User login

They enrolled in medical school to practice rural medicine. What happened?

SALINA, KAN. – The University of Kansas School of Medicine–Salina opened in 2011 – a one-building campus in the heart of wheat country dedicated to producing the rural doctors that the country needs.

Now, 8 years later, the school’s first graduates are settling into their chosen practices – and locales. And those choices are cause for both hope and despair.

Of the eight graduates, just three chose to go where the shortages are most evident. Two went to small cities with populations of fewer than 50,000. And three chose the big cities of Topeka (estimated 2018 population: 125,904) and Wichita (389,255) instead.

But the mission is critical: About two-thirds of the primary care health professional shortage areas designated by the federal Health Resources and Services Administration in June were in rural or partially rural areas. And it’s only getting worse.

As more baby boomer doctors in rural areas reach retirement age, not nearly enough physicians are willing to take their place. By 2030, the New England Journal of Medicine predicts, nearly a quarter fewer rural physicians will be practicing medicine than today. Over half of rural doctors were at least 50 years old in 2017.

So Salina’s creation of a few rural physicians a year is a start, and, surprisingly, one of the country’s most promising.

Only 40 out of the nation’s more than 180 medical schools offer a rural track. The Association of American Medical Colleges ranked KU School of Medicine, which includes Salina, Wichita and Kansas City campuses, in the 96th percentile last year for producing doctors working in rural settings 10-15 years after graduation.

“The addition of one physician is huge,” said William Cathcart-Rake, MD, the founding dean of the Salina campus. “One physician choosing to come may be the difference of communities surviving or dissolving.”

The draw of rural life

By placing the new campus in Salina (population: 46,716), surrounded by small towns for at least 50 miles in every direction, the university hoped to attract and foster students who had – and would deepen – a bond to rural communities.

And, for some, it worked out pretty much as planned.

One of the school’s first graduates, Sara Ritterling Patry, MD, lives in Hutchinson (population: 40,623). Less than an hour from Wichita, it isn’t the most rural community, but it’s small enough that she still runs into her patients at Dillons, the local grocery store.

“Just being in a smaller community like this feels like to me that I can actually get to know my patients and spend a little extra time with them,” she said.

After all, part of the allure of a rural practice is providing care womb to tomb. The doctor learns how to deliver the town’s babies, while serving as the county coroner and the public health expert all at once, said Robert Moser, MD, the head of the University of Kansas School of Medicine–Salina and former head of the state health department.

He would know – he worked for 22 years in Tribune, Kan. (population: 742).

For another of the original Salina eight, Tyson Wisinger, MD, that calling brought him back to his hometown of Phillipsburg (population: 2,486) after his residency. His kids will go to his old high school, where his graduating class was all of 13 people, and he’ll take care of their baseball teammates. Plus, they’ll grow up living minutes away from generations of extended family.

“I can’t have imagined a situation that could have been more rewarding,” Dr. Wisinger said.

The rural challenge

But the road to rural family medicine also includes a thing called “windshield time” – the amount of time needed to travel between clinics or head to the closest Walmart.

Then there’s figuring out just how far their patients will need to drive to get to the nearest hospital – which for Daniel Linville, MD, and Jill Corpstein Linville, MD, is a solid 4 hours for more advanced care from their new practice in Lakin, Kan. (population: 2,195).

Their outpost in southwestern Kansas can feel a little bit like a fishbowl. “We do life with some of our patients,” Dr. Corpstein Linville said.

Already, the Linvilles have delivered babies and handled a variety of ailments there.

The pair met and married during their 4 years in Salina – they jokingly call it a “full-service med school.” They completed a family medicine residency in Muncie, Ind. Then they were recruited by a rural practice that helped them avoid what Dr. Moser calls the most dreaded words in rural medicine: “solo practice.”

New doctors don’t want to practice alone, especially as they develop their sea legs, because of the strains of constantly being on call and having singular responsibility for a town. Telemedicine, where doctors can easily consult with other physicians around the country via Web video or phone, is helping, as are physician assistants.

Diverging from the path

Claire Hinrichsen Groskurth, MD, another member of the first graduating class, always intended to return to a small town similar to where she grew up.

“The first thing that threw me off was I fell in love with surgery and ob.gyn.,” she said. “Then the second thing that threw me off was marrying another doctor,” whose life goals headed in a different direction.

She’d been a member of the Scholars in Rural Health program at Kansas University that seeks out rural college students who are interested in medicine. She also had committed to the Kansas Medical Student Loan program, which promises to forgive physicians’ tuition and gives a monthly stipend if they agree to work in counties that need physicians, or in other critical capacities.

But when she realized she might specialize, she decided to take out federal loans for her final years. She had to pay back the first year of the special loan with 15% interest.

Plus, her now-husband, who went to Kansas University’s Wichita campus, needed to be in a large enough city to accommodate further training to become a surgeon. So Dr. Hinrichsen Groskurth delivers babies as she thought she would – but in Wichita.

The spousal coin can flip both ways: Dr. Ritterling Patry needed to find a place that worked for her husband’s farming of corn, sorghum, soybeans and wheat. So the smaller city of Hutchinson it was.

Flaws in the pipeline

Most medical school students come from urban areas and are destined to stay there, said Alan Morgan, the head of the National Rural Health Association. Producing doctors for the vast swaths of rural America needs to be more of a priority at every step in the education pipeline, experts said.

Many academic centers sell students on the party line that they’ll be overworked, underappreciated and underpaid, according to Mark Deutchman, MD, director of the University of Colorado School of Medicine’s rural program. “They take people who are interested in primary care or rural and beat it out of them throughout their training,” he said.

And that kind of rhetoric often influences the opinion of their medical school peers, which those in rural health might resent.

“Small does not mean stupid,” Dr. Moser said.

Medical students everywhere should be exposed to rural options, according to Randall Longenecker, MD, who runs Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine’s rural programs in Athens.

“If a medical student never ever goes to a rural place, they never find out,” he said. “That’s why students need to meet rural doctors who love what they do.”

The federal government recently allocated $20 million in grants to help create 27 rural residency programs – institutions where newly minted doctors go for practical training before they can be fully licensed. That’s a big jump from the 92 programs now active.

For Dr. Corpstein Linville, the pipeline also needs to start at more schools like Salina that are promoting rural medicine from day one.

“So when you hear rural medicine, you know that it’s a thing and don’t kind of cringe,” she said. “You don’t think it’s someone taking care of a cow.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

SALINA, KAN. – The University of Kansas School of Medicine–Salina opened in 2011 – a one-building campus in the heart of wheat country dedicated to producing the rural doctors that the country needs.

Now, 8 years later, the school’s first graduates are settling into their chosen practices – and locales. And those choices are cause for both hope and despair.

Of the eight graduates, just three chose to go where the shortages are most evident. Two went to small cities with populations of fewer than 50,000. And three chose the big cities of Topeka (estimated 2018 population: 125,904) and Wichita (389,255) instead.

But the mission is critical: About two-thirds of the primary care health professional shortage areas designated by the federal Health Resources and Services Administration in June were in rural or partially rural areas. And it’s only getting worse.

As more baby boomer doctors in rural areas reach retirement age, not nearly enough physicians are willing to take their place. By 2030, the New England Journal of Medicine predicts, nearly a quarter fewer rural physicians will be practicing medicine than today. Over half of rural doctors were at least 50 years old in 2017.

So Salina’s creation of a few rural physicians a year is a start, and, surprisingly, one of the country’s most promising.

Only 40 out of the nation’s more than 180 medical schools offer a rural track. The Association of American Medical Colleges ranked KU School of Medicine, which includes Salina, Wichita and Kansas City campuses, in the 96th percentile last year for producing doctors working in rural settings 10-15 years after graduation.

“The addition of one physician is huge,” said William Cathcart-Rake, MD, the founding dean of the Salina campus. “One physician choosing to come may be the difference of communities surviving or dissolving.”

The draw of rural life

By placing the new campus in Salina (population: 46,716), surrounded by small towns for at least 50 miles in every direction, the university hoped to attract and foster students who had – and would deepen – a bond to rural communities.

And, for some, it worked out pretty much as planned.

One of the school’s first graduates, Sara Ritterling Patry, MD, lives in Hutchinson (population: 40,623). Less than an hour from Wichita, it isn’t the most rural community, but it’s small enough that she still runs into her patients at Dillons, the local grocery store.

“Just being in a smaller community like this feels like to me that I can actually get to know my patients and spend a little extra time with them,” she said.

After all, part of the allure of a rural practice is providing care womb to tomb. The doctor learns how to deliver the town’s babies, while serving as the county coroner and the public health expert all at once, said Robert Moser, MD, the head of the University of Kansas School of Medicine–Salina and former head of the state health department.

He would know – he worked for 22 years in Tribune, Kan. (population: 742).

For another of the original Salina eight, Tyson Wisinger, MD, that calling brought him back to his hometown of Phillipsburg (population: 2,486) after his residency. His kids will go to his old high school, where his graduating class was all of 13 people, and he’ll take care of their baseball teammates. Plus, they’ll grow up living minutes away from generations of extended family.

“I can’t have imagined a situation that could have been more rewarding,” Dr. Wisinger said.

The rural challenge

But the road to rural family medicine also includes a thing called “windshield time” – the amount of time needed to travel between clinics or head to the closest Walmart.

Then there’s figuring out just how far their patients will need to drive to get to the nearest hospital – which for Daniel Linville, MD, and Jill Corpstein Linville, MD, is a solid 4 hours for more advanced care from their new practice in Lakin, Kan. (population: 2,195).

Their outpost in southwestern Kansas can feel a little bit like a fishbowl. “We do life with some of our patients,” Dr. Corpstein Linville said.

Already, the Linvilles have delivered babies and handled a variety of ailments there.

The pair met and married during their 4 years in Salina – they jokingly call it a “full-service med school.” They completed a family medicine residency in Muncie, Ind. Then they were recruited by a rural practice that helped them avoid what Dr. Moser calls the most dreaded words in rural medicine: “solo practice.”

New doctors don’t want to practice alone, especially as they develop their sea legs, because of the strains of constantly being on call and having singular responsibility for a town. Telemedicine, where doctors can easily consult with other physicians around the country via Web video or phone, is helping, as are physician assistants.

Diverging from the path

Claire Hinrichsen Groskurth, MD, another member of the first graduating class, always intended to return to a small town similar to where she grew up.

“The first thing that threw me off was I fell in love with surgery and ob.gyn.,” she said. “Then the second thing that threw me off was marrying another doctor,” whose life goals headed in a different direction.

She’d been a member of the Scholars in Rural Health program at Kansas University that seeks out rural college students who are interested in medicine. She also had committed to the Kansas Medical Student Loan program, which promises to forgive physicians’ tuition and gives a monthly stipend if they agree to work in counties that need physicians, or in other critical capacities.

But when she realized she might specialize, she decided to take out federal loans for her final years. She had to pay back the first year of the special loan with 15% interest.

Plus, her now-husband, who went to Kansas University’s Wichita campus, needed to be in a large enough city to accommodate further training to become a surgeon. So Dr. Hinrichsen Groskurth delivers babies as she thought she would – but in Wichita.

The spousal coin can flip both ways: Dr. Ritterling Patry needed to find a place that worked for her husband’s farming of corn, sorghum, soybeans and wheat. So the smaller city of Hutchinson it was.

Flaws in the pipeline

Most medical school students come from urban areas and are destined to stay there, said Alan Morgan, the head of the National Rural Health Association. Producing doctors for the vast swaths of rural America needs to be more of a priority at every step in the education pipeline, experts said.

Many academic centers sell students on the party line that they’ll be overworked, underappreciated and underpaid, according to Mark Deutchman, MD, director of the University of Colorado School of Medicine’s rural program. “They take people who are interested in primary care or rural and beat it out of them throughout their training,” he said.

And that kind of rhetoric often influences the opinion of their medical school peers, which those in rural health might resent.

“Small does not mean stupid,” Dr. Moser said.

Medical students everywhere should be exposed to rural options, according to Randall Longenecker, MD, who runs Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine’s rural programs in Athens.

“If a medical student never ever goes to a rural place, they never find out,” he said. “That’s why students need to meet rural doctors who love what they do.”

The federal government recently allocated $20 million in grants to help create 27 rural residency programs – institutions where newly minted doctors go for practical training before they can be fully licensed. That’s a big jump from the 92 programs now active.

For Dr. Corpstein Linville, the pipeline also needs to start at more schools like Salina that are promoting rural medicine from day one.

“So when you hear rural medicine, you know that it’s a thing and don’t kind of cringe,” she said. “You don’t think it’s someone taking care of a cow.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

SALINA, KAN. – The University of Kansas School of Medicine–Salina opened in 2011 – a one-building campus in the heart of wheat country dedicated to producing the rural doctors that the country needs.

Now, 8 years later, the school’s first graduates are settling into their chosen practices – and locales. And those choices are cause for both hope and despair.

Of the eight graduates, just three chose to go where the shortages are most evident. Two went to small cities with populations of fewer than 50,000. And three chose the big cities of Topeka (estimated 2018 population: 125,904) and Wichita (389,255) instead.

But the mission is critical: About two-thirds of the primary care health professional shortage areas designated by the federal Health Resources and Services Administration in June were in rural or partially rural areas. And it’s only getting worse.

As more baby boomer doctors in rural areas reach retirement age, not nearly enough physicians are willing to take their place. By 2030, the New England Journal of Medicine predicts, nearly a quarter fewer rural physicians will be practicing medicine than today. Over half of rural doctors were at least 50 years old in 2017.

So Salina’s creation of a few rural physicians a year is a start, and, surprisingly, one of the country’s most promising.

Only 40 out of the nation’s more than 180 medical schools offer a rural track. The Association of American Medical Colleges ranked KU School of Medicine, which includes Salina, Wichita and Kansas City campuses, in the 96th percentile last year for producing doctors working in rural settings 10-15 years after graduation.

“The addition of one physician is huge,” said William Cathcart-Rake, MD, the founding dean of the Salina campus. “One physician choosing to come may be the difference of communities surviving or dissolving.”

The draw of rural life

By placing the new campus in Salina (population: 46,716), surrounded by small towns for at least 50 miles in every direction, the university hoped to attract and foster students who had – and would deepen – a bond to rural communities.

And, for some, it worked out pretty much as planned.

One of the school’s first graduates, Sara Ritterling Patry, MD, lives in Hutchinson (population: 40,623). Less than an hour from Wichita, it isn’t the most rural community, but it’s small enough that she still runs into her patients at Dillons, the local grocery store.

“Just being in a smaller community like this feels like to me that I can actually get to know my patients and spend a little extra time with them,” she said.

After all, part of the allure of a rural practice is providing care womb to tomb. The doctor learns how to deliver the town’s babies, while serving as the county coroner and the public health expert all at once, said Robert Moser, MD, the head of the University of Kansas School of Medicine–Salina and former head of the state health department.

He would know – he worked for 22 years in Tribune, Kan. (population: 742).

For another of the original Salina eight, Tyson Wisinger, MD, that calling brought him back to his hometown of Phillipsburg (population: 2,486) after his residency. His kids will go to his old high school, where his graduating class was all of 13 people, and he’ll take care of their baseball teammates. Plus, they’ll grow up living minutes away from generations of extended family.

“I can’t have imagined a situation that could have been more rewarding,” Dr. Wisinger said.

The rural challenge

But the road to rural family medicine also includes a thing called “windshield time” – the amount of time needed to travel between clinics or head to the closest Walmart.

Then there’s figuring out just how far their patients will need to drive to get to the nearest hospital – which for Daniel Linville, MD, and Jill Corpstein Linville, MD, is a solid 4 hours for more advanced care from their new practice in Lakin, Kan. (population: 2,195).

Their outpost in southwestern Kansas can feel a little bit like a fishbowl. “We do life with some of our patients,” Dr. Corpstein Linville said.

Already, the Linvilles have delivered babies and handled a variety of ailments there.

The pair met and married during their 4 years in Salina – they jokingly call it a “full-service med school.” They completed a family medicine residency in Muncie, Ind. Then they were recruited by a rural practice that helped them avoid what Dr. Moser calls the most dreaded words in rural medicine: “solo practice.”

New doctors don’t want to practice alone, especially as they develop their sea legs, because of the strains of constantly being on call and having singular responsibility for a town. Telemedicine, where doctors can easily consult with other physicians around the country via Web video or phone, is helping, as are physician assistants.

Diverging from the path

Claire Hinrichsen Groskurth, MD, another member of the first graduating class, always intended to return to a small town similar to where she grew up.

“The first thing that threw me off was I fell in love with surgery and ob.gyn.,” she said. “Then the second thing that threw me off was marrying another doctor,” whose life goals headed in a different direction.

She’d been a member of the Scholars in Rural Health program at Kansas University that seeks out rural college students who are interested in medicine. She also had committed to the Kansas Medical Student Loan program, which promises to forgive physicians’ tuition and gives a monthly stipend if they agree to work in counties that need physicians, or in other critical capacities.

But when she realized she might specialize, she decided to take out federal loans for her final years. She had to pay back the first year of the special loan with 15% interest.

Plus, her now-husband, who went to Kansas University’s Wichita campus, needed to be in a large enough city to accommodate further training to become a surgeon. So Dr. Hinrichsen Groskurth delivers babies as she thought she would – but in Wichita.

The spousal coin can flip both ways: Dr. Ritterling Patry needed to find a place that worked for her husband’s farming of corn, sorghum, soybeans and wheat. So the smaller city of Hutchinson it was.

Flaws in the pipeline

Most medical school students come from urban areas and are destined to stay there, said Alan Morgan, the head of the National Rural Health Association. Producing doctors for the vast swaths of rural America needs to be more of a priority at every step in the education pipeline, experts said.

Many academic centers sell students on the party line that they’ll be overworked, underappreciated and underpaid, according to Mark Deutchman, MD, director of the University of Colorado School of Medicine’s rural program. “They take people who are interested in primary care or rural and beat it out of them throughout their training,” he said.

And that kind of rhetoric often influences the opinion of their medical school peers, which those in rural health might resent.

“Small does not mean stupid,” Dr. Moser said.

Medical students everywhere should be exposed to rural options, according to Randall Longenecker, MD, who runs Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine’s rural programs in Athens.

“If a medical student never ever goes to a rural place, they never find out,” he said. “That’s why students need to meet rural doctors who love what they do.”

The federal government recently allocated $20 million in grants to help create 27 rural residency programs – institutions where newly minted doctors go for practical training before they can be fully licensed. That’s a big jump from the 92 programs now active.

For Dr. Corpstein Linville, the pipeline also needs to start at more schools like Salina that are promoting rural medicine from day one.

“So when you hear rural medicine, you know that it’s a thing and don’t kind of cringe,” she said. “You don’t think it’s someone taking care of a cow.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service. It is an editorially independent program of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation that is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.

Trump: No health insurance, no U.S. entry

Health insurance or the ability to pay for care soon will be a requirement for immigrants seeking U.S. visas, under a proclamation from President Trump.

Effective Nov. 3, 2019, visa applicants must demonstrate to immigration authorities that they can obtain coverage by an approved health insurer within 30 days of entering the United States or show evidence they possess the financial resources to pay for foreseeable medical costs. Approved coverage includes, but is not limited to, an employer-sponsored plan, an unsubsidized health plan offered in the individual market, a family member’s plan, or a visitor health insurance plan that provides coverage for at least 364 days, according to the proclamation.

President Trump said that the restriction protects Americans from bearing the burden of uncompensated health care costs generated by immigrants.

“While our health care system grapples with the challenges caused by uncompensated care, the United States government is making the problem worse by admitting thousands of aliens who have not demonstrated any ability to pay for their health care costs,” President Trump said in the proclamation. “Notably, data show that lawful immigrants are about three times more likely than United States citizens to lack health insurance. Immigrants who enter this country should not further saddle our health care system, and subsequently American taxpayers, with higher costs.”

The rule does not apply to refugees or asylum seekers, immigrants holding valid visas prior to Nov. 3, noncitizen children of U.S. citizens, unaccompanied minors, or permanent residents returning to the country after less than a year overseas.

The rule is the latest in a series of immigration restrictions by President Trump. Most recently in August 2019, the Trump administration amended the federal public charge rule, a longstanding policy that allows authorities to refuse to admit immigrants into the United States – or to adjust their legal status – if they are deemed likely to become a public charge. The revised regulation allows officials to consider previously excluded programs in their determination, including nonemergency Medicaid for nonpregnant adults, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and several housing programs.

The proclamation is consistent with the President’s recent public charge rule, and it is sound immigration policy, said Dale Wilcox, executive director and general counsel for the Immigration Reform Law Institute.

“If U.S. citizens are responsible for the health care costs of the world, then the world will show up at our doorstep for free health care,” Mr. Wilcox said in an interview. “That is unfair to American citizens and would financially devastate health care providers. The impact of this proclamation would be a more manageable immigration policy that welcomes immigrants who will contribute to our country as well as benefit from it.”

J. Wesley Boyd, MD, of the Center for Bioethics at Harvard University, Boston, said he was saddened to learn about the proclamation, adding that the Trump administration is relying on inaccurate information and falsified facts to justify the new restriction. Dr. Boyd, cofounder of the Human Rights and Asylum Clinic at Cambridge Health Alliance in Cambridge, Mass., coauthored a 2018 study finding that immigrants pay more into the U.S. health care system than they use.

That analysis, which examined 188 peer-reviewed studies related to immigrants and U.S. health care expenditures, found that per capita expenditures from private and public insurance sources were about 40% lower for immigrants, compared with native-born Americans. Expenditures for undocumented immigrants were even lower. Immigrants also made a greater contribution to Medicare’s trust fund than they withdrew, the study found (Int J Health Serv. 2018 Aug. 8 doi: 10.1177/0020731418791963).

Immigrants use less health care resources because they are generally younger and healthier than native-born Americans, and they are less likely to access health care services – regardless of health status, Dr. Boyd said in an interview. In addition, many immigrants who contribute to Medicare through payroll and/or taxes are no longer in the U.S. when they reach Medicare age.

“The Trump administration, in this case, is making yet another set of excuses for why they are trying to keep immigrants out of the country,” Dr. Boyd said. “The potential impact of this restriction is devastating. Obviously, the Trump administration is doing anything that it possibly can to try to limit immigrants from coming into our country and seeking a better life for themselves.”

The proclamation also could have a chilling effect on immigrants currently in the United States who are in need of medical treatment, Dr. Boyd noted.

“The real effect is you’re going to have immigrants who are already here, not [accessing] health care when they need it, for fear they somehow become known to the government,” he said.

Health insurance or the ability to pay for care soon will be a requirement for immigrants seeking U.S. visas, under a proclamation from President Trump.

Effective Nov. 3, 2019, visa applicants must demonstrate to immigration authorities that they can obtain coverage by an approved health insurer within 30 days of entering the United States or show evidence they possess the financial resources to pay for foreseeable medical costs. Approved coverage includes, but is not limited to, an employer-sponsored plan, an unsubsidized health plan offered in the individual market, a family member’s plan, or a visitor health insurance plan that provides coverage for at least 364 days, according to the proclamation.

President Trump said that the restriction protects Americans from bearing the burden of uncompensated health care costs generated by immigrants.

“While our health care system grapples with the challenges caused by uncompensated care, the United States government is making the problem worse by admitting thousands of aliens who have not demonstrated any ability to pay for their health care costs,” President Trump said in the proclamation. “Notably, data show that lawful immigrants are about three times more likely than United States citizens to lack health insurance. Immigrants who enter this country should not further saddle our health care system, and subsequently American taxpayers, with higher costs.”

The rule does not apply to refugees or asylum seekers, immigrants holding valid visas prior to Nov. 3, noncitizen children of U.S. citizens, unaccompanied minors, or permanent residents returning to the country after less than a year overseas.

The rule is the latest in a series of immigration restrictions by President Trump. Most recently in August 2019, the Trump administration amended the federal public charge rule, a longstanding policy that allows authorities to refuse to admit immigrants into the United States – or to adjust their legal status – if they are deemed likely to become a public charge. The revised regulation allows officials to consider previously excluded programs in their determination, including nonemergency Medicaid for nonpregnant adults, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and several housing programs.

The proclamation is consistent with the President’s recent public charge rule, and it is sound immigration policy, said Dale Wilcox, executive director and general counsel for the Immigration Reform Law Institute.

“If U.S. citizens are responsible for the health care costs of the world, then the world will show up at our doorstep for free health care,” Mr. Wilcox said in an interview. “That is unfair to American citizens and would financially devastate health care providers. The impact of this proclamation would be a more manageable immigration policy that welcomes immigrants who will contribute to our country as well as benefit from it.”

J. Wesley Boyd, MD, of the Center for Bioethics at Harvard University, Boston, said he was saddened to learn about the proclamation, adding that the Trump administration is relying on inaccurate information and falsified facts to justify the new restriction. Dr. Boyd, cofounder of the Human Rights and Asylum Clinic at Cambridge Health Alliance in Cambridge, Mass., coauthored a 2018 study finding that immigrants pay more into the U.S. health care system than they use.

That analysis, which examined 188 peer-reviewed studies related to immigrants and U.S. health care expenditures, found that per capita expenditures from private and public insurance sources were about 40% lower for immigrants, compared with native-born Americans. Expenditures for undocumented immigrants were even lower. Immigrants also made a greater contribution to Medicare’s trust fund than they withdrew, the study found (Int J Health Serv. 2018 Aug. 8 doi: 10.1177/0020731418791963).

Immigrants use less health care resources because they are generally younger and healthier than native-born Americans, and they are less likely to access health care services – regardless of health status, Dr. Boyd said in an interview. In addition, many immigrants who contribute to Medicare through payroll and/or taxes are no longer in the U.S. when they reach Medicare age.

“The Trump administration, in this case, is making yet another set of excuses for why they are trying to keep immigrants out of the country,” Dr. Boyd said. “The potential impact of this restriction is devastating. Obviously, the Trump administration is doing anything that it possibly can to try to limit immigrants from coming into our country and seeking a better life for themselves.”

The proclamation also could have a chilling effect on immigrants currently in the United States who are in need of medical treatment, Dr. Boyd noted.

“The real effect is you’re going to have immigrants who are already here, not [accessing] health care when they need it, for fear they somehow become known to the government,” he said.

Health insurance or the ability to pay for care soon will be a requirement for immigrants seeking U.S. visas, under a proclamation from President Trump.

Effective Nov. 3, 2019, visa applicants must demonstrate to immigration authorities that they can obtain coverage by an approved health insurer within 30 days of entering the United States or show evidence they possess the financial resources to pay for foreseeable medical costs. Approved coverage includes, but is not limited to, an employer-sponsored plan, an unsubsidized health plan offered in the individual market, a family member’s plan, or a visitor health insurance plan that provides coverage for at least 364 days, according to the proclamation.

President Trump said that the restriction protects Americans from bearing the burden of uncompensated health care costs generated by immigrants.

“While our health care system grapples with the challenges caused by uncompensated care, the United States government is making the problem worse by admitting thousands of aliens who have not demonstrated any ability to pay for their health care costs,” President Trump said in the proclamation. “Notably, data show that lawful immigrants are about three times more likely than United States citizens to lack health insurance. Immigrants who enter this country should not further saddle our health care system, and subsequently American taxpayers, with higher costs.”

The rule does not apply to refugees or asylum seekers, immigrants holding valid visas prior to Nov. 3, noncitizen children of U.S. citizens, unaccompanied minors, or permanent residents returning to the country after less than a year overseas.

The rule is the latest in a series of immigration restrictions by President Trump. Most recently in August 2019, the Trump administration amended the federal public charge rule, a longstanding policy that allows authorities to refuse to admit immigrants into the United States – or to adjust their legal status – if they are deemed likely to become a public charge. The revised regulation allows officials to consider previously excluded programs in their determination, including nonemergency Medicaid for nonpregnant adults, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, and several housing programs.

The proclamation is consistent with the President’s recent public charge rule, and it is sound immigration policy, said Dale Wilcox, executive director and general counsel for the Immigration Reform Law Institute.

“If U.S. citizens are responsible for the health care costs of the world, then the world will show up at our doorstep for free health care,” Mr. Wilcox said in an interview. “That is unfair to American citizens and would financially devastate health care providers. The impact of this proclamation would be a more manageable immigration policy that welcomes immigrants who will contribute to our country as well as benefit from it.”

J. Wesley Boyd, MD, of the Center for Bioethics at Harvard University, Boston, said he was saddened to learn about the proclamation, adding that the Trump administration is relying on inaccurate information and falsified facts to justify the new restriction. Dr. Boyd, cofounder of the Human Rights and Asylum Clinic at Cambridge Health Alliance in Cambridge, Mass., coauthored a 2018 study finding that immigrants pay more into the U.S. health care system than they use.

That analysis, which examined 188 peer-reviewed studies related to immigrants and U.S. health care expenditures, found that per capita expenditures from private and public insurance sources were about 40% lower for immigrants, compared with native-born Americans. Expenditures for undocumented immigrants were even lower. Immigrants also made a greater contribution to Medicare’s trust fund than they withdrew, the study found (Int J Health Serv. 2018 Aug. 8 doi: 10.1177/0020731418791963).

Immigrants use less health care resources because they are generally younger and healthier than native-born Americans, and they are less likely to access health care services – regardless of health status, Dr. Boyd said in an interview. In addition, many immigrants who contribute to Medicare through payroll and/or taxes are no longer in the U.S. when they reach Medicare age.

“The Trump administration, in this case, is making yet another set of excuses for why they are trying to keep immigrants out of the country,” Dr. Boyd said. “The potential impact of this restriction is devastating. Obviously, the Trump administration is doing anything that it possibly can to try to limit immigrants from coming into our country and seeking a better life for themselves.”

The proclamation also could have a chilling effect on immigrants currently in the United States who are in need of medical treatment, Dr. Boyd noted.

“The real effect is you’re going to have immigrants who are already here, not [accessing] health care when they need it, for fear they somehow become known to the government,” he said.

New consensus recommendations on bleeding in acquired hemophilia

New consensus statements, released by a group of 36 experts, provide specific recommendations related to monitoring bleeding and assessing efficacy of treatment in patients with acquired hemophilia.

A global survey was developed by a nine-member steering committee with expertise in the hemostatic management of patients with acquired hemophilia. The Delphi methodology was used to obtain consensus on a list of statements on the location-specific treatment of bleeding in acquired hemophilia.

“The initial survey was circulated via email for refinement and was formally corroborated at a face-to-face meeting,” wrote Andreas Tiede, MD, PhD, of Hannover (Germany) Medical School and fellow experts. The report is published in Haemophilia.

The key areas outlined include the initial management of bleeding, and management of location-specific bleeding, including urological, gastrointestinal, muscle, and pharyngeal bleeds, as well as intracranial and postpartum hemorrhage.

If an expert hematologist is not available, and the bleeding event is life‐threatening, the emergency physician should initiate treatment in accordance with local or national recommendations, according to the initial management guidelines.

With respect to urological bleeds, the best interval for evaluating successful achievement of hemostasis is every 6-12 hours. The experts also reported that, if first-line hemostatic therapy is not effective, more intensive treatment should be considered every 6-12 hours.

In the management of intracranial hemorrhage, the frequency of clinical evaluation is subject to the particular scenario, and it can vary from every 2 hours (for clinical assessment) to every 24 hours (for imaging studies), they wrote.

If initial hemostatic treatment is not effective, more intensive therapy should be considered every 6 hours, they recommended.

“The statement addressing optimal frequency for assessing hemostasis in intracranial bleeds was the subject of much deliberation among the steering committee regarding timing of assessment,” the experts acknowledged.

The geographic diversity and global representation of expert participants were major strengths of these recommendations. However, these statements did not consider socioeconomic parameters or geopolitical differences that could affect patient care. As a result, they may not be applicable to all patient populations.

The manuscript was funded by Novo Nordisk AG. The authors reported having financial affiliations with Novo Nordisk and several other companies.

SOURCE: Tiede A et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Sep 13. doi: 10.1111/hae.13844.

New consensus statements, released by a group of 36 experts, provide specific recommendations related to monitoring bleeding and assessing efficacy of treatment in patients with acquired hemophilia.

A global survey was developed by a nine-member steering committee with expertise in the hemostatic management of patients with acquired hemophilia. The Delphi methodology was used to obtain consensus on a list of statements on the location-specific treatment of bleeding in acquired hemophilia.

“The initial survey was circulated via email for refinement and was formally corroborated at a face-to-face meeting,” wrote Andreas Tiede, MD, PhD, of Hannover (Germany) Medical School and fellow experts. The report is published in Haemophilia.

The key areas outlined include the initial management of bleeding, and management of location-specific bleeding, including urological, gastrointestinal, muscle, and pharyngeal bleeds, as well as intracranial and postpartum hemorrhage.

If an expert hematologist is not available, and the bleeding event is life‐threatening, the emergency physician should initiate treatment in accordance with local or national recommendations, according to the initial management guidelines.

With respect to urological bleeds, the best interval for evaluating successful achievement of hemostasis is every 6-12 hours. The experts also reported that, if first-line hemostatic therapy is not effective, more intensive treatment should be considered every 6-12 hours.

In the management of intracranial hemorrhage, the frequency of clinical evaluation is subject to the particular scenario, and it can vary from every 2 hours (for clinical assessment) to every 24 hours (for imaging studies), they wrote.

If initial hemostatic treatment is not effective, more intensive therapy should be considered every 6 hours, they recommended.

“The statement addressing optimal frequency for assessing hemostasis in intracranial bleeds was the subject of much deliberation among the steering committee regarding timing of assessment,” the experts acknowledged.

The geographic diversity and global representation of expert participants were major strengths of these recommendations. However, these statements did not consider socioeconomic parameters or geopolitical differences that could affect patient care. As a result, they may not be applicable to all patient populations.

The manuscript was funded by Novo Nordisk AG. The authors reported having financial affiliations with Novo Nordisk and several other companies.

SOURCE: Tiede A et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Sep 13. doi: 10.1111/hae.13844.

New consensus statements, released by a group of 36 experts, provide specific recommendations related to monitoring bleeding and assessing efficacy of treatment in patients with acquired hemophilia.

A global survey was developed by a nine-member steering committee with expertise in the hemostatic management of patients with acquired hemophilia. The Delphi methodology was used to obtain consensus on a list of statements on the location-specific treatment of bleeding in acquired hemophilia.

“The initial survey was circulated via email for refinement and was formally corroborated at a face-to-face meeting,” wrote Andreas Tiede, MD, PhD, of Hannover (Germany) Medical School and fellow experts. The report is published in Haemophilia.

The key areas outlined include the initial management of bleeding, and management of location-specific bleeding, including urological, gastrointestinal, muscle, and pharyngeal bleeds, as well as intracranial and postpartum hemorrhage.

If an expert hematologist is not available, and the bleeding event is life‐threatening, the emergency physician should initiate treatment in accordance with local or national recommendations, according to the initial management guidelines.

With respect to urological bleeds, the best interval for evaluating successful achievement of hemostasis is every 6-12 hours. The experts also reported that, if first-line hemostatic therapy is not effective, more intensive treatment should be considered every 6-12 hours.

In the management of intracranial hemorrhage, the frequency of clinical evaluation is subject to the particular scenario, and it can vary from every 2 hours (for clinical assessment) to every 24 hours (for imaging studies), they wrote.

If initial hemostatic treatment is not effective, more intensive therapy should be considered every 6 hours, they recommended.

“The statement addressing optimal frequency for assessing hemostasis in intracranial bleeds was the subject of much deliberation among the steering committee regarding timing of assessment,” the experts acknowledged.

The geographic diversity and global representation of expert participants were major strengths of these recommendations. However, these statements did not consider socioeconomic parameters or geopolitical differences that could affect patient care. As a result, they may not be applicable to all patient populations.

The manuscript was funded by Novo Nordisk AG. The authors reported having financial affiliations with Novo Nordisk and several other companies.

SOURCE: Tiede A et al. Haemophilia. 2019 Sep 13. doi: 10.1111/hae.13844.

FROM HAEMOPHILIA

Influenza: U.S. activity was low this summer

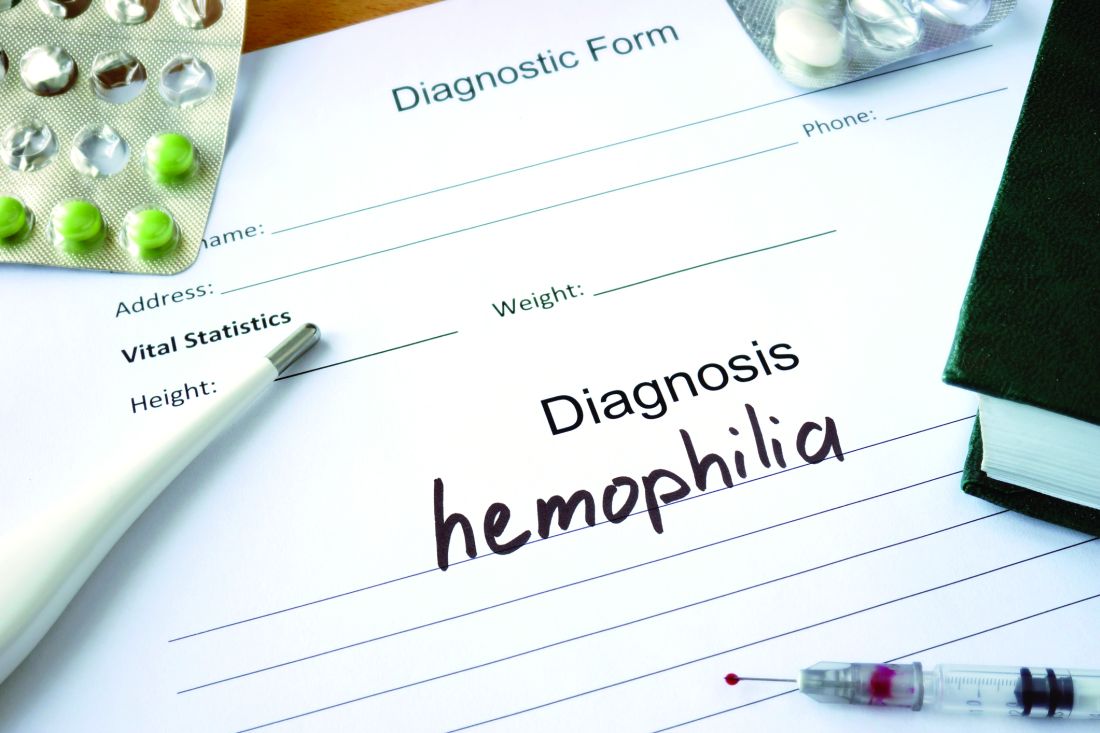

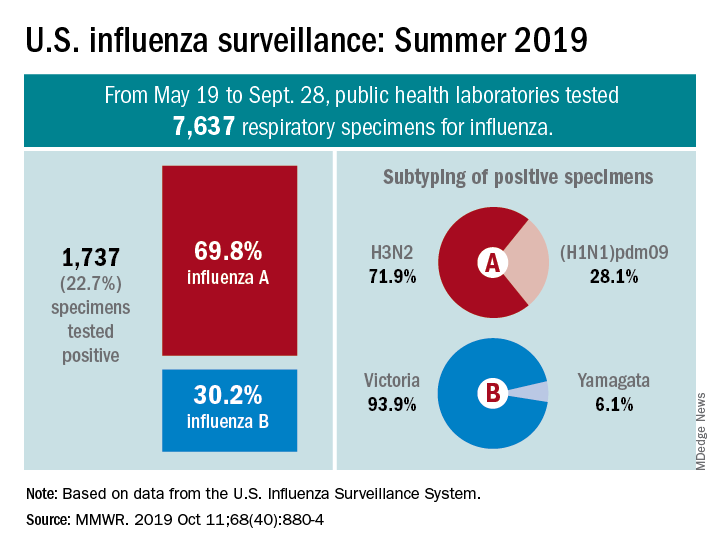

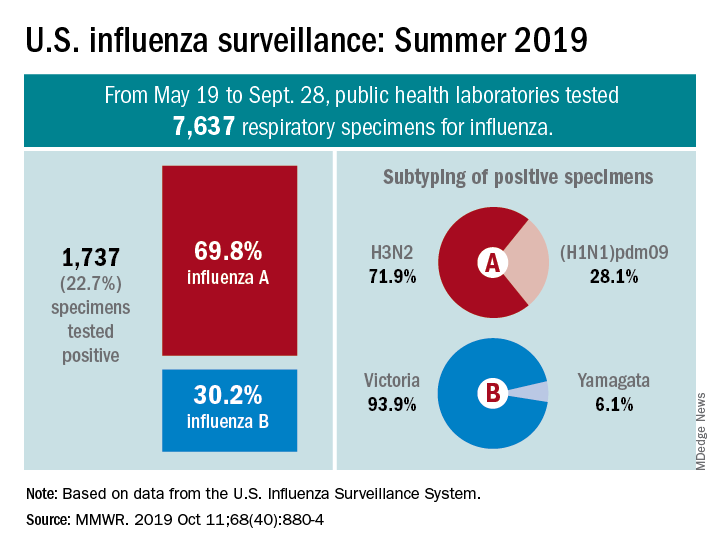

Influenza activity in the United States was typically low over the summer months, with influenza A(H3N2) viruses predominating, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

From May 19 to Sept. 28, 2019, weekly flu activity – measured by the percentage of outpatient visits to health care professionals for influenza-like illness (ILI) – was below the national baseline of 2.2%, ranging from 0.7% to 1.4%. Since mid-August, however, when the rate was last 0.7%, it has been climbing slowly but steadily and was up to 1.3% for the week ending Sept. 28, CDC data show.

The various public health laboratories of the U.S. Influenza Surveillance System tested over 7,600 respiratory samples from May 19 to Sept. 28, and 22.7% were positive for influenza viruses, Scott Epperson, DVM, and associates at the CDC’s influenza division said Oct. 10 in the MMWR.

Of the 1,737 samples found to be positive, 69.8% were influenza A and 30.2% were influenza B. The subtype split among specimens positive for Influenza A was 71.9% A(H3N2) and 28.1% A(H1N1)pdm09, while the samples positive for influenza B went 93.9% B/Victoria and 6.1% B/Yamagata, they reported.

Over the same time period in the Southern Hemisphere, “seasonal influenza viruses circulated widely, with influenza A(H3) predominating in many regions; however, influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and influenza B viruses were predominant in some countries,” the CDC investigators noted.

They also reported the World Health Organization recommendations for the Southern Hemisphere’s 2020 flu vaccines. Components of the egg-based trivalent vaccine are an A/Brisbane/02/2018(H1N1)pdm09-like virus, an A/South Australia/34/2019(H3N2)-like virus, and a B/Washington/02/2019-like virus(B/Victoria lineage). The recommended quadrivalent vaccine adds a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus(B/Yamagata lineage), they wrote.

“It is too early in the season to know which viruses will circulate in the United States later this fall and winter or how severe the season might be; however, regardless of what is circulating, the best protection against influenza is an influenza vaccination,” Dr. Epperson and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Epperson S et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11;68(40):880-4.

Influenza activity in the United States was typically low over the summer months, with influenza A(H3N2) viruses predominating, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

From May 19 to Sept. 28, 2019, weekly flu activity – measured by the percentage of outpatient visits to health care professionals for influenza-like illness (ILI) – was below the national baseline of 2.2%, ranging from 0.7% to 1.4%. Since mid-August, however, when the rate was last 0.7%, it has been climbing slowly but steadily and was up to 1.3% for the week ending Sept. 28, CDC data show.

The various public health laboratories of the U.S. Influenza Surveillance System tested over 7,600 respiratory samples from May 19 to Sept. 28, and 22.7% were positive for influenza viruses, Scott Epperson, DVM, and associates at the CDC’s influenza division said Oct. 10 in the MMWR.

Of the 1,737 samples found to be positive, 69.8% were influenza A and 30.2% were influenza B. The subtype split among specimens positive for Influenza A was 71.9% A(H3N2) and 28.1% A(H1N1)pdm09, while the samples positive for influenza B went 93.9% B/Victoria and 6.1% B/Yamagata, they reported.

Over the same time period in the Southern Hemisphere, “seasonal influenza viruses circulated widely, with influenza A(H3) predominating in many regions; however, influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and influenza B viruses were predominant in some countries,” the CDC investigators noted.

They also reported the World Health Organization recommendations for the Southern Hemisphere’s 2020 flu vaccines. Components of the egg-based trivalent vaccine are an A/Brisbane/02/2018(H1N1)pdm09-like virus, an A/South Australia/34/2019(H3N2)-like virus, and a B/Washington/02/2019-like virus(B/Victoria lineage). The recommended quadrivalent vaccine adds a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus(B/Yamagata lineage), they wrote.

“It is too early in the season to know which viruses will circulate in the United States later this fall and winter or how severe the season might be; however, regardless of what is circulating, the best protection against influenza is an influenza vaccination,” Dr. Epperson and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Epperson S et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11;68(40):880-4.

Influenza activity in the United States was typically low over the summer months, with influenza A(H3N2) viruses predominating, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

From May 19 to Sept. 28, 2019, weekly flu activity – measured by the percentage of outpatient visits to health care professionals for influenza-like illness (ILI) – was below the national baseline of 2.2%, ranging from 0.7% to 1.4%. Since mid-August, however, when the rate was last 0.7%, it has been climbing slowly but steadily and was up to 1.3% for the week ending Sept. 28, CDC data show.

The various public health laboratories of the U.S. Influenza Surveillance System tested over 7,600 respiratory samples from May 19 to Sept. 28, and 22.7% were positive for influenza viruses, Scott Epperson, DVM, and associates at the CDC’s influenza division said Oct. 10 in the MMWR.

Of the 1,737 samples found to be positive, 69.8% were influenza A and 30.2% were influenza B. The subtype split among specimens positive for Influenza A was 71.9% A(H3N2) and 28.1% A(H1N1)pdm09, while the samples positive for influenza B went 93.9% B/Victoria and 6.1% B/Yamagata, they reported.

Over the same time period in the Southern Hemisphere, “seasonal influenza viruses circulated widely, with influenza A(H3) predominating in many regions; however, influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 and influenza B viruses were predominant in some countries,” the CDC investigators noted.

They also reported the World Health Organization recommendations for the Southern Hemisphere’s 2020 flu vaccines. Components of the egg-based trivalent vaccine are an A/Brisbane/02/2018(H1N1)pdm09-like virus, an A/South Australia/34/2019(H3N2)-like virus, and a B/Washington/02/2019-like virus(B/Victoria lineage). The recommended quadrivalent vaccine adds a B/Phuket/3073/2013-like virus(B/Yamagata lineage), they wrote.

“It is too early in the season to know which viruses will circulate in the United States later this fall and winter or how severe the season might be; however, regardless of what is circulating, the best protection against influenza is an influenza vaccination,” Dr. Epperson and associates wrote.

SOURCE: Epperson S et al. MMWR. 2019 Oct 11;68(40):880-4.

FROM MMWR

Tape strips useful to identify biomarkers in skin of young children with atopic dermatitis

Adhesive according to a study published online on October 9 in JAMA Dermatology.

“Minimally invasive approaches that accurately capture key immune and barrier biomarkers in the skin of patients with early-onset pediatric AD are needed,” wrote Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and coauthors. “Because tissue biopsies are considered the criterion standard for evaluating dysregulation in AD lesional and nonlesional skin, it is crucial to understand whether tape-strip profiling can accurately yield key AD-related biomarkers.”

In their cross-sectional study, researchers used large D-Squame tape strips to collect skin samples from 51 children under the age of 5 years (mean, 1.7-1.8 years), including 21 with moderate to severe AD and 30 controls who did not have AD. Samples were collected from lesional skin inside the crook of the elbow and nonlesional skin, on the same arm, then subjected to gene- and protein-expression analysis to identify skin biomarkers of disease.

The participants tolerated the tape stripping well, and there were no clinical effects of the procedure. The authors were able to detect mRNA in 70 of 71 samples.

They then analyzed a panel of 15 cellular markers that assessed markers of monocytes and macrophages, T cells, activated TH2 cells, dendritic cells and dendritic-cell subsets, and Langerhans cells. They found that most showed significant differences between lesional AD skin and normal skin.

They also found that levels of OX40 ligand receptor, a marker associated with atopic dendritic cells, the inducible T-cell costimulatory activation marker, CD209, CD123, and langerin protein, were also significantly higher in nonlesional AD skin.

When comparing lesional and nonlesional skin samples in the AD patients, the authors saw significant differences only in levels of colony-stimulating factor 1 and 2.

The authors noted that some of the mediators detected from the tape-strip samples had not been detected or evaluated in previous studies of the use of tape strips in AD. These included measures of cellular infiltrates, atopic dendritic cells, and key inflammatory markers.

“The novel epidermal cytokines IL [interleukin]–33 and IL-17C, which are currently targeted in clinical trials of patients with AD, were also highlighted as novel tape-strip biomarkers and demonstrated significant correlations with AD severity,” they wrote.

“Because tape stripping is painless, nonscarring, and allows repeated sampling, it may be associated with benefits for longitudinal pediatric studies and clinical trials, in which serial measures are needed to identify predictors of response, course, and comorbidities,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by the Northwestern University Skin Disease Research Center and the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, and partly by a grant to two authors from Regeneron and Sanofi. Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported receiving grants from Regeneron during the study, and had other disclosures related to multiple pharmaceutical companies. Another author also received grants from Regeneron during the study, and another author had disclosures related to various manufacturers; no disclosures were reported for the remaining authors.

SOURCE: Guttman-Yassky E et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2983.

Skin biomarkers of atopic dermatitis (AD) are not well studied in children despite the fact that the disease largely affects this age group. Part of the challenge is the difficulty obtaining samples from children because phlebotomy and skin biopsies can cause trauma and anxiety both in children and their guardians. Better, noninvasive sampling techniques are needed.

This and another recent study show that tape stripping achieves skin samples that can provide clinically relevant AD DNA-expression levels and biomarkers that have been shown in multiple other studies – including some AD biomarkers not previously reported. Importantly, these biomarkers distinguish between children with AD and those without, and even between lesional and nonlesional skin.

While it remains to be seen if these biomarkers can predict disease outcomes or response to medication, this study shows that tape stripping in children with AD is a viable and useful method for future studies.

Leslie Castelo-Soccio, MD, PhD, is with the department of dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2792). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Skin biomarkers of atopic dermatitis (AD) are not well studied in children despite the fact that the disease largely affects this age group. Part of the challenge is the difficulty obtaining samples from children because phlebotomy and skin biopsies can cause trauma and anxiety both in children and their guardians. Better, noninvasive sampling techniques are needed.

This and another recent study show that tape stripping achieves skin samples that can provide clinically relevant AD DNA-expression levels and biomarkers that have been shown in multiple other studies – including some AD biomarkers not previously reported. Importantly, these biomarkers distinguish between children with AD and those without, and even between lesional and nonlesional skin.

While it remains to be seen if these biomarkers can predict disease outcomes or response to medication, this study shows that tape stripping in children with AD is a viable and useful method for future studies.

Leslie Castelo-Soccio, MD, PhD, is with the department of dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2792). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Skin biomarkers of atopic dermatitis (AD) are not well studied in children despite the fact that the disease largely affects this age group. Part of the challenge is the difficulty obtaining samples from children because phlebotomy and skin biopsies can cause trauma and anxiety both in children and their guardians. Better, noninvasive sampling techniques are needed.

This and another recent study show that tape stripping achieves skin samples that can provide clinically relevant AD DNA-expression levels and biomarkers that have been shown in multiple other studies – including some AD biomarkers not previously reported. Importantly, these biomarkers distinguish between children with AD and those without, and even between lesional and nonlesional skin.

While it remains to be seen if these biomarkers can predict disease outcomes or response to medication, this study shows that tape stripping in children with AD is a viable and useful method for future studies.

Leslie Castelo-Soccio, MD, PhD, is with the department of dermatology at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2792). No conflicts of interest were reported.

Adhesive according to a study published online on October 9 in JAMA Dermatology.

“Minimally invasive approaches that accurately capture key immune and barrier biomarkers in the skin of patients with early-onset pediatric AD are needed,” wrote Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and coauthors. “Because tissue biopsies are considered the criterion standard for evaluating dysregulation in AD lesional and nonlesional skin, it is crucial to understand whether tape-strip profiling can accurately yield key AD-related biomarkers.”

In their cross-sectional study, researchers used large D-Squame tape strips to collect skin samples from 51 children under the age of 5 years (mean, 1.7-1.8 years), including 21 with moderate to severe AD and 30 controls who did not have AD. Samples were collected from lesional skin inside the crook of the elbow and nonlesional skin, on the same arm, then subjected to gene- and protein-expression analysis to identify skin biomarkers of disease.

The participants tolerated the tape stripping well, and there were no clinical effects of the procedure. The authors were able to detect mRNA in 70 of 71 samples.

They then analyzed a panel of 15 cellular markers that assessed markers of monocytes and macrophages, T cells, activated TH2 cells, dendritic cells and dendritic-cell subsets, and Langerhans cells. They found that most showed significant differences between lesional AD skin and normal skin.

They also found that levels of OX40 ligand receptor, a marker associated with atopic dendritic cells, the inducible T-cell costimulatory activation marker, CD209, CD123, and langerin protein, were also significantly higher in nonlesional AD skin.

When comparing lesional and nonlesional skin samples in the AD patients, the authors saw significant differences only in levels of colony-stimulating factor 1 and 2.

The authors noted that some of the mediators detected from the tape-strip samples had not been detected or evaluated in previous studies of the use of tape strips in AD. These included measures of cellular infiltrates, atopic dendritic cells, and key inflammatory markers.

“The novel epidermal cytokines IL [interleukin]–33 and IL-17C, which are currently targeted in clinical trials of patients with AD, were also highlighted as novel tape-strip biomarkers and demonstrated significant correlations with AD severity,” they wrote.

“Because tape stripping is painless, nonscarring, and allows repeated sampling, it may be associated with benefits for longitudinal pediatric studies and clinical trials, in which serial measures are needed to identify predictors of response, course, and comorbidities,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by the Northwestern University Skin Disease Research Center and the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, and partly by a grant to two authors from Regeneron and Sanofi. Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported receiving grants from Regeneron during the study, and had other disclosures related to multiple pharmaceutical companies. Another author also received grants from Regeneron during the study, and another author had disclosures related to various manufacturers; no disclosures were reported for the remaining authors.

SOURCE: Guttman-Yassky E et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2983.

Adhesive according to a study published online on October 9 in JAMA Dermatology.

“Minimally invasive approaches that accurately capture key immune and barrier biomarkers in the skin of patients with early-onset pediatric AD are needed,” wrote Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, professor of dermatology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and coauthors. “Because tissue biopsies are considered the criterion standard for evaluating dysregulation in AD lesional and nonlesional skin, it is crucial to understand whether tape-strip profiling can accurately yield key AD-related biomarkers.”

In their cross-sectional study, researchers used large D-Squame tape strips to collect skin samples from 51 children under the age of 5 years (mean, 1.7-1.8 years), including 21 with moderate to severe AD and 30 controls who did not have AD. Samples were collected from lesional skin inside the crook of the elbow and nonlesional skin, on the same arm, then subjected to gene- and protein-expression analysis to identify skin biomarkers of disease.

The participants tolerated the tape stripping well, and there were no clinical effects of the procedure. The authors were able to detect mRNA in 70 of 71 samples.

They then analyzed a panel of 15 cellular markers that assessed markers of monocytes and macrophages, T cells, activated TH2 cells, dendritic cells and dendritic-cell subsets, and Langerhans cells. They found that most showed significant differences between lesional AD skin and normal skin.

They also found that levels of OX40 ligand receptor, a marker associated with atopic dendritic cells, the inducible T-cell costimulatory activation marker, CD209, CD123, and langerin protein, were also significantly higher in nonlesional AD skin.

When comparing lesional and nonlesional skin samples in the AD patients, the authors saw significant differences only in levels of colony-stimulating factor 1 and 2.

The authors noted that some of the mediators detected from the tape-strip samples had not been detected or evaluated in previous studies of the use of tape strips in AD. These included measures of cellular infiltrates, atopic dendritic cells, and key inflammatory markers.

“The novel epidermal cytokines IL [interleukin]–33 and IL-17C, which are currently targeted in clinical trials of patients with AD, were also highlighted as novel tape-strip biomarkers and demonstrated significant correlations with AD severity,” they wrote.

“Because tape stripping is painless, nonscarring, and allows repeated sampling, it may be associated with benefits for longitudinal pediatric studies and clinical trials, in which serial measures are needed to identify predictors of response, course, and comorbidities,” the authors concluded.

The study was supported by the Northwestern University Skin Disease Research Center and the Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, and partly by a grant to two authors from Regeneron and Sanofi. Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported receiving grants from Regeneron during the study, and had other disclosures related to multiple pharmaceutical companies. Another author also received grants from Regeneron during the study, and another author had disclosures related to various manufacturers; no disclosures were reported for the remaining authors.

SOURCE: Guttman-Yassky E et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2019 Oct 9. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.2983.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Whitening of skin remains charged topic at Skin of Color meeting

NEW YORK – , judging from an informal survey of those attending the Skin of Color Update 2019, where this topic was introduced.

When the Skin of Color conference chair, Eliot Battle, MD, founder of Cultura Dermatology and Laser Center, Washington, asked who in the audience considered total body whitening to be “wrong,” the show of hands was substantial. He then offered some perspective.

“How many think breast augmentation is wrong?” he asked. “How many think changing your hair color is wrong? Before we cast judgment, let’s think a little about how our patients feel.”

Although he acknowledged the difficulty of separating a racial context from the cultural perception of lighter skin as desirable, Dr. Battle contended that choices regarding appearance are complex. He cautioned against moral judgments blind to this complexity.

“As physicians we need to keep ourselves in check, to keep ourselves from making judgments [regarding lightening agents],” he said.

The two other panelists participating in the same session made compatible observations. Although the other two panelists limited most of their presentations to skin lightening for clinical indications, such as melasma and other disorders of hyperpigmentation, they acknowledged and addressed the sense of discomfort the topic raises.

“To many patients, depigmentation is a passport to society,” said Pearl Grimes, MD, director of the Vitiligo and Pigmentation Institute, Los Angeles. Although she considers this a global issue, not an issue unique to the black population, she counseled dermatologists to “respect the vicissitudes and issues of pigmentation” that she said include the patient’s concerns about beauty, class, and privilege.

Sensitive to the desire of some patients for lighter skin, Cheryl Burgess, MD, founder of the Center for Dermatology and Dermatologic Surgery, Washington, opened her talk by displaying the Time Magazine cover of O.J. Simpson at the time he was accused of murder. The photo appeared to have been intentionally darkened in an effort that was thought by many to make him appear more sinister.

This might be an appropriate example of what skin pigment represents to some segments of American society, but Dr. Battle said that the quest for lighter skin is a global phenomenon. He claims that Asia, India, and Africa are now among the fastest growing and largest markets for skin lightening strategies. The options in those areas of the world, like the United States, are proliferating quickly.

Many of the rapidly expanding options have not yet proved to be effective or safe. The antioxidant glutathione, which is being used for a long list of proven and unproven indications, is among these, according to Dr. Battle. In many clinics where this drug is administered intravenously to avoid degradation in the gastrointestinal tract, he suggested there is reason to believe the staff has little training in safety monitoring.

There are no long-term studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of glutathione for skin lightening, according to Dr. Battle, but there are many case reports of serious toxicities, including death. He listed thyroid dysfunction, renal impairment, and liver dysfunction among adverse events potentially related to glutathione.

“When I gave this talk a year ago, there were no clinics in Washington [offering glutathione]. Now there are seven,” he said.

Even for those dermatologists uncomfortable offering skin lightening for cosmetic purposes, ignoring the demand is ill advised, he said. Evaluating and advising patients on the safety of these agents is one reason to become involved, said Dr. Battle, who noted that specialists in dermatology are uniquely trained to monitor drugs for this application.

“You can tell a patient to stop, but they won’t stop,” said Dr. Battle. He maintained that organized medicine, including the American Academy of Dermatology, should take a role in evaluating the safety and efficacy of lightening agents even when used only for cosmetic indications.

Currently, there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved therapies for whitening of the skin.

“This is such an important question, and I think we need to figure it out,” Dr. Battle said. “Not a day goes by in our practice when we are not asked about skin lightening.”

Dr. Battle reported no relevant disclosures; Dr. Grimes and Dr. Burgess reported multiple financial relationships with industry that are not necessarily relevant to this topic.

NEW YORK – , judging from an informal survey of those attending the Skin of Color Update 2019, where this topic was introduced.

When the Skin of Color conference chair, Eliot Battle, MD, founder of Cultura Dermatology and Laser Center, Washington, asked who in the audience considered total body whitening to be “wrong,” the show of hands was substantial. He then offered some perspective.

“How many think breast augmentation is wrong?” he asked. “How many think changing your hair color is wrong? Before we cast judgment, let’s think a little about how our patients feel.”

Although he acknowledged the difficulty of separating a racial context from the cultural perception of lighter skin as desirable, Dr. Battle contended that choices regarding appearance are complex. He cautioned against moral judgments blind to this complexity.

“As physicians we need to keep ourselves in check, to keep ourselves from making judgments [regarding lightening agents],” he said.

The two other panelists participating in the same session made compatible observations. Although the other two panelists limited most of their presentations to skin lightening for clinical indications, such as melasma and other disorders of hyperpigmentation, they acknowledged and addressed the sense of discomfort the topic raises.

“To many patients, depigmentation is a passport to society,” said Pearl Grimes, MD, director of the Vitiligo and Pigmentation Institute, Los Angeles. Although she considers this a global issue, not an issue unique to the black population, she counseled dermatologists to “respect the vicissitudes and issues of pigmentation” that she said include the patient’s concerns about beauty, class, and privilege.

Sensitive to the desire of some patients for lighter skin, Cheryl Burgess, MD, founder of the Center for Dermatology and Dermatologic Surgery, Washington, opened her talk by displaying the Time Magazine cover of O.J. Simpson at the time he was accused of murder. The photo appeared to have been intentionally darkened in an effort that was thought by many to make him appear more sinister.

This might be an appropriate example of what skin pigment represents to some segments of American society, but Dr. Battle said that the quest for lighter skin is a global phenomenon. He claims that Asia, India, and Africa are now among the fastest growing and largest markets for skin lightening strategies. The options in those areas of the world, like the United States, are proliferating quickly.

Many of the rapidly expanding options have not yet proved to be effective or safe. The antioxidant glutathione, which is being used for a long list of proven and unproven indications, is among these, according to Dr. Battle. In many clinics where this drug is administered intravenously to avoid degradation in the gastrointestinal tract, he suggested there is reason to believe the staff has little training in safety monitoring.

There are no long-term studies evaluating the safety and efficacy of glutathione for skin lightening, according to Dr. Battle, but there are many case reports of serious toxicities, including death. He listed thyroid dysfunction, renal impairment, and liver dysfunction among adverse events potentially related to glutathione.

“When I gave this talk a year ago, there were no clinics in Washington [offering glutathione]. Now there are seven,” he said.

Even for those dermatologists uncomfortable offering skin lightening for cosmetic purposes, ignoring the demand is ill advised, he said. Evaluating and advising patients on the safety of these agents is one reason to become involved, said Dr. Battle, who noted that specialists in dermatology are uniquely trained to monitor drugs for this application.

“You can tell a patient to stop, but they won’t stop,” said Dr. Battle. He maintained that organized medicine, including the American Academy of Dermatology, should take a role in evaluating the safety and efficacy of lightening agents even when used only for cosmetic indications.

Currently, there are no Food and Drug Administration–approved therapies for whitening of the skin.

“This is such an important question, and I think we need to figure it out,” Dr. Battle said. “Not a day goes by in our practice when we are not asked about skin lightening.”

Dr. Battle reported no relevant disclosures; Dr. Grimes and Dr. Burgess reported multiple financial relationships with industry that are not necessarily relevant to this topic.

NEW YORK – , judging from an informal survey of those attending the Skin of Color Update 2019, where this topic was introduced.

When the Skin of Color conference chair, Eliot Battle, MD, founder of Cultura Dermatology and Laser Center, Washington, asked who in the audience considered total body whitening to be “wrong,” the show of hands was substantial. He then offered some perspective.

“How many think breast augmentation is wrong?” he asked. “How many think changing your hair color is wrong? Before we cast judgment, let’s think a little about how our patients feel.”

Although he acknowledged the difficulty of separating a racial context from the cultural perception of lighter skin as desirable, Dr. Battle contended that choices regarding appearance are complex. He cautioned against moral judgments blind to this complexity.