User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Potentially dangerous mix: Antiretrovirals and drugs of abuse

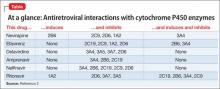

Patients with HIV often receive antiretroviral therapy, which includes non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors. Opiate, amphetamine, cocaine, and Cannabis abuse are common among this population.1 Many of these substances and antiretroviral medications undergo hepatic metabolism by cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes, which could lead to adverse events (Table2).

MDMA

The synthetic derivative of the amphetamine 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA [“Ecstasy” or “Molly”]) is metabolized by CYP2D6; thus, coadministration of MDMA with ritonavir can result in MDMA toxicity. This can induce a dangerous, potentially fatal serotonin syndrome characterized by tachycardia, arrhythmia, hyperthermia, seizures, myocardial infarction, rhabdomyolysis, renal or liver failure, and death.3

Opiates

Opiates are metabolized by CYP2D6 and, sometimes by CYP3A4. Metabolism of opiates, such as oxycodone, is decreased when these drugs are coadministered with a CYP2D6 inhibitor—potentially leading to toxicity.

Analgesic effect may be augmented when a CYP2D6 inhibitor is started, and decreased when the agent is stopped. Inducers of CYP2D6 or CYP3A4 can lead to decreased analgesia and oxycodone withdrawal.

Efavirenz can cause methadone withdrawal. Methadone inhibition of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 can increase the serum level of antiretroviral medications, with adverse effects and resulting poor compliance.4

Cannabis

Tetrahydrocannabinol is metabolized by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. Cannabis and CYP3A4 inhibitor co-utilization can cause toxicity, evidenced by paranoia, hallucinations, delusions, depersonalization, tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension. Co-exposure of antiretroviral agents in occasional Cannabis users yields only a small change metabolically; however, nonadherence has been reported more frequently in heavy users.5

Education can help

The variability of CYP genotypes makes it important to understand drug metabolism as an aid to improving outcomes among patients with HIV who abuse drugs. Because of the risk for adverse effects, discuss the dangers of substance abuse with patients for whom antiretroviral therapy has been prescribed.

Clinical education should improve compliance and prognosis in patients with HIV. Advise drug users about pharmaceutical effects and risks of co-utilization. This might help some patients limit the use of illicit substances—and will help physicians manage pharmacotherapy with greater safety.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arvguidelines/22/hiv-and-illicit-drug-users. Updated March 27, 2012. Accessed July 26, 2013.

2. Walubo A. The role of cytochrome P450 in antiretroviral drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2007;3(4):583-598.

3. Papaseit E, Vázquez A, Pérez-Mañá C, et al. Surviving life-threatening MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine,ecstasy) toxicity caused by ritonavir (RTV).

Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(7):1239-1240.

4. Antoniou T, Tseng AL. Interactions between recreational drugs and antiretroviral agents. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(10):1598-1613.

5. Bonn-Miller MO, Oser ML, Bucossi MM, et al. Cannabis use and HIV antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-related symptoms. J Behav Med. 2014;37(1):1-10.

3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, opiates

Patients with HIV often receive antiretroviral therapy, which includes non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors. Opiate, amphetamine, cocaine, and Cannabis abuse are common among this population.1 Many of these substances and antiretroviral medications undergo hepatic metabolism by cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes, which could lead to adverse events (Table2).

MDMA

The synthetic derivative of the amphetamine 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA [“Ecstasy” or “Molly”]) is metabolized by CYP2D6; thus, coadministration of MDMA with ritonavir can result in MDMA toxicity. This can induce a dangerous, potentially fatal serotonin syndrome characterized by tachycardia, arrhythmia, hyperthermia, seizures, myocardial infarction, rhabdomyolysis, renal or liver failure, and death.3

Opiates

Opiates are metabolized by CYP2D6 and, sometimes by CYP3A4. Metabolism of opiates, such as oxycodone, is decreased when these drugs are coadministered with a CYP2D6 inhibitor—potentially leading to toxicity.

Analgesic effect may be augmented when a CYP2D6 inhibitor is started, and decreased when the agent is stopped. Inducers of CYP2D6 or CYP3A4 can lead to decreased analgesia and oxycodone withdrawal.

Efavirenz can cause methadone withdrawal. Methadone inhibition of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 can increase the serum level of antiretroviral medications, with adverse effects and resulting poor compliance.4

Cannabis

Tetrahydrocannabinol is metabolized by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. Cannabis and CYP3A4 inhibitor co-utilization can cause toxicity, evidenced by paranoia, hallucinations, delusions, depersonalization, tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension. Co-exposure of antiretroviral agents in occasional Cannabis users yields only a small change metabolically; however, nonadherence has been reported more frequently in heavy users.5

Education can help

The variability of CYP genotypes makes it important to understand drug metabolism as an aid to improving outcomes among patients with HIV who abuse drugs. Because of the risk for adverse effects, discuss the dangers of substance abuse with patients for whom antiretroviral therapy has been prescribed.

Clinical education should improve compliance and prognosis in patients with HIV. Advise drug users about pharmaceutical effects and risks of co-utilization. This might help some patients limit the use of illicit substances—and will help physicians manage pharmacotherapy with greater safety.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Patients with HIV often receive antiretroviral therapy, which includes non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors and protease inhibitors. Opiate, amphetamine, cocaine, and Cannabis abuse are common among this population.1 Many of these substances and antiretroviral medications undergo hepatic metabolism by cytochrome P450 (CYP) isoenzymes, which could lead to adverse events (Table2).

MDMA

The synthetic derivative of the amphetamine 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA [“Ecstasy” or “Molly”]) is metabolized by CYP2D6; thus, coadministration of MDMA with ritonavir can result in MDMA toxicity. This can induce a dangerous, potentially fatal serotonin syndrome characterized by tachycardia, arrhythmia, hyperthermia, seizures, myocardial infarction, rhabdomyolysis, renal or liver failure, and death.3

Opiates

Opiates are metabolized by CYP2D6 and, sometimes by CYP3A4. Metabolism of opiates, such as oxycodone, is decreased when these drugs are coadministered with a CYP2D6 inhibitor—potentially leading to toxicity.

Analgesic effect may be augmented when a CYP2D6 inhibitor is started, and decreased when the agent is stopped. Inducers of CYP2D6 or CYP3A4 can lead to decreased analgesia and oxycodone withdrawal.

Efavirenz can cause methadone withdrawal. Methadone inhibition of CYP2D6 and CYP3A4 can increase the serum level of antiretroviral medications, with adverse effects and resulting poor compliance.4

Cannabis

Tetrahydrocannabinol is metabolized by CYP3A4 and CYP2D6. Cannabis and CYP3A4 inhibitor co-utilization can cause toxicity, evidenced by paranoia, hallucinations, delusions, depersonalization, tachycardia, and orthostatic hypotension. Co-exposure of antiretroviral agents in occasional Cannabis users yields only a small change metabolically; however, nonadherence has been reported more frequently in heavy users.5

Education can help

The variability of CYP genotypes makes it important to understand drug metabolism as an aid to improving outcomes among patients with HIV who abuse drugs. Because of the risk for adverse effects, discuss the dangers of substance abuse with patients for whom antiretroviral therapy has been prescribed.

Clinical education should improve compliance and prognosis in patients with HIV. Advise drug users about pharmaceutical effects and risks of co-utilization. This might help some patients limit the use of illicit substances—and will help physicians manage pharmacotherapy with greater safety.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arvguidelines/22/hiv-and-illicit-drug-users. Updated March 27, 2012. Accessed July 26, 2013.

2. Walubo A. The role of cytochrome P450 in antiretroviral drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2007;3(4):583-598.

3. Papaseit E, Vázquez A, Pérez-Mañá C, et al. Surviving life-threatening MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine,ecstasy) toxicity caused by ritonavir (RTV).

Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(7):1239-1240.

4. Antoniou T, Tseng AL. Interactions between recreational drugs and antiretroviral agents. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(10):1598-1613.

5. Bonn-Miller MO, Oser ML, Bucossi MM, et al. Cannabis use and HIV antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-related symptoms. J Behav Med. 2014;37(1):1-10.

1. Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1-infected adults and adolescents. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/html/1/adult-and-adolescent-arvguidelines/22/hiv-and-illicit-drug-users. Updated March 27, 2012. Accessed July 26, 2013.

2. Walubo A. The role of cytochrome P450 in antiretroviral drug interactions. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2007;3(4):583-598.

3. Papaseit E, Vázquez A, Pérez-Mañá C, et al. Surviving life-threatening MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine,ecstasy) toxicity caused by ritonavir (RTV).

Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(7):1239-1240.

4. Antoniou T, Tseng AL. Interactions between recreational drugs and antiretroviral agents. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(10):1598-1613.

5. Bonn-Miller MO, Oser ML, Bucossi MM, et al. Cannabis use and HIV antiretroviral therapy adherence and HIV-related symptoms. J Behav Med. 2014;37(1):1-10.

3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, opiates

3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, opiates

Acting strange after trying to ‘get numb’

CASE Numb and confused

Mr. L, age 17, is admitted to the hospital after ingesting 24 diphenhydramine 25-mg tablets in 3 hours as a possible suicide attempt. His parents witnessed him behaving strangely and brought him to the hospital. They state that their son was visibly agitated and acting inappropriately. He was seen talking to birds, trees, and the walls of the house.

Mr. L says he is upset because he broke up with his girlfriend a week earlier after she asked if they could “take a break.” He says that he took the diphenhydramine because he wanted to “get numb” to deal with the emotional stress caused by the break-up.

After the break-up, Mr. L experienced middle-to-late insomnia and was unable to get more than 3 or 4 hours of sleep a night. He reports significant fatigue, depressed mood, anhedonia, impaired concentration, and psychomotor retardation. He denies homicidal ideation or auditory and visual hallucinations.

As an aside, Mr. L reports that, for the past year, he had difficulties with gender identity, sometimes thinking that he might be better off if he had been born a girl and that he felt uncomfortable in a male body.

Which treatment option would you choose for Mr. L’s substance abuse?

a) refer him to a 12-step program

b) begin supportive measures

c) administer activated charcoal

d) prescribe a benzodiazepine to control agitation

The authors’ observations

As youths gain increasing access to medical and pharmaceutical knowledge through the Internet and other sources, it appears that adolescent drug abuse has, in part, shifted toward more easily attainable over-the-counter (OTC) medications. Diphenhydramine, a first-generation antihistamine, can be abused for its effects on the CNS, such as disturbed coordination, irritability, paresthesia, blurred vision, and depression. Effects of diphenhydramine are increased by the presence of alcohol, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, diazepam, hypnotics, sedatives, tranquilizers, and other CNS depressants. In 2011, diphenhydramine abuse was involved in 19,012 emergency room visits, of which 9,301 were for drug-related suicide attempts.1

Diphenhydramine is an inverse agonist of the histamine H1 receptor.2 It is a member of the ethanolamine subclass of antihistaminergic agents.3 By reversing the effects of histamine on capillaries, diphenhydramine can reduce the intensity of allergic symptoms. Diphenhydramine also crosses the blood–brain barrier and antagonizes H1 receptors centrally.

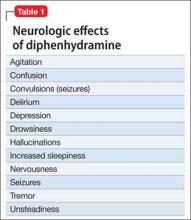

Used as a common sleep aid and allergy medication, the drug works primarily as an H1 receptor partial agonist, but also is a strong competitive antagonist at muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.4 It is abused for its sedative effects and its capacity to cause delirium and hallucinations.5 Diphenhydramine can have a stimulatory effect in children and young adults, instead of the sedating properties seen in adults.6 Such misuse is concerning because diphenhydramine overdose can lead to delirium, confusion, and hallucinations, tachycardia, seizures, mydriasis, xerostomia, urinary retention, ileus, anhidrosis, and hyperthermia. In severe cases it has been associated with cardiac arrhythmias, rhabdomyolysis, status epilepticus, and death.4,6 Neurologic symptoms of diphenhydramine overdose are listed in Table 1.

HISTORY Polysubstance abuse

Mr. L has a 2-year history of major depressive disorder and a history of Cannabis abuse with physiological dependence; Robitussin (base active ingredient, guaifenesin) and hydrocodone abuse with physiological dependence; 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) abuse; and diphenhydramine abuse. He also has a history of gender dysphoria, although he reports that these feelings have become less severe over the past year.

Mr. L attends bi-weekly appointments with an outpatient psychiatrist and reportedly adheres to his medication regimen: fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and risperidone, 1 mg at bedtime. He denies previous suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, homicidal ideation, or homicidal attempts. He reports no history of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse. He gets good grades in school and has no outstanding academic problems.

Mr. L began using Cannabis at age 14; his last use was 3 weeks before admission. He is guarded about his use of Robitussin, hydrocodone, and MDMA. However, Mr. L reports that he has researched diphenhydramine on the internet and believes that he can safely take up to 1,200 mg without overdosing. He reports normally taking 450 mg of diphenhydramine daily. Mr. L reports difficulty urinating after using diphenhydramine but no other physical complaints.

Mr. L lives with his father and stepmother and has a history of one psychiatric hospitalization at a different facility 2 months ago, followed by outpatient therapy. He obtained his Graduate Equivalency Diploma (GED) and plans to attend college.

At age 5, Mr. L emigrated from Turkey to the United States with his parents. His mother returned to Turkey when he was age 6 and has had no contact with her son since. Whenever Mr. L visits Turkey with his father, the patient refuses to see her, as per collaterals. He gets along well with his stepmother, who is his maternal aunt. Mr. L has been bullied at school and reportedly has few friends.

On mental status examination, Mr. L has an appropriate appearance and appears to be his stated age. He shows good eye contact and is cooperative. Muscle tone and gait are within normal limits. He has no abnormal movements. Speech, thought processes, and associations are normal. He denies auditory hallucinations, visual hallucinations, suicidal ideation (although he presented with a probable suicide attempt), or homicidal ideation. No delusions are elicited.

Mr. L shows poor judgment about his drug use and situation. He demonstrates limited insight, because he says his only goal is to get out of the hospital. He is alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He shows no memory or knowledge impairment. He appears euthymic with an inappropriate and constricted affect. On neurologic exam, he had mild tremors in his hands. The authors’ observationsTreatment for diphenhydramine overdose should begin quickly to prevent life-threatening effects and reduce the risk for mortality. The toxin can be removed from the patient’s GI tract with activated charcoal or gastric lavage if the patient presents within 1 hour of ingesting the substance. Administering IV fluids will prevent dehydration. Cardiac functioning is monitored and benzodiazepines could be administered to manage seizures.

Key elements of a toxicologic physical examination include:

• eyes: pupillary size, symmetry, and response to light (vertical or horizontal nystagmus)

• oropharynx: moist or dry mucous membranes, presence or absence of the gag reflex, distinctive odors

• abdomen: presence or absence and quality of bowel sounds

• skin: warm and dry, warm and sweaty, or cool

• neurologic: level of consciousness and mental status, presence of tremors, seizures, or other movement disorders, presence or absence and quality of deep tendon reflexes.7

If a child or adolescent patient cannot communicate how much of a drug he (she) has ingested, questions to ask parents or other informants include:

• Was the medication purchased recently, and if so was the bottle or box full before the patient took the pills?

• If the medication was not new, how many pills were in the bottle before the patient got to it?

• If the medication was prescribed, how many pills were originally prescribed, when was the medication prescribed, and how many pills were already taken prior to the patient getting to the bottle?

• How many pills were left in the bottle?

• How many pills were seen around the area where the patient was found?

• How many pills were found in the patient’s mouth?7

Recommendations

It is well known that OTC medication abuse is a growing medical problem (Table 2). Antihistamines, including diphenhydramine, are readily available to minors and adults. Because of the powerful sedating effects of antihistamines, many adolescent health practitioners give them to patients who have insomnia as a sleep aid.8 As in our case, antihistamines are used recreationally for their hallucinogenic effects, at dosages of 300 to 700 mg.9 Severe symptoms of toxicity, such as delirium and psychosis, seizures, and coma, occur at dosages ≥1,000 mg.9

With growing abuse of these medications, we aim to encourage detailed history taking about abuse of OTC drugs, especially diphenhydramine in adolescent patients.

Outcome Improvement, discharge

Mr. L is given a dual diagnosis of diphenhydramine-induced psychotic disorder with

hallucinations and diphenhydramine-induced depressive disorder, both with onset during intoxication. He also is given a provisional diagnosis of psychotic disorder not otherwise specified and major depressive disorder. Last, he is given a diagnosis of Cannabis dependence with physiological dependence, MDMA abuse, hydrocodone abuse, and Robitussin abuse.

Mr. L is maintained on fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and risperidone, 1 mg at bedtime and 0.5 mg in the morning. He receives milieu, individual, group, recreational, and medical therapy while in the hospital. Symptoms abate and he is discharged with a plan to follow up with outpatient providers.

Bottom Line

Abuse of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, such as diphenhydramine, among youths is a growing problem. Remember to question adolescents who appear intoxicated or to have overdosed not only about abuse of alcohol and illicit substances but also of common—and easily and legally accessible—OTC drugs.

Related Resources

• Carr BC. Efficacy, abuse, and toxicity of over-the-counter cough and cold medicines in the pediatric population. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(2):184-188.

• Thomas A, Nallur DG, Jones N, et al. Diphenhydramine abuse and detoxification: a brief review and case report. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(1):101-105.

Drug Brand Names

Diazepam • Valium Hydrocodone • Vicodin

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl Risperidone • Risperdal

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. http://www.samhsa. gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.htm. Published May 2013. Accessed on September 29, 2014.

2. Yamashiro K, Kiryu J, Tsujikawa A, et al. Suppressive effects of histamine H1 receptor antagonist diphenhydramine on the leukocyte infiltration during endotoxin-induced uveitis. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73(1):69-80.

3. Skidgel RA, Kaplan AP, Erdos EG. Histamine, bradykinin, and their antagonists. In: Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 12th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2011: 911-935.

4. Vearrier D, Curtis JA. Case files of the medical toxicology fellowship at Drexel University. Rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome following acute diphenhydramine overdose. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7(3):213-219.

5. Ho M, Tsai K, Liu C. Diphenhydramine overdose related delirium: a case report. Journal of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;17(2):77-79.

6. Krenzelok EP, Anderson GM, Mirick M. Massive diphenhydramine overdose resulting in death. Ann Emerg Med. 1982;11(4):212-213.

7. Inaba AS. Toxicologic teasers: Testing your knowledge of clinical toxicology. Hawaii Med J. 1998;57(4):471-473.

8. Kaplan SL. Busner J. The use of prn and stat medication in three child psychiatric inpatient settings. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):161-164.

9. Radovanovic D, Meier PJ, Guirguis M, et al. Dose-dependent toxicity of diphenhydramine overdose. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19(9):489-495.

CASE Numb and confused

Mr. L, age 17, is admitted to the hospital after ingesting 24 diphenhydramine 25-mg tablets in 3 hours as a possible suicide attempt. His parents witnessed him behaving strangely and brought him to the hospital. They state that their son was visibly agitated and acting inappropriately. He was seen talking to birds, trees, and the walls of the house.

Mr. L says he is upset because he broke up with his girlfriend a week earlier after she asked if they could “take a break.” He says that he took the diphenhydramine because he wanted to “get numb” to deal with the emotional stress caused by the break-up.

After the break-up, Mr. L experienced middle-to-late insomnia and was unable to get more than 3 or 4 hours of sleep a night. He reports significant fatigue, depressed mood, anhedonia, impaired concentration, and psychomotor retardation. He denies homicidal ideation or auditory and visual hallucinations.

As an aside, Mr. L reports that, for the past year, he had difficulties with gender identity, sometimes thinking that he might be better off if he had been born a girl and that he felt uncomfortable in a male body.

Which treatment option would you choose for Mr. L’s substance abuse?

a) refer him to a 12-step program

b) begin supportive measures

c) administer activated charcoal

d) prescribe a benzodiazepine to control agitation

The authors’ observations

As youths gain increasing access to medical and pharmaceutical knowledge through the Internet and other sources, it appears that adolescent drug abuse has, in part, shifted toward more easily attainable over-the-counter (OTC) medications. Diphenhydramine, a first-generation antihistamine, can be abused for its effects on the CNS, such as disturbed coordination, irritability, paresthesia, blurred vision, and depression. Effects of diphenhydramine are increased by the presence of alcohol, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, diazepam, hypnotics, sedatives, tranquilizers, and other CNS depressants. In 2011, diphenhydramine abuse was involved in 19,012 emergency room visits, of which 9,301 were for drug-related suicide attempts.1

Diphenhydramine is an inverse agonist of the histamine H1 receptor.2 It is a member of the ethanolamine subclass of antihistaminergic agents.3 By reversing the effects of histamine on capillaries, diphenhydramine can reduce the intensity of allergic symptoms. Diphenhydramine also crosses the blood–brain barrier and antagonizes H1 receptors centrally.

Used as a common sleep aid and allergy medication, the drug works primarily as an H1 receptor partial agonist, but also is a strong competitive antagonist at muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.4 It is abused for its sedative effects and its capacity to cause delirium and hallucinations.5 Diphenhydramine can have a stimulatory effect in children and young adults, instead of the sedating properties seen in adults.6 Such misuse is concerning because diphenhydramine overdose can lead to delirium, confusion, and hallucinations, tachycardia, seizures, mydriasis, xerostomia, urinary retention, ileus, anhidrosis, and hyperthermia. In severe cases it has been associated with cardiac arrhythmias, rhabdomyolysis, status epilepticus, and death.4,6 Neurologic symptoms of diphenhydramine overdose are listed in Table 1.

HISTORY Polysubstance abuse

Mr. L has a 2-year history of major depressive disorder and a history of Cannabis abuse with physiological dependence; Robitussin (base active ingredient, guaifenesin) and hydrocodone abuse with physiological dependence; 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) abuse; and diphenhydramine abuse. He also has a history of gender dysphoria, although he reports that these feelings have become less severe over the past year.

Mr. L attends bi-weekly appointments with an outpatient psychiatrist and reportedly adheres to his medication regimen: fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and risperidone, 1 mg at bedtime. He denies previous suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, homicidal ideation, or homicidal attempts. He reports no history of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse. He gets good grades in school and has no outstanding academic problems.

Mr. L began using Cannabis at age 14; his last use was 3 weeks before admission. He is guarded about his use of Robitussin, hydrocodone, and MDMA. However, Mr. L reports that he has researched diphenhydramine on the internet and believes that he can safely take up to 1,200 mg without overdosing. He reports normally taking 450 mg of diphenhydramine daily. Mr. L reports difficulty urinating after using diphenhydramine but no other physical complaints.

Mr. L lives with his father and stepmother and has a history of one psychiatric hospitalization at a different facility 2 months ago, followed by outpatient therapy. He obtained his Graduate Equivalency Diploma (GED) and plans to attend college.

At age 5, Mr. L emigrated from Turkey to the United States with his parents. His mother returned to Turkey when he was age 6 and has had no contact with her son since. Whenever Mr. L visits Turkey with his father, the patient refuses to see her, as per collaterals. He gets along well with his stepmother, who is his maternal aunt. Mr. L has been bullied at school and reportedly has few friends.

On mental status examination, Mr. L has an appropriate appearance and appears to be his stated age. He shows good eye contact and is cooperative. Muscle tone and gait are within normal limits. He has no abnormal movements. Speech, thought processes, and associations are normal. He denies auditory hallucinations, visual hallucinations, suicidal ideation (although he presented with a probable suicide attempt), or homicidal ideation. No delusions are elicited.

Mr. L shows poor judgment about his drug use and situation. He demonstrates limited insight, because he says his only goal is to get out of the hospital. He is alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He shows no memory or knowledge impairment. He appears euthymic with an inappropriate and constricted affect. On neurologic exam, he had mild tremors in his hands. The authors’ observationsTreatment for diphenhydramine overdose should begin quickly to prevent life-threatening effects and reduce the risk for mortality. The toxin can be removed from the patient’s GI tract with activated charcoal or gastric lavage if the patient presents within 1 hour of ingesting the substance. Administering IV fluids will prevent dehydration. Cardiac functioning is monitored and benzodiazepines could be administered to manage seizures.

Key elements of a toxicologic physical examination include:

• eyes: pupillary size, symmetry, and response to light (vertical or horizontal nystagmus)

• oropharynx: moist or dry mucous membranes, presence or absence of the gag reflex, distinctive odors

• abdomen: presence or absence and quality of bowel sounds

• skin: warm and dry, warm and sweaty, or cool

• neurologic: level of consciousness and mental status, presence of tremors, seizures, or other movement disorders, presence or absence and quality of deep tendon reflexes.7

If a child or adolescent patient cannot communicate how much of a drug he (she) has ingested, questions to ask parents or other informants include:

• Was the medication purchased recently, and if so was the bottle or box full before the patient took the pills?

• If the medication was not new, how many pills were in the bottle before the patient got to it?

• If the medication was prescribed, how many pills were originally prescribed, when was the medication prescribed, and how many pills were already taken prior to the patient getting to the bottle?

• How many pills were left in the bottle?

• How many pills were seen around the area where the patient was found?

• How many pills were found in the patient’s mouth?7

Recommendations

It is well known that OTC medication abuse is a growing medical problem (Table 2). Antihistamines, including diphenhydramine, are readily available to minors and adults. Because of the powerful sedating effects of antihistamines, many adolescent health practitioners give them to patients who have insomnia as a sleep aid.8 As in our case, antihistamines are used recreationally for their hallucinogenic effects, at dosages of 300 to 700 mg.9 Severe symptoms of toxicity, such as delirium and psychosis, seizures, and coma, occur at dosages ≥1,000 mg.9

With growing abuse of these medications, we aim to encourage detailed history taking about abuse of OTC drugs, especially diphenhydramine in adolescent patients.

Outcome Improvement, discharge

Mr. L is given a dual diagnosis of diphenhydramine-induced psychotic disorder with

hallucinations and diphenhydramine-induced depressive disorder, both with onset during intoxication. He also is given a provisional diagnosis of psychotic disorder not otherwise specified and major depressive disorder. Last, he is given a diagnosis of Cannabis dependence with physiological dependence, MDMA abuse, hydrocodone abuse, and Robitussin abuse.

Mr. L is maintained on fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and risperidone, 1 mg at bedtime and 0.5 mg in the morning. He receives milieu, individual, group, recreational, and medical therapy while in the hospital. Symptoms abate and he is discharged with a plan to follow up with outpatient providers.

Bottom Line

Abuse of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, such as diphenhydramine, among youths is a growing problem. Remember to question adolescents who appear intoxicated or to have overdosed not only about abuse of alcohol and illicit substances but also of common—and easily and legally accessible—OTC drugs.

Related Resources

• Carr BC. Efficacy, abuse, and toxicity of over-the-counter cough and cold medicines in the pediatric population. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(2):184-188.

• Thomas A, Nallur DG, Jones N, et al. Diphenhydramine abuse and detoxification: a brief review and case report. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(1):101-105.

Drug Brand Names

Diazepam • Valium Hydrocodone • Vicodin

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl Risperidone • Risperdal

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Numb and confused

Mr. L, age 17, is admitted to the hospital after ingesting 24 diphenhydramine 25-mg tablets in 3 hours as a possible suicide attempt. His parents witnessed him behaving strangely and brought him to the hospital. They state that their son was visibly agitated and acting inappropriately. He was seen talking to birds, trees, and the walls of the house.

Mr. L says he is upset because he broke up with his girlfriend a week earlier after she asked if they could “take a break.” He says that he took the diphenhydramine because he wanted to “get numb” to deal with the emotional stress caused by the break-up.

After the break-up, Mr. L experienced middle-to-late insomnia and was unable to get more than 3 or 4 hours of sleep a night. He reports significant fatigue, depressed mood, anhedonia, impaired concentration, and psychomotor retardation. He denies homicidal ideation or auditory and visual hallucinations.

As an aside, Mr. L reports that, for the past year, he had difficulties with gender identity, sometimes thinking that he might be better off if he had been born a girl and that he felt uncomfortable in a male body.

Which treatment option would you choose for Mr. L’s substance abuse?

a) refer him to a 12-step program

b) begin supportive measures

c) administer activated charcoal

d) prescribe a benzodiazepine to control agitation

The authors’ observations

As youths gain increasing access to medical and pharmaceutical knowledge through the Internet and other sources, it appears that adolescent drug abuse has, in part, shifted toward more easily attainable over-the-counter (OTC) medications. Diphenhydramine, a first-generation antihistamine, can be abused for its effects on the CNS, such as disturbed coordination, irritability, paresthesia, blurred vision, and depression. Effects of diphenhydramine are increased by the presence of alcohol, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, diazepam, hypnotics, sedatives, tranquilizers, and other CNS depressants. In 2011, diphenhydramine abuse was involved in 19,012 emergency room visits, of which 9,301 were for drug-related suicide attempts.1

Diphenhydramine is an inverse agonist of the histamine H1 receptor.2 It is a member of the ethanolamine subclass of antihistaminergic agents.3 By reversing the effects of histamine on capillaries, diphenhydramine can reduce the intensity of allergic symptoms. Diphenhydramine also crosses the blood–brain barrier and antagonizes H1 receptors centrally.

Used as a common sleep aid and allergy medication, the drug works primarily as an H1 receptor partial agonist, but also is a strong competitive antagonist at muscarinic acetylcholine receptors.4 It is abused for its sedative effects and its capacity to cause delirium and hallucinations.5 Diphenhydramine can have a stimulatory effect in children and young adults, instead of the sedating properties seen in adults.6 Such misuse is concerning because diphenhydramine overdose can lead to delirium, confusion, and hallucinations, tachycardia, seizures, mydriasis, xerostomia, urinary retention, ileus, anhidrosis, and hyperthermia. In severe cases it has been associated with cardiac arrhythmias, rhabdomyolysis, status epilepticus, and death.4,6 Neurologic symptoms of diphenhydramine overdose are listed in Table 1.

HISTORY Polysubstance abuse

Mr. L has a 2-year history of major depressive disorder and a history of Cannabis abuse with physiological dependence; Robitussin (base active ingredient, guaifenesin) and hydrocodone abuse with physiological dependence; 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) abuse; and diphenhydramine abuse. He also has a history of gender dysphoria, although he reports that these feelings have become less severe over the past year.

Mr. L attends bi-weekly appointments with an outpatient psychiatrist and reportedly adheres to his medication regimen: fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and risperidone, 1 mg at bedtime. He denies previous suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, homicidal ideation, or homicidal attempts. He reports no history of physical, sexual, or emotional abuse. He gets good grades in school and has no outstanding academic problems.

Mr. L began using Cannabis at age 14; his last use was 3 weeks before admission. He is guarded about his use of Robitussin, hydrocodone, and MDMA. However, Mr. L reports that he has researched diphenhydramine on the internet and believes that he can safely take up to 1,200 mg without overdosing. He reports normally taking 450 mg of diphenhydramine daily. Mr. L reports difficulty urinating after using diphenhydramine but no other physical complaints.

Mr. L lives with his father and stepmother and has a history of one psychiatric hospitalization at a different facility 2 months ago, followed by outpatient therapy. He obtained his Graduate Equivalency Diploma (GED) and plans to attend college.

At age 5, Mr. L emigrated from Turkey to the United States with his parents. His mother returned to Turkey when he was age 6 and has had no contact with her son since. Whenever Mr. L visits Turkey with his father, the patient refuses to see her, as per collaterals. He gets along well with his stepmother, who is his maternal aunt. Mr. L has been bullied at school and reportedly has few friends.

On mental status examination, Mr. L has an appropriate appearance and appears to be his stated age. He shows good eye contact and is cooperative. Muscle tone and gait are within normal limits. He has no abnormal movements. Speech, thought processes, and associations are normal. He denies auditory hallucinations, visual hallucinations, suicidal ideation (although he presented with a probable suicide attempt), or homicidal ideation. No delusions are elicited.

Mr. L shows poor judgment about his drug use and situation. He demonstrates limited insight, because he says his only goal is to get out of the hospital. He is alert, awake, and oriented to person, place, and time. He shows no memory or knowledge impairment. He appears euthymic with an inappropriate and constricted affect. On neurologic exam, he had mild tremors in his hands. The authors’ observationsTreatment for diphenhydramine overdose should begin quickly to prevent life-threatening effects and reduce the risk for mortality. The toxin can be removed from the patient’s GI tract with activated charcoal or gastric lavage if the patient presents within 1 hour of ingesting the substance. Administering IV fluids will prevent dehydration. Cardiac functioning is monitored and benzodiazepines could be administered to manage seizures.

Key elements of a toxicologic physical examination include:

• eyes: pupillary size, symmetry, and response to light (vertical or horizontal nystagmus)

• oropharynx: moist or dry mucous membranes, presence or absence of the gag reflex, distinctive odors

• abdomen: presence or absence and quality of bowel sounds

• skin: warm and dry, warm and sweaty, or cool

• neurologic: level of consciousness and mental status, presence of tremors, seizures, or other movement disorders, presence or absence and quality of deep tendon reflexes.7

If a child or adolescent patient cannot communicate how much of a drug he (she) has ingested, questions to ask parents or other informants include:

• Was the medication purchased recently, and if so was the bottle or box full before the patient took the pills?

• If the medication was not new, how many pills were in the bottle before the patient got to it?

• If the medication was prescribed, how many pills were originally prescribed, when was the medication prescribed, and how many pills were already taken prior to the patient getting to the bottle?

• How many pills were left in the bottle?

• How many pills were seen around the area where the patient was found?

• How many pills were found in the patient’s mouth?7

Recommendations

It is well known that OTC medication abuse is a growing medical problem (Table 2). Antihistamines, including diphenhydramine, are readily available to minors and adults. Because of the powerful sedating effects of antihistamines, many adolescent health practitioners give them to patients who have insomnia as a sleep aid.8 As in our case, antihistamines are used recreationally for their hallucinogenic effects, at dosages of 300 to 700 mg.9 Severe symptoms of toxicity, such as delirium and psychosis, seizures, and coma, occur at dosages ≥1,000 mg.9

With growing abuse of these medications, we aim to encourage detailed history taking about abuse of OTC drugs, especially diphenhydramine in adolescent patients.

Outcome Improvement, discharge

Mr. L is given a dual diagnosis of diphenhydramine-induced psychotic disorder with

hallucinations and diphenhydramine-induced depressive disorder, both with onset during intoxication. He also is given a provisional diagnosis of psychotic disorder not otherwise specified and major depressive disorder. Last, he is given a diagnosis of Cannabis dependence with physiological dependence, MDMA abuse, hydrocodone abuse, and Robitussin abuse.

Mr. L is maintained on fluoxetine, 40 mg/d, and risperidone, 1 mg at bedtime and 0.5 mg in the morning. He receives milieu, individual, group, recreational, and medical therapy while in the hospital. Symptoms abate and he is discharged with a plan to follow up with outpatient providers.

Bottom Line

Abuse of over-the-counter (OTC) drugs, such as diphenhydramine, among youths is a growing problem. Remember to question adolescents who appear intoxicated or to have overdosed not only about abuse of alcohol and illicit substances but also of common—and easily and legally accessible—OTC drugs.

Related Resources

• Carr BC. Efficacy, abuse, and toxicity of over-the-counter cough and cold medicines in the pediatric population. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(2):184-188.

• Thomas A, Nallur DG, Jones N, et al. Diphenhydramine abuse and detoxification: a brief review and case report. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(1):101-105.

Drug Brand Names

Diazepam • Valium Hydrocodone • Vicodin

Diphenhydramine • Benadryl Risperidone • Risperdal

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. http://www.samhsa. gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.htm. Published May 2013. Accessed on September 29, 2014.

2. Yamashiro K, Kiryu J, Tsujikawa A, et al. Suppressive effects of histamine H1 receptor antagonist diphenhydramine on the leukocyte infiltration during endotoxin-induced uveitis. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73(1):69-80.

3. Skidgel RA, Kaplan AP, Erdos EG. Histamine, bradykinin, and their antagonists. In: Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 12th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2011: 911-935.

4. Vearrier D, Curtis JA. Case files of the medical toxicology fellowship at Drexel University. Rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome following acute diphenhydramine overdose. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7(3):213-219.

5. Ho M, Tsai K, Liu C. Diphenhydramine overdose related delirium: a case report. Journal of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;17(2):77-79.

6. Krenzelok EP, Anderson GM, Mirick M. Massive diphenhydramine overdose resulting in death. Ann Emerg Med. 1982;11(4):212-213.

7. Inaba AS. Toxicologic teasers: Testing your knowledge of clinical toxicology. Hawaii Med J. 1998;57(4):471-473.

8. Kaplan SL. Busner J. The use of prn and stat medication in three child psychiatric inpatient settings. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):161-164.

9. Radovanovic D, Meier PJ, Guirguis M, et al. Dose-dependent toxicity of diphenhydramine overdose. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19(9):489-495.

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2011: National estimates of drug-related emergency department visits. http://www.samhsa. gov/data/2k13/DAWN2k11ED/DAWN2k11ED.htm. Published May 2013. Accessed on September 29, 2014.

2. Yamashiro K, Kiryu J, Tsujikawa A, et al. Suppressive effects of histamine H1 receptor antagonist diphenhydramine on the leukocyte infiltration during endotoxin-induced uveitis. Exp Eye Res. 2001;73(1):69-80.

3. Skidgel RA, Kaplan AP, Erdos EG. Histamine, bradykinin, and their antagonists. In: Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 12th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2011: 911-935.

4. Vearrier D, Curtis JA. Case files of the medical toxicology fellowship at Drexel University. Rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome following acute diphenhydramine overdose. J Med Toxicol. 2011;7(3):213-219.

5. Ho M, Tsai K, Liu C. Diphenhydramine overdose related delirium: a case report. Journal of Emergency and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;17(2):77-79.

6. Krenzelok EP, Anderson GM, Mirick M. Massive diphenhydramine overdose resulting in death. Ann Emerg Med. 1982;11(4):212-213.

7. Inaba AS. Toxicologic teasers: Testing your knowledge of clinical toxicology. Hawaii Med J. 1998;57(4):471-473.

8. Kaplan SL. Busner J. The use of prn and stat medication in three child psychiatric inpatient settings. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):161-164.

9. Radovanovic D, Meier PJ, Guirguis M, et al. Dose-dependent toxicity of diphenhydramine overdose. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2000;19(9):489-495.

How to assess the merits of psychological and neuropsychological test evaluations

Psychological and neuropsychological test evaluations, like all consultative diagnostic services, can vary in quality and clinical utility. Many of these examinations provide valuable insights and helpful recommendations; regrettably, some assessments are only marginally beneficial and can contribute to diagnostic confusion and uncertainty.

When weighing the pros and cons of evaluations, consider these best practices.

Gold-standard tests ought to be in-cluded in the assessment. These include (but are not limited to) the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV); Wechsler Memory Scale-Fourth Edition (WMS-IV); Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS); Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-Third Edition (WIAT-III); and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2). These tests have a strong evidence base that:

• demonstrates good reliability (ie, produce consistent and accurate scores across examiners and time intervals and are relatively free of measurement error)

• demonstrates good validity (ie, have been shown to measure aspects of psychological and neuropsychological functioning that they claim to measure).

Many gold-standard tests are normed on national samples and are stratified by age, sex, ethnicity or race, educational level, and geographic region. They also include normative data based on the performance of patients who have neuropsychiatric syndromes often seen by psychiatrists in practice.1

The test battery ought to comprise cognitive and neuropsychological measures as well as affective and behavioral measures. When feasible, these tests should be supplemented by informant-based measures of neuropsychiatric functioning to obtain a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s capacities and skills.

An estimated premorbid baseline should be established. This is done by taking a relevant history and administering tests, such as the National Adult Reading Test (NART), that can be used to compare against current test performance. This testing-in-context approach helps differentiate long-term limitations in information processing, which might be attributed to a DSM-5 intellectual disability, specific learning disorder, or other neurodevelopmental disorder, from a known or suspected recent neurobehavioral change.

Tests in the assessment should tap a broad set of neurobehavioral functions. Doing so ensures that, when a patient is referred with a change in cognition or other aspects of mental status, it will be easier to determine whether clinically significant score discrepancies exist across different ability and skill domains. Such dissociations in performance can have important implications for the differential diagnosis and everyday functioning.

Tests that are sensitive to a patient’s over-reporting of symptoms should be used as part of the evaluation in cases of suspected malingering—especially subtle simulation that might elude identification with brief screening-level measures.2 These tests can include the Test of Memory Malingering (TOMM) and the Structured Interview of Reported Symptoms, 2nd edition (SIRS-2).

Test recommendations ought to be grounded in findings; practical; and relatively easy to implement. They also should be consistent with the treatment setting and the patient’s lifestyle, values, and treatment preferences.3

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Geisinger KF, Bracken BA, Carlson JF, et al, eds. APA handbook of testing and assessment in psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2013.

2. Brady MC, Scher LM, Newman W. “I just saw Big Bird. He was 100 feet tall!” Malingering in the emergency department. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(10):33-38,40.

3. McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, et al. Patient p for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):595-602.

Psychological and neuropsychological test evaluations, like all consultative diagnostic services, can vary in quality and clinical utility. Many of these examinations provide valuable insights and helpful recommendations; regrettably, some assessments are only marginally beneficial and can contribute to diagnostic confusion and uncertainty.

When weighing the pros and cons of evaluations, consider these best practices.

Gold-standard tests ought to be in-cluded in the assessment. These include (but are not limited to) the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV); Wechsler Memory Scale-Fourth Edition (WMS-IV); Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS); Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-Third Edition (WIAT-III); and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2). These tests have a strong evidence base that:

• demonstrates good reliability (ie, produce consistent and accurate scores across examiners and time intervals and are relatively free of measurement error)

• demonstrates good validity (ie, have been shown to measure aspects of psychological and neuropsychological functioning that they claim to measure).

Many gold-standard tests are normed on national samples and are stratified by age, sex, ethnicity or race, educational level, and geographic region. They also include normative data based on the performance of patients who have neuropsychiatric syndromes often seen by psychiatrists in practice.1

The test battery ought to comprise cognitive and neuropsychological measures as well as affective and behavioral measures. When feasible, these tests should be supplemented by informant-based measures of neuropsychiatric functioning to obtain a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s capacities and skills.

An estimated premorbid baseline should be established. This is done by taking a relevant history and administering tests, such as the National Adult Reading Test (NART), that can be used to compare against current test performance. This testing-in-context approach helps differentiate long-term limitations in information processing, which might be attributed to a DSM-5 intellectual disability, specific learning disorder, or other neurodevelopmental disorder, from a known or suspected recent neurobehavioral change.

Tests in the assessment should tap a broad set of neurobehavioral functions. Doing so ensures that, when a patient is referred with a change in cognition or other aspects of mental status, it will be easier to determine whether clinically significant score discrepancies exist across different ability and skill domains. Such dissociations in performance can have important implications for the differential diagnosis and everyday functioning.

Tests that are sensitive to a patient’s over-reporting of symptoms should be used as part of the evaluation in cases of suspected malingering—especially subtle simulation that might elude identification with brief screening-level measures.2 These tests can include the Test of Memory Malingering (TOMM) and the Structured Interview of Reported Symptoms, 2nd edition (SIRS-2).

Test recommendations ought to be grounded in findings; practical; and relatively easy to implement. They also should be consistent with the treatment setting and the patient’s lifestyle, values, and treatment preferences.3

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Psychological and neuropsychological test evaluations, like all consultative diagnostic services, can vary in quality and clinical utility. Many of these examinations provide valuable insights and helpful recommendations; regrettably, some assessments are only marginally beneficial and can contribute to diagnostic confusion and uncertainty.

When weighing the pros and cons of evaluations, consider these best practices.

Gold-standard tests ought to be in-cluded in the assessment. These include (but are not limited to) the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Fourth Edition (WAIS-IV); Wechsler Memory Scale-Fourth Edition (WMS-IV); Delis-Kaplan Executive Function System (D-KEFS); Wechsler Individual Achievement Test-Third Edition (WIAT-III); and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 (MMPI-2). These tests have a strong evidence base that:

• demonstrates good reliability (ie, produce consistent and accurate scores across examiners and time intervals and are relatively free of measurement error)

• demonstrates good validity (ie, have been shown to measure aspects of psychological and neuropsychological functioning that they claim to measure).

Many gold-standard tests are normed on national samples and are stratified by age, sex, ethnicity or race, educational level, and geographic region. They also include normative data based on the performance of patients who have neuropsychiatric syndromes often seen by psychiatrists in practice.1

The test battery ought to comprise cognitive and neuropsychological measures as well as affective and behavioral measures. When feasible, these tests should be supplemented by informant-based measures of neuropsychiatric functioning to obtain a comprehensive assessment of the patient’s capacities and skills.

An estimated premorbid baseline should be established. This is done by taking a relevant history and administering tests, such as the National Adult Reading Test (NART), that can be used to compare against current test performance. This testing-in-context approach helps differentiate long-term limitations in information processing, which might be attributed to a DSM-5 intellectual disability, specific learning disorder, or other neurodevelopmental disorder, from a known or suspected recent neurobehavioral change.

Tests in the assessment should tap a broad set of neurobehavioral functions. Doing so ensures that, when a patient is referred with a change in cognition or other aspects of mental status, it will be easier to determine whether clinically significant score discrepancies exist across different ability and skill domains. Such dissociations in performance can have important implications for the differential diagnosis and everyday functioning.

Tests that are sensitive to a patient’s over-reporting of symptoms should be used as part of the evaluation in cases of suspected malingering—especially subtle simulation that might elude identification with brief screening-level measures.2 These tests can include the Test of Memory Malingering (TOMM) and the Structured Interview of Reported Symptoms, 2nd edition (SIRS-2).

Test recommendations ought to be grounded in findings; practical; and relatively easy to implement. They also should be consistent with the treatment setting and the patient’s lifestyle, values, and treatment preferences.3

Disclosure

Dr. Pollak reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Geisinger KF, Bracken BA, Carlson JF, et al, eds. APA handbook of testing and assessment in psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2013.

2. Brady MC, Scher LM, Newman W. “I just saw Big Bird. He was 100 feet tall!” Malingering in the emergency department. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(10):33-38,40.

3. McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, et al. Patient p for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):595-602.

1. Geisinger KF, Bracken BA, Carlson JF, et al, eds. APA handbook of testing and assessment in psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press; 2013.

2. Brady MC, Scher LM, Newman W. “I just saw Big Bird. He was 100 feet tall!” Malingering in the emergency department. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(10):33-38,40.

3. McHugh RK, Whitton SW, Peckham AD, et al. Patient p for psychological vs pharmacologic treatment of psychiatric disorders: a meta-analytic review. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(6):595-602.

Treating bipolar mania in the outpatient setting: Risk vs reward

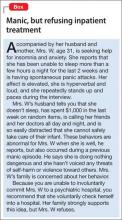

Manic episodes, by definition, are associated with significant social or occupational impairment.1 Some manic patients are violent or engage in reckless behaviors that can harm themselves or others, such as speeding, disrupting traffic, or playing with fire. When these patients present to a psychiatrist’s outpatient practice, involuntary hospitalization might be justified.

However, some manic patients, in spite of their elevated, expansive, or irritable mood state, never behave dangerously and might not meet legal criteria for involuntary hospitalization, although these criteria differ from state to state. These patients might see a psychiatrist because manic symptoms such as irritability, talkativeness, and impulsivity are bothersome to their family members but pose no serious danger (Box). In this situation, the psychiatrist can strongly encourage the patient to seek voluntary hospitalization or attend a partial hospitalization program. If the patient declines, the psychiatrist is left with 2 choices: initiate treatment in the outpatient setting or refuse to treat the patient and refer to another provider.

Treating “non-dangerous” mania in the outpatient setting is fraught with challenges:

• the possibility that the patient’s condition will progress to dangerousness

• poor adherence to treatment because of the patient’s limited insight

• the large amount of time required from the psychiatrist and care team to adequately manage the manic episode (eg, time spent with family members, frequent patient visits, and managing communications from the patient).

There are no guidelines to assist the office-based practitioner in treating mania in the outpatient setting. When considering dosing and optimal medication combinations for treating mania, clinical trials may be of limited value because most of these studies only included hospitalized manic patients.

Because of this dearth of knowledge, we provide recommendations based on our review of the literature and from our experience working with manic patients who refuse voluntary hospitalization and could not be hospitalized against their will. These recommendations are organized into 3 sections: diagnostic approach, treatment strategy, and family involvement.

Diagnostic approach

Making a diagnosis of mania might seem straightforward for clinicians who work in inpatient settings; however, mania might not present with classic florid symptoms among outpatients. Patients might have a chief concern of irritability, dysphoria, anxiety, or “insomnia,” which may lead clinicians to focus initially on non-bipolar conditions.2

During the interview, it is important to assess for any current DSM-5 symptoms of a manic episode, while being careful not to accept a patient’s denial of symptoms. Patients with mania often have poor insight and are unaware of changes from their baseline state when manic.3 Alternatively, manic patients may want you to believe that they are well and could minimize or deny all symptoms. Therefore, it is important to pay attention to mental status examination findings, such as hyperverbal speech, elated affect, psychomotor agitation, a tangential thought process, or flight of ideas.

Countertransference feelings of diagnostic confusion or frustration after long patient monologues or multiple interruptions by the patient should be incorporated into the diagnostic assessment. Family members or friends often can provide objective observations of behavioral changes necessary to secure the diagnosis.

Treatment strategy

Decision points. When treating manic outpatients, assess the need for hospitalization at each visit. Advantages of the inpatient setting include:

• the possibility of rapid medication adjustments

• continuous observation to ensure the patient’s safety

• keeping the patient temporarily removed from his community to prevent irreversible social and economic harms.

However, a challenge with hospitalization is third-party payers’ influence on a patient’s length of stay, which may lead to rapid medication changes that may not be clinically ideal.

At each outpatient visit, explore with the patient and family emerging symptoms that could justify involuntary hospitalization. Document whether you recommended inpatient hospitalization, the patient’s response to the recommendation, that you are aware and have considered the risks associated with outpatient care, and that you have discussed these risks with the patient and family.

For patients well-known to the psychiatrist, a history of dangerous mania may lead him (her) to strongly recommend hospitalization, whereas a pre-existing therapeutic alliance and no current or distant history of dangerous mania may lead the clinician to look for alternatives to inpatient care. Concomitant drug or alcohol use may increase the likelihood of mania becoming dangerous, making outpatient treatment ill-advised and riskier for everyone involved.

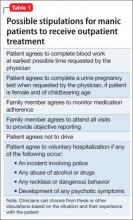

In exchange for agreeing to provide outpatient care for mania, it often is helpful to negotiate with the patient and family a threshold level of symptoms or behavior that will result in the patient agreeing to voluntary hospitalization (Table 1). Such an agreement can include stopping outpatient treatment if the patient does not improve significantly after 2 or 3 weeks or develops psychotic symptoms. The negotiation also can include partial hospitalization as an option, so long as the patient’s mania continues to be non-dangerous.

Obtaining pretreatment blood work can help a clinician determine whether a medication is safe to prescribe and establish causality if laboratory abnormalities arise after treatment begins. Ideally, the psychiatrist should follow consensus guidelines developed by the International Society for Bipolar Disorders4 or the American Psychiatric Association (APA)5 and order appropriate laboratory tests before prescribing anti-manic medications. Determine the pregnancy status of female patients of child-bearing age before prescribing a potentially teratogenic medication, especially because mania is associated with increased libido.6

Manic patients might be too disorganized to follow up with recommendations for laboratory testing, or could wait several days before completing blood work. Although not ideal, to avoid delaying treatment, a clinician might need to prescribe medication at the initial office visit, without pretreatment laboratory results. When the patient is more organized, complete the blood work. Keeping home pregnancy tests in the office can help rule out pregnancy before prescribing medication.

Medication. Meta-analyses have established the efficacy of mood stabilizers and antipsychotics for treating mania,7,8 and several consensus guidelines have incorporated these findings into treatment algorithms.9

For a patient already taking medications recommended by the guidelines, assess treatment adherence during the initial interview by questioning the patient and family. When the logistics of phlebotomy permit, obtaining the blood level of psychotropics can show the presence of any detectable drug concentration, which demonstrates that the patient has taken the medication recently.

If there is no evidence of nonadherence, an initial step might be to increase the dosage of the antipsychotic or mood stabilizer that the patient is already taking, ensuring that the dosage is optimized based on FDA indications and clinical trials data. The recommended rate of dosage adjustments differs among medications; however, optimal dosing should be reached quickly because a World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry task force recommends that a mania treatment trial not exceed 2 weeks.10

Dosage increases can be made at weekly visits or sooner, based on treatment response and tolerability. If there is no benefit after optimizing the dosage, the next step would be to add a mood stabilizer to a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA), or vice versa to promote additive or synergistic medication effects.11 Switching one medication for the other should be avoided unless there are tolerability concerns.

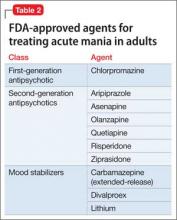

For a patient who is not taking any medications, select a treatment that balances rapid stabilization with long-term efficacy and tolerability. Table 2 lists FDA-approved treatments for mania. Lamotrigine provides prophylactic efficacy with few associated risks, but it has no anti-manic effects and would be a poor choice for most actively manic patients. Most studies indicate that antipsychotics work faster than lithium at the 1-week mark; however, this may be a function of the lithium titration schedule followed in the protocols, the severity of mania among enrolled patients, the inclusion of typically non-responsive manic patients (eg, mixed) in the analysis, and the antipsychotic’s sedative potential relative to lithium. Although the anti-manic and prophylactic potential of lithium and valproate might make them an ideal first-line option, antipsychotics could stabilize a manic patient faster, especially if agitation is present.12,13

Breaking mania quickly is important when treating patients in the outpatient setting. In these situations, a reasonable choice is to prescribe a SGA, because of their rapid onset of effect, low potential for switch to depression, and utility in treating classic, mixed, or psychotic mania.10 Oral loading of valproate (20 mg/kg) is another option. An inpatient study that used an oral-loading strategy demonstrated a similar time to response as olanzapine,14 in contrast to an inpatient15 and an outpatient study16 that employed a standard starting dosage for each patient and led to slower improvement compared with olanzapine.

SGAs should be dosed moderately and lower than if the patient were hospitalized, to avoid alienating the patient from treatment by causing intolerable side effects. In particular, patients and their families should be warned about immediate risks, such as orthostasis or extrapyramidal symptoms. Although treatment guidelines recommend combination therapy as a possible first-line option,9 in the outpatient setting, monotherapy with an optimally dosed, rapid-acting agent is preferred to promote medication adherence and avoid potentially dangerous sedation. Manic patients experience increased distractibility and verbal memory and executive function impairments that can interfere with medication adherence.17 Therefore, patients are more likely to follow a simpler regimen. If SGA or valproate monotherapy does not control mania, begin combination treatment with a mood stabilizer and SGA. If the patient experiences remission with SGA monotherapy, the risks and benefits of maintaining the SGA vs switching to a mood stabilizer can be discussed.

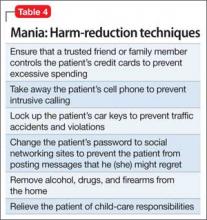

Provide medication “as needed” for agitation—additional SGA dosing or a benzodiazepine—and explain to family members when their use is warranted. Benzodiazepines can provide short-term benefits for manic patients: anxiety relief, sedation, and anti-manic efficacy as monotherapy18-20 and in combination with other medications.21 Studies showing monotherapy efficacy employed high dosages of benzodiazepines (lorazepam mean dosage, 14 mg/d; clonazepam mean dosage, 13 mg/d)19 and high dosages of antipsychotics as needed,18,20 and often were associated with excessive sedation and ataxia.18,19 This makes benzodiazepine monotherapy a potentially dangerous approach for outpatient treatment of mania. IM lorazepam treated manic agitation less quickly than IM olanzapine, suggesting that SGAs are preferable in the outpatient setting because rapid control of agitation is crucial.22 If prescribed, a trusted family member should dispense benzodiazepines to the patient to minimize misuse because of impulsivity, distractibility, desperation to sleep, or pleasure seeking.

SGAs have the benefit of sedation but occasionally additional sleep medications are required. Benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs), such as zolpidem, eszopiclone, and zaleplon, should be used with caution. Although these medicines are effective in treating insomnia in individuals with primary insomnia23 and major depression,24 they have not been studied in manic patients. The decreased need for sleep in mania is phenomenologically25 and perhaps biologically different than insomnia in major depression.26 Therefore, mania-associated sleep disturbance might not respond to BZRAs. BzRAs also might induce somnambulism and other parasomnias,27 especially when used in combination with psychotropics, such as valproate28; it is unclear if the manic state itself increases this risk further. Sedating antihistamines with anticholinergic blockade, such as diphenhydramine and low dosages (<100 mg/d) of quetiapine, are best used only in combination with anti-manic medications because of putative link between anticholinergic blockade and manic induction.29 Less studied but safer options include novel anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin), melatonin, and melatonin receptor agonists. Sedating antidepressants, such as mirtazapine and trazodone, should be avoided.25

Important adjunctive treatment steps include discontinuing all pro-manic agents, including antidepressants, stimulants, and steroids, and discouraging use of caffeine, energy drinks, illicit drugs, and alcohol. The patient should return for office visits at least weekly, and possibly more frequently, depending on severity. Telephone check-in calls between scheduled visits may be necessary until the mania is broken.

Psychotherapy. Other than supportive therapy and psychoeducation, other forms of psychotherapy during mania are not indicated. Psychotherapy trials in bipolar disorder do not inform anti-manic efficacy because few have enrolled acutely manic patients and most report long-term benefits rather than short-term efficacy for the index manic episode.30 Educate patients about the importance of maintaining regular social rhythms and taking medication as prescribed. Manic patients might not be aware that they are acting differently during manic episodes, therefore efforts to improve the patient’s insight are unlikely to succeed. More time should be spent emphasizing the importance of adherence to treatment and taking anti-manic medications as prescribed. This discussion can be enhanced by focusing on the medication’s potential to reduce the unpleasant symptoms of mania, including irritability, insomnia, anxiety, and racing thoughts. At the first visit, discuss setting boundaries with the patient to reduce mania-driven, intrusive phone calls. A patient might develop insight after mania has resolved and he (she) can appreciate social or economic harm that occurred while manic. This discussion might foster adherence to maintenance treatment. Advise your patient to limit activities that may increase stimulation and perpetuate the mania, such as exercise, parties, concerts, or crowded shopping malls. Also, recommend that your patient stop working temporarily, to reduce stress and prevent any manic-driven interactions that could result in job loss.

If your patient has an established relationship with a psychotherapist, discuss with the therapist the plan to initiate mania treatment in the outpatient setting and work as a collaborative team, assuming that the patient has granted permission to share information. Encourage the therapist to increase the frequency of sessions with the patient to enable greater monitoring of changes in the patient’s manic symptoms.

Family involvement

Family support is crucial when treating mania in the outpatient setting. Lacking insight and organization, manic patients require the “auxiliary” judgment of trusted family members to ensure treatment success. The family should identify a single person to act as the liaison between the family and the psychiatrist. The psychiatrist should instruct this individual to accompany the patient to each clinic visit and provide regular updates on the patient’s adherence to treatment, changes in symptoms, and any new behaviors that would justify involuntary hospitalization. The treatment plan should be clearly communicated to this individual to ensure that it is implemented correctly. Ideally, this individual would be someone who understands that bipolar disorder is a mental illness, who can tolerate the patient’s potential resentment of them for taking on this role, and who can influence the patient and the other family members to adhere to the treatment plan.

This family member also should watch the patient take medication to rule out nonadherence if the patient’s condition does not improve.

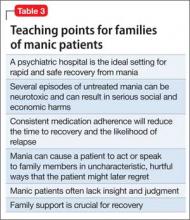

Provide extensive psychoeducation to the family (Table 3). Discuss these teaching points and their implications at length during the first visit and reinforce them at subsequent visits. Advise spouses that the acute manic period is not the time to make major decisions about their marriage or to engage in couple’s therapy. These options are better explored after the patient recovers from the manic episode.