User login

What is your diagnosis? - March 2019

Partial malrotation and cecal volvulus after colonoscopy

The patient presented with partial malrotation and cecal volvulus after colonoscopy, which was confirmed by abdominal computed tomography scan. The patient gave consent and taken urgently to the operating room where she underwent an exploratory laparotomy and right hemicolectomy. Upon entering the abdomen, a mesenteroaxial cecal volvulus was noted immediately. The involved colon segment was dusky without frank necrosis. The distal ascending and proximal transverse colon were tethered to the left abdominal wall, and the ascending colon lacked its usual retroperitoneal attachments, consistent with partial malrotation. The adhesions were lysed, and a right hemicolectomy with primary side-to-side ileocolonic anastomosis was performed. The patient recovered well and was discharged to home on postoperative day 4.

Screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer is a commonly performed procedure with an established survival benefit. Up to one-third of patients experience abdominal pain, nausea, or bloating afterward, which may last hours to several days. Fortunately, severe complications including hemorrhage, perforation, and death are rare, with a total incidence of 0.28%.1 Although abdominal pain is common after colonoscopy, severe pain that persists or worsens warrants investigation. Perforation is the most frequently encountered complication in this context, although splenic injury/rupture and intestinal obstruction do occur. Cecal volvulus is a very rare complication with few reports in the literature.2,3 Colonic malrotation, which occurs in up to 0.5% of the population, increases the risk of volvulus owing to a lack of retroperitoneal attachments. This diagnosis should be considered for patients with known risk factors for volvulus.

References

1. Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:638-58.

2. Viney R, Fordan SV, Fisher WE, et al. Cecal volvulus after colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3211-2.

3. Anderson JR, Spence RA, Wilson BG, et al. Gangrenous caecal volvulus after colonoscopy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:439-40.

Partial malrotation and cecal volvulus after colonoscopy

The patient presented with partial malrotation and cecal volvulus after colonoscopy, which was confirmed by abdominal computed tomography scan. The patient gave consent and taken urgently to the operating room where she underwent an exploratory laparotomy and right hemicolectomy. Upon entering the abdomen, a mesenteroaxial cecal volvulus was noted immediately. The involved colon segment was dusky without frank necrosis. The distal ascending and proximal transverse colon were tethered to the left abdominal wall, and the ascending colon lacked its usual retroperitoneal attachments, consistent with partial malrotation. The adhesions were lysed, and a right hemicolectomy with primary side-to-side ileocolonic anastomosis was performed. The patient recovered well and was discharged to home on postoperative day 4.

Screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer is a commonly performed procedure with an established survival benefit. Up to one-third of patients experience abdominal pain, nausea, or bloating afterward, which may last hours to several days. Fortunately, severe complications including hemorrhage, perforation, and death are rare, with a total incidence of 0.28%.1 Although abdominal pain is common after colonoscopy, severe pain that persists or worsens warrants investigation. Perforation is the most frequently encountered complication in this context, although splenic injury/rupture and intestinal obstruction do occur. Cecal volvulus is a very rare complication with few reports in the literature.2,3 Colonic malrotation, which occurs in up to 0.5% of the population, increases the risk of volvulus owing to a lack of retroperitoneal attachments. This diagnosis should be considered for patients with known risk factors for volvulus.

References

1. Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:638-58.

2. Viney R, Fordan SV, Fisher WE, et al. Cecal volvulus after colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3211-2.

3. Anderson JR, Spence RA, Wilson BG, et al. Gangrenous caecal volvulus after colonoscopy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:439-40.

Partial malrotation and cecal volvulus after colonoscopy

The patient presented with partial malrotation and cecal volvulus after colonoscopy, which was confirmed by abdominal computed tomography scan. The patient gave consent and taken urgently to the operating room where she underwent an exploratory laparotomy and right hemicolectomy. Upon entering the abdomen, a mesenteroaxial cecal volvulus was noted immediately. The involved colon segment was dusky without frank necrosis. The distal ascending and proximal transverse colon were tethered to the left abdominal wall, and the ascending colon lacked its usual retroperitoneal attachments, consistent with partial malrotation. The adhesions were lysed, and a right hemicolectomy with primary side-to-side ileocolonic anastomosis was performed. The patient recovered well and was discharged to home on postoperative day 4.

Screening colonoscopy for colorectal cancer is a commonly performed procedure with an established survival benefit. Up to one-third of patients experience abdominal pain, nausea, or bloating afterward, which may last hours to several days. Fortunately, severe complications including hemorrhage, perforation, and death are rare, with a total incidence of 0.28%.1 Although abdominal pain is common after colonoscopy, severe pain that persists or worsens warrants investigation. Perforation is the most frequently encountered complication in this context, although splenic injury/rupture and intestinal obstruction do occur. Cecal volvulus is a very rare complication with few reports in the literature.2,3 Colonic malrotation, which occurs in up to 0.5% of the population, increases the risk of volvulus owing to a lack of retroperitoneal attachments. This diagnosis should be considered for patients with known risk factors for volvulus.

References

1. Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:638-58.

2. Viney R, Fordan SV, Fisher WE, et al. Cecal volvulus after colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:3211-2.

3. Anderson JR, Spence RA, Wilson BG, et al. Gangrenous caecal volvulus after colonoscopy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983;286:439-40.

A 56-year-old woman with no prior medical history presented to the emergency department with abdominal pain 12 hours after a screening colonoscopy.

The procedure was uneventful with no suspicious masses or lesions detected and no biopsies performed. The patient was discharged to home after recovery from anesthesia, where she slept for several hours. She was awoken with right-sided abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal distension. Her nausea, distension, and abdominal pain worsened as the evening progressed, prompting the patient to seek evaluation at the emergency department.

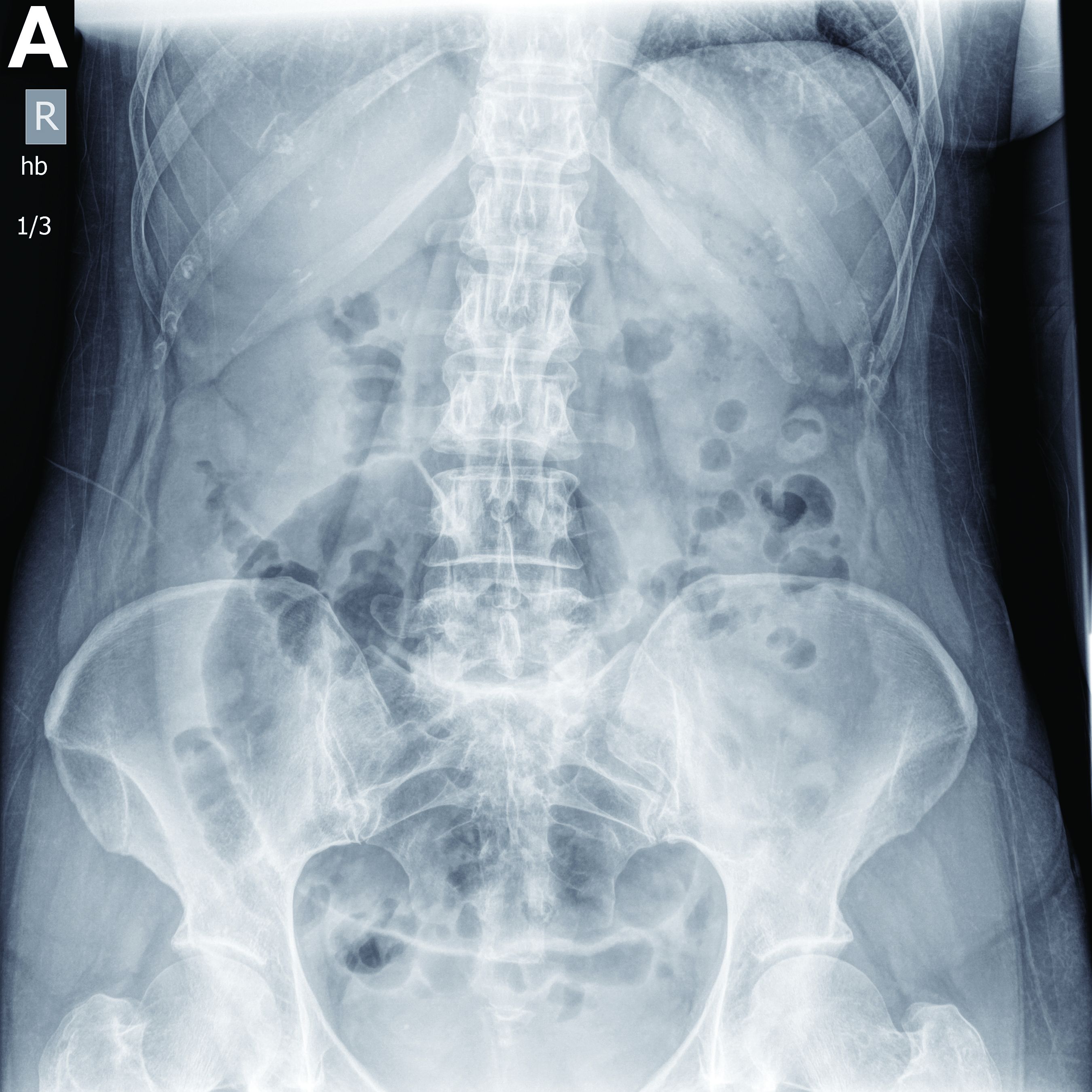

On examination, she was afebrile with normal vital signs. Her abdomen was mildly distended with right-sided tenderness but no peritoneal signs. Her white blood cell count was 8.5 × 109/L and all of her other laboratory values were normal. An upright abdominal radiograph showed no evidence of free air under the diaphragm, although a markedly dilated colon on the right side was noted (Figure A). An abdominal computed tomography scan was obtained (Figure B).

AHA: Consider obesity as CVD risk factor in children

The American Heart Association has included obesity and severe obesity in its updated scientific statement outlining risk factors and considerations for cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk pediatric patients.

The scientific statement is an update to a 2006 American Heart Association (AHA) statement, adding details about obesity as an at-risk condition and severe obesity as a moderate-risk condition. Other additions include classifying type 2 diabetes as a high-risk condition and expanding on new risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) among patients who received treatment for childhood cancer.

The AHA said the statement is aimed at pediatric cardiologists, primary care physicians, and subspecialists who care for at-risk pediatric patients, as well as providers who will care for these patients as they transition to adult life.

Obesity

In the AHA scientific statement, Sarah de Ferranti, MD, MPH, of Boston Children’s Hospital, chair of the writing group, and her colleagues, highlighted a 2016 study that identified a twofold to threefold higher risk of CVD-related mortality among patients who were overweight or obese, compared with patients of normal weight (Diabetes Care. 2016 Nov;39[11]:1996-2003).

Patients with obesity and severe obesity are at increased risk of aortic or coronary fatty streaks, dyslipidemia, high blood pressure, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance, as well as inflammatory and oxidative stress, the AHA writing group noted.

They estimated that approximately 6% of U.S. children aged 2-19 years old are considered severely obese.

After identifying patients with obesity, the writing group said, a “multimodal and graduated approach to treatment” for these patients is generally warranted, with a focus on dietary and lifestyle changes, and use of pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery if indicated.

However, the authors said therapeutic life change modification “is limited in severe obesity because of small effect size and difficulty with sustainability,” while use of pharmacotherapy for treatment of pediatric obesity remains understudied and medications such as orlistat and metformin offer only modest weight loss.

Bariatric surgery, “the only treatment for severe pediatric obesity consistently associated with clinically meaningful and durable weight loss,” is not consistently offered to patients under 12 years old, they added.

Diabetes

The AHA statement also addresses risks from type 1 (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D). Children with T1D and T2D are at increased risk for dyslipidemia, hypertension, microalbuminuria, and obesity. Annual screening for these patients is indicated, and cardiovascular risk factor reduction can be achieved by managing hyperglycemia, controlling weight gain as a result of medication, and implementing therapeutic lifestyle changes, when possible.

Childhood cancer

As survival rates from childhood cancer have improved, there is a need to address the increased risk of cardiovascular-related mortality (estimated at 8-10 times higher than the general population) as well as cancer relapse, according to the writing group.

Among patients recruited to the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, there was a 9-fold increase in cerebrovascular accident, 10-fold increased risk of coronary artery disease, and 15-fold increase in heart failure for childhood cancer survivors, compared with their siblings who were cancer free.

Cancer treatments such as radiation exposure are linked to increased rates of myocardial infarction, heart failure, valvular abnormalities, and pericardial disease at a twofold to sixfold higher rate when administered at a greater than 1,500 centigray dose, compared to cancer survivors who did not receive radiation, the authors wrote.

Anthracycline treatment is associated with a dose-dependent increase in the risk of dilated cardiomyopathy, while hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may increase the risk of CVD-related mortality from heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, and rhythm disorders.

In treating childhood cancer survivors for CVD risk factors, “a low threshold should be used when considering the initiation of pharmacological agents because of the high risk of these youth,” and standard pharmacotherapies can be used, the authors said. “Treatment of cardiovascular risk factors should consider the cancer therapies the patient has received previously.”

In the AHA statement, Dr. de Ferranti and her colleagues also outlined epidemiology, screening, and treatment data for other cardiovascular risk factors such as familial hypercholesterolemia, Lipoprotein(a), hypertension, chronic kidney disease, congenital heart disease, Kawasaki disease, and heart transplantation.

Some members of the writing group reported research grants from Amgen, Sanofi, the Wisconsin Partnership Program, and the National Institutes of Health. One author reported unpaid consultancies with Novo Nordisk, Orexigen, and Vivus.

SOURCE: de Ferranti SD et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 25. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000618.

The American Heart Association has included obesity and severe obesity in its updated scientific statement outlining risk factors and considerations for cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk pediatric patients.

The scientific statement is an update to a 2006 American Heart Association (AHA) statement, adding details about obesity as an at-risk condition and severe obesity as a moderate-risk condition. Other additions include classifying type 2 diabetes as a high-risk condition and expanding on new risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) among patients who received treatment for childhood cancer.

The AHA said the statement is aimed at pediatric cardiologists, primary care physicians, and subspecialists who care for at-risk pediatric patients, as well as providers who will care for these patients as they transition to adult life.

Obesity

In the AHA scientific statement, Sarah de Ferranti, MD, MPH, of Boston Children’s Hospital, chair of the writing group, and her colleagues, highlighted a 2016 study that identified a twofold to threefold higher risk of CVD-related mortality among patients who were overweight or obese, compared with patients of normal weight (Diabetes Care. 2016 Nov;39[11]:1996-2003).

Patients with obesity and severe obesity are at increased risk of aortic or coronary fatty streaks, dyslipidemia, high blood pressure, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance, as well as inflammatory and oxidative stress, the AHA writing group noted.

They estimated that approximately 6% of U.S. children aged 2-19 years old are considered severely obese.

After identifying patients with obesity, the writing group said, a “multimodal and graduated approach to treatment” for these patients is generally warranted, with a focus on dietary and lifestyle changes, and use of pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery if indicated.

However, the authors said therapeutic life change modification “is limited in severe obesity because of small effect size and difficulty with sustainability,” while use of pharmacotherapy for treatment of pediatric obesity remains understudied and medications such as orlistat and metformin offer only modest weight loss.

Bariatric surgery, “the only treatment for severe pediatric obesity consistently associated with clinically meaningful and durable weight loss,” is not consistently offered to patients under 12 years old, they added.

Diabetes

The AHA statement also addresses risks from type 1 (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D). Children with T1D and T2D are at increased risk for dyslipidemia, hypertension, microalbuminuria, and obesity. Annual screening for these patients is indicated, and cardiovascular risk factor reduction can be achieved by managing hyperglycemia, controlling weight gain as a result of medication, and implementing therapeutic lifestyle changes, when possible.

Childhood cancer

As survival rates from childhood cancer have improved, there is a need to address the increased risk of cardiovascular-related mortality (estimated at 8-10 times higher than the general population) as well as cancer relapse, according to the writing group.

Among patients recruited to the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, there was a 9-fold increase in cerebrovascular accident, 10-fold increased risk of coronary artery disease, and 15-fold increase in heart failure for childhood cancer survivors, compared with their siblings who were cancer free.

Cancer treatments such as radiation exposure are linked to increased rates of myocardial infarction, heart failure, valvular abnormalities, and pericardial disease at a twofold to sixfold higher rate when administered at a greater than 1,500 centigray dose, compared to cancer survivors who did not receive radiation, the authors wrote.

Anthracycline treatment is associated with a dose-dependent increase in the risk of dilated cardiomyopathy, while hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may increase the risk of CVD-related mortality from heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, and rhythm disorders.

In treating childhood cancer survivors for CVD risk factors, “a low threshold should be used when considering the initiation of pharmacological agents because of the high risk of these youth,” and standard pharmacotherapies can be used, the authors said. “Treatment of cardiovascular risk factors should consider the cancer therapies the patient has received previously.”

In the AHA statement, Dr. de Ferranti and her colleagues also outlined epidemiology, screening, and treatment data for other cardiovascular risk factors such as familial hypercholesterolemia, Lipoprotein(a), hypertension, chronic kidney disease, congenital heart disease, Kawasaki disease, and heart transplantation.

Some members of the writing group reported research grants from Amgen, Sanofi, the Wisconsin Partnership Program, and the National Institutes of Health. One author reported unpaid consultancies with Novo Nordisk, Orexigen, and Vivus.

SOURCE: de Ferranti SD et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 25. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000618.

The American Heart Association has included obesity and severe obesity in its updated scientific statement outlining risk factors and considerations for cardiovascular risk reduction in high-risk pediatric patients.

The scientific statement is an update to a 2006 American Heart Association (AHA) statement, adding details about obesity as an at-risk condition and severe obesity as a moderate-risk condition. Other additions include classifying type 2 diabetes as a high-risk condition and expanding on new risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) among patients who received treatment for childhood cancer.

The AHA said the statement is aimed at pediatric cardiologists, primary care physicians, and subspecialists who care for at-risk pediatric patients, as well as providers who will care for these patients as they transition to adult life.

Obesity

In the AHA scientific statement, Sarah de Ferranti, MD, MPH, of Boston Children’s Hospital, chair of the writing group, and her colleagues, highlighted a 2016 study that identified a twofold to threefold higher risk of CVD-related mortality among patients who were overweight or obese, compared with patients of normal weight (Diabetes Care. 2016 Nov;39[11]:1996-2003).

Patients with obesity and severe obesity are at increased risk of aortic or coronary fatty streaks, dyslipidemia, high blood pressure, hyperglycemia, and insulin resistance, as well as inflammatory and oxidative stress, the AHA writing group noted.

They estimated that approximately 6% of U.S. children aged 2-19 years old are considered severely obese.

After identifying patients with obesity, the writing group said, a “multimodal and graduated approach to treatment” for these patients is generally warranted, with a focus on dietary and lifestyle changes, and use of pharmacotherapy and bariatric surgery if indicated.

However, the authors said therapeutic life change modification “is limited in severe obesity because of small effect size and difficulty with sustainability,” while use of pharmacotherapy for treatment of pediatric obesity remains understudied and medications such as orlistat and metformin offer only modest weight loss.

Bariatric surgery, “the only treatment for severe pediatric obesity consistently associated with clinically meaningful and durable weight loss,” is not consistently offered to patients under 12 years old, they added.

Diabetes

The AHA statement also addresses risks from type 1 (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D). Children with T1D and T2D are at increased risk for dyslipidemia, hypertension, microalbuminuria, and obesity. Annual screening for these patients is indicated, and cardiovascular risk factor reduction can be achieved by managing hyperglycemia, controlling weight gain as a result of medication, and implementing therapeutic lifestyle changes, when possible.

Childhood cancer

As survival rates from childhood cancer have improved, there is a need to address the increased risk of cardiovascular-related mortality (estimated at 8-10 times higher than the general population) as well as cancer relapse, according to the writing group.

Among patients recruited to the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, there was a 9-fold increase in cerebrovascular accident, 10-fold increased risk of coronary artery disease, and 15-fold increase in heart failure for childhood cancer survivors, compared with their siblings who were cancer free.

Cancer treatments such as radiation exposure are linked to increased rates of myocardial infarction, heart failure, valvular abnormalities, and pericardial disease at a twofold to sixfold higher rate when administered at a greater than 1,500 centigray dose, compared to cancer survivors who did not receive radiation, the authors wrote.

Anthracycline treatment is associated with a dose-dependent increase in the risk of dilated cardiomyopathy, while hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may increase the risk of CVD-related mortality from heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, cardiomyopathy, coronary artery disease, and rhythm disorders.

In treating childhood cancer survivors for CVD risk factors, “a low threshold should be used when considering the initiation of pharmacological agents because of the high risk of these youth,” and standard pharmacotherapies can be used, the authors said. “Treatment of cardiovascular risk factors should consider the cancer therapies the patient has received previously.”

In the AHA statement, Dr. de Ferranti and her colleagues also outlined epidemiology, screening, and treatment data for other cardiovascular risk factors such as familial hypercholesterolemia, Lipoprotein(a), hypertension, chronic kidney disease, congenital heart disease, Kawasaki disease, and heart transplantation.

Some members of the writing group reported research grants from Amgen, Sanofi, the Wisconsin Partnership Program, and the National Institutes of Health. One author reported unpaid consultancies with Novo Nordisk, Orexigen, and Vivus.

SOURCE: de Ferranti SD et al. Circulation. 2019 Feb 25. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000618.

FROM CIRCULATION

Enteral therapy can reverse Crohn’s disease

Consider enteral therapy in Crohn’s disease, with caveats. A lawsuit against ABIM draws $200,000 in donation support. A combination model predicts imminent preeclampsia. And the FDA wants more safety data on 12 sunscreen active ingredients.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Consider enteral therapy in Crohn’s disease, with caveats. A lawsuit against ABIM draws $200,000 in donation support. A combination model predicts imminent preeclampsia. And the FDA wants more safety data on 12 sunscreen active ingredients.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Consider enteral therapy in Crohn’s disease, with caveats. A lawsuit against ABIM draws $200,000 in donation support. A combination model predicts imminent preeclampsia. And the FDA wants more safety data on 12 sunscreen active ingredients.

Amazon Alexa

Apple Podcasts

Google Podcasts

Spotify

Three key points: AGA comments on vision for continued board certification

Reforming MOC is a priority for AGA so our comments were extensive. Here are three key points we made.

Recertification shouldn’t burden physicians

In an era of epidemic physician burnout threatening access to care from reductions in the physician workforce, we seek a recertification pathway that is not unnecessarily burdensome, while maintaining relevance to the practice of a matured, experienced clinician.

Requirements should be relevant to practice

Requirements need to be relevant to practice and able to be adopted by our physicians with minimal additional investment in an already overburdened practice environment. Physicians have a narrowly defined practice and that assessments and certification should be “tailored to a diplomate’s area of practice.” However, it is necessary that physicians have knowledge outside of a narrow subspecialty, and thus the specialty societies should help the Boards identify what constitutes the key “core knowledge, judgment and skills” for the specialty. It is AGA’s view that this knowledge should be much less detailed than the expectations for initial board certification.

Certification ≠ credential

The issue of continuous certification being misappropriated as an employment credential is not acceptable. AGA calls on the commission to make it unequivocally clear that board certification should not be used in any way as a requirement for hospital credentialing.

MOC is a hot topic on the AGA Community. We’re listening.

Reforming MOC is a priority for AGA so our comments were extensive. Here are three key points we made.

Recertification shouldn’t burden physicians

In an era of epidemic physician burnout threatening access to care from reductions in the physician workforce, we seek a recertification pathway that is not unnecessarily burdensome, while maintaining relevance to the practice of a matured, experienced clinician.

Requirements should be relevant to practice

Requirements need to be relevant to practice and able to be adopted by our physicians with minimal additional investment in an already overburdened practice environment. Physicians have a narrowly defined practice and that assessments and certification should be “tailored to a diplomate’s area of practice.” However, it is necessary that physicians have knowledge outside of a narrow subspecialty, and thus the specialty societies should help the Boards identify what constitutes the key “core knowledge, judgment and skills” for the specialty. It is AGA’s view that this knowledge should be much less detailed than the expectations for initial board certification.

Certification ≠ credential

The issue of continuous certification being misappropriated as an employment credential is not acceptable. AGA calls on the commission to make it unequivocally clear that board certification should not be used in any way as a requirement for hospital credentialing.

MOC is a hot topic on the AGA Community. We’re listening.

Reforming MOC is a priority for AGA so our comments were extensive. Here are three key points we made.

Recertification shouldn’t burden physicians

In an era of epidemic physician burnout threatening access to care from reductions in the physician workforce, we seek a recertification pathway that is not unnecessarily burdensome, while maintaining relevance to the practice of a matured, experienced clinician.

Requirements should be relevant to practice

Requirements need to be relevant to practice and able to be adopted by our physicians with minimal additional investment in an already overburdened practice environment. Physicians have a narrowly defined practice and that assessments and certification should be “tailored to a diplomate’s area of practice.” However, it is necessary that physicians have knowledge outside of a narrow subspecialty, and thus the specialty societies should help the Boards identify what constitutes the key “core knowledge, judgment and skills” for the specialty. It is AGA’s view that this knowledge should be much less detailed than the expectations for initial board certification.

Certification ≠ credential

The issue of continuous certification being misappropriated as an employment credential is not acceptable. AGA calls on the commission to make it unequivocally clear that board certification should not be used in any way as a requirement for hospital credentialing.

MOC is a hot topic on the AGA Community. We’re listening.

Training the endo-athlete – an update in ergonomics in endoscopy

As physicians, we work hard to take excellent care of our patients. Years of thoughtful practice and continuous learning allow us to deliver the best that medicine can provide. We often take poor care of ourselves, which can lead to burnout and physical injuries. As gastroenterologists, we spend substantial time performing endoscopic procedures that require repetitive motions such as flexion and extension of the wrist and fingers and torsional movements of the right hand, which may lead to overuse injuries. The volume of endoscopic procedures performed by a typical gastroenterologist has increased significantly in the past 20 years. Moreover, experts predict that by 2020 we will have too few endoscopists to meet clinical demands.1 It is imperative that we do whatever possible to ensure overuse injuries do not prematurely prevent us from providing much-needed care. One way to achieve this goal is to focus on ergonomics. The study of ergonomics, derived from the Greek words ergo (work) and nomos (law), seeks to optimize the interface between the worker, the equipment, and the work environment. This article reviews basic ergonomic principles that endoscopists can apply today and possible innovations that may improve endoscopic ergonomics in the future.

Breadth of the problem

Examinations of injuries related to endoscopy are limited to survey-based and small controlled studies with a 39%-89% overall prevalence of pain or musculoskeletal injuries reported.2 In a survey of 684 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy members examining injury prevalence and risk factors,3 53% experienced an injury believed to be definitely or probably related to endoscopy. Risk factors included higher procedure volume (more than 20 cases/wk), greater number of hours spent performing endoscopy (more than 16 h/wk), and total number of years spent performing endoscopy2,4. Community practitioners reported injuries at higher rates than those in an academic center. Other suggested but unproven risk factors include age5, sex, hand size, room design, and level of training in ergonomics and endoscopy2. Injuries can be severe and may lead to work load reduction, missed days of work3-5, reduction of activities outside of work, and long-term disability2.

Most surveys reflect symptoms localized to the back, neck, shoulder, elbow, hands/fingers, and thumbs likely from overuse causing strain and soft-tissue microtrauma6. Without time to heal, these injuries may lead to connective tissue weakening and permanent damage. Repetitive hand movements in endoscopy include left thumb abduction, flexion, and extension while manipulating dials and right wrist flexion, extension, and deviation from torqueing the insertion tube. The use of torque is a necessary part of successful colonoscopy; during scope reduction and maneuvering through the sigmoid colon, torque forces and forces applied against the wall of the colon are highest. When of sufficient magnitude and duration, these forces are associated with an increased risk of thumb and wrist injuries. These movements may result in “endoscopist’s thumb“ (i.e., de Quervain’s tenosynovitis) and carpal tunnel syndrome2. Prolonged standing and lead aprons are implicated in back and neck injuries;2,7-9 two-piece aprons,7,10 and antifatigue mats7 are recommended to decrease pressure on the lumbar and cervical disks as well as delay muscle fatigue.

Position of equipment

Endoscopist and patient positioning can be optimized. In the absence of direct data about ergonomics in endoscopy, we rely on surgical laparoscopy data.11,12These studies show that monitors placed directly in front of surgeons at eye-level (rather than off to the side or at the head of the bed) reduced neck and shoulder muscle activity. Monitors should be placed with a height 20 cm lower than the height of the surgeon (endoscopist), suggesting that optimized monitor height should be at eye-level or lower to prevent neck strain. Estimates based on computer simulation and laparoscopy practitioners show that the optimal distance between the endoscopist/surgeon and a 14” monitor is between 52 and 182 cm, which allows for the least amount of image degradation. Many modern monitors are larger (19”-26”), which allows for placement farther from the endoscopist without losing image quality. Bed height affects both spine and arm position; surgical data again suggest that optimal bed height is between elbow height and 10 cm below elbow height.

Immediate practice points

Since poor monitor placement was identified as a major risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries, the first steps in our endoscopy unit were to improve our sightlines. Our adjustable monitors previously were locked into a specific height, and those same monitors now easily are adjusted to heights appropriate to the endoscopist. Our practice has endoscopists from 61” to 77” tall, meaning we needed monitors that could adjust over a 16” height. When designing new endoscopy suites, monitors that adjust from 93 to 162 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height. We use adjustable-height beds; a bed that adjusts between 85 and 120 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height.

We also moved our monitors to be closer to the opposite side of the bed to accommodate the 3’ to 6’ appropriate to our 16” screens. Our endoscopy suites have cushioned washable mats placed where endoscopists stand that allow for slight instability of the legs, leading to subtle movements of the legs and increased blood flow to reduce foot and leg injuries. We attempt an athletic stance (the endo-athlete) during endoscopy: shoulders back, chest out, knees bent, and feet hip-width apart pointed at the endoscopy screen (Figure 1). These mats help prevent pelvic girdle twisting and turning that may lead to awkward positions and instead leave the endoscopist in an optimized position for the procedure. We encourage endoscopists to keep the scope in the most neutral position possible to reduce overuse of torque and the forces on the wrists and thumbs. When possible, we use two-piece lead aprons for procedures that require fluoroscopy, which transfers some of the weight of the apron from the shoulders to the hips and reduces upper-body strain. Optimization of the room for therapeutic procedures is even more important (with dual screens both fulfilling the criteria we have listed earlier) given the extra weight of the lead on the body. We suggest that, if procedures are performed in cramped endoscopy rooms, placement of additional monitors can help alleviate neck strain and rotation.

Working with our nurses was imperative. We first had our nurses watch videos on appropriate ergonomics in the endoscopy suite. Given that endoscopists usually are concentrating their attention on the screens in the suite, we tasked our nurses to not only monitor our patients, but also to observe the physical stance of the endoscopists. Our nurses are encouraged to help our endoscopists focus on their working stance: the nurses help with monitor positioning, and verbal cues when endoscopists are contorting their bodies unnaturally. This intervention requires open two-way communication in the endoscopy suite where safety of both the patient and staff is paramount. We are fortunate to be at an institution that trains fellows; we have two endoscopists in the suite at any time, which allows for additional two-way feedback between fellows and attendings to improve ergonomic positioning.

We also encourage some preventative exercises of the upper extremities to reduce pain and injuries. Stretches should emphasize finger, wrist, forearm, and shoulder flexion and extension. Even a minute of stretching between procedures allows for muscle relaxation and may lead to a decrease in overuse injuries. Adding these elements may seem inefficient and unnecessary if you have never had an injury, but we suggest the following paradigm: think of yourself as an endo-athlete. Similar to an athlete, you have worked years to gain the skills you possess. Taking a few moments to reduce your chances of a career-slowing (or career-ending) injury can pay long-term dividends.

Future remedies

Although there have been substantial advances in endoscopic imaging technology, the process of endoscope rotation and tip deflection has changed little since the development of flexible endoscopy. A freshman engineering student tasked with designing a device to navigate, examine, and provide therapy in the human colon likely would create a device that does not resemble the scope that we use daily to accomplish the task. Numerous investigators currently are working on novel devices designed to examine and deliver therapy to the digestive tract. These devices may diminish an endoscopist’s injury risk through the use of better ergonomic principles. This section is not intended to be a comprehensive review and is not an endorsement of any particular product. Rather, we hope it provides a glimpse into a possible future.

Reducing gravitational load

The concept of a mechanical device to hold some or all of the weight of the endoscope was first published in 197413. Since then, a number of products have been described for this purpose.14-17 In general, these consist of a simple metal tube with a hemicylindrical plastic clip, similar to a microphone stand, or a yoke/strap with a plastic scope holder in the front akin to what a percussionist in a marching band might wear. For a variety of reasons, including limited mobility and issues with disinfection, these devices have not gained traction.

Novel control mechanisms

Some of the largest forces on the endoscopist relate to moving the wheels on the scope head to effect tip deflection via a cable linkage. Because the wheels rotate only in one axis, the options for altering and adjusting load are few. One proposed solution is the use of a system with a fully detachable endoscope handle with a joystick style control deck (E210; Invendo Medical, Kissing, Germany). The control deck uses electromechanical assistance — as opposed to pure mechanical force — to transmit energy to the shaft of the instrument. Such assistive technologies have the potential to decrease injuries by decreased load, particularly on the carpometacarpal joint. Other devices seek to decrease the need for torque and high-load tip deflection though the use of self-propelled, disposable colonoscopes that use an aviation-style joystick (Aer-o-scope; GI View, Kissing, Germany). Although interesting and potentially useful, neither product is currently available for clinical use in the United States.

Robots and magnets

Magnetically controlled wireless capsules have been studied in vivo in human beings on several occasions in the United Kingdom and Asia. Wired colonic capsules are currently under development in the United States. These products use joystick-style controls to direct movement of the capsule. Optimal visualization often requires the patient to rotate through numerous positions and, at least in the stomach, to drink significant quantities of fluid to ensure adequate distention. At present, these devices provide only diagnostic capabilities.

Conclusions

The performance of endoscopy inherently places its practitioners at risk of biomechanical injury. Fortunately, there are numerous ways we can optimize our environment and ourselves. We should treat our bodies as professional athletes do: use good form, encourage colleagues to observe and provide feedback on our actions, optimize our practice facilities, and stretch our muscles. In the future, technological innovations, such as ergonomically designed endoscope handles and self-propelled colonoscopies, may reduce the inherent physical stresses of endoscopy. In doing so, hopefully we can preserve our own health and continue to better the health of our patients as well.

References

1. Rabin RC. Gastroenterologist shortage is forecast. (Available at: www.nytimes.com/2009/01/09/health/research/09gastro.html.) The New York Times, Jan. 9;2009.

2. Pedrosa MC, Farraye FA, Shergill AK. et al. Minimizing occupational hazards in endoscopy: personal protective equipment, radiation safety, and ergonomics. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:227-35.

3. Ridtitid W, Coté GA, Leung W, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for musculoskeletal injuries related to endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:294-302.e294.

4. Geraghty J, George R, Babbs C. A questionnaire study assessing overuse injuries in United Kingdom endoscopists and any effect from the introduction of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program on these injuries. Gastrointest Endos. 2011;73:1069-70.

5. Kuwabara T, Urabe Y, Hiyama T, et al. Prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal pain in Japanese gastrointestinal endoscopists: a controlled study. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1488-93.

6. Rempel DM, Harrison RJ, Barnhart S. Work-related cumulative trauma disorders of the upper extremity. JAMA 1992;267:838-42.

7. O’Sullivan S, Bridge G, Ponich T. Musculoskeletal injuries among ERCP endoscopists in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2002;16:369-74.

8. Moore B, vanSonnenberg E, Casola G. et al. The relationship between back pain and lead apron use in radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:191-3.

9. Ross AM, Segal J, Borenstein D, et al. Prevalence of spinal disc disease among interventional cardiologists. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:68-70.

10. Buschbacher R. Overuse syndromes among endoscopists. Endoscopy. 1994;26:539-44.

11. Matern U, Faist M, Kehl K, et al. Monitor position in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:436-40.

12. Haveran LA, Novitsky YW, Czerniach DR, et al. Optimizing laparoscopic task efficiency: the role of camera and monitor positions. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:980-4.

13. Nivatvongs S, Goldberg SM. Holder for the fiberoptic colonoscope. Dis Colon Rectum. 1974;17:273-4.

14. Eusebio EB. A practical aid in colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:996-7.

15. Rattan J, Rozen P. A new colonoscope holder. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:639-40.

16. Marks G. A new technique of hand reversal using a harness-type endoscope holder for twin-knob colonoscopy and flexible fiberoptic sigmoidoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:567-8.

17. Hayashi Y, Sunada K, Yamamoto H. Prototype holder adequately supports the overtube in balloon-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:682.

Dr. Young is professor of medicine, director, digestive disease division, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Commander Singla is assistant professor of medicine, Uniformed Services University, director, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Services, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Major Kwok is assistant professor of medicine, Uniformed Services University, associate fellowship program director, gastroenterology, National Capital Consortium, Bethesda, Md.; and Dr. Deriban is associate professor of medicine, fellowship program director, gastroenterology, University Hospital Skopje, Macedonia.

As physicians, we work hard to take excellent care of our patients. Years of thoughtful practice and continuous learning allow us to deliver the best that medicine can provide. We often take poor care of ourselves, which can lead to burnout and physical injuries. As gastroenterologists, we spend substantial time performing endoscopic procedures that require repetitive motions such as flexion and extension of the wrist and fingers and torsional movements of the right hand, which may lead to overuse injuries. The volume of endoscopic procedures performed by a typical gastroenterologist has increased significantly in the past 20 years. Moreover, experts predict that by 2020 we will have too few endoscopists to meet clinical demands.1 It is imperative that we do whatever possible to ensure overuse injuries do not prematurely prevent us from providing much-needed care. One way to achieve this goal is to focus on ergonomics. The study of ergonomics, derived from the Greek words ergo (work) and nomos (law), seeks to optimize the interface between the worker, the equipment, and the work environment. This article reviews basic ergonomic principles that endoscopists can apply today and possible innovations that may improve endoscopic ergonomics in the future.

Breadth of the problem

Examinations of injuries related to endoscopy are limited to survey-based and small controlled studies with a 39%-89% overall prevalence of pain or musculoskeletal injuries reported.2 In a survey of 684 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy members examining injury prevalence and risk factors,3 53% experienced an injury believed to be definitely or probably related to endoscopy. Risk factors included higher procedure volume (more than 20 cases/wk), greater number of hours spent performing endoscopy (more than 16 h/wk), and total number of years spent performing endoscopy2,4. Community practitioners reported injuries at higher rates than those in an academic center. Other suggested but unproven risk factors include age5, sex, hand size, room design, and level of training in ergonomics and endoscopy2. Injuries can be severe and may lead to work load reduction, missed days of work3-5, reduction of activities outside of work, and long-term disability2.

Most surveys reflect symptoms localized to the back, neck, shoulder, elbow, hands/fingers, and thumbs likely from overuse causing strain and soft-tissue microtrauma6. Without time to heal, these injuries may lead to connective tissue weakening and permanent damage. Repetitive hand movements in endoscopy include left thumb abduction, flexion, and extension while manipulating dials and right wrist flexion, extension, and deviation from torqueing the insertion tube. The use of torque is a necessary part of successful colonoscopy; during scope reduction and maneuvering through the sigmoid colon, torque forces and forces applied against the wall of the colon are highest. When of sufficient magnitude and duration, these forces are associated with an increased risk of thumb and wrist injuries. These movements may result in “endoscopist’s thumb“ (i.e., de Quervain’s tenosynovitis) and carpal tunnel syndrome2. Prolonged standing and lead aprons are implicated in back and neck injuries;2,7-9 two-piece aprons,7,10 and antifatigue mats7 are recommended to decrease pressure on the lumbar and cervical disks as well as delay muscle fatigue.

Position of equipment

Endoscopist and patient positioning can be optimized. In the absence of direct data about ergonomics in endoscopy, we rely on surgical laparoscopy data.11,12These studies show that monitors placed directly in front of surgeons at eye-level (rather than off to the side or at the head of the bed) reduced neck and shoulder muscle activity. Monitors should be placed with a height 20 cm lower than the height of the surgeon (endoscopist), suggesting that optimized monitor height should be at eye-level or lower to prevent neck strain. Estimates based on computer simulation and laparoscopy practitioners show that the optimal distance between the endoscopist/surgeon and a 14” monitor is between 52 and 182 cm, which allows for the least amount of image degradation. Many modern monitors are larger (19”-26”), which allows for placement farther from the endoscopist without losing image quality. Bed height affects both spine and arm position; surgical data again suggest that optimal bed height is between elbow height and 10 cm below elbow height.

Immediate practice points

Since poor monitor placement was identified as a major risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries, the first steps in our endoscopy unit were to improve our sightlines. Our adjustable monitors previously were locked into a specific height, and those same monitors now easily are adjusted to heights appropriate to the endoscopist. Our practice has endoscopists from 61” to 77” tall, meaning we needed monitors that could adjust over a 16” height. When designing new endoscopy suites, monitors that adjust from 93 to 162 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height. We use adjustable-height beds; a bed that adjusts between 85 and 120 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height.

We also moved our monitors to be closer to the opposite side of the bed to accommodate the 3’ to 6’ appropriate to our 16” screens. Our endoscopy suites have cushioned washable mats placed where endoscopists stand that allow for slight instability of the legs, leading to subtle movements of the legs and increased blood flow to reduce foot and leg injuries. We attempt an athletic stance (the endo-athlete) during endoscopy: shoulders back, chest out, knees bent, and feet hip-width apart pointed at the endoscopy screen (Figure 1). These mats help prevent pelvic girdle twisting and turning that may lead to awkward positions and instead leave the endoscopist in an optimized position for the procedure. We encourage endoscopists to keep the scope in the most neutral position possible to reduce overuse of torque and the forces on the wrists and thumbs. When possible, we use two-piece lead aprons for procedures that require fluoroscopy, which transfers some of the weight of the apron from the shoulders to the hips and reduces upper-body strain. Optimization of the room for therapeutic procedures is even more important (with dual screens both fulfilling the criteria we have listed earlier) given the extra weight of the lead on the body. We suggest that, if procedures are performed in cramped endoscopy rooms, placement of additional monitors can help alleviate neck strain and rotation.

Working with our nurses was imperative. We first had our nurses watch videos on appropriate ergonomics in the endoscopy suite. Given that endoscopists usually are concentrating their attention on the screens in the suite, we tasked our nurses to not only monitor our patients, but also to observe the physical stance of the endoscopists. Our nurses are encouraged to help our endoscopists focus on their working stance: the nurses help with monitor positioning, and verbal cues when endoscopists are contorting their bodies unnaturally. This intervention requires open two-way communication in the endoscopy suite where safety of both the patient and staff is paramount. We are fortunate to be at an institution that trains fellows; we have two endoscopists in the suite at any time, which allows for additional two-way feedback between fellows and attendings to improve ergonomic positioning.

We also encourage some preventative exercises of the upper extremities to reduce pain and injuries. Stretches should emphasize finger, wrist, forearm, and shoulder flexion and extension. Even a minute of stretching between procedures allows for muscle relaxation and may lead to a decrease in overuse injuries. Adding these elements may seem inefficient and unnecessary if you have never had an injury, but we suggest the following paradigm: think of yourself as an endo-athlete. Similar to an athlete, you have worked years to gain the skills you possess. Taking a few moments to reduce your chances of a career-slowing (or career-ending) injury can pay long-term dividends.

Future remedies

Although there have been substantial advances in endoscopic imaging technology, the process of endoscope rotation and tip deflection has changed little since the development of flexible endoscopy. A freshman engineering student tasked with designing a device to navigate, examine, and provide therapy in the human colon likely would create a device that does not resemble the scope that we use daily to accomplish the task. Numerous investigators currently are working on novel devices designed to examine and deliver therapy to the digestive tract. These devices may diminish an endoscopist’s injury risk through the use of better ergonomic principles. This section is not intended to be a comprehensive review and is not an endorsement of any particular product. Rather, we hope it provides a glimpse into a possible future.

Reducing gravitational load

The concept of a mechanical device to hold some or all of the weight of the endoscope was first published in 197413. Since then, a number of products have been described for this purpose.14-17 In general, these consist of a simple metal tube with a hemicylindrical plastic clip, similar to a microphone stand, or a yoke/strap with a plastic scope holder in the front akin to what a percussionist in a marching band might wear. For a variety of reasons, including limited mobility and issues with disinfection, these devices have not gained traction.

Novel control mechanisms

Some of the largest forces on the endoscopist relate to moving the wheels on the scope head to effect tip deflection via a cable linkage. Because the wheels rotate only in one axis, the options for altering and adjusting load are few. One proposed solution is the use of a system with a fully detachable endoscope handle with a joystick style control deck (E210; Invendo Medical, Kissing, Germany). The control deck uses electromechanical assistance — as opposed to pure mechanical force — to transmit energy to the shaft of the instrument. Such assistive technologies have the potential to decrease injuries by decreased load, particularly on the carpometacarpal joint. Other devices seek to decrease the need for torque and high-load tip deflection though the use of self-propelled, disposable colonoscopes that use an aviation-style joystick (Aer-o-scope; GI View, Kissing, Germany). Although interesting and potentially useful, neither product is currently available for clinical use in the United States.

Robots and magnets

Magnetically controlled wireless capsules have been studied in vivo in human beings on several occasions in the United Kingdom and Asia. Wired colonic capsules are currently under development in the United States. These products use joystick-style controls to direct movement of the capsule. Optimal visualization often requires the patient to rotate through numerous positions and, at least in the stomach, to drink significant quantities of fluid to ensure adequate distention. At present, these devices provide only diagnostic capabilities.

Conclusions

The performance of endoscopy inherently places its practitioners at risk of biomechanical injury. Fortunately, there are numerous ways we can optimize our environment and ourselves. We should treat our bodies as professional athletes do: use good form, encourage colleagues to observe and provide feedback on our actions, optimize our practice facilities, and stretch our muscles. In the future, technological innovations, such as ergonomically designed endoscope handles and self-propelled colonoscopies, may reduce the inherent physical stresses of endoscopy. In doing so, hopefully we can preserve our own health and continue to better the health of our patients as well.

References

1. Rabin RC. Gastroenterologist shortage is forecast. (Available at: www.nytimes.com/2009/01/09/health/research/09gastro.html.) The New York Times, Jan. 9;2009.

2. Pedrosa MC, Farraye FA, Shergill AK. et al. Minimizing occupational hazards in endoscopy: personal protective equipment, radiation safety, and ergonomics. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:227-35.

3. Ridtitid W, Coté GA, Leung W, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for musculoskeletal injuries related to endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:294-302.e294.

4. Geraghty J, George R, Babbs C. A questionnaire study assessing overuse injuries in United Kingdom endoscopists and any effect from the introduction of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program on these injuries. Gastrointest Endos. 2011;73:1069-70.

5. Kuwabara T, Urabe Y, Hiyama T, et al. Prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal pain in Japanese gastrointestinal endoscopists: a controlled study. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1488-93.

6. Rempel DM, Harrison RJ, Barnhart S. Work-related cumulative trauma disorders of the upper extremity. JAMA 1992;267:838-42.

7. O’Sullivan S, Bridge G, Ponich T. Musculoskeletal injuries among ERCP endoscopists in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2002;16:369-74.

8. Moore B, vanSonnenberg E, Casola G. et al. The relationship between back pain and lead apron use in radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:191-3.

9. Ross AM, Segal J, Borenstein D, et al. Prevalence of spinal disc disease among interventional cardiologists. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:68-70.

10. Buschbacher R. Overuse syndromes among endoscopists. Endoscopy. 1994;26:539-44.

11. Matern U, Faist M, Kehl K, et al. Monitor position in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:436-40.

12. Haveran LA, Novitsky YW, Czerniach DR, et al. Optimizing laparoscopic task efficiency: the role of camera and monitor positions. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:980-4.

13. Nivatvongs S, Goldberg SM. Holder for the fiberoptic colonoscope. Dis Colon Rectum. 1974;17:273-4.

14. Eusebio EB. A practical aid in colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:996-7.

15. Rattan J, Rozen P. A new colonoscope holder. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:639-40.

16. Marks G. A new technique of hand reversal using a harness-type endoscope holder for twin-knob colonoscopy and flexible fiberoptic sigmoidoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:567-8.

17. Hayashi Y, Sunada K, Yamamoto H. Prototype holder adequately supports the overtube in balloon-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:682.

Dr. Young is professor of medicine, director, digestive disease division, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Commander Singla is assistant professor of medicine, Uniformed Services University, director, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Services, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Major Kwok is assistant professor of medicine, Uniformed Services University, associate fellowship program director, gastroenterology, National Capital Consortium, Bethesda, Md.; and Dr. Deriban is associate professor of medicine, fellowship program director, gastroenterology, University Hospital Skopje, Macedonia.

As physicians, we work hard to take excellent care of our patients. Years of thoughtful practice and continuous learning allow us to deliver the best that medicine can provide. We often take poor care of ourselves, which can lead to burnout and physical injuries. As gastroenterologists, we spend substantial time performing endoscopic procedures that require repetitive motions such as flexion and extension of the wrist and fingers and torsional movements of the right hand, which may lead to overuse injuries. The volume of endoscopic procedures performed by a typical gastroenterologist has increased significantly in the past 20 years. Moreover, experts predict that by 2020 we will have too few endoscopists to meet clinical demands.1 It is imperative that we do whatever possible to ensure overuse injuries do not prematurely prevent us from providing much-needed care. One way to achieve this goal is to focus on ergonomics. The study of ergonomics, derived from the Greek words ergo (work) and nomos (law), seeks to optimize the interface between the worker, the equipment, and the work environment. This article reviews basic ergonomic principles that endoscopists can apply today and possible innovations that may improve endoscopic ergonomics in the future.

Breadth of the problem

Examinations of injuries related to endoscopy are limited to survey-based and small controlled studies with a 39%-89% overall prevalence of pain or musculoskeletal injuries reported.2 In a survey of 684 American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy members examining injury prevalence and risk factors,3 53% experienced an injury believed to be definitely or probably related to endoscopy. Risk factors included higher procedure volume (more than 20 cases/wk), greater number of hours spent performing endoscopy (more than 16 h/wk), and total number of years spent performing endoscopy2,4. Community practitioners reported injuries at higher rates than those in an academic center. Other suggested but unproven risk factors include age5, sex, hand size, room design, and level of training in ergonomics and endoscopy2. Injuries can be severe and may lead to work load reduction, missed days of work3-5, reduction of activities outside of work, and long-term disability2.

Most surveys reflect symptoms localized to the back, neck, shoulder, elbow, hands/fingers, and thumbs likely from overuse causing strain and soft-tissue microtrauma6. Without time to heal, these injuries may lead to connective tissue weakening and permanent damage. Repetitive hand movements in endoscopy include left thumb abduction, flexion, and extension while manipulating dials and right wrist flexion, extension, and deviation from torqueing the insertion tube. The use of torque is a necessary part of successful colonoscopy; during scope reduction and maneuvering through the sigmoid colon, torque forces and forces applied against the wall of the colon are highest. When of sufficient magnitude and duration, these forces are associated with an increased risk of thumb and wrist injuries. These movements may result in “endoscopist’s thumb“ (i.e., de Quervain’s tenosynovitis) and carpal tunnel syndrome2. Prolonged standing and lead aprons are implicated in back and neck injuries;2,7-9 two-piece aprons,7,10 and antifatigue mats7 are recommended to decrease pressure on the lumbar and cervical disks as well as delay muscle fatigue.

Position of equipment

Endoscopist and patient positioning can be optimized. In the absence of direct data about ergonomics in endoscopy, we rely on surgical laparoscopy data.11,12These studies show that monitors placed directly in front of surgeons at eye-level (rather than off to the side or at the head of the bed) reduced neck and shoulder muscle activity. Monitors should be placed with a height 20 cm lower than the height of the surgeon (endoscopist), suggesting that optimized monitor height should be at eye-level or lower to prevent neck strain. Estimates based on computer simulation and laparoscopy practitioners show that the optimal distance between the endoscopist/surgeon and a 14” monitor is between 52 and 182 cm, which allows for the least amount of image degradation. Many modern monitors are larger (19”-26”), which allows for placement farther from the endoscopist without losing image quality. Bed height affects both spine and arm position; surgical data again suggest that optimal bed height is between elbow height and 10 cm below elbow height.

Immediate practice points

Since poor monitor placement was identified as a major risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries, the first steps in our endoscopy unit were to improve our sightlines. Our adjustable monitors previously were locked into a specific height, and those same monitors now easily are adjusted to heights appropriate to the endoscopist. Our practice has endoscopists from 61” to 77” tall, meaning we needed monitors that could adjust over a 16” height. When designing new endoscopy suites, monitors that adjust from 93 to 162 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height. We use adjustable-height beds; a bed that adjusts between 85 and 120 cm would accommodate the 5th percentile of female height to the 95th percentile of male height.

We also moved our monitors to be closer to the opposite side of the bed to accommodate the 3’ to 6’ appropriate to our 16” screens. Our endoscopy suites have cushioned washable mats placed where endoscopists stand that allow for slight instability of the legs, leading to subtle movements of the legs and increased blood flow to reduce foot and leg injuries. We attempt an athletic stance (the endo-athlete) during endoscopy: shoulders back, chest out, knees bent, and feet hip-width apart pointed at the endoscopy screen (Figure 1). These mats help prevent pelvic girdle twisting and turning that may lead to awkward positions and instead leave the endoscopist in an optimized position for the procedure. We encourage endoscopists to keep the scope in the most neutral position possible to reduce overuse of torque and the forces on the wrists and thumbs. When possible, we use two-piece lead aprons for procedures that require fluoroscopy, which transfers some of the weight of the apron from the shoulders to the hips and reduces upper-body strain. Optimization of the room for therapeutic procedures is even more important (with dual screens both fulfilling the criteria we have listed earlier) given the extra weight of the lead on the body. We suggest that, if procedures are performed in cramped endoscopy rooms, placement of additional monitors can help alleviate neck strain and rotation.

Working with our nurses was imperative. We first had our nurses watch videos on appropriate ergonomics in the endoscopy suite. Given that endoscopists usually are concentrating their attention on the screens in the suite, we tasked our nurses to not only monitor our patients, but also to observe the physical stance of the endoscopists. Our nurses are encouraged to help our endoscopists focus on their working stance: the nurses help with monitor positioning, and verbal cues when endoscopists are contorting their bodies unnaturally. This intervention requires open two-way communication in the endoscopy suite where safety of both the patient and staff is paramount. We are fortunate to be at an institution that trains fellows; we have two endoscopists in the suite at any time, which allows for additional two-way feedback between fellows and attendings to improve ergonomic positioning.

We also encourage some preventative exercises of the upper extremities to reduce pain and injuries. Stretches should emphasize finger, wrist, forearm, and shoulder flexion and extension. Even a minute of stretching between procedures allows for muscle relaxation and may lead to a decrease in overuse injuries. Adding these elements may seem inefficient and unnecessary if you have never had an injury, but we suggest the following paradigm: think of yourself as an endo-athlete. Similar to an athlete, you have worked years to gain the skills you possess. Taking a few moments to reduce your chances of a career-slowing (or career-ending) injury can pay long-term dividends.

Future remedies

Although there have been substantial advances in endoscopic imaging technology, the process of endoscope rotation and tip deflection has changed little since the development of flexible endoscopy. A freshman engineering student tasked with designing a device to navigate, examine, and provide therapy in the human colon likely would create a device that does not resemble the scope that we use daily to accomplish the task. Numerous investigators currently are working on novel devices designed to examine and deliver therapy to the digestive tract. These devices may diminish an endoscopist’s injury risk through the use of better ergonomic principles. This section is not intended to be a comprehensive review and is not an endorsement of any particular product. Rather, we hope it provides a glimpse into a possible future.

Reducing gravitational load

The concept of a mechanical device to hold some or all of the weight of the endoscope was first published in 197413. Since then, a number of products have been described for this purpose.14-17 In general, these consist of a simple metal tube with a hemicylindrical plastic clip, similar to a microphone stand, or a yoke/strap with a plastic scope holder in the front akin to what a percussionist in a marching band might wear. For a variety of reasons, including limited mobility and issues with disinfection, these devices have not gained traction.

Novel control mechanisms

Some of the largest forces on the endoscopist relate to moving the wheels on the scope head to effect tip deflection via a cable linkage. Because the wheels rotate only in one axis, the options for altering and adjusting load are few. One proposed solution is the use of a system with a fully detachable endoscope handle with a joystick style control deck (E210; Invendo Medical, Kissing, Germany). The control deck uses electromechanical assistance — as opposed to pure mechanical force — to transmit energy to the shaft of the instrument. Such assistive technologies have the potential to decrease injuries by decreased load, particularly on the carpometacarpal joint. Other devices seek to decrease the need for torque and high-load tip deflection though the use of self-propelled, disposable colonoscopes that use an aviation-style joystick (Aer-o-scope; GI View, Kissing, Germany). Although interesting and potentially useful, neither product is currently available for clinical use in the United States.

Robots and magnets

Magnetically controlled wireless capsules have been studied in vivo in human beings on several occasions in the United Kingdom and Asia. Wired colonic capsules are currently under development in the United States. These products use joystick-style controls to direct movement of the capsule. Optimal visualization often requires the patient to rotate through numerous positions and, at least in the stomach, to drink significant quantities of fluid to ensure adequate distention. At present, these devices provide only diagnostic capabilities.

Conclusions

The performance of endoscopy inherently places its practitioners at risk of biomechanical injury. Fortunately, there are numerous ways we can optimize our environment and ourselves. We should treat our bodies as professional athletes do: use good form, encourage colleagues to observe and provide feedback on our actions, optimize our practice facilities, and stretch our muscles. In the future, technological innovations, such as ergonomically designed endoscope handles and self-propelled colonoscopies, may reduce the inherent physical stresses of endoscopy. In doing so, hopefully we can preserve our own health and continue to better the health of our patients as well.

References

1. Rabin RC. Gastroenterologist shortage is forecast. (Available at: www.nytimes.com/2009/01/09/health/research/09gastro.html.) The New York Times, Jan. 9;2009.

2. Pedrosa MC, Farraye FA, Shergill AK. et al. Minimizing occupational hazards in endoscopy: personal protective equipment, radiation safety, and ergonomics. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:227-35.

3. Ridtitid W, Coté GA, Leung W, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for musculoskeletal injuries related to endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:294-302.e294.

4. Geraghty J, George R, Babbs C. A questionnaire study assessing overuse injuries in United Kingdom endoscopists and any effect from the introduction of the National Bowel Cancer Screening Program on these injuries. Gastrointest Endos. 2011;73:1069-70.

5. Kuwabara T, Urabe Y, Hiyama T, et al. Prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal pain in Japanese gastrointestinal endoscopists: a controlled study. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1488-93.

6. Rempel DM, Harrison RJ, Barnhart S. Work-related cumulative trauma disorders of the upper extremity. JAMA 1992;267:838-42.

7. O’Sullivan S, Bridge G, Ponich T. Musculoskeletal injuries among ERCP endoscopists in Canada. Can J Gastroenterol. 2002;16:369-74.

8. Moore B, vanSonnenberg E, Casola G. et al. The relationship between back pain and lead apron use in radiologists. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:191-3.

9. Ross AM, Segal J, Borenstein D, et al. Prevalence of spinal disc disease among interventional cardiologists. Am J Cardiol. 1997;79:68-70.

10. Buschbacher R. Overuse syndromes among endoscopists. Endoscopy. 1994;26:539-44.

11. Matern U, Faist M, Kehl K, et al. Monitor position in laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:436-40.

12. Haveran LA, Novitsky YW, Czerniach DR, et al. Optimizing laparoscopic task efficiency: the role of camera and monitor positions. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:980-4.

13. Nivatvongs S, Goldberg SM. Holder for the fiberoptic colonoscope. Dis Colon Rectum. 1974;17:273-4.

14. Eusebio EB. A practical aid in colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32:996-7.

15. Rattan J, Rozen P. A new colonoscope holder. Dis Colon Rectum. 1987;30:639-40.

16. Marks G. A new technique of hand reversal using a harness-type endoscope holder for twin-knob colonoscopy and flexible fiberoptic sigmoidoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24:567-8.

17. Hayashi Y, Sunada K, Yamamoto H. Prototype holder adequately supports the overtube in balloon-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:682.

Dr. Young is professor of medicine, director, digestive disease division, Uniformed Services University, Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Commander Singla is assistant professor of medicine, Uniformed Services University, director, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Services, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md.; Dr. Major Kwok is assistant professor of medicine, Uniformed Services University, associate fellowship program director, gastroenterology, National Capital Consortium, Bethesda, Md.; and Dr. Deriban is associate professor of medicine, fellowship program director, gastroenterology, University Hospital Skopje, Macedonia.

ZUMA-1 update: Axi-cel responses persist at 2 years

HOUSTON – With a median follow-up now exceeding 2 years, 39% of refractory large B-cell lymphoma patients enrolled in the pivotal ZUMA-1 trial have maintained ongoing response to axicabtagene ciloleucel, according to an investigator involved in the study.

Median duration of response to axi-cel and median overall survival have not yet been reached, while a recent subset analysis showed that nearly half of patients with certain high-risk characteristics had a durable response, said investigator Sattva S. Neelapu, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Evidence of B-cell recovery and a decrease in detectable, gene-marked CAR T cells have been noted in further follow-up, suggesting that functional CAR T-cell persistence may not be required for long-term remissions, Dr. Neelapu added.

“These data support [the conclusion] that axi-cel induces durable remissions in patients with large B-cell lymphoma who otherwise lack curative options,” Dr. Neelapu said at the Transplantation & Cellular Therapy Meetings.

The update on the phase 1/2 ZUMA-1 study included 108 patients with refractory large B-cell lymphoma who received axi-cel, the CD19-directed autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy.

In a previously reported 1-year update on the trial, 42% of patients had ongoing responses, Dr. Neelapu said. In the present update, with a median follow-up of 27.1 months, ongoing responses were seen in 39%, most of whom (37%) were in complete response, according to the data presented.

Thirty-three patients in the phase 2 portion of ZUMA-1 were known to have double-expressor or high-grade B-cell lymphoma, according to the investigator. In this high-risk subset, 48% were in ongoing complete response at the 2-year follow-up.

Progression-free survival in ZUMA-1 plateaued at the 6 month-follow-up, according to Dr. Neelapu, who said that plateau has been largely maintained, with just 10 patients progressing since then. Median progression-free survival is 5.9 months and median overall survival has not been reached, with a 24-month overall survival of 51%.

Late-onset serious adverse events mainly consisted of manageable infections, none of which were considered related to axi-cel treatment, according to Dr. Neelapu.

The proportion of ongoing responders with detectable CAR T-cells has decreased over time, from 95% at 3 months to 66% at 24 months, Dr. Neelapu reported. Meanwhile, the proportion of ongoing responders with detectable B cells after axi-cel treatment has gone from 17% to 75%.

More details on the 2-year follow-up data from ZUMA-1 were reported recently in the Lancet Oncology (2019 Jan;20[1]:31-42).

Funding for ZUMA-1 came from Kite and the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society. Dr. Neelapu reported disclosures related to Kite, Celgene, Cellectis, Merck, Poseida, Acerta, Karus, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, and Unum Therapeutics.

The meeting was held by the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. At its meeting, the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation announced a new name for the society: American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT).

SOURCE: Neelapu SS et al. TCT 2019, Abstract 82.

HOUSTON – With a median follow-up now exceeding 2 years, 39% of refractory large B-cell lymphoma patients enrolled in the pivotal ZUMA-1 trial have maintained ongoing response to axicabtagene ciloleucel, according to an investigator involved in the study.

Median duration of response to axi-cel and median overall survival have not yet been reached, while a recent subset analysis showed that nearly half of patients with certain high-risk characteristics had a durable response, said investigator Sattva S. Neelapu, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Evidence of B-cell recovery and a decrease in detectable, gene-marked CAR T cells have been noted in further follow-up, suggesting that functional CAR T-cell persistence may not be required for long-term remissions, Dr. Neelapu added.

“These data support [the conclusion] that axi-cel induces durable remissions in patients with large B-cell lymphoma who otherwise lack curative options,” Dr. Neelapu said at the Transplantation & Cellular Therapy Meetings.