User login

In Case You Missed It: COVID

Medical boards pressured to let it slide when doctors spread COVID misinformation

Tennessee’s Board of Medical Examiners unanimously adopted in September 2021 a statement that said doctors spreading COVID misinformation – such as suggesting that vaccines contain microchips – could jeopardize their license to practice.

“I’m very glad that we’re taking this step,” Dr. Stephen Loyd, MD, the panel’s vice president, said at the time. “If you’re spreading this willful misinformation, for me it’s going to be really hard to do anything other than put you on probation or take your license for a year. There has to be a message sent for this. It’s not okay.”

The board’s statement was posted on a government website.

The growing tension in Tennessee between conservative lawmakers and the state’s medical board may be the most prominent example in the country. But the Federation of State Medical Boards, which created the language adopted by at least 15 state boards, is tracking legislation introduced by Republicans in at least 14 states that would restrict a medical board’s authority to discipline doctors for their advice on COVID.

Humayun Chaudhry, DO, the federation’s CEO, called it “an unwelcome trend.” The nonprofit association, based in Euless, Tex., said the statement is merely a COVID-specific restatement of an existing rule: that doctors who engage in behavior that puts patients at risk could face disciplinary action.

Although doctors have leeway to decide which treatments to provide, the medical boards that oversee them have broad authority over licensing. Often, doctors are investigated for violating guidelines on prescribing high-powered drugs. But physicians are sometimes punished for other “unprofessional conduct.” In 2013, Tennessee’s board fined U.S. Rep. Scott DesJarlais for separately having sexual relations with two female patients more than a decade earlier.

Still, stopping doctors from sharing unsound medical advice has proved challenging. Even defining misinformation has been difficult. And during the pandemic, resistance from some state legislatures is complicating the effort.

A relatively small group of physicians peddle COVID misinformation, but many of them associate with America’s Frontline Doctors. Its founder, Simone Gold, MD, has claimed patients are dying from COVID treatments, not the virus itself. Sherri Tenpenny, DO, said in a legislative hearing in Ohio that the COVID vaccine could magnetize patients. Stella Immanuel, MD, has pushed hydroxychloroquine as a COVID cure in Texas, although clinical trials showed that it had no benefit. None of them agreed to requests for comment.

The Texas Medical Board fined Dr. Immanuel $500 for not informing a patient of the risks associated with using hydroxychloroquine as an off-label COVID treatment.

In Tennessee, state lawmakers called a special legislative session in October to address COVID restrictions, and Republican Gov. Bill Lee signed a sweeping package of bills that push back against pandemic rules. One included language directed at the medical board’s recent COVID policy statement, making it more difficult for the panel to investigate complaints about physicians’ advice on COVID vaccines or treatments.

In November, Republican state Rep. John Ragan sent the medical board a letter demanding that the statement be deleted from the state’s website. Rep. Ragan leads a legislative panel that had raised the prospect of defunding the state’s health department over its promotion of COVID vaccines to teens.

Among his demands, Rep. Ragan listed 20 questions he wanted the medical board to answer in writing, including why the misinformation “policy” was proposed nearly two years into the pandemic, which scholars would determine what constitutes misinformation, and how was the “policy” not an infringement on the doctor-patient relationship.

“If you fail to act promptly, your organization will be required to appear before the Joint Government Operations Committee to explain your inaction,” Rep. Ragan wrote in the letter, obtained by Kaiser Health News and Nashville Public Radio.

In response to a request for comment, Rep. Ragan said that “any executive agency, including Board of Medical Examiners, that refuses to follow the law is subject to dissolution.”

He set a deadline of Dec. 7.

In Florida, a Republican-sponsored bill making its way through the state legislature proposes to ban medical boards from revoking or threatening to revoke doctors’ licenses for what they say unless “direct physical harm” of a patient occurred. If the publicized complaint can’t be proved, the board could owe a doctor up to $1.5 million in damages.

Although Florida’s medical board has not adopted the Federation of State Medical Boards’ COVID misinformation statement, the panel has considered misinformation complaints against physicians, including the state’s surgeon general, Joseph Ladapo, MD, PhD.

Dr. Chaudhry said he’s surprised just how many COVID-related complaints are being filed across the country. Often, boards do not publicize investigations before a violation of ethics or standards is confirmed. But in response to a survey by the federation in late 2021, two-thirds of state boards reported an increase in misinformation complaints. And the federation said 12 boards had taken action against a licensed physician.

“At the end of the day, if a physician who is licensed engages in activity that causes harm, the state medical boards are the ones that historically have been set up to look into the situation and make a judgment about what happened or didn’t happen,” Dr. Chaudhry said. “And if you start to chip away at that, it becomes a slippery slope.”

The Georgia Composite Medical Board adopted a version of the federation’s misinformation guidance in early November and has been receiving 10-20 complaints each month, said Debi Dalton, MD, the chairperson. Two months in, no one had been sanctioned.

Dr. Dalton said that even putting out a misinformation policy leaves some “gray” area. Generally, physicians are expected to follow the “consensus,” rather than “the newest information that pops up on social media,” she said.

“We expect physicians to think ethically, professionally, and with the safety of patients in mind,” Dr. Dalton said.

A few physician groups are resisting attempts to root out misinformation, including the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons, known for its stands against government regulation.

Some medical boards have opted against taking a public stand against misinformation.

The Alabama Board of Medical Examiners discussed signing on to the federation’s statement, according to the minutes from an October meeting. But after debating the potential legal ramifications in a private executive session, the board opted not to act.

In Tennessee, the Board of Medical Examiners met on the day Rep. Ragan had set as the deadline and voted to remove the misinformation statement from its website to avoid being called into a legislative hearing. But then, in late January, the board decided to stick with the policy – although it did not republish the statement online immediately – and more specifically defined misinformation, calling it “content that is false, inaccurate or misleading, even if spread unintentionally.”

Board members acknowledged they would likely get more pushback from lawmakers but said they wanted to protect their profession from interference.

“Doctors who are putting forth good evidence-based medicine deserve the protection of this board so they can actually say: ‘Hey, I’m in line with this guideline, and this is a source of truth,’” said Melanie Blake, MD, the board’s president. “We should be a source of truth.”

The medical board was looking into nearly 30 open complaints related to COVID when its misinformation statement came down from its website. As of early February, no Tennessee physician had faced disciplinary action.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation. This story is part of a partnership that includes Nashville Public Radio, NPR, and KHN.

Tennessee’s Board of Medical Examiners unanimously adopted in September 2021 a statement that said doctors spreading COVID misinformation – such as suggesting that vaccines contain microchips – could jeopardize their license to practice.

“I’m very glad that we’re taking this step,” Dr. Stephen Loyd, MD, the panel’s vice president, said at the time. “If you’re spreading this willful misinformation, for me it’s going to be really hard to do anything other than put you on probation or take your license for a year. There has to be a message sent for this. It’s not okay.”

The board’s statement was posted on a government website.

The growing tension in Tennessee between conservative lawmakers and the state’s medical board may be the most prominent example in the country. But the Federation of State Medical Boards, which created the language adopted by at least 15 state boards, is tracking legislation introduced by Republicans in at least 14 states that would restrict a medical board’s authority to discipline doctors for their advice on COVID.

Humayun Chaudhry, DO, the federation’s CEO, called it “an unwelcome trend.” The nonprofit association, based in Euless, Tex., said the statement is merely a COVID-specific restatement of an existing rule: that doctors who engage in behavior that puts patients at risk could face disciplinary action.

Although doctors have leeway to decide which treatments to provide, the medical boards that oversee them have broad authority over licensing. Often, doctors are investigated for violating guidelines on prescribing high-powered drugs. But physicians are sometimes punished for other “unprofessional conduct.” In 2013, Tennessee’s board fined U.S. Rep. Scott DesJarlais for separately having sexual relations with two female patients more than a decade earlier.

Still, stopping doctors from sharing unsound medical advice has proved challenging. Even defining misinformation has been difficult. And during the pandemic, resistance from some state legislatures is complicating the effort.

A relatively small group of physicians peddle COVID misinformation, but many of them associate with America’s Frontline Doctors. Its founder, Simone Gold, MD, has claimed patients are dying from COVID treatments, not the virus itself. Sherri Tenpenny, DO, said in a legislative hearing in Ohio that the COVID vaccine could magnetize patients. Stella Immanuel, MD, has pushed hydroxychloroquine as a COVID cure in Texas, although clinical trials showed that it had no benefit. None of them agreed to requests for comment.

The Texas Medical Board fined Dr. Immanuel $500 for not informing a patient of the risks associated with using hydroxychloroquine as an off-label COVID treatment.

In Tennessee, state lawmakers called a special legislative session in October to address COVID restrictions, and Republican Gov. Bill Lee signed a sweeping package of bills that push back against pandemic rules. One included language directed at the medical board’s recent COVID policy statement, making it more difficult for the panel to investigate complaints about physicians’ advice on COVID vaccines or treatments.

In November, Republican state Rep. John Ragan sent the medical board a letter demanding that the statement be deleted from the state’s website. Rep. Ragan leads a legislative panel that had raised the prospect of defunding the state’s health department over its promotion of COVID vaccines to teens.

Among his demands, Rep. Ragan listed 20 questions he wanted the medical board to answer in writing, including why the misinformation “policy” was proposed nearly two years into the pandemic, which scholars would determine what constitutes misinformation, and how was the “policy” not an infringement on the doctor-patient relationship.

“If you fail to act promptly, your organization will be required to appear before the Joint Government Operations Committee to explain your inaction,” Rep. Ragan wrote in the letter, obtained by Kaiser Health News and Nashville Public Radio.

In response to a request for comment, Rep. Ragan said that “any executive agency, including Board of Medical Examiners, that refuses to follow the law is subject to dissolution.”

He set a deadline of Dec. 7.

In Florida, a Republican-sponsored bill making its way through the state legislature proposes to ban medical boards from revoking or threatening to revoke doctors’ licenses for what they say unless “direct physical harm” of a patient occurred. If the publicized complaint can’t be proved, the board could owe a doctor up to $1.5 million in damages.

Although Florida’s medical board has not adopted the Federation of State Medical Boards’ COVID misinformation statement, the panel has considered misinformation complaints against physicians, including the state’s surgeon general, Joseph Ladapo, MD, PhD.

Dr. Chaudhry said he’s surprised just how many COVID-related complaints are being filed across the country. Often, boards do not publicize investigations before a violation of ethics or standards is confirmed. But in response to a survey by the federation in late 2021, two-thirds of state boards reported an increase in misinformation complaints. And the federation said 12 boards had taken action against a licensed physician.

“At the end of the day, if a physician who is licensed engages in activity that causes harm, the state medical boards are the ones that historically have been set up to look into the situation and make a judgment about what happened or didn’t happen,” Dr. Chaudhry said. “And if you start to chip away at that, it becomes a slippery slope.”

The Georgia Composite Medical Board adopted a version of the federation’s misinformation guidance in early November and has been receiving 10-20 complaints each month, said Debi Dalton, MD, the chairperson. Two months in, no one had been sanctioned.

Dr. Dalton said that even putting out a misinformation policy leaves some “gray” area. Generally, physicians are expected to follow the “consensus,” rather than “the newest information that pops up on social media,” she said.

“We expect physicians to think ethically, professionally, and with the safety of patients in mind,” Dr. Dalton said.

A few physician groups are resisting attempts to root out misinformation, including the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons, known for its stands against government regulation.

Some medical boards have opted against taking a public stand against misinformation.

The Alabama Board of Medical Examiners discussed signing on to the federation’s statement, according to the minutes from an October meeting. But after debating the potential legal ramifications in a private executive session, the board opted not to act.

In Tennessee, the Board of Medical Examiners met on the day Rep. Ragan had set as the deadline and voted to remove the misinformation statement from its website to avoid being called into a legislative hearing. But then, in late January, the board decided to stick with the policy – although it did not republish the statement online immediately – and more specifically defined misinformation, calling it “content that is false, inaccurate or misleading, even if spread unintentionally.”

Board members acknowledged they would likely get more pushback from lawmakers but said they wanted to protect their profession from interference.

“Doctors who are putting forth good evidence-based medicine deserve the protection of this board so they can actually say: ‘Hey, I’m in line with this guideline, and this is a source of truth,’” said Melanie Blake, MD, the board’s president. “We should be a source of truth.”

The medical board was looking into nearly 30 open complaints related to COVID when its misinformation statement came down from its website. As of early February, no Tennessee physician had faced disciplinary action.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation. This story is part of a partnership that includes Nashville Public Radio, NPR, and KHN.

Tennessee’s Board of Medical Examiners unanimously adopted in September 2021 a statement that said doctors spreading COVID misinformation – such as suggesting that vaccines contain microchips – could jeopardize their license to practice.

“I’m very glad that we’re taking this step,” Dr. Stephen Loyd, MD, the panel’s vice president, said at the time. “If you’re spreading this willful misinformation, for me it’s going to be really hard to do anything other than put you on probation or take your license for a year. There has to be a message sent for this. It’s not okay.”

The board’s statement was posted on a government website.

The growing tension in Tennessee between conservative lawmakers and the state’s medical board may be the most prominent example in the country. But the Federation of State Medical Boards, which created the language adopted by at least 15 state boards, is tracking legislation introduced by Republicans in at least 14 states that would restrict a medical board’s authority to discipline doctors for their advice on COVID.

Humayun Chaudhry, DO, the federation’s CEO, called it “an unwelcome trend.” The nonprofit association, based in Euless, Tex., said the statement is merely a COVID-specific restatement of an existing rule: that doctors who engage in behavior that puts patients at risk could face disciplinary action.

Although doctors have leeway to decide which treatments to provide, the medical boards that oversee them have broad authority over licensing. Often, doctors are investigated for violating guidelines on prescribing high-powered drugs. But physicians are sometimes punished for other “unprofessional conduct.” In 2013, Tennessee’s board fined U.S. Rep. Scott DesJarlais for separately having sexual relations with two female patients more than a decade earlier.

Still, stopping doctors from sharing unsound medical advice has proved challenging. Even defining misinformation has been difficult. And during the pandemic, resistance from some state legislatures is complicating the effort.

A relatively small group of physicians peddle COVID misinformation, but many of them associate with America’s Frontline Doctors. Its founder, Simone Gold, MD, has claimed patients are dying from COVID treatments, not the virus itself. Sherri Tenpenny, DO, said in a legislative hearing in Ohio that the COVID vaccine could magnetize patients. Stella Immanuel, MD, has pushed hydroxychloroquine as a COVID cure in Texas, although clinical trials showed that it had no benefit. None of them agreed to requests for comment.

The Texas Medical Board fined Dr. Immanuel $500 for not informing a patient of the risks associated with using hydroxychloroquine as an off-label COVID treatment.

In Tennessee, state lawmakers called a special legislative session in October to address COVID restrictions, and Republican Gov. Bill Lee signed a sweeping package of bills that push back against pandemic rules. One included language directed at the medical board’s recent COVID policy statement, making it more difficult for the panel to investigate complaints about physicians’ advice on COVID vaccines or treatments.

In November, Republican state Rep. John Ragan sent the medical board a letter demanding that the statement be deleted from the state’s website. Rep. Ragan leads a legislative panel that had raised the prospect of defunding the state’s health department over its promotion of COVID vaccines to teens.

Among his demands, Rep. Ragan listed 20 questions he wanted the medical board to answer in writing, including why the misinformation “policy” was proposed nearly two years into the pandemic, which scholars would determine what constitutes misinformation, and how was the “policy” not an infringement on the doctor-patient relationship.

“If you fail to act promptly, your organization will be required to appear before the Joint Government Operations Committee to explain your inaction,” Rep. Ragan wrote in the letter, obtained by Kaiser Health News and Nashville Public Radio.

In response to a request for comment, Rep. Ragan said that “any executive agency, including Board of Medical Examiners, that refuses to follow the law is subject to dissolution.”

He set a deadline of Dec. 7.

In Florida, a Republican-sponsored bill making its way through the state legislature proposes to ban medical boards from revoking or threatening to revoke doctors’ licenses for what they say unless “direct physical harm” of a patient occurred. If the publicized complaint can’t be proved, the board could owe a doctor up to $1.5 million in damages.

Although Florida’s medical board has not adopted the Federation of State Medical Boards’ COVID misinformation statement, the panel has considered misinformation complaints against physicians, including the state’s surgeon general, Joseph Ladapo, MD, PhD.

Dr. Chaudhry said he’s surprised just how many COVID-related complaints are being filed across the country. Often, boards do not publicize investigations before a violation of ethics or standards is confirmed. But in response to a survey by the federation in late 2021, two-thirds of state boards reported an increase in misinformation complaints. And the federation said 12 boards had taken action against a licensed physician.

“At the end of the day, if a physician who is licensed engages in activity that causes harm, the state medical boards are the ones that historically have been set up to look into the situation and make a judgment about what happened or didn’t happen,” Dr. Chaudhry said. “And if you start to chip away at that, it becomes a slippery slope.”

The Georgia Composite Medical Board adopted a version of the federation’s misinformation guidance in early November and has been receiving 10-20 complaints each month, said Debi Dalton, MD, the chairperson. Two months in, no one had been sanctioned.

Dr. Dalton said that even putting out a misinformation policy leaves some “gray” area. Generally, physicians are expected to follow the “consensus,” rather than “the newest information that pops up on social media,” she said.

“We expect physicians to think ethically, professionally, and with the safety of patients in mind,” Dr. Dalton said.

A few physician groups are resisting attempts to root out misinformation, including the Association of American Physicians and Surgeons, known for its stands against government regulation.

Some medical boards have opted against taking a public stand against misinformation.

The Alabama Board of Medical Examiners discussed signing on to the federation’s statement, according to the minutes from an October meeting. But after debating the potential legal ramifications in a private executive session, the board opted not to act.

In Tennessee, the Board of Medical Examiners met on the day Rep. Ragan had set as the deadline and voted to remove the misinformation statement from its website to avoid being called into a legislative hearing. But then, in late January, the board decided to stick with the policy – although it did not republish the statement online immediately – and more specifically defined misinformation, calling it “content that is false, inaccurate or misleading, even if spread unintentionally.”

Board members acknowledged they would likely get more pushback from lawmakers but said they wanted to protect their profession from interference.

“Doctors who are putting forth good evidence-based medicine deserve the protection of this board so they can actually say: ‘Hey, I’m in line with this guideline, and this is a source of truth,’” said Melanie Blake, MD, the board’s president. “We should be a source of truth.”

The medical board was looking into nearly 30 open complaints related to COVID when its misinformation statement came down from its website. As of early February, no Tennessee physician had faced disciplinary action.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation. This story is part of a partnership that includes Nashville Public Radio, NPR, and KHN.

New study shows natural immunity to COVID has enduring strength

It’s a matter of quality, not quantity. That’s the gist of a new Israeli study that shows that unvaccinated people with a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection create antibodies that are more effective in the long run compared with others who were vaccinated but never infected.

“While the quantity of antibodies decreases with time in both COVID-19 recovered patients and vaccinated individuals, ” lead author Carmit Cohen, PhD, said in an interview.

This difference could explain why previously infected patients appear to be better protected against a new infection than those who have only been vaccinated, according to a news release attached to the research.

One key caveat: This research does not include people from the later part of the pandemic.

This means there is a catch in terms of timing, William Schaffner, MD, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., said when asked to comment on the study: “The study involved only the early COVID strains – it has no information on either the Delta or Omicron variants. Thus, the results primarily are of scientific or historical interest but are not immediately relevant to the current situation.”

The findings come from an early release of a study to be presented at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases in April.

An unexpected finding of the study showed that obese people had better protection – a higher and more sustained immune response – compared with overweight and normal-weight individuals.

“The results in the obese group were indeed unexpected and need further research to confirm or dispute,” Dr. Schaffner said. “Obesity does predispose to more severe disease.”

A focus on earlier strains

Dr. Cohen – a senior research assistant in infectious disease prevention at the Sheba Medical Center in Ramat Gan, Israel – and her colleagues recruited participants between March 25, 2020 and Nov. 25, 2020 and completed analysis in April 2021. This means they assessed people with a history of infection from the original, the Alpha, and some Beta strains of SARS-CoV-2.

Dr. Cohen indicated that the next phase of their research will examine innate and acquired immune responses to the more recent Delta and Omicron variants.

The investigators analyzed the antibody-induced immune response up to 1 year in 130 COVID-19 recovered but unvaccinated individuals versus up to 8 months among 402 others matched by age and body mass index (BMI) and without previous infection who received two doses of the Pfizer vaccine.

The numbers of antibodies a month after vaccination were higher than those in the COVID-19 recovered patients. However, these numbers also declined more steeply in the vaccinated group, they note.

To assess the antibody performance, the investigators used the avidity index. This assay measures antibody function based on the strength of the interactions between the antibody and the viral antigen.

They found that the avidity index was higher in vaccinated individuals than in recovered patients initially but changes over time. At up to 6 months, the index did not significantly change in vaccinated individuals, whereas it gradually increased in recovered patients. This increase would potentially protect them from reinfection, the authors note.

These findings stand in stark contrast to an Oct. 29, 2021, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study that found that COVID-19 vaccines provided five times the protection of natural immunity.

Those results, published in the organization’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, suggest that vaccination helps people mount a higher, stronger, and more consistent level of immunity against COVID-19 hospitalization than infection alone for at least 6 months.

Protection linked to obesity

Another finding that ran against the scientific grain was the data about obesity.

There was a higher and more persistent antibody performance among people with a BMI of 30 kg/m2.

This could relate to greater disease severity and/or a more pronounced initial response to infection among the obese group.

“Our hypothesis is that patients with obesity begin with a more pronounced response – reflected also by the disease manifestation – and the trend of decline is similar, therefore the kinetics of immune response remain higher throughout the study,” Dr. Cohen said.

“The results in the obese group were indeed unexpected and need further research to confirm or dispute,” said Dr. Schaffner, who is also the current medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. “Obesity does predispose to more severe disease.”

Before the boosters

Along with using participants from only the earlier part of the pandemic, another limitation of the study was that the vaccinated group had only two doses of vaccine; boosters were not given during the time of the study, Dr. Schaffner said.

“Again, not the current situation.”

“That said, the strength and duration of natural immunity provided by the early variants was solid for up to a year, confirming previous reports,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s a matter of quality, not quantity. That’s the gist of a new Israeli study that shows that unvaccinated people with a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection create antibodies that are more effective in the long run compared with others who were vaccinated but never infected.

“While the quantity of antibodies decreases with time in both COVID-19 recovered patients and vaccinated individuals, ” lead author Carmit Cohen, PhD, said in an interview.

This difference could explain why previously infected patients appear to be better protected against a new infection than those who have only been vaccinated, according to a news release attached to the research.

One key caveat: This research does not include people from the later part of the pandemic.

This means there is a catch in terms of timing, William Schaffner, MD, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., said when asked to comment on the study: “The study involved only the early COVID strains – it has no information on either the Delta or Omicron variants. Thus, the results primarily are of scientific or historical interest but are not immediately relevant to the current situation.”

The findings come from an early release of a study to be presented at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases in April.

An unexpected finding of the study showed that obese people had better protection – a higher and more sustained immune response – compared with overweight and normal-weight individuals.

“The results in the obese group were indeed unexpected and need further research to confirm or dispute,” Dr. Schaffner said. “Obesity does predispose to more severe disease.”

A focus on earlier strains

Dr. Cohen – a senior research assistant in infectious disease prevention at the Sheba Medical Center in Ramat Gan, Israel – and her colleagues recruited participants between March 25, 2020 and Nov. 25, 2020 and completed analysis in April 2021. This means they assessed people with a history of infection from the original, the Alpha, and some Beta strains of SARS-CoV-2.

Dr. Cohen indicated that the next phase of their research will examine innate and acquired immune responses to the more recent Delta and Omicron variants.

The investigators analyzed the antibody-induced immune response up to 1 year in 130 COVID-19 recovered but unvaccinated individuals versus up to 8 months among 402 others matched by age and body mass index (BMI) and without previous infection who received two doses of the Pfizer vaccine.

The numbers of antibodies a month after vaccination were higher than those in the COVID-19 recovered patients. However, these numbers also declined more steeply in the vaccinated group, they note.

To assess the antibody performance, the investigators used the avidity index. This assay measures antibody function based on the strength of the interactions between the antibody and the viral antigen.

They found that the avidity index was higher in vaccinated individuals than in recovered patients initially but changes over time. At up to 6 months, the index did not significantly change in vaccinated individuals, whereas it gradually increased in recovered patients. This increase would potentially protect them from reinfection, the authors note.

These findings stand in stark contrast to an Oct. 29, 2021, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study that found that COVID-19 vaccines provided five times the protection of natural immunity.

Those results, published in the organization’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, suggest that vaccination helps people mount a higher, stronger, and more consistent level of immunity against COVID-19 hospitalization than infection alone for at least 6 months.

Protection linked to obesity

Another finding that ran against the scientific grain was the data about obesity.

There was a higher and more persistent antibody performance among people with a BMI of 30 kg/m2.

This could relate to greater disease severity and/or a more pronounced initial response to infection among the obese group.

“Our hypothesis is that patients with obesity begin with a more pronounced response – reflected also by the disease manifestation – and the trend of decline is similar, therefore the kinetics of immune response remain higher throughout the study,” Dr. Cohen said.

“The results in the obese group were indeed unexpected and need further research to confirm or dispute,” said Dr. Schaffner, who is also the current medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. “Obesity does predispose to more severe disease.”

Before the boosters

Along with using participants from only the earlier part of the pandemic, another limitation of the study was that the vaccinated group had only two doses of vaccine; boosters were not given during the time of the study, Dr. Schaffner said.

“Again, not the current situation.”

“That said, the strength and duration of natural immunity provided by the early variants was solid for up to a year, confirming previous reports,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

It’s a matter of quality, not quantity. That’s the gist of a new Israeli study that shows that unvaccinated people with a prior SARS-CoV-2 infection create antibodies that are more effective in the long run compared with others who were vaccinated but never infected.

“While the quantity of antibodies decreases with time in both COVID-19 recovered patients and vaccinated individuals, ” lead author Carmit Cohen, PhD, said in an interview.

This difference could explain why previously infected patients appear to be better protected against a new infection than those who have only been vaccinated, according to a news release attached to the research.

One key caveat: This research does not include people from the later part of the pandemic.

This means there is a catch in terms of timing, William Schaffner, MD, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., said when asked to comment on the study: “The study involved only the early COVID strains – it has no information on either the Delta or Omicron variants. Thus, the results primarily are of scientific or historical interest but are not immediately relevant to the current situation.”

The findings come from an early release of a study to be presented at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases in April.

An unexpected finding of the study showed that obese people had better protection – a higher and more sustained immune response – compared with overweight and normal-weight individuals.

“The results in the obese group were indeed unexpected and need further research to confirm or dispute,” Dr. Schaffner said. “Obesity does predispose to more severe disease.”

A focus on earlier strains

Dr. Cohen – a senior research assistant in infectious disease prevention at the Sheba Medical Center in Ramat Gan, Israel – and her colleagues recruited participants between March 25, 2020 and Nov. 25, 2020 and completed analysis in April 2021. This means they assessed people with a history of infection from the original, the Alpha, and some Beta strains of SARS-CoV-2.

Dr. Cohen indicated that the next phase of their research will examine innate and acquired immune responses to the more recent Delta and Omicron variants.

The investigators analyzed the antibody-induced immune response up to 1 year in 130 COVID-19 recovered but unvaccinated individuals versus up to 8 months among 402 others matched by age and body mass index (BMI) and without previous infection who received two doses of the Pfizer vaccine.

The numbers of antibodies a month after vaccination were higher than those in the COVID-19 recovered patients. However, these numbers also declined more steeply in the vaccinated group, they note.

To assess the antibody performance, the investigators used the avidity index. This assay measures antibody function based on the strength of the interactions between the antibody and the viral antigen.

They found that the avidity index was higher in vaccinated individuals than in recovered patients initially but changes over time. At up to 6 months, the index did not significantly change in vaccinated individuals, whereas it gradually increased in recovered patients. This increase would potentially protect them from reinfection, the authors note.

These findings stand in stark contrast to an Oct. 29, 2021, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study that found that COVID-19 vaccines provided five times the protection of natural immunity.

Those results, published in the organization’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, suggest that vaccination helps people mount a higher, stronger, and more consistent level of immunity against COVID-19 hospitalization than infection alone for at least 6 months.

Protection linked to obesity

Another finding that ran against the scientific grain was the data about obesity.

There was a higher and more persistent antibody performance among people with a BMI of 30 kg/m2.

This could relate to greater disease severity and/or a more pronounced initial response to infection among the obese group.

“Our hypothesis is that patients with obesity begin with a more pronounced response – reflected also by the disease manifestation – and the trend of decline is similar, therefore the kinetics of immune response remain higher throughout the study,” Dr. Cohen said.

“The results in the obese group were indeed unexpected and need further research to confirm or dispute,” said Dr. Schaffner, who is also the current medical director of the National Foundation for Infectious Diseases. “Obesity does predispose to more severe disease.”

Before the boosters

Along with using participants from only the earlier part of the pandemic, another limitation of the study was that the vaccinated group had only two doses of vaccine; boosters were not given during the time of the study, Dr. Schaffner said.

“Again, not the current situation.”

“That said, the strength and duration of natural immunity provided by the early variants was solid for up to a year, confirming previous reports,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

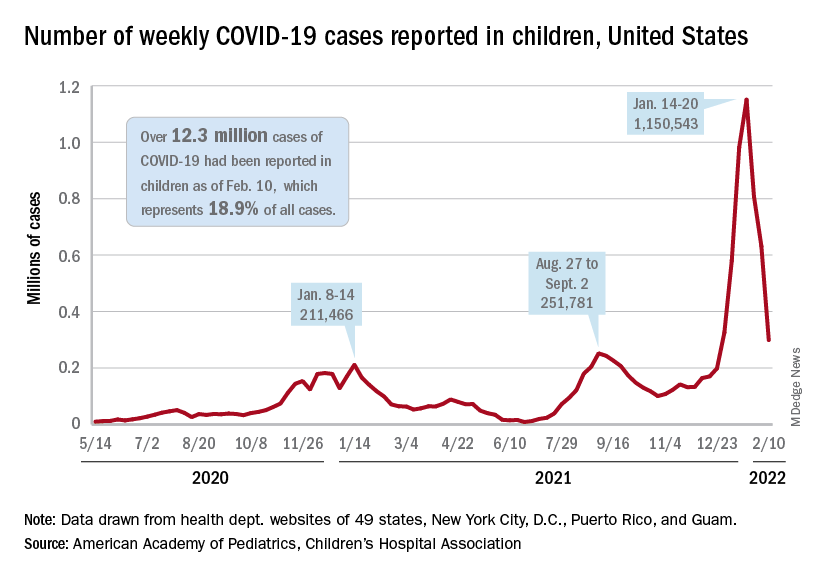

Children and COVID: Weekly cases down by more than half

A third consecutive week of declines in new COVID-19 cases among children has brought the weekly count down by 74% since the Omicron surge peaked in mid-January, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and by 74% from the peak of 1.15 million cases recorded for the week of Jan. 14-20, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. They also noted that the weekly tally was still higher than anything seen during the Delta surge.

The total number of pediatric cases was over 12.3 million as of Feb. 10, with children representing 18.9% of cases in all ages, according to the AAP/CHA report. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the two measures at 10.4 million and 17.3% on its COVID Data Tracker, based on availability of age data for 59.6 million total cases as of Feb. 14. The CDC also reported that 1,282 children have died from COVID-19 so far, which is about 0.17% of all deaths with age data available.

The AAP and CHA have been collecting data from state and territorial health departments, which have not always been consistently available over the course of the pandemic. Also, the CDC defines children as those under age 18 years, but that upper boundary varies from 14 to 20 among the states.

The decline of the Omicron variant also can be seen in new admissions of children with confirmed COVID-19, which continued to drop. The 7-day average of 435 admissions per day for the week of Feb. 6-12 was less than half of the peak seen in mid-January, when it reached 914 per day. The daily admission rate on Feb. 12 was 0.60 per 100,000 children aged 0-17 years – again, less than half the peak rate of 1.25 reported on Jan. 16, CDC data show.

The fading threat of Omicron also seems to be reflected in recent vaccination trends. Both initial doses and completions declined for the fourth consecutive week (Feb. 3-9) among children aged 5-11 years, while initiations held steady for 12- to 17-year-olds but completions declined for the third straight week, the AAP said in its separate vaccination report, which is based on data from the CDC.

As of Feb. 14, almost 32% of children aged 5-11 – that’s almost 9.2 million individuals – had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and just over 24% (6.9 million) were fully vaccinated, the CDC reported. For children aged 12-17, the corresponding figures are 67% (16.9 million) and 57% (14.4 million). Newly available data from the CDC also indicate that 19.5% (2.8 million) of children aged 12-17 have received a booster dose.

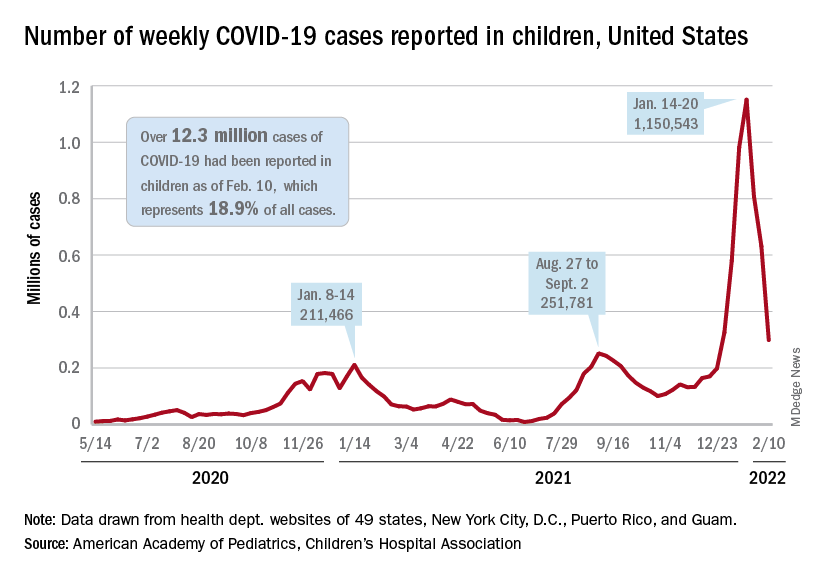

A third consecutive week of declines in new COVID-19 cases among children has brought the weekly count down by 74% since the Omicron surge peaked in mid-January, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and by 74% from the peak of 1.15 million cases recorded for the week of Jan. 14-20, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. They also noted that the weekly tally was still higher than anything seen during the Delta surge.

The total number of pediatric cases was over 12.3 million as of Feb. 10, with children representing 18.9% of cases in all ages, according to the AAP/CHA report. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the two measures at 10.4 million and 17.3% on its COVID Data Tracker, based on availability of age data for 59.6 million total cases as of Feb. 14. The CDC also reported that 1,282 children have died from COVID-19 so far, which is about 0.17% of all deaths with age data available.

The AAP and CHA have been collecting data from state and territorial health departments, which have not always been consistently available over the course of the pandemic. Also, the CDC defines children as those under age 18 years, but that upper boundary varies from 14 to 20 among the states.

The decline of the Omicron variant also can be seen in new admissions of children with confirmed COVID-19, which continued to drop. The 7-day average of 435 admissions per day for the week of Feb. 6-12 was less than half of the peak seen in mid-January, when it reached 914 per day. The daily admission rate on Feb. 12 was 0.60 per 100,000 children aged 0-17 years – again, less than half the peak rate of 1.25 reported on Jan. 16, CDC data show.

The fading threat of Omicron also seems to be reflected in recent vaccination trends. Both initial doses and completions declined for the fourth consecutive week (Feb. 3-9) among children aged 5-11 years, while initiations held steady for 12- to 17-year-olds but completions declined for the third straight week, the AAP said in its separate vaccination report, which is based on data from the CDC.

As of Feb. 14, almost 32% of children aged 5-11 – that’s almost 9.2 million individuals – had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and just over 24% (6.9 million) were fully vaccinated, the CDC reported. For children aged 12-17, the corresponding figures are 67% (16.9 million) and 57% (14.4 million). Newly available data from the CDC also indicate that 19.5% (2.8 million) of children aged 12-17 have received a booster dose.

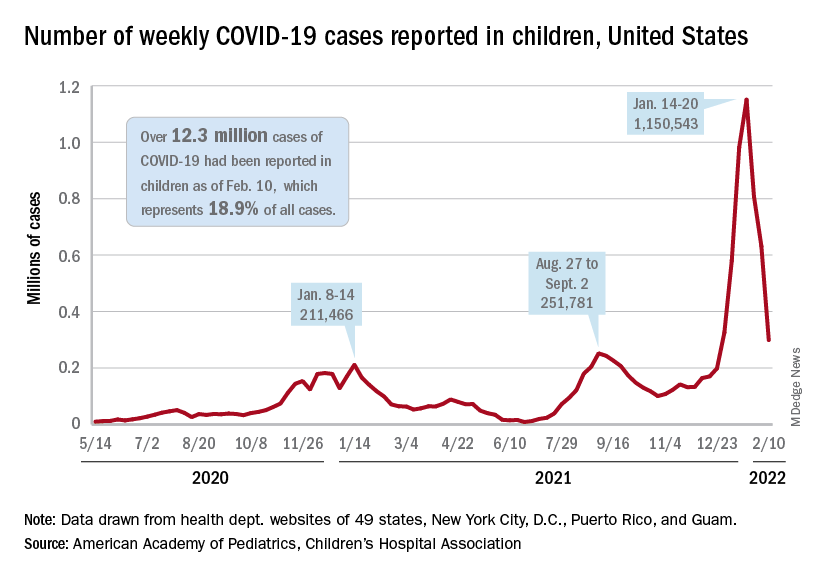

A third consecutive week of declines in new COVID-19 cases among children has brought the weekly count down by 74% since the Omicron surge peaked in mid-January, based on data from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

and by 74% from the peak of 1.15 million cases recorded for the week of Jan. 14-20, the AAP and CHA said in their weekly COVID report. They also noted that the weekly tally was still higher than anything seen during the Delta surge.

The total number of pediatric cases was over 12.3 million as of Feb. 10, with children representing 18.9% of cases in all ages, according to the AAP/CHA report. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention puts the two measures at 10.4 million and 17.3% on its COVID Data Tracker, based on availability of age data for 59.6 million total cases as of Feb. 14. The CDC also reported that 1,282 children have died from COVID-19 so far, which is about 0.17% of all deaths with age data available.

The AAP and CHA have been collecting data from state and territorial health departments, which have not always been consistently available over the course of the pandemic. Also, the CDC defines children as those under age 18 years, but that upper boundary varies from 14 to 20 among the states.

The decline of the Omicron variant also can be seen in new admissions of children with confirmed COVID-19, which continued to drop. The 7-day average of 435 admissions per day for the week of Feb. 6-12 was less than half of the peak seen in mid-January, when it reached 914 per day. The daily admission rate on Feb. 12 was 0.60 per 100,000 children aged 0-17 years – again, less than half the peak rate of 1.25 reported on Jan. 16, CDC data show.

The fading threat of Omicron also seems to be reflected in recent vaccination trends. Both initial doses and completions declined for the fourth consecutive week (Feb. 3-9) among children aged 5-11 years, while initiations held steady for 12- to 17-year-olds but completions declined for the third straight week, the AAP said in its separate vaccination report, which is based on data from the CDC.

As of Feb. 14, almost 32% of children aged 5-11 – that’s almost 9.2 million individuals – had received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and just over 24% (6.9 million) were fully vaccinated, the CDC reported. For children aged 12-17, the corresponding figures are 67% (16.9 million) and 57% (14.4 million). Newly available data from the CDC also indicate that 19.5% (2.8 million) of children aged 12-17 have received a booster dose.

Long COVID symptoms linked to effects on vagus nerve

Several long COVID symptoms could be linked to the effects of the coronavirus on a vital central nerve, according to new research being released in the spring.

The vagus nerve, which runs from the brain into the body, connects to the heart, lungs, intestines, and several muscles involved with swallowing. It plays a role in several body functions that control heart rate, speech, the gag reflex, sweating, and digestion.

Those with long COVID and vagus nerve problems could face long-term issues with their voice, a hard time swallowing, dizziness, a high heart rate, low blood pressure, and diarrhea, the study authors found.

Their findings will be presented at the 2022 European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases in late April.

“Most long COVID subjects with vagus nerve dysfunction symptoms had a range of significant, clinically relevant, structural and/or functional alterations in their vagus nerve, including nerve thickening, trouble swallowing, and symptoms of impaired breathing,” the study authors wrote. “Our findings so far thus point at vagus nerve dysfunction as a central pathophysiological feature of long COVID.”

Researchers from the University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol in Barcelona performed a study to look at vagus nerve functioning in long COVID patients. Among 348 patients, about 66% had at least one symptom that suggested vagus nerve dysfunction. The researchers did a broad evaluation with imaging and functional tests for 22 patients in the university’s Long COVID Clinic from March to June 2021.

Of the 22 patients, 20 were women, and the median age was 44. The most frequent symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction were diarrhea (73%), high heart rates (59%), dizziness (45%), swallowing problems (45%), voice problems (45%), and low blood pressure (14%).

Almost all (19 of 22 patients) had three or more symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction. The average length of symptoms was 14 months.

Of 22 patients, 6 had a change in the vagus nerve in the neck, which the researchers observed by ultrasound. They had a thickening of the vagus nerve and increased “echogenicity,” which suggests inflammation.

What’s more, 10 of 22 patients had flattened “diaphragmatic curves” during a thoracic ultrasound, which means the diaphragm doesn’t move as well as it should during breathing, and abnormal breathing. In another assessment, 10 of 16 patients had lower maximum inspiration pressures, suggesting a weakness in breathing muscles.

Eating and digestion were also impaired in some patients, with 13 reporting trouble with swallowing. During a gastric and bowel function assessment, eight patients couldn’t move food from the esophagus to the stomach as well as they should, while nine patients had acid reflux. Three patients had a hiatal hernia, which happens when the upper part of the stomach bulges through the diaphragm into the chest cavity.

The voices of some patients changed as well. Eight patients had an abnormal voice handicap index 30 test, which is a standard way to measure voice function. Among those, seven patients had dysphonia, or persistent voice problems.

The study is ongoing, and the research team is continuing to recruit patients to study the links between long COVID and the vagus nerve. The full paper isn’t yet available, and the research hasn’t yet been peer reviewed.

“The study appears to add to a growing collection of data suggesting at least some of the symptoms of long COVID is mediated through a direct impact on the nervous system,” David Strain, MD, a clinical senior lecturer at the University of Exeter (England), told the Science Media Centre.

“Establishing vagal nerve damage is useful information, as there are recognized, albeit not perfect, treatments for other causes of vagal nerve dysfunction that may be extrapolated to be beneficial for people with this type of long COVID,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Several long COVID symptoms could be linked to the effects of the coronavirus on a vital central nerve, according to new research being released in the spring.

The vagus nerve, which runs from the brain into the body, connects to the heart, lungs, intestines, and several muscles involved with swallowing. It plays a role in several body functions that control heart rate, speech, the gag reflex, sweating, and digestion.

Those with long COVID and vagus nerve problems could face long-term issues with their voice, a hard time swallowing, dizziness, a high heart rate, low blood pressure, and diarrhea, the study authors found.

Their findings will be presented at the 2022 European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases in late April.

“Most long COVID subjects with vagus nerve dysfunction symptoms had a range of significant, clinically relevant, structural and/or functional alterations in their vagus nerve, including nerve thickening, trouble swallowing, and symptoms of impaired breathing,” the study authors wrote. “Our findings so far thus point at vagus nerve dysfunction as a central pathophysiological feature of long COVID.”

Researchers from the University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol in Barcelona performed a study to look at vagus nerve functioning in long COVID patients. Among 348 patients, about 66% had at least one symptom that suggested vagus nerve dysfunction. The researchers did a broad evaluation with imaging and functional tests for 22 patients in the university’s Long COVID Clinic from March to June 2021.

Of the 22 patients, 20 were women, and the median age was 44. The most frequent symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction were diarrhea (73%), high heart rates (59%), dizziness (45%), swallowing problems (45%), voice problems (45%), and low blood pressure (14%).

Almost all (19 of 22 patients) had three or more symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction. The average length of symptoms was 14 months.

Of 22 patients, 6 had a change in the vagus nerve in the neck, which the researchers observed by ultrasound. They had a thickening of the vagus nerve and increased “echogenicity,” which suggests inflammation.

What’s more, 10 of 22 patients had flattened “diaphragmatic curves” during a thoracic ultrasound, which means the diaphragm doesn’t move as well as it should during breathing, and abnormal breathing. In another assessment, 10 of 16 patients had lower maximum inspiration pressures, suggesting a weakness in breathing muscles.

Eating and digestion were also impaired in some patients, with 13 reporting trouble with swallowing. During a gastric and bowel function assessment, eight patients couldn’t move food from the esophagus to the stomach as well as they should, while nine patients had acid reflux. Three patients had a hiatal hernia, which happens when the upper part of the stomach bulges through the diaphragm into the chest cavity.

The voices of some patients changed as well. Eight patients had an abnormal voice handicap index 30 test, which is a standard way to measure voice function. Among those, seven patients had dysphonia, or persistent voice problems.

The study is ongoing, and the research team is continuing to recruit patients to study the links between long COVID and the vagus nerve. The full paper isn’t yet available, and the research hasn’t yet been peer reviewed.

“The study appears to add to a growing collection of data suggesting at least some of the symptoms of long COVID is mediated through a direct impact on the nervous system,” David Strain, MD, a clinical senior lecturer at the University of Exeter (England), told the Science Media Centre.

“Establishing vagal nerve damage is useful information, as there are recognized, albeit not perfect, treatments for other causes of vagal nerve dysfunction that may be extrapolated to be beneficial for people with this type of long COVID,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Several long COVID symptoms could be linked to the effects of the coronavirus on a vital central nerve, according to new research being released in the spring.

The vagus nerve, which runs from the brain into the body, connects to the heart, lungs, intestines, and several muscles involved with swallowing. It plays a role in several body functions that control heart rate, speech, the gag reflex, sweating, and digestion.

Those with long COVID and vagus nerve problems could face long-term issues with their voice, a hard time swallowing, dizziness, a high heart rate, low blood pressure, and diarrhea, the study authors found.

Their findings will be presented at the 2022 European Congress of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases in late April.

“Most long COVID subjects with vagus nerve dysfunction symptoms had a range of significant, clinically relevant, structural and/or functional alterations in their vagus nerve, including nerve thickening, trouble swallowing, and symptoms of impaired breathing,” the study authors wrote. “Our findings so far thus point at vagus nerve dysfunction as a central pathophysiological feature of long COVID.”

Researchers from the University Hospital Germans Trias i Pujol in Barcelona performed a study to look at vagus nerve functioning in long COVID patients. Among 348 patients, about 66% had at least one symptom that suggested vagus nerve dysfunction. The researchers did a broad evaluation with imaging and functional tests for 22 patients in the university’s Long COVID Clinic from March to June 2021.

Of the 22 patients, 20 were women, and the median age was 44. The most frequent symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction were diarrhea (73%), high heart rates (59%), dizziness (45%), swallowing problems (45%), voice problems (45%), and low blood pressure (14%).

Almost all (19 of 22 patients) had three or more symptoms related to vagus nerve dysfunction. The average length of symptoms was 14 months.

Of 22 patients, 6 had a change in the vagus nerve in the neck, which the researchers observed by ultrasound. They had a thickening of the vagus nerve and increased “echogenicity,” which suggests inflammation.

What’s more, 10 of 22 patients had flattened “diaphragmatic curves” during a thoracic ultrasound, which means the diaphragm doesn’t move as well as it should during breathing, and abnormal breathing. In another assessment, 10 of 16 patients had lower maximum inspiration pressures, suggesting a weakness in breathing muscles.

Eating and digestion were also impaired in some patients, with 13 reporting trouble with swallowing. During a gastric and bowel function assessment, eight patients couldn’t move food from the esophagus to the stomach as well as they should, while nine patients had acid reflux. Three patients had a hiatal hernia, which happens when the upper part of the stomach bulges through the diaphragm into the chest cavity.

The voices of some patients changed as well. Eight patients had an abnormal voice handicap index 30 test, which is a standard way to measure voice function. Among those, seven patients had dysphonia, or persistent voice problems.

The study is ongoing, and the research team is continuing to recruit patients to study the links between long COVID and the vagus nerve. The full paper isn’t yet available, and the research hasn’t yet been peer reviewed.

“The study appears to add to a growing collection of data suggesting at least some of the symptoms of long COVID is mediated through a direct impact on the nervous system,” David Strain, MD, a clinical senior lecturer at the University of Exeter (England), told the Science Media Centre.

“Establishing vagal nerve damage is useful information, as there are recognized, albeit not perfect, treatments for other causes of vagal nerve dysfunction that may be extrapolated to be beneficial for people with this type of long COVID,” he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Estrogen supplementation may reduce COVID-19 death risk

Estrogen supplementation is associated with a reduced risk of death from COVID-19 among postmenopausal women, new research suggests.

The findings, from a nationwide study using data from Sweden, were published online Feb. 14 in BMJ Open by Malin Sund, MD, PhD, of Umeå (Sweden) University Faculty of Medicine and colleagues.

Among postmenopausal women aged 50-80 years with verified COVID-19, those receiving estrogen as part of hormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms were less than half as likely to die from it as those not receiving estrogen, even after adjustment for confounders.

“This study shows an association between estrogen levels and COVID-19 death. Consequently, drugs increasing estrogen levels may have a role in therapeutic efforts to alleviate COVID-19 severity in postmenopausal women and could be studied in randomized control trials,” the investigators write.

However, coauthor Anne-Marie Fors Connolly, MD, PhD, a resident in clinical microbiology at Umeå University, cautioned: “This is an observational study. Further clinical studies are needed to verify these results before recommending clinicians to consider estrogen supplementation.”

Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, agrees.

He told the U.K. Science and Media Centre: “This is an observational study comparing three groups of women based on whether they used hormonal therapy to boost estrogen levels or who had, as a result of treatment for breast cancer ... reduced estrogen levels or neither. The findings are apparently dramatic.”

“At the very least, great caution should be exercised in thinking that menopausal hormone therapy will have substantial, or even any, benefits in dealing with COVID-19,” he warned.

Do women die less frequently from COVID-19 than men?

Studies conducted early in the pandemic suggest women may be protected from poor outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared with men, even after adjustment for confounders.

According to more recent data from the Swedish Public Health Agency, of the 16,501 people who have died from COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic, about 45% are women and 55% are men. About 70% who have received intensive care because of COVID-19 are men, although cumulative data suggest that women are nearly as likely to die from COVID-19 as men, Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

For the current study, a total of 14,685 women aged 50-80 years were included, of whom 17.3% (2,535) had received estrogen supplementation, 81.2% (11,923) had native estrogen levels with no breast cancer or estrogen supplementation (controls), and 1.5% (227) had decreased estrogen levels because of breast cancer and antiestrogen treatment.

The group with decreased estrogen levels had a more than twofold risk of dying from COVID-19 compared with controls (odds ratio, 2.35), but this difference was no longer significant after adjustments for potential confounders including age, income, and educational level, and weighted Charlson Comorbidity Index (wCCI).

However, the group with augmented estrogen levels had a decreased risk of dying from COVID-19 before (odds ratio, 0.45) and after (OR, 0.47) adjustment.

The percentages of patients who died of COVID-19 were 4.6% of controls, 10.1% of those with decreased estrogen, and 2.1% with increased estrogen.

Not surprisingly, the risk of dying from COVID-19 also increased with age (OR of 1.15 for every year increase in age) and comorbidities (OR, 1.13 per increase in wCCI). Low income and having only a primary level education also increased the odds of dying from COVID-19.

Data on obesity, a known risk factor for COVID-19 death, weren’t reported.

“Obesity would have been a very relevant variable to include. Unfortunately, this information is not present in the nationwide registry data that we used for our study,” Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

While the data are observational and can’t be used to inform treatment, Dr. Connolly pointed to a U.S. randomized clinical trial currently recruiting patients that will investigate the effect of estradiol and progesterone therapy in 120 adults hospitalized with COVID-19.

In the meantime, she warned doctors and patients: “Please do not consider ending antiestrogen treatment following breast cancer – this is a necessary treatment for the cancer.”

Dr. Evans noted, “There are short-term benefits of menopausal hormone therapy but women should not, based on this or other observational studies, be advised to take HRT [hormone replacement therapy] for a supposed benefit on death from COVID-19.”

The study had several nonpharmaceutical industry funders, including Umeå University and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. The authors and Dr. Evans have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Estrogen supplementation is associated with a reduced risk of death from COVID-19 among postmenopausal women, new research suggests.

The findings, from a nationwide study using data from Sweden, were published online Feb. 14 in BMJ Open by Malin Sund, MD, PhD, of Umeå (Sweden) University Faculty of Medicine and colleagues.

Among postmenopausal women aged 50-80 years with verified COVID-19, those receiving estrogen as part of hormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms were less than half as likely to die from it as those not receiving estrogen, even after adjustment for confounders.

“This study shows an association between estrogen levels and COVID-19 death. Consequently, drugs increasing estrogen levels may have a role in therapeutic efforts to alleviate COVID-19 severity in postmenopausal women and could be studied in randomized control trials,” the investigators write.

However, coauthor Anne-Marie Fors Connolly, MD, PhD, a resident in clinical microbiology at Umeå University, cautioned: “This is an observational study. Further clinical studies are needed to verify these results before recommending clinicians to consider estrogen supplementation.”

Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, agrees.

He told the U.K. Science and Media Centre: “This is an observational study comparing three groups of women based on whether they used hormonal therapy to boost estrogen levels or who had, as a result of treatment for breast cancer ... reduced estrogen levels or neither. The findings are apparently dramatic.”

“At the very least, great caution should be exercised in thinking that menopausal hormone therapy will have substantial, or even any, benefits in dealing with COVID-19,” he warned.

Do women die less frequently from COVID-19 than men?

Studies conducted early in the pandemic suggest women may be protected from poor outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared with men, even after adjustment for confounders.

According to more recent data from the Swedish Public Health Agency, of the 16,501 people who have died from COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic, about 45% are women and 55% are men. About 70% who have received intensive care because of COVID-19 are men, although cumulative data suggest that women are nearly as likely to die from COVID-19 as men, Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

For the current study, a total of 14,685 women aged 50-80 years were included, of whom 17.3% (2,535) had received estrogen supplementation, 81.2% (11,923) had native estrogen levels with no breast cancer or estrogen supplementation (controls), and 1.5% (227) had decreased estrogen levels because of breast cancer and antiestrogen treatment.

The group with decreased estrogen levels had a more than twofold risk of dying from COVID-19 compared with controls (odds ratio, 2.35), but this difference was no longer significant after adjustments for potential confounders including age, income, and educational level, and weighted Charlson Comorbidity Index (wCCI).

However, the group with augmented estrogen levels had a decreased risk of dying from COVID-19 before (odds ratio, 0.45) and after (OR, 0.47) adjustment.

The percentages of patients who died of COVID-19 were 4.6% of controls, 10.1% of those with decreased estrogen, and 2.1% with increased estrogen.

Not surprisingly, the risk of dying from COVID-19 also increased with age (OR of 1.15 for every year increase in age) and comorbidities (OR, 1.13 per increase in wCCI). Low income and having only a primary level education also increased the odds of dying from COVID-19.

Data on obesity, a known risk factor for COVID-19 death, weren’t reported.

“Obesity would have been a very relevant variable to include. Unfortunately, this information is not present in the nationwide registry data that we used for our study,” Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

While the data are observational and can’t be used to inform treatment, Dr. Connolly pointed to a U.S. randomized clinical trial currently recruiting patients that will investigate the effect of estradiol and progesterone therapy in 120 adults hospitalized with COVID-19.

In the meantime, she warned doctors and patients: “Please do not consider ending antiestrogen treatment following breast cancer – this is a necessary treatment for the cancer.”

Dr. Evans noted, “There are short-term benefits of menopausal hormone therapy but women should not, based on this or other observational studies, be advised to take HRT [hormone replacement therapy] for a supposed benefit on death from COVID-19.”

The study had several nonpharmaceutical industry funders, including Umeå University and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. The authors and Dr. Evans have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Estrogen supplementation is associated with a reduced risk of death from COVID-19 among postmenopausal women, new research suggests.

The findings, from a nationwide study using data from Sweden, were published online Feb. 14 in BMJ Open by Malin Sund, MD, PhD, of Umeå (Sweden) University Faculty of Medicine and colleagues.

Among postmenopausal women aged 50-80 years with verified COVID-19, those receiving estrogen as part of hormone replacement therapy for menopausal symptoms were less than half as likely to die from it as those not receiving estrogen, even after adjustment for confounders.

“This study shows an association between estrogen levels and COVID-19 death. Consequently, drugs increasing estrogen levels may have a role in therapeutic efforts to alleviate COVID-19 severity in postmenopausal women and could be studied in randomized control trials,” the investigators write.

However, coauthor Anne-Marie Fors Connolly, MD, PhD, a resident in clinical microbiology at Umeå University, cautioned: “This is an observational study. Further clinical studies are needed to verify these results before recommending clinicians to consider estrogen supplementation.”

Stephen Evans, professor of pharmacoepidemiology, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, agrees.

He told the U.K. Science and Media Centre: “This is an observational study comparing three groups of women based on whether they used hormonal therapy to boost estrogen levels or who had, as a result of treatment for breast cancer ... reduced estrogen levels or neither. The findings are apparently dramatic.”

“At the very least, great caution should be exercised in thinking that menopausal hormone therapy will have substantial, or even any, benefits in dealing with COVID-19,” he warned.

Do women die less frequently from COVID-19 than men?

Studies conducted early in the pandemic suggest women may be protected from poor outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection, compared with men, even after adjustment for confounders.

According to more recent data from the Swedish Public Health Agency, of the 16,501 people who have died from COVID-19 since the start of the pandemic, about 45% are women and 55% are men. About 70% who have received intensive care because of COVID-19 are men, although cumulative data suggest that women are nearly as likely to die from COVID-19 as men, Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

For the current study, a total of 14,685 women aged 50-80 years were included, of whom 17.3% (2,535) had received estrogen supplementation, 81.2% (11,923) had native estrogen levels with no breast cancer or estrogen supplementation (controls), and 1.5% (227) had decreased estrogen levels because of breast cancer and antiestrogen treatment.

The group with decreased estrogen levels had a more than twofold risk of dying from COVID-19 compared with controls (odds ratio, 2.35), but this difference was no longer significant after adjustments for potential confounders including age, income, and educational level, and weighted Charlson Comorbidity Index (wCCI).

However, the group with augmented estrogen levels had a decreased risk of dying from COVID-19 before (odds ratio, 0.45) and after (OR, 0.47) adjustment.

The percentages of patients who died of COVID-19 were 4.6% of controls, 10.1% of those with decreased estrogen, and 2.1% with increased estrogen.

Not surprisingly, the risk of dying from COVID-19 also increased with age (OR of 1.15 for every year increase in age) and comorbidities (OR, 1.13 per increase in wCCI). Low income and having only a primary level education also increased the odds of dying from COVID-19.

Data on obesity, a known risk factor for COVID-19 death, weren’t reported.

“Obesity would have been a very relevant variable to include. Unfortunately, this information is not present in the nationwide registry data that we used for our study,” Dr. Connolly told this news organization.

While the data are observational and can’t be used to inform treatment, Dr. Connolly pointed to a U.S. randomized clinical trial currently recruiting patients that will investigate the effect of estradiol and progesterone therapy in 120 adults hospitalized with COVID-19.

In the meantime, she warned doctors and patients: “Please do not consider ending antiestrogen treatment following breast cancer – this is a necessary treatment for the cancer.”

Dr. Evans noted, “There are short-term benefits of menopausal hormone therapy but women should not, based on this or other observational studies, be advised to take HRT [hormone replacement therapy] for a supposed benefit on death from COVID-19.”

The study had several nonpharmaceutical industry funders, including Umeå University and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation. The authors and Dr. Evans have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM BMJ OPEN

Can cancer patients get approved COVID therapies?

In mid-November, Kevin Billingsley, MD, MBA, chief medical officer at Yale Cancer Center, New Haven, Conn., was keeping a close eye on the new COVID variant sweeping across South Africa. Six weeks later, the Omicron variant had become the dominant strain in the U.S. – and the Yale health system was no exception.

“As we entered January, we had a breathtaking rate of infection in our hospital,” said Dr. Billingsley, who also leads clinical care at the Smilow Cancer Hospital. “Some of the newly authorized COVID agents were available but not widely enough to make a clinically meaningful impact to protect all high-risk individuals during this surge.”

That left the team at Yale with difficult decisions about who would receive these treatments and who wouldn’t.

The health system convened a COVID-19 immunocompromised working group to identify which patients should get priority access to one of the promising drugs authorized to treat the infection – the monoclonal antibody sotrovimab and antiviral pills Paxlovid and molnupiravir – or the sole available option to prevent it, Evusheld.

“Although clinically sound, none of these decisions have been easy,” Dr. Billingsley told this news organization. “We have done a lot of case-by-case reviewing and a lot of handwringing. Omicron has been a wild ride for us all, and we have been doing the best we can with limited resources.”

‘We’re seeing incredible variability’

The team at Yale is not alone. The restricted supply of COVID-19 treatments has led many oncologists and other experts across the U.S. to create carefully curated lists of their most vulnerable patients.

In late December, the National Institutes of Health published broad criteria to help clinicians prioritize patients most likely to benefit from these therapies. A handful of state health departments, including those in Michigan and Minnesota, established their own standards. Patients with cancer – specifically those with hematologic malignancies and receiving oncology therapies that compromise the immune system – appeared at the top of everyone’s list.

But ultimately individual decisions about who receives these drugs and how they’re allocated fell to institutions.

“Overall, what we’re seeing is incredible variability across the country, because there’s no uniform agreement on what comprises best practices on allocating scarce resources,” said Matthew Wynia, MD, MPH, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Bioethics and Humanities at the University of Colorado, Aurora. “There are so many people at the top of most lists, and the drugs are in such short supply, that there’s no guarantee even those in the top tier will get it.”

This news organization spoke to experts across the country about their experiences accessing these treatments during the Omicron surge and their strategies prioritizing patients with cancer.

Dealing with limited supply

Overall, the limited supply of COVID-19 drugs means not every patient who’s eligible to receive a treatment will get one.

A snapshot of the past 2 weeks, for instance, shows that the count of new infections hit almost 4.3 million, while distribution of the two antiviral pills Paxlovid and molnupiravir and the monoclonal antibody sotrovimab reached just over 600,000 courses.