User login

Slow breathing: An effective, pragmatic analgesic technique?

MILWAUKEE – Mindfulness-based practices are effective in reducing pain perceptions, but a more easily taught breath control technique also showed efficacy in a recent study. Slow, rhythmic breathing alone, even without the additional attentional components of mindfulness, had significant analgesic effects in a human experimental model of pain.

“Slow breathing is much easier to perform” than mindfulness-based meditation, Fadel Zeidan, PhD, said at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society. More research into the technique may offer a “clinically pragmatic” nonpharmacologic option for pain control, he said. And there may be some similarities between how the two techniques work: like mindfulness meditation, slow, rhythmic breathing’s analgesic properties are not dependent on the endogenous opioid system, said Dr. Zeidan, assistant professor of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. His interests include mindfulness meditation–based pain relief.

In previous work, Dr. Zeidan and his collaborators had shown that the analgesic effect of mindfulness practices is not mediated by endogenous opioids. Participants in a study were trained in mindfulness meditation, and then exposed to a pain stimulus. Compared with a control group who listened to an audiobook rather than using mindfulness practices when exposed to pain, the meditators experienced a significant reduction in pain unpleasantness (J Neurosci. 16 March 2016;36[11]:3391-7).

In the experiment, both the meditation and the control group received first an intravenous saline solution, and then the opioid antagonist naloxone, which blocks endogenous opioids. When receiving naloxone, the meditators experienced reductions in the perceived unpleasantness of pain that were similar to what they experienced when they had received saline, showing that endogenous opioids weren’t responsible for meditation’s analgesic effects.

After verifying those findings, said Dr. Zeidan, he became interested in conducting a “graded analytical dissection of mindfulness,” to see exactly which components of the practice are nonopioidergic.

With mindfulness meditation, participants engage in slow, rhythmic breathing, and they learn about observation and appraisal practices, which can briefly be described as “the awareness of arising sensory events without reaction,” Dr. Zeidan said.

Mere belief in meditation in combination with the slow rhythmic breathing might have an analgesic effect, he said. In effect, this is sham mindfulness.

To try to tease out the contributions of each component of mindfulness meditation, Dr. Zeidan and his colleagues devised an experiment that trained participants in one of three ways. Over the course of four 20-minute sessions, randomized participants were trained in slow breathing techniques, with a goal respiratory rate of 6 breaths per minute; in mindfulness meditation techniques; or in a sham mindfulness technique that did not teach specific mindfulness principles.

The randomized participants were subject to a painful heat stimulus before the training to establish a baseline.

After training, they returned for two further sessions. At each visit, they experienced the noxious stimulus with no medication. After a rest period, they then received either high-dose intravenous naloxone or saline. The allocation was randomized and administration of the study drug was double-blinded.

With naloxone or saline infusion ongoing, participants were then again subjected to the painful heat stimulus.

“All manipulations effectively reduced the respiration rate,” by 18%-21%, Dr. Zeidan said.

However, with the introduction of naloxone, both the slow-breathing group and the mindfulness group maintained reductions in pain unpleasantness, while those in the sham group had significant increases in pain unpleasantness. Reductions in pain unpleasantness ranged from 11% to 18% for these two groups, while the initial 8% reduction for the sham group climbed to a 13% increase in pain unpleasantness when this group received naloxone.

An unexpected finding was how effective slow breathing alone was as an analgesic. “There’s really something here,” said Dr. Zeidan, in reference to the analgesic effect of breath control. He explained that the slow breathing technique training was done with the aid of a device that emitted a blue glow that dimmed and brightened at the target respiratory rate.

Dr. Zeidan added that few participants were able to slow their breathing to 6 respirations per minute, but that the average rate did slow to about 12 from the normal 16 or so breaths per minute.

Dr. Zeidan reported no conflicts of interest. The National Institutes of Health funded the research.

MILWAUKEE – Mindfulness-based practices are effective in reducing pain perceptions, but a more easily taught breath control technique also showed efficacy in a recent study. Slow, rhythmic breathing alone, even without the additional attentional components of mindfulness, had significant analgesic effects in a human experimental model of pain.

“Slow breathing is much easier to perform” than mindfulness-based meditation, Fadel Zeidan, PhD, said at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society. More research into the technique may offer a “clinically pragmatic” nonpharmacologic option for pain control, he said. And there may be some similarities between how the two techniques work: like mindfulness meditation, slow, rhythmic breathing’s analgesic properties are not dependent on the endogenous opioid system, said Dr. Zeidan, assistant professor of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. His interests include mindfulness meditation–based pain relief.

In previous work, Dr. Zeidan and his collaborators had shown that the analgesic effect of mindfulness practices is not mediated by endogenous opioids. Participants in a study were trained in mindfulness meditation, and then exposed to a pain stimulus. Compared with a control group who listened to an audiobook rather than using mindfulness practices when exposed to pain, the meditators experienced a significant reduction in pain unpleasantness (J Neurosci. 16 March 2016;36[11]:3391-7).

In the experiment, both the meditation and the control group received first an intravenous saline solution, and then the opioid antagonist naloxone, which blocks endogenous opioids. When receiving naloxone, the meditators experienced reductions in the perceived unpleasantness of pain that were similar to what they experienced when they had received saline, showing that endogenous opioids weren’t responsible for meditation’s analgesic effects.

After verifying those findings, said Dr. Zeidan, he became interested in conducting a “graded analytical dissection of mindfulness,” to see exactly which components of the practice are nonopioidergic.

With mindfulness meditation, participants engage in slow, rhythmic breathing, and they learn about observation and appraisal practices, which can briefly be described as “the awareness of arising sensory events without reaction,” Dr. Zeidan said.

Mere belief in meditation in combination with the slow rhythmic breathing might have an analgesic effect, he said. In effect, this is sham mindfulness.

To try to tease out the contributions of each component of mindfulness meditation, Dr. Zeidan and his colleagues devised an experiment that trained participants in one of three ways. Over the course of four 20-minute sessions, randomized participants were trained in slow breathing techniques, with a goal respiratory rate of 6 breaths per minute; in mindfulness meditation techniques; or in a sham mindfulness technique that did not teach specific mindfulness principles.

The randomized participants were subject to a painful heat stimulus before the training to establish a baseline.

After training, they returned for two further sessions. At each visit, they experienced the noxious stimulus with no medication. After a rest period, they then received either high-dose intravenous naloxone or saline. The allocation was randomized and administration of the study drug was double-blinded.

With naloxone or saline infusion ongoing, participants were then again subjected to the painful heat stimulus.

“All manipulations effectively reduced the respiration rate,” by 18%-21%, Dr. Zeidan said.

However, with the introduction of naloxone, both the slow-breathing group and the mindfulness group maintained reductions in pain unpleasantness, while those in the sham group had significant increases in pain unpleasantness. Reductions in pain unpleasantness ranged from 11% to 18% for these two groups, while the initial 8% reduction for the sham group climbed to a 13% increase in pain unpleasantness when this group received naloxone.

An unexpected finding was how effective slow breathing alone was as an analgesic. “There’s really something here,” said Dr. Zeidan, in reference to the analgesic effect of breath control. He explained that the slow breathing technique training was done with the aid of a device that emitted a blue glow that dimmed and brightened at the target respiratory rate.

Dr. Zeidan added that few participants were able to slow their breathing to 6 respirations per minute, but that the average rate did slow to about 12 from the normal 16 or so breaths per minute.

Dr. Zeidan reported no conflicts of interest. The National Institutes of Health funded the research.

MILWAUKEE – Mindfulness-based practices are effective in reducing pain perceptions, but a more easily taught breath control technique also showed efficacy in a recent study. Slow, rhythmic breathing alone, even without the additional attentional components of mindfulness, had significant analgesic effects in a human experimental model of pain.

“Slow breathing is much easier to perform” than mindfulness-based meditation, Fadel Zeidan, PhD, said at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society. More research into the technique may offer a “clinically pragmatic” nonpharmacologic option for pain control, he said. And there may be some similarities between how the two techniques work: like mindfulness meditation, slow, rhythmic breathing’s analgesic properties are not dependent on the endogenous opioid system, said Dr. Zeidan, assistant professor of anesthesiology at the University of California, San Diego. His interests include mindfulness meditation–based pain relief.

In previous work, Dr. Zeidan and his collaborators had shown that the analgesic effect of mindfulness practices is not mediated by endogenous opioids. Participants in a study were trained in mindfulness meditation, and then exposed to a pain stimulus. Compared with a control group who listened to an audiobook rather than using mindfulness practices when exposed to pain, the meditators experienced a significant reduction in pain unpleasantness (J Neurosci. 16 March 2016;36[11]:3391-7).

In the experiment, both the meditation and the control group received first an intravenous saline solution, and then the opioid antagonist naloxone, which blocks endogenous opioids. When receiving naloxone, the meditators experienced reductions in the perceived unpleasantness of pain that were similar to what they experienced when they had received saline, showing that endogenous opioids weren’t responsible for meditation’s analgesic effects.

After verifying those findings, said Dr. Zeidan, he became interested in conducting a “graded analytical dissection of mindfulness,” to see exactly which components of the practice are nonopioidergic.

With mindfulness meditation, participants engage in slow, rhythmic breathing, and they learn about observation and appraisal practices, which can briefly be described as “the awareness of arising sensory events without reaction,” Dr. Zeidan said.

Mere belief in meditation in combination with the slow rhythmic breathing might have an analgesic effect, he said. In effect, this is sham mindfulness.

To try to tease out the contributions of each component of mindfulness meditation, Dr. Zeidan and his colleagues devised an experiment that trained participants in one of three ways. Over the course of four 20-minute sessions, randomized participants were trained in slow breathing techniques, with a goal respiratory rate of 6 breaths per minute; in mindfulness meditation techniques; or in a sham mindfulness technique that did not teach specific mindfulness principles.

The randomized participants were subject to a painful heat stimulus before the training to establish a baseline.

After training, they returned for two further sessions. At each visit, they experienced the noxious stimulus with no medication. After a rest period, they then received either high-dose intravenous naloxone or saline. The allocation was randomized and administration of the study drug was double-blinded.

With naloxone or saline infusion ongoing, participants were then again subjected to the painful heat stimulus.

“All manipulations effectively reduced the respiration rate,” by 18%-21%, Dr. Zeidan said.

However, with the introduction of naloxone, both the slow-breathing group and the mindfulness group maintained reductions in pain unpleasantness, while those in the sham group had significant increases in pain unpleasantness. Reductions in pain unpleasantness ranged from 11% to 18% for these two groups, while the initial 8% reduction for the sham group climbed to a 13% increase in pain unpleasantness when this group received naloxone.

An unexpected finding was how effective slow breathing alone was as an analgesic. “There’s really something here,” said Dr. Zeidan, in reference to the analgesic effect of breath control. He explained that the slow breathing technique training was done with the aid of a device that emitted a blue glow that dimmed and brightened at the target respiratory rate.

Dr. Zeidan added that few participants were able to slow their breathing to 6 respirations per minute, but that the average rate did slow to about 12 from the normal 16 or so breaths per minute.

Dr. Zeidan reported no conflicts of interest. The National Institutes of Health funded the research.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

Sleep, chronic pain, and OUD have a complex relationship

MILWAUKEE – Individuals with chronic pain frequently have disrupted sleep and also may be at risk for opioid use disorder. However, even with advanced monitoring, it’s not clear how sleep modulates pain and opioid cravings.

Sleep has an impact on positive and negative affect, but new research shows that the link between sleep and mood states that may contribute to opioid use disorder is not straightforward. At the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Patrick Finan, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, discussed how sleep and mood affect cravings for opioids among those in treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD).

said Dr. Finan, who told attendees that one key question he and his colleagues were seeking to answer was whether those with OUD and chronic pain had more disturbed sleep than those with OUD alone. Also, the researchers wanted to know whether the ups and downs of sleep on a day-to-day basis were reflected in pain scores among those with OUD, as would be predicted by prevailing models.

Finally, two “proximal indicators” of relapse risk, affect and heroin craving, might be affected by both sleep and pain, and Dr. Finan and collaborators sought to explore that association.

The work was part of a larger study looking at the natural history of OUD and OUD with comorbid chronic pain. To participate in this parent study, adults with OUD had to be seeking treatment or currently enrolled in methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatment, and without current major depressive disorder. Also, patients could not have a history of significant mental illness, cognitive impairment, or a medical condition that would interfere with study participation. A total of 56 patients participated, and 20 of these individuals also had chronic pain.

Those with OUD and chronic pain qualified if they had pain (not related to opioid withdrawal) averaging above 3 on a 0-10 pain rating scale over the past week; additional criteria included pain for at least the past 3 months, with 10 or more days per month of pain.

Pain ratings were captured via a smartphone app that prompted participants to enter a pain rating at three random times during each day. Each evening, patients also completed a sleep diary giving information about bedtime, sleep onset latency, waking after sleep onset, and wake time for the preceding day.

A self-applied ambulatory electroencephalogram applied to the forehead was used for up to 7 consecutive nights to capture sleep continuity estimates; the device has been validated against polysomnography data in other work. Participants were given incentives to use the device, and this “yielded strong adherence,” with an average of 5 nights of use per participant, Dr. Finan said.

Patients were an average age of about 49 years, and were 75% male. African American participants made up just over half of the cohort, and 43% were white. Participants were roughly evenly divided in the type of maintenance therapy they were taking. Overall, 39% of participants had a positive urine toxicology screen.

For patients with chronic pain, 45% of all momentary pain reports had a pain score over zero, with a mean of 32 days of pain. Looking at the data another way, 58% of all patient-days had at least one momentary report of pain greater than zero, said Dr. Finan. On average, participants recorded a pain score of 2.27.

Brief Pain Inventory scores at baseline showed a mean severity of 5, and a pain interference score of 5.07.

Participants with OUD and chronic pain did not differ across any EEG-recorded sleep measures, compared with those with OUD alone. However, subjective reports of sleep were actually better overall for those with chronic pain than the objective EEG reports. The EEG recordings captured an average of 9.11 minutes more of waking after sleep onset (P less than .001). Also, total sleep time was 10.37 minutes shorter as recorded by the EEG than by self-report (P less than .001). Overall sleep efficiency was also worse by 5.96 minutes according to the EEG, compared with self-report (P less than .001).

“Sleep is objectively poor but subjectively ‘normal’ and variable in opioid use disorder patients,” Dr. Finan said. In aggregate, however, neither diary-based subjective nor EEG-based objective sleep measures differed between those with and without chronic pain in the research cohort. This phenomenon of sleep efficiency being self-reported as higher than objective measures capture sleep has also been seen in those newly abstinent from cocaine, Dr. Finan said, adding that it’s possible individuals with substance use disorder who are new to treatment simply feel better than they have in some time along many dimensions, with sleep being one such domain.

Pain on a given day didn’t predict poor sleep on that night, except that sleep onset took slightly longer (P = .01), said Dr. Finan. He noted that “there was no substantive effect on other sleep continuity parameters.”

Looking at how negative affect mediated craving for heroin, Dr. Finan and colleagues found that negative affect–related craving was significantly greater for those with chronic pain (P less than .001). Unlike findings in patients without OUD, having disrupted sleep continuity was more associated with increased daily negative affect, rather than decreased positive affect. And this increased negative affect was associated with heroin cravings, said Dr. Finan. “In the past few years, we’ve seen quite a few studies that have found some abnormalities in the reward system in patients with chronic pain.” Whether poor sleep is a mediator of these abnormalities deserves further study.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Finan reported no outside sources of funding.

MILWAUKEE – Individuals with chronic pain frequently have disrupted sleep and also may be at risk for opioid use disorder. However, even with advanced monitoring, it’s not clear how sleep modulates pain and opioid cravings.

Sleep has an impact on positive and negative affect, but new research shows that the link between sleep and mood states that may contribute to opioid use disorder is not straightforward. At the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Patrick Finan, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, discussed how sleep and mood affect cravings for opioids among those in treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD).

said Dr. Finan, who told attendees that one key question he and his colleagues were seeking to answer was whether those with OUD and chronic pain had more disturbed sleep than those with OUD alone. Also, the researchers wanted to know whether the ups and downs of sleep on a day-to-day basis were reflected in pain scores among those with OUD, as would be predicted by prevailing models.

Finally, two “proximal indicators” of relapse risk, affect and heroin craving, might be affected by both sleep and pain, and Dr. Finan and collaborators sought to explore that association.

The work was part of a larger study looking at the natural history of OUD and OUD with comorbid chronic pain. To participate in this parent study, adults with OUD had to be seeking treatment or currently enrolled in methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatment, and without current major depressive disorder. Also, patients could not have a history of significant mental illness, cognitive impairment, or a medical condition that would interfere with study participation. A total of 56 patients participated, and 20 of these individuals also had chronic pain.

Those with OUD and chronic pain qualified if they had pain (not related to opioid withdrawal) averaging above 3 on a 0-10 pain rating scale over the past week; additional criteria included pain for at least the past 3 months, with 10 or more days per month of pain.

Pain ratings were captured via a smartphone app that prompted participants to enter a pain rating at three random times during each day. Each evening, patients also completed a sleep diary giving information about bedtime, sleep onset latency, waking after sleep onset, and wake time for the preceding day.

A self-applied ambulatory electroencephalogram applied to the forehead was used for up to 7 consecutive nights to capture sleep continuity estimates; the device has been validated against polysomnography data in other work. Participants were given incentives to use the device, and this “yielded strong adherence,” with an average of 5 nights of use per participant, Dr. Finan said.

Patients were an average age of about 49 years, and were 75% male. African American participants made up just over half of the cohort, and 43% were white. Participants were roughly evenly divided in the type of maintenance therapy they were taking. Overall, 39% of participants had a positive urine toxicology screen.

For patients with chronic pain, 45% of all momentary pain reports had a pain score over zero, with a mean of 32 days of pain. Looking at the data another way, 58% of all patient-days had at least one momentary report of pain greater than zero, said Dr. Finan. On average, participants recorded a pain score of 2.27.

Brief Pain Inventory scores at baseline showed a mean severity of 5, and a pain interference score of 5.07.

Participants with OUD and chronic pain did not differ across any EEG-recorded sleep measures, compared with those with OUD alone. However, subjective reports of sleep were actually better overall for those with chronic pain than the objective EEG reports. The EEG recordings captured an average of 9.11 minutes more of waking after sleep onset (P less than .001). Also, total sleep time was 10.37 minutes shorter as recorded by the EEG than by self-report (P less than .001). Overall sleep efficiency was also worse by 5.96 minutes according to the EEG, compared with self-report (P less than .001).

“Sleep is objectively poor but subjectively ‘normal’ and variable in opioid use disorder patients,” Dr. Finan said. In aggregate, however, neither diary-based subjective nor EEG-based objective sleep measures differed between those with and without chronic pain in the research cohort. This phenomenon of sleep efficiency being self-reported as higher than objective measures capture sleep has also been seen in those newly abstinent from cocaine, Dr. Finan said, adding that it’s possible individuals with substance use disorder who are new to treatment simply feel better than they have in some time along many dimensions, with sleep being one such domain.

Pain on a given day didn’t predict poor sleep on that night, except that sleep onset took slightly longer (P = .01), said Dr. Finan. He noted that “there was no substantive effect on other sleep continuity parameters.”

Looking at how negative affect mediated craving for heroin, Dr. Finan and colleagues found that negative affect–related craving was significantly greater for those with chronic pain (P less than .001). Unlike findings in patients without OUD, having disrupted sleep continuity was more associated with increased daily negative affect, rather than decreased positive affect. And this increased negative affect was associated with heroin cravings, said Dr. Finan. “In the past few years, we’ve seen quite a few studies that have found some abnormalities in the reward system in patients with chronic pain.” Whether poor sleep is a mediator of these abnormalities deserves further study.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Finan reported no outside sources of funding.

MILWAUKEE – Individuals with chronic pain frequently have disrupted sleep and also may be at risk for opioid use disorder. However, even with advanced monitoring, it’s not clear how sleep modulates pain and opioid cravings.

Sleep has an impact on positive and negative affect, but new research shows that the link between sleep and mood states that may contribute to opioid use disorder is not straightforward. At the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Patrick Finan, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, discussed how sleep and mood affect cravings for opioids among those in treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD).

said Dr. Finan, who told attendees that one key question he and his colleagues were seeking to answer was whether those with OUD and chronic pain had more disturbed sleep than those with OUD alone. Also, the researchers wanted to know whether the ups and downs of sleep on a day-to-day basis were reflected in pain scores among those with OUD, as would be predicted by prevailing models.

Finally, two “proximal indicators” of relapse risk, affect and heroin craving, might be affected by both sleep and pain, and Dr. Finan and collaborators sought to explore that association.

The work was part of a larger study looking at the natural history of OUD and OUD with comorbid chronic pain. To participate in this parent study, adults with OUD had to be seeking treatment or currently enrolled in methadone or buprenorphine maintenance treatment, and without current major depressive disorder. Also, patients could not have a history of significant mental illness, cognitive impairment, or a medical condition that would interfere with study participation. A total of 56 patients participated, and 20 of these individuals also had chronic pain.

Those with OUD and chronic pain qualified if they had pain (not related to opioid withdrawal) averaging above 3 on a 0-10 pain rating scale over the past week; additional criteria included pain for at least the past 3 months, with 10 or more days per month of pain.

Pain ratings were captured via a smartphone app that prompted participants to enter a pain rating at three random times during each day. Each evening, patients also completed a sleep diary giving information about bedtime, sleep onset latency, waking after sleep onset, and wake time for the preceding day.

A self-applied ambulatory electroencephalogram applied to the forehead was used for up to 7 consecutive nights to capture sleep continuity estimates; the device has been validated against polysomnography data in other work. Participants were given incentives to use the device, and this “yielded strong adherence,” with an average of 5 nights of use per participant, Dr. Finan said.

Patients were an average age of about 49 years, and were 75% male. African American participants made up just over half of the cohort, and 43% were white. Participants were roughly evenly divided in the type of maintenance therapy they were taking. Overall, 39% of participants had a positive urine toxicology screen.

For patients with chronic pain, 45% of all momentary pain reports had a pain score over zero, with a mean of 32 days of pain. Looking at the data another way, 58% of all patient-days had at least one momentary report of pain greater than zero, said Dr. Finan. On average, participants recorded a pain score of 2.27.

Brief Pain Inventory scores at baseline showed a mean severity of 5, and a pain interference score of 5.07.

Participants with OUD and chronic pain did not differ across any EEG-recorded sleep measures, compared with those with OUD alone. However, subjective reports of sleep were actually better overall for those with chronic pain than the objective EEG reports. The EEG recordings captured an average of 9.11 minutes more of waking after sleep onset (P less than .001). Also, total sleep time was 10.37 minutes shorter as recorded by the EEG than by self-report (P less than .001). Overall sleep efficiency was also worse by 5.96 minutes according to the EEG, compared with self-report (P less than .001).

“Sleep is objectively poor but subjectively ‘normal’ and variable in opioid use disorder patients,” Dr. Finan said. In aggregate, however, neither diary-based subjective nor EEG-based objective sleep measures differed between those with and without chronic pain in the research cohort. This phenomenon of sleep efficiency being self-reported as higher than objective measures capture sleep has also been seen in those newly abstinent from cocaine, Dr. Finan said, adding that it’s possible individuals with substance use disorder who are new to treatment simply feel better than they have in some time along many dimensions, with sleep being one such domain.

Pain on a given day didn’t predict poor sleep on that night, except that sleep onset took slightly longer (P = .01), said Dr. Finan. He noted that “there was no substantive effect on other sleep continuity parameters.”

Looking at how negative affect mediated craving for heroin, Dr. Finan and colleagues found that negative affect–related craving was significantly greater for those with chronic pain (P less than .001). Unlike findings in patients without OUD, having disrupted sleep continuity was more associated with increased daily negative affect, rather than decreased positive affect. And this increased negative affect was associated with heroin cravings, said Dr. Finan. “In the past few years, we’ve seen quite a few studies that have found some abnormalities in the reward system in patients with chronic pain.” Whether poor sleep is a mediator of these abnormalities deserves further study.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Finan reported no outside sources of funding.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

Outpatient program successfully tackles substance use and chronic pain

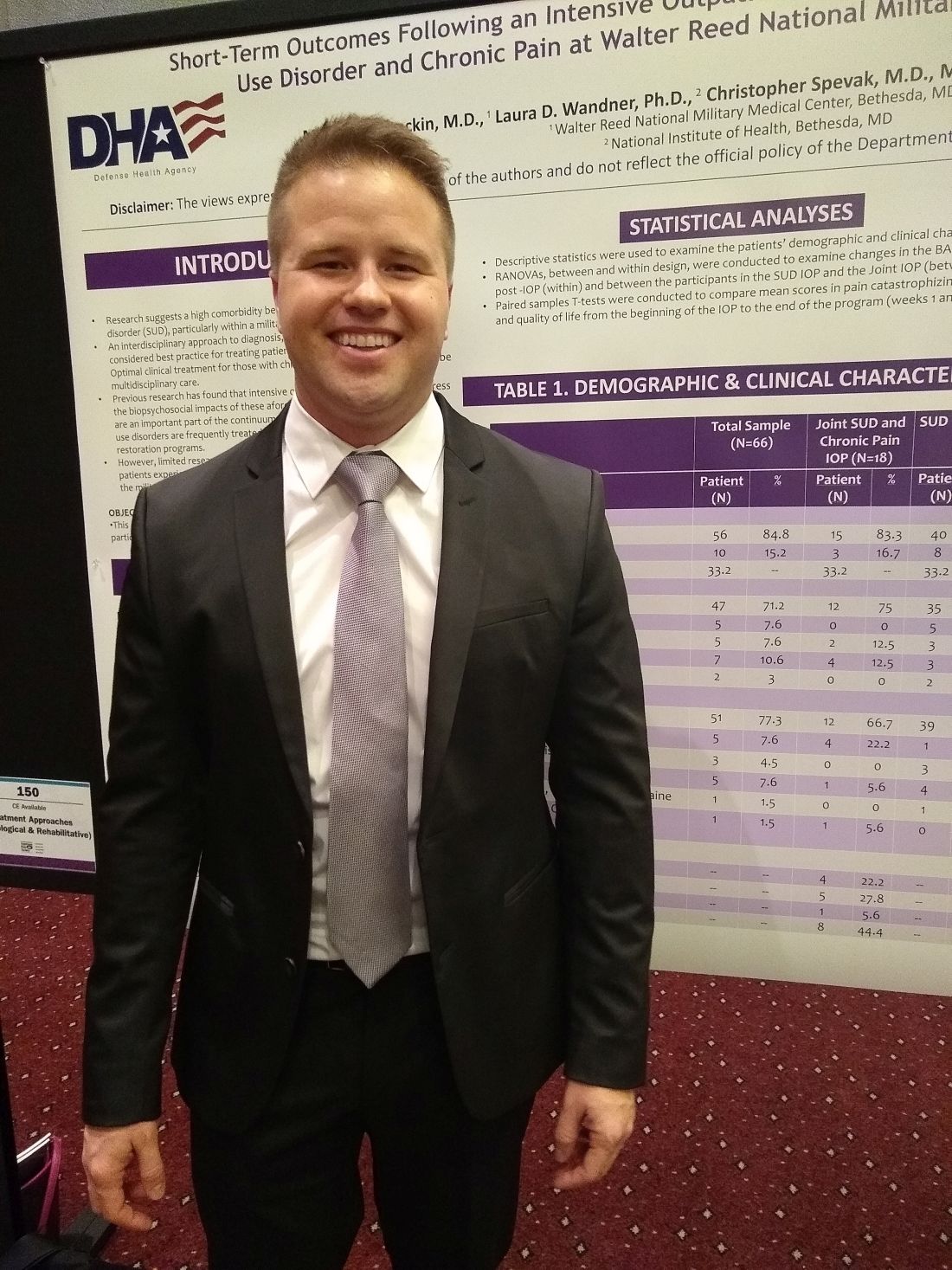

MILWAUKEE – An interdisciplinary intensive outpatient treatment program addressing chronic pain and substance use disorder effectively addressed both diagnoses in a military population.

Intensive outpatient programs (IOPs) frequently address these conditions within a biopsychosocial format, but it’s not common for IOPs to have this dual focus on chronic pain and substance use disorder (SUD), said Michael Stockin, MD, speaking in an interview at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Dr. Stockin said he and his collaborators recognized that, especially among a military population, the two conditions have considerable overlap, so it made sense to integrate behavioral treatment for both conditions in an intensive outpatient program. “Our hypothesis was that if you can use an intensive outpatient program to address substance use disorder, maybe you can actually add a chronic pain curriculum – like a functional restoration program to it.

“As a result of our study, we did find that there were significant differences in worst pain scores as a result of the program. In the people who took both the substance use disorder and chronic pain curriculum, we found significant reductions in total impairment, worst pain, and they also had less … substance use as well,” said Dr. Stockin.

In a quality improvement project, Dr. Stockin and collaborators compared short-term outcomes for patients who received IOP treatment addressing both chronic pain and SUD with those receiving SUD-only IOP.

For those participating in the joint IOP, scores indicating worst pain on the 0-10 numeric rating scale were reduced significantly, from 7.55 to 6.23 (P = .013). Scores on a functional measure of impairment, the Pain Outcomes Questionnaire Short Form (POQ-SF) also dropped significantly, from 84.92 to 63.50 (P = .034). The vitality domain of the POQ-SF also showed that patients had less impairment after participation in the joint IOP, with scores in that domain dropping from 20.17 to 17.25 (P = .024).

Looking at the total cohort, patient scores on the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM) dropped significantly from baseline to the end of the intervention, indicating reduced substance use (P = .041). Mean scores for participants in the joint IOP were higher at baseline than for those in the SUD-only IOP (1.000 vs. 0.565). However, those participating in the joint IOP had lower mean postintervention BAM scores than the SUD-only cohort (0.071 vs. 0.174).

American veterans experience more severe pain and have a higher prevalence of chronic pain than nonveterans. Similarly, wrote Dr. Stockin, a chronic pain fellow in pain management at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues in the poster presentation.

The project enrolled a total of 66 patients (10 female and 56 male). Of these, 18 participated in the joint SUD–chronic pain program, and 48 received usual treatment of the SUD-only IOP treatment. The mean overall age was 33.2 years, and 71.2% of participants were white.

Overall, 51 patients (77.3%) of participants had alcohol use disorder. Participants included active duty service members, veterans, and their dependents. Opioid and cannabis use disorders were experienced by a total of eight patients, and seven more patients had diagnoses of alcohol use disorder along with other substance use disorders.

All patients completed the BAM and received urine toxicology and alcohol breath testing at enrollment; drug and alcohol screening was completed at other points during the IOP treatment for both groups as well.

The joint IOP ran 3 full days a week, with a substance use curriculum in the morning and a pain management program in the afternoon; the SUD-only participants had three morning sessions weekly. Both interventions lasted 6 weeks, and Dr. Stockin said he and his colleagues would like to acquire longitudinal data to assess the durability of gains seen from the joint IOP.

The multidisciplinary team running the joint IOP was made up of an addiction/pain medicine physician, a clinical health psychologist, a physical therapist, social workers, and a nurse.

“This project is the first of its kind to find a significant reduction in pain burden while concurrently treating addiction and pain in an outpatient military health care setting,” Dr. Stockin and colleagues wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

“We had outcomes in both substance use and chronic pain that were positive, so it suggests that in the military health system, people may actually benefit from treating both chronic pain and substance use disorder concurrently. If you could harmonize those programs, you might be able to get good outcomes for soldiers and their families,” Dr. Stockin said.

Dr. Stockin reported no conflicts of interest. The project was funded by the Defense Health Agency.

MILWAUKEE – An interdisciplinary intensive outpatient treatment program addressing chronic pain and substance use disorder effectively addressed both diagnoses in a military population.

Intensive outpatient programs (IOPs) frequently address these conditions within a biopsychosocial format, but it’s not common for IOPs to have this dual focus on chronic pain and substance use disorder (SUD), said Michael Stockin, MD, speaking in an interview at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Dr. Stockin said he and his collaborators recognized that, especially among a military population, the two conditions have considerable overlap, so it made sense to integrate behavioral treatment for both conditions in an intensive outpatient program. “Our hypothesis was that if you can use an intensive outpatient program to address substance use disorder, maybe you can actually add a chronic pain curriculum – like a functional restoration program to it.

“As a result of our study, we did find that there were significant differences in worst pain scores as a result of the program. In the people who took both the substance use disorder and chronic pain curriculum, we found significant reductions in total impairment, worst pain, and they also had less … substance use as well,” said Dr. Stockin.

In a quality improvement project, Dr. Stockin and collaborators compared short-term outcomes for patients who received IOP treatment addressing both chronic pain and SUD with those receiving SUD-only IOP.

For those participating in the joint IOP, scores indicating worst pain on the 0-10 numeric rating scale were reduced significantly, from 7.55 to 6.23 (P = .013). Scores on a functional measure of impairment, the Pain Outcomes Questionnaire Short Form (POQ-SF) also dropped significantly, from 84.92 to 63.50 (P = .034). The vitality domain of the POQ-SF also showed that patients had less impairment after participation in the joint IOP, with scores in that domain dropping from 20.17 to 17.25 (P = .024).

Looking at the total cohort, patient scores on the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM) dropped significantly from baseline to the end of the intervention, indicating reduced substance use (P = .041). Mean scores for participants in the joint IOP were higher at baseline than for those in the SUD-only IOP (1.000 vs. 0.565). However, those participating in the joint IOP had lower mean postintervention BAM scores than the SUD-only cohort (0.071 vs. 0.174).

American veterans experience more severe pain and have a higher prevalence of chronic pain than nonveterans. Similarly, wrote Dr. Stockin, a chronic pain fellow in pain management at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues in the poster presentation.

The project enrolled a total of 66 patients (10 female and 56 male). Of these, 18 participated in the joint SUD–chronic pain program, and 48 received usual treatment of the SUD-only IOP treatment. The mean overall age was 33.2 years, and 71.2% of participants were white.

Overall, 51 patients (77.3%) of participants had alcohol use disorder. Participants included active duty service members, veterans, and their dependents. Opioid and cannabis use disorders were experienced by a total of eight patients, and seven more patients had diagnoses of alcohol use disorder along with other substance use disorders.

All patients completed the BAM and received urine toxicology and alcohol breath testing at enrollment; drug and alcohol screening was completed at other points during the IOP treatment for both groups as well.

The joint IOP ran 3 full days a week, with a substance use curriculum in the morning and a pain management program in the afternoon; the SUD-only participants had three morning sessions weekly. Both interventions lasted 6 weeks, and Dr. Stockin said he and his colleagues would like to acquire longitudinal data to assess the durability of gains seen from the joint IOP.

The multidisciplinary team running the joint IOP was made up of an addiction/pain medicine physician, a clinical health psychologist, a physical therapist, social workers, and a nurse.

“This project is the first of its kind to find a significant reduction in pain burden while concurrently treating addiction and pain in an outpatient military health care setting,” Dr. Stockin and colleagues wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

“We had outcomes in both substance use and chronic pain that were positive, so it suggests that in the military health system, people may actually benefit from treating both chronic pain and substance use disorder concurrently. If you could harmonize those programs, you might be able to get good outcomes for soldiers and their families,” Dr. Stockin said.

Dr. Stockin reported no conflicts of interest. The project was funded by the Defense Health Agency.

MILWAUKEE – An interdisciplinary intensive outpatient treatment program addressing chronic pain and substance use disorder effectively addressed both diagnoses in a military population.

Intensive outpatient programs (IOPs) frequently address these conditions within a biopsychosocial format, but it’s not common for IOPs to have this dual focus on chronic pain and substance use disorder (SUD), said Michael Stockin, MD, speaking in an interview at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Dr. Stockin said he and his collaborators recognized that, especially among a military population, the two conditions have considerable overlap, so it made sense to integrate behavioral treatment for both conditions in an intensive outpatient program. “Our hypothesis was that if you can use an intensive outpatient program to address substance use disorder, maybe you can actually add a chronic pain curriculum – like a functional restoration program to it.

“As a result of our study, we did find that there were significant differences in worst pain scores as a result of the program. In the people who took both the substance use disorder and chronic pain curriculum, we found significant reductions in total impairment, worst pain, and they also had less … substance use as well,” said Dr. Stockin.

In a quality improvement project, Dr. Stockin and collaborators compared short-term outcomes for patients who received IOP treatment addressing both chronic pain and SUD with those receiving SUD-only IOP.

For those participating in the joint IOP, scores indicating worst pain on the 0-10 numeric rating scale were reduced significantly, from 7.55 to 6.23 (P = .013). Scores on a functional measure of impairment, the Pain Outcomes Questionnaire Short Form (POQ-SF) also dropped significantly, from 84.92 to 63.50 (P = .034). The vitality domain of the POQ-SF also showed that patients had less impairment after participation in the joint IOP, with scores in that domain dropping from 20.17 to 17.25 (P = .024).

Looking at the total cohort, patient scores on the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM) dropped significantly from baseline to the end of the intervention, indicating reduced substance use (P = .041). Mean scores for participants in the joint IOP were higher at baseline than for those in the SUD-only IOP (1.000 vs. 0.565). However, those participating in the joint IOP had lower mean postintervention BAM scores than the SUD-only cohort (0.071 vs. 0.174).

American veterans experience more severe pain and have a higher prevalence of chronic pain than nonveterans. Similarly, wrote Dr. Stockin, a chronic pain fellow in pain management at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md., and colleagues in the poster presentation.

The project enrolled a total of 66 patients (10 female and 56 male). Of these, 18 participated in the joint SUD–chronic pain program, and 48 received usual treatment of the SUD-only IOP treatment. The mean overall age was 33.2 years, and 71.2% of participants were white.

Overall, 51 patients (77.3%) of participants had alcohol use disorder. Participants included active duty service members, veterans, and their dependents. Opioid and cannabis use disorders were experienced by a total of eight patients, and seven more patients had diagnoses of alcohol use disorder along with other substance use disorders.

All patients completed the BAM and received urine toxicology and alcohol breath testing at enrollment; drug and alcohol screening was completed at other points during the IOP treatment for both groups as well.

The joint IOP ran 3 full days a week, with a substance use curriculum in the morning and a pain management program in the afternoon; the SUD-only participants had three morning sessions weekly. Both interventions lasted 6 weeks, and Dr. Stockin said he and his colleagues would like to acquire longitudinal data to assess the durability of gains seen from the joint IOP.

The multidisciplinary team running the joint IOP was made up of an addiction/pain medicine physician, a clinical health psychologist, a physical therapist, social workers, and a nurse.

“This project is the first of its kind to find a significant reduction in pain burden while concurrently treating addiction and pain in an outpatient military health care setting,” Dr. Stockin and colleagues wrote in the poster accompanying the presentation.

“We had outcomes in both substance use and chronic pain that were positive, so it suggests that in the military health system, people may actually benefit from treating both chronic pain and substance use disorder concurrently. If you could harmonize those programs, you might be able to get good outcomes for soldiers and their families,” Dr. Stockin said.

Dr. Stockin reported no conflicts of interest. The project was funded by the Defense Health Agency.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

Key clinical point: An intensive, 6-week joint substance use disorder and chronic pain intensive outpatient program significantly reduced both substance use and pain.

Major finding: Patients had less pain and reduced substance use after completing the program, compared with baseline (P = .013 and .041, respectively).

Study details: A quality improvement project including 66 patients at a military health facility.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Defense Health Agency. Dr. Stockin reported no conflicts of interest.

In chronic pain, catastrophizing contributes to disrupted brain circuitry

MILWAUKEE – When a patient with acute pain tumbles into a chronic pain state, many factors are at play, according to the widely accepted biopsychosocial theory of pain. Emotional, cognitive, and environmental components all contribute to the persistent and recalcitrant symptoms chronic pain patients experience.

Now, modern neuroimaging techniques show how for some, pain signals hijack the brain’s regulatory networks, allowing rumination and catastrophizing to intrude on the exteroception that’s critical to how humans interact with one another and the world. Interrupting catastrophizing with nonpharmacologic techniques yields measurable improvements – and there’s promise that a single treatment session can make a lasting difference.

“Psychosocial phenotypes, such as catastrophizing, are part of a complex biopsychosocial web of contributors to chronic pain. ,” said Robert R. Edwards, PhD, a psychologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School (Boston) Pain Management Center. Dr. Edwards moderated a session focused on catastrophizing at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Through magnetic resonance imaging techniques that measure functional connectivity, researchers can now see how nodes in the brain form connected networks that are differentially activated.

For example, the brain’s salience network (SLN) responds to stimuli that merit attention, such as evoked or clinical pain, Vitaly Napadow, PhD, said during his presentation. Key nodes in the SLN include the anterior cingulate cortex, the anterior insula, and the anterior temporoparietal junction. One function of the salience network, he said, is to regulate switching between the default mode network (DMN) – an interoceptive network – and the central executive network, usually active in exteroceptive tasks.

“The default mode network has been found to play an important role in pain processing,” Dr. Napadow said. These brain regions are more active in self-referential cognition – thinking about oneself – than when performing external tasks, he said. Consistently, studies have found decreased DMN deactivation in patients with chronic pain; essentially, the constant low hum of pain-focused DMN activity never turns off in a chronic pain state.

For patients with chronic pain, high levels of catastrophizing mean greater impact on functional brain connectivity, said Dr. Napadow, director of the Center for Integrative Pain NeuroImaging at the Martino Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Looking at patients with chronic low back pain, he and his research team looked for connections between the DMN and the insula, which has a central role in pain processing. This connectivity was increased only in patients with high catastrophizing scores, said Dr. Napadow, with increased DMN-insula connectivity associated with increased pain scores only for this subgroup (Pain. 2019 Mar 4. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001541).

“The model that we’re moving toward is that chronic pain leads to a blurring in the canonical network” of brain connectivity, Dr. Napadow said. “The speculation here is that the DMN-SLN linkage could be a sort of neural substrate for a common perception that chronic pain patients have – that their pain becomes part of who they are. Their interoceptive state becomes linked to the pain they are feeling: They are their pain.”

Where to turn with this information, which has large clinical implications? “Catastrophizing is a consistent risk factor for poor pain treatment outcomes, especially when we’re talking about pharmacologic treatments,” Dr. Edwards said. Also, chronic pain patients with the highest catastrophizing scores have the most opioid-related side effects, he said.

“Cognitive-behavioral therapy is potentially the most effective at reducing this risk factor,” said Dr. Edwards, noting that long-term effects were seen at 6 and 12 months post treatment. “These are significant, moderate-sized effects; there is some evidence that effects are largest in those with the highest baseline pain catastrophizing scores.”

“CBT is considered the gold standard, mainly because it’s the best studied” among treatment modalities, psychologist Beth Darnall, PhD, pointed out in her presentation. There’s evidence that other nonpharmacologic interventions can reduce catastrophizing: Psychology-informed yoga practices, physical therapy, and certain medical devices, such as high-frequency transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation units, may all have efficacy against catastrophizing and the downward spiral of chronic pain.

Still, a randomized controlled trial of CBT for pain in patients with fibromyalgia showed that the benefit, measured as reduction in pain interference with daily functioning, was almost twice as high in the high-catastrophizing group, “suggesting the potential utility of this method for patients at greatest risk,” said Dr. Edwards.

“We see a specific pattern of alterations in chronic pain similar to that seen in anxiety disorder; this suggests that some individuals are primed for the experience of pain,” said Dr. Darnall, clinical professor of anesthesiology, perioperative medicine, and pain medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. “We are not born with the understanding of how to modulate pain and the distress it causes us.”

When she talks to patients, Dr. Darnall said: “I describe pain as being our ‘harm alarm.’ ... I like to describe it to people that ‘you have a very protective nervous system.’ ”

Dr. Darnall and her colleagues reported success with a pilot study of a single 2.5-hour-long session that addressed pain catastrophizing. From a baseline score of 26.1 on the Pain Catastrophizing Scale to a score of 13.8 at week 4, the 57 participants saw a significant decrease in mean scores on the scale (d [effect size] = 1.15).

On the strength of these early findings, Dr. Darnall and her collaborators are embarking on a randomized controlled trial ; the 3-arm comparative effectiveness study will compare a single-session intervention against 8 weeks of CBT or education-only classes for individuals with catastrophizing and chronic pain. The trial is structured to test the hypothesis that the single-session intervention will be noninferior to the full 8 weeks of CBT, Dr. Darnall said.

Building on the importance of avoiding stigmatizing and pejorative terms when talking about pain and catastrophizing, Dr. Darnall said she’s moved away from using the term “catastrophizing” in patient interactions. The one-session intervention is called “Empowered Relief – Train Your Brain Away from Pain.”

There’s a practical promise to a single-session class: Dr. Darnall has taught up to 85 patients at once, she said, adding, “This is a low-cost and scalable intervention.”

Dr. Edwards and Dr. Napadow reported funding from the National Institutes of Health, and they reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Darnall reported funding from the NIH and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. She serves on the scientific advisory board of Axial Healthcare and has several commercial publications about pain.

MILWAUKEE – When a patient with acute pain tumbles into a chronic pain state, many factors are at play, according to the widely accepted biopsychosocial theory of pain. Emotional, cognitive, and environmental components all contribute to the persistent and recalcitrant symptoms chronic pain patients experience.

Now, modern neuroimaging techniques show how for some, pain signals hijack the brain’s regulatory networks, allowing rumination and catastrophizing to intrude on the exteroception that’s critical to how humans interact with one another and the world. Interrupting catastrophizing with nonpharmacologic techniques yields measurable improvements – and there’s promise that a single treatment session can make a lasting difference.

“Psychosocial phenotypes, such as catastrophizing, are part of a complex biopsychosocial web of contributors to chronic pain. ,” said Robert R. Edwards, PhD, a psychologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School (Boston) Pain Management Center. Dr. Edwards moderated a session focused on catastrophizing at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Through magnetic resonance imaging techniques that measure functional connectivity, researchers can now see how nodes in the brain form connected networks that are differentially activated.

For example, the brain’s salience network (SLN) responds to stimuli that merit attention, such as evoked or clinical pain, Vitaly Napadow, PhD, said during his presentation. Key nodes in the SLN include the anterior cingulate cortex, the anterior insula, and the anterior temporoparietal junction. One function of the salience network, he said, is to regulate switching between the default mode network (DMN) – an interoceptive network – and the central executive network, usually active in exteroceptive tasks.

“The default mode network has been found to play an important role in pain processing,” Dr. Napadow said. These brain regions are more active in self-referential cognition – thinking about oneself – than when performing external tasks, he said. Consistently, studies have found decreased DMN deactivation in patients with chronic pain; essentially, the constant low hum of pain-focused DMN activity never turns off in a chronic pain state.

For patients with chronic pain, high levels of catastrophizing mean greater impact on functional brain connectivity, said Dr. Napadow, director of the Center for Integrative Pain NeuroImaging at the Martino Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Looking at patients with chronic low back pain, he and his research team looked for connections between the DMN and the insula, which has a central role in pain processing. This connectivity was increased only in patients with high catastrophizing scores, said Dr. Napadow, with increased DMN-insula connectivity associated with increased pain scores only for this subgroup (Pain. 2019 Mar 4. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001541).

“The model that we’re moving toward is that chronic pain leads to a blurring in the canonical network” of brain connectivity, Dr. Napadow said. “The speculation here is that the DMN-SLN linkage could be a sort of neural substrate for a common perception that chronic pain patients have – that their pain becomes part of who they are. Their interoceptive state becomes linked to the pain they are feeling: They are their pain.”

Where to turn with this information, which has large clinical implications? “Catastrophizing is a consistent risk factor for poor pain treatment outcomes, especially when we’re talking about pharmacologic treatments,” Dr. Edwards said. Also, chronic pain patients with the highest catastrophizing scores have the most opioid-related side effects, he said.

“Cognitive-behavioral therapy is potentially the most effective at reducing this risk factor,” said Dr. Edwards, noting that long-term effects were seen at 6 and 12 months post treatment. “These are significant, moderate-sized effects; there is some evidence that effects are largest in those with the highest baseline pain catastrophizing scores.”

“CBT is considered the gold standard, mainly because it’s the best studied” among treatment modalities, psychologist Beth Darnall, PhD, pointed out in her presentation. There’s evidence that other nonpharmacologic interventions can reduce catastrophizing: Psychology-informed yoga practices, physical therapy, and certain medical devices, such as high-frequency transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation units, may all have efficacy against catastrophizing and the downward spiral of chronic pain.

Still, a randomized controlled trial of CBT for pain in patients with fibromyalgia showed that the benefit, measured as reduction in pain interference with daily functioning, was almost twice as high in the high-catastrophizing group, “suggesting the potential utility of this method for patients at greatest risk,” said Dr. Edwards.

“We see a specific pattern of alterations in chronic pain similar to that seen in anxiety disorder; this suggests that some individuals are primed for the experience of pain,” said Dr. Darnall, clinical professor of anesthesiology, perioperative medicine, and pain medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. “We are not born with the understanding of how to modulate pain and the distress it causes us.”

When she talks to patients, Dr. Darnall said: “I describe pain as being our ‘harm alarm.’ ... I like to describe it to people that ‘you have a very protective nervous system.’ ”

Dr. Darnall and her colleagues reported success with a pilot study of a single 2.5-hour-long session that addressed pain catastrophizing. From a baseline score of 26.1 on the Pain Catastrophizing Scale to a score of 13.8 at week 4, the 57 participants saw a significant decrease in mean scores on the scale (d [effect size] = 1.15).

On the strength of these early findings, Dr. Darnall and her collaborators are embarking on a randomized controlled trial ; the 3-arm comparative effectiveness study will compare a single-session intervention against 8 weeks of CBT or education-only classes for individuals with catastrophizing and chronic pain. The trial is structured to test the hypothesis that the single-session intervention will be noninferior to the full 8 weeks of CBT, Dr. Darnall said.

Building on the importance of avoiding stigmatizing and pejorative terms when talking about pain and catastrophizing, Dr. Darnall said she’s moved away from using the term “catastrophizing” in patient interactions. The one-session intervention is called “Empowered Relief – Train Your Brain Away from Pain.”

There’s a practical promise to a single-session class: Dr. Darnall has taught up to 85 patients at once, she said, adding, “This is a low-cost and scalable intervention.”

Dr. Edwards and Dr. Napadow reported funding from the National Institutes of Health, and they reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Darnall reported funding from the NIH and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. She serves on the scientific advisory board of Axial Healthcare and has several commercial publications about pain.

MILWAUKEE – When a patient with acute pain tumbles into a chronic pain state, many factors are at play, according to the widely accepted biopsychosocial theory of pain. Emotional, cognitive, and environmental components all contribute to the persistent and recalcitrant symptoms chronic pain patients experience.

Now, modern neuroimaging techniques show how for some, pain signals hijack the brain’s regulatory networks, allowing rumination and catastrophizing to intrude on the exteroception that’s critical to how humans interact with one another and the world. Interrupting catastrophizing with nonpharmacologic techniques yields measurable improvements – and there’s promise that a single treatment session can make a lasting difference.

“Psychosocial phenotypes, such as catastrophizing, are part of a complex biopsychosocial web of contributors to chronic pain. ,” said Robert R. Edwards, PhD, a psychologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital/Harvard Medical School (Boston) Pain Management Center. Dr. Edwards moderated a session focused on catastrophizing at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society.

Through magnetic resonance imaging techniques that measure functional connectivity, researchers can now see how nodes in the brain form connected networks that are differentially activated.

For example, the brain’s salience network (SLN) responds to stimuli that merit attention, such as evoked or clinical pain, Vitaly Napadow, PhD, said during his presentation. Key nodes in the SLN include the anterior cingulate cortex, the anterior insula, and the anterior temporoparietal junction. One function of the salience network, he said, is to regulate switching between the default mode network (DMN) – an interoceptive network – and the central executive network, usually active in exteroceptive tasks.

“The default mode network has been found to play an important role in pain processing,” Dr. Napadow said. These brain regions are more active in self-referential cognition – thinking about oneself – than when performing external tasks, he said. Consistently, studies have found decreased DMN deactivation in patients with chronic pain; essentially, the constant low hum of pain-focused DMN activity never turns off in a chronic pain state.

For patients with chronic pain, high levels of catastrophizing mean greater impact on functional brain connectivity, said Dr. Napadow, director of the Center for Integrative Pain NeuroImaging at the Martino Center for Biomedical Imaging at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Looking at patients with chronic low back pain, he and his research team looked for connections between the DMN and the insula, which has a central role in pain processing. This connectivity was increased only in patients with high catastrophizing scores, said Dr. Napadow, with increased DMN-insula connectivity associated with increased pain scores only for this subgroup (Pain. 2019 Mar 4. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001541).

“The model that we’re moving toward is that chronic pain leads to a blurring in the canonical network” of brain connectivity, Dr. Napadow said. “The speculation here is that the DMN-SLN linkage could be a sort of neural substrate for a common perception that chronic pain patients have – that their pain becomes part of who they are. Their interoceptive state becomes linked to the pain they are feeling: They are their pain.”

Where to turn with this information, which has large clinical implications? “Catastrophizing is a consistent risk factor for poor pain treatment outcomes, especially when we’re talking about pharmacologic treatments,” Dr. Edwards said. Also, chronic pain patients with the highest catastrophizing scores have the most opioid-related side effects, he said.

“Cognitive-behavioral therapy is potentially the most effective at reducing this risk factor,” said Dr. Edwards, noting that long-term effects were seen at 6 and 12 months post treatment. “These are significant, moderate-sized effects; there is some evidence that effects are largest in those with the highest baseline pain catastrophizing scores.”

“CBT is considered the gold standard, mainly because it’s the best studied” among treatment modalities, psychologist Beth Darnall, PhD, pointed out in her presentation. There’s evidence that other nonpharmacologic interventions can reduce catastrophizing: Psychology-informed yoga practices, physical therapy, and certain medical devices, such as high-frequency transcutaneous electric nerve stimulation units, may all have efficacy against catastrophizing and the downward spiral of chronic pain.

Still, a randomized controlled trial of CBT for pain in patients with fibromyalgia showed that the benefit, measured as reduction in pain interference with daily functioning, was almost twice as high in the high-catastrophizing group, “suggesting the potential utility of this method for patients at greatest risk,” said Dr. Edwards.

“We see a specific pattern of alterations in chronic pain similar to that seen in anxiety disorder; this suggests that some individuals are primed for the experience of pain,” said Dr. Darnall, clinical professor of anesthesiology, perioperative medicine, and pain medicine at Stanford (Calif.) University. “We are not born with the understanding of how to modulate pain and the distress it causes us.”

When she talks to patients, Dr. Darnall said: “I describe pain as being our ‘harm alarm.’ ... I like to describe it to people that ‘you have a very protective nervous system.’ ”

Dr. Darnall and her colleagues reported success with a pilot study of a single 2.5-hour-long session that addressed pain catastrophizing. From a baseline score of 26.1 on the Pain Catastrophizing Scale to a score of 13.8 at week 4, the 57 participants saw a significant decrease in mean scores on the scale (d [effect size] = 1.15).

On the strength of these early findings, Dr. Darnall and her collaborators are embarking on a randomized controlled trial ; the 3-arm comparative effectiveness study will compare a single-session intervention against 8 weeks of CBT or education-only classes for individuals with catastrophizing and chronic pain. The trial is structured to test the hypothesis that the single-session intervention will be noninferior to the full 8 weeks of CBT, Dr. Darnall said.

Building on the importance of avoiding stigmatizing and pejorative terms when talking about pain and catastrophizing, Dr. Darnall said she’s moved away from using the term “catastrophizing” in patient interactions. The one-session intervention is called “Empowered Relief – Train Your Brain Away from Pain.”

There’s a practical promise to a single-session class: Dr. Darnall has taught up to 85 patients at once, she said, adding, “This is a low-cost and scalable intervention.”

Dr. Edwards and Dr. Napadow reported funding from the National Institutes of Health, and they reported no conflicts of interest. Dr. Darnall reported funding from the NIH and the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. She serves on the scientific advisory board of Axial Healthcare and has several commercial publications about pain.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

In pain treatment, racial bias common among physician trainees

MILWAUKEE – More than 40% of white physician trainees demonstrated racial bias in medical decision making about treatment of low back pain, as did 31% of nonwhite trainees. However, just 6% of white residents and fellows, and 10% of the nonwhite residents and fellows, reported that patient race had factored into their treatment decisions in a virtual patient task.

The 444 medical residents and fellows who participated viewed video vignettes presenting 12 virtual patients who presented with low back pain, wrote Alexis Grant of Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis and her colleagues. In a poster presentation at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Ms. Grant, a doctoral student in clinical psychology, and her collaborators explained that participants agreed to view a series of 12 videos of virtual patients.

The videos presented male and female virtual patients who were black or white and who had jobs associated with low or high socioeconomic status (SES). Information in text vignettes accompanying the videos included occupation, pain etiology, physical exam findings, and pain intensity by self-report.

After viewing the videos and reading the vignettes, participating clinicians were asked to use a 0-100 visual analog scale to report their likelihood of referring patients to a pain specialist or to physical therapy and of recommending opioid or nonopioid analgesia.

“Next, they rated the degree to which they considered different sources of patient information when making treatment decision,” Ms. Grant and her coauthors wrote. Statistical analysis “examined the extent to which providers demonstrated statistically reliable treatment differences across patient race and SES.” These findings were compared with how clinicians reported they used patient race and SES in decision making.

Demonstrated race-based decision making occurred for 41% of white and 31% of nonwhite clinicians. About two-thirds of providers (67.3%) were white, and of the remainder, 26.3% were Asian, 4.4% were classified as “other,” and 2.1% were black. The respondents were aged a mean 29.7 years, and were 42.3% female.

In addition, Ms. Grant and her coauthors estimated provider SES by asking about parental SES, dividing respondents into low (less than $38,000), medium ($38,000-$75,000), and high (greater than $75,000) SES categories.

and similar across levels of provider SES, at 41%, 43%, and 38% for low, medium, and high SES residents and fellows, respectively. However, the disconnect between reported and demonstrated bias that was seen with race was not seen with SES bias, with 43%-48% of providers in each SES group reporting that they had factored patient SES into their treatment decision making.

“These results suggest that providers have low awareness of making different pain treatment decisions” for black patients, compared with decision making for white patients, Ms. Grant and her colleagues wrote. “Decision-making awareness did not substantially differ across provider race or SES.” She and her collaborators called for more research into whether raising awareness about demonstrated racial bias in decision making can improve both racial and socioeconomic gaps in pain care.

The authors reported funding from the National Institutes of Health. They reported no conflicts of interest.

MILWAUKEE – More than 40% of white physician trainees demonstrated racial bias in medical decision making about treatment of low back pain, as did 31% of nonwhite trainees. However, just 6% of white residents and fellows, and 10% of the nonwhite residents and fellows, reported that patient race had factored into their treatment decisions in a virtual patient task.

The 444 medical residents and fellows who participated viewed video vignettes presenting 12 virtual patients who presented with low back pain, wrote Alexis Grant of Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis and her colleagues. In a poster presentation at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Ms. Grant, a doctoral student in clinical psychology, and her collaborators explained that participants agreed to view a series of 12 videos of virtual patients.

The videos presented male and female virtual patients who were black or white and who had jobs associated with low or high socioeconomic status (SES). Information in text vignettes accompanying the videos included occupation, pain etiology, physical exam findings, and pain intensity by self-report.

After viewing the videos and reading the vignettes, participating clinicians were asked to use a 0-100 visual analog scale to report their likelihood of referring patients to a pain specialist or to physical therapy and of recommending opioid or nonopioid analgesia.

“Next, they rated the degree to which they considered different sources of patient information when making treatment decision,” Ms. Grant and her coauthors wrote. Statistical analysis “examined the extent to which providers demonstrated statistically reliable treatment differences across patient race and SES.” These findings were compared with how clinicians reported they used patient race and SES in decision making.

Demonstrated race-based decision making occurred for 41% of white and 31% of nonwhite clinicians. About two-thirds of providers (67.3%) were white, and of the remainder, 26.3% were Asian, 4.4% were classified as “other,” and 2.1% were black. The respondents were aged a mean 29.7 years, and were 42.3% female.

In addition, Ms. Grant and her coauthors estimated provider SES by asking about parental SES, dividing respondents into low (less than $38,000), medium ($38,000-$75,000), and high (greater than $75,000) SES categories.

and similar across levels of provider SES, at 41%, 43%, and 38% for low, medium, and high SES residents and fellows, respectively. However, the disconnect between reported and demonstrated bias that was seen with race was not seen with SES bias, with 43%-48% of providers in each SES group reporting that they had factored patient SES into their treatment decision making.

“These results suggest that providers have low awareness of making different pain treatment decisions” for black patients, compared with decision making for white patients, Ms. Grant and her colleagues wrote. “Decision-making awareness did not substantially differ across provider race or SES.” She and her collaborators called for more research into whether raising awareness about demonstrated racial bias in decision making can improve both racial and socioeconomic gaps in pain care.

The authors reported funding from the National Institutes of Health. They reported no conflicts of interest.

MILWAUKEE – More than 40% of white physician trainees demonstrated racial bias in medical decision making about treatment of low back pain, as did 31% of nonwhite trainees. However, just 6% of white residents and fellows, and 10% of the nonwhite residents and fellows, reported that patient race had factored into their treatment decisions in a virtual patient task.

The 444 medical residents and fellows who participated viewed video vignettes presenting 12 virtual patients who presented with low back pain, wrote Alexis Grant of Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis and her colleagues. In a poster presentation at the scientific meeting of the American Pain Society, Ms. Grant, a doctoral student in clinical psychology, and her collaborators explained that participants agreed to view a series of 12 videos of virtual patients.

The videos presented male and female virtual patients who were black or white and who had jobs associated with low or high socioeconomic status (SES). Information in text vignettes accompanying the videos included occupation, pain etiology, physical exam findings, and pain intensity by self-report.

After viewing the videos and reading the vignettes, participating clinicians were asked to use a 0-100 visual analog scale to report their likelihood of referring patients to a pain specialist or to physical therapy and of recommending opioid or nonopioid analgesia.

“Next, they rated the degree to which they considered different sources of patient information when making treatment decision,” Ms. Grant and her coauthors wrote. Statistical analysis “examined the extent to which providers demonstrated statistically reliable treatment differences across patient race and SES.” These findings were compared with how clinicians reported they used patient race and SES in decision making.

Demonstrated race-based decision making occurred for 41% of white and 31% of nonwhite clinicians. About two-thirds of providers (67.3%) were white, and of the remainder, 26.3% were Asian, 4.4% were classified as “other,” and 2.1% were black. The respondents were aged a mean 29.7 years, and were 42.3% female.

In addition, Ms. Grant and her coauthors estimated provider SES by asking about parental SES, dividing respondents into low (less than $38,000), medium ($38,000-$75,000), and high (greater than $75,000) SES categories.

and similar across levels of provider SES, at 41%, 43%, and 38% for low, medium, and high SES residents and fellows, respectively. However, the disconnect between reported and demonstrated bias that was seen with race was not seen with SES bias, with 43%-48% of providers in each SES group reporting that they had factored patient SES into their treatment decision making.

“These results suggest that providers have low awareness of making different pain treatment decisions” for black patients, compared with decision making for white patients, Ms. Grant and her colleagues wrote. “Decision-making awareness did not substantially differ across provider race or SES.” She and her collaborators called for more research into whether raising awareness about demonstrated racial bias in decision making can improve both racial and socioeconomic gaps in pain care.

The authors reported funding from the National Institutes of Health. They reported no conflicts of interest.

REPORTING FROM APS 2019

‘Fibro-fog’ confirmed with objective ambulatory testing