User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

It’s time to retire the president question

The president question – “Who’s the current president?” – has been a standard one of basic neurology assessments for years, probably since the answer was Ulysses S. Grant. It’s routinely asked by doctors, nurses, EEG techs, medical students, and pretty much anyone else trying to figure out someone’s mental status.

When I first began doing this, the answer was “George Bush” (at that time there’d only been one president by that name, so clarification wasn’t needed). Back then people answered the question (right or wrong) and we moved on. I don’t recall ever getting a dirty look, political lecture, or eye roll as a response.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple anymore. As people have become increasingly polarized, it’s become seemingly impossible to get a response without a statement of support or anger. At best I get a straight answer. At worst I get a lecture on the “perils of a non-White society” (that was last week). Then they want my opinion, and years of practice have taught me to never discuss politics with patients, regardless of which side they’re on.

I don’t recall this being a problem until the late ‘90s, when the answer was “Clinton.” Occasionally I’d get a sarcastic comment referring to the Lewinsky affair, but that was about it.

Since then it’s gradually escalated, to where the question has become worthless. I don’t have time to hear a political diatribe from either side. This is a doctor appointment, not a debate club. The insistence by some that Trump won leaves me guessing if the person is stubborn or serious, and either way it shouldn’t be my job to figure that out. I take your appointment seriously, so the least you can do is the same.

So I’ve ditched the question for good. The current date, the location of my office, and other less controversial things will have to do. I’m here to take care of you, not have you try to pick a fight or make a political statement.

You’d think such a simple, time-honored, assessment question wouldn’t become such a problem. But

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The president question – “Who’s the current president?” – has been a standard one of basic neurology assessments for years, probably since the answer was Ulysses S. Grant. It’s routinely asked by doctors, nurses, EEG techs, medical students, and pretty much anyone else trying to figure out someone’s mental status.

When I first began doing this, the answer was “George Bush” (at that time there’d only been one president by that name, so clarification wasn’t needed). Back then people answered the question (right or wrong) and we moved on. I don’t recall ever getting a dirty look, political lecture, or eye roll as a response.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple anymore. As people have become increasingly polarized, it’s become seemingly impossible to get a response without a statement of support or anger. At best I get a straight answer. At worst I get a lecture on the “perils of a non-White society” (that was last week). Then they want my opinion, and years of practice have taught me to never discuss politics with patients, regardless of which side they’re on.

I don’t recall this being a problem until the late ‘90s, when the answer was “Clinton.” Occasionally I’d get a sarcastic comment referring to the Lewinsky affair, but that was about it.

Since then it’s gradually escalated, to where the question has become worthless. I don’t have time to hear a political diatribe from either side. This is a doctor appointment, not a debate club. The insistence by some that Trump won leaves me guessing if the person is stubborn or serious, and either way it shouldn’t be my job to figure that out. I take your appointment seriously, so the least you can do is the same.

So I’ve ditched the question for good. The current date, the location of my office, and other less controversial things will have to do. I’m here to take care of you, not have you try to pick a fight or make a political statement.

You’d think such a simple, time-honored, assessment question wouldn’t become such a problem. But

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

The president question – “Who’s the current president?” – has been a standard one of basic neurology assessments for years, probably since the answer was Ulysses S. Grant. It’s routinely asked by doctors, nurses, EEG techs, medical students, and pretty much anyone else trying to figure out someone’s mental status.

When I first began doing this, the answer was “George Bush” (at that time there’d only been one president by that name, so clarification wasn’t needed). Back then people answered the question (right or wrong) and we moved on. I don’t recall ever getting a dirty look, political lecture, or eye roll as a response.

Unfortunately, it’s not that simple anymore. As people have become increasingly polarized, it’s become seemingly impossible to get a response without a statement of support or anger. At best I get a straight answer. At worst I get a lecture on the “perils of a non-White society” (that was last week). Then they want my opinion, and years of practice have taught me to never discuss politics with patients, regardless of which side they’re on.

I don’t recall this being a problem until the late ‘90s, when the answer was “Clinton.” Occasionally I’d get a sarcastic comment referring to the Lewinsky affair, but that was about it.

Since then it’s gradually escalated, to where the question has become worthless. I don’t have time to hear a political diatribe from either side. This is a doctor appointment, not a debate club. The insistence by some that Trump won leaves me guessing if the person is stubborn or serious, and either way it shouldn’t be my job to figure that out. I take your appointment seriously, so the least you can do is the same.

So I’ve ditched the question for good. The current date, the location of my office, and other less controversial things will have to do. I’m here to take care of you, not have you try to pick a fight or make a political statement.

You’d think such a simple, time-honored, assessment question wouldn’t become such a problem. But

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

COVID-19 ‘long-haul’ symptoms overlap with ME/CFS

People experiencing long-term symptoms following acute COVID-19 infection are increasingly meeting criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), a phenomenon that highlights the need for unified research and clinical approaches, speakers said at a press briefing March 25 held by the advocacy group MEAction.

“Post-COVID lingering illness was predictable. Similar lingering fatigue syndromes have been reported in the scientific literature for nearly 100 years, following a variety of well-documented infections with viruses, bacteria, fungi, and even protozoa,” said Anthony Komaroff, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Core criteria for ME/CFS established by the Institute of Medicine in 2015 include substantial decrement in functioning for at least 6 months, postexertional malaise (PEM), or a worsening of symptoms following even minor exertion (often described as “crashes”), unrefreshing sleep, and cognitive impairment and/or orthostatic intolerance.

Patients with ME/CFS also commonly experience painful headaches, muscle or joint aches, and allergies/other sensitivities. Although many patients can trace their symptoms to an initiating infection, “the cause is often unclear because the diagnosis is often delayed for months or years after symptom onset,” said Lucinda Bateman, MD, founder of the Bateman Horne Center, Salt Lake City, who leads a clinician coalition that aims to improve ME/CFS management.

In an international survey of 3762 COVID-19 “long-haulers” published in a preprint in December of 2020, the most frequent symptoms reported at least 6 months after illness onset were fatigue in 78%, PEM in 72%, and cognitive dysfunction (“brain fog”) in 55%. At the time of the survey, 45% reported requiring reduced work schedules because of their illness, and 22% reported being unable to work at all.

Dr. Bateman said those findings align with her experience so far with 12 COVID-19 “long haulers” who self-referred to her ME/CFS and fibromyalgia specialty clinic. Nine of the 12 met criteria for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) based on the 10-minute NASA Lean Test, she said, and half also met the 2016 American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia.

“Some were severely impaired. We suspect a small fiber polyneuropathy in about half, and mast cell activation syndrome in more than half. We look forward to doing more testing,” Dr. Bateman said.

To be sure, Dr. Komaroff noted, there are some differences. “Long COVID” patients will often experience breathlessness and ongoing anosmia (loss of taste and smell), which aren’t typical of ME/CFS.

But, he said, “many of the symptoms are quite similar ... My guess is that ME/CFS is an illness with a final common pathway that can be triggered by different things,” said Dr. Komaroff, a senior physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and editor-in-chief of the Harvard Health Letter.

Based on previous data about CFS suggesting a 10% rate of symptoms persisting at least a year following a variety of infectious agents and the predicted 200 million COVID-19 cases globally by the end of 2021, Dr. Komaroff estimated that about 20 million cases of “long COVID” would be expected in the next year.

‘A huge investment’

On the research side, the National Institutes of Health recently appropriated $1.15 billion dollars over the next 4 years to investigate “the heterogeneity in the recovery process after COVID and to develop treatments for those suffering from [postacute COVID-19 syndrome]” according to a Feb. 5, 2021, blog from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

That same day, another NINDS blog announced “new resources for large-scale ME/CFS research” and emphasized the tie-in with long–COVID-19 syndrome.

“That’s a huge investment. In my opinion, there will be several lingering illnesses following COVID,” Dr. Komaroff said, adding, “It’s my bet that long COVID will prove to be caused by certain kinds of abnormalities in the brain, some of the same abnormalities already identified in ME/CFS. Research will determine whether that’s right or wrong.”

In 2017, NINDS had announced a large increase in funding for ME/CFS research, including the creation of four dedicated research centers. In April 2019, NINDS held a 2-day conference highlighting that ongoing work, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

During the briefing, NINDS clinical director Avindra Nath, MD, described a comprehensive ongoing ME/CFS intramural study he’s been leading since 2016.

He’s now also overseeing two long–COVID-19 studies, one of which has a protocol similar to that of the ME/CFS study and will include individuals who are still experiencing long-term symptoms following confirmed cases of COVID-19. The aim is to screen about 1,300 patients. Several task forces are now examining all of these data together.

“Each aspect is now being analyzed … What we learn from one applies to the other,” Dr. Nath said.

Advice for clinicians

In interviews, Dr. Bateman and Dr. Nath offered clinical advice for managing patients who meet ME/CFS criteria, whether they had confirmed or suspected COVID-19, a different infection, or unknown trigger(s).

Dr. Bateman advised that clinicians assess patients for each of the symptoms individually. “Besides exercise intolerance and PEM, the most commonly missed is orthostatic intolerance. It really doesn’t matter what the cause is, it’s amenable to supportive treatment. It’s one aspect of the illness that contributes to severely impaired function. My plea to all physicians would be for sure to assess for [orthostatic intolerance], and gain an understanding about activity management and avoiding PEM symptoms.”

Dr. Nath noted that an often-challenging situation is when tests for the infectious agent and other blood work come back negative, yet the patient still reports multiple debilitating symptoms. This has been a particular issue with long COVID-19, since many patients became ill early in the pandemic before the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for SARS-CoV-2 were widely available.

“The physician can only order tests that are available at their labs. I think what the physician should do is handle symptoms symptomatically but also refer patients to specialists who are taking care of these patients or to research studies,” he said.

Dr. Bateman added, “Whether they had a documented COVID infection – we just have to let go of that in 2020. Way too many people didn’t have access to a test or the timing wasn’t amenable. If people meet criteria for ME/CFS, it’s irrelevant … It’s mainly a clinical diagnosis. It’s not reliant on identifying the infectious trigger.”

Dr. Komaroff, who began caring for then-termed “chronic fatigue syndrome” patients and researching the condition more than 30 years ago, said that “every cloud has its silver lining. The increased focus on postinfectious fatigue syndrome is a silver lining in my mind around the terrible dark cloud that is the pandemic of COVID.”

Dr. Komaroff has received personal fees from Serimmune Inc., Ono Pharma, and Deallus, and grants from the NIH. Dr. Bateman is employed by the Bateman Horne Center, which receives grants from the NIH, and fees from Exagen Inc., and Teva Pharmaceutical. Dr. Nath is an NIH employee.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People experiencing long-term symptoms following acute COVID-19 infection are increasingly meeting criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), a phenomenon that highlights the need for unified research and clinical approaches, speakers said at a press briefing March 25 held by the advocacy group MEAction.

“Post-COVID lingering illness was predictable. Similar lingering fatigue syndromes have been reported in the scientific literature for nearly 100 years, following a variety of well-documented infections with viruses, bacteria, fungi, and even protozoa,” said Anthony Komaroff, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Core criteria for ME/CFS established by the Institute of Medicine in 2015 include substantial decrement in functioning for at least 6 months, postexertional malaise (PEM), or a worsening of symptoms following even minor exertion (often described as “crashes”), unrefreshing sleep, and cognitive impairment and/or orthostatic intolerance.

Patients with ME/CFS also commonly experience painful headaches, muscle or joint aches, and allergies/other sensitivities. Although many patients can trace their symptoms to an initiating infection, “the cause is often unclear because the diagnosis is often delayed for months or years after symptom onset,” said Lucinda Bateman, MD, founder of the Bateman Horne Center, Salt Lake City, who leads a clinician coalition that aims to improve ME/CFS management.

In an international survey of 3762 COVID-19 “long-haulers” published in a preprint in December of 2020, the most frequent symptoms reported at least 6 months after illness onset were fatigue in 78%, PEM in 72%, and cognitive dysfunction (“brain fog”) in 55%. At the time of the survey, 45% reported requiring reduced work schedules because of their illness, and 22% reported being unable to work at all.

Dr. Bateman said those findings align with her experience so far with 12 COVID-19 “long haulers” who self-referred to her ME/CFS and fibromyalgia specialty clinic. Nine of the 12 met criteria for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) based on the 10-minute NASA Lean Test, she said, and half also met the 2016 American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia.

“Some were severely impaired. We suspect a small fiber polyneuropathy in about half, and mast cell activation syndrome in more than half. We look forward to doing more testing,” Dr. Bateman said.

To be sure, Dr. Komaroff noted, there are some differences. “Long COVID” patients will often experience breathlessness and ongoing anosmia (loss of taste and smell), which aren’t typical of ME/CFS.

But, he said, “many of the symptoms are quite similar ... My guess is that ME/CFS is an illness with a final common pathway that can be triggered by different things,” said Dr. Komaroff, a senior physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and editor-in-chief of the Harvard Health Letter.

Based on previous data about CFS suggesting a 10% rate of symptoms persisting at least a year following a variety of infectious agents and the predicted 200 million COVID-19 cases globally by the end of 2021, Dr. Komaroff estimated that about 20 million cases of “long COVID” would be expected in the next year.

‘A huge investment’

On the research side, the National Institutes of Health recently appropriated $1.15 billion dollars over the next 4 years to investigate “the heterogeneity in the recovery process after COVID and to develop treatments for those suffering from [postacute COVID-19 syndrome]” according to a Feb. 5, 2021, blog from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

That same day, another NINDS blog announced “new resources for large-scale ME/CFS research” and emphasized the tie-in with long–COVID-19 syndrome.

“That’s a huge investment. In my opinion, there will be several lingering illnesses following COVID,” Dr. Komaroff said, adding, “It’s my bet that long COVID will prove to be caused by certain kinds of abnormalities in the brain, some of the same abnormalities already identified in ME/CFS. Research will determine whether that’s right or wrong.”

In 2017, NINDS had announced a large increase in funding for ME/CFS research, including the creation of four dedicated research centers. In April 2019, NINDS held a 2-day conference highlighting that ongoing work, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

During the briefing, NINDS clinical director Avindra Nath, MD, described a comprehensive ongoing ME/CFS intramural study he’s been leading since 2016.

He’s now also overseeing two long–COVID-19 studies, one of which has a protocol similar to that of the ME/CFS study and will include individuals who are still experiencing long-term symptoms following confirmed cases of COVID-19. The aim is to screen about 1,300 patients. Several task forces are now examining all of these data together.

“Each aspect is now being analyzed … What we learn from one applies to the other,” Dr. Nath said.

Advice for clinicians

In interviews, Dr. Bateman and Dr. Nath offered clinical advice for managing patients who meet ME/CFS criteria, whether they had confirmed or suspected COVID-19, a different infection, or unknown trigger(s).

Dr. Bateman advised that clinicians assess patients for each of the symptoms individually. “Besides exercise intolerance and PEM, the most commonly missed is orthostatic intolerance. It really doesn’t matter what the cause is, it’s amenable to supportive treatment. It’s one aspect of the illness that contributes to severely impaired function. My plea to all physicians would be for sure to assess for [orthostatic intolerance], and gain an understanding about activity management and avoiding PEM symptoms.”

Dr. Nath noted that an often-challenging situation is when tests for the infectious agent and other blood work come back negative, yet the patient still reports multiple debilitating symptoms. This has been a particular issue with long COVID-19, since many patients became ill early in the pandemic before the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for SARS-CoV-2 were widely available.

“The physician can only order tests that are available at their labs. I think what the physician should do is handle symptoms symptomatically but also refer patients to specialists who are taking care of these patients or to research studies,” he said.

Dr. Bateman added, “Whether they had a documented COVID infection – we just have to let go of that in 2020. Way too many people didn’t have access to a test or the timing wasn’t amenable. If people meet criteria for ME/CFS, it’s irrelevant … It’s mainly a clinical diagnosis. It’s not reliant on identifying the infectious trigger.”

Dr. Komaroff, who began caring for then-termed “chronic fatigue syndrome” patients and researching the condition more than 30 years ago, said that “every cloud has its silver lining. The increased focus on postinfectious fatigue syndrome is a silver lining in my mind around the terrible dark cloud that is the pandemic of COVID.”

Dr. Komaroff has received personal fees from Serimmune Inc., Ono Pharma, and Deallus, and grants from the NIH. Dr. Bateman is employed by the Bateman Horne Center, which receives grants from the NIH, and fees from Exagen Inc., and Teva Pharmaceutical. Dr. Nath is an NIH employee.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People experiencing long-term symptoms following acute COVID-19 infection are increasingly meeting criteria for myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS), a phenomenon that highlights the need for unified research and clinical approaches, speakers said at a press briefing March 25 held by the advocacy group MEAction.

“Post-COVID lingering illness was predictable. Similar lingering fatigue syndromes have been reported in the scientific literature for nearly 100 years, following a variety of well-documented infections with viruses, bacteria, fungi, and even protozoa,” said Anthony Komaroff, MD, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Core criteria for ME/CFS established by the Institute of Medicine in 2015 include substantial decrement in functioning for at least 6 months, postexertional malaise (PEM), or a worsening of symptoms following even minor exertion (often described as “crashes”), unrefreshing sleep, and cognitive impairment and/or orthostatic intolerance.

Patients with ME/CFS also commonly experience painful headaches, muscle or joint aches, and allergies/other sensitivities. Although many patients can trace their symptoms to an initiating infection, “the cause is often unclear because the diagnosis is often delayed for months or years after symptom onset,” said Lucinda Bateman, MD, founder of the Bateman Horne Center, Salt Lake City, who leads a clinician coalition that aims to improve ME/CFS management.

In an international survey of 3762 COVID-19 “long-haulers” published in a preprint in December of 2020, the most frequent symptoms reported at least 6 months after illness onset were fatigue in 78%, PEM in 72%, and cognitive dysfunction (“brain fog”) in 55%. At the time of the survey, 45% reported requiring reduced work schedules because of their illness, and 22% reported being unable to work at all.

Dr. Bateman said those findings align with her experience so far with 12 COVID-19 “long haulers” who self-referred to her ME/CFS and fibromyalgia specialty clinic. Nine of the 12 met criteria for postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS) based on the 10-minute NASA Lean Test, she said, and half also met the 2016 American College of Rheumatology criteria for fibromyalgia.

“Some were severely impaired. We suspect a small fiber polyneuropathy in about half, and mast cell activation syndrome in more than half. We look forward to doing more testing,” Dr. Bateman said.

To be sure, Dr. Komaroff noted, there are some differences. “Long COVID” patients will often experience breathlessness and ongoing anosmia (loss of taste and smell), which aren’t typical of ME/CFS.

But, he said, “many of the symptoms are quite similar ... My guess is that ME/CFS is an illness with a final common pathway that can be triggered by different things,” said Dr. Komaroff, a senior physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, and editor-in-chief of the Harvard Health Letter.

Based on previous data about CFS suggesting a 10% rate of symptoms persisting at least a year following a variety of infectious agents and the predicted 200 million COVID-19 cases globally by the end of 2021, Dr. Komaroff estimated that about 20 million cases of “long COVID” would be expected in the next year.

‘A huge investment’

On the research side, the National Institutes of Health recently appropriated $1.15 billion dollars over the next 4 years to investigate “the heterogeneity in the recovery process after COVID and to develop treatments for those suffering from [postacute COVID-19 syndrome]” according to a Feb. 5, 2021, blog from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS).

That same day, another NINDS blog announced “new resources for large-scale ME/CFS research” and emphasized the tie-in with long–COVID-19 syndrome.

“That’s a huge investment. In my opinion, there will be several lingering illnesses following COVID,” Dr. Komaroff said, adding, “It’s my bet that long COVID will prove to be caused by certain kinds of abnormalities in the brain, some of the same abnormalities already identified in ME/CFS. Research will determine whether that’s right or wrong.”

In 2017, NINDS had announced a large increase in funding for ME/CFS research, including the creation of four dedicated research centers. In April 2019, NINDS held a 2-day conference highlighting that ongoing work, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

During the briefing, NINDS clinical director Avindra Nath, MD, described a comprehensive ongoing ME/CFS intramural study he’s been leading since 2016.

He’s now also overseeing two long–COVID-19 studies, one of which has a protocol similar to that of the ME/CFS study and will include individuals who are still experiencing long-term symptoms following confirmed cases of COVID-19. The aim is to screen about 1,300 patients. Several task forces are now examining all of these data together.

“Each aspect is now being analyzed … What we learn from one applies to the other,” Dr. Nath said.

Advice for clinicians

In interviews, Dr. Bateman and Dr. Nath offered clinical advice for managing patients who meet ME/CFS criteria, whether they had confirmed or suspected COVID-19, a different infection, or unknown trigger(s).

Dr. Bateman advised that clinicians assess patients for each of the symptoms individually. “Besides exercise intolerance and PEM, the most commonly missed is orthostatic intolerance. It really doesn’t matter what the cause is, it’s amenable to supportive treatment. It’s one aspect of the illness that contributes to severely impaired function. My plea to all physicians would be for sure to assess for [orthostatic intolerance], and gain an understanding about activity management and avoiding PEM symptoms.”

Dr. Nath noted that an often-challenging situation is when tests for the infectious agent and other blood work come back negative, yet the patient still reports multiple debilitating symptoms. This has been a particular issue with long COVID-19, since many patients became ill early in the pandemic before the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for SARS-CoV-2 were widely available.

“The physician can only order tests that are available at their labs. I think what the physician should do is handle symptoms symptomatically but also refer patients to specialists who are taking care of these patients or to research studies,” he said.

Dr. Bateman added, “Whether they had a documented COVID infection – we just have to let go of that in 2020. Way too many people didn’t have access to a test or the timing wasn’t amenable. If people meet criteria for ME/CFS, it’s irrelevant … It’s mainly a clinical diagnosis. It’s not reliant on identifying the infectious trigger.”

Dr. Komaroff, who began caring for then-termed “chronic fatigue syndrome” patients and researching the condition more than 30 years ago, said that “every cloud has its silver lining. The increased focus on postinfectious fatigue syndrome is a silver lining in my mind around the terrible dark cloud that is the pandemic of COVID.”

Dr. Komaroff has received personal fees from Serimmune Inc., Ono Pharma, and Deallus, and grants from the NIH. Dr. Bateman is employed by the Bateman Horne Center, which receives grants from the NIH, and fees from Exagen Inc., and Teva Pharmaceutical. Dr. Nath is an NIH employee.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Step therapy: Inside the fight against insurance companies and fail-first medicine

Every day Melissa Fulton, RN, MSN, FNP, APRN-C, shows up to work, she’s ready for another fight. An advanced practice nurse who specializes in multiple sclerosis care, Ms. Fulton said she typically spends more than a third of her time battling it out with insurance companies over drugs she knows her patients need but that insurers don’t want to cover. Instead, they want the patient to first receive less expensive and often less efficacious drugs, even if that goes against recommendations and, in some cases, against the patient’s medical history.

The maddening protocol – familiar to health care providers everywhere – is known as “step therapy.” It forces patients to try alternative medications – medications that often fail – before receiving the one initially prescribed. The process can take weeks or months, which is time that some patients don’t have. Step therapy was sold as a way to lower costs. However, beyond the ethically problematic notion of forcing sick patients to receiver cheaper alternatives that are ineffective, research has also shown it may actually be more costly in the long run.

Ms. Fulton, who works at Saunders Medical Center in Wahoo, Neb., is a veteran in the war against step therapy. She is used to pushing her appeals up the insurance company chain of command, past nonmedical reviewers, until her patient’s case finally lands on the desk of someone with a neurology background. She said that can take three or four appeals – a judge might even get involved – and the patient could still lose. “This happens constantly,” she said, “but we fight like hell.”

Fortunately, life may soon get a little easier for Ms. Fulton. In late March, a bill to restrict step therapy made it through the Nebraska state legislature and is on its way to the governor’s desk. The Step Therapy Reform Act doesn’t outright ban the practice; however, it will put guardrails in place. It requires that insurers respond to appeals within certain time frames, and it creates key exemptions.

When the governor signs off, Nebraska will join more than two dozen other states that already have step therapy restrictions on the books, according to Hannah Lynch, MPS, associate director of federal government relations and health policy at the National Psoriasis Foundation, a leading advocate to reform and protect against the insurance practice. “There’s a lot of frustration out there,” Ms. Lynch said. “It really hinders providers’ ability to make decisions they think will have the best outcomes.”

Driven by coalitions of doctors, nurses, and patients, laws reining in step therapy have been adopted at a relatively quick clip, mostly within the past 5 years. Recent additions include South Dakota and North Carolina, which adopted step therapy laws in 2020, and Arkansas, which passed a law earlier this year.

Ms. Lynch attributed growing support to rising out-of-pocket drug costs and the introduction of biologic drugs, which are often more effective but also more expensive. Like Nebraska’s law, most step therapy reform legislation carves out exemptions and requires timely appeals processes; however, many of the laws still have significant gaps, such as not including certain types of insurance plans.

Ideally, Ms. Lynch said, the protections would apply to all types of health plans that are regulated at the state level, such as Medicaid, state employee health plans, and coverage sold through state insurance exchanges. Closing loopholes in the laws is a top priority for advocates, she added, pointing to work currently underway in Arkansas to extend its new protections to Medicaid expansion patients.

“With so many outside stakeholders, you have to compromise – it’s a give and take,” Ms. Lynch said. Still, when it comes to fighting step therapy, she says, “Any protection on the books is always our first goal when we go into a state.”

Putting patients first

Lisa Arkin, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said she finds herself “swimming upstream every day in the fight with insurance.” Her patients are typically on their second or third stop and have more complex disorders. Dr. Arkin said that the problem with step therapy is that it tries to squeeze all patients into the same box, even if the circumstances don’t fit.

Her state passed restrictions on step therapy in 2019, but the measures only went into effect last year. Under the Wisconsin law, patients can be granted an exemption if an alternative treatment is contraindicated, likely to cause harm, or expected to be ineffective. Patients can also be exempt if their current treatment is working.

Dr. Arkin, an outspoken advocate for curbing step therapy, says the Wisconsin law is “very strong.” However, because it only applies to certain health plans – state employee health plans and those purchased in the state’s health insurance exchange – fewer than half the state’s patients benefit from its protections. She notes that some of the most severe presentations she treats occur in patients who rely on Medicaid coverage and already face barriers to care.

“I’m a doctor who puts up a fuss [with insurers], but that’s not fair – we shouldn’t have to do that,” Dr. Arkin said. “To me, it’s really critical to make this an even playing field so this law affords protection to everyone I see in the clinic.”

Major medical associations caution against step therapy as well. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Medical Association have called out the risks to patient safety and health. In fact, in 2019, after the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services gave new authority to Medicare Advantage plans to start using step therapy, dozens of national medical groups called out the agency for allowing a practice that could potentially hurt patients and undercut the physician-patient decision-making process.

Last year, in a new position paper from the American College of Physicians, authors laid out recommendations for combating step therapy’s side effects. These recommendations included making related data transparent to the public and minimizing the policy’s disruptions to care. Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, MACP, a member of the committee that issued the position paper and who is a primary care physician in Georgia, said such insurance practices need to be designed with “strong input from frontline physicians, not clipboard physicians.

“What we want from insurers is understanding, transparency, and the least burdensome protocol to provide patients the care they need at a cost-effective price they can afford,” said Dr. Fincher, who is also the current president of the ACP. “The focus needs to be on what’s in the patient’s best interest.”

Every year a new fight

“We all dread January,” said Dr. Fincher. That is the worst month, she added, because new health benefits go into effect, which means patients who are responding well to certain treatments may suddenly face new restrictions.

Another aggravating aspect of step therapy? It is often difficult – if not impossible – to access information on specific step therapy protocols in a patient’s health plan in real time in the exam room, where treatment conversations actually take place. In a more patient-centered world, Dr. Fincher said, she would be able to use the electronic health record system to quickly identify whether a patient’s plan covers a particular treatment and, if not, what the alternatives are.

Georgia’s new step therapy law went into effect last year. Like laws in other states, it spells out step therapy exemptions and sets time frames in which insurers must respond to exceptions and appeals. Dr. Fincher, who spoke in favor of the new law, said she’s “happy for any step forward.” Still, the growing burden of prior authorization rules are an utter “time sink” for her and her staff.

“I have to justify my decisions to nondoctors before I even get to a doctor, and that’s really frustrating,” she said. “We’re talking about people here, not widgets.”

Advocates in Nevada are hoping this is the year a step therapy bill will make it into law in their state. As of March, one had yet to be introduced in the state legislature. Tom McCoy, director of state government affairs at the Nevada Chronic Care Collaborative, said existing Nevada law already prohibits nonmedical drug switching during a policy year; however, insurers can still make changes the following year.

A bill to rein in step therapy was proposed previously, Mr. McCoy said, but it never got off the ground. The collaborative, as well as about two dozen organizations representing Nevada providers and patients, are now calling on state lawmakers to make the issue a priority in the current session.

“The health plans have a lot of power – a lot,” Mr. McCoy said. “We’re hoping to get a [legislative] sponsor in 2021 ... but it’s also been a really hard year to connect legislators with patients and doctors, and being able to hear their stories really does make a difference.”

In Nebraska, Marcus Snow, MD, a rheumatologist at Nebraska Medicine, in Omaha, said that the state’s new step therapy law will be a “great first step in helping to provide some guardrails” around the practice. He noted that turnaround requirements for insurer responses are “sorely needed.” However, he said that, because the bill doesn’t apply to all health plans, many Nebraskans still won’t benefit.

Dealing with step therapy is a daily “headache” for Dr. Snow, who says navigating the bureaucracy of prior authorization seems to be getting worse every year. Like his peers around the country, he spends an inordinate amount of time pushing appeals up the insurance company ranks to get access to treatments he believes will be most effective. But Snow says that, more than just being a mountain of tiresome red tape, these practices also intrude on the patient-provider relationship, casting an unsettling sense of uncertainty that the ultimate decision about the best course of action isn’t up to the doctor and patient at all.

“In the end, the insurance company is the judge and jury of my prescription,” Dr. Snow said. “They’d argue I can still prescribe it, but if it costs $70,000 a year – I don’t know who can afford that.”

Ms. Lynch, at the National Psoriasis Foundation, said their step therapy advocacy will continue to take a two-pronged approach. They will push for new and expanded protections at both state and federal levels. Protections are needed at both levels to make sure that all health plans regulated by all entities are covered. In the U.S. Senate and the House, step therapy bills were reintroduced this year. They would apply to health plans subject to the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act, which governs employer-sponsored health coverage, and could close a big gap in existing protections. Oregon, New Jersey, and Arizona are at the top of the foundation’s advocacy list this year, according to Ms. Lynch.

“Folks are really starting to pay more attention to this issue,” she said. “And hearing those real-world stories and frustrations is definitely one of the most effective tools we have.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Every day Melissa Fulton, RN, MSN, FNP, APRN-C, shows up to work, she’s ready for another fight. An advanced practice nurse who specializes in multiple sclerosis care, Ms. Fulton said she typically spends more than a third of her time battling it out with insurance companies over drugs she knows her patients need but that insurers don’t want to cover. Instead, they want the patient to first receive less expensive and often less efficacious drugs, even if that goes against recommendations and, in some cases, against the patient’s medical history.

The maddening protocol – familiar to health care providers everywhere – is known as “step therapy.” It forces patients to try alternative medications – medications that often fail – before receiving the one initially prescribed. The process can take weeks or months, which is time that some patients don’t have. Step therapy was sold as a way to lower costs. However, beyond the ethically problematic notion of forcing sick patients to receiver cheaper alternatives that are ineffective, research has also shown it may actually be more costly in the long run.

Ms. Fulton, who works at Saunders Medical Center in Wahoo, Neb., is a veteran in the war against step therapy. She is used to pushing her appeals up the insurance company chain of command, past nonmedical reviewers, until her patient’s case finally lands on the desk of someone with a neurology background. She said that can take three or four appeals – a judge might even get involved – and the patient could still lose. “This happens constantly,” she said, “but we fight like hell.”

Fortunately, life may soon get a little easier for Ms. Fulton. In late March, a bill to restrict step therapy made it through the Nebraska state legislature and is on its way to the governor’s desk. The Step Therapy Reform Act doesn’t outright ban the practice; however, it will put guardrails in place. It requires that insurers respond to appeals within certain time frames, and it creates key exemptions.

When the governor signs off, Nebraska will join more than two dozen other states that already have step therapy restrictions on the books, according to Hannah Lynch, MPS, associate director of federal government relations and health policy at the National Psoriasis Foundation, a leading advocate to reform and protect against the insurance practice. “There’s a lot of frustration out there,” Ms. Lynch said. “It really hinders providers’ ability to make decisions they think will have the best outcomes.”

Driven by coalitions of doctors, nurses, and patients, laws reining in step therapy have been adopted at a relatively quick clip, mostly within the past 5 years. Recent additions include South Dakota and North Carolina, which adopted step therapy laws in 2020, and Arkansas, which passed a law earlier this year.

Ms. Lynch attributed growing support to rising out-of-pocket drug costs and the introduction of biologic drugs, which are often more effective but also more expensive. Like Nebraska’s law, most step therapy reform legislation carves out exemptions and requires timely appeals processes; however, many of the laws still have significant gaps, such as not including certain types of insurance plans.

Ideally, Ms. Lynch said, the protections would apply to all types of health plans that are regulated at the state level, such as Medicaid, state employee health plans, and coverage sold through state insurance exchanges. Closing loopholes in the laws is a top priority for advocates, she added, pointing to work currently underway in Arkansas to extend its new protections to Medicaid expansion patients.

“With so many outside stakeholders, you have to compromise – it’s a give and take,” Ms. Lynch said. Still, when it comes to fighting step therapy, she says, “Any protection on the books is always our first goal when we go into a state.”

Putting patients first

Lisa Arkin, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said she finds herself “swimming upstream every day in the fight with insurance.” Her patients are typically on their second or third stop and have more complex disorders. Dr. Arkin said that the problem with step therapy is that it tries to squeeze all patients into the same box, even if the circumstances don’t fit.

Her state passed restrictions on step therapy in 2019, but the measures only went into effect last year. Under the Wisconsin law, patients can be granted an exemption if an alternative treatment is contraindicated, likely to cause harm, or expected to be ineffective. Patients can also be exempt if their current treatment is working.

Dr. Arkin, an outspoken advocate for curbing step therapy, says the Wisconsin law is “very strong.” However, because it only applies to certain health plans – state employee health plans and those purchased in the state’s health insurance exchange – fewer than half the state’s patients benefit from its protections. She notes that some of the most severe presentations she treats occur in patients who rely on Medicaid coverage and already face barriers to care.

“I’m a doctor who puts up a fuss [with insurers], but that’s not fair – we shouldn’t have to do that,” Dr. Arkin said. “To me, it’s really critical to make this an even playing field so this law affords protection to everyone I see in the clinic.”

Major medical associations caution against step therapy as well. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Medical Association have called out the risks to patient safety and health. In fact, in 2019, after the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services gave new authority to Medicare Advantage plans to start using step therapy, dozens of national medical groups called out the agency for allowing a practice that could potentially hurt patients and undercut the physician-patient decision-making process.

Last year, in a new position paper from the American College of Physicians, authors laid out recommendations for combating step therapy’s side effects. These recommendations included making related data transparent to the public and minimizing the policy’s disruptions to care. Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, MACP, a member of the committee that issued the position paper and who is a primary care physician in Georgia, said such insurance practices need to be designed with “strong input from frontline physicians, not clipboard physicians.

“What we want from insurers is understanding, transparency, and the least burdensome protocol to provide patients the care they need at a cost-effective price they can afford,” said Dr. Fincher, who is also the current president of the ACP. “The focus needs to be on what’s in the patient’s best interest.”

Every year a new fight

“We all dread January,” said Dr. Fincher. That is the worst month, she added, because new health benefits go into effect, which means patients who are responding well to certain treatments may suddenly face new restrictions.

Another aggravating aspect of step therapy? It is often difficult – if not impossible – to access information on specific step therapy protocols in a patient’s health plan in real time in the exam room, where treatment conversations actually take place. In a more patient-centered world, Dr. Fincher said, she would be able to use the electronic health record system to quickly identify whether a patient’s plan covers a particular treatment and, if not, what the alternatives are.

Georgia’s new step therapy law went into effect last year. Like laws in other states, it spells out step therapy exemptions and sets time frames in which insurers must respond to exceptions and appeals. Dr. Fincher, who spoke in favor of the new law, said she’s “happy for any step forward.” Still, the growing burden of prior authorization rules are an utter “time sink” for her and her staff.

“I have to justify my decisions to nondoctors before I even get to a doctor, and that’s really frustrating,” she said. “We’re talking about people here, not widgets.”

Advocates in Nevada are hoping this is the year a step therapy bill will make it into law in their state. As of March, one had yet to be introduced in the state legislature. Tom McCoy, director of state government affairs at the Nevada Chronic Care Collaborative, said existing Nevada law already prohibits nonmedical drug switching during a policy year; however, insurers can still make changes the following year.

A bill to rein in step therapy was proposed previously, Mr. McCoy said, but it never got off the ground. The collaborative, as well as about two dozen organizations representing Nevada providers and patients, are now calling on state lawmakers to make the issue a priority in the current session.

“The health plans have a lot of power – a lot,” Mr. McCoy said. “We’re hoping to get a [legislative] sponsor in 2021 ... but it’s also been a really hard year to connect legislators with patients and doctors, and being able to hear their stories really does make a difference.”

In Nebraska, Marcus Snow, MD, a rheumatologist at Nebraska Medicine, in Omaha, said that the state’s new step therapy law will be a “great first step in helping to provide some guardrails” around the practice. He noted that turnaround requirements for insurer responses are “sorely needed.” However, he said that, because the bill doesn’t apply to all health plans, many Nebraskans still won’t benefit.

Dealing with step therapy is a daily “headache” for Dr. Snow, who says navigating the bureaucracy of prior authorization seems to be getting worse every year. Like his peers around the country, he spends an inordinate amount of time pushing appeals up the insurance company ranks to get access to treatments he believes will be most effective. But Snow says that, more than just being a mountain of tiresome red tape, these practices also intrude on the patient-provider relationship, casting an unsettling sense of uncertainty that the ultimate decision about the best course of action isn’t up to the doctor and patient at all.

“In the end, the insurance company is the judge and jury of my prescription,” Dr. Snow said. “They’d argue I can still prescribe it, but if it costs $70,000 a year – I don’t know who can afford that.”

Ms. Lynch, at the National Psoriasis Foundation, said their step therapy advocacy will continue to take a two-pronged approach. They will push for new and expanded protections at both state and federal levels. Protections are needed at both levels to make sure that all health plans regulated by all entities are covered. In the U.S. Senate and the House, step therapy bills were reintroduced this year. They would apply to health plans subject to the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act, which governs employer-sponsored health coverage, and could close a big gap in existing protections. Oregon, New Jersey, and Arizona are at the top of the foundation’s advocacy list this year, according to Ms. Lynch.

“Folks are really starting to pay more attention to this issue,” she said. “And hearing those real-world stories and frustrations is definitely one of the most effective tools we have.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Every day Melissa Fulton, RN, MSN, FNP, APRN-C, shows up to work, she’s ready for another fight. An advanced practice nurse who specializes in multiple sclerosis care, Ms. Fulton said she typically spends more than a third of her time battling it out with insurance companies over drugs she knows her patients need but that insurers don’t want to cover. Instead, they want the patient to first receive less expensive and often less efficacious drugs, even if that goes against recommendations and, in some cases, against the patient’s medical history.

The maddening protocol – familiar to health care providers everywhere – is known as “step therapy.” It forces patients to try alternative medications – medications that often fail – before receiving the one initially prescribed. The process can take weeks or months, which is time that some patients don’t have. Step therapy was sold as a way to lower costs. However, beyond the ethically problematic notion of forcing sick patients to receiver cheaper alternatives that are ineffective, research has also shown it may actually be more costly in the long run.

Ms. Fulton, who works at Saunders Medical Center in Wahoo, Neb., is a veteran in the war against step therapy. She is used to pushing her appeals up the insurance company chain of command, past nonmedical reviewers, until her patient’s case finally lands on the desk of someone with a neurology background. She said that can take three or four appeals – a judge might even get involved – and the patient could still lose. “This happens constantly,” she said, “but we fight like hell.”

Fortunately, life may soon get a little easier for Ms. Fulton. In late March, a bill to restrict step therapy made it through the Nebraska state legislature and is on its way to the governor’s desk. The Step Therapy Reform Act doesn’t outright ban the practice; however, it will put guardrails in place. It requires that insurers respond to appeals within certain time frames, and it creates key exemptions.

When the governor signs off, Nebraska will join more than two dozen other states that already have step therapy restrictions on the books, according to Hannah Lynch, MPS, associate director of federal government relations and health policy at the National Psoriasis Foundation, a leading advocate to reform and protect against the insurance practice. “There’s a lot of frustration out there,” Ms. Lynch said. “It really hinders providers’ ability to make decisions they think will have the best outcomes.”

Driven by coalitions of doctors, nurses, and patients, laws reining in step therapy have been adopted at a relatively quick clip, mostly within the past 5 years. Recent additions include South Dakota and North Carolina, which adopted step therapy laws in 2020, and Arkansas, which passed a law earlier this year.

Ms. Lynch attributed growing support to rising out-of-pocket drug costs and the introduction of biologic drugs, which are often more effective but also more expensive. Like Nebraska’s law, most step therapy reform legislation carves out exemptions and requires timely appeals processes; however, many of the laws still have significant gaps, such as not including certain types of insurance plans.

Ideally, Ms. Lynch said, the protections would apply to all types of health plans that are regulated at the state level, such as Medicaid, state employee health plans, and coverage sold through state insurance exchanges. Closing loopholes in the laws is a top priority for advocates, she added, pointing to work currently underway in Arkansas to extend its new protections to Medicaid expansion patients.

“With so many outside stakeholders, you have to compromise – it’s a give and take,” Ms. Lynch said. Still, when it comes to fighting step therapy, she says, “Any protection on the books is always our first goal when we go into a state.”

Putting patients first

Lisa Arkin, MD, a pediatric dermatologist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said she finds herself “swimming upstream every day in the fight with insurance.” Her patients are typically on their second or third stop and have more complex disorders. Dr. Arkin said that the problem with step therapy is that it tries to squeeze all patients into the same box, even if the circumstances don’t fit.

Her state passed restrictions on step therapy in 2019, but the measures only went into effect last year. Under the Wisconsin law, patients can be granted an exemption if an alternative treatment is contraindicated, likely to cause harm, or expected to be ineffective. Patients can also be exempt if their current treatment is working.

Dr. Arkin, an outspoken advocate for curbing step therapy, says the Wisconsin law is “very strong.” However, because it only applies to certain health plans – state employee health plans and those purchased in the state’s health insurance exchange – fewer than half the state’s patients benefit from its protections. She notes that some of the most severe presentations she treats occur in patients who rely on Medicaid coverage and already face barriers to care.

“I’m a doctor who puts up a fuss [with insurers], but that’s not fair – we shouldn’t have to do that,” Dr. Arkin said. “To me, it’s really critical to make this an even playing field so this law affords protection to everyone I see in the clinic.”

Major medical associations caution against step therapy as well. The American Society of Clinical Oncology and the American Medical Association have called out the risks to patient safety and health. In fact, in 2019, after the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services gave new authority to Medicare Advantage plans to start using step therapy, dozens of national medical groups called out the agency for allowing a practice that could potentially hurt patients and undercut the physician-patient decision-making process.

Last year, in a new position paper from the American College of Physicians, authors laid out recommendations for combating step therapy’s side effects. These recommendations included making related data transparent to the public and minimizing the policy’s disruptions to care. Jacqueline W. Fincher, MD, MACP, a member of the committee that issued the position paper and who is a primary care physician in Georgia, said such insurance practices need to be designed with “strong input from frontline physicians, not clipboard physicians.

“What we want from insurers is understanding, transparency, and the least burdensome protocol to provide patients the care they need at a cost-effective price they can afford,” said Dr. Fincher, who is also the current president of the ACP. “The focus needs to be on what’s in the patient’s best interest.”

Every year a new fight

“We all dread January,” said Dr. Fincher. That is the worst month, she added, because new health benefits go into effect, which means patients who are responding well to certain treatments may suddenly face new restrictions.

Another aggravating aspect of step therapy? It is often difficult – if not impossible – to access information on specific step therapy protocols in a patient’s health plan in real time in the exam room, where treatment conversations actually take place. In a more patient-centered world, Dr. Fincher said, she would be able to use the electronic health record system to quickly identify whether a patient’s plan covers a particular treatment and, if not, what the alternatives are.

Georgia’s new step therapy law went into effect last year. Like laws in other states, it spells out step therapy exemptions and sets time frames in which insurers must respond to exceptions and appeals. Dr. Fincher, who spoke in favor of the new law, said she’s “happy for any step forward.” Still, the growing burden of prior authorization rules are an utter “time sink” for her and her staff.

“I have to justify my decisions to nondoctors before I even get to a doctor, and that’s really frustrating,” she said. “We’re talking about people here, not widgets.”

Advocates in Nevada are hoping this is the year a step therapy bill will make it into law in their state. As of March, one had yet to be introduced in the state legislature. Tom McCoy, director of state government affairs at the Nevada Chronic Care Collaborative, said existing Nevada law already prohibits nonmedical drug switching during a policy year; however, insurers can still make changes the following year.

A bill to rein in step therapy was proposed previously, Mr. McCoy said, but it never got off the ground. The collaborative, as well as about two dozen organizations representing Nevada providers and patients, are now calling on state lawmakers to make the issue a priority in the current session.

“The health plans have a lot of power – a lot,” Mr. McCoy said. “We’re hoping to get a [legislative] sponsor in 2021 ... but it’s also been a really hard year to connect legislators with patients and doctors, and being able to hear their stories really does make a difference.”

In Nebraska, Marcus Snow, MD, a rheumatologist at Nebraska Medicine, in Omaha, said that the state’s new step therapy law will be a “great first step in helping to provide some guardrails” around the practice. He noted that turnaround requirements for insurer responses are “sorely needed.” However, he said that, because the bill doesn’t apply to all health plans, many Nebraskans still won’t benefit.

Dealing with step therapy is a daily “headache” for Dr. Snow, who says navigating the bureaucracy of prior authorization seems to be getting worse every year. Like his peers around the country, he spends an inordinate amount of time pushing appeals up the insurance company ranks to get access to treatments he believes will be most effective. But Snow says that, more than just being a mountain of tiresome red tape, these practices also intrude on the patient-provider relationship, casting an unsettling sense of uncertainty that the ultimate decision about the best course of action isn’t up to the doctor and patient at all.

“In the end, the insurance company is the judge and jury of my prescription,” Dr. Snow said. “They’d argue I can still prescribe it, but if it costs $70,000 a year – I don’t know who can afford that.”

Ms. Lynch, at the National Psoriasis Foundation, said their step therapy advocacy will continue to take a two-pronged approach. They will push for new and expanded protections at both state and federal levels. Protections are needed at both levels to make sure that all health plans regulated by all entities are covered. In the U.S. Senate and the House, step therapy bills were reintroduced this year. They would apply to health plans subject to the federal Employee Retirement Income Security Act, which governs employer-sponsored health coverage, and could close a big gap in existing protections. Oregon, New Jersey, and Arizona are at the top of the foundation’s advocacy list this year, according to Ms. Lynch.

“Folks are really starting to pay more attention to this issue,” she said. “And hearing those real-world stories and frustrations is definitely one of the most effective tools we have.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Encephalopathy common, often lethal in hospitalized patients with COVID-19

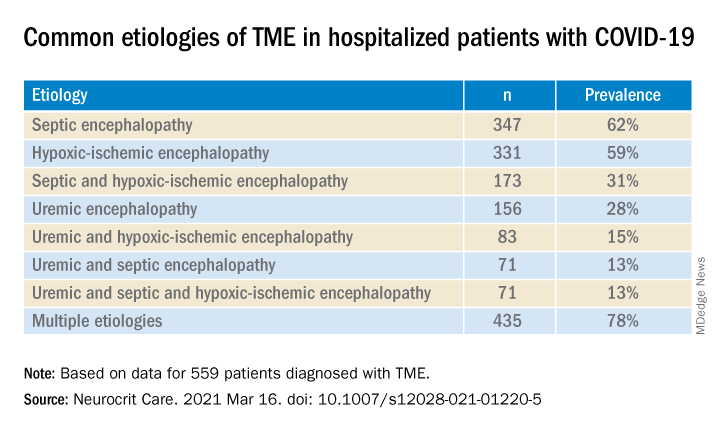

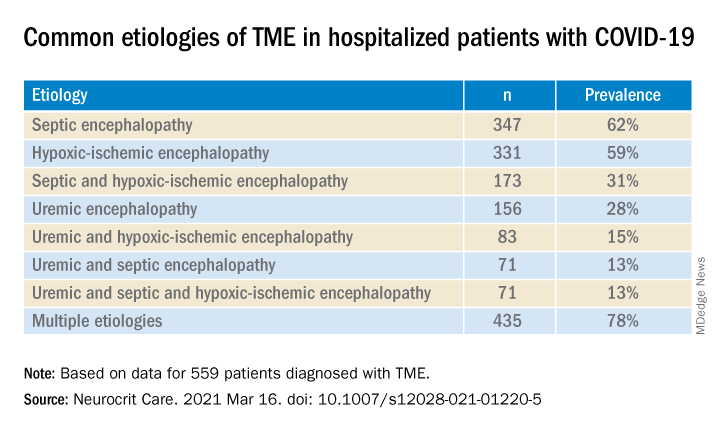

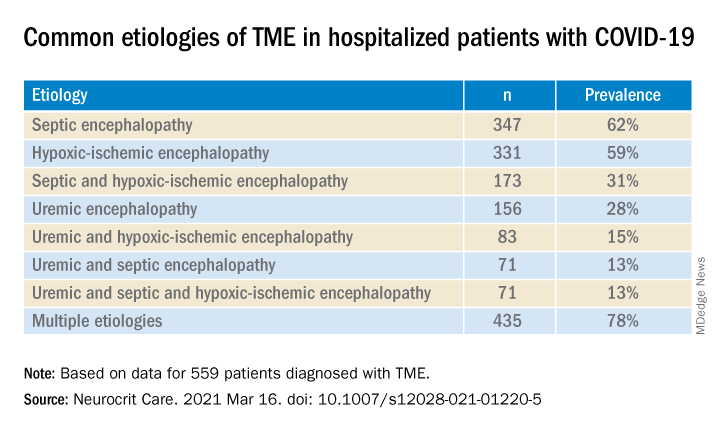

, new research shows. Results of a retrospective study show that of almost 4,500 patients with COVID-19, 12% were diagnosed with TME. Of these, 78% developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission. Septic encephalopathy, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and uremia were the most common causes, although multiple causes were present in close to 80% of patients. TME was also associated with a 24% higher risk of in-hospital death.

“We found that close to one in eight patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 had TME that was not attributed to the effects of sedatives, and that this is incredibly common among these patients who are critically ill” said lead author Jennifer A. Frontera, MD, New York University.

“The general principle of our findings is to be more aggressive in TME; and from a neurologist perspective, the way to do this is to eliminate the effects of sedation, which is a confounder,” she said.

The study was published online March 16 in Neurocritical Care.

Drilling down

“Many neurological complications of COVID-19 are sequelae of severe illness or secondary effects of multisystem organ failure, but our previous work identified TME as the most common neurological complication,” Dr. Frontera said.

Previous research investigating encephalopathy among patients with COVID-19 included patients who may have been sedated or have had a positive Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) result.

“A lot of the delirium literature is effectively heterogeneous because there are a number of patients who are on sedative medication that, if you could turn it off, these patients would return to normal. Some may have underlying neurological issues that can be addressed, but you can›t get to the bottom of this unless you turn off the sedation,” Dr. Frontera noted.

“We wanted to be specific and try to drill down to see what the underlying cause of the encephalopathy was,” she said.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data on 4,491 patients (≥ 18 years old) with COVID-19 who were admitted to four New York City hospitals between March 1, 2020, and May 20, 2020. Of these, 559 (12%) with TME were compared with 3,932 patients without TME.

The researchers looked at index admissions and included patients who had:

- New changes in mental status or significant worsening of mental status (in patients with baseline abnormal mental status).

- Hyperglycemia or with transient focal neurologic deficits that resolved with glucose correction.

- An adequate washout of sedating medications (when relevant) prior to mental status assessment.

Potential etiologies included electrolyte abnormalities, organ failure, hypertensive encephalopathy, sepsis or active infection, fever, nutritional deficiency, and environmental injury.

Foreign environment

Most (78%) of the 559 patients diagnosed with TME had already developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission, the authors report. The most common etiologies of TME among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are listed below.

Compared with patients without TME, those with TME – (all Ps < .001):

- Were older (76 vs. 62 years).

- Had higher rates of dementia (27% vs. 3%).

- Had higher rates of psychiatric history (20% vs. 10%).

- Were more often intubated (37% vs. 20%).

- Had a longer length of hospital stay (7.9 vs. 6.0 days).

- Were less often discharged home (25% vs. 66%).

“It’s no surprise that older patients and people with dementia or psychiatric illness are predisposed to becoming encephalopathic,” said Dr. Frontera. “Being in a foreign environment, such as a hospital, or being sleep-deprived in the ICU is likely to make them more confused during their hospital stay.”

Delirium as a symptom

In-hospital mortality or discharge to hospice was considerably higher in the TME versus non-TME patients (44% vs. 18%, respectively).

When the researchers adjusted for confounders (age, sex, race, worse Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score during hospitalization, ventilator status, study week, hospital location, and ICU care level) and excluded patients receiving only comfort care, they found that TME was associated with a 24% increased risk of in-hospital death (30% in patients with TME vs. 16% in those without TME).

The highest mortality risk was associated with hypoxemia, with 42% of patients with HIE dying during hospitalization, compared with 16% of patients without HIE (adjusted hazard ratio 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.00; P = .001).

“Not all patients who are intubated require sedation, but there’s generally a lot of hesitation in reducing or stopping sedation in some patients,” Dr. Frontera observed.

She acknowledged there are “many extremely sick patients whom you can’t ventilate without sedation.”

Nevertheless, “delirium in and of itself does not cause death. It’s a symptom, not a disease, and we have to figure out what causes it. Delirium might not need to be sedated, and it’s more important to see what the causal problem is.”

Independent predictor of death

Commenting on the study, Panayiotis N. Varelas, MD, PhD, vice president of the Neurocritical Care Society, said the study “approached the TME issue better than previously, namely allowing time for sedatives to wear off to have a better sample of patients with this syndrome.”

Dr. Varelas, who is chairman of the department of neurology and professor of neurology at Albany (N.Y.) Medical College, emphasized that TME “is not benign and, in patients with COVID-19, it is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality.”

“One should take all possible measures … to avoid desaturation and hypotensive episodes and also aggressively treat SAE and uremic encephalopathy in hopes of improving the outcomes,” added Dr. Varelas, who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting on the study, Mitchell Elkind, MD, professor of neurology and epidemiology at Columbia University in New York, who was not associated with the research, said it “nicely distinguishes among the different causes of encephalopathy, including sepsis, hypoxia, and kidney failure … emphasizing just how sick these patients are.”

The study received no direct funding. Individual investigators were supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The investigators, Dr. Varelas, and Dr. Elkind have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. Results of a retrospective study show that of almost 4,500 patients with COVID-19, 12% were diagnosed with TME. Of these, 78% developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission. Septic encephalopathy, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and uremia were the most common causes, although multiple causes were present in close to 80% of patients. TME was also associated with a 24% higher risk of in-hospital death.

“We found that close to one in eight patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 had TME that was not attributed to the effects of sedatives, and that this is incredibly common among these patients who are critically ill” said lead author Jennifer A. Frontera, MD, New York University.

“The general principle of our findings is to be more aggressive in TME; and from a neurologist perspective, the way to do this is to eliminate the effects of sedation, which is a confounder,” she said.

The study was published online March 16 in Neurocritical Care.

Drilling down

“Many neurological complications of COVID-19 are sequelae of severe illness or secondary effects of multisystem organ failure, but our previous work identified TME as the most common neurological complication,” Dr. Frontera said.

Previous research investigating encephalopathy among patients with COVID-19 included patients who may have been sedated or have had a positive Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) result.

“A lot of the delirium literature is effectively heterogeneous because there are a number of patients who are on sedative medication that, if you could turn it off, these patients would return to normal. Some may have underlying neurological issues that can be addressed, but you can›t get to the bottom of this unless you turn off the sedation,” Dr. Frontera noted.

“We wanted to be specific and try to drill down to see what the underlying cause of the encephalopathy was,” she said.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data on 4,491 patients (≥ 18 years old) with COVID-19 who were admitted to four New York City hospitals between March 1, 2020, and May 20, 2020. Of these, 559 (12%) with TME were compared with 3,932 patients without TME.

The researchers looked at index admissions and included patients who had:

- New changes in mental status or significant worsening of mental status (in patients with baseline abnormal mental status).

- Hyperglycemia or with transient focal neurologic deficits that resolved with glucose correction.

- An adequate washout of sedating medications (when relevant) prior to mental status assessment.

Potential etiologies included electrolyte abnormalities, organ failure, hypertensive encephalopathy, sepsis or active infection, fever, nutritional deficiency, and environmental injury.

Foreign environment

Most (78%) of the 559 patients diagnosed with TME had already developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission, the authors report. The most common etiologies of TME among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 are listed below.

Compared with patients without TME, those with TME – (all Ps < .001):

- Were older (76 vs. 62 years).

- Had higher rates of dementia (27% vs. 3%).

- Had higher rates of psychiatric history (20% vs. 10%).

- Were more often intubated (37% vs. 20%).

- Had a longer length of hospital stay (7.9 vs. 6.0 days).

- Were less often discharged home (25% vs. 66%).

“It’s no surprise that older patients and people with dementia or psychiatric illness are predisposed to becoming encephalopathic,” said Dr. Frontera. “Being in a foreign environment, such as a hospital, or being sleep-deprived in the ICU is likely to make them more confused during their hospital stay.”

Delirium as a symptom

In-hospital mortality or discharge to hospice was considerably higher in the TME versus non-TME patients (44% vs. 18%, respectively).

When the researchers adjusted for confounders (age, sex, race, worse Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score during hospitalization, ventilator status, study week, hospital location, and ICU care level) and excluded patients receiving only comfort care, they found that TME was associated with a 24% increased risk of in-hospital death (30% in patients with TME vs. 16% in those without TME).

The highest mortality risk was associated with hypoxemia, with 42% of patients with HIE dying during hospitalization, compared with 16% of patients without HIE (adjusted hazard ratio 1.56; 95% confidence interval, 1.21-2.00; P = .001).

“Not all patients who are intubated require sedation, but there’s generally a lot of hesitation in reducing or stopping sedation in some patients,” Dr. Frontera observed.

She acknowledged there are “many extremely sick patients whom you can’t ventilate without sedation.”

Nevertheless, “delirium in and of itself does not cause death. It’s a symptom, not a disease, and we have to figure out what causes it. Delirium might not need to be sedated, and it’s more important to see what the causal problem is.”

Independent predictor of death

Commenting on the study, Panayiotis N. Varelas, MD, PhD, vice president of the Neurocritical Care Society, said the study “approached the TME issue better than previously, namely allowing time for sedatives to wear off to have a better sample of patients with this syndrome.”

Dr. Varelas, who is chairman of the department of neurology and professor of neurology at Albany (N.Y.) Medical College, emphasized that TME “is not benign and, in patients with COVID-19, it is an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality.”

“One should take all possible measures … to avoid desaturation and hypotensive episodes and also aggressively treat SAE and uremic encephalopathy in hopes of improving the outcomes,” added Dr. Varelas, who was not involved with the study.

Also commenting on the study, Mitchell Elkind, MD, professor of neurology and epidemiology at Columbia University in New York, who was not associated with the research, said it “nicely distinguishes among the different causes of encephalopathy, including sepsis, hypoxia, and kidney failure … emphasizing just how sick these patients are.”

The study received no direct funding. Individual investigators were supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging and the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The investigators, Dr. Varelas, and Dr. Elkind have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, new research shows. Results of a retrospective study show that of almost 4,500 patients with COVID-19, 12% were diagnosed with TME. Of these, 78% developed encephalopathy immediately prior to hospital admission. Septic encephalopathy, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), and uremia were the most common causes, although multiple causes were present in close to 80% of patients. TME was also associated with a 24% higher risk of in-hospital death.

“We found that close to one in eight patients who were hospitalized with COVID-19 had TME that was not attributed to the effects of sedatives, and that this is incredibly common among these patients who are critically ill” said lead author Jennifer A. Frontera, MD, New York University.

“The general principle of our findings is to be more aggressive in TME; and from a neurologist perspective, the way to do this is to eliminate the effects of sedation, which is a confounder,” she said.

The study was published online March 16 in Neurocritical Care.

Drilling down

“Many neurological complications of COVID-19 are sequelae of severe illness or secondary effects of multisystem organ failure, but our previous work identified TME as the most common neurological complication,” Dr. Frontera said.

Previous research investigating encephalopathy among patients with COVID-19 included patients who may have been sedated or have had a positive Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) result.

“A lot of the delirium literature is effectively heterogeneous because there are a number of patients who are on sedative medication that, if you could turn it off, these patients would return to normal. Some may have underlying neurological issues that can be addressed, but you can›t get to the bottom of this unless you turn off the sedation,” Dr. Frontera noted.

“We wanted to be specific and try to drill down to see what the underlying cause of the encephalopathy was,” she said.

The researchers retrospectively analyzed data on 4,491 patients (≥ 18 years old) with COVID-19 who were admitted to four New York City hospitals between March 1, 2020, and May 20, 2020. Of these, 559 (12%) with TME were compared with 3,932 patients without TME.

The researchers looked at index admissions and included patients who had: