User login

New genetic subtypes could facilitate precision medicine in DLBCL

Four genetic subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) showed multiple distinct mutations, gene expression signatures, and treatment responses, researchers reported.

The findings “may provide a conceptual edifice on which to develop precision therapies for these aggressive cancers,” Roland Schmitz, PhD, and his associates wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Other DLBCL studies have focused on individual mutations, but therapeutic response probably hinges on “constellations of genetic aberrations,” wrote Dr. Schmitz of the National Cancer Institute and his associates.

Therefore, they used exome and transcriptome sequencing, deep amplicon resequencing of 372 genes, and DNA copy-number analysis to analyze 572 fresh-frozen DLBCL biopsy specimens, nearly all of which were treatment-naïve.

This multiplatform approach yielded four genetic subtypes: MCD, so named for its co-occurring MYD88L265P and CD79B mutations; BN2, which has BCL6 fusions and NOTCH2 mutations; N1, which has NOTCH1 mutations; and EZB, which has EZH2 mutations and BCL2 translocations. Most MCD and N1 specimens were activated B-cell–like (ABC) tumors, EZB specimens were primarily germinal-center B-cell–like (GCB) tumors, and BN2 specimens included ABC, GCB, and unclassified cases.

A closer look at 119 previously untreated patients linked genetic subtypes with significant differences in progression-free survival (P less than .0001) and overall survival (P = .0002) following R-CHOP or CHOP-like chemotherapy.

The BN2 and EZB subtypes “[had] much more favorable outcomes than the MCD and N1 subtypes,” Dr. Schmitz and his associates said. “Analysis of genetic pathways suggested that MCD and BN2 DLBCLs rely on ‘chronic active’ B-cell receptor signaling that is amenable to therapeutic inhibition.”

Genetically subtyping DLBCL could help guide patients into appropriate clinical trials, the investigators wrote. For example, patients with the N1 subtype might be candidates for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, given N1’s prominent T-cell gene expression and poor response to R-CHOP.

Funders included the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, the Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung fur Krebsforschung (Deutsche Krebshilfe), the Washington University in St. Louis, and the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund. Dr. Schmitz disclosed research funding from Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung fur Krebsforschung (Deutsche Krebshilfe).

SOURCE: Schmitz et al. New Eng J Med. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801445.

Four genetic subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) showed multiple distinct mutations, gene expression signatures, and treatment responses, researchers reported.

The findings “may provide a conceptual edifice on which to develop precision therapies for these aggressive cancers,” Roland Schmitz, PhD, and his associates wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Other DLBCL studies have focused on individual mutations, but therapeutic response probably hinges on “constellations of genetic aberrations,” wrote Dr. Schmitz of the National Cancer Institute and his associates.

Therefore, they used exome and transcriptome sequencing, deep amplicon resequencing of 372 genes, and DNA copy-number analysis to analyze 572 fresh-frozen DLBCL biopsy specimens, nearly all of which were treatment-naïve.

This multiplatform approach yielded four genetic subtypes: MCD, so named for its co-occurring MYD88L265P and CD79B mutations; BN2, which has BCL6 fusions and NOTCH2 mutations; N1, which has NOTCH1 mutations; and EZB, which has EZH2 mutations and BCL2 translocations. Most MCD and N1 specimens were activated B-cell–like (ABC) tumors, EZB specimens were primarily germinal-center B-cell–like (GCB) tumors, and BN2 specimens included ABC, GCB, and unclassified cases.

A closer look at 119 previously untreated patients linked genetic subtypes with significant differences in progression-free survival (P less than .0001) and overall survival (P = .0002) following R-CHOP or CHOP-like chemotherapy.

The BN2 and EZB subtypes “[had] much more favorable outcomes than the MCD and N1 subtypes,” Dr. Schmitz and his associates said. “Analysis of genetic pathways suggested that MCD and BN2 DLBCLs rely on ‘chronic active’ B-cell receptor signaling that is amenable to therapeutic inhibition.”

Genetically subtyping DLBCL could help guide patients into appropriate clinical trials, the investigators wrote. For example, patients with the N1 subtype might be candidates for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, given N1’s prominent T-cell gene expression and poor response to R-CHOP.

Funders included the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, the Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung fur Krebsforschung (Deutsche Krebshilfe), the Washington University in St. Louis, and the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund. Dr. Schmitz disclosed research funding from Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung fur Krebsforschung (Deutsche Krebshilfe).

SOURCE: Schmitz et al. New Eng J Med. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801445.

Four genetic subtypes of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) showed multiple distinct mutations, gene expression signatures, and treatment responses, researchers reported.

The findings “may provide a conceptual edifice on which to develop precision therapies for these aggressive cancers,” Roland Schmitz, PhD, and his associates wrote in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Other DLBCL studies have focused on individual mutations, but therapeutic response probably hinges on “constellations of genetic aberrations,” wrote Dr. Schmitz of the National Cancer Institute and his associates.

Therefore, they used exome and transcriptome sequencing, deep amplicon resequencing of 372 genes, and DNA copy-number analysis to analyze 572 fresh-frozen DLBCL biopsy specimens, nearly all of which were treatment-naïve.

This multiplatform approach yielded four genetic subtypes: MCD, so named for its co-occurring MYD88L265P and CD79B mutations; BN2, which has BCL6 fusions and NOTCH2 mutations; N1, which has NOTCH1 mutations; and EZB, which has EZH2 mutations and BCL2 translocations. Most MCD and N1 specimens were activated B-cell–like (ABC) tumors, EZB specimens were primarily germinal-center B-cell–like (GCB) tumors, and BN2 specimens included ABC, GCB, and unclassified cases.

A closer look at 119 previously untreated patients linked genetic subtypes with significant differences in progression-free survival (P less than .0001) and overall survival (P = .0002) following R-CHOP or CHOP-like chemotherapy.

The BN2 and EZB subtypes “[had] much more favorable outcomes than the MCD and N1 subtypes,” Dr. Schmitz and his associates said. “Analysis of genetic pathways suggested that MCD and BN2 DLBCLs rely on ‘chronic active’ B-cell receptor signaling that is amenable to therapeutic inhibition.”

Genetically subtyping DLBCL could help guide patients into appropriate clinical trials, the investigators wrote. For example, patients with the N1 subtype might be candidates for immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy, given N1’s prominent T-cell gene expression and poor response to R-CHOP.

Funders included the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, the Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung fur Krebsforschung (Deutsche Krebshilfe), the Washington University in St. Louis, and the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund. Dr. Schmitz disclosed research funding from Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung fur Krebsforschung (Deutsche Krebshilfe).

SOURCE: Schmitz et al. New Eng J Med. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801445.

FROM NEJM

Key clinical point: Multiplatform analyses identified four new genetic subtypes of DLBCL.

Major finding: The subtypes were distinguishable based on multiple genetic aberrations, phenotypes, and treatment responses.

Study details: Study of 574 DLBCL samples using exome and transcriptome sequencing, array-based DNA copy-number analysis, and targeted amplicon resequencing of 372 genes.

Disclosures: Funders included the National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, the Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung fur Krebsforschung (Deutsche Krebshilfe), the Washington University in St. Louis, and the Kay Kendall Leukaemia Fund. Dr. Schmitz disclosed research funding from Dr. Mildred Scheel Stiftung fur Krebsforschung (Deutsche Krebshilfe).

Source: Schmitz et al. New Eng J Med. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1801445.

Palliative care screening, sleep devices, novel biologics

Palliative and end-of-life care

Nurse-driven palliative care screening

Palliative care (PC) aims to improve quality of life for patients with a life-threatening illness, providing holistic patient-centered support along the continuum of the disease process. Although frequently implemented in critical care settings, integrating PC in the neuro ICU has been difficult to adopt in practice due to the uncertainty in prognostication of definitive outcomes and practice culture beliefs such as the self-fulfilling prophecy (Frontera, et al. Crit Care Med. 2015;43[9]:1964; Rubin, et al. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23[2]:134; Knies, et al. Semin Neurol. 2016;36[6]:631).

At our institution, a nursing education project was conducted to pilot nurse-driven PC screenings on admission to the neuro ICU. The project evaluated nurse comfort and knowledge with identifying and recommending PC consults. Pre- and post-intervention surveys revealed that education and introduction of a PC screening tool significantly increased nurse comfort and knowledge of PC eligibility.

PC in the neuro ICU can exist to contribute to successful outcomes in patient and family care. Within neurocritical care, incorporating PC is essential to provide extra support to patients and families (Frontera, et al. 2015).

For these reasons and data from the project, nurse-driven screening may encourage appropriate early PC consults. Patient-centered care is the ultimate goal in the management of our patients. Nurse-driven PC screening can help bring various unmet PC needs to the health-care team for opportunities that might not have been met or otherwise assessed. Consider implementing nurse-driven PC screening protocols at your institution to aid in collaborative and proactive interdisciplinary care.

Danielle McCamey, ACNP

Steering Committee Member

Sleep medicine

Diagnostics, devices, and sleep

The past several months have been busy for the Sleep Medicine NetWork. We have been working to represent the interests of our membership and our patients in many arenas.

Devices coded as E0464, defined as life support mechanical ventilators used with mask-based ventilation in the home are being more frequently used. According to the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), there has been an 89-fold increase in billing for E0464 ventilators for Medicare and its beneficiaries between 2009 and 2015, increasing from $3.8M to $340M. In response, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) requested a response to specific questions related to these devices.

In 2018, the CHEST Sleep Medicine NetWork will be participating in a Federal Drug Association-sponsored workshop entitled “Study Design Considerations for Devices including Digital Health Technologies for Sleep-Disordered Breathing (SDB) in Adults,” along with other national organizations and leaders in our field. This workshop will address available technologies for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of SDB, as well as trends for digital health technologies and clinical trial design considerations.

Finally, the Sleep Medicine NetWork has wasted no time after a successful CHEST 2017 in Toronto in planning for the next annual meeting in San Antonio. We are excited to present an exciting curriculum in Sleep Medicine at CHEST 2018, so stay tuned.

Aneesa M. Das, MD, FCCP

NetWork Chair

Occupational and environmental health

Post-deployment lung disease

Since the early 1990s, ongoing military deployments to Southwest Asia remain a unique challenge from a pulmonary symptomology and diagnostic perspective.

Various airborne hazards in the deployment environment include geologic dusts, burn pit smoke, vehicle emissions, and industrial air pollution. Exposures can give rise to both acute respiratory symptoms and, in some instances, chronic lung disease. Currently, data are limited on whether inhalation of airborne particulate matter by military personnel is linked to increases in pulmonary diseases (Morris MJ, et al. US Army Med Dep J. 2016:173).

Ongoing research by the Veterans Affairs continues to enroll post-deployed personnel in an Airborne Hazard and Burn Pit Registry. Past approaches in evaluation of deployed individuals ranged from common tests such as spirometry, HRCT scanning, full PFTs, bronchoprovocation challenges, and, in some instances, lung biopsies (Krefft SD, et al. Fed Pract. 2015;32[6]:32). More novel evaluations of postdeployment dyspnea include impulse oscillometry, exhaled nitric oxide, bronchoscopy, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing (Huprikar, et al. Chest. 2016;150[4]:S934A).

Members of the CHEST Occupational and Environmental Health NetWork are currently updating comprehensive approaches to evaluate military personnel with chronic respiratory symptoms from deployments. Continued emphasis, however, should be placed on diagnosing and treating common diseases such as asthma, exercise-induced bronchospasm, GERD, and upper airway disorders.

Pedro F. Lucero, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Clinical pulmonary medicine

Biologics – Birth of a new era of precision management in asthma

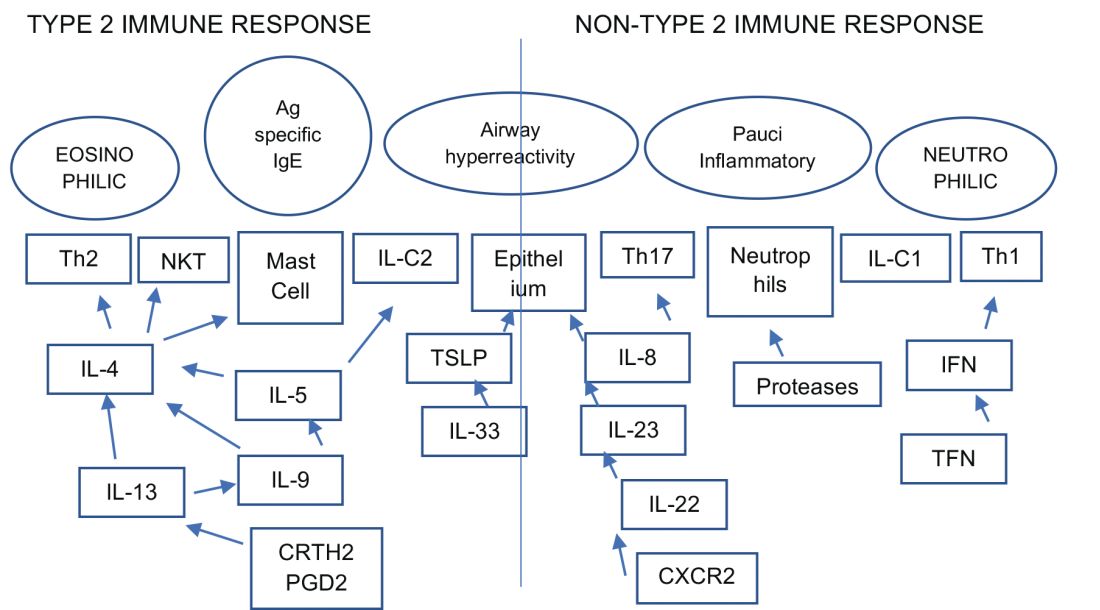

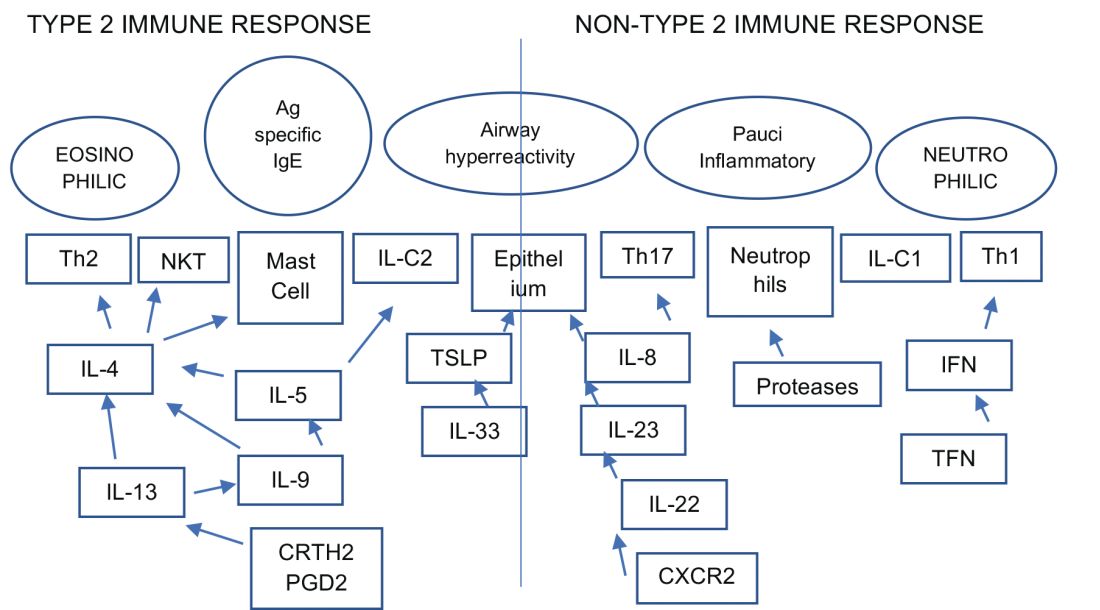

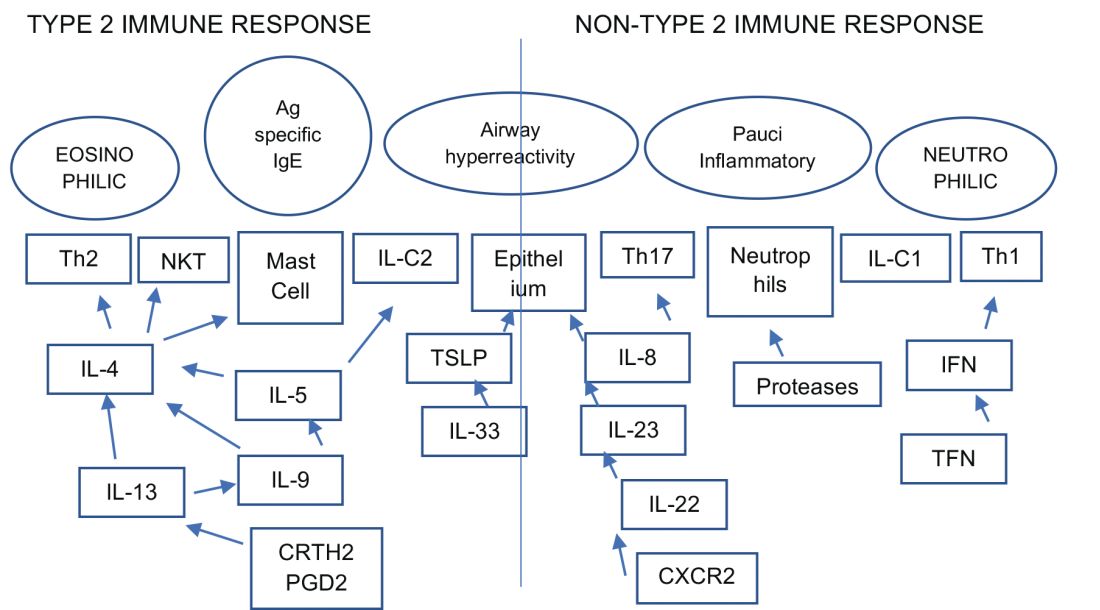

An estimated 10% to 20% of patients with severe uncontrolled asthma do not respond to maximal best standard treatments, leading to substantial health-care costs. A paradigm shift is now underway in our approach to the care of these patients with the emergence of novel biologics targeting the complex and interconnected inflammatory pathways in asthma that result in a diverse profile of asthma endotypes and phenotypes (Fig 1).

Current FDA-approved biologics primarily target patients with a T2 high phenotype (Table1).

Dupilumab binds to the alpha unit of the IL-4 receptor and blocks both IL-4 and IL-13. It shows potential efficacy in patients with T2 high asthma with or without eosinophilia but has not yet received FDA approval.

Multiple newer biologics are currently in development (Table 2).

Pulmonologists need to get familiar with the logistics of administration of these novel agents. The two common methods of administering biologics are (1) buy and bill – where the provider buys the drug directly from the distributor; and (2) assignment of benefits (typically administered by a Pharmacy Benefit Manager) - specific dose of the medication is shipped to the physician’s office and physician only bills for the administration. CPT and J codes are shown in Table 1.

Shyamsunder Subramanian, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Palliative and end-of-life care

Nurse-driven palliative care screening

Palliative care (PC) aims to improve quality of life for patients with a life-threatening illness, providing holistic patient-centered support along the continuum of the disease process. Although frequently implemented in critical care settings, integrating PC in the neuro ICU has been difficult to adopt in practice due to the uncertainty in prognostication of definitive outcomes and practice culture beliefs such as the self-fulfilling prophecy (Frontera, et al. Crit Care Med. 2015;43[9]:1964; Rubin, et al. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23[2]:134; Knies, et al. Semin Neurol. 2016;36[6]:631).

At our institution, a nursing education project was conducted to pilot nurse-driven PC screenings on admission to the neuro ICU. The project evaluated nurse comfort and knowledge with identifying and recommending PC consults. Pre- and post-intervention surveys revealed that education and introduction of a PC screening tool significantly increased nurse comfort and knowledge of PC eligibility.

PC in the neuro ICU can exist to contribute to successful outcomes in patient and family care. Within neurocritical care, incorporating PC is essential to provide extra support to patients and families (Frontera, et al. 2015).

For these reasons and data from the project, nurse-driven screening may encourage appropriate early PC consults. Patient-centered care is the ultimate goal in the management of our patients. Nurse-driven PC screening can help bring various unmet PC needs to the health-care team for opportunities that might not have been met or otherwise assessed. Consider implementing nurse-driven PC screening protocols at your institution to aid in collaborative and proactive interdisciplinary care.

Danielle McCamey, ACNP

Steering Committee Member

Sleep medicine

Diagnostics, devices, and sleep

The past several months have been busy for the Sleep Medicine NetWork. We have been working to represent the interests of our membership and our patients in many arenas.

Devices coded as E0464, defined as life support mechanical ventilators used with mask-based ventilation in the home are being more frequently used. According to the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), there has been an 89-fold increase in billing for E0464 ventilators for Medicare and its beneficiaries between 2009 and 2015, increasing from $3.8M to $340M. In response, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) requested a response to specific questions related to these devices.

In 2018, the CHEST Sleep Medicine NetWork will be participating in a Federal Drug Association-sponsored workshop entitled “Study Design Considerations for Devices including Digital Health Technologies for Sleep-Disordered Breathing (SDB) in Adults,” along with other national organizations and leaders in our field. This workshop will address available technologies for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of SDB, as well as trends for digital health technologies and clinical trial design considerations.

Finally, the Sleep Medicine NetWork has wasted no time after a successful CHEST 2017 in Toronto in planning for the next annual meeting in San Antonio. We are excited to present an exciting curriculum in Sleep Medicine at CHEST 2018, so stay tuned.

Aneesa M. Das, MD, FCCP

NetWork Chair

Occupational and environmental health

Post-deployment lung disease

Since the early 1990s, ongoing military deployments to Southwest Asia remain a unique challenge from a pulmonary symptomology and diagnostic perspective.

Various airborne hazards in the deployment environment include geologic dusts, burn pit smoke, vehicle emissions, and industrial air pollution. Exposures can give rise to both acute respiratory symptoms and, in some instances, chronic lung disease. Currently, data are limited on whether inhalation of airborne particulate matter by military personnel is linked to increases in pulmonary diseases (Morris MJ, et al. US Army Med Dep J. 2016:173).

Ongoing research by the Veterans Affairs continues to enroll post-deployed personnel in an Airborne Hazard and Burn Pit Registry. Past approaches in evaluation of deployed individuals ranged from common tests such as spirometry, HRCT scanning, full PFTs, bronchoprovocation challenges, and, in some instances, lung biopsies (Krefft SD, et al. Fed Pract. 2015;32[6]:32). More novel evaluations of postdeployment dyspnea include impulse oscillometry, exhaled nitric oxide, bronchoscopy, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing (Huprikar, et al. Chest. 2016;150[4]:S934A).

Members of the CHEST Occupational and Environmental Health NetWork are currently updating comprehensive approaches to evaluate military personnel with chronic respiratory symptoms from deployments. Continued emphasis, however, should be placed on diagnosing and treating common diseases such as asthma, exercise-induced bronchospasm, GERD, and upper airway disorders.

Pedro F. Lucero, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Clinical pulmonary medicine

Biologics – Birth of a new era of precision management in asthma

An estimated 10% to 20% of patients with severe uncontrolled asthma do not respond to maximal best standard treatments, leading to substantial health-care costs. A paradigm shift is now underway in our approach to the care of these patients with the emergence of novel biologics targeting the complex and interconnected inflammatory pathways in asthma that result in a diverse profile of asthma endotypes and phenotypes (Fig 1).

Current FDA-approved biologics primarily target patients with a T2 high phenotype (Table1).

Dupilumab binds to the alpha unit of the IL-4 receptor and blocks both IL-4 and IL-13. It shows potential efficacy in patients with T2 high asthma with or without eosinophilia but has not yet received FDA approval.

Multiple newer biologics are currently in development (Table 2).

Pulmonologists need to get familiar with the logistics of administration of these novel agents. The two common methods of administering biologics are (1) buy and bill – where the provider buys the drug directly from the distributor; and (2) assignment of benefits (typically administered by a Pharmacy Benefit Manager) - specific dose of the medication is shipped to the physician’s office and physician only bills for the administration. CPT and J codes are shown in Table 1.

Shyamsunder Subramanian, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Palliative and end-of-life care

Nurse-driven palliative care screening

Palliative care (PC) aims to improve quality of life for patients with a life-threatening illness, providing holistic patient-centered support along the continuum of the disease process. Although frequently implemented in critical care settings, integrating PC in the neuro ICU has been difficult to adopt in practice due to the uncertainty in prognostication of definitive outcomes and practice culture beliefs such as the self-fulfilling prophecy (Frontera, et al. Crit Care Med. 2015;43[9]:1964; Rubin, et al. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2017;23[2]:134; Knies, et al. Semin Neurol. 2016;36[6]:631).

At our institution, a nursing education project was conducted to pilot nurse-driven PC screenings on admission to the neuro ICU. The project evaluated nurse comfort and knowledge with identifying and recommending PC consults. Pre- and post-intervention surveys revealed that education and introduction of a PC screening tool significantly increased nurse comfort and knowledge of PC eligibility.

PC in the neuro ICU can exist to contribute to successful outcomes in patient and family care. Within neurocritical care, incorporating PC is essential to provide extra support to patients and families (Frontera, et al. 2015).

For these reasons and data from the project, nurse-driven screening may encourage appropriate early PC consults. Patient-centered care is the ultimate goal in the management of our patients. Nurse-driven PC screening can help bring various unmet PC needs to the health-care team for opportunities that might not have been met or otherwise assessed. Consider implementing nurse-driven PC screening protocols at your institution to aid in collaborative and proactive interdisciplinary care.

Danielle McCamey, ACNP

Steering Committee Member

Sleep medicine

Diagnostics, devices, and sleep

The past several months have been busy for the Sleep Medicine NetWork. We have been working to represent the interests of our membership and our patients in many arenas.

Devices coded as E0464, defined as life support mechanical ventilators used with mask-based ventilation in the home are being more frequently used. According to the Office of the Inspector General (OIG), there has been an 89-fold increase in billing for E0464 ventilators for Medicare and its beneficiaries between 2009 and 2015, increasing from $3.8M to $340M. In response, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) requested a response to specific questions related to these devices.

In 2018, the CHEST Sleep Medicine NetWork will be participating in a Federal Drug Association-sponsored workshop entitled “Study Design Considerations for Devices including Digital Health Technologies for Sleep-Disordered Breathing (SDB) in Adults,” along with other national organizations and leaders in our field. This workshop will address available technologies for the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of SDB, as well as trends for digital health technologies and clinical trial design considerations.

Finally, the Sleep Medicine NetWork has wasted no time after a successful CHEST 2017 in Toronto in planning for the next annual meeting in San Antonio. We are excited to present an exciting curriculum in Sleep Medicine at CHEST 2018, so stay tuned.

Aneesa M. Das, MD, FCCP

NetWork Chair

Occupational and environmental health

Post-deployment lung disease

Since the early 1990s, ongoing military deployments to Southwest Asia remain a unique challenge from a pulmonary symptomology and diagnostic perspective.

Various airborne hazards in the deployment environment include geologic dusts, burn pit smoke, vehicle emissions, and industrial air pollution. Exposures can give rise to both acute respiratory symptoms and, in some instances, chronic lung disease. Currently, data are limited on whether inhalation of airborne particulate matter by military personnel is linked to increases in pulmonary diseases (Morris MJ, et al. US Army Med Dep J. 2016:173).

Ongoing research by the Veterans Affairs continues to enroll post-deployed personnel in an Airborne Hazard and Burn Pit Registry. Past approaches in evaluation of deployed individuals ranged from common tests such as spirometry, HRCT scanning, full PFTs, bronchoprovocation challenges, and, in some instances, lung biopsies (Krefft SD, et al. Fed Pract. 2015;32[6]:32). More novel evaluations of postdeployment dyspnea include impulse oscillometry, exhaled nitric oxide, bronchoscopy, and cardiopulmonary exercise testing (Huprikar, et al. Chest. 2016;150[4]:S934A).

Members of the CHEST Occupational and Environmental Health NetWork are currently updating comprehensive approaches to evaluate military personnel with chronic respiratory symptoms from deployments. Continued emphasis, however, should be placed on diagnosing and treating common diseases such as asthma, exercise-induced bronchospasm, GERD, and upper airway disorders.

Pedro F. Lucero, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Clinical pulmonary medicine

Biologics – Birth of a new era of precision management in asthma

An estimated 10% to 20% of patients with severe uncontrolled asthma do not respond to maximal best standard treatments, leading to substantial health-care costs. A paradigm shift is now underway in our approach to the care of these patients with the emergence of novel biologics targeting the complex and interconnected inflammatory pathways in asthma that result in a diverse profile of asthma endotypes and phenotypes (Fig 1).

Current FDA-approved biologics primarily target patients with a T2 high phenotype (Table1).

Dupilumab binds to the alpha unit of the IL-4 receptor and blocks both IL-4 and IL-13. It shows potential efficacy in patients with T2 high asthma with or without eosinophilia but has not yet received FDA approval.

Multiple newer biologics are currently in development (Table 2).

Pulmonologists need to get familiar with the logistics of administration of these novel agents. The two common methods of administering biologics are (1) buy and bill – where the provider buys the drug directly from the distributor; and (2) assignment of benefits (typically administered by a Pharmacy Benefit Manager) - specific dose of the medication is shipped to the physician’s office and physician only bills for the administration. CPT and J codes are shown in Table 1.

Shyamsunder Subramanian, MD, FCCP

Steering Committee Member

Transgender women on HT have lower bone density, more fat mass than men

CHICAGO – according to findings from a recent Brazilian study.

“Lumbar spine density was lower than in reference men but similar to that of reference women,” said Tayane Muniz Fighera, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Lower lumbar spine density in transgender women was associated with lower appendicular lean mass and higher total fat mass, with correlation coefficients of 0.327 and 0.334, respectively (P = .0001 for both).

Dr. Fighera and her colleagues looked at the independent contribution of age, estradiol level, appendicular lean mass, and fat mass to bone mineral density (BMD) in the transgender patients, using linear regression analysis. Total fat mass and appendicular lean mass were both independent predictors of bone mineral density (P = .001 and P = .022, respectively). For femur BMD, age, and total fat mass were predictors (P = .001 and P = .000, respectively).

The study aimed to assess bone mineral density as well as other aspects of body composition within a cohort of transgender women initiating hormone therapy in order to determine how estrogen therapy affected BMD and assess the prevalence of low bone mass among this population.

The hypothesis, said Dr. Fighera, was that hormone therapy for transgender women might decrease muscle mass and increase fat mass, “leading to less bone surface strain and smaller bone size over time,” said Dr. Fighera, of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Previous work has shown conflicting results, she said. “While some studies report that estrogen therapy is able to increase bone mass, others have observed no difference in BMD” despite the use of hormone therapy. The studies showing an association between estrogen therapy and decreased bone mass were those that followed patients for longer periods of time – 2 years or longer, she said.

Dr. Fighera explained that in Brazil, individuals with gender dysphoria have free access to hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery through the public health service.

A total of 142 transgender women enrolled in the study, conducted at outpatient endocrine clinics for transgender people in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The clinics’ standardized hormone therapy protocol used daily estradiol valerate 1-4 mg, daily conjugated equine estrogen 0.625-2.5 mg, or daily transdermal 17 beta estradiol 0.5-2 mg. The estrogen therapy was accompanied by either spironolactone 50-150 mg per day, or cyproterone acetate 50-100 mg per day.

For comparison, the investigators enrolled 22 men and 17 women aged 18-40 years. All participants received a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan 3 months after those in the transgender arm began hormone therapy, and a second scan at 12 months. For the first year, participants were seen for clinical evaluation and lab studies every 3 months; they were seen every 6 months thereafter.

Although ranges were wide, estradiol levels in transgender women were, on average, approximately intermediate between the female and male control values. Total testosterone for transgender women was an average 1.17 nmol/L, closer to female (0.79 nmol/L) than male (16.39 nmol/L) values.

In a subgroup of 46 participants, Dr. Fighera and her colleagues also examined change over time for transgender women who remained on hormone therapy. Though they did find that appendicular lean mass declined and total fat mass increased from baseline, these changes in body composition were not associated with significant decreases in any BMD measurement when the DXA scan was repeated at 31 months.

Participants’ mean age was 33.7 years, and the mean BMI was 25.4 kg/m2. One-third of participants had already undergone gender-affirming surgery , and most (86.6%) had some previous exposure to hormone therapy. Almost all (96%) of study participants were white.

At 18%, “the prevalence of low bone mass for age was fairly high in this sample of [transgender women] from southern Brazil,” said Dr. Fighera. She called for more work to track change over time in hormone therapy–related bone loss for transgender women. “Until then, monitoring of bone mass should be considered in this population; nonpharmacological lifestyle-related strategies for preventing bone loss may benefit transgender women” who receive long-term hormone therapy, she said.

None of the study authors had disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Fighera T et al. ENDO 2018, Abstract OR 25-5.

CHICAGO – according to findings from a recent Brazilian study.

“Lumbar spine density was lower than in reference men but similar to that of reference women,” said Tayane Muniz Fighera, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Lower lumbar spine density in transgender women was associated with lower appendicular lean mass and higher total fat mass, with correlation coefficients of 0.327 and 0.334, respectively (P = .0001 for both).

Dr. Fighera and her colleagues looked at the independent contribution of age, estradiol level, appendicular lean mass, and fat mass to bone mineral density (BMD) in the transgender patients, using linear regression analysis. Total fat mass and appendicular lean mass were both independent predictors of bone mineral density (P = .001 and P = .022, respectively). For femur BMD, age, and total fat mass were predictors (P = .001 and P = .000, respectively).

The study aimed to assess bone mineral density as well as other aspects of body composition within a cohort of transgender women initiating hormone therapy in order to determine how estrogen therapy affected BMD and assess the prevalence of low bone mass among this population.

The hypothesis, said Dr. Fighera, was that hormone therapy for transgender women might decrease muscle mass and increase fat mass, “leading to less bone surface strain and smaller bone size over time,” said Dr. Fighera, of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Previous work has shown conflicting results, she said. “While some studies report that estrogen therapy is able to increase bone mass, others have observed no difference in BMD” despite the use of hormone therapy. The studies showing an association between estrogen therapy and decreased bone mass were those that followed patients for longer periods of time – 2 years or longer, she said.

Dr. Fighera explained that in Brazil, individuals with gender dysphoria have free access to hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery through the public health service.

A total of 142 transgender women enrolled in the study, conducted at outpatient endocrine clinics for transgender people in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The clinics’ standardized hormone therapy protocol used daily estradiol valerate 1-4 mg, daily conjugated equine estrogen 0.625-2.5 mg, or daily transdermal 17 beta estradiol 0.5-2 mg. The estrogen therapy was accompanied by either spironolactone 50-150 mg per day, or cyproterone acetate 50-100 mg per day.

For comparison, the investigators enrolled 22 men and 17 women aged 18-40 years. All participants received a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan 3 months after those in the transgender arm began hormone therapy, and a second scan at 12 months. For the first year, participants were seen for clinical evaluation and lab studies every 3 months; they were seen every 6 months thereafter.

Although ranges were wide, estradiol levels in transgender women were, on average, approximately intermediate between the female and male control values. Total testosterone for transgender women was an average 1.17 nmol/L, closer to female (0.79 nmol/L) than male (16.39 nmol/L) values.

In a subgroup of 46 participants, Dr. Fighera and her colleagues also examined change over time for transgender women who remained on hormone therapy. Though they did find that appendicular lean mass declined and total fat mass increased from baseline, these changes in body composition were not associated with significant decreases in any BMD measurement when the DXA scan was repeated at 31 months.

Participants’ mean age was 33.7 years, and the mean BMI was 25.4 kg/m2. One-third of participants had already undergone gender-affirming surgery , and most (86.6%) had some previous exposure to hormone therapy. Almost all (96%) of study participants were white.

At 18%, “the prevalence of low bone mass for age was fairly high in this sample of [transgender women] from southern Brazil,” said Dr. Fighera. She called for more work to track change over time in hormone therapy–related bone loss for transgender women. “Until then, monitoring of bone mass should be considered in this population; nonpharmacological lifestyle-related strategies for preventing bone loss may benefit transgender women” who receive long-term hormone therapy, she said.

None of the study authors had disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Fighera T et al. ENDO 2018, Abstract OR 25-5.

CHICAGO – according to findings from a recent Brazilian study.

“Lumbar spine density was lower than in reference men but similar to that of reference women,” said Tayane Muniz Fighera, MD, speaking at the annual meeting of the Endocrine Society.

Lower lumbar spine density in transgender women was associated with lower appendicular lean mass and higher total fat mass, with correlation coefficients of 0.327 and 0.334, respectively (P = .0001 for both).

Dr. Fighera and her colleagues looked at the independent contribution of age, estradiol level, appendicular lean mass, and fat mass to bone mineral density (BMD) in the transgender patients, using linear regression analysis. Total fat mass and appendicular lean mass were both independent predictors of bone mineral density (P = .001 and P = .022, respectively). For femur BMD, age, and total fat mass were predictors (P = .001 and P = .000, respectively).

The study aimed to assess bone mineral density as well as other aspects of body composition within a cohort of transgender women initiating hormone therapy in order to determine how estrogen therapy affected BMD and assess the prevalence of low bone mass among this population.

The hypothesis, said Dr. Fighera, was that hormone therapy for transgender women might decrease muscle mass and increase fat mass, “leading to less bone surface strain and smaller bone size over time,” said Dr. Fighera, of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil.

Previous work has shown conflicting results, she said. “While some studies report that estrogen therapy is able to increase bone mass, others have observed no difference in BMD” despite the use of hormone therapy. The studies showing an association between estrogen therapy and decreased bone mass were those that followed patients for longer periods of time – 2 years or longer, she said.

Dr. Fighera explained that in Brazil, individuals with gender dysphoria have free access to hormone therapy and gender-affirming surgery through the public health service.

A total of 142 transgender women enrolled in the study, conducted at outpatient endocrine clinics for transgender people in Porto Alegre, Brazil. The clinics’ standardized hormone therapy protocol used daily estradiol valerate 1-4 mg, daily conjugated equine estrogen 0.625-2.5 mg, or daily transdermal 17 beta estradiol 0.5-2 mg. The estrogen therapy was accompanied by either spironolactone 50-150 mg per day, or cyproterone acetate 50-100 mg per day.

For comparison, the investigators enrolled 22 men and 17 women aged 18-40 years. All participants received a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan 3 months after those in the transgender arm began hormone therapy, and a second scan at 12 months. For the first year, participants were seen for clinical evaluation and lab studies every 3 months; they were seen every 6 months thereafter.

Although ranges were wide, estradiol levels in transgender women were, on average, approximately intermediate between the female and male control values. Total testosterone for transgender women was an average 1.17 nmol/L, closer to female (0.79 nmol/L) than male (16.39 nmol/L) values.

In a subgroup of 46 participants, Dr. Fighera and her colleagues also examined change over time for transgender women who remained on hormone therapy. Though they did find that appendicular lean mass declined and total fat mass increased from baseline, these changes in body composition were not associated with significant decreases in any BMD measurement when the DXA scan was repeated at 31 months.

Participants’ mean age was 33.7 years, and the mean BMI was 25.4 kg/m2. One-third of participants had already undergone gender-affirming surgery , and most (86.6%) had some previous exposure to hormone therapy. Almost all (96%) of study participants were white.

At 18%, “the prevalence of low bone mass for age was fairly high in this sample of [transgender women] from southern Brazil,” said Dr. Fighera. She called for more work to track change over time in hormone therapy–related bone loss for transgender women. “Until then, monitoring of bone mass should be considered in this population; nonpharmacological lifestyle-related strategies for preventing bone loss may benefit transgender women” who receive long-term hormone therapy, she said.

None of the study authors had disclosures to report.

SOURCE: Fighera T et al. ENDO 2018, Abstract OR 25-5.

REPORTING FROM ENDO 2018

Key clinical point: Transgender women on hormone therapy have bone mass more similar to women than men.

Major finding: Lower lumbar spine density was associated with higher total fat mass (P = .001).

Study details: Study of 142 transgender women receiving hormone therapy, tracked over time and compared with 22 men and 17 women for reference.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by the Brazilian government. The authors reported that they have no conflicts of interest.

Source: Fighera T et al. ENDO 2018, Abstract OR 25-5.

FDA approves marketing for retinal imaging device that uses artificial intelligence

The Food and Drug Administration has permitted the marketing of IDx-DR, a retinal imaging device that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to detect greater than a mild level of diabetic retinopathy in adult patients with diabetes. It also is the first authorized device that provides a screening tool without the need of an eye care specialist, making it ideal for health care providers who do not specialize in eye care.

“Early detection of retinopathy is an important part of managing care for the millions of people with diabetes, yet many patients with diabetes are not adequately screened for diabetic retinopathy.” About 50% of people with diabetes do not have the recommended annual retinopathy screening exam, Malvina Eydelman, MD, director of the division of ophthalmic, and ear, nose, and throat devices at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health noted in a press release.

The software behind IDx-DR utilizes an artificial intelligence program to analyze retinal images captured by a retinal camera, the Topcon NW400. After one or more images are taken, they are uploaded to a Cloud server, on which IDx-DR software is installed, where they can be analyzed using an algorithm. In cases in which the images are of sufficient quality, the software provides the doctor with one of two results: “More than mild diabetic retinopathy detected: refer to an eye care professional” or “Negative for more than mild diabetic retinopathy; rescreen in 12 months.”

If a positive result is detected, patients should see an eye care specialist for further diagnostic evaluation and treatment as soon as possible.

The FDA reviewed data obtained from a clinical study prior to approving IDx-DR for marketing. The study looked at retinal images from 900 patients at 10 primary care sites. The aim of the study was to determine how often IDx-DR was correct in identifying mild diabetic retinopathy. The device was accurate nearly 90% of the time, correctly identifying mild diabetic retinopathy 87.4% of the time. It was also able to identify correctly patients who did not have mild diabetic retinopathy 89.5% of the time.

IDx-DR was approved via the FDA’s De Novo premarket review pathway, which offers a way to approve novel, low to moderate risk devices for which there are no similar devices previously approved. It also was granted a Breakthrough Device designation, because of its effectiveness in treating or diagnosing a irreversibly debilitating disease or condition.

Michael Abramoff, MD, PhD, and founder and president of IDx, said in an interview: “The FDA’s authorization to market IDx-DR is a historic moment that will launch a transformation in the way U.S. health care is delivered. Autonomous AI systems have massive potential to improve health care productivity, lower health care costs, and improve accessibility and quality. As the first of its kind to be authorized for commercialization, IDx-DR provides a roadmap for the safe and responsible use of AI in medicine.”

IDx-DR is intended to identify mild diabetic retinopathy and should not be used to detect rapidly progressive cases of diabetic retinopathy, particularly in pregnant women in which the disease can progress quickly. Patients with a history of laser treatment, surgery, or injections in the eye and other types of retinopathy, including radiation retinopathy, should not use IDx-DR.

For more information on other uses of AI in the treatment of diabetic disorders, click here.

The Food and Drug Administration has permitted the marketing of IDx-DR, a retinal imaging device that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to detect greater than a mild level of diabetic retinopathy in adult patients with diabetes. It also is the first authorized device that provides a screening tool without the need of an eye care specialist, making it ideal for health care providers who do not specialize in eye care.

“Early detection of retinopathy is an important part of managing care for the millions of people with diabetes, yet many patients with diabetes are not adequately screened for diabetic retinopathy.” About 50% of people with diabetes do not have the recommended annual retinopathy screening exam, Malvina Eydelman, MD, director of the division of ophthalmic, and ear, nose, and throat devices at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health noted in a press release.

The software behind IDx-DR utilizes an artificial intelligence program to analyze retinal images captured by a retinal camera, the Topcon NW400. After one or more images are taken, they are uploaded to a Cloud server, on which IDx-DR software is installed, where they can be analyzed using an algorithm. In cases in which the images are of sufficient quality, the software provides the doctor with one of two results: “More than mild diabetic retinopathy detected: refer to an eye care professional” or “Negative for more than mild diabetic retinopathy; rescreen in 12 months.”

If a positive result is detected, patients should see an eye care specialist for further diagnostic evaluation and treatment as soon as possible.

The FDA reviewed data obtained from a clinical study prior to approving IDx-DR for marketing. The study looked at retinal images from 900 patients at 10 primary care sites. The aim of the study was to determine how often IDx-DR was correct in identifying mild diabetic retinopathy. The device was accurate nearly 90% of the time, correctly identifying mild diabetic retinopathy 87.4% of the time. It was also able to identify correctly patients who did not have mild diabetic retinopathy 89.5% of the time.

IDx-DR was approved via the FDA’s De Novo premarket review pathway, which offers a way to approve novel, low to moderate risk devices for which there are no similar devices previously approved. It also was granted a Breakthrough Device designation, because of its effectiveness in treating or diagnosing a irreversibly debilitating disease or condition.

Michael Abramoff, MD, PhD, and founder and president of IDx, said in an interview: “The FDA’s authorization to market IDx-DR is a historic moment that will launch a transformation in the way U.S. health care is delivered. Autonomous AI systems have massive potential to improve health care productivity, lower health care costs, and improve accessibility and quality. As the first of its kind to be authorized for commercialization, IDx-DR provides a roadmap for the safe and responsible use of AI in medicine.”

IDx-DR is intended to identify mild diabetic retinopathy and should not be used to detect rapidly progressive cases of diabetic retinopathy, particularly in pregnant women in which the disease can progress quickly. Patients with a history of laser treatment, surgery, or injections in the eye and other types of retinopathy, including radiation retinopathy, should not use IDx-DR.

For more information on other uses of AI in the treatment of diabetic disorders, click here.

The Food and Drug Administration has permitted the marketing of IDx-DR, a retinal imaging device that uses artificial intelligence (AI) to detect greater than a mild level of diabetic retinopathy in adult patients with diabetes. It also is the first authorized device that provides a screening tool without the need of an eye care specialist, making it ideal for health care providers who do not specialize in eye care.

“Early detection of retinopathy is an important part of managing care for the millions of people with diabetes, yet many patients with diabetes are not adequately screened for diabetic retinopathy.” About 50% of people with diabetes do not have the recommended annual retinopathy screening exam, Malvina Eydelman, MD, director of the division of ophthalmic, and ear, nose, and throat devices at the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health noted in a press release.

The software behind IDx-DR utilizes an artificial intelligence program to analyze retinal images captured by a retinal camera, the Topcon NW400. After one or more images are taken, they are uploaded to a Cloud server, on which IDx-DR software is installed, where they can be analyzed using an algorithm. In cases in which the images are of sufficient quality, the software provides the doctor with one of two results: “More than mild diabetic retinopathy detected: refer to an eye care professional” or “Negative for more than mild diabetic retinopathy; rescreen in 12 months.”

If a positive result is detected, patients should see an eye care specialist for further diagnostic evaluation and treatment as soon as possible.

The FDA reviewed data obtained from a clinical study prior to approving IDx-DR for marketing. The study looked at retinal images from 900 patients at 10 primary care sites. The aim of the study was to determine how often IDx-DR was correct in identifying mild diabetic retinopathy. The device was accurate nearly 90% of the time, correctly identifying mild diabetic retinopathy 87.4% of the time. It was also able to identify correctly patients who did not have mild diabetic retinopathy 89.5% of the time.

IDx-DR was approved via the FDA’s De Novo premarket review pathway, which offers a way to approve novel, low to moderate risk devices for which there are no similar devices previously approved. It also was granted a Breakthrough Device designation, because of its effectiveness in treating or diagnosing a irreversibly debilitating disease or condition.

Michael Abramoff, MD, PhD, and founder and president of IDx, said in an interview: “The FDA’s authorization to market IDx-DR is a historic moment that will launch a transformation in the way U.S. health care is delivered. Autonomous AI systems have massive potential to improve health care productivity, lower health care costs, and improve accessibility and quality. As the first of its kind to be authorized for commercialization, IDx-DR provides a roadmap for the safe and responsible use of AI in medicine.”

IDx-DR is intended to identify mild diabetic retinopathy and should not be used to detect rapidly progressive cases of diabetic retinopathy, particularly in pregnant women in which the disease can progress quickly. Patients with a history of laser treatment, surgery, or injections in the eye and other types of retinopathy, including radiation retinopathy, should not use IDx-DR.

For more information on other uses of AI in the treatment of diabetic disorders, click here.

Make the Diagnosis - May 2018

Generally, school-aged children are most often affected. Infections are more likely in late winter and early spring. The virus is spread via respiratory secretions, blood products, and transmission from mother to fetus. The cutaneous findings occur about 10 days after exposure to the virus. By that time, the risk of being contagious is low.

Healthy individuals have no sequelae from fifth disease and require no treatment. However, in patients with hemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell disease, an aplastic crisis can be triggered. In patients with deficient immune systems, parvovirus B19 may cause infection and anemia, requiring hospitalization. Pregnant women exposed to parvovirus B19 are at risk for hydrops fetalis and rarely, fetal malformations or fetal demise. Other uncommon associations include hepatitis, vasculitides, and neurologic disease.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected]. This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Generally, school-aged children are most often affected. Infections are more likely in late winter and early spring. The virus is spread via respiratory secretions, blood products, and transmission from mother to fetus. The cutaneous findings occur about 10 days after exposure to the virus. By that time, the risk of being contagious is low.

Healthy individuals have no sequelae from fifth disease and require no treatment. However, in patients with hemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell disease, an aplastic crisis can be triggered. In patients with deficient immune systems, parvovirus B19 may cause infection and anemia, requiring hospitalization. Pregnant women exposed to parvovirus B19 are at risk for hydrops fetalis and rarely, fetal malformations or fetal demise. Other uncommon associations include hepatitis, vasculitides, and neurologic disease.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected]. This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Generally, school-aged children are most often affected. Infections are more likely in late winter and early spring. The virus is spread via respiratory secretions, blood products, and transmission from mother to fetus. The cutaneous findings occur about 10 days after exposure to the virus. By that time, the risk of being contagious is low.

Healthy individuals have no sequelae from fifth disease and require no treatment. However, in patients with hemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell disease, an aplastic crisis can be triggered. In patients with deficient immune systems, parvovirus B19 may cause infection and anemia, requiring hospitalization. Pregnant women exposed to parvovirus B19 are at risk for hydrops fetalis and rarely, fetal malformations or fetal demise. Other uncommon associations include hepatitis, vasculitides, and neurologic disease.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at edermatologynews.com. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to [email protected]. This case and photo were submitted by Dr. Bilu Martin.

Residual single-site ovarian cancer surpasses multisite outcomes

NEW ORLEANS – When complete resection of advanced-stage, epithelial ovarian cancer is not possible, surgical resection that leaves a small volume of residual tumor at a single site produces significantly better outcomes than leaving minimal residual cancer at multiple sites, according to a review of 510 patients at two U.S. centers.

“In the past, we separated these patients based on whether they had a complete resection, R0 disease, or had 1 cm or less of residual disease” regardless of the number of sites with this small amount of residual tumor. The third category was patients with more than 1 cm of residual tumor at one or more sites, explained Dr. Manning-Geist in an interview. “What we did was break down the patients with 1 cm or less of residual tumor into those with one site or multiple sites. This is the first reported study to use number of sites” as a clinical characteristic for analysis in this context.

The message from the findings is that, while the goal of debulking surgery in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer is complete tumor resection, if that can’t be achieved, the next goal is to leave residual tumor at just a single site, she concluded. A question that remains is whether primary debulking surgery is preferable to neoadjuvant treatment followed by interval debulking surgery. In the results Dr. Manning-Geist presented, patients who underwent primary debulking had better outcomes than those with neoadjuvant therapy followed by interval debulking, but these two subgroups also had different clinical characteristics.

The study used data from 510 patients with stage IIIC or IV epithelial ovarian cancer treated at either Brigham and Women’s or Massachusetts General Hospital during 2010-2015. The study cohort included 240 patients who underwent primary debulking surgery and 270 who first received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and then underwent interval debulking surgery. The patients who received neoadjuvant therapy were, on average, older (65 years vs. 63 years), had a higher prevalence of stage IV disease (44% vs. 16%), and had a higher prevalence of tumors with serous histology (93% vs. 77%), compared with patients who underwent primary debulking.

Complete tumor resections occurred in 39% of the primary debulking patients and in 64% of those who received neoadjuvant therapy; residual disease of 1 cm or less at one site occurred in 17% and 13%, respectively; minimal residual disease at multiple sites remained in 28% and 17% respectively; and the remaining patients had residual disease of more than 1 cm in at least one site, 16% and 6% respectively.

For this analysis, Dr. Manning-Geist and her associates considered residual disease at any of seven possible sites: diaphragm, upper abdomen, bowel mesentary, bowel serosa, abdominal peritoneum, pelvis, and nodal. Even if multiple individual metastases remained within one of these sites after surgery, it was categorized as a single site of residual disease.

Among patients who underwent primary debulking surgery, progression-free survival persisted for a median of 23 months among patients with full resection, 19 months in patients with a single site with minimal residual disease, 13 months among those with multiple sites of residual disease, and 10 months in patients with more than 1 cm of residual tumor. Median overall survival in these four subgroups was not yet reached, 64 months, 50 months, and 49 months, respectively.

Among patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and then underwent interval debulking surgery, median durations of progression-free survival were 14 months, 12 months, 10 months, and 6 months, respectively. Median overall survival rates were 58 months, 37 months, 26 months, and 33 months, respectively. Within each of these four analyses, the differences in both survival and progression-free survival across the four subgroups was statistically significant, with a P less than .001 for each analysis.

In multivariate analyses, among patients who underwent primary debulking surgery, the significant linkages with worsening progression-free and overall survival were age, cancer stage, and amount and site number of residual disease. Among patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking residual disease diameter and site number of residual tumor was the only significant determinant for both progression-free and overall survival, Dr. Manning-Geist reported.

Dr. Manning-Geist had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Manning-Geist B et al. SGO 2018, Abstract 43.

NEW ORLEANS – When complete resection of advanced-stage, epithelial ovarian cancer is not possible, surgical resection that leaves a small volume of residual tumor at a single site produces significantly better outcomes than leaving minimal residual cancer at multiple sites, according to a review of 510 patients at two U.S. centers.

“In the past, we separated these patients based on whether they had a complete resection, R0 disease, or had 1 cm or less of residual disease” regardless of the number of sites with this small amount of residual tumor. The third category was patients with more than 1 cm of residual tumor at one or more sites, explained Dr. Manning-Geist in an interview. “What we did was break down the patients with 1 cm or less of residual tumor into those with one site or multiple sites. This is the first reported study to use number of sites” as a clinical characteristic for analysis in this context.

The message from the findings is that, while the goal of debulking surgery in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer is complete tumor resection, if that can’t be achieved, the next goal is to leave residual tumor at just a single site, she concluded. A question that remains is whether primary debulking surgery is preferable to neoadjuvant treatment followed by interval debulking surgery. In the results Dr. Manning-Geist presented, patients who underwent primary debulking had better outcomes than those with neoadjuvant therapy followed by interval debulking, but these two subgroups also had different clinical characteristics.

The study used data from 510 patients with stage IIIC or IV epithelial ovarian cancer treated at either Brigham and Women’s or Massachusetts General Hospital during 2010-2015. The study cohort included 240 patients who underwent primary debulking surgery and 270 who first received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and then underwent interval debulking surgery. The patients who received neoadjuvant therapy were, on average, older (65 years vs. 63 years), had a higher prevalence of stage IV disease (44% vs. 16%), and had a higher prevalence of tumors with serous histology (93% vs. 77%), compared with patients who underwent primary debulking.

Complete tumor resections occurred in 39% of the primary debulking patients and in 64% of those who received neoadjuvant therapy; residual disease of 1 cm or less at one site occurred in 17% and 13%, respectively; minimal residual disease at multiple sites remained in 28% and 17% respectively; and the remaining patients had residual disease of more than 1 cm in at least one site, 16% and 6% respectively.

For this analysis, Dr. Manning-Geist and her associates considered residual disease at any of seven possible sites: diaphragm, upper abdomen, bowel mesentary, bowel serosa, abdominal peritoneum, pelvis, and nodal. Even if multiple individual metastases remained within one of these sites after surgery, it was categorized as a single site of residual disease.

Among patients who underwent primary debulking surgery, progression-free survival persisted for a median of 23 months among patients with full resection, 19 months in patients with a single site with minimal residual disease, 13 months among those with multiple sites of residual disease, and 10 months in patients with more than 1 cm of residual tumor. Median overall survival in these four subgroups was not yet reached, 64 months, 50 months, and 49 months, respectively.

Among patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and then underwent interval debulking surgery, median durations of progression-free survival were 14 months, 12 months, 10 months, and 6 months, respectively. Median overall survival rates were 58 months, 37 months, 26 months, and 33 months, respectively. Within each of these four analyses, the differences in both survival and progression-free survival across the four subgroups was statistically significant, with a P less than .001 for each analysis.

In multivariate analyses, among patients who underwent primary debulking surgery, the significant linkages with worsening progression-free and overall survival were age, cancer stage, and amount and site number of residual disease. Among patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking residual disease diameter and site number of residual tumor was the only significant determinant for both progression-free and overall survival, Dr. Manning-Geist reported.

Dr. Manning-Geist had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Manning-Geist B et al. SGO 2018, Abstract 43.

NEW ORLEANS – When complete resection of advanced-stage, epithelial ovarian cancer is not possible, surgical resection that leaves a small volume of residual tumor at a single site produces significantly better outcomes than leaving minimal residual cancer at multiple sites, according to a review of 510 patients at two U.S. centers.

“In the past, we separated these patients based on whether they had a complete resection, R0 disease, or had 1 cm or less of residual disease” regardless of the number of sites with this small amount of residual tumor. The third category was patients with more than 1 cm of residual tumor at one or more sites, explained Dr. Manning-Geist in an interview. “What we did was break down the patients with 1 cm or less of residual tumor into those with one site or multiple sites. This is the first reported study to use number of sites” as a clinical characteristic for analysis in this context.

The message from the findings is that, while the goal of debulking surgery in patients with advanced epithelial ovarian cancer is complete tumor resection, if that can’t be achieved, the next goal is to leave residual tumor at just a single site, she concluded. A question that remains is whether primary debulking surgery is preferable to neoadjuvant treatment followed by interval debulking surgery. In the results Dr. Manning-Geist presented, patients who underwent primary debulking had better outcomes than those with neoadjuvant therapy followed by interval debulking, but these two subgroups also had different clinical characteristics.

The study used data from 510 patients with stage IIIC or IV epithelial ovarian cancer treated at either Brigham and Women’s or Massachusetts General Hospital during 2010-2015. The study cohort included 240 patients who underwent primary debulking surgery and 270 who first received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and then underwent interval debulking surgery. The patients who received neoadjuvant therapy were, on average, older (65 years vs. 63 years), had a higher prevalence of stage IV disease (44% vs. 16%), and had a higher prevalence of tumors with serous histology (93% vs. 77%), compared with patients who underwent primary debulking.

Complete tumor resections occurred in 39% of the primary debulking patients and in 64% of those who received neoadjuvant therapy; residual disease of 1 cm or less at one site occurred in 17% and 13%, respectively; minimal residual disease at multiple sites remained in 28% and 17% respectively; and the remaining patients had residual disease of more than 1 cm in at least one site, 16% and 6% respectively.

For this analysis, Dr. Manning-Geist and her associates considered residual disease at any of seven possible sites: diaphragm, upper abdomen, bowel mesentary, bowel serosa, abdominal peritoneum, pelvis, and nodal. Even if multiple individual metastases remained within one of these sites after surgery, it was categorized as a single site of residual disease.

Among patients who underwent primary debulking surgery, progression-free survival persisted for a median of 23 months among patients with full resection, 19 months in patients with a single site with minimal residual disease, 13 months among those with multiple sites of residual disease, and 10 months in patients with more than 1 cm of residual tumor. Median overall survival in these four subgroups was not yet reached, 64 months, 50 months, and 49 months, respectively.

Among patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy and then underwent interval debulking surgery, median durations of progression-free survival were 14 months, 12 months, 10 months, and 6 months, respectively. Median overall survival rates were 58 months, 37 months, 26 months, and 33 months, respectively. Within each of these four analyses, the differences in both survival and progression-free survival across the four subgroups was statistically significant, with a P less than .001 for each analysis.

In multivariate analyses, among patients who underwent primary debulking surgery, the significant linkages with worsening progression-free and overall survival were age, cancer stage, and amount and site number of residual disease. Among patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by interval debulking residual disease diameter and site number of residual tumor was the only significant determinant for both progression-free and overall survival, Dr. Manning-Geist reported.

Dr. Manning-Geist had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Manning-Geist B et al. SGO 2018, Abstract 43.

REPORTING FROM SGO 2018

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Median overall survival after primary debulking was 64 months with single-site residual disease and 50 months with multisite disease.

Study details: Retrospective review of 510 patients from two U.S. centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Manning-Geist had no disclosures.

Source: Manning-Geist BL et al. SGO 2018, Abstract 43.

Extracapsular spread predicts survival in SLN+ melanoma

CHICAGO – Extracapsular extension, or extracapsular spread (ECS), has been recognized as a risk factor in melanoma patients with macrometastatic (N+) disease, but a study from the United Kingdom has found it may also be an important indicator of progression-free and overall survival in patients who have sentinel node positive (SLN+) micrometastatic disease, a researcher reported at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

“There is limited published data on ECS in micrometastatic disease, although there is progression-free survival data published in the literature,” Michelle Lo, MBCHB, MRCS, of Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals, in Norwich, England, said in presenting the results. “The goal of the study was to determine the incidence of ECS in the micrometastatic group and to determine the prognostic significance of this.”

The study found that the incidence of ECS in the N+ group was significantly higher than the SLN+ group, 52.4% vs. 16.2% (P less than .0001). ECS proved to be a significant prognostic indicator of disease-specific survival and overall survival for both N+ and SLN+ disease. “There was no statistical difference in Breslow thickness between the two groups regardless of ECS,” she said.

Both the N+ and SLN+ groups with ECS had more lymph nodes than the ECS-absent subgroups, Dr. Lo said. However, in the ECS-absent subgroups, N+ patients had twice the number of lymph nodes than SLN+ patients. “This would suggest that ECS is a high-risk phenotype from the outset of metastases rather than something that’s developed over time,” she said. “Our data is in line with international staging data.”

The ECS-absent SLN– disease group had the most favorable survival outcomes, while those with ECS-present N+ disease had the worst outcomes. The prognosis of ECS-present, SLN+ patients was statistically similar to the ECS-absent, N+ group, she said.

In patients with SLN+ disease, Breslow thickness and N-stage were independent prognostic indicators for progression-free survival (hazard ratio 2.4, P less than .0001) and disease-free survival (HR 2.3, P less than .0001), Dr. Lo noted that median progression-free survival in SLN+ and N+ disease was 20 and 10 months, respectively. “Within our cohort of patients with ECS present in the micrometastatic group, their disease progressed within 3 years,” she said.

A multivariate analysis showed the survival data from this study was consistent with American Joint Committee on Cancer staging criteria, Dr. Lo said. “ECS is well recognized in the macrometastatic group, but we demonstrated from our data that the incidence of ECS in the micrometastatic group is one in six. It’s an independent risk factor for disease progression and an independent risk factor for worst disease-specific and overall survival, and it upstages micrometastatic disease.” ECS upstages stage III disease in a fashion similar to that of ulceration in primary melanoma, she said.

“In the absence of data to suggest otherwise, we would still recommend completion lymph node dissection in our micrometastatic group where ECS is present, and we would advocate that ECS should be included as an independent staging variable in the future,” Dr. Lo said.

Dr. Lo and her coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Lo M, et al. SSO 2018 Abstract 70.

CHICAGO – Extracapsular extension, or extracapsular spread (ECS), has been recognized as a risk factor in melanoma patients with macrometastatic (N+) disease, but a study from the United Kingdom has found it may also be an important indicator of progression-free and overall survival in patients who have sentinel node positive (SLN+) micrometastatic disease, a researcher reported at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

“There is limited published data on ECS in micrometastatic disease, although there is progression-free survival data published in the literature,” Michelle Lo, MBCHB, MRCS, of Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals, in Norwich, England, said in presenting the results. “The goal of the study was to determine the incidence of ECS in the micrometastatic group and to determine the prognostic significance of this.”

The study found that the incidence of ECS in the N+ group was significantly higher than the SLN+ group, 52.4% vs. 16.2% (P less than .0001). ECS proved to be a significant prognostic indicator of disease-specific survival and overall survival for both N+ and SLN+ disease. “There was no statistical difference in Breslow thickness between the two groups regardless of ECS,” she said.

Both the N+ and SLN+ groups with ECS had more lymph nodes than the ECS-absent subgroups, Dr. Lo said. However, in the ECS-absent subgroups, N+ patients had twice the number of lymph nodes than SLN+ patients. “This would suggest that ECS is a high-risk phenotype from the outset of metastases rather than something that’s developed over time,” she said. “Our data is in line with international staging data.”

The ECS-absent SLN– disease group had the most favorable survival outcomes, while those with ECS-present N+ disease had the worst outcomes. The prognosis of ECS-present, SLN+ patients was statistically similar to the ECS-absent, N+ group, she said.

In patients with SLN+ disease, Breslow thickness and N-stage were independent prognostic indicators for progression-free survival (hazard ratio 2.4, P less than .0001) and disease-free survival (HR 2.3, P less than .0001), Dr. Lo noted that median progression-free survival in SLN+ and N+ disease was 20 and 10 months, respectively. “Within our cohort of patients with ECS present in the micrometastatic group, their disease progressed within 3 years,” she said.

A multivariate analysis showed the survival data from this study was consistent with American Joint Committee on Cancer staging criteria, Dr. Lo said. “ECS is well recognized in the macrometastatic group, but we demonstrated from our data that the incidence of ECS in the micrometastatic group is one in six. It’s an independent risk factor for disease progression and an independent risk factor for worst disease-specific and overall survival, and it upstages micrometastatic disease.” ECS upstages stage III disease in a fashion similar to that of ulceration in primary melanoma, she said.

“In the absence of data to suggest otherwise, we would still recommend completion lymph node dissection in our micrometastatic group where ECS is present, and we would advocate that ECS should be included as an independent staging variable in the future,” Dr. Lo said.

Dr. Lo and her coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Lo M, et al. SSO 2018 Abstract 70.

CHICAGO – Extracapsular extension, or extracapsular spread (ECS), has been recognized as a risk factor in melanoma patients with macrometastatic (N+) disease, but a study from the United Kingdom has found it may also be an important indicator of progression-free and overall survival in patients who have sentinel node positive (SLN+) micrometastatic disease, a researcher reported at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium.

“There is limited published data on ECS in micrometastatic disease, although there is progression-free survival data published in the literature,” Michelle Lo, MBCHB, MRCS, of Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals, in Norwich, England, said in presenting the results. “The goal of the study was to determine the incidence of ECS in the micrometastatic group and to determine the prognostic significance of this.”

The study found that the incidence of ECS in the N+ group was significantly higher than the SLN+ group, 52.4% vs. 16.2% (P less than .0001). ECS proved to be a significant prognostic indicator of disease-specific survival and overall survival for both N+ and SLN+ disease. “There was no statistical difference in Breslow thickness between the two groups regardless of ECS,” she said.

Both the N+ and SLN+ groups with ECS had more lymph nodes than the ECS-absent subgroups, Dr. Lo said. However, in the ECS-absent subgroups, N+ patients had twice the number of lymph nodes than SLN+ patients. “This would suggest that ECS is a high-risk phenotype from the outset of metastases rather than something that’s developed over time,” she said. “Our data is in line with international staging data.”