User login

Perception of Resources Spent on Defensive Medicine and History of Being Sued Among Hospitalists: Results from a National Survey

Annual healthcare costs in the United States are over $3 trillion and are garnering significant national attention.1 The United States spends approximately 2.5 times more per capita on healthcare when compared to other developed nations.2 One source of unnecessary cost in healthcare is defensive medicine. Defensive medicine has been defined by Congress as occurring “when doctors order tests, procedures, or visits, or avoid certain high-risk patients or procedures, primarily (but not necessarily) because of concern about malpractice liability.”3

Though difficult to assess, in 1 study, defensive medicine was estimated to cost $45 billion annually.4 While general agreement exists that physicians practice defensive medicine, the extent of defensive practices and the subsequent impact on healthcare costs remain unclear. This is especially true for a group of clinicians that is rapidly increasing in number: hospitalists. Currently, there are more than 50,000 hospitalists in the United States,5 yet the prevalence of defensive medicine in this relatively new specialty is unknown. Inpatient care is complex and time constraints can impede establishing an optimal therapeutic relationship with the patient, potentially raising liability fears. We therefore sought to quantify hospitalist physician estimates of the cost of defensive medicine and assess correlates of their estimates. As being sued might spur defensive behaviors, we also assessed how many hospitalists reported being sued and whether this was associated with their estimates of defensive medicine.

METHODS

Survey Questionnaire

In a previously published survey-based analysis, we reported on physician practice and overuse for 2 common scenarios in hospital medicine: preoperative evaluation and management of uncomplicated syncope.6 After responding to the vignettes, each physician was asked to provide demographic and employment information and malpractice history. In addition, they were asked the following: In your best estimation, what percentage of healthcare-related resources (eg, hospital admissions, diagnostic testing, treatment) are spent purely because of defensive medicine concerns? __________% resources

Survey Sample & Administration

The survey was sent to a sample of 1753 hospitalists, randomly identified through the Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM) database of members and annual meeting attendees. It is estimated that almost 30% of practicing hospitalists in the United States are members of the SHM.5 A full description of the sampling methodology was previously published.6 Selected hospitalists were mailed surveys, a $20 financial incentive, and subsequent reminders between June and October 2011.

The study was exempted from institutional review board review by the University of Michigan and the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

Variables

The primary outcome of interest was the response to the “% resources” estimated to be spent on defensive medicine. This was analyzed as a continuous variable. Independent variables included the following: VA employment, malpractice insurance payer, employer, history of malpractice lawsuit, sex, race, and years practicing as a physician.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Descriptive statistics were first calculated for all variables. Next, bivariable comparisons between the outcome variables and other variables of interest were performed. Multivariable comparisons were made using linear regression for the outcome of estimated resources spent on defensive medicine. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 1753 surveys mailed, 253 were excluded due to incorrect addresses or because the recipients were not practicing hospitalists. A total of 1020 were completed and returned, yielding a 68% response rate (1020 out of 1500 eligible). The hospitalist respondents were in practice for an average of 11 years (range 1-40 years). Respondents represented all 50 states and had a diverse background of experience and demographic characteristics, which has been previously described.6

Resources Estimated Spent on Defensive Medicine

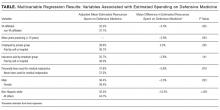

Hospitalists reported, on average, that they believed defensive medicine accounted for 37.5% (standard deviation, 20.2%) of all healthcare spending. Results from the multivariable regression are presented in the Table. Hospitalists affiliated with a VA hospital reported 5.5% less in resources spent on defensive medicine than those not affiliated with a VA hospital (32.2% VA vs 37.7% non-VA, P = 0.025). For every 10 years in practice, the estimate of resources spent on defensive medicine decreased by 3% (P = 0.003). Those who were male (36.4% male vs 39.4% female, P = 0.023) and non-Hispanic white (32.5% non-Hispanic white vs 44.7% other, P ≤ 0.001) also estimated less resources spent on defensive medicine. We did not find an association between a hospitalist reporting being sued and their perception of resources spent on defensive medicine.

Risk of Being Sued

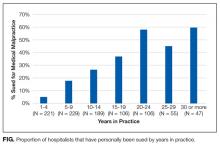

Over a quarter of our sample (25.6%) reported having been sued at least once for medical malpractice. The proportion of hospitalists that reported a history of being sued generally increased with more years of practice (Figure). For those who had been in practice for at least 20 years, more than half (55%) had been sued at least once during their career.

DISCUSSION

In a national survey, hospitalists estimated that almost 40% of all healthcare-related resources are spent purely because of defensive medicine concerns. This estimate was affected by personal demographic and employment factors. Our second major finding is that over one-quarter of a large random sample of hospitalist physicians reported being sued for malpractice.

Hospitalist perceptions of defensive medicine varied significantly based on employment at a VA hospital, with VA-affiliated hospitalists reporting less estimated spending on defensive medicine. This effect may reflect a less litigious environment within the VA, even though physicians practicing within the VA can be reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank.7 The different environment may be due to the VA’s patient mix (VA patients tend to be poorer, older, sicker, and have more mental illness)8; however, it could also be due to its de facto practice of a form of enterprise liability, in which, by law, the VA assumes responsibility for negligence, sheltering its physicians from direct liability.

We also found that the higher the number of years a hospitalist reported practicing, the lower the perception of resources being spent on defensive medicine. The reason for this finding is unclear. There has been a recent focus on high-value care and overspending, and perhaps younger hospitalists are more aware of these initiatives and thus have higher estimates. Additionally, non-Hispanic white male respondents estimated a lower amount spent on defensive medicine compared with other respondents. This is consistent with previous studies of risk perception which have noted a “white male effect” in which white males generally perceive a wide range of risks to be lower than female and non-white individuals, likely due to sociopolitical factors.9 Here, the white male effect is particularly interesting, considering that male physicians are almost 2.5 times as likely as female physicians to report being sued.10

Similar to prior studies,11 there was no association with personal liability claim experience and perceived resources spent on defensive medicine. It is unclear why personal experience of being sued does not appear to be associated with perceptions of defensive medicine practice. It is possible that the fear of being sued is worse than the actual experience or that physicians believe that lawsuits are either random events or inevitable and, as a result, do not change their practice patterns.

The lifetime risk of being named in a malpractice suit is substantial for hospitalists: in our study, over half of hospitalists in practice for 20 years or more reported they had been sued. This corresponds with the projection made by Jena and colleagues,12 which estimated that 55% of internal medicine physicians will be sued by the age of 45, a number just slightly higher than the average for all physicians.

Our study has important limitations. Our sample was of hospitalists and therefore may not be reflective of other medical specialties. Second, due to the nature of the study design, the responses to spending on defensive medicine may not represent actual practice. Third, we did not confirm details such as place of employment or history of lawsuit, and this may be subject to recall bias. However, physicians are unlikely to forget having been sued. Finally, this survey is observational and cross-sectional. Our data imply association rather than causation. Without longitudinal data, it is impossible to know if years of practice correlate with perceived defensive medicine spending due to a generational effect or a longitudinal effect (such as more confidence in diagnostic skills with more years of practice).

Despite these limitations, our survey has important policy implications. First, we found that defensive medicine is perceived by hospitalists to be costly. Although physicians likely overestimated the cost (37.5%, or an estimated $1 trillion is far higher than previous estimates of approximately 2% of all healthcare spending),4 it also demonstrates the extent to which physicians feel as though the medical care that is provided may be unnecessary. Second, at least a quarter of hospitalist physicians have been sued, and the risk of being named as a defendant in a lawsuit increases the longer they have been in clinical practice.

Given these findings, policies aimed to reduce the practice of defensive medicine may help the rising costs of healthcare. Reducing defensive medicine requires decreasing physician fears of liability and related reporting. Traditional tort reforms (with the exception of damage caps) have not been proven to do this. And damage caps can be inequitable, hard to pass, and even found to be unconstitutional in some states.13 However, other reform options hold promise in reducing liability fears, including enterprise liability, safe harbor legislation, and health courts.13 Finally, shared decision-making models may also provide a method to reduce defensive fears as well.6

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Society of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Scott Flanders, Andrew Hickner, and David Ratz for their assistance with this project.

Disclosure

The authors received financial support from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation, the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center for Clinical Management Research, the University of Michigan Specialist-Hospitalist Allied Research Program, and the Ann Arbor University of Michigan VA Patient Safety Enhancement Program.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the Society of Hospital Medicine.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditures 2014 Highlights. 2015; https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html. Accessed on July 28, 2016.

2. OECD. Health expenditure per capita. Health at a Glance 2015. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2015.

3. U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. Defensive Medicine and Medical Malpractice. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; July 1994. OTA-H-602.

4. Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1569-1577. PubMed

5. Society of Hospital Medicine. Society of Hospital Medicine: Membership. 2017; http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Membership/Web/Membership/Membership_Landing_Page.aspx?hkey=97f40c85-fdcd-411f-b3f6-e617bc38a2c5. Accessed on January 5, 2017.

6. Kachalia A, Berg A, Fagerlin A, et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):100-108. PubMed

7. Pugatch MB. Federal tort claims and military medical malpractice. J Legal Nurse Consulting. 2008;19(2):3-6.

8. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown K, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2015. PubMed

9. Finucane ML, Slovic P, Mertz CK, Flynn J, Satterfield TA. Gender, race, and perceived risk: the ‘white male’ effect. Health, Risk & Society. 2000;2(2):159-172.

10. Unwin E, Woolf K, Wadlow C, Potts HW, Dacre J. Sex differences in medico-legal action against doctors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2015;13:172. PubMed

11. Glassman PA, Rolph JE, Petersen LP, Bradley MA, Kravitz RL. Physicians’ personal malpractice experiences are not related to defensive clinical practices. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1996;21(2):219-241. PubMed

12. Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629-636. PubMed

13. Mello MM, Studdert DM, Kachalia A. The medical liability climate and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2014;312(20):2146-2155. PubMed

Annual healthcare costs in the United States are over $3 trillion and are garnering significant national attention.1 The United States spends approximately 2.5 times more per capita on healthcare when compared to other developed nations.2 One source of unnecessary cost in healthcare is defensive medicine. Defensive medicine has been defined by Congress as occurring “when doctors order tests, procedures, or visits, or avoid certain high-risk patients or procedures, primarily (but not necessarily) because of concern about malpractice liability.”3

Though difficult to assess, in 1 study, defensive medicine was estimated to cost $45 billion annually.4 While general agreement exists that physicians practice defensive medicine, the extent of defensive practices and the subsequent impact on healthcare costs remain unclear. This is especially true for a group of clinicians that is rapidly increasing in number: hospitalists. Currently, there are more than 50,000 hospitalists in the United States,5 yet the prevalence of defensive medicine in this relatively new specialty is unknown. Inpatient care is complex and time constraints can impede establishing an optimal therapeutic relationship with the patient, potentially raising liability fears. We therefore sought to quantify hospitalist physician estimates of the cost of defensive medicine and assess correlates of their estimates. As being sued might spur defensive behaviors, we also assessed how many hospitalists reported being sued and whether this was associated with their estimates of defensive medicine.

METHODS

Survey Questionnaire

In a previously published survey-based analysis, we reported on physician practice and overuse for 2 common scenarios in hospital medicine: preoperative evaluation and management of uncomplicated syncope.6 After responding to the vignettes, each physician was asked to provide demographic and employment information and malpractice history. In addition, they were asked the following: In your best estimation, what percentage of healthcare-related resources (eg, hospital admissions, diagnostic testing, treatment) are spent purely because of defensive medicine concerns? __________% resources

Survey Sample & Administration

The survey was sent to a sample of 1753 hospitalists, randomly identified through the Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM) database of members and annual meeting attendees. It is estimated that almost 30% of practicing hospitalists in the United States are members of the SHM.5 A full description of the sampling methodology was previously published.6 Selected hospitalists were mailed surveys, a $20 financial incentive, and subsequent reminders between June and October 2011.

The study was exempted from institutional review board review by the University of Michigan and the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

Variables

The primary outcome of interest was the response to the “% resources” estimated to be spent on defensive medicine. This was analyzed as a continuous variable. Independent variables included the following: VA employment, malpractice insurance payer, employer, history of malpractice lawsuit, sex, race, and years practicing as a physician.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Descriptive statistics were first calculated for all variables. Next, bivariable comparisons between the outcome variables and other variables of interest were performed. Multivariable comparisons were made using linear regression for the outcome of estimated resources spent on defensive medicine. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 1753 surveys mailed, 253 were excluded due to incorrect addresses or because the recipients were not practicing hospitalists. A total of 1020 were completed and returned, yielding a 68% response rate (1020 out of 1500 eligible). The hospitalist respondents were in practice for an average of 11 years (range 1-40 years). Respondents represented all 50 states and had a diverse background of experience and demographic characteristics, which has been previously described.6

Resources Estimated Spent on Defensive Medicine

Hospitalists reported, on average, that they believed defensive medicine accounted for 37.5% (standard deviation, 20.2%) of all healthcare spending. Results from the multivariable regression are presented in the Table. Hospitalists affiliated with a VA hospital reported 5.5% less in resources spent on defensive medicine than those not affiliated with a VA hospital (32.2% VA vs 37.7% non-VA, P = 0.025). For every 10 years in practice, the estimate of resources spent on defensive medicine decreased by 3% (P = 0.003). Those who were male (36.4% male vs 39.4% female, P = 0.023) and non-Hispanic white (32.5% non-Hispanic white vs 44.7% other, P ≤ 0.001) also estimated less resources spent on defensive medicine. We did not find an association between a hospitalist reporting being sued and their perception of resources spent on defensive medicine.

Risk of Being Sued

Over a quarter of our sample (25.6%) reported having been sued at least once for medical malpractice. The proportion of hospitalists that reported a history of being sued generally increased with more years of practice (Figure). For those who had been in practice for at least 20 years, more than half (55%) had been sued at least once during their career.

DISCUSSION

In a national survey, hospitalists estimated that almost 40% of all healthcare-related resources are spent purely because of defensive medicine concerns. This estimate was affected by personal demographic and employment factors. Our second major finding is that over one-quarter of a large random sample of hospitalist physicians reported being sued for malpractice.

Hospitalist perceptions of defensive medicine varied significantly based on employment at a VA hospital, with VA-affiliated hospitalists reporting less estimated spending on defensive medicine. This effect may reflect a less litigious environment within the VA, even though physicians practicing within the VA can be reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank.7 The different environment may be due to the VA’s patient mix (VA patients tend to be poorer, older, sicker, and have more mental illness)8; however, it could also be due to its de facto practice of a form of enterprise liability, in which, by law, the VA assumes responsibility for negligence, sheltering its physicians from direct liability.

We also found that the higher the number of years a hospitalist reported practicing, the lower the perception of resources being spent on defensive medicine. The reason for this finding is unclear. There has been a recent focus on high-value care and overspending, and perhaps younger hospitalists are more aware of these initiatives and thus have higher estimates. Additionally, non-Hispanic white male respondents estimated a lower amount spent on defensive medicine compared with other respondents. This is consistent with previous studies of risk perception which have noted a “white male effect” in which white males generally perceive a wide range of risks to be lower than female and non-white individuals, likely due to sociopolitical factors.9 Here, the white male effect is particularly interesting, considering that male physicians are almost 2.5 times as likely as female physicians to report being sued.10

Similar to prior studies,11 there was no association with personal liability claim experience and perceived resources spent on defensive medicine. It is unclear why personal experience of being sued does not appear to be associated with perceptions of defensive medicine practice. It is possible that the fear of being sued is worse than the actual experience or that physicians believe that lawsuits are either random events or inevitable and, as a result, do not change their practice patterns.

The lifetime risk of being named in a malpractice suit is substantial for hospitalists: in our study, over half of hospitalists in practice for 20 years or more reported they had been sued. This corresponds with the projection made by Jena and colleagues,12 which estimated that 55% of internal medicine physicians will be sued by the age of 45, a number just slightly higher than the average for all physicians.

Our study has important limitations. Our sample was of hospitalists and therefore may not be reflective of other medical specialties. Second, due to the nature of the study design, the responses to spending on defensive medicine may not represent actual practice. Third, we did not confirm details such as place of employment or history of lawsuit, and this may be subject to recall bias. However, physicians are unlikely to forget having been sued. Finally, this survey is observational and cross-sectional. Our data imply association rather than causation. Without longitudinal data, it is impossible to know if years of practice correlate with perceived defensive medicine spending due to a generational effect or a longitudinal effect (such as more confidence in diagnostic skills with more years of practice).

Despite these limitations, our survey has important policy implications. First, we found that defensive medicine is perceived by hospitalists to be costly. Although physicians likely overestimated the cost (37.5%, or an estimated $1 trillion is far higher than previous estimates of approximately 2% of all healthcare spending),4 it also demonstrates the extent to which physicians feel as though the medical care that is provided may be unnecessary. Second, at least a quarter of hospitalist physicians have been sued, and the risk of being named as a defendant in a lawsuit increases the longer they have been in clinical practice.

Given these findings, policies aimed to reduce the practice of defensive medicine may help the rising costs of healthcare. Reducing defensive medicine requires decreasing physician fears of liability and related reporting. Traditional tort reforms (with the exception of damage caps) have not been proven to do this. And damage caps can be inequitable, hard to pass, and even found to be unconstitutional in some states.13 However, other reform options hold promise in reducing liability fears, including enterprise liability, safe harbor legislation, and health courts.13 Finally, shared decision-making models may also provide a method to reduce defensive fears as well.6

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Society of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Scott Flanders, Andrew Hickner, and David Ratz for their assistance with this project.

Disclosure

The authors received financial support from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation, the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center for Clinical Management Research, the University of Michigan Specialist-Hospitalist Allied Research Program, and the Ann Arbor University of Michigan VA Patient Safety Enhancement Program.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the Society of Hospital Medicine.

Annual healthcare costs in the United States are over $3 trillion and are garnering significant national attention.1 The United States spends approximately 2.5 times more per capita on healthcare when compared to other developed nations.2 One source of unnecessary cost in healthcare is defensive medicine. Defensive medicine has been defined by Congress as occurring “when doctors order tests, procedures, or visits, or avoid certain high-risk patients or procedures, primarily (but not necessarily) because of concern about malpractice liability.”3

Though difficult to assess, in 1 study, defensive medicine was estimated to cost $45 billion annually.4 While general agreement exists that physicians practice defensive medicine, the extent of defensive practices and the subsequent impact on healthcare costs remain unclear. This is especially true for a group of clinicians that is rapidly increasing in number: hospitalists. Currently, there are more than 50,000 hospitalists in the United States,5 yet the prevalence of defensive medicine in this relatively new specialty is unknown. Inpatient care is complex and time constraints can impede establishing an optimal therapeutic relationship with the patient, potentially raising liability fears. We therefore sought to quantify hospitalist physician estimates of the cost of defensive medicine and assess correlates of their estimates. As being sued might spur defensive behaviors, we also assessed how many hospitalists reported being sued and whether this was associated with their estimates of defensive medicine.

METHODS

Survey Questionnaire

In a previously published survey-based analysis, we reported on physician practice and overuse for 2 common scenarios in hospital medicine: preoperative evaluation and management of uncomplicated syncope.6 After responding to the vignettes, each physician was asked to provide demographic and employment information and malpractice history. In addition, they were asked the following: In your best estimation, what percentage of healthcare-related resources (eg, hospital admissions, diagnostic testing, treatment) are spent purely because of defensive medicine concerns? __________% resources

Survey Sample & Administration

The survey was sent to a sample of 1753 hospitalists, randomly identified through the Society of Hospital Medicine’s (SHM) database of members and annual meeting attendees. It is estimated that almost 30% of practicing hospitalists in the United States are members of the SHM.5 A full description of the sampling methodology was previously published.6 Selected hospitalists were mailed surveys, a $20 financial incentive, and subsequent reminders between June and October 2011.

The study was exempted from institutional review board review by the University of Michigan and the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System.

Variables

The primary outcome of interest was the response to the “% resources” estimated to be spent on defensive medicine. This was analyzed as a continuous variable. Independent variables included the following: VA employment, malpractice insurance payer, employer, history of malpractice lawsuit, sex, race, and years practicing as a physician.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Descriptive statistics were first calculated for all variables. Next, bivariable comparisons between the outcome variables and other variables of interest were performed. Multivariable comparisons were made using linear regression for the outcome of estimated resources spent on defensive medicine. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Of the 1753 surveys mailed, 253 were excluded due to incorrect addresses or because the recipients were not practicing hospitalists. A total of 1020 were completed and returned, yielding a 68% response rate (1020 out of 1500 eligible). The hospitalist respondents were in practice for an average of 11 years (range 1-40 years). Respondents represented all 50 states and had a diverse background of experience and demographic characteristics, which has been previously described.6

Resources Estimated Spent on Defensive Medicine

Hospitalists reported, on average, that they believed defensive medicine accounted for 37.5% (standard deviation, 20.2%) of all healthcare spending. Results from the multivariable regression are presented in the Table. Hospitalists affiliated with a VA hospital reported 5.5% less in resources spent on defensive medicine than those not affiliated with a VA hospital (32.2% VA vs 37.7% non-VA, P = 0.025). For every 10 years in practice, the estimate of resources spent on defensive medicine decreased by 3% (P = 0.003). Those who were male (36.4% male vs 39.4% female, P = 0.023) and non-Hispanic white (32.5% non-Hispanic white vs 44.7% other, P ≤ 0.001) also estimated less resources spent on defensive medicine. We did not find an association between a hospitalist reporting being sued and their perception of resources spent on defensive medicine.

Risk of Being Sued

Over a quarter of our sample (25.6%) reported having been sued at least once for medical malpractice. The proportion of hospitalists that reported a history of being sued generally increased with more years of practice (Figure). For those who had been in practice for at least 20 years, more than half (55%) had been sued at least once during their career.

DISCUSSION

In a national survey, hospitalists estimated that almost 40% of all healthcare-related resources are spent purely because of defensive medicine concerns. This estimate was affected by personal demographic and employment factors. Our second major finding is that over one-quarter of a large random sample of hospitalist physicians reported being sued for malpractice.

Hospitalist perceptions of defensive medicine varied significantly based on employment at a VA hospital, with VA-affiliated hospitalists reporting less estimated spending on defensive medicine. This effect may reflect a less litigious environment within the VA, even though physicians practicing within the VA can be reported to the National Practitioner Data Bank.7 The different environment may be due to the VA’s patient mix (VA patients tend to be poorer, older, sicker, and have more mental illness)8; however, it could also be due to its de facto practice of a form of enterprise liability, in which, by law, the VA assumes responsibility for negligence, sheltering its physicians from direct liability.

We also found that the higher the number of years a hospitalist reported practicing, the lower the perception of resources being spent on defensive medicine. The reason for this finding is unclear. There has been a recent focus on high-value care and overspending, and perhaps younger hospitalists are more aware of these initiatives and thus have higher estimates. Additionally, non-Hispanic white male respondents estimated a lower amount spent on defensive medicine compared with other respondents. This is consistent with previous studies of risk perception which have noted a “white male effect” in which white males generally perceive a wide range of risks to be lower than female and non-white individuals, likely due to sociopolitical factors.9 Here, the white male effect is particularly interesting, considering that male physicians are almost 2.5 times as likely as female physicians to report being sued.10

Similar to prior studies,11 there was no association with personal liability claim experience and perceived resources spent on defensive medicine. It is unclear why personal experience of being sued does not appear to be associated with perceptions of defensive medicine practice. It is possible that the fear of being sued is worse than the actual experience or that physicians believe that lawsuits are either random events or inevitable and, as a result, do not change their practice patterns.

The lifetime risk of being named in a malpractice suit is substantial for hospitalists: in our study, over half of hospitalists in practice for 20 years or more reported they had been sued. This corresponds with the projection made by Jena and colleagues,12 which estimated that 55% of internal medicine physicians will be sued by the age of 45, a number just slightly higher than the average for all physicians.

Our study has important limitations. Our sample was of hospitalists and therefore may not be reflective of other medical specialties. Second, due to the nature of the study design, the responses to spending on defensive medicine may not represent actual practice. Third, we did not confirm details such as place of employment or history of lawsuit, and this may be subject to recall bias. However, physicians are unlikely to forget having been sued. Finally, this survey is observational and cross-sectional. Our data imply association rather than causation. Without longitudinal data, it is impossible to know if years of practice correlate with perceived defensive medicine spending due to a generational effect or a longitudinal effect (such as more confidence in diagnostic skills with more years of practice).

Despite these limitations, our survey has important policy implications. First, we found that defensive medicine is perceived by hospitalists to be costly. Although physicians likely overestimated the cost (37.5%, or an estimated $1 trillion is far higher than previous estimates of approximately 2% of all healthcare spending),4 it also demonstrates the extent to which physicians feel as though the medical care that is provided may be unnecessary. Second, at least a quarter of hospitalist physicians have been sued, and the risk of being named as a defendant in a lawsuit increases the longer they have been in clinical practice.

Given these findings, policies aimed to reduce the practice of defensive medicine may help the rising costs of healthcare. Reducing defensive medicine requires decreasing physician fears of liability and related reporting. Traditional tort reforms (with the exception of damage caps) have not been proven to do this. And damage caps can be inequitable, hard to pass, and even found to be unconstitutional in some states.13 However, other reform options hold promise in reducing liability fears, including enterprise liability, safe harbor legislation, and health courts.13 Finally, shared decision-making models may also provide a method to reduce defensive fears as well.6

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Society of Hospital Medicine, Dr. Scott Flanders, Andrew Hickner, and David Ratz for their assistance with this project.

Disclosure

The authors received financial support from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation, the Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Center for Clinical Management Research, the University of Michigan Specialist-Hospitalist Allied Research Program, and the Ann Arbor University of Michigan VA Patient Safety Enhancement Program.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Foundation, the Department of Veterans Affairs, or the Society of Hospital Medicine.

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditures 2014 Highlights. 2015; https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html. Accessed on July 28, 2016.

2. OECD. Health expenditure per capita. Health at a Glance 2015. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2015.

3. U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. Defensive Medicine and Medical Malpractice. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; July 1994. OTA-H-602.

4. Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1569-1577. PubMed

5. Society of Hospital Medicine. Society of Hospital Medicine: Membership. 2017; http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Membership/Web/Membership/Membership_Landing_Page.aspx?hkey=97f40c85-fdcd-411f-b3f6-e617bc38a2c5. Accessed on January 5, 2017.

6. Kachalia A, Berg A, Fagerlin A, et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):100-108. PubMed

7. Pugatch MB. Federal tort claims and military medical malpractice. J Legal Nurse Consulting. 2008;19(2):3-6.

8. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown K, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2015. PubMed

9. Finucane ML, Slovic P, Mertz CK, Flynn J, Satterfield TA. Gender, race, and perceived risk: the ‘white male’ effect. Health, Risk & Society. 2000;2(2):159-172.

10. Unwin E, Woolf K, Wadlow C, Potts HW, Dacre J. Sex differences in medico-legal action against doctors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2015;13:172. PubMed

11. Glassman PA, Rolph JE, Petersen LP, Bradley MA, Kravitz RL. Physicians’ personal malpractice experiences are not related to defensive clinical practices. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1996;21(2):219-241. PubMed

12. Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629-636. PubMed

13. Mello MM, Studdert DM, Kachalia A. The medical liability climate and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2014;312(20):2146-2155. PubMed

1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National Health Expenditures 2014 Highlights. 2015; https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html. Accessed on July 28, 2016.

2. OECD. Health expenditure per capita. Health at a Glance 2015. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2015.

3. U.S. Congress, Office of Technology Assessment. Defensive Medicine and Medical Malpractice. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; July 1994. OTA-H-602.

4. Mello MM, Chandra A, Gawande AA, Studdert DM. National costs of the medical liability system. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1569-1577. PubMed

5. Society of Hospital Medicine. Society of Hospital Medicine: Membership. 2017; http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Web/Membership/Web/Membership/Membership_Landing_Page.aspx?hkey=97f40c85-fdcd-411f-b3f6-e617bc38a2c5. Accessed on January 5, 2017.

6. Kachalia A, Berg A, Fagerlin A, et al. Overuse of testing in preoperative evaluation and syncope: a survey of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(2):100-108. PubMed

7. Pugatch MB. Federal tort claims and military medical malpractice. J Legal Nurse Consulting. 2008;19(2):3-6.

8. Eibner C, Krull H, Brown K, et al. Current and projected characteristics and unique health care needs of the patient population served by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2015. PubMed

9. Finucane ML, Slovic P, Mertz CK, Flynn J, Satterfield TA. Gender, race, and perceived risk: the ‘white male’ effect. Health, Risk & Society. 2000;2(2):159-172.

10. Unwin E, Woolf K, Wadlow C, Potts HW, Dacre J. Sex differences in medico-legal action against doctors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2015;13:172. PubMed

11. Glassman PA, Rolph JE, Petersen LP, Bradley MA, Kravitz RL. Physicians’ personal malpractice experiences are not related to defensive clinical practices. J Health Polit Policy Law. 1996;21(2):219-241. PubMed

12. Jena AB, Seabury S, Lakdawalla D, Chandra A. Malpractice risk according to physician specialty. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(7):629-636. PubMed

13. Mello MM, Studdert DM, Kachalia A. The medical liability climate and prospects for reform. JAMA. 2014;312(20):2146-2155. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

2018 Directory of VA and DoD Facilities

December 2017 Digital Edition

Click here to access the December 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- Driving-Related Coping Thoughts in Post-9/11 Combat Veterans With and Without Comorbid PTSD and TBI

- Innovative Therapies for Severe Asthma

- Lumbar Microlaminectomy vs Traditional Laminectomy

- Medication-Induced Pruritus From Direct Oral Anticoagulants

- She’s Not My Mother: 24-Year-Old Man With Capgras Delusion

- A Needs Review of Caregivers for Adults With Traumatic Brain Injury

Click here to access the December 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- Driving-Related Coping Thoughts in Post-9/11 Combat Veterans With and Without Comorbid PTSD and TBI

- Innovative Therapies for Severe Asthma

- Lumbar Microlaminectomy vs Traditional Laminectomy

- Medication-Induced Pruritus From Direct Oral Anticoagulants

- She’s Not My Mother: 24-Year-Old Man With Capgras Delusion

- A Needs Review of Caregivers for Adults With Traumatic Brain Injury

Click here to access the December 2017 Digital Edition.

Table of Contents

- Driving-Related Coping Thoughts in Post-9/11 Combat Veterans With and Without Comorbid PTSD and TBI

- Innovative Therapies for Severe Asthma

- Lumbar Microlaminectomy vs Traditional Laminectomy

- Medication-Induced Pruritus From Direct Oral Anticoagulants

- She’s Not My Mother: 24-Year-Old Man With Capgras Delusion

- A Needs Review of Caregivers for Adults With Traumatic Brain Injury

Chronic Urticaria: It’s More Than Just Antihistamines!

CE/CME No: CR-1801

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Differentiate between acute and chronic urticaria.

• List common history questions required for the diagnosis of chronic urticaria.

• Explain a stepwise plan for treatment of chronic urticaria.

• Describe serologic testing that should be ordered for chronic urticaria.

• Demonstrate knowledge of when to refer patients to a specialist for alternative treatment options.

FACULTY

Randy D. Danielsen is Professor and Dean of the Arizona School of Health Sciences, and Director of the Center for the Future of the Health Professions at A.T. Still University in Mesa, Arizona. Gabriel Ortiz practices at Breathe America El Paso in Texas and is a former AAPA liaison to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) and National Institutes of Health/National Asthma Education and Prevention Program—Coordinating Committee. Susan Symington has practiced in allergy, asthma, and immunology for more than 10 years. She is the current AAPA liaison to theAAAAI and is President-Elect of the AAPA-Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology subspecialty organization.

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through December 31, 2018.

Article begins on next page >>

The discomfort caused by an urticarial rash, along with its unpredictable course, can interfere with a patient’s sleep and work/school. Adding to the frustration of patients and providers alike, an underlying cause is seldom identified. But a stepwise treatment approach can bring relief to all.

Urticaria, often referred to as hives, is a common cutaneous disorder with a lifetime incidence between 15% and 25%.1 Urticaria is characterized by recurring pruritic wheals that arise due to allergic and nonallergic reactions to internal and external agents. The name urticaria comes from the Latin word for “nettle,” urtica, derived from the Latin word uro, meaning “to burn.”2

Urticaria can be debilitating for patients, who may complain of a burning sensation. It can last for years in some and reduces quality of life for many. Recently, more successful treatments for urticaria have emerged that can provide tremendous relief.

It is important to understand some of the ways to diagnose and treat patients in a primary care setting and also to know when referral is appropriate. This article will discuss the diagnosis, treatment, and referral process for patients with chronic urticaria.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Hives most commonly arise from an immunologic reaction in the superficial skin layers that results in the release of histamine, which causes swelling, itching, and erythema. The mast cell is the major effector cell in the pathophysiology of urticaria.3 In immunologic urticaria, the antigen binds to immunoglobulin (Ig) E on the mast cell surface, causing degranulation and release of histamine, which accounts for the wheals and itching associated with the condition. Histamine binds to H1 and H2 receptors in the skin to cause arteriolar dilation, venous constriction, and increased capillary permeability, accounting for the accompanying swelling.3 Not all urticaria is mediated by IgE; it can result from systemic disease processes in the body that are immune related but not related to IgE. An example would be autoimmune urticaria.

Urticaria commonly occurs with angioedema, which is marked by a greater degree of swelling and results from mast cell activation in the deeper dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Either condition can occur independently, however. Angioedema typically affects the lips, tongue, face, pharynx, and bilateral extremities; rarely, it affects the gastrointestinal tract. Angioedema may be hereditary, but its nonhereditary causes can be similar to those of urticaria.3 For example, a patient could be severely allergic to cat dander and, when exposed to this allergic trigger, develop swelling of the lips, facial edema, and flushing.

FORMS OF URTICARIA

Urticaria can be broadly divided based on the duration of illness: less than six weeks is termed acute urticaria, and continuous or intermittent presence for six weeks or more, chronic urticaria.4

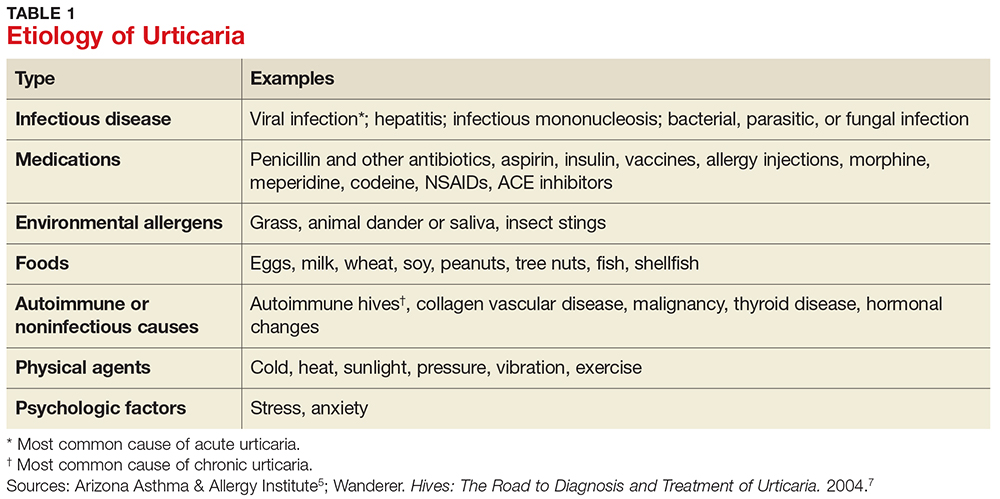

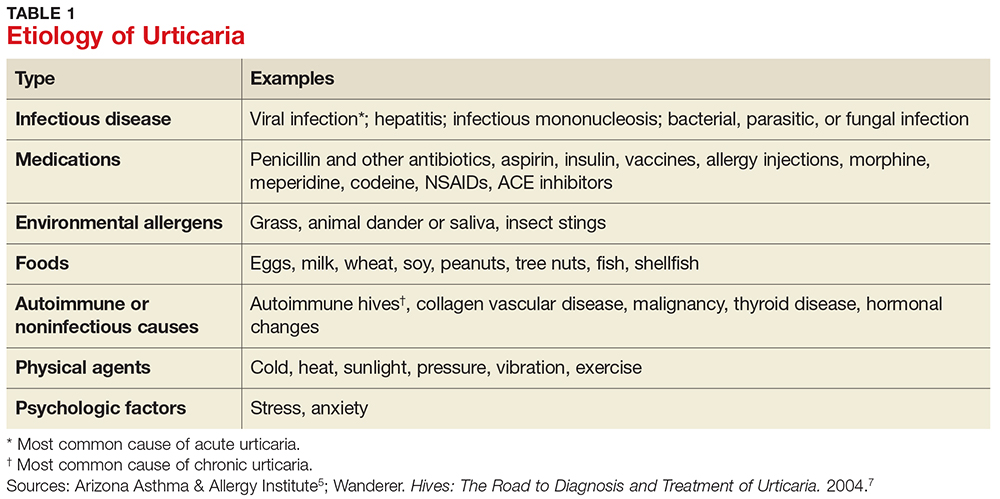

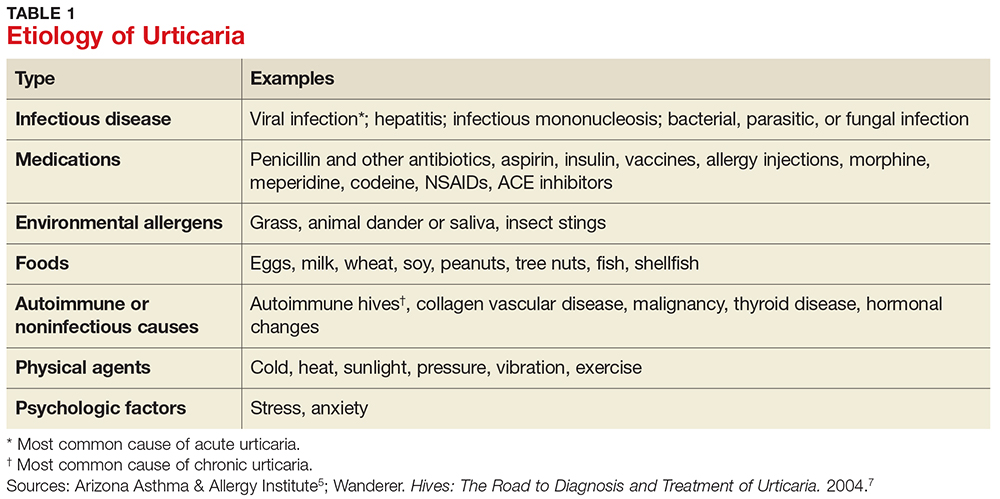

Acute urticaria may occur in any age group but is most often seen in children.1 Acute urticaria and angioedema frequently resolve within a few days, without an identified cause. An inciting cause can be identified in only about 15% to 20% of cases; the most common cause is viral infection, followed by foods, drugs, insect stings, transfusion reactions, and, rarely, contactants and inhalants (see Table 1).1,5 Acute urticaria that is not associated with angioedema or respiratory distress is usually self-limited. The condition typically resolves before extensive evaluation, including testing for possible allergic triggers, can be done. The associated skin lesions are often self-limited or can be controlled symptomatically with antihistamines and avoidance of known possible triggers.1

Chronic urticaria, sometimes called chronic idiopathic urticaria, is more common in adults, occurs on most days of the week, and, as noted, persists for more than six weeks with no identifiable triggers.6 It affects about 0.5% to 1% of the population (lifetime prevalence).3 Approximately 45% of patients with chronic urticaria have accompanying episodes of angioedema, and 30% to 50% have an autoimmune process involving autoantibodies against the thyroid, IgE, or the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcR1).3 The diagnosis is based primarily on clinical history and presentation; this will guide the determination of what types of diagnostic testing are necessary.

Chronic urticaria requires an extensive, but not indiscriminate, evaluation with history, physical examination, allergy testing, and laboratory testing for immune system, liver, kidney, thyroid, and collagen vascular diseases.3 Unfortunately, an identifiable cause of chronic urticaria is found in only 10% to 20% of patients; most cases are idiopathic.3,7

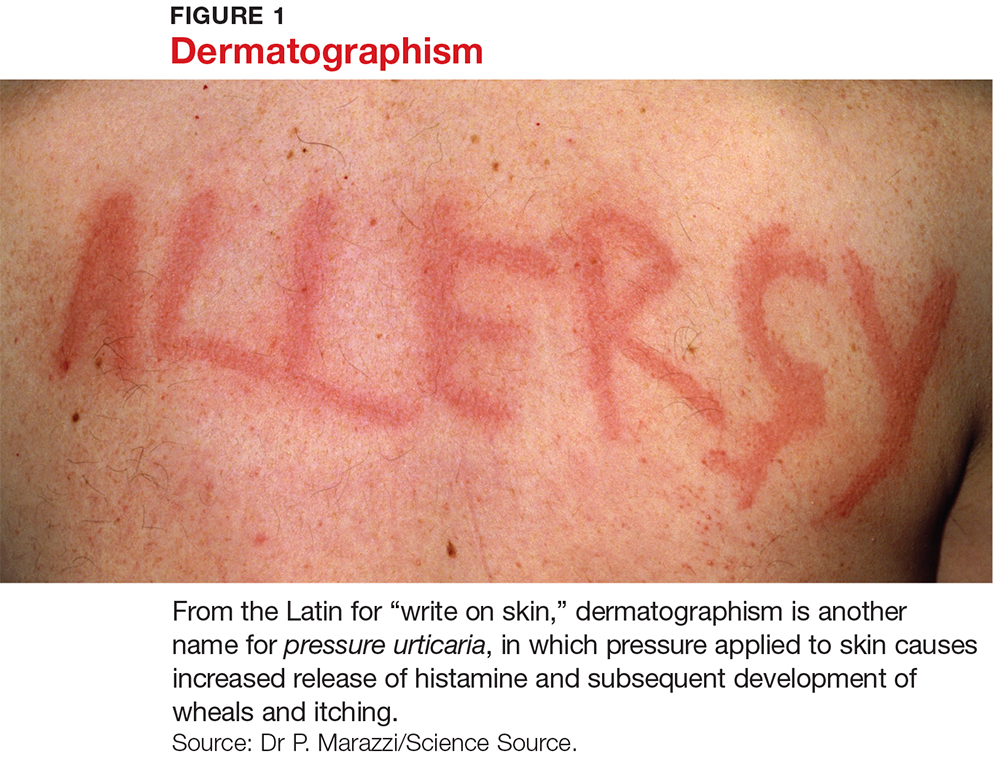

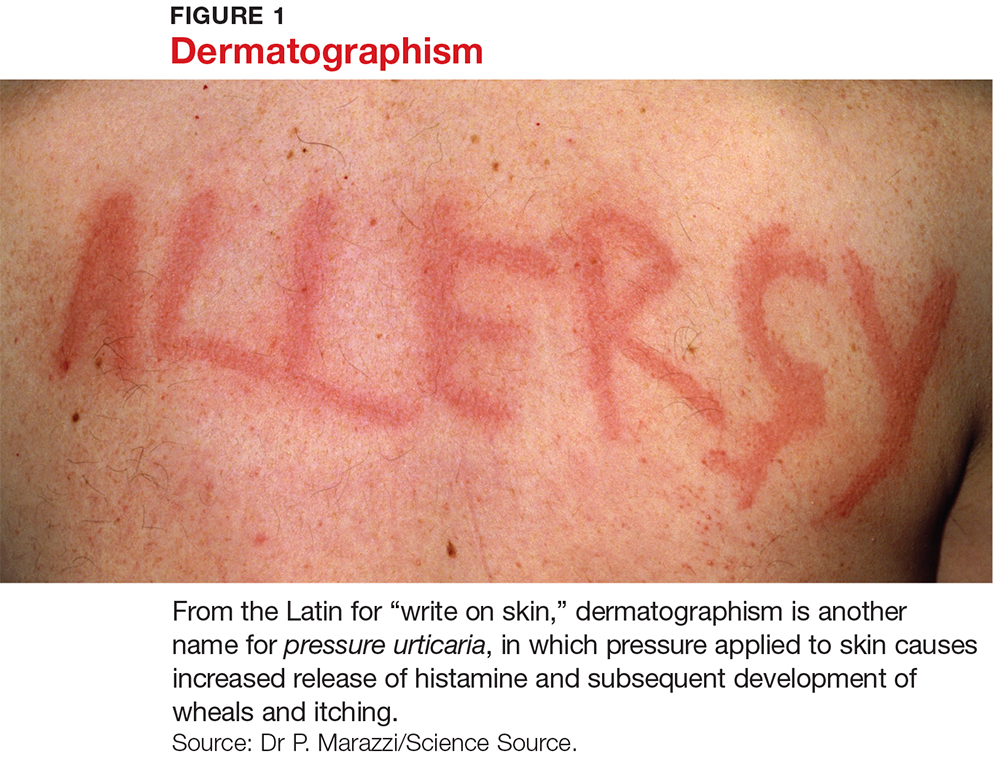

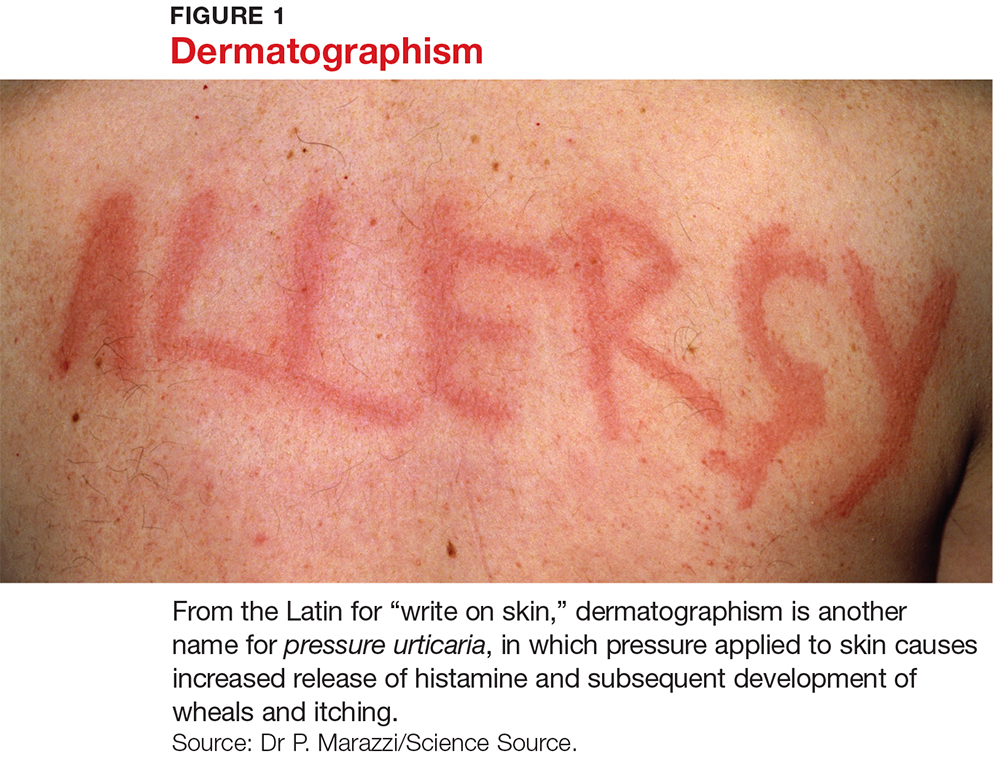

Several forms of chronic urticaria can be precipitated by physical stimuli, such as exercise, generalized heat, or sweating (cholinergic urticaria); localized heat (localized heat urticaria); low temperatures (cold urticaria); sun exposure (solar urticaria); water (aquagenic urticaria); and vibration.1 In another form (pressure urticaria), pressure on the skin increases histamine release, leading to the development of wheals and itching; this form is also called dermatographism, which means “write on skin” (see Figure 1). These types of urticaria should be evaluated and treated by a board-certified allergist, as there are special evaluations that can confirm the diagnosis.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The main feature of urticaria is raised skin lesions that appear pale to pink to erythematous and most commonly are intensely pruritic (see Figure 2). These lesions range from a few millimeters to several centimeters in size and may coalesce.

Characteristically, evanescent old lesions resolve, and new ones develop over 24 hours, usually without scarring. Scratching generally worsens dermatographism, with new urticaria produced over the scratched area. Any area of the body may be involved.

The lesions of early urticaria may vary in size and blanch when pressure is applied. An individual hive may last minutes or up to 24 hours and may reoccur intermittently on various sites on the body for an unspecified period of time.1,6

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Other dermatologic conditions may be mistaken for chronic urticaria. Common rashes that may mimic it include anaphylaxis, atopic dermatitis, medication allergy or fixed drug eruption, ACE inhibitor–related angioedema, mastocytosis, contact dermatitis, autoimmune thyroid disease, bullous pemphigoid, and dermatitis herpetiformis.

Patients should be encouraged to bring pictures of the rash to the office visit, since the rash may have waned at the time of the visit and diagnosis based on the patient’s description alone can be challenging. Most rashes in the differential can be identified or eliminated through a careful history and complete physical exam. When necessary, serologic testing and skin punch biopsies can elucidate and confirm the diagnosis.

EVALUATION

History and physical examination

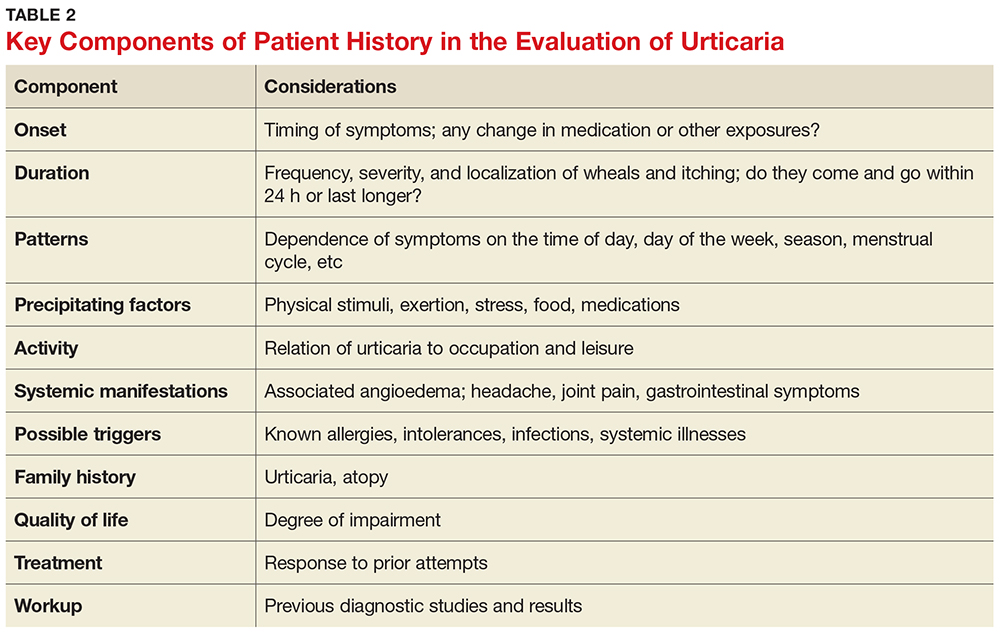

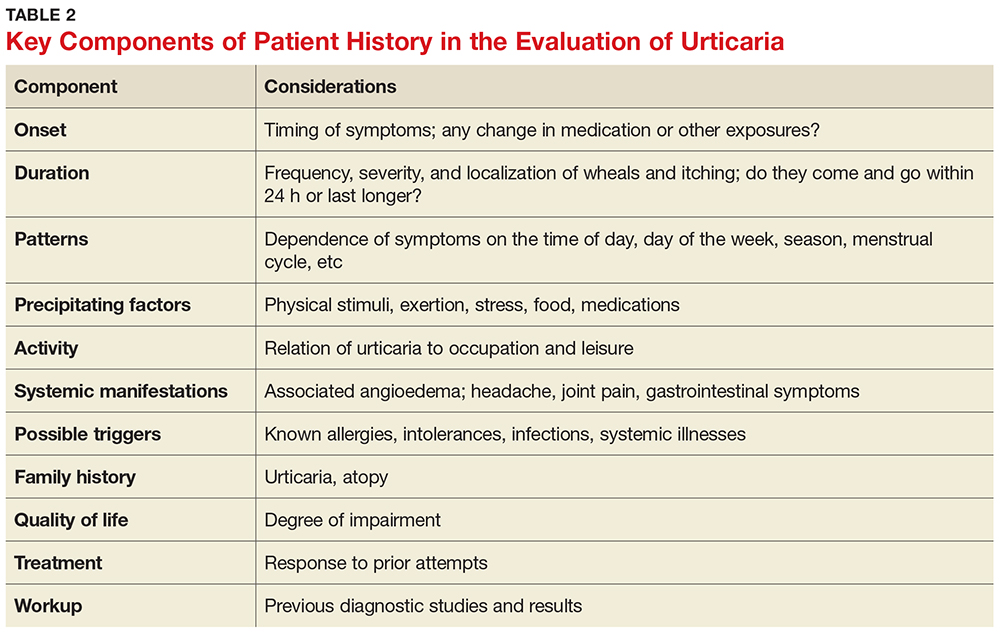

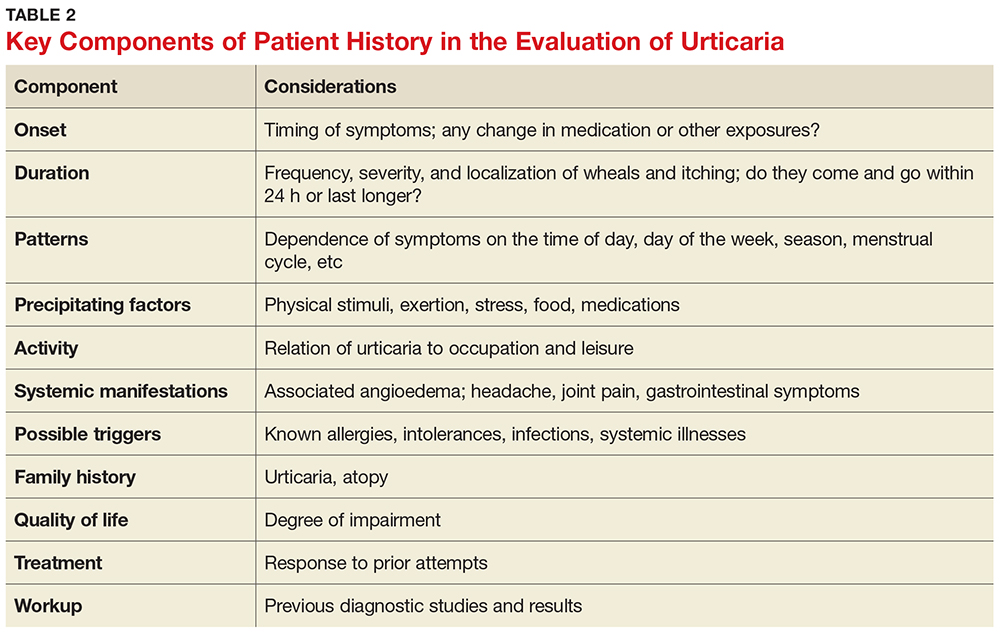

The medical history is the most important part of the evaluation of a patient with urticaria. The information that should be elicited and documented during the history is shown in Table 2.

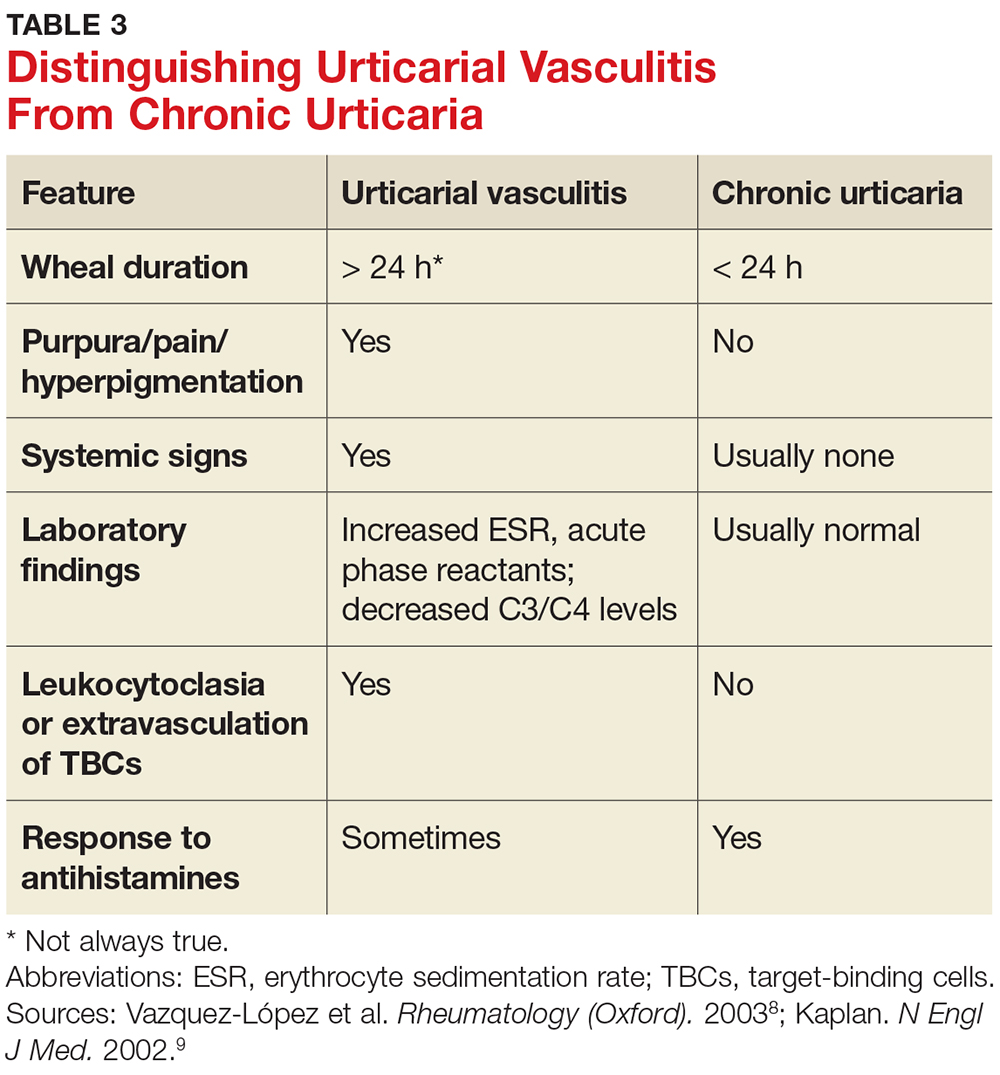

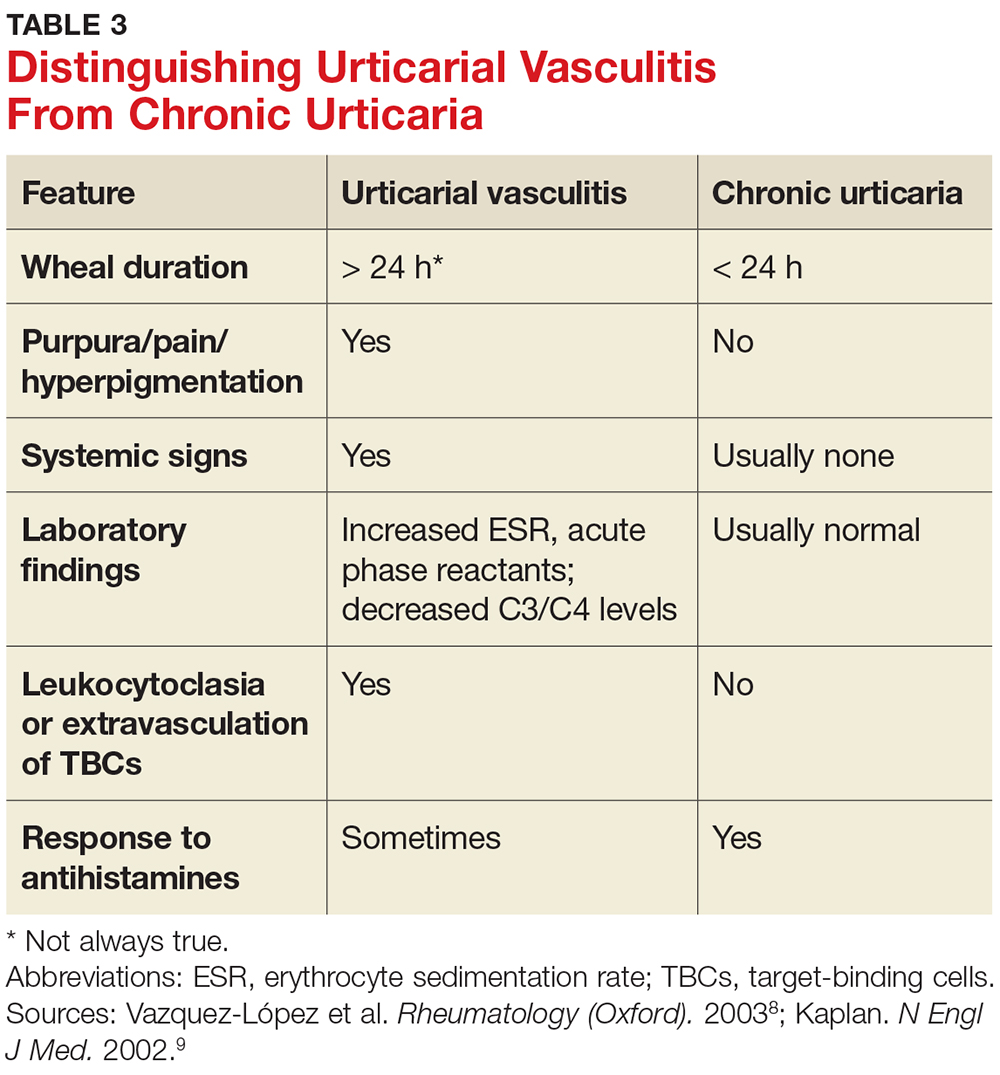

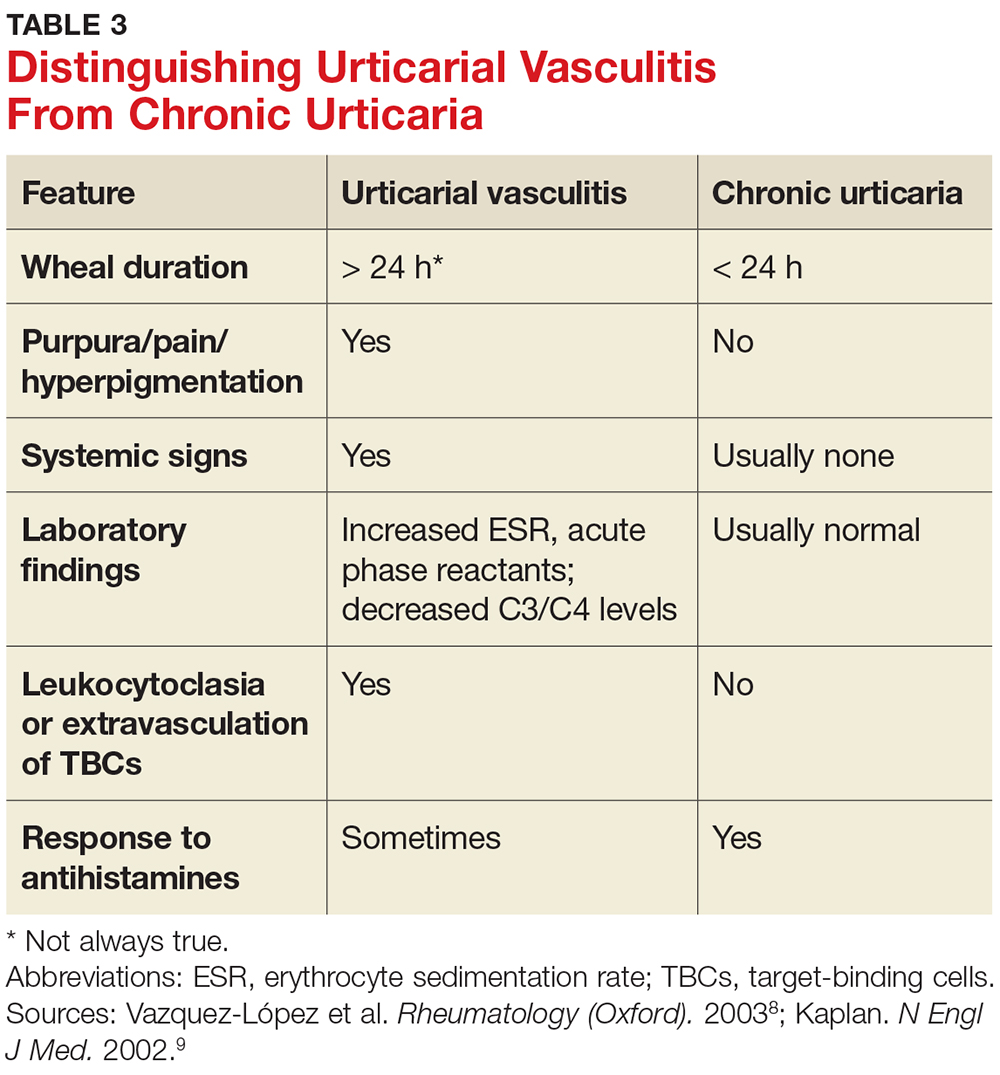

A general comprehensive physical exam should be undertaken and the findings carefully documented. As noted, it can be helpful for patients to bring in pictures of the rash if the lesions wax and wane. It is also important to assess whether the urticarial lesions blanch when palpated, since this is a characteristic feature of acute and chronic urticarial lesions (but not of those with an autoimmune, cholinergic, or vasculitic cause). Thus, blanching of the wheal is a key finding on physical exam to discriminate between possible causes.8 Lesions pigmented with purpuric areas that scar or last longer than 24 hours suggest urticarial vasculitis; other features that distinguish urticarial vasculitis from chronic urticaria are listed in Table 3.2

Laboratory evaluation

Although there is no consensus regarding appropriate laboratory testing, the following tests should be considered for patients with chronic urticaria after completion of a thorough history and physical exam: complete blood count (CBC) with differential; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and/or C-reactive protein (CRP); chemistry panel and hepatic panel; and thyroid-stimulating hormone, antimicrosomal antibodies, and antithyroglobulin antibodies measurements.7

While the CBC is usually within normal limits, if eosinophilia is present, a workup for an atopic disorder or parasitic infection should be considered. If the ESR/CRP results are positive, consider ordering a larger antinuclear antibody (ANA) panel. Note: The utility of performing these tests routinely for chronic urticaria patients is unclear, as studies have demonstrated that results are usually normal. But it is important to order the appropriate tests to help you rule in or out a likely diagnosis.

Additional testing may be indicated by non-IgE or possible autoimmune findings on the history and/or physical exam. This can include a functional autoantibody assay (for autoantibodies to the high-affinity IgE receptor [FcR1]); complement analysis (eg, C3, C4, CH50), especially when concerned about hereditary angioedema; stool analysis for ova and parasites; Helicobacter pylori workup (there is limited experimental evidence to recommend this, however); hepatitis B and C workup; chest radiograph and/or other imaging studies; ANA panel; rheumatoid factor; cryoglobulin levels; skin biopsy; and urinalysis.7

Local urticaria can occur following contact with allergens via an IgE-mediated mechanism. If an allergen is suspected as a possible trigger, serologic testing to assess allergen-specific IgE levels that may be contributing to the urticaria can be performed in a primary care setting. The specific IgE levels most commonly assessed are for the endemic outdoor aeroallergens (eg, pets [cat, dog], dust mites); measurement of food-specific IgE levels can be ordered if a specific allergy is a concern. Allergy skin prick testing for immediate hypersensitivity and a physical challenge test are usually performed in an allergy office by board-certified allergists.

Skin biopsy should be done on all lesions concerning for urticarial vasculitis (see Table 4).2 Biopsy is also important if the hives are painful rather than pruritic, as this may suggest a different cause. The clinician should consider more detailed lab testing and skin biopsy if urticaria does not respond to therapy as anticipated. Also, specific lab testing may be required screening for certain planned medical therapies (eg, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase enzyme deficiency screening before dapsone or hydroxychloroquine therapy).3

MANAGEMENT

Nonpharmacologic therapy

Treatment of the underlying cause, if identified, may be helpful and should be considered. For example, if a thyroid disorder is found on serologic testing, correcting the disorder may resolve the urticaria.9 Similarly, if a complement deficiency consistent with hereditary angioedema is detected, there are medications to correct it, which can be life-saving.3 Medications for treating hereditary angioedema are best prescribed in an allergy practice.

If triggers are discovered, the patient must be made aware of them and advised to avoid them as much as possible; however, total avoidance can be very difficult. Other common potentiating factors—such as alcohol overuse, excessive tiredness, emotional stress, hyperthermia, and use of aspirin and NSAIDs—should be avoided.10 These factors can worsen what is already triggering the urticaria and make it more difficult to treat; an example would be a patient who develops urticaria from a new household dog and is taking anti-inflammatory drugs for arthritis symptoms.

Topical agents rarely result in any improvement, and their use is therefore discouraged. In fact, high-potency corticosteroids may cause dermal atrophy.11 Also, dietary changes are not indicated for most patients with chronic urticaria, because undiscovered allergy to food or food additives is not likely to be responsible.4

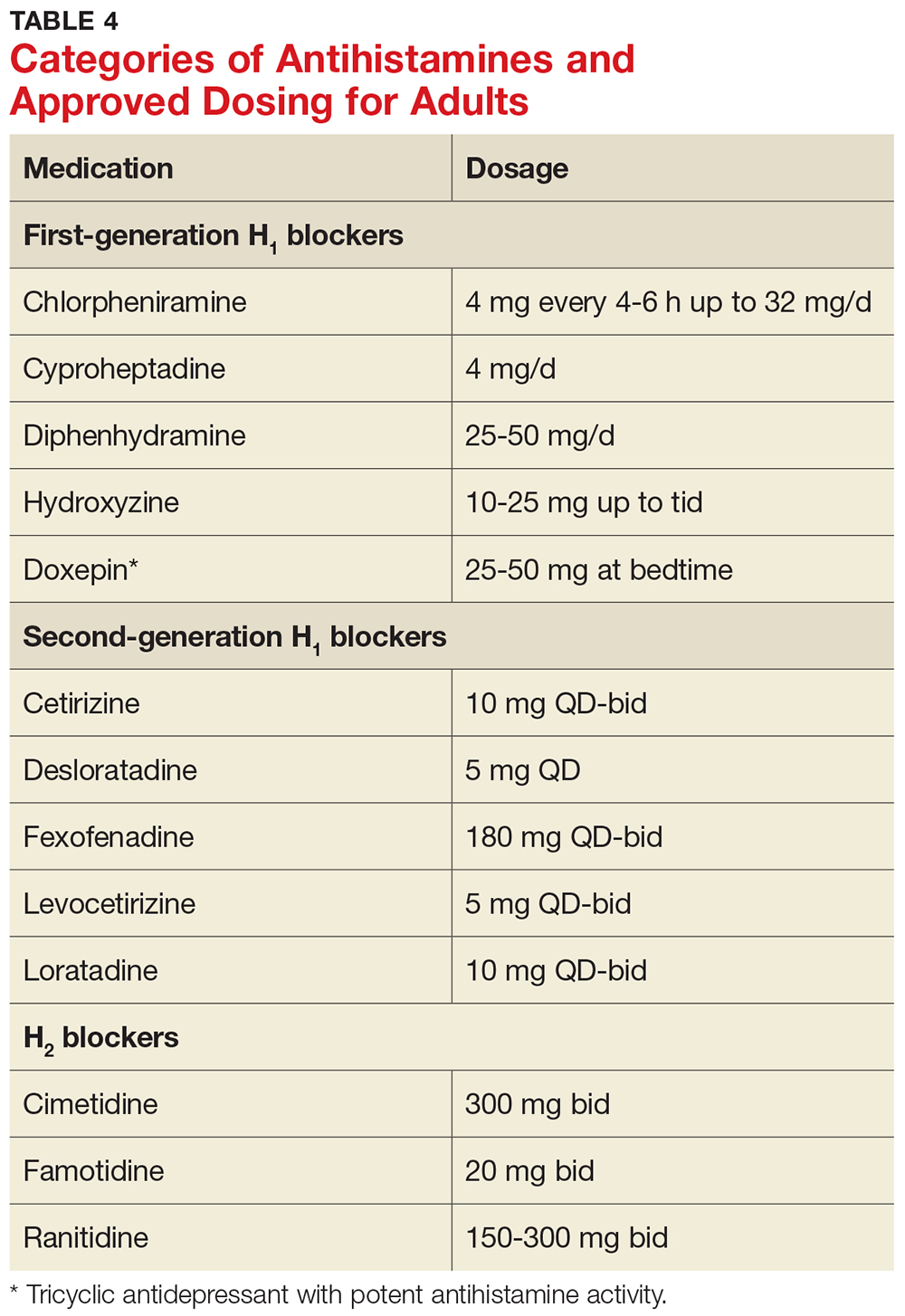

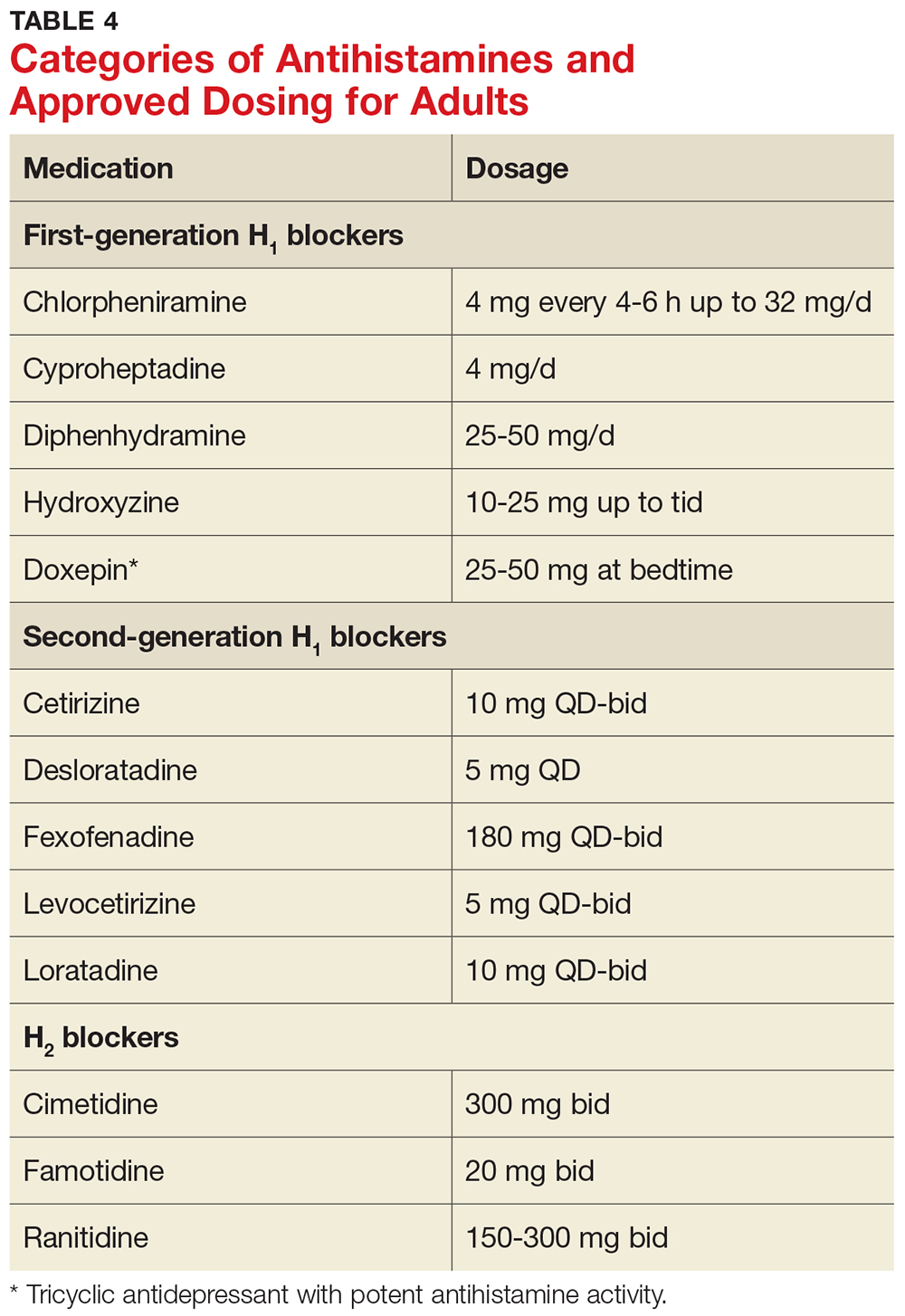

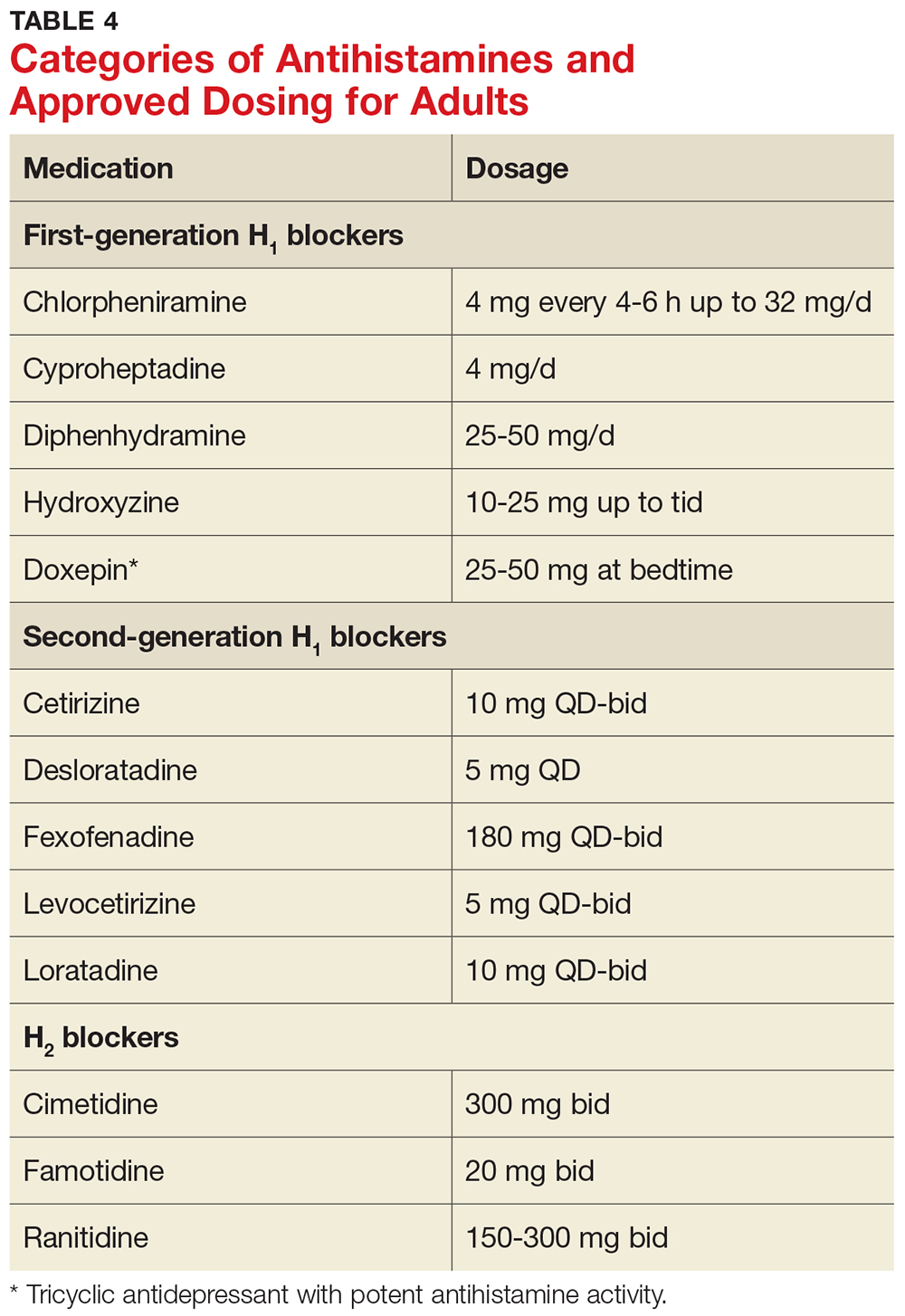

Antihistamines

Antihistamines are the most commonly used pharmacologic treatment for chronic urticaria (see Table 4). H2-receptor blockers, taken in combination with first- and second-generation H1-receptor blockers, have been reported to be more efficacious than H1 antihistamines alone for the treatment of chronic urticaria.6 This added efficacy may be related to pharmacologic interactions and increased blood levels achieved with first-generation antihistamines. Increased doses of second-generation antihistamines—as high as four times the standard dose—are advocated by the 2014 Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters (JTFPP) for the diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria.4

A stepwise approach to treatment is imperative. The JTFPP guidelines (available at www.allergyparameters.org) are summarized below.

Step 1: Administer a second-generation antihistamine at the standard therapeutic dose (see Table 4) and avoid triggers, NSAIDs, and other exacerbating factors.

If symptom control is not achieved in one to two weeks, move on to

Step 2: Increase therapy by one or more of the following methods: increase the dose of the second-generation antihistamine used in Step 1 (up to 4x the standard dose); add another second-generation antihistamine to the regimen; add an H2 blocker (ranitidine, famotidine, cimetidine); and/or add a leukotriene-receptor antagonist (montelukast 10 mg/d).

If these measures do not result in adequate symptom control, it’s time for

Step 3: Gradually increase the dose of H1 antihistamine(s) and discontinue any medications added in Step 2 that did not appear beneficial. Add a first-generation antihistamine (hydroxyzine, doxepin, cyproheptadine), which should be taken at bedtime due to risk for sedation.12

If symptoms are not controlled by Step 3 measures, or if the patient is unable to tolerate an increased dose of first-generation antihistamines, the urticaria is considered refractory. At this point, the clinician should consider referral to an allergy specialist for

Step 4: Add an alternative medication, such as cyclosporine (an anti-inflammatory, immunosuppressive agent) or omalizumab (a monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to IgE).

It should be noted that while the recent FDA approval of omalizumab for treatment of chronic urticaria has been life-changing for many patients, the product label does carry a black box warning about anaphylaxis. Because special monitoring is needed (and prior authorization will likely be required by the patient’s insurer), omalizumab is best prescribed in an allergy office.

It is not uncommon for patients with chronic urticaria to require multiple medications to control their symptoms. Once controlled, they will require maintenance and reevaluation on a regular basis.13

When to refer

Clinicians must know when to refer a patient with chronic urticaria to an allergist/immunologist. Referral is indicated when an underlying disorder is suspected, when symptoms are not controlled with Steps 1 to 3 of the management guidelines, or when the patient requires repeated or prolonged treatment with glucocorticoids.

Unfortunately, out of frustration on both the provider and the patient side, glucocorticoids may be started, after determining that that is “all that works” for the patient. There appears to be a limited role for glucocorticoids, so they should be avoided unless absolutely necessary (ie, if there is no response to antihistamines).

If signs and symptoms suggest urticarial vasculitis, it is prudent to consider referral to a specialist in rheumatology. Urticarial vasculitis requires a special skin punch biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.8 The biopsy procedure may be performed by a primary care provider; if the clinician is not comfortable doing so, referral to an appropriate dermatology provider is indicated.

PATIENT EDUCATION/REASSURANCE

Effective patient education is critical, because patients often experience considerable distress as the symptoms of chronic urticaria wax and wane unpredictably. It is not uncommon for patients with this condition to complain of symptoms that interfere with work, school, and sleep. Reassurance can help to alleviate frustration and anxiety. Patients should understand that the symptoms of chronic urticaria can be successfully managed in the majority of patients, and that chronic idiopathic urticaria is rarely permanent, with about 50% of patients experiencing remission within one year.6

CONCLUSION

The diagnosis of chronic urticaria is based primarily on the presentation, clinical history, and laboratory workup. Management of this chronic and uncomfortable condition requires the identification and exclusion of possible triggers, followed by effective patient education/counseling and a personalized management plan. By knowing when to suspect chronic urticaria, being familiar with the approach to evaluation and initial treatment, and knowing when referral to a specialist is indicated, primary care providers can help their patients find a path to relief.

1. Riedl MA, Ortiz G, Casillas AM. A primary care guide to managing chronic urticaria. JAAPA. 2003;16:WEB.

2. Grieve M. Nettles. http://botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/n/nettle03.html. Accessed December 19, 2017.

3. Powell RJ, Du Toit GL, Siddique N, et al; British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. BSACI guidelines for the management of chronic urticaria and angioedema. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37(5):631-650.

4. Bernstein JA, Lang DM, Khan DA, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria: 2014 update. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(5):1270-1277.

5. Arizona Asthma & Allergy Institute. Possible causes of hives. www.azsneeze.com/hives. Accessed December 19, 2017.

6. Kozel MM, Mekkes JR, Bossuyt PM, Bos JD. Natural course of physical and chronic urticaria and angioedema in 220 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45(3):387-391.

7. Wanderer AA. Hives: The Road to Diagnosis and Treatment of Urticaria. Bozeman, MT: Anson Publishing; 2004.

8. Vazquez-López F, Maldonado-Seral C, Soler-Sánchez T, et al. Surface microscopy for discriminating between common urticaria and urticarial vasculitis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2003;42(9):1079-1082.

9. Kaplan AP. Chronic urticaria and angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(3):175-179.

10. Yadav S, Bajaj AK. Management of difficult urticaria. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54(3):275-279.

11. Ellingsen AR, Thestrup-Pedersen K. Treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria with topical steroids. An open trial. Acta Derm Venereol. 1996;76(1):43-44.

12. Goldsobel AB, Rohr AS, Siegel SC, et al. Efficacy of doxepin in the treatment of chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;78(5 pt 1):867-873.

13. Ferrer M, Bartra J, Gimenez-Arnau A, et al. Management of urticaria: not too complicated, not too simple. Clin Exp Allergy. 2015;45(4):731-743.

CE/CME No: CR-1801

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Differentiate between acute and chronic urticaria.

• List common history questions required for the diagnosis of chronic urticaria.

• Explain a stepwise plan for treatment of chronic urticaria.

• Describe serologic testing that should be ordered for chronic urticaria.

• Demonstrate knowledge of when to refer patients to a specialist for alternative treatment options.

FACULTY

Randy D. Danielsen is Professor and Dean of the Arizona School of Health Sciences, and Director of the Center for the Future of the Health Professions at A.T. Still University in Mesa, Arizona. Gabriel Ortiz practices at Breathe America El Paso in Texas and is a former AAPA liaison to the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) and National Institutes of Health/National Asthma Education and Prevention Program—Coordinating Committee. Susan Symington has practiced in allergy, asthma, and immunology for more than 10 years. She is the current AAPA liaison to theAAAAI and is President-Elect of the AAPA-Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology subspecialty organization.

The authors have no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid through December 31, 2018.

Article begins on next page >>

The discomfort caused by an urticarial rash, along with its unpredictable course, can interfere with a patient’s sleep and work/school. Adding to the frustration of patients and providers alike, an underlying cause is seldom identified. But a stepwise treatment approach can bring relief to all.

Urticaria, often referred to as hives, is a common cutaneous disorder with a lifetime incidence between 15% and 25%.1 Urticaria is characterized by recurring pruritic wheals that arise due to allergic and nonallergic reactions to internal and external agents. The name urticaria comes from the Latin word for “nettle,” urtica, derived from the Latin word uro, meaning “to burn.”2

Urticaria can be debilitating for patients, who may complain of a burning sensation. It can last for years in some and reduces quality of life for many. Recently, more successful treatments for urticaria have emerged that can provide tremendous relief.

It is important to understand some of the ways to diagnose and treat patients in a primary care setting and also to know when referral is appropriate. This article will discuss the diagnosis, treatment, and referral process for patients with chronic urticaria.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Hives most commonly arise from an immunologic reaction in the superficial skin layers that results in the release of histamine, which causes swelling, itching, and erythema. The mast cell is the major effector cell in the pathophysiology of urticaria.3 In immunologic urticaria, the antigen binds to immunoglobulin (Ig) E on the mast cell surface, causing degranulation and release of histamine, which accounts for the wheals and itching associated with the condition. Histamine binds to H1 and H2 receptors in the skin to cause arteriolar dilation, venous constriction, and increased capillary permeability, accounting for the accompanying swelling.3 Not all urticaria is mediated by IgE; it can result from systemic disease processes in the body that are immune related but not related to IgE. An example would be autoimmune urticaria.

Urticaria commonly occurs with angioedema, which is marked by a greater degree of swelling and results from mast cell activation in the deeper dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Either condition can occur independently, however. Angioedema typically affects the lips, tongue, face, pharynx, and bilateral extremities; rarely, it affects the gastrointestinal tract. Angioedema may be hereditary, but its nonhereditary causes can be similar to those of urticaria.3 For example, a patient could be severely allergic to cat dander and, when exposed to this allergic trigger, develop swelling of the lips, facial edema, and flushing.

FORMS OF URTICARIA

Urticaria can be broadly divided based on the duration of illness: less than six weeks is termed acute urticaria, and continuous or intermittent presence for six weeks or more, chronic urticaria.4

Acute urticaria may occur in any age group but is most often seen in children.1 Acute urticaria and angioedema frequently resolve within a few days, without an identified cause. An inciting cause can be identified in only about 15% to 20% of cases; the most common cause is viral infection, followed by foods, drugs, insect stings, transfusion reactions, and, rarely, contactants and inhalants (see Table 1).1,5 Acute urticaria that is not associated with angioedema or respiratory distress is usually self-limited. The condition typically resolves before extensive evaluation, including testing for possible allergic triggers, can be done. The associated skin lesions are often self-limited or can be controlled symptomatically with antihistamines and avoidance of known possible triggers.1

Chronic urticaria, sometimes called chronic idiopathic urticaria, is more common in adults, occurs on most days of the week, and, as noted, persists for more than six weeks with no identifiable triggers.6 It affects about 0.5% to 1% of the population (lifetime prevalence).3 Approximately 45% of patients with chronic urticaria have accompanying episodes of angioedema, and 30% to 50% have an autoimmune process involving autoantibodies against the thyroid, IgE, or the high-affinity IgE receptor (FcR1).3 The diagnosis is based primarily on clinical history and presentation; this will guide the determination of what types of diagnostic testing are necessary.

Chronic urticaria requires an extensive, but not indiscriminate, evaluation with history, physical examination, allergy testing, and laboratory testing for immune system, liver, kidney, thyroid, and collagen vascular diseases.3 Unfortunately, an identifiable cause of chronic urticaria is found in only 10% to 20% of patients; most cases are idiopathic.3,7

Several forms of chronic urticaria can be precipitated by physical stimuli, such as exercise, generalized heat, or sweating (cholinergic urticaria); localized heat (localized heat urticaria); low temperatures (cold urticaria); sun exposure (solar urticaria); water (aquagenic urticaria); and vibration.1 In another form (pressure urticaria), pressure on the skin increases histamine release, leading to the development of wheals and itching; this form is also called dermatographism, which means “write on skin” (see Figure 1). These types of urticaria should be evaluated and treated by a board-certified allergist, as there are special evaluations that can confirm the diagnosis.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The main feature of urticaria is raised skin lesions that appear pale to pink to erythematous and most commonly are intensely pruritic (see Figure 2). These lesions range from a few millimeters to several centimeters in size and may coalesce.

Characteristically, evanescent old lesions resolve, and new ones develop over 24 hours, usually without scarring. Scratching generally worsens dermatographism, with new urticaria produced over the scratched area. Any area of the body may be involved.

The lesions of early urticaria may vary in size and blanch when pressure is applied. An individual hive may last minutes or up to 24 hours and may reoccur intermittently on various sites on the body for an unspecified period of time.1,6

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Other dermatologic conditions may be mistaken for chronic urticaria. Common rashes that may mimic it include anaphylaxis, atopic dermatitis, medication allergy or fixed drug eruption, ACE inhibitor–related angioedema, mastocytosis, contact dermatitis, autoimmune thyroid disease, bullous pemphigoid, and dermatitis herpetiformis.

Patients should be encouraged to bring pictures of the rash to the office visit, since the rash may have waned at the time of the visit and diagnosis based on the patient’s description alone can be challenging. Most rashes in the differential can be identified or eliminated through a careful history and complete physical exam. When necessary, serologic testing and skin punch biopsies can elucidate and confirm the diagnosis.

EVALUATION

History and physical examination

The medical history is the most important part of the evaluation of a patient with urticaria. The information that should be elicited and documented during the history is shown in Table 2.

A general comprehensive physical exam should be undertaken and the findings carefully documented. As noted, it can be helpful for patients to bring in pictures of the rash if the lesions wax and wane. It is also important to assess whether the urticarial lesions blanch when palpated, since this is a characteristic feature of acute and chronic urticarial lesions (but not of those with an autoimmune, cholinergic, or vasculitic cause). Thus, blanching of the wheal is a key finding on physical exam to discriminate between possible causes.8 Lesions pigmented with purpuric areas that scar or last longer than 24 hours suggest urticarial vasculitis; other features that distinguish urticarial vasculitis from chronic urticaria are listed in Table 3.2

Laboratory evaluation

Although there is no consensus regarding appropriate laboratory testing, the following tests should be considered for patients with chronic urticaria after completion of a thorough history and physical exam: complete blood count (CBC) with differential; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and/or C-reactive protein (CRP); chemistry panel and hepatic panel; and thyroid-stimulating hormone, antimicrosomal antibodies, and antithyroglobulin antibodies measurements.7

While the CBC is usually within normal limits, if eosinophilia is present, a workup for an atopic disorder or parasitic infection should be considered. If the ESR/CRP results are positive, consider ordering a larger antinuclear antibody (ANA) panel. Note: The utility of performing these tests routinely for chronic urticaria patients is unclear, as studies have demonstrated that results are usually normal. But it is important to order the appropriate tests to help you rule in or out a likely diagnosis.

Additional testing may be indicated by non-IgE or possible autoimmune findings on the history and/or physical exam. This can include a functional autoantibody assay (for autoantibodies to the high-affinity IgE receptor [FcR1]); complement analysis (eg, C3, C4, CH50), especially when concerned about hereditary angioedema; stool analysis for ova and parasites; Helicobacter pylori workup (there is limited experimental evidence to recommend this, however); hepatitis B and C workup; chest radiograph and/or other imaging studies; ANA panel; rheumatoid factor; cryoglobulin levels; skin biopsy; and urinalysis.7

Local urticaria can occur following contact with allergens via an IgE-mediated mechanism. If an allergen is suspected as a possible trigger, serologic testing to assess allergen-specific IgE levels that may be contributing to the urticaria can be performed in a primary care setting. The specific IgE levels most commonly assessed are for the endemic outdoor aeroallergens (eg, pets [cat, dog], dust mites); measurement of food-specific IgE levels can be ordered if a specific allergy is a concern. Allergy skin prick testing for immediate hypersensitivity and a physical challenge test are usually performed in an allergy office by board-certified allergists.

Skin biopsy should be done on all lesions concerning for urticarial vasculitis (see Table 4).2 Biopsy is also important if the hives are painful rather than pruritic, as this may suggest a different cause. The clinician should consider more detailed lab testing and skin biopsy if urticaria does not respond to therapy as anticipated. Also, specific lab testing may be required screening for certain planned medical therapies (eg, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase enzyme deficiency screening before dapsone or hydroxychloroquine therapy).3

MANAGEMENT

Nonpharmacologic therapy

Treatment of the underlying cause, if identified, may be helpful and should be considered. For example, if a thyroid disorder is found on serologic testing, correcting the disorder may resolve the urticaria.9 Similarly, if a complement deficiency consistent with hereditary angioedema is detected, there are medications to correct it, which can be life-saving.3 Medications for treating hereditary angioedema are best prescribed in an allergy practice.

If triggers are discovered, the patient must be made aware of them and advised to avoid them as much as possible; however, total avoidance can be very difficult. Other common potentiating factors—such as alcohol overuse, excessive tiredness, emotional stress, hyperthermia, and use of aspirin and NSAIDs—should be avoided.10 These factors can worsen what is already triggering the urticaria and make it more difficult to treat; an example would be a patient who develops urticaria from a new household dog and is taking anti-inflammatory drugs for arthritis symptoms.

Topical agents rarely result in any improvement, and their use is therefore discouraged. In fact, high-potency corticosteroids may cause dermal atrophy.11 Also, dietary changes are not indicated for most patients with chronic urticaria, because undiscovered allergy to food or food additives is not likely to be responsible.4

Antihistamines

Antihistamines are the most commonly used pharmacologic treatment for chronic urticaria (see Table 4). H2-receptor blockers, taken in combination with first- and second-generation H1-receptor blockers, have been reported to be more efficacious than H1 antihistamines alone for the treatment of chronic urticaria.6 This added efficacy may be related to pharmacologic interactions and increased blood levels achieved with first-generation antihistamines. Increased doses of second-generation antihistamines—as high as four times the standard dose—are advocated by the 2014 Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters (JTFPP) for the diagnosis and management of acute and chronic urticaria.4

A stepwise approach to treatment is imperative. The JTFPP guidelines (available at www.allergyparameters.org) are summarized below.

Step 1: Administer a second-generation antihistamine at the standard therapeutic dose (see Table 4) and avoid triggers, NSAIDs, and other exacerbating factors.

If symptom control is not achieved in one to two weeks, move on to

Step 2: Increase therapy by one or more of the following methods: increase the dose of the second-generation antihistamine used in Step 1 (up to 4x the standard dose); add another second-generation antihistamine to the regimen; add an H2 blocker (ranitidine, famotidine, cimetidine); and/or add a leukotriene-receptor antagonist (montelukast 10 mg/d).

If these measures do not result in adequate symptom control, it’s time for