User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Revisiting delirious mania; Correcting an error

Revisiting delirious mania

After treating a young woman with delirious mania, we were compelled to comment on the case report “Confused and nearly naked after going on spending sprees” (Cases That Test Your Skills,

A young woman with bipolar I disorder and mild intellectual disability was brought to our inpatient psychiatric unit after she disappeared from her home. Her family reported she was not compliant with her medications, and she recently showed deterioration marked by bizarre and violent behaviors for the previous month.

Although her presentation was consistent with earlier manic episodes, additional behaviors indicated an increase in severity. The patient was only oriented to name, was disrobing, had urinary and fecal incontinence, and showed purposeless hyperactivity such as continuously dancing in circles.

Because we thought she was experiencing a severe exacerbation of bipolar disorder, the patient was started on 4 different antipsychotic trials (typical and atypical) and 2 mood stabilizers, all of which did not produce adequate response. Even after augmentation with nightly long-acting benzodiazepines, the patient’s symptoms remained unchanged.

The patient received a diagnosis of delirious mania, with the underlying mechanism being severe catatonia. A literature search revealed electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and benzodiazepines as first-line treatments, and discouraged use of typical antipsychotics because of an increased risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome and malignant delirious mania.1 Because ECT was not available at our facility, we initiated benzodiazepines,

We agree it is prudent to rule out any medical illnesses that could cause delirium. Interestingly, in our patient a head CT revealed small calcifications suggestive of cysticercosis, which have been seen on imaging since age 13. We suggest that this finding contributed to her disinhibition, prolonged her recovery, and could explain why she did not respond adequately to medications.

Diagnosing and treating delirious mania in our patient was challenging. As mentioned by Davis et al, there is no classification of delirious mania in DSM-5. In addition, there are no large-scale studies to educate psychiatrists about the prevalence and appropriate treatment of this disorder.

Our treatment approach differed from that of Davis et al in that we chose scheduled benzodiazepines rather than antipsychotics to target the patient’s catatonia. However, both patients improved, prompting us to further question the mechanism behind this presentation.

We encourage the addition of delirious mania to the next edition of DSM. Without classification and establishment of this diagnosis, psychiatrists are unlikely to consider this serious and potentially fatal syndrome. Delirious mania is mysterious and rare and its inner workings are not fully elucidated.

Sabina Bera, MD MSc

PGY-2 Psychiatry Resident

Mohammed Molla, MD, DFAPA

Interim Joint Chair and Program Director

University of California Los Angeles-Kern

Psychiatry Training Program

Bakersfield, California

Reference

1. Jacobowski NL, Heckers S, Bobo WV. Delirious mania: detection, diagnosis, and clinical management in the acute setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):15-28.

Correcting an error

In his informative guest editorial "

David A. Gorelick, MD, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry

Maryland Psychiatric Research Center

University of Maryland

Baltimore, Maryland

Revisiting delirious mania

After treating a young woman with delirious mania, we were compelled to comment on the case report “Confused and nearly naked after going on spending sprees” (Cases That Test Your Skills,

A young woman with bipolar I disorder and mild intellectual disability was brought to our inpatient psychiatric unit after she disappeared from her home. Her family reported she was not compliant with her medications, and she recently showed deterioration marked by bizarre and violent behaviors for the previous month.

Although her presentation was consistent with earlier manic episodes, additional behaviors indicated an increase in severity. The patient was only oriented to name, was disrobing, had urinary and fecal incontinence, and showed purposeless hyperactivity such as continuously dancing in circles.

Because we thought she was experiencing a severe exacerbation of bipolar disorder, the patient was started on 4 different antipsychotic trials (typical and atypical) and 2 mood stabilizers, all of which did not produce adequate response. Even after augmentation with nightly long-acting benzodiazepines, the patient’s symptoms remained unchanged.

The patient received a diagnosis of delirious mania, with the underlying mechanism being severe catatonia. A literature search revealed electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and benzodiazepines as first-line treatments, and discouraged use of typical antipsychotics because of an increased risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome and malignant delirious mania.1 Because ECT was not available at our facility, we initiated benzodiazepines,

We agree it is prudent to rule out any medical illnesses that could cause delirium. Interestingly, in our patient a head CT revealed small calcifications suggestive of cysticercosis, which have been seen on imaging since age 13. We suggest that this finding contributed to her disinhibition, prolonged her recovery, and could explain why she did not respond adequately to medications.

Diagnosing and treating delirious mania in our patient was challenging. As mentioned by Davis et al, there is no classification of delirious mania in DSM-5. In addition, there are no large-scale studies to educate psychiatrists about the prevalence and appropriate treatment of this disorder.

Our treatment approach differed from that of Davis et al in that we chose scheduled benzodiazepines rather than antipsychotics to target the patient’s catatonia. However, both patients improved, prompting us to further question the mechanism behind this presentation.

We encourage the addition of delirious mania to the next edition of DSM. Without classification and establishment of this diagnosis, psychiatrists are unlikely to consider this serious and potentially fatal syndrome. Delirious mania is mysterious and rare and its inner workings are not fully elucidated.

Sabina Bera, MD MSc

PGY-2 Psychiatry Resident

Mohammed Molla, MD, DFAPA

Interim Joint Chair and Program Director

University of California Los Angeles-Kern

Psychiatry Training Program

Bakersfield, California

Reference

1. Jacobowski NL, Heckers S, Bobo WV. Delirious mania: detection, diagnosis, and clinical management in the acute setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):15-28.

Correcting an error

In his informative guest editorial "

David A. Gorelick, MD, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry

Maryland Psychiatric Research Center

University of Maryland

Baltimore, Maryland

Revisiting delirious mania

After treating a young woman with delirious mania, we were compelled to comment on the case report “Confused and nearly naked after going on spending sprees” (Cases That Test Your Skills,

A young woman with bipolar I disorder and mild intellectual disability was brought to our inpatient psychiatric unit after she disappeared from her home. Her family reported she was not compliant with her medications, and she recently showed deterioration marked by bizarre and violent behaviors for the previous month.

Although her presentation was consistent with earlier manic episodes, additional behaviors indicated an increase in severity. The patient was only oriented to name, was disrobing, had urinary and fecal incontinence, and showed purposeless hyperactivity such as continuously dancing in circles.

Because we thought she was experiencing a severe exacerbation of bipolar disorder, the patient was started on 4 different antipsychotic trials (typical and atypical) and 2 mood stabilizers, all of which did not produce adequate response. Even after augmentation with nightly long-acting benzodiazepines, the patient’s symptoms remained unchanged.

The patient received a diagnosis of delirious mania, with the underlying mechanism being severe catatonia. A literature search revealed electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) and benzodiazepines as first-line treatments, and discouraged use of typical antipsychotics because of an increased risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome and malignant delirious mania.1 Because ECT was not available at our facility, we initiated benzodiazepines,

We agree it is prudent to rule out any medical illnesses that could cause delirium. Interestingly, in our patient a head CT revealed small calcifications suggestive of cysticercosis, which have been seen on imaging since age 13. We suggest that this finding contributed to her disinhibition, prolonged her recovery, and could explain why she did not respond adequately to medications.

Diagnosing and treating delirious mania in our patient was challenging. As mentioned by Davis et al, there is no classification of delirious mania in DSM-5. In addition, there are no large-scale studies to educate psychiatrists about the prevalence and appropriate treatment of this disorder.

Our treatment approach differed from that of Davis et al in that we chose scheduled benzodiazepines rather than antipsychotics to target the patient’s catatonia. However, both patients improved, prompting us to further question the mechanism behind this presentation.

We encourage the addition of delirious mania to the next edition of DSM. Without classification and establishment of this diagnosis, psychiatrists are unlikely to consider this serious and potentially fatal syndrome. Delirious mania is mysterious and rare and its inner workings are not fully elucidated.

Sabina Bera, MD MSc

PGY-2 Psychiatry Resident

Mohammed Molla, MD, DFAPA

Interim Joint Chair and Program Director

University of California Los Angeles-Kern

Psychiatry Training Program

Bakersfield, California

Reference

1. Jacobowski NL, Heckers S, Bobo WV. Delirious mania: detection, diagnosis, and clinical management in the acute setting. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):15-28.

Correcting an error

In his informative guest editorial "

David A. Gorelick, MD, PhD

Professor of Psychiatry

Maryland Psychiatric Research Center

University of Maryland

Baltimore, Maryland

Worsening agitation and hallucinations: Could it be PTSD?

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

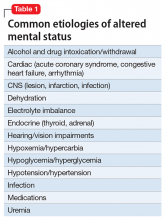

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

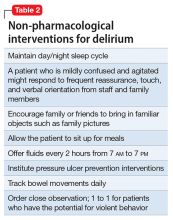

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

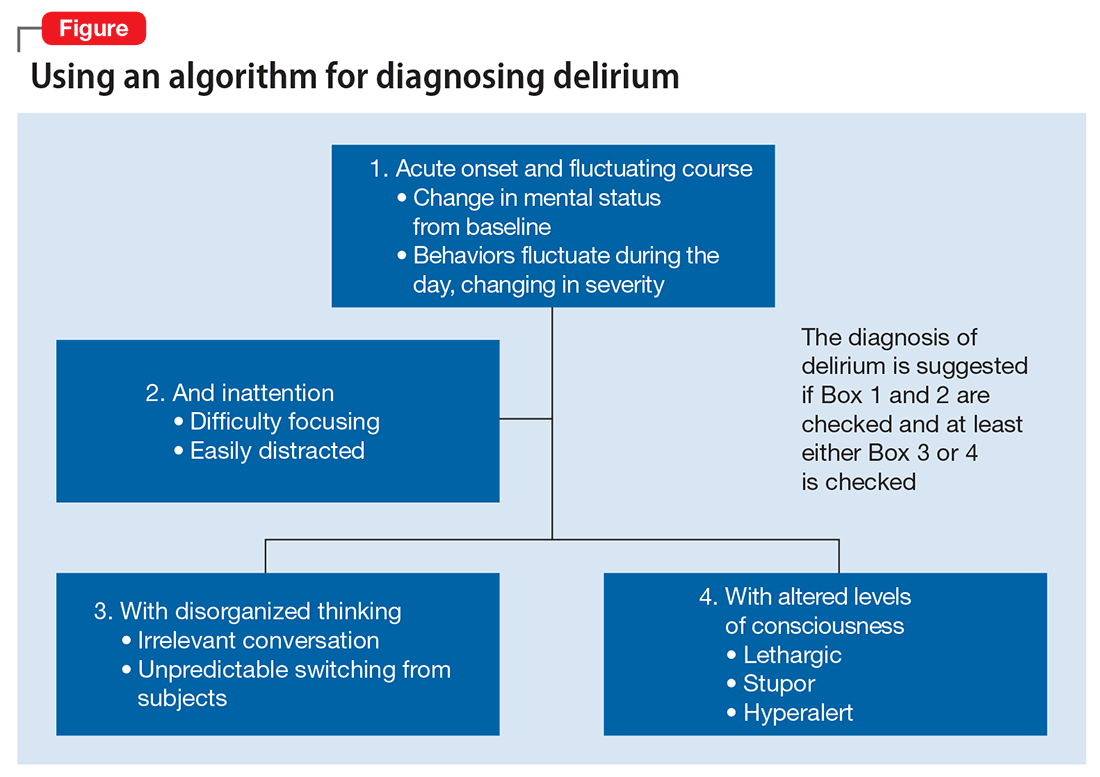

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

1. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

2. Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haldoperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A, et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub2.

5. Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

6. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):550.

7. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S, et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1425-1431.

8. de la Cruz, M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433.

9. Swigart SE, Kishi Y, Thurber S, et al. Misdiagnosed delirium in patient referrals to a university-based hospital psychiatry department. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):104-108.

10. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

11. Dasgupta M, Hillier LM. Factors associated with prolonged delirium: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):373-394.

12. Detweiler MB, Kenneth A, Bader G, et al. Can improved intra- and inter-team communication reduce missed delirium? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(2):211-224.

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

1. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

2. Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haldoperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A, et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub2.

5. Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

6. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):550.

7. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S, et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1425-1431.

8. de la Cruz, M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433.

9. Swigart SE, Kishi Y, Thurber S, et al. Misdiagnosed delirium in patient referrals to a university-based hospital psychiatry department. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):104-108.

10. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

11. Dasgupta M, Hillier LM. Factors associated with prolonged delirium: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):373-394.

12. Detweiler MB, Kenneth A, Bader G, et al. Can improved intra- and inter-team communication reduce missed delirium? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(2):211-224.

1. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

2. Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haldoperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A, et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub2.

5. Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

6. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):550.

7. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S, et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1425-1431.

8. de la Cruz, M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433.

9. Swigart SE, Kishi Y, Thurber S, et al. Misdiagnosed delirium in patient referrals to a university-based hospital psychiatry department. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):104-108.

10. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

11. Dasgupta M, Hillier LM. Factors associated with prolonged delirium: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):373-394.

12. Detweiler MB, Kenneth A, Bader G, et al. Can improved intra- and inter-team communication reduce missed delirium? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(2):211-224.

Alcohol-use disorders after bariatric surgery: The case for targeted group therapy

Maladaptive alcohol use has emerged as a risk for a subset of individuals who have undergone weight loss surgery (WLS); studies report they are vulnerable to consuming alcohol in greater quantities or more frequently.1,2 Estimates of the prevalence of “high-risk” or “hazardous” alcohol use after WLS range from 4% to 28%,3,4 while the prevalence of alcohol use meeting DSM-IV-TR5 criteria for alcohol use disorders (AUDs) hovers around 10%.6

Heavy alcohol users or patients who have active AUD at the time of WLS are at greater risk for continuation of these problems after surgery.2,6 For patients with a long-remitted history of AUD, the evidence regarding risk for post-WLS relapse is lacking, and some evidence suggests they may have better weight loss outcomes after WLS.7

However, approximately two-third of cases of post-WLS alcohol problems occur in patients who have had no history of such problems before surgery.5,8,9 Reported prevalence rates of new-onset alcohol problems range from 3% to 18%,6,9 with the modal finding being approximately 7% to 8%. New-onset alcohol problems appear to occur at a considerable latency after surgery. One study found little risk at 1 year post-surgery, but a significant increase in AUD symptoms at 2 years.6 Another study identified 3 years post-surgery as a high-risk time point,8 and yet another reported a linear increase in the risk for developing alcohol problems for at least 10 years after WLS.10

This article describes a group treatment protocol developed specifically for patients with post-WLS substance use disorder (SUD), and explores:

- risk factors and causal mechanisms of post-WLS AUDs

- weight stigma and emotional stressors

- the role of specialized treatment

- group treatment based on the Health at Every Size® (HAES)-oriented, trauma-informed and fat acceptance framework.

Post-WLS patients with alcohol problems may be a distinct phenotype among people with substance abuse issues. For this reason, they may have a need to address their experiences and issues specific to WLS as part of their alcohol treatment.

Etiology

Risk factors. Empirical findings have identified few predictors or risk factors for post-WLS SUD. These patients are more likely to be male and of a younger age.6 Notably, the vast majority of individuals reporting post-WLS alcohol problems have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), rather than other WLS procedures, such as the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band,6,11 suggesting some physiological mechanism specific to RYGB.

Other potential predictors of postoperative alcohol problems include a pre-operative history of depression, generalized anxiety disorder, smoking, and/or recreational drug use.3,6 Likewise, patients with depression or anxiety disorder symptoms after surgery also may be at higher risk for postoperative alcohol problems.4 The evidence of an association between postoperative weight outcomes and post-WLS alcohol problems is mixed.3,12 Interestingly, patients who had no personal history of substance abuse but who have a family history may have a higher risk of new-onset alcohol problems after surgery.9,12

Causal mechanisms. The etiology of post-WLS alcohol problems is not well understood. If anything, epidemiological data suggest that larger-bodied individuals tend to consume lower levels of alcohol and have lower rates of AUD than individuals in the general population with thinner bodies.13 However, an association has been found between a family history of SUD, but not a personal history, and being large.14 This suggests a shared etiological pathway between addiction and being “overweight,” of which the onset of AUD after RYGB may be a manifestation.

Human and animal studies have shown that WLS may affect alcohol use differently in specific subgroups. Studies have shown that wild-type rats greatly increase their consumption of, or operant responding for, alcohol after RYGB,15 while genetically “alcohol-preferring” rats decrease consumption of, or responding for, alcohol after RYGB.16 A human study likewise found some patients decreased alcohol use or experienced improvement of or remission of AUD symptoms after WLS.4 Combined with the finding that a family history of substance abuse is related to risk for post-operative AUD, these data suggest a potential genetic vulnerability or protection in some individuals.

Turning to potential psychosocial explanations, the lay media has popularized the concepts of “addiction transfer,” or “transfer addiction,”12 with the implication that some patients, who had a preoperative history of “food addiction,” transfer that “addiction” after surgery to substances of abuse.

However, the “addiction transfer” model has a number of flaws:

- it is stigmatizing, because it assumes the patient possesses an innate, chronic, and inalterable pathology

- it relies upon the validity of the controversial construct of “food addiction,” a construct of mixed scientific evidence.17

Further, our knowledge of post-WLS SUD argues against “addiction transfer.” As noted, postoperative alcohol problems are more likely to develop years after surgery, rather than in the first few months afterward when eating is most significantly curtailed. Additionally, post-WLS alcohol problems are significantly more likely to occur after RYGB than other procedures, whereas the “addiction transfer” model would hypothesize that all WLS patients would be at equal risk for postoperative “addiction transfer,” because their eating is similarly affected after surgery.

Links to RYGB. Some clues to physiological mechanisms underlying alcohol problems after RYGB have been identified. After surgery, many RYGB patients report a quicker effect from a smaller amount of alcohol than was the case pre-surgery.18 Studies have demonstrated a number of changes in the pharmacodynamics of alcohol after RYGB not seen in other WLS procedures19:

- a much faster time to peak blood (or breath) alcohol content (BAC)

- significantly higher peak BAC

- a precipitous initial decline in perceived intoxication.18,20

Anatomical features of RYGB may explain such changes.8 However, an increased response to both IV alcohol and IV morphine after RYGB21,22 in rodents suggests that gastrointestinal tract changes are not solely responsible for changes in alcohol use. Emerging research reports that WLS has been found to cause alterations in brain reward pathways,23 which may be an additional contributor to changes in alcohol misuse after surgery.

However, even combined, pharmacokinetic and neurobiological factors cannot entirely explain new-onset alcohol problems after WLS; if they could, one would expect to see a much higher prevalence of this complication. Some psychosocial factors are likely involved as well.

Emotional stressors. One possibility involves a mismatch between post-WLS stressors and coping skills. After WLS, these patients face a multitude of challenges inherent in adjusting to changes in lifestyle, weight, body image, and social functioning, which most individuals would find daunting. These challenges become even more acute in the absence of appropriate psychoeducation, preparation, and intervention from qualified professionals. Individuals who lack effective and adaptive coping skills and supports may have a particularly heightened vulnerability to increased alcohol use in the setting of post-surgery changes in brain reward circuits and pharmacodynamics in alcohol metabolism. For example, one patient reported that her spouse’s pressure to “do something about her weight” was a significant factor in her decision to undergo surgery, but that her spouse was blaming and unsupportive when post-WLS complications developed. The patient believed that these experiences helped fuel development of her post-RYGB alcohol abuse.

Specialized treatment

The number of patients experiencing post-WLS alcohol problems likely will continue to grow, given that the risk of onset of has been shown increase over years. Already, post-WLS patients are proportionally overrepresented among substance abuse treatment populations.24 Empirically, however, we do not know yet if these patients need a different type of addiction treatment than patients who have not had WLS.

Some evidence suggests that post-WLS patients with alcohol problems may be a distinct phenotype within the general population with alcohol problems, as their presentations differ in several ways, including their demographics, alcohol use patterns, and premorbid functioning. A number of studies have found that, despite their increased pharmacodynamic sensitivity to alcohol, people with post-WLS AUDs actually consume a larger amount of alcohol on both typical and maximum drinking days than other individuals with AUDs.24 Additionally, although the median age of onset for AUD is around age 20,25 patients presenting with new-onset, post-WLS alcohol problems are usually in their late 30s, or even 40s or 50s. Further, many of these patients were quite high functioning before their alcohol problems, and are unlikely to identify with the cultural stereotype of a person with AUD (eg, homeless, unemployed), which may hamper or delay their own willingness to accept that they have a problem. These phenotypic differences suggest that post-WLS patients may require substance abuse treatment approaches tailored to their unique presentation. There are additional factors specific to the experiences of being larger-bodied and WLS that also may need to be addressed in specialized treatment for post-WLS addiction patients.

Weight stigma. By definition, patients who have undergone WLS have spent a significant portion of their lives inhabiting larger bodies, an experience that, in our culture, can produce adverse psychosocial effects. Compared with the general population, patients seeking WLS exhibit psychological distress equivalent to psychiatric patients.26 Weight stigma or weight bias—negative judgments directed toward people in larger bodies—is pervasive and continues to increase.27 Further, evidence suggests that, unlike almost all other stigmatized groups, people in larger bodies tend to internalize this stigma, holding an unfavorable attitude toward their own social group.28 Weight stigma impacts the well-being of people all along the weight spectrum, affecting many domains including educational achievements and classroom experiences, job opportunities, salaries, and medical care.27 Weight stigma increases the likelihood of bullying, teasing, and harassment for both adults and children.27 Weight bias has been associated with any number of adverse psychosocial effects, including symptoms of depression, anxiety, and eating pathology; poor body image; and a decrease in healthy self-care behaviors.29-33

Weight stigma makes it more difficult for people to enjoy physical activities, nourish their bodies, and manage stress, which contributes to poorer health outcomes and lower quality of life.33,34 For example, one study showed that, regardless of actual body mass index, people experiencing weight stigma have significantly increased risk of developing an illness or dying.35

Factors specific to WLS. WLS may lead to significant changes in eating habits, and some patients experience a sense of loss, particularly if eating represented one of their primary coping strategies—this may represent a heightened emotional vulnerability for developing AUD.

The fairly rapid and substantial weight loss that WLS produces can lead to sweeping changes in lifestyle, body image, and functional factors for many individuals. Patients often report profound changes, both positive and negative, in their relationships and interactions not only with people in their support network, but also with strangers.36

After the first year or 2 post-WLS, it is fairly common for patients to regain some weight, sometimes in significant amounts.37 This can lead to a sense of “failure.” Life stressors, including difficulties in important relationships, can further add to patients’ vulnerability. For example, one patient noticed that when she was at her thinnest after WLS, drivers were more likely to stop for her when she crossed the street, which pleased but also angered her because they hadn’t extended the same courtesy before WLS. After she regained a significant amount of weight, she began to notice drivers stopping for her less and less frequently. This took her back to her previous feelings of being ignored but now with the certainty that she would be treated better if she were thinner.

Patients also may experience ambivalence about changes in their body size. One might expect that body image would improve after weight loss, but the evidence is mixed.38 Although there is some evidence that body image improves in the short term after WLS,38 other research indicates that body image does not improve with weight loss.39 However, the evidence is clear that the appearance of excess skin after weight loss worsens some patients’ body image.40

To date, there has been no research examining treatment modalities for this population. Because experiences common to individuals who have had WLS could play a role in the development of AUD after surgery, it is intuitive that it would be important to address these factors when designing a treatment plan for post-WLS substance abuse.

Group treatment approach

In 2013, in response to the increase in rates of post-WLS addictions presenting to West End Clinic, an outpatient dual-diagnosis (addiction and psychiatry) service at Massachusetts General Hospital, a specialized treatment group was developed. Nine patients have enrolled since October 2013.

The Post-WLS Addictions Group (PWAG) was designed to be HAES-oriented, trauma-informed, and run within a fat acceptance framework. The HAES model prioritizes a weight-neutral approach that sees health and well-being as multifaceted. This approach directs both patient and clinician to focus on improving health behaviors and reducing internalized weight bias, while building a supportive community that buffers against external cultural weight bias.41

Trauma-informed care42 emphasizes the principles of safety, trustworthiness, and transparency; peer support; collaboration and mutuality; empowerment; and awareness of cultural, historical, and gender issues. In the context of PWAG, weight stigma is conceptualized as a traumatic experience.43 The fat acceptance approach promotes a culture that accepts people of every size with dignity and equality in all aspects of life.44

Self-care emphasis. The HAES model encourages patients to allow their bodies to determine what weight to settle at, and to focus on sustainable health-enhancing behaviors rather than weight loss. Patients who asked about the PWAG were told that this group would not explicitly support, or even encourage, continued pursuit of weight loss per se, but instead would assist patients with relapse prevention, mindful eating, improving self-care, and ongoing stress management. Moving away from a focus on weight loss and toward improvement of self-care skills allowed patients to focus on behaviors and outcomes over which they had more direct control and were more likely to yield immediate benefits.

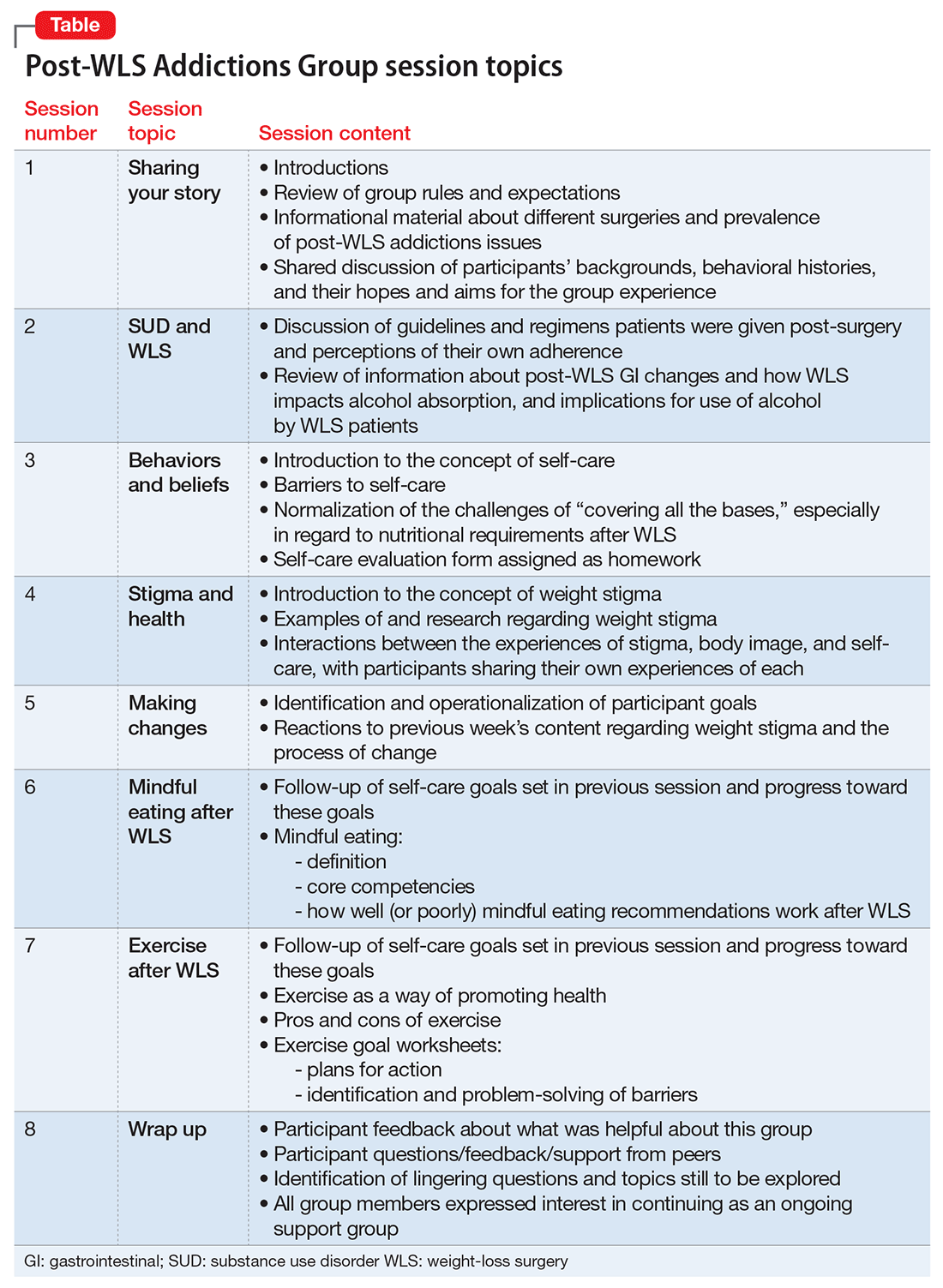

All of the PWAG group members were in early recovery from an SUD, with a minimum of 4 weeks of abstinence; all had at least 1 co-occurring mental health diagnosis. A licensed independent clinical social worker (LICSW) and a physician familiar with bariatric surgery ran the sessions. The group met weekly for 1 hour. The 8 weekly sessions included both psychoeducation and discussion, with each session covering different topics (Table). The first 20 minutes of each session were devoted to an educational presentation; the remaining 40 minutes for reflection and discussion. In sessions 2 through 8, participants were asked about any recent use or cravings, and problem-solving techniques were employed as needed.

The PWAG group leader herself is a large person who modeled fat acceptance and follows the HAES approach; she led the group using both this experience and her specialized clinical training. As is the case with other addictions recovery treatment modalities, clinicians with lived experience may add a valuable component to both the program design and patient experience.

After the first 8 sessions, all members expressed interest in continuing as an ongoing relapse prevention and HAES support group, and they reported that meeting regularly was very helpful. The group continued with the LICSW alone, who continued to share HAES-oriented and fat acceptance information and resources that group members requested specifically. Over time, new members joined following an individual orientation session with the group leader, and the group has revisited each of the psychoeducational topics repeatedly, though not in a formally structured way.

Process and observations. Participants described high levels of excitement and hopefulness about being in a group with other WLS patients who had developed SUDs. They had a particular interest in reviewing medical/anatomical information about WLS and understanding more about the potential reasons for the elevated risk for developing SUD following WLS. Discussions regarding weight stigma proved to be quite emotional; most participants reported that this material readily related to their own experiences with weight stigma, but they had never discussed these ideas before.

Participants explored the role that grief, loss, guilt, and shame had in the decision to have WLS, the development of SUDs, weight regain or medical complications from the surgery or from substance abuse, career and relationship changes, and worsened body image. Another theme that emerged was the various reasons that prompted the members have WLS that they may not have been conscious of, or willing to discuss with others, such as pressure from a spouse, fears of remaining single due to their size, and a desire to finally “fit in.”

Repeatedly, group members expressed how satisfied and emotionally validated they felt being with people with similar experiences. Most of them had felt alone. They reported a belief that “everyone else” who had WLS was doing well, and that they were the exceptions. Such beliefs and emotions increased the risk of relapse and decreased participants’ ability to develop more positive coping strategies and self-care skills.

Participants reported that feeling less alone, understanding how stigma impacts health and well-being, and focusing on the general benefits of good self-care rather than the pursuit of weight loss were particularly helpful. The HAES and fat acceptance approaches have given group members new ways to think about their bodies and decreased shame. Several group members reported that if they had learned about the HAES approach prior to having a WLS, they might have made a different decision about having surgery, or at least might have been better prepared to handle the emotional and psychological challenges after WLS.

Although evidence for post-WLS addictions is fairly robust, causal mechanisms are not well understood, and research identifying specific risk factors is lacking. Because post-WLS patients with addictions seem to represent a specific phenotype, specialized treatment might be indicated. Future research will be needed to determine optimal treatment approaches for post-WLS addictions. However, a number of aspects are likely to be important. For example, it is likely that unaddressed experiences of weight stigma contribute to challenges, including substance abuse, after WLS; therefore, clinicians involved in the care of individuals presenting with post-WLS SUD should be knowledgeable about weight stigma and how to address it. Because of the specific nature of post-WLS addictions, patients often feel alone and isolated, and seem to benefit from the specialized group setting. We note that the PWAG group leader is herself a large person who models fat acceptance and follows the HAES approach, and therefore led the group using this experience and her specialized clinical training. As with other addiction recovery treatment modalities, clinicians who have lived the experience can add a valuable component to the program design and patient experience.

2. Lent MR, Hayes SM, Wood GC, et al. Smoking and alcohol use in gastric bypass patients. Eat Behav. 2013;14(4):460-463.

4. Wee CC, Mukamal KJ, Huskey KW, et al. High-risk alcohol use after weight loss surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(3):508-513.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

6. King WC, Chen JY, Mitchell JE, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders before and after bariatric surgery. JAMA. 2012;307(23):2516-2525.

9. Ivezaj V, Saules KK, Schuh LM. New-onset substance use disorder after gastric bypass surgery: rates and associated characteristics. Obes Surg. 2014;24(11):1975-1980.

10. Svensson PA, Anveden Å, Romeo S, et al. Alcohol consumption and alcohol problems after bariatric surgery in the Swedish obese subjects study. Obesity. 2013;21(12):2444-2451.

11. Ostlund MP, Backman O, Marsk R, et al. Increased admission for alcohol dependence after gastric bypass surgery compared with restrictive bariatric surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(4):374-377.

13. Gearhardt AN, Corbin WR. Body mass index and alcohol consumption: family history of alcoholism as a moderator. Psychol Addict Behav. 2009;23(2):216-225.

14. Grucza RA, Krueger RF, Racette SB, et al. The emerging link between alcoholism risk and obesity in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(12):1301-1308.

15. Davis JF, Tracy AL, Schurdak JD, et al. Roux en y gastric bypass increases ethanol intake in the rat. Obes Surg. 2013;23(7):920-930.

16. Davis JF, Schurdak JD, Magrisso IJ, et al. Gastric bypass surgery attenuates ethanol consumption in ethanol-preferring rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72(5):354-360.

18. Pepino MY, Okunade AL, Eagon JC, et al. Effect of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: converting 2 alcoholic drinks to 4. JAMA Surg. 2015

19. Changchien EM, Woodard GA, Hernandez-Boussard T, et al. Normal alcohol metabolism after gastric banding and sleeve gastrectomy: a case-cross-over trial. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;215(4):475-479.

22. Polston JE, Pritchett CE, Tomasko JM, et al. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass increases intravenous ethanol self-administration in dietary obese rats. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e83741. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083741.

26. Higgs ML, Wade T, Cescato M, et al. Differences between treatment seekers in an obese population: medical intervention vs. dietary restriction. J Behav Med. 1997;20(4):391-405.

35. Sutin AR, Stephan Y, Terracciano A. Weight discrimination and risk of mortality. Psychol Sci. 2015;26(11):1803-1811.

36. Sogg S, Gorman MJ. Interpersonal changes and challenges after weight loss surgery. Prim Psychiatry. 2008;15(8):61-66.

37. Yanos BR, Saules KK, Schuh LM, et al. Predictors of lowest weight and long-term weight regain among Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg. 2015;25(8):1364-1370.

40. van der Beek E, Te Riele W, Specken TF, et al. The impact of reconstructive procedures following bariatric surgery on patient well-being and quality of life. Obes Surg. 2010;20(1):36-41.

Maladaptive alcohol use has emerged as a risk for a subset of individuals who have undergone weight loss surgery (WLS); studies report they are vulnerable to consuming alcohol in greater quantities or more frequently.1,2 Estimates of the prevalence of “high-risk” or “hazardous” alcohol use after WLS range from 4% to 28%,3,4 while the prevalence of alcohol use meeting DSM-IV-TR5 criteria for alcohol use disorders (AUDs) hovers around 10%.6

Heavy alcohol users or patients who have active AUD at the time of WLS are at greater risk for continuation of these problems after surgery.2,6 For patients with a long-remitted history of AUD, the evidence regarding risk for post-WLS relapse is lacking, and some evidence suggests they may have better weight loss outcomes after WLS.7