User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Thinking Outside the DRG Box

When choosing quality improvement activities, hospitalists have no shortage of choices. In this column, I offer a strategic guide for hospitalists as they assess where best to spend their energy as the shift to value-based care progresses. This includes the introduction of MACRA, the landmark new payment program for doctors and other clinicians (aka the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015), with its incentives for participation in alternative payment models.

Since 1983, Medicare has reimbursed hospitals using a lump-sum payment known as a diagnosis-related group, or DRG. Since then, hospitals have focused a good deal of their energy on removing needless expenses from the hospitalization to improve their bottom line, recognizing the DRG payment they receive is relatively fixed. To this end, a major strategy has been to use hospitalists to decrease length of stay and “right size” the utilization of in-hospital tests and treatments.

However, things are changing as we enter the era of alternative payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments. The lens Medicare (and, to a great extent, commercial payors) peers through to assess inpatient hospital costs is the DRG payment amount. Beyond that, Medicare has little visibility into the actual costs hospitals incur. Since hospital spending equates to the payment amount for a DRG, it becomes apparent that the incremental opportunity for hospitalists to improve value (quality divided by cost) in alternative payment models stems from payments outside the DRG. Such payments include those related to the post-acute period such as nursing and rehabilitation facilities, readmissions, and part B activity (e.g., consultants and outpatient tests).

What does this mean for hospitalists? MACRA begins in 2019, but initial payments will be based on 2017 performance. The associated advantage of participating in an “advanced alternative payment model” where there is accountability for care beyond the hospitalization is that hospitalists will be rewarded for taking costs out of the post-acute time period.

To be clear, hospitalists should remain agents of in-hospital efficiency and quality. After all, that is how we add value to the hospitals in which we practice. All things being equal, however, hospitalists should focus on practices that will improve value beyond the four walls of the hospital.

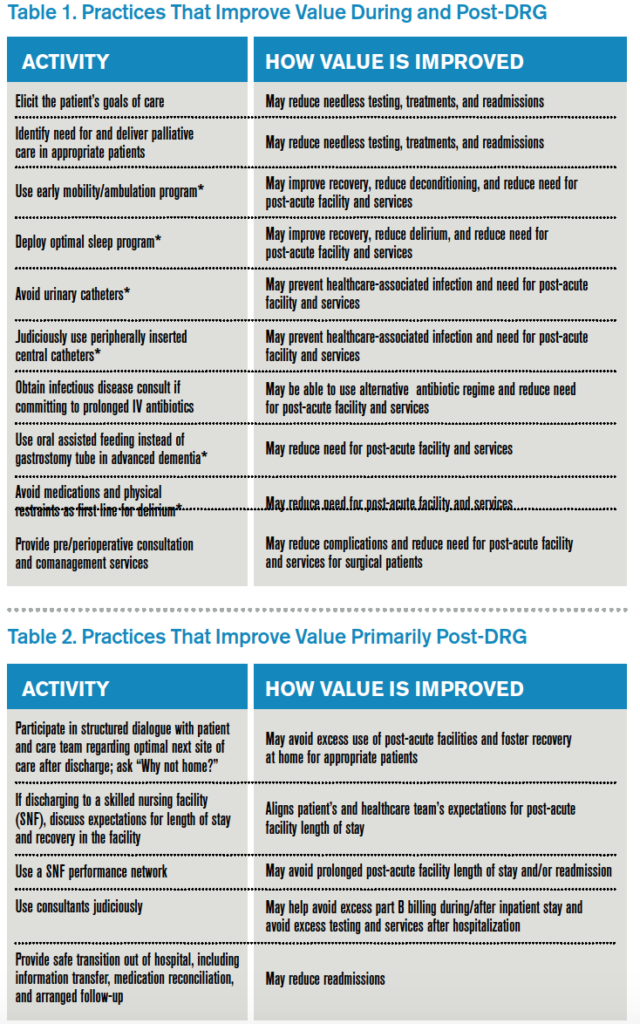

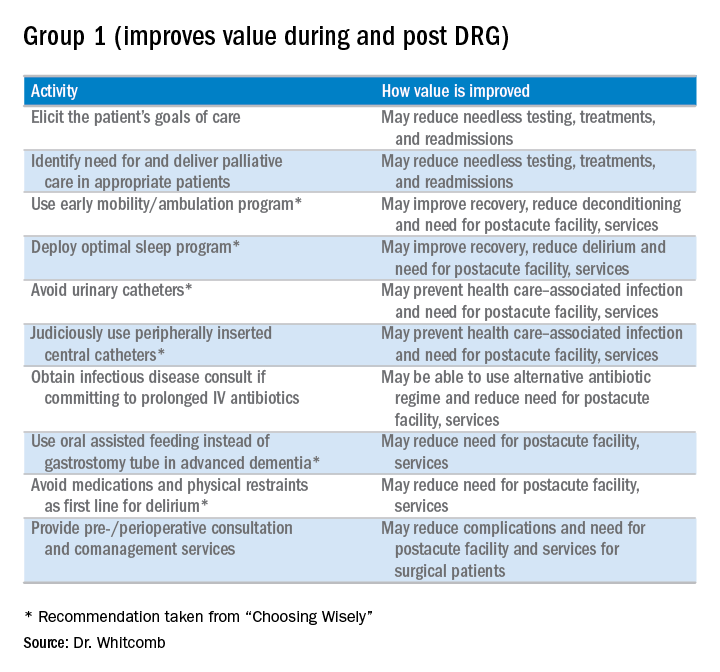

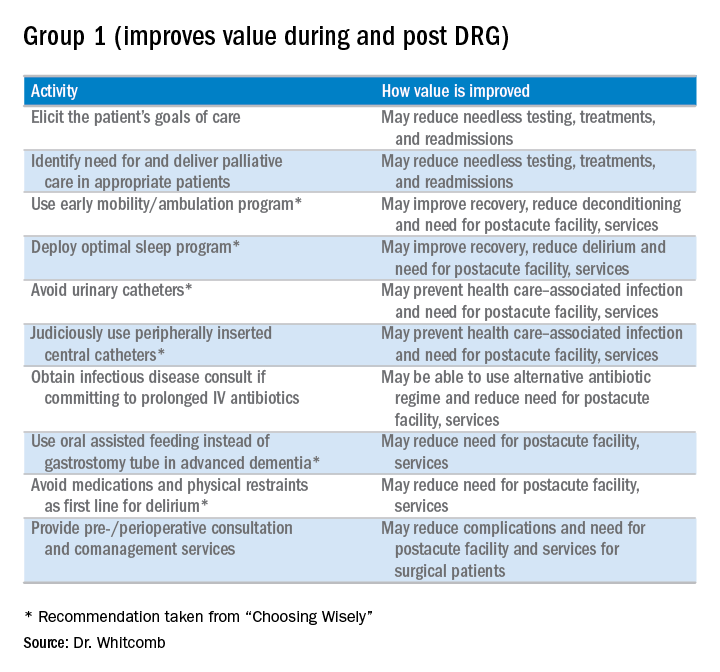

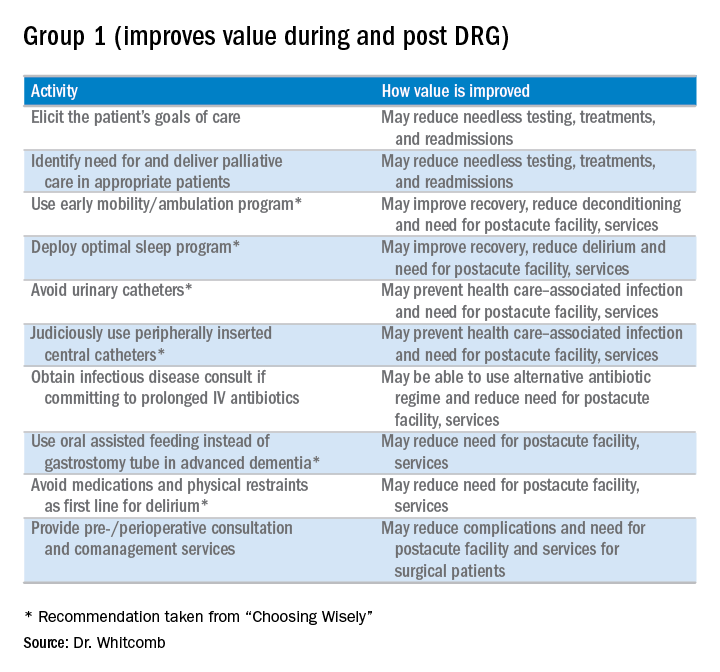

Here is my shortlist of these practices. While there is crossover between the categories, I divide the practices into those that improve value during the DRG period and also post-DRG and those that improve value primarily post-DRG (thanks to Choosing Wisely for contributing to the recommendations with an asterisk1):

Thinking outside the DRG box will require an adjustment to the approach taken by hospitalists because the current demands are often more than enough for a day’s work. Hospitalists will be called upon to innovate and fashion better approaches to care. This will require support by other members of the healthcare team so hospitalists can work smarter, not harder, to meet the requirements of a changing healthcare system. A prerequisite is better payment models that align financial incentives so that providing higher-value care is sustainable and appropriately rewarded.

Reference

Clinician lists. Choosing Wisely website. Accessed October 25, 2016.

When choosing quality improvement activities, hospitalists have no shortage of choices. In this column, I offer a strategic guide for hospitalists as they assess where best to spend their energy as the shift to value-based care progresses. This includes the introduction of MACRA, the landmark new payment program for doctors and other clinicians (aka the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015), with its incentives for participation in alternative payment models.

Since 1983, Medicare has reimbursed hospitals using a lump-sum payment known as a diagnosis-related group, or DRG. Since then, hospitals have focused a good deal of their energy on removing needless expenses from the hospitalization to improve their bottom line, recognizing the DRG payment they receive is relatively fixed. To this end, a major strategy has been to use hospitalists to decrease length of stay and “right size” the utilization of in-hospital tests and treatments.

However, things are changing as we enter the era of alternative payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments. The lens Medicare (and, to a great extent, commercial payors) peers through to assess inpatient hospital costs is the DRG payment amount. Beyond that, Medicare has little visibility into the actual costs hospitals incur. Since hospital spending equates to the payment amount for a DRG, it becomes apparent that the incremental opportunity for hospitalists to improve value (quality divided by cost) in alternative payment models stems from payments outside the DRG. Such payments include those related to the post-acute period such as nursing and rehabilitation facilities, readmissions, and part B activity (e.g., consultants and outpatient tests).

What does this mean for hospitalists? MACRA begins in 2019, but initial payments will be based on 2017 performance. The associated advantage of participating in an “advanced alternative payment model” where there is accountability for care beyond the hospitalization is that hospitalists will be rewarded for taking costs out of the post-acute time period.

To be clear, hospitalists should remain agents of in-hospital efficiency and quality. After all, that is how we add value to the hospitals in which we practice. All things being equal, however, hospitalists should focus on practices that will improve value beyond the four walls of the hospital.

Here is my shortlist of these practices. While there is crossover between the categories, I divide the practices into those that improve value during the DRG period and also post-DRG and those that improve value primarily post-DRG (thanks to Choosing Wisely for contributing to the recommendations with an asterisk1):

Thinking outside the DRG box will require an adjustment to the approach taken by hospitalists because the current demands are often more than enough for a day’s work. Hospitalists will be called upon to innovate and fashion better approaches to care. This will require support by other members of the healthcare team so hospitalists can work smarter, not harder, to meet the requirements of a changing healthcare system. A prerequisite is better payment models that align financial incentives so that providing higher-value care is sustainable and appropriately rewarded.

Reference

Clinician lists. Choosing Wisely website. Accessed October 25, 2016.

When choosing quality improvement activities, hospitalists have no shortage of choices. In this column, I offer a strategic guide for hospitalists as they assess where best to spend their energy as the shift to value-based care progresses. This includes the introduction of MACRA, the landmark new payment program for doctors and other clinicians (aka the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015), with its incentives for participation in alternative payment models.

Since 1983, Medicare has reimbursed hospitals using a lump-sum payment known as a diagnosis-related group, or DRG. Since then, hospitals have focused a good deal of their energy on removing needless expenses from the hospitalization to improve their bottom line, recognizing the DRG payment they receive is relatively fixed. To this end, a major strategy has been to use hospitalists to decrease length of stay and “right size” the utilization of in-hospital tests and treatments.

However, things are changing as we enter the era of alternative payment models such as accountable care organizations (ACOs) and bundled payments. The lens Medicare (and, to a great extent, commercial payors) peers through to assess inpatient hospital costs is the DRG payment amount. Beyond that, Medicare has little visibility into the actual costs hospitals incur. Since hospital spending equates to the payment amount for a DRG, it becomes apparent that the incremental opportunity for hospitalists to improve value (quality divided by cost) in alternative payment models stems from payments outside the DRG. Such payments include those related to the post-acute period such as nursing and rehabilitation facilities, readmissions, and part B activity (e.g., consultants and outpatient tests).

What does this mean for hospitalists? MACRA begins in 2019, but initial payments will be based on 2017 performance. The associated advantage of participating in an “advanced alternative payment model” where there is accountability for care beyond the hospitalization is that hospitalists will be rewarded for taking costs out of the post-acute time period.

To be clear, hospitalists should remain agents of in-hospital efficiency and quality. After all, that is how we add value to the hospitals in which we practice. All things being equal, however, hospitalists should focus on practices that will improve value beyond the four walls of the hospital.

Here is my shortlist of these practices. While there is crossover between the categories, I divide the practices into those that improve value during the DRG period and also post-DRG and those that improve value primarily post-DRG (thanks to Choosing Wisely for contributing to the recommendations with an asterisk1):

Thinking outside the DRG box will require an adjustment to the approach taken by hospitalists because the current demands are often more than enough for a day’s work. Hospitalists will be called upon to innovate and fashion better approaches to care. This will require support by other members of the healthcare team so hospitalists can work smarter, not harder, to meet the requirements of a changing healthcare system. A prerequisite is better payment models that align financial incentives so that providing higher-value care is sustainable and appropriately rewarded.

Reference

Clinician lists. Choosing Wisely website. Accessed October 25, 2016.

Tips for Working with Difficult Doctors

As a hospitalist, caring for critically ill or injured patients can be stressful and demanding. Working with difficult doctors, those who exhibit intimidating and disruptive behaviors such as verbal outbursts and physical threats as well as passive activities such as refusing to perform assigned tasks, can make the work environment even more challenging.1 Some docs are routinely reluctant—or refuse—to answer questions or return phone calls or pages. Some communicate in condescending language or voice intonation; some are brutally impatient.1

The most difficult doctors to work with are those who are not aligned with the hospital’s or treatment team’s goals and those who aren’t open to feedback and coaching, says Rob Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, regional chief medical officer of Sound Physicians, based in Tacoma, Wash.

“If physicians are aware of a practice’s guidelines and goals but simply won’t comply with them, it makes it harder on everyone else who is pulling the ship in the same direction,” he says.

Unruly physicians don’t just annoy their coworkers. According to a sentinel event alert from The Joint Commission, they can:

- foster medical errors;

- contribute to poor patient satisfaction;

- contribute to preventable adverse outcomes;

- increase the cost of care;

- undermine team effectiveness; and

- cause qualified clinicians, administrators, and managers to seek new positions in more professional environments.1

“These issues are all connected,” says Stephen R. Nichols, MD, chief of clinical operations performance at the Schumacher Group in Brownwood, Texas. “Disruptive behaviors create mitigated communications and dissatisfaction among staff, which bleeds over into other aspects that are involved secondarily.”

Stephen M. Paskoff, Esq., president and CEO of ELI in Atlanta, can attest to the most severe consequences of bad behavior on patient care.

At one institution, a surgeon’s disruptive behavior lead to a coworker forgetting to perform a procedure and a patient dying.2 In another incident, the emergency department stopped calling on a medical subspecialist who was predictably abusive. The subspecialist knew how to treat a specific patient with an unusual intervention. Since the specialist was not consulted initially, the patient ended up in the intensive care unit.2

One bad hospitalist can bring down the reputation of an entire team.

“Many programs are incentivized based on medical staff and primary-care physicians’ perceptions of their care, so there are direct and indirect consequences,” Dr. Zipper says.

The bottom line, says Felix Aguirre, MD, SFHM, vice president of medical affairs at IPC Healthcare in North Hollywood, Calif., is that it only takes one bad experience to tarnish a group, but it takes many positive experiences to erase the damage.

The Roots of Evil

Intimidating and disruptive behavior stems from both individual and systemic factors. Care providers who exhibit characteristics such as self-centeredness, immaturity, or defensiveness can be more prone to unprofessional behavior. They can lack interpersonal, coping, or conflict-management skills.1

Systemic factors are marked by pressures related to increased productivity demands, cost-containment requirements, embedded hierarchies, and fear of litigation in the healthcare environment. These pressures can be further exacerbated by changes to or differences in the authority, autonomy, empowerment, and roles or values of professionals on the healthcare team as well as by the continual daily changes in shifts, rotations, and interdepartmental support staff. This dynamic creates challenges for interprofessional communication and development of trust among team members.1

According to The Joint Commission, intimidating and disruptive behaviors are often manifested by healthcare professionals in positions of power.1 But other members of the care team can be problematic as well.

“In my experience, conflicts usually revolve around different perspectives and objectives, even if both parties are acting respectfully,” Dr. Zipper says. “Sometimes, however, providers or other care team members are tired or stressed and don’t behave professionally.”

Paskoff, who has more than 40 years of experience in healthcare-related workplace issues, including serving as an investigator for the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, says some doctors learn bad behaviors from their mentors and that behaviors can be passed down through generations because they are tolerated.

“When I asked one physician who had outstanding training and an outstanding technical reputation how he became abusive, he said, ‘I learned from the best.’” Paskoff was actually able to track the doctor’s training to the late 1800s and physicians who were known for similar behaviors.

Confronting Those Who Misbehave

Dr. Zipper says physicians should confront behavioral issues directly.

“I will typically discuss a complaint with a doctor privately, and ask him or her what happened without being accusatory,” he says. “I try to provide as much concrete and objective information as I can. The doctor needs to know that you are trying to help him or her succeed. That said, if something is clearly bad behavior, feedback should be direct and include a statement such as, ‘This is not how we behave in this practice.’”

At times, it may not be possible to discuss an emergent matter, such as during a code blue.

“However, I will often ask if anyone on the code team has any ideas or concerns before ending the code,” Dr. Nichols says. “Then after the critical time has passed, it is important to debrief and reconnect with the team, especially the less-experienced members who may have lingering concerns.”

For many employees, however, it is difficult to report disruptive behaviors. This is due to a fear of retaliation and the stigma associated with “blowing the whistle” on a colleague as well as a general reluctance to confront an intimidator.1

If an employee cannot muster the courage to confront a disruptive coworker or if the issue isn’t resolved by talking with the difficult individual, an employee should be a good citizen and report bad behavior to the appropriate hospital authority in a timely manner, says A. Kevin Troutman, Esq., a partner at Fisher Phillips in Houston and a former healthcare human resources executive.

Hospitals accredited by The Joint Commission are required to create a code of conduct that defines disruptive and inappropriate behaviors. In addition, leaders must create and implement a process for managing these behaviors.1

Helping Difficult Doctors

After a physician or another employee has been called out for bad behavior, steps need to be taken to correct the problem. Robert Fuller, Esq., an attorney with Nelson Hardiman, LLP, in Los Angeles, has found a positive-oriented intervention called “the 3-Ds”—which stands for diagnose, design, and do—that has been a successful tool for achieving positive change. The strategy involves a supervisor and employee mutually developing a worksheet to diagnose the problem. Next, they design a remediation and improvement plan. Finally, they implement the plan and specify dates to achieve certain milestones. Coworkers should be informed of the plan and be urged to support it.

“Make it clear that the positive aspect of this plan turns to progressive discipline, including termination, if the employee doesn’t improve or abandons the plan of action,” Fuller says. In most cases, troublemakers will make a sincere effort to control disruptive tendencies.

Troutman suggests enlisting the assistance of a respected peer.

“Have a senior-level doctor help the noncompliant physician understand why his or her behavior creates problems for everyone, including the doctor himself,” he says. “Also, consider connecting compensation and other rewards to job performance, which encompasses good behavior and good citizenship within the organization. Make expectations and consequences clear.”

If an employee has a recent change in behavior, ask if there is a reason.

“It is my experience that sudden changes in behaviors are often the result of a personal or clinical issue, so it is important and humane to make certain that there is not some other cause for the change before assuming someone is simply being disruptive or difficult,” Dr. Nichols says.

Many healthcare institutions are now setting up centers of professionalism. Paskoff reports that The Center for Professionalism and Peer Support (CPPS) was created in 2008 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston to educate the hospital community regarding professionalism and manage unprofessional behavior.3 CPPS has established standards of behavior and a framework to deal with difficult behaviors.

“An employee is told what he or she is doing wrong, receives counseling, and is given resources to improve,” he explains. “If an employee doesn’t improve, he or she is told that the behavior won’t be tolerated.”

Dismissing Bad Employees

After addressing the specifics of unacceptable behavior and explaining the consequences of repeating it, leadership should monitor subsequent conduct and provide feedback.

“If the employee commits other violations or behaves badly, promptly address the misconduct again and make it clear that further such actions will not be tolerated,” Troutman says. “Expect immediate and sustained improvement and compliance. Be consistent, and if bad conduct continues after an opportunity to improve, do not prolong anyone’s suffering. Instead, terminate the disruptive employee. When you do, make the reasons clear.”

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. The Joint Commission website. Accessed April 17, 2015.

- Whittemore AD, New England Society for Vascular Surgery. The impact of professionalism on safe surgical care. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(2):415-419.

- Shapiro J, Whittemore A, Tsen LC. Instituting a culture of professionalism: the establishment of a center for professionalism and peer support. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014;40(4):168-177.

As a hospitalist, caring for critically ill or injured patients can be stressful and demanding. Working with difficult doctors, those who exhibit intimidating and disruptive behaviors such as verbal outbursts and physical threats as well as passive activities such as refusing to perform assigned tasks, can make the work environment even more challenging.1 Some docs are routinely reluctant—or refuse—to answer questions or return phone calls or pages. Some communicate in condescending language or voice intonation; some are brutally impatient.1

The most difficult doctors to work with are those who are not aligned with the hospital’s or treatment team’s goals and those who aren’t open to feedback and coaching, says Rob Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, regional chief medical officer of Sound Physicians, based in Tacoma, Wash.

“If physicians are aware of a practice’s guidelines and goals but simply won’t comply with them, it makes it harder on everyone else who is pulling the ship in the same direction,” he says.

Unruly physicians don’t just annoy their coworkers. According to a sentinel event alert from The Joint Commission, they can:

- foster medical errors;

- contribute to poor patient satisfaction;

- contribute to preventable adverse outcomes;

- increase the cost of care;

- undermine team effectiveness; and

- cause qualified clinicians, administrators, and managers to seek new positions in more professional environments.1

“These issues are all connected,” says Stephen R. Nichols, MD, chief of clinical operations performance at the Schumacher Group in Brownwood, Texas. “Disruptive behaviors create mitigated communications and dissatisfaction among staff, which bleeds over into other aspects that are involved secondarily.”

Stephen M. Paskoff, Esq., president and CEO of ELI in Atlanta, can attest to the most severe consequences of bad behavior on patient care.

At one institution, a surgeon’s disruptive behavior lead to a coworker forgetting to perform a procedure and a patient dying.2 In another incident, the emergency department stopped calling on a medical subspecialist who was predictably abusive. The subspecialist knew how to treat a specific patient with an unusual intervention. Since the specialist was not consulted initially, the patient ended up in the intensive care unit.2

One bad hospitalist can bring down the reputation of an entire team.

“Many programs are incentivized based on medical staff and primary-care physicians’ perceptions of their care, so there are direct and indirect consequences,” Dr. Zipper says.

The bottom line, says Felix Aguirre, MD, SFHM, vice president of medical affairs at IPC Healthcare in North Hollywood, Calif., is that it only takes one bad experience to tarnish a group, but it takes many positive experiences to erase the damage.

The Roots of Evil

Intimidating and disruptive behavior stems from both individual and systemic factors. Care providers who exhibit characteristics such as self-centeredness, immaturity, or defensiveness can be more prone to unprofessional behavior. They can lack interpersonal, coping, or conflict-management skills.1

Systemic factors are marked by pressures related to increased productivity demands, cost-containment requirements, embedded hierarchies, and fear of litigation in the healthcare environment. These pressures can be further exacerbated by changes to or differences in the authority, autonomy, empowerment, and roles or values of professionals on the healthcare team as well as by the continual daily changes in shifts, rotations, and interdepartmental support staff. This dynamic creates challenges for interprofessional communication and development of trust among team members.1

According to The Joint Commission, intimidating and disruptive behaviors are often manifested by healthcare professionals in positions of power.1 But other members of the care team can be problematic as well.

“In my experience, conflicts usually revolve around different perspectives and objectives, even if both parties are acting respectfully,” Dr. Zipper says. “Sometimes, however, providers or other care team members are tired or stressed and don’t behave professionally.”

Paskoff, who has more than 40 years of experience in healthcare-related workplace issues, including serving as an investigator for the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, says some doctors learn bad behaviors from their mentors and that behaviors can be passed down through generations because they are tolerated.

“When I asked one physician who had outstanding training and an outstanding technical reputation how he became abusive, he said, ‘I learned from the best.’” Paskoff was actually able to track the doctor’s training to the late 1800s and physicians who were known for similar behaviors.

Confronting Those Who Misbehave

Dr. Zipper says physicians should confront behavioral issues directly.

“I will typically discuss a complaint with a doctor privately, and ask him or her what happened without being accusatory,” he says. “I try to provide as much concrete and objective information as I can. The doctor needs to know that you are trying to help him or her succeed. That said, if something is clearly bad behavior, feedback should be direct and include a statement such as, ‘This is not how we behave in this practice.’”

At times, it may not be possible to discuss an emergent matter, such as during a code blue.

“However, I will often ask if anyone on the code team has any ideas or concerns before ending the code,” Dr. Nichols says. “Then after the critical time has passed, it is important to debrief and reconnect with the team, especially the less-experienced members who may have lingering concerns.”

For many employees, however, it is difficult to report disruptive behaviors. This is due to a fear of retaliation and the stigma associated with “blowing the whistle” on a colleague as well as a general reluctance to confront an intimidator.1

If an employee cannot muster the courage to confront a disruptive coworker or if the issue isn’t resolved by talking with the difficult individual, an employee should be a good citizen and report bad behavior to the appropriate hospital authority in a timely manner, says A. Kevin Troutman, Esq., a partner at Fisher Phillips in Houston and a former healthcare human resources executive.

Hospitals accredited by The Joint Commission are required to create a code of conduct that defines disruptive and inappropriate behaviors. In addition, leaders must create and implement a process for managing these behaviors.1

Helping Difficult Doctors

After a physician or another employee has been called out for bad behavior, steps need to be taken to correct the problem. Robert Fuller, Esq., an attorney with Nelson Hardiman, LLP, in Los Angeles, has found a positive-oriented intervention called “the 3-Ds”—which stands for diagnose, design, and do—that has been a successful tool for achieving positive change. The strategy involves a supervisor and employee mutually developing a worksheet to diagnose the problem. Next, they design a remediation and improvement plan. Finally, they implement the plan and specify dates to achieve certain milestones. Coworkers should be informed of the plan and be urged to support it.

“Make it clear that the positive aspect of this plan turns to progressive discipline, including termination, if the employee doesn’t improve or abandons the plan of action,” Fuller says. In most cases, troublemakers will make a sincere effort to control disruptive tendencies.

Troutman suggests enlisting the assistance of a respected peer.

“Have a senior-level doctor help the noncompliant physician understand why his or her behavior creates problems for everyone, including the doctor himself,” he says. “Also, consider connecting compensation and other rewards to job performance, which encompasses good behavior and good citizenship within the organization. Make expectations and consequences clear.”

If an employee has a recent change in behavior, ask if there is a reason.

“It is my experience that sudden changes in behaviors are often the result of a personal or clinical issue, so it is important and humane to make certain that there is not some other cause for the change before assuming someone is simply being disruptive or difficult,” Dr. Nichols says.

Many healthcare institutions are now setting up centers of professionalism. Paskoff reports that The Center for Professionalism and Peer Support (CPPS) was created in 2008 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston to educate the hospital community regarding professionalism and manage unprofessional behavior.3 CPPS has established standards of behavior and a framework to deal with difficult behaviors.

“An employee is told what he or she is doing wrong, receives counseling, and is given resources to improve,” he explains. “If an employee doesn’t improve, he or she is told that the behavior won’t be tolerated.”

Dismissing Bad Employees

After addressing the specifics of unacceptable behavior and explaining the consequences of repeating it, leadership should monitor subsequent conduct and provide feedback.

“If the employee commits other violations or behaves badly, promptly address the misconduct again and make it clear that further such actions will not be tolerated,” Troutman says. “Expect immediate and sustained improvement and compliance. Be consistent, and if bad conduct continues after an opportunity to improve, do not prolong anyone’s suffering. Instead, terminate the disruptive employee. When you do, make the reasons clear.”

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. The Joint Commission website. Accessed April 17, 2015.

- Whittemore AD, New England Society for Vascular Surgery. The impact of professionalism on safe surgical care. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(2):415-419.

- Shapiro J, Whittemore A, Tsen LC. Instituting a culture of professionalism: the establishment of a center for professionalism and peer support. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014;40(4):168-177.

As a hospitalist, caring for critically ill or injured patients can be stressful and demanding. Working with difficult doctors, those who exhibit intimidating and disruptive behaviors such as verbal outbursts and physical threats as well as passive activities such as refusing to perform assigned tasks, can make the work environment even more challenging.1 Some docs are routinely reluctant—or refuse—to answer questions or return phone calls or pages. Some communicate in condescending language or voice intonation; some are brutally impatient.1

The most difficult doctors to work with are those who are not aligned with the hospital’s or treatment team’s goals and those who aren’t open to feedback and coaching, says Rob Zipper, MD, MMM, SFHM, regional chief medical officer of Sound Physicians, based in Tacoma, Wash.

“If physicians are aware of a practice’s guidelines and goals but simply won’t comply with them, it makes it harder on everyone else who is pulling the ship in the same direction,” he says.

Unruly physicians don’t just annoy their coworkers. According to a sentinel event alert from The Joint Commission, they can:

- foster medical errors;

- contribute to poor patient satisfaction;

- contribute to preventable adverse outcomes;

- increase the cost of care;

- undermine team effectiveness; and

- cause qualified clinicians, administrators, and managers to seek new positions in more professional environments.1

“These issues are all connected,” says Stephen R. Nichols, MD, chief of clinical operations performance at the Schumacher Group in Brownwood, Texas. “Disruptive behaviors create mitigated communications and dissatisfaction among staff, which bleeds over into other aspects that are involved secondarily.”

Stephen M. Paskoff, Esq., president and CEO of ELI in Atlanta, can attest to the most severe consequences of bad behavior on patient care.

At one institution, a surgeon’s disruptive behavior lead to a coworker forgetting to perform a procedure and a patient dying.2 In another incident, the emergency department stopped calling on a medical subspecialist who was predictably abusive. The subspecialist knew how to treat a specific patient with an unusual intervention. Since the specialist was not consulted initially, the patient ended up in the intensive care unit.2

One bad hospitalist can bring down the reputation of an entire team.

“Many programs are incentivized based on medical staff and primary-care physicians’ perceptions of their care, so there are direct and indirect consequences,” Dr. Zipper says.

The bottom line, says Felix Aguirre, MD, SFHM, vice president of medical affairs at IPC Healthcare in North Hollywood, Calif., is that it only takes one bad experience to tarnish a group, but it takes many positive experiences to erase the damage.

The Roots of Evil

Intimidating and disruptive behavior stems from both individual and systemic factors. Care providers who exhibit characteristics such as self-centeredness, immaturity, or defensiveness can be more prone to unprofessional behavior. They can lack interpersonal, coping, or conflict-management skills.1

Systemic factors are marked by pressures related to increased productivity demands, cost-containment requirements, embedded hierarchies, and fear of litigation in the healthcare environment. These pressures can be further exacerbated by changes to or differences in the authority, autonomy, empowerment, and roles or values of professionals on the healthcare team as well as by the continual daily changes in shifts, rotations, and interdepartmental support staff. This dynamic creates challenges for interprofessional communication and development of trust among team members.1

According to The Joint Commission, intimidating and disruptive behaviors are often manifested by healthcare professionals in positions of power.1 But other members of the care team can be problematic as well.

“In my experience, conflicts usually revolve around different perspectives and objectives, even if both parties are acting respectfully,” Dr. Zipper says. “Sometimes, however, providers or other care team members are tired or stressed and don’t behave professionally.”

Paskoff, who has more than 40 years of experience in healthcare-related workplace issues, including serving as an investigator for the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, says some doctors learn bad behaviors from their mentors and that behaviors can be passed down through generations because they are tolerated.

“When I asked one physician who had outstanding training and an outstanding technical reputation how he became abusive, he said, ‘I learned from the best.’” Paskoff was actually able to track the doctor’s training to the late 1800s and physicians who were known for similar behaviors.

Confronting Those Who Misbehave

Dr. Zipper says physicians should confront behavioral issues directly.

“I will typically discuss a complaint with a doctor privately, and ask him or her what happened without being accusatory,” he says. “I try to provide as much concrete and objective information as I can. The doctor needs to know that you are trying to help him or her succeed. That said, if something is clearly bad behavior, feedback should be direct and include a statement such as, ‘This is not how we behave in this practice.’”

At times, it may not be possible to discuss an emergent matter, such as during a code blue.

“However, I will often ask if anyone on the code team has any ideas or concerns before ending the code,” Dr. Nichols says. “Then after the critical time has passed, it is important to debrief and reconnect with the team, especially the less-experienced members who may have lingering concerns.”

For many employees, however, it is difficult to report disruptive behaviors. This is due to a fear of retaliation and the stigma associated with “blowing the whistle” on a colleague as well as a general reluctance to confront an intimidator.1

If an employee cannot muster the courage to confront a disruptive coworker or if the issue isn’t resolved by talking with the difficult individual, an employee should be a good citizen and report bad behavior to the appropriate hospital authority in a timely manner, says A. Kevin Troutman, Esq., a partner at Fisher Phillips in Houston and a former healthcare human resources executive.

Hospitals accredited by The Joint Commission are required to create a code of conduct that defines disruptive and inappropriate behaviors. In addition, leaders must create and implement a process for managing these behaviors.1

Helping Difficult Doctors

After a physician or another employee has been called out for bad behavior, steps need to be taken to correct the problem. Robert Fuller, Esq., an attorney with Nelson Hardiman, LLP, in Los Angeles, has found a positive-oriented intervention called “the 3-Ds”—which stands for diagnose, design, and do—that has been a successful tool for achieving positive change. The strategy involves a supervisor and employee mutually developing a worksheet to diagnose the problem. Next, they design a remediation and improvement plan. Finally, they implement the plan and specify dates to achieve certain milestones. Coworkers should be informed of the plan and be urged to support it.

“Make it clear that the positive aspect of this plan turns to progressive discipline, including termination, if the employee doesn’t improve or abandons the plan of action,” Fuller says. In most cases, troublemakers will make a sincere effort to control disruptive tendencies.

Troutman suggests enlisting the assistance of a respected peer.

“Have a senior-level doctor help the noncompliant physician understand why his or her behavior creates problems for everyone, including the doctor himself,” he says. “Also, consider connecting compensation and other rewards to job performance, which encompasses good behavior and good citizenship within the organization. Make expectations and consequences clear.”

If an employee has a recent change in behavior, ask if there is a reason.

“It is my experience that sudden changes in behaviors are often the result of a personal or clinical issue, so it is important and humane to make certain that there is not some other cause for the change before assuming someone is simply being disruptive or difficult,” Dr. Nichols says.

Many healthcare institutions are now setting up centers of professionalism. Paskoff reports that The Center for Professionalism and Peer Support (CPPS) was created in 2008 at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston to educate the hospital community regarding professionalism and manage unprofessional behavior.3 CPPS has established standards of behavior and a framework to deal with difficult behaviors.

“An employee is told what he or she is doing wrong, receives counseling, and is given resources to improve,” he explains. “If an employee doesn’t improve, he or she is told that the behavior won’t be tolerated.”

Dismissing Bad Employees

After addressing the specifics of unacceptable behavior and explaining the consequences of repeating it, leadership should monitor subsequent conduct and provide feedback.

“If the employee commits other violations or behaves badly, promptly address the misconduct again and make it clear that further such actions will not be tolerated,” Troutman says. “Expect immediate and sustained improvement and compliance. Be consistent, and if bad conduct continues after an opportunity to improve, do not prolong anyone’s suffering. Instead, terminate the disruptive employee. When you do, make the reasons clear.”

Karen Appold is a medical writer in Pennsylvania.

References

- Behaviors that undermine a culture of safety. The Joint Commission website. Accessed April 17, 2015.

- Whittemore AD, New England Society for Vascular Surgery. The impact of professionalism on safe surgical care. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(2):415-419.

- Shapiro J, Whittemore A, Tsen LC. Instituting a culture of professionalism: the establishment of a center for professionalism and peer support. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2014;40(4):168-177.

VIDEO: Tips & Strategies for the Hospital Medicine Job Search

Dr. Thomas Frederickson, Dr. Benjamin Frizner, and Dr. Darlene Tad-y are all experienced at hiring and mentoring hospitalists at all career stages. They offer tips and strategies for assessing opportunity and negotiating your ideal HM job.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dr. Thomas Frederickson, Dr. Benjamin Frizner, and Dr. Darlene Tad-y are all experienced at hiring and mentoring hospitalists at all career stages. They offer tips and strategies for assessing opportunity and negotiating your ideal HM job.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dr. Thomas Frederickson, Dr. Benjamin Frizner, and Dr. Darlene Tad-y are all experienced at hiring and mentoring hospitalists at all career stages. They offer tips and strategies for assessing opportunity and negotiating your ideal HM job.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

QUIZ: What is the Rate of Postoperative Atrial Fibrillation after Non-Cardiac Surgery?

[WpProQuiz 16]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 16]

[WpProQuiz 16]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 16]

[WpProQuiz 16]

[WpProQuiz_toplist 16]

Strategies for Preventing Patient Falls

Between 700,000 and 1 million people fall each year in U.S. hospitals, and about a third of those result in injuries that add an additional 6.3 days to hospital stays, according to a report from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Some 11,000 falls are fatal. The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare has now issued a report on the subject called “Preventing Patient Falls: A Systematic Approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare Project.”1

“We try to pick those topics that healthcare organizations just haven’t been able to fully tackle even though they’ve put a lot of time and resources into trying to fix them,” says Kelly Barnes, MS, a center project lead in the Center for Transforming Healthcare at The Joint Commission.

The Joint Commission project involved seven hospitals that used Robust Process Improvement, which incorporates tools from Lean Six Sigma and change management methodologies, to reduce falls with injury on inpatient pilot units within their organizations.

During the project, each organization identified the specific factors that led to falls with injury in their environment and developed solutions targeted to those factors. The organizations identified 30 root causes and developed 21 targeted solutions. Because the contributing factors were different at each organization, solution sets were unique to each. Afterward, the organizations saw an aggregate 35% reduction in falls and a 62% reduction in falls with injury.

“One of the takeaways is that you really need support across an organization to have success,” Barnes says. “The more engaged the entire organization is from top down all the way to the bottom, the more successful people are in solving the problems.”

The study resulted in a Targeted Solutions Tool (TST), free to all Joint Commission–accredited customers, to help hospitals.

“You can put your data right into the tool,” Barnes says. “It tells you what your top contributing factors are, and it gives you the solutions that have worked for those contributing factors at other organizations.”

Reference

Health Research & Educational Trust. Preventing patient falls: a systematic approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare project. Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence website.

Between 700,000 and 1 million people fall each year in U.S. hospitals, and about a third of those result in injuries that add an additional 6.3 days to hospital stays, according to a report from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Some 11,000 falls are fatal. The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare has now issued a report on the subject called “Preventing Patient Falls: A Systematic Approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare Project.”1

“We try to pick those topics that healthcare organizations just haven’t been able to fully tackle even though they’ve put a lot of time and resources into trying to fix them,” says Kelly Barnes, MS, a center project lead in the Center for Transforming Healthcare at The Joint Commission.

The Joint Commission project involved seven hospitals that used Robust Process Improvement, which incorporates tools from Lean Six Sigma and change management methodologies, to reduce falls with injury on inpatient pilot units within their organizations.

During the project, each organization identified the specific factors that led to falls with injury in their environment and developed solutions targeted to those factors. The organizations identified 30 root causes and developed 21 targeted solutions. Because the contributing factors were different at each organization, solution sets were unique to each. Afterward, the organizations saw an aggregate 35% reduction in falls and a 62% reduction in falls with injury.

“One of the takeaways is that you really need support across an organization to have success,” Barnes says. “The more engaged the entire organization is from top down all the way to the bottom, the more successful people are in solving the problems.”

The study resulted in a Targeted Solutions Tool (TST), free to all Joint Commission–accredited customers, to help hospitals.

“You can put your data right into the tool,” Barnes says. “It tells you what your top contributing factors are, and it gives you the solutions that have worked for those contributing factors at other organizations.”

Reference

Health Research & Educational Trust. Preventing patient falls: a systematic approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare project. Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence website.

Between 700,000 and 1 million people fall each year in U.S. hospitals, and about a third of those result in injuries that add an additional 6.3 days to hospital stays, according to a report from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Some 11,000 falls are fatal. The Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare has now issued a report on the subject called “Preventing Patient Falls: A Systematic Approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare Project.”1

“We try to pick those topics that healthcare organizations just haven’t been able to fully tackle even though they’ve put a lot of time and resources into trying to fix them,” says Kelly Barnes, MS, a center project lead in the Center for Transforming Healthcare at The Joint Commission.

The Joint Commission project involved seven hospitals that used Robust Process Improvement, which incorporates tools from Lean Six Sigma and change management methodologies, to reduce falls with injury on inpatient pilot units within their organizations.

During the project, each organization identified the specific factors that led to falls with injury in their environment and developed solutions targeted to those factors. The organizations identified 30 root causes and developed 21 targeted solutions. Because the contributing factors were different at each organization, solution sets were unique to each. Afterward, the organizations saw an aggregate 35% reduction in falls and a 62% reduction in falls with injury.

“One of the takeaways is that you really need support across an organization to have success,” Barnes says. “The more engaged the entire organization is from top down all the way to the bottom, the more successful people are in solving the problems.”

The study resulted in a Targeted Solutions Tool (TST), free to all Joint Commission–accredited customers, to help hospitals.

“You can put your data right into the tool,” Barnes says. “It tells you what your top contributing factors are, and it gives you the solutions that have worked for those contributing factors at other organizations.”

Reference

Health Research & Educational Trust. Preventing patient falls: a systematic approach from the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare project. Hospitals in Pursuit of Excellence website.

Helping Patients Quit Smoking

Inpatient hospitalization can be a key time for patients to quit smoking, according to an abstract called “No More Butts: An Automated System for Inpatient Smoking Cessation Team Consults.”1

“Tobacco smoking continues to be one of the most important public health threats that we face,” says lead author Sujatha Sankaran, MD, assistant clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director of smoking cessation at the University of California, San Francisco. “Hospitalization is an extremely important moment and provides an excellent opportunity to counsel and provide cessation resources for people who are concerned about their health.”

Inpatients who receive smoking cessation counseling, nicotine replacement, and referral to outpatient resources have increased quit rates six weeks after hospital discharge, their research showed.

However, according to the abstract, in 2014:

- 34.5% of tobacco users admitted to one 600-bed academic hospital were documented as having received and accepted tobacco cessation counseling

- 45.7% of tobacco users received nicotine replacement therapy

- 1.35% of tobacco users received after-discharge consultations to outpatient smoking cessation resources

Researchers piloted a system in which a dedicated respiratory therapist–staffed smoking cessation consult service was trained to provide targeted tobacco cessation services to all inpatients who use tobacco. Of 1944 patients identified as using tobacco, 1545 received and accepted cessation counseling from a trained member of the Smoking Cessation Team, 1526 received nicotine replacement therapy, and 464 received an electronic referral to either a telephone or in-person quit line

“Hospitalists know firsthand the serious harm that tobacco use causes to patients but often are overwhelmed by the acute issues of patients and are unable to fully address tobacco use with hospitalized patients,” Dr. Sankaran says. “An automated cessation service can help lessen this burden by providing automatic cessation resources to all tobacco users.”

Reference

- Sankaran S, Burke R, O’Keefe S. No more butts: an automated system for inpatient smoking cessation team consults [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(suppl 1). Accessed November 9, 2016.

Inpatient hospitalization can be a key time for patients to quit smoking, according to an abstract called “No More Butts: An Automated System for Inpatient Smoking Cessation Team Consults.”1

“Tobacco smoking continues to be one of the most important public health threats that we face,” says lead author Sujatha Sankaran, MD, assistant clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director of smoking cessation at the University of California, San Francisco. “Hospitalization is an extremely important moment and provides an excellent opportunity to counsel and provide cessation resources for people who are concerned about their health.”

Inpatients who receive smoking cessation counseling, nicotine replacement, and referral to outpatient resources have increased quit rates six weeks after hospital discharge, their research showed.

However, according to the abstract, in 2014:

- 34.5% of tobacco users admitted to one 600-bed academic hospital were documented as having received and accepted tobacco cessation counseling

- 45.7% of tobacco users received nicotine replacement therapy

- 1.35% of tobacco users received after-discharge consultations to outpatient smoking cessation resources

Researchers piloted a system in which a dedicated respiratory therapist–staffed smoking cessation consult service was trained to provide targeted tobacco cessation services to all inpatients who use tobacco. Of 1944 patients identified as using tobacco, 1545 received and accepted cessation counseling from a trained member of the Smoking Cessation Team, 1526 received nicotine replacement therapy, and 464 received an electronic referral to either a telephone or in-person quit line

“Hospitalists know firsthand the serious harm that tobacco use causes to patients but often are overwhelmed by the acute issues of patients and are unable to fully address tobacco use with hospitalized patients,” Dr. Sankaran says. “An automated cessation service can help lessen this burden by providing automatic cessation resources to all tobacco users.”

Reference

- Sankaran S, Burke R, O’Keefe S. No more butts: an automated system for inpatient smoking cessation team consults [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(suppl 1). Accessed November 9, 2016.

Inpatient hospitalization can be a key time for patients to quit smoking, according to an abstract called “No More Butts: An Automated System for Inpatient Smoking Cessation Team Consults.”1

“Tobacco smoking continues to be one of the most important public health threats that we face,” says lead author Sujatha Sankaran, MD, assistant clinical professor in the division of hospital medicine and medical director of smoking cessation at the University of California, San Francisco. “Hospitalization is an extremely important moment and provides an excellent opportunity to counsel and provide cessation resources for people who are concerned about their health.”

Inpatients who receive smoking cessation counseling, nicotine replacement, and referral to outpatient resources have increased quit rates six weeks after hospital discharge, their research showed.

However, according to the abstract, in 2014:

- 34.5% of tobacco users admitted to one 600-bed academic hospital were documented as having received and accepted tobacco cessation counseling

- 45.7% of tobacco users received nicotine replacement therapy

- 1.35% of tobacco users received after-discharge consultations to outpatient smoking cessation resources

Researchers piloted a system in which a dedicated respiratory therapist–staffed smoking cessation consult service was trained to provide targeted tobacco cessation services to all inpatients who use tobacco. Of 1944 patients identified as using tobacco, 1545 received and accepted cessation counseling from a trained member of the Smoking Cessation Team, 1526 received nicotine replacement therapy, and 464 received an electronic referral to either a telephone or in-person quit line

“Hospitalists know firsthand the serious harm that tobacco use causes to patients but often are overwhelmed by the acute issues of patients and are unable to fully address tobacco use with hospitalized patients,” Dr. Sankaran says. “An automated cessation service can help lessen this burden by providing automatic cessation resources to all tobacco users.”

Reference

- Sankaran S, Burke R, O’Keefe S. No more butts: an automated system for inpatient smoking cessation team consults [abstract]. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(suppl 1). Accessed November 9, 2016.

Hospitalists See Benefit from Working with ‘Surgicalists’

Time was critical. He needed surgery right away to remove his gallbladder. But for that, he needed a surgeon.

“There was a surgeon on call, but the surgeon was not picking up the phone,” Dr. Singh says. “I’m scratching my head. Why is the surgeon not calling back? Where is the surgeon? Did the pager get lost? What if the patient has a bad outcome?”

Eventually, Dr. Singh had to give up on the on-call surgeon, and the patient was flown to a hospital 45 miles away in downtown Sacramento. His surgery had been delayed for almost 12 hours.

The man lived largely due to good luck, Dr. Singh says. The unresponsive surgeon had disciplinary proceedings started against his license but retired rather than face the consequences.

Today, hospitalists at Sutter Amador no longer have to anxiously wait for those responses to emergency pages. It’s one of many hospitals that have turned to a “surgicalist” model, with a surgeon always on hand at the hospital. Surgicalists perform both emergency procedures and procedures that are tied to a hospital admission, without which a patient can’t be discharged. Although it is growing in popularity, the model is still only seen in a small fraction of hospitals.

The model is widely supported by hospitalists because it brings several advantages, mainly a greater availability of the surgeon for consult.

“We don’t have to hunt them down, trying to call their office, trying to see if they’re available to call back,” says Dr. Singh, who is now also the chair of medical staff performance at Sutter Amador and adds that the change has helped with his job satisfaction.

A Clear Delineation

Arrangements between hospitalists and surgicalists vary depending on the hospital, but there typically are clearly delineated criteria on who cares for whom, with the more urgent surgical cases tending to fall under the surgicalists’ care and those with less urgent problems, even though surgery might be involved, tending to go to hospitalists.

When a surgery-related question or the need for actual surgery arises, the model calls for a quick response time from the surgicalist. Hospitalists and surgicalists collaborate on ways to reduce length of stay and prevent readmissions since they share the same institutional goals. Hospitalists are also more in tune with the needs of the surgeons, for instance, not feeding a patient who is going to need quick surgery and not administering blood thinners when a surgery is imminent unless there’s an overriding reason not to do so.

One advantage of this collaboration is that a hospitalist working alongside a surgicalist can get extra surgery-related guidance even when surgery probably isn’t needed, says John Nelson, MD, MHM, a hospitalist at Overlake Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash., a hospitalist management consultant, and a past president of SHM.

“Maybe the opinion of a general surgeon could be useful, but maybe I can get along without it because the general surgeons are busy. It’s going to be hard for them to find time to see this patient, and they’re not going to be very interested in it,” he says. “But if instead I have a surgical hospitalist who’s there all day, it’s much less of a bother for them to come by and take a look at my patient.”

Remaining Challenges

The model is not without its hurdles. When surgicalists are on a 24-hour shift, the patients will see a new one each day, sometimes prompting them to ask, “Who’s my doctor?” Also, complex cases can pose a challenge as they move from one surgicalist to another day to day.

John Maa, MD, who wrote a seminal paper on surgicalists in 2007 based on an early surgicalist model he started at San Mateo Medical Center in California,1 says he is now concerned that the principles he helped make popular—the absorption of surgeons into a system as they work hand in hand with other hospital staff all the time—might be eroding. Some small staffing companies are calling themselves surgicalists, promising fast response times, but are actually locum tenens surgeons under a surgicalist guise, he says.

Properly rolled out, surgicalist programs mean a much better working relationship between hospitalists and surgeons, says Lynette Scherer, MD, FACS, chief medical officer at Surgical Affiliates Management Group in Sacramento. The company, founded in 1996, employs about 200 surgeons, twice as many as three years ago, Dr. Scherer says, but the company declined to share what that amounts to in full-time equivalent positions.

“The hospitalists know all of our algorithms, and they know when to call us,” Dr. Scherer says. “We share the patients on the inpatient side as we need to. We keep the ones that are appropriate for us, and they keep the ones that are appropriate for them.”

The details depend on the hospital, she says.

“Whenever we go to a new site, we sit down with the hospitalist team and say, ‘What do you need here?’ And our admitting grids are different based on what the different needs of the hospitals are.”

To stay on top of complex cases with very sick patients, the medical director rounds with the team nearly every day to help guide that care, Dr. Scherer says.

At Sutter Amador, the arrival of the surgicalist model has helped shorten the length of stay by almost one day for surgery admissions, Dr. Singh says.

Reported outcomes, however, seem to be mixed.

In 2008, Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento switched from a nine-surgeon call panel to four surgeons who covered the acute-care surgery service in 24-hour shifts. Researchers looked at outcomes from 2007, before the new model was adopted, and from the four subsequent years. The results were published in 2014 in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.2

The total number of operations rose significantly, with 497 performed in 2007 and 640 in 2011. The percentage of cases with complications also fell significantly, from 21% in 2007 to 12% in 2011, with a low of 11% in 2010.

But the mortality rate rose significantly, from 1.4% in 2007 to 2.2% in 2011, with a high of 4.1% in 2008. The study authors note that the mortality rate ultimately fell back to levels not statistically significantly higher than the rate before the service. They suggested the spike could have been due to a greater willingness by the service to treat severely ill patients and due to the “immaturity” of the service in its earlier years. The percentage of cases with a readmission fell from 6.4% in 2007 to 4.7% in 2011, with a low of 3% in 2009, but that change wasn’t quite statistically significant.

“The data’s really bearing out that emergency patients are different in terms of the care they demand,” Dr. Scherer says. “So the patient with alcoholic cirrhosis who presents with a hole in his colon is very different than somebody who presents for an elective colon resection. And you can really reduce complications when you have a team of educated people taking care of these patients.”

Dr. Nelson says adopting the model “just means you’re a smoother operator and you can provide better service to people.” He adds that for any hospital that is getting poor surgical coverage and is paying for it, “it might make sense to consider it.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

References

- Maa J, Carter JT, Gosnell JE, Wachter R, Harris HW. The surgical hospitalist: a new model for emergency surgical care. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(5):704-711.

- O’Mara MS, Scherer L, Wisner D, Owens LJ. Sustainability and success of the acute care surgery model in the nontrauma setting. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(1):90-98.

Time was critical. He needed surgery right away to remove his gallbladder. But for that, he needed a surgeon.

“There was a surgeon on call, but the surgeon was not picking up the phone,” Dr. Singh says. “I’m scratching my head. Why is the surgeon not calling back? Where is the surgeon? Did the pager get lost? What if the patient has a bad outcome?”

Eventually, Dr. Singh had to give up on the on-call surgeon, and the patient was flown to a hospital 45 miles away in downtown Sacramento. His surgery had been delayed for almost 12 hours.

The man lived largely due to good luck, Dr. Singh says. The unresponsive surgeon had disciplinary proceedings started against his license but retired rather than face the consequences.

Today, hospitalists at Sutter Amador no longer have to anxiously wait for those responses to emergency pages. It’s one of many hospitals that have turned to a “surgicalist” model, with a surgeon always on hand at the hospital. Surgicalists perform both emergency procedures and procedures that are tied to a hospital admission, without which a patient can’t be discharged. Although it is growing in popularity, the model is still only seen in a small fraction of hospitals.

The model is widely supported by hospitalists because it brings several advantages, mainly a greater availability of the surgeon for consult.

“We don’t have to hunt them down, trying to call their office, trying to see if they’re available to call back,” says Dr. Singh, who is now also the chair of medical staff performance at Sutter Amador and adds that the change has helped with his job satisfaction.

A Clear Delineation

Arrangements between hospitalists and surgicalists vary depending on the hospital, but there typically are clearly delineated criteria on who cares for whom, with the more urgent surgical cases tending to fall under the surgicalists’ care and those with less urgent problems, even though surgery might be involved, tending to go to hospitalists.

When a surgery-related question or the need for actual surgery arises, the model calls for a quick response time from the surgicalist. Hospitalists and surgicalists collaborate on ways to reduce length of stay and prevent readmissions since they share the same institutional goals. Hospitalists are also more in tune with the needs of the surgeons, for instance, not feeding a patient who is going to need quick surgery and not administering blood thinners when a surgery is imminent unless there’s an overriding reason not to do so.

One advantage of this collaboration is that a hospitalist working alongside a surgicalist can get extra surgery-related guidance even when surgery probably isn’t needed, says John Nelson, MD, MHM, a hospitalist at Overlake Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash., a hospitalist management consultant, and a past president of SHM.

“Maybe the opinion of a general surgeon could be useful, but maybe I can get along without it because the general surgeons are busy. It’s going to be hard for them to find time to see this patient, and they’re not going to be very interested in it,” he says. “But if instead I have a surgical hospitalist who’s there all day, it’s much less of a bother for them to come by and take a look at my patient.”

Remaining Challenges

The model is not without its hurdles. When surgicalists are on a 24-hour shift, the patients will see a new one each day, sometimes prompting them to ask, “Who’s my doctor?” Also, complex cases can pose a challenge as they move from one surgicalist to another day to day.

John Maa, MD, who wrote a seminal paper on surgicalists in 2007 based on an early surgicalist model he started at San Mateo Medical Center in California,1 says he is now concerned that the principles he helped make popular—the absorption of surgeons into a system as they work hand in hand with other hospital staff all the time—might be eroding. Some small staffing companies are calling themselves surgicalists, promising fast response times, but are actually locum tenens surgeons under a surgicalist guise, he says.

Properly rolled out, surgicalist programs mean a much better working relationship between hospitalists and surgeons, says Lynette Scherer, MD, FACS, chief medical officer at Surgical Affiliates Management Group in Sacramento. The company, founded in 1996, employs about 200 surgeons, twice as many as three years ago, Dr. Scherer says, but the company declined to share what that amounts to in full-time equivalent positions.

“The hospitalists know all of our algorithms, and they know when to call us,” Dr. Scherer says. “We share the patients on the inpatient side as we need to. We keep the ones that are appropriate for us, and they keep the ones that are appropriate for them.”

The details depend on the hospital, she says.

“Whenever we go to a new site, we sit down with the hospitalist team and say, ‘What do you need here?’ And our admitting grids are different based on what the different needs of the hospitals are.”

To stay on top of complex cases with very sick patients, the medical director rounds with the team nearly every day to help guide that care, Dr. Scherer says.

At Sutter Amador, the arrival of the surgicalist model has helped shorten the length of stay by almost one day for surgery admissions, Dr. Singh says.

Reported outcomes, however, seem to be mixed.

In 2008, Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento switched from a nine-surgeon call panel to four surgeons who covered the acute-care surgery service in 24-hour shifts. Researchers looked at outcomes from 2007, before the new model was adopted, and from the four subsequent years. The results were published in 2014 in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.2

The total number of operations rose significantly, with 497 performed in 2007 and 640 in 2011. The percentage of cases with complications also fell significantly, from 21% in 2007 to 12% in 2011, with a low of 11% in 2010.

But the mortality rate rose significantly, from 1.4% in 2007 to 2.2% in 2011, with a high of 4.1% in 2008. The study authors note that the mortality rate ultimately fell back to levels not statistically significantly higher than the rate before the service. They suggested the spike could have been due to a greater willingness by the service to treat severely ill patients and due to the “immaturity” of the service in its earlier years. The percentage of cases with a readmission fell from 6.4% in 2007 to 4.7% in 2011, with a low of 3% in 2009, but that change wasn’t quite statistically significant.

“The data’s really bearing out that emergency patients are different in terms of the care they demand,” Dr. Scherer says. “So the patient with alcoholic cirrhosis who presents with a hole in his colon is very different than somebody who presents for an elective colon resection. And you can really reduce complications when you have a team of educated people taking care of these patients.”

Dr. Nelson says adopting the model “just means you’re a smoother operator and you can provide better service to people.” He adds that for any hospital that is getting poor surgical coverage and is paying for it, “it might make sense to consider it.”

Thomas R. Collins is a freelance medical writer based in Florida.

References

- Maa J, Carter JT, Gosnell JE, Wachter R, Harris HW. The surgical hospitalist: a new model for emergency surgical care. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(5):704-711.

- O’Mara MS, Scherer L, Wisner D, Owens LJ. Sustainability and success of the acute care surgery model in the nontrauma setting. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219(1):90-98.

Time was critical. He needed surgery right away to remove his gallbladder. But for that, he needed a surgeon.

“There was a surgeon on call, but the surgeon was not picking up the phone,” Dr. Singh says. “I’m scratching my head. Why is the surgeon not calling back? Where is the surgeon? Did the pager get lost? What if the patient has a bad outcome?”

Eventually, Dr. Singh had to give up on the on-call surgeon, and the patient was flown to a hospital 45 miles away in downtown Sacramento. His surgery had been delayed for almost 12 hours.

The man lived largely due to good luck, Dr. Singh says. The unresponsive surgeon had disciplinary proceedings started against his license but retired rather than face the consequences.

Today, hospitalists at Sutter Amador no longer have to anxiously wait for those responses to emergency pages. It’s one of many hospitals that have turned to a “surgicalist” model, with a surgeon always on hand at the hospital. Surgicalists perform both emergency procedures and procedures that are tied to a hospital admission, without which a patient can’t be discharged. Although it is growing in popularity, the model is still only seen in a small fraction of hospitals.

The model is widely supported by hospitalists because it brings several advantages, mainly a greater availability of the surgeon for consult.

“We don’t have to hunt them down, trying to call their office, trying to see if they’re available to call back,” says Dr. Singh, who is now also the chair of medical staff performance at Sutter Amador and adds that the change has helped with his job satisfaction.

A Clear Delineation

Arrangements between hospitalists and surgicalists vary depending on the hospital, but there typically are clearly delineated criteria on who cares for whom, with the more urgent surgical cases tending to fall under the surgicalists’ care and those with less urgent problems, even though surgery might be involved, tending to go to hospitalists.

When a surgery-related question or the need for actual surgery arises, the model calls for a quick response time from the surgicalist. Hospitalists and surgicalists collaborate on ways to reduce length of stay and prevent readmissions since they share the same institutional goals. Hospitalists are also more in tune with the needs of the surgeons, for instance, not feeding a patient who is going to need quick surgery and not administering blood thinners when a surgery is imminent unless there’s an overriding reason not to do so.

One advantage of this collaboration is that a hospitalist working alongside a surgicalist can get extra surgery-related guidance even when surgery probably isn’t needed, says John Nelson, MD, MHM, a hospitalist at Overlake Medical Center in Bellevue, Wash., a hospitalist management consultant, and a past president of SHM.

“Maybe the opinion of a general surgeon could be useful, but maybe I can get along without it because the general surgeons are busy. It’s going to be hard for them to find time to see this patient, and they’re not going to be very interested in it,” he says. “But if instead I have a surgical hospitalist who’s there all day, it’s much less of a bother for them to come by and take a look at my patient.”

Remaining Challenges

The model is not without its hurdles. When surgicalists are on a 24-hour shift, the patients will see a new one each day, sometimes prompting them to ask, “Who’s my doctor?” Also, complex cases can pose a challenge as they move from one surgicalist to another day to day.

John Maa, MD, who wrote a seminal paper on surgicalists in 2007 based on an early surgicalist model he started at San Mateo Medical Center in California,1 says he is now concerned that the principles he helped make popular—the absorption of surgeons into a system as they work hand in hand with other hospital staff all the time—might be eroding. Some small staffing companies are calling themselves surgicalists, promising fast response times, but are actually locum tenens surgeons under a surgicalist guise, he says.

Properly rolled out, surgicalist programs mean a much better working relationship between hospitalists and surgeons, says Lynette Scherer, MD, FACS, chief medical officer at Surgical Affiliates Management Group in Sacramento. The company, founded in 1996, employs about 200 surgeons, twice as many as three years ago, Dr. Scherer says, but the company declined to share what that amounts to in full-time equivalent positions.

“The hospitalists know all of our algorithms, and they know when to call us,” Dr. Scherer says. “We share the patients on the inpatient side as we need to. We keep the ones that are appropriate for us, and they keep the ones that are appropriate for them.”

The details depend on the hospital, she says.

“Whenever we go to a new site, we sit down with the hospitalist team and say, ‘What do you need here?’ And our admitting grids are different based on what the different needs of the hospitals are.”

To stay on top of complex cases with very sick patients, the medical director rounds with the team nearly every day to help guide that care, Dr. Scherer says.

At Sutter Amador, the arrival of the surgicalist model has helped shorten the length of stay by almost one day for surgery admissions, Dr. Singh says.

Reported outcomes, however, seem to be mixed.

In 2008, Sutter Medical Center in Sacramento switched from a nine-surgeon call panel to four surgeons who covered the acute-care surgery service in 24-hour shifts. Researchers looked at outcomes from 2007, before the new model was adopted, and from the four subsequent years. The results were published in 2014 in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.2

The total number of operations rose significantly, with 497 performed in 2007 and 640 in 2011. The percentage of cases with complications also fell significantly, from 21% in 2007 to 12% in 2011, with a low of 11% in 2010.