User login

News and Views that Matter to Physicians

U.S. to jump-start antibiotic resistance research

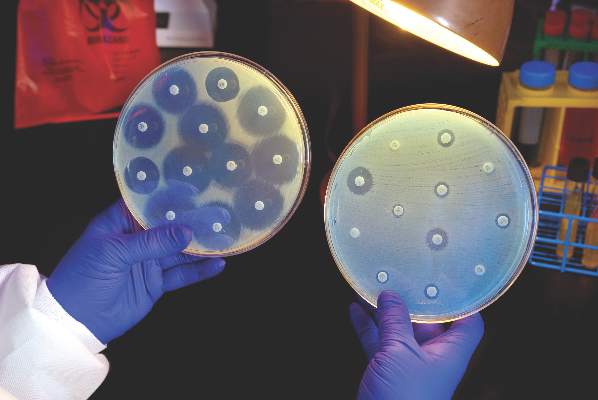

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing $67 million to help U.S. health departments address antibiotic resistance and related patient safety concerns.

The new funding was made available through the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC), according to a CDC statement, and will support seven new regional laboratories with specialized capabilities allowing rapid detection and identification of emerging antibiotic resistant threats.

The CDC said it would distribute funds to all 50 state health departments, six local health departments (Chicago, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Philadelphia), and Puerto Rico, beginning Aug. 1, 2016. The agency said the grants would allow every state health department lab to test for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and ultimately perform whole genome sequencing on intestinal bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, and many Campylobacter strains.

The agency intends to provide support teams in nine state health departments for rapid response activities designed to “quickly identify and respond to the threat” of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea in the United States, and will support high-level expertise to implement antimicrobial resistance activities in six states.

The CDC also said the promised funding would strengthen states’ ability to conduct foodborne disease tracking, investigation, and prevention, as it includes increased support for the PulseNet and OutbreakNet systems and for the Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence, as well as support for the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS).

Global partnerships

Complementing the new CDC grants was an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that it would partner with the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, U.K.), and Boston University School of Law to create one of the world’s largest public-private partnerships focused on preclinical discovery and development of new antimicrobial products.

According to an HHS statement, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will bring together “multiple domestic and international partners and capabilities to find potential antibiotics and move them through preclinical testing to enable safety and efficacy testing in humans and greatly reducing the business risk,” to make antimicrobial development more attractive to private sector investment.

HHS said the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) would provide $30 million during the first year of CARB-X, and up to $250 million during the 5-year project. CARB-X will provide funding for research and development, and technical assistance for companies with innovative and promising solutions to antibiotic resistance, HHS said.

“Our hope is that the combination of technical expertise and life science entrepreneurship experience within the CARB-X’s life science accelerators will remove barriers for companies pursuing the development of the next novel drug, diagnostic, or vaccine to combat this public health threat,” said Joe Larsen, PhD, acting BARDA deputy director, in the HHS statement.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing $67 million to help U.S. health departments address antibiotic resistance and related patient safety concerns.

The new funding was made available through the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC), according to a CDC statement, and will support seven new regional laboratories with specialized capabilities allowing rapid detection and identification of emerging antibiotic resistant threats.

The CDC said it would distribute funds to all 50 state health departments, six local health departments (Chicago, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Philadelphia), and Puerto Rico, beginning Aug. 1, 2016. The agency said the grants would allow every state health department lab to test for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and ultimately perform whole genome sequencing on intestinal bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, and many Campylobacter strains.

The agency intends to provide support teams in nine state health departments for rapid response activities designed to “quickly identify and respond to the threat” of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea in the United States, and will support high-level expertise to implement antimicrobial resistance activities in six states.

The CDC also said the promised funding would strengthen states’ ability to conduct foodborne disease tracking, investigation, and prevention, as it includes increased support for the PulseNet and OutbreakNet systems and for the Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence, as well as support for the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS).

Global partnerships

Complementing the new CDC grants was an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that it would partner with the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, U.K.), and Boston University School of Law to create one of the world’s largest public-private partnerships focused on preclinical discovery and development of new antimicrobial products.

According to an HHS statement, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will bring together “multiple domestic and international partners and capabilities to find potential antibiotics and move them through preclinical testing to enable safety and efficacy testing in humans and greatly reducing the business risk,” to make antimicrobial development more attractive to private sector investment.

HHS said the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) would provide $30 million during the first year of CARB-X, and up to $250 million during the 5-year project. CARB-X will provide funding for research and development, and technical assistance for companies with innovative and promising solutions to antibiotic resistance, HHS said.

“Our hope is that the combination of technical expertise and life science entrepreneurship experience within the CARB-X’s life science accelerators will remove barriers for companies pursuing the development of the next novel drug, diagnostic, or vaccine to combat this public health threat,” said Joe Larsen, PhD, acting BARDA deputy director, in the HHS statement.

On Twitter @richpizzi

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is providing $67 million to help U.S. health departments address antibiotic resistance and related patient safety concerns.

The new funding was made available through the CDC’s Epidemiology and Laboratory Capacity for Infectious Diseases Cooperative Agreement (ELC), according to a CDC statement, and will support seven new regional laboratories with specialized capabilities allowing rapid detection and identification of emerging antibiotic resistant threats.

The CDC said it would distribute funds to all 50 state health departments, six local health departments (Chicago, the District of Columbia, Houston, Los Angeles County, New York City, and Philadelphia), and Puerto Rico, beginning Aug. 1, 2016. The agency said the grants would allow every state health department lab to test for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and ultimately perform whole genome sequencing on intestinal bacteria, including Salmonella, Shigella, and many Campylobacter strains.

The agency intends to provide support teams in nine state health departments for rapid response activities designed to “quickly identify and respond to the threat” of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea in the United States, and will support high-level expertise to implement antimicrobial resistance activities in six states.

The CDC also said the promised funding would strengthen states’ ability to conduct foodborne disease tracking, investigation, and prevention, as it includes increased support for the PulseNet and OutbreakNet systems and for the Integrated Food Safety Centers of Excellence, as well as support for the National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System (NARMS).

Global partnerships

Complementing the new CDC grants was an announcement from the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services that it would partner with the Wellcome Trust of London, the AMR Centre of Alderley Park (Cheshire, U.K.), and Boston University School of Law to create one of the world’s largest public-private partnerships focused on preclinical discovery and development of new antimicrobial products.

According to an HHS statement, the Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria Biopharmaceutical Accelerator (CARB-X) will bring together “multiple domestic and international partners and capabilities to find potential antibiotics and move them through preclinical testing to enable safety and efficacy testing in humans and greatly reducing the business risk,” to make antimicrobial development more attractive to private sector investment.

HHS said the federal Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) would provide $30 million during the first year of CARB-X, and up to $250 million during the 5-year project. CARB-X will provide funding for research and development, and technical assistance for companies with innovative and promising solutions to antibiotic resistance, HHS said.

“Our hope is that the combination of technical expertise and life science entrepreneurship experience within the CARB-X’s life science accelerators will remove barriers for companies pursuing the development of the next novel drug, diagnostic, or vaccine to combat this public health threat,” said Joe Larsen, PhD, acting BARDA deputy director, in the HHS statement.

On Twitter @richpizzi

Simple colon surgery bundle accelerated outcomes improvement

SAN DIEGO – Implementation of a simple colon bundle decreased the rate of colonic and enteric resections faster, compared with improvements seen for other procedures, according to a study that involved 23 hospitals in Tennessee.

At the American College of Surgeons/National Surgical Quality Improvement Program National Conference, Brian J. Daley, MD, discussed findings from an analysis conducted by members of the Tennessee Surgical Quality Collaborative (TSQC), which he described as “a collection of surgeons who put aside their hospital and regional affiliations to work together to help each other and to help our fellow Tennesseans.” Established in 2008 with member hospitals, the TSQC has grown to 23 member hospitals, including 18 community hospitals and 5 academic medical centers. It provides data on nearly 600 surgeons across the state. “While this only represents about half of the surgical procedures in the state, there is sufficient statistical power to make comments about our surgical performance,” said Dr. Daley of the department of surgery at the University of Tennessee Medical Center, Knoxville.

To quantify TSQC’s impact on surgical outcomes, surgeons at the member hospitals evaluated the TSQC colon bundle, which was developed in 2012 and implemented in 2013. It bundles four processes of care: maintaining intraoperative oxygen delivery, maintaining a temperature of 36° C, making sure the patient’s blood glucose is normal, and choosing the appropriate antibiotics. “We kept it simple: easy, not expensive, and hopefully helpful,” Dr. Daley said.

With other procedures as a baseline, they used statistical analyses to determine if implementation of the bundle led to an incremental acceleration of reduced complications, compared with other improvements observed in other procedures. “To understand our outcomes, we needed to prove three points: that the trend improved [a negative trend in the resection rate], that this negative trend was more negative than trends for other comparator procedures, and that the trend for intercept was not equal to the comparator in any way,” Dr. Daley explained.

Following adoption of the bundle, he and his associates observed that the rate of decrease in postoperative recurrences was greater in colectomy, compared with that for all other surgical procedures (P less than .001 for both the trend and the intercept statistical models). Adoption of the bundle also positively impacted decreases in postoperative recurrences among enterectomy cases (P less than .001 for both the trend and the intercept statistical models).

“We were able to demonstrate that our TSQC bundle paid dividends in improving colectomy outcomes,” Dr. Daley concluded. “We have seen these efforts spill over into enterectomy. From this we can also infer that participation in the collaborative improves outcomes and is imperative to maintain the acceleration in surgical improvement.”

Dr. Daley reported that he and his coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Implementation of a simple colon bundle decreased the rate of colonic and enteric resections faster, compared with improvements seen for other procedures, according to a study that involved 23 hospitals in Tennessee.

At the American College of Surgeons/National Surgical Quality Improvement Program National Conference, Brian J. Daley, MD, discussed findings from an analysis conducted by members of the Tennessee Surgical Quality Collaborative (TSQC), which he described as “a collection of surgeons who put aside their hospital and regional affiliations to work together to help each other and to help our fellow Tennesseans.” Established in 2008 with member hospitals, the TSQC has grown to 23 member hospitals, including 18 community hospitals and 5 academic medical centers. It provides data on nearly 600 surgeons across the state. “While this only represents about half of the surgical procedures in the state, there is sufficient statistical power to make comments about our surgical performance,” said Dr. Daley of the department of surgery at the University of Tennessee Medical Center, Knoxville.

To quantify TSQC’s impact on surgical outcomes, surgeons at the member hospitals evaluated the TSQC colon bundle, which was developed in 2012 and implemented in 2013. It bundles four processes of care: maintaining intraoperative oxygen delivery, maintaining a temperature of 36° C, making sure the patient’s blood glucose is normal, and choosing the appropriate antibiotics. “We kept it simple: easy, not expensive, and hopefully helpful,” Dr. Daley said.

With other procedures as a baseline, they used statistical analyses to determine if implementation of the bundle led to an incremental acceleration of reduced complications, compared with other improvements observed in other procedures. “To understand our outcomes, we needed to prove three points: that the trend improved [a negative trend in the resection rate], that this negative trend was more negative than trends for other comparator procedures, and that the trend for intercept was not equal to the comparator in any way,” Dr. Daley explained.

Following adoption of the bundle, he and his associates observed that the rate of decrease in postoperative recurrences was greater in colectomy, compared with that for all other surgical procedures (P less than .001 for both the trend and the intercept statistical models). Adoption of the bundle also positively impacted decreases in postoperative recurrences among enterectomy cases (P less than .001 for both the trend and the intercept statistical models).

“We were able to demonstrate that our TSQC bundle paid dividends in improving colectomy outcomes,” Dr. Daley concluded. “We have seen these efforts spill over into enterectomy. From this we can also infer that participation in the collaborative improves outcomes and is imperative to maintain the acceleration in surgical improvement.”

Dr. Daley reported that he and his coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Implementation of a simple colon bundle decreased the rate of colonic and enteric resections faster, compared with improvements seen for other procedures, according to a study that involved 23 hospitals in Tennessee.

At the American College of Surgeons/National Surgical Quality Improvement Program National Conference, Brian J. Daley, MD, discussed findings from an analysis conducted by members of the Tennessee Surgical Quality Collaborative (TSQC), which he described as “a collection of surgeons who put aside their hospital and regional affiliations to work together to help each other and to help our fellow Tennesseans.” Established in 2008 with member hospitals, the TSQC has grown to 23 member hospitals, including 18 community hospitals and 5 academic medical centers. It provides data on nearly 600 surgeons across the state. “While this only represents about half of the surgical procedures in the state, there is sufficient statistical power to make comments about our surgical performance,” said Dr. Daley of the department of surgery at the University of Tennessee Medical Center, Knoxville.

To quantify TSQC’s impact on surgical outcomes, surgeons at the member hospitals evaluated the TSQC colon bundle, which was developed in 2012 and implemented in 2013. It bundles four processes of care: maintaining intraoperative oxygen delivery, maintaining a temperature of 36° C, making sure the patient’s blood glucose is normal, and choosing the appropriate antibiotics. “We kept it simple: easy, not expensive, and hopefully helpful,” Dr. Daley said.

With other procedures as a baseline, they used statistical analyses to determine if implementation of the bundle led to an incremental acceleration of reduced complications, compared with other improvements observed in other procedures. “To understand our outcomes, we needed to prove three points: that the trend improved [a negative trend in the resection rate], that this negative trend was more negative than trends for other comparator procedures, and that the trend for intercept was not equal to the comparator in any way,” Dr. Daley explained.

Following adoption of the bundle, he and his associates observed that the rate of decrease in postoperative recurrences was greater in colectomy, compared with that for all other surgical procedures (P less than .001 for both the trend and the intercept statistical models). Adoption of the bundle also positively impacted decreases in postoperative recurrences among enterectomy cases (P less than .001 for both the trend and the intercept statistical models).

“We were able to demonstrate that our TSQC bundle paid dividends in improving colectomy outcomes,” Dr. Daley concluded. “We have seen these efforts spill over into enterectomy. From this we can also infer that participation in the collaborative improves outcomes and is imperative to maintain the acceleration in surgical improvement.”

Dr. Daley reported that he and his coauthors had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE ACS NSQIP NATIONAL CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Adoption of a colon bundle by a collaborative of Tennessee hospitals improved certain colectomy outcomes.

Major finding: Following adoption of a colon bundle, the rate of decrease in postoperative recurrences was greater in colectomy than for all other surgical procedures (P less than .001 for both the trend and the intercept statistical models).

Data source: An analysis conducted by members of the Tennessee Surgical Quality Collaborative, which included 23 hospitals in the state.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

In septic shock, vasopressin not better than norepinephrine

Vasopressin was no better than norepinephrine in preventing kidney failure when used as a first-line treatment for septic shock, according to a report published online Aug. 2 in JAMA.

In a multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial comparing the two approaches in 408 ICU patients with septic shock, the early use of vasopressin didn’t reduce the number of days free of kidney failure, compared with standard norepinephrine.

However, “the 95% confidence intervals of the difference between [study] groups has an upper limit of 5 days in favor of vasopressin, which could be clinically important,” said Anthony C. Gordon, MD, of Charing Cross Hospital and Imperial College London, and his associates. “Therefore, these results are still consistent with a potentially clinically important benefit for vasopressin; but a larger trial would be needed to confirm or refute this.”

Norepinephrine is the recommended first-line vasopressor for septic shock, but “there has been a growing interest in the use of vasopressin” ever since researchers described a relative deficiency of vasopressin in the disorder, Dr. Gordon and his associates noted.

“Preclinical and small clinical studies have suggested that vasopressin may be better able to maintain glomerular filtration rate and improve creatinine clearance, compared with norepinephrine,” the investigators said, and other studies have suggested that combining vasopressin with corticosteroids may prevent deterioration in organ function and reduce the duration of shock, thereby improving survival.

To examine those possibilities, they performed the VANISH (Vasopressin vs. Norepinephrine as Initial Therapy in Septic Shock) trial, assessing patients age 16 years and older at 18 general adult ICUs in the United Kingdom during a 2-year period. The study participants were randomly assigned to receive vasopressin plus hydrocortisone (100 patients), vasopressin plus matching placebo (104 patients), norepinephrine plus hydrocortisone (101 patients), or norepinephrine plus matching placebo (103 patients).

The primary outcome measure was the number of days alive and free of kidney failure during the 28 days following randomization. There was no significant difference among the four study groups in the number or the distribution of kidney-failure–free days, the investigators said (JAMA. 2016 Aug 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10485).

In addition, the percentage of survivors who never developed kidney failure was not significantly different between the two groups who received vasopressin (57.0%) and the two who received norepinephrine (59.2%). And the median number of days free of kidney failure in the subgroup of patients who died or developed kidney failure was not significantly different between those receiving vasopressin (9 days) and those receiving norepinephrine (13 days).

The quantities of IV fluids administered, the total fluid balance, serum lactate levels, and heart rate were all similar across the four study groups. There also was no significant difference in 28-day mortality between patients who received vasopressin (30.9%) and those who received norepinephrine (27.5%). Adverse event profiles also were comparable.

However, the rate of renal replacement therapy was 25.4% with vasopressin, significantly lower than the 35.3% rate in the norepinephrine group. The use of such therapy was not controlled in the trial and was initiated according to the treating physicians’ preference. “It is therefore not possible to know why renal replacement therapy was or was not started,” Dr. Gordon and his associates noted.

The use of renal replacement therapy wasn’t a primary outcome of the trial. Nevertheless, it is an important patient-centered outcome and may be a factor to consider when treating adults who have septic shock, the researchers added.

The study was supported by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research and the U.K. Intensive Care Foundation. Dr. Gordon reported ties to Ferring, HCA International, Orion, and Tenax Therapeutics; his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Vasopressin was no better than norepinephrine in preventing kidney failure when used as a first-line treatment for septic shock, according to a report published online Aug. 2 in JAMA.

In a multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial comparing the two approaches in 408 ICU patients with septic shock, the early use of vasopressin didn’t reduce the number of days free of kidney failure, compared with standard norepinephrine.

However, “the 95% confidence intervals of the difference between [study] groups has an upper limit of 5 days in favor of vasopressin, which could be clinically important,” said Anthony C. Gordon, MD, of Charing Cross Hospital and Imperial College London, and his associates. “Therefore, these results are still consistent with a potentially clinically important benefit for vasopressin; but a larger trial would be needed to confirm or refute this.”

Norepinephrine is the recommended first-line vasopressor for septic shock, but “there has been a growing interest in the use of vasopressin” ever since researchers described a relative deficiency of vasopressin in the disorder, Dr. Gordon and his associates noted.

“Preclinical and small clinical studies have suggested that vasopressin may be better able to maintain glomerular filtration rate and improve creatinine clearance, compared with norepinephrine,” the investigators said, and other studies have suggested that combining vasopressin with corticosteroids may prevent deterioration in organ function and reduce the duration of shock, thereby improving survival.

To examine those possibilities, they performed the VANISH (Vasopressin vs. Norepinephrine as Initial Therapy in Septic Shock) trial, assessing patients age 16 years and older at 18 general adult ICUs in the United Kingdom during a 2-year period. The study participants were randomly assigned to receive vasopressin plus hydrocortisone (100 patients), vasopressin plus matching placebo (104 patients), norepinephrine plus hydrocortisone (101 patients), or norepinephrine plus matching placebo (103 patients).

The primary outcome measure was the number of days alive and free of kidney failure during the 28 days following randomization. There was no significant difference among the four study groups in the number or the distribution of kidney-failure–free days, the investigators said (JAMA. 2016 Aug 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10485).

In addition, the percentage of survivors who never developed kidney failure was not significantly different between the two groups who received vasopressin (57.0%) and the two who received norepinephrine (59.2%). And the median number of days free of kidney failure in the subgroup of patients who died or developed kidney failure was not significantly different between those receiving vasopressin (9 days) and those receiving norepinephrine (13 days).

The quantities of IV fluids administered, the total fluid balance, serum lactate levels, and heart rate were all similar across the four study groups. There also was no significant difference in 28-day mortality between patients who received vasopressin (30.9%) and those who received norepinephrine (27.5%). Adverse event profiles also were comparable.

However, the rate of renal replacement therapy was 25.4% with vasopressin, significantly lower than the 35.3% rate in the norepinephrine group. The use of such therapy was not controlled in the trial and was initiated according to the treating physicians’ preference. “It is therefore not possible to know why renal replacement therapy was or was not started,” Dr. Gordon and his associates noted.

The use of renal replacement therapy wasn’t a primary outcome of the trial. Nevertheless, it is an important patient-centered outcome and may be a factor to consider when treating adults who have septic shock, the researchers added.

The study was supported by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research and the U.K. Intensive Care Foundation. Dr. Gordon reported ties to Ferring, HCA International, Orion, and Tenax Therapeutics; his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Vasopressin was no better than norepinephrine in preventing kidney failure when used as a first-line treatment for septic shock, according to a report published online Aug. 2 in JAMA.

In a multicenter, double-blind, randomized trial comparing the two approaches in 408 ICU patients with septic shock, the early use of vasopressin didn’t reduce the number of days free of kidney failure, compared with standard norepinephrine.

However, “the 95% confidence intervals of the difference between [study] groups has an upper limit of 5 days in favor of vasopressin, which could be clinically important,” said Anthony C. Gordon, MD, of Charing Cross Hospital and Imperial College London, and his associates. “Therefore, these results are still consistent with a potentially clinically important benefit for vasopressin; but a larger trial would be needed to confirm or refute this.”

Norepinephrine is the recommended first-line vasopressor for septic shock, but “there has been a growing interest in the use of vasopressin” ever since researchers described a relative deficiency of vasopressin in the disorder, Dr. Gordon and his associates noted.

“Preclinical and small clinical studies have suggested that vasopressin may be better able to maintain glomerular filtration rate and improve creatinine clearance, compared with norepinephrine,” the investigators said, and other studies have suggested that combining vasopressin with corticosteroids may prevent deterioration in organ function and reduce the duration of shock, thereby improving survival.

To examine those possibilities, they performed the VANISH (Vasopressin vs. Norepinephrine as Initial Therapy in Septic Shock) trial, assessing patients age 16 years and older at 18 general adult ICUs in the United Kingdom during a 2-year period. The study participants were randomly assigned to receive vasopressin plus hydrocortisone (100 patients), vasopressin plus matching placebo (104 patients), norepinephrine plus hydrocortisone (101 patients), or norepinephrine plus matching placebo (103 patients).

The primary outcome measure was the number of days alive and free of kidney failure during the 28 days following randomization. There was no significant difference among the four study groups in the number or the distribution of kidney-failure–free days, the investigators said (JAMA. 2016 Aug 2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.10485).

In addition, the percentage of survivors who never developed kidney failure was not significantly different between the two groups who received vasopressin (57.0%) and the two who received norepinephrine (59.2%). And the median number of days free of kidney failure in the subgroup of patients who died or developed kidney failure was not significantly different between those receiving vasopressin (9 days) and those receiving norepinephrine (13 days).

The quantities of IV fluids administered, the total fluid balance, serum lactate levels, and heart rate were all similar across the four study groups. There also was no significant difference in 28-day mortality between patients who received vasopressin (30.9%) and those who received norepinephrine (27.5%). Adverse event profiles also were comparable.

However, the rate of renal replacement therapy was 25.4% with vasopressin, significantly lower than the 35.3% rate in the norepinephrine group. The use of such therapy was not controlled in the trial and was initiated according to the treating physicians’ preference. “It is therefore not possible to know why renal replacement therapy was or was not started,” Dr. Gordon and his associates noted.

The use of renal replacement therapy wasn’t a primary outcome of the trial. Nevertheless, it is an important patient-centered outcome and may be a factor to consider when treating adults who have septic shock, the researchers added.

The study was supported by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research and the U.K. Intensive Care Foundation. Dr. Gordon reported ties to Ferring, HCA International, Orion, and Tenax Therapeutics; his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Vasopressin didn’t perform better than norepinephrine in preventing kidney failure when used as a first-line treatment for septic shock.

Major finding: The primary outcome measure – the number of days alive and free of kidney failure during the first month of treatment – was not significantly different among the four study groups.

Data source: A multicenter, double-blind, randomized clinical trial involving 408 ICU patients treated in the United Kingdom during a 2-year period.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the U.K. National Institute for Health Research and the U.K. Intensive Care Foundation. Dr. Gordon reported ties to Ferring, HCA International, Orion, and Tenax Therapeutics; his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Interhospital patient transfers must be standardized

Imagine the following scenario: a hospitalist on the previous shift accepted a patient from another hospital and received a verbal sign-out at the time of acceptance. Now, 14 hours later, a bed at your hospital is finally available. You were advised that the patient was hemodynamically stable, but that was 8 hours ago. The patient arrives in respiratory distress with a blood pressure of 75/40, and phenylephrine running through a 20g IV in the forearm.

A 400-page printout of the patient’s electronic chart arrives – but no discharge summary is found. You are now responsible for stabilizing the patient and getting to the bottom of why your patient decompensated.

The above vignette is the “worst-case” scenario, yet it highlights how treacherous interhospital transfer can be. A recent study, published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (doi: 10.1002/jhm.2515), found increased in-hospital mortality (adjusted odds ratio 1.36 [1.29-1.43]) for medical interhospital transfer patients as compared with those admitted from the ED. When care is transferred between hospitals, additional hurdles such as lack of face-to-face sign-out, delays in transport and bed availability, and lack of electronic medical record (EMR) interoperability all contribute to miscommunication and may lead to errors in diagnosis and delay of definitive care.

Diametrically opposed to our many victories in providing technologically advanced medical care, our inability to coordinate even the most basic care across hospitals is an unfortunate reality of our fragmented health care system, and must be promptly addressed.

There currently exists no widely accepted standard of care for communication between hospitals regarding transferred patients. Commonalities include a mandatory three-way recorded physician verbal handoff and a transmission of an insurance face sheet. However, real-time concurrent EMR connectivity and clinical status updates as frequently as every 2 hours in critically ill patients are uncommon, as our own study found (doi: 10.1002/jhm.2577).

The lack of a standard of care for interhospital handoffs is, in part, why every transfer is potentially problematic. Many tertiary referral centers receive patients from more than 100 different hospitals and networks, amplifying the need for universal expectations. With differences in expectations among sending and receiving hospitals, there is ample room for variable outcomes, ranging from smooth transfers to the worst-case scenario described above. Enhanced shared decision making between providers at both hospitals, facilitated via communication tools and transfer centers, could lead to more fluid care of the transferred patient.

In order to establish standardized interhospital handoffs, a multicenter study is needed to examine outcomes of various transfer practices. A standard of communication and transfer handoff practices, based on those that lead to better outcomes, could potentially be established. Until this is studied, it is imperative that hospital systems and the government work to adopt broader EMR interoperability and radiology networks; comprehensive health information exchanges can minimize redundancy and provide real-time clinical data to make transfers safer.

Ideally, interhospital transfer should provide no more risk to a patient than a routine shift change of care providers.

Dr. Dana Herrigel is associate program director, internal medicine residency at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. Dr. Madeline Carroll is PGY-3 internal medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Imagine the following scenario: a hospitalist on the previous shift accepted a patient from another hospital and received a verbal sign-out at the time of acceptance. Now, 14 hours later, a bed at your hospital is finally available. You were advised that the patient was hemodynamically stable, but that was 8 hours ago. The patient arrives in respiratory distress with a blood pressure of 75/40, and phenylephrine running through a 20g IV in the forearm.

A 400-page printout of the patient’s electronic chart arrives – but no discharge summary is found. You are now responsible for stabilizing the patient and getting to the bottom of why your patient decompensated.

The above vignette is the “worst-case” scenario, yet it highlights how treacherous interhospital transfer can be. A recent study, published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (doi: 10.1002/jhm.2515), found increased in-hospital mortality (adjusted odds ratio 1.36 [1.29-1.43]) for medical interhospital transfer patients as compared with those admitted from the ED. When care is transferred between hospitals, additional hurdles such as lack of face-to-face sign-out, delays in transport and bed availability, and lack of electronic medical record (EMR) interoperability all contribute to miscommunication and may lead to errors in diagnosis and delay of definitive care.

Diametrically opposed to our many victories in providing technologically advanced medical care, our inability to coordinate even the most basic care across hospitals is an unfortunate reality of our fragmented health care system, and must be promptly addressed.

There currently exists no widely accepted standard of care for communication between hospitals regarding transferred patients. Commonalities include a mandatory three-way recorded physician verbal handoff and a transmission of an insurance face sheet. However, real-time concurrent EMR connectivity and clinical status updates as frequently as every 2 hours in critically ill patients are uncommon, as our own study found (doi: 10.1002/jhm.2577).

The lack of a standard of care for interhospital handoffs is, in part, why every transfer is potentially problematic. Many tertiary referral centers receive patients from more than 100 different hospitals and networks, amplifying the need for universal expectations. With differences in expectations among sending and receiving hospitals, there is ample room for variable outcomes, ranging from smooth transfers to the worst-case scenario described above. Enhanced shared decision making between providers at both hospitals, facilitated via communication tools and transfer centers, could lead to more fluid care of the transferred patient.

In order to establish standardized interhospital handoffs, a multicenter study is needed to examine outcomes of various transfer practices. A standard of communication and transfer handoff practices, based on those that lead to better outcomes, could potentially be established. Until this is studied, it is imperative that hospital systems and the government work to adopt broader EMR interoperability and radiology networks; comprehensive health information exchanges can minimize redundancy and provide real-time clinical data to make transfers safer.

Ideally, interhospital transfer should provide no more risk to a patient than a routine shift change of care providers.

Dr. Dana Herrigel is associate program director, internal medicine residency at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. Dr. Madeline Carroll is PGY-3 internal medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Imagine the following scenario: a hospitalist on the previous shift accepted a patient from another hospital and received a verbal sign-out at the time of acceptance. Now, 14 hours later, a bed at your hospital is finally available. You were advised that the patient was hemodynamically stable, but that was 8 hours ago. The patient arrives in respiratory distress with a blood pressure of 75/40, and phenylephrine running through a 20g IV in the forearm.

A 400-page printout of the patient’s electronic chart arrives – but no discharge summary is found. You are now responsible for stabilizing the patient and getting to the bottom of why your patient decompensated.

The above vignette is the “worst-case” scenario, yet it highlights how treacherous interhospital transfer can be. A recent study, published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine (doi: 10.1002/jhm.2515), found increased in-hospital mortality (adjusted odds ratio 1.36 [1.29-1.43]) for medical interhospital transfer patients as compared with those admitted from the ED. When care is transferred between hospitals, additional hurdles such as lack of face-to-face sign-out, delays in transport and bed availability, and lack of electronic medical record (EMR) interoperability all contribute to miscommunication and may lead to errors in diagnosis and delay of definitive care.

Diametrically opposed to our many victories in providing technologically advanced medical care, our inability to coordinate even the most basic care across hospitals is an unfortunate reality of our fragmented health care system, and must be promptly addressed.

There currently exists no widely accepted standard of care for communication between hospitals regarding transferred patients. Commonalities include a mandatory three-way recorded physician verbal handoff and a transmission of an insurance face sheet. However, real-time concurrent EMR connectivity and clinical status updates as frequently as every 2 hours in critically ill patients are uncommon, as our own study found (doi: 10.1002/jhm.2577).

The lack of a standard of care for interhospital handoffs is, in part, why every transfer is potentially problematic. Many tertiary referral centers receive patients from more than 100 different hospitals and networks, amplifying the need for universal expectations. With differences in expectations among sending and receiving hospitals, there is ample room for variable outcomes, ranging from smooth transfers to the worst-case scenario described above. Enhanced shared decision making between providers at both hospitals, facilitated via communication tools and transfer centers, could lead to more fluid care of the transferred patient.

In order to establish standardized interhospital handoffs, a multicenter study is needed to examine outcomes of various transfer practices. A standard of communication and transfer handoff practices, based on those that lead to better outcomes, could potentially be established. Until this is studied, it is imperative that hospital systems and the government work to adopt broader EMR interoperability and radiology networks; comprehensive health information exchanges can minimize redundancy and provide real-time clinical data to make transfers safer.

Ideally, interhospital transfer should provide no more risk to a patient than a routine shift change of care providers.

Dr. Dana Herrigel is associate program director, internal medicine residency at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, N.J. Dr. Madeline Carroll is PGY-3 internal medicine at Robert Wood Johnson Medical School.

Daily fish oil dose boosts healing after heart attack

A daily dose of omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil significantly improved heart function in adults after heart attacks, based on data from a randomized trial of 358 heart attack survivors. The findings were published online Aug. 1 in Circulation.

Patients who received 4 grams of omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil (O-3FA) for 6 months had significant reductions in left ventricular end-systolic volume index (–5.8%) and noninfarct myocardial fibrosis (–5.6%), compared with placebo patients, Bobak Heydari, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

The effects remained significant after adjusting for factors including guideline-based standard post-heart attack medical therapies, they noted.

Treatment with omega-3 fatty acids (O-3FA) “also was associated with a significant reduction of both biomarkers of inflammation (myeloperoxidase, lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2) and myocardial fibrosis (ST2),” the researchers wrote. “We therefore speculate that O-3FA treatment provides the aforementioned improvement in LV remodeling and noninfarct myocardial fibrosis through suppression of inflammation at both systemic and myocardial levels during the convalescent healing phase after acute MI,” they noted.

The results build on data from a previous study showing an association between daily doses of O-3FA and improved survival rates in heart attack patients, but the specific impact on heart structure and tissue has not been well studied, the researchers noted (Circulation. 2016;134:378-91 doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.115.019949).

The OMEGA-REMODEL trial (Omega-3 Acid Ethyl Esters on Left Ventricular Remodeling After Acute Myocardial Infarction) was designed to assess the impact of omega-3 fatty acids on heart healing after a heart attack. The average age of the patients was about 60 years. Demographic characteristics and cardiovascular disease histories were not significantly different between the groups.

Compliance for both treatment and placebo groups was 96% based on pill counts. Nausea was the most common side effect, reported by 5.9% of treatment patients and 5.4% of placebo patients. No serious adverse events associated with treatment were reported.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the possible use of over-the-counter fish oil supplementation by patients, the researchers noted. “However, dose-response relationship between O-3FA therapy and our main study endpoints strongly supported our intention-to-treat analysis,” they said.

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A daily dose of omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil significantly improved heart function in adults after heart attacks, based on data from a randomized trial of 358 heart attack survivors. The findings were published online Aug. 1 in Circulation.

Patients who received 4 grams of omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil (O-3FA) for 6 months had significant reductions in left ventricular end-systolic volume index (–5.8%) and noninfarct myocardial fibrosis (–5.6%), compared with placebo patients, Bobak Heydari, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

The effects remained significant after adjusting for factors including guideline-based standard post-heart attack medical therapies, they noted.

Treatment with omega-3 fatty acids (O-3FA) “also was associated with a significant reduction of both biomarkers of inflammation (myeloperoxidase, lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2) and myocardial fibrosis (ST2),” the researchers wrote. “We therefore speculate that O-3FA treatment provides the aforementioned improvement in LV remodeling and noninfarct myocardial fibrosis through suppression of inflammation at both systemic and myocardial levels during the convalescent healing phase after acute MI,” they noted.

The results build on data from a previous study showing an association between daily doses of O-3FA and improved survival rates in heart attack patients, but the specific impact on heart structure and tissue has not been well studied, the researchers noted (Circulation. 2016;134:378-91 doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.115.019949).

The OMEGA-REMODEL trial (Omega-3 Acid Ethyl Esters on Left Ventricular Remodeling After Acute Myocardial Infarction) was designed to assess the impact of omega-3 fatty acids on heart healing after a heart attack. The average age of the patients was about 60 years. Demographic characteristics and cardiovascular disease histories were not significantly different between the groups.

Compliance for both treatment and placebo groups was 96% based on pill counts. Nausea was the most common side effect, reported by 5.9% of treatment patients and 5.4% of placebo patients. No serious adverse events associated with treatment were reported.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the possible use of over-the-counter fish oil supplementation by patients, the researchers noted. “However, dose-response relationship between O-3FA therapy and our main study endpoints strongly supported our intention-to-treat analysis,” they said.

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

A daily dose of omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil significantly improved heart function in adults after heart attacks, based on data from a randomized trial of 358 heart attack survivors. The findings were published online Aug. 1 in Circulation.

Patients who received 4 grams of omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil (O-3FA) for 6 months had significant reductions in left ventricular end-systolic volume index (–5.8%) and noninfarct myocardial fibrosis (–5.6%), compared with placebo patients, Bobak Heydari, MD, MPH, of Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and colleagues.

The effects remained significant after adjusting for factors including guideline-based standard post-heart attack medical therapies, they noted.

Treatment with omega-3 fatty acids (O-3FA) “also was associated with a significant reduction of both biomarkers of inflammation (myeloperoxidase, lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2) and myocardial fibrosis (ST2),” the researchers wrote. “We therefore speculate that O-3FA treatment provides the aforementioned improvement in LV remodeling and noninfarct myocardial fibrosis through suppression of inflammation at both systemic and myocardial levels during the convalescent healing phase after acute MI,” they noted.

The results build on data from a previous study showing an association between daily doses of O-3FA and improved survival rates in heart attack patients, but the specific impact on heart structure and tissue has not been well studied, the researchers noted (Circulation. 2016;134:378-91 doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.115.019949).

The OMEGA-REMODEL trial (Omega-3 Acid Ethyl Esters on Left Ventricular Remodeling After Acute Myocardial Infarction) was designed to assess the impact of omega-3 fatty acids on heart healing after a heart attack. The average age of the patients was about 60 years. Demographic characteristics and cardiovascular disease histories were not significantly different between the groups.

Compliance for both treatment and placebo groups was 96% based on pill counts. Nausea was the most common side effect, reported by 5.9% of treatment patients and 5.4% of placebo patients. No serious adverse events associated with treatment were reported.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the possible use of over-the-counter fish oil supplementation by patients, the researchers noted. “However, dose-response relationship between O-3FA therapy and our main study endpoints strongly supported our intention-to-treat analysis,” they said.

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM CIRCULATION

Key clinical point: A daily dose of omega-3 fatty acids for 6 months after a heart attack improved heart function and reduced scarring.

Major finding: Heart attack patients who received 4 grams of omega-3 fatty acids from fish oil daily had significant reductions in both left ventricular end-systolic volume index (-5.8%) and noninfarct myocardial fibrosis (-5.6%), compared with placebo patients after 6 months.

Data source: A randomized trial of 360 heart attack survivors.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Post-AMI death risk model has high predictive accuracy

An updated risk model based on data from patients presenting after acute myocardial infarction to a broad spectrum of U.S. hospitals appears to predict with a high degree of accuracy which patients are at the greatest risk for in-hospital mortality, investigators say.

Created from data on more than 240,000 patients presenting to one of 655 U.S. hospitals in 2012 and 2013 following ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non–ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI), the model identified the following independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality: age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, presentation to the hospital after cardiac arrest, presentation in cardiogenic shock, presentation in heart failure, presentation with STEMI, creatinine clearance, and troponin ratio, reported Robert L. McNamara, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The investigators are participants in the ACTION (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network) Registry–GWTG (Get With the Guidelines).

“The new ACTION Registry–GWTG in-hospital mortality risk model and risk score represent robust, parsimonious, and contemporary risk adjustment methodology for use in routine clinical care and hospital quality assessment. The addition of risk adjustment for patients presenting after cardiac arrest is critically important and enables a fairer assessment across hospitals with varied case mix,” they wrote (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Aug 1;68[6]:626-35).

The revised risk model has the potential to facilitate hospital quality assessments and help investigators to identify specific factors that could help clinicians even further lower death rates, the investigators write.

Further mortality reductions?

Although improvements in care of patients with acute MI over the last several decades have driven the in-hospital death rate from 29% in 1969 down to less than 7% today, there are still more than 100,000 AMI-related in-hospital deaths in the United States annually, with wide variations across hospitals, Dr. McNamara and colleagues noted.

A previous risk model published by ACTION Registry–GWTG members included data on patients treated at 306 U.S. hospitals and provided a simple, validated in-hospital mortality and risk score.

Since that model was published, however, the dataset was expanded to include patients presenting after cardiac arrest at the time of AMI presentation.

“Being able to adjust for cardiac arrest is critical because it is a well-documented predictor of mortality. Moreover, continued improvement in AMI care mandates periodic updates to the risk models so that hospitals can assess their quality as contemporary care continues to evolve,” the authors wrote.

To see whether they could develop a new and improved model and risk score, they analyzed data on 243,440 patients treated at one of 655 hospitals in the voluntary network. Data on 145,952 patients (60% of the total), 57,039 of whom presented with STEMI, and 88,913 of whom presented with NSTEMI, were used to for the derivation sample.

Data on the remaining 97,488 (38,060 with STEMI and 59,428 with NSTEMI) were used to create the validation sample.

The authors found that for the total cohort, the in-hospital mortality rate was 4.6%. In multivariate models controlled for demographic and clinical factors, independent risk factors significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (validation cohort) were:

• Presentation after cardiac arrest (odds ratio, 5.15).

• Presentation in cardiogenic shock (OR, 4.22).

• Presentation in heart failure (OR, 1.83).

• STEMI on electrocardiography (OR, 1.81).

• Age, per 5 years (OR, 1.24).

• Systolic BP, per 10 mm Hg decrease (OR, 1.19).

• Creatinine clearance per 5/mL/min/1.73 m2 decrease (OR, 1.11).

• Heart rate per 10 beats/min (OR, 1.09).

• Troponin ratio, per 5 units (OR, 1.05).

The 95% confidence intervals for all of the above factors were significant.

The C-statistic, a standard measure of the predictive accuracy of a logistic regression model, was 0.88, indicating that the final ACTION Registry–GWTG in-hospital mortality model had a high level of discrimination in both the derivation and validation populations, the authors state.

The ACTION Registry–GWTG is a Program of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, with funding from Schering-Plough and the Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi Pharmaceutical Partnership. Dr. McNamara serves on a clinical trials endpoint adjudication committee for Pfizer. Other coauthors reported multiple financial relationships with pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

Data analyses for the risk models developed by the ACTION Registry generally showed good accuracy and precision. The calibration information showed that patients with a cardiac arrest experienced much greater risk for mortality than did the other major groups (STEMI, NSTEMI, or no cardiac arrest). Until now, clinicians and researchers have generally used either the TIMI [Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction] or GRACE [Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events] score to guide therapeutic decisions. With the advent of the ACTION score, which appears to be most helpful for patients with moderate to severe disease, and the HEART [history, ECG, age, risk factor, troponin] score, which targets care for patients with minimal to mild disease, there are other options. Recently, the DAPT (Dual Antiplatelet Therapy) investigators published a prediction algorithm that provides yet another prognostic score to assess risk of ischemic events and risk of bleeding in patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention. The key variables in the DAPT score are age, cigarette smoking, diabetes, MI at presentation, previous percutaneous coronary intervention or previous MI, use of a paclitaxel-eluting stent, stent diameter of less than 3 mm, heart failure or reduced ejection fraction, and use of a vein graft stent.

A comprehensive cross validation and comparison across at least some of the algorithms – TIMI, GRACE, HEART, DAPT, and ACTION – would help at this point. Interventions and decision points have evolved over the past 15 years, and evaluation of relatively contemporary data would be especially helpful. For example, the HEART score is likely to be used in situations in which the negative predictive capabilities are most important. The ACTION score is likely to be most useful in severely ill patients and to provide guidance for newer interventions. If detailed information concerning stents is available, then the DAPT score should prove helpful.

It is likely that one score does not fit all. Each algorithm provides a useful summary of risk to help guide decision making for patients with ischemic symptoms, depending on the severity of the signs and symptoms at presentation and the duration of the follow-up interval. Consensus building would help to move this field forward for hospital-based management of patients evaluated for cardiac ischemia.

Peter W.F. Wilson, MD, of the Atlanta VAMC and Emory Clinical Cardiovascular Research

Institute, Atlanta; and Ralph B. D’Agostino Sr., PhD, of the department of mathematics and statistics, Boston University, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Aug 1;68[6]:636-8). They reported no relevant disclosures.

Data analyses for the risk models developed by the ACTION Registry generally showed good accuracy and precision. The calibration information showed that patients with a cardiac arrest experienced much greater risk for mortality than did the other major groups (STEMI, NSTEMI, or no cardiac arrest). Until now, clinicians and researchers have generally used either the TIMI [Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction] or GRACE [Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events] score to guide therapeutic decisions. With the advent of the ACTION score, which appears to be most helpful for patients with moderate to severe disease, and the HEART [history, ECG, age, risk factor, troponin] score, which targets care for patients with minimal to mild disease, there are other options. Recently, the DAPT (Dual Antiplatelet Therapy) investigators published a prediction algorithm that provides yet another prognostic score to assess risk of ischemic events and risk of bleeding in patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention. The key variables in the DAPT score are age, cigarette smoking, diabetes, MI at presentation, previous percutaneous coronary intervention or previous MI, use of a paclitaxel-eluting stent, stent diameter of less than 3 mm, heart failure or reduced ejection fraction, and use of a vein graft stent.

A comprehensive cross validation and comparison across at least some of the algorithms – TIMI, GRACE, HEART, DAPT, and ACTION – would help at this point. Interventions and decision points have evolved over the past 15 years, and evaluation of relatively contemporary data would be especially helpful. For example, the HEART score is likely to be used in situations in which the negative predictive capabilities are most important. The ACTION score is likely to be most useful in severely ill patients and to provide guidance for newer interventions. If detailed information concerning stents is available, then the DAPT score should prove helpful.

It is likely that one score does not fit all. Each algorithm provides a useful summary of risk to help guide decision making for patients with ischemic symptoms, depending on the severity of the signs and symptoms at presentation and the duration of the follow-up interval. Consensus building would help to move this field forward for hospital-based management of patients evaluated for cardiac ischemia.

Peter W.F. Wilson, MD, of the Atlanta VAMC and Emory Clinical Cardiovascular Research

Institute, Atlanta; and Ralph B. D’Agostino Sr., PhD, of the department of mathematics and statistics, Boston University, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Aug 1;68[6]:636-8). They reported no relevant disclosures.

Data analyses for the risk models developed by the ACTION Registry generally showed good accuracy and precision. The calibration information showed that patients with a cardiac arrest experienced much greater risk for mortality than did the other major groups (STEMI, NSTEMI, or no cardiac arrest). Until now, clinicians and researchers have generally used either the TIMI [Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction] or GRACE [Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events] score to guide therapeutic decisions. With the advent of the ACTION score, which appears to be most helpful for patients with moderate to severe disease, and the HEART [history, ECG, age, risk factor, troponin] score, which targets care for patients with minimal to mild disease, there are other options. Recently, the DAPT (Dual Antiplatelet Therapy) investigators published a prediction algorithm that provides yet another prognostic score to assess risk of ischemic events and risk of bleeding in patients who have undergone percutaneous coronary intervention. The key variables in the DAPT score are age, cigarette smoking, diabetes, MI at presentation, previous percutaneous coronary intervention or previous MI, use of a paclitaxel-eluting stent, stent diameter of less than 3 mm, heart failure or reduced ejection fraction, and use of a vein graft stent.

A comprehensive cross validation and comparison across at least some of the algorithms – TIMI, GRACE, HEART, DAPT, and ACTION – would help at this point. Interventions and decision points have evolved over the past 15 years, and evaluation of relatively contemporary data would be especially helpful. For example, the HEART score is likely to be used in situations in which the negative predictive capabilities are most important. The ACTION score is likely to be most useful in severely ill patients and to provide guidance for newer interventions. If detailed information concerning stents is available, then the DAPT score should prove helpful.

It is likely that one score does not fit all. Each algorithm provides a useful summary of risk to help guide decision making for patients with ischemic symptoms, depending on the severity of the signs and symptoms at presentation and the duration of the follow-up interval. Consensus building would help to move this field forward for hospital-based management of patients evaluated for cardiac ischemia.

Peter W.F. Wilson, MD, of the Atlanta VAMC and Emory Clinical Cardiovascular Research

Institute, Atlanta; and Ralph B. D’Agostino Sr., PhD, of the department of mathematics and statistics, Boston University, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Aug 1;68[6]:636-8). They reported no relevant disclosures.

An updated risk model based on data from patients presenting after acute myocardial infarction to a broad spectrum of U.S. hospitals appears to predict with a high degree of accuracy which patients are at the greatest risk for in-hospital mortality, investigators say.

Created from data on more than 240,000 patients presenting to one of 655 U.S. hospitals in 2012 and 2013 following ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non–ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI), the model identified the following independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality: age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, presentation to the hospital after cardiac arrest, presentation in cardiogenic shock, presentation in heart failure, presentation with STEMI, creatinine clearance, and troponin ratio, reported Robert L. McNamara, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The investigators are participants in the ACTION (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network) Registry–GWTG (Get With the Guidelines).

“The new ACTION Registry–GWTG in-hospital mortality risk model and risk score represent robust, parsimonious, and contemporary risk adjustment methodology for use in routine clinical care and hospital quality assessment. The addition of risk adjustment for patients presenting after cardiac arrest is critically important and enables a fairer assessment across hospitals with varied case mix,” they wrote (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Aug 1;68[6]:626-35).

The revised risk model has the potential to facilitate hospital quality assessments and help investigators to identify specific factors that could help clinicians even further lower death rates, the investigators write.

Further mortality reductions?

Although improvements in care of patients with acute MI over the last several decades have driven the in-hospital death rate from 29% in 1969 down to less than 7% today, there are still more than 100,000 AMI-related in-hospital deaths in the United States annually, with wide variations across hospitals, Dr. McNamara and colleagues noted.

A previous risk model published by ACTION Registry–GWTG members included data on patients treated at 306 U.S. hospitals and provided a simple, validated in-hospital mortality and risk score.

Since that model was published, however, the dataset was expanded to include patients presenting after cardiac arrest at the time of AMI presentation.

“Being able to adjust for cardiac arrest is critical because it is a well-documented predictor of mortality. Moreover, continued improvement in AMI care mandates periodic updates to the risk models so that hospitals can assess their quality as contemporary care continues to evolve,” the authors wrote.

To see whether they could develop a new and improved model and risk score, they analyzed data on 243,440 patients treated at one of 655 hospitals in the voluntary network. Data on 145,952 patients (60% of the total), 57,039 of whom presented with STEMI, and 88,913 of whom presented with NSTEMI, were used to for the derivation sample.

Data on the remaining 97,488 (38,060 with STEMI and 59,428 with NSTEMI) were used to create the validation sample.

The authors found that for the total cohort, the in-hospital mortality rate was 4.6%. In multivariate models controlled for demographic and clinical factors, independent risk factors significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (validation cohort) were:

• Presentation after cardiac arrest (odds ratio, 5.15).

• Presentation in cardiogenic shock (OR, 4.22).

• Presentation in heart failure (OR, 1.83).

• STEMI on electrocardiography (OR, 1.81).

• Age, per 5 years (OR, 1.24).

• Systolic BP, per 10 mm Hg decrease (OR, 1.19).

• Creatinine clearance per 5/mL/min/1.73 m2 decrease (OR, 1.11).

• Heart rate per 10 beats/min (OR, 1.09).

• Troponin ratio, per 5 units (OR, 1.05).

The 95% confidence intervals for all of the above factors were significant.

The C-statistic, a standard measure of the predictive accuracy of a logistic regression model, was 0.88, indicating that the final ACTION Registry–GWTG in-hospital mortality model had a high level of discrimination in both the derivation and validation populations, the authors state.

The ACTION Registry–GWTG is a Program of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, with funding from Schering-Plough and the Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi Pharmaceutical Partnership. Dr. McNamara serves on a clinical trials endpoint adjudication committee for Pfizer. Other coauthors reported multiple financial relationships with pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

An updated risk model based on data from patients presenting after acute myocardial infarction to a broad spectrum of U.S. hospitals appears to predict with a high degree of accuracy which patients are at the greatest risk for in-hospital mortality, investigators say.

Created from data on more than 240,000 patients presenting to one of 655 U.S. hospitals in 2012 and 2013 following ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non–ST-segment elevation MI (NSTEMI), the model identified the following independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality: age, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, presentation to the hospital after cardiac arrest, presentation in cardiogenic shock, presentation in heart failure, presentation with STEMI, creatinine clearance, and troponin ratio, reported Robert L. McNamara, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

The investigators are participants in the ACTION (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network) Registry–GWTG (Get With the Guidelines).

“The new ACTION Registry–GWTG in-hospital mortality risk model and risk score represent robust, parsimonious, and contemporary risk adjustment methodology for use in routine clinical care and hospital quality assessment. The addition of risk adjustment for patients presenting after cardiac arrest is critically important and enables a fairer assessment across hospitals with varied case mix,” they wrote (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016 Aug 1;68[6]:626-35).

The revised risk model has the potential to facilitate hospital quality assessments and help investigators to identify specific factors that could help clinicians even further lower death rates, the investigators write.

Further mortality reductions?

Although improvements in care of patients with acute MI over the last several decades have driven the in-hospital death rate from 29% in 1969 down to less than 7% today, there are still more than 100,000 AMI-related in-hospital deaths in the United States annually, with wide variations across hospitals, Dr. McNamara and colleagues noted.

A previous risk model published by ACTION Registry–GWTG members included data on patients treated at 306 U.S. hospitals and provided a simple, validated in-hospital mortality and risk score.

Since that model was published, however, the dataset was expanded to include patients presenting after cardiac arrest at the time of AMI presentation.

“Being able to adjust for cardiac arrest is critical because it is a well-documented predictor of mortality. Moreover, continued improvement in AMI care mandates periodic updates to the risk models so that hospitals can assess their quality as contemporary care continues to evolve,” the authors wrote.

To see whether they could develop a new and improved model and risk score, they analyzed data on 243,440 patients treated at one of 655 hospitals in the voluntary network. Data on 145,952 patients (60% of the total), 57,039 of whom presented with STEMI, and 88,913 of whom presented with NSTEMI, were used to for the derivation sample.

Data on the remaining 97,488 (38,060 with STEMI and 59,428 with NSTEMI) were used to create the validation sample.

The authors found that for the total cohort, the in-hospital mortality rate was 4.6%. In multivariate models controlled for demographic and clinical factors, independent risk factors significantly associated with in-hospital mortality (validation cohort) were:

• Presentation after cardiac arrest (odds ratio, 5.15).

• Presentation in cardiogenic shock (OR, 4.22).

• Presentation in heart failure (OR, 1.83).

• STEMI on electrocardiography (OR, 1.81).

• Age, per 5 years (OR, 1.24).

• Systolic BP, per 10 mm Hg decrease (OR, 1.19).

• Creatinine clearance per 5/mL/min/1.73 m2 decrease (OR, 1.11).

• Heart rate per 10 beats/min (OR, 1.09).

• Troponin ratio, per 5 units (OR, 1.05).

The 95% confidence intervals for all of the above factors were significant.

The C-statistic, a standard measure of the predictive accuracy of a logistic regression model, was 0.88, indicating that the final ACTION Registry–GWTG in-hospital mortality model had a high level of discrimination in both the derivation and validation populations, the authors state.

The ACTION Registry–GWTG is a Program of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, with funding from Schering-Plough and the Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi Pharmaceutical Partnership. Dr. McNamara serves on a clinical trials endpoint adjudication committee for Pfizer. Other coauthors reported multiple financial relationships with pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF CARDIOLOGY

Key clinical point: An updated cardiac mortality risk model may help to further reduce in-hospital deaths following acute myocardial infarction.

Major finding: The C-statistic for the model, a measure of predictive accuracy, was 0.88.

Data source: Updated risk model and in-hospital mortality score based on data from 243,440 patients following an AMI in 655 U.S. hospitals.

Disclosures: The ACTION Registry-GWTG is a Program of the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, with funding from Schering-Plough and the Bristol-Myers Squibb/Sanofi Pharmaceutical Partnership. Dr. McNamara serves on a clinical trials endpoint adjudication committee for Pfizer. Other coauthors reported multiple financial relationships with pharmaceutical and medical device companies.

Two incretin-based drugs linked to increased bile duct disease but not pancreatitis

At least two incretin-based drugs – glucagon-like peptide 1 agonists and dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors – do not appear to increase the risk of acute pancreatitis in individuals with diabetes but are associated with an increased risk of bile duct and gallbladder disease.

Two studies examining the impact on the pancreas of incretin-based drugs, including dipeptidyl peptidase 4 (DPP-4) inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) agonists, have been published online August 1 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Incretin-based drugs have been associated with increased risk of elevated pancreatic enzyme levels, while GLP-1 has been shown to increase the proliferation and activity of cholangiocytes, which have raised concerns of an impact on the bile duct, gallbladder, and pancreas.

The first study was an international, population-based cohort study using the health records of more than 1.5 million individuals with type 2 diabetes, who began treatment with antidiabetic drugs between January 2007 and June 2013.

Analysis of these data showed there was no difference in the risk of hospitalization for acute pancreatitis between those taking incretin-based drugs and those on two or more other oral antidiabetic medications (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Aug 1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1522).

The study also found no significant increase in the risk of acute pancreatitis either with DPP-4 inhibitors or GLP-1 agonists, nor was there any increase with a longer duration of use or in patients with a history of acute or chronic pancreatitis.

Most previous observational studies of incretin-based drugs and pancreatitis had reported null findings, but four studies did find a positive association. Laurent Azoulay, PhD, from the Lady Davis Institute at Montreal’s Jewish General Hospital, and his coauthors suggested this heterogeneity was likely the result of methodologic shortcomings such as the use of inappropriate comparator groups and confoundings.

“Although it remains possible that these drugs may be associated with acute pancreatitis, the upper limit of our 95% [confidence interval] suggests that this risk is likely to be small,” the authors wrote. “Thus, the findings of this study should provide some reassurance to patients treated with incretin-based drugs.”

Meanwhile, a second population-based cohort study in 71,368 patients starting an antidiabetic drug found the use of GLP-1 analogues was associated with a significant 79% increase in the risk of bile duct and gallbladder disease, compared with the use of at least two other oral antidiabetic medications.

When stratified by duration of use, individuals taking GLP-1 analogues for less than 180 days showed a twofold increase in the risk of bile duct and gallbladder disease (adjusted hazard ratio, 2.01; 95% CI, 1.23-3.29) but those taking the drugs for longer than 180 days did not show an increased risk.

The use of GLP-1 analogues was also associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of undergoing a cholecystectomy.

However, the study found no increased risk of bile duct or gallbladder disease with DPP-4 inhibitors (JAMA Intern Med. 2016 Aug 1. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1531).