User login

Caplacizumab may enhance treatment of aTTP

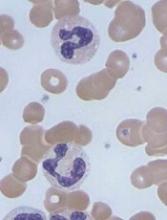

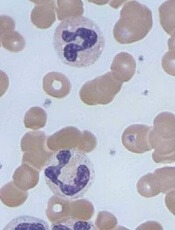

Caplacizumab can improve upon standard care for patients with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP), according to results reported by Ablynx, the company developing caplacizumab.

In the phase 3 HERCULES trial, researchers compared caplacizumab, an anti-von Willebrand factor nanobody, plus standard care to placebo plus standard care in patients with aTTP.

Patients who received caplacizumab had a significant reduction in time to platelet count response.

In addition, they were significantly less likely than patients who received placebo to achieve the combined endpoint of aTTP-related death, aTTP recurrence, and experiencing at least 1 major thromboembolic event during the treatment period.

The safety profile of caplacizumab in this trial was said to be consistent with results from the phase 2 TITAN trial.

“The results of this landmark trial constitute a complete game-changer for patients with aTTP,” said HERCULES investigator Marie Scully, MBBS, of the University College Hospital in London, UK.

“They will revolutionize how we manage the acute phase of the disease, which is when patients are at highest risk for organ damage, recurrence, and death.”

Treatment

The HERCULES trial included 145 patients with an acute episode of aTTP. They were randomized 1:1 to receive either caplacizumab or placebo in addition to daily plasma exchange and immunosuppression (standard of care).

Patients received a single intravenous bolus of 10 mg of caplacizumab or placebo followed by a daily subcutaneous dose of 10 mg of caplacizumab or placebo until 30 days after the last daily plasma exchange.

If, at the end of this treatment period, there was evidence of persistent underlying disease activity indicative of an imminent risk for recurrence, the treatment could be extended for additional 7-day periods up to a maximum of 28 days. Patients were followed for a further 28 days after discontinuation of treatment.

In all, 71 patients received caplacizumab, and 58 (80.6%) of them completed the treatment. Seventy-three patients received placebo, and 50 of these patients (68.5%) completed treatment.

Baseline characteristics

At baseline, the mean age was 44.9 in the caplacizumab arm and 47.3 in the placebo arm. A majority of patients in both arms were female—68.1% and 69.9%, respectively.

The proportion of patients with an initial aTTP episode was 66.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 46.6% in the placebo arm. The proportion with a recurrent episode was 33.3% and 53.4%, respectively.

Most patients in both arms had ADAMTS13 activity below 10% at baseline—81.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 90.3% in the placebo arm.

The mean platelet count at baseline was 32.0 x 109/L in the caplacizumab arm and 39.1 x 109/L in the placebo arm.

Efficacy

The study’s primary endpoint was the time to confirmed normalization of platelet count response. There was a significant reduction in time to platelet count response in the caplacizumab arm compared to the placebo arm. The platelet normalization rate ratio was 1.55 (P<0.01).

A key secondary endpoint was the combination of aTTP-related death, aTTP recurrence, and at least 1 major thromboembolic event during study treatment. The incidence of this combined endpoint was 12.7% (n=9) in the caplacizumab arm and 49.3% (n=36) in the placebo arm (P<0.0001).

The incidence of aTTP-related death was 0% (n=0) in the caplacizumab arm and 4.1% (n=3) in the placebo arm. The incidence of aTTP recurrence was 4.2% (n=3) and 38.4% (n=28), respectively. And the incidence of at least 1 major thromboembolic event was 8.5% (n=6) and 8.2% (n=6), respectively.

Another key secondary endpoint was the incidence of aTTP recurrence during the overall study period, which was 12.7% (n=9) in the caplacizumab arm and 38.4% (n=28) in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

The incidence of aTTP recurrence during the follow-up period alone was 9.1% (n=6) in the caplacizumab arm and 0% (n=0) in the placebo arm.

A third key secondary endpoint was the percentage of patients with refractory aTTP, which was 0% (n=0) in the caplacizumab arm and 4.2% (n=3) in the placebo arm (P=0.0572).

Safety

The number and nature of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were similar between the treatment arms, according to Ablynx. The proportion of patients with at least 1 treatment-emergent AE was 97.2% in the caplacizumab arm and 97.3% in the placebo arm.

The proportion of patients with at least 1 study-drug-related AE was 57.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 43.8% in the placebo arm. The rate of discontinuation due to at least 1 AE was 7.0% and 12.3%, respectively.

The incidence of bleeding-related AEs was higher in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—66.2% and 49.3%, respectively. However, most bleeding-related events were mild or moderate in severity.

The proportion of patients with at least 1 serious AE was 39.4% (n=28) in the caplacizumab arm and 53.4% (n=39) in the placebo arm. The proportion of patients with at least 1 study-drug-related serious AE was 14.1% (n=10) and 5.5% (n=4), respectively.

During the treatment period, there were no deaths in the caplacizumab arm and 3 deaths in the placebo arm. There was 1 death in the caplacizumab arm during the follow-up period, but it was considered unrelated to caplacizumab. ![]()

Caplacizumab can improve upon standard care for patients with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP), according to results reported by Ablynx, the company developing caplacizumab.

In the phase 3 HERCULES trial, researchers compared caplacizumab, an anti-von Willebrand factor nanobody, plus standard care to placebo plus standard care in patients with aTTP.

Patients who received caplacizumab had a significant reduction in time to platelet count response.

In addition, they were significantly less likely than patients who received placebo to achieve the combined endpoint of aTTP-related death, aTTP recurrence, and experiencing at least 1 major thromboembolic event during the treatment period.

The safety profile of caplacizumab in this trial was said to be consistent with results from the phase 2 TITAN trial.

“The results of this landmark trial constitute a complete game-changer for patients with aTTP,” said HERCULES investigator Marie Scully, MBBS, of the University College Hospital in London, UK.

“They will revolutionize how we manage the acute phase of the disease, which is when patients are at highest risk for organ damage, recurrence, and death.”

Treatment

The HERCULES trial included 145 patients with an acute episode of aTTP. They were randomized 1:1 to receive either caplacizumab or placebo in addition to daily plasma exchange and immunosuppression (standard of care).

Patients received a single intravenous bolus of 10 mg of caplacizumab or placebo followed by a daily subcutaneous dose of 10 mg of caplacizumab or placebo until 30 days after the last daily plasma exchange.

If, at the end of this treatment period, there was evidence of persistent underlying disease activity indicative of an imminent risk for recurrence, the treatment could be extended for additional 7-day periods up to a maximum of 28 days. Patients were followed for a further 28 days after discontinuation of treatment.

In all, 71 patients received caplacizumab, and 58 (80.6%) of them completed the treatment. Seventy-three patients received placebo, and 50 of these patients (68.5%) completed treatment.

Baseline characteristics

At baseline, the mean age was 44.9 in the caplacizumab arm and 47.3 in the placebo arm. A majority of patients in both arms were female—68.1% and 69.9%, respectively.

The proportion of patients with an initial aTTP episode was 66.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 46.6% in the placebo arm. The proportion with a recurrent episode was 33.3% and 53.4%, respectively.

Most patients in both arms had ADAMTS13 activity below 10% at baseline—81.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 90.3% in the placebo arm.

The mean platelet count at baseline was 32.0 x 109/L in the caplacizumab arm and 39.1 x 109/L in the placebo arm.

Efficacy

The study’s primary endpoint was the time to confirmed normalization of platelet count response. There was a significant reduction in time to platelet count response in the caplacizumab arm compared to the placebo arm. The platelet normalization rate ratio was 1.55 (P<0.01).

A key secondary endpoint was the combination of aTTP-related death, aTTP recurrence, and at least 1 major thromboembolic event during study treatment. The incidence of this combined endpoint was 12.7% (n=9) in the caplacizumab arm and 49.3% (n=36) in the placebo arm (P<0.0001).

The incidence of aTTP-related death was 0% (n=0) in the caplacizumab arm and 4.1% (n=3) in the placebo arm. The incidence of aTTP recurrence was 4.2% (n=3) and 38.4% (n=28), respectively. And the incidence of at least 1 major thromboembolic event was 8.5% (n=6) and 8.2% (n=6), respectively.

Another key secondary endpoint was the incidence of aTTP recurrence during the overall study period, which was 12.7% (n=9) in the caplacizumab arm and 38.4% (n=28) in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

The incidence of aTTP recurrence during the follow-up period alone was 9.1% (n=6) in the caplacizumab arm and 0% (n=0) in the placebo arm.

A third key secondary endpoint was the percentage of patients with refractory aTTP, which was 0% (n=0) in the caplacizumab arm and 4.2% (n=3) in the placebo arm (P=0.0572).

Safety

The number and nature of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were similar between the treatment arms, according to Ablynx. The proportion of patients with at least 1 treatment-emergent AE was 97.2% in the caplacizumab arm and 97.3% in the placebo arm.

The proportion of patients with at least 1 study-drug-related AE was 57.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 43.8% in the placebo arm. The rate of discontinuation due to at least 1 AE was 7.0% and 12.3%, respectively.

The incidence of bleeding-related AEs was higher in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—66.2% and 49.3%, respectively. However, most bleeding-related events were mild or moderate in severity.

The proportion of patients with at least 1 serious AE was 39.4% (n=28) in the caplacizumab arm and 53.4% (n=39) in the placebo arm. The proportion of patients with at least 1 study-drug-related serious AE was 14.1% (n=10) and 5.5% (n=4), respectively.

During the treatment period, there were no deaths in the caplacizumab arm and 3 deaths in the placebo arm. There was 1 death in the caplacizumab arm during the follow-up period, but it was considered unrelated to caplacizumab. ![]()

Caplacizumab can improve upon standard care for patients with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (aTTP), according to results reported by Ablynx, the company developing caplacizumab.

In the phase 3 HERCULES trial, researchers compared caplacizumab, an anti-von Willebrand factor nanobody, plus standard care to placebo plus standard care in patients with aTTP.

Patients who received caplacizumab had a significant reduction in time to platelet count response.

In addition, they were significantly less likely than patients who received placebo to achieve the combined endpoint of aTTP-related death, aTTP recurrence, and experiencing at least 1 major thromboembolic event during the treatment period.

The safety profile of caplacizumab in this trial was said to be consistent with results from the phase 2 TITAN trial.

“The results of this landmark trial constitute a complete game-changer for patients with aTTP,” said HERCULES investigator Marie Scully, MBBS, of the University College Hospital in London, UK.

“They will revolutionize how we manage the acute phase of the disease, which is when patients are at highest risk for organ damage, recurrence, and death.”

Treatment

The HERCULES trial included 145 patients with an acute episode of aTTP. They were randomized 1:1 to receive either caplacizumab or placebo in addition to daily plasma exchange and immunosuppression (standard of care).

Patients received a single intravenous bolus of 10 mg of caplacizumab or placebo followed by a daily subcutaneous dose of 10 mg of caplacizumab or placebo until 30 days after the last daily plasma exchange.

If, at the end of this treatment period, there was evidence of persistent underlying disease activity indicative of an imminent risk for recurrence, the treatment could be extended for additional 7-day periods up to a maximum of 28 days. Patients were followed for a further 28 days after discontinuation of treatment.

In all, 71 patients received caplacizumab, and 58 (80.6%) of them completed the treatment. Seventy-three patients received placebo, and 50 of these patients (68.5%) completed treatment.

Baseline characteristics

At baseline, the mean age was 44.9 in the caplacizumab arm and 47.3 in the placebo arm. A majority of patients in both arms were female—68.1% and 69.9%, respectively.

The proportion of patients with an initial aTTP episode was 66.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 46.6% in the placebo arm. The proportion with a recurrent episode was 33.3% and 53.4%, respectively.

Most patients in both arms had ADAMTS13 activity below 10% at baseline—81.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 90.3% in the placebo arm.

The mean platelet count at baseline was 32.0 x 109/L in the caplacizumab arm and 39.1 x 109/L in the placebo arm.

Efficacy

The study’s primary endpoint was the time to confirmed normalization of platelet count response. There was a significant reduction in time to platelet count response in the caplacizumab arm compared to the placebo arm. The platelet normalization rate ratio was 1.55 (P<0.01).

A key secondary endpoint was the combination of aTTP-related death, aTTP recurrence, and at least 1 major thromboembolic event during study treatment. The incidence of this combined endpoint was 12.7% (n=9) in the caplacizumab arm and 49.3% (n=36) in the placebo arm (P<0.0001).

The incidence of aTTP-related death was 0% (n=0) in the caplacizumab arm and 4.1% (n=3) in the placebo arm. The incidence of aTTP recurrence was 4.2% (n=3) and 38.4% (n=28), respectively. And the incidence of at least 1 major thromboembolic event was 8.5% (n=6) and 8.2% (n=6), respectively.

Another key secondary endpoint was the incidence of aTTP recurrence during the overall study period, which was 12.7% (n=9) in the caplacizumab arm and 38.4% (n=28) in the placebo arm (P<0.001).

The incidence of aTTP recurrence during the follow-up period alone was 9.1% (n=6) in the caplacizumab arm and 0% (n=0) in the placebo arm.

A third key secondary endpoint was the percentage of patients with refractory aTTP, which was 0% (n=0) in the caplacizumab arm and 4.2% (n=3) in the placebo arm (P=0.0572).

Safety

The number and nature of treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were similar between the treatment arms, according to Ablynx. The proportion of patients with at least 1 treatment-emergent AE was 97.2% in the caplacizumab arm and 97.3% in the placebo arm.

The proportion of patients with at least 1 study-drug-related AE was 57.7% in the caplacizumab arm and 43.8% in the placebo arm. The rate of discontinuation due to at least 1 AE was 7.0% and 12.3%, respectively.

The incidence of bleeding-related AEs was higher in the caplacizumab arm than the placebo arm—66.2% and 49.3%, respectively. However, most bleeding-related events were mild or moderate in severity.

The proportion of patients with at least 1 serious AE was 39.4% (n=28) in the caplacizumab arm and 53.4% (n=39) in the placebo arm. The proportion of patients with at least 1 study-drug-related serious AE was 14.1% (n=10) and 5.5% (n=4), respectively.

During the treatment period, there were no deaths in the caplacizumab arm and 3 deaths in the placebo arm. There was 1 death in the caplacizumab arm during the follow-up period, but it was considered unrelated to caplacizumab. ![]()

Drug receives breakthrough designation for HL

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation to brentuximab vedotin (BV, Adcetris) for use in combination with chemotherapy as frontline treatment of advanced classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).

Seattle Genetics and Takeda plan to submit a supplemental biologics license application seeking approval for BV in this indication before the end of this year.

The breakthrough designation is based on positive topline results from the phase 3 ECHELON-1 trial.

Full results from this trial are expected to be presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting in December.

BV is an antibody-drug conjugate consisting of an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody attached by a protease-cleavable linker to a microtubule disrupting agent, monomethyl auristatin E.

BV is currently FDA-approved to treat:

- Classical HL after failure of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (auto-HSCT) or after failure of at least 2 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimens in patients who are not auto-HSCT candidates

- Classical HL patients at high risk of relapse or progression as post-auto-HSCT consolidation.

BV also has accelerated approval from the FDA for the treatment of systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma after failure of at least 1 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimen. This approval is based on overall response rate. Continued approval of BV for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

ECHELON-1 trial

In this phase 3 trial, researchers compared BV in combination with doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine to a recognized standard of care chemotherapy regimen in patients with previously untreated, advanced classical HL.

The study enrolled 1334 patients who had a histologically confirmed diagnosis of stage III or IV classical HL and had not been previously treated with systemic chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

The study’s primary endpoint is modified progression-free survival (PFS) per an independent review facility. Modified PFS is defined as the time to progression, death, or receipt of additional anticancer therapy for patients who are not in complete response after completion of frontline therapy.

There was a significant improvement in modified PFS in the BV arm compared to the control arm (hazard ratio=0.770; P=0.035). The 2-year modified PFS rate was 82.1% in the BV arm and 77.2% in the control arm.

An interim analysis of overall survival revealed a trend in favor of the BV arm.

The safety profile of BV plus chemotherapy was consistent with the profile known for the single-agent components of the regimen.

About breakthrough designation

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions.

The designation entitles the company developing a therapy to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation to brentuximab vedotin (BV, Adcetris) for use in combination with chemotherapy as frontline treatment of advanced classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).

Seattle Genetics and Takeda plan to submit a supplemental biologics license application seeking approval for BV in this indication before the end of this year.

The breakthrough designation is based on positive topline results from the phase 3 ECHELON-1 trial.

Full results from this trial are expected to be presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting in December.

BV is an antibody-drug conjugate consisting of an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody attached by a protease-cleavable linker to a microtubule disrupting agent, monomethyl auristatin E.

BV is currently FDA-approved to treat:

- Classical HL after failure of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (auto-HSCT) or after failure of at least 2 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimens in patients who are not auto-HSCT candidates

- Classical HL patients at high risk of relapse or progression as post-auto-HSCT consolidation.

BV also has accelerated approval from the FDA for the treatment of systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma after failure of at least 1 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimen. This approval is based on overall response rate. Continued approval of BV for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

ECHELON-1 trial

In this phase 3 trial, researchers compared BV in combination with doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine to a recognized standard of care chemotherapy regimen in patients with previously untreated, advanced classical HL.

The study enrolled 1334 patients who had a histologically confirmed diagnosis of stage III or IV classical HL and had not been previously treated with systemic chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

The study’s primary endpoint is modified progression-free survival (PFS) per an independent review facility. Modified PFS is defined as the time to progression, death, or receipt of additional anticancer therapy for patients who are not in complete response after completion of frontline therapy.

There was a significant improvement in modified PFS in the BV arm compared to the control arm (hazard ratio=0.770; P=0.035). The 2-year modified PFS rate was 82.1% in the BV arm and 77.2% in the control arm.

An interim analysis of overall survival revealed a trend in favor of the BV arm.

The safety profile of BV plus chemotherapy was consistent with the profile known for the single-agent components of the regimen.

About breakthrough designation

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions.

The designation entitles the company developing a therapy to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted breakthrough therapy designation to brentuximab vedotin (BV, Adcetris) for use in combination with chemotherapy as frontline treatment of advanced classical Hodgkin lymphoma (HL).

Seattle Genetics and Takeda plan to submit a supplemental biologics license application seeking approval for BV in this indication before the end of this year.

The breakthrough designation is based on positive topline results from the phase 3 ECHELON-1 trial.

Full results from this trial are expected to be presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting in December.

BV is an antibody-drug conjugate consisting of an anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody attached by a protease-cleavable linker to a microtubule disrupting agent, monomethyl auristatin E.

BV is currently FDA-approved to treat:

- Classical HL after failure of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (auto-HSCT) or after failure of at least 2 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimens in patients who are not auto-HSCT candidates

- Classical HL patients at high risk of relapse or progression as post-auto-HSCT consolidation.

BV also has accelerated approval from the FDA for the treatment of systemic anaplastic large-cell lymphoma after failure of at least 1 prior multi-agent chemotherapy regimen. This approval is based on overall response rate. Continued approval of BV for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in confirmatory trials.

ECHELON-1 trial

In this phase 3 trial, researchers compared BV in combination with doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine to a recognized standard of care chemotherapy regimen in patients with previously untreated, advanced classical HL.

The study enrolled 1334 patients who had a histologically confirmed diagnosis of stage III or IV classical HL and had not been previously treated with systemic chemotherapy or radiotherapy.

The study’s primary endpoint is modified progression-free survival (PFS) per an independent review facility. Modified PFS is defined as the time to progression, death, or receipt of additional anticancer therapy for patients who are not in complete response after completion of frontline therapy.

There was a significant improvement in modified PFS in the BV arm compared to the control arm (hazard ratio=0.770; P=0.035). The 2-year modified PFS rate was 82.1% in the BV arm and 77.2% in the control arm.

An interim analysis of overall survival revealed a trend in favor of the BV arm.

The safety profile of BV plus chemotherapy was consistent with the profile known for the single-agent components of the regimen.

About breakthrough designation

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions.

The designation entitles the company developing a therapy to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need. ![]()

FDA grants EUA to Zika testing system

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for Chembio Diagnostics, Inc.’s DPP® Zika System.

The system includes the DPP Zika IgM Assay, which enables in vitro qualitative detection of human IgM antibodies to Zika virus, and the DPP Micro Reader, which is a portable, hand-held device intended to reduce the risk of human error during test interpretation.

The DPP Zika System provides results in 15 to 20 minutes from 10 µL of blood.

The system is designed to detect Zika virus IgM antibodies in finger-stick whole blood, EDTA venous whole blood, EDTA plasma (each collected alongside a patient-matched serum specimen), or serum (plain or separation gel) specimens.

The EUA for the DPP Zika System does not mean it is FDA cleared or approved.

An EUA allows for the use of unapproved medical products (or unapproved uses of approved medical products) in an emergency. The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The EUA for the DPP Zika System means the test is only authorized as long as circumstances exist to justify the emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for the detection of Zika virus, unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

Testing using the DPP Zika System is authorized to be conducted by laboratories in the US that are certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988, 42 U.S.C. § 263a, to perform high complexity tests, or by similarly qualified non-US laboratories.

The DPP Zika System can be used to test individuals who meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Zika virus clinical criteria (eg, a history of clinical signs and symptoms associated with Zika virus infection) and/or CDC Zika virus epidemiological criteria (eg, a history of residence in or travel to a geographic region with active Zika transmission at the time of travel or other epidemiological criteria for which Zika virus testing may be indicated).

The DPP Zika System can be used starting 8 days after symptom onset or risk of exposure and for up to 12 weeks after that point.

Where there are reactive results from the DPP Zika IgM Assay, confirmation of the presence of anti-Zika IgM antibodies requires additional testing and/or consideration alongside test results for other patient-matched specimens using the latest CDC testing algorithms for the diagnosis of Zika virus infection.

Development of the DPP Zika System has been funded, in part, with federal funds from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response in the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Chembio Diagnostics, Inc. has been awarded a contract for $5.9 million to develop the product and obtain EUA and 510(k) clearance from the FDA, with the potential of $13.2 million in total funding from BARDA if all options are exercised, to advance clinical development of the DPP Zika System and DPP® Zika/Dengue/Chikungunya System.

More information on the DPP Zika System and other Zika tests granted EUAs can be found on the FDA’s EUA page. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for Chembio Diagnostics, Inc.’s DPP® Zika System.

The system includes the DPP Zika IgM Assay, which enables in vitro qualitative detection of human IgM antibodies to Zika virus, and the DPP Micro Reader, which is a portable, hand-held device intended to reduce the risk of human error during test interpretation.

The DPP Zika System provides results in 15 to 20 minutes from 10 µL of blood.

The system is designed to detect Zika virus IgM antibodies in finger-stick whole blood, EDTA venous whole blood, EDTA plasma (each collected alongside a patient-matched serum specimen), or serum (plain or separation gel) specimens.

The EUA for the DPP Zika System does not mean it is FDA cleared or approved.

An EUA allows for the use of unapproved medical products (or unapproved uses of approved medical products) in an emergency. The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The EUA for the DPP Zika System means the test is only authorized as long as circumstances exist to justify the emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for the detection of Zika virus, unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

Testing using the DPP Zika System is authorized to be conducted by laboratories in the US that are certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988, 42 U.S.C. § 263a, to perform high complexity tests, or by similarly qualified non-US laboratories.

The DPP Zika System can be used to test individuals who meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Zika virus clinical criteria (eg, a history of clinical signs and symptoms associated with Zika virus infection) and/or CDC Zika virus epidemiological criteria (eg, a history of residence in or travel to a geographic region with active Zika transmission at the time of travel or other epidemiological criteria for which Zika virus testing may be indicated).

The DPP Zika System can be used starting 8 days after symptom onset or risk of exposure and for up to 12 weeks after that point.

Where there are reactive results from the DPP Zika IgM Assay, confirmation of the presence of anti-Zika IgM antibodies requires additional testing and/or consideration alongside test results for other patient-matched specimens using the latest CDC testing algorithms for the diagnosis of Zika virus infection.

Development of the DPP Zika System has been funded, in part, with federal funds from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response in the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Chembio Diagnostics, Inc. has been awarded a contract for $5.9 million to develop the product and obtain EUA and 510(k) clearance from the FDA, with the potential of $13.2 million in total funding from BARDA if all options are exercised, to advance clinical development of the DPP Zika System and DPP® Zika/Dengue/Chikungunya System.

More information on the DPP Zika System and other Zika tests granted EUAs can be found on the FDA’s EUA page. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted emergency use authorization (EUA) for Chembio Diagnostics, Inc.’s DPP® Zika System.

The system includes the DPP Zika IgM Assay, which enables in vitro qualitative detection of human IgM antibodies to Zika virus, and the DPP Micro Reader, which is a portable, hand-held device intended to reduce the risk of human error during test interpretation.

The DPP Zika System provides results in 15 to 20 minutes from 10 µL of blood.

The system is designed to detect Zika virus IgM antibodies in finger-stick whole blood, EDTA venous whole blood, EDTA plasma (each collected alongside a patient-matched serum specimen), or serum (plain or separation gel) specimens.

The EUA for the DPP Zika System does not mean it is FDA cleared or approved.

An EUA allows for the use of unapproved medical products (or unapproved uses of approved medical products) in an emergency. The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The EUA for the DPP Zika System means the test is only authorized as long as circumstances exist to justify the emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for the detection of Zika virus, unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

Testing using the DPP Zika System is authorized to be conducted by laboratories in the US that are certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988, 42 U.S.C. § 263a, to perform high complexity tests, or by similarly qualified non-US laboratories.

The DPP Zika System can be used to test individuals who meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Zika virus clinical criteria (eg, a history of clinical signs and symptoms associated with Zika virus infection) and/or CDC Zika virus epidemiological criteria (eg, a history of residence in or travel to a geographic region with active Zika transmission at the time of travel or other epidemiological criteria for which Zika virus testing may be indicated).

The DPP Zika System can be used starting 8 days after symptom onset or risk of exposure and for up to 12 weeks after that point.

Where there are reactive results from the DPP Zika IgM Assay, confirmation of the presence of anti-Zika IgM antibodies requires additional testing and/or consideration alongside test results for other patient-matched specimens using the latest CDC testing algorithms for the diagnosis of Zika virus infection.

Development of the DPP Zika System has been funded, in part, with federal funds from the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) within the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Preparedness and Response in the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Chembio Diagnostics, Inc. has been awarded a contract for $5.9 million to develop the product and obtain EUA and 510(k) clearance from the FDA, with the potential of $13.2 million in total funding from BARDA if all options are exercised, to advance clinical development of the DPP Zika System and DPP® Zika/Dengue/Chikungunya System.

More information on the DPP Zika System and other Zika tests granted EUAs can be found on the FDA’s EUA page. ![]()

Do PPIs Pose a Danger to Kidneys?

Q) Is it true that PPI use can cause kidney disease?

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been available in the United States since 1990, with OTC options available since 2009. While these medications play a vital role in the treatment of gastrointestinal (GI) conditions, observational studies have linked PPI use to serious adverse events, including dementia, community-acquired pneumonia, hip fracture, and Clostridium difficile infection.1-4

Studies have also found an association between PPI use and kidney problems such as acute kidney injury (AKI), acute interstitial nephritis, and incident chronic kidney disease (CKD).5-7 One observational study used the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) national databases to track the renal outcomes of 173,321 new PPI users and 20,270 new histamine H2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) users over the course of five years. Those who used PPIs demonstrated a significant risk for decreased renal function, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), doubled serum creatinine levels, and progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).8

Another study of 10,482 patients (322 PPI; 956 H2RA; 9,204 nonusers) and a replicate study of 248,751 patients (16,900 PPI; 6,640 H2RA; 225,211 nonusers) with an initial eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 also found an association between PPI use and incident CKD, which persisted when compared to the other groups. Additionally, twice-daily PPI use was associated with a higher CKD risk than once-daily use.9

The pathophysiology of PPI use and kidney deterioration is poorly understood at this point. It is known that AKI can increase the risk for CKD, and AKI has been an assumed precursor to PPI-associated CKD. However, a study by Xie and colleagues reported an association between PPI use and increased risk for CKD, progression of CKD, and ESRD in the absence of preceding AKI. Using the VA databases, the researchers identified 144,032 new users of acid-suppressing medications (125,596 PPI; 18,436 H2RA) who had no history of kidney disease and followed them for five years. PPI users were found to be at increased risk for CKD, and a graded association was discovered between length of PPI use and risk for CKD.10

While these studies are observational and therefore do not prove causation, they do suggest a need for attentive monitoring of kidney function in patients using PPIs. Evaluating the need for PPIs and inquiring about OTC use of these medications is highly recommended, as research has found 25% to 70% of PPI prescriptions are not prescribed for an appropriate indication.11 Considerations regarding PPI use should include dosage, length of use, and whether alternate use of an H2RA is appropriate. —CAS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

1. Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(4):410-416.

2. Lambert AA, Lam JO, Paik JJ, et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2015;10(6):e0128004.

3. Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006; 296(24):2947-2953.

4. Dial S, Alrasadi K, Manoukian C, et al. Risk of Clostridium difficile diarrhea among hospital inpatients prescribed proton pump inhibitors: cohort and case-control studies. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):33-38.

5. Klepser DG, Collier DS, Cochran GL. Proton pump inhibitors and acute kidney injury: a nested case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:150.

6. Blank ML, Parkin L, Paul C, et al. A nationwide nested case-control study indicates an increased risk of acute interstitial nephritis with proton pump inhibitor use. Kidney Int. 2014;86:837-844.

7. Antoniou T, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3(2):E166-171.

8. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(10):3153-3163.

9. Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):238-246.

10. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Long-term kidney outcomes among users of proton pump inhibitors without intervening acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2017;91(6):1482-1494.

11. Forgacs I, Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ. 2008;336(7634):2-3.

Q) Is it true that PPI use can cause kidney disease?

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been available in the United States since 1990, with OTC options available since 2009. While these medications play a vital role in the treatment of gastrointestinal (GI) conditions, observational studies have linked PPI use to serious adverse events, including dementia, community-acquired pneumonia, hip fracture, and Clostridium difficile infection.1-4

Studies have also found an association between PPI use and kidney problems such as acute kidney injury (AKI), acute interstitial nephritis, and incident chronic kidney disease (CKD).5-7 One observational study used the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) national databases to track the renal outcomes of 173,321 new PPI users and 20,270 new histamine H2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) users over the course of five years. Those who used PPIs demonstrated a significant risk for decreased renal function, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), doubled serum creatinine levels, and progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).8

Another study of 10,482 patients (322 PPI; 956 H2RA; 9,204 nonusers) and a replicate study of 248,751 patients (16,900 PPI; 6,640 H2RA; 225,211 nonusers) with an initial eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 also found an association between PPI use and incident CKD, which persisted when compared to the other groups. Additionally, twice-daily PPI use was associated with a higher CKD risk than once-daily use.9

The pathophysiology of PPI use and kidney deterioration is poorly understood at this point. It is known that AKI can increase the risk for CKD, and AKI has been an assumed precursor to PPI-associated CKD. However, a study by Xie and colleagues reported an association between PPI use and increased risk for CKD, progression of CKD, and ESRD in the absence of preceding AKI. Using the VA databases, the researchers identified 144,032 new users of acid-suppressing medications (125,596 PPI; 18,436 H2RA) who had no history of kidney disease and followed them for five years. PPI users were found to be at increased risk for CKD, and a graded association was discovered between length of PPI use and risk for CKD.10

While these studies are observational and therefore do not prove causation, they do suggest a need for attentive monitoring of kidney function in patients using PPIs. Evaluating the need for PPIs and inquiring about OTC use of these medications is highly recommended, as research has found 25% to 70% of PPI prescriptions are not prescribed for an appropriate indication.11 Considerations regarding PPI use should include dosage, length of use, and whether alternate use of an H2RA is appropriate. —CAS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

Q) Is it true that PPI use can cause kidney disease?

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been available in the United States since 1990, with OTC options available since 2009. While these medications play a vital role in the treatment of gastrointestinal (GI) conditions, observational studies have linked PPI use to serious adverse events, including dementia, community-acquired pneumonia, hip fracture, and Clostridium difficile infection.1-4

Studies have also found an association between PPI use and kidney problems such as acute kidney injury (AKI), acute interstitial nephritis, and incident chronic kidney disease (CKD).5-7 One observational study used the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) national databases to track the renal outcomes of 173,321 new PPI users and 20,270 new histamine H2 receptor antagonist (H2RA) users over the course of five years. Those who used PPIs demonstrated a significant risk for decreased renal function, lower estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), doubled serum creatinine levels, and progression to end-stage renal disease (ESRD).8

Another study of 10,482 patients (322 PPI; 956 H2RA; 9,204 nonusers) and a replicate study of 248,751 patients (16,900 PPI; 6,640 H2RA; 225,211 nonusers) with an initial eGFR ≥ 60 mL/min/1.73m2 also found an association between PPI use and incident CKD, which persisted when compared to the other groups. Additionally, twice-daily PPI use was associated with a higher CKD risk than once-daily use.9

The pathophysiology of PPI use and kidney deterioration is poorly understood at this point. It is known that AKI can increase the risk for CKD, and AKI has been an assumed precursor to PPI-associated CKD. However, a study by Xie and colleagues reported an association between PPI use and increased risk for CKD, progression of CKD, and ESRD in the absence of preceding AKI. Using the VA databases, the researchers identified 144,032 new users of acid-suppressing medications (125,596 PPI; 18,436 H2RA) who had no history of kidney disease and followed them for five years. PPI users were found to be at increased risk for CKD, and a graded association was discovered between length of PPI use and risk for CKD.10

While these studies are observational and therefore do not prove causation, they do suggest a need for attentive monitoring of kidney function in patients using PPIs. Evaluating the need for PPIs and inquiring about OTC use of these medications is highly recommended, as research has found 25% to 70% of PPI prescriptions are not prescribed for an appropriate indication.11 Considerations regarding PPI use should include dosage, length of use, and whether alternate use of an H2RA is appropriate. —CAS

Cynthia A. Smith, DNP, CNN-NP, FNP-BC, APRN

Renal Consultants, PLLC, South Charleston, West Virginia

1. Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(4):410-416.

2. Lambert AA, Lam JO, Paik JJ, et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2015;10(6):e0128004.

3. Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006; 296(24):2947-2953.

4. Dial S, Alrasadi K, Manoukian C, et al. Risk of Clostridium difficile diarrhea among hospital inpatients prescribed proton pump inhibitors: cohort and case-control studies. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):33-38.

5. Klepser DG, Collier DS, Cochran GL. Proton pump inhibitors and acute kidney injury: a nested case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:150.

6. Blank ML, Parkin L, Paul C, et al. A nationwide nested case-control study indicates an increased risk of acute interstitial nephritis with proton pump inhibitor use. Kidney Int. 2014;86:837-844.

7. Antoniou T, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3(2):E166-171.

8. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(10):3153-3163.

9. Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):238-246.

10. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Long-term kidney outcomes among users of proton pump inhibitors without intervening acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2017;91(6):1482-1494.

11. Forgacs I, Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ. 2008;336(7634):2-3.

1. Gomm W, von Holt K, Thomé F, et al. Association of proton pump inhibitors with risk of dementia: a pharmacoepidemiological claims data analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(4):410-416.

2. Lambert AA, Lam JO, Paik JJ, et al. Risk of community-acquired pneumonia with outpatient proton-pump inhibitor therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2015;10(6):e0128004.

3. Yang YX, Lewis JD, Epstein S, Metz DC. Long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy and risk of hip fracture. JAMA. 2006; 296(24):2947-2953.

4. Dial S, Alrasadi K, Manoukian C, et al. Risk of Clostridium difficile diarrhea among hospital inpatients prescribed proton pump inhibitors: cohort and case-control studies. CMAJ. 2004;171(1):33-38.

5. Klepser DG, Collier DS, Cochran GL. Proton pump inhibitors and acute kidney injury: a nested case-control study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:150.

6. Blank ML, Parkin L, Paul C, et al. A nationwide nested case-control study indicates an increased risk of acute interstitial nephritis with proton pump inhibitor use. Kidney Int. 2014;86:837-844.

7. Antoniou T, Macdonald EM, Hollands S, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and the risk of acute kidney injury in older patients: a population-based cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2015;3(2):E166-171.

8. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of incident CKD and progression to ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(10):3153-3163.

9. Lazarus B, Chen Y, Wilson FP, et al. Proton pump inhibitor use and the risk of chronic kidney disease. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):238-246.

10. Xie Y, Bowe B, Li T, et al. Long-term kidney outcomes among users of proton pump inhibitors without intervening acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2017;91(6):1482-1494.

11. Forgacs I, Loganayagam A. Overprescribing proton pump inhibitors. BMJ. 2008;336(7634):2-3.

Sepsis time to treatment

Clinical question: Does early identification and treatment of sepsis using protocols improve outcomes?

Background: International clinical guidelines recommend early detection and treatment of sepsis with broad spectrum antibiotics and intravenous fluids which are supported by preclinical and observation studies that show a reduction in avoidable deaths. However, controversy remains in the timing of these treatments on how it relates to patient outcomes such as risk-adjusted mortality.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study using data reported to the New York State Department of Health from April 1, 2014, to June 30, 2016.

Setting: New York hospitals.

Synopsis: For patients with sepsis and septic shock, a sepsis protocol was initiated within 6 hours after arrival in the emergency department and had all items in a 3-hour bundle of care (that is, blood cultures, broad-spectrum antibiotic, and lactate measurement) completed within 12 hours. Among 49,331 patients at 149 hospitals, higher risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality was associated with longer time to the completion of the bundle (P less than .001), administration of antibiotics (P less than .001), but not completion of a bolus of intravenous fluids (P = .21).

Study limitations include being nonrandomized, hospitals all from one state possibly introducing epidemiologic distinct features of sepsis inherent to the region, and accuracy of the data collection (that is, start time).

No association was found between time to completion of the initial bolus of fluids and improved outcomes in risk-adjusted mortality; however, the analysis of time of the initial fluid bolus was most vulnerable to confounding; a causal relationship will need further study.

Bottom line: A lower risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality was associated with rapid administration of antibiotics and a faster completion of a 3-hour bundle of sepsis care, but there was no discernable association with the rapid administration of initial bolus of intravenous fluids.

Citation: Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, et al. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:2235-44.

Dr. Choe is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Clinical question: Does early identification and treatment of sepsis using protocols improve outcomes?

Background: International clinical guidelines recommend early detection and treatment of sepsis with broad spectrum antibiotics and intravenous fluids which are supported by preclinical and observation studies that show a reduction in avoidable deaths. However, controversy remains in the timing of these treatments on how it relates to patient outcomes such as risk-adjusted mortality.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study using data reported to the New York State Department of Health from April 1, 2014, to June 30, 2016.

Setting: New York hospitals.

Synopsis: For patients with sepsis and septic shock, a sepsis protocol was initiated within 6 hours after arrival in the emergency department and had all items in a 3-hour bundle of care (that is, blood cultures, broad-spectrum antibiotic, and lactate measurement) completed within 12 hours. Among 49,331 patients at 149 hospitals, higher risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality was associated with longer time to the completion of the bundle (P less than .001), administration of antibiotics (P less than .001), but not completion of a bolus of intravenous fluids (P = .21).

Study limitations include being nonrandomized, hospitals all from one state possibly introducing epidemiologic distinct features of sepsis inherent to the region, and accuracy of the data collection (that is, start time).

No association was found between time to completion of the initial bolus of fluids and improved outcomes in risk-adjusted mortality; however, the analysis of time of the initial fluid bolus was most vulnerable to confounding; a causal relationship will need further study.

Bottom line: A lower risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality was associated with rapid administration of antibiotics and a faster completion of a 3-hour bundle of sepsis care, but there was no discernable association with the rapid administration of initial bolus of intravenous fluids.

Citation: Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, et al. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:2235-44.

Dr. Choe is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

Clinical question: Does early identification and treatment of sepsis using protocols improve outcomes?

Background: International clinical guidelines recommend early detection and treatment of sepsis with broad spectrum antibiotics and intravenous fluids which are supported by preclinical and observation studies that show a reduction in avoidable deaths. However, controversy remains in the timing of these treatments on how it relates to patient outcomes such as risk-adjusted mortality.

Study design: Retrospective cohort study using data reported to the New York State Department of Health from April 1, 2014, to June 30, 2016.

Setting: New York hospitals.

Synopsis: For patients with sepsis and septic shock, a sepsis protocol was initiated within 6 hours after arrival in the emergency department and had all items in a 3-hour bundle of care (that is, blood cultures, broad-spectrum antibiotic, and lactate measurement) completed within 12 hours. Among 49,331 patients at 149 hospitals, higher risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality was associated with longer time to the completion of the bundle (P less than .001), administration of antibiotics (P less than .001), but not completion of a bolus of intravenous fluids (P = .21).

Study limitations include being nonrandomized, hospitals all from one state possibly introducing epidemiologic distinct features of sepsis inherent to the region, and accuracy of the data collection (that is, start time).

No association was found between time to completion of the initial bolus of fluids and improved outcomes in risk-adjusted mortality; however, the analysis of time of the initial fluid bolus was most vulnerable to confounding; a causal relationship will need further study.

Bottom line: A lower risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality was associated with rapid administration of antibiotics and a faster completion of a 3-hour bundle of sepsis care, but there was no discernable association with the rapid administration of initial bolus of intravenous fluids.

Citation: Seymour CW, Gesten F, Prescott HC, et al. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376:2235-44.

Dr. Choe is a hospitalist at Ochsner Health System, New Orleans.

How Does Gender Influence Perceived Health in Older People With MS?

Older men adapt more poorly to aging with multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with older women, according to research published in the July–August issue of International Journal of MS Care. Health and lifestyle behaviors may put older men with MS at greater risk of health decline, said the authors. Older women, however, appear to have more confidence in their ability to cope with challenges and control the course of their disease.

Healthy Aging With MS

Improved longevity in patients with MS has increased interest in understanding factors associated with healthy aging. Previous studies suggested that factors such as depression, disability, decreased levels of social support, and unemployment predict health-related quality of life in MS.

Two studies examining sex differences in health-related quality of life in young to middle-aged patients with MS found that the association between disability and health-related quality of life was stronger in men than in women. No studies, however, have examined sex differences in health perception among older people with MS, according to the authors.

Analysis of a Canadian Postal Survey

To determine whether older women and men with MS have different health and lifestyle behaviors and whether there are sex differences in contributors to perceived health, Dr. Ploughman and colleagues analyzed data from the Canadian Survey of Health, Lifestyle, and Aging With MS. This cross-sectional study included Canadians older than 55 who had had MS for at least 20 years. Of 921 people contacted, 743 (577 women) returned the mailed questionnaire.

The questionnaire asked about biologic factors (eg, comorbid conditions, years since MS diagnosis), symptoms (eg, depression, anxiety, fatigue, and stress), function (eg, disability and participation), and individual and environmental factors (eg, socioeconomic status, education, and social or health support). Researchers used multiple regression analysis to build explanatory models of health perception.

Older Men With MS Were Less Resilient

Investigators found no differences in disability between men and women, nor differences in age, years of education, or years since MS diagnosis. Older men had lower perceived health and lower resilience, and participated less in life roles than did older women.

In addition, men had more depressive symptoms, and women reported more anxiety. Women also reported higher adherence to a healthy diet (ie, one high in fruits and vegetables and low in meat). Men consumed more alcohol weekly.

Depression was the strongest predictor of health perception in women and men. Other contributors included household participation, fatigue, resilience, and disability in women and physical activity, financial flexibility, and alcohol use in men.

More research is necessary to examine healthy aging in the oldest people with MS, such as octogenarians, said the authors.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Ploughman M, Collins K, Wallack EM, et al. Women’s and men’s differing experiences of health, lifestyle, and aging with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2017;19(4):165-171.

Older men adapt more poorly to aging with multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with older women, according to research published in the July–August issue of International Journal of MS Care. Health and lifestyle behaviors may put older men with MS at greater risk of health decline, said the authors. Older women, however, appear to have more confidence in their ability to cope with challenges and control the course of their disease.

Healthy Aging With MS

Improved longevity in patients with MS has increased interest in understanding factors associated with healthy aging. Previous studies suggested that factors such as depression, disability, decreased levels of social support, and unemployment predict health-related quality of life in MS.

Two studies examining sex differences in health-related quality of life in young to middle-aged patients with MS found that the association between disability and health-related quality of life was stronger in men than in women. No studies, however, have examined sex differences in health perception among older people with MS, according to the authors.

Analysis of a Canadian Postal Survey

To determine whether older women and men with MS have different health and lifestyle behaviors and whether there are sex differences in contributors to perceived health, Dr. Ploughman and colleagues analyzed data from the Canadian Survey of Health, Lifestyle, and Aging With MS. This cross-sectional study included Canadians older than 55 who had had MS for at least 20 years. Of 921 people contacted, 743 (577 women) returned the mailed questionnaire.

The questionnaire asked about biologic factors (eg, comorbid conditions, years since MS diagnosis), symptoms (eg, depression, anxiety, fatigue, and stress), function (eg, disability and participation), and individual and environmental factors (eg, socioeconomic status, education, and social or health support). Researchers used multiple regression analysis to build explanatory models of health perception.

Older Men With MS Were Less Resilient

Investigators found no differences in disability between men and women, nor differences in age, years of education, or years since MS diagnosis. Older men had lower perceived health and lower resilience, and participated less in life roles than did older women.

In addition, men had more depressive symptoms, and women reported more anxiety. Women also reported higher adherence to a healthy diet (ie, one high in fruits and vegetables and low in meat). Men consumed more alcohol weekly.

Depression was the strongest predictor of health perception in women and men. Other contributors included household participation, fatigue, resilience, and disability in women and physical activity, financial flexibility, and alcohol use in men.

More research is necessary to examine healthy aging in the oldest people with MS, such as octogenarians, said the authors.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Ploughman M, Collins K, Wallack EM, et al. Women’s and men’s differing experiences of health, lifestyle, and aging with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2017;19(4):165-171.

Older men adapt more poorly to aging with multiple sclerosis (MS), compared with older women, according to research published in the July–August issue of International Journal of MS Care. Health and lifestyle behaviors may put older men with MS at greater risk of health decline, said the authors. Older women, however, appear to have more confidence in their ability to cope with challenges and control the course of their disease.

Healthy Aging With MS

Improved longevity in patients with MS has increased interest in understanding factors associated with healthy aging. Previous studies suggested that factors such as depression, disability, decreased levels of social support, and unemployment predict health-related quality of life in MS.

Two studies examining sex differences in health-related quality of life in young to middle-aged patients with MS found that the association between disability and health-related quality of life was stronger in men than in women. No studies, however, have examined sex differences in health perception among older people with MS, according to the authors.

Analysis of a Canadian Postal Survey

To determine whether older women and men with MS have different health and lifestyle behaviors and whether there are sex differences in contributors to perceived health, Dr. Ploughman and colleagues analyzed data from the Canadian Survey of Health, Lifestyle, and Aging With MS. This cross-sectional study included Canadians older than 55 who had had MS for at least 20 years. Of 921 people contacted, 743 (577 women) returned the mailed questionnaire.

The questionnaire asked about biologic factors (eg, comorbid conditions, years since MS diagnosis), symptoms (eg, depression, anxiety, fatigue, and stress), function (eg, disability and participation), and individual and environmental factors (eg, socioeconomic status, education, and social or health support). Researchers used multiple regression analysis to build explanatory models of health perception.

Older Men With MS Were Less Resilient

Investigators found no differences in disability between men and women, nor differences in age, years of education, or years since MS diagnosis. Older men had lower perceived health and lower resilience, and participated less in life roles than did older women.

In addition, men had more depressive symptoms, and women reported more anxiety. Women also reported higher adherence to a healthy diet (ie, one high in fruits and vegetables and low in meat). Men consumed more alcohol weekly.

Depression was the strongest predictor of health perception in women and men. Other contributors included household participation, fatigue, resilience, and disability in women and physical activity, financial flexibility, and alcohol use in men.

More research is necessary to examine healthy aging in the oldest people with MS, such as octogenarians, said the authors.

—Erica Tricarico

Suggested Reading

Ploughman M, Collins K, Wallack EM, et al. Women’s and men’s differing experiences of health, lifestyle, and aging with multiple sclerosis. Int J MS Care. 2017;19(4):165-171.

Curcumin May Improve Memory in Cognitively Normal Patients

LONDON—Daily oral curcumin may improve memory and attention in cognitively normal middle-aged and older adults, according to a study presented at the 2017 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“The FDDNP-PET findings raise the possibility that decreases in plaque and tangle accumulation in brain regions modulating mood and memory are associated with curcumin supplementation,” said Gary W. Small, MD, Professor of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences and Parlow-Solomon Professor on Aging at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues.

Previous studies suggested that curcumin’s anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiamyloid, and possible antitau properties may provide neuroprotective benefits. Prior human trials of the effects of curcumin on cognition were inconclusive, however.

To examine the effects of curcumin on memory performance in nondemented adults and explore its potential impact on brain amyloid plaques and tau tangles using FDDNP-PET, Dr. Small and colleagues conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Forty participants ranging in age from 51 to 84 were randomized to a bioavailable formulation of curcumin (90 mg twice daily) or placebo for 18 months. To confirm subject compliance, investigators obtained curcumin blood levels at baseline and at 18 months.

The primary outcomes were verbal (Buschke Selective Reminding Test [SRT]) and visual (Brief Visual Memory Test-Revised) memory. Change in attention (Trail Making Test, Part A) was a secondary outcome. Researchers also assessed mood using the Beck Depression Inventory.

Among the 40 participants, 30 underwent baseline and post-treatment FDDNP-PET scans. Regions of interest included the amygdala, hypothalamus, medial and lateral temporal lobe, posterior cingulate cortex, parietal lobe, frontal lobe, and motor cortex. Data analyses included mixed-effects general linear models with age and education as covariates, and effect-size estimates.

The study population’s mean age was about 63, and 22 participants were women. SRT Consistent Long-Term Retrieval scores improved in the curcumin group, but not in the placebo group. Other memory scores, including the SRT Total and Long-Term Storage, as well as visual memory, also improved in the curcumin group. None of the memory measures changed significantly in the placebo group, said the researchers.

Daily curcumin also improved attention and mood. Researchers observed a significant difference between curcumin and placebo in Trail Making Test, Part A scores.

After 18 months, FDDNP binding was lower in the curcumin group than in the placebo group in the amygdala and the hypothalamus. In addition, the placebo group showed a significant increase in amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the hypothalamus, compared with baseline.

Four patients in the curcumin group and two patients in the placebo group experienced gastrointestinal side effects (primarily transient abdominal pain, gastritis, and nausea). “This relatively inexpensive and nontoxic treatment may have a potential for not only improving age-related memory decline, but also as a prevention therapy, possibly staving off progression, and eventually future symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Small and colleagues.

—Erica Tricarico

LONDON—Daily oral curcumin may improve memory and attention in cognitively normal middle-aged and older adults, according to a study presented at the 2017 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“The FDDNP-PET findings raise the possibility that decreases in plaque and tangle accumulation in brain regions modulating mood and memory are associated with curcumin supplementation,” said Gary W. Small, MD, Professor of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences and Parlow-Solomon Professor on Aging at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues.

Previous studies suggested that curcumin’s anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiamyloid, and possible antitau properties may provide neuroprotective benefits. Prior human trials of the effects of curcumin on cognition were inconclusive, however.

To examine the effects of curcumin on memory performance in nondemented adults and explore its potential impact on brain amyloid plaques and tau tangles using FDDNP-PET, Dr. Small and colleagues conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Forty participants ranging in age from 51 to 84 were randomized to a bioavailable formulation of curcumin (90 mg twice daily) or placebo for 18 months. To confirm subject compliance, investigators obtained curcumin blood levels at baseline and at 18 months.

The primary outcomes were verbal (Buschke Selective Reminding Test [SRT]) and visual (Brief Visual Memory Test-Revised) memory. Change in attention (Trail Making Test, Part A) was a secondary outcome. Researchers also assessed mood using the Beck Depression Inventory.

Among the 40 participants, 30 underwent baseline and post-treatment FDDNP-PET scans. Regions of interest included the amygdala, hypothalamus, medial and lateral temporal lobe, posterior cingulate cortex, parietal lobe, frontal lobe, and motor cortex. Data analyses included mixed-effects general linear models with age and education as covariates, and effect-size estimates.

The study population’s mean age was about 63, and 22 participants were women. SRT Consistent Long-Term Retrieval scores improved in the curcumin group, but not in the placebo group. Other memory scores, including the SRT Total and Long-Term Storage, as well as visual memory, also improved in the curcumin group. None of the memory measures changed significantly in the placebo group, said the researchers.

Daily curcumin also improved attention and mood. Researchers observed a significant difference between curcumin and placebo in Trail Making Test, Part A scores.

After 18 months, FDDNP binding was lower in the curcumin group than in the placebo group in the amygdala and the hypothalamus. In addition, the placebo group showed a significant increase in amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the hypothalamus, compared with baseline.

Four patients in the curcumin group and two patients in the placebo group experienced gastrointestinal side effects (primarily transient abdominal pain, gastritis, and nausea). “This relatively inexpensive and nontoxic treatment may have a potential for not only improving age-related memory decline, but also as a prevention therapy, possibly staving off progression, and eventually future symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Small and colleagues.

—Erica Tricarico

LONDON—Daily oral curcumin may improve memory and attention in cognitively normal middle-aged and older adults, according to a study presented at the 2017 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

“The FDDNP-PET findings raise the possibility that decreases in plaque and tangle accumulation in brain regions modulating mood and memory are associated with curcumin supplementation,” said Gary W. Small, MD, Professor of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences and Parlow-Solomon Professor on Aging at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles, and colleagues.

Previous studies suggested that curcumin’s anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiamyloid, and possible antitau properties may provide neuroprotective benefits. Prior human trials of the effects of curcumin on cognition were inconclusive, however.

To examine the effects of curcumin on memory performance in nondemented adults and explore its potential impact on brain amyloid plaques and tau tangles using FDDNP-PET, Dr. Small and colleagues conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Forty participants ranging in age from 51 to 84 were randomized to a bioavailable formulation of curcumin (90 mg twice daily) or placebo for 18 months. To confirm subject compliance, investigators obtained curcumin blood levels at baseline and at 18 months.

The primary outcomes were verbal (Buschke Selective Reminding Test [SRT]) and visual (Brief Visual Memory Test-Revised) memory. Change in attention (Trail Making Test, Part A) was a secondary outcome. Researchers also assessed mood using the Beck Depression Inventory.

Among the 40 participants, 30 underwent baseline and post-treatment FDDNP-PET scans. Regions of interest included the amygdala, hypothalamus, medial and lateral temporal lobe, posterior cingulate cortex, parietal lobe, frontal lobe, and motor cortex. Data analyses included mixed-effects general linear models with age and education as covariates, and effect-size estimates.

The study population’s mean age was about 63, and 22 participants were women. SRT Consistent Long-Term Retrieval scores improved in the curcumin group, but not in the placebo group. Other memory scores, including the SRT Total and Long-Term Storage, as well as visual memory, also improved in the curcumin group. None of the memory measures changed significantly in the placebo group, said the researchers.

Daily curcumin also improved attention and mood. Researchers observed a significant difference between curcumin and placebo in Trail Making Test, Part A scores.

After 18 months, FDDNP binding was lower in the curcumin group than in the placebo group in the amygdala and the hypothalamus. In addition, the placebo group showed a significant increase in amyloid plaques and tau tangles in the hypothalamus, compared with baseline.

Four patients in the curcumin group and two patients in the placebo group experienced gastrointestinal side effects (primarily transient abdominal pain, gastritis, and nausea). “This relatively inexpensive and nontoxic treatment may have a potential for not only improving age-related memory decline, but also as a prevention therapy, possibly staving off progression, and eventually future symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Small and colleagues.

—Erica Tricarico

VIDEO: Clinicians have community resources for suicide prevention efforts

Suicide prevention requires a multifaceted, comprehensive clinical effort, coupled with an equally comprehensive community effort.

“The clinician isn’t in it alone – none of us can do this alone,” explained Eileen Zeller, lead public health advisor with the suicide prevention branch of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

In an interview at an event sponsored by Education Development Center and the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, Ms. Zeller discussed new initiatives to get suicide prevention resources to clinicians and communities .

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Suicide prevention requires a multifaceted, comprehensive clinical effort, coupled with an equally comprehensive community effort.

“The clinician isn’t in it alone – none of us can do this alone,” explained Eileen Zeller, lead public health advisor with the suicide prevention branch of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

In an interview at an event sponsored by Education Development Center and the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, Ms. Zeller discussed new initiatives to get suicide prevention resources to clinicians and communities .

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Suicide prevention requires a multifaceted, comprehensive clinical effort, coupled with an equally comprehensive community effort.

“The clinician isn’t in it alone – none of us can do this alone,” explained Eileen Zeller, lead public health advisor with the suicide prevention branch of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

In an interview at an event sponsored by Education Development Center and the National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention, Ms. Zeller discussed new initiatives to get suicide prevention resources to clinicians and communities .