User login

Aerobic exercise may mitigate age-related cognitive decline

published in Neurology.

“The effect of aerobic exercise on executive function was more pronounced as age increased, suggesting that it may mitigate age-related declines,” wrote Yaakov Stern, PhD, chief of cognitive neuroscience in the department of neurology at Columbia University, New York, and his research colleagues.

Research indicates that aerobic exercise provides cognitive benefits across the lifespan, but controlled exercise studies have been limited to elderly individuals, the researchers wrote. To examine the effects of aerobic exercise on cognitive function in younger, healthy adults, they conducted a randomized, parallel-group, observer-masked, community-based clinical trial. The investigators enrolled 132 cognitively normal people aged 20-67 years with aerobic capacity below the median. About 70% were women, and participants’ mean age was about 40 years.

“We hypothesized that aerobic exercise would have cognitive benefits, even in this younger age range, but that age might moderate the nature or degree of the benefit,” Dr. Stern and his colleagues wrote.

Participants were nonsmoking, habitual nonexercisers with below-average fitness by American Heart Association standards. The investigators used baseline aerobic capacity testing to establish safe exercise measures and heart rate targets.

The investigators randomly assigned participants to a group that performed aerobic exercise or to a control group that performed stretching and toning four times per week for 6 months. Outcome measures included domains of cognitive function (such as executive function, episodic memory, processing speed, language, and attention), everyday function, aerobic capacity, body mass index, and cortical thickness.

During a 2-week run-in period, participants went to their choice of five YMCA of New York City fitness centers three times per week. They had to attend at least five of these sessions to stay in the study. In both study arms, training sessions consisted of 10-15 minutes of warm-up and cooldown and 30-40 minutes of workout. Coaches contacted participants weekly to monitor their progress, and participants wore heart rate monitors during each session. Exercises in the control group were designed to promote flexibility and improve core strength. In the aerobic exercise group, participants had a choice of exercises such as walking on a treadmill, cycling on a stationary bike, or using an elliptical machine, and they gradually increased their exercise intensity to 75% of maximum heart rate by week 5. A total of 94 participants – 50 in the control group and 44 in the aerobic exercise group – completed the 6-month trial.

Executive function, but not other cognitive measures, improved significantly in the aerobic exercise group. The effect on executive function was greater in older participants. For example, at age 40 years, the executive function measure increased by 0.228 standard deviation units from baseline; at age 60, it increased by 0.596 standard deviation units.

In addition, cortical thickness increased significantly in the aerobic exercise group in the left caudal middle frontal cortex Brodmann area; this effect did not differ by age. Improvement on executive function in the aerobic exercise group was greater among participants without an APOE E4 allele, contrasting with the findings of prior studies.

“Since a difference of 0.5 standard deviations is equivalent to 20 years of age-related difference in performance on these tests, the people who exercised were testing as if they were about 10 years younger at age 40 and about 20 years younger at age 60,” Dr. Stern said in a press release. “Since thinking skills at the start of the study were poorer for participants who were older, our findings suggest that aerobic exercise is more likely to improve age-related declines in thinking skills rather than improve performance in those without a decline.”

Furthermore, aerobic exercise significantly increased aerobic capacity and significantly decreased body mass index, whereas stretching and toning did not.

“Participants in this trial scheduled their exercise sessions on their own and exercised by themselves,” the authors noted. “In addition, they were allowed to choose whatever aerobic exercise modality they preferred, so long as they reached target heart rates, enhancing the flexibility of the intervention.” Limitations of the study include its relatively small sample size and the large number of participants who dropped out of the study between consenting to participate and randomization.

The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Stern reported receiving a grant from the California Walnut Commission and consulting with Eli Lilly, Axovant Sciences, Takeda, and AbbVie. A coauthor reported grant support from AposTherapy, LIH Medical, and the Everest Foundation.

SOURCE: Stern Y et al. Neurology. 2019 Jan 30. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007003.

published in Neurology.

“The effect of aerobic exercise on executive function was more pronounced as age increased, suggesting that it may mitigate age-related declines,” wrote Yaakov Stern, PhD, chief of cognitive neuroscience in the department of neurology at Columbia University, New York, and his research colleagues.

Research indicates that aerobic exercise provides cognitive benefits across the lifespan, but controlled exercise studies have been limited to elderly individuals, the researchers wrote. To examine the effects of aerobic exercise on cognitive function in younger, healthy adults, they conducted a randomized, parallel-group, observer-masked, community-based clinical trial. The investigators enrolled 132 cognitively normal people aged 20-67 years with aerobic capacity below the median. About 70% were women, and participants’ mean age was about 40 years.

“We hypothesized that aerobic exercise would have cognitive benefits, even in this younger age range, but that age might moderate the nature or degree of the benefit,” Dr. Stern and his colleagues wrote.

Participants were nonsmoking, habitual nonexercisers with below-average fitness by American Heart Association standards. The investigators used baseline aerobic capacity testing to establish safe exercise measures and heart rate targets.

The investigators randomly assigned participants to a group that performed aerobic exercise or to a control group that performed stretching and toning four times per week for 6 months. Outcome measures included domains of cognitive function (such as executive function, episodic memory, processing speed, language, and attention), everyday function, aerobic capacity, body mass index, and cortical thickness.

During a 2-week run-in period, participants went to their choice of five YMCA of New York City fitness centers three times per week. They had to attend at least five of these sessions to stay in the study. In both study arms, training sessions consisted of 10-15 minutes of warm-up and cooldown and 30-40 minutes of workout. Coaches contacted participants weekly to monitor their progress, and participants wore heart rate monitors during each session. Exercises in the control group were designed to promote flexibility and improve core strength. In the aerobic exercise group, participants had a choice of exercises such as walking on a treadmill, cycling on a stationary bike, or using an elliptical machine, and they gradually increased their exercise intensity to 75% of maximum heart rate by week 5. A total of 94 participants – 50 in the control group and 44 in the aerobic exercise group – completed the 6-month trial.

Executive function, but not other cognitive measures, improved significantly in the aerobic exercise group. The effect on executive function was greater in older participants. For example, at age 40 years, the executive function measure increased by 0.228 standard deviation units from baseline; at age 60, it increased by 0.596 standard deviation units.

In addition, cortical thickness increased significantly in the aerobic exercise group in the left caudal middle frontal cortex Brodmann area; this effect did not differ by age. Improvement on executive function in the aerobic exercise group was greater among participants without an APOE E4 allele, contrasting with the findings of prior studies.

“Since a difference of 0.5 standard deviations is equivalent to 20 years of age-related difference in performance on these tests, the people who exercised were testing as if they were about 10 years younger at age 40 and about 20 years younger at age 60,” Dr. Stern said in a press release. “Since thinking skills at the start of the study were poorer for participants who were older, our findings suggest that aerobic exercise is more likely to improve age-related declines in thinking skills rather than improve performance in those without a decline.”

Furthermore, aerobic exercise significantly increased aerobic capacity and significantly decreased body mass index, whereas stretching and toning did not.

“Participants in this trial scheduled their exercise sessions on their own and exercised by themselves,” the authors noted. “In addition, they were allowed to choose whatever aerobic exercise modality they preferred, so long as they reached target heart rates, enhancing the flexibility of the intervention.” Limitations of the study include its relatively small sample size and the large number of participants who dropped out of the study between consenting to participate and randomization.

The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Stern reported receiving a grant from the California Walnut Commission and consulting with Eli Lilly, Axovant Sciences, Takeda, and AbbVie. A coauthor reported grant support from AposTherapy, LIH Medical, and the Everest Foundation.

SOURCE: Stern Y et al. Neurology. 2019 Jan 30. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007003.

published in Neurology.

“The effect of aerobic exercise on executive function was more pronounced as age increased, suggesting that it may mitigate age-related declines,” wrote Yaakov Stern, PhD, chief of cognitive neuroscience in the department of neurology at Columbia University, New York, and his research colleagues.

Research indicates that aerobic exercise provides cognitive benefits across the lifespan, but controlled exercise studies have been limited to elderly individuals, the researchers wrote. To examine the effects of aerobic exercise on cognitive function in younger, healthy adults, they conducted a randomized, parallel-group, observer-masked, community-based clinical trial. The investigators enrolled 132 cognitively normal people aged 20-67 years with aerobic capacity below the median. About 70% were women, and participants’ mean age was about 40 years.

“We hypothesized that aerobic exercise would have cognitive benefits, even in this younger age range, but that age might moderate the nature or degree of the benefit,” Dr. Stern and his colleagues wrote.

Participants were nonsmoking, habitual nonexercisers with below-average fitness by American Heart Association standards. The investigators used baseline aerobic capacity testing to establish safe exercise measures and heart rate targets.

The investigators randomly assigned participants to a group that performed aerobic exercise or to a control group that performed stretching and toning four times per week for 6 months. Outcome measures included domains of cognitive function (such as executive function, episodic memory, processing speed, language, and attention), everyday function, aerobic capacity, body mass index, and cortical thickness.

During a 2-week run-in period, participants went to their choice of five YMCA of New York City fitness centers three times per week. They had to attend at least five of these sessions to stay in the study. In both study arms, training sessions consisted of 10-15 minutes of warm-up and cooldown and 30-40 minutes of workout. Coaches contacted participants weekly to monitor their progress, and participants wore heart rate monitors during each session. Exercises in the control group were designed to promote flexibility and improve core strength. In the aerobic exercise group, participants had a choice of exercises such as walking on a treadmill, cycling on a stationary bike, or using an elliptical machine, and they gradually increased their exercise intensity to 75% of maximum heart rate by week 5. A total of 94 participants – 50 in the control group and 44 in the aerobic exercise group – completed the 6-month trial.

Executive function, but not other cognitive measures, improved significantly in the aerobic exercise group. The effect on executive function was greater in older participants. For example, at age 40 years, the executive function measure increased by 0.228 standard deviation units from baseline; at age 60, it increased by 0.596 standard deviation units.

In addition, cortical thickness increased significantly in the aerobic exercise group in the left caudal middle frontal cortex Brodmann area; this effect did not differ by age. Improvement on executive function in the aerobic exercise group was greater among participants without an APOE E4 allele, contrasting with the findings of prior studies.

“Since a difference of 0.5 standard deviations is equivalent to 20 years of age-related difference in performance on these tests, the people who exercised were testing as if they were about 10 years younger at age 40 and about 20 years younger at age 60,” Dr. Stern said in a press release. “Since thinking skills at the start of the study were poorer for participants who were older, our findings suggest that aerobic exercise is more likely to improve age-related declines in thinking skills rather than improve performance in those without a decline.”

Furthermore, aerobic exercise significantly increased aerobic capacity and significantly decreased body mass index, whereas stretching and toning did not.

“Participants in this trial scheduled their exercise sessions on their own and exercised by themselves,” the authors noted. “In addition, they were allowed to choose whatever aerobic exercise modality they preferred, so long as they reached target heart rates, enhancing the flexibility of the intervention.” Limitations of the study include its relatively small sample size and the large number of participants who dropped out of the study between consenting to participate and randomization.

The trial was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Stern reported receiving a grant from the California Walnut Commission and consulting with Eli Lilly, Axovant Sciences, Takeda, and AbbVie. A coauthor reported grant support from AposTherapy, LIH Medical, and the Everest Foundation.

SOURCE: Stern Y et al. Neurology. 2019 Jan 30. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007003.

FROM NEUROLOGY

Key clinical point: Among adults with below-average fitness, a 6-month aerobic exercise program significantly improves executive function.

Major finding: The effect is more pronounced as age increases.

Study details: A randomized, parallel-group, observer-masked, community-based clinical trial of 132 cognitively normal adults aged 20-67 years.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Stern reported receiving a grant from the California Walnut Commission and consulted with Eli Lilly, Axovant Sciences, Takeda, and AbbVie. Another reported grant support from AposTherapy, LIH Medical, and the Everest Foundation.

Source: Stern Y et al. Neurology. 2019 Jan 30. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007003.

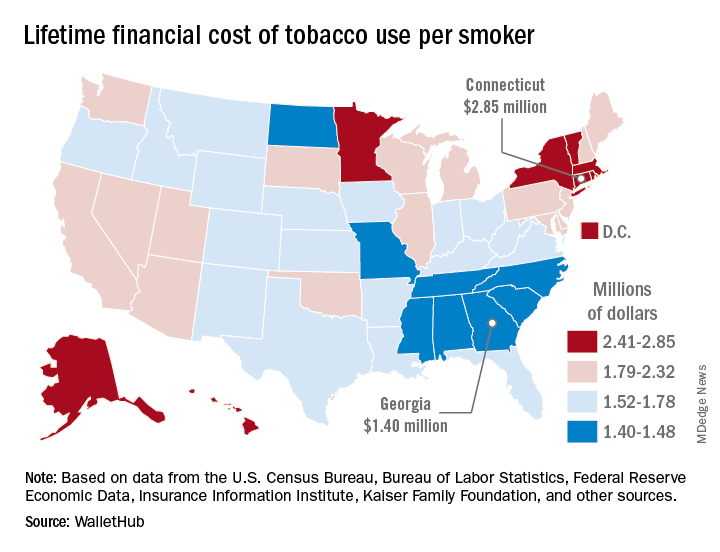

Lifetime cost of tobacco use tops $1.9 million per smoker

according to the personal financial website WalletHub.

Economic and societal losses related to 37.8 million U.S. tobacco users – including out-of-pocket spending for cigarettes, health care expenses, and lost income – top $300 billion annually, but those costs vary considerably by state, WalletHub said in a recent report.

The state with the highest lifetime cost per smoker is Connecticut, with an estimated total of $2.85 million. That works out to just under $56,000 a year for 51 years because lifetime use was defined as one pack a day starting at age 18 years and continuing until age 69 years. New York has the second-highest lifetime cost, which also rounds off to $2.85 million, followed by the District of Columbia ($2.81 million), Massachusetts ($2.76 million), and Rhode Island ($2.68 million), WalletHub said.

Georgia has the lowest lifetime cost of any state – $1.40 million per smoker – followed by Missouri at $1.41 million, North Carolina at $1.42 million, Mississippi at $1.43 million, and South Carolina at $1.44 million, according to the report.

WalletHub’s formula for total lifetime cost has five components: out-of-pocket cost (one pack of cigarettes per day for 51 years), financial opportunity cost (defined as “the amount of return a person would have earned by instead investing that money in the stock market”), health care cost (spending on treatment for smoking-related health complications), income loss (an average 8% decrease caused by absenteeism and lost productivity), and other costs (loss of a homeowner’s insurance credit and costs of secondhand exposure).

The analysis was based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Insurance Information Institute, Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, NYsmokefree.com, Federal Reserve Economic Data, Kaiser Family Foundation, and the Independent Insurance Agents & Brokers of America.

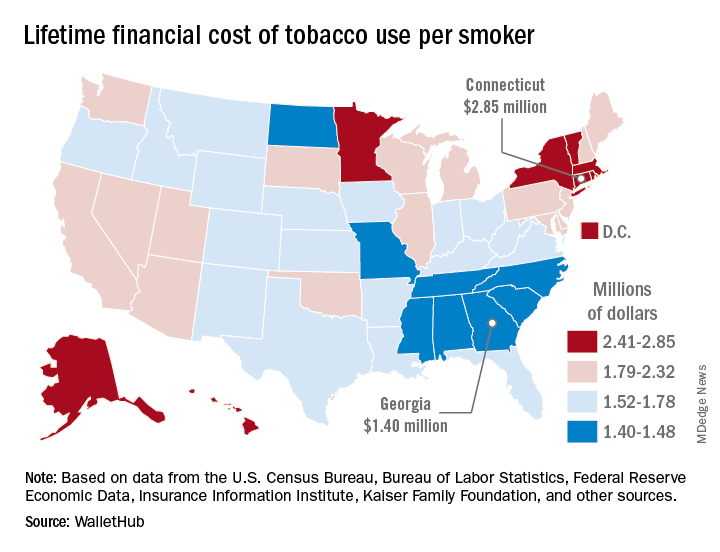

according to the personal financial website WalletHub.

Economic and societal losses related to 37.8 million U.S. tobacco users – including out-of-pocket spending for cigarettes, health care expenses, and lost income – top $300 billion annually, but those costs vary considerably by state, WalletHub said in a recent report.

The state with the highest lifetime cost per smoker is Connecticut, with an estimated total of $2.85 million. That works out to just under $56,000 a year for 51 years because lifetime use was defined as one pack a day starting at age 18 years and continuing until age 69 years. New York has the second-highest lifetime cost, which also rounds off to $2.85 million, followed by the District of Columbia ($2.81 million), Massachusetts ($2.76 million), and Rhode Island ($2.68 million), WalletHub said.

Georgia has the lowest lifetime cost of any state – $1.40 million per smoker – followed by Missouri at $1.41 million, North Carolina at $1.42 million, Mississippi at $1.43 million, and South Carolina at $1.44 million, according to the report.

WalletHub’s formula for total lifetime cost has five components: out-of-pocket cost (one pack of cigarettes per day for 51 years), financial opportunity cost (defined as “the amount of return a person would have earned by instead investing that money in the stock market”), health care cost (spending on treatment for smoking-related health complications), income loss (an average 8% decrease caused by absenteeism and lost productivity), and other costs (loss of a homeowner’s insurance credit and costs of secondhand exposure).

The analysis was based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Insurance Information Institute, Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, NYsmokefree.com, Federal Reserve Economic Data, Kaiser Family Foundation, and the Independent Insurance Agents & Brokers of America.

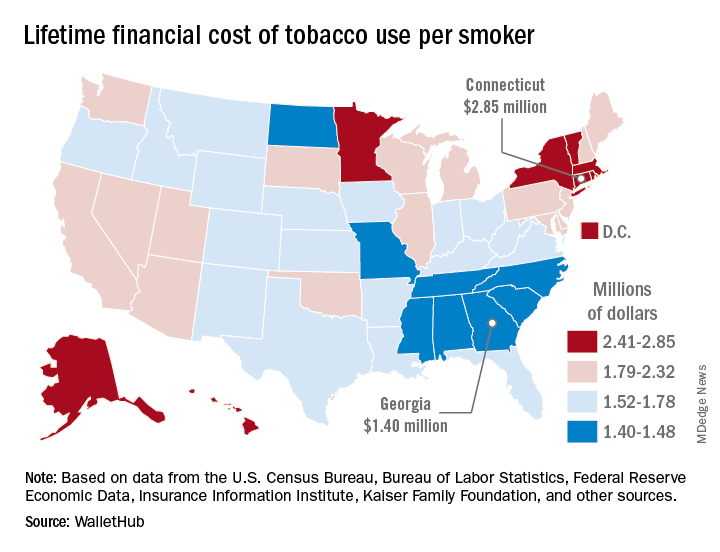

according to the personal financial website WalletHub.

Economic and societal losses related to 37.8 million U.S. tobacco users – including out-of-pocket spending for cigarettes, health care expenses, and lost income – top $300 billion annually, but those costs vary considerably by state, WalletHub said in a recent report.

The state with the highest lifetime cost per smoker is Connecticut, with an estimated total of $2.85 million. That works out to just under $56,000 a year for 51 years because lifetime use was defined as one pack a day starting at age 18 years and continuing until age 69 years. New York has the second-highest lifetime cost, which also rounds off to $2.85 million, followed by the District of Columbia ($2.81 million), Massachusetts ($2.76 million), and Rhode Island ($2.68 million), WalletHub said.

Georgia has the lowest lifetime cost of any state – $1.40 million per smoker – followed by Missouri at $1.41 million, North Carolina at $1.42 million, Mississippi at $1.43 million, and South Carolina at $1.44 million, according to the report.

WalletHub’s formula for total lifetime cost has five components: out-of-pocket cost (one pack of cigarettes per day for 51 years), financial opportunity cost (defined as “the amount of return a person would have earned by instead investing that money in the stock market”), health care cost (spending on treatment for smoking-related health complications), income loss (an average 8% decrease caused by absenteeism and lost productivity), and other costs (loss of a homeowner’s insurance credit and costs of secondhand exposure).

The analysis was based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Insurance Information Institute, Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids, NYsmokefree.com, Federal Reserve Economic Data, Kaiser Family Foundation, and the Independent Insurance Agents & Brokers of America.

Pulmonary hypertension linked to complications after head and neck procedures

SAN DIEGO – Patients with , compared with their counterparts who do not have the condition. They also face an increase in total charges and length of stay.

The findings come from what is believed to be the first study of its kind to investigate the impact of pulmonary hypertension (PHTN) on major head and neck procedures. “PHTN is a common condition which affects the caliber of lung vasculature, with varied symptom presentation from shortness of breath to syncope, with an estimated prevalence of 2.5 to 7.1 million new cases each year worldwide,” one of the study authors, Nirali M. Patel, said at the Triological Society’s Combined Sections Meeting. “Due to improved therapeutic options, there is an enhanced survival of PHTN patients and higher prevalence of this disease. PHTN has some significant systemic implications. Therefore, cardiopulmonary clearance and a clear understanding of postoperative complications are very important.”

Previous studies have shown PHTN to be an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality in noncardiac procedures, said Ms. Patel, a fourth-year medical student at New Jersey Medical School, Newark. Furthermore, the rate of pulmonary complications is reported to be between 11% and 44.8% following radical head and neck cancer resection. “Despite these findings, there is currently a lack of information regarding perioperative morbidity and mortality of patients with PHTN undergoing major head and neck procedures,” she said.

The researchers queried the National Inpatient Survey from 2002 to 2013 for all cases of major head and neck surgery based on the ICD-9 codes for esophagectomy, glossectomy, laryngectomy, mandibulectomy, and pharyngectomy. They divided patients into two groups: those who had PHTN and those who did not, and performed demographic analyses as well as univariate and multivariate regression analyses.

Ms. Patel reported findings from a cohort of 46,311 patients. Of these, 46,073 had PHTN and 238 did not. The two groups were similar in age (a mean of 69 vs. 60 years in those with and without PHTN, respectively) and race (80% white vs. 79% white, respectively), but there were significantly fewer male patients in the PHTN group (57% vs. 70%; P less than .0001).

Several patient comorbidities were increased in the PHTN group, compared with the non-PHTN group, including coagulopathy (8.4% vs. 3.1%; P less than .0001), chronic heart failure (22.4% vs. 4.1%; P less than .0001), complicated diabetes (4.6% vs. 1.2%; P less than .0001), fluid and electrolyte disorders (30% vs. 18.3%; P less than .0001), and hypertension (63.3% vs. 43.7%; P less than .0001).

Postoperatively, patients with PHTN had a longer length of stay (a mean of 15.80 vs. 11.50 days, respectively; P less than .0001) as well as significantly higher total charges (a mean of $162,021.06 vs. $107,309.46, respectively; P less than .0001). When the researchers evaluated postoperative outcomes between the two cohorts, patients with PHTN had significantly higher rates of cardiac complications (9.2% vs. 3.5%; P less than .0001), iatrogenic pulmonary embolism (2.1% vs. 0.3%; P = .001), pulmonary edema (2.1% vs. 0.4%; P = .003), venous thrombotic events (4.6% vs. 1%; P less than. 0001), pulmonary insufficiency (17.2% vs. 9.7%; P less than .0001), and pneumonia (9.7% vs. 6%; P = .027), as well as higher rates of postoperative tracheostomy (8.4% vs. 4.5%; P = .007).

Multivariate analysis revealed that the following factors predicted in-hospital mortality: coagulopathy, chronic heart failure, fluid and electrolyte disorders, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, hypothyroidism, liver disease, obesity, paralysis, and renal failure. Despite these findings, there was no significant change in overall hospital mortality for those with PHTN, with an odds ratio of 1.055.

“Our study is not without its limitations, many of which are inherent to the use of a database, which is subject to errors in coding and sampling,” Ms. Patel noted at the meeting, which was jointly sponsored by the Triological Society and the American College of Surgeons. “Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable information on the impact of PHTN on major head and neck procedures.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Patel N et al. Triological CSM, Abstracts.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with , compared with their counterparts who do not have the condition. They also face an increase in total charges and length of stay.

The findings come from what is believed to be the first study of its kind to investigate the impact of pulmonary hypertension (PHTN) on major head and neck procedures. “PHTN is a common condition which affects the caliber of lung vasculature, with varied symptom presentation from shortness of breath to syncope, with an estimated prevalence of 2.5 to 7.1 million new cases each year worldwide,” one of the study authors, Nirali M. Patel, said at the Triological Society’s Combined Sections Meeting. “Due to improved therapeutic options, there is an enhanced survival of PHTN patients and higher prevalence of this disease. PHTN has some significant systemic implications. Therefore, cardiopulmonary clearance and a clear understanding of postoperative complications are very important.”

Previous studies have shown PHTN to be an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality in noncardiac procedures, said Ms. Patel, a fourth-year medical student at New Jersey Medical School, Newark. Furthermore, the rate of pulmonary complications is reported to be between 11% and 44.8% following radical head and neck cancer resection. “Despite these findings, there is currently a lack of information regarding perioperative morbidity and mortality of patients with PHTN undergoing major head and neck procedures,” she said.

The researchers queried the National Inpatient Survey from 2002 to 2013 for all cases of major head and neck surgery based on the ICD-9 codes for esophagectomy, glossectomy, laryngectomy, mandibulectomy, and pharyngectomy. They divided patients into two groups: those who had PHTN and those who did not, and performed demographic analyses as well as univariate and multivariate regression analyses.

Ms. Patel reported findings from a cohort of 46,311 patients. Of these, 46,073 had PHTN and 238 did not. The two groups were similar in age (a mean of 69 vs. 60 years in those with and without PHTN, respectively) and race (80% white vs. 79% white, respectively), but there were significantly fewer male patients in the PHTN group (57% vs. 70%; P less than .0001).

Several patient comorbidities were increased in the PHTN group, compared with the non-PHTN group, including coagulopathy (8.4% vs. 3.1%; P less than .0001), chronic heart failure (22.4% vs. 4.1%; P less than .0001), complicated diabetes (4.6% vs. 1.2%; P less than .0001), fluid and electrolyte disorders (30% vs. 18.3%; P less than .0001), and hypertension (63.3% vs. 43.7%; P less than .0001).

Postoperatively, patients with PHTN had a longer length of stay (a mean of 15.80 vs. 11.50 days, respectively; P less than .0001) as well as significantly higher total charges (a mean of $162,021.06 vs. $107,309.46, respectively; P less than .0001). When the researchers evaluated postoperative outcomes between the two cohorts, patients with PHTN had significantly higher rates of cardiac complications (9.2% vs. 3.5%; P less than .0001), iatrogenic pulmonary embolism (2.1% vs. 0.3%; P = .001), pulmonary edema (2.1% vs. 0.4%; P = .003), venous thrombotic events (4.6% vs. 1%; P less than. 0001), pulmonary insufficiency (17.2% vs. 9.7%; P less than .0001), and pneumonia (9.7% vs. 6%; P = .027), as well as higher rates of postoperative tracheostomy (8.4% vs. 4.5%; P = .007).

Multivariate analysis revealed that the following factors predicted in-hospital mortality: coagulopathy, chronic heart failure, fluid and electrolyte disorders, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, hypothyroidism, liver disease, obesity, paralysis, and renal failure. Despite these findings, there was no significant change in overall hospital mortality for those with PHTN, with an odds ratio of 1.055.

“Our study is not without its limitations, many of which are inherent to the use of a database, which is subject to errors in coding and sampling,” Ms. Patel noted at the meeting, which was jointly sponsored by the Triological Society and the American College of Surgeons. “Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable information on the impact of PHTN on major head and neck procedures.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Patel N et al. Triological CSM, Abstracts.

SAN DIEGO – Patients with , compared with their counterparts who do not have the condition. They also face an increase in total charges and length of stay.

The findings come from what is believed to be the first study of its kind to investigate the impact of pulmonary hypertension (PHTN) on major head and neck procedures. “PHTN is a common condition which affects the caliber of lung vasculature, with varied symptom presentation from shortness of breath to syncope, with an estimated prevalence of 2.5 to 7.1 million new cases each year worldwide,” one of the study authors, Nirali M. Patel, said at the Triological Society’s Combined Sections Meeting. “Due to improved therapeutic options, there is an enhanced survival of PHTN patients and higher prevalence of this disease. PHTN has some significant systemic implications. Therefore, cardiopulmonary clearance and a clear understanding of postoperative complications are very important.”

Previous studies have shown PHTN to be an independent predictor of morbidity and mortality in noncardiac procedures, said Ms. Patel, a fourth-year medical student at New Jersey Medical School, Newark. Furthermore, the rate of pulmonary complications is reported to be between 11% and 44.8% following radical head and neck cancer resection. “Despite these findings, there is currently a lack of information regarding perioperative morbidity and mortality of patients with PHTN undergoing major head and neck procedures,” she said.

The researchers queried the National Inpatient Survey from 2002 to 2013 for all cases of major head and neck surgery based on the ICD-9 codes for esophagectomy, glossectomy, laryngectomy, mandibulectomy, and pharyngectomy. They divided patients into two groups: those who had PHTN and those who did not, and performed demographic analyses as well as univariate and multivariate regression analyses.

Ms. Patel reported findings from a cohort of 46,311 patients. Of these, 46,073 had PHTN and 238 did not. The two groups were similar in age (a mean of 69 vs. 60 years in those with and without PHTN, respectively) and race (80% white vs. 79% white, respectively), but there were significantly fewer male patients in the PHTN group (57% vs. 70%; P less than .0001).

Several patient comorbidities were increased in the PHTN group, compared with the non-PHTN group, including coagulopathy (8.4% vs. 3.1%; P less than .0001), chronic heart failure (22.4% vs. 4.1%; P less than .0001), complicated diabetes (4.6% vs. 1.2%; P less than .0001), fluid and electrolyte disorders (30% vs. 18.3%; P less than .0001), and hypertension (63.3% vs. 43.7%; P less than .0001).

Postoperatively, patients with PHTN had a longer length of stay (a mean of 15.80 vs. 11.50 days, respectively; P less than .0001) as well as significantly higher total charges (a mean of $162,021.06 vs. $107,309.46, respectively; P less than .0001). When the researchers evaluated postoperative outcomes between the two cohorts, patients with PHTN had significantly higher rates of cardiac complications (9.2% vs. 3.5%; P less than .0001), iatrogenic pulmonary embolism (2.1% vs. 0.3%; P = .001), pulmonary edema (2.1% vs. 0.4%; P = .003), venous thrombotic events (4.6% vs. 1%; P less than. 0001), pulmonary insufficiency (17.2% vs. 9.7%; P less than .0001), and pneumonia (9.7% vs. 6%; P = .027), as well as higher rates of postoperative tracheostomy (8.4% vs. 4.5%; P = .007).

Multivariate analysis revealed that the following factors predicted in-hospital mortality: coagulopathy, chronic heart failure, fluid and electrolyte disorders, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, hypothyroidism, liver disease, obesity, paralysis, and renal failure. Despite these findings, there was no significant change in overall hospital mortality for those with PHTN, with an odds ratio of 1.055.

“Our study is not without its limitations, many of which are inherent to the use of a database, which is subject to errors in coding and sampling,” Ms. Patel noted at the meeting, which was jointly sponsored by the Triological Society and the American College of Surgeons. “Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable information on the impact of PHTN on major head and neck procedures.

She reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Patel N et al. Triological CSM, Abstracts.

REPORTING FROM THE TRIOLOGICAL CSM

Key clinical point: Pulmonary hypertension (PHTN) is linked with certain head and neck surgical complications.

Major finding: For patients undergoing head and neck surgery, PHTN is associated with an increased risk of cardiac complications (9.2% vs. 3.5%) and iatrogenic pulmonary embolism (2.1% vs. 0.3%).

Study details: A retrospective analysis of 46,311 patient records from the National Inpatient Survey.

Disclosures: The researchers reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Patel N et al. Triological CSM, Abstracts.

Guardian angel or watchdog? Pills of capecitabine contain sensors

Recently, a woman with advanced colorectal cancer at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, was taking capecitabine (Xeloda) in the morning but skipping her evening dose.

Her hands hurt, and she couldn’t open the childproof cap. Her daughter had been doing it for her in the morning but wasn’t around to help out at night.

It was the kind of problem that might have gone on for days or weeks until the next clinic visit, and, even then, be addressed only if the woman remembered to mention it.

But that’s not what happened. The care team realized pretty much right away that she was skipping the p.m. dose because the woman was taking her capecitabine in a gel cap with an adherence sensor.

The sensor, a sandwich of copper, silicon, and magnesium in a millimeter square, sent out an electric ping when she took her dose, activated by stomach acid; the ping was picked up by an adhesive bandage patch the woman wore, which relayed the signal to an app on her smartphone; the phone passed it on to a server cloud that the woman had given her providers permission to access.

They monitored her adherence on a Web portal, along with heart rate and activity data, also captured by the patch. The system is called Proteus Discover, from Proteus Digital Health.

Instead of taking days or weeks, the care team quickly realized that she wasn’t taking her evening dose of capecitabine. They contacted her, replaced the childproof cap, and twice-daily dosing resumed.

Expanded use in oncology?

Seven other advanced colorectal cancer patients have participated in the University of Minnesota (UM) pilot project, the first use of the device in oncology. “It’s gone so well that it’s annoying to me to not have this for all my patients. I’m already feeling frustrated that I can’t just put this in all the drugs that I give orally,” said Edward Greeno, MD, an oncologist/hematologist at the university, and the Proteus point man.

“You would assume that cancer patients would be hypercompliant, but it turns out they have the same compliance problems” as other patients, plus additional hurdles, he said, including complex regimens and drug toxicity.

“Every patient we have approached so far has been enthusiastic. They might be a little bit annoyed that I know they haven’t been taking their pills, but they are also glad that I am there to hold them responsible and help them. My intention is to roll this out much more broadly,” he said. That just might happen. Dr. Greeno is working with Proteus to roll the sensor out at UM and oncology programs elsewhere.

A slow, careful rollout

The device was cleared by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012. After more than 180,000 ingestions, there have been no safety issues, besides occasional skin irritation from the patch, which is waterproof and meant to be worn for a week, then replaced. It pings if it’s taken off. The sensor is passes through the body like food.

Patients can communicate with providers over the phone app, which also sends reminders when it’s time to take the next pill.

So far, Proteus has worked with ten health systems in the United States, and more are in the works. Commercialization efforts have focused mostly on blood pressure, cholesterol, and type 2 diabetes drugs, the bad boys of drug adherence, but the system has also been piloted for hepatitis C treatment, and trials are underway for HIV preexposure prophylaxis.

Among the company’s many favorable studies, the system has already been demonstrated to be a viable alternative to directly observed therapy in tuberculosis, the current gold-standard, but hugely labor and resource intensive (PLoS One. 2013;8[1]:e53373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053373).

Proteus can’t be picked up at the local Walgreens. The company works closely with clients and is being careful in its rollout. For one thing, each sensor has to be programed for the specific drug it’s being used with, but also, and as with any new technology, business and payment models are still being worked out.

UM’s partner in the oncology project, Fairview Health Services, pays Proteus when patients hit an adherence rate of 80%, but how much they pay is a proprietary secret. “Most of the cost issue is still not in the public domain,” said Scooter Plowman, MD, the company’s medical director.

In 2017, FDA approved a version of the antipsychotic aripiprazole embedded with the Proteus sensor. The rollout of “Abilify MyCite” by Otsuka Pharmaceuticals has been similarly cautious, under contract with health systems.

“Otsuka has been very smart in the approach they are taking,” Dr. Plowman said.

He wouldn’t give details, but Proteus is in talks with other pharmaceutical makers to bring pills with sensors to the market.

A new fix for an old problem

Proteus isn’t alone in the ingestible event marker (IEM) market. The FDA is reviewing a rival sensor from etectRx, in Gainesville, Fla.

The technology is a little different; the etectRx sensor is a microchip made out of magnesium and silver chloride that’s embedded on the inside of a gel cap. Instead of an electric blip, it sends out a radio wave when activated by stomach acid. It’s larger than the Proteus offering, but still has room to spare in a gel cap.

The signal is stronger, so patients wear a neck pendant instead of a patch to pick it up. The pendant does not capture heart rate or activity data. It’s not meant to be worn continuously and can come off after it pings the system.

The two systems are otherwise similar; etectRx also uses a phone app to relay adherence data to a server cloud clinicians can access, with patient permission. As with Proteus, everything works as long as the phone is on. President and CEO Harry Travis anticipates clearance in 2019.

Adherence is a huge and well-known problem in medicine; only about half of patients take medications as they are prescribed. People end up in the ED or the hospital with problems that might have been avoided. Providers and payers want solutions.

Industry is bringing technology to bear on the problem. The payoff will be huge for the winners; analysts project multiple billion dollar growth in the adherence technology sector.

Most companies, however, are pinning their hopes on indirect approaches, bottle caps that ping when opened, for instance, or coaching apps for smart phones. IEMs seem to be ahead of the curve.

Guardian angel or watchdog?

Whether that’s a good thing or bad thing depends on who you talk to, but patients do seem more likely to take their medications if a sensor is on board.

Dr. Plowman said he thinks IEMs improve adherence because, with their own health at stake, patients want to do better, and IEM systems provide the extra help they need, complete with positive feedback.

But patients also know they are being watched. The technology is barely off the ground, but concerns have already been raised about surveillance. It’s not hard to imagine insurance companies demanding proof of adherence before paying for expensive drugs. There are privacy concerns as well; everything is encrypted with IEMs, but hackers are clever.

Dr. Plowman and Mr. Travis acknowledged the concerns, and also that there’s no way to know how IEMs – if they take off – will play out in coming decades; it’s a lot like the Internet in 1992.

The intent is for the systems to remain voluntary, as they are now, perhaps with inducements for patients to use them, maybe lower insurance premiums.

“There is something inherently personal about swallowable data,” Dr. Plowman said. “It’s something we take tremendous efforts to protect.” As for compulsory use, “we take enormous strides to prevent that. It’s a major priority.”

“Always, there will be an opt-out” option, said Mr. Travis.

It’s important to consider the potential for IEMs to move medicine forward. When patients with acute bone fractures in one study, for instance, were sent home with the usual handful of oxycodone tablets, it turned out that they only took a median of six. Researchers knew that because the subjects took their oxycodone in an etectRx capsule. It’s was an important insight in the midst of an opioid epidemic (Anesth Analg. 2017 Dec;125[6]:2105-12).

Dr. Greeno is an adviser for Proteus; the company covers his travel costs.

Recently, a woman with advanced colorectal cancer at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, was taking capecitabine (Xeloda) in the morning but skipping her evening dose.

Her hands hurt, and she couldn’t open the childproof cap. Her daughter had been doing it for her in the morning but wasn’t around to help out at night.

It was the kind of problem that might have gone on for days or weeks until the next clinic visit, and, even then, be addressed only if the woman remembered to mention it.

But that’s not what happened. The care team realized pretty much right away that she was skipping the p.m. dose because the woman was taking her capecitabine in a gel cap with an adherence sensor.

The sensor, a sandwich of copper, silicon, and magnesium in a millimeter square, sent out an electric ping when she took her dose, activated by stomach acid; the ping was picked up by an adhesive bandage patch the woman wore, which relayed the signal to an app on her smartphone; the phone passed it on to a server cloud that the woman had given her providers permission to access.

They monitored her adherence on a Web portal, along with heart rate and activity data, also captured by the patch. The system is called Proteus Discover, from Proteus Digital Health.

Instead of taking days or weeks, the care team quickly realized that she wasn’t taking her evening dose of capecitabine. They contacted her, replaced the childproof cap, and twice-daily dosing resumed.

Expanded use in oncology?

Seven other advanced colorectal cancer patients have participated in the University of Minnesota (UM) pilot project, the first use of the device in oncology. “It’s gone so well that it’s annoying to me to not have this for all my patients. I’m already feeling frustrated that I can’t just put this in all the drugs that I give orally,” said Edward Greeno, MD, an oncologist/hematologist at the university, and the Proteus point man.

“You would assume that cancer patients would be hypercompliant, but it turns out they have the same compliance problems” as other patients, plus additional hurdles, he said, including complex regimens and drug toxicity.

“Every patient we have approached so far has been enthusiastic. They might be a little bit annoyed that I know they haven’t been taking their pills, but they are also glad that I am there to hold them responsible and help them. My intention is to roll this out much more broadly,” he said. That just might happen. Dr. Greeno is working with Proteus to roll the sensor out at UM and oncology programs elsewhere.

A slow, careful rollout

The device was cleared by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012. After more than 180,000 ingestions, there have been no safety issues, besides occasional skin irritation from the patch, which is waterproof and meant to be worn for a week, then replaced. It pings if it’s taken off. The sensor is passes through the body like food.

Patients can communicate with providers over the phone app, which also sends reminders when it’s time to take the next pill.

So far, Proteus has worked with ten health systems in the United States, and more are in the works. Commercialization efforts have focused mostly on blood pressure, cholesterol, and type 2 diabetes drugs, the bad boys of drug adherence, but the system has also been piloted for hepatitis C treatment, and trials are underway for HIV preexposure prophylaxis.

Among the company’s many favorable studies, the system has already been demonstrated to be a viable alternative to directly observed therapy in tuberculosis, the current gold-standard, but hugely labor and resource intensive (PLoS One. 2013;8[1]:e53373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053373).

Proteus can’t be picked up at the local Walgreens. The company works closely with clients and is being careful in its rollout. For one thing, each sensor has to be programed for the specific drug it’s being used with, but also, and as with any new technology, business and payment models are still being worked out.

UM’s partner in the oncology project, Fairview Health Services, pays Proteus when patients hit an adherence rate of 80%, but how much they pay is a proprietary secret. “Most of the cost issue is still not in the public domain,” said Scooter Plowman, MD, the company’s medical director.

In 2017, FDA approved a version of the antipsychotic aripiprazole embedded with the Proteus sensor. The rollout of “Abilify MyCite” by Otsuka Pharmaceuticals has been similarly cautious, under contract with health systems.

“Otsuka has been very smart in the approach they are taking,” Dr. Plowman said.

He wouldn’t give details, but Proteus is in talks with other pharmaceutical makers to bring pills with sensors to the market.

A new fix for an old problem

Proteus isn’t alone in the ingestible event marker (IEM) market. The FDA is reviewing a rival sensor from etectRx, in Gainesville, Fla.

The technology is a little different; the etectRx sensor is a microchip made out of magnesium and silver chloride that’s embedded on the inside of a gel cap. Instead of an electric blip, it sends out a radio wave when activated by stomach acid. It’s larger than the Proteus offering, but still has room to spare in a gel cap.

The signal is stronger, so patients wear a neck pendant instead of a patch to pick it up. The pendant does not capture heart rate or activity data. It’s not meant to be worn continuously and can come off after it pings the system.

The two systems are otherwise similar; etectRx also uses a phone app to relay adherence data to a server cloud clinicians can access, with patient permission. As with Proteus, everything works as long as the phone is on. President and CEO Harry Travis anticipates clearance in 2019.

Adherence is a huge and well-known problem in medicine; only about half of patients take medications as they are prescribed. People end up in the ED or the hospital with problems that might have been avoided. Providers and payers want solutions.

Industry is bringing technology to bear on the problem. The payoff will be huge for the winners; analysts project multiple billion dollar growth in the adherence technology sector.

Most companies, however, are pinning their hopes on indirect approaches, bottle caps that ping when opened, for instance, or coaching apps for smart phones. IEMs seem to be ahead of the curve.

Guardian angel or watchdog?

Whether that’s a good thing or bad thing depends on who you talk to, but patients do seem more likely to take their medications if a sensor is on board.

Dr. Plowman said he thinks IEMs improve adherence because, with their own health at stake, patients want to do better, and IEM systems provide the extra help they need, complete with positive feedback.

But patients also know they are being watched. The technology is barely off the ground, but concerns have already been raised about surveillance. It’s not hard to imagine insurance companies demanding proof of adherence before paying for expensive drugs. There are privacy concerns as well; everything is encrypted with IEMs, but hackers are clever.

Dr. Plowman and Mr. Travis acknowledged the concerns, and also that there’s no way to know how IEMs – if they take off – will play out in coming decades; it’s a lot like the Internet in 1992.

The intent is for the systems to remain voluntary, as they are now, perhaps with inducements for patients to use them, maybe lower insurance premiums.

“There is something inherently personal about swallowable data,” Dr. Plowman said. “It’s something we take tremendous efforts to protect.” As for compulsory use, “we take enormous strides to prevent that. It’s a major priority.”

“Always, there will be an opt-out” option, said Mr. Travis.

It’s important to consider the potential for IEMs to move medicine forward. When patients with acute bone fractures in one study, for instance, were sent home with the usual handful of oxycodone tablets, it turned out that they only took a median of six. Researchers knew that because the subjects took their oxycodone in an etectRx capsule. It’s was an important insight in the midst of an opioid epidemic (Anesth Analg. 2017 Dec;125[6]:2105-12).

Dr. Greeno is an adviser for Proteus; the company covers his travel costs.

Recently, a woman with advanced colorectal cancer at the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, was taking capecitabine (Xeloda) in the morning but skipping her evening dose.

Her hands hurt, and she couldn’t open the childproof cap. Her daughter had been doing it for her in the morning but wasn’t around to help out at night.

It was the kind of problem that might have gone on for days or weeks until the next clinic visit, and, even then, be addressed only if the woman remembered to mention it.

But that’s not what happened. The care team realized pretty much right away that she was skipping the p.m. dose because the woman was taking her capecitabine in a gel cap with an adherence sensor.

The sensor, a sandwich of copper, silicon, and magnesium in a millimeter square, sent out an electric ping when she took her dose, activated by stomach acid; the ping was picked up by an adhesive bandage patch the woman wore, which relayed the signal to an app on her smartphone; the phone passed it on to a server cloud that the woman had given her providers permission to access.

They monitored her adherence on a Web portal, along with heart rate and activity data, also captured by the patch. The system is called Proteus Discover, from Proteus Digital Health.

Instead of taking days or weeks, the care team quickly realized that she wasn’t taking her evening dose of capecitabine. They contacted her, replaced the childproof cap, and twice-daily dosing resumed.

Expanded use in oncology?

Seven other advanced colorectal cancer patients have participated in the University of Minnesota (UM) pilot project, the first use of the device in oncology. “It’s gone so well that it’s annoying to me to not have this for all my patients. I’m already feeling frustrated that I can’t just put this in all the drugs that I give orally,” said Edward Greeno, MD, an oncologist/hematologist at the university, and the Proteus point man.

“You would assume that cancer patients would be hypercompliant, but it turns out they have the same compliance problems” as other patients, plus additional hurdles, he said, including complex regimens and drug toxicity.

“Every patient we have approached so far has been enthusiastic. They might be a little bit annoyed that I know they haven’t been taking their pills, but they are also glad that I am there to hold them responsible and help them. My intention is to roll this out much more broadly,” he said. That just might happen. Dr. Greeno is working with Proteus to roll the sensor out at UM and oncology programs elsewhere.

A slow, careful rollout

The device was cleared by the Food and Drug Administration in 2012. After more than 180,000 ingestions, there have been no safety issues, besides occasional skin irritation from the patch, which is waterproof and meant to be worn for a week, then replaced. It pings if it’s taken off. The sensor is passes through the body like food.

Patients can communicate with providers over the phone app, which also sends reminders when it’s time to take the next pill.

So far, Proteus has worked with ten health systems in the United States, and more are in the works. Commercialization efforts have focused mostly on blood pressure, cholesterol, and type 2 diabetes drugs, the bad boys of drug adherence, but the system has also been piloted for hepatitis C treatment, and trials are underway for HIV preexposure prophylaxis.

Among the company’s many favorable studies, the system has already been demonstrated to be a viable alternative to directly observed therapy in tuberculosis, the current gold-standard, but hugely labor and resource intensive (PLoS One. 2013;8[1]:e53373. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053373).

Proteus can’t be picked up at the local Walgreens. The company works closely with clients and is being careful in its rollout. For one thing, each sensor has to be programed for the specific drug it’s being used with, but also, and as with any new technology, business and payment models are still being worked out.

UM’s partner in the oncology project, Fairview Health Services, pays Proteus when patients hit an adherence rate of 80%, but how much they pay is a proprietary secret. “Most of the cost issue is still not in the public domain,” said Scooter Plowman, MD, the company’s medical director.

In 2017, FDA approved a version of the antipsychotic aripiprazole embedded with the Proteus sensor. The rollout of “Abilify MyCite” by Otsuka Pharmaceuticals has been similarly cautious, under contract with health systems.

“Otsuka has been very smart in the approach they are taking,” Dr. Plowman said.

He wouldn’t give details, but Proteus is in talks with other pharmaceutical makers to bring pills with sensors to the market.

A new fix for an old problem

Proteus isn’t alone in the ingestible event marker (IEM) market. The FDA is reviewing a rival sensor from etectRx, in Gainesville, Fla.

The technology is a little different; the etectRx sensor is a microchip made out of magnesium and silver chloride that’s embedded on the inside of a gel cap. Instead of an electric blip, it sends out a radio wave when activated by stomach acid. It’s larger than the Proteus offering, but still has room to spare in a gel cap.

The signal is stronger, so patients wear a neck pendant instead of a patch to pick it up. The pendant does not capture heart rate or activity data. It’s not meant to be worn continuously and can come off after it pings the system.

The two systems are otherwise similar; etectRx also uses a phone app to relay adherence data to a server cloud clinicians can access, with patient permission. As with Proteus, everything works as long as the phone is on. President and CEO Harry Travis anticipates clearance in 2019.

Adherence is a huge and well-known problem in medicine; only about half of patients take medications as they are prescribed. People end up in the ED or the hospital with problems that might have been avoided. Providers and payers want solutions.

Industry is bringing technology to bear on the problem. The payoff will be huge for the winners; analysts project multiple billion dollar growth in the adherence technology sector.

Most companies, however, are pinning their hopes on indirect approaches, bottle caps that ping when opened, for instance, or coaching apps for smart phones. IEMs seem to be ahead of the curve.

Guardian angel or watchdog?

Whether that’s a good thing or bad thing depends on who you talk to, but patients do seem more likely to take their medications if a sensor is on board.

Dr. Plowman said he thinks IEMs improve adherence because, with their own health at stake, patients want to do better, and IEM systems provide the extra help they need, complete with positive feedback.

But patients also know they are being watched. The technology is barely off the ground, but concerns have already been raised about surveillance. It’s not hard to imagine insurance companies demanding proof of adherence before paying for expensive drugs. There are privacy concerns as well; everything is encrypted with IEMs, but hackers are clever.

Dr. Plowman and Mr. Travis acknowledged the concerns, and also that there’s no way to know how IEMs – if they take off – will play out in coming decades; it’s a lot like the Internet in 1992.

The intent is for the systems to remain voluntary, as they are now, perhaps with inducements for patients to use them, maybe lower insurance premiums.

“There is something inherently personal about swallowable data,” Dr. Plowman said. “It’s something we take tremendous efforts to protect.” As for compulsory use, “we take enormous strides to prevent that. It’s a major priority.”

“Always, there will be an opt-out” option, said Mr. Travis.

It’s important to consider the potential for IEMs to move medicine forward. When patients with acute bone fractures in one study, for instance, were sent home with the usual handful of oxycodone tablets, it turned out that they only took a median of six. Researchers knew that because the subjects took their oxycodone in an etectRx capsule. It’s was an important insight in the midst of an opioid epidemic (Anesth Analg. 2017 Dec;125[6]:2105-12).

Dr. Greeno is an adviser for Proteus; the company covers his travel costs.

Penicillin allergy

A 75-year-old man presents with fever, chills, and facial pain. He had an upper respiratory infection 3 weeks ago and has had persistent sinus drainage since. He has tried nasal irrigation and nasal steroids without improvement.

Over the past 5 days, he has had thicker postnasal drip, the development of facial pain, and today fevers as high as 102 degrees. He has a history of giant cell arteritis, for which he takes 30 mg of prednisone daily; coronary artery disease; and hypertension. He has a penicillin allergy (rash on chest, back, and arms 25 years ago). Exam reveals temperature of 101.5 and tenderness over left maxillary sinus.

What treatment do you recommend?

A. Amoxicillin/clavulanate.

B. Cefpodoxime.

C. Levofloxacin.

D. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

I think cefpodoxime is probably the best of these choices to treat sinusitis in this patient. Choosing amoxicillin /clavulanate is an option only if you could give the patient a test dose in a controlled setting. I think giving this patient levofloxacin poses greater risk than a penicillin rechallenge. This patient is elderly and on prednisone, both of which increase his risk of tendon rupture if given a quinolone. Also, the Food and Drug Administration released a warning recently regarding increased risk of aortic disease in patients with cardiovascular risk factors who receive fluoroquinolones.1

Merin Kuruvilla, MD, and colleagues described oral amoxicillin challenge for patients with a history of low-risk penicillin allergy (described as benign rash, benign somatic symptoms, or unknown history with penicillin exposure more than 12 months prior).2 The study was done in a single allergy practice where 38 of 50 patients with penicillin allergy histories qualified for the study. Of the 38 eligible patients, 20 consented to oral rechallenge in clinic, and none of them developed immediate or delayed hypersensitivity reactions.

Melissa Iammatteo, MD, et al. studied 155 patients with a history of non–life-threatening penicillin reactions.3 Study participants received placebo followed by a two-step graded challenge to amoxicillin. No reaction occurred in 77% of patients, while 20% of patients had nonallergic reactions, which were equal between placebo and amoxicillin. Only 2.6 % had allergic reactions, all of which were classified as mild.

Reported penicillin allergy occurs in about 10% of community patients, but 90% of these patients can tolerate penicillins.4 Patients reporting a penicillin allergy have increased risk for drug resistance and prolonged hospital stays.5

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology recommended more widespread and routine performance of penicillin allergy testing in patients with a history of allergy to penicillin or other beta-lactam antibiotics.6 Patients who have penicillin allergy histories are more likely to receive drugs, such as clindamycin or a fluoroquinolone, that may carry much greater risks than a beta-lactam antibiotic. It also leads to more vancomycin use, which increases risk of vancomycin resistance.

Allergic reactions to cephalosporins are very infrequent in patients with a penicillin allergy. Eric Macy, MD, and colleagues studied all members of Kaiser Permanente Southern California health plan who had received cephalosporins over a 2-year period.7 More than 275,000 courses were given to patients with penicillin allergy, with only about 1% having an allergic reaction and only three cases of anaphylaxis.

Pearl: Most patients with a history of penicillin allergy will tolerate penicillins and cephalosporins. Penicillin allergy testing should be done to assess if they have a penicillin allergy, and in low-risk patients (patients who do not recall the allergy or had a maculopapular rash), consideration for oral rechallenge in a controlled setting may be an option. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Food and Drug Administration. “FDA warns about increased risk of ruptures or tears in the aorta blood vessel with fluoroquinolone antibiotics in certain patients,” 2018 Dec 20.

2. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018 Nov;121(5):627-8.

3. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019 Jan;7(1):236-43.

4. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017 Nov;37(4):643-62.

5. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Mar;133(3):790-6.

6. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017 Mar - Apr;5(2):333-4.

7. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Mar;135(3):745-52.e5.

A 75-year-old man presents with fever, chills, and facial pain. He had an upper respiratory infection 3 weeks ago and has had persistent sinus drainage since. He has tried nasal irrigation and nasal steroids without improvement.

Over the past 5 days, he has had thicker postnasal drip, the development of facial pain, and today fevers as high as 102 degrees. He has a history of giant cell arteritis, for which he takes 30 mg of prednisone daily; coronary artery disease; and hypertension. He has a penicillin allergy (rash on chest, back, and arms 25 years ago). Exam reveals temperature of 101.5 and tenderness over left maxillary sinus.

What treatment do you recommend?

A. Amoxicillin/clavulanate.

B. Cefpodoxime.

C. Levofloxacin.

D. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

I think cefpodoxime is probably the best of these choices to treat sinusitis in this patient. Choosing amoxicillin /clavulanate is an option only if you could give the patient a test dose in a controlled setting. I think giving this patient levofloxacin poses greater risk than a penicillin rechallenge. This patient is elderly and on prednisone, both of which increase his risk of tendon rupture if given a quinolone. Also, the Food and Drug Administration released a warning recently regarding increased risk of aortic disease in patients with cardiovascular risk factors who receive fluoroquinolones.1

Merin Kuruvilla, MD, and colleagues described oral amoxicillin challenge for patients with a history of low-risk penicillin allergy (described as benign rash, benign somatic symptoms, or unknown history with penicillin exposure more than 12 months prior).2 The study was done in a single allergy practice where 38 of 50 patients with penicillin allergy histories qualified for the study. Of the 38 eligible patients, 20 consented to oral rechallenge in clinic, and none of them developed immediate or delayed hypersensitivity reactions.

Melissa Iammatteo, MD, et al. studied 155 patients with a history of non–life-threatening penicillin reactions.3 Study participants received placebo followed by a two-step graded challenge to amoxicillin. No reaction occurred in 77% of patients, while 20% of patients had nonallergic reactions, which were equal between placebo and amoxicillin. Only 2.6 % had allergic reactions, all of which were classified as mild.

Reported penicillin allergy occurs in about 10% of community patients, but 90% of these patients can tolerate penicillins.4 Patients reporting a penicillin allergy have increased risk for drug resistance and prolonged hospital stays.5

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology recommended more widespread and routine performance of penicillin allergy testing in patients with a history of allergy to penicillin or other beta-lactam antibiotics.6 Patients who have penicillin allergy histories are more likely to receive drugs, such as clindamycin or a fluoroquinolone, that may carry much greater risks than a beta-lactam antibiotic. It also leads to more vancomycin use, which increases risk of vancomycin resistance.

Allergic reactions to cephalosporins are very infrequent in patients with a penicillin allergy. Eric Macy, MD, and colleagues studied all members of Kaiser Permanente Southern California health plan who had received cephalosporins over a 2-year period.7 More than 275,000 courses were given to patients with penicillin allergy, with only about 1% having an allergic reaction and only three cases of anaphylaxis.

Pearl: Most patients with a history of penicillin allergy will tolerate penicillins and cephalosporins. Penicillin allergy testing should be done to assess if they have a penicillin allergy, and in low-risk patients (patients who do not recall the allergy or had a maculopapular rash), consideration for oral rechallenge in a controlled setting may be an option. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Food and Drug Administration. “FDA warns about increased risk of ruptures or tears in the aorta blood vessel with fluoroquinolone antibiotics in certain patients,” 2018 Dec 20.

2. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018 Nov;121(5):627-8.

3. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019 Jan;7(1):236-43.

4. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017 Nov;37(4):643-62.

5. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Mar;133(3):790-6.

6. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017 Mar - Apr;5(2):333-4.

7. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Mar;135(3):745-52.e5.

A 75-year-old man presents with fever, chills, and facial pain. He had an upper respiratory infection 3 weeks ago and has had persistent sinus drainage since. He has tried nasal irrigation and nasal steroids without improvement.

Over the past 5 days, he has had thicker postnasal drip, the development of facial pain, and today fevers as high as 102 degrees. He has a history of giant cell arteritis, for which he takes 30 mg of prednisone daily; coronary artery disease; and hypertension. He has a penicillin allergy (rash on chest, back, and arms 25 years ago). Exam reveals temperature of 101.5 and tenderness over left maxillary sinus.

What treatment do you recommend?

A. Amoxicillin/clavulanate.

B. Cefpodoxime.

C. Levofloxacin.

D. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole.

I think cefpodoxime is probably the best of these choices to treat sinusitis in this patient. Choosing amoxicillin /clavulanate is an option only if you could give the patient a test dose in a controlled setting. I think giving this patient levofloxacin poses greater risk than a penicillin rechallenge. This patient is elderly and on prednisone, both of which increase his risk of tendon rupture if given a quinolone. Also, the Food and Drug Administration released a warning recently regarding increased risk of aortic disease in patients with cardiovascular risk factors who receive fluoroquinolones.1

Merin Kuruvilla, MD, and colleagues described oral amoxicillin challenge for patients with a history of low-risk penicillin allergy (described as benign rash, benign somatic symptoms, or unknown history with penicillin exposure more than 12 months prior).2 The study was done in a single allergy practice where 38 of 50 patients with penicillin allergy histories qualified for the study. Of the 38 eligible patients, 20 consented to oral rechallenge in clinic, and none of them developed immediate or delayed hypersensitivity reactions.

Melissa Iammatteo, MD, et al. studied 155 patients with a history of non–life-threatening penicillin reactions.3 Study participants received placebo followed by a two-step graded challenge to amoxicillin. No reaction occurred in 77% of patients, while 20% of patients had nonallergic reactions, which were equal between placebo and amoxicillin. Only 2.6 % had allergic reactions, all of which were classified as mild.

Reported penicillin allergy occurs in about 10% of community patients, but 90% of these patients can tolerate penicillins.4 Patients reporting a penicillin allergy have increased risk for drug resistance and prolonged hospital stays.5

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology recommended more widespread and routine performance of penicillin allergy testing in patients with a history of allergy to penicillin or other beta-lactam antibiotics.6 Patients who have penicillin allergy histories are more likely to receive drugs, such as clindamycin or a fluoroquinolone, that may carry much greater risks than a beta-lactam antibiotic. It also leads to more vancomycin use, which increases risk of vancomycin resistance.

Allergic reactions to cephalosporins are very infrequent in patients with a penicillin allergy. Eric Macy, MD, and colleagues studied all members of Kaiser Permanente Southern California health plan who had received cephalosporins over a 2-year period.7 More than 275,000 courses were given to patients with penicillin allergy, with only about 1% having an allergic reaction and only three cases of anaphylaxis.

Pearl: Most patients with a history of penicillin allergy will tolerate penicillins and cephalosporins. Penicillin allergy testing should be done to assess if they have a penicillin allergy, and in low-risk patients (patients who do not recall the allergy or had a maculopapular rash), consideration for oral rechallenge in a controlled setting may be an option. Dr. Paauw is professor of medicine in the division of general internal medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, and serves as third-year medical student clerkship director at the University of Washington. Contact Dr. Paauw at [email protected].

References

1. Food and Drug Administration. “FDA warns about increased risk of ruptures or tears in the aorta blood vessel with fluoroquinolone antibiotics in certain patients,” 2018 Dec 20.

2. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018 Nov;121(5):627-8.

3. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019 Jan;7(1):236-43.

4. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2017 Nov;37(4):643-62.

5. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Mar;133(3):790-6.

6. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017 Mar - Apr;5(2):333-4.

7. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Mar;135(3):745-52.e5.

The personal cancer vaccine NEO-PV-01 shows promise in metastatic cancers

WASHINGTON – according to findings from the ongoing phase 1b NT-001study of patients with metastatic melanoma, smoking-associated non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and bladder cancer.

No vaccine-related serious adverse events occurred in 34 patients in a per-protocol set who were treated with the regimen, Siwen Hu-Lieskovan, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.

“We found that NEO-PV-01 in combination with nivolumab was very safe; we did not see any grade 3 to grade 4 toxicity associated with the combination,” said Dr. Hu-Lieskovan, a medical oncologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Most adverse events that occurred were mild and related to the local injection, she noted.

Although safety was the primary endpoint of the study, Dr. Hu-Lieskovan and her colleagues also looked at immune responses and treatment efficacy, however, with respect to translational data her presentation addressed only the findings in the melanoma and lung cancer patients.

All patients exhibited an immune response to the vaccine, with 56% of the epitopes generating CD4- and/or CD8-positive T cell responses.

“These immune responses were very durable and still could be detected 52 weeks into the treatment,” she said. Additionally, epitope spreading – increased immune response targeting nonvaccine epitopes (which is indirect evidence of vaccine-induced tumor toxicity) – was observed in 8 of 10 patients tested.

The study subjects, including 16 adults with melanoma, 11 with NSCLC, and 7 with bladder cancer, were treated with nivolumab every 2 weeks for 12 weeks prior to vaccination (while their personalized vaccine was being developed). NEO-PV-01 – which included up to 20 unique peptides plus the immunostimulant poly-ICLC – was then administered subcutaneously in five priming doses followed by two booster doses over the next 12 weeks. Of note, very few patients had programmed cell death protein 1 expression of 50% or greater, including only 13.3%, 28.6%, and 0% of the melanoma, NSCLC, and bladder cancer patients, respectively, and tumor mutation burden was consistent with published reports, she said.

As for efficacy, 11 of 16 melanoma patients (68.6%) had either a partial response (8 pre vaccination and an additional 3 post vaccination) or stable disease. One (6.3%) had a postvaccination complete response, Dr. Hu-Lieskovan said.

“[This is] much better than the historical data,” she noted, adding that 12 patients (75%) are still on the study and continuing treatment with response duration of at least 39.7 weeks.

Of the 11 NSCLC patients, 5 (45.5%) had a partial response (3 pre vaccination and 2 post vaccination), and none had a complete response. Seven (63.6%) remained on the study and were continuing treatment, and response duration was at least 30.6 weeks.

An exploratory analysis of tumor responses after vaccination showed that the majority of melanoma patients and half of the lung cancer patients had further tumor shrinkage after vaccination, and some patients were converted to responders. Most – including some with stable or progressive disease – stayed on treatment, she said.

The findings demonstrate that NEO-PV-01 is very well tolerated and associated with post vaccine responses observed after week 24.

“We saw evidence of vaccination-induced immune response specific to the injected vaccine, as well as epitope spreading, and the T cells induced by these neoantigens can traffic into the tumor and they seem to be functional,” she concluded.

Dr. Hu-Lieskovan reported receiving consulting fees and/or research support from Amgen, BMS, Genmab, Merck, and Vaccinex. She is the UCLA site principal investigator for the NT-001 study and has conducted contracted research for Astellas, F Star, Genentech, Nektar Therapeutics, Neon Therapeutics, Pfizer, Plexxikon, and Xencor.

SOURCE: Hu-Lieskovan S et al. SITC 2018, Abstract 07.

WASHINGTON – according to findings from the ongoing phase 1b NT-001study of patients with metastatic melanoma, smoking-associated non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and bladder cancer.

No vaccine-related serious adverse events occurred in 34 patients in a per-protocol set who were treated with the regimen, Siwen Hu-Lieskovan, MD, PhD, reported at the annual meeting of the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer.