User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Drug-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: Rare but serious

Mr. P, age 67, presents to the clinic with vision changes and memory loss following a fall in his home due to limb weakness. Six years ago, his care team diagnosed him with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Mr. P’s current medication regimen includes methotrexate 20 mg once weekly and etanercept 50 mg once weekly, and he has been stable on this plan for 3 years. Mr. P also was recently diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD), but has not yet started treatment. Following a complete workup, an MRI of Mr. P’s brain revealed white matter demyelination. Due to these findings, he is scheduled for a brain biopsy, which confirms a diagnosis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

PML is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV), or JC polyomavirus, named for the first patient identified to have contracted the virus.1 Asymptomatic infection of JCV often occurs in childhood, and antibodies are found in ≤70% of healthy adults. In most individuals, JCV remains latent in the kidneys and lymphoid organs, but immunosuppression can cause it to reactivate.2

JCV infects oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and neurons, which results in white matter demyelination. Due to this demyelination, individuals can experience visual field defects, speech disturbances, ataxia, paresthesia, and cognitive impairments.2 Limb weakness presents in 60% of patients with PML, visual disturbances in 20%, and gait disturbances in 65%.3 Progression of these symptoms can lead to a more severe clinical presentation, including focal seizures in ≤10% of patients, and the mortality rate is 30% to 50%.3 Patients with comorbid HIV have a mortality rate ≤90%.2

Currently, there are no biomarkers that can identify PML in its early stages. A PML diagnosis is typically based on the patient’s clinical presentation, radiological imaging, and detection of JCV DNA. A brain biopsy is the gold standard for PML diagnosis.1

Interestingly, data suggest that glial cells harboring JCV in the brain express receptors for serotonin and dopamine.4 Researchers pinpointed 5HT2A receptors as JCV entry points into cells, and theorized that medications competing for binding, such as certain psychotropic agents, might decrease JCV entry. Cells lacking the 5HT2A receptor have shown immunity to JCV infection and the ability of cells to be infected was restored through transfection of 5HT2A receptors.4

Immunosuppressant medications can cause PML

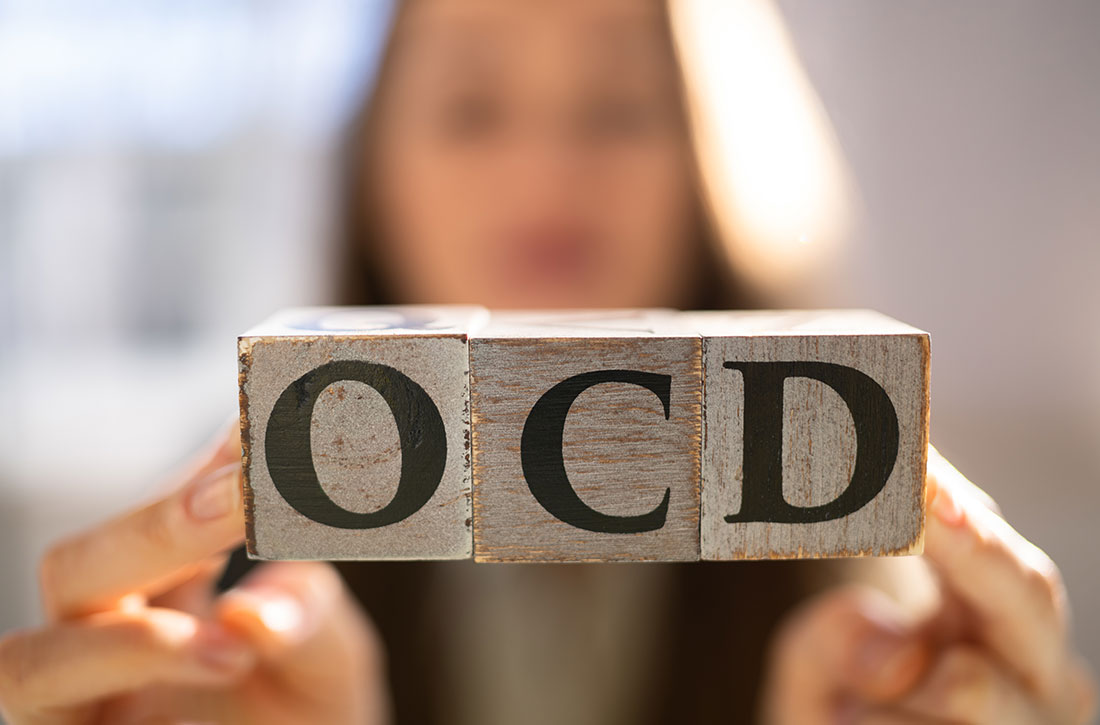

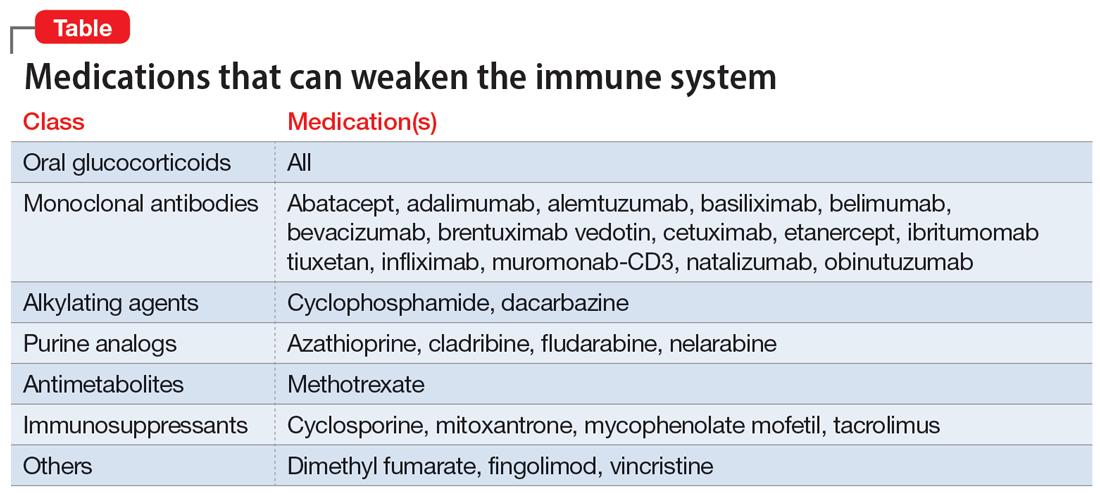

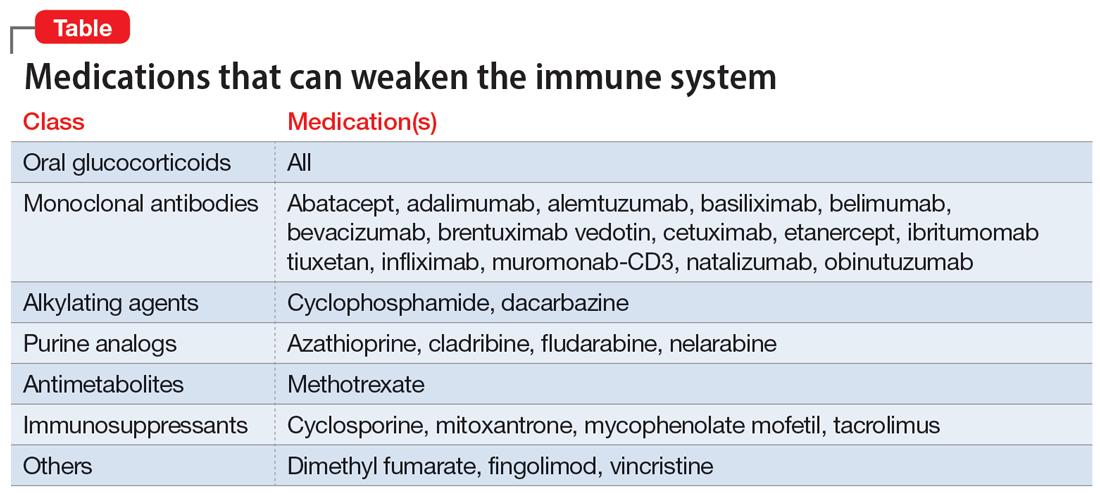

PML was initially seen in individuals with conditions that cause immunosuppression, such as malignancies and HIV. However, “drug-induced PML” refers to cases in which drug-induced immunosuppression creates an environment that allows JCV to reactivate and disseminate back into the CNS.4 It is important to emphasize that drug-induced PML is a very rare effect of certain immunosuppressant medications. Medications that can weaken the immune system include glucocorticoids, monoclonal antibodies, alkylating agents, purine analogues, antimetabolites, and immunosuppressants (Table).1

These medications are used to treat conditions such as multiple sclerosis, RA, psoriatic arthritis, and lupus. Although drug-induced PML can result from the use of any of these agents, the highest incidence (1%) is found with natalizumab. Rates of incidence with other agents are either unknown or as low as .002%.1 Evidence suggests that the risk for PML increases with the duration of therapy.5

Continue to: Management

Management: Stop the offending agent, restore immune function

Specific pharmacologic treatments for PML are lacking. Management of drug-induced PML starts with discontinuing the offending agent. Restoring immune function has been found to be the most effective approach to treat PML.3 Restoration is possible through interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-7, and T-cell infusions. Other treatment options are theoretical and include the development of a JCV vaccine to stimulate host response, plasma exchange to remove the medication from the host, and antiviral therapy targeting JCV replication. Diclofenac, isotretinoin, and mefloquine can inhibit JCV replication.3

Based on the theory that JCV requires 5HT2A receptors for entry into cells, researchers have studied medications that block this receptor as a treatment for PML. The first-generation antipsychotic chlorpromazine did not show benefit when combined with cidofovir, a replication inhibitor.3 Antipsychotics agents such as ziprasidone and olanzapine have shown in vitro inhibition of JCV, while risperidone has mixed results, with 1 trial failing to find a difference on JCV in fetal glial cells.3 Second-generation antipsychotics may be the preferred option due to more potent antagonism of the 5HT2A receptors and fewer adverse effects compared to agents such as chlorpromazine.4 The antidepressant mirtazapine has shown to have promising results, with evidence indicating that earlier initiation is more beneficial.3 Overall, data involving the use of medications that act on the 5HT2A receptor are mixed. Recent data suggest that JCV might enter cells independent of 5HT2A receptors; however, more research in this area is needed.2

The best strategy for treating drug-induced PML has not yet been determined. While combination therapy is thought to be more successful than monotherapy, ultimately, it depends on the patient’s immune response. If a psychotropic medication is chosen as adjunct treatment for drug-induced PML, it is prudent to assess the patient’s entire clinical picture to determine the specific indication for therapy (ie, treating symptomatology or drug-induced PML).

CASE CONTINUED

Following diagnosis, Mr. P is provided supportive therapy, and his care team discontinues methotrexate and etanercept. Although data are mixed on the efficacy of medications that work on 5HT2A receptors, because Mr. P was recently diagnosed with MDD, he is started on mirtazapine 15 mg/d at night in an attempt to manage both MDD and PML. It is possible that his depressive symptoms developed as a result of drug-induced PML rather than major depressive disorder. Discontinuing methotrexate and etanercept stabilizes Mr. P’s PML symptoms but leads to an exacerbation of his RA symptoms. Mr. P is initiated on hyd

Related Resources

- Castle D, Robertson NP. Treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol. 2019;266(10):2587-2589. doi:10.1007/s00415-019-09501-y

Drug Brand Names

Abatacept • Orencia

Adalimumab • Humira

Alemtuzumab • Campath

Azathioprine • Azasan, Imuran

Basiliximab • Simulect

Belimumab • Benlysta

Bevacizumab • Avastin

Brentuximab vedotin • Adcetris

Cetuximab • Erbitux

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine, Largactil

Cidofovir • Vistide

Cladribine • Mavenclad

Cyclophosphamide • Cytoxan

Cyclosporine • Gengraf, Neoral

Dacarbazine • DTIC-Dome

Diclofenac • Cambia, Zorvolex

Dimethyl fumarate • Tecfidera

Etanercept • Enbrel

Fingolimod • Gilenya

Fludarabine • Fludara

Hydroxychloroquine • Plaquenil

Ibritumomab tiuxetan • Zevalin

Infliximab • Avsola, Inflectra

Isotretinoin • Absorica, Claravis

Mefloquine • Lariam

Methotrexate • Rheumatrex, Trexall

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Mitoxantrone • Novantrone

Muromonab-CD3 • Orthoclone OKT3

Mycophenolate mofetil • CellCept

Natalizumab • Tysabri

Nelarabine • Arranon

Obinutuzumab • Gazyva

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tacrolimus • Prograf

Vincristine • Vincasar PFS

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Yukitake M. Drug-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2018;9(1):37-47. doi:10.1111/cen3.12440

2. Alstadhaug KB, Myhr KM, Rinaldo CH. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2017;137(23-24):10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092

3. Williamson EML, Berger JR. Diagnosis and treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with multiple sclerosis therapies. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(4):961-973. doi:10.1007/s13311-017-0570-7

4. Altschuler EL, Kast RE. The atypical antipsychotic agents ziprasidone, risperidone and olanzapine as treatment for and prophylaxis against progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65(3):585-586.

5. Vinhas de Souza M, Keller-Stanislawski B, Blake K, et al. Drug-induced PML: a global agenda for a global challenge. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(4):747-750. doi:10.1038/clpt.2012.4

Mr. P, age 67, presents to the clinic with vision changes and memory loss following a fall in his home due to limb weakness. Six years ago, his care team diagnosed him with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Mr. P’s current medication regimen includes methotrexate 20 mg once weekly and etanercept 50 mg once weekly, and he has been stable on this plan for 3 years. Mr. P also was recently diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD), but has not yet started treatment. Following a complete workup, an MRI of Mr. P’s brain revealed white matter demyelination. Due to these findings, he is scheduled for a brain biopsy, which confirms a diagnosis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

PML is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV), or JC polyomavirus, named for the first patient identified to have contracted the virus.1 Asymptomatic infection of JCV often occurs in childhood, and antibodies are found in ≤70% of healthy adults. In most individuals, JCV remains latent in the kidneys and lymphoid organs, but immunosuppression can cause it to reactivate.2

JCV infects oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and neurons, which results in white matter demyelination. Due to this demyelination, individuals can experience visual field defects, speech disturbances, ataxia, paresthesia, and cognitive impairments.2 Limb weakness presents in 60% of patients with PML, visual disturbances in 20%, and gait disturbances in 65%.3 Progression of these symptoms can lead to a more severe clinical presentation, including focal seizures in ≤10% of patients, and the mortality rate is 30% to 50%.3 Patients with comorbid HIV have a mortality rate ≤90%.2

Currently, there are no biomarkers that can identify PML in its early stages. A PML diagnosis is typically based on the patient’s clinical presentation, radiological imaging, and detection of JCV DNA. A brain biopsy is the gold standard for PML diagnosis.1

Interestingly, data suggest that glial cells harboring JCV in the brain express receptors for serotonin and dopamine.4 Researchers pinpointed 5HT2A receptors as JCV entry points into cells, and theorized that medications competing for binding, such as certain psychotropic agents, might decrease JCV entry. Cells lacking the 5HT2A receptor have shown immunity to JCV infection and the ability of cells to be infected was restored through transfection of 5HT2A receptors.4

Immunosuppressant medications can cause PML

PML was initially seen in individuals with conditions that cause immunosuppression, such as malignancies and HIV. However, “drug-induced PML” refers to cases in which drug-induced immunosuppression creates an environment that allows JCV to reactivate and disseminate back into the CNS.4 It is important to emphasize that drug-induced PML is a very rare effect of certain immunosuppressant medications. Medications that can weaken the immune system include glucocorticoids, monoclonal antibodies, alkylating agents, purine analogues, antimetabolites, and immunosuppressants (Table).1

These medications are used to treat conditions such as multiple sclerosis, RA, psoriatic arthritis, and lupus. Although drug-induced PML can result from the use of any of these agents, the highest incidence (1%) is found with natalizumab. Rates of incidence with other agents are either unknown or as low as .002%.1 Evidence suggests that the risk for PML increases with the duration of therapy.5

Continue to: Management

Management: Stop the offending agent, restore immune function

Specific pharmacologic treatments for PML are lacking. Management of drug-induced PML starts with discontinuing the offending agent. Restoring immune function has been found to be the most effective approach to treat PML.3 Restoration is possible through interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-7, and T-cell infusions. Other treatment options are theoretical and include the development of a JCV vaccine to stimulate host response, plasma exchange to remove the medication from the host, and antiviral therapy targeting JCV replication. Diclofenac, isotretinoin, and mefloquine can inhibit JCV replication.3

Based on the theory that JCV requires 5HT2A receptors for entry into cells, researchers have studied medications that block this receptor as a treatment for PML. The first-generation antipsychotic chlorpromazine did not show benefit when combined with cidofovir, a replication inhibitor.3 Antipsychotics agents such as ziprasidone and olanzapine have shown in vitro inhibition of JCV, while risperidone has mixed results, with 1 trial failing to find a difference on JCV in fetal glial cells.3 Second-generation antipsychotics may be the preferred option due to more potent antagonism of the 5HT2A receptors and fewer adverse effects compared to agents such as chlorpromazine.4 The antidepressant mirtazapine has shown to have promising results, with evidence indicating that earlier initiation is more beneficial.3 Overall, data involving the use of medications that act on the 5HT2A receptor are mixed. Recent data suggest that JCV might enter cells independent of 5HT2A receptors; however, more research in this area is needed.2

The best strategy for treating drug-induced PML has not yet been determined. While combination therapy is thought to be more successful than monotherapy, ultimately, it depends on the patient’s immune response. If a psychotropic medication is chosen as adjunct treatment for drug-induced PML, it is prudent to assess the patient’s entire clinical picture to determine the specific indication for therapy (ie, treating symptomatology or drug-induced PML).

CASE CONTINUED

Following diagnosis, Mr. P is provided supportive therapy, and his care team discontinues methotrexate and etanercept. Although data are mixed on the efficacy of medications that work on 5HT2A receptors, because Mr. P was recently diagnosed with MDD, he is started on mirtazapine 15 mg/d at night in an attempt to manage both MDD and PML. It is possible that his depressive symptoms developed as a result of drug-induced PML rather than major depressive disorder. Discontinuing methotrexate and etanercept stabilizes Mr. P’s PML symptoms but leads to an exacerbation of his RA symptoms. Mr. P is initiated on hyd

Related Resources

- Castle D, Robertson NP. Treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol. 2019;266(10):2587-2589. doi:10.1007/s00415-019-09501-y

Drug Brand Names

Abatacept • Orencia

Adalimumab • Humira

Alemtuzumab • Campath

Azathioprine • Azasan, Imuran

Basiliximab • Simulect

Belimumab • Benlysta

Bevacizumab • Avastin

Brentuximab vedotin • Adcetris

Cetuximab • Erbitux

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine, Largactil

Cidofovir • Vistide

Cladribine • Mavenclad

Cyclophosphamide • Cytoxan

Cyclosporine • Gengraf, Neoral

Dacarbazine • DTIC-Dome

Diclofenac • Cambia, Zorvolex

Dimethyl fumarate • Tecfidera

Etanercept • Enbrel

Fingolimod • Gilenya

Fludarabine • Fludara

Hydroxychloroquine • Plaquenil

Ibritumomab tiuxetan • Zevalin

Infliximab • Avsola, Inflectra

Isotretinoin • Absorica, Claravis

Mefloquine • Lariam

Methotrexate • Rheumatrex, Trexall

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Mitoxantrone • Novantrone

Muromonab-CD3 • Orthoclone OKT3

Mycophenolate mofetil • CellCept

Natalizumab • Tysabri

Nelarabine • Arranon

Obinutuzumab • Gazyva

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tacrolimus • Prograf

Vincristine • Vincasar PFS

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Mr. P, age 67, presents to the clinic with vision changes and memory loss following a fall in his home due to limb weakness. Six years ago, his care team diagnosed him with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Mr. P’s current medication regimen includes methotrexate 20 mg once weekly and etanercept 50 mg once weekly, and he has been stable on this plan for 3 years. Mr. P also was recently diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD), but has not yet started treatment. Following a complete workup, an MRI of Mr. P’s brain revealed white matter demyelination. Due to these findings, he is scheduled for a brain biopsy, which confirms a diagnosis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

PML is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV), or JC polyomavirus, named for the first patient identified to have contracted the virus.1 Asymptomatic infection of JCV often occurs in childhood, and antibodies are found in ≤70% of healthy adults. In most individuals, JCV remains latent in the kidneys and lymphoid organs, but immunosuppression can cause it to reactivate.2

JCV infects oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and neurons, which results in white matter demyelination. Due to this demyelination, individuals can experience visual field defects, speech disturbances, ataxia, paresthesia, and cognitive impairments.2 Limb weakness presents in 60% of patients with PML, visual disturbances in 20%, and gait disturbances in 65%.3 Progression of these symptoms can lead to a more severe clinical presentation, including focal seizures in ≤10% of patients, and the mortality rate is 30% to 50%.3 Patients with comorbid HIV have a mortality rate ≤90%.2

Currently, there are no biomarkers that can identify PML in its early stages. A PML diagnosis is typically based on the patient’s clinical presentation, radiological imaging, and detection of JCV DNA. A brain biopsy is the gold standard for PML diagnosis.1

Interestingly, data suggest that glial cells harboring JCV in the brain express receptors for serotonin and dopamine.4 Researchers pinpointed 5HT2A receptors as JCV entry points into cells, and theorized that medications competing for binding, such as certain psychotropic agents, might decrease JCV entry. Cells lacking the 5HT2A receptor have shown immunity to JCV infection and the ability of cells to be infected was restored through transfection of 5HT2A receptors.4

Immunosuppressant medications can cause PML

PML was initially seen in individuals with conditions that cause immunosuppression, such as malignancies and HIV. However, “drug-induced PML” refers to cases in which drug-induced immunosuppression creates an environment that allows JCV to reactivate and disseminate back into the CNS.4 It is important to emphasize that drug-induced PML is a very rare effect of certain immunosuppressant medications. Medications that can weaken the immune system include glucocorticoids, monoclonal antibodies, alkylating agents, purine analogues, antimetabolites, and immunosuppressants (Table).1

These medications are used to treat conditions such as multiple sclerosis, RA, psoriatic arthritis, and lupus. Although drug-induced PML can result from the use of any of these agents, the highest incidence (1%) is found with natalizumab. Rates of incidence with other agents are either unknown or as low as .002%.1 Evidence suggests that the risk for PML increases with the duration of therapy.5

Continue to: Management

Management: Stop the offending agent, restore immune function

Specific pharmacologic treatments for PML are lacking. Management of drug-induced PML starts with discontinuing the offending agent. Restoring immune function has been found to be the most effective approach to treat PML.3 Restoration is possible through interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-7, and T-cell infusions. Other treatment options are theoretical and include the development of a JCV vaccine to stimulate host response, plasma exchange to remove the medication from the host, and antiviral therapy targeting JCV replication. Diclofenac, isotretinoin, and mefloquine can inhibit JCV replication.3

Based on the theory that JCV requires 5HT2A receptors for entry into cells, researchers have studied medications that block this receptor as a treatment for PML. The first-generation antipsychotic chlorpromazine did not show benefit when combined with cidofovir, a replication inhibitor.3 Antipsychotics agents such as ziprasidone and olanzapine have shown in vitro inhibition of JCV, while risperidone has mixed results, with 1 trial failing to find a difference on JCV in fetal glial cells.3 Second-generation antipsychotics may be the preferred option due to more potent antagonism of the 5HT2A receptors and fewer adverse effects compared to agents such as chlorpromazine.4 The antidepressant mirtazapine has shown to have promising results, with evidence indicating that earlier initiation is more beneficial.3 Overall, data involving the use of medications that act on the 5HT2A receptor are mixed. Recent data suggest that JCV might enter cells independent of 5HT2A receptors; however, more research in this area is needed.2

The best strategy for treating drug-induced PML has not yet been determined. While combination therapy is thought to be more successful than monotherapy, ultimately, it depends on the patient’s immune response. If a psychotropic medication is chosen as adjunct treatment for drug-induced PML, it is prudent to assess the patient’s entire clinical picture to determine the specific indication for therapy (ie, treating symptomatology or drug-induced PML).

CASE CONTINUED

Following diagnosis, Mr. P is provided supportive therapy, and his care team discontinues methotrexate and etanercept. Although data are mixed on the efficacy of medications that work on 5HT2A receptors, because Mr. P was recently diagnosed with MDD, he is started on mirtazapine 15 mg/d at night in an attempt to manage both MDD and PML. It is possible that his depressive symptoms developed as a result of drug-induced PML rather than major depressive disorder. Discontinuing methotrexate and etanercept stabilizes Mr. P’s PML symptoms but leads to an exacerbation of his RA symptoms. Mr. P is initiated on hyd

Related Resources

- Castle D, Robertson NP. Treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol. 2019;266(10):2587-2589. doi:10.1007/s00415-019-09501-y

Drug Brand Names

Abatacept • Orencia

Adalimumab • Humira

Alemtuzumab • Campath

Azathioprine • Azasan, Imuran

Basiliximab • Simulect

Belimumab • Benlysta

Bevacizumab • Avastin

Brentuximab vedotin • Adcetris

Cetuximab • Erbitux

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine, Largactil

Cidofovir • Vistide

Cladribine • Mavenclad

Cyclophosphamide • Cytoxan

Cyclosporine • Gengraf, Neoral

Dacarbazine • DTIC-Dome

Diclofenac • Cambia, Zorvolex

Dimethyl fumarate • Tecfidera

Etanercept • Enbrel

Fingolimod • Gilenya

Fludarabine • Fludara

Hydroxychloroquine • Plaquenil

Ibritumomab tiuxetan • Zevalin

Infliximab • Avsola, Inflectra

Isotretinoin • Absorica, Claravis

Mefloquine • Lariam

Methotrexate • Rheumatrex, Trexall

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Mitoxantrone • Novantrone

Muromonab-CD3 • Orthoclone OKT3

Mycophenolate mofetil • CellCept

Natalizumab • Tysabri

Nelarabine • Arranon

Obinutuzumab • Gazyva

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tacrolimus • Prograf

Vincristine • Vincasar PFS

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Yukitake M. Drug-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2018;9(1):37-47. doi:10.1111/cen3.12440

2. Alstadhaug KB, Myhr KM, Rinaldo CH. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2017;137(23-24):10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092

3. Williamson EML, Berger JR. Diagnosis and treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with multiple sclerosis therapies. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(4):961-973. doi:10.1007/s13311-017-0570-7

4. Altschuler EL, Kast RE. The atypical antipsychotic agents ziprasidone, risperidone and olanzapine as treatment for and prophylaxis against progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65(3):585-586.

5. Vinhas de Souza M, Keller-Stanislawski B, Blake K, et al. Drug-induced PML: a global agenda for a global challenge. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(4):747-750. doi:10.1038/clpt.2012.4

1. Yukitake M. Drug-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2018;9(1):37-47. doi:10.1111/cen3.12440

2. Alstadhaug KB, Myhr KM, Rinaldo CH. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2017;137(23-24):10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092

3. Williamson EML, Berger JR. Diagnosis and treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with multiple sclerosis therapies. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(4):961-973. doi:10.1007/s13311-017-0570-7

4. Altschuler EL, Kast RE. The atypical antipsychotic agents ziprasidone, risperidone and olanzapine as treatment for and prophylaxis against progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65(3):585-586.

5. Vinhas de Souza M, Keller-Stanislawski B, Blake K, et al. Drug-induced PML: a global agenda for a global challenge. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(4):747-750. doi:10.1038/clpt.2012.4

Hold or not to hold: Navigating involuntary commitment

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

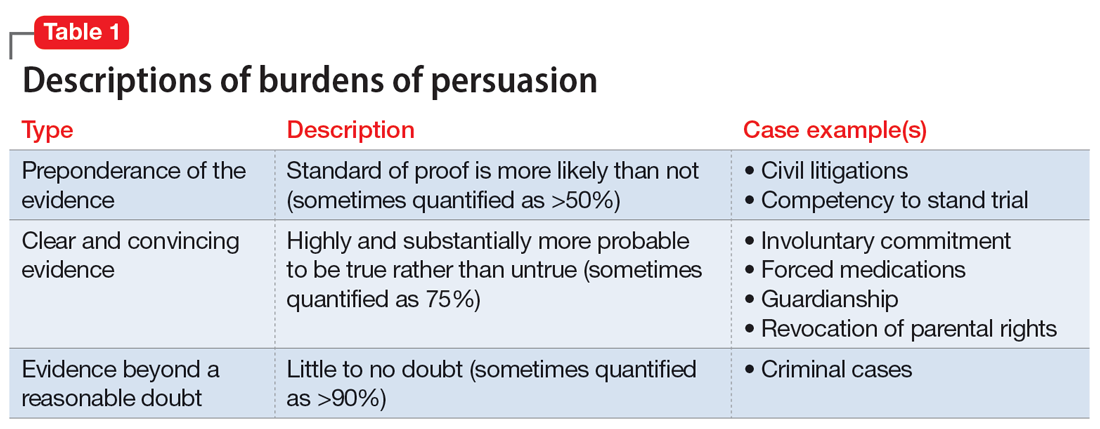

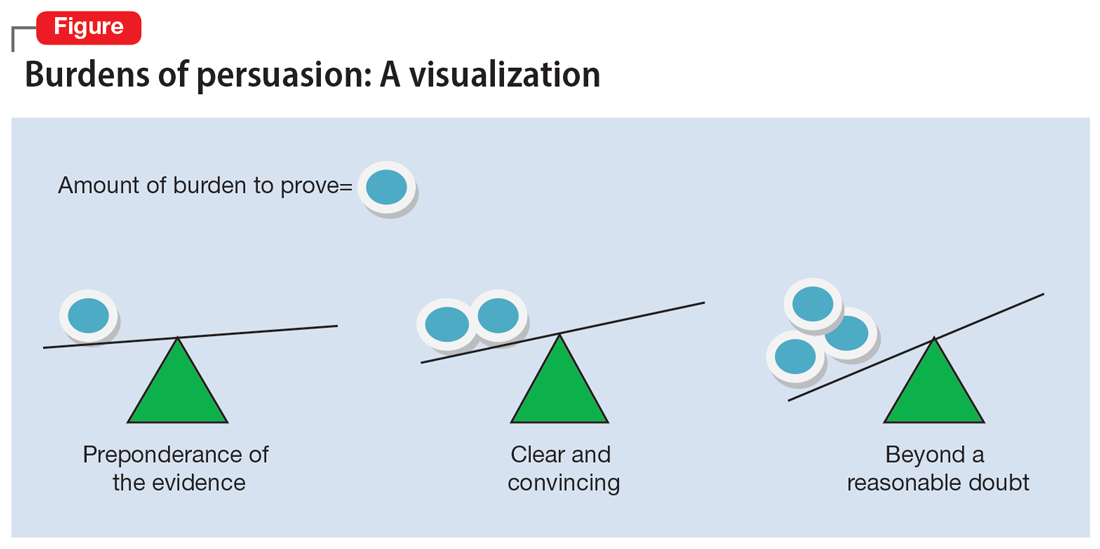

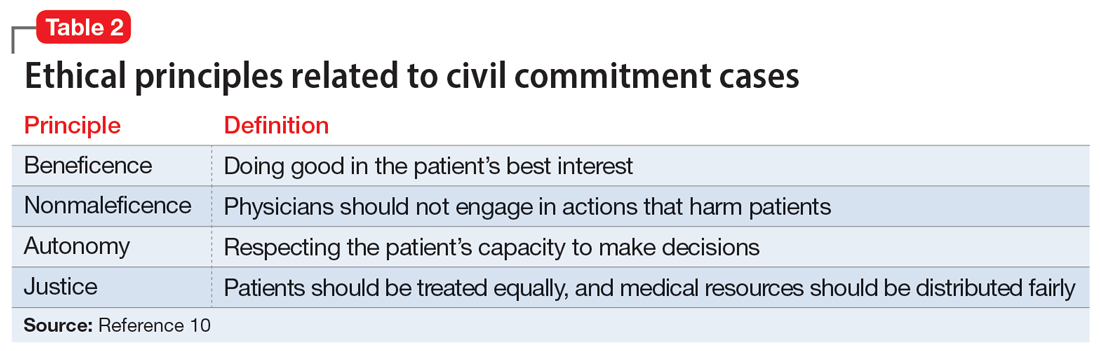

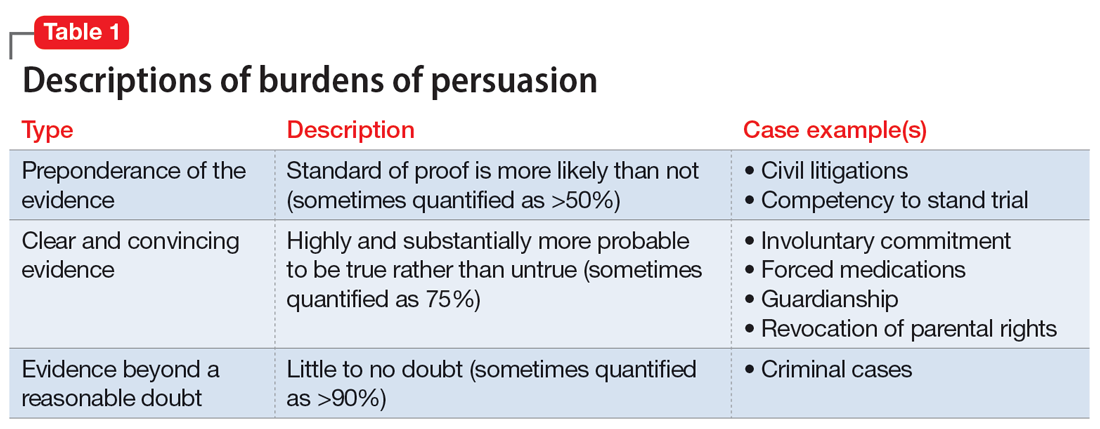

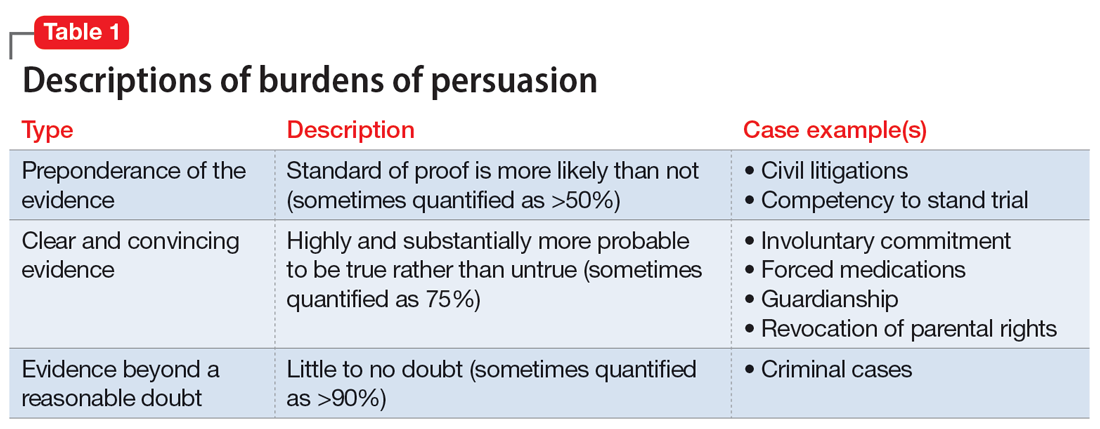

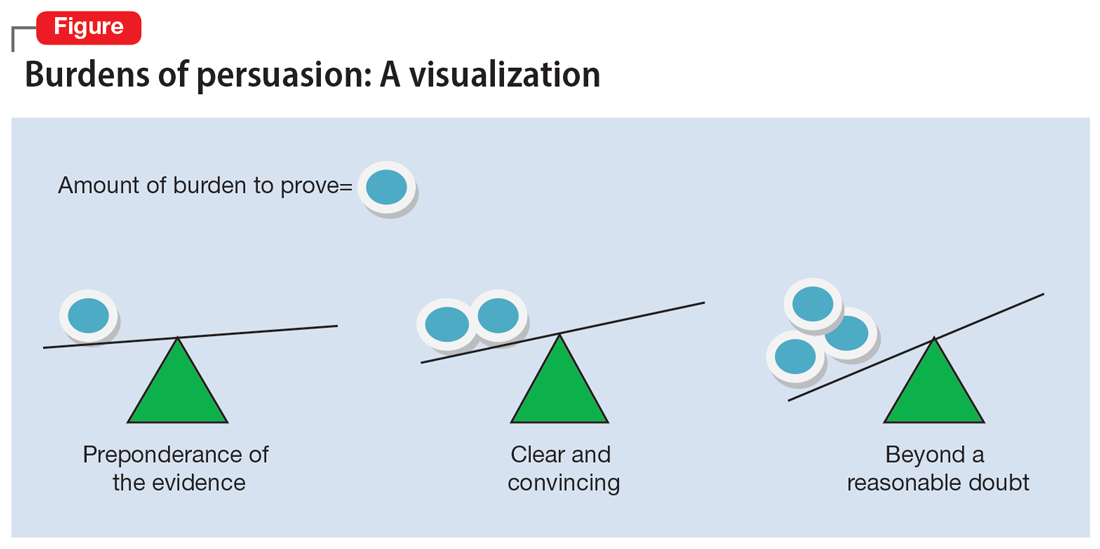

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

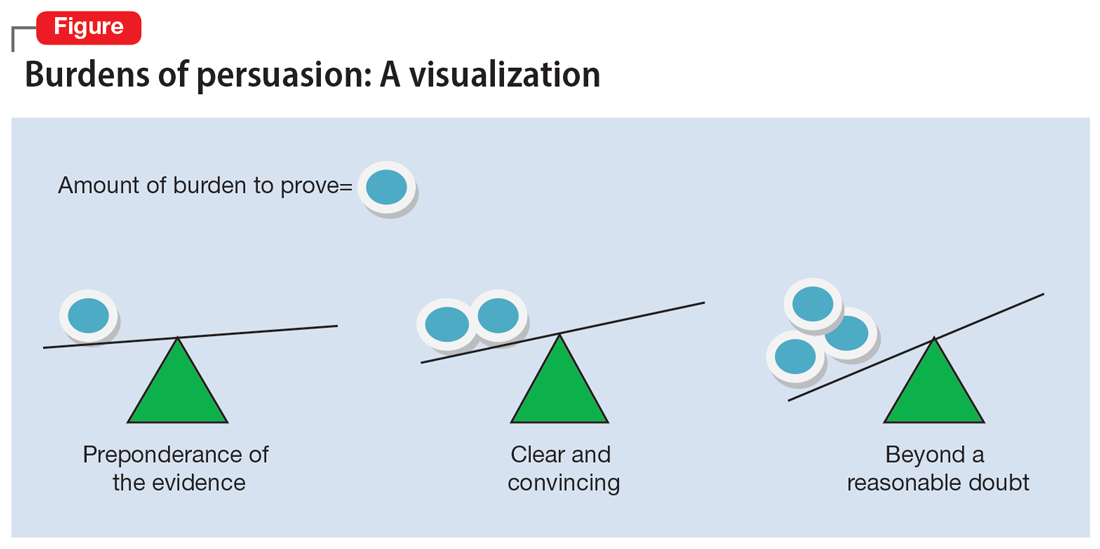

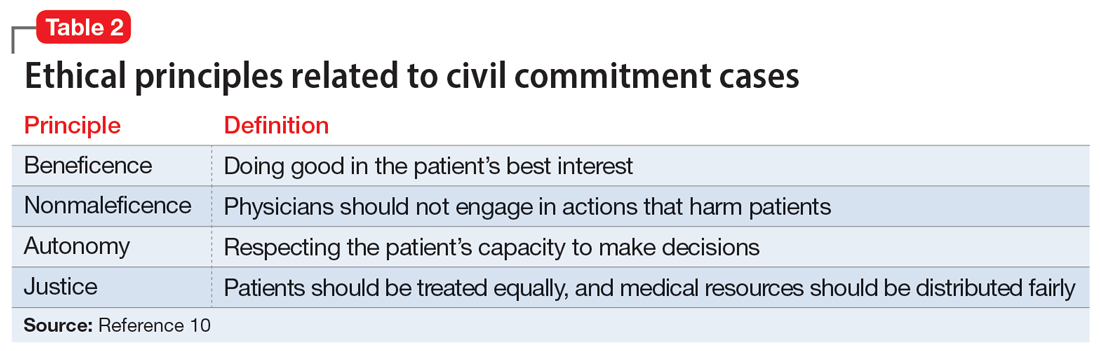

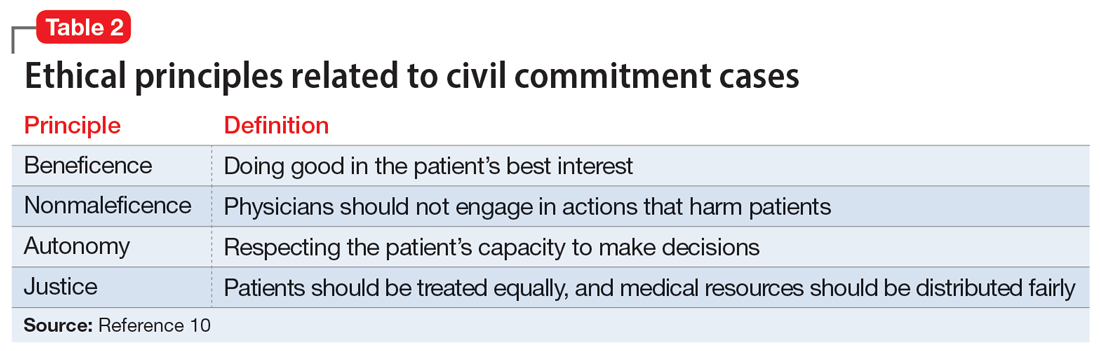

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

CASE Depressed and suicidal

Police arrive at the home of Mr. H, age 50, after his wife calls 911. She reports he has depression and she saw him in bed brandishing a firearm as if he wanted to hurt himself. Upon arrival, the officers enter the house and find Mr. H in bed without a firearm. Mr. H says little to the officers about the alleged events, but acknowledges he has depression and is willing to go the hospital for further evaluation. Neither his wife nor the officers locate a firearm in the home.

EVALUATION Emergency detention

In the emergency department (ED), Mr. H’s laboratory results and physical examination findings are normal. He acknowledges feeling depressed over the past 2 weeks. Though he cannot identify any precipitants, he says he has experienced anhedonia, lack of appetite, decreased energy, and changes in his sleep patterns. When asked about the day’s events concerning the firearm, Mr. H becomes guarded and does not give a clear answer regarding having thoughts of suicide.

The evaluating psychiatrist obtains collateral from Mr. H’s wife and reviews his medical records. There are no active prescriptions on file and the psychiatrist notices that last year there was a suicide attempt involving a firearm. Following that episode, Mr. H was hospitalized, treated with sertraline 50 mg/d, and discharged with a diagnosis of major depressive disorder. There was no legal or substance abuse history.

In the ED, the psychiatrist conducts a psychiatric evaluation, including a suicide risk assessment, and determines Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life. Mr. H’s psychiatrist explains there are 2 treatment options: to be admitted to the hospital or to be discharged. The psychiatrist recommends hospital admission to Mr. H for his safety and stabilization. Mr. H says he prefers to return home.

Because the psychiatrist believes Mr. H is at imminent risk of ending his life and there is no less restrictive setting for treatment, he implements an emergency detention. In Ohio, this allows Mr. H to be held in the hospital for no more than 3 court days in accordance with state law. Before Mr. H’s emergency detention periods ends, the psychiatrist will need to decide whether Mr. H can be safely discharged. If the psychiatrist determines that Mr. H still needs treatment, the court will be petitioned for a civil commitment hearing.

[polldaddy:11189291]

The author’s observations

In some cases, courts allow information a psychiatrist does not directly obtain from a patient to be admitted as testimony in a civil commitment hearing. However, some jurisdictions consider sources of information not obtained directly from the patient as hearsay and thus inadmissible.1 Though each source listed may provide credible information that could be presented at a hearing, the psychiatrist should discuss with the patient the information obtained from these sources to ensure it is admissable.2 A discussion with Mr. H about the factors that led to his hospital arrival will avoid the psychiatrist’s reliance on what another person has heard or seen when providing testimony. Even when a psychiatrist is not faced with an issue of admissibility, caution must be taken with third-party reports.3

TREATMENT Civil commitment hearing

Before the emergency detention period expires, Mr. H’s psychiatrist determines that he remains at imminent risk of self-harm. To continue hospitalization, the psychiatrist files a petition for civil commitment and testifies at the commitment hearing. He reports that Mr. H suffers from a substantial mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The psychiatrist also testifies that the least restrictive environment for treatment continues to be inpatient hospitalization, because Mr. H is still at imminent risk of harming himself.

Continue to: Following the psychiatrist's...

Following the psychiatrist’s testimony, the magistrate finds that Mr. H is a mentally ill person subject to hospitalization given his mood disorder that grossly impairs his judgment and behavior. The magistrate orders that Mr. H be civilly committed to the hospital.

[polldaddy:11189293]

The author’s observations

The psychiatrist’s testimony mirrors the language regarding civil commitment in the Ohio Revised Code.4 Other elements considered for mental illness in Ohio are a substantial disorder of memory, thought, orientation, or perception that grossly impairs one’s capacity to recognize reality or meet the demands of life.4 The definition of what constitutes a mental disorder varies by state, but the burden of persuasion—the standard by which the court must be convinced—is generally uniform.5 In the 1979 case Addington v Texas, the United States Supreme Court concluded that in a civil commitment hearing, the minimum standard of proof for involuntary commitment must be clear and convincing evidence.6 Neither medical certainty nor substantial probability are burdens of persuasions.6 Instead, these terms may be presented in a forensic report when an examiner outlines their opinion. Table 1 and the Figure provide more detail on burdens of persuasion.

TREATMENT Civil commitment and patient rights

At a regularly scheduled treatment team meeting, the team informs Mr. H that he has been civilly committed for further treatment. Mr. H becomes upset and tells the team the decision is a complete violation of his rights. After a long rant, Mr. H walks out of the room, saying, “I did not even know when this hearing was.” A member of the treatment team becomes concerned that Mr. H may not have been notified of the hearing.

[polldaddy:11189294]

The author’s observations

It is not clear if Mr. H had been notified of his civil commitment hearing. If Mr. H had not been notified, his rights would have been compromised. Lessard v Schmidt (1972) outlined that individuals involved in a civil commitment hearing should be afforded the same rights as those involved in criminal proceedings.7 Mr. H should have been notified of his hearing and afforded the opportunity to have the assignment of counsel, the right to appear, the right to testify, the right to present witnesses and other evidence, and the right to confront witnesses.

Without notification of the hearing, the only right that would have remained intact for Mr. H would have been the assignment of counsel in his absence and without his knowledge. If Mr. H had been notified of the hearing and did not want to attend, yet still desired legal counsel, he could have waived his presence voluntarily after discussing this option with his attorney.8,9

Continue to: OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

OUTCOME Stabilization and discharge

During his 10-day stay, Mr. H is treated with sertraline 50 mg/d and engages in individual and group therapy. He shows noticeable improvement in his depressive symptoms and reports having no thoughts of suicide or self-harm. The treatment team determines it is appropriate to discharge him home (the firearm was never found) and involves his wife in safety planning and follow-up care. On the day of his discharge, Mr. H reflects on his treatment and civil commitment. He says, “I did not know a judge could order me to be hospitalized.”

[polldaddy:11189297]

The author’s observations

The physician’s decision to pursue civil commitment is best described by the legal doctrines of police powers and parens patriae. Other relevant ethical principles are described in Table 2.10

Though ethical principles may play a role in civil commitment, parens patriae and police powers is the answer with respect to the State.11Parens patriae is Latin for the “parent of the country” and grants the State the power to protect those residents who are most vulnerable. Police power is the authority of the State to enact and enforce rules that limit the rights of individuals for the greater good of ensuring health, safety, and welfare of all citizens.

Bottom Line

Psychiatrists are entrusted with recognizing when a patient, due to mental illness, is a danger to themselves or others and in need of treatment. After an emergency detention period, if the patient remains a danger to themselves or others and does not want to voluntarily receive treatment, a court hearing is required. As an expert witness, the treating psychiatrist should know the factors of law in their jurisdiction that determine civil commitment.

Related Resources

- Extreme Risk Protection Orders. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. https://www.jhsph.edu/research/ centers-and-institutes/johns-hopkins-center-for-gun-violenceprevention-and-policy/research/extreme-risk-protectionorders/

- Gutheil TG. The Psychiatrist as Expert Witness. 2nd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2009.

- Landmark Cases 2014. American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. https://www.aapl.org/landmark-cases

Drug Brand Names

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

1. Pinals DA, Mossman D. Evaluation for Civil Commitment. Oxford University Press; 2012.

2. Thatcher BT, Mossman D. Testifying for civil commitment: help unwilling patients get the treatment they need. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8(11):51-56.

3. Marett CP, Mossman D. What is your liability for involuntary commitment based on faulty information? Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):21-25,33.

4. Ohio Rev Code § 5122.01 (2018).

5. The Burden of Proof. University of Minnesota. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://open.lib.umn.edu/criminallaw/chapter/2-4-the-burden-of-proof/

6. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Forensic Psychiatry. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

7. Gold LH, Frierson RL, eds. The American Psychiatric Association Publishing Textbook of Suicide Assessment and Management. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020.

8. Cook J. Good lawyering and bad role models: the role of respondent’s counsel in a civil commitment hearing. Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics. 2000;14(1):179-195.

9. Ferris CE. The search for due process in civil commitment hearings: how procedural realities have altered substantive standards. Vanderbilt Law Rev. 2008;61(3):959-981.

10. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Civil Commitment and the Mental Health Care Continuum: Historical Trends and Principles for Law and Practice. 2019. Accessed January 23, 2022. https://www.samhsa.gov/resource/ebp/civil-commitment-mental-health-care-continuum-historical-trends-principles-law

11. Melton GB, Petrila J, Poythress NG, et al. Psychological Evaluations for the Courts: A Handbook for Mental Health Profession. 4th ed. Guilford Press; 2018.

Preparing patients with serious mental illness for extreme HEAT

Climate change is causing intense heat waves that threaten human health across the globe.

A confluence of factors increases risk

Thermoregulatory dysfunction is thought to be intrinsic to patients with schizophrenia partly due to dysregulated dopaminergic neurotransmission.2 This is compounded by these patients’ higher burden of chronic medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, which together with psychotropic (ie, antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines) and medical medications (ie, certain antihypertensives, diuretics, treatment for urinary incontinence) further disrupt the body’s cooling strategies and increase vulnerability to heat-related illnesses.1,3 Antipsychotics commonly prescribed to patients with SMI increase hyperthermia risk largely by 2 mechanisms: central and peripheral thermal dysregulation, and anticholinergic properties (ie, olanzapine, clozapine, chlorpromazine).2,3 Other anticholinergic medications prescribed to treat extrapyramidal symptoms (ie, diphenhydramine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl), anxiety, depression, and insomnia (ie, paroxetine, trazodone, doxepin) further add insult to injury because they impair sweating, which decreases the body’s ability to eliminate heat through evaporation.2,3 Additionally, high temperature exacerbates psychiatric symptoms in patients with SMI, resulting in increased hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

How to keep patients safe

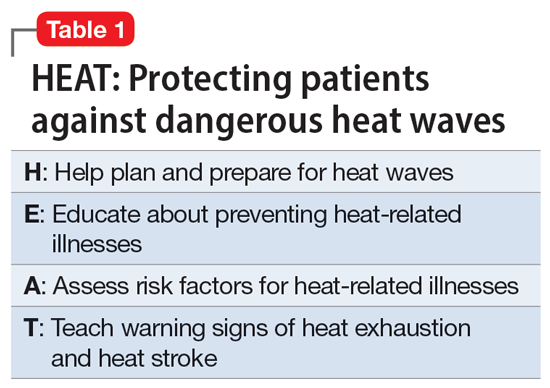

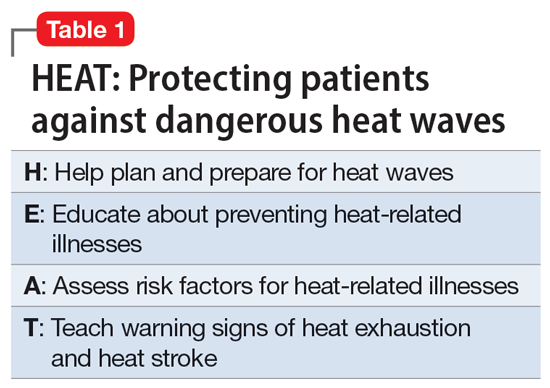

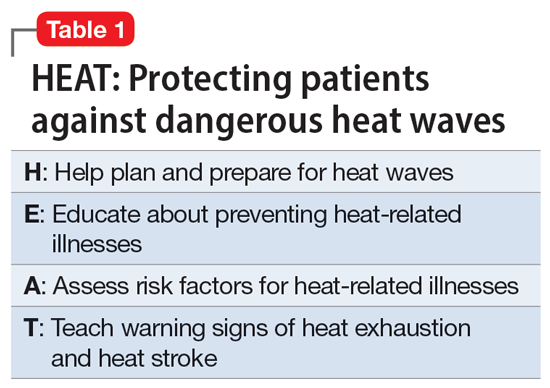

The acronym HEAT provides a framework that psychiatrists can use to highlight the importance of planning for heat waves in their institution and guiding discussions with individual patients about heat-related illnesses (Table 1).

Help the health care system where you work plan and prepare for heat waves. In-service training in mental health settings such as outpatient clinics, shelters, group homes, and residential programs can help staff identify patients at particular risk and reinforce key prevention messages.

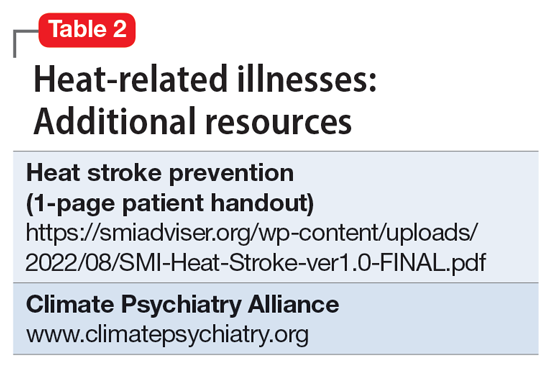

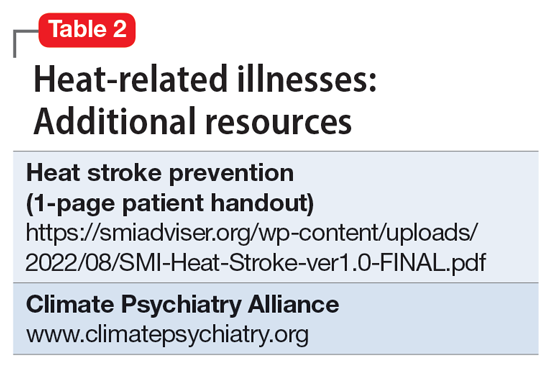

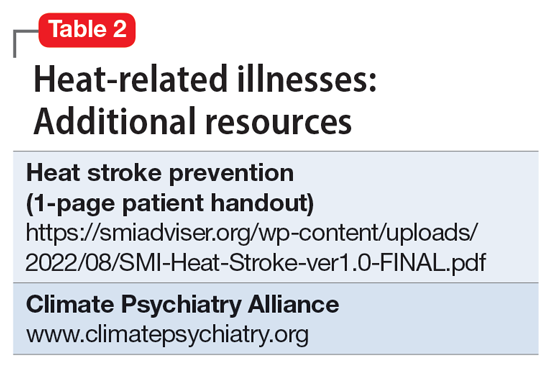

Educate patients and their caregivers on strategies for preventing heat-related illness. Informational materials can be distributed in clinics, residential settings, and day programs. A 1-page downloadable pamphlet available at https://smiadviser.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SMI-Heat-Stroke-ver1.0-FINAL.pdf summarizes key prevention messages of staying hydrated, staying cool, and staying safe.

Assess personalized heat-related risks. Inquire about patients’ daily activities, access to air conditioning, and water intake. Minimize the use of anticholinergic medications. Identify who patients can turn to for assistance, especially for those who struggle with cognitive impairment and social isolation.

Teach patients, caregivers, and staff the signs and symptoms of heat exhaustion and heat stroke and how to respond in such situations.

HEAT focuses psychiatric clinicians on preparing and protecting patients with SMI against dangerous heat waves. Clinicians can take a proactive leadership role in disseminating basic principles of heat-related illness prevention and heat-wave toolkits by using resources available from organizations such as the Climate Psychiatry Alliance (Table 2). They can also initiate advocacy efforts to raise awareness about the elevated risks of heat-related illnesses in this vulnerable population.

1. Schmeltz MT, Gamble JL. Risk characterization of hospitalizations for mental illness and/or behavioral disorders with concurrent heat-related illness. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186509. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186509

2. Lee CP, Chen PJ, Chang CM. Heat stroke during treatment with olanzapine, trihexyphenidyl, and trazodone in a patient with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2015;27(6):380-385.

3. Bongers KS, Salahudeen MS, Peterson GM. Drug-associated non-pyrogenic hyperthermia: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(1):9-16.

Climate change is causing intense heat waves that threaten human health across the globe.

A confluence of factors increases risk

Thermoregulatory dysfunction is thought to be intrinsic to patients with schizophrenia partly due to dysregulated dopaminergic neurotransmission.2 This is compounded by these patients’ higher burden of chronic medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, which together with psychotropic (ie, antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines) and medical medications (ie, certain antihypertensives, diuretics, treatment for urinary incontinence) further disrupt the body’s cooling strategies and increase vulnerability to heat-related illnesses.1,3 Antipsychotics commonly prescribed to patients with SMI increase hyperthermia risk largely by 2 mechanisms: central and peripheral thermal dysregulation, and anticholinergic properties (ie, olanzapine, clozapine, chlorpromazine).2,3 Other anticholinergic medications prescribed to treat extrapyramidal symptoms (ie, diphenhydramine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl), anxiety, depression, and insomnia (ie, paroxetine, trazodone, doxepin) further add insult to injury because they impair sweating, which decreases the body’s ability to eliminate heat through evaporation.2,3 Additionally, high temperature exacerbates psychiatric symptoms in patients with SMI, resulting in increased hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

How to keep patients safe

The acronym HEAT provides a framework that psychiatrists can use to highlight the importance of planning for heat waves in their institution and guiding discussions with individual patients about heat-related illnesses (Table 1).

Help the health care system where you work plan and prepare for heat waves. In-service training in mental health settings such as outpatient clinics, shelters, group homes, and residential programs can help staff identify patients at particular risk and reinforce key prevention messages.

Educate patients and their caregivers on strategies for preventing heat-related illness. Informational materials can be distributed in clinics, residential settings, and day programs. A 1-page downloadable pamphlet available at https://smiadviser.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SMI-Heat-Stroke-ver1.0-FINAL.pdf summarizes key prevention messages of staying hydrated, staying cool, and staying safe.

Assess personalized heat-related risks. Inquire about patients’ daily activities, access to air conditioning, and water intake. Minimize the use of anticholinergic medications. Identify who patients can turn to for assistance, especially for those who struggle with cognitive impairment and social isolation.

Teach patients, caregivers, and staff the signs and symptoms of heat exhaustion and heat stroke and how to respond in such situations.

HEAT focuses psychiatric clinicians on preparing and protecting patients with SMI against dangerous heat waves. Clinicians can take a proactive leadership role in disseminating basic principles of heat-related illness prevention and heat-wave toolkits by using resources available from organizations such as the Climate Psychiatry Alliance (Table 2). They can also initiate advocacy efforts to raise awareness about the elevated risks of heat-related illnesses in this vulnerable population.

Climate change is causing intense heat waves that threaten human health across the globe.

A confluence of factors increases risk

Thermoregulatory dysfunction is thought to be intrinsic to patients with schizophrenia partly due to dysregulated dopaminergic neurotransmission.2 This is compounded by these patients’ higher burden of chronic medical comorbidities such as cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses, which together with psychotropic (ie, antipsychotics, antidepressants, lithium, benzodiazepines) and medical medications (ie, certain antihypertensives, diuretics, treatment for urinary incontinence) further disrupt the body’s cooling strategies and increase vulnerability to heat-related illnesses.1,3 Antipsychotics commonly prescribed to patients with SMI increase hyperthermia risk largely by 2 mechanisms: central and peripheral thermal dysregulation, and anticholinergic properties (ie, olanzapine, clozapine, chlorpromazine).2,3 Other anticholinergic medications prescribed to treat extrapyramidal symptoms (ie, diphenhydramine, benztropine, trihexyphenidyl), anxiety, depression, and insomnia (ie, paroxetine, trazodone, doxepin) further add insult to injury because they impair sweating, which decreases the body’s ability to eliminate heat through evaporation.2,3 Additionally, high temperature exacerbates psychiatric symptoms in patients with SMI, resulting in increased hospitalizations and emergency department visits.

How to keep patients safe

The acronym HEAT provides a framework that psychiatrists can use to highlight the importance of planning for heat waves in their institution and guiding discussions with individual patients about heat-related illnesses (Table 1).

Help the health care system where you work plan and prepare for heat waves. In-service training in mental health settings such as outpatient clinics, shelters, group homes, and residential programs can help staff identify patients at particular risk and reinforce key prevention messages.

Educate patients and their caregivers on strategies for preventing heat-related illness. Informational materials can be distributed in clinics, residential settings, and day programs. A 1-page downloadable pamphlet available at https://smiadviser.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/SMI-Heat-Stroke-ver1.0-FINAL.pdf summarizes key prevention messages of staying hydrated, staying cool, and staying safe.

Assess personalized heat-related risks. Inquire about patients’ daily activities, access to air conditioning, and water intake. Minimize the use of anticholinergic medications. Identify who patients can turn to for assistance, especially for those who struggle with cognitive impairment and social isolation.

Teach patients, caregivers, and staff the signs and symptoms of heat exhaustion and heat stroke and how to respond in such situations.

HEAT focuses psychiatric clinicians on preparing and protecting patients with SMI against dangerous heat waves. Clinicians can take a proactive leadership role in disseminating basic principles of heat-related illness prevention and heat-wave toolkits by using resources available from organizations such as the Climate Psychiatry Alliance (Table 2). They can also initiate advocacy efforts to raise awareness about the elevated risks of heat-related illnesses in this vulnerable population.

1. Schmeltz MT, Gamble JL. Risk characterization of hospitalizations for mental illness and/or behavioral disorders with concurrent heat-related illness. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186509. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186509

2. Lee CP, Chen PJ, Chang CM. Heat stroke during treatment with olanzapine, trihexyphenidyl, and trazodone in a patient with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2015;27(6):380-385.

3. Bongers KS, Salahudeen MS, Peterson GM. Drug-associated non-pyrogenic hyperthermia: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(1):9-16.

1. Schmeltz MT, Gamble JL. Risk characterization of hospitalizations for mental illness and/or behavioral disorders with concurrent heat-related illness. PLoS One. 2017;12(10):e0186509. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0186509

2. Lee CP, Chen PJ, Chang CM. Heat stroke during treatment with olanzapine, trihexyphenidyl, and trazodone in a patient with schizophrenia. Acta Neuropsychiatrica. 2015;27(6):380-385.

3. Bongers KS, Salahudeen MS, Peterson GM. Drug-associated non-pyrogenic hyperthermia: a narrative review. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(1):9-16.

Lithium for bipolar disorder: Which patients will respond?

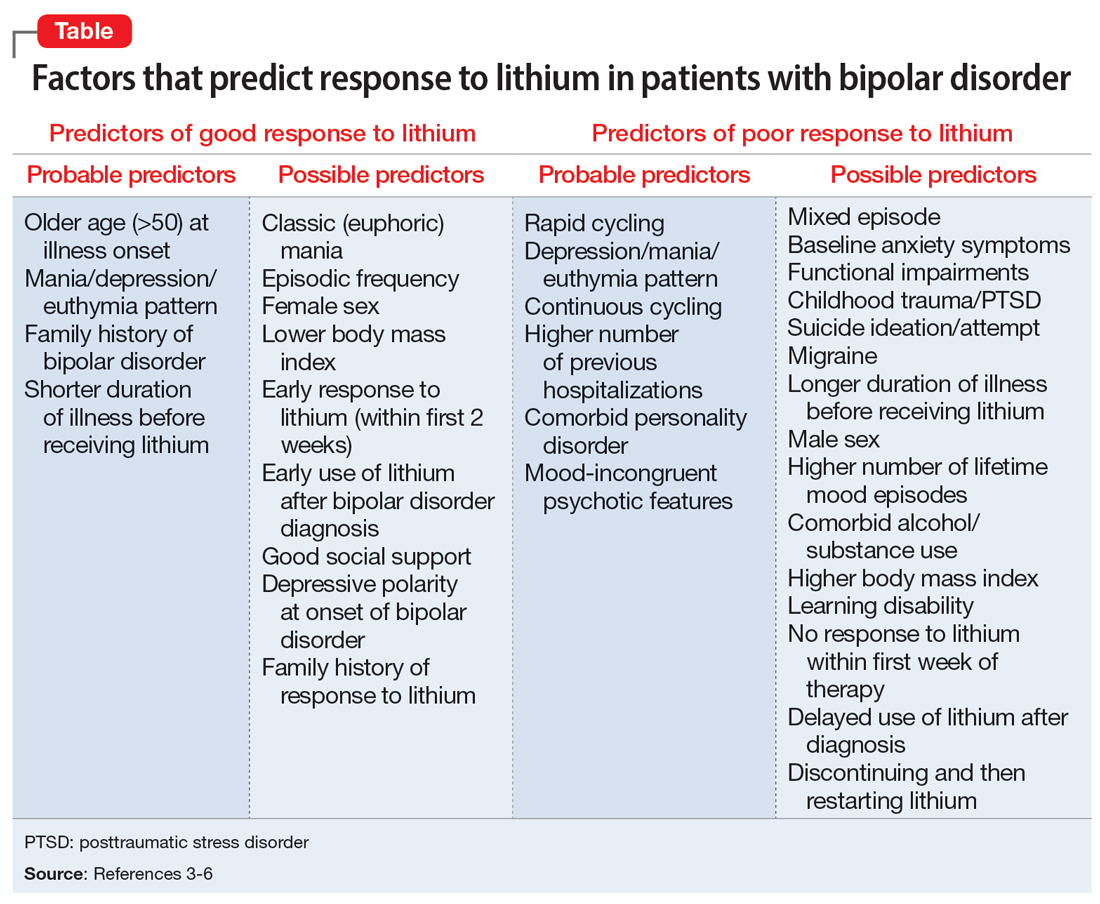

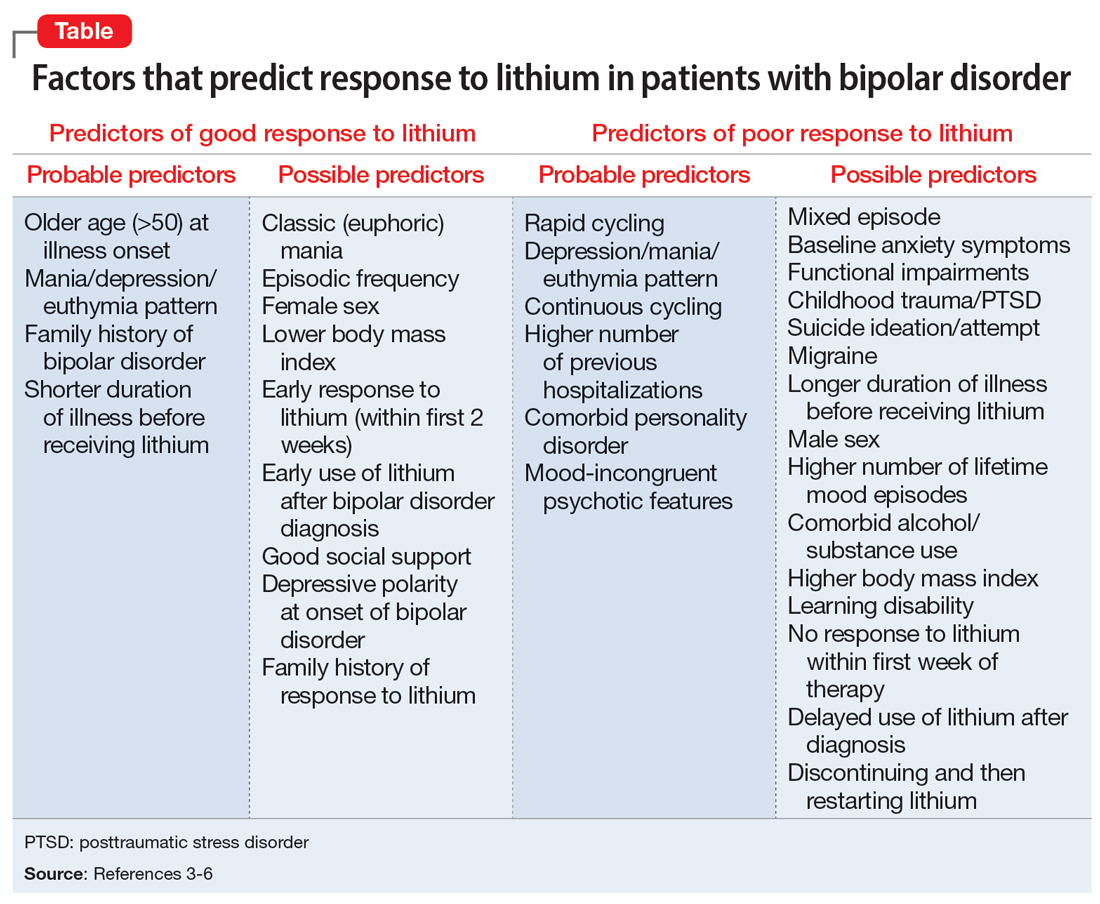

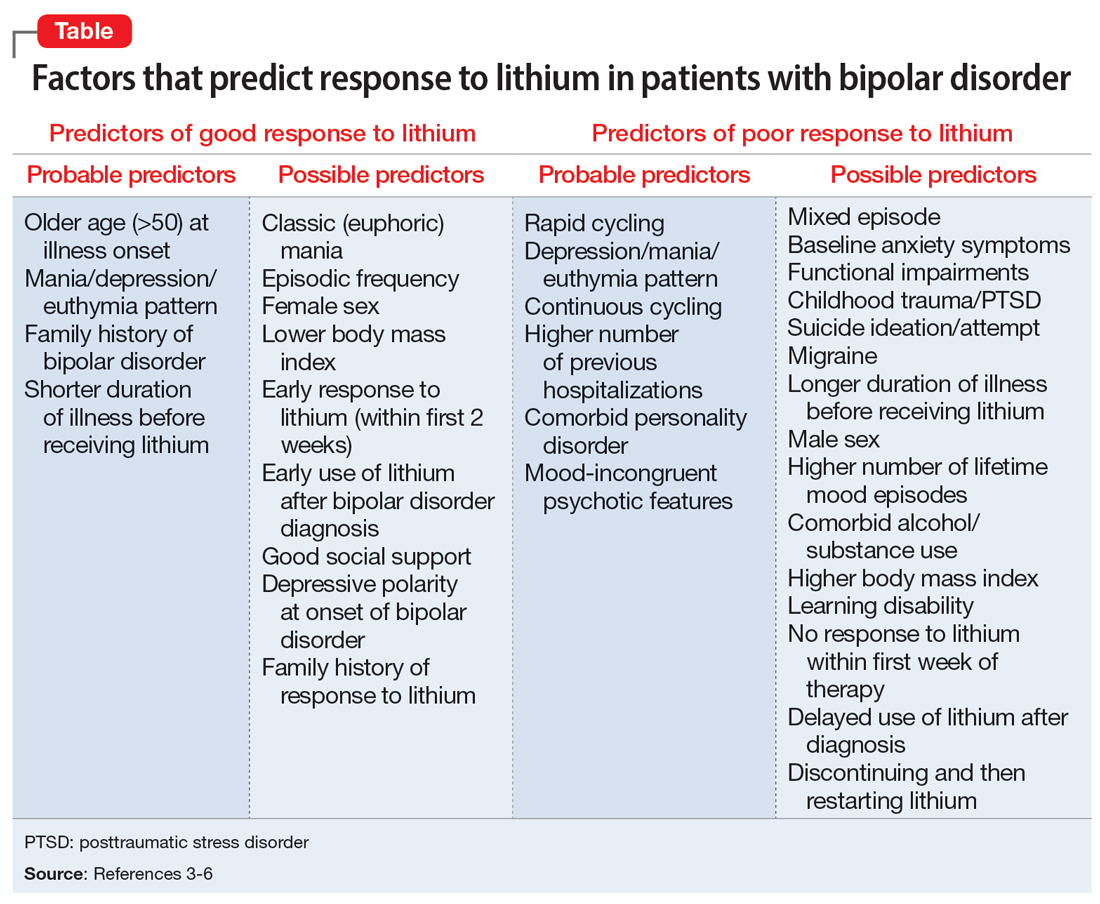

Though Cade discovered it 70 years ago, lithium is still considered the gold standard treatment for preventing manic and depressive phases of bipolar disorder (BD). In addition to its primary indication as a mood stabilizer, lithium has demonstrated efficacy as an augmenting medication for unipolar major depressive disorder.1 While lithium is a first-line agent for BD, it does not improve symptoms in every patient. In a 2004 meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials of patients with BD, Geddes et al2 found lithium was more effective than placebo in preventing the recurrence of mania, with 60% in the lithium group remaining stable compared to 40% in the placebo group. Being able to predict which patients will respond to lithium is crucial to prevent unnecessary exposure to lithium, which can produce significant adverse effects, including somnolence, nausea, diarrhea, and hypothyroidism.2

Several studies have investigated various clinical factors that might predict which patients with BD will respond to lithium. In a review, Kleindienst et al3 highlighted 3 factors that predicted a positive response to lithium:

- fewer hospitalizations prior to treatment

- an episodic course characterized sequentially by mania, depression, and then euthymia

- a later age (>50) at onset of BD.

Recent studies and reviews have isolated additional positive predictors, including having a family history of BD and a shorter duration of illness before receiving lithium, as well as negative predictors, such as rapid cycling, a large number of previous hospitalizations, a depression/mania/euthymia pattern, mood-incongruent psychotic features, and the presence of residual symptoms between mood episodes.3,4

The Table provides a list of probable and possible positive and negative predictors for therapeutic response to lithium in patients with BD.3-6 While relevant, the factors listed as possible predictors may not carry as much influence on lithium responsivity as those categorized as probable predictors.

Because of heterogeneity among studies, clinicians should consider their patient’s presentation as a whole, rather than basing medication choice on independent factors. Ultimately, more studies are required to fully determine the most relevant clinical parameters for lithium response. Overall, however, it appears these clinical factors could be extremely useful to guide psychiatrists in the optimal use of lithium while caring for patients with BD.

1. Crossley NA, Bauer M. Acceleration and augmentation of antidepressants with lithium for depressive disorders: two meta-analyses of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(6):935-940.

2. Geddes JR, Burgess S, Hawton K, et al. Long-term lithium therapy for bipolar disorder: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;1m61(2):217-222.

3. Kleindienst N, Engel RR, Greil W. Which clinical factors predict response to prophylactic lithium? A systematic review for bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(5):404-417.

4. Kleindienst N, Engel RR, Greil W. Psychosocial and demographic factors associated with response to prophylactic lithium: a systematic review for bipolar disorders. Psychol Med. 2005;35(12):1685-1694.

5. Hui TP, Kandola A, Shen L, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;140(2):94-115.

6. Grillault Laroche D, Etain B, Severus E, et al. Socio-demographic and clinical predictors of outcome to long-term treatment with lithium in bipolar disorders: a systematic review of the contemporary literature and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2020;8(1):40.

Though Cade discovered it 70 years ago, lithium is still considered the gold standard treatment for preventing manic and depressive phases of bipolar disorder (BD). In addition to its primary indication as a mood stabilizer, lithium has demonstrated efficacy as an augmenting medication for unipolar major depressive disorder.1 While lithium is a first-line agent for BD, it does not improve symptoms in every patient. In a 2004 meta-analysis of 5 randomized controlled trials of patients with BD, Geddes et al2 found lithium was more effective than placebo in preventing the recurrence of mania, with 60% in the lithium group remaining stable compared to 40% in the placebo group. Being able to predict which patients will respond to lithium is crucial to prevent unnecessary exposure to lithium, which can produce significant adverse effects, including somnolence, nausea, diarrhea, and hypothyroidism.2

Several studies have investigated various clinical factors that might predict which patients with BD will respond to lithium. In a review, Kleindienst et al3 highlighted 3 factors that predicted a positive response to lithium:

- fewer hospitalizations prior to treatment

- an episodic course characterized sequentially by mania, depression, and then euthymia

- a later age (>50) at onset of BD.

Recent studies and reviews have isolated additional positive predictors, including having a family history of BD and a shorter duration of illness before receiving lithium, as well as negative predictors, such as rapid cycling, a large number of previous hospitalizations, a depression/mania/euthymia pattern, mood-incongruent psychotic features, and the presence of residual symptoms between mood episodes.3,4

The Table provides a list of probable and possible positive and negative predictors for therapeutic response to lithium in patients with BD.3-6 While relevant, the factors listed as possible predictors may not carry as much influence on lithium responsivity as those categorized as probable predictors.

Because of heterogeneity among studies, clinicians should consider their patient’s presentation as a whole, rather than basing medication choice on independent factors. Ultimately, more studies are required to fully determine the most relevant clinical parameters for lithium response. Overall, however, it appears these clinical factors could be extremely useful to guide psychiatrists in the optimal use of lithium while caring for patients with BD.