User login

Not enough evidence for primary care to routinely conduct dental screenings

Routine screenings for signs of cavities and gum disease by primary care clinicians may not catch patients most at risk of these conditions, according to a statement by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) that was published in JAMA.

Suggesting ways to improve oral health also may fail to engage the patients who most need the message, the group said in its statement.

The task force is not suggesting that primary care providers stop all oral health screening of adults or that they never discuss ways to improve oral health. But the current evidence of the most effective oral health screenings or enhancement strategies in primary care settings received an “I” rating, for “Inconclusive.” The highest ranking a screening can receive is an “A” or “B,” which indicate that there is strong evidence for conducting a screening, while a “C” would indicate that clinicians could rarely provide a screening, and a “D” would indicate not to, given the current evidence.

Primary care clinicians should immediately refer any patients with apparent caries or gum disease to a dentist, the USPSTF noted. But what clinicians should do for patients who have no obvious oral health problems is up for debate.

“The ‘I’ is a note about where the evidence is at this point and then a call for more research to see if we can’t get some more clarity for next time,” said John Ruiz, PhD, professor of clinical psychology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who is a member of the task force.

More than 90% of U.S. adults may have caries, including 26% with untreated caries that can cause serious infections or tooth loss. In addition, 42% of adults have some type of gum disease. More than two-thirds of Americans aged 65 or older have gum disease, and it is the leading cause of tooth loss in this population. People earning low incomes and those who do not have health insurance or who belong to a marginalized racial or ethnic group are at greater risk of the harms of caries and gum disease.

“Oral health care is important to overall health,” and any new research on oral health screening and enhancement efforts should be demographically representative of adults affected by these conditions, Dr. Ruiz said.

In an accompanying editorial, oral health researchers from the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, San Francisco, echoed the call for representative research and encouraged closer collaboration between primary care providers and dentists to promote oral health.

“Oral health screening and referral by medical primary care clinicians can help ensure that individuals get to the dental chair to receive needed interventions that can benefit both oral and potentially overall health,” the authors wrote. “Likewise, medical challenges and oral mucosal manifestations of chronic health conditions detected at a dental visit should result in medical referral, allowing prompt evaluation and treatment.”

Lack of data

The USPSTF defined oral health screenings for patients older than 18 who have no obvious signs of caries or gum disease as looking at a patient’s mouth during physical exams. Additionally, clinicians might use prediction models to identify patients at greater risk of facing these problems.

Strategies to improve oral health include providing encouragement to patients to reduce intake of refined sugar, to floss and brush effectively to reduce bacteria, and to use fluoride gels, fluoride varnishes, or other kinds of sealants to make caries harder to form.

A literature review found that there has been limited analysis of primary care clinicians performing these tasks. Perhaps unsurprisingly, more such studies about dentists existed, leaving an open field for dedicated studies about what primary care clinicians should do to optimize oral health with patients.

“Clinicians, in the absence of clear guidelines, should continue to use their best judgment,” Dr. Ruiz said.

One dentist interviewed said screening could be as simple as doctors asking patients how often they brush their teeth and giving patients a toothbrush as part of the office visit.

“It all comes down to, ‘Is the person brushing their teeth?’ ” said Jennifer Hartshorn, DDS, who specializes in community and preventive dentistry at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

“By all means look in their mouth, ask how much they are brushing, and urge them to find a dental home if at all possible,” Dr. Hartshorn said, especially for patients who smoke or have conditions such as dry mouth, which can increase the risk of oral disease.

Dr. Ruiz and Dr. Hartshorn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Routine screenings for signs of cavities and gum disease by primary care clinicians may not catch patients most at risk of these conditions, according to a statement by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) that was published in JAMA.

Suggesting ways to improve oral health also may fail to engage the patients who most need the message, the group said in its statement.

The task force is not suggesting that primary care providers stop all oral health screening of adults or that they never discuss ways to improve oral health. But the current evidence of the most effective oral health screenings or enhancement strategies in primary care settings received an “I” rating, for “Inconclusive.” The highest ranking a screening can receive is an “A” or “B,” which indicate that there is strong evidence for conducting a screening, while a “C” would indicate that clinicians could rarely provide a screening, and a “D” would indicate not to, given the current evidence.

Primary care clinicians should immediately refer any patients with apparent caries or gum disease to a dentist, the USPSTF noted. But what clinicians should do for patients who have no obvious oral health problems is up for debate.

“The ‘I’ is a note about where the evidence is at this point and then a call for more research to see if we can’t get some more clarity for next time,” said John Ruiz, PhD, professor of clinical psychology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who is a member of the task force.

More than 90% of U.S. adults may have caries, including 26% with untreated caries that can cause serious infections or tooth loss. In addition, 42% of adults have some type of gum disease. More than two-thirds of Americans aged 65 or older have gum disease, and it is the leading cause of tooth loss in this population. People earning low incomes and those who do not have health insurance or who belong to a marginalized racial or ethnic group are at greater risk of the harms of caries and gum disease.

“Oral health care is important to overall health,” and any new research on oral health screening and enhancement efforts should be demographically representative of adults affected by these conditions, Dr. Ruiz said.

In an accompanying editorial, oral health researchers from the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, San Francisco, echoed the call for representative research and encouraged closer collaboration between primary care providers and dentists to promote oral health.

“Oral health screening and referral by medical primary care clinicians can help ensure that individuals get to the dental chair to receive needed interventions that can benefit both oral and potentially overall health,” the authors wrote. “Likewise, medical challenges and oral mucosal manifestations of chronic health conditions detected at a dental visit should result in medical referral, allowing prompt evaluation and treatment.”

Lack of data

The USPSTF defined oral health screenings for patients older than 18 who have no obvious signs of caries or gum disease as looking at a patient’s mouth during physical exams. Additionally, clinicians might use prediction models to identify patients at greater risk of facing these problems.

Strategies to improve oral health include providing encouragement to patients to reduce intake of refined sugar, to floss and brush effectively to reduce bacteria, and to use fluoride gels, fluoride varnishes, or other kinds of sealants to make caries harder to form.

A literature review found that there has been limited analysis of primary care clinicians performing these tasks. Perhaps unsurprisingly, more such studies about dentists existed, leaving an open field for dedicated studies about what primary care clinicians should do to optimize oral health with patients.

“Clinicians, in the absence of clear guidelines, should continue to use their best judgment,” Dr. Ruiz said.

One dentist interviewed said screening could be as simple as doctors asking patients how often they brush their teeth and giving patients a toothbrush as part of the office visit.

“It all comes down to, ‘Is the person brushing their teeth?’ ” said Jennifer Hartshorn, DDS, who specializes in community and preventive dentistry at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

“By all means look in their mouth, ask how much they are brushing, and urge them to find a dental home if at all possible,” Dr. Hartshorn said, especially for patients who smoke or have conditions such as dry mouth, which can increase the risk of oral disease.

Dr. Ruiz and Dr. Hartshorn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Routine screenings for signs of cavities and gum disease by primary care clinicians may not catch patients most at risk of these conditions, according to a statement by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) that was published in JAMA.

Suggesting ways to improve oral health also may fail to engage the patients who most need the message, the group said in its statement.

The task force is not suggesting that primary care providers stop all oral health screening of adults or that they never discuss ways to improve oral health. But the current evidence of the most effective oral health screenings or enhancement strategies in primary care settings received an “I” rating, for “Inconclusive.” The highest ranking a screening can receive is an “A” or “B,” which indicate that there is strong evidence for conducting a screening, while a “C” would indicate that clinicians could rarely provide a screening, and a “D” would indicate not to, given the current evidence.

Primary care clinicians should immediately refer any patients with apparent caries or gum disease to a dentist, the USPSTF noted. But what clinicians should do for patients who have no obvious oral health problems is up for debate.

“The ‘I’ is a note about where the evidence is at this point and then a call for more research to see if we can’t get some more clarity for next time,” said John Ruiz, PhD, professor of clinical psychology at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who is a member of the task force.

More than 90% of U.S. adults may have caries, including 26% with untreated caries that can cause serious infections or tooth loss. In addition, 42% of adults have some type of gum disease. More than two-thirds of Americans aged 65 or older have gum disease, and it is the leading cause of tooth loss in this population. People earning low incomes and those who do not have health insurance or who belong to a marginalized racial or ethnic group are at greater risk of the harms of caries and gum disease.

“Oral health care is important to overall health,” and any new research on oral health screening and enhancement efforts should be demographically representative of adults affected by these conditions, Dr. Ruiz said.

In an accompanying editorial, oral health researchers from the National Institutes of Health and the University of California, San Francisco, echoed the call for representative research and encouraged closer collaboration between primary care providers and dentists to promote oral health.

“Oral health screening and referral by medical primary care clinicians can help ensure that individuals get to the dental chair to receive needed interventions that can benefit both oral and potentially overall health,” the authors wrote. “Likewise, medical challenges and oral mucosal manifestations of chronic health conditions detected at a dental visit should result in medical referral, allowing prompt evaluation and treatment.”

Lack of data

The USPSTF defined oral health screenings for patients older than 18 who have no obvious signs of caries or gum disease as looking at a patient’s mouth during physical exams. Additionally, clinicians might use prediction models to identify patients at greater risk of facing these problems.

Strategies to improve oral health include providing encouragement to patients to reduce intake of refined sugar, to floss and brush effectively to reduce bacteria, and to use fluoride gels, fluoride varnishes, or other kinds of sealants to make caries harder to form.

A literature review found that there has been limited analysis of primary care clinicians performing these tasks. Perhaps unsurprisingly, more such studies about dentists existed, leaving an open field for dedicated studies about what primary care clinicians should do to optimize oral health with patients.

“Clinicians, in the absence of clear guidelines, should continue to use their best judgment,” Dr. Ruiz said.

One dentist interviewed said screening could be as simple as doctors asking patients how often they brush their teeth and giving patients a toothbrush as part of the office visit.

“It all comes down to, ‘Is the person brushing their teeth?’ ” said Jennifer Hartshorn, DDS, who specializes in community and preventive dentistry at the University of Iowa, Iowa City.

“By all means look in their mouth, ask how much they are brushing, and urge them to find a dental home if at all possible,” Dr. Hartshorn said, especially for patients who smoke or have conditions such as dry mouth, which can increase the risk of oral disease.

Dr. Ruiz and Dr. Hartshorn report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA

Report cards, additional observer improve adenoma detection rate

Although multimodal interventions like extra training with periodic feedback showed some signs of improving ADR, withdrawal time monitoring was not significantly associated with a better detection rate, reported Anshul Arora, MD, of Western University, London, Ont., and colleagues.

“Given the increased risk of postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer associated with low ADR, improving [this performance metric] has become a major focus for quality improvement,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

They noted that “numerous strategies” have been evaluated for this purpose, which may be sorted into three groups: endoscopy unit–level interventions (i.e., system changes), procedure-targeted interventions (i.e., technique changes), and technology-based interventions.

“Of these categories, endoscopy unit–level interventions are perhaps the easiest to implement widely because they generally require fewer changes in the technical aspect of how a colonoscopy is performed,” the investigators wrote. “Thus, the objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to identify endoscopy unit–level interventions aimed at improving ADRs and their effectiveness.”

To this end, Dr. Arora and colleagues analyzed data from 34 randomized controlled trials and observational studies involving 1,501 endoscopists and 371,041 procedures. They evaluated the relationship between ADR and implementation of four interventions: a performance report card, a multimodal intervention (e.g., training sessions with periodic feedback), presence of an additional observer, and withdrawal time monitoring.

Provision of report cards was associated with the greatest improvement in ADR, at 28% (odds ratio, 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 1.13-1.45; P less than .001), followed by presence of an additional observer, which bumped ADR by 25% (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.43; P = .002). The impact of multimodal interventions was “borderline significant,” the investigators wrote, with an 18% improvement in ADR (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.00-1.40; P = .05). In contrast, withdrawal time monitoring showed no significant benefit (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.93-1.96; P = .11).

In their discussion, Dr. Arora and colleagues offered guidance on the use of report cards, which were associated with the greatest improvement in ADR.

“We found that benchmarking individual endoscopists against their peers was important for improving ADR performance because this was the common thread among all report card–based interventions,” they wrote. “In terms of the method of delivery for feedback, only one study used public reporting of colonoscopy quality indicators, whereas the rest delivered report cards privately to physicians. This suggests that confidential feedback did not impede self-improvement, which is desirable to avoid stigmatization of low ADR performers.”

The findings also suggest that additional observers can boost ADR without specialized training.

“[The benefit of an additional observer] may be explained by the presence of a second set of eyes to identify polyps or, more pragmatically, by the Hawthorne effect, whereby endoscopists may be more careful because they know someone else is watching the screen,” the investigators wrote. “Regardless, extra training for the observer does not seem to be necessary because the three RCTs [evaluating this intervention] all used endoscopy nurses who did not receive any additional polyp detection training. Thus, endoscopy unit nurses should be encouraged to speak up should they see a polyp the endoscopist missed.”

The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

The effectiveness of colonoscopy to prevent colorectal cancer depends on the quality of the exam. Adenoma detection rate (ADR) is a validated quality indicator, associated with lower risk of postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. There are multiple interventions that can improve endoscopists’ ADR, but it is unclear which ones are higher yield than others. This study summarizes the existing studies on various interventions and finds the largest increase in ADR with the use of physician report cards. This is not surprising, as report cards both provide measurement and are an intervention for improvement.

Interestingly the included studies mostly used individual confidential report cards, and demonstrated an improvement in ADR. Having a second set of eyes looking at the monitor was also associated with increase in ADR. Whether it’s the observer picking up missed polyps, or the endoscopist doing a more thorough exam because someone else is watching the screen, is unclear. This is the same principle that current computer assisted detection (CADe) devices help with. While having a second observer may not be practical or cost effective, and CADe is expensive, the take-away is that there are multiple ways to improve ADR, and at the very least every physician should be receiving report cards or feedback on their quality indicators and working towards achieving and exceeding the minimum benchmarks.

Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, is the Robert M. and Mary H. Glickman professor of medicine, New York University Grossman School of Medicine where she also holds a professorship in population health. She serves as director of outcomes research in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, and codirector of Translational Research Education and Careers (TREC). She disclosed serving as an adviser for Motus-GI and Iterative Health.

The effectiveness of colonoscopy to prevent colorectal cancer depends on the quality of the exam. Adenoma detection rate (ADR) is a validated quality indicator, associated with lower risk of postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. There are multiple interventions that can improve endoscopists’ ADR, but it is unclear which ones are higher yield than others. This study summarizes the existing studies on various interventions and finds the largest increase in ADR with the use of physician report cards. This is not surprising, as report cards both provide measurement and are an intervention for improvement.

Interestingly the included studies mostly used individual confidential report cards, and demonstrated an improvement in ADR. Having a second set of eyes looking at the monitor was also associated with increase in ADR. Whether it’s the observer picking up missed polyps, or the endoscopist doing a more thorough exam because someone else is watching the screen, is unclear. This is the same principle that current computer assisted detection (CADe) devices help with. While having a second observer may not be practical or cost effective, and CADe is expensive, the take-away is that there are multiple ways to improve ADR, and at the very least every physician should be receiving report cards or feedback on their quality indicators and working towards achieving and exceeding the minimum benchmarks.

Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, is the Robert M. and Mary H. Glickman professor of medicine, New York University Grossman School of Medicine where she also holds a professorship in population health. She serves as director of outcomes research in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, and codirector of Translational Research Education and Careers (TREC). She disclosed serving as an adviser for Motus-GI and Iterative Health.

The effectiveness of colonoscopy to prevent colorectal cancer depends on the quality of the exam. Adenoma detection rate (ADR) is a validated quality indicator, associated with lower risk of postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer. There are multiple interventions that can improve endoscopists’ ADR, but it is unclear which ones are higher yield than others. This study summarizes the existing studies on various interventions and finds the largest increase in ADR with the use of physician report cards. This is not surprising, as report cards both provide measurement and are an intervention for improvement.

Interestingly the included studies mostly used individual confidential report cards, and demonstrated an improvement in ADR. Having a second set of eyes looking at the monitor was also associated with increase in ADR. Whether it’s the observer picking up missed polyps, or the endoscopist doing a more thorough exam because someone else is watching the screen, is unclear. This is the same principle that current computer assisted detection (CADe) devices help with. While having a second observer may not be practical or cost effective, and CADe is expensive, the take-away is that there are multiple ways to improve ADR, and at the very least every physician should be receiving report cards or feedback on their quality indicators and working towards achieving and exceeding the minimum benchmarks.

Aasma Shaukat, MD, MPH, is the Robert M. and Mary H. Glickman professor of medicine, New York University Grossman School of Medicine where she also holds a professorship in population health. She serves as director of outcomes research in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, and codirector of Translational Research Education and Careers (TREC). She disclosed serving as an adviser for Motus-GI and Iterative Health.

Although multimodal interventions like extra training with periodic feedback showed some signs of improving ADR, withdrawal time monitoring was not significantly associated with a better detection rate, reported Anshul Arora, MD, of Western University, London, Ont., and colleagues.

“Given the increased risk of postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer associated with low ADR, improving [this performance metric] has become a major focus for quality improvement,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

They noted that “numerous strategies” have been evaluated for this purpose, which may be sorted into three groups: endoscopy unit–level interventions (i.e., system changes), procedure-targeted interventions (i.e., technique changes), and technology-based interventions.

“Of these categories, endoscopy unit–level interventions are perhaps the easiest to implement widely because they generally require fewer changes in the technical aspect of how a colonoscopy is performed,” the investigators wrote. “Thus, the objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to identify endoscopy unit–level interventions aimed at improving ADRs and their effectiveness.”

To this end, Dr. Arora and colleagues analyzed data from 34 randomized controlled trials and observational studies involving 1,501 endoscopists and 371,041 procedures. They evaluated the relationship between ADR and implementation of four interventions: a performance report card, a multimodal intervention (e.g., training sessions with periodic feedback), presence of an additional observer, and withdrawal time monitoring.

Provision of report cards was associated with the greatest improvement in ADR, at 28% (odds ratio, 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 1.13-1.45; P less than .001), followed by presence of an additional observer, which bumped ADR by 25% (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.43; P = .002). The impact of multimodal interventions was “borderline significant,” the investigators wrote, with an 18% improvement in ADR (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.00-1.40; P = .05). In contrast, withdrawal time monitoring showed no significant benefit (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.93-1.96; P = .11).

In their discussion, Dr. Arora and colleagues offered guidance on the use of report cards, which were associated with the greatest improvement in ADR.

“We found that benchmarking individual endoscopists against their peers was important for improving ADR performance because this was the common thread among all report card–based interventions,” they wrote. “In terms of the method of delivery for feedback, only one study used public reporting of colonoscopy quality indicators, whereas the rest delivered report cards privately to physicians. This suggests that confidential feedback did not impede self-improvement, which is desirable to avoid stigmatization of low ADR performers.”

The findings also suggest that additional observers can boost ADR without specialized training.

“[The benefit of an additional observer] may be explained by the presence of a second set of eyes to identify polyps or, more pragmatically, by the Hawthorne effect, whereby endoscopists may be more careful because they know someone else is watching the screen,” the investigators wrote. “Regardless, extra training for the observer does not seem to be necessary because the three RCTs [evaluating this intervention] all used endoscopy nurses who did not receive any additional polyp detection training. Thus, endoscopy unit nurses should be encouraged to speak up should they see a polyp the endoscopist missed.”

The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Although multimodal interventions like extra training with periodic feedback showed some signs of improving ADR, withdrawal time monitoring was not significantly associated with a better detection rate, reported Anshul Arora, MD, of Western University, London, Ont., and colleagues.

“Given the increased risk of postcolonoscopy colorectal cancer associated with low ADR, improving [this performance metric] has become a major focus for quality improvement,” the investigators wrote in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology.

They noted that “numerous strategies” have been evaluated for this purpose, which may be sorted into three groups: endoscopy unit–level interventions (i.e., system changes), procedure-targeted interventions (i.e., technique changes), and technology-based interventions.

“Of these categories, endoscopy unit–level interventions are perhaps the easiest to implement widely because they generally require fewer changes in the technical aspect of how a colonoscopy is performed,” the investigators wrote. “Thus, the objective of this study was to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to identify endoscopy unit–level interventions aimed at improving ADRs and their effectiveness.”

To this end, Dr. Arora and colleagues analyzed data from 34 randomized controlled trials and observational studies involving 1,501 endoscopists and 371,041 procedures. They evaluated the relationship between ADR and implementation of four interventions: a performance report card, a multimodal intervention (e.g., training sessions with periodic feedback), presence of an additional observer, and withdrawal time monitoring.

Provision of report cards was associated with the greatest improvement in ADR, at 28% (odds ratio, 1.28; 95% confidence interval, 1.13-1.45; P less than .001), followed by presence of an additional observer, which bumped ADR by 25% (OR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.09-1.43; P = .002). The impact of multimodal interventions was “borderline significant,” the investigators wrote, with an 18% improvement in ADR (OR, 1.18; 95% CI, 1.00-1.40; P = .05). In contrast, withdrawal time monitoring showed no significant benefit (OR, 1.35; 95% CI, 0.93-1.96; P = .11).

In their discussion, Dr. Arora and colleagues offered guidance on the use of report cards, which were associated with the greatest improvement in ADR.

“We found that benchmarking individual endoscopists against their peers was important for improving ADR performance because this was the common thread among all report card–based interventions,” they wrote. “In terms of the method of delivery for feedback, only one study used public reporting of colonoscopy quality indicators, whereas the rest delivered report cards privately to physicians. This suggests that confidential feedback did not impede self-improvement, which is desirable to avoid stigmatization of low ADR performers.”

The findings also suggest that additional observers can boost ADR without specialized training.

“[The benefit of an additional observer] may be explained by the presence of a second set of eyes to identify polyps or, more pragmatically, by the Hawthorne effect, whereby endoscopists may be more careful because they know someone else is watching the screen,” the investigators wrote. “Regardless, extra training for the observer does not seem to be necessary because the three RCTs [evaluating this intervention] all used endoscopy nurses who did not receive any additional polyp detection training. Thus, endoscopy unit nurses should be encouraged to speak up should they see a polyp the endoscopist missed.”

The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Short aspirin therapy noninferior to DAPT for 1 year after PCI for ACS

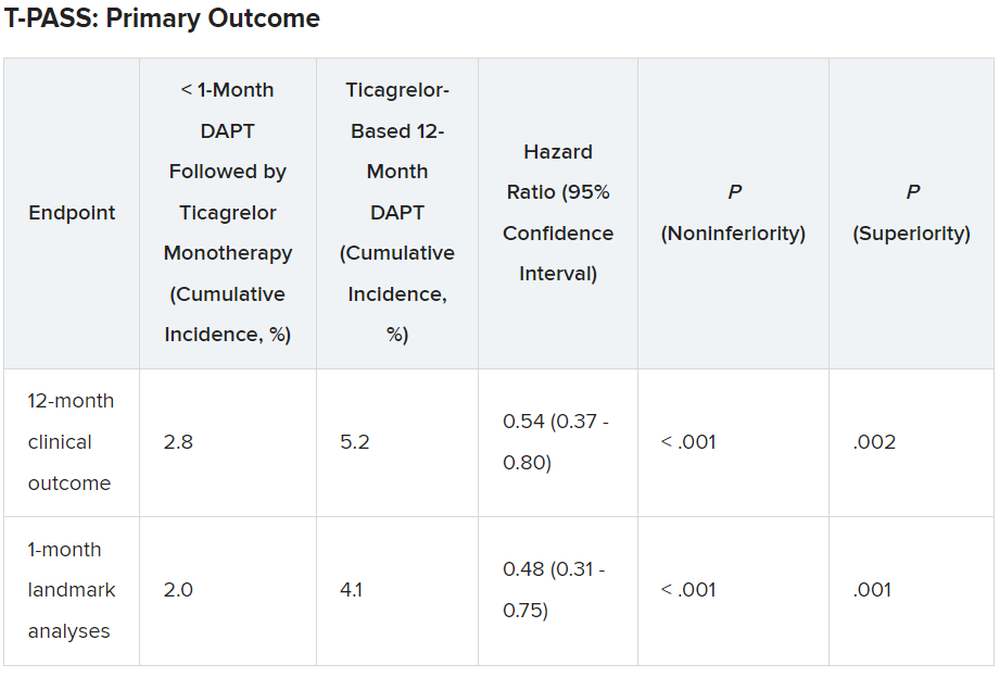

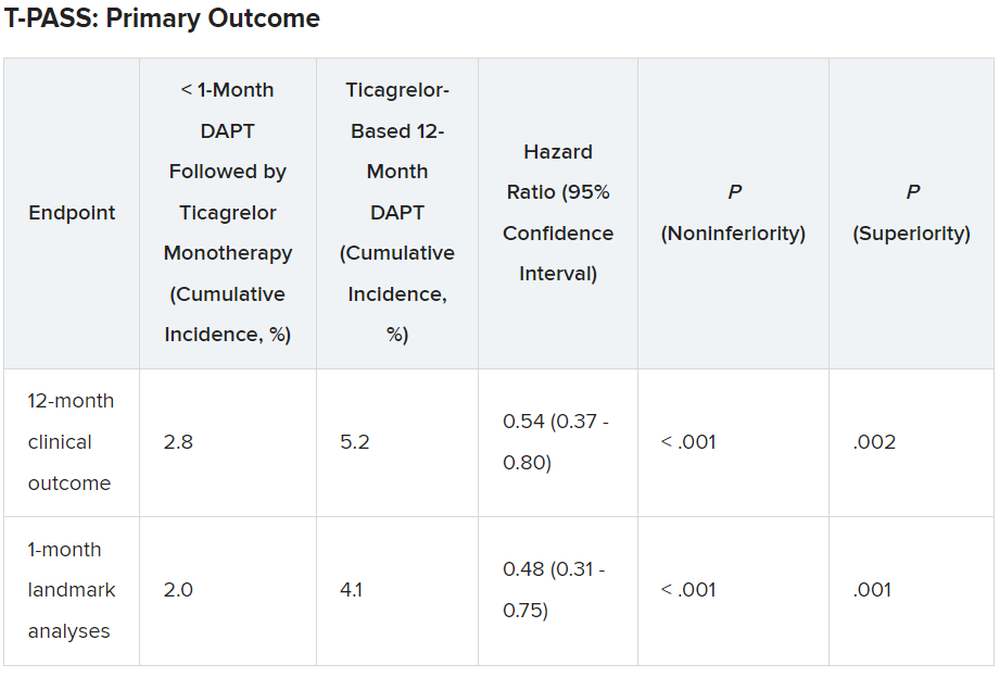

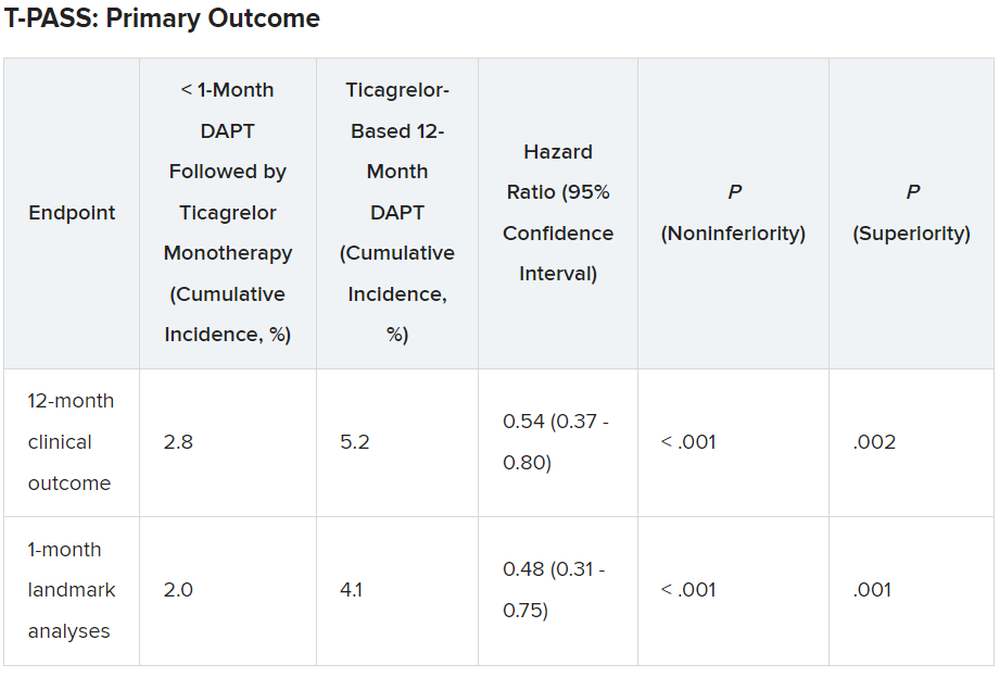

SAN FRANCISCO – Stopping aspirin within 1 month of implanting a drug-eluting stent (DES) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) followed by ticagrelor monotherapy was shown to be noninferior to 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in net adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in the T-PASS trial.

of death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, stroke, and major bleeding, primarily due to a significant reduction in bleeding events,” senior author Myeong-Ki Hong, MD, PhD, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, told attendees at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

“This study provides evidence that stopping aspirin within 1 month after implantation of drug-eluting stents for ticagrelor monotherapy is a reasonable alternative to 12-month DAPT as for adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events,” Dr. Hong concluded.

The study was published in Circulation ahead of print to coincide with the presentation.

Three months to 1 month

Previous trials (TICO and TWILIGHT) have shown that ticagrelor monotherapy after 3 months of DAPT can be safe and effectively prevent ischemic events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in ACS or high-risk PCI patients.

The current study aimed to investigate whether ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT was noninferior to 12 months of ticagrelor-based DAPT for preventing adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in patients with ACS undergoing PCI with a DES implant.

T-PASS, carried out at 24 centers in Korea, enrolled ACS patients aged 19 years or older who received an ultrathin, bioresorbable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent (Orsiro, Biotronik). They were randomized 1:1 to ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT (n = 1,426) or to ticagrelor-based DAPT for 12 months (n = 1,424).

The primary outcome measure was net adverse clinical events (NACE) at 12 months, consisting of major bleeding plus major adverse cardiovascular events. All patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

The study could enroll patients aged 19-80 years. It excluded anyone with active bleeding, at increased risk for bleeding, with anemia (hemoglobin ≤ 8 g/dL), platelets less than 100,000/mcL, need for oral anticoagulation therapy, current or potential pregnancy, or a life expectancy less than 1 year.

Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced. The extended monotherapy and DAPT arms had an average age of 61 ± 10 years, were 84% and 83% male and had diabetes mellitus in 30% and 29%, respectively, with 74% of each group admitted via the emergency room. ST-elevation myocardial infarction occurred in 40% and 41% of patients in each group, respectively.

Results showed that stopping aspirin early was noninferior and possibly superior to 12 months of DAPT.

For the 12-month clinical outcome, fewer patients in the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm reached the primary clinical endpoint of NACE versus the ticagrelor-based 12-month DAPT arm, both in terms of noninferiority (P < .001) and superiority (P = .002). Similar results were found for the 1-month landmark analyses.

For both the 12-month clinical outcome and the 1-month landmark analyses, the curves for the two arms began to diverge at about 150 days, with the one for ticagrelor monotherapy essentially flattening out just after that and the one for the 12-month DAPT therapy continuing to rise out to the 1-year point.

In the less than 1 month DAPT arm, aspirin was stopped at a median of 16 days. Panelist Adnan Kastrati, MD, Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Technische Universität, Munich, Germany, asked Dr. Hong about the criteria for the point at which aspirin was stopped in the less than 1 month arm.

Dr. Hong replied: “Actually, we recommend less than 1 month, so therefore in some patients, it was the operator’s decision,” depending on risk factors for stopping or continuing aspirin. He said that in some patients it may be reasonable to stop aspirin even in 7-10 days. Fewer than 10% of patients in the less than 1 month arm continued on aspirin past 30 days, but a few continued on it to the 1-year point.

There was no difference between the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm and the 12-month DAPT arm in terms of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at 1 year (1.8% vs. 2.2%, respectively; hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.50-1.41; log-rank, P = .51).

However, the 12-month DAPT arm showed a significantly greater incidence of major bleeding at 1 year: 3.4% versus 1.2% for less than 1 month aspirin arm (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.20-0.61; log-rank, P < .001).

Dr. Hong said that a limitation of the study was that it was open label and not placebo controlled. However, an independent clinical event adjudication committee assessed all clinical outcomes.

Lead discussant Marco Valgimigli, MD, PhD, Cardiocentro Ticino Foundation, Lugano, Switzerland, noted that T-PASS is the fifth study to investigate ticagrelor monotherapy versus a DAPT, giving randomized data on almost 22,000 patients.

“T-PASS showed very consistently with the prior four studies that by dropping aspirin and continuation with ticagrelor therapy, compared with the standard DAPT regimen, is associated with no penalty ... and in fact leading to a very significant and clinically very convincing risk reduction, and I would like to underline major bleeding risk reduction,” he said, pointing out that this study comes from the same research group that carried out the TICO trial.

Dr. Hong has received institutional research grants from Samjin Pharmaceutical and Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical, and speaker’s fees from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Kastrati has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Valgimigli has received grant support/research contracts from Terumo Medical and AstraZeneca; consultant fees/honoraria/speaker’s bureau for Terumo Medical Corporation, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo/Eli Lilly, Amgen, Alvimedica, AstraZenca, Idorsia, Coreflow, Vifor, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and iVascular. The study was funded by Biotronik.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – Stopping aspirin within 1 month of implanting a drug-eluting stent (DES) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) followed by ticagrelor monotherapy was shown to be noninferior to 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in net adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in the T-PASS trial.

of death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, stroke, and major bleeding, primarily due to a significant reduction in bleeding events,” senior author Myeong-Ki Hong, MD, PhD, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, told attendees at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

“This study provides evidence that stopping aspirin within 1 month after implantation of drug-eluting stents for ticagrelor monotherapy is a reasonable alternative to 12-month DAPT as for adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events,” Dr. Hong concluded.

The study was published in Circulation ahead of print to coincide with the presentation.

Three months to 1 month

Previous trials (TICO and TWILIGHT) have shown that ticagrelor monotherapy after 3 months of DAPT can be safe and effectively prevent ischemic events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in ACS or high-risk PCI patients.

The current study aimed to investigate whether ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT was noninferior to 12 months of ticagrelor-based DAPT for preventing adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in patients with ACS undergoing PCI with a DES implant.

T-PASS, carried out at 24 centers in Korea, enrolled ACS patients aged 19 years or older who received an ultrathin, bioresorbable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent (Orsiro, Biotronik). They were randomized 1:1 to ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT (n = 1,426) or to ticagrelor-based DAPT for 12 months (n = 1,424).

The primary outcome measure was net adverse clinical events (NACE) at 12 months, consisting of major bleeding plus major adverse cardiovascular events. All patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

The study could enroll patients aged 19-80 years. It excluded anyone with active bleeding, at increased risk for bleeding, with anemia (hemoglobin ≤ 8 g/dL), platelets less than 100,000/mcL, need for oral anticoagulation therapy, current or potential pregnancy, or a life expectancy less than 1 year.

Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced. The extended monotherapy and DAPT arms had an average age of 61 ± 10 years, were 84% and 83% male and had diabetes mellitus in 30% and 29%, respectively, with 74% of each group admitted via the emergency room. ST-elevation myocardial infarction occurred in 40% and 41% of patients in each group, respectively.

Results showed that stopping aspirin early was noninferior and possibly superior to 12 months of DAPT.

For the 12-month clinical outcome, fewer patients in the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm reached the primary clinical endpoint of NACE versus the ticagrelor-based 12-month DAPT arm, both in terms of noninferiority (P < .001) and superiority (P = .002). Similar results were found for the 1-month landmark analyses.

For both the 12-month clinical outcome and the 1-month landmark analyses, the curves for the two arms began to diverge at about 150 days, with the one for ticagrelor monotherapy essentially flattening out just after that and the one for the 12-month DAPT therapy continuing to rise out to the 1-year point.

In the less than 1 month DAPT arm, aspirin was stopped at a median of 16 days. Panelist Adnan Kastrati, MD, Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Technische Universität, Munich, Germany, asked Dr. Hong about the criteria for the point at which aspirin was stopped in the less than 1 month arm.

Dr. Hong replied: “Actually, we recommend less than 1 month, so therefore in some patients, it was the operator’s decision,” depending on risk factors for stopping or continuing aspirin. He said that in some patients it may be reasonable to stop aspirin even in 7-10 days. Fewer than 10% of patients in the less than 1 month arm continued on aspirin past 30 days, but a few continued on it to the 1-year point.

There was no difference between the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm and the 12-month DAPT arm in terms of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at 1 year (1.8% vs. 2.2%, respectively; hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.50-1.41; log-rank, P = .51).

However, the 12-month DAPT arm showed a significantly greater incidence of major bleeding at 1 year: 3.4% versus 1.2% for less than 1 month aspirin arm (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.20-0.61; log-rank, P < .001).

Dr. Hong said that a limitation of the study was that it was open label and not placebo controlled. However, an independent clinical event adjudication committee assessed all clinical outcomes.

Lead discussant Marco Valgimigli, MD, PhD, Cardiocentro Ticino Foundation, Lugano, Switzerland, noted that T-PASS is the fifth study to investigate ticagrelor monotherapy versus a DAPT, giving randomized data on almost 22,000 patients.

“T-PASS showed very consistently with the prior four studies that by dropping aspirin and continuation with ticagrelor therapy, compared with the standard DAPT regimen, is associated with no penalty ... and in fact leading to a very significant and clinically very convincing risk reduction, and I would like to underline major bleeding risk reduction,” he said, pointing out that this study comes from the same research group that carried out the TICO trial.

Dr. Hong has received institutional research grants from Samjin Pharmaceutical and Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical, and speaker’s fees from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Kastrati has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Valgimigli has received grant support/research contracts from Terumo Medical and AstraZeneca; consultant fees/honoraria/speaker’s bureau for Terumo Medical Corporation, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo/Eli Lilly, Amgen, Alvimedica, AstraZenca, Idorsia, Coreflow, Vifor, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and iVascular. The study was funded by Biotronik.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

SAN FRANCISCO – Stopping aspirin within 1 month of implanting a drug-eluting stent (DES) for acute coronary syndrome (ACS) followed by ticagrelor monotherapy was shown to be noninferior to 12 months of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) in net adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in the T-PASS trial.

of death, myocardial infarction, stent thrombosis, stroke, and major bleeding, primarily due to a significant reduction in bleeding events,” senior author Myeong-Ki Hong, MD, PhD, Yonsei University, Seoul, Korea, told attendees at the Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics annual meeting, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

“This study provides evidence that stopping aspirin within 1 month after implantation of drug-eluting stents for ticagrelor monotherapy is a reasonable alternative to 12-month DAPT as for adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events,” Dr. Hong concluded.

The study was published in Circulation ahead of print to coincide with the presentation.

Three months to 1 month

Previous trials (TICO and TWILIGHT) have shown that ticagrelor monotherapy after 3 months of DAPT can be safe and effectively prevent ischemic events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in ACS or high-risk PCI patients.

The current study aimed to investigate whether ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT was noninferior to 12 months of ticagrelor-based DAPT for preventing adverse cardiovascular and bleeding events in patients with ACS undergoing PCI with a DES implant.

T-PASS, carried out at 24 centers in Korea, enrolled ACS patients aged 19 years or older who received an ultrathin, bioresorbable polymer sirolimus-eluting stent (Orsiro, Biotronik). They were randomized 1:1 to ticagrelor monotherapy after less than 1 month of DAPT (n = 1,426) or to ticagrelor-based DAPT for 12 months (n = 1,424).

The primary outcome measure was net adverse clinical events (NACE) at 12 months, consisting of major bleeding plus major adverse cardiovascular events. All patients were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.

The study could enroll patients aged 19-80 years. It excluded anyone with active bleeding, at increased risk for bleeding, with anemia (hemoglobin ≤ 8 g/dL), platelets less than 100,000/mcL, need for oral anticoagulation therapy, current or potential pregnancy, or a life expectancy less than 1 year.

Baseline characteristics of the two groups were well balanced. The extended monotherapy and DAPT arms had an average age of 61 ± 10 years, were 84% and 83% male and had diabetes mellitus in 30% and 29%, respectively, with 74% of each group admitted via the emergency room. ST-elevation myocardial infarction occurred in 40% and 41% of patients in each group, respectively.

Results showed that stopping aspirin early was noninferior and possibly superior to 12 months of DAPT.

For the 12-month clinical outcome, fewer patients in the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm reached the primary clinical endpoint of NACE versus the ticagrelor-based 12-month DAPT arm, both in terms of noninferiority (P < .001) and superiority (P = .002). Similar results were found for the 1-month landmark analyses.

For both the 12-month clinical outcome and the 1-month landmark analyses, the curves for the two arms began to diverge at about 150 days, with the one for ticagrelor monotherapy essentially flattening out just after that and the one for the 12-month DAPT therapy continuing to rise out to the 1-year point.

In the less than 1 month DAPT arm, aspirin was stopped at a median of 16 days. Panelist Adnan Kastrati, MD, Deutsches Herzzentrum München, Technische Universität, Munich, Germany, asked Dr. Hong about the criteria for the point at which aspirin was stopped in the less than 1 month arm.

Dr. Hong replied: “Actually, we recommend less than 1 month, so therefore in some patients, it was the operator’s decision,” depending on risk factors for stopping or continuing aspirin. He said that in some patients it may be reasonable to stop aspirin even in 7-10 days. Fewer than 10% of patients in the less than 1 month arm continued on aspirin past 30 days, but a few continued on it to the 1-year point.

There was no difference between the less than 1 month DAPT followed by ticagrelor monotherapy arm and the 12-month DAPT arm in terms of major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events at 1 year (1.8% vs. 2.2%, respectively; hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.50-1.41; log-rank, P = .51).

However, the 12-month DAPT arm showed a significantly greater incidence of major bleeding at 1 year: 3.4% versus 1.2% for less than 1 month aspirin arm (HR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.20-0.61; log-rank, P < .001).

Dr. Hong said that a limitation of the study was that it was open label and not placebo controlled. However, an independent clinical event adjudication committee assessed all clinical outcomes.

Lead discussant Marco Valgimigli, MD, PhD, Cardiocentro Ticino Foundation, Lugano, Switzerland, noted that T-PASS is the fifth study to investigate ticagrelor monotherapy versus a DAPT, giving randomized data on almost 22,000 patients.

“T-PASS showed very consistently with the prior four studies that by dropping aspirin and continuation with ticagrelor therapy, compared with the standard DAPT regimen, is associated with no penalty ... and in fact leading to a very significant and clinically very convincing risk reduction, and I would like to underline major bleeding risk reduction,” he said, pointing out that this study comes from the same research group that carried out the TICO trial.

Dr. Hong has received institutional research grants from Samjin Pharmaceutical and Chong Kun Dang Pharmaceutical, and speaker’s fees from Medtronic and Edwards Lifesciences. Dr. Kastrati has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Valgimigli has received grant support/research contracts from Terumo Medical and AstraZeneca; consultant fees/honoraria/speaker’s bureau for Terumo Medical Corporation, Bayer, Daiichi Sankyo/Eli Lilly, Amgen, Alvimedica, AstraZenca, Idorsia, Coreflow, Vifor, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and iVascular. The study was funded by Biotronik.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT TCT 2023

Outcomes of PF ablation for AFib similar between sexes

TOPLINE:

results of a large registry study show.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included all 1,568 patients (mean age 64.5 years and 35.3% women) in the MANIFEST-PF registry, which includes 24 European centers that began using PFA for treating AFib after regulatory approval in 2021.

- Researchers categorized patients by sex and evaluated them for clinical outcomes of PFA, including freedom from AFib and adverse events.

- All patients underwent pulmonary vein isolation (Farawave, Boston Scientific) and were followed up at 3, 6, and 12 months.

- The primary effectiveness outcome was freedom from atrial arrhythmia outside the 90-day blanking period lasting 30 seconds or longer.

- The primary safety outcome included the composite of acute (less than 7 days post-procedure) and chronic (more than 7 days post-procedure) major adverse events, including atrioesophageal fistula, symptomatic pulmonary vein stenosis, cardiac tamponade/perforation requiring intervention or surgery, stroke or systemic thromboembolism, persistent phrenic nerve injury, vascular access complications requiring surgery, coronary artery spasm, and death.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was no significant difference in 12-month recurrence of atrial arrhythmia between male and female patients (79.0% vs 76.3%; P = .28), with greater overall effectiveness in the paroxysmal AFib cohort (men, 82.5% vs women, 80.2%; P = .30) than in the persistent AF/long-standing persistent AFib cohort (men, 73.3% vs women, 67.3%; P = .40).

- Repeated ablation rates were similar between sexes (men, 8.3% vs women, 10.0%; P = .32).

- Among patients who underwent repeat ablation, pulmonary vein isolation durability was higher in female than in male patients (per vein, 82.6% vs 68.1%; P = .15 and per patient, 63.0% vs 37.8%; P = .005).

- Major adverse events occurred in 2.5% of women and 1.5% of men (P = .19), with such events mostly consisting of cardiac tamponade (women, 1.4% vs men, 1.0%; P = .46) and stroke (0.4% vs 0.4%, P > .99), and with no atrioesophageal fistulas or symptomatic pulmonary valve stenosis in either group.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results are important, as women are underrepresented in prior ablation studies and the results have been mixed with regards to both safety and effectiveness using conventional ablation strategies such as radiofrequency or cryoablation,” lead author Mohit Turagam, MD, associate professor of medicine (cardiology), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, said in a press release.

In an accompanying commentary, Peter M. Kistler, MBBS, PhD, Department of Cardiology, Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and a colleague said that the study authors should be congratulated “for presenting much-needed data on sex-specific outcomes in catheter ablation,” which “reassuringly” suggest that success and safety for AFib ablation are comparable between the sexes, although the study does have “important limitations.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Turagam and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Researchers can’t rule out the possibility that treatment selection and unmeasured confounders between sexes affected the validity of the study findings. The median number of follow-up 24-hour Holter monitors used for AFib monitoring was only two, which may have resulted in inaccurate estimates of AFib recurrence rates and treatment effectiveness.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Boston Scientific Corporation, the PFA device manufacturer. Turagam has no relevant conflicts of interest; see paper for disclosures of other study authors. The commentary authors have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

results of a large registry study show.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included all 1,568 patients (mean age 64.5 years and 35.3% women) in the MANIFEST-PF registry, which includes 24 European centers that began using PFA for treating AFib after regulatory approval in 2021.

- Researchers categorized patients by sex and evaluated them for clinical outcomes of PFA, including freedom from AFib and adverse events.

- All patients underwent pulmonary vein isolation (Farawave, Boston Scientific) and were followed up at 3, 6, and 12 months.

- The primary effectiveness outcome was freedom from atrial arrhythmia outside the 90-day blanking period lasting 30 seconds or longer.

- The primary safety outcome included the composite of acute (less than 7 days post-procedure) and chronic (more than 7 days post-procedure) major adverse events, including atrioesophageal fistula, symptomatic pulmonary vein stenosis, cardiac tamponade/perforation requiring intervention or surgery, stroke or systemic thromboembolism, persistent phrenic nerve injury, vascular access complications requiring surgery, coronary artery spasm, and death.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was no significant difference in 12-month recurrence of atrial arrhythmia between male and female patients (79.0% vs 76.3%; P = .28), with greater overall effectiveness in the paroxysmal AFib cohort (men, 82.5% vs women, 80.2%; P = .30) than in the persistent AF/long-standing persistent AFib cohort (men, 73.3% vs women, 67.3%; P = .40).

- Repeated ablation rates were similar between sexes (men, 8.3% vs women, 10.0%; P = .32).

- Among patients who underwent repeat ablation, pulmonary vein isolation durability was higher in female than in male patients (per vein, 82.6% vs 68.1%; P = .15 and per patient, 63.0% vs 37.8%; P = .005).

- Major adverse events occurred in 2.5% of women and 1.5% of men (P = .19), with such events mostly consisting of cardiac tamponade (women, 1.4% vs men, 1.0%; P = .46) and stroke (0.4% vs 0.4%, P > .99), and with no atrioesophageal fistulas or symptomatic pulmonary valve stenosis in either group.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results are important, as women are underrepresented in prior ablation studies and the results have been mixed with regards to both safety and effectiveness using conventional ablation strategies such as radiofrequency or cryoablation,” lead author Mohit Turagam, MD, associate professor of medicine (cardiology), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, said in a press release.

In an accompanying commentary, Peter M. Kistler, MBBS, PhD, Department of Cardiology, Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and a colleague said that the study authors should be congratulated “for presenting much-needed data on sex-specific outcomes in catheter ablation,” which “reassuringly” suggest that success and safety for AFib ablation are comparable between the sexes, although the study does have “important limitations.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Turagam and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Researchers can’t rule out the possibility that treatment selection and unmeasured confounders between sexes affected the validity of the study findings. The median number of follow-up 24-hour Holter monitors used for AFib monitoring was only two, which may have resulted in inaccurate estimates of AFib recurrence rates and treatment effectiveness.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Boston Scientific Corporation, the PFA device manufacturer. Turagam has no relevant conflicts of interest; see paper for disclosures of other study authors. The commentary authors have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

results of a large registry study show.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included all 1,568 patients (mean age 64.5 years and 35.3% women) in the MANIFEST-PF registry, which includes 24 European centers that began using PFA for treating AFib after regulatory approval in 2021.

- Researchers categorized patients by sex and evaluated them for clinical outcomes of PFA, including freedom from AFib and adverse events.

- All patients underwent pulmonary vein isolation (Farawave, Boston Scientific) and were followed up at 3, 6, and 12 months.

- The primary effectiveness outcome was freedom from atrial arrhythmia outside the 90-day blanking period lasting 30 seconds or longer.

- The primary safety outcome included the composite of acute (less than 7 days post-procedure) and chronic (more than 7 days post-procedure) major adverse events, including atrioesophageal fistula, symptomatic pulmonary vein stenosis, cardiac tamponade/perforation requiring intervention or surgery, stroke or systemic thromboembolism, persistent phrenic nerve injury, vascular access complications requiring surgery, coronary artery spasm, and death.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was no significant difference in 12-month recurrence of atrial arrhythmia between male and female patients (79.0% vs 76.3%; P = .28), with greater overall effectiveness in the paroxysmal AFib cohort (men, 82.5% vs women, 80.2%; P = .30) than in the persistent AF/long-standing persistent AFib cohort (men, 73.3% vs women, 67.3%; P = .40).

- Repeated ablation rates were similar between sexes (men, 8.3% vs women, 10.0%; P = .32).

- Among patients who underwent repeat ablation, pulmonary vein isolation durability was higher in female than in male patients (per vein, 82.6% vs 68.1%; P = .15 and per patient, 63.0% vs 37.8%; P = .005).

- Major adverse events occurred in 2.5% of women and 1.5% of men (P = .19), with such events mostly consisting of cardiac tamponade (women, 1.4% vs men, 1.0%; P = .46) and stroke (0.4% vs 0.4%, P > .99), and with no atrioesophageal fistulas or symptomatic pulmonary valve stenosis in either group.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results are important, as women are underrepresented in prior ablation studies and the results have been mixed with regards to both safety and effectiveness using conventional ablation strategies such as radiofrequency or cryoablation,” lead author Mohit Turagam, MD, associate professor of medicine (cardiology), Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, said in a press release.

In an accompanying commentary, Peter M. Kistler, MBBS, PhD, Department of Cardiology, Alfred Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, and a colleague said that the study authors should be congratulated “for presenting much-needed data on sex-specific outcomes in catheter ablation,” which “reassuringly” suggest that success and safety for AFib ablation are comparable between the sexes, although the study does have “important limitations.”

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by Turagam and colleagues. It was published online in JAMA Cardiology.

LIMITATIONS:

Researchers can’t rule out the possibility that treatment selection and unmeasured confounders between sexes affected the validity of the study findings. The median number of follow-up 24-hour Holter monitors used for AFib monitoring was only two, which may have resulted in inaccurate estimates of AFib recurrence rates and treatment effectiveness.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by Boston Scientific Corporation, the PFA device manufacturer. Turagam has no relevant conflicts of interest; see paper for disclosures of other study authors. The commentary authors have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Newer antiobesity meds lower the body’s defended fat mass

The current highly effective antiobesity medications approved for treating obesity (semaglutide), under review (tirzepatide), or in late-stage clinical trials “appear to lower the body’s target and defended fat mass [set point]” but do not permanently fix it at a lower point, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, PhD, explained in a lecture during the annual meeting of the Obesity Society.

It is very likely that patients with obesity will have to take these antiobesity medications “forever,” he said, “until we identify and can repair the cellular and molecular mechanisms that the body uses to regulate body fat mass throughout the life cycle and that are dysfunctional in obesity.”

“The body is able to regulate fat mass at multiple stages during development,” Dr. Kaplan, from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, explained, “and when it doesn’t do it appropriately, that becomes the physiological basis of obesity.”

The loss of baby fat, as well as fat changes during puberty, menopause, aging, and, in particular, during and after pregnancy, “all occur without conscious or purposeful input,” he noted.

The body uses food intake and energy expenditure to reach and defend its intended fat mass, and there is an evolutionary benefit to doing this.

For example, people recovering from an acute illness can regain the lost fat and weight. A woman can support a pregnancy and lactation by increasing fat mass.

However, “the idea that [with antiobesity medications] we should be aiming for a fixed lower amount of fat is probably not a good idea.” Dr. Kaplan cautioned.

People need the flexibility to recover lost fat and weight after an acute illness or injury, and pregnant women need to gain an appropriate amount of body fat to support pregnancy and lactation.

Intermittent therapy: A practical strategy?

The long-term benefit of antiobesity medications requires continuous use, Dr. Kaplan noted. For example, in the STEP 1 trial of semaglutide in patients with obesity and without diabetes, when treatment was stopped at 68 weeks, average weight increased through 120 weeks, although it did not return to baseline levels.

Intermittent antiobesity therapy may be an effective, “very practical strategy” to maintain weight loss, which would also “address current challenges of high cost, limited drug availability, and inadequate access to care.”

“Until we have strategies for decreasing the cost of effective obesity treatment, and ensuring more equitable access to obesity care,” Dr. Kaplan said, “optimizing algorithms for the use of intermittent therapy may be an effective stopgap measure.”

Dr. Kaplan is or has recently been a paid consultant for Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and multiple pharmaceutical companies developing antiobesity medications.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The current highly effective antiobesity medications approved for treating obesity (semaglutide), under review (tirzepatide), or in late-stage clinical trials “appear to lower the body’s target and defended fat mass [set point]” but do not permanently fix it at a lower point, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, PhD, explained in a lecture during the annual meeting of the Obesity Society.

It is very likely that patients with obesity will have to take these antiobesity medications “forever,” he said, “until we identify and can repair the cellular and molecular mechanisms that the body uses to regulate body fat mass throughout the life cycle and that are dysfunctional in obesity.”

“The body is able to regulate fat mass at multiple stages during development,” Dr. Kaplan, from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, explained, “and when it doesn’t do it appropriately, that becomes the physiological basis of obesity.”

The loss of baby fat, as well as fat changes during puberty, menopause, aging, and, in particular, during and after pregnancy, “all occur without conscious or purposeful input,” he noted.

The body uses food intake and energy expenditure to reach and defend its intended fat mass, and there is an evolutionary benefit to doing this.

For example, people recovering from an acute illness can regain the lost fat and weight. A woman can support a pregnancy and lactation by increasing fat mass.

However, “the idea that [with antiobesity medications] we should be aiming for a fixed lower amount of fat is probably not a good idea.” Dr. Kaplan cautioned.

People need the flexibility to recover lost fat and weight after an acute illness or injury, and pregnant women need to gain an appropriate amount of body fat to support pregnancy and lactation.

Intermittent therapy: A practical strategy?

The long-term benefit of antiobesity medications requires continuous use, Dr. Kaplan noted. For example, in the STEP 1 trial of semaglutide in patients with obesity and without diabetes, when treatment was stopped at 68 weeks, average weight increased through 120 weeks, although it did not return to baseline levels.

Intermittent antiobesity therapy may be an effective, “very practical strategy” to maintain weight loss, which would also “address current challenges of high cost, limited drug availability, and inadequate access to care.”

“Until we have strategies for decreasing the cost of effective obesity treatment, and ensuring more equitable access to obesity care,” Dr. Kaplan said, “optimizing algorithms for the use of intermittent therapy may be an effective stopgap measure.”

Dr. Kaplan is or has recently been a paid consultant for Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and multiple pharmaceutical companies developing antiobesity medications.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The current highly effective antiobesity medications approved for treating obesity (semaglutide), under review (tirzepatide), or in late-stage clinical trials “appear to lower the body’s target and defended fat mass [set point]” but do not permanently fix it at a lower point, Lee M. Kaplan, MD, PhD, explained in a lecture during the annual meeting of the Obesity Society.

It is very likely that patients with obesity will have to take these antiobesity medications “forever,” he said, “until we identify and can repair the cellular and molecular mechanisms that the body uses to regulate body fat mass throughout the life cycle and that are dysfunctional in obesity.”

“The body is able to regulate fat mass at multiple stages during development,” Dr. Kaplan, from Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, explained, “and when it doesn’t do it appropriately, that becomes the physiological basis of obesity.”

The loss of baby fat, as well as fat changes during puberty, menopause, aging, and, in particular, during and after pregnancy, “all occur without conscious or purposeful input,” he noted.

The body uses food intake and energy expenditure to reach and defend its intended fat mass, and there is an evolutionary benefit to doing this.

For example, people recovering from an acute illness can regain the lost fat and weight. A woman can support a pregnancy and lactation by increasing fat mass.

However, “the idea that [with antiobesity medications] we should be aiming for a fixed lower amount of fat is probably not a good idea.” Dr. Kaplan cautioned.

People need the flexibility to recover lost fat and weight after an acute illness or injury, and pregnant women need to gain an appropriate amount of body fat to support pregnancy and lactation.

Intermittent therapy: A practical strategy?

The long-term benefit of antiobesity medications requires continuous use, Dr. Kaplan noted. For example, in the STEP 1 trial of semaglutide in patients with obesity and without diabetes, when treatment was stopped at 68 weeks, average weight increased through 120 weeks, although it did not return to baseline levels.

Intermittent antiobesity therapy may be an effective, “very practical strategy” to maintain weight loss, which would also “address current challenges of high cost, limited drug availability, and inadequate access to care.”

“Until we have strategies for decreasing the cost of effective obesity treatment, and ensuring more equitable access to obesity care,” Dr. Kaplan said, “optimizing algorithms for the use of intermittent therapy may be an effective stopgap measure.”

Dr. Kaplan is or has recently been a paid consultant for Eli Lilly, Novo Nordisk, and multiple pharmaceutical companies developing antiobesity medications.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM OBESITYWEEK® 2023

Essential oils: How safe? How effective?

Essential oils (EOs), which are concentrated plant-based oils, have become ubiquitous over the past decade. Given the far reach of EOs and their longtime use in traditional, complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine, it is imperative that clinicians have some knowledge of the potential benefits, risks, and overall efficacy.

Commonly used for aromatic benefits (aromatherapy), EOs are now also incorporated into a multitude of products promoting health and wellness. EOs are sold as individual products and can be a component in consumer goods such as cosmetics, body care/hygiene/beauty products, laundry detergents, insect repellents, over-the-counter medications, and food.

The review that follows presents the most current evidence available. With that said, it’s important to keep in mind some caveats that relate to this evidence. First, the studies cited tend to have a small sample size. Second, a majority of these studies were conducted in countries where there appears to be a significant culture of EO use, which could contribute to confirmation bias. Finally, in a number of the studies, there is concern for publication bias as well as a discrepancy between calculated statistical significance and actual clinical relevance.

What are essential oils?

EOs generally are made by extracting the oil from leaves, bark, flowers, seeds/fruit, rinds, and/or roots by steaming or pressing parts of a plant. It can take several pounds of plant material to produce a single bottle of EO, which usually contains ≥ 15 to 30 mL (.5 to 1 oz).1

Some commonly used EOs in the United States are lavender, peppermint, rose, clary sage, tea tree, eucalyptus, and citrus; however, there are approximately 300 EOs available.2 EOs are used most often via topical application, inhalation, or ingestion.

As with any botanical agent, EOs are complex substances often containing a multitude of chemical compounds.1 Because of the complex makeup of EOs, which often contain up to 100 volatile organic compounds, and their wide-ranging potential effects, applying the scientific method to study effectiveness poses a challenge that has limited their adoption in evidence-based practice.2

Availability and cost. EOs can be purchased at large retailers (eg, grocery stores, drug stores) and smaller health food stores, as well as on the Internet. Various EO vehicles, such as inhalers and topical creams, also can be purchased at these stores.

Continue to: The cost varies...

The cost varies enormously by manufacturer and type of plant used to make the EO. Common EOs such as peppermint and lavender oil generally cost $10 to $25, while rarer plant oils can cost $80 or more per bottle.

How safe are essential oils?

Patients may assume EOs are harmless because they are derived from natural plants and have been used medicinally for centuries. However, care must be taken with their use.

The safest way to use EOs is topically, although due to their highly concentrated nature, EOs should be diluted in an unscented neutral carrier oil such as coconut, jojoba, olive, or sweet almond.3 Ingestion of certain oils can cause hepatotoxicity, seizures, and even death.3 In fact, patients should speak with a knowledgeable physician before purchasing any oral EO capsules.

Whether used topically or ingested, all EOs carry risk for skin irritation and allergic reactions, and oral ingestion may result in some negative gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects.4 A case report of 3 patients published in 2007 identified the potential for lavender and tea tree EOs to be endocrine disruptors.5

Inhalation of EOs may be harmful, as they emit many volatile organic compounds, some of which are considered potentially hazardous.6 At this time, there is insufficient evidence regarding inhaled EOs and their direct connection to respiratory health. It is reasonable to suggest, however, that the prolonged use of EOs and their use by patients who have lung conditions such as asthma or COPD should be avoided.7

Continue to: How are quality and purity assessed?

How are quality and purity assessed?

Like other dietary supplements, EOs are not regulated. No US regulatory agencies (eg, the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] or Department of Agriculture [USDA]) certify or approve EOs for quality and purity. Bottles labeled with “QAI” for Quality Assurance International or “USDA Organic” will ensure the plant constituents used in the EO are from organic farming but do not attest to quality or purity.

Manufacturers commonly use marketing terms such as “therapeutic grade” or “pure” to sell products, but again, these terms do not reflect the product’s quality or purity. A labeled single EO may contain contaminants, alcohol, or additional ingredients.7 When choosing to use EOs, identifying reputable brands is essential; one resource is the independent testing organization ConsumerLab.com.

It is important to assess the manufacturer and read ingredient labels before purchasing an EO to understand what the product contains. Reputable companies will identify the plant ingredient, usually by the formal Latin binomial name, and explain the extraction process. A more certain way to assess the quality and purity of an EO is to ask the manufacturer to provide a certificate of analysis and gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy (GC/MS) data for the specific product. Some manufacturers offer GC/MS test results on their website Quality page.8 Others have detailed information on quality and testing, and GC/MS test reports can be obtained.9 Yet another manufacturer has test results on a product page matching reports to batch codes.10

Which conditions have evidence of benefit from essential oils?

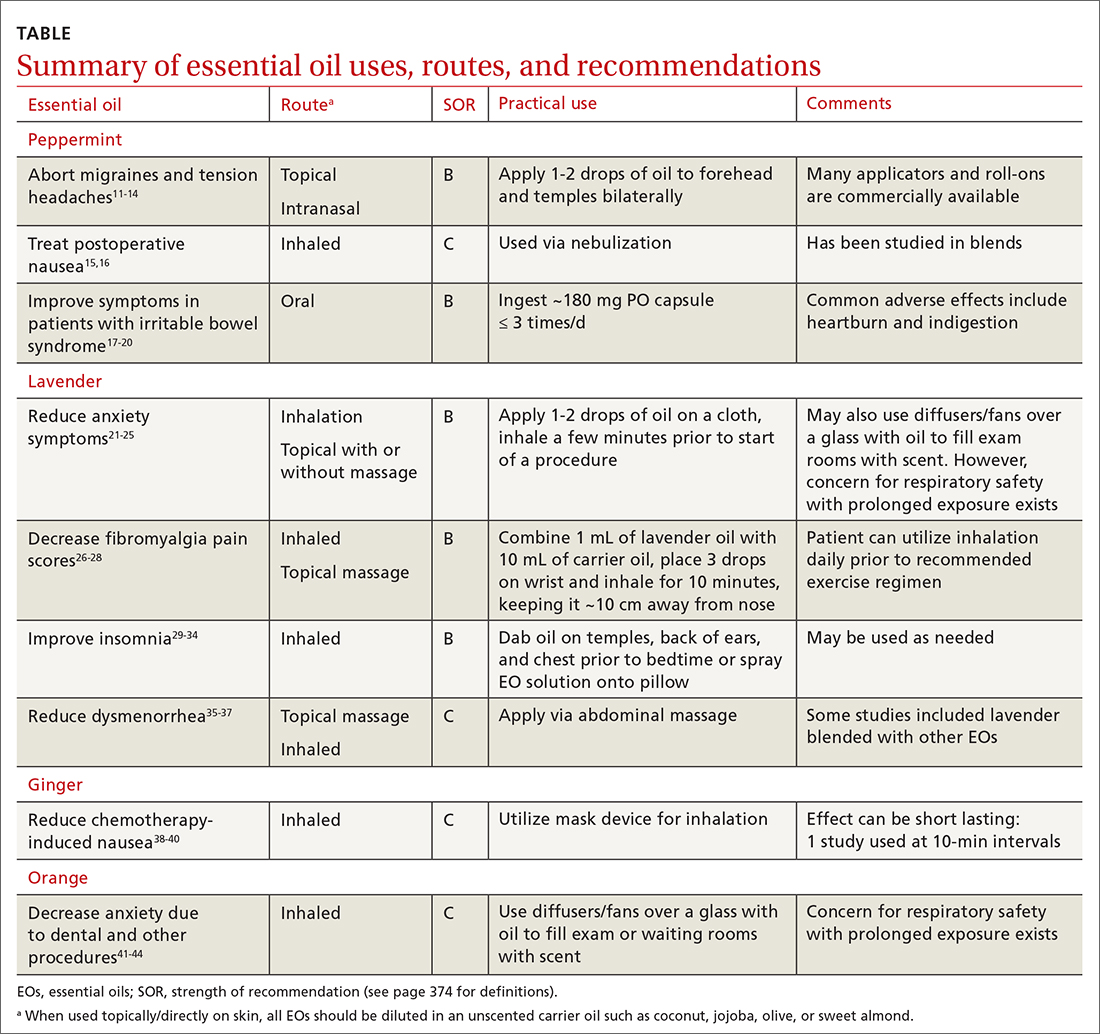

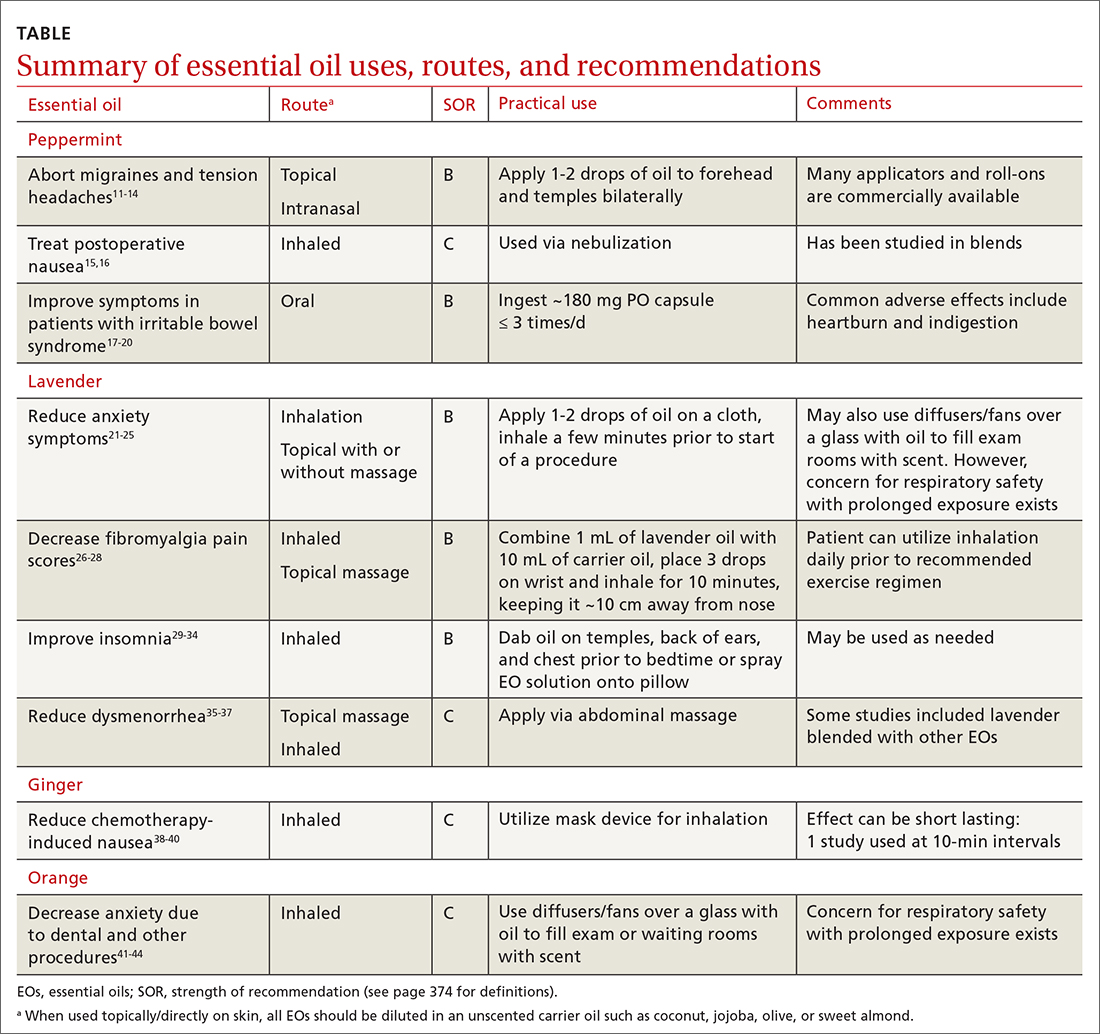

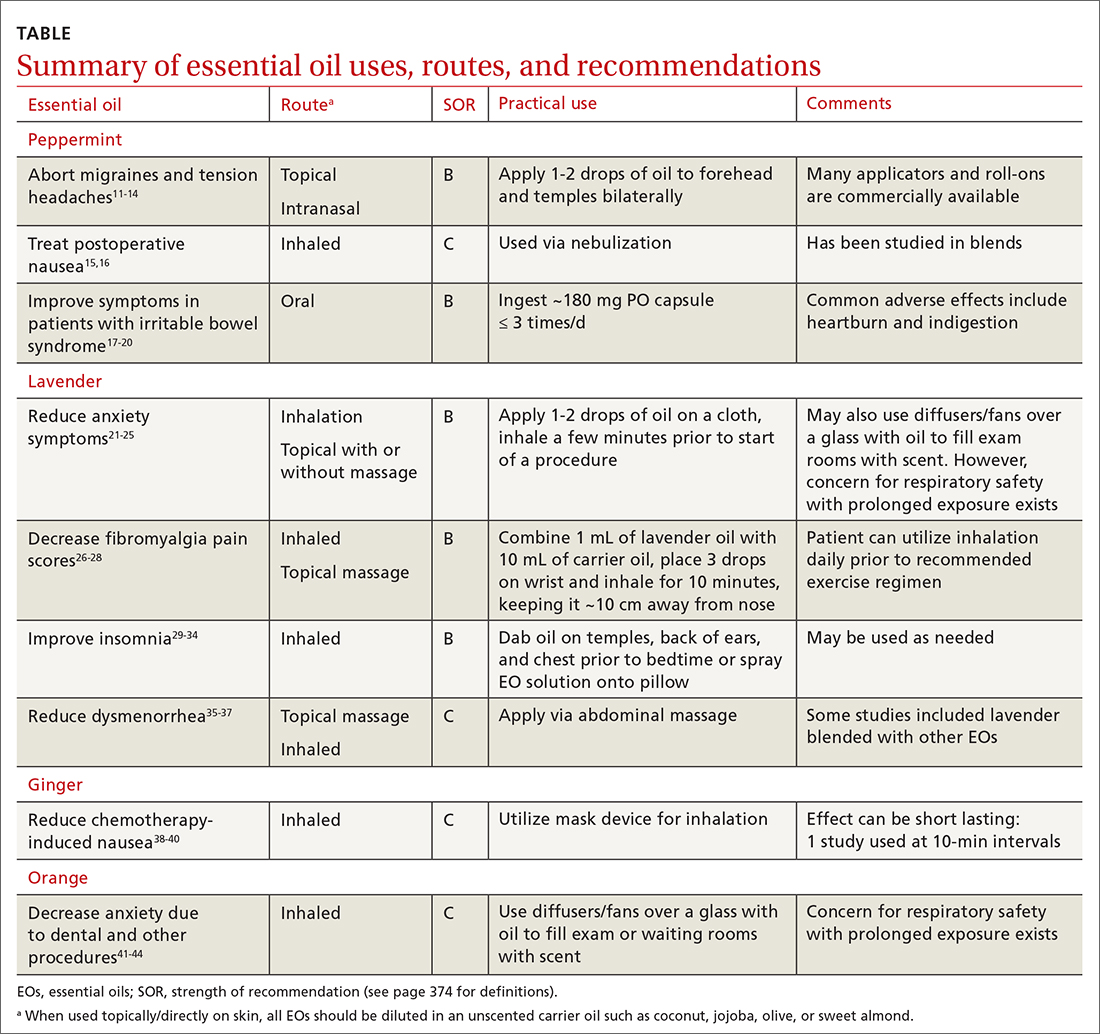

EOs currently are being studied for treatment of many conditions—including pain, GI disorders, behavioral health disorders, and women’s health issues. The TABLE summarizes the conditions treated, outcomes, and practical applications of EOs.11-44

Pain

Headache. As an adjunct to available medications and procedures for headache treatment, EOs are one of the nonpharmacologic modalities that patients and clinicians have at their disposal for both migraine and tension-type headaches. A systematic review of 19 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining the effects of herbal ingredients for the acute treatment or prophylaxis of migraines found certain topically applied or inhaled EOs, such as peppermint and chamomile, to be effective for migraine pain alleviation; however, topically applied rose oil was not effective.11-13 Note: “topical application” in these studies implies application of the EO to ≥ 1 of the following areas: temples, forehead, behind ears, or above upper lip/below the nose.

Continue to: One RCT with 120 patients...

One RCT with 120 patients evaluated diluted intranasal peppermint oil and found that it reduced migraine intensity at similar rates to intranasal lidocaine.13 In this study, patients were randomized to receive one of the following: 4% lidocaine, 1.5% peppermint EO, or placebo. Two drops of the intranasal intervention were self-administered while the patient was in a supine position with their head suspended off the edge of the surface on which they were lying. They were instructed to stay in this position for at least 30 seconds after administration.

With regard to tension headache treatment, there is limited literature on the use of EOs. One study found that a preparation of peppermint oil applied topically to the temples and forehead of study participants resulted in significant analgesic effect.14

Fibromyalgia. Usual treatments for fibromyalgia include exercise, antidepressant and anticonvulsant medications, and stress management. Evidence also supports the use of inhaled and topically applied (with and without massage) lavender oil to improve symptoms.26 Positive effects may be related to the analgesic, anti-inflammatory, sleep-regulating, and anxiety-reducing effects of the major volatile compounds contained in lavender oil.

In one RCT with 42 patients with fibromyalgia, the use of inhaled lavender oil was shown to increase the perception of well-being (assessed on the validated SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire) after 4 weeks.27 In this study, the patient applied 3 drops of an oil mixture, comprising 1 mL lavender EO and 10 mL of fixed neutral base oil, to the wrist and inhaled for 10 minutes before going to bed.

The use of a topical oil blend labeled “Oil 24” (containing camphor, rosemary, eucalyptus, peppermint, aloe vera, and lemon/orange) also has been shown to be more effective than placebo in managing fibromyalgia symptoms. A randomized controlled pilot study of 153 participants found that regular application of Oil 24 improved scores on pain scales and the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire.28

Continue to: GI disorders

GI disorders