User login

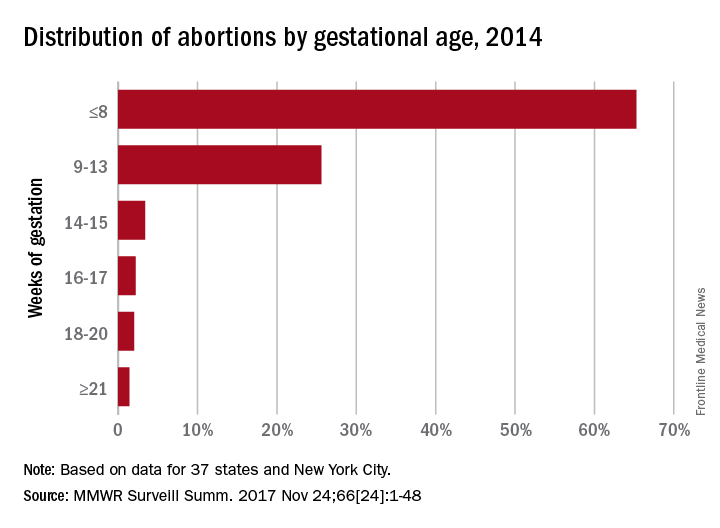

Two-thirds of abortions occur by 8 weeks’ gestation

, although there was variation by maternal age and race/ethnicity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

That year, 65.3% of abortions were performed at a gestational age of 8 weeks or earlier, with 25.6% occurring at 9-13 weeks. Gestational distribution of the remaining abortions was fairly even: 3.4% at 14-15 weeks, 2.2% at 16-17 weeks, 2.0% at 18-20 weeks, and 1.4% at 21 weeks or later, the CDC investigators reported (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017 Nov 25;66[24]:1-48).

The percentage of abortions occurring at 8 weeks or earlier was lowest for the youngest age group and increased along with maternal age: 43% for those under 15 years of age and progressing up to 72.5% for women over age 40. That scenario was basically reversed for all of the other gestational periods, as the under-15 group had the highest percentage for 9-13 weeks (34.4%), 14-15 (6.7%), 16-17 (3.6%), 18-20 (5.0%), and 21 weeks and later (7.3%). Those over age 40 had the lowest or almost the lowest percentage in each period, reported Tara C. Jatlaoui, MD, and her associates.

The data for gestational period analysis came from 37 states and New York City. New York State, along with 12 other states, did not report, did not report by gestational age, or did not meet reporting standards.

, although there was variation by maternal age and race/ethnicity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

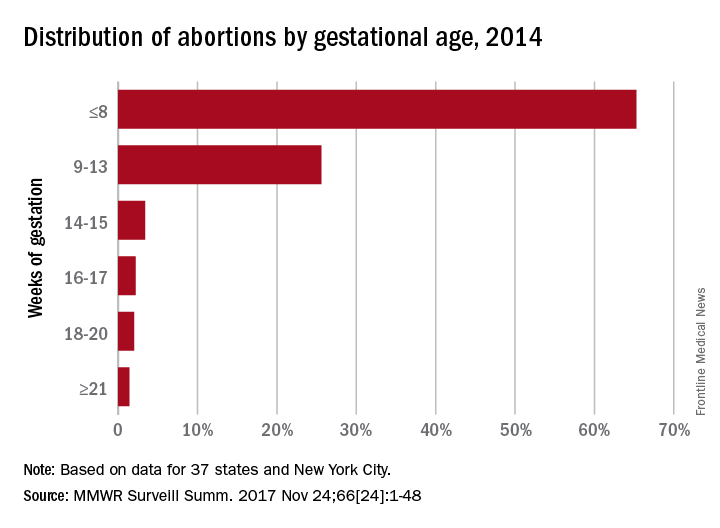

That year, 65.3% of abortions were performed at a gestational age of 8 weeks or earlier, with 25.6% occurring at 9-13 weeks. Gestational distribution of the remaining abortions was fairly even: 3.4% at 14-15 weeks, 2.2% at 16-17 weeks, 2.0% at 18-20 weeks, and 1.4% at 21 weeks or later, the CDC investigators reported (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017 Nov 25;66[24]:1-48).

The percentage of abortions occurring at 8 weeks or earlier was lowest for the youngest age group and increased along with maternal age: 43% for those under 15 years of age and progressing up to 72.5% for women over age 40. That scenario was basically reversed for all of the other gestational periods, as the under-15 group had the highest percentage for 9-13 weeks (34.4%), 14-15 (6.7%), 16-17 (3.6%), 18-20 (5.0%), and 21 weeks and later (7.3%). Those over age 40 had the lowest or almost the lowest percentage in each period, reported Tara C. Jatlaoui, MD, and her associates.

The data for gestational period analysis came from 37 states and New York City. New York State, along with 12 other states, did not report, did not report by gestational age, or did not meet reporting standards.

, although there was variation by maternal age and race/ethnicity, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

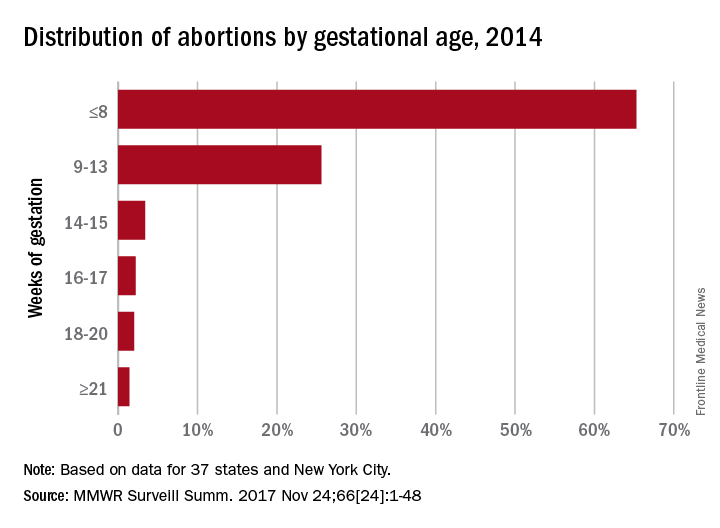

That year, 65.3% of abortions were performed at a gestational age of 8 weeks or earlier, with 25.6% occurring at 9-13 weeks. Gestational distribution of the remaining abortions was fairly even: 3.4% at 14-15 weeks, 2.2% at 16-17 weeks, 2.0% at 18-20 weeks, and 1.4% at 21 weeks or later, the CDC investigators reported (MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017 Nov 25;66[24]:1-48).

The percentage of abortions occurring at 8 weeks or earlier was lowest for the youngest age group and increased along with maternal age: 43% for those under 15 years of age and progressing up to 72.5% for women over age 40. That scenario was basically reversed for all of the other gestational periods, as the under-15 group had the highest percentage for 9-13 weeks (34.4%), 14-15 (6.7%), 16-17 (3.6%), 18-20 (5.0%), and 21 weeks and later (7.3%). Those over age 40 had the lowest or almost the lowest percentage in each period, reported Tara C. Jatlaoui, MD, and her associates.

The data for gestational period analysis came from 37 states and New York City. New York State, along with 12 other states, did not report, did not report by gestational age, or did not meet reporting standards.

FROM MMWR SURVEILLANCE SUMMARIES

The clear and present future: Telehealth and telemedicine in obstetrics and gynecology

I recently spoke with 2 outstanding leaders in our field, members of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) task force on telehealth and telemedicine, about the future of providing health care to women in remote locations.

Haywood Brown, MD, is President of ACOG for 2017–2018 and is F. Bayard Carter Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, and Peter Nielsen, MD, is Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and Obstetrician-in-Chief at Children’s Hospital of San Antonio. Dr. Nielsen is a retired US Army colonel.

Why an ACOG telehealth task force?

Haywood Brown, MD: Our overall goals in telehealth and telemedicine are to coordinate and better facilitate the health care of women in remote locations and to improve maternal morbidity and mortality. Telehealth can be used on both an outpatient and an inpatient basis.

Outpatient telehealth is used for consultations. In maternal-fetal medicine, for instance, we use it for ultrasonography consultations. I also have used telehealth technology to “see” a pregnant patient with type 1diabetes. During our sessions, I managed her blood sugar levels and did all the other things I would have done if we had been together at my clinic. Without telehealth technology, however, this patient would have needed to drive 4 hours round-trip for each appointment.

Our colleagues in rural communities and at lower-level hospitals can use telehealth and telemedicine as aids in treating their high-risk patients, such as those with preeclampsia, prematurity risk, or other conditions. Physicians can consult with specialists through a face-to-face conversation that takes place through telecommunications. The result is that the quality of care for women in our communities is improved.

Genetic counseling, infertility consultation, and fetal anomaly management are some of the other applications. Our task force is discussing different ways to improve patient care and ways to collaborate with our colleagues around the country. Ultimately, we are developing best practices—a model for the best uses of technology to improve women’s health care in the United States.

Task force focus: Telehealth technology, billing, services

Dr. Brown: Our task force, a diverse group of members from all over the country, represents the spectrum of ObGyns. Although task force members have various levels of telehealth experience, all are very interested in these new channels of communication. The task force also includes billers, who understand billing ramifications, and payers, who know firsthand what will and will not be paid.

Technology and its availability is the most important topic for the task force. While some communities have Internet service, not all do. We need to determine which areas need service, how much it would cost, and who pays for it. Can a hospital afford it? A practice? Their partners? Identifying partners in tertiary care settings is a task force goal.

We are engaging a broad range of experts to study all the components and associated costs of technology, licensing, and cross-state credentialing. Gathering this information will help in developing a best practices model that general ObGyns can use.

Telehealth is redefining aspects of care: prenatal care (how many visits are required?), postpartum care, and other types of services that can be done remotely. Genetic counseling—who can provide it, what education is required—is another topic of discussion. Once we surmount the billing obstacles, we can do much with teleconferencing, such as provide genetic consultation with ObGyns in various settings.

The terms "telehealth" and "telemedicine" are often used interchangeably. Telemedicine is the older phrase, while telehealth entered the vernacular more recently and encompasses a broader definition.

The HealthIT.gov website explains the differences in terminology this way1:

- The Health Resources Services Administration defines telehealth as the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, public health and health administration. Technologies include videoconferencing, the Internet, store-and-forward imaging, streaming media, and terrestrial and wireless communications.

- Telehealth is different from telemedicine because it refers to a broader scope of remote health care services than telemedicine. While telemedicine refers specifically to remote clinical services, telehealth can refer to remote nonclinical services, such as provider training, administrative meetings, and continuing medical education, in addition to clinical services.

A World Health Organization report, however, uses the 2 terms synonymously and interchangeably, defining telemedicine as2:

- The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.

The American Telemedicine Association (ATA) describes their use of the terms this way3:

- ATA largely views telemedicine and telehealth to be interchangeable terms, encompassing a wide definition of remote healthcare, although telehealth may not always involve clinical care.

References

- HealthIT.gov website. Frequently asked questions. https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/frequently-asked-questions/485. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in member states. 2010. http://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_telemedicine_2010.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- American Telemedicine Association. About telemedicine: the ultimate frontier for superior healthcare delivery. http://www.americantelemed.org/about/about-telemedicine. Accessed November 15, 2017.

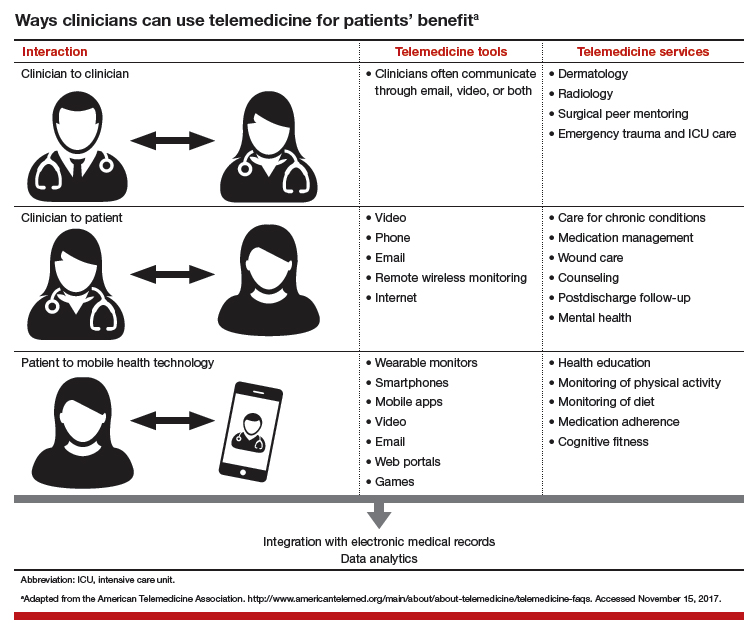

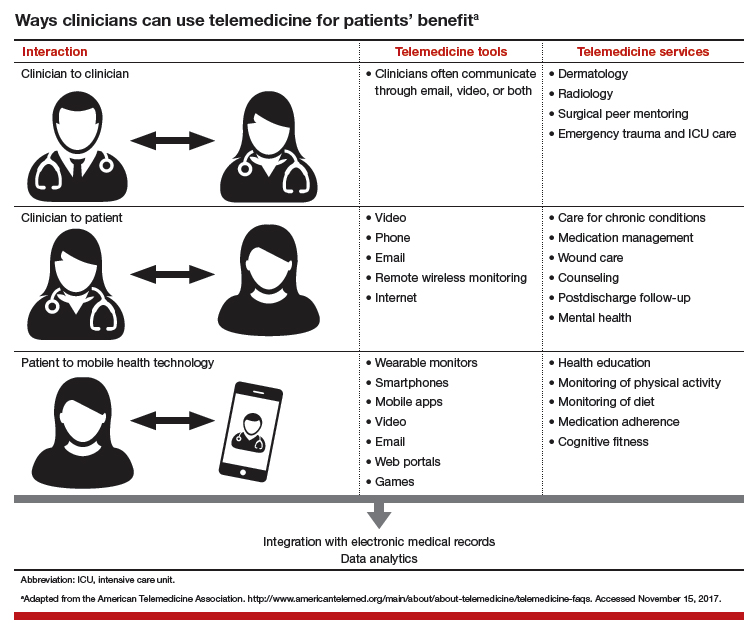

Learn about ways clinicians can use telemedicine.

Making progress in rural and underserved communities

Peter Nielsen, MD: When we saw that some high-risk obstetrics patients were having a difficult time getting to our downtown San Antonio office—the trip from surrounding communities was taking too long, or city driving and parking were stressful or too costly—we looked to improve access to care. Collaborating with a health care network that has a hospital in a town north of San Antonio, we set up a pilot program to provide telemedicine perinatal consultation services.

In this kind of service, which occurs entirely in real time, ultrasound images taken at the hospital are streamed by high-speed fiberoptic cable to our office, where a maternal-fetal medicine physician views them. If a repeat image or a different image is needed, the physician requests another scan. Linked to the physician and listening through an earpiece, the ultrasonographer performs the new scan with little delay and without disturbing the patient. The conversation between physician and ultrasonographer is private.

After ultrasound scanning is complete, the patient goes to a private room at the hospital for a video conference with our physician in San Antonio, who has reviewed the images in the PACS (picture archiving and communication system) or ultrasound recording system. They discuss the images, the findings, and the follow-up.

We tested the technology during a 6-month pilot program to make sure it worked at the highest quality and safety levels. Then the program went live and we started seeing patients remotely. Now we have a robust telemedicine training capability at that hospital outside San Antonio, and we are looking to expand to other south and west Texas areas, some even farther from our office.

I have done some of these remote consultations. In response to my informal queries about the experience, patients said that no one else was offering it, and they were participating for the first time. Naturally they had questions and concerns. Nevertheless, patients, family members, and the ultrasonographer and physicians in the communities seem to think this is a high-quality, safe program that makes it easier for patients to access health care.

Patients uniformly describe these consultations in positive terms. They do not have to drive far, into the city, and deal with traffic; parking is easy and free; and less travel means much less time off from work. Given these very practical advantages, patients are interested in having more appointments done remotely. In addition, they say the appointment itself is easy, being there is effortless, and they feel their physician is sitting in the same room. It is like video chatting with family members—they are comfortable with the technology.

Related article:

Landmark women’s health care remains law of the land

The patients’ perspective

Dr. Brown: Patient satisfaction is an important issue. In psychiatry, dermatology, and other disciplines, patients have indicated that they are very satisfied with telehealth sessions. Telehealth in obstetrics and gynecology, I think, will receive similar positive feedback.

The issue of driving distance led us to reconsider the number of face-to-face prenatal visits a normal, healthy patient needs. These days, a patient can use a prenatal care app to track her weight and blood pressure and send the data to her physician. Besides being convenient, these monitoring apps can give a patient an important sense of control. Our pilot programs found that a patient who self-monitors understands her weight gain better and is more in tune with it. Apps and other technologies can thus improve quality of care and, in reducing the number of trips to an office, increase patient satisfaction.

Many people use or are familiar with the programs Skype and FaceTime (audiovideo chat software), and I envision that our postpartum task force will recommend using such programs for follow-up appointments. For each visit, the question to ask is whether the patient really needs to meet with her physician in person, or can she stay with her new baby and receive postpartum counseling at home. I am excited about the potential of telehealth in obstetrics and gynecology. Our task force is exploring that potential.

Telehealth for both routine and specialized care

Dr. Brown: Specialized care applications are here. In a pilot program in Wisconsin, a colleague has been providing remote psychiatric care. Perhaps such a program can be used to follow up on patients with postpartum depression. In addition, other psychiatry colleagues have long been using telehealth for adolescent behavior follow-ups, and we can do this too.

Another colleague has been performing remote perinatal follow-up for children with congenital anomalies. The physician interacts with the parent or parents as well as the patient. This seems to represent only the tip of the iceberg of what can be done in terms of follow-up.

We can also use telehealth in infertility settings. High-risk patients can benefit, too. Our guidelines say patients with preeclampsia should be seen within 3 days to 1 week. Many are transferred from low-access hospitals to our office. This follow-up, however, also can be done remotely, with patients at health department clinics or even at home. Reporting blood pressure readings and health-related feelings to a physician during a teleconsultation removes driving as a potential inconvenience or obstacle.

Telemedicine can be advantageous in gynecology. Physicians are doing important work with telecolposcopy as a follow-up to abnormal Pap test findings in patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

Routine wound care, which is commonly needed, can be performed in the home by a home health nurse telecommunicating with a physician. I can see broad telehealth use, and indeed our dermatology colleagues have been practicing telemedicine for quite some time.

Read about solving financial barriers and physician shortages.

An affordable solution to financial barriers and physician shortages

Dr. Nielsen: Telehealth can reduce barriers to care. For example, knowing that our teleconsultation services are covered by insurance, referring physicians and patients are more likely to try them and continue to use them. Payers are on board as well. Other barriers can be harder to overcome, particularly for patients at risk for complex diagnoses and medical decisions. Our pilot program, however, has demonstrated success in this area. It has provided safe, high-quality imaging, accurate diagnoses, productive discussions, and helpful management recommendations.

Telehealth also helps address relative and absolute physician shortages. In some areas, a relative shortage may indicate misdistribution. In other areas, specialists simply are too few in number. This absolute shortage of specialists likely will increase, as many communities are too small to sustain and support having them in person.

Outpatients can obtain care 5 days a week with telemedicine, as opposed to only 1 to 3 times a month in person. Physicians travel to remote clinics that are staffed only 1 or 2 days a month. Where the window for care is so small, patients and physicians are likely to turn to telemedicine. In addition, that utility results in better use of resources. For example, studies that were performed earlier would not need to be repeated, since you could access centrally located archives.

Related article:

ICD-10-CM code changes: What's new for 2018

Dr. Brown: For teleconsultations and televisits, all that payers need do is modify the billing codes they use for our usual services. Once that is done, payers can develop a payment model that works for both themselves and the teleconsultants.

The US health care system is fragmented. Health care is provided in various facilities, including federally qualified health centers and health department clinics. As Dr. Nielsen said, physicians travel to remote facilities once or twice a week or even a month, whereas telehealth can be offered 5 days a week. Many residents go to remote clinics, where an attending physician is required. Instead of an attending driving there, he or she could be teleconsulting—interacting with residents and patients from afar. So, telehealth is a win-win situation. It increases access to physicians and facilitates appropriate interactions with them, wherever they are. Telehealth can be an important contribution to developing a more effective health care delivery system than the fragmented one we have now.

Effective health care delivery is so important for obstetrics and gynecology, and the reported workforce challenges are real. A maternal-fetal medicine physician is unlikely to travel to remote communities once a week or even every 2 weeks, but that same physician can teleconsult multiple days each week.

How telehealth can close service gaps

Dr. Brown: Having established relationships with physicians in other clinics and communities paves the way for teleconsultation and remote supervision. Technology can help Planned Parenthood and other clinics continue to provide contraceptive counseling and other health care services. Even medical abortions can be supervised through teleconsultation.

With funds to Medicaid being cut, with the potential for Planned Parenthood to be defunded, physicians must think of ways they can continue to provide care to all patients and communities. By addressing these issues now, we will be ready to take charge of patient care, wherever it is needed.

But, we need partners, no question. We need hospital partners in all communities, and especially in rural communities. Rural hospitals and maternity care are at risk. Health care in rural communities faces many challenges. Telehealth, teleconferencing, and teleconsultation not only can improve access to services, but also can curb travel costs as well as costs to the communities and hospitals.

Who pays the operating costs, and who benefits

Dr. Brown: Payers are already discovering that teleconsultations are as billable as in-person visits. In addition, physicians are realizing that remote consultation can work as well as in-person consultation, with its own merits and advantages. Education is key—education about billing and about what is doable in telehealth. We can learn from colleagues in other specialties.

Dr. Nielsen: Several entities and groups must start covering the technology costs. Federal and state entities need to determine how the country’s information infrastructure can be improved to give rural areas access to high-quality, high-speed, wide-bandwidth communications, which will help expand telehealth and increase other industries’ opportunities to grow and sustain these communities. Improving the infrastructure also can help keep rural areas sustainable.

Health care systems themselves can join federal, state, and local governments in building this infrastructure. They can also start identifying opportunities to support and sustain physicians and hospitals in smaller towns and start combating the perception that the infrastructure is being developed only to migrate patients over to accessing their care through telehealth provided by physicians in the larger cities.

Many payers see telehealth as improving access and outcomes and already support it, but more payers need to become involved. All need to understand how routine and complex consultations, even inpatient consultations, can be performed remotely and can be properly reimbursed, and incentivized with payments for improved outcomes and value.

As barriers fall and telehealth improves, acceptance by patients and physicians will increase. In addition, telehealth will enter medical education in a significant way. The instruction that students, residents, and Fellows receive will be enhanced by new telehealth approaches in various specialties, and residents will come out of these programs with telehealth experience and a sense of both financial benefits and payment structures. This early exposure will pique their interest in using telehealth and advocating its use where it may never before have been considered, owing to real and perceived barriers.

Read about telehealth solutions for ObGyns.

Learning from other specialties and agencies

Dr. Brown: The physician shortage negatively affects access to health care in rural areas. Many city and suburban physicians, including ObGyns, want to stay where they are. Education is needed to show them that a rural practice can be successful. They would have a good patient base and be able to use telehealth to improve care and maintain contact with tertiary care centers.

Several task force members have described their experience within their health systems, and we hope to borrow from that. A health system in South Dakota received a Health Resources and Services Administration grant to use telehealth and teleconsultation in the Indian Health Service (IHS). To women who access their health care through the IHS, being able to remain in the community is culturally important. Telehealth and teleconsultation bring care to these women where they live.

To develop the best telehealth and teleconsultation model, we are borrowing from these health systems and from the experience of our colleagues in dermatology, behavioral health, psychiatry, and other disciplines. These physicians already have overcome many hurdles and discovered the importance of patient satisfaction in providing remote health care.

Patients will benefit in various ways, and here is another example: A clinic refers a patient to an ObGyn to discuss whether it is possible to have a vaginal birth after a cesarean delivery. The drive to the ObGyn’s office takes an hour, but the patient just as easily could have had all her questions answered during a teleconsultation.

Related articles:

Telehealth and you (4-part audiocast)

Telehealth recommendations for ObGyns

Dr. Brown: Our task force will develop recommended best practices for telehealth. We will outline how a practice can engage with telehealth and will address licensing requirements, as a practice must be licensed in each state where it uses telehealth. Our goal is to help our specialty get started in telehealth and telemedicine.

In practices with telehealth, it will be incumbent on ObGyns to identify any barriers to care. For example, we are concerned about early discontinuation of breastfeeding, particularly among African American communities. Fortunately, we have learned that video chat follow-ups can help improve breastfeeding continuation rates.

It also will be incumbent on ObGyns to think differently about how best to follow up. For a patient who calls to say she thinks she has mastitis, much of the consultation can be handled by telephone or video conference with the physician and a nurse practi‑tioner, and then medication can be prescribed without the need for in-person follow-up. We must then determine how to ensure these follow-up methods are compensated.

Direct-to-patient virtual visits

- Virtual home visits

- Low-risk pregnancy

- Postpartum visits

- Lactation support

- Routine gynecologic care

- Postoperative follow-up

Remote patient monitoring

- Chronic disease management

- Antenatal testing

- Fetal heart rate monitoring

- Transfer of care

Final thoughts

Dr. Nielsen: It is time for all US health care players to more seriously and aggressively consider how telehealth can improve health care access, quality, and safety. Even more important, patients and physicians in small communities need to feel that they can access specialists and care that is as good as those available in larger communities without having to pull up stakes and move.

Telehealth can help small communities become sustainable over the long term. As the majority of the people in this country are born in and receive health care in community hospitals, not large tertiary care centers, the state of US health care should be measured by the ability to provide as much care as is technically possible in the small communities where patients live and work and raise their kids.

Dr. Brown: More than 50% of all babies are born in hospitals where fewer than 1,000 deliveries are performed, and almost 40% are born in hospitals where fewer than 500 are performed. To provide high-level care and have patients feel comfortable, to improve morbidity and mortality, we need telehealth and telemedicine.

If I can help a physician in East Africa place a Bakri balloon for postpartum hemorrhaging, surely I can help a physician in rural areas of Wyoming, South Dakota, or North Carolina deal with this obstetric emergency. In obstetrics and gynecology, telehealth and telemedicine have great potential in terms of morbidity and mortality, but we are also doing genetic counseling and a great deal of patient follow-up, and so much more can be done.

That is the key, and the reason for the training, the task force, the deliberations, and the best practices model that we will be sharing with our colleagues.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

I recently spoke with 2 outstanding leaders in our field, members of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) task force on telehealth and telemedicine, about the future of providing health care to women in remote locations.

Haywood Brown, MD, is President of ACOG for 2017–2018 and is F. Bayard Carter Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, and Peter Nielsen, MD, is Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and Obstetrician-in-Chief at Children’s Hospital of San Antonio. Dr. Nielsen is a retired US Army colonel.

Why an ACOG telehealth task force?

Haywood Brown, MD: Our overall goals in telehealth and telemedicine are to coordinate and better facilitate the health care of women in remote locations and to improve maternal morbidity and mortality. Telehealth can be used on both an outpatient and an inpatient basis.

Outpatient telehealth is used for consultations. In maternal-fetal medicine, for instance, we use it for ultrasonography consultations. I also have used telehealth technology to “see” a pregnant patient with type 1diabetes. During our sessions, I managed her blood sugar levels and did all the other things I would have done if we had been together at my clinic. Without telehealth technology, however, this patient would have needed to drive 4 hours round-trip for each appointment.

Our colleagues in rural communities and at lower-level hospitals can use telehealth and telemedicine as aids in treating their high-risk patients, such as those with preeclampsia, prematurity risk, or other conditions. Physicians can consult with specialists through a face-to-face conversation that takes place through telecommunications. The result is that the quality of care for women in our communities is improved.

Genetic counseling, infertility consultation, and fetal anomaly management are some of the other applications. Our task force is discussing different ways to improve patient care and ways to collaborate with our colleagues around the country. Ultimately, we are developing best practices—a model for the best uses of technology to improve women’s health care in the United States.

Task force focus: Telehealth technology, billing, services

Dr. Brown: Our task force, a diverse group of members from all over the country, represents the spectrum of ObGyns. Although task force members have various levels of telehealth experience, all are very interested in these new channels of communication. The task force also includes billers, who understand billing ramifications, and payers, who know firsthand what will and will not be paid.

Technology and its availability is the most important topic for the task force. While some communities have Internet service, not all do. We need to determine which areas need service, how much it would cost, and who pays for it. Can a hospital afford it? A practice? Their partners? Identifying partners in tertiary care settings is a task force goal.

We are engaging a broad range of experts to study all the components and associated costs of technology, licensing, and cross-state credentialing. Gathering this information will help in developing a best practices model that general ObGyns can use.

Telehealth is redefining aspects of care: prenatal care (how many visits are required?), postpartum care, and other types of services that can be done remotely. Genetic counseling—who can provide it, what education is required—is another topic of discussion. Once we surmount the billing obstacles, we can do much with teleconferencing, such as provide genetic consultation with ObGyns in various settings.

The terms "telehealth" and "telemedicine" are often used interchangeably. Telemedicine is the older phrase, while telehealth entered the vernacular more recently and encompasses a broader definition.

The HealthIT.gov website explains the differences in terminology this way1:

- The Health Resources Services Administration defines telehealth as the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, public health and health administration. Technologies include videoconferencing, the Internet, store-and-forward imaging, streaming media, and terrestrial and wireless communications.

- Telehealth is different from telemedicine because it refers to a broader scope of remote health care services than telemedicine. While telemedicine refers specifically to remote clinical services, telehealth can refer to remote nonclinical services, such as provider training, administrative meetings, and continuing medical education, in addition to clinical services.

A World Health Organization report, however, uses the 2 terms synonymously and interchangeably, defining telemedicine as2:

- The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.

The American Telemedicine Association (ATA) describes their use of the terms this way3:

- ATA largely views telemedicine and telehealth to be interchangeable terms, encompassing a wide definition of remote healthcare, although telehealth may not always involve clinical care.

References

- HealthIT.gov website. Frequently asked questions. https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/frequently-asked-questions/485. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in member states. 2010. http://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_telemedicine_2010.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- American Telemedicine Association. About telemedicine: the ultimate frontier for superior healthcare delivery. http://www.americantelemed.org/about/about-telemedicine. Accessed November 15, 2017.

Learn about ways clinicians can use telemedicine.

Making progress in rural and underserved communities

Peter Nielsen, MD: When we saw that some high-risk obstetrics patients were having a difficult time getting to our downtown San Antonio office—the trip from surrounding communities was taking too long, or city driving and parking were stressful or too costly—we looked to improve access to care. Collaborating with a health care network that has a hospital in a town north of San Antonio, we set up a pilot program to provide telemedicine perinatal consultation services.

In this kind of service, which occurs entirely in real time, ultrasound images taken at the hospital are streamed by high-speed fiberoptic cable to our office, where a maternal-fetal medicine physician views them. If a repeat image or a different image is needed, the physician requests another scan. Linked to the physician and listening through an earpiece, the ultrasonographer performs the new scan with little delay and without disturbing the patient. The conversation between physician and ultrasonographer is private.

After ultrasound scanning is complete, the patient goes to a private room at the hospital for a video conference with our physician in San Antonio, who has reviewed the images in the PACS (picture archiving and communication system) or ultrasound recording system. They discuss the images, the findings, and the follow-up.

We tested the technology during a 6-month pilot program to make sure it worked at the highest quality and safety levels. Then the program went live and we started seeing patients remotely. Now we have a robust telemedicine training capability at that hospital outside San Antonio, and we are looking to expand to other south and west Texas areas, some even farther from our office.

I have done some of these remote consultations. In response to my informal queries about the experience, patients said that no one else was offering it, and they were participating for the first time. Naturally they had questions and concerns. Nevertheless, patients, family members, and the ultrasonographer and physicians in the communities seem to think this is a high-quality, safe program that makes it easier for patients to access health care.

Patients uniformly describe these consultations in positive terms. They do not have to drive far, into the city, and deal with traffic; parking is easy and free; and less travel means much less time off from work. Given these very practical advantages, patients are interested in having more appointments done remotely. In addition, they say the appointment itself is easy, being there is effortless, and they feel their physician is sitting in the same room. It is like video chatting with family members—they are comfortable with the technology.

Related article:

Landmark women’s health care remains law of the land

The patients’ perspective

Dr. Brown: Patient satisfaction is an important issue. In psychiatry, dermatology, and other disciplines, patients have indicated that they are very satisfied with telehealth sessions. Telehealth in obstetrics and gynecology, I think, will receive similar positive feedback.

The issue of driving distance led us to reconsider the number of face-to-face prenatal visits a normal, healthy patient needs. These days, a patient can use a prenatal care app to track her weight and blood pressure and send the data to her physician. Besides being convenient, these monitoring apps can give a patient an important sense of control. Our pilot programs found that a patient who self-monitors understands her weight gain better and is more in tune with it. Apps and other technologies can thus improve quality of care and, in reducing the number of trips to an office, increase patient satisfaction.

Many people use or are familiar with the programs Skype and FaceTime (audiovideo chat software), and I envision that our postpartum task force will recommend using such programs for follow-up appointments. For each visit, the question to ask is whether the patient really needs to meet with her physician in person, or can she stay with her new baby and receive postpartum counseling at home. I am excited about the potential of telehealth in obstetrics and gynecology. Our task force is exploring that potential.

Telehealth for both routine and specialized care

Dr. Brown: Specialized care applications are here. In a pilot program in Wisconsin, a colleague has been providing remote psychiatric care. Perhaps such a program can be used to follow up on patients with postpartum depression. In addition, other psychiatry colleagues have long been using telehealth for adolescent behavior follow-ups, and we can do this too.

Another colleague has been performing remote perinatal follow-up for children with congenital anomalies. The physician interacts with the parent or parents as well as the patient. This seems to represent only the tip of the iceberg of what can be done in terms of follow-up.

We can also use telehealth in infertility settings. High-risk patients can benefit, too. Our guidelines say patients with preeclampsia should be seen within 3 days to 1 week. Many are transferred from low-access hospitals to our office. This follow-up, however, also can be done remotely, with patients at health department clinics or even at home. Reporting blood pressure readings and health-related feelings to a physician during a teleconsultation removes driving as a potential inconvenience or obstacle.

Telemedicine can be advantageous in gynecology. Physicians are doing important work with telecolposcopy as a follow-up to abnormal Pap test findings in patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

Routine wound care, which is commonly needed, can be performed in the home by a home health nurse telecommunicating with a physician. I can see broad telehealth use, and indeed our dermatology colleagues have been practicing telemedicine for quite some time.

Read about solving financial barriers and physician shortages.

An affordable solution to financial barriers and physician shortages

Dr. Nielsen: Telehealth can reduce barriers to care. For example, knowing that our teleconsultation services are covered by insurance, referring physicians and patients are more likely to try them and continue to use them. Payers are on board as well. Other barriers can be harder to overcome, particularly for patients at risk for complex diagnoses and medical decisions. Our pilot program, however, has demonstrated success in this area. It has provided safe, high-quality imaging, accurate diagnoses, productive discussions, and helpful management recommendations.

Telehealth also helps address relative and absolute physician shortages. In some areas, a relative shortage may indicate misdistribution. In other areas, specialists simply are too few in number. This absolute shortage of specialists likely will increase, as many communities are too small to sustain and support having them in person.

Outpatients can obtain care 5 days a week with telemedicine, as opposed to only 1 to 3 times a month in person. Physicians travel to remote clinics that are staffed only 1 or 2 days a month. Where the window for care is so small, patients and physicians are likely to turn to telemedicine. In addition, that utility results in better use of resources. For example, studies that were performed earlier would not need to be repeated, since you could access centrally located archives.

Related article:

ICD-10-CM code changes: What's new for 2018

Dr. Brown: For teleconsultations and televisits, all that payers need do is modify the billing codes they use for our usual services. Once that is done, payers can develop a payment model that works for both themselves and the teleconsultants.

The US health care system is fragmented. Health care is provided in various facilities, including federally qualified health centers and health department clinics. As Dr. Nielsen said, physicians travel to remote facilities once or twice a week or even a month, whereas telehealth can be offered 5 days a week. Many residents go to remote clinics, where an attending physician is required. Instead of an attending driving there, he or she could be teleconsulting—interacting with residents and patients from afar. So, telehealth is a win-win situation. It increases access to physicians and facilitates appropriate interactions with them, wherever they are. Telehealth can be an important contribution to developing a more effective health care delivery system than the fragmented one we have now.

Effective health care delivery is so important for obstetrics and gynecology, and the reported workforce challenges are real. A maternal-fetal medicine physician is unlikely to travel to remote communities once a week or even every 2 weeks, but that same physician can teleconsult multiple days each week.

How telehealth can close service gaps

Dr. Brown: Having established relationships with physicians in other clinics and communities paves the way for teleconsultation and remote supervision. Technology can help Planned Parenthood and other clinics continue to provide contraceptive counseling and other health care services. Even medical abortions can be supervised through teleconsultation.

With funds to Medicaid being cut, with the potential for Planned Parenthood to be defunded, physicians must think of ways they can continue to provide care to all patients and communities. By addressing these issues now, we will be ready to take charge of patient care, wherever it is needed.

But, we need partners, no question. We need hospital partners in all communities, and especially in rural communities. Rural hospitals and maternity care are at risk. Health care in rural communities faces many challenges. Telehealth, teleconferencing, and teleconsultation not only can improve access to services, but also can curb travel costs as well as costs to the communities and hospitals.

Who pays the operating costs, and who benefits

Dr. Brown: Payers are already discovering that teleconsultations are as billable as in-person visits. In addition, physicians are realizing that remote consultation can work as well as in-person consultation, with its own merits and advantages. Education is key—education about billing and about what is doable in telehealth. We can learn from colleagues in other specialties.

Dr. Nielsen: Several entities and groups must start covering the technology costs. Federal and state entities need to determine how the country’s information infrastructure can be improved to give rural areas access to high-quality, high-speed, wide-bandwidth communications, which will help expand telehealth and increase other industries’ opportunities to grow and sustain these communities. Improving the infrastructure also can help keep rural areas sustainable.

Health care systems themselves can join federal, state, and local governments in building this infrastructure. They can also start identifying opportunities to support and sustain physicians and hospitals in smaller towns and start combating the perception that the infrastructure is being developed only to migrate patients over to accessing their care through telehealth provided by physicians in the larger cities.

Many payers see telehealth as improving access and outcomes and already support it, but more payers need to become involved. All need to understand how routine and complex consultations, even inpatient consultations, can be performed remotely and can be properly reimbursed, and incentivized with payments for improved outcomes and value.

As barriers fall and telehealth improves, acceptance by patients and physicians will increase. In addition, telehealth will enter medical education in a significant way. The instruction that students, residents, and Fellows receive will be enhanced by new telehealth approaches in various specialties, and residents will come out of these programs with telehealth experience and a sense of both financial benefits and payment structures. This early exposure will pique their interest in using telehealth and advocating its use where it may never before have been considered, owing to real and perceived barriers.

Read about telehealth solutions for ObGyns.

Learning from other specialties and agencies

Dr. Brown: The physician shortage negatively affects access to health care in rural areas. Many city and suburban physicians, including ObGyns, want to stay where they are. Education is needed to show them that a rural practice can be successful. They would have a good patient base and be able to use telehealth to improve care and maintain contact with tertiary care centers.

Several task force members have described their experience within their health systems, and we hope to borrow from that. A health system in South Dakota received a Health Resources and Services Administration grant to use telehealth and teleconsultation in the Indian Health Service (IHS). To women who access their health care through the IHS, being able to remain in the community is culturally important. Telehealth and teleconsultation bring care to these women where they live.

To develop the best telehealth and teleconsultation model, we are borrowing from these health systems and from the experience of our colleagues in dermatology, behavioral health, psychiatry, and other disciplines. These physicians already have overcome many hurdles and discovered the importance of patient satisfaction in providing remote health care.

Patients will benefit in various ways, and here is another example: A clinic refers a patient to an ObGyn to discuss whether it is possible to have a vaginal birth after a cesarean delivery. The drive to the ObGyn’s office takes an hour, but the patient just as easily could have had all her questions answered during a teleconsultation.

Related articles:

Telehealth and you (4-part audiocast)

Telehealth recommendations for ObGyns

Dr. Brown: Our task force will develop recommended best practices for telehealth. We will outline how a practice can engage with telehealth and will address licensing requirements, as a practice must be licensed in each state where it uses telehealth. Our goal is to help our specialty get started in telehealth and telemedicine.

In practices with telehealth, it will be incumbent on ObGyns to identify any barriers to care. For example, we are concerned about early discontinuation of breastfeeding, particularly among African American communities. Fortunately, we have learned that video chat follow-ups can help improve breastfeeding continuation rates.

It also will be incumbent on ObGyns to think differently about how best to follow up. For a patient who calls to say she thinks she has mastitis, much of the consultation can be handled by telephone or video conference with the physician and a nurse practi‑tioner, and then medication can be prescribed without the need for in-person follow-up. We must then determine how to ensure these follow-up methods are compensated.

Direct-to-patient virtual visits

- Virtual home visits

- Low-risk pregnancy

- Postpartum visits

- Lactation support

- Routine gynecologic care

- Postoperative follow-up

Remote patient monitoring

- Chronic disease management

- Antenatal testing

- Fetal heart rate monitoring

- Transfer of care

Final thoughts

Dr. Nielsen: It is time for all US health care players to more seriously and aggressively consider how telehealth can improve health care access, quality, and safety. Even more important, patients and physicians in small communities need to feel that they can access specialists and care that is as good as those available in larger communities without having to pull up stakes and move.

Telehealth can help small communities become sustainable over the long term. As the majority of the people in this country are born in and receive health care in community hospitals, not large tertiary care centers, the state of US health care should be measured by the ability to provide as much care as is technically possible in the small communities where patients live and work and raise their kids.

Dr. Brown: More than 50% of all babies are born in hospitals where fewer than 1,000 deliveries are performed, and almost 40% are born in hospitals where fewer than 500 are performed. To provide high-level care and have patients feel comfortable, to improve morbidity and mortality, we need telehealth and telemedicine.

If I can help a physician in East Africa place a Bakri balloon for postpartum hemorrhaging, surely I can help a physician in rural areas of Wyoming, South Dakota, or North Carolina deal with this obstetric emergency. In obstetrics and gynecology, telehealth and telemedicine have great potential in terms of morbidity and mortality, but we are also doing genetic counseling and a great deal of patient follow-up, and so much more can be done.

That is the key, and the reason for the training, the task force, the deliberations, and the best practices model that we will be sharing with our colleagues.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

I recently spoke with 2 outstanding leaders in our field, members of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) task force on telehealth and telemedicine, about the future of providing health care to women in remote locations.

Haywood Brown, MD, is President of ACOG for 2017–2018 and is F. Bayard Carter Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Duke University Medical Center in Durham, North Carolina, and Peter Nielsen, MD, is Professor and Vice Chair of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and Obstetrician-in-Chief at Children’s Hospital of San Antonio. Dr. Nielsen is a retired US Army colonel.

Why an ACOG telehealth task force?

Haywood Brown, MD: Our overall goals in telehealth and telemedicine are to coordinate and better facilitate the health care of women in remote locations and to improve maternal morbidity and mortality. Telehealth can be used on both an outpatient and an inpatient basis.

Outpatient telehealth is used for consultations. In maternal-fetal medicine, for instance, we use it for ultrasonography consultations. I also have used telehealth technology to “see” a pregnant patient with type 1diabetes. During our sessions, I managed her blood sugar levels and did all the other things I would have done if we had been together at my clinic. Without telehealth technology, however, this patient would have needed to drive 4 hours round-trip for each appointment.

Our colleagues in rural communities and at lower-level hospitals can use telehealth and telemedicine as aids in treating their high-risk patients, such as those with preeclampsia, prematurity risk, or other conditions. Physicians can consult with specialists through a face-to-face conversation that takes place through telecommunications. The result is that the quality of care for women in our communities is improved.

Genetic counseling, infertility consultation, and fetal anomaly management are some of the other applications. Our task force is discussing different ways to improve patient care and ways to collaborate with our colleagues around the country. Ultimately, we are developing best practices—a model for the best uses of technology to improve women’s health care in the United States.

Task force focus: Telehealth technology, billing, services

Dr. Brown: Our task force, a diverse group of members from all over the country, represents the spectrum of ObGyns. Although task force members have various levels of telehealth experience, all are very interested in these new channels of communication. The task force also includes billers, who understand billing ramifications, and payers, who know firsthand what will and will not be paid.

Technology and its availability is the most important topic for the task force. While some communities have Internet service, not all do. We need to determine which areas need service, how much it would cost, and who pays for it. Can a hospital afford it? A practice? Their partners? Identifying partners in tertiary care settings is a task force goal.

We are engaging a broad range of experts to study all the components and associated costs of technology, licensing, and cross-state credentialing. Gathering this information will help in developing a best practices model that general ObGyns can use.

Telehealth is redefining aspects of care: prenatal care (how many visits are required?), postpartum care, and other types of services that can be done remotely. Genetic counseling—who can provide it, what education is required—is another topic of discussion. Once we surmount the billing obstacles, we can do much with teleconferencing, such as provide genetic consultation with ObGyns in various settings.

The terms "telehealth" and "telemedicine" are often used interchangeably. Telemedicine is the older phrase, while telehealth entered the vernacular more recently and encompasses a broader definition.

The HealthIT.gov website explains the differences in terminology this way1:

- The Health Resources Services Administration defines telehealth as the use of electronic information and telecommunications technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, public health and health administration. Technologies include videoconferencing, the Internet, store-and-forward imaging, streaming media, and terrestrial and wireless communications.

- Telehealth is different from telemedicine because it refers to a broader scope of remote health care services than telemedicine. While telemedicine refers specifically to remote clinical services, telehealth can refer to remote nonclinical services, such as provider training, administrative meetings, and continuing medical education, in addition to clinical services.

A World Health Organization report, however, uses the 2 terms synonymously and interchangeably, defining telemedicine as2:

- The delivery of health care services, where distance is a critical factor, by all health care professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of health care providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities.

The American Telemedicine Association (ATA) describes their use of the terms this way3:

- ATA largely views telemedicine and telehealth to be interchangeable terms, encompassing a wide definition of remote healthcare, although telehealth may not always involve clinical care.

References

- HealthIT.gov website. Frequently asked questions. https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/frequently-asked-questions/485. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- World Health Organization. Telemedicine: opportunities and developments in member states. 2010. http://www.who.int/goe/publications/goe_telemedicine_2010.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2017.

- American Telemedicine Association. About telemedicine: the ultimate frontier for superior healthcare delivery. http://www.americantelemed.org/about/about-telemedicine. Accessed November 15, 2017.

Learn about ways clinicians can use telemedicine.

Making progress in rural and underserved communities

Peter Nielsen, MD: When we saw that some high-risk obstetrics patients were having a difficult time getting to our downtown San Antonio office—the trip from surrounding communities was taking too long, or city driving and parking were stressful or too costly—we looked to improve access to care. Collaborating with a health care network that has a hospital in a town north of San Antonio, we set up a pilot program to provide telemedicine perinatal consultation services.

In this kind of service, which occurs entirely in real time, ultrasound images taken at the hospital are streamed by high-speed fiberoptic cable to our office, where a maternal-fetal medicine physician views them. If a repeat image or a different image is needed, the physician requests another scan. Linked to the physician and listening through an earpiece, the ultrasonographer performs the new scan with little delay and without disturbing the patient. The conversation between physician and ultrasonographer is private.

After ultrasound scanning is complete, the patient goes to a private room at the hospital for a video conference with our physician in San Antonio, who has reviewed the images in the PACS (picture archiving and communication system) or ultrasound recording system. They discuss the images, the findings, and the follow-up.

We tested the technology during a 6-month pilot program to make sure it worked at the highest quality and safety levels. Then the program went live and we started seeing patients remotely. Now we have a robust telemedicine training capability at that hospital outside San Antonio, and we are looking to expand to other south and west Texas areas, some even farther from our office.

I have done some of these remote consultations. In response to my informal queries about the experience, patients said that no one else was offering it, and they were participating for the first time. Naturally they had questions and concerns. Nevertheless, patients, family members, and the ultrasonographer and physicians in the communities seem to think this is a high-quality, safe program that makes it easier for patients to access health care.

Patients uniformly describe these consultations in positive terms. They do not have to drive far, into the city, and deal with traffic; parking is easy and free; and less travel means much less time off from work. Given these very practical advantages, patients are interested in having more appointments done remotely. In addition, they say the appointment itself is easy, being there is effortless, and they feel their physician is sitting in the same room. It is like video chatting with family members—they are comfortable with the technology.

Related article:

Landmark women’s health care remains law of the land

The patients’ perspective

Dr. Brown: Patient satisfaction is an important issue. In psychiatry, dermatology, and other disciplines, patients have indicated that they are very satisfied with telehealth sessions. Telehealth in obstetrics and gynecology, I think, will receive similar positive feedback.

The issue of driving distance led us to reconsider the number of face-to-face prenatal visits a normal, healthy patient needs. These days, a patient can use a prenatal care app to track her weight and blood pressure and send the data to her physician. Besides being convenient, these monitoring apps can give a patient an important sense of control. Our pilot programs found that a patient who self-monitors understands her weight gain better and is more in tune with it. Apps and other technologies can thus improve quality of care and, in reducing the number of trips to an office, increase patient satisfaction.

Many people use or are familiar with the programs Skype and FaceTime (audiovideo chat software), and I envision that our postpartum task force will recommend using such programs for follow-up appointments. For each visit, the question to ask is whether the patient really needs to meet with her physician in person, or can she stay with her new baby and receive postpartum counseling at home. I am excited about the potential of telehealth in obstetrics and gynecology. Our task force is exploring that potential.

Telehealth for both routine and specialized care

Dr. Brown: Specialized care applications are here. In a pilot program in Wisconsin, a colleague has been providing remote psychiatric care. Perhaps such a program can be used to follow up on patients with postpartum depression. In addition, other psychiatry colleagues have long been using telehealth for adolescent behavior follow-ups, and we can do this too.

Another colleague has been performing remote perinatal follow-up for children with congenital anomalies. The physician interacts with the parent or parents as well as the patient. This seems to represent only the tip of the iceberg of what can be done in terms of follow-up.

We can also use telehealth in infertility settings. High-risk patients can benefit, too. Our guidelines say patients with preeclampsia should be seen within 3 days to 1 week. Many are transferred from low-access hospitals to our office. This follow-up, however, also can be done remotely, with patients at health department clinics or even at home. Reporting blood pressure readings and health-related feelings to a physician during a teleconsultation removes driving as a potential inconvenience or obstacle.

Telemedicine can be advantageous in gynecology. Physicians are doing important work with telecolposcopy as a follow-up to abnormal Pap test findings in patients in sub-Saharan Africa.

Routine wound care, which is commonly needed, can be performed in the home by a home health nurse telecommunicating with a physician. I can see broad telehealth use, and indeed our dermatology colleagues have been practicing telemedicine for quite some time.

Read about solving financial barriers and physician shortages.

An affordable solution to financial barriers and physician shortages

Dr. Nielsen: Telehealth can reduce barriers to care. For example, knowing that our teleconsultation services are covered by insurance, referring physicians and patients are more likely to try them and continue to use them. Payers are on board as well. Other barriers can be harder to overcome, particularly for patients at risk for complex diagnoses and medical decisions. Our pilot program, however, has demonstrated success in this area. It has provided safe, high-quality imaging, accurate diagnoses, productive discussions, and helpful management recommendations.

Telehealth also helps address relative and absolute physician shortages. In some areas, a relative shortage may indicate misdistribution. In other areas, specialists simply are too few in number. This absolute shortage of specialists likely will increase, as many communities are too small to sustain and support having them in person.

Outpatients can obtain care 5 days a week with telemedicine, as opposed to only 1 to 3 times a month in person. Physicians travel to remote clinics that are staffed only 1 or 2 days a month. Where the window for care is so small, patients and physicians are likely to turn to telemedicine. In addition, that utility results in better use of resources. For example, studies that were performed earlier would not need to be repeated, since you could access centrally located archives.

Related article:

ICD-10-CM code changes: What's new for 2018

Dr. Brown: For teleconsultations and televisits, all that payers need do is modify the billing codes they use for our usual services. Once that is done, payers can develop a payment model that works for both themselves and the teleconsultants.

The US health care system is fragmented. Health care is provided in various facilities, including federally qualified health centers and health department clinics. As Dr. Nielsen said, physicians travel to remote facilities once or twice a week or even a month, whereas telehealth can be offered 5 days a week. Many residents go to remote clinics, where an attending physician is required. Instead of an attending driving there, he or she could be teleconsulting—interacting with residents and patients from afar. So, telehealth is a win-win situation. It increases access to physicians and facilitates appropriate interactions with them, wherever they are. Telehealth can be an important contribution to developing a more effective health care delivery system than the fragmented one we have now.

Effective health care delivery is so important for obstetrics and gynecology, and the reported workforce challenges are real. A maternal-fetal medicine physician is unlikely to travel to remote communities once a week or even every 2 weeks, but that same physician can teleconsult multiple days each week.

How telehealth can close service gaps

Dr. Brown: Having established relationships with physicians in other clinics and communities paves the way for teleconsultation and remote supervision. Technology can help Planned Parenthood and other clinics continue to provide contraceptive counseling and other health care services. Even medical abortions can be supervised through teleconsultation.

With funds to Medicaid being cut, with the potential for Planned Parenthood to be defunded, physicians must think of ways they can continue to provide care to all patients and communities. By addressing these issues now, we will be ready to take charge of patient care, wherever it is needed.

But, we need partners, no question. We need hospital partners in all communities, and especially in rural communities. Rural hospitals and maternity care are at risk. Health care in rural communities faces many challenges. Telehealth, teleconferencing, and teleconsultation not only can improve access to services, but also can curb travel costs as well as costs to the communities and hospitals.

Who pays the operating costs, and who benefits

Dr. Brown: Payers are already discovering that teleconsultations are as billable as in-person visits. In addition, physicians are realizing that remote consultation can work as well as in-person consultation, with its own merits and advantages. Education is key—education about billing and about what is doable in telehealth. We can learn from colleagues in other specialties.

Dr. Nielsen: Several entities and groups must start covering the technology costs. Federal and state entities need to determine how the country’s information infrastructure can be improved to give rural areas access to high-quality, high-speed, wide-bandwidth communications, which will help expand telehealth and increase other industries’ opportunities to grow and sustain these communities. Improving the infrastructure also can help keep rural areas sustainable.

Health care systems themselves can join federal, state, and local governments in building this infrastructure. They can also start identifying opportunities to support and sustain physicians and hospitals in smaller towns and start combating the perception that the infrastructure is being developed only to migrate patients over to accessing their care through telehealth provided by physicians in the larger cities.

Many payers see telehealth as improving access and outcomes and already support it, but more payers need to become involved. All need to understand how routine and complex consultations, even inpatient consultations, can be performed remotely and can be properly reimbursed, and incentivized with payments for improved outcomes and value.

As barriers fall and telehealth improves, acceptance by patients and physicians will increase. In addition, telehealth will enter medical education in a significant way. The instruction that students, residents, and Fellows receive will be enhanced by new telehealth approaches in various specialties, and residents will come out of these programs with telehealth experience and a sense of both financial benefits and payment structures. This early exposure will pique their interest in using telehealth and advocating its use where it may never before have been considered, owing to real and perceived barriers.

Read about telehealth solutions for ObGyns.

Learning from other specialties and agencies

Dr. Brown: The physician shortage negatively affects access to health care in rural areas. Many city and suburban physicians, including ObGyns, want to stay where they are. Education is needed to show them that a rural practice can be successful. They would have a good patient base and be able to use telehealth to improve care and maintain contact with tertiary care centers.

Several task force members have described their experience within their health systems, and we hope to borrow from that. A health system in South Dakota received a Health Resources and Services Administration grant to use telehealth and teleconsultation in the Indian Health Service (IHS). To women who access their health care through the IHS, being able to remain in the community is culturally important. Telehealth and teleconsultation bring care to these women where they live.

To develop the best telehealth and teleconsultation model, we are borrowing from these health systems and from the experience of our colleagues in dermatology, behavioral health, psychiatry, and other disciplines. These physicians already have overcome many hurdles and discovered the importance of patient satisfaction in providing remote health care.

Patients will benefit in various ways, and here is another example: A clinic refers a patient to an ObGyn to discuss whether it is possible to have a vaginal birth after a cesarean delivery. The drive to the ObGyn’s office takes an hour, but the patient just as easily could have had all her questions answered during a teleconsultation.

Related articles:

Telehealth and you (4-part audiocast)

Telehealth recommendations for ObGyns

Dr. Brown: Our task force will develop recommended best practices for telehealth. We will outline how a practice can engage with telehealth and will address licensing requirements, as a practice must be licensed in each state where it uses telehealth. Our goal is to help our specialty get started in telehealth and telemedicine.

In practices with telehealth, it will be incumbent on ObGyns to identify any barriers to care. For example, we are concerned about early discontinuation of breastfeeding, particularly among African American communities. Fortunately, we have learned that video chat follow-ups can help improve breastfeeding continuation rates.

It also will be incumbent on ObGyns to think differently about how best to follow up. For a patient who calls to say she thinks she has mastitis, much of the consultation can be handled by telephone or video conference with the physician and a nurse practi‑tioner, and then medication can be prescribed without the need for in-person follow-up. We must then determine how to ensure these follow-up methods are compensated.

Direct-to-patient virtual visits

- Virtual home visits

- Low-risk pregnancy

- Postpartum visits

- Lactation support

- Routine gynecologic care

- Postoperative follow-up

Remote patient monitoring

- Chronic disease management

- Antenatal testing

- Fetal heart rate monitoring

- Transfer of care

Final thoughts

Dr. Nielsen: It is time for all US health care players to more seriously and aggressively consider how telehealth can improve health care access, quality, and safety. Even more important, patients and physicians in small communities need to feel that they can access specialists and care that is as good as those available in larger communities without having to pull up stakes and move.

Telehealth can help small communities become sustainable over the long term. As the majority of the people in this country are born in and receive health care in community hospitals, not large tertiary care centers, the state of US health care should be measured by the ability to provide as much care as is technically possible in the small communities where patients live and work and raise their kids.

Dr. Brown: More than 50% of all babies are born in hospitals where fewer than 1,000 deliveries are performed, and almost 40% are born in hospitals where fewer than 500 are performed. To provide high-level care and have patients feel comfortable, to improve morbidity and mortality, we need telehealth and telemedicine.

If I can help a physician in East Africa place a Bakri balloon for postpartum hemorrhaging, surely I can help a physician in rural areas of Wyoming, South Dakota, or North Carolina deal with this obstetric emergency. In obstetrics and gynecology, telehealth and telemedicine have great potential in terms of morbidity and mortality, but we are also doing genetic counseling and a great deal of patient follow-up, and so much more can be done.

That is the key, and the reason for the training, the task force, the deliberations, and the best practices model that we will be sharing with our colleagues.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Supreme Court decisions in 2017 that affected your practice

Despite being short-handed (there were only 8 justices for most of the Term), the United States Supreme Court decided a number of important cases during its most recent Term, which concluded on June 27, 2017. Among the 69 cases, several are of particular interest to ObGyns.

1. Arbitration in health care

In Kindred Nursing Centers v Clark, the Court decided an important case involving arbitration in health care.1

At stake. The families of 2 people who died after being in a long-term care facility filed lawsuits against the facility, claiming personal injury, violations of Kentucky statutes regarding long-term care facilities, and wrongful death. However, during admission to the facility, the patients (technically, their agents under a power of attorney) signed an agreement that any disputes would be taken to arbitration. The facility successfully had the lawsuits dismissed.

Final ruling. The Supreme Court agreed that the case had to go to arbitration rather than to court, even though the arbitration clause violated state law. The Federal Arbitration Act (FAA) preempts state law. The Court has been very aggressive in enforcing arbitration agreements and striking down state laws that are inconsistent with the FAA. This case emphasizes that the FAA applies in the health care context.

The case suggests both a warning and an opportunity for health care providers. The warning is that arbitration clauses will be enforced; thoughtlessly entering into arbitration for future disputes may be dangerous. Among other things, the decision of arbitrators is essentially unreviewable. Appellate courts review the decisions of lower courts, but there is no such review in arbitration. Furthermore, arbitration may be stacked in favor of commercial entities that often use arbitrators.

The opportunity for health care providers lies in that it may be possible to include arbitration clauses in agreements with patients. This should be considered only after obtaining legal advice. The agreements should, for example, be consistent with the obligations to patients (in the case of the Kentucky facility, it made clear that accepting the arbitration agreement was not necessary in order to receive care or be admitted to the facility). Because arbitration agreements are becoming ubiquitous and rigorously enforced by federal courts, arbitration is bound to have an important function in health care.

2. Pharmaceuticals

Biologics and biosimilars

Biologics play an important role in health care. Eight of the top 10 selling drugs in 2016 were biologics.2 The case of Sandoz v Amgen involved biosimilar pharmaceuticals, essentially the generics of biologic drugs.3

At stake. While biologics hold great promise in medicine, they are generally very expensive. Just as with generics, brand-name companies (generally referred to as “reference” biologics) want to keep biosimilars off the market for as long as possible, thereby extending the advantages of monopolistic pricing. This Term the Supreme Court considered the statutory rules for licensing biosimilar drugs.

Final ruling. The Court’s decision will allow biosimilar companies to speed up the licensing process by at least 180 days. This is a modest win for patients and their physicians, but the legal issues around biosimilars will need additional attention.

Class action suits

In another case, the Court made it more difficult to file class action suits against pharmaceutical companies in state courts.4 Although this is a fairly technical decision, it is likely to have a significant impact in pharmaceutical liability by limiting classactions.

3. The travel ban

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists joined other medical organizations in an amicus curiae (friend of the court) brief to challenge President Trump’s “travel ban.”5