User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Key questions to ask patients who are veterans

The Mission Act—signed into law in 2018—recognizes that the health care needs of patients who are veterans can no longer be fully served by the Veterans Health Administration.1 This act allows some veterans who are enrolled in the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system or otherwise entitled to VA care to access treatment outside of VA facilities.1 As a result, psychiatrists may treat veterans more frequently.

During such patients’ initial visit, obtaining a detailed history of their military service can reveal vital clinical information and establish a therapeutic alliance that can help foster positive treatment outcomes. Here we offer an A-to-L list of important questions to ask veterans about their military service, and explanations of why these questions are valuable.

Attained rank. What rank did you attain during your military service? Did you retire from the military? How many years did you serve?

Asking about your patient’s rank, retirement status, and time in service is vital to understanding their military experience. By military law, only individuals who retired from the military can use their rank as an identifier after they leave the military, although some veterans may not wish to be called by their rank in a clinical setting.

Branch. Which branch of the military did you serve? Were you in Active Duty, the Reserves, or the National Guard?

Military members often take great pride in service of their specific branch. Each branch has its own language, culture, values, and exposures. If your patient has served in a combination of Active Duty, Reserves, and/or National Guard, ask how much time they spent in each.

Culture. What part of the military culture was positive or negative for you?

Continue to: There is a clear culture...

There is a clear culture within the military. Some veterans may feel lost without the military structure, and even devalued without the respect of rank. Others may feel jaded and spiteful about the strict military culture, procedures, and expectations.

Discharge. When, why, and under what circumstances were you discharged? What type of discharge did you receive?

There are 6 types of discharge: Honorable, General, Other than Honorable (OTH), Entry Level Separation, Bad Conduct, and Dishonorable. The type of discharge a veteran received may impact what resources are available to them. It also can influence a veteran’s perception of their military career.

Exposures. Were you exposed to combat, death, explosive blasts, or hazardous chemicals?

Do not ask a veteran if they have killed anyone. This question is both disrespectful and highly presumptuous because most veterans have not killed anyone. Be respectful of their experiences. Depending on the veteran’s mission, they may have unique exposures (Agent Orange, burn pits, detainee camps, etc.). Consider asking follow-up questions to learn the details of these exposures.

Continue to: Family impact

Family impact. How has your military service impacted your family?

A veteran’s military service often affects family members. Deployments can cause strain on marital relationships, children’s birthdays and special events may be missed, and extended family may have negative reactions to military service. Understanding the impact on the veteran’s family members can help uncover potential stressful relationships as well as help enhance any positive support systems that are available at home.

Go. Where were you stationed? Were you deployed?

Training location, geography of combat theater, peace-keeping locations, and area of station can all profoundly impact a veteran’s military experience. Ask follow-up questions about their duty stations, deployment locations, and experiences with these locations.

Hot water. Did you ever get into “trouble” while serving the military (eg, lose rank, get arrested, etc.)? How did you respond to the military’s method of discipline?

Continue to: Although it may be difficult...

Although it may be difficult or uncomfortable to ask your patient if they experienced any disciplinary action, this information may prove useful. It can help provide context when you discuss the veteran’s ease of assimilation into civilian life and other important information regarding the type of discharge.

Injuries. Have you experienced any moral, physical, sexual, emotional, or concussive injuries?

Moral injury, guilt, and regret are common for veterans. Not all injuries are from combat. Your patient may have experienced sexual assault, hazing rituals, pranks, etc.

Job. What was your job in the military? What kind of security clearance did you have?

Note that not all veterans’ “jobs” in the military accurately reflect the duties and tasks that they actually performed. Security clearance will often influence the duties and tasks they were required to perform.

Continue to: Keeping it inside

Keeping it inside. Do you have anyone to talk with about your military experiences?

Many veterans feel uncomfortable discussing their experiences with others. Some veterans may be concerned that others will not understand what they went through. Some might perceive that disclosing their experiences could burden other people, or they may be concerned that explaining their experiences may be too shocking. Asking this question may present an opportunity for you to suggest psychotherapy for your patient.

Life as a civilian. How is your life different as a civilian? How have you adjusted to civilian life?

During the process of assimilation into civilian life, veterans may experience symptoms of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or other disorders. These symptoms may emerge and/or become exacerbated during their transition to civilian life.

1. VA MISSION Act of 2018 (VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act), S 2372, 115th Cong, 2nd Sess, HR Doc No. 115-671 (2018).

The Mission Act—signed into law in 2018—recognizes that the health care needs of patients who are veterans can no longer be fully served by the Veterans Health Administration.1 This act allows some veterans who are enrolled in the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system or otherwise entitled to VA care to access treatment outside of VA facilities.1 As a result, psychiatrists may treat veterans more frequently.

During such patients’ initial visit, obtaining a detailed history of their military service can reveal vital clinical information and establish a therapeutic alliance that can help foster positive treatment outcomes. Here we offer an A-to-L list of important questions to ask veterans about their military service, and explanations of why these questions are valuable.

Attained rank. What rank did you attain during your military service? Did you retire from the military? How many years did you serve?

Asking about your patient’s rank, retirement status, and time in service is vital to understanding their military experience. By military law, only individuals who retired from the military can use their rank as an identifier after they leave the military, although some veterans may not wish to be called by their rank in a clinical setting.

Branch. Which branch of the military did you serve? Were you in Active Duty, the Reserves, or the National Guard?

Military members often take great pride in service of their specific branch. Each branch has its own language, culture, values, and exposures. If your patient has served in a combination of Active Duty, Reserves, and/or National Guard, ask how much time they spent in each.

Culture. What part of the military culture was positive or negative for you?

Continue to: There is a clear culture...

There is a clear culture within the military. Some veterans may feel lost without the military structure, and even devalued without the respect of rank. Others may feel jaded and spiteful about the strict military culture, procedures, and expectations.

Discharge. When, why, and under what circumstances were you discharged? What type of discharge did you receive?

There are 6 types of discharge: Honorable, General, Other than Honorable (OTH), Entry Level Separation, Bad Conduct, and Dishonorable. The type of discharge a veteran received may impact what resources are available to them. It also can influence a veteran’s perception of their military career.

Exposures. Were you exposed to combat, death, explosive blasts, or hazardous chemicals?

Do not ask a veteran if they have killed anyone. This question is both disrespectful and highly presumptuous because most veterans have not killed anyone. Be respectful of their experiences. Depending on the veteran’s mission, they may have unique exposures (Agent Orange, burn pits, detainee camps, etc.). Consider asking follow-up questions to learn the details of these exposures.

Continue to: Family impact

Family impact. How has your military service impacted your family?

A veteran’s military service often affects family members. Deployments can cause strain on marital relationships, children’s birthdays and special events may be missed, and extended family may have negative reactions to military service. Understanding the impact on the veteran’s family members can help uncover potential stressful relationships as well as help enhance any positive support systems that are available at home.

Go. Where were you stationed? Were you deployed?

Training location, geography of combat theater, peace-keeping locations, and area of station can all profoundly impact a veteran’s military experience. Ask follow-up questions about their duty stations, deployment locations, and experiences with these locations.

Hot water. Did you ever get into “trouble” while serving the military (eg, lose rank, get arrested, etc.)? How did you respond to the military’s method of discipline?

Continue to: Although it may be difficult...

Although it may be difficult or uncomfortable to ask your patient if they experienced any disciplinary action, this information may prove useful. It can help provide context when you discuss the veteran’s ease of assimilation into civilian life and other important information regarding the type of discharge.

Injuries. Have you experienced any moral, physical, sexual, emotional, or concussive injuries?

Moral injury, guilt, and regret are common for veterans. Not all injuries are from combat. Your patient may have experienced sexual assault, hazing rituals, pranks, etc.

Job. What was your job in the military? What kind of security clearance did you have?

Note that not all veterans’ “jobs” in the military accurately reflect the duties and tasks that they actually performed. Security clearance will often influence the duties and tasks they were required to perform.

Continue to: Keeping it inside

Keeping it inside. Do you have anyone to talk with about your military experiences?

Many veterans feel uncomfortable discussing their experiences with others. Some veterans may be concerned that others will not understand what they went through. Some might perceive that disclosing their experiences could burden other people, or they may be concerned that explaining their experiences may be too shocking. Asking this question may present an opportunity for you to suggest psychotherapy for your patient.

Life as a civilian. How is your life different as a civilian? How have you adjusted to civilian life?

During the process of assimilation into civilian life, veterans may experience symptoms of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or other disorders. These symptoms may emerge and/or become exacerbated during their transition to civilian life.

The Mission Act—signed into law in 2018—recognizes that the health care needs of patients who are veterans can no longer be fully served by the Veterans Health Administration.1 This act allows some veterans who are enrolled in the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system or otherwise entitled to VA care to access treatment outside of VA facilities.1 As a result, psychiatrists may treat veterans more frequently.

During such patients’ initial visit, obtaining a detailed history of their military service can reveal vital clinical information and establish a therapeutic alliance that can help foster positive treatment outcomes. Here we offer an A-to-L list of important questions to ask veterans about their military service, and explanations of why these questions are valuable.

Attained rank. What rank did you attain during your military service? Did you retire from the military? How many years did you serve?

Asking about your patient’s rank, retirement status, and time in service is vital to understanding their military experience. By military law, only individuals who retired from the military can use their rank as an identifier after they leave the military, although some veterans may not wish to be called by their rank in a clinical setting.

Branch. Which branch of the military did you serve? Were you in Active Duty, the Reserves, or the National Guard?

Military members often take great pride in service of their specific branch. Each branch has its own language, culture, values, and exposures. If your patient has served in a combination of Active Duty, Reserves, and/or National Guard, ask how much time they spent in each.

Culture. What part of the military culture was positive or negative for you?

Continue to: There is a clear culture...

There is a clear culture within the military. Some veterans may feel lost without the military structure, and even devalued without the respect of rank. Others may feel jaded and spiteful about the strict military culture, procedures, and expectations.

Discharge. When, why, and under what circumstances were you discharged? What type of discharge did you receive?

There are 6 types of discharge: Honorable, General, Other than Honorable (OTH), Entry Level Separation, Bad Conduct, and Dishonorable. The type of discharge a veteran received may impact what resources are available to them. It also can influence a veteran’s perception of their military career.

Exposures. Were you exposed to combat, death, explosive blasts, or hazardous chemicals?

Do not ask a veteran if they have killed anyone. This question is both disrespectful and highly presumptuous because most veterans have not killed anyone. Be respectful of their experiences. Depending on the veteran’s mission, they may have unique exposures (Agent Orange, burn pits, detainee camps, etc.). Consider asking follow-up questions to learn the details of these exposures.

Continue to: Family impact

Family impact. How has your military service impacted your family?

A veteran’s military service often affects family members. Deployments can cause strain on marital relationships, children’s birthdays and special events may be missed, and extended family may have negative reactions to military service. Understanding the impact on the veteran’s family members can help uncover potential stressful relationships as well as help enhance any positive support systems that are available at home.

Go. Where were you stationed? Were you deployed?

Training location, geography of combat theater, peace-keeping locations, and area of station can all profoundly impact a veteran’s military experience. Ask follow-up questions about their duty stations, deployment locations, and experiences with these locations.

Hot water. Did you ever get into “trouble” while serving the military (eg, lose rank, get arrested, etc.)? How did you respond to the military’s method of discipline?

Continue to: Although it may be difficult...

Although it may be difficult or uncomfortable to ask your patient if they experienced any disciplinary action, this information may prove useful. It can help provide context when you discuss the veteran’s ease of assimilation into civilian life and other important information regarding the type of discharge.

Injuries. Have you experienced any moral, physical, sexual, emotional, or concussive injuries?

Moral injury, guilt, and regret are common for veterans. Not all injuries are from combat. Your patient may have experienced sexual assault, hazing rituals, pranks, etc.

Job. What was your job in the military? What kind of security clearance did you have?

Note that not all veterans’ “jobs” in the military accurately reflect the duties and tasks that they actually performed. Security clearance will often influence the duties and tasks they were required to perform.

Continue to: Keeping it inside

Keeping it inside. Do you have anyone to talk with about your military experiences?

Many veterans feel uncomfortable discussing their experiences with others. Some veterans may be concerned that others will not understand what they went through. Some might perceive that disclosing their experiences could burden other people, or they may be concerned that explaining their experiences may be too shocking. Asking this question may present an opportunity for you to suggest psychotherapy for your patient.

Life as a civilian. How is your life different as a civilian? How have you adjusted to civilian life?

During the process of assimilation into civilian life, veterans may experience symptoms of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, anxiety, or other disorders. These symptoms may emerge and/or become exacerbated during their transition to civilian life.

1. VA MISSION Act of 2018 (VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act), S 2372, 115th Cong, 2nd Sess, HR Doc No. 115-671 (2018).

1. VA MISSION Act of 2018 (VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act), S 2372, 115th Cong, 2nd Sess, HR Doc No. 115-671 (2018).

Helping survivors of human trafficking

Human trafficking (HT) is a secretive, multibillion dollar criminal industry involving the use of coercion, threats, and fraud to force individuals to engage in labor or commercial sex acts. In 2017, the International Labour Organization estimated that 24.9 million people worldwide were victims of forced labor (ie, working under threat or coercion).1 Risk factors for individuals who are vulnerable to HT include recent migration, substance use, housing insecurity, runaway youth, and mental illness. Traffickers continue the cycle of HT through isolation and emotional, physical, financial, and verbal abuse.

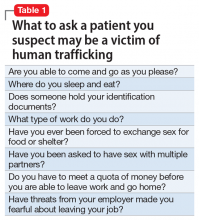

Survivors of HT may avoid seeking health care due to cultural reasons or feelings of guilt, isolation, distrust, or fear of criminal sanctions. There can be missed opportunities for victims to obtain help through health care services, law enforcement, child welfare services, or even family or friends. In a study of 173 survivors of HT in the United States, 68% of those who were currently trafficked visited with a health care professional at least once and were not identified as being trafficked.2 Psychiatrists rarely receive education on HT, which can lead to missed opportunities for identifying victims. Table 1 lists screening questions psychiatrists can ask patients they suspect may be trafficked.

The psychiatric sequelae of trafficking

Survivors of HT commonly experience psychiatric illness, substance use, pain, sexually transmitted diseases, and unplanned pregnancies.3 Here we discuss some of the psychiatric conditions that are common among HT survivors, and outline a multidisciplinary approach to their care.

PTSD, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Studies suggest survivors of HT who seek care have a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3 Survivors may have experienced multiple repetitive trauma, such as physical and sexual abuse.3 Compared with survivors of forced labor trafficking, survivors of sex trafficking have higher rates of childhood abuse, violence during trafficking, severe symptoms of PTSD, and comorbid depression and PTSD.4 For survivors with PTSD, consider psychosocial interventions that address social support, coping strategies, and community reintegration.5 Survivors can also benefit from trauma-informed care that focuses on the cognitive aspect of the trauma, such as cognitive processing therapy, which involves cognitive restructuring without a written account of the trauma.6

Substance use disorders. Some individuals who are trafficked may be forced to use drugs of abuse or alcohol, while others may use substances to help cope while they are being trafficked or afterwards.3 For these patients, motivational interviewing may be beneficial. Also, consider referring them to detoxification or rehabilitation programs.

Suicide and self-harm. In a study of 98 HT survivors in England, 33% reported a history of self-harm before receiving care and 25% engaged in self-harm during care.7 After engaging in self-harm, survivors of HT were more likely to be admitted to psychiatric inpatient units than were patients who had not been trafficked.7 It is crucial to conduct a suicide risk assessment as part of the trauma-informed care of these patients.

Other conditions. In addition to psychiatric illness, survivors of HT may experience physical symptoms such as headache, back pain, stomach pain, fatigue, dizziness, memory problems, and weight loss.3 Referral to other specialties may be necessary for addressing any of the patient’s other conditions.

Continue to: Use a multidisciplinary approach

Use a multidisciplinary approach

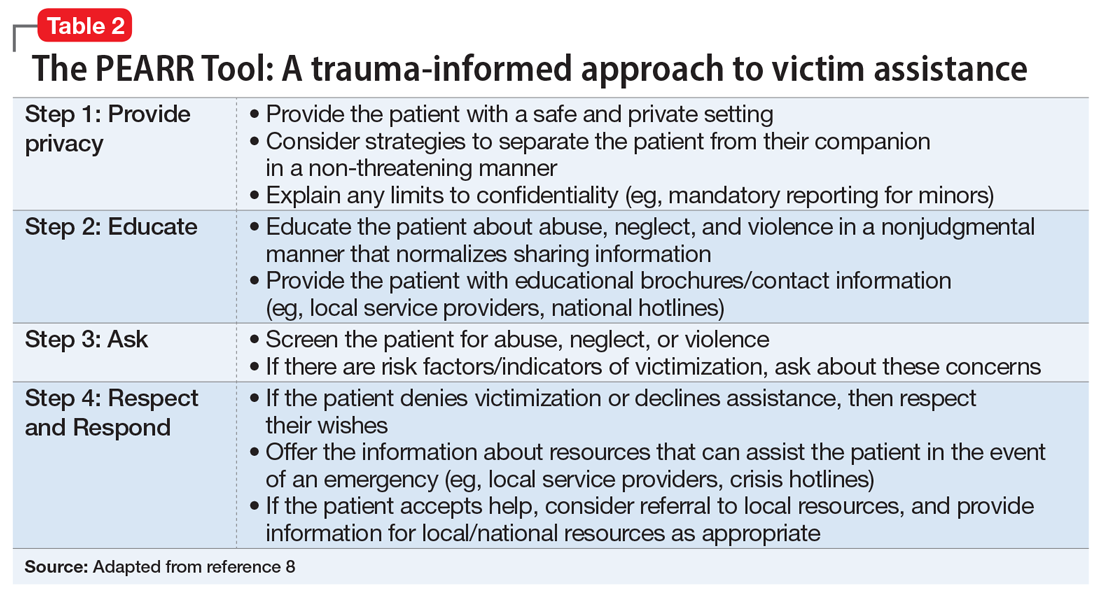

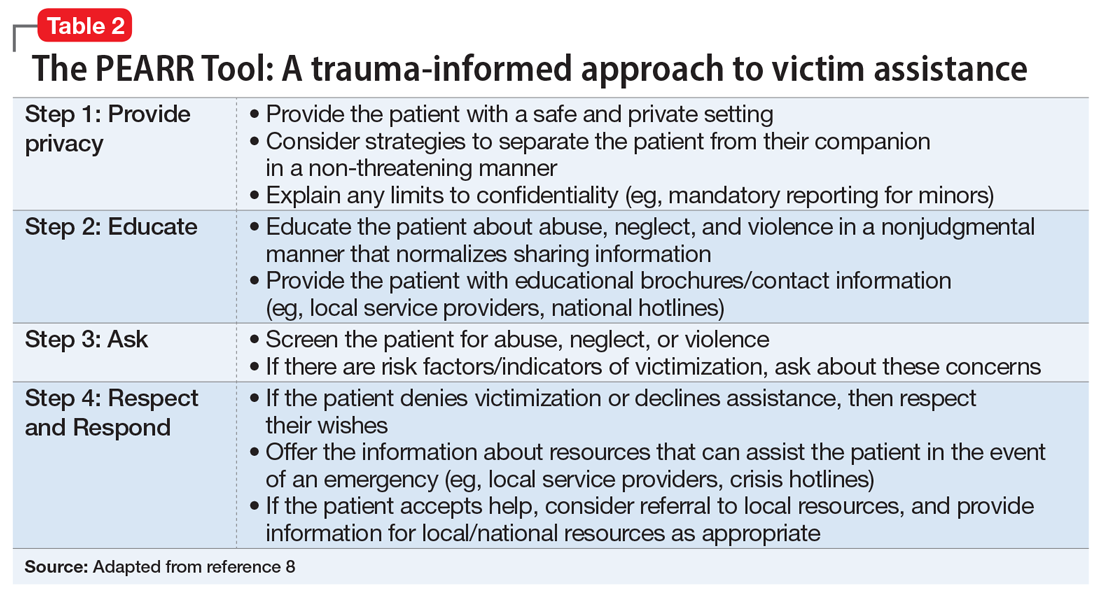

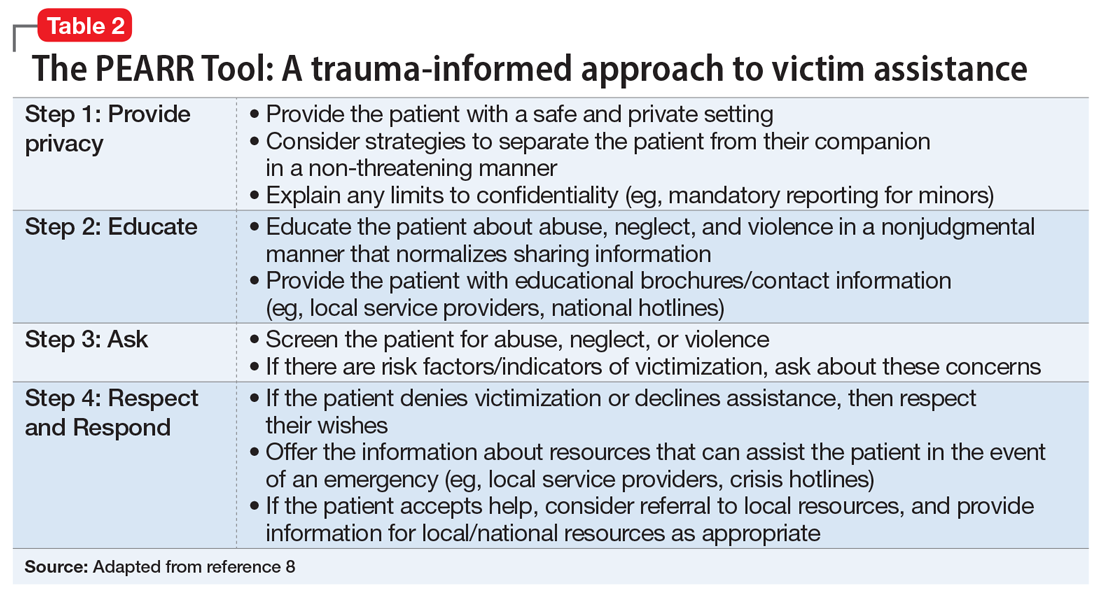

Treatment for survivors of HT should be tailored to their specific mental health needs by including psychopharmacology; individual, group, or family psychotherapy; and peer advocate support. Rehabilitation, social services, and case management should also be considered. The care of survivors of HT benefits from a multidisciplinary, culturally-sensitive, and trauma-informed approach. Table 28 describes the PEARR Tool (Provide privacy, Educate, Ask, Respect, and Respond), which offers physicians 4 steps for addressing abuse, neglect, or violence with their patients. Also, the National Human Trafficking Hotline (1-888-373-7888) is available 24/7 for trafficked persons, survivors, and health care professionals to provide guidance on reporting laws and finding additional resources such as housing and legal services.

1. International Labour Organization, the Walk Free Foundation. Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: forced labour and forced marriage. Published 2017. Accessed January 14, 2021. www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_575479/lang--en/index.htm

2. Chisolm-Straker M, Baldwin S, Gaïgbé-Togbé B, et al. Health care and human trafficking: we are seeing the unseen. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(3):1220-1233.

3. Ottisova L, Hemmings S, Howard LM, et al. Prevalence and risk of violence and the mental, physical and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: an updated systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25(4):317-341.

4. Hopper EK, Gonzalez LD. A comparison of psychological symptoms in survivors of sex and labor trafficking. Behav Med. 2018;44(3):177-188.

5. Okech D, Hanseen N, Howard W, et al. Social support, dysfunctional coping, and community reintegration as predictors of PTSD among human trafficking survivors. Behav Med. 2018;44(3):209-218.

6. Salami T, Gordon M, Coverdale J, et al. What therapies are favored in the treatment of the psychological sequelae of trauma in human trafficking victims? J Psychiatr Pract. 2018;24(2):87-96.

7. Borschmann R, Oram S, Kinner SA, et al. Self-harm among adult victims of human trafficking who accessed secondary mental health services in England. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(2):207-210.

8. Using the PEARR Tool. Dignity Health. Published 2019. Accessed January 14, 2021. https://www.dignityhealth.org/hello-humankindness/human-trafficking/victimcentered-and-trauma-informed/using-the-pearr-tool

Human trafficking (HT) is a secretive, multibillion dollar criminal industry involving the use of coercion, threats, and fraud to force individuals to engage in labor or commercial sex acts. In 2017, the International Labour Organization estimated that 24.9 million people worldwide were victims of forced labor (ie, working under threat or coercion).1 Risk factors for individuals who are vulnerable to HT include recent migration, substance use, housing insecurity, runaway youth, and mental illness. Traffickers continue the cycle of HT through isolation and emotional, physical, financial, and verbal abuse.

Survivors of HT may avoid seeking health care due to cultural reasons or feelings of guilt, isolation, distrust, or fear of criminal sanctions. There can be missed opportunities for victims to obtain help through health care services, law enforcement, child welfare services, or even family or friends. In a study of 173 survivors of HT in the United States, 68% of those who were currently trafficked visited with a health care professional at least once and were not identified as being trafficked.2 Psychiatrists rarely receive education on HT, which can lead to missed opportunities for identifying victims. Table 1 lists screening questions psychiatrists can ask patients they suspect may be trafficked.

The psychiatric sequelae of trafficking

Survivors of HT commonly experience psychiatric illness, substance use, pain, sexually transmitted diseases, and unplanned pregnancies.3 Here we discuss some of the psychiatric conditions that are common among HT survivors, and outline a multidisciplinary approach to their care.

PTSD, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Studies suggest survivors of HT who seek care have a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3 Survivors may have experienced multiple repetitive trauma, such as physical and sexual abuse.3 Compared with survivors of forced labor trafficking, survivors of sex trafficking have higher rates of childhood abuse, violence during trafficking, severe symptoms of PTSD, and comorbid depression and PTSD.4 For survivors with PTSD, consider psychosocial interventions that address social support, coping strategies, and community reintegration.5 Survivors can also benefit from trauma-informed care that focuses on the cognitive aspect of the trauma, such as cognitive processing therapy, which involves cognitive restructuring without a written account of the trauma.6

Substance use disorders. Some individuals who are trafficked may be forced to use drugs of abuse or alcohol, while others may use substances to help cope while they are being trafficked or afterwards.3 For these patients, motivational interviewing may be beneficial. Also, consider referring them to detoxification or rehabilitation programs.

Suicide and self-harm. In a study of 98 HT survivors in England, 33% reported a history of self-harm before receiving care and 25% engaged in self-harm during care.7 After engaging in self-harm, survivors of HT were more likely to be admitted to psychiatric inpatient units than were patients who had not been trafficked.7 It is crucial to conduct a suicide risk assessment as part of the trauma-informed care of these patients.

Other conditions. In addition to psychiatric illness, survivors of HT may experience physical symptoms such as headache, back pain, stomach pain, fatigue, dizziness, memory problems, and weight loss.3 Referral to other specialties may be necessary for addressing any of the patient’s other conditions.

Continue to: Use a multidisciplinary approach

Use a multidisciplinary approach

Treatment for survivors of HT should be tailored to their specific mental health needs by including psychopharmacology; individual, group, or family psychotherapy; and peer advocate support. Rehabilitation, social services, and case management should also be considered. The care of survivors of HT benefits from a multidisciplinary, culturally-sensitive, and trauma-informed approach. Table 28 describes the PEARR Tool (Provide privacy, Educate, Ask, Respect, and Respond), which offers physicians 4 steps for addressing abuse, neglect, or violence with their patients. Also, the National Human Trafficking Hotline (1-888-373-7888) is available 24/7 for trafficked persons, survivors, and health care professionals to provide guidance on reporting laws and finding additional resources such as housing and legal services.

Human trafficking (HT) is a secretive, multibillion dollar criminal industry involving the use of coercion, threats, and fraud to force individuals to engage in labor or commercial sex acts. In 2017, the International Labour Organization estimated that 24.9 million people worldwide were victims of forced labor (ie, working under threat or coercion).1 Risk factors for individuals who are vulnerable to HT include recent migration, substance use, housing insecurity, runaway youth, and mental illness. Traffickers continue the cycle of HT through isolation and emotional, physical, financial, and verbal abuse.

Survivors of HT may avoid seeking health care due to cultural reasons or feelings of guilt, isolation, distrust, or fear of criminal sanctions. There can be missed opportunities for victims to obtain help through health care services, law enforcement, child welfare services, or even family or friends. In a study of 173 survivors of HT in the United States, 68% of those who were currently trafficked visited with a health care professional at least once and were not identified as being trafficked.2 Psychiatrists rarely receive education on HT, which can lead to missed opportunities for identifying victims. Table 1 lists screening questions psychiatrists can ask patients they suspect may be trafficked.

The psychiatric sequelae of trafficking

Survivors of HT commonly experience psychiatric illness, substance use, pain, sexually transmitted diseases, and unplanned pregnancies.3 Here we discuss some of the psychiatric conditions that are common among HT survivors, and outline a multidisciplinary approach to their care.

PTSD, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders. Studies suggest survivors of HT who seek care have a high prevalence of depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).3 Survivors may have experienced multiple repetitive trauma, such as physical and sexual abuse.3 Compared with survivors of forced labor trafficking, survivors of sex trafficking have higher rates of childhood abuse, violence during trafficking, severe symptoms of PTSD, and comorbid depression and PTSD.4 For survivors with PTSD, consider psychosocial interventions that address social support, coping strategies, and community reintegration.5 Survivors can also benefit from trauma-informed care that focuses on the cognitive aspect of the trauma, such as cognitive processing therapy, which involves cognitive restructuring without a written account of the trauma.6

Substance use disorders. Some individuals who are trafficked may be forced to use drugs of abuse or alcohol, while others may use substances to help cope while they are being trafficked or afterwards.3 For these patients, motivational interviewing may be beneficial. Also, consider referring them to detoxification or rehabilitation programs.

Suicide and self-harm. In a study of 98 HT survivors in England, 33% reported a history of self-harm before receiving care and 25% engaged in self-harm during care.7 After engaging in self-harm, survivors of HT were more likely to be admitted to psychiatric inpatient units than were patients who had not been trafficked.7 It is crucial to conduct a suicide risk assessment as part of the trauma-informed care of these patients.

Other conditions. In addition to psychiatric illness, survivors of HT may experience physical symptoms such as headache, back pain, stomach pain, fatigue, dizziness, memory problems, and weight loss.3 Referral to other specialties may be necessary for addressing any of the patient’s other conditions.

Continue to: Use a multidisciplinary approach

Use a multidisciplinary approach

Treatment for survivors of HT should be tailored to their specific mental health needs by including psychopharmacology; individual, group, or family psychotherapy; and peer advocate support. Rehabilitation, social services, and case management should also be considered. The care of survivors of HT benefits from a multidisciplinary, culturally-sensitive, and trauma-informed approach. Table 28 describes the PEARR Tool (Provide privacy, Educate, Ask, Respect, and Respond), which offers physicians 4 steps for addressing abuse, neglect, or violence with their patients. Also, the National Human Trafficking Hotline (1-888-373-7888) is available 24/7 for trafficked persons, survivors, and health care professionals to provide guidance on reporting laws and finding additional resources such as housing and legal services.

1. International Labour Organization, the Walk Free Foundation. Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: forced labour and forced marriage. Published 2017. Accessed January 14, 2021. www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_575479/lang--en/index.htm

2. Chisolm-Straker M, Baldwin S, Gaïgbé-Togbé B, et al. Health care and human trafficking: we are seeing the unseen. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(3):1220-1233.

3. Ottisova L, Hemmings S, Howard LM, et al. Prevalence and risk of violence and the mental, physical and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: an updated systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25(4):317-341.

4. Hopper EK, Gonzalez LD. A comparison of psychological symptoms in survivors of sex and labor trafficking. Behav Med. 2018;44(3):177-188.

5. Okech D, Hanseen N, Howard W, et al. Social support, dysfunctional coping, and community reintegration as predictors of PTSD among human trafficking survivors. Behav Med. 2018;44(3):209-218.

6. Salami T, Gordon M, Coverdale J, et al. What therapies are favored in the treatment of the psychological sequelae of trauma in human trafficking victims? J Psychiatr Pract. 2018;24(2):87-96.

7. Borschmann R, Oram S, Kinner SA, et al. Self-harm among adult victims of human trafficking who accessed secondary mental health services in England. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(2):207-210.

8. Using the PEARR Tool. Dignity Health. Published 2019. Accessed January 14, 2021. https://www.dignityhealth.org/hello-humankindness/human-trafficking/victimcentered-and-trauma-informed/using-the-pearr-tool

1. International Labour Organization, the Walk Free Foundation. Global Estimates of Modern Slavery: forced labour and forced marriage. Published 2017. Accessed January 14, 2021. www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_575479/lang--en/index.htm

2. Chisolm-Straker M, Baldwin S, Gaïgbé-Togbé B, et al. Health care and human trafficking: we are seeing the unseen. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(3):1220-1233.

3. Ottisova L, Hemmings S, Howard LM, et al. Prevalence and risk of violence and the mental, physical and sexual health problems associated with human trafficking: an updated systematic review. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2016;25(4):317-341.

4. Hopper EK, Gonzalez LD. A comparison of psychological symptoms in survivors of sex and labor trafficking. Behav Med. 2018;44(3):177-188.

5. Okech D, Hanseen N, Howard W, et al. Social support, dysfunctional coping, and community reintegration as predictors of PTSD among human trafficking survivors. Behav Med. 2018;44(3):209-218.

6. Salami T, Gordon M, Coverdale J, et al. What therapies are favored in the treatment of the psychological sequelae of trauma in human trafficking victims? J Psychiatr Pract. 2018;24(2):87-96.

7. Borschmann R, Oram S, Kinner SA, et al. Self-harm among adult victims of human trafficking who accessed secondary mental health services in England. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(2):207-210.

8. Using the PEARR Tool. Dignity Health. Published 2019. Accessed January 14, 2021. https://www.dignityhealth.org/hello-humankindness/human-trafficking/victimcentered-and-trauma-informed/using-the-pearr-tool

Patient Handout: Safe practices during the COVID-19 pandemic

In addition to sharing this handout (see PDF link) with your patients, Dr. Gupta also recommends advising them to watch the video Hand-washing Steps Using the WHO Technique, which is available at https://youtu.be/IisgnbMfKvI

In addition to sharing this handout (see PDF link) with your patients, Dr. Gupta also recommends advising them to watch the video Hand-washing Steps Using the WHO Technique, which is available at https://youtu.be/IisgnbMfKvI

In addition to sharing this handout (see PDF link) with your patients, Dr. Gupta also recommends advising them to watch the video Hand-washing Steps Using the WHO Technique, which is available at https://youtu.be/IisgnbMfKvI

Psychcast: Nursing home consultations supporting documents

Body Text

Body Text

Body Text

Reducing COVID-19 opioid deaths

Editor's Note: Due to updated statistics from the CDC, the online version of this article has been modified from the version that appears in the printed edition of the January 2021 issue of Current Psychiatry.

Individuals with mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs) are particularly susceptible to negative effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The collision of the COVID-19 pandemic and the drug overdose epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for physicians, policymakers, and health care professionals to optimize care for individuals with SUDs because they may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of the virus due to compromised respiratory and immune function, and poor social support.1 In this commentary, we highlight the challenges of the drug overdose epidemic, and recommend strategies to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among patients with SUDs.

A crisis exacerbated by COVID-19

The current drug overdose epidemic has become an American public health nightmare. According to preliminary data released by the CDC on December 17, 2020, there were more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths in the United States in the 12 months ending May 2020.2,3 This is the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period. The CDC also noted that while overdose deaths were already increasing in the months preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, the latest numbers suggest an acceleration of overdose deaths during the pandemic.

What is causing this significant loss of life? Prescription opioids and illegal opioids such as heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl are the main agents associated with overdose deaths. These opioids were responsible for 61% (28,647) of drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2014.4 In 2015, the opioid overdose death rate increased by 15.6%.5

The increase in the number of opioid overdose deaths in part coincides with a sharp increase in the availability and use of heroin. Heroin overdose deaths have more than tripled since 2010, but heroin is not the only opiate involved. Fentanyl, a synthetic, short-acting opioid that is approved for managing pain in patients with advanced cancers, is 50 times more potent than heroin. The abuse of prescribed fentanyl has been accelerating over the past decade, as is the use of illicitly produced fentanyl. Evidence from US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) seizure records shows heroin is being adulterated with illicit fentanyl to enhance the potency of the heroin.6,7 Mixing illicit fentanyl with heroin may be contributing to the recent increase in heroin overdose fatalities. According to the CDC, overdose deaths related to synthetic opioids increased 38.4% from the 12-month period leading up to June 2019 compared with the 12-month period leading up to May 2020.2,3 Postmortem studies of individuals who died from a heroin overdose have frequently found the presence of fentanyl along with heroin.8 Overdose deaths involving heroin may be occurring because individuals may be unknowingly using heroin adulterated with fentanyl.9 In addition, carfentanil, a powerful new synthetic fentanyl, has been recently identified in heroin mixtures. Carfentanil is 10,000 times stronger than morphine. Even in miniscule amounts, carfentanil can suppress breathing to the degree that multiple doses of naloxone are needed to restore respirations.

Initial studies indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has been exacerbating this situation. Wainwright et al10 conducted an analysis of urine drug test results of patients with SUDs from 4 months before and 4 months after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020. Compared with before COVID-19, the proportion of specimens testing positive since COVID-19 increased from 3.80% to 7.32% for fentanyl and from 1.29% to 2.09% for heroin.10

A similar drug testing study found that during the pandemic, the proportion of positive results (positivity) increased by 35% for non-prescribed fentanyl and 44% for heroin.11 Positivity for non-prescribed fentanyl increased significantly among patients who tested positive for other drugs, including by 89% for amphetamines; 48% for benzodiazepines; 34% for cocaine; and 39% for opiates (P < .1 for all).11

In a review of electronic medical records, Ochalek et al12 found that the number of nonfatal opioid overdoses in an emergency department in Virginia increased from 102 in March-June 2019 to 227 in March-June 2020. In an issue brief published on October 31, 2020, the American Medical Association reported increase in opioid and other drug-related overdoses in more than 40 states during the COVID-19 pandemic.13

Continue to: Strategies for intervention...

Strategies for intervention

A multi-dimensional approach is needed to protect the public from this growing opioid overdose epidemic. To address this challenging task, we recommend several strategies:

Enhance access to virtual treatment

Even when in-person treatment cannot take place due to COVID-19-related restrictions, it is vital that services are accessible to patients with SUDs during this pandemic. Examples of virtual treatment include:

- Telehealth for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) using buprenorphine (recently updated guidance from the US DEA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] allows this method of prescribing)

- Teletherapy to prevent relapse

- Remote drug screens by sending saliva or urine kits to patients' homes, visiting patients to collect fluid samples, or asking patients to come to a "drive-through" facility to provide samples

- Virtual (online) Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, and similar meetings to provide support in the absence of in-person meetings.

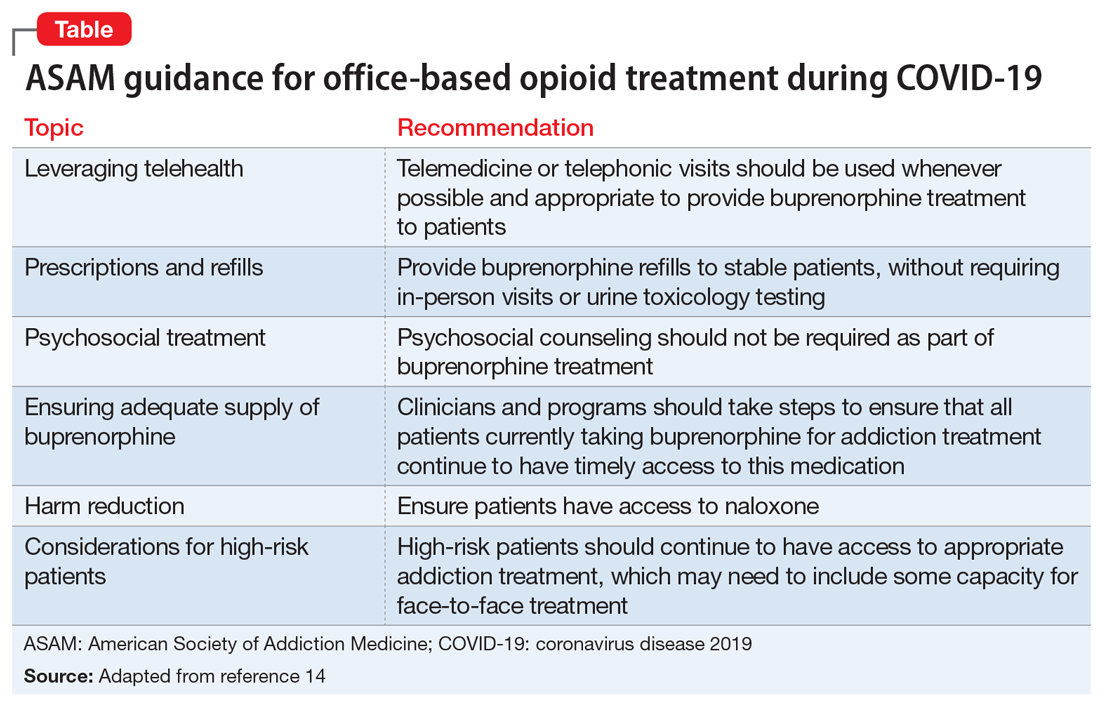

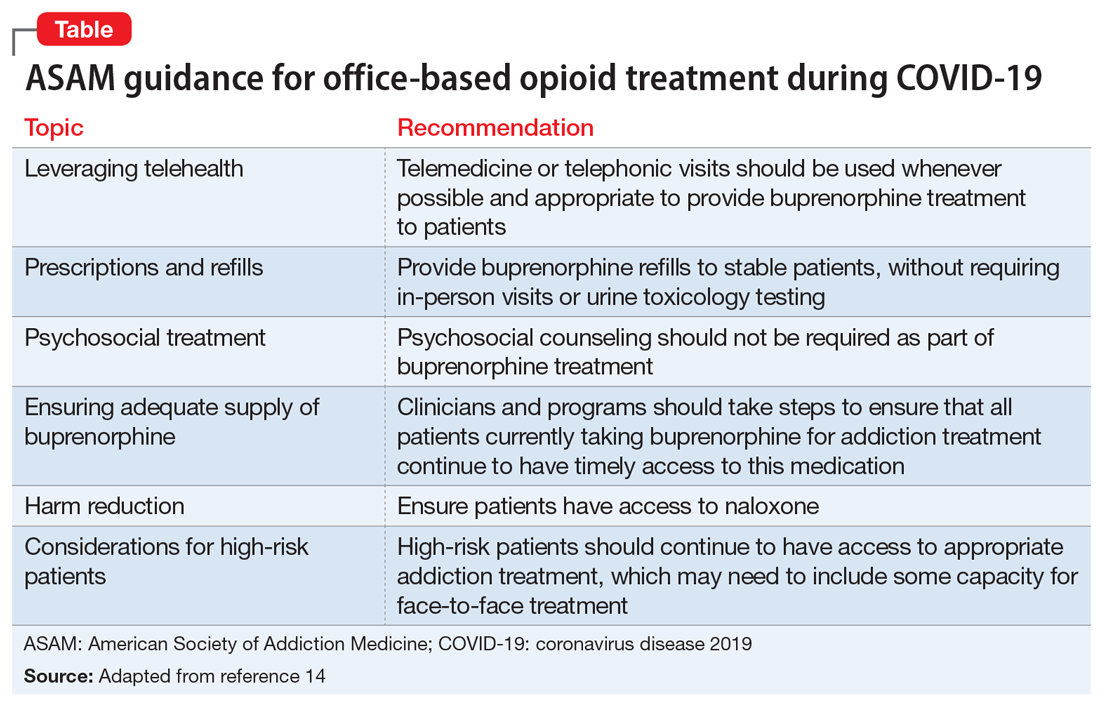

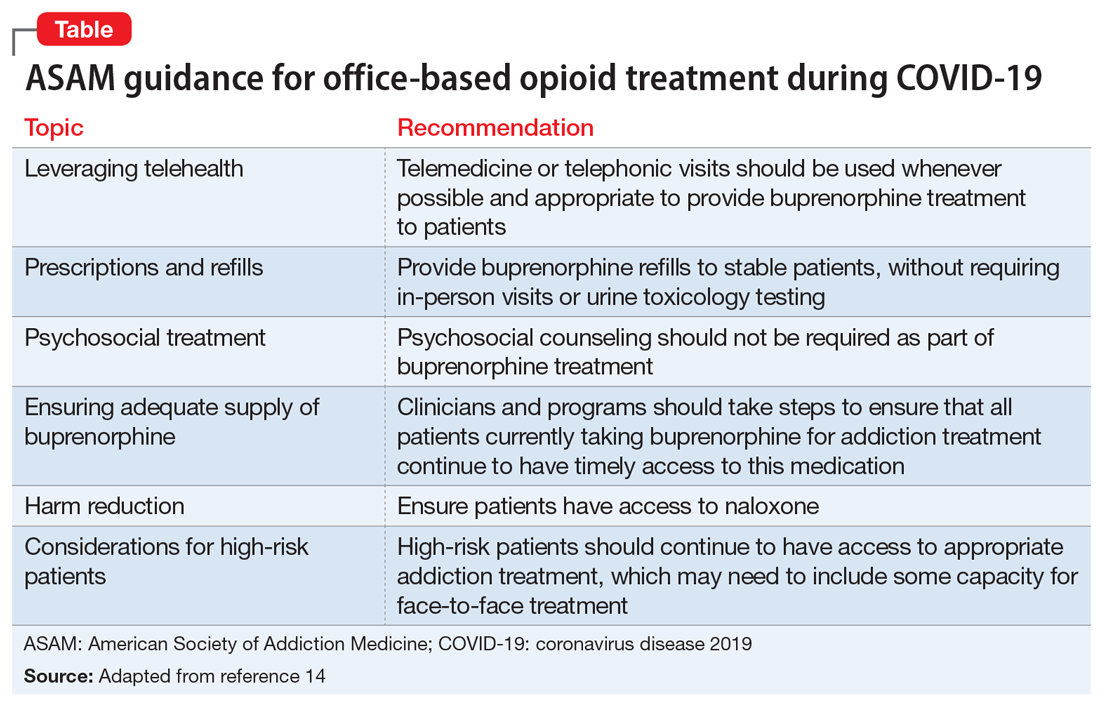

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) offers guidance to treatment programs to focus on infection control and mitigation. The Table14 summarizes the ASAM recommendations for office-based opioid treatment during COVID-19.

Expand access to treatment

This includes access to MAT (such as buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone, naltrexone, and depot naltrexone) and, equally important, to psychosocial treatment, counseling, and/or recovery services. Recent legislative changes have increased the number of patients that a qualified physician can treat with buprenorphine/naloxone from 100 to 275, and allowed physician extenders to prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone in office-based settings. A recent population-based, retrospective Canadian study showed that opioid agonist treatment decreased the risk of mortality among opioid users, and the protective effects of this treatment increased as fentanyl and other synthetic opioids became common in the illicit drug supply.15 However, because of the shortage of psychiatrists and addiction medicine specialists in several regions of the United States, access to treatment is extremely limited and often inadequate. This constitutes a major public health crisis and contributes to our inability to intervene effectively in the opioid epidemic. Telepsychiatry programs can bring needed services to underserved areas, but they need additional support and development. Further, involving other specialties is paramount for treating this epidemic. Integrating MAT in primary care settings can improve access to treatment. Harm-reduction approaches, such as syringe exchange programs, can play an important role in reducing the adverse consequences associated with heroin use and establish health care relationships with at-risk individuals. Syringe exchange programs can also reduce the rate of infections associated with IV drug use, such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus.

Continue to: Increase education on naloxone...

Increase education on naloxone

Naloxone is a safe and effective opioid antagonist used to treat opioid overdoses. Timely access to naloxone is of the essence when treating opioid-related overdoses. Many states have enacted laws allowing health care professionals, law enforcement officers, and patients and relatives to obtain naloxone without a physician's prescription. It appears this approach may be yielding results. For example, the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition distributed >101,000 free overdose rescue kits that included naloxone and recorded 13,392 confirmed cases of overdose rescue with naloxone from 2013 to 2019.16

Divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system to treatment

We need to develop programs to divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system, which is focused on punishment, to interventions that focus on treatment. Data indicates high recidivism rates for incarcerated individuals with SUDs who do not have access to treatment after they are released. Recognizing this, communities are developing programs that divert low-level offenders from the criminal justice system into treatment. For instance, in Seattle, the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion is a pilot program developed to divert low-level drug and prostitution offenders into community-based treatment and support services. This helps provide housing, health care, job training, treatment, and mental health support. Innovative programs are needed to provide SUD treatment in the rehabilitation programs of correctional facilities and ensure case managers and discharge planners can transition participants to community treatment programs upon their release.

Develop early identification and prevention programs

These programs should focus on individuals at high risk, such as patients with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric disorders, those with chronic pain, and at-risk children whose parents abuse opiates. Traditional addiction treatment programs typically do not address patients with complex conditions or special populations, such as adolescents or pregnant women with substance use issues. Evidence-based approaches such as Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT), and prevention approaches that target students in middle schools and high schools need to be more widely available.

Improve education on opioid prescribing

Responsible opioid prescribing for clinicians should include education about the regular use of prescription drug monitoring programs, urine drug screening, avoiding co-prescription of opioids with sedative-hypnotic medications, and better linkage with addiction treatment.

Treat comorbid psychiatric conditions

It is critical to both identify and effectively treat underlying affective, anxiety, and psychotic disorders in patients with SUDs. Anxiety, depression, and emotional dysregulation often contribute to worsening substance abuse, abuse of prescription drugs, diversion of prescribed drugs, and an increased risk of overdoses and suicides. Effective treatment of comorbid psychiatric conditions also may reduce relapses.

Increase research on causes and treatments

Through research, we must expand our knowledge to better understand the factors that contribute to this epidemic and develop better treatments. These efforts may allow for the development of prevention mechanisms. For example, a recent study found that the continued use of opioid medications after an overdose was associated with a high risk of a repeated overdosecall out material?.17 At the end of a 2-year observation, 17% (confidence interval [CI]: 14% to 20%) of patients receiving a high daily dosage of a prescribed opioid had a repeat overdose compared with 15% (CI: 10% to 21%) of those receiving a moderate dosage, 9% (CI: 6% to 14%) of those receiving a low dosage, and 8% (CI: 6% to 11%) of those receiving no opioids.17 Of the patients who overdosed on prescribed opiates, 30% switched to a new prescriber after their overdose, many of whom may not have been aware of the previous overdose. From a public health perspective, it would make sense for prescribers to know of prior opioid and/or benzodiazepine overdoses. This could be reported by emergency department clinicians, law enforcement, and hospitals into a prescription drug monitoring program, which is readily available to prescribers in most states.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Scott Proescholdbell, MPH, Injury and Violence Prevention Branch, Chronic Disease and Injury Section, Division of Public Health, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, for his assistance.

Bottom Line

The collision of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and the drug overdose epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for health care professionals to optimize care for individuals with substance use disorders. Suggested interventions include enhancing access to medication-assisted treatment and virtual treatment, improving education about naloxone and safe opioid prescribing practices, and diverting at-risk patients from the criminal justice system to interventions that focus on treatment.

1. Volkow ND. Collision of the COVID-19 and addiction epidemics. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(1):61-62.

2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose deaths accelerating during COVID-19. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2020/p1218-overdose-deaths-covid-19.html

3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics Vital Statistics Rapid Release. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Accessed December 30, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

4.Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, et al. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths -- United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;64(50-51):1378-1382.

5.Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, et al. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths -- United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452.

6.US Drug Enforcement Administration. DEA issues nationwide alert on fentanyl as threat to health and public safety. Published March 19, 2015. Accessed October 28, 2020. http://www.dea.gov/divisions/hq/2015/hq031815.shtml

7.Gladden RM, Martinez P, Seth P. Fentanyl law enforcement submissions and increases in synthetic opioid-involved overdose deaths - 27 states, 2013-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(33):837-843.

8.Algren DA, Monteilh CP, Punja M, et al. Fentanyl-associated fatalities among illicit drug users in Wayne County, Michigan (July 2005-May 2006). J Med Toxicol. 2013;9(1):106-115.

9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Increases in fentanyl drug confiscations and fentanyl-related overdose fatalities. HAN Health Advisory. Published October 26, 2015. Accessed October 28, 2020. http://emergency.cdc.gov/han/han00384.asp

10.Wainwright JJ, Mikre M, Whitley P, et al. Analysis of drug test results before and after the us declaration of a national emergency concerning the COVID-19 outbreak. JAMA. 2020;324(16):1674-1677.

11.Niles JK, Gudin J, Radliff J, et al. The opioid epidemic within the COVID-19 pandemic: drug testing in 2020 [published online October 8, 2020]. Population Health Management. doi: 10.1089/pop.2020.0230

12.Ochalek TA, Cumpston KL, Wills BK, et al. Nonfatal opioid overdoses at an urban emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(16):1673-1674.

13.American Medical Association. Issue brief: reports of increases in opioid- and other drug-related overdose and other concerns during COVID pandemic. Published October 31, 2020. Accessed November 9, 2020. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2020-11/issue-brief-increases-in-opioid-related-overdose.pdf

14.American Society of Addiction Medicine. Caring for patients during the COVID-19 pandemic: ASAM COVID-19 Task Force recommendations. Accessed October 30, 2020. https://www.asam.org/docs/default-source/covid-19/medication-formulation-and-dosage-guidance-(1).pdf

15.Pearce LA, Min JE, Piske M, et al. Opioid agonist treatment and risk of mortality during opioid overdose public health emergency: population based retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;368:m772. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m772

16.North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition. NCHRC'S community-based overdose prevention project. Accessed March 29, 2020. http://www.nchrc.org/programs-and-services

17.Larochelle MR, Liebschutz JM, Zhang F, et al. Opioid prescribing after nonfatal overdose and association with repeated overdose: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(1):1-9.

Editor's Note: Due to updated statistics from the CDC, the online version of this article has been modified from the version that appears in the printed edition of the January 2021 issue of Current Psychiatry.

Individuals with mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs) are particularly susceptible to negative effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The collision of the COVID-19 pandemic and the drug overdose epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for physicians, policymakers, and health care professionals to optimize care for individuals with SUDs because they may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of the virus due to compromised respiratory and immune function, and poor social support.1 In this commentary, we highlight the challenges of the drug overdose epidemic, and recommend strategies to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among patients with SUDs.

A crisis exacerbated by COVID-19

The current drug overdose epidemic has become an American public health nightmare. According to preliminary data released by the CDC on December 17, 2020, there were more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths in the United States in the 12 months ending May 2020.2,3 This is the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period. The CDC also noted that while overdose deaths were already increasing in the months preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, the latest numbers suggest an acceleration of overdose deaths during the pandemic.

What is causing this significant loss of life? Prescription opioids and illegal opioids such as heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl are the main agents associated with overdose deaths. These opioids were responsible for 61% (28,647) of drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2014.4 In 2015, the opioid overdose death rate increased by 15.6%.5

The increase in the number of opioid overdose deaths in part coincides with a sharp increase in the availability and use of heroin. Heroin overdose deaths have more than tripled since 2010, but heroin is not the only opiate involved. Fentanyl, a synthetic, short-acting opioid that is approved for managing pain in patients with advanced cancers, is 50 times more potent than heroin. The abuse of prescribed fentanyl has been accelerating over the past decade, as is the use of illicitly produced fentanyl. Evidence from US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) seizure records shows heroin is being adulterated with illicit fentanyl to enhance the potency of the heroin.6,7 Mixing illicit fentanyl with heroin may be contributing to the recent increase in heroin overdose fatalities. According to the CDC, overdose deaths related to synthetic opioids increased 38.4% from the 12-month period leading up to June 2019 compared with the 12-month period leading up to May 2020.2,3 Postmortem studies of individuals who died from a heroin overdose have frequently found the presence of fentanyl along with heroin.8 Overdose deaths involving heroin may be occurring because individuals may be unknowingly using heroin adulterated with fentanyl.9 In addition, carfentanil, a powerful new synthetic fentanyl, has been recently identified in heroin mixtures. Carfentanil is 10,000 times stronger than morphine. Even in miniscule amounts, carfentanil can suppress breathing to the degree that multiple doses of naloxone are needed to restore respirations.

Initial studies indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has been exacerbating this situation. Wainwright et al10 conducted an analysis of urine drug test results of patients with SUDs from 4 months before and 4 months after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020. Compared with before COVID-19, the proportion of specimens testing positive since COVID-19 increased from 3.80% to 7.32% for fentanyl and from 1.29% to 2.09% for heroin.10

A similar drug testing study found that during the pandemic, the proportion of positive results (positivity) increased by 35% for non-prescribed fentanyl and 44% for heroin.11 Positivity for non-prescribed fentanyl increased significantly among patients who tested positive for other drugs, including by 89% for amphetamines; 48% for benzodiazepines; 34% for cocaine; and 39% for opiates (P < .1 for all).11

In a review of electronic medical records, Ochalek et al12 found that the number of nonfatal opioid overdoses in an emergency department in Virginia increased from 102 in March-June 2019 to 227 in March-June 2020. In an issue brief published on October 31, 2020, the American Medical Association reported increase in opioid and other drug-related overdoses in more than 40 states during the COVID-19 pandemic.13

Continue to: Strategies for intervention...

Strategies for intervention

A multi-dimensional approach is needed to protect the public from this growing opioid overdose epidemic. To address this challenging task, we recommend several strategies:

Enhance access to virtual treatment

Even when in-person treatment cannot take place due to COVID-19-related restrictions, it is vital that services are accessible to patients with SUDs during this pandemic. Examples of virtual treatment include:

- Telehealth for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) using buprenorphine (recently updated guidance from the US DEA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] allows this method of prescribing)

- Teletherapy to prevent relapse

- Remote drug screens by sending saliva or urine kits to patients' homes, visiting patients to collect fluid samples, or asking patients to come to a "drive-through" facility to provide samples

- Virtual (online) Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, and similar meetings to provide support in the absence of in-person meetings.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) offers guidance to treatment programs to focus on infection control and mitigation. The Table14 summarizes the ASAM recommendations for office-based opioid treatment during COVID-19.

Expand access to treatment

This includes access to MAT (such as buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone, naltrexone, and depot naltrexone) and, equally important, to psychosocial treatment, counseling, and/or recovery services. Recent legislative changes have increased the number of patients that a qualified physician can treat with buprenorphine/naloxone from 100 to 275, and allowed physician extenders to prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone in office-based settings. A recent population-based, retrospective Canadian study showed that opioid agonist treatment decreased the risk of mortality among opioid users, and the protective effects of this treatment increased as fentanyl and other synthetic opioids became common in the illicit drug supply.15 However, because of the shortage of psychiatrists and addiction medicine specialists in several regions of the United States, access to treatment is extremely limited and often inadequate. This constitutes a major public health crisis and contributes to our inability to intervene effectively in the opioid epidemic. Telepsychiatry programs can bring needed services to underserved areas, but they need additional support and development. Further, involving other specialties is paramount for treating this epidemic. Integrating MAT in primary care settings can improve access to treatment. Harm-reduction approaches, such as syringe exchange programs, can play an important role in reducing the adverse consequences associated with heroin use and establish health care relationships with at-risk individuals. Syringe exchange programs can also reduce the rate of infections associated with IV drug use, such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus.

Continue to: Increase education on naloxone...

Increase education on naloxone

Naloxone is a safe and effective opioid antagonist used to treat opioid overdoses. Timely access to naloxone is of the essence when treating opioid-related overdoses. Many states have enacted laws allowing health care professionals, law enforcement officers, and patients and relatives to obtain naloxone without a physician's prescription. It appears this approach may be yielding results. For example, the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition distributed >101,000 free overdose rescue kits that included naloxone and recorded 13,392 confirmed cases of overdose rescue with naloxone from 2013 to 2019.16

Divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system to treatment

We need to develop programs to divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system, which is focused on punishment, to interventions that focus on treatment. Data indicates high recidivism rates for incarcerated individuals with SUDs who do not have access to treatment after they are released. Recognizing this, communities are developing programs that divert low-level offenders from the criminal justice system into treatment. For instance, in Seattle, the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion is a pilot program developed to divert low-level drug and prostitution offenders into community-based treatment and support services. This helps provide housing, health care, job training, treatment, and mental health support. Innovative programs are needed to provide SUD treatment in the rehabilitation programs of correctional facilities and ensure case managers and discharge planners can transition participants to community treatment programs upon their release.

Develop early identification and prevention programs

These programs should focus on individuals at high risk, such as patients with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric disorders, those with chronic pain, and at-risk children whose parents abuse opiates. Traditional addiction treatment programs typically do not address patients with complex conditions or special populations, such as adolescents or pregnant women with substance use issues. Evidence-based approaches such as Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT), and prevention approaches that target students in middle schools and high schools need to be more widely available.

Improve education on opioid prescribing

Responsible opioid prescribing for clinicians should include education about the regular use of prescription drug monitoring programs, urine drug screening, avoiding co-prescription of opioids with sedative-hypnotic medications, and better linkage with addiction treatment.

Treat comorbid psychiatric conditions

It is critical to both identify and effectively treat underlying affective, anxiety, and psychotic disorders in patients with SUDs. Anxiety, depression, and emotional dysregulation often contribute to worsening substance abuse, abuse of prescription drugs, diversion of prescribed drugs, and an increased risk of overdoses and suicides. Effective treatment of comorbid psychiatric conditions also may reduce relapses.

Increase research on causes and treatments

Through research, we must expand our knowledge to better understand the factors that contribute to this epidemic and develop better treatments. These efforts may allow for the development of prevention mechanisms. For example, a recent study found that the continued use of opioid medications after an overdose was associated with a high risk of a repeated overdosecall out material?.17 At the end of a 2-year observation, 17% (confidence interval [CI]: 14% to 20%) of patients receiving a high daily dosage of a prescribed opioid had a repeat overdose compared with 15% (CI: 10% to 21%) of those receiving a moderate dosage, 9% (CI: 6% to 14%) of those receiving a low dosage, and 8% (CI: 6% to 11%) of those receiving no opioids.17 Of the patients who overdosed on prescribed opiates, 30% switched to a new prescriber after their overdose, many of whom may not have been aware of the previous overdose. From a public health perspective, it would make sense for prescribers to know of prior opioid and/or benzodiazepine overdoses. This could be reported by emergency department clinicians, law enforcement, and hospitals into a prescription drug monitoring program, which is readily available to prescribers in most states.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Scott Proescholdbell, MPH, Injury and Violence Prevention Branch, Chronic Disease and Injury Section, Division of Public Health, North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, for his assistance.

Bottom Line

The collision of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and the drug overdose epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for health care professionals to optimize care for individuals with substance use disorders. Suggested interventions include enhancing access to medication-assisted treatment and virtual treatment, improving education about naloxone and safe opioid prescribing practices, and diverting at-risk patients from the criminal justice system to interventions that focus on treatment.

Editor's Note: Due to updated statistics from the CDC, the online version of this article has been modified from the version that appears in the printed edition of the January 2021 issue of Current Psychiatry.

Individuals with mental health and substance use disorders (SUDs) are particularly susceptible to negative effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The collision of the COVID-19 pandemic and the drug overdose epidemic has highlighted the urgent need for physicians, policymakers, and health care professionals to optimize care for individuals with SUDs because they may be particularly vulnerable to the effects of the virus due to compromised respiratory and immune function, and poor social support.1 In this commentary, we highlight the challenges of the drug overdose epidemic, and recommend strategies to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic among patients with SUDs.

A crisis exacerbated by COVID-19

The current drug overdose epidemic has become an American public health nightmare. According to preliminary data released by the CDC on December 17, 2020, there were more than 81,000 drug overdose deaths in the United States in the 12 months ending May 2020.2,3 This is the highest number of overdose deaths ever recorded in a 12-month period. The CDC also noted that while overdose deaths were already increasing in the months preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, the latest numbers suggest an acceleration of overdose deaths during the pandemic.

What is causing this significant loss of life? Prescription opioids and illegal opioids such as heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl are the main agents associated with overdose deaths. These opioids were responsible for 61% (28,647) of drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2014.4 In 2015, the opioid overdose death rate increased by 15.6%.5

The increase in the number of opioid overdose deaths in part coincides with a sharp increase in the availability and use of heroin. Heroin overdose deaths have more than tripled since 2010, but heroin is not the only opiate involved. Fentanyl, a synthetic, short-acting opioid that is approved for managing pain in patients with advanced cancers, is 50 times more potent than heroin. The abuse of prescribed fentanyl has been accelerating over the past decade, as is the use of illicitly produced fentanyl. Evidence from US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) seizure records shows heroin is being adulterated with illicit fentanyl to enhance the potency of the heroin.6,7 Mixing illicit fentanyl with heroin may be contributing to the recent increase in heroin overdose fatalities. According to the CDC, overdose deaths related to synthetic opioids increased 38.4% from the 12-month period leading up to June 2019 compared with the 12-month period leading up to May 2020.2,3 Postmortem studies of individuals who died from a heroin overdose have frequently found the presence of fentanyl along with heroin.8 Overdose deaths involving heroin may be occurring because individuals may be unknowingly using heroin adulterated with fentanyl.9 In addition, carfentanil, a powerful new synthetic fentanyl, has been recently identified in heroin mixtures. Carfentanil is 10,000 times stronger than morphine. Even in miniscule amounts, carfentanil can suppress breathing to the degree that multiple doses of naloxone are needed to restore respirations.

Initial studies indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic has been exacerbating this situation. Wainwright et al10 conducted an analysis of urine drug test results of patients with SUDs from 4 months before and 4 months after COVID-19 was declared a national emergency on March 13, 2020. Compared with before COVID-19, the proportion of specimens testing positive since COVID-19 increased from 3.80% to 7.32% for fentanyl and from 1.29% to 2.09% for heroin.10

A similar drug testing study found that during the pandemic, the proportion of positive results (positivity) increased by 35% for non-prescribed fentanyl and 44% for heroin.11 Positivity for non-prescribed fentanyl increased significantly among patients who tested positive for other drugs, including by 89% for amphetamines; 48% for benzodiazepines; 34% for cocaine; and 39% for opiates (P < .1 for all).11

In a review of electronic medical records, Ochalek et al12 found that the number of nonfatal opioid overdoses in an emergency department in Virginia increased from 102 in March-June 2019 to 227 in March-June 2020. In an issue brief published on October 31, 2020, the American Medical Association reported increase in opioid and other drug-related overdoses in more than 40 states during the COVID-19 pandemic.13

Continue to: Strategies for intervention...

Strategies for intervention

A multi-dimensional approach is needed to protect the public from this growing opioid overdose epidemic. To address this challenging task, we recommend several strategies:

Enhance access to virtual treatment

Even when in-person treatment cannot take place due to COVID-19-related restrictions, it is vital that services are accessible to patients with SUDs during this pandemic. Examples of virtual treatment include:

- Telehealth for medication-assisted treatment (MAT) using buprenorphine (recently updated guidance from the US DEA and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] allows this method of prescribing)

- Teletherapy to prevent relapse

- Remote drug screens by sending saliva or urine kits to patients' homes, visiting patients to collect fluid samples, or asking patients to come to a "drive-through" facility to provide samples

- Virtual (online) Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, SMART Recovery, and similar meetings to provide support in the absence of in-person meetings.

The American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) offers guidance to treatment programs to focus on infection control and mitigation. The Table14 summarizes the ASAM recommendations for office-based opioid treatment during COVID-19.

Expand access to treatment

This includes access to MAT (such as buprenorphine/naloxone, methadone, naltrexone, and depot naltrexone) and, equally important, to psychosocial treatment, counseling, and/or recovery services. Recent legislative changes have increased the number of patients that a qualified physician can treat with buprenorphine/naloxone from 100 to 275, and allowed physician extenders to prescribe buprenorphine/naloxone in office-based settings. A recent population-based, retrospective Canadian study showed that opioid agonist treatment decreased the risk of mortality among opioid users, and the protective effects of this treatment increased as fentanyl and other synthetic opioids became common in the illicit drug supply.15 However, because of the shortage of psychiatrists and addiction medicine specialists in several regions of the United States, access to treatment is extremely limited and often inadequate. This constitutes a major public health crisis and contributes to our inability to intervene effectively in the opioid epidemic. Telepsychiatry programs can bring needed services to underserved areas, but they need additional support and development. Further, involving other specialties is paramount for treating this epidemic. Integrating MAT in primary care settings can improve access to treatment. Harm-reduction approaches, such as syringe exchange programs, can play an important role in reducing the adverse consequences associated with heroin use and establish health care relationships with at-risk individuals. Syringe exchange programs can also reduce the rate of infections associated with IV drug use, such as human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus.

Continue to: Increase education on naloxone...

Increase education on naloxone

Naloxone is a safe and effective opioid antagonist used to treat opioid overdoses. Timely access to naloxone is of the essence when treating opioid-related overdoses. Many states have enacted laws allowing health care professionals, law enforcement officers, and patients and relatives to obtain naloxone without a physician's prescription. It appears this approach may be yielding results. For example, the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition distributed >101,000 free overdose rescue kits that included naloxone and recorded 13,392 confirmed cases of overdose rescue with naloxone from 2013 to 2019.16

Divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system to treatment

We need to develop programs to divert patients with SUDs from the criminal justice system, which is focused on punishment, to interventions that focus on treatment. Data indicates high recidivism rates for incarcerated individuals with SUDs who do not have access to treatment after they are released. Recognizing this, communities are developing programs that divert low-level offenders from the criminal justice system into treatment. For instance, in Seattle, the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion is a pilot program developed to divert low-level drug and prostitution offenders into community-based treatment and support services. This helps provide housing, health care, job training, treatment, and mental health support. Innovative programs are needed to provide SUD treatment in the rehabilitation programs of correctional facilities and ensure case managers and discharge planners can transition participants to community treatment programs upon their release.

Develop early identification and prevention programs

These programs should focus on individuals at high risk, such as patients with comorbid SUDs and psychiatric disorders, those with chronic pain, and at-risk children whose parents abuse opiates. Traditional addiction treatment programs typically do not address patients with complex conditions or special populations, such as adolescents or pregnant women with substance use issues. Evidence-based approaches such as Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT), Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT), and prevention approaches that target students in middle schools and high schools need to be more widely available.