User login

Fecal transplantation suggests IBS efficacy in small, randomized studies

WASHINGTON –

In the more positive of the two studies, patients with “bloating-predominant” IBS received a freshly prepared FMT from either a selected donor or from their own stool as a placebo control. After 12 weeks, the percentage of patients reporting clinically meaningful improvements in both abdominal bloating and in IBS symptoms was roughly twice as high, about 56%, among the 43 actively treated patients as the 26% rate of patients reporting these changes among 19 controls, Tom Holvoet, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.®Further follow-up of 22 patients who had significant improvement of their IBS symptoms at 12 weeks after treatment showed that, 1 year later, 6 of the 22 (27%) maintained their improved state while the other 73% of patients relapsed, suggesting that retreatment may be necessary for many, said Dr. Holvoet, a gastroenterologist at Ghent (Belgium) University. Five of the six patients who showed a prolonged response had received a donor FMT, while the sixth patient was from the control group that received a transplant of material prepared from the patient’s own stool.

“I think some patients would be willing to have multiple treatments,” Dr. Holvoet said in an interview. “These are highly motivated patients; you need to be highly motivated to undergo this treatment, and if they see an effect they’ll be motivated for retreatment,” he predicted.

The single-center study enrolled patients 18-75 years old with refractory IBS, based on the Rome III criteria, with intermittent diarrhea and severe bloating. Each patient received a single FMT. Patients in the active-treatment arm received their FMT from either of two donors selected for their “rich microbial diversity,” and demonstrated efficacy in an earlier pilot study with 12 patients (Gut. 2017 May;66[5]:980-2). In addition to a higher rate of improvement of abdominal bloating and IBS symptoms, the donor FMT also led to a significantly better improvement in IBS-related quality of life. Preliminary analysis of the intestinal microbiome profile of patients in the study suggested that specific changes to the microbiome were linked with treatment success.

Dr. Holvoet highlighted that more research is needed to identify ideal patients to treat this way, and to simplify and streamline the FMT process.

“Our study is a good first step, but we need to figure out what is happening in these patients,” Dr. Holvoet said in an interview.

Results from the second study failed to show a statistically significant benefit from FMT, compared with placebo, for the primary endpoint, but it did show benefit in one secondary endpoint.

This study enrolled 48 patients 19-65 years old with moderate to severe, diarrhea-predominant IBS, based on the Rome III definitions, at any of three U.S. centers. The researchers randomized patients to either immediate treatment for 3 days with an encapsulated, frozen fecal preparation obtained from the OpenBiome stool bank or placebo capsules. After 12 weeks, the average change from baseline in the IBS–Symptom Severity Score (SSS), the study’s primary endpoint, was virtually identical in both arms of the study. In both treatment groups the average baseline IBS-SSS was nearly 300, and in both treatment groups the SSS dropped sharply after 1 week into the study and then remained stable at this lower level in both groups during the next 11 weeks. Patients then underwent a second round of treatment in a crossover design. During a second 12 weeks of follow-up the average IBS-SSS remained steady among the patients who received placebo as their second treatment, but the patients who received active treatment as their second dose showed a further significant decline in their SSS, so that after the second 12-week follow-up the average score was 76 points lower in patients who recently had active treatment than those who recently received placebo, a statistically significant difference for this clinically meaningful point difference, reported Lawrence J. Brandt, MD, professor of medicine and surgery at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

In addition, the 12 patients in the study who had postinfection IBS showed the most dramatic reduction from baseline in their IBS-SSS 12 weeks after active treatment, compared with placebo. In contrast, 33 other patients in the study with noninfectious IBS etiologies showed on average no difference between active and placebo treatment in their 12-week change in SSS.

Preliminary findings in this study also showed some correlations between certain microbiome changes and better clinical responses to FMT, Dr. Brandt noted.

Dr. Holvoet and Dr. Brandt had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Holvoet T et al. DDW 2018. Presentation 617; Aroniadis OC et al. Presentation 742.

WASHINGTON –

In the more positive of the two studies, patients with “bloating-predominant” IBS received a freshly prepared FMT from either a selected donor or from their own stool as a placebo control. After 12 weeks, the percentage of patients reporting clinically meaningful improvements in both abdominal bloating and in IBS symptoms was roughly twice as high, about 56%, among the 43 actively treated patients as the 26% rate of patients reporting these changes among 19 controls, Tom Holvoet, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.®Further follow-up of 22 patients who had significant improvement of their IBS symptoms at 12 weeks after treatment showed that, 1 year later, 6 of the 22 (27%) maintained their improved state while the other 73% of patients relapsed, suggesting that retreatment may be necessary for many, said Dr. Holvoet, a gastroenterologist at Ghent (Belgium) University. Five of the six patients who showed a prolonged response had received a donor FMT, while the sixth patient was from the control group that received a transplant of material prepared from the patient’s own stool.

“I think some patients would be willing to have multiple treatments,” Dr. Holvoet said in an interview. “These are highly motivated patients; you need to be highly motivated to undergo this treatment, and if they see an effect they’ll be motivated for retreatment,” he predicted.

The single-center study enrolled patients 18-75 years old with refractory IBS, based on the Rome III criteria, with intermittent diarrhea and severe bloating. Each patient received a single FMT. Patients in the active-treatment arm received their FMT from either of two donors selected for their “rich microbial diversity,” and demonstrated efficacy in an earlier pilot study with 12 patients (Gut. 2017 May;66[5]:980-2). In addition to a higher rate of improvement of abdominal bloating and IBS symptoms, the donor FMT also led to a significantly better improvement in IBS-related quality of life. Preliminary analysis of the intestinal microbiome profile of patients in the study suggested that specific changes to the microbiome were linked with treatment success.

Dr. Holvoet highlighted that more research is needed to identify ideal patients to treat this way, and to simplify and streamline the FMT process.

“Our study is a good first step, but we need to figure out what is happening in these patients,” Dr. Holvoet said in an interview.

Results from the second study failed to show a statistically significant benefit from FMT, compared with placebo, for the primary endpoint, but it did show benefit in one secondary endpoint.

This study enrolled 48 patients 19-65 years old with moderate to severe, diarrhea-predominant IBS, based on the Rome III definitions, at any of three U.S. centers. The researchers randomized patients to either immediate treatment for 3 days with an encapsulated, frozen fecal preparation obtained from the OpenBiome stool bank or placebo capsules. After 12 weeks, the average change from baseline in the IBS–Symptom Severity Score (SSS), the study’s primary endpoint, was virtually identical in both arms of the study. In both treatment groups the average baseline IBS-SSS was nearly 300, and in both treatment groups the SSS dropped sharply after 1 week into the study and then remained stable at this lower level in both groups during the next 11 weeks. Patients then underwent a second round of treatment in a crossover design. During a second 12 weeks of follow-up the average IBS-SSS remained steady among the patients who received placebo as their second treatment, but the patients who received active treatment as their second dose showed a further significant decline in their SSS, so that after the second 12-week follow-up the average score was 76 points lower in patients who recently had active treatment than those who recently received placebo, a statistically significant difference for this clinically meaningful point difference, reported Lawrence J. Brandt, MD, professor of medicine and surgery at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

In addition, the 12 patients in the study who had postinfection IBS showed the most dramatic reduction from baseline in their IBS-SSS 12 weeks after active treatment, compared with placebo. In contrast, 33 other patients in the study with noninfectious IBS etiologies showed on average no difference between active and placebo treatment in their 12-week change in SSS.

Preliminary findings in this study also showed some correlations between certain microbiome changes and better clinical responses to FMT, Dr. Brandt noted.

Dr. Holvoet and Dr. Brandt had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Holvoet T et al. DDW 2018. Presentation 617; Aroniadis OC et al. Presentation 742.

WASHINGTON –

In the more positive of the two studies, patients with “bloating-predominant” IBS received a freshly prepared FMT from either a selected donor or from their own stool as a placebo control. After 12 weeks, the percentage of patients reporting clinically meaningful improvements in both abdominal bloating and in IBS symptoms was roughly twice as high, about 56%, among the 43 actively treated patients as the 26% rate of patients reporting these changes among 19 controls, Tom Holvoet, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week.®Further follow-up of 22 patients who had significant improvement of their IBS symptoms at 12 weeks after treatment showed that, 1 year later, 6 of the 22 (27%) maintained their improved state while the other 73% of patients relapsed, suggesting that retreatment may be necessary for many, said Dr. Holvoet, a gastroenterologist at Ghent (Belgium) University. Five of the six patients who showed a prolonged response had received a donor FMT, while the sixth patient was from the control group that received a transplant of material prepared from the patient’s own stool.

“I think some patients would be willing to have multiple treatments,” Dr. Holvoet said in an interview. “These are highly motivated patients; you need to be highly motivated to undergo this treatment, and if they see an effect they’ll be motivated for retreatment,” he predicted.

The single-center study enrolled patients 18-75 years old with refractory IBS, based on the Rome III criteria, with intermittent diarrhea and severe bloating. Each patient received a single FMT. Patients in the active-treatment arm received their FMT from either of two donors selected for their “rich microbial diversity,” and demonstrated efficacy in an earlier pilot study with 12 patients (Gut. 2017 May;66[5]:980-2). In addition to a higher rate of improvement of abdominal bloating and IBS symptoms, the donor FMT also led to a significantly better improvement in IBS-related quality of life. Preliminary analysis of the intestinal microbiome profile of patients in the study suggested that specific changes to the microbiome were linked with treatment success.

Dr. Holvoet highlighted that more research is needed to identify ideal patients to treat this way, and to simplify and streamline the FMT process.

“Our study is a good first step, but we need to figure out what is happening in these patients,” Dr. Holvoet said in an interview.

Results from the second study failed to show a statistically significant benefit from FMT, compared with placebo, for the primary endpoint, but it did show benefit in one secondary endpoint.

This study enrolled 48 patients 19-65 years old with moderate to severe, diarrhea-predominant IBS, based on the Rome III definitions, at any of three U.S. centers. The researchers randomized patients to either immediate treatment for 3 days with an encapsulated, frozen fecal preparation obtained from the OpenBiome stool bank or placebo capsules. After 12 weeks, the average change from baseline in the IBS–Symptom Severity Score (SSS), the study’s primary endpoint, was virtually identical in both arms of the study. In both treatment groups the average baseline IBS-SSS was nearly 300, and in both treatment groups the SSS dropped sharply after 1 week into the study and then remained stable at this lower level in both groups during the next 11 weeks. Patients then underwent a second round of treatment in a crossover design. During a second 12 weeks of follow-up the average IBS-SSS remained steady among the patients who received placebo as their second treatment, but the patients who received active treatment as their second dose showed a further significant decline in their SSS, so that after the second 12-week follow-up the average score was 76 points lower in patients who recently had active treatment than those who recently received placebo, a statistically significant difference for this clinically meaningful point difference, reported Lawrence J. Brandt, MD, professor of medicine and surgery at Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York.

In addition, the 12 patients in the study who had postinfection IBS showed the most dramatic reduction from baseline in their IBS-SSS 12 weeks after active treatment, compared with placebo. In contrast, 33 other patients in the study with noninfectious IBS etiologies showed on average no difference between active and placebo treatment in their 12-week change in SSS.

Preliminary findings in this study also showed some correlations between certain microbiome changes and better clinical responses to FMT, Dr. Brandt noted.

Dr. Holvoet and Dr. Brandt had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Holvoet T et al. DDW 2018. Presentation 617; Aroniadis OC et al. Presentation 742.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2018

Key clinical point: Results from two small randomized studies suggest that fecal microbiome transplantation may help some IBS patients.

Major finding: In one study, fecal transplantation linked with a doubling of patients having reduced IBS symptoms, compared with placebo, .

Study details: A single-center randomized study with 62 patients and a multicenter randomized crossover study with 48 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Holvoet and Dr. Brandt had no disclosures.

Source: Holvoet T et al. DDW 2018. Presentation 617; Aroniadis OC et al. Presentation 742.

Trial data suggest beneficial class effects of SGLT2 inhibitors, including dapagliflozin

ORLANDO – a post hoc analysis of data from the EXSCEL trial suggested.

The findings are consistent with those from published cardiovascular outcomes trials (CVOTs) of sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors other than dapagliflozin, real-world data, and findings from non-CVOTs of dapagliflozin, Lindsay Clegg, PhD, reported in a late-breaking poster at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In EXSCEL – a CVOT of once-weekly treatment with the glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist exenatide added to usual care in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus – 10% of patients took an SGLT2 inhibitor, and about half of those took dapagliflozin. For the current analysis, the effects of all SGLT2 inhibitors and dapagliflozin alone were evaluated in EXSCEL patients who received placebo.

“Just looking at that placebo data, we wanted to ask what the impact of SGLT2 inhibition was on the adjudicated cardiovascular events, as well as all-cause death and eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate] in this population,” Dr. Clegg, a postdoctoral fellow with the AstraZeneca Quantitative Clinical Pharmacology Group in Gaithersburg, Md., said in an interview.

In two propensity-matched cohorts, including a cohort of 709 SGLT2 inhibitor users and a cohort of 709 non-SGLT2 inhibitor users, SGLT2 inhibitors and dapagliflozin alone were found to numerically decrease the major adverse cardiac event (MACE) hazard ratio, and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced all-cause mortality risk, she explained.

MACE events – a composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke – occurred in 28 versus 44 patients in the SGLT2 and non-SGLT2 inhibitor groups, respectively (event rate per 100 patient-years, 3.41 vs. 4.45; adjusted HR, 0.79). Dr. Clegg noted that this hazard ratio is “very consistent with what has been seen in the CVOTs for [the SGLT2 inhibitors] empagliflozin and canagliflozin in literature.”

The corresponding figures for dapagliflozin were 11 versus 22 events (event rate per 100 patient-years, 2.69 vs. 4.54; aHR, 0.55).

“So those weren’t statistically significant, but those point estimates were very similar to literature,” she said.

All-cause mortality events occurred in 14 versus 37 patients in the SGLT2 and non-SGLT2 inhibitor groups, respectively (event rate per 100 patient-years, 1.61 vs. 3.34; aHR, 0.50), and in 7 versus 13 dapagliflozin patients within these groups, respectively (event rate per 100 patient-years, 1.62 vs. 2.42; aHR, 0.66).

The overall SGLT2 inhibitor all-cause mortality findings were very similar to what was seen in CVD-REAL, a real-world evidence trial which looked at cardiovascular outcomes in new users of SGLT-2 inhibitors, and the differences were statistically significant for the treatment effect.

“For dapagliflozin, the numbers were pretty similar as well. Not statistically significant, because the number of subjects was smaller, but similar,” Dr. Clegg said.

“On eGFR looking at renal function ... subjects not using an SGLT2 inhibitor had about a 1 mL/min per year decline, which is what we would expect for this population. At baseline the median eGFR was about 80, so it’s a fairly healthy population, because exenatide isn’t used in people with poor renal function,” she explained.

The effects of SGLT2 inhibitors overall, and dapagliflozin alone, were associated with the statistically significant increase in the eGFR slope over time – an outcome that the Food and Drug Administration now recognizes as a surrogate endpoint for renal outcomes, she added. “And again, that’s very consistent with what was seen for [the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin] in the literature.”

Empagliflozin and canagliflozin (another SGLT2 inhibitor) have been shown to reduce MACE, all-cause mortality, and renal events in CVOTs, and real-world evidence suggests a class effect benefit, but dapagliflozin CVOT data have not yet been published.

“Overall this was a nice dataset where we had these adjudicated events to look at outcomes with SGLT2 inhibitors and with [dapagliflozin] specifically, and what we see is very encouraging and suggestive of a class effect,” she concluded, noting that findings from the ongoing phase 3 DECLARE-TIMI58 dapagliflozin CVOT should be released later this year.

Dr. Clegg is employed by AstraZeneca. She reported having no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Clegg L et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 130-LB.

ORLANDO – a post hoc analysis of data from the EXSCEL trial suggested.

The findings are consistent with those from published cardiovascular outcomes trials (CVOTs) of sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors other than dapagliflozin, real-world data, and findings from non-CVOTs of dapagliflozin, Lindsay Clegg, PhD, reported in a late-breaking poster at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In EXSCEL – a CVOT of once-weekly treatment with the glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist exenatide added to usual care in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus – 10% of patients took an SGLT2 inhibitor, and about half of those took dapagliflozin. For the current analysis, the effects of all SGLT2 inhibitors and dapagliflozin alone were evaluated in EXSCEL patients who received placebo.

“Just looking at that placebo data, we wanted to ask what the impact of SGLT2 inhibition was on the adjudicated cardiovascular events, as well as all-cause death and eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate] in this population,” Dr. Clegg, a postdoctoral fellow with the AstraZeneca Quantitative Clinical Pharmacology Group in Gaithersburg, Md., said in an interview.

In two propensity-matched cohorts, including a cohort of 709 SGLT2 inhibitor users and a cohort of 709 non-SGLT2 inhibitor users, SGLT2 inhibitors and dapagliflozin alone were found to numerically decrease the major adverse cardiac event (MACE) hazard ratio, and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced all-cause mortality risk, she explained.

MACE events – a composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke – occurred in 28 versus 44 patients in the SGLT2 and non-SGLT2 inhibitor groups, respectively (event rate per 100 patient-years, 3.41 vs. 4.45; adjusted HR, 0.79). Dr. Clegg noted that this hazard ratio is “very consistent with what has been seen in the CVOTs for [the SGLT2 inhibitors] empagliflozin and canagliflozin in literature.”

The corresponding figures for dapagliflozin were 11 versus 22 events (event rate per 100 patient-years, 2.69 vs. 4.54; aHR, 0.55).

“So those weren’t statistically significant, but those point estimates were very similar to literature,” she said.

All-cause mortality events occurred in 14 versus 37 patients in the SGLT2 and non-SGLT2 inhibitor groups, respectively (event rate per 100 patient-years, 1.61 vs. 3.34; aHR, 0.50), and in 7 versus 13 dapagliflozin patients within these groups, respectively (event rate per 100 patient-years, 1.62 vs. 2.42; aHR, 0.66).

The overall SGLT2 inhibitor all-cause mortality findings were very similar to what was seen in CVD-REAL, a real-world evidence trial which looked at cardiovascular outcomes in new users of SGLT-2 inhibitors, and the differences were statistically significant for the treatment effect.

“For dapagliflozin, the numbers were pretty similar as well. Not statistically significant, because the number of subjects was smaller, but similar,” Dr. Clegg said.

“On eGFR looking at renal function ... subjects not using an SGLT2 inhibitor had about a 1 mL/min per year decline, which is what we would expect for this population. At baseline the median eGFR was about 80, so it’s a fairly healthy population, because exenatide isn’t used in people with poor renal function,” she explained.

The effects of SGLT2 inhibitors overall, and dapagliflozin alone, were associated with the statistically significant increase in the eGFR slope over time – an outcome that the Food and Drug Administration now recognizes as a surrogate endpoint for renal outcomes, she added. “And again, that’s very consistent with what was seen for [the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin] in the literature.”

Empagliflozin and canagliflozin (another SGLT2 inhibitor) have been shown to reduce MACE, all-cause mortality, and renal events in CVOTs, and real-world evidence suggests a class effect benefit, but dapagliflozin CVOT data have not yet been published.

“Overall this was a nice dataset where we had these adjudicated events to look at outcomes with SGLT2 inhibitors and with [dapagliflozin] specifically, and what we see is very encouraging and suggestive of a class effect,” she concluded, noting that findings from the ongoing phase 3 DECLARE-TIMI58 dapagliflozin CVOT should be released later this year.

Dr. Clegg is employed by AstraZeneca. She reported having no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Clegg L et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 130-LB.

ORLANDO – a post hoc analysis of data from the EXSCEL trial suggested.

The findings are consistent with those from published cardiovascular outcomes trials (CVOTs) of sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitors other than dapagliflozin, real-world data, and findings from non-CVOTs of dapagliflozin, Lindsay Clegg, PhD, reported in a late-breaking poster at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

In EXSCEL – a CVOT of once-weekly treatment with the glucagonlike peptide–1 receptor agonist exenatide added to usual care in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus – 10% of patients took an SGLT2 inhibitor, and about half of those took dapagliflozin. For the current analysis, the effects of all SGLT2 inhibitors and dapagliflozin alone were evaluated in EXSCEL patients who received placebo.

“Just looking at that placebo data, we wanted to ask what the impact of SGLT2 inhibition was on the adjudicated cardiovascular events, as well as all-cause death and eGFR [estimated glomerular filtration rate] in this population,” Dr. Clegg, a postdoctoral fellow with the AstraZeneca Quantitative Clinical Pharmacology Group in Gaithersburg, Md., said in an interview.

In two propensity-matched cohorts, including a cohort of 709 SGLT2 inhibitor users and a cohort of 709 non-SGLT2 inhibitor users, SGLT2 inhibitors and dapagliflozin alone were found to numerically decrease the major adverse cardiac event (MACE) hazard ratio, and SGLT2 inhibitors significantly reduced all-cause mortality risk, she explained.

MACE events – a composite endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI, or nonfatal stroke – occurred in 28 versus 44 patients in the SGLT2 and non-SGLT2 inhibitor groups, respectively (event rate per 100 patient-years, 3.41 vs. 4.45; adjusted HR, 0.79). Dr. Clegg noted that this hazard ratio is “very consistent with what has been seen in the CVOTs for [the SGLT2 inhibitors] empagliflozin and canagliflozin in literature.”

The corresponding figures for dapagliflozin were 11 versus 22 events (event rate per 100 patient-years, 2.69 vs. 4.54; aHR, 0.55).

“So those weren’t statistically significant, but those point estimates were very similar to literature,” she said.

All-cause mortality events occurred in 14 versus 37 patients in the SGLT2 and non-SGLT2 inhibitor groups, respectively (event rate per 100 patient-years, 1.61 vs. 3.34; aHR, 0.50), and in 7 versus 13 dapagliflozin patients within these groups, respectively (event rate per 100 patient-years, 1.62 vs. 2.42; aHR, 0.66).

The overall SGLT2 inhibitor all-cause mortality findings were very similar to what was seen in CVD-REAL, a real-world evidence trial which looked at cardiovascular outcomes in new users of SGLT-2 inhibitors, and the differences were statistically significant for the treatment effect.

“For dapagliflozin, the numbers were pretty similar as well. Not statistically significant, because the number of subjects was smaller, but similar,” Dr. Clegg said.

“On eGFR looking at renal function ... subjects not using an SGLT2 inhibitor had about a 1 mL/min per year decline, which is what we would expect for this population. At baseline the median eGFR was about 80, so it’s a fairly healthy population, because exenatide isn’t used in people with poor renal function,” she explained.

The effects of SGLT2 inhibitors overall, and dapagliflozin alone, were associated with the statistically significant increase in the eGFR slope over time – an outcome that the Food and Drug Administration now recognizes as a surrogate endpoint for renal outcomes, she added. “And again, that’s very consistent with what was seen for [the SGLT2 inhibitor empagliflozin] in the literature.”

Empagliflozin and canagliflozin (another SGLT2 inhibitor) have been shown to reduce MACE, all-cause mortality, and renal events in CVOTs, and real-world evidence suggests a class effect benefit, but dapagliflozin CVOT data have not yet been published.

“Overall this was a nice dataset where we had these adjudicated events to look at outcomes with SGLT2 inhibitors and with [dapagliflozin] specifically, and what we see is very encouraging and suggestive of a class effect,” she concluded, noting that findings from the ongoing phase 3 DECLARE-TIMI58 dapagliflozin CVOT should be released later this year.

Dr. Clegg is employed by AstraZeneca. She reported having no other disclosures.

SOURCE: Clegg L et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 130-LB.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point: Sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors, including dapagliflozin, have beneficial class effects on major adverse cardiac events, all-cause mortality, and renal function.

Major finding: MACE occurred in 28 versus 44 patients in the SGLT2 and non-SGLT2 inhibitor groups, respectively (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.79).

Study details: A post hoc analysis of data from 1,418 EXSCEL trial subjects.

Disclosures: Dr. Clegg is employed by AstraZeneca. She reported having no other disclosures.

Source: Clegg L et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 130-LB.

CDC now offering CME course on HPV vaccination

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is now offering a CME course to educate clinicians about the importance of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in protecting adolescents from certain types of cancer and to provide them with the skills and resources to make effective HPV vaccine recommendations.

The course is a Web-on-demand video that will teach clinicians how to be successful in making HPV vaccination recommendations, how to communicate HPV vaccination information to parents and patients, and how to properly answer parents’ questions. Currently, the CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for adolescents at 11- to 12-years-of-age. The CDC hopes this will reduce missed opportunities to protect patients against HPV.

Speakers in the video include Alix Casler, MD, of the Orlando Family Physician Association; Linda Fu, MD, MS, of Children’s National Health System in Washington; Todd Wolynn, MD, president and CEO of Kids Plus Pediatrics, Pittsburgh; and Wendy Sue Swanson, MD, MBE, a pediatrician who is chief of digital innovation at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

The course was initiated in Jan. 16, 2018, and will continue until Jan. 16, 2020. Anyone who provides immunization to patients can participate.

The course is called “Routinely Recommending Cancer Prevention: HPV Vaccination at 11 and 12 as a Standard of Care.” Read more about the course on and download it from the CDC’s website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is now offering a CME course to educate clinicians about the importance of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in protecting adolescents from certain types of cancer and to provide them with the skills and resources to make effective HPV vaccine recommendations.

The course is a Web-on-demand video that will teach clinicians how to be successful in making HPV vaccination recommendations, how to communicate HPV vaccination information to parents and patients, and how to properly answer parents’ questions. Currently, the CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for adolescents at 11- to 12-years-of-age. The CDC hopes this will reduce missed opportunities to protect patients against HPV.

Speakers in the video include Alix Casler, MD, of the Orlando Family Physician Association; Linda Fu, MD, MS, of Children’s National Health System in Washington; Todd Wolynn, MD, president and CEO of Kids Plus Pediatrics, Pittsburgh; and Wendy Sue Swanson, MD, MBE, a pediatrician who is chief of digital innovation at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

The course was initiated in Jan. 16, 2018, and will continue until Jan. 16, 2020. Anyone who provides immunization to patients can participate.

The course is called “Routinely Recommending Cancer Prevention: HPV Vaccination at 11 and 12 as a Standard of Care.” Read more about the course on and download it from the CDC’s website.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is now offering a CME course to educate clinicians about the importance of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in protecting adolescents from certain types of cancer and to provide them with the skills and resources to make effective HPV vaccine recommendations.

The course is a Web-on-demand video that will teach clinicians how to be successful in making HPV vaccination recommendations, how to communicate HPV vaccination information to parents and patients, and how to properly answer parents’ questions. Currently, the CDC recommends the HPV vaccine for adolescents at 11- to 12-years-of-age. The CDC hopes this will reduce missed opportunities to protect patients against HPV.

Speakers in the video include Alix Casler, MD, of the Orlando Family Physician Association; Linda Fu, MD, MS, of Children’s National Health System in Washington; Todd Wolynn, MD, president and CEO of Kids Plus Pediatrics, Pittsburgh; and Wendy Sue Swanson, MD, MBE, a pediatrician who is chief of digital innovation at Seattle Children’s Hospital.

The course was initiated in Jan. 16, 2018, and will continue until Jan. 16, 2020. Anyone who provides immunization to patients can participate.

The course is called “Routinely Recommending Cancer Prevention: HPV Vaccination at 11 and 12 as a Standard of Care.” Read more about the course on and download it from the CDC’s website.

Snapping Biceps Femoris Tendon

ABSTRACT

A 23-year-old male active duty soldier presented with a biceps femoris tendon snapping over the fibular head with flexion of the knee beyond 90°. Surgical release of anomalous anterolateral tibial and lateral fibular insertions provided relief of snapping with no other repair or reconstruction required. The soldier quickly returned to full running and active duty.

Snapping biceps femoris tendon is a rare but potential cause of pain and dysfunction in the lateral knee. The possible anatomical variations and the cause of snapping must be considered when determining the operative approaches to this condition.

Continue to: Snapping in the knee...

Snapping in the knee is not as common as in other joints, such as the hip or ankle. The snapping sensation can occur from several pathologies, including the following: lateral meniscal tears, iliotibial band syndrome, proximal tibiofibular instability, snapping popliteus, peroneal nerve compression/neuritis, lateral discoid meniscus, rheumatoid nodules, plicae, congenital snapping knee, exostoses, or previous trauma.1,2 A detailed history must be provided, and physical examination and appropriate imaging must be performed to narrow down the differential diagnosis and prescribe the appropriate course of treatment for snapping.

Snapping biceps femoris syndrome is a rare cause of knee snapping. This condition has been described in various case reports.2-13 The reasons for a snapping biceps femoris can vary, and the treating provider must be ready to accommodate and treat these causes. The symptoms typically include an audible, and usually visual, lateral snapping distal to the knee joint and over the fibular head. Imaging may reveal bony abnormalities such as fibular exostoses. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can aid in determining any anomalous or abnormal insertions of the biceps femoris tendon. The snapping can be debilitating, particularly in athletes or patients with high-demand occupations, and surgical intervention is often warranted.

We present a case of an active-duty military service member with symptomatic unilateral snapping biceps femoris and review the literature for treatment of this condition. Surgical release allowed the patient a quick and unrestricted return to full mission capabilities.

The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE REPORT

A 23-year-old active-duty soldier presented to the orthopedic clinic with several months of noticeable snapping and pain over the lateral knee with attempted running and deep squatting activities, resulting in difficulty to perform his army duties. The patient reported no history of antecedent trauma. No locking of the knee or paresthesia distally into the leg or foot was observed.

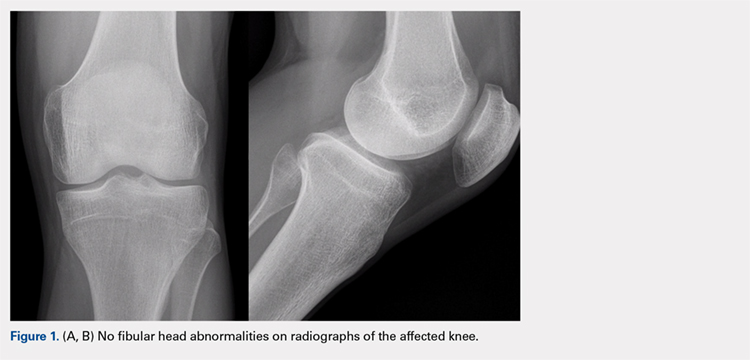

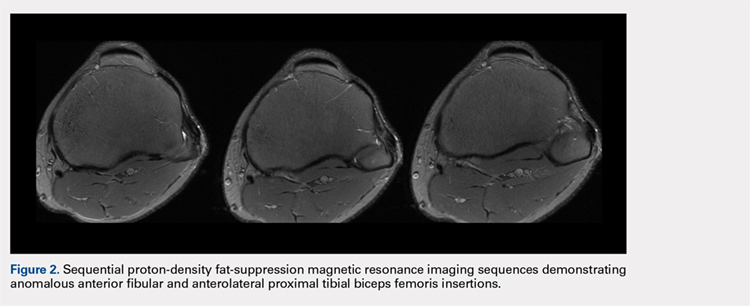

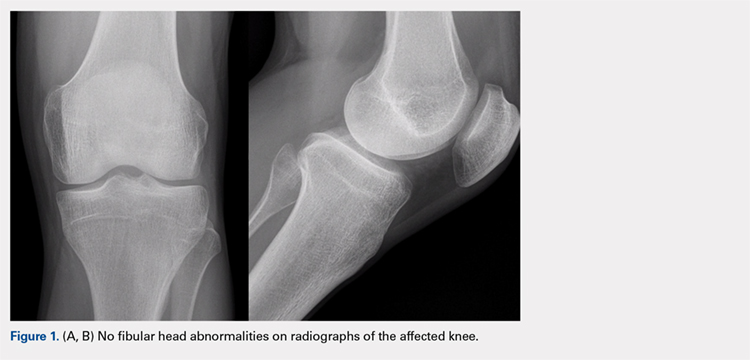

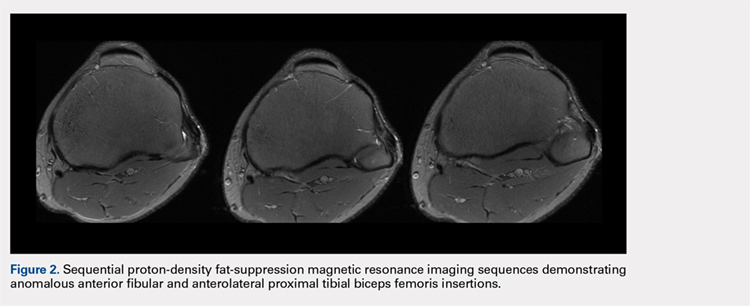

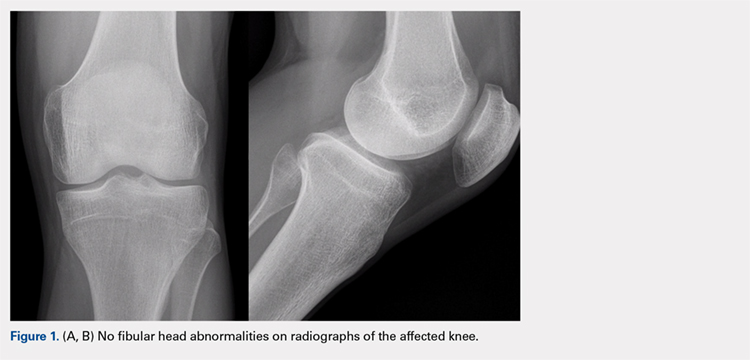

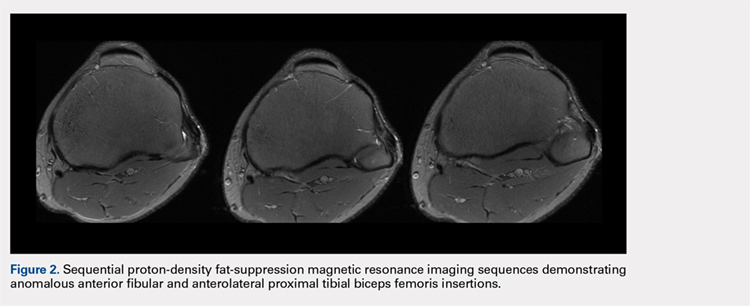

The physical examination revealed a palpable and observable snapping of the long head of the biceps tendon over the fibular head with squatting beyond 90° in the left knee. The patient presented with full strength and no instability or joint line pain throughout the knee. Application of a posterior-to-anterior directed force over the biceps femoris proximal to the insertion allowed the patient to perform a deep squat without snapping. The radiographs demonstrated no abnormal fibular morphology (Figures 1A, 1B). Axial MRI images demonstrated an anomalous slip of the tendon inserting on the anterolateral aspect of the proximal tibia in addition to the normal insertion on the posterolateral and lateral edge of the fibular head (Figure 2) as described by Terry and LaPrade.14

Continue to: A conservative treatment with physical therapy...

A conservative treatment with physical therapy, activity modification, and a Cho-Pat knee strap (to provide a posterior-to-anterior buttress and to prevent snapping) was attempted for 4 weeks. However, the patient could not tolerate the strap, and the activity restraints prevented him from performing his job as an active-duty soldier. Given the failure of conservative treatment, operative intervention was elected.

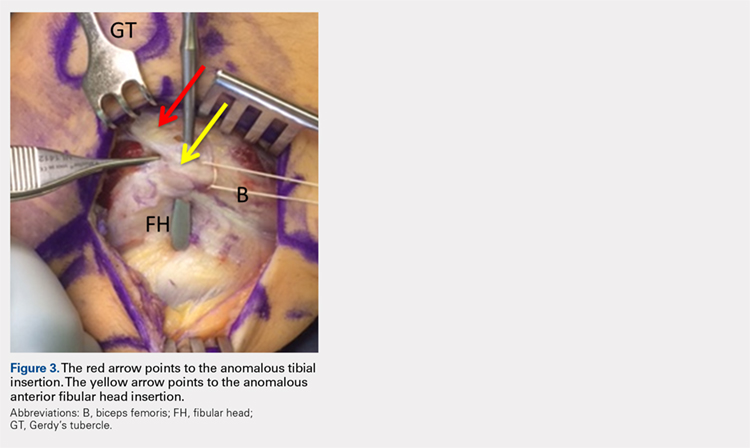

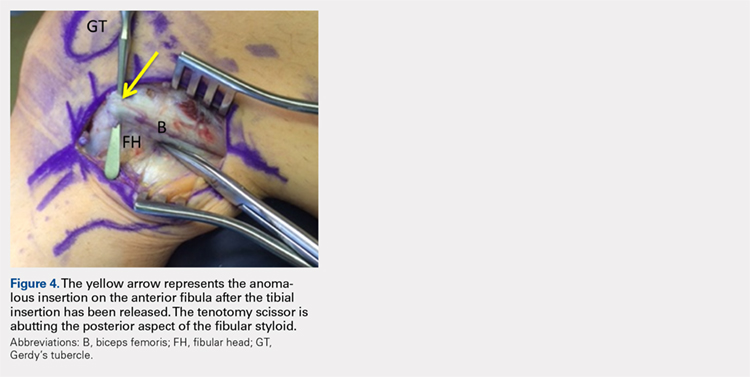

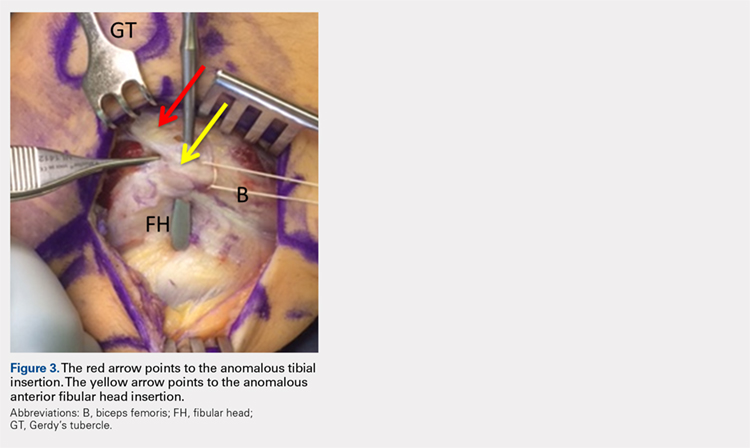

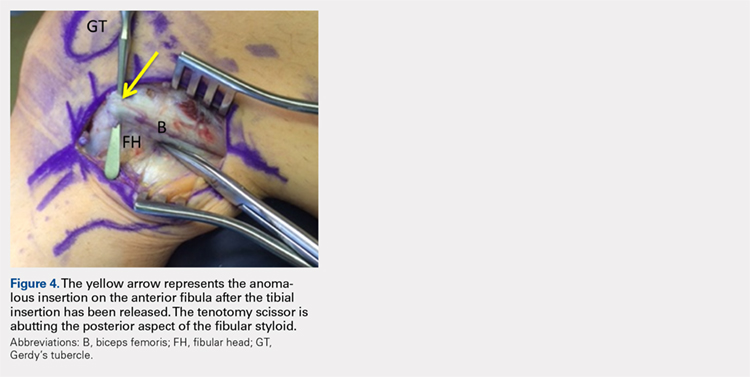

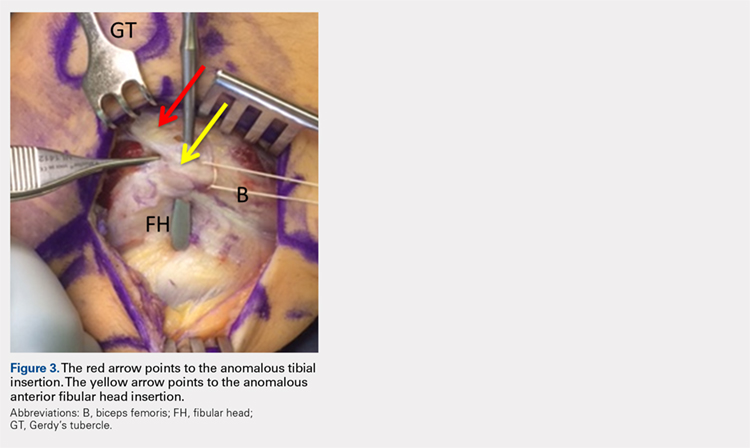

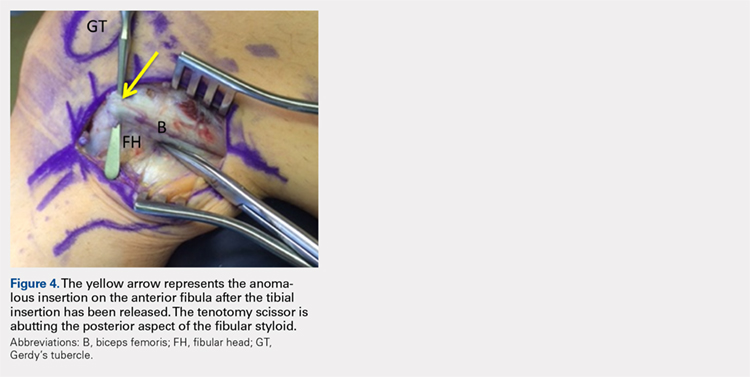

Upon exploration of the biceps femoris insertion, the accessory anterolateral tibial insertion was readily identified (Figure 3). Notably, the expected normal lateral edge insertion was thickened and extended beyond the lateral edge, distal, and anterior on to the fibular head (Figure 4). The anterolateral tibial band was released first. However, the snapping remained evident. The thickened anterior fibular accessory band was then released back to its normal, lateral edge, and at this point, no further snapping was observed with deep flexion of the knee. Inspection of the remaining posterolateral and lateral edge insertion demonstrated a healthy, 1-cm thick tendinous insertion. The accessory slips were completely excised, and the incision was closed without any additional repair or re-insertion (Figure 5). The patient presented no complications postoperatively. He was allowed to bear weight as tolerated and was limited to stretching and gravity resistance training for 4 weeks. At 1 month, the patient was released to progress back to full activity. By 8 weeks postoperative, he remained free of snapping and resumed his regular running routine and military duties without restriction or pain.

DISCUSSION

Release of the anomalous bands with no further repair or re-insertion of the biceps femoris allowed this active-duty soldier to resume full running and duty-related activities in <2 months. In this particular patient, given his anatomy, the treatment was successful. The literature indicates that optimal results and surgical approach depend upon the pathological anatomy encountered.

Date and colleagues4 described a similar anatomical anomaly as with our patient, whom after the release of tibial insertion, snapping was still observed, thus requiring the release of anterior fibular insertion. They noted the necessity of suturing the accessory limbs onto the periosteum of the fibular head to achieve a stable biceps femoris.

In other cases, abnormal bony anatomy of the fibula has been shown to cause snapping. Vavalle and Capozzi5 described a case of snapping biceps in a marathon runner, who needed partial resection of the fibular head to eliminate snapping. The runner made a full return to the sport. Fung and colleagues2 described a similar approach to a 17-year-old cyclist; however, this patient presented exostoses of the bilateral fibular heads. The exostoses were bilaterally excised, and the snapping ceased. Kristensen and colleagues13 described a patient with an anomalous tibial insertion. Rather than releasing the tibial insertion, a partial resection of the fibular head allowed for cessation of snapping.

Other authors advocate the detachment and anatomic re-insertion of the biceps femoris into the fibular head. Bernhardson and LaPrade6 reported a series of 3 patients requiring this approach with excellent results. Bansal and colleagues8 were the first to describe a soccer player with an isolated injury to the knee as a traumatic cause for a snapping biceps femoris. After failure of conservative treatment attempts, exploration and re-insertion through a bone tunnel allowed for return to the sport. Hernandez and colleagues11 and Lokiec and colleagues12 both described the reproduction of the normal biceps femoris anatomy through re-insertion procedures after identifying patients with abnormal anatomical insertions as causes for snapping.

CONCLUSION

We presented a case of an active military service member with a unilateral snapping biceps femoris tendon due to an anomalous distal insertion on both the proximal tibia and anterior fibular head. The release of abnormal insertions and maintenance of his normal anatomical insertion allowed for a quick and effective return to running and duty at full capacity. Although other surgical approaches have been described to include partial fibular head resection or anatomical re-insertion, we believe that the approach to this rare condition should be anatomy-based as the causes of snapping can significantly vary. We believe that if the normal posterolateral and lateral edge insertions of the biceps femoris are intact, removal of the abnormal anatomy without any repair or reconstruction can safely lead to successful surgical outcomes.

- Barker JU, Strauss EJ, Lodha S, Bach BR Jr. Extra-articular mimickers of lateral meniscal tears. Sports Health. 2011;3(1):82-88.

- Fung DA, Frey S, Markbreiter L. Bilateral symptomatic snapping biceps femoris tendon due to fibular exostosis. J Knee Surg. 2008;21(1):55-57.

- Mirchandani M, Gandhi P, Cai P. Poster 175 bilateral symptomatic snapping knee from biceps femoris tendon subluxation–an atypical cause of bilateral knee pain: a case report. PM R. 2016;8(9S):S218-S219.

- Date H, Hayakawa K, Yamada H. Snapping knee due to the biceps femoris tendon treated with repositioning of the anomalous tibial insertion. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(8):1581-1583.

- Vavalle G, Capozzi M. Symptomatic snapping knee from biceps femoris tendon subluxation: an unusual case of lateral pain in a marathon runner. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11(4):263-266.

- Bernhardson AS, LaPrade RF. Snapping biceps femoris tendon treated with an anatomic repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(8):1110-1112.

- Guillin R, Mendoza-Ruiz JJ, Moser T, Ropars M, Duvauferrier R, Cardinal E. Snapping biceps femoris tendon: a dynamic real-time sonographic evaluation. J Clin Ultrasound. 2010;38(8):435-437.

- Bansal R, Taylor C, Pimpalnerkar AL. Snapping knee: an unusual biceps femoris tendon injury. Knee. 2005;12(6):458-460.

- Bagchi K, Grelsamer RP. Partial fibular head resection for bilateral snapping biceps femoris tendon. Orthopedics. 2003;26(11):1147-1149.

- Kissenberth MJ, Wilckens JH. The snapping biceps femoris tendon. Am J Knee Surg. 2000;13(1):25-28.

- Hernandez JA, Rius M. Noonan KJ. Snapping knee from anomalous biceps femoris tendon insertion: a case report. Iowa Orthop J. 1996;16:161-163.

- Lokiec F, Velkes S, Schindler A, Pritsch M. The snapping biceps femoris syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(283):205-206.

- Kristensen G, Nielsen K, Blyme PJ. Snapping knee from biceps femoris tendon. A case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 1989;60(5):621.

- Terry GC, LaPrade RF. The biceps femoris muscle complex at the knee. Its anatomy and injury patterns associated with acute anterolateral-anteromedial rotator instability. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:2-8.

ABSTRACT

A 23-year-old male active duty soldier presented with a biceps femoris tendon snapping over the fibular head with flexion of the knee beyond 90°. Surgical release of anomalous anterolateral tibial and lateral fibular insertions provided relief of snapping with no other repair or reconstruction required. The soldier quickly returned to full running and active duty.

Snapping biceps femoris tendon is a rare but potential cause of pain and dysfunction in the lateral knee. The possible anatomical variations and the cause of snapping must be considered when determining the operative approaches to this condition.

Continue to: Snapping in the knee...

Snapping in the knee is not as common as in other joints, such as the hip or ankle. The snapping sensation can occur from several pathologies, including the following: lateral meniscal tears, iliotibial band syndrome, proximal tibiofibular instability, snapping popliteus, peroneal nerve compression/neuritis, lateral discoid meniscus, rheumatoid nodules, plicae, congenital snapping knee, exostoses, or previous trauma.1,2 A detailed history must be provided, and physical examination and appropriate imaging must be performed to narrow down the differential diagnosis and prescribe the appropriate course of treatment for snapping.

Snapping biceps femoris syndrome is a rare cause of knee snapping. This condition has been described in various case reports.2-13 The reasons for a snapping biceps femoris can vary, and the treating provider must be ready to accommodate and treat these causes. The symptoms typically include an audible, and usually visual, lateral snapping distal to the knee joint and over the fibular head. Imaging may reveal bony abnormalities such as fibular exostoses. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can aid in determining any anomalous or abnormal insertions of the biceps femoris tendon. The snapping can be debilitating, particularly in athletes or patients with high-demand occupations, and surgical intervention is often warranted.

We present a case of an active-duty military service member with symptomatic unilateral snapping biceps femoris and review the literature for treatment of this condition. Surgical release allowed the patient a quick and unrestricted return to full mission capabilities.

The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE REPORT

A 23-year-old active-duty soldier presented to the orthopedic clinic with several months of noticeable snapping and pain over the lateral knee with attempted running and deep squatting activities, resulting in difficulty to perform his army duties. The patient reported no history of antecedent trauma. No locking of the knee or paresthesia distally into the leg or foot was observed.

The physical examination revealed a palpable and observable snapping of the long head of the biceps tendon over the fibular head with squatting beyond 90° in the left knee. The patient presented with full strength and no instability or joint line pain throughout the knee. Application of a posterior-to-anterior directed force over the biceps femoris proximal to the insertion allowed the patient to perform a deep squat without snapping. The radiographs demonstrated no abnormal fibular morphology (Figures 1A, 1B). Axial MRI images demonstrated an anomalous slip of the tendon inserting on the anterolateral aspect of the proximal tibia in addition to the normal insertion on the posterolateral and lateral edge of the fibular head (Figure 2) as described by Terry and LaPrade.14

Continue to: A conservative treatment with physical therapy...

A conservative treatment with physical therapy, activity modification, and a Cho-Pat knee strap (to provide a posterior-to-anterior buttress and to prevent snapping) was attempted for 4 weeks. However, the patient could not tolerate the strap, and the activity restraints prevented him from performing his job as an active-duty soldier. Given the failure of conservative treatment, operative intervention was elected.

Upon exploration of the biceps femoris insertion, the accessory anterolateral tibial insertion was readily identified (Figure 3). Notably, the expected normal lateral edge insertion was thickened and extended beyond the lateral edge, distal, and anterior on to the fibular head (Figure 4). The anterolateral tibial band was released first. However, the snapping remained evident. The thickened anterior fibular accessory band was then released back to its normal, lateral edge, and at this point, no further snapping was observed with deep flexion of the knee. Inspection of the remaining posterolateral and lateral edge insertion demonstrated a healthy, 1-cm thick tendinous insertion. The accessory slips were completely excised, and the incision was closed without any additional repair or re-insertion (Figure 5). The patient presented no complications postoperatively. He was allowed to bear weight as tolerated and was limited to stretching and gravity resistance training for 4 weeks. At 1 month, the patient was released to progress back to full activity. By 8 weeks postoperative, he remained free of snapping and resumed his regular running routine and military duties without restriction or pain.

DISCUSSION

Release of the anomalous bands with no further repair or re-insertion of the biceps femoris allowed this active-duty soldier to resume full running and duty-related activities in <2 months. In this particular patient, given his anatomy, the treatment was successful. The literature indicates that optimal results and surgical approach depend upon the pathological anatomy encountered.

Date and colleagues4 described a similar anatomical anomaly as with our patient, whom after the release of tibial insertion, snapping was still observed, thus requiring the release of anterior fibular insertion. They noted the necessity of suturing the accessory limbs onto the periosteum of the fibular head to achieve a stable biceps femoris.

In other cases, abnormal bony anatomy of the fibula has been shown to cause snapping. Vavalle and Capozzi5 described a case of snapping biceps in a marathon runner, who needed partial resection of the fibular head to eliminate snapping. The runner made a full return to the sport. Fung and colleagues2 described a similar approach to a 17-year-old cyclist; however, this patient presented exostoses of the bilateral fibular heads. The exostoses were bilaterally excised, and the snapping ceased. Kristensen and colleagues13 described a patient with an anomalous tibial insertion. Rather than releasing the tibial insertion, a partial resection of the fibular head allowed for cessation of snapping.

Other authors advocate the detachment and anatomic re-insertion of the biceps femoris into the fibular head. Bernhardson and LaPrade6 reported a series of 3 patients requiring this approach with excellent results. Bansal and colleagues8 were the first to describe a soccer player with an isolated injury to the knee as a traumatic cause for a snapping biceps femoris. After failure of conservative treatment attempts, exploration and re-insertion through a bone tunnel allowed for return to the sport. Hernandez and colleagues11 and Lokiec and colleagues12 both described the reproduction of the normal biceps femoris anatomy through re-insertion procedures after identifying patients with abnormal anatomical insertions as causes for snapping.

CONCLUSION

We presented a case of an active military service member with a unilateral snapping biceps femoris tendon due to an anomalous distal insertion on both the proximal tibia and anterior fibular head. The release of abnormal insertions and maintenance of his normal anatomical insertion allowed for a quick and effective return to running and duty at full capacity. Although other surgical approaches have been described to include partial fibular head resection or anatomical re-insertion, we believe that the approach to this rare condition should be anatomy-based as the causes of snapping can significantly vary. We believe that if the normal posterolateral and lateral edge insertions of the biceps femoris are intact, removal of the abnormal anatomy without any repair or reconstruction can safely lead to successful surgical outcomes.

ABSTRACT

A 23-year-old male active duty soldier presented with a biceps femoris tendon snapping over the fibular head with flexion of the knee beyond 90°. Surgical release of anomalous anterolateral tibial and lateral fibular insertions provided relief of snapping with no other repair or reconstruction required. The soldier quickly returned to full running and active duty.

Snapping biceps femoris tendon is a rare but potential cause of pain and dysfunction in the lateral knee. The possible anatomical variations and the cause of snapping must be considered when determining the operative approaches to this condition.

Continue to: Snapping in the knee...

Snapping in the knee is not as common as in other joints, such as the hip or ankle. The snapping sensation can occur from several pathologies, including the following: lateral meniscal tears, iliotibial band syndrome, proximal tibiofibular instability, snapping popliteus, peroneal nerve compression/neuritis, lateral discoid meniscus, rheumatoid nodules, plicae, congenital snapping knee, exostoses, or previous trauma.1,2 A detailed history must be provided, and physical examination and appropriate imaging must be performed to narrow down the differential diagnosis and prescribe the appropriate course of treatment for snapping.

Snapping biceps femoris syndrome is a rare cause of knee snapping. This condition has been described in various case reports.2-13 The reasons for a snapping biceps femoris can vary, and the treating provider must be ready to accommodate and treat these causes. The symptoms typically include an audible, and usually visual, lateral snapping distal to the knee joint and over the fibular head. Imaging may reveal bony abnormalities such as fibular exostoses. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can aid in determining any anomalous or abnormal insertions of the biceps femoris tendon. The snapping can be debilitating, particularly in athletes or patients with high-demand occupations, and surgical intervention is often warranted.

We present a case of an active-duty military service member with symptomatic unilateral snapping biceps femoris and review the literature for treatment of this condition. Surgical release allowed the patient a quick and unrestricted return to full mission capabilities.

The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE REPORT

A 23-year-old active-duty soldier presented to the orthopedic clinic with several months of noticeable snapping and pain over the lateral knee with attempted running and deep squatting activities, resulting in difficulty to perform his army duties. The patient reported no history of antecedent trauma. No locking of the knee or paresthesia distally into the leg or foot was observed.

The physical examination revealed a palpable and observable snapping of the long head of the biceps tendon over the fibular head with squatting beyond 90° in the left knee. The patient presented with full strength and no instability or joint line pain throughout the knee. Application of a posterior-to-anterior directed force over the biceps femoris proximal to the insertion allowed the patient to perform a deep squat without snapping. The radiographs demonstrated no abnormal fibular morphology (Figures 1A, 1B). Axial MRI images demonstrated an anomalous slip of the tendon inserting on the anterolateral aspect of the proximal tibia in addition to the normal insertion on the posterolateral and lateral edge of the fibular head (Figure 2) as described by Terry and LaPrade.14

Continue to: A conservative treatment with physical therapy...

A conservative treatment with physical therapy, activity modification, and a Cho-Pat knee strap (to provide a posterior-to-anterior buttress and to prevent snapping) was attempted for 4 weeks. However, the patient could not tolerate the strap, and the activity restraints prevented him from performing his job as an active-duty soldier. Given the failure of conservative treatment, operative intervention was elected.

Upon exploration of the biceps femoris insertion, the accessory anterolateral tibial insertion was readily identified (Figure 3). Notably, the expected normal lateral edge insertion was thickened and extended beyond the lateral edge, distal, and anterior on to the fibular head (Figure 4). The anterolateral tibial band was released first. However, the snapping remained evident. The thickened anterior fibular accessory band was then released back to its normal, lateral edge, and at this point, no further snapping was observed with deep flexion of the knee. Inspection of the remaining posterolateral and lateral edge insertion demonstrated a healthy, 1-cm thick tendinous insertion. The accessory slips were completely excised, and the incision was closed without any additional repair or re-insertion (Figure 5). The patient presented no complications postoperatively. He was allowed to bear weight as tolerated and was limited to stretching and gravity resistance training for 4 weeks. At 1 month, the patient was released to progress back to full activity. By 8 weeks postoperative, he remained free of snapping and resumed his regular running routine and military duties without restriction or pain.

DISCUSSION

Release of the anomalous bands with no further repair or re-insertion of the biceps femoris allowed this active-duty soldier to resume full running and duty-related activities in <2 months. In this particular patient, given his anatomy, the treatment was successful. The literature indicates that optimal results and surgical approach depend upon the pathological anatomy encountered.

Date and colleagues4 described a similar anatomical anomaly as with our patient, whom after the release of tibial insertion, snapping was still observed, thus requiring the release of anterior fibular insertion. They noted the necessity of suturing the accessory limbs onto the periosteum of the fibular head to achieve a stable biceps femoris.

In other cases, abnormal bony anatomy of the fibula has been shown to cause snapping. Vavalle and Capozzi5 described a case of snapping biceps in a marathon runner, who needed partial resection of the fibular head to eliminate snapping. The runner made a full return to the sport. Fung and colleagues2 described a similar approach to a 17-year-old cyclist; however, this patient presented exostoses of the bilateral fibular heads. The exostoses were bilaterally excised, and the snapping ceased. Kristensen and colleagues13 described a patient with an anomalous tibial insertion. Rather than releasing the tibial insertion, a partial resection of the fibular head allowed for cessation of snapping.

Other authors advocate the detachment and anatomic re-insertion of the biceps femoris into the fibular head. Bernhardson and LaPrade6 reported a series of 3 patients requiring this approach with excellent results. Bansal and colleagues8 were the first to describe a soccer player with an isolated injury to the knee as a traumatic cause for a snapping biceps femoris. After failure of conservative treatment attempts, exploration and re-insertion through a bone tunnel allowed for return to the sport. Hernandez and colleagues11 and Lokiec and colleagues12 both described the reproduction of the normal biceps femoris anatomy through re-insertion procedures after identifying patients with abnormal anatomical insertions as causes for snapping.

CONCLUSION

We presented a case of an active military service member with a unilateral snapping biceps femoris tendon due to an anomalous distal insertion on both the proximal tibia and anterior fibular head. The release of abnormal insertions and maintenance of his normal anatomical insertion allowed for a quick and effective return to running and duty at full capacity. Although other surgical approaches have been described to include partial fibular head resection or anatomical re-insertion, we believe that the approach to this rare condition should be anatomy-based as the causes of snapping can significantly vary. We believe that if the normal posterolateral and lateral edge insertions of the biceps femoris are intact, removal of the abnormal anatomy without any repair or reconstruction can safely lead to successful surgical outcomes.

- Barker JU, Strauss EJ, Lodha S, Bach BR Jr. Extra-articular mimickers of lateral meniscal tears. Sports Health. 2011;3(1):82-88.

- Fung DA, Frey S, Markbreiter L. Bilateral symptomatic snapping biceps femoris tendon due to fibular exostosis. J Knee Surg. 2008;21(1):55-57.

- Mirchandani M, Gandhi P, Cai P. Poster 175 bilateral symptomatic snapping knee from biceps femoris tendon subluxation–an atypical cause of bilateral knee pain: a case report. PM R. 2016;8(9S):S218-S219.

- Date H, Hayakawa K, Yamada H. Snapping knee due to the biceps femoris tendon treated with repositioning of the anomalous tibial insertion. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(8):1581-1583.

- Vavalle G, Capozzi M. Symptomatic snapping knee from biceps femoris tendon subluxation: an unusual case of lateral pain in a marathon runner. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11(4):263-266.

- Bernhardson AS, LaPrade RF. Snapping biceps femoris tendon treated with an anatomic repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(8):1110-1112.

- Guillin R, Mendoza-Ruiz JJ, Moser T, Ropars M, Duvauferrier R, Cardinal E. Snapping biceps femoris tendon: a dynamic real-time sonographic evaluation. J Clin Ultrasound. 2010;38(8):435-437.

- Bansal R, Taylor C, Pimpalnerkar AL. Snapping knee: an unusual biceps femoris tendon injury. Knee. 2005;12(6):458-460.

- Bagchi K, Grelsamer RP. Partial fibular head resection for bilateral snapping biceps femoris tendon. Orthopedics. 2003;26(11):1147-1149.

- Kissenberth MJ, Wilckens JH. The snapping biceps femoris tendon. Am J Knee Surg. 2000;13(1):25-28.

- Hernandez JA, Rius M. Noonan KJ. Snapping knee from anomalous biceps femoris tendon insertion: a case report. Iowa Orthop J. 1996;16:161-163.

- Lokiec F, Velkes S, Schindler A, Pritsch M. The snapping biceps femoris syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(283):205-206.

- Kristensen G, Nielsen K, Blyme PJ. Snapping knee from biceps femoris tendon. A case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 1989;60(5):621.

- Terry GC, LaPrade RF. The biceps femoris muscle complex at the knee. Its anatomy and injury patterns associated with acute anterolateral-anteromedial rotator instability. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:2-8.

- Barker JU, Strauss EJ, Lodha S, Bach BR Jr. Extra-articular mimickers of lateral meniscal tears. Sports Health. 2011;3(1):82-88.

- Fung DA, Frey S, Markbreiter L. Bilateral symptomatic snapping biceps femoris tendon due to fibular exostosis. J Knee Surg. 2008;21(1):55-57.

- Mirchandani M, Gandhi P, Cai P. Poster 175 bilateral symptomatic snapping knee from biceps femoris tendon subluxation–an atypical cause of bilateral knee pain: a case report. PM R. 2016;8(9S):S218-S219.

- Date H, Hayakawa K, Yamada H. Snapping knee due to the biceps femoris tendon treated with repositioning of the anomalous tibial insertion. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012;20(8):1581-1583.

- Vavalle G, Capozzi M. Symptomatic snapping knee from biceps femoris tendon subluxation: an unusual case of lateral pain in a marathon runner. J Orthop Traumatol. 2010;11(4):263-266.

- Bernhardson AS, LaPrade RF. Snapping biceps femoris tendon treated with an anatomic repair. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(8):1110-1112.

- Guillin R, Mendoza-Ruiz JJ, Moser T, Ropars M, Duvauferrier R, Cardinal E. Snapping biceps femoris tendon: a dynamic real-time sonographic evaluation. J Clin Ultrasound. 2010;38(8):435-437.

- Bansal R, Taylor C, Pimpalnerkar AL. Snapping knee: an unusual biceps femoris tendon injury. Knee. 2005;12(6):458-460.

- Bagchi K, Grelsamer RP. Partial fibular head resection for bilateral snapping biceps femoris tendon. Orthopedics. 2003;26(11):1147-1149.

- Kissenberth MJ, Wilckens JH. The snapping biceps femoris tendon. Am J Knee Surg. 2000;13(1):25-28.

- Hernandez JA, Rius M. Noonan KJ. Snapping knee from anomalous biceps femoris tendon insertion: a case report. Iowa Orthop J. 1996;16:161-163.

- Lokiec F, Velkes S, Schindler A, Pritsch M. The snapping biceps femoris syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(283):205-206.

- Kristensen G, Nielsen K, Blyme PJ. Snapping knee from biceps femoris tendon. A case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 1989;60(5):621.

- Terry GC, LaPrade RF. The biceps femoris muscle complex at the knee. Its anatomy and injury patterns associated with acute anterolateral-anteromedial rotator instability. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:2-8.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Snapping biceps femoris is a rare, but debilitating condition.

- Understanding the pathology from an anatomical perspective is key.

- For bone abnormalities, correct the bony pathology to relieve the snapping.

- For soft tissue abnormalities, both excisional and reconstructive approaches can be utilized.

- Preservation of normal anatomy, when possible, can help expedite recovery.

CREDENCE canagliflozin trial halted because of efficacy

The CREDENCE trial, which was investigating whether the antidiabetes drug canagliflozin (Invokana) plus standard of care could safely help prevent or slow chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with type 2 diabetes, has been ended early because it has already achieved prespecified efficacy criteria, Janssen announced in a press release. These criteria included risk reduction in the composite endpoint of time to dialysis or kidney transplant, doubling of serum creatinine, and renal or cardiovascular death.

In CANVAS, the cardiovascular outcomes trial for canagliflozin, treatment was linked to reductions in progression of albuminuria and the composite outcome of a sustained 40% reduction in the estimated glomerular filtration rate, the need for renal replacement therapy, or death from renal causes, compared with placebo, but those didn’t reach statistical significance.

CREDENCE (Evaluation of the Effects of Canagliflozin on Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Participants With Diabetic Nephropathy) is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter trial that enrolled roughly 4,400 patients with type 2 diabetes and established kidney disease who had been receiving ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers for at least 4 weeks prior to randomization.

The decision to halt CREDENCE came about after a review of data by the study’s independent data monitoring committee during a planned interim analysis. The resulting recommendation was based on the efficacy findings, the exact data for which have not yet been released.

Canagliflozin, a sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, in conjunction with diet and exercise, can help improve glycemic control. In the context of kidney disease and type 2 diabetes, canagliflozin has been associated with increased risk of dehydration, vaginal or penile yeast infections, and amputations of all or part of the foot or leg. It has also been associated with ketoacidosis, kidney problems, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, and urinary tract infections.

More information can be found in the press release. Full prescribing information can be found on the Food and Drug Administration website.

The CREDENCE trial, which was investigating whether the antidiabetes drug canagliflozin (Invokana) plus standard of care could safely help prevent or slow chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with type 2 diabetes, has been ended early because it has already achieved prespecified efficacy criteria, Janssen announced in a press release. These criteria included risk reduction in the composite endpoint of time to dialysis or kidney transplant, doubling of serum creatinine, and renal or cardiovascular death.

In CANVAS, the cardiovascular outcomes trial for canagliflozin, treatment was linked to reductions in progression of albuminuria and the composite outcome of a sustained 40% reduction in the estimated glomerular filtration rate, the need for renal replacement therapy, or death from renal causes, compared with placebo, but those didn’t reach statistical significance.

CREDENCE (Evaluation of the Effects of Canagliflozin on Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Participants With Diabetic Nephropathy) is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter trial that enrolled roughly 4,400 patients with type 2 diabetes and established kidney disease who had been receiving ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers for at least 4 weeks prior to randomization.

The decision to halt CREDENCE came about after a review of data by the study’s independent data monitoring committee during a planned interim analysis. The resulting recommendation was based on the efficacy findings, the exact data for which have not yet been released.

Canagliflozin, a sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, in conjunction with diet and exercise, can help improve glycemic control. In the context of kidney disease and type 2 diabetes, canagliflozin has been associated with increased risk of dehydration, vaginal or penile yeast infections, and amputations of all or part of the foot or leg. It has also been associated with ketoacidosis, kidney problems, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, and urinary tract infections.

More information can be found in the press release. Full prescribing information can be found on the Food and Drug Administration website.

The CREDENCE trial, which was investigating whether the antidiabetes drug canagliflozin (Invokana) plus standard of care could safely help prevent or slow chronic kidney disease (CKD) in patients with type 2 diabetes, has been ended early because it has already achieved prespecified efficacy criteria, Janssen announced in a press release. These criteria included risk reduction in the composite endpoint of time to dialysis or kidney transplant, doubling of serum creatinine, and renal or cardiovascular death.

In CANVAS, the cardiovascular outcomes trial for canagliflozin, treatment was linked to reductions in progression of albuminuria and the composite outcome of a sustained 40% reduction in the estimated glomerular filtration rate, the need for renal replacement therapy, or death from renal causes, compared with placebo, but those didn’t reach statistical significance.

CREDENCE (Evaluation of the Effects of Canagliflozin on Renal and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Participants With Diabetic Nephropathy) is a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter trial that enrolled roughly 4,400 patients with type 2 diabetes and established kidney disease who had been receiving ACE inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers for at least 4 weeks prior to randomization.

The decision to halt CREDENCE came about after a review of data by the study’s independent data monitoring committee during a planned interim analysis. The resulting recommendation was based on the efficacy findings, the exact data for which have not yet been released.

Canagliflozin, a sodium-glucose transporter 2 (SGLT2) inhibitor, in conjunction with diet and exercise, can help improve glycemic control. In the context of kidney disease and type 2 diabetes, canagliflozin has been associated with increased risk of dehydration, vaginal or penile yeast infections, and amputations of all or part of the foot or leg. It has also been associated with ketoacidosis, kidney problems, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, and urinary tract infections.

More information can be found in the press release. Full prescribing information can be found on the Food and Drug Administration website.

CVD-REAL 2: Lower mortality, CV risks with SGLT-2i vs. DPP-4i treatment in T2DM

ORLANDO – according to findings from the CVD-REAL 2 study.

CVD-REAL 2 is a real-world, observational cohort study involving the analysis of health records for two matched cohorts of patients with T2DM from 12 countries across the globe, including 181,620 SGLT-2 inhibitor recipients and 181,620 DPP-4 inhibitor recipients who were newly initiated on their respective treatments between December 2012 and November 2017. The respective rates of all-cause death were 0.83 and 1.33 per 100 patient-years (4,768 events; hazard ratio, 0.51), Shun Kohsaka, MD, of Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, and his colleagues reported in a late-breaking poster at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“HRs for all-cause death consistently favored SGLT-2 inhibitor vs. DPP-4 inhibitor in each country,” the investigators noted. “Directionally, the same results were observed in other cardiovascular outcomes, including [hospitalization for heart failure (HHF)], and the composite of all-cause death or HHF but modestly for [myocardial infarction] and stroke.”

The rates of hospitalization for heart failure per 100 patient-years were 0.80 and 1.08 in the SGLT-2 inhibitor and DPP-4 inhibitor groups (3,875 events; HR, 0.68), and for HHF plus all-cause death, they were 1.55 and 2.22 per 100 patient-years (7,807 events; HR, 0.67), respectively. The rates of myocardial infarction in the groups, respectively, were 0.53 and 0.58 per 100 patient-years (2,298 events; HR, 0.90), and for stroke, they were 0.82 and 0.99 per 100 patient-years (3,747 events; HR, 0.84), the investigators reported.

Study subjects in both cohorts had a mean age of 58 years, and 30% and 29% in the SGLT-2 inhibitor and DPP-4 inhibitor groups, respectively, had established cardiovascular disease. Only those newly initiated on either an SGLT-2 inhibitor or DPP-4 inhibitor were selected from each data source; fixed-dose combinations were allowed as long as there was no use of either drug during the year prior to enrollment.

In the SGLT-2 inhibitor cohort, most exposures (60.1%) were to dapagliflozin, followed by canagliflozin (23.8%) and empagliflozin (12.1%). The remaining exposures were to ipragliflozin, tofogliflozin, or luseogliflozin (0.3-2.8%). In the DPP-4 inhibitor group, most exposures (49.7%) were to sitagliptin, 18.9% were to linagliptin, 10.4% were to saxagliptin, and the remaining exposures were to alogliptin, gemigliptin, teneligliptin, anagliptin, evogliptin, and trelagliptin (0.1%-4.7%).

Those in the SGLT-2 inhibitor group were followed for a mean of 439 days, and those in the DPP-4 inhibitor group were followed for a mean of 446 days.

“The results were consistent across the subgroups of patients with and without established [cardiovascular disease], favoring SGLT-2 inhibitor vs. DPP-4 inhibitor for all outcomes,” they noted.

Both DPP-4 inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors are widely used in T2DM, and although clinical trials demonstrated lower risk of cardiovascular events with SGLT-2 inhibitors and a neutral effect on cardiovascular events with DPP-4 inhibitors, large comparative studies are lacking, the investigators explained.

Though limited by the possibility of residual, unmeasured confounding, as well as by a lack of mortality data in Japan and Singapore apart from the inpatient setting, the findings of this “large, contemporary analysis of real-world administrative data” are complementary to those from previous observational studies and clinical trials, they concluded, noting that “SGLT-2 inhibitor experience in real-world practice is still relatively short and longer-term follow-up is required to examine whether effects are sustained over time.”

The CVD-REAL studies are sponsored by AstraZeneca. Dr. Kohsaka reported receiving research support from Bayer Yakuhin and Daiichi Sankyo and serving on the speaker’s bureau for Bayer Yakuhin and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

SOURCE: Kohsaka S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 124-LB.

ORLANDO – according to findings from the CVD-REAL 2 study.

CVD-REAL 2 is a real-world, observational cohort study involving the analysis of health records for two matched cohorts of patients with T2DM from 12 countries across the globe, including 181,620 SGLT-2 inhibitor recipients and 181,620 DPP-4 inhibitor recipients who were newly initiated on their respective treatments between December 2012 and November 2017. The respective rates of all-cause death were 0.83 and 1.33 per 100 patient-years (4,768 events; hazard ratio, 0.51), Shun Kohsaka, MD, of Keio University School of Medicine, Tokyo, and his colleagues reported in a late-breaking poster at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

“HRs for all-cause death consistently favored SGLT-2 inhibitor vs. DPP-4 inhibitor in each country,” the investigators noted. “Directionally, the same results were observed in other cardiovascular outcomes, including [hospitalization for heart failure (HHF)], and the composite of all-cause death or HHF but modestly for [myocardial infarction] and stroke.”

The rates of hospitalization for heart failure per 100 patient-years were 0.80 and 1.08 in the SGLT-2 inhibitor and DPP-4 inhibitor groups (3,875 events; HR, 0.68), and for HHF plus all-cause death, they were 1.55 and 2.22 per 100 patient-years (7,807 events; HR, 0.67), respectively. The rates of myocardial infarction in the groups, respectively, were 0.53 and 0.58 per 100 patient-years (2,298 events; HR, 0.90), and for stroke, they were 0.82 and 0.99 per 100 patient-years (3,747 events; HR, 0.84), the investigators reported.

Study subjects in both cohorts had a mean age of 58 years, and 30% and 29% in the SGLT-2 inhibitor and DPP-4 inhibitor groups, respectively, had established cardiovascular disease. Only those newly initiated on either an SGLT-2 inhibitor or DPP-4 inhibitor were selected from each data source; fixed-dose combinations were allowed as long as there was no use of either drug during the year prior to enrollment.

In the SGLT-2 inhibitor cohort, most exposures (60.1%) were to dapagliflozin, followed by canagliflozin (23.8%) and empagliflozin (12.1%). The remaining exposures were to ipragliflozin, tofogliflozin, or luseogliflozin (0.3-2.8%). In the DPP-4 inhibitor group, most exposures (49.7%) were to sitagliptin, 18.9% were to linagliptin, 10.4% were to saxagliptin, and the remaining exposures were to alogliptin, gemigliptin, teneligliptin, anagliptin, evogliptin, and trelagliptin (0.1%-4.7%).

Those in the SGLT-2 inhibitor group were followed for a mean of 439 days, and those in the DPP-4 inhibitor group were followed for a mean of 446 days.