User login

Managing hyperhidrosis, HS: Ask questions first

A wide variety of medications exists for treating hyperhidrosis, a dermatologist told colleagues, but before prescribing anything to a pediatric patient, he recommended, ask the patient a simple question: “What bothers you the most?”

The answer will provide guidance for developing a step-by-step treatment strategy and help provide the patient “a set of realistic expectations in terms of what the response will look like,” George Hightower, MD, PhD, a pediatric dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego, said at MedscapeLive’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

A similar question-based approach will help guide therapy for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), he said.

With regards to hyperhidrosis, Dr. Hightower said that patients most commonly complain that their underarms are too smelly, too sweaty, and red, itchy, or painful. Causes, he said, can include irritation/contact dermatitis, folliculitis, and seborrheic dermatitis, as well as hyperhidrosis or HS.

Primary focal axillary hyperhidrosis is defined as focal, visible, excessive sweating for at least 6 months without an apparent cause plus at least two of the following characteristics: Sweating is bilateral and relatively symmetric, it impairs daily activities, it starts before the age of 25 with at least one episode per week (many patients have it daily), a family history of idiopathic hyperhidrosis is present, and focal sweating does not occur during sleep.

Secondary hyperhidrosis can be linked to other conditions, such as a spinal column injury, Dr. Hightower noted.

The first step on the treatment ladder is topical 20% aluminum chloride, which is available over the counter. This should be applied nightly for 1 week then every 1-2 weeks, Dr. Hightower recommended. All of his patients with hyperhidrosis have had at least one trial of this treatment.

The next option is daily topical treatment with 2.4% glycopyrronium tosylate (Qbrexza) cloths, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for primary axillary hyperhidrosis in patients aged 9 and older. According to the prescribing information, dry mouth was by far the most common treatment-associated adverse effect in clinical trials (24% versus almost 6% among those on vehicle). As for skin reactions, erythema occurred in about 17% of both the intervention and vehicle groups, and burning/stinging occurred in 14% of those on treatment and almost 17% of those on vehicle.

“If they’re not able to get access to the cloths due to [insurance] coverage issues, or they don’t allow them to reach the clinical endpoint desired, then I use an oral daily glycopyrrolate pill,” Dr. Hightower said.

He recommends 1 mg to 6 mg daily of the anticholinergic drug, which has been used off-label for hyperhidrosis for several years. A 2012 study of 31 children with hyperhidrosis, he noted, supported the use of the drug. The retrospective study found that 90% of the patients, at a mean daily dose of 2 mg, experienced improvements, reported as major in 71%. In addition, patients experienced improvement within hours of taking the medication, and benefits disappeared within a day of stopping the medication. In the study, patients were on the treatment for an average of 2.1 years, and 29% experienced side effects, which were dose related; the most common were dry mouth in 26% and dry eyes in 10%.

According to goodrx.com, a month’s supply of 2 mg of the drug costs as little as $13 with a discount or coupon.

The next steps in treatment are procedural interventions such as microwave-based therapies.

Dr. Hightower said that patients should be advised that treatment may take years, and to encourage them to return for follow-up. He suggested this helpful message: “We’re still trying to find the best treatment for you, and we’ll need to see you back in the office.”

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Dr. Hightower said that too often, HS goes undiagnosed for a significant period of time, preventing patients from seeing a dermatologist for treatment. Hallmarks of HS include inflammatory nodules, abscesses, and scarring, he said. “It can be disfiguring, painful, embarrassing, and associated with significantly decreased quality of life. Early recognition in terms of making and solidifying the diagnosis is important so we can prevent further worsening of the disease.”

The goal of treatment include preventing scars and unnecessary emergency department visits, and stopping flares from worsening, Dr. Hightower said. For specifics, he pointed to clinical management guidelines released by the United States and Canadian hidradenitis suppurativa foundations in 2019.

Make sure to set individualized treatment goals and understand the impact of treatment on the patient’s interactions with family, school, and peers, he said. And keep in mind that “parent-defined goals may be different from patient-defined goals.”

Dr. Hightower reported no relevant disclosures. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company

A wide variety of medications exists for treating hyperhidrosis, a dermatologist told colleagues, but before prescribing anything to a pediatric patient, he recommended, ask the patient a simple question: “What bothers you the most?”

The answer will provide guidance for developing a step-by-step treatment strategy and help provide the patient “a set of realistic expectations in terms of what the response will look like,” George Hightower, MD, PhD, a pediatric dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego, said at MedscapeLive’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

A similar question-based approach will help guide therapy for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), he said.

With regards to hyperhidrosis, Dr. Hightower said that patients most commonly complain that their underarms are too smelly, too sweaty, and red, itchy, or painful. Causes, he said, can include irritation/contact dermatitis, folliculitis, and seborrheic dermatitis, as well as hyperhidrosis or HS.

Primary focal axillary hyperhidrosis is defined as focal, visible, excessive sweating for at least 6 months without an apparent cause plus at least two of the following characteristics: Sweating is bilateral and relatively symmetric, it impairs daily activities, it starts before the age of 25 with at least one episode per week (many patients have it daily), a family history of idiopathic hyperhidrosis is present, and focal sweating does not occur during sleep.

Secondary hyperhidrosis can be linked to other conditions, such as a spinal column injury, Dr. Hightower noted.

The first step on the treatment ladder is topical 20% aluminum chloride, which is available over the counter. This should be applied nightly for 1 week then every 1-2 weeks, Dr. Hightower recommended. All of his patients with hyperhidrosis have had at least one trial of this treatment.

The next option is daily topical treatment with 2.4% glycopyrronium tosylate (Qbrexza) cloths, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for primary axillary hyperhidrosis in patients aged 9 and older. According to the prescribing information, dry mouth was by far the most common treatment-associated adverse effect in clinical trials (24% versus almost 6% among those on vehicle). As for skin reactions, erythema occurred in about 17% of both the intervention and vehicle groups, and burning/stinging occurred in 14% of those on treatment and almost 17% of those on vehicle.

“If they’re not able to get access to the cloths due to [insurance] coverage issues, or they don’t allow them to reach the clinical endpoint desired, then I use an oral daily glycopyrrolate pill,” Dr. Hightower said.

He recommends 1 mg to 6 mg daily of the anticholinergic drug, which has been used off-label for hyperhidrosis for several years. A 2012 study of 31 children with hyperhidrosis, he noted, supported the use of the drug. The retrospective study found that 90% of the patients, at a mean daily dose of 2 mg, experienced improvements, reported as major in 71%. In addition, patients experienced improvement within hours of taking the medication, and benefits disappeared within a day of stopping the medication. In the study, patients were on the treatment for an average of 2.1 years, and 29% experienced side effects, which were dose related; the most common were dry mouth in 26% and dry eyes in 10%.

According to goodrx.com, a month’s supply of 2 mg of the drug costs as little as $13 with a discount or coupon.

The next steps in treatment are procedural interventions such as microwave-based therapies.

Dr. Hightower said that patients should be advised that treatment may take years, and to encourage them to return for follow-up. He suggested this helpful message: “We’re still trying to find the best treatment for you, and we’ll need to see you back in the office.”

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Dr. Hightower said that too often, HS goes undiagnosed for a significant period of time, preventing patients from seeing a dermatologist for treatment. Hallmarks of HS include inflammatory nodules, abscesses, and scarring, he said. “It can be disfiguring, painful, embarrassing, and associated with significantly decreased quality of life. Early recognition in terms of making and solidifying the diagnosis is important so we can prevent further worsening of the disease.”

The goal of treatment include preventing scars and unnecessary emergency department visits, and stopping flares from worsening, Dr. Hightower said. For specifics, he pointed to clinical management guidelines released by the United States and Canadian hidradenitis suppurativa foundations in 2019.

Make sure to set individualized treatment goals and understand the impact of treatment on the patient’s interactions with family, school, and peers, he said. And keep in mind that “parent-defined goals may be different from patient-defined goals.”

Dr. Hightower reported no relevant disclosures. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company

A wide variety of medications exists for treating hyperhidrosis, a dermatologist told colleagues, but before prescribing anything to a pediatric patient, he recommended, ask the patient a simple question: “What bothers you the most?”

The answer will provide guidance for developing a step-by-step treatment strategy and help provide the patient “a set of realistic expectations in terms of what the response will look like,” George Hightower, MD, PhD, a pediatric dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, San Diego, said at MedscapeLive’s Women’s & Pediatric Dermatology Seminar.

A similar question-based approach will help guide therapy for patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS), he said.

With regards to hyperhidrosis, Dr. Hightower said that patients most commonly complain that their underarms are too smelly, too sweaty, and red, itchy, or painful. Causes, he said, can include irritation/contact dermatitis, folliculitis, and seborrheic dermatitis, as well as hyperhidrosis or HS.

Primary focal axillary hyperhidrosis is defined as focal, visible, excessive sweating for at least 6 months without an apparent cause plus at least two of the following characteristics: Sweating is bilateral and relatively symmetric, it impairs daily activities, it starts before the age of 25 with at least one episode per week (many patients have it daily), a family history of idiopathic hyperhidrosis is present, and focal sweating does not occur during sleep.

Secondary hyperhidrosis can be linked to other conditions, such as a spinal column injury, Dr. Hightower noted.

The first step on the treatment ladder is topical 20% aluminum chloride, which is available over the counter. This should be applied nightly for 1 week then every 1-2 weeks, Dr. Hightower recommended. All of his patients with hyperhidrosis have had at least one trial of this treatment.

The next option is daily topical treatment with 2.4% glycopyrronium tosylate (Qbrexza) cloths, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for primary axillary hyperhidrosis in patients aged 9 and older. According to the prescribing information, dry mouth was by far the most common treatment-associated adverse effect in clinical trials (24% versus almost 6% among those on vehicle). As for skin reactions, erythema occurred in about 17% of both the intervention and vehicle groups, and burning/stinging occurred in 14% of those on treatment and almost 17% of those on vehicle.

“If they’re not able to get access to the cloths due to [insurance] coverage issues, or they don’t allow them to reach the clinical endpoint desired, then I use an oral daily glycopyrrolate pill,” Dr. Hightower said.

He recommends 1 mg to 6 mg daily of the anticholinergic drug, which has been used off-label for hyperhidrosis for several years. A 2012 study of 31 children with hyperhidrosis, he noted, supported the use of the drug. The retrospective study found that 90% of the patients, at a mean daily dose of 2 mg, experienced improvements, reported as major in 71%. In addition, patients experienced improvement within hours of taking the medication, and benefits disappeared within a day of stopping the medication. In the study, patients were on the treatment for an average of 2.1 years, and 29% experienced side effects, which were dose related; the most common were dry mouth in 26% and dry eyes in 10%.

According to goodrx.com, a month’s supply of 2 mg of the drug costs as little as $13 with a discount or coupon.

The next steps in treatment are procedural interventions such as microwave-based therapies.

Dr. Hightower said that patients should be advised that treatment may take years, and to encourage them to return for follow-up. He suggested this helpful message: “We’re still trying to find the best treatment for you, and we’ll need to see you back in the office.”

Hidradenitis suppurativa

Dr. Hightower said that too often, HS goes undiagnosed for a significant period of time, preventing patients from seeing a dermatologist for treatment. Hallmarks of HS include inflammatory nodules, abscesses, and scarring, he said. “It can be disfiguring, painful, embarrassing, and associated with significantly decreased quality of life. Early recognition in terms of making and solidifying the diagnosis is important so we can prevent further worsening of the disease.”

The goal of treatment include preventing scars and unnecessary emergency department visits, and stopping flares from worsening, Dr. Hightower said. For specifics, he pointed to clinical management guidelines released by the United States and Canadian hidradenitis suppurativa foundations in 2019.

Make sure to set individualized treatment goals and understand the impact of treatment on the patient’s interactions with family, school, and peers, he said. And keep in mind that “parent-defined goals may be different from patient-defined goals.”

Dr. Hightower reported no relevant disclosures. MedscapeLive and this news organization are owned by the same parent company

FROM MEDSCAPELIVE WOMEN’S & PEDIATRIC DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Psychological difficulties persist among patients with IBD

Psychological issues in patients with inflammatory bowel disease should be addressed at both personal and systemic levels, according to a review of current literature.

In a review published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, researchers highlighted data on the burden of mental disorders in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients and presented several strategies for addressing them.

“From a systems perspective, underrecognized and/or suboptimally treated mental health problems in patients with IBD are associated with increased disability, poorer adherence, and more admissions and surgeries, driving increased health care utilization and costs,” Maia S. Kredentser, PhD, of the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, and colleagues wrote, citing a 2018 study’s findings.

“There is ample evidence for a higher prevalence of mental disorders in IBD, in particular depression and anxiety, compared with the general population,” the authors wrote.

They cited a recent population-based study in which the incident rate ratios were significantly higher for IBD patients, compared with matched controls for depression (IRR, 1.58), anxiety disorder (IRR, 1.39), bipolar disorder (IRR, 1.82), and schizophrenia (IRR, 1.64).

Mental disorders associated with IBD also include issues of body image and sexuality. Although research on the impact of disease activity on sexual function is inconsistent, one study suggested that body image “may be an important target of treatment in women reporting poor quality of life and psychological distress,” the researchers noted. A French study from 2017 published in the Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis showed that approximately half of men and women reported problems with erectile or sexual dysfunction.

Issues related to environmental stressors may contribute to IBD by promoting chronic inflammation, the researchers wrote. For example, data from longitudinal, population-based research suggest that adverse childhood experiences can promote proinflammatory states across inflammatory illnesses. Research has also suggested that people with IBD have higher rates of these adverse childhood experiences than the general population. However, data also show that many are able to cope and adapt: “Many patients with IBD are resilient, experience growth, and in fact, thrive,” the researchers added. One longitudinal study suggested that patients with IBD who identified with “thriving” had “stronger coping efficacy (the perceived ability to meet illness demands), illness acceptance, and social support and lower depression” and that this was associated with life satisfaction 6 months later.

Fatigue also has been shown to be a factor for patients with IBD. The researchers cited one population-based study showing fatigue in 57%-72% of IBD patients with active disease. IBD patients with quiescent disease also report fatigue. The psychological and behavioral factors driving fatigue could be related to mental disorders or other factors such as suboptimal sleep, stress, and use of caffeine and alcohol, they noted. Management strategies include improving sleep hygiene and evaluation of mental health concerns.

Seek complete picture before treatment

“Addressing psychological comorbidity in IBD requires individual and systemic approaches focused on both the prevention and treatment of mental health concerns,” the researchers wrote. “Because of the pervasiveness of psychological comorbidities in IBD, and recent evidence that they may be part of the disease process itself, assessment of psychological functioning in IBD is considered an essential aspect of disease management.”

Evidence-based psychological interventions include cognitive-behavioral therapy, which includes training in relaxation; treatment with clinical hypnosis; and encouraging mindfulness through acceptance and commitment therapy, which focuses on developing psychological flexibility to cope with suffering. In addition, a small but evolving body of research shows some benefit to motivational interviewing (a strategy focused on behavior change) for IBD patients. Notably, one review of four studies showed benefits of motivational interviewing for improving medication adherence and advice seeking, the researchers reported.

Although several psychological treatment options exist for addressing mental health issues in IBD, randomized trials are needed. “To facilitate this important research and optimize patient care, the integration of psychologists and other mental health providers into IBD care is considered best practice and provides exciting opportunities for improving patient care and outcomes,” the researchers concluded.

Address mental health to ease disease burden

“There is a large burden of mental health issues in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, with depression and anxiety leading the way,” Kim L. Isaacs, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

“There are multiple reasons for this, including dealing with chronic pain, social concerns around using the bathroom, body-image issues due to surgery, and drug side effects. There is increasing evidence that the inflammatory process in IBD may be driving some of the changes in the brain which lead to further mental health dysfunction,” she noted.

“Addressing depression, anxiety, [and] sleep disturbance in patients will not only improve quality of life from a mental health perspective but has been shown to improve control of disease,” Dr. Isaacs emphasized.

“Small things like increased medication compliance have a large impact on disease management and decreased need for hospitalization and hospitalization,” said Dr. Isaacs. “As gastroenterologists we need to expand our focus beyond the gut and address the emotional needs of our patients – identifying those patients who need increased mental health support.”

Barriers to better care

The greatest barriers to treating mental health issues in IBD patients are time and knowledge, said Dr. Isaacs. “Many gastroenterologists have limited time in the office to do more than address the acute issues of the patients such as rectal bleeding and worsening diarrhea. It takes time and trust to explore what is going on in a patient’s life. Is the patient anxious and depressed? How are they coping with their current disease manifestations? Simple screening tools may help with this, but then there need to be resources to support interventions.”

Some IBD practices, especially academic ones, have a psychologist in the IBD center or one that’s readily available for consultation. “This is an investment for the practice that may reduce significantly disease burden. The IBD specialty home model includes resources for management of psychiatric issues and nutritional concerns as well as disease management,” she added.

More research in several areas can help reduce the mental health burden of IBD. “On the immunology/biology side, understanding how the microbiome affects the brain/gut may allow for more directed mental health treatment. On the disease management side, larger trials directed at psychiatric interventions may help to determine which therapy is best for each patient,” Dr. Isaacs said. “Further work developing health care systems, such as the medical home, that allow for maximum disease management and decreased system costs will go far in implementation of models of care that address the needs of the entire patient with inflammatory bowel disease.”

The review received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Isaacs disclosed consulting on the data safety monitoring board for Janssen.

Psychological issues in patients with inflammatory bowel disease should be addressed at both personal and systemic levels, according to a review of current literature.

In a review published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, researchers highlighted data on the burden of mental disorders in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients and presented several strategies for addressing them.

“From a systems perspective, underrecognized and/or suboptimally treated mental health problems in patients with IBD are associated with increased disability, poorer adherence, and more admissions and surgeries, driving increased health care utilization and costs,” Maia S. Kredentser, PhD, of the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, and colleagues wrote, citing a 2018 study’s findings.

“There is ample evidence for a higher prevalence of mental disorders in IBD, in particular depression and anxiety, compared with the general population,” the authors wrote.

They cited a recent population-based study in which the incident rate ratios were significantly higher for IBD patients, compared with matched controls for depression (IRR, 1.58), anxiety disorder (IRR, 1.39), bipolar disorder (IRR, 1.82), and schizophrenia (IRR, 1.64).

Mental disorders associated with IBD also include issues of body image and sexuality. Although research on the impact of disease activity on sexual function is inconsistent, one study suggested that body image “may be an important target of treatment in women reporting poor quality of life and psychological distress,” the researchers noted. A French study from 2017 published in the Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis showed that approximately half of men and women reported problems with erectile or sexual dysfunction.

Issues related to environmental stressors may contribute to IBD by promoting chronic inflammation, the researchers wrote. For example, data from longitudinal, population-based research suggest that adverse childhood experiences can promote proinflammatory states across inflammatory illnesses. Research has also suggested that people with IBD have higher rates of these adverse childhood experiences than the general population. However, data also show that many are able to cope and adapt: “Many patients with IBD are resilient, experience growth, and in fact, thrive,” the researchers added. One longitudinal study suggested that patients with IBD who identified with “thriving” had “stronger coping efficacy (the perceived ability to meet illness demands), illness acceptance, and social support and lower depression” and that this was associated with life satisfaction 6 months later.

Fatigue also has been shown to be a factor for patients with IBD. The researchers cited one population-based study showing fatigue in 57%-72% of IBD patients with active disease. IBD patients with quiescent disease also report fatigue. The psychological and behavioral factors driving fatigue could be related to mental disorders or other factors such as suboptimal sleep, stress, and use of caffeine and alcohol, they noted. Management strategies include improving sleep hygiene and evaluation of mental health concerns.

Seek complete picture before treatment

“Addressing psychological comorbidity in IBD requires individual and systemic approaches focused on both the prevention and treatment of mental health concerns,” the researchers wrote. “Because of the pervasiveness of psychological comorbidities in IBD, and recent evidence that they may be part of the disease process itself, assessment of psychological functioning in IBD is considered an essential aspect of disease management.”

Evidence-based psychological interventions include cognitive-behavioral therapy, which includes training in relaxation; treatment with clinical hypnosis; and encouraging mindfulness through acceptance and commitment therapy, which focuses on developing psychological flexibility to cope with suffering. In addition, a small but evolving body of research shows some benefit to motivational interviewing (a strategy focused on behavior change) for IBD patients. Notably, one review of four studies showed benefits of motivational interviewing for improving medication adherence and advice seeking, the researchers reported.

Although several psychological treatment options exist for addressing mental health issues in IBD, randomized trials are needed. “To facilitate this important research and optimize patient care, the integration of psychologists and other mental health providers into IBD care is considered best practice and provides exciting opportunities for improving patient care and outcomes,” the researchers concluded.

Address mental health to ease disease burden

“There is a large burden of mental health issues in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, with depression and anxiety leading the way,” Kim L. Isaacs, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

“There are multiple reasons for this, including dealing with chronic pain, social concerns around using the bathroom, body-image issues due to surgery, and drug side effects. There is increasing evidence that the inflammatory process in IBD may be driving some of the changes in the brain which lead to further mental health dysfunction,” she noted.

“Addressing depression, anxiety, [and] sleep disturbance in patients will not only improve quality of life from a mental health perspective but has been shown to improve control of disease,” Dr. Isaacs emphasized.

“Small things like increased medication compliance have a large impact on disease management and decreased need for hospitalization and hospitalization,” said Dr. Isaacs. “As gastroenterologists we need to expand our focus beyond the gut and address the emotional needs of our patients – identifying those patients who need increased mental health support.”

Barriers to better care

The greatest barriers to treating mental health issues in IBD patients are time and knowledge, said Dr. Isaacs. “Many gastroenterologists have limited time in the office to do more than address the acute issues of the patients such as rectal bleeding and worsening diarrhea. It takes time and trust to explore what is going on in a patient’s life. Is the patient anxious and depressed? How are they coping with their current disease manifestations? Simple screening tools may help with this, but then there need to be resources to support interventions.”

Some IBD practices, especially academic ones, have a psychologist in the IBD center or one that’s readily available for consultation. “This is an investment for the practice that may reduce significantly disease burden. The IBD specialty home model includes resources for management of psychiatric issues and nutritional concerns as well as disease management,” she added.

More research in several areas can help reduce the mental health burden of IBD. “On the immunology/biology side, understanding how the microbiome affects the brain/gut may allow for more directed mental health treatment. On the disease management side, larger trials directed at psychiatric interventions may help to determine which therapy is best for each patient,” Dr. Isaacs said. “Further work developing health care systems, such as the medical home, that allow for maximum disease management and decreased system costs will go far in implementation of models of care that address the needs of the entire patient with inflammatory bowel disease.”

The review received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Isaacs disclosed consulting on the data safety monitoring board for Janssen.

Psychological issues in patients with inflammatory bowel disease should be addressed at both personal and systemic levels, according to a review of current literature.

In a review published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, researchers highlighted data on the burden of mental disorders in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients and presented several strategies for addressing them.

“From a systems perspective, underrecognized and/or suboptimally treated mental health problems in patients with IBD are associated with increased disability, poorer adherence, and more admissions and surgeries, driving increased health care utilization and costs,” Maia S. Kredentser, PhD, of the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, and colleagues wrote, citing a 2018 study’s findings.

“There is ample evidence for a higher prevalence of mental disorders in IBD, in particular depression and anxiety, compared with the general population,” the authors wrote.

They cited a recent population-based study in which the incident rate ratios were significantly higher for IBD patients, compared with matched controls for depression (IRR, 1.58), anxiety disorder (IRR, 1.39), bipolar disorder (IRR, 1.82), and schizophrenia (IRR, 1.64).

Mental disorders associated with IBD also include issues of body image and sexuality. Although research on the impact of disease activity on sexual function is inconsistent, one study suggested that body image “may be an important target of treatment in women reporting poor quality of life and psychological distress,” the researchers noted. A French study from 2017 published in the Journal of Crohn’s and Colitis showed that approximately half of men and women reported problems with erectile or sexual dysfunction.

Issues related to environmental stressors may contribute to IBD by promoting chronic inflammation, the researchers wrote. For example, data from longitudinal, population-based research suggest that adverse childhood experiences can promote proinflammatory states across inflammatory illnesses. Research has also suggested that people with IBD have higher rates of these adverse childhood experiences than the general population. However, data also show that many are able to cope and adapt: “Many patients with IBD are resilient, experience growth, and in fact, thrive,” the researchers added. One longitudinal study suggested that patients with IBD who identified with “thriving” had “stronger coping efficacy (the perceived ability to meet illness demands), illness acceptance, and social support and lower depression” and that this was associated with life satisfaction 6 months later.

Fatigue also has been shown to be a factor for patients with IBD. The researchers cited one population-based study showing fatigue in 57%-72% of IBD patients with active disease. IBD patients with quiescent disease also report fatigue. The psychological and behavioral factors driving fatigue could be related to mental disorders or other factors such as suboptimal sleep, stress, and use of caffeine and alcohol, they noted. Management strategies include improving sleep hygiene and evaluation of mental health concerns.

Seek complete picture before treatment

“Addressing psychological comorbidity in IBD requires individual and systemic approaches focused on both the prevention and treatment of mental health concerns,” the researchers wrote. “Because of the pervasiveness of psychological comorbidities in IBD, and recent evidence that they may be part of the disease process itself, assessment of psychological functioning in IBD is considered an essential aspect of disease management.”

Evidence-based psychological interventions include cognitive-behavioral therapy, which includes training in relaxation; treatment with clinical hypnosis; and encouraging mindfulness through acceptance and commitment therapy, which focuses on developing psychological flexibility to cope with suffering. In addition, a small but evolving body of research shows some benefit to motivational interviewing (a strategy focused on behavior change) for IBD patients. Notably, one review of four studies showed benefits of motivational interviewing for improving medication adherence and advice seeking, the researchers reported.

Although several psychological treatment options exist for addressing mental health issues in IBD, randomized trials are needed. “To facilitate this important research and optimize patient care, the integration of psychologists and other mental health providers into IBD care is considered best practice and provides exciting opportunities for improving patient care and outcomes,” the researchers concluded.

Address mental health to ease disease burden

“There is a large burden of mental health issues in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, with depression and anxiety leading the way,” Kim L. Isaacs, MD, of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said in an interview.

“There are multiple reasons for this, including dealing with chronic pain, social concerns around using the bathroom, body-image issues due to surgery, and drug side effects. There is increasing evidence that the inflammatory process in IBD may be driving some of the changes in the brain which lead to further mental health dysfunction,” she noted.

“Addressing depression, anxiety, [and] sleep disturbance in patients will not only improve quality of life from a mental health perspective but has been shown to improve control of disease,” Dr. Isaacs emphasized.

“Small things like increased medication compliance have a large impact on disease management and decreased need for hospitalization and hospitalization,” said Dr. Isaacs. “As gastroenterologists we need to expand our focus beyond the gut and address the emotional needs of our patients – identifying those patients who need increased mental health support.”

Barriers to better care

The greatest barriers to treating mental health issues in IBD patients are time and knowledge, said Dr. Isaacs. “Many gastroenterologists have limited time in the office to do more than address the acute issues of the patients such as rectal bleeding and worsening diarrhea. It takes time and trust to explore what is going on in a patient’s life. Is the patient anxious and depressed? How are they coping with their current disease manifestations? Simple screening tools may help with this, but then there need to be resources to support interventions.”

Some IBD practices, especially academic ones, have a psychologist in the IBD center or one that’s readily available for consultation. “This is an investment for the practice that may reduce significantly disease burden. The IBD specialty home model includes resources for management of psychiatric issues and nutritional concerns as well as disease management,” she added.

More research in several areas can help reduce the mental health burden of IBD. “On the immunology/biology side, understanding how the microbiome affects the brain/gut may allow for more directed mental health treatment. On the disease management side, larger trials directed at psychiatric interventions may help to determine which therapy is best for each patient,” Dr. Isaacs said. “Further work developing health care systems, such as the medical home, that allow for maximum disease management and decreased system costs will go far in implementation of models of care that address the needs of the entire patient with inflammatory bowel disease.”

The review received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Isaacs disclosed consulting on the data safety monitoring board for Janssen.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

New ‘minimal monitoring’ approach to HCV treatment may simplify care

A novel minimal monitoring (MINMON) approach to hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment was safe and achieved sustained virology response (SVR) compared to current clinical standards in treatment-naive patients without evidence of decompensated cirrhosis, according to a recent study.

“This model may allow for HCV elimination, while minimizing resource use and face-to-face contact,” said investigator Sunil S. Solomon, MBBS, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the urgent need for simple and safe models of HCV [care] delivery.”

Dr. Solomon described the new approach to HCV treatment during a presentation at this year’s Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections virtual meeting.

Study design

ACTG A5360 was an international, single-arm, open-label, phase 4 trial that enrolled 400 patients across 38 treatment sites.

The researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of the MINMON approach in treatment-naive individuals who had no evidence of decompensated cirrhosis. Study participants received a fixed-dose, single-tablet regimen of sofosbuvir 400 mg/velpatasvir 100 mg once daily for 12 weeks.

The MINMON approach comprised four key elements: no pretreatment genotyping, all tablets dispensed at study entry, no scheduled on-treatment clinic visits/labs, and two remote contacts at weeks 4 (adherence evaluation) and 22 (scheduled SVR visit). Unplanned visits for patients concerns were permitted.

Key eligibility criteria included active HCV infection (HCV RNA > 1,000 IU/mL) and no prior HCV treatment history. Persons with HIV coinfection (50% or less of sample) and compensated cirrhosis (20% or less of sample) were also eligible. Persons with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and decompensated cirrhosis were excluded.

The primary efficacy endpoint was SVR, defined as HCV RNA less than the lower limit of quantification in the first sample at least 22 weeks post treatment initiation. The primary safety endpoint was any serious adverse events (AEs) occurring between treatment initiation and week 28.

Results

Among 400 patients enrolled, 399 (99.8%) were included in the primary efficacy analysis and 397 (99.3%) were included in the safety analysis. The median age of participants was 47 years, and 35% were female sex at birth. At baseline, 166 (42%) patients had HIV coinfection and 34 (9%) had compensated cirrhosis.

After analysis, the researchers found that remote contact was successful at weeks 4 and 22 for 394 (98.7%) and 335 (84.0%) participants, respectively.

In total, 15 (3.8%) participants recorded 21 unplanned visits, 3 (14.3%) of which were due to AEs, none of which were treatment related. Three participants reported losing study medications and one participant prematurely discontinued therapy due to an AE.

HCV RNA data at SVR were available for 396 participants. Overall, 379 patients (95.0%) achieved SVR (95% confidence interval [CI], 92.4%-96.7%).

“The study was not powered for SVR by subgroups, which explains why we observed wide confidence intervals in our forest plot,” Dr. Solomon said.

With respect to safety, serious AEs were reported in 14 (3.5%) participants through week 24 visit, none of which were treatment related or resulted in death.

Dr. Solomon acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the single-arm design. As a result, there was no direct comparison to standard monitoring practices. In addition, these results may not be generalizable to all nonresearch treatment sites.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has required us to pivot clinical programs to minimize in-person contact, and promote more remote approaches, which is really the essence of the MINMON approach,” Dr. Solomon explained.

“There are really wonderful results in the population that was studied, but may reflect a more adherent patient population,” said moderator Robert T. Schooley, MD, of the University of California, San Diego.

During a discussion, Dr. Solomon noted that the MINMON approach may be further explored in patients who are actively injecting drugs, as these patients were not well represented in the present study.

Dr. Solomon disclosed financial relationships with Gilead Sciences and Abbott Diagnostics. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Gilead Sciences.

A novel minimal monitoring (MINMON) approach to hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment was safe and achieved sustained virology response (SVR) compared to current clinical standards in treatment-naive patients without evidence of decompensated cirrhosis, according to a recent study.

“This model may allow for HCV elimination, while minimizing resource use and face-to-face contact,” said investigator Sunil S. Solomon, MBBS, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the urgent need for simple and safe models of HCV [care] delivery.”

Dr. Solomon described the new approach to HCV treatment during a presentation at this year’s Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections virtual meeting.

Study design

ACTG A5360 was an international, single-arm, open-label, phase 4 trial that enrolled 400 patients across 38 treatment sites.

The researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of the MINMON approach in treatment-naive individuals who had no evidence of decompensated cirrhosis. Study participants received a fixed-dose, single-tablet regimen of sofosbuvir 400 mg/velpatasvir 100 mg once daily for 12 weeks.

The MINMON approach comprised four key elements: no pretreatment genotyping, all tablets dispensed at study entry, no scheduled on-treatment clinic visits/labs, and two remote contacts at weeks 4 (adherence evaluation) and 22 (scheduled SVR visit). Unplanned visits for patients concerns were permitted.

Key eligibility criteria included active HCV infection (HCV RNA > 1,000 IU/mL) and no prior HCV treatment history. Persons with HIV coinfection (50% or less of sample) and compensated cirrhosis (20% or less of sample) were also eligible. Persons with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and decompensated cirrhosis were excluded.

The primary efficacy endpoint was SVR, defined as HCV RNA less than the lower limit of quantification in the first sample at least 22 weeks post treatment initiation. The primary safety endpoint was any serious adverse events (AEs) occurring between treatment initiation and week 28.

Results

Among 400 patients enrolled, 399 (99.8%) were included in the primary efficacy analysis and 397 (99.3%) were included in the safety analysis. The median age of participants was 47 years, and 35% were female sex at birth. At baseline, 166 (42%) patients had HIV coinfection and 34 (9%) had compensated cirrhosis.

After analysis, the researchers found that remote contact was successful at weeks 4 and 22 for 394 (98.7%) and 335 (84.0%) participants, respectively.

In total, 15 (3.8%) participants recorded 21 unplanned visits, 3 (14.3%) of which were due to AEs, none of which were treatment related. Three participants reported losing study medications and one participant prematurely discontinued therapy due to an AE.

HCV RNA data at SVR were available for 396 participants. Overall, 379 patients (95.0%) achieved SVR (95% confidence interval [CI], 92.4%-96.7%).

“The study was not powered for SVR by subgroups, which explains why we observed wide confidence intervals in our forest plot,” Dr. Solomon said.

With respect to safety, serious AEs were reported in 14 (3.5%) participants through week 24 visit, none of which were treatment related or resulted in death.

Dr. Solomon acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the single-arm design. As a result, there was no direct comparison to standard monitoring practices. In addition, these results may not be generalizable to all nonresearch treatment sites.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has required us to pivot clinical programs to minimize in-person contact, and promote more remote approaches, which is really the essence of the MINMON approach,” Dr. Solomon explained.

“There are really wonderful results in the population that was studied, but may reflect a more adherent patient population,” said moderator Robert T. Schooley, MD, of the University of California, San Diego.

During a discussion, Dr. Solomon noted that the MINMON approach may be further explored in patients who are actively injecting drugs, as these patients were not well represented in the present study.

Dr. Solomon disclosed financial relationships with Gilead Sciences and Abbott Diagnostics. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Gilead Sciences.

A novel minimal monitoring (MINMON) approach to hepatitis C virus (HCV) treatment was safe and achieved sustained virology response (SVR) compared to current clinical standards in treatment-naive patients without evidence of decompensated cirrhosis, according to a recent study.

“This model may allow for HCV elimination, while minimizing resource use and face-to-face contact,” said investigator Sunil S. Solomon, MBBS, PhD, of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore. “The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the urgent need for simple and safe models of HCV [care] delivery.”

Dr. Solomon described the new approach to HCV treatment during a presentation at this year’s Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections virtual meeting.

Study design

ACTG A5360 was an international, single-arm, open-label, phase 4 trial that enrolled 400 patients across 38 treatment sites.

The researchers evaluated the efficacy and safety of the MINMON approach in treatment-naive individuals who had no evidence of decompensated cirrhosis. Study participants received a fixed-dose, single-tablet regimen of sofosbuvir 400 mg/velpatasvir 100 mg once daily for 12 weeks.

The MINMON approach comprised four key elements: no pretreatment genotyping, all tablets dispensed at study entry, no scheduled on-treatment clinic visits/labs, and two remote contacts at weeks 4 (adherence evaluation) and 22 (scheduled SVR visit). Unplanned visits for patients concerns were permitted.

Key eligibility criteria included active HCV infection (HCV RNA > 1,000 IU/mL) and no prior HCV treatment history. Persons with HIV coinfection (50% or less of sample) and compensated cirrhosis (20% or less of sample) were also eligible. Persons with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and decompensated cirrhosis were excluded.

The primary efficacy endpoint was SVR, defined as HCV RNA less than the lower limit of quantification in the first sample at least 22 weeks post treatment initiation. The primary safety endpoint was any serious adverse events (AEs) occurring between treatment initiation and week 28.

Results

Among 400 patients enrolled, 399 (99.8%) were included in the primary efficacy analysis and 397 (99.3%) were included in the safety analysis. The median age of participants was 47 years, and 35% were female sex at birth. At baseline, 166 (42%) patients had HIV coinfection and 34 (9%) had compensated cirrhosis.

After analysis, the researchers found that remote contact was successful at weeks 4 and 22 for 394 (98.7%) and 335 (84.0%) participants, respectively.

In total, 15 (3.8%) participants recorded 21 unplanned visits, 3 (14.3%) of which were due to AEs, none of which were treatment related. Three participants reported losing study medications and one participant prematurely discontinued therapy due to an AE.

HCV RNA data at SVR were available for 396 participants. Overall, 379 patients (95.0%) achieved SVR (95% confidence interval [CI], 92.4%-96.7%).

“The study was not powered for SVR by subgroups, which explains why we observed wide confidence intervals in our forest plot,” Dr. Solomon said.

With respect to safety, serious AEs were reported in 14 (3.5%) participants through week 24 visit, none of which were treatment related or resulted in death.

Dr. Solomon acknowledged that a key limitation of the study was the single-arm design. As a result, there was no direct comparison to standard monitoring practices. In addition, these results may not be generalizable to all nonresearch treatment sites.

“The COVID-19 pandemic has required us to pivot clinical programs to minimize in-person contact, and promote more remote approaches, which is really the essence of the MINMON approach,” Dr. Solomon explained.

“There are really wonderful results in the population that was studied, but may reflect a more adherent patient population,” said moderator Robert T. Schooley, MD, of the University of California, San Diego.

During a discussion, Dr. Solomon noted that the MINMON approach may be further explored in patients who are actively injecting drugs, as these patients were not well represented in the present study.

Dr. Solomon disclosed financial relationships with Gilead Sciences and Abbott Diagnostics. The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and Gilead Sciences.

FROM CROI 2021

Nearly 20% of lupus patients have severe infection in first decade after diagnosis

People with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) experienced significantly higher rates of first severe infections, a higher number of severe infections overall, and greater infection-related mortality, compared with controls, based on data from a population-based cohort study of more than 30,000 individuals.

Infections remain a leading cause of morbidity and early mortality in patients with SLE, wrote Kai Zhao, MSc, of Arthritis Research Canada, Richmond, and colleagues. However, “limitations from existing studies including selected samples, small sizes, and prevalent cohorts can negatively affect the accuracy of both the absolute and relative risk estimates of infections in SLE at the population level,” they said.

In a study published in Rheumatology, the researchers identified 5,169 people newly diagnosed with SLE between Jan. 1, 1997, and March 31, 2015, and matched them with 25,845 non-SLE controls using an administrative health database of all health care services funded in British Columbia during the time period. The investigators said the study is the first “to evaluate the risk of severe infections in a large population-based and incident SLE cohort.”

The average age of the patients was 46.9 at the time of their index SLE diagnosis, and 86% were women. The average follow-up period was approximately 10 years.

The primary outcome was the first severe infection after the onset of SLE that required hospitalization or occurred in the hospital setting. A total of 955 (18.5%) first severe infections occurred in the SLE group, compared with 1,988 (7.7%) in the controls, for incidence rates of 19.7 events per 1,000 person-years and 7.6 events per 1,000 person-years, respectively, yielding an 82% increased risk of severe infection for SLE patients after adjustment for confounding baseline factors.

Secondary outcomes of the total number of severe infections and infection-related mortality both showed significant increases in SLE patients, compared with controls. The total number of severe infections in the SLE and control groups was 1,898 and 3,114, respectively, with an adjusted risk ratio of 2.07.

As for mortality, a total of 539 deaths occurred in SLE patients during the study period, and 114 (21%) were related to severe infection. A total of 1,495 deaths occurred in the control group, including 269 (18%) related to severe infection. The adjusted hazard ratio was 1.61 after adjustment for confounding baseline variables.

The risks for first severe infection, total number of severe infections, and infection-related mortality were “independent of traditional risk factors for infection and the results remain robust in the presence of an unmeasured confounder (smoking) and competing risk of death,” the researchers said. Reasons for the increased risk are uncertain, but likely result from intrinsic factors such as immune system dysfunction and extrinsic factors such as the impact of immunosuppressive medications. “Future research can focus on quantifying the relative contributions of these intrinsic and extrinsic factors on the increased infection risk in SLE patients,” they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors linked to the observational design, including possible misdiagnosis of SLE and inaccurate measure of SLE onset, the researchers noted. In addition, no data were available for certain confounders such as smoking and nonhospitalized infections, they said.

However, the results were strengthened by the large size and general population and the use of sensitivity analyses, they noted. For SLE patients, “increased awareness of the risk of infections can identify their early signs and potentially prevent hospitalizations,” and clinicians can promote infection prevention strategies, including vaccinations when appropriate, they added.

Based on their findings, “we recommend a closer surveillance for severe infections in SLE patients and risk assessment for severe infections for SLE patients after diagnosis,” the researchers emphasized. “Further studies are warranted to further identify risk factors for infections in SLE patients to develop personalized treatment regimens and to select treatment in practice by synthesizing patient information,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

People with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) experienced significantly higher rates of first severe infections, a higher number of severe infections overall, and greater infection-related mortality, compared with controls, based on data from a population-based cohort study of more than 30,000 individuals.

Infections remain a leading cause of morbidity and early mortality in patients with SLE, wrote Kai Zhao, MSc, of Arthritis Research Canada, Richmond, and colleagues. However, “limitations from existing studies including selected samples, small sizes, and prevalent cohorts can negatively affect the accuracy of both the absolute and relative risk estimates of infections in SLE at the population level,” they said.

In a study published in Rheumatology, the researchers identified 5,169 people newly diagnosed with SLE between Jan. 1, 1997, and March 31, 2015, and matched them with 25,845 non-SLE controls using an administrative health database of all health care services funded in British Columbia during the time period. The investigators said the study is the first “to evaluate the risk of severe infections in a large population-based and incident SLE cohort.”

The average age of the patients was 46.9 at the time of their index SLE diagnosis, and 86% were women. The average follow-up period was approximately 10 years.

The primary outcome was the first severe infection after the onset of SLE that required hospitalization or occurred in the hospital setting. A total of 955 (18.5%) first severe infections occurred in the SLE group, compared with 1,988 (7.7%) in the controls, for incidence rates of 19.7 events per 1,000 person-years and 7.6 events per 1,000 person-years, respectively, yielding an 82% increased risk of severe infection for SLE patients after adjustment for confounding baseline factors.

Secondary outcomes of the total number of severe infections and infection-related mortality both showed significant increases in SLE patients, compared with controls. The total number of severe infections in the SLE and control groups was 1,898 and 3,114, respectively, with an adjusted risk ratio of 2.07.

As for mortality, a total of 539 deaths occurred in SLE patients during the study period, and 114 (21%) were related to severe infection. A total of 1,495 deaths occurred in the control group, including 269 (18%) related to severe infection. The adjusted hazard ratio was 1.61 after adjustment for confounding baseline variables.

The risks for first severe infection, total number of severe infections, and infection-related mortality were “independent of traditional risk factors for infection and the results remain robust in the presence of an unmeasured confounder (smoking) and competing risk of death,” the researchers said. Reasons for the increased risk are uncertain, but likely result from intrinsic factors such as immune system dysfunction and extrinsic factors such as the impact of immunosuppressive medications. “Future research can focus on quantifying the relative contributions of these intrinsic and extrinsic factors on the increased infection risk in SLE patients,” they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors linked to the observational design, including possible misdiagnosis of SLE and inaccurate measure of SLE onset, the researchers noted. In addition, no data were available for certain confounders such as smoking and nonhospitalized infections, they said.

However, the results were strengthened by the large size and general population and the use of sensitivity analyses, they noted. For SLE patients, “increased awareness of the risk of infections can identify their early signs and potentially prevent hospitalizations,” and clinicians can promote infection prevention strategies, including vaccinations when appropriate, they added.

Based on their findings, “we recommend a closer surveillance for severe infections in SLE patients and risk assessment for severe infections for SLE patients after diagnosis,” the researchers emphasized. “Further studies are warranted to further identify risk factors for infections in SLE patients to develop personalized treatment regimens and to select treatment in practice by synthesizing patient information,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

People with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) experienced significantly higher rates of first severe infections, a higher number of severe infections overall, and greater infection-related mortality, compared with controls, based on data from a population-based cohort study of more than 30,000 individuals.

Infections remain a leading cause of morbidity and early mortality in patients with SLE, wrote Kai Zhao, MSc, of Arthritis Research Canada, Richmond, and colleagues. However, “limitations from existing studies including selected samples, small sizes, and prevalent cohorts can negatively affect the accuracy of both the absolute and relative risk estimates of infections in SLE at the population level,” they said.

In a study published in Rheumatology, the researchers identified 5,169 people newly diagnosed with SLE between Jan. 1, 1997, and March 31, 2015, and matched them with 25,845 non-SLE controls using an administrative health database of all health care services funded in British Columbia during the time period. The investigators said the study is the first “to evaluate the risk of severe infections in a large population-based and incident SLE cohort.”

The average age of the patients was 46.9 at the time of their index SLE diagnosis, and 86% were women. The average follow-up period was approximately 10 years.

The primary outcome was the first severe infection after the onset of SLE that required hospitalization or occurred in the hospital setting. A total of 955 (18.5%) first severe infections occurred in the SLE group, compared with 1,988 (7.7%) in the controls, for incidence rates of 19.7 events per 1,000 person-years and 7.6 events per 1,000 person-years, respectively, yielding an 82% increased risk of severe infection for SLE patients after adjustment for confounding baseline factors.

Secondary outcomes of the total number of severe infections and infection-related mortality both showed significant increases in SLE patients, compared with controls. The total number of severe infections in the SLE and control groups was 1,898 and 3,114, respectively, with an adjusted risk ratio of 2.07.

As for mortality, a total of 539 deaths occurred in SLE patients during the study period, and 114 (21%) were related to severe infection. A total of 1,495 deaths occurred in the control group, including 269 (18%) related to severe infection. The adjusted hazard ratio was 1.61 after adjustment for confounding baseline variables.

The risks for first severe infection, total number of severe infections, and infection-related mortality were “independent of traditional risk factors for infection and the results remain robust in the presence of an unmeasured confounder (smoking) and competing risk of death,” the researchers said. Reasons for the increased risk are uncertain, but likely result from intrinsic factors such as immune system dysfunction and extrinsic factors such as the impact of immunosuppressive medications. “Future research can focus on quantifying the relative contributions of these intrinsic and extrinsic factors on the increased infection risk in SLE patients,” they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors linked to the observational design, including possible misdiagnosis of SLE and inaccurate measure of SLE onset, the researchers noted. In addition, no data were available for certain confounders such as smoking and nonhospitalized infections, they said.

However, the results were strengthened by the large size and general population and the use of sensitivity analyses, they noted. For SLE patients, “increased awareness of the risk of infections can identify their early signs and potentially prevent hospitalizations,” and clinicians can promote infection prevention strategies, including vaccinations when appropriate, they added.

Based on their findings, “we recommend a closer surveillance for severe infections in SLE patients and risk assessment for severe infections for SLE patients after diagnosis,” the researchers emphasized. “Further studies are warranted to further identify risk factors for infections in SLE patients to develop personalized treatment regimens and to select treatment in practice by synthesizing patient information,” they concluded.

The study was supported by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM RHEUMATOLOGY

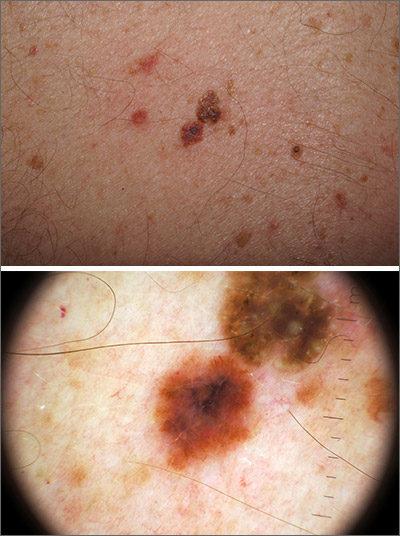

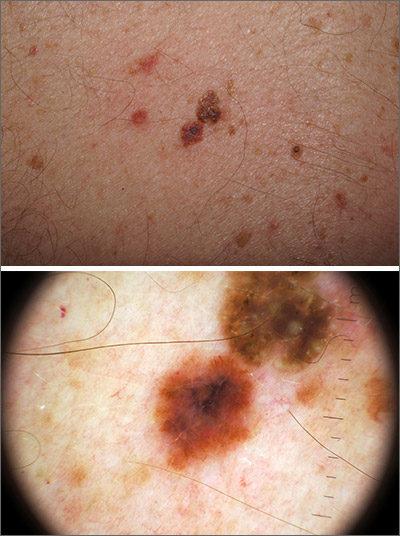

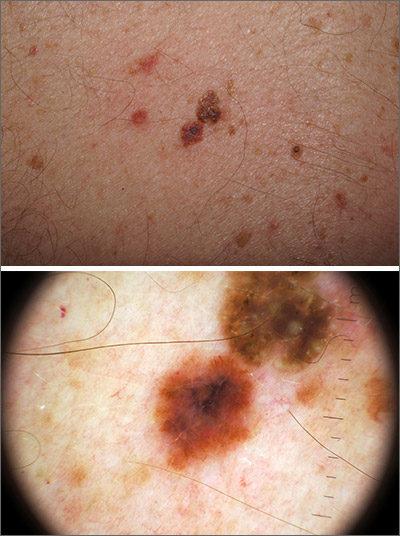

Outlier lesion on the back

In addition to the patient’s SK, the second finding was diagnosed as a thin melanoma. The clinical appearance of SKs and nevi or melanoma can overlap. Dermoscopy is a helpful tool in distinguishing between them, even when juxtaposed in a collision lesion such as this.1

Dermoscopy of the superior portion of the lesion demonstrated a well-demarcated brown, waxy papule with milia-like cysts, consistent with an SK. Inferiorly, the dermoscopic features included atypical pigment network, asymmetrical streaks, and blue-white veil, suggestive of melanoma or an atypical melanocytic neoplasm. A deep-shave biopsy was performed of the lower section, aiming for a narrow margin (1-3 mm) of normal skin. The biopsy confirmed a superficial spreading melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.5 mm with 0 mitoses per high-power field.

A deep-shave biopsy was chosen over a punch biopsy because the latter would be unlikely to sample the entire lesion.

One month after the initial biopsy, a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin was performed. The planned follow-up for the patient was skin exams every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then annually for life.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Blum A, Siggs G, Marghoob AA, et al. Collision skin lesions-results of a multicenter study of the International Dermoscopy Society (IDS). Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:51-62. doi:10.5826/dpc.0704a12

In addition to the patient’s SK, the second finding was diagnosed as a thin melanoma. The clinical appearance of SKs and nevi or melanoma can overlap. Dermoscopy is a helpful tool in distinguishing between them, even when juxtaposed in a collision lesion such as this.1

Dermoscopy of the superior portion of the lesion demonstrated a well-demarcated brown, waxy papule with milia-like cysts, consistent with an SK. Inferiorly, the dermoscopic features included atypical pigment network, asymmetrical streaks, and blue-white veil, suggestive of melanoma or an atypical melanocytic neoplasm. A deep-shave biopsy was performed of the lower section, aiming for a narrow margin (1-3 mm) of normal skin. The biopsy confirmed a superficial spreading melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.5 mm with 0 mitoses per high-power field.

A deep-shave biopsy was chosen over a punch biopsy because the latter would be unlikely to sample the entire lesion.

One month after the initial biopsy, a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin was performed. The planned follow-up for the patient was skin exams every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then annually for life.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

In addition to the patient’s SK, the second finding was diagnosed as a thin melanoma. The clinical appearance of SKs and nevi or melanoma can overlap. Dermoscopy is a helpful tool in distinguishing between them, even when juxtaposed in a collision lesion such as this.1

Dermoscopy of the superior portion of the lesion demonstrated a well-demarcated brown, waxy papule with milia-like cysts, consistent with an SK. Inferiorly, the dermoscopic features included atypical pigment network, asymmetrical streaks, and blue-white veil, suggestive of melanoma or an atypical melanocytic neoplasm. A deep-shave biopsy was performed of the lower section, aiming for a narrow margin (1-3 mm) of normal skin. The biopsy confirmed a superficial spreading melanoma with a Breslow depth of 0.5 mm with 0 mitoses per high-power field.

A deep-shave biopsy was chosen over a punch biopsy because the latter would be unlikely to sample the entire lesion.

One month after the initial biopsy, a wide local excision with a 1-cm margin was performed. The planned follow-up for the patient was skin exams every 3 months for the first year, every 6 months for the next 4 years, and then annually for life.

Text courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD, medical director, MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME. Photos courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained).

1. Blum A, Siggs G, Marghoob AA, et al. Collision skin lesions-results of a multicenter study of the International Dermoscopy Society (IDS). Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:51-62. doi:10.5826/dpc.0704a12

1. Blum A, Siggs G, Marghoob AA, et al. Collision skin lesions-results of a multicenter study of the International Dermoscopy Society (IDS). Dermatol Pract Concept. 2017;7:51-62. doi:10.5826/dpc.0704a12

Microaggressions, racism, and antiracism: The role of gastroenterology

On a busy call day, Oviea (a second-year gastroenterology fellow), paused in the hallway to listen to a conversation between an endoscopy nurse and a patient. The nurse was requesting the patient’s permission for a gastroenterology fellow to participate in their care and the patient, well acquainted with the role from prior procedures, immediately agreed. Oviea entered the patient’s room, introduced himself as “Dr. Akpotaire, the gastroenterology fellow,” as he had with hundreds of other patients during his fellowship, and completed the informed consent. The interaction was brief but pleasant. As Oviea was leaving the room, the patient asked: “When will I meet the doctor”?

This question was familiar to Oviea. Despite always introducing himself by title and wearing matching identification, many patients had dismissed his credentials since graduating from medical school. His answer was equally familiar: “I am a doctor, and Dr. X, the supervising physician, will meet you soon.” With the patient seemingly placated, Oviea delivered the consent form to the procedure room. Minutes later, he was surprised to learn that the patient specifically requested that he not be allowed to participate in their care. This in combination with the patient’s initial dismissal of Oviea’s credentials, left a sting. While none of the other team members outwardly questioned the reason for the patient’s change of heart, Oviea continued to wonder if the patient’s decision was because of his race.

Beyond gastroenterology, similar experiences are common in other spheres. The Twitter thread #BlackintheIvory recounts stories of microaggressions and structural racism in medicine and academia. The cumulative toll of these experiences leads to departures of Black physicians including Uché Blackstock, MD;1 Aysha Khoury, MD, MPH;2 Ben Danielson, MD;3 Princess Dennar, MD;4 and others.

Microaggressions as proxy for bias

The term microaggression was coined by Chester Pierce, MD, the first Black tenured professor at Massachusetts General Hospital in the 1970’s, to describe the frequent, yet subtle dismissals Black Americans experienced in society. Over time, the term has been expanded to include “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative slights and insults” to any marginalized group.5

While the term microaggressions is useful in contextualizing individual experiences, it narrowly focuses on conscious or unconscious interpersonal prejudices. In medicine, this misdirects attention away from the policies and practices that create and reinforce prejudices; these policies and practices do so by systematically excluding underrepresented minority (URM) physicians,6 defined by the American Association of Medical Colleges as physicians who are Black, Hispanic, Native Americans, and Alaska Natives,7 from the medical workforce. Ultimately, this leads to and exacerbates poor health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority patients.

Microaggressions represent our society’s deepest and oldest biases and are rooted in structural racism, as well as misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, ableism, and other prejudices.8 For URM physicians, experiences like the example above are frequently caused by structural racism.

Structural racism in medicine

Structural racism refers to the policies, practices, cultural representations, and norms that reinforce inequities by providing privileges to White people at the disadvantage of non-White people.9 In 1910, Abraham Flexner, commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation and the American Medical Association, wrote that African American physicians should be trained in hygiene rather than surgery and should primarily serve as “sanitarians” whose purpose was to “protect Whites” from common diseases like tuberculosis.10 The 1910 Flexner Report also emphasized the importance of prerequisite basic sciences education and recommended that only two of the seven existing Black medical schools remain open because Flexner believed that only these schools had the potential to meet the new requirements for medical education.11 A recent analysis found that, had the other five medical schools affiliated with historically Black colleges and universities remained open, this would have resulted in an additional 33,315 Black medical school graduates by 2019.12 Structural racism explains why the majority of practicing physicians, medical educators, National Institutes of Health–funded researchers, and hospital executives are White and, similarly, why White patients are overrepresented in clinical trials, have better health outcomes, and live longer lives than several racial and ethnic minority groups.13

The murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd and the inequitable toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black, Hispanic, and Native American people renewed the dialogue regarding structural racism in America. Beyond criminal justice and police reform, the current social justice movement demands that structural racism is examined in all spheres. In medicine and health care, acknowledging the history of exclusion and exploitation of Black people and other URM groups is an important first step, but this must be followed by a commitment to an antiracist future for the benefit of all medical professionals and patients.14,15

Antiracism as a path forward

Antiracism refers to actions and policies that seek to dismantle structural racism. While individuals can and should engage in antiracist actions, it is equally important for organizations and government to actively participate in this process as well.

Individual and interpersonal levels

Gastroenterologists should advocate an end to racist practices within their organizations (e.g., unjustified use of race-based corrections in diagnostic algorithms and practice guidelines),16 and interrupt microaggressions and racist actions in real time (e.g., overpolicing of underrepresented groups in health care settings).17 Gastroenterologists from underrepresented groups may also need to unlearn internalized racism, which is defined as acceptance by members of disadvantaged races of the negative messages about their own abilities and intrinsic worth.18

Organizational level

Gastroenterology divisions and practices must ensure that the entire workforce, including leadership, reflects the diversity of our country. Underrepresented groups represent 33% of the U.S. population, but only 9.1% of gastroenterology fellows and 10% of gastroenterology faculty are from underrepresented groups.19 In addition to diversifying the field of gastroenterology through financial and operational support of pipeline educational programs, organizations should also promote the scholarship of URM groups, whose work is often undervalued, and redistribute power by elevating voices that have been historically absent.20 Gastroenterology practices should also collect high-quality patient data disaggregated by demographic factors. Doing so will enable rapid identification of disparate health outcomes by demographic variables and inform interventions to eliminate identified disparities.

Government level

The “Executive Order On Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government” issued by President Biden on Jan. 20, 2021, is an example of how government can promote antiracism.21 The executive order states that domestic policies cause group inequities and calls for the removal of systemic barriers in current and future domestic policies. The executive order outlines several additional ways to improve equity in current and future policy, including engagement, consultation, and coordination with members of underserved communities. The details outlined in the executive order should serve as the foundation for establishing new standards at the state, county, and city levels as well. Gastroenterologists can influence government by voting for officials at all levels that support and promote these standards.

Conclusion

Beyond calling out microaggressions in real time, we must also interrogate the biases, policies, and practices that support them in medicine and beyond. As Black gastroenterologists who have experienced microaggressions and overt acts of racism, we ground Oviea’s experience in structural racism and offer strategies that individuals, organizations, and governing institutions can adopt toward an antiracist future. This model can be applied to experiences rooted in misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, ableism, and other prejudices.

As a nation, we must make an active and collective choice to address structural racism. In health care, doing so will strengthen communities, enhance the lived experiences of URM physician colleagues, and save patient lives. Gastroenterologists, as trusted health care providers, are uniquely positioned to lead the way.

Dr. Akpotaire is a second-year GI fellow in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Issaka is an assistant professor with both the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, and the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington.

References