User login

Oncology Mergers Are on the Rise. How Can Independent Practices Survive?

When he completed his fellowship at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, Moshe Chasky, MD, joined a small five-person practice that rented space from the city’s Jefferson Hospital in Philadelphia. The arrangement seemed to work well for the hospital and the small practice, which remained independent.

Within 10 years, the hospital sought to buy the practice, Alliance Cancer Specialists.

But the oncologists at Alliance did not want to join Jefferson.

The hospital eventually entered into an exclusive agreement with its own medical group to provide inpatient oncology/hematology services at three Jefferson Health–Northeast hospitals and stripped Dr. Chasky and his colleagues of their privileges at those facilities, Medscape Medical News reported last year.

said Jeff Patton, MD, CEO of OneOncology, a management services organization.

A 2020 report from the Community Oncology Alliance (COA), for instance, tracked mergers, acquisitions, and closures in the community oncology setting and found the number of practices acquired by hospitals, known as vertical integration, nearly tripled from 2010 to 2020.

“Some hospitals are pretty predatory in their approach,” Dr. Patton said. If hospitals have their own oncology program, “they’ll employ the referring doctors and then discourage them or prevent them from referring patients to our independent practices that are not owned by the hospital.”

Still, in the face of growing pressure to join hospitals, some community oncology practices are finding ways to survive and maintain their independence.

A Growing Trend

The latest data continue to show a clear trend: Consolidation in oncology is on the rise.

A 2024 study revealed that the pace of consolidation seems to be increasing.

The analysis found that, between 2015 and 2022, the number of medical oncologists increased by 14% and the number of medical oncologists per practice increased by 40%, while the number of practices decreased by 18%.

While about 44% of practices remain independent, the percentage of medical oncologists working in practices with more than 25 clinicians has increased from 34% in 2015 to 44% in 2022. By 2022, the largest 102 practices in the United States employed more than 40% of all medical oncologists.

“The rate of consolidation seems to be rapid,” study coauthor Parsa Erfani, MD, an internal medicine resident at Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, explained.

Consolidation appears to breed more consolidation. The researchers found, for instance, that markets with greater hospital consolidation and more hospital beds per capita were more likely to undergo consolidation in oncology.

Consolidation may be higher in these markets “because hospitals or health systems are buying up oncology practices or conversely because oncology practices are merging to compete more effectively with larger hospitals in the area,” Dr. Erfani told this news organization.

Mergers among independent practices, known as horizontal integration, have also been on the rise, according to the 2020 COA report. These mergers can help counter pressures from hospitals seeking to acquire community practices as well as prevent practices and their clinics from closing.

Although Dr. Erfani’s research wasn’t designed to determine the factors behind consolidation, he and his colleagues point to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the federal 340B Drug Pricing Program as potential drivers of this trend.

The ACA encouraged consolidation as a way to improve efficiency and created the need for ever-larger information systems to collect and report quality data. But these data collection and reporting requirements have become increasingly difficult for smaller practices to take on.

The 340B Program, however, may be a bigger contributing factor to consolidation. Created in 1992, the 340B Program allows qualifying hospitals and clinics that treat low-income and uninsured patients to buy outpatient prescription drugs at a 25%-50% discount.

Hospitals seeking to capitalize on the margins possible under the 340B Program will “buy all the referring physicians in a market so that the medical oncology group is left with little choice but to sell to the hospital,” said Dr. Patton.

“Those 340B dollars are worth a lot to hospitals,” said David A. Eagle, MD, a hematologist/oncologist with New York Cancer & Blood Specialists and past president of COA. The program “creates an appetite for nonprofit hospitals to want to grow their medical oncology programs,” he told this news organization.

Declining Medicare reimbursement has also hit independent practices hard.

Over the past 15 years, compared with inflation, physicians have gotten “a pay rate decrease from Medicare,” said Dr. Patton. Payers have followed that lead and tried to cut pay for clinicians, especially those who do not have market share, he said. Paying them less is “disingenuous knowing that our costs of providing care are going up,” he said.

Less Access, Higher Costs, Worse Care?

Many studies have demonstrated that, when hospitals become behemoths in a given market, healthcare costs go up.

“There are robust data showing that consolidation increases healthcare costs by reducing competition, including in oncology,” wrote Dr. Erfani and colleagues.

Oncology practices that are owned by hospitals bill facility fees for outpatient chemotherapy treatment, adding another layer of cost, the researchers explained, citing a 2019 Health Economics study.

Another analysis, published in 2020, found that hospital prices for the top 37 infused cancer drugs averaged 86% more per unit than the price charged by physician offices. Hospital outpatient departments charged even more, on average, for drugs — 128% more for nivolumab and 428% more for fluorouracil, for instance.

In their 2024 analysis, Dr. Erfani and colleagues also found that increased hospital market concentration was associated with worse quality of care, across all assessed patient satisfaction measures, and may result in worse access to care as well.

Overall, these consolidation “trends have important implications for cancer care cost, quality, and access,” the authors concluded.

Navigating the Consolidation Trend

In the face of mounting pressure to join hospitals, community oncology practices have typically relied on horizontal mergers to maintain their independence. An increasing number of practices, however, are now turning to another strategy: Management services organizations.

According to some oncologists, a core benefit of joining a management services organization is their community practices can maintain autonomy, hold on to referrals, and benefit from access to a wider network of peers and recently approved treatments such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies.

In these arrangements, the management company also provides business assistance to practices, including help with billing and collection, payer negotiations, supply chain issues, and credentialing, as well as recruiting, hiring, and marketing.

These management organizations, which include American Oncology Network, Integrated Oncology Network, OneOncology, and Verdi Oncology, are, however, backed by private equity. According to a 2022 report, private equity–backed management organizations have ramped up arrangements with community oncology practices over the past few years — a trend that has concerned some experts.

The authors of a recent analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine explained that, although private equity involvement in physician practices may enable operational efficiencies, “critics point to potential conflicts of interest” and highlight concerns that patients “may face additional barriers to both accessibility and affordability of care.”

The difference, according to some oncologists, is their practices are not owned by the management services organization; instead, the practices enter contracts that outline the boundaries of the relationship and stipulate fees to the management organizations.

In 2020, Dr. Chasky’s practice, Alliance Cancer Specialists, joined The US Oncology Network, a management services organization wholly owned by McKesson. The organization provides the practice with capital and other resources, as well as access to the Sarah Cannon Research Institute, so patients can participate in clinical trials.

“We totally function as an independent practice,” said Dr. Chasky. “We make our own management decisions,” he said. For instance, if Alliance wants to hire a new clinician, US Oncology helps with the recruitment. “But at the end of the day, it’s our practice,” he said.

Davey Daniel, MD — whose community practice joined the management services organization OneOncology — has seen the benefits of being part of a larger network. For instance, bispecific therapies for leukemias, lymphomas, and multiple myeloma are typically administered at academic centers because of the risk for cytokine release syndrome.

However, physician leaders in the OneOncology network “came up with a playbook on how to do it safely” in the community setting, said Dr. Daniel. “It meant that we were adopting FDA newly approved therapies in a very short course.”

Being able to draw from a wider pool of expertise has had other advantages. Dr. Daniel can lean on pathologists and research scientists in the network for advice on targeted therapy use. “We’re actually bringing precision medicine expertise to the community,” Dr. Daniel said.

Dr. Chasky and Dr. Eagle, whose practice is also part of OneOncology, said that continuing to work in the community setting has allowed them greater flexibility.

Dr. Eagle explained that New York Cancer & Blood Specialists tries to offer patients an appointment within 2 days of a referral, and it allows walk-in visits.

Dr. Chasky leans into the flexibility by having staff stay late, when needed, to ensure that all patients are seen. “We’re there for our patients at all hours,” Dr. Chasky said, adding that often “you don’t have that flexibility when you work for a big hospital system.”

The bottom line is community oncology can still thrive, said Nick Ferreyros, managing director of COA, “as long as we have a healthy competitive ecosystem where [we] are valued and seen as an important part of our cancer care system.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When he completed his fellowship at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, Moshe Chasky, MD, joined a small five-person practice that rented space from the city’s Jefferson Hospital in Philadelphia. The arrangement seemed to work well for the hospital and the small practice, which remained independent.

Within 10 years, the hospital sought to buy the practice, Alliance Cancer Specialists.

But the oncologists at Alliance did not want to join Jefferson.

The hospital eventually entered into an exclusive agreement with its own medical group to provide inpatient oncology/hematology services at three Jefferson Health–Northeast hospitals and stripped Dr. Chasky and his colleagues of their privileges at those facilities, Medscape Medical News reported last year.

said Jeff Patton, MD, CEO of OneOncology, a management services organization.

A 2020 report from the Community Oncology Alliance (COA), for instance, tracked mergers, acquisitions, and closures in the community oncology setting and found the number of practices acquired by hospitals, known as vertical integration, nearly tripled from 2010 to 2020.

“Some hospitals are pretty predatory in their approach,” Dr. Patton said. If hospitals have their own oncology program, “they’ll employ the referring doctors and then discourage them or prevent them from referring patients to our independent practices that are not owned by the hospital.”

Still, in the face of growing pressure to join hospitals, some community oncology practices are finding ways to survive and maintain their independence.

A Growing Trend

The latest data continue to show a clear trend: Consolidation in oncology is on the rise.

A 2024 study revealed that the pace of consolidation seems to be increasing.

The analysis found that, between 2015 and 2022, the number of medical oncologists increased by 14% and the number of medical oncologists per practice increased by 40%, while the number of practices decreased by 18%.

While about 44% of practices remain independent, the percentage of medical oncologists working in practices with more than 25 clinicians has increased from 34% in 2015 to 44% in 2022. By 2022, the largest 102 practices in the United States employed more than 40% of all medical oncologists.

“The rate of consolidation seems to be rapid,” study coauthor Parsa Erfani, MD, an internal medicine resident at Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, explained.

Consolidation appears to breed more consolidation. The researchers found, for instance, that markets with greater hospital consolidation and more hospital beds per capita were more likely to undergo consolidation in oncology.

Consolidation may be higher in these markets “because hospitals or health systems are buying up oncology practices or conversely because oncology practices are merging to compete more effectively with larger hospitals in the area,” Dr. Erfani told this news organization.

Mergers among independent practices, known as horizontal integration, have also been on the rise, according to the 2020 COA report. These mergers can help counter pressures from hospitals seeking to acquire community practices as well as prevent practices and their clinics from closing.

Although Dr. Erfani’s research wasn’t designed to determine the factors behind consolidation, he and his colleagues point to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the federal 340B Drug Pricing Program as potential drivers of this trend.

The ACA encouraged consolidation as a way to improve efficiency and created the need for ever-larger information systems to collect and report quality data. But these data collection and reporting requirements have become increasingly difficult for smaller practices to take on.

The 340B Program, however, may be a bigger contributing factor to consolidation. Created in 1992, the 340B Program allows qualifying hospitals and clinics that treat low-income and uninsured patients to buy outpatient prescription drugs at a 25%-50% discount.

Hospitals seeking to capitalize on the margins possible under the 340B Program will “buy all the referring physicians in a market so that the medical oncology group is left with little choice but to sell to the hospital,” said Dr. Patton.

“Those 340B dollars are worth a lot to hospitals,” said David A. Eagle, MD, a hematologist/oncologist with New York Cancer & Blood Specialists and past president of COA. The program “creates an appetite for nonprofit hospitals to want to grow their medical oncology programs,” he told this news organization.

Declining Medicare reimbursement has also hit independent practices hard.

Over the past 15 years, compared with inflation, physicians have gotten “a pay rate decrease from Medicare,” said Dr. Patton. Payers have followed that lead and tried to cut pay for clinicians, especially those who do not have market share, he said. Paying them less is “disingenuous knowing that our costs of providing care are going up,” he said.

Less Access, Higher Costs, Worse Care?

Many studies have demonstrated that, when hospitals become behemoths in a given market, healthcare costs go up.

“There are robust data showing that consolidation increases healthcare costs by reducing competition, including in oncology,” wrote Dr. Erfani and colleagues.

Oncology practices that are owned by hospitals bill facility fees for outpatient chemotherapy treatment, adding another layer of cost, the researchers explained, citing a 2019 Health Economics study.

Another analysis, published in 2020, found that hospital prices for the top 37 infused cancer drugs averaged 86% more per unit than the price charged by physician offices. Hospital outpatient departments charged even more, on average, for drugs — 128% more for nivolumab and 428% more for fluorouracil, for instance.

In their 2024 analysis, Dr. Erfani and colleagues also found that increased hospital market concentration was associated with worse quality of care, across all assessed patient satisfaction measures, and may result in worse access to care as well.

Overall, these consolidation “trends have important implications for cancer care cost, quality, and access,” the authors concluded.

Navigating the Consolidation Trend

In the face of mounting pressure to join hospitals, community oncology practices have typically relied on horizontal mergers to maintain their independence. An increasing number of practices, however, are now turning to another strategy: Management services organizations.

According to some oncologists, a core benefit of joining a management services organization is their community practices can maintain autonomy, hold on to referrals, and benefit from access to a wider network of peers and recently approved treatments such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies.

In these arrangements, the management company also provides business assistance to practices, including help with billing and collection, payer negotiations, supply chain issues, and credentialing, as well as recruiting, hiring, and marketing.

These management organizations, which include American Oncology Network, Integrated Oncology Network, OneOncology, and Verdi Oncology, are, however, backed by private equity. According to a 2022 report, private equity–backed management organizations have ramped up arrangements with community oncology practices over the past few years — a trend that has concerned some experts.

The authors of a recent analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine explained that, although private equity involvement in physician practices may enable operational efficiencies, “critics point to potential conflicts of interest” and highlight concerns that patients “may face additional barriers to both accessibility and affordability of care.”

The difference, according to some oncologists, is their practices are not owned by the management services organization; instead, the practices enter contracts that outline the boundaries of the relationship and stipulate fees to the management organizations.

In 2020, Dr. Chasky’s practice, Alliance Cancer Specialists, joined The US Oncology Network, a management services organization wholly owned by McKesson. The organization provides the practice with capital and other resources, as well as access to the Sarah Cannon Research Institute, so patients can participate in clinical trials.

“We totally function as an independent practice,” said Dr. Chasky. “We make our own management decisions,” he said. For instance, if Alliance wants to hire a new clinician, US Oncology helps with the recruitment. “But at the end of the day, it’s our practice,” he said.

Davey Daniel, MD — whose community practice joined the management services organization OneOncology — has seen the benefits of being part of a larger network. For instance, bispecific therapies for leukemias, lymphomas, and multiple myeloma are typically administered at academic centers because of the risk for cytokine release syndrome.

However, physician leaders in the OneOncology network “came up with a playbook on how to do it safely” in the community setting, said Dr. Daniel. “It meant that we were adopting FDA newly approved therapies in a very short course.”

Being able to draw from a wider pool of expertise has had other advantages. Dr. Daniel can lean on pathologists and research scientists in the network for advice on targeted therapy use. “We’re actually bringing precision medicine expertise to the community,” Dr. Daniel said.

Dr. Chasky and Dr. Eagle, whose practice is also part of OneOncology, said that continuing to work in the community setting has allowed them greater flexibility.

Dr. Eagle explained that New York Cancer & Blood Specialists tries to offer patients an appointment within 2 days of a referral, and it allows walk-in visits.

Dr. Chasky leans into the flexibility by having staff stay late, when needed, to ensure that all patients are seen. “We’re there for our patients at all hours,” Dr. Chasky said, adding that often “you don’t have that flexibility when you work for a big hospital system.”

The bottom line is community oncology can still thrive, said Nick Ferreyros, managing director of COA, “as long as we have a healthy competitive ecosystem where [we] are valued and seen as an important part of our cancer care system.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

When he completed his fellowship at Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, Moshe Chasky, MD, joined a small five-person practice that rented space from the city’s Jefferson Hospital in Philadelphia. The arrangement seemed to work well for the hospital and the small practice, which remained independent.

Within 10 years, the hospital sought to buy the practice, Alliance Cancer Specialists.

But the oncologists at Alliance did not want to join Jefferson.

The hospital eventually entered into an exclusive agreement with its own medical group to provide inpatient oncology/hematology services at three Jefferson Health–Northeast hospitals and stripped Dr. Chasky and his colleagues of their privileges at those facilities, Medscape Medical News reported last year.

said Jeff Patton, MD, CEO of OneOncology, a management services organization.

A 2020 report from the Community Oncology Alliance (COA), for instance, tracked mergers, acquisitions, and closures in the community oncology setting and found the number of practices acquired by hospitals, known as vertical integration, nearly tripled from 2010 to 2020.

“Some hospitals are pretty predatory in their approach,” Dr. Patton said. If hospitals have their own oncology program, “they’ll employ the referring doctors and then discourage them or prevent them from referring patients to our independent practices that are not owned by the hospital.”

Still, in the face of growing pressure to join hospitals, some community oncology practices are finding ways to survive and maintain their independence.

A Growing Trend

The latest data continue to show a clear trend: Consolidation in oncology is on the rise.

A 2024 study revealed that the pace of consolidation seems to be increasing.

The analysis found that, between 2015 and 2022, the number of medical oncologists increased by 14% and the number of medical oncologists per practice increased by 40%, while the number of practices decreased by 18%.

While about 44% of practices remain independent, the percentage of medical oncologists working in practices with more than 25 clinicians has increased from 34% in 2015 to 44% in 2022. By 2022, the largest 102 practices in the United States employed more than 40% of all medical oncologists.

“The rate of consolidation seems to be rapid,” study coauthor Parsa Erfani, MD, an internal medicine resident at Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Boston, explained.

Consolidation appears to breed more consolidation. The researchers found, for instance, that markets with greater hospital consolidation and more hospital beds per capita were more likely to undergo consolidation in oncology.

Consolidation may be higher in these markets “because hospitals or health systems are buying up oncology practices or conversely because oncology practices are merging to compete more effectively with larger hospitals in the area,” Dr. Erfani told this news organization.

Mergers among independent practices, known as horizontal integration, have also been on the rise, according to the 2020 COA report. These mergers can help counter pressures from hospitals seeking to acquire community practices as well as prevent practices and their clinics from closing.

Although Dr. Erfani’s research wasn’t designed to determine the factors behind consolidation, he and his colleagues point to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the federal 340B Drug Pricing Program as potential drivers of this trend.

The ACA encouraged consolidation as a way to improve efficiency and created the need for ever-larger information systems to collect and report quality data. But these data collection and reporting requirements have become increasingly difficult for smaller practices to take on.

The 340B Program, however, may be a bigger contributing factor to consolidation. Created in 1992, the 340B Program allows qualifying hospitals and clinics that treat low-income and uninsured patients to buy outpatient prescription drugs at a 25%-50% discount.

Hospitals seeking to capitalize on the margins possible under the 340B Program will “buy all the referring physicians in a market so that the medical oncology group is left with little choice but to sell to the hospital,” said Dr. Patton.

“Those 340B dollars are worth a lot to hospitals,” said David A. Eagle, MD, a hematologist/oncologist with New York Cancer & Blood Specialists and past president of COA. The program “creates an appetite for nonprofit hospitals to want to grow their medical oncology programs,” he told this news organization.

Declining Medicare reimbursement has also hit independent practices hard.

Over the past 15 years, compared with inflation, physicians have gotten “a pay rate decrease from Medicare,” said Dr. Patton. Payers have followed that lead and tried to cut pay for clinicians, especially those who do not have market share, he said. Paying them less is “disingenuous knowing that our costs of providing care are going up,” he said.

Less Access, Higher Costs, Worse Care?

Many studies have demonstrated that, when hospitals become behemoths in a given market, healthcare costs go up.

“There are robust data showing that consolidation increases healthcare costs by reducing competition, including in oncology,” wrote Dr. Erfani and colleagues.

Oncology practices that are owned by hospitals bill facility fees for outpatient chemotherapy treatment, adding another layer of cost, the researchers explained, citing a 2019 Health Economics study.

Another analysis, published in 2020, found that hospital prices for the top 37 infused cancer drugs averaged 86% more per unit than the price charged by physician offices. Hospital outpatient departments charged even more, on average, for drugs — 128% more for nivolumab and 428% more for fluorouracil, for instance.

In their 2024 analysis, Dr. Erfani and colleagues also found that increased hospital market concentration was associated with worse quality of care, across all assessed patient satisfaction measures, and may result in worse access to care as well.

Overall, these consolidation “trends have important implications for cancer care cost, quality, and access,” the authors concluded.

Navigating the Consolidation Trend

In the face of mounting pressure to join hospitals, community oncology practices have typically relied on horizontal mergers to maintain their independence. An increasing number of practices, however, are now turning to another strategy: Management services organizations.

According to some oncologists, a core benefit of joining a management services organization is their community practices can maintain autonomy, hold on to referrals, and benefit from access to a wider network of peers and recently approved treatments such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies.

In these arrangements, the management company also provides business assistance to practices, including help with billing and collection, payer negotiations, supply chain issues, and credentialing, as well as recruiting, hiring, and marketing.

These management organizations, which include American Oncology Network, Integrated Oncology Network, OneOncology, and Verdi Oncology, are, however, backed by private equity. According to a 2022 report, private equity–backed management organizations have ramped up arrangements with community oncology practices over the past few years — a trend that has concerned some experts.

The authors of a recent analysis in JAMA Internal Medicine explained that, although private equity involvement in physician practices may enable operational efficiencies, “critics point to potential conflicts of interest” and highlight concerns that patients “may face additional barriers to both accessibility and affordability of care.”

The difference, according to some oncologists, is their practices are not owned by the management services organization; instead, the practices enter contracts that outline the boundaries of the relationship and stipulate fees to the management organizations.

In 2020, Dr. Chasky’s practice, Alliance Cancer Specialists, joined The US Oncology Network, a management services organization wholly owned by McKesson. The organization provides the practice with capital and other resources, as well as access to the Sarah Cannon Research Institute, so patients can participate in clinical trials.

“We totally function as an independent practice,” said Dr. Chasky. “We make our own management decisions,” he said. For instance, if Alliance wants to hire a new clinician, US Oncology helps with the recruitment. “But at the end of the day, it’s our practice,” he said.

Davey Daniel, MD — whose community practice joined the management services organization OneOncology — has seen the benefits of being part of a larger network. For instance, bispecific therapies for leukemias, lymphomas, and multiple myeloma are typically administered at academic centers because of the risk for cytokine release syndrome.

However, physician leaders in the OneOncology network “came up with a playbook on how to do it safely” in the community setting, said Dr. Daniel. “It meant that we were adopting FDA newly approved therapies in a very short course.”

Being able to draw from a wider pool of expertise has had other advantages. Dr. Daniel can lean on pathologists and research scientists in the network for advice on targeted therapy use. “We’re actually bringing precision medicine expertise to the community,” Dr. Daniel said.

Dr. Chasky and Dr. Eagle, whose practice is also part of OneOncology, said that continuing to work in the community setting has allowed them greater flexibility.

Dr. Eagle explained that New York Cancer & Blood Specialists tries to offer patients an appointment within 2 days of a referral, and it allows walk-in visits.

Dr. Chasky leans into the flexibility by having staff stay late, when needed, to ensure that all patients are seen. “We’re there for our patients at all hours,” Dr. Chasky said, adding that often “you don’t have that flexibility when you work for a big hospital system.”

The bottom line is community oncology can still thrive, said Nick Ferreyros, managing director of COA, “as long as we have a healthy competitive ecosystem where [we] are valued and seen as an important part of our cancer care system.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Platinum Add-On Improves Survival in Early TNBC

presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The outcomes of the South Korean study, dubbed PEARLY, provide strong evidence for incorporating carboplatin into both the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings in patients with early-stage TNBC, said lead investigator and presenter Joohyuk Sohn, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea.

In early-stage TNBC, carboplatin is already being incorporated into the neoadjuvant setting on the basis of trial results from KEYNOTE-522 that demonstrated improved pathologic complete response rates and event-free survival with the platinum alongside pembrolizumab.

However, the overall survival benefit of carboplatin in this setting remains unclear, as does the benefit of platinum add-on in the adjuvant setting, Dr. Sohn explained.

Dr. Sohn and colleagues randomized 868 patients evenly to either standard treatment — doxorubicin, anthracycline, and cyclophosphamide followed by a taxane — or an experimental arm that added carboplatin to the taxane phase of treatment.

About 30% of women were treated in the adjuvant setting, the rest in the neoadjuvant setting. The two arms of the study were generally well balanced — about 80% of patients had stage II disease, half were node negative, and 11% had deleterious germline mutations.

The primary endpoint, event-free survival, was broadly defined. Events included disease progression, local or distant recurrence, occurrence of a second primary cancer, inoperable status after neoadjuvant therapy, or death from any cause.

Adding carboplatin increased 5-year event-free survival rates from 75.1% to 82.3% (hazard ratio [HR], 0.67; P = .012) with the benefit holding across various subgroup analyses and particularly strong for adjuvant carboplatin (HR, 0.26).

Five-year overall survival was also better in the carboplatin arm — 90.7% vs 87% in the control arm (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.42-1.02) — but that benefit did not reach statistical significance (P = .057)

Invasive disease-free survival (HR, 0.73) and distant recurrence-free survival (HR, 0.77) favored carboplatin, but the results also weren’t statistically significant.

Overall, 46% of patients had a pathologic complete response with carboplatin vs nearly 40% in the control arm. The pathologic complete response benefit from carboplatin add-on was consistent with past reports.

As expected, adding carboplatin to treatment increased hematologic toxicity and other adverse events, with three-quarters of patients experiencing grade 3 or worse adverse events vs 56.7% of control participants. There was one death in the carboplatin arm from pneumonia and two in the control arm — one from septic shock and the other from suicide.

Dr. Sohn and colleagues, however, did not observe a quality of life difference between the two groups.

“The PEARLY trial provides compelling evidence for including carboplatin in the treatment of early-stage TNBC,” Dr. Sohn concluded, adding that the results underscore the benefit in the neoadjuvant setting and suggest “potential applicability in the adjuvant setting post surgery.”

Study discussant Javier Cortes, MD, PhD, believes that the PEARLY provides a strong signal for adding carboplatin in the adjuvant setting.

“That’s something I would do in my clinical practice,” said Dr. Cortes, head of the International Breast Cancer Center in Barcelona, Spain. “After ASCO this year, I would offer taxanes plus carboplatin following anthracyclines.”

An audience member, William Sikov, MD, a breast cancer specialist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, said he hopes “we’ve reached the end of a road that started many years ago in terms of incorporating carboplatin as part of neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy for triple-negative breast cancer, where we finally [reach] consensus that this is necessary in our triple-negative patients.”

The work was funded by the government of South Korea and others. Dr. Sohn reported stock in Daiichi Sankyo and research funding from Daiichi and other companies. Dr. Cortes disclosed numerous industry ties, including honoraria, research funding, and/or travel expenses from AstraZeneca, Daiichi, and others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The outcomes of the South Korean study, dubbed PEARLY, provide strong evidence for incorporating carboplatin into both the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings in patients with early-stage TNBC, said lead investigator and presenter Joohyuk Sohn, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea.

In early-stage TNBC, carboplatin is already being incorporated into the neoadjuvant setting on the basis of trial results from KEYNOTE-522 that demonstrated improved pathologic complete response rates and event-free survival with the platinum alongside pembrolizumab.

However, the overall survival benefit of carboplatin in this setting remains unclear, as does the benefit of platinum add-on in the adjuvant setting, Dr. Sohn explained.

Dr. Sohn and colleagues randomized 868 patients evenly to either standard treatment — doxorubicin, anthracycline, and cyclophosphamide followed by a taxane — or an experimental arm that added carboplatin to the taxane phase of treatment.

About 30% of women were treated in the adjuvant setting, the rest in the neoadjuvant setting. The two arms of the study were generally well balanced — about 80% of patients had stage II disease, half were node negative, and 11% had deleterious germline mutations.

The primary endpoint, event-free survival, was broadly defined. Events included disease progression, local or distant recurrence, occurrence of a second primary cancer, inoperable status after neoadjuvant therapy, or death from any cause.

Adding carboplatin increased 5-year event-free survival rates from 75.1% to 82.3% (hazard ratio [HR], 0.67; P = .012) with the benefit holding across various subgroup analyses and particularly strong for adjuvant carboplatin (HR, 0.26).

Five-year overall survival was also better in the carboplatin arm — 90.7% vs 87% in the control arm (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.42-1.02) — but that benefit did not reach statistical significance (P = .057)

Invasive disease-free survival (HR, 0.73) and distant recurrence-free survival (HR, 0.77) favored carboplatin, but the results also weren’t statistically significant.

Overall, 46% of patients had a pathologic complete response with carboplatin vs nearly 40% in the control arm. The pathologic complete response benefit from carboplatin add-on was consistent with past reports.

As expected, adding carboplatin to treatment increased hematologic toxicity and other adverse events, with three-quarters of patients experiencing grade 3 or worse adverse events vs 56.7% of control participants. There was one death in the carboplatin arm from pneumonia and two in the control arm — one from septic shock and the other from suicide.

Dr. Sohn and colleagues, however, did not observe a quality of life difference between the two groups.

“The PEARLY trial provides compelling evidence for including carboplatin in the treatment of early-stage TNBC,” Dr. Sohn concluded, adding that the results underscore the benefit in the neoadjuvant setting and suggest “potential applicability in the adjuvant setting post surgery.”

Study discussant Javier Cortes, MD, PhD, believes that the PEARLY provides a strong signal for adding carboplatin in the adjuvant setting.

“That’s something I would do in my clinical practice,” said Dr. Cortes, head of the International Breast Cancer Center in Barcelona, Spain. “After ASCO this year, I would offer taxanes plus carboplatin following anthracyclines.”

An audience member, William Sikov, MD, a breast cancer specialist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, said he hopes “we’ve reached the end of a road that started many years ago in terms of incorporating carboplatin as part of neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy for triple-negative breast cancer, where we finally [reach] consensus that this is necessary in our triple-negative patients.”

The work was funded by the government of South Korea and others. Dr. Sohn reported stock in Daiichi Sankyo and research funding from Daiichi and other companies. Dr. Cortes disclosed numerous industry ties, including honoraria, research funding, and/or travel expenses from AstraZeneca, Daiichi, and others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

presented at the annual meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO).

The outcomes of the South Korean study, dubbed PEARLY, provide strong evidence for incorporating carboplatin into both the neoadjuvant and adjuvant settings in patients with early-stage TNBC, said lead investigator and presenter Joohyuk Sohn, MD, PhD, a medical oncologist at Yonsei University, Seoul, South Korea.

In early-stage TNBC, carboplatin is already being incorporated into the neoadjuvant setting on the basis of trial results from KEYNOTE-522 that demonstrated improved pathologic complete response rates and event-free survival with the platinum alongside pembrolizumab.

However, the overall survival benefit of carboplatin in this setting remains unclear, as does the benefit of platinum add-on in the adjuvant setting, Dr. Sohn explained.

Dr. Sohn and colleagues randomized 868 patients evenly to either standard treatment — doxorubicin, anthracycline, and cyclophosphamide followed by a taxane — or an experimental arm that added carboplatin to the taxane phase of treatment.

About 30% of women were treated in the adjuvant setting, the rest in the neoadjuvant setting. The two arms of the study were generally well balanced — about 80% of patients had stage II disease, half were node negative, and 11% had deleterious germline mutations.

The primary endpoint, event-free survival, was broadly defined. Events included disease progression, local or distant recurrence, occurrence of a second primary cancer, inoperable status after neoadjuvant therapy, or death from any cause.

Adding carboplatin increased 5-year event-free survival rates from 75.1% to 82.3% (hazard ratio [HR], 0.67; P = .012) with the benefit holding across various subgroup analyses and particularly strong for adjuvant carboplatin (HR, 0.26).

Five-year overall survival was also better in the carboplatin arm — 90.7% vs 87% in the control arm (HR, 0.65; 95% CI, 0.42-1.02) — but that benefit did not reach statistical significance (P = .057)

Invasive disease-free survival (HR, 0.73) and distant recurrence-free survival (HR, 0.77) favored carboplatin, but the results also weren’t statistically significant.

Overall, 46% of patients had a pathologic complete response with carboplatin vs nearly 40% in the control arm. The pathologic complete response benefit from carboplatin add-on was consistent with past reports.

As expected, adding carboplatin to treatment increased hematologic toxicity and other adverse events, with three-quarters of patients experiencing grade 3 or worse adverse events vs 56.7% of control participants. There was one death in the carboplatin arm from pneumonia and two in the control arm — one from septic shock and the other from suicide.

Dr. Sohn and colleagues, however, did not observe a quality of life difference between the two groups.

“The PEARLY trial provides compelling evidence for including carboplatin in the treatment of early-stage TNBC,” Dr. Sohn concluded, adding that the results underscore the benefit in the neoadjuvant setting and suggest “potential applicability in the adjuvant setting post surgery.”

Study discussant Javier Cortes, MD, PhD, believes that the PEARLY provides a strong signal for adding carboplatin in the adjuvant setting.

“That’s something I would do in my clinical practice,” said Dr. Cortes, head of the International Breast Cancer Center in Barcelona, Spain. “After ASCO this year, I would offer taxanes plus carboplatin following anthracyclines.”

An audience member, William Sikov, MD, a breast cancer specialist at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, said he hopes “we’ve reached the end of a road that started many years ago in terms of incorporating carboplatin as part of neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy for triple-negative breast cancer, where we finally [reach] consensus that this is necessary in our triple-negative patients.”

The work was funded by the government of South Korea and others. Dr. Sohn reported stock in Daiichi Sankyo and research funding from Daiichi and other companies. Dr. Cortes disclosed numerous industry ties, including honoraria, research funding, and/or travel expenses from AstraZeneca, Daiichi, and others.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASCO 2024

Anti-CD20 Therapy for Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis

Data have shown that CD20-expressing B cells are crucial to the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (MS). First approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for MS in 2017, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapies including ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, and ublituximab have proven effective at controlling the symptoms of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).

In this ReCAP, Dr Fred D. Lublin, of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, discusses recent data on anti-CD20 agents for RRMS, including results presented at the 2024 meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC).

He discusses a protocol examining the effect on RRMS of extending dosage intervals or stopping anti-CD20 therapy after 1 or 2 years of treatment based on results suggesting that the B cells that return post depletion are predominantly regulatory rather than pathogenic.

Next, Dr Lublin discusses a paper presented at CMSC on risks for serious infections in individuals taking ocrelizumab or ofatumumab. Major predictors were found to be progressive disease, prior use of a disease-modifying therapy, and longer duration of therapy.

Finally, he considers recent studies comparing rituximab, an anti-CD20 therapy not approved for MS in the United States but commonly used off-label internationally, with more recent therapies such as ocrelizumab. Data currently indicate that an increased risk for infections are associated with rituximab vs ocrelizumab, but further research is under way.

--

Fred D. Lublin, MD, Director, The Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY

Fred D. Lublin, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Sources of Funding for Research: Novartis; Biogen; Sanofi; NMSS; NIH; Brainstorm Cell Therapeutics

Consulting Agreements/Advisory Boards/DSMB: Biogen; EMD Serono; Novartis; Actelion/Janssen; Sanofi/Genzyme; Roche/Genentech; Horizon Therapeutics/Amgen; Bristol Myers Squibb; Mapi Pharma; Brainstorm Cell Therapeutics; Mylan/Viatris; Immunic; Avotres; Neurogene; LabCorp; Entelexo Biotherapeutics; Neuralight; SetPoint Medical; Hexal/Sandoz; Baim Institute; Sudo Biosciences; Lapix Therapeutics; Biohaven Pharmaceuticals; Abata Therapeutics; Cognito Therapeutics; ImmPACT Bio

Speaker: Sanofi

Stock Options: Avotres; Neuralight; Lapix Therapeutics; Entelexo

I may discuss unapproved agents that are in the MS developmental pipeline without any recommendation on their use.

Data have shown that CD20-expressing B cells are crucial to the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (MS). First approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for MS in 2017, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapies including ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, and ublituximab have proven effective at controlling the symptoms of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).

In this ReCAP, Dr Fred D. Lublin, of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, discusses recent data on anti-CD20 agents for RRMS, including results presented at the 2024 meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC).

He discusses a protocol examining the effect on RRMS of extending dosage intervals or stopping anti-CD20 therapy after 1 or 2 years of treatment based on results suggesting that the B cells that return post depletion are predominantly regulatory rather than pathogenic.

Next, Dr Lublin discusses a paper presented at CMSC on risks for serious infections in individuals taking ocrelizumab or ofatumumab. Major predictors were found to be progressive disease, prior use of a disease-modifying therapy, and longer duration of therapy.

Finally, he considers recent studies comparing rituximab, an anti-CD20 therapy not approved for MS in the United States but commonly used off-label internationally, with more recent therapies such as ocrelizumab. Data currently indicate that an increased risk for infections are associated with rituximab vs ocrelizumab, but further research is under way.

--

Fred D. Lublin, MD, Director, The Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY

Fred D. Lublin, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Sources of Funding for Research: Novartis; Biogen; Sanofi; NMSS; NIH; Brainstorm Cell Therapeutics

Consulting Agreements/Advisory Boards/DSMB: Biogen; EMD Serono; Novartis; Actelion/Janssen; Sanofi/Genzyme; Roche/Genentech; Horizon Therapeutics/Amgen; Bristol Myers Squibb; Mapi Pharma; Brainstorm Cell Therapeutics; Mylan/Viatris; Immunic; Avotres; Neurogene; LabCorp; Entelexo Biotherapeutics; Neuralight; SetPoint Medical; Hexal/Sandoz; Baim Institute; Sudo Biosciences; Lapix Therapeutics; Biohaven Pharmaceuticals; Abata Therapeutics; Cognito Therapeutics; ImmPACT Bio

Speaker: Sanofi

Stock Options: Avotres; Neuralight; Lapix Therapeutics; Entelexo

I may discuss unapproved agents that are in the MS developmental pipeline without any recommendation on their use.

Data have shown that CD20-expressing B cells are crucial to the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis (MS). First approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for MS in 2017, anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody therapies including ocrelizumab, ofatumumab, and ublituximab have proven effective at controlling the symptoms of relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS).

In this ReCAP, Dr Fred D. Lublin, of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, discusses recent data on anti-CD20 agents for RRMS, including results presented at the 2024 meeting of the Consortium of Multiple Sclerosis Centers (CMSC).

He discusses a protocol examining the effect on RRMS of extending dosage intervals or stopping anti-CD20 therapy after 1 or 2 years of treatment based on results suggesting that the B cells that return post depletion are predominantly regulatory rather than pathogenic.

Next, Dr Lublin discusses a paper presented at CMSC on risks for serious infections in individuals taking ocrelizumab or ofatumumab. Major predictors were found to be progressive disease, prior use of a disease-modifying therapy, and longer duration of therapy.

Finally, he considers recent studies comparing rituximab, an anti-CD20 therapy not approved for MS in the United States but commonly used off-label internationally, with more recent therapies such as ocrelizumab. Data currently indicate that an increased risk for infections are associated with rituximab vs ocrelizumab, but further research is under way.

--

Fred D. Lublin, MD, Director, The Corinne Goldsmith Dickinson Center for Multiple Sclerosis, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY

Fred D. Lublin, MD, has disclosed the following relevant financial relationships:

Sources of Funding for Research: Novartis; Biogen; Sanofi; NMSS; NIH; Brainstorm Cell Therapeutics

Consulting Agreements/Advisory Boards/DSMB: Biogen; EMD Serono; Novartis; Actelion/Janssen; Sanofi/Genzyme; Roche/Genentech; Horizon Therapeutics/Amgen; Bristol Myers Squibb; Mapi Pharma; Brainstorm Cell Therapeutics; Mylan/Viatris; Immunic; Avotres; Neurogene; LabCorp; Entelexo Biotherapeutics; Neuralight; SetPoint Medical; Hexal/Sandoz; Baim Institute; Sudo Biosciences; Lapix Therapeutics; Biohaven Pharmaceuticals; Abata Therapeutics; Cognito Therapeutics; ImmPACT Bio

Speaker: Sanofi

Stock Options: Avotres; Neuralight; Lapix Therapeutics; Entelexo

I may discuss unapproved agents that are in the MS developmental pipeline without any recommendation on their use.

Treatment of Infantile Hemangiomas in Concomitant Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Should Prompt Evaluation for Cardiac Rhabdomyomas Prior to Initiation of Propranolol

To the Editor:

Cardiac rhabdomyomas are benign hamartomas that are common in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC).1 We describe a patient who presented with large infantile hemangiomas (IHs) and hypopigmented macules, which prompted further testing that eventually showed concomitant multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in the context of TSC.

A 5-week-old girl—who was born at 38 weeks and 3 days’ gestation via uncomplicated vaginal delivery—was referred to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple erythematous lesions on the scalp and left buttock that were first noticed 2 weeks prior to presentation. There was a family history of seizures in the patient’s mother. The patient’s older brother did not have similar symptoms.

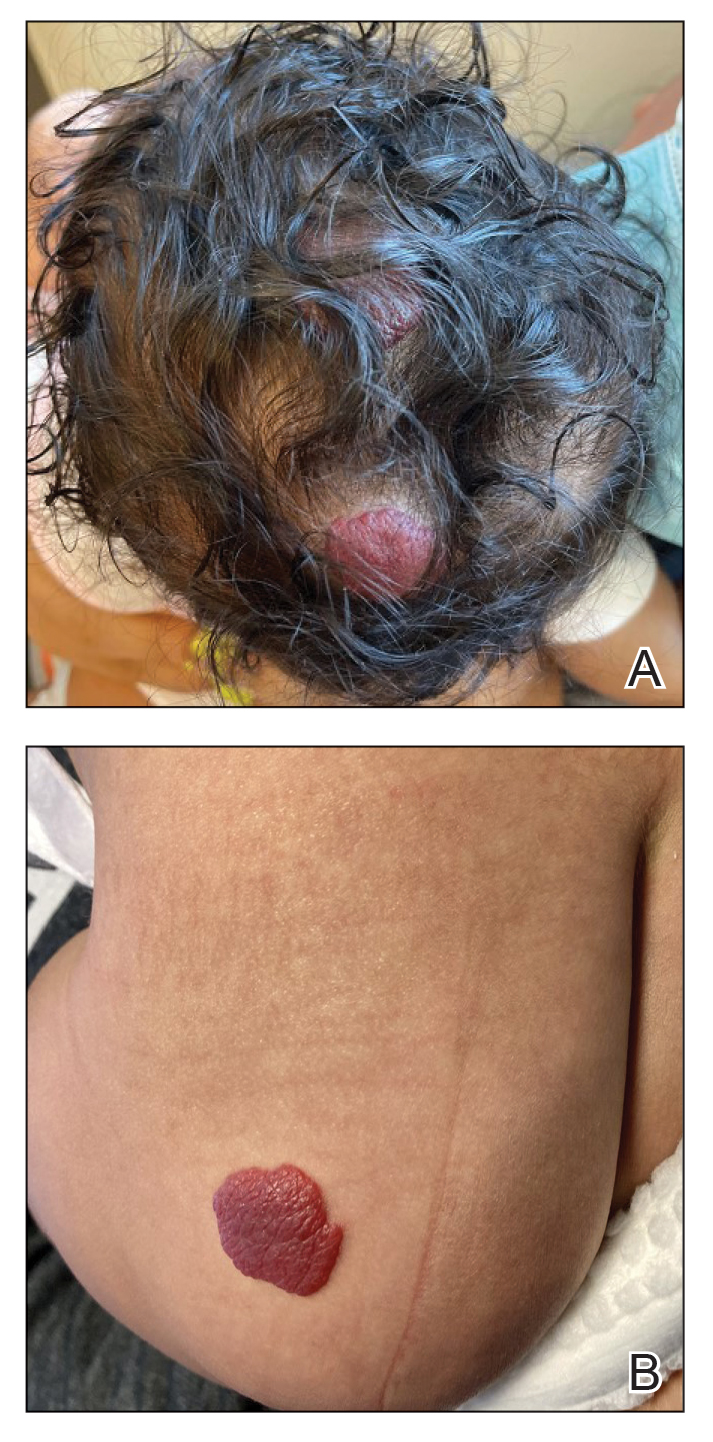

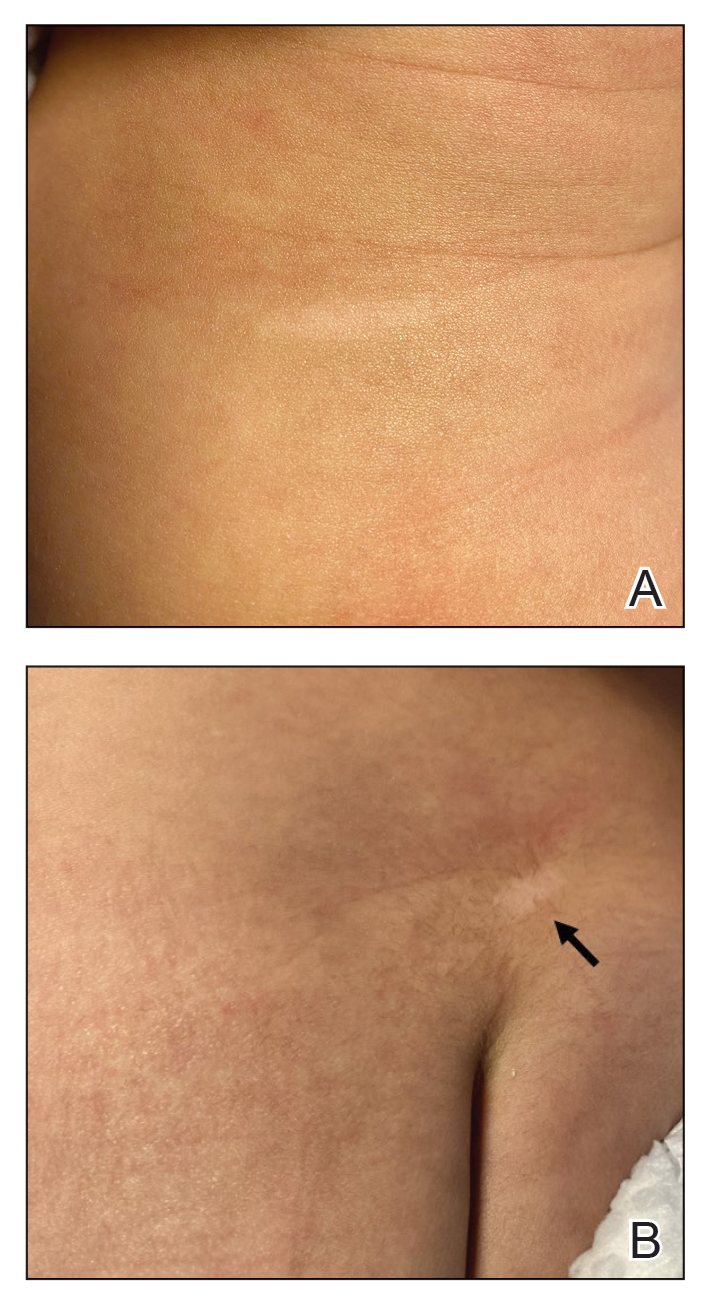

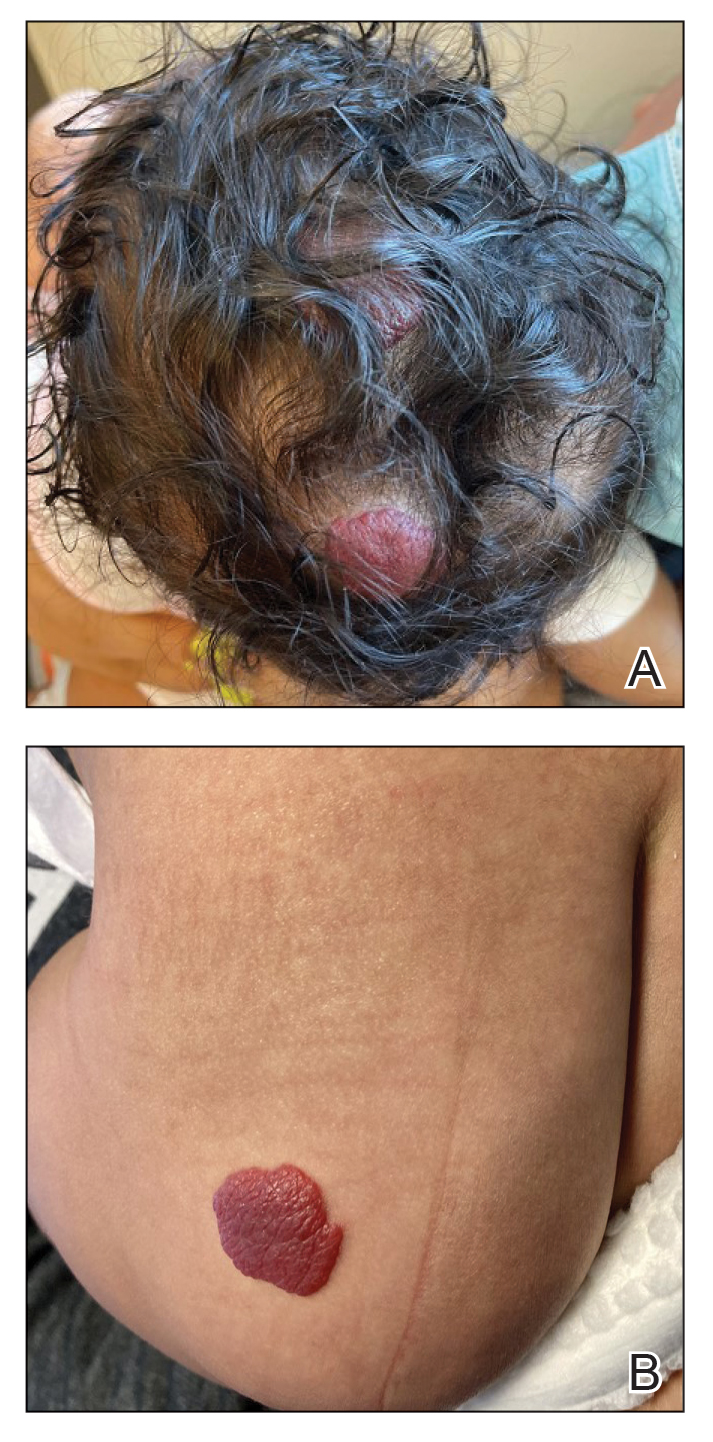

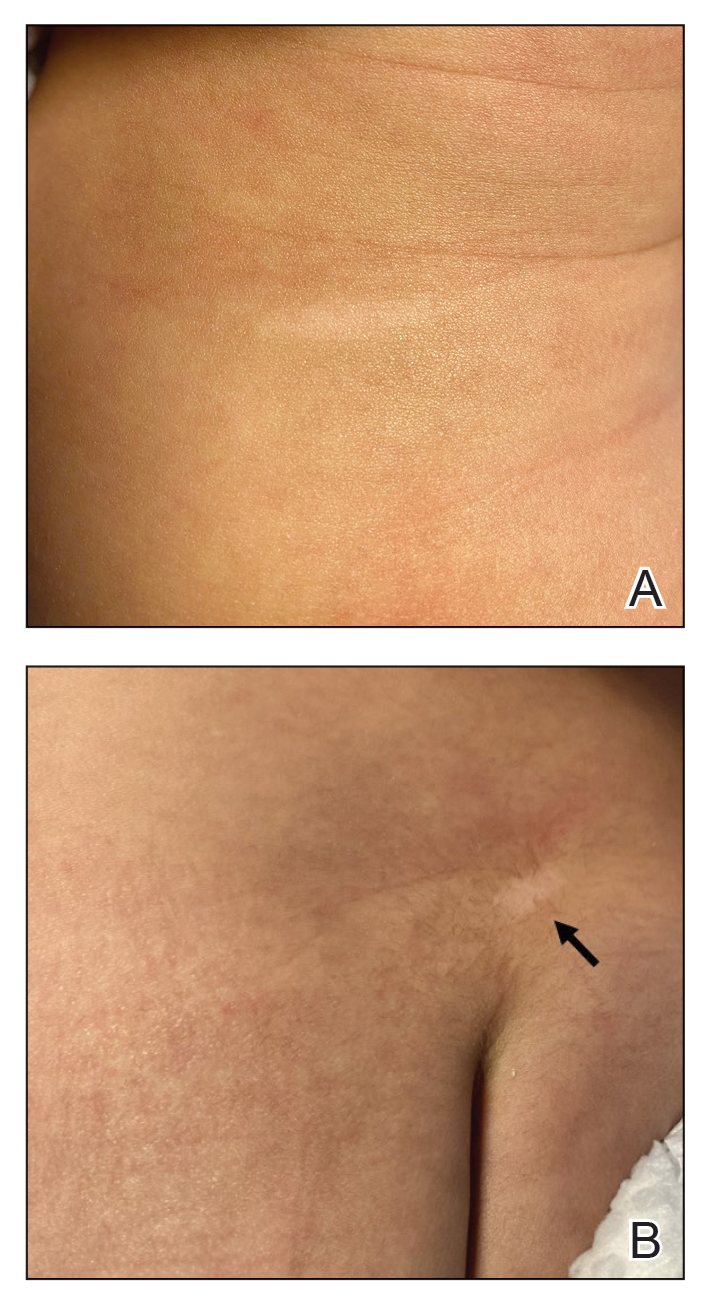

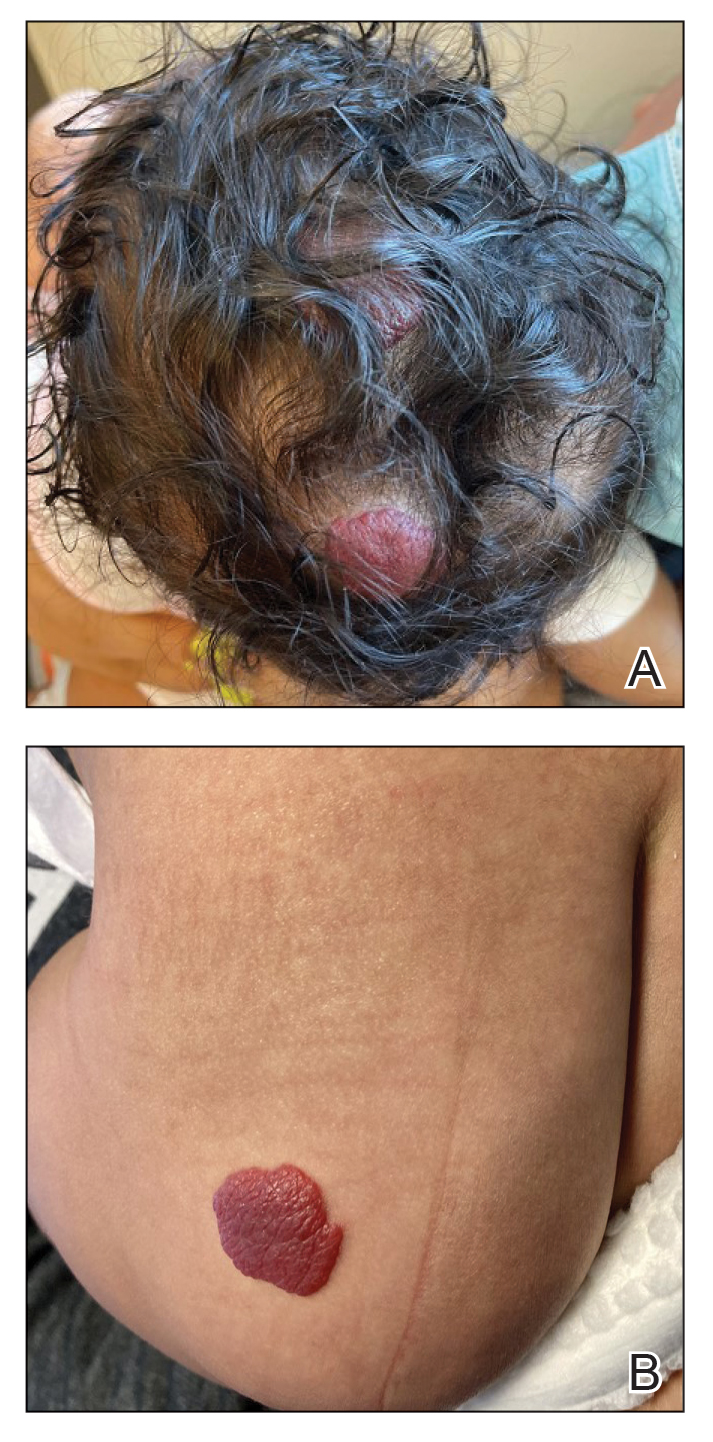

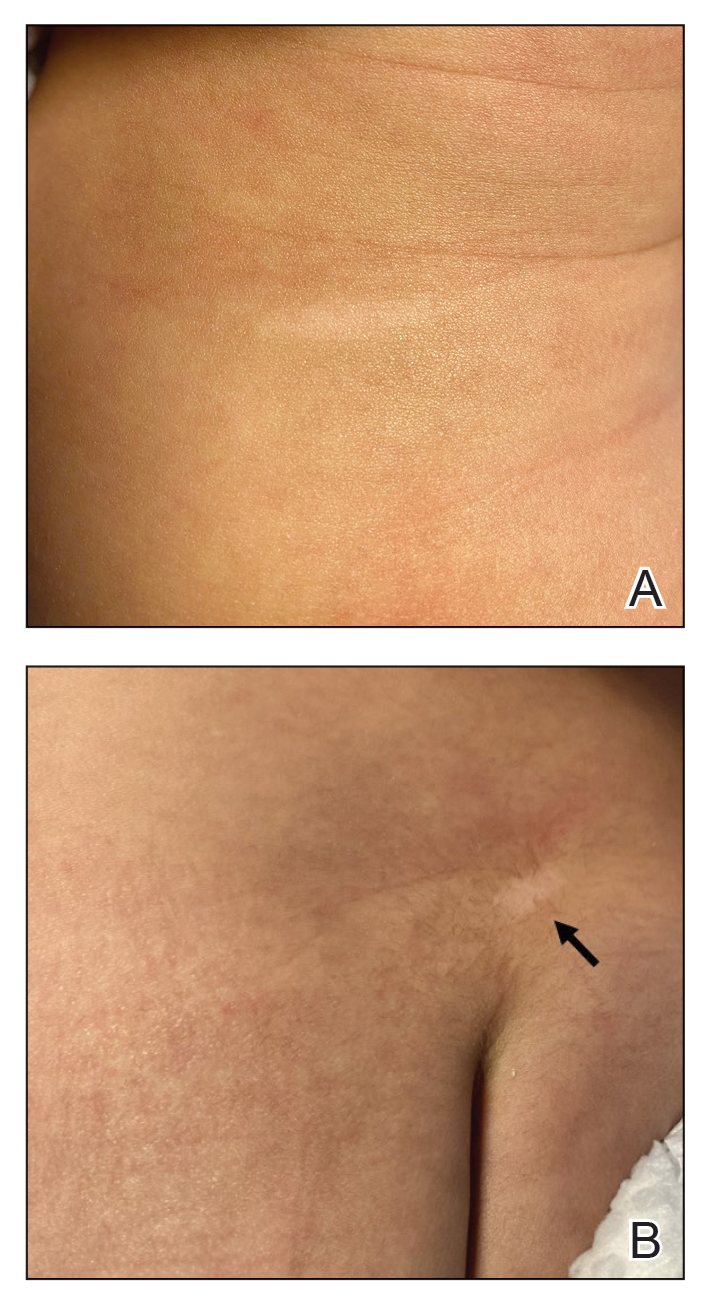

Physical examination revealed 2 nonulcerating erythematous nodules on the middle and posterior left vertex scalp that measured 2.5×2 cm (Figure 1A) as well as 1 bright red plaque on the left buttock (Figure 1B). Five hypopigmented macules, ranging from 5 mm to 1.5 cm in diameter, also were detected on the left thorax (Figure 2A) as well as the middle and lower back (Figure 2B). These findings, along with the history of seizures in the patient’s mother, prompted further evaluation of the family history, which uncovered TSC in the patient’s mother, maternal aunt, and maternal grandmother.

The large IHs on the scalp did not pose concerns for potential functional impairment but were still considered high risk for permanent alopecia based on clinical practice guidelines for the management of IH.2 Treatment with oral propranolol was recommended; however, because of a strong suspicion of TSC due to the presence of 5 hypopigmented macules measuring more than 5 mm in diameter (≥3 hypopigmented macules of ≥5 mm is one of the major criterion for TSC), the patient was referred to cardiology prior to initiation of propranolol.

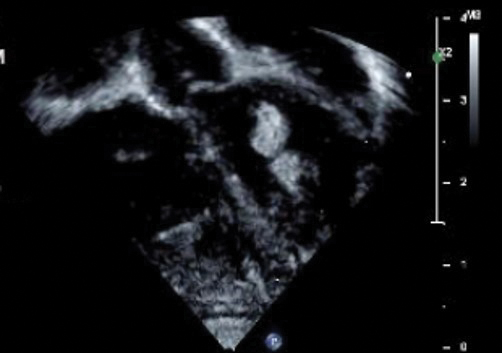

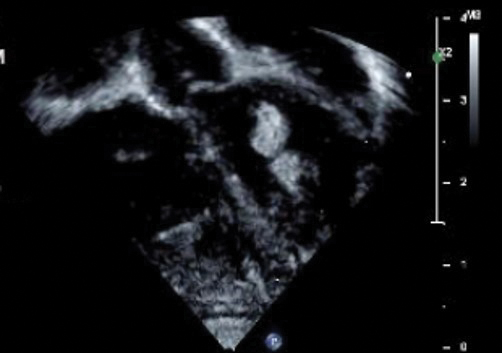

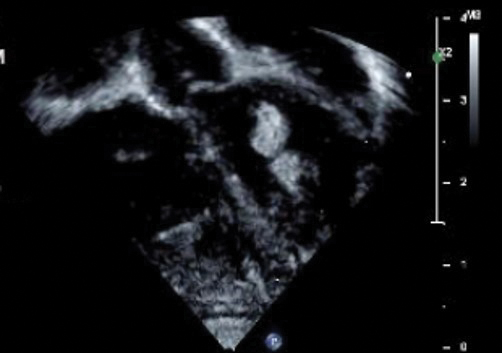

Echocardiography revealed 3 intracardiac masses measuring 4 to 5 mm in diameter in the left ventricle (LV), along the interventricular septum and the LV posterior wall. These masses were consistent with rhabdomyomas (Figure 3)—a major criterion for TSC—which had not been detected by prenatal ultrasonography. No obstruction to LV inflow or outflow was observed. Additionally, no arrhythmias were detected on electrocardiography.

The patient was cleared for propranolol, which was slowly uptitrated to 2 mg/kg/d. She completed the course without adverse effects. The treatment of IH was successful with substantial reduction in size over the following months until clearance. She also was referred to neurology for magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, which showed a 3-mm subependymal nodule in the lateral right ventricle, another major feature of TSC.

Cardiac rhabdomyomas are benign hamartomas that affect as many as 80% of patients with TSC1 and are primarily localized in the ventricles. Although cardiac rhabdomyomas usually regress over time, they can compromise ventricular function or valvular function, or both, and result in outflow obstruction, arrhythmias, and Wolff- Parkinson-White syndrome.3 Surgical resection may be needed in patients whose condition is refractory to medical management for heart failure.

The pathophysiologic mechanism behind the natural involution of cardiac rhabdomyomas has not been fully elucidated. It has been hypothesized that these masses stem from the inability of rhabdomyoma cells to divide after birth due to their embryonic myocyte derivation.4

According to the TSC diagnostic criteria from the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex International Consensus Group, at least 2 major features or 1 major and 2 minor features are required to make a definitive diagnosis of TSC. Cutaneous signs represent more than one-third of major features of TSC; almost all patients with TSC have skin findings.5

Identification of pathogenic mutations in either TSC1 (on chromosome 9q34.3, encoding for hamartin) or TSC2 (on chromosome 16p13.3, encoding for tuberin), resulting in constitutive activation of mammalian target of rapamycin and subsequent increased cell growth, is sufficient for a definitive diagnosis of TSC. However, mutations cannot be identified by conventional genetic testing in as many as one-quarter of patients with TSC; therefore, a negative result does not exclude TSC if the patient meets clinical diagnostic criteria.

Although a cardiology workup is indicated prior to initiating propranolol in the presence of possible cardiac rhabdomyomas, most of those lesions are hemodynamically stable and do not require treatment. There also is no contraindication for β-blocker therapy. In fact, propranolol has been reported as a successful treatment in rhabdomyoma-associated arrhythmias in children.6 Notably, obstructive cardiac rhabdomyomas have been successfully treated with mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, such as sirolimus7 and everolimus.8

Baseline cardiology screening with echocardiography prior to initiating propranolol for treatment of IH is not routinely indicated in babies with uncomplicated IH. However, in a patient with TSC, cardiology screening is necessary to rule out rhabdomyomas with associated arrhythmias or obstructed blood flow, or both, prior to initiating treatment.

We presented a case of concomitant IH and TSC in a patient with cardiac rhabdomyomas. The manifestation of large IHs in our patient prompted further testing that revealed multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in the context of TSC. It is imperative for cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and dermatologists to be familiar with the TSC diagnostic criteria so that they can reach a prompt diagnosis and make appropriate referrals for further evaluation of cardiac, neurologic, and ophthalmologic signs.

- Frudit P, Vitturi BK, Navarro FC, et al. Multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in tuberous sclerosis complex: case report and review of the literature. Autops Case Rep. 2019;9:e2019125. doi:10.4322/acr.2019.125

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al; Subcommittee on the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:e20183475. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3475

- Venugopalan P, Babu JS, Al-Bulushi A. Right atrial rhabdomyoma acting as the substrate for Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in a 3-month-old infant. Acta Cardiol. 2005;60:543-545. doi:10.2143/AC.60.5.2004977

- DiMario FJ Jr, Diana D, Leopold H, et al. Evolution of cardiac rhabdomyoma in tuberous sclerosis complex. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1996;35:615-619. doi:10.1177/000992289603501202

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.001

- Kathare PA, Muthuswamy KS, Sadasivan J, et al. Incessant ventricular tachycardia due to multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in an infant with tuberous sclerosis. Indian Heart J. 2013;65:111-113. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2012.12.003

- Breathnach C, Pears J, Franklin O, et al. Rapid regression of left ventricular outflow tract rhabdomyoma after sirolimus therapy. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1199-e1202. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3293

- Chang J-S, Chiou P-Y, Yao S-H, et al. Regression of neonatal cardiac rhabdomyoma in two months through low-dose everolimus therapy: a report of three cases. Pediatr Cardiol. 2017;38:1478-1484. doi:10.1007/s00246-017-1688-4

To the Editor:

Cardiac rhabdomyomas are benign hamartomas that are common in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC).1 We describe a patient who presented with large infantile hemangiomas (IHs) and hypopigmented macules, which prompted further testing that eventually showed concomitant multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in the context of TSC.

A 5-week-old girl—who was born at 38 weeks and 3 days’ gestation via uncomplicated vaginal delivery—was referred to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple erythematous lesions on the scalp and left buttock that were first noticed 2 weeks prior to presentation. There was a family history of seizures in the patient’s mother. The patient’s older brother did not have similar symptoms.

Physical examination revealed 2 nonulcerating erythematous nodules on the middle and posterior left vertex scalp that measured 2.5×2 cm (Figure 1A) as well as 1 bright red plaque on the left buttock (Figure 1B). Five hypopigmented macules, ranging from 5 mm to 1.5 cm in diameter, also were detected on the left thorax (Figure 2A) as well as the middle and lower back (Figure 2B). These findings, along with the history of seizures in the patient’s mother, prompted further evaluation of the family history, which uncovered TSC in the patient’s mother, maternal aunt, and maternal grandmother.

The large IHs on the scalp did not pose concerns for potential functional impairment but were still considered high risk for permanent alopecia based on clinical practice guidelines for the management of IH.2 Treatment with oral propranolol was recommended; however, because of a strong suspicion of TSC due to the presence of 5 hypopigmented macules measuring more than 5 mm in diameter (≥3 hypopigmented macules of ≥5 mm is one of the major criterion for TSC), the patient was referred to cardiology prior to initiation of propranolol.

Echocardiography revealed 3 intracardiac masses measuring 4 to 5 mm in diameter in the left ventricle (LV), along the interventricular septum and the LV posterior wall. These masses were consistent with rhabdomyomas (Figure 3)—a major criterion for TSC—which had not been detected by prenatal ultrasonography. No obstruction to LV inflow or outflow was observed. Additionally, no arrhythmias were detected on electrocardiography.

The patient was cleared for propranolol, which was slowly uptitrated to 2 mg/kg/d. She completed the course without adverse effects. The treatment of IH was successful with substantial reduction in size over the following months until clearance. She also was referred to neurology for magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, which showed a 3-mm subependymal nodule in the lateral right ventricle, another major feature of TSC.

Cardiac rhabdomyomas are benign hamartomas that affect as many as 80% of patients with TSC1 and are primarily localized in the ventricles. Although cardiac rhabdomyomas usually regress over time, they can compromise ventricular function or valvular function, or both, and result in outflow obstruction, arrhythmias, and Wolff- Parkinson-White syndrome.3 Surgical resection may be needed in patients whose condition is refractory to medical management for heart failure.

The pathophysiologic mechanism behind the natural involution of cardiac rhabdomyomas has not been fully elucidated. It has been hypothesized that these masses stem from the inability of rhabdomyoma cells to divide after birth due to their embryonic myocyte derivation.4

According to the TSC diagnostic criteria from the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex International Consensus Group, at least 2 major features or 1 major and 2 minor features are required to make a definitive diagnosis of TSC. Cutaneous signs represent more than one-third of major features of TSC; almost all patients with TSC have skin findings.5

Identification of pathogenic mutations in either TSC1 (on chromosome 9q34.3, encoding for hamartin) or TSC2 (on chromosome 16p13.3, encoding for tuberin), resulting in constitutive activation of mammalian target of rapamycin and subsequent increased cell growth, is sufficient for a definitive diagnosis of TSC. However, mutations cannot be identified by conventional genetic testing in as many as one-quarter of patients with TSC; therefore, a negative result does not exclude TSC if the patient meets clinical diagnostic criteria.

Although a cardiology workup is indicated prior to initiating propranolol in the presence of possible cardiac rhabdomyomas, most of those lesions are hemodynamically stable and do not require treatment. There also is no contraindication for β-blocker therapy. In fact, propranolol has been reported as a successful treatment in rhabdomyoma-associated arrhythmias in children.6 Notably, obstructive cardiac rhabdomyomas have been successfully treated with mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, such as sirolimus7 and everolimus.8

Baseline cardiology screening with echocardiography prior to initiating propranolol for treatment of IH is not routinely indicated in babies with uncomplicated IH. However, in a patient with TSC, cardiology screening is necessary to rule out rhabdomyomas with associated arrhythmias or obstructed blood flow, or both, prior to initiating treatment.

We presented a case of concomitant IH and TSC in a patient with cardiac rhabdomyomas. The manifestation of large IHs in our patient prompted further testing that revealed multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in the context of TSC. It is imperative for cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and dermatologists to be familiar with the TSC diagnostic criteria so that they can reach a prompt diagnosis and make appropriate referrals for further evaluation of cardiac, neurologic, and ophthalmologic signs.

To the Editor:

Cardiac rhabdomyomas are benign hamartomas that are common in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC).1 We describe a patient who presented with large infantile hemangiomas (IHs) and hypopigmented macules, which prompted further testing that eventually showed concomitant multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in the context of TSC.

A 5-week-old girl—who was born at 38 weeks and 3 days’ gestation via uncomplicated vaginal delivery—was referred to our pediatric dermatology clinic for evaluation of multiple erythematous lesions on the scalp and left buttock that were first noticed 2 weeks prior to presentation. There was a family history of seizures in the patient’s mother. The patient’s older brother did not have similar symptoms.

Physical examination revealed 2 nonulcerating erythematous nodules on the middle and posterior left vertex scalp that measured 2.5×2 cm (Figure 1A) as well as 1 bright red plaque on the left buttock (Figure 1B). Five hypopigmented macules, ranging from 5 mm to 1.5 cm in diameter, also were detected on the left thorax (Figure 2A) as well as the middle and lower back (Figure 2B). These findings, along with the history of seizures in the patient’s mother, prompted further evaluation of the family history, which uncovered TSC in the patient’s mother, maternal aunt, and maternal grandmother.

The large IHs on the scalp did not pose concerns for potential functional impairment but were still considered high risk for permanent alopecia based on clinical practice guidelines for the management of IH.2 Treatment with oral propranolol was recommended; however, because of a strong suspicion of TSC due to the presence of 5 hypopigmented macules measuring more than 5 mm in diameter (≥3 hypopigmented macules of ≥5 mm is one of the major criterion for TSC), the patient was referred to cardiology prior to initiation of propranolol.

Echocardiography revealed 3 intracardiac masses measuring 4 to 5 mm in diameter in the left ventricle (LV), along the interventricular septum and the LV posterior wall. These masses were consistent with rhabdomyomas (Figure 3)—a major criterion for TSC—which had not been detected by prenatal ultrasonography. No obstruction to LV inflow or outflow was observed. Additionally, no arrhythmias were detected on electrocardiography.

The patient was cleared for propranolol, which was slowly uptitrated to 2 mg/kg/d. She completed the course without adverse effects. The treatment of IH was successful with substantial reduction in size over the following months until clearance. She also was referred to neurology for magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, which showed a 3-mm subependymal nodule in the lateral right ventricle, another major feature of TSC.

Cardiac rhabdomyomas are benign hamartomas that affect as many as 80% of patients with TSC1 and are primarily localized in the ventricles. Although cardiac rhabdomyomas usually regress over time, they can compromise ventricular function or valvular function, or both, and result in outflow obstruction, arrhythmias, and Wolff- Parkinson-White syndrome.3 Surgical resection may be needed in patients whose condition is refractory to medical management for heart failure.

The pathophysiologic mechanism behind the natural involution of cardiac rhabdomyomas has not been fully elucidated. It has been hypothesized that these masses stem from the inability of rhabdomyoma cells to divide after birth due to their embryonic myocyte derivation.4

According to the TSC diagnostic criteria from the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex International Consensus Group, at least 2 major features or 1 major and 2 minor features are required to make a definitive diagnosis of TSC. Cutaneous signs represent more than one-third of major features of TSC; almost all patients with TSC have skin findings.5

Identification of pathogenic mutations in either TSC1 (on chromosome 9q34.3, encoding for hamartin) or TSC2 (on chromosome 16p13.3, encoding for tuberin), resulting in constitutive activation of mammalian target of rapamycin and subsequent increased cell growth, is sufficient for a definitive diagnosis of TSC. However, mutations cannot be identified by conventional genetic testing in as many as one-quarter of patients with TSC; therefore, a negative result does not exclude TSC if the patient meets clinical diagnostic criteria.

Although a cardiology workup is indicated prior to initiating propranolol in the presence of possible cardiac rhabdomyomas, most of those lesions are hemodynamically stable and do not require treatment. There also is no contraindication for β-blocker therapy. In fact, propranolol has been reported as a successful treatment in rhabdomyoma-associated arrhythmias in children.6 Notably, obstructive cardiac rhabdomyomas have been successfully treated with mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitors, such as sirolimus7 and everolimus.8

Baseline cardiology screening with echocardiography prior to initiating propranolol for treatment of IH is not routinely indicated in babies with uncomplicated IH. However, in a patient with TSC, cardiology screening is necessary to rule out rhabdomyomas with associated arrhythmias or obstructed blood flow, or both, prior to initiating treatment.

We presented a case of concomitant IH and TSC in a patient with cardiac rhabdomyomas. The manifestation of large IHs in our patient prompted further testing that revealed multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in the context of TSC. It is imperative for cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, and dermatologists to be familiar with the TSC diagnostic criteria so that they can reach a prompt diagnosis and make appropriate referrals for further evaluation of cardiac, neurologic, and ophthalmologic signs.

- Frudit P, Vitturi BK, Navarro FC, et al. Multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in tuberous sclerosis complex: case report and review of the literature. Autops Case Rep. 2019;9:e2019125. doi:10.4322/acr.2019.125

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al; Subcommittee on the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:e20183475. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3475

- Venugopalan P, Babu JS, Al-Bulushi A. Right atrial rhabdomyoma acting as the substrate for Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in a 3-month-old infant. Acta Cardiol. 2005;60:543-545. doi:10.2143/AC.60.5.2004977

- DiMario FJ Jr, Diana D, Leopold H, et al. Evolution of cardiac rhabdomyoma in tuberous sclerosis complex. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1996;35:615-619. doi:10.1177/000992289603501202

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.001

- Kathare PA, Muthuswamy KS, Sadasivan J, et al. Incessant ventricular tachycardia due to multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in an infant with tuberous sclerosis. Indian Heart J. 2013;65:111-113. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2012.12.003

- Breathnach C, Pears J, Franklin O, et al. Rapid regression of left ventricular outflow tract rhabdomyoma after sirolimus therapy. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1199-e1202. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3293

- Chang J-S, Chiou P-Y, Yao S-H, et al. Regression of neonatal cardiac rhabdomyoma in two months through low-dose everolimus therapy: a report of three cases. Pediatr Cardiol. 2017;38:1478-1484. doi:10.1007/s00246-017-1688-4

- Frudit P, Vitturi BK, Navarro FC, et al. Multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in tuberous sclerosis complex: case report and review of the literature. Autops Case Rep. 2019;9:e2019125. doi:10.4322/acr.2019.125

- Krowchuk DP, Frieden IJ, Mancini AJ, et al; Subcommittee on the Management of Infantile Hemangiomas. Clinical practice guideline for the management of infantile hemangiomas. Pediatrics. 2019;143:e20183475. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-3475

- Venugopalan P, Babu JS, Al-Bulushi A. Right atrial rhabdomyoma acting as the substrate for Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in a 3-month-old infant. Acta Cardiol. 2005;60:543-545. doi:10.2143/AC.60.5.2004977

- DiMario FJ Jr, Diana D, Leopold H, et al. Evolution of cardiac rhabdomyoma in tuberous sclerosis complex. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1996;35:615-619. doi:10.1177/000992289603501202

- Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol. 2013;49:243-254. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2013.08.001

- Kathare PA, Muthuswamy KS, Sadasivan J, et al. Incessant ventricular tachycardia due to multiple cardiac rhabdomyomas in an infant with tuberous sclerosis. Indian Heart J. 2013;65:111-113. doi:10.1016/j.ihj.2012.12.003

- Breathnach C, Pears J, Franklin O, et al. Rapid regression of left ventricular outflow tract rhabdomyoma after sirolimus therapy. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e1199-e1202. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3293

- Chang J-S, Chiou P-Y, Yao S-H, et al. Regression of neonatal cardiac rhabdomyoma in two months through low-dose everolimus therapy: a report of three cases. Pediatr Cardiol. 2017;38:1478-1484. doi:10.1007/s00246-017-1688-4

Practice Points

- Dermatologists may see patients with infantile hemangiomas (IHs) and tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC); therefore, they should be familiar with TSC diagnostic criteria to reach a prompt diagnosis and make appropriate referrals.

- Cardiologic evaluation is not routinely required prior to systemic treatment of IH, but knowledge of cardiac findings in TSC should prompt cardiologic clearance prior to β-blocker initiation.

Diabetic Foot Infections: A Peptide’s Potential Promise

At the recent American Diabetes Association (ADA) Scientific Sessions, researchers unveiled promising data on a novel antimicrobial peptide PL-5 spray. This innovative treatment shows significant promise for managing mild to moderate infected diabetic foot ulcers.

Of the 1.6 million people with diabetes in the United States and the tens of millions of similar people worldwide, 50% will require antimicrobials at some time during their life cycle. Diabetic foot infections are difficult to treat because of their resistance to conventional therapies, often leading to severe complications, including amputations.

To address this issue, the antimicrobial peptide PL-5 spray was developed with a novel mechanism of action to potentially improve treatment outcomes. The study aimed to assess the clinical efficacy and safety of the PL-5 spray combined with standard debridement procedures in treating mild to moderate diabetic foot ulcers.

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial was conducted in four hospitals across China. Participants with mild to moderate diabetic foot ulcers were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to either the PL-5 group or the placebo group, both receiving standard debridement. The primary endpoint was clinical efficacy at day 1 after the end of treatment (EOT1). Secondary endpoints included clinical efficacy at day 7 (EOT7), microbiological efficacy, drug-resistant bacteria clearance rate, wound healing rate, and safety outcomes evaluated at both EOT1 and EOT7.

The study included 47 participants, with 32 in the PL-5 group and 15 in the placebo group. Both groups had statistically comparable demographic and clinical characteristics. The primary endpoint showed a higher clinical efficacy (cure/improvement ratio) in the PL-5 group, compared with the control group (1.33 vs 0.55; P =.0764), suggesting a positive trend but not reaching statistical significance in this population.

Among the secondary endpoints, clinical efficacy at EOT7 was significantly higher in the PL-5 group than in the control group (1.6 vs 0.86). Microbial eradication rates were notably better in the PL-5 group at both EOT1 (57.89% vs 33.33%) and EOT7 (64.71% vs 40.00%). The clearance rates of drug-resistant bacteria were also higher in the PL-5 group at EOT1 (71.43% vs 50%).

Of importance, safety parameters showed no significant differences between the two groups (24.24% vs 33.33%), highlighting the favorable safety profile of PL-5 spray.

The study presented at the ADA Scientific Sessions provides a glint of promising evidence supporting the potential efficacy and safety of PL-5 spray in treating mild to moderate diabetic foot infections. Despite the limited sample size, the results suggest that PL-5 spray may enhance the recovery speed of diabetic foot wounds, particularly in clearing drug-resistant bacterial infections. These findings justify further investigation with larger sample sizes to confirm or refute the efficacy and potentially establish PL-5 spray as a standard treatment option in diabetic foot care.

The novel antimicrobial peptide PL-5 spray shows potential in addressing the challenging issue of diabetic foot infections. This recent ADA presentation sparked significant interest and discussions about the future of diabetic foot ulcer treatments, emphasizing the importance of innovative approaches in managing complex diabetic complications.

Dr. Armstrong is a professor of surgery and director of limb preservation at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. He reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.