User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Next-gen sputum PCR panel boosts CAP diagnostics

NEW ORLEANS – A next-generation lower respiratory tract sputum polymerase chain reaction (PCR) film array panel identified etiologic pathogens in 100% of a group of patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia, Kathryn Hendrickson, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The investigational new diagnostic assay, the BioFire Pneumonia Panel, is now under Food and Drug Administration review for marketing clearance. (CAP), observed Dr. Hendrickson, an internal medicine resident at Providence Portland (Ore.) Medical Center. The new product is designed to complement the currently available respiratory panels from BioFire.

“Rapid-detection results in less empiric antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. When it’s FDA approved, this investigational sputum PCR panel will simplify the diagnostic bundle while improving antibiotic stewardship,” she observed.

She presented a prospective study of 63 patients with CAP hospitalized at the medical center, all of whom were evaluated by two laboratory methods: the hospital’s standard bundle of diagnostic tests and the new BioFire film array panel. The purpose was to determine if there was a difference between the two tests in the detection rate of viral and/or bacterial pathogens as well as the clinical significance of any such differences; that is, was there an impact on days of treatment and length of hospital stay?

Traditional diagnostic methods detect an etiologic pathogen in at best half of hospitalized CAP patients, and the results take too much time. So Providence Portland Medical Center adopted as its standard diagnostic bundle a nasopharyngeal swab and a BioFire film array PCR that’s currently on the market and can detect nine viruses and three bacteria, along with urine antigens for Legionella sp. and Streptococcus pneumoniae, nucleic acid amplification testing for S. pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, and blood and sputum cultures. In contrast, the investigational panel probes for 17 viruses, 18 bacterial pathogens, and seven antibiotic-resistant genes; it also measures procalcitonin levels in order to distinguish between bacterial colonization and invasion.

The new BioFire Pneumonia Panel detected a mean of 1.4 species of pathogenic bacteria in 79% of patients, while the standard diagnostic bundle detected 0.7 species in 59% of patients. The investigational panel identified a mean of 1.0 species of viral pathogens in 86% of the CAP patients; the standard bundle detected a mean of 0.6 species in 56%.

All told, any CAP pathogen was detected in 100% of patients using the new panel, with a mean of 2.5 different pathogens identified. The standard bundle detected any pathogen in 84% of patients, with half as many different pathogens found, according to Dr. Hendrickson.

A peak procalcitonin level of 0.25 ng/mL or less, which was defined as bacterial colonization, was associated with a mean 7 days of treatment, while a level above that threshold was associated with 11.3 days of treatment. Patients with a peak procalcitonin of 0.25 ng/mL or less had an average hospital length of stay of 5.9 days, versus 7.8 days for those with a higher procalcitonin indicative of bacterial invasion.

The new biofilm assay reports information about the abundance of 15 of the 18 bacterial targets in the sample. However, in contrast to peak procalcitonin, Dr. Hendrickson and her coinvestigators didn’t find this bacterial quantitation feature to be substantially more useful than a coin flip in distinguishing bacterial colonization from invasion.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the head-to-head comparative study, which was supported by BioFire Diagnostics.

NEW ORLEANS – A next-generation lower respiratory tract sputum polymerase chain reaction (PCR) film array panel identified etiologic pathogens in 100% of a group of patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia, Kathryn Hendrickson, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The investigational new diagnostic assay, the BioFire Pneumonia Panel, is now under Food and Drug Administration review for marketing clearance. (CAP), observed Dr. Hendrickson, an internal medicine resident at Providence Portland (Ore.) Medical Center. The new product is designed to complement the currently available respiratory panels from BioFire.

“Rapid-detection results in less empiric antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. When it’s FDA approved, this investigational sputum PCR panel will simplify the diagnostic bundle while improving antibiotic stewardship,” she observed.

She presented a prospective study of 63 patients with CAP hospitalized at the medical center, all of whom were evaluated by two laboratory methods: the hospital’s standard bundle of diagnostic tests and the new BioFire film array panel. The purpose was to determine if there was a difference between the two tests in the detection rate of viral and/or bacterial pathogens as well as the clinical significance of any such differences; that is, was there an impact on days of treatment and length of hospital stay?

Traditional diagnostic methods detect an etiologic pathogen in at best half of hospitalized CAP patients, and the results take too much time. So Providence Portland Medical Center adopted as its standard diagnostic bundle a nasopharyngeal swab and a BioFire film array PCR that’s currently on the market and can detect nine viruses and three bacteria, along with urine antigens for Legionella sp. and Streptococcus pneumoniae, nucleic acid amplification testing for S. pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, and blood and sputum cultures. In contrast, the investigational panel probes for 17 viruses, 18 bacterial pathogens, and seven antibiotic-resistant genes; it also measures procalcitonin levels in order to distinguish between bacterial colonization and invasion.

The new BioFire Pneumonia Panel detected a mean of 1.4 species of pathogenic bacteria in 79% of patients, while the standard diagnostic bundle detected 0.7 species in 59% of patients. The investigational panel identified a mean of 1.0 species of viral pathogens in 86% of the CAP patients; the standard bundle detected a mean of 0.6 species in 56%.

All told, any CAP pathogen was detected in 100% of patients using the new panel, with a mean of 2.5 different pathogens identified. The standard bundle detected any pathogen in 84% of patients, with half as many different pathogens found, according to Dr. Hendrickson.

A peak procalcitonin level of 0.25 ng/mL or less, which was defined as bacterial colonization, was associated with a mean 7 days of treatment, while a level above that threshold was associated with 11.3 days of treatment. Patients with a peak procalcitonin of 0.25 ng/mL or less had an average hospital length of stay of 5.9 days, versus 7.8 days for those with a higher procalcitonin indicative of bacterial invasion.

The new biofilm assay reports information about the abundance of 15 of the 18 bacterial targets in the sample. However, in contrast to peak procalcitonin, Dr. Hendrickson and her coinvestigators didn’t find this bacterial quantitation feature to be substantially more useful than a coin flip in distinguishing bacterial colonization from invasion.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the head-to-head comparative study, which was supported by BioFire Diagnostics.

NEW ORLEANS – A next-generation lower respiratory tract sputum polymerase chain reaction (PCR) film array panel identified etiologic pathogens in 100% of a group of patients hospitalized for community-acquired pneumonia, Kathryn Hendrickson, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

The investigational new diagnostic assay, the BioFire Pneumonia Panel, is now under Food and Drug Administration review for marketing clearance. (CAP), observed Dr. Hendrickson, an internal medicine resident at Providence Portland (Ore.) Medical Center. The new product is designed to complement the currently available respiratory panels from BioFire.

“Rapid-detection results in less empiric antibiotic use in hospitalized patients. When it’s FDA approved, this investigational sputum PCR panel will simplify the diagnostic bundle while improving antibiotic stewardship,” she observed.

She presented a prospective study of 63 patients with CAP hospitalized at the medical center, all of whom were evaluated by two laboratory methods: the hospital’s standard bundle of diagnostic tests and the new BioFire film array panel. The purpose was to determine if there was a difference between the two tests in the detection rate of viral and/or bacterial pathogens as well as the clinical significance of any such differences; that is, was there an impact on days of treatment and length of hospital stay?

Traditional diagnostic methods detect an etiologic pathogen in at best half of hospitalized CAP patients, and the results take too much time. So Providence Portland Medical Center adopted as its standard diagnostic bundle a nasopharyngeal swab and a BioFire film array PCR that’s currently on the market and can detect nine viruses and three bacteria, along with urine antigens for Legionella sp. and Streptococcus pneumoniae, nucleic acid amplification testing for S. pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus, and blood and sputum cultures. In contrast, the investigational panel probes for 17 viruses, 18 bacterial pathogens, and seven antibiotic-resistant genes; it also measures procalcitonin levels in order to distinguish between bacterial colonization and invasion.

The new BioFire Pneumonia Panel detected a mean of 1.4 species of pathogenic bacteria in 79% of patients, while the standard diagnostic bundle detected 0.7 species in 59% of patients. The investigational panel identified a mean of 1.0 species of viral pathogens in 86% of the CAP patients; the standard bundle detected a mean of 0.6 species in 56%.

All told, any CAP pathogen was detected in 100% of patients using the new panel, with a mean of 2.5 different pathogens identified. The standard bundle detected any pathogen in 84% of patients, with half as many different pathogens found, according to Dr. Hendrickson.

A peak procalcitonin level of 0.25 ng/mL or less, which was defined as bacterial colonization, was associated with a mean 7 days of treatment, while a level above that threshold was associated with 11.3 days of treatment. Patients with a peak procalcitonin of 0.25 ng/mL or less had an average hospital length of stay of 5.9 days, versus 7.8 days for those with a higher procalcitonin indicative of bacterial invasion.

The new biofilm assay reports information about the abundance of 15 of the 18 bacterial targets in the sample. However, in contrast to peak procalcitonin, Dr. Hendrickson and her coinvestigators didn’t find this bacterial quantitation feature to be substantially more useful than a coin flip in distinguishing bacterial colonization from invasion.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding the head-to-head comparative study, which was supported by BioFire Diagnostics.

REPORTING FROM ACP INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A new CAP diagnostic panel represents a significant advance in clinical care.

Major finding: The investigational BioFire Pneumonia Panel identified specific pathogens in 100% of patients hospitalized for CAP, compared with 84% using the hospital’s standard test bundle.

Study details: This was a prospective head-to-head study comparing two approaches to identification of specific pathogens in 63 patients hospitalized for CAP.

Disclosures: The study was supported by BioFire Diagnostics. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Larger vegetation size associated with increased risk of embolism and mortality in infective endocarditis

Clinical question: In patients with infective endocarditis, does a vegetation size greater than 10 mm impart a greater embolic risk?

Background: A vegetation size greater than 10 mm has historically been used as the cutoff for increased risk of embolization in infective endocarditis, and this cutoff forms a key part of the American Heart Association guidelines for early surgical intervention. However, this cutoff is derived primarily from observational data from small studies.

Study design: Meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized clinical trials.

Setting: An English-language literature search from PubMed and EMBASE performed May 2017.

Synopsis: The authors identified 21 unique studies evaluating the association of vegetation size greater than 10 mm with embolic events in adult patients with infective endocarditis. This accounted for a total of 6,646 unique patients and 5,116 vegetations. Analysis of these data found that patients with a vegetation size greater than 10 mm had significantly increased odds of embolic events (odds ratio, 2.28; P less than .001) and mortality (OR, 1.63; P = .009), compared with those with a vegetation size less than 10 mm.

Limitations of this research include the potential for selection bias in the original studies, and the inability to incorporate information relating to microbiologic results, antibiotic use, and the location of systemic embolization. Interestingly, as vegetations with a size of exactly 10 mm were variably categorized in the original studies, this meta-analysis was unable to reach a conclusion on the risk of embolic events for instances when vegetation size is equal to 10 mm.

Bottom line: Patients with infective endocarditis and a vegetation size greater than 10 mm may have significantly increased odds of embolic events and mortality, compared with those with vegetation size less than 10 mm.

Citation: Mohananey D et al. Association of vegetation size with embolic risk in patients with infective endocarditis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. Apr 1;178(4):502-10.

Dr. Winters is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: In patients with infective endocarditis, does a vegetation size greater than 10 mm impart a greater embolic risk?

Background: A vegetation size greater than 10 mm has historically been used as the cutoff for increased risk of embolization in infective endocarditis, and this cutoff forms a key part of the American Heart Association guidelines for early surgical intervention. However, this cutoff is derived primarily from observational data from small studies.

Study design: Meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized clinical trials.

Setting: An English-language literature search from PubMed and EMBASE performed May 2017.

Synopsis: The authors identified 21 unique studies evaluating the association of vegetation size greater than 10 mm with embolic events in adult patients with infective endocarditis. This accounted for a total of 6,646 unique patients and 5,116 vegetations. Analysis of these data found that patients with a vegetation size greater than 10 mm had significantly increased odds of embolic events (odds ratio, 2.28; P less than .001) and mortality (OR, 1.63; P = .009), compared with those with a vegetation size less than 10 mm.

Limitations of this research include the potential for selection bias in the original studies, and the inability to incorporate information relating to microbiologic results, antibiotic use, and the location of systemic embolization. Interestingly, as vegetations with a size of exactly 10 mm were variably categorized in the original studies, this meta-analysis was unable to reach a conclusion on the risk of embolic events for instances when vegetation size is equal to 10 mm.

Bottom line: Patients with infective endocarditis and a vegetation size greater than 10 mm may have significantly increased odds of embolic events and mortality, compared with those with vegetation size less than 10 mm.

Citation: Mohananey D et al. Association of vegetation size with embolic risk in patients with infective endocarditis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. Apr 1;178(4):502-10.

Dr. Winters is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: In patients with infective endocarditis, does a vegetation size greater than 10 mm impart a greater embolic risk?

Background: A vegetation size greater than 10 mm has historically been used as the cutoff for increased risk of embolization in infective endocarditis, and this cutoff forms a key part of the American Heart Association guidelines for early surgical intervention. However, this cutoff is derived primarily from observational data from small studies.

Study design: Meta-analysis of observational studies and randomized clinical trials.

Setting: An English-language literature search from PubMed and EMBASE performed May 2017.

Synopsis: The authors identified 21 unique studies evaluating the association of vegetation size greater than 10 mm with embolic events in adult patients with infective endocarditis. This accounted for a total of 6,646 unique patients and 5,116 vegetations. Analysis of these data found that patients with a vegetation size greater than 10 mm had significantly increased odds of embolic events (odds ratio, 2.28; P less than .001) and mortality (OR, 1.63; P = .009), compared with those with a vegetation size less than 10 mm.

Limitations of this research include the potential for selection bias in the original studies, and the inability to incorporate information relating to microbiologic results, antibiotic use, and the location of systemic embolization. Interestingly, as vegetations with a size of exactly 10 mm were variably categorized in the original studies, this meta-analysis was unable to reach a conclusion on the risk of embolic events for instances when vegetation size is equal to 10 mm.

Bottom line: Patients with infective endocarditis and a vegetation size greater than 10 mm may have significantly increased odds of embolic events and mortality, compared with those with vegetation size less than 10 mm.

Citation: Mohananey D et al. Association of vegetation size with embolic risk in patients with infective endocarditis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. Apr 1;178(4):502-10.

Dr. Winters is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Prophylactic haloperidol does not improve survival in critically ill patients

Clinical question: Does prophylactic use of haloperidol in critically ill patients at high risk of delirium improve survival at 28 days?

Background: Delirium occurs frequently in critically ill patients and can lead to increased ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, duration of mechanical ventilation, and mortality. Prior research into the use of prophylactic antipsychotic administration has yielded inconsistent results.

Study design: Double-blind, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 21 ICUs in the Netherlands, from July 2013 to March 2017.

Synopsis: A total of 1,789 critically ill adults with an anticipated ICU stay of at least 2 days were randomized to receive 1 mg of haloperidol, 2 mg of haloperidol, or a placebo three times daily. All study sites used “best practice” delirium prevention (for example, early mobilization, noise reduction, protocols aiming to prevent oversedation). The primary outcome was defined as the number of days patients survived in the 28 days following inclusion, and secondary outcome measures included number of days survived in 90 days, delirium incidence, number of delirium-free and coma-free days, duration of mechanical ventilation, and length of ICU and hospital stay. The 1-mg haloperidol group was stopped early because of futility. There was no significant difference between the 2-mg haloperidol group and the placebo group for the primary outcome (P = .93), or any of the secondary outcomes.Bottom line: In a population of critically ill patients at high risk of delirium, prophylactic haloperidol did not significantly improve 28-day survival, nor did it significantly reduce the incidence of delirium or length of stay.

Citation: van den Boogaard M et al. Effect of haloperidol on survival among critically ill adults with a high risk of delirium: The REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018 Feb 20;319(7):680-90.

Dr. Winters is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: Does prophylactic use of haloperidol in critically ill patients at high risk of delirium improve survival at 28 days?

Background: Delirium occurs frequently in critically ill patients and can lead to increased ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, duration of mechanical ventilation, and mortality. Prior research into the use of prophylactic antipsychotic administration has yielded inconsistent results.

Study design: Double-blind, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 21 ICUs in the Netherlands, from July 2013 to March 2017.

Synopsis: A total of 1,789 critically ill adults with an anticipated ICU stay of at least 2 days were randomized to receive 1 mg of haloperidol, 2 mg of haloperidol, or a placebo three times daily. All study sites used “best practice” delirium prevention (for example, early mobilization, noise reduction, protocols aiming to prevent oversedation). The primary outcome was defined as the number of days patients survived in the 28 days following inclusion, and secondary outcome measures included number of days survived in 90 days, delirium incidence, number of delirium-free and coma-free days, duration of mechanical ventilation, and length of ICU and hospital stay. The 1-mg haloperidol group was stopped early because of futility. There was no significant difference between the 2-mg haloperidol group and the placebo group for the primary outcome (P = .93), or any of the secondary outcomes.Bottom line: In a population of critically ill patients at high risk of delirium, prophylactic haloperidol did not significantly improve 28-day survival, nor did it significantly reduce the incidence of delirium or length of stay.

Citation: van den Boogaard M et al. Effect of haloperidol on survival among critically ill adults with a high risk of delirium: The REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018 Feb 20;319(7):680-90.

Dr. Winters is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: Does prophylactic use of haloperidol in critically ill patients at high risk of delirium improve survival at 28 days?

Background: Delirium occurs frequently in critically ill patients and can lead to increased ICU length of stay, hospital length of stay, duration of mechanical ventilation, and mortality. Prior research into the use of prophylactic antipsychotic administration has yielded inconsistent results.

Study design: Double-blind, randomized, controlled trial.

Setting: 21 ICUs in the Netherlands, from July 2013 to March 2017.

Synopsis: A total of 1,789 critically ill adults with an anticipated ICU stay of at least 2 days were randomized to receive 1 mg of haloperidol, 2 mg of haloperidol, or a placebo three times daily. All study sites used “best practice” delirium prevention (for example, early mobilization, noise reduction, protocols aiming to prevent oversedation). The primary outcome was defined as the number of days patients survived in the 28 days following inclusion, and secondary outcome measures included number of days survived in 90 days, delirium incidence, number of delirium-free and coma-free days, duration of mechanical ventilation, and length of ICU and hospital stay. The 1-mg haloperidol group was stopped early because of futility. There was no significant difference between the 2-mg haloperidol group and the placebo group for the primary outcome (P = .93), or any of the secondary outcomes.Bottom line: In a population of critically ill patients at high risk of delirium, prophylactic haloperidol did not significantly improve 28-day survival, nor did it significantly reduce the incidence of delirium or length of stay.

Citation: van den Boogaard M et al. Effect of haloperidol on survival among critically ill adults with a high risk of delirium: The REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018 Feb 20;319(7):680-90.

Dr. Winters is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Discharge opioid prescriptions for many surgical hospitalizations may be unnecessary

Background: Prescription opioids play a significant role in the current opioid epidemic. Opioids used for nonmedical purposes often are obtained from the prescription of friends and family members, and a majority of heroin users report that their first opioid exposure was via a prescription opioid. Prescription of opioids following low-risk surgical procedures has increased over the past decade.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: Two Boston-area acute care hospitals from May 2014 to September 2016.

Synopsis: The authors identified 6,548 inpatient surgical hospitalizations lasting longer than 1 day with a discharge to home in which the patient used no opioid medications in the final 24 hours prior to discharge. Of these, 43.7% received an opioid prescription at discharge. The mean prescription morphine milligram equivalents (MME) provided to this group was 343. The authors identified these cases as instances in which overprescription of opiates may have occurred. Surgical services that tended to have more patients still using opioids at the time of discharge had a higher likelihood of potential overprescription. For patients who used opioids during the final 24 hours of their hospitalization and received an opioid prescription at discharge, inpatient MME use and prescription MME were only weakly correlated (R2 = 0.112). The retrospective two-site design of this study may limit its generalizability.

Bottom line: In postoperative surgical patients, overprescription of opioid medications may occur frequently.

Citation: Chen EY et al. Correlation between 24-hour predischarge opioid use and amount of opioids prescribed at hospital discharge. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(2):e174859.

Dr. Salber is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Background: Prescription opioids play a significant role in the current opioid epidemic. Opioids used for nonmedical purposes often are obtained from the prescription of friends and family members, and a majority of heroin users report that their first opioid exposure was via a prescription opioid. Prescription of opioids following low-risk surgical procedures has increased over the past decade.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: Two Boston-area acute care hospitals from May 2014 to September 2016.

Synopsis: The authors identified 6,548 inpatient surgical hospitalizations lasting longer than 1 day with a discharge to home in which the patient used no opioid medications in the final 24 hours prior to discharge. Of these, 43.7% received an opioid prescription at discharge. The mean prescription morphine milligram equivalents (MME) provided to this group was 343. The authors identified these cases as instances in which overprescription of opiates may have occurred. Surgical services that tended to have more patients still using opioids at the time of discharge had a higher likelihood of potential overprescription. For patients who used opioids during the final 24 hours of their hospitalization and received an opioid prescription at discharge, inpatient MME use and prescription MME were only weakly correlated (R2 = 0.112). The retrospective two-site design of this study may limit its generalizability.

Bottom line: In postoperative surgical patients, overprescription of opioid medications may occur frequently.

Citation: Chen EY et al. Correlation between 24-hour predischarge opioid use and amount of opioids prescribed at hospital discharge. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(2):e174859.

Dr. Salber is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Background: Prescription opioids play a significant role in the current opioid epidemic. Opioids used for nonmedical purposes often are obtained from the prescription of friends and family members, and a majority of heroin users report that their first opioid exposure was via a prescription opioid. Prescription of opioids following low-risk surgical procedures has increased over the past decade.

Study design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: Two Boston-area acute care hospitals from May 2014 to September 2016.

Synopsis: The authors identified 6,548 inpatient surgical hospitalizations lasting longer than 1 day with a discharge to home in which the patient used no opioid medications in the final 24 hours prior to discharge. Of these, 43.7% received an opioid prescription at discharge. The mean prescription morphine milligram equivalents (MME) provided to this group was 343. The authors identified these cases as instances in which overprescription of opiates may have occurred. Surgical services that tended to have more patients still using opioids at the time of discharge had a higher likelihood of potential overprescription. For patients who used opioids during the final 24 hours of their hospitalization and received an opioid prescription at discharge, inpatient MME use and prescription MME were only weakly correlated (R2 = 0.112). The retrospective two-site design of this study may limit its generalizability.

Bottom line: In postoperative surgical patients, overprescription of opioid medications may occur frequently.

Citation: Chen EY et al. Correlation between 24-hour predischarge opioid use and amount of opioids prescribed at hospital discharge. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(2):e174859.

Dr. Salber is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Making the referral and navigating care

Be familiar with local post-acute care resources

Presenter

Elisabeth Schainker, MD, MSc

Session title

Making the referral and navigating “A Whole New World” of care

Session summary

By describing different types of post-acute care clinical services, Dr. Schainker empowered the HM18 audience to rethink how to best identify patients and conditions appropriate for transitions of care, from short-term acute care environments to long-term acute care places, inpatient rehabs, or skilled nursing facilities.

With increasing numbers of pediatric patients with medical complexity, who are dependent on technology devices and complicated care needs, hospitalists need to be knowledgeable about the rules of engagement for prolonged or enhanced recoveries, families’ needs, and insurance qualifications. The role of the hospitalist is to make sure that things are in place for safe and successful discharges, keeping in mind patients’ complexity, resources available within family and community, and fair assessments of readmission risks.

Whether rehab needs pertain to pulmonary, medical, or post NICU stays – length of stay averaging 70-80 days – hospitalists still need to ensure that patients have a clear potential to do better and transition to home eventually. There are inadequate numbers of such pediatric post-acute care facilities, 36 hospitals to be precise. Franciscan Children’s, where Dr. Schainker practices, was beautifully represented in a short movie played during the session at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. The protagonists in the movie were children: Mae and Luke.

Key takeaways for HM

1. Knowledge: Post-acute care services facilitate safe discharges of complex medical patients that eventually get home.

2. Attitude: Hospitalists need to identify what would benefit their patients and counsel families, as well as make proper and timely referrals.

3. Behavior: Hospitalists should be familiar with local resources and engage with available providers of post-acute care services.

Dr. Giordano is a pediatric neurosurgery hospitalist at Columbia University Medical Center in New York.

Be familiar with local post-acute care resources

Be familiar with local post-acute care resources

Presenter

Elisabeth Schainker, MD, MSc

Session title

Making the referral and navigating “A Whole New World” of care

Session summary

By describing different types of post-acute care clinical services, Dr. Schainker empowered the HM18 audience to rethink how to best identify patients and conditions appropriate for transitions of care, from short-term acute care environments to long-term acute care places, inpatient rehabs, or skilled nursing facilities.

With increasing numbers of pediatric patients with medical complexity, who are dependent on technology devices and complicated care needs, hospitalists need to be knowledgeable about the rules of engagement for prolonged or enhanced recoveries, families’ needs, and insurance qualifications. The role of the hospitalist is to make sure that things are in place for safe and successful discharges, keeping in mind patients’ complexity, resources available within family and community, and fair assessments of readmission risks.

Whether rehab needs pertain to pulmonary, medical, or post NICU stays – length of stay averaging 70-80 days – hospitalists still need to ensure that patients have a clear potential to do better and transition to home eventually. There are inadequate numbers of such pediatric post-acute care facilities, 36 hospitals to be precise. Franciscan Children’s, where Dr. Schainker practices, was beautifully represented in a short movie played during the session at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. The protagonists in the movie were children: Mae and Luke.

Key takeaways for HM

1. Knowledge: Post-acute care services facilitate safe discharges of complex medical patients that eventually get home.

2. Attitude: Hospitalists need to identify what would benefit their patients and counsel families, as well as make proper and timely referrals.

3. Behavior: Hospitalists should be familiar with local resources and engage with available providers of post-acute care services.

Dr. Giordano is a pediatric neurosurgery hospitalist at Columbia University Medical Center in New York.

Presenter

Elisabeth Schainker, MD, MSc

Session title

Making the referral and navigating “A Whole New World” of care

Session summary

By describing different types of post-acute care clinical services, Dr. Schainker empowered the HM18 audience to rethink how to best identify patients and conditions appropriate for transitions of care, from short-term acute care environments to long-term acute care places, inpatient rehabs, or skilled nursing facilities.

With increasing numbers of pediatric patients with medical complexity, who are dependent on technology devices and complicated care needs, hospitalists need to be knowledgeable about the rules of engagement for prolonged or enhanced recoveries, families’ needs, and insurance qualifications. The role of the hospitalist is to make sure that things are in place for safe and successful discharges, keeping in mind patients’ complexity, resources available within family and community, and fair assessments of readmission risks.

Whether rehab needs pertain to pulmonary, medical, or post NICU stays – length of stay averaging 70-80 days – hospitalists still need to ensure that patients have a clear potential to do better and transition to home eventually. There are inadequate numbers of such pediatric post-acute care facilities, 36 hospitals to be precise. Franciscan Children’s, where Dr. Schainker practices, was beautifully represented in a short movie played during the session at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine. The protagonists in the movie were children: Mae and Luke.

Key takeaways for HM

1. Knowledge: Post-acute care services facilitate safe discharges of complex medical patients that eventually get home.

2. Attitude: Hospitalists need to identify what would benefit their patients and counsel families, as well as make proper and timely referrals.

3. Behavior: Hospitalists should be familiar with local resources and engage with available providers of post-acute care services.

Dr. Giordano is a pediatric neurosurgery hospitalist at Columbia University Medical Center in New York.

Ranked: State of the states’ health care

In the wild world of health care rankings, a year can make a big difference … or not.

Iowa fell from second to ninth over the course of the last year while Connecticut and South Dakota moved out of the top 10 to make way for Colorado and Maryland, according to WalletHub.

There was less movement at the other end of the rankings, however, with no change at all in the bottom five: Louisiana finished 51st again (the rankings include the District of Columbia), preceded by fellow repeaters Mississippi (50), Alaska (49), Arkansas (48), and North Carolina (47). Texas and Nevada did manage to move on up out of the bottom 11 – to 38th and 40th, respectively – at the expense of Oklahoma and Tennessee, WalletHub reported.

For 2018, the company compared the states and D.C. “across 40 measures of cost, accessibility and outcome,” which is five more measures than last year and a possible explanation for the changes at the top. The cost dimension’s five metrics included cost of medical visits and share of high out-of-pocket medical spending. The accessibility dimension consisted of 21 metrics, including average emergency department wait time and share of insured children. The outcomes dimension included 14 metrics, among them maternal mortality rate and share of adults with type 2 diabetes.

Vermont did well in both the outcomes (first) and cost (third) dimensions but only middle of the pack (23rd) in access. The District of Columbia was ranked first in cost and Maine was the leader in access. The lowest-ranked states in each category were Alaska (cost), Texas (access), and Mississippi (outcomes), according to the WalletHub analysis, which was based on data from such sources as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the United Health Foundation.

In the wild world of health care rankings, a year can make a big difference … or not.

Iowa fell from second to ninth over the course of the last year while Connecticut and South Dakota moved out of the top 10 to make way for Colorado and Maryland, according to WalletHub.

There was less movement at the other end of the rankings, however, with no change at all in the bottom five: Louisiana finished 51st again (the rankings include the District of Columbia), preceded by fellow repeaters Mississippi (50), Alaska (49), Arkansas (48), and North Carolina (47). Texas and Nevada did manage to move on up out of the bottom 11 – to 38th and 40th, respectively – at the expense of Oklahoma and Tennessee, WalletHub reported.

For 2018, the company compared the states and D.C. “across 40 measures of cost, accessibility and outcome,” which is five more measures than last year and a possible explanation for the changes at the top. The cost dimension’s five metrics included cost of medical visits and share of high out-of-pocket medical spending. The accessibility dimension consisted of 21 metrics, including average emergency department wait time and share of insured children. The outcomes dimension included 14 metrics, among them maternal mortality rate and share of adults with type 2 diabetes.

Vermont did well in both the outcomes (first) and cost (third) dimensions but only middle of the pack (23rd) in access. The District of Columbia was ranked first in cost and Maine was the leader in access. The lowest-ranked states in each category were Alaska (cost), Texas (access), and Mississippi (outcomes), according to the WalletHub analysis, which was based on data from such sources as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the United Health Foundation.

In the wild world of health care rankings, a year can make a big difference … or not.

Iowa fell from second to ninth over the course of the last year while Connecticut and South Dakota moved out of the top 10 to make way for Colorado and Maryland, according to WalletHub.

There was less movement at the other end of the rankings, however, with no change at all in the bottom five: Louisiana finished 51st again (the rankings include the District of Columbia), preceded by fellow repeaters Mississippi (50), Alaska (49), Arkansas (48), and North Carolina (47). Texas and Nevada did manage to move on up out of the bottom 11 – to 38th and 40th, respectively – at the expense of Oklahoma and Tennessee, WalletHub reported.

For 2018, the company compared the states and D.C. “across 40 measures of cost, accessibility and outcome,” which is five more measures than last year and a possible explanation for the changes at the top. The cost dimension’s five metrics included cost of medical visits and share of high out-of-pocket medical spending. The accessibility dimension consisted of 21 metrics, including average emergency department wait time and share of insured children. The outcomes dimension included 14 metrics, among them maternal mortality rate and share of adults with type 2 diabetes.

Vermont did well in both the outcomes (first) and cost (third) dimensions but only middle of the pack (23rd) in access. The District of Columbia was ranked first in cost and Maine was the leader in access. The lowest-ranked states in each category were Alaska (cost), Texas (access), and Mississippi (outcomes), according to the WalletHub analysis, which was based on data from such sources as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Health Resources & Services Administration, and the United Health Foundation.

Catheter ablation of AF in patients with heart failure decreases mortality and HF admissions

Background: Rhythm control with medical therapy has been shown to not be superior to rate control for patients with both heart failure and AF. Rhythm control by ablation has been associated with positive outcomes in this same population, but its effectiveness, compared with medical therapy for patient-centered outcomes, has not been demonstrated.

Study design: Multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled superiority trial.

Setting: 33 hospitals from Europe, Australia, and the United States during 2008-2016.

Synopsis: A total of 363 patients with HF with LVEF less than 35%, New York Heart Association II-IV symptoms, and permanent or paroxysmal AF who had previously failed or declined antiarrhythmic medications were randomly assigned to undergo ablation by pulmonary vein isolation or to medical therapy. The primary outcome – a composite of death or hospitalization for heart failure – was significantly lower in the ablation group, compared with the medical therapy group (28.5% vs. 44.6%; P = .006) with a number needed to treat of 8.3. The secondary outcomes of all-cause mortality and heart failure admissions were also significantly lower in the ablation group (13.4% vs. 25%; P = .01 and 20.7% vs. 35.9%; P = .004 respectively). The burden of AF, as identified by patient implantable devices was significantly lower in the ablation group, suggesting the likely mechanism of ablation benefit. Limitations of this study include its small sample size and lack of physician or patient blinding to treatment assignment.

Bottom line: Compared with medical therapy, catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation for patients with symptomatic heart failure with LVEF less than 35% was associated with significantly decreased mortality and heart failure admissions.

Citation: Marrouche N et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Eng J Med. 2018 Feb 1; 378:417-27.

Dr. Salber is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Background: Rhythm control with medical therapy has been shown to not be superior to rate control for patients with both heart failure and AF. Rhythm control by ablation has been associated with positive outcomes in this same population, but its effectiveness, compared with medical therapy for patient-centered outcomes, has not been demonstrated.

Study design: Multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled superiority trial.

Setting: 33 hospitals from Europe, Australia, and the United States during 2008-2016.

Synopsis: A total of 363 patients with HF with LVEF less than 35%, New York Heart Association II-IV symptoms, and permanent or paroxysmal AF who had previously failed or declined antiarrhythmic medications were randomly assigned to undergo ablation by pulmonary vein isolation or to medical therapy. The primary outcome – a composite of death or hospitalization for heart failure – was significantly lower in the ablation group, compared with the medical therapy group (28.5% vs. 44.6%; P = .006) with a number needed to treat of 8.3. The secondary outcomes of all-cause mortality and heart failure admissions were also significantly lower in the ablation group (13.4% vs. 25%; P = .01 and 20.7% vs. 35.9%; P = .004 respectively). The burden of AF, as identified by patient implantable devices was significantly lower in the ablation group, suggesting the likely mechanism of ablation benefit. Limitations of this study include its small sample size and lack of physician or patient blinding to treatment assignment.

Bottom line: Compared with medical therapy, catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation for patients with symptomatic heart failure with LVEF less than 35% was associated with significantly decreased mortality and heart failure admissions.

Citation: Marrouche N et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Eng J Med. 2018 Feb 1; 378:417-27.

Dr. Salber is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Background: Rhythm control with medical therapy has been shown to not be superior to rate control for patients with both heart failure and AF. Rhythm control by ablation has been associated with positive outcomes in this same population, but its effectiveness, compared with medical therapy for patient-centered outcomes, has not been demonstrated.

Study design: Multicenter, open-label, randomized, controlled superiority trial.

Setting: 33 hospitals from Europe, Australia, and the United States during 2008-2016.

Synopsis: A total of 363 patients with HF with LVEF less than 35%, New York Heart Association II-IV symptoms, and permanent or paroxysmal AF who had previously failed or declined antiarrhythmic medications were randomly assigned to undergo ablation by pulmonary vein isolation or to medical therapy. The primary outcome – a composite of death or hospitalization for heart failure – was significantly lower in the ablation group, compared with the medical therapy group (28.5% vs. 44.6%; P = .006) with a number needed to treat of 8.3. The secondary outcomes of all-cause mortality and heart failure admissions were also significantly lower in the ablation group (13.4% vs. 25%; P = .01 and 20.7% vs. 35.9%; P = .004 respectively). The burden of AF, as identified by patient implantable devices was significantly lower in the ablation group, suggesting the likely mechanism of ablation benefit. Limitations of this study include its small sample size and lack of physician or patient blinding to treatment assignment.

Bottom line: Compared with medical therapy, catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation for patients with symptomatic heart failure with LVEF less than 35% was associated with significantly decreased mortality and heart failure admissions.

Citation: Marrouche N et al. Catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation with heart failure. N Eng J Med. 2018 Feb 1; 378:417-27.

Dr. Salber is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Patent foramen ovale may be associated with increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke

Clinical question: Are patients with patent foramen ovale (PFO) at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke?

Background: Prior research has identified an association between PFO and risk of stroke. However, little is known about the effect of a preoperatively diagnosed PFO on perioperative stroke risk.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Three Massachusetts hospitals, from January 2007 to December 2015.

Synopsis: The charts of 150,198 adult patients who underwent noncardiac surgery were reviewed for ICD codes for PFO. The primary outcome was perioperative ischemic stroke within 30 days of surgery, as identified via ICD code and subsequent chart review. After they adjusted for confounding variables, the study authors found that patients with PFO had an increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke (odds ratio, 2.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.96-3.63; P less than .001) compared with patients without PFO. These findings were replicated in a propensity score–matched cohort to adjust for baseline differences between PFO and non-PFO groups. Patients with PFO also had a significantly increased risk of large-vessel territory ischemia and more severe neurologic deficits.

Given the observational design, this study could not establish a causal relationship between presence of a PFO and perioperative stroke. While the results support the consideration of PFO as a risk factor for perioperative stroke, research into whether this risk can be mitigated is needed.

Bottom line: Patients with PFO undergoing noncardiac surgery may be at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke.

Citation: Ng PY et al. Association of preoperatively diagnosed patent foramen ovale with perioperative ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2018 Feb 6;319(5):452-62.

Dr. Roy is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: Are patients with patent foramen ovale (PFO) at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke?

Background: Prior research has identified an association between PFO and risk of stroke. However, little is known about the effect of a preoperatively diagnosed PFO on perioperative stroke risk.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Three Massachusetts hospitals, from January 2007 to December 2015.

Synopsis: The charts of 150,198 adult patients who underwent noncardiac surgery were reviewed for ICD codes for PFO. The primary outcome was perioperative ischemic stroke within 30 days of surgery, as identified via ICD code and subsequent chart review. After they adjusted for confounding variables, the study authors found that patients with PFO had an increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke (odds ratio, 2.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.96-3.63; P less than .001) compared with patients without PFO. These findings were replicated in a propensity score–matched cohort to adjust for baseline differences between PFO and non-PFO groups. Patients with PFO also had a significantly increased risk of large-vessel territory ischemia and more severe neurologic deficits.

Given the observational design, this study could not establish a causal relationship between presence of a PFO and perioperative stroke. While the results support the consideration of PFO as a risk factor for perioperative stroke, research into whether this risk can be mitigated is needed.

Bottom line: Patients with PFO undergoing noncardiac surgery may be at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke.

Citation: Ng PY et al. Association of preoperatively diagnosed patent foramen ovale with perioperative ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2018 Feb 6;319(5):452-62.

Dr. Roy is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Clinical question: Are patients with patent foramen ovale (PFO) at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke?

Background: Prior research has identified an association between PFO and risk of stroke. However, little is known about the effect of a preoperatively diagnosed PFO on perioperative stroke risk.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Three Massachusetts hospitals, from January 2007 to December 2015.

Synopsis: The charts of 150,198 adult patients who underwent noncardiac surgery were reviewed for ICD codes for PFO. The primary outcome was perioperative ischemic stroke within 30 days of surgery, as identified via ICD code and subsequent chart review. After they adjusted for confounding variables, the study authors found that patients with PFO had an increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke (odds ratio, 2.66; 95% confidence interval, 1.96-3.63; P less than .001) compared with patients without PFO. These findings were replicated in a propensity score–matched cohort to adjust for baseline differences between PFO and non-PFO groups. Patients with PFO also had a significantly increased risk of large-vessel territory ischemia and more severe neurologic deficits.

Given the observational design, this study could not establish a causal relationship between presence of a PFO and perioperative stroke. While the results support the consideration of PFO as a risk factor for perioperative stroke, research into whether this risk can be mitigated is needed.

Bottom line: Patients with PFO undergoing noncardiac surgery may be at increased risk of perioperative ischemic stroke.

Citation: Ng PY et al. Association of preoperatively diagnosed patent foramen ovale with perioperative ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2018 Feb 6;319(5):452-62.

Dr. Roy is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor in medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Documentation and billing: Tips for hospitalists

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

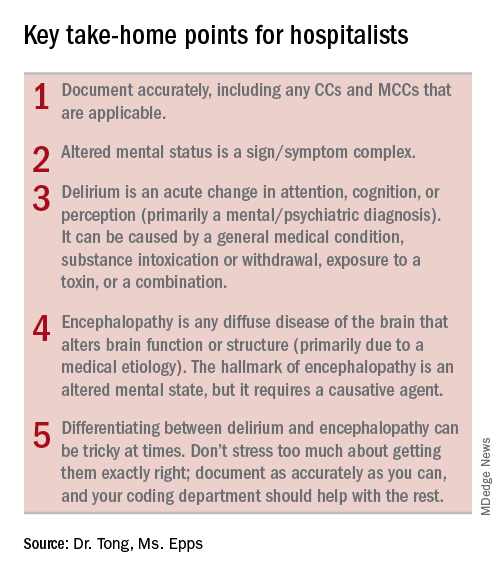

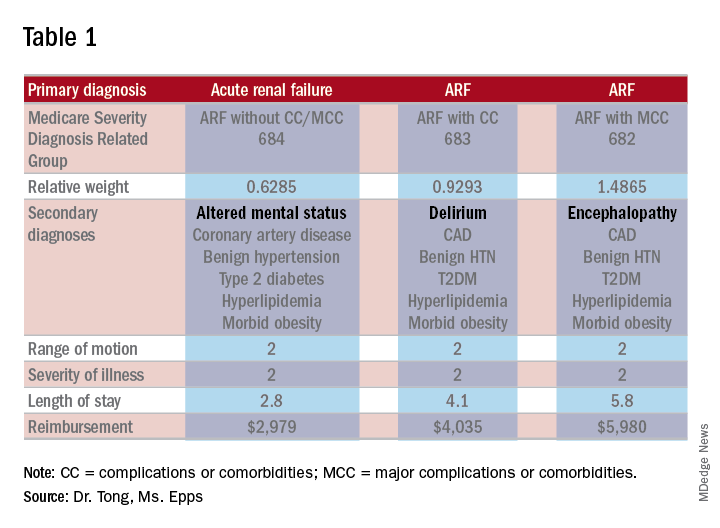

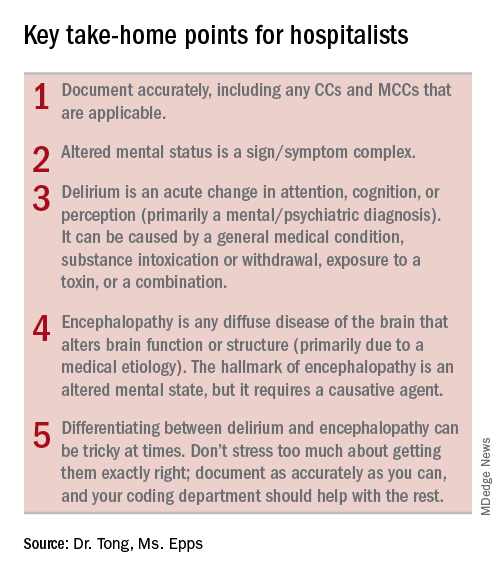

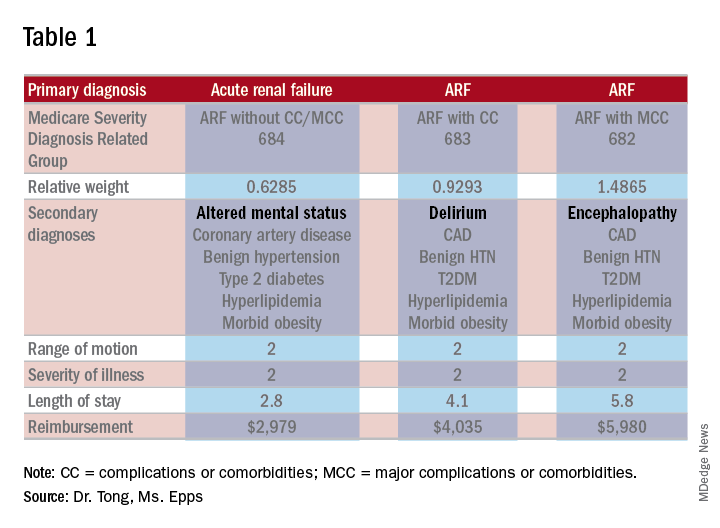

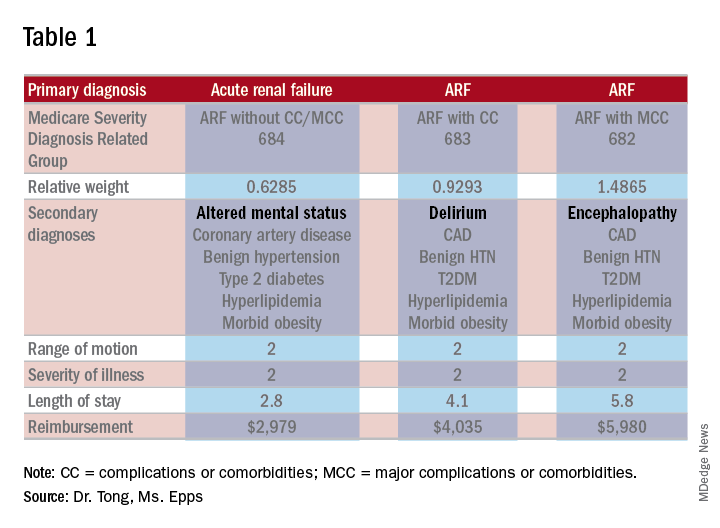

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

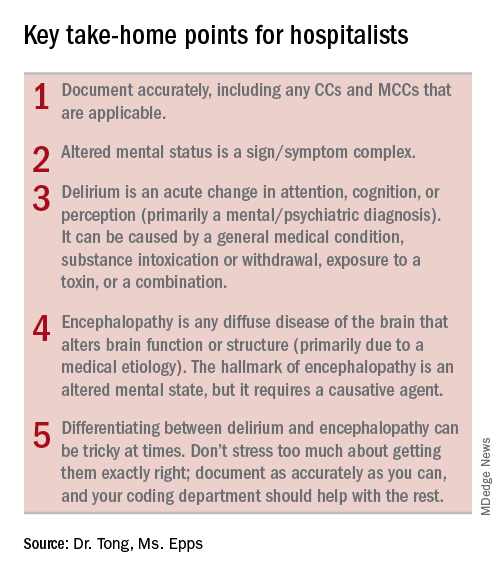

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

Is it AMS, Delirium, or Encephalopathy?

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.

During residency, physicians are trained to care for patients and write notes that are clinically useful. However, physicians are often not taught about how documentation affects reimbursement and quality measures. Our purpose here, and in articles to follow, is to give readers tools to enable them to more accurately reflect the complexity and work that is done for accurate reimbursements.

If you were to get in a car accident, the body shop would document the damage done and submit it to the insurance company. It’s the body shop’s responsibility to record the damage, not the insurance company’s. So while documentation can seem onerous, the insurance company is not going to scour the chart to find diagnoses missed in the note. That would be like the body shop doing repair work without documenting the damage but then somehow expecting to get paid.

For the insurance company, “If you didn’t document it, it didn’t happen.” The body shop should not underdocument and say there were only a few scratches on the right rear panel if it was severely damaged. Likewise, it should not overbill and say the front bumper was damaged if it was not. The goal is not to bill as much as possible but rather to document appropriately.

Terminology

The expected length of stay (LOS) and the expected mortality for a particular patient is determined by how sick the patient appears to be based on the medical record documentation. So documenting all the appropriate diagnoses makes the LOS index (actual LOS divided by expected LOS) and mortality index more accurate as well. It is particularly important to document when a condition is (or is not) “present on admission”.

While physician payments can be based on evaluation and management coding, the hospital’s reimbursement is largely determined by physician documentation. Hospitals are paid by Medicare on a capitated basis according to the Acute Inpatient Prospective Payment System. The amount paid is determined by the base rate of the hospital multiplied by the relative weight (RW) of the Medicare Severity Diagnosis Related Group (MS-DRG).

The base rate is adjusted by the wage index of the hospital location. Hospitals that serve a high proportion of low income patients receive a Disproportionate Share Hospital adjustment. The base rate is not something hospitalists have control over.

The RW, however, is determined by the primary diagnosis (reason for admission) and whether or not there are complications or comorbidities (CCs) or major complications or comorbidities (MCCs). The more CCs and MCCs a patient has, the higher the severity of illness and expected increased resources needed to care for that patient.

Diagnoses are currently coded using ICD-10 used by the World Health Organization. The ICD-10 of the primary diagnosis is mapped to an MS-DRG. Many, but not all, MS-DRGs have increasing reimbursements for CCs and MCCs. Coders map the ICD-10 of the principal diagnosis along with any associated CCs or MCCs to the MS-DRG code. The relative weights for different DRGs can found on table 5 of the Medicare website (see reference 1).

Altered mental status versus delirium versus encephalopathy

As an example, let’s look at the difference in RW, LOS, and reimbursement in an otherwise identical patient based on documenting altered mental status (AMS), delirium, or encephalopathy. (see Table 1)

As one can see, RW, estimated LOS, and reimbursement would significantly increase for the patient with delirium (CC) or encephalopathy (MCC) versus AMS (no CC/MCC). A list of which diagnoses are considered CC’s versus MCC’s are on tables 6J and 6I, respectively, on the same Medicare website as table 5.

The difference between AMS, delirium, and encephalopathy

AMS is a sign/symptom complex similar to shortness of breath before an etiology is found. AMS can be the presenting symptom; when a specific etiology is found, however, a more specific diagnosis should be used such as delirium or encephalopathy.

Delirium, according to the DSM-5, is an acute change in the level of attention, cognition, or perception from baseline that developed over hours or days and tends to fluctuate during the course of a day. The change described is not better explained by a preexisting or evolving neurocognitive disorder and does not occur in the context of a severely reduced level of arousal, such as coma. There is evidence from the history, physical examination, or laboratory findings that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a general medical condition, substance intoxication or withdrawal, exposure to a toxin, or more than one cause.

The National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke defines encephalopathy as “any diffuse disease of the brain that alters brain function or structure. Encephalopathy may be caused by an infectious agent, metabolic or mitochondrial dysfunction, brain tumor or increased intracranial pressure, prolonged exposure to toxic elements, chronic progressive trauma, poor nutrition, or lack of oxygen or blood flow to the brain. The hallmark of encephalopathy is an altered mental state.”

It is confusing since there is a lot of overlap in the definitions of delirium and encephalopathy. One way to tease this out conceptually is noting that delirium is listed under mental, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental disorders, while encephalopathy appears under disorders of the nervous system. One can think of delirium as more of a “mental/psychiatric” diagnosis, while encephalopathy is caused by more “medical” causes.

If a patient who is normally not altered presents with confusion because of an infection or metabolic derangement, one can diagnose and document the cause of an acute encephalopathy. However, let’s say a patient is admitted in the morning with an infection, is started on treatment, but is not initially confused. If he/she later becomes confused at night, one could err conservatively and document delirium caused by sundowning.

Differentiating delirium and encephalopathy can be especially difficult in patients who have dementia with episodic confusion when they present with an infection and confusion. If the confusion is within what family members/caretakers say is “normal,” then one shouldn’t document encephalopathy. As a provider, one shouldn’t focus on all the rules and exceptions, just document as specifically and accurately as possible and the coders should take care of the rest.

Dr. Tong is an assistant professor of hospital medicine and an assistant director of the clinical research program at Emory University, Atlanta. Ms. Epps is director of clinical documentation improvement at Emory Healthcare, Atlanta.

References

1. “Acute Inpatient PPS.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/index.html.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

3. “Details for title: FY 2018 Final Rule and Correction Notice Tables.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Accessed 2/17/18. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page-Items/FY2018-IPPS-Final-Rule-Tables.html.

4. “Encephalopathy Information Page.” National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke. Accessed on 2/17/18. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Encephalopathy-Information-Page.

5. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1992. http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37958.

Positive change through advocacy