User login

Bazedoxifene effectively prevents glucocorticoid-induced bone loss in RA

Key clinical point: Treatment with bazedoxifene for 48 weeks significantly increased bone mineral density (BMD) of L-spine and decreased bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) receiving low-dose glucocorticoids.

Major finding: Treatment with bazedoxifene significantly increased L-spine BMD (0.015 g/cm2; P = .007), whereas the change in the control group was not significant (0.002 g/cm2; P = .694). At 24 weeks, all bone turnover biomarkers decreased significantly with bazedoxifene, which persisted to 48 weeks (all P less than .01), whereas recovery observed in the control group was not significant.

Study details: The data come from an open-label study involving 114 postmenopausal women with osteopenia who had been receiving low-dose glucocorticoids for RA and were randomly assigned to either daily bazedoxifene (20 mg/day) with calcium and vitamin D or only calcium and vitamin D (control group).

Disclosures: The study was supported by a research grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Korea Ltd. YK Sung reported receiving research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Pfizer, and JW Pharmaceutical.

Source: Cho SK et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021 Jul 2. doi: 10.1186/s13075-021-02564-1.

Key clinical point: Treatment with bazedoxifene for 48 weeks significantly increased bone mineral density (BMD) of L-spine and decreased bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) receiving low-dose glucocorticoids.

Major finding: Treatment with bazedoxifene significantly increased L-spine BMD (0.015 g/cm2; P = .007), whereas the change in the control group was not significant (0.002 g/cm2; P = .694). At 24 weeks, all bone turnover biomarkers decreased significantly with bazedoxifene, which persisted to 48 weeks (all P less than .01), whereas recovery observed in the control group was not significant.

Study details: The data come from an open-label study involving 114 postmenopausal women with osteopenia who had been receiving low-dose glucocorticoids for RA and were randomly assigned to either daily bazedoxifene (20 mg/day) with calcium and vitamin D or only calcium and vitamin D (control group).

Disclosures: The study was supported by a research grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Korea Ltd. YK Sung reported receiving research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Pfizer, and JW Pharmaceutical.

Source: Cho SK et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021 Jul 2. doi: 10.1186/s13075-021-02564-1.

Key clinical point: Treatment with bazedoxifene for 48 weeks significantly increased bone mineral density (BMD) of L-spine and decreased bone turnover markers in postmenopausal women with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) receiving low-dose glucocorticoids.

Major finding: Treatment with bazedoxifene significantly increased L-spine BMD (0.015 g/cm2; P = .007), whereas the change in the control group was not significant (0.002 g/cm2; P = .694). At 24 weeks, all bone turnover biomarkers decreased significantly with bazedoxifene, which persisted to 48 weeks (all P less than .01), whereas recovery observed in the control group was not significant.

Study details: The data come from an open-label study involving 114 postmenopausal women with osteopenia who had been receiving low-dose glucocorticoids for RA and were randomly assigned to either daily bazedoxifene (20 mg/day) with calcium and vitamin D or only calcium and vitamin D (control group).

Disclosures: The study was supported by a research grant from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals Korea Ltd. YK Sung reported receiving research grants from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, Pfizer, and JW Pharmaceutical.

Source: Cho SK et al. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021 Jul 2. doi: 10.1186/s13075-021-02564-1.

RA: No significant change in efficacy and safety after adalimumab to CT-P17 switch

Key clinical point: In patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA), adalimumab biosimilar CT-P17 and reference adalimumab showed comparable efficacy and safety during 1 year of treatment even after switching to CT-P17 from reference adalimumab.

Major finding: At 52 weeks, the proportion of patients achieving a 20%/50%/70% improvement by American College of Rheumatology criteria was comparable among those who continued CT-P17 (80.5%/66.3%/44.6%), continued reference adalimumab (77.8%/62.1%/49.0%), or switched to CT-P17 (82.2%/66.4%/47.4%), respectively. Similar proportions of patients in each treatment group experienced 1 or more treatment-emergent adverse events.

Study details: This was a 52-week, randomized, phase 3 study of 607 patients with active RA who received either 40 mg (100 mg/mL) CT-P17 or reference adalimumab subcutaneously every 2 weeks until week 24. Later, patients receiving CT-P17 continued to receive the same, whereas those receiving reference adalimumab either continued the same or switched to CT-P17.

Disclosures: This work was supported by Celltrion, Inc. Some of the authors reported receiving research grants, consulting, speaker fees, and/or honoraria from various sources. SJ Lee, SH Kim, YJ Bae, GE Yang, and JK Yoo declared being employees of Celltrion, Inc.

Source: Furst DE et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Jun 17. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab460.

Key clinical point: In patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA), adalimumab biosimilar CT-P17 and reference adalimumab showed comparable efficacy and safety during 1 year of treatment even after switching to CT-P17 from reference adalimumab.

Major finding: At 52 weeks, the proportion of patients achieving a 20%/50%/70% improvement by American College of Rheumatology criteria was comparable among those who continued CT-P17 (80.5%/66.3%/44.6%), continued reference adalimumab (77.8%/62.1%/49.0%), or switched to CT-P17 (82.2%/66.4%/47.4%), respectively. Similar proportions of patients in each treatment group experienced 1 or more treatment-emergent adverse events.

Study details: This was a 52-week, randomized, phase 3 study of 607 patients with active RA who received either 40 mg (100 mg/mL) CT-P17 or reference adalimumab subcutaneously every 2 weeks until week 24. Later, patients receiving CT-P17 continued to receive the same, whereas those receiving reference adalimumab either continued the same or switched to CT-P17.

Disclosures: This work was supported by Celltrion, Inc. Some of the authors reported receiving research grants, consulting, speaker fees, and/or honoraria from various sources. SJ Lee, SH Kim, YJ Bae, GE Yang, and JK Yoo declared being employees of Celltrion, Inc.

Source: Furst DE et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Jun 17. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab460.

Key clinical point: In patients with active rheumatoid arthritis (RA), adalimumab biosimilar CT-P17 and reference adalimumab showed comparable efficacy and safety during 1 year of treatment even after switching to CT-P17 from reference adalimumab.

Major finding: At 52 weeks, the proportion of patients achieving a 20%/50%/70% improvement by American College of Rheumatology criteria was comparable among those who continued CT-P17 (80.5%/66.3%/44.6%), continued reference adalimumab (77.8%/62.1%/49.0%), or switched to CT-P17 (82.2%/66.4%/47.4%), respectively. Similar proportions of patients in each treatment group experienced 1 or more treatment-emergent adverse events.

Study details: This was a 52-week, randomized, phase 3 study of 607 patients with active RA who received either 40 mg (100 mg/mL) CT-P17 or reference adalimumab subcutaneously every 2 weeks until week 24. Later, patients receiving CT-P17 continued to receive the same, whereas those receiving reference adalimumab either continued the same or switched to CT-P17.

Disclosures: This work was supported by Celltrion, Inc. Some of the authors reported receiving research grants, consulting, speaker fees, and/or honoraria from various sources. SJ Lee, SH Kim, YJ Bae, GE Yang, and JK Yoo declared being employees of Celltrion, Inc.

Source: Furst DE et al. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021 Jun 17. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab460.

Commentary: RA August 2021

Recently, ACR guidelines were published on the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, emphasizing use of supplemental calcium and vitamin D and antiresorptive therapy. This randomized, controlled, open-label trial by Cho et al looks at the efficacy of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in preventing bone loss and fractures in postmenopausal RA patients with osteopenia on long-term glucocorticoids. Patients were randomized to bazedoxefine, a 3rd-generation SERM vs no therapy in addition to background calcium and vitamin D supplementation and bone mineral density (BMD) and trabecular bone score (TBS). Bone turnover markers were assessed over the course of 48 weeks, in addition to adverse events. Prednisone dose was relatively low, with a baseline of ~3 mg/day. Bone density increased by almost 2% in the L spine (P < 0.05), but the increases in BMD at the femoral neck and TBS were not significant. Bone turnover markers did decrease in the bazedoxefine group, though not in the control group. These findings are not striking but are promising given the short duration of the study (<1 year), and potentially deserves longer-term follow-up, both for evaluation of efficacy as well as long-term safety. In the US, the medication is only available in combination with estrogen, and thus it is not currently a practical option for RA patients with GIOP.

Despite wider availability of both synthetic and biologic DMARDs for treatment of RA in recent years, persistent pain is an issue for many patients, perhaps due to peripheral sensitization. Though it seems almost unnecessary to investigate the utility of glucocorticoids for treatment of RA-related pain, the magnitude and duration of their benefit is unknown. McWilliams et al take the approach of quantitatively analyzing the benefit of glucocorticoids in RA over time in their systematic review and meta-analysis. The study looked at both spontaneous and evoked pain, and evaluated 65 studies that mostly used pain visual analogue scale, tender joint count, and Ritchie Articular Index. Reduction in spontaneous pain was greatest in the 0-3-month time period, with smaller reductions in 3-6 months and >6 month. A similar pattern was seen in evaluation of the time course of evoked pain. As such, the benefits of long-term systemic glucocorticoid therapy may not outweigh its well-known risks, especially in patients with persistent pain. Whether this is due to non-inflammatory sources of pain or other mechanisms remains unknown and is likely heavily impacted by the specific clinical scenario.

Due to the potential long-terms side effects of chronic immunosuppression, including long-term glucocorticoid therapy in patients with persistent pain in RA, the course and predictors of unacceptable pain are of interest. Eberhard et al examined an inception cohort of RA patients in a single center in Sweden over the course of 5 years. They were found to have reduction of VAS pain from inclusion to 6 months, but pain levels largely stayed the same during the rest of the follow-up period. The proportion of patients with unacceptable pain also decreased but remained stable at about 30% after 1 year, with 20% having unacceptable pain and low inflammation and about 10% having high inflammation and unacceptable pain. The study found seropositivity, high inflammatory parameters, high DAS28 and severe patient-reported outcomes to be predictive of high inflammation and unacceptable pain and lower age, higher VAS pain, and low ESR to be predictive of low inflammation and unacceptable pain. These findings highlight the importance of examining non-inflammatory mechanisms of pain as well as identifying treatments; however, in evaluating the risk of immunosuppression and glucocorticoid therapy, it does not guide increasing or reducing treatment in RA patients with persistent pain.

Recently, ACR guidelines were published on the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, emphasizing use of supplemental calcium and vitamin D and antiresorptive therapy. This randomized, controlled, open-label trial by Cho et al looks at the efficacy of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in preventing bone loss and fractures in postmenopausal RA patients with osteopenia on long-term glucocorticoids. Patients were randomized to bazedoxefine, a 3rd-generation SERM vs no therapy in addition to background calcium and vitamin D supplementation and bone mineral density (BMD) and trabecular bone score (TBS). Bone turnover markers were assessed over the course of 48 weeks, in addition to adverse events. Prednisone dose was relatively low, with a baseline of ~3 mg/day. Bone density increased by almost 2% in the L spine (P < 0.05), but the increases in BMD at the femoral neck and TBS were not significant. Bone turnover markers did decrease in the bazedoxefine group, though not in the control group. These findings are not striking but are promising given the short duration of the study (<1 year), and potentially deserves longer-term follow-up, both for evaluation of efficacy as well as long-term safety. In the US, the medication is only available in combination with estrogen, and thus it is not currently a practical option for RA patients with GIOP.

Despite wider availability of both synthetic and biologic DMARDs for treatment of RA in recent years, persistent pain is an issue for many patients, perhaps due to peripheral sensitization. Though it seems almost unnecessary to investigate the utility of glucocorticoids for treatment of RA-related pain, the magnitude and duration of their benefit is unknown. McWilliams et al take the approach of quantitatively analyzing the benefit of glucocorticoids in RA over time in their systematic review and meta-analysis. The study looked at both spontaneous and evoked pain, and evaluated 65 studies that mostly used pain visual analogue scale, tender joint count, and Ritchie Articular Index. Reduction in spontaneous pain was greatest in the 0-3-month time period, with smaller reductions in 3-6 months and >6 month. A similar pattern was seen in evaluation of the time course of evoked pain. As such, the benefits of long-term systemic glucocorticoid therapy may not outweigh its well-known risks, especially in patients with persistent pain. Whether this is due to non-inflammatory sources of pain or other mechanisms remains unknown and is likely heavily impacted by the specific clinical scenario.

Due to the potential long-terms side effects of chronic immunosuppression, including long-term glucocorticoid therapy in patients with persistent pain in RA, the course and predictors of unacceptable pain are of interest. Eberhard et al examined an inception cohort of RA patients in a single center in Sweden over the course of 5 years. They were found to have reduction of VAS pain from inclusion to 6 months, but pain levels largely stayed the same during the rest of the follow-up period. The proportion of patients with unacceptable pain also decreased but remained stable at about 30% after 1 year, with 20% having unacceptable pain and low inflammation and about 10% having high inflammation and unacceptable pain. The study found seropositivity, high inflammatory parameters, high DAS28 and severe patient-reported outcomes to be predictive of high inflammation and unacceptable pain and lower age, higher VAS pain, and low ESR to be predictive of low inflammation and unacceptable pain. These findings highlight the importance of examining non-inflammatory mechanisms of pain as well as identifying treatments; however, in evaluating the risk of immunosuppression and glucocorticoid therapy, it does not guide increasing or reducing treatment in RA patients with persistent pain.

Recently, ACR guidelines were published on the prevention and treatment of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis, emphasizing use of supplemental calcium and vitamin D and antiresorptive therapy. This randomized, controlled, open-label trial by Cho et al looks at the efficacy of selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in preventing bone loss and fractures in postmenopausal RA patients with osteopenia on long-term glucocorticoids. Patients were randomized to bazedoxefine, a 3rd-generation SERM vs no therapy in addition to background calcium and vitamin D supplementation and bone mineral density (BMD) and trabecular bone score (TBS). Bone turnover markers were assessed over the course of 48 weeks, in addition to adverse events. Prednisone dose was relatively low, with a baseline of ~3 mg/day. Bone density increased by almost 2% in the L spine (P < 0.05), but the increases in BMD at the femoral neck and TBS were not significant. Bone turnover markers did decrease in the bazedoxefine group, though not in the control group. These findings are not striking but are promising given the short duration of the study (<1 year), and potentially deserves longer-term follow-up, both for evaluation of efficacy as well as long-term safety. In the US, the medication is only available in combination with estrogen, and thus it is not currently a practical option for RA patients with GIOP.

Despite wider availability of both synthetic and biologic DMARDs for treatment of RA in recent years, persistent pain is an issue for many patients, perhaps due to peripheral sensitization. Though it seems almost unnecessary to investigate the utility of glucocorticoids for treatment of RA-related pain, the magnitude and duration of their benefit is unknown. McWilliams et al take the approach of quantitatively analyzing the benefit of glucocorticoids in RA over time in their systematic review and meta-analysis. The study looked at both spontaneous and evoked pain, and evaluated 65 studies that mostly used pain visual analogue scale, tender joint count, and Ritchie Articular Index. Reduction in spontaneous pain was greatest in the 0-3-month time period, with smaller reductions in 3-6 months and >6 month. A similar pattern was seen in evaluation of the time course of evoked pain. As such, the benefits of long-term systemic glucocorticoid therapy may not outweigh its well-known risks, especially in patients with persistent pain. Whether this is due to non-inflammatory sources of pain or other mechanisms remains unknown and is likely heavily impacted by the specific clinical scenario.

Due to the potential long-terms side effects of chronic immunosuppression, including long-term glucocorticoid therapy in patients with persistent pain in RA, the course and predictors of unacceptable pain are of interest. Eberhard et al examined an inception cohort of RA patients in a single center in Sweden over the course of 5 years. They were found to have reduction of VAS pain from inclusion to 6 months, but pain levels largely stayed the same during the rest of the follow-up period. The proportion of patients with unacceptable pain also decreased but remained stable at about 30% after 1 year, with 20% having unacceptable pain and low inflammation and about 10% having high inflammation and unacceptable pain. The study found seropositivity, high inflammatory parameters, high DAS28 and severe patient-reported outcomes to be predictive of high inflammation and unacceptable pain and lower age, higher VAS pain, and low ESR to be predictive of low inflammation and unacceptable pain. These findings highlight the importance of examining non-inflammatory mechanisms of pain as well as identifying treatments; however, in evaluating the risk of immunosuppression and glucocorticoid therapy, it does not guide increasing or reducing treatment in RA patients with persistent pain.

In sickness and in health: Spouses can share risk for cardiac events

A study from Japan suggests that a history of cardiovascular events in a spouse may elevate risk for future CV events in the other partner, with one caveat: Men in the cohort study were at increased risk if their wives had such a history, but the association was only one way. The risk of events didn’t go up for women with husbands who had previously experienced a CV event.

The results highlight the need for clinicians to screen and possibly intervene with a primary CV prevention strategy “not only first-degree relatives but also spouses with a history of cardiovascular disease,” which is not currently part of the primary prevention guidelines, Hiroyuki Ohbe, MD, University of Tokyo, told this news organization.

In their study published online July 9 in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, Dr. Ohbe and Hideo Yasunaga, MD, PhD, of the same institution, assessed the risk of subsequent CV events in adults with a spouse who had experienced a stroke of any kind or had clinical ischemic heart disease such as angina or myocardial infarction.

Johanna Contreras, MD, director of heart failure at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, is not surprised by the finding that a wife’s CV history is linked to the CV risk in the husband.

“I see this often in my practice. When you live with someone, you also behave in a similar way as the other person,” Dr. Contreras told this news organization. “For example, couples who live together are likely to both exercise and have a healthy diet and not smoke.”

And most notably, she said, “the women are usually the ones who drive the healthy behaviors in the family; they watch what the family eats, where they eat, when they eat, and the men tend to allow the women to guide this behavior.”

Dr. Ohbe and Dr. Yasunaga agree, proposing that different results for men and women in the analysis may be because of the dependence of working-aged men on their wives for major aspects of lifestyle, such as diet and exercise. Moreover, they write, increased psychological and physical stress from taking care of a spouse with CV disease may also play a role, as caregivers often neglect their own health.

The team identified 13,759 adults in a large administrative database with no history of CV disease whose spouse had such a history at their first health checkup; they were the exposure group. The team matched each of them with up to four individuals (n = 55,027) who had no CV disease history and spouses without CV disease at their first health checkup; they were the nonexposure group.

The mean observation period was 7.9 years from the first health checkup, at which the subjects’ mean age was 56 years. During the follow-up, more people in the exposure group than the nonexposure group had a history of CV events, 0.6% versus 0.4%.

In the overall cohort, the hazard ratio for future severe CV events – heart failure hospitalization or MI – in those with spouses with a history of CV disease was 1.48 (95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.90).

When stratified by sex, men whose wives had CV disease showed a significantly increased risk of a future severe CV event (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.22-2.32). But women with husbands with CV disease did not (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.82-1.83).

The results of all four sensitivity analyses were similar to those of the primary analysis, both in the overall cohort and in the cohorts stratified by sex. The investigators performed multivariate survival analyses: one that excluded people whose partners had died, one that included death by any cause as an outcome, and one with propensity score matching.

Further studies are needed to confirm their observations and test whether a primary prevention strategy targeted at married couples could reduce CV events, note Dr. Ohbe and Dr. Yasunaga.

The findings have implications for everyday clinical practice, Dr. Contreras said. “When I see a patient who is married and has had a heart attack, I will insist on seeing the partner as well, and I will counsel them on working together to change their lifestyle,” she said in an interview.

“Often when you have that discussion with the couple after one has a heart attack, they quit smoking together, they go the gym together, and they get healthier together,” she said. “That’s now a very important conversation we have before they leave the hospital.”

The study was supported by grants from the Japan Ministry of Health, Ministry of Labour and Welfare, and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Dr. Ohbe, Dr. Yasunaga, and Dr. Contreras have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study from Japan suggests that a history of cardiovascular events in a spouse may elevate risk for future CV events in the other partner, with one caveat: Men in the cohort study were at increased risk if their wives had such a history, but the association was only one way. The risk of events didn’t go up for women with husbands who had previously experienced a CV event.

The results highlight the need for clinicians to screen and possibly intervene with a primary CV prevention strategy “not only first-degree relatives but also spouses with a history of cardiovascular disease,” which is not currently part of the primary prevention guidelines, Hiroyuki Ohbe, MD, University of Tokyo, told this news organization.

In their study published online July 9 in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, Dr. Ohbe and Hideo Yasunaga, MD, PhD, of the same institution, assessed the risk of subsequent CV events in adults with a spouse who had experienced a stroke of any kind or had clinical ischemic heart disease such as angina or myocardial infarction.

Johanna Contreras, MD, director of heart failure at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, is not surprised by the finding that a wife’s CV history is linked to the CV risk in the husband.

“I see this often in my practice. When you live with someone, you also behave in a similar way as the other person,” Dr. Contreras told this news organization. “For example, couples who live together are likely to both exercise and have a healthy diet and not smoke.”

And most notably, she said, “the women are usually the ones who drive the healthy behaviors in the family; they watch what the family eats, where they eat, when they eat, and the men tend to allow the women to guide this behavior.”

Dr. Ohbe and Dr. Yasunaga agree, proposing that different results for men and women in the analysis may be because of the dependence of working-aged men on their wives for major aspects of lifestyle, such as diet and exercise. Moreover, they write, increased psychological and physical stress from taking care of a spouse with CV disease may also play a role, as caregivers often neglect their own health.

The team identified 13,759 adults in a large administrative database with no history of CV disease whose spouse had such a history at their first health checkup; they were the exposure group. The team matched each of them with up to four individuals (n = 55,027) who had no CV disease history and spouses without CV disease at their first health checkup; they were the nonexposure group.

The mean observation period was 7.9 years from the first health checkup, at which the subjects’ mean age was 56 years. During the follow-up, more people in the exposure group than the nonexposure group had a history of CV events, 0.6% versus 0.4%.

In the overall cohort, the hazard ratio for future severe CV events – heart failure hospitalization or MI – in those with spouses with a history of CV disease was 1.48 (95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.90).

When stratified by sex, men whose wives had CV disease showed a significantly increased risk of a future severe CV event (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.22-2.32). But women with husbands with CV disease did not (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.82-1.83).

The results of all four sensitivity analyses were similar to those of the primary analysis, both in the overall cohort and in the cohorts stratified by sex. The investigators performed multivariate survival analyses: one that excluded people whose partners had died, one that included death by any cause as an outcome, and one with propensity score matching.

Further studies are needed to confirm their observations and test whether a primary prevention strategy targeted at married couples could reduce CV events, note Dr. Ohbe and Dr. Yasunaga.

The findings have implications for everyday clinical practice, Dr. Contreras said. “When I see a patient who is married and has had a heart attack, I will insist on seeing the partner as well, and I will counsel them on working together to change their lifestyle,” she said in an interview.

“Often when you have that discussion with the couple after one has a heart attack, they quit smoking together, they go the gym together, and they get healthier together,” she said. “That’s now a very important conversation we have before they leave the hospital.”

The study was supported by grants from the Japan Ministry of Health, Ministry of Labour and Welfare, and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Dr. Ohbe, Dr. Yasunaga, and Dr. Contreras have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A study from Japan suggests that a history of cardiovascular events in a spouse may elevate risk for future CV events in the other partner, with one caveat: Men in the cohort study were at increased risk if their wives had such a history, but the association was only one way. The risk of events didn’t go up for women with husbands who had previously experienced a CV event.

The results highlight the need for clinicians to screen and possibly intervene with a primary CV prevention strategy “not only first-degree relatives but also spouses with a history of cardiovascular disease,” which is not currently part of the primary prevention guidelines, Hiroyuki Ohbe, MD, University of Tokyo, told this news organization.

In their study published online July 9 in Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, Dr. Ohbe and Hideo Yasunaga, MD, PhD, of the same institution, assessed the risk of subsequent CV events in adults with a spouse who had experienced a stroke of any kind or had clinical ischemic heart disease such as angina or myocardial infarction.

Johanna Contreras, MD, director of heart failure at Mount Sinai Health System in New York, is not surprised by the finding that a wife’s CV history is linked to the CV risk in the husband.

“I see this often in my practice. When you live with someone, you also behave in a similar way as the other person,” Dr. Contreras told this news organization. “For example, couples who live together are likely to both exercise and have a healthy diet and not smoke.”

And most notably, she said, “the women are usually the ones who drive the healthy behaviors in the family; they watch what the family eats, where they eat, when they eat, and the men tend to allow the women to guide this behavior.”

Dr. Ohbe and Dr. Yasunaga agree, proposing that different results for men and women in the analysis may be because of the dependence of working-aged men on their wives for major aspects of lifestyle, such as diet and exercise. Moreover, they write, increased psychological and physical stress from taking care of a spouse with CV disease may also play a role, as caregivers often neglect their own health.

The team identified 13,759 adults in a large administrative database with no history of CV disease whose spouse had such a history at their first health checkup; they were the exposure group. The team matched each of them with up to four individuals (n = 55,027) who had no CV disease history and spouses without CV disease at their first health checkup; they were the nonexposure group.

The mean observation period was 7.9 years from the first health checkup, at which the subjects’ mean age was 56 years. During the follow-up, more people in the exposure group than the nonexposure group had a history of CV events, 0.6% versus 0.4%.

In the overall cohort, the hazard ratio for future severe CV events – heart failure hospitalization or MI – in those with spouses with a history of CV disease was 1.48 (95% confidence interval, 1.15-1.90).

When stratified by sex, men whose wives had CV disease showed a significantly increased risk of a future severe CV event (HR, 1.68; 95% CI, 1.22-2.32). But women with husbands with CV disease did not (HR, 1.22; 95% CI, 0.82-1.83).

The results of all four sensitivity analyses were similar to those of the primary analysis, both in the overall cohort and in the cohorts stratified by sex. The investigators performed multivariate survival analyses: one that excluded people whose partners had died, one that included death by any cause as an outcome, and one with propensity score matching.

Further studies are needed to confirm their observations and test whether a primary prevention strategy targeted at married couples could reduce CV events, note Dr. Ohbe and Dr. Yasunaga.

The findings have implications for everyday clinical practice, Dr. Contreras said. “When I see a patient who is married and has had a heart attack, I will insist on seeing the partner as well, and I will counsel them on working together to change their lifestyle,” she said in an interview.

“Often when you have that discussion with the couple after one has a heart attack, they quit smoking together, they go the gym together, and they get healthier together,” she said. “That’s now a very important conversation we have before they leave the hospital.”

The study was supported by grants from the Japan Ministry of Health, Ministry of Labour and Welfare, and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. Dr. Ohbe, Dr. Yasunaga, and Dr. Contreras have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

PUFAs a promising add-on for borderline personality disorder

Marine omega-3 fatty acids may be a promising add-on therapy for improving symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD), new research suggests.

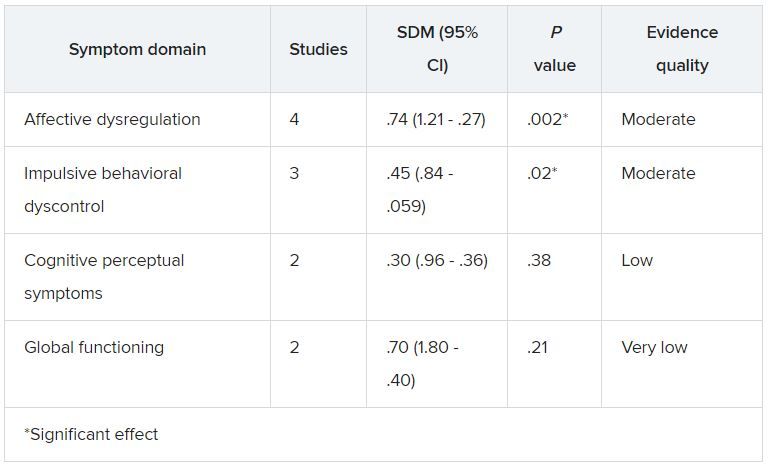

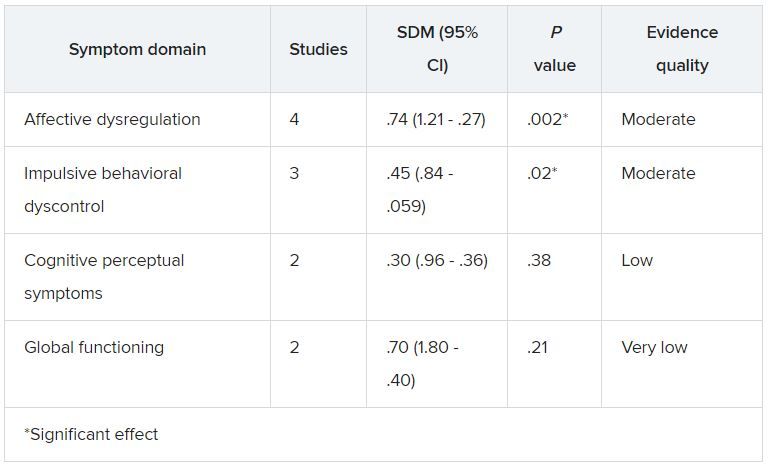

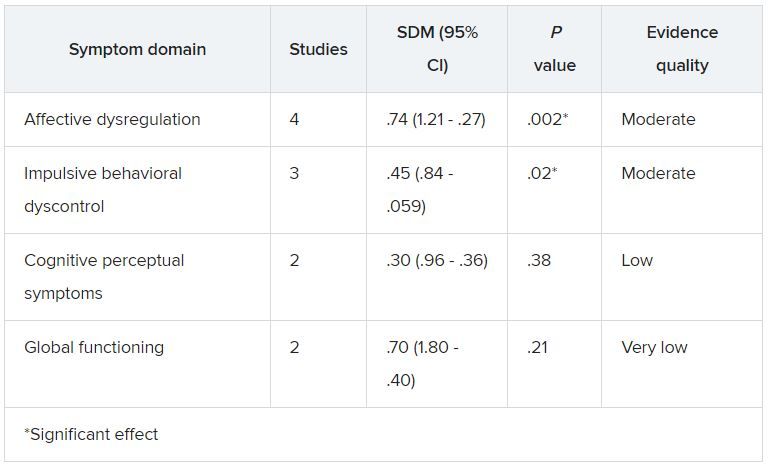

A meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials showed that adjunctive omega-3 fatty polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) significantly reduced overall BPD symptom severity, particularly affect dysregulation and impulsive behavior.

“Given the mechanisms of action and beneficial side effect profile, this [analysis] suggests that omega-3 fatty acids could be considered as add-on treatment” for patients with BPD, senior author Roel J. T. Mocking MD, PhD, resident in psychiatry and postdoctoral researcher at Academisch Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Urgent need

“There are several effective treatments, but not all patients respond sufficiently,” which points to an urgent need for additional treatment options, Dr. Mocking said.

He noted that, although “several prior studies showed promising effects of omega-3 fatty acids” for patients with BPD, those studies were relatively small, which precluded more definitive overall conclusions.

The investigators wanted to combine results of the earlier studies to provide a combined estimate of overall effectiveness of the use of omega-3 fatty acids for patients with BP, with the intention of “guiding clinicians and individuals suffering from borderline personality disorder to decide on whether they should add omega-3 fatty acids to their treatment.”

The analyzed four studies that had a total of 137 patients. Three of the studies included patients diagnosed with BPD; one included individuals with recurrent self-harm, most of whom were also diagnosed with BPD.

Omega-3 fatty acids were used as monotherapy in one study. In the other studies, they were used as add-on therapy to other agents, such as antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and/or valproic acid. None of the studies included patients who were taking antipsychotics.

The type of omega-3 PUFAs were derived from marine rather than plant sources.

Three studies compared omega-3 fatty acids with placebo. One study compared valproic acid monotherapy with valproic acid plus omega-3 fatty acids and did not include a placebo group.

Significant symptom reduction

Random-effects meta-analyses showed an “overall significant decreasing effect” of omega-3 fatty acids on overall BPD symptom severity (standardized difference in means, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.91-0.17; P = .004) in the omega-3 group compared with the control group, with a medium effect size.

The investigators added that there was “no relevant heterogeneity” (P = .45).

Although heterogeneity was “more pronounced” in the affective dysregulation symptom domain, it did not reach statistical significance, the researchers noted.

The impulsive behavioral dyscontrol and cognitive perceptual symptom domains had “no relevant heterogeneity.” On the other hand, there was “substantial heterogeneity” in the global functioning symptom group.

Omega-3 fatty acids “have multiple bioactive roles in the brain. For example, they form essential components of the membrane of brain cells and thereby influence the structure and functioning of the brain. They also have an effect on inflammation levels in the brain,” Dr. Mocking said.

“Because we cannot synthesize these omega-3 fatty acids ourselves, we are dependent on our diet. The main dietary source of omega-3 fatty acids is fatty fish. However, since the industrial revolution, we eat less and less fatty fish, risking deficiency of omega-3 fatty acids causing brain dysfunction,” he added.

Dr. Mocking noted that

This “suggests that they could be combined to increase overall effectiveness,” he said.

Important benefit

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the benefit of omega-3 “on impulsivity and mood symptoms is especially important, as these are some of the most debilitating aspects of BPD and lead to service utilization, such as ER, primary care, and specialty care.”

In addition, “impulsivity often presages suicidality,” he noted.

Dr. McIntyre, who is also chair and executive director of the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation in Toronto and was not involved with the study, called the effect size “quite reasonable.”

“The mechanistic story is very strong around anti-inflammatory effect, which particularly implied mood and cognition. In other words, inflammation is highly associated with mood and cognitive difficulties,” he said.

However, Dr. McIntyre also pointed to several significant challenges, including “quality assurance on the purchase of the product of fish oil, as it is not sufficiently regulated.” It is also unclear which individuals are more likely to benefit from it.

For example, major depressive disorder data have shown that “fish oils are not as effective as we hoped but are especially effective in people with baseline elevation of inflammatory markers,” Dr. McIntyre said.

“In other words, is there a way to identify a biomarkers/biosignature or phenomenology that’s more likely to identify a subgroup of people with BPD who might benefit benefiting from omega-3?” he asked.

Dr. Mocking and the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and AbbVie. Dr. McIntyre is also CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Marine omega-3 fatty acids may be a promising add-on therapy for improving symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD), new research suggests.

A meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials showed that adjunctive omega-3 fatty polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) significantly reduced overall BPD symptom severity, particularly affect dysregulation and impulsive behavior.

“Given the mechanisms of action and beneficial side effect profile, this [analysis] suggests that omega-3 fatty acids could be considered as add-on treatment” for patients with BPD, senior author Roel J. T. Mocking MD, PhD, resident in psychiatry and postdoctoral researcher at Academisch Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Urgent need

“There are several effective treatments, but not all patients respond sufficiently,” which points to an urgent need for additional treatment options, Dr. Mocking said.

He noted that, although “several prior studies showed promising effects of omega-3 fatty acids” for patients with BPD, those studies were relatively small, which precluded more definitive overall conclusions.

The investigators wanted to combine results of the earlier studies to provide a combined estimate of overall effectiveness of the use of omega-3 fatty acids for patients with BP, with the intention of “guiding clinicians and individuals suffering from borderline personality disorder to decide on whether they should add omega-3 fatty acids to their treatment.”

The analyzed four studies that had a total of 137 patients. Three of the studies included patients diagnosed with BPD; one included individuals with recurrent self-harm, most of whom were also diagnosed with BPD.

Omega-3 fatty acids were used as monotherapy in one study. In the other studies, they were used as add-on therapy to other agents, such as antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and/or valproic acid. None of the studies included patients who were taking antipsychotics.

The type of omega-3 PUFAs were derived from marine rather than plant sources.

Three studies compared omega-3 fatty acids with placebo. One study compared valproic acid monotherapy with valproic acid plus omega-3 fatty acids and did not include a placebo group.

Significant symptom reduction

Random-effects meta-analyses showed an “overall significant decreasing effect” of omega-3 fatty acids on overall BPD symptom severity (standardized difference in means, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.91-0.17; P = .004) in the omega-3 group compared with the control group, with a medium effect size.

The investigators added that there was “no relevant heterogeneity” (P = .45).

Although heterogeneity was “more pronounced” in the affective dysregulation symptom domain, it did not reach statistical significance, the researchers noted.

The impulsive behavioral dyscontrol and cognitive perceptual symptom domains had “no relevant heterogeneity.” On the other hand, there was “substantial heterogeneity” in the global functioning symptom group.

Omega-3 fatty acids “have multiple bioactive roles in the brain. For example, they form essential components of the membrane of brain cells and thereby influence the structure and functioning of the brain. They also have an effect on inflammation levels in the brain,” Dr. Mocking said.

“Because we cannot synthesize these omega-3 fatty acids ourselves, we are dependent on our diet. The main dietary source of omega-3 fatty acids is fatty fish. However, since the industrial revolution, we eat less and less fatty fish, risking deficiency of omega-3 fatty acids causing brain dysfunction,” he added.

Dr. Mocking noted that

This “suggests that they could be combined to increase overall effectiveness,” he said.

Important benefit

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the benefit of omega-3 “on impulsivity and mood symptoms is especially important, as these are some of the most debilitating aspects of BPD and lead to service utilization, such as ER, primary care, and specialty care.”

In addition, “impulsivity often presages suicidality,” he noted.

Dr. McIntyre, who is also chair and executive director of the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation in Toronto and was not involved with the study, called the effect size “quite reasonable.”

“The mechanistic story is very strong around anti-inflammatory effect, which particularly implied mood and cognition. In other words, inflammation is highly associated with mood and cognitive difficulties,” he said.

However, Dr. McIntyre also pointed to several significant challenges, including “quality assurance on the purchase of the product of fish oil, as it is not sufficiently regulated.” It is also unclear which individuals are more likely to benefit from it.

For example, major depressive disorder data have shown that “fish oils are not as effective as we hoped but are especially effective in people with baseline elevation of inflammatory markers,” Dr. McIntyre said.

“In other words, is there a way to identify a biomarkers/biosignature or phenomenology that’s more likely to identify a subgroup of people with BPD who might benefit benefiting from omega-3?” he asked.

Dr. Mocking and the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and AbbVie. Dr. McIntyre is also CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Marine omega-3 fatty acids may be a promising add-on therapy for improving symptoms of borderline personality disorder (BPD), new research suggests.

A meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials showed that adjunctive omega-3 fatty polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) significantly reduced overall BPD symptom severity, particularly affect dysregulation and impulsive behavior.

“Given the mechanisms of action and beneficial side effect profile, this [analysis] suggests that omega-3 fatty acids could be considered as add-on treatment” for patients with BPD, senior author Roel J. T. Mocking MD, PhD, resident in psychiatry and postdoctoral researcher at Academisch Medisch Centrum, Amsterdam, said in an interview.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Urgent need

“There are several effective treatments, but not all patients respond sufficiently,” which points to an urgent need for additional treatment options, Dr. Mocking said.

He noted that, although “several prior studies showed promising effects of omega-3 fatty acids” for patients with BPD, those studies were relatively small, which precluded more definitive overall conclusions.

The investigators wanted to combine results of the earlier studies to provide a combined estimate of overall effectiveness of the use of omega-3 fatty acids for patients with BP, with the intention of “guiding clinicians and individuals suffering from borderline personality disorder to decide on whether they should add omega-3 fatty acids to their treatment.”

The analyzed four studies that had a total of 137 patients. Three of the studies included patients diagnosed with BPD; one included individuals with recurrent self-harm, most of whom were also diagnosed with BPD.

Omega-3 fatty acids were used as monotherapy in one study. In the other studies, they were used as add-on therapy to other agents, such as antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and/or valproic acid. None of the studies included patients who were taking antipsychotics.

The type of omega-3 PUFAs were derived from marine rather than plant sources.

Three studies compared omega-3 fatty acids with placebo. One study compared valproic acid monotherapy with valproic acid plus omega-3 fatty acids and did not include a placebo group.

Significant symptom reduction

Random-effects meta-analyses showed an “overall significant decreasing effect” of omega-3 fatty acids on overall BPD symptom severity (standardized difference in means, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.91-0.17; P = .004) in the omega-3 group compared with the control group, with a medium effect size.

The investigators added that there was “no relevant heterogeneity” (P = .45).

Although heterogeneity was “more pronounced” in the affective dysregulation symptom domain, it did not reach statistical significance, the researchers noted.

The impulsive behavioral dyscontrol and cognitive perceptual symptom domains had “no relevant heterogeneity.” On the other hand, there was “substantial heterogeneity” in the global functioning symptom group.

Omega-3 fatty acids “have multiple bioactive roles in the brain. For example, they form essential components of the membrane of brain cells and thereby influence the structure and functioning of the brain. They also have an effect on inflammation levels in the brain,” Dr. Mocking said.

“Because we cannot synthesize these omega-3 fatty acids ourselves, we are dependent on our diet. The main dietary source of omega-3 fatty acids is fatty fish. However, since the industrial revolution, we eat less and less fatty fish, risking deficiency of omega-3 fatty acids causing brain dysfunction,” he added.

Dr. Mocking noted that

This “suggests that they could be combined to increase overall effectiveness,” he said.

Important benefit

Commenting on the study, Roger McIntyre, MD, professor of psychiatry and pharmacology, University of Toronto, and head of the mood disorders psychopharmacology unit, said that the benefit of omega-3 “on impulsivity and mood symptoms is especially important, as these are some of the most debilitating aspects of BPD and lead to service utilization, such as ER, primary care, and specialty care.”

In addition, “impulsivity often presages suicidality,” he noted.

Dr. McIntyre, who is also chair and executive director of the Brain and Cognition Discovery Foundation in Toronto and was not involved with the study, called the effect size “quite reasonable.”

“The mechanistic story is very strong around anti-inflammatory effect, which particularly implied mood and cognition. In other words, inflammation is highly associated with mood and cognitive difficulties,” he said.

However, Dr. McIntyre also pointed to several significant challenges, including “quality assurance on the purchase of the product of fish oil, as it is not sufficiently regulated.” It is also unclear which individuals are more likely to benefit from it.

For example, major depressive disorder data have shown that “fish oils are not as effective as we hoped but are especially effective in people with baseline elevation of inflammatory markers,” Dr. McIntyre said.

“In other words, is there a way to identify a biomarkers/biosignature or phenomenology that’s more likely to identify a subgroup of people with BPD who might benefit benefiting from omega-3?” he asked.

Dr. Mocking and the other investigators reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. McIntyre has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/Chinese National Natural Research Foundation and speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Allergan, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Eisai, Minerva, Intra-Cellular, and AbbVie. Dr. McIntyre is also CEO of AltMed.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mayo Clinic again named best hospital in U.S. for gynecology

This year, the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. again ranked as the top hospital for gynecology, according to U.S. News and World Report, which released its annual rankings today.

The top five hospitals for gynecology were the same this year and were in the same order. In second place again this year was Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, followed by the Cleveland Clinic, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Rounding out the top 10 were (6) Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Virginia; (7) the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital; (8) Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland; and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Stanford Health Care–Stanford Hospital, Palo Alto, California, which tied for the ninth spot.

U.S. News compared more than 4,750 medical centers nationwide in 15 specialties. Of those, 531 were recognized as Best Regional Hospitals on the basis of their strong performance in multiple areas of care.

In 12 of the specialties, including gynecology, rankings are determined by a data-driven analysis that combines performance measures in structure, process, and outcomes. Rankings in three other specialties – ophthalmology, psychiatry, and rheumatology – rely on expert opinion alone, according to the U.S. News methodology report.

The top 20 hospitals overall were also named to the Honor Roll.

Mayo Clinic was again no. 1 on the honor roll, a ranking it has held for 6 years in a row, according to a press release.

In other top specialties, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center ranked no. 1 in cancer; the Cleveland Clinic is no. 1 in cardiology and heart surgery; and the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, is no. 1 in orthopedics.

A full list of rankings is available on the magazine’s website.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This year, the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. again ranked as the top hospital for gynecology, according to U.S. News and World Report, which released its annual rankings today.

The top five hospitals for gynecology were the same this year and were in the same order. In second place again this year was Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, followed by the Cleveland Clinic, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Rounding out the top 10 were (6) Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Virginia; (7) the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital; (8) Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland; and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Stanford Health Care–Stanford Hospital, Palo Alto, California, which tied for the ninth spot.

U.S. News compared more than 4,750 medical centers nationwide in 15 specialties. Of those, 531 were recognized as Best Regional Hospitals on the basis of their strong performance in multiple areas of care.

In 12 of the specialties, including gynecology, rankings are determined by a data-driven analysis that combines performance measures in structure, process, and outcomes. Rankings in three other specialties – ophthalmology, psychiatry, and rheumatology – rely on expert opinion alone, according to the U.S. News methodology report.

The top 20 hospitals overall were also named to the Honor Roll.

Mayo Clinic was again no. 1 on the honor roll, a ranking it has held for 6 years in a row, according to a press release.

In other top specialties, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center ranked no. 1 in cancer; the Cleveland Clinic is no. 1 in cardiology and heart surgery; and the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, is no. 1 in orthopedics.

A full list of rankings is available on the magazine’s website.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This year, the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. again ranked as the top hospital for gynecology, according to U.S. News and World Report, which released its annual rankings today.

The top five hospitals for gynecology were the same this year and were in the same order. In second place again this year was Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, followed by the Cleveland Clinic, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, and the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Rounding out the top 10 were (6) Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Virginia; (7) the University of Alabama at Birmingham Hospital; (8) Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland; and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, and Stanford Health Care–Stanford Hospital, Palo Alto, California, which tied for the ninth spot.

U.S. News compared more than 4,750 medical centers nationwide in 15 specialties. Of those, 531 were recognized as Best Regional Hospitals on the basis of their strong performance in multiple areas of care.

In 12 of the specialties, including gynecology, rankings are determined by a data-driven analysis that combines performance measures in structure, process, and outcomes. Rankings in three other specialties – ophthalmology, psychiatry, and rheumatology – rely on expert opinion alone, according to the U.S. News methodology report.

The top 20 hospitals overall were also named to the Honor Roll.

Mayo Clinic was again no. 1 on the honor roll, a ranking it has held for 6 years in a row, according to a press release.

In other top specialties, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center ranked no. 1 in cancer; the Cleveland Clinic is no. 1 in cardiology and heart surgery; and the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, is no. 1 in orthopedics.

A full list of rankings is available on the magazine’s website.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Women with sickle cell disease have high rates of unintended pregnancy and low use of LARC

Key clinical point: Women with sickle cell disease report high rates of unplanned pregnancy and limited knowledge and use of long-acting reversible contraception despite the high-risk nature of pregnancy for sickle cell disease patients.

Major finding: In a survey of 78 women with sickle cell disease, 73% had an average of 2.5 pregnancies, and 58% reported unplanned pregnancies. The most frequently reported contraception in the study population was condoms (87%), followed by birth control pills (46%), medroxyprogesterone (44%), and withdrawal (44%), while 22% reported use of long-acting reversible contraception.

Study details: The data come from a survey of 78 women aged 28-65 years with sickle cell disease seen at a single adult and pediatric sickle cell treatment center.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Pecker LH et al. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021 Jun 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2021.05.005.

Key clinical point: Women with sickle cell disease report high rates of unplanned pregnancy and limited knowledge and use of long-acting reversible contraception despite the high-risk nature of pregnancy for sickle cell disease patients.

Major finding: In a survey of 78 women with sickle cell disease, 73% had an average of 2.5 pregnancies, and 58% reported unplanned pregnancies. The most frequently reported contraception in the study population was condoms (87%), followed by birth control pills (46%), medroxyprogesterone (44%), and withdrawal (44%), while 22% reported use of long-acting reversible contraception.

Study details: The data come from a survey of 78 women aged 28-65 years with sickle cell disease seen at a single adult and pediatric sickle cell treatment center.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Pecker LH et al. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021 Jun 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2021.05.005.

Key clinical point: Women with sickle cell disease report high rates of unplanned pregnancy and limited knowledge and use of long-acting reversible contraception despite the high-risk nature of pregnancy for sickle cell disease patients.

Major finding: In a survey of 78 women with sickle cell disease, 73% had an average of 2.5 pregnancies, and 58% reported unplanned pregnancies. The most frequently reported contraception in the study population was condoms (87%), followed by birth control pills (46%), medroxyprogesterone (44%), and withdrawal (44%), while 22% reported use of long-acting reversible contraception.

Study details: The data come from a survey of 78 women aged 28-65 years with sickle cell disease seen at a single adult and pediatric sickle cell treatment center.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Pecker LH et al. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021 Jun 9. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2021.05.005.

Cesarean delivery impacts outcomes of postplacental IUD placement

Key clinical point: Cesarean delivery was independently associated with missing strings and expulsion of an IUD placed after delivery.

Major finding: Among women who underwent postplacental copper IUD placement, missing strings were noted in 47.9% 34.2% of women at postpartum visits 1 and 2, respectively, and 8.9% experience expulsions by visit 2. Cesarean delivery was associated with a significantly increased risk of missing strings, but a decreased risk of IUD expulsion (adjusted risk ratios 6.21 and 0.24, respectively).

Study details: The data come from 705 women who underwent postplacental insertion of a copper T380A IUD. The women were assessed at postpartum visits at 45-90 days and again at 6-9 months.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Barboza da Silva Nobrega A et al. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Jul 1. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13806.

Key clinical point: Cesarean delivery was independently associated with missing strings and expulsion of an IUD placed after delivery.

Major finding: Among women who underwent postplacental copper IUD placement, missing strings were noted in 47.9% 34.2% of women at postpartum visits 1 and 2, respectively, and 8.9% experience expulsions by visit 2. Cesarean delivery was associated with a significantly increased risk of missing strings, but a decreased risk of IUD expulsion (adjusted risk ratios 6.21 and 0.24, respectively).

Study details: The data come from 705 women who underwent postplacental insertion of a copper T380A IUD. The women were assessed at postpartum visits at 45-90 days and again at 6-9 months.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Barboza da Silva Nobrega A et al. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Jul 1. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13806.

Key clinical point: Cesarean delivery was independently associated with missing strings and expulsion of an IUD placed after delivery.

Major finding: Among women who underwent postplacental copper IUD placement, missing strings were noted in 47.9% 34.2% of women at postpartum visits 1 and 2, respectively, and 8.9% experience expulsions by visit 2. Cesarean delivery was associated with a significantly increased risk of missing strings, but a decreased risk of IUD expulsion (adjusted risk ratios 6.21 and 0.24, respectively).

Study details: The data come from 705 women who underwent postplacental insertion of a copper T380A IUD. The women were assessed at postpartum visits at 45-90 days and again at 6-9 months.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Barboza da Silva Nobrega A et al. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021 Jul 1. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.13806.

Combination oral contraceptive shows safety and efficacy

Key clinical point: An oral contraceptive combining 15 mg estetrol and 3 mg drospirinone prevented pregnancy and promoted predictable bleeding patterns in women aged 18 to 35 years compared with a placebo during a study period of up to 13 cycles.

Major finding: The Pearl Index overall was 0.47 pregnancies per 100 women-years, and the method failure Pearl Index was 0.29 pregnancies per 100 women-years. Scheduled bleeding or spotting occurred in approximately 92% to 95% of the women during 12 cycles of contraceptive use.

Study details: The data come from an open-label, multicenter, phase 3 clinical trial including 69 sites in Europe and Russia. The study population included 1,553 women aged 18-30 years. The primary outcome measures were the Pearl Index measure of contraceptive effectiveness for women aged 18-35 years, bleeding patterns, and adverse events.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Gemzell-Danielsson K et al. BJOG. 2021 Jul 10. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16840.

Key clinical point: An oral contraceptive combining 15 mg estetrol and 3 mg drospirinone prevented pregnancy and promoted predictable bleeding patterns in women aged 18 to 35 years compared with a placebo during a study period of up to 13 cycles.

Major finding: The Pearl Index overall was 0.47 pregnancies per 100 women-years, and the method failure Pearl Index was 0.29 pregnancies per 100 women-years. Scheduled bleeding or spotting occurred in approximately 92% to 95% of the women during 12 cycles of contraceptive use.

Study details: The data come from an open-label, multicenter, phase 3 clinical trial including 69 sites in Europe and Russia. The study population included 1,553 women aged 18-30 years. The primary outcome measures were the Pearl Index measure of contraceptive effectiveness for women aged 18-35 years, bleeding patterns, and adverse events.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Gemzell-Danielsson K et al. BJOG. 2021 Jul 10. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16840.

Key clinical point: An oral contraceptive combining 15 mg estetrol and 3 mg drospirinone prevented pregnancy and promoted predictable bleeding patterns in women aged 18 to 35 years compared with a placebo during a study period of up to 13 cycles.

Major finding: The Pearl Index overall was 0.47 pregnancies per 100 women-years, and the method failure Pearl Index was 0.29 pregnancies per 100 women-years. Scheduled bleeding or spotting occurred in approximately 92% to 95% of the women during 12 cycles of contraceptive use.

Study details: The data come from an open-label, multicenter, phase 3 clinical trial including 69 sites in Europe and Russia. The study population included 1,553 women aged 18-30 years. The primary outcome measures were the Pearl Index measure of contraceptive effectiveness for women aged 18-35 years, bleeding patterns, and adverse events.

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Gemzell-Danielsson K et al. BJOG. 2021 Jul 10. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16840.

Oral contraceptive use eases symptoms of premenstrual syndrome

Key clinical point: Overall, oral contraceptives were more effective than placebo for treating symptoms of PMS and PMDD, but none of the combined oral contraceptives stood out as more effective than the others, and oral contraceptives had no apparent impact on premenstrual depressive symptoms.

Major finding: In a pairwise meta-analysis, combined oral contraceptives showed no effectiveness compared to placebo for reducing premenstrual depressive symptoms, with a standardized mean difference of 0.22. However, combined oral contraceptive use overall was moderately effective compared to placebo for improving premenstrual symptomatology overall (standardized mean difference 0.41).

Study details: The data come from a meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials including 1,205 women aged approximately 24-37 years who reported premenstrual syndrome (PMS) or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: De Wit AE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.06.090.

Key clinical point: Overall, oral contraceptives were more effective than placebo for treating symptoms of PMS and PMDD, but none of the combined oral contraceptives stood out as more effective than the others, and oral contraceptives had no apparent impact on premenstrual depressive symptoms.

Major finding: In a pairwise meta-analysis, combined oral contraceptives showed no effectiveness compared to placebo for reducing premenstrual depressive symptoms, with a standardized mean difference of 0.22. However, combined oral contraceptive use overall was moderately effective compared to placebo for improving premenstrual symptomatology overall (standardized mean difference 0.41).

Study details: The data come from a meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials including 1,205 women aged approximately 24-37 years who reported premenstrual syndrome (PMS) or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: De Wit AE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.06.090.

Key clinical point: Overall, oral contraceptives were more effective than placebo for treating symptoms of PMS and PMDD, but none of the combined oral contraceptives stood out as more effective than the others, and oral contraceptives had no apparent impact on premenstrual depressive symptoms.

Major finding: In a pairwise meta-analysis, combined oral contraceptives showed no effectiveness compared to placebo for reducing premenstrual depressive symptoms, with a standardized mean difference of 0.22. However, combined oral contraceptive use overall was moderately effective compared to placebo for improving premenstrual symptomatology overall (standardized mean difference 0.41).

Study details: The data come from a meta-analysis of nine randomized clinical trials including 1,205 women aged approximately 24-37 years who reported premenstrual syndrome (PMS) or premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

Disclosures: The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: De Wit AE et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021 Jul 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2021.06.090.