User login

Common outcome measures for AD lack adequate reporting of race, skin tone

, according to results from a systematic review.

“AD is associated with considerable heterogeneity across different races and skin tones,” presenting study author Trisha Kaundinya said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis symposium. “Compared with lighter skin tones, darker skin tones more commonly have diffuse xerosis, Dennis-Morgan lines, hyperlinearity of the palms, periorbital dark circles, lichenification, and prurigo nodularis. This heterogeneity can be challenging to assess in clinical trials and in practice.”

The Harmonizing Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) group has selected several scales by international consensus. For clinical trials, the group recommends the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). In clinical practice, the HOME group recommends the POEM, Patient-Oriented Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (PO-SCORAD), and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)-itch measures. “The psychometric validity and reliability of these outcome measures have undergone robust investigation before, but the validity and reliability of these outcome measures remains uncertain across different races, ethnicities, and skin tones,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, in collaboration with Andrew F. Alexis, MD, MPH, vice-chair for diversity and inclusion for the department of dermatology at Weill-Cornell Medicine, New York, and Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD, at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, sought to examine reporting of race, ethnicity, and skin tone, and to compare results across these groups from studies of psychometric properties for outcome measures in AD. Under the mentorship of Dr. Silverberg, Ms. Kaundinya, a medical student at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her research associates conducted a systematic review that searched PubMed and Embase and identified 165 relevant published studies of 41,146 individuals.

Of the individuals participating in these 165 studies, 73% had an unspecified racial background, 18% were White, 4% were Asian, 2% were Black, 2% were Hispanic, 1% were multiracial/other, and the remainder were American Indian/Alaskan Native. Only 55 of the studies (33%) reported the distribution of race or ethnicity, 5 (3%) reported the distribution of skin tone, and 16 (10%) reported psychometric differences in patients with different races, ethnicities, or skin tones. In addition, only 5 of 113 (4%) studies that did not report race, ethnicity, or skin tone–based differences acknowledged absence of stratification as a limitation.

Of note, significant differential item functioning was found between race subgroups for one or more items of the PO-SCORAD, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Itch Questionnaire (PIQ) Short Forms, POEM, DLQI, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Itchy Quality of Life (ItchyQOL) scale, 5-dimensions (5D) itch scale, Short Form (SF)-12, and NRS-itch. “Correlations of the POEM with the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) differed the most between skin of color and lighter skin,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

“The POEM did seem to correlate similarly with the DLQI and the EASI in both white and nonwhite participants, which may indicate why this trifecta of instruments is recommended by the HOME group. One study found that substituting the erythema component of the EASI scale with greyness for darker skin, in which erythema is more challenging to assess, did not significantly improve the reliability of EASI. This indicates that further research is needed to investigate how EASI can be modified to perform better in darker skin tones.”

She pointed out that some studies of clinician-reported outcome measures were underpowered to detect meaningful differences between patient subgroups. “There were also insufficient data to perform meta-regression of differences between patient subgroups,” she said. “Overall, future studies are needed to determine whether outcome measures recommended by the HOME and other tools perform equally well across diverse patient populations. This systematic review indicates significant reporting and knowledge gaps for psychometric properties of outcome measures by race, ethnicity, or skin tone in AD.”

Ms. Kaundinya reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Silverberg, the study’s senior author, is a consultant to and/or an advisory board member for several pharmaceutical companies. He is also a speaker for Regeneron and Sanofi and has received a grant from Galderma.

, according to results from a systematic review.

“AD is associated with considerable heterogeneity across different races and skin tones,” presenting study author Trisha Kaundinya said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis symposium. “Compared with lighter skin tones, darker skin tones more commonly have diffuse xerosis, Dennis-Morgan lines, hyperlinearity of the palms, periorbital dark circles, lichenification, and prurigo nodularis. This heterogeneity can be challenging to assess in clinical trials and in practice.”

The Harmonizing Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) group has selected several scales by international consensus. For clinical trials, the group recommends the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). In clinical practice, the HOME group recommends the POEM, Patient-Oriented Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (PO-SCORAD), and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)-itch measures. “The psychometric validity and reliability of these outcome measures have undergone robust investigation before, but the validity and reliability of these outcome measures remains uncertain across different races, ethnicities, and skin tones,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, in collaboration with Andrew F. Alexis, MD, MPH, vice-chair for diversity and inclusion for the department of dermatology at Weill-Cornell Medicine, New York, and Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD, at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, sought to examine reporting of race, ethnicity, and skin tone, and to compare results across these groups from studies of psychometric properties for outcome measures in AD. Under the mentorship of Dr. Silverberg, Ms. Kaundinya, a medical student at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her research associates conducted a systematic review that searched PubMed and Embase and identified 165 relevant published studies of 41,146 individuals.

Of the individuals participating in these 165 studies, 73% had an unspecified racial background, 18% were White, 4% were Asian, 2% were Black, 2% were Hispanic, 1% were multiracial/other, and the remainder were American Indian/Alaskan Native. Only 55 of the studies (33%) reported the distribution of race or ethnicity, 5 (3%) reported the distribution of skin tone, and 16 (10%) reported psychometric differences in patients with different races, ethnicities, or skin tones. In addition, only 5 of 113 (4%) studies that did not report race, ethnicity, or skin tone–based differences acknowledged absence of stratification as a limitation.

Of note, significant differential item functioning was found between race subgroups for one or more items of the PO-SCORAD, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Itch Questionnaire (PIQ) Short Forms, POEM, DLQI, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Itchy Quality of Life (ItchyQOL) scale, 5-dimensions (5D) itch scale, Short Form (SF)-12, and NRS-itch. “Correlations of the POEM with the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) differed the most between skin of color and lighter skin,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

“The POEM did seem to correlate similarly with the DLQI and the EASI in both white and nonwhite participants, which may indicate why this trifecta of instruments is recommended by the HOME group. One study found that substituting the erythema component of the EASI scale with greyness for darker skin, in which erythema is more challenging to assess, did not significantly improve the reliability of EASI. This indicates that further research is needed to investigate how EASI can be modified to perform better in darker skin tones.”

She pointed out that some studies of clinician-reported outcome measures were underpowered to detect meaningful differences between patient subgroups. “There were also insufficient data to perform meta-regression of differences between patient subgroups,” she said. “Overall, future studies are needed to determine whether outcome measures recommended by the HOME and other tools perform equally well across diverse patient populations. This systematic review indicates significant reporting and knowledge gaps for psychometric properties of outcome measures by race, ethnicity, or skin tone in AD.”

Ms. Kaundinya reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Silverberg, the study’s senior author, is a consultant to and/or an advisory board member for several pharmaceutical companies. He is also a speaker for Regeneron and Sanofi and has received a grant from Galderma.

, according to results from a systematic review.

“AD is associated with considerable heterogeneity across different races and skin tones,” presenting study author Trisha Kaundinya said at the Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatitis symposium. “Compared with lighter skin tones, darker skin tones more commonly have diffuse xerosis, Dennis-Morgan lines, hyperlinearity of the palms, periorbital dark circles, lichenification, and prurigo nodularis. This heterogeneity can be challenging to assess in clinical trials and in practice.”

The Harmonizing Outcome Measures for Eczema (HOME) group has selected several scales by international consensus. For clinical trials, the group recommends the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM), Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI), and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). In clinical practice, the HOME group recommends the POEM, Patient-Oriented Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (PO-SCORAD), and the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS)-itch measures. “The psychometric validity and reliability of these outcome measures have undergone robust investigation before, but the validity and reliability of these outcome measures remains uncertain across different races, ethnicities, and skin tones,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

Jonathan Silverberg, MD, PhD, associate professor of dermatology at George Washington University, Washington, in collaboration with Andrew F. Alexis, MD, MPH, vice-chair for diversity and inclusion for the department of dermatology at Weill-Cornell Medicine, New York, and Jacob P. Thyssen, MD, PhD, at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, sought to examine reporting of race, ethnicity, and skin tone, and to compare results across these groups from studies of psychometric properties for outcome measures in AD. Under the mentorship of Dr. Silverberg, Ms. Kaundinya, a medical student at Northwestern University, Chicago, and her research associates conducted a systematic review that searched PubMed and Embase and identified 165 relevant published studies of 41,146 individuals.

Of the individuals participating in these 165 studies, 73% had an unspecified racial background, 18% were White, 4% were Asian, 2% were Black, 2% were Hispanic, 1% were multiracial/other, and the remainder were American Indian/Alaskan Native. Only 55 of the studies (33%) reported the distribution of race or ethnicity, 5 (3%) reported the distribution of skin tone, and 16 (10%) reported psychometric differences in patients with different races, ethnicities, or skin tones. In addition, only 5 of 113 (4%) studies that did not report race, ethnicity, or skin tone–based differences acknowledged absence of stratification as a limitation.

Of note, significant differential item functioning was found between race subgroups for one or more items of the PO-SCORAD, the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Itch Questionnaire (PIQ) Short Forms, POEM, DLQI, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Itchy Quality of Life (ItchyQOL) scale, 5-dimensions (5D) itch scale, Short Form (SF)-12, and NRS-itch. “Correlations of the POEM with the Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) differed the most between skin of color and lighter skin,” Ms. Kaundinya said.

“The POEM did seem to correlate similarly with the DLQI and the EASI in both white and nonwhite participants, which may indicate why this trifecta of instruments is recommended by the HOME group. One study found that substituting the erythema component of the EASI scale with greyness for darker skin, in which erythema is more challenging to assess, did not significantly improve the reliability of EASI. This indicates that further research is needed to investigate how EASI can be modified to perform better in darker skin tones.”

She pointed out that some studies of clinician-reported outcome measures were underpowered to detect meaningful differences between patient subgroups. “There were also insufficient data to perform meta-regression of differences between patient subgroups,” she said. “Overall, future studies are needed to determine whether outcome measures recommended by the HOME and other tools perform equally well across diverse patient populations. This systematic review indicates significant reporting and knowledge gaps for psychometric properties of outcome measures by race, ethnicity, or skin tone in AD.”

Ms. Kaundinya reported having no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Silverberg, the study’s senior author, is a consultant to and/or an advisory board member for several pharmaceutical companies. He is also a speaker for Regeneron and Sanofi and has received a grant from Galderma.

FROM REVOLUTIONIZING AD 2021

MDs rebut claims of toxic culture after resident suicides

The tragic loss of three medical residents in our beloved South Bronx hospital shook us to the core. They were our colleagues and friends – promising young physicians whose lives and contributions to our hospital family will never be forgotten. We miss them and we grieve them.

We have been keenly aware of the growing trend of physician suicides across the country. That’s one of the reasons why, years ago, we established the nationally recognized Helping Healers Heal program across our health system and more recently expanded other mental health counseling and support to our frontline clinicians.

Our focus is wellness and prevention, as well as helping address the sadness, anxiety, and depression that so many of us experience after a traumatic event. During the surge of the COVID pandemic, these programs proved to be essential, as we expanded these services to all staff, not just those on the frontlines of patient care.

We share Dr. Pamela Wible’s concerns about the physician suicide crisis in this country. However, she misrepresented our residency program and made numerous statements that are false and simply hurtful.

Out of respect for our colleagues and their families, we cannot share everything that we know about this tragic and irreparable loss. But we must set the record straight about a number of incorrect references made by Dr. Wible:

1. We lost two residents to suicide. Though no less horrific, the third death was investigated and declared an accident by the police department.

2. Resident work hours and workload are closely monitored to follow guidance set by the New York State Department of Health and by ACGME. In fact, at the peak of the COVID pandemic, when we were caring for nearly 130 intubated patients at a time, we adopted a strict residency program schedule with built-in breaks and reduced shifts and hours. Even at that tasking time, no one worked more than 80 hours. Although the maximum number of patients assigned to an intern allowed by ACGME is 10, we rarely have more than five or six patients assigned to each of our interns.

3. We swiftly investigate any allegation and do not hesitate to take the appropriate action against anyone who does not honor our values of professionalism and respect.

4. Our ACGME survey results are close to the mean of all internal medicine residency programs in the country. The fact that the results range from 75% to 95% clearly indicates that residents respond independently, and there is no coaching.

5. No resident has ever been threatened to have their visa canceled or withdrawn. Never. And the implication that we were intolerant because of their nationality is reprehensible. At NYC Health + Hospitals, we celebrate diversity. We are deeply committed to serving everyone, regardless of where they come from, what language they speak, what religion they practice. If you spend one day, or one hour, in our facility, you will see and feel our pride and commitment to this mission. We take pride in the fact that our staff and residents reflect the diversity of the community we serve.

6. As for the allegations of “toxic culture at Lincoln” – many of our graduates chose to stay on as attendings, serve the local community, and train new residents. Out of the 67 attendings in our department, 24 are former graduates. They are being joined by another five graduates from this year’s graduating class. There is no better testament to how our graduates feel about our residency program, Department of Medicine, and Lincoln Hospital.

Dr. Wible poses a legitimate question: How to prevent another suicide. No one has the exact answer. But it is a question we will keep asking ourselves as we continue to do all we can to meet our residents’ needs, extend the social and mental health support they need to thrive, and provide the learning and training they need to offer the best care to our patients.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The tragic loss of three medical residents in our beloved South Bronx hospital shook us to the core. They were our colleagues and friends – promising young physicians whose lives and contributions to our hospital family will never be forgotten. We miss them and we grieve them.

We have been keenly aware of the growing trend of physician suicides across the country. That’s one of the reasons why, years ago, we established the nationally recognized Helping Healers Heal program across our health system and more recently expanded other mental health counseling and support to our frontline clinicians.

Our focus is wellness and prevention, as well as helping address the sadness, anxiety, and depression that so many of us experience after a traumatic event. During the surge of the COVID pandemic, these programs proved to be essential, as we expanded these services to all staff, not just those on the frontlines of patient care.

We share Dr. Pamela Wible’s concerns about the physician suicide crisis in this country. However, she misrepresented our residency program and made numerous statements that are false and simply hurtful.

Out of respect for our colleagues and their families, we cannot share everything that we know about this tragic and irreparable loss. But we must set the record straight about a number of incorrect references made by Dr. Wible:

1. We lost two residents to suicide. Though no less horrific, the third death was investigated and declared an accident by the police department.

2. Resident work hours and workload are closely monitored to follow guidance set by the New York State Department of Health and by ACGME. In fact, at the peak of the COVID pandemic, when we were caring for nearly 130 intubated patients at a time, we adopted a strict residency program schedule with built-in breaks and reduced shifts and hours. Even at that tasking time, no one worked more than 80 hours. Although the maximum number of patients assigned to an intern allowed by ACGME is 10, we rarely have more than five or six patients assigned to each of our interns.

3. We swiftly investigate any allegation and do not hesitate to take the appropriate action against anyone who does not honor our values of professionalism and respect.

4. Our ACGME survey results are close to the mean of all internal medicine residency programs in the country. The fact that the results range from 75% to 95% clearly indicates that residents respond independently, and there is no coaching.

5. No resident has ever been threatened to have their visa canceled or withdrawn. Never. And the implication that we were intolerant because of their nationality is reprehensible. At NYC Health + Hospitals, we celebrate diversity. We are deeply committed to serving everyone, regardless of where they come from, what language they speak, what religion they practice. If you spend one day, or one hour, in our facility, you will see and feel our pride and commitment to this mission. We take pride in the fact that our staff and residents reflect the diversity of the community we serve.

6. As for the allegations of “toxic culture at Lincoln” – many of our graduates chose to stay on as attendings, serve the local community, and train new residents. Out of the 67 attendings in our department, 24 are former graduates. They are being joined by another five graduates from this year’s graduating class. There is no better testament to how our graduates feel about our residency program, Department of Medicine, and Lincoln Hospital.

Dr. Wible poses a legitimate question: How to prevent another suicide. No one has the exact answer. But it is a question we will keep asking ourselves as we continue to do all we can to meet our residents’ needs, extend the social and mental health support they need to thrive, and provide the learning and training they need to offer the best care to our patients.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The tragic loss of three medical residents in our beloved South Bronx hospital shook us to the core. They were our colleagues and friends – promising young physicians whose lives and contributions to our hospital family will never be forgotten. We miss them and we grieve them.

We have been keenly aware of the growing trend of physician suicides across the country. That’s one of the reasons why, years ago, we established the nationally recognized Helping Healers Heal program across our health system and more recently expanded other mental health counseling and support to our frontline clinicians.

Our focus is wellness and prevention, as well as helping address the sadness, anxiety, and depression that so many of us experience after a traumatic event. During the surge of the COVID pandemic, these programs proved to be essential, as we expanded these services to all staff, not just those on the frontlines of patient care.

We share Dr. Pamela Wible’s concerns about the physician suicide crisis in this country. However, she misrepresented our residency program and made numerous statements that are false and simply hurtful.

Out of respect for our colleagues and their families, we cannot share everything that we know about this tragic and irreparable loss. But we must set the record straight about a number of incorrect references made by Dr. Wible:

1. We lost two residents to suicide. Though no less horrific, the third death was investigated and declared an accident by the police department.

2. Resident work hours and workload are closely monitored to follow guidance set by the New York State Department of Health and by ACGME. In fact, at the peak of the COVID pandemic, when we were caring for nearly 130 intubated patients at a time, we adopted a strict residency program schedule with built-in breaks and reduced shifts and hours. Even at that tasking time, no one worked more than 80 hours. Although the maximum number of patients assigned to an intern allowed by ACGME is 10, we rarely have more than five or six patients assigned to each of our interns.

3. We swiftly investigate any allegation and do not hesitate to take the appropriate action against anyone who does not honor our values of professionalism and respect.

4. Our ACGME survey results are close to the mean of all internal medicine residency programs in the country. The fact that the results range from 75% to 95% clearly indicates that residents respond independently, and there is no coaching.

5. No resident has ever been threatened to have their visa canceled or withdrawn. Never. And the implication that we were intolerant because of their nationality is reprehensible. At NYC Health + Hospitals, we celebrate diversity. We are deeply committed to serving everyone, regardless of where they come from, what language they speak, what religion they practice. If you spend one day, or one hour, in our facility, you will see and feel our pride and commitment to this mission. We take pride in the fact that our staff and residents reflect the diversity of the community we serve.

6. As for the allegations of “toxic culture at Lincoln” – many of our graduates chose to stay on as attendings, serve the local community, and train new residents. Out of the 67 attendings in our department, 24 are former graduates. They are being joined by another five graduates from this year’s graduating class. There is no better testament to how our graduates feel about our residency program, Department of Medicine, and Lincoln Hospital.

Dr. Wible poses a legitimate question: How to prevent another suicide. No one has the exact answer. But it is a question we will keep asking ourselves as we continue to do all we can to meet our residents’ needs, extend the social and mental health support they need to thrive, and provide the learning and training they need to offer the best care to our patients.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Former rheumatologist settles civil fraud claims for $2 million

A former rheumatologist in Billings, Mont., and his business have agreed to pay more than $2 million to settle civil claims for alleged False Claims Act violations, according to Acting U.S. Attorney for the District of Montana Leif M. Johnson.

Enrico Arguelles, MD, and his business, the Arthritis & Osteoporosis Center (AOC), which closed in September 2018, agreed to the settlement with the U.S. Attorney’s Office on July 14.

Under terms of the settlement, Dr. Arguelles and the AOC must pay $1,268,646 and relinquish any claim to $802,018 in Medicare payment suspensions held in escrow for AOC for the past 4 years by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Attempts to reach Dr. Arguelles or his attorney for comment were unsuccessful.

“This civil settlement resolves claims of improper medical treatments and false billing to a federal program. Over billed and unnecessary claims, like the ones at issue in this case, drive up the costs for providing care to the people who really need it,” Mr. Johnson said in a statement.

Among the allegations, related to diagnosis and treatment of RA, were improper billing for MRI scans, improper billing for patient visits, and administration of biologic infusions such as infliximab (Remicade) for some patients who did not have seronegative RA, from Jan. 1, 2015, to the closure of the AOC office in 2018, the press release from the Department of Justice stated.

The press release notes that the settlement is not an admission of liability by Dr. Arguelles or AOC, nor a concession by the United States that its case is not well founded.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Michael A. Kakuk represented the United States in the case, which was investigated by the U.S. Attorney’s Office’s Health Care Fraud Investigative Team, Department of Health & Human Services Office of Inspector General, and FBI.

Special Agent in Charge Curt L. Muller, of the HHS-OIG, said in the statement: “Working with our law enforcement partners, we will hold accountable individuals who provide medically unnecessary treatments and pass along the cost to taxpayers.”

According to the Billings Gazette, Dr. Arguelles’ offices in Billings were raided on March 31, 2017, by agents from the HHS-OIG, FBI, and Montana Medicaid Fraud Control Unit.

A spokesperson for the OIG did not disclose to the Gazette the nature of the raid or what, if anything, was found, as it was an open investigation.

In the month after the raid, the Gazette reported, the FBI set up a hotline for patients after a number of them began calling state and federal authorities with concerns “about the medical care they have received at Arthritis & Osteoporosis Center,” Katherine Harris, an OIG spokeswoman, said in a statement.

The settlement comes after the previous fiscal year saw significant recovery of funds for U.S. medical fraud cases.

As this news organization has reported, the OIG recently announced that it had won or negotiated more than $1.8 billion in health care fraud settlements over the past fiscal year. The Department of Justice opened 1,148 criminal health care fraud investigations and 1,079 civil health care fraud investigations from Oct. 1, 2019, to Sept. 30, 2020.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A former rheumatologist in Billings, Mont., and his business have agreed to pay more than $2 million to settle civil claims for alleged False Claims Act violations, according to Acting U.S. Attorney for the District of Montana Leif M. Johnson.

Enrico Arguelles, MD, and his business, the Arthritis & Osteoporosis Center (AOC), which closed in September 2018, agreed to the settlement with the U.S. Attorney’s Office on July 14.

Under terms of the settlement, Dr. Arguelles and the AOC must pay $1,268,646 and relinquish any claim to $802,018 in Medicare payment suspensions held in escrow for AOC for the past 4 years by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Attempts to reach Dr. Arguelles or his attorney for comment were unsuccessful.

“This civil settlement resolves claims of improper medical treatments and false billing to a federal program. Over billed and unnecessary claims, like the ones at issue in this case, drive up the costs for providing care to the people who really need it,” Mr. Johnson said in a statement.

Among the allegations, related to diagnosis and treatment of RA, were improper billing for MRI scans, improper billing for patient visits, and administration of biologic infusions such as infliximab (Remicade) for some patients who did not have seronegative RA, from Jan. 1, 2015, to the closure of the AOC office in 2018, the press release from the Department of Justice stated.

The press release notes that the settlement is not an admission of liability by Dr. Arguelles or AOC, nor a concession by the United States that its case is not well founded.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Michael A. Kakuk represented the United States in the case, which was investigated by the U.S. Attorney’s Office’s Health Care Fraud Investigative Team, Department of Health & Human Services Office of Inspector General, and FBI.

Special Agent in Charge Curt L. Muller, of the HHS-OIG, said in the statement: “Working with our law enforcement partners, we will hold accountable individuals who provide medically unnecessary treatments and pass along the cost to taxpayers.”

According to the Billings Gazette, Dr. Arguelles’ offices in Billings were raided on March 31, 2017, by agents from the HHS-OIG, FBI, and Montana Medicaid Fraud Control Unit.

A spokesperson for the OIG did not disclose to the Gazette the nature of the raid or what, if anything, was found, as it was an open investigation.

In the month after the raid, the Gazette reported, the FBI set up a hotline for patients after a number of them began calling state and federal authorities with concerns “about the medical care they have received at Arthritis & Osteoporosis Center,” Katherine Harris, an OIG spokeswoman, said in a statement.

The settlement comes after the previous fiscal year saw significant recovery of funds for U.S. medical fraud cases.

As this news organization has reported, the OIG recently announced that it had won or negotiated more than $1.8 billion in health care fraud settlements over the past fiscal year. The Department of Justice opened 1,148 criminal health care fraud investigations and 1,079 civil health care fraud investigations from Oct. 1, 2019, to Sept. 30, 2020.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A former rheumatologist in Billings, Mont., and his business have agreed to pay more than $2 million to settle civil claims for alleged False Claims Act violations, according to Acting U.S. Attorney for the District of Montana Leif M. Johnson.

Enrico Arguelles, MD, and his business, the Arthritis & Osteoporosis Center (AOC), which closed in September 2018, agreed to the settlement with the U.S. Attorney’s Office on July 14.

Under terms of the settlement, Dr. Arguelles and the AOC must pay $1,268,646 and relinquish any claim to $802,018 in Medicare payment suspensions held in escrow for AOC for the past 4 years by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Attempts to reach Dr. Arguelles or his attorney for comment were unsuccessful.

“This civil settlement resolves claims of improper medical treatments and false billing to a federal program. Over billed and unnecessary claims, like the ones at issue in this case, drive up the costs for providing care to the people who really need it,” Mr. Johnson said in a statement.

Among the allegations, related to diagnosis and treatment of RA, were improper billing for MRI scans, improper billing for patient visits, and administration of biologic infusions such as infliximab (Remicade) for some patients who did not have seronegative RA, from Jan. 1, 2015, to the closure of the AOC office in 2018, the press release from the Department of Justice stated.

The press release notes that the settlement is not an admission of liability by Dr. Arguelles or AOC, nor a concession by the United States that its case is not well founded.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Michael A. Kakuk represented the United States in the case, which was investigated by the U.S. Attorney’s Office’s Health Care Fraud Investigative Team, Department of Health & Human Services Office of Inspector General, and FBI.

Special Agent in Charge Curt L. Muller, of the HHS-OIG, said in the statement: “Working with our law enforcement partners, we will hold accountable individuals who provide medically unnecessary treatments and pass along the cost to taxpayers.”

According to the Billings Gazette, Dr. Arguelles’ offices in Billings were raided on March 31, 2017, by agents from the HHS-OIG, FBI, and Montana Medicaid Fraud Control Unit.

A spokesperson for the OIG did not disclose to the Gazette the nature of the raid or what, if anything, was found, as it was an open investigation.

In the month after the raid, the Gazette reported, the FBI set up a hotline for patients after a number of them began calling state and federal authorities with concerns “about the medical care they have received at Arthritis & Osteoporosis Center,” Katherine Harris, an OIG spokeswoman, said in a statement.

The settlement comes after the previous fiscal year saw significant recovery of funds for U.S. medical fraud cases.

As this news organization has reported, the OIG recently announced that it had won or negotiated more than $1.8 billion in health care fraud settlements over the past fiscal year. The Department of Justice opened 1,148 criminal health care fraud investigations and 1,079 civil health care fraud investigations from Oct. 1, 2019, to Sept. 30, 2020.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The VA, California, and NYC requiring employee vaccinations

-- or, in the case of California and New York City, undergo regular testing.

The VA becomes the first federal agency to mandate COVID vaccinations for workers. In a news release, VA Secretary Denis McDonough said the mandate is “the best way to keep Veterans safe, especially as the Delta variant spreads across the country.”

VA health care personnel -- including doctors, dentists, podiatrists, optometrists, registered nurses, physician assistants, and chiropractors -- have 8 weeks to become fully vaccinated, the news release said. The New York Times reported that about 115,000 workers will be affected.

The trifecta of federal-state-municipal vaccine requirements arrived as the nation searches for ways to get more people vaccinated to tamp down the Delta variant.

Some organizations, including the military, have already said vaccinations will be required as soon as the Food and Drug Administration formally approves the vaccines, which are now given under emergency use authorizations. The FDA has said the Pfizer vaccine could receive full approval within months.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom said the requirements he announced July 27 were the first in the nation on the state level.

“As the state’s largest employer, we are leading by example and requiring all state and health care workers to show proof of vaccination or be tested regularly, and we are encouraging local governments and businesses to do the same,” he said in a news release.

California employees must provide proof of vaccination or get tested at least once a week. The policy starts Aug. 2 for state employees and Aug. 9 for state health care workers and employees of congregate facilities, such as jails or homeless shelters.

California, especially the southern part of the state, is grappling with a COVID-19 surge. The state’s daily case rate more than quadrupled, from a low of 1.9 cases per 100,000 in May to at least 9.5 cases per 100,000 today, the release said.

In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio had previously announced that city health and hospital employees and those working in Department of Health and Mental Hygiene clinical settings would be required to provide proof of vaccination or have regular testing.

On July 27 he expanded the rule to cover all city employees, with a Sept. 13 deadline for most of them, according to a news release.

“This is what it takes to continue our recovery for all of us while fighting back the Delta variant,” Mayor de Blasio said. “It’s going to take all of us to finally end the fight against COVID-19.”

“We have a moral responsibility to take every precaution possible to ensure we keep ourselves, our colleagues and loved ones safe,” NYC Health + Hospitals President and CEO Mitchell Katz, MD, said in the release. “Our city’s new testing requirement for city workers provides more [peace] of mind until more people get their safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine.”

NBC News reported the plan would affect about 340,000 employees.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

-- or, in the case of California and New York City, undergo regular testing.

The VA becomes the first federal agency to mandate COVID vaccinations for workers. In a news release, VA Secretary Denis McDonough said the mandate is “the best way to keep Veterans safe, especially as the Delta variant spreads across the country.”

VA health care personnel -- including doctors, dentists, podiatrists, optometrists, registered nurses, physician assistants, and chiropractors -- have 8 weeks to become fully vaccinated, the news release said. The New York Times reported that about 115,000 workers will be affected.

The trifecta of federal-state-municipal vaccine requirements arrived as the nation searches for ways to get more people vaccinated to tamp down the Delta variant.

Some organizations, including the military, have already said vaccinations will be required as soon as the Food and Drug Administration formally approves the vaccines, which are now given under emergency use authorizations. The FDA has said the Pfizer vaccine could receive full approval within months.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom said the requirements he announced July 27 were the first in the nation on the state level.

“As the state’s largest employer, we are leading by example and requiring all state and health care workers to show proof of vaccination or be tested regularly, and we are encouraging local governments and businesses to do the same,” he said in a news release.

California employees must provide proof of vaccination or get tested at least once a week. The policy starts Aug. 2 for state employees and Aug. 9 for state health care workers and employees of congregate facilities, such as jails or homeless shelters.

California, especially the southern part of the state, is grappling with a COVID-19 surge. The state’s daily case rate more than quadrupled, from a low of 1.9 cases per 100,000 in May to at least 9.5 cases per 100,000 today, the release said.

In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio had previously announced that city health and hospital employees and those working in Department of Health and Mental Hygiene clinical settings would be required to provide proof of vaccination or have regular testing.

On July 27 he expanded the rule to cover all city employees, with a Sept. 13 deadline for most of them, according to a news release.

“This is what it takes to continue our recovery for all of us while fighting back the Delta variant,” Mayor de Blasio said. “It’s going to take all of us to finally end the fight against COVID-19.”

“We have a moral responsibility to take every precaution possible to ensure we keep ourselves, our colleagues and loved ones safe,” NYC Health + Hospitals President and CEO Mitchell Katz, MD, said in the release. “Our city’s new testing requirement for city workers provides more [peace] of mind until more people get their safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine.”

NBC News reported the plan would affect about 340,000 employees.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

-- or, in the case of California and New York City, undergo regular testing.

The VA becomes the first federal agency to mandate COVID vaccinations for workers. In a news release, VA Secretary Denis McDonough said the mandate is “the best way to keep Veterans safe, especially as the Delta variant spreads across the country.”

VA health care personnel -- including doctors, dentists, podiatrists, optometrists, registered nurses, physician assistants, and chiropractors -- have 8 weeks to become fully vaccinated, the news release said. The New York Times reported that about 115,000 workers will be affected.

The trifecta of federal-state-municipal vaccine requirements arrived as the nation searches for ways to get more people vaccinated to tamp down the Delta variant.

Some organizations, including the military, have already said vaccinations will be required as soon as the Food and Drug Administration formally approves the vaccines, which are now given under emergency use authorizations. The FDA has said the Pfizer vaccine could receive full approval within months.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom said the requirements he announced July 27 were the first in the nation on the state level.

“As the state’s largest employer, we are leading by example and requiring all state and health care workers to show proof of vaccination or be tested regularly, and we are encouraging local governments and businesses to do the same,” he said in a news release.

California employees must provide proof of vaccination or get tested at least once a week. The policy starts Aug. 2 for state employees and Aug. 9 for state health care workers and employees of congregate facilities, such as jails or homeless shelters.

California, especially the southern part of the state, is grappling with a COVID-19 surge. The state’s daily case rate more than quadrupled, from a low of 1.9 cases per 100,000 in May to at least 9.5 cases per 100,000 today, the release said.

In New York City, Mayor Bill de Blasio had previously announced that city health and hospital employees and those working in Department of Health and Mental Hygiene clinical settings would be required to provide proof of vaccination or have regular testing.

On July 27 he expanded the rule to cover all city employees, with a Sept. 13 deadline for most of them, according to a news release.

“This is what it takes to continue our recovery for all of us while fighting back the Delta variant,” Mayor de Blasio said. “It’s going to take all of us to finally end the fight against COVID-19.”

“We have a moral responsibility to take every precaution possible to ensure we keep ourselves, our colleagues and loved ones safe,” NYC Health + Hospitals President and CEO Mitchell Katz, MD, said in the release. “Our city’s new testing requirement for city workers provides more [peace] of mind until more people get their safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine.”

NBC News reported the plan would affect about 340,000 employees.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Children and COVID: Vaccinations, new cases both rising

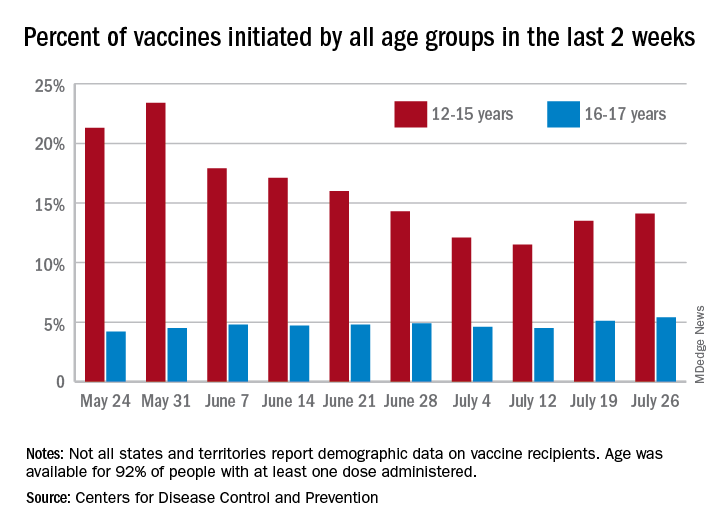

COVID-19 vaccine initiations rose in U.S. children for the second consecutive week, but new pediatric cases jumped by 64% in just 1 week, according to new data.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

“After decreases in weekly reported cases over the past couple of months, in July we have seen steady increases in cases added to the cumulative total,” the AAP noted. In this latest reversal of COVID fortunes, the steady increase in new cases is in its fourth consecutive week since hitting a low of 8,447 in late June.

As of July 22, the total number of reported cases was over 4.12 million in 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, and there have been 349 deaths in children in the 46 jurisdictions reporting age distributions of COVID-19 deaths, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Meanwhile, over 9.3 million children received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of July 26, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccine initiation rose for the second week in a row after falling for several weeks as 301,000 children aged 12-15 years and almost 115,000 children aged 16-17 got their first dose during the week ending July 26. Children aged 12-15 represented 14.1% (up from 13.5% a week before) of all first vaccinations and 16- to 17-year-olds were 5.4% (up from 5.1%) of all vaccine initiators, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

Just over 37% of all 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine since the CDC approved its use for children under age 16 in May, and almost 28% are fully vaccinated. Use in children aged 16-17 started earlier (December 2020), and 48% of that age group have received a first dose and over 39% have completed the vaccine regimen, the CDC said.

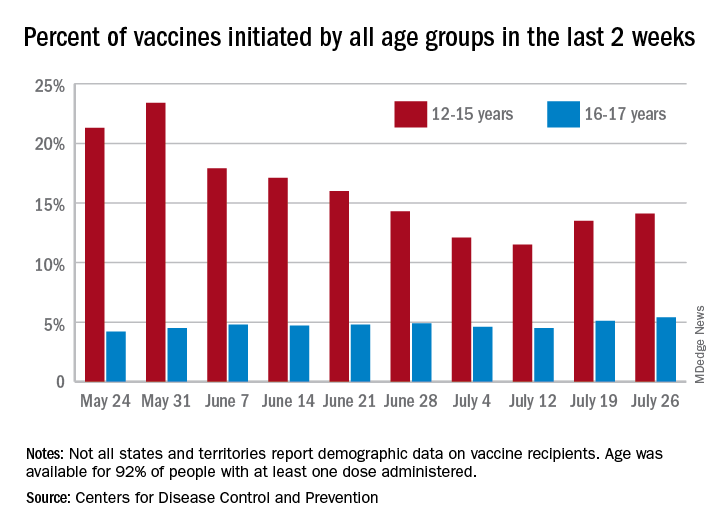

COVID-19 vaccine initiations rose in U.S. children for the second consecutive week, but new pediatric cases jumped by 64% in just 1 week, according to new data.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

“After decreases in weekly reported cases over the past couple of months, in July we have seen steady increases in cases added to the cumulative total,” the AAP noted. In this latest reversal of COVID fortunes, the steady increase in new cases is in its fourth consecutive week since hitting a low of 8,447 in late June.

As of July 22, the total number of reported cases was over 4.12 million in 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, and there have been 349 deaths in children in the 46 jurisdictions reporting age distributions of COVID-19 deaths, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Meanwhile, over 9.3 million children received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of July 26, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccine initiation rose for the second week in a row after falling for several weeks as 301,000 children aged 12-15 years and almost 115,000 children aged 16-17 got their first dose during the week ending July 26. Children aged 12-15 represented 14.1% (up from 13.5% a week before) of all first vaccinations and 16- to 17-year-olds were 5.4% (up from 5.1%) of all vaccine initiators, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

Just over 37% of all 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine since the CDC approved its use for children under age 16 in May, and almost 28% are fully vaccinated. Use in children aged 16-17 started earlier (December 2020), and 48% of that age group have received a first dose and over 39% have completed the vaccine regimen, the CDC said.

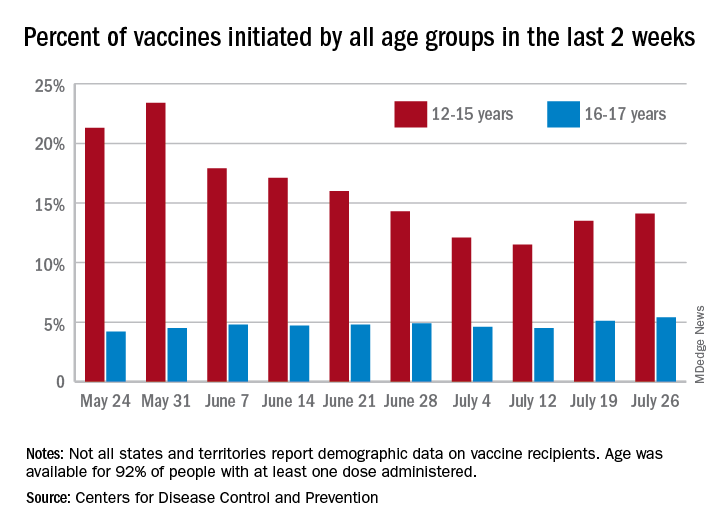

COVID-19 vaccine initiations rose in U.S. children for the second consecutive week, but new pediatric cases jumped by 64% in just 1 week, according to new data.

the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association said in their weekly COVID-19 report.

“After decreases in weekly reported cases over the past couple of months, in July we have seen steady increases in cases added to the cumulative total,” the AAP noted. In this latest reversal of COVID fortunes, the steady increase in new cases is in its fourth consecutive week since hitting a low of 8,447 in late June.

As of July 22, the total number of reported cases was over 4.12 million in 49 states, the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, and there have been 349 deaths in children in the 46 jurisdictions reporting age distributions of COVID-19 deaths, the AAP and CHA said in their report.

Meanwhile, over 9.3 million children received at least one dose of COVID vaccine as of July 26, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Vaccine initiation rose for the second week in a row after falling for several weeks as 301,000 children aged 12-15 years and almost 115,000 children aged 16-17 got their first dose during the week ending July 26. Children aged 12-15 represented 14.1% (up from 13.5% a week before) of all first vaccinations and 16- to 17-year-olds were 5.4% (up from 5.1%) of all vaccine initiators, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

Just over 37% of all 12- to 15-year-olds have received at least one dose of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine since the CDC approved its use for children under age 16 in May, and almost 28% are fully vaccinated. Use in children aged 16-17 started earlier (December 2020), and 48% of that age group have received a first dose and over 39% have completed the vaccine regimen, the CDC said.

COVID-19 vaccination does not increase risk of flare in patients with lupus

COVID-19 vaccinations appear to be well tolerated in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and come with a low risk of flare, according to the results of a global, web-based survey.

“Disseminating these reassuring data might prove crucial to increasing vaccine coverage in patients with SLE,” wrote lead author Renaud Felten, MD, of Strasbourg (France) University Hospital. Their results were published as a comment in Lancet Rheumatology.

To assess vaccine tolerability among lupus patients, the cross-sectional Tolerance and Consequences of Vaccination Against COVID-19 in Lupus Patients (VACOLUP) study analyzed a 43-question survey of 696 participants with a self-reported, medically confirmed diagnosis of SLE from 30 countries between March 22, 2021, and May 17, 2021. The cohort was 96% women, and their median age was 42 (interquartile range, 34-51). Nearly 36% of respondents were from Italy, 27% were from Chile, 13% were from France, and just under 9% were Americans. All participants received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and 49% received a second dose. The most common vaccines were Pfizer-BioNTech (57%), Sinovac (22%), AstraZeneca (10%), and Moderna (8%).

Only 21 participants (3%) reported a medically confirmed SLE flare after a median of 3 days (IQR, 0-29) post COVID vaccination, with most experiencing musculoskeletal symptoms (90%) and fatigue (86%). Of the 21 cases, 15 reported a subsequent change in SLE treatment and 4 were admitted to the hospital. A previous flare that occurred within a year before vaccination was associated with an increased risk of flare post vaccination (relative risk, 5.52; 95% confidence interval, 2.17-14.03; P < .0001).

Side effects – including swelling, soreness, fever, chills, fatigue, joint and muscle pain, nausea, and headache – were reported in 45% of participants (n = 316) after their first dose and in 53% of the 343 participants who received a second dose. There was no notable difference in the likelihood of side effects across gender and age or in patients who received mRNA vaccines, compared with vaccines with other modes of action. Patients who reported side effects after the first dose were more likely to also report them after the second, compared with those who reported none (109 [81%] of 135 vs. 72 [35%] of 205; RR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.88-2.82; P < .0001).

In the majority of cases (2,232 of 2,683), the side effects were of minor or moderate intensity and did not affect the participants’ ability to perform daily tasks. The study found no significant association between side effects and a SLE flare and SLE medications or previous SLE disease manifestations.

When asked to comment on the study, Amit Saxena, MD, of the Lupus Center at New York University Langone Health, said: “What we are seeing is pretty mild to moderate in terms of follow-up side effects or lupus-related activity. Several studies have shown this amongst our autoimmune rheumatology cohort, as well as what I’ve seen clinically in my own patients. More than anything else, numbers are the most important, and this is a large study.”

He acknowledged the benefits of going directly to patients to gauge their responses and reactions, giving them the opportunity to share concerns that physicians may not think about.

“As rheumatologists, we tend to focus on certain things that might not necessarily be what the patients themselves focus on,” he said. “I think the fact that this questionnaire dealt with a lot of what people complain about – fatigue, sore arm, things that we know are part of getting the vaccine – they aren’t necessarily things we capture with tools that screen for lupus flares, for example.”

More than anything, Dr. Saxena commended the study’s timeliness. “Patients are constantly asking us about the vaccine, and there’s so much misinformation,” he said. “People say, ‘Because I have lupus, I was told not to get vaccinated.’ I don’t know where they get that information from; we are telling everyone to get it, especially our lupus patients.”

The authors recognized their study’s main limitation as the self-reported and subjective nature of the survey, which they attempted to mitigate by asking for medically confirmed flares only. They noted, however, that the short median time between vaccination and flare onset could be caused by patients confusing expected side effects for something more serious, meaning the 3% figure “could be an overestimation of the actual flare rate.”

“Vaccination is recommended for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases according to the American College of Rheumatology,” they added, “irrespective of disease activity and severity.”

Several authors reported potential conflicts of interest, including receiving consultancy fees and grants from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, and Janssen, all unrelated to the study.

COVID-19 vaccinations appear to be well tolerated in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and come with a low risk of flare, according to the results of a global, web-based survey.

“Disseminating these reassuring data might prove crucial to increasing vaccine coverage in patients with SLE,” wrote lead author Renaud Felten, MD, of Strasbourg (France) University Hospital. Their results were published as a comment in Lancet Rheumatology.

To assess vaccine tolerability among lupus patients, the cross-sectional Tolerance and Consequences of Vaccination Against COVID-19 in Lupus Patients (VACOLUP) study analyzed a 43-question survey of 696 participants with a self-reported, medically confirmed diagnosis of SLE from 30 countries between March 22, 2021, and May 17, 2021. The cohort was 96% women, and their median age was 42 (interquartile range, 34-51). Nearly 36% of respondents were from Italy, 27% were from Chile, 13% were from France, and just under 9% were Americans. All participants received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and 49% received a second dose. The most common vaccines were Pfizer-BioNTech (57%), Sinovac (22%), AstraZeneca (10%), and Moderna (8%).

Only 21 participants (3%) reported a medically confirmed SLE flare after a median of 3 days (IQR, 0-29) post COVID vaccination, with most experiencing musculoskeletal symptoms (90%) and fatigue (86%). Of the 21 cases, 15 reported a subsequent change in SLE treatment and 4 were admitted to the hospital. A previous flare that occurred within a year before vaccination was associated with an increased risk of flare post vaccination (relative risk, 5.52; 95% confidence interval, 2.17-14.03; P < .0001).

Side effects – including swelling, soreness, fever, chills, fatigue, joint and muscle pain, nausea, and headache – were reported in 45% of participants (n = 316) after their first dose and in 53% of the 343 participants who received a second dose. There was no notable difference in the likelihood of side effects across gender and age or in patients who received mRNA vaccines, compared with vaccines with other modes of action. Patients who reported side effects after the first dose were more likely to also report them after the second, compared with those who reported none (109 [81%] of 135 vs. 72 [35%] of 205; RR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.88-2.82; P < .0001).

In the majority of cases (2,232 of 2,683), the side effects were of minor or moderate intensity and did not affect the participants’ ability to perform daily tasks. The study found no significant association between side effects and a SLE flare and SLE medications or previous SLE disease manifestations.

When asked to comment on the study, Amit Saxena, MD, of the Lupus Center at New York University Langone Health, said: “What we are seeing is pretty mild to moderate in terms of follow-up side effects or lupus-related activity. Several studies have shown this amongst our autoimmune rheumatology cohort, as well as what I’ve seen clinically in my own patients. More than anything else, numbers are the most important, and this is a large study.”

He acknowledged the benefits of going directly to patients to gauge their responses and reactions, giving them the opportunity to share concerns that physicians may not think about.

“As rheumatologists, we tend to focus on certain things that might not necessarily be what the patients themselves focus on,” he said. “I think the fact that this questionnaire dealt with a lot of what people complain about – fatigue, sore arm, things that we know are part of getting the vaccine – they aren’t necessarily things we capture with tools that screen for lupus flares, for example.”

More than anything, Dr. Saxena commended the study’s timeliness. “Patients are constantly asking us about the vaccine, and there’s so much misinformation,” he said. “People say, ‘Because I have lupus, I was told not to get vaccinated.’ I don’t know where they get that information from; we are telling everyone to get it, especially our lupus patients.”

The authors recognized their study’s main limitation as the self-reported and subjective nature of the survey, which they attempted to mitigate by asking for medically confirmed flares only. They noted, however, that the short median time between vaccination and flare onset could be caused by patients confusing expected side effects for something more serious, meaning the 3% figure “could be an overestimation of the actual flare rate.”

“Vaccination is recommended for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases according to the American College of Rheumatology,” they added, “irrespective of disease activity and severity.”

Several authors reported potential conflicts of interest, including receiving consultancy fees and grants from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, and Janssen, all unrelated to the study.

COVID-19 vaccinations appear to be well tolerated in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and come with a low risk of flare, according to the results of a global, web-based survey.

“Disseminating these reassuring data might prove crucial to increasing vaccine coverage in patients with SLE,” wrote lead author Renaud Felten, MD, of Strasbourg (France) University Hospital. Their results were published as a comment in Lancet Rheumatology.

To assess vaccine tolerability among lupus patients, the cross-sectional Tolerance and Consequences of Vaccination Against COVID-19 in Lupus Patients (VACOLUP) study analyzed a 43-question survey of 696 participants with a self-reported, medically confirmed diagnosis of SLE from 30 countries between March 22, 2021, and May 17, 2021. The cohort was 96% women, and their median age was 42 (interquartile range, 34-51). Nearly 36% of respondents were from Italy, 27% were from Chile, 13% were from France, and just under 9% were Americans. All participants received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine, and 49% received a second dose. The most common vaccines were Pfizer-BioNTech (57%), Sinovac (22%), AstraZeneca (10%), and Moderna (8%).

Only 21 participants (3%) reported a medically confirmed SLE flare after a median of 3 days (IQR, 0-29) post COVID vaccination, with most experiencing musculoskeletal symptoms (90%) and fatigue (86%). Of the 21 cases, 15 reported a subsequent change in SLE treatment and 4 were admitted to the hospital. A previous flare that occurred within a year before vaccination was associated with an increased risk of flare post vaccination (relative risk, 5.52; 95% confidence interval, 2.17-14.03; P < .0001).

Side effects – including swelling, soreness, fever, chills, fatigue, joint and muscle pain, nausea, and headache – were reported in 45% of participants (n = 316) after their first dose and in 53% of the 343 participants who received a second dose. There was no notable difference in the likelihood of side effects across gender and age or in patients who received mRNA vaccines, compared with vaccines with other modes of action. Patients who reported side effects after the first dose were more likely to also report them after the second, compared with those who reported none (109 [81%] of 135 vs. 72 [35%] of 205; RR, 2.30; 95% CI, 1.88-2.82; P < .0001).

In the majority of cases (2,232 of 2,683), the side effects were of minor or moderate intensity and did not affect the participants’ ability to perform daily tasks. The study found no significant association between side effects and a SLE flare and SLE medications or previous SLE disease manifestations.

When asked to comment on the study, Amit Saxena, MD, of the Lupus Center at New York University Langone Health, said: “What we are seeing is pretty mild to moderate in terms of follow-up side effects or lupus-related activity. Several studies have shown this amongst our autoimmune rheumatology cohort, as well as what I’ve seen clinically in my own patients. More than anything else, numbers are the most important, and this is a large study.”

He acknowledged the benefits of going directly to patients to gauge their responses and reactions, giving them the opportunity to share concerns that physicians may not think about.

“As rheumatologists, we tend to focus on certain things that might not necessarily be what the patients themselves focus on,” he said. “I think the fact that this questionnaire dealt with a lot of what people complain about – fatigue, sore arm, things that we know are part of getting the vaccine – they aren’t necessarily things we capture with tools that screen for lupus flares, for example.”

More than anything, Dr. Saxena commended the study’s timeliness. “Patients are constantly asking us about the vaccine, and there’s so much misinformation,” he said. “People say, ‘Because I have lupus, I was told not to get vaccinated.’ I don’t know where they get that information from; we are telling everyone to get it, especially our lupus patients.”

The authors recognized their study’s main limitation as the self-reported and subjective nature of the survey, which they attempted to mitigate by asking for medically confirmed flares only. They noted, however, that the short median time between vaccination and flare onset could be caused by patients confusing expected side effects for something more serious, meaning the 3% figure “could be an overestimation of the actual flare rate.”

“Vaccination is recommended for patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases according to the American College of Rheumatology,” they added, “irrespective of disease activity and severity.”

Several authors reported potential conflicts of interest, including receiving consultancy fees and grants from Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, AbbVie, and Janssen, all unrelated to the study.

FROM THE LANCET RHEUMATOLOGY

Accelerated surgery for hip fracture did not lower risk of mortality or major complications

Background: Patients diagnosed with a hip fracture are at substantial risk of major complications and mortality. Observational studies have suggested that accelerated surgery for a hip fracture is associated with lower risk of mortality and major complications.

Study design: International, randomized, controlled trial (RCT).

Setting: 69 hospitals in 17 countries.

Synopsis: This RCT enrolled 2,970 patients with a hip fracture, aged 45 years and older. The median time from hip fracture diagnosis to surgery was 6 h in the accelerated surgery group (n = 1,487) and 24 h in the standard-care group (n = 1,483). A total of 140 (9%) patients assigned to accelerated surgery and 154 (10%) assigned to standard care died at 90 days after randomization (P = .40). Composite of major complications (mortality, nonfatal MI, stroke, venous thromboembolism, sepsis, pneumonia, life-threatening bleeding, and major bleeding) occurred in 321 (22%) patients assigned to accelerated surgery and 331 (22%) assigned to standard care at 90 days after randomization (p = .71). However, accelerated surgery was associated with lower risk of delirium, urinary tract infection, andmoderate to severe pain and resulted in faster mobilization and shorter length of stay.

Practical limitations include the additional resources needed for an accelerated surgical pathway such as staffing and operating room time. Furthermore, this study included only patients diagnosed during regular working hours.

Bottom line: Among patients with a hip fracture, accelerated surgery did not lower the risk of the coprimary outcomes of mortality or a composite of major complications at 90 days compared with standard care.

Citation: Borges F et al. Accelerated surgery versus standard care in hip fracture (HIP ATTACK): An international, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 29; 395(10225), 698-708.

Dr. Miller is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Patients diagnosed with a hip fracture are at substantial risk of major complications and mortality. Observational studies have suggested that accelerated surgery for a hip fracture is associated with lower risk of mortality and major complications.

Study design: International, randomized, controlled trial (RCT).

Setting: 69 hospitals in 17 countries.

Synopsis: This RCT enrolled 2,970 patients with a hip fracture, aged 45 years and older. The median time from hip fracture diagnosis to surgery was 6 h in the accelerated surgery group (n = 1,487) and 24 h in the standard-care group (n = 1,483). A total of 140 (9%) patients assigned to accelerated surgery and 154 (10%) assigned to standard care died at 90 days after randomization (P = .40). Composite of major complications (mortality, nonfatal MI, stroke, venous thromboembolism, sepsis, pneumonia, life-threatening bleeding, and major bleeding) occurred in 321 (22%) patients assigned to accelerated surgery and 331 (22%) assigned to standard care at 90 days after randomization (p = .71). However, accelerated surgery was associated with lower risk of delirium, urinary tract infection, andmoderate to severe pain and resulted in faster mobilization and shorter length of stay.

Practical limitations include the additional resources needed for an accelerated surgical pathway such as staffing and operating room time. Furthermore, this study included only patients diagnosed during regular working hours.

Bottom line: Among patients with a hip fracture, accelerated surgery did not lower the risk of the coprimary outcomes of mortality or a composite of major complications at 90 days compared with standard care.

Citation: Borges F et al. Accelerated surgery versus standard care in hip fracture (HIP ATTACK): An international, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 29; 395(10225), 698-708.

Dr. Miller is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Background: Patients diagnosed with a hip fracture are at substantial risk of major complications and mortality. Observational studies have suggested that accelerated surgery for a hip fracture is associated with lower risk of mortality and major complications.

Study design: International, randomized, controlled trial (RCT).

Setting: 69 hospitals in 17 countries.

Synopsis: This RCT enrolled 2,970 patients with a hip fracture, aged 45 years and older. The median time from hip fracture diagnosis to surgery was 6 h in the accelerated surgery group (n = 1,487) and 24 h in the standard-care group (n = 1,483). A total of 140 (9%) patients assigned to accelerated surgery and 154 (10%) assigned to standard care died at 90 days after randomization (P = .40). Composite of major complications (mortality, nonfatal MI, stroke, venous thromboembolism, sepsis, pneumonia, life-threatening bleeding, and major bleeding) occurred in 321 (22%) patients assigned to accelerated surgery and 331 (22%) assigned to standard care at 90 days after randomization (p = .71). However, accelerated surgery was associated with lower risk of delirium, urinary tract infection, andmoderate to severe pain and resulted in faster mobilization and shorter length of stay.

Practical limitations include the additional resources needed for an accelerated surgical pathway such as staffing and operating room time. Furthermore, this study included only patients diagnosed during regular working hours.

Bottom line: Among patients with a hip fracture, accelerated surgery did not lower the risk of the coprimary outcomes of mortality or a composite of major complications at 90 days compared with standard care.

Citation: Borges F et al. Accelerated surgery versus standard care in hip fracture (HIP ATTACK): An international, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet. 2020 Feb 29; 395(10225), 698-708.

Dr. Miller is assistant professor of medicine, section of hospital medicine, at the University of Virginia School of Medicine, Charlottesville.

Direct oral anticoagulants: Competition brought no cost relief

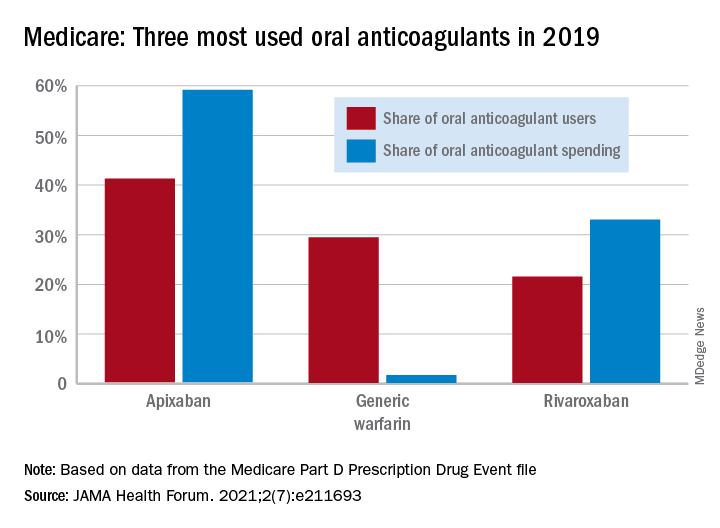

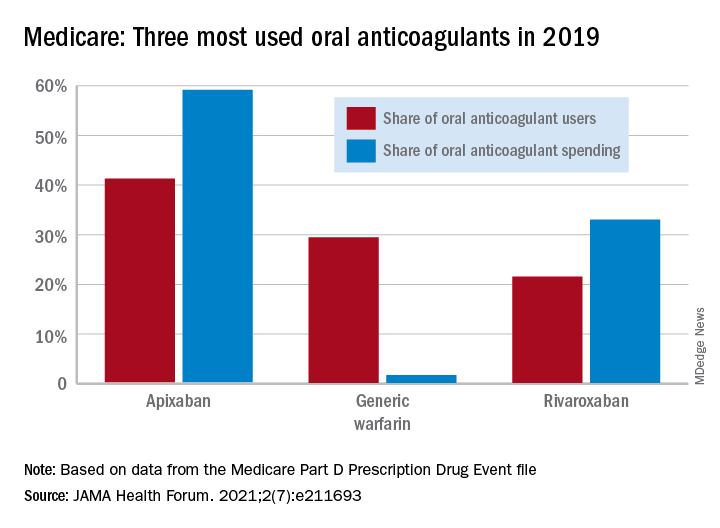

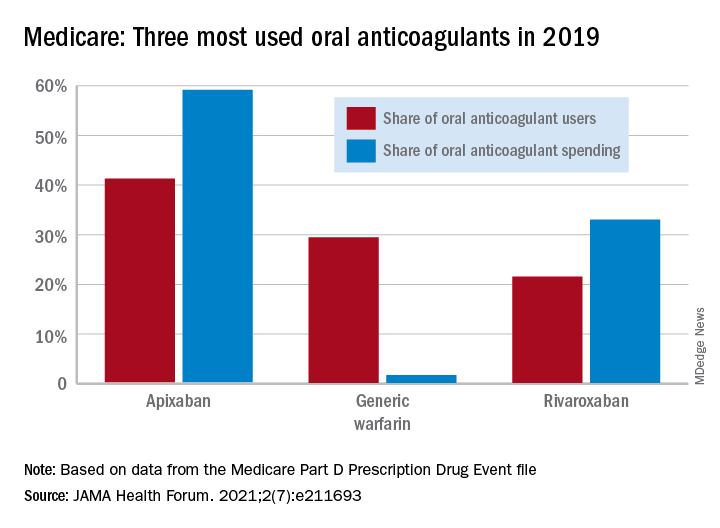

Medicare Part D spending for oral anticoagulants has risen by almost 1,600% since 2011, while the number of users has increased by just 95%, according to a new study.

In 2011, the year after the first direct oral anticoagulant (DOACs) was approved, Medicare Part D spent $0.44 billion on all oral anticoagulants. By 2019, when there a total of four DOACs on the market, spending was $7.38 billion, an increase of 1,577%, Aaron Troy, MD, MPH, and Timothy S. Anderson, MD, MAS, said in JAMA Health Forum.

Over that same time, the number of beneficiaries using oral anticoagulants went from 2.68 million to 5.24 million, they said, based on data from the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event file.

“While higher prices for novel therapeutics like DOACs, which offer clear benefits, such as decreased drug-drug interactions and improved persistence, may partly reflect value and help drive innovation, the patterns and effects of spending on novel medications still merit attention,” they noted.

One pattern of use looked like this: 0.2 million Medicare beneficiaries took DOACs in 2011,compared with 3.5 million in 2019, while the number of warfarin users dropped from 2.48 million to 1.74 million, the investigators reported.

As for spending over the study period, the cost to treat one beneficiary with atrial fibrillation increased by 9.3% each year for apixaban (a DOAC that was the most popular oral anticoagulant in 2019), decreased 27.6% per year for generic warfarin, and increased 9.5% per year for rivaroxaban, said Dr. Troy and Dr. Anderson of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Rising Part D enrollment had an effect on spending growth, as did increased use of oral anticoagulants in general. The introduction of competing DOACs, however, “did not substantially curb annual spending increases, suggesting a lack of price competition, which is consistent with trends observed in other therapeutic categories,” they wrote.

Dr. Anderson has received research grants from the National Institute on Aging and the American College of Cardiology outside of this study and honoraria from Alosa Health. No other disclosures were reported.

Medicare Part D spending for oral anticoagulants has risen by almost 1,600% since 2011, while the number of users has increased by just 95%, according to a new study.

In 2011, the year after the first direct oral anticoagulant (DOACs) was approved, Medicare Part D spent $0.44 billion on all oral anticoagulants. By 2019, when there a total of four DOACs on the market, spending was $7.38 billion, an increase of 1,577%, Aaron Troy, MD, MPH, and Timothy S. Anderson, MD, MAS, said in JAMA Health Forum.

Over that same time, the number of beneficiaries using oral anticoagulants went from 2.68 million to 5.24 million, they said, based on data from the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event file.

“While higher prices for novel therapeutics like DOACs, which offer clear benefits, such as decreased drug-drug interactions and improved persistence, may partly reflect value and help drive innovation, the patterns and effects of spending on novel medications still merit attention,” they noted.

One pattern of use looked like this: 0.2 million Medicare beneficiaries took DOACs in 2011,compared with 3.5 million in 2019, while the number of warfarin users dropped from 2.48 million to 1.74 million, the investigators reported.

As for spending over the study period, the cost to treat one beneficiary with atrial fibrillation increased by 9.3% each year for apixaban (a DOAC that was the most popular oral anticoagulant in 2019), decreased 27.6% per year for generic warfarin, and increased 9.5% per year for rivaroxaban, said Dr. Troy and Dr. Anderson of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Rising Part D enrollment had an effect on spending growth, as did increased use of oral anticoagulants in general. The introduction of competing DOACs, however, “did not substantially curb annual spending increases, suggesting a lack of price competition, which is consistent with trends observed in other therapeutic categories,” they wrote.

Dr. Anderson has received research grants from the National Institute on Aging and the American College of Cardiology outside of this study and honoraria from Alosa Health. No other disclosures were reported.

Medicare Part D spending for oral anticoagulants has risen by almost 1,600% since 2011, while the number of users has increased by just 95%, according to a new study.

In 2011, the year after the first direct oral anticoagulant (DOACs) was approved, Medicare Part D spent $0.44 billion on all oral anticoagulants. By 2019, when there a total of four DOACs on the market, spending was $7.38 billion, an increase of 1,577%, Aaron Troy, MD, MPH, and Timothy S. Anderson, MD, MAS, said in JAMA Health Forum.

Over that same time, the number of beneficiaries using oral anticoagulants went from 2.68 million to 5.24 million, they said, based on data from the Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Event file.

“While higher prices for novel therapeutics like DOACs, which offer clear benefits, such as decreased drug-drug interactions and improved persistence, may partly reflect value and help drive innovation, the patterns and effects of spending on novel medications still merit attention,” they noted.

One pattern of use looked like this: 0.2 million Medicare beneficiaries took DOACs in 2011,compared with 3.5 million in 2019, while the number of warfarin users dropped from 2.48 million to 1.74 million, the investigators reported.

As for spending over the study period, the cost to treat one beneficiary with atrial fibrillation increased by 9.3% each year for apixaban (a DOAC that was the most popular oral anticoagulant in 2019), decreased 27.6% per year for generic warfarin, and increased 9.5% per year for rivaroxaban, said Dr. Troy and Dr. Anderson of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.

Rising Part D enrollment had an effect on spending growth, as did increased use of oral anticoagulants in general. The introduction of competing DOACs, however, “did not substantially curb annual spending increases, suggesting a lack of price competition, which is consistent with trends observed in other therapeutic categories,” they wrote.

Dr. Anderson has received research grants from the National Institute on Aging and the American College of Cardiology outside of this study and honoraria from Alosa Health. No other disclosures were reported.

FROM JAMA HEALTH FORUM

Dementia caregivers benefit from telehealth support

The program combines information, education, and skills training to help participants overcome specific challenges.