User login

Gene variants linked to survival after HSCT

New research has revealed a link between rare gene variants and survival after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Researchers performed exome sequencing in nearly 2500 HSCT recipients and their matched, unrelated donors.

The sequencing revealed several gene variants—in both donors and recipients—that were significantly associated with overall survival (OS), transplant-related mortality (TRM), and disease-related mortality (DRM) after HSCT.

Qianqian Zhu, PhD, of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York, and her colleagues described these findings in Blood.

The team performed exome sequencing—using the Illumina HumanExome BeadChip—in patients who participated in the DISCOVeRY-BMT study.

This included 2473 HSCT recipients who had acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndromes. It also included 2221 donors who were a 10/10 human leukocyte antigen match for each recipient.

The researchers looked at genetic variants in donors and recipients and assessed the variants’ associations with OS, TRM, and DRM.

Variants in recipients

Analyses revealed an increased risk of TRM when there was a mismatch between donors and recipients for a variant in TEX38—rs200092801. The increased risk was even more pronounced when either the recipient or the donor was female.

Among the recipients mismatched with their donors at rs200092801, every female recipient and every recipient with a female donor died from TRM. In comparison, 44% of the male recipients with male donors died from TRM.

The researchers said the rs200092801 variant may prompt the production of a mutant peptide that can be presented by MHC-I molecules to immune cells to trigger downstream immune response and TRM.

Dr Zhu and her colleagues also identified variants that appeared to have a positive impact on TRM and OS.

Recipients who had any of 6 variants in the gene OR51D1 had a decreased risk of TRM and improved OS.

The variants (rs138224979, rs148606808, rs141786655, rs61745314, rs200394876, and rs149135276) were not associated with DRM, so the researchers concluded that the improvement in OS was driven by protection against TRM.

Donor variants linked to OS

Donors had variants in 4 genes—ALPP, EMID1, SLC44A5, and LRP1—that were associated with OS but not TRM or DRM.

The 3 variants identified in ALPP (rs144454460, rs140078460, and rs142493383) were associated with improved OS.

And the 2 variants in SLC44A5 (rs143004355 and rs149696907) were associated with worse OS.

There were 2 variants in EMID1. One was associated with improved OS (rs34772704), and the other was associated with decreased OS (rs139996840).

And there were 27 variants in LRP1. Some had a positive association with OS, and others had a negative association.

Donor variants linked to TRM and DRM

Six variants in the HHAT gene were associated with TRM. Five of the variants appeared to have a protective effect against TRM (rs145455128, rs146916002, rs61744143, rs149597734, and rs145943928). For the other variant (rs141591165), the apparent effect was inconsistent between patient cohorts.

There were 3 variants in LYZL4 associated with DRM. Two were associated with an increased risk of DRM (rs147770623 and rs76947105), and 1 appeared to have a protective effect (rs181886204).

Six variants in NT5E appeared to have a protective effect against DRM (rs200250022, rs200369370, rs41271617, rs200648774, rs144719925, and rs145505137).

The researchers said the variants in NT5E probably reduce the enzyme activity of the gene. This supports preclinical findings showing that targeted blockade of NT5E can slow tumor growth.

“We have just started to uncover the biological relevance of these new and unexpected genes to a patient’s survival after [HSCT],” Dr Zhu said.

“Our findings shed light on new areas that were not considered before, but we need to further replicate and test our findings. We’re hoping that additional studies of this type will continue to discover novel genes leading to improved outcomes for patients.”

New research has revealed a link between rare gene variants and survival after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Researchers performed exome sequencing in nearly 2500 HSCT recipients and their matched, unrelated donors.

The sequencing revealed several gene variants—in both donors and recipients—that were significantly associated with overall survival (OS), transplant-related mortality (TRM), and disease-related mortality (DRM) after HSCT.

Qianqian Zhu, PhD, of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York, and her colleagues described these findings in Blood.

The team performed exome sequencing—using the Illumina HumanExome BeadChip—in patients who participated in the DISCOVeRY-BMT study.

This included 2473 HSCT recipients who had acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndromes. It also included 2221 donors who were a 10/10 human leukocyte antigen match for each recipient.

The researchers looked at genetic variants in donors and recipients and assessed the variants’ associations with OS, TRM, and DRM.

Variants in recipients

Analyses revealed an increased risk of TRM when there was a mismatch between donors and recipients for a variant in TEX38—rs200092801. The increased risk was even more pronounced when either the recipient or the donor was female.

Among the recipients mismatched with their donors at rs200092801, every female recipient and every recipient with a female donor died from TRM. In comparison, 44% of the male recipients with male donors died from TRM.

The researchers said the rs200092801 variant may prompt the production of a mutant peptide that can be presented by MHC-I molecules to immune cells to trigger downstream immune response and TRM.

Dr Zhu and her colleagues also identified variants that appeared to have a positive impact on TRM and OS.

Recipients who had any of 6 variants in the gene OR51D1 had a decreased risk of TRM and improved OS.

The variants (rs138224979, rs148606808, rs141786655, rs61745314, rs200394876, and rs149135276) were not associated with DRM, so the researchers concluded that the improvement in OS was driven by protection against TRM.

Donor variants linked to OS

Donors had variants in 4 genes—ALPP, EMID1, SLC44A5, and LRP1—that were associated with OS but not TRM or DRM.

The 3 variants identified in ALPP (rs144454460, rs140078460, and rs142493383) were associated with improved OS.

And the 2 variants in SLC44A5 (rs143004355 and rs149696907) were associated with worse OS.

There were 2 variants in EMID1. One was associated with improved OS (rs34772704), and the other was associated with decreased OS (rs139996840).

And there were 27 variants in LRP1. Some had a positive association with OS, and others had a negative association.

Donor variants linked to TRM and DRM

Six variants in the HHAT gene were associated with TRM. Five of the variants appeared to have a protective effect against TRM (rs145455128, rs146916002, rs61744143, rs149597734, and rs145943928). For the other variant (rs141591165), the apparent effect was inconsistent between patient cohorts.

There were 3 variants in LYZL4 associated with DRM. Two were associated with an increased risk of DRM (rs147770623 and rs76947105), and 1 appeared to have a protective effect (rs181886204).

Six variants in NT5E appeared to have a protective effect against DRM (rs200250022, rs200369370, rs41271617, rs200648774, rs144719925, and rs145505137).

The researchers said the variants in NT5E probably reduce the enzyme activity of the gene. This supports preclinical findings showing that targeted blockade of NT5E can slow tumor growth.

“We have just started to uncover the biological relevance of these new and unexpected genes to a patient’s survival after [HSCT],” Dr Zhu said.

“Our findings shed light on new areas that were not considered before, but we need to further replicate and test our findings. We’re hoping that additional studies of this type will continue to discover novel genes leading to improved outcomes for patients.”

New research has revealed a link between rare gene variants and survival after hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT).

Researchers performed exome sequencing in nearly 2500 HSCT recipients and their matched, unrelated donors.

The sequencing revealed several gene variants—in both donors and recipients—that were significantly associated with overall survival (OS), transplant-related mortality (TRM), and disease-related mortality (DRM) after HSCT.

Qianqian Zhu, PhD, of Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center in Buffalo, New York, and her colleagues described these findings in Blood.

The team performed exome sequencing—using the Illumina HumanExome BeadChip—in patients who participated in the DISCOVeRY-BMT study.

This included 2473 HSCT recipients who had acute myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, or myelodysplastic syndromes. It also included 2221 donors who were a 10/10 human leukocyte antigen match for each recipient.

The researchers looked at genetic variants in donors and recipients and assessed the variants’ associations with OS, TRM, and DRM.

Variants in recipients

Analyses revealed an increased risk of TRM when there was a mismatch between donors and recipients for a variant in TEX38—rs200092801. The increased risk was even more pronounced when either the recipient or the donor was female.

Among the recipients mismatched with their donors at rs200092801, every female recipient and every recipient with a female donor died from TRM. In comparison, 44% of the male recipients with male donors died from TRM.

The researchers said the rs200092801 variant may prompt the production of a mutant peptide that can be presented by MHC-I molecules to immune cells to trigger downstream immune response and TRM.

Dr Zhu and her colleagues also identified variants that appeared to have a positive impact on TRM and OS.

Recipients who had any of 6 variants in the gene OR51D1 had a decreased risk of TRM and improved OS.

The variants (rs138224979, rs148606808, rs141786655, rs61745314, rs200394876, and rs149135276) were not associated with DRM, so the researchers concluded that the improvement in OS was driven by protection against TRM.

Donor variants linked to OS

Donors had variants in 4 genes—ALPP, EMID1, SLC44A5, and LRP1—that were associated with OS but not TRM or DRM.

The 3 variants identified in ALPP (rs144454460, rs140078460, and rs142493383) were associated with improved OS.

And the 2 variants in SLC44A5 (rs143004355 and rs149696907) were associated with worse OS.

There were 2 variants in EMID1. One was associated with improved OS (rs34772704), and the other was associated with decreased OS (rs139996840).

And there were 27 variants in LRP1. Some had a positive association with OS, and others had a negative association.

Donor variants linked to TRM and DRM

Six variants in the HHAT gene were associated with TRM. Five of the variants appeared to have a protective effect against TRM (rs145455128, rs146916002, rs61744143, rs149597734, and rs145943928). For the other variant (rs141591165), the apparent effect was inconsistent between patient cohorts.

There were 3 variants in LYZL4 associated with DRM. Two were associated with an increased risk of DRM (rs147770623 and rs76947105), and 1 appeared to have a protective effect (rs181886204).

Six variants in NT5E appeared to have a protective effect against DRM (rs200250022, rs200369370, rs41271617, rs200648774, rs144719925, and rs145505137).

The researchers said the variants in NT5E probably reduce the enzyme activity of the gene. This supports preclinical findings showing that targeted blockade of NT5E can slow tumor growth.

“We have just started to uncover the biological relevance of these new and unexpected genes to a patient’s survival after [HSCT],” Dr Zhu said.

“Our findings shed light on new areas that were not considered before, but we need to further replicate and test our findings. We’re hoping that additional studies of this type will continue to discover novel genes leading to improved outcomes for patients.”

Tazemetostat exhibits antitumor activity in phase 1 trial

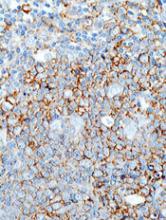

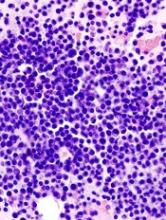

The EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat demonstrated a “favorable safety profile and antitumor activity” in a phase 1 study, according to researchers.

The drug produced responses in 8 of 21 patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), including 3 complete responses (CRs).

The maximum tolerated dose of tazemetostat was not reached, and there were no fatal adverse events (AEs) related to treatment.

Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs included thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, hepatocellular injury, and hypertension.

Antoine Italiano, MD, PhD, of Institut Bergonié in Bordeaux, France, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Oncology. The trial was sponsored by Epizyme and Eisai.

The study enrolled 64 patients—43 with solid tumors and 21 with B-cell NHL. The following characteristics and dosing information pertain only to the patients with NHL.

Thirteen patients had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), 7 had follicular lymphoma (FL), and 1 had marginal zone lymphoma (MZL).

The patients’ median age was 62 (range, 53-70), and 71% were male. They had an ECOG performance status of 0 (62%) or 1 (38%).

Most patients had received at least 3 prior therapies—38% had 3, 14% had 4, and 33% had 5 or more prior therapies. Forty-eight percent had prior hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

The patients received escalating doses of tazemetostat twice daily—100 mg (n=1), 200 mg (n=2), 400 mg (n=1), 800 mg (n=8), and 1600 mg (n=4).

The remaining 5 patients were enrolled in a substudy to evaluate food effect. These patients received a single 200 mg dose on day -8 and day -1, with or without food, followed by 400 mg twice daily starting on day 1. Specific results on the food effects were not included in the paper.

Safety

In the entire study cohort, there was 1 dose-limiting toxicity—grade 4 thrombocytopenia—at the 1600 mg dose. The maximum tolerated dose of tazemetostat was not reached, but the researchers decided upon 800 mg twice daily as the recommended phase 2 dose.

Overall, 77% (n=49) of patients had treatment-related AEs. Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs included thrombocytopenia (4%, n=2), neutropenia (4%, n=2), hepatocellular injury (2%, n=1), and hypertension (2%, n=1).

Serious treatment-related AEs were neutropenia in 1 patient (800 mg group) and anemia and thrombocytopenia in another patient (1600 mg group).

Seven patients (11%) had fatal AEs, but none were considered treatment-related. They included general physical health deterioration (1 at 200 mg, 1 at 1600 mg, and 2 at 400 mg), respiratory distress (2 at 400 mg), and septic shock (1 at 1600 mg).

Efficacy

Eight of the 21 NHL patients responded to treatment. Three patients had a CR—1 with DLBCL and 2 with FL. Of the 5 partial responders, 3 had DLBCL, 1 had FL, and 1 had MZL.

The median time to first response was 3.5 months, and the median duration of response was 12.4 months.

The 3 complete responders remained on tazemetostat beyond 27.6 months (FL patient), 28.8 months (FL patient), and 33.6 months (DLBCL patient).

Two of the 43 patients with solid tumors responded to tazemetostat—1 with a CR and 1 with a partial response.

The complete responder had an INI1-negative malignant rhabdoid tumor, and the partial responder had a SMARCA4-negative malignant rhabdoid tumor of the ovary.

“Today’s publication in The Lancet Oncology reports the safety and tolerability endpoints for tazemetostat in this study, which enabled further evaluation of EZH2 inhibition in INI1- and SMARCA4-negative solid tumors and NHL,” Dr Italiano said. “I’m also encouraged by the preliminary antitumor activity observed in this study.”

The EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat demonstrated a “favorable safety profile and antitumor activity” in a phase 1 study, according to researchers.

The drug produced responses in 8 of 21 patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), including 3 complete responses (CRs).

The maximum tolerated dose of tazemetostat was not reached, and there were no fatal adverse events (AEs) related to treatment.

Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs included thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, hepatocellular injury, and hypertension.

Antoine Italiano, MD, PhD, of Institut Bergonié in Bordeaux, France, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Oncology. The trial was sponsored by Epizyme and Eisai.

The study enrolled 64 patients—43 with solid tumors and 21 with B-cell NHL. The following characteristics and dosing information pertain only to the patients with NHL.

Thirteen patients had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), 7 had follicular lymphoma (FL), and 1 had marginal zone lymphoma (MZL).

The patients’ median age was 62 (range, 53-70), and 71% were male. They had an ECOG performance status of 0 (62%) or 1 (38%).

Most patients had received at least 3 prior therapies—38% had 3, 14% had 4, and 33% had 5 or more prior therapies. Forty-eight percent had prior hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

The patients received escalating doses of tazemetostat twice daily—100 mg (n=1), 200 mg (n=2), 400 mg (n=1), 800 mg (n=8), and 1600 mg (n=4).

The remaining 5 patients were enrolled in a substudy to evaluate food effect. These patients received a single 200 mg dose on day -8 and day -1, with or without food, followed by 400 mg twice daily starting on day 1. Specific results on the food effects were not included in the paper.

Safety

In the entire study cohort, there was 1 dose-limiting toxicity—grade 4 thrombocytopenia—at the 1600 mg dose. The maximum tolerated dose of tazemetostat was not reached, but the researchers decided upon 800 mg twice daily as the recommended phase 2 dose.

Overall, 77% (n=49) of patients had treatment-related AEs. Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs included thrombocytopenia (4%, n=2), neutropenia (4%, n=2), hepatocellular injury (2%, n=1), and hypertension (2%, n=1).

Serious treatment-related AEs were neutropenia in 1 patient (800 mg group) and anemia and thrombocytopenia in another patient (1600 mg group).

Seven patients (11%) had fatal AEs, but none were considered treatment-related. They included general physical health deterioration (1 at 200 mg, 1 at 1600 mg, and 2 at 400 mg), respiratory distress (2 at 400 mg), and septic shock (1 at 1600 mg).

Efficacy

Eight of the 21 NHL patients responded to treatment. Three patients had a CR—1 with DLBCL and 2 with FL. Of the 5 partial responders, 3 had DLBCL, 1 had FL, and 1 had MZL.

The median time to first response was 3.5 months, and the median duration of response was 12.4 months.

The 3 complete responders remained on tazemetostat beyond 27.6 months (FL patient), 28.8 months (FL patient), and 33.6 months (DLBCL patient).

Two of the 43 patients with solid tumors responded to tazemetostat—1 with a CR and 1 with a partial response.

The complete responder had an INI1-negative malignant rhabdoid tumor, and the partial responder had a SMARCA4-negative malignant rhabdoid tumor of the ovary.

“Today’s publication in The Lancet Oncology reports the safety and tolerability endpoints for tazemetostat in this study, which enabled further evaluation of EZH2 inhibition in INI1- and SMARCA4-negative solid tumors and NHL,” Dr Italiano said. “I’m also encouraged by the preliminary antitumor activity observed in this study.”

The EZH2 inhibitor tazemetostat demonstrated a “favorable safety profile and antitumor activity” in a phase 1 study, according to researchers.

The drug produced responses in 8 of 21 patients with relapsed/refractory B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), including 3 complete responses (CRs).

The maximum tolerated dose of tazemetostat was not reached, and there were no fatal adverse events (AEs) related to treatment.

Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs included thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, hepatocellular injury, and hypertension.

Antoine Italiano, MD, PhD, of Institut Bergonié in Bordeaux, France, and his colleagues reported these results in The Lancet Oncology. The trial was sponsored by Epizyme and Eisai.

The study enrolled 64 patients—43 with solid tumors and 21 with B-cell NHL. The following characteristics and dosing information pertain only to the patients with NHL.

Thirteen patients had diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), 7 had follicular lymphoma (FL), and 1 had marginal zone lymphoma (MZL).

The patients’ median age was 62 (range, 53-70), and 71% were male. They had an ECOG performance status of 0 (62%) or 1 (38%).

Most patients had received at least 3 prior therapies—38% had 3, 14% had 4, and 33% had 5 or more prior therapies. Forty-eight percent had prior hematopoietic stem cell transplant.

The patients received escalating doses of tazemetostat twice daily—100 mg (n=1), 200 mg (n=2), 400 mg (n=1), 800 mg (n=8), and 1600 mg (n=4).

The remaining 5 patients were enrolled in a substudy to evaluate food effect. These patients received a single 200 mg dose on day -8 and day -1, with or without food, followed by 400 mg twice daily starting on day 1. Specific results on the food effects were not included in the paper.

Safety

In the entire study cohort, there was 1 dose-limiting toxicity—grade 4 thrombocytopenia—at the 1600 mg dose. The maximum tolerated dose of tazemetostat was not reached, but the researchers decided upon 800 mg twice daily as the recommended phase 2 dose.

Overall, 77% (n=49) of patients had treatment-related AEs. Grade 3/4 treatment-related AEs included thrombocytopenia (4%, n=2), neutropenia (4%, n=2), hepatocellular injury (2%, n=1), and hypertension (2%, n=1).

Serious treatment-related AEs were neutropenia in 1 patient (800 mg group) and anemia and thrombocytopenia in another patient (1600 mg group).

Seven patients (11%) had fatal AEs, but none were considered treatment-related. They included general physical health deterioration (1 at 200 mg, 1 at 1600 mg, and 2 at 400 mg), respiratory distress (2 at 400 mg), and septic shock (1 at 1600 mg).

Efficacy

Eight of the 21 NHL patients responded to treatment. Three patients had a CR—1 with DLBCL and 2 with FL. Of the 5 partial responders, 3 had DLBCL, 1 had FL, and 1 had MZL.

The median time to first response was 3.5 months, and the median duration of response was 12.4 months.

The 3 complete responders remained on tazemetostat beyond 27.6 months (FL patient), 28.8 months (FL patient), and 33.6 months (DLBCL patient).

Two of the 43 patients with solid tumors responded to tazemetostat—1 with a CR and 1 with a partial response.

The complete responder had an INI1-negative malignant rhabdoid tumor, and the partial responder had a SMARCA4-negative malignant rhabdoid tumor of the ovary.

“Today’s publication in The Lancet Oncology reports the safety and tolerability endpoints for tazemetostat in this study, which enabled further evaluation of EZH2 inhibition in INI1- and SMARCA4-negative solid tumors and NHL,” Dr Italiano said. “I’m also encouraged by the preliminary antitumor activity observed in this study.”

Selinexor receives fast track designation for MM

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to selinexor for the treatment of patients with penta-refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The patients must have received at least 3 prior lines of therapy that included an alkylating agent, a glucocorticoid, bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and daratumumab.

In addition, the patients must have disease that is refractory to at least 1 proteasome inhibitor, at least 1 immunomodulatory agent, glucocorticoids, daratumumab, and the patients’ most recent therapy.

“The designation of fast track for selinexor represents important recognition by the FDA of the potential of this anticancer agent to address the significant unmet need in the treatment of patients with penta-refractory myeloma that has continued to progress despite available therapies,” said Sharon Shacham, PhD, founder, president, and chief scientific officer of Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

About selinexor

Selinexor (formerly KPT-330) is a first-in-class, oral selective inhibitor of nuclear export compound.

Selinexor functions by binding with and inhibiting the nuclear export protein XPO1 (also called CRM1), leading to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus. This reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function and is believed to lead to apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

Selinexor is currently being evaluated in several clinical trials across multiple cancer indications.

In the phase 2 STORM trial, researchers are testing selinexor in combination with low-dose dexamethasone for patients with penta-refractory MM. Karyopharm Therapeutics plans to report top-line data from this study at the end of this month.

Trials of selinexor were placed on partial clinical hold in mid-March last year due to a lack of information about serious adverse events. However, the hold was lifted for trials of patients with hematologic malignancies at the end of that same month.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to selinexor for the treatment of patients with penta-refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The patients must have received at least 3 prior lines of therapy that included an alkylating agent, a glucocorticoid, bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and daratumumab.

In addition, the patients must have disease that is refractory to at least 1 proteasome inhibitor, at least 1 immunomodulatory agent, glucocorticoids, daratumumab, and the patients’ most recent therapy.

“The designation of fast track for selinexor represents important recognition by the FDA of the potential of this anticancer agent to address the significant unmet need in the treatment of patients with penta-refractory myeloma that has continued to progress despite available therapies,” said Sharon Shacham, PhD, founder, president, and chief scientific officer of Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

About selinexor

Selinexor (formerly KPT-330) is a first-in-class, oral selective inhibitor of nuclear export compound.

Selinexor functions by binding with and inhibiting the nuclear export protein XPO1 (also called CRM1), leading to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus. This reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function and is believed to lead to apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

Selinexor is currently being evaluated in several clinical trials across multiple cancer indications.

In the phase 2 STORM trial, researchers are testing selinexor in combination with low-dose dexamethasone for patients with penta-refractory MM. Karyopharm Therapeutics plans to report top-line data from this study at the end of this month.

Trials of selinexor were placed on partial clinical hold in mid-March last year due to a lack of information about serious adverse events. However, the hold was lifted for trials of patients with hematologic malignancies at the end of that same month.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted fast track designation to selinexor for the treatment of patients with penta-refractory multiple myeloma (MM).

The patients must have received at least 3 prior lines of therapy that included an alkylating agent, a glucocorticoid, bortezomib, carfilzomib, lenalidomide, pomalidomide, and daratumumab.

In addition, the patients must have disease that is refractory to at least 1 proteasome inhibitor, at least 1 immunomodulatory agent, glucocorticoids, daratumumab, and the patients’ most recent therapy.

“The designation of fast track for selinexor represents important recognition by the FDA of the potential of this anticancer agent to address the significant unmet need in the treatment of patients with penta-refractory myeloma that has continued to progress despite available therapies,” said Sharon Shacham, PhD, founder, president, and chief scientific officer of Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc., the company developing selinexor.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

About selinexor

Selinexor (formerly KPT-330) is a first-in-class, oral selective inhibitor of nuclear export compound.

Selinexor functions by binding with and inhibiting the nuclear export protein XPO1 (also called CRM1), leading to the accumulation of tumor suppressor proteins in the cell nucleus. This reinitiates and amplifies their tumor suppressor function and is believed to lead to apoptosis in cancer cells while largely sparing normal cells.

Selinexor is currently being evaluated in several clinical trials across multiple cancer indications.

In the phase 2 STORM trial, researchers are testing selinexor in combination with low-dose dexamethasone for patients with penta-refractory MM. Karyopharm Therapeutics plans to report top-line data from this study at the end of this month.

Trials of selinexor were placed on partial clinical hold in mid-March last year due to a lack of information about serious adverse events. However, the hold was lifted for trials of patients with hematologic malignancies at the end of that same month.

Caffeine for apnea of prematurity found safe, effective at 11 years

Caffeine for apnea of prematurity was neurobehaviorally safe and significantly improved fine motor coordination, visuomotor integration, visual perception, and visuospatial organization at 11-year follow-up, according to the results of a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial.

“There was little evidence for differences between the caffeine and placebo groups on tests of general intelligence, attention, executive function, and behavior. This highlights the long-term safety and efficacy of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity in very-low-birth-weight neonates,” wrote Ines M. Mürner-Lavanchy, PhD, of Monash University, Clayton, Australia, and her associates. The Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity (CAP) trial, the first to assess long-term neurobehavioral outcomes of neonatal caffeine therapy, was published online April 11 in Pediatrics.

Neonatal caffeine therapy significantly lowered the risk of death before 18 months, cerebral palsy, cognitive delay, severe hearing loss, and bilateral blindness, as has been reported (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1893-902). By 5 years, caffeine no longer showed significant benefits, apart from improved motor performance, Dr. Mürner-Lavanchy and her associates noted.

At 11 years, available data from 870 patients showed generally similar neurobehavioral outcomes between groups, although the caffeine group scored higher on most scales. The most apparent benefits included visuomotor integration (mean difference from placebo, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.0-3.7; P less than .05), visual perception (2.0; 95% CI, 0.3-3.8; P = .02), fine motor coordination (2.9; 95% CI, 0.7-5.1; P = .01), and Rey Complex Figure copy accuracy, a measure of visuospatial organization (1.2; 95% CI, 0.4-2.0; P = .003).

Eleven-year follow-up data were missing for 22% of patients, but their birth characteristics and childhood outcomes resembled those of patients with available data, the investigators said. “Therefore, we are confident that the outcomes of the whole cohort are reflected in the present results with sufficient accuracy.”

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research provided funding. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mürner-Lavanchy IM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4047.

Caffeine for apnea of prematurity was neurobehaviorally safe and significantly improved fine motor coordination, visuomotor integration, visual perception, and visuospatial organization at 11-year follow-up, according to the results of a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial.

“There was little evidence for differences between the caffeine and placebo groups on tests of general intelligence, attention, executive function, and behavior. This highlights the long-term safety and efficacy of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity in very-low-birth-weight neonates,” wrote Ines M. Mürner-Lavanchy, PhD, of Monash University, Clayton, Australia, and her associates. The Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity (CAP) trial, the first to assess long-term neurobehavioral outcomes of neonatal caffeine therapy, was published online April 11 in Pediatrics.

Neonatal caffeine therapy significantly lowered the risk of death before 18 months, cerebral palsy, cognitive delay, severe hearing loss, and bilateral blindness, as has been reported (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1893-902). By 5 years, caffeine no longer showed significant benefits, apart from improved motor performance, Dr. Mürner-Lavanchy and her associates noted.

At 11 years, available data from 870 patients showed generally similar neurobehavioral outcomes between groups, although the caffeine group scored higher on most scales. The most apparent benefits included visuomotor integration (mean difference from placebo, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.0-3.7; P less than .05), visual perception (2.0; 95% CI, 0.3-3.8; P = .02), fine motor coordination (2.9; 95% CI, 0.7-5.1; P = .01), and Rey Complex Figure copy accuracy, a measure of visuospatial organization (1.2; 95% CI, 0.4-2.0; P = .003).

Eleven-year follow-up data were missing for 22% of patients, but their birth characteristics and childhood outcomes resembled those of patients with available data, the investigators said. “Therefore, we are confident that the outcomes of the whole cohort are reflected in the present results with sufficient accuracy.”

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research provided funding. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mürner-Lavanchy IM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4047.

Caffeine for apnea of prematurity was neurobehaviorally safe and significantly improved fine motor coordination, visuomotor integration, visual perception, and visuospatial organization at 11-year follow-up, according to the results of a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial.

“There was little evidence for differences between the caffeine and placebo groups on tests of general intelligence, attention, executive function, and behavior. This highlights the long-term safety and efficacy of caffeine therapy for apnea of prematurity in very-low-birth-weight neonates,” wrote Ines M. Mürner-Lavanchy, PhD, of Monash University, Clayton, Australia, and her associates. The Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity (CAP) trial, the first to assess long-term neurobehavioral outcomes of neonatal caffeine therapy, was published online April 11 in Pediatrics.

Neonatal caffeine therapy significantly lowered the risk of death before 18 months, cerebral palsy, cognitive delay, severe hearing loss, and bilateral blindness, as has been reported (N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1893-902). By 5 years, caffeine no longer showed significant benefits, apart from improved motor performance, Dr. Mürner-Lavanchy and her associates noted.

At 11 years, available data from 870 patients showed generally similar neurobehavioral outcomes between groups, although the caffeine group scored higher on most scales. The most apparent benefits included visuomotor integration (mean difference from placebo, 1.8; 95% confidence interval, 0.0-3.7; P less than .05), visual perception (2.0; 95% CI, 0.3-3.8; P = .02), fine motor coordination (2.9; 95% CI, 0.7-5.1; P = .01), and Rey Complex Figure copy accuracy, a measure of visuospatial organization (1.2; 95% CI, 0.4-2.0; P = .003).

Eleven-year follow-up data were missing for 22% of patients, but their birth characteristics and childhood outcomes resembled those of patients with available data, the investigators said. “Therefore, we are confident that the outcomes of the whole cohort are reflected in the present results with sufficient accuracy.”

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research provided funding. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Mürner-Lavanchy IM et al. Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4047.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 11 years, the caffeine group outperformed the placebo group on measures of fine motor coordination (P = .01), visuomotor integration (P less than .05), visual perception (P = .02), and visuospatial organization (P = .003).

Study details: The Caffeine for Apnea of Prematurity (CAP) trial, a double-blind, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of 870 very-low-birth-weight infants (500-1,250 g).

Disclosures: The Canadian Institutes of Health Research provided funding. The investigators reported having no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Pediatrics. 2018 Apr 11. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-4047.

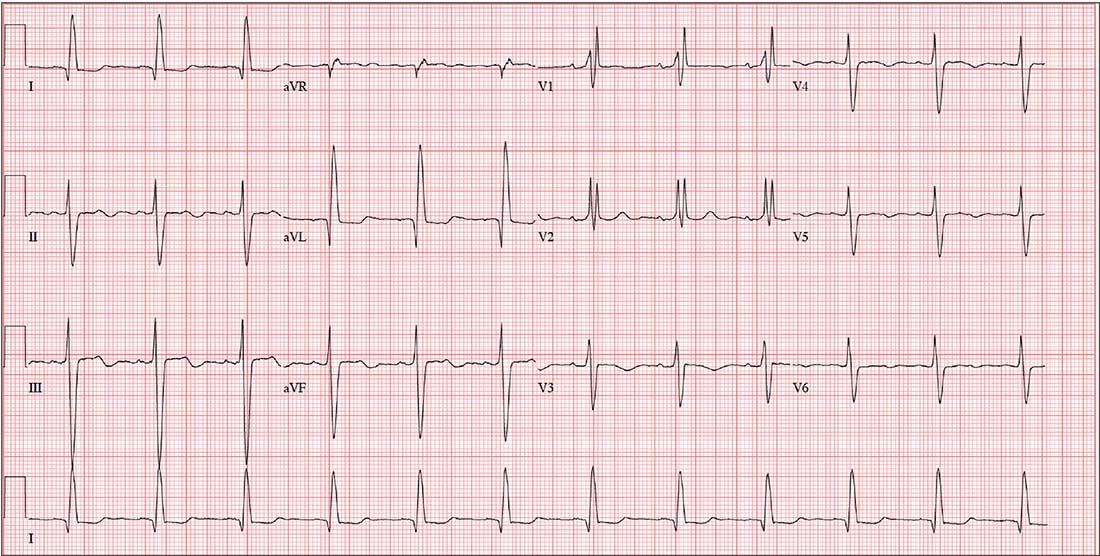

This Evaluation Is a Heart-stopper

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm with left-axis deviation, a right bundle branch block (RBBB), and a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB).

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, with a consistent PR interval and a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min.

A left-axis deviation is indicated by an R-wave axis of –48°, which is less than the upper limit of normal (–30°).

Criteria for an RBBB include a QRS duration ≥ 120 ms with an RSR’ complex in lead V1. A terminal broad S wave in lead I, often seen with RBBB, is not evident in this ECG.

Finally, the criteria for LAFB include S waves > R waves in leads I, II, and aVF, which are well illustrated in this ECG. The combination of an RBBB and an LAFB is consistent with bifascicular block and places the patient at increased risk for complete heart block

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm with left-axis deviation, a right bundle branch block (RBBB), and a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB).

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, with a consistent PR interval and a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min.

A left-axis deviation is indicated by an R-wave axis of –48°, which is less than the upper limit of normal (–30°).

Criteria for an RBBB include a QRS duration ≥ 120 ms with an RSR’ complex in lead V1. A terminal broad S wave in lead I, often seen with RBBB, is not evident in this ECG.

Finally, the criteria for LAFB include S waves > R waves in leads I, II, and aVF, which are well illustrated in this ECG. The combination of an RBBB and an LAFB is consistent with bifascicular block and places the patient at increased risk for complete heart block

ANSWER

The correct interpretation includes normal sinus rhythm with left-axis deviation, a right bundle branch block (RBBB), and a left anterior fascicular block (LAFB).

Normal sinus rhythm is evidenced by a P for every QRS and a QRS for every P, with a consistent PR interval and a rate between 60 and 100 beats/min.

A left-axis deviation is indicated by an R-wave axis of –48°, which is less than the upper limit of normal (–30°).

Criteria for an RBBB include a QRS duration ≥ 120 ms with an RSR’ complex in lead V1. A terminal broad S wave in lead I, often seen with RBBB, is not evident in this ECG.

Finally, the criteria for LAFB include S waves > R waves in leads I, II, and aVF, which are well illustrated in this ECG. The combination of an RBBB and an LAFB is consistent with bifascicular block and places the patient at increased risk for complete heart block

A 79-year-old man with a history of aortic stenosis presents for preoperative evaluation for aortic valve replacement versus transcatheter aortic valve placement. Over the past three months, he has developed worsening shortness of breath, dyspnea on exertion, chest tightness, and lightheadedness, but no frank syncope. One month ago, he was hospitalized for heart failure, which improved with IV diuresis.

An echocardiogram performed one week ago showed an aortic valve area of 0.5 cm, with a peak velocity of 5.4 m/s and a mean gradient of 64 mm Hg. The left ventricular function was normal, with an ejection fraction of 72%. The pulmonary artery pressure measured 40 mm Hg. Other findings included mild-to-moderate mitral and tricuspid valve regurgitation.

Cardiac history is also positive for coronary artery disease, with a recent coronary angiogram showing 60% stenosis in the proximal left anterior descending artery and 80% stenosis of the mid-portion of the right coronary artery.

Medical history is positive for hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and osteoarthritis. Surgical history includes bilateral knee replacements. Current medications include aspirin, furosemide, metformin, atorvastatin, and metoprolol. The patient is allergic to sulfa-containing medications.

Social history reveals that he is a retired police officer who is married and has three adult children. He does not smoke, enjoys an occasional beer, and denies recreational drug use. Family history is notable for coronary artery disease, hypertension, and diabetes.

Review of systems reveals no additional complaints. It is noted that he wears hearing aids and glasses.

Vital signs include a blood pressure of 110/64 mm Hg; pulse, 70 beats/min; and respiratory rate, 14 breaths/min-1. O2 saturation is 96% on room air. His weight is 214 lb and his height, 74 in.

On physical exam, you find a congenial but inquisitive male in no distress, with jugular venous distention at 8 cm, clear lung fields, and a regular heart rate and rhythm. There is a grade 3/6 systolic ejection murmur at the right upper sternal border but no extra heart sounds or rubs. The abdomen is soft and nontender. Peripheral pulses are 2+ bilaterally without femoral bruits, and surgical scars are present over both knees. There is trace pitting edema bilaterally in the lower extremities. The neurologic exam is intact, without focal signs.

An ECG, obtained as part of his preoperative workup, reveals a ventricular rate of 71 beats/min; PR interval, 152 ms; QRS duration, 142 ms; QT/QTc interval, 476/517 ms; P axis, 76°; R axis, –48°; and T axis, 161°. What is your interpretation?

Video: SHM provides resources and community for practice administrators

ORLANDO – In a video interview, Ms. Tiffani Panek, SFHM, CLHM, who is the division manager of administration at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, discussed the scope of SHM resources available for practice administrators.

She details how there are “an incredible number of resources for practice administrators that are available from SHM,” and she recommends the SHM website’s practice administrator’s page, with helpful links, including to their mentorship program. She describes how, just this year, “we are launching a podcast series called ‘The Leadership Launchpad Essentials.’ ”

In addition: “We [also] have our own HMX [Hospital Medicine Exchange] community, and I would say of any resource the practice administrator should access on a regular basis, that would be the one.” That’s the place that practice managers can go to network with their community, according to Ms. Panek.

ORLANDO – In a video interview, Ms. Tiffani Panek, SFHM, CLHM, who is the division manager of administration at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, discussed the scope of SHM resources available for practice administrators.

She details how there are “an incredible number of resources for practice administrators that are available from SHM,” and she recommends the SHM website’s practice administrator’s page, with helpful links, including to their mentorship program. She describes how, just this year, “we are launching a podcast series called ‘The Leadership Launchpad Essentials.’ ”

In addition: “We [also] have our own HMX [Hospital Medicine Exchange] community, and I would say of any resource the practice administrator should access on a regular basis, that would be the one.” That’s the place that practice managers can go to network with their community, according to Ms. Panek.

ORLANDO – In a video interview, Ms. Tiffani Panek, SFHM, CLHM, who is the division manager of administration at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, discussed the scope of SHM resources available for practice administrators.

She details how there are “an incredible number of resources for practice administrators that are available from SHM,” and she recommends the SHM website’s practice administrator’s page, with helpful links, including to their mentorship program. She describes how, just this year, “we are launching a podcast series called ‘The Leadership Launchpad Essentials.’ ”

In addition: “We [also] have our own HMX [Hospital Medicine Exchange] community, and I would say of any resource the practice administrator should access on a regular basis, that would be the one.” That’s the place that practice managers can go to network with their community, according to Ms. Panek.

REPORTING FROM HM18

Tackling gender disparities in hospital medicine

ORLANDO – If you think enough progress is being made to fix gender disparity in medical leadership, consider this observation made in an HM18 session on Tuesday by speaker Elizabeth Harry, MD, SFHM, assistant program director, internal medicine residency: director of wellness, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.*

“One might say, ‘Well, that’s okay, we’ll just let it even itself out. I mean, it’s getting better and we’re getting more women positions of leadership,’ ” she said. “But if we continue at the current rate that we are at, of women getting positions of leadership, we will get gender parity in leadership in 67 years – so the year 2085 ... I’m hoping that we as a group can say, ‘That’s a little too slow for our taste. We would like to accelerate this process a little bit.’ ”

The jarring number came near the start of the “Gender Disparities in Hospital Medicine: Where Do We Stand?” session, in which Dr. Harry explored the ways in which gender disparity manifests itself and coaxed ideas for improvement from the audience.

But that was just one of the jarring numbers. Even though women make up 78% of the health care workforce, only 14% of executive officers are women, Dr. Harry said.

And it’s not that large numbers of women joining the physician workforce is a relatively recent phenomenon. There is close to a 50/50 gender split in medical school applicants, students, and residents. But, after that, the parity falls away. Only 38% of medical school faculty members are women, only 21% of full professors are women, and only 16% of deans (Pediatr Res. 2015 Nov;78[5]:589-93).

“There’s definitely a leaky pipeline here,” Dr. Harry said.

She highlighted the ways in which gender disparity seems to be baked into medical education, research, and culture. One study found that women used professional titles 95% of the time when introducing men at internal medicine grand rounds, compared with 49% when men were introducing women (J Womens Health 2017 May;26[5]:413-9).

In hospital medicine, a 2015 study found that women make $14,000 a year less than men, and about $30,000 less in pediatrics. (J Hosp Med. 2015 Aug;10[8]:486-90).

Dr. Harry told the audience to think about the gender disparity problem in a structured way, similar to a design process, by defining the problem, thinking of ideas, developing prototypes to put those ideas into action, and testing them.

During this session, audience members made some suggestions to simplify some of life’s logistics: creating rooms in which physicians could nurse their babies, with a phone and a laptop to make use of the room more practical; building flexible schedules to allow for picking up children and running errands; and – Dr. Harry’s favorite – installing an Amazon locker at hospitals that would allow doctors to pick up packages and make returns.

One audience member asked why the tenor of the conversation seemed to involve an implicit acceptance that it was up to women to handle errands, wondering, “Why are we anchoring on to that?” Dr. Harry agreed that it is up to each household to decide how to divide those responsibilities, and that, personally, she and her husband divide them evenly.

“So what I want to encourage you to do is actually take one of these prototypes home and try it – and it’s not going to work the first time,” Dr. Harry said. “This is culture change, and culture change is really, really hard. That means it takes time and means you’ll have to knock on lots of doors to get to where you want to be eventually.”

Correction, 4/11/18: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Harry's position at Brigham and Women's.

ORLANDO – If you think enough progress is being made to fix gender disparity in medical leadership, consider this observation made in an HM18 session on Tuesday by speaker Elizabeth Harry, MD, SFHM, assistant program director, internal medicine residency: director of wellness, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.*

“One might say, ‘Well, that’s okay, we’ll just let it even itself out. I mean, it’s getting better and we’re getting more women positions of leadership,’ ” she said. “But if we continue at the current rate that we are at, of women getting positions of leadership, we will get gender parity in leadership in 67 years – so the year 2085 ... I’m hoping that we as a group can say, ‘That’s a little too slow for our taste. We would like to accelerate this process a little bit.’ ”

The jarring number came near the start of the “Gender Disparities in Hospital Medicine: Where Do We Stand?” session, in which Dr. Harry explored the ways in which gender disparity manifests itself and coaxed ideas for improvement from the audience.

But that was just one of the jarring numbers. Even though women make up 78% of the health care workforce, only 14% of executive officers are women, Dr. Harry said.

And it’s not that large numbers of women joining the physician workforce is a relatively recent phenomenon. There is close to a 50/50 gender split in medical school applicants, students, and residents. But, after that, the parity falls away. Only 38% of medical school faculty members are women, only 21% of full professors are women, and only 16% of deans (Pediatr Res. 2015 Nov;78[5]:589-93).

“There’s definitely a leaky pipeline here,” Dr. Harry said.

She highlighted the ways in which gender disparity seems to be baked into medical education, research, and culture. One study found that women used professional titles 95% of the time when introducing men at internal medicine grand rounds, compared with 49% when men were introducing women (J Womens Health 2017 May;26[5]:413-9).

In hospital medicine, a 2015 study found that women make $14,000 a year less than men, and about $30,000 less in pediatrics. (J Hosp Med. 2015 Aug;10[8]:486-90).

Dr. Harry told the audience to think about the gender disparity problem in a structured way, similar to a design process, by defining the problem, thinking of ideas, developing prototypes to put those ideas into action, and testing them.

During this session, audience members made some suggestions to simplify some of life’s logistics: creating rooms in which physicians could nurse their babies, with a phone and a laptop to make use of the room more practical; building flexible schedules to allow for picking up children and running errands; and – Dr. Harry’s favorite – installing an Amazon locker at hospitals that would allow doctors to pick up packages and make returns.

One audience member asked why the tenor of the conversation seemed to involve an implicit acceptance that it was up to women to handle errands, wondering, “Why are we anchoring on to that?” Dr. Harry agreed that it is up to each household to decide how to divide those responsibilities, and that, personally, she and her husband divide them evenly.

“So what I want to encourage you to do is actually take one of these prototypes home and try it – and it’s not going to work the first time,” Dr. Harry said. “This is culture change, and culture change is really, really hard. That means it takes time and means you’ll have to knock on lots of doors to get to where you want to be eventually.”

Correction, 4/11/18: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Harry's position at Brigham and Women's.

ORLANDO – If you think enough progress is being made to fix gender disparity in medical leadership, consider this observation made in an HM18 session on Tuesday by speaker Elizabeth Harry, MD, SFHM, assistant program director, internal medicine residency: director of wellness, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.*

“One might say, ‘Well, that’s okay, we’ll just let it even itself out. I mean, it’s getting better and we’re getting more women positions of leadership,’ ” she said. “But if we continue at the current rate that we are at, of women getting positions of leadership, we will get gender parity in leadership in 67 years – so the year 2085 ... I’m hoping that we as a group can say, ‘That’s a little too slow for our taste. We would like to accelerate this process a little bit.’ ”

The jarring number came near the start of the “Gender Disparities in Hospital Medicine: Where Do We Stand?” session, in which Dr. Harry explored the ways in which gender disparity manifests itself and coaxed ideas for improvement from the audience.

But that was just one of the jarring numbers. Even though women make up 78% of the health care workforce, only 14% of executive officers are women, Dr. Harry said.

And it’s not that large numbers of women joining the physician workforce is a relatively recent phenomenon. There is close to a 50/50 gender split in medical school applicants, students, and residents. But, after that, the parity falls away. Only 38% of medical school faculty members are women, only 21% of full professors are women, and only 16% of deans (Pediatr Res. 2015 Nov;78[5]:589-93).

“There’s definitely a leaky pipeline here,” Dr. Harry said.

She highlighted the ways in which gender disparity seems to be baked into medical education, research, and culture. One study found that women used professional titles 95% of the time when introducing men at internal medicine grand rounds, compared with 49% when men were introducing women (J Womens Health 2017 May;26[5]:413-9).

In hospital medicine, a 2015 study found that women make $14,000 a year less than men, and about $30,000 less in pediatrics. (J Hosp Med. 2015 Aug;10[8]:486-90).

Dr. Harry told the audience to think about the gender disparity problem in a structured way, similar to a design process, by defining the problem, thinking of ideas, developing prototypes to put those ideas into action, and testing them.

During this session, audience members made some suggestions to simplify some of life’s logistics: creating rooms in which physicians could nurse their babies, with a phone and a laptop to make use of the room more practical; building flexible schedules to allow for picking up children and running errands; and – Dr. Harry’s favorite – installing an Amazon locker at hospitals that would allow doctors to pick up packages and make returns.

One audience member asked why the tenor of the conversation seemed to involve an implicit acceptance that it was up to women to handle errands, wondering, “Why are we anchoring on to that?” Dr. Harry agreed that it is up to each household to decide how to divide those responsibilities, and that, personally, she and her husband divide them evenly.

“So what I want to encourage you to do is actually take one of these prototypes home and try it – and it’s not going to work the first time,” Dr. Harry said. “This is culture change, and culture change is really, really hard. That means it takes time and means you’ll have to knock on lots of doors to get to where you want to be eventually.”

Correction, 4/11/18: An earlier version of this article misstated Dr. Harry's position at Brigham and Women's.

REPORTING FROM HM18

How complications drive post-surgery spending upward

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Post-hospital care after major surgery is a significant driver of overall surgery-related spending, and hospitals are focused on reducing this spending as payers move away from the fee-for-service model.

with a trend toward utilizing more expensive inpatient post-acute care and less outpatient care, according to an analysis of more than 700,000 Medicare procedures presented at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

This cross-sectional cohort study involved 707,943 cases in the Medicare database of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), colectomy, and total hip replacement (THR) from January 2009 to June 2012. The study found postoperative complication rates of 32% for CABG, 31% for colectomy, and 5% for THR. Postoperative complications resulted in an additional $4,083 spent on post-acute care following a CABG, an additional $4,049 after a colectomy, and an additional $1,742 after a THR.

This spending followed an increasing utilization of inpatient post-acute care and decreasing use of outpatient settings. “Relative to clinically similar patients with an uncomplicated course, patients who experienced a postoperative complication were more likely to utilize inpatient post-acute care than outpatient care,” Dr. Kanters said. For CABG, utilization rates of inpatient post-acute care increased 9.6% versus a decrease of 10.4% for outpatient post-acute care; for colectomy, inpatient post-acute care utilization increased 7.3% versus a drop of 6.2% for outpatient care; and for THR, inpatient post-acute care utilization rose 5.3% versus a drop of 2.4% for outpatient post-acute care. “The greatest impact is seen in the higher-risk procedures,” Dr. Kanters said.

The complications included cardiopulmonary complications, venous thromboembolism, renal failure, surgical site infections, and postoperative hemorrhage.

“Reductions in post-acute care spending will be central to hospitals’ efforts to reduce episode costs around major surgery,” Dr. Kanters said. “It is understood that complications are associated with increased cost, and this study helps quantify to what degree complications drive differences in spending on post-acute care.”

Hospitals’ efforts to reduce post-acute care spending must focus on preventing complications. “Thus, quality improvement efforts that reduce postoperative complications will be a key component of success in emerging payment reform,” Dr. Kanters noted

Session moderator Courtney Balentine, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, asked Dr. Kanters whether the research considered the incentives hospital systems have for referring patients to their own post-acute care facilities. “Post-acute care association with a single hospital has been documented as a likely incentive for discharge to a non-home destination,” Dr. Kanters replied, which leads to higher utilization of “certain” post-acute care facilities and higher costs. However, she said, this study’s dataset could not parse out that trend. “That’s certainly something that needs to be investigated,” she said.

Dr. Kanters and her coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Source: Kanters AE. Annual Academic Surgical Congress 2018.

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Post-hospital care after major surgery is a significant driver of overall surgery-related spending, and hospitals are focused on reducing this spending as payers move away from the fee-for-service model.

with a trend toward utilizing more expensive inpatient post-acute care and less outpatient care, according to an analysis of more than 700,000 Medicare procedures presented at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

This cross-sectional cohort study involved 707,943 cases in the Medicare database of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), colectomy, and total hip replacement (THR) from January 2009 to June 2012. The study found postoperative complication rates of 32% for CABG, 31% for colectomy, and 5% for THR. Postoperative complications resulted in an additional $4,083 spent on post-acute care following a CABG, an additional $4,049 after a colectomy, and an additional $1,742 after a THR.

This spending followed an increasing utilization of inpatient post-acute care and decreasing use of outpatient settings. “Relative to clinically similar patients with an uncomplicated course, patients who experienced a postoperative complication were more likely to utilize inpatient post-acute care than outpatient care,” Dr. Kanters said. For CABG, utilization rates of inpatient post-acute care increased 9.6% versus a decrease of 10.4% for outpatient post-acute care; for colectomy, inpatient post-acute care utilization increased 7.3% versus a drop of 6.2% for outpatient care; and for THR, inpatient post-acute care utilization rose 5.3% versus a drop of 2.4% for outpatient post-acute care. “The greatest impact is seen in the higher-risk procedures,” Dr. Kanters said.

The complications included cardiopulmonary complications, venous thromboembolism, renal failure, surgical site infections, and postoperative hemorrhage.

“Reductions in post-acute care spending will be central to hospitals’ efforts to reduce episode costs around major surgery,” Dr. Kanters said. “It is understood that complications are associated with increased cost, and this study helps quantify to what degree complications drive differences in spending on post-acute care.”

Hospitals’ efforts to reduce post-acute care spending must focus on preventing complications. “Thus, quality improvement efforts that reduce postoperative complications will be a key component of success in emerging payment reform,” Dr. Kanters noted

Session moderator Courtney Balentine, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, asked Dr. Kanters whether the research considered the incentives hospital systems have for referring patients to their own post-acute care facilities. “Post-acute care association with a single hospital has been documented as a likely incentive for discharge to a non-home destination,” Dr. Kanters replied, which leads to higher utilization of “certain” post-acute care facilities and higher costs. However, she said, this study’s dataset could not parse out that trend. “That’s certainly something that needs to be investigated,” she said.

Dr. Kanters and her coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Source: Kanters AE. Annual Academic Surgical Congress 2018.

JACKSONVILLE, FLA. – Post-hospital care after major surgery is a significant driver of overall surgery-related spending, and hospitals are focused on reducing this spending as payers move away from the fee-for-service model.

with a trend toward utilizing more expensive inpatient post-acute care and less outpatient care, according to an analysis of more than 700,000 Medicare procedures presented at the Association for Academic Surgery/Society of University Surgeons Academic Surgical Congress.

This cross-sectional cohort study involved 707,943 cases in the Medicare database of coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), colectomy, and total hip replacement (THR) from January 2009 to June 2012. The study found postoperative complication rates of 32% for CABG, 31% for colectomy, and 5% for THR. Postoperative complications resulted in an additional $4,083 spent on post-acute care following a CABG, an additional $4,049 after a colectomy, and an additional $1,742 after a THR.

This spending followed an increasing utilization of inpatient post-acute care and decreasing use of outpatient settings. “Relative to clinically similar patients with an uncomplicated course, patients who experienced a postoperative complication were more likely to utilize inpatient post-acute care than outpatient care,” Dr. Kanters said. For CABG, utilization rates of inpatient post-acute care increased 9.6% versus a decrease of 10.4% for outpatient post-acute care; for colectomy, inpatient post-acute care utilization increased 7.3% versus a drop of 6.2% for outpatient care; and for THR, inpatient post-acute care utilization rose 5.3% versus a drop of 2.4% for outpatient post-acute care. “The greatest impact is seen in the higher-risk procedures,” Dr. Kanters said.

The complications included cardiopulmonary complications, venous thromboembolism, renal failure, surgical site infections, and postoperative hemorrhage.

“Reductions in post-acute care spending will be central to hospitals’ efforts to reduce episode costs around major surgery,” Dr. Kanters said. “It is understood that complications are associated with increased cost, and this study helps quantify to what degree complications drive differences in spending on post-acute care.”

Hospitals’ efforts to reduce post-acute care spending must focus on preventing complications. “Thus, quality improvement efforts that reduce postoperative complications will be a key component of success in emerging payment reform,” Dr. Kanters noted

Session moderator Courtney Balentine, MD, of the University of Alabama at Birmingham, asked Dr. Kanters whether the research considered the incentives hospital systems have for referring patients to their own post-acute care facilities. “Post-acute care association with a single hospital has been documented as a likely incentive for discharge to a non-home destination,” Dr. Kanters replied, which leads to higher utilization of “certain” post-acute care facilities and higher costs. However, she said, this study’s dataset could not parse out that trend. “That’s certainly something that needs to be investigated,” she said.

Dr. Kanters and her coauthors had no financial relationships to disclose.

Source: Kanters AE. Annual Academic Surgical Congress 2018.

AT THE ANNUAL ACADEMIC SURGICAL CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Complications after major surgery are a huge driver of increasing post-acute care spending.

Major finding: Complications after major surgery that led to post-acute care increased costs by $4,083 for coronary artery bypass grafting, $4,049 for colectomy, and $1,742 for total hip replacement.

Data source: Cross-sectional cohort study of all Medicare beneficiaries who had coronary artery bypass graft (n = 281,940), colectomy (n = 189,229) and total hip replacement (n = 231,773) between January 2009 and June 2012.

Disclosures: Dr. Kanters and her coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

Source: Kanters AE. Annual Academic Surgical Congress 2018.

Early reading aloud, play reduced hyperactivity at school entry

and had sustained behavioral effects after the program was completed, according to results of a randomized clinical trial.

The Video Interaction Project (VIP), in which parents review and reflect upon recordings of themselves interacting with their children, is a low-cost, scalable intervention that has a “high potential” for enhancing social and emotional development by reducing disruptive behaviors, the study authors reported in Pediatrics.

The study included 675 parent-child dyads enrolled post partum at an urban public hospital serving low-income families. Of that group, 450 families were randomized to the VIP program from 0 to 3 years of age, a control group, or a third group that included a different intervention called Building Blocks that incorporates parenting education newsletters, learning materials, and parent questionnaires.

In the VIP intervention, parent-child dyads participated in up to 15 one-on-one sessions from 2 weeks of age to 3 years. In each 30-minute session, the parent and child were video recorded for 5 minutes of play or shared reading; immediately afterward, the parent would review the video with a bilingual facilitator to identify positive interactions and reflect on them.

As previously reported, the VIP intervention had enhanced children’s social and emotional development. Compared with controls, children in the VIP group had higher scores in imitation/play and attention at the end of the program and lower scores in separation distress, hyperactivity, and externalizing problems, according to investigators.

Now, investigators are reporting results that include a second phase of random assignment to VIP from 3-5 years or a control group. The second-phase VIP intervention included nine 30- to 45-minute sessions enhanced with new strategies designed to support the rapidly emerging developmental capacities of preschoolers, Dr. Mendelsohn and associates said. Ultimately, 252 families completed the 4.5 year assessment.

Those new strategies included building sessions around themes (such as birthday party), incorporation of writing into play (such as party invitations), focusing on story characters’ feelings, and video recording both reading and play, with the story serving as the basis for the play.

The initial VIP 0-3 year intervention and the VIP 3-5 year intervention were both independently associated with improved T-scores at 4.5 years on Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition, rating scales, with Cohen’s d effect sizes ranging from approximately –0.25 to –0.30, according to investigators.

Participating in both VIP interventions was associated with a significant reduction in hyperactivity (effect size, –0.63; P = 0.001), Dr. Mendelsohn and his associates also reported.

Moreover, participation in the first VIP session was associated with a reduction in clinically significant hyperactivity (relative risk reduction, 69%; P = .03), they added.

The cost of the VIP program for 0-3 years is approximately $175-$200 per child per year, including staff, equipment, rent, and other expenses, according to the report, which notes that one interventionist can provide services for 400-500 families.

Taken together, these findings suggest the VIP intervention is a low-cost intervention that may prevent poverty-related disparities, investigators said.

“In this study, we provide strong support for the use of pediatric primary care to promote positive parenting activities such as reading aloud and play and the potential for such programs to promote social-emotional development as reflected through reductions in disruptive behaviors,” they wrote.

Dr. Mendelsohn and his coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; the Tiger Foundation; the Marks Family Foundation; Children of Bellevue; KiDS of New York University Foundation; and Rhodebeck Charitable Trust. Several of the investigators were supported in part by awards or grants.

SOURCE: Mendelsohn AL et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173393.

and had sustained behavioral effects after the program was completed, according to results of a randomized clinical trial.

The Video Interaction Project (VIP), in which parents review and reflect upon recordings of themselves interacting with their children, is a low-cost, scalable intervention that has a “high potential” for enhancing social and emotional development by reducing disruptive behaviors, the study authors reported in Pediatrics.

The study included 675 parent-child dyads enrolled post partum at an urban public hospital serving low-income families. Of that group, 450 families were randomized to the VIP program from 0 to 3 years of age, a control group, or a third group that included a different intervention called Building Blocks that incorporates parenting education newsletters, learning materials, and parent questionnaires.

In the VIP intervention, parent-child dyads participated in up to 15 one-on-one sessions from 2 weeks of age to 3 years. In each 30-minute session, the parent and child were video recorded for 5 minutes of play or shared reading; immediately afterward, the parent would review the video with a bilingual facilitator to identify positive interactions and reflect on them.

As previously reported, the VIP intervention had enhanced children’s social and emotional development. Compared with controls, children in the VIP group had higher scores in imitation/play and attention at the end of the program and lower scores in separation distress, hyperactivity, and externalizing problems, according to investigators.

Now, investigators are reporting results that include a second phase of random assignment to VIP from 3-5 years or a control group. The second-phase VIP intervention included nine 30- to 45-minute sessions enhanced with new strategies designed to support the rapidly emerging developmental capacities of preschoolers, Dr. Mendelsohn and associates said. Ultimately, 252 families completed the 4.5 year assessment.

Those new strategies included building sessions around themes (such as birthday party), incorporation of writing into play (such as party invitations), focusing on story characters’ feelings, and video recording both reading and play, with the story serving as the basis for the play.

The initial VIP 0-3 year intervention and the VIP 3-5 year intervention were both independently associated with improved T-scores at 4.5 years on Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition, rating scales, with Cohen’s d effect sizes ranging from approximately –0.25 to –0.30, according to investigators.

Participating in both VIP interventions was associated with a significant reduction in hyperactivity (effect size, –0.63; P = 0.001), Dr. Mendelsohn and his associates also reported.

Moreover, participation in the first VIP session was associated with a reduction in clinically significant hyperactivity (relative risk reduction, 69%; P = .03), they added.

The cost of the VIP program for 0-3 years is approximately $175-$200 per child per year, including staff, equipment, rent, and other expenses, according to the report, which notes that one interventionist can provide services for 400-500 families.

Taken together, these findings suggest the VIP intervention is a low-cost intervention that may prevent poverty-related disparities, investigators said.

“In this study, we provide strong support for the use of pediatric primary care to promote positive parenting activities such as reading aloud and play and the potential for such programs to promote social-emotional development as reflected through reductions in disruptive behaviors,” they wrote.

Dr. Mendelsohn and his coauthors reported no relevant financial disclosures. The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; the Tiger Foundation; the Marks Family Foundation; Children of Bellevue; KiDS of New York University Foundation; and Rhodebeck Charitable Trust. Several of the investigators were supported in part by awards or grants.

SOURCE: Mendelsohn AL et al. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5):e20173393.

and had sustained behavioral effects after the program was completed, according to results of a randomized clinical trial.

The Video Interaction Project (VIP), in which parents review and reflect upon recordings of themselves interacting with their children, is a low-cost, scalable intervention that has a “high potential” for enhancing social and emotional development by reducing disruptive behaviors, the study authors reported in Pediatrics.

The study included 675 parent-child dyads enrolled post partum at an urban public hospital serving low-income families. Of that group, 450 families were randomized to the VIP program from 0 to 3 years of age, a control group, or a third group that included a different intervention called Building Blocks that incorporates parenting education newsletters, learning materials, and parent questionnaires.

In the VIP intervention, parent-child dyads participated in up to 15 one-on-one sessions from 2 weeks of age to 3 years. In each 30-minute session, the parent and child were video recorded for 5 minutes of play or shared reading; immediately afterward, the parent would review the video with a bilingual facilitator to identify positive interactions and reflect on them.