User login

Peds, FPs flunk screening children for obstructive sleep apnea

DENVER – A high degree of unwarranted practice variation exists among pediatricians and family physicians with regard to screening children for obstructive sleep apnea in accord with current evidence-based practice guidelines, Sarah M. Honaker, Ph.D., said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommend that children with frequent snoring be referred for a sleep study or to a sleep specialist or otolaryngologist because of the damaging consequences of living with untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). But Dr. Honaker’s study of 8,135 children aged 1-12 years seen at five university-affiliated urban primary care pediatric clinics demonstrated that the identification rate of suspected OSA was abysmally low, and physician practice on this score varied enormously.

“There is a critical need to develop enhanced implementation strategies to support primary care providers’ adherence to evidence-based practice for pediatric OSA,” declared Dr. Honaker of Indiana University in Indianapolis.

She and her coinvestigators have developed a computer decision support system designed to do just that. Known as CHICA, for Child Health Improvement through Computer Automation, the system works like this: While in the clinic waiting room, the parent is handed a computer tablet and asked to complete 20 yes/no items designed to identify priority areas for the primary care provider to address during the current visit. The items are individually tailored based upon the child’s age, past medical history, and previous responses.

One item asks if the child snores three or more nights per week, a well-established indicator of increased risk for OSA. If the answer is yes, CHICA instantly sends a prompt to the child’s electronic medical record noting that the parent reports the child is a frequent snorer and this might indicate OSA.

The primary care provider can either ignore the prompt or respond during or after the visit in one of three ways: “I am concerned about OSA,” “I do not suspect OSA,” or “The parent in the examining room denies hearing frequent snoring.”

The mean age of the patients in Dr. Honaker’s study was 5.8 years, and 83% of the 8,135 children had Medicaid coverage. Parental cooperation with CHICA was high: 98.5% of parents addressed the snoring question. They reported that 28.5% of the children snored at least 3 nights per week, generating a total of 1,094 CHICA prompts to the primary care providers. Forty-four percent of providers didn’t respond to the prompt, which Dr. Honaker said is a typical rate for this sort of computerized assist intervention. Of those who did respond, only 15.9% indicated they suspected OSA. Sixty-three percent declared they didn’t suspect OSA, and the remainder said the parent in the examining room didn’t report frequent snoring.

Although responding providers indicated they suspected OSA in 15.9% of the children, that’s a low figure for frequent snorers. Moreover, 31% of children who got the CHICA frequent snoring prompt were overweight or obese, and 17% had attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms, both known risk factors for OSA. Some of the kids had both risk factors, but 39% had at least one in addition to their frequent snoring, Dr. Honaker noted.

The investigators carried out multivariate logistic regression analyses of child, provider, and clinic characteristics in search of predictors associated with physician concern that a child might have OSA. It turned out that none of the provider characteristics had any bearing on this endpoint. It didn’t matter if a physician’s specialty was pediatrics or family medicine. Providers had been in practice for 3-42 years, with a mean of 15.1 years, but years in practice weren’t associated with a physician’s rate of identification of possible pediatric OSA. Individual provider rates varied enormously, though. Some physicians never suspected OSA, others did so in nearly 50% of children flagged by the CHICA prompt.

“It’s not clear that type of training plays a large role in this area,” she commented.

The only relevant patient factor was age: children aged 1-2.5 years were 73% less likely to generate physician suspicion of OSA.

“Surprisingly, none of the patient health factors were predictive. So having ADHD symptoms or being overweight or obese did not make it more likely that a child would elicit concern for OSA,” Dr. Honaker observed.

However, which of the five clinics the child attended turned out to make a big difference. Rates of suspected OSA in children with a CHICA snoring prompt ranged from a low of 5% at one clinic to 27% at another.

Dr. Honaker’s recent review of the literature led her to conclude that the Indiana University experience is hardly unique. Despite documented high rates of pediatric sleep disorders in primary care settings, screening and treatment rates are low. Primary care physicians receive little training in sleep medicine (Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:31-9).

What’s next for CHICA?

Dr. Honaker and coworkers have developed a beefed up CHICA decision support system known as the CHICA OSA Module. In addition to generating a prompt in the medical record if a parent indicates the child snores three or more nights per week, additional OSA signs and symptoms, if present, will be noted on the screen, along with a comment that American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend referral when OSA is suspected. Dr. Honaker plans to conduct a controlled trial in which some clinics get the CHICA OSA Module while others use the older CHICA system.

Her study was funded by the American Sleep Medicine Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – A high degree of unwarranted practice variation exists among pediatricians and family physicians with regard to screening children for obstructive sleep apnea in accord with current evidence-based practice guidelines, Sarah M. Honaker, Ph.D., said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommend that children with frequent snoring be referred for a sleep study or to a sleep specialist or otolaryngologist because of the damaging consequences of living with untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). But Dr. Honaker’s study of 8,135 children aged 1-12 years seen at five university-affiliated urban primary care pediatric clinics demonstrated that the identification rate of suspected OSA was abysmally low, and physician practice on this score varied enormously.

“There is a critical need to develop enhanced implementation strategies to support primary care providers’ adherence to evidence-based practice for pediatric OSA,” declared Dr. Honaker of Indiana University in Indianapolis.

She and her coinvestigators have developed a computer decision support system designed to do just that. Known as CHICA, for Child Health Improvement through Computer Automation, the system works like this: While in the clinic waiting room, the parent is handed a computer tablet and asked to complete 20 yes/no items designed to identify priority areas for the primary care provider to address during the current visit. The items are individually tailored based upon the child’s age, past medical history, and previous responses.

One item asks if the child snores three or more nights per week, a well-established indicator of increased risk for OSA. If the answer is yes, CHICA instantly sends a prompt to the child’s electronic medical record noting that the parent reports the child is a frequent snorer and this might indicate OSA.

The primary care provider can either ignore the prompt or respond during or after the visit in one of three ways: “I am concerned about OSA,” “I do not suspect OSA,” or “The parent in the examining room denies hearing frequent snoring.”

The mean age of the patients in Dr. Honaker’s study was 5.8 years, and 83% of the 8,135 children had Medicaid coverage. Parental cooperation with CHICA was high: 98.5% of parents addressed the snoring question. They reported that 28.5% of the children snored at least 3 nights per week, generating a total of 1,094 CHICA prompts to the primary care providers. Forty-four percent of providers didn’t respond to the prompt, which Dr. Honaker said is a typical rate for this sort of computerized assist intervention. Of those who did respond, only 15.9% indicated they suspected OSA. Sixty-three percent declared they didn’t suspect OSA, and the remainder said the parent in the examining room didn’t report frequent snoring.

Although responding providers indicated they suspected OSA in 15.9% of the children, that’s a low figure for frequent snorers. Moreover, 31% of children who got the CHICA frequent snoring prompt were overweight or obese, and 17% had attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms, both known risk factors for OSA. Some of the kids had both risk factors, but 39% had at least one in addition to their frequent snoring, Dr. Honaker noted.

The investigators carried out multivariate logistic regression analyses of child, provider, and clinic characteristics in search of predictors associated with physician concern that a child might have OSA. It turned out that none of the provider characteristics had any bearing on this endpoint. It didn’t matter if a physician’s specialty was pediatrics or family medicine. Providers had been in practice for 3-42 years, with a mean of 15.1 years, but years in practice weren’t associated with a physician’s rate of identification of possible pediatric OSA. Individual provider rates varied enormously, though. Some physicians never suspected OSA, others did so in nearly 50% of children flagged by the CHICA prompt.

“It’s not clear that type of training plays a large role in this area,” she commented.

The only relevant patient factor was age: children aged 1-2.5 years were 73% less likely to generate physician suspicion of OSA.

“Surprisingly, none of the patient health factors were predictive. So having ADHD symptoms or being overweight or obese did not make it more likely that a child would elicit concern for OSA,” Dr. Honaker observed.

However, which of the five clinics the child attended turned out to make a big difference. Rates of suspected OSA in children with a CHICA snoring prompt ranged from a low of 5% at one clinic to 27% at another.

Dr. Honaker’s recent review of the literature led her to conclude that the Indiana University experience is hardly unique. Despite documented high rates of pediatric sleep disorders in primary care settings, screening and treatment rates are low. Primary care physicians receive little training in sleep medicine (Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:31-9).

What’s next for CHICA?

Dr. Honaker and coworkers have developed a beefed up CHICA decision support system known as the CHICA OSA Module. In addition to generating a prompt in the medical record if a parent indicates the child snores three or more nights per week, additional OSA signs and symptoms, if present, will be noted on the screen, along with a comment that American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend referral when OSA is suspected. Dr. Honaker plans to conduct a controlled trial in which some clinics get the CHICA OSA Module while others use the older CHICA system.

Her study was funded by the American Sleep Medicine Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – A high degree of unwarranted practice variation exists among pediatricians and family physicians with regard to screening children for obstructive sleep apnea in accord with current evidence-based practice guidelines, Sarah M. Honaker, Ph.D., said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommend that children with frequent snoring be referred for a sleep study or to a sleep specialist or otolaryngologist because of the damaging consequences of living with untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). But Dr. Honaker’s study of 8,135 children aged 1-12 years seen at five university-affiliated urban primary care pediatric clinics demonstrated that the identification rate of suspected OSA was abysmally low, and physician practice on this score varied enormously.

“There is a critical need to develop enhanced implementation strategies to support primary care providers’ adherence to evidence-based practice for pediatric OSA,” declared Dr. Honaker of Indiana University in Indianapolis.

She and her coinvestigators have developed a computer decision support system designed to do just that. Known as CHICA, for Child Health Improvement through Computer Automation, the system works like this: While in the clinic waiting room, the parent is handed a computer tablet and asked to complete 20 yes/no items designed to identify priority areas for the primary care provider to address during the current visit. The items are individually tailored based upon the child’s age, past medical history, and previous responses.

One item asks if the child snores three or more nights per week, a well-established indicator of increased risk for OSA. If the answer is yes, CHICA instantly sends a prompt to the child’s electronic medical record noting that the parent reports the child is a frequent snorer and this might indicate OSA.

The primary care provider can either ignore the prompt or respond during or after the visit in one of three ways: “I am concerned about OSA,” “I do not suspect OSA,” or “The parent in the examining room denies hearing frequent snoring.”

The mean age of the patients in Dr. Honaker’s study was 5.8 years, and 83% of the 8,135 children had Medicaid coverage. Parental cooperation with CHICA was high: 98.5% of parents addressed the snoring question. They reported that 28.5% of the children snored at least 3 nights per week, generating a total of 1,094 CHICA prompts to the primary care providers. Forty-four percent of providers didn’t respond to the prompt, which Dr. Honaker said is a typical rate for this sort of computerized assist intervention. Of those who did respond, only 15.9% indicated they suspected OSA. Sixty-three percent declared they didn’t suspect OSA, and the remainder said the parent in the examining room didn’t report frequent snoring.

Although responding providers indicated they suspected OSA in 15.9% of the children, that’s a low figure for frequent snorers. Moreover, 31% of children who got the CHICA frequent snoring prompt were overweight or obese, and 17% had attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms, both known risk factors for OSA. Some of the kids had both risk factors, but 39% had at least one in addition to their frequent snoring, Dr. Honaker noted.

The investigators carried out multivariate logistic regression analyses of child, provider, and clinic characteristics in search of predictors associated with physician concern that a child might have OSA. It turned out that none of the provider characteristics had any bearing on this endpoint. It didn’t matter if a physician’s specialty was pediatrics or family medicine. Providers had been in practice for 3-42 years, with a mean of 15.1 years, but years in practice weren’t associated with a physician’s rate of identification of possible pediatric OSA. Individual provider rates varied enormously, though. Some physicians never suspected OSA, others did so in nearly 50% of children flagged by the CHICA prompt.

“It’s not clear that type of training plays a large role in this area,” she commented.

The only relevant patient factor was age: children aged 1-2.5 years were 73% less likely to generate physician suspicion of OSA.

“Surprisingly, none of the patient health factors were predictive. So having ADHD symptoms or being overweight or obese did not make it more likely that a child would elicit concern for OSA,” Dr. Honaker observed.

However, which of the five clinics the child attended turned out to make a big difference. Rates of suspected OSA in children with a CHICA snoring prompt ranged from a low of 5% at one clinic to 27% at another.

Dr. Honaker’s recent review of the literature led her to conclude that the Indiana University experience is hardly unique. Despite documented high rates of pediatric sleep disorders in primary care settings, screening and treatment rates are low. Primary care physicians receive little training in sleep medicine (Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:31-9).

What’s next for CHICA?

Dr. Honaker and coworkers have developed a beefed up CHICA decision support system known as the CHICA OSA Module. In addition to generating a prompt in the medical record if a parent indicates the child snores three or more nights per week, additional OSA signs and symptoms, if present, will be noted on the screen, along with a comment that American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend referral when OSA is suspected. Dr. Honaker plans to conduct a controlled trial in which some clinics get the CHICA OSA Module while others use the older CHICA system.

Her study was funded by the American Sleep Medicine Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SLEEP 2016

Key clinical point: Huge unwarranted practice variations exist in primary care physicians’ adherence to evidence-based guidelines for identification of obstructive sleep apnea in children.

Major finding: Although 39% of a large group of children reportedly snored at least three nights per week and had at least one additional major risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea, only 15.9% of the children elicited suspicion of the disorder on the part of primary care providers despite an electronic prompt.

Data source: This was an observational study in which 8,135 children aged 1-12 years were screened for obstructive sleep apnea using a computer-assisted decision support system known as CHICA, linked to the patients’ electronic medical record.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the American Sleep Medicine Foundation. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Sleep Apnea in Later Life More Than Doubles Subsequent Alzheimer’s Risk

DENVER – Obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed later in life is associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Omonigho Bubu reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

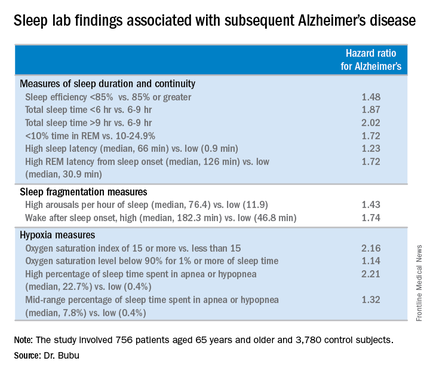

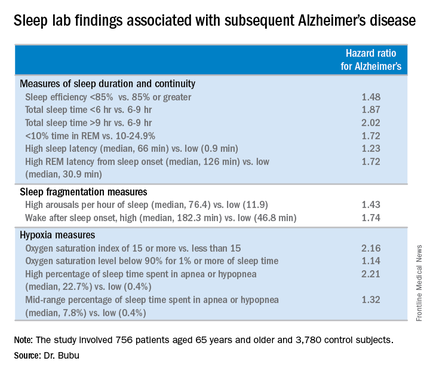

He presented a retrospective cohort study in which a dose-reponse relationship was apparent. The more severe an individual’s obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as reflected in a higher apnea-hypopnea index on polysomnography, the greater the risk of later being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, compared with matched controls during up to 13 years of follow-up.

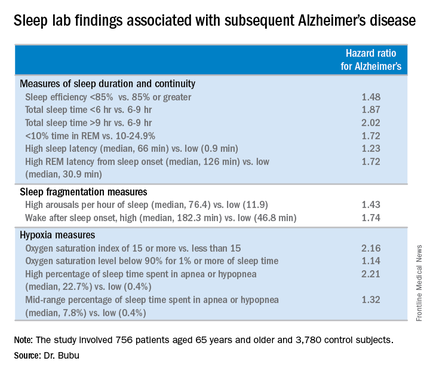

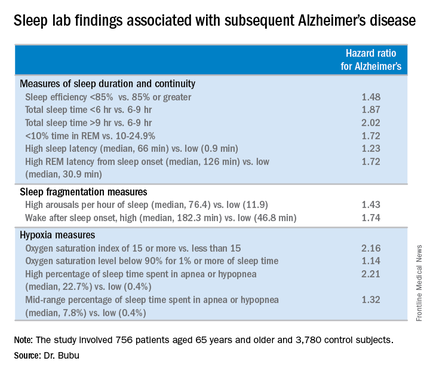

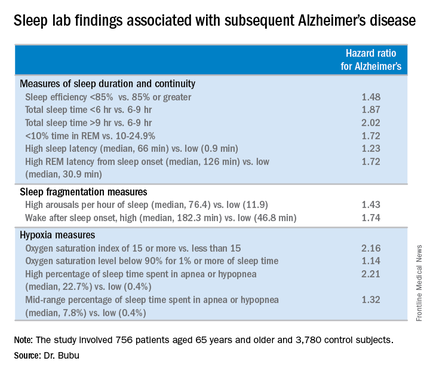

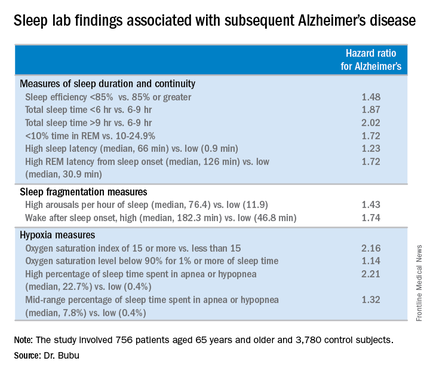

The study also identified several possible contributing factors for the observed OSA/Alzheimer’s relationship. Those OSA patients with more severe sleep fragmentation, nocturnal hypoxia, and abnormal sleep duration were significantly more likely to subsequently develop Alzheimer’s disease than were OSA patients with less severely disrupted sleep measures, added Dr. Bubu of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

The study included 756 patients aged 65 years and older with no history of cognitive decline when diagnosed with OSA by polysomnography at Tampa General Hospital during 2001-2005. They were matched by age, race, sex, body mass index, and zip code to two control groups totaling 3,780 subjects. The controls, drawn from outpatient medical clinics at the hospital, had a variety of medical problems but no sleep disorders or cognitive impairment.

During a mean 10.5-year follow-up period, 513 subjects were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, according to Medicare data. In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, and education level, OSA was independently associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk. Further adjustment for alcohol intake, smoking, use of sleep medications, and chronic medical conditions didn’t substantially change the results.

However, the investigators were not able to control for apolipoprotein E (APOE)–epsilon 4 allele status, which is a known risk factor for both OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, so it makes one wonder whether the association is “all related to APOE,” said Dr. Richard J. Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., when asked to comment on the study.

Time to onset of Alzheimer’s disease was shorter in the OSA patients: The mean time to diagnosis was 60.8 months after diagnosis of OSA, compared with 73 and 78 months in members of the two control groups who developed the dementia.

When the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease was stratified according to baseline OSA severity, a dose-response effect was seen. Mild OSA, defined as 5-14 apnea-hypopnea events per hour of sleep, was associated with a 1.67-fold greater risk than in controls. The moderate OSA group, who had 15-29 events per hour, had a 1.81-fold increased risk. Patients with severe OSA, with 30 or more events per hour, had a 2.63-fold increased risk.

Gender, race, and education modified the relationship between OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Bubu said. Women with OSA had a 2.28-fold greater risk of later developing the disease, compared with controls; men had a 1.42-fold increased risk. African-Americans with OSA were at 2.56-fold greater risk than were controls, while Hispanics with OSA were at 1.8-fold increased risk and non-Hispanic whites were at 1.87-fold increased risk. OSA patients with a high school education or less were at 2.73 times greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease than were controls, those with at least some college or technical school were at 1.82-fold risk, and OSA patients who’d been to graduate school had a 1.31-fold increased risk.

“Our results definitely show that OSA precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. But we cannot say that’s causation. That will be left to future research examining the potential mechanisms we’ve identified,” Dr. Bubu said in an interview.

A key missing link in establishing a causal relationship is the lack of data on how many of the older patients diagnosed with OSA accepted treatment for the condition, and what their response rates were. In other words, it remains to be seen whether OSA occurring later in life is a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease as opposed to an early expression of the dementing disease process whereby treatment of the sleep disorder doesn’t affect the progressive cognitive decline.

Both short sleep duration of less than 6 hours as well as a mean total sleep time greater than 9 hours in patients with OSA were associated with significantly increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, compared with a sleep time of 6-9 hours. Patients with a high sleep-onset latency in the sleep lab, a high REM latency from sleep onset, a low percentage of time spent in REM, an oxygen saturation level of less than 90% for at least 1% of sleep time, and/or a high number of arousals per hour of sleep were also at increased risk of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease.

The study was supported by the Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute. Dr. Bubu reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed later in life is associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Omonigho Bubu reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

He presented a retrospective cohort study in which a dose-reponse relationship was apparent. The more severe an individual’s obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as reflected in a higher apnea-hypopnea index on polysomnography, the greater the risk of later being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, compared with matched controls during up to 13 years of follow-up.

The study also identified several possible contributing factors for the observed OSA/Alzheimer’s relationship. Those OSA patients with more severe sleep fragmentation, nocturnal hypoxia, and abnormal sleep duration were significantly more likely to subsequently develop Alzheimer’s disease than were OSA patients with less severely disrupted sleep measures, added Dr. Bubu of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

The study included 756 patients aged 65 years and older with no history of cognitive decline when diagnosed with OSA by polysomnography at Tampa General Hospital during 2001-2005. They were matched by age, race, sex, body mass index, and zip code to two control groups totaling 3,780 subjects. The controls, drawn from outpatient medical clinics at the hospital, had a variety of medical problems but no sleep disorders or cognitive impairment.

During a mean 10.5-year follow-up period, 513 subjects were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, according to Medicare data. In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, and education level, OSA was independently associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk. Further adjustment for alcohol intake, smoking, use of sleep medications, and chronic medical conditions didn’t substantially change the results.

However, the investigators were not able to control for apolipoprotein E (APOE)–epsilon 4 allele status, which is a known risk factor for both OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, so it makes one wonder whether the association is “all related to APOE,” said Dr. Richard J. Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., when asked to comment on the study.

Time to onset of Alzheimer’s disease was shorter in the OSA patients: The mean time to diagnosis was 60.8 months after diagnosis of OSA, compared with 73 and 78 months in members of the two control groups who developed the dementia.

When the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease was stratified according to baseline OSA severity, a dose-response effect was seen. Mild OSA, defined as 5-14 apnea-hypopnea events per hour of sleep, was associated with a 1.67-fold greater risk than in controls. The moderate OSA group, who had 15-29 events per hour, had a 1.81-fold increased risk. Patients with severe OSA, with 30 or more events per hour, had a 2.63-fold increased risk.

Gender, race, and education modified the relationship between OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Bubu said. Women with OSA had a 2.28-fold greater risk of later developing the disease, compared with controls; men had a 1.42-fold increased risk. African-Americans with OSA were at 2.56-fold greater risk than were controls, while Hispanics with OSA were at 1.8-fold increased risk and non-Hispanic whites were at 1.87-fold increased risk. OSA patients with a high school education or less were at 2.73 times greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease than were controls, those with at least some college or technical school were at 1.82-fold risk, and OSA patients who’d been to graduate school had a 1.31-fold increased risk.

“Our results definitely show that OSA precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. But we cannot say that’s causation. That will be left to future research examining the potential mechanisms we’ve identified,” Dr. Bubu said in an interview.

A key missing link in establishing a causal relationship is the lack of data on how many of the older patients diagnosed with OSA accepted treatment for the condition, and what their response rates were. In other words, it remains to be seen whether OSA occurring later in life is a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease as opposed to an early expression of the dementing disease process whereby treatment of the sleep disorder doesn’t affect the progressive cognitive decline.

Both short sleep duration of less than 6 hours as well as a mean total sleep time greater than 9 hours in patients with OSA were associated with significantly increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, compared with a sleep time of 6-9 hours. Patients with a high sleep-onset latency in the sleep lab, a high REM latency from sleep onset, a low percentage of time spent in REM, an oxygen saturation level of less than 90% for at least 1% of sleep time, and/or a high number of arousals per hour of sleep were also at increased risk of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease.

The study was supported by the Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute. Dr. Bubu reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed later in life is associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Omonigho Bubu reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

He presented a retrospective cohort study in which a dose-reponse relationship was apparent. The more severe an individual’s obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as reflected in a higher apnea-hypopnea index on polysomnography, the greater the risk of later being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, compared with matched controls during up to 13 years of follow-up.

The study also identified several possible contributing factors for the observed OSA/Alzheimer’s relationship. Those OSA patients with more severe sleep fragmentation, nocturnal hypoxia, and abnormal sleep duration were significantly more likely to subsequently develop Alzheimer’s disease than were OSA patients with less severely disrupted sleep measures, added Dr. Bubu of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

The study included 756 patients aged 65 years and older with no history of cognitive decline when diagnosed with OSA by polysomnography at Tampa General Hospital during 2001-2005. They were matched by age, race, sex, body mass index, and zip code to two control groups totaling 3,780 subjects. The controls, drawn from outpatient medical clinics at the hospital, had a variety of medical problems but no sleep disorders or cognitive impairment.

During a mean 10.5-year follow-up period, 513 subjects were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, according to Medicare data. In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, and education level, OSA was independently associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk. Further adjustment for alcohol intake, smoking, use of sleep medications, and chronic medical conditions didn’t substantially change the results.

However, the investigators were not able to control for apolipoprotein E (APOE)–epsilon 4 allele status, which is a known risk factor for both OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, so it makes one wonder whether the association is “all related to APOE,” said Dr. Richard J. Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., when asked to comment on the study.

Time to onset of Alzheimer’s disease was shorter in the OSA patients: The mean time to diagnosis was 60.8 months after diagnosis of OSA, compared with 73 and 78 months in members of the two control groups who developed the dementia.

When the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease was stratified according to baseline OSA severity, a dose-response effect was seen. Mild OSA, defined as 5-14 apnea-hypopnea events per hour of sleep, was associated with a 1.67-fold greater risk than in controls. The moderate OSA group, who had 15-29 events per hour, had a 1.81-fold increased risk. Patients with severe OSA, with 30 or more events per hour, had a 2.63-fold increased risk.

Gender, race, and education modified the relationship between OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Bubu said. Women with OSA had a 2.28-fold greater risk of later developing the disease, compared with controls; men had a 1.42-fold increased risk. African-Americans with OSA were at 2.56-fold greater risk than were controls, while Hispanics with OSA were at 1.8-fold increased risk and non-Hispanic whites were at 1.87-fold increased risk. OSA patients with a high school education or less were at 2.73 times greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease than were controls, those with at least some college or technical school were at 1.82-fold risk, and OSA patients who’d been to graduate school had a 1.31-fold increased risk.

“Our results definitely show that OSA precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. But we cannot say that’s causation. That will be left to future research examining the potential mechanisms we’ve identified,” Dr. Bubu said in an interview.

A key missing link in establishing a causal relationship is the lack of data on how many of the older patients diagnosed with OSA accepted treatment for the condition, and what their response rates were. In other words, it remains to be seen whether OSA occurring later in life is a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease as opposed to an early expression of the dementing disease process whereby treatment of the sleep disorder doesn’t affect the progressive cognitive decline.

Both short sleep duration of less than 6 hours as well as a mean total sleep time greater than 9 hours in patients with OSA were associated with significantly increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, compared with a sleep time of 6-9 hours. Patients with a high sleep-onset latency in the sleep lab, a high REM latency from sleep onset, a low percentage of time spent in REM, an oxygen saturation level of less than 90% for at least 1% of sleep time, and/or a high number of arousals per hour of sleep were also at increased risk of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease.

The study was supported by the Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute. Dr. Bubu reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SLEEP 2016

Sleep apnea in later life more than doubles subsequent Alzheimer’s risk

DENVER – Obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed later in life is associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Omonigho Bubu reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

He presented a retrospective cohort study in which a dose-reponse relationship was apparent. The more severe an individual’s obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as reflected in a higher apnea-hypopnea index on polysomnography, the greater the risk of later being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, compared with matched controls during up to 13 years of follow-up.

The study also identified several possible contributing factors for the observed OSA/Alzheimer’s relationship. Those OSA patients with more severe sleep fragmentation, nocturnal hypoxia, and abnormal sleep duration were significantly more likely to subsequently develop Alzheimer’s disease than were OSA patients with less severely disrupted sleep measures, added Dr. Bubu of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

The study included 756 patients aged 65 years and older with no history of cognitive decline when diagnosed with OSA by polysomnography at Tampa General Hospital during 2001-2005. They were matched by age, race, sex, body mass index, and zip code to two control groups totaling 3,780 subjects. The controls, drawn from outpatient medical clinics at the hospital, had a variety of medical problems but no sleep disorders or cognitive impairment.

During a mean 10.5-year follow-up period, 513 subjects were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, according to Medicare data. In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, and education level, OSA was independently associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk. Further adjustment for alcohol intake, smoking, use of sleep medications, and chronic medical conditions didn’t substantially change the results.

However, the investigators were not able to control for apolipoprotein E (APOE)–epsilon 4 allele status, which is a known risk factor for both OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, so it makes one wonder whether the association is “all related to APOE,” said Dr. Richard J. Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., when asked to comment on the study.

Time to onset of Alzheimer’s disease was shorter in the OSA patients: The mean time to diagnosis was 60.8 months after diagnosis of OSA, compared with 73 and 78 months in members of the two control groups who developed the dementia.

When the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease was stratified according to baseline OSA severity, a dose-response effect was seen. Mild OSA, defined as 5-14 apnea-hypopnea events per hour of sleep, was associated with a 1.67-fold greater risk than in controls. The moderate OSA group, who had 15-29 events per hour, had a 1.81-fold increased risk. Patients with severe OSA, with 30 or more events per hour, had a 2.63-fold increased risk.

Gender, race, and education modified the relationship between OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Bubu said. Women with OSA had a 2.28-fold greater risk of later developing the disease, compared with controls; men had a 1.42-fold increased risk. African-Americans with OSA were at 2.56-fold greater risk than were controls, while Hispanics with OSA were at 1.8-fold increased risk and non-Hispanic whites were at 1.87-fold increased risk. OSA patients with a high school education or less were at 2.73 times greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease than were controls, those with at least some college or technical school were at 1.82-fold risk, and OSA patients who’d been to graduate school had a 1.31-fold increased risk.

“Our results definitely show that OSA precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. But we cannot say that’s causation. That will be left to future research examining the potential mechanisms we’ve identified,” Dr. Bubu said in an interview.

A key missing link in establishing a causal relationship is the lack of data on how many of the older patients diagnosed with OSA accepted treatment for the condition, and what their response rates were. In other words, it remains to be seen whether OSA occurring later in life is a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease as opposed to an early expression of the dementing disease process whereby treatment of the sleep disorder doesn’t affect the progressive cognitive decline.

Both short sleep duration of less than 6 hours as well as a mean total sleep time greater than 9 hours in patients with OSA were associated with significantly increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, compared with a sleep time of 6-9 hours. Patients with a high sleep-onset latency in the sleep lab, a high REM latency from sleep onset, a low percentage of time spent in REM, an oxygen saturation level of less than 90% for at least 1% of sleep time, and/or a high number of arousals per hour of sleep were also at increased risk of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease.

The study was supported by the Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute. Dr. Bubu reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed later in life is associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Omonigho Bubu reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

He presented a retrospective cohort study in which a dose-reponse relationship was apparent. The more severe an individual’s obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as reflected in a higher apnea-hypopnea index on polysomnography, the greater the risk of later being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, compared with matched controls during up to 13 years of follow-up.

The study also identified several possible contributing factors for the observed OSA/Alzheimer’s relationship. Those OSA patients with more severe sleep fragmentation, nocturnal hypoxia, and abnormal sleep duration were significantly more likely to subsequently develop Alzheimer’s disease than were OSA patients with less severely disrupted sleep measures, added Dr. Bubu of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

The study included 756 patients aged 65 years and older with no history of cognitive decline when diagnosed with OSA by polysomnography at Tampa General Hospital during 2001-2005. They were matched by age, race, sex, body mass index, and zip code to two control groups totaling 3,780 subjects. The controls, drawn from outpatient medical clinics at the hospital, had a variety of medical problems but no sleep disorders or cognitive impairment.

During a mean 10.5-year follow-up period, 513 subjects were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, according to Medicare data. In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, and education level, OSA was independently associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk. Further adjustment for alcohol intake, smoking, use of sleep medications, and chronic medical conditions didn’t substantially change the results.

However, the investigators were not able to control for apolipoprotein E (APOE)–epsilon 4 allele status, which is a known risk factor for both OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, so it makes one wonder whether the association is “all related to APOE,” said Dr. Richard J. Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., when asked to comment on the study.

Time to onset of Alzheimer’s disease was shorter in the OSA patients: The mean time to diagnosis was 60.8 months after diagnosis of OSA, compared with 73 and 78 months in members of the two control groups who developed the dementia.

When the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease was stratified according to baseline OSA severity, a dose-response effect was seen. Mild OSA, defined as 5-14 apnea-hypopnea events per hour of sleep, was associated with a 1.67-fold greater risk than in controls. The moderate OSA group, who had 15-29 events per hour, had a 1.81-fold increased risk. Patients with severe OSA, with 30 or more events per hour, had a 2.63-fold increased risk.

Gender, race, and education modified the relationship between OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Bubu said. Women with OSA had a 2.28-fold greater risk of later developing the disease, compared with controls; men had a 1.42-fold increased risk. African-Americans with OSA were at 2.56-fold greater risk than were controls, while Hispanics with OSA were at 1.8-fold increased risk and non-Hispanic whites were at 1.87-fold increased risk. OSA patients with a high school education or less were at 2.73 times greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease than were controls, those with at least some college or technical school were at 1.82-fold risk, and OSA patients who’d been to graduate school had a 1.31-fold increased risk.

“Our results definitely show that OSA precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. But we cannot say that’s causation. That will be left to future research examining the potential mechanisms we’ve identified,” Dr. Bubu said in an interview.

A key missing link in establishing a causal relationship is the lack of data on how many of the older patients diagnosed with OSA accepted treatment for the condition, and what their response rates were. In other words, it remains to be seen whether OSA occurring later in life is a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease as opposed to an early expression of the dementing disease process whereby treatment of the sleep disorder doesn’t affect the progressive cognitive decline.

Both short sleep duration of less than 6 hours as well as a mean total sleep time greater than 9 hours in patients with OSA were associated with significantly increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, compared with a sleep time of 6-9 hours. Patients with a high sleep-onset latency in the sleep lab, a high REM latency from sleep onset, a low percentage of time spent in REM, an oxygen saturation level of less than 90% for at least 1% of sleep time, and/or a high number of arousals per hour of sleep were also at increased risk of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease.

The study was supported by the Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute. Dr. Bubu reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – Obstructive sleep apnea diagnosed later in life is associated with an increased likelihood of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Omonigho Bubu reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

He presented a retrospective cohort study in which a dose-reponse relationship was apparent. The more severe an individual’s obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as reflected in a higher apnea-hypopnea index on polysomnography, the greater the risk of later being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, compared with matched controls during up to 13 years of follow-up.

The study also identified several possible contributing factors for the observed OSA/Alzheimer’s relationship. Those OSA patients with more severe sleep fragmentation, nocturnal hypoxia, and abnormal sleep duration were significantly more likely to subsequently develop Alzheimer’s disease than were OSA patients with less severely disrupted sleep measures, added Dr. Bubu of the University of South Florida, Tampa.

The study included 756 patients aged 65 years and older with no history of cognitive decline when diagnosed with OSA by polysomnography at Tampa General Hospital during 2001-2005. They were matched by age, race, sex, body mass index, and zip code to two control groups totaling 3,780 subjects. The controls, drawn from outpatient medical clinics at the hospital, had a variety of medical problems but no sleep disorders or cognitive impairment.

During a mean 10.5-year follow-up period, 513 subjects were diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, according to Medicare data. In a Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for age, sex, race, body mass index, and education level, OSA was independently associated with a 2.2-fold increased risk. Further adjustment for alcohol intake, smoking, use of sleep medications, and chronic medical conditions didn’t substantially change the results.

However, the investigators were not able to control for apolipoprotein E (APOE)–epsilon 4 allele status, which is a known risk factor for both OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, so it makes one wonder whether the association is “all related to APOE,” said Dr. Richard J. Caselli, professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., when asked to comment on the study.

Time to onset of Alzheimer’s disease was shorter in the OSA patients: The mean time to diagnosis was 60.8 months after diagnosis of OSA, compared with 73 and 78 months in members of the two control groups who developed the dementia.

When the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease was stratified according to baseline OSA severity, a dose-response effect was seen. Mild OSA, defined as 5-14 apnea-hypopnea events per hour of sleep, was associated with a 1.67-fold greater risk than in controls. The moderate OSA group, who had 15-29 events per hour, had a 1.81-fold increased risk. Patients with severe OSA, with 30 or more events per hour, had a 2.63-fold increased risk.

Gender, race, and education modified the relationship between OSA and Alzheimer’s disease, Dr. Bubu said. Women with OSA had a 2.28-fold greater risk of later developing the disease, compared with controls; men had a 1.42-fold increased risk. African-Americans with OSA were at 2.56-fold greater risk than were controls, while Hispanics with OSA were at 1.8-fold increased risk and non-Hispanic whites were at 1.87-fold increased risk. OSA patients with a high school education or less were at 2.73 times greater risk of Alzheimer’s disease than were controls, those with at least some college or technical school were at 1.82-fold risk, and OSA patients who’d been to graduate school had a 1.31-fold increased risk.

“Our results definitely show that OSA precedes the onset of Alzheimer’s disease. But we cannot say that’s causation. That will be left to future research examining the potential mechanisms we’ve identified,” Dr. Bubu said in an interview.

A key missing link in establishing a causal relationship is the lack of data on how many of the older patients diagnosed with OSA accepted treatment for the condition, and what their response rates were. In other words, it remains to be seen whether OSA occurring later in life is a modifiable risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease as opposed to an early expression of the dementing disease process whereby treatment of the sleep disorder doesn’t affect the progressive cognitive decline.

Both short sleep duration of less than 6 hours as well as a mean total sleep time greater than 9 hours in patients with OSA were associated with significantly increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, compared with a sleep time of 6-9 hours. Patients with a high sleep-onset latency in the sleep lab, a high REM latency from sleep onset, a low percentage of time spent in REM, an oxygen saturation level of less than 90% for at least 1% of sleep time, and/or a high number of arousals per hour of sleep were also at increased risk of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease.

The study was supported by the Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute. Dr. Bubu reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SLEEP 2016

Key clinical point: Patients diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea after age 65 may be at increased risk of later developing Alzheimer’s disease.

Major finding: A dose-response effect was seen: obstructive sleep apnea classified as mild was associated with a 1.67-fold increased risk of subsequent Alzheimer’s disease, moderate with a 1.81-fold risk, and severe obstructive sleep apnea carried a 2.63-fold increased risk.

Data source: This was a retrospective cohort study including 756 patients age 65 or older with no history of cognitive impairment who were diagnosed with obstructive sleep apnea during 2001-2005 and 3,780 matched controls, all followed for up to 13 years.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the Byrd Alzheimer’s Institute. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

Insomnia Is Pervasive in Adult Neurodevelopmental Disorders

DENVER – Adults with ADHD or autism spectrum disorder experience a high burden of sleep disturbances, especially insomnia, Dr. Anastasios Galanopoulos reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

This has previously been established to be the case in pediatric patients with these neurodevelopmental disorders. However, sleep pathology hasn’t previously been well studied in affected adults, according to Dr. Galanopoulos, a consulting psychiatrist at Maudsley Hospital and King’s College London.

He presented a cross-sectional study of insomnia in a clinically representative sample comprising 164 adult patients: 98 with a DSM-5 diagnosis of ADHD, 30 with autism spectrum disorder, and 34 carrying both diagnoses.

Fully 91% of participants fell into the “poor” sleep category on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Moreover, 44% of subjects had either moderate or severe clinical insomnia as reflected in a score of 15 or more on the Insomnia Severity Index. The rate of high sleep disruption scores was similar, regardless of whether the diagnosis was ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, or both.

Anxiety but not depression ratings on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale correlated with insomnia scores, regardless of neurodevelopmental diagnosis. Insomnia scores also increased in concert with higher levels of hyperactivity symptoms as scored on the Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale. In contrast, inattentiveness scores were unrelated to insomnia.

Hyperactivity scores on the Barkley scale were significantly higher in adults with ADHD than in those with autism spectrum disorder. On the other hand, anxiety scores were higher in adults with autism spectrum disorder.

While the burden of sleep disturbances is similarly high in adults with ADHD and autism spectrum disorder, the underlying mechanism may well be different. For this reason, Dr. Galanopoulos and coinvestigators have begun studies systematically looking at various possible interventions for sleep disorders in adults with neurodevelopmental disorders.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted without commercial support.

DENVER – Adults with ADHD or autism spectrum disorder experience a high burden of sleep disturbances, especially insomnia, Dr. Anastasios Galanopoulos reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

This has previously been established to be the case in pediatric patients with these neurodevelopmental disorders. However, sleep pathology hasn’t previously been well studied in affected adults, according to Dr. Galanopoulos, a consulting psychiatrist at Maudsley Hospital and King’s College London.

He presented a cross-sectional study of insomnia in a clinically representative sample comprising 164 adult patients: 98 with a DSM-5 diagnosis of ADHD, 30 with autism spectrum disorder, and 34 carrying both diagnoses.

Fully 91% of participants fell into the “poor” sleep category on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Moreover, 44% of subjects had either moderate or severe clinical insomnia as reflected in a score of 15 or more on the Insomnia Severity Index. The rate of high sleep disruption scores was similar, regardless of whether the diagnosis was ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, or both.

Anxiety but not depression ratings on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale correlated with insomnia scores, regardless of neurodevelopmental diagnosis. Insomnia scores also increased in concert with higher levels of hyperactivity symptoms as scored on the Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale. In contrast, inattentiveness scores were unrelated to insomnia.

Hyperactivity scores on the Barkley scale were significantly higher in adults with ADHD than in those with autism spectrum disorder. On the other hand, anxiety scores were higher in adults with autism spectrum disorder.

While the burden of sleep disturbances is similarly high in adults with ADHD and autism spectrum disorder, the underlying mechanism may well be different. For this reason, Dr. Galanopoulos and coinvestigators have begun studies systematically looking at various possible interventions for sleep disorders in adults with neurodevelopmental disorders.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted without commercial support.

DENVER – Adults with ADHD or autism spectrum disorder experience a high burden of sleep disturbances, especially insomnia, Dr. Anastasios Galanopoulos reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

This has previously been established to be the case in pediatric patients with these neurodevelopmental disorders. However, sleep pathology hasn’t previously been well studied in affected adults, according to Dr. Galanopoulos, a consulting psychiatrist at Maudsley Hospital and King’s College London.

He presented a cross-sectional study of insomnia in a clinically representative sample comprising 164 adult patients: 98 with a DSM-5 diagnosis of ADHD, 30 with autism spectrum disorder, and 34 carrying both diagnoses.

Fully 91% of participants fell into the “poor” sleep category on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Moreover, 44% of subjects had either moderate or severe clinical insomnia as reflected in a score of 15 or more on the Insomnia Severity Index. The rate of high sleep disruption scores was similar, regardless of whether the diagnosis was ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, or both.

Anxiety but not depression ratings on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale correlated with insomnia scores, regardless of neurodevelopmental diagnosis. Insomnia scores also increased in concert with higher levels of hyperactivity symptoms as scored on the Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale. In contrast, inattentiveness scores were unrelated to insomnia.

Hyperactivity scores on the Barkley scale were significantly higher in adults with ADHD than in those with autism spectrum disorder. On the other hand, anxiety scores were higher in adults with autism spectrum disorder.

While the burden of sleep disturbances is similarly high in adults with ADHD and autism spectrum disorder, the underlying mechanism may well be different. For this reason, Dr. Galanopoulos and coinvestigators have begun studies systematically looking at various possible interventions for sleep disorders in adults with neurodevelopmental disorders.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted without commercial support.

AT SLEEP 2016

Insomnia is pervasive in adult neurodevelopmental disorders

DENVER – Adults with ADHD or autism spectrum disorder experience a high burden of sleep disturbances, especially insomnia, Dr. Anastasios Galanopoulos reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

This has previously been established to be the case in pediatric patients with these neurodevelopmental disorders. However, sleep pathology hasn’t previously been well studied in affected adults, according to Dr. Galanopoulos, a consulting psychiatrist at Maudsley Hospital and King’s College London.

He presented a cross-sectional study of insomnia in a clinically representative sample comprising 164 adult patients: 98 with a DSM-5 diagnosis of ADHD, 30 with autism spectrum disorder, and 34 carrying both diagnoses.

Fully 91% of participants fell into the “poor” sleep category on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Moreover, 44% of subjects had either moderate or severe clinical insomnia as reflected in a score of 15 or more on the Insomnia Severity Index. The rate of high sleep disruption scores was similar, regardless of whether the diagnosis was ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, or both.

Anxiety but not depression ratings on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale correlated with insomnia scores, regardless of neurodevelopmental diagnosis. Insomnia scores also increased in concert with higher levels of hyperactivity symptoms as scored on the Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale. In contrast, inattentiveness scores were unrelated to insomnia.

Hyperactivity scores on the Barkley scale were significantly higher in adults with ADHD than in those with autism spectrum disorder. On the other hand, anxiety scores were higher in adults with autism spectrum disorder.

While the burden of sleep disturbances is similarly high in adults with ADHD and autism spectrum disorder, the underlying mechanism may well be different. For this reason, Dr. Galanopoulos and coinvestigators have begun studies systematically looking at various possible interventions for sleep disorders in adults with neurodevelopmental disorders.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted without commercial support.

DENVER – Adults with ADHD or autism spectrum disorder experience a high burden of sleep disturbances, especially insomnia, Dr. Anastasios Galanopoulos reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

This has previously been established to be the case in pediatric patients with these neurodevelopmental disorders. However, sleep pathology hasn’t previously been well studied in affected adults, according to Dr. Galanopoulos, a consulting psychiatrist at Maudsley Hospital and King’s College London.

He presented a cross-sectional study of insomnia in a clinically representative sample comprising 164 adult patients: 98 with a DSM-5 diagnosis of ADHD, 30 with autism spectrum disorder, and 34 carrying both diagnoses.

Fully 91% of participants fell into the “poor” sleep category on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Moreover, 44% of subjects had either moderate or severe clinical insomnia as reflected in a score of 15 or more on the Insomnia Severity Index. The rate of high sleep disruption scores was similar, regardless of whether the diagnosis was ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, or both.

Anxiety but not depression ratings on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale correlated with insomnia scores, regardless of neurodevelopmental diagnosis. Insomnia scores also increased in concert with higher levels of hyperactivity symptoms as scored on the Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale. In contrast, inattentiveness scores were unrelated to insomnia.

Hyperactivity scores on the Barkley scale were significantly higher in adults with ADHD than in those with autism spectrum disorder. On the other hand, anxiety scores were higher in adults with autism spectrum disorder.

While the burden of sleep disturbances is similarly high in adults with ADHD and autism spectrum disorder, the underlying mechanism may well be different. For this reason, Dr. Galanopoulos and coinvestigators have begun studies systematically looking at various possible interventions for sleep disorders in adults with neurodevelopmental disorders.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted without commercial support.

DENVER – Adults with ADHD or autism spectrum disorder experience a high burden of sleep disturbances, especially insomnia, Dr. Anastasios Galanopoulos reported at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

This has previously been established to be the case in pediatric patients with these neurodevelopmental disorders. However, sleep pathology hasn’t previously been well studied in affected adults, according to Dr. Galanopoulos, a consulting psychiatrist at Maudsley Hospital and King’s College London.

He presented a cross-sectional study of insomnia in a clinically representative sample comprising 164 adult patients: 98 with a DSM-5 diagnosis of ADHD, 30 with autism spectrum disorder, and 34 carrying both diagnoses.

Fully 91% of participants fell into the “poor” sleep category on the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Moreover, 44% of subjects had either moderate or severe clinical insomnia as reflected in a score of 15 or more on the Insomnia Severity Index. The rate of high sleep disruption scores was similar, regardless of whether the diagnosis was ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, or both.

Anxiety but not depression ratings on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale correlated with insomnia scores, regardless of neurodevelopmental diagnosis. Insomnia scores also increased in concert with higher levels of hyperactivity symptoms as scored on the Barkley Adult ADHD Rating Scale. In contrast, inattentiveness scores were unrelated to insomnia.

Hyperactivity scores on the Barkley scale were significantly higher in adults with ADHD than in those with autism spectrum disorder. On the other hand, anxiety scores were higher in adults with autism spectrum disorder.

While the burden of sleep disturbances is similarly high in adults with ADHD and autism spectrum disorder, the underlying mechanism may well be different. For this reason, Dr. Galanopoulos and coinvestigators have begun studies systematically looking at various possible interventions for sleep disorders in adults with neurodevelopmental disorders.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted without commercial support.

AT SLEEP 2016

Key clinical point: Clinically significant insomnia is extremely common in adults with ADHD or autism spectrum disorder.

Major finding: 44% of adults with ADHD, autism spectrum disorder, or both diagnoses had moderate or severe insomnia on the validated Insomnia Severity Index.

Data source: This was a cross-sectional study of insomnia in 164 adults with neurodevelopmental disorders.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, which was conducted without commercial support.

SLEEP TIGHT: CPAP may be vasculoprotective in stroke/TIA

DENVER – Long-term continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack resulted in improved cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, better neurologic function, and a reduction in the recurrent vascular event rate, compared with usual care in the SLEEP TIGHT study.

“Up to 25% of patients will have a stroke, cardiovascular event, or death within 90 days after a minor stroke or TIA [transient ischemic attack] despite current preventive strategies. And, importantly, patients with a TIA or stroke have a high prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea – on the order of 60%-80%,” explained Dr. H. Klar Yaggi at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

SLEEP TIGHT’s findings support the hypothesis that diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent minor stroke or TIA will address a major unmet need for better methods of reducing the high vascular risk present in this population, said Dr. Yaggi of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

SLEEP TIGHT was a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored phase II, 12-month, multicenter, single-blind, randomized, proof-of-concept study. It included 252 patients, 80% of whom had a recent minor stroke, the rest a TIA. These were patients with high levels of cardiovascular risk factors: two-thirds had hypertension, half were hyperlipidemic, 40% had diabetes, 15% had a prior MI, 10% had atrial fibrillation, and the group’s mean body mass index was 30 kg/m2. Polysomnography revealed that 76% of subjects had sleep apnea as defined by an apnea-hypopnea index of at least 5 events per hour. In fact, they averaged about 23 events per hour, putting them in the moderate-severity range. As is common among stroke/TIA patients with sleep apnea, they experienced less daytime sleepiness than is typical in a sleep clinic population, with a mean baseline Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 7.

Participants were randomized to one of three groups: a usual care control group, a CPAP arm, or an enhanced CPAP arm. The enhanced intervention protocol was designed to boost CPAP adherence; it included targeted education, a customized cognitive intervention, and additional CPAP support beyond the standard CPAP protocols used in sleep medicine clinics. Patients with sleep apnea in the two intervention arms were then placed on CPAP.

At 1 year of follow-up, the stroke rate was 8.7 per 100 patient-years in the usual care group, compared with 5.5 per 100 person-years in the combined intervention arms. The composite cardiovascular event rate, composed of all-cause mortality, acute MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or urgent coronary revascularization, was 13.1 per 100 person-years with usual care and 11.0 in the CPAP intervention arms. While these results are encouraging, SLEEP TIGHT wasn’t powered to show significant differences in these hard events.

Outcomes across the board didn’t differ significantly between the CPAP and enhanced CPAP groups. And since the mean number of hours of CPAP use per night was also similar in the two groups – 3.9 hours with standard CPAP and 4.3 hours with enhanced CPAP – it’s likely that the phase III trial will rely upon the much simpler standard CPAP intervention, according to Dr. Yaggi.

He deemed CPAP adherence in this stroke/TIA population to be similar to the rates typically seen in routine sleep medicine practice. Roughly 40% of the stroke/TIA patients were rated as having good adherence, 30% made some use of the therapy, and 30% had no or poor adherence.

Nonetheless, patients in the two intervention arms did significantly better than the usual care group in terms of 1-year changes in insulin resistance and glycosylated hemoglobin. They also had lower 24-hour mean systolic blood pressure and were more likely to convert to a favorable pattern of nocturnal blood pressure dipping. However, no differences between the intervention and usual care groups were seen in levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, the two markers of systemic inflammation analyzed. Nor did the CPAP intervention provide any benefit in terms of heart rate variability and other measures of autonomic function.

Fifty-eight percent of patients in the intervention arms ended up with a desirable National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of 0-1, compared with 38% of the usual care group. In addition, daytime sleepiness as reflected in Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores was reduced at last follow-up to a significantly greater extent in the CPAP groups, Dr. Yaggi noted.

Greater CPAP use was associated with a favorable trend for improvement in the modified Rankin score, a measure of functional ability: a 0.3-point reduction with no or poor CPAP use, a 0.4-point decrease with some use, and a 0.9-point reduction with good use.

The encouraging results will be helpful in designing a planned much larger, event-driven, definitive phase III trial, Dr. Yaggi said.

Dr. Yaggi reported having no financial conflicts regarding this National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute-sponsored study.

DENVER – Long-term continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack resulted in improved cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, better neurologic function, and a reduction in the recurrent vascular event rate, compared with usual care in the SLEEP TIGHT study.

“Up to 25% of patients will have a stroke, cardiovascular event, or death within 90 days after a minor stroke or TIA [transient ischemic attack] despite current preventive strategies. And, importantly, patients with a TIA or stroke have a high prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea – on the order of 60%-80%,” explained Dr. H. Klar Yaggi at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

SLEEP TIGHT’s findings support the hypothesis that diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent minor stroke or TIA will address a major unmet need for better methods of reducing the high vascular risk present in this population, said Dr. Yaggi of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

SLEEP TIGHT was a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored phase II, 12-month, multicenter, single-blind, randomized, proof-of-concept study. It included 252 patients, 80% of whom had a recent minor stroke, the rest a TIA. These were patients with high levels of cardiovascular risk factors: two-thirds had hypertension, half were hyperlipidemic, 40% had diabetes, 15% had a prior MI, 10% had atrial fibrillation, and the group’s mean body mass index was 30 kg/m2. Polysomnography revealed that 76% of subjects had sleep apnea as defined by an apnea-hypopnea index of at least 5 events per hour. In fact, they averaged about 23 events per hour, putting them in the moderate-severity range. As is common among stroke/TIA patients with sleep apnea, they experienced less daytime sleepiness than is typical in a sleep clinic population, with a mean baseline Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 7.

Participants were randomized to one of three groups: a usual care control group, a CPAP arm, or an enhanced CPAP arm. The enhanced intervention protocol was designed to boost CPAP adherence; it included targeted education, a customized cognitive intervention, and additional CPAP support beyond the standard CPAP protocols used in sleep medicine clinics. Patients with sleep apnea in the two intervention arms were then placed on CPAP.

At 1 year of follow-up, the stroke rate was 8.7 per 100 patient-years in the usual care group, compared with 5.5 per 100 person-years in the combined intervention arms. The composite cardiovascular event rate, composed of all-cause mortality, acute MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or urgent coronary revascularization, was 13.1 per 100 person-years with usual care and 11.0 in the CPAP intervention arms. While these results are encouraging, SLEEP TIGHT wasn’t powered to show significant differences in these hard events.

Outcomes across the board didn’t differ significantly between the CPAP and enhanced CPAP groups. And since the mean number of hours of CPAP use per night was also similar in the two groups – 3.9 hours with standard CPAP and 4.3 hours with enhanced CPAP – it’s likely that the phase III trial will rely upon the much simpler standard CPAP intervention, according to Dr. Yaggi.

He deemed CPAP adherence in this stroke/TIA population to be similar to the rates typically seen in routine sleep medicine practice. Roughly 40% of the stroke/TIA patients were rated as having good adherence, 30% made some use of the therapy, and 30% had no or poor adherence.

Nonetheless, patients in the two intervention arms did significantly better than the usual care group in terms of 1-year changes in insulin resistance and glycosylated hemoglobin. They also had lower 24-hour mean systolic blood pressure and were more likely to convert to a favorable pattern of nocturnal blood pressure dipping. However, no differences between the intervention and usual care groups were seen in levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, the two markers of systemic inflammation analyzed. Nor did the CPAP intervention provide any benefit in terms of heart rate variability and other measures of autonomic function.

Fifty-eight percent of patients in the intervention arms ended up with a desirable National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of 0-1, compared with 38% of the usual care group. In addition, daytime sleepiness as reflected in Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores was reduced at last follow-up to a significantly greater extent in the CPAP groups, Dr. Yaggi noted.

Greater CPAP use was associated with a favorable trend for improvement in the modified Rankin score, a measure of functional ability: a 0.3-point reduction with no or poor CPAP use, a 0.4-point decrease with some use, and a 0.9-point reduction with good use.

The encouraging results will be helpful in designing a planned much larger, event-driven, definitive phase III trial, Dr. Yaggi said.

Dr. Yaggi reported having no financial conflicts regarding this National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute-sponsored study.

DENVER – Long-term continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent mild stroke or transient ischemic attack resulted in improved cardiovascular and metabolic risk factors, better neurologic function, and a reduction in the recurrent vascular event rate, compared with usual care in the SLEEP TIGHT study.

“Up to 25% of patients will have a stroke, cardiovascular event, or death within 90 days after a minor stroke or TIA [transient ischemic attack] despite current preventive strategies. And, importantly, patients with a TIA or stroke have a high prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea – on the order of 60%-80%,” explained Dr. H. Klar Yaggi at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

SLEEP TIGHT’s findings support the hypothesis that diagnosis and treatment of sleep apnea in patients with a recent minor stroke or TIA will address a major unmet need for better methods of reducing the high vascular risk present in this population, said Dr. Yaggi of Yale University in New Haven, Conn.

SLEEP TIGHT was a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored phase II, 12-month, multicenter, single-blind, randomized, proof-of-concept study. It included 252 patients, 80% of whom had a recent minor stroke, the rest a TIA. These were patients with high levels of cardiovascular risk factors: two-thirds had hypertension, half were hyperlipidemic, 40% had diabetes, 15% had a prior MI, 10% had atrial fibrillation, and the group’s mean body mass index was 30 kg/m2. Polysomnography revealed that 76% of subjects had sleep apnea as defined by an apnea-hypopnea index of at least 5 events per hour. In fact, they averaged about 23 events per hour, putting them in the moderate-severity range. As is common among stroke/TIA patients with sleep apnea, they experienced less daytime sleepiness than is typical in a sleep clinic population, with a mean baseline Epworth Sleepiness Scale score of 7.

Participants were randomized to one of three groups: a usual care control group, a CPAP arm, or an enhanced CPAP arm. The enhanced intervention protocol was designed to boost CPAP adherence; it included targeted education, a customized cognitive intervention, and additional CPAP support beyond the standard CPAP protocols used in sleep medicine clinics. Patients with sleep apnea in the two intervention arms were then placed on CPAP.

At 1 year of follow-up, the stroke rate was 8.7 per 100 patient-years in the usual care group, compared with 5.5 per 100 person-years in the combined intervention arms. The composite cardiovascular event rate, composed of all-cause mortality, acute MI, stroke, hospitalization for unstable angina, or urgent coronary revascularization, was 13.1 per 100 person-years with usual care and 11.0 in the CPAP intervention arms. While these results are encouraging, SLEEP TIGHT wasn’t powered to show significant differences in these hard events.

Outcomes across the board didn’t differ significantly between the CPAP and enhanced CPAP groups. And since the mean number of hours of CPAP use per night was also similar in the two groups – 3.9 hours with standard CPAP and 4.3 hours with enhanced CPAP – it’s likely that the phase III trial will rely upon the much simpler standard CPAP intervention, according to Dr. Yaggi.

He deemed CPAP adherence in this stroke/TIA population to be similar to the rates typically seen in routine sleep medicine practice. Roughly 40% of the stroke/TIA patients were rated as having good adherence, 30% made some use of the therapy, and 30% had no or poor adherence.

Nonetheless, patients in the two intervention arms did significantly better than the usual care group in terms of 1-year changes in insulin resistance and glycosylated hemoglobin. They also had lower 24-hour mean systolic blood pressure and were more likely to convert to a favorable pattern of nocturnal blood pressure dipping. However, no differences between the intervention and usual care groups were seen in levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein and interleukin-6, the two markers of systemic inflammation analyzed. Nor did the CPAP intervention provide any benefit in terms of heart rate variability and other measures of autonomic function.

Fifty-eight percent of patients in the intervention arms ended up with a desirable National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of 0-1, compared with 38% of the usual care group. In addition, daytime sleepiness as reflected in Epworth Sleepiness Scale scores was reduced at last follow-up to a significantly greater extent in the CPAP groups, Dr. Yaggi noted.

Greater CPAP use was associated with a favorable trend for improvement in the modified Rankin score, a measure of functional ability: a 0.3-point reduction with no or poor CPAP use, a 0.4-point decrease with some use, and a 0.9-point reduction with good use.

The encouraging results will be helpful in designing a planned much larger, event-driven, definitive phase III trial, Dr. Yaggi said.

Dr. Yaggi reported having no financial conflicts regarding this National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute-sponsored study.

AT SLEEP 2016