User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Higher hospital mortality in pediatric emergency transfer patients

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

I’ve learned so much this summer from working with Dr. Patrick Brady to better understand characteristics of pediatric patients who undergo clinical deterioration and unplanned transfers to the ICU. I’m very grateful to have spent my summer with a mentor who really cared about my growth as a student, and a fantastic group of physicians in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

After data analysis, we discovered that children who have had an emergency transfer event spend a longer time in the ICU and in the hospital. After comparing hospital mortality, we can conclude that emergency transfer patients have a higher likelihood of hospital mortality.

From this preliminary research, the emergency transfer metric in children’s hospitals has the potential to enable more rapid learning and systems improvement. We have a few next steps to investigate these next couple months as well. We want to compare medical diagnoses and complex chronic conditions between the emergency transfer cases and controls. We also hope to describe the incidence using a patient-days denominator. Finally, our long term goals are to identify predictors for an emergency transfer event in children.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

I’ve learned so much this summer from working with Dr. Patrick Brady to better understand characteristics of pediatric patients who undergo clinical deterioration and unplanned transfers to the ICU. I’m very grateful to have spent my summer with a mentor who really cared about my growth as a student, and a fantastic group of physicians in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

After data analysis, we discovered that children who have had an emergency transfer event spend a longer time in the ICU and in the hospital. After comparing hospital mortality, we can conclude that emergency transfer patients have a higher likelihood of hospital mortality.

From this preliminary research, the emergency transfer metric in children’s hospitals has the potential to enable more rapid learning and systems improvement. We have a few next steps to investigate these next couple months as well. We want to compare medical diagnoses and complex chronic conditions between the emergency transfer cases and controls. We also hope to describe the incidence using a patient-days denominator. Finally, our long term goals are to identify predictors for an emergency transfer event in children.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-2018 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second, and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

I’ve learned so much this summer from working with Dr. Patrick Brady to better understand characteristics of pediatric patients who undergo clinical deterioration and unplanned transfers to the ICU. I’m very grateful to have spent my summer with a mentor who really cared about my growth as a student, and a fantastic group of physicians in the Division of Hospital Medicine at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center.

After data analysis, we discovered that children who have had an emergency transfer event spend a longer time in the ICU and in the hospital. After comparing hospital mortality, we can conclude that emergency transfer patients have a higher likelihood of hospital mortality.

From this preliminary research, the emergency transfer metric in children’s hospitals has the potential to enable more rapid learning and systems improvement. We have a few next steps to investigate these next couple months as well. We want to compare medical diagnoses and complex chronic conditions between the emergency transfer cases and controls. We also hope to describe the incidence using a patient-days denominator. Finally, our long term goals are to identify predictors for an emergency transfer event in children.

Farah Hussain is a 2nd-year medical student at University of Cincinnati College of Medicine and student researcher at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Her research interests involve bettering patient care to vulnerable populations.

Elderly patients’ view and the discussion of discontinuing cancer screening

Clinical question: How do elderly patients feel about discontinuing cancer screening, and how should their doctors communicate this topic to them?

Background: Subjecting patients with limited life expectancy to cancer screening can cause harm, but patient preference on the subject and the manner physicians communicate this recommendation is unknown.

Setting: Four programs associated with an urban academic center.

Synopsis: Through interviews, questionnaires, and medical records of 40 community-dwelling adults, over the age of 65, the study found that participants support discontinuing cancer screening based on individual health status. Participants preferred that physicians use health and functional status rather than risks and benefits of test or life expectancy. They do not understand the predictors of life expectancy, are doubtful of physicians’ ability to predict it, and feel discussing it is depressing. While participants were divided on whether the term “life expectancy” should be used, they preferred “this test will not extend your life” to “you may not live long enough to benefit from this test.”

The study is limited to one center with participants with high levels of trust in their established physician which may not reflect other patients. The study required self-reporting and thus is susceptible to recall bias. Decisions of hypothetical examples could be discordant with actual decisions a participant might make.

Bottom line: Elderly patients are amenable to stopping cancer screening when communicated by their established physician and prefer to not discuss life expectancy.

Citation: Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, et.al. Older adults’ views and communication preferences about cancer screening and cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2017; 2017 Jun 12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1778.

Dr. Kochar is hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Clinical question: How do elderly patients feel about discontinuing cancer screening, and how should their doctors communicate this topic to them?

Background: Subjecting patients with limited life expectancy to cancer screening can cause harm, but patient preference on the subject and the manner physicians communicate this recommendation is unknown.

Setting: Four programs associated with an urban academic center.

Synopsis: Through interviews, questionnaires, and medical records of 40 community-dwelling adults, over the age of 65, the study found that participants support discontinuing cancer screening based on individual health status. Participants preferred that physicians use health and functional status rather than risks and benefits of test or life expectancy. They do not understand the predictors of life expectancy, are doubtful of physicians’ ability to predict it, and feel discussing it is depressing. While participants were divided on whether the term “life expectancy” should be used, they preferred “this test will not extend your life” to “you may not live long enough to benefit from this test.”

The study is limited to one center with participants with high levels of trust in their established physician which may not reflect other patients. The study required self-reporting and thus is susceptible to recall bias. Decisions of hypothetical examples could be discordant with actual decisions a participant might make.

Bottom line: Elderly patients are amenable to stopping cancer screening when communicated by their established physician and prefer to not discuss life expectancy.

Citation: Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, et.al. Older adults’ views and communication preferences about cancer screening and cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2017; 2017 Jun 12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1778.

Dr. Kochar is hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Clinical question: How do elderly patients feel about discontinuing cancer screening, and how should their doctors communicate this topic to them?

Background: Subjecting patients with limited life expectancy to cancer screening can cause harm, but patient preference on the subject and the manner physicians communicate this recommendation is unknown.

Setting: Four programs associated with an urban academic center.

Synopsis: Through interviews, questionnaires, and medical records of 40 community-dwelling adults, over the age of 65, the study found that participants support discontinuing cancer screening based on individual health status. Participants preferred that physicians use health and functional status rather than risks and benefits of test or life expectancy. They do not understand the predictors of life expectancy, are doubtful of physicians’ ability to predict it, and feel discussing it is depressing. While participants were divided on whether the term “life expectancy” should be used, they preferred “this test will not extend your life” to “you may not live long enough to benefit from this test.”

The study is limited to one center with participants with high levels of trust in their established physician which may not reflect other patients. The study required self-reporting and thus is susceptible to recall bias. Decisions of hypothetical examples could be discordant with actual decisions a participant might make.

Bottom line: Elderly patients are amenable to stopping cancer screening when communicated by their established physician and prefer to not discuss life expectancy.

Citation: Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, et.al. Older adults’ views and communication preferences about cancer screening and cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2017; 2017 Jun 12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1778.

Dr. Kochar is hospitalist and assistant professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Understanding patient process flow

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

This phase of the QI project aims at a thorough understanding of the process flow of a patient, from being transferred from outside the hospital, receiving tertiary care services at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, to being discharged to a rehabilitation facility/skilled nursing facility.

I am conducting interviews with key stakeholders to understand the current processes and needs for improvement. The key stakeholders include but are not limited to infectious disease, hospital medicine, nursing, case management, and psychiatry services.

I have developed an interview guide to facilitate the interviews. Based on a framework similar to SWOT analysis, the key questions include: (1) what makes this patient population particularly difficult to receive appropriate care/support? (2) What makes them difficult to be discharged when tertiary service is completed? (3) What can help them stay longer in the community and delay/prevent readmission?

I am working on retrieving clinical data from medical records and an infectious disease service database, and am going to analyze current patient status. Key metrics will include but not limited to length of stay, 30‐day readmission rate, patient satisfaction rating, infectious disease provider follow-up rate, and hospitalization cost.

A challenge I foresee I will encounter is deciding on a focused area for the improvement project. The constraints may be coming from clinical data availability or the willingness for the stakeholder to participate. For this purpose, I am going to ask each stakeholder about their priorities, and what they view as the most urgent or important aspects to improve. I also hope to identify stakeholders who might already have been thinking or working on improving care for this patient population.

I will address the data availability issue by following up closely with the infectious disease service. After I develop a general sense of the data, I will work with the interdisciplinary team to decide on a focused area for improvement.

One unexpected thing I learned during the last month was project planning. Initially, I was struggling with putting the details of the project together. I recalled later that at business school we often use timelines to facilitate project planning. I carved out two hours of my time. On a piece of paper, I wrote down one-by-one the tasks I need to accomplish for each phase of the study. I also set up an internal deadline for communications and deliverables with my advisor. Now I can track my progress much better and am confident that the project will move towards its landmarks.

Yun Li is an MD/MBA student attending Geisel School of Medicine and Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from Hanover College double-majoring in Economics and Biological Chemistry. Ms. Li participated in research in injury epidemiology and genetics, and has conducted studies on traditional Tibetan medicine, rural health, health NGOs, and digital health. Her career interest is practicing hospital medicine and geriatrics as a clinician/administrator, either in the US or China. Ms. Li is a student member of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

This phase of the QI project aims at a thorough understanding of the process flow of a patient, from being transferred from outside the hospital, receiving tertiary care services at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, to being discharged to a rehabilitation facility/skilled nursing facility.

I am conducting interviews with key stakeholders to understand the current processes and needs for improvement. The key stakeholders include but are not limited to infectious disease, hospital medicine, nursing, case management, and psychiatry services.

I have developed an interview guide to facilitate the interviews. Based on a framework similar to SWOT analysis, the key questions include: (1) what makes this patient population particularly difficult to receive appropriate care/support? (2) What makes them difficult to be discharged when tertiary service is completed? (3) What can help them stay longer in the community and delay/prevent readmission?

I am working on retrieving clinical data from medical records and an infectious disease service database, and am going to analyze current patient status. Key metrics will include but not limited to length of stay, 30‐day readmission rate, patient satisfaction rating, infectious disease provider follow-up rate, and hospitalization cost.

A challenge I foresee I will encounter is deciding on a focused area for the improvement project. The constraints may be coming from clinical data availability or the willingness for the stakeholder to participate. For this purpose, I am going to ask each stakeholder about their priorities, and what they view as the most urgent or important aspects to improve. I also hope to identify stakeholders who might already have been thinking or working on improving care for this patient population.

I will address the data availability issue by following up closely with the infectious disease service. After I develop a general sense of the data, I will work with the interdisciplinary team to decide on a focused area for improvement.

One unexpected thing I learned during the last month was project planning. Initially, I was struggling with putting the details of the project together. I recalled later that at business school we often use timelines to facilitate project planning. I carved out two hours of my time. On a piece of paper, I wrote down one-by-one the tasks I need to accomplish for each phase of the study. I also set up an internal deadline for communications and deliverables with my advisor. Now I can track my progress much better and am confident that the project will move towards its landmarks.

Yun Li is an MD/MBA student attending Geisel School of Medicine and Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from Hanover College double-majoring in Economics and Biological Chemistry. Ms. Li participated in research in injury epidemiology and genetics, and has conducted studies on traditional Tibetan medicine, rural health, health NGOs, and digital health. Her career interest is practicing hospital medicine and geriatrics as a clinician/administrator, either in the US or China. Ms. Li is a student member of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Editor’s note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform health care and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the longitudinal (18-month) program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a monthly basis.

This phase of the QI project aims at a thorough understanding of the process flow of a patient, from being transferred from outside the hospital, receiving tertiary care services at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, to being discharged to a rehabilitation facility/skilled nursing facility.

I am conducting interviews with key stakeholders to understand the current processes and needs for improvement. The key stakeholders include but are not limited to infectious disease, hospital medicine, nursing, case management, and psychiatry services.

I have developed an interview guide to facilitate the interviews. Based on a framework similar to SWOT analysis, the key questions include: (1) what makes this patient population particularly difficult to receive appropriate care/support? (2) What makes them difficult to be discharged when tertiary service is completed? (3) What can help them stay longer in the community and delay/prevent readmission?

I am working on retrieving clinical data from medical records and an infectious disease service database, and am going to analyze current patient status. Key metrics will include but not limited to length of stay, 30‐day readmission rate, patient satisfaction rating, infectious disease provider follow-up rate, and hospitalization cost.

A challenge I foresee I will encounter is deciding on a focused area for the improvement project. The constraints may be coming from clinical data availability or the willingness for the stakeholder to participate. For this purpose, I am going to ask each stakeholder about their priorities, and what they view as the most urgent or important aspects to improve. I also hope to identify stakeholders who might already have been thinking or working on improving care for this patient population.

I will address the data availability issue by following up closely with the infectious disease service. After I develop a general sense of the data, I will work with the interdisciplinary team to decide on a focused area for improvement.

One unexpected thing I learned during the last month was project planning. Initially, I was struggling with putting the details of the project together. I recalled later that at business school we often use timelines to facilitate project planning. I carved out two hours of my time. On a piece of paper, I wrote down one-by-one the tasks I need to accomplish for each phase of the study. I also set up an internal deadline for communications and deliverables with my advisor. Now I can track my progress much better and am confident that the project will move towards its landmarks.

Yun Li is an MD/MBA student attending Geisel School of Medicine and Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth. She obtained her Bachelor of Arts degree from Hanover College double-majoring in Economics and Biological Chemistry. Ms. Li participated in research in injury epidemiology and genetics, and has conducted studies on traditional Tibetan medicine, rural health, health NGOs, and digital health. Her career interest is practicing hospital medicine and geriatrics as a clinician/administrator, either in the US or China. Ms. Li is a student member of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Patient handoffs and research methods

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

As I wrap up my work for the summer, I am happy to reflect on my wonderful experiences. One of my greatest lessons from my mentors, Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. Juan Rojas, is the development of a complete methods section and the careful necessity of approaching data and writing the abstract. I now realize the necessity of carefully maintaining a written account of how we approached the data, as it allows us to both communicate it to our audience and to look back on how to further organize it.

Furthermore, my approach towards research significantly shifted in the time I spent this summer. Previously, I would focus primarily on results; however, from having performed a comprehensive literature review, I now focus on the way the data was approached and presented, the way the team kept careful track of methods, and the way they use previous research to establish their project. My previous experience was around quantitative research; the way that research teams approach qualitative research often differs from one another, often requiring a special level of ingenuity in approach and analysis, often due to the highly variable data.

After my experience at University of Chicago, I feel significantly more comfortable approaching research. One of my greatest goals regarding my research was to gain a better understanding of the interaction between various departments and the general ward in order to better prepare myself to be an effective physician. By asking the question, “What do you think is the most important factor regarding the management of this patient?”, I fully realized my deep interest in medical management: any research I approach as a physician would be closely intertwined to clinical medicine.

I am very, very thankful for the opportunity to learn from highly experienced physicians and researchers, and I will use this experience going forward with any clinical and research experiences I encounter.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

As I wrap up my work for the summer, I am happy to reflect on my wonderful experiences. One of my greatest lessons from my mentors, Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. Juan Rojas, is the development of a complete methods section and the careful necessity of approaching data and writing the abstract. I now realize the necessity of carefully maintaining a written account of how we approached the data, as it allows us to both communicate it to our audience and to look back on how to further organize it.

Furthermore, my approach towards research significantly shifted in the time I spent this summer. Previously, I would focus primarily on results; however, from having performed a comprehensive literature review, I now focus on the way the data was approached and presented, the way the team kept careful track of methods, and the way they use previous research to establish their project. My previous experience was around quantitative research; the way that research teams approach qualitative research often differs from one another, often requiring a special level of ingenuity in approach and analysis, often due to the highly variable data.

After my experience at University of Chicago, I feel significantly more comfortable approaching research. One of my greatest goals regarding my research was to gain a better understanding of the interaction between various departments and the general ward in order to better prepare myself to be an effective physician. By asking the question, “What do you think is the most important factor regarding the management of this patient?”, I fully realized my deep interest in medical management: any research I approach as a physician would be closely intertwined to clinical medicine.

I am very, very thankful for the opportunity to learn from highly experienced physicians and researchers, and I will use this experience going forward with any clinical and research experiences I encounter.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

Editor’s Note: The Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM’s) Physician in Training Committee launched a scholarship program in 2015 for medical students to help transform healthcare and revolutionize patient care. The program has been expanded for the 2017-18 year, offering two options for students to receive funding and engage in scholarly work during their first, second and third years of medical school. As a part of the program, recipients are required to write about their experience on a biweekly basis.

As I wrap up my work for the summer, I am happy to reflect on my wonderful experiences. One of my greatest lessons from my mentors, Dr. Vineet Arora and Dr. Juan Rojas, is the development of a complete methods section and the careful necessity of approaching data and writing the abstract. I now realize the necessity of carefully maintaining a written account of how we approached the data, as it allows us to both communicate it to our audience and to look back on how to further organize it.

Furthermore, my approach towards research significantly shifted in the time I spent this summer. Previously, I would focus primarily on results; however, from having performed a comprehensive literature review, I now focus on the way the data was approached and presented, the way the team kept careful track of methods, and the way they use previous research to establish their project. My previous experience was around quantitative research; the way that research teams approach qualitative research often differs from one another, often requiring a special level of ingenuity in approach and analysis, often due to the highly variable data.

After my experience at University of Chicago, I feel significantly more comfortable approaching research. One of my greatest goals regarding my research was to gain a better understanding of the interaction between various departments and the general ward in order to better prepare myself to be an effective physician. By asking the question, “What do you think is the most important factor regarding the management of this patient?”, I fully realized my deep interest in medical management: any research I approach as a physician would be closely intertwined to clinical medicine.

I am very, very thankful for the opportunity to learn from highly experienced physicians and researchers, and I will use this experience going forward with any clinical and research experiences I encounter.

Anton Garazha is a medical student at Chicago Medical School at Rosalind Franklin University in North Chicago. He received his bachelor of science degree in biology from Loyola University in Chicago in 2015 and his master of biomedical science degree from Rosalind Franklin University in 2016. Anton is very interested in community outreach and quality improvement, and in his spare time tutors students in science-based subjects.

VIDEO: U.S. hypertension guidelines reset threshold to 130/80 mm Hg

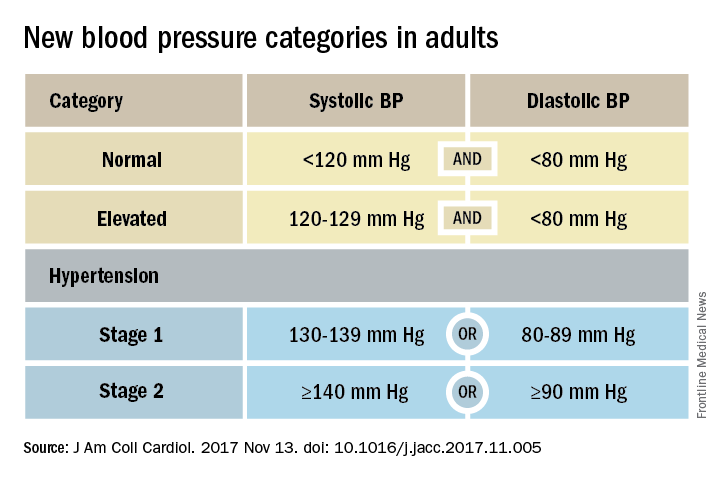

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

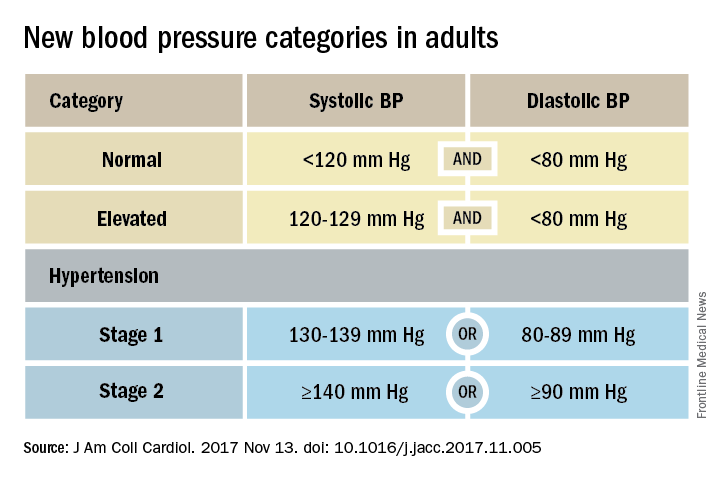

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

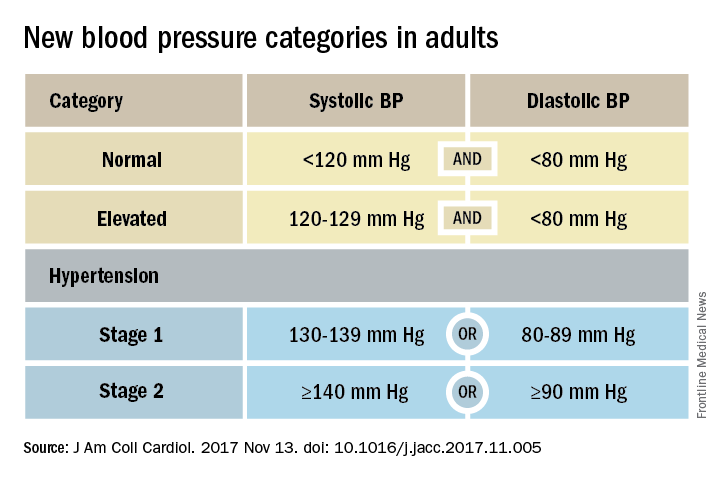

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

[email protected]

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Doctors’ and nurses’ predictions of ICU outcomes have variable accuracy

Clinical question: How accurate are doctors and nurses at predicting survival and functional outcomes in critically ill patients?

Background: Doctors have been shown to have moderate accuracy at predicting in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients; however, little is known about their ability to predict longer-term outcomes.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Synopsis: Physicians and nurses predicted survival and functional outcomes for critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation or vasopressors. Outcomes predicted were in-hospital and 6-month mortality and ability to return to original residence, toilet independently, ambulate stairs, remember most things, think clearly, and solve problems.

Six-month follow-up was completed for 299 patients. Accuracy was highest when either physicians or nurses expressed confidence in their predictions; doctors confident in their predications of 6-month survival had a positive likelihood ratio of 33.00 (95% CI, 8.34-130.63). Both doctors and nurses least accurately predicted cognitive function (positive LR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.36-4.12; negative LR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.61-0.92 for doctors, positive LR, 1.50; 95% CI, 0.86-2.60; negative LR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.73-1.06 for nurses), while doctors most accurately predicated 6-month mortality (positive LR, 5.91; 95% CI, 3.74-9.32; negative LR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.33-0.52) and nurses most accurately predicted in-hospital mortality (positive LR, 4.71; 95% CI, 2.94-7.56; negative LR, 0.6; 95% CI,0.49-0.75).

Bottom line: Doctors and nurses were better at predicting mortality than they were at predicting cognition, and their predicted outcomes were most accurate when they expressed a high degree of confidence in the predictions.

Citation: Detsky ME, Harhay MO, Bayard DF, et al. Discriminative accuracy of physician and nurse predictions for survival and functional outcomes 6 months after an ICU admission. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2187-95.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Clinical question: How accurate are doctors and nurses at predicting survival and functional outcomes in critically ill patients?

Background: Doctors have been shown to have moderate accuracy at predicting in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients; however, little is known about their ability to predict longer-term outcomes.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Synopsis: Physicians and nurses predicted survival and functional outcomes for critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation or vasopressors. Outcomes predicted were in-hospital and 6-month mortality and ability to return to original residence, toilet independently, ambulate stairs, remember most things, think clearly, and solve problems.

Six-month follow-up was completed for 299 patients. Accuracy was highest when either physicians or nurses expressed confidence in their predictions; doctors confident in their predications of 6-month survival had a positive likelihood ratio of 33.00 (95% CI, 8.34-130.63). Both doctors and nurses least accurately predicted cognitive function (positive LR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.36-4.12; negative LR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.61-0.92 for doctors, positive LR, 1.50; 95% CI, 0.86-2.60; negative LR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.73-1.06 for nurses), while doctors most accurately predicated 6-month mortality (positive LR, 5.91; 95% CI, 3.74-9.32; negative LR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.33-0.52) and nurses most accurately predicted in-hospital mortality (positive LR, 4.71; 95% CI, 2.94-7.56; negative LR, 0.6; 95% CI,0.49-0.75).

Bottom line: Doctors and nurses were better at predicting mortality than they were at predicting cognition, and their predicted outcomes were most accurate when they expressed a high degree of confidence in the predictions.

Citation: Detsky ME, Harhay MO, Bayard DF, et al. Discriminative accuracy of physician and nurse predictions for survival and functional outcomes 6 months after an ICU admission. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2187-95.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Clinical question: How accurate are doctors and nurses at predicting survival and functional outcomes in critically ill patients?

Background: Doctors have been shown to have moderate accuracy at predicting in-hospital mortality in critically ill patients; however, little is known about their ability to predict longer-term outcomes.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Synopsis: Physicians and nurses predicted survival and functional outcomes for critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation or vasopressors. Outcomes predicted were in-hospital and 6-month mortality and ability to return to original residence, toilet independently, ambulate stairs, remember most things, think clearly, and solve problems.

Six-month follow-up was completed for 299 patients. Accuracy was highest when either physicians or nurses expressed confidence in their predictions; doctors confident in their predications of 6-month survival had a positive likelihood ratio of 33.00 (95% CI, 8.34-130.63). Both doctors and nurses least accurately predicted cognitive function (positive LR, 2.36; 95% CI, 1.36-4.12; negative LR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.61-0.92 for doctors, positive LR, 1.50; 95% CI, 0.86-2.60; negative LR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.73-1.06 for nurses), while doctors most accurately predicated 6-month mortality (positive LR, 5.91; 95% CI, 3.74-9.32; negative LR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.33-0.52) and nurses most accurately predicted in-hospital mortality (positive LR, 4.71; 95% CI, 2.94-7.56; negative LR, 0.6; 95% CI,0.49-0.75).

Bottom line: Doctors and nurses were better at predicting mortality than they were at predicting cognition, and their predicted outcomes were most accurate when they expressed a high degree of confidence in the predictions.

Citation: Detsky ME, Harhay MO, Bayard DF, et al. Discriminative accuracy of physician and nurse predictions for survival and functional outcomes 6 months after an ICU admission. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2187-95.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

ARDS incidence is declining. Is it a preventable syndrome?

TORONTO – The incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is on the decline, according to a retrospective, population-based cohort study conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“This is very promising data in combating this syndrome,” reported Augustin Joseph of the Mayo Clinic, and “it suggests that ARDS may in part be a completely preventable disease.”

To see if ARDS incidence has continued to decline, Mr. Joseph’s group studied all patients admitted during 2009-2014 to the Mayo Clinic’s ICU, the only facility in the county that cares for ARDS patients. From 82,388 ICU admissions, they identified 505 patients with ARDS according to the Berlin definition of ARDS developed in 2012.

The number of annual cases dropped from 108 in 2009 to 59 in 2014, and the incidence steadily declined from 74.5 cases per 100,000 in 2009 to 39.3 per 100,000 in 2014.

Median age was 67 years in 2009 and 62 years in 2014. Hospital mortality ranged from 15% to 26% during the study period, while hospital length of stay ranged from 8 to 15 days, with no clear decline in either.

“For hospital and ICU mortality and hospital and ICU length of stay, we did not see much difference [from 2009 to 2014], so the overall picture between the Guangxi Li study and mine was that we did not see much of a difference in the patients who had ARDS, but [in terms of] preventing ARDS, the incidence has continued to decline,” Mr. Joseph reported.

While the earlier study used the American-European Consensus Conference (AECC) definition of ARDS, Mr. Joseph and his colleagues diagnosed ARDS according to the Berlin definition. One of the major changes seen in the new Berlin rules is that acute lung injury no longer exists and patients with a P/F ratio (PaO2/FiO2 ratio, or the ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen) between 200 and 300 are now considered to have “mild ARDS,” Mr. Joseph explained. With the AECC definition, a P/F ratio in this range was classified as acute lung injury and only one less than 200 was considered ARDS.

The researchers are now trying to parse out how changing ARDS diagnosis and management at their institution might be contributing to declining incidence, said Mr. Joseph.

TORONTO – The incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is on the decline, according to a retrospective, population-based cohort study conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“This is very promising data in combating this syndrome,” reported Augustin Joseph of the Mayo Clinic, and “it suggests that ARDS may in part be a completely preventable disease.”

To see if ARDS incidence has continued to decline, Mr. Joseph’s group studied all patients admitted during 2009-2014 to the Mayo Clinic’s ICU, the only facility in the county that cares for ARDS patients. From 82,388 ICU admissions, they identified 505 patients with ARDS according to the Berlin definition of ARDS developed in 2012.

The number of annual cases dropped from 108 in 2009 to 59 in 2014, and the incidence steadily declined from 74.5 cases per 100,000 in 2009 to 39.3 per 100,000 in 2014.

Median age was 67 years in 2009 and 62 years in 2014. Hospital mortality ranged from 15% to 26% during the study period, while hospital length of stay ranged from 8 to 15 days, with no clear decline in either.

“For hospital and ICU mortality and hospital and ICU length of stay, we did not see much difference [from 2009 to 2014], so the overall picture between the Guangxi Li study and mine was that we did not see much of a difference in the patients who had ARDS, but [in terms of] preventing ARDS, the incidence has continued to decline,” Mr. Joseph reported.

While the earlier study used the American-European Consensus Conference (AECC) definition of ARDS, Mr. Joseph and his colleagues diagnosed ARDS according to the Berlin definition. One of the major changes seen in the new Berlin rules is that acute lung injury no longer exists and patients with a P/F ratio (PaO2/FiO2 ratio, or the ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen) between 200 and 300 are now considered to have “mild ARDS,” Mr. Joseph explained. With the AECC definition, a P/F ratio in this range was classified as acute lung injury and only one less than 200 was considered ARDS.

The researchers are now trying to parse out how changing ARDS diagnosis and management at their institution might be contributing to declining incidence, said Mr. Joseph.

TORONTO – The incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is on the decline, according to a retrospective, population-based cohort study conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“This is very promising data in combating this syndrome,” reported Augustin Joseph of the Mayo Clinic, and “it suggests that ARDS may in part be a completely preventable disease.”

To see if ARDS incidence has continued to decline, Mr. Joseph’s group studied all patients admitted during 2009-2014 to the Mayo Clinic’s ICU, the only facility in the county that cares for ARDS patients. From 82,388 ICU admissions, they identified 505 patients with ARDS according to the Berlin definition of ARDS developed in 2012.

The number of annual cases dropped from 108 in 2009 to 59 in 2014, and the incidence steadily declined from 74.5 cases per 100,000 in 2009 to 39.3 per 100,000 in 2014.

Median age was 67 years in 2009 and 62 years in 2014. Hospital mortality ranged from 15% to 26% during the study period, while hospital length of stay ranged from 8 to 15 days, with no clear decline in either.

“For hospital and ICU mortality and hospital and ICU length of stay, we did not see much difference [from 2009 to 2014], so the overall picture between the Guangxi Li study and mine was that we did not see much of a difference in the patients who had ARDS, but [in terms of] preventing ARDS, the incidence has continued to decline,” Mr. Joseph reported.

While the earlier study used the American-European Consensus Conference (AECC) definition of ARDS, Mr. Joseph and his colleagues diagnosed ARDS according to the Berlin definition. One of the major changes seen in the new Berlin rules is that acute lung injury no longer exists and patients with a P/F ratio (PaO2/FiO2 ratio, or the ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure to fractional inspired oxygen) between 200 and 300 are now considered to have “mild ARDS,” Mr. Joseph explained. With the AECC definition, a P/F ratio in this range was classified as acute lung injury and only one less than 200 was considered ARDS.

The researchers are now trying to parse out how changing ARDS diagnosis and management at their institution might be contributing to declining incidence, said Mr. Joseph.

AT CHEST 2017

Key clinical point: The incidence of acute respiratory distress syndrome is declining, an indication that it may be preventable, according to researchers.

Major finding: The number of annual cases dropped from 108 in 2009 to 59 in 2014, and the incidence steadily declined from 74.5 cases per 100,000 in 2009 to 39.3 per 100,000 in 2014.

Data source: Retrospective, population-based cohort study of all (505) patients admitted to the ICU for ARDS at a single center.

Disclosures: The authors reported having no relevant disclosures.

Incidental lung nodules are frequently not mentioned in hospital discharge summary

Clinical question: How often are incidentally found pulmonary nodules and instructions for follow-up included in the discharge summary?

Background: Lung nodules are frequent incidental findings on imaging, but it is unclear whether patients are subsequently receiving the recommended follow-up.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Synopsis: The authors identified 7,173 patients who had undergone abdominal CT scans during their admission and reviewed charts of 402 patients who had incidentally found pulmonary nodules identified on the scans. For each of the patients, discharge summaries were evaluated to determine whether they made reference to the nodules and whether follow-up instructions were included. Of the 208 patients noted to have nodules requiring follow-up, only 48 (23%) had discharge summaries that mentioned the nodules. Factors associated with including the nodules in the discharge summary were the radiologist recommending further surveillance, radiologist including the nodule in the summary heading of the report, and being on a medical as opposed to a surgical service. The authors concluded that systems-based approaches to incidentally found lung nodules are needed to ensure adequate follow-up.

Bottom line: Incidentally found lung nodules are often not included in discharge documentation and therefore may not receive the recommended follow-up.

Citation: Bates R, Plooster C, Croghan I, et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules reported on CT abdominal imaging: Frequency and factors affecting inclusion in the hospital discharge summary. J Hosp Med. 2017;6:454-7.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Clinical question: How often are incidentally found pulmonary nodules and instructions for follow-up included in the discharge summary?

Background: Lung nodules are frequent incidental findings on imaging, but it is unclear whether patients are subsequently receiving the recommended follow-up.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Synopsis: The authors identified 7,173 patients who had undergone abdominal CT scans during their admission and reviewed charts of 402 patients who had incidentally found pulmonary nodules identified on the scans. For each of the patients, discharge summaries were evaluated to determine whether they made reference to the nodules and whether follow-up instructions were included. Of the 208 patients noted to have nodules requiring follow-up, only 48 (23%) had discharge summaries that mentioned the nodules. Factors associated with including the nodules in the discharge summary were the radiologist recommending further surveillance, radiologist including the nodule in the summary heading of the report, and being on a medical as opposed to a surgical service. The authors concluded that systems-based approaches to incidentally found lung nodules are needed to ensure adequate follow-up.

Bottom line: Incidentally found lung nodules are often not included in discharge documentation and therefore may not receive the recommended follow-up.

Citation: Bates R, Plooster C, Croghan I, et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules reported on CT abdominal imaging: Frequency and factors affecting inclusion in the hospital discharge summary. J Hosp Med. 2017;6:454-7.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Clinical question: How often are incidentally found pulmonary nodules and instructions for follow-up included in the discharge summary?

Background: Lung nodules are frequent incidental findings on imaging, but it is unclear whether patients are subsequently receiving the recommended follow-up.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study.

Synopsis: The authors identified 7,173 patients who had undergone abdominal CT scans during their admission and reviewed charts of 402 patients who had incidentally found pulmonary nodules identified on the scans. For each of the patients, discharge summaries were evaluated to determine whether they made reference to the nodules and whether follow-up instructions were included. Of the 208 patients noted to have nodules requiring follow-up, only 48 (23%) had discharge summaries that mentioned the nodules. Factors associated with including the nodules in the discharge summary were the radiologist recommending further surveillance, radiologist including the nodule in the summary heading of the report, and being on a medical as opposed to a surgical service. The authors concluded that systems-based approaches to incidentally found lung nodules are needed to ensure adequate follow-up.

Bottom line: Incidentally found lung nodules are often not included in discharge documentation and therefore may not receive the recommended follow-up.

Citation: Bates R, Plooster C, Croghan I, et al. Incidental pulmonary nodules reported on CT abdominal imaging: Frequency and factors affecting inclusion in the hospital discharge summary. J Hosp Med. 2017;6:454-7.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Home noninvasive ventilation reduces COPD readmissions

Clinical question: Is there a benefit to home noninvasive ventilation (NIV) following a hospital admission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation?

Background: Preventing hospital readmission following a COPD exacerbation is a priority; however, the role of NIV in this situation remains uncertain.

Setting: 13 medical centers in the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Investigators randomized 116 patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia (paCO2 less than 53) 2-4 weeks following a COPD exacerbation to either home oxygen therapy with NIV or to home oxygen therapy alone. The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of time to readmission or death within 12 months. They found that the median time to this endpoint was significantly longer in the intervention group (1.4 vs. 4.3 months; 95% CI, 0.31-0.77; P = .002) and that the absolute risk reduction was 17.0% (80.4% vs. 63.4%; 95% CI, 0.1%-34.0%). The differences were driven by readmissions, as the mortality rate did not differ significantly between groups, although the study was not powered to evaluate this. Of note, the median NIV settings were 24/4, which constitutes a “high-pressure strategy” which may account for the benefits seen in this study that have been absent in some other trials.

Bottom line: NIV reduced readmissions in patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia several weeks following an acute exacerbation.

Citation: Murphy PB, Rehal S, Arbane G, et al. Effect of home noninvasive ventilation with oxygen therapy vs. oxygen therapy alone on hospital readmission or death after an acute COPD exacerbation, a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2177-86.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Clinical question: Is there a benefit to home noninvasive ventilation (NIV) following a hospital admission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation?

Background: Preventing hospital readmission following a COPD exacerbation is a priority; however, the role of NIV in this situation remains uncertain.

Setting: 13 medical centers in the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Investigators randomized 116 patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia (paCO2 less than 53) 2-4 weeks following a COPD exacerbation to either home oxygen therapy with NIV or to home oxygen therapy alone. The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of time to readmission or death within 12 months. They found that the median time to this endpoint was significantly longer in the intervention group (1.4 vs. 4.3 months; 95% CI, 0.31-0.77; P = .002) and that the absolute risk reduction was 17.0% (80.4% vs. 63.4%; 95% CI, 0.1%-34.0%). The differences were driven by readmissions, as the mortality rate did not differ significantly between groups, although the study was not powered to evaluate this. Of note, the median NIV settings were 24/4, which constitutes a “high-pressure strategy” which may account for the benefits seen in this study that have been absent in some other trials.

Bottom line: NIV reduced readmissions in patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia several weeks following an acute exacerbation.

Citation: Murphy PB, Rehal S, Arbane G, et al. Effect of home noninvasive ventilation with oxygen therapy vs. oxygen therapy alone on hospital readmission or death after an acute COPD exacerbation, a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2177-86.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Clinical question: Is there a benefit to home noninvasive ventilation (NIV) following a hospital admission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation?

Background: Preventing hospital readmission following a COPD exacerbation is a priority; however, the role of NIV in this situation remains uncertain.

Setting: 13 medical centers in the United Kingdom.

Synopsis: Investigators randomized 116 patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia (paCO2 less than 53) 2-4 weeks following a COPD exacerbation to either home oxygen therapy with NIV or to home oxygen therapy alone. The study’s primary endpoint was a composite of time to readmission or death within 12 months. They found that the median time to this endpoint was significantly longer in the intervention group (1.4 vs. 4.3 months; 95% CI, 0.31-0.77; P = .002) and that the absolute risk reduction was 17.0% (80.4% vs. 63.4%; 95% CI, 0.1%-34.0%). The differences were driven by readmissions, as the mortality rate did not differ significantly between groups, although the study was not powered to evaluate this. Of note, the median NIV settings were 24/4, which constitutes a “high-pressure strategy” which may account for the benefits seen in this study that have been absent in some other trials.

Bottom line: NIV reduced readmissions in patients with COPD and persistent hypercapnia several weeks following an acute exacerbation.

Citation: Murphy PB, Rehal S, Arbane G, et al. Effect of home noninvasive ventilation with oxygen therapy vs. oxygen therapy alone on hospital readmission or death after an acute COPD exacerbation, a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;317(21):2177-86.

Dr. Herscher is assistant professor, division of hospital medicine, Icahn School of Medicine of the Mount Sinai Health System.

Medical malpractice and the hospitalist: Reasons for optimism

Fear of malpractice litigation weighs on many physicians, including hospitalists. Specific concerns that physicians have about facing a malpractice claim include stigmatization, loss of confidence in one’s own clinical skills, and a possible personal financial toll if an award exceeds the limit of one’s malpractice insurance.

Physician worries about malpractice are increasingly being raised during discussions of burnout, with a recent National Academy of Medicine discussion paper listing malpractice concerns as a possible factor that could contribute to physician burnout.1

Malpractice fears also influence physician behavior generally, leading to defensive medicine, though the actual costs of defensive medicine are debated. A national survey of physicians by Bishop and colleagues found that 91% felt that physicians order more tests and procedures than patients require in order to try to avoid malpractice claims.3 A survey of 1,020 hospitalists asked what testing they would undertake when provided clinical vignettes involving preoperative evaluation and syncope.4 Overuse of testing was common among hospitalists, and most hospitalists who overused testing specified that a desire to reassure either themselves or the patient or patient’s family was the reason for ordering the unnecessary testing.

The extent to which this overuse was driven by liability fears specifically is not clear. Overuse of testing was less common among physicians associated with Veterans Affairs Hospitals, who generally are not subject to personal medical malpractice liability. But a history of a prior malpractice claim was not associated with significantly greater overuse in the survey.

Hospitalists’ concerns about medical liability notwithstanding, data on the absolute malpractice risk of hospitalists and current trends in medical liability are both encouraging. An important source of our understanding about the national medical malpractice landscape is CRICO Strategies National Comparative Benchmarking System (CBS), which includes the malpractice experience from multiple insurers and represents 400 hospitals and 165,000 physicians. A December 2014 analysis of cases involving hospitalists from the CBS database showed that the malpractice claims rate for hospitalists was lower than those for other comparable groups of physicians.5 Hospitalists (in internal medicine) had a claims rate of 0.52 claims per 100 physician coverage years, which was significantly lower than the claims rate for nonhospitalist internal medicine physicians (with a rate of 1.91 claims per 100 physician-coverage years) and for emergency medicine physicians (with a rate of 3.50 claims per 100 physician-coverage years).

A remarkable national trend in medical malpractice, based on an analysis of data supplied by the National Practitioner Data Bank, is that the overall rate of paid claims is decreasing. From 1992 to 2014, the overall rate of paid claims dropped 55.7%.7 To varying degrees, the drop in paid claims has occurred across all specialties, with internal medicine in particular dropping 46.1%. The reason for this decrease in paid claims is not clear. Improvements in patient safety are one possible explanation, with tort reforms also possibly contributing to this trend. An additional potential factor, which will likely become more important as it becomes more widespread, is the advent of communication and resolution programs (also known as disclosure, apology, and offer programs).

In communication and resolution programs, the response to a malpractice claim is to investigate the circumstances surrounding the adverse event underlying the claim to determine if it was the result of medical error. When the investigation finds no medical error, then the claim is defended. However, in cases in which there was a medical error leading to patient harm, then the error is disclosed to the patient and family, and an offer of compensation is made.

One of the most prominent communication and resolution programs exists at the University of Michigan, and published experience from this program shows that, after implementation of the program, significant drops were seen in the number of malpractice lawsuits, the time it took to resolve malpractice claims, the amount paid in patient compensation on malpractice claims, and the costs involved with litigating malpractice claims.8 One of the goals of communication and resolution programs is to utilize the information from the investigations of whether medical errors occurred to find areas where patient safety systems can be improved, thereby using the medical malpractice system to promote patient safety. Although the University of Michigan’s experience with its communication and resolution program is very encouraging, it remains to be seen how widely such programs will be adopted. Medical malpractice is primarily governed at the state level, and the liability laws of some states are more conducive than others to the implementation of these programs.

Hospitalist concerns about medical malpractice are likely to persist, as being named in a malpractice lawsuit is stressful, regardless of the outcome of the case. Contributing to the stress of facing a malpractice claim, cases typically take 3-5 years to be resolved. However, the risk for hospitalists of facing a medical malpractice claim is relatively low. Moreover, given national trends, hospitalists’ liability risk would be expected to remain low or decrease moving forward.

Dr. Schaffer is an attending physician in the Hospital Medicine Unit at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, an instructor at Harvard Medical School, and a senior clinical analytics specialist at CRICO/Risk Management Foundation of the Harvard Medical Institutions, all in Boston. Dr. Kachalia is an attending physician in the Hospital Medicine Unit at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, an associate professor at Harvard Medical School, and the chief quality officer at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

References

1. Dyrbye LN et al. Burnout among health care professionals: A call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. National Academy of Medicine Perspectives. 2017 Jul 5.