User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Let’s talk about poor concordance between diagnosis and treatment!

I enjoy the intellectual insights in Dr. Nasrallah’s From the Editor essays in Current Psychiatry. For future editorials, I suggest a few topics for him to discuss:

• There is poor concordance between diagnosis and treatment by psychiatrists, compared with other medical specialties, because we do not have tests or measures to employ both before and after treatment. In other words, we have not standardized our evaluation or treatment. Despite my 4 videos on YouTube and an e-book, Standardizing psychiatric care, I have not received an enthusiastic response or discussion from the American Psychiatric Association (APA) or academic psychiatrists— knowing that this step is crucial to integration of care with primary care physicians (PCPs) and other physicians. We must be a leader in training PCPs and other clinicians about how we care for our patients.

• The practice of medicine is local. In this region of North Carolina, however, the private practice of psychiatry is disappearing. It is almost impossible to start a successful practice, primarily because of managed care.

• The goals of psychiatric treatment have not been adopted by all professionals. This includes returning patients to optimal functioning at no less than 80% to 90% of their capacity in self care and professional, school, social, and home settings, and to having at least 85% of psychiatric symptoms under control, with the least possible number of medication side effects.

• Treatment of psychiatric symptoms is highly individual, and therefore the dosage of each medication must be titrated carefully. This important aspect of treatment has not been well-emphasized in training or by the leadership of the APA.

• Treatment in psychiatry is a combination of the right medication and lowest effective dosage to minimize side effects. Therefore it is a polypharmacy, and we must accept it and educate patients accordingly.

I hope that Dr. Nasrallah’s influential editorials will shed light on these topics, and begin a national and international debate on these issues.

V. Sagar Sethi, MD, PhD

Carmel Psychiatric Associates, PA

Charlotte, North Carolina

I enjoy the intellectual insights in Dr. Nasrallah’s From the Editor essays in Current Psychiatry. For future editorials, I suggest a few topics for him to discuss:

• There is poor concordance between diagnosis and treatment by psychiatrists, compared with other medical specialties, because we do not have tests or measures to employ both before and after treatment. In other words, we have not standardized our evaluation or treatment. Despite my 4 videos on YouTube and an e-book, Standardizing psychiatric care, I have not received an enthusiastic response or discussion from the American Psychiatric Association (APA) or academic psychiatrists— knowing that this step is crucial to integration of care with primary care physicians (PCPs) and other physicians. We must be a leader in training PCPs and other clinicians about how we care for our patients.

• The practice of medicine is local. In this region of North Carolina, however, the private practice of psychiatry is disappearing. It is almost impossible to start a successful practice, primarily because of managed care.

• The goals of psychiatric treatment have not been adopted by all professionals. This includes returning patients to optimal functioning at no less than 80% to 90% of their capacity in self care and professional, school, social, and home settings, and to having at least 85% of psychiatric symptoms under control, with the least possible number of medication side effects.

• Treatment of psychiatric symptoms is highly individual, and therefore the dosage of each medication must be titrated carefully. This important aspect of treatment has not been well-emphasized in training or by the leadership of the APA.

• Treatment in psychiatry is a combination of the right medication and lowest effective dosage to minimize side effects. Therefore it is a polypharmacy, and we must accept it and educate patients accordingly.

I hope that Dr. Nasrallah’s influential editorials will shed light on these topics, and begin a national and international debate on these issues.

V. Sagar Sethi, MD, PhD

Carmel Psychiatric Associates, PA

Charlotte, North Carolina

I enjoy the intellectual insights in Dr. Nasrallah’s From the Editor essays in Current Psychiatry. For future editorials, I suggest a few topics for him to discuss:

• There is poor concordance between diagnosis and treatment by psychiatrists, compared with other medical specialties, because we do not have tests or measures to employ both before and after treatment. In other words, we have not standardized our evaluation or treatment. Despite my 4 videos on YouTube and an e-book, Standardizing psychiatric care, I have not received an enthusiastic response or discussion from the American Psychiatric Association (APA) or academic psychiatrists— knowing that this step is crucial to integration of care with primary care physicians (PCPs) and other physicians. We must be a leader in training PCPs and other clinicians about how we care for our patients.

• The practice of medicine is local. In this region of North Carolina, however, the private practice of psychiatry is disappearing. It is almost impossible to start a successful practice, primarily because of managed care.

• The goals of psychiatric treatment have not been adopted by all professionals. This includes returning patients to optimal functioning at no less than 80% to 90% of their capacity in self care and professional, school, social, and home settings, and to having at least 85% of psychiatric symptoms under control, with the least possible number of medication side effects.

• Treatment of psychiatric symptoms is highly individual, and therefore the dosage of each medication must be titrated carefully. This important aspect of treatment has not been well-emphasized in training or by the leadership of the APA.

• Treatment in psychiatry is a combination of the right medication and lowest effective dosage to minimize side effects. Therefore it is a polypharmacy, and we must accept it and educate patients accordingly.

I hope that Dr. Nasrallah’s influential editorials will shed light on these topics, and begin a national and international debate on these issues.

V. Sagar Sethi, MD, PhD

Carmel Psychiatric Associates, PA

Charlotte, North Carolina

Eating fish during pregnancy

In Dr. Nasrallah’s Editorial on reducing the risk of schizophrenia in a child (For couples seeking to conceive, offer advice on reducing the risk of schizophrenia, Current Psychiatry, From the Editor, August 2014, p. 11-12, 44; [http://bit.ly/1zAcnUq]), he advised a couple to “Get a good obstetrician well before conception; get the mother immunized against infections; eat a lot of fish (omega-3 fatty acids)…”

Some people are concerned about mercury levels in fish and suggest limiting fish consumption during pregnancy. I do not follow this literature and do not know which fish to recommend and avoid and the current status of the evidence. If people still believe this, should I suggest omega-3 fatty acid supplements instead of eating a lot of fish?

Oommen Mammen, MD

Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I recommend wild salmon as the best source of omega-3 fatty acids from fish. I avoid farmed salmon because that’s where some contamination has been reported. Absent the availability of wild salmon, I recommend omega-3 fatty acid supplements.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair Department of Neurology & Psychiatry

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

In Dr. Nasrallah’s Editorial on reducing the risk of schizophrenia in a child (For couples seeking to conceive, offer advice on reducing the risk of schizophrenia, Current Psychiatry, From the Editor, August 2014, p. 11-12, 44; [http://bit.ly/1zAcnUq]), he advised a couple to “Get a good obstetrician well before conception; get the mother immunized against infections; eat a lot of fish (omega-3 fatty acids)…”

Some people are concerned about mercury levels in fish and suggest limiting fish consumption during pregnancy. I do not follow this literature and do not know which fish to recommend and avoid and the current status of the evidence. If people still believe this, should I suggest omega-3 fatty acid supplements instead of eating a lot of fish?

Oommen Mammen, MD

Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I recommend wild salmon as the best source of omega-3 fatty acids from fish. I avoid farmed salmon because that’s where some contamination has been reported. Absent the availability of wild salmon, I recommend omega-3 fatty acid supplements.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair Department of Neurology & Psychiatry

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

In Dr. Nasrallah’s Editorial on reducing the risk of schizophrenia in a child (For couples seeking to conceive, offer advice on reducing the risk of schizophrenia, Current Psychiatry, From the Editor, August 2014, p. 11-12, 44; [http://bit.ly/1zAcnUq]), he advised a couple to “Get a good obstetrician well before conception; get the mother immunized against infections; eat a lot of fish (omega-3 fatty acids)…”

Some people are concerned about mercury levels in fish and suggest limiting fish consumption during pregnancy. I do not follow this literature and do not know which fish to recommend and avoid and the current status of the evidence. If people still believe this, should I suggest omega-3 fatty acid supplements instead of eating a lot of fish?

Oommen Mammen, MD

Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Dr. Nasrallah responds

I recommend wild salmon as the best source of omega-3 fatty acids from fish. I avoid farmed salmon because that’s where some contamination has been reported. Absent the availability of wild salmon, I recommend omega-3 fatty acid supplements.

Henry A. Nasrallah, MD

Professor and Chair Department of Neurology & Psychiatry

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

St. Louis, Missouri

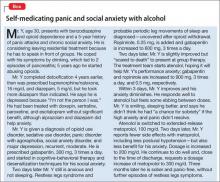

After substance withdrawal, underlying psychiatric symptoms emerge

When treating patients who abuse substances, it is important to watch for underlying clinical conditions that have been suppressed, relieved, or muted by alcohol or drugs. Many of these conditions can be mistaken for signs of withdrawal, drug-seeking, or new conditions arising from loss of euphoria from the drug. Prompt recognition of these disorders and use of appropriate non-addictive treatments can prevent “against medical advice” discharges, relapses, and unneeded suffering in many cases.

Because the brain is the target organ, these conditions are either neurologic or psychiatric in nosology. Although psychiatric clinicians might not be familiar with neurologic conditions, quick recognition and treatment is necessary.

Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements of sleep

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) has 2 key components: paresthesia and akathisia. Although primarily involving the lower extremities, involvement also can include the upper extremities, torso, and head.

Paresthesia differs from typical neuropathies in that it usually is not painful; rather, patients describe an odd sensation using terms such as ticklish, “creepy-crawly,” and other uncomfortable sensations.

Akathisia is a motor restlessness and need to move. The patient might feel momentary relief by moving or rubbing the extremities, only to have the paresthesia return quickly followed by the akathisia. Generally, reclining is the most prominent position that produces symptoms, but they can occur while sitting.

The cause of RLS is an abnormality of central dopamine or iron, or both, in the substantia nigra; iron is a cofactor in dopamine synthesis. All RLS patients should have a serum ferritin level drawn and if <50 μg/dL, be treated with iron supplementation. Dopamine agonists, such as ropinirole, pramipexole, and carbidopa/levodopa, are effective (Table 1); other useful agents include benzodiazepines such as clonazepam and opioids such as hydrocodone.

When a patient withdraws from benzodiazepines or narcotics, RLS can emerge and cause suffering until it is diagnosed and treated. Typical myalgia in opioid withdrawal can confound the diagnosis. The immediate-release (IR) and extended-release (ER) formulations of gabapentin often are a good choice when treating benzodiazepine or narcotic withdrawal. The side effect profile of gabapentin is relatively benign, with somnolence often reported by non-substance abusers, but it is unlikely that addicts, who have grown tolerant to more potent agents such as benzodiazepines and opioids, will complain of sleepiness. Studies have shown that gabapentin is useful in managing withdrawal as well as anxiety and insomnia.1,2 A randomized trial showed that gabapentin increases abstinence rates and decreases heavy drinking.2 The agent has a short half-life (5 to 7 hours); the IR form needs to be dosed at least 3 times a day to be effective. An ER formulation of gabapentin was released in 2013 with the sole indication for RLS.

Gabapentin is not significantly metabolized by the liver, has a 3% rate of protein binding, and is excreted by the kidneys—making it safe for patients who abuse alcohol or opioids and have impaired hepatic function. Typical starting dosages of IR gabapentin are 100 to 300 mg, 3 times daily, if symptoms are present in the daytime. Asymmetric dosing can be helpful, with larger or single dosages given at bedtime (eg, 100 mg in morning, 100 mg in afternoon, 300 mg at bedtime). Dosing varies from patient to patient, from 300 mg to 3,600 mg/d. Increasing dosages produce lower bioavailability because of saturation in absorption or at the blood-brain barrier. At 100 mg every 8 hours, bioavailability is 80% but at 1,600 mg every 8 hours it drops to 27%.3

Periodic limb movements of sleep (PLMS) essentially is akathisia during sleep, and occurs in most patients with RLS. The patient feels tired in the morning because of lack of deep stage-N3 sleep. Because of the inverse relationship between serotonin and dopamine, most selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors can exacerbate RLS and PLMS.4,5 Other culprits include antipsychotics, antiemetics, and antihistamines. The differential diagnosis includes withdrawal from opioids and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which may be comorbid with RLS. There are many causes of secondary RLS including renal failure, pregnancy, varicose veins, and neuropathy.

Tremor

Benign familial, or essential, tremor is a fine intention tremor that can be suppressed by alcohol or benzodiazepines. After detoxification from either of these substances, persistent tremor can re-emerge; often, it is benign, although cerebellar and parkinsonian tremors must be ruled out. Essential tremor can be treated with gabapentin or beta blockers such as propranolol or metoprolol (Table 2).

Anxiety and panic disorder

Social anxiety often presents in addiction treatment centers in the context of group therapy, speaking in 12-step meetings, and having the patient describe his (her) autobiography and history of addiction. Because social anxiety disorder is the third most common psychiatric disorder after simple phobia and major depressive disorder,6 it is not surprising that it emerges after withdrawal.

Patients with social anxiety disorder might self-medicate with alcohol or drugs, especially benzodiazepines (Box). Residential treatment presents an excellent environment for desensitization to fears of public speaking; early recognition is key. Apprehension about group therapy, presenting a substance abuse history, or speaking at a 12-step meeting can lead to premature or “against medical advice” discharge.

Panic disorder commonly is comorbid with substance abuse. Many patients will arrive at treatment with a prescription for benzodiazepines. Because the risk of cross-addiction is high among recovering addicts, benzodiazepines should be avoided. Treating underlying anxiety is crucial for fostering sobriety. Generalized anxiety disorder is common among patients with an addiction, and can lead to relapse if not addressed. Use of non-addictive medications and cognitive therapy is useful in addressing this condition.

A quandary might arise in states where medical marijuana is legal, because Cannabis can be prescribed for anxiety disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Promoting abstinence from all substances can present a challenge in patients with anxiety disorders who live in these states.

Medications for anxiety and panic disorder include gabapentin, buspirone, hydroxyzine, beta blockers, and atypical antipsychotics (Table 2). Only buspirone and hydroxyzine are FDA-approved for anxiety; buspirone monotherapy generally is ineffective for panic disorder.

Explaining to patients how anxiety arises, such as how classical conditioning leads to specific phobias, can be therapeutic. Describing Klein’s false suffocation alarm theory of panic attacks can illustrate the importance of practicing slow, deep breathing to prevent hyperventilation.7 Also, relabeling a panic attack with self-talk statements such as “I know what this is. It’s just a panic attack” can be helpful. Smartphone apps are available to help patients cope with anxiety and acute panic.8

Mood disorders

Many patients with bipolar disorder experience substance abuse at some point; estimates are that up to 57% of patients have a comorbid addiction.6,9 Persons with a mood disorder are at high risk of substance abuse because of genetic factors; patients also might self-medicate their mood symptoms.

After alcohol or drugs are withdrawn, mood disorders can emerge or resurge. Often, patients enter treatment taking antidepressants and mood stabilizers and usually haven’t been truthful with their treatment provider about their substance abuse. Care must be taken to ascertain whether mood symptoms are secondary to substance abuse. Asking “What’s the longest period of abstinence you’ve had in 2 years and how did you feel emotionally?” often will help you identify a secondary mood disorder. For example, a response of “6 months and I felt really depressed the entire time” would indicate a primary depressive disorder.

Because CNS depressants, such as alcohol and benzodiazepines, can exacerbate a mood disorder, consider continuing or resuming a mood stabilizer or antidepressant during substance abuse treatment. When meeting a new patient, perform an independent evaluation, because substance use can mimic bipolar and depressive disorders. Careful assessment of suicidal ideation is necessary for all patients.

Sleep disorders

Insomnia—as a primary or secondary disorder—is common among patients with a substance use disorder. Insomnia always needs to be addressed. Not sleeping well interferes with cognition and energy and makes depression and bipolar disorder worse. Some experts recommend “waiting out” the insomnia, hoping that sobriety will resolve it—but it might not.

Initial insomnia can be treated with melatonin, 3 to 6 mg at bedtime or earlier in the evening.10-12 Melatonin acts by regulating circadian rhythms, but can cause increased dreaming and nightmares; therefore, it should be avoided in patients who struggle with nightmares. Trazodone, 50 to 150 mg at bedtime, is an inexpensive sleep aid for initial insomnia and doesn’t cause weight gain, which many drugs with antihistaminic properties can. Prazosin, 1 to 2 mg initially, for nightmares in PTSD is effective.13

Antipsychotics might be necessary if nothing else works; quetiapine is effective for sleep and the ER form is FDA-approved as an add-on agent in major depression. Low-dose doxepin (≤10 mg) is effective for middle insomnia.14 At these low dosages, troublesome side effects of tricyclic antidepressants can be avoided.

As many as 40% of adults with ADHD have a delayed sleep-phase disorder. Ask your patient if she is a “night owl,” how chronic the condition is, and when her best sleep occurs.15-17 Morning light and evening melatonin can help, but often are insufficient. Many patients present with undiagnosed or untreated sleep apnea, which can cause excessive daytime sleepiness. Referral to a sleep center is prudent; use of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale is a quick way to assess excessive daytime sleepiness.18

ADHD

ADHD commonly is comorbid with a substance use disorder. Patients might present with an earlier diagnosis, including treatment. Several drugs of abuse can alleviate ADHD symptoms, including amphetamines, opioids, cocaine, and Cannabis; self-medicating is common. Because opioids increase dopamine release, a report of improved work and school performance while taking opioids early in addiction can be a clue to an ADHD diagnosis.

Explaining ADHD as a syndrome of “interest-based attention” helps. If a residential treatment program uses reading and writing assignments, a patient with ADHD might struggle and will need extra help and time and a quiet place to do assignments.19,20 A non-addictive medication, such as atomoxetine, can help, but has an antidepressant-like delay of 3 to 5 weeks until onset of symptom relief. Using a long-acting stimulant can be effective and quick, with an effect size 3 to 4 times higher than atomoxetine; such agents should be avoided in patients who abuse amphetamines.

Studies show that treating ADHD, even with stimulants, neither helps nor hurts outcomes in substance use. Lisdexamfetamine is difficult to abuse and is an inactive prodrug (a bond of lysine and dextroamphetamine) that requires enzymatic cleavage and activation by red blood cells; these characteristics creates a long-acting medication that has a lower abuse liability than other drugs for ADHD. However, abuse can occur and the drug must be used cautiously. Earley’s medication guide referenced below recommends that lisdexamfetamine and other stimulants should be avoided if possible in patients in recovery. However, it adds that specialists in treating ADHD in substance-abusing patients should weigh the potential benefits of stimulant use against the risk of relapse.17 Many patients enter treatment with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder that might, in fact, be comorbid with ADHD.

Chronic pain

Many substance abuse patients began taking opioids for acute, then chronic, pain before their use escalated to addiction. These are challenging patients; often, they are referred for treatment without true addiction.

Keep in mind that dependence is not addiction. Pseudo-addiction is a condition in which pain is undertreated and the patient takes more medication to obtain relief, calls for early refills, and displays drug-seeking behavior but is not using drugs to achieve euphoria. A thorough history and physical and referrals to specialists such as orthopedic surgeons and pain specialists are necessary. Explaining opioid-induced hyperalgesia is important to help the patient understand that (1) pain can be made worse by increasing the dosage of an opioid because of supersensitivity and (2) many patients who are weaned off these drugs will experience a decrease or complete relief of pain.21

Gabapentin, duloxetine, or amitriptyline can be beneficial for chronic pain, as well as mindfulness techniques, physical therapy, and complementary and alternative medicine. Pregabalin can produce euphoria and often should be avoided.

A medication guide for recovery

Paul Earley, MD, former medical director at Talbott Recovery in Atlanta, Georgia, publishes an online guide that classifies medications into categories:

• A: safe

• B: use only under the supervision of an addiction medicine specialist or doctor

• C: completely avoid if the patient is in recovery.17

The Talbott guide lists all stimulants in category C, (except for atomoxetine, which is category A). Hydroxyzine is listed under category B. Many programs for impaired professionals and state medical boards use the Guide, and will question the prescribing of any medication from categories B and C.17

Related Resources

• Spiegel DR, Kumari N, Petri JD. Safer use of benzodiazepines for alcohol detoxification. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(10):10-15.

• Kelly TM, Daley DC, Douaihy AB. Treatment of substance abusing patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addict Behav. 2012;37(1):11-24.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Hydrocodone • Vicodin

Atenolol • Tenormin Hydroxyzine • Vistaril, Atarax

Atomoxetine • Strattera Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Buprenorphine/ naloxone • Suboxone Metoprolol • Lopressor, Toprol

Buspirone • BuSpar Paroxetine • Paxil

Carbidopa-levodopa • Sinemet Pramipexole • Mirapex

Clonazepam • Klonopin Prazosin • Minipress

Diazepam • Valium Pregabalin • Lyrica

Doxepin • Silenor, Adapin, Sinequan Propranolol • Inderal

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Quetiapine • Seroquel

Escitalopram • Lexapro Ropinirole • Requip

Gabapentin • Neurontin, Horizant Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Desyrel

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Stock CJ, Carpenter L, Ying J, et al. Gabapentin versus chlordiazepoxide for outpatient alcohol detoxification treatment. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(7-8):961-969.

2. Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, et al. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77.

3. Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, et al. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010; 49(10):661-669.

4. Yang C, White DP, Winkelman JW. Antidepressants and periodic leg movements of sleep. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(6):510-514.

5. Hoque R, Chesson AL Jr. Pharmacologically induced/ exacerbated restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements of sleep, and REM behavior disorder/ REM sleep without atonia: literature review, qualitative scoring, and comparative analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010; 6(1):79-83.

6. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169-184.

7. Klein DF. False suffocation alarms, spontaneous panics, and related conditions. An integrative hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(4):306-317.

8. Holland K. The 17 best anxiety iPhone & Android apps of 2014. http://www.healthline.com/health-slideshow/top-anxiety-iphone-android-apps. Accessed October 28, 2014.

9. Chengappa KN, Levine J, Gershon S, et al. Lifetime prevalence of substance or alcohol abuse and dependence among subjects with bipolar I and II disorders in a voluntary registry. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2(3 Pt 1):191-195.

10. Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders [published online May 17, 2013]. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063773.

11. Wade AG, Ford I, Crawford G, et al. Efficacy of prolonged release melatonin in insomnia patients aged 55-80 years: quality of sleep and next-day alertness outcomes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(10):2597-2605.

12. Srinivasan V, Brzezinski A, Pandi-Perumal SR, et al. Melatonin agonists in primary insomnia and depression-associated insomnia: are they superior to sedative-hypnotics? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(4):913-923.

13. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

14. Scharf M, Rogowski R, Hull S, et al. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 1 mg, 3 mg, and 6 mg in elderly patients with primary insomnia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(10):1557-1564.

15. Baird AL, Coogan AN, Siddiqui A, et al. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is associated with alterations in circadian rhythms at the behavioural, endocrine and molecular levels. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(10):988-995.

16. Yoon SY, Jain U, Shapiro C. Sleep in attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: past, present, and future. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(4):371-388.

17. Earley PH, Merkin B, Skipper G. The medication guide for safe recovery. Revision 1.7. http://paulearley.net/index. php?option=com_docman&Itemid=239. Published March 2014. Accessed October 28, 2014.

18. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540-545.

19. Dodson W. Secrets of the ADHD brain. ADDitude. http:// www.additudemag.com/adhd/article/10117.html. Accessed October 28, 2014.

20. Wilens TE, Dodson W. A clinical perspective of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adulthood. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(10):1301-1313.

21. Lee M, Silverman SM, Hansen H, et al. A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician. 2011;14(2):145-161.

When treating patients who abuse substances, it is important to watch for underlying clinical conditions that have been suppressed, relieved, or muted by alcohol or drugs. Many of these conditions can be mistaken for signs of withdrawal, drug-seeking, or new conditions arising from loss of euphoria from the drug. Prompt recognition of these disorders and use of appropriate non-addictive treatments can prevent “against medical advice” discharges, relapses, and unneeded suffering in many cases.

Because the brain is the target organ, these conditions are either neurologic or psychiatric in nosology. Although psychiatric clinicians might not be familiar with neurologic conditions, quick recognition and treatment is necessary.

Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements of sleep

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) has 2 key components: paresthesia and akathisia. Although primarily involving the lower extremities, involvement also can include the upper extremities, torso, and head.

Paresthesia differs from typical neuropathies in that it usually is not painful; rather, patients describe an odd sensation using terms such as ticklish, “creepy-crawly,” and other uncomfortable sensations.

Akathisia is a motor restlessness and need to move. The patient might feel momentary relief by moving or rubbing the extremities, only to have the paresthesia return quickly followed by the akathisia. Generally, reclining is the most prominent position that produces symptoms, but they can occur while sitting.

The cause of RLS is an abnormality of central dopamine or iron, or both, in the substantia nigra; iron is a cofactor in dopamine synthesis. All RLS patients should have a serum ferritin level drawn and if <50 μg/dL, be treated with iron supplementation. Dopamine agonists, such as ropinirole, pramipexole, and carbidopa/levodopa, are effective (Table 1); other useful agents include benzodiazepines such as clonazepam and opioids such as hydrocodone.

When a patient withdraws from benzodiazepines or narcotics, RLS can emerge and cause suffering until it is diagnosed and treated. Typical myalgia in opioid withdrawal can confound the diagnosis. The immediate-release (IR) and extended-release (ER) formulations of gabapentin often are a good choice when treating benzodiazepine or narcotic withdrawal. The side effect profile of gabapentin is relatively benign, with somnolence often reported by non-substance abusers, but it is unlikely that addicts, who have grown tolerant to more potent agents such as benzodiazepines and opioids, will complain of sleepiness. Studies have shown that gabapentin is useful in managing withdrawal as well as anxiety and insomnia.1,2 A randomized trial showed that gabapentin increases abstinence rates and decreases heavy drinking.2 The agent has a short half-life (5 to 7 hours); the IR form needs to be dosed at least 3 times a day to be effective. An ER formulation of gabapentin was released in 2013 with the sole indication for RLS.

Gabapentin is not significantly metabolized by the liver, has a 3% rate of protein binding, and is excreted by the kidneys—making it safe for patients who abuse alcohol or opioids and have impaired hepatic function. Typical starting dosages of IR gabapentin are 100 to 300 mg, 3 times daily, if symptoms are present in the daytime. Asymmetric dosing can be helpful, with larger or single dosages given at bedtime (eg, 100 mg in morning, 100 mg in afternoon, 300 mg at bedtime). Dosing varies from patient to patient, from 300 mg to 3,600 mg/d. Increasing dosages produce lower bioavailability because of saturation in absorption or at the blood-brain barrier. At 100 mg every 8 hours, bioavailability is 80% but at 1,600 mg every 8 hours it drops to 27%.3

Periodic limb movements of sleep (PLMS) essentially is akathisia during sleep, and occurs in most patients with RLS. The patient feels tired in the morning because of lack of deep stage-N3 sleep. Because of the inverse relationship between serotonin and dopamine, most selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors can exacerbate RLS and PLMS.4,5 Other culprits include antipsychotics, antiemetics, and antihistamines. The differential diagnosis includes withdrawal from opioids and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which may be comorbid with RLS. There are many causes of secondary RLS including renal failure, pregnancy, varicose veins, and neuropathy.

Tremor

Benign familial, or essential, tremor is a fine intention tremor that can be suppressed by alcohol or benzodiazepines. After detoxification from either of these substances, persistent tremor can re-emerge; often, it is benign, although cerebellar and parkinsonian tremors must be ruled out. Essential tremor can be treated with gabapentin or beta blockers such as propranolol or metoprolol (Table 2).

Anxiety and panic disorder

Social anxiety often presents in addiction treatment centers in the context of group therapy, speaking in 12-step meetings, and having the patient describe his (her) autobiography and history of addiction. Because social anxiety disorder is the third most common psychiatric disorder after simple phobia and major depressive disorder,6 it is not surprising that it emerges after withdrawal.

Patients with social anxiety disorder might self-medicate with alcohol or drugs, especially benzodiazepines (Box). Residential treatment presents an excellent environment for desensitization to fears of public speaking; early recognition is key. Apprehension about group therapy, presenting a substance abuse history, or speaking at a 12-step meeting can lead to premature or “against medical advice” discharge.

Panic disorder commonly is comorbid with substance abuse. Many patients will arrive at treatment with a prescription for benzodiazepines. Because the risk of cross-addiction is high among recovering addicts, benzodiazepines should be avoided. Treating underlying anxiety is crucial for fostering sobriety. Generalized anxiety disorder is common among patients with an addiction, and can lead to relapse if not addressed. Use of non-addictive medications and cognitive therapy is useful in addressing this condition.

A quandary might arise in states where medical marijuana is legal, because Cannabis can be prescribed for anxiety disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Promoting abstinence from all substances can present a challenge in patients with anxiety disorders who live in these states.

Medications for anxiety and panic disorder include gabapentin, buspirone, hydroxyzine, beta blockers, and atypical antipsychotics (Table 2). Only buspirone and hydroxyzine are FDA-approved for anxiety; buspirone monotherapy generally is ineffective for panic disorder.

Explaining to patients how anxiety arises, such as how classical conditioning leads to specific phobias, can be therapeutic. Describing Klein’s false suffocation alarm theory of panic attacks can illustrate the importance of practicing slow, deep breathing to prevent hyperventilation.7 Also, relabeling a panic attack with self-talk statements such as “I know what this is. It’s just a panic attack” can be helpful. Smartphone apps are available to help patients cope with anxiety and acute panic.8

Mood disorders

Many patients with bipolar disorder experience substance abuse at some point; estimates are that up to 57% of patients have a comorbid addiction.6,9 Persons with a mood disorder are at high risk of substance abuse because of genetic factors; patients also might self-medicate their mood symptoms.

After alcohol or drugs are withdrawn, mood disorders can emerge or resurge. Often, patients enter treatment taking antidepressants and mood stabilizers and usually haven’t been truthful with their treatment provider about their substance abuse. Care must be taken to ascertain whether mood symptoms are secondary to substance abuse. Asking “What’s the longest period of abstinence you’ve had in 2 years and how did you feel emotionally?” often will help you identify a secondary mood disorder. For example, a response of “6 months and I felt really depressed the entire time” would indicate a primary depressive disorder.

Because CNS depressants, such as alcohol and benzodiazepines, can exacerbate a mood disorder, consider continuing or resuming a mood stabilizer or antidepressant during substance abuse treatment. When meeting a new patient, perform an independent evaluation, because substance use can mimic bipolar and depressive disorders. Careful assessment of suicidal ideation is necessary for all patients.

Sleep disorders

Insomnia—as a primary or secondary disorder—is common among patients with a substance use disorder. Insomnia always needs to be addressed. Not sleeping well interferes with cognition and energy and makes depression and bipolar disorder worse. Some experts recommend “waiting out” the insomnia, hoping that sobriety will resolve it—but it might not.

Initial insomnia can be treated with melatonin, 3 to 6 mg at bedtime or earlier in the evening.10-12 Melatonin acts by regulating circadian rhythms, but can cause increased dreaming and nightmares; therefore, it should be avoided in patients who struggle with nightmares. Trazodone, 50 to 150 mg at bedtime, is an inexpensive sleep aid for initial insomnia and doesn’t cause weight gain, which many drugs with antihistaminic properties can. Prazosin, 1 to 2 mg initially, for nightmares in PTSD is effective.13

Antipsychotics might be necessary if nothing else works; quetiapine is effective for sleep and the ER form is FDA-approved as an add-on agent in major depression. Low-dose doxepin (≤10 mg) is effective for middle insomnia.14 At these low dosages, troublesome side effects of tricyclic antidepressants can be avoided.

As many as 40% of adults with ADHD have a delayed sleep-phase disorder. Ask your patient if she is a “night owl,” how chronic the condition is, and when her best sleep occurs.15-17 Morning light and evening melatonin can help, but often are insufficient. Many patients present with undiagnosed or untreated sleep apnea, which can cause excessive daytime sleepiness. Referral to a sleep center is prudent; use of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale is a quick way to assess excessive daytime sleepiness.18

ADHD

ADHD commonly is comorbid with a substance use disorder. Patients might present with an earlier diagnosis, including treatment. Several drugs of abuse can alleviate ADHD symptoms, including amphetamines, opioids, cocaine, and Cannabis; self-medicating is common. Because opioids increase dopamine release, a report of improved work and school performance while taking opioids early in addiction can be a clue to an ADHD diagnosis.

Explaining ADHD as a syndrome of “interest-based attention” helps. If a residential treatment program uses reading and writing assignments, a patient with ADHD might struggle and will need extra help and time and a quiet place to do assignments.19,20 A non-addictive medication, such as atomoxetine, can help, but has an antidepressant-like delay of 3 to 5 weeks until onset of symptom relief. Using a long-acting stimulant can be effective and quick, with an effect size 3 to 4 times higher than atomoxetine; such agents should be avoided in patients who abuse amphetamines.

Studies show that treating ADHD, even with stimulants, neither helps nor hurts outcomes in substance use. Lisdexamfetamine is difficult to abuse and is an inactive prodrug (a bond of lysine and dextroamphetamine) that requires enzymatic cleavage and activation by red blood cells; these characteristics creates a long-acting medication that has a lower abuse liability than other drugs for ADHD. However, abuse can occur and the drug must be used cautiously. Earley’s medication guide referenced below recommends that lisdexamfetamine and other stimulants should be avoided if possible in patients in recovery. However, it adds that specialists in treating ADHD in substance-abusing patients should weigh the potential benefits of stimulant use against the risk of relapse.17 Many patients enter treatment with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder that might, in fact, be comorbid with ADHD.

Chronic pain

Many substance abuse patients began taking opioids for acute, then chronic, pain before their use escalated to addiction. These are challenging patients; often, they are referred for treatment without true addiction.

Keep in mind that dependence is not addiction. Pseudo-addiction is a condition in which pain is undertreated and the patient takes more medication to obtain relief, calls for early refills, and displays drug-seeking behavior but is not using drugs to achieve euphoria. A thorough history and physical and referrals to specialists such as orthopedic surgeons and pain specialists are necessary. Explaining opioid-induced hyperalgesia is important to help the patient understand that (1) pain can be made worse by increasing the dosage of an opioid because of supersensitivity and (2) many patients who are weaned off these drugs will experience a decrease or complete relief of pain.21

Gabapentin, duloxetine, or amitriptyline can be beneficial for chronic pain, as well as mindfulness techniques, physical therapy, and complementary and alternative medicine. Pregabalin can produce euphoria and often should be avoided.

A medication guide for recovery

Paul Earley, MD, former medical director at Talbott Recovery in Atlanta, Georgia, publishes an online guide that classifies medications into categories:

• A: safe

• B: use only under the supervision of an addiction medicine specialist or doctor

• C: completely avoid if the patient is in recovery.17

The Talbott guide lists all stimulants in category C, (except for atomoxetine, which is category A). Hydroxyzine is listed under category B. Many programs for impaired professionals and state medical boards use the Guide, and will question the prescribing of any medication from categories B and C.17

Related Resources

• Spiegel DR, Kumari N, Petri JD. Safer use of benzodiazepines for alcohol detoxification. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(10):10-15.

• Kelly TM, Daley DC, Douaihy AB. Treatment of substance abusing patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addict Behav. 2012;37(1):11-24.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Hydrocodone • Vicodin

Atenolol • Tenormin Hydroxyzine • Vistaril, Atarax

Atomoxetine • Strattera Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Buprenorphine/ naloxone • Suboxone Metoprolol • Lopressor, Toprol

Buspirone • BuSpar Paroxetine • Paxil

Carbidopa-levodopa • Sinemet Pramipexole • Mirapex

Clonazepam • Klonopin Prazosin • Minipress

Diazepam • Valium Pregabalin • Lyrica

Doxepin • Silenor, Adapin, Sinequan Propranolol • Inderal

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Quetiapine • Seroquel

Escitalopram • Lexapro Ropinirole • Requip

Gabapentin • Neurontin, Horizant Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Desyrel

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

When treating patients who abuse substances, it is important to watch for underlying clinical conditions that have been suppressed, relieved, or muted by alcohol or drugs. Many of these conditions can be mistaken for signs of withdrawal, drug-seeking, or new conditions arising from loss of euphoria from the drug. Prompt recognition of these disorders and use of appropriate non-addictive treatments can prevent “against medical advice” discharges, relapses, and unneeded suffering in many cases.

Because the brain is the target organ, these conditions are either neurologic or psychiatric in nosology. Although psychiatric clinicians might not be familiar with neurologic conditions, quick recognition and treatment is necessary.

Restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements of sleep

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) has 2 key components: paresthesia and akathisia. Although primarily involving the lower extremities, involvement also can include the upper extremities, torso, and head.

Paresthesia differs from typical neuropathies in that it usually is not painful; rather, patients describe an odd sensation using terms such as ticklish, “creepy-crawly,” and other uncomfortable sensations.

Akathisia is a motor restlessness and need to move. The patient might feel momentary relief by moving or rubbing the extremities, only to have the paresthesia return quickly followed by the akathisia. Generally, reclining is the most prominent position that produces symptoms, but they can occur while sitting.

The cause of RLS is an abnormality of central dopamine or iron, or both, in the substantia nigra; iron is a cofactor in dopamine synthesis. All RLS patients should have a serum ferritin level drawn and if <50 μg/dL, be treated with iron supplementation. Dopamine agonists, such as ropinirole, pramipexole, and carbidopa/levodopa, are effective (Table 1); other useful agents include benzodiazepines such as clonazepam and opioids such as hydrocodone.

When a patient withdraws from benzodiazepines or narcotics, RLS can emerge and cause suffering until it is diagnosed and treated. Typical myalgia in opioid withdrawal can confound the diagnosis. The immediate-release (IR) and extended-release (ER) formulations of gabapentin often are a good choice when treating benzodiazepine or narcotic withdrawal. The side effect profile of gabapentin is relatively benign, with somnolence often reported by non-substance abusers, but it is unlikely that addicts, who have grown tolerant to more potent agents such as benzodiazepines and opioids, will complain of sleepiness. Studies have shown that gabapentin is useful in managing withdrawal as well as anxiety and insomnia.1,2 A randomized trial showed that gabapentin increases abstinence rates and decreases heavy drinking.2 The agent has a short half-life (5 to 7 hours); the IR form needs to be dosed at least 3 times a day to be effective. An ER formulation of gabapentin was released in 2013 with the sole indication for RLS.

Gabapentin is not significantly metabolized by the liver, has a 3% rate of protein binding, and is excreted by the kidneys—making it safe for patients who abuse alcohol or opioids and have impaired hepatic function. Typical starting dosages of IR gabapentin are 100 to 300 mg, 3 times daily, if symptoms are present in the daytime. Asymmetric dosing can be helpful, with larger or single dosages given at bedtime (eg, 100 mg in morning, 100 mg in afternoon, 300 mg at bedtime). Dosing varies from patient to patient, from 300 mg to 3,600 mg/d. Increasing dosages produce lower bioavailability because of saturation in absorption or at the blood-brain barrier. At 100 mg every 8 hours, bioavailability is 80% but at 1,600 mg every 8 hours it drops to 27%.3

Periodic limb movements of sleep (PLMS) essentially is akathisia during sleep, and occurs in most patients with RLS. The patient feels tired in the morning because of lack of deep stage-N3 sleep. Because of the inverse relationship between serotonin and dopamine, most selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors can exacerbate RLS and PLMS.4,5 Other culprits include antipsychotics, antiemetics, and antihistamines. The differential diagnosis includes withdrawal from opioids and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which may be comorbid with RLS. There are many causes of secondary RLS including renal failure, pregnancy, varicose veins, and neuropathy.

Tremor

Benign familial, or essential, tremor is a fine intention tremor that can be suppressed by alcohol or benzodiazepines. After detoxification from either of these substances, persistent tremor can re-emerge; often, it is benign, although cerebellar and parkinsonian tremors must be ruled out. Essential tremor can be treated with gabapentin or beta blockers such as propranolol or metoprolol (Table 2).

Anxiety and panic disorder

Social anxiety often presents in addiction treatment centers in the context of group therapy, speaking in 12-step meetings, and having the patient describe his (her) autobiography and history of addiction. Because social anxiety disorder is the third most common psychiatric disorder after simple phobia and major depressive disorder,6 it is not surprising that it emerges after withdrawal.

Patients with social anxiety disorder might self-medicate with alcohol or drugs, especially benzodiazepines (Box). Residential treatment presents an excellent environment for desensitization to fears of public speaking; early recognition is key. Apprehension about group therapy, presenting a substance abuse history, or speaking at a 12-step meeting can lead to premature or “against medical advice” discharge.

Panic disorder commonly is comorbid with substance abuse. Many patients will arrive at treatment with a prescription for benzodiazepines. Because the risk of cross-addiction is high among recovering addicts, benzodiazepines should be avoided. Treating underlying anxiety is crucial for fostering sobriety. Generalized anxiety disorder is common among patients with an addiction, and can lead to relapse if not addressed. Use of non-addictive medications and cognitive therapy is useful in addressing this condition.

A quandary might arise in states where medical marijuana is legal, because Cannabis can be prescribed for anxiety disorders and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Promoting abstinence from all substances can present a challenge in patients with anxiety disorders who live in these states.

Medications for anxiety and panic disorder include gabapentin, buspirone, hydroxyzine, beta blockers, and atypical antipsychotics (Table 2). Only buspirone and hydroxyzine are FDA-approved for anxiety; buspirone monotherapy generally is ineffective for panic disorder.

Explaining to patients how anxiety arises, such as how classical conditioning leads to specific phobias, can be therapeutic. Describing Klein’s false suffocation alarm theory of panic attacks can illustrate the importance of practicing slow, deep breathing to prevent hyperventilation.7 Also, relabeling a panic attack with self-talk statements such as “I know what this is. It’s just a panic attack” can be helpful. Smartphone apps are available to help patients cope with anxiety and acute panic.8

Mood disorders

Many patients with bipolar disorder experience substance abuse at some point; estimates are that up to 57% of patients have a comorbid addiction.6,9 Persons with a mood disorder are at high risk of substance abuse because of genetic factors; patients also might self-medicate their mood symptoms.

After alcohol or drugs are withdrawn, mood disorders can emerge or resurge. Often, patients enter treatment taking antidepressants and mood stabilizers and usually haven’t been truthful with their treatment provider about their substance abuse. Care must be taken to ascertain whether mood symptoms are secondary to substance abuse. Asking “What’s the longest period of abstinence you’ve had in 2 years and how did you feel emotionally?” often will help you identify a secondary mood disorder. For example, a response of “6 months and I felt really depressed the entire time” would indicate a primary depressive disorder.

Because CNS depressants, such as alcohol and benzodiazepines, can exacerbate a mood disorder, consider continuing or resuming a mood stabilizer or antidepressant during substance abuse treatment. When meeting a new patient, perform an independent evaluation, because substance use can mimic bipolar and depressive disorders. Careful assessment of suicidal ideation is necessary for all patients.

Sleep disorders

Insomnia—as a primary or secondary disorder—is common among patients with a substance use disorder. Insomnia always needs to be addressed. Not sleeping well interferes with cognition and energy and makes depression and bipolar disorder worse. Some experts recommend “waiting out” the insomnia, hoping that sobriety will resolve it—but it might not.

Initial insomnia can be treated with melatonin, 3 to 6 mg at bedtime or earlier in the evening.10-12 Melatonin acts by regulating circadian rhythms, but can cause increased dreaming and nightmares; therefore, it should be avoided in patients who struggle with nightmares. Trazodone, 50 to 150 mg at bedtime, is an inexpensive sleep aid for initial insomnia and doesn’t cause weight gain, which many drugs with antihistaminic properties can. Prazosin, 1 to 2 mg initially, for nightmares in PTSD is effective.13

Antipsychotics might be necessary if nothing else works; quetiapine is effective for sleep and the ER form is FDA-approved as an add-on agent in major depression. Low-dose doxepin (≤10 mg) is effective for middle insomnia.14 At these low dosages, troublesome side effects of tricyclic antidepressants can be avoided.

As many as 40% of adults with ADHD have a delayed sleep-phase disorder. Ask your patient if she is a “night owl,” how chronic the condition is, and when her best sleep occurs.15-17 Morning light and evening melatonin can help, but often are insufficient. Many patients present with undiagnosed or untreated sleep apnea, which can cause excessive daytime sleepiness. Referral to a sleep center is prudent; use of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale is a quick way to assess excessive daytime sleepiness.18

ADHD

ADHD commonly is comorbid with a substance use disorder. Patients might present with an earlier diagnosis, including treatment. Several drugs of abuse can alleviate ADHD symptoms, including amphetamines, opioids, cocaine, and Cannabis; self-medicating is common. Because opioids increase dopamine release, a report of improved work and school performance while taking opioids early in addiction can be a clue to an ADHD diagnosis.

Explaining ADHD as a syndrome of “interest-based attention” helps. If a residential treatment program uses reading and writing assignments, a patient with ADHD might struggle and will need extra help and time and a quiet place to do assignments.19,20 A non-addictive medication, such as atomoxetine, can help, but has an antidepressant-like delay of 3 to 5 weeks until onset of symptom relief. Using a long-acting stimulant can be effective and quick, with an effect size 3 to 4 times higher than atomoxetine; such agents should be avoided in patients who abuse amphetamines.

Studies show that treating ADHD, even with stimulants, neither helps nor hurts outcomes in substance use. Lisdexamfetamine is difficult to abuse and is an inactive prodrug (a bond of lysine and dextroamphetamine) that requires enzymatic cleavage and activation by red blood cells; these characteristics creates a long-acting medication that has a lower abuse liability than other drugs for ADHD. However, abuse can occur and the drug must be used cautiously. Earley’s medication guide referenced below recommends that lisdexamfetamine and other stimulants should be avoided if possible in patients in recovery. However, it adds that specialists in treating ADHD in substance-abusing patients should weigh the potential benefits of stimulant use against the risk of relapse.17 Many patients enter treatment with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder that might, in fact, be comorbid with ADHD.

Chronic pain

Many substance abuse patients began taking opioids for acute, then chronic, pain before their use escalated to addiction. These are challenging patients; often, they are referred for treatment without true addiction.

Keep in mind that dependence is not addiction. Pseudo-addiction is a condition in which pain is undertreated and the patient takes more medication to obtain relief, calls for early refills, and displays drug-seeking behavior but is not using drugs to achieve euphoria. A thorough history and physical and referrals to specialists such as orthopedic surgeons and pain specialists are necessary. Explaining opioid-induced hyperalgesia is important to help the patient understand that (1) pain can be made worse by increasing the dosage of an opioid because of supersensitivity and (2) many patients who are weaned off these drugs will experience a decrease or complete relief of pain.21

Gabapentin, duloxetine, or amitriptyline can be beneficial for chronic pain, as well as mindfulness techniques, physical therapy, and complementary and alternative medicine. Pregabalin can produce euphoria and often should be avoided.

A medication guide for recovery

Paul Earley, MD, former medical director at Talbott Recovery in Atlanta, Georgia, publishes an online guide that classifies medications into categories:

• A: safe

• B: use only under the supervision of an addiction medicine specialist or doctor

• C: completely avoid if the patient is in recovery.17

The Talbott guide lists all stimulants in category C, (except for atomoxetine, which is category A). Hydroxyzine is listed under category B. Many programs for impaired professionals and state medical boards use the Guide, and will question the prescribing of any medication from categories B and C.17

Related Resources

• Spiegel DR, Kumari N, Petri JD. Safer use of benzodiazepines for alcohol detoxification. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(10):10-15.

• Kelly TM, Daley DC, Douaihy AB. Treatment of substance abusing patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders. Addict Behav. 2012;37(1):11-24.

Drug Brand Names

Amitriptyline • Elavil Hydrocodone • Vicodin

Atenolol • Tenormin Hydroxyzine • Vistaril, Atarax

Atomoxetine • Strattera Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Buprenorphine/ naloxone • Suboxone Metoprolol • Lopressor, Toprol

Buspirone • BuSpar Paroxetine • Paxil

Carbidopa-levodopa • Sinemet Pramipexole • Mirapex

Clonazepam • Klonopin Prazosin • Minipress

Diazepam • Valium Pregabalin • Lyrica

Doxepin • Silenor, Adapin, Sinequan Propranolol • Inderal

Duloxetine • Cymbalta Quetiapine • Seroquel

Escitalopram • Lexapro Ropinirole • Requip

Gabapentin • Neurontin, Horizant Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Desyrel

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Stock CJ, Carpenter L, Ying J, et al. Gabapentin versus chlordiazepoxide for outpatient alcohol detoxification treatment. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(7-8):961-969.

2. Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, et al. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77.

3. Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, et al. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010; 49(10):661-669.

4. Yang C, White DP, Winkelman JW. Antidepressants and periodic leg movements of sleep. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(6):510-514.

5. Hoque R, Chesson AL Jr. Pharmacologically induced/ exacerbated restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements of sleep, and REM behavior disorder/ REM sleep without atonia: literature review, qualitative scoring, and comparative analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010; 6(1):79-83.

6. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169-184.

7. Klein DF. False suffocation alarms, spontaneous panics, and related conditions. An integrative hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(4):306-317.

8. Holland K. The 17 best anxiety iPhone & Android apps of 2014. http://www.healthline.com/health-slideshow/top-anxiety-iphone-android-apps. Accessed October 28, 2014.

9. Chengappa KN, Levine J, Gershon S, et al. Lifetime prevalence of substance or alcohol abuse and dependence among subjects with bipolar I and II disorders in a voluntary registry. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2(3 Pt 1):191-195.

10. Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders [published online May 17, 2013]. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063773.

11. Wade AG, Ford I, Crawford G, et al. Efficacy of prolonged release melatonin in insomnia patients aged 55-80 years: quality of sleep and next-day alertness outcomes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(10):2597-2605.

12. Srinivasan V, Brzezinski A, Pandi-Perumal SR, et al. Melatonin agonists in primary insomnia and depression-associated insomnia: are they superior to sedative-hypnotics? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(4):913-923.

13. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

14. Scharf M, Rogowski R, Hull S, et al. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 1 mg, 3 mg, and 6 mg in elderly patients with primary insomnia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(10):1557-1564.

15. Baird AL, Coogan AN, Siddiqui A, et al. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is associated with alterations in circadian rhythms at the behavioural, endocrine and molecular levels. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(10):988-995.

16. Yoon SY, Jain U, Shapiro C. Sleep in attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: past, present, and future. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(4):371-388.

17. Earley PH, Merkin B, Skipper G. The medication guide for safe recovery. Revision 1.7. http://paulearley.net/index. php?option=com_docman&Itemid=239. Published March 2014. Accessed October 28, 2014.

18. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540-545.

19. Dodson W. Secrets of the ADHD brain. ADDitude. http:// www.additudemag.com/adhd/article/10117.html. Accessed October 28, 2014.

20. Wilens TE, Dodson W. A clinical perspective of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adulthood. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(10):1301-1313.

21. Lee M, Silverman SM, Hansen H, et al. A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician. 2011;14(2):145-161.

1. Stock CJ, Carpenter L, Ying J, et al. Gabapentin versus chlordiazepoxide for outpatient alcohol detoxification treatment. Ann Pharmacother. 2013;47(7-8):961-969.

2. Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V, et al. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77.

3. Bockbrader HN, Wesche D, Miller R, et al. A comparison of the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of pregabalin and gabapentin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2010; 49(10):661-669.

4. Yang C, White DP, Winkelman JW. Antidepressants and periodic leg movements of sleep. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(6):510-514.

5. Hoque R, Chesson AL Jr. Pharmacologically induced/ exacerbated restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movements of sleep, and REM behavior disorder/ REM sleep without atonia: literature review, qualitative scoring, and comparative analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010; 6(1):79-83.

6. Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(3):169-184.

7. Klein DF. False suffocation alarms, spontaneous panics, and related conditions. An integrative hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(4):306-317.

8. Holland K. The 17 best anxiety iPhone & Android apps of 2014. http://www.healthline.com/health-slideshow/top-anxiety-iphone-android-apps. Accessed October 28, 2014.

9. Chengappa KN, Levine J, Gershon S, et al. Lifetime prevalence of substance or alcohol abuse and dependence among subjects with bipolar I and II disorders in a voluntary registry. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2(3 Pt 1):191-195.

10. Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: melatonin for the treatment of primary sleep disorders [published online May 17, 2013]. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63773. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063773.

11. Wade AG, Ford I, Crawford G, et al. Efficacy of prolonged release melatonin in insomnia patients aged 55-80 years: quality of sleep and next-day alertness outcomes. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(10):2597-2605.

12. Srinivasan V, Brzezinski A, Pandi-Perumal SR, et al. Melatonin agonists in primary insomnia and depression-associated insomnia: are they superior to sedative-hypnotics? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2011;35(4):913-923.

13. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003-1010.

14. Scharf M, Rogowski R, Hull S, et al. Efficacy and safety of doxepin 1 mg, 3 mg, and 6 mg in elderly patients with primary insomnia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(10):1557-1564.

15. Baird AL, Coogan AN, Siddiqui A, et al. Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder is associated with alterations in circadian rhythms at the behavioural, endocrine and molecular levels. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(10):988-995.

16. Yoon SY, Jain U, Shapiro C. Sleep in attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: past, present, and future. Sleep Med Rev. 2012;16(4):371-388.

17. Earley PH, Merkin B, Skipper G. The medication guide for safe recovery. Revision 1.7. http://paulearley.net/index. php?option=com_docman&Itemid=239. Published March 2014. Accessed October 28, 2014.

18. Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540-545.

19. Dodson W. Secrets of the ADHD brain. ADDitude. http:// www.additudemag.com/adhd/article/10117.html. Accessed October 28, 2014.

20. Wilens TE, Dodson W. A clinical perspective of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adulthood. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(10):1301-1313.

21. Lee M, Silverman SM, Hansen H, et al. A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician. 2011;14(2):145-161.

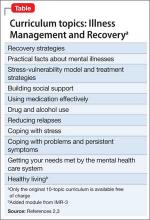

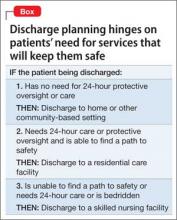

A guide to the mysteries of maintenance of certification

As part of a general trend among all medical specialty boards, the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) instituted a recertification process for all new general psychiatry certifications on October 1, 1994.1 In 2000, the individual specialties that constitute the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) subsequently agreed to develop a comprehensive maintenance of certification (MOC) process to demonstrate ongoing learning and competency beyond what could be captured by a recertification examination alone.

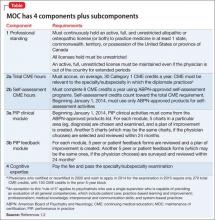

All ABMS member boards now use a 4-part process for recertification. For ABPN, those 4 core components are listed in the Table.1,2

ABPN component 1 (maintaining an unrestricted medical license) and component 4 (passing the recertification examination) are straightforward; however, requirements for continuing medical education (CME), including the specific need to accrue ABPN-approved self-assessment (SA) CME hours, and the Improvement in Medical Practice (performance in practice, or PIP) module, have stoked significant commentary and confusion.

Based on feedback,3,4 ABPN in 2014:

• modified the SA and PIP requirements for physicians who certified or recertified between 2005 and 2011

• changed the specific requirement for the PIP feedback component.

These modifications only added to feelings of uncertainty about the MOC process among many psychiatrists.5

Given the professional and personal importance attached to maintaining one’s general and subspecialty certifications, the 2 parts of this article—here and in the January 2015 issue—have been constructed to highlight current ABPN MOC requirements and provide resources for understanding, tracking, and completing the SA and PIP portions.

In addition to this review, I urge all physicians who are subject to MOC to read the 20-page revised MOC Program bookleta (version 2.1, May 2014).5

aDownload the booklet at www.abpn.com/downloads/moc/ moc_web_doc.pdf.

Who must recertify?

As of October 1, 1994, all physicians who achieve ABPN certifications in general psychiatry are issued a 10-year, time-limited certificate that expires on December 31 of the 10th year.3 Note that the 10-year, time-limited certificate in child and adolescent psychiatry began in 1995 and expires 10 years later on December 31.

Certificates in the subspecialties (addiction psychiatry, forensic psychiatry, geriatric psychiatry, etc.), including those issued before October 1, 1994, are 10-year, time-limited certificates that expire on December 31.3 This expiration date often is overlooked by physicians who are exempt from the MOC process for their general psychiatry, or child and adolescent psychiatry certification. There is no exemption for any subspecialty certificate (aside from child and adolescent psychiatry before 1995), regardless of the date of issue.

Moreover, physicians who hold a certificate in a subspecialty also must maintain certification in their specialty (general psychiatry) to apply for recertification in their subspecialization. One exception: Diplomates in child and adolescent psychiatry do not need to maintain current certification in general psychiatry for their subspecialty certification to remain valid or to recertify in child and adolescent psychiatry.

The need to maintain multiple certifications can seem onerous, but note that CME, SA, and PIP activities that have been completed in one area of specialization or subspecialization accrue and count for multiple certifications for diplomates certified in 2 or more areas.5

Get started!

Tracking your progress is critical to keeping up with MOC requirements. You can do this with a personal spreadsheet or by using online resources. Although it is not required, ABPN has established a system that allows diplomates to create and maintain, at no cost, a physician folio on the ABPN server that facilitates documentation of CME hours, including specific SA hours, and PIP module completion.6 All diplomates are required to maintain records of SA activities, CME activities, and PIP units; the ABPN will audit approximately 5% of examination applications.5

Regardless of what documentation method you choose, you should establish an active profile on the ABPN site (www.abpn. com/folios), confirm your contact information, and, if you are not active clinically, update your clinical status. ABPN requires that diplomates self-report their clinical status every 24 months—information that is available to the public. Clinical status also identifies to ABPN those PIP modules that you must complete.

ABPN recognizes 3 categories of clinical status5:

1. Clinically active. Provided any amount of direct or consultative care, or both, in the preceding 24 months, including supervision of residents.

a) Engaged in direct or consultative care, or both, sufficient to complete Improvement in Medical Practice (PIP) units.

b) Engaged in direct or consultative care, or both, that is insufficient to complete PIP units.

2. Clinically inactive. Did not provide direct or consultative care in the preceding 24 months.

3. Status unknown. No information is available on clinical activity.

Based on these definitions, physicians in Category 1a are required to complete all components of the MOC program, including PIP units; physicians in Category 1b or Category 2 are required to complete all components of the MOC program except PIP units.

A change in status from Category 1b or 2 to Category 1a (eg, moving from a purely administrative position to one with clinical duties) requires completion of ≥1 PIP unit.

The easy parts

Licenses. Maintaining your unrestricted professional license(s) is mandatory; the language of this requirement is unambiguous (Table).5 The plural form of license is intentional: Some physicians have medical licenses in multiple states and, in some jurisdictions, licenses are required to supervise physician assistants and other personnel or to prescribe controlled substances. Any restriction on a professional license should be discussed with ABPN and resolved to prevent rejection of the examination application.5

Examinations. For physicians who are not yet enrolled in the continuous-MOC (C-MOC) process (to be discussed in Part 2 of this article), an application to take the examination in Year 10 can be filed in Year 9 of the cycle—after the CME, SA, and PIP requirements are completed. Once a diplomate becomes subject to the C-MOC process by certifying or recertifying from 2012 onwards, completion of each 3-year module of CME, SA, and PIP will not coincide with the 10-year time frame of the examination.

The application deadline for all MOC examinations typically is the year before the examination; the examination should be taken in the year the certificate expires, although it can be taken earlier if desired.7 The examinations are computer-based and administered at a certified testing center. For diplomates who have more than 1 ABPN certificate and want to combine multiple examinations into 1 test session, a reduced fee structure applies.

The general psychiatry examination comprises 220 single-answer, multiple-choice questions that must be completed within 290 minutes, with 10 extra minutes allotted to read on-screen instructions, sign in, and complete a post-examination survey.8 The combined examinations comprise 100 questions from each ABPN specialty or subspecialty area.5

The content of the 2015 general psychiatry examinationb is available on the ABPN Web site.7 Note that the recertification examination in general psychiatry does not cover neurology topics.

bDownload the outline of the examination at www.abpn.com/ downloads/content_outlines/MOC/2015-MOC-Psych-blueprint-060314-EWM-MR.pdf.

Examinations administered in 2015 and 2016 will use only diagnostic criteria that have not changed from DSM-IV-TR9: Neither obsolete diagnoses or subtypes from DSM-IV-TR nor new diagnoses or subtypes in DSM-5 (eg, hoarding disorder) will be tested.9 Diagnoses that are exactly or substantially the same will be tested; these include diagnoses:

• with a name change only (eg, “phonological disorder” in DSM-IV-TR is “speech sound disorder” in DSM-5)

• expanded into >1 new diagnosis (eg, hypochondriasis was expanded to 2 new diagnoses: somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder)

• subsumed or combined into a new diagnosis (eg, substance use and dependence are now combined into substance use disorder in DSM-5).9

For these diagnoses, both DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 diagnoses will be provided on examinations.