User login

Can taming inflammation help reduce aggression?

Several psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury, autism, and posttraumatic stress disorder, are associated with a dysregulated immune response and elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers. Inflammation has long been associated with an increased risk of aggressive behavior.1,2 By taming immune system dysregulation, we might be able to more effectively reduce inflammation, and thus reduce aggression, in patients with psychiatric illness.

Inflammation and psychiatric symptoms

An overactivated immune response has been empirically correlated to the development of psychiatric symptoms. Inducing systemic inflammation has adverse effects on cognition and behavior, whereas suppressing inflammation can dramatically improve sensorium and mood. Brain regions involved in arousal and alarm are particularly susceptible to inflammation. Subcortical areas, such as the basal ganglia, and cortical circuits, such as the amygdala and anterior insula, are affected by neuroinflammation. Several modifiable factors, including a diet rich in high glycemic food, improper sleep hygiene, tobacco use, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and excess psychosocial stressors, can contribute to systemic inflammation and the development of psychiatric symptoms. Oral diseases, such as tooth decay, periodontitis, and gingivitis, also contribute significantly to overall inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory agents

Using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as augmentation to standard treatments has shown promise in several psychiatric illnesses. For example, low-dose aspirin, 81 mg/d, has demonstrated reliable results as an adjunctive treatment for depression.3 Research also has shown that the use of ibuprofen may reduce the chances of individuals seeking psychiatric care.3

Individuals who are at high risk for psychosis and schizophrenia have measurable increases in inflammatory microglial activity.4 The severity of psychotic symptoms corresponds to the magnitude of the immune response; this suggests that neuroinflammation is a risk factor for psychosis, and that anti-inflammatory treatments might help prevent or ameliorate psychosis.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 70 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia who were taking an antipsychotic were randomized to adjunctive aspirin, 1,000 mg/d, or placebo.5 Participants who received aspirin had significant improvement as measured by changes in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score.5

Targeting C-reactive protein

Inflammation has long been associated with impulsive aggression. C-reactive protein (CRP) is a biomarker produced in the liver in response to inflammatory triggers. In a study of 213 inpatients with schizophrenia, researchers compared 57 patients with higher levels of CRP (>1 mg/dL) with 156 patients with normal levels (<1 mg/dL).2 Compared with patients with normal CRP levels, those with higher levels displayed increased aggressive behavior. Researchers found that the chance of being physically restrained during hospitalization was almost 2.5 times greater for patients with elevated CRP levels on admission compared with those with normal CRP levels.

Statins have long been used to reduce C-reactive peptides in patients with cardiovascular conditions. The use of simvastatin has been shown to significantly reduce negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.6

Continue to: Vitamin C also can effectively...

Vitamin C also can effectively lower CRP levels. In a 2-month study, 396 participants with elevated CRP levels received vitamin C, 1,000 mg/d, vitamin E, 800 IU/d, or placebo.7 Although vitamin E didn’t reduce CRP levels, vitamin C reduced CRP by 25.3% compared with placebo. Vitamin C is as effective as statins in controlling this biomarker.

Several nonpharmacologic measures also can help reduce the immune system’s activation of CRP, including increased physical activity, increased intake of low glycemic food and supplemental omega-3 fatty acids, improved dental hygiene, and enhanced sleep.

Using a relatively simple and inexpensive laboratory test for measuring CRP might help predict or stratify the risk of aggressive behavior among psychiatric inpatients. For psychiatric patients with elevated inflammatory markers, the interventions described here may be useful as adjunctive treatments to help reduce aggression and injury in an inpatient setting.

1. Coccaro EF, Lee R, Coussons-Read M. Elevated plasma inflammatory markers in individuals with intermittent explosive disorder and correlation with aggression in humans. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):158-165.

2. Barzilay R, Lobel T, Krivoy A, et al. Elevated C-reactive protein levels in schizophrenia inpatients is associated with aggressive behavior. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;31:8-12.

3. Köhler O, Peterson L, Mors O, et al. Inflammation and depression: combined use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and NSAIDs or paracetamol and psychiatric outcomes. Brain and Behavior. 2015;5(8):e00338. doi: 10.1002/brb3.338.

4. Bloomfield PS, Selvaraj S, Veronese M, et al. M icroglial activity in people at ultra high risk of psychosis and in schizophrenia; an [11C]PBR28 PET brain imaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(1):44-52.

5. Laan W, Grobbee DE, Selten JP, et al. Adjuvant aspirin therapy reduces symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):520-527.

6. Tajik-Esmaeeli S, Moazen-Zadeh E, Abbasi N, et al. Simvastatin adjunct therapy for negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(2):87-94.

7. Block G, Jensen CD, Dalvi TB, et al. Vitamin C treatment reduces elevated C-reactive protein. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(1):70-77.

Several psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury, autism, and posttraumatic stress disorder, are associated with a dysregulated immune response and elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers. Inflammation has long been associated with an increased risk of aggressive behavior.1,2 By taming immune system dysregulation, we might be able to more effectively reduce inflammation, and thus reduce aggression, in patients with psychiatric illness.

Inflammation and psychiatric symptoms

An overactivated immune response has been empirically correlated to the development of psychiatric symptoms. Inducing systemic inflammation has adverse effects on cognition and behavior, whereas suppressing inflammation can dramatically improve sensorium and mood. Brain regions involved in arousal and alarm are particularly susceptible to inflammation. Subcortical areas, such as the basal ganglia, and cortical circuits, such as the amygdala and anterior insula, are affected by neuroinflammation. Several modifiable factors, including a diet rich in high glycemic food, improper sleep hygiene, tobacco use, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and excess psychosocial stressors, can contribute to systemic inflammation and the development of psychiatric symptoms. Oral diseases, such as tooth decay, periodontitis, and gingivitis, also contribute significantly to overall inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory agents

Using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as augmentation to standard treatments has shown promise in several psychiatric illnesses. For example, low-dose aspirin, 81 mg/d, has demonstrated reliable results as an adjunctive treatment for depression.3 Research also has shown that the use of ibuprofen may reduce the chances of individuals seeking psychiatric care.3

Individuals who are at high risk for psychosis and schizophrenia have measurable increases in inflammatory microglial activity.4 The severity of psychotic symptoms corresponds to the magnitude of the immune response; this suggests that neuroinflammation is a risk factor for psychosis, and that anti-inflammatory treatments might help prevent or ameliorate psychosis.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 70 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia who were taking an antipsychotic were randomized to adjunctive aspirin, 1,000 mg/d, or placebo.5 Participants who received aspirin had significant improvement as measured by changes in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score.5

Targeting C-reactive protein

Inflammation has long been associated with impulsive aggression. C-reactive protein (CRP) is a biomarker produced in the liver in response to inflammatory triggers. In a study of 213 inpatients with schizophrenia, researchers compared 57 patients with higher levels of CRP (>1 mg/dL) with 156 patients with normal levels (<1 mg/dL).2 Compared with patients with normal CRP levels, those with higher levels displayed increased aggressive behavior. Researchers found that the chance of being physically restrained during hospitalization was almost 2.5 times greater for patients with elevated CRP levels on admission compared with those with normal CRP levels.

Statins have long been used to reduce C-reactive peptides in patients with cardiovascular conditions. The use of simvastatin has been shown to significantly reduce negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.6

Continue to: Vitamin C also can effectively...

Vitamin C also can effectively lower CRP levels. In a 2-month study, 396 participants with elevated CRP levels received vitamin C, 1,000 mg/d, vitamin E, 800 IU/d, or placebo.7 Although vitamin E didn’t reduce CRP levels, vitamin C reduced CRP by 25.3% compared with placebo. Vitamin C is as effective as statins in controlling this biomarker.

Several nonpharmacologic measures also can help reduce the immune system’s activation of CRP, including increased physical activity, increased intake of low glycemic food and supplemental omega-3 fatty acids, improved dental hygiene, and enhanced sleep.

Using a relatively simple and inexpensive laboratory test for measuring CRP might help predict or stratify the risk of aggressive behavior among psychiatric inpatients. For psychiatric patients with elevated inflammatory markers, the interventions described here may be useful as adjunctive treatments to help reduce aggression and injury in an inpatient setting.

Several psychiatric disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, Alzheimer’s disease, traumatic brain injury, autism, and posttraumatic stress disorder, are associated with a dysregulated immune response and elevated levels of inflammatory biomarkers. Inflammation has long been associated with an increased risk of aggressive behavior.1,2 By taming immune system dysregulation, we might be able to more effectively reduce inflammation, and thus reduce aggression, in patients with psychiatric illness.

Inflammation and psychiatric symptoms

An overactivated immune response has been empirically correlated to the development of psychiatric symptoms. Inducing systemic inflammation has adverse effects on cognition and behavior, whereas suppressing inflammation can dramatically improve sensorium and mood. Brain regions involved in arousal and alarm are particularly susceptible to inflammation. Subcortical areas, such as the basal ganglia, and cortical circuits, such as the amygdala and anterior insula, are affected by neuroinflammation. Several modifiable factors, including a diet rich in high glycemic food, improper sleep hygiene, tobacco use, a sedentary lifestyle, obesity, and excess psychosocial stressors, can contribute to systemic inflammation and the development of psychiatric symptoms. Oral diseases, such as tooth decay, periodontitis, and gingivitis, also contribute significantly to overall inflammation.

Anti-inflammatory agents

Using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as augmentation to standard treatments has shown promise in several psychiatric illnesses. For example, low-dose aspirin, 81 mg/d, has demonstrated reliable results as an adjunctive treatment for depression.3 Research also has shown that the use of ibuprofen may reduce the chances of individuals seeking psychiatric care.3

Individuals who are at high risk for psychosis and schizophrenia have measurable increases in inflammatory microglial activity.4 The severity of psychotic symptoms corresponds to the magnitude of the immune response; this suggests that neuroinflammation is a risk factor for psychosis, and that anti-inflammatory treatments might help prevent or ameliorate psychosis.

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 70 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia who were taking an antipsychotic were randomized to adjunctive aspirin, 1,000 mg/d, or placebo.5 Participants who received aspirin had significant improvement as measured by changes in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score.5

Targeting C-reactive protein

Inflammation has long been associated with impulsive aggression. C-reactive protein (CRP) is a biomarker produced in the liver in response to inflammatory triggers. In a study of 213 inpatients with schizophrenia, researchers compared 57 patients with higher levels of CRP (>1 mg/dL) with 156 patients with normal levels (<1 mg/dL).2 Compared with patients with normal CRP levels, those with higher levels displayed increased aggressive behavior. Researchers found that the chance of being physically restrained during hospitalization was almost 2.5 times greater for patients with elevated CRP levels on admission compared with those with normal CRP levels.

Statins have long been used to reduce C-reactive peptides in patients with cardiovascular conditions. The use of simvastatin has been shown to significantly reduce negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia.6

Continue to: Vitamin C also can effectively...

Vitamin C also can effectively lower CRP levels. In a 2-month study, 396 participants with elevated CRP levels received vitamin C, 1,000 mg/d, vitamin E, 800 IU/d, or placebo.7 Although vitamin E didn’t reduce CRP levels, vitamin C reduced CRP by 25.3% compared with placebo. Vitamin C is as effective as statins in controlling this biomarker.

Several nonpharmacologic measures also can help reduce the immune system’s activation of CRP, including increased physical activity, increased intake of low glycemic food and supplemental omega-3 fatty acids, improved dental hygiene, and enhanced sleep.

Using a relatively simple and inexpensive laboratory test for measuring CRP might help predict or stratify the risk of aggressive behavior among psychiatric inpatients. For psychiatric patients with elevated inflammatory markers, the interventions described here may be useful as adjunctive treatments to help reduce aggression and injury in an inpatient setting.

1. Coccaro EF, Lee R, Coussons-Read M. Elevated plasma inflammatory markers in individuals with intermittent explosive disorder and correlation with aggression in humans. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):158-165.

2. Barzilay R, Lobel T, Krivoy A, et al. Elevated C-reactive protein levels in schizophrenia inpatients is associated with aggressive behavior. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;31:8-12.

3. Köhler O, Peterson L, Mors O, et al. Inflammation and depression: combined use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and NSAIDs or paracetamol and psychiatric outcomes. Brain and Behavior. 2015;5(8):e00338. doi: 10.1002/brb3.338.

4. Bloomfield PS, Selvaraj S, Veronese M, et al. M icroglial activity in people at ultra high risk of psychosis and in schizophrenia; an [11C]PBR28 PET brain imaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(1):44-52.

5. Laan W, Grobbee DE, Selten JP, et al. Adjuvant aspirin therapy reduces symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):520-527.

6. Tajik-Esmaeeli S, Moazen-Zadeh E, Abbasi N, et al. Simvastatin adjunct therapy for negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(2):87-94.

7. Block G, Jensen CD, Dalvi TB, et al. Vitamin C treatment reduces elevated C-reactive protein. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(1):70-77.

1. Coccaro EF, Lee R, Coussons-Read M. Elevated plasma inflammatory markers in individuals with intermittent explosive disorder and correlation with aggression in humans. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(2):158-165.

2. Barzilay R, Lobel T, Krivoy A, et al. Elevated C-reactive protein levels in schizophrenia inpatients is associated with aggressive behavior. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;31:8-12.

3. Köhler O, Peterson L, Mors O, et al. Inflammation and depression: combined use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and NSAIDs or paracetamol and psychiatric outcomes. Brain and Behavior. 2015;5(8):e00338. doi: 10.1002/brb3.338.

4. Bloomfield PS, Selvaraj S, Veronese M, et al. M icroglial activity in people at ultra high risk of psychosis and in schizophrenia; an [11C]PBR28 PET brain imaging study. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(1):44-52.

5. Laan W, Grobbee DE, Selten JP, et al. Adjuvant aspirin therapy reduces symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(5):520-527.

6. Tajik-Esmaeeli S, Moazen-Zadeh E, Abbasi N, et al. Simvastatin adjunct therapy for negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2017;32(2):87-94.

7. Block G, Jensen CD, Dalvi TB, et al. Vitamin C treatment reduces elevated C-reactive protein. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(1):70-77.

Fever, tachycardia, and tachypnea during a psychotic exacerbation

CASE Posing a threat to his family

Mr. C, age 23, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia with daily auditory hallucinations 4 years earlier, is transferred from an outside psychiatric hospital to our emergency department (ED) after developing fever, tachycardia, headache, and nasal congestion for the past day. He had been admitted to the psychiatric hospital 3 weeks ago due to concerns he was experiencing increased hallucinations and delusions and posed a threat to his sister and her children, with whom he had been living.

Mr. C tells us that while at the psychiatric hospital, he had been started on clozapine, 250 mg/d. He said that prior to clozapine, he had been taking risperidone. We are unable to confirm past treatment information with the psychiatric hospital, including exactly when the clozapine had been started or how fast it had been titrated. We also were not able to obtain information on his prior medication regimen.

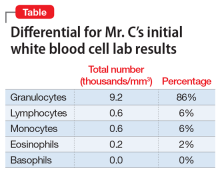

In the ED, Mr. C is febrile (39.4°C; 102.9°F), tachycardic (160 beats per minute; reference range 60 to 100), and tachypneic (24 breaths per minute; reference range 12 to 20). His blood pressure is 130/68 mm Hg, and his lactate level is 2.3 mmol/L (reference range <1.9 mmol/L). After he receives 3 liters of fluid, Mr. C’s heart rate decreases to 117 and his lactate level to 1.1 mmol/L. His white blood cell count is 10.6 × 103/mm3 (reference range 4.0 to 10.0 × 103/mm3); a differential can be found in the Table. His electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrates sinus tachycardia and a QTc of 510 ms (reference range <430 ms), but is otherwise unremarkable. His creatinine kinase (CK) level is within normal limits at 76 U/L (reference range 52 to 336 U/L). A C-reactive protein (CRP) level was not drawn at this time. Other than marijuana and cocaine use, Mr. C’s medical history is unremarkable.

Mr. C is admitted to the hospital and is started on treatment for sepsis. On the evening of Day 1, Mr. C experiences worsening tachycardia (140 beats per minute) and tachypnea (≥40 breaths per minute). His temperature increases to 103.3°F, and his blood pressure drops to 97/55 mm Hg. His troponin level is 19.0 ng/mL (reference range <0.01 ng/mL) and CK level is 491 U/L.

As Mr. C continues to deteriorate, a rapid response is called and he is placed on non-rebreather oxygen and transferred to the medical intensive care unit (MICU).

[polldaddy:10226034]

The authors’ observations

With Mr. C’s presenting symptoms, multiple conditions were included in the differential diagnosis. The initial concern was for sepsis. Sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.1 Organ dysfunction is defined by a quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score ≥2 and is associated with an increased probability of mortality (>10%). Although no infection had been identified in Mr. C, the combination of fever, altered vital signs, and elevated lactate level in the setting of a qSOFA score of 2 (for respiratory rate and blood pressure) raised suspicion enough to start empiric treatment.

With Mr. C’s subsequent deterioration on the evening of Day 1, we considered cardiopulmonary etiologies. His symptoms of dyspnea, hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, and fever were nonspecific and thus required consideration of multiple life-threatening etiologies. Thygesen et al2 published an expert consensus of the definition of myocardial infarction, which was of concern given our patient’s elevated troponin level. Because there was already concern for sepsis, the addition of cardiac symptoms required us to consider infectious endocarditis.3 Sudden onset of dyspnea and a drop in blood pressure were concerning for pulmonary embolism, although our patient did not have the usual risk factors (cancer, immobilization, recent surgery, etc.).4 Additionally, in light of Mr. C’s psychiatric history and recent stressors of being moved from his sister’s house and admitted to a psychiatric hospital, coupled with dyspnea and hypotension, we included Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the differential.5,6 This disease often occurs in response to an emotional or physical stressor and is characterized by transient systolic dysfunction in the setting of ventricular wall-motion abnormalities reaching beyond the distribution of a single coronary artery. Acute ECG and biomarker findings mimic those of myocardial infarction.6

Continue to: Finally, we needed to consider...

Finally, we needed to consider the potential adverse effects of clozapine. Clozapine is a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) used to treat patients with schizophrenia for whom other antipsychotic medications are ineffective. Clozapine has been shown to be more effective than first-generation antipsychotics (FGA) in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia.7 It has also been shown to be more effective than several SGAs, including quetiapine, risperidone, and olanzapine.7 In fact, in patients with an insufficient therapeutic response to an SGA, clozapine proves to be more effective than switching to a different SGA. As a result of more than 20 years of research, clozapine is the gold-standard for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.7 Yet despite this strong evidence supporting its use in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, the medication continues to be underutilized, especially in patients at risk for suicide.7

It appears that clozapine remains a third-choice medication in the treatment of schizophrenia largely due to its serious adverse effect profile.7 The medication includes several black-box warnings, including severe neutropenia, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, syncope, seizures, myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, and mitral valve incompetence.8 Tachycardia, bradycardia, and orthostatic hypotension are all clozapine-related adverse effects associated with autonomic dysfunction, which can result in serious long-term cardiac complications.9 With regards to the drug’s neutropenia risk, the establishment of the Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program has allowed for safer use of clozapine and reduced deaths due to clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Clinicians and pharmacists must be certified in order to prescribe clozapine, and patients must be registered and undergo frequent absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring.

Clozapine-induced myocarditis, a condition observed in up to 3% of patients started on the medication,9 is more likely to develop early on during treatment, with a median time of detection of 16 days following drug initiation.10 Myocarditis often presents with nonspecific signs and symptoms that include chest pain, tachycardia, palpitations, dyspnea, fever, flu-like symptoms, and/or hypotension.

[polldaddy:10226036]

The authors’ observations

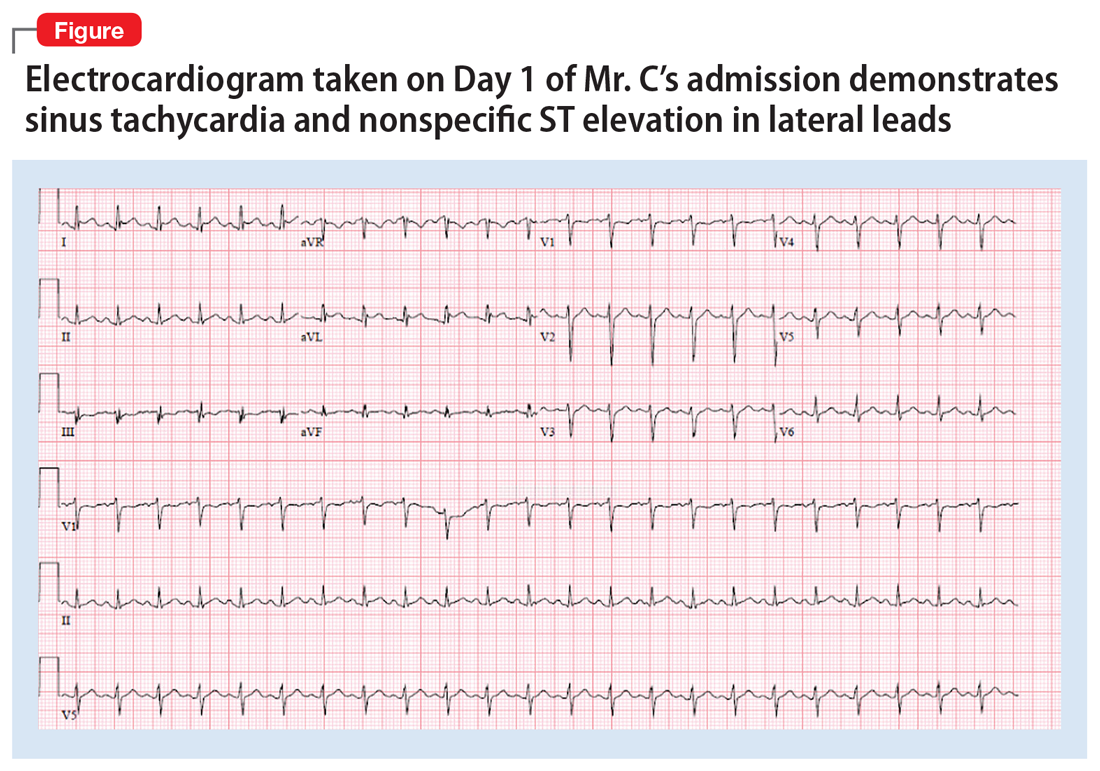

Initial workup in the MICU for Mr. C included an ABG analysis, ECG, and cardiology consult. The ABG analysis demonstrated metabolic alkalosis; his ECG demonstrated sinus tachycardia and nonspecific ST elevation in the lateral leads (Figure). The cardiology consult team started Mr. C on treatment for a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), which it believed to be most likely due to myocarditis with secondary demand ischemia, and less likely acute coronary syndrome. The cardiology consult team also recommended performing a workup for pulmonary emboli and infectious endocarditis if Mr. C’s symptoms persist or the infectious source could not be identified.

EVALUATION Gradual improvement

Mr. C demonstrates gradual improvement as his workup continues, and clozapine is held on the recommendation of the cardiac consult team. By Day 2, he stops complaining of auditory hallucinations, and does not report their return during the rest of his stay. His troponin level decreases to 8.6 ng/mL and lactate level to 1.4 mmol/L; trending is stopped for both. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is elevated at 59 mm/hr (reference range 0 to 22 mm/hr), along with a CRP level of 21 mg/L (reference range <8.0 mg/L). An echocardiogram demonstrates a 40% ejection fraction (reference range 55% to 75%) and moderate global hypokinesis. The cardiology consult team is concerned for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy with sepsis as a source of adrenergic surge vs myopericarditis of viral etiology. The cardiology team also suggests continued stoppage of clozapine, because the medication can cause hypotension and tachycardia.

Continue to: On Day 3...

On Day 3, Mr. C’s ST elevation resolves on ECG, and his CK level decreases to 70 U/L, at which point trending is stopped. On Day 5, Mr. C undergoes MRI, which demonstrates an ejection fraction of 55% and confirms myocarditis. No infectious source is identified.

By Day 6, with all other sources ruled out, clozapine is confirmed as the source of myocarditis for Mr. C.

The authors’ observations

Close cardiovascular monitoring should occur during the first 4 weeks after starting clozapine because 80% of cases of clozapine-induced myocarditis occur within 4 weeks of clozapine initiation.10 Baseline CRP, troponin I/T, and vital signs should be obtained before starting clozapine.11 Vital signs must be monitored to assess for fever, tachycardia, and deviations from baseline blood pressures.11 Although eosinophil counts and percentages can also be considered in addition to a baseline CRP value, they have not proven to be sensitive or specific for clozapine-induced myocarditis.12 A baseline echocardiogram can also be obtained, but is not necessary, especially given that it may not be readily available in all clinics, and could therefore delay initiation of clozapine and limit its use. C-reactive protein and troponin levels should be assessed weekly during the first 6 weeks of clozapine therapy.11 For symptomatic patients presenting with concern for clozapine-induced myocarditis, a CRP level >100 mg/L has 100% sensitivity in detecting clozapine-induced myocarditis.13 Clozapine should also be stopped if troponins levels reach twice the upper limit of normal. More mild elevations of CRP and troponins in the setting of persistent tachycardia or signs of an infectious process should be followed by daily CRP and troponins levels until these features resolve.11

Mr. C’s case highlights clinical features that clinicians should consider when screening for myocarditis. The development of myocarditis is associated with quick titrations of clozapine during Days 1 to 9. In this case, Mr. C had recently been titrated at an outside hospital, and the time frame during which this titration occurred was unknown. Given this lack of information, the potential for a rapid titration should alert the clinician to the risk of developing myocarditis. Increased age is also associated with an increased risk of myocarditis, with a 31% increase for each decade. Further, the concomitant use of valproate sodium during the titration period also increases the risk of myocarditis 2.5-fold.14

When evaluating a patient such as Mr. C, an important clinical sign that must not be overlooked is that an elevation of body temperature of 1°C is expected to give rise to a 10-beats-per-minute increase in heart rate when the fever is the result of an infection.15 During Day 1 of his hospitalization, Mr. C was tachycardic to 160 beats per minute, with a fever of 39.4°C. Thus, his heart rate was elevated well beyond what would be expected from a fever secondary to an infectious process. This further illustrates the need to consider adverse effects caused by medication, such as clozapine-induced tachycardia.

Continue to: While clozapine had already been stopped...

While clozapine had already been stopped in Mr. C, it is conceivable that other patients would potentially continue receiving it because of the medication’s demonstrated efficacy in reducing hallucinations; however, this would result in worsening and potentially serious cardiac symptoms.

[polldaddy:10226037]

The authors’ observations

A diagnosis of clozapine-induced myocarditis should be followed by a prompt discontinuation of clozapine. Discontinuation of the drug should lead to spontaneous resolution of the myocarditis, with significantly improved left ventricular function observed within 5 days.13 Historically, rechallenging a patient with clozapine was not recommended, due to fear of recurrence of myocarditis. However, recent case studies indicate that myocarditis need not be an absolute contraindication to restarting clozapine.16 Rather, the risks must be balanced against demonstrated efficacy in patients who had a limited response to other antipsychotics, as was the case with Mr. C. For these patients, the decision to rechallenge should be made with the patient’s informed consent and involve slow dose titration and increased monitoring.17 Should this rechallenge fail, another antipsychotic plus augmentation with a mood stabilizer or ECT may be more efficacious than an antipsychotic alone.18,19

OUTCOME Return to the psychiatric hospital

On Day 8, Mr. C is medically cleared; he had not reported auditory hallucinations since Day 2. He is discharged back to the psychiatric hospital for additional medication management of his schizophrenia.

Bottom Line

Clozapine-induced myocarditis should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients who present with nonspecific complaints and have an incomplete history pertaining to clozapine use. After discontinuing clozapine, and after myocarditis symptoms resolve, consider restarting clozapine in patients who have limited response to other treatments. If rechallenging fails, another antipsychotic plus augmentation with a mood stabilizer or electroconvulsive therapy may be more efficacious than an antipsychotic alone.

Related Resources

- Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy [REMS] Program. What is the Clozapine REMS Program? https://www.clozapinerems.com.

- Keating D, McWilliams S, Schneider I, et al. Pharmacological guidelines for schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparison of recommendations for the first episode. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e013881.

- Curto M, Girardi N, Lionetto L, et al. Systematic review of clozapine cardiotoxicity. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(7):68.

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproate • Depacon

1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810.

2. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2551-2567.

3. Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD. Infective endocarditis. Lancet. 2016;387(10021):882-893.

4. Stein PD, Terrin ML, Hales CA, et al. Clinical, laboratory, roentgenographic, and electrocardiographic findings in patients with acute pulmonary embolism and no pre-existing cardiac or pulmonary disease. Chest. 1991;100(3):598-603.

5. Summers MR, Lennon RJ, Prasad A. Pre-morbid psychiatric and cardiovascular diseases in apical ballooning syndrome (tako-tsubo/stress-induced cardiomyopathy): potential pre-disposing factors? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(7):700-701.

6. Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):929-938.

7. Warnez S, Alessi-Severini S. Clozapine: a review of clinical practice guidelines and prescribing trends. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:102.

8. Clozaril [package insert]. Rosemont, PA: HLS Therapeutics (USA), Inc.; 2016.

9. Ronaldson KJ. Cardiovascular disease in clozapine-treated Patients: evidence, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):777-795.

10. Haas SJ, Hill R, Krum H, et al. Clozapine-associated myocarditis: a review of 116 cases of suspected myocarditis associated with the use of clozapine in Australia during 1993-2003. Drug Saf. 2007;30(1):47-57.

11. Goldsmith DR, Cotes RO. An unmet need: a clozapine-induced myocarditis screening protocol. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2017;19(4): doi: 10.4088/PCC.16l02083.

12. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, McNeil JJ. Evolution of troponin, C-reactive protein and eosinophil count with the onset of clozapine-induced myocarditis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(5):486-487.

13. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, et al. A new monitoring protocol for clozapine-induced myocarditis based on an analysis of 75 cases and 94 controls. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(6):458-465.

14. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, et al. Rapid clozapine dose titration and concomitant sodium valproate increase the risk of myocarditis with clozapine: a case-control study. Schizophr Res. 2012;141(2-3):173-178.

15. Davies P, Maconochie I. The relationship between body temperature, heart rate and respiratory rate in children. Emerg Med J. 2009;26(9):641-643.

16. Cook SC, Ferguson BA, Cotes RO, et al. Clozapine-induced myocarditis: prevention and considerations in rechallenge. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(6):685-690.

17. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, et al. Observations from 8 cases of clozapine rechallenge after development of myocarditis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(2):252-254.

18. Singh SP, Singh V, Kar N, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants in treating the negative symptoms of chronic schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(3):174-179.

19. Wenzheng W, Chengcheng PU, Jiangling Jiang, et al. Efficacy and safety of treating patients with refractory schizophrenia with antipsychotic medication and adjunctive electroconvulsive therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015;27(4):206-219.

CASE Posing a threat to his family

Mr. C, age 23, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia with daily auditory hallucinations 4 years earlier, is transferred from an outside psychiatric hospital to our emergency department (ED) after developing fever, tachycardia, headache, and nasal congestion for the past day. He had been admitted to the psychiatric hospital 3 weeks ago due to concerns he was experiencing increased hallucinations and delusions and posed a threat to his sister and her children, with whom he had been living.

Mr. C tells us that while at the psychiatric hospital, he had been started on clozapine, 250 mg/d. He said that prior to clozapine, he had been taking risperidone. We are unable to confirm past treatment information with the psychiatric hospital, including exactly when the clozapine had been started or how fast it had been titrated. We also were not able to obtain information on his prior medication regimen.

In the ED, Mr. C is febrile (39.4°C; 102.9°F), tachycardic (160 beats per minute; reference range 60 to 100), and tachypneic (24 breaths per minute; reference range 12 to 20). His blood pressure is 130/68 mm Hg, and his lactate level is 2.3 mmol/L (reference range <1.9 mmol/L). After he receives 3 liters of fluid, Mr. C’s heart rate decreases to 117 and his lactate level to 1.1 mmol/L. His white blood cell count is 10.6 × 103/mm3 (reference range 4.0 to 10.0 × 103/mm3); a differential can be found in the Table. His electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrates sinus tachycardia and a QTc of 510 ms (reference range <430 ms), but is otherwise unremarkable. His creatinine kinase (CK) level is within normal limits at 76 U/L (reference range 52 to 336 U/L). A C-reactive protein (CRP) level was not drawn at this time. Other than marijuana and cocaine use, Mr. C’s medical history is unremarkable.

Mr. C is admitted to the hospital and is started on treatment for sepsis. On the evening of Day 1, Mr. C experiences worsening tachycardia (140 beats per minute) and tachypnea (≥40 breaths per minute). His temperature increases to 103.3°F, and his blood pressure drops to 97/55 mm Hg. His troponin level is 19.0 ng/mL (reference range <0.01 ng/mL) and CK level is 491 U/L.

As Mr. C continues to deteriorate, a rapid response is called and he is placed on non-rebreather oxygen and transferred to the medical intensive care unit (MICU).

[polldaddy:10226034]

The authors’ observations

With Mr. C’s presenting symptoms, multiple conditions were included in the differential diagnosis. The initial concern was for sepsis. Sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.1 Organ dysfunction is defined by a quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score ≥2 and is associated with an increased probability of mortality (>10%). Although no infection had been identified in Mr. C, the combination of fever, altered vital signs, and elevated lactate level in the setting of a qSOFA score of 2 (for respiratory rate and blood pressure) raised suspicion enough to start empiric treatment.

With Mr. C’s subsequent deterioration on the evening of Day 1, we considered cardiopulmonary etiologies. His symptoms of dyspnea, hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, and fever were nonspecific and thus required consideration of multiple life-threatening etiologies. Thygesen et al2 published an expert consensus of the definition of myocardial infarction, which was of concern given our patient’s elevated troponin level. Because there was already concern for sepsis, the addition of cardiac symptoms required us to consider infectious endocarditis.3 Sudden onset of dyspnea and a drop in blood pressure were concerning for pulmonary embolism, although our patient did not have the usual risk factors (cancer, immobilization, recent surgery, etc.).4 Additionally, in light of Mr. C’s psychiatric history and recent stressors of being moved from his sister’s house and admitted to a psychiatric hospital, coupled with dyspnea and hypotension, we included Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the differential.5,6 This disease often occurs in response to an emotional or physical stressor and is characterized by transient systolic dysfunction in the setting of ventricular wall-motion abnormalities reaching beyond the distribution of a single coronary artery. Acute ECG and biomarker findings mimic those of myocardial infarction.6

Continue to: Finally, we needed to consider...

Finally, we needed to consider the potential adverse effects of clozapine. Clozapine is a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) used to treat patients with schizophrenia for whom other antipsychotic medications are ineffective. Clozapine has been shown to be more effective than first-generation antipsychotics (FGA) in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia.7 It has also been shown to be more effective than several SGAs, including quetiapine, risperidone, and olanzapine.7 In fact, in patients with an insufficient therapeutic response to an SGA, clozapine proves to be more effective than switching to a different SGA. As a result of more than 20 years of research, clozapine is the gold-standard for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.7 Yet despite this strong evidence supporting its use in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, the medication continues to be underutilized, especially in patients at risk for suicide.7

It appears that clozapine remains a third-choice medication in the treatment of schizophrenia largely due to its serious adverse effect profile.7 The medication includes several black-box warnings, including severe neutropenia, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, syncope, seizures, myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, and mitral valve incompetence.8 Tachycardia, bradycardia, and orthostatic hypotension are all clozapine-related adverse effects associated with autonomic dysfunction, which can result in serious long-term cardiac complications.9 With regards to the drug’s neutropenia risk, the establishment of the Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program has allowed for safer use of clozapine and reduced deaths due to clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Clinicians and pharmacists must be certified in order to prescribe clozapine, and patients must be registered and undergo frequent absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring.

Clozapine-induced myocarditis, a condition observed in up to 3% of patients started on the medication,9 is more likely to develop early on during treatment, with a median time of detection of 16 days following drug initiation.10 Myocarditis often presents with nonspecific signs and symptoms that include chest pain, tachycardia, palpitations, dyspnea, fever, flu-like symptoms, and/or hypotension.

[polldaddy:10226036]

The authors’ observations

Initial workup in the MICU for Mr. C included an ABG analysis, ECG, and cardiology consult. The ABG analysis demonstrated metabolic alkalosis; his ECG demonstrated sinus tachycardia and nonspecific ST elevation in the lateral leads (Figure). The cardiology consult team started Mr. C on treatment for a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), which it believed to be most likely due to myocarditis with secondary demand ischemia, and less likely acute coronary syndrome. The cardiology consult team also recommended performing a workup for pulmonary emboli and infectious endocarditis if Mr. C’s symptoms persist or the infectious source could not be identified.

EVALUATION Gradual improvement

Mr. C demonstrates gradual improvement as his workup continues, and clozapine is held on the recommendation of the cardiac consult team. By Day 2, he stops complaining of auditory hallucinations, and does not report their return during the rest of his stay. His troponin level decreases to 8.6 ng/mL and lactate level to 1.4 mmol/L; trending is stopped for both. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is elevated at 59 mm/hr (reference range 0 to 22 mm/hr), along with a CRP level of 21 mg/L (reference range <8.0 mg/L). An echocardiogram demonstrates a 40% ejection fraction (reference range 55% to 75%) and moderate global hypokinesis. The cardiology consult team is concerned for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy with sepsis as a source of adrenergic surge vs myopericarditis of viral etiology. The cardiology team also suggests continued stoppage of clozapine, because the medication can cause hypotension and tachycardia.

Continue to: On Day 3...

On Day 3, Mr. C’s ST elevation resolves on ECG, and his CK level decreases to 70 U/L, at which point trending is stopped. On Day 5, Mr. C undergoes MRI, which demonstrates an ejection fraction of 55% and confirms myocarditis. No infectious source is identified.

By Day 6, with all other sources ruled out, clozapine is confirmed as the source of myocarditis for Mr. C.

The authors’ observations

Close cardiovascular monitoring should occur during the first 4 weeks after starting clozapine because 80% of cases of clozapine-induced myocarditis occur within 4 weeks of clozapine initiation.10 Baseline CRP, troponin I/T, and vital signs should be obtained before starting clozapine.11 Vital signs must be monitored to assess for fever, tachycardia, and deviations from baseline blood pressures.11 Although eosinophil counts and percentages can also be considered in addition to a baseline CRP value, they have not proven to be sensitive or specific for clozapine-induced myocarditis.12 A baseline echocardiogram can also be obtained, but is not necessary, especially given that it may not be readily available in all clinics, and could therefore delay initiation of clozapine and limit its use. C-reactive protein and troponin levels should be assessed weekly during the first 6 weeks of clozapine therapy.11 For symptomatic patients presenting with concern for clozapine-induced myocarditis, a CRP level >100 mg/L has 100% sensitivity in detecting clozapine-induced myocarditis.13 Clozapine should also be stopped if troponins levels reach twice the upper limit of normal. More mild elevations of CRP and troponins in the setting of persistent tachycardia or signs of an infectious process should be followed by daily CRP and troponins levels until these features resolve.11

Mr. C’s case highlights clinical features that clinicians should consider when screening for myocarditis. The development of myocarditis is associated with quick titrations of clozapine during Days 1 to 9. In this case, Mr. C had recently been titrated at an outside hospital, and the time frame during which this titration occurred was unknown. Given this lack of information, the potential for a rapid titration should alert the clinician to the risk of developing myocarditis. Increased age is also associated with an increased risk of myocarditis, with a 31% increase for each decade. Further, the concomitant use of valproate sodium during the titration period also increases the risk of myocarditis 2.5-fold.14

When evaluating a patient such as Mr. C, an important clinical sign that must not be overlooked is that an elevation of body temperature of 1°C is expected to give rise to a 10-beats-per-minute increase in heart rate when the fever is the result of an infection.15 During Day 1 of his hospitalization, Mr. C was tachycardic to 160 beats per minute, with a fever of 39.4°C. Thus, his heart rate was elevated well beyond what would be expected from a fever secondary to an infectious process. This further illustrates the need to consider adverse effects caused by medication, such as clozapine-induced tachycardia.

Continue to: While clozapine had already been stopped...

While clozapine had already been stopped in Mr. C, it is conceivable that other patients would potentially continue receiving it because of the medication’s demonstrated efficacy in reducing hallucinations; however, this would result in worsening and potentially serious cardiac symptoms.

[polldaddy:10226037]

The authors’ observations

A diagnosis of clozapine-induced myocarditis should be followed by a prompt discontinuation of clozapine. Discontinuation of the drug should lead to spontaneous resolution of the myocarditis, with significantly improved left ventricular function observed within 5 days.13 Historically, rechallenging a patient with clozapine was not recommended, due to fear of recurrence of myocarditis. However, recent case studies indicate that myocarditis need not be an absolute contraindication to restarting clozapine.16 Rather, the risks must be balanced against demonstrated efficacy in patients who had a limited response to other antipsychotics, as was the case with Mr. C. For these patients, the decision to rechallenge should be made with the patient’s informed consent and involve slow dose titration and increased monitoring.17 Should this rechallenge fail, another antipsychotic plus augmentation with a mood stabilizer or ECT may be more efficacious than an antipsychotic alone.18,19

OUTCOME Return to the psychiatric hospital

On Day 8, Mr. C is medically cleared; he had not reported auditory hallucinations since Day 2. He is discharged back to the psychiatric hospital for additional medication management of his schizophrenia.

Bottom Line

Clozapine-induced myocarditis should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients who present with nonspecific complaints and have an incomplete history pertaining to clozapine use. After discontinuing clozapine, and after myocarditis symptoms resolve, consider restarting clozapine in patients who have limited response to other treatments. If rechallenging fails, another antipsychotic plus augmentation with a mood stabilizer or electroconvulsive therapy may be more efficacious than an antipsychotic alone.

Related Resources

- Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy [REMS] Program. What is the Clozapine REMS Program? https://www.clozapinerems.com.

- Keating D, McWilliams S, Schneider I, et al. Pharmacological guidelines for schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparison of recommendations for the first episode. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e013881.

- Curto M, Girardi N, Lionetto L, et al. Systematic review of clozapine cardiotoxicity. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(7):68.

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproate • Depacon

CASE Posing a threat to his family

Mr. C, age 23, who was diagnosed with schizophrenia with daily auditory hallucinations 4 years earlier, is transferred from an outside psychiatric hospital to our emergency department (ED) after developing fever, tachycardia, headache, and nasal congestion for the past day. He had been admitted to the psychiatric hospital 3 weeks ago due to concerns he was experiencing increased hallucinations and delusions and posed a threat to his sister and her children, with whom he had been living.

Mr. C tells us that while at the psychiatric hospital, he had been started on clozapine, 250 mg/d. He said that prior to clozapine, he had been taking risperidone. We are unable to confirm past treatment information with the psychiatric hospital, including exactly when the clozapine had been started or how fast it had been titrated. We also were not able to obtain information on his prior medication regimen.

In the ED, Mr. C is febrile (39.4°C; 102.9°F), tachycardic (160 beats per minute; reference range 60 to 100), and tachypneic (24 breaths per minute; reference range 12 to 20). His blood pressure is 130/68 mm Hg, and his lactate level is 2.3 mmol/L (reference range <1.9 mmol/L). After he receives 3 liters of fluid, Mr. C’s heart rate decreases to 117 and his lactate level to 1.1 mmol/L. His white blood cell count is 10.6 × 103/mm3 (reference range 4.0 to 10.0 × 103/mm3); a differential can be found in the Table. His electrocardiogram (ECG) demonstrates sinus tachycardia and a QTc of 510 ms (reference range <430 ms), but is otherwise unremarkable. His creatinine kinase (CK) level is within normal limits at 76 U/L (reference range 52 to 336 U/L). A C-reactive protein (CRP) level was not drawn at this time. Other than marijuana and cocaine use, Mr. C’s medical history is unremarkable.

Mr. C is admitted to the hospital and is started on treatment for sepsis. On the evening of Day 1, Mr. C experiences worsening tachycardia (140 beats per minute) and tachypnea (≥40 breaths per minute). His temperature increases to 103.3°F, and his blood pressure drops to 97/55 mm Hg. His troponin level is 19.0 ng/mL (reference range <0.01 ng/mL) and CK level is 491 U/L.

As Mr. C continues to deteriorate, a rapid response is called and he is placed on non-rebreather oxygen and transferred to the medical intensive care unit (MICU).

[polldaddy:10226034]

The authors’ observations

With Mr. C’s presenting symptoms, multiple conditions were included in the differential diagnosis. The initial concern was for sepsis. Sepsis is defined as life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection.1 Organ dysfunction is defined by a quick Sepsis-Related Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA) score ≥2 and is associated with an increased probability of mortality (>10%). Although no infection had been identified in Mr. C, the combination of fever, altered vital signs, and elevated lactate level in the setting of a qSOFA score of 2 (for respiratory rate and blood pressure) raised suspicion enough to start empiric treatment.

With Mr. C’s subsequent deterioration on the evening of Day 1, we considered cardiopulmonary etiologies. His symptoms of dyspnea, hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, and fever were nonspecific and thus required consideration of multiple life-threatening etiologies. Thygesen et al2 published an expert consensus of the definition of myocardial infarction, which was of concern given our patient’s elevated troponin level. Because there was already concern for sepsis, the addition of cardiac symptoms required us to consider infectious endocarditis.3 Sudden onset of dyspnea and a drop in blood pressure were concerning for pulmonary embolism, although our patient did not have the usual risk factors (cancer, immobilization, recent surgery, etc.).4 Additionally, in light of Mr. C’s psychiatric history and recent stressors of being moved from his sister’s house and admitted to a psychiatric hospital, coupled with dyspnea and hypotension, we included Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the differential.5,6 This disease often occurs in response to an emotional or physical stressor and is characterized by transient systolic dysfunction in the setting of ventricular wall-motion abnormalities reaching beyond the distribution of a single coronary artery. Acute ECG and biomarker findings mimic those of myocardial infarction.6

Continue to: Finally, we needed to consider...

Finally, we needed to consider the potential adverse effects of clozapine. Clozapine is a second-generation antipsychotic (SGA) used to treat patients with schizophrenia for whom other antipsychotic medications are ineffective. Clozapine has been shown to be more effective than first-generation antipsychotics (FGA) in reducing symptoms of schizophrenia.7 It has also been shown to be more effective than several SGAs, including quetiapine, risperidone, and olanzapine.7 In fact, in patients with an insufficient therapeutic response to an SGA, clozapine proves to be more effective than switching to a different SGA. As a result of more than 20 years of research, clozapine is the gold-standard for treatment-resistant schizophrenia.7 Yet despite this strong evidence supporting its use in patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, the medication continues to be underutilized, especially in patients at risk for suicide.7

It appears that clozapine remains a third-choice medication in the treatment of schizophrenia largely due to its serious adverse effect profile.7 The medication includes several black-box warnings, including severe neutropenia, orthostatic hypotension, bradycardia, syncope, seizures, myocarditis, cardiomyopathy, and mitral valve incompetence.8 Tachycardia, bradycardia, and orthostatic hypotension are all clozapine-related adverse effects associated with autonomic dysfunction, which can result in serious long-term cardiac complications.9 With regards to the drug’s neutropenia risk, the establishment of the Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program has allowed for safer use of clozapine and reduced deaths due to clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Clinicians and pharmacists must be certified in order to prescribe clozapine, and patients must be registered and undergo frequent absolute neutrophil count (ANC) monitoring.

Clozapine-induced myocarditis, a condition observed in up to 3% of patients started on the medication,9 is more likely to develop early on during treatment, with a median time of detection of 16 days following drug initiation.10 Myocarditis often presents with nonspecific signs and symptoms that include chest pain, tachycardia, palpitations, dyspnea, fever, flu-like symptoms, and/or hypotension.

[polldaddy:10226036]

The authors’ observations

Initial workup in the MICU for Mr. C included an ABG analysis, ECG, and cardiology consult. The ABG analysis demonstrated metabolic alkalosis; his ECG demonstrated sinus tachycardia and nonspecific ST elevation in the lateral leads (Figure). The cardiology consult team started Mr. C on treatment for a non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), which it believed to be most likely due to myocarditis with secondary demand ischemia, and less likely acute coronary syndrome. The cardiology consult team also recommended performing a workup for pulmonary emboli and infectious endocarditis if Mr. C’s symptoms persist or the infectious source could not be identified.

EVALUATION Gradual improvement

Mr. C demonstrates gradual improvement as his workup continues, and clozapine is held on the recommendation of the cardiac consult team. By Day 2, he stops complaining of auditory hallucinations, and does not report their return during the rest of his stay. His troponin level decreases to 8.6 ng/mL and lactate level to 1.4 mmol/L; trending is stopped for both. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is elevated at 59 mm/hr (reference range 0 to 22 mm/hr), along with a CRP level of 21 mg/L (reference range <8.0 mg/L). An echocardiogram demonstrates a 40% ejection fraction (reference range 55% to 75%) and moderate global hypokinesis. The cardiology consult team is concerned for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy with sepsis as a source of adrenergic surge vs myopericarditis of viral etiology. The cardiology team also suggests continued stoppage of clozapine, because the medication can cause hypotension and tachycardia.

Continue to: On Day 3...

On Day 3, Mr. C’s ST elevation resolves on ECG, and his CK level decreases to 70 U/L, at which point trending is stopped. On Day 5, Mr. C undergoes MRI, which demonstrates an ejection fraction of 55% and confirms myocarditis. No infectious source is identified.

By Day 6, with all other sources ruled out, clozapine is confirmed as the source of myocarditis for Mr. C.

The authors’ observations

Close cardiovascular monitoring should occur during the first 4 weeks after starting clozapine because 80% of cases of clozapine-induced myocarditis occur within 4 weeks of clozapine initiation.10 Baseline CRP, troponin I/T, and vital signs should be obtained before starting clozapine.11 Vital signs must be monitored to assess for fever, tachycardia, and deviations from baseline blood pressures.11 Although eosinophil counts and percentages can also be considered in addition to a baseline CRP value, they have not proven to be sensitive or specific for clozapine-induced myocarditis.12 A baseline echocardiogram can also be obtained, but is not necessary, especially given that it may not be readily available in all clinics, and could therefore delay initiation of clozapine and limit its use. C-reactive protein and troponin levels should be assessed weekly during the first 6 weeks of clozapine therapy.11 For symptomatic patients presenting with concern for clozapine-induced myocarditis, a CRP level >100 mg/L has 100% sensitivity in detecting clozapine-induced myocarditis.13 Clozapine should also be stopped if troponins levels reach twice the upper limit of normal. More mild elevations of CRP and troponins in the setting of persistent tachycardia or signs of an infectious process should be followed by daily CRP and troponins levels until these features resolve.11

Mr. C’s case highlights clinical features that clinicians should consider when screening for myocarditis. The development of myocarditis is associated with quick titrations of clozapine during Days 1 to 9. In this case, Mr. C had recently been titrated at an outside hospital, and the time frame during which this titration occurred was unknown. Given this lack of information, the potential for a rapid titration should alert the clinician to the risk of developing myocarditis. Increased age is also associated with an increased risk of myocarditis, with a 31% increase for each decade. Further, the concomitant use of valproate sodium during the titration period also increases the risk of myocarditis 2.5-fold.14

When evaluating a patient such as Mr. C, an important clinical sign that must not be overlooked is that an elevation of body temperature of 1°C is expected to give rise to a 10-beats-per-minute increase in heart rate when the fever is the result of an infection.15 During Day 1 of his hospitalization, Mr. C was tachycardic to 160 beats per minute, with a fever of 39.4°C. Thus, his heart rate was elevated well beyond what would be expected from a fever secondary to an infectious process. This further illustrates the need to consider adverse effects caused by medication, such as clozapine-induced tachycardia.

Continue to: While clozapine had already been stopped...

While clozapine had already been stopped in Mr. C, it is conceivable that other patients would potentially continue receiving it because of the medication’s demonstrated efficacy in reducing hallucinations; however, this would result in worsening and potentially serious cardiac symptoms.

[polldaddy:10226037]

The authors’ observations

A diagnosis of clozapine-induced myocarditis should be followed by a prompt discontinuation of clozapine. Discontinuation of the drug should lead to spontaneous resolution of the myocarditis, with significantly improved left ventricular function observed within 5 days.13 Historically, rechallenging a patient with clozapine was not recommended, due to fear of recurrence of myocarditis. However, recent case studies indicate that myocarditis need not be an absolute contraindication to restarting clozapine.16 Rather, the risks must be balanced against demonstrated efficacy in patients who had a limited response to other antipsychotics, as was the case with Mr. C. For these patients, the decision to rechallenge should be made with the patient’s informed consent and involve slow dose titration and increased monitoring.17 Should this rechallenge fail, another antipsychotic plus augmentation with a mood stabilizer or ECT may be more efficacious than an antipsychotic alone.18,19

OUTCOME Return to the psychiatric hospital

On Day 8, Mr. C is medically cleared; he had not reported auditory hallucinations since Day 2. He is discharged back to the psychiatric hospital for additional medication management of his schizophrenia.

Bottom Line

Clozapine-induced myocarditis should be included in the differential diagnosis for patients who present with nonspecific complaints and have an incomplete history pertaining to clozapine use. After discontinuing clozapine, and after myocarditis symptoms resolve, consider restarting clozapine in patients who have limited response to other treatments. If rechallenging fails, another antipsychotic plus augmentation with a mood stabilizer or electroconvulsive therapy may be more efficacious than an antipsychotic alone.

Related Resources

- Clozapine Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy [REMS] Program. What is the Clozapine REMS Program? https://www.clozapinerems.com.

- Keating D, McWilliams S, Schneider I, et al. Pharmacological guidelines for schizophrenia: a systematic review and comparison of recommendations for the first episode. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e013881.

- Curto M, Girardi N, Lionetto L, et al. Systematic review of clozapine cardiotoxicity. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(7):68.

Drug Brand Names

Clozapine • Clozaril

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Valproate • Depacon

1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810.

2. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2551-2567.

3. Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD. Infective endocarditis. Lancet. 2016;387(10021):882-893.

4. Stein PD, Terrin ML, Hales CA, et al. Clinical, laboratory, roentgenographic, and electrocardiographic findings in patients with acute pulmonary embolism and no pre-existing cardiac or pulmonary disease. Chest. 1991;100(3):598-603.

5. Summers MR, Lennon RJ, Prasad A. Pre-morbid psychiatric and cardiovascular diseases in apical ballooning syndrome (tako-tsubo/stress-induced cardiomyopathy): potential pre-disposing factors? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(7):700-701.

6. Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):929-938.

7. Warnez S, Alessi-Severini S. Clozapine: a review of clinical practice guidelines and prescribing trends. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:102.

8. Clozaril [package insert]. Rosemont, PA: HLS Therapeutics (USA), Inc.; 2016.

9. Ronaldson KJ. Cardiovascular disease in clozapine-treated Patients: evidence, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):777-795.

10. Haas SJ, Hill R, Krum H, et al. Clozapine-associated myocarditis: a review of 116 cases of suspected myocarditis associated with the use of clozapine in Australia during 1993-2003. Drug Saf. 2007;30(1):47-57.

11. Goldsmith DR, Cotes RO. An unmet need: a clozapine-induced myocarditis screening protocol. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2017;19(4): doi: 10.4088/PCC.16l02083.

12. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, McNeil JJ. Evolution of troponin, C-reactive protein and eosinophil count with the onset of clozapine-induced myocarditis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(5):486-487.

13. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, et al. A new monitoring protocol for clozapine-induced myocarditis based on an analysis of 75 cases and 94 controls. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(6):458-465.

14. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, et al. Rapid clozapine dose titration and concomitant sodium valproate increase the risk of myocarditis with clozapine: a case-control study. Schizophr Res. 2012;141(2-3):173-178.

15. Davies P, Maconochie I. The relationship between body temperature, heart rate and respiratory rate in children. Emerg Med J. 2009;26(9):641-643.

16. Cook SC, Ferguson BA, Cotes RO, et al. Clozapine-induced myocarditis: prevention and considerations in rechallenge. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(6):685-690.

17. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, et al. Observations from 8 cases of clozapine rechallenge after development of myocarditis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(2):252-254.

18. Singh SP, Singh V, Kar N, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants in treating the negative symptoms of chronic schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(3):174-179.

19. Wenzheng W, Chengcheng PU, Jiangling Jiang, et al. Efficacy and safety of treating patients with refractory schizophrenia with antipsychotic medication and adjunctive electroconvulsive therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015;27(4):206-219.

1. Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801-810.

2. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2551-2567.

3. Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD. Infective endocarditis. Lancet. 2016;387(10021):882-893.

4. Stein PD, Terrin ML, Hales CA, et al. Clinical, laboratory, roentgenographic, and electrocardiographic findings in patients with acute pulmonary embolism and no pre-existing cardiac or pulmonary disease. Chest. 1991;100(3):598-603.

5. Summers MR, Lennon RJ, Prasad A. Pre-morbid psychiatric and cardiovascular diseases in apical ballooning syndrome (tako-tsubo/stress-induced cardiomyopathy): potential pre-disposing factors? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(7):700-701.

6. Templin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of Takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(10):929-938.

7. Warnez S, Alessi-Severini S. Clozapine: a review of clinical practice guidelines and prescribing trends. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:102.

8. Clozaril [package insert]. Rosemont, PA: HLS Therapeutics (USA), Inc.; 2016.

9. Ronaldson KJ. Cardiovascular disease in clozapine-treated Patients: evidence, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs. 2017;31(9):777-795.

10. Haas SJ, Hill R, Krum H, et al. Clozapine-associated myocarditis: a review of 116 cases of suspected myocarditis associated with the use of clozapine in Australia during 1993-2003. Drug Saf. 2007;30(1):47-57.

11. Goldsmith DR, Cotes RO. An unmet need: a clozapine-induced myocarditis screening protocol. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2017;19(4): doi: 10.4088/PCC.16l02083.

12. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, McNeil JJ. Evolution of troponin, C-reactive protein and eosinophil count with the onset of clozapine-induced myocarditis. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49(5):486-487.

13. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, et al. A new monitoring protocol for clozapine-induced myocarditis based on an analysis of 75 cases and 94 controls. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45(6):458-465.

14. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, et al. Rapid clozapine dose titration and concomitant sodium valproate increase the risk of myocarditis with clozapine: a case-control study. Schizophr Res. 2012;141(2-3):173-178.

15. Davies P, Maconochie I. The relationship between body temperature, heart rate and respiratory rate in children. Emerg Med J. 2009;26(9):641-643.

16. Cook SC, Ferguson BA, Cotes RO, et al. Clozapine-induced myocarditis: prevention and considerations in rechallenge. Psychosomatics. 2015;56(6):685-690.

17. Ronaldson KJ, Fitzgerald PB, Taylor AJ, et al. Observations from 8 cases of clozapine rechallenge after development of myocarditis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(2):252-254.

18. Singh SP, Singh V, Kar N, et al. Efficacy of antidepressants in treating the negative symptoms of chronic schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;197(3):174-179.

19. Wenzheng W, Chengcheng PU, Jiangling Jiang, et al. Efficacy and safety of treating patients with refractory schizophrenia with antipsychotic medication and adjunctive electroconvulsive therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015;27(4):206-219.

Psychotropic-induced hyponatremia

Hyponatremia is a common, multifactorial clinical condition. Hyponatremia is usually defined as a plasma sodium level <135 mmol/L; however, some studies define it as a level <130 mmol/L. Hyponatremia results from the inability of the kidney to excrete a sufficient amount of fluid, or is due to excessive fluid intake. Increases in osmolality stimulate thirst and result in increased fluid intake. This increase in osmolality is recognized by the osmoreceptors located in the hypothalamus, which release antidiuretic hormone (ADH). Antidiuretic hormone works on the collecting ducts within the kidneys, triggering increased fluid reabsorption resulting in decreased fluid loss and a reduction in thirst.

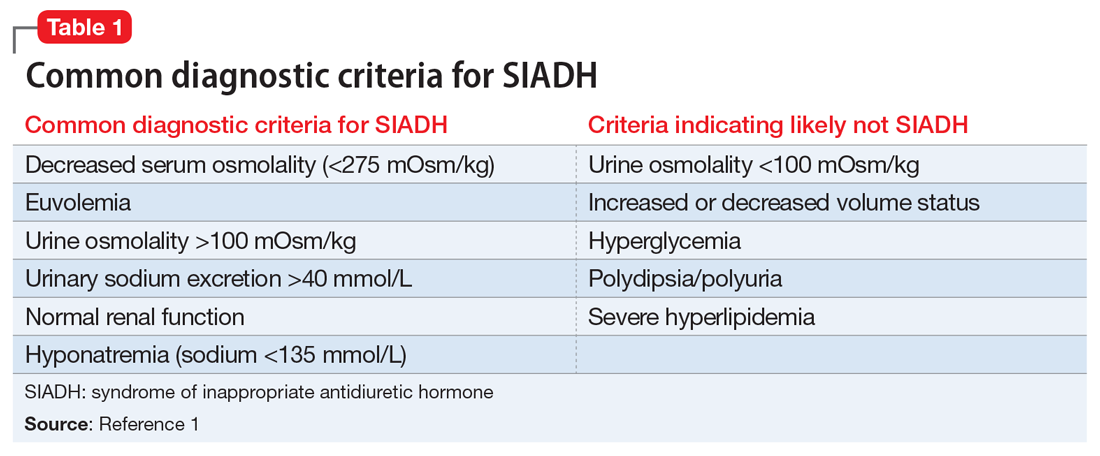

The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) occurs when there is persistent ADH stimulation resulting in hyponatremia. SIADH commonly presents as euvolemic hyponatremia. Common diagnostic criteria for SIADH are listed in Table 1.1

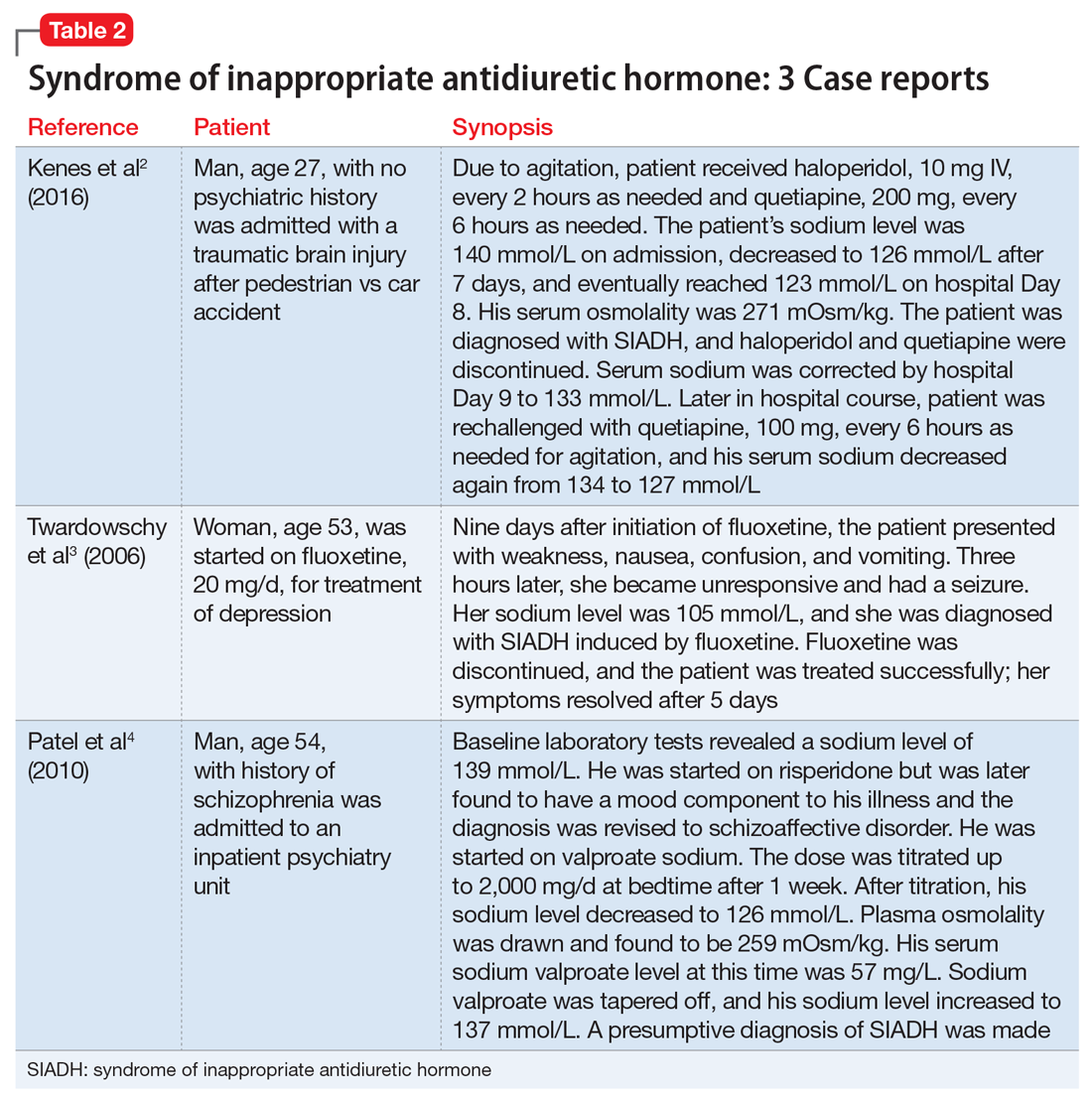

Medications are a major cause of SIADH, and psychotropics are a primary offender. Most of the data for drug-induced SIADH come from case reports and small case series, such as those described in Table 2.2-4 The extent to which each psychotropic class causes SIADH remains unknown. In this article, we focus on 3 classes of psychotropics, and their role in causing SIADH.

Antidepressants

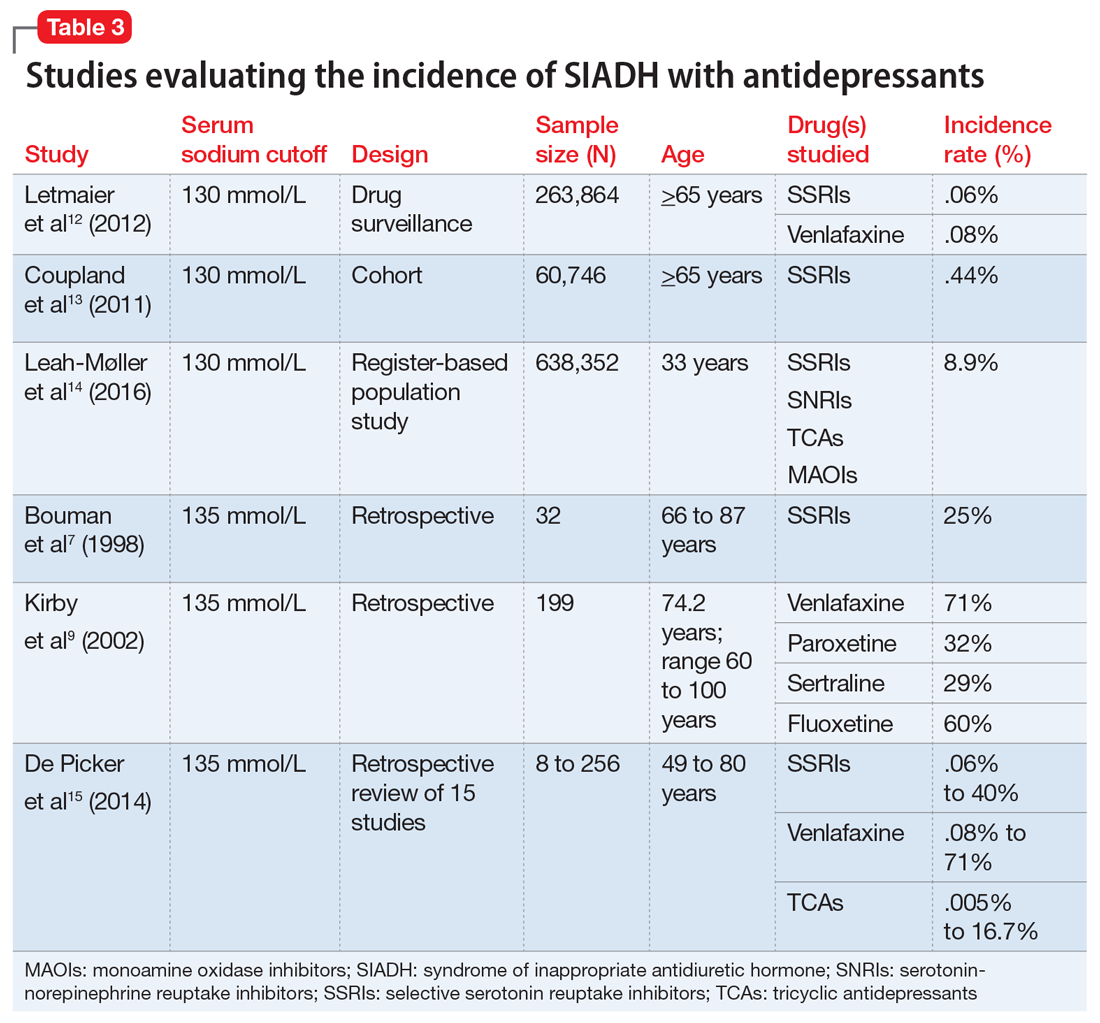

There is a fair amount of data associating antidepressants with SIADH. The incidence of SIADH with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) varies greatly among studies, from .06% to 40%.5-12 This wide variation is due to the way each study defined hyponatremia. A higher incidence was found when hyponatremia was defined as <135 mmol/L as opposed to <130 mmol/L. A large cohort study of SSRIs found that there was an increased risk with fluoxetine, escitalopram, and citalopram (.078% to .085%) vs paroxetine and sertraline (.033% to .053%).13 Studies comparing the incidence of SIADH with SSRIs and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) found that the rates were equal or slightly higher with the SNRI venlafaxine.13 SNRIs as a group have an estimated incidence of .08% to 4%, based on studies that defined hyponatremia as <130 mmol/L.13,14 Tricyclic antidepressants have an estimated incidence of .005% to 16.7%, based on a retrospective study that reviewed 15 studies and 100 case reports.15 Mirtazapine and bupropion do not have enough evidence to obtain a true definition of incidence; case reports for these drugs suggest a causal link for hyponatremia. Table 37,9,12-15 provides an overview of the incidence rate of hyponatremia for select antidepressants. It is clear that a more stringent cutoff for hyponatremia (<130 mmol/L) reduces the incidence rates. More evidence is needed to identify the true incidence and prevalence of SIADH with these agents.

Antipsychotics

Compared with antidepressants, there’s less evidence linking SIADH with antipsychotics; this data come mainly from case reports and observational studies. Serrano et al16 reported on a cross-sectional study that included 88 patients receiving clozapine, 61 patients receiving other atypical antipsychotics, 23 patients receiving typical antipsychotics, and 11 patients receiving both typical and atypical antipsychotics. They reported incidence rates of 3.4% for clozapine, 4.9% for atypical antipsychotics, 26.1% for typical antipsychotics, and 9.1% for the group receiving both typical and atypical antipsychotics.16 The primary theory for the decreased incidence of SIADH with use of atypical antipsychotics is related to decreased rates of psychogenic polydipsia leading to lower incidence of hyponatremia.

Mood stabilizers

Several studies have associated carbamazepine/oxcarbazepine, valproic acid, and lamotrigine with SIADH.17-23 Studies show incidence rates ranging from 4.8% to 41.5% for these medications. Carbamazepine appears to have the highest incidence of SIADH. A limitation of these studies is the small sample sizes, which ranged from 12 to 60 participants.

Pathophysiology

The kidneys are responsible for maintaining homeostasis between bodily fluids and serum sodium levels. ADH, which is produced by the hypothalamus, plays a significant role in fluid balance, thirst, and fluid retention. Inappropriate and continuous secretion of ADH, despite normal or high fluid status, results in hyposmolality and hyponatremia. The specific mechanisms by which psychotropic medications cause SIADH are listed in Table 4.24

Diagnosis

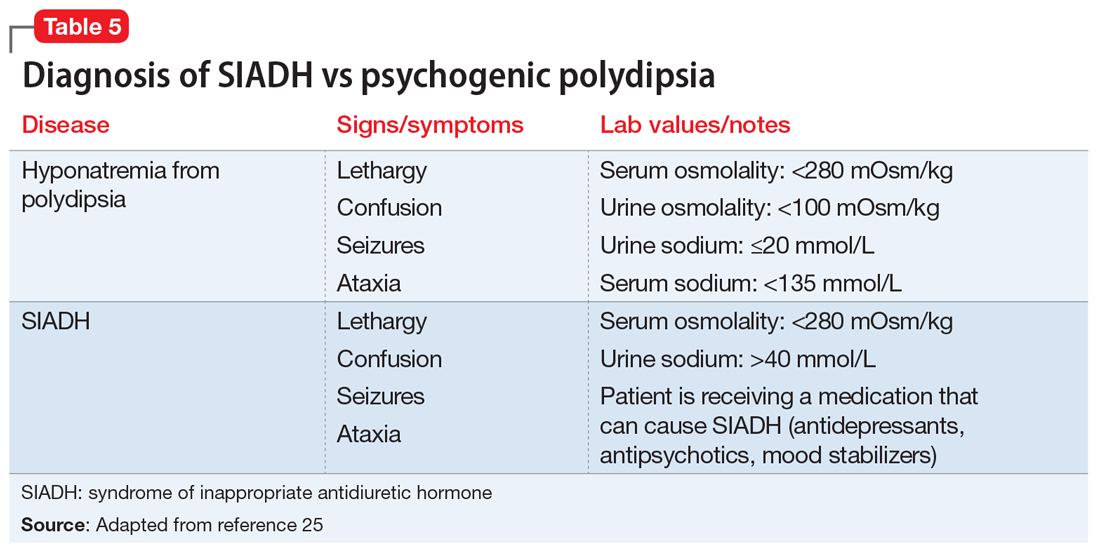

Diagnosis of SIADH can be complex because there are many clinical reasons a patient may have hyponatremia. For example, SIADH and psychogenic polydipsia both result in hyponatremia, and sometimes the 2 conditions can be difficult to distinguish. Hyponatremia is typically discovered by routine blood testing if the patient is asymptomatic. Table 525 highlights the major laboratory markers that distinguish SIADH and psychogenic polydipsia.

Continue to: Treatment

Treatment

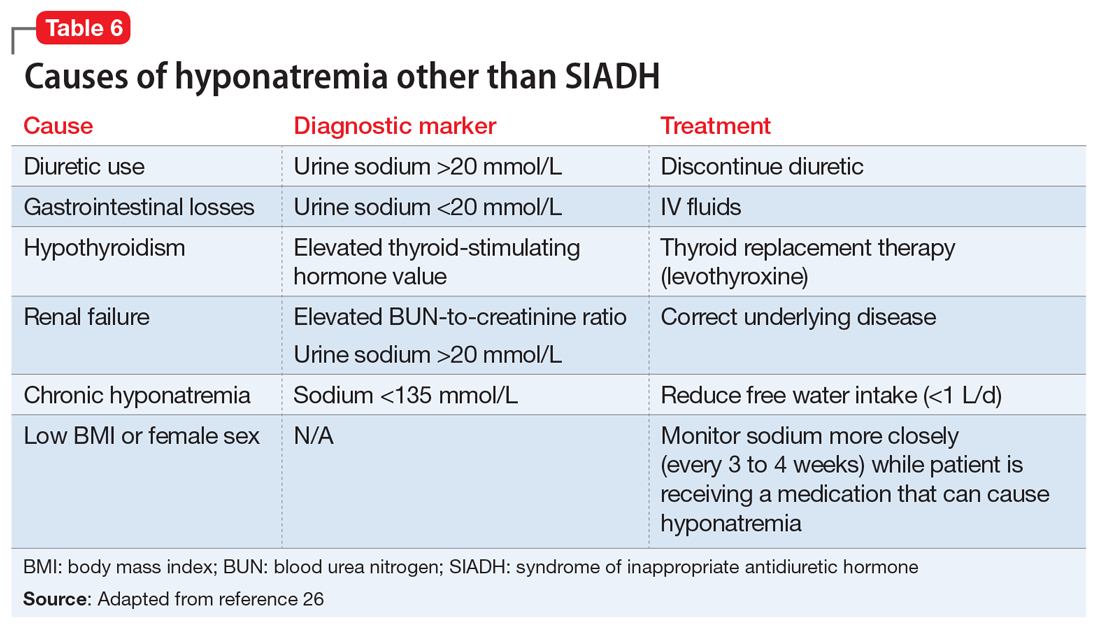

The primary treatment for SIADH is cessation of the offending agent. Based on the patient’s clinical presentation, free water restriction (.5 to 1 L/d) can be implemented to increase serum sodium levels. If the patient is having neurologic complications due to the severity of hyponatremia, correction with hypertonic saline is indicated. Upon resolution, the recommended course of action is to switch to a medication in a different class. Re-challenging the patient with the same medication is not recommended unless there is no other alternative class of medication.24 Table 626 highlights other causes of hyponatremia, what laboratory markers to assess, and how to treat high-risk individuals.

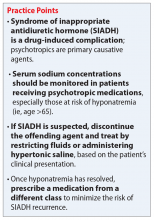

Hyponatremia is a complex medical complication that can be life-threatening. Psychotropics are a relatively common cause of hyponatremia, specifically SIADH. Older adults appear to be at highest risk, as most case reports are in patients age ≥65. Patients who are prescribed psychotropics should be treated with the lowest effective dose and monitored for signs and symptoms of hyponatremia throughout therapy.

Related Resources

- Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, et al. Clinical practice guidelines on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatremia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170(3):G1-G47.

- Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hyponatremia: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2013;126(10 Suppl 1):S1-S42.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clozapine • Clozaril

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Haloperidol • Haldol

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Levathyroxine • Levothroid

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Valproic acid • Depakote

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Sahay M, Sahay R. Hyponatremia: a practical approach. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18(6):760-771.

2. Kenes MT, Hamblin S, Tumuluri SS, et al. Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone in a patient receiving high-dose haloperidol and quetiapine therapy. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(2):e29-e30. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.15110392.

3. Twardowschy CA, Bertolucci CB, Gracia Cde M, et al. Severe hyponatremia and the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) associated with fluoxetine: case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2006;64(1):142-145.

4. Patel KR, Meesala A, Stanilla JK. Sodium valproate–induced hyponatremia: a case report. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(5):PCC.09100941. doi: 10.4088/PCC.09100941.

5. Pillans PI, Coulter DM. Fluoxetine and hyponatraemia—a potential hazard in the elderly. N Z Med J. 1994;107(973):85‑86.