User login

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP): 2014 National Conference and Exhibition

Tailored MBSR intervention helped moms in treatment for opioid addiction

SAN DIEGO – A tailored version of the mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program benefited mothers in treatment for opioid addiction, according to a small qualitative analysis presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The intervention was the first in the United States to teach mindfulness-based parenting techniques to mothers with opioid addiction, lead investigator Diane J. Abatemarco, Ph.D., M.S.W., said in an interview.

“Mindfulness-based parenting is an effective method to enhance parenting, increase bonding and attachment, and reduce parental anxiety, stress, and reactivity,” added Dr. Abatemarco of the department of pediatrics and director of pediatric population health research at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children and Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Parents with substance-use disorders tend to suffer more stress than do other parents, and stress increases the risk of relapse among former users, Dr. Abatemarco and her associates noted. Mindfulness-based stress reduction – which focuses on compassion, nonjudgment, emotional awareness, and self-regulation – has been explored in studies of addiction and parenting, but rarely as combined approach for both stressors, said the researchers.

Therefore, they conducted a single-arm study of 34 mothers of infants or young children who were in outpatient treatment for opioid addiction, they said. Participants averaged 30 years of age, most were white and unmarried, and about half had a high school education or less, they reported.

As in traditional MBSR, the mothers attended 12 weekly group sessions to learn sitting meditation and loving-kindness techniques, said the investigators. But because of participants’ past substance abuse and high rates of childhood trauma – including family violence, sexual assault, and emotional mistreatment – they struggled with the loving-kindness techniques that are typically used in MBSR courses, said Dr. Abatemarco. “Loving-kindness is difficult for those of us who have had adverse childhood exposure or trauma as a result of abuse and neglect,” she added. “We need to realize this and ensure that the program is trauma-informed, so that we come to kindness in different ways. “The researchers therefore introduced terms such as ‘caring for yourself,’ and ‘being gentle to yourself,’ and added loving-kindness practice only after participants had begun learning sitting meditation, she said.

Mothers said two techniques particularly helped them feel more compassion toward themselves, pay more attention to their children, and elicit their children’s cooperation more often, Dr. Abatemarco and her associates reported. These included the STOP practice – which is used in some MBSR courses and stands for “stop, take a breath, observe, proceed” – and the “settle your glitter” approach, in which participants filled a globe of water with three different colors of glitter to symbolize emotions, physical sensations, and thoughts, the investigators said. The mothers then carried the sealed globes around with them and, when stressed, shook them and watched the glitter settle, symbolizing the mental effects of breathing and allowing thoughts and sensations to pass, they reported. “Moms say that just looking at the globe after it is shaken reminds them that they can easily get to a place of peace and that better decisions are available to them,” added Dr. Abatemarco.

The investigators are planning another study to test the intervention’s effects on substance use, parenting, and childhood outcomes, said Dr. Abatemarco. They also are starting a mindfulness-based parenting and childbirth course for inner-city black women who are pregnant and at risk for preterm birth, she added.

The Children’s Bureau of the Administration for Children and Families funded the study. The researchers declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – A tailored version of the mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program benefited mothers in treatment for opioid addiction, according to a small qualitative analysis presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The intervention was the first in the United States to teach mindfulness-based parenting techniques to mothers with opioid addiction, lead investigator Diane J. Abatemarco, Ph.D., M.S.W., said in an interview.

“Mindfulness-based parenting is an effective method to enhance parenting, increase bonding and attachment, and reduce parental anxiety, stress, and reactivity,” added Dr. Abatemarco of the department of pediatrics and director of pediatric population health research at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children and Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Parents with substance-use disorders tend to suffer more stress than do other parents, and stress increases the risk of relapse among former users, Dr. Abatemarco and her associates noted. Mindfulness-based stress reduction – which focuses on compassion, nonjudgment, emotional awareness, and self-regulation – has been explored in studies of addiction and parenting, but rarely as combined approach for both stressors, said the researchers.

Therefore, they conducted a single-arm study of 34 mothers of infants or young children who were in outpatient treatment for opioid addiction, they said. Participants averaged 30 years of age, most were white and unmarried, and about half had a high school education or less, they reported.

As in traditional MBSR, the mothers attended 12 weekly group sessions to learn sitting meditation and loving-kindness techniques, said the investigators. But because of participants’ past substance abuse and high rates of childhood trauma – including family violence, sexual assault, and emotional mistreatment – they struggled with the loving-kindness techniques that are typically used in MBSR courses, said Dr. Abatemarco. “Loving-kindness is difficult for those of us who have had adverse childhood exposure or trauma as a result of abuse and neglect,” she added. “We need to realize this and ensure that the program is trauma-informed, so that we come to kindness in different ways. “The researchers therefore introduced terms such as ‘caring for yourself,’ and ‘being gentle to yourself,’ and added loving-kindness practice only after participants had begun learning sitting meditation, she said.

Mothers said two techniques particularly helped them feel more compassion toward themselves, pay more attention to their children, and elicit their children’s cooperation more often, Dr. Abatemarco and her associates reported. These included the STOP practice – which is used in some MBSR courses and stands for “stop, take a breath, observe, proceed” – and the “settle your glitter” approach, in which participants filled a globe of water with three different colors of glitter to symbolize emotions, physical sensations, and thoughts, the investigators said. The mothers then carried the sealed globes around with them and, when stressed, shook them and watched the glitter settle, symbolizing the mental effects of breathing and allowing thoughts and sensations to pass, they reported. “Moms say that just looking at the globe after it is shaken reminds them that they can easily get to a place of peace and that better decisions are available to them,” added Dr. Abatemarco.

The investigators are planning another study to test the intervention’s effects on substance use, parenting, and childhood outcomes, said Dr. Abatemarco. They also are starting a mindfulness-based parenting and childbirth course for inner-city black women who are pregnant and at risk for preterm birth, she added.

The Children’s Bureau of the Administration for Children and Families funded the study. The researchers declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – A tailored version of the mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program benefited mothers in treatment for opioid addiction, according to a small qualitative analysis presented at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

The intervention was the first in the United States to teach mindfulness-based parenting techniques to mothers with opioid addiction, lead investigator Diane J. Abatemarco, Ph.D., M.S.W., said in an interview.

“Mindfulness-based parenting is an effective method to enhance parenting, increase bonding and attachment, and reduce parental anxiety, stress, and reactivity,” added Dr. Abatemarco of the department of pediatrics and director of pediatric population health research at Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children and Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia.

Parents with substance-use disorders tend to suffer more stress than do other parents, and stress increases the risk of relapse among former users, Dr. Abatemarco and her associates noted. Mindfulness-based stress reduction – which focuses on compassion, nonjudgment, emotional awareness, and self-regulation – has been explored in studies of addiction and parenting, but rarely as combined approach for both stressors, said the researchers.

Therefore, they conducted a single-arm study of 34 mothers of infants or young children who were in outpatient treatment for opioid addiction, they said. Participants averaged 30 years of age, most were white and unmarried, and about half had a high school education or less, they reported.

As in traditional MBSR, the mothers attended 12 weekly group sessions to learn sitting meditation and loving-kindness techniques, said the investigators. But because of participants’ past substance abuse and high rates of childhood trauma – including family violence, sexual assault, and emotional mistreatment – they struggled with the loving-kindness techniques that are typically used in MBSR courses, said Dr. Abatemarco. “Loving-kindness is difficult for those of us who have had adverse childhood exposure or trauma as a result of abuse and neglect,” she added. “We need to realize this and ensure that the program is trauma-informed, so that we come to kindness in different ways. “The researchers therefore introduced terms such as ‘caring for yourself,’ and ‘being gentle to yourself,’ and added loving-kindness practice only after participants had begun learning sitting meditation, she said.

Mothers said two techniques particularly helped them feel more compassion toward themselves, pay more attention to their children, and elicit their children’s cooperation more often, Dr. Abatemarco and her associates reported. These included the STOP practice – which is used in some MBSR courses and stands for “stop, take a breath, observe, proceed” – and the “settle your glitter” approach, in which participants filled a globe of water with three different colors of glitter to symbolize emotions, physical sensations, and thoughts, the investigators said. The mothers then carried the sealed globes around with them and, when stressed, shook them and watched the glitter settle, symbolizing the mental effects of breathing and allowing thoughts and sensations to pass, they reported. “Moms say that just looking at the globe after it is shaken reminds them that they can easily get to a place of peace and that better decisions are available to them,” added Dr. Abatemarco.

The investigators are planning another study to test the intervention’s effects on substance use, parenting, and childhood outcomes, said Dr. Abatemarco. They also are starting a mindfulness-based parenting and childbirth course for inner-city black women who are pregnant and at risk for preterm birth, she added.

The Children’s Bureau of the Administration for Children and Families funded the study. The researchers declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

Key clinical point: An adapted version of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) benefited mothers in treatment for opioid addiction.

Major finding: Mothers reported improvements in children’s cooperative behaviors and their ability to pay attention to their children and be compassionate to themselves.

Data source: Single-arm qualitative study of 34 mothers in outpatient treatment for opioid addiction.

Disclosures: The Children’s Bureau of the Administration for Children and Families funded the study. The researchers declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

Prompt frenotomy can improve nursing for mom, baby

SAN DIEGO – Pediatricians should perform frenotomy to release tongue-tie if an affected baby is struggling to nurse and the mother reports breast pain and trauma as a result, according to Dr. Anthony Magit.

“There are so few problems with this procedure, and it works so well that there is really no excuse for not doing it when it’s indicated,” added Dr. James Murphy, a pediatrician and certified lactation consultant based in San Diego.

About 4% of babies are born with tongue-tie (or ankyloglossia), an anatomic variation in the frenulum that restricts the tongue’s movement. The condition impedes nursing and can later cause problems with speech articulation, particularly for languages such as Spanish that require a relatively high amount of tongue movement, said Dr. Magit, professor of surgery at the University of California, San Diego.

Babies with tongue-tie may latch poorly, chomp at the breast, fuss, or fall asleep while nursing, and fail to gain weight normally, Dr. Magit added. Their mothers tend to develop painful, engorged breasts, which increases their risk for mastitis and is a reason to perform frenotomy promptly, he said. “If frenotomy is performed early – at 1 or 2 days of age – you will see more rapid improvement, whereas if it’s done at 2-3 weeks old, the mom is less likely to have problems completely resolve,” Dr. Magit emphasized at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

If tongue-tie is suspected, a tongue depressor can be used to elevate the tongue and visualize the frenulum, said Dr. Magit. Tongue-tie appears as an unusually short, long, tight, or thickened frenulum (or frenum) that may be pyramidal, triangular, vertical, or even bumplike, Dr. Murphy added. The lateral edge of the tongue may form the shape of a W, V, or heart, and the baby’s lips may appear cobblestoned as a result of trauma during attempts to nurse, he said.

When Dr. Murphy suspects tongue-tie, he said he lays the baby on its back on an examining table with the shoulders slightly elevated on a blanket. Then he pulls the lower jaw gently down with both thumbs while using his palms to restrain the baby’s arms by the sides. This approach enables him to best see the frenulum and to observe the extent to which it is restricting the tongue’s movement, he added. An assistant uses the same hold technique when he performs frenotomies, Dr. Murphy added.

Frenotomy in newborns requires no anesthesia and can be performed in a nursery or office, said Dr. Magit. The infant is swaddled, a grooved retractor is used to direct the tongue toward the palate, the frenulum is clamped to create crush injury and direct the line of incision, and scissors are used to clip the frenulum within 1-2 mm of the junction of Wharton’s ducts, he said. After the procedure, the tongue is swept with a gloved finger and stretched to ensure complete release of the frenulum, Dr. Magit added. Most mothers report an immediate improvement in breastfeeding, including better latch, suction, and milk flow, he said.

Frenotomy in older infants and young children requires general anesthetic in the operating room, while children older than 5 years can undergo the procedure under local anesthetic in an office setting, Dr. Magit said. Complications after frenotomy are “extremely rare,” and include scarring or recurrent ankyloglossia and trauma to Wharton’s ducts, he added. Parents should be told that it is normal for yellow transitional tissue to develop at the wound site during healing, said Dr. Murphy.

Adults with tongue-tie also can benefit from frenotomy because the condition causes chronic tightness of muscles surrounding the tongue, said Dr. Murphy. “When you snip that fibrous band, the surrounding muscles relax, the hyoid bone goes down, and the larynx goes down,” he said. He has released frenula in adults and has had them report a dramatic improvement in sleep afterward, he noted.

Dr. Murphy and Dr. Magit declared no relevant financial conflicts.

SAN DIEGO – Pediatricians should perform frenotomy to release tongue-tie if an affected baby is struggling to nurse and the mother reports breast pain and trauma as a result, according to Dr. Anthony Magit.

“There are so few problems with this procedure, and it works so well that there is really no excuse for not doing it when it’s indicated,” added Dr. James Murphy, a pediatrician and certified lactation consultant based in San Diego.

About 4% of babies are born with tongue-tie (or ankyloglossia), an anatomic variation in the frenulum that restricts the tongue’s movement. The condition impedes nursing and can later cause problems with speech articulation, particularly for languages such as Spanish that require a relatively high amount of tongue movement, said Dr. Magit, professor of surgery at the University of California, San Diego.

Babies with tongue-tie may latch poorly, chomp at the breast, fuss, or fall asleep while nursing, and fail to gain weight normally, Dr. Magit added. Their mothers tend to develop painful, engorged breasts, which increases their risk for mastitis and is a reason to perform frenotomy promptly, he said. “If frenotomy is performed early – at 1 or 2 days of age – you will see more rapid improvement, whereas if it’s done at 2-3 weeks old, the mom is less likely to have problems completely resolve,” Dr. Magit emphasized at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

If tongue-tie is suspected, a tongue depressor can be used to elevate the tongue and visualize the frenulum, said Dr. Magit. Tongue-tie appears as an unusually short, long, tight, or thickened frenulum (or frenum) that may be pyramidal, triangular, vertical, or even bumplike, Dr. Murphy added. The lateral edge of the tongue may form the shape of a W, V, or heart, and the baby’s lips may appear cobblestoned as a result of trauma during attempts to nurse, he said.

When Dr. Murphy suspects tongue-tie, he said he lays the baby on its back on an examining table with the shoulders slightly elevated on a blanket. Then he pulls the lower jaw gently down with both thumbs while using his palms to restrain the baby’s arms by the sides. This approach enables him to best see the frenulum and to observe the extent to which it is restricting the tongue’s movement, he added. An assistant uses the same hold technique when he performs frenotomies, Dr. Murphy added.

Frenotomy in newborns requires no anesthesia and can be performed in a nursery or office, said Dr. Magit. The infant is swaddled, a grooved retractor is used to direct the tongue toward the palate, the frenulum is clamped to create crush injury and direct the line of incision, and scissors are used to clip the frenulum within 1-2 mm of the junction of Wharton’s ducts, he said. After the procedure, the tongue is swept with a gloved finger and stretched to ensure complete release of the frenulum, Dr. Magit added. Most mothers report an immediate improvement in breastfeeding, including better latch, suction, and milk flow, he said.

Frenotomy in older infants and young children requires general anesthetic in the operating room, while children older than 5 years can undergo the procedure under local anesthetic in an office setting, Dr. Magit said. Complications after frenotomy are “extremely rare,” and include scarring or recurrent ankyloglossia and trauma to Wharton’s ducts, he added. Parents should be told that it is normal for yellow transitional tissue to develop at the wound site during healing, said Dr. Murphy.

Adults with tongue-tie also can benefit from frenotomy because the condition causes chronic tightness of muscles surrounding the tongue, said Dr. Murphy. “When you snip that fibrous band, the surrounding muscles relax, the hyoid bone goes down, and the larynx goes down,” he said. He has released frenula in adults and has had them report a dramatic improvement in sleep afterward, he noted.

Dr. Murphy and Dr. Magit declared no relevant financial conflicts.

SAN DIEGO – Pediatricians should perform frenotomy to release tongue-tie if an affected baby is struggling to nurse and the mother reports breast pain and trauma as a result, according to Dr. Anthony Magit.

“There are so few problems with this procedure, and it works so well that there is really no excuse for not doing it when it’s indicated,” added Dr. James Murphy, a pediatrician and certified lactation consultant based in San Diego.

About 4% of babies are born with tongue-tie (or ankyloglossia), an anatomic variation in the frenulum that restricts the tongue’s movement. The condition impedes nursing and can later cause problems with speech articulation, particularly for languages such as Spanish that require a relatively high amount of tongue movement, said Dr. Magit, professor of surgery at the University of California, San Diego.

Babies with tongue-tie may latch poorly, chomp at the breast, fuss, or fall asleep while nursing, and fail to gain weight normally, Dr. Magit added. Their mothers tend to develop painful, engorged breasts, which increases their risk for mastitis and is a reason to perform frenotomy promptly, he said. “If frenotomy is performed early – at 1 or 2 days of age – you will see more rapid improvement, whereas if it’s done at 2-3 weeks old, the mom is less likely to have problems completely resolve,” Dr. Magit emphasized at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

If tongue-tie is suspected, a tongue depressor can be used to elevate the tongue and visualize the frenulum, said Dr. Magit. Tongue-tie appears as an unusually short, long, tight, or thickened frenulum (or frenum) that may be pyramidal, triangular, vertical, or even bumplike, Dr. Murphy added. The lateral edge of the tongue may form the shape of a W, V, or heart, and the baby’s lips may appear cobblestoned as a result of trauma during attempts to nurse, he said.

When Dr. Murphy suspects tongue-tie, he said he lays the baby on its back on an examining table with the shoulders slightly elevated on a blanket. Then he pulls the lower jaw gently down with both thumbs while using his palms to restrain the baby’s arms by the sides. This approach enables him to best see the frenulum and to observe the extent to which it is restricting the tongue’s movement, he added. An assistant uses the same hold technique when he performs frenotomies, Dr. Murphy added.

Frenotomy in newborns requires no anesthesia and can be performed in a nursery or office, said Dr. Magit. The infant is swaddled, a grooved retractor is used to direct the tongue toward the palate, the frenulum is clamped to create crush injury and direct the line of incision, and scissors are used to clip the frenulum within 1-2 mm of the junction of Wharton’s ducts, he said. After the procedure, the tongue is swept with a gloved finger and stretched to ensure complete release of the frenulum, Dr. Magit added. Most mothers report an immediate improvement in breastfeeding, including better latch, suction, and milk flow, he said.

Frenotomy in older infants and young children requires general anesthetic in the operating room, while children older than 5 years can undergo the procedure under local anesthetic in an office setting, Dr. Magit said. Complications after frenotomy are “extremely rare,” and include scarring or recurrent ankyloglossia and trauma to Wharton’s ducts, he added. Parents should be told that it is normal for yellow transitional tissue to develop at the wound site during healing, said Dr. Murphy.

Adults with tongue-tie also can benefit from frenotomy because the condition causes chronic tightness of muscles surrounding the tongue, said Dr. Murphy. “When you snip that fibrous band, the surrounding muscles relax, the hyoid bone goes down, and the larynx goes down,” he said. He has released frenula in adults and has had them report a dramatic improvement in sleep afterward, he noted.

Dr. Murphy and Dr. Magit declared no relevant financial conflicts.

How to know when a recurrent infection signals something more

SAN DIEGO – Children who parents describe as “always sick” often are immunologically normal, but knowing when to suspect otherwise is crucial, according to Dr. Meg Fisher.

“When parents tell you their child is sick all the time, they are. They’re literally just recovering from one thing when they pick up the next,” said Dr. Fisher, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Monmouth Medical Center in West Orange, N.J.

Children under 2 years of age typically acquire 4-10 symptomatic respiratory infections per year – and up to 13 if they are in day care, Dr. Fisher said. These children also normally develop one to four gastrointestinal infections per year, she added. And children older than 2 years average four to eight respiratory infections and up to two gastrointestinal infections annually, she said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics .

Certain types of infections always merit a closer look, Dr. Fisher emphasized. Invasive infections, recurrent meningitis, excessive episodes of respiratory disease, chronic diarrhea, recurrent urinary tract infections, and recurrent skin and soft tissue infections can indicate immunodeficient disorders, inherited diseases such as cystic fibrosis, or anatomic abnormalities that predispose children to serious infections, she said. “The site of recurrent infections is really going to help you determine which subspecialist you need,” she added.

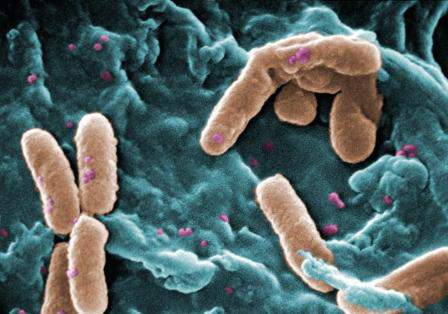

Culture results also provide clues about underlying conditions. “If you ever recover Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the respiratory tract of a child, you should automatically think about cystic fibrosis,” Dr. Fisher said. Pseudomonas is often isolated from stool samples, but is not normally found in a child’s respiratory tract, she explained.

“Unusual organisms and abnormal laboratory results should always trigger a follow-up evaluation,” Dr. Stuart Abramson said in a related presentation. The most common primary immunodeficiency disorders include selective IgA deficiency – which affects 1 in 500 children – IgG2deficiency, transient hypogammaglobulinemia of infancy, and DiGeorge anomaly, said Dr. Abramson, who is director of allergy and immunology services at Shannon Medical Center in San Angelo, Tex. Less common primary immunodeficiencies affect 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 200,000 children and include B-cell disorders, T-cell disorders, phagocytic disorders, and complement disorders, he said at the meeting.

Of the four stages of testing for primary immunodeficiencies, only the first stage needs to be done by the primary care pediatrician; testing at the first stage includes taking a history and physical examination, complete blood count and differential, and quantitative immunoglobulin levels for IgA, IgG, and IgM, said Dr. Fisher. A child who needs further testing “might be better served by an immunologist,” she added.

Pediatricians should consider first-stage testing if a patient presents with one or more warning signs of a primary immunodeficiency in children, Dr. Abramson said.

Those warning signs are:

• Four or more new ear infections within 1 year.

• Two or more serious sinus infections within 1 year.

• Two or more months on antibiotics with little effect.

• Two or more pneumonias within 1 year.

• Failure of an infant to gain weight or grow normally.

• Recurrent, deep abscesses of the skin or organs.

• Persistent oral thrush or cutaneous mycoses.

• Need for intravenous antibiotics to clear infections.

• Two or more deep-seated infections, including septicemia.

• A family history of primary immunodeficiency.

(This list was assembled by the Jeffrey Modell Foundation.)

Dr. Fisher and Dr. Abramson declared no relevant financial relationships.

SAN DIEGO – Children who parents describe as “always sick” often are immunologically normal, but knowing when to suspect otherwise is crucial, according to Dr. Meg Fisher.

“When parents tell you their child is sick all the time, they are. They’re literally just recovering from one thing when they pick up the next,” said Dr. Fisher, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Monmouth Medical Center in West Orange, N.J.

Children under 2 years of age typically acquire 4-10 symptomatic respiratory infections per year – and up to 13 if they are in day care, Dr. Fisher said. These children also normally develop one to four gastrointestinal infections per year, she added. And children older than 2 years average four to eight respiratory infections and up to two gastrointestinal infections annually, she said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics .

Certain types of infections always merit a closer look, Dr. Fisher emphasized. Invasive infections, recurrent meningitis, excessive episodes of respiratory disease, chronic diarrhea, recurrent urinary tract infections, and recurrent skin and soft tissue infections can indicate immunodeficient disorders, inherited diseases such as cystic fibrosis, or anatomic abnormalities that predispose children to serious infections, she said. “The site of recurrent infections is really going to help you determine which subspecialist you need,” she added.

Culture results also provide clues about underlying conditions. “If you ever recover Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the respiratory tract of a child, you should automatically think about cystic fibrosis,” Dr. Fisher said. Pseudomonas is often isolated from stool samples, but is not normally found in a child’s respiratory tract, she explained.

“Unusual organisms and abnormal laboratory results should always trigger a follow-up evaluation,” Dr. Stuart Abramson said in a related presentation. The most common primary immunodeficiency disorders include selective IgA deficiency – which affects 1 in 500 children – IgG2deficiency, transient hypogammaglobulinemia of infancy, and DiGeorge anomaly, said Dr. Abramson, who is director of allergy and immunology services at Shannon Medical Center in San Angelo, Tex. Less common primary immunodeficiencies affect 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 200,000 children and include B-cell disorders, T-cell disorders, phagocytic disorders, and complement disorders, he said at the meeting.

Of the four stages of testing for primary immunodeficiencies, only the first stage needs to be done by the primary care pediatrician; testing at the first stage includes taking a history and physical examination, complete blood count and differential, and quantitative immunoglobulin levels for IgA, IgG, and IgM, said Dr. Fisher. A child who needs further testing “might be better served by an immunologist,” she added.

Pediatricians should consider first-stage testing if a patient presents with one or more warning signs of a primary immunodeficiency in children, Dr. Abramson said.

Those warning signs are:

• Four or more new ear infections within 1 year.

• Two or more serious sinus infections within 1 year.

• Two or more months on antibiotics with little effect.

• Two or more pneumonias within 1 year.

• Failure of an infant to gain weight or grow normally.

• Recurrent, deep abscesses of the skin or organs.

• Persistent oral thrush or cutaneous mycoses.

• Need for intravenous antibiotics to clear infections.

• Two or more deep-seated infections, including septicemia.

• A family history of primary immunodeficiency.

(This list was assembled by the Jeffrey Modell Foundation.)

Dr. Fisher and Dr. Abramson declared no relevant financial relationships.

SAN DIEGO – Children who parents describe as “always sick” often are immunologically normal, but knowing when to suspect otherwise is crucial, according to Dr. Meg Fisher.

“When parents tell you their child is sick all the time, they are. They’re literally just recovering from one thing when they pick up the next,” said Dr. Fisher, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at Monmouth Medical Center in West Orange, N.J.

Children under 2 years of age typically acquire 4-10 symptomatic respiratory infections per year – and up to 13 if they are in day care, Dr. Fisher said. These children also normally develop one to four gastrointestinal infections per year, she added. And children older than 2 years average four to eight respiratory infections and up to two gastrointestinal infections annually, she said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics .

Certain types of infections always merit a closer look, Dr. Fisher emphasized. Invasive infections, recurrent meningitis, excessive episodes of respiratory disease, chronic diarrhea, recurrent urinary tract infections, and recurrent skin and soft tissue infections can indicate immunodeficient disorders, inherited diseases such as cystic fibrosis, or anatomic abnormalities that predispose children to serious infections, she said. “The site of recurrent infections is really going to help you determine which subspecialist you need,” she added.

Culture results also provide clues about underlying conditions. “If you ever recover Pseudomonas aeruginosa from the respiratory tract of a child, you should automatically think about cystic fibrosis,” Dr. Fisher said. Pseudomonas is often isolated from stool samples, but is not normally found in a child’s respiratory tract, she explained.

“Unusual organisms and abnormal laboratory results should always trigger a follow-up evaluation,” Dr. Stuart Abramson said in a related presentation. The most common primary immunodeficiency disorders include selective IgA deficiency – which affects 1 in 500 children – IgG2deficiency, transient hypogammaglobulinemia of infancy, and DiGeorge anomaly, said Dr. Abramson, who is director of allergy and immunology services at Shannon Medical Center in San Angelo, Tex. Less common primary immunodeficiencies affect 1 in 50,000 to 1 in 200,000 children and include B-cell disorders, T-cell disorders, phagocytic disorders, and complement disorders, he said at the meeting.

Of the four stages of testing for primary immunodeficiencies, only the first stage needs to be done by the primary care pediatrician; testing at the first stage includes taking a history and physical examination, complete blood count and differential, and quantitative immunoglobulin levels for IgA, IgG, and IgM, said Dr. Fisher. A child who needs further testing “might be better served by an immunologist,” she added.

Pediatricians should consider first-stage testing if a patient presents with one or more warning signs of a primary immunodeficiency in children, Dr. Abramson said.

Those warning signs are:

• Four or more new ear infections within 1 year.

• Two or more serious sinus infections within 1 year.

• Two or more months on antibiotics with little effect.

• Two or more pneumonias within 1 year.

• Failure of an infant to gain weight or grow normally.

• Recurrent, deep abscesses of the skin or organs.

• Persistent oral thrush or cutaneous mycoses.

• Need for intravenous antibiotics to clear infections.

• Two or more deep-seated infections, including septicemia.

• A family history of primary immunodeficiency.

(This list was assembled by the Jeffrey Modell Foundation.)

Dr. Fisher and Dr. Abramson declared no relevant financial relationships.

How and when to screen for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

SAN DIEGO – Pediatricians should screen patients for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy if a first- or second-degree relative has been diagnosed with the condition or has a history of sudden death, said Dr. Kevin Shannon, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center.

“Anybody with a family history of HCM, including uncles, cousins, parents, and siblings, should be screened,” he emphasized. “Even if they don’t have obstructive HCM, they will often have a murmur, most commonly at the upper sternal border.” The murmur is typically late-peaking and worsens during Valsalva, he added.

HCM is the most common cause of sudden death in athletes and is the most common genetic cardiac disease, affecting about 1 in 500 young adults (Circulation 1995;92:785-9). The autosomal dominant inheritance pattern shows varying degrees of penetrance, translating to a range of phenotypes, Dr. Shannon said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Even if your family member didn’t have hypertrophy until age 30, you can get it at age 5, and the opposite can also be true,” he noted.

HCM can be a silent disease until it causes sudden death. However, pediatricians should ask patients about exercise tolerance and should consider HCM in patients who describe a substantial drop in sports performance, Dr. Shannon said. An athlete with HCM might say that he or she always finished the field lap first and is now second to last, and a soccer player with a field position might say, “Now I finish the runs after the goalies,” he said.

A resting electrocardiogram is not sufficient to exclude HCM, Dr. Shannon emphasized. Because up to 10% of patients with HCM have normal ECGs, children whose parents or grandparents have HCM should have an echocardiogram every 5 years until puberty, and then every year until they turn 20 years old or finish growing, he said. But ECGs also are important because they may become abnormal before the echocardiogram does, Dr. Shannon said. If the ECG becomes abnormal, pediatricians should tell parents that the echocardiogram is likely to become abnormal and should advise them to steer the child away from competitive athletics, he said.

Twenty-four hour ambulatory (Holter) ECGs also are part of risk stratification in patients with HCM, Dr. Shannon said. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association recommend Holter monitoring for the initial evaluation of patients with HCM and for patients with HCM who develop palpitations or lightheadedness (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;58:2703-38).

Dr. Shannon reported no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Pediatricians should screen patients for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy if a first- or second-degree relative has been diagnosed with the condition or has a history of sudden death, said Dr. Kevin Shannon, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center.

“Anybody with a family history of HCM, including uncles, cousins, parents, and siblings, should be screened,” he emphasized. “Even if they don’t have obstructive HCM, they will often have a murmur, most commonly at the upper sternal border.” The murmur is typically late-peaking and worsens during Valsalva, he added.

HCM is the most common cause of sudden death in athletes and is the most common genetic cardiac disease, affecting about 1 in 500 young adults (Circulation 1995;92:785-9). The autosomal dominant inheritance pattern shows varying degrees of penetrance, translating to a range of phenotypes, Dr. Shannon said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Even if your family member didn’t have hypertrophy until age 30, you can get it at age 5, and the opposite can also be true,” he noted.

HCM can be a silent disease until it causes sudden death. However, pediatricians should ask patients about exercise tolerance and should consider HCM in patients who describe a substantial drop in sports performance, Dr. Shannon said. An athlete with HCM might say that he or she always finished the field lap first and is now second to last, and a soccer player with a field position might say, “Now I finish the runs after the goalies,” he said.

A resting electrocardiogram is not sufficient to exclude HCM, Dr. Shannon emphasized. Because up to 10% of patients with HCM have normal ECGs, children whose parents or grandparents have HCM should have an echocardiogram every 5 years until puberty, and then every year until they turn 20 years old or finish growing, he said. But ECGs also are important because they may become abnormal before the echocardiogram does, Dr. Shannon said. If the ECG becomes abnormal, pediatricians should tell parents that the echocardiogram is likely to become abnormal and should advise them to steer the child away from competitive athletics, he said.

Twenty-four hour ambulatory (Holter) ECGs also are part of risk stratification in patients with HCM, Dr. Shannon said. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association recommend Holter monitoring for the initial evaluation of patients with HCM and for patients with HCM who develop palpitations or lightheadedness (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;58:2703-38).

Dr. Shannon reported no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO – Pediatricians should screen patients for hypertrophic cardiomyopathy if a first- or second-degree relative has been diagnosed with the condition or has a history of sudden death, said Dr. Kevin Shannon, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center.

“Anybody with a family history of HCM, including uncles, cousins, parents, and siblings, should be screened,” he emphasized. “Even if they don’t have obstructive HCM, they will often have a murmur, most commonly at the upper sternal border.” The murmur is typically late-peaking and worsens during Valsalva, he added.

HCM is the most common cause of sudden death in athletes and is the most common genetic cardiac disease, affecting about 1 in 500 young adults (Circulation 1995;92:785-9). The autosomal dominant inheritance pattern shows varying degrees of penetrance, translating to a range of phenotypes, Dr. Shannon said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Even if your family member didn’t have hypertrophy until age 30, you can get it at age 5, and the opposite can also be true,” he noted.

HCM can be a silent disease until it causes sudden death. However, pediatricians should ask patients about exercise tolerance and should consider HCM in patients who describe a substantial drop in sports performance, Dr. Shannon said. An athlete with HCM might say that he or she always finished the field lap first and is now second to last, and a soccer player with a field position might say, “Now I finish the runs after the goalies,” he said.

A resting electrocardiogram is not sufficient to exclude HCM, Dr. Shannon emphasized. Because up to 10% of patients with HCM have normal ECGs, children whose parents or grandparents have HCM should have an echocardiogram every 5 years until puberty, and then every year until they turn 20 years old or finish growing, he said. But ECGs also are important because they may become abnormal before the echocardiogram does, Dr. Shannon said. If the ECG becomes abnormal, pediatricians should tell parents that the echocardiogram is likely to become abnormal and should advise them to steer the child away from competitive athletics, he said.

Twenty-four hour ambulatory (Holter) ECGs also are part of risk stratification in patients with HCM, Dr. Shannon said. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association recommend Holter monitoring for the initial evaluation of patients with HCM and for patients with HCM who develop palpitations or lightheadedness (J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011;58:2703-38).

Dr. Shannon reported no conflicts of interest.

Avoid misdiagnosing pediatric viral myocarditis

SAN DIEGO– Pediatricians are at risk of misdiagnosing myocarditis despite its severity. That’s because children tend to present with abdominal symptoms and a history of a recent viral illness that lacked signs of cardiac involvement, Dr. Kevin Shannon said.

“Typically, they have a bout of flu, they seem to be getting better, and then they start vomiting or having stomach pain again,” he said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Viruses ranging from adenovirus to varicella have been implicated in myocarditis in children (J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:642-5; Pediatr. Cardiol. 2011;32:1241-3). Pediatricians should watch for patients who were recently ill and are now presenting with an apparent relapse and tachycardia that is worse than how they appear overall, said Dr. Shannon, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center. “A lot of these children will seem more ill than their vomiting will suggest,” he added. “They’ll have a heart rate of 180 [beats per minute] that is out proportion to how they look.”

Fluid therapy does not improve tachycardia and may even worsen it, indicating that dehydration is not the underlying cause, said Dr. Shannon. Children with viral myocarditis also often have acute upper-right quadrant pain as a result of hepatic distension, he said.

Laboratory findings can be very helpful. Cardiac troponin T is almost always elevated in children with myocarditis (Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2012;28:1173-8), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate also may be high. Electrocardiography can show a variety of focal or diffuse abnormalities, none of which are pathognomonic for the condition, Dr. Shannon said. Focal abnormalities can mimic an ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), he added.

On chest x-ray, the heart margins also are often normal because the heart has not yet enlarged to compensate for impaired function, said Dr. Shannon. “This is a poorly functioning, normal-sized heart,” he added. Chest films often will reveal interstitial edema that might be misinterpreted as interstitial pneumonia, in keeping with the child’s recent illness.

Treatment of acquired myocarditis is based on supportive care, said Dr. Shannon, adding that use of immunomodulators in children with myocarditis is controversial. “If they have low blood pressure, they need volume, even if their heart rate gets higher,” he added. “If they don’t tolerate fluid therapy, they need inotropes and sometimes intubation.”

Dr. Shannon reported no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO– Pediatricians are at risk of misdiagnosing myocarditis despite its severity. That’s because children tend to present with abdominal symptoms and a history of a recent viral illness that lacked signs of cardiac involvement, Dr. Kevin Shannon said.

“Typically, they have a bout of flu, they seem to be getting better, and then they start vomiting or having stomach pain again,” he said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Viruses ranging from adenovirus to varicella have been implicated in myocarditis in children (J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:642-5; Pediatr. Cardiol. 2011;32:1241-3). Pediatricians should watch for patients who were recently ill and are now presenting with an apparent relapse and tachycardia that is worse than how they appear overall, said Dr. Shannon, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center. “A lot of these children will seem more ill than their vomiting will suggest,” he added. “They’ll have a heart rate of 180 [beats per minute] that is out proportion to how they look.”

Fluid therapy does not improve tachycardia and may even worsen it, indicating that dehydration is not the underlying cause, said Dr. Shannon. Children with viral myocarditis also often have acute upper-right quadrant pain as a result of hepatic distension, he said.

Laboratory findings can be very helpful. Cardiac troponin T is almost always elevated in children with myocarditis (Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2012;28:1173-8), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate also may be high. Electrocardiography can show a variety of focal or diffuse abnormalities, none of which are pathognomonic for the condition, Dr. Shannon said. Focal abnormalities can mimic an ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), he added.

On chest x-ray, the heart margins also are often normal because the heart has not yet enlarged to compensate for impaired function, said Dr. Shannon. “This is a poorly functioning, normal-sized heart,” he added. Chest films often will reveal interstitial edema that might be misinterpreted as interstitial pneumonia, in keeping with the child’s recent illness.

Treatment of acquired myocarditis is based on supportive care, said Dr. Shannon, adding that use of immunomodulators in children with myocarditis is controversial. “If they have low blood pressure, they need volume, even if their heart rate gets higher,” he added. “If they don’t tolerate fluid therapy, they need inotropes and sometimes intubation.”

Dr. Shannon reported no conflicts of interest.

SAN DIEGO– Pediatricians are at risk of misdiagnosing myocarditis despite its severity. That’s because children tend to present with abdominal symptoms and a history of a recent viral illness that lacked signs of cardiac involvement, Dr. Kevin Shannon said.

“Typically, they have a bout of flu, they seem to be getting better, and then they start vomiting or having stomach pain again,” he said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Viruses ranging from adenovirus to varicella have been implicated in myocarditis in children (J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010;48:642-5; Pediatr. Cardiol. 2011;32:1241-3). Pediatricians should watch for patients who were recently ill and are now presenting with an apparent relapse and tachycardia that is worse than how they appear overall, said Dr. Shannon, a pediatric cardiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, Medical Center. “A lot of these children will seem more ill than their vomiting will suggest,” he added. “They’ll have a heart rate of 180 [beats per minute] that is out proportion to how they look.”

Fluid therapy does not improve tachycardia and may even worsen it, indicating that dehydration is not the underlying cause, said Dr. Shannon. Children with viral myocarditis also often have acute upper-right quadrant pain as a result of hepatic distension, he said.

Laboratory findings can be very helpful. Cardiac troponin T is almost always elevated in children with myocarditis (Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2012;28:1173-8), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate also may be high. Electrocardiography can show a variety of focal or diffuse abnormalities, none of which are pathognomonic for the condition, Dr. Shannon said. Focal abnormalities can mimic an ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), he added.

On chest x-ray, the heart margins also are often normal because the heart has not yet enlarged to compensate for impaired function, said Dr. Shannon. “This is a poorly functioning, normal-sized heart,” he added. Chest films often will reveal interstitial edema that might be misinterpreted as interstitial pneumonia, in keeping with the child’s recent illness.

Treatment of acquired myocarditis is based on supportive care, said Dr. Shannon, adding that use of immunomodulators in children with myocarditis is controversial. “If they have low blood pressure, they need volume, even if their heart rate gets higher,” he added. “If they don’t tolerate fluid therapy, they need inotropes and sometimes intubation.”

Dr. Shannon reported no conflicts of interest.

Survey: Pediatric hospitalists are treating more acutely ill children

SAN DIEGO – Pediatric hospitalists are treating a greater proportion of acutely ill children than ever before, results from the largest and most up-to-date national survey suggests.

“What we’re seeing is that our colleagues in ambulatory medicine are treating a large swath of patients that used to spend 1, 2, 3, or even more days in the hospital,” Dr. Erin Stucky Fisher said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Given that those patients are no longer being hospitalized, and given that our emergency room colleagues stabilize and discharge yet another group of ill patients, patients who are admitted require a higher level of acute care thinking. More often the skill sets required for hospital medicine will require clinicians to be able to care for patients that require multiple visits daily and acute care decision making 24/7.”

In an effort to describe current pediatric hospitalist work trends, Dr. Fisher and her associates sent a survey to 1,260 members of the AAP’s Section of Hospital Medicine during the winter of 2012-2013. A total of 542 completed the survey for a response rate of 43%, making it the largest cohort of pediatric hospitalists surveyed to date. Of these, 64% were female and 85% were white.

Slightly more than half of respondents (51%) reported working 6-7 or 8-14 consecutive days when on service, with 57% spending 40-60 hours of on-site time per service week, and 28% spending more than 60 hours. Fewer than half (43%) provide 24/7 in-house coverage, 34% take call from home, and 23% use a hybrid model for after-hours coverage.

Nearly all respondents (97%) cover general pediatric units, and 49% consult in emergency medicine departments. Other common areas of coverage include the observation unit (36%), well baby nursery (34%), intermediate care/step-down unit (27%), and the pediatric intensive care unit (9%).

More than two-third of respondents (43%) routinely comanage surgery patients, 23% provide consultation to surgery patients, and nearly one-third (29%) participate in rapid response teams. In addition, 21% provide a sedation service and 11% provide a diagnostic referral service. While only 6% currently provide patient emergency transport, this is of interest as a partnership opportunity with critical care colleagues.

The most common procedure performed by respondents are lumbar puncture (88%), followed by arterial puncture (29%), intubation of children without teeth (29%), venipuncture (28%), peripheral IV placement (26%), and bladder catheterization (20%).

Findings “not surprising but notable – as the field has evolved – are that there is increasing provision of critical care and emergency level services,” said Dr. Fisher, a pediatric hospitalist at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. “This reflects both the need for these services and a fact reported in other studies on hospitalized patients over the years: In all hospital settings, patients that are admitted – particularly children – are sicker. Many leaders and clinicians in hospital settings state that hospitals are or soon will be in essence a high-end critical care ICU, a step-down ICU, and an emergency department. Nowadays there are fewer patients admitted who are what would be considered standard ward patients. For community sites that’s particularly telling, because hospitalists in those settings are having to care for many sicker patients because there aren’t [enough] critical care physicians available in those environments.”

The study’s lead author is Dr. Daniel A. Rauch, a pediatrician based in Elmhurst, N.Y. Dr. Fisher reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

SAN DIEGO – Pediatric hospitalists are treating a greater proportion of acutely ill children than ever before, results from the largest and most up-to-date national survey suggests.

“What we’re seeing is that our colleagues in ambulatory medicine are treating a large swath of patients that used to spend 1, 2, 3, or even more days in the hospital,” Dr. Erin Stucky Fisher said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Given that those patients are no longer being hospitalized, and given that our emergency room colleagues stabilize and discharge yet another group of ill patients, patients who are admitted require a higher level of acute care thinking. More often the skill sets required for hospital medicine will require clinicians to be able to care for patients that require multiple visits daily and acute care decision making 24/7.”

In an effort to describe current pediatric hospitalist work trends, Dr. Fisher and her associates sent a survey to 1,260 members of the AAP’s Section of Hospital Medicine during the winter of 2012-2013. A total of 542 completed the survey for a response rate of 43%, making it the largest cohort of pediatric hospitalists surveyed to date. Of these, 64% were female and 85% were white.

Slightly more than half of respondents (51%) reported working 6-7 or 8-14 consecutive days when on service, with 57% spending 40-60 hours of on-site time per service week, and 28% spending more than 60 hours. Fewer than half (43%) provide 24/7 in-house coverage, 34% take call from home, and 23% use a hybrid model for after-hours coverage.

Nearly all respondents (97%) cover general pediatric units, and 49% consult in emergency medicine departments. Other common areas of coverage include the observation unit (36%), well baby nursery (34%), intermediate care/step-down unit (27%), and the pediatric intensive care unit (9%).

More than two-third of respondents (43%) routinely comanage surgery patients, 23% provide consultation to surgery patients, and nearly one-third (29%) participate in rapid response teams. In addition, 21% provide a sedation service and 11% provide a diagnostic referral service. While only 6% currently provide patient emergency transport, this is of interest as a partnership opportunity with critical care colleagues.

The most common procedure performed by respondents are lumbar puncture (88%), followed by arterial puncture (29%), intubation of children without teeth (29%), venipuncture (28%), peripheral IV placement (26%), and bladder catheterization (20%).

Findings “not surprising but notable – as the field has evolved – are that there is increasing provision of critical care and emergency level services,” said Dr. Fisher, a pediatric hospitalist at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. “This reflects both the need for these services and a fact reported in other studies on hospitalized patients over the years: In all hospital settings, patients that are admitted – particularly children – are sicker. Many leaders and clinicians in hospital settings state that hospitals are or soon will be in essence a high-end critical care ICU, a step-down ICU, and an emergency department. Nowadays there are fewer patients admitted who are what would be considered standard ward patients. For community sites that’s particularly telling, because hospitalists in those settings are having to care for many sicker patients because there aren’t [enough] critical care physicians available in those environments.”

The study’s lead author is Dr. Daniel A. Rauch, a pediatrician based in Elmhurst, N.Y. Dr. Fisher reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

SAN DIEGO – Pediatric hospitalists are treating a greater proportion of acutely ill children than ever before, results from the largest and most up-to-date national survey suggests.

“What we’re seeing is that our colleagues in ambulatory medicine are treating a large swath of patients that used to spend 1, 2, 3, or even more days in the hospital,” Dr. Erin Stucky Fisher said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Given that those patients are no longer being hospitalized, and given that our emergency room colleagues stabilize and discharge yet another group of ill patients, patients who are admitted require a higher level of acute care thinking. More often the skill sets required for hospital medicine will require clinicians to be able to care for patients that require multiple visits daily and acute care decision making 24/7.”

In an effort to describe current pediatric hospitalist work trends, Dr. Fisher and her associates sent a survey to 1,260 members of the AAP’s Section of Hospital Medicine during the winter of 2012-2013. A total of 542 completed the survey for a response rate of 43%, making it the largest cohort of pediatric hospitalists surveyed to date. Of these, 64% were female and 85% were white.

Slightly more than half of respondents (51%) reported working 6-7 or 8-14 consecutive days when on service, with 57% spending 40-60 hours of on-site time per service week, and 28% spending more than 60 hours. Fewer than half (43%) provide 24/7 in-house coverage, 34% take call from home, and 23% use a hybrid model for after-hours coverage.

Nearly all respondents (97%) cover general pediatric units, and 49% consult in emergency medicine departments. Other common areas of coverage include the observation unit (36%), well baby nursery (34%), intermediate care/step-down unit (27%), and the pediatric intensive care unit (9%).

More than two-third of respondents (43%) routinely comanage surgery patients, 23% provide consultation to surgery patients, and nearly one-third (29%) participate in rapid response teams. In addition, 21% provide a sedation service and 11% provide a diagnostic referral service. While only 6% currently provide patient emergency transport, this is of interest as a partnership opportunity with critical care colleagues.

The most common procedure performed by respondents are lumbar puncture (88%), followed by arterial puncture (29%), intubation of children without teeth (29%), venipuncture (28%), peripheral IV placement (26%), and bladder catheterization (20%).

Findings “not surprising but notable – as the field has evolved – are that there is increasing provision of critical care and emergency level services,” said Dr. Fisher, a pediatric hospitalist at Rady Children’s Hospital–San Diego and professor of clinical pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego. “This reflects both the need for these services and a fact reported in other studies on hospitalized patients over the years: In all hospital settings, patients that are admitted – particularly children – are sicker. Many leaders and clinicians in hospital settings state that hospitals are or soon will be in essence a high-end critical care ICU, a step-down ICU, and an emergency department. Nowadays there are fewer patients admitted who are what would be considered standard ward patients. For community sites that’s particularly telling, because hospitalists in those settings are having to care for many sicker patients because there aren’t [enough] critical care physicians available in those environments.”

The study’s lead author is Dr. Daniel A. Rauch, a pediatrician based in Elmhurst, N.Y. Dr. Fisher reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

AT THE AAP NATIONAL CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Pediatric hospitalists are treating more acutely ill children than ever before.

Major finding: Nearly half of pediatric hospitalists (49%) consult in emergency medicine departments, 43% routinely comanage surgery patients, 23% provide consultation to surgery patients, and nearly one-third (29%) participate in rapid response teams.

Data source: Responses from a survey sent to 1,260 members of the AAP’s Section of Hospital Medicine during the winter of 2012-2013.

Disclosures: Dr. Fisher reported having no financial disclosures.

Animal-related trauma: No small impact on kids

SAN DIEGO – Animal-related trauma is a significant cause of morbidity and occasional mortality, results from a 10-year, single-center study showed.

Nearly half of the injuries required operative intervention and injury patterns varied according to gender, race, and the type of animal involved, Dr. Jason W. Nielsen said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In an effort to investigate pediatric animal-related trauma to compare injury patterns and guide prevention efforts, Dr. Nielsen and his associates performed a retrospective analysis of patients aged 18 years and younger who were admitted to Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, with ICD-9 external cause of injury codes for animal trauma from 2004 to 2013. Of the 14,605 trauma admissions during that decade, 565 (3.9%) were animal related.

Children admitted with other forms of trauma (the baseline group) were similar in age to those admitted with animal-related trauma (a mean of 7.8 years vs. 7.2 years, respectively). However, males predominated in the baseline trauma group (62.8% vs. 37.2% female), while the genders were more balanced in the animal-related trauma group (48.7% male vs. 51.3% female). Racial differences appear to be amplified in the animal trauma group (80.9% white, 6.9% African American, and 12.2% other vs. 72.9% white, 16.3% African American, and 18.8% other in the baseline group). There were two deaths over the 10-year period (0.35%). One was dog-related involving an infant. The other involved an unhelmeted rider on a horse who suffered a devastating head injury.

The mean Injury Severity Score among patients in the animal-related trauma group was 3.6 and their mean hospital stay was 1.98 days, yet nearly half (48.5%) required operations. After presenting to the emergency department, two-thirds (66%) went to the floor, 28.5% went to the operating room, and just 5.5% went to the pediatric intensive care unit.

Most injuries involved dogs (340 cases or 60%) and horses (155 cases or 27%). Dog injuries were more common among boys, compared with girls (57.2% vs. 42.8%, respectively; P< .001), and the most common sites of injury were the face (52%) and the extremities (31%), with 59.7% of cases requiring an operative procedure. The dog breed was reported in 65.3% of cases, of which pit bulls were the majority (25.2%), followed by Labradors (10.8%), German shepherds (9.5%), and Rottweilers (6.3%). More than half of injuries (60%) came from nonfamily dogs, usually when the dog was in the care of a family member or a friend.

Trauma from horse-related injuries occurred in girls more often than in boys (69% vs. 31%; P< .001), and only 26% of those who sustained injuries were wearing a helmet. “Male patients with horse-related injuries tended to be younger, have higher injury severity scores, and also were more likely to be kicked,” added Dr. Nielsen, who is a surgical critical care resident at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. “Females were older (an average of 10.6 years), with falls being the most common injury [in about 60% of cases].” The most common sites of injury were the head and face (35%), the extremities (29%), and the abdomen (17%). “Horse injuries were also associated with fractures and had high rates of lacerations, abrasions, and a significant proportion of traumatic brain injuries,” he said.

Dr. Nielsen concluded his presentation by noting that patterns of injury from animal-related trauma “are based on patient gender and the animal species involved. In general, use of protective equipment such as helmets was low. We found that identification of high-risk situations and populations serve as valuable information for future prevention efforts, as well as for parent and patient education.”

Dr. Nielsen reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

SAN DIEGO – Animal-related trauma is a significant cause of morbidity and occasional mortality, results from a 10-year, single-center study showed.

Nearly half of the injuries required operative intervention and injury patterns varied according to gender, race, and the type of animal involved, Dr. Jason W. Nielsen said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In an effort to investigate pediatric animal-related trauma to compare injury patterns and guide prevention efforts, Dr. Nielsen and his associates performed a retrospective analysis of patients aged 18 years and younger who were admitted to Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, with ICD-9 external cause of injury codes for animal trauma from 2004 to 2013. Of the 14,605 trauma admissions during that decade, 565 (3.9%) were animal related.

Children admitted with other forms of trauma (the baseline group) were similar in age to those admitted with animal-related trauma (a mean of 7.8 years vs. 7.2 years, respectively). However, males predominated in the baseline trauma group (62.8% vs. 37.2% female), while the genders were more balanced in the animal-related trauma group (48.7% male vs. 51.3% female). Racial differences appear to be amplified in the animal trauma group (80.9% white, 6.9% African American, and 12.2% other vs. 72.9% white, 16.3% African American, and 18.8% other in the baseline group). There were two deaths over the 10-year period (0.35%). One was dog-related involving an infant. The other involved an unhelmeted rider on a horse who suffered a devastating head injury.

The mean Injury Severity Score among patients in the animal-related trauma group was 3.6 and their mean hospital stay was 1.98 days, yet nearly half (48.5%) required operations. After presenting to the emergency department, two-thirds (66%) went to the floor, 28.5% went to the operating room, and just 5.5% went to the pediatric intensive care unit.

Most injuries involved dogs (340 cases or 60%) and horses (155 cases or 27%). Dog injuries were more common among boys, compared with girls (57.2% vs. 42.8%, respectively; P< .001), and the most common sites of injury were the face (52%) and the extremities (31%), with 59.7% of cases requiring an operative procedure. The dog breed was reported in 65.3% of cases, of which pit bulls were the majority (25.2%), followed by Labradors (10.8%), German shepherds (9.5%), and Rottweilers (6.3%). More than half of injuries (60%) came from nonfamily dogs, usually when the dog was in the care of a family member or a friend.

Trauma from horse-related injuries occurred in girls more often than in boys (69% vs. 31%; P< .001), and only 26% of those who sustained injuries were wearing a helmet. “Male patients with horse-related injuries tended to be younger, have higher injury severity scores, and also were more likely to be kicked,” added Dr. Nielsen, who is a surgical critical care resident at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. “Females were older (an average of 10.6 years), with falls being the most common injury [in about 60% of cases].” The most common sites of injury were the head and face (35%), the extremities (29%), and the abdomen (17%). “Horse injuries were also associated with fractures and had high rates of lacerations, abrasions, and a significant proportion of traumatic brain injuries,” he said.

Dr. Nielsen concluded his presentation by noting that patterns of injury from animal-related trauma “are based on patient gender and the animal species involved. In general, use of protective equipment such as helmets was low. We found that identification of high-risk situations and populations serve as valuable information for future prevention efforts, as well as for parent and patient education.”

Dr. Nielsen reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

SAN DIEGO – Animal-related trauma is a significant cause of morbidity and occasional mortality, results from a 10-year, single-center study showed.

Nearly half of the injuries required operative intervention and injury patterns varied according to gender, race, and the type of animal involved, Dr. Jason W. Nielsen said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

In an effort to investigate pediatric animal-related trauma to compare injury patterns and guide prevention efforts, Dr. Nielsen and his associates performed a retrospective analysis of patients aged 18 years and younger who were admitted to Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio, with ICD-9 external cause of injury codes for animal trauma from 2004 to 2013. Of the 14,605 trauma admissions during that decade, 565 (3.9%) were animal related.

Children admitted with other forms of trauma (the baseline group) were similar in age to those admitted with animal-related trauma (a mean of 7.8 years vs. 7.2 years, respectively). However, males predominated in the baseline trauma group (62.8% vs. 37.2% female), while the genders were more balanced in the animal-related trauma group (48.7% male vs. 51.3% female). Racial differences appear to be amplified in the animal trauma group (80.9% white, 6.9% African American, and 12.2% other vs. 72.9% white, 16.3% African American, and 18.8% other in the baseline group). There were two deaths over the 10-year period (0.35%). One was dog-related involving an infant. The other involved an unhelmeted rider on a horse who suffered a devastating head injury.

The mean Injury Severity Score among patients in the animal-related trauma group was 3.6 and their mean hospital stay was 1.98 days, yet nearly half (48.5%) required operations. After presenting to the emergency department, two-thirds (66%) went to the floor, 28.5% went to the operating room, and just 5.5% went to the pediatric intensive care unit.

Most injuries involved dogs (340 cases or 60%) and horses (155 cases or 27%). Dog injuries were more common among boys, compared with girls (57.2% vs. 42.8%, respectively; P< .001), and the most common sites of injury were the face (52%) and the extremities (31%), with 59.7% of cases requiring an operative procedure. The dog breed was reported in 65.3% of cases, of which pit bulls were the majority (25.2%), followed by Labradors (10.8%), German shepherds (9.5%), and Rottweilers (6.3%). More than half of injuries (60%) came from nonfamily dogs, usually when the dog was in the care of a family member or a friend.

Trauma from horse-related injuries occurred in girls more often than in boys (69% vs. 31%; P< .001), and only 26% of those who sustained injuries were wearing a helmet. “Male patients with horse-related injuries tended to be younger, have higher injury severity scores, and also were more likely to be kicked,” added Dr. Nielsen, who is a surgical critical care resident at Nationwide Children’s Hospital. “Females were older (an average of 10.6 years), with falls being the most common injury [in about 60% of cases].” The most common sites of injury were the head and face (35%), the extremities (29%), and the abdomen (17%). “Horse injuries were also associated with fractures and had high rates of lacerations, abrasions, and a significant proportion of traumatic brain injuries,” he said.

Dr. Nielsen concluded his presentation by noting that patterns of injury from animal-related trauma “are based on patient gender and the animal species involved. In general, use of protective equipment such as helmets was low. We found that identification of high-risk situations and populations serve as valuable information for future prevention efforts, as well as for parent and patient education.”

Dr. Nielsen reported having no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @dougbrunk

AT THE AAP NATIONAL CONFERENCE

Key clinical point: Animal-related trauma is a significant cause of morbidity in children.

Major finding: Nearly half of children admitted to the hospital with an injury caused by animal-related trauma (48.5%) required an operative procedure.

Data source: A review of 565 cases of animal-related trauma in patients aged 18 years and younger who presented to a single hospital between 2004 and 2013.

Disclosures: Dr. Nielsen reported having no financial disclosures.

How to Handle Questions About Vaccine Safety

SAN DIEGO – Parental concerns about vaccine safety are a reality of pediatric practice. False perceptions that vaccines are dangerous or unnecessary have eroded herd immunity to the extent that almost 600 measles cases have been reported thus far in 2014 – an unprecedented number, Dr. Paul Offit said at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Dr. Offit recommended strategies for handling some of the most common questions and concerns parents raise about vaccine safety. He is director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, and is the Maurice R. Hilleman Professor of Vaccinology and professor of pediatrics at the University of Pennsylvania, also in Philadelphia.

Parents may ask: How do you know vaccines are safe? I researched them on the Internet and learned they’re not.

“When people say they’ve done their research on a vaccine and have decided not to get it, what they really mean is they’ve read other people’s opinions on the Internet,” Dr. Offit said. Parents need to understand that not all information sources are equivalent, and that a vaccine must undergo extensive testing before the Food and Drug Administration licenses it or the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend it, he said. “The phase III trials invariably involve thousands of children,” he added.

But the package insert for the vaccine lists a lot of adverse events.

Any adverse event reported before the vaccine is licensed will be listed on the package insert, whether or not the vaccine caused the event, Dr. Offit said. For example, the original package insert for the chicken pox (varicella) vaccine listed fractured leg as an adverse event, because one recipient of the varicella vaccine broke his or her leg within 42 days after receiving the vaccine, he said. “Package inserts are not a medical communication document,” he added. “They are a legal communication document.”

Why are people being compensated for vaccine harm if it isn’t a problem?

The question refers to the National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program, which has paid more than $2.8 billion in compensation awards to petitioners since 1989. The program is “a large and tempting pool of money for personal injury lawyers to file compensatory injury suits on behalf of their clients,” Dr. Offit said. But just because a court awarded damages for harm does not mean the vaccine actually caused harm, he said. “The courts are never a place to determine scientific truths. The place you do that is in the scientific venue, by studies.”

Vaccines can contain potential allergens, primarily gelatin (a stabilizer) and latex (in vials or syringes that contain natural rubber), Dr. Offit noted. However, the rate of truly severe reactions to vaccines is extremely low – about one case per 1-2 million doses of vaccine, he said. An exception is yellow fever vaccine , which has caused fatal anaphylaxis, and oral polio vaccine also “had the potential to revert to wild type, which is why we went to the fully inactivated polio vaccine by the year 2000,” Dr. Offit noted. Thrombocytopenia is a potential adverse reaction of some vaccines, but is rare, and there are no compelling data associating measles vaccine with encephalopathy, he said.