User login

About half of FDA expedited approvals lack double-blind trials

About half of the drugs approved under the Food and Drug Administrations’s Breakthrough Therapy designation have lacked the gold-standard evidence of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, according to a new JAMA report.

“This study of all FDA approvals granted Breakthrough Therapy designation from 2012 through 2017 suggests that pivotal trials supporting these approvals commonly lacked randomization, double-blinding, and control groups, used surrogate markers as primary end points, and enrolled small numbers of patients,” wrote Jeremy Puthumana and his coauthors. “Furthermore, more than half were based on a single, pivotal trial.”

The average premarket development time was about 5 years, but regulatory review of these agents took less than 7 months on average, the report found.

Mr. Puthumana, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his coauthors, reviewed all 46 of the drugs and biologics approved by the FDA from 2012 to 2017 under the designation. The Breakthrough Therapy designation allows for the rapid review of drugs and biologics for serious or life-threatening conditions where there is preliminary evidence demonstrating a substantial improvement over existing therapies. The researchers identified all pivotal trials supporting approval, looking at randomization, blinding, comparator group, primary endpoint, and patient numbers.

Of these drugs, most (25) were oncologic agents. Other indications were infectious disease (8), genetic or metabolic disorders (5), and other unspecified purposes (8). The median number of patients enrolled among all pivotal trials supporting an indication approval was 222.

Most of the approvals (27) were based on randomized trials, 21 (45.7%) were based on double-blind randomization, 25 (54.3%) employed an active or placebo comparator group, and 10 (21.7%) used a clinical primary endpoint.

Compared with drugs without accelerated approval, drugs with accelerated approval status were less likely to be examined in randomized or double-blinded trials(24 vs. 3 and 20 vs. 1, respectively), and were less likely to include a control group (32 vs. 3).

However, all drugs with Accelerated Approval status underwent at least one clinical safety or efficacy-focused postmarketing requirement, as did 64.3% of those without that status.

“Patients and physicians may have misconceptions about the strength of evidence supporting breakthrough approvals,” the authors wrote. “FDA-required postmarketing studies will be critical to confirm the clinical benefit and safety of these promising, newly approved therapies.”

Mr. Puthumana reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Puthumana J et al. JAMA. 2018;320(3):301-3.

Expedited drug approvals raise concerns that important questions about safety and effectiveness might be insufficiently answered before an agent makes it to pharmacy shelves, Austin B. Frakt, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Several key facts suggest that the Food and Drug Administration’s expedited review programs may invite greater risks than benefits, he wrote.

Most new drugs are approved with relatively little data about long-term outcomes.

More than two-thirds of approvals are based on studies lasting less than 6 months.

The FDA approves novel therapeutic agents more quickly than do similar regulatory bodies in Europe and Canada, with a median time of 6 months for cancer drug approval.

Expedited reviews have increased in the last 2 decades. The increase is driven by drugs that are not first in their class, implying that they aren’t addressing unmet needs.

“The idea that doing something more quickly means it is not done as well has considerable face validity,” Dr. Frakt wrote. Nevertheless, at least one study suggests that expedited FDA approvals do confer substantial gains in quality of life. “[The study suggests] that the FDA’s expedited drug review programs include drugs that provide greater benefits than those undergoing conventional review. Indeed, to the extent the expedited programs handle drugs for conditions for which there is unmet medical need, relatively larger QALY [quality-adjusted life-year] gains are to be expected.”

However, drugs subject to less FDA scrutiny are more likely to exhibit safety problems, be withdrawn from the market, or carry black box warnings. But in some cases, at least, the trade-off seems worth it.

“Because expedited review programs are intended for drugs that treat serious conditions and address unmet medical needs, accepting greater risk may be reasonable and more consistent with patients’ preferences,” he said. “However, because many of these drugs also come with high price tags, financed with public funds through Medicare, Medicaid, and other programs, the patients’ point of view is not the only one of relevance. A consideration of cost is also reasonable from the point of view of taxpayers.”

Dr. Frakt is director of the Partnered Evidence-based Policy Resource Center at the Boston Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. His remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2018;320[3]:225-6).

Expedited drug approvals raise concerns that important questions about safety and effectiveness might be insufficiently answered before an agent makes it to pharmacy shelves, Austin B. Frakt, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Several key facts suggest that the Food and Drug Administration’s expedited review programs may invite greater risks than benefits, he wrote.

Most new drugs are approved with relatively little data about long-term outcomes.

More than two-thirds of approvals are based on studies lasting less than 6 months.

The FDA approves novel therapeutic agents more quickly than do similar regulatory bodies in Europe and Canada, with a median time of 6 months for cancer drug approval.

Expedited reviews have increased in the last 2 decades. The increase is driven by drugs that are not first in their class, implying that they aren’t addressing unmet needs.

“The idea that doing something more quickly means it is not done as well has considerable face validity,” Dr. Frakt wrote. Nevertheless, at least one study suggests that expedited FDA approvals do confer substantial gains in quality of life. “[The study suggests] that the FDA’s expedited drug review programs include drugs that provide greater benefits than those undergoing conventional review. Indeed, to the extent the expedited programs handle drugs for conditions for which there is unmet medical need, relatively larger QALY [quality-adjusted life-year] gains are to be expected.”

However, drugs subject to less FDA scrutiny are more likely to exhibit safety problems, be withdrawn from the market, or carry black box warnings. But in some cases, at least, the trade-off seems worth it.

“Because expedited review programs are intended for drugs that treat serious conditions and address unmet medical needs, accepting greater risk may be reasonable and more consistent with patients’ preferences,” he said. “However, because many of these drugs also come with high price tags, financed with public funds through Medicare, Medicaid, and other programs, the patients’ point of view is not the only one of relevance. A consideration of cost is also reasonable from the point of view of taxpayers.”

Dr. Frakt is director of the Partnered Evidence-based Policy Resource Center at the Boston Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. His remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2018;320[3]:225-6).

Expedited drug approvals raise concerns that important questions about safety and effectiveness might be insufficiently answered before an agent makes it to pharmacy shelves, Austin B. Frakt, PhD, wrote in an accompanying editorial.

Several key facts suggest that the Food and Drug Administration’s expedited review programs may invite greater risks than benefits, he wrote.

Most new drugs are approved with relatively little data about long-term outcomes.

More than two-thirds of approvals are based on studies lasting less than 6 months.

The FDA approves novel therapeutic agents more quickly than do similar regulatory bodies in Europe and Canada, with a median time of 6 months for cancer drug approval.

Expedited reviews have increased in the last 2 decades. The increase is driven by drugs that are not first in their class, implying that they aren’t addressing unmet needs.

“The idea that doing something more quickly means it is not done as well has considerable face validity,” Dr. Frakt wrote. Nevertheless, at least one study suggests that expedited FDA approvals do confer substantial gains in quality of life. “[The study suggests] that the FDA’s expedited drug review programs include drugs that provide greater benefits than those undergoing conventional review. Indeed, to the extent the expedited programs handle drugs for conditions for which there is unmet medical need, relatively larger QALY [quality-adjusted life-year] gains are to be expected.”

However, drugs subject to less FDA scrutiny are more likely to exhibit safety problems, be withdrawn from the market, or carry black box warnings. But in some cases, at least, the trade-off seems worth it.

“Because expedited review programs are intended for drugs that treat serious conditions and address unmet medical needs, accepting greater risk may be reasonable and more consistent with patients’ preferences,” he said. “However, because many of these drugs also come with high price tags, financed with public funds through Medicare, Medicaid, and other programs, the patients’ point of view is not the only one of relevance. A consideration of cost is also reasonable from the point of view of taxpayers.”

Dr. Frakt is director of the Partnered Evidence-based Policy Resource Center at the Boston Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. His remarks are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2018;320[3]:225-6).

About half of the drugs approved under the Food and Drug Administrations’s Breakthrough Therapy designation have lacked the gold-standard evidence of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, according to a new JAMA report.

“This study of all FDA approvals granted Breakthrough Therapy designation from 2012 through 2017 suggests that pivotal trials supporting these approvals commonly lacked randomization, double-blinding, and control groups, used surrogate markers as primary end points, and enrolled small numbers of patients,” wrote Jeremy Puthumana and his coauthors. “Furthermore, more than half were based on a single, pivotal trial.”

The average premarket development time was about 5 years, but regulatory review of these agents took less than 7 months on average, the report found.

Mr. Puthumana, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his coauthors, reviewed all 46 of the drugs and biologics approved by the FDA from 2012 to 2017 under the designation. The Breakthrough Therapy designation allows for the rapid review of drugs and biologics for serious or life-threatening conditions where there is preliminary evidence demonstrating a substantial improvement over existing therapies. The researchers identified all pivotal trials supporting approval, looking at randomization, blinding, comparator group, primary endpoint, and patient numbers.

Of these drugs, most (25) were oncologic agents. Other indications were infectious disease (8), genetic or metabolic disorders (5), and other unspecified purposes (8). The median number of patients enrolled among all pivotal trials supporting an indication approval was 222.

Most of the approvals (27) were based on randomized trials, 21 (45.7%) were based on double-blind randomization, 25 (54.3%) employed an active or placebo comparator group, and 10 (21.7%) used a clinical primary endpoint.

Compared with drugs without accelerated approval, drugs with accelerated approval status were less likely to be examined in randomized or double-blinded trials(24 vs. 3 and 20 vs. 1, respectively), and were less likely to include a control group (32 vs. 3).

However, all drugs with Accelerated Approval status underwent at least one clinical safety or efficacy-focused postmarketing requirement, as did 64.3% of those without that status.

“Patients and physicians may have misconceptions about the strength of evidence supporting breakthrough approvals,” the authors wrote. “FDA-required postmarketing studies will be critical to confirm the clinical benefit and safety of these promising, newly approved therapies.”

Mr. Puthumana reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Puthumana J et al. JAMA. 2018;320(3):301-3.

About half of the drugs approved under the Food and Drug Administrations’s Breakthrough Therapy designation have lacked the gold-standard evidence of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, according to a new JAMA report.

“This study of all FDA approvals granted Breakthrough Therapy designation from 2012 through 2017 suggests that pivotal trials supporting these approvals commonly lacked randomization, double-blinding, and control groups, used surrogate markers as primary end points, and enrolled small numbers of patients,” wrote Jeremy Puthumana and his coauthors. “Furthermore, more than half were based on a single, pivotal trial.”

The average premarket development time was about 5 years, but regulatory review of these agents took less than 7 months on average, the report found.

Mr. Puthumana, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and his coauthors, reviewed all 46 of the drugs and biologics approved by the FDA from 2012 to 2017 under the designation. The Breakthrough Therapy designation allows for the rapid review of drugs and biologics for serious or life-threatening conditions where there is preliminary evidence demonstrating a substantial improvement over existing therapies. The researchers identified all pivotal trials supporting approval, looking at randomization, blinding, comparator group, primary endpoint, and patient numbers.

Of these drugs, most (25) were oncologic agents. Other indications were infectious disease (8), genetic or metabolic disorders (5), and other unspecified purposes (8). The median number of patients enrolled among all pivotal trials supporting an indication approval was 222.

Most of the approvals (27) were based on randomized trials, 21 (45.7%) were based on double-blind randomization, 25 (54.3%) employed an active or placebo comparator group, and 10 (21.7%) used a clinical primary endpoint.

Compared with drugs without accelerated approval, drugs with accelerated approval status were less likely to be examined in randomized or double-blinded trials(24 vs. 3 and 20 vs. 1, respectively), and were less likely to include a control group (32 vs. 3).

However, all drugs with Accelerated Approval status underwent at least one clinical safety or efficacy-focused postmarketing requirement, as did 64.3% of those without that status.

“Patients and physicians may have misconceptions about the strength of evidence supporting breakthrough approvals,” the authors wrote. “FDA-required postmarketing studies will be critical to confirm the clinical benefit and safety of these promising, newly approved therapies.”

Mr. Puthumana reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Puthumana J et al. JAMA. 2018;320(3):301-3.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Just 45.7% of drugs granted Breakthrough Therapy approval by the Food and Drug Administration went through a double-blind, randomized study.

Study details: The review comprised 46 drugs granted Breakthrough status from 2012 to 2017.

Disclosures: Mr. Puthumana reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Puthumana J et al. JAMA. 2018;320[3]:301-3.

CMS considers expanding telemedicine payments

Payment for more telemedicine services could be in store for physicians and other health providers if new proposals in the latest fee schedule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are finalized.

Under the proposed physician fee schedule, announced July 12, the CMS would expand services that qualify for telemedicine payments and add reimbursement for virtual check-ins by phone or other technologies, such as Skype. Telemedicine clinicians would also be paid for time spent reviewing patient photos sent by text or e-mail under the suggested changes.

Such telehealth services would aid patients who have transportation difficulties by creating more opportunities for them to access personalized care, said CMS Administrator Seema Verma.

“CMS is committed to modernizing the Medicare program by leveraging technologies, such as audio/video applications or patient-facing health portals, that will help beneficiaries access high-quality services in a convenient manner,” Ms. Verma said in a statement.

Under the proposal, physicians could bill separately for brief, non–face-to-face patient check-ins with patients via communication technology beginning January 2019. In addition, the proposed rule carves out payments for the remote professional evaluation of patient-transmitted information conducted via prerecorded “store and forward” video or image technology. Doctors could use both services to determine whether an office visit or other service is warranted, according to the proposed rule.

The services would have limitations on when they could be separately billed. In cases where the brief communication technology–based service originated from a related evaluation and management (E/M) service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician or other qualified health care professional, the service would be considered “bundled” into that previous E/M service and could not be billed separately. Similarly, a photo evaluation could not be separately billed if it stemmed from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician, or if the evaluation results in an in-person E/M office visit with the same doctor.

Under the proposal, health providers could perform the newly covered telehealth services only with established patients, but the CMS is seeking comments as to whether in certain cases, such as dermatological or ophthalmological instances, it might be appropriate for a new patient to receive the services. Agency officials also want to know what types of communication technology are used by physicians in furnishing check-in services, including whether audio-only telephone interactions are sufficient, compared with interactions that are enhanced with video. The CMS is asking physicians whether it would be clinically appropriate to apply a frequency limitation on the use of the proposed telehealth services by the same physician.

Latoya Thomas, director of the American Telemedicine Association’s State Policy Resource Center, said the proposal is exciting because it acknowledges the pervasive growth, accessibility, and acceptance of technology advances.

“In expanding reimbursement to providers for more modality-neutral and site-neutral virtual care, such as store-and-forward and remote patient monitoring, [the rules] address longstanding barriers to broader dissemination of telehealth,” Ms. Thomas said in an interview. “By making available ‘virtual check ins’ to every Medicare beneficiary, it can improve patient engagement and reduce unnecessary trips back to their provider’s office.”

James P. Marcin, MD, a telemedicine physician and director of the Center for Health and Technology at UC Davis Children’s Hospital in Sacramento, Calif., said he was pleased with the proposed telehealth changes, but he noted that more work remains to address further telemedicine challenges.

“The needle is finally moving, albeit too slowly for some of us,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “There are still some areas users of telemedicine and organizations supporting the use of telemedicine want to address, including the need for verbal informed consent, the requirements for established relationships with patients, and of course, rate valuations for the remote patient monitoring and professional codes. But again, this is good news for patients.”

Public comments on the proposed rule are due by Sept. 10, 2018. Comments can be submitted to regulations.gov.

Payment for more telemedicine services could be in store for physicians and other health providers if new proposals in the latest fee schedule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are finalized.

Under the proposed physician fee schedule, announced July 12, the CMS would expand services that qualify for telemedicine payments and add reimbursement for virtual check-ins by phone or other technologies, such as Skype. Telemedicine clinicians would also be paid for time spent reviewing patient photos sent by text or e-mail under the suggested changes.

Such telehealth services would aid patients who have transportation difficulties by creating more opportunities for them to access personalized care, said CMS Administrator Seema Verma.

“CMS is committed to modernizing the Medicare program by leveraging technologies, such as audio/video applications or patient-facing health portals, that will help beneficiaries access high-quality services in a convenient manner,” Ms. Verma said in a statement.

Under the proposal, physicians could bill separately for brief, non–face-to-face patient check-ins with patients via communication technology beginning January 2019. In addition, the proposed rule carves out payments for the remote professional evaluation of patient-transmitted information conducted via prerecorded “store and forward” video or image technology. Doctors could use both services to determine whether an office visit or other service is warranted, according to the proposed rule.

The services would have limitations on when they could be separately billed. In cases where the brief communication technology–based service originated from a related evaluation and management (E/M) service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician or other qualified health care professional, the service would be considered “bundled” into that previous E/M service and could not be billed separately. Similarly, a photo evaluation could not be separately billed if it stemmed from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician, or if the evaluation results in an in-person E/M office visit with the same doctor.

Under the proposal, health providers could perform the newly covered telehealth services only with established patients, but the CMS is seeking comments as to whether in certain cases, such as dermatological or ophthalmological instances, it might be appropriate for a new patient to receive the services. Agency officials also want to know what types of communication technology are used by physicians in furnishing check-in services, including whether audio-only telephone interactions are sufficient, compared with interactions that are enhanced with video. The CMS is asking physicians whether it would be clinically appropriate to apply a frequency limitation on the use of the proposed telehealth services by the same physician.

Latoya Thomas, director of the American Telemedicine Association’s State Policy Resource Center, said the proposal is exciting because it acknowledges the pervasive growth, accessibility, and acceptance of technology advances.

“In expanding reimbursement to providers for more modality-neutral and site-neutral virtual care, such as store-and-forward and remote patient monitoring, [the rules] address longstanding barriers to broader dissemination of telehealth,” Ms. Thomas said in an interview. “By making available ‘virtual check ins’ to every Medicare beneficiary, it can improve patient engagement and reduce unnecessary trips back to their provider’s office.”

James P. Marcin, MD, a telemedicine physician and director of the Center for Health and Technology at UC Davis Children’s Hospital in Sacramento, Calif., said he was pleased with the proposed telehealth changes, but he noted that more work remains to address further telemedicine challenges.

“The needle is finally moving, albeit too slowly for some of us,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “There are still some areas users of telemedicine and organizations supporting the use of telemedicine want to address, including the need for verbal informed consent, the requirements for established relationships with patients, and of course, rate valuations for the remote patient monitoring and professional codes. But again, this is good news for patients.”

Public comments on the proposed rule are due by Sept. 10, 2018. Comments can be submitted to regulations.gov.

Payment for more telemedicine services could be in store for physicians and other health providers if new proposals in the latest fee schedule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services are finalized.

Under the proposed physician fee schedule, announced July 12, the CMS would expand services that qualify for telemedicine payments and add reimbursement for virtual check-ins by phone or other technologies, such as Skype. Telemedicine clinicians would also be paid for time spent reviewing patient photos sent by text or e-mail under the suggested changes.

Such telehealth services would aid patients who have transportation difficulties by creating more opportunities for them to access personalized care, said CMS Administrator Seema Verma.

“CMS is committed to modernizing the Medicare program by leveraging technologies, such as audio/video applications or patient-facing health portals, that will help beneficiaries access high-quality services in a convenient manner,” Ms. Verma said in a statement.

Under the proposal, physicians could bill separately for brief, non–face-to-face patient check-ins with patients via communication technology beginning January 2019. In addition, the proposed rule carves out payments for the remote professional evaluation of patient-transmitted information conducted via prerecorded “store and forward” video or image technology. Doctors could use both services to determine whether an office visit or other service is warranted, according to the proposed rule.

The services would have limitations on when they could be separately billed. In cases where the brief communication technology–based service originated from a related evaluation and management (E/M) service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician or other qualified health care professional, the service would be considered “bundled” into that previous E/M service and could not be billed separately. Similarly, a photo evaluation could not be separately billed if it stemmed from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days by the same physician, or if the evaluation results in an in-person E/M office visit with the same doctor.

Under the proposal, health providers could perform the newly covered telehealth services only with established patients, but the CMS is seeking comments as to whether in certain cases, such as dermatological or ophthalmological instances, it might be appropriate for a new patient to receive the services. Agency officials also want to know what types of communication technology are used by physicians in furnishing check-in services, including whether audio-only telephone interactions are sufficient, compared with interactions that are enhanced with video. The CMS is asking physicians whether it would be clinically appropriate to apply a frequency limitation on the use of the proposed telehealth services by the same physician.

Latoya Thomas, director of the American Telemedicine Association’s State Policy Resource Center, said the proposal is exciting because it acknowledges the pervasive growth, accessibility, and acceptance of technology advances.

“In expanding reimbursement to providers for more modality-neutral and site-neutral virtual care, such as store-and-forward and remote patient monitoring, [the rules] address longstanding barriers to broader dissemination of telehealth,” Ms. Thomas said in an interview. “By making available ‘virtual check ins’ to every Medicare beneficiary, it can improve patient engagement and reduce unnecessary trips back to their provider’s office.”

James P. Marcin, MD, a telemedicine physician and director of the Center for Health and Technology at UC Davis Children’s Hospital in Sacramento, Calif., said he was pleased with the proposed telehealth changes, but he noted that more work remains to address further telemedicine challenges.

“The needle is finally moving, albeit too slowly for some of us,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “There are still some areas users of telemedicine and organizations supporting the use of telemedicine want to address, including the need for verbal informed consent, the requirements for established relationships with patients, and of course, rate valuations for the remote patient monitoring and professional codes. But again, this is good news for patients.”

Public comments on the proposed rule are due by Sept. 10, 2018. Comments can be submitted to regulations.gov.

ACA coverage mandate leads to more insurance for young women, early gynecologic cancer diagnoses

Young women are more likely to be insured and diagnosed with gynecologic cancers at an early stage after the Affordable Care Act’s dependent coverage mandate than before the mandate went into effect, according to a new study from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“We know if these women are identified early and treated early, they are much more likely to live longer and have their cancer go into remission,” Anna Jo Bodurtha Smith, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, stated in a press release.

Dr. Smith and her colleague, Amanda N. Fader, MD, evaluated 1,912 gynecologic cancer cases before the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and 2,059 cases after the ACA in women who were aged 21-26 years. They also analyzed 9,782 and 10,456 pre-ACA and post-ACA cases in women aged 27-35 years. The researchers obtained the pre-ACA data, which included cases of uterine, cervical, vaginal and vulvar cancer, from the 2006-2009 surveys in the National Cancer Database; post-ACA data were obtained from the 2011-2014 surveys in the same database. Using a difference-in-differences study design to compare both age groups, they assessed factors such as diagnosis stage, insurance status, and whether the patients received fertility-sparing treatment. The study results were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The researchers found post-ACA insurance coverage increased (difference in differences, 2.2%; 95% confidence interval, −4.0 to 0.1; P = .04) in women aged 21-26 years, compared with women aged 27-35 years, with a significant increase in cases of gynecological cancer being detected early (difference in differences, 3.6%; 95% CI, 0.4-6.9; P = .03) in the women aged 21-26 years, compared with women aged 27-35 years. While both groups showed an increase in fertility-sparing treatments post ACA, there was no significant difference in differences between the two groups.

Insurance status affected whether women were diagnosed with gynecologic cancer early or received fertility-sparing treatment, as women who were privately insured had a greater likelihood of early diagnoses of gynecologic cancer and receiving fertility-sparing treatment, compared with women who were publicly insured or did not have insurance.

“As the debate on how we insure women goes on, reminding ourselves that these insurance gains have huge impacts on people’s lives is the big takeaway here,” Dr. Smith stated in the release.

Researchers noted limitations to the study included its 80% power to detect overall pre-post differences of 4% due to its design, lack of power due to the small sample size for women with gynecologic cancer in the younger cohort, and change in coverage status due to external economic factors.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Smith AJB, Fader AN. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002592.

Young women are more likely to be insured and diagnosed with gynecologic cancers at an early stage after the Affordable Care Act’s dependent coverage mandate than before the mandate went into effect, according to a new study from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“We know if these women are identified early and treated early, they are much more likely to live longer and have their cancer go into remission,” Anna Jo Bodurtha Smith, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, stated in a press release.

Dr. Smith and her colleague, Amanda N. Fader, MD, evaluated 1,912 gynecologic cancer cases before the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and 2,059 cases after the ACA in women who were aged 21-26 years. They also analyzed 9,782 and 10,456 pre-ACA and post-ACA cases in women aged 27-35 years. The researchers obtained the pre-ACA data, which included cases of uterine, cervical, vaginal and vulvar cancer, from the 2006-2009 surveys in the National Cancer Database; post-ACA data were obtained from the 2011-2014 surveys in the same database. Using a difference-in-differences study design to compare both age groups, they assessed factors such as diagnosis stage, insurance status, and whether the patients received fertility-sparing treatment. The study results were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The researchers found post-ACA insurance coverage increased (difference in differences, 2.2%; 95% confidence interval, −4.0 to 0.1; P = .04) in women aged 21-26 years, compared with women aged 27-35 years, with a significant increase in cases of gynecological cancer being detected early (difference in differences, 3.6%; 95% CI, 0.4-6.9; P = .03) in the women aged 21-26 years, compared with women aged 27-35 years. While both groups showed an increase in fertility-sparing treatments post ACA, there was no significant difference in differences between the two groups.

Insurance status affected whether women were diagnosed with gynecologic cancer early or received fertility-sparing treatment, as women who were privately insured had a greater likelihood of early diagnoses of gynecologic cancer and receiving fertility-sparing treatment, compared with women who were publicly insured or did not have insurance.

“As the debate on how we insure women goes on, reminding ourselves that these insurance gains have huge impacts on people’s lives is the big takeaway here,” Dr. Smith stated in the release.

Researchers noted limitations to the study included its 80% power to detect overall pre-post differences of 4% due to its design, lack of power due to the small sample size for women with gynecologic cancer in the younger cohort, and change in coverage status due to external economic factors.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Smith AJB, Fader AN. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002592.

Young women are more likely to be insured and diagnosed with gynecologic cancers at an early stage after the Affordable Care Act’s dependent coverage mandate than before the mandate went into effect, according to a new study from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

“We know if these women are identified early and treated early, they are much more likely to live longer and have their cancer go into remission,” Anna Jo Bodurtha Smith, MD, MPH, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, stated in a press release.

Dr. Smith and her colleague, Amanda N. Fader, MD, evaluated 1,912 gynecologic cancer cases before the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and 2,059 cases after the ACA in women who were aged 21-26 years. They also analyzed 9,782 and 10,456 pre-ACA and post-ACA cases in women aged 27-35 years. The researchers obtained the pre-ACA data, which included cases of uterine, cervical, vaginal and vulvar cancer, from the 2006-2009 surveys in the National Cancer Database; post-ACA data were obtained from the 2011-2014 surveys in the same database. Using a difference-in-differences study design to compare both age groups, they assessed factors such as diagnosis stage, insurance status, and whether the patients received fertility-sparing treatment. The study results were published in Obstetrics & Gynecology.

The researchers found post-ACA insurance coverage increased (difference in differences, 2.2%; 95% confidence interval, −4.0 to 0.1; P = .04) in women aged 21-26 years, compared with women aged 27-35 years, with a significant increase in cases of gynecological cancer being detected early (difference in differences, 3.6%; 95% CI, 0.4-6.9; P = .03) in the women aged 21-26 years, compared with women aged 27-35 years. While both groups showed an increase in fertility-sparing treatments post ACA, there was no significant difference in differences between the two groups.

Insurance status affected whether women were diagnosed with gynecologic cancer early or received fertility-sparing treatment, as women who were privately insured had a greater likelihood of early diagnoses of gynecologic cancer and receiving fertility-sparing treatment, compared with women who were publicly insured or did not have insurance.

“As the debate on how we insure women goes on, reminding ourselves that these insurance gains have huge impacts on people’s lives is the big takeaway here,” Dr. Smith stated in the release.

Researchers noted limitations to the study included its 80% power to detect overall pre-post differences of 4% due to its design, lack of power due to the small sample size for women with gynecologic cancer in the younger cohort, and change in coverage status due to external economic factors.

The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Smith AJB, Fader AN. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002592.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

Key clinical point: Under the Affordable Care Act dependent coverage mandate, more young women are likely to be insured and receive early gynecological cancer diagnoses than before the law was passed.

Major finding: There was a 2.2% increase in insured young women and a 3.6% increase in early cancer diagnoses, according to a difference-in-differences model.

Data source: An analysis of 1,912 pre-ACA and 2,059 post-ACA gynecologic cancer cases in women aged 21-26 years and 9,782 pre-ACA and 10,456 post-ACA cases in women aged 27-35 years obtained from the National Cancer Center Database in a study with a difference-in-differences design.

Disclosures: The authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

Source: Smith AJB, Fader AN. Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Jun. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002592.

Lab results may help predict complications in ALL treatment

(ALL) who were treated with four-drug induction therapy.

Kasper Warrick, MD, and his colleagues at Indiana University in Indianapolis reported findings from a retrospective study of 73 ALL patients at their hospital. They performed chart reviews comparing a cohort of 42 patients who were discharged on day 4 of their induction treatment with 31 similar patients who had a longer hospital stay or admission to the intensive care unit. The report was published in Leukemia Research.

Univariate analysis found that patients with a longer length of stay were more likely to have a fever, pretransfusion hemoglobin of less than 8 g/dL, lower serum bicarbonate values, abnormal serum calcium, and abnormal serum phosphate. Multivariate stepwise logistic regression found that low serum bicarbonate and a lower platelet count on day 4 of admission was predictive of a prolonged hospital stay. About a third of patients from each group had an unplanned readmission within 30 days.

The researchers concluded that early discharge is safe in only a subgroup of high-risk ALL patients undergoing induction chemotherapy. “Treating physicians could opt for a discharge only after normalization of electrolyte abnormalities and renal functions, and when no transfusion support is needed (stable hematocrit and platelet count),” they wrote. Even in those cases, they recommended “aggressive and close outpatient follow” since patients are vulnerable to complications and readmissions.

SOURCE: Warrick K et al. Leuk Res. 2018 Jun 30:71:36-42.

(ALL) who were treated with four-drug induction therapy.

Kasper Warrick, MD, and his colleagues at Indiana University in Indianapolis reported findings from a retrospective study of 73 ALL patients at their hospital. They performed chart reviews comparing a cohort of 42 patients who were discharged on day 4 of their induction treatment with 31 similar patients who had a longer hospital stay or admission to the intensive care unit. The report was published in Leukemia Research.

Univariate analysis found that patients with a longer length of stay were more likely to have a fever, pretransfusion hemoglobin of less than 8 g/dL, lower serum bicarbonate values, abnormal serum calcium, and abnormal serum phosphate. Multivariate stepwise logistic regression found that low serum bicarbonate and a lower platelet count on day 4 of admission was predictive of a prolonged hospital stay. About a third of patients from each group had an unplanned readmission within 30 days.

The researchers concluded that early discharge is safe in only a subgroup of high-risk ALL patients undergoing induction chemotherapy. “Treating physicians could opt for a discharge only after normalization of electrolyte abnormalities and renal functions, and when no transfusion support is needed (stable hematocrit and platelet count),” they wrote. Even in those cases, they recommended “aggressive and close outpatient follow” since patients are vulnerable to complications and readmissions.

SOURCE: Warrick K et al. Leuk Res. 2018 Jun 30:71:36-42.

(ALL) who were treated with four-drug induction therapy.

Kasper Warrick, MD, and his colleagues at Indiana University in Indianapolis reported findings from a retrospective study of 73 ALL patients at their hospital. They performed chart reviews comparing a cohort of 42 patients who were discharged on day 4 of their induction treatment with 31 similar patients who had a longer hospital stay or admission to the intensive care unit. The report was published in Leukemia Research.

Univariate analysis found that patients with a longer length of stay were more likely to have a fever, pretransfusion hemoglobin of less than 8 g/dL, lower serum bicarbonate values, abnormal serum calcium, and abnormal serum phosphate. Multivariate stepwise logistic regression found that low serum bicarbonate and a lower platelet count on day 4 of admission was predictive of a prolonged hospital stay. About a third of patients from each group had an unplanned readmission within 30 days.

The researchers concluded that early discharge is safe in only a subgroup of high-risk ALL patients undergoing induction chemotherapy. “Treating physicians could opt for a discharge only after normalization of electrolyte abnormalities and renal functions, and when no transfusion support is needed (stable hematocrit and platelet count),” they wrote. Even in those cases, they recommended “aggressive and close outpatient follow” since patients are vulnerable to complications and readmissions.

SOURCE: Warrick K et al. Leuk Res. 2018 Jun 30:71:36-42.

FROM LEUKEMIA RESEARCH

Better ICU staff communication with family may improve end-of-life choices

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Although the results by White and colleagues “cannot be interpreted as clinically directive,” the study offers a glimpse of the path forward in improving the experience of families with critically ill loved ones, Daniela Lamas, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:2431-2).

The study didn’t meet its primary endpoint of reducing surrogates’ psychological symptoms at 6 months, but it did lead to an improved ICU experience, with better clinician communication. There was another finding that deserves a close look: In the intervention group, ICU length of stay was shorter and in-hospital mortality greater, although mortality among those who survived to discharge was similar at 6 months.

These findings suggest that the intervention did not lead to the premature death of patients who would have otherwise done well, but rather was associated with a shorter dying process for those who faced a dismal prognosis, according to Dr. Lamas.

“As we increasingly look beyond mortality as the primary outcome that matters, seeking to maximize quality of life and minimize suffering, this work represents an ‘end of the beginning’ by suggesting the next steps in moving closer to achieving these goals.”

Dr. Lamas is a pulmonary and critical care doctor at Brigham & Women’s Hospital and on the faculty at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

A nurse-led support intervention for the families of critically ill patients did little to ease families’ psychological symptoms, but it did improve their perception of staff communication and family-centered care in the intensive care unit.

The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter and the in-unit death rate higher among patients whose families received the intervention – a finding that suggests difficult end-of-life choices may have been eased, reported Douglas B. White, MD, and his colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75).

“The intervention resulted in significant improvements in markers of the quality of decision making, including the patient- and family-centeredness of care and the quality of clinician-family communication. Taken together, these findings suggest that the intervention allowed surrogates to transition a patient’s treatment to comfort-focused care when doing so aligned with the patient’s values,” wrote Dr. White of the University of Pittsburgh. “A previous study that was conducted in the context of advanced illness suggested that treatment that accords with the patient’s preferences may lead to shorter survival among those who prioritize comfort over longevity.”

The trial randomized 1,420 patients and their family surrogates in five ICUs to usual care, or to the multicomponent family-support intervention. The primary outcome was change in the surrogates’ scores on the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) at 6 months. The secondary outcomes were changes in Impact of Event Scale (IES; a measure of posttraumatic stress) the Quality of Communication (QOC) scale, quality of clinician-family communication measured by the Patient Perception of Patient Centeredness (PPPC) scale and the mean length of ICU stay.

The intervention was delivered by nurses who received special training on communication and other skills needed to support the families of critically ill patients. Nurses met with families every day and arranged regular meetings with ICU clinicians. A quality improvement specialist incorporated the family support into daily work flow.

In a fully adjusted model, there was no significant between-group difference in the 6-month HADS scores (11.7 vs. 12 points). Likewise, there was no significant difference between the groups in the mean IES score at 6 months.

Family members in the active group did rate the quality of clinician-family communication as significantly better, and they also gave significantly higher ratings to the quality of patient- and family-centered care during the ICU stay.

The shorter length of stay was reflected in the time to death among patients who died during the stay (4.4 days in the intervention group vs. 6.8 days in the control group), although there was no significant difference in length of stay among patients who survived to discharge. Significantly more patients in the intervention group died in the ICU as well (36% vs. 28.5%); however, there was no significant difference in 6-month mortality (60.4% vs. 55.4%).

The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White reported having no financial disclosures

FROM NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Key clinical point: A family communication intervention didn’t improve 6-month psychological symptoms among those with loved ones in intensive care units.

Major finding: There was no significant difference on the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale at 6 months (11.7 vs. 12 points).

Study details: The study randomized 1,420 ICU patients and surrogates to the intervention or to usual care.

Disclosures: The study was supported by an Innovation Award from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center Health System and by the Greenwell Foundation. Dr. White had no financial disclosures.

Source: White et al. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2365-75.

Intranasal naloxone promising for type 1 hypoglycemia

ORLANDO –

“This has been a clinical problem for a very long time, and we see it all the time. A patient comes into my clinic, the nurses check their blood sugar, it’s 50 mg/dL, and they’re just sitting there without any symptoms,” said lead investigator Sandra Aleksic, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

As blood glucose in the brain drops, people get confused, and their behavioral defenses are compromised. They might crash if they’re driving. “If you have HAAF, it makes you prone to more hypoglycemia, which blunts your response even more. It’s a vicious cycle,” she said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Endogenous opioids are at least partly to blame. Hypoglycemia induces release of beta-endorphin, which in turn inhibits production of epinephrine. Einstein investigators have shown in previous small studies with healthy subjects that morphine blunts the response to induced hypoglycemia, and intravenous naloxone – an opioid blocker – prevents HAAF (Diabetes. 2017 Nov;66[11]:2764-73).

Intravenous naloxone, however, isn’t practical for outpatients, so the team wanted to see whether intranasal naloxone also prevented HAAF. The results “are very promising, but this is preliminary.” If it pans out, though, patients may one day carry intranasal naloxone along with their glucose pills and glucagon to treat hypoglycemia. “Any time they are getting low, they would take the spray,” Dr. Aleksic said.

The team used hypoglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamps to drop blood glucose levels in seven healthy subjects down to 54 mg/dL for 2 hours twice in one day and gave them hourly sprays of either intranasal saline or 4 mg of intranasal naloxone; hypoglycemia was induced again for 2 hours the following day. The 2-day experiment was repeated 5 weeks later.

Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first hypoglycemic episode on day 1 and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 pg/mL plus or minus 190 versus 857 pg/mL plus or minus 134; P = .4). The third episode, meanwhile, placed placebo subjects into HAAF (first hypoglycemic episode 1,375 pg/mL plus or minus 182 versus 858 pg/mL plus or minus 235; P = .004). There was also a trend toward higher hepatic glucose production in the naloxone group.

“These findings suggest that HAAF can be prevented by acute blockade of opioid receptors during hypoglycemia. ... Acute self-administration of intranasal naloxone could be an effective and feasible real-world approach to ameliorate HAAF in type 1 diabetes,” the investigators concluded. A trial in patients with T1DM is being considered.

Dr. Aleksic estimated that patients with T1DM drop blood glucose below 54 mg/dL maybe three or four times a month, on average, depending on how well they manage the condition. For now, it’s unknown how long protection from naloxone would last.

The study subjects were men, 43 years old, on average, with a mean body mass index of 26 kg/m2.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures, and there was no industry funding for the work.

SOURCE: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB.

ORLANDO –

“This has been a clinical problem for a very long time, and we see it all the time. A patient comes into my clinic, the nurses check their blood sugar, it’s 50 mg/dL, and they’re just sitting there without any symptoms,” said lead investigator Sandra Aleksic, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

As blood glucose in the brain drops, people get confused, and their behavioral defenses are compromised. They might crash if they’re driving. “If you have HAAF, it makes you prone to more hypoglycemia, which blunts your response even more. It’s a vicious cycle,” she said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Endogenous opioids are at least partly to blame. Hypoglycemia induces release of beta-endorphin, which in turn inhibits production of epinephrine. Einstein investigators have shown in previous small studies with healthy subjects that morphine blunts the response to induced hypoglycemia, and intravenous naloxone – an opioid blocker – prevents HAAF (Diabetes. 2017 Nov;66[11]:2764-73).

Intravenous naloxone, however, isn’t practical for outpatients, so the team wanted to see whether intranasal naloxone also prevented HAAF. The results “are very promising, but this is preliminary.” If it pans out, though, patients may one day carry intranasal naloxone along with their glucose pills and glucagon to treat hypoglycemia. “Any time they are getting low, they would take the spray,” Dr. Aleksic said.

The team used hypoglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamps to drop blood glucose levels in seven healthy subjects down to 54 mg/dL for 2 hours twice in one day and gave them hourly sprays of either intranasal saline or 4 mg of intranasal naloxone; hypoglycemia was induced again for 2 hours the following day. The 2-day experiment was repeated 5 weeks later.

Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first hypoglycemic episode on day 1 and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 pg/mL plus or minus 190 versus 857 pg/mL plus or minus 134; P = .4). The third episode, meanwhile, placed placebo subjects into HAAF (first hypoglycemic episode 1,375 pg/mL plus or minus 182 versus 858 pg/mL plus or minus 235; P = .004). There was also a trend toward higher hepatic glucose production in the naloxone group.

“These findings suggest that HAAF can be prevented by acute blockade of opioid receptors during hypoglycemia. ... Acute self-administration of intranasal naloxone could be an effective and feasible real-world approach to ameliorate HAAF in type 1 diabetes,” the investigators concluded. A trial in patients with T1DM is being considered.

Dr. Aleksic estimated that patients with T1DM drop blood glucose below 54 mg/dL maybe three or four times a month, on average, depending on how well they manage the condition. For now, it’s unknown how long protection from naloxone would last.

The study subjects were men, 43 years old, on average, with a mean body mass index of 26 kg/m2.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures, and there was no industry funding for the work.

SOURCE: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB.

ORLANDO –

“This has been a clinical problem for a very long time, and we see it all the time. A patient comes into my clinic, the nurses check their blood sugar, it’s 50 mg/dL, and they’re just sitting there without any symptoms,” said lead investigator Sandra Aleksic, MD, of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

As blood glucose in the brain drops, people get confused, and their behavioral defenses are compromised. They might crash if they’re driving. “If you have HAAF, it makes you prone to more hypoglycemia, which blunts your response even more. It’s a vicious cycle,” she said at the annual scientific sessions of the American Diabetes Association.

Endogenous opioids are at least partly to blame. Hypoglycemia induces release of beta-endorphin, which in turn inhibits production of epinephrine. Einstein investigators have shown in previous small studies with healthy subjects that morphine blunts the response to induced hypoglycemia, and intravenous naloxone – an opioid blocker – prevents HAAF (Diabetes. 2017 Nov;66[11]:2764-73).

Intravenous naloxone, however, isn’t practical for outpatients, so the team wanted to see whether intranasal naloxone also prevented HAAF. The results “are very promising, but this is preliminary.” If it pans out, though, patients may one day carry intranasal naloxone along with their glucose pills and glucagon to treat hypoglycemia. “Any time they are getting low, they would take the spray,” Dr. Aleksic said.

The team used hypoglycemic, hyperinsulinemic clamps to drop blood glucose levels in seven healthy subjects down to 54 mg/dL for 2 hours twice in one day and gave them hourly sprays of either intranasal saline or 4 mg of intranasal naloxone; hypoglycemia was induced again for 2 hours the following day. The 2-day experiment was repeated 5 weeks later.

Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first hypoglycemic episode on day 1 and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 pg/mL plus or minus 190 versus 857 pg/mL plus or minus 134; P = .4). The third episode, meanwhile, placed placebo subjects into HAAF (first hypoglycemic episode 1,375 pg/mL plus or minus 182 versus 858 pg/mL plus or minus 235; P = .004). There was also a trend toward higher hepatic glucose production in the naloxone group.

“These findings suggest that HAAF can be prevented by acute blockade of opioid receptors during hypoglycemia. ... Acute self-administration of intranasal naloxone could be an effective and feasible real-world approach to ameliorate HAAF in type 1 diabetes,” the investigators concluded. A trial in patients with T1DM is being considered.

Dr. Aleksic estimated that patients with T1DM drop blood glucose below 54 mg/dL maybe three or four times a month, on average, depending on how well they manage the condition. For now, it’s unknown how long protection from naloxone would last.

The study subjects were men, 43 years old, on average, with a mean body mass index of 26 kg/m2.

The investigators didn’t have any disclosures, and there was no industry funding for the work.

SOURCE: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB.

REPORTING FROM ADA 2018

Key clinical point: Intranasal naloxone might be just the ticket to prevent hypoglycemia-associated autonomic failure in type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Major finding: Overall, there was no difference in peak epinephrine levels between the first day 1 hypoglycemic episode and the third episode on day 2 in subjects randomized to naloxone (942 plus or minus 190 pg/mL versus 857 plus or minus 134 pg/mL; P = 0.4).

Study details: Randomized trial with seven healthy volunteers

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators didn’t have any disclosures.

Source: Aleksic S et al. ADA 2018, Abstract 10-LB

Transgender Care in the Primary Care Setting: A Review of Guidelines and Literature

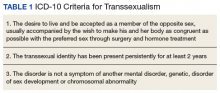

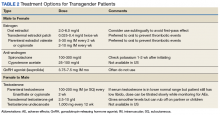

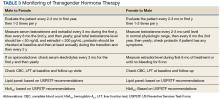

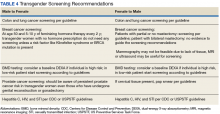

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals face significant difficulties in obtaining high-quality,compassionate medical care, much of which has been attributed to inadequate provider knowledge. In this article, the authors present a transgender patient seen in primary care and discuss the knowledge gleaned to inform future care of this patient as well as the care of other similar patients.

The following case discussion and review of the literature also seeks to improve the practice of other primary care providers (PCPs) who are inexperienced in this arena. This article aims to review the basics to permit PCPs to venture into transgender care, including a review of basic terminology; a few interactive tips; and basics in medical and hormonal treatment, follow-up, contraindications, and risk. More details can be obtained through electronic consultation (Transgender eConsult) in the VA.

Case Presentation

A 35-year-old patient who was assigned male sex at birth presented to the primary care clinic to discuss her desire to undergo male-to-female (MTF) transition. The patient stated that she had started taking female estrogen hormones 9 years previously purchased from craigslist without a prescription. She tried oral contraceptives as well as oral and injectable estradiol. While the patient was taking injectable estradiol she had breast growth, decreased anxiety, weight gain, and a feeling of peacefulness. The patient also reported that she had received several laser treatments for whole body hair removal, beginning 8 to 10 years before and more regularly in the past 2 to 3 years. She asked whether transition-related care could be provided, because she could no longer afford the hormones.

The patient wanted to transition because she felt that “Women are beautiful, the way they carry themselves, wear their hair, their nails, I want to be like that.” She also mentioned that when she watched TV, she envisioned herself as a woman. She reported that she enjoyed wearing her mother’s clothing since age 10, which made her feel more like herself. The patient noted that she had desired to remove her body hair since childhood but could not afford to do it until recently. She bought female clothing, shoes and makeup, and did her nails from a young age. The patient also reported that she did not “know what transgender was” until a decade ago.

The patient struggled with her identity growing up; however, she tried not to think about it or talk about it with anyone. She related that she was ashamed of her thoughts and that only recently had made peace with being transgender. Thus, she pursued talking to her medical provider about transitioning. The patient reported that she felt more energetic when taking female hormones and was better able to discuss the issue. Specifically, she noted that if she were not on estrogen now she would not be able to talk about transitioning.

The patient related that she has done extensive research about transitioning, including reading online about other transgender people. She noted that she was aware of “possible backlash with society,” but ultimately, she had decided that transitioning was the right decision for her.

She expressed a desire to have an orchiectomy and continue hormonal therapy to permit her “to have a more feminine face, soft skin, hairless body, big breasts, more fat around the hips, and a high-pitched voice.” She additionally related a desire to be in a stable relationship and be her true self. She also stated that she had not identified herself as a female to anyone yet but would like to soon. The patient reported a history of depression, especially during her military service when she wanted to be a woman but did not feel she understood what was going on or how to manage her feelings. She said that for the past 2 months she felt much happier since beginning to take estradiol 4 mg orally daily, which she had found online. She also tried to purchase anti-androgen medication but could not afford it. In addition, she said that she would like to eventually proceed with gender affirmation surgery.

She was currently having sex with men, primarily via anal receptive intercourse. She had no history of sexually transmitted infections but reported that she did not use condoms regularly. She had no history of physical or sexual abuse. The patient was offered referral to the HIV clinic to receive HIV preexposure prophylaxis therapy (emtricitabine + tenofovir), which she declined, but she was counseled on safe sex practice.

The patient was referred to psychiatry both for supportive mental health care and to clarify that her concomitant mental health issues would not preclude the prescription of gender-affirming hormone treatment. Based on the psychiatric evaluation, the patient was felt to be appropriate for treatment with feminizing hormone therapy. The psychiatric assessment also noted that although the patient had a history of psychosis, she was not exhibiting psychotic symptoms currently, and this would not be a contraindication to treatment.

After discussion of the risks and benefits of cross-sex hormone therapy, the patient was started on estradiol 4 mg orally daily, as well as spironolactone 50 mg daily. She was then switched to estradiol 10 mg intramuscular every 2 weeks with the aim of using a less thrombogenic route of administration.

Treatment Outcomes

The patient remains under care. She has had follow-up visits every 3 months to ensure appropriate signs of feminization and monitoring of adverse effects (AEs). The patient’s testosterone and estradiol levels are being checked every 3 months to ensure total testosterone is 1,2

After 12 months on therapy with estradiol and spironolactone, the patient notes that her mood has improved, she feels more energetic, she has gained some weight, and her skin is softer. Her voice pitch, with the help of speech therapy, is gradually changing to what she perceives as more feminine. Hormone levels and electrolytes are all in an acceptable range, and blood sugar and blood pressure (BP) are within normal range. The patient will be offered age-appropriate cancer screening at the appropriate time.

Discussion

The treatment of gender-nonconforming individuals has come a long way since Lili Elbe, the transgender artist depicted in The Danish Girl, underwent gender-affirmation surgery in the early 20th century. Lili and people like her paved the way for other transgender individuals by doggedly pursuing gender-affirming medical treatment although they faced rejection by society and forged a difficult path. In recent years, an increasing number of transgender individuals have begun to seek mainstream medical care; however, PCPs often lack the knowledge and training to properly interact with and care for transgender patients.3,4

Terminology

Although someone’s sex is typically assigned at birth based on the external appearance of their genitalia, gender identity refers to a person’s internal sense of self and how they fit in to the world. People often use these 2 terms interchangeably in everyday language, but these terms are different.1,2

Transgender refers to a person whose gender identity differs from the sex that was assigned at birth. A transgender man or transman, or female-to-male (FTM) transgender person, is an individual who is assigned female sex at birth but identifies as a male. A transgender woman, or transwoman or a male-to-female (MTF) transgender person, is an individual who is assigned male sex at birth but identifies as female. A nontransgender person may be referred to as cisgender.

Transsexual is a medical term and refers to a transgender individual who sought medical intervention to transition to their identified gender.

Sexual orientation describes sexual attraction only and is not related to gender identity. The sexual orientation of a transgender person is determined by emotional and/or physical attraction and not gender identity.

Gender dysphoria refers to the distress experienced by an individual when one’s gender identity and sex are not completely congruent.

Improving Patient Interaction

Transgender patients might avoid seeking care due to previous negative experiences or a fear of being judged. It is very important to create a safe environment where the patients feel comfortable. Meeting patients “where they are” without judgment will enhance the patient-physician relationship. It is necessary to train all clinic staff about the importance of transgender health issues. All staff should address the patient with the name, pronouns, and gender identity that the patient prefers. For patients with a gender identity that is not strictly male or female (nonbinary patients), gender-neutral pronouns, such as they/them/their, may be chosen. It is helpful to be direct in asking: What is your preferred name? When I speak about you to other providers, what pronouns do you prefer I use, he, she, they? This information can then be documented in the electronic health record (EHR) so that all staff know from visit to visit. Thank the patient for the clarification.

The physical examination can be uncomfortable for both the patient and the physician. Experience and familiarity with the current recommendations can help. The physical examination should be relevant to the anatomy that is present, regardless of the gender presentation. An anatomic survey of the organs currently present in an individual can be useful.1 The physician should be sensitive in examining and obtaining information from the patient, focusing on only those issues relevant to the presenting concern. Chest and genital examinations may be particularly distressing for patients. If a chest or genital examination is indicated, the provider and patient should have a discussion explaining the importance of the examination and how the patient’s comfort can be optimized.

Medical Treatment