User login

Expert: There’s no single treatment for fibromyalgia

SAN DIEGO – There are many potential treatments for fibromyalgia, but a large number of them – NSAIDs, opioids, cannabis and more – come with caveats and nothing beats an old stand-by: physical rehabilitation.

With exercise, “we’re getting the muscles moving, and we’re getting [patients] used to stimulation that will hopefully deaden that pain response over time,” David E.J. Bazzo, MD, said at Pain Care for Primary Care. Still, “it’s going to take multiple things to best treat your patients.”

Fibromyalgia is unique, said Dr. Bazzo, professor of family medicine and public health at the University of California, San Diego. Diagnosis is based on self-reported symptoms since no laboratory tests are available. For diagnostic criteria, he recommends those released by the American College of Rheumatology in 2010 and 2011 and updated in 2016. The criteria, he said, recognize the importance of cognitive symptoms, unrefreshing sleep, fatigue, and certain somatic symptoms (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46[3]:319-29).

Poor sleep is an especially important problem in fibromyalgia, Dr. Bazzo said, although it’s “a bit of a chicken-and-egg discussion.” It’s not clear which comes first, but “we know that both happen hand-in-hand. We need to work on people’s sleep as one of the primary targets.”

When it comes to treatment, “you have to validate this person’s symptoms and say, ‘Yes, I believe you. I know that you are suffering, and that you’re having pain,’ ” Dr. Bazzo said at the meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. He advised clinicians to keep in mind conditions that can accompany fibromyalgia, such as depression, that may require other treatment options.

Dr. Bazzo offered advice about these approaches to treatment:

- Exercise. Research supports treadmill and cycle ergometry (BMJ 2002;325:185).

- Opioids. “There’s no convincing evidence that opioids have a role in treating fibromyalgia initially. If you’ve tried everything and patients have had problems, are just not responsive or had side effects, you could consider opioids. But that should be at the tail end of everything because the data is not there,” he said.

- Tramadol. “It’s like an opioid with potential for addiction,” he said. “Don’t just use it willy-nilly. Make sure you have a reason and a good plan. Would it be my first thing? No. Is it something that I keep in my back pocket when other things aren’t working? Perhaps. Would I use it before an opioid? For sure.”

- Second-line therapies. According to Dr. Bazzo, these include antiepileptics such as gabapentin and pregabalin, low-dose cyclobenzaprine, and dual reuptake inhibitors such as duloxetine. There are many other second-line options, he said, from behavioral approaches to yoga to guided physical therapy.

- NSAIDs. Not helpful.

- Cannabis. May interact with other medications.

- Pain clinics. Make sure you refer patients to a pain clinic that embraces a multidisciplinary approach, he said, not one that only offers “pain pills or shots.”

Dr. Bazzo reported no relevant conflicts of interest. The Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

SAN DIEGO – There are many potential treatments for fibromyalgia, but a large number of them – NSAIDs, opioids, cannabis and more – come with caveats and nothing beats an old stand-by: physical rehabilitation.

With exercise, “we’re getting the muscles moving, and we’re getting [patients] used to stimulation that will hopefully deaden that pain response over time,” David E.J. Bazzo, MD, said at Pain Care for Primary Care. Still, “it’s going to take multiple things to best treat your patients.”

Fibromyalgia is unique, said Dr. Bazzo, professor of family medicine and public health at the University of California, San Diego. Diagnosis is based on self-reported symptoms since no laboratory tests are available. For diagnostic criteria, he recommends those released by the American College of Rheumatology in 2010 and 2011 and updated in 2016. The criteria, he said, recognize the importance of cognitive symptoms, unrefreshing sleep, fatigue, and certain somatic symptoms (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46[3]:319-29).

Poor sleep is an especially important problem in fibromyalgia, Dr. Bazzo said, although it’s “a bit of a chicken-and-egg discussion.” It’s not clear which comes first, but “we know that both happen hand-in-hand. We need to work on people’s sleep as one of the primary targets.”

When it comes to treatment, “you have to validate this person’s symptoms and say, ‘Yes, I believe you. I know that you are suffering, and that you’re having pain,’ ” Dr. Bazzo said at the meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. He advised clinicians to keep in mind conditions that can accompany fibromyalgia, such as depression, that may require other treatment options.

Dr. Bazzo offered advice about these approaches to treatment:

- Exercise. Research supports treadmill and cycle ergometry (BMJ 2002;325:185).

- Opioids. “There’s no convincing evidence that opioids have a role in treating fibromyalgia initially. If you’ve tried everything and patients have had problems, are just not responsive or had side effects, you could consider opioids. But that should be at the tail end of everything because the data is not there,” he said.

- Tramadol. “It’s like an opioid with potential for addiction,” he said. “Don’t just use it willy-nilly. Make sure you have a reason and a good plan. Would it be my first thing? No. Is it something that I keep in my back pocket when other things aren’t working? Perhaps. Would I use it before an opioid? For sure.”

- Second-line therapies. According to Dr. Bazzo, these include antiepileptics such as gabapentin and pregabalin, low-dose cyclobenzaprine, and dual reuptake inhibitors such as duloxetine. There are many other second-line options, he said, from behavioral approaches to yoga to guided physical therapy.

- NSAIDs. Not helpful.

- Cannabis. May interact with other medications.

- Pain clinics. Make sure you refer patients to a pain clinic that embraces a multidisciplinary approach, he said, not one that only offers “pain pills or shots.”

Dr. Bazzo reported no relevant conflicts of interest. The Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

SAN DIEGO – There are many potential treatments for fibromyalgia, but a large number of them – NSAIDs, opioids, cannabis and more – come with caveats and nothing beats an old stand-by: physical rehabilitation.

With exercise, “we’re getting the muscles moving, and we’re getting [patients] used to stimulation that will hopefully deaden that pain response over time,” David E.J. Bazzo, MD, said at Pain Care for Primary Care. Still, “it’s going to take multiple things to best treat your patients.”

Fibromyalgia is unique, said Dr. Bazzo, professor of family medicine and public health at the University of California, San Diego. Diagnosis is based on self-reported symptoms since no laboratory tests are available. For diagnostic criteria, he recommends those released by the American College of Rheumatology in 2010 and 2011 and updated in 2016. The criteria, he said, recognize the importance of cognitive symptoms, unrefreshing sleep, fatigue, and certain somatic symptoms (Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;46[3]:319-29).

Poor sleep is an especially important problem in fibromyalgia, Dr. Bazzo said, although it’s “a bit of a chicken-and-egg discussion.” It’s not clear which comes first, but “we know that both happen hand-in-hand. We need to work on people’s sleep as one of the primary targets.”

When it comes to treatment, “you have to validate this person’s symptoms and say, ‘Yes, I believe you. I know that you are suffering, and that you’re having pain,’ ” Dr. Bazzo said at the meeting held by the American Pain Society and Global Academy for Medical Education. He advised clinicians to keep in mind conditions that can accompany fibromyalgia, such as depression, that may require other treatment options.

Dr. Bazzo offered advice about these approaches to treatment:

- Exercise. Research supports treadmill and cycle ergometry (BMJ 2002;325:185).

- Opioids. “There’s no convincing evidence that opioids have a role in treating fibromyalgia initially. If you’ve tried everything and patients have had problems, are just not responsive or had side effects, you could consider opioids. But that should be at the tail end of everything because the data is not there,” he said.

- Tramadol. “It’s like an opioid with potential for addiction,” he said. “Don’t just use it willy-nilly. Make sure you have a reason and a good plan. Would it be my first thing? No. Is it something that I keep in my back pocket when other things aren’t working? Perhaps. Would I use it before an opioid? For sure.”

- Second-line therapies. According to Dr. Bazzo, these include antiepileptics such as gabapentin and pregabalin, low-dose cyclobenzaprine, and dual reuptake inhibitors such as duloxetine. There are many other second-line options, he said, from behavioral approaches to yoga to guided physical therapy.

- NSAIDs. Not helpful.

- Cannabis. May interact with other medications.

- Pain clinics. Make sure you refer patients to a pain clinic that embraces a multidisciplinary approach, he said, not one that only offers “pain pills or shots.”

Dr. Bazzo reported no relevant conflicts of interest. The Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PAIN CARE FOR PRIMARY CARE

Shifting drugs from Part B to Part D could be costly to patients

A shift in Medicare drug coverage from Part B to Part D might save the government some money but could end up costing some patients in the long run.

Analysis of the 75 brand-name drugs with the highest Part B expenditures ($21.6 billion annually at 2018 prices) indicated that the government could save between $17.6 billion and $20.1 billion after rebates by switching coverage to Part D, Thomas J. Hwang of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates said.

The potential for greater overall savings, however, “was constrained by the fact that 33 (44%) of the studied brand-name drugs were in protected classes, which HHS has reported precludes meaningful price negotiation by Part D plans,” they wrote.

The proposal also could have a “material impact” on patient out-of-pocket costs, although the impact would vary based on the drug as well as patients’ insurance coverage in addition to Medicare (JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417).

For example, moving drug coverage to Part D would lower out-of-pocket costs for the majority of the 75 drugs for patients with Medigap supplemental insurance, but out-of-pocket costs could go up for almost 40% of products. Patients who would benefit most from the shift would be those who qualify for the low-income subsidy, which can eliminate coinsurance requirements.

“By contrast, for patients with Medigap insurance, out-of-pocket costs in Part D were estimated to exceed the annual premium costs for supplemental insurance [approximately 47-56 of the 75 drugs],” Mr. Hwang and his colleagues added. “Out-of-pocket costs would be increased under the proposed policy for beneficiaries with Medigap but without Part D coverage.”

The analysis was limited by the inability to predict the proposed transition’s impact on insurance premiums or drug utilization. Patients who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid were excluded.

SOURCE: Hwang TJ et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417.

Policy analysts need to be careful and do their due diligence to ensure all consequences of the policy options are fully understood, especially as pharmaceuticals account for greater costs in the Medicare program. Future policy analyses must, like Mr. Hwang and his associates did, account for changes to Medicare costs as well as beneficiary costs to understand the overall effects of policy changes.

Francis Crosson, MD, chairman of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, and Jon Christianson, PhD, vice chairman of MedPAC, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Int Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6146 ).

Policy analysts need to be careful and do their due diligence to ensure all consequences of the policy options are fully understood, especially as pharmaceuticals account for greater costs in the Medicare program. Future policy analyses must, like Mr. Hwang and his associates did, account for changes to Medicare costs as well as beneficiary costs to understand the overall effects of policy changes.

Francis Crosson, MD, chairman of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, and Jon Christianson, PhD, vice chairman of MedPAC, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Int Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6146 ).

Policy analysts need to be careful and do their due diligence to ensure all consequences of the policy options are fully understood, especially as pharmaceuticals account for greater costs in the Medicare program. Future policy analyses must, like Mr. Hwang and his associates did, account for changes to Medicare costs as well as beneficiary costs to understand the overall effects of policy changes.

Francis Crosson, MD, chairman of the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, and Jon Christianson, PhD, vice chairman of MedPAC, made these comments in an accompanying editorial (JAMA Int Med. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6146 ).

A shift in Medicare drug coverage from Part B to Part D might save the government some money but could end up costing some patients in the long run.

Analysis of the 75 brand-name drugs with the highest Part B expenditures ($21.6 billion annually at 2018 prices) indicated that the government could save between $17.6 billion and $20.1 billion after rebates by switching coverage to Part D, Thomas J. Hwang of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates said.

The potential for greater overall savings, however, “was constrained by the fact that 33 (44%) of the studied brand-name drugs were in protected classes, which HHS has reported precludes meaningful price negotiation by Part D plans,” they wrote.

The proposal also could have a “material impact” on patient out-of-pocket costs, although the impact would vary based on the drug as well as patients’ insurance coverage in addition to Medicare (JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417).

For example, moving drug coverage to Part D would lower out-of-pocket costs for the majority of the 75 drugs for patients with Medigap supplemental insurance, but out-of-pocket costs could go up for almost 40% of products. Patients who would benefit most from the shift would be those who qualify for the low-income subsidy, which can eliminate coinsurance requirements.

“By contrast, for patients with Medigap insurance, out-of-pocket costs in Part D were estimated to exceed the annual premium costs for supplemental insurance [approximately 47-56 of the 75 drugs],” Mr. Hwang and his colleagues added. “Out-of-pocket costs would be increased under the proposed policy for beneficiaries with Medigap but without Part D coverage.”

The analysis was limited by the inability to predict the proposed transition’s impact on insurance premiums or drug utilization. Patients who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid were excluded.

SOURCE: Hwang TJ et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417.

A shift in Medicare drug coverage from Part B to Part D might save the government some money but could end up costing some patients in the long run.

Analysis of the 75 brand-name drugs with the highest Part B expenditures ($21.6 billion annually at 2018 prices) indicated that the government could save between $17.6 billion and $20.1 billion after rebates by switching coverage to Part D, Thomas J. Hwang of Harvard Medical School, Boston, and his associates said.

The potential for greater overall savings, however, “was constrained by the fact that 33 (44%) of the studied brand-name drugs were in protected classes, which HHS has reported precludes meaningful price negotiation by Part D plans,” they wrote.

The proposal also could have a “material impact” on patient out-of-pocket costs, although the impact would vary based on the drug as well as patients’ insurance coverage in addition to Medicare (JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417).

For example, moving drug coverage to Part D would lower out-of-pocket costs for the majority of the 75 drugs for patients with Medigap supplemental insurance, but out-of-pocket costs could go up for almost 40% of products. Patients who would benefit most from the shift would be those who qualify for the low-income subsidy, which can eliminate coinsurance requirements.

“By contrast, for patients with Medigap insurance, out-of-pocket costs in Part D were estimated to exceed the annual premium costs for supplemental insurance [approximately 47-56 of the 75 drugs],” Mr. Hwang and his colleagues added. “Out-of-pocket costs would be increased under the proposed policy for beneficiaries with Medigap but without Part D coverage.”

The analysis was limited by the inability to predict the proposed transition’s impact on insurance premiums or drug utilization. Patients who were dually eligible for Medicare and Medicaid were excluded.

SOURCE: Hwang TJ et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Shifting drug coverage to Part D would save the government money.

Major finding: For patients with Medigap plans, costs could increase on as many as 40% of the drugs studied.

Study details: Researchers examined the 75 drugs with the highest Part B expenditures in 2016 and, using 2018 prices, estimated the effect of moving these drugs into the Part D prescription drug program.

Disclosures: No relevant conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Hwang TJ et al. JAMA Int Med. 2019. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.6417.

Pregnancy problems predict cardiovascular future

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Think of pregnancy as a cardiovascular stress test, Carole A. Warnes, MD, urged at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

Pregnancy complications may unmask a predisposition to premature cardiovascular disease. Yet a woman’s reproductive history is often overlooked in this regard, despite the fact that cardiovascular disease is the number-one cause of death in women, observed Dr. Warnes, the Snowmass conference director and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“I think reproductive history is often overlooked as a predictor of cardiovascular and even peripheral vascular events. I suspect many of us don’t routinely ask our patients about miscarriages and stillbirths. We might think about preeclampsia, but these are also hallmarks of trouble to come,” the cardiologist said.

Indeed, this point was underscored in a retrospective Danish national population-based cohort registry study of more than 1 million women followed for nearly 16 million person-years after one or more miscarriages, stillbirths, or live singleton births. Women with stillbirths were 2.69-fold more likely to have an MI, 2.42-fold more likely to develop renovascular hypertension, and 1.74-fold more likely to have a stroke during follow-up than those with no stillbirths.

Moreover, women with miscarriages were 1.13-, 1.2-, and 1.16-fold more likely to have an MI, renovascular hypertension, and stroke, respectively, than women with no miscarriages. And the risks were additive: For each additional miscarriage, the risks of MI, renovascular hypertension, and stroke increased by 9%, 19%, and 13%, respectively (Circulation. 2013;127[17]:1775-82).

The concept of maternal placental syndromes encompasses four events believed to originate from diseased placental blood vessels: preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, placental abruption, and placental infarction. In a population-based retrospective study known as CHAMPS (Cardiovascular Health After Maternal Placental Syndromes), conducted in more than 1 million Ontario women who were free from cardiovascular disease prior to their first delivery, 7% were diagnosed with a maternal placental syndrome. Their incidence of a composite endpoint comprised of hospitalization or revascularization for CAD, peripheral artery disease, or cerebrovascular disease at least 90 days after delivery discharge was double that of women without a maternal placental syndrome.

“These women manifested their first cardiovascular event at an average age of 38, not 50 or 60,” Dr. Warnes said.

The risk of premature cardiovascular disease was magnified 4.4-fold in women with a maternal placental syndrome plus an intrauterine fetal death, compared with those with neither, after adjustment for sociodemographic factors and other potential confounders, and by 3.1-fold in women with a maternal placental syndrome and poor fetal growth (Lancet. 2005;366[9499]:1797-803).

These findings were independently confirmed recently in a population-based retrospective study of nearly 303,000 Florida women free of prepregnancy hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, or renal disease who were followed for a median of 4.9 years after their first delivery. During that relative brief follow-up period, the adjusted risk of cardiovascular disease was increased by 19% in those with a maternal placental syndrome, compared with those without. And the risk was additive: women with more than one maternal placental syndrome had a 43% greater short-term risk of developing cardiovascular disease, compared with those with none. And when women with a maternal placental syndrome also had a preterm birth or a small-for-gestational age baby, their risk increased 45% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215[4]:484.e1-484.e14).

It’s not just preeclampsia, which affects 3%-5% of all pregnancies, and gestational hypertension – defined as high blood pressure arising only after 20 weeks’ gestation and without proteinuria – that have been linked to future premature cardiovascular disease. In the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966, in which investigators have followed 10,314 women born in that year for 39 years, any form of high blood pressure during pregnancy was a harbinger of subsequent cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. That included chronic isolated systolic and isolated diastolic hypertension (Circulation. 2013;127[6]:681-90).

The pathophysiologic processes involved in complicated pregnancies echo those of CAD and stroke: inflammation, altered angiogenesis, vasculopathy, thrombosis, and insulin resistance. Still unsettled, however, is the chicken-versus-egg question of whether preeclampsia and other pregnancy complications represent the initial expression of an adverse phenotype associated with early development of cardiovascular disease or the complications injure the vascular endothelium and thereby trigger accelerated atherosclerosis. In any case, markers of endothelial activation have been documented up to 15 years after an episode of preeclampsia, Dr. Warnes said.

All of these data underscore the importance of identifying at-risk women based upon reproductive history, scheduling additional medical checkups so they don’t drop off the radar for the next 20 years, encouraging lifestyle modification, and giving consideration to early initiation of antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapies.

“Pregnancy complications give us a glimpse of this awful disease trajectory at a time when women are completely asymptomatic and we could intervene and perhaps change outcomes with targeted therapy when it might be expected to work better and patients might be more receptive to such interventions,” she said.

Dr. Warnes reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Think of pregnancy as a cardiovascular stress test, Carole A. Warnes, MD, urged at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

Pregnancy complications may unmask a predisposition to premature cardiovascular disease. Yet a woman’s reproductive history is often overlooked in this regard, despite the fact that cardiovascular disease is the number-one cause of death in women, observed Dr. Warnes, the Snowmass conference director and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“I think reproductive history is often overlooked as a predictor of cardiovascular and even peripheral vascular events. I suspect many of us don’t routinely ask our patients about miscarriages and stillbirths. We might think about preeclampsia, but these are also hallmarks of trouble to come,” the cardiologist said.

Indeed, this point was underscored in a retrospective Danish national population-based cohort registry study of more than 1 million women followed for nearly 16 million person-years after one or more miscarriages, stillbirths, or live singleton births. Women with stillbirths were 2.69-fold more likely to have an MI, 2.42-fold more likely to develop renovascular hypertension, and 1.74-fold more likely to have a stroke during follow-up than those with no stillbirths.

Moreover, women with miscarriages were 1.13-, 1.2-, and 1.16-fold more likely to have an MI, renovascular hypertension, and stroke, respectively, than women with no miscarriages. And the risks were additive: For each additional miscarriage, the risks of MI, renovascular hypertension, and stroke increased by 9%, 19%, and 13%, respectively (Circulation. 2013;127[17]:1775-82).

The concept of maternal placental syndromes encompasses four events believed to originate from diseased placental blood vessels: preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, placental abruption, and placental infarction. In a population-based retrospective study known as CHAMPS (Cardiovascular Health After Maternal Placental Syndromes), conducted in more than 1 million Ontario women who were free from cardiovascular disease prior to their first delivery, 7% were diagnosed with a maternal placental syndrome. Their incidence of a composite endpoint comprised of hospitalization or revascularization for CAD, peripheral artery disease, or cerebrovascular disease at least 90 days after delivery discharge was double that of women without a maternal placental syndrome.

“These women manifested their first cardiovascular event at an average age of 38, not 50 or 60,” Dr. Warnes said.

The risk of premature cardiovascular disease was magnified 4.4-fold in women with a maternal placental syndrome plus an intrauterine fetal death, compared with those with neither, after adjustment for sociodemographic factors and other potential confounders, and by 3.1-fold in women with a maternal placental syndrome and poor fetal growth (Lancet. 2005;366[9499]:1797-803).

These findings were independently confirmed recently in a population-based retrospective study of nearly 303,000 Florida women free of prepregnancy hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, or renal disease who were followed for a median of 4.9 years after their first delivery. During that relative brief follow-up period, the adjusted risk of cardiovascular disease was increased by 19% in those with a maternal placental syndrome, compared with those without. And the risk was additive: women with more than one maternal placental syndrome had a 43% greater short-term risk of developing cardiovascular disease, compared with those with none. And when women with a maternal placental syndrome also had a preterm birth or a small-for-gestational age baby, their risk increased 45% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215[4]:484.e1-484.e14).

It’s not just preeclampsia, which affects 3%-5% of all pregnancies, and gestational hypertension – defined as high blood pressure arising only after 20 weeks’ gestation and without proteinuria – that have been linked to future premature cardiovascular disease. In the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966, in which investigators have followed 10,314 women born in that year for 39 years, any form of high blood pressure during pregnancy was a harbinger of subsequent cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. That included chronic isolated systolic and isolated diastolic hypertension (Circulation. 2013;127[6]:681-90).

The pathophysiologic processes involved in complicated pregnancies echo those of CAD and stroke: inflammation, altered angiogenesis, vasculopathy, thrombosis, and insulin resistance. Still unsettled, however, is the chicken-versus-egg question of whether preeclampsia and other pregnancy complications represent the initial expression of an adverse phenotype associated with early development of cardiovascular disease or the complications injure the vascular endothelium and thereby trigger accelerated atherosclerosis. In any case, markers of endothelial activation have been documented up to 15 years after an episode of preeclampsia, Dr. Warnes said.

All of these data underscore the importance of identifying at-risk women based upon reproductive history, scheduling additional medical checkups so they don’t drop off the radar for the next 20 years, encouraging lifestyle modification, and giving consideration to early initiation of antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapies.

“Pregnancy complications give us a glimpse of this awful disease trajectory at a time when women are completely asymptomatic and we could intervene and perhaps change outcomes with targeted therapy when it might be expected to work better and patients might be more receptive to such interventions,” she said.

Dr. Warnes reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

SNOWMASS, COLO. – Think of pregnancy as a cardiovascular stress test, Carole A. Warnes, MD, urged at the Annual Cardiovascular Conference at Snowmass sponsored by the American College of Cardiology.

Pregnancy complications may unmask a predisposition to premature cardiovascular disease. Yet a woman’s reproductive history is often overlooked in this regard, despite the fact that cardiovascular disease is the number-one cause of death in women, observed Dr. Warnes, the Snowmass conference director and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

“I think reproductive history is often overlooked as a predictor of cardiovascular and even peripheral vascular events. I suspect many of us don’t routinely ask our patients about miscarriages and stillbirths. We might think about preeclampsia, but these are also hallmarks of trouble to come,” the cardiologist said.

Indeed, this point was underscored in a retrospective Danish national population-based cohort registry study of more than 1 million women followed for nearly 16 million person-years after one or more miscarriages, stillbirths, or live singleton births. Women with stillbirths were 2.69-fold more likely to have an MI, 2.42-fold more likely to develop renovascular hypertension, and 1.74-fold more likely to have a stroke during follow-up than those with no stillbirths.

Moreover, women with miscarriages were 1.13-, 1.2-, and 1.16-fold more likely to have an MI, renovascular hypertension, and stroke, respectively, than women with no miscarriages. And the risks were additive: For each additional miscarriage, the risks of MI, renovascular hypertension, and stroke increased by 9%, 19%, and 13%, respectively (Circulation. 2013;127[17]:1775-82).

The concept of maternal placental syndromes encompasses four events believed to originate from diseased placental blood vessels: preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, placental abruption, and placental infarction. In a population-based retrospective study known as CHAMPS (Cardiovascular Health After Maternal Placental Syndromes), conducted in more than 1 million Ontario women who were free from cardiovascular disease prior to their first delivery, 7% were diagnosed with a maternal placental syndrome. Their incidence of a composite endpoint comprised of hospitalization or revascularization for CAD, peripheral artery disease, or cerebrovascular disease at least 90 days after delivery discharge was double that of women without a maternal placental syndrome.

“These women manifested their first cardiovascular event at an average age of 38, not 50 or 60,” Dr. Warnes said.

The risk of premature cardiovascular disease was magnified 4.4-fold in women with a maternal placental syndrome plus an intrauterine fetal death, compared with those with neither, after adjustment for sociodemographic factors and other potential confounders, and by 3.1-fold in women with a maternal placental syndrome and poor fetal growth (Lancet. 2005;366[9499]:1797-803).

These findings were independently confirmed recently in a population-based retrospective study of nearly 303,000 Florida women free of prepregnancy hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, or renal disease who were followed for a median of 4.9 years after their first delivery. During that relative brief follow-up period, the adjusted risk of cardiovascular disease was increased by 19% in those with a maternal placental syndrome, compared with those without. And the risk was additive: women with more than one maternal placental syndrome had a 43% greater short-term risk of developing cardiovascular disease, compared with those with none. And when women with a maternal placental syndrome also had a preterm birth or a small-for-gestational age baby, their risk increased 45% (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215[4]:484.e1-484.e14).

It’s not just preeclampsia, which affects 3%-5% of all pregnancies, and gestational hypertension – defined as high blood pressure arising only after 20 weeks’ gestation and without proteinuria – that have been linked to future premature cardiovascular disease. In the Northern Finland Birth Cohort 1966, in which investigators have followed 10,314 women born in that year for 39 years, any form of high blood pressure during pregnancy was a harbinger of subsequent cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic kidney disease. That included chronic isolated systolic and isolated diastolic hypertension (Circulation. 2013;127[6]:681-90).

The pathophysiologic processes involved in complicated pregnancies echo those of CAD and stroke: inflammation, altered angiogenesis, vasculopathy, thrombosis, and insulin resistance. Still unsettled, however, is the chicken-versus-egg question of whether preeclampsia and other pregnancy complications represent the initial expression of an adverse phenotype associated with early development of cardiovascular disease or the complications injure the vascular endothelium and thereby trigger accelerated atherosclerosis. In any case, markers of endothelial activation have been documented up to 15 years after an episode of preeclampsia, Dr. Warnes said.

All of these data underscore the importance of identifying at-risk women based upon reproductive history, scheduling additional medical checkups so they don’t drop off the radar for the next 20 years, encouraging lifestyle modification, and giving consideration to early initiation of antihypertensive and lipid-lowering therapies.

“Pregnancy complications give us a glimpse of this awful disease trajectory at a time when women are completely asymptomatic and we could intervene and perhaps change outcomes with targeted therapy when it might be expected to work better and patients might be more receptive to such interventions,” she said.

Dr. Warnes reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM ACC SNOWMASS 2019

FDA approves generic Advair Diskus

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a generic version of the Advair Diskus, a complex device-drug combination containing fluticasone propionate and salmeterol inhalation powder.

The generic device will be available in three strengths: fluticasone propionate 100 mcg/ salmeterol 50 mcg, fluticasone propionate 250 mcg/ salmeterol 50 mcg and fluticasone propionate 500 mcg/ salmeterol 50 mcg, according to the FDA announcement. It will be marketed by Mylan as Wixela Inhub and will launch in late February, according to a statement from Mylan.

Advair Diskus is among the most commonly used treatments for asthma and for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), so it’s hoped this approval will increase access to the therapy, FDA officials said in a statement.

This approval is part of the FDA’s “longstanding commitment to advance access to lower cost, high quality generic alternatives,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “People living with asthma and COPD know too well the critical importance of having access to the treatment they need to feel better. Today’s approval will bring more competition to the market which will ultimately benefit the patients who rely on this drug.”

Wixela Inhub is indicated for twice-daily treatment of asthma in patients aged 4 years and older who are not adequately controlled by long-term asthma control treatments or whose disease warrants treatment with a combination of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta agonists. It also is indicated for maintenance of COPD and reduction of COPD exacerbations.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a generic version of the Advair Diskus, a complex device-drug combination containing fluticasone propionate and salmeterol inhalation powder.

The generic device will be available in three strengths: fluticasone propionate 100 mcg/ salmeterol 50 mcg, fluticasone propionate 250 mcg/ salmeterol 50 mcg and fluticasone propionate 500 mcg/ salmeterol 50 mcg, according to the FDA announcement. It will be marketed by Mylan as Wixela Inhub and will launch in late February, according to a statement from Mylan.

Advair Diskus is among the most commonly used treatments for asthma and for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), so it’s hoped this approval will increase access to the therapy, FDA officials said in a statement.

This approval is part of the FDA’s “longstanding commitment to advance access to lower cost, high quality generic alternatives,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “People living with asthma and COPD know too well the critical importance of having access to the treatment they need to feel better. Today’s approval will bring more competition to the market which will ultimately benefit the patients who rely on this drug.”

Wixela Inhub is indicated for twice-daily treatment of asthma in patients aged 4 years and older who are not adequately controlled by long-term asthma control treatments or whose disease warrants treatment with a combination of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta agonists. It also is indicated for maintenance of COPD and reduction of COPD exacerbations.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved a generic version of the Advair Diskus, a complex device-drug combination containing fluticasone propionate and salmeterol inhalation powder.

The generic device will be available in three strengths: fluticasone propionate 100 mcg/ salmeterol 50 mcg, fluticasone propionate 250 mcg/ salmeterol 50 mcg and fluticasone propionate 500 mcg/ salmeterol 50 mcg, according to the FDA announcement. It will be marketed by Mylan as Wixela Inhub and will launch in late February, according to a statement from Mylan.

Advair Diskus is among the most commonly used treatments for asthma and for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), so it’s hoped this approval will increase access to the therapy, FDA officials said in a statement.

This approval is part of the FDA’s “longstanding commitment to advance access to lower cost, high quality generic alternatives,” Janet Woodcock, MD, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a statement. “People living with asthma and COPD know too well the critical importance of having access to the treatment they need to feel better. Today’s approval will bring more competition to the market which will ultimately benefit the patients who rely on this drug.”

Wixela Inhub is indicated for twice-daily treatment of asthma in patients aged 4 years and older who are not adequately controlled by long-term asthma control treatments or whose disease warrants treatment with a combination of inhaled corticosteroids and long-acting beta agonists. It also is indicated for maintenance of COPD and reduction of COPD exacerbations.

AHA report highlights CVD burden, declines in smoking, sleep importance

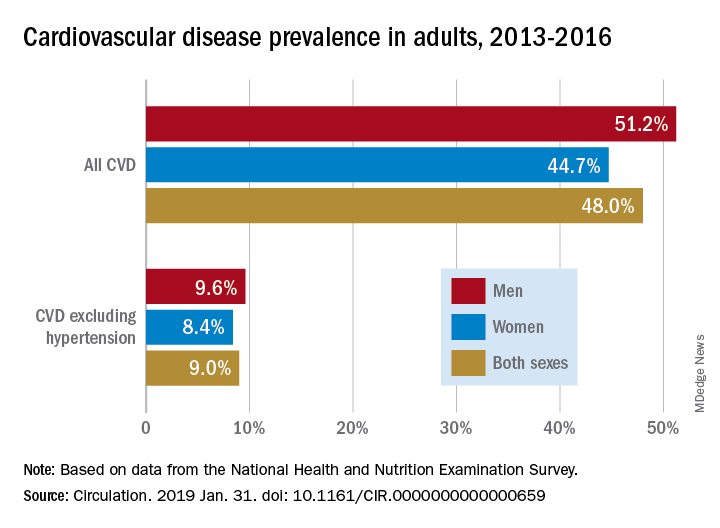

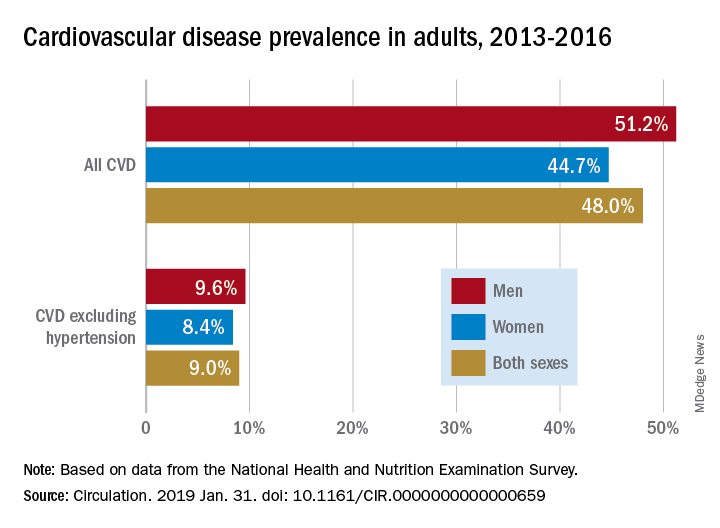

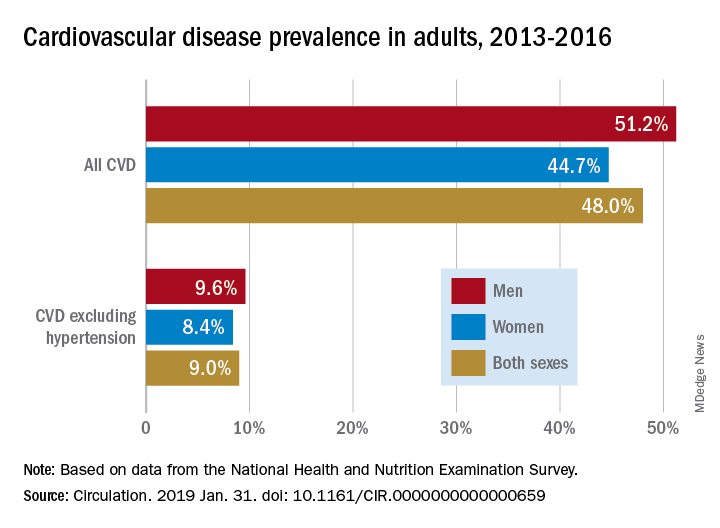

Almost half of U.S. adults now have some form of cardiovascular disease, according to the latest annual statistical update from the American Heart Association.

The prevalence is driven in part by the recently changed definition of hypertension, from 140/90 to 130/80 mm Hg, said authors of the American Heart Association Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics–2019 Update.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths are up, though smoking rates continue to decline, and adults are getting more exercise (Circulation. 2019;139. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659).

The update includes a new section on sleep and cardiovascular health, an enhanced focus on social determinants of health, and further evidence-based approaches to behavior change, according to the update’s authors, led by chair Emelia J. Benjamin, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University, and vice chair Paul Muntner, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

High blood pressure is an “overwhelming presence” that drives heart disease and stroke and can’t be dismissed in the fight against cardiovascular disease, AHA President Ivor J. Benjamin, MD, said in a statement. “Eliminating high blood pressure could have a larger impact on CVD deaths than the elimination of all other risk factors among women, and all except smoking among men.”

Using data from 2013 to 2016, 46% of adults in the United States had hypertension, and in 2016 there were 82,735 deaths attributable primarily to high blood pressure, according to the update.

Total direct costs of hypertension could approach $221 billion by 2035, according to projections in the report.

After decades of decline, U.S. cardiovascular disease deaths increased to 840,678 in 2016, up from 836,546 in 2015, the report says.

Smoking rate declines represent some of the most significant improvements outlined in the report, according to an AHA news release.

Ninety-four percent of adolescents were nonsmokers in the 2015-2016 period, which is up from 76% in 1999-2000, according to the report. The proportion of adult nonsmokers increased to 79% in 2015-2016, up from 73% in 1999-2000.

The new chapter on the importance of sleep cites data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that only 65.2% of Americans have a healthy sleep duration (at least 7 hours), with even lower rates among non-Hispanic blacks, native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and multiracial non-Hispanic individuals.

Short sleep duration is associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality, total CVD, and coronary heart disease, according to a meta-analysis cited in the report. Long sleep duration, defined as greater than 8 hours, also was associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality, total CVD, coronary heart disease, and stroke.

Members of the statistical update writing group reported disclosures related to the American Heart Association, National Institutes of Health, Amgen, Sanofi, Roche, Abbott, Biogen, Medtronic, and others.

SOURCE: Benjamin EJ et al. Circulation. 2019 Jan 31.

The latest statistics on heart disease and stroke include some metrics that indicate progress, and others that suggest opportunities for improvement.

Tobacco use continues to decline; however, among high school students, e-cigarette use is up to 11.3%, which is concerning.

One bright spot is that the proportion of inactive adults has dropped to 30% in 2016, down from 40% in 2007. Despite that improvement, however, the prevalence of obesity increased significantly over the decade, to the point where nearly 40% of adults are obese and 7.7% are severely obese.

Although 48% of U.S. adults now have cardiovascular disease, according to this latest update, the number drops to just 9% when hypertension is excluded. Even so, 9% represents more than 24.3 million Americans who have coronary artery disease, stroke, or heart failure.

The cost of cardiovascular disease is astronomical, exceeding $351 billion in 2014-1205, with costs projected to increase sharply for older adults over the next few decades.

Starting in 2020, the AHA will begin charting progress in CVD using a metric called health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE), which relies on morbidity and mortality patterns to reflect the number of years a person can expect to live. Patients and the general public may find this metric more understandable than statistics about death rates and cardiovascular risk factors.

Mariell Jessup, MD, is chief science and medical officer for the American Heart Association. Her view on the latest statistical update was derived from a commentary that accompanied the update.

The latest statistics on heart disease and stroke include some metrics that indicate progress, and others that suggest opportunities for improvement.

Tobacco use continues to decline; however, among high school students, e-cigarette use is up to 11.3%, which is concerning.

One bright spot is that the proportion of inactive adults has dropped to 30% in 2016, down from 40% in 2007. Despite that improvement, however, the prevalence of obesity increased significantly over the decade, to the point where nearly 40% of adults are obese and 7.7% are severely obese.

Although 48% of U.S. adults now have cardiovascular disease, according to this latest update, the number drops to just 9% when hypertension is excluded. Even so, 9% represents more than 24.3 million Americans who have coronary artery disease, stroke, or heart failure.

The cost of cardiovascular disease is astronomical, exceeding $351 billion in 2014-1205, with costs projected to increase sharply for older adults over the next few decades.

Starting in 2020, the AHA will begin charting progress in CVD using a metric called health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE), which relies on morbidity and mortality patterns to reflect the number of years a person can expect to live. Patients and the general public may find this metric more understandable than statistics about death rates and cardiovascular risk factors.

Mariell Jessup, MD, is chief science and medical officer for the American Heart Association. Her view on the latest statistical update was derived from a commentary that accompanied the update.

The latest statistics on heart disease and stroke include some metrics that indicate progress, and others that suggest opportunities for improvement.

Tobacco use continues to decline; however, among high school students, e-cigarette use is up to 11.3%, which is concerning.

One bright spot is that the proportion of inactive adults has dropped to 30% in 2016, down from 40% in 2007. Despite that improvement, however, the prevalence of obesity increased significantly over the decade, to the point where nearly 40% of adults are obese and 7.7% are severely obese.

Although 48% of U.S. adults now have cardiovascular disease, according to this latest update, the number drops to just 9% when hypertension is excluded. Even so, 9% represents more than 24.3 million Americans who have coronary artery disease, stroke, or heart failure.

The cost of cardiovascular disease is astronomical, exceeding $351 billion in 2014-1205, with costs projected to increase sharply for older adults over the next few decades.

Starting in 2020, the AHA will begin charting progress in CVD using a metric called health-adjusted life expectancy (HALE), which relies on morbidity and mortality patterns to reflect the number of years a person can expect to live. Patients and the general public may find this metric more understandable than statistics about death rates and cardiovascular risk factors.

Mariell Jessup, MD, is chief science and medical officer for the American Heart Association. Her view on the latest statistical update was derived from a commentary that accompanied the update.

Almost half of U.S. adults now have some form of cardiovascular disease, according to the latest annual statistical update from the American Heart Association.

The prevalence is driven in part by the recently changed definition of hypertension, from 140/90 to 130/80 mm Hg, said authors of the American Heart Association Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics–2019 Update.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths are up, though smoking rates continue to decline, and adults are getting more exercise (Circulation. 2019;139. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659).

The update includes a new section on sleep and cardiovascular health, an enhanced focus on social determinants of health, and further evidence-based approaches to behavior change, according to the update’s authors, led by chair Emelia J. Benjamin, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University, and vice chair Paul Muntner, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

High blood pressure is an “overwhelming presence” that drives heart disease and stroke and can’t be dismissed in the fight against cardiovascular disease, AHA President Ivor J. Benjamin, MD, said in a statement. “Eliminating high blood pressure could have a larger impact on CVD deaths than the elimination of all other risk factors among women, and all except smoking among men.”

Using data from 2013 to 2016, 46% of adults in the United States had hypertension, and in 2016 there were 82,735 deaths attributable primarily to high blood pressure, according to the update.

Total direct costs of hypertension could approach $221 billion by 2035, according to projections in the report.

After decades of decline, U.S. cardiovascular disease deaths increased to 840,678 in 2016, up from 836,546 in 2015, the report says.

Smoking rate declines represent some of the most significant improvements outlined in the report, according to an AHA news release.

Ninety-four percent of adolescents were nonsmokers in the 2015-2016 period, which is up from 76% in 1999-2000, according to the report. The proportion of adult nonsmokers increased to 79% in 2015-2016, up from 73% in 1999-2000.

The new chapter on the importance of sleep cites data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that only 65.2% of Americans have a healthy sleep duration (at least 7 hours), with even lower rates among non-Hispanic blacks, native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and multiracial non-Hispanic individuals.

Short sleep duration is associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality, total CVD, and coronary heart disease, according to a meta-analysis cited in the report. Long sleep duration, defined as greater than 8 hours, also was associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality, total CVD, coronary heart disease, and stroke.

Members of the statistical update writing group reported disclosures related to the American Heart Association, National Institutes of Health, Amgen, Sanofi, Roche, Abbott, Biogen, Medtronic, and others.

SOURCE: Benjamin EJ et al. Circulation. 2019 Jan 31.

Almost half of U.S. adults now have some form of cardiovascular disease, according to the latest annual statistical update from the American Heart Association.

The prevalence is driven in part by the recently changed definition of hypertension, from 140/90 to 130/80 mm Hg, said authors of the American Heart Association Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics–2019 Update.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths are up, though smoking rates continue to decline, and adults are getting more exercise (Circulation. 2019;139. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659).

The update includes a new section on sleep and cardiovascular health, an enhanced focus on social determinants of health, and further evidence-based approaches to behavior change, according to the update’s authors, led by chair Emelia J. Benjamin, MD, professor of medicine and epidemiology at Boston University, and vice chair Paul Muntner, PhD, professor of epidemiology at the University of Alabama, Birmingham.

High blood pressure is an “overwhelming presence” that drives heart disease and stroke and can’t be dismissed in the fight against cardiovascular disease, AHA President Ivor J. Benjamin, MD, said in a statement. “Eliminating high blood pressure could have a larger impact on CVD deaths than the elimination of all other risk factors among women, and all except smoking among men.”

Using data from 2013 to 2016, 46% of adults in the United States had hypertension, and in 2016 there were 82,735 deaths attributable primarily to high blood pressure, according to the update.

Total direct costs of hypertension could approach $221 billion by 2035, according to projections in the report.

After decades of decline, U.S. cardiovascular disease deaths increased to 840,678 in 2016, up from 836,546 in 2015, the report says.

Smoking rate declines represent some of the most significant improvements outlined in the report, according to an AHA news release.

Ninety-four percent of adolescents were nonsmokers in the 2015-2016 period, which is up from 76% in 1999-2000, according to the report. The proportion of adult nonsmokers increased to 79% in 2015-2016, up from 73% in 1999-2000.

The new chapter on the importance of sleep cites data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that only 65.2% of Americans have a healthy sleep duration (at least 7 hours), with even lower rates among non-Hispanic blacks, native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, and multiracial non-Hispanic individuals.

Short sleep duration is associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality, total CVD, and coronary heart disease, according to a meta-analysis cited in the report. Long sleep duration, defined as greater than 8 hours, also was associated with higher risk of all-cause mortality, total CVD, coronary heart disease, and stroke.

Members of the statistical update writing group reported disclosures related to the American Heart Association, National Institutes of Health, Amgen, Sanofi, Roche, Abbott, Biogen, Medtronic, and others.

SOURCE: Benjamin EJ et al. Circulation. 2019 Jan 31.

FROM CIRCULATION

Flu activity ticks up for second week in a row

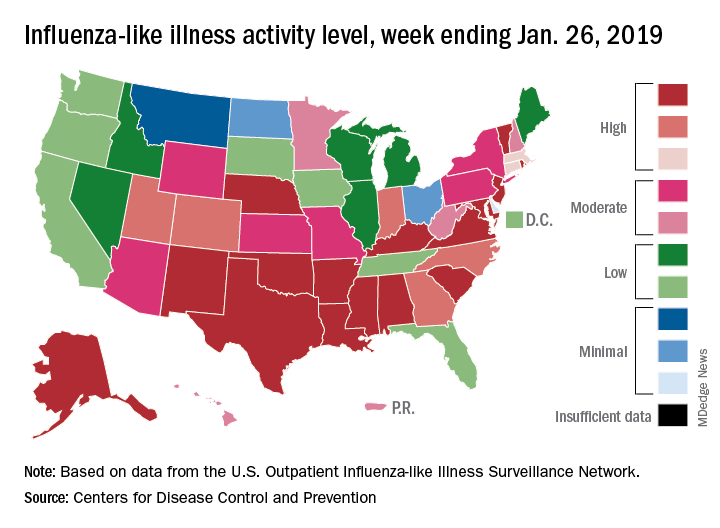

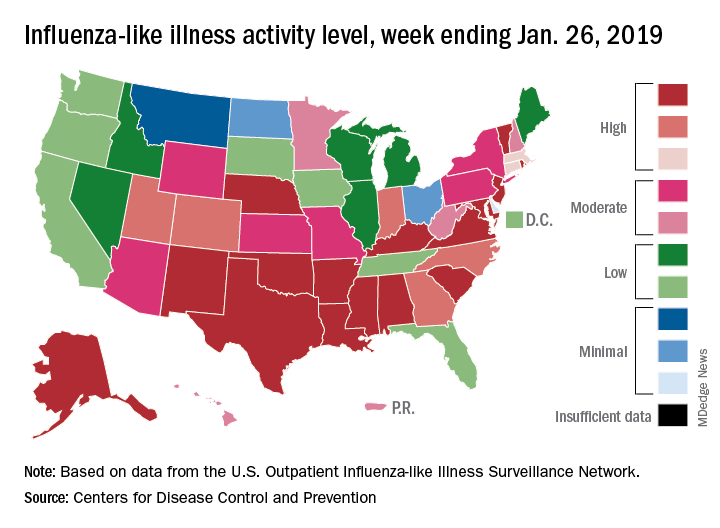

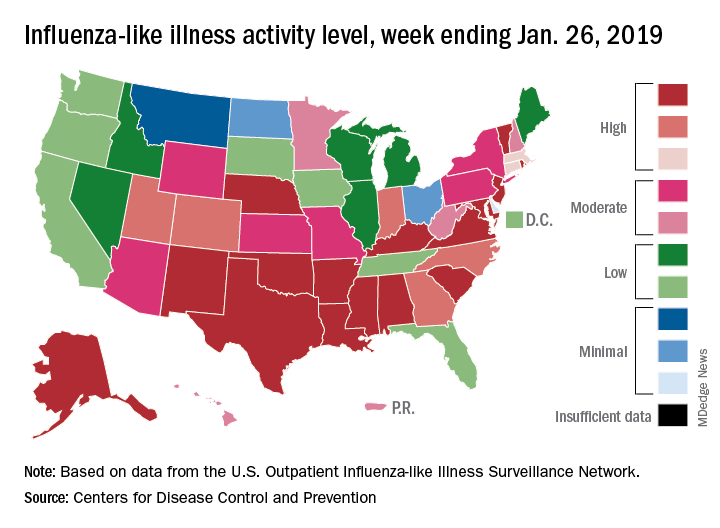

Influenza activity increased for a second straight week after a 2-week drop and by one measure has topped the high reached in late December, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Jan. 26, 2019, there were 16 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, compared with 12 states during the week ending Dec. 29. With another seven states at levels 8 and 9, that makes 23 in the high range for the week ending Jan. 26, again putting it above the 19 reported for Dec. 29, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 1.

By another measure, however, that December peak in activity remains the seasonal high. The proportion of outpatient visits for ILI that week was 4.0%, compared with the 3.8% reported for Jan. 26. That’s up from 3.3% the week before and 3.1% the week before that, which in turn was the second week of a 2-week decline in activity in early January, CDC data show.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending Jan. 26, but both occurred the previous week. For the 2018-2019 flu season so far, a total of 24 pediatric flu deaths have been reported, the CDC said. At the same point in the 2017-2018 flu season, there had been 84 such deaths, according to the CDC’s Influenza-Associated Pediatric Mortality Surveillance System.

There were 143 overall flu-related deaths during the week of Jan. 19, which is the most recent week available. That is down from 189 the week before, but the Jan. 19 reporting is only 75% complete, data from the National Center for Health Statistics show.

Influenza activity increased for a second straight week after a 2-week drop and by one measure has topped the high reached in late December, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Jan. 26, 2019, there were 16 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, compared with 12 states during the week ending Dec. 29. With another seven states at levels 8 and 9, that makes 23 in the high range for the week ending Jan. 26, again putting it above the 19 reported for Dec. 29, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 1.

By another measure, however, that December peak in activity remains the seasonal high. The proportion of outpatient visits for ILI that week was 4.0%, compared with the 3.8% reported for Jan. 26. That’s up from 3.3% the week before and 3.1% the week before that, which in turn was the second week of a 2-week decline in activity in early January, CDC data show.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending Jan. 26, but both occurred the previous week. For the 2018-2019 flu season so far, a total of 24 pediatric flu deaths have been reported, the CDC said. At the same point in the 2017-2018 flu season, there had been 84 such deaths, according to the CDC’s Influenza-Associated Pediatric Mortality Surveillance System.

There were 143 overall flu-related deaths during the week of Jan. 19, which is the most recent week available. That is down from 189 the week before, but the Jan. 19 reporting is only 75% complete, data from the National Center for Health Statistics show.

Influenza activity increased for a second straight week after a 2-week drop and by one measure has topped the high reached in late December, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

For the week ending Jan. 26, 2019, there were 16 states at level 10 on the CDC’s 1-10 scale of influenza-like illness (ILI) activity, compared with 12 states during the week ending Dec. 29. With another seven states at levels 8 and 9, that makes 23 in the high range for the week ending Jan. 26, again putting it above the 19 reported for Dec. 29, the CDC’s influenza division reported Feb. 1.

By another measure, however, that December peak in activity remains the seasonal high. The proportion of outpatient visits for ILI that week was 4.0%, compared with the 3.8% reported for Jan. 26. That’s up from 3.3% the week before and 3.1% the week before that, which in turn was the second week of a 2-week decline in activity in early January, CDC data show.

Two flu-related pediatric deaths were reported during the week ending Jan. 26, but both occurred the previous week. For the 2018-2019 flu season so far, a total of 24 pediatric flu deaths have been reported, the CDC said. At the same point in the 2017-2018 flu season, there had been 84 such deaths, according to the CDC’s Influenza-Associated Pediatric Mortality Surveillance System.

There were 143 overall flu-related deaths during the week of Jan. 19, which is the most recent week available. That is down from 189 the week before, but the Jan. 19 reporting is only 75% complete, data from the National Center for Health Statistics show.

Outcomes could improve with Oncology Care Model treatment plans

Treatment plans derived under the Oncology Care Model (OCM) improved performance on some quality measures and patient-reported outcomes, according to a study performed at three cancer centers.

Physicians and care teams at the University of Alabama, Birmingham; University of South Alabama, Monroeville; and AtlantiCare Cancer Care Institute, Egg Harbor Township, N.J., applied for participation in the Oncology Care Model introduced by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation.

“The goal of OCM is to utilize appropriately aligned financial incentives to enable improved care coordination, appropriateness of care, and access to care for beneficiaries undergoing chemotherapy,” according to CMS. “OCM encourages participating practices to improve care and lower costs through an episode-based payment model that financially incentivizes high-quality, coordinated care.”

Lead author Gabrielle Rocque, MD, assistant professor at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, noted that “these three cancer centers believed that leveraging the OCM requirement of treatment plan delivery would create an opportunity to improve care quality.”

They found that “implementation of OCM [treatment plans] has provided an opportunity to improve performance quality measures,” the authors concluded.

The project engaged 33 clinical providers and 171 women with breast cancer. The intervention group included 74 women aged 18 years and older with stage I to III breast cancer who were either planning on or already receiving chemotherapy; they were compared with a historical control group of 86 patients who received chemotherapy (J Oncol Pract. 2019. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00390).

Clinical providers engaged in self-study CME courses on quality standards relevant to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancer and on psychosocial distress, then prepared patient treatment plans including patient-reported outcomes surveys that were connected to the clinical data platform. Fifteen American Society of Clinical Oncology Quality Oncology Practice Initiative measures were selected to compare the treatment and outcomes of the intervention and control groups.

“Statistically significant differences were found on nine measures, with performance higher among those in the intervention group,” Dr. Rocque and her colleagues noted. “Responses to questions that pertained to management of pain, emotional distress, and documentation of advanced directives had the greatest difference.” The areas that showed improvement aligned with indications linked to performance-based payments.

The study has several limitations. AtlantiCare Cancer Care Institute transitioned from a research phase to standard of care after 12 patients, altering the desired accrual of patients for the study. Additionally, “the quality improvement driver is not known because no manner existed to discern differences on the basis of documentation versus change in practice,” the investigators wrote.

That being said, the study authors stated that “the incorporation of technology solutions to meet requirements for participation in payment reform initiatives may provide a platform to effect patient outcomes.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society and Genentech. Dr. Rocque reported support from Genentech and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Rocque G et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00390.

Treatment plans derived under the Oncology Care Model (OCM) improved performance on some quality measures and patient-reported outcomes, according to a study performed at three cancer centers.

Physicians and care teams at the University of Alabama, Birmingham; University of South Alabama, Monroeville; and AtlantiCare Cancer Care Institute, Egg Harbor Township, N.J., applied for participation in the Oncology Care Model introduced by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation.

“The goal of OCM is to utilize appropriately aligned financial incentives to enable improved care coordination, appropriateness of care, and access to care for beneficiaries undergoing chemotherapy,” according to CMS. “OCM encourages participating practices to improve care and lower costs through an episode-based payment model that financially incentivizes high-quality, coordinated care.”

Lead author Gabrielle Rocque, MD, assistant professor at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, noted that “these three cancer centers believed that leveraging the OCM requirement of treatment plan delivery would create an opportunity to improve care quality.”

They found that “implementation of OCM [treatment plans] has provided an opportunity to improve performance quality measures,” the authors concluded.

The project engaged 33 clinical providers and 171 women with breast cancer. The intervention group included 74 women aged 18 years and older with stage I to III breast cancer who were either planning on or already receiving chemotherapy; they were compared with a historical control group of 86 patients who received chemotherapy (J Oncol Pract. 2019. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00390).

Clinical providers engaged in self-study CME courses on quality standards relevant to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancer and on psychosocial distress, then prepared patient treatment plans including patient-reported outcomes surveys that were connected to the clinical data platform. Fifteen American Society of Clinical Oncology Quality Oncology Practice Initiative measures were selected to compare the treatment and outcomes of the intervention and control groups.

“Statistically significant differences were found on nine measures, with performance higher among those in the intervention group,” Dr. Rocque and her colleagues noted. “Responses to questions that pertained to management of pain, emotional distress, and documentation of advanced directives had the greatest difference.” The areas that showed improvement aligned with indications linked to performance-based payments.

The study has several limitations. AtlantiCare Cancer Care Institute transitioned from a research phase to standard of care after 12 patients, altering the desired accrual of patients for the study. Additionally, “the quality improvement driver is not known because no manner existed to discern differences on the basis of documentation versus change in practice,” the investigators wrote.

That being said, the study authors stated that “the incorporation of technology solutions to meet requirements for participation in payment reform initiatives may provide a platform to effect patient outcomes.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society and Genentech. Dr. Rocque reported support from Genentech and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Rocque G et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00390.

Treatment plans derived under the Oncology Care Model (OCM) improved performance on some quality measures and patient-reported outcomes, according to a study performed at three cancer centers.

Physicians and care teams at the University of Alabama, Birmingham; University of South Alabama, Monroeville; and AtlantiCare Cancer Care Institute, Egg Harbor Township, N.J., applied for participation in the Oncology Care Model introduced by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation.

“The goal of OCM is to utilize appropriately aligned financial incentives to enable improved care coordination, appropriateness of care, and access to care for beneficiaries undergoing chemotherapy,” according to CMS. “OCM encourages participating practices to improve care and lower costs through an episode-based payment model that financially incentivizes high-quality, coordinated care.”

Lead author Gabrielle Rocque, MD, assistant professor at the University of Alabama, Birmingham, noted that “these three cancer centers believed that leveraging the OCM requirement of treatment plan delivery would create an opportunity to improve care quality.”

They found that “implementation of OCM [treatment plans] has provided an opportunity to improve performance quality measures,” the authors concluded.

The project engaged 33 clinical providers and 171 women with breast cancer. The intervention group included 74 women aged 18 years and older with stage I to III breast cancer who were either planning on or already receiving chemotherapy; they were compared with a historical control group of 86 patients who received chemotherapy (J Oncol Pract. 2019. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00390).

Clinical providers engaged in self-study CME courses on quality standards relevant to human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)–positive breast cancer and on psychosocial distress, then prepared patient treatment plans including patient-reported outcomes surveys that were connected to the clinical data platform. Fifteen American Society of Clinical Oncology Quality Oncology Practice Initiative measures were selected to compare the treatment and outcomes of the intervention and control groups.

“Statistically significant differences were found on nine measures, with performance higher among those in the intervention group,” Dr. Rocque and her colleagues noted. “Responses to questions that pertained to management of pain, emotional distress, and documentation of advanced directives had the greatest difference.” The areas that showed improvement aligned with indications linked to performance-based payments.

The study has several limitations. AtlantiCare Cancer Care Institute transitioned from a research phase to standard of care after 12 patients, altering the desired accrual of patients for the study. Additionally, “the quality improvement driver is not known because no manner existed to discern differences on the basis of documentation versus change in practice,” the investigators wrote.

That being said, the study authors stated that “the incorporation of technology solutions to meet requirements for participation in payment reform initiatives may provide a platform to effect patient outcomes.”

The study was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society and Genentech. Dr. Rocque reported support from Genentech and Pfizer.

SOURCE: Rocque G et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00390.

FROM JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Key clinical point: The CMS Oncology Care Model is showing promise to improve care.

Major finding: Intervention group saw statistically significant improvement in 9 of 15 quality measures, most notably those pertaining to pain management, emotional distress, and documentation of advanced directives.

Study details: A quality improvement project involving 171 breast cancer patients and 33 clinical providers.

Disclosures: The study was supported by grants from the American Cancer Society and Genentech. Dr. Rocque reported support from Genentech and Pfizer.

Source: Rocque G et al. J Oncol Pract. 2019. doi: 10. 1200/JOP.18.00390.

Elective hernia repair preferable in patients with chronic liver disease

Elective hernia repair in patients with chronic liver disease was far safer than emergent repair and carried an acceptable level of morbidity and mortality, according to an analysis of all cases performed at the Cleveland Clinic from 2001-2015.

In a chart review of 253 patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) who underwent hernia repair between January 2001 and December 2015, the rate of postoperative 30-day morbidity and mortality was 27% for nonemergent repairs, compared with 60% in emergent repairs.

The 90-day mortality rate also was higher for emergent repairs (10%) than for nonemergent repairs (3.7%), reported Clayton C. Petro, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and his coauthors.

Thirty-day morbidity and mortality was defined as incidence of surgical-site infection (SSI), wound dehiscence, bacterial peritonitis, decompensated liver failure, postoperative admission to the intensive care unit, unplanned hospital readmission, unplanned reoperation, and 30-day mortality. CLD severity was determined using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), age-adjusted CCI, Child-Turcott-Pugh Score, laboratory values, and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) Score.

Of the 253 patients, 186 (74%) had nonemergent repairs and 67 (26%) had emergent repairs; 91 patients (36%) experienced a total of 159 morbidity and mortality events, Dr. Petro and coauthors said.

Emergent repairs had significantly higher rates of postoperative ICU admission than nonemergent repairs (27% vs. 5%; P less than .0001). Emergent repairs also had higher rates of bacterial peritonitis (10% vs 3%; P = .02), unplanned reoperation (9% vs 1%; P = .005), and unplanned readmission (27% vs 14%, P = .02).

“This large single-center cohort of 253 CLD patients suggests that non-emergent hernia repairs have relatively acceptable rates of [morbidity and mortality], even with advanced liver disease,” the authors wrote. “The dramatic increase in postoperative complications and 90-day mortality in the emergent setting supports the practice of elective repair when possible.”

No disclosures or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Petro C et al. Am J Surg. 2019:217;59-65.

Elective hernia repair in patients with chronic liver disease was far safer than emergent repair and carried an acceptable level of morbidity and mortality, according to an analysis of all cases performed at the Cleveland Clinic from 2001-2015.

In a chart review of 253 patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) who underwent hernia repair between January 2001 and December 2015, the rate of postoperative 30-day morbidity and mortality was 27% for nonemergent repairs, compared with 60% in emergent repairs.

The 90-day mortality rate also was higher for emergent repairs (10%) than for nonemergent repairs (3.7%), reported Clayton C. Petro, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and his coauthors.

Thirty-day morbidity and mortality was defined as incidence of surgical-site infection (SSI), wound dehiscence, bacterial peritonitis, decompensated liver failure, postoperative admission to the intensive care unit, unplanned hospital readmission, unplanned reoperation, and 30-day mortality. CLD severity was determined using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), age-adjusted CCI, Child-Turcott-Pugh Score, laboratory values, and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) Score.

Of the 253 patients, 186 (74%) had nonemergent repairs and 67 (26%) had emergent repairs; 91 patients (36%) experienced a total of 159 morbidity and mortality events, Dr. Petro and coauthors said.

Emergent repairs had significantly higher rates of postoperative ICU admission than nonemergent repairs (27% vs. 5%; P less than .0001). Emergent repairs also had higher rates of bacterial peritonitis (10% vs 3%; P = .02), unplanned reoperation (9% vs 1%; P = .005), and unplanned readmission (27% vs 14%, P = .02).

“This large single-center cohort of 253 CLD patients suggests that non-emergent hernia repairs have relatively acceptable rates of [morbidity and mortality], even with advanced liver disease,” the authors wrote. “The dramatic increase in postoperative complications and 90-day mortality in the emergent setting supports the practice of elective repair when possible.”

No disclosures or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Petro C et al. Am J Surg. 2019:217;59-65.

Elective hernia repair in patients with chronic liver disease was far safer than emergent repair and carried an acceptable level of morbidity and mortality, according to an analysis of all cases performed at the Cleveland Clinic from 2001-2015.

In a chart review of 253 patients with chronic liver disease (CLD) who underwent hernia repair between January 2001 and December 2015, the rate of postoperative 30-day morbidity and mortality was 27% for nonemergent repairs, compared with 60% in emergent repairs.

The 90-day mortality rate also was higher for emergent repairs (10%) than for nonemergent repairs (3.7%), reported Clayton C. Petro, MD, of the Cleveland Clinic, and his coauthors.

Thirty-day morbidity and mortality was defined as incidence of surgical-site infection (SSI), wound dehiscence, bacterial peritonitis, decompensated liver failure, postoperative admission to the intensive care unit, unplanned hospital readmission, unplanned reoperation, and 30-day mortality. CLD severity was determined using the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), age-adjusted CCI, Child-Turcott-Pugh Score, laboratory values, and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) Score.

Of the 253 patients, 186 (74%) had nonemergent repairs and 67 (26%) had emergent repairs; 91 patients (36%) experienced a total of 159 morbidity and mortality events, Dr. Petro and coauthors said.

Emergent repairs had significantly higher rates of postoperative ICU admission than nonemergent repairs (27% vs. 5%; P less than .0001). Emergent repairs also had higher rates of bacterial peritonitis (10% vs 3%; P = .02), unplanned reoperation (9% vs 1%; P = .005), and unplanned readmission (27% vs 14%, P = .02).

“This large single-center cohort of 253 CLD patients suggests that non-emergent hernia repairs have relatively acceptable rates of [morbidity and mortality], even with advanced liver disease,” the authors wrote. “The dramatic increase in postoperative complications and 90-day mortality in the emergent setting supports the practice of elective repair when possible.”

No disclosures or conflicts of interest were reported.

SOURCE: Petro C et al. Am J Surg. 2019:217;59-65.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Emergent hernia repairs had higher morbidity and mortality than nonemergent repairs in patients with chronic liver disease.

Major finding: The rate of postoperative 30-day morbidity and mortality was 27% for nonemergent repairs, compared with 60% in emergent repairs.

Study details: Chart review of 253 CLD patients who underwent hernia repair between January 2001 and December 2015.

Disclosures: No disclosures or conflicts of interest were reported.

Source: Petro C et al. Am J Surg. 2019:217;59-65.

The blinding lies of depression

Numb and empty, I continued to drive home in a daze. My mind focused only on the light ahead changing from yellow to red. “Remember to step on the brake,” commanded the internal boss to my stunned mind. No tears, I continued to drive as green blinked its eye.

Earlier that afternoon as I stepped out of my second outpatient appointment of the day, the office administrator’s assistant gingerly informed me, “The guy who answered the phone for your no-show said she passed.”

“Passed? Like … died?” I asked in shock.

She nodded. “I looked her up in the system. She passed away 2 Saturdays ago.”