User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

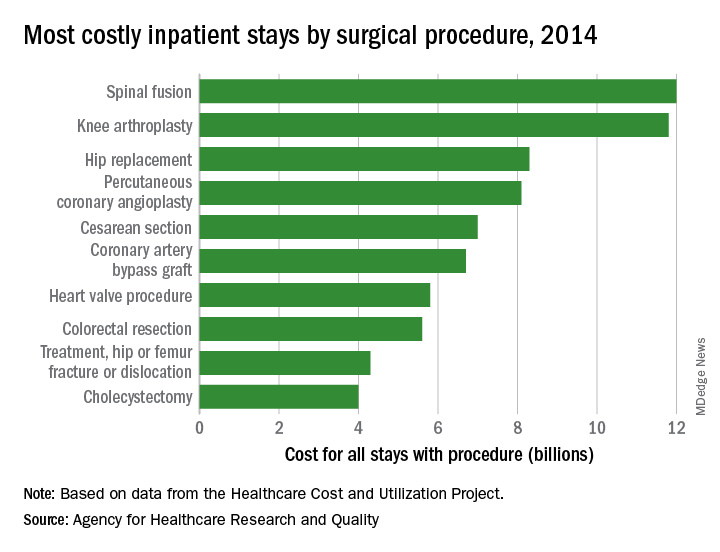

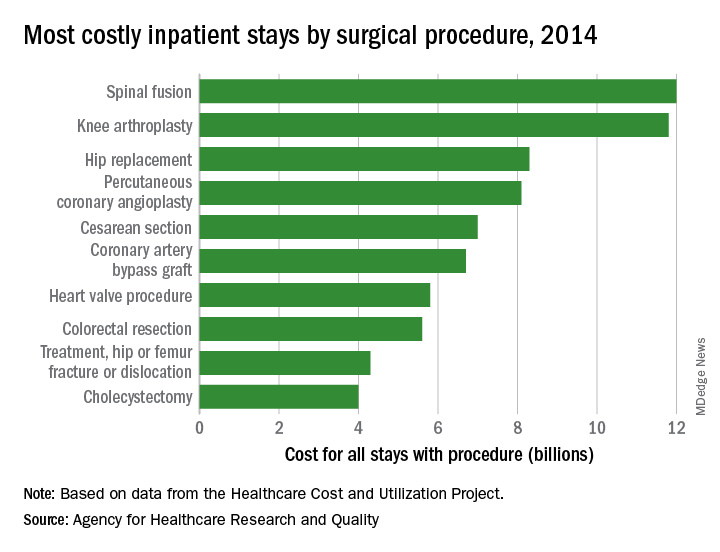

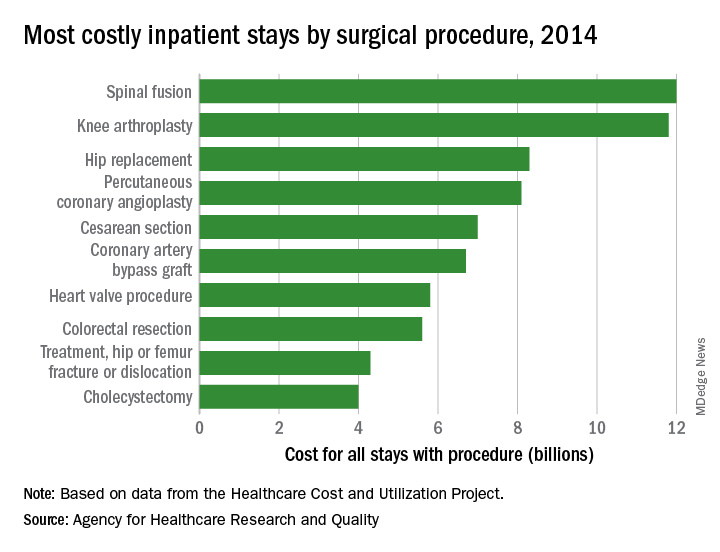

Surgeries account for almost half of hospital costs

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Of the 35.4 million inpatient stays in 2014 – the last full year of ICD-9-CM coding – 10.1 million (28.6%) involved at least one any-listed surgical procedure, and 25.2 million (71.4%) did not. The total cost of all admissions was $386.2 billion, of which $187.1 billion (48.4%) went for stays with surgeries and $199.1 billion (51.6%) went for nonsurgical stays, the AHRQ reported in a statistical brief.

There were five other musculoskeletal procedures among the 20 most costly surgery-related admissions: knee arthroplasty was second at $11.8 billion, hip replacement was third at $8.3 billion, treatment of hip and femur fracture/dislocation was ninth at $4.3 billion, amputation of lower extremity was 13th at $2.5 billion, and treatment of lower extremity (other than hip or femur) fracture/dislocation was 14th at $2.4 billion. Those six procedures combined were $41.2 billion in hospital costs, which was a quarter of the total for all stays with a first-listed OR procedure, the AHRQ said.

The nonmusculoskeletal procedures in the top five were percutaneous coronary angioplasty in fourth, with an aggregate cost of $8.1 billion, and cesarean section in fifth at an even $7 billion. Coronary artery bypass graft, the most expensive procedure per stay ($52,000) among the top 20 procedures, was sixth in aggregate cost at $6.7 billion, according to the AHRQ researchers.

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Of the 35.4 million inpatient stays in 2014 – the last full year of ICD-9-CM coding – 10.1 million (28.6%) involved at least one any-listed surgical procedure, and 25.2 million (71.4%) did not. The total cost of all admissions was $386.2 billion, of which $187.1 billion (48.4%) went for stays with surgeries and $199.1 billion (51.6%) went for nonsurgical stays, the AHRQ reported in a statistical brief.

There were five other musculoskeletal procedures among the 20 most costly surgery-related admissions: knee arthroplasty was second at $11.8 billion, hip replacement was third at $8.3 billion, treatment of hip and femur fracture/dislocation was ninth at $4.3 billion, amputation of lower extremity was 13th at $2.5 billion, and treatment of lower extremity (other than hip or femur) fracture/dislocation was 14th at $2.4 billion. Those six procedures combined were $41.2 billion in hospital costs, which was a quarter of the total for all stays with a first-listed OR procedure, the AHRQ said.

The nonmusculoskeletal procedures in the top five were percutaneous coronary angioplasty in fourth, with an aggregate cost of $8.1 billion, and cesarean section in fifth at an even $7 billion. Coronary artery bypass graft, the most expensive procedure per stay ($52,000) among the top 20 procedures, was sixth in aggregate cost at $6.7 billion, according to the AHRQ researchers.

according to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

Of the 35.4 million inpatient stays in 2014 – the last full year of ICD-9-CM coding – 10.1 million (28.6%) involved at least one any-listed surgical procedure, and 25.2 million (71.4%) did not. The total cost of all admissions was $386.2 billion, of which $187.1 billion (48.4%) went for stays with surgeries and $199.1 billion (51.6%) went for nonsurgical stays, the AHRQ reported in a statistical brief.

There were five other musculoskeletal procedures among the 20 most costly surgery-related admissions: knee arthroplasty was second at $11.8 billion, hip replacement was third at $8.3 billion, treatment of hip and femur fracture/dislocation was ninth at $4.3 billion, amputation of lower extremity was 13th at $2.5 billion, and treatment of lower extremity (other than hip or femur) fracture/dislocation was 14th at $2.4 billion. Those six procedures combined were $41.2 billion in hospital costs, which was a quarter of the total for all stays with a first-listed OR procedure, the AHRQ said.

The nonmusculoskeletal procedures in the top five were percutaneous coronary angioplasty in fourth, with an aggregate cost of $8.1 billion, and cesarean section in fifth at an even $7 billion. Coronary artery bypass graft, the most expensive procedure per stay ($52,000) among the top 20 procedures, was sixth in aggregate cost at $6.7 billion, according to the AHRQ researchers.

24-hour ambulatory BP measurements strongly predict mortality

Ambulatory measurements of blood pressure more strongly predicted all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than did BP measured in the clinic, according to analysis of a large patient registry in Spain.

The results also showed an increased risk of death associated with white coat hypertension and an even stronger association between death and masked hypertension. They were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Previous investigations had found that 24-hour ambulatory BP measurements were better predictors of patient outcomes than those obtained in the clinic or at home, but those investigations were small or population based.“In these studies, the number of clinical outcomes was limited, which reduced the ability to assess the predictive value of clinic blood pressure data as compared with ambulatory data,” reported José R. Banegas, MD, of the department of preventive medicine and public health at the Autonomous University of Madrid and his colleagues.

To better define the prognostic value of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure measurement, Dr. Banegas and his colleagues looked at data on a large cohort of primary care patients in the Spanish Ambulatory Blood Pressure Registry. Their analysis included 63,910 adults recruited to the registry during 2004-2014.

Patients had blood pressure measurements taken in the clinic according to standard procedures. Afterward, they had ambulatory blood pressure monitoring that used an automated device programmed to record BP every 20 minutes during the day and every 30 minutes at night.

They found that overall clinic and ambulatory blood pressure measurements had a relatively similar magnitude of association with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

However, clinic systolic pressure lost its predictive power for all-cause mortality after adjustment for 24-hour ambulatory systolic pressure. The hazard ratio for all-cause mortality dropped from 1.54 before the adjustment to 1.02 after the adjustment, Dr. Banegas and his colleagues reported.

By contrast, ambulatory systolic pressure kept its predictive value after accounting for clinical systolic pressure, with a hazard ratio for all-cause mortality of 1.58 before and after the adjustment, they said in the report.

The strongest association with all-cause mortality was found in patients with masked hypertension – normal clinic readings but elevated ambulatory readings. The hazard ratio for all-cause mortality in that group was 2.83 when adjusted for clinic blood pressure, with similar findings reported for cardiovascular mortality.

White coat hypertension was also associated with increased risk of mortality. The finding of elevated clinic BP and normal 24-hour ambulatory BP had a hazard ratio of 1.79 for all-cause mortality after adjustment for clinic BP, results showed.

“In our study, white coat hypertension was not benign, which may be due in part to the higher mean blood pressure over 24 hours in these patients (119.9/71.9 mm Hg vs. 116.6/70.6 mm Hg in normotensive patients; P less than .001) or to their metabolic phenotype,” the investigators wrote.

Lacer Laboratories, the Spanish Society of Hypertension, and some European government agencies supported the study. Dr. Banegas reported grants from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria and personal fees from Lacer. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Vascular Dynamics USA, Relypsa USA, Novartis Pharma USA, Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Lacer Laboratories Spain, and others.

SOURCE: Banegas JR et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1509-20.

The investigation by Dr. Banegas and colleagues confirms that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is useful for assessing blood pressure, the most important and treatable factor contributing to death and disability.

The registry study addresses several clinically relevant issues. In particular, ambulatory blood pressure measures more strongly predicted all-cause and cardiovascular mortality as compared with blood pressure measured in the clinic.

Moreover, the highest hazard ratio of death was seen in patients with masked hypertension, or those with normal clinic-measured blood pressure but elevated ambulatory measurements.

Finally, patients with white coat hypertension (elevated clinic but normal ambulatory blood pressure) had a risk of cardiovascular death twice as high as patients with normal clinic and ambulatory values.

The ominous effect of white coat hypertension has been noted by others, and it is probably related to the increasing magnitude (that is, the difference between clinic blood pressure and ambulatory blood pressure) to white coat hypertension with age.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring equipment has evolved and is much lighter than in the past, making it more acceptable to patients.

With more patients undergoing ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, several countries established ambulatory monitoring registries, such as the Spanish registry evaluated in this study.

Ultimately, one hopes the results of this registry study would serve as one more spur to providers and device manufacturers to initiate a registry in the United States.

Raymond R. Townsend, MD, is from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. These comments are based on his editorial that appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine . Dr. Townsend reported disclosures related to Medtronic, AXIO, and CLARUS Therapeutics, among others.

The investigation by Dr. Banegas and colleagues confirms that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is useful for assessing blood pressure, the most important and treatable factor contributing to death and disability.

The registry study addresses several clinically relevant issues. In particular, ambulatory blood pressure measures more strongly predicted all-cause and cardiovascular mortality as compared with blood pressure measured in the clinic.

Moreover, the highest hazard ratio of death was seen in patients with masked hypertension, or those with normal clinic-measured blood pressure but elevated ambulatory measurements.

Finally, patients with white coat hypertension (elevated clinic but normal ambulatory blood pressure) had a risk of cardiovascular death twice as high as patients with normal clinic and ambulatory values.

The ominous effect of white coat hypertension has been noted by others, and it is probably related to the increasing magnitude (that is, the difference between clinic blood pressure and ambulatory blood pressure) to white coat hypertension with age.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring equipment has evolved and is much lighter than in the past, making it more acceptable to patients.

With more patients undergoing ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, several countries established ambulatory monitoring registries, such as the Spanish registry evaluated in this study.

Ultimately, one hopes the results of this registry study would serve as one more spur to providers and device manufacturers to initiate a registry in the United States.

Raymond R. Townsend, MD, is from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. These comments are based on his editorial that appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine . Dr. Townsend reported disclosures related to Medtronic, AXIO, and CLARUS Therapeutics, among others.

The investigation by Dr. Banegas and colleagues confirms that ambulatory blood pressure monitoring is useful for assessing blood pressure, the most important and treatable factor contributing to death and disability.

The registry study addresses several clinically relevant issues. In particular, ambulatory blood pressure measures more strongly predicted all-cause and cardiovascular mortality as compared with blood pressure measured in the clinic.

Moreover, the highest hazard ratio of death was seen in patients with masked hypertension, or those with normal clinic-measured blood pressure but elevated ambulatory measurements.

Finally, patients with white coat hypertension (elevated clinic but normal ambulatory blood pressure) had a risk of cardiovascular death twice as high as patients with normal clinic and ambulatory values.

The ominous effect of white coat hypertension has been noted by others, and it is probably related to the increasing magnitude (that is, the difference between clinic blood pressure and ambulatory blood pressure) to white coat hypertension with age.

Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring equipment has evolved and is much lighter than in the past, making it more acceptable to patients.

With more patients undergoing ambulatory blood pressure monitoring, several countries established ambulatory monitoring registries, such as the Spanish registry evaluated in this study.

Ultimately, one hopes the results of this registry study would serve as one more spur to providers and device manufacturers to initiate a registry in the United States.

Raymond R. Townsend, MD, is from the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. These comments are based on his editorial that appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine . Dr. Townsend reported disclosures related to Medtronic, AXIO, and CLARUS Therapeutics, among others.

Ambulatory measurements of blood pressure more strongly predicted all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than did BP measured in the clinic, according to analysis of a large patient registry in Spain.

The results also showed an increased risk of death associated with white coat hypertension and an even stronger association between death and masked hypertension. They were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Previous investigations had found that 24-hour ambulatory BP measurements were better predictors of patient outcomes than those obtained in the clinic or at home, but those investigations were small or population based.“In these studies, the number of clinical outcomes was limited, which reduced the ability to assess the predictive value of clinic blood pressure data as compared with ambulatory data,” reported José R. Banegas, MD, of the department of preventive medicine and public health at the Autonomous University of Madrid and his colleagues.

To better define the prognostic value of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure measurement, Dr. Banegas and his colleagues looked at data on a large cohort of primary care patients in the Spanish Ambulatory Blood Pressure Registry. Their analysis included 63,910 adults recruited to the registry during 2004-2014.

Patients had blood pressure measurements taken in the clinic according to standard procedures. Afterward, they had ambulatory blood pressure monitoring that used an automated device programmed to record BP every 20 minutes during the day and every 30 minutes at night.

They found that overall clinic and ambulatory blood pressure measurements had a relatively similar magnitude of association with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

However, clinic systolic pressure lost its predictive power for all-cause mortality after adjustment for 24-hour ambulatory systolic pressure. The hazard ratio for all-cause mortality dropped from 1.54 before the adjustment to 1.02 after the adjustment, Dr. Banegas and his colleagues reported.

By contrast, ambulatory systolic pressure kept its predictive value after accounting for clinical systolic pressure, with a hazard ratio for all-cause mortality of 1.58 before and after the adjustment, they said in the report.

The strongest association with all-cause mortality was found in patients with masked hypertension – normal clinic readings but elevated ambulatory readings. The hazard ratio for all-cause mortality in that group was 2.83 when adjusted for clinic blood pressure, with similar findings reported for cardiovascular mortality.

White coat hypertension was also associated with increased risk of mortality. The finding of elevated clinic BP and normal 24-hour ambulatory BP had a hazard ratio of 1.79 for all-cause mortality after adjustment for clinic BP, results showed.

“In our study, white coat hypertension was not benign, which may be due in part to the higher mean blood pressure over 24 hours in these patients (119.9/71.9 mm Hg vs. 116.6/70.6 mm Hg in normotensive patients; P less than .001) or to their metabolic phenotype,” the investigators wrote.

Lacer Laboratories, the Spanish Society of Hypertension, and some European government agencies supported the study. Dr. Banegas reported grants from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria and personal fees from Lacer. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Vascular Dynamics USA, Relypsa USA, Novartis Pharma USA, Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Lacer Laboratories Spain, and others.

SOURCE: Banegas JR et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1509-20.

Ambulatory measurements of blood pressure more strongly predicted all-cause and cardiovascular mortality than did BP measured in the clinic, according to analysis of a large patient registry in Spain.

The results also showed an increased risk of death associated with white coat hypertension and an even stronger association between death and masked hypertension. They were published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Previous investigations had found that 24-hour ambulatory BP measurements were better predictors of patient outcomes than those obtained in the clinic or at home, but those investigations were small or population based.“In these studies, the number of clinical outcomes was limited, which reduced the ability to assess the predictive value of clinic blood pressure data as compared with ambulatory data,” reported José R. Banegas, MD, of the department of preventive medicine and public health at the Autonomous University of Madrid and his colleagues.

To better define the prognostic value of 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure measurement, Dr. Banegas and his colleagues looked at data on a large cohort of primary care patients in the Spanish Ambulatory Blood Pressure Registry. Their analysis included 63,910 adults recruited to the registry during 2004-2014.

Patients had blood pressure measurements taken in the clinic according to standard procedures. Afterward, they had ambulatory blood pressure monitoring that used an automated device programmed to record BP every 20 minutes during the day and every 30 minutes at night.

They found that overall clinic and ambulatory blood pressure measurements had a relatively similar magnitude of association with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality.

However, clinic systolic pressure lost its predictive power for all-cause mortality after adjustment for 24-hour ambulatory systolic pressure. The hazard ratio for all-cause mortality dropped from 1.54 before the adjustment to 1.02 after the adjustment, Dr. Banegas and his colleagues reported.

By contrast, ambulatory systolic pressure kept its predictive value after accounting for clinical systolic pressure, with a hazard ratio for all-cause mortality of 1.58 before and after the adjustment, they said in the report.

The strongest association with all-cause mortality was found in patients with masked hypertension – normal clinic readings but elevated ambulatory readings. The hazard ratio for all-cause mortality in that group was 2.83 when adjusted for clinic blood pressure, with similar findings reported for cardiovascular mortality.

White coat hypertension was also associated with increased risk of mortality. The finding of elevated clinic BP and normal 24-hour ambulatory BP had a hazard ratio of 1.79 for all-cause mortality after adjustment for clinic BP, results showed.

“In our study, white coat hypertension was not benign, which may be due in part to the higher mean blood pressure over 24 hours in these patients (119.9/71.9 mm Hg vs. 116.6/70.6 mm Hg in normotensive patients; P less than .001) or to their metabolic phenotype,” the investigators wrote.

Lacer Laboratories, the Spanish Society of Hypertension, and some European government agencies supported the study. Dr. Banegas reported grants from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria and personal fees from Lacer. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Vascular Dynamics USA, Relypsa USA, Novartis Pharma USA, Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Lacer Laboratories Spain, and others.

SOURCE: Banegas JR et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1509-20.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Modeling showed a stronger association between ambulatory systolic pressure and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.58 per 1-SD pressure increase) than between clinic systolic pressure and all-cause mortality (adjusted HR, 1.02).

Study details: Retrospective analysis of mortality from a cohort of 63,910 adults recruited to a registry in Spain during 2004-2014.

Disclosures: Lacer Laboratories, the Spanish Society of Hypertension, and some European government agencies supported the study. Dr. Banegas reported grants from Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria and personal fees from Lacer. Coauthors reported disclosures related to Vascular Dynamics USA, Relypsa USA, Novartis Pharma USA, Daiichi Sankyo, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Lacer Laboratories Spain, and others.

Source: Banegas JR et al. N Engl J Med 2018;378:1509-20.

High 5-year mortality in patients admitted with heart failure regardless of ejection fraction

Background: Heart failure with preserved EF is a common cause of inpatient admission and previously was thought to carry a better prognosis than heart failure with reduced EF. Recent analysis using data from Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry has shown similarly poor survival rates at 30 days and 1 year when compared with heart failure with reduced EF.

Study design: Multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 276 hospitals in the GWTG-HF registry during 2005-2009, with 5 years of follow-up through 2014.

Synopsis: A total 39,982 patients who were admitted for heart failure during 2005-2009 were included in the study with stratification into three groups based on ejection fraction; 18,398 (46%) with heart failure with reduced EF; 2,385 (8.2%) with heart failure with borderline EF; and 18,299 (46%) with heart failure with preserved EF. The 5-year mortality rate for the entire cohort was 75.4% with similar mortality rates for patient with preserved EF (75.3%), compared with those with reduced EF (75.7%).

Bottom line: Among patients hospitalized with heart failure, irrespective of their ejection fraction, the 5-year survival rates were equally dismal. Hospitalists may wish to use this information in goals of care discussions.

Citation: Shah KS et al. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction: 5-year outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Oct 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.074.

Dr. Gomez-Sanchez is a hospitalist at the University of Virginia Medical Center.

Background: Heart failure with preserved EF is a common cause of inpatient admission and previously was thought to carry a better prognosis than heart failure with reduced EF. Recent analysis using data from Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry has shown similarly poor survival rates at 30 days and 1 year when compared with heart failure with reduced EF.

Study design: Multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 276 hospitals in the GWTG-HF registry during 2005-2009, with 5 years of follow-up through 2014.

Synopsis: A total 39,982 patients who were admitted for heart failure during 2005-2009 were included in the study with stratification into three groups based on ejection fraction; 18,398 (46%) with heart failure with reduced EF; 2,385 (8.2%) with heart failure with borderline EF; and 18,299 (46%) with heart failure with preserved EF. The 5-year mortality rate for the entire cohort was 75.4% with similar mortality rates for patient with preserved EF (75.3%), compared with those with reduced EF (75.7%).

Bottom line: Among patients hospitalized with heart failure, irrespective of their ejection fraction, the 5-year survival rates were equally dismal. Hospitalists may wish to use this information in goals of care discussions.

Citation: Shah KS et al. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction: 5-year outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Oct 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.074.

Dr. Gomez-Sanchez is a hospitalist at the University of Virginia Medical Center.

Background: Heart failure with preserved EF is a common cause of inpatient admission and previously was thought to carry a better prognosis than heart failure with reduced EF. Recent analysis using data from Get With the Guidelines–Heart Failure (GWTG-HF) registry has shown similarly poor survival rates at 30 days and 1 year when compared with heart failure with reduced EF.

Study design: Multicenter retrospective cohort study.

Setting: 276 hospitals in the GWTG-HF registry during 2005-2009, with 5 years of follow-up through 2014.

Synopsis: A total 39,982 patients who were admitted for heart failure during 2005-2009 were included in the study with stratification into three groups based on ejection fraction; 18,398 (46%) with heart failure with reduced EF; 2,385 (8.2%) with heart failure with borderline EF; and 18,299 (46%) with heart failure with preserved EF. The 5-year mortality rate for the entire cohort was 75.4% with similar mortality rates for patient with preserved EF (75.3%), compared with those with reduced EF (75.7%).

Bottom line: Among patients hospitalized with heart failure, irrespective of their ejection fraction, the 5-year survival rates were equally dismal. Hospitalists may wish to use this information in goals of care discussions.

Citation: Shah KS et al. Heart failure with preserved, borderline, and reduced ejection fraction: 5-year outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Oct 31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.08.074.

Dr. Gomez-Sanchez is a hospitalist at the University of Virginia Medical Center.

Do hospitalists improve inpatient outcomes?

Long continues the debate on what impact hospitalists have on inpatient outcomes. This issue has been playing out in the medical literature for 20 years, since the coining of the term in 1997. In a recent iteration of the debate, a study was published in JAMA Internal Medicine entitled “Comparison of Hospital Resource Use and Outcomes Among Hospitalists, Primary Care Physicians, and Other Generalists.”

The study retrospectively evaluated health care resources and outcomes from over a half-million Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized in 2013 for 20 common diagnosis-related groups, by type of physician provider (hospitalist, their primary care physician, or other generalist). The study found that nonhospitalists used more consultations and had longer lengths of stays, compared with hospitalists. In addition, relative to hospitalists, PCPs were more likely to discharge patients to home, had similar readmission rates, and lower 30-day mortality rates, but generalists were less likely to discharge patients home, had higher readmission rates, and higher mortality rates.

As hospitalists, we need to understand and acknowledge that most of our patients are “brand new” to us, and it is paramount that we use all available resources to gain a deep understanding of the patient in as short a time as possible. For example, ensuring all medical records available are reviewed, at least as much as possible, including a medical list (including a medication reconciliation). Interviewing family members or caregivers is also obviously a “best practice.” As well, having the insight of the PCP in these patients’ care is unquestionably good for us, for the PCP, and for the patient.

With good communication processes and an eye for excellence in care transitions, hospitalists can and should achieve the best outcomes for all of their patients. I look forward to more research in this arena, including a better understanding of the mechanisms by which we can all reliably produce excellent outcomes for the patients we serve.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

• Locums vs. F/T Hospitalists: Do Temps Stack Up? by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

• Rounds: Are We Spinning Our Wheels? by Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM

• Up Your Game in APP Integration by Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM

Long continues the debate on what impact hospitalists have on inpatient outcomes. This issue has been playing out in the medical literature for 20 years, since the coining of the term in 1997. In a recent iteration of the debate, a study was published in JAMA Internal Medicine entitled “Comparison of Hospital Resource Use and Outcomes Among Hospitalists, Primary Care Physicians, and Other Generalists.”

The study retrospectively evaluated health care resources and outcomes from over a half-million Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized in 2013 for 20 common diagnosis-related groups, by type of physician provider (hospitalist, their primary care physician, or other generalist). The study found that nonhospitalists used more consultations and had longer lengths of stays, compared with hospitalists. In addition, relative to hospitalists, PCPs were more likely to discharge patients to home, had similar readmission rates, and lower 30-day mortality rates, but generalists were less likely to discharge patients home, had higher readmission rates, and higher mortality rates.

As hospitalists, we need to understand and acknowledge that most of our patients are “brand new” to us, and it is paramount that we use all available resources to gain a deep understanding of the patient in as short a time as possible. For example, ensuring all medical records available are reviewed, at least as much as possible, including a medical list (including a medication reconciliation). Interviewing family members or caregivers is also obviously a “best practice.” As well, having the insight of the PCP in these patients’ care is unquestionably good for us, for the PCP, and for the patient.

With good communication processes and an eye for excellence in care transitions, hospitalists can and should achieve the best outcomes for all of their patients. I look forward to more research in this arena, including a better understanding of the mechanisms by which we can all reliably produce excellent outcomes for the patients we serve.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

• Locums vs. F/T Hospitalists: Do Temps Stack Up? by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

• Rounds: Are We Spinning Our Wheels? by Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM

• Up Your Game in APP Integration by Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM

Long continues the debate on what impact hospitalists have on inpatient outcomes. This issue has been playing out in the medical literature for 20 years, since the coining of the term in 1997. In a recent iteration of the debate, a study was published in JAMA Internal Medicine entitled “Comparison of Hospital Resource Use and Outcomes Among Hospitalists, Primary Care Physicians, and Other Generalists.”

The study retrospectively evaluated health care resources and outcomes from over a half-million Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized in 2013 for 20 common diagnosis-related groups, by type of physician provider (hospitalist, their primary care physician, or other generalist). The study found that nonhospitalists used more consultations and had longer lengths of stays, compared with hospitalists. In addition, relative to hospitalists, PCPs were more likely to discharge patients to home, had similar readmission rates, and lower 30-day mortality rates, but generalists were less likely to discharge patients home, had higher readmission rates, and higher mortality rates.

As hospitalists, we need to understand and acknowledge that most of our patients are “brand new” to us, and it is paramount that we use all available resources to gain a deep understanding of the patient in as short a time as possible. For example, ensuring all medical records available are reviewed, at least as much as possible, including a medical list (including a medication reconciliation). Interviewing family members or caregivers is also obviously a “best practice.” As well, having the insight of the PCP in these patients’ care is unquestionably good for us, for the PCP, and for the patient.

With good communication processes and an eye for excellence in care transitions, hospitalists can and should achieve the best outcomes for all of their patients. I look forward to more research in this arena, including a better understanding of the mechanisms by which we can all reliably produce excellent outcomes for the patients we serve.

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Also on The Hospital Leader …

• Locums vs. F/T Hospitalists: Do Temps Stack Up? by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

• Rounds: Are We Spinning Our Wheels? by Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, MHM

• Up Your Game in APP Integration by Tracy Cardin, ACNP-BC, SFHM

Short Takes

Giving iron supplements every other day may be superior to daily divided doses

Serum hepcidin levels and iron absorption were compared in women given daily dosing of ferrous sulfate, women given alternate-day dosing, and women given two divided doses daily. Women on the alternate-day regimen and the single-day regimens had higher iron absorption and lower hepcidin levels than did the women on the split-dosing regimen; these findings need to be confirmed in patients with iron-deficiency anemia.

Immediate percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the culprit lesion only in patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock may lead to better outcomes, even in those with multivessel disease

A total of 706 patients with multivessel coronary artery disease who presented with acute MI and cardiogenic shock were randomized to either PCI of the culprit lesion only (followed by optional staged revascularization of nonculprit lesions) or to immediate multivessel PCI. Patients who received PCI of the culprit lesion only had a lower 30-day risk of death or severe renal failure leading to renal-replacement therapy than did those who underwent immediate multivessel PCI.

Citation: Thiele H et al. PCI strategies in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710261 (epub ahead of print).

Giving iron supplements every other day may be superior to daily divided doses

Serum hepcidin levels and iron absorption were compared in women given daily dosing of ferrous sulfate, women given alternate-day dosing, and women given two divided doses daily. Women on the alternate-day regimen and the single-day regimens had higher iron absorption and lower hepcidin levels than did the women on the split-dosing regimen; these findings need to be confirmed in patients with iron-deficiency anemia.

Immediate percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the culprit lesion only in patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock may lead to better outcomes, even in those with multivessel disease

A total of 706 patients with multivessel coronary artery disease who presented with acute MI and cardiogenic shock were randomized to either PCI of the culprit lesion only (followed by optional staged revascularization of nonculprit lesions) or to immediate multivessel PCI. Patients who received PCI of the culprit lesion only had a lower 30-day risk of death or severe renal failure leading to renal-replacement therapy than did those who underwent immediate multivessel PCI.

Citation: Thiele H et al. PCI strategies in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710261 (epub ahead of print).

Giving iron supplements every other day may be superior to daily divided doses

Serum hepcidin levels and iron absorption were compared in women given daily dosing of ferrous sulfate, women given alternate-day dosing, and women given two divided doses daily. Women on the alternate-day regimen and the single-day regimens had higher iron absorption and lower hepcidin levels than did the women on the split-dosing regimen; these findings need to be confirmed in patients with iron-deficiency anemia.

Immediate percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of the culprit lesion only in patients presenting with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock may lead to better outcomes, even in those with multivessel disease

A total of 706 patients with multivessel coronary artery disease who presented with acute MI and cardiogenic shock were randomized to either PCI of the culprit lesion only (followed by optional staged revascularization of nonculprit lesions) or to immediate multivessel PCI. Patients who received PCI of the culprit lesion only had a lower 30-day risk of death or severe renal failure leading to renal-replacement therapy than did those who underwent immediate multivessel PCI.

Citation: Thiele H et al. PCI strategies in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. N Engl J Med. 2017 Oct. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710261 (epub ahead of print).

Common infections are potent risk factor for MI, stroke

ORLANDO – , according to a “big data” registry study from the United Kingdom.

“Our data show infection was just as much a risk factor or more compared with the traditional atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors,” Paul Carter, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Dr. Carter of Aston Medical School in Birmingham, England, presented a retrospective analysis from the ACALM (Algorithm for Comorbidities Associated with Length of stay and Mortality) study of administrative data on all of the more than 1.22 million patients admitted to seven U.K. hospitals in 2000-2013. His analysis included all 34,027 adults aged 40 years or older admitted with a urinary tract or respiratory infection on their index hospitalization who had no history of ischemic heart disease or ischemic stroke.

These patients, with a mean age of 73 years, 59% of whom were women, were compared with an equal number of age- and gender-matched adults whose index hospitalization was for reasons other than ischemic heart disease, stroke, urinary tract infection (UTI), or respiratory infection – the two most common infections resulting in hospitalization in the United Kingdom.

Patients with a respiratory infection or UTI had a 9.9% incidence of new-onset ischemic heart disease and a 4.1% rate of ischemic stroke during follow-up starting upon discharge from their index hospitalization, significantly higher than the 5.9% and 1.5% rates in controls. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for demographics, standard cardiovascular risk factors, and the top 10 causes of mortality in the United Kingdom, patients with respiratory infection or UTI as their admitting diagnosis had a 1.36-fold increased likelihood of developing ischemic heart disease post discharge and a 2.5-fold greater risk of ischemic stroke than matched controls.

Moreover, mortality following diagnosis of ischemic heart disease was 75.2% in patients whose index hospitalization was for infection, compared with 51.1% in controls who developed ischemic heart disease without a history of hospitalization for infection, for an adjusted 2.98-fold increased likelihood of death. Similarly, mortality after an ischemic stroke was 59.8% in patients with a prior severe infection, compared with 30.8% in controls, which translated to an adjusted 3.1-fold increased risk of death post stroke in patients with a prior hospitalization for infection.

In the multivariate analysis, hospitalization for infection was a stronger risk factor for subsequent ischemic stroke than was atrial fibrillation, heart failure, type 1 or type 2 diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia. The risk of ischemic heart disease in patients with an infectious disease hospitalization was similar to the risks associated with most of those recognized risk factors.

Two possible mechanisms by which infection might predispose to subsequent ischemic heart disease and stroke are via a direct effect whereby pathogens such as Chlamydia pneumoniae are taken up into arterial plaques, where they cause a local inflammatory response, or an indirect effect in which systemic inflammation primes the atherosclerotic plaque through distribution of inflammatory cytokines, according to Dr. Carter.

He said the ACALM findings are particularly intriguing when considered in the context of the 2017 results of the landmark CANTOS trial, in which canakinumab (Ilaris), a targeted anti-inflammatory agent that inhibits the interleukin-1 beta innate immunity pathway, reduced recurrent ischemic events in post-MI patients who had high systemic inflammation as evidenced by their elevated C-reactive protein level but a normal-range LDL cholesterol (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914).

“If atherosclerosis is an inflammatory condition, this begs the question of whether other inflammatory conditions, like infection, which induces a large systemic inflammatory response, might drive atherosclerosis,” Dr. Carter commented.

“It’s now very well understood that inflammatory mediators, cells, and processes are involved in every step from the initial endothelial dysfunction that leads to uptake of LDL, inflammatory cells, and monocytes all the way through to plaque progression and rupture, where Th1 cytokines have been implicated in causing that rupture, and ultimately in patient presentation at the hospital,” he added.

He sees the ACALM findings as hypothesis generating, serving to help lay the groundwork for future clinical trials of vaccine or anti-inflammatory antibiotic therapies.

Dr. Carter reported having no financial conflicts related to his presentation.

SOURCE: Carter P. ACC 2018, Abstract 1325M-0.

ORLANDO – , according to a “big data” registry study from the United Kingdom.

“Our data show infection was just as much a risk factor or more compared with the traditional atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors,” Paul Carter, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Dr. Carter of Aston Medical School in Birmingham, England, presented a retrospective analysis from the ACALM (Algorithm for Comorbidities Associated with Length of stay and Mortality) study of administrative data on all of the more than 1.22 million patients admitted to seven U.K. hospitals in 2000-2013. His analysis included all 34,027 adults aged 40 years or older admitted with a urinary tract or respiratory infection on their index hospitalization who had no history of ischemic heart disease or ischemic stroke.

These patients, with a mean age of 73 years, 59% of whom were women, were compared with an equal number of age- and gender-matched adults whose index hospitalization was for reasons other than ischemic heart disease, stroke, urinary tract infection (UTI), or respiratory infection – the two most common infections resulting in hospitalization in the United Kingdom.

Patients with a respiratory infection or UTI had a 9.9% incidence of new-onset ischemic heart disease and a 4.1% rate of ischemic stroke during follow-up starting upon discharge from their index hospitalization, significantly higher than the 5.9% and 1.5% rates in controls. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for demographics, standard cardiovascular risk factors, and the top 10 causes of mortality in the United Kingdom, patients with respiratory infection or UTI as their admitting diagnosis had a 1.36-fold increased likelihood of developing ischemic heart disease post discharge and a 2.5-fold greater risk of ischemic stroke than matched controls.

Moreover, mortality following diagnosis of ischemic heart disease was 75.2% in patients whose index hospitalization was for infection, compared with 51.1% in controls who developed ischemic heart disease without a history of hospitalization for infection, for an adjusted 2.98-fold increased likelihood of death. Similarly, mortality after an ischemic stroke was 59.8% in patients with a prior severe infection, compared with 30.8% in controls, which translated to an adjusted 3.1-fold increased risk of death post stroke in patients with a prior hospitalization for infection.

In the multivariate analysis, hospitalization for infection was a stronger risk factor for subsequent ischemic stroke than was atrial fibrillation, heart failure, type 1 or type 2 diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia. The risk of ischemic heart disease in patients with an infectious disease hospitalization was similar to the risks associated with most of those recognized risk factors.

Two possible mechanisms by which infection might predispose to subsequent ischemic heart disease and stroke are via a direct effect whereby pathogens such as Chlamydia pneumoniae are taken up into arterial plaques, where they cause a local inflammatory response, or an indirect effect in which systemic inflammation primes the atherosclerotic plaque through distribution of inflammatory cytokines, according to Dr. Carter.

He said the ACALM findings are particularly intriguing when considered in the context of the 2017 results of the landmark CANTOS trial, in which canakinumab (Ilaris), a targeted anti-inflammatory agent that inhibits the interleukin-1 beta innate immunity pathway, reduced recurrent ischemic events in post-MI patients who had high systemic inflammation as evidenced by their elevated C-reactive protein level but a normal-range LDL cholesterol (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914).

“If atherosclerosis is an inflammatory condition, this begs the question of whether other inflammatory conditions, like infection, which induces a large systemic inflammatory response, might drive atherosclerosis,” Dr. Carter commented.

“It’s now very well understood that inflammatory mediators, cells, and processes are involved in every step from the initial endothelial dysfunction that leads to uptake of LDL, inflammatory cells, and monocytes all the way through to plaque progression and rupture, where Th1 cytokines have been implicated in causing that rupture, and ultimately in patient presentation at the hospital,” he added.

He sees the ACALM findings as hypothesis generating, serving to help lay the groundwork for future clinical trials of vaccine or anti-inflammatory antibiotic therapies.

Dr. Carter reported having no financial conflicts related to his presentation.

SOURCE: Carter P. ACC 2018, Abstract 1325M-0.

ORLANDO – , according to a “big data” registry study from the United Kingdom.

“Our data show infection was just as much a risk factor or more compared with the traditional atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk factors,” Paul Carter, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology.

Dr. Carter of Aston Medical School in Birmingham, England, presented a retrospective analysis from the ACALM (Algorithm for Comorbidities Associated with Length of stay and Mortality) study of administrative data on all of the more than 1.22 million patients admitted to seven U.K. hospitals in 2000-2013. His analysis included all 34,027 adults aged 40 years or older admitted with a urinary tract or respiratory infection on their index hospitalization who had no history of ischemic heart disease or ischemic stroke.

These patients, with a mean age of 73 years, 59% of whom were women, were compared with an equal number of age- and gender-matched adults whose index hospitalization was for reasons other than ischemic heart disease, stroke, urinary tract infection (UTI), or respiratory infection – the two most common infections resulting in hospitalization in the United Kingdom.

Patients with a respiratory infection or UTI had a 9.9% incidence of new-onset ischemic heart disease and a 4.1% rate of ischemic stroke during follow-up starting upon discharge from their index hospitalization, significantly higher than the 5.9% and 1.5% rates in controls. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis adjusted for demographics, standard cardiovascular risk factors, and the top 10 causes of mortality in the United Kingdom, patients with respiratory infection or UTI as their admitting diagnosis had a 1.36-fold increased likelihood of developing ischemic heart disease post discharge and a 2.5-fold greater risk of ischemic stroke than matched controls.

Moreover, mortality following diagnosis of ischemic heart disease was 75.2% in patients whose index hospitalization was for infection, compared with 51.1% in controls who developed ischemic heart disease without a history of hospitalization for infection, for an adjusted 2.98-fold increased likelihood of death. Similarly, mortality after an ischemic stroke was 59.8% in patients with a prior severe infection, compared with 30.8% in controls, which translated to an adjusted 3.1-fold increased risk of death post stroke in patients with a prior hospitalization for infection.

In the multivariate analysis, hospitalization for infection was a stronger risk factor for subsequent ischemic stroke than was atrial fibrillation, heart failure, type 1 or type 2 diabetes, hypertension, or hyperlipidemia. The risk of ischemic heart disease in patients with an infectious disease hospitalization was similar to the risks associated with most of those recognized risk factors.

Two possible mechanisms by which infection might predispose to subsequent ischemic heart disease and stroke are via a direct effect whereby pathogens such as Chlamydia pneumoniae are taken up into arterial plaques, where they cause a local inflammatory response, or an indirect effect in which systemic inflammation primes the atherosclerotic plaque through distribution of inflammatory cytokines, according to Dr. Carter.

He said the ACALM findings are particularly intriguing when considered in the context of the 2017 results of the landmark CANTOS trial, in which canakinumab (Ilaris), a targeted anti-inflammatory agent that inhibits the interleukin-1 beta innate immunity pathway, reduced recurrent ischemic events in post-MI patients who had high systemic inflammation as evidenced by their elevated C-reactive protein level but a normal-range LDL cholesterol (N Engl J Med. 2017 Aug 27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914).

“If atherosclerosis is an inflammatory condition, this begs the question of whether other inflammatory conditions, like infection, which induces a large systemic inflammatory response, might drive atherosclerosis,” Dr. Carter commented.

“It’s now very well understood that inflammatory mediators, cells, and processes are involved in every step from the initial endothelial dysfunction that leads to uptake of LDL, inflammatory cells, and monocytes all the way through to plaque progression and rupture, where Th1 cytokines have been implicated in causing that rupture, and ultimately in patient presentation at the hospital,” he added.

He sees the ACALM findings as hypothesis generating, serving to help lay the groundwork for future clinical trials of vaccine or anti-inflammatory antibiotic therapies.

Dr. Carter reported having no financial conflicts related to his presentation.

SOURCE: Carter P. ACC 2018, Abstract 1325M-0.

REPORTING FROM ACC 2018

Key clinical point: Once patients have been hospitalized for a respiratory infection or UTI, their postdischarge risk of ischemic stroke is 2.5-fold greater than in those without such a history.

Major finding: Patients with a history of hospitalization for UTI or a respiratory infection who later develop ischemic heart disease or stroke have a threefold higher mortality risk than those without such a hospitalization.

Study details: This was a retrospective study of more than 68,000 subjects in the U.K. ACALM registry study.

Disclosures: The study presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Source: Carter P. ACC 2018, Abstract 1325M-0.

From #MeToo to troponins: Updates in hospital medicine

How do you summarize a year’s worth of hospitalist-relevant research in an hour? If you’re Cynthia Cooper, MD, and Barbara Slawski, MD, MS, SFHM, you do it with teamwork, rigor, and style.

When the two physicians signed on for the 2018 “Update in Hospital Medicine” talk, they knew the bar was high. The updates talk is a perennial crowd favorite at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual conferences, and this year’s talk, which touched on topics from #MeToo to kidney injury, didn’t disappoint.

“One of the things that made the news a lot this last year is gender bias, so we thought we’d start out with that,” said Dr. Slawski, chief of the section of perioperative medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

In a retrospective observational study, the investigators looked at archived grand rounds video to see how often speakers with doctoral degrees were introduced by title, rather than by first name. Mixed-gender evaluators found that females were much more likely than were males to introduce either females or males by title (P less than .001).

“Have any of you ever had this experience? Me, too,” said Dr. Slawski, to wide and prolonged applause.

Females introducing males were almost twice as likely to use the speaker’s title as when males introduced females (95% vs. 49%; P less than .001). These revelations, said Dr. Slawski, present an “opportunity for improving professional interactions in an environment of mutual respect,” a comment that the room again greeted with a round of applause.

The inpatient syncope evaluation was made a little easier with another top study presented by Dr. Slawski. Using a large multinational database, investigators looked at a subgroup of patients with syncope who were admitted to the hospital. They found that fewer than 2% of patients with syncope were diagnosed with pulmonary embolus (PE) or deep venous thrombosis within 90 days of the index admission. For Dr. Slawski, this means clinicians may be able to relax their worry about thromboembolic events just a bit: “Although this diagnosis should be considered, not all patients need evaluation,” she said.

Dr. Slawski did point out that this observational, retrospective trial differed in many ways from the earlier-published PESIT trial that found a rate of 17% for PE among patients hospitalized for syncope.

Another common clinical dilemma – how to rule out MI in low-risk patients – was addressed in a meta-analysis looking at high-sensitivity troponin T levels in patients with negative ECGs.

In patients coming to the emergency department with a suspicion of acute coronary syndrome, investigators found just a 0.49% incidence of cardiac events in patients who had no ECG evidence of new ischemia and very-low high-sensitivity troponin T. The study looked at two proposed lower limits – less than .0005 mcg/L and less than .003 mcg/L.

Between these two levels, “Sensitivity and negative predictive values were about the same; no patients had mortality within 30 days if they met the criteria,” said Dr. Slawski. However, “You have to remember that sensitivity was below the preset consensus of 99%,” she said; the pooled sensitivity was 98.7%, with fairly high heterogeneity between studies. Also, she said, “If you’re going to use this strategy as your hospital, you have to remember that these values are specific to the assay” at your particular institution.

Dr. Cooper, a nephrologist who practices hospital medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, ran through several kidney-related studies. Among these was a retrospective study of the use of IV contrast for computerized tomography (CT), examining the risk of acute kidney injury when patients who received IV contrast were compared both with those who had a CT without contrast and with those who did not have CT. Nearly 17,000 patients were included, with propensity matching used to limit confounding.

Both in this study and in a later meta-analysis, no significant differences were seen in acute kidney injury, the need for renal replacement therapy, or mortality after CT with contrast. However, Dr. Cooper said that as a nephrologist, “This doesn’t make physiological sense to me, so I’m not convinced,” she said. “Ultimately, we need to have a randomized, controlled trial, though it’s hard to imagine” just how such a study could be structured and conducted, she said.

“Influenza H3N2 has dominated outbreaks in the United States over the last few years,” and this fact contributed significantly to the severity of the past year’s influenza season, said Dr. Cooper. Not only does this strain “seem to have greater variability in how often it mutates,” but “it’s also less likely to grow in egg media – so it’s less likely to appear in the vaccine,” she said.

Antivirals are effective only if instituted promptly, meaning that many patients who are admitted to the hospital with influenza and pulmonary infiltrates are beyond this window. Building on what was known about the theoretical efficacy of both macrolides and NSAID medications, a group of researchers in Hong Kong conducted a randomized placebo-controlled trial to compare outcomes when 500 mg of clarithromycin and 200 mg of naproxen were added on days 1 and 2 of hospitalization.

When these two interventions were added to the usual regime of amoxicillin clavulanate, oseltamivir, and esomeprazole, hospital stay was 1 day shorter. Importantly, said Dr. Cooper, 30-day and 90-day mortality rates were shorter and there was a significant reduction in viral titer. This is a strategy Dr. Cooper plans to implement. “My expectation is just like this past year, next year will likely be a bad year for influenza,” she said.

How do you summarize a year’s worth of hospitalist-relevant research in an hour? If you’re Cynthia Cooper, MD, and Barbara Slawski, MD, MS, SFHM, you do it with teamwork, rigor, and style.

When the two physicians signed on for the 2018 “Update in Hospital Medicine” talk, they knew the bar was high. The updates talk is a perennial crowd favorite at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual conferences, and this year’s talk, which touched on topics from #MeToo to kidney injury, didn’t disappoint.

“One of the things that made the news a lot this last year is gender bias, so we thought we’d start out with that,” said Dr. Slawski, chief of the section of perioperative medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

In a retrospective observational study, the investigators looked at archived grand rounds video to see how often speakers with doctoral degrees were introduced by title, rather than by first name. Mixed-gender evaluators found that females were much more likely than were males to introduce either females or males by title (P less than .001).

“Have any of you ever had this experience? Me, too,” said Dr. Slawski, to wide and prolonged applause.

Females introducing males were almost twice as likely to use the speaker’s title as when males introduced females (95% vs. 49%; P less than .001). These revelations, said Dr. Slawski, present an “opportunity for improving professional interactions in an environment of mutual respect,” a comment that the room again greeted with a round of applause.

The inpatient syncope evaluation was made a little easier with another top study presented by Dr. Slawski. Using a large multinational database, investigators looked at a subgroup of patients with syncope who were admitted to the hospital. They found that fewer than 2% of patients with syncope were diagnosed with pulmonary embolus (PE) or deep venous thrombosis within 90 days of the index admission. For Dr. Slawski, this means clinicians may be able to relax their worry about thromboembolic events just a bit: “Although this diagnosis should be considered, not all patients need evaluation,” she said.

Dr. Slawski did point out that this observational, retrospective trial differed in many ways from the earlier-published PESIT trial that found a rate of 17% for PE among patients hospitalized for syncope.

Another common clinical dilemma – how to rule out MI in low-risk patients – was addressed in a meta-analysis looking at high-sensitivity troponin T levels in patients with negative ECGs.

In patients coming to the emergency department with a suspicion of acute coronary syndrome, investigators found just a 0.49% incidence of cardiac events in patients who had no ECG evidence of new ischemia and very-low high-sensitivity troponin T. The study looked at two proposed lower limits – less than .0005 mcg/L and less than .003 mcg/L.

Between these two levels, “Sensitivity and negative predictive values were about the same; no patients had mortality within 30 days if they met the criteria,” said Dr. Slawski. However, “You have to remember that sensitivity was below the preset consensus of 99%,” she said; the pooled sensitivity was 98.7%, with fairly high heterogeneity between studies. Also, she said, “If you’re going to use this strategy as your hospital, you have to remember that these values are specific to the assay” at your particular institution.

Dr. Cooper, a nephrologist who practices hospital medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, ran through several kidney-related studies. Among these was a retrospective study of the use of IV contrast for computerized tomography (CT), examining the risk of acute kidney injury when patients who received IV contrast were compared both with those who had a CT without contrast and with those who did not have CT. Nearly 17,000 patients were included, with propensity matching used to limit confounding.

Both in this study and in a later meta-analysis, no significant differences were seen in acute kidney injury, the need for renal replacement therapy, or mortality after CT with contrast. However, Dr. Cooper said that as a nephrologist, “This doesn’t make physiological sense to me, so I’m not convinced,” she said. “Ultimately, we need to have a randomized, controlled trial, though it’s hard to imagine” just how such a study could be structured and conducted, she said.

“Influenza H3N2 has dominated outbreaks in the United States over the last few years,” and this fact contributed significantly to the severity of the past year’s influenza season, said Dr. Cooper. Not only does this strain “seem to have greater variability in how often it mutates,” but “it’s also less likely to grow in egg media – so it’s less likely to appear in the vaccine,” she said.

Antivirals are effective only if instituted promptly, meaning that many patients who are admitted to the hospital with influenza and pulmonary infiltrates are beyond this window. Building on what was known about the theoretical efficacy of both macrolides and NSAID medications, a group of researchers in Hong Kong conducted a randomized placebo-controlled trial to compare outcomes when 500 mg of clarithromycin and 200 mg of naproxen were added on days 1 and 2 of hospitalization.

When these two interventions were added to the usual regime of amoxicillin clavulanate, oseltamivir, and esomeprazole, hospital stay was 1 day shorter. Importantly, said Dr. Cooper, 30-day and 90-day mortality rates were shorter and there was a significant reduction in viral titer. This is a strategy Dr. Cooper plans to implement. “My expectation is just like this past year, next year will likely be a bad year for influenza,” she said.

How do you summarize a year’s worth of hospitalist-relevant research in an hour? If you’re Cynthia Cooper, MD, and Barbara Slawski, MD, MS, SFHM, you do it with teamwork, rigor, and style.

When the two physicians signed on for the 2018 “Update in Hospital Medicine” talk, they knew the bar was high. The updates talk is a perennial crowd favorite at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual conferences, and this year’s talk, which touched on topics from #MeToo to kidney injury, didn’t disappoint.

“One of the things that made the news a lot this last year is gender bias, so we thought we’d start out with that,” said Dr. Slawski, chief of the section of perioperative medicine at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee.

In a retrospective observational study, the investigators looked at archived grand rounds video to see how often speakers with doctoral degrees were introduced by title, rather than by first name. Mixed-gender evaluators found that females were much more likely than were males to introduce either females or males by title (P less than .001).

“Have any of you ever had this experience? Me, too,” said Dr. Slawski, to wide and prolonged applause.

Females introducing males were almost twice as likely to use the speaker’s title as when males introduced females (95% vs. 49%; P less than .001). These revelations, said Dr. Slawski, present an “opportunity for improving professional interactions in an environment of mutual respect,” a comment that the room again greeted with a round of applause.

The inpatient syncope evaluation was made a little easier with another top study presented by Dr. Slawski. Using a large multinational database, investigators looked at a subgroup of patients with syncope who were admitted to the hospital. They found that fewer than 2% of patients with syncope were diagnosed with pulmonary embolus (PE) or deep venous thrombosis within 90 days of the index admission. For Dr. Slawski, this means clinicians may be able to relax their worry about thromboembolic events just a bit: “Although this diagnosis should be considered, not all patients need evaluation,” she said.

Dr. Slawski did point out that this observational, retrospective trial differed in many ways from the earlier-published PESIT trial that found a rate of 17% for PE among patients hospitalized for syncope.

Another common clinical dilemma – how to rule out MI in low-risk patients – was addressed in a meta-analysis looking at high-sensitivity troponin T levels in patients with negative ECGs.

In patients coming to the emergency department with a suspicion of acute coronary syndrome, investigators found just a 0.49% incidence of cardiac events in patients who had no ECG evidence of new ischemia and very-low high-sensitivity troponin T. The study looked at two proposed lower limits – less than .0005 mcg/L and less than .003 mcg/L.

Between these two levels, “Sensitivity and negative predictive values were about the same; no patients had mortality within 30 days if they met the criteria,” said Dr. Slawski. However, “You have to remember that sensitivity was below the preset consensus of 99%,” she said; the pooled sensitivity was 98.7%, with fairly high heterogeneity between studies. Also, she said, “If you’re going to use this strategy as your hospital, you have to remember that these values are specific to the assay” at your particular institution.

Dr. Cooper, a nephrologist who practices hospital medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, ran through several kidney-related studies. Among these was a retrospective study of the use of IV contrast for computerized tomography (CT), examining the risk of acute kidney injury when patients who received IV contrast were compared both with those who had a CT without contrast and with those who did not have CT. Nearly 17,000 patients were included, with propensity matching used to limit confounding.

Both in this study and in a later meta-analysis, no significant differences were seen in acute kidney injury, the need for renal replacement therapy, or mortality after CT with contrast. However, Dr. Cooper said that as a nephrologist, “This doesn’t make physiological sense to me, so I’m not convinced,” she said. “Ultimately, we need to have a randomized, controlled trial, though it’s hard to imagine” just how such a study could be structured and conducted, she said.

“Influenza H3N2 has dominated outbreaks in the United States over the last few years,” and this fact contributed significantly to the severity of the past year’s influenza season, said Dr. Cooper. Not only does this strain “seem to have greater variability in how often it mutates,” but “it’s also less likely to grow in egg media – so it’s less likely to appear in the vaccine,” she said.

Antivirals are effective only if instituted promptly, meaning that many patients who are admitted to the hospital with influenza and pulmonary infiltrates are beyond this window. Building on what was known about the theoretical efficacy of both macrolides and NSAID medications, a group of researchers in Hong Kong conducted a randomized placebo-controlled trial to compare outcomes when 500 mg of clarithromycin and 200 mg of naproxen were added on days 1 and 2 of hospitalization.

When these two interventions were added to the usual regime of amoxicillin clavulanate, oseltamivir, and esomeprazole, hospital stay was 1 day shorter. Importantly, said Dr. Cooper, 30-day and 90-day mortality rates were shorter and there was a significant reduction in viral titer. This is a strategy Dr. Cooper plans to implement. “My expectation is just like this past year, next year will likely be a bad year for influenza,” she said.

Use procalcitonin-guided algorithms to guide antibiotic therapy for acute respiratory infections to improve patient outcomes

Clinical question: How does using procalcitonin levels for adults with acute respiratory infections (ARIs) affect patient outcomes?

Background: While the ARI diagnosis encompasses bacterial, viral, and inflammatory etiologies, as many as 75% of ARIs are treated with antibiotics. Procalcitonin is a biomarker released by tissues in response to bacterial infections. Its production is also inhibited by interferon-gamma, a cytokine released in response to viral infections, therefore, making procalcitonin a biomarker of particular interest to support the use of antibiotic therapy in the treatment of ARIs.

Study design: Cochrane Review.

Setting: Medical wards, intensive care units, primary care clinics, and emergency departments across 12 countries.

Synopsis: The review included 26 randomized control trials of 6,708 immunocompetent adults with ARIs who received antibiotics either based on procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy or routine care. Primary endpoints evaluated included all-cause mortality and treatment failure at 30 days. Secondary endpoints were antibiotic use, antibiotic-related side effects, and length of hospital stay. There were significantly fewer deaths in the procalcitonin-guided group than in the control group (286/8.6% vs. 336/10%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.99; P = .037). Treatment failure was not statistically different between the procalcitonin-guided participants and the controls. Of the secondary endpoints, antibiotic use and antibiotic-related side effects were lower in the procalcitonin-guided group (5.7 days vs. 8.1 days; P less than .001; and 16.3% vs. 22.1%; P less than .001). Each of the RCTs had varying algorithms for the use of procalcitonin-guided therapy, so no specific treatment guidelines can be gleaned from this review.

Bottom line: Procalcitonin-guided algorithms are associated with lower mortality, lower antibiotic exposure, and lower antibiotic-related side effects. However, more research is needed to determine best practice algorithms for using procalcitonin levels to guide treatment decisions.

Citation: Schuetz P et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd007498.pub3.

Dr. Sundar is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Clinical question: How does using procalcitonin levels for adults with acute respiratory infections (ARIs) affect patient outcomes?

Background: While the ARI diagnosis encompasses bacterial, viral, and inflammatory etiologies, as many as 75% of ARIs are treated with antibiotics. Procalcitonin is a biomarker released by tissues in response to bacterial infections. Its production is also inhibited by interferon-gamma, a cytokine released in response to viral infections, therefore, making procalcitonin a biomarker of particular interest to support the use of antibiotic therapy in the treatment of ARIs.

Study design: Cochrane Review.

Setting: Medical wards, intensive care units, primary care clinics, and emergency departments across 12 countries.

Synopsis: The review included 26 randomized control trials of 6,708 immunocompetent adults with ARIs who received antibiotics either based on procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy or routine care. Primary endpoints evaluated included all-cause mortality and treatment failure at 30 days. Secondary endpoints were antibiotic use, antibiotic-related side effects, and length of hospital stay. There were significantly fewer deaths in the procalcitonin-guided group than in the control group (286/8.6% vs. 336/10%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.99; P = .037). Treatment failure was not statistically different between the procalcitonin-guided participants and the controls. Of the secondary endpoints, antibiotic use and antibiotic-related side effects were lower in the procalcitonin-guided group (5.7 days vs. 8.1 days; P less than .001; and 16.3% vs. 22.1%; P less than .001). Each of the RCTs had varying algorithms for the use of procalcitonin-guided therapy, so no specific treatment guidelines can be gleaned from this review.

Bottom line: Procalcitonin-guided algorithms are associated with lower mortality, lower antibiotic exposure, and lower antibiotic-related side effects. However, more research is needed to determine best practice algorithms for using procalcitonin levels to guide treatment decisions.

Citation: Schuetz P et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd007498.pub3.

Dr. Sundar is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Clinical question: How does using procalcitonin levels for adults with acute respiratory infections (ARIs) affect patient outcomes?

Background: While the ARI diagnosis encompasses bacterial, viral, and inflammatory etiologies, as many as 75% of ARIs are treated with antibiotics. Procalcitonin is a biomarker released by tissues in response to bacterial infections. Its production is also inhibited by interferon-gamma, a cytokine released in response to viral infections, therefore, making procalcitonin a biomarker of particular interest to support the use of antibiotic therapy in the treatment of ARIs.

Study design: Cochrane Review.

Setting: Medical wards, intensive care units, primary care clinics, and emergency departments across 12 countries.

Synopsis: The review included 26 randomized control trials of 6,708 immunocompetent adults with ARIs who received antibiotics either based on procalcitonin-guided antibiotic therapy or routine care. Primary endpoints evaluated included all-cause mortality and treatment failure at 30 days. Secondary endpoints were antibiotic use, antibiotic-related side effects, and length of hospital stay. There were significantly fewer deaths in the procalcitonin-guided group than in the control group (286/8.6% vs. 336/10%; adjusted odds ratio, 0.83; 95% confidence interval, 0.70-0.99; P = .037). Treatment failure was not statistically different between the procalcitonin-guided participants and the controls. Of the secondary endpoints, antibiotic use and antibiotic-related side effects were lower in the procalcitonin-guided group (5.7 days vs. 8.1 days; P less than .001; and 16.3% vs. 22.1%; P less than .001). Each of the RCTs had varying algorithms for the use of procalcitonin-guided therapy, so no specific treatment guidelines can be gleaned from this review.

Bottom line: Procalcitonin-guided algorithms are associated with lower mortality, lower antibiotic exposure, and lower antibiotic-related side effects. However, more research is needed to determine best practice algorithms for using procalcitonin levels to guide treatment decisions.

Citation: Schuetz P et al. Procalcitonin to initiate or discontinue antibiotics in acute respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Oct 12. doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd007498.pub3.

Dr. Sundar is assistant professor of medicine in the division of hospital medicine, Emory University, Atlanta.

Launching into the future

Hospital Medicine: 10 years ago

My first Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Conference was HM08, and it changed the course of my professional career.

I was a first-year hospitalist from an academic program of fewer than 10 physicians. My knowledge about my field did not extend much beyond the clinical practice of hospital medicine. I remember sitting at the airport on my way to HM08 and excitedly looking over the schedule for the meeting. I diligently circled the sessions that I was looking forward to attending, the majority of which focused on the clinical tracks. But by the end of the meeting, in additional to valuable medical knowledge, I walked away with novel insights that launched me into my future.