User login

New Guidance on Genetic Testing for Kidney Disease

A new consensus statement recommended genetic testing for all categories of kidney diseases whenever a genetic cause is suspected and offered guidance on who to test, which tests are the most useful, and how to talk to patients about results.

The statement, published online in the American Journal of Kidney Diseases, is the work of four dozen authors — including patients, nephrologists, experts in clinical and laboratory genetics, kidney pathology, genetic counseling, and ethics. The experts were brought together by the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) with the goal of broadening use and understanding of the tests.

About 10% or more of kidney diseases in adults and 70% of selected chronic kidney diseases (CKDs) in children have genetic causes. But nephrologists have reported a lack of education about genetic testing, and other barriers to wider use, including limited access to testing, cost, insurance coverage, and a small number of genetic counselors who are versed in kidney genetics.

Genetic testing “in the kidney field is a little less developed than in other fields,” said co–lead author Nora Franceschini, MD, MPH, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, Chapel Hill, and a nephrologist who studies the genetic epidemiology of hypertension and kidney and cardiovascular diseases.

There are already many known variants that play a role in various kidney diseases and more are on the horizon, Dr. Franceschini told this news organization. More genetic tests will be available in the near future. “The workforce needs to be prepared,” she said.

The statement is an initial step that gets clinicians thinking about testing in a more systematic way, said Dr. Franceschini. “Genetic testing is just another test that physicians can use to complete the story when evaluating patients.

“I think clinicians are ready to implement” testing, said Dr. Franceschini. “We just need to have better guidance.”

Who, When, What to Test

The NKF statement is not the first to try to address gaps in use and knowledge. A European Renal Association Working Group published guidelines in 2022.

The NKF Working Group came up with 56 recommendations and separate algorithms to guide testing for adult and pediatric individuals who are considered at-risk (and currently asymptomatic) and for those who already have clinical disease.

Testing can help determine a cause if there’s an atypical clinical presentation, and it can help avoid biopsies, said the group. Tests can also guide choice of therapy.

For at-risk individuals, there are two broad situations in which testing might be considered: In family members of a patient who already has kidney disease and in potential kidney donors. But testing at-risk children younger than 18 years should only be done if there is an intervention available that could prevent, treat, or slow progression of disease, said the authors.

For patients with an established genetic diagnosis, at-risk family members should be tested with the known single-gene variant diagnostic instead of a broad panel, said the group.

Single-gene variant testing is most appropriate in situations when clinical disease is already evident or when there is known genetic disease in the family, according to the NKF panel. A large diagnostic panel that covers the many common genetic causes of kidney disease is recommended for the majority of patients.

The group recommended that apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) testing should be included in gene panels for CKD, and it should be offered to any patient “with clinical findings suggestive of APOL1-association nephropathy, regardless of race and ethnicity.”

High-risk APOL1 genotypes confer a 5- to 10-fold increased risk for CKD and are found in one out of seven individuals of African ancestry, which means the focus has largely been on testing those with that ancestry.

However, with many unknowns about APOL1, the NKF panel did not want to “profile” individuals and suggest that testing should not be based on skin color or race/ethnicity, said Dr. Franceschini.

In addition, only about 10% of those with the variant develop disease, so testing is not currently warranted for those who do not already have kidney disease, said the group.

They also recommended against the use of polygenic risk scores, saying that there are not enough data from diverse populations in genome-wide association studies for kidney disease or on their clinical utility.

More Education Needed; Many Barriers

The authors acknowledged that nephrologists generally receive little education in genetics and lack support for interpreting and discussing results.

“Nephrologists should be provided with training and best practice resources to interpret genetic testing and discuss the results with individuals and their families,” they wrote, adding that there’s a need for genomic medicine boards at academic centers that would be available to help nephrologists interpret results and plot clinical management.

The group did not, however, cite some of the other barriers to adoption of testing, including a limited number of sites offering testing, cost, and lack of insurance coverage for the diagnostics.

Medicare may cover genetic testing for kidney disease when an individual has symptoms and there is a Food and Drug Administration–approved test. Joseph Vassalotti, MD, chief medical officer for the NKF, said private insurance may cover the testing if the nephrologist deems it medically necessary, but that he usually confirms coverage before initiating testing. The often-used Renasight panel, which tests for 385 genes related to kidney diseases, costs $300-$400 out of pocket, Dr. Vassalotti told this news organization.

In a survey of 149 nephrologists conducted in 2021, both users (46%) and nonusers of the tests (69%) said that high cost was the most significant perceived barrier to implementing widespread testing. A third of users and almost two thirds of nonusers said that poor availability or lack of ease of testing was the second most significant barrier.

Clinics that test for kidney genes “are largely confined to large academic centers and some specialty clinics,” said Dominic Raj, MD, the Bert B. Brooks chair, and Divya Shankaranarayanan, MD, director of the Kidney Precision Medicine Clinic, both at George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences, Washington, DC, in an email.

Testing is also limited by cultural barriers, lack of genetic literacy, and patients’ concerns that a positive result could lead to a loss of health insurance coverage, said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan.

Paper Will Help Expand Use

A lack of consensus has also held back expansion. The new statement “may lead to increased and possibly judicious utilization of genetic testing in nephrology practices,” said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan. “Most importantly, the panel has given specific guidance as to what type of genetic test platform is likely to yield the best and most cost-effective yield.”

The most effective use is “in monogenic kidney diseases and to a lesser extent in oligogenic kidney disease,” said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan, adding that testing is of less-certain utility in polygenic kidney diseases, “where complex genetic and epigenetic factors determine the phenotype.”

Genetic testing might be especially useful “in atypical clinical presentations” and can help clinicians avoid unnecessary expensive and extensive investigations when multiple organ systems are involved, they said.

“Most importantly, [testing] might prevent unnecessary and potentially harmful treatment and enable targeted specific treatment, when available,” said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan.

Dr. Franceschini and Dr. Shankaranarayanan reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Raj disclosed that he received consulting fees and honoraria from Novo Nordisk and is a national leader for the company’s Zeus trial, studying whether ziltivekimab reduces the risk for cardiovascular events in cardiovascular disease, CKD, and inflammation. He also participated in a study of Natera’s Renasight, a 385-gene panel for kidney disease.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new consensus statement recommended genetic testing for all categories of kidney diseases whenever a genetic cause is suspected and offered guidance on who to test, which tests are the most useful, and how to talk to patients about results.

The statement, published online in the American Journal of Kidney Diseases, is the work of four dozen authors — including patients, nephrologists, experts in clinical and laboratory genetics, kidney pathology, genetic counseling, and ethics. The experts were brought together by the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) with the goal of broadening use and understanding of the tests.

About 10% or more of kidney diseases in adults and 70% of selected chronic kidney diseases (CKDs) in children have genetic causes. But nephrologists have reported a lack of education about genetic testing, and other barriers to wider use, including limited access to testing, cost, insurance coverage, and a small number of genetic counselors who are versed in kidney genetics.

Genetic testing “in the kidney field is a little less developed than in other fields,” said co–lead author Nora Franceschini, MD, MPH, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, Chapel Hill, and a nephrologist who studies the genetic epidemiology of hypertension and kidney and cardiovascular diseases.

There are already many known variants that play a role in various kidney diseases and more are on the horizon, Dr. Franceschini told this news organization. More genetic tests will be available in the near future. “The workforce needs to be prepared,” she said.

The statement is an initial step that gets clinicians thinking about testing in a more systematic way, said Dr. Franceschini. “Genetic testing is just another test that physicians can use to complete the story when evaluating patients.

“I think clinicians are ready to implement” testing, said Dr. Franceschini. “We just need to have better guidance.”

Who, When, What to Test

The NKF statement is not the first to try to address gaps in use and knowledge. A European Renal Association Working Group published guidelines in 2022.

The NKF Working Group came up with 56 recommendations and separate algorithms to guide testing for adult and pediatric individuals who are considered at-risk (and currently asymptomatic) and for those who already have clinical disease.

Testing can help determine a cause if there’s an atypical clinical presentation, and it can help avoid biopsies, said the group. Tests can also guide choice of therapy.

For at-risk individuals, there are two broad situations in which testing might be considered: In family members of a patient who already has kidney disease and in potential kidney donors. But testing at-risk children younger than 18 years should only be done if there is an intervention available that could prevent, treat, or slow progression of disease, said the authors.

For patients with an established genetic diagnosis, at-risk family members should be tested with the known single-gene variant diagnostic instead of a broad panel, said the group.

Single-gene variant testing is most appropriate in situations when clinical disease is already evident or when there is known genetic disease in the family, according to the NKF panel. A large diagnostic panel that covers the many common genetic causes of kidney disease is recommended for the majority of patients.

The group recommended that apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) testing should be included in gene panels for CKD, and it should be offered to any patient “with clinical findings suggestive of APOL1-association nephropathy, regardless of race and ethnicity.”

High-risk APOL1 genotypes confer a 5- to 10-fold increased risk for CKD and are found in one out of seven individuals of African ancestry, which means the focus has largely been on testing those with that ancestry.

However, with many unknowns about APOL1, the NKF panel did not want to “profile” individuals and suggest that testing should not be based on skin color or race/ethnicity, said Dr. Franceschini.

In addition, only about 10% of those with the variant develop disease, so testing is not currently warranted for those who do not already have kidney disease, said the group.

They also recommended against the use of polygenic risk scores, saying that there are not enough data from diverse populations in genome-wide association studies for kidney disease or on their clinical utility.

More Education Needed; Many Barriers

The authors acknowledged that nephrologists generally receive little education in genetics and lack support for interpreting and discussing results.

“Nephrologists should be provided with training and best practice resources to interpret genetic testing and discuss the results with individuals and their families,” they wrote, adding that there’s a need for genomic medicine boards at academic centers that would be available to help nephrologists interpret results and plot clinical management.

The group did not, however, cite some of the other barriers to adoption of testing, including a limited number of sites offering testing, cost, and lack of insurance coverage for the diagnostics.

Medicare may cover genetic testing for kidney disease when an individual has symptoms and there is a Food and Drug Administration–approved test. Joseph Vassalotti, MD, chief medical officer for the NKF, said private insurance may cover the testing if the nephrologist deems it medically necessary, but that he usually confirms coverage before initiating testing. The often-used Renasight panel, which tests for 385 genes related to kidney diseases, costs $300-$400 out of pocket, Dr. Vassalotti told this news organization.

In a survey of 149 nephrologists conducted in 2021, both users (46%) and nonusers of the tests (69%) said that high cost was the most significant perceived barrier to implementing widespread testing. A third of users and almost two thirds of nonusers said that poor availability or lack of ease of testing was the second most significant barrier.

Clinics that test for kidney genes “are largely confined to large academic centers and some specialty clinics,” said Dominic Raj, MD, the Bert B. Brooks chair, and Divya Shankaranarayanan, MD, director of the Kidney Precision Medicine Clinic, both at George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences, Washington, DC, in an email.

Testing is also limited by cultural barriers, lack of genetic literacy, and patients’ concerns that a positive result could lead to a loss of health insurance coverage, said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan.

Paper Will Help Expand Use

A lack of consensus has also held back expansion. The new statement “may lead to increased and possibly judicious utilization of genetic testing in nephrology practices,” said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan. “Most importantly, the panel has given specific guidance as to what type of genetic test platform is likely to yield the best and most cost-effective yield.”

The most effective use is “in monogenic kidney diseases and to a lesser extent in oligogenic kidney disease,” said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan, adding that testing is of less-certain utility in polygenic kidney diseases, “where complex genetic and epigenetic factors determine the phenotype.”

Genetic testing might be especially useful “in atypical clinical presentations” and can help clinicians avoid unnecessary expensive and extensive investigations when multiple organ systems are involved, they said.

“Most importantly, [testing] might prevent unnecessary and potentially harmful treatment and enable targeted specific treatment, when available,” said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan.

Dr. Franceschini and Dr. Shankaranarayanan reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Raj disclosed that he received consulting fees and honoraria from Novo Nordisk and is a national leader for the company’s Zeus trial, studying whether ziltivekimab reduces the risk for cardiovascular events in cardiovascular disease, CKD, and inflammation. He also participated in a study of Natera’s Renasight, a 385-gene panel for kidney disease.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new consensus statement recommended genetic testing for all categories of kidney diseases whenever a genetic cause is suspected and offered guidance on who to test, which tests are the most useful, and how to talk to patients about results.

The statement, published online in the American Journal of Kidney Diseases, is the work of four dozen authors — including patients, nephrologists, experts in clinical and laboratory genetics, kidney pathology, genetic counseling, and ethics. The experts were brought together by the National Kidney Foundation (NKF) with the goal of broadening use and understanding of the tests.

About 10% or more of kidney diseases in adults and 70% of selected chronic kidney diseases (CKDs) in children have genetic causes. But nephrologists have reported a lack of education about genetic testing, and other barriers to wider use, including limited access to testing, cost, insurance coverage, and a small number of genetic counselors who are versed in kidney genetics.

Genetic testing “in the kidney field is a little less developed than in other fields,” said co–lead author Nora Franceschini, MD, MPH, a professor of epidemiology at the University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, Chapel Hill, and a nephrologist who studies the genetic epidemiology of hypertension and kidney and cardiovascular diseases.

There are already many known variants that play a role in various kidney diseases and more are on the horizon, Dr. Franceschini told this news organization. More genetic tests will be available in the near future. “The workforce needs to be prepared,” she said.

The statement is an initial step that gets clinicians thinking about testing in a more systematic way, said Dr. Franceschini. “Genetic testing is just another test that physicians can use to complete the story when evaluating patients.

“I think clinicians are ready to implement” testing, said Dr. Franceschini. “We just need to have better guidance.”

Who, When, What to Test

The NKF statement is not the first to try to address gaps in use and knowledge. A European Renal Association Working Group published guidelines in 2022.

The NKF Working Group came up with 56 recommendations and separate algorithms to guide testing for adult and pediatric individuals who are considered at-risk (and currently asymptomatic) and for those who already have clinical disease.

Testing can help determine a cause if there’s an atypical clinical presentation, and it can help avoid biopsies, said the group. Tests can also guide choice of therapy.

For at-risk individuals, there are two broad situations in which testing might be considered: In family members of a patient who already has kidney disease and in potential kidney donors. But testing at-risk children younger than 18 years should only be done if there is an intervention available that could prevent, treat, or slow progression of disease, said the authors.

For patients with an established genetic diagnosis, at-risk family members should be tested with the known single-gene variant diagnostic instead of a broad panel, said the group.

Single-gene variant testing is most appropriate in situations when clinical disease is already evident or when there is known genetic disease in the family, according to the NKF panel. A large diagnostic panel that covers the many common genetic causes of kidney disease is recommended for the majority of patients.

The group recommended that apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) testing should be included in gene panels for CKD, and it should be offered to any patient “with clinical findings suggestive of APOL1-association nephropathy, regardless of race and ethnicity.”

High-risk APOL1 genotypes confer a 5- to 10-fold increased risk for CKD and are found in one out of seven individuals of African ancestry, which means the focus has largely been on testing those with that ancestry.

However, with many unknowns about APOL1, the NKF panel did not want to “profile” individuals and suggest that testing should not be based on skin color or race/ethnicity, said Dr. Franceschini.

In addition, only about 10% of those with the variant develop disease, so testing is not currently warranted for those who do not already have kidney disease, said the group.

They also recommended against the use of polygenic risk scores, saying that there are not enough data from diverse populations in genome-wide association studies for kidney disease or on their clinical utility.

More Education Needed; Many Barriers

The authors acknowledged that nephrologists generally receive little education in genetics and lack support for interpreting and discussing results.

“Nephrologists should be provided with training and best practice resources to interpret genetic testing and discuss the results with individuals and their families,” they wrote, adding that there’s a need for genomic medicine boards at academic centers that would be available to help nephrologists interpret results and plot clinical management.

The group did not, however, cite some of the other barriers to adoption of testing, including a limited number of sites offering testing, cost, and lack of insurance coverage for the diagnostics.

Medicare may cover genetic testing for kidney disease when an individual has symptoms and there is a Food and Drug Administration–approved test. Joseph Vassalotti, MD, chief medical officer for the NKF, said private insurance may cover the testing if the nephrologist deems it medically necessary, but that he usually confirms coverage before initiating testing. The often-used Renasight panel, which tests for 385 genes related to kidney diseases, costs $300-$400 out of pocket, Dr. Vassalotti told this news organization.

In a survey of 149 nephrologists conducted in 2021, both users (46%) and nonusers of the tests (69%) said that high cost was the most significant perceived barrier to implementing widespread testing. A third of users and almost two thirds of nonusers said that poor availability or lack of ease of testing was the second most significant barrier.

Clinics that test for kidney genes “are largely confined to large academic centers and some specialty clinics,” said Dominic Raj, MD, the Bert B. Brooks chair, and Divya Shankaranarayanan, MD, director of the Kidney Precision Medicine Clinic, both at George Washington University School of Medicine & Health Sciences, Washington, DC, in an email.

Testing is also limited by cultural barriers, lack of genetic literacy, and patients’ concerns that a positive result could lead to a loss of health insurance coverage, said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan.

Paper Will Help Expand Use

A lack of consensus has also held back expansion. The new statement “may lead to increased and possibly judicious utilization of genetic testing in nephrology practices,” said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan. “Most importantly, the panel has given specific guidance as to what type of genetic test platform is likely to yield the best and most cost-effective yield.”

The most effective use is “in monogenic kidney diseases and to a lesser extent in oligogenic kidney disease,” said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan, adding that testing is of less-certain utility in polygenic kidney diseases, “where complex genetic and epigenetic factors determine the phenotype.”

Genetic testing might be especially useful “in atypical clinical presentations” and can help clinicians avoid unnecessary expensive and extensive investigations when multiple organ systems are involved, they said.

“Most importantly, [testing] might prevent unnecessary and potentially harmful treatment and enable targeted specific treatment, when available,” said Dr. Raj and Dr. Shankaranarayanan.

Dr. Franceschini and Dr. Shankaranarayanan reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Raj disclosed that he received consulting fees and honoraria from Novo Nordisk and is a national leader for the company’s Zeus trial, studying whether ziltivekimab reduces the risk for cardiovascular events in cardiovascular disease, CKD, and inflammation. He also participated in a study of Natera’s Renasight, a 385-gene panel for kidney disease.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF KIDNEY DISEASES

Can Addressing Depression Reduce Chemo Toxicity in Older Adults?

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial to evaluate whether greater reductions in grade 3 chemotherapy-related toxicities occurred with geriatric assessment-driven interventions vs standard care.

- A total of 605 patients aged 65 years and older with any stage of solid malignancy were included, with 402 randomized to the intervention arm and 203 to the standard-of-care arm.

- Mental health was assessed using the Mental Health Inventory 13, and chemotherapy toxicity was graded by the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0.

- Patients in the intervention arm received recommendations from a multidisciplinary team based on their baseline GA, while those in the standard-of-care arm received only the baseline assessment results.

- The study was conducted at City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California, and patients were followed throughout treatment or for up to 6 months from starting chemotherapy.

TAKEAWAY:

- According to the authors, patients with depression had increased chemotherapy toxicity in the standard-of-care arm (70.7% vs 54.3%; P = .02) but not in the GA-driven intervention arm (54.3% vs 48.5%; P = .27).

- The association between depression and chemotherapy toxicity was also seen after adjustment for the Cancer and Aging Research Group toxicity score (odds ratio, [OR], 1.98; 95% CI, 1.07-3.65) and for demographic, disease, and treatment factors (OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.03-3.85).

- No significant association was found between anxiety and chemotherapy toxicity in either the standard-of-care arm (univariate OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.61-1.88) or the GA-driven intervention arm (univariate OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.78-1.71).

- The authors stated that depression was associated with increased odds of hematologic-only toxicities (OR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.13-5.56) in the standard-of-care arm.

- An analysis of a small subgroup found associations between elevated anxiety symptoms and increased risk for hematologic and nonhematologic chemotherapy toxicities.

IN PRACTICE:

“The current study showed that elevated depression symptoms are associated with increased risk of severe chemotherapy toxicities in older adults with cancer. This risk was mitigated in those in the GA intervention arm, which suggests that addressing elevated depression symptoms may lower the risk of toxicities,” the authors wrote. “Overall, elevated anxiety symptoms were not associated with risk for severe chemotherapy toxicity.”

SOURCE:

Reena V. Jayani, MD, MSCI, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, was the first and corresponding author for this paper. This study was published online August 4, 2024, in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The thresholds for depression and anxiety used in the Mental Health Inventory 13 were based on an English-speaking population, which may not be fully applicable to Chinese- and Spanish-speaking patients included in the study. Depression and anxiety were not evaluated by a mental health professional or with a structured interview to assess formal diagnostic criteria. Psychiatric medication used at the time of baseline GA was not included in the analysis. The study is a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial, and it is not known which components of the interventions affected mental health.

DISCLOSURES:

This research project was supported by the UniHealth Foundation, the City of Hope Center for Cancer and Aging, and the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor disclosed receiving institutional research funding from AstraZeneca and Brooklyn ImmunoTherapeutics and consulting for multiple pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Adagene, and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. William Dale, MD, PhD, of City of Hope National Medical Center, served as senior author and a principal investigator. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial to evaluate whether greater reductions in grade 3 chemotherapy-related toxicities occurred with geriatric assessment-driven interventions vs standard care.

- A total of 605 patients aged 65 years and older with any stage of solid malignancy were included, with 402 randomized to the intervention arm and 203 to the standard-of-care arm.

- Mental health was assessed using the Mental Health Inventory 13, and chemotherapy toxicity was graded by the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0.

- Patients in the intervention arm received recommendations from a multidisciplinary team based on their baseline GA, while those in the standard-of-care arm received only the baseline assessment results.

- The study was conducted at City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California, and patients were followed throughout treatment or for up to 6 months from starting chemotherapy.

TAKEAWAY:

- According to the authors, patients with depression had increased chemotherapy toxicity in the standard-of-care arm (70.7% vs 54.3%; P = .02) but not in the GA-driven intervention arm (54.3% vs 48.5%; P = .27).

- The association between depression and chemotherapy toxicity was also seen after adjustment for the Cancer and Aging Research Group toxicity score (odds ratio, [OR], 1.98; 95% CI, 1.07-3.65) and for demographic, disease, and treatment factors (OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.03-3.85).

- No significant association was found between anxiety and chemotherapy toxicity in either the standard-of-care arm (univariate OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.61-1.88) or the GA-driven intervention arm (univariate OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.78-1.71).

- The authors stated that depression was associated with increased odds of hematologic-only toxicities (OR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.13-5.56) in the standard-of-care arm.

- An analysis of a small subgroup found associations between elevated anxiety symptoms and increased risk for hematologic and nonhematologic chemotherapy toxicities.

IN PRACTICE:

“The current study showed that elevated depression symptoms are associated with increased risk of severe chemotherapy toxicities in older adults with cancer. This risk was mitigated in those in the GA intervention arm, which suggests that addressing elevated depression symptoms may lower the risk of toxicities,” the authors wrote. “Overall, elevated anxiety symptoms were not associated with risk for severe chemotherapy toxicity.”

SOURCE:

Reena V. Jayani, MD, MSCI, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, was the first and corresponding author for this paper. This study was published online August 4, 2024, in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The thresholds for depression and anxiety used in the Mental Health Inventory 13 were based on an English-speaking population, which may not be fully applicable to Chinese- and Spanish-speaking patients included in the study. Depression and anxiety were not evaluated by a mental health professional or with a structured interview to assess formal diagnostic criteria. Psychiatric medication used at the time of baseline GA was not included in the analysis. The study is a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial, and it is not known which components of the interventions affected mental health.

DISCLOSURES:

This research project was supported by the UniHealth Foundation, the City of Hope Center for Cancer and Aging, and the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor disclosed receiving institutional research funding from AstraZeneca and Brooklyn ImmunoTherapeutics and consulting for multiple pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Adagene, and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. William Dale, MD, PhD, of City of Hope National Medical Center, served as senior author and a principal investigator. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

- Researchers conducted a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial to evaluate whether greater reductions in grade 3 chemotherapy-related toxicities occurred with geriatric assessment-driven interventions vs standard care.

- A total of 605 patients aged 65 years and older with any stage of solid malignancy were included, with 402 randomized to the intervention arm and 203 to the standard-of-care arm.

- Mental health was assessed using the Mental Health Inventory 13, and chemotherapy toxicity was graded by the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0.

- Patients in the intervention arm received recommendations from a multidisciplinary team based on their baseline GA, while those in the standard-of-care arm received only the baseline assessment results.

- The study was conducted at City of Hope National Medical Center in Duarte, California, and patients were followed throughout treatment or for up to 6 months from starting chemotherapy.

TAKEAWAY:

- According to the authors, patients with depression had increased chemotherapy toxicity in the standard-of-care arm (70.7% vs 54.3%; P = .02) but not in the GA-driven intervention arm (54.3% vs 48.5%; P = .27).

- The association between depression and chemotherapy toxicity was also seen after adjustment for the Cancer and Aging Research Group toxicity score (odds ratio, [OR], 1.98; 95% CI, 1.07-3.65) and for demographic, disease, and treatment factors (OR, 2.00; 95% CI, 1.03-3.85).

- No significant association was found between anxiety and chemotherapy toxicity in either the standard-of-care arm (univariate OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.61-1.88) or the GA-driven intervention arm (univariate OR, 1.15; 95% CI, 0.78-1.71).

- The authors stated that depression was associated with increased odds of hematologic-only toxicities (OR, 2.50; 95% CI, 1.13-5.56) in the standard-of-care arm.

- An analysis of a small subgroup found associations between elevated anxiety symptoms and increased risk for hematologic and nonhematologic chemotherapy toxicities.

IN PRACTICE:

“The current study showed that elevated depression symptoms are associated with increased risk of severe chemotherapy toxicities in older adults with cancer. This risk was mitigated in those in the GA intervention arm, which suggests that addressing elevated depression symptoms may lower the risk of toxicities,” the authors wrote. “Overall, elevated anxiety symptoms were not associated with risk for severe chemotherapy toxicity.”

SOURCE:

Reena V. Jayani, MD, MSCI, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, was the first and corresponding author for this paper. This study was published online August 4, 2024, in Cancer.

LIMITATIONS:

The thresholds for depression and anxiety used in the Mental Health Inventory 13 were based on an English-speaking population, which may not be fully applicable to Chinese- and Spanish-speaking patients included in the study. Depression and anxiety were not evaluated by a mental health professional or with a structured interview to assess formal diagnostic criteria. Psychiatric medication used at the time of baseline GA was not included in the analysis. The study is a secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial, and it is not known which components of the interventions affected mental health.

DISCLOSURES:

This research project was supported by the UniHealth Foundation, the City of Hope Center for Cancer and Aging, and the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor disclosed receiving institutional research funding from AstraZeneca and Brooklyn ImmunoTherapeutics and consulting for multiple pharmaceutical companies, including AbbVie, Adagene, and Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals. William Dale, MD, PhD, of City of Hope National Medical Center, served as senior author and a principal investigator. Additional disclosures are noted in the original article.

This article was created using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Support Researchers with a Donation to the AGA Research Foundation

By joining others in donating to the AGA Research Foundation, you will ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

The AGA Research Foundation remains committed to providing young researchers with unprecedented research opportunities. Each year, we receive a caliber of nominations for AGA research awards. You can help gifted investigators as they work to advance the understanding of digestive diseases through their novel research objectives.

As an AGA member, you can help fund discoveries that will continue to improve GI practice and better patient care.

AGA grants have led to discoveries, including new approaches to down-regulate intestinal inflammation, a test for genetic predisposition to colon cancer and autoimmune liver disease treatments. The importance of these awards is evidenced by the fact that virtually every major advance leading to the understanding, prevention, treatment, and cure of digestive diseases has been made in the research laboratory of a talented young investigator.

Donate to the AGA Research Foundation to ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

Three Easy Ways To Give

Online: Donate at www.foundation.gastro.org.

Through the mail:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Over the phone: 301-222-4002

All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of U.S. law.

By joining others in donating to the AGA Research Foundation, you will ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

The AGA Research Foundation remains committed to providing young researchers with unprecedented research opportunities. Each year, we receive a caliber of nominations for AGA research awards. You can help gifted investigators as they work to advance the understanding of digestive diseases through their novel research objectives.

As an AGA member, you can help fund discoveries that will continue to improve GI practice and better patient care.

AGA grants have led to discoveries, including new approaches to down-regulate intestinal inflammation, a test for genetic predisposition to colon cancer and autoimmune liver disease treatments. The importance of these awards is evidenced by the fact that virtually every major advance leading to the understanding, prevention, treatment, and cure of digestive diseases has been made in the research laboratory of a talented young investigator.

Donate to the AGA Research Foundation to ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

Three Easy Ways To Give

Online: Donate at www.foundation.gastro.org.

Through the mail:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Over the phone: 301-222-4002

All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of U.S. law.

By joining others in donating to the AGA Research Foundation, you will ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

The AGA Research Foundation remains committed to providing young researchers with unprecedented research opportunities. Each year, we receive a caliber of nominations for AGA research awards. You can help gifted investigators as they work to advance the understanding of digestive diseases through their novel research objectives.

As an AGA member, you can help fund discoveries that will continue to improve GI practice and better patient care.

AGA grants have led to discoveries, including new approaches to down-regulate intestinal inflammation, a test for genetic predisposition to colon cancer and autoimmune liver disease treatments. The importance of these awards is evidenced by the fact that virtually every major advance leading to the understanding, prevention, treatment, and cure of digestive diseases has been made in the research laboratory of a talented young investigator.

Donate to the AGA Research Foundation to ensure that researchers have opportunities to continue their lifesaving work.

Three Easy Ways To Give

Online: Donate at www.foundation.gastro.org.

Through the mail:

AGA Research Foundation

4930 Del Ray Avenue

Bethesda, MD 20814

Over the phone: 301-222-4002

All gifts are tax-deductible to the fullest extent of U.S. law.

FDA Approves First Blood Test for Colorectal Cancer

In late July, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first use of a liquid biopsy (blood test) for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. The test, called Shield, launched commercially the first week of August and is the first blood test to be approved by the FDA as a primary screening option for CRC that meets requirements for Medicare reimbursement.

While the convenience of a blood test could potentially encourage more people to get screened, expert consensus is that blood tests can’t prevent CRC and should not be considered a replacement for a colonoscopy. Modeling studies and expert consensus published earlier this year in Gastroenterology and in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology shed light on the perils of liquid biopsy.

“Based on their current characteristics, blood tests should not be recommended to replace established colorectal cancer screening tests, since blood tests are neither as effective nor as cost-effective, and would worsen outcomes,” said David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, chair, AGA CRC Workshop chair and lead author of an expert commentary on liquid biopsy for CRC screening.

Five Key Takeaways

- A blood test for CRC that meets minimal CMS criteria for sensitivity and performed every 3 years would likely result in better outcomes than no screening.

- A blood test for CRC offers a simple process that could encourage more people to participate in screening. Patients who may have declined colonoscopy should understand the need for a colonoscopy if findings are abnormal.

- Because blood tests for CRC are predicted to be less effective and more costly than currently established screening programs, they cannot be recommended to replace established effective screening methods.

- Although blood tests would improve outcomes in currently unscreened people, substituting blood tests for a currently effective test would worsen patient outcomes and increase cost.

- Potential benchmarks that industry might use to assess an effective blood test for CRC going forward would be sensitivity for stage I-III CRC of > 90%, with sensitivity for advanced adenomas of > 40%-50%.

“Unless we have the expectation of high sensitivity and specificity, blood-based colorectal cancer tests could lead to false positive and false negative results, which are both bad for patient outcomes,” said John M. Carethers, MD, AGAF, AGA past president and vice chancellor for health sciences at the University of California San Diego.

In late July, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first use of a liquid biopsy (blood test) for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. The test, called Shield, launched commercially the first week of August and is the first blood test to be approved by the FDA as a primary screening option for CRC that meets requirements for Medicare reimbursement.

While the convenience of a blood test could potentially encourage more people to get screened, expert consensus is that blood tests can’t prevent CRC and should not be considered a replacement for a colonoscopy. Modeling studies and expert consensus published earlier this year in Gastroenterology and in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology shed light on the perils of liquid biopsy.

“Based on their current characteristics, blood tests should not be recommended to replace established colorectal cancer screening tests, since blood tests are neither as effective nor as cost-effective, and would worsen outcomes,” said David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, chair, AGA CRC Workshop chair and lead author of an expert commentary on liquid biopsy for CRC screening.

Five Key Takeaways

- A blood test for CRC that meets minimal CMS criteria for sensitivity and performed every 3 years would likely result in better outcomes than no screening.

- A blood test for CRC offers a simple process that could encourage more people to participate in screening. Patients who may have declined colonoscopy should understand the need for a colonoscopy if findings are abnormal.

- Because blood tests for CRC are predicted to be less effective and more costly than currently established screening programs, they cannot be recommended to replace established effective screening methods.

- Although blood tests would improve outcomes in currently unscreened people, substituting blood tests for a currently effective test would worsen patient outcomes and increase cost.

- Potential benchmarks that industry might use to assess an effective blood test for CRC going forward would be sensitivity for stage I-III CRC of > 90%, with sensitivity for advanced adenomas of > 40%-50%.

“Unless we have the expectation of high sensitivity and specificity, blood-based colorectal cancer tests could lead to false positive and false negative results, which are both bad for patient outcomes,” said John M. Carethers, MD, AGAF, AGA past president and vice chancellor for health sciences at the University of California San Diego.

In late July, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first use of a liquid biopsy (blood test) for colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. The test, called Shield, launched commercially the first week of August and is the first blood test to be approved by the FDA as a primary screening option for CRC that meets requirements for Medicare reimbursement.

While the convenience of a blood test could potentially encourage more people to get screened, expert consensus is that blood tests can’t prevent CRC and should not be considered a replacement for a colonoscopy. Modeling studies and expert consensus published earlier this year in Gastroenterology and in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology shed light on the perils of liquid biopsy.

“Based on their current characteristics, blood tests should not be recommended to replace established colorectal cancer screening tests, since blood tests are neither as effective nor as cost-effective, and would worsen outcomes,” said David Lieberman, MD, AGAF, chair, AGA CRC Workshop chair and lead author of an expert commentary on liquid biopsy for CRC screening.

Five Key Takeaways

- A blood test for CRC that meets minimal CMS criteria for sensitivity and performed every 3 years would likely result in better outcomes than no screening.

- A blood test for CRC offers a simple process that could encourage more people to participate in screening. Patients who may have declined colonoscopy should understand the need for a colonoscopy if findings are abnormal.

- Because blood tests for CRC are predicted to be less effective and more costly than currently established screening programs, they cannot be recommended to replace established effective screening methods.

- Although blood tests would improve outcomes in currently unscreened people, substituting blood tests for a currently effective test would worsen patient outcomes and increase cost.

- Potential benchmarks that industry might use to assess an effective blood test for CRC going forward would be sensitivity for stage I-III CRC of > 90%, with sensitivity for advanced adenomas of > 40%-50%.

“Unless we have the expectation of high sensitivity and specificity, blood-based colorectal cancer tests could lead to false positive and false negative results, which are both bad for patient outcomes,” said John M. Carethers, MD, AGAF, AGA past president and vice chancellor for health sciences at the University of California San Diego.

Free Med School Alone Won’t Boost Diversity

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

We need more diverse students — more students from disadvantaged and underrepresented backgrounds in medical school. That is not a controversial take. That’s not even a new thought.

What is a hot take, however, is that free medical school alone is not going to accomplish this goal. In fact, based on data and what people think and are saying, that’s just reality.

I recently chatted about whether or not free medical school would motivate more students to pursue primary care. That was New York University’s (NYU’s) goal. If you haven’t seen that video, check it out. Now I want to explore whether free medical school would actually create a more diverse medical student body.

This topic is especially important now because, in 2023, the Supreme Court ended affirmative action for college admissions, and this naturally has a downstream effect when it comes to getting into medical school. Right now, about 6% of US physicians are Black or Hispanic/Latina, and around 0.1%-0.3% identify as Indigenous Americans, Native Hawaiians, or Pacific Islanders.

Is free medical school the answer? Well, that’s based on a huge assumption that the cost of medical school — incoming debt — is the single greatest barrier for students from diverse backgrounds, as if every single student from every background had the same level of resources in the same opportunity and were all equally competitive prior to applying, and just the prospect of debt is what caused the disparity. I don’t know if that’s reality. Let’s take a look at NYU.

After the free tuition announcement, total applications to the medical school went up nearly 50%. And from underrepresented groups, it was 100%. In 2019, the associate dean for admissions said, “A key driver was to remove a financial disincentive that dissuades people from pursuing a path in medicine.” But the acceptance rate stayed under 3%, and the average Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) and grade point average (GPA) to get in went up. Basically, the school just became more competitive.

I will always commend anyone, anywhere, who is making medical school more affordable and more accessible. With NYU, it seems a tuition gift just made it harder for students from disadvantaged backgrounds to actually get in. I mean, congratulations, you got more applications. This probably helped in ratings, and you got mentioned in news headlines, but are you actually achieving your mission?

At NYU, over the last few years, Black students made up about 11% of the medical school class, which is actually down from 2017 before the tuition gift. Students from low-income backgrounds, whom this would really benefit, used to make up around 12% of the class prior to the free tuition announcement, and now it’s around 3%-7%.

According to students from underrepresented backgrounds, the outreach and the equal opportunity need to start way earlier. The K-12 process needs to be addressed, as do mentorship opportunities and guidance throughout college, MCAT prep, resources for interviews, research opportunities, and so much more.

The following quote is from an interview with an interventional cardiology fellow who came here as a refugee: “For me, growing up, basic necessities like a quiet study space, high-speed internet, healthy meals and proper sleep were luxuries of which I could only dream. After resettling in the US as a political refugee, I lived in circumstances where such comforts were out of reach, and my path to medical school seemed insurmountable.”

I also spoke to a friend in pediatric cancer, Michael Galvez, MD, who was outspoken about the need to improve representation in medicine, about what he thought would actually work to diversify medical schools. He mentioned adversity scores or looking at the distance traveled for applicants, as well as efforts to recruit from local, state, and community colleges, which often reflect local underserved populations.

Dr. Galvez also agreed that although such metrics as GPA and MCAT are important, medical schools should also consider the impact applicants may have had for local, underserved communities and life experiences that may represent significant potential contributions applicants can make for public health.

The effort needs to start early. If we take a look at one of the most diverse medical schools in the country, UC Davis, we can see how this makes a difference. At UC Davis, in the class of 2026, about half of the 133 students come from underrepresented backgrounds in medicine. I’m taking a look at their website from the Office of Student and Resident Diversity, and it lists:

- K-12 outreach programs

- Undergraduate and community college programs

- Specific plans for postbaccalaureate students

- Support systems

- Resources for students that extend far beyond just premedical students

My home institution, Stanford School of Medicine, has similar programs as well, with similar ways for students from underrepresented backgrounds to find support and mentorship. This all makes a huge difference.

Regarding the actual admissions process for medical school, I’ll highlight the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the adaptions they’ve made to create a more fair and holistic process. It includes:

- A clear mission statement about diversity enhancement

- Anonymous voting

- A larger group to avoid bias

- Not showing academic metrics to interviewers

- Implicit association tests and trainings

- Removing photos from applications

- Appointing women, minorities, and young people with less implicit bias to the committees

Does this seem like a lot? It is, because a comprehensive approach is what it takes to build a more diverse US physician workforce, which will provide more culturally competent care, empower future generations, break down barriers and disparities in health care, and ultimately improve public health. Free tuition is awesome. I’m jealous. But on its own to solve these problems? This all feels like a misguided attempt.

Dr. Patel is clinical instructor, Department of Pediatrics, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, and pediatric hospitalist at Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of NewYork-Presbyterian, New York, and Benioff Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Francisco. He disclosed ties with Medumo Inc.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

We need more diverse students — more students from disadvantaged and underrepresented backgrounds in medical school. That is not a controversial take. That’s not even a new thought.

What is a hot take, however, is that free medical school alone is not going to accomplish this goal. In fact, based on data and what people think and are saying, that’s just reality.

I recently chatted about whether or not free medical school would motivate more students to pursue primary care. That was New York University’s (NYU’s) goal. If you haven’t seen that video, check it out. Now I want to explore whether free medical school would actually create a more diverse medical student body.

This topic is especially important now because, in 2023, the Supreme Court ended affirmative action for college admissions, and this naturally has a downstream effect when it comes to getting into medical school. Right now, about 6% of US physicians are Black or Hispanic/Latina, and around 0.1%-0.3% identify as Indigenous Americans, Native Hawaiians, or Pacific Islanders.

Is free medical school the answer? Well, that’s based on a huge assumption that the cost of medical school — incoming debt — is the single greatest barrier for students from diverse backgrounds, as if every single student from every background had the same level of resources in the same opportunity and were all equally competitive prior to applying, and just the prospect of debt is what caused the disparity. I don’t know if that’s reality. Let’s take a look at NYU.

After the free tuition announcement, total applications to the medical school went up nearly 50%. And from underrepresented groups, it was 100%. In 2019, the associate dean for admissions said, “A key driver was to remove a financial disincentive that dissuades people from pursuing a path in medicine.” But the acceptance rate stayed under 3%, and the average Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) and grade point average (GPA) to get in went up. Basically, the school just became more competitive.

I will always commend anyone, anywhere, who is making medical school more affordable and more accessible. With NYU, it seems a tuition gift just made it harder for students from disadvantaged backgrounds to actually get in. I mean, congratulations, you got more applications. This probably helped in ratings, and you got mentioned in news headlines, but are you actually achieving your mission?

At NYU, over the last few years, Black students made up about 11% of the medical school class, which is actually down from 2017 before the tuition gift. Students from low-income backgrounds, whom this would really benefit, used to make up around 12% of the class prior to the free tuition announcement, and now it’s around 3%-7%.

According to students from underrepresented backgrounds, the outreach and the equal opportunity need to start way earlier. The K-12 process needs to be addressed, as do mentorship opportunities and guidance throughout college, MCAT prep, resources for interviews, research opportunities, and so much more.

The following quote is from an interview with an interventional cardiology fellow who came here as a refugee: “For me, growing up, basic necessities like a quiet study space, high-speed internet, healthy meals and proper sleep were luxuries of which I could only dream. After resettling in the US as a political refugee, I lived in circumstances where such comforts were out of reach, and my path to medical school seemed insurmountable.”

I also spoke to a friend in pediatric cancer, Michael Galvez, MD, who was outspoken about the need to improve representation in medicine, about what he thought would actually work to diversify medical schools. He mentioned adversity scores or looking at the distance traveled for applicants, as well as efforts to recruit from local, state, and community colleges, which often reflect local underserved populations.

Dr. Galvez also agreed that although such metrics as GPA and MCAT are important, medical schools should also consider the impact applicants may have had for local, underserved communities and life experiences that may represent significant potential contributions applicants can make for public health.

The effort needs to start early. If we take a look at one of the most diverse medical schools in the country, UC Davis, we can see how this makes a difference. At UC Davis, in the class of 2026, about half of the 133 students come from underrepresented backgrounds in medicine. I’m taking a look at their website from the Office of Student and Resident Diversity, and it lists:

- K-12 outreach programs

- Undergraduate and community college programs

- Specific plans for postbaccalaureate students

- Support systems

- Resources for students that extend far beyond just premedical students

My home institution, Stanford School of Medicine, has similar programs as well, with similar ways for students from underrepresented backgrounds to find support and mentorship. This all makes a huge difference.

Regarding the actual admissions process for medical school, I’ll highlight the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the adaptions they’ve made to create a more fair and holistic process. It includes:

- A clear mission statement about diversity enhancement

- Anonymous voting

- A larger group to avoid bias

- Not showing academic metrics to interviewers

- Implicit association tests and trainings

- Removing photos from applications

- Appointing women, minorities, and young people with less implicit bias to the committees

Does this seem like a lot? It is, because a comprehensive approach is what it takes to build a more diverse US physician workforce, which will provide more culturally competent care, empower future generations, break down barriers and disparities in health care, and ultimately improve public health. Free tuition is awesome. I’m jealous. But on its own to solve these problems? This all feels like a misguided attempt.

Dr. Patel is clinical instructor, Department of Pediatrics, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, and pediatric hospitalist at Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of NewYork-Presbyterian, New York, and Benioff Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Francisco. He disclosed ties with Medumo Inc.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

We need more diverse students — more students from disadvantaged and underrepresented backgrounds in medical school. That is not a controversial take. That’s not even a new thought.

What is a hot take, however, is that free medical school alone is not going to accomplish this goal. In fact, based on data and what people think and are saying, that’s just reality.

I recently chatted about whether or not free medical school would motivate more students to pursue primary care. That was New York University’s (NYU’s) goal. If you haven’t seen that video, check it out. Now I want to explore whether free medical school would actually create a more diverse medical student body.

This topic is especially important now because, in 2023, the Supreme Court ended affirmative action for college admissions, and this naturally has a downstream effect when it comes to getting into medical school. Right now, about 6% of US physicians are Black or Hispanic/Latina, and around 0.1%-0.3% identify as Indigenous Americans, Native Hawaiians, or Pacific Islanders.

Is free medical school the answer? Well, that’s based on a huge assumption that the cost of medical school — incoming debt — is the single greatest barrier for students from diverse backgrounds, as if every single student from every background had the same level of resources in the same opportunity and were all equally competitive prior to applying, and just the prospect of debt is what caused the disparity. I don’t know if that’s reality. Let’s take a look at NYU.

After the free tuition announcement, total applications to the medical school went up nearly 50%. And from underrepresented groups, it was 100%. In 2019, the associate dean for admissions said, “A key driver was to remove a financial disincentive that dissuades people from pursuing a path in medicine.” But the acceptance rate stayed under 3%, and the average Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) and grade point average (GPA) to get in went up. Basically, the school just became more competitive.

I will always commend anyone, anywhere, who is making medical school more affordable and more accessible. With NYU, it seems a tuition gift just made it harder for students from disadvantaged backgrounds to actually get in. I mean, congratulations, you got more applications. This probably helped in ratings, and you got mentioned in news headlines, but are you actually achieving your mission?

At NYU, over the last few years, Black students made up about 11% of the medical school class, which is actually down from 2017 before the tuition gift. Students from low-income backgrounds, whom this would really benefit, used to make up around 12% of the class prior to the free tuition announcement, and now it’s around 3%-7%.

According to students from underrepresented backgrounds, the outreach and the equal opportunity need to start way earlier. The K-12 process needs to be addressed, as do mentorship opportunities and guidance throughout college, MCAT prep, resources for interviews, research opportunities, and so much more.

The following quote is from an interview with an interventional cardiology fellow who came here as a refugee: “For me, growing up, basic necessities like a quiet study space, high-speed internet, healthy meals and proper sleep were luxuries of which I could only dream. After resettling in the US as a political refugee, I lived in circumstances where such comforts were out of reach, and my path to medical school seemed insurmountable.”

I also spoke to a friend in pediatric cancer, Michael Galvez, MD, who was outspoken about the need to improve representation in medicine, about what he thought would actually work to diversify medical schools. He mentioned adversity scores or looking at the distance traveled for applicants, as well as efforts to recruit from local, state, and community colleges, which often reflect local underserved populations.

Dr. Galvez also agreed that although such metrics as GPA and MCAT are important, medical schools should also consider the impact applicants may have had for local, underserved communities and life experiences that may represent significant potential contributions applicants can make for public health.

The effort needs to start early. If we take a look at one of the most diverse medical schools in the country, UC Davis, we can see how this makes a difference. At UC Davis, in the class of 2026, about half of the 133 students come from underrepresented backgrounds in medicine. I’m taking a look at their website from the Office of Student and Resident Diversity, and it lists:

- K-12 outreach programs

- Undergraduate and community college programs

- Specific plans for postbaccalaureate students

- Support systems

- Resources for students that extend far beyond just premedical students

My home institution, Stanford School of Medicine, has similar programs as well, with similar ways for students from underrepresented backgrounds to find support and mentorship. This all makes a huge difference.

Regarding the actual admissions process for medical school, I’ll highlight the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the adaptions they’ve made to create a more fair and holistic process. It includes:

- A clear mission statement about diversity enhancement

- Anonymous voting

- A larger group to avoid bias

- Not showing academic metrics to interviewers

- Implicit association tests and trainings

- Removing photos from applications

- Appointing women, minorities, and young people with less implicit bias to the committees

Does this seem like a lot? It is, because a comprehensive approach is what it takes to build a more diverse US physician workforce, which will provide more culturally competent care, empower future generations, break down barriers and disparities in health care, and ultimately improve public health. Free tuition is awesome. I’m jealous. But on its own to solve these problems? This all feels like a misguided attempt.

Dr. Patel is clinical instructor, Department of Pediatrics, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, and pediatric hospitalist at Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital of NewYork-Presbyterian, New York, and Benioff Children’s Hospital, University of California, San Francisco. He disclosed ties with Medumo Inc.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

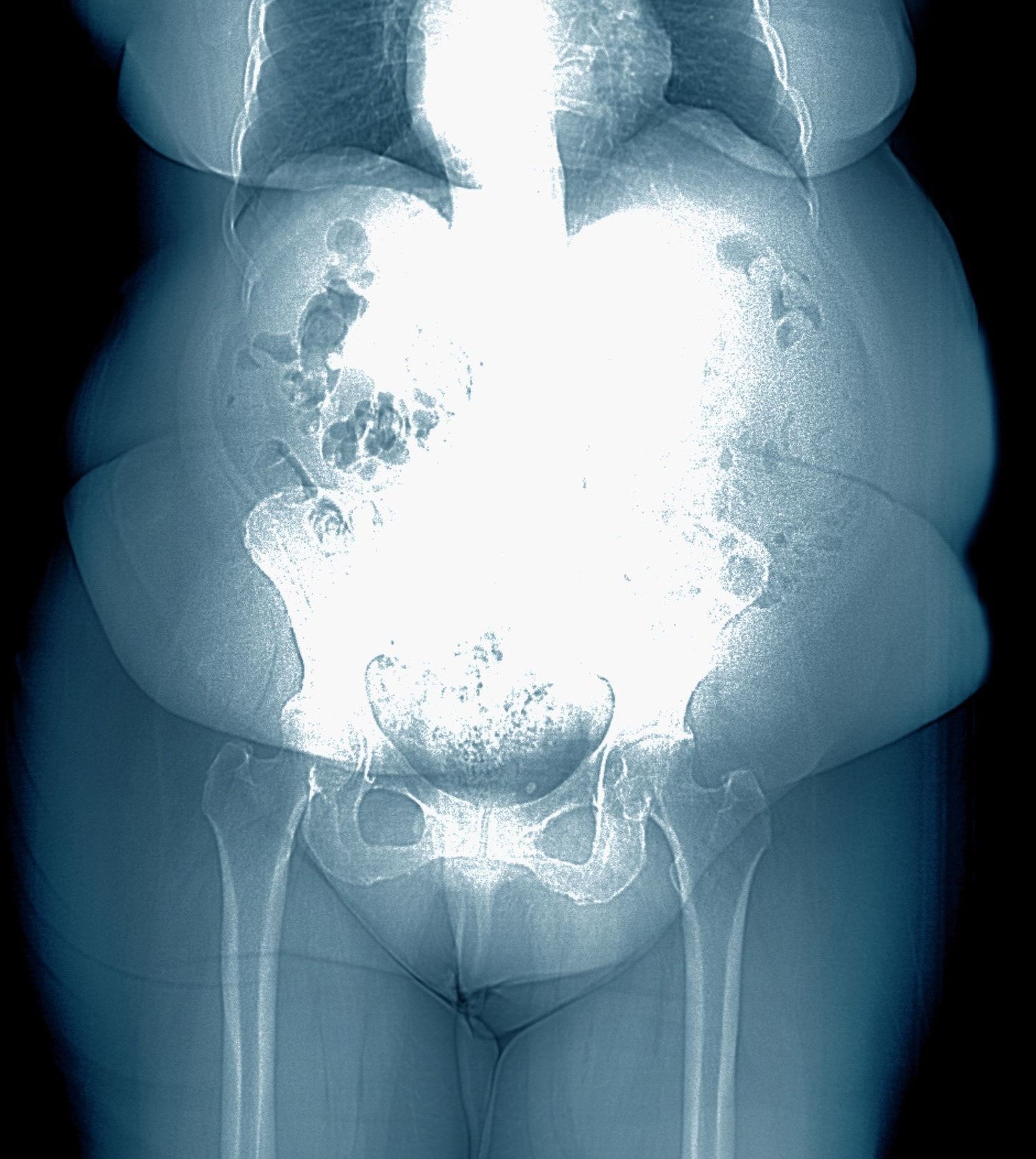

Weight gain despite dieting

Binge-eating disorder is more prevalent in women than men and has one of the strongest associations with obesity; among patients with obesity, lifetime prevalence of binge eating is approximately 5.5%. Large population studies suggest that binge-eating disorder may be present in 2%-4% of adolescents, with a mean age of onset of 12-13 years. This patient probably had milder binge-eating disorder as an adolescent and young adult, which was exacerbated by the pandemic.

Both new diagnoses and reports of clinical worsening in patients with preexisting diagnoses of binge-eating disorder during the pandemic have been documented. Food insecurity has been associated with binge eating, consistent with this patient's anxiety over food and grocery availability during the pandemic. The definition of binge-eating disorder includes recurrent specific episodes of overeating that are not consistent with the patient's usual behavior, eating to the point of being uncomfortably full, eating more quickly or when not hungry, and having feelings of loss of control during episodes and of guilt or disgust afterward.

Obesity and eating disorders share some common risk factors and approaches to management. Binge eating has been associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, asthma, sleep disorders, and menstrual disorders, all of which are also affected by obesity. The presence of both conditions increases the adverse outcomes associated with each, including negative impacts on cardiometabolic and psychological health. Workup of patients presenting with binge eating and obesity should always include complete blood/metabolic panels and cardiovascular and renal health, as well as assessments of nutrition status, electrolyte imbalances, gastrointestinal reflux disease, and chronic pain.

In general, where binge-eating disorder and obesity are concurrent, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for binge-eating disorder should be the first priority, with obesity management (medication or surgery) to follow. CBT has the strongest evidence of benefit for patients with binge-eating disorder and is the recommended treatment approach. Other psychotherapeutic interventions that may be of benefit include dialectical behavioral therapy (to reduce binge-eating frequency), technology-based options, and family-based therapy when symptoms are recognized in children or adolescents. Structured behavioral weight management strategies for management of obesity and overweight do not increase symptoms of eating disorders and may instead relieve some symptoms. An emerging approach to binge eating in patients with obesity is CBT that integrates therapeutic approaches to both issues.

Medications to treat binge-eating disorder are limited and should not be used without concurrent psychotherapy; lisdexamfetamine has demonstrated benefit, is recommended by the American Psychiatric Association, and is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically to treat adults with binge-eating disorder.

The success of psychological interventions and lifestyle modifications for obesity is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions. The American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations recommend treatment with antiobesity medications along with lifestyle modifications for patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and weight-related complications (BMI > 27). Recommended medications include phentermine-topiramate and bupropion-naltrexone (which may benefit those with binge-eating disorder), as well as injectable glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) at the approved dosage for obesity management (semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly or liraglutide 3.0 mg daily). Orlistat is not recommended. Ongoing research on the potential benefit of GLP-1 RAs in management of binge eating offers additional support for a role in patients, like this one, with binge-eating disorder and obesity.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Binge-eating disorder is more prevalent in women than men and has one of the strongest associations with obesity; among patients with obesity, lifetime prevalence of binge eating is approximately 5.5%. Large population studies suggest that binge-eating disorder may be present in 2%-4% of adolescents, with a mean age of onset of 12-13 years. This patient probably had milder binge-eating disorder as an adolescent and young adult, which was exacerbated by the pandemic.

Both new diagnoses and reports of clinical worsening in patients with preexisting diagnoses of binge-eating disorder during the pandemic have been documented. Food insecurity has been associated with binge eating, consistent with this patient's anxiety over food and grocery availability during the pandemic. The definition of binge-eating disorder includes recurrent specific episodes of overeating that are not consistent with the patient's usual behavior, eating to the point of being uncomfortably full, eating more quickly or when not hungry, and having feelings of loss of control during episodes and of guilt or disgust afterward.

Obesity and eating disorders share some common risk factors and approaches to management. Binge eating has been associated with type 2 diabetes, hypertension, asthma, sleep disorders, and menstrual disorders, all of which are also affected by obesity. The presence of both conditions increases the adverse outcomes associated with each, including negative impacts on cardiometabolic and psychological health. Workup of patients presenting with binge eating and obesity should always include complete blood/metabolic panels and cardiovascular and renal health, as well as assessments of nutrition status, electrolyte imbalances, gastrointestinal reflux disease, and chronic pain.

In general, where binge-eating disorder and obesity are concurrent, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) for binge-eating disorder should be the first priority, with obesity management (medication or surgery) to follow. CBT has the strongest evidence of benefit for patients with binge-eating disorder and is the recommended treatment approach. Other psychotherapeutic interventions that may be of benefit include dialectical behavioral therapy (to reduce binge-eating frequency), technology-based options, and family-based therapy when symptoms are recognized in children or adolescents. Structured behavioral weight management strategies for management of obesity and overweight do not increase symptoms of eating disorders and may instead relieve some symptoms. An emerging approach to binge eating in patients with obesity is CBT that integrates therapeutic approaches to both issues.

Medications to treat binge-eating disorder are limited and should not be used without concurrent psychotherapy; lisdexamfetamine has demonstrated benefit, is recommended by the American Psychiatric Association, and is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration specifically to treat adults with binge-eating disorder.

The success of psychological interventions and lifestyle modifications for obesity is heavily dependent on the individual's ability and motivation to comply with recommended interventions. The American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations recommend treatment with antiobesity medications along with lifestyle modifications for patients with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) and weight-related complications (BMI > 27). Recommended medications include phentermine-topiramate and bupropion-naltrexone (which may benefit those with binge-eating disorder), as well as injectable glucagon-like peptide receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) at the approved dosage for obesity management (semaglutide 2.4 mg weekly or liraglutide 3.0 mg daily). Orlistat is not recommended. Ongoing research on the potential benefit of GLP-1 RAs in management of binge eating offers additional support for a role in patients, like this one, with binge-eating disorder and obesity.

Carolyn Newberry, MD, Assistant Professor of Medicine, Director of GI Nutrition, Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology (ICHANGE), Division of Gastroenterology, Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York, NY.

Disclosure: Carolyn Newberry, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Baster International; InBody.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Binge-eating disorder is more prevalent in women than men and has one of the strongest associations with obesity; among patients with obesity, lifetime prevalence of binge eating is approximately 5.5%. Large population studies suggest that binge-eating disorder may be present in 2%-4% of adolescents, with a mean age of onset of 12-13 years. This patient probably had milder binge-eating disorder as an adolescent and young adult, which was exacerbated by the pandemic.