User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

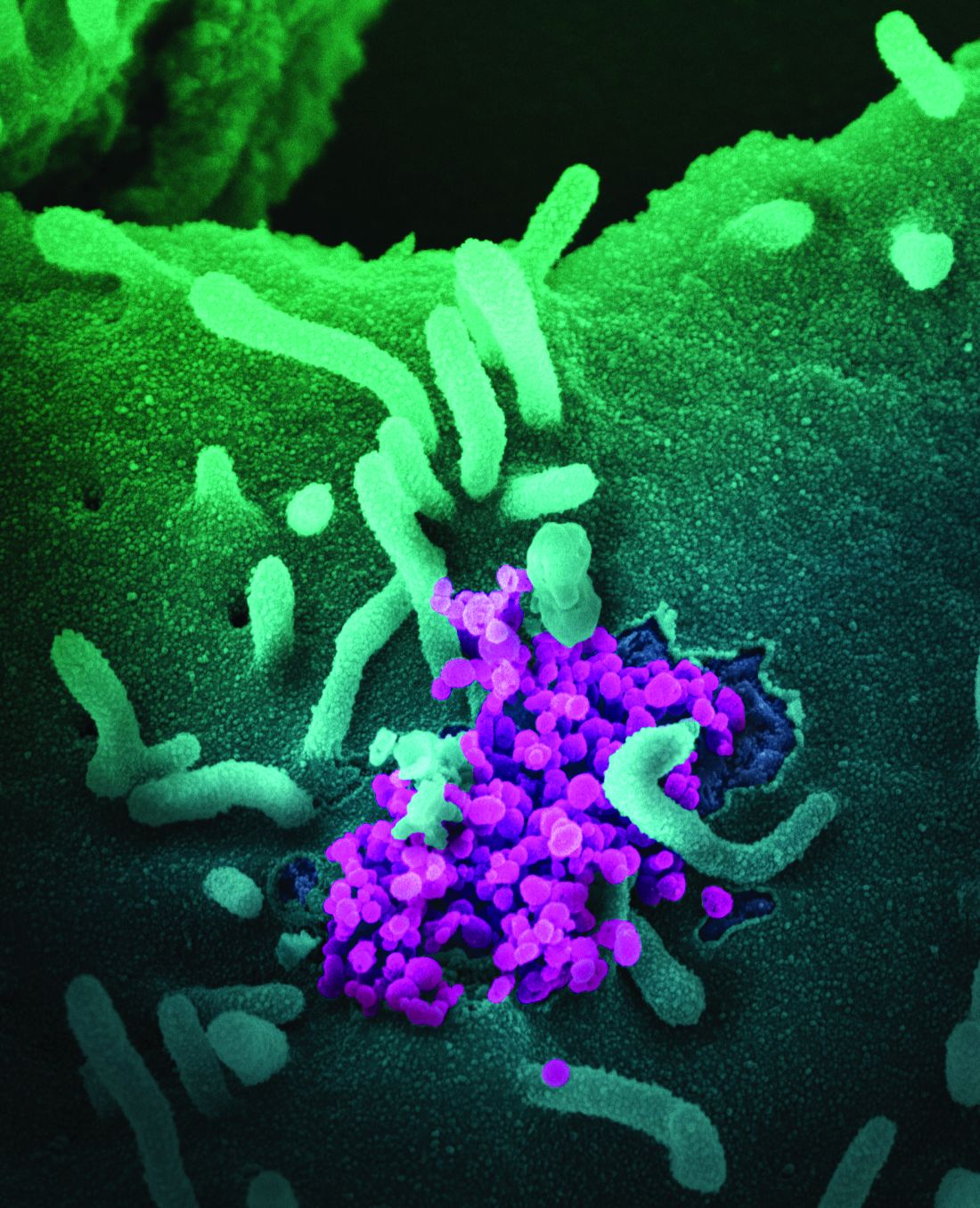

PPE protected critical care staff from COVID-19 transmission

, a new study has found.

“Other staff, other areas of the hospital, and the wider community are more likely sources of infection,” said lead author Kate El Bouzidi, MRCP, South London Specialist Virology Centre, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London.

She noted that 60% of critical care staff were symptomatic during the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic and 20% were antibody positive, with 10% asymptomatic. “Staff acquisition peaked 3 weeks before the peak of COVID-19 ICU admission, and personal protective equipment (PPE) was effective at preventing transmission from patients.” Working in other areas of the hospital was associated with higher seroprevalence, Dr. El Bouzidi noted.

The findings were presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

The novel coronavirus was spreading around the world, and when it reached northern Italy, medical authorities began to think in terms of how it might overwhelm the health care system in the United Kingdom, explained Dr. El Bouzidi.

“There was a lot of interest at this time about health care workers who were particularly vulnerable and also about the allocation of resources and rationing of care, particularly in intensive care,” she said. “And this only intensified when our prime minister was admitted to intensive care. About this time, antibody testing also became available.”

The goal of their study was to determine the SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in critical care staff, as well as look at the correlation between antibody status, prior swab testing, and COVID-19 symptoms.

The survey was conducted at Kings College Hospital in London, which is a tertiary-care teaching center. The critical care department is one of the largest in the United Kingdom. The authors estimate that more than 800 people worked in the critical care units, and between March and April 2020, more than 2,000 patients with COVID-19 were admitted, of whom 180 required care in the ICU.

“There was good PPE available in the ICU units right from the start,” she said, “and staff testing was available.”

All staff working in the critical care department participated in the study, which required serum samples and completion of a questionnaire. The samples were tested via six different assays to measure receptor-binding domain, nucleoprotein, and tri-spike, with one antibody result determined for each sample.

Of the 625 staff members, 384 (61.4%) had previously reported experiencing symptoms and 124 (19.8%) had sent a swab for testing. COVID-19 infection had been confirmed in 37 of those health care workers (29.8%).

Overall, 21% were positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, of whom 9.9% had been asymptomatic.

“We were surprised to find that 61% of staff reported symptoms they felt could be consistent with COVID-19,” she said, noting that fatigue, headache, and cough were the most common symptoms reported. “Seroprevalence was reported in 31% of symptomatic staff and in 5% of those without symptoms.”

Seroprevalence differed by role in a critical care unit, although it did not significantly differ by factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, or underlying conditions. Consultants, who are senior physicians, were twice as likely to test positive, compared with junior doctors. The reason for this finding is not clear, but it may lie in the nature of their work responsibilities, such as performing more aerosol-generating procedures in the ICU or in other departments.

The investigators looked at the timing of infections and found that they preceded peak of patient admissions by 3 weeks, with peak onset of staff symptoms in early March. At this time, Dr. El Bouzidi noted, there were very few patients with COVID-19 in the hospital, and good PPE was available throughout this time period.

“Staff were unlikely to be infected by ICU patients, and therefore PPE was largely effective,” she said. “Other sources of infection were more likely to be the cause, such as interactions with other staff, meetings, or contact in break rooms. Routine mask-wearing throughout the hospital was only encouraged as of June 15.”

There were several limitations to the study, such as the cross-sectional design, reliance on response/recall, the fact that antibody tests are unlikely to detect all previous infections, and no genomic data were available to confirm infections. Even though the study had limitations, Dr. El Bouzidi concluded that ICU staff are unlikely to contract COVID-19 from patients but that other staff, other areas of the hospital, and the wider community are more likely sources of infection.

These findings, she added, demonstrate that PPE was effective at preventing transmission from patients and that protective measures need to be maintained when staff is away from the bedside.

In commenting on the study, Greg S. Martin, MD, professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary, allergy, critical care and sleep medicine, Emory University, Atlanta, noted that, even though the study was conducted almost a year ago, the results are still relevant with regard to the effectiveness of PPE.

“There was a huge amount of uncertainty about PPE – what was most effective, could we reuse it, how to sterilize it, what about surfaces, and so on,” he said. “Even for people who work in ICU and who are familiar with the environment and familiar with the patients, there was 1,000 times more uncertainty about everything they were doing.”

Dr. Martin believes that the situation has improved. “It’s not that we take COVID more lightly, but I think the staff is more comfortable dealing with it,” he said. “They now know what they need to do on an hourly and daily basis to stay safe. The PPE had become second nature to them now, with all the other precautions.”

, a new study has found.

“Other staff, other areas of the hospital, and the wider community are more likely sources of infection,” said lead author Kate El Bouzidi, MRCP, South London Specialist Virology Centre, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London.

She noted that 60% of critical care staff were symptomatic during the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic and 20% were antibody positive, with 10% asymptomatic. “Staff acquisition peaked 3 weeks before the peak of COVID-19 ICU admission, and personal protective equipment (PPE) was effective at preventing transmission from patients.” Working in other areas of the hospital was associated with higher seroprevalence, Dr. El Bouzidi noted.

The findings were presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

The novel coronavirus was spreading around the world, and when it reached northern Italy, medical authorities began to think in terms of how it might overwhelm the health care system in the United Kingdom, explained Dr. El Bouzidi.

“There was a lot of interest at this time about health care workers who were particularly vulnerable and also about the allocation of resources and rationing of care, particularly in intensive care,” she said. “And this only intensified when our prime minister was admitted to intensive care. About this time, antibody testing also became available.”

The goal of their study was to determine the SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in critical care staff, as well as look at the correlation between antibody status, prior swab testing, and COVID-19 symptoms.

The survey was conducted at Kings College Hospital in London, which is a tertiary-care teaching center. The critical care department is one of the largest in the United Kingdom. The authors estimate that more than 800 people worked in the critical care units, and between March and April 2020, more than 2,000 patients with COVID-19 were admitted, of whom 180 required care in the ICU.

“There was good PPE available in the ICU units right from the start,” she said, “and staff testing was available.”

All staff working in the critical care department participated in the study, which required serum samples and completion of a questionnaire. The samples were tested via six different assays to measure receptor-binding domain, nucleoprotein, and tri-spike, with one antibody result determined for each sample.

Of the 625 staff members, 384 (61.4%) had previously reported experiencing symptoms and 124 (19.8%) had sent a swab for testing. COVID-19 infection had been confirmed in 37 of those health care workers (29.8%).

Overall, 21% were positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, of whom 9.9% had been asymptomatic.

“We were surprised to find that 61% of staff reported symptoms they felt could be consistent with COVID-19,” she said, noting that fatigue, headache, and cough were the most common symptoms reported. “Seroprevalence was reported in 31% of symptomatic staff and in 5% of those without symptoms.”

Seroprevalence differed by role in a critical care unit, although it did not significantly differ by factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, or underlying conditions. Consultants, who are senior physicians, were twice as likely to test positive, compared with junior doctors. The reason for this finding is not clear, but it may lie in the nature of their work responsibilities, such as performing more aerosol-generating procedures in the ICU or in other departments.

The investigators looked at the timing of infections and found that they preceded peak of patient admissions by 3 weeks, with peak onset of staff symptoms in early March. At this time, Dr. El Bouzidi noted, there were very few patients with COVID-19 in the hospital, and good PPE was available throughout this time period.

“Staff were unlikely to be infected by ICU patients, and therefore PPE was largely effective,” she said. “Other sources of infection were more likely to be the cause, such as interactions with other staff, meetings, or contact in break rooms. Routine mask-wearing throughout the hospital was only encouraged as of June 15.”

There were several limitations to the study, such as the cross-sectional design, reliance on response/recall, the fact that antibody tests are unlikely to detect all previous infections, and no genomic data were available to confirm infections. Even though the study had limitations, Dr. El Bouzidi concluded that ICU staff are unlikely to contract COVID-19 from patients but that other staff, other areas of the hospital, and the wider community are more likely sources of infection.

These findings, she added, demonstrate that PPE was effective at preventing transmission from patients and that protective measures need to be maintained when staff is away from the bedside.

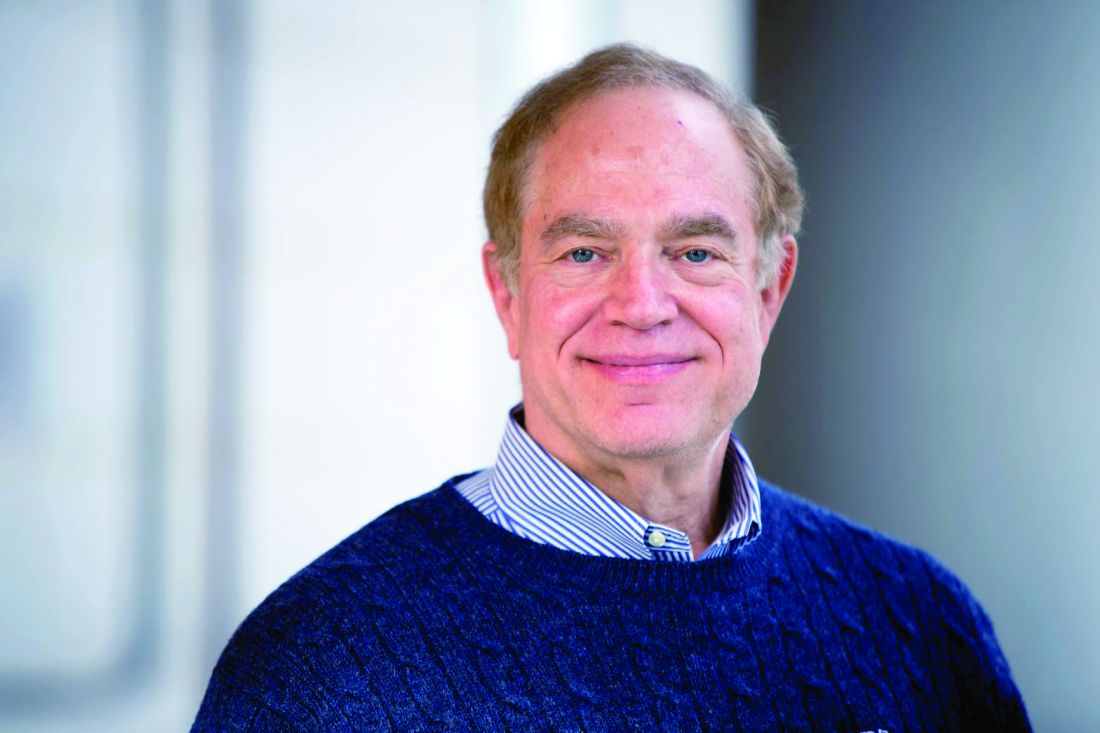

In commenting on the study, Greg S. Martin, MD, professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary, allergy, critical care and sleep medicine, Emory University, Atlanta, noted that, even though the study was conducted almost a year ago, the results are still relevant with regard to the effectiveness of PPE.

“There was a huge amount of uncertainty about PPE – what was most effective, could we reuse it, how to sterilize it, what about surfaces, and so on,” he said. “Even for people who work in ICU and who are familiar with the environment and familiar with the patients, there was 1,000 times more uncertainty about everything they were doing.”

Dr. Martin believes that the situation has improved. “It’s not that we take COVID more lightly, but I think the staff is more comfortable dealing with it,” he said. “They now know what they need to do on an hourly and daily basis to stay safe. The PPE had become second nature to them now, with all the other precautions.”

, a new study has found.

“Other staff, other areas of the hospital, and the wider community are more likely sources of infection,” said lead author Kate El Bouzidi, MRCP, South London Specialist Virology Centre, King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London.

She noted that 60% of critical care staff were symptomatic during the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic and 20% were antibody positive, with 10% asymptomatic. “Staff acquisition peaked 3 weeks before the peak of COVID-19 ICU admission, and personal protective equipment (PPE) was effective at preventing transmission from patients.” Working in other areas of the hospital was associated with higher seroprevalence, Dr. El Bouzidi noted.

The findings were presented at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine.

The novel coronavirus was spreading around the world, and when it reached northern Italy, medical authorities began to think in terms of how it might overwhelm the health care system in the United Kingdom, explained Dr. El Bouzidi.

“There was a lot of interest at this time about health care workers who were particularly vulnerable and also about the allocation of resources and rationing of care, particularly in intensive care,” she said. “And this only intensified when our prime minister was admitted to intensive care. About this time, antibody testing also became available.”

The goal of their study was to determine the SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in critical care staff, as well as look at the correlation between antibody status, prior swab testing, and COVID-19 symptoms.

The survey was conducted at Kings College Hospital in London, which is a tertiary-care teaching center. The critical care department is one of the largest in the United Kingdom. The authors estimate that more than 800 people worked in the critical care units, and between March and April 2020, more than 2,000 patients with COVID-19 were admitted, of whom 180 required care in the ICU.

“There was good PPE available in the ICU units right from the start,” she said, “and staff testing was available.”

All staff working in the critical care department participated in the study, which required serum samples and completion of a questionnaire. The samples were tested via six different assays to measure receptor-binding domain, nucleoprotein, and tri-spike, with one antibody result determined for each sample.

Of the 625 staff members, 384 (61.4%) had previously reported experiencing symptoms and 124 (19.8%) had sent a swab for testing. COVID-19 infection had been confirmed in 37 of those health care workers (29.8%).

Overall, 21% were positive for SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, of whom 9.9% had been asymptomatic.

“We were surprised to find that 61% of staff reported symptoms they felt could be consistent with COVID-19,” she said, noting that fatigue, headache, and cough were the most common symptoms reported. “Seroprevalence was reported in 31% of symptomatic staff and in 5% of those without symptoms.”

Seroprevalence differed by role in a critical care unit, although it did not significantly differ by factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, or underlying conditions. Consultants, who are senior physicians, were twice as likely to test positive, compared with junior doctors. The reason for this finding is not clear, but it may lie in the nature of their work responsibilities, such as performing more aerosol-generating procedures in the ICU or in other departments.

The investigators looked at the timing of infections and found that they preceded peak of patient admissions by 3 weeks, with peak onset of staff symptoms in early March. At this time, Dr. El Bouzidi noted, there were very few patients with COVID-19 in the hospital, and good PPE was available throughout this time period.

“Staff were unlikely to be infected by ICU patients, and therefore PPE was largely effective,” she said. “Other sources of infection were more likely to be the cause, such as interactions with other staff, meetings, or contact in break rooms. Routine mask-wearing throughout the hospital was only encouraged as of June 15.”

There were several limitations to the study, such as the cross-sectional design, reliance on response/recall, the fact that antibody tests are unlikely to detect all previous infections, and no genomic data were available to confirm infections. Even though the study had limitations, Dr. El Bouzidi concluded that ICU staff are unlikely to contract COVID-19 from patients but that other staff, other areas of the hospital, and the wider community are more likely sources of infection.

These findings, she added, demonstrate that PPE was effective at preventing transmission from patients and that protective measures need to be maintained when staff is away from the bedside.

In commenting on the study, Greg S. Martin, MD, professor of medicine in the division of pulmonary, allergy, critical care and sleep medicine, Emory University, Atlanta, noted that, even though the study was conducted almost a year ago, the results are still relevant with regard to the effectiveness of PPE.

“There was a huge amount of uncertainty about PPE – what was most effective, could we reuse it, how to sterilize it, what about surfaces, and so on,” he said. “Even for people who work in ICU and who are familiar with the environment and familiar with the patients, there was 1,000 times more uncertainty about everything they were doing.”

Dr. Martin believes that the situation has improved. “It’s not that we take COVID more lightly, but I think the staff is more comfortable dealing with it,” he said. “They now know what they need to do on an hourly and daily basis to stay safe. The PPE had become second nature to them now, with all the other precautions.”

FROM CCC50

Prostate drugs tied to lower risk for Parkinson’s disease

new research suggests. Treatment of BPH with terazosin (Hytrin), doxazosin (Cardura), or alfuzosin (Uroxatral), all of which enhance glycolysis, was associated with a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease than patients taking a drug used for the same indication, tamsulosin (Flomax), which does not affect glycolysis.

“If giving someone terazosin or similar medications truly reduces their risk of disease, these results could have significant clinical implications for neurologists,” said lead author Jacob E. Simmering, PhD, assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

There are few reliable neuroprotective treatments for Parkinson’s disease, he said. “We can manage some of the symptoms, but we can’t stop it from progressing. If a randomized trial finds the same result, this will provide a new option to slow progression of Parkinson’s disease.”

The pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease is heterogeneous, however, and not all patients may benefit from glycolysis-enhancing drugs, the investigators noted. Future research will be needed to identify potential candidates for this treatment, and clarify the effects of these drugs, they wrote.

The findings were published online Feb. 1, 2021, in JAMA Neurology.

Time-dependent effects

The major risk factor for Parkinson’s disease is age, which is associated with impaired energy metabolism. Glycolysis is decreased among patients with Parkinson’s disease, yet impaired energy metabolism has not been investigated widely as a pathogenic factor in the disease, the authors wrote.

Studies have indicated that terazosin increases the activity of an enzyme important in glycolysis. Doxazosin and alfuzosin have a similar mechanism of action and enhance energy metabolism. Tamsulosin, a structurally unrelated drug, has the same mechanism of action as the other three drugs, but does not enhance energy metabolism.

In this report, the researchers investigated the hypothesis that patients who received therapy with terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin would have a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease than patients receiving tamsulosin. To do that, they used health care utilization data from Denmark and the United States, including the Danish National Prescription Registry, the Danish National Patient Registry, the Danish Civil Registration System, and the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan database.

The investigators searched the records for patients who filled prescriptions for any of the four drugs of interest. They excluded any patients who developed Parkinson’s disease within 1 year of starting medication. Because use of these drugs is rare among women, they included only men in their analysis.

They looked at patient outcomes beginning at 1 year after the initiation of treatment. They also required patients to fill at least two prescriptions before the beginning of follow-up. Patients who switched from tamsulosin to any of the other drugs, or vice versa, were excluded from analysis.

The investigators used propensity-score matching to ensure that patients in the tamsulosin and terazosin/doxazosin/alfuzosin groups were similar in terms of their other potential risk factors. The primary outcome was the development of Parkinson’s disease.

They identified 52,365 propensity score–matched pairs in the Danish registries and 94,883 pairs in the Truven database. The mean age was 67.9 years in the Danish registries and 63.8 years in the Truven database, and follow-up was approximately 5 years and 3 years respectively. Baseline covariates were well balanced between cohorts.

Among Danish patients, those who took terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin had a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease versus those who took tamsulosin (hazard ratio, 0.88). Similarly, patients in the Truven database who took terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin had a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease than those who took tamsulosin (HR, 0.63).

In both cohorts, the risk for Parkinson’s disease among patients receiving terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin, compared with those receiving tamsulosin, decreased with increasing numbers of prescriptions filled. Long-term treatment with any of the three glycolysis-enhancing drugs was associated with greater risk reduction in the Danish (HR, 0.79) and Truven (HR, 0.46) cohorts versus tamsulosin.

Differences in case definitions, which may reflect how Parkinson’s disease was managed, complicate comparisons between the Danish and Truven cohorts, said Dr. Simmering. Another challenge is the source of the data. “The Truven data set was derived from insurance claims from people with private insurance or Medicare supplemental plans,” he said. “This group is quite large but may not be representative of everyone in the United States. We would also only be able to follow people while they were on one insurance plan. If they switched coverage to a company that doesn’t contribute data, we would lose them.”

The Danish database, however, includes all residents of Denmark. Only people who left the country were lost to follow-up.

The results support the hypothesis that increasing energy in cells slows disease progression, Dr. Simmering added. “There are a few conditions, mostly REM sleep disorders, that are associated with future diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Right now, we don’t have anything to offer people at elevated risk of Parkinson’s disease that might prevent the disease. If a controlled trial finds that terazosin slows or prevents Parkinson’s disease, we would have something truly protective to offer these patients.”

Biomarker needed

Commenting on the results, Alberto J. Espay, MD, MSc, professor of neurology at the University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center, was cautious. “These findings are of unclear applicability to any particular patient without a biomarker for a deficit of glycolysis that these drugs are presumed to affect,” Dr. Espay said. “Hence, there is no feasible or warranted change in practice as a result of this study.”

Pathogenic mechanisms are heterogeneous among patients with Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Espay added. “We will need to understand who among the large biological universe of Parkinson’s patients may have impaired energy metabolism as a pathogenic mechanism to be selected for a future clinical trial evaluating terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin as a potential disease-modifying intervention.”

Parkinson’s disease is not one disease, but a group of disorders with unique biological abnormalities, said Dr. Espay. “We know so much about ‘Parkinson’s disease’ and next to nothing about the biology of individuals with Parkinson’s disease.”

This situation has enabled the development of symptomatic treatments, such as dopaminergic therapies, but failed to yield disease-modifying treatments, he said.

The University of Iowa contributed funds for this study. Dr. Simmering has received pilot funding from the University of Iowa Institute for Clinical and Translational Science. He had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Espay disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests. Treatment of BPH with terazosin (Hytrin), doxazosin (Cardura), or alfuzosin (Uroxatral), all of which enhance glycolysis, was associated with a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease than patients taking a drug used for the same indication, tamsulosin (Flomax), which does not affect glycolysis.

“If giving someone terazosin or similar medications truly reduces their risk of disease, these results could have significant clinical implications for neurologists,” said lead author Jacob E. Simmering, PhD, assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

There are few reliable neuroprotective treatments for Parkinson’s disease, he said. “We can manage some of the symptoms, but we can’t stop it from progressing. If a randomized trial finds the same result, this will provide a new option to slow progression of Parkinson’s disease.”

The pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease is heterogeneous, however, and not all patients may benefit from glycolysis-enhancing drugs, the investigators noted. Future research will be needed to identify potential candidates for this treatment, and clarify the effects of these drugs, they wrote.

The findings were published online Feb. 1, 2021, in JAMA Neurology.

Time-dependent effects

The major risk factor for Parkinson’s disease is age, which is associated with impaired energy metabolism. Glycolysis is decreased among patients with Parkinson’s disease, yet impaired energy metabolism has not been investigated widely as a pathogenic factor in the disease, the authors wrote.

Studies have indicated that terazosin increases the activity of an enzyme important in glycolysis. Doxazosin and alfuzosin have a similar mechanism of action and enhance energy metabolism. Tamsulosin, a structurally unrelated drug, has the same mechanism of action as the other three drugs, but does not enhance energy metabolism.

In this report, the researchers investigated the hypothesis that patients who received therapy with terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin would have a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease than patients receiving tamsulosin. To do that, they used health care utilization data from Denmark and the United States, including the Danish National Prescription Registry, the Danish National Patient Registry, the Danish Civil Registration System, and the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan database.

The investigators searched the records for patients who filled prescriptions for any of the four drugs of interest. They excluded any patients who developed Parkinson’s disease within 1 year of starting medication. Because use of these drugs is rare among women, they included only men in their analysis.

They looked at patient outcomes beginning at 1 year after the initiation of treatment. They also required patients to fill at least two prescriptions before the beginning of follow-up. Patients who switched from tamsulosin to any of the other drugs, or vice versa, were excluded from analysis.

The investigators used propensity-score matching to ensure that patients in the tamsulosin and terazosin/doxazosin/alfuzosin groups were similar in terms of their other potential risk factors. The primary outcome was the development of Parkinson’s disease.

They identified 52,365 propensity score–matched pairs in the Danish registries and 94,883 pairs in the Truven database. The mean age was 67.9 years in the Danish registries and 63.8 years in the Truven database, and follow-up was approximately 5 years and 3 years respectively. Baseline covariates were well balanced between cohorts.

Among Danish patients, those who took terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin had a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease versus those who took tamsulosin (hazard ratio, 0.88). Similarly, patients in the Truven database who took terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin had a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease than those who took tamsulosin (HR, 0.63).

In both cohorts, the risk for Parkinson’s disease among patients receiving terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin, compared with those receiving tamsulosin, decreased with increasing numbers of prescriptions filled. Long-term treatment with any of the three glycolysis-enhancing drugs was associated with greater risk reduction in the Danish (HR, 0.79) and Truven (HR, 0.46) cohorts versus tamsulosin.

Differences in case definitions, which may reflect how Parkinson’s disease was managed, complicate comparisons between the Danish and Truven cohorts, said Dr. Simmering. Another challenge is the source of the data. “The Truven data set was derived from insurance claims from people with private insurance or Medicare supplemental plans,” he said. “This group is quite large but may not be representative of everyone in the United States. We would also only be able to follow people while they were on one insurance plan. If they switched coverage to a company that doesn’t contribute data, we would lose them.”

The Danish database, however, includes all residents of Denmark. Only people who left the country were lost to follow-up.

The results support the hypothesis that increasing energy in cells slows disease progression, Dr. Simmering added. “There are a few conditions, mostly REM sleep disorders, that are associated with future diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Right now, we don’t have anything to offer people at elevated risk of Parkinson’s disease that might prevent the disease. If a controlled trial finds that terazosin slows or prevents Parkinson’s disease, we would have something truly protective to offer these patients.”

Biomarker needed

Commenting on the results, Alberto J. Espay, MD, MSc, professor of neurology at the University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center, was cautious. “These findings are of unclear applicability to any particular patient without a biomarker for a deficit of glycolysis that these drugs are presumed to affect,” Dr. Espay said. “Hence, there is no feasible or warranted change in practice as a result of this study.”

Pathogenic mechanisms are heterogeneous among patients with Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Espay added. “We will need to understand who among the large biological universe of Parkinson’s patients may have impaired energy metabolism as a pathogenic mechanism to be selected for a future clinical trial evaluating terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin as a potential disease-modifying intervention.”

Parkinson’s disease is not one disease, but a group of disorders with unique biological abnormalities, said Dr. Espay. “We know so much about ‘Parkinson’s disease’ and next to nothing about the biology of individuals with Parkinson’s disease.”

This situation has enabled the development of symptomatic treatments, such as dopaminergic therapies, but failed to yield disease-modifying treatments, he said.

The University of Iowa contributed funds for this study. Dr. Simmering has received pilot funding from the University of Iowa Institute for Clinical and Translational Science. He had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Espay disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests. Treatment of BPH with terazosin (Hytrin), doxazosin (Cardura), or alfuzosin (Uroxatral), all of which enhance glycolysis, was associated with a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease than patients taking a drug used for the same indication, tamsulosin (Flomax), which does not affect glycolysis.

“If giving someone terazosin or similar medications truly reduces their risk of disease, these results could have significant clinical implications for neurologists,” said lead author Jacob E. Simmering, PhD, assistant professor of internal medicine at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

There are few reliable neuroprotective treatments for Parkinson’s disease, he said. “We can manage some of the symptoms, but we can’t stop it from progressing. If a randomized trial finds the same result, this will provide a new option to slow progression of Parkinson’s disease.”

The pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease is heterogeneous, however, and not all patients may benefit from glycolysis-enhancing drugs, the investigators noted. Future research will be needed to identify potential candidates for this treatment, and clarify the effects of these drugs, they wrote.

The findings were published online Feb. 1, 2021, in JAMA Neurology.

Time-dependent effects

The major risk factor for Parkinson’s disease is age, which is associated with impaired energy metabolism. Glycolysis is decreased among patients with Parkinson’s disease, yet impaired energy metabolism has not been investigated widely as a pathogenic factor in the disease, the authors wrote.

Studies have indicated that terazosin increases the activity of an enzyme important in glycolysis. Doxazosin and alfuzosin have a similar mechanism of action and enhance energy metabolism. Tamsulosin, a structurally unrelated drug, has the same mechanism of action as the other three drugs, but does not enhance energy metabolism.

In this report, the researchers investigated the hypothesis that patients who received therapy with terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin would have a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease than patients receiving tamsulosin. To do that, they used health care utilization data from Denmark and the United States, including the Danish National Prescription Registry, the Danish National Patient Registry, the Danish Civil Registration System, and the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan database.

The investigators searched the records for patients who filled prescriptions for any of the four drugs of interest. They excluded any patients who developed Parkinson’s disease within 1 year of starting medication. Because use of these drugs is rare among women, they included only men in their analysis.

They looked at patient outcomes beginning at 1 year after the initiation of treatment. They also required patients to fill at least two prescriptions before the beginning of follow-up. Patients who switched from tamsulosin to any of the other drugs, or vice versa, were excluded from analysis.

The investigators used propensity-score matching to ensure that patients in the tamsulosin and terazosin/doxazosin/alfuzosin groups were similar in terms of their other potential risk factors. The primary outcome was the development of Parkinson’s disease.

They identified 52,365 propensity score–matched pairs in the Danish registries and 94,883 pairs in the Truven database. The mean age was 67.9 years in the Danish registries and 63.8 years in the Truven database, and follow-up was approximately 5 years and 3 years respectively. Baseline covariates were well balanced between cohorts.

Among Danish patients, those who took terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin had a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease versus those who took tamsulosin (hazard ratio, 0.88). Similarly, patients in the Truven database who took terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin had a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease than those who took tamsulosin (HR, 0.63).

In both cohorts, the risk for Parkinson’s disease among patients receiving terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin, compared with those receiving tamsulosin, decreased with increasing numbers of prescriptions filled. Long-term treatment with any of the three glycolysis-enhancing drugs was associated with greater risk reduction in the Danish (HR, 0.79) and Truven (HR, 0.46) cohorts versus tamsulosin.

Differences in case definitions, which may reflect how Parkinson’s disease was managed, complicate comparisons between the Danish and Truven cohorts, said Dr. Simmering. Another challenge is the source of the data. “The Truven data set was derived from insurance claims from people with private insurance or Medicare supplemental plans,” he said. “This group is quite large but may not be representative of everyone in the United States. We would also only be able to follow people while they were on one insurance plan. If they switched coverage to a company that doesn’t contribute data, we would lose them.”

The Danish database, however, includes all residents of Denmark. Only people who left the country were lost to follow-up.

The results support the hypothesis that increasing energy in cells slows disease progression, Dr. Simmering added. “There are a few conditions, mostly REM sleep disorders, that are associated with future diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Right now, we don’t have anything to offer people at elevated risk of Parkinson’s disease that might prevent the disease. If a controlled trial finds that terazosin slows or prevents Parkinson’s disease, we would have something truly protective to offer these patients.”

Biomarker needed

Commenting on the results, Alberto J. Espay, MD, MSc, professor of neurology at the University of Cincinnati Academic Health Center, was cautious. “These findings are of unclear applicability to any particular patient without a biomarker for a deficit of glycolysis that these drugs are presumed to affect,” Dr. Espay said. “Hence, there is no feasible or warranted change in practice as a result of this study.”

Pathogenic mechanisms are heterogeneous among patients with Parkinson’s disease, Dr. Espay added. “We will need to understand who among the large biological universe of Parkinson’s patients may have impaired energy metabolism as a pathogenic mechanism to be selected for a future clinical trial evaluating terazosin, doxazosin, or alfuzosin as a potential disease-modifying intervention.”

Parkinson’s disease is not one disease, but a group of disorders with unique biological abnormalities, said Dr. Espay. “We know so much about ‘Parkinson’s disease’ and next to nothing about the biology of individuals with Parkinson’s disease.”

This situation has enabled the development of symptomatic treatments, such as dopaminergic therapies, but failed to yield disease-modifying treatments, he said.

The University of Iowa contributed funds for this study. Dr. Simmering has received pilot funding from the University of Iowa Institute for Clinical and Translational Science. He had no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Espay disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Researchers examine factors associated with opioid use among migraineurs

Among patients with migraine who use prescription medications, the increasing use of prescription opioids is associated with chronic migraine, more severe disability, and anxiety and depression, according to an analysis published in the January issue of Headache . The use of prescription opioids also is associated with treatment-related variables such as poor acute treatment optimization and treatment in a pain clinic. The results indicate the continued need to educate patients and clinicians about the potential risks of opioids for migraineurs, according to the researchers.

In the Migraine in America Symptoms and Treatment (MAST) study, which the researchers analyzed for their investigation, one-third of migraineurs who use acute prescriptions reported using opioids. Among opioid users, 42% took opioids on 4 or more days per month. “These findings are like [those of] a previous report from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study and more recent findings from the Observational Survey of the Epidemiology, Treatment, and Care of Migraine (OVERCOME) study,” said Richard Lipton, MD, Edwin S. Lowe professor and vice chair of neurology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York. “High rates of opioid use are problematic because opioid use is associated with worsening of migraine over time.”

Opioids remain in widespread use for migraine, even though guidelines recommend against this treatment. Among migraineurs, opioid use is associated with more severe headache-related disability and greater use of health care resources. Opioid use also increases the risk of progressing from episodic migraine to chronic migraine.

A review of MAST data

Dr. Lipton and colleagues set out to identify the variables associated with the frequency of opioid use in people with migraine. Among the variables that they sought to examine were demographic characteristics, comorbidities, headache characteristics, medication use, and patterns of health care use. Dr. Lipton’s group hypothesized that migraine-related severity and burden would increase with increasing frequency of opioid use.

To conduct their research, the investigators examined data from the MAST study, a nationwide sample of American adults with migraine. They focused specifically on participants who reported receiving prescription acute medications. Participants eligible for this analysis reported 3 or more headache days in the previous 3 months and at least 1 monthly headache day in the previous month. In all, 15,133 participants met these criteria.

Dr. Lipton and colleagues categorized participants into four groups based on their frequency of opioid use. The groups had no opioid use, 3 or fewer monthly days of opioid use, 4 to 9 monthly days of opioid use, and 10 or more days of monthly opioid use. The last category is consistent with the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 criteria for overuse of opioids in migraine.

At baseline, MAST participants provided information about variables such as gender, age, marital status, smoking status, education, and income. Participants also reported how many times in the previous 6 months they had visited a primary care doctor, a neurologist, a headache specialist, or a pain specialist. Dr. Lipton’s group calculated monthly headache days using the number of days during the previous 3 months affected by headache. The Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire was used to measure headache-related disability. The four-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4) was used to screen for anxiety and depression, and the Migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire (mTOQ-4) evaluated participants’ treatment optimization.

Men predominated among opioid users

The investigators included 4,701 MAST participants in their analysis. The population’s mean age was 45 years, and 71.6% of participants were women. Of the entire sample, 67.5% reported no opioid use, and 32.5% reported opioid use. Of the total study population, 18.7% of patients took opioids 3 or fewer days per month, 6.5% took opioids 4 to 9 days per month, and 7.3% took opioids on 10 or more days per month.

Opioid users did not differ from nonusers on race or marital status. Men were overrepresented among all groups of opioid users, however. In addition, opioid use was more prevalent among participants with fewer than 4 years of college education (34.9%) than among participants with 4 or more years of college (30.8%). The proportion of participants with fewer than 4 years of college increased with increasing monthly opioid use. Furthermore, opioid use increased with decreasing household income. As opioid use increased, rates of employment decreased. Approximately 33% of the entire sample were obese, and the proportion of obese participants increased with increasing days per month of opioid use.

The most frequent setting during the previous 6 months for participants seeking care was primary care (49.7%). The next most frequent setting was neurology units (20.9%), pain clinics (8.3%), and headache clinics (7.7%). The prevalence of opioid use was 37.5% among participants with primary care visits, 37.3% among participants with neurologist visits, 43.0% among participants with headache clinic visits, and 53.5% with pain clinic visits.

About 15% of the population had chronic migraine. The prevalence of chronic migraine increased with increasing frequency of opioid use. About 49% of the sample had allodynia, and the prevalence of allodynia increased with increasing frequency of opioid use. Overall, disability was moderate to severe in 57.3% of participants. Participants who used opioids on 3 or fewer days per month had the lowest prevalence of moderate to severe disability (50.2%), and participants who used opioids on 10 or more days per month had the highest prevalence of moderate to severe disability (83.8%).

Approximately 21% of participants had anxiety or depression. The lowest prevalence of anxiety or depression was among participants who took opioids on 3 or fewer days per month (17.4%), and the highest prevalence was among participants who took opioids on 10 or more days per month (43.2%). About 39% of the population had very poor to poor treatment optimization. Among opioid nonusers, 35.6% had very poor to poor treatment optimization, and 59.4% of participants who used opioids on 10 or more days per month had very poor to poor treatment optimization.

Dr. Lipton and colleagues also examined the study population’s use of triptans. Overall, 51.5% of participants reported taking triptans. The prevalence of triptan use was highest among participants who did not use opioids (64.1%) and lowest among participants who used opioids on 3 or fewer days per month (20.5%). Triptan use increased as monthly days of opioid use increased.

Pain clinics and opioid prescription

“In the general population, women are more likely to receive opioids than men,” said Dr. Lipton. “This [finding] could reflect, in part, that women have more pain disorders than men and are more likely to seek medical care for pain than men.” In the current study, however, men with migraine were more likely to receive opioid prescriptions than were women with migraine. One potential explanation for this finding is that men with migraine are less likely to receive a migraine diagnosis, which might attenuate opioid prescribing, than women with migraine. “It may be that opioids are perceived to be serious drugs for serious pain, and that some physicians may be more likely to prescribe opioids to men because the disorder is taken more seriously in men than women,” said Dr. Lipton.

The observation that opioids were more likely to be prescribed for people treated in pain clinics “is consistent with my understanding of practice patterns,” he added. “Generally, neurologists strive to find effective acute treatment alternatives to opioids. The emergence of [drug classes known as] gepants and ditans provides a helpful set of alternatives to tritpans.”

Dr. Lipton and his colleagues plan further research into the treatment of migraineurs. “In a claims analysis, we showed that when people with migraine fail a triptan, they are most likely to get an opioid as their next drug,” he said. “Reasonable [clinicians] might disagree on the next step. The next step, in the absence of contraindications, could be a different oral triptan, a nonoral triptan, or a gepant or ditan. We are planning a randomized trial to probe this question.”

Why are opioids still being used?

The study’s reliance on patients’ self-report and its retrospective design are two of its weaknesses, said Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews. One strength, however, is that the stratified sampling methodology produced a study population that accurately reflects the demographic characteristics of the U.S. adult population, he added. Another strength is the investigators’ examination of opioid use by patient characteristics such as marital status, education, income, obesity, and smoking.

Given the harmful effects of opioids in migraine, it is hard to understand why as much as one-third of study participants using acute care medication for migraine were using opioids, said Dr. Rapoport. Using opioids for the acute treatment of migraine attacks often indicates inadequate treatment optimization, which leads to ongoing headache. As a consequence, patients may take more medication, which can increase headache frequency and lead to diagnoses of chronic migraine and medication overuse headache. Although the study found an association between the increased use of opioids and decreased household income and increased unemployment, smoking, and obesity, “it is not possible to assign causality to any of these associations, even though some would argue that decreased socioeconomic status was somehow related to more headache, disability, obesity, smoking, and unemployment,” he added.

“The paper suggests that future research should look at the risk factors for use of opioids and should determine if depression is a risk factor for or a consequence of opioid use,” said Dr. Rapoport. “Interventional studies designed to improve the acute care of migraine attacks might be able to reduce the use of opioids. I have not used opioids or butalbital-containing medication in my office for many years.”

This study was funded and sponsored by Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories group of companies, Princeton, N.J. Dr. Lipton has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund. He serves as a consultant, serves as an advisory board member, or has received honoraria from Alder, Allergan, American Headache Society, Autonomic Technologies, Biohaven, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Eli Lilly, eNeura Therapeutics, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Teva, Inc. He receives royalties from Wolff’s Headache, 8th Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) and holds stock options in eNeura Therapeutics and Biohaven.

SOURCE: Lipton RB, et al. Headache. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14018. 2020;61(1):103-16.

Among patients with migraine who use prescription medications, the increasing use of prescription opioids is associated with chronic migraine, more severe disability, and anxiety and depression, according to an analysis published in the January issue of Headache . The use of prescription opioids also is associated with treatment-related variables such as poor acute treatment optimization and treatment in a pain clinic. The results indicate the continued need to educate patients and clinicians about the potential risks of opioids for migraineurs, according to the researchers.

In the Migraine in America Symptoms and Treatment (MAST) study, which the researchers analyzed for their investigation, one-third of migraineurs who use acute prescriptions reported using opioids. Among opioid users, 42% took opioids on 4 or more days per month. “These findings are like [those of] a previous report from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study and more recent findings from the Observational Survey of the Epidemiology, Treatment, and Care of Migraine (OVERCOME) study,” said Richard Lipton, MD, Edwin S. Lowe professor and vice chair of neurology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York. “High rates of opioid use are problematic because opioid use is associated with worsening of migraine over time.”

Opioids remain in widespread use for migraine, even though guidelines recommend against this treatment. Among migraineurs, opioid use is associated with more severe headache-related disability and greater use of health care resources. Opioid use also increases the risk of progressing from episodic migraine to chronic migraine.

A review of MAST data

Dr. Lipton and colleagues set out to identify the variables associated with the frequency of opioid use in people with migraine. Among the variables that they sought to examine were demographic characteristics, comorbidities, headache characteristics, medication use, and patterns of health care use. Dr. Lipton’s group hypothesized that migraine-related severity and burden would increase with increasing frequency of opioid use.

To conduct their research, the investigators examined data from the MAST study, a nationwide sample of American adults with migraine. They focused specifically on participants who reported receiving prescription acute medications. Participants eligible for this analysis reported 3 or more headache days in the previous 3 months and at least 1 monthly headache day in the previous month. In all, 15,133 participants met these criteria.

Dr. Lipton and colleagues categorized participants into four groups based on their frequency of opioid use. The groups had no opioid use, 3 or fewer monthly days of opioid use, 4 to 9 monthly days of opioid use, and 10 or more days of monthly opioid use. The last category is consistent with the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 criteria for overuse of opioids in migraine.

At baseline, MAST participants provided information about variables such as gender, age, marital status, smoking status, education, and income. Participants also reported how many times in the previous 6 months they had visited a primary care doctor, a neurologist, a headache specialist, or a pain specialist. Dr. Lipton’s group calculated monthly headache days using the number of days during the previous 3 months affected by headache. The Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire was used to measure headache-related disability. The four-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4) was used to screen for anxiety and depression, and the Migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire (mTOQ-4) evaluated participants’ treatment optimization.

Men predominated among opioid users

The investigators included 4,701 MAST participants in their analysis. The population’s mean age was 45 years, and 71.6% of participants were women. Of the entire sample, 67.5% reported no opioid use, and 32.5% reported opioid use. Of the total study population, 18.7% of patients took opioids 3 or fewer days per month, 6.5% took opioids 4 to 9 days per month, and 7.3% took opioids on 10 or more days per month.

Opioid users did not differ from nonusers on race or marital status. Men were overrepresented among all groups of opioid users, however. In addition, opioid use was more prevalent among participants with fewer than 4 years of college education (34.9%) than among participants with 4 or more years of college (30.8%). The proportion of participants with fewer than 4 years of college increased with increasing monthly opioid use. Furthermore, opioid use increased with decreasing household income. As opioid use increased, rates of employment decreased. Approximately 33% of the entire sample were obese, and the proportion of obese participants increased with increasing days per month of opioid use.

The most frequent setting during the previous 6 months for participants seeking care was primary care (49.7%). The next most frequent setting was neurology units (20.9%), pain clinics (8.3%), and headache clinics (7.7%). The prevalence of opioid use was 37.5% among participants with primary care visits, 37.3% among participants with neurologist visits, 43.0% among participants with headache clinic visits, and 53.5% with pain clinic visits.

About 15% of the population had chronic migraine. The prevalence of chronic migraine increased with increasing frequency of opioid use. About 49% of the sample had allodynia, and the prevalence of allodynia increased with increasing frequency of opioid use. Overall, disability was moderate to severe in 57.3% of participants. Participants who used opioids on 3 or fewer days per month had the lowest prevalence of moderate to severe disability (50.2%), and participants who used opioids on 10 or more days per month had the highest prevalence of moderate to severe disability (83.8%).

Approximately 21% of participants had anxiety or depression. The lowest prevalence of anxiety or depression was among participants who took opioids on 3 or fewer days per month (17.4%), and the highest prevalence was among participants who took opioids on 10 or more days per month (43.2%). About 39% of the population had very poor to poor treatment optimization. Among opioid nonusers, 35.6% had very poor to poor treatment optimization, and 59.4% of participants who used opioids on 10 or more days per month had very poor to poor treatment optimization.

Dr. Lipton and colleagues also examined the study population’s use of triptans. Overall, 51.5% of participants reported taking triptans. The prevalence of triptan use was highest among participants who did not use opioids (64.1%) and lowest among participants who used opioids on 3 or fewer days per month (20.5%). Triptan use increased as monthly days of opioid use increased.

Pain clinics and opioid prescription

“In the general population, women are more likely to receive opioids than men,” said Dr. Lipton. “This [finding] could reflect, in part, that women have more pain disorders than men and are more likely to seek medical care for pain than men.” In the current study, however, men with migraine were more likely to receive opioid prescriptions than were women with migraine. One potential explanation for this finding is that men with migraine are less likely to receive a migraine diagnosis, which might attenuate opioid prescribing, than women with migraine. “It may be that opioids are perceived to be serious drugs for serious pain, and that some physicians may be more likely to prescribe opioids to men because the disorder is taken more seriously in men than women,” said Dr. Lipton.

The observation that opioids were more likely to be prescribed for people treated in pain clinics “is consistent with my understanding of practice patterns,” he added. “Generally, neurologists strive to find effective acute treatment alternatives to opioids. The emergence of [drug classes known as] gepants and ditans provides a helpful set of alternatives to tritpans.”

Dr. Lipton and his colleagues plan further research into the treatment of migraineurs. “In a claims analysis, we showed that when people with migraine fail a triptan, they are most likely to get an opioid as their next drug,” he said. “Reasonable [clinicians] might disagree on the next step. The next step, in the absence of contraindications, could be a different oral triptan, a nonoral triptan, or a gepant or ditan. We are planning a randomized trial to probe this question.”

Why are opioids still being used?

The study’s reliance on patients’ self-report and its retrospective design are two of its weaknesses, said Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews. One strength, however, is that the stratified sampling methodology produced a study population that accurately reflects the demographic characteristics of the U.S. adult population, he added. Another strength is the investigators’ examination of opioid use by patient characteristics such as marital status, education, income, obesity, and smoking.

Given the harmful effects of opioids in migraine, it is hard to understand why as much as one-third of study participants using acute care medication for migraine were using opioids, said Dr. Rapoport. Using opioids for the acute treatment of migraine attacks often indicates inadequate treatment optimization, which leads to ongoing headache. As a consequence, patients may take more medication, which can increase headache frequency and lead to diagnoses of chronic migraine and medication overuse headache. Although the study found an association between the increased use of opioids and decreased household income and increased unemployment, smoking, and obesity, “it is not possible to assign causality to any of these associations, even though some would argue that decreased socioeconomic status was somehow related to more headache, disability, obesity, smoking, and unemployment,” he added.

“The paper suggests that future research should look at the risk factors for use of opioids and should determine if depression is a risk factor for or a consequence of opioid use,” said Dr. Rapoport. “Interventional studies designed to improve the acute care of migraine attacks might be able to reduce the use of opioids. I have not used opioids or butalbital-containing medication in my office for many years.”

This study was funded and sponsored by Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories group of companies, Princeton, N.J. Dr. Lipton has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund. He serves as a consultant, serves as an advisory board member, or has received honoraria from Alder, Allergan, American Headache Society, Autonomic Technologies, Biohaven, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Eli Lilly, eNeura Therapeutics, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Teva, Inc. He receives royalties from Wolff’s Headache, 8th Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) and holds stock options in eNeura Therapeutics and Biohaven.

SOURCE: Lipton RB, et al. Headache. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14018. 2020;61(1):103-16.

Among patients with migraine who use prescription medications, the increasing use of prescription opioids is associated with chronic migraine, more severe disability, and anxiety and depression, according to an analysis published in the January issue of Headache . The use of prescription opioids also is associated with treatment-related variables such as poor acute treatment optimization and treatment in a pain clinic. The results indicate the continued need to educate patients and clinicians about the potential risks of opioids for migraineurs, according to the researchers.

In the Migraine in America Symptoms and Treatment (MAST) study, which the researchers analyzed for their investigation, one-third of migraineurs who use acute prescriptions reported using opioids. Among opioid users, 42% took opioids on 4 or more days per month. “These findings are like [those of] a previous report from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study and more recent findings from the Observational Survey of the Epidemiology, Treatment, and Care of Migraine (OVERCOME) study,” said Richard Lipton, MD, Edwin S. Lowe professor and vice chair of neurology at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx, New York. “High rates of opioid use are problematic because opioid use is associated with worsening of migraine over time.”

Opioids remain in widespread use for migraine, even though guidelines recommend against this treatment. Among migraineurs, opioid use is associated with more severe headache-related disability and greater use of health care resources. Opioid use also increases the risk of progressing from episodic migraine to chronic migraine.

A review of MAST data

Dr. Lipton and colleagues set out to identify the variables associated with the frequency of opioid use in people with migraine. Among the variables that they sought to examine were demographic characteristics, comorbidities, headache characteristics, medication use, and patterns of health care use. Dr. Lipton’s group hypothesized that migraine-related severity and burden would increase with increasing frequency of opioid use.

To conduct their research, the investigators examined data from the MAST study, a nationwide sample of American adults with migraine. They focused specifically on participants who reported receiving prescription acute medications. Participants eligible for this analysis reported 3 or more headache days in the previous 3 months and at least 1 monthly headache day in the previous month. In all, 15,133 participants met these criteria.

Dr. Lipton and colleagues categorized participants into four groups based on their frequency of opioid use. The groups had no opioid use, 3 or fewer monthly days of opioid use, 4 to 9 monthly days of opioid use, and 10 or more days of monthly opioid use. The last category is consistent with the International Classification of Headache Disorders-3 criteria for overuse of opioids in migraine.

At baseline, MAST participants provided information about variables such as gender, age, marital status, smoking status, education, and income. Participants also reported how many times in the previous 6 months they had visited a primary care doctor, a neurologist, a headache specialist, or a pain specialist. Dr. Lipton’s group calculated monthly headache days using the number of days during the previous 3 months affected by headache. The Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) questionnaire was used to measure headache-related disability. The four-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4) was used to screen for anxiety and depression, and the Migraine Treatment Optimization Questionnaire (mTOQ-4) evaluated participants’ treatment optimization.

Men predominated among opioid users

The investigators included 4,701 MAST participants in their analysis. The population’s mean age was 45 years, and 71.6% of participants were women. Of the entire sample, 67.5% reported no opioid use, and 32.5% reported opioid use. Of the total study population, 18.7% of patients took opioids 3 or fewer days per month, 6.5% took opioids 4 to 9 days per month, and 7.3% took opioids on 10 or more days per month.

Opioid users did not differ from nonusers on race or marital status. Men were overrepresented among all groups of opioid users, however. In addition, opioid use was more prevalent among participants with fewer than 4 years of college education (34.9%) than among participants with 4 or more years of college (30.8%). The proportion of participants with fewer than 4 years of college increased with increasing monthly opioid use. Furthermore, opioid use increased with decreasing household income. As opioid use increased, rates of employment decreased. Approximately 33% of the entire sample were obese, and the proportion of obese participants increased with increasing days per month of opioid use.

The most frequent setting during the previous 6 months for participants seeking care was primary care (49.7%). The next most frequent setting was neurology units (20.9%), pain clinics (8.3%), and headache clinics (7.7%). The prevalence of opioid use was 37.5% among participants with primary care visits, 37.3% among participants with neurologist visits, 43.0% among participants with headache clinic visits, and 53.5% with pain clinic visits.

About 15% of the population had chronic migraine. The prevalence of chronic migraine increased with increasing frequency of opioid use. About 49% of the sample had allodynia, and the prevalence of allodynia increased with increasing frequency of opioid use. Overall, disability was moderate to severe in 57.3% of participants. Participants who used opioids on 3 or fewer days per month had the lowest prevalence of moderate to severe disability (50.2%), and participants who used opioids on 10 or more days per month had the highest prevalence of moderate to severe disability (83.8%).

Approximately 21% of participants had anxiety or depression. The lowest prevalence of anxiety or depression was among participants who took opioids on 3 or fewer days per month (17.4%), and the highest prevalence was among participants who took opioids on 10 or more days per month (43.2%). About 39% of the population had very poor to poor treatment optimization. Among opioid nonusers, 35.6% had very poor to poor treatment optimization, and 59.4% of participants who used opioids on 10 or more days per month had very poor to poor treatment optimization.

Dr. Lipton and colleagues also examined the study population’s use of triptans. Overall, 51.5% of participants reported taking triptans. The prevalence of triptan use was highest among participants who did not use opioids (64.1%) and lowest among participants who used opioids on 3 or fewer days per month (20.5%). Triptan use increased as monthly days of opioid use increased.

Pain clinics and opioid prescription

“In the general population, women are more likely to receive opioids than men,” said Dr. Lipton. “This [finding] could reflect, in part, that women have more pain disorders than men and are more likely to seek medical care for pain than men.” In the current study, however, men with migraine were more likely to receive opioid prescriptions than were women with migraine. One potential explanation for this finding is that men with migraine are less likely to receive a migraine diagnosis, which might attenuate opioid prescribing, than women with migraine. “It may be that opioids are perceived to be serious drugs for serious pain, and that some physicians may be more likely to prescribe opioids to men because the disorder is taken more seriously in men than women,” said Dr. Lipton.

The observation that opioids were more likely to be prescribed for people treated in pain clinics “is consistent with my understanding of practice patterns,” he added. “Generally, neurologists strive to find effective acute treatment alternatives to opioids. The emergence of [drug classes known as] gepants and ditans provides a helpful set of alternatives to tritpans.”

Dr. Lipton and his colleagues plan further research into the treatment of migraineurs. “In a claims analysis, we showed that when people with migraine fail a triptan, they are most likely to get an opioid as their next drug,” he said. “Reasonable [clinicians] might disagree on the next step. The next step, in the absence of contraindications, could be a different oral triptan, a nonoral triptan, or a gepant or ditan. We are planning a randomized trial to probe this question.”

Why are opioids still being used?

The study’s reliance on patients’ self-report and its retrospective design are two of its weaknesses, said Alan M. Rapoport, MD, clinical professor of neurology at the University of California, Los Angeles, and editor-in-chief of Neurology Reviews. One strength, however, is that the stratified sampling methodology produced a study population that accurately reflects the demographic characteristics of the U.S. adult population, he added. Another strength is the investigators’ examination of opioid use by patient characteristics such as marital status, education, income, obesity, and smoking.

Given the harmful effects of opioids in migraine, it is hard to understand why as much as one-third of study participants using acute care medication for migraine were using opioids, said Dr. Rapoport. Using opioids for the acute treatment of migraine attacks often indicates inadequate treatment optimization, which leads to ongoing headache. As a consequence, patients may take more medication, which can increase headache frequency and lead to diagnoses of chronic migraine and medication overuse headache. Although the study found an association between the increased use of opioids and decreased household income and increased unemployment, smoking, and obesity, “it is not possible to assign causality to any of these associations, even though some would argue that decreased socioeconomic status was somehow related to more headache, disability, obesity, smoking, and unemployment,” he added.

“The paper suggests that future research should look at the risk factors for use of opioids and should determine if depression is a risk factor for or a consequence of opioid use,” said Dr. Rapoport. “Interventional studies designed to improve the acute care of migraine attacks might be able to reduce the use of opioids. I have not used opioids or butalbital-containing medication in my office for many years.”

This study was funded and sponsored by Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories group of companies, Princeton, N.J. Dr. Lipton has received grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Headache Foundation, and the Migraine Research Fund. He serves as a consultant, serves as an advisory board member, or has received honoraria from Alder, Allergan, American Headache Society, Autonomic Technologies, Biohaven, Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, Eli Lilly, eNeura Therapeutics, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and Teva, Inc. He receives royalties from Wolff’s Headache, 8th Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) and holds stock options in eNeura Therapeutics and Biohaven.

SOURCE: Lipton RB, et al. Headache. https://doi.org/10.1111/head.14018. 2020;61(1):103-16.

FROM HEADACHE

PFO closure reduces migraine: New meta-analysis

A meta-analysis of two randomized studies evaluating patent foramen ovale (PFO) closure as a treatment strategy for migraine has shown significant benefits in several key endpoints, prompting the authors to conclude the approach warrants reevaluation.

The pooled analysis of patient-level data from the PRIMA and PREMIUM studies, both of which evaluated the Amplatzer PFO Occluder device (Abbott Vascular), showed that

The study, led by Mohammad K. Mojadidi, MD, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, was published online in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology on Feb. 8, 2021.

Commenting on the article, the coauthor of an accompanying editorial, Zubair Ahmed, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic said the meta-analysis gave some useful new information but is not enough to recommend PFO closure routinely for patients with migraine.

“This meta-analysis looked at different endpoints that are more relevant to current clinical practice than those in the two original studies, and the results show that we shouldn’t rule out PFO closure as a treatment strategy for some migraine patients,” Dr. Ahmed stated. “But we’re still not sure exactly which patients are most likely to benefit from this approach, and we need additional studies to gain more understanding on that.”

The study authors noted that there is an established link between the presence of PFO and migraine, especially migraine with aura. In observational studies of PFO closure for cryptogenic stroke, the vast majority of patients who also had migraine reported a more than 50% reduction in migraine days per month after PFO closure.

However, two recent randomized clinical trials evaluating the Amplatzer PFO Occluder device for reducing the frequency and duration of episodic migraine headaches did not meet their respective primary endpoints, although they did show significant benefit of PFO closure in most of their secondary endpoints.

The current meta-analysis pooled individual participant data from the two trials to increase the power to detect the effect of percutaneous PFO closure for treating patients with episodic migraine compared with medical therapy alone.

In the two studies including a total of 337 patients, 176 were randomized to PFO closure and 161 to medical treatment only. At 12 months, three of the four efficacy endpoints evaluated in the meta-analysis were significantly reduced in the PFO-closure group. These were mean reduction of monthly migraine days (–3.1 days vs. –1.9 days; P = .02), mean reduction of monthly migraine attacks (–2.0 vs. –1.4; P = .01), and number of patients who experienced complete cessation of migraine (9% vs. 0.7%; P < .001).

The responder rate, defined as more than a 50% reduction in migraine attacks, showed a trend towards an increase in the PFO-closure group but did not achieve statistical significance (38% vs. 29%; P = .13).

For the safety analysis, nine procedure-related and four device-related adverse events occurred in 245 patients who eventually received devices. All events were transient and resolved.

Better effect in patients with aura

Patients with migraine with aura, in particular frequent aura, had a significantly greater reduction in migraine days and a higher incidence of complete migraine cessation following PFO closure versus no closure, the authors reported.

In those without aura, PFO closure did not significantly reduce migraine days or improve complete headache cessation. However, some patients without aura did respond to PFO closure, which was statistically significant for reduction of migraine attacks (–2.0 vs. –1.0; P = .03).

“The interaction between the brain that is susceptible to migraine and the plethora of potential triggers is complex. A PFO may be the potential pathway for a variety of chemical triggers, such as serotonin from platelets, and although less frequent, some people with migraine without aura may trigger their migraine through this mechanism,” the researchers suggested. This hypothesis will be tested in the RELIEF trial, which is now being planned.

In the accompanying editorial, Dr. Ahmed and coauthor Robert J. Sommer, MD, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, pointed out that the meta-analysis demonstrates benefit of PFO closure in the migraine population for the first time.

“Moreover, the investigators defined a population of patients who may benefit most from PFO closure, those with migraine with frequent aura, suggesting that these may be different physiologically than other migraine subtypes. The analysis also places the PRIMA and PREMIUM outcomes in the context of endpoints that are more practical and are more commonly assessed in current clinical trials,” the editorialists noted.

Many unanswered questions

But the editorialists highlighted several significant limitations of the analysis, including “pooling of patient cohorts, methods, and outcome measures that might not be entirely comparable,” which they say could have introduced bias.