User login

Traumatic brain injury tied to long-term sleep problems

Veterans who have suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) are significantly more likely to develop insomnia and other sleep problems years later compared to their counterparts who have not suffered a brain injury, a new study shows.

Results of a large longitudinal study show that those with TBI were about 40% more likely to develop insomnia, sleep apnea, excessive daytime sleepiness, or another sleep disorder in later years, after adjusting for demographics and medical and psychiatric conditions.

Interestingly, the association with sleep disorders was strongest among those with mild TBI versus a more severe brain injury.

The study showed that the risk for sleep disorders increased up to 14 years after a brain injury, an indicator that “clinicians should really pay attention to sleep disorders in TBI patients both in the short term and the long term,” study investigator Yue Leng, MD, PhD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 3 in Neurology.

First long-term look

TBI is common among veterans, who may have sleep complaints or psychiatric symptoms, but previous studies into the consequences of TBI have examined the short- vs. long-term impact, said Dr. Leng.

To examine the longitudinal association between TBI and sleep disorders, the investigators examined data on 98,709 Veterans Health Administration patients diagnosed with TBI and an age-matched group of the same number of veterans who had not received such a diagnosis. The mean age of the participants was 49 years at baseline, and 11.7% were women. Of the TBI cases, 49.6% were mild.

Researchers used an exposure survey and diagnostic codes to establish TBI and its severity.

Patients with TBI were more likely to be male and were much more likely to have a psychiatric condition, such as a mood disorder (22.4% vs. 9.3%), anxiety (10.5% vs. 4.4%), posttraumatic stress disorder (19.5% vs. 4.4%), or substance abuse (11.4% vs. 5.2%). They were also more likely to smoke or use tobacco (13.5% vs. 8.7%).

Researchers assessed a number of sleep disorders, including insomnia, hypersomnia disorders, narcolepsy, sleep-related breathing disorders, and sleep-related movement disorders.

During a follow-up period that averaged 5 years but ranged up to 14 years, 23.4% of veterans with TBI and 15.8% of those without TBI developed a sleep disorder.

After adjusting for age, sex, race, education, and income, those who had suffered a TBI were 50% more likely to develop any sleep disorder, compared with those who had not had a TBI (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.47-1.53.)

After controlling for medical conditions that included diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular disease, as well as psychiatric disorders such as mood disorders, anxiety, PTSD, substance use disorder, and tobacco use, the HR for developing a sleep disorder was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.37-1.44).

The association with TBI was stronger for some sleep disorders. Adjusted HRs were 1.50 (95% CI, 1.45-1.55) for insomnia, 1.50 (95% CI, 1.39-1.61) for hypersomnia, 1.33 (95% CI, 1.16-1.52) for sleep-related movement disorders, and 1.28 (95% CI, 1.24-1.32) for sleep apnea.

It’s unclear what causes postinjury sleep problems, but it could be that TBI induces structural brain damage, or it could affect melatonin secretion or wake-promoting neurons.

Damage to arousal-promoting neurons could help explain the reason the link between TBI and sleep disorders was strongest for insomnia and hypersomnia, although the exact mechanism is unclear, said Dr. Leng.

Greater risk with mild TBI

Overall, the association was stronger for mild TBI than for moderate to severe TBI. This, said Dr. Leng, might be because of differences in the brain injury mechanism.

Mild TBI often involves repetitive concussive or subconcussive injuries, such as sports injuries or blast injury among active-duty military personnel. This type of injury is more likely to cause diffuse axonal injury and inflammation, whereas moderate or severe TBI is often attributable to a direct blow with more focal but severe damage, explained Dr. Leng.

She noted that veterans with mild TBI were more likely to have a psychiatric condition, but because the study controlled for such conditions, this doesn’t fully explain the stronger association between mild TBI and sleep disorders.

Further studies are needed to sort out the exact mechanisms, she said.

The association between TBI and risk for sleep disorders was reduced somewhat but was still moderate in an analysis that excluded patients who developed a sleep disorder within 2 years of a brain injury.

This analysis, said Dr. Leng, helped ensure that the sleep disorder developed after the brain injury.

The researchers could not examine the trajectory of sleep problems, so it’s not clear whether sleep problems worsen or get better over time, said Dr. Leng.

Because PTSD also leads to sleep problems, the researchers thought that having both PTSD and TBI might increase the risk for sleep problems. “But actually we found the association was pretty similar in those with, and without, PTSD, so that was kind of contrary to our hypothesis,” she said.

The new results underline the need for more screening for sleep disorders among patients with TBI, both in the short term and the long term, said Dr. Leng. “Clinicians should ask TBI patients about their sleep, and they should follow that up,” she said.

She added that long-term sleep disorders can affect a patient’s health and can lead to psychiatric problems and neurodegenerative diseases.

Depending on the type of sleep disorder, there are a number of possible treatments. For example, for patients with sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure treatment may be considered.

‘Outstanding’ research

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director, Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology; CEO, Brainsport, Team Neurologist, the Florida Panthers of the National Hockey League; and past president, Florida Society of Neurology, said the study is “by far” the largest to investigate the correlation between sleep disorders and head trauma.

The design and outcome measures “were well thought out,” and the researchers “did an outstanding job in sorting through and analyzing the data,” said Dr. Conidi.

He added that he was particularly impressed with how the researchers addressed PTSD, which is highly prevalent among veterans with head trauma and is known to affect sleep.

The new results “solidify what those of us who see individuals with TBI have observed over the years: that there is a higher incidence of all types of sleep disorders” in individuals with a TBI, said Dr. Conidi.

However, he questioned the study’s use of guidelines to classify the various types of head trauma. These guidelines, he said, “are based on loss of consciousness, which we have started to move away from when classifying TBI.”

In addition, Dr. Conidi said he “would have loved to have seen” some correlation with neuroimaging studies, such as those used to assess subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and diffuse axonal injury, but that this “could be an impetus for future studies.”

In “a perfect world,” all patients with a TBI would undergo a polysomnography study in a sleep laboratory, but insurance companies now rarely cover such studies and have attempted to have clinicians shift to home sleep studies, said Dr. Conidi. “These are marginal at best for screening for sleep disorders,” he noted.

At his centers, every TBI patient is screened for sleep disorders and, whenever possible, undergoes formal evaluation in the sleep lab, he added.

The study was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Leng and Dr. Conidi have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Veterans who have suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) are significantly more likely to develop insomnia and other sleep problems years later compared to their counterparts who have not suffered a brain injury, a new study shows.

Results of a large longitudinal study show that those with TBI were about 40% more likely to develop insomnia, sleep apnea, excessive daytime sleepiness, or another sleep disorder in later years, after adjusting for demographics and medical and psychiatric conditions.

Interestingly, the association with sleep disorders was strongest among those with mild TBI versus a more severe brain injury.

The study showed that the risk for sleep disorders increased up to 14 years after a brain injury, an indicator that “clinicians should really pay attention to sleep disorders in TBI patients both in the short term and the long term,” study investigator Yue Leng, MD, PhD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 3 in Neurology.

First long-term look

TBI is common among veterans, who may have sleep complaints or psychiatric symptoms, but previous studies into the consequences of TBI have examined the short- vs. long-term impact, said Dr. Leng.

To examine the longitudinal association between TBI and sleep disorders, the investigators examined data on 98,709 Veterans Health Administration patients diagnosed with TBI and an age-matched group of the same number of veterans who had not received such a diagnosis. The mean age of the participants was 49 years at baseline, and 11.7% were women. Of the TBI cases, 49.6% were mild.

Researchers used an exposure survey and diagnostic codes to establish TBI and its severity.

Patients with TBI were more likely to be male and were much more likely to have a psychiatric condition, such as a mood disorder (22.4% vs. 9.3%), anxiety (10.5% vs. 4.4%), posttraumatic stress disorder (19.5% vs. 4.4%), or substance abuse (11.4% vs. 5.2%). They were also more likely to smoke or use tobacco (13.5% vs. 8.7%).

Researchers assessed a number of sleep disorders, including insomnia, hypersomnia disorders, narcolepsy, sleep-related breathing disorders, and sleep-related movement disorders.

During a follow-up period that averaged 5 years but ranged up to 14 years, 23.4% of veterans with TBI and 15.8% of those without TBI developed a sleep disorder.

After adjusting for age, sex, race, education, and income, those who had suffered a TBI were 50% more likely to develop any sleep disorder, compared with those who had not had a TBI (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.47-1.53.)

After controlling for medical conditions that included diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular disease, as well as psychiatric disorders such as mood disorders, anxiety, PTSD, substance use disorder, and tobacco use, the HR for developing a sleep disorder was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.37-1.44).

The association with TBI was stronger for some sleep disorders. Adjusted HRs were 1.50 (95% CI, 1.45-1.55) for insomnia, 1.50 (95% CI, 1.39-1.61) for hypersomnia, 1.33 (95% CI, 1.16-1.52) for sleep-related movement disorders, and 1.28 (95% CI, 1.24-1.32) for sleep apnea.

It’s unclear what causes postinjury sleep problems, but it could be that TBI induces structural brain damage, or it could affect melatonin secretion or wake-promoting neurons.

Damage to arousal-promoting neurons could help explain the reason the link between TBI and sleep disorders was strongest for insomnia and hypersomnia, although the exact mechanism is unclear, said Dr. Leng.

Greater risk with mild TBI

Overall, the association was stronger for mild TBI than for moderate to severe TBI. This, said Dr. Leng, might be because of differences in the brain injury mechanism.

Mild TBI often involves repetitive concussive or subconcussive injuries, such as sports injuries or blast injury among active-duty military personnel. This type of injury is more likely to cause diffuse axonal injury and inflammation, whereas moderate or severe TBI is often attributable to a direct blow with more focal but severe damage, explained Dr. Leng.

She noted that veterans with mild TBI were more likely to have a psychiatric condition, but because the study controlled for such conditions, this doesn’t fully explain the stronger association between mild TBI and sleep disorders.

Further studies are needed to sort out the exact mechanisms, she said.

The association between TBI and risk for sleep disorders was reduced somewhat but was still moderate in an analysis that excluded patients who developed a sleep disorder within 2 years of a brain injury.

This analysis, said Dr. Leng, helped ensure that the sleep disorder developed after the brain injury.

The researchers could not examine the trajectory of sleep problems, so it’s not clear whether sleep problems worsen or get better over time, said Dr. Leng.

Because PTSD also leads to sleep problems, the researchers thought that having both PTSD and TBI might increase the risk for sleep problems. “But actually we found the association was pretty similar in those with, and without, PTSD, so that was kind of contrary to our hypothesis,” she said.

The new results underline the need for more screening for sleep disorders among patients with TBI, both in the short term and the long term, said Dr. Leng. “Clinicians should ask TBI patients about their sleep, and they should follow that up,” she said.

She added that long-term sleep disorders can affect a patient’s health and can lead to psychiatric problems and neurodegenerative diseases.

Depending on the type of sleep disorder, there are a number of possible treatments. For example, for patients with sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure treatment may be considered.

‘Outstanding’ research

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director, Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology; CEO, Brainsport, Team Neurologist, the Florida Panthers of the National Hockey League; and past president, Florida Society of Neurology, said the study is “by far” the largest to investigate the correlation between sleep disorders and head trauma.

The design and outcome measures “were well thought out,” and the researchers “did an outstanding job in sorting through and analyzing the data,” said Dr. Conidi.

He added that he was particularly impressed with how the researchers addressed PTSD, which is highly prevalent among veterans with head trauma and is known to affect sleep.

The new results “solidify what those of us who see individuals with TBI have observed over the years: that there is a higher incidence of all types of sleep disorders” in individuals with a TBI, said Dr. Conidi.

However, he questioned the study’s use of guidelines to classify the various types of head trauma. These guidelines, he said, “are based on loss of consciousness, which we have started to move away from when classifying TBI.”

In addition, Dr. Conidi said he “would have loved to have seen” some correlation with neuroimaging studies, such as those used to assess subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and diffuse axonal injury, but that this “could be an impetus for future studies.”

In “a perfect world,” all patients with a TBI would undergo a polysomnography study in a sleep laboratory, but insurance companies now rarely cover such studies and have attempted to have clinicians shift to home sleep studies, said Dr. Conidi. “These are marginal at best for screening for sleep disorders,” he noted.

At his centers, every TBI patient is screened for sleep disorders and, whenever possible, undergoes formal evaluation in the sleep lab, he added.

The study was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Leng and Dr. Conidi have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Veterans who have suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) are significantly more likely to develop insomnia and other sleep problems years later compared to their counterparts who have not suffered a brain injury, a new study shows.

Results of a large longitudinal study show that those with TBI were about 40% more likely to develop insomnia, sleep apnea, excessive daytime sleepiness, or another sleep disorder in later years, after adjusting for demographics and medical and psychiatric conditions.

Interestingly, the association with sleep disorders was strongest among those with mild TBI versus a more severe brain injury.

The study showed that the risk for sleep disorders increased up to 14 years after a brain injury, an indicator that “clinicians should really pay attention to sleep disorders in TBI patients both in the short term and the long term,” study investigator Yue Leng, MD, PhD, assistant professor, department of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, University of California, San Francisco, told this news organization.

The study was published online March 3 in Neurology.

First long-term look

TBI is common among veterans, who may have sleep complaints or psychiatric symptoms, but previous studies into the consequences of TBI have examined the short- vs. long-term impact, said Dr. Leng.

To examine the longitudinal association between TBI and sleep disorders, the investigators examined data on 98,709 Veterans Health Administration patients diagnosed with TBI and an age-matched group of the same number of veterans who had not received such a diagnosis. The mean age of the participants was 49 years at baseline, and 11.7% were women. Of the TBI cases, 49.6% were mild.

Researchers used an exposure survey and diagnostic codes to establish TBI and its severity.

Patients with TBI were more likely to be male and were much more likely to have a psychiatric condition, such as a mood disorder (22.4% vs. 9.3%), anxiety (10.5% vs. 4.4%), posttraumatic stress disorder (19.5% vs. 4.4%), or substance abuse (11.4% vs. 5.2%). They were also more likely to smoke or use tobacco (13.5% vs. 8.7%).

Researchers assessed a number of sleep disorders, including insomnia, hypersomnia disorders, narcolepsy, sleep-related breathing disorders, and sleep-related movement disorders.

During a follow-up period that averaged 5 years but ranged up to 14 years, 23.4% of veterans with TBI and 15.8% of those without TBI developed a sleep disorder.

After adjusting for age, sex, race, education, and income, those who had suffered a TBI were 50% more likely to develop any sleep disorder, compared with those who had not had a TBI (hazard ratio, 1.50; 95% confidence interval, 1.47-1.53.)

After controlling for medical conditions that included diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction, and cerebrovascular disease, as well as psychiatric disorders such as mood disorders, anxiety, PTSD, substance use disorder, and tobacco use, the HR for developing a sleep disorder was 1.41 (95% CI, 1.37-1.44).

The association with TBI was stronger for some sleep disorders. Adjusted HRs were 1.50 (95% CI, 1.45-1.55) for insomnia, 1.50 (95% CI, 1.39-1.61) for hypersomnia, 1.33 (95% CI, 1.16-1.52) for sleep-related movement disorders, and 1.28 (95% CI, 1.24-1.32) for sleep apnea.

It’s unclear what causes postinjury sleep problems, but it could be that TBI induces structural brain damage, or it could affect melatonin secretion or wake-promoting neurons.

Damage to arousal-promoting neurons could help explain the reason the link between TBI and sleep disorders was strongest for insomnia and hypersomnia, although the exact mechanism is unclear, said Dr. Leng.

Greater risk with mild TBI

Overall, the association was stronger for mild TBI than for moderate to severe TBI. This, said Dr. Leng, might be because of differences in the brain injury mechanism.

Mild TBI often involves repetitive concussive or subconcussive injuries, such as sports injuries or blast injury among active-duty military personnel. This type of injury is more likely to cause diffuse axonal injury and inflammation, whereas moderate or severe TBI is often attributable to a direct blow with more focal but severe damage, explained Dr. Leng.

She noted that veterans with mild TBI were more likely to have a psychiatric condition, but because the study controlled for such conditions, this doesn’t fully explain the stronger association between mild TBI and sleep disorders.

Further studies are needed to sort out the exact mechanisms, she said.

The association between TBI and risk for sleep disorders was reduced somewhat but was still moderate in an analysis that excluded patients who developed a sleep disorder within 2 years of a brain injury.

This analysis, said Dr. Leng, helped ensure that the sleep disorder developed after the brain injury.

The researchers could not examine the trajectory of sleep problems, so it’s not clear whether sleep problems worsen or get better over time, said Dr. Leng.

Because PTSD also leads to sleep problems, the researchers thought that having both PTSD and TBI might increase the risk for sleep problems. “But actually we found the association was pretty similar in those with, and without, PTSD, so that was kind of contrary to our hypothesis,” she said.

The new results underline the need for more screening for sleep disorders among patients with TBI, both in the short term and the long term, said Dr. Leng. “Clinicians should ask TBI patients about their sleep, and they should follow that up,” she said.

She added that long-term sleep disorders can affect a patient’s health and can lead to psychiatric problems and neurodegenerative diseases.

Depending on the type of sleep disorder, there are a number of possible treatments. For example, for patients with sleep apnea, continuous positive airway pressure treatment may be considered.

‘Outstanding’ research

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director, Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology; CEO, Brainsport, Team Neurologist, the Florida Panthers of the National Hockey League; and past president, Florida Society of Neurology, said the study is “by far” the largest to investigate the correlation between sleep disorders and head trauma.

The design and outcome measures “were well thought out,” and the researchers “did an outstanding job in sorting through and analyzing the data,” said Dr. Conidi.

He added that he was particularly impressed with how the researchers addressed PTSD, which is highly prevalent among veterans with head trauma and is known to affect sleep.

The new results “solidify what those of us who see individuals with TBI have observed over the years: that there is a higher incidence of all types of sleep disorders” in individuals with a TBI, said Dr. Conidi.

However, he questioned the study’s use of guidelines to classify the various types of head trauma. These guidelines, he said, “are based on loss of consciousness, which we have started to move away from when classifying TBI.”

In addition, Dr. Conidi said he “would have loved to have seen” some correlation with neuroimaging studies, such as those used to assess subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and diffuse axonal injury, but that this “could be an impetus for future studies.”

In “a perfect world,” all patients with a TBI would undergo a polysomnography study in a sleep laboratory, but insurance companies now rarely cover such studies and have attempted to have clinicians shift to home sleep studies, said Dr. Conidi. “These are marginal at best for screening for sleep disorders,” he noted.

At his centers, every TBI patient is screened for sleep disorders and, whenever possible, undergoes formal evaluation in the sleep lab, he added.

The study was supported by the U.S. Army Medical Research and Material Command and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Dr. Leng and Dr. Conidi have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Vaginal pH may predict CIN 2 progression in HIV-positive women

Elevated vaginal pH at the time of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 diagnosis may be a useful marker of CIN 2 persistence/progression, as well as the rate of persistence/progression in HIV-positive women, new research suggests.

“We analyzed data from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study [WIHS], an observational, longitudinal cohort of women with and without HIV to determine factors that may influence CIN 2 natural history,” said Kate Michel, PhD, MPH, of Georgetown University, Washington. She presented the results at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

As previous data have shown a high incidence of CIN 2 progression among women with HIV, the researchers evaluated the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) type, local immune response, and markers of the cervicovaginal microbiome on the risk of CIN 2 persistence/progression.

Within the cohort, follow-up visits occur every 6 months, and clinical data is collected via questionnaires, physical and gynecologic exams, and biological samples. As no specific treatment is offered in the WIHS, treatment for cervical abnormalities is abstracted from medical records.

In the present study, Dr. Michel and colleagues selected up to four banked cervicovaginal lavage (CVL) samples per woman, with the first sample selected 6-12 months prior to CIN 2 diagnosis, the second at CIN 2 diagnosis, the third between CIN 2 diagnosis and outcome, and the fourth at the outcome visit.

The investigators performed HPV typing and muiltiplex immune mediator testing on each CVL sample. Lab results from WIHS core testing were also extracted, including plasma CD4+ T-cell count and HIV viral load, as well as vaginal pH and Nugent’s score.

Study outcomes included persistence/progression and regression, defined as a subsequent CIN 2 or CIN 3 diagnosis and subsequent CIN 1 or normal diagnosis, respectively. Logistic regression models were used to determine CIN 2 regression versus persistence/progression.

Results

A total of 337 samples were obtained and 94 women were included in the analysis. Key demographic and behavioral factor were similar at CIN 2 diagnosis.

The majority of participants were African American (53.2%) and on antiretroviral therapy (66.0%). The most prevalent high-risk types were HPV-58 (18.4%) and HPV-16 (17.5%).

After a median 12.5 years of follow-up, 33 participants (35.1%) with incident CIN 2 had a subsequent CIN 2/CIN 3 diagnosis and those who regressed had a higher CD4 T-cell count at CIN 2 diagnosis (P = .02).

Each subsequent high-risk HPV type identified at the pre–CIN 2 visit was associated with higher odds of CIN2 persistence/progression (odds ratio, 2.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-4.50).

Bacterial vaginosis (adjusted OR, 5.08; 95% CI, 1.30-19.94) and vaginal pH (aOR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.15-4.50) at the CIN 2 diagnosis visit were each associated with increased odds of CIN 2 persistence/progression.

Vaginal pH greater than 4.5 at CIN 2 diagnosis was also associated with unadjusted time to CIN 2 persistence/progression (log rank P = .002) and an increased rate of CIN 2 persistence/progression (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.37; 95% CI, 1.26-8.99).

Furthermore, among participants who did not receive CIN 2 treatment, vaginal pH remained associated with greater odds of CIN 2 persistence/progression (OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.19-5.13). Cervicovaginal immune mediator levels were not associated with CIN 2 persistence/progression.

“The most striking finding from this work was that vaginal pH was associated with higher odds of, quicker time to, and increased hazard of CIN 2 persistence/progression,” Dr. Michel said. “We postulate this effect is mediated by the cervical microbiome, but more work is needed to establish the exact mechanism.”

“It would be interesting to test whether this association might be explained by different vaginal cleaning techniques, such as douching,” said moderator Ronald T. Mitsuyasu, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“We’re currently working on an analysis of cervicovaginal bacterial species to explore the microbiome in more detail,” Dr. Michel concluded.

Dr. Michel disclosed no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by multiple sources, including the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Cancer Institute, and the Georgetown-Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science.

Elevated vaginal pH at the time of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 diagnosis may be a useful marker of CIN 2 persistence/progression, as well as the rate of persistence/progression in HIV-positive women, new research suggests.

“We analyzed data from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study [WIHS], an observational, longitudinal cohort of women with and without HIV to determine factors that may influence CIN 2 natural history,” said Kate Michel, PhD, MPH, of Georgetown University, Washington. She presented the results at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

As previous data have shown a high incidence of CIN 2 progression among women with HIV, the researchers evaluated the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) type, local immune response, and markers of the cervicovaginal microbiome on the risk of CIN 2 persistence/progression.

Within the cohort, follow-up visits occur every 6 months, and clinical data is collected via questionnaires, physical and gynecologic exams, and biological samples. As no specific treatment is offered in the WIHS, treatment for cervical abnormalities is abstracted from medical records.

In the present study, Dr. Michel and colleagues selected up to four banked cervicovaginal lavage (CVL) samples per woman, with the first sample selected 6-12 months prior to CIN 2 diagnosis, the second at CIN 2 diagnosis, the third between CIN 2 diagnosis and outcome, and the fourth at the outcome visit.

The investigators performed HPV typing and muiltiplex immune mediator testing on each CVL sample. Lab results from WIHS core testing were also extracted, including plasma CD4+ T-cell count and HIV viral load, as well as vaginal pH and Nugent’s score.

Study outcomes included persistence/progression and regression, defined as a subsequent CIN 2 or CIN 3 diagnosis and subsequent CIN 1 or normal diagnosis, respectively. Logistic regression models were used to determine CIN 2 regression versus persistence/progression.

Results

A total of 337 samples were obtained and 94 women were included in the analysis. Key demographic and behavioral factor were similar at CIN 2 diagnosis.

The majority of participants were African American (53.2%) and on antiretroviral therapy (66.0%). The most prevalent high-risk types were HPV-58 (18.4%) and HPV-16 (17.5%).

After a median 12.5 years of follow-up, 33 participants (35.1%) with incident CIN 2 had a subsequent CIN 2/CIN 3 diagnosis and those who regressed had a higher CD4 T-cell count at CIN 2 diagnosis (P = .02).

Each subsequent high-risk HPV type identified at the pre–CIN 2 visit was associated with higher odds of CIN2 persistence/progression (odds ratio, 2.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-4.50).

Bacterial vaginosis (adjusted OR, 5.08; 95% CI, 1.30-19.94) and vaginal pH (aOR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.15-4.50) at the CIN 2 diagnosis visit were each associated with increased odds of CIN 2 persistence/progression.

Vaginal pH greater than 4.5 at CIN 2 diagnosis was also associated with unadjusted time to CIN 2 persistence/progression (log rank P = .002) and an increased rate of CIN 2 persistence/progression (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.37; 95% CI, 1.26-8.99).

Furthermore, among participants who did not receive CIN 2 treatment, vaginal pH remained associated with greater odds of CIN 2 persistence/progression (OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.19-5.13). Cervicovaginal immune mediator levels were not associated with CIN 2 persistence/progression.

“The most striking finding from this work was that vaginal pH was associated with higher odds of, quicker time to, and increased hazard of CIN 2 persistence/progression,” Dr. Michel said. “We postulate this effect is mediated by the cervical microbiome, but more work is needed to establish the exact mechanism.”

“It would be interesting to test whether this association might be explained by different vaginal cleaning techniques, such as douching,” said moderator Ronald T. Mitsuyasu, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“We’re currently working on an analysis of cervicovaginal bacterial species to explore the microbiome in more detail,” Dr. Michel concluded.

Dr. Michel disclosed no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by multiple sources, including the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Cancer Institute, and the Georgetown-Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science.

Elevated vaginal pH at the time of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 diagnosis may be a useful marker of CIN 2 persistence/progression, as well as the rate of persistence/progression in HIV-positive women, new research suggests.

“We analyzed data from the Women’s Interagency HIV Study [WIHS], an observational, longitudinal cohort of women with and without HIV to determine factors that may influence CIN 2 natural history,” said Kate Michel, PhD, MPH, of Georgetown University, Washington. She presented the results at the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections.

As previous data have shown a high incidence of CIN 2 progression among women with HIV, the researchers evaluated the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) type, local immune response, and markers of the cervicovaginal microbiome on the risk of CIN 2 persistence/progression.

Within the cohort, follow-up visits occur every 6 months, and clinical data is collected via questionnaires, physical and gynecologic exams, and biological samples. As no specific treatment is offered in the WIHS, treatment for cervical abnormalities is abstracted from medical records.

In the present study, Dr. Michel and colleagues selected up to four banked cervicovaginal lavage (CVL) samples per woman, with the first sample selected 6-12 months prior to CIN 2 diagnosis, the second at CIN 2 diagnosis, the third between CIN 2 diagnosis and outcome, and the fourth at the outcome visit.

The investigators performed HPV typing and muiltiplex immune mediator testing on each CVL sample. Lab results from WIHS core testing were also extracted, including plasma CD4+ T-cell count and HIV viral load, as well as vaginal pH and Nugent’s score.

Study outcomes included persistence/progression and regression, defined as a subsequent CIN 2 or CIN 3 diagnosis and subsequent CIN 1 or normal diagnosis, respectively. Logistic regression models were used to determine CIN 2 regression versus persistence/progression.

Results

A total of 337 samples were obtained and 94 women were included in the analysis. Key demographic and behavioral factor were similar at CIN 2 diagnosis.

The majority of participants were African American (53.2%) and on antiretroviral therapy (66.0%). The most prevalent high-risk types were HPV-58 (18.4%) and HPV-16 (17.5%).

After a median 12.5 years of follow-up, 33 participants (35.1%) with incident CIN 2 had a subsequent CIN 2/CIN 3 diagnosis and those who regressed had a higher CD4 T-cell count at CIN 2 diagnosis (P = .02).

Each subsequent high-risk HPV type identified at the pre–CIN 2 visit was associated with higher odds of CIN2 persistence/progression (odds ratio, 2.27; 95% confidence interval, 1.15-4.50).

Bacterial vaginosis (adjusted OR, 5.08; 95% CI, 1.30-19.94) and vaginal pH (aOR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.15-4.50) at the CIN 2 diagnosis visit were each associated with increased odds of CIN 2 persistence/progression.

Vaginal pH greater than 4.5 at CIN 2 diagnosis was also associated with unadjusted time to CIN 2 persistence/progression (log rank P = .002) and an increased rate of CIN 2 persistence/progression (adjusted hazard ratio, 3.37; 95% CI, 1.26-8.99).

Furthermore, among participants who did not receive CIN 2 treatment, vaginal pH remained associated with greater odds of CIN 2 persistence/progression (OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 1.19-5.13). Cervicovaginal immune mediator levels were not associated with CIN 2 persistence/progression.

“The most striking finding from this work was that vaginal pH was associated with higher odds of, quicker time to, and increased hazard of CIN 2 persistence/progression,” Dr. Michel said. “We postulate this effect is mediated by the cervical microbiome, but more work is needed to establish the exact mechanism.”

“It would be interesting to test whether this association might be explained by different vaginal cleaning techniques, such as douching,” said moderator Ronald T. Mitsuyasu, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“We’re currently working on an analysis of cervicovaginal bacterial species to explore the microbiome in more detail,” Dr. Michel concluded.

Dr. Michel disclosed no conflicts of interest. The study was supported by multiple sources, including the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, the National Cancer Institute, and the Georgetown-Howard Universities Center for Clinical and Translational Science.

FROM CROI 2021

mCODE: Improving data sharing to enhance cancer care

An initiative designed to improve sharing of patient data may provide “tremendous benefits” in cancer care and research, according to authors of a review article.

The goals of the initiative, called Minimal Common Oncology Data Elements (mCODE), were to identify the data elements in electronic health records that are “essential” for making treatment decisions and create “a standardized computable data format” that would improve the exchange of data across EHRs, according to the mCODE website.

Travis J. Osterman, DO, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., and colleagues described the mCODE initiative in a review published in JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics.

At present, commercially available EHRs are poorly designed to support modern oncology workflow, requiring laborious data entry and lacking a common library of oncology-specific discrete data elements. As an example, most EHRs poorly support the needs of precision oncology and clinical genetics, since next-generation sequencing and genetic test results are almost universally reported in PDF files.

In addition, basic, operational oncology data (e.g., cancer staging, adverse event documentation, response to treatment, etc.) are captured in EHRs primarily as an unstructured narrative.

Computable, analytical data are found for only the small percentage of patients in clinical trials. Even then, some degree of manual data abstraction is regularly required.

Interoperability of EHRs between practices and health care institutions is often so poor that the transfer of basic cancer-related information as analyzable data is difficult or even impossible.

Making progress: The 21st Century Cures Act

The American Society of Clinical Oncology has a more than 15-year history of developing oncology data standards. Unfortunately, progress in implementing these standards has been glacially slow. Impediments have included:

- A lack of conformance with clinical workflows.

- Failure to test standards on specific-use cases during pilot testing.

- A focus on data exchange, rather than the practical impediments to data entry.

- Poor engagement with EHR vendors in distributing clinical information modules with an oncology-specific focus

- Instability of data interoperability technologies.

The 21st Century Cures Act, which became law in December 2016, mandated improvement in the interoperability of health information through the development of data standards and application programming interfaces.

In early 2020, final rules for implementation required technology vendors to employ application programming interfaces using a single interoperability resource. In addition, payers were required to use the United States Core Data for Interoperability Standard for data exchange. These requirements were intended to provide patients with access to their own health care data “without special effort.”

As a fortunate byproduct, since EHR vendors are required to implement application program interfaces using the Health Level Seven International (HL7) Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource (FHIR) Specification, the final rules could enable systems like mCODE to be more easily integrated with existing EHRs.

Lessons from CancerLinQ

ASCO created the health technology platform CancerLinQ in 2014, envisioning that it could become an oncology-focused learning health system – a system in which internal data and experience are systematically integrated with external evidence, allowing knowledge to be put into practice.

CancerLinQ extracts data from EHRs and other sources via direct software connections. CancerLinQ then aggregates, harmonizes, and normalizes the data in a cloud-based environment.

The data are available to participating practices for quality improvement in patient care and secondary research. In 2020, records of cancer patients in the CancerLinQ database surpassed 2 million.

CancerLinQ has been successful. However, because of the nature of the EHR ecosystem and the scope and variability of data capture by clinicians, supporting a true learning health system has proven to be a formidable task. Postprocessing manual review using trained human curators is laborious and unsustainable.

The CancerLinQ experience illustrated that basic cancer-pertinent data should be standardized in the EHR and collected prospectively.

The mCODE model

The mCODE initiative seeks to facilitate progress in care quality, clinical research, and health care policy by developing and maintaining a standard, computable, interoperable data format.

Guiding principles that were adopted early in mCODE’s development included:

- A collaborative, noncommercial, use case–driven developmental model.

- Iterative processes.

- User-driven development, refinement, and maintenance.

- Low ongoing maintenance requirements.

A foundational moment in mCODE’s development involved achieving consensus among stakeholders that the project would fail if EHR vendors required additional data entry by users.

After pilot work, a real-world endpoints project, working-group deliberation, public comment, and refinement, the final data standard included six primary domains: patient, disease, laboratory data/vital signs, genomics, treatment, and outcome.

Each domain is further divided into several concepts with specific associated data elements. The data elements are modeled into value sets that specify the possible values for the data element.

To test mCODE, eight organizations representing oncology EHR vendors, standards developers, and research organizations participated in a cancer interoperability track. The comments helped refine mCODE version 1.0, which was released in March 2020 and is accessible via the mCODE website.

Additions will likely be reviewed by a technical review group after external piloting of new use cases.

Innovation, not regulation

Every interaction between a patient and care provider yields information that could lead to improved safety and better outcomes. To be successful, the information must be collected in a computable format so it can be aggregated with data from other patients, analyzed without manual curation, and shared through interoperable systems. Those data should also be secure enough to protect the privacy of individual patients.

mCODE is a consensus data standard for oncology that provides an infrastructure to share patient data between oncology practices and health care systems while promising little to no additional data entry on the part of clinicians. Adoption by sites will be critical, however.

Publishing the standard through the HL7 FHIR technology demonstrated to EHR vendors and regulatory agencies the stability of HL7, an essential requirement for its incorporation into software.

EHR vendors and others are engaged in the CodeX HL7 FHIR Accelerator to design projects to expand and/or modify mCODE. Their creativity and innovativeness via the external advisory mCODE council and/or CodeX will be encouraged to help mCODE reach its full potential.

As part of CodeX, the Community of Practice, an open forum for end users, was established to provide regular updates about mCODE-related initiatives and use cases to solicit in-progress input, according to Robert S. Miller, MD, medical director of CancerLinQ and an author of the mCODE review.

For mCODE to be embraced by all stakeholders, there should be no additional regulations. By engaging stakeholders in an enterprise that supports innovation and collaboration – without additional regulation – mCODE could maximize the potential of EHRs that, until now, have assisted us only marginally in accomplishing those goals.

mCODE is a joint venture of ASCO/CancerLinQ, the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Foundation, the MITRE Corporation, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

Dr. Osterman disclosed a grant from the National Cancer Institute and relationships with Infostratix, eHealth, AstraZeneca, Outcomes Insights, Biodesix, MD Outlook, GenomOncology, Cota Healthcare, GE Healthcare, and Microsoft. Dr. Miller and the third review author disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

An initiative designed to improve sharing of patient data may provide “tremendous benefits” in cancer care and research, according to authors of a review article.

The goals of the initiative, called Minimal Common Oncology Data Elements (mCODE), were to identify the data elements in electronic health records that are “essential” for making treatment decisions and create “a standardized computable data format” that would improve the exchange of data across EHRs, according to the mCODE website.

Travis J. Osterman, DO, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., and colleagues described the mCODE initiative in a review published in JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics.

At present, commercially available EHRs are poorly designed to support modern oncology workflow, requiring laborious data entry and lacking a common library of oncology-specific discrete data elements. As an example, most EHRs poorly support the needs of precision oncology and clinical genetics, since next-generation sequencing and genetic test results are almost universally reported in PDF files.

In addition, basic, operational oncology data (e.g., cancer staging, adverse event documentation, response to treatment, etc.) are captured in EHRs primarily as an unstructured narrative.

Computable, analytical data are found for only the small percentage of patients in clinical trials. Even then, some degree of manual data abstraction is regularly required.

Interoperability of EHRs between practices and health care institutions is often so poor that the transfer of basic cancer-related information as analyzable data is difficult or even impossible.

Making progress: The 21st Century Cures Act

The American Society of Clinical Oncology has a more than 15-year history of developing oncology data standards. Unfortunately, progress in implementing these standards has been glacially slow. Impediments have included:

- A lack of conformance with clinical workflows.

- Failure to test standards on specific-use cases during pilot testing.

- A focus on data exchange, rather than the practical impediments to data entry.

- Poor engagement with EHR vendors in distributing clinical information modules with an oncology-specific focus

- Instability of data interoperability technologies.

The 21st Century Cures Act, which became law in December 2016, mandated improvement in the interoperability of health information through the development of data standards and application programming interfaces.

In early 2020, final rules for implementation required technology vendors to employ application programming interfaces using a single interoperability resource. In addition, payers were required to use the United States Core Data for Interoperability Standard for data exchange. These requirements were intended to provide patients with access to their own health care data “without special effort.”

As a fortunate byproduct, since EHR vendors are required to implement application program interfaces using the Health Level Seven International (HL7) Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource (FHIR) Specification, the final rules could enable systems like mCODE to be more easily integrated with existing EHRs.

Lessons from CancerLinQ

ASCO created the health technology platform CancerLinQ in 2014, envisioning that it could become an oncology-focused learning health system – a system in which internal data and experience are systematically integrated with external evidence, allowing knowledge to be put into practice.

CancerLinQ extracts data from EHRs and other sources via direct software connections. CancerLinQ then aggregates, harmonizes, and normalizes the data in a cloud-based environment.

The data are available to participating practices for quality improvement in patient care and secondary research. In 2020, records of cancer patients in the CancerLinQ database surpassed 2 million.

CancerLinQ has been successful. However, because of the nature of the EHR ecosystem and the scope and variability of data capture by clinicians, supporting a true learning health system has proven to be a formidable task. Postprocessing manual review using trained human curators is laborious and unsustainable.

The CancerLinQ experience illustrated that basic cancer-pertinent data should be standardized in the EHR and collected prospectively.

The mCODE model

The mCODE initiative seeks to facilitate progress in care quality, clinical research, and health care policy by developing and maintaining a standard, computable, interoperable data format.

Guiding principles that were adopted early in mCODE’s development included:

- A collaborative, noncommercial, use case–driven developmental model.

- Iterative processes.

- User-driven development, refinement, and maintenance.

- Low ongoing maintenance requirements.

A foundational moment in mCODE’s development involved achieving consensus among stakeholders that the project would fail if EHR vendors required additional data entry by users.

After pilot work, a real-world endpoints project, working-group deliberation, public comment, and refinement, the final data standard included six primary domains: patient, disease, laboratory data/vital signs, genomics, treatment, and outcome.

Each domain is further divided into several concepts with specific associated data elements. The data elements are modeled into value sets that specify the possible values for the data element.

To test mCODE, eight organizations representing oncology EHR vendors, standards developers, and research organizations participated in a cancer interoperability track. The comments helped refine mCODE version 1.0, which was released in March 2020 and is accessible via the mCODE website.

Additions will likely be reviewed by a technical review group after external piloting of new use cases.

Innovation, not regulation

Every interaction between a patient and care provider yields information that could lead to improved safety and better outcomes. To be successful, the information must be collected in a computable format so it can be aggregated with data from other patients, analyzed without manual curation, and shared through interoperable systems. Those data should also be secure enough to protect the privacy of individual patients.

mCODE is a consensus data standard for oncology that provides an infrastructure to share patient data between oncology practices and health care systems while promising little to no additional data entry on the part of clinicians. Adoption by sites will be critical, however.

Publishing the standard through the HL7 FHIR technology demonstrated to EHR vendors and regulatory agencies the stability of HL7, an essential requirement for its incorporation into software.

EHR vendors and others are engaged in the CodeX HL7 FHIR Accelerator to design projects to expand and/or modify mCODE. Their creativity and innovativeness via the external advisory mCODE council and/or CodeX will be encouraged to help mCODE reach its full potential.

As part of CodeX, the Community of Practice, an open forum for end users, was established to provide regular updates about mCODE-related initiatives and use cases to solicit in-progress input, according to Robert S. Miller, MD, medical director of CancerLinQ and an author of the mCODE review.

For mCODE to be embraced by all stakeholders, there should be no additional regulations. By engaging stakeholders in an enterprise that supports innovation and collaboration – without additional regulation – mCODE could maximize the potential of EHRs that, until now, have assisted us only marginally in accomplishing those goals.

mCODE is a joint venture of ASCO/CancerLinQ, the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Foundation, the MITRE Corporation, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

Dr. Osterman disclosed a grant from the National Cancer Institute and relationships with Infostratix, eHealth, AstraZeneca, Outcomes Insights, Biodesix, MD Outlook, GenomOncology, Cota Healthcare, GE Healthcare, and Microsoft. Dr. Miller and the third review author disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

An initiative designed to improve sharing of patient data may provide “tremendous benefits” in cancer care and research, according to authors of a review article.

The goals of the initiative, called Minimal Common Oncology Data Elements (mCODE), were to identify the data elements in electronic health records that are “essential” for making treatment decisions and create “a standardized computable data format” that would improve the exchange of data across EHRs, according to the mCODE website.

Travis J. Osterman, DO, of Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tenn., and colleagues described the mCODE initiative in a review published in JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics.

At present, commercially available EHRs are poorly designed to support modern oncology workflow, requiring laborious data entry and lacking a common library of oncology-specific discrete data elements. As an example, most EHRs poorly support the needs of precision oncology and clinical genetics, since next-generation sequencing and genetic test results are almost universally reported in PDF files.

In addition, basic, operational oncology data (e.g., cancer staging, adverse event documentation, response to treatment, etc.) are captured in EHRs primarily as an unstructured narrative.

Computable, analytical data are found for only the small percentage of patients in clinical trials. Even then, some degree of manual data abstraction is regularly required.

Interoperability of EHRs between practices and health care institutions is often so poor that the transfer of basic cancer-related information as analyzable data is difficult or even impossible.

Making progress: The 21st Century Cures Act

The American Society of Clinical Oncology has a more than 15-year history of developing oncology data standards. Unfortunately, progress in implementing these standards has been glacially slow. Impediments have included:

- A lack of conformance with clinical workflows.

- Failure to test standards on specific-use cases during pilot testing.

- A focus on data exchange, rather than the practical impediments to data entry.

- Poor engagement with EHR vendors in distributing clinical information modules with an oncology-specific focus

- Instability of data interoperability technologies.

The 21st Century Cures Act, which became law in December 2016, mandated improvement in the interoperability of health information through the development of data standards and application programming interfaces.

In early 2020, final rules for implementation required technology vendors to employ application programming interfaces using a single interoperability resource. In addition, payers were required to use the United States Core Data for Interoperability Standard for data exchange. These requirements were intended to provide patients with access to their own health care data “without special effort.”

As a fortunate byproduct, since EHR vendors are required to implement application program interfaces using the Health Level Seven International (HL7) Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource (FHIR) Specification, the final rules could enable systems like mCODE to be more easily integrated with existing EHRs.

Lessons from CancerLinQ

ASCO created the health technology platform CancerLinQ in 2014, envisioning that it could become an oncology-focused learning health system – a system in which internal data and experience are systematically integrated with external evidence, allowing knowledge to be put into practice.

CancerLinQ extracts data from EHRs and other sources via direct software connections. CancerLinQ then aggregates, harmonizes, and normalizes the data in a cloud-based environment.

The data are available to participating practices for quality improvement in patient care and secondary research. In 2020, records of cancer patients in the CancerLinQ database surpassed 2 million.

CancerLinQ has been successful. However, because of the nature of the EHR ecosystem and the scope and variability of data capture by clinicians, supporting a true learning health system has proven to be a formidable task. Postprocessing manual review using trained human curators is laborious and unsustainable.

The CancerLinQ experience illustrated that basic cancer-pertinent data should be standardized in the EHR and collected prospectively.

The mCODE model

The mCODE initiative seeks to facilitate progress in care quality, clinical research, and health care policy by developing and maintaining a standard, computable, interoperable data format.

Guiding principles that were adopted early in mCODE’s development included:

- A collaborative, noncommercial, use case–driven developmental model.

- Iterative processes.

- User-driven development, refinement, and maintenance.

- Low ongoing maintenance requirements.

A foundational moment in mCODE’s development involved achieving consensus among stakeholders that the project would fail if EHR vendors required additional data entry by users.

After pilot work, a real-world endpoints project, working-group deliberation, public comment, and refinement, the final data standard included six primary domains: patient, disease, laboratory data/vital signs, genomics, treatment, and outcome.

Each domain is further divided into several concepts with specific associated data elements. The data elements are modeled into value sets that specify the possible values for the data element.

To test mCODE, eight organizations representing oncology EHR vendors, standards developers, and research organizations participated in a cancer interoperability track. The comments helped refine mCODE version 1.0, which was released in March 2020 and is accessible via the mCODE website.

Additions will likely be reviewed by a technical review group after external piloting of new use cases.

Innovation, not regulation

Every interaction between a patient and care provider yields information that could lead to improved safety and better outcomes. To be successful, the information must be collected in a computable format so it can be aggregated with data from other patients, analyzed without manual curation, and shared through interoperable systems. Those data should also be secure enough to protect the privacy of individual patients.

mCODE is a consensus data standard for oncology that provides an infrastructure to share patient data between oncology practices and health care systems while promising little to no additional data entry on the part of clinicians. Adoption by sites will be critical, however.

Publishing the standard through the HL7 FHIR technology demonstrated to EHR vendors and regulatory agencies the stability of HL7, an essential requirement for its incorporation into software.

EHR vendors and others are engaged in the CodeX HL7 FHIR Accelerator to design projects to expand and/or modify mCODE. Their creativity and innovativeness via the external advisory mCODE council and/or CodeX will be encouraged to help mCODE reach its full potential.

As part of CodeX, the Community of Practice, an open forum for end users, was established to provide regular updates about mCODE-related initiatives and use cases to solicit in-progress input, according to Robert S. Miller, MD, medical director of CancerLinQ and an author of the mCODE review.

For mCODE to be embraced by all stakeholders, there should be no additional regulations. By engaging stakeholders in an enterprise that supports innovation and collaboration – without additional regulation – mCODE could maximize the potential of EHRs that, until now, have assisted us only marginally in accomplishing those goals.

mCODE is a joint venture of ASCO/CancerLinQ, the Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology Foundation, the MITRE Corporation, the American Society for Radiation Oncology, and the Society of Surgical Oncology.

Dr. Osterman disclosed a grant from the National Cancer Institute and relationships with Infostratix, eHealth, AstraZeneca, Outcomes Insights, Biodesix, MD Outlook, GenomOncology, Cota Healthcare, GE Healthcare, and Microsoft. Dr. Miller and the third review author disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

FROM JCO CLINICAL CANCER INFORMATICS

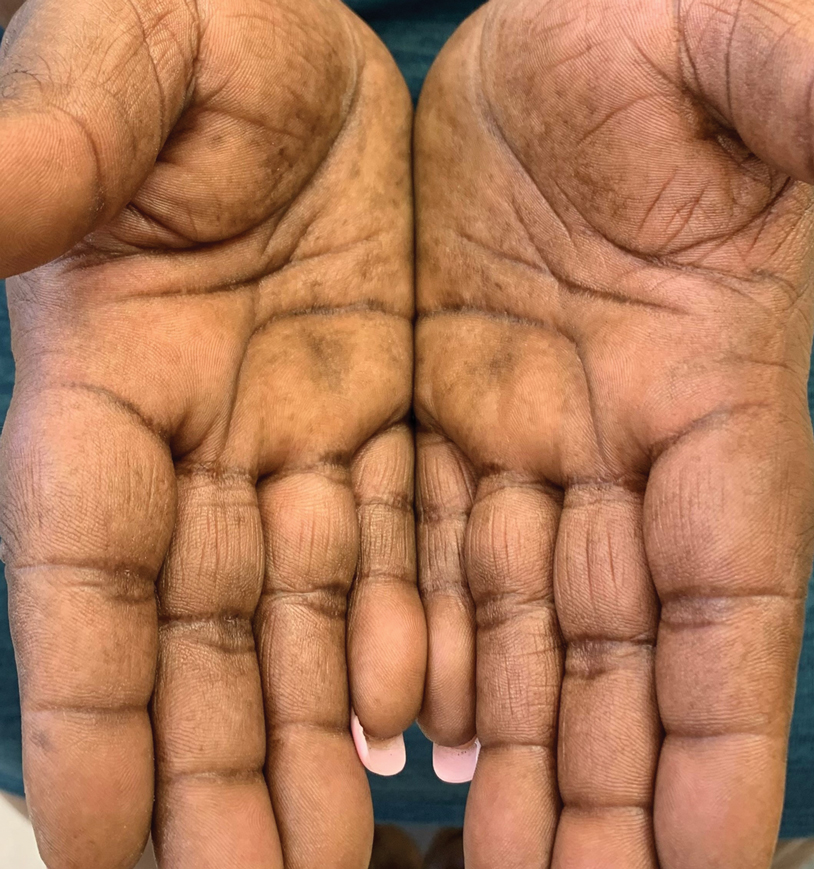

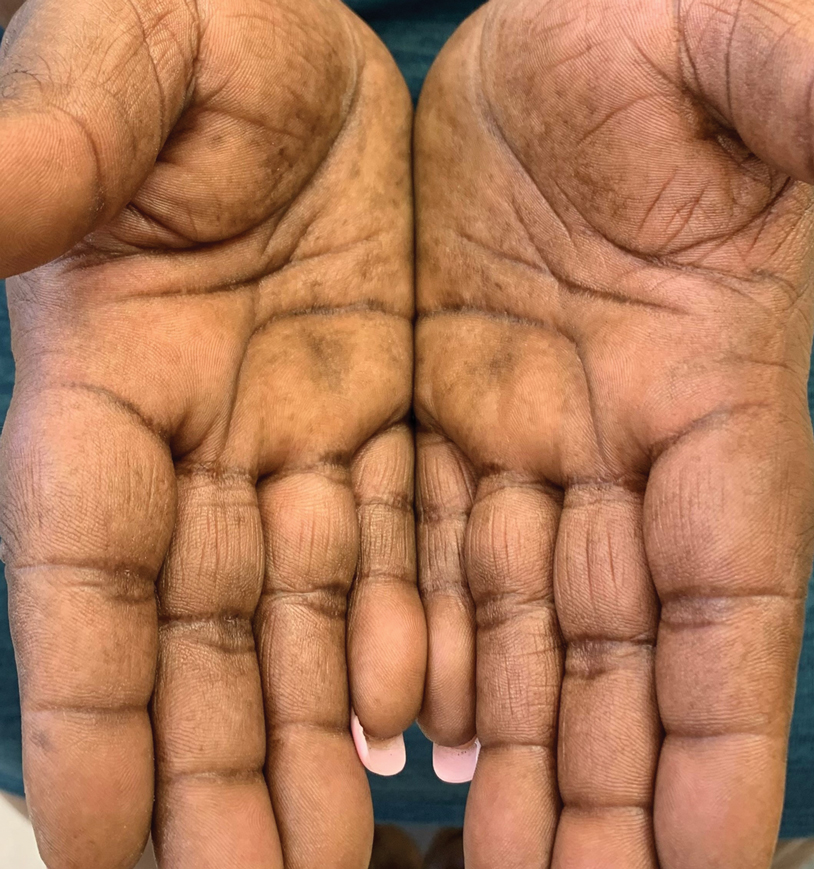

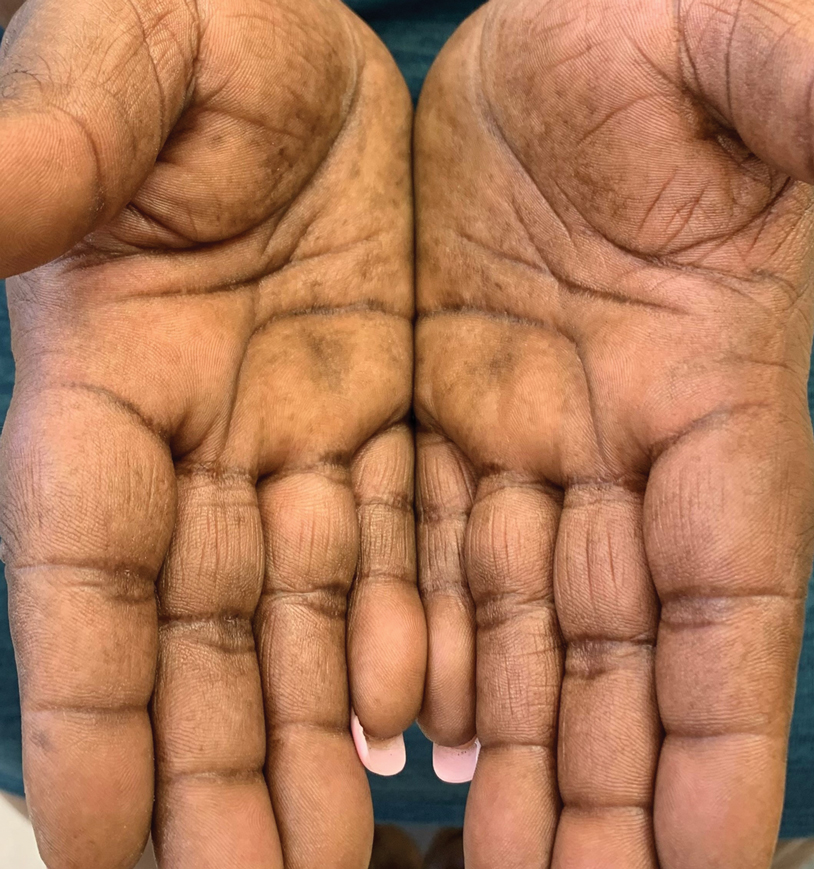

Thick Hyperkeratotic Plaques on the Palms and Soles

The Diagnosis: Keratoderma Climactericum

Keratoderma climactericum was first reported in 1934 by Haxthausen1 as nonpruritic circumscribed hyperkeratosis located mainly on the palms and soles. The initial eruption was described as discrete lesions with an oval or round shape that progressed to less-defined, confluent, hyperkeratotic patches with fissures.1 Keratoderma climactericum also may be referred to as Haxthausen disease and is considered an acquired palmoplantar keratoderma.2

Keratoderma climactericum is a rare dermatologic disorder that presents in women of menopausal age who have no family or personal history of skin disease. Keratoderma climactericum is associated with hypertension and obesity.2 Keratotic lesions usually first occur on the plantar surfaces with eventual development of fissuring and hyperkeratosis that causes painful walking. The keratotic lesions on the plantar surfaces often are nonpruritic and gradually become confluent over time. As the disease progresses, keratotic lesions appear on the central palms, which can lead to confluent hyperkeratosis on the palmar surfaces (Figure 1).2 The exact mechanism of keratoderma climactericum has not been described but is believed to be due to hormonal dysregulation.2

In 1986, Deschamps et al3 presented 10 cases of keratoderma climactericum occurring in menopausal women with an average age of 57 years. The lesions began on the soles at areas of greatest pressure. Histopathology for each patient showed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, irregular hyperplasia, interpapillary ridges, and exocytosis of lymphocytes in the epidermis. Seven patients were treated with etretinate, which first led to the removal of palmar lesions, followed by improvement in plantar lesions and pain when walking. There was no association of keratoderma climactericum and sex hormones, as hormone levels were negative or normal for each patient.3

Three cases of keratoderma climactericum following bilateral oophorectomy in young women were reported by Wachtel4 in 1981. Unlike in women of menopausal age, there was no association of keratoderma climactericum with hypertension or obesity. Additionally, the lesions on the palms and soles were more diffusely distributed than in women of menopausal age. Estrogen administration completely reversed each patient's hyperkeratotic palms and soles.4 A definitive pathogenic role of estrogens in the development of keratoderma climactericum has yet to be determined.2

Histopathology is not specific for keratoderma climactericum, making the disease a clinical diagnosis. However, a biopsy may be useful to rule out palmoplantar psoriasis.2 Clinical information such as the age and sex of the patient, distribution of disease, presence of fissuring, and progression of disease from soles to palms should be considered when making a diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum. The differential diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum should include fungal infections, contact dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, underlying malignancy, and pityriasis rubra pilaris.

Treatment options for keratoderma climactericum include salicylic acid, emollients, oral retinoids, urea ointments, estriol cream, and topical steroids.5,6 Our patient was prescribed acitretin 25 mg daily and ammonium lactate to apply topically as needed for dry skin. Five months after the initial presentation, fissures and dry skin on the bilateral soles were still present. Ammonium lactate was discontinued, and the patient was prescribed urea cream 40%. Fifteen months after the initial presentation, the patient reported substantial improvement on the hands and feet and noted that she no longer needed the urea cream. Physical examination revealed no presence of hyperkeratosis or fissuring on the palms (Figure 2), and mild hyperkeratosis was present on the plantar surfaces of the feet (Figure 3). The patient continued to use acitretin to prevent disease relapse.

Keratoderma climactericum is an unusual and debilitating condition that occurs in women of menopausal age. It is diagnosed by its specific clinical presentation. More common diagnoses such as tinea and dermatitis should be ruled out before considering keratoderma climactericum.

- Haxthausen H. Keratoderma climactericum. Br J Dermatol. 1934;46:161-167.

- Patel S, Zirwas M, English JC. Acquired palmoplantar keratoderma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:1-11.

- Deschamps P, Leroy D, Pedailles S, et al. Keratoderma climactericum (Haxthausen's disease): clinical signs, laboratory findings and etretinate treatment in 10 patients. Dermatologica. 1986;172:258-262.

- Wachtel TJ. Plantar and palmar hyperkeratosis in young castrated women. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:270-271.

- Bristow I. The management of heel fissures using a steroid impregnated tape (Haelan) in a patient with Keratoderma climactericum. Podiatry Now. 2008;11:22-23.

- Mendes-Bastos P. Plantar keratoderma climactericum: successful improvement with a topical estriol cream. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:811-813.

The Diagnosis: Keratoderma Climactericum

Keratoderma climactericum was first reported in 1934 by Haxthausen1 as nonpruritic circumscribed hyperkeratosis located mainly on the palms and soles. The initial eruption was described as discrete lesions with an oval or round shape that progressed to less-defined, confluent, hyperkeratotic patches with fissures.1 Keratoderma climactericum also may be referred to as Haxthausen disease and is considered an acquired palmoplantar keratoderma.2

Keratoderma climactericum is a rare dermatologic disorder that presents in women of menopausal age who have no family or personal history of skin disease. Keratoderma climactericum is associated with hypertension and obesity.2 Keratotic lesions usually first occur on the plantar surfaces with eventual development of fissuring and hyperkeratosis that causes painful walking. The keratotic lesions on the plantar surfaces often are nonpruritic and gradually become confluent over time. As the disease progresses, keratotic lesions appear on the central palms, which can lead to confluent hyperkeratosis on the palmar surfaces (Figure 1).2 The exact mechanism of keratoderma climactericum has not been described but is believed to be due to hormonal dysregulation.2

In 1986, Deschamps et al3 presented 10 cases of keratoderma climactericum occurring in menopausal women with an average age of 57 years. The lesions began on the soles at areas of greatest pressure. Histopathology for each patient showed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, irregular hyperplasia, interpapillary ridges, and exocytosis of lymphocytes in the epidermis. Seven patients were treated with etretinate, which first led to the removal of palmar lesions, followed by improvement in plantar lesions and pain when walking. There was no association of keratoderma climactericum and sex hormones, as hormone levels were negative or normal for each patient.3

Three cases of keratoderma climactericum following bilateral oophorectomy in young women were reported by Wachtel4 in 1981. Unlike in women of menopausal age, there was no association of keratoderma climactericum with hypertension or obesity. Additionally, the lesions on the palms and soles were more diffusely distributed than in women of menopausal age. Estrogen administration completely reversed each patient's hyperkeratotic palms and soles.4 A definitive pathogenic role of estrogens in the development of keratoderma climactericum has yet to be determined.2

Histopathology is not specific for keratoderma climactericum, making the disease a clinical diagnosis. However, a biopsy may be useful to rule out palmoplantar psoriasis.2 Clinical information such as the age and sex of the patient, distribution of disease, presence of fissuring, and progression of disease from soles to palms should be considered when making a diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum. The differential diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum should include fungal infections, contact dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, underlying malignancy, and pityriasis rubra pilaris.

Treatment options for keratoderma climactericum include salicylic acid, emollients, oral retinoids, urea ointments, estriol cream, and topical steroids.5,6 Our patient was prescribed acitretin 25 mg daily and ammonium lactate to apply topically as needed for dry skin. Five months after the initial presentation, fissures and dry skin on the bilateral soles were still present. Ammonium lactate was discontinued, and the patient was prescribed urea cream 40%. Fifteen months after the initial presentation, the patient reported substantial improvement on the hands and feet and noted that she no longer needed the urea cream. Physical examination revealed no presence of hyperkeratosis or fissuring on the palms (Figure 2), and mild hyperkeratosis was present on the plantar surfaces of the feet (Figure 3). The patient continued to use acitretin to prevent disease relapse.

Keratoderma climactericum is an unusual and debilitating condition that occurs in women of menopausal age. It is diagnosed by its specific clinical presentation. More common diagnoses such as tinea and dermatitis should be ruled out before considering keratoderma climactericum.

The Diagnosis: Keratoderma Climactericum

Keratoderma climactericum was first reported in 1934 by Haxthausen1 as nonpruritic circumscribed hyperkeratosis located mainly on the palms and soles. The initial eruption was described as discrete lesions with an oval or round shape that progressed to less-defined, confluent, hyperkeratotic patches with fissures.1 Keratoderma climactericum also may be referred to as Haxthausen disease and is considered an acquired palmoplantar keratoderma.2

Keratoderma climactericum is a rare dermatologic disorder that presents in women of menopausal age who have no family or personal history of skin disease. Keratoderma climactericum is associated with hypertension and obesity.2 Keratotic lesions usually first occur on the plantar surfaces with eventual development of fissuring and hyperkeratosis that causes painful walking. The keratotic lesions on the plantar surfaces often are nonpruritic and gradually become confluent over time. As the disease progresses, keratotic lesions appear on the central palms, which can lead to confluent hyperkeratosis on the palmar surfaces (Figure 1).2 The exact mechanism of keratoderma climactericum has not been described but is believed to be due to hormonal dysregulation.2

In 1986, Deschamps et al3 presented 10 cases of keratoderma climactericum occurring in menopausal women with an average age of 57 years. The lesions began on the soles at areas of greatest pressure. Histopathology for each patient showed orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, irregular hyperplasia, interpapillary ridges, and exocytosis of lymphocytes in the epidermis. Seven patients were treated with etretinate, which first led to the removal of palmar lesions, followed by improvement in plantar lesions and pain when walking. There was no association of keratoderma climactericum and sex hormones, as hormone levels were negative or normal for each patient.3

Three cases of keratoderma climactericum following bilateral oophorectomy in young women were reported by Wachtel4 in 1981. Unlike in women of menopausal age, there was no association of keratoderma climactericum with hypertension or obesity. Additionally, the lesions on the palms and soles were more diffusely distributed than in women of menopausal age. Estrogen administration completely reversed each patient's hyperkeratotic palms and soles.4 A definitive pathogenic role of estrogens in the development of keratoderma climactericum has yet to be determined.2

Histopathology is not specific for keratoderma climactericum, making the disease a clinical diagnosis. However, a biopsy may be useful to rule out palmoplantar psoriasis.2 Clinical information such as the age and sex of the patient, distribution of disease, presence of fissuring, and progression of disease from soles to palms should be considered when making a diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum. The differential diagnosis of keratoderma climactericum should include fungal infections, contact dermatitis, irritant dermatitis, psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, underlying malignancy, and pityriasis rubra pilaris.

Treatment options for keratoderma climactericum include salicylic acid, emollients, oral retinoids, urea ointments, estriol cream, and topical steroids.5,6 Our patient was prescribed acitretin 25 mg daily and ammonium lactate to apply topically as needed for dry skin. Five months after the initial presentation, fissures and dry skin on the bilateral soles were still present. Ammonium lactate was discontinued, and the patient was prescribed urea cream 40%. Fifteen months after the initial presentation, the patient reported substantial improvement on the hands and feet and noted that she no longer needed the urea cream. Physical examination revealed no presence of hyperkeratosis or fissuring on the palms (Figure 2), and mild hyperkeratosis was present on the plantar surfaces of the feet (Figure 3). The patient continued to use acitretin to prevent disease relapse.

Keratoderma climactericum is an unusual and debilitating condition that occurs in women of menopausal age. It is diagnosed by its specific clinical presentation. More common diagnoses such as tinea and dermatitis should be ruled out before considering keratoderma climactericum.

- Haxthausen H. Keratoderma climactericum. Br J Dermatol. 1934;46:161-167.

- Patel S, Zirwas M, English JC. Acquired palmoplantar keratoderma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:1-11.

- Deschamps P, Leroy D, Pedailles S, et al. Keratoderma climactericum (Haxthausen's disease): clinical signs, laboratory findings and etretinate treatment in 10 patients. Dermatologica. 1986;172:258-262.

- Wachtel TJ. Plantar and palmar hyperkeratosis in young castrated women. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:270-271.

- Bristow I. The management of heel fissures using a steroid impregnated tape (Haelan) in a patient with Keratoderma climactericum. Podiatry Now. 2008;11:22-23.

- Mendes-Bastos P. Plantar keratoderma climactericum: successful improvement with a topical estriol cream. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:811-813.

- Haxthausen H. Keratoderma climactericum. Br J Dermatol. 1934;46:161-167.

- Patel S, Zirwas M, English JC. Acquired palmoplantar keratoderma. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2007;8:1-11.

- Deschamps P, Leroy D, Pedailles S, et al. Keratoderma climactericum (Haxthausen's disease): clinical signs, laboratory findings and etretinate treatment in 10 patients. Dermatologica. 1986;172:258-262.

- Wachtel TJ. Plantar and palmar hyperkeratosis in young castrated women. Int J Dermatol. 1981;20:270-271.

- Bristow I. The management of heel fissures using a steroid impregnated tape (Haelan) in a patient with Keratoderma climactericum. Podiatry Now. 2008;11:22-23.