User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Transforming glycemic control at Norwalk Hospital

SHM eQUIPS program yields new protocols, guidelines

The Hospitalist recently sat down with Nancy J. Rennert, MD, FACE, FACP, CPHQ, chief of endocrinology and diabetes at Norwalk (Conn.) Hospital, Western Connecticut Health Network, to discuss her institution’s glycemic control initiatives.

Tell us a bit about your program:

Norwalk Hospital is a 366-bed community teaching hospital founded 125 years ago, now part of the growing Western Connecticut Health Network. Our residency and fellowship training programs are affiliated with Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and we are a branch campus of the University of Vermont, Burlington.

With leadership support, we created our Glycemic Care Team (GCT) 4 years ago to focus on improving the quality of care for persons with diabetes who were admitted to our hospital (often for another primary medical reason). Our hospitalists – 8 on the teaching service and 11 on the nonteaching service – are key players in our efforts as they care for the majority of medical inpatients. GCT is interdisciplinary and includes stakeholders at all levels, including quality, pharmacy, nutrition, hospital medicine, diabetes education, administrative leadership, endocrinology, information technology, point-of-care testing/pathology, surgery and more. We meet monthly with an agenda that includes safety events, glucometrics, and discussion of policies and protocols. Subgroups complete tasks in between the monthly meetings, and we bring in other clinical specialties as indicated based on the issues at hand.

What prior challenges did you encounter that led you to enroll in the Glycemic Control (GC) eQUIPS Program?

In order to know if our GCT was making a positive difference, we needed to first measure our baseline metrics and then identify our goals and develop our processes. We wanted actionable data analysis and the ability to differentiate areas of our hospital such as individual clinical units. After researching the options, we chose SHM’s GC eQUIPS Program, which we found to be user friendly. The national benchmarking was an important aspect for us as well. As a kick-off event, I invited Greg Maynard, MD, MHM, a hospitalist and the chief quality officer, UC Davis Medical Center, to speak on inpatient diabetes and was thrilled when he accepted my invitation. This provided an exciting start to our journey with SHM’s eQUIPS data management program.

As we began to obtain baseline measurements of glucose control, we needed a standardized, validated tool. The point-of-care glucose meters generated an enormous amount of data, but we were unable to sort this and analyze it in a meaningful and potentially actionable way. We were especially concerned about hypoglycemia. Our first task was to develop a prescriber ordered and nurse driven hypoglycemia protocol. How would we measure the overall effectiveness and success of the stepwise components of the protocol? The eQUIPS hypoglycemia management report was ideal in that it detailed metrics in stepwise fashion as it related to our protocol. For example, we were able to see the time from detection of hypoglycemia to the next point-of-care glucose check and to resolution of the event.

In addition, we wanted some comparative benchmarking data. The GC eQUIPS Program has a robust database of U.S. hospitals, which helped us define our ultimate goal – to be in the upper quartile of all measures. And we did it! Because of the amazing teamwork and leadership support, we were able to achieve national distinction from SHM as a “Top Performer” hospital for glycemic care.

How did the program help you and the team design your initiatives?

Data are powerful and convincing. We post and report our eQUIPS Glucometrics to our clinical staff monthly by unit, and through this process, we obtain the necessary “buy-ins” as well as participation to design clinical protocols and order sets. For example, we noted that many patients would be placed on “sliding scale”/coverage insulin alone at the time of hospital admission. This often would not be adjusted during the hospital stay. Our data showed that this practice was associated with more glucose fluctuations and hypoglycemia. When we reviewed this with our hospitalists, we achieved consensus and developed basal/bolus correction insulin protocols, which are embedded in the admission care sets. Following use of these order sets, we noted less hypoglycemia (decreased from 5.9% and remains less than 3.6%) and lower glucose variability. With the help of the eQUIPS metrics and benchmarking, we now have more than 20 protocols and safety rules built into our EHR system.

What were the key benefits that the GC eQUIPS Program provided that you were unable to find elsewhere?

The unique features we found most useful are the national benchmarking and “real-world” data presentation. National benchmarking allows us to compare ourselves with other hospitals (we can sort for like hospitals or all hospitals) and to periodically evaluate our processes and reexamine our goals. As part of this program, we can communicate with leaders of other high-performing hospitals and share strategies and challenges as well as discuss successes and failures. The quarterly benchmark webinar is another opportunity to be part of this professional community and we often pick up helpful information.

We particularly like the hyperglycemia/hypoglycemia scatter plots, which demonstrate the practical and important impact of glycemic control. Often there is a see-saw effect in which, if one parameter goes up, the other goes down; finding the sweet spot between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia is key and clinically important.

Do you have any other comments to share related to your institution’s participation in the program?

We are fortunate to have many successes driven by our participation with the GC eQUIPS Program:

- Coordination of capillary blood glucose (CBG) testing, insulin administration and meal delivery: Use of rapid-acting insulin premeal is standard of care and requires that CBG testing, insulin, and meal delivery be precisely coordinated for optimal insulin action. We developed a process in which the catering associate calls the nurse using a voice-activated pager when the meal tray leaves the kitchen. Then, the nurse checks the CBG and gives insulin when the tray arrives. The tray contains a card to empower the patient to wait for the nurse to administer insulin prior to eating. This also provides an opportunity for nutritional education and carbohydrate awareness. Implementation of this process increased the percentage of patients who had a CBG and insulin administration within 15 minutes before a meal from less than 10% to more than 60%.

- Patient education regarding insulin use: In many cases, hospital patients may be started on insulin and their oral agents may be discontinued. This can be confusing and frightening to patients who often do not know if they will need to be on insulin long term. Our GCT created a script for the staff nurse to inform and reassure patients that this is standard practice and does not mean that they will need to remain on insulin after hospital discharge. The clinical team will communicate with the patient and together they will review treatment options. We have received many positive reviews from patients and staff for improving communication around this aspect of insulin therapy.

- Clinician and leader education: When our data revealed an uptick in hypoglycemia in our critical care units, we engaged the physicians, nurses, and staff and reviewed patient charts to identify potential process changes. To keep hypoglycemia in the spotlight, our director of critical care added hypoglycemia to the ICU checklist, which is discussed on all team clinical rounds. We are also developing an electronic metric (24-hour glucose maximum and minimum values) that can be quickly reviewed by the clinical team daily.

- Hypoglycemia and hyperkalemia: Analysis of our hypoglycemia data revealed a higher-than-expected rate in the ED in patients who did not have a diabetes diagnosis. Further review showed that this was associated with insulin treatment of hyperkalemia. Subsequently, we engaged our resident trainees and other team members in a study to characterize this hypoglycemia-hyperkalemia, and we have recently submitted a manuscript for publication detailing our findings and recommendations for glucose monitoring in these patients.

- Guideline for medical consultation on nonmedical services: Based on review of glucometrics on the nonmedical units and discussions with our hospitalist teams, we designed a guideline that includes recommendations for Medical Consultation in Nonmedical Admissions. Comanagement by a medical consultant will be requested earlier, and we will monitor if this influences glucometrics, patient and hospitalist satisfaction, etc.

- Medical student and house staff education: Two of our GCT hospitalists organize a monthly patient safety conference. After the students and trainees are asked to propose actionable solutions, the hospitalists discuss proposals generated at our GCT meetings. The students and trainees have the opportunity to participate in quality improvement, and we get great ideas from them as well.

Perhaps our biggest success is our Glycemic Care Team itself. We now receive questions and items to review from all departments and are seen as the hospital’s expert team on diabetes and hyperglycemia. It is truly a pleasure to lead this group of extremely high functioning and dedicated professionals. It is said that “team work makes the dream work.” Moving forward, I hope to expand our Glycemic Care Team to all the hospitals in our network.

SHM eQUIPS program yields new protocols, guidelines

SHM eQUIPS program yields new protocols, guidelines

The Hospitalist recently sat down with Nancy J. Rennert, MD, FACE, FACP, CPHQ, chief of endocrinology and diabetes at Norwalk (Conn.) Hospital, Western Connecticut Health Network, to discuss her institution’s glycemic control initiatives.

Tell us a bit about your program:

Norwalk Hospital is a 366-bed community teaching hospital founded 125 years ago, now part of the growing Western Connecticut Health Network. Our residency and fellowship training programs are affiliated with Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and we are a branch campus of the University of Vermont, Burlington.

With leadership support, we created our Glycemic Care Team (GCT) 4 years ago to focus on improving the quality of care for persons with diabetes who were admitted to our hospital (often for another primary medical reason). Our hospitalists – 8 on the teaching service and 11 on the nonteaching service – are key players in our efforts as they care for the majority of medical inpatients. GCT is interdisciplinary and includes stakeholders at all levels, including quality, pharmacy, nutrition, hospital medicine, diabetes education, administrative leadership, endocrinology, information technology, point-of-care testing/pathology, surgery and more. We meet monthly with an agenda that includes safety events, glucometrics, and discussion of policies and protocols. Subgroups complete tasks in between the monthly meetings, and we bring in other clinical specialties as indicated based on the issues at hand.

What prior challenges did you encounter that led you to enroll in the Glycemic Control (GC) eQUIPS Program?

In order to know if our GCT was making a positive difference, we needed to first measure our baseline metrics and then identify our goals and develop our processes. We wanted actionable data analysis and the ability to differentiate areas of our hospital such as individual clinical units. After researching the options, we chose SHM’s GC eQUIPS Program, which we found to be user friendly. The national benchmarking was an important aspect for us as well. As a kick-off event, I invited Greg Maynard, MD, MHM, a hospitalist and the chief quality officer, UC Davis Medical Center, to speak on inpatient diabetes and was thrilled when he accepted my invitation. This provided an exciting start to our journey with SHM’s eQUIPS data management program.

As we began to obtain baseline measurements of glucose control, we needed a standardized, validated tool. The point-of-care glucose meters generated an enormous amount of data, but we were unable to sort this and analyze it in a meaningful and potentially actionable way. We were especially concerned about hypoglycemia. Our first task was to develop a prescriber ordered and nurse driven hypoglycemia protocol. How would we measure the overall effectiveness and success of the stepwise components of the protocol? The eQUIPS hypoglycemia management report was ideal in that it detailed metrics in stepwise fashion as it related to our protocol. For example, we were able to see the time from detection of hypoglycemia to the next point-of-care glucose check and to resolution of the event.

In addition, we wanted some comparative benchmarking data. The GC eQUIPS Program has a robust database of U.S. hospitals, which helped us define our ultimate goal – to be in the upper quartile of all measures. And we did it! Because of the amazing teamwork and leadership support, we were able to achieve national distinction from SHM as a “Top Performer” hospital for glycemic care.

How did the program help you and the team design your initiatives?

Data are powerful and convincing. We post and report our eQUIPS Glucometrics to our clinical staff monthly by unit, and through this process, we obtain the necessary “buy-ins” as well as participation to design clinical protocols and order sets. For example, we noted that many patients would be placed on “sliding scale”/coverage insulin alone at the time of hospital admission. This often would not be adjusted during the hospital stay. Our data showed that this practice was associated with more glucose fluctuations and hypoglycemia. When we reviewed this with our hospitalists, we achieved consensus and developed basal/bolus correction insulin protocols, which are embedded in the admission care sets. Following use of these order sets, we noted less hypoglycemia (decreased from 5.9% and remains less than 3.6%) and lower glucose variability. With the help of the eQUIPS metrics and benchmarking, we now have more than 20 protocols and safety rules built into our EHR system.

What were the key benefits that the GC eQUIPS Program provided that you were unable to find elsewhere?

The unique features we found most useful are the national benchmarking and “real-world” data presentation. National benchmarking allows us to compare ourselves with other hospitals (we can sort for like hospitals or all hospitals) and to periodically evaluate our processes and reexamine our goals. As part of this program, we can communicate with leaders of other high-performing hospitals and share strategies and challenges as well as discuss successes and failures. The quarterly benchmark webinar is another opportunity to be part of this professional community and we often pick up helpful information.

We particularly like the hyperglycemia/hypoglycemia scatter plots, which demonstrate the practical and important impact of glycemic control. Often there is a see-saw effect in which, if one parameter goes up, the other goes down; finding the sweet spot between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia is key and clinically important.

Do you have any other comments to share related to your institution’s participation in the program?

We are fortunate to have many successes driven by our participation with the GC eQUIPS Program:

- Coordination of capillary blood glucose (CBG) testing, insulin administration and meal delivery: Use of rapid-acting insulin premeal is standard of care and requires that CBG testing, insulin, and meal delivery be precisely coordinated for optimal insulin action. We developed a process in which the catering associate calls the nurse using a voice-activated pager when the meal tray leaves the kitchen. Then, the nurse checks the CBG and gives insulin when the tray arrives. The tray contains a card to empower the patient to wait for the nurse to administer insulin prior to eating. This also provides an opportunity for nutritional education and carbohydrate awareness. Implementation of this process increased the percentage of patients who had a CBG and insulin administration within 15 minutes before a meal from less than 10% to more than 60%.

- Patient education regarding insulin use: In many cases, hospital patients may be started on insulin and their oral agents may be discontinued. This can be confusing and frightening to patients who often do not know if they will need to be on insulin long term. Our GCT created a script for the staff nurse to inform and reassure patients that this is standard practice and does not mean that they will need to remain on insulin after hospital discharge. The clinical team will communicate with the patient and together they will review treatment options. We have received many positive reviews from patients and staff for improving communication around this aspect of insulin therapy.

- Clinician and leader education: When our data revealed an uptick in hypoglycemia in our critical care units, we engaged the physicians, nurses, and staff and reviewed patient charts to identify potential process changes. To keep hypoglycemia in the spotlight, our director of critical care added hypoglycemia to the ICU checklist, which is discussed on all team clinical rounds. We are also developing an electronic metric (24-hour glucose maximum and minimum values) that can be quickly reviewed by the clinical team daily.

- Hypoglycemia and hyperkalemia: Analysis of our hypoglycemia data revealed a higher-than-expected rate in the ED in patients who did not have a diabetes diagnosis. Further review showed that this was associated with insulin treatment of hyperkalemia. Subsequently, we engaged our resident trainees and other team members in a study to characterize this hypoglycemia-hyperkalemia, and we have recently submitted a manuscript for publication detailing our findings and recommendations for glucose monitoring in these patients.

- Guideline for medical consultation on nonmedical services: Based on review of glucometrics on the nonmedical units and discussions with our hospitalist teams, we designed a guideline that includes recommendations for Medical Consultation in Nonmedical Admissions. Comanagement by a medical consultant will be requested earlier, and we will monitor if this influences glucometrics, patient and hospitalist satisfaction, etc.

- Medical student and house staff education: Two of our GCT hospitalists organize a monthly patient safety conference. After the students and trainees are asked to propose actionable solutions, the hospitalists discuss proposals generated at our GCT meetings. The students and trainees have the opportunity to participate in quality improvement, and we get great ideas from them as well.

Perhaps our biggest success is our Glycemic Care Team itself. We now receive questions and items to review from all departments and are seen as the hospital’s expert team on diabetes and hyperglycemia. It is truly a pleasure to lead this group of extremely high functioning and dedicated professionals. It is said that “team work makes the dream work.” Moving forward, I hope to expand our Glycemic Care Team to all the hospitals in our network.

The Hospitalist recently sat down with Nancy J. Rennert, MD, FACE, FACP, CPHQ, chief of endocrinology and diabetes at Norwalk (Conn.) Hospital, Western Connecticut Health Network, to discuss her institution’s glycemic control initiatives.

Tell us a bit about your program:

Norwalk Hospital is a 366-bed community teaching hospital founded 125 years ago, now part of the growing Western Connecticut Health Network. Our residency and fellowship training programs are affiliated with Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and we are a branch campus of the University of Vermont, Burlington.

With leadership support, we created our Glycemic Care Team (GCT) 4 years ago to focus on improving the quality of care for persons with diabetes who were admitted to our hospital (often for another primary medical reason). Our hospitalists – 8 on the teaching service and 11 on the nonteaching service – are key players in our efforts as they care for the majority of medical inpatients. GCT is interdisciplinary and includes stakeholders at all levels, including quality, pharmacy, nutrition, hospital medicine, diabetes education, administrative leadership, endocrinology, information technology, point-of-care testing/pathology, surgery and more. We meet monthly with an agenda that includes safety events, glucometrics, and discussion of policies and protocols. Subgroups complete tasks in between the monthly meetings, and we bring in other clinical specialties as indicated based on the issues at hand.

What prior challenges did you encounter that led you to enroll in the Glycemic Control (GC) eQUIPS Program?

In order to know if our GCT was making a positive difference, we needed to first measure our baseline metrics and then identify our goals and develop our processes. We wanted actionable data analysis and the ability to differentiate areas of our hospital such as individual clinical units. After researching the options, we chose SHM’s GC eQUIPS Program, which we found to be user friendly. The national benchmarking was an important aspect for us as well. As a kick-off event, I invited Greg Maynard, MD, MHM, a hospitalist and the chief quality officer, UC Davis Medical Center, to speak on inpatient diabetes and was thrilled when he accepted my invitation. This provided an exciting start to our journey with SHM’s eQUIPS data management program.

As we began to obtain baseline measurements of glucose control, we needed a standardized, validated tool. The point-of-care glucose meters generated an enormous amount of data, but we were unable to sort this and analyze it in a meaningful and potentially actionable way. We were especially concerned about hypoglycemia. Our first task was to develop a prescriber ordered and nurse driven hypoglycemia protocol. How would we measure the overall effectiveness and success of the stepwise components of the protocol? The eQUIPS hypoglycemia management report was ideal in that it detailed metrics in stepwise fashion as it related to our protocol. For example, we were able to see the time from detection of hypoglycemia to the next point-of-care glucose check and to resolution of the event.

In addition, we wanted some comparative benchmarking data. The GC eQUIPS Program has a robust database of U.S. hospitals, which helped us define our ultimate goal – to be in the upper quartile of all measures. And we did it! Because of the amazing teamwork and leadership support, we were able to achieve national distinction from SHM as a “Top Performer” hospital for glycemic care.

How did the program help you and the team design your initiatives?

Data are powerful and convincing. We post and report our eQUIPS Glucometrics to our clinical staff monthly by unit, and through this process, we obtain the necessary “buy-ins” as well as participation to design clinical protocols and order sets. For example, we noted that many patients would be placed on “sliding scale”/coverage insulin alone at the time of hospital admission. This often would not be adjusted during the hospital stay. Our data showed that this practice was associated with more glucose fluctuations and hypoglycemia. When we reviewed this with our hospitalists, we achieved consensus and developed basal/bolus correction insulin protocols, which are embedded in the admission care sets. Following use of these order sets, we noted less hypoglycemia (decreased from 5.9% and remains less than 3.6%) and lower glucose variability. With the help of the eQUIPS metrics and benchmarking, we now have more than 20 protocols and safety rules built into our EHR system.

What were the key benefits that the GC eQUIPS Program provided that you were unable to find elsewhere?

The unique features we found most useful are the national benchmarking and “real-world” data presentation. National benchmarking allows us to compare ourselves with other hospitals (we can sort for like hospitals or all hospitals) and to periodically evaluate our processes and reexamine our goals. As part of this program, we can communicate with leaders of other high-performing hospitals and share strategies and challenges as well as discuss successes and failures. The quarterly benchmark webinar is another opportunity to be part of this professional community and we often pick up helpful information.

We particularly like the hyperglycemia/hypoglycemia scatter plots, which demonstrate the practical and important impact of glycemic control. Often there is a see-saw effect in which, if one parameter goes up, the other goes down; finding the sweet spot between hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia is key and clinically important.

Do you have any other comments to share related to your institution’s participation in the program?

We are fortunate to have many successes driven by our participation with the GC eQUIPS Program:

- Coordination of capillary blood glucose (CBG) testing, insulin administration and meal delivery: Use of rapid-acting insulin premeal is standard of care and requires that CBG testing, insulin, and meal delivery be precisely coordinated for optimal insulin action. We developed a process in which the catering associate calls the nurse using a voice-activated pager when the meal tray leaves the kitchen. Then, the nurse checks the CBG and gives insulin when the tray arrives. The tray contains a card to empower the patient to wait for the nurse to administer insulin prior to eating. This also provides an opportunity for nutritional education and carbohydrate awareness. Implementation of this process increased the percentage of patients who had a CBG and insulin administration within 15 minutes before a meal from less than 10% to more than 60%.

- Patient education regarding insulin use: In many cases, hospital patients may be started on insulin and their oral agents may be discontinued. This can be confusing and frightening to patients who often do not know if they will need to be on insulin long term. Our GCT created a script for the staff nurse to inform and reassure patients that this is standard practice and does not mean that they will need to remain on insulin after hospital discharge. The clinical team will communicate with the patient and together they will review treatment options. We have received many positive reviews from patients and staff for improving communication around this aspect of insulin therapy.

- Clinician and leader education: When our data revealed an uptick in hypoglycemia in our critical care units, we engaged the physicians, nurses, and staff and reviewed patient charts to identify potential process changes. To keep hypoglycemia in the spotlight, our director of critical care added hypoglycemia to the ICU checklist, which is discussed on all team clinical rounds. We are also developing an electronic metric (24-hour glucose maximum and minimum values) that can be quickly reviewed by the clinical team daily.

- Hypoglycemia and hyperkalemia: Analysis of our hypoglycemia data revealed a higher-than-expected rate in the ED in patients who did not have a diabetes diagnosis. Further review showed that this was associated with insulin treatment of hyperkalemia. Subsequently, we engaged our resident trainees and other team members in a study to characterize this hypoglycemia-hyperkalemia, and we have recently submitted a manuscript for publication detailing our findings and recommendations for glucose monitoring in these patients.

- Guideline for medical consultation on nonmedical services: Based on review of glucometrics on the nonmedical units and discussions with our hospitalist teams, we designed a guideline that includes recommendations for Medical Consultation in Nonmedical Admissions. Comanagement by a medical consultant will be requested earlier, and we will monitor if this influences glucometrics, patient and hospitalist satisfaction, etc.

- Medical student and house staff education: Two of our GCT hospitalists organize a monthly patient safety conference. After the students and trainees are asked to propose actionable solutions, the hospitalists discuss proposals generated at our GCT meetings. The students and trainees have the opportunity to participate in quality improvement, and we get great ideas from them as well.

Perhaps our biggest success is our Glycemic Care Team itself. We now receive questions and items to review from all departments and are seen as the hospital’s expert team on diabetes and hyperglycemia. It is truly a pleasure to lead this group of extremely high functioning and dedicated professionals. It is said that “team work makes the dream work.” Moving forward, I hope to expand our Glycemic Care Team to all the hospitals in our network.

Beware bacteremia suspicious of colon cancer

Clinical question: Is bacteremia from certain microbes associated with colorectal cancer?

Background: Streptococcus bovis bacteremia is classically associated with colorectal cancer. A number of other bacterial species have been found in colorectal cancer microbiota and may even exert oncogenic effects. However, it is not known whether bacteremia from these microbes is associated with colorectal cancer.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Public hospitals in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: Using the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (representing greater than 90% of inpatient services provided in Hong Kong), researchers identified 15,215 patients with bacteremia from 11 genera of bacteria known to be present in the colorectal cancer microbiota, including Bacteroides, Clostridium, Filifactor, Fusobacterium, Gemella, Granulicatella, Parvimonas, Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, Solobacterium, and Streptococcus. Compared with matched controls without bacteremia, a higher proportion of exposed patients had a subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer (1.69% vs. 1.16%; hazard ratio, 1.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.40-2.12). Bacteremia with other organisms was not associated with colorectal cancer, and bacteremia with the preidentified organisms was not associated with other types of non–colorectal cancer or nonmalignant gastrointestinal diseases, with the exception of a few genera commonly associated with diverticulitis.

Given the observational nature of this study, no causal relationship can be established. It is not clear if these species are involved in the oncogenesis of colorectal cancer or if colorectal tumors merely serve as a site of entry for bacteria into the bloodstream.

Bottom line: Bacteremia with certain bacterial genera is associated with colon cancer and should prompt consideration of colonoscopy to evaluate for malignancy.

Citation: Kwong TNY et al. Association between bacteremia from specific microbes and subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2018 Aug;155(2):383-90.

Dr. Scarpato is clinical instructor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Is bacteremia from certain microbes associated with colorectal cancer?

Background: Streptococcus bovis bacteremia is classically associated with colorectal cancer. A number of other bacterial species have been found in colorectal cancer microbiota and may even exert oncogenic effects. However, it is not known whether bacteremia from these microbes is associated with colorectal cancer.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Public hospitals in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: Using the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (representing greater than 90% of inpatient services provided in Hong Kong), researchers identified 15,215 patients with bacteremia from 11 genera of bacteria known to be present in the colorectal cancer microbiota, including Bacteroides, Clostridium, Filifactor, Fusobacterium, Gemella, Granulicatella, Parvimonas, Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, Solobacterium, and Streptococcus. Compared with matched controls without bacteremia, a higher proportion of exposed patients had a subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer (1.69% vs. 1.16%; hazard ratio, 1.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.40-2.12). Bacteremia with other organisms was not associated with colorectal cancer, and bacteremia with the preidentified organisms was not associated with other types of non–colorectal cancer or nonmalignant gastrointestinal diseases, with the exception of a few genera commonly associated with diverticulitis.

Given the observational nature of this study, no causal relationship can be established. It is not clear if these species are involved in the oncogenesis of colorectal cancer or if colorectal tumors merely serve as a site of entry for bacteria into the bloodstream.

Bottom line: Bacteremia with certain bacterial genera is associated with colon cancer and should prompt consideration of colonoscopy to evaluate for malignancy.

Citation: Kwong TNY et al. Association between bacteremia from specific microbes and subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2018 Aug;155(2):383-90.

Dr. Scarpato is clinical instructor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Clinical question: Is bacteremia from certain microbes associated with colorectal cancer?

Background: Streptococcus bovis bacteremia is classically associated with colorectal cancer. A number of other bacterial species have been found in colorectal cancer microbiota and may even exert oncogenic effects. However, it is not known whether bacteremia from these microbes is associated with colorectal cancer.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Public hospitals in Hong Kong.

Synopsis: Using the Clinical Data Analysis and Reporting System (representing greater than 90% of inpatient services provided in Hong Kong), researchers identified 15,215 patients with bacteremia from 11 genera of bacteria known to be present in the colorectal cancer microbiota, including Bacteroides, Clostridium, Filifactor, Fusobacterium, Gemella, Granulicatella, Parvimonas, Peptostreptococcus, Prevotella, Solobacterium, and Streptococcus. Compared with matched controls without bacteremia, a higher proportion of exposed patients had a subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer (1.69% vs. 1.16%; hazard ratio, 1.72; 95% confidence interval, 1.40-2.12). Bacteremia with other organisms was not associated with colorectal cancer, and bacteremia with the preidentified organisms was not associated with other types of non–colorectal cancer or nonmalignant gastrointestinal diseases, with the exception of a few genera commonly associated with diverticulitis.

Given the observational nature of this study, no causal relationship can be established. It is not clear if these species are involved in the oncogenesis of colorectal cancer or if colorectal tumors merely serve as a site of entry for bacteria into the bloodstream.

Bottom line: Bacteremia with certain bacterial genera is associated with colon cancer and should prompt consideration of colonoscopy to evaluate for malignancy.

Citation: Kwong TNY et al. Association between bacteremia from specific microbes and subsequent diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 2018 Aug;155(2):383-90.

Dr. Scarpato is clinical instructor in the division of hospital medicine, University of Colorado, Denver.

Invasive strategy increased bleeding risk in frail older AMI patients

Frail older patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) may be at increased bleeding risk if managed with an invasive strategy, results of a large U.S. registry study suggest.

The increased bleeding risk was seen among frail older AMI patients who underwent cardiac catheterization, but it was not seen in those treated with more conservative medical management, according to study results.

That finding highlights the conundrum with invasive management strategies for frail patients with AMI, wrote John A. Dodson, MD, MPH, of New York University and study coinvestigators.

“Awareness of vulnerability and greater utilization of evidence-based strategies to reduce bleeding, including radial access and properly dose-adjusted anticoagulant therapies, may mitigate some bleeding events,” they wrote in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Results of this study, the first large U.S. registry analysis evaluating in-hospital bleeding risk in frail older adults with AMI, confirm findings from several previous small cohort studies linking frailty in AMI patients to in-hospital bleeding, investigators reported.

The analysis included a total of 129,330 AMI patients in the ACTION (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network) registry who were aged at least 65 years in 2015 or 2016.

About one in six of these older patients were frail, as defined by a composite score based on impaired walking, cognition, and activities of daily living, investigators reported.

The bleeding rate was significantly higher among frail patients undergoing cardiac catheterization, at 9.4% for patients rated as having vulnerable/mild frailty and 9.9% for patients with moderate to severe frailty (P less than.001), compared with fit/well patients, whose rate was 6.5%, investigators wrote. By contrast, there was no significant difference in bleeding rates for frail versus nonfrail patients managed conservatively, they said.

After adjusting for bleeding risk factors, frailty was independently associated with increased risk of bleeding, compared with fit/well status, with odds ratios of 1.33 for vulnerable/mild frailty and 1.40 for moderate to severe frailty. Again, no association was found between frailty and bleeding risk in patients managed conservatively, according to investigators.

Frail patients in the ACTION registry were more often older and female and less likely to undergo cardiac catheterization when compared with fit or well patients, they added in the report.

Like the small cohort studies that preceded it, this large U.S. registry study shows that frailty is an “important additional risk factor” among older adults with AMI who are managed with an invasive strategy, investigators said.

“When applicable, estimation of bleeding risk in frail patients before invasive care may facilitate clinical decision making and the informed consent process,” they wrote.

The ACTION registry, an ongoing quality improvement initiative sponsored by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, started collecting frailty characteristics among hospitalized AMI patients in 2015, investigators noted.

Dr. Dodson reported support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging and from the American Heart Association. Study coauthors provided disclosures related to Bayer, Janssen, Abbott Vascular, Jarvik Heart, LifeCuff Technologies, and Ancora Heart. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Nov 26;11:2287-96

SOURCE: Dodson JA et al. JACC Cardiovasc Intv. 2018;11:2287-96.

This analysis is important and has clinical implications beyond those of previous analyses linking frailty to poor outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease, according to John A. Bittl, MD.

“The present study helps to transform the rote recording of frailty from a mere quality metric in the medical record into an actionable diagnosis,” Dr. Bittl said in an editorial comment on the findings.

Results of the study show an association between invasive cardiac procedures and increased bleeding in frail patients with AMI.

The benefits of an invasive procedure might be outweighed by the incremental risk added by frailty in older AMI patients at low to moderate risk of poor outcomes, Dr. Bittl suggested.

By contrast, frail older AMI patients at high risk for poor outcomes might be better candidates for an invasive procedure if they can undergo a transradial approach, he said, noting that in the study by Dodson and colleagues, only 26% of frail patients received radial access despite randomized trials showing the approach reduces risk of bleeding.

“In this way, diagnosing frailty in a patient with AMI facilitates clinical decision making and helps to personalize an approach to optimize outcomes,” Dr. Bittl concluded.

Dr. Bittl is with the Interventional Cardiology Group, Florida Hospital Ocala (Fla.) He reported no relationships relevant to his editorial comment ( JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Nov 26;11[2];2297-93 ).

This analysis is important and has clinical implications beyond those of previous analyses linking frailty to poor outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease, according to John A. Bittl, MD.

“The present study helps to transform the rote recording of frailty from a mere quality metric in the medical record into an actionable diagnosis,” Dr. Bittl said in an editorial comment on the findings.

Results of the study show an association between invasive cardiac procedures and increased bleeding in frail patients with AMI.

The benefits of an invasive procedure might be outweighed by the incremental risk added by frailty in older AMI patients at low to moderate risk of poor outcomes, Dr. Bittl suggested.

By contrast, frail older AMI patients at high risk for poor outcomes might be better candidates for an invasive procedure if they can undergo a transradial approach, he said, noting that in the study by Dodson and colleagues, only 26% of frail patients received radial access despite randomized trials showing the approach reduces risk of bleeding.

“In this way, diagnosing frailty in a patient with AMI facilitates clinical decision making and helps to personalize an approach to optimize outcomes,” Dr. Bittl concluded.

Dr. Bittl is with the Interventional Cardiology Group, Florida Hospital Ocala (Fla.) He reported no relationships relevant to his editorial comment ( JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Nov 26;11[2];2297-93 ).

This analysis is important and has clinical implications beyond those of previous analyses linking frailty to poor outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease, according to John A. Bittl, MD.

“The present study helps to transform the rote recording of frailty from a mere quality metric in the medical record into an actionable diagnosis,” Dr. Bittl said in an editorial comment on the findings.

Results of the study show an association between invasive cardiac procedures and increased bleeding in frail patients with AMI.

The benefits of an invasive procedure might be outweighed by the incremental risk added by frailty in older AMI patients at low to moderate risk of poor outcomes, Dr. Bittl suggested.

By contrast, frail older AMI patients at high risk for poor outcomes might be better candidates for an invasive procedure if they can undergo a transradial approach, he said, noting that in the study by Dodson and colleagues, only 26% of frail patients received radial access despite randomized trials showing the approach reduces risk of bleeding.

“In this way, diagnosing frailty in a patient with AMI facilitates clinical decision making and helps to personalize an approach to optimize outcomes,” Dr. Bittl concluded.

Dr. Bittl is with the Interventional Cardiology Group, Florida Hospital Ocala (Fla.) He reported no relationships relevant to his editorial comment ( JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Nov 26;11[2];2297-93 ).

Frail older patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) may be at increased bleeding risk if managed with an invasive strategy, results of a large U.S. registry study suggest.

The increased bleeding risk was seen among frail older AMI patients who underwent cardiac catheterization, but it was not seen in those treated with more conservative medical management, according to study results.

That finding highlights the conundrum with invasive management strategies for frail patients with AMI, wrote John A. Dodson, MD, MPH, of New York University and study coinvestigators.

“Awareness of vulnerability and greater utilization of evidence-based strategies to reduce bleeding, including radial access and properly dose-adjusted anticoagulant therapies, may mitigate some bleeding events,” they wrote in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Results of this study, the first large U.S. registry analysis evaluating in-hospital bleeding risk in frail older adults with AMI, confirm findings from several previous small cohort studies linking frailty in AMI patients to in-hospital bleeding, investigators reported.

The analysis included a total of 129,330 AMI patients in the ACTION (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network) registry who were aged at least 65 years in 2015 or 2016.

About one in six of these older patients were frail, as defined by a composite score based on impaired walking, cognition, and activities of daily living, investigators reported.

The bleeding rate was significantly higher among frail patients undergoing cardiac catheterization, at 9.4% for patients rated as having vulnerable/mild frailty and 9.9% for patients with moderate to severe frailty (P less than.001), compared with fit/well patients, whose rate was 6.5%, investigators wrote. By contrast, there was no significant difference in bleeding rates for frail versus nonfrail patients managed conservatively, they said.

After adjusting for bleeding risk factors, frailty was independently associated with increased risk of bleeding, compared with fit/well status, with odds ratios of 1.33 for vulnerable/mild frailty and 1.40 for moderate to severe frailty. Again, no association was found between frailty and bleeding risk in patients managed conservatively, according to investigators.

Frail patients in the ACTION registry were more often older and female and less likely to undergo cardiac catheterization when compared with fit or well patients, they added in the report.

Like the small cohort studies that preceded it, this large U.S. registry study shows that frailty is an “important additional risk factor” among older adults with AMI who are managed with an invasive strategy, investigators said.

“When applicable, estimation of bleeding risk in frail patients before invasive care may facilitate clinical decision making and the informed consent process,” they wrote.

The ACTION registry, an ongoing quality improvement initiative sponsored by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, started collecting frailty characteristics among hospitalized AMI patients in 2015, investigators noted.

Dr. Dodson reported support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging and from the American Heart Association. Study coauthors provided disclosures related to Bayer, Janssen, Abbott Vascular, Jarvik Heart, LifeCuff Technologies, and Ancora Heart. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Nov 26;11:2287-96

SOURCE: Dodson JA et al. JACC Cardiovasc Intv. 2018;11:2287-96.

Frail older patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) may be at increased bleeding risk if managed with an invasive strategy, results of a large U.S. registry study suggest.

The increased bleeding risk was seen among frail older AMI patients who underwent cardiac catheterization, but it was not seen in those treated with more conservative medical management, according to study results.

That finding highlights the conundrum with invasive management strategies for frail patients with AMI, wrote John A. Dodson, MD, MPH, of New York University and study coinvestigators.

“Awareness of vulnerability and greater utilization of evidence-based strategies to reduce bleeding, including radial access and properly dose-adjusted anticoagulant therapies, may mitigate some bleeding events,” they wrote in JACC: Cardiovascular Interventions.

Results of this study, the first large U.S. registry analysis evaluating in-hospital bleeding risk in frail older adults with AMI, confirm findings from several previous small cohort studies linking frailty in AMI patients to in-hospital bleeding, investigators reported.

The analysis included a total of 129,330 AMI patients in the ACTION (Acute Coronary Treatment and Intervention Outcomes Network) registry who were aged at least 65 years in 2015 or 2016.

About one in six of these older patients were frail, as defined by a composite score based on impaired walking, cognition, and activities of daily living, investigators reported.

The bleeding rate was significantly higher among frail patients undergoing cardiac catheterization, at 9.4% for patients rated as having vulnerable/mild frailty and 9.9% for patients with moderate to severe frailty (P less than.001), compared with fit/well patients, whose rate was 6.5%, investigators wrote. By contrast, there was no significant difference in bleeding rates for frail versus nonfrail patients managed conservatively, they said.

After adjusting for bleeding risk factors, frailty was independently associated with increased risk of bleeding, compared with fit/well status, with odds ratios of 1.33 for vulnerable/mild frailty and 1.40 for moderate to severe frailty. Again, no association was found between frailty and bleeding risk in patients managed conservatively, according to investigators.

Frail patients in the ACTION registry were more often older and female and less likely to undergo cardiac catheterization when compared with fit or well patients, they added in the report.

Like the small cohort studies that preceded it, this large U.S. registry study shows that frailty is an “important additional risk factor” among older adults with AMI who are managed with an invasive strategy, investigators said.

“When applicable, estimation of bleeding risk in frail patients before invasive care may facilitate clinical decision making and the informed consent process,” they wrote.

The ACTION registry, an ongoing quality improvement initiative sponsored by the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association, started collecting frailty characteristics among hospitalized AMI patients in 2015, investigators noted.

Dr. Dodson reported support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging and from the American Heart Association. Study coauthors provided disclosures related to Bayer, Janssen, Abbott Vascular, Jarvik Heart, LifeCuff Technologies, and Ancora Heart. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Nov 26;11:2287-96

SOURCE: Dodson JA et al. JACC Cardiovasc Intv. 2018;11:2287-96.

FROM JACC: CARDIOVASCULAR INTERVENTIONS

Key clinical point: Frail older patients with acute myocardial infarction may be at increased bleeding risk if managed with an invasive strategy.

Major finding: Frailty was associated with increased risk of bleeding, with odds ratios of 1.33 and 1.40, compared with fit or well patients.

Study details: Analysis including 129,330 AMI patients in a U.S. registry who were at least 65 years of age.

Disclosures: Researchers reported support from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging, as well as other disclosures related to Bayer, Janssen, Abbott Vascular, Jarvik Heart, LifeCuff Technologies, and Ancora Heart.

Source: Dodson JA et al. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018 Nov 26;11:2287-96.

In the Literature - Short Takes

Sepsis Campaign bundles shortened to 1 hour

In response to the 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, the 3-hour and 6-hour bundles have been combined and shortened into a 1-hour bundle to emphasize the emergent nature of sepsis. Elements of the bundle remain to same: measuring lactate, obtaining blood cultures, administration of broad-spectrume antibiotics, administration of 30mL/kg crystalloid, and vasopressors when necessary.

Citation: Levy MM et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle: 2018 update. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(6):997-1000

Early ED discharge for PE

This randomized trial showed that low-risk emergency department patients diagnosed with pulmonary embolism who were discharged from the ED with rivaroxaban within 24 hours of presentation had decreased length of stay and nearly $2,500 in cost savings, compared with patients treated according to standard of care (often including hospitalization) without increased risk of bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism, or death.

Citation: Peacock WF et al. Emergency department discharge of pulmonary embolus patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2018. doi: 10.1111/acem.13451.

Outbreak of coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoids

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports a recent outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use, because of contamination with vitmin K antagonist agents. All patients who report synthetic cannabinoid use should be screened with INR testing, especially prior to procedures.

Citation: Outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use. CDC Health Alert Network. June 27, 2018.

Lumbar puncture safe when performed on patients on dual-antiplatelet therapy

In a retrospective review of 100 adult patients who underwent lumbar puncture procedures while taking dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, Mayo clinic investigators found no epidural hematomas or other serious complications with at least 3 months of follow-up. This study was nto powered to detect the risk of spinal hematoma so caution and open discussion with patients still is recommended.

Citation: Carabenciov ID et al. Safety of lumbar puncture performed on dual anti-platelet therapy. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93(5):627-9.

Sepsis Campaign bundles shortened to 1 hour

In response to the 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, the 3-hour and 6-hour bundles have been combined and shortened into a 1-hour bundle to emphasize the emergent nature of sepsis. Elements of the bundle remain to same: measuring lactate, obtaining blood cultures, administration of broad-spectrume antibiotics, administration of 30mL/kg crystalloid, and vasopressors when necessary.

Citation: Levy MM et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle: 2018 update. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(6):997-1000

Early ED discharge for PE

This randomized trial showed that low-risk emergency department patients diagnosed with pulmonary embolism who were discharged from the ED with rivaroxaban within 24 hours of presentation had decreased length of stay and nearly $2,500 in cost savings, compared with patients treated according to standard of care (often including hospitalization) without increased risk of bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism, or death.

Citation: Peacock WF et al. Emergency department discharge of pulmonary embolus patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2018. doi: 10.1111/acem.13451.

Outbreak of coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoids

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports a recent outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use, because of contamination with vitmin K antagonist agents. All patients who report synthetic cannabinoid use should be screened with INR testing, especially prior to procedures.

Citation: Outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use. CDC Health Alert Network. June 27, 2018.

Lumbar puncture safe when performed on patients on dual-antiplatelet therapy

In a retrospective review of 100 adult patients who underwent lumbar puncture procedures while taking dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, Mayo clinic investigators found no epidural hematomas or other serious complications with at least 3 months of follow-up. This study was nto powered to detect the risk of spinal hematoma so caution and open discussion with patients still is recommended.

Citation: Carabenciov ID et al. Safety of lumbar puncture performed on dual anti-platelet therapy. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93(5):627-9.

Sepsis Campaign bundles shortened to 1 hour

In response to the 2016 Surviving Sepsis Campaign guidelines, the 3-hour and 6-hour bundles have been combined and shortened into a 1-hour bundle to emphasize the emergent nature of sepsis. Elements of the bundle remain to same: measuring lactate, obtaining blood cultures, administration of broad-spectrume antibiotics, administration of 30mL/kg crystalloid, and vasopressors when necessary.

Citation: Levy MM et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundle: 2018 update. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(6):997-1000

Early ED discharge for PE

This randomized trial showed that low-risk emergency department patients diagnosed with pulmonary embolism who were discharged from the ED with rivaroxaban within 24 hours of presentation had decreased length of stay and nearly $2,500 in cost savings, compared with patients treated according to standard of care (often including hospitalization) without increased risk of bleeding, recurrent venous thromboembolism, or death.

Citation: Peacock WF et al. Emergency department discharge of pulmonary embolus patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2018. doi: 10.1111/acem.13451.

Outbreak of coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoids

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports a recent outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use, because of contamination with vitmin K antagonist agents. All patients who report synthetic cannabinoid use should be screened with INR testing, especially prior to procedures.

Citation: Outbreak of life-threatening coagulopathy associated with synthetic cannabinoid use. CDC Health Alert Network. June 27, 2018.

Lumbar puncture safe when performed on patients on dual-antiplatelet therapy

In a retrospective review of 100 adult patients who underwent lumbar puncture procedures while taking dual-antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel, Mayo clinic investigators found no epidural hematomas or other serious complications with at least 3 months of follow-up. This study was nto powered to detect the risk of spinal hematoma so caution and open discussion with patients still is recommended.

Citation: Carabenciov ID et al. Safety of lumbar puncture performed on dual anti-platelet therapy. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2018;93(5):627-9.

Consider omitting CSF testing in older, low-risk febrile infants

Risk stratification tools that omit lumbar puncture accurately classified most well-appearing febrile infants with invasive bacterial infections as being at low risk, results of a recent study show.

The modified Philadelphia criteria were highly sensitive for risk stratifying febrile infants, in a recent validation study based on a large, multicenter sample, investigators report. No infants with bacterial meningitis were classified as low risk using the modified criteria, which do not include routine testing of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Two infants with bacterial meningitis, both younger than 28 days old, were classified as low risk using the Rochester criteria, which also avoid routine lumbar puncture, investigators reported.

“Our findings support the use of the modified Philadelphia criteria without routine CSF testing for febrile infants in the second month of life,” the investigators said in their report, published in Pediatrics.

However, to confirm the safety of omitting CSF testing in low-risk febrile infants older than 28 days, a prospective study will be needed, cautioned the researchers, led by Paul L. Aronson, MD, of the department of pediatrics at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Nevertheless, some clinicians do not automatically perform CSF testing in infants older than 28 days because of the rarity of bacterial meningitis in that age group, they said in the report.

The study by Dr. Aronson and colleagues was based on data for infants younger than 60 days of age seen in the emergency departments of 9 hospitals between July 2011 and June 2016. The final sample included 135 infants with invasive bacterial infections, including 118 who had bacteremia without meningitis and 17 who had bacterial meningitis, along with 249 matched febrile infant controls.

A total of 25 infants with invasive bacterial infections were classified as low risk by the Rochester criteria, and 11 of those were low risk by the modified Philadelphia criteria, investigators said.

Compared with the modified Philadelphia criteria, the Rochester criteria had a lower sensitivity (81.5% vs. 91.9%; P = 0.01) and a higher specificity (59.8 vs. 34.5%; P less than 0.001).

Out of the 11 infants deemed low risk per the modified Philadelphia criteria, none were diagnosed with bacterial meningitis. By contrast, 2 of the 25 infants who were low risk per the Rochester criteria had bacterial meningitis, and both were younger than or equal to 28 days of age. “Both of these infants would have been classified as high risk per the modified Philadelphia criteria,” Dr. Aronson and his coauthors said.

Based on the findings of this study, caution should be exercised in applying low-risk criteria to infants 28 days of age or younger, according to the investigators.

they wrote.

Dr. Aronson and his coauthors reported that they had no relevant disclosures. One coauthor reported serving as an expert witness in malpractice cases involving evaluation of febrile children.

SOURCE: Aronson PL et al. Pediatrics. 13 Nov 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1879).

While the modified Philadelphia criteria did not misidentify any infant older than 28 days with bacterial meningitis as low risk, limitations of the study design should be “recognized and weighed” before adopting a change in clinical practice, wrote M. Douglas Baker, MD.

Those limitations, Dr. Baker wrote, include frequent use of automated white blood cell differential counts, exclusion of eligible infants at some study locations, and clinical documentation of appearance that was not uniform across sites.

The conclusions of the study, however, are “sound,” he added.

“The modified Philadelphia criteria, which does not include routine cerebrospinal fluid testing, identifies most infants who are febrile with invasive bacterial infections,” he wrote. But modification of the Philadelphia tool reduces its sensitivity and “jeopardizes safe use for its original purpose,” Dr. Baker said.

“The original Philadelphia criteria were intended to safely identify infants who were at a low enough risk of having concurrent bacterial infections to safely manage their febrile illnesses at home without the use of antibiotics,” he wrote. “Those criteria performed well, approaching 100% sensitivity, when applied to different study populations.”

Dr. Baker added that when evaluating and managing fever in infants, “thoughtful omission” of lumbar puncture requires disclosure of the likelihood of bacterial meningitis, and the risks of delayed diagnosis of the condition, which can have potential lifelong consequences.

“All stakeholders need to understand the data at hand and accept responsibility for the outcomes of their decisions,” he wrote.

M. Douglas Baker, MD, is affiliated with Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 13 Nov 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2861). He declared no conflicts of interest.

While the modified Philadelphia criteria did not misidentify any infant older than 28 days with bacterial meningitis as low risk, limitations of the study design should be “recognized and weighed” before adopting a change in clinical practice, wrote M. Douglas Baker, MD.

Those limitations, Dr. Baker wrote, include frequent use of automated white blood cell differential counts, exclusion of eligible infants at some study locations, and clinical documentation of appearance that was not uniform across sites.

The conclusions of the study, however, are “sound,” he added.

“The modified Philadelphia criteria, which does not include routine cerebrospinal fluid testing, identifies most infants who are febrile with invasive bacterial infections,” he wrote. But modification of the Philadelphia tool reduces its sensitivity and “jeopardizes safe use for its original purpose,” Dr. Baker said.

“The original Philadelphia criteria were intended to safely identify infants who were at a low enough risk of having concurrent bacterial infections to safely manage their febrile illnesses at home without the use of antibiotics,” he wrote. “Those criteria performed well, approaching 100% sensitivity, when applied to different study populations.”

Dr. Baker added that when evaluating and managing fever in infants, “thoughtful omission” of lumbar puncture requires disclosure of the likelihood of bacterial meningitis, and the risks of delayed diagnosis of the condition, which can have potential lifelong consequences.

“All stakeholders need to understand the data at hand and accept responsibility for the outcomes of their decisions,” he wrote.

M. Douglas Baker, MD, is affiliated with Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 13 Nov 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2861). He declared no conflicts of interest.

While the modified Philadelphia criteria did not misidentify any infant older than 28 days with bacterial meningitis as low risk, limitations of the study design should be “recognized and weighed” before adopting a change in clinical practice, wrote M. Douglas Baker, MD.

Those limitations, Dr. Baker wrote, include frequent use of automated white blood cell differential counts, exclusion of eligible infants at some study locations, and clinical documentation of appearance that was not uniform across sites.

The conclusions of the study, however, are “sound,” he added.

“The modified Philadelphia criteria, which does not include routine cerebrospinal fluid testing, identifies most infants who are febrile with invasive bacterial infections,” he wrote. But modification of the Philadelphia tool reduces its sensitivity and “jeopardizes safe use for its original purpose,” Dr. Baker said.

“The original Philadelphia criteria were intended to safely identify infants who were at a low enough risk of having concurrent bacterial infections to safely manage their febrile illnesses at home without the use of antibiotics,” he wrote. “Those criteria performed well, approaching 100% sensitivity, when applied to different study populations.”

Dr. Baker added that when evaluating and managing fever in infants, “thoughtful omission” of lumbar puncture requires disclosure of the likelihood of bacterial meningitis, and the risks of delayed diagnosis of the condition, which can have potential lifelong consequences.

“All stakeholders need to understand the data at hand and accept responsibility for the outcomes of their decisions,” he wrote.

M. Douglas Baker, MD, is affiliated with Johns Hopkins All Children’s Hospital, St. Petersburg, Fla. These comments are taken from an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 13 Nov 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-2861). He declared no conflicts of interest.

Risk stratification tools that omit lumbar puncture accurately classified most well-appearing febrile infants with invasive bacterial infections as being at low risk, results of a recent study show.

The modified Philadelphia criteria were highly sensitive for risk stratifying febrile infants, in a recent validation study based on a large, multicenter sample, investigators report. No infants with bacterial meningitis were classified as low risk using the modified criteria, which do not include routine testing of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Two infants with bacterial meningitis, both younger than 28 days old, were classified as low risk using the Rochester criteria, which also avoid routine lumbar puncture, investigators reported.

“Our findings support the use of the modified Philadelphia criteria without routine CSF testing for febrile infants in the second month of life,” the investigators said in their report, published in Pediatrics.

However, to confirm the safety of omitting CSF testing in low-risk febrile infants older than 28 days, a prospective study will be needed, cautioned the researchers, led by Paul L. Aronson, MD, of the department of pediatrics at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Nevertheless, some clinicians do not automatically perform CSF testing in infants older than 28 days because of the rarity of bacterial meningitis in that age group, they said in the report.

The study by Dr. Aronson and colleagues was based on data for infants younger than 60 days of age seen in the emergency departments of 9 hospitals between July 2011 and June 2016. The final sample included 135 infants with invasive bacterial infections, including 118 who had bacteremia without meningitis and 17 who had bacterial meningitis, along with 249 matched febrile infant controls.

A total of 25 infants with invasive bacterial infections were classified as low risk by the Rochester criteria, and 11 of those were low risk by the modified Philadelphia criteria, investigators said.

Compared with the modified Philadelphia criteria, the Rochester criteria had a lower sensitivity (81.5% vs. 91.9%; P = 0.01) and a higher specificity (59.8 vs. 34.5%; P less than 0.001).

Out of the 11 infants deemed low risk per the modified Philadelphia criteria, none were diagnosed with bacterial meningitis. By contrast, 2 of the 25 infants who were low risk per the Rochester criteria had bacterial meningitis, and both were younger than or equal to 28 days of age. “Both of these infants would have been classified as high risk per the modified Philadelphia criteria,” Dr. Aronson and his coauthors said.

Based on the findings of this study, caution should be exercised in applying low-risk criteria to infants 28 days of age or younger, according to the investigators.

they wrote.

Dr. Aronson and his coauthors reported that they had no relevant disclosures. One coauthor reported serving as an expert witness in malpractice cases involving evaluation of febrile children.

SOURCE: Aronson PL et al. Pediatrics. 13 Nov 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1879).

Risk stratification tools that omit lumbar puncture accurately classified most well-appearing febrile infants with invasive bacterial infections as being at low risk, results of a recent study show.

The modified Philadelphia criteria were highly sensitive for risk stratifying febrile infants, in a recent validation study based on a large, multicenter sample, investigators report. No infants with bacterial meningitis were classified as low risk using the modified criteria, which do not include routine testing of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Two infants with bacterial meningitis, both younger than 28 days old, were classified as low risk using the Rochester criteria, which also avoid routine lumbar puncture, investigators reported.

“Our findings support the use of the modified Philadelphia criteria without routine CSF testing for febrile infants in the second month of life,” the investigators said in their report, published in Pediatrics.

However, to confirm the safety of omitting CSF testing in low-risk febrile infants older than 28 days, a prospective study will be needed, cautioned the researchers, led by Paul L. Aronson, MD, of the department of pediatrics at Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

Nevertheless, some clinicians do not automatically perform CSF testing in infants older than 28 days because of the rarity of bacterial meningitis in that age group, they said in the report.

The study by Dr. Aronson and colleagues was based on data for infants younger than 60 days of age seen in the emergency departments of 9 hospitals between July 2011 and June 2016. The final sample included 135 infants with invasive bacterial infections, including 118 who had bacteremia without meningitis and 17 who had bacterial meningitis, along with 249 matched febrile infant controls.

A total of 25 infants with invasive bacterial infections were classified as low risk by the Rochester criteria, and 11 of those were low risk by the modified Philadelphia criteria, investigators said.

Compared with the modified Philadelphia criteria, the Rochester criteria had a lower sensitivity (81.5% vs. 91.9%; P = 0.01) and a higher specificity (59.8 vs. 34.5%; P less than 0.001).

Out of the 11 infants deemed low risk per the modified Philadelphia criteria, none were diagnosed with bacterial meningitis. By contrast, 2 of the 25 infants who were low risk per the Rochester criteria had bacterial meningitis, and both were younger than or equal to 28 days of age. “Both of these infants would have been classified as high risk per the modified Philadelphia criteria,” Dr. Aronson and his coauthors said.

Based on the findings of this study, caution should be exercised in applying low-risk criteria to infants 28 days of age or younger, according to the investigators.

they wrote.

Dr. Aronson and his coauthors reported that they had no relevant disclosures. One coauthor reported serving as an expert witness in malpractice cases involving evaluation of febrile children.

SOURCE: Aronson PL et al. Pediatrics. 13 Nov 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-1879).

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: The modified Philadelphia criteria, which omit lumbar puncture, accurately classified febrile infants as low risk, though prospective studies are needed to confirm the safety of routinely omitting cerebrospinal testing.

Major finding: Zero of 11 infants classified as low risk had a diagnosis of bacterial meningitis.

Study details: An analysis including 135 non–ill-appearing infants younger than 60 days of age with invasive bacterial infections and 249 matched febrile infant controls.

Disclosures: Dr. Aronson and his coauthors reported no financial conflicts. One coauthor reported serving as an expert witness in malpractice cases involving febrile children.

Source: Aronson PL et al. Pediatrics. 13 Nov 2018. doi: 10.1542/peds. 2018-1879.

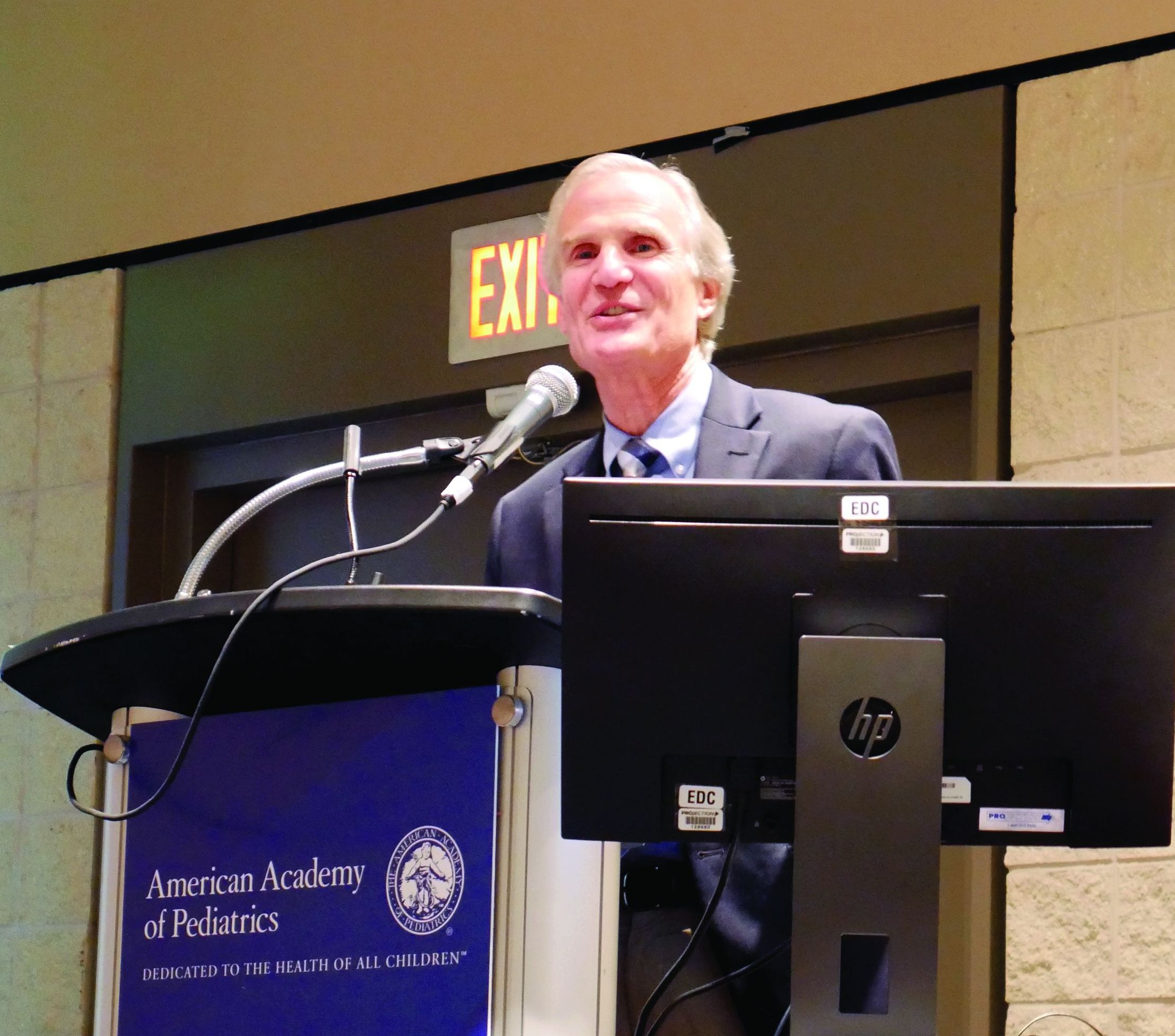

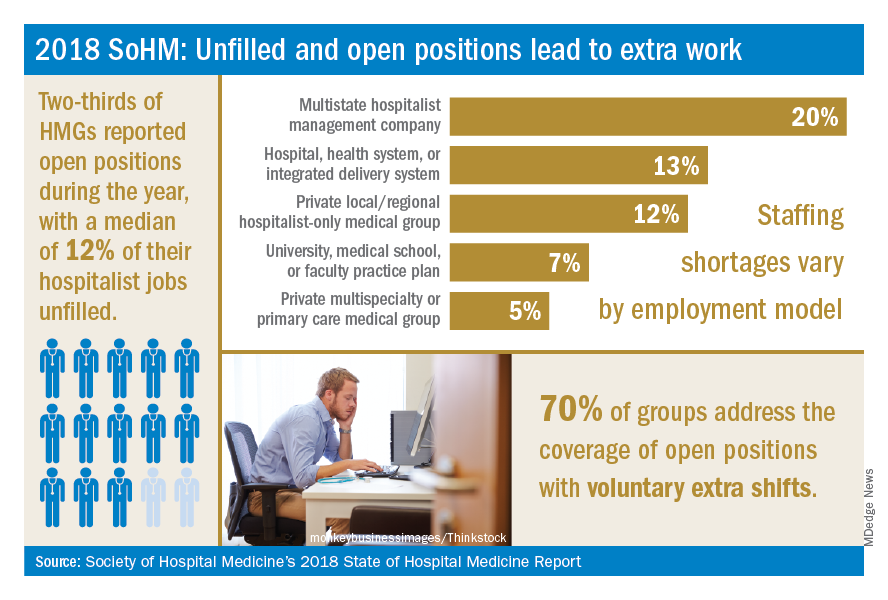

How do hospital medicine groups deal with staffing shortages?

Persistent demand for hospitalists nationally

During the last two decades, the United States health care labor market had an almost insatiable appetite for hospitalists, driving the specialty from nothing to over 50,000 members. Evidence of persistent demand for hospitalists abounds in the freshly released 2018 State of Hospital Medicine (SoHM) report: rising salaries, growing responsibility for the overall hospital census, and a diversifying scope of services.

The SoHM offers fascinating and detailed insights into these trends, as well as hundreds of other aspects of the field’s growth. Unfortunately, this expanding and dynamic labor market has a challenging side for hospitals, management companies, and hospitalist group leaders – we are constantly recruiting and dealing with open positions!

As a multisite leader at an academic health system, I’m looking toward the next season of recruitment with excitement. In the fall and winter we’re fortunate to receive applications from the best and brightest graduating residents and hospitalists. I realize this is a blessing, particularly compared with programs in rural areas that may not hear from many applicants. However, even when we succeed at filling the openings, there is an inevitable trickle of talent out of our clinical labor pool during the spring and summer. One person is invited to spend 20% of their time leading a teaching program, another secures a highly coveted grant, and yet another has to move because their spouse is relocated. By then, we don’t have a packed roster of applicants and have to solve the challenge in other ways. What does the typical hospital medicine program do when faced with this circumstance?

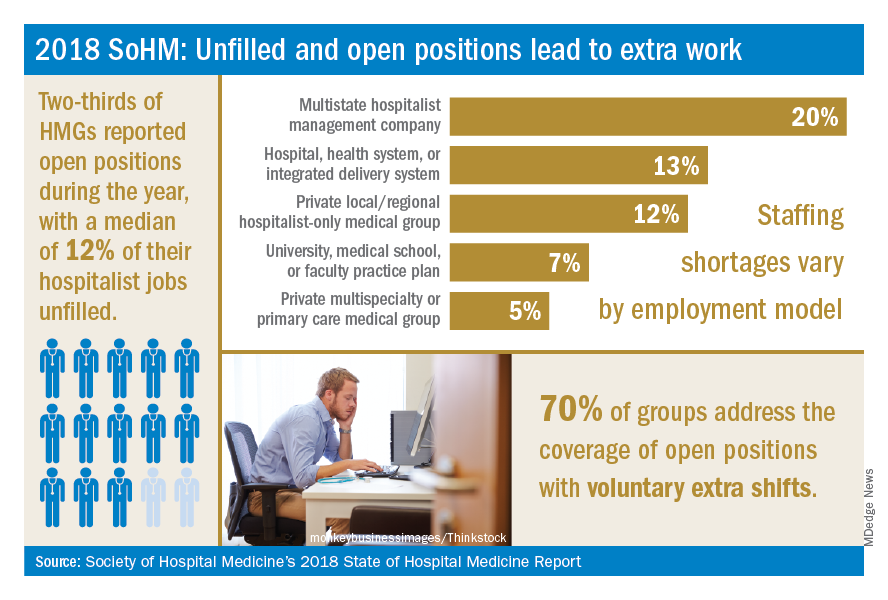

The 2018 SoHM survey first asked program leaders whether they had open and unfilled physician positions during the last year because of turnover, growth, or other factors. On average, 66% of groups serving adults and 48% of groups serving children said “yes.” For the job seekers out there, take note of some important regional differences: The regions with the highest percentage of programs dealing with unfilled positions were the East and West Coasts at 79% and 73%, respectively.

Next, the survey asked respondents to describe the percentage of total approved physician staffing that was open or unfilled during the year. On average, 12% of positions went unfilled, with important variation between different types of employers. For a typical HM group with 15 full-time equivalents, that means constantly working short two physicians!

Not only is it hard for group leaders to manage chronic understaffing, it definitely takes a toll on the group. We asked leaders to describe all of the ways their groups address coverage of the open positions. The most common tactics were for existing hospitalists to perform voluntary extra shifts (70%) and the use of moonlighters (57%). Also important were the use of locum tenens physicians (44%) and just leaving some shifts uncovered (31%).