User login

Falling Through the Cracks

A 61-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) for persistent headache that began after he fell in his bathroom 4 days earlier. He described the headache as generalized and constant, rating the severity as a 5 on a scale of 0 to 10. The patient denied any associated neck pain or changes in headache quality with position change. He reported a 3-day history of nausea and four episodes of vomiting.

Headache after a fall raises concern for intracranial hemorrhage, particularly if this patient is on anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications. Subdural hematoma (SDH) would be more likely than epidural or subarachnoid hematoma (SAH) given the duration of days without progression. While nausea and vomiting are nonspecific, persistent vomiting may indicate increased intracranial pressure (eg, from an intracranial mass or SDH), particularly if provoked by positional changes. Without a history of fever or neck stiffness, meningitis is less likely unless the patient has a history of immunosuppression. Secondary causes of headache include vascular etiologies (eg, hemorrhagic cerebrovascular accident [CVA], arterial dissection, aneurysm, vasculitis), systemic causes (eg, chronic hypoxia/hypercapnia, hypertension), or medication overuse or withdrawal. In this patient, traumatic head injury with resultant postconcussive symptoms, though a diagnosis of exclusion, should also be considered. If the patient has a history of migraines, it is essential to obtain a history of typical migraine symptoms. More information regarding the mechanism of the fall is also essential to help elucidate a potential cause.

The patient had a 1-year history of recurrent loss of consciousness resulting in falls. After each fall, he quickly regained consciousness and exhibited no residual deficits or confusion. These episodes occurred suddenly when the patient was performing normal daily activities such as walking, driving, doing light chores, and standing up from a seated position. Immediately before this most recent fall, the patient stood up from a chair, walked toward the bathroom and, without any warning signs, lost consciousness. He denied dizziness, lightheadedness, nausea, or diaphoresis immediately before or after the fall. He also reported experiencing intermittent palpitations, but these did not appear to be related to the syncopal episodes. He denied experiencing chest pain, shortness of breath, or seizures.

The differential diagnosis for syncope is broad; therefore, it is important to identify features that suggest an etiology requiring urgent management. In this patient, cardiac etiologies such as arrhythmia (eg, atrial fibrillation [AF], ventricular tachycardia, heart block), ischemia, heart failure, and structural heart disease (eg, valvular abnormalities, cardiomyopathies) must be considered. His complaints of intermittent palpitations could suggest arrhythmia; however, the absence of a correlation to the syncopal episodes and other associated cardiac symptoms makes arrhythmias such as AF less likely. Medication side effects provoking cardiac conduction disturbances, heart block, or hypotension should be considered. Ischemic heart disease and heart failure are possible causes despite the absence of chest pain and dyspnea. While the exertional nature of the patient’s symptoms could support cardiac etiologies, it could also be indicative of recurrent pulmonary embolism or right ventricular dysfunction/strain, such as chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH).

Neurologic causes of syncope should also be included in the differential diagnosis. Seizure is less likely the underlying cause in this case since the patient regained consciousness quickly after each episode and reported no residual deficits, confusion, incontinence, or oral trauma. While less likely, other neurovascular causes can be considered, including transient ischemic attack (TIA), CVA, SAH, or vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

Neurocardiogenic syncope is less likely due to lack of a clear trigger or classical prodromal symptoms. Without a history of volume loss, orthostatic syncope is also unlikely. Other possibilities include adrenal insufficiency or an autonomic dysfunction resulting from diabetic neuropathy, chronic kidney disease, amyloidosis, spinal cord injury, or neurologic diseases (eg, Parkinson disease, Lewy body dementia). Thus far, the provided history is not suggestive of these etiologies. Other causes for loss of consciousness include hypoglycemia, sleep disorders (eg, narcolepsy), or psychiatric causes.

About 10 months prior to this presentation, the patient had presented to the hospital for evaluation of headache and was found to have bilateral SDH requiring burr hole evacuation. At that time, he was on anticoagulation therapy for a history of left superficial femoral vein thrombosis with negative workup for hypercoagulability. Warfarin was discontinued after the SDH was diagnosed. Regarding the patient’s social history, although he reported drinking two glasses of wine with dinner each night and smoking marijuana afterward, all syncopal events occurred during the daytime.

The history of prior SDH should raise suspicion for recurrent SDH, particularly considering the patient’s ongoing alcohol use. History of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and possible exertional syncope might suggest recurrent pulmonary embolism or CTEPH as an etiology. DVT and TIA/CVA secondary to paradoxical embolism are also possible. Depending on extent of alcohol use, intoxication and cardiomyopathy with secondary arrhythmias are possibilities.

The basic workup should focus on identifying any acute intracranial processes that may explain the patient’s presentation and evaluating for syncope. This includes a complete blood count with differential, electrolytes, hepatic panel (based on patient’s history of alcohol use), and coagulation studies. Troponins and B-type natriuretic peptide would help assess for cardiac disease, and a urine/serum drug test would be beneficial to screen for substance use. Considering the patient’s prior history of SDH, head imaging should be obtained. If the patient were to exhibit focal neurologic deficits or persistent alterations in consciousness (thereby raising the index of suspicion for TIA or CVA), perfusion/diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies should be obtained. If obtaining a brain MRI is not practical, then a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) of the head and neck should be obtained. A noncontrast head CT would be sufficient to reveal the presence of SDH. An electroencephalogram (EEG) to assess for seizure should be performed if the patient is noted to have any focal neurologic findings or complaints consistent with seizure. With possible exertional syncope, an electrocardiogram (ECG) and transthoracic echocardiogram (with bubble study to assess for patent foramen ovale) should be obtained urgently.

The patient had a history of hypertension and irritable bowel syndrome, for which he took metoprolol and duloxetine, respectively. Eight months prior to the current ED presentation, he was admitted to the hospital for a syncope workup after falling and sustaining a fractured jaw and torn rotator cuff. ECG and continuous telemetry monitoring showed normal sinus rhythm, normal intervals, and rare episodes of sinus tachycardia, but no evidence of arrhythmia. An echocardiogram demonstrated normal ejection fraction and chamber sizes; CT and MRI of the brain showed no residual SDH; and EEG monitoring showed no seizure activity. It was determined that the patient’s syncopal episodes were multifactorial; possible etiologies included episodic hypotension from irritable bowel syndrome—related diarrhea, paroxysmal arrhythmias, and ongoing substance use.

The patient was discharged home with a 14-day Holter monitor. Rare episodes of AF (total burden 0.4%) were detected, and dronedarone was prescribed for rhythm control; he remained off anticoagulation therapy due to the history of SDH. Over the next few months, cardiology, electrophysiology, and neurology consultants concluded that paroxysmal AF was the likely etiology of the patient’s syncopal episodes. The patient was considered high risk for CVA, but the risk of bleeding from syncope-related falls was too high to resume anticoagulation therapy.

One month prior to the current ED presentation, the patient underwent a left atrial appendage closure with a WATCHMAN implant to avoid long-term anticoagulation. After the procedure, he was started on warfarin with plans to permanently discontinue anticoagulation after 6 to 8 weeks of completed therapy. He had been on warfarin for 3 weeks prior the most recent fall and current ED visit.At the time of this presentation, the patient was on dronedarone, duloxetine, metoprolol, and warfarin. On exam, he was alert and in no distress. His temperature was 36.8 °C, heart rate 98 beats per minute , blood pressure (BP) 110/75 mm Hg (with no orthostatic changes), respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 95% on room air. He had a regular heart rate and rhythm, clear lung fields, and a benign abdominal exam. He was oriented to time, place, and person. His pupils were equal in size and reactive to light, and sensation and strength were equal bilaterally with no focal neurologic deficits. His neck was supple, and head movements did not cause any symptoms. His musculoskeletal exam was notable for right supraspinatus weakness upon abduction of arm to 90° and a positive impingement sign. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm with normal intervals. Laboratory findings were notable only for an international normalized ratio of 4.9. CT of the head did not show any pathology. The patient was admitted to the medicine floor for further evaluation.

At this point in his clinical course, the patient has had a thorough workup—one that has largely been unrevealing aside from paroxysmal AF. With his current presentation, acute intracranial causes remain on the differential, but the normal CT scan essentially excludes hemorrhage or mass. Although previous MRI studies have been negative and no focal neurologic findings have been described throughout his course, given the patient’s repeated presentations for syncope, intracranial vessel imaging should be obtained to exclude anatomical abnormalities or focal stenosis that could cause recurrent TIAs.

Seizure is also a consideration, but prior EEG and normal neurologic exam makes this less likely. While cardiac workup for syncope has been reassuring, the patient’s history of AF should continue to remain a consideration even though this is less likely the underlying cause since he is now taking dronedarone. He should be placed on telemetry upon admission. While negative orthostatic vital signs make orthostatic syncope less likely, this could be confounded by use of beta-blockers. Overall, the patient’s case remains a challenging one, with the etiology of his syncope remaining unclear at this time.

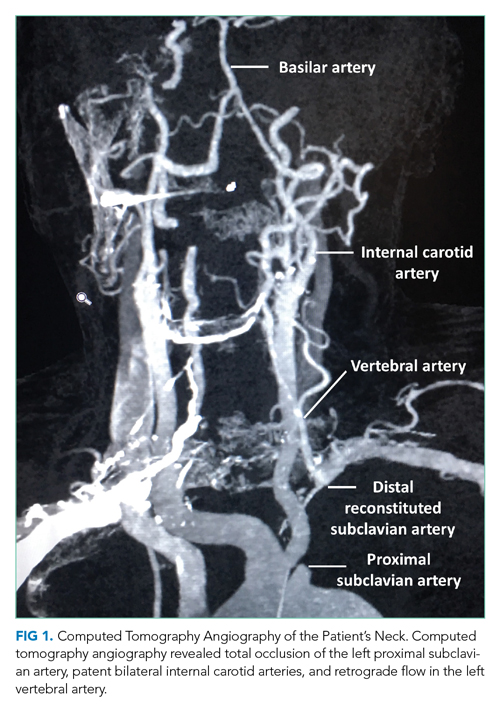

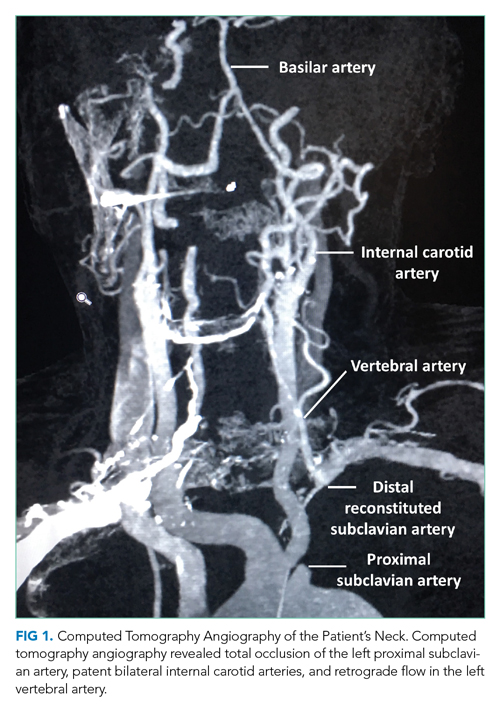

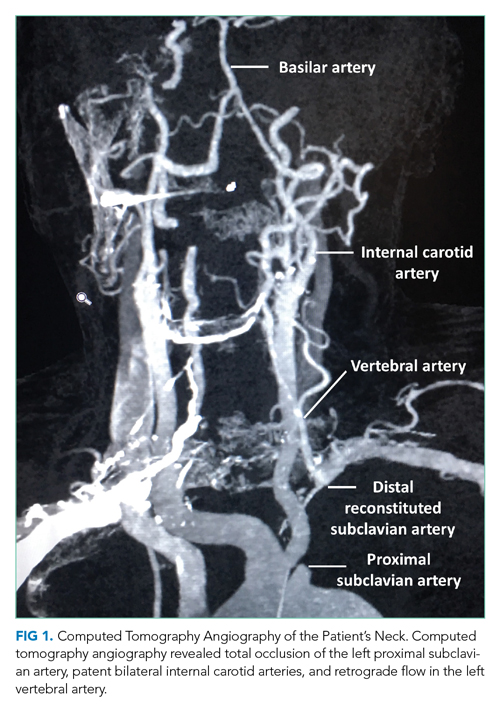

During this hospitalization, possible etiologies for recurrent syncope and falls were reviewed. The burden of verifiable AF was too low to explain the patient’s recurrent syncopal episodes. Further review of his medical record revealed that a carotid ultrasound was obtained a year earlier in the course of a previous hospitalization. The ultrasound report described patent carotid arteries and retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery consistent with ipsilateral subclavian stenosis. At the time, the ultrasound was interpreted as reassuring based on the lack of significant carotid stenosis; the findings were thought to be unrelated to the patient’s syncopal episodes. On further questioning, the patient noted that minimal exertion such as unloading a few items from the dishwasher caused left arm pain and paresthesia, accompanied by headache and lightheadedness. He also reported using his left arm more frequently following a right shoulder injury. Repeat physical exam found an inter-arm systolic BP difference (IASBPD) >40 mm Hg and left-arm claudication. CT-angiogram of the neck was obtained and showed total occlusion of the left proximal subclavian artery, patent bilateral internal carotid arteries, and retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery (Figure 1).

Subclavian steal syndrome (SSS) results from compromised flow to the distal arm or brainstem circulation due to a proximal subclavian artery occlusion or stenosis (prior to the origin of the vertebral artery).1,2 Subclavian stenosis may cause lowered pressure in the distal subclavian artery, creating a gradient for blood flow from the contralateral vertebral artery through the basilar artery to the ipsilateral vertebral artery, ultimately supplying blood flow to the affected subclavian artery distal to the occlusion (subclavian steal phenomenon). Flow reversal in the vertebrobasilar system can result in hypoperfusion of the brainstem (ie, vertebrobasilar insufficiency), which can cause a variety of neurologic symptoms, including SSS. While atherosclerosis is the most common cause of subclavian steal, it may be due to other conditions (eg, Takayasu arteritis, thoracic outlet syndrome, congenital heart disease).

Clinically, although many patients with proximal subclavian stenosis are asymptomatic (even in cases wherein angiographic flow reversal is detected), it is critical that clinicians be familiar with common symptoms associated with the diagnosis. Symptoms may include arm claudication related to hypoperfusion of the extremity, particularly when performing activities, as was observed in this patient. Neurologic symptoms are less common but include symptoms consistent with compromised posterior circulation such as dizziness, vertigo, ataxia, diplopia, nystagmus, impaired vision (blurring of vision, hemianopia), otologic symptoms (tinnitus, hearing loss), and/or syncope (ie, “drop attacks”). The patient’s initial complaints of sudden syncope are consistent with this presentation, as are his history of headache and lightheadedness upon use of his left arm.

Diagnostically, a gradient in upper extremity BP >15 mm Hg (as seen in this patient) or findings of arterial insufficiency would suggest subclavian stenosis. Duplex ultrasound is a reliable imaging modality and can demonstrate proximal subclavian stenosis (sensitivity of 90.9% and specificity of 82.5% for predicting >70% of stenosis cases) and ipsilateral vertebral artery flow reversal.1 Transcranial Doppler studies can be obtained to assess for basilar artery flow reversal as well. CTA/MRA can help delineate location, severity, and cause of stenosis. However, detection of vertebral or basilar artery flow reversal does not always correlate with the development of neurologic symptoms.

For patients with asymptomatic subclavian stenosis, medical management with aspirin, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins should be considered given the high likelihood for other atherosclerotic disease. Management of SSS may include percutaneous/surgical intervention in combination with medical therapy, particularly for patients with severe symptomatic disease (arm claudication, posterior circulation deficits, or coronary ischemia in patients with history of coronary bypass utilizing the left internal mammary artery).

The patient was diagnosed with SSS. Cardiovascular medicine and vascular surgery services were asked to evaluate the patient for a revascularization procedure. Because the patient’s anterior circulation was intact, several specialists remained skeptical of SSS as the cause of his syncope. As such, further evaluation for arrhythmia was recommended. The patient’s arm claudication was thought to be due to SSS; however, the well-established retrograde flow via the vertebral artery made a revascularization procedure nonurgent. Moreover, continuation of warfarin was necessary in the setting of his recent left atrial appendage closure and prior history of DVT. It was determined that the risks of discontinuing anticoagulation in order to surgically treat his subclavian stenosis outweighed the benefits. In the meantime, brachial-radial index measurement and a 30-day event monitor were ordered to further assess for arrhythmias. The patient reported being overwhelmed by diagnostic testing without resolution of his syncopal episodes and missed some of his scheduled appointments. One month later, he fell again and sustained vertebral fractures at C1, C4, and L1, and a subsequent SDH requiring craniotomy with a bone flap followed by clot evacuation. The 30-day event monitor report did not reveal any arrhythmias before, during, or after multiple syncopal events that occurred in the period leading up to this fall. The patient later died in a neurology intensive care unit.

DISCUSSION

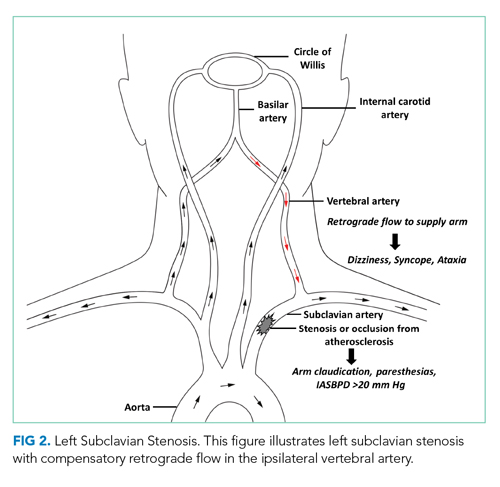

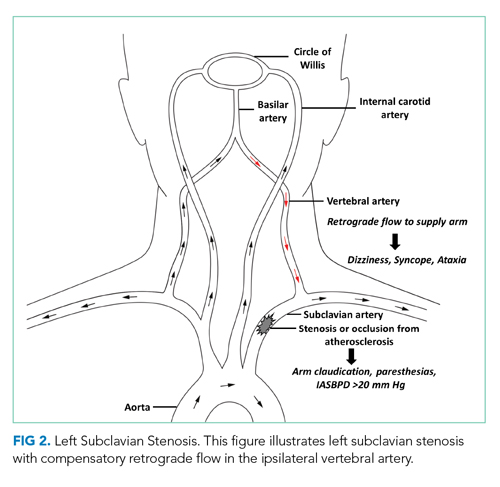

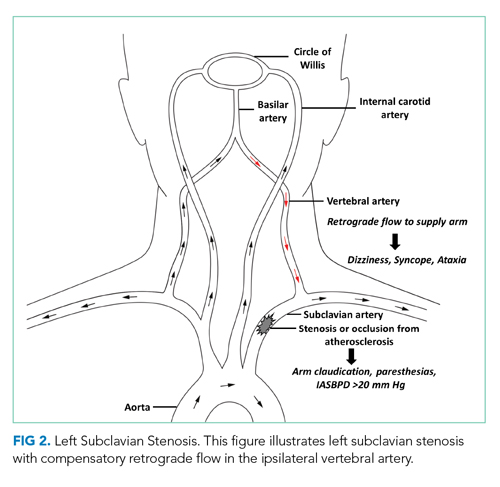

SSS often stems from atherosclerotic arterial disease that leads to stenosis or occlusion of the proximal subclavian artery, causing decreased pressure distal to the lesion. The left subclavian artery is affected more often than the right because of its acute angle of origin, which presumably causes turbulence and predisposes to atherosclerosis.3 Compromised blood flow to the arm causes exertional arm claudication and paresthesia. The compensatory retrograde flow in the ipsilateral vertebral artery causes symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency such as dizziness, vertigo, and syncope (Figure 2). This conglomerate of symptoms from subclavian steal, by definition, comprises SSS. The most remarkable signs of SSS are IASBPD >20 mm Hg and, less commonly, reproducible arm claudication.

Diagnosis of SSS requires a careful correlation of clinical history, physical examination, and radiologic findings. Over 80% of patients with subclavian disease have concomitant lesions (eg, in carotid arteries) that can affect collateral circulation.4 While symptoms of SSS may vary depending on the adequacy of collaterals, patent anterior circulation does not, by default, prevent SSS in patients with subclavian stenosis.3 In one study, neurologic symptoms were found in 36% of individuals with subclavian stenosis and concomitant carotid atherosclerotic lesions, and in only 5% in patients without carotid lesions.5

A key step in diagnosis is measurement of bilateral arm BP as elevated IASBPDs are highly sensitive for subclavian steal. More than 80% of patients with IASBPD >20 mm Hg have evidence of this condition on Doppler ultrasound.3 Higher differentials in BP correlate with occurrence of symptoms (~30% of patients with IASBPD 40-50 mm Hg, and ~40% of those with IASBPD >50 mm Hg).6

The severity of subclavian stenosis is traditionally classified by imaging into three separate grades or stages based on the direction of blood flow in vertebral arteries. Grade I involves no retrograde flow; grade II involves cardiac cycle dependent alternating antegrade and retrograde flow; and grade III involves permanent retrograde flow (complete steal).7 Our patient’s care was impacted by an unsupported conventional belief that grade II SSS may involve more hemodynamic instability and produce more severe symptoms compared to permanent retrograde flow (grade III), which would result in more stability with a reset of hemodynamics in posterior circulation.7 This hypothesis has been disproven in the past, and our patient’s tragic outcome also demonstrates that complete steal is not harmless.8 Our patient had permanent retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery, and he suffered classic symptoms of SSS, with devastating consequences. Moreover, increased demand or exertion can enhance the retrograde flow even in grade III stenosis and can precipitate neurologic symptoms of SSS, including syncope. This case provides an important lesson: Management of patients with SSS should depend on the severity of symptoms, not solely on radiologic grading.

Management of SSS is often medical for atherosclerosis and hypertension, especially if symptoms are mild and infrequent. Less than 10% patients with radiologic evidence of subclavian stenosis are symptomatic, and <20% patients with symptomatic SSS require revascularization.3 Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) and stenting have become the most favored surgical approach rather than extra-anatomic revascularization techniques.7 Both endovascular interventions and open revascularization carry an excellent success rate with low morbidity. Patients undergoing PTA have a combined rate of 3.6% for CVA and death9 and a 5-year primary patency rate10 of 82%. Bypass surgery appears similarly well tolerated, with low perioperative CVA/mortality, and a 10-year primary patency rate of 92%.11 For patients with SSS and coexisting disease in the anterior circulation, carotid endarterectomy is prioritized over subclavian revascularization as repair of the anterior circulation often resolves symptoms of SSS.12

In our patient, SSS presented with classic vertebrobasilar and brachial symptoms, but several features of his presentation made the diagnosis a challenge. First, his history suggested several potential causes of syncope, including arrhythmia, orthostatic hypotension, and substance use. Second, he reported arm paresthesia and claudication only when specifically prompted and after a targeted history was obtained. Third, there were no consistent triggers for his syncopal episodes. The patient noted that he lost consciousness when walking, driving, doing light chores, and arising from a seated position. These atypical triggers of syncope were not consistent with any of the illnesses considered during the initial workup, and therefore resulted in a broad differential, delaying the targeted workup for SSS. The wisdom of parsimony may also have played an unintended role: In clinical practice, common things are common, and explanation of most or all symptoms with a known diagnosis is often correct rather than addition of uncommon disorders.

Unfortunately, this patient kept falling through the cracks. Several providers believed that AF and alcohol use were the likely causes of his syncope. This assumption enabled a less than rigorous appraisal of the critical ultrasound report. If SSS had been on the differential, assessing the patient for the associated signs and symptoms might have led to an earlier diagnosis.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- SSS should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with syncope, especially when common diagnoses have been ruled out.

- Incidentally detected retrograde vertebral flow on ultrasound should never be dismissed, and the patients should be assessed for signs and symptoms of subclavian steal.

- A difference in inter-arm systolic blood pressure >20 mm Hg is highly suggestive of subclavian stenosis.

- SSS has excellent prognosis with appropriate medical treatment or revascularization.

1. Mousa AY, Morkous R, Broce M, et al. Validation of subclavian duplex velocity criteria to grade severity of subclavian artery stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65(6):1779-1785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2016.12.098

2. Potter BJ, Pinto DS. Subclavian steal syndrome. Circulation. 2014;129(22):2320-2323. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.113.006653

3. Labropoulos N, Nandivada P, Bekelis K. Prevalence and impact of the subclavian steal syndrome. Ann Surg. 2010;252(1):166-170. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0b013e3181e3375a

4. Fields WS, Lemak NA. Joint study of extracranial arterial occlusion. VII. Subclavian steal--a review of 168 cases. JAMA. 1972;222(9):1139-1143. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1972.03210090019004

5. Hennerici M, Klemm C, Rautenberg W. The subclavian steal phenomenon: a common vascular disorder with rare neurologic deficits. Neurology. 1988;38(5): 669-673. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.38.5.669

6. Clark CE, Taylor RS, Shore AC, Ukoumunne OC, Campbell JL. Association of a difference in systolic blood pressure between arms with vascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9819):905-914. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61710-8

7. Osiro S, Zurada A, Gielecki J, Shoja MM, Tubbs RS, Loukas M. A review of subclavian steal syndrome with clinical correlation. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(5):RA57-RA63. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.882721

8. Thomassen L, Aarli JA. Subclavian steal phenomenon. Clinical and hemodynamic aspects. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;90(4):241-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb02714.x

9. De Vries JP, Jager LC, Van den Berg JC, et al. Durability of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for obstructive lesions of proximal subclavian artery: long-term results. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(1):19-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2004.09.030

10. Wang KQ, Wang ZG, Yang BZ, et al. Long-term results of endovascular therapy for proximal subclavian arterial obstructive lesions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123(1):45-50. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2010.01.008

11. AbuRahma AF, Robinson PA, Jennings TG. Carotid-subclavian bypass grafting with polytetrafluoroethylene grafts for symptomatic subclavian artery stenosis or occlusion: a 20-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32(3):411-418; discussion 418-419. https://doi.org/10.1067/mva.2000.108644

12. Smith JM, Koury HI, Hafner CD, Welling RE. Subclavian steal syndrome. A review of 59 consecutive cases. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1994;35(1):11-14.

A 61-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) for persistent headache that began after he fell in his bathroom 4 days earlier. He described the headache as generalized and constant, rating the severity as a 5 on a scale of 0 to 10. The patient denied any associated neck pain or changes in headache quality with position change. He reported a 3-day history of nausea and four episodes of vomiting.

Headache after a fall raises concern for intracranial hemorrhage, particularly if this patient is on anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications. Subdural hematoma (SDH) would be more likely than epidural or subarachnoid hematoma (SAH) given the duration of days without progression. While nausea and vomiting are nonspecific, persistent vomiting may indicate increased intracranial pressure (eg, from an intracranial mass or SDH), particularly if provoked by positional changes. Without a history of fever or neck stiffness, meningitis is less likely unless the patient has a history of immunosuppression. Secondary causes of headache include vascular etiologies (eg, hemorrhagic cerebrovascular accident [CVA], arterial dissection, aneurysm, vasculitis), systemic causes (eg, chronic hypoxia/hypercapnia, hypertension), or medication overuse or withdrawal. In this patient, traumatic head injury with resultant postconcussive symptoms, though a diagnosis of exclusion, should also be considered. If the patient has a history of migraines, it is essential to obtain a history of typical migraine symptoms. More information regarding the mechanism of the fall is also essential to help elucidate a potential cause.

The patient had a 1-year history of recurrent loss of consciousness resulting in falls. After each fall, he quickly regained consciousness and exhibited no residual deficits or confusion. These episodes occurred suddenly when the patient was performing normal daily activities such as walking, driving, doing light chores, and standing up from a seated position. Immediately before this most recent fall, the patient stood up from a chair, walked toward the bathroom and, without any warning signs, lost consciousness. He denied dizziness, lightheadedness, nausea, or diaphoresis immediately before or after the fall. He also reported experiencing intermittent palpitations, but these did not appear to be related to the syncopal episodes. He denied experiencing chest pain, shortness of breath, or seizures.

The differential diagnosis for syncope is broad; therefore, it is important to identify features that suggest an etiology requiring urgent management. In this patient, cardiac etiologies such as arrhythmia (eg, atrial fibrillation [AF], ventricular tachycardia, heart block), ischemia, heart failure, and structural heart disease (eg, valvular abnormalities, cardiomyopathies) must be considered. His complaints of intermittent palpitations could suggest arrhythmia; however, the absence of a correlation to the syncopal episodes and other associated cardiac symptoms makes arrhythmias such as AF less likely. Medication side effects provoking cardiac conduction disturbances, heart block, or hypotension should be considered. Ischemic heart disease and heart failure are possible causes despite the absence of chest pain and dyspnea. While the exertional nature of the patient’s symptoms could support cardiac etiologies, it could also be indicative of recurrent pulmonary embolism or right ventricular dysfunction/strain, such as chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH).

Neurologic causes of syncope should also be included in the differential diagnosis. Seizure is less likely the underlying cause in this case since the patient regained consciousness quickly after each episode and reported no residual deficits, confusion, incontinence, or oral trauma. While less likely, other neurovascular causes can be considered, including transient ischemic attack (TIA), CVA, SAH, or vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

Neurocardiogenic syncope is less likely due to lack of a clear trigger or classical prodromal symptoms. Without a history of volume loss, orthostatic syncope is also unlikely. Other possibilities include adrenal insufficiency or an autonomic dysfunction resulting from diabetic neuropathy, chronic kidney disease, amyloidosis, spinal cord injury, or neurologic diseases (eg, Parkinson disease, Lewy body dementia). Thus far, the provided history is not suggestive of these etiologies. Other causes for loss of consciousness include hypoglycemia, sleep disorders (eg, narcolepsy), or psychiatric causes.

About 10 months prior to this presentation, the patient had presented to the hospital for evaluation of headache and was found to have bilateral SDH requiring burr hole evacuation. At that time, he was on anticoagulation therapy for a history of left superficial femoral vein thrombosis with negative workup for hypercoagulability. Warfarin was discontinued after the SDH was diagnosed. Regarding the patient’s social history, although he reported drinking two glasses of wine with dinner each night and smoking marijuana afterward, all syncopal events occurred during the daytime.

The history of prior SDH should raise suspicion for recurrent SDH, particularly considering the patient’s ongoing alcohol use. History of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and possible exertional syncope might suggest recurrent pulmonary embolism or CTEPH as an etiology. DVT and TIA/CVA secondary to paradoxical embolism are also possible. Depending on extent of alcohol use, intoxication and cardiomyopathy with secondary arrhythmias are possibilities.

The basic workup should focus on identifying any acute intracranial processes that may explain the patient’s presentation and evaluating for syncope. This includes a complete blood count with differential, electrolytes, hepatic panel (based on patient’s history of alcohol use), and coagulation studies. Troponins and B-type natriuretic peptide would help assess for cardiac disease, and a urine/serum drug test would be beneficial to screen for substance use. Considering the patient’s prior history of SDH, head imaging should be obtained. If the patient were to exhibit focal neurologic deficits or persistent alterations in consciousness (thereby raising the index of suspicion for TIA or CVA), perfusion/diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies should be obtained. If obtaining a brain MRI is not practical, then a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) of the head and neck should be obtained. A noncontrast head CT would be sufficient to reveal the presence of SDH. An electroencephalogram (EEG) to assess for seizure should be performed if the patient is noted to have any focal neurologic findings or complaints consistent with seizure. With possible exertional syncope, an electrocardiogram (ECG) and transthoracic echocardiogram (with bubble study to assess for patent foramen ovale) should be obtained urgently.

The patient had a history of hypertension and irritable bowel syndrome, for which he took metoprolol and duloxetine, respectively. Eight months prior to the current ED presentation, he was admitted to the hospital for a syncope workup after falling and sustaining a fractured jaw and torn rotator cuff. ECG and continuous telemetry monitoring showed normal sinus rhythm, normal intervals, and rare episodes of sinus tachycardia, but no evidence of arrhythmia. An echocardiogram demonstrated normal ejection fraction and chamber sizes; CT and MRI of the brain showed no residual SDH; and EEG monitoring showed no seizure activity. It was determined that the patient’s syncopal episodes were multifactorial; possible etiologies included episodic hypotension from irritable bowel syndrome—related diarrhea, paroxysmal arrhythmias, and ongoing substance use.

The patient was discharged home with a 14-day Holter monitor. Rare episodes of AF (total burden 0.4%) were detected, and dronedarone was prescribed for rhythm control; he remained off anticoagulation therapy due to the history of SDH. Over the next few months, cardiology, electrophysiology, and neurology consultants concluded that paroxysmal AF was the likely etiology of the patient’s syncopal episodes. The patient was considered high risk for CVA, but the risk of bleeding from syncope-related falls was too high to resume anticoagulation therapy.

One month prior to the current ED presentation, the patient underwent a left atrial appendage closure with a WATCHMAN implant to avoid long-term anticoagulation. After the procedure, he was started on warfarin with plans to permanently discontinue anticoagulation after 6 to 8 weeks of completed therapy. He had been on warfarin for 3 weeks prior the most recent fall and current ED visit.At the time of this presentation, the patient was on dronedarone, duloxetine, metoprolol, and warfarin. On exam, he was alert and in no distress. His temperature was 36.8 °C, heart rate 98 beats per minute , blood pressure (BP) 110/75 mm Hg (with no orthostatic changes), respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 95% on room air. He had a regular heart rate and rhythm, clear lung fields, and a benign abdominal exam. He was oriented to time, place, and person. His pupils were equal in size and reactive to light, and sensation and strength were equal bilaterally with no focal neurologic deficits. His neck was supple, and head movements did not cause any symptoms. His musculoskeletal exam was notable for right supraspinatus weakness upon abduction of arm to 90° and a positive impingement sign. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm with normal intervals. Laboratory findings were notable only for an international normalized ratio of 4.9. CT of the head did not show any pathology. The patient was admitted to the medicine floor for further evaluation.

At this point in his clinical course, the patient has had a thorough workup—one that has largely been unrevealing aside from paroxysmal AF. With his current presentation, acute intracranial causes remain on the differential, but the normal CT scan essentially excludes hemorrhage or mass. Although previous MRI studies have been negative and no focal neurologic findings have been described throughout his course, given the patient’s repeated presentations for syncope, intracranial vessel imaging should be obtained to exclude anatomical abnormalities or focal stenosis that could cause recurrent TIAs.

Seizure is also a consideration, but prior EEG and normal neurologic exam makes this less likely. While cardiac workup for syncope has been reassuring, the patient’s history of AF should continue to remain a consideration even though this is less likely the underlying cause since he is now taking dronedarone. He should be placed on telemetry upon admission. While negative orthostatic vital signs make orthostatic syncope less likely, this could be confounded by use of beta-blockers. Overall, the patient’s case remains a challenging one, with the etiology of his syncope remaining unclear at this time.

During this hospitalization, possible etiologies for recurrent syncope and falls were reviewed. The burden of verifiable AF was too low to explain the patient’s recurrent syncopal episodes. Further review of his medical record revealed that a carotid ultrasound was obtained a year earlier in the course of a previous hospitalization. The ultrasound report described patent carotid arteries and retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery consistent with ipsilateral subclavian stenosis. At the time, the ultrasound was interpreted as reassuring based on the lack of significant carotid stenosis; the findings were thought to be unrelated to the patient’s syncopal episodes. On further questioning, the patient noted that minimal exertion such as unloading a few items from the dishwasher caused left arm pain and paresthesia, accompanied by headache and lightheadedness. He also reported using his left arm more frequently following a right shoulder injury. Repeat physical exam found an inter-arm systolic BP difference (IASBPD) >40 mm Hg and left-arm claudication. CT-angiogram of the neck was obtained and showed total occlusion of the left proximal subclavian artery, patent bilateral internal carotid arteries, and retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery (Figure 1).

Subclavian steal syndrome (SSS) results from compromised flow to the distal arm or brainstem circulation due to a proximal subclavian artery occlusion or stenosis (prior to the origin of the vertebral artery).1,2 Subclavian stenosis may cause lowered pressure in the distal subclavian artery, creating a gradient for blood flow from the contralateral vertebral artery through the basilar artery to the ipsilateral vertebral artery, ultimately supplying blood flow to the affected subclavian artery distal to the occlusion (subclavian steal phenomenon). Flow reversal in the vertebrobasilar system can result in hypoperfusion of the brainstem (ie, vertebrobasilar insufficiency), which can cause a variety of neurologic symptoms, including SSS. While atherosclerosis is the most common cause of subclavian steal, it may be due to other conditions (eg, Takayasu arteritis, thoracic outlet syndrome, congenital heart disease).

Clinically, although many patients with proximal subclavian stenosis are asymptomatic (even in cases wherein angiographic flow reversal is detected), it is critical that clinicians be familiar with common symptoms associated with the diagnosis. Symptoms may include arm claudication related to hypoperfusion of the extremity, particularly when performing activities, as was observed in this patient. Neurologic symptoms are less common but include symptoms consistent with compromised posterior circulation such as dizziness, vertigo, ataxia, diplopia, nystagmus, impaired vision (blurring of vision, hemianopia), otologic symptoms (tinnitus, hearing loss), and/or syncope (ie, “drop attacks”). The patient’s initial complaints of sudden syncope are consistent with this presentation, as are his history of headache and lightheadedness upon use of his left arm.

Diagnostically, a gradient in upper extremity BP >15 mm Hg (as seen in this patient) or findings of arterial insufficiency would suggest subclavian stenosis. Duplex ultrasound is a reliable imaging modality and can demonstrate proximal subclavian stenosis (sensitivity of 90.9% and specificity of 82.5% for predicting >70% of stenosis cases) and ipsilateral vertebral artery flow reversal.1 Transcranial Doppler studies can be obtained to assess for basilar artery flow reversal as well. CTA/MRA can help delineate location, severity, and cause of stenosis. However, detection of vertebral or basilar artery flow reversal does not always correlate with the development of neurologic symptoms.

For patients with asymptomatic subclavian stenosis, medical management with aspirin, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins should be considered given the high likelihood for other atherosclerotic disease. Management of SSS may include percutaneous/surgical intervention in combination with medical therapy, particularly for patients with severe symptomatic disease (arm claudication, posterior circulation deficits, or coronary ischemia in patients with history of coronary bypass utilizing the left internal mammary artery).

The patient was diagnosed with SSS. Cardiovascular medicine and vascular surgery services were asked to evaluate the patient for a revascularization procedure. Because the patient’s anterior circulation was intact, several specialists remained skeptical of SSS as the cause of his syncope. As such, further evaluation for arrhythmia was recommended. The patient’s arm claudication was thought to be due to SSS; however, the well-established retrograde flow via the vertebral artery made a revascularization procedure nonurgent. Moreover, continuation of warfarin was necessary in the setting of his recent left atrial appendage closure and prior history of DVT. It was determined that the risks of discontinuing anticoagulation in order to surgically treat his subclavian stenosis outweighed the benefits. In the meantime, brachial-radial index measurement and a 30-day event monitor were ordered to further assess for arrhythmias. The patient reported being overwhelmed by diagnostic testing without resolution of his syncopal episodes and missed some of his scheduled appointments. One month later, he fell again and sustained vertebral fractures at C1, C4, and L1, and a subsequent SDH requiring craniotomy with a bone flap followed by clot evacuation. The 30-day event monitor report did not reveal any arrhythmias before, during, or after multiple syncopal events that occurred in the period leading up to this fall. The patient later died in a neurology intensive care unit.

DISCUSSION

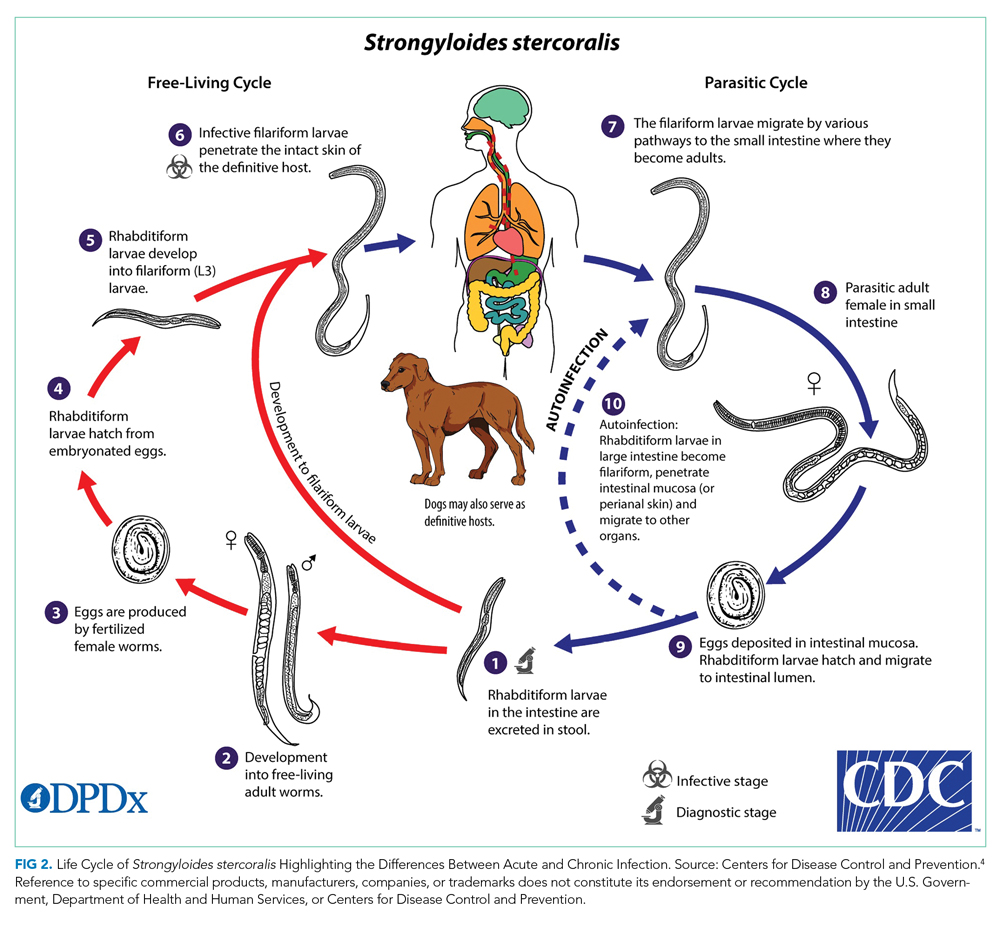

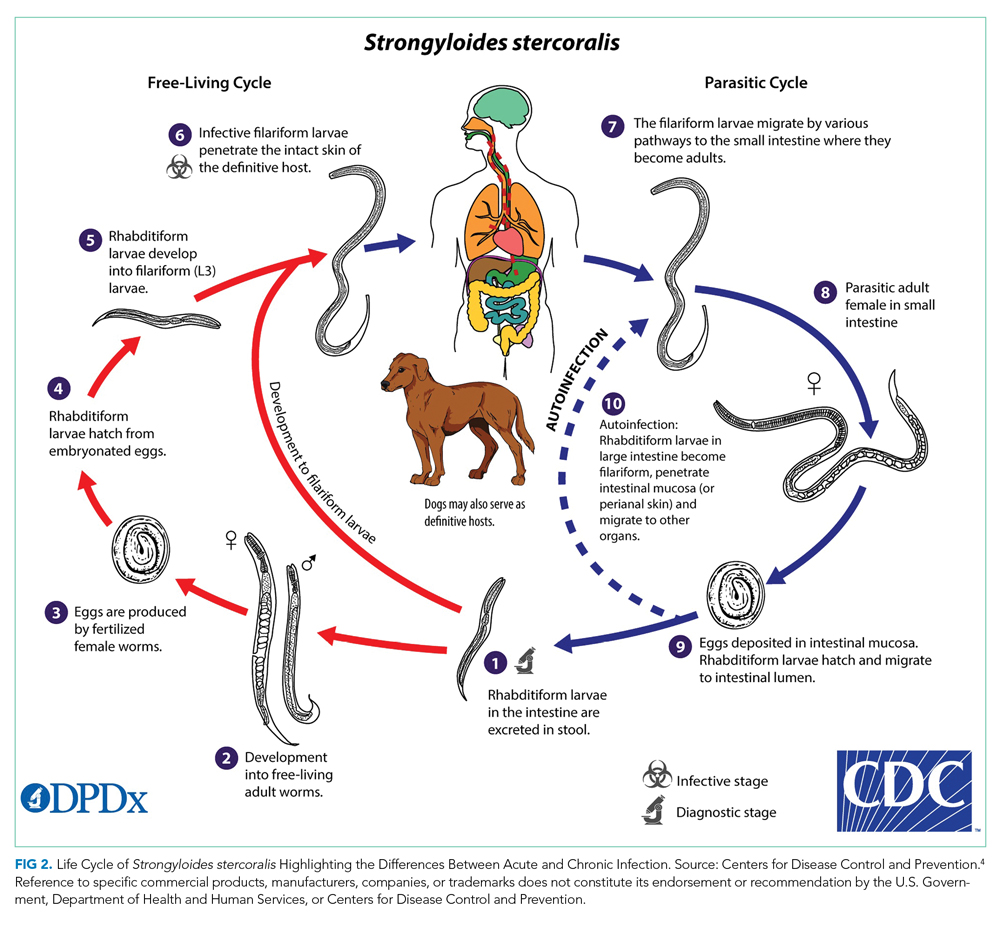

SSS often stems from atherosclerotic arterial disease that leads to stenosis or occlusion of the proximal subclavian artery, causing decreased pressure distal to the lesion. The left subclavian artery is affected more often than the right because of its acute angle of origin, which presumably causes turbulence and predisposes to atherosclerosis.3 Compromised blood flow to the arm causes exertional arm claudication and paresthesia. The compensatory retrograde flow in the ipsilateral vertebral artery causes symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency such as dizziness, vertigo, and syncope (Figure 2). This conglomerate of symptoms from subclavian steal, by definition, comprises SSS. The most remarkable signs of SSS are IASBPD >20 mm Hg and, less commonly, reproducible arm claudication.

Diagnosis of SSS requires a careful correlation of clinical history, physical examination, and radiologic findings. Over 80% of patients with subclavian disease have concomitant lesions (eg, in carotid arteries) that can affect collateral circulation.4 While symptoms of SSS may vary depending on the adequacy of collaterals, patent anterior circulation does not, by default, prevent SSS in patients with subclavian stenosis.3 In one study, neurologic symptoms were found in 36% of individuals with subclavian stenosis and concomitant carotid atherosclerotic lesions, and in only 5% in patients without carotid lesions.5

A key step in diagnosis is measurement of bilateral arm BP as elevated IASBPDs are highly sensitive for subclavian steal. More than 80% of patients with IASBPD >20 mm Hg have evidence of this condition on Doppler ultrasound.3 Higher differentials in BP correlate with occurrence of symptoms (~30% of patients with IASBPD 40-50 mm Hg, and ~40% of those with IASBPD >50 mm Hg).6

The severity of subclavian stenosis is traditionally classified by imaging into three separate grades or stages based on the direction of blood flow in vertebral arteries. Grade I involves no retrograde flow; grade II involves cardiac cycle dependent alternating antegrade and retrograde flow; and grade III involves permanent retrograde flow (complete steal).7 Our patient’s care was impacted by an unsupported conventional belief that grade II SSS may involve more hemodynamic instability and produce more severe symptoms compared to permanent retrograde flow (grade III), which would result in more stability with a reset of hemodynamics in posterior circulation.7 This hypothesis has been disproven in the past, and our patient’s tragic outcome also demonstrates that complete steal is not harmless.8 Our patient had permanent retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery, and he suffered classic symptoms of SSS, with devastating consequences. Moreover, increased demand or exertion can enhance the retrograde flow even in grade III stenosis and can precipitate neurologic symptoms of SSS, including syncope. This case provides an important lesson: Management of patients with SSS should depend on the severity of symptoms, not solely on radiologic grading.

Management of SSS is often medical for atherosclerosis and hypertension, especially if symptoms are mild and infrequent. Less than 10% patients with radiologic evidence of subclavian stenosis are symptomatic, and <20% patients with symptomatic SSS require revascularization.3 Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) and stenting have become the most favored surgical approach rather than extra-anatomic revascularization techniques.7 Both endovascular interventions and open revascularization carry an excellent success rate with low morbidity. Patients undergoing PTA have a combined rate of 3.6% for CVA and death9 and a 5-year primary patency rate10 of 82%. Bypass surgery appears similarly well tolerated, with low perioperative CVA/mortality, and a 10-year primary patency rate of 92%.11 For patients with SSS and coexisting disease in the anterior circulation, carotid endarterectomy is prioritized over subclavian revascularization as repair of the anterior circulation often resolves symptoms of SSS.12

In our patient, SSS presented with classic vertebrobasilar and brachial symptoms, but several features of his presentation made the diagnosis a challenge. First, his history suggested several potential causes of syncope, including arrhythmia, orthostatic hypotension, and substance use. Second, he reported arm paresthesia and claudication only when specifically prompted and after a targeted history was obtained. Third, there were no consistent triggers for his syncopal episodes. The patient noted that he lost consciousness when walking, driving, doing light chores, and arising from a seated position. These atypical triggers of syncope were not consistent with any of the illnesses considered during the initial workup, and therefore resulted in a broad differential, delaying the targeted workup for SSS. The wisdom of parsimony may also have played an unintended role: In clinical practice, common things are common, and explanation of most or all symptoms with a known diagnosis is often correct rather than addition of uncommon disorders.

Unfortunately, this patient kept falling through the cracks. Several providers believed that AF and alcohol use were the likely causes of his syncope. This assumption enabled a less than rigorous appraisal of the critical ultrasound report. If SSS had been on the differential, assessing the patient for the associated signs and symptoms might have led to an earlier diagnosis.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- SSS should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with syncope, especially when common diagnoses have been ruled out.

- Incidentally detected retrograde vertebral flow on ultrasound should never be dismissed, and the patients should be assessed for signs and symptoms of subclavian steal.

- A difference in inter-arm systolic blood pressure >20 mm Hg is highly suggestive of subclavian stenosis.

- SSS has excellent prognosis with appropriate medical treatment or revascularization.

A 61-year-old man presented to the emergency department (ED) for persistent headache that began after he fell in his bathroom 4 days earlier. He described the headache as generalized and constant, rating the severity as a 5 on a scale of 0 to 10. The patient denied any associated neck pain or changes in headache quality with position change. He reported a 3-day history of nausea and four episodes of vomiting.

Headache after a fall raises concern for intracranial hemorrhage, particularly if this patient is on anticoagulant or antiplatelet medications. Subdural hematoma (SDH) would be more likely than epidural or subarachnoid hematoma (SAH) given the duration of days without progression. While nausea and vomiting are nonspecific, persistent vomiting may indicate increased intracranial pressure (eg, from an intracranial mass or SDH), particularly if provoked by positional changes. Without a history of fever or neck stiffness, meningitis is less likely unless the patient has a history of immunosuppression. Secondary causes of headache include vascular etiologies (eg, hemorrhagic cerebrovascular accident [CVA], arterial dissection, aneurysm, vasculitis), systemic causes (eg, chronic hypoxia/hypercapnia, hypertension), or medication overuse or withdrawal. In this patient, traumatic head injury with resultant postconcussive symptoms, though a diagnosis of exclusion, should also be considered. If the patient has a history of migraines, it is essential to obtain a history of typical migraine symptoms. More information regarding the mechanism of the fall is also essential to help elucidate a potential cause.

The patient had a 1-year history of recurrent loss of consciousness resulting in falls. After each fall, he quickly regained consciousness and exhibited no residual deficits or confusion. These episodes occurred suddenly when the patient was performing normal daily activities such as walking, driving, doing light chores, and standing up from a seated position. Immediately before this most recent fall, the patient stood up from a chair, walked toward the bathroom and, without any warning signs, lost consciousness. He denied dizziness, lightheadedness, nausea, or diaphoresis immediately before or after the fall. He also reported experiencing intermittent palpitations, but these did not appear to be related to the syncopal episodes. He denied experiencing chest pain, shortness of breath, or seizures.

The differential diagnosis for syncope is broad; therefore, it is important to identify features that suggest an etiology requiring urgent management. In this patient, cardiac etiologies such as arrhythmia (eg, atrial fibrillation [AF], ventricular tachycardia, heart block), ischemia, heart failure, and structural heart disease (eg, valvular abnormalities, cardiomyopathies) must be considered. His complaints of intermittent palpitations could suggest arrhythmia; however, the absence of a correlation to the syncopal episodes and other associated cardiac symptoms makes arrhythmias such as AF less likely. Medication side effects provoking cardiac conduction disturbances, heart block, or hypotension should be considered. Ischemic heart disease and heart failure are possible causes despite the absence of chest pain and dyspnea. While the exertional nature of the patient’s symptoms could support cardiac etiologies, it could also be indicative of recurrent pulmonary embolism or right ventricular dysfunction/strain, such as chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH).

Neurologic causes of syncope should also be included in the differential diagnosis. Seizure is less likely the underlying cause in this case since the patient regained consciousness quickly after each episode and reported no residual deficits, confusion, incontinence, or oral trauma. While less likely, other neurovascular causes can be considered, including transient ischemic attack (TIA), CVA, SAH, or vertebrobasilar insufficiency.

Neurocardiogenic syncope is less likely due to lack of a clear trigger or classical prodromal symptoms. Without a history of volume loss, orthostatic syncope is also unlikely. Other possibilities include adrenal insufficiency or an autonomic dysfunction resulting from diabetic neuropathy, chronic kidney disease, amyloidosis, spinal cord injury, or neurologic diseases (eg, Parkinson disease, Lewy body dementia). Thus far, the provided history is not suggestive of these etiologies. Other causes for loss of consciousness include hypoglycemia, sleep disorders (eg, narcolepsy), or psychiatric causes.

About 10 months prior to this presentation, the patient had presented to the hospital for evaluation of headache and was found to have bilateral SDH requiring burr hole evacuation. At that time, he was on anticoagulation therapy for a history of left superficial femoral vein thrombosis with negative workup for hypercoagulability. Warfarin was discontinued after the SDH was diagnosed. Regarding the patient’s social history, although he reported drinking two glasses of wine with dinner each night and smoking marijuana afterward, all syncopal events occurred during the daytime.

The history of prior SDH should raise suspicion for recurrent SDH, particularly considering the patient’s ongoing alcohol use. History of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and possible exertional syncope might suggest recurrent pulmonary embolism or CTEPH as an etiology. DVT and TIA/CVA secondary to paradoxical embolism are also possible. Depending on extent of alcohol use, intoxication and cardiomyopathy with secondary arrhythmias are possibilities.

The basic workup should focus on identifying any acute intracranial processes that may explain the patient’s presentation and evaluating for syncope. This includes a complete blood count with differential, electrolytes, hepatic panel (based on patient’s history of alcohol use), and coagulation studies. Troponins and B-type natriuretic peptide would help assess for cardiac disease, and a urine/serum drug test would be beneficial to screen for substance use. Considering the patient’s prior history of SDH, head imaging should be obtained. If the patient were to exhibit focal neurologic deficits or persistent alterations in consciousness (thereby raising the index of suspicion for TIA or CVA), perfusion/diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies should be obtained. If obtaining a brain MRI is not practical, then a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) of the head and neck should be obtained. A noncontrast head CT would be sufficient to reveal the presence of SDH. An electroencephalogram (EEG) to assess for seizure should be performed if the patient is noted to have any focal neurologic findings or complaints consistent with seizure. With possible exertional syncope, an electrocardiogram (ECG) and transthoracic echocardiogram (with bubble study to assess for patent foramen ovale) should be obtained urgently.

The patient had a history of hypertension and irritable bowel syndrome, for which he took metoprolol and duloxetine, respectively. Eight months prior to the current ED presentation, he was admitted to the hospital for a syncope workup after falling and sustaining a fractured jaw and torn rotator cuff. ECG and continuous telemetry monitoring showed normal sinus rhythm, normal intervals, and rare episodes of sinus tachycardia, but no evidence of arrhythmia. An echocardiogram demonstrated normal ejection fraction and chamber sizes; CT and MRI of the brain showed no residual SDH; and EEG monitoring showed no seizure activity. It was determined that the patient’s syncopal episodes were multifactorial; possible etiologies included episodic hypotension from irritable bowel syndrome—related diarrhea, paroxysmal arrhythmias, and ongoing substance use.

The patient was discharged home with a 14-day Holter monitor. Rare episodes of AF (total burden 0.4%) were detected, and dronedarone was prescribed for rhythm control; he remained off anticoagulation therapy due to the history of SDH. Over the next few months, cardiology, electrophysiology, and neurology consultants concluded that paroxysmal AF was the likely etiology of the patient’s syncopal episodes. The patient was considered high risk for CVA, but the risk of bleeding from syncope-related falls was too high to resume anticoagulation therapy.

One month prior to the current ED presentation, the patient underwent a left atrial appendage closure with a WATCHMAN implant to avoid long-term anticoagulation. After the procedure, he was started on warfarin with plans to permanently discontinue anticoagulation after 6 to 8 weeks of completed therapy. He had been on warfarin for 3 weeks prior the most recent fall and current ED visit.At the time of this presentation, the patient was on dronedarone, duloxetine, metoprolol, and warfarin. On exam, he was alert and in no distress. His temperature was 36.8 °C, heart rate 98 beats per minute , blood pressure (BP) 110/75 mm Hg (with no orthostatic changes), respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 95% on room air. He had a regular heart rate and rhythm, clear lung fields, and a benign abdominal exam. He was oriented to time, place, and person. His pupils were equal in size and reactive to light, and sensation and strength were equal bilaterally with no focal neurologic deficits. His neck was supple, and head movements did not cause any symptoms. His musculoskeletal exam was notable for right supraspinatus weakness upon abduction of arm to 90° and a positive impingement sign. ECG showed normal sinus rhythm with normal intervals. Laboratory findings were notable only for an international normalized ratio of 4.9. CT of the head did not show any pathology. The patient was admitted to the medicine floor for further evaluation.

At this point in his clinical course, the patient has had a thorough workup—one that has largely been unrevealing aside from paroxysmal AF. With his current presentation, acute intracranial causes remain on the differential, but the normal CT scan essentially excludes hemorrhage or mass. Although previous MRI studies have been negative and no focal neurologic findings have been described throughout his course, given the patient’s repeated presentations for syncope, intracranial vessel imaging should be obtained to exclude anatomical abnormalities or focal stenosis that could cause recurrent TIAs.

Seizure is also a consideration, but prior EEG and normal neurologic exam makes this less likely. While cardiac workup for syncope has been reassuring, the patient’s history of AF should continue to remain a consideration even though this is less likely the underlying cause since he is now taking dronedarone. He should be placed on telemetry upon admission. While negative orthostatic vital signs make orthostatic syncope less likely, this could be confounded by use of beta-blockers. Overall, the patient’s case remains a challenging one, with the etiology of his syncope remaining unclear at this time.

During this hospitalization, possible etiologies for recurrent syncope and falls were reviewed. The burden of verifiable AF was too low to explain the patient’s recurrent syncopal episodes. Further review of his medical record revealed that a carotid ultrasound was obtained a year earlier in the course of a previous hospitalization. The ultrasound report described patent carotid arteries and retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery consistent with ipsilateral subclavian stenosis. At the time, the ultrasound was interpreted as reassuring based on the lack of significant carotid stenosis; the findings were thought to be unrelated to the patient’s syncopal episodes. On further questioning, the patient noted that minimal exertion such as unloading a few items from the dishwasher caused left arm pain and paresthesia, accompanied by headache and lightheadedness. He also reported using his left arm more frequently following a right shoulder injury. Repeat physical exam found an inter-arm systolic BP difference (IASBPD) >40 mm Hg and left-arm claudication. CT-angiogram of the neck was obtained and showed total occlusion of the left proximal subclavian artery, patent bilateral internal carotid arteries, and retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery (Figure 1).

Subclavian steal syndrome (SSS) results from compromised flow to the distal arm or brainstem circulation due to a proximal subclavian artery occlusion or stenosis (prior to the origin of the vertebral artery).1,2 Subclavian stenosis may cause lowered pressure in the distal subclavian artery, creating a gradient for blood flow from the contralateral vertebral artery through the basilar artery to the ipsilateral vertebral artery, ultimately supplying blood flow to the affected subclavian artery distal to the occlusion (subclavian steal phenomenon). Flow reversal in the vertebrobasilar system can result in hypoperfusion of the brainstem (ie, vertebrobasilar insufficiency), which can cause a variety of neurologic symptoms, including SSS. While atherosclerosis is the most common cause of subclavian steal, it may be due to other conditions (eg, Takayasu arteritis, thoracic outlet syndrome, congenital heart disease).

Clinically, although many patients with proximal subclavian stenosis are asymptomatic (even in cases wherein angiographic flow reversal is detected), it is critical that clinicians be familiar with common symptoms associated with the diagnosis. Symptoms may include arm claudication related to hypoperfusion of the extremity, particularly when performing activities, as was observed in this patient. Neurologic symptoms are less common but include symptoms consistent with compromised posterior circulation such as dizziness, vertigo, ataxia, diplopia, nystagmus, impaired vision (blurring of vision, hemianopia), otologic symptoms (tinnitus, hearing loss), and/or syncope (ie, “drop attacks”). The patient’s initial complaints of sudden syncope are consistent with this presentation, as are his history of headache and lightheadedness upon use of his left arm.

Diagnostically, a gradient in upper extremity BP >15 mm Hg (as seen in this patient) or findings of arterial insufficiency would suggest subclavian stenosis. Duplex ultrasound is a reliable imaging modality and can demonstrate proximal subclavian stenosis (sensitivity of 90.9% and specificity of 82.5% for predicting >70% of stenosis cases) and ipsilateral vertebral artery flow reversal.1 Transcranial Doppler studies can be obtained to assess for basilar artery flow reversal as well. CTA/MRA can help delineate location, severity, and cause of stenosis. However, detection of vertebral or basilar artery flow reversal does not always correlate with the development of neurologic symptoms.

For patients with asymptomatic subclavian stenosis, medical management with aspirin, beta-blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and statins should be considered given the high likelihood for other atherosclerotic disease. Management of SSS may include percutaneous/surgical intervention in combination with medical therapy, particularly for patients with severe symptomatic disease (arm claudication, posterior circulation deficits, or coronary ischemia in patients with history of coronary bypass utilizing the left internal mammary artery).

The patient was diagnosed with SSS. Cardiovascular medicine and vascular surgery services were asked to evaluate the patient for a revascularization procedure. Because the patient’s anterior circulation was intact, several specialists remained skeptical of SSS as the cause of his syncope. As such, further evaluation for arrhythmia was recommended. The patient’s arm claudication was thought to be due to SSS; however, the well-established retrograde flow via the vertebral artery made a revascularization procedure nonurgent. Moreover, continuation of warfarin was necessary in the setting of his recent left atrial appendage closure and prior history of DVT. It was determined that the risks of discontinuing anticoagulation in order to surgically treat his subclavian stenosis outweighed the benefits. In the meantime, brachial-radial index measurement and a 30-day event monitor were ordered to further assess for arrhythmias. The patient reported being overwhelmed by diagnostic testing without resolution of his syncopal episodes and missed some of his scheduled appointments. One month later, he fell again and sustained vertebral fractures at C1, C4, and L1, and a subsequent SDH requiring craniotomy with a bone flap followed by clot evacuation. The 30-day event monitor report did not reveal any arrhythmias before, during, or after multiple syncopal events that occurred in the period leading up to this fall. The patient later died in a neurology intensive care unit.

DISCUSSION

SSS often stems from atherosclerotic arterial disease that leads to stenosis or occlusion of the proximal subclavian artery, causing decreased pressure distal to the lesion. The left subclavian artery is affected more often than the right because of its acute angle of origin, which presumably causes turbulence and predisposes to atherosclerosis.3 Compromised blood flow to the arm causes exertional arm claudication and paresthesia. The compensatory retrograde flow in the ipsilateral vertebral artery causes symptoms of vertebrobasilar insufficiency such as dizziness, vertigo, and syncope (Figure 2). This conglomerate of symptoms from subclavian steal, by definition, comprises SSS. The most remarkable signs of SSS are IASBPD >20 mm Hg and, less commonly, reproducible arm claudication.

Diagnosis of SSS requires a careful correlation of clinical history, physical examination, and radiologic findings. Over 80% of patients with subclavian disease have concomitant lesions (eg, in carotid arteries) that can affect collateral circulation.4 While symptoms of SSS may vary depending on the adequacy of collaterals, patent anterior circulation does not, by default, prevent SSS in patients with subclavian stenosis.3 In one study, neurologic symptoms were found in 36% of individuals with subclavian stenosis and concomitant carotid atherosclerotic lesions, and in only 5% in patients without carotid lesions.5

A key step in diagnosis is measurement of bilateral arm BP as elevated IASBPDs are highly sensitive for subclavian steal. More than 80% of patients with IASBPD >20 mm Hg have evidence of this condition on Doppler ultrasound.3 Higher differentials in BP correlate with occurrence of symptoms (~30% of patients with IASBPD 40-50 mm Hg, and ~40% of those with IASBPD >50 mm Hg).6

The severity of subclavian stenosis is traditionally classified by imaging into three separate grades or stages based on the direction of blood flow in vertebral arteries. Grade I involves no retrograde flow; grade II involves cardiac cycle dependent alternating antegrade and retrograde flow; and grade III involves permanent retrograde flow (complete steal).7 Our patient’s care was impacted by an unsupported conventional belief that grade II SSS may involve more hemodynamic instability and produce more severe symptoms compared to permanent retrograde flow (grade III), which would result in more stability with a reset of hemodynamics in posterior circulation.7 This hypothesis has been disproven in the past, and our patient’s tragic outcome also demonstrates that complete steal is not harmless.8 Our patient had permanent retrograde flow in the left vertebral artery, and he suffered classic symptoms of SSS, with devastating consequences. Moreover, increased demand or exertion can enhance the retrograde flow even in grade III stenosis and can precipitate neurologic symptoms of SSS, including syncope. This case provides an important lesson: Management of patients with SSS should depend on the severity of symptoms, not solely on radiologic grading.

Management of SSS is often medical for atherosclerosis and hypertension, especially if symptoms are mild and infrequent. Less than 10% patients with radiologic evidence of subclavian stenosis are symptomatic, and <20% patients with symptomatic SSS require revascularization.3 Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) and stenting have become the most favored surgical approach rather than extra-anatomic revascularization techniques.7 Both endovascular interventions and open revascularization carry an excellent success rate with low morbidity. Patients undergoing PTA have a combined rate of 3.6% for CVA and death9 and a 5-year primary patency rate10 of 82%. Bypass surgery appears similarly well tolerated, with low perioperative CVA/mortality, and a 10-year primary patency rate of 92%.11 For patients with SSS and coexisting disease in the anterior circulation, carotid endarterectomy is prioritized over subclavian revascularization as repair of the anterior circulation often resolves symptoms of SSS.12

In our patient, SSS presented with classic vertebrobasilar and brachial symptoms, but several features of his presentation made the diagnosis a challenge. First, his history suggested several potential causes of syncope, including arrhythmia, orthostatic hypotension, and substance use. Second, he reported arm paresthesia and claudication only when specifically prompted and after a targeted history was obtained. Third, there were no consistent triggers for his syncopal episodes. The patient noted that he lost consciousness when walking, driving, doing light chores, and arising from a seated position. These atypical triggers of syncope were not consistent with any of the illnesses considered during the initial workup, and therefore resulted in a broad differential, delaying the targeted workup for SSS. The wisdom of parsimony may also have played an unintended role: In clinical practice, common things are common, and explanation of most or all symptoms with a known diagnosis is often correct rather than addition of uncommon disorders.

Unfortunately, this patient kept falling through the cracks. Several providers believed that AF and alcohol use were the likely causes of his syncope. This assumption enabled a less than rigorous appraisal of the critical ultrasound report. If SSS had been on the differential, assessing the patient for the associated signs and symptoms might have led to an earlier diagnosis.

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- SSS should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with syncope, especially when common diagnoses have been ruled out.

- Incidentally detected retrograde vertebral flow on ultrasound should never be dismissed, and the patients should be assessed for signs and symptoms of subclavian steal.

- A difference in inter-arm systolic blood pressure >20 mm Hg is highly suggestive of subclavian stenosis.

- SSS has excellent prognosis with appropriate medical treatment or revascularization.

1. Mousa AY, Morkous R, Broce M, et al. Validation of subclavian duplex velocity criteria to grade severity of subclavian artery stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65(6):1779-1785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2016.12.098

2. Potter BJ, Pinto DS. Subclavian steal syndrome. Circulation. 2014;129(22):2320-2323. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.113.006653

3. Labropoulos N, Nandivada P, Bekelis K. Prevalence and impact of the subclavian steal syndrome. Ann Surg. 2010;252(1):166-170. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0b013e3181e3375a

4. Fields WS, Lemak NA. Joint study of extracranial arterial occlusion. VII. Subclavian steal--a review of 168 cases. JAMA. 1972;222(9):1139-1143. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1972.03210090019004

5. Hennerici M, Klemm C, Rautenberg W. The subclavian steal phenomenon: a common vascular disorder with rare neurologic deficits. Neurology. 1988;38(5): 669-673. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.38.5.669

6. Clark CE, Taylor RS, Shore AC, Ukoumunne OC, Campbell JL. Association of a difference in systolic blood pressure between arms with vascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9819):905-914. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61710-8

7. Osiro S, Zurada A, Gielecki J, Shoja MM, Tubbs RS, Loukas M. A review of subclavian steal syndrome with clinical correlation. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(5):RA57-RA63. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.882721

8. Thomassen L, Aarli JA. Subclavian steal phenomenon. Clinical and hemodynamic aspects. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;90(4):241-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb02714.x

9. De Vries JP, Jager LC, Van den Berg JC, et al. Durability of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for obstructive lesions of proximal subclavian artery: long-term results. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(1):19-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2004.09.030

10. Wang KQ, Wang ZG, Yang BZ, et al. Long-term results of endovascular therapy for proximal subclavian arterial obstructive lesions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123(1):45-50. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2010.01.008

11. AbuRahma AF, Robinson PA, Jennings TG. Carotid-subclavian bypass grafting with polytetrafluoroethylene grafts for symptomatic subclavian artery stenosis or occlusion: a 20-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32(3):411-418; discussion 418-419. https://doi.org/10.1067/mva.2000.108644

12. Smith JM, Koury HI, Hafner CD, Welling RE. Subclavian steal syndrome. A review of 59 consecutive cases. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1994;35(1):11-14.

1. Mousa AY, Morkous R, Broce M, et al. Validation of subclavian duplex velocity criteria to grade severity of subclavian artery stenosis. J Vasc Surg. 2017;65(6):1779-1785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2016.12.098

2. Potter BJ, Pinto DS. Subclavian steal syndrome. Circulation. 2014;129(22):2320-2323. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.113.006653

3. Labropoulos N, Nandivada P, Bekelis K. Prevalence and impact of the subclavian steal syndrome. Ann Surg. 2010;252(1):166-170. https://doi.org/10.1097/sla.0b013e3181e3375a

4. Fields WS, Lemak NA. Joint study of extracranial arterial occlusion. VII. Subclavian steal--a review of 168 cases. JAMA. 1972;222(9):1139-1143. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1972.03210090019004

5. Hennerici M, Klemm C, Rautenberg W. The subclavian steal phenomenon: a common vascular disorder with rare neurologic deficits. Neurology. 1988;38(5): 669-673. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.38.5.669

6. Clark CE, Taylor RS, Shore AC, Ukoumunne OC, Campbell JL. Association of a difference in systolic blood pressure between arms with vascular disease and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9819):905-914. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61710-8

7. Osiro S, Zurada A, Gielecki J, Shoja MM, Tubbs RS, Loukas M. A review of subclavian steal syndrome with clinical correlation. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18(5):RA57-RA63. https://doi.org/10.12659/msm.882721

8. Thomassen L, Aarli JA. Subclavian steal phenomenon. Clinical and hemodynamic aspects. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;90(4):241-244. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.1994.tb02714.x

9. De Vries JP, Jager LC, Van den Berg JC, et al. Durability of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for obstructive lesions of proximal subclavian artery: long-term results. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41(1):19-23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvs.2004.09.030

10. Wang KQ, Wang ZG, Yang BZ, et al. Long-term results of endovascular therapy for proximal subclavian arterial obstructive lesions. Chin Med J (Engl). 2010;123(1):45-50. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.2010.01.008

11. AbuRahma AF, Robinson PA, Jennings TG. Carotid-subclavian bypass grafting with polytetrafluoroethylene grafts for symptomatic subclavian artery stenosis or occlusion: a 20-year experience. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32(3):411-418; discussion 418-419. https://doi.org/10.1067/mva.2000.108644

12. Smith JM, Koury HI, Hafner CD, Welling RE. Subclavian steal syndrome. A review of 59 consecutive cases. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1994;35(1):11-14.

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Buried Deep

This icon represents the patient’s case. Each paragraph that follows represents the discussant’s thoughts.

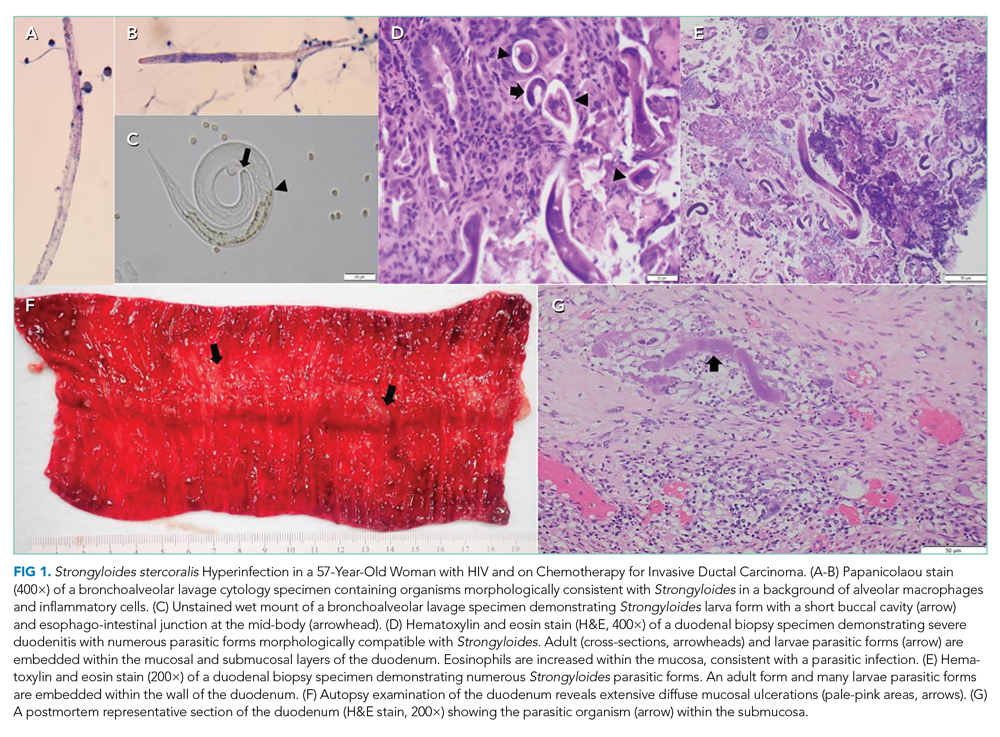

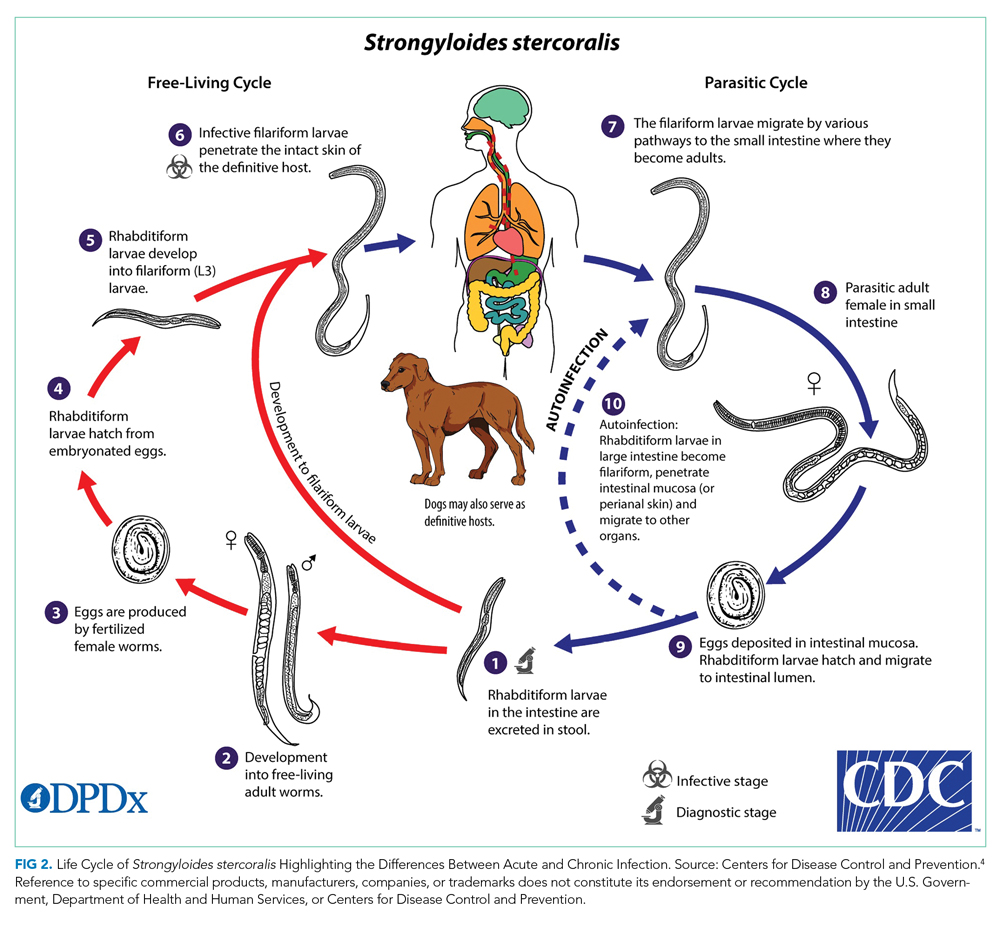

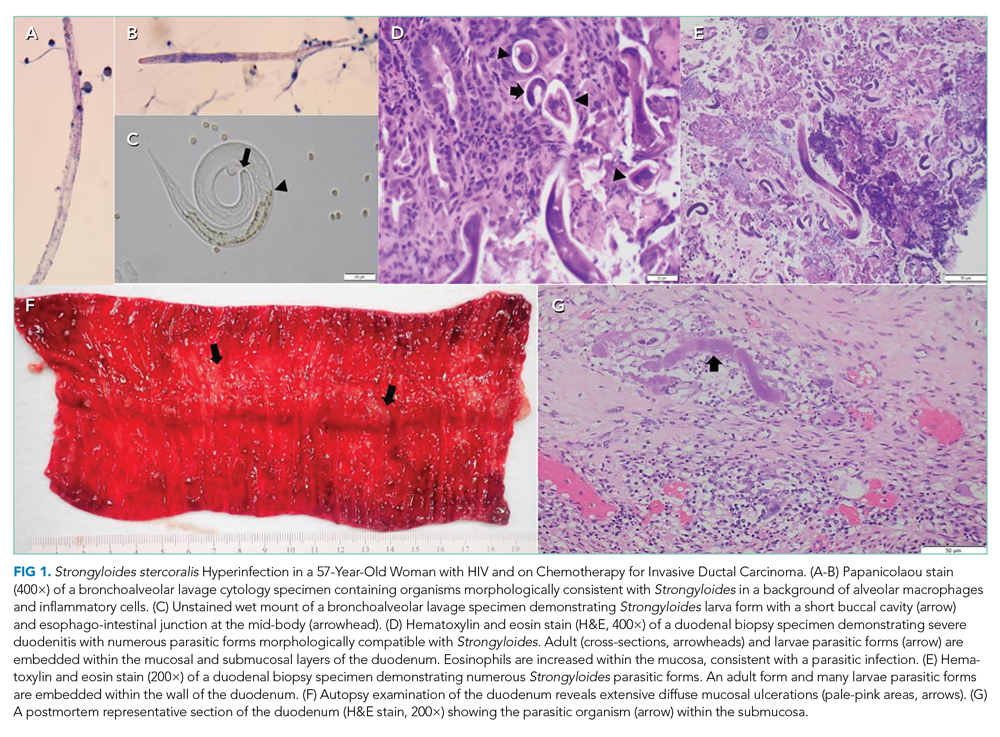

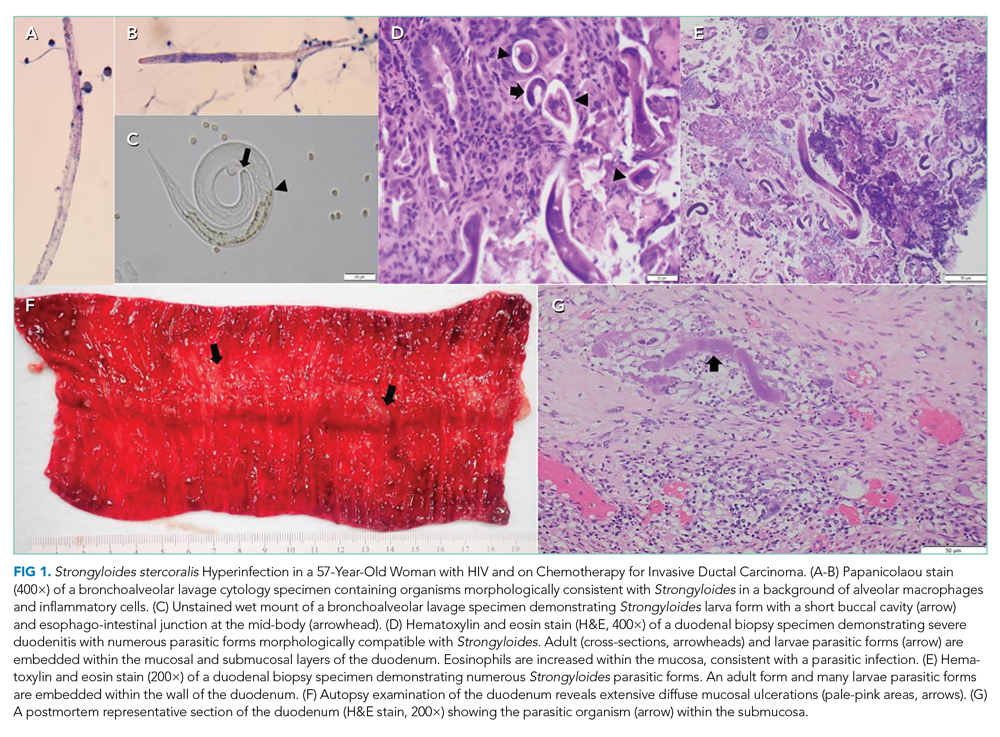

A 56-year-old-woman with a history of HIV and locally invasive ductal carcinoma recently treated with mastectomy and adjuvant doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide, now on paclitaxel, was transferred from another hospital with worsening nausea, epigastric pain, and dyspnea. She had been admitted multiple times to both this hospital and another hospital and had extensive workup over the previous 2 months for gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding and progressive dyspnea with orthopnea and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea in the setting of a documented 43-lb weight loss.

Her past medical history was otherwise significant only for the events of the previous few months. Eight months earlier, she was diagnosed with grade 3 triple-negative (estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2) invasive ductal carcinoma and underwent mastectomy with negative sentinel lymph node biopsy. She completed four cycles of adjuvant doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide and most recently completed cycle three of paclitaxel chemotherapy.

Her HIV disease was controlled with an antiretroviral regimen of dolutegravir/rilpivirine. She had an undetectable viral load for 20 years (CD4, 239 cells/μL 2 weeks prior to transfer).

Her social history included a 1-pack-year smoking history. She denied alcohol or illicit drug use. Family history included pancreatic cancer in her father and endometrial cancer in her paternal grandmother. She was originally from Mexico but moved to Illinois 27 years earlier.

Work-up for her dyspnea was initiated 7 weeks earlier: noncontrast CT of the chest showed extensive diffuse interstitial thickening and ground-glass opacities bilaterally. Bronchoscopy showed no gross abnormalities, and bronchial washings were negative for bacteria, fungi, Pneumocystis jirovecii , acid-fast bacilli, and cancer. She also had a TTE, which showed an ejection fraction of 65% to 70% and was only significant for a pulmonary artery systolic pressure of 45 mm Hg . She was diagnosed with paclitaxel-induced pneumonitis and was discharged home with prednisone 50 mg daily, dapsone, pantoprazole, and 2 L oxygen via nasal cannula.

Two weeks later, she was admitted for coffee-ground emesis and epigastric pain. Her hemoglobin was 5.9 g/dL, for which she was transfused 3 units of packed red blood cells. EGD showed bleeding from diffuse duodenitis, which was treated with argon plasma coagulation. She was also found to have bilateral pulmonary emboli and lower-extremity deep venous thromboses. An inferior vena cava filter was placed, and she was discharged. One week later, she was readmitted with melena, and repeat EGD showed multiple duodenal ulcers with no active bleeding. Colonoscopy was normal. She was continued on prednisone 40 mg daily, as any attempts at tapering the dose resulted in hypotension.