would have had to explain to you what an N95 mask is, how it is designed to filter out 95% of fine particles, defined as stuff in the air less than 2.5 microns in size.

But of course, you know that now. The N95 had its moment – a moment that seemed to be passing as the concentration of airborne coronavirus particles decreased.

But, as the poet said, all that is less than 2.5 microns in size is not coronavirus. Wildfire smoke is also chock full of fine particulate matter. And so, N95s are having something of a comeback.

That’s why an article that took a deep look at what happens to our cardiovascular system when we wear N95 masks caught my eye.

Mask wearing has been the subject of intense debate around the country. While the vast majority of evidence, as well as the personal experience of thousands of doctors, suggests that wearing a mask has no significant physiologic effects, it’s not hard to find those who suggest that mask wearing depletes oxygen levels, or leads to infection, or has other bizarre effects.

In a world of conflicting opinions, a controlled study is a wonderful thing, and that’s what appeared in JAMA Network Open.

This isn’t a huge study, but it’s big enough to make some important conclusions. Thirty individuals, all young and healthy, half female, were enrolled. Each participant spent 3 days in a metabolic chamber; this is essentially a giant, airtight room where all the inputs (oxygen levels and so on) and outputs (carbon dioxide levels and so on) can be precisely measured.

After a day of getting used to the environment, the participants spent a day either wearing an N95 mask or not for 16 waking hours. On the next day, they switched. Every other variable was controlled, from the calories in their diet to the temperature of the room itself.

They engaged in light exercise twice during the day – riding a stationary bike – and a host of physiologic parameters were measured. The question being, would the wearing of the mask for 16 hours straight change anything?

And the answer is yes, some things changed, but not by much.

Here’s a graph of the heart rate over time. You can see some separation, with higher heart rates during the mask-wearing day, particularly around 11 a.m. – when light exercise was scheduled.

Zooming in on the exercise period makes the difference more clear. The heart rate was about eight beats/min higher while masked and engaging in exercise. Systolic blood pressure was about 6 mm Hg higher. Oxygen saturation was lower by 0.7%.

So yes, exercising while wearing an N95 mask might be different from exercising without an N95 mask. But nothing here looks dangerous to me. The 0.7% decrease in oxygen saturation is smaller than the typical measurement error of a pulse oximeter. The authors write that venous pH decreased during the masked day, which is of more interest to me as a nephrologist, but they don’t show that data even in the supplement. I suspect it didn’t decrease much.

They also showed that respiratory rate during exercise decreased in the masked condition. That doesn’t really make sense when you think about it in the context of the other findings, which are all suggestive of increased metabolic rate and sympathetic drive. Does that call the whole procedure into question? No, but it’s worth noting.

These were young, healthy people. You could certainly argue that those with more vulnerable cardiopulmonary status might have had different effects from mask wearing, but without a specific study in those people, it’s just conjecture. Clearly, this study lets us conclude that mask wearing at rest has less of an effect than mask wearing during exercise.

But remember that, in reality, we are wearing masks for a reason. One could imagine a study where this metabolic chamber was filled with wildfire smoke at a concentration similar to what we saw in New York. In that situation, we might find that wearing an N95 is quite helpful. The thing is, studying masks in isolation is useful because you can control so many variables. But masks aren’t used in isolation. In fact, that’s sort of their defining characteristic.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Insurers poised to crack down on off-label Ozempic prescriptions

The warning letters, first reported by The Washington Post, include threats such as the possibility of reporting “suspected inappropriate or fraudulent activity ... to the state licensure board, federal and/or state law enforcement.”

It’s the latest chapter in the story of the popular, highly effective, and very expensive drug intended for diabetes that results in quick weight loss. Off-label prescribing means a medicine has been prescribed for a reason other than the uses approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The practice is common and legal (the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality says one in five prescriptions in the U.S. are off label).

But insurance companies are pushing back because many do not cover weight loss medications, while they do cover diabetes treatments. The insurance company letters suggest that prescribers are failing to document in a person’s medical record that the person actually has diabetes.

Ozempic, which is FDA approved for treatment of diabetes, is similar to the drug Wegovy, which is approved to be used for weight loss. Ozempic typically costs more than $900 per month. Both Wegovy and Ozempic contain semaglutide, which mimics a hormone that helps the brain regulate appetite and food intake. Clinical studies show that after taking semaglutide for more than 5 years, people lose on average 17% of their body weight. But once they stop taking it, most people regain much of the weight.

Demand for both Ozempic and Wegovy has been surging, leading to shortages and tactics to acquire the drugs outside of the United States, as well as warnings from public health officials about the dangers of knockoff versions of the drugs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says 42% of people in the United States are obese.

“Obesity is a complex disease involving an excessive amount of body fat,” the Mayo Clinic explained. “Obesity isn’t just a cosmetic concern. It’s a medical problem that increases the risk of other diseases and health problems, such as heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and certain cancers.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The warning letters, first reported by The Washington Post, include threats such as the possibility of reporting “suspected inappropriate or fraudulent activity ... to the state licensure board, federal and/or state law enforcement.”

It’s the latest chapter in the story of the popular, highly effective, and very expensive drug intended for diabetes that results in quick weight loss. Off-label prescribing means a medicine has been prescribed for a reason other than the uses approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The practice is common and legal (the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality says one in five prescriptions in the U.S. are off label).

But insurance companies are pushing back because many do not cover weight loss medications, while they do cover diabetes treatments. The insurance company letters suggest that prescribers are failing to document in a person’s medical record that the person actually has diabetes.

Ozempic, which is FDA approved for treatment of diabetes, is similar to the drug Wegovy, which is approved to be used for weight loss. Ozempic typically costs more than $900 per month. Both Wegovy and Ozempic contain semaglutide, which mimics a hormone that helps the brain regulate appetite and food intake. Clinical studies show that after taking semaglutide for more than 5 years, people lose on average 17% of their body weight. But once they stop taking it, most people regain much of the weight.

Demand for both Ozempic and Wegovy has been surging, leading to shortages and tactics to acquire the drugs outside of the United States, as well as warnings from public health officials about the dangers of knockoff versions of the drugs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says 42% of people in the United States are obese.

“Obesity is a complex disease involving an excessive amount of body fat,” the Mayo Clinic explained. “Obesity isn’t just a cosmetic concern. It’s a medical problem that increases the risk of other diseases and health problems, such as heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and certain cancers.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The warning letters, first reported by The Washington Post, include threats such as the possibility of reporting “suspected inappropriate or fraudulent activity ... to the state licensure board, federal and/or state law enforcement.”

It’s the latest chapter in the story of the popular, highly effective, and very expensive drug intended for diabetes that results in quick weight loss. Off-label prescribing means a medicine has been prescribed for a reason other than the uses approved by the Food and Drug Administration. The practice is common and legal (the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality says one in five prescriptions in the U.S. are off label).

But insurance companies are pushing back because many do not cover weight loss medications, while they do cover diabetes treatments. The insurance company letters suggest that prescribers are failing to document in a person’s medical record that the person actually has diabetes.

Ozempic, which is FDA approved for treatment of diabetes, is similar to the drug Wegovy, which is approved to be used for weight loss. Ozempic typically costs more than $900 per month. Both Wegovy and Ozempic contain semaglutide, which mimics a hormone that helps the brain regulate appetite and food intake. Clinical studies show that after taking semaglutide for more than 5 years, people lose on average 17% of their body weight. But once they stop taking it, most people regain much of the weight.

Demand for both Ozempic and Wegovy has been surging, leading to shortages and tactics to acquire the drugs outside of the United States, as well as warnings from public health officials about the dangers of knockoff versions of the drugs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says 42% of people in the United States are obese.

“Obesity is a complex disease involving an excessive amount of body fat,” the Mayo Clinic explained. “Obesity isn’t just a cosmetic concern. It’s a medical problem that increases the risk of other diseases and health problems, such as heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, and certain cancers.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Popular weight loss drugs can carry some unpleasant side effects

Johnna Mendenall had never been “the skinny friend,” she said, but the demands of motherhood – along with a sedentary desk job – made weight management even more difficult. Worried that family type 2 diabetes would catch up with her, she decided to start Wegovy shots for weight loss.

She was nervous about potential side effects. It took 5 days of staring at the Wegovy pen before she worked up the nerve for her first .25-milligram shot. And sure enough, the side effects came on strong.

“The nausea kicked in,” she said. “When I increased my dose to 1 milligram, I spent the entire night from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. vomiting. I almost quit that day.”

While gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms seem to be the most common, a laundry list of others has been discussed in the news, on TikTok, and across online forums. Those include “Ozempic face,” or the gaunt look some get after taking the medication, along with hair loss, anxiety, depression, and debilitating fatigue.

Ms. Mendenall’s primary side effects have been vomiting, fatigue, and severe constipation, but she has also seen some positive changes: The “food noise,” or the urge to eat when she isn’t hungry, is gone. Since her first dose 12 weeks ago, she has gone from 236 pounds to 215.

Warning label

Wegovy’s active ingredient, semaglutide, mimics the role of a natural hormone called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), which helps you feel well fed. Semaglutide is used at a lower dose under the brand name Ozempic, which is approved for type 2 diabetes and used off-label for weight loss.

Both Ozempic and Wegovy come with a warning label for potential side effects, the most common ones being nausea, diarrhea, stomach pain, and vomiting.

With the surging popularity of semaglutide, more people are getting prescriptions through telemedicine companies, forgoing more in-depth consultations, leading to more side effects, said Caroline Apovian, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and codirector of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Specialists say starting with low doses and gradually increasing over time helps avoid side effects, but insurance companies often require a faster timeline to continue covering the medication, Dr. Apovian said.

“Insurance companies are practicing medicine for us by demanding the patient go up in dosage [too quickly],” she explained.

Ms. Mendenall’s insurance has paid for her Wegovy shots, but without that coverage, she said it would cost her $1,200 per month.

There are similar medications on the market, such as liraglutide, sold under the name Saxenda. But it is a daily, rather than a weekly, shot and also comes with side effects and has been shown to be less effective. In one clinical trial, the people being studied saw their average body weight over 68 weeks drop by 15.8% with semaglutide, and by 6.4% with liraglutide.

Tirzepatide, branded Mounjaro – a type 2 diabetes drug made by Eli Lilly that may soon gain Food and Drug Administration approval for weight loss – could have fewer side effects. In clinical trials, 44% of those taking semaglutide had nausea and 31% reported diarrhea, compared with 33% and 23% of those taking tirzepatide, although no trial has directly compared the two agents.

Loss of bowel control

For now, Wegovy and Saxenda are the only GLP-1 agonist shots authorized for weight loss, and their maker, Danish drug company Novo Nordisk, is facing its second shortage of Wegovy amid growing demand.

Personal stories online about semaglutide range from overwhelmingly positive – just what some need to win a lifelong battle with obesity – to harsh scenarios with potentially long-term health consequences, and everything in between.

One private community on Reddit is dedicated to a particularly unpleasant side effect: loss of bowel control while sleeping. Others have reported uncontrollable vomiting.

Kimberly Carew of Clearwater, Fla., started on .5 milligrams of Ozempic last year after her rheumatologist and endocrinologist suggested it to treat her type 2 diabetes. She was told it came with the bonus of weight loss, which she was hoping would help with her joint and back pain.

But after she increased the dose to 1 milligram, her GI symptoms, which started out mild, became unbearable. She couldn’t keep food down, and when she vomited, the food would often come up whole, she said.

“One night I ate ramen before bed. And the next morning, it came out just as it went down,” said Ms. Carew, 42, a registered mental health counseling intern. “I was getting severe heartburn and could not take a couple bites of food without getting nauseous.”

She also had “sulfur burps,” a side effect discussed by some Ozempic users, causing her to taste rotten egg sometimes.

She was diagnosed with gastroparesis. Some types of gastroparesis can be resolved by discontinuing GLP-1 medications, as referenced in two case reports in the Journal of Investigative Medicine.

Gut hormone

GI symptoms are most common with semaglutide because the hormone it imitates, GLP-1, is secreted by cells in the stomach, small intestines, and pancreas, said Anne Peters, MD, director of the USC Clinical Diabetes Programs.

“This is the deal: The side effects are real because it’s a gut hormone. It’s increasing the level of something your body already has,” she said.

But, like Dr. Apovian, Dr. Peters said those side effects can likely be avoided if shots are started at the lowest doses and gradually adjusted up.

While the average starting dose is .25 milligrams, Dr. Peters said she often starts her patients on about an eighth of that – just “a whiff of a dose.”

“It’ll take them months to get up to the starting dose, but what’s the rush?”

Dr. Peters said she also avoids giving diabetes patients the maximum dose, which is 2 milligrams per week for Ozempic (and 2.4 milligrams for Wegovy for weight loss).

When asked about the drugs’ side effects, Novo Nordisk responded that “GLP-1 receptor agonists are a well-established class of medicines, which have demonstrated long-term safety in clinical trials. The most common adverse reactions, as with all GLP-1 [agonists], are gastrointestinal related.”

Is it the drug or the weight loss?

Still, non-gastrointestinal side effects such as hair loss, mood changes, and sunken facial features are reported among semaglutide users across the Internet. While these cases are often anecdotal, they can be very heartfelt.

Celina Horvath Myers, also known as CelinaSpookyBoo, a Canadian YouTuber who took Ozempic for type 2 diabetes, said she began having intense panic attacks and depression after starting the medication.

“Who I have been these last couple weeks, has probably been the scariest time of my life,” she said on her YouTube channel.

While severe depression and anxiety are not established side effects of the medication, some people get anhedonia, said W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, director of obesity medicine in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Cleveland Clinic. But that could be a natural consequence of lower appetite, he said, given that food gives most people pleasure in the moment.

Many other reported changes come from the weight loss itself, not the medication, said Dr. Butsch.

“These are drugs that change the body’s weight regulatory system,” he said. “When someone loses weight, you get the shrinking of the fat cells, as well as the atrophy of the muscles. This rapid weight loss may give the appearance of one’s face changing.”

For some people, like Ms. Mendenall, the side effects are worth it. For others, like Ms. Carew, they’re intolerable.

Ms. Carew said she stopped the medication after about 7 months, and gradually worked up to eating solid foods again.

“It’s the American way, we’ve all got to be thin and beautiful,” she said. “But I feel like it’s very unsafe because we just don’t know how seriously our bodies will react to these things in the long term. People see it as a quick fix, but it comes with risks.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Johnna Mendenall had never been “the skinny friend,” she said, but the demands of motherhood – along with a sedentary desk job – made weight management even more difficult. Worried that family type 2 diabetes would catch up with her, she decided to start Wegovy shots for weight loss.

She was nervous about potential side effects. It took 5 days of staring at the Wegovy pen before she worked up the nerve for her first .25-milligram shot. And sure enough, the side effects came on strong.

“The nausea kicked in,” she said. “When I increased my dose to 1 milligram, I spent the entire night from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. vomiting. I almost quit that day.”

While gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms seem to be the most common, a laundry list of others has been discussed in the news, on TikTok, and across online forums. Those include “Ozempic face,” or the gaunt look some get after taking the medication, along with hair loss, anxiety, depression, and debilitating fatigue.

Ms. Mendenall’s primary side effects have been vomiting, fatigue, and severe constipation, but she has also seen some positive changes: The “food noise,” or the urge to eat when she isn’t hungry, is gone. Since her first dose 12 weeks ago, she has gone from 236 pounds to 215.

Warning label

Wegovy’s active ingredient, semaglutide, mimics the role of a natural hormone called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), which helps you feel well fed. Semaglutide is used at a lower dose under the brand name Ozempic, which is approved for type 2 diabetes and used off-label for weight loss.

Both Ozempic and Wegovy come with a warning label for potential side effects, the most common ones being nausea, diarrhea, stomach pain, and vomiting.

With the surging popularity of semaglutide, more people are getting prescriptions through telemedicine companies, forgoing more in-depth consultations, leading to more side effects, said Caroline Apovian, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and codirector of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Specialists say starting with low doses and gradually increasing over time helps avoid side effects, but insurance companies often require a faster timeline to continue covering the medication, Dr. Apovian said.

“Insurance companies are practicing medicine for us by demanding the patient go up in dosage [too quickly],” she explained.

Ms. Mendenall’s insurance has paid for her Wegovy shots, but without that coverage, she said it would cost her $1,200 per month.

There are similar medications on the market, such as liraglutide, sold under the name Saxenda. But it is a daily, rather than a weekly, shot and also comes with side effects and has been shown to be less effective. In one clinical trial, the people being studied saw their average body weight over 68 weeks drop by 15.8% with semaglutide, and by 6.4% with liraglutide.

Tirzepatide, branded Mounjaro – a type 2 diabetes drug made by Eli Lilly that may soon gain Food and Drug Administration approval for weight loss – could have fewer side effects. In clinical trials, 44% of those taking semaglutide had nausea and 31% reported diarrhea, compared with 33% and 23% of those taking tirzepatide, although no trial has directly compared the two agents.

Loss of bowel control

For now, Wegovy and Saxenda are the only GLP-1 agonist shots authorized for weight loss, and their maker, Danish drug company Novo Nordisk, is facing its second shortage of Wegovy amid growing demand.

Personal stories online about semaglutide range from overwhelmingly positive – just what some need to win a lifelong battle with obesity – to harsh scenarios with potentially long-term health consequences, and everything in between.

One private community on Reddit is dedicated to a particularly unpleasant side effect: loss of bowel control while sleeping. Others have reported uncontrollable vomiting.

Kimberly Carew of Clearwater, Fla., started on .5 milligrams of Ozempic last year after her rheumatologist and endocrinologist suggested it to treat her type 2 diabetes. She was told it came with the bonus of weight loss, which she was hoping would help with her joint and back pain.

But after she increased the dose to 1 milligram, her GI symptoms, which started out mild, became unbearable. She couldn’t keep food down, and when she vomited, the food would often come up whole, she said.

“One night I ate ramen before bed. And the next morning, it came out just as it went down,” said Ms. Carew, 42, a registered mental health counseling intern. “I was getting severe heartburn and could not take a couple bites of food without getting nauseous.”

She also had “sulfur burps,” a side effect discussed by some Ozempic users, causing her to taste rotten egg sometimes.

She was diagnosed with gastroparesis. Some types of gastroparesis can be resolved by discontinuing GLP-1 medications, as referenced in two case reports in the Journal of Investigative Medicine.

Gut hormone

GI symptoms are most common with semaglutide because the hormone it imitates, GLP-1, is secreted by cells in the stomach, small intestines, and pancreas, said Anne Peters, MD, director of the USC Clinical Diabetes Programs.

“This is the deal: The side effects are real because it’s a gut hormone. It’s increasing the level of something your body already has,” she said.

But, like Dr. Apovian, Dr. Peters said those side effects can likely be avoided if shots are started at the lowest doses and gradually adjusted up.

While the average starting dose is .25 milligrams, Dr. Peters said she often starts her patients on about an eighth of that – just “a whiff of a dose.”

“It’ll take them months to get up to the starting dose, but what’s the rush?”

Dr. Peters said she also avoids giving diabetes patients the maximum dose, which is 2 milligrams per week for Ozempic (and 2.4 milligrams for Wegovy for weight loss).

When asked about the drugs’ side effects, Novo Nordisk responded that “GLP-1 receptor agonists are a well-established class of medicines, which have demonstrated long-term safety in clinical trials. The most common adverse reactions, as with all GLP-1 [agonists], are gastrointestinal related.”

Is it the drug or the weight loss?

Still, non-gastrointestinal side effects such as hair loss, mood changes, and sunken facial features are reported among semaglutide users across the Internet. While these cases are often anecdotal, they can be very heartfelt.

Celina Horvath Myers, also known as CelinaSpookyBoo, a Canadian YouTuber who took Ozempic for type 2 diabetes, said she began having intense panic attacks and depression after starting the medication.

“Who I have been these last couple weeks, has probably been the scariest time of my life,” she said on her YouTube channel.

While severe depression and anxiety are not established side effects of the medication, some people get anhedonia, said W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, director of obesity medicine in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Cleveland Clinic. But that could be a natural consequence of lower appetite, he said, given that food gives most people pleasure in the moment.

Many other reported changes come from the weight loss itself, not the medication, said Dr. Butsch.

“These are drugs that change the body’s weight regulatory system,” he said. “When someone loses weight, you get the shrinking of the fat cells, as well as the atrophy of the muscles. This rapid weight loss may give the appearance of one’s face changing.”

For some people, like Ms. Mendenall, the side effects are worth it. For others, like Ms. Carew, they’re intolerable.

Ms. Carew said she stopped the medication after about 7 months, and gradually worked up to eating solid foods again.

“It’s the American way, we’ve all got to be thin and beautiful,” she said. “But I feel like it’s very unsafe because we just don’t know how seriously our bodies will react to these things in the long term. People see it as a quick fix, but it comes with risks.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Johnna Mendenall had never been “the skinny friend,” she said, but the demands of motherhood – along with a sedentary desk job – made weight management even more difficult. Worried that family type 2 diabetes would catch up with her, she decided to start Wegovy shots for weight loss.

She was nervous about potential side effects. It took 5 days of staring at the Wegovy pen before she worked up the nerve for her first .25-milligram shot. And sure enough, the side effects came on strong.

“The nausea kicked in,” she said. “When I increased my dose to 1 milligram, I spent the entire night from 10 p.m. to 5 a.m. vomiting. I almost quit that day.”

While gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms seem to be the most common, a laundry list of others has been discussed in the news, on TikTok, and across online forums. Those include “Ozempic face,” or the gaunt look some get after taking the medication, along with hair loss, anxiety, depression, and debilitating fatigue.

Ms. Mendenall’s primary side effects have been vomiting, fatigue, and severe constipation, but she has also seen some positive changes: The “food noise,” or the urge to eat when she isn’t hungry, is gone. Since her first dose 12 weeks ago, she has gone from 236 pounds to 215.

Warning label

Wegovy’s active ingredient, semaglutide, mimics the role of a natural hormone called glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1), which helps you feel well fed. Semaglutide is used at a lower dose under the brand name Ozempic, which is approved for type 2 diabetes and used off-label for weight loss.

Both Ozempic and Wegovy come with a warning label for potential side effects, the most common ones being nausea, diarrhea, stomach pain, and vomiting.

With the surging popularity of semaglutide, more people are getting prescriptions through telemedicine companies, forgoing more in-depth consultations, leading to more side effects, said Caroline Apovian, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and codirector of the Center for Weight Management and Wellness at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

Specialists say starting with low doses and gradually increasing over time helps avoid side effects, but insurance companies often require a faster timeline to continue covering the medication, Dr. Apovian said.

“Insurance companies are practicing medicine for us by demanding the patient go up in dosage [too quickly],” she explained.

Ms. Mendenall’s insurance has paid for her Wegovy shots, but without that coverage, she said it would cost her $1,200 per month.

There are similar medications on the market, such as liraglutide, sold under the name Saxenda. But it is a daily, rather than a weekly, shot and also comes with side effects and has been shown to be less effective. In one clinical trial, the people being studied saw their average body weight over 68 weeks drop by 15.8% with semaglutide, and by 6.4% with liraglutide.

Tirzepatide, branded Mounjaro – a type 2 diabetes drug made by Eli Lilly that may soon gain Food and Drug Administration approval for weight loss – could have fewer side effects. In clinical trials, 44% of those taking semaglutide had nausea and 31% reported diarrhea, compared with 33% and 23% of those taking tirzepatide, although no trial has directly compared the two agents.

Loss of bowel control

For now, Wegovy and Saxenda are the only GLP-1 agonist shots authorized for weight loss, and their maker, Danish drug company Novo Nordisk, is facing its second shortage of Wegovy amid growing demand.

Personal stories online about semaglutide range from overwhelmingly positive – just what some need to win a lifelong battle with obesity – to harsh scenarios with potentially long-term health consequences, and everything in between.

One private community on Reddit is dedicated to a particularly unpleasant side effect: loss of bowel control while sleeping. Others have reported uncontrollable vomiting.

Kimberly Carew of Clearwater, Fla., started on .5 milligrams of Ozempic last year after her rheumatologist and endocrinologist suggested it to treat her type 2 diabetes. She was told it came with the bonus of weight loss, which she was hoping would help with her joint and back pain.

But after she increased the dose to 1 milligram, her GI symptoms, which started out mild, became unbearable. She couldn’t keep food down, and when she vomited, the food would often come up whole, she said.

“One night I ate ramen before bed. And the next morning, it came out just as it went down,” said Ms. Carew, 42, a registered mental health counseling intern. “I was getting severe heartburn and could not take a couple bites of food without getting nauseous.”

She also had “sulfur burps,” a side effect discussed by some Ozempic users, causing her to taste rotten egg sometimes.

She was diagnosed with gastroparesis. Some types of gastroparesis can be resolved by discontinuing GLP-1 medications, as referenced in two case reports in the Journal of Investigative Medicine.

Gut hormone

GI symptoms are most common with semaglutide because the hormone it imitates, GLP-1, is secreted by cells in the stomach, small intestines, and pancreas, said Anne Peters, MD, director of the USC Clinical Diabetes Programs.

“This is the deal: The side effects are real because it’s a gut hormone. It’s increasing the level of something your body already has,” she said.

But, like Dr. Apovian, Dr. Peters said those side effects can likely be avoided if shots are started at the lowest doses and gradually adjusted up.

While the average starting dose is .25 milligrams, Dr. Peters said she often starts her patients on about an eighth of that – just “a whiff of a dose.”

“It’ll take them months to get up to the starting dose, but what’s the rush?”

Dr. Peters said she also avoids giving diabetes patients the maximum dose, which is 2 milligrams per week for Ozempic (and 2.4 milligrams for Wegovy for weight loss).

When asked about the drugs’ side effects, Novo Nordisk responded that “GLP-1 receptor agonists are a well-established class of medicines, which have demonstrated long-term safety in clinical trials. The most common adverse reactions, as with all GLP-1 [agonists], are gastrointestinal related.”

Is it the drug or the weight loss?

Still, non-gastrointestinal side effects such as hair loss, mood changes, and sunken facial features are reported among semaglutide users across the Internet. While these cases are often anecdotal, they can be very heartfelt.

Celina Horvath Myers, also known as CelinaSpookyBoo, a Canadian YouTuber who took Ozempic for type 2 diabetes, said she began having intense panic attacks and depression after starting the medication.

“Who I have been these last couple weeks, has probably been the scariest time of my life,” she said on her YouTube channel.

While severe depression and anxiety are not established side effects of the medication, some people get anhedonia, said W. Scott Butsch, MD, MSc, director of obesity medicine in the Bariatric and Metabolic Institute at Cleveland Clinic. But that could be a natural consequence of lower appetite, he said, given that food gives most people pleasure in the moment.

Many other reported changes come from the weight loss itself, not the medication, said Dr. Butsch.

“These are drugs that change the body’s weight regulatory system,” he said. “When someone loses weight, you get the shrinking of the fat cells, as well as the atrophy of the muscles. This rapid weight loss may give the appearance of one’s face changing.”

For some people, like Ms. Mendenall, the side effects are worth it. For others, like Ms. Carew, they’re intolerable.

Ms. Carew said she stopped the medication after about 7 months, and gradually worked up to eating solid foods again.

“It’s the American way, we’ve all got to be thin and beautiful,” she said. “But I feel like it’s very unsafe because we just don’t know how seriously our bodies will react to these things in the long term. People see it as a quick fix, but it comes with risks.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Low-dose oral minoxidil for hair loss soars after NYT article

.

The weekly rate of first-time low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) prescriptions per 10,000 outpatient encounters was “significantly higher 8 weeks after vs. 8 weeks before article publication,” at 0.9 prescriptions, compared with 0.5 per 10,000, wrote the authors of the research letter, published in JAMA Network Open. There was no similar bump for first-time finasteride or hypertension prescriptions, wrote the authors, from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Truveta, a company that provides EHR data from U.S. health care systems.

The New York Times article noted that LDOM was relatively unknown to patients and doctors – and not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating hair loss – but that it was inexpensive, safe, and very effective for many individuals. “The article did not report new research findings or large-scale randomized evidence,” wrote the authors of the JAMA study.

Rodney Sinclair, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Melbourne, who conducted the original research on LDOM and hair loss and was quoted in the Times story, told this news organization that “the sharp uplift after the New York Times article was on the back of a gradual increase.” He added that “the momentum for minoxidil prescriptions is increasing,” so much so that it has led to a global shortage of LDOM. The drug appears to still be widely available in the United States, however. It is not on the ASHP shortages list.

“There has been growing momentum for minoxidil use since I first presented our data about 6 years ago,” Dr. Sinclair said. He noted that 2022 International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery survey data found that 26% of treating physicians always or often prescribed off-label oral minoxidil, up from 10% in 2019 and 0% in 2017, while another 20% said they prescribed it sometimes.

The authors of the new study looked at prescriptions for patients at eight health care systems before and after the Times article was published in August 2022. They calculated the rate of first-time oral minoxidil prescriptions for 2.5 mg and 5 mg tablets, excluding 10 mg tablets, which are prescribed for hypertension.

Among those receiving first-time prescriptions, 2,846 received them in the 7 months before the article and 3,695 in the 5 months after publication. Men (43.6% after vs. 37.7% before publication) and White individuals (68.6% after vs. 60.8% before publication) accounted for a higher proportion of prescriptions after the article was published. There was a 2.4-fold increase in first-time prescriptions among men, and a 1.7-fold increase among females, while people with comorbidities accounted for a smaller proportion after the publication.

“Socioeconomic factors, such as access to health care and education and income levels, may be associated with individuals seeking low-dose oral minoxidil after article publication,” wrote the authors.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said that he was not surprised to see an uptick in prescriptions after the Times article.

He and his colleagues were curious as to whether the article might have prompted newfound interest in LDOM. They experienced an uptick at George Washington, which Dr. Friedman thought could have been because he was quoted in the Times story. He and colleagues conducted a national survey of dermatologists asking if more patients had called, emailed, or come in to the office asking about LDOM after the article’s publication. “Over 85% said yes,” Dr. Friedman said in the interview. He and his coauthors also found a huge increase in Google searches for terms such as hair loss, alopecia, and minoxidil in the weeks after the article, he said.

The results are expected to published soon in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

“I think a lot of people know about [LDOM] and it’s certainly has gained a lot more attention and acceptance in recent years,” said Dr. Friedman, but he added that “there’s no question” that the Times article increased interest.

That is not necessarily a bad thing, he said. “With one article, education on a common disease was disseminated worldwide in a way that no one doctor can do,” he said. The article was truthful, evidence-based, and included expert dermatologists, he noted.

“It probably got people who never thought twice about their hair thinning to actually think that there’s hope,” he said, adding that it also likely prompted them to seek care, and, more importantly, “to seek care from the person who should be taking care of this, which is the dermatologist.”

However, the article might also inspire some people to think LDOM can help when it can’t, or they might insist on a prescription when another medication is more appropriate, said Dr. Friedman.

Both he and Dr. Sinclair expect demand for LDOM to continue increasing.

“Word of mouth will drive the next wave of prescriptions,” said Dr. Sinclair. “We are continuing to do work to improve safety, to understand its mechanism of action, and identify ways to improve equity of access to treatment for men and women who are concerned about their hair loss and motivated to treat it,” he said.

Dr. Sinclair and Dr. Friedman report no relevant financial relationships.

.

The weekly rate of first-time low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) prescriptions per 10,000 outpatient encounters was “significantly higher 8 weeks after vs. 8 weeks before article publication,” at 0.9 prescriptions, compared with 0.5 per 10,000, wrote the authors of the research letter, published in JAMA Network Open. There was no similar bump for first-time finasteride or hypertension prescriptions, wrote the authors, from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Truveta, a company that provides EHR data from U.S. health care systems.

The New York Times article noted that LDOM was relatively unknown to patients and doctors – and not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating hair loss – but that it was inexpensive, safe, and very effective for many individuals. “The article did not report new research findings or large-scale randomized evidence,” wrote the authors of the JAMA study.

Rodney Sinclair, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Melbourne, who conducted the original research on LDOM and hair loss and was quoted in the Times story, told this news organization that “the sharp uplift after the New York Times article was on the back of a gradual increase.” He added that “the momentum for minoxidil prescriptions is increasing,” so much so that it has led to a global shortage of LDOM. The drug appears to still be widely available in the United States, however. It is not on the ASHP shortages list.

“There has been growing momentum for minoxidil use since I first presented our data about 6 years ago,” Dr. Sinclair said. He noted that 2022 International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery survey data found that 26% of treating physicians always or often prescribed off-label oral minoxidil, up from 10% in 2019 and 0% in 2017, while another 20% said they prescribed it sometimes.

The authors of the new study looked at prescriptions for patients at eight health care systems before and after the Times article was published in August 2022. They calculated the rate of first-time oral minoxidil prescriptions for 2.5 mg and 5 mg tablets, excluding 10 mg tablets, which are prescribed for hypertension.

Among those receiving first-time prescriptions, 2,846 received them in the 7 months before the article and 3,695 in the 5 months after publication. Men (43.6% after vs. 37.7% before publication) and White individuals (68.6% after vs. 60.8% before publication) accounted for a higher proportion of prescriptions after the article was published. There was a 2.4-fold increase in first-time prescriptions among men, and a 1.7-fold increase among females, while people with comorbidities accounted for a smaller proportion after the publication.

“Socioeconomic factors, such as access to health care and education and income levels, may be associated with individuals seeking low-dose oral minoxidil after article publication,” wrote the authors.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said that he was not surprised to see an uptick in prescriptions after the Times article.

He and his colleagues were curious as to whether the article might have prompted newfound interest in LDOM. They experienced an uptick at George Washington, which Dr. Friedman thought could have been because he was quoted in the Times story. He and colleagues conducted a national survey of dermatologists asking if more patients had called, emailed, or come in to the office asking about LDOM after the article’s publication. “Over 85% said yes,” Dr. Friedman said in the interview. He and his coauthors also found a huge increase in Google searches for terms such as hair loss, alopecia, and minoxidil in the weeks after the article, he said.

The results are expected to published soon in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.

“I think a lot of people know about [LDOM] and it’s certainly has gained a lot more attention and acceptance in recent years,” said Dr. Friedman, but he added that “there’s no question” that the Times article increased interest.

That is not necessarily a bad thing, he said. “With one article, education on a common disease was disseminated worldwide in a way that no one doctor can do,” he said. The article was truthful, evidence-based, and included expert dermatologists, he noted.

“It probably got people who never thought twice about their hair thinning to actually think that there’s hope,” he said, adding that it also likely prompted them to seek care, and, more importantly, “to seek care from the person who should be taking care of this, which is the dermatologist.”

However, the article might also inspire some people to think LDOM can help when it can’t, or they might insist on a prescription when another medication is more appropriate, said Dr. Friedman.

Both he and Dr. Sinclair expect demand for LDOM to continue increasing.

“Word of mouth will drive the next wave of prescriptions,” said Dr. Sinclair. “We are continuing to do work to improve safety, to understand its mechanism of action, and identify ways to improve equity of access to treatment for men and women who are concerned about their hair loss and motivated to treat it,” he said.

Dr. Sinclair and Dr. Friedman report no relevant financial relationships.

.

The weekly rate of first-time low-dose oral minoxidil (LDOM) prescriptions per 10,000 outpatient encounters was “significantly higher 8 weeks after vs. 8 weeks before article publication,” at 0.9 prescriptions, compared with 0.5 per 10,000, wrote the authors of the research letter, published in JAMA Network Open. There was no similar bump for first-time finasteride or hypertension prescriptions, wrote the authors, from Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Truveta, a company that provides EHR data from U.S. health care systems.

The New York Times article noted that LDOM was relatively unknown to patients and doctors – and not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for treating hair loss – but that it was inexpensive, safe, and very effective for many individuals. “The article did not report new research findings or large-scale randomized evidence,” wrote the authors of the JAMA study.

Rodney Sinclair, MD, professor of dermatology at the University of Melbourne, who conducted the original research on LDOM and hair loss and was quoted in the Times story, told this news organization that “the sharp uplift after the New York Times article was on the back of a gradual increase.” He added that “the momentum for minoxidil prescriptions is increasing,” so much so that it has led to a global shortage of LDOM. The drug appears to still be widely available in the United States, however. It is not on the ASHP shortages list.

“There has been growing momentum for minoxidil use since I first presented our data about 6 years ago,” Dr. Sinclair said. He noted that 2022 International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery survey data found that 26% of treating physicians always or often prescribed off-label oral minoxidil, up from 10% in 2019 and 0% in 2017, while another 20% said they prescribed it sometimes.

The authors of the new study looked at prescriptions for patients at eight health care systems before and after the Times article was published in August 2022. They calculated the rate of first-time oral minoxidil prescriptions for 2.5 mg and 5 mg tablets, excluding 10 mg tablets, which are prescribed for hypertension.

Among those receiving first-time prescriptions, 2,846 received them in the 7 months before the article and 3,695 in the 5 months after publication. Men (43.6% after vs. 37.7% before publication) and White individuals (68.6% after vs. 60.8% before publication) accounted for a higher proportion of prescriptions after the article was published. There was a 2.4-fold increase in first-time prescriptions among men, and a 1.7-fold increase among females, while people with comorbidities accounted for a smaller proportion after the publication.

“Socioeconomic factors, such as access to health care and education and income levels, may be associated with individuals seeking low-dose oral minoxidil after article publication,” wrote the authors.

In an interview, Adam Friedman, MD, professor and chair of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, said that he was not surprised to see an uptick in prescriptions after the Times article.

He and his colleagues were curious as to whether the article might have prompted newfound interest in LDOM. They experienced an uptick at George Washington, which Dr. Friedman thought could have been because he was quoted in the Times story. He and colleagues conducted a national survey of dermatologists asking if more patients had called, emailed, or come in to the office asking about LDOM after the article’s publication. “Over 85% said yes,” Dr. Friedman said in the interview. He and his coauthors also found a huge increase in Google searches for terms such as hair loss, alopecia, and minoxidil in the weeks after the article, he said.

The results are expected to published soon in the Journal of Drugs in Dermatology.