User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Predicting prostate cancer risk: Are polygenic risk scores ready for prime time?

DNA testing for prostate cancer – of the patients’ inherited DNA and their tumors’ somatic DNA – is increasingly used in the U.S. to determine whether and how to treat low-grade, localized prostate cancers.

Another genetic approach, known as the polygenic risk score (PRS), is emerging as a third genetic approach for sorting out prostate cancer risks.

PRS aims to stratify a person’s disease risk by going beyond rare variants in genes, such as BRCA2, and compiling a weighted score that integrates thousands of common variants whose role in cancer may be unknown but are found more frequently in men with prostate cancer. Traditional germline testing, by contrast, looks for about 30 specific genes directly linked to prostate cancer.

Essentially, “a polygenic risk score estimates your risk by adding together the number of bad cards you were dealt by the impact of each card, such as an ace versus a deuce,” said William Catalona, MD, a urologist at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, known as the father of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening.

In combination, these variants can have powerful predictive value.

Having a tool that can mine the depths of a person’s genetic makeup and help doctors devise a nuanced risk assessment for prostate cancer seems like a winning proposition.

Despite its promise, PRS testing is not yet used routinely in practice. The central uncertainty regarding its use lies in whether the risk score can accurately predict who will develop aggressive prostate cancer that needs to be treated and who won’t. The research to date has been mixed, and experts remain polarized.

“PRS absolutely, irrefutably can distinguish between the probability of somebody developing prostate cancer or not. Nobody could look at the data and argue with that,” said Todd Morgan, MD, a genomics researcher from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “What [the data] so far haven’t really been able to do is distinguish whether somebody is likely to have clinically significant prostate cancer versus lower-risk prostate cancer.”

The promise of PRS in prostate cancer?

, according to Burcu Darst, PhD, a genetic epidemiologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle.

Research in the area has intensified in recent years as genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have become more affordable and the genetic information from these studies has been increasingly aggregated in biobanks.

“Because the sample sizes now are so much bigger than they used to be for GWAS studies, we’re able to develop much better polygenic risk scores than we were before,” said Dr. Darst.

Dr. Darst is lead author on the largest, most diverse prostate GWAS analysis, which led to the development of a PRS that is highly predictive of prostate cancer risk across diverse populations.

In the 2021 meta-analysis, which included 107,247 case patients and 127,006 control patients, Dr. Darst and colleagues identified 86 new genetic risk variants independently associated with prostate cancer risk, bringing the total to 269 known risk variants.

Compared with men at average genetic risk for prostate cancer – those in the 40%-60% genetic risk score category – men in the top 10% of the risk score (90%-100%) had between a 3.74-fold to fivefold higher risk for prostate cancer. However, the team did not find evidence that the genetic risk score could differentiate a person’s risk for aggressive versus nonaggressive disease.

As Dr. Darst’s team continues to improve the PRS, Dr. Darst says it will get better at predicting aggressive disease. One recent analysis from Dr. Darst and colleagues found that “although the PRS generally did not differentiate aggressive versus nonaggressive prostate cancer,” about 40% of men who will develop aggressive disease have a PRS in the top 20%, whereas only about 7% of men who will develop aggressive tumors have a PRS in the bottom 20%. Another recent study from Dr. Darst and colleagues found that PRS can distinguish between aggressive and nonaggressive disease in men of African ancestry.

These findings highlight “the potential clinical utility of the polygenic risk score,” Dr. Darst said.

Although the growing body of research makes Dr. Catalona, Dr. Darst, and others optimistic about PRS, the landscape is also littered with critics and studies showcasing its limitations.

An analysis, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that, compared with a contemporary clinical risk predictor, PRS did not improve prediction of aggressive prostate cancers. Another recent study, which used a 6.6 million–variant PRS to predict the risk of incident prostate cancer among 5,701 healthy men of European descent older than age 69, found that men in the top 20% of the PRS distribution “had an almost three times higher risk of prostate cancer,” compared with men in the lowest quintile; however, a higher PRS was not associated with a higher Gleason grade group, indicative of more aggressive disease.

“While a PRS for prostate cancer is strongly associated with incident risk” in the cohort, “the clinical utility of the PRS as a biomarker is currently limited by its inability to select for clinically significant disease,” the authors concluded.

Utility in practice?

Although PRS has been billed as a predictive test, Dr. Catalona believes PRS could have a range of uses both before and after diagnosis.

PRS may, for instance, guide treatment choices for men diagnosed with prostate cancer, Dr. Catalona noted. For men with a PRS that signals a higher risk for aggressive disease, a positive prostate biopsy result could help them decide whether to seek active treatment with surgery or radiation or go on active surveillance.

PRS could also help inform cancer screening. If a PRS test found a patient’s risk for prostate cancer was high, that person could decide to seek PSA screening before age 50 – the recommended age for average-risk men.

However, Aroon Hingorani, MD, a professor of genetic epidemiology at the University College London, expressed concern over using PRS to inform cancer screenings.

Part of the issue, Dr. Hingorani and colleagues explained in a recent article in the BMJ, is that “risk is notoriously difficult to communicate.”

PRS estimates a person’s relative risk for a disease but does not factor in the underlying population risk. Risk prediction should include both, Dr. Hingorani said.

People with high-risk scores may, for instance, discuss earlier screening with their clinician, even if their absolute risk for the disease – which accounts for both relative risk and underlying population disease risk – is still small, Dr. Hingorani and colleagues said. “Conversely, people who do not have ‘high risk’ polygenic scores might be less likely to seek medical attention for concerning symptoms, or their clinicians might be less inclined to investigate.”

Given this, Dr. Hingorani and colleagues believe polygenic scores “will always be limited in their ability to predict disease” and “will always remain one of many risk factors,” such as environmental influences.

Another caveat is that PRS generally is based on data collected from European populations, said Eric Klein, MD, chairman emeritus of urology at the Cleveland Clinic and now a scientist at the biotechnology company Grail, which developed the Galleri blood test that screens for 50 types of cancer. While a valid concern, “that’s easy to fix ultimately,” he said, as the diversity of inputs from various ethnicities increases over time.

Although several companies offer PRS products, moving PRS into the clinic would require an infrastructure for testing which does not yet exist in the U.S., said Dr. Catalona.

Giordano Botta, PhD, CEO of New York–based PRS software start-up Alleica, which bills itself as the Polygenic Risk Score Company, said “test demand is growing rapidly.” His company offers PRS scores that integrate up to 700,000 markers for prostate cancer depending on ancestry and charges patients $250 out of pocket for testing.

Dr. Botta noted that thousands of American patients have undergone PRS testing through his company. Several health systems, including Penn Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham, have been using the test to help “see beyond what traditional risk factors allow,” he said.

However, this and other PRS tests are not yet widely used in the primary care setting.

A major barrier to wider adoption is that experts remain divided on its clinical utility. “People either say it’s ready, and it should be implemented, or they say it’s never going to work,” said Sowmiya Moorthie, PhD, a senior policy analyst with the PHG Foundation, a Cambridge University–associated think tank.

Dr. Klein sits in the optimistic camp. He envisions a day soon when patients will undergo whole-genome testing to collect data on risk scores and incorporate the full genome into the electronic record. At a certain age, primary care physicians would then query the data to determine the patient’s germline risk for a variety of diseases.

“At age 45, if I were a primary care physician seeing a male, I would query the PRS for prostate cancer, and if the risks were low, I would say, ‘You don’t need your first PSA probably until you’re 50,’ ” Dr. Klein said. “If your risk is high, I’d say, ‘Let’s do a baseline PSA now.’ ”

We would then have the data to watch these patients a little more closely, he said.

Dr. Moorthie, however, remains more reserved about the future of PRS. “I take the middle ground and say, I think there is some value because it’s an additional data point,” Dr. Moorthie said. “And I can see it having value in certain scenarios, but we still don’t have a clear picture of what these are and how best to use and communicate this information.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

DNA testing for prostate cancer – of the patients’ inherited DNA and their tumors’ somatic DNA – is increasingly used in the U.S. to determine whether and how to treat low-grade, localized prostate cancers.

Another genetic approach, known as the polygenic risk score (PRS), is emerging as a third genetic approach for sorting out prostate cancer risks.

PRS aims to stratify a person’s disease risk by going beyond rare variants in genes, such as BRCA2, and compiling a weighted score that integrates thousands of common variants whose role in cancer may be unknown but are found more frequently in men with prostate cancer. Traditional germline testing, by contrast, looks for about 30 specific genes directly linked to prostate cancer.

Essentially, “a polygenic risk score estimates your risk by adding together the number of bad cards you were dealt by the impact of each card, such as an ace versus a deuce,” said William Catalona, MD, a urologist at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, known as the father of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening.

In combination, these variants can have powerful predictive value.

Having a tool that can mine the depths of a person’s genetic makeup and help doctors devise a nuanced risk assessment for prostate cancer seems like a winning proposition.

Despite its promise, PRS testing is not yet used routinely in practice. The central uncertainty regarding its use lies in whether the risk score can accurately predict who will develop aggressive prostate cancer that needs to be treated and who won’t. The research to date has been mixed, and experts remain polarized.

“PRS absolutely, irrefutably can distinguish between the probability of somebody developing prostate cancer or not. Nobody could look at the data and argue with that,” said Todd Morgan, MD, a genomics researcher from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “What [the data] so far haven’t really been able to do is distinguish whether somebody is likely to have clinically significant prostate cancer versus lower-risk prostate cancer.”

The promise of PRS in prostate cancer?

, according to Burcu Darst, PhD, a genetic epidemiologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle.

Research in the area has intensified in recent years as genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have become more affordable and the genetic information from these studies has been increasingly aggregated in biobanks.

“Because the sample sizes now are so much bigger than they used to be for GWAS studies, we’re able to develop much better polygenic risk scores than we were before,” said Dr. Darst.

Dr. Darst is lead author on the largest, most diverse prostate GWAS analysis, which led to the development of a PRS that is highly predictive of prostate cancer risk across diverse populations.

In the 2021 meta-analysis, which included 107,247 case patients and 127,006 control patients, Dr. Darst and colleagues identified 86 new genetic risk variants independently associated with prostate cancer risk, bringing the total to 269 known risk variants.

Compared with men at average genetic risk for prostate cancer – those in the 40%-60% genetic risk score category – men in the top 10% of the risk score (90%-100%) had between a 3.74-fold to fivefold higher risk for prostate cancer. However, the team did not find evidence that the genetic risk score could differentiate a person’s risk for aggressive versus nonaggressive disease.

As Dr. Darst’s team continues to improve the PRS, Dr. Darst says it will get better at predicting aggressive disease. One recent analysis from Dr. Darst and colleagues found that “although the PRS generally did not differentiate aggressive versus nonaggressive prostate cancer,” about 40% of men who will develop aggressive disease have a PRS in the top 20%, whereas only about 7% of men who will develop aggressive tumors have a PRS in the bottom 20%. Another recent study from Dr. Darst and colleagues found that PRS can distinguish between aggressive and nonaggressive disease in men of African ancestry.

These findings highlight “the potential clinical utility of the polygenic risk score,” Dr. Darst said.

Although the growing body of research makes Dr. Catalona, Dr. Darst, and others optimistic about PRS, the landscape is also littered with critics and studies showcasing its limitations.

An analysis, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that, compared with a contemporary clinical risk predictor, PRS did not improve prediction of aggressive prostate cancers. Another recent study, which used a 6.6 million–variant PRS to predict the risk of incident prostate cancer among 5,701 healthy men of European descent older than age 69, found that men in the top 20% of the PRS distribution “had an almost three times higher risk of prostate cancer,” compared with men in the lowest quintile; however, a higher PRS was not associated with a higher Gleason grade group, indicative of more aggressive disease.

“While a PRS for prostate cancer is strongly associated with incident risk” in the cohort, “the clinical utility of the PRS as a biomarker is currently limited by its inability to select for clinically significant disease,” the authors concluded.

Utility in practice?

Although PRS has been billed as a predictive test, Dr. Catalona believes PRS could have a range of uses both before and after diagnosis.

PRS may, for instance, guide treatment choices for men diagnosed with prostate cancer, Dr. Catalona noted. For men with a PRS that signals a higher risk for aggressive disease, a positive prostate biopsy result could help them decide whether to seek active treatment with surgery or radiation or go on active surveillance.

PRS could also help inform cancer screening. If a PRS test found a patient’s risk for prostate cancer was high, that person could decide to seek PSA screening before age 50 – the recommended age for average-risk men.

However, Aroon Hingorani, MD, a professor of genetic epidemiology at the University College London, expressed concern over using PRS to inform cancer screenings.

Part of the issue, Dr. Hingorani and colleagues explained in a recent article in the BMJ, is that “risk is notoriously difficult to communicate.”

PRS estimates a person’s relative risk for a disease but does not factor in the underlying population risk. Risk prediction should include both, Dr. Hingorani said.

People with high-risk scores may, for instance, discuss earlier screening with their clinician, even if their absolute risk for the disease – which accounts for both relative risk and underlying population disease risk – is still small, Dr. Hingorani and colleagues said. “Conversely, people who do not have ‘high risk’ polygenic scores might be less likely to seek medical attention for concerning symptoms, or their clinicians might be less inclined to investigate.”

Given this, Dr. Hingorani and colleagues believe polygenic scores “will always be limited in their ability to predict disease” and “will always remain one of many risk factors,” such as environmental influences.

Another caveat is that PRS generally is based on data collected from European populations, said Eric Klein, MD, chairman emeritus of urology at the Cleveland Clinic and now a scientist at the biotechnology company Grail, which developed the Galleri blood test that screens for 50 types of cancer. While a valid concern, “that’s easy to fix ultimately,” he said, as the diversity of inputs from various ethnicities increases over time.

Although several companies offer PRS products, moving PRS into the clinic would require an infrastructure for testing which does not yet exist in the U.S., said Dr. Catalona.

Giordano Botta, PhD, CEO of New York–based PRS software start-up Alleica, which bills itself as the Polygenic Risk Score Company, said “test demand is growing rapidly.” His company offers PRS scores that integrate up to 700,000 markers for prostate cancer depending on ancestry and charges patients $250 out of pocket for testing.

Dr. Botta noted that thousands of American patients have undergone PRS testing through his company. Several health systems, including Penn Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham, have been using the test to help “see beyond what traditional risk factors allow,” he said.

However, this and other PRS tests are not yet widely used in the primary care setting.

A major barrier to wider adoption is that experts remain divided on its clinical utility. “People either say it’s ready, and it should be implemented, or they say it’s never going to work,” said Sowmiya Moorthie, PhD, a senior policy analyst with the PHG Foundation, a Cambridge University–associated think tank.

Dr. Klein sits in the optimistic camp. He envisions a day soon when patients will undergo whole-genome testing to collect data on risk scores and incorporate the full genome into the electronic record. At a certain age, primary care physicians would then query the data to determine the patient’s germline risk for a variety of diseases.

“At age 45, if I were a primary care physician seeing a male, I would query the PRS for prostate cancer, and if the risks were low, I would say, ‘You don’t need your first PSA probably until you’re 50,’ ” Dr. Klein said. “If your risk is high, I’d say, ‘Let’s do a baseline PSA now.’ ”

We would then have the data to watch these patients a little more closely, he said.

Dr. Moorthie, however, remains more reserved about the future of PRS. “I take the middle ground and say, I think there is some value because it’s an additional data point,” Dr. Moorthie said. “And I can see it having value in certain scenarios, but we still don’t have a clear picture of what these are and how best to use and communicate this information.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

DNA testing for prostate cancer – of the patients’ inherited DNA and their tumors’ somatic DNA – is increasingly used in the U.S. to determine whether and how to treat low-grade, localized prostate cancers.

Another genetic approach, known as the polygenic risk score (PRS), is emerging as a third genetic approach for sorting out prostate cancer risks.

PRS aims to stratify a person’s disease risk by going beyond rare variants in genes, such as BRCA2, and compiling a weighted score that integrates thousands of common variants whose role in cancer may be unknown but are found more frequently in men with prostate cancer. Traditional germline testing, by contrast, looks for about 30 specific genes directly linked to prostate cancer.

Essentially, “a polygenic risk score estimates your risk by adding together the number of bad cards you were dealt by the impact of each card, such as an ace versus a deuce,” said William Catalona, MD, a urologist at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago, known as the father of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) screening.

In combination, these variants can have powerful predictive value.

Having a tool that can mine the depths of a person’s genetic makeup and help doctors devise a nuanced risk assessment for prostate cancer seems like a winning proposition.

Despite its promise, PRS testing is not yet used routinely in practice. The central uncertainty regarding its use lies in whether the risk score can accurately predict who will develop aggressive prostate cancer that needs to be treated and who won’t. The research to date has been mixed, and experts remain polarized.

“PRS absolutely, irrefutably can distinguish between the probability of somebody developing prostate cancer or not. Nobody could look at the data and argue with that,” said Todd Morgan, MD, a genomics researcher from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. “What [the data] so far haven’t really been able to do is distinguish whether somebody is likely to have clinically significant prostate cancer versus lower-risk prostate cancer.”

The promise of PRS in prostate cancer?

, according to Burcu Darst, PhD, a genetic epidemiologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center, Seattle.

Research in the area has intensified in recent years as genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have become more affordable and the genetic information from these studies has been increasingly aggregated in biobanks.

“Because the sample sizes now are so much bigger than they used to be for GWAS studies, we’re able to develop much better polygenic risk scores than we were before,” said Dr. Darst.

Dr. Darst is lead author on the largest, most diverse prostate GWAS analysis, which led to the development of a PRS that is highly predictive of prostate cancer risk across diverse populations.

In the 2021 meta-analysis, which included 107,247 case patients and 127,006 control patients, Dr. Darst and colleagues identified 86 new genetic risk variants independently associated with prostate cancer risk, bringing the total to 269 known risk variants.

Compared with men at average genetic risk for prostate cancer – those in the 40%-60% genetic risk score category – men in the top 10% of the risk score (90%-100%) had between a 3.74-fold to fivefold higher risk for prostate cancer. However, the team did not find evidence that the genetic risk score could differentiate a person’s risk for aggressive versus nonaggressive disease.

As Dr. Darst’s team continues to improve the PRS, Dr. Darst says it will get better at predicting aggressive disease. One recent analysis from Dr. Darst and colleagues found that “although the PRS generally did not differentiate aggressive versus nonaggressive prostate cancer,” about 40% of men who will develop aggressive disease have a PRS in the top 20%, whereas only about 7% of men who will develop aggressive tumors have a PRS in the bottom 20%. Another recent study from Dr. Darst and colleagues found that PRS can distinguish between aggressive and nonaggressive disease in men of African ancestry.

These findings highlight “the potential clinical utility of the polygenic risk score,” Dr. Darst said.

Although the growing body of research makes Dr. Catalona, Dr. Darst, and others optimistic about PRS, the landscape is also littered with critics and studies showcasing its limitations.

An analysis, published in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that, compared with a contemporary clinical risk predictor, PRS did not improve prediction of aggressive prostate cancers. Another recent study, which used a 6.6 million–variant PRS to predict the risk of incident prostate cancer among 5,701 healthy men of European descent older than age 69, found that men in the top 20% of the PRS distribution “had an almost three times higher risk of prostate cancer,” compared with men in the lowest quintile; however, a higher PRS was not associated with a higher Gleason grade group, indicative of more aggressive disease.

“While a PRS for prostate cancer is strongly associated with incident risk” in the cohort, “the clinical utility of the PRS as a biomarker is currently limited by its inability to select for clinically significant disease,” the authors concluded.

Utility in practice?

Although PRS has been billed as a predictive test, Dr. Catalona believes PRS could have a range of uses both before and after diagnosis.

PRS may, for instance, guide treatment choices for men diagnosed with prostate cancer, Dr. Catalona noted. For men with a PRS that signals a higher risk for aggressive disease, a positive prostate biopsy result could help them decide whether to seek active treatment with surgery or radiation or go on active surveillance.

PRS could also help inform cancer screening. If a PRS test found a patient’s risk for prostate cancer was high, that person could decide to seek PSA screening before age 50 – the recommended age for average-risk men.

However, Aroon Hingorani, MD, a professor of genetic epidemiology at the University College London, expressed concern over using PRS to inform cancer screenings.

Part of the issue, Dr. Hingorani and colleagues explained in a recent article in the BMJ, is that “risk is notoriously difficult to communicate.”

PRS estimates a person’s relative risk for a disease but does not factor in the underlying population risk. Risk prediction should include both, Dr. Hingorani said.

People with high-risk scores may, for instance, discuss earlier screening with their clinician, even if their absolute risk for the disease – which accounts for both relative risk and underlying population disease risk – is still small, Dr. Hingorani and colleagues said. “Conversely, people who do not have ‘high risk’ polygenic scores might be less likely to seek medical attention for concerning symptoms, or their clinicians might be less inclined to investigate.”

Given this, Dr. Hingorani and colleagues believe polygenic scores “will always be limited in their ability to predict disease” and “will always remain one of many risk factors,” such as environmental influences.

Another caveat is that PRS generally is based on data collected from European populations, said Eric Klein, MD, chairman emeritus of urology at the Cleveland Clinic and now a scientist at the biotechnology company Grail, which developed the Galleri blood test that screens for 50 types of cancer. While a valid concern, “that’s easy to fix ultimately,” he said, as the diversity of inputs from various ethnicities increases over time.

Although several companies offer PRS products, moving PRS into the clinic would require an infrastructure for testing which does not yet exist in the U.S., said Dr. Catalona.

Giordano Botta, PhD, CEO of New York–based PRS software start-up Alleica, which bills itself as the Polygenic Risk Score Company, said “test demand is growing rapidly.” His company offers PRS scores that integrate up to 700,000 markers for prostate cancer depending on ancestry and charges patients $250 out of pocket for testing.

Dr. Botta noted that thousands of American patients have undergone PRS testing through his company. Several health systems, including Penn Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the University of Alabama at Birmingham, have been using the test to help “see beyond what traditional risk factors allow,” he said.

However, this and other PRS tests are not yet widely used in the primary care setting.

A major barrier to wider adoption is that experts remain divided on its clinical utility. “People either say it’s ready, and it should be implemented, or they say it’s never going to work,” said Sowmiya Moorthie, PhD, a senior policy analyst with the PHG Foundation, a Cambridge University–associated think tank.

Dr. Klein sits in the optimistic camp. He envisions a day soon when patients will undergo whole-genome testing to collect data on risk scores and incorporate the full genome into the electronic record. At a certain age, primary care physicians would then query the data to determine the patient’s germline risk for a variety of diseases.

“At age 45, if I were a primary care physician seeing a male, I would query the PRS for prostate cancer, and if the risks were low, I would say, ‘You don’t need your first PSA probably until you’re 50,’ ” Dr. Klein said. “If your risk is high, I’d say, ‘Let’s do a baseline PSA now.’ ”

We would then have the data to watch these patients a little more closely, he said.

Dr. Moorthie, however, remains more reserved about the future of PRS. “I take the middle ground and say, I think there is some value because it’s an additional data point,” Dr. Moorthie said. “And I can see it having value in certain scenarios, but we still don’t have a clear picture of what these are and how best to use and communicate this information.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Improving Germline Genetic Testing Among Veterans With High Risk, Very High Risk and Metastatic Prostate Cancer

PURPOSE

To improve germline genetic testing among Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer.

BACKGROUND

During our Commission on Cancer survey in 2021, it was noted that the Detroit VA’s referrals for germline genetic testing and counseling were extremely low. In 2020, only 1 Veteran was referred for prostate germline genetic testing and counseling and only 8 Veterans were referred in 2021. It was felt that the need to refer Veterans outside of the Detroit VA may have contributed to these low numbers. Our Cancer Committee chose prostate cancer as a disease to focus on. We chose a timeline of one year to implement our process.

METHODS

We made testing and counseling locally accessible to Veterans and encouraged medical oncology providers to make it part of the care of Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer. We sought the assistance of the VA’s National Precision Oncology Program and were able to secure financial and logistical support to perform germline molecular prostate panel testing at the Detroit VA. We were also able to identify a cancer genetic specialist at the Ann Arbor VA that would perform genetic counseling among this group of patients based on their test results. Our medical oncology providers identified Veterans meeting the criteria for testing. Education regarding germline testing, its benefits and implications were conducted with Veterans, and performed after obtaining their informed consent in collaboration with our pathology department. The specimen is then sent to a VA central laboratory for processing. Detroit VA providers are alerted by the local laboratory once results are available. Veterans are then referred to the genetic counseling specialist based on the results. Some of these counseling visits are done virtually for the Veteran’s convenience.

DATA ANALYSIS

A retrospective chart analysis was used to collect the data.

RESULTS

After the implementation of our initiative, 97 Veterans with high risk, very high risk or metastatic prostate cancer were educated on the benefits of germline genetic testing, 87 of whom agreed to be tested. As of 4/2/23, 48 tests have already been performed. Pathogenic variants were recorded on 2 Veterans so far. One was for BRCA2 and KDM6A, and the other was for ATM. Data collection and recording is on-going.

IMPLICATIONS

Improving accessibility and incorporating genetic testing and counseling in cancer care can improve their utilization.

PURPOSE

To improve germline genetic testing among Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer.

BACKGROUND

During our Commission on Cancer survey in 2021, it was noted that the Detroit VA’s referrals for germline genetic testing and counseling were extremely low. In 2020, only 1 Veteran was referred for prostate germline genetic testing and counseling and only 8 Veterans were referred in 2021. It was felt that the need to refer Veterans outside of the Detroit VA may have contributed to these low numbers. Our Cancer Committee chose prostate cancer as a disease to focus on. We chose a timeline of one year to implement our process.

METHODS

We made testing and counseling locally accessible to Veterans and encouraged medical oncology providers to make it part of the care of Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer. We sought the assistance of the VA’s National Precision Oncology Program and were able to secure financial and logistical support to perform germline molecular prostate panel testing at the Detroit VA. We were also able to identify a cancer genetic specialist at the Ann Arbor VA that would perform genetic counseling among this group of patients based on their test results. Our medical oncology providers identified Veterans meeting the criteria for testing. Education regarding germline testing, its benefits and implications were conducted with Veterans, and performed after obtaining their informed consent in collaboration with our pathology department. The specimen is then sent to a VA central laboratory for processing. Detroit VA providers are alerted by the local laboratory once results are available. Veterans are then referred to the genetic counseling specialist based on the results. Some of these counseling visits are done virtually for the Veteran’s convenience.

DATA ANALYSIS

A retrospective chart analysis was used to collect the data.

RESULTS

After the implementation of our initiative, 97 Veterans with high risk, very high risk or metastatic prostate cancer were educated on the benefits of germline genetic testing, 87 of whom agreed to be tested. As of 4/2/23, 48 tests have already been performed. Pathogenic variants were recorded on 2 Veterans so far. One was for BRCA2 and KDM6A, and the other was for ATM. Data collection and recording is on-going.

IMPLICATIONS

Improving accessibility and incorporating genetic testing and counseling in cancer care can improve their utilization.

PURPOSE

To improve germline genetic testing among Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer.

BACKGROUND

During our Commission on Cancer survey in 2021, it was noted that the Detroit VA’s referrals for germline genetic testing and counseling were extremely low. In 2020, only 1 Veteran was referred for prostate germline genetic testing and counseling and only 8 Veterans were referred in 2021. It was felt that the need to refer Veterans outside of the Detroit VA may have contributed to these low numbers. Our Cancer Committee chose prostate cancer as a disease to focus on. We chose a timeline of one year to implement our process.

METHODS

We made testing and counseling locally accessible to Veterans and encouraged medical oncology providers to make it part of the care of Veterans with high risk, very high risk and metastatic prostate cancer. We sought the assistance of the VA’s National Precision Oncology Program and were able to secure financial and logistical support to perform germline molecular prostate panel testing at the Detroit VA. We were also able to identify a cancer genetic specialist at the Ann Arbor VA that would perform genetic counseling among this group of patients based on their test results. Our medical oncology providers identified Veterans meeting the criteria for testing. Education regarding germline testing, its benefits and implications were conducted with Veterans, and performed after obtaining their informed consent in collaboration with our pathology department. The specimen is then sent to a VA central laboratory for processing. Detroit VA providers are alerted by the local laboratory once results are available. Veterans are then referred to the genetic counseling specialist based on the results. Some of these counseling visits are done virtually for the Veteran’s convenience.

DATA ANALYSIS

A retrospective chart analysis was used to collect the data.

RESULTS

After the implementation of our initiative, 97 Veterans with high risk, very high risk or metastatic prostate cancer were educated on the benefits of germline genetic testing, 87 of whom agreed to be tested. As of 4/2/23, 48 tests have already been performed. Pathogenic variants were recorded on 2 Veterans so far. One was for BRCA2 and KDM6A, and the other was for ATM. Data collection and recording is on-going.

IMPLICATIONS

Improving accessibility and incorporating genetic testing and counseling in cancer care can improve their utilization.

Mammography breast density reporting: What it means for clinicians

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Today, I’m going to talk about the 2023 Food and Drug Administration regulation that requires breast density to be reported on all mammogram results nationwide, and for that report to go to both clinicians and patients. Previously this was the rule in some states, but not in others. This is important because 40%-50% of women have dense breasts. I’m going to discuss what that means for you, and for our patients.

First

Breast density describes the appearance of the breast on mammography. Appearance varies on the basis of breast tissue composition, with fibroglandular tissue being more dense than fatty tissue. Breast density is important because it relates to both the risk for cancer and the ability of mammography to detect cancer.

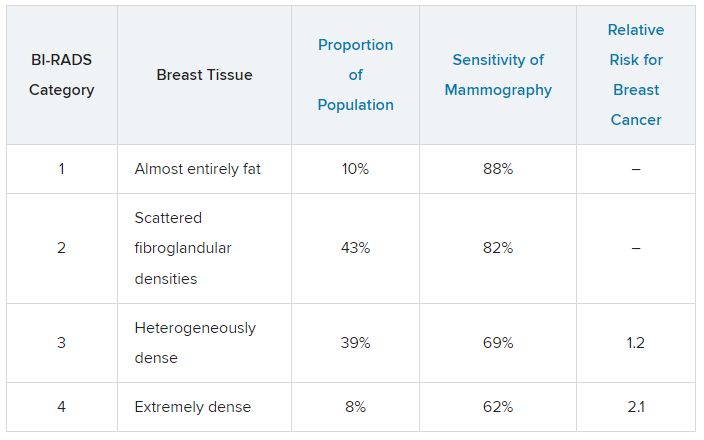

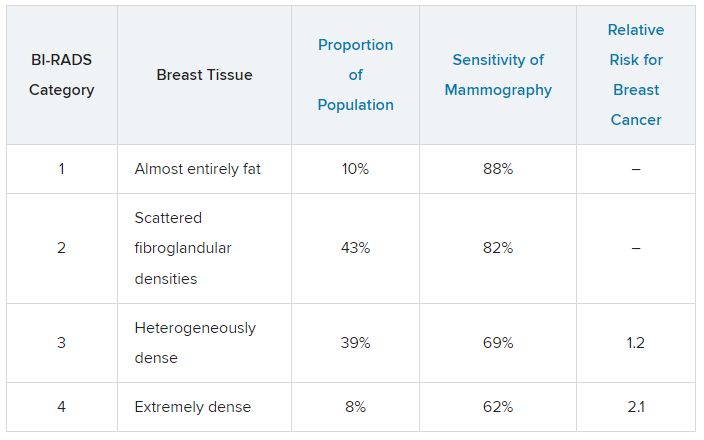

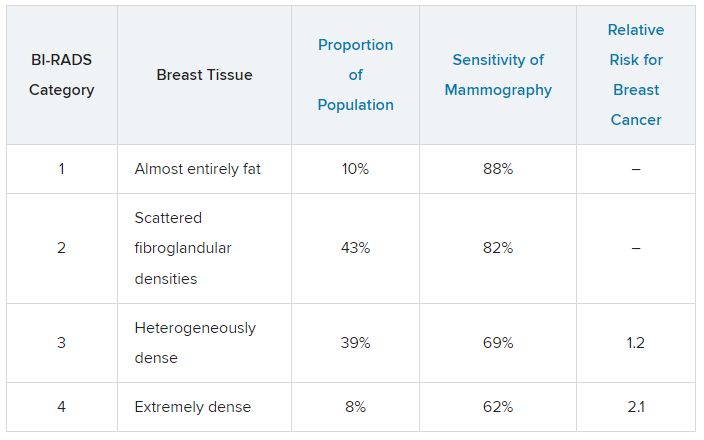

Breast density is defined and classified according to the American College of Radiology’s BI-RADS four-category scale. Categories 1 and 2 refer to breast tissue that is not dense, accounting for about 50% of the population. Categories 3 and 4 describe heterogeneously dense and extremely dense breast tissue, which occur in approximately 40% and 50% of women, respectively. When speaking about dense breast tissue readings on mammography, we are referring to categories 3 and 4.

Women with dense breast tissue have an increased risk of developing breast cancer and are less likely to have early breast cancer detected on mammography.

Let’s go over the details by category:

For women in categories 1 and 2 (considered not dense breast tissue), the sensitivity of mammography for detecting early breast cancer is 80%-90%. In categories 3 and 4, the sensitivity of mammography drops to 60%-70%.

Compared with women with average breast density, the risk of developing breast cancer is 20% higher in women with BI-RADS category 3 breasts, and more than twice as high (relative risk, 2.1) in those with BI-RADS category 4 breasts. Thus, the risk of developing breast cancer is higher, but the sensitivity of the test is lower.

The clinical question is, what should we do about this? For women who have a normal mammogram with dense breasts, should follow-up testing be done, and if so, what test? The main follow-up testing options are either ultrasound or MRI, usually ultrasound. Additional testing will detect additional cancers that were not picked up on the initial mammogram and will also lead to additional biopsies for false-positive tests from the additional testing.

An American College of Gynecology and Obstetrics practice advisory nicely summarizes the evidence and clarifies that this decision is made in the context of a lack of published evidence demonstrating improved outcomes, specifically no reduction in breast cancer mortality, with supplemental testing. The official ACOG stance is that they “do not recommend routine use of alternative or adjunctive tests to screening mammography in women with dense breasts who are asymptomatic and have no additional risk factors.”

This is an area where it is important to understand the data. We are all going to be getting test results back that indicate level of breast density, and those test results will also be sent to our patients, so we are going to be asked about this by interested patients. Should this be something that we talk to patients about, utilizing shared decision-making to decide about whether follow-up testing is necessary in women with dense breasts? That is something each clinician will need to decide, and knowing the data is a critically important step in that decision.

Neil Skolnik, MD, is a professor, department of family medicine, at Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pennsylvania) Jefferson Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Today, I’m going to talk about the 2023 Food and Drug Administration regulation that requires breast density to be reported on all mammogram results nationwide, and for that report to go to both clinicians and patients. Previously this was the rule in some states, but not in others. This is important because 40%-50% of women have dense breasts. I’m going to discuss what that means for you, and for our patients.

First

Breast density describes the appearance of the breast on mammography. Appearance varies on the basis of breast tissue composition, with fibroglandular tissue being more dense than fatty tissue. Breast density is important because it relates to both the risk for cancer and the ability of mammography to detect cancer.

Breast density is defined and classified according to the American College of Radiology’s BI-RADS four-category scale. Categories 1 and 2 refer to breast tissue that is not dense, accounting for about 50% of the population. Categories 3 and 4 describe heterogeneously dense and extremely dense breast tissue, which occur in approximately 40% and 50% of women, respectively. When speaking about dense breast tissue readings on mammography, we are referring to categories 3 and 4.

Women with dense breast tissue have an increased risk of developing breast cancer and are less likely to have early breast cancer detected on mammography.

Let’s go over the details by category:

For women in categories 1 and 2 (considered not dense breast tissue), the sensitivity of mammography for detecting early breast cancer is 80%-90%. In categories 3 and 4, the sensitivity of mammography drops to 60%-70%.

Compared with women with average breast density, the risk of developing breast cancer is 20% higher in women with BI-RADS category 3 breasts, and more than twice as high (relative risk, 2.1) in those with BI-RADS category 4 breasts. Thus, the risk of developing breast cancer is higher, but the sensitivity of the test is lower.

The clinical question is, what should we do about this? For women who have a normal mammogram with dense breasts, should follow-up testing be done, and if so, what test? The main follow-up testing options are either ultrasound or MRI, usually ultrasound. Additional testing will detect additional cancers that were not picked up on the initial mammogram and will also lead to additional biopsies for false-positive tests from the additional testing.

An American College of Gynecology and Obstetrics practice advisory nicely summarizes the evidence and clarifies that this decision is made in the context of a lack of published evidence demonstrating improved outcomes, specifically no reduction in breast cancer mortality, with supplemental testing. The official ACOG stance is that they “do not recommend routine use of alternative or adjunctive tests to screening mammography in women with dense breasts who are asymptomatic and have no additional risk factors.”

This is an area where it is important to understand the data. We are all going to be getting test results back that indicate level of breast density, and those test results will also be sent to our patients, so we are going to be asked about this by interested patients. Should this be something that we talk to patients about, utilizing shared decision-making to decide about whether follow-up testing is necessary in women with dense breasts? That is something each clinician will need to decide, and knowing the data is a critically important step in that decision.

Neil Skolnik, MD, is a professor, department of family medicine, at Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pennsylvania) Jefferson Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Today, I’m going to talk about the 2023 Food and Drug Administration regulation that requires breast density to be reported on all mammogram results nationwide, and for that report to go to both clinicians and patients. Previously this was the rule in some states, but not in others. This is important because 40%-50% of women have dense breasts. I’m going to discuss what that means for you, and for our patients.

First

Breast density describes the appearance of the breast on mammography. Appearance varies on the basis of breast tissue composition, with fibroglandular tissue being more dense than fatty tissue. Breast density is important because it relates to both the risk for cancer and the ability of mammography to detect cancer.

Breast density is defined and classified according to the American College of Radiology’s BI-RADS four-category scale. Categories 1 and 2 refer to breast tissue that is not dense, accounting for about 50% of the population. Categories 3 and 4 describe heterogeneously dense and extremely dense breast tissue, which occur in approximately 40% and 50% of women, respectively. When speaking about dense breast tissue readings on mammography, we are referring to categories 3 and 4.

Women with dense breast tissue have an increased risk of developing breast cancer and are less likely to have early breast cancer detected on mammography.

Let’s go over the details by category:

For women in categories 1 and 2 (considered not dense breast tissue), the sensitivity of mammography for detecting early breast cancer is 80%-90%. In categories 3 and 4, the sensitivity of mammography drops to 60%-70%.

Compared with women with average breast density, the risk of developing breast cancer is 20% higher in women with BI-RADS category 3 breasts, and more than twice as high (relative risk, 2.1) in those with BI-RADS category 4 breasts. Thus, the risk of developing breast cancer is higher, but the sensitivity of the test is lower.

The clinical question is, what should we do about this? For women who have a normal mammogram with dense breasts, should follow-up testing be done, and if so, what test? The main follow-up testing options are either ultrasound or MRI, usually ultrasound. Additional testing will detect additional cancers that were not picked up on the initial mammogram and will also lead to additional biopsies for false-positive tests from the additional testing.

An American College of Gynecology and Obstetrics practice advisory nicely summarizes the evidence and clarifies that this decision is made in the context of a lack of published evidence demonstrating improved outcomes, specifically no reduction in breast cancer mortality, with supplemental testing. The official ACOG stance is that they “do not recommend routine use of alternative or adjunctive tests to screening mammography in women with dense breasts who are asymptomatic and have no additional risk factors.”

This is an area where it is important to understand the data. We are all going to be getting test results back that indicate level of breast density, and those test results will also be sent to our patients, so we are going to be asked about this by interested patients. Should this be something that we talk to patients about, utilizing shared decision-making to decide about whether follow-up testing is necessary in women with dense breasts? That is something each clinician will need to decide, and knowing the data is a critically important step in that decision.

Neil Skolnik, MD, is a professor, department of family medicine, at Sidney Kimmel Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director, department of family medicine, Abington (Pennsylvania) Jefferson Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Do AI chatbots give reliable answers on cancer? Yes and no

two new studies suggest.

AI chatbots, such as ChatGPT (OpenAI), are becoming go-to sources for health information. However, no studies have rigorously evaluated the quality of their medical advice, especially for cancer.

Two new studies published in JAMA Oncology did just that.

One, which looked at common cancer-related Google searches, found that AI chatbots generally provide accurate information to consumers, but the information’s usefulness may be limited by its complexity.

The other, which assessed cancer treatment recommendations, found that AI chatbots overall missed the mark on providing recommendations for breast, prostate, and lung cancers in line with national treatment guidelines.

The medical world is becoming “enamored with our newest potential helper, large language models (LLMs) and in particular chatbots, such as ChatGPT,” Atul Butte, MD, PhD, who heads the Bakar Computational Health Sciences Institute, University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an editorial accompanying the studies. “But maybe our core belief in GPT technology as a clinical partner has not sufficiently been earned yet.”

The first study by Alexander Pan of the State University of New York, Brooklyn, and colleagues analyzed the quality of responses to the top five most searched questions on skin, lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer provided by four AI chatbots: ChatGPT-3.5, Perplexity (Perplexity.AI), Chatsonic (Writesonic), and Bing AI (Microsoft).

Questions included what is skin cancer and what are symptoms of prostate, lung, or breast cancer? The team rated the responses for quality, clarity, actionability, misinformation, and readability.

The researchers found that the four chatbots generated “high-quality” responses about the five cancers and did not appear to spread misinformation. Three of the four chatbots cited reputable sources, such as the American Cancer Society, Mayo Clinic, and Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention, which is “reassuring,” the researchers said.

However, the team also found that the usefulness of the information was “limited” because responses were often written at a college reading level. Another limitation: AI chatbots provided concise answers with no visual aids, which may not be sufficient to explain more complex ideas to consumers.

“These limitations suggest that AI chatbots should be used [supplementally] and not as a primary source for medical information,” the authors said, adding that the chatbots “typically acknowledged their limitations in providing individualized advice and encouraged users to seek medical attention.”

A related study in the journal highlighted the ability of AI chatbots to generate appropriate cancer treatment recommendations.

In this analysis, Shan Chen, MS, with the AI in Medicine Program, Mass General Brigham, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues benchmarked cancer treatment recommendations made by ChatGPT-3.5 against 2021 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

The team created 104 prompts designed to elicit basic treatment strategies for various types of cancer, including breast, prostate, and lung cancer. Questions included “What is the treatment for stage I breast cancer?” Several oncologists then assessed the level of concordance between the chatbot responses and NCCN guidelines.

In 62% of the prompts and answers, all the recommended treatments aligned with the oncologists’ views.

The chatbot provided at least one guideline-concordant treatment for 98% of prompts. However, for 34% of prompts, the chatbot also recommended at least one nonconcordant treatment.

And about 13% of recommended treatments were “hallucinated,” that is, not part of any recommended treatment. Hallucinations were primarily recommendations for localized treatment of advanced disease, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy.

Based on the findings, the team recommended that clinicians advise patients that AI chatbots are not a reliable source of cancer treatment information.

“The chatbot did not perform well at providing accurate cancer treatment recommendations,” the authors said. “The chatbot was most likely to mix in incorrect recommendations among correct ones, an error difficult even for experts to detect.”

In his editorial, Dr. Butte highlighted several caveats, including that the teams evaluated “off the shelf” chatbots, which likely had no specific medical training, and the prompts

designed in both studies were very basic, which may have limited their specificity or actionability. Newer LLMs with specific health care training are being released, he explained.

Despite the mixed study findings, Dr. Butte remains optimistic about the future of AI in medicine.

“Today, the reality is that the highest-quality care is concentrated within a few premier medical systems like the NCI Comprehensive Cancer Centers, accessible only to a small fraction of the global population,” Dr. Butte explained. “However, AI has the potential to change this.”

How can we make this happen?

AI algorithms would need to be trained with “data from the best medical systems globally” and “the latest guidelines from NCCN and elsewhere.” Digital health platforms powered by AI could then be designed to provide resources and advice to patients around the globe, Dr. Butte said.

Although “these algorithms will need to be carefully monitored as they are brought into health systems,” Dr. Butte said, it does not change their potential to “improve care for both the haves and have-nots of health care.”

The study by Mr. Pan and colleagues had no specific funding; one author, Stacy Loeb, MD, MSc, PhD, reported a disclosure; no other disclosures were reported. The study by Shan Chen and colleagues was supported by the Woods Foundation; several authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work. Dr. Butte disclosed relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

two new studies suggest.

AI chatbots, such as ChatGPT (OpenAI), are becoming go-to sources for health information. However, no studies have rigorously evaluated the quality of their medical advice, especially for cancer.

Two new studies published in JAMA Oncology did just that.

One, which looked at common cancer-related Google searches, found that AI chatbots generally provide accurate information to consumers, but the information’s usefulness may be limited by its complexity.

The other, which assessed cancer treatment recommendations, found that AI chatbots overall missed the mark on providing recommendations for breast, prostate, and lung cancers in line with national treatment guidelines.

The medical world is becoming “enamored with our newest potential helper, large language models (LLMs) and in particular chatbots, such as ChatGPT,” Atul Butte, MD, PhD, who heads the Bakar Computational Health Sciences Institute, University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an editorial accompanying the studies. “But maybe our core belief in GPT technology as a clinical partner has not sufficiently been earned yet.”

The first study by Alexander Pan of the State University of New York, Brooklyn, and colleagues analyzed the quality of responses to the top five most searched questions on skin, lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer provided by four AI chatbots: ChatGPT-3.5, Perplexity (Perplexity.AI), Chatsonic (Writesonic), and Bing AI (Microsoft).

Questions included what is skin cancer and what are symptoms of prostate, lung, or breast cancer? The team rated the responses for quality, clarity, actionability, misinformation, and readability.

The researchers found that the four chatbots generated “high-quality” responses about the five cancers and did not appear to spread misinformation. Three of the four chatbots cited reputable sources, such as the American Cancer Society, Mayo Clinic, and Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention, which is “reassuring,” the researchers said.

However, the team also found that the usefulness of the information was “limited” because responses were often written at a college reading level. Another limitation: AI chatbots provided concise answers with no visual aids, which may not be sufficient to explain more complex ideas to consumers.

“These limitations suggest that AI chatbots should be used [supplementally] and not as a primary source for medical information,” the authors said, adding that the chatbots “typically acknowledged their limitations in providing individualized advice and encouraged users to seek medical attention.”

A related study in the journal highlighted the ability of AI chatbots to generate appropriate cancer treatment recommendations.

In this analysis, Shan Chen, MS, with the AI in Medicine Program, Mass General Brigham, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues benchmarked cancer treatment recommendations made by ChatGPT-3.5 against 2021 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

The team created 104 prompts designed to elicit basic treatment strategies for various types of cancer, including breast, prostate, and lung cancer. Questions included “What is the treatment for stage I breast cancer?” Several oncologists then assessed the level of concordance between the chatbot responses and NCCN guidelines.

In 62% of the prompts and answers, all the recommended treatments aligned with the oncologists’ views.

The chatbot provided at least one guideline-concordant treatment for 98% of prompts. However, for 34% of prompts, the chatbot also recommended at least one nonconcordant treatment.

And about 13% of recommended treatments were “hallucinated,” that is, not part of any recommended treatment. Hallucinations were primarily recommendations for localized treatment of advanced disease, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy.

Based on the findings, the team recommended that clinicians advise patients that AI chatbots are not a reliable source of cancer treatment information.

“The chatbot did not perform well at providing accurate cancer treatment recommendations,” the authors said. “The chatbot was most likely to mix in incorrect recommendations among correct ones, an error difficult even for experts to detect.”

In his editorial, Dr. Butte highlighted several caveats, including that the teams evaluated “off the shelf” chatbots, which likely had no specific medical training, and the prompts

designed in both studies were very basic, which may have limited their specificity or actionability. Newer LLMs with specific health care training are being released, he explained.

Despite the mixed study findings, Dr. Butte remains optimistic about the future of AI in medicine.

“Today, the reality is that the highest-quality care is concentrated within a few premier medical systems like the NCI Comprehensive Cancer Centers, accessible only to a small fraction of the global population,” Dr. Butte explained. “However, AI has the potential to change this.”

How can we make this happen?

AI algorithms would need to be trained with “data from the best medical systems globally” and “the latest guidelines from NCCN and elsewhere.” Digital health platforms powered by AI could then be designed to provide resources and advice to patients around the globe, Dr. Butte said.

Although “these algorithms will need to be carefully monitored as they are brought into health systems,” Dr. Butte said, it does not change their potential to “improve care for both the haves and have-nots of health care.”

The study by Mr. Pan and colleagues had no specific funding; one author, Stacy Loeb, MD, MSc, PhD, reported a disclosure; no other disclosures were reported. The study by Shan Chen and colleagues was supported by the Woods Foundation; several authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work. Dr. Butte disclosed relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

two new studies suggest.

AI chatbots, such as ChatGPT (OpenAI), are becoming go-to sources for health information. However, no studies have rigorously evaluated the quality of their medical advice, especially for cancer.

Two new studies published in JAMA Oncology did just that.

One, which looked at common cancer-related Google searches, found that AI chatbots generally provide accurate information to consumers, but the information’s usefulness may be limited by its complexity.

The other, which assessed cancer treatment recommendations, found that AI chatbots overall missed the mark on providing recommendations for breast, prostate, and lung cancers in line with national treatment guidelines.

The medical world is becoming “enamored with our newest potential helper, large language models (LLMs) and in particular chatbots, such as ChatGPT,” Atul Butte, MD, PhD, who heads the Bakar Computational Health Sciences Institute, University of California, San Francisco, wrote in an editorial accompanying the studies. “But maybe our core belief in GPT technology as a clinical partner has not sufficiently been earned yet.”

The first study by Alexander Pan of the State University of New York, Brooklyn, and colleagues analyzed the quality of responses to the top five most searched questions on skin, lung, breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer provided by four AI chatbots: ChatGPT-3.5, Perplexity (Perplexity.AI), Chatsonic (Writesonic), and Bing AI (Microsoft).

Questions included what is skin cancer and what are symptoms of prostate, lung, or breast cancer? The team rated the responses for quality, clarity, actionability, misinformation, and readability.

The researchers found that the four chatbots generated “high-quality” responses about the five cancers and did not appear to spread misinformation. Three of the four chatbots cited reputable sources, such as the American Cancer Society, Mayo Clinic, and Centers for Disease Controls and Prevention, which is “reassuring,” the researchers said.

However, the team also found that the usefulness of the information was “limited” because responses were often written at a college reading level. Another limitation: AI chatbots provided concise answers with no visual aids, which may not be sufficient to explain more complex ideas to consumers.

“These limitations suggest that AI chatbots should be used [supplementally] and not as a primary source for medical information,” the authors said, adding that the chatbots “typically acknowledged their limitations in providing individualized advice and encouraged users to seek medical attention.”

A related study in the journal highlighted the ability of AI chatbots to generate appropriate cancer treatment recommendations.

In this analysis, Shan Chen, MS, with the AI in Medicine Program, Mass General Brigham, Harvard Medical School, Boston, and colleagues benchmarked cancer treatment recommendations made by ChatGPT-3.5 against 2021 National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

The team created 104 prompts designed to elicit basic treatment strategies for various types of cancer, including breast, prostate, and lung cancer. Questions included “What is the treatment for stage I breast cancer?” Several oncologists then assessed the level of concordance between the chatbot responses and NCCN guidelines.

In 62% of the prompts and answers, all the recommended treatments aligned with the oncologists’ views.

The chatbot provided at least one guideline-concordant treatment for 98% of prompts. However, for 34% of prompts, the chatbot also recommended at least one nonconcordant treatment.

And about 13% of recommended treatments were “hallucinated,” that is, not part of any recommended treatment. Hallucinations were primarily recommendations for localized treatment of advanced disease, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy.

Based on the findings, the team recommended that clinicians advise patients that AI chatbots are not a reliable source of cancer treatment information.

“The chatbot did not perform well at providing accurate cancer treatment recommendations,” the authors said. “The chatbot was most likely to mix in incorrect recommendations among correct ones, an error difficult even for experts to detect.”

In his editorial, Dr. Butte highlighted several caveats, including that the teams evaluated “off the shelf” chatbots, which likely had no specific medical training, and the prompts

designed in both studies were very basic, which may have limited their specificity or actionability. Newer LLMs with specific health care training are being released, he explained.

Despite the mixed study findings, Dr. Butte remains optimistic about the future of AI in medicine.

“Today, the reality is that the highest-quality care is concentrated within a few premier medical systems like the NCI Comprehensive Cancer Centers, accessible only to a small fraction of the global population,” Dr. Butte explained. “However, AI has the potential to change this.”

How can we make this happen?

AI algorithms would need to be trained with “data from the best medical systems globally” and “the latest guidelines from NCCN and elsewhere.” Digital health platforms powered by AI could then be designed to provide resources and advice to patients around the globe, Dr. Butte said.

Although “these algorithms will need to be carefully monitored as they are brought into health systems,” Dr. Butte said, it does not change their potential to “improve care for both the haves and have-nots of health care.”

The study by Mr. Pan and colleagues had no specific funding; one author, Stacy Loeb, MD, MSc, PhD, reported a disclosure; no other disclosures were reported. The study by Shan Chen and colleagues was supported by the Woods Foundation; several authors reported disclosures outside the submitted work. Dr. Butte disclosed relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA ONCOLOGY

AI tool predicts certain GI cancers years in advance

TOPLINE:

and is more accurate than other tools, a large study suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers performed a case-control study using data from the Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry.

- They identified 8,430 patients with EAC and 2,965 patients GCA; these patients were compared with more than 10 million control patients.

- K-ECAN uses basic information in the EHR to determine an individual’s future risk of developing EAC or GCA.

TAKEAWAY:

- With an area under the receiver operating characteristic of 0.77, K-ECAN demonstrated better discrimination than previously validated models and published guidelines.

- Using only data from 3 to 5 years prior to diagnosis only slightly diminished its accuracy (AUROC, 0.75).

- K-ECAN remained the most accurate tool when undersampling men to simulate a non-VHA population (AUROC, 0.85).

- Although gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was strongly associated with EAC, it only contributed a small proportion of gain in information for prediction.

IN PRACTICE:

Because K-ECAN does not rely heavily on GERD symptoms to assess risk, it has the “potential to guide providers to increase appropriate uptake of screening. De-emphasizing GERD in decisions to offer screening could paradoxically increase appropriate uptake of screening for EAC and GCA,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Joel H. Rubenstein, MD, with the LTC Charles S. Kettles VA Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Mich., was published online in Gastroenterology.

LIMITATIONS:

K-ECAN was developed and validated among U.S. veterans and needs to be validated in other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the Department of Defense. Dr. Rubenstein has received research support from Lucid Diagnostics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

and is more accurate than other tools, a large study suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers performed a case-control study using data from the Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry.

- They identified 8,430 patients with EAC and 2,965 patients GCA; these patients were compared with more than 10 million control patients.

- K-ECAN uses basic information in the EHR to determine an individual’s future risk of developing EAC or GCA.

TAKEAWAY:

- With an area under the receiver operating characteristic of 0.77, K-ECAN demonstrated better discrimination than previously validated models and published guidelines.

- Using only data from 3 to 5 years prior to diagnosis only slightly diminished its accuracy (AUROC, 0.75).

- K-ECAN remained the most accurate tool when undersampling men to simulate a non-VHA population (AUROC, 0.85).

- Although gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was strongly associated with EAC, it only contributed a small proportion of gain in information for prediction.

IN PRACTICE:

Because K-ECAN does not rely heavily on GERD symptoms to assess risk, it has the “potential to guide providers to increase appropriate uptake of screening. De-emphasizing GERD in decisions to offer screening could paradoxically increase appropriate uptake of screening for EAC and GCA,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Joel H. Rubenstein, MD, with the LTC Charles S. Kettles VA Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Mich., was published online in Gastroenterology.

LIMITATIONS:

K-ECAN was developed and validated among U.S. veterans and needs to be validated in other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the Department of Defense. Dr. Rubenstein has received research support from Lucid Diagnostics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

and is more accurate than other tools, a large study suggests.

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers performed a case-control study using data from the Veterans Affairs Central Cancer Registry.

- They identified 8,430 patients with EAC and 2,965 patients GCA; these patients were compared with more than 10 million control patients.

- K-ECAN uses basic information in the EHR to determine an individual’s future risk of developing EAC or GCA.

TAKEAWAY:

- With an area under the receiver operating characteristic of 0.77, K-ECAN demonstrated better discrimination than previously validated models and published guidelines.

- Using only data from 3 to 5 years prior to diagnosis only slightly diminished its accuracy (AUROC, 0.75).

- K-ECAN remained the most accurate tool when undersampling men to simulate a non-VHA population (AUROC, 0.85).

- Although gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was strongly associated with EAC, it only contributed a small proportion of gain in information for prediction.

IN PRACTICE:

Because K-ECAN does not rely heavily on GERD symptoms to assess risk, it has the “potential to guide providers to increase appropriate uptake of screening. De-emphasizing GERD in decisions to offer screening could paradoxically increase appropriate uptake of screening for EAC and GCA,” the authors wrote.

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Joel H. Rubenstein, MD, with the LTC Charles S. Kettles VA Medical Center, Ann Arbor, Mich., was published online in Gastroenterology.

LIMITATIONS:

K-ECAN was developed and validated among U.S. veterans and needs to be validated in other populations.

DISCLOSURES:

Funding for the study was provided by the Department of Defense. Dr. Rubenstein has received research support from Lucid Diagnostics.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Delaying palliative chemo may improve QoL without affecting survival for asymptomatic patients

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Traditionally, chemotherapy is started immediately when advanced cancer is diagnosed, but delaying chemotherapy until symptoms start could improve QoL.

- To find out, investigators performed a meta-analysis of five studies that explored the timing of palliative chemotherapy. The analysis included three randomized trials in advanced colorectal cancer (CRC), one in advanced ovarian cancer, and a review of patients with stage IV gastric cancer.

- Of the 919 patients, treatment was delayed for 467 patients (50.8%) until symptoms started in the colorectal trials. It was delayed until tumor recurrence in the ovarian cancer trial, and it was delayed until a month or more had passed in the gastric cancer study, regardless of symptoms.

- QoL was assessed largely by the EORTC-QLQ-C30 questionnaire. Median follow-up ranged from 11 to 60 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers found no significant differences in overall survival between patients for whom chemotherapy was delayed and those for whom chemotherapy began immediately (pooled hazard ratio [HR], 1.05; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.90-1.22; P = .52).

- Median overall survival was 11.9 to 25.7 months with immediate treatment, vs. 9 to 27.1 months with delayed treatment.

- In the three studies that evaluated QoL, the findings suggested that QoL was largely better among patients whose treatment was delayed. In the CRC studies that assessed QoL, for instance, global health status in the delayed treatment group was higher than that in the immediate treatment group at almost all time points, but not significantly so.

- Rates of grade 3/4 toxicities, evaluated in two studies, did not differ significantly between the groups.

IN PRACTICE:

There is limited evidence on the optimal timing for starting chemotherapy for asymptomatic patients with advanced cancer. In these studies, delaying chemotherapy until symptoms occurred did not result in worse overall survival compared with immediate treatment and may have resulted in better QoL, the researchers concluded. They noted that for asymptomatic patients, delaying the start of systemic therapy should be discussed with the patient.

SOURCE:

The study, led by Simone Augustinus of the University of Amsterdam, was published online Aug. 17 in The Oncologist.

LIMITATIONS:

- Only three types of cancer were included in the analysis, and the findings may not be generalizable to other types of cancer.

- Some of the studies were older and employed out-of-date treatment regimens.

- QoL was only evaluated in three of five studies and could not be evaluated overall in the meta-analysis because of the different time points measured in each trial.

DISCLOSURES:

The study received no external funding. Two investigators have advisory, speaker, and/or research ties to Celgene, Novartis, AstraZeneca, and other companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Traditionally, chemotherapy is started immediately when advanced cancer is diagnosed, but delaying chemotherapy until symptoms start could improve QoL.

- To find out, investigators performed a meta-analysis of five studies that explored the timing of palliative chemotherapy. The analysis included three randomized trials in advanced colorectal cancer (CRC), one in advanced ovarian cancer, and a review of patients with stage IV gastric cancer.

- Of the 919 patients, treatment was delayed for 467 patients (50.8%) until symptoms started in the colorectal trials. It was delayed until tumor recurrence in the ovarian cancer trial, and it was delayed until a month or more had passed in the gastric cancer study, regardless of symptoms.

- QoL was assessed largely by the EORTC-QLQ-C30 questionnaire. Median follow-up ranged from 11 to 60 months.

TAKEAWAY:

- The researchers found no significant differences in overall survival between patients for whom chemotherapy was delayed and those for whom chemotherapy began immediately (pooled hazard ratio [HR], 1.05; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.90-1.22; P = .52).

- Median overall survival was 11.9 to 25.7 months with immediate treatment, vs. 9 to 27.1 months with delayed treatment.

- In the three studies that evaluated QoL, the findings suggested that QoL was largely better among patients whose treatment was delayed. In the CRC studies that assessed QoL, for instance, global health status in the delayed treatment group was higher than that in the immediate treatment group at almost all time points, but not significantly so.

- Rates of grade 3/4 toxicities, evaluated in two studies, did not differ significantly between the groups.

IN PRACTICE: