User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Evidence suggests fondaparinux is more effective than LMWH in prevention of VTE and total DVT in the postoperative setting

Clinical question: How do pentasaccharides compare to other anticoagulants in postoperative venous thromboembolism prevention?

Background: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a leading cause of preventable hospital related death. Pentasaccharides selectively inhibit factor Xa to inhibit clotting and exhibit a lower risk of heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) compared to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and unfractionated heparin. We lack a formal recommendation regarding the pentasaccharides superiority or inferiority, relative to other anticoagulants, in the perioperative setting.

Study design: Cochrane review.

Setting: Hospital and outpatient.

Synopsis: Authors searched randomized controlled trials involving pentasaccharides versus other VTE prophylaxis to obtain 25 studies totaling 21,004 subjects undergoing orthopedic, abdominal, cardiac bypass, thoracic, and bariatric surgery; hospitalized patients, immobilized patients, and those with superficial venous thrombosis. Selected studies pertained to fondaparinux and VTE prevention. Fondaparinux was superior to placebo in prevention of DVT and VTE. Compared to LMWH, fondaparinux reduced total VTE (RR, 0.55, 95% CI, 0.42-0.73) and DVT (RR, 0.54, 95% CI, 0.40-0.71), but carried a higher rate of major bleeding compared to placebo (RR, 2.56, 95% CI, 1.48-4.44) and LMWH (RR, 1.38, 95% CI, 1.09-1.75). The all cause death and major adverse events for fondaparinux versus placebo and LMWH were not statistically significant. Limitations of this review include the predominance of orthopedic patients, variable duration of treatment, and low-moderate quality data.

Bottom line: Fondaparinux demonstrates better perioperative total VTE and DVT reduction compared to LMWH, but it increases the incidence of major bleeding.

Reference: Dong K, Song Y, Li X, Ding J, Gao Z, Lu D, Zhu Y. Pentasaccharides for the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Oct 31;10:CD005134.

Dr. Coleman is an assistant professor of clinical medicine at Cooper Medical School at Rowan University. She works as a hospitalist at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J.

Clinical question: How do pentasaccharides compare to other anticoagulants in postoperative venous thromboembolism prevention?

Background: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a leading cause of preventable hospital related death. Pentasaccharides selectively inhibit factor Xa to inhibit clotting and exhibit a lower risk of heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) compared to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and unfractionated heparin. We lack a formal recommendation regarding the pentasaccharides superiority or inferiority, relative to other anticoagulants, in the perioperative setting.

Study design: Cochrane review.

Setting: Hospital and outpatient.

Synopsis: Authors searched randomized controlled trials involving pentasaccharides versus other VTE prophylaxis to obtain 25 studies totaling 21,004 subjects undergoing orthopedic, abdominal, cardiac bypass, thoracic, and bariatric surgery; hospitalized patients, immobilized patients, and those with superficial venous thrombosis. Selected studies pertained to fondaparinux and VTE prevention. Fondaparinux was superior to placebo in prevention of DVT and VTE. Compared to LMWH, fondaparinux reduced total VTE (RR, 0.55, 95% CI, 0.42-0.73) and DVT (RR, 0.54, 95% CI, 0.40-0.71), but carried a higher rate of major bleeding compared to placebo (RR, 2.56, 95% CI, 1.48-4.44) and LMWH (RR, 1.38, 95% CI, 1.09-1.75). The all cause death and major adverse events for fondaparinux versus placebo and LMWH were not statistically significant. Limitations of this review include the predominance of orthopedic patients, variable duration of treatment, and low-moderate quality data.

Bottom line: Fondaparinux demonstrates better perioperative total VTE and DVT reduction compared to LMWH, but it increases the incidence of major bleeding.

Reference: Dong K, Song Y, Li X, Ding J, Gao Z, Lu D, Zhu Y. Pentasaccharides for the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Oct 31;10:CD005134.

Dr. Coleman is an assistant professor of clinical medicine at Cooper Medical School at Rowan University. She works as a hospitalist at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J.

Clinical question: How do pentasaccharides compare to other anticoagulants in postoperative venous thromboembolism prevention?

Background: Venous thromboembolism (VTE) remains a leading cause of preventable hospital related death. Pentasaccharides selectively inhibit factor Xa to inhibit clotting and exhibit a lower risk of heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) compared to low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) and unfractionated heparin. We lack a formal recommendation regarding the pentasaccharides superiority or inferiority, relative to other anticoagulants, in the perioperative setting.

Study design: Cochrane review.

Setting: Hospital and outpatient.

Synopsis: Authors searched randomized controlled trials involving pentasaccharides versus other VTE prophylaxis to obtain 25 studies totaling 21,004 subjects undergoing orthopedic, abdominal, cardiac bypass, thoracic, and bariatric surgery; hospitalized patients, immobilized patients, and those with superficial venous thrombosis. Selected studies pertained to fondaparinux and VTE prevention. Fondaparinux was superior to placebo in prevention of DVT and VTE. Compared to LMWH, fondaparinux reduced total VTE (RR, 0.55, 95% CI, 0.42-0.73) and DVT (RR, 0.54, 95% CI, 0.40-0.71), but carried a higher rate of major bleeding compared to placebo (RR, 2.56, 95% CI, 1.48-4.44) and LMWH (RR, 1.38, 95% CI, 1.09-1.75). The all cause death and major adverse events for fondaparinux versus placebo and LMWH were not statistically significant. Limitations of this review include the predominance of orthopedic patients, variable duration of treatment, and low-moderate quality data.

Bottom line: Fondaparinux demonstrates better perioperative total VTE and DVT reduction compared to LMWH, but it increases the incidence of major bleeding.

Reference: Dong K, Song Y, Li X, Ding J, Gao Z, Lu D, Zhu Y. Pentasaccharides for the prevention of venous thromboembolism. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Oct 31;10:CD005134.

Dr. Coleman is an assistant professor of clinical medicine at Cooper Medical School at Rowan University. She works as a hospitalist at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J.

Trending at SHM

Top 10 reasons to attend 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy

It’s your last chance to register for the 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA), which will be held Feb. 26-28 in Tempe, Ariz. Looking for some reasons to attend? Here are the top 10:

- Education. Develop and refine your knowledge in quality and patient safety.

- Desert beauty. Enjoy sunny Tempe, or travel to nearby Phoenix or Scottsdale.

- Curriculum development. Return to your institution with a collection of new educational strategies and curriculum development tactics.

- Professional development. Hone your skills and be the best that you can be to meet the increasing demand for medical educators who are well versed in patient safety and quality.

- Relationships. Build your network with faculty mentors and colleagues who have similar career interests.

- Institutional backing. Engage your institutional leaders to support and implement a quality and patient safety curriculum to meet the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies and improve patient care.

- Hands-on learning. Engage in an interactive learning environment, with a 10:1 student to faculty ratio, including facilitated large-group sessions, small-group exercises, and panel discussions.

- Variety. Each day has its own topic that breaks down into subtopics, covering the breadth of information you need to know to succeed.

- Faculty. All sessions are led by experienced physicians known for their ability to practice and teach quality improvement and patient safety, mentor junior faculty, and guide educators in curriculum development.

- Resources. Leave with a toolkit of educational resources and curricular tools for quality and safety education.

Reserve your spot today before the meeting sells out at www.shmqsea.org.

SHM committees address practice management topics

SHM’s Practice Management Committee has been researching, deliberating case studies, and authoring timely content to further define HM’s role in key health care innovations. As the specialty has grown and evolved, so have hospitalists’ involvement in comanagement relationships.

The committee recently released a white paper addressing the evolution of comanagement in hospital medicine. Be on the lookout for that in early 2017.

Similarly, telemedicine is rapidly expanding, and the committee found it imperative to clarify the who, what, when, where, why, and how of telemedicine programs in hospital medicine. You can also expect this white paper in early 2017.

The committee also has created guidelines on how to raise awareness of cultural humility in your HM group. Deemed the “5 R’s of Cultural Humility,” look for a campaign around the guidelines to launch at HM17 in May in Las Vegas.

SHM’s Health Information Technology Committee has been diligently analyzing and reporting on survey results that captured hospitalists’ attitudes toward electronic health records. The purpose of this white paper is to effect change on EHR systems by informing conversations with decision makers, and to provide HM a definitive voice in the landscape of the tumultuous world of EHRs. More information is coming soon.

Make a difference with SHM

Grow professionally, expand your curriculum vitae, and get involved in work you are passionate about with colleagues across the country with SHM’s volunteer experiences. New opportunities are constantly being added that will bolster your strengths, sharpen your professional acumen and enhance your profile in the hospital medicine community at www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved.

Leadership Academy 2017 has a new look

Don’t miss out on the only leadership program designed specifically for hospitalists. SHM Leadership Academy 2017 will be at the JW Marriott Camelback Inn in Scottsdale, Ariz., on Oct. 23-26.

For the first time, the Leadership Academy prerequisite of attendance in the first-level, Foundations course has been removed. Essential Strategies (formerly Leadership Foundations), Influential Management, and Mastering Teamwork courses are available to all attendees, regardless of previous attendance. Prior participants have made recommendations to help interested registrants determine which course fits them best in their leadership journey.

All three courses run concurrently over the span of 4 days. This expanded meeting will provide attendees with world-class networking opportunities, creating opportunities for a more engaging, impactful educational experience.

Learn more about SHM’s Leadership Academy at www.shmleadershipacademy.org.

Earn dues credits with the Membership Ambassador Program

Help SHM grow its network of hospitalists and continue to provide education, networking, and career advancement for its members. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/refer today.

Brett Radler is SHM's communications specialist.

Top 10 reasons to attend 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy

It’s your last chance to register for the 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA), which will be held Feb. 26-28 in Tempe, Ariz. Looking for some reasons to attend? Here are the top 10:

- Education. Develop and refine your knowledge in quality and patient safety.

- Desert beauty. Enjoy sunny Tempe, or travel to nearby Phoenix or Scottsdale.

- Curriculum development. Return to your institution with a collection of new educational strategies and curriculum development tactics.

- Professional development. Hone your skills and be the best that you can be to meet the increasing demand for medical educators who are well versed in patient safety and quality.

- Relationships. Build your network with faculty mentors and colleagues who have similar career interests.

- Institutional backing. Engage your institutional leaders to support and implement a quality and patient safety curriculum to meet the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies and improve patient care.

- Hands-on learning. Engage in an interactive learning environment, with a 10:1 student to faculty ratio, including facilitated large-group sessions, small-group exercises, and panel discussions.

- Variety. Each day has its own topic that breaks down into subtopics, covering the breadth of information you need to know to succeed.

- Faculty. All sessions are led by experienced physicians known for their ability to practice and teach quality improvement and patient safety, mentor junior faculty, and guide educators in curriculum development.

- Resources. Leave with a toolkit of educational resources and curricular tools for quality and safety education.

Reserve your spot today before the meeting sells out at www.shmqsea.org.

SHM committees address practice management topics

SHM’s Practice Management Committee has been researching, deliberating case studies, and authoring timely content to further define HM’s role in key health care innovations. As the specialty has grown and evolved, so have hospitalists’ involvement in comanagement relationships.

The committee recently released a white paper addressing the evolution of comanagement in hospital medicine. Be on the lookout for that in early 2017.

Similarly, telemedicine is rapidly expanding, and the committee found it imperative to clarify the who, what, when, where, why, and how of telemedicine programs in hospital medicine. You can also expect this white paper in early 2017.

The committee also has created guidelines on how to raise awareness of cultural humility in your HM group. Deemed the “5 R’s of Cultural Humility,” look for a campaign around the guidelines to launch at HM17 in May in Las Vegas.

SHM’s Health Information Technology Committee has been diligently analyzing and reporting on survey results that captured hospitalists’ attitudes toward electronic health records. The purpose of this white paper is to effect change on EHR systems by informing conversations with decision makers, and to provide HM a definitive voice in the landscape of the tumultuous world of EHRs. More information is coming soon.

Make a difference with SHM

Grow professionally, expand your curriculum vitae, and get involved in work you are passionate about with colleagues across the country with SHM’s volunteer experiences. New opportunities are constantly being added that will bolster your strengths, sharpen your professional acumen and enhance your profile in the hospital medicine community at www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved.

Leadership Academy 2017 has a new look

Don’t miss out on the only leadership program designed specifically for hospitalists. SHM Leadership Academy 2017 will be at the JW Marriott Camelback Inn in Scottsdale, Ariz., on Oct. 23-26.

For the first time, the Leadership Academy prerequisite of attendance in the first-level, Foundations course has been removed. Essential Strategies (formerly Leadership Foundations), Influential Management, and Mastering Teamwork courses are available to all attendees, regardless of previous attendance. Prior participants have made recommendations to help interested registrants determine which course fits them best in their leadership journey.

All three courses run concurrently over the span of 4 days. This expanded meeting will provide attendees with world-class networking opportunities, creating opportunities for a more engaging, impactful educational experience.

Learn more about SHM’s Leadership Academy at www.shmleadershipacademy.org.

Earn dues credits with the Membership Ambassador Program

Help SHM grow its network of hospitalists and continue to provide education, networking, and career advancement for its members. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/refer today.

Brett Radler is SHM's communications specialist.

Top 10 reasons to attend 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy

It’s your last chance to register for the 2017 Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA), which will be held Feb. 26-28 in Tempe, Ariz. Looking for some reasons to attend? Here are the top 10:

- Education. Develop and refine your knowledge in quality and patient safety.

- Desert beauty. Enjoy sunny Tempe, or travel to nearby Phoenix or Scottsdale.

- Curriculum development. Return to your institution with a collection of new educational strategies and curriculum development tactics.

- Professional development. Hone your skills and be the best that you can be to meet the increasing demand for medical educators who are well versed in patient safety and quality.

- Relationships. Build your network with faculty mentors and colleagues who have similar career interests.

- Institutional backing. Engage your institutional leaders to support and implement a quality and patient safety curriculum to meet the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies and improve patient care.

- Hands-on learning. Engage in an interactive learning environment, with a 10:1 student to faculty ratio, including facilitated large-group sessions, small-group exercises, and panel discussions.

- Variety. Each day has its own topic that breaks down into subtopics, covering the breadth of information you need to know to succeed.

- Faculty. All sessions are led by experienced physicians known for their ability to practice and teach quality improvement and patient safety, mentor junior faculty, and guide educators in curriculum development.

- Resources. Leave with a toolkit of educational resources and curricular tools for quality and safety education.

Reserve your spot today before the meeting sells out at www.shmqsea.org.

SHM committees address practice management topics

SHM’s Practice Management Committee has been researching, deliberating case studies, and authoring timely content to further define HM’s role in key health care innovations. As the specialty has grown and evolved, so have hospitalists’ involvement in comanagement relationships.

The committee recently released a white paper addressing the evolution of comanagement in hospital medicine. Be on the lookout for that in early 2017.

Similarly, telemedicine is rapidly expanding, and the committee found it imperative to clarify the who, what, when, where, why, and how of telemedicine programs in hospital medicine. You can also expect this white paper in early 2017.

The committee also has created guidelines on how to raise awareness of cultural humility in your HM group. Deemed the “5 R’s of Cultural Humility,” look for a campaign around the guidelines to launch at HM17 in May in Las Vegas.

SHM’s Health Information Technology Committee has been diligently analyzing and reporting on survey results that captured hospitalists’ attitudes toward electronic health records. The purpose of this white paper is to effect change on EHR systems by informing conversations with decision makers, and to provide HM a definitive voice in the landscape of the tumultuous world of EHRs. More information is coming soon.

Make a difference with SHM

Grow professionally, expand your curriculum vitae, and get involved in work you are passionate about with colleagues across the country with SHM’s volunteer experiences. New opportunities are constantly being added that will bolster your strengths, sharpen your professional acumen and enhance your profile in the hospital medicine community at www.hospitalmedicine.org/getinvolved.

Leadership Academy 2017 has a new look

Don’t miss out on the only leadership program designed specifically for hospitalists. SHM Leadership Academy 2017 will be at the JW Marriott Camelback Inn in Scottsdale, Ariz., on Oct. 23-26.

For the first time, the Leadership Academy prerequisite of attendance in the first-level, Foundations course has been removed. Essential Strategies (formerly Leadership Foundations), Influential Management, and Mastering Teamwork courses are available to all attendees, regardless of previous attendance. Prior participants have made recommendations to help interested registrants determine which course fits them best in their leadership journey.

All three courses run concurrently over the span of 4 days. This expanded meeting will provide attendees with world-class networking opportunities, creating opportunities for a more engaging, impactful educational experience.

Learn more about SHM’s Leadership Academy at www.shmleadershipacademy.org.

Earn dues credits with the Membership Ambassador Program

Help SHM grow its network of hospitalists and continue to provide education, networking, and career advancement for its members. Visit www.hospitalmedicine.org/refer today.

Brett Radler is SHM's communications specialist.

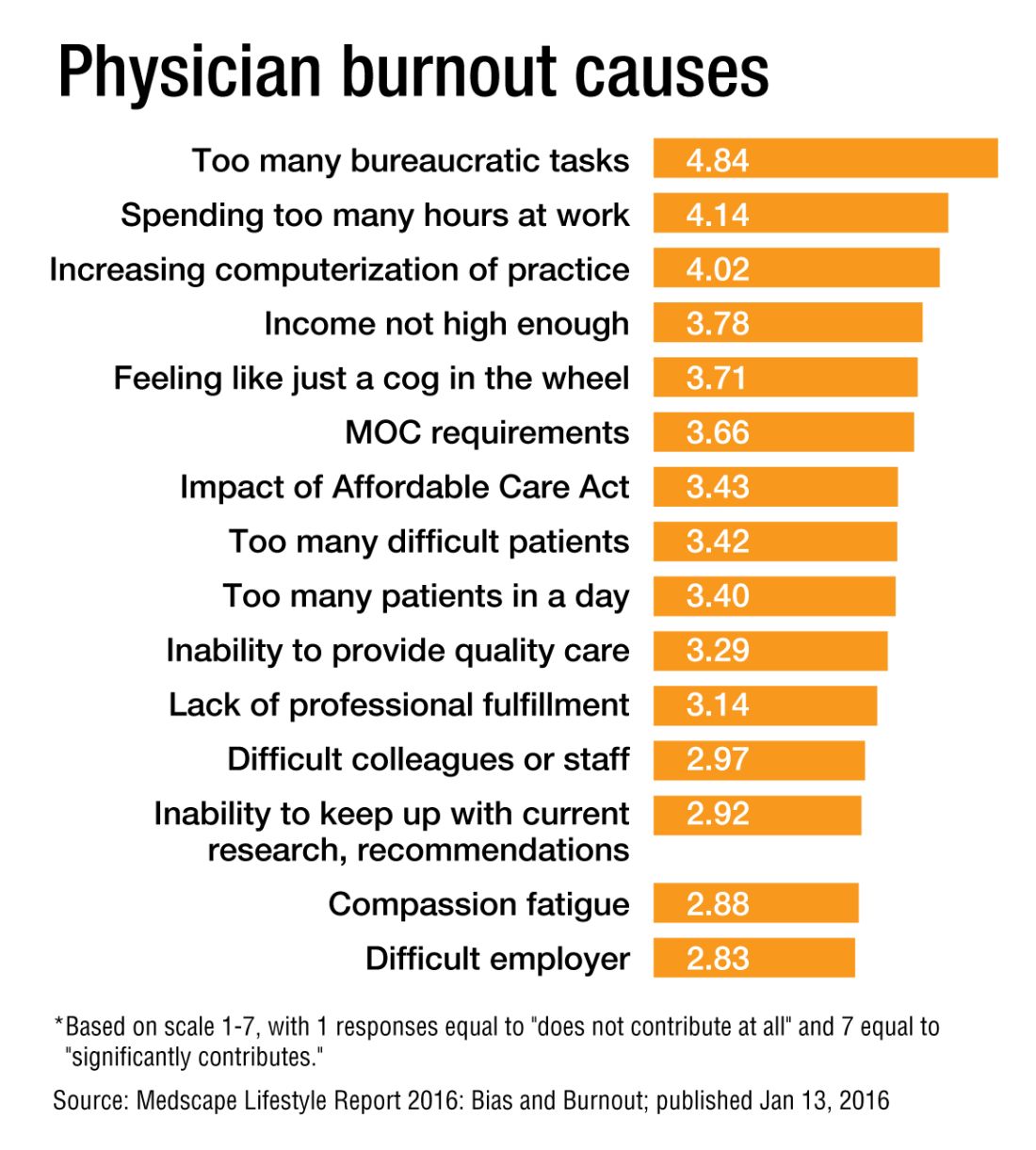

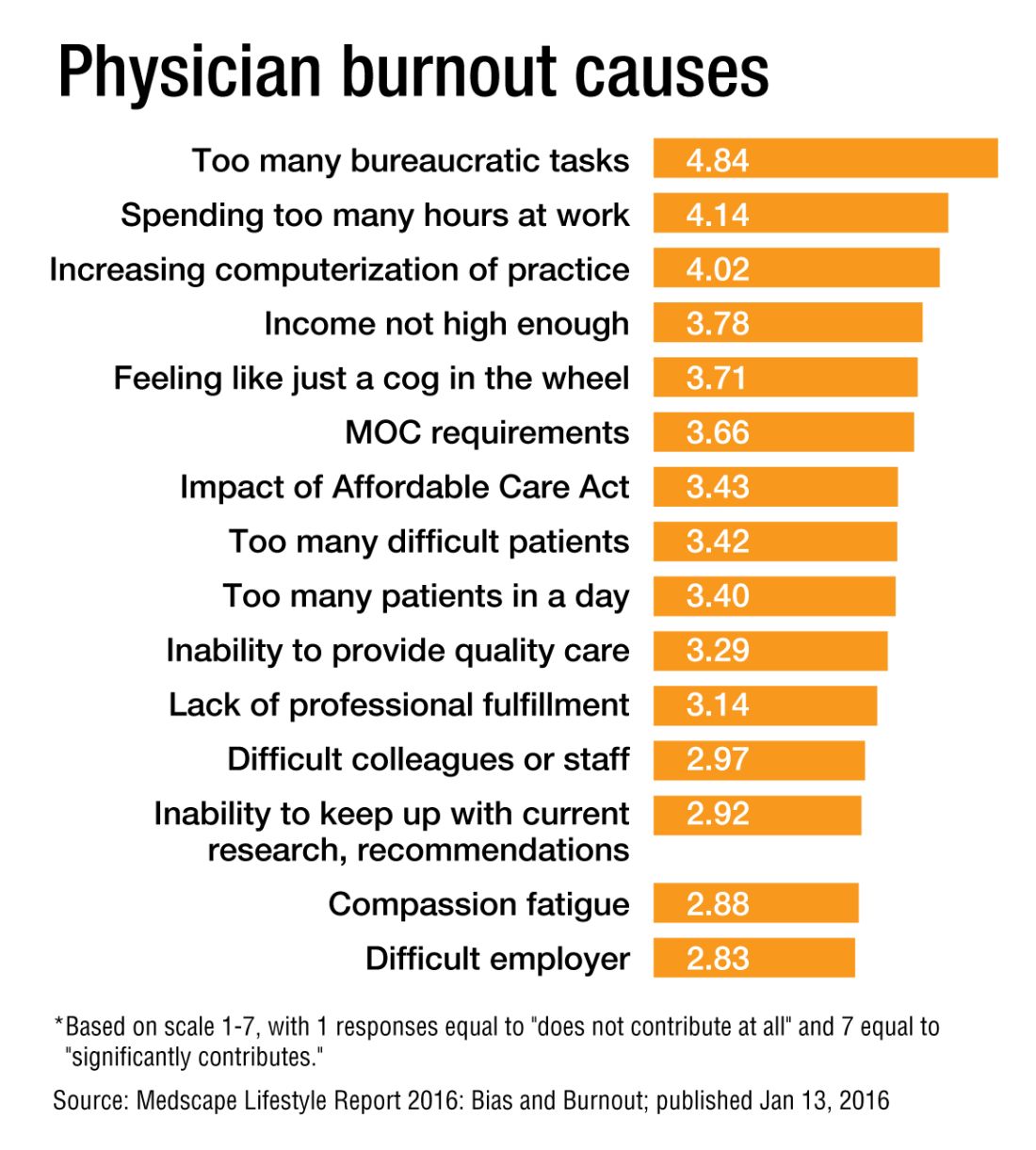

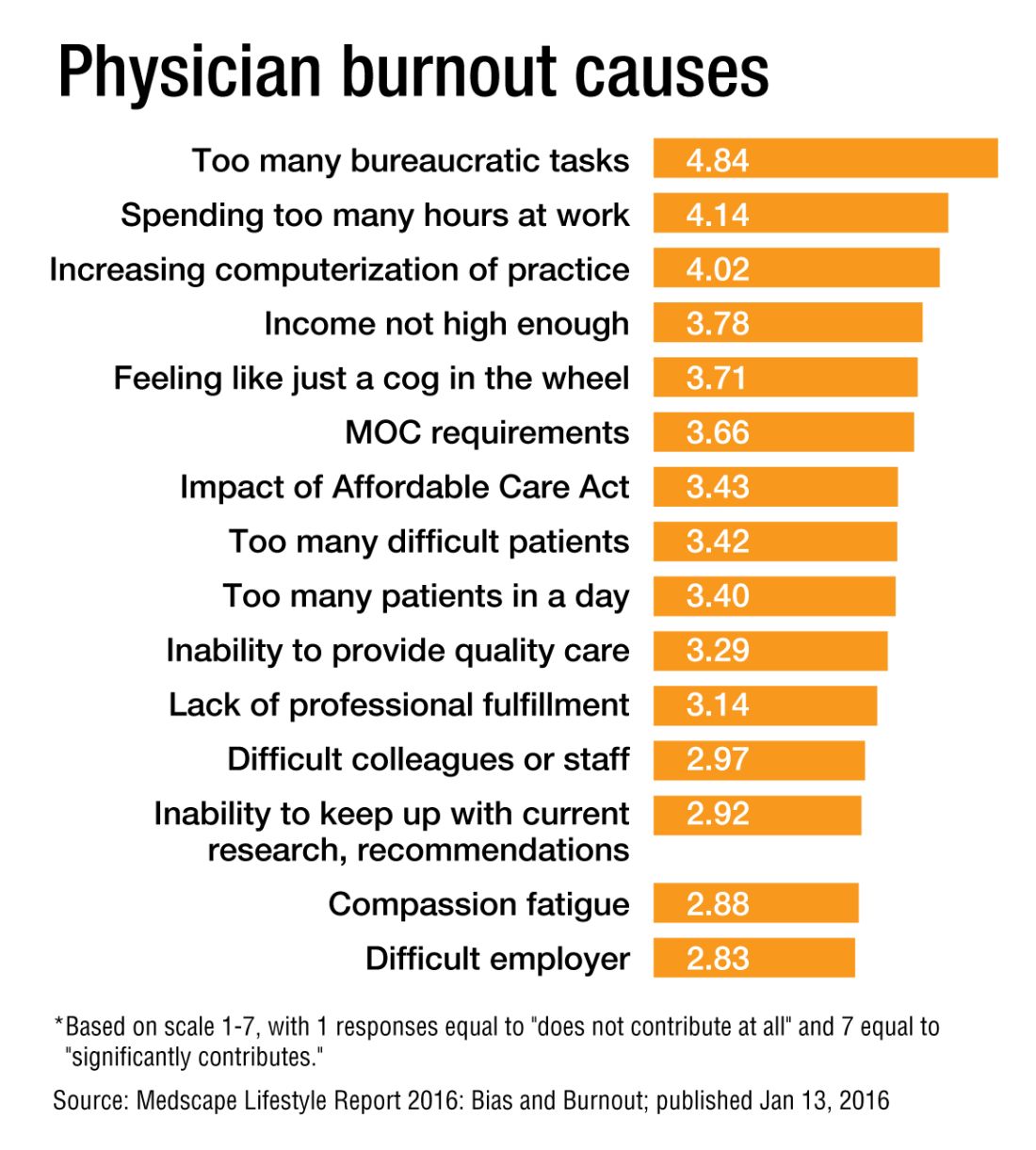

Don’t assume work is sole burnout determinant

Physician burnout is almost always linked to issues at work. Blame is placed on added duties piled onto a to-do list that barely makes enough time for prolonged patient interaction in the first place. Fault is laid upon the hours and hours per week – or even per day – wasted on cumbersome data entry into bulky electronic health record (EHR) systems.

But Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician and burnout coach/consultant, says burnout should not be viewed as job specific. “To say that burnout is always about work is absolutely an error,” said Dr. Drummond, whose website is www.thehappymd.com. “You can have people flame out spectacularly at work and nothing has changed about work at all. It’s because something’s going on at home that’s made it impossible to recharge on their time off. And, that list of recharge-blocking issues is huge.”

Money problems, marital problems, family problems: Dr. Drummond says any and all of those issues can eliminate the doctor’s ability to recharge at home.

“The strain of your practice continues, but now without the ability to balance your energy with some recovery when you’re away from the hospital, burnout can come on very rapidly,” he said. “So when you see a colleague flaming out at work, one of the questions you must ask is, “How is it going at home?” You may be the first to learn their spouse left them 2 weeks ago.”

Dr. Drummond’s advice is: Don’t always blame the stresses of work. Build your recharge strategy (rest, hobbies, date nights) and make sure you maintain your recharge capabilities.

“Ideally, with a hospitalist-type schedule, when you’re on you’re on and when you’re off you’re off,” he said. “It should be easier to create that boundary for hospitalists than other specialists who chart from home or are on call.

The “off switch” on your doctor programming is called a boundary ritual. Pick some activity you do on the way home from work, saying to yourself ‘with this action, I am coming all the way home.’ It can be as simple as a deep releasing breath as you step out of your car at home. Make sure you take that breath and let it all go before you walk into the house after each shift.”

Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout, refers to this phenomenon as “work-home interference.” On the bright side for hospitalists, he says, is that aspects of HM work schedules may help mitigate burnout; some work can be left at the hospital when shifts end, rather than following physicians into their home lives.

But Dr. West acknowledged that the rigors of the traditional 7-on/7-off schedule come with their own unique burnout challenges for hospitalists as well.

“A hospitalist can say ‘Well, jeez, I’m on nights for the next week, and that means during the day I’m sleeping and recovering,’” Dr. West explained. “Well, how do you maintain a family life for that period of time when you’re basically off-cycle with your family? There are those kinds of stressors. It’s a mixed bag for hospitalists there.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Physician burnout is almost always linked to issues at work. Blame is placed on added duties piled onto a to-do list that barely makes enough time for prolonged patient interaction in the first place. Fault is laid upon the hours and hours per week – or even per day – wasted on cumbersome data entry into bulky electronic health record (EHR) systems.

But Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician and burnout coach/consultant, says burnout should not be viewed as job specific. “To say that burnout is always about work is absolutely an error,” said Dr. Drummond, whose website is www.thehappymd.com. “You can have people flame out spectacularly at work and nothing has changed about work at all. It’s because something’s going on at home that’s made it impossible to recharge on their time off. And, that list of recharge-blocking issues is huge.”

Money problems, marital problems, family problems: Dr. Drummond says any and all of those issues can eliminate the doctor’s ability to recharge at home.

“The strain of your practice continues, but now without the ability to balance your energy with some recovery when you’re away from the hospital, burnout can come on very rapidly,” he said. “So when you see a colleague flaming out at work, one of the questions you must ask is, “How is it going at home?” You may be the first to learn their spouse left them 2 weeks ago.”

Dr. Drummond’s advice is: Don’t always blame the stresses of work. Build your recharge strategy (rest, hobbies, date nights) and make sure you maintain your recharge capabilities.

“Ideally, with a hospitalist-type schedule, when you’re on you’re on and when you’re off you’re off,” he said. “It should be easier to create that boundary for hospitalists than other specialists who chart from home or are on call.

The “off switch” on your doctor programming is called a boundary ritual. Pick some activity you do on the way home from work, saying to yourself ‘with this action, I am coming all the way home.’ It can be as simple as a deep releasing breath as you step out of your car at home. Make sure you take that breath and let it all go before you walk into the house after each shift.”

Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout, refers to this phenomenon as “work-home interference.” On the bright side for hospitalists, he says, is that aspects of HM work schedules may help mitigate burnout; some work can be left at the hospital when shifts end, rather than following physicians into their home lives.

But Dr. West acknowledged that the rigors of the traditional 7-on/7-off schedule come with their own unique burnout challenges for hospitalists as well.

“A hospitalist can say ‘Well, jeez, I’m on nights for the next week, and that means during the day I’m sleeping and recovering,’” Dr. West explained. “Well, how do you maintain a family life for that period of time when you’re basically off-cycle with your family? There are those kinds of stressors. It’s a mixed bag for hospitalists there.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Physician burnout is almost always linked to issues at work. Blame is placed on added duties piled onto a to-do list that barely makes enough time for prolonged patient interaction in the first place. Fault is laid upon the hours and hours per week – or even per day – wasted on cumbersome data entry into bulky electronic health record (EHR) systems.

But Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician and burnout coach/consultant, says burnout should not be viewed as job specific. “To say that burnout is always about work is absolutely an error,” said Dr. Drummond, whose website is www.thehappymd.com. “You can have people flame out spectacularly at work and nothing has changed about work at all. It’s because something’s going on at home that’s made it impossible to recharge on their time off. And, that list of recharge-blocking issues is huge.”

Money problems, marital problems, family problems: Dr. Drummond says any and all of those issues can eliminate the doctor’s ability to recharge at home.

“The strain of your practice continues, but now without the ability to balance your energy with some recovery when you’re away from the hospital, burnout can come on very rapidly,” he said. “So when you see a colleague flaming out at work, one of the questions you must ask is, “How is it going at home?” You may be the first to learn their spouse left them 2 weeks ago.”

Dr. Drummond’s advice is: Don’t always blame the stresses of work. Build your recharge strategy (rest, hobbies, date nights) and make sure you maintain your recharge capabilities.

“Ideally, with a hospitalist-type schedule, when you’re on you’re on and when you’re off you’re off,” he said. “It should be easier to create that boundary for hospitalists than other specialists who chart from home or are on call.

The “off switch” on your doctor programming is called a boundary ritual. Pick some activity you do on the way home from work, saying to yourself ‘with this action, I am coming all the way home.’ It can be as simple as a deep releasing breath as you step out of your car at home. Make sure you take that breath and let it all go before you walk into the house after each shift.”

Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout, refers to this phenomenon as “work-home interference.” On the bright side for hospitalists, he says, is that aspects of HM work schedules may help mitigate burnout; some work can be left at the hospital when shifts end, rather than following physicians into their home lives.

But Dr. West acknowledged that the rigors of the traditional 7-on/7-off schedule come with their own unique burnout challenges for hospitalists as well.

“A hospitalist can say ‘Well, jeez, I’m on nights for the next week, and that means during the day I’m sleeping and recovering,’” Dr. West explained. “Well, how do you maintain a family life for that period of time when you’re basically off-cycle with your family? There are those kinds of stressors. It’s a mixed bag for hospitalists there.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

Hot-button issue: physician burnout

Some 15 years ago, when Daniel Roberts, MD, FHM, decided at the end of his medical residency that his career path was going to be that of a hospitalist, he heard the same thing. A lot.

“Geesh, don’t you think you’re going to burn out?”

The reasons for such a response are well known in HM circles: the 7-on, 7-off shift structure; the constant rounding; the push-pull between clinical, administrative, and – what many would term – clerical work.

“The truth is somewhere between,” Dr. Roberts said.

Burnout is a hot topic among hospitalists and all of health care these days, as the increasing burdens of a system in seemingly constant change have fostered pressures inside and out of hospitals. Increasingly, researchers are studying and publishing about how to recognize burnout, ways to deal with, or even proactively address the issues. Some MDs – experts in physician burnout – make a living by touring the country and talking about the issue.

But what causes burnout, specifically and exactly?

“The simplistic answer is that burnout is what happens when resources do not meet demand,” said Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout. “The more complicated answer, which, at this point, is fairly solidly evidence based actually, is that there are five broad categories of drivers of physician distress and burnout.”

Dr. West’s hierarchy of stressors encompasses:

• Work effort.

• Work efficiency.

• Work-home interference.

• A sense of meaning.

• “Flexibility, control, and autonomy.”

Basically, the five drivers lead to this: Physicians who work too much and too inefficiently, with too little control and sense of purpose, end up flaming out more so than do doctors who work fewer hours, with fewer obstacles – all the while feeling satisfied with their autonomy and value.

Academic hospitalist John Yoon, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, says that health care has to work harder to promote its benefits as being more important than a highly paid profession. Instead, health care should focus on giving meaning to its practitioners.

“I think it is time for leaders of HM groups to honestly discuss the intrinsic meaning and essential ‘calling’ of what it means to be a good hospitalist,” Dr. Yoon wrote in an email interview with The Hospitalist. “What can we do to make the hospitalist vocation a meaningful, long-term career, so that they do not feel like simply revenue-generating ‘pawns’ in a medical-bureaucratic system?”

A ‘meaningful’ career

The modern discussion of burnout as a phenomenon traces back to the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a three-pronged test that measures emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.1 But why does burnout hit physicians – hospitalists, in particular – so intensely? In part, it’s because – like their predecessors in emergency medicine – hospitalists are responsible for managing the care of patients other specialties consult with, operate on, or for whom they run tests.

“Once the patients come up from the emergency room or get admitted to the hospital from the outside, the hospitalist is the one who is largely running that show,” said Dr. West, whose researchshows that HM doctors suffer burnout more than the average across medical specialties.2 “So they’re the front line of inpatient medicine.”

Another factor contributing to burnout’s impact on hospitalists is that the specialty’s rank and file (by definition) work within the walls of institutions that have a lot of contentious and complicated issues that – while outside the purview of HM – can directly or indirectly affect the field. Dr. West calls it the hassle factor.

“You want to get a test in the hospital and, even though you’re the attending on the service, you end up going through three layers of bureaucracy with an insurance company to be able to finally get what you know that patient needs,” he said. “Anything like that contributes to the burnout problem because it pulls the physician away from what they want to be doing, what is purposeful, what is meaningful for them.”

For Dr. Yoon, the exhaustion and cynicism borne out by the work of Maslach and Dr. West’s team are measures indicative of a field where physicians struggle more and more to “make sense of why their practice is worthwhile.

“In the contemporary medical literature, we have been encouraged to adopt the concepts and practices of industrial engineering and quality improvement,” Dr. Yoon added. “In other words, it seems that to the extent physicians’ aspirations to practice good medicine are confined to the narrow and unimaginative constraints of mere scientific technique (more data, higher ‘quality,’ better outcomes) physicians will struggle to recognize and respond to their practice as meaningful. There is no intrinsic meaning to simply being a ‘cog’ in a medical-industrial process or an ‘independent variable’ in an economic equation.”

Finding meaning in one’s job, of course, is less empirical an endpoint than using a reversal agent for a GI bleed. Therein lies the challenge of battling burnout, whose causes and interventions can be as varied as the people who suffer the syndrome.

Local, customized solutions

Once a group leader identifies the symptoms of burnout, the obvious question is how to address it.

Dr. West and his colleagues have identified two broad categories of interventions: individual-focused approaches and organizational solutions. Physician-centered efforts include such tacks as mindfulness, stress reduction, resilience training and small-group communication. Institutional-level changes are, typically, much harder to implement and make successful.

“It doesn’t make sense to ... simply send physicians to stress-management training so that they’re better equipped to deal with a system that is not working to improve itself,” Dr. West said. “The system and the leadership in that system needs to take responsibility from an organizational standpoint.”

Health care as a whole has worked to address the systems-level issue. Duty-hour regulations have been reined in for trainees to be proactive in addressing both fatigue and its inevitable endpoint: burnout.

In a report, “Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,”3 published online Dec. 5 in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers concluded that interventions associated with small benefits “may be boosted by adoption of organization-directed approaches.

“This finding provides support for the view that burnout is a problem of the whole health care organization, rather than individuals,” they wrote.

But the issue typically remains a local one, as group leaders need to realize that what could cause or contribute to burnout in one employee might be enjoyable to another.

“The prospect of doing that was daunting,” Dr. Roberts recalled. “I didn’t know much about EHRs and it was going to be a lot of meetings ... and [it] was going to take me away from patient care. It really ended up being rewarding, despite all the time and frustration, because I got to help represent the interests of my hospitalist colleagues, the physician assistants, and nurses that I work with in trying to avoid some real problems that could have arisen in the EHR.”

Doing that work appealed to Dr. Roberts, so he embraced it. That approach is one championed by Thom Mayer, MD, FACEP, FAAP, executive vice president of EmCare, founder and CEO of BestPractices Inc., medical director for the NFL Players Association, and clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University, Washington, and University of Virginia, Charlottesville. Dr. Mayer travels the country talking about burnout and suggests a three-pronged approach.

First, find what you like about your job and maximize those duties.

Second, label those tasks that are tolerable and don’t allow them to become issues leading to burnout.

Third, and perhaps most difficult, “take the things [you] hate and eliminate them to the best extent possible from [your] job.”

“I’ll give you an example,” he said. “What I hear from emergency physicians and hospitalists is: ‘What do I hate? Well, I hate chronic pain patients.’ Well, does that mean you’re going to be able to eliminate the fact that there are chronic pain patients? No. But, what you can do is ... really drill down on it, and say ‘Why do you hate that?’ The answer is, “Well, I don’t have a strategy for it.” No one likes doing things when they don’t know what they’re doing.

“Now you take the chronic pain patient and the problem is, most of us just haven’t really thought that out. Most of us haven’t sat down with our colleagues and said, “What are you doing that’s working? How are you handling these people? What are the scripts that I can use, the evidence-based language that I can use? What alternatives can I give them?” Instead of just assuming that the only answer to the problem of chronic pain is opioids.”

The silent epidemic

So if there are measurements for burnout, and even best practices on how to address it, why is the issue one that Dr. Mayer calls a silent epidemic? One word: stigma.

“We as physicians can’t afford to propagate that stigma any further,” Dr. Roberts said. “People who have even tougher jobs than we have, involving combat and hostage negotiation and things like that, have found a way to have honest conversations about the impact of their work on their lives. There is no reason physicians shouldn’t be able to slowly change the culture of medicine to be able to do that, so that there isn’t a stigma around saying, ‘I need some time away before this begins to impact the safety of our patients.’ ”

Dr. West said that when data show that as many as half of all physicians show symptoms of burnout, there is no need to stigmatize a group that large.

Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician, coach, and consultant on burnout prevention, said that the No. 1 mistake physicians and leaders make about burnout is labeling it a “problem.”

“Burnout does not have a single solution because it is not a problem to begin with,” he added. “Burnout is a classic dilemma – a never-ending balancing act. Think of the balancing act of burnout as a teeter-totter, like the one you see in a children’s playground. On one side is the energy you put into your practice and larger life … and on the other side your ability to recharge your energy levels.

“To prevent burnout you must keep your energy expenditure and your recharge activities in balance to keep this teeter-totter in a relatively horizontal position. And the way you address the dilemma is with a strategy: three to five individual tools you use to lower your stress levels or recharge your energy balance.”

And a strategy is a long-term approach to a long-term problem, he said.

“Burnout is not necessarily a terminal condition,” Dr. Roberts said. “If we can structure their work and the balance in their life in such a way that they don’t experience it, or that when they do experience it, they can recognize it and make the changes they need to avoid it getting worse, I think we’d be better off as a profession.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

1. Maslach C, Jackson S. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behavior. 1981;2:99-113

2. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-81.

3. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Brower P. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online Dec. 5, 2016 ahead of print]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674.

Some 15 years ago, when Daniel Roberts, MD, FHM, decided at the end of his medical residency that his career path was going to be that of a hospitalist, he heard the same thing. A lot.

“Geesh, don’t you think you’re going to burn out?”

The reasons for such a response are well known in HM circles: the 7-on, 7-off shift structure; the constant rounding; the push-pull between clinical, administrative, and – what many would term – clerical work.

“The truth is somewhere between,” Dr. Roberts said.

Burnout is a hot topic among hospitalists and all of health care these days, as the increasing burdens of a system in seemingly constant change have fostered pressures inside and out of hospitals. Increasingly, researchers are studying and publishing about how to recognize burnout, ways to deal with, or even proactively address the issues. Some MDs – experts in physician burnout – make a living by touring the country and talking about the issue.

But what causes burnout, specifically and exactly?

“The simplistic answer is that burnout is what happens when resources do not meet demand,” said Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout. “The more complicated answer, which, at this point, is fairly solidly evidence based actually, is that there are five broad categories of drivers of physician distress and burnout.”

Dr. West’s hierarchy of stressors encompasses:

• Work effort.

• Work efficiency.

• Work-home interference.

• A sense of meaning.

• “Flexibility, control, and autonomy.”

Basically, the five drivers lead to this: Physicians who work too much and too inefficiently, with too little control and sense of purpose, end up flaming out more so than do doctors who work fewer hours, with fewer obstacles – all the while feeling satisfied with their autonomy and value.

Academic hospitalist John Yoon, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, says that health care has to work harder to promote its benefits as being more important than a highly paid profession. Instead, health care should focus on giving meaning to its practitioners.

“I think it is time for leaders of HM groups to honestly discuss the intrinsic meaning and essential ‘calling’ of what it means to be a good hospitalist,” Dr. Yoon wrote in an email interview with The Hospitalist. “What can we do to make the hospitalist vocation a meaningful, long-term career, so that they do not feel like simply revenue-generating ‘pawns’ in a medical-bureaucratic system?”

A ‘meaningful’ career

The modern discussion of burnout as a phenomenon traces back to the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a three-pronged test that measures emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.1 But why does burnout hit physicians – hospitalists, in particular – so intensely? In part, it’s because – like their predecessors in emergency medicine – hospitalists are responsible for managing the care of patients other specialties consult with, operate on, or for whom they run tests.

“Once the patients come up from the emergency room or get admitted to the hospital from the outside, the hospitalist is the one who is largely running that show,” said Dr. West, whose researchshows that HM doctors suffer burnout more than the average across medical specialties.2 “So they’re the front line of inpatient medicine.”

Another factor contributing to burnout’s impact on hospitalists is that the specialty’s rank and file (by definition) work within the walls of institutions that have a lot of contentious and complicated issues that – while outside the purview of HM – can directly or indirectly affect the field. Dr. West calls it the hassle factor.

“You want to get a test in the hospital and, even though you’re the attending on the service, you end up going through three layers of bureaucracy with an insurance company to be able to finally get what you know that patient needs,” he said. “Anything like that contributes to the burnout problem because it pulls the physician away from what they want to be doing, what is purposeful, what is meaningful for them.”

For Dr. Yoon, the exhaustion and cynicism borne out by the work of Maslach and Dr. West’s team are measures indicative of a field where physicians struggle more and more to “make sense of why their practice is worthwhile.

“In the contemporary medical literature, we have been encouraged to adopt the concepts and practices of industrial engineering and quality improvement,” Dr. Yoon added. “In other words, it seems that to the extent physicians’ aspirations to practice good medicine are confined to the narrow and unimaginative constraints of mere scientific technique (more data, higher ‘quality,’ better outcomes) physicians will struggle to recognize and respond to their practice as meaningful. There is no intrinsic meaning to simply being a ‘cog’ in a medical-industrial process or an ‘independent variable’ in an economic equation.”

Finding meaning in one’s job, of course, is less empirical an endpoint than using a reversal agent for a GI bleed. Therein lies the challenge of battling burnout, whose causes and interventions can be as varied as the people who suffer the syndrome.

Local, customized solutions

Once a group leader identifies the symptoms of burnout, the obvious question is how to address it.

Dr. West and his colleagues have identified two broad categories of interventions: individual-focused approaches and organizational solutions. Physician-centered efforts include such tacks as mindfulness, stress reduction, resilience training and small-group communication. Institutional-level changes are, typically, much harder to implement and make successful.

“It doesn’t make sense to ... simply send physicians to stress-management training so that they’re better equipped to deal with a system that is not working to improve itself,” Dr. West said. “The system and the leadership in that system needs to take responsibility from an organizational standpoint.”

Health care as a whole has worked to address the systems-level issue. Duty-hour regulations have been reined in for trainees to be proactive in addressing both fatigue and its inevitable endpoint: burnout.

In a report, “Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,”3 published online Dec. 5 in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers concluded that interventions associated with small benefits “may be boosted by adoption of organization-directed approaches.

“This finding provides support for the view that burnout is a problem of the whole health care organization, rather than individuals,” they wrote.

But the issue typically remains a local one, as group leaders need to realize that what could cause or contribute to burnout in one employee might be enjoyable to another.

“The prospect of doing that was daunting,” Dr. Roberts recalled. “I didn’t know much about EHRs and it was going to be a lot of meetings ... and [it] was going to take me away from patient care. It really ended up being rewarding, despite all the time and frustration, because I got to help represent the interests of my hospitalist colleagues, the physician assistants, and nurses that I work with in trying to avoid some real problems that could have arisen in the EHR.”

Doing that work appealed to Dr. Roberts, so he embraced it. That approach is one championed by Thom Mayer, MD, FACEP, FAAP, executive vice president of EmCare, founder and CEO of BestPractices Inc., medical director for the NFL Players Association, and clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University, Washington, and University of Virginia, Charlottesville. Dr. Mayer travels the country talking about burnout and suggests a three-pronged approach.

First, find what you like about your job and maximize those duties.

Second, label those tasks that are tolerable and don’t allow them to become issues leading to burnout.

Third, and perhaps most difficult, “take the things [you] hate and eliminate them to the best extent possible from [your] job.”

“I’ll give you an example,” he said. “What I hear from emergency physicians and hospitalists is: ‘What do I hate? Well, I hate chronic pain patients.’ Well, does that mean you’re going to be able to eliminate the fact that there are chronic pain patients? No. But, what you can do is ... really drill down on it, and say ‘Why do you hate that?’ The answer is, “Well, I don’t have a strategy for it.” No one likes doing things when they don’t know what they’re doing.

“Now you take the chronic pain patient and the problem is, most of us just haven’t really thought that out. Most of us haven’t sat down with our colleagues and said, “What are you doing that’s working? How are you handling these people? What are the scripts that I can use, the evidence-based language that I can use? What alternatives can I give them?” Instead of just assuming that the only answer to the problem of chronic pain is opioids.”

The silent epidemic

So if there are measurements for burnout, and even best practices on how to address it, why is the issue one that Dr. Mayer calls a silent epidemic? One word: stigma.

“We as physicians can’t afford to propagate that stigma any further,” Dr. Roberts said. “People who have even tougher jobs than we have, involving combat and hostage negotiation and things like that, have found a way to have honest conversations about the impact of their work on their lives. There is no reason physicians shouldn’t be able to slowly change the culture of medicine to be able to do that, so that there isn’t a stigma around saying, ‘I need some time away before this begins to impact the safety of our patients.’ ”

Dr. West said that when data show that as many as half of all physicians show symptoms of burnout, there is no need to stigmatize a group that large.

Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician, coach, and consultant on burnout prevention, said that the No. 1 mistake physicians and leaders make about burnout is labeling it a “problem.”

“Burnout does not have a single solution because it is not a problem to begin with,” he added. “Burnout is a classic dilemma – a never-ending balancing act. Think of the balancing act of burnout as a teeter-totter, like the one you see in a children’s playground. On one side is the energy you put into your practice and larger life … and on the other side your ability to recharge your energy levels.

“To prevent burnout you must keep your energy expenditure and your recharge activities in balance to keep this teeter-totter in a relatively horizontal position. And the way you address the dilemma is with a strategy: three to five individual tools you use to lower your stress levels or recharge your energy balance.”

And a strategy is a long-term approach to a long-term problem, he said.

“Burnout is not necessarily a terminal condition,” Dr. Roberts said. “If we can structure their work and the balance in their life in such a way that they don’t experience it, or that when they do experience it, they can recognize it and make the changes they need to avoid it getting worse, I think we’d be better off as a profession.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

1. Maslach C, Jackson S. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behavior. 1981;2:99-113

2. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-81.

3. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Brower P. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online Dec. 5, 2016 ahead of print]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674.

Some 15 years ago, when Daniel Roberts, MD, FHM, decided at the end of his medical residency that his career path was going to be that of a hospitalist, he heard the same thing. A lot.

“Geesh, don’t you think you’re going to burn out?”

The reasons for such a response are well known in HM circles: the 7-on, 7-off shift structure; the constant rounding; the push-pull between clinical, administrative, and – what many would term – clerical work.

“The truth is somewhere between,” Dr. Roberts said.

Burnout is a hot topic among hospitalists and all of health care these days, as the increasing burdens of a system in seemingly constant change have fostered pressures inside and out of hospitals. Increasingly, researchers are studying and publishing about how to recognize burnout, ways to deal with, or even proactively address the issues. Some MDs – experts in physician burnout – make a living by touring the country and talking about the issue.

But what causes burnout, specifically and exactly?

“The simplistic answer is that burnout is what happens when resources do not meet demand,” said Colin West, MD, PhD, FACP, of the departments of internal medicine and health sciences research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a leading researcher on the topic of burnout. “The more complicated answer, which, at this point, is fairly solidly evidence based actually, is that there are five broad categories of drivers of physician distress and burnout.”

Dr. West’s hierarchy of stressors encompasses:

• Work effort.

• Work efficiency.

• Work-home interference.

• A sense of meaning.

• “Flexibility, control, and autonomy.”

Basically, the five drivers lead to this: Physicians who work too much and too inefficiently, with too little control and sense of purpose, end up flaming out more so than do doctors who work fewer hours, with fewer obstacles – all the while feeling satisfied with their autonomy and value.

Academic hospitalist John Yoon, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Chicago, says that health care has to work harder to promote its benefits as being more important than a highly paid profession. Instead, health care should focus on giving meaning to its practitioners.

“I think it is time for leaders of HM groups to honestly discuss the intrinsic meaning and essential ‘calling’ of what it means to be a good hospitalist,” Dr. Yoon wrote in an email interview with The Hospitalist. “What can we do to make the hospitalist vocation a meaningful, long-term career, so that they do not feel like simply revenue-generating ‘pawns’ in a medical-bureaucratic system?”

A ‘meaningful’ career

The modern discussion of burnout as a phenomenon traces back to the Maslach Burnout Inventory, a three-pronged test that measures emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.1 But why does burnout hit physicians – hospitalists, in particular – so intensely? In part, it’s because – like their predecessors in emergency medicine – hospitalists are responsible for managing the care of patients other specialties consult with, operate on, or for whom they run tests.

“Once the patients come up from the emergency room or get admitted to the hospital from the outside, the hospitalist is the one who is largely running that show,” said Dr. West, whose researchshows that HM doctors suffer burnout more than the average across medical specialties.2 “So they’re the front line of inpatient medicine.”

Another factor contributing to burnout’s impact on hospitalists is that the specialty’s rank and file (by definition) work within the walls of institutions that have a lot of contentious and complicated issues that – while outside the purview of HM – can directly or indirectly affect the field. Dr. West calls it the hassle factor.

“You want to get a test in the hospital and, even though you’re the attending on the service, you end up going through three layers of bureaucracy with an insurance company to be able to finally get what you know that patient needs,” he said. “Anything like that contributes to the burnout problem because it pulls the physician away from what they want to be doing, what is purposeful, what is meaningful for them.”

For Dr. Yoon, the exhaustion and cynicism borne out by the work of Maslach and Dr. West’s team are measures indicative of a field where physicians struggle more and more to “make sense of why their practice is worthwhile.

“In the contemporary medical literature, we have been encouraged to adopt the concepts and practices of industrial engineering and quality improvement,” Dr. Yoon added. “In other words, it seems that to the extent physicians’ aspirations to practice good medicine are confined to the narrow and unimaginative constraints of mere scientific technique (more data, higher ‘quality,’ better outcomes) physicians will struggle to recognize and respond to their practice as meaningful. There is no intrinsic meaning to simply being a ‘cog’ in a medical-industrial process or an ‘independent variable’ in an economic equation.”

Finding meaning in one’s job, of course, is less empirical an endpoint than using a reversal agent for a GI bleed. Therein lies the challenge of battling burnout, whose causes and interventions can be as varied as the people who suffer the syndrome.

Local, customized solutions

Once a group leader identifies the symptoms of burnout, the obvious question is how to address it.

Dr. West and his colleagues have identified two broad categories of interventions: individual-focused approaches and organizational solutions. Physician-centered efforts include such tacks as mindfulness, stress reduction, resilience training and small-group communication. Institutional-level changes are, typically, much harder to implement and make successful.

“It doesn’t make sense to ... simply send physicians to stress-management training so that they’re better equipped to deal with a system that is not working to improve itself,” Dr. West said. “The system and the leadership in that system needs to take responsibility from an organizational standpoint.”

Health care as a whole has worked to address the systems-level issue. Duty-hour regulations have been reined in for trainees to be proactive in addressing both fatigue and its inevitable endpoint: burnout.

In a report, “Controlled Interventions to Reduce Burnout in Physicians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,”3 published online Dec. 5 in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers concluded that interventions associated with small benefits “may be boosted by adoption of organization-directed approaches.

“This finding provides support for the view that burnout is a problem of the whole health care organization, rather than individuals,” they wrote.

But the issue typically remains a local one, as group leaders need to realize that what could cause or contribute to burnout in one employee might be enjoyable to another.

“The prospect of doing that was daunting,” Dr. Roberts recalled. “I didn’t know much about EHRs and it was going to be a lot of meetings ... and [it] was going to take me away from patient care. It really ended up being rewarding, despite all the time and frustration, because I got to help represent the interests of my hospitalist colleagues, the physician assistants, and nurses that I work with in trying to avoid some real problems that could have arisen in the EHR.”

Doing that work appealed to Dr. Roberts, so he embraced it. That approach is one championed by Thom Mayer, MD, FACEP, FAAP, executive vice president of EmCare, founder and CEO of BestPractices Inc., medical director for the NFL Players Association, and clinical professor of emergency medicine at George Washington University, Washington, and University of Virginia, Charlottesville. Dr. Mayer travels the country talking about burnout and suggests a three-pronged approach.

First, find what you like about your job and maximize those duties.

Second, label those tasks that are tolerable and don’t allow them to become issues leading to burnout.

Third, and perhaps most difficult, “take the things [you] hate and eliminate them to the best extent possible from [your] job.”

“I’ll give you an example,” he said. “What I hear from emergency physicians and hospitalists is: ‘What do I hate? Well, I hate chronic pain patients.’ Well, does that mean you’re going to be able to eliminate the fact that there are chronic pain patients? No. But, what you can do is ... really drill down on it, and say ‘Why do you hate that?’ The answer is, “Well, I don’t have a strategy for it.” No one likes doing things when they don’t know what they’re doing.

“Now you take the chronic pain patient and the problem is, most of us just haven’t really thought that out. Most of us haven’t sat down with our colleagues and said, “What are you doing that’s working? How are you handling these people? What are the scripts that I can use, the evidence-based language that I can use? What alternatives can I give them?” Instead of just assuming that the only answer to the problem of chronic pain is opioids.”

The silent epidemic

So if there are measurements for burnout, and even best practices on how to address it, why is the issue one that Dr. Mayer calls a silent epidemic? One word: stigma.

“We as physicians can’t afford to propagate that stigma any further,” Dr. Roberts said. “People who have even tougher jobs than we have, involving combat and hostage negotiation and things like that, have found a way to have honest conversations about the impact of their work on their lives. There is no reason physicians shouldn’t be able to slowly change the culture of medicine to be able to do that, so that there isn’t a stigma around saying, ‘I need some time away before this begins to impact the safety of our patients.’ ”

Dr. West said that when data show that as many as half of all physicians show symptoms of burnout, there is no need to stigmatize a group that large.

Dike Drummond, MD, a family physician, coach, and consultant on burnout prevention, said that the No. 1 mistake physicians and leaders make about burnout is labeling it a “problem.”

“Burnout does not have a single solution because it is not a problem to begin with,” he added. “Burnout is a classic dilemma – a never-ending balancing act. Think of the balancing act of burnout as a teeter-totter, like the one you see in a children’s playground. On one side is the energy you put into your practice and larger life … and on the other side your ability to recharge your energy levels.

“To prevent burnout you must keep your energy expenditure and your recharge activities in balance to keep this teeter-totter in a relatively horizontal position. And the way you address the dilemma is with a strategy: three to five individual tools you use to lower your stress levels or recharge your energy balance.”

And a strategy is a long-term approach to a long-term problem, he said.

“Burnout is not necessarily a terminal condition,” Dr. Roberts said. “If we can structure their work and the balance in their life in such a way that they don’t experience it, or that when they do experience it, they can recognize it and make the changes they need to avoid it getting worse, I think we’d be better off as a profession.”

Richard Quinn is a freelance writer in New Jersey.

References

1. Maslach C, Jackson S. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behavior. 1981;2:99-113

2. Roberts DL, Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. A national comparison of burnout and work-life balance among internal medicine hospitalists and outpatient general internists. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):176-81.

3. Panagioti M, Panagopoulou E, Brower P. Controlled interventions to reduce burnout in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online Dec. 5, 2016 ahead of print]. JAMA Intern Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7674.

Turnover rate for hospitalist groups trending downward

According to the 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report based on 2015 data, the median physician turnover rate for hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only is 6.9%, lower compared with results from prior surveys. Particularly, turnover in 2010 was more than double the current rate (see Figure 1). This steady decline over the years is intriguing, yet encouraging, since hospital medicine is well known for its high turnover compared to other specialties.

Similarly, results from State of Hospital Medicine surveys also reveal a consistent trend for groups with no turnover. As expected, lower turnover rate usually parallels with higher percentage of groups with no turnover. This year, 40.2% of hospitalist groups reported no physician turnover at all, continuing the upward trend from 2014 (38.1%) and 2012 (36%). It is speculating that these groups are not just simply fortunate, but rather work zealously to build a strong internal culture within the group and proactively create a shared vision, values, accountability, and career goals.

Sources in search of why providers leave a practice and advice on specific strategies to retain them are abundant. To secure retention, at a minimum, employers, leaders, or administrators should pay close attention to such basic factors as work schedules, workload, and compensation – and even consider using national and regional data from the State of Hospital Medicine Report for benchmarking to remain attractive and competitive in the market. Low or no turnover rate indicates workforce stability and program credibility, and allows cost saving as the overall estimated cost of turnover (losing a provider and hiring another one) ranges from $400,000 to $600,000 per provider.1

The turnover data further delineates differences based on academic status, Medicare Indirect Medical Education (IME) program status, and geographic region. For instance, the academic groups consistently report a higher turnover rate, compared with the nonacademic groups. The latter mirrors the overall decreasing trend of physician turnover. Non-teaching hospitals also score significantly higher on the number of groups with no turnover (42% as opposed to 24%-27% for teaching hospitals). Geographically, HMGs in the South and Midwest regions of the United States are the winners this year, with more than 50% of the groups reporting no turnover at all.

Specific information regarding turnover for nurse practitioners and physician assistants (NPs/PAs) can also be found in the report. This rate has been increasing slightly compared with the past, with a subsequent drop in the percentage of groups reporting no turnover. Yet, the overall percentage with no turnover for NPs/PAs remains impressively high at 62%.

The turnover rates for HMGs serving both adults and children, and groups serving children only, appear somewhat similar to those of groups serving adults only, though we cannot reliably analyze the data, elucidate significant differences, or detect any meaningful trends from these two groups because of insufficient numbers of responders.

The downward trend of hospitalist turnover found in SHM’s 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report is reassuring, indicative of a higher retention rate and an extended stability for many programs. Although some hospitalists continue to shop around, most leaders and employers of HMGs work endlessly to strengthen their programs in hope to minimize turnover. The promising data likely reflect such effort. Hopefully, this trend will continue when the next State of Hospital Medicine report comes out.

Dr. Vuong is a hospitalist at HealthPartners Medical Group in St Paul, Minn., and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Reference

1. Frenz, D (2016). The staggering costs of physician turnover. Today’s Hospitalist.

According to the 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report based on 2015 data, the median physician turnover rate for hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only is 6.9%, lower compared with results from prior surveys. Particularly, turnover in 2010 was more than double the current rate (see Figure 1). This steady decline over the years is intriguing, yet encouraging, since hospital medicine is well known for its high turnover compared to other specialties.

Similarly, results from State of Hospital Medicine surveys also reveal a consistent trend for groups with no turnover. As expected, lower turnover rate usually parallels with higher percentage of groups with no turnover. This year, 40.2% of hospitalist groups reported no physician turnover at all, continuing the upward trend from 2014 (38.1%) and 2012 (36%). It is speculating that these groups are not just simply fortunate, but rather work zealously to build a strong internal culture within the group and proactively create a shared vision, values, accountability, and career goals.

Sources in search of why providers leave a practice and advice on specific strategies to retain them are abundant. To secure retention, at a minimum, employers, leaders, or administrators should pay close attention to such basic factors as work schedules, workload, and compensation – and even consider using national and regional data from the State of Hospital Medicine Report for benchmarking to remain attractive and competitive in the market. Low or no turnover rate indicates workforce stability and program credibility, and allows cost saving as the overall estimated cost of turnover (losing a provider and hiring another one) ranges from $400,000 to $600,000 per provider.1

The turnover data further delineates differences based on academic status, Medicare Indirect Medical Education (IME) program status, and geographic region. For instance, the academic groups consistently report a higher turnover rate, compared with the nonacademic groups. The latter mirrors the overall decreasing trend of physician turnover. Non-teaching hospitals also score significantly higher on the number of groups with no turnover (42% as opposed to 24%-27% for teaching hospitals). Geographically, HMGs in the South and Midwest regions of the United States are the winners this year, with more than 50% of the groups reporting no turnover at all.

Specific information regarding turnover for nurse practitioners and physician assistants (NPs/PAs) can also be found in the report. This rate has been increasing slightly compared with the past, with a subsequent drop in the percentage of groups reporting no turnover. Yet, the overall percentage with no turnover for NPs/PAs remains impressively high at 62%.

The turnover rates for HMGs serving both adults and children, and groups serving children only, appear somewhat similar to those of groups serving adults only, though we cannot reliably analyze the data, elucidate significant differences, or detect any meaningful trends from these two groups because of insufficient numbers of responders.

The downward trend of hospitalist turnover found in SHM’s 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report is reassuring, indicative of a higher retention rate and an extended stability for many programs. Although some hospitalists continue to shop around, most leaders and employers of HMGs work endlessly to strengthen their programs in hope to minimize turnover. The promising data likely reflect such effort. Hopefully, this trend will continue when the next State of Hospital Medicine report comes out.

Dr. Vuong is a hospitalist at HealthPartners Medical Group in St Paul, Minn., and an assistant professor of medicine at the University of Minnesota. He is a member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Reference

1. Frenz, D (2016). The staggering costs of physician turnover. Today’s Hospitalist.

According to the 2016 State of Hospital Medicine Report based on 2015 data, the median physician turnover rate for hospital medicine groups (HMGs) serving adults only is 6.9%, lower compared with results from prior surveys. Particularly, turnover in 2010 was more than double the current rate (see Figure 1). This steady decline over the years is intriguing, yet encouraging, since hospital medicine is well known for its high turnover compared to other specialties.

Similarly, results from State of Hospital Medicine surveys also reveal a consistent trend for groups with no turnover. As expected, lower turnover rate usually parallels with higher percentage of groups with no turnover. This year, 40.2% of hospitalist groups reported no physician turnover at all, continuing the upward trend from 2014 (38.1%) and 2012 (36%). It is speculating that these groups are not just simply fortunate, but rather work zealously to build a strong internal culture within the group and proactively create a shared vision, values, accountability, and career goals.

Sources in search of why providers leave a practice and advice on specific strategies to retain them are abundant. To secure retention, at a minimum, employers, leaders, or administrators should pay close attention to such basic factors as work schedules, workload, and compensation – and even consider using national and regional data from the State of Hospital Medicine Report for benchmarking to remain attractive and competitive in the market. Low or no turnover rate indicates workforce stability and program credibility, and allows cost saving as the overall estimated cost of turnover (losing a provider and hiring another one) ranges from $400,000 to $600,000 per provider.1

The turnover data further delineates differences based on academic status, Medicare Indirect Medical Education (IME) program status, and geographic region. For instance, the academic groups consistently report a higher turnover rate, compared with the nonacademic groups. The latter mirrors the overall decreasing trend of physician turnover. Non-teaching hospitals also score significantly higher on the number of groups with no turnover (42% as opposed to 24%-27% for teaching hospitals). Geographically, HMGs in the South and Midwest regions of the United States are the winners this year, with more than 50% of the groups reporting no turnover at all.

Specific information regarding turnover for nurse practitioners and physician assistants (NPs/PAs) can also be found in the report. This rate has been increasing slightly compared with the past, with a subsequent drop in the percentage of groups reporting no turnover. Yet, the overall percentage with no turnover for NPs/PAs remains impressively high at 62%.