User login

Standing BP measures improve hypertension diagnosis

TOPLINE:

results of a new study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 125 adults, mean age 49 years and 62% female, who were free of cardiovascular disease and had no previous history of hypertension.

- Researchers collected data on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), and three BP measurements in the seated position, then three in the standing position.

- They assessed overall diagnostic accuracy of seated and standing BP using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve and considered a Bayes factor (BF) of 3 or greater as significant.

- They defined the presence of hypertension (HTN) by the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and 2023 European Society of Hypertension HTN guidelines based on ABPM.

- Sensitivity and specificity of standing BP was determined using cutoffs derived from Youden index, while sensitivity and specificity of seated BP was determined using the cutoff of 130/80 mm Hg and by 140/90 mm Hg.

TAKEAWAY:

- The AUROC for standing office systolic blood pressure (SBP; 0.81; 0.71-0.92) was significantly higher than for seated office SBP (0.70; 0.49-0.91) in diagnosing HTN when defined as an average 24-hour SBP ≥ 125 mm Hg (BF = 11.8), and significantly higher for seated versus standing office diastolic blood pressure (DBP; 0.65; 0.49-0.82) in diagnosing HTN when defined as an average 24-hour DBP ≥ 75 mm Hg (BF = 4.9).

- The AUROCs for adding standing office BP to seated office BP improved the accuracy of detecting HTN, compared with seated office BP alone when HTN was defined as an average 24-hour SBP/DBP ≥ 125/75 mm Hg or daytime SBP/DBP ≥ 130/80 mm Hg, or when defined as an average 24-hour SBP/DBP ≥ 130/80 mm Hg or daytime SBP/DBP ≥ 135/85 mm Hg (all BFs > 3).

- Sensitivity of standing SBP was 71%, compared with 43% for seated SBP.

IN PRACTICE:

The “excellent diagnostic performance” for standing BP measures revealed by the study “highlights that standing office BP has acceptable discriminative capabilities in identifying the presence of hypertension in adults,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by John M. Giacona, Hypertension Section, department of internal medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and colleagues. It was published online in Scientific Reports.

LIMITATIONS:

As the study enrolled only adults free of comorbidities who were not taking antihypertensive medications, the results may not be applicable to other patients. The study design was retrospective, and the order of BP measurements was not randomized (standing BP measurements were obtained only after seated BP).

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

results of a new study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 125 adults, mean age 49 years and 62% female, who were free of cardiovascular disease and had no previous history of hypertension.

- Researchers collected data on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), and three BP measurements in the seated position, then three in the standing position.

- They assessed overall diagnostic accuracy of seated and standing BP using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve and considered a Bayes factor (BF) of 3 or greater as significant.

- They defined the presence of hypertension (HTN) by the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and 2023 European Society of Hypertension HTN guidelines based on ABPM.

- Sensitivity and specificity of standing BP was determined using cutoffs derived from Youden index, while sensitivity and specificity of seated BP was determined using the cutoff of 130/80 mm Hg and by 140/90 mm Hg.

TAKEAWAY:

- The AUROC for standing office systolic blood pressure (SBP; 0.81; 0.71-0.92) was significantly higher than for seated office SBP (0.70; 0.49-0.91) in diagnosing HTN when defined as an average 24-hour SBP ≥ 125 mm Hg (BF = 11.8), and significantly higher for seated versus standing office diastolic blood pressure (DBP; 0.65; 0.49-0.82) in diagnosing HTN when defined as an average 24-hour DBP ≥ 75 mm Hg (BF = 4.9).

- The AUROCs for adding standing office BP to seated office BP improved the accuracy of detecting HTN, compared with seated office BP alone when HTN was defined as an average 24-hour SBP/DBP ≥ 125/75 mm Hg or daytime SBP/DBP ≥ 130/80 mm Hg, or when defined as an average 24-hour SBP/DBP ≥ 130/80 mm Hg or daytime SBP/DBP ≥ 135/85 mm Hg (all BFs > 3).

- Sensitivity of standing SBP was 71%, compared with 43% for seated SBP.

IN PRACTICE:

The “excellent diagnostic performance” for standing BP measures revealed by the study “highlights that standing office BP has acceptable discriminative capabilities in identifying the presence of hypertension in adults,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by John M. Giacona, Hypertension Section, department of internal medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and colleagues. It was published online in Scientific Reports.

LIMITATIONS:

As the study enrolled only adults free of comorbidities who were not taking antihypertensive medications, the results may not be applicable to other patients. The study design was retrospective, and the order of BP measurements was not randomized (standing BP measurements were obtained only after seated BP).

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

results of a new study suggest.

METHODOLOGY:

- The study included 125 adults, mean age 49 years and 62% female, who were free of cardiovascular disease and had no previous history of hypertension.

- Researchers collected data on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM), and three BP measurements in the seated position, then three in the standing position.

- They assessed overall diagnostic accuracy of seated and standing BP using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve and considered a Bayes factor (BF) of 3 or greater as significant.

- They defined the presence of hypertension (HTN) by the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association and 2023 European Society of Hypertension HTN guidelines based on ABPM.

- Sensitivity and specificity of standing BP was determined using cutoffs derived from Youden index, while sensitivity and specificity of seated BP was determined using the cutoff of 130/80 mm Hg and by 140/90 mm Hg.

TAKEAWAY:

- The AUROC for standing office systolic blood pressure (SBP; 0.81; 0.71-0.92) was significantly higher than for seated office SBP (0.70; 0.49-0.91) in diagnosing HTN when defined as an average 24-hour SBP ≥ 125 mm Hg (BF = 11.8), and significantly higher for seated versus standing office diastolic blood pressure (DBP; 0.65; 0.49-0.82) in diagnosing HTN when defined as an average 24-hour DBP ≥ 75 mm Hg (BF = 4.9).

- The AUROCs for adding standing office BP to seated office BP improved the accuracy of detecting HTN, compared with seated office BP alone when HTN was defined as an average 24-hour SBP/DBP ≥ 125/75 mm Hg or daytime SBP/DBP ≥ 130/80 mm Hg, or when defined as an average 24-hour SBP/DBP ≥ 130/80 mm Hg or daytime SBP/DBP ≥ 135/85 mm Hg (all BFs > 3).

- Sensitivity of standing SBP was 71%, compared with 43% for seated SBP.

IN PRACTICE:

The “excellent diagnostic performance” for standing BP measures revealed by the study “highlights that standing office BP has acceptable discriminative capabilities in identifying the presence of hypertension in adults,” the authors write.

SOURCE:

The study was conducted by John M. Giacona, Hypertension Section, department of internal medicine, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and colleagues. It was published online in Scientific Reports.

LIMITATIONS:

As the study enrolled only adults free of comorbidities who were not taking antihypertensive medications, the results may not be applicable to other patients. The study design was retrospective, and the order of BP measurements was not randomized (standing BP measurements were obtained only after seated BP).

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves tirzepatide for treating obesity

Eli Lilly will market tirzepatide injections for weight management under the trade name Zepbound. It was approved in May 2022 for treating type 2 diabetes. The new indication is for adults with either obesity, defined as a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater, or overweight, with a BMI of 27 or greater with at least one weight-related comorbidity, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia.

“Obesity and overweight are serious conditions that can be associated with some of the leading causes of death, such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes,” said John Sharretts, MD, director of the division of diabetes, lipid disorders, and obesity in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “In light of increasing rates of both obesity and overweight in the United States, today’s approval addresses an unmet medical need.”

A once-weekly injection, tirzepatide reduces appetite by activating two gut hormones, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). The dosage is increased over 4-20 weeks to achieve a weekly dose target of 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg maximum.

Efficacy was established in two pivotal randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of adults with obesity or overweight plus another condition. One trial measured weight reduction after 72 weeks in a total of 2,519 patients without diabetes who received either 5 mg, 10 mg or 15 mg of tirzepatide once weekly. Those who received the 15-mg dose achieved on average 18% of their initial body weight, compared with placebo.

The other pivotal trial enrolled a total of 938 patients with type 2 diabetes. These patients achieved an average weight loss of 12% with once-weekly tirzepatide compared to placebo.

Another trial, which was presented at the 2023 Obesity Week meeting and was published in Nature Medicine, showed clinically meaningful added weight loss for adults with obesity who did not have diabetes and who had already experienced weight loss of at least 5% after a 12-week intensive lifestyle intervention.

Another trial, which was reported at the 2023 annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, found that tirzepatide continued to produce “highly significant weight loss” when the drug was continued in a 1-year follow-up trial. Those who discontinued taking the drug regained some weight but not all.

Tirzepatide can cause gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, and abdominal pain or discomfort. Site reactions, hypersensitivity, hair loss, burping, and gastrointestinal reflux disease have also been reported.

The medication should not be used by patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer or by patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. It should also not be used in combination with Mounjaro or another GLP-1 receptor agonist. The safety and effectiveness of the coadministration of tirzepatide with other medications for weight management have not been established.

Zepbound should go to market in the United States by the end of 2023, with an anticipated monthly list price of $1,060, according to a news release from Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Eli Lilly will market tirzepatide injections for weight management under the trade name Zepbound. It was approved in May 2022 for treating type 2 diabetes. The new indication is for adults with either obesity, defined as a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater, or overweight, with a BMI of 27 or greater with at least one weight-related comorbidity, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia.

“Obesity and overweight are serious conditions that can be associated with some of the leading causes of death, such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes,” said John Sharretts, MD, director of the division of diabetes, lipid disorders, and obesity in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “In light of increasing rates of both obesity and overweight in the United States, today’s approval addresses an unmet medical need.”

A once-weekly injection, tirzepatide reduces appetite by activating two gut hormones, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). The dosage is increased over 4-20 weeks to achieve a weekly dose target of 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg maximum.

Efficacy was established in two pivotal randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of adults with obesity or overweight plus another condition. One trial measured weight reduction after 72 weeks in a total of 2,519 patients without diabetes who received either 5 mg, 10 mg or 15 mg of tirzepatide once weekly. Those who received the 15-mg dose achieved on average 18% of their initial body weight, compared with placebo.

The other pivotal trial enrolled a total of 938 patients with type 2 diabetes. These patients achieved an average weight loss of 12% with once-weekly tirzepatide compared to placebo.

Another trial, which was presented at the 2023 Obesity Week meeting and was published in Nature Medicine, showed clinically meaningful added weight loss for adults with obesity who did not have diabetes and who had already experienced weight loss of at least 5% after a 12-week intensive lifestyle intervention.

Another trial, which was reported at the 2023 annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, found that tirzepatide continued to produce “highly significant weight loss” when the drug was continued in a 1-year follow-up trial. Those who discontinued taking the drug regained some weight but not all.

Tirzepatide can cause gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, and abdominal pain or discomfort. Site reactions, hypersensitivity, hair loss, burping, and gastrointestinal reflux disease have also been reported.

The medication should not be used by patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer or by patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. It should also not be used in combination with Mounjaro or another GLP-1 receptor agonist. The safety and effectiveness of the coadministration of tirzepatide with other medications for weight management have not been established.

Zepbound should go to market in the United States by the end of 2023, with an anticipated monthly list price of $1,060, according to a news release from Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Eli Lilly will market tirzepatide injections for weight management under the trade name Zepbound. It was approved in May 2022 for treating type 2 diabetes. The new indication is for adults with either obesity, defined as a body mass index of 30 kg/m2 or greater, or overweight, with a BMI of 27 or greater with at least one weight-related comorbidity, including hypertension, type 2 diabetes, or dyslipidemia.

“Obesity and overweight are serious conditions that can be associated with some of the leading causes of death, such as heart disease, stroke, and diabetes,” said John Sharretts, MD, director of the division of diabetes, lipid disorders, and obesity in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. “In light of increasing rates of both obesity and overweight in the United States, today’s approval addresses an unmet medical need.”

A once-weekly injection, tirzepatide reduces appetite by activating two gut hormones, glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide (GIP). The dosage is increased over 4-20 weeks to achieve a weekly dose target of 5 mg, 10 mg, or 15 mg maximum.

Efficacy was established in two pivotal randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of adults with obesity or overweight plus another condition. One trial measured weight reduction after 72 weeks in a total of 2,519 patients without diabetes who received either 5 mg, 10 mg or 15 mg of tirzepatide once weekly. Those who received the 15-mg dose achieved on average 18% of their initial body weight, compared with placebo.

The other pivotal trial enrolled a total of 938 patients with type 2 diabetes. These patients achieved an average weight loss of 12% with once-weekly tirzepatide compared to placebo.

Another trial, which was presented at the 2023 Obesity Week meeting and was published in Nature Medicine, showed clinically meaningful added weight loss for adults with obesity who did not have diabetes and who had already experienced weight loss of at least 5% after a 12-week intensive lifestyle intervention.

Another trial, which was reported at the 2023 annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes, found that tirzepatide continued to produce “highly significant weight loss” when the drug was continued in a 1-year follow-up trial. Those who discontinued taking the drug regained some weight but not all.

Tirzepatide can cause gastrointestinal side effects, such as nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, constipation, and abdominal pain or discomfort. Site reactions, hypersensitivity, hair loss, burping, and gastrointestinal reflux disease have also been reported.

The medication should not be used by patients with a personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer or by patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome type 2. It should also not be used in combination with Mounjaro or another GLP-1 receptor agonist. The safety and effectiveness of the coadministration of tirzepatide with other medications for weight management have not been established.

Zepbound should go to market in the United States by the end of 2023, with an anticipated monthly list price of $1,060, according to a news release from Eli Lilly.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Microsimulation model identifies 4-year window for pancreatic cancer screening

, based on a microsimulation model.

To seize this opportunity, however, a greater understanding of natural disease course is needed, along with more sensitive screening tools, reported Brechtje D. M. Koopmann, MD, of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues.

Previous studies have suggested that the window of opportunity for pancreatic cancer screening may span decades, with estimates ranging from 12 to 50 years, the investigators wrote. Their report was published in Gastroenterology.

“Unfortunately, the poor results of pancreatic cancer screening do not align with this assumption, leaving unanswered whether this large window of opportunity truly exists,” they noted. “Microsimulation modeling, combined with available, if limited data, can provide new information on the natural disease course.”

For the present study, the investigators used the Microsimulation Screening Analysis (MISCAN) model, which has guided development of screening programs around the world for cervical, breast, and colorectal cancer. The model incorporates natural disease course, screening, and demographic data, then uses observable inputs such as precursor lesion prevalence and cancer incidence to estimate unobservable outcomes like stage durations and precursor lesion onset.

Dr. Koopmann and colleagues programmed this model with Dutch pancreatic cancer incidence data and findings from Japanese autopsy cases without pancreatic cancer.

First, the model offered insights into precursor lesion prevalence.

The estimated prevalence of any cystic lesion in the pancreas was 6.1% for individuals 50 years of age and 29.6% for those 80 years of age. Solid precursor lesions (PanINs) were estimated to be mainly multifocal (three or more lesions) in individuals older than 80 years. By this age, almost 12% had at least two PanINs. For those lesions that eventually became cancerous, the mean time since cyst onset was estimated to be 8.8 years, and mean time since PanIN onset was 9.0 years.

However, less than 10% of cystic and PanIN lesions progress to become cancers. PanIN lesions are not visible on imaging, and therefore current screening focuses on finding cystic precursor lesions, although these represent only about 10% of pancreatic cancers.

“Given the low pancreatic cancer progression risk of cysts, evaluation of the efficiency of current surveillance guidelines is necessary,” the investigators noted.

Screening should instead focus on identifying high-grade dysplastic lesions, they suggested. While these lesions may have a very low estimated prevalence, at just 0.3% among individuals 90 years of age, they present the greatest risk of pancreatic cancer.

For precursor cysts exhibiting HGD that progressed to pancreatic cancer, the mean interval between dysplasia and cancer was just 4 years. Among 13.7% of individuals, the interval was less than 1 year, suggesting an even shorter window of opportunity for screening.

Beyond this brief timeframe, low test sensitivity explains why screening efforts to date have fallen short, the investigators wrote.

Better tests are “urgently needed,” they added, while acknowledging the challenges inherent to this endeavor. Previous research has shown that precursor lesions in the pancreas are often less than 5 mm in diameter, making them extremely challenging to detect. An effective tool would need to identify solid precursor lesions (PanINs), and also need to simultaneously determine grade of dysplasia.

“Biomarkers could be the future in this matter,” the investigators suggested.

Dr. Koopmann and colleagues concluded by noting that more research is needed to characterize the pathophysiology of pancreatic cancer. On their part, “the current model will be validated, adjusted, and improved whenever new data from autopsy or prospective surveillance studies become available.”

The study was funded in part by Maag Lever Darm Stichting. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

We continue to search for a way to effectively screen for and prevent pancreatic cancer. Most pancreatic cancers come from pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasms (PanINs), which are essentially invisible on imaging. Pancreatic cysts are relatively common, and only a small number will progress to cancer. Screening via MRI or EUS can look for high-risk features of visible cysts or find early-stage cancers, but whom to screen, how often, and what to do with the results remains unclear. Many of the steps from development of the initial cyst or PanIN to the transformation to cancer cannot be observed, and as such this is a perfect application for disease modeling that allows us to fill in the gaps of what can be observed and estimate what we cannot see.

Mary Linton B. Peters, MD, MS, is a medical oncologist specializing in hepatic and pancreatobiliary cancers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, and a senior scientist at the Institute for Technology Assessment of Massachusetts General Hospital. She reports unrelated institutional research funding from NuCana and Helsinn.

We continue to search for a way to effectively screen for and prevent pancreatic cancer. Most pancreatic cancers come from pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasms (PanINs), which are essentially invisible on imaging. Pancreatic cysts are relatively common, and only a small number will progress to cancer. Screening via MRI or EUS can look for high-risk features of visible cysts or find early-stage cancers, but whom to screen, how often, and what to do with the results remains unclear. Many of the steps from development of the initial cyst or PanIN to the transformation to cancer cannot be observed, and as such this is a perfect application for disease modeling that allows us to fill in the gaps of what can be observed and estimate what we cannot see.

Mary Linton B. Peters, MD, MS, is a medical oncologist specializing in hepatic and pancreatobiliary cancers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, and a senior scientist at the Institute for Technology Assessment of Massachusetts General Hospital. She reports unrelated institutional research funding from NuCana and Helsinn.

We continue to search for a way to effectively screen for and prevent pancreatic cancer. Most pancreatic cancers come from pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasms (PanINs), which are essentially invisible on imaging. Pancreatic cysts are relatively common, and only a small number will progress to cancer. Screening via MRI or EUS can look for high-risk features of visible cysts or find early-stage cancers, but whom to screen, how often, and what to do with the results remains unclear. Many of the steps from development of the initial cyst or PanIN to the transformation to cancer cannot be observed, and as such this is a perfect application for disease modeling that allows us to fill in the gaps of what can be observed and estimate what we cannot see.

Mary Linton B. Peters, MD, MS, is a medical oncologist specializing in hepatic and pancreatobiliary cancers at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, an assistant professor at Harvard Medical School, and a senior scientist at the Institute for Technology Assessment of Massachusetts General Hospital. She reports unrelated institutional research funding from NuCana and Helsinn.

, based on a microsimulation model.

To seize this opportunity, however, a greater understanding of natural disease course is needed, along with more sensitive screening tools, reported Brechtje D. M. Koopmann, MD, of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues.

Previous studies have suggested that the window of opportunity for pancreatic cancer screening may span decades, with estimates ranging from 12 to 50 years, the investigators wrote. Their report was published in Gastroenterology.

“Unfortunately, the poor results of pancreatic cancer screening do not align with this assumption, leaving unanswered whether this large window of opportunity truly exists,” they noted. “Microsimulation modeling, combined with available, if limited data, can provide new information on the natural disease course.”

For the present study, the investigators used the Microsimulation Screening Analysis (MISCAN) model, which has guided development of screening programs around the world for cervical, breast, and colorectal cancer. The model incorporates natural disease course, screening, and demographic data, then uses observable inputs such as precursor lesion prevalence and cancer incidence to estimate unobservable outcomes like stage durations and precursor lesion onset.

Dr. Koopmann and colleagues programmed this model with Dutch pancreatic cancer incidence data and findings from Japanese autopsy cases without pancreatic cancer.

First, the model offered insights into precursor lesion prevalence.

The estimated prevalence of any cystic lesion in the pancreas was 6.1% for individuals 50 years of age and 29.6% for those 80 years of age. Solid precursor lesions (PanINs) were estimated to be mainly multifocal (three or more lesions) in individuals older than 80 years. By this age, almost 12% had at least two PanINs. For those lesions that eventually became cancerous, the mean time since cyst onset was estimated to be 8.8 years, and mean time since PanIN onset was 9.0 years.

However, less than 10% of cystic and PanIN lesions progress to become cancers. PanIN lesions are not visible on imaging, and therefore current screening focuses on finding cystic precursor lesions, although these represent only about 10% of pancreatic cancers.

“Given the low pancreatic cancer progression risk of cysts, evaluation of the efficiency of current surveillance guidelines is necessary,” the investigators noted.

Screening should instead focus on identifying high-grade dysplastic lesions, they suggested. While these lesions may have a very low estimated prevalence, at just 0.3% among individuals 90 years of age, they present the greatest risk of pancreatic cancer.

For precursor cysts exhibiting HGD that progressed to pancreatic cancer, the mean interval between dysplasia and cancer was just 4 years. Among 13.7% of individuals, the interval was less than 1 year, suggesting an even shorter window of opportunity for screening.

Beyond this brief timeframe, low test sensitivity explains why screening efforts to date have fallen short, the investigators wrote.

Better tests are “urgently needed,” they added, while acknowledging the challenges inherent to this endeavor. Previous research has shown that precursor lesions in the pancreas are often less than 5 mm in diameter, making them extremely challenging to detect. An effective tool would need to identify solid precursor lesions (PanINs), and also need to simultaneously determine grade of dysplasia.

“Biomarkers could be the future in this matter,” the investigators suggested.

Dr. Koopmann and colleagues concluded by noting that more research is needed to characterize the pathophysiology of pancreatic cancer. On their part, “the current model will be validated, adjusted, and improved whenever new data from autopsy or prospective surveillance studies become available.”

The study was funded in part by Maag Lever Darm Stichting. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

, based on a microsimulation model.

To seize this opportunity, however, a greater understanding of natural disease course is needed, along with more sensitive screening tools, reported Brechtje D. M. Koopmann, MD, of Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and colleagues.

Previous studies have suggested that the window of opportunity for pancreatic cancer screening may span decades, with estimates ranging from 12 to 50 years, the investigators wrote. Their report was published in Gastroenterology.

“Unfortunately, the poor results of pancreatic cancer screening do not align with this assumption, leaving unanswered whether this large window of opportunity truly exists,” they noted. “Microsimulation modeling, combined with available, if limited data, can provide new information on the natural disease course.”

For the present study, the investigators used the Microsimulation Screening Analysis (MISCAN) model, which has guided development of screening programs around the world for cervical, breast, and colorectal cancer. The model incorporates natural disease course, screening, and demographic data, then uses observable inputs such as precursor lesion prevalence and cancer incidence to estimate unobservable outcomes like stage durations and precursor lesion onset.

Dr. Koopmann and colleagues programmed this model with Dutch pancreatic cancer incidence data and findings from Japanese autopsy cases without pancreatic cancer.

First, the model offered insights into precursor lesion prevalence.

The estimated prevalence of any cystic lesion in the pancreas was 6.1% for individuals 50 years of age and 29.6% for those 80 years of age. Solid precursor lesions (PanINs) were estimated to be mainly multifocal (three or more lesions) in individuals older than 80 years. By this age, almost 12% had at least two PanINs. For those lesions that eventually became cancerous, the mean time since cyst onset was estimated to be 8.8 years, and mean time since PanIN onset was 9.0 years.

However, less than 10% of cystic and PanIN lesions progress to become cancers. PanIN lesions are not visible on imaging, and therefore current screening focuses on finding cystic precursor lesions, although these represent only about 10% of pancreatic cancers.

“Given the low pancreatic cancer progression risk of cysts, evaluation of the efficiency of current surveillance guidelines is necessary,” the investigators noted.

Screening should instead focus on identifying high-grade dysplastic lesions, they suggested. While these lesions may have a very low estimated prevalence, at just 0.3% among individuals 90 years of age, they present the greatest risk of pancreatic cancer.

For precursor cysts exhibiting HGD that progressed to pancreatic cancer, the mean interval between dysplasia and cancer was just 4 years. Among 13.7% of individuals, the interval was less than 1 year, suggesting an even shorter window of opportunity for screening.

Beyond this brief timeframe, low test sensitivity explains why screening efforts to date have fallen short, the investigators wrote.

Better tests are “urgently needed,” they added, while acknowledging the challenges inherent to this endeavor. Previous research has shown that precursor lesions in the pancreas are often less than 5 mm in diameter, making them extremely challenging to detect. An effective tool would need to identify solid precursor lesions (PanINs), and also need to simultaneously determine grade of dysplasia.

“Biomarkers could be the future in this matter,” the investigators suggested.

Dr. Koopmann and colleagues concluded by noting that more research is needed to characterize the pathophysiology of pancreatic cancer. On their part, “the current model will be validated, adjusted, and improved whenever new data from autopsy or prospective surveillance studies become available.”

The study was funded in part by Maag Lever Darm Stichting. The investigators disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Alopecia Universalis Treated With Tofacitinib: The Role of JAK/STAT Inhibitors in Hair Regrowth

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease that immunopathogenetically is thought to be due to breakdown of the immune privilege of the proximal hair follicle during the anagen growth phase. Alopecia areata has been reported to have a lifetime prevalence of 1.7%.1 Recent studies have specifically identified cytotoxic CD8+ NKG2D+ T cells as being responsible for the activation of AA.2-4 Two interleukins—IL-2 and IL-15—have been implicated to be cytotoxic sensitizers allowing CD8+ T cells to secrete IFN-γ and recognize autoantigens via major histocompatibility complex class I.5,6 Janus kinases (JAKs) are enzymes that play major roles in many different molecular processes. Specifically, JAK1/3 has been determined to arbitrate IL-15 activation of receptors on CD8+ T cells.7 These cells then interact with CD4 T cells, mast cells, and other inflammatory cells to cause destruction of the hair follicle without damage to the keratinocyte and melanocyte stem cells, allowing for reversible yet relapsing hair loss.8

Treatment of AA is difficult, requiring patience and strict compliance while taking into account duration of disease, age at presentation, site involvement, patient expectations, cost and insurance coverage, prior therapies, and any comorbidities. At the time of this case, no US Food and Drug Administration–approved drug regimen existed for the treatment of AA, and, to date, no treatment is preventative.4 We present a case of a patient with alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that was refractory to intralesional triamcinolone, clobetasol, minoxidil, and UVB brush therapy yet was successfully treated with tofacitinib.

Case Report

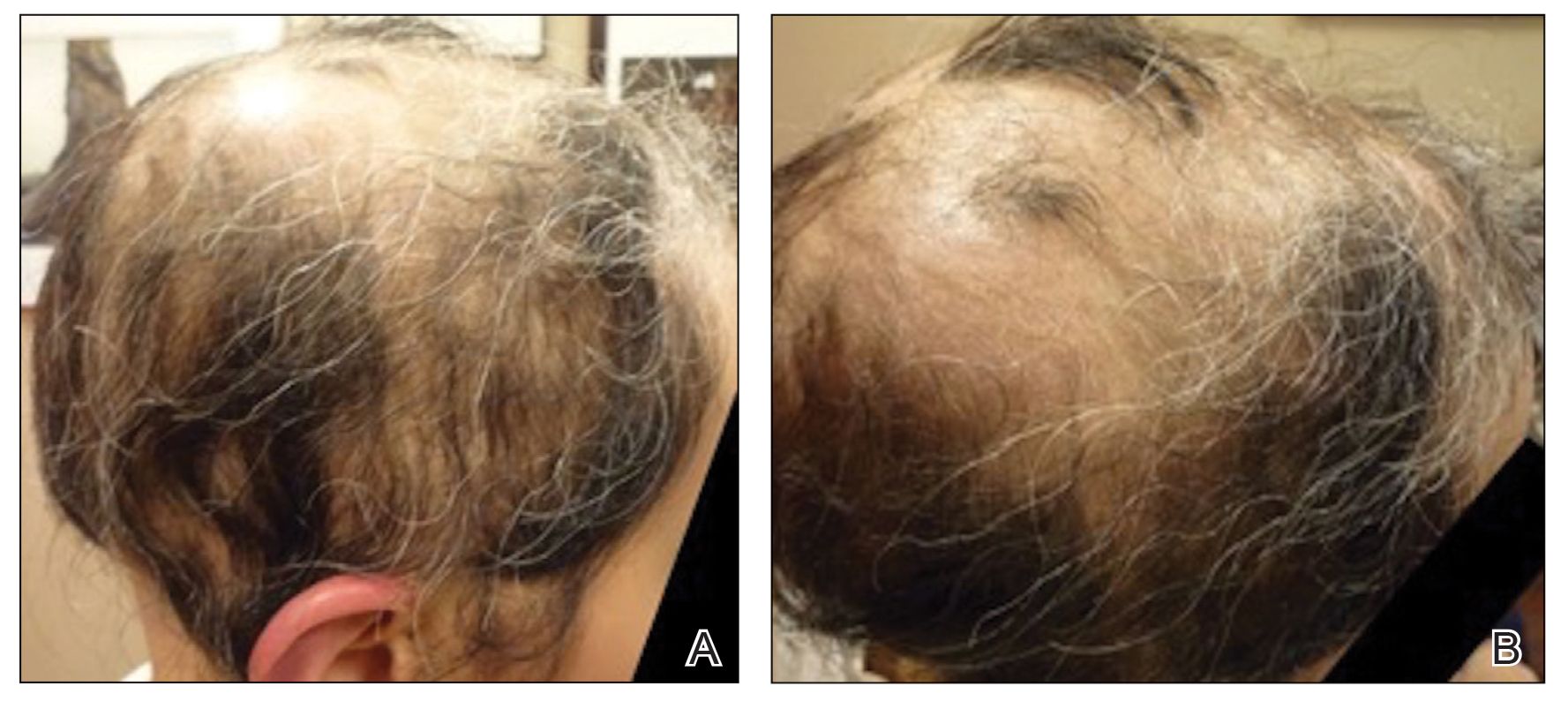

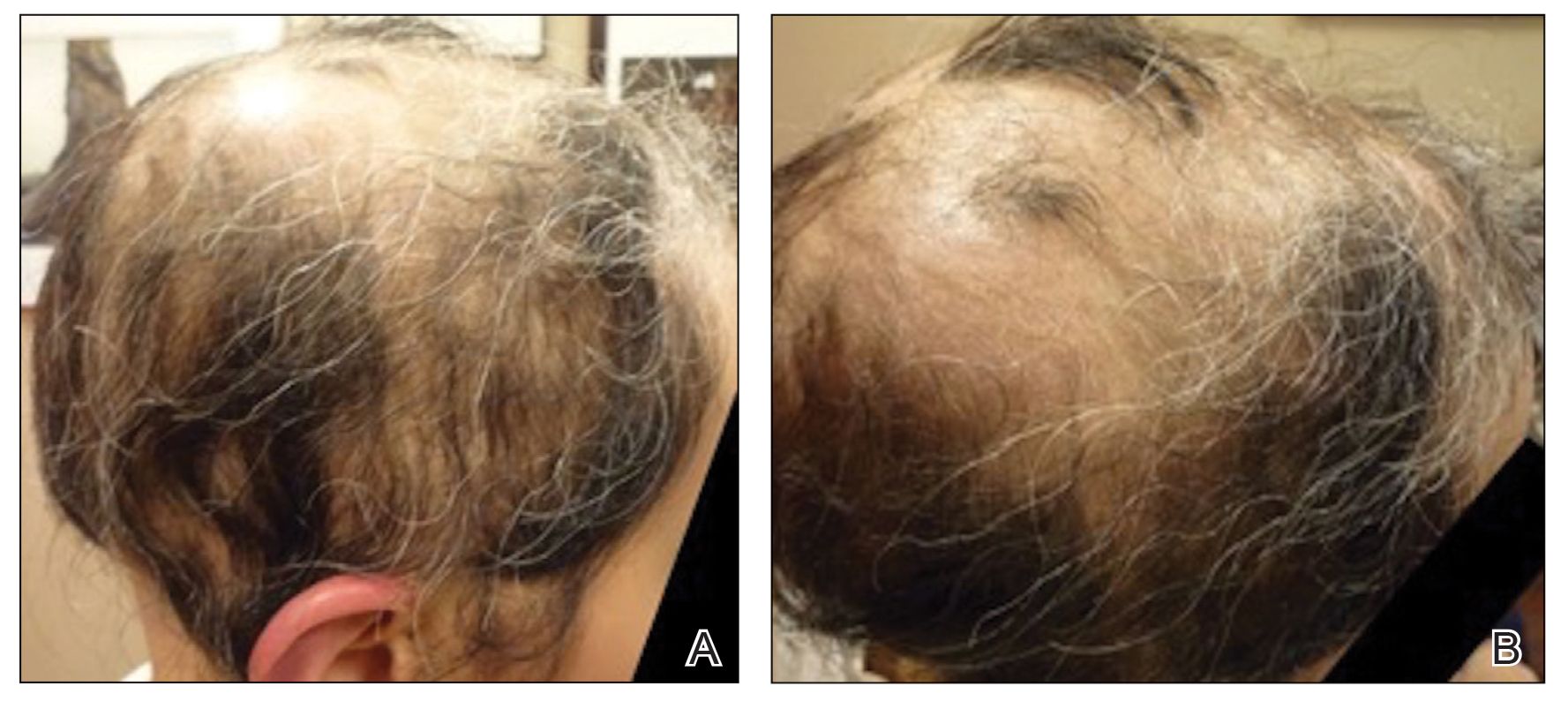

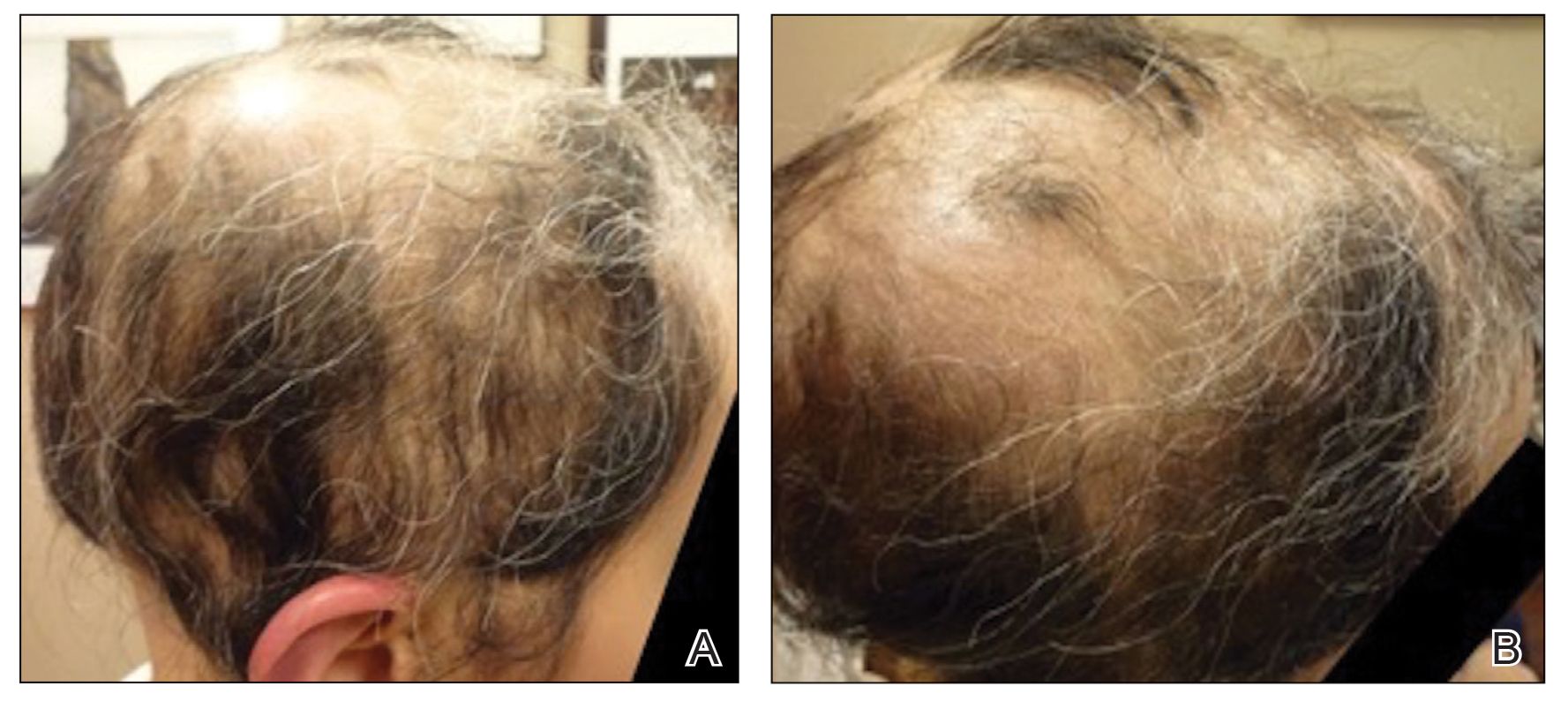

A 29-year-old otherwise-healthy woman presented to our clinic for treatment of alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that flared intermittently despite various treatments. Her medical history was unremarkable; however, she had a brother with alopecia universalis. She had no family history of any other autoimmune disorders. At the current presentation, the patient was known to have alopecia universalis with scant evidence of exclamation-point hairs on dermoscopy. Her treatment plan at this point consisted of intralesional triamcinolone to the active areas at 10 mg/mL every 4 weeks, plus clobetasol foam 0.05% at bedtime, minoxidil foam 5% at bedtime, and a UVB brush 3 times a week for 6 months before progressing to universalis type because of hair loss in the eyebrows and eyelashes. This treatment plan continued for 1 year with minimal improvement of the alopecia (Figure 1).

The patient was dissatisfied and wanted to discontinue therapy. Because these treatment options were exhausted with minimal benefit, the patient was then considered for treatment with tofacitinib. Baseline studies were performed, including purified protein derivative, complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid profile, and liver function tests, all of which were within reference range. Insurance initially denied coverage of this therapy; a prior authorization was subsequently submitted and denied. A letter of medical necessity was then proposed, and approval for tofacitinib was finally granted. The patient was started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and was monitored every 2 months with a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panels, and liver function tests. She had a platelet count of 112,000/μL (reference range, 150,000–450,000/μL) at baseline, and continued monitoring revealed a platelet count of 83,000 after 7 months of treatment. This platelet abnormality was evaluated by a hematologist and found to be within reference range; subsequent monitoring did not reveal any abnormalities.

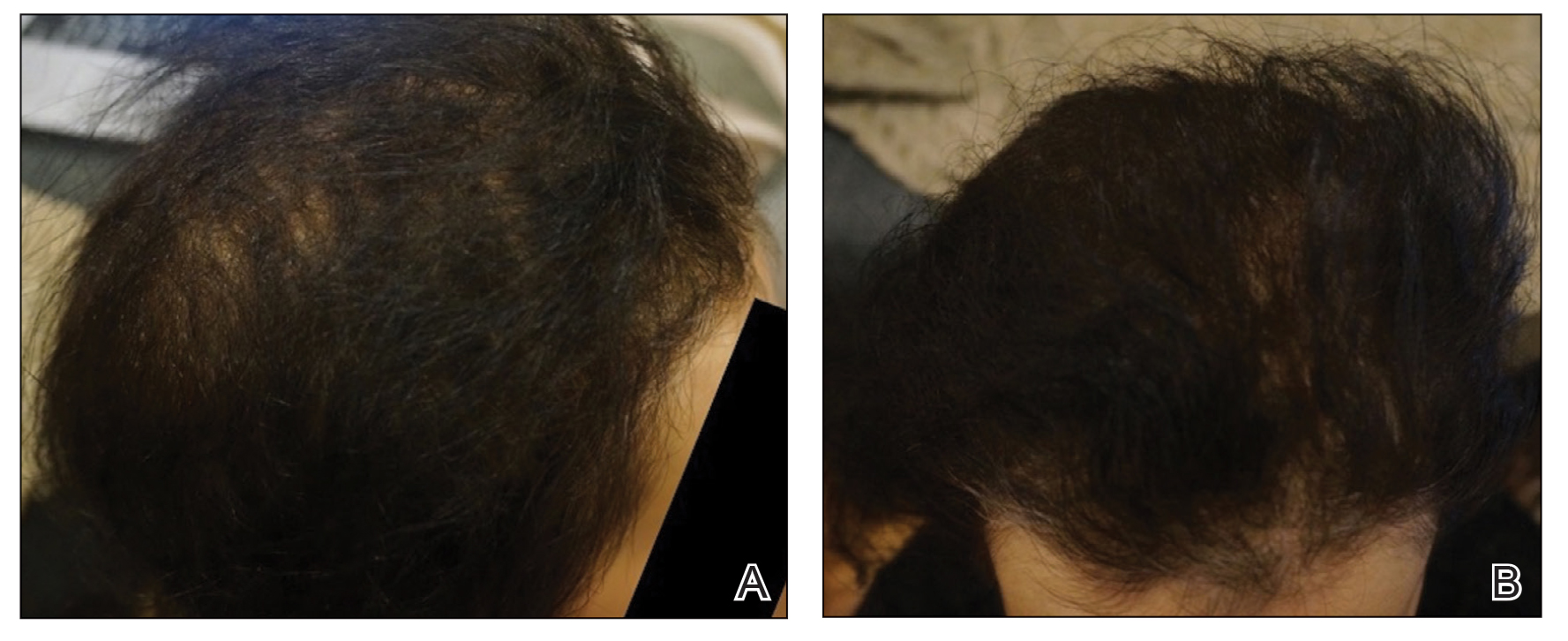

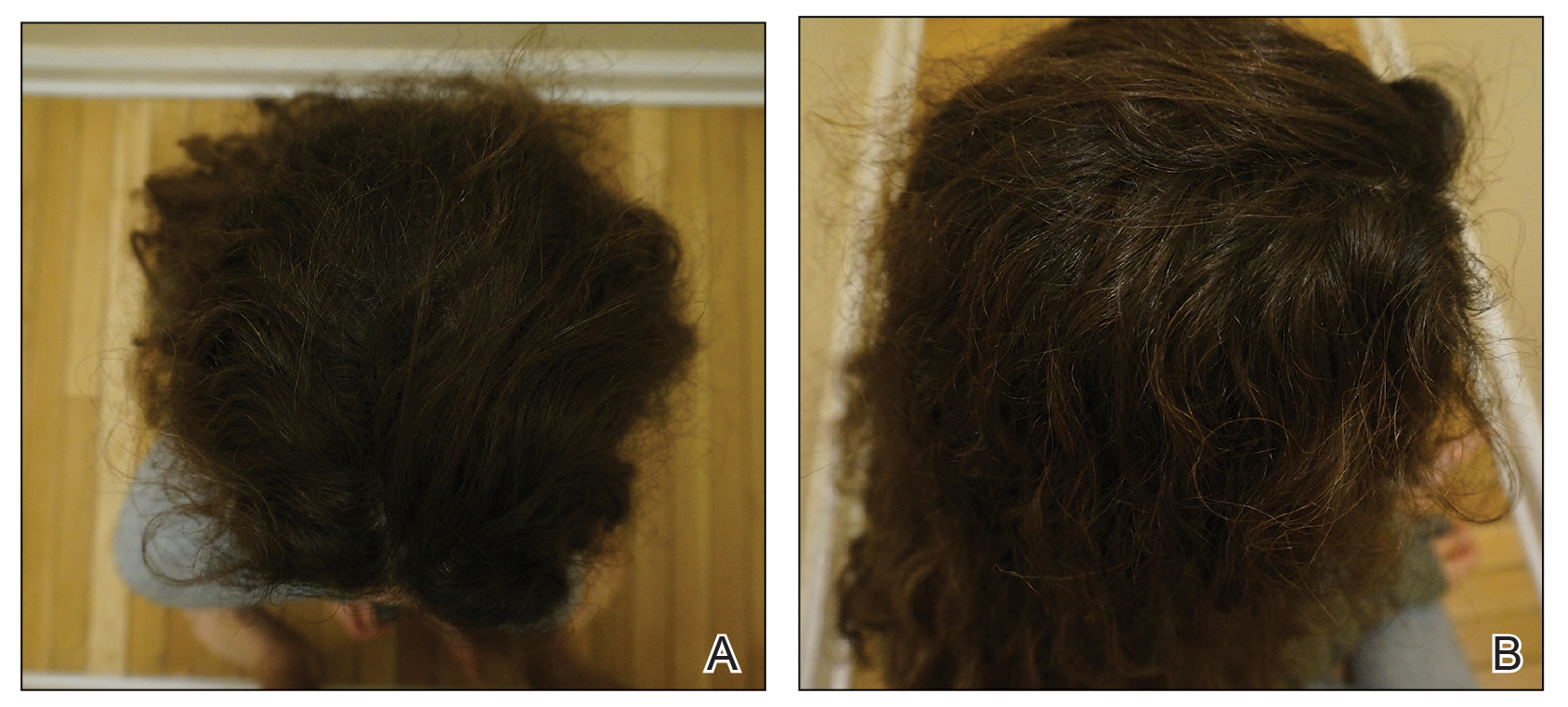

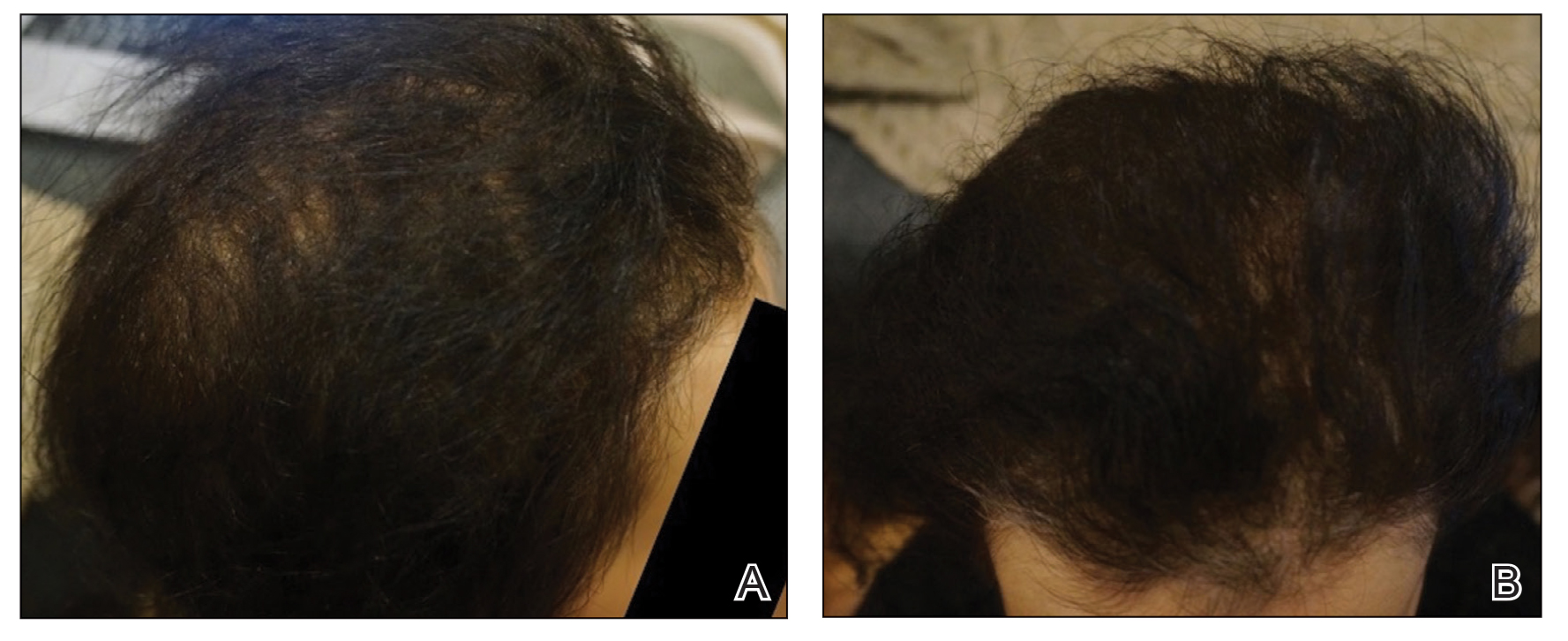

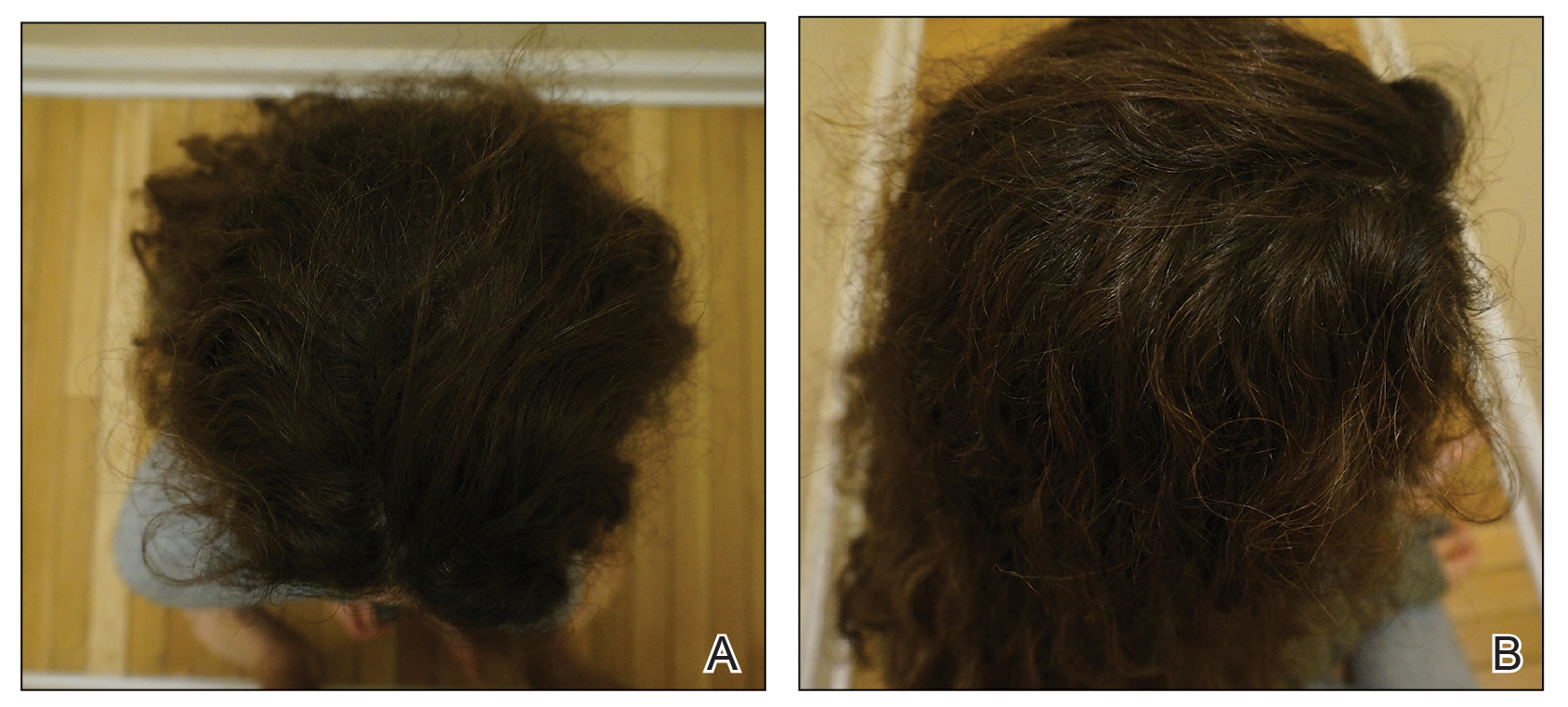

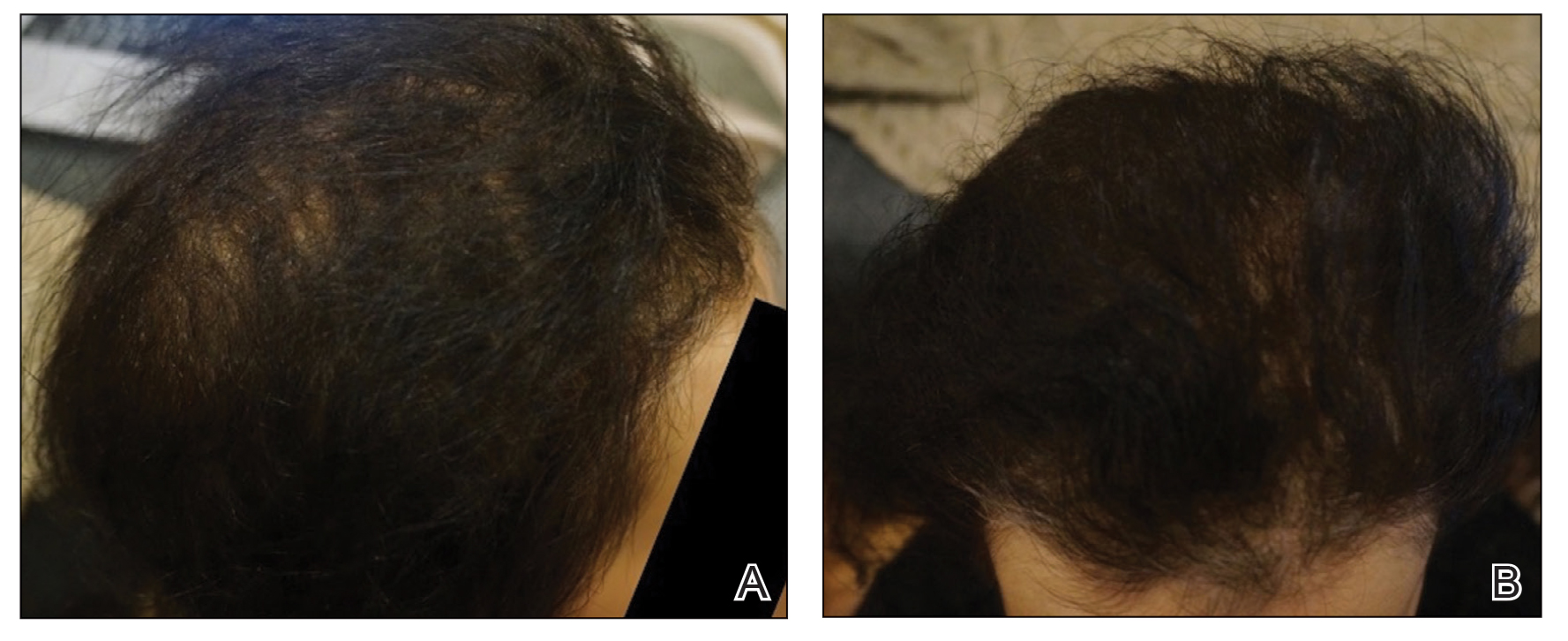

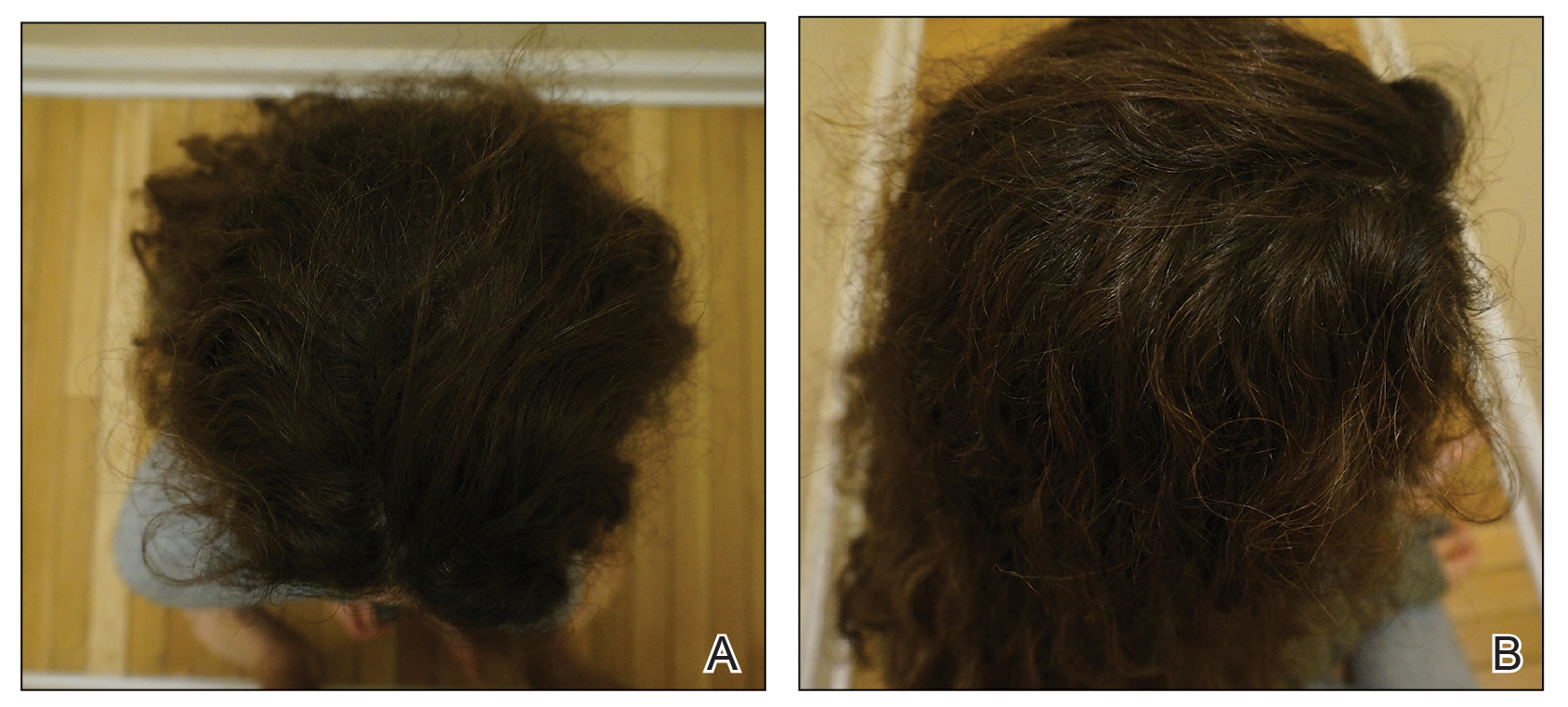

Initial hair growth on the scalp was diffuse with thin, white to light brown hairs in areas of hair loss at months 1 and 2, with progressive hair growth over months 3 to 7. Eyebrow hair growth was noted beginning at month 6. One year later, only hair regrowth occurred without any adverse events (Figure 2). After 5 years of treatment, the patient had a full head of thick hair (Figure 3). The tofacitinib dosage was 5 mg twice daily at initiation, and after 1 year increased to 10 mg twice daily. Her medical insurance subsequently changed and the regimen was adjusted to an 11-mg tablet and 5-mg tablet daily. She remained on this regimen with success.

Comment

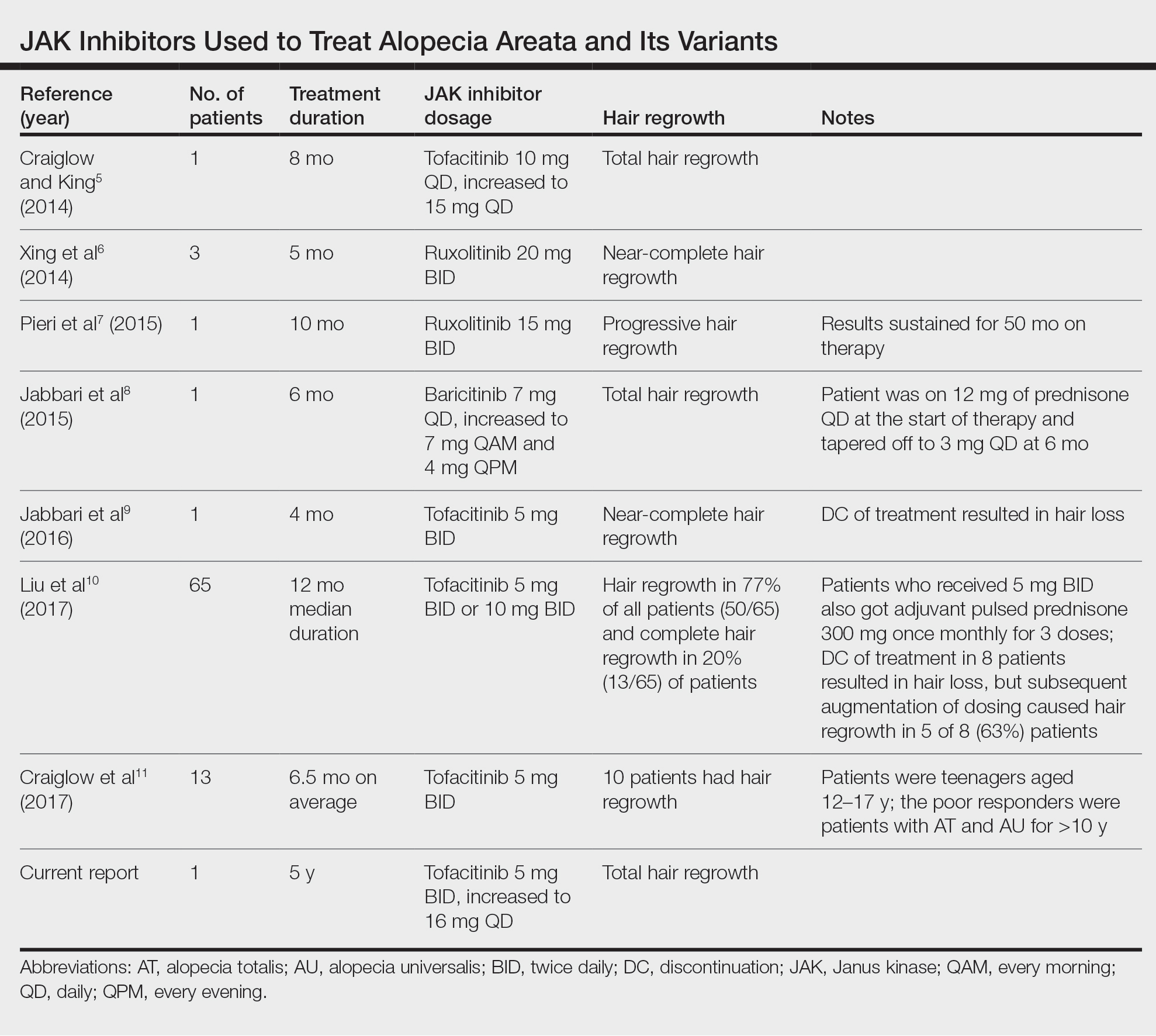

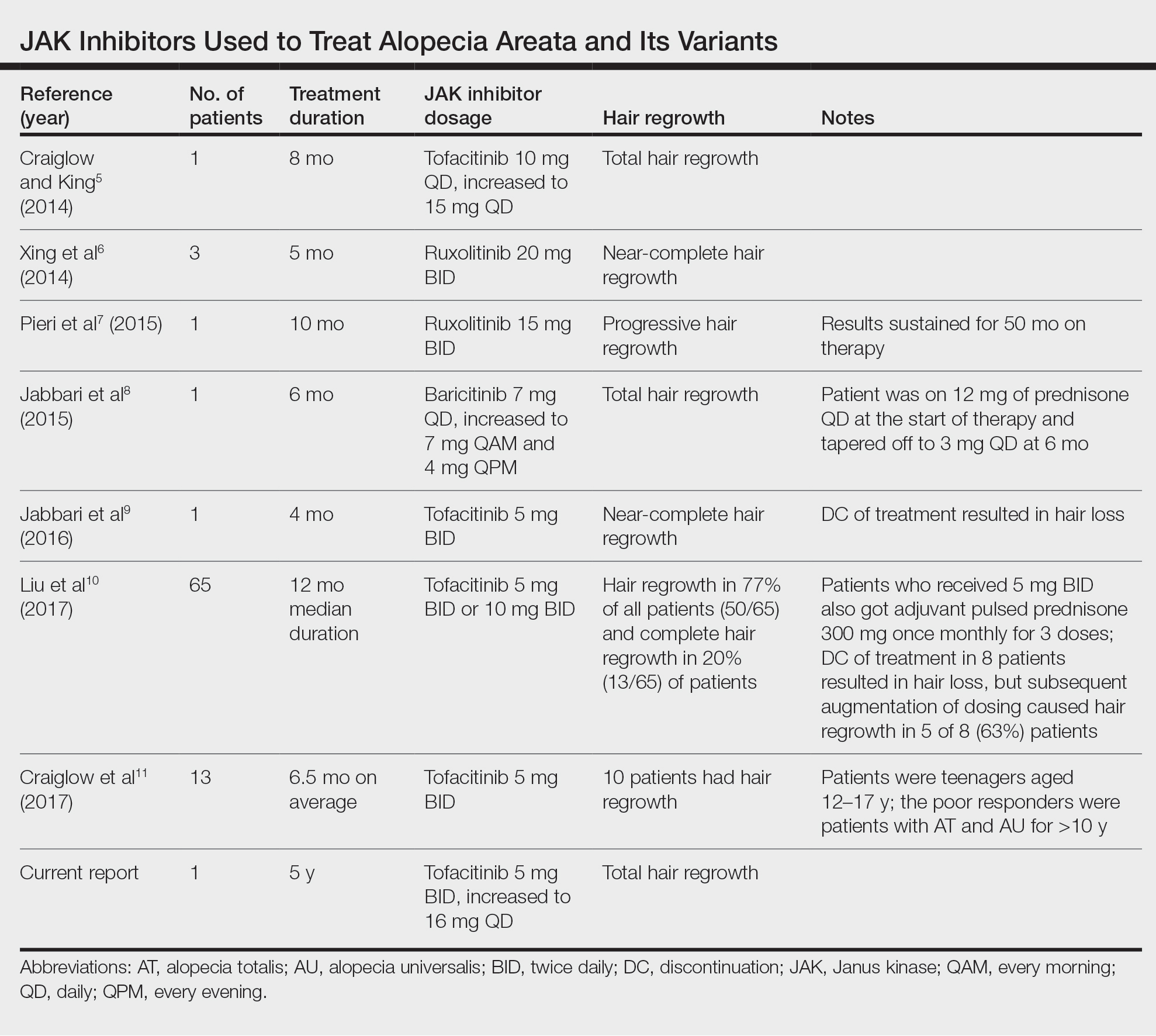

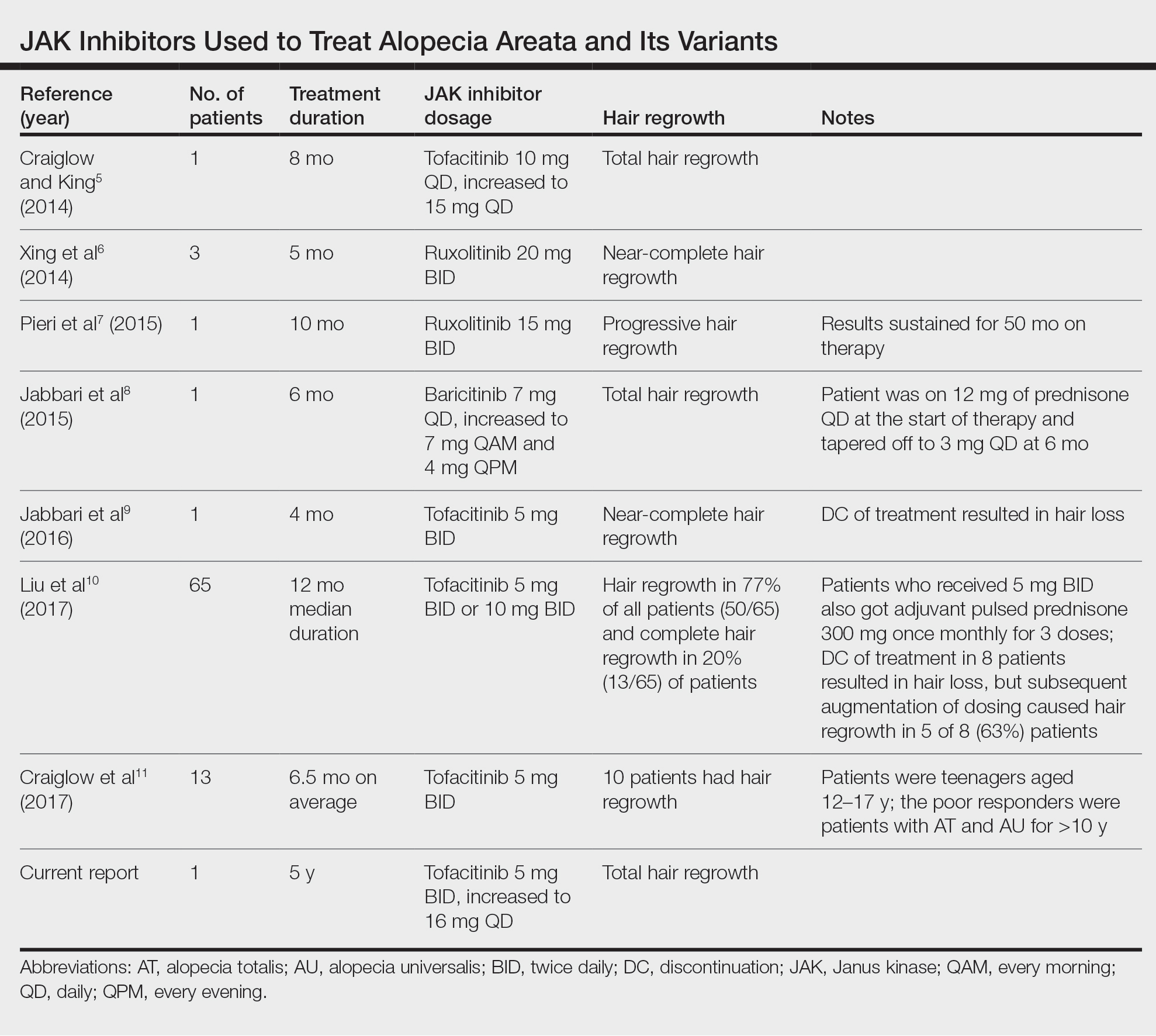

Use of JAK Inhibitors—Reports and studies have shed light on the use and efficacy of JAK inhibitors in AA (Table).5-11 Tofacitinib is a selective JAK1/3 inhibitor that predominantly inhibits JAK3 but also inhibits JAK1, albeit to a lesser degree, which interferes with the JAK/STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) cascade responsible for the production, differentiation, and function of various B cells, T cells, and natural killer cells.2 Although it was developed for the management of allograft rejection, tofacitinib has made headway in rheumatology for treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis who are unable to take or are not responding to methotrexate.2 Since 2014, tofacitinib has been introduced to the therapeutic realm for AA but is not yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.3,4

In 2014, Craiglow and King5 reported use of tofacitinib with dosages beginning at 10 mg/d and increasing to 15 mg/d in a patient with alopecia universalis and psoriasis. Total hair regrowth was noted after 8 months of therapy.5 Xing et al6 described 3 patients treated with ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor approved for the treatment of myelofibrosis, at an oral dose of 20 mg twice daily with near-complete hair regrowth after 5 months of treatment.6 Biopsies from lesions at baseline and after 3 months of therapy revealed a reduction in perifollicular T cells and in HLA class I and II expression in follicles.6 A patient in Italy with essential thrombocythemia and concurrent alopecia universalis was enrolled in a clinical trial with ruxolitinib and was treated with 15 mg twice daily. After 10 months of treatment, the patient had progressive hair regrowth that was sustained for more than 50 months of therapy.7 Baricitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor, was used in a 17-year-old adolescent boy to assess efficacy of the drug in

A recent retrospective study assessing response to tofacitinib in adults with AA (>40% hair loss), alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, and stable or progressive diseases for at least 6 months determined a clinical response in 50 of 65 (77%) patients, with 13 patients exhibiting a complete response.10 Patients in this study were started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily with the addition of adjuvant pulsed prednisone (300 mg once monthly for 3 doses) with or without doubled dosing of tofacitinib if they had a halt in hair regrowth. This study demonstrated some benefit when pulsed prednisone was combined with the daily tofacitinib therapy. However, the study emphasized the importance of maintenance therapy, as 8 patients experienced hair loss with discontinuation after previously having hair regrowth; 5 (63%) of these patients experienced regrowth with augmentation of dosing or addition of adjuvant therapy.10

Another group of investigators assessed the efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg in 13 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, most with alopecia universalis (46% [6/13]); 10 of 13 (77%) patients responded to treatment with a mean duration of 6.5 months. The patients who had alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis for more than 10 years were poor responders to tofacitinib, and in fact, 1 of 13 (33%) patients in the study who did not respond to therapy had disease for 12 years.11 Therefore, starting tofacitinib either long-term or intermittently should be considered in children diagnosed early with severe AA, alopecia totalis, or alopecia universalis to prevent irreversible hair loss or progressive disease12,13; however, further data are required to assess efficacy and long-term benefits of this type of regimen.

Safety Profile—Widespread use of a medication is determined not only by its efficacy profile but also its safety profile. With any medication that exhibits immunosuppressive effects, adverse events must be considered and thoroughly discussed with patients and their primary care physicians. A prospective, open-label, single-arm trial examined the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily in the treatment of AA and its more severe forms over 3 months.12 Of the 66 patients who completed the trial, 64% (42/66) exhibited a positive response to tofacitinib. Relapse was noted in 8.5 weeks after discontinuation of tofacitinib, reiterating the potential need for a maintenance regimen. In this study, 25.8% (17/66) of patients experienced infections as adverse events including (in decreasing order) upper respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, herpes zoster, conjunctivitis, bronchitis, mononucleosis, and paronychia. No reports of new or recurrent malignancy were noted. Other more constitutional adverse events were noted including headaches, abdominal pain, acne, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, pruritus, hot flashes, cough, folliculitis, weight gain, dry eyes, and amenorrhea. One patient with a pre-existing liver condition experienced transaminitis that resolved with weight loss. There also were noted increases in low- and high-density lipoprotein levels.12 Our patient with baseline thrombocytopenia had mild drops in platelet count that subsequently stabilized and did not result in any bleeding abnormalities.

Duration of Therapy—Tofacitinib has demonstrated some preliminary success in the management of AA, but the appropriate duration of treatment requires further investigation. Our patient has been on tofacitinib for more than 5 years. She started at a total dosage of 10 mg/d, which increased to 16 mg/d. Initial dosing with maintenance regimens needs to be established for further widespread use to maximize benefit and minimize harm.

At what point do we decide to continue or stop treatment in patients who do not respond as expected or plateau? This is another critical question; our patient had periods of slowed growth and plateauing, but knowing the risks and benefits, she continued the medication and eventually experienced improved regrowth again.

Conclusion

Throughout the literature and in our patient, tofacitinib has demonstrated efficacy in treating AA. When other conventional therapies have failed, use of tofacitinib should be considered.

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, et al. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmstead County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628-633.

- Borazan NH, Furst DE. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, nonopioid analgesics, & drugs used in gout. In: Katzung BG, Trevor AJ, eds. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 13th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2015:618-642.

- Shapiro J. Current treatment of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S42-S44.

- Shapiro J. Dermatologic therapy: alopecia areata update. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:301.

- Craiglow BG, King BA. Killing two birds with one stone: oral tofacitinib reverses alopecia universalis in a patient with plaque psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2988-2990.

- Xing L, Dai Z, Jabbari A, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med. 2014;20:1043-1049.

- Pieri L, Guglielmelli P, Vannucchi AM. Ruxolitinib-induced reversal of alopecia universalis in a patient with essential thrombocythemia. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:82-83.

- Jabbari A, Dai Z, Xing L, et al. Reversal of alopecia areata following treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib. EbioMedicine. 2015;2:351-355.

- Jabbari A, Nguyen N, Cerise JE, et al. Treatment of an alopecia areata patient with tofacitinib results in regrowth of hair and changes in serum and skin biomarkers. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:642-643.

- Liu LY, Craiglow BG, Dai F, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata and variants: a study of 90 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:22-28.

- Craiglow BG, Liu LY, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata and variants in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:29-32.

- Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:E89776.

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Emerging drugs for alopecia areata: JAK inhibitors. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2018;23:77-81.

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease that immunopathogenetically is thought to be due to breakdown of the immune privilege of the proximal hair follicle during the anagen growth phase. Alopecia areata has been reported to have a lifetime prevalence of 1.7%.1 Recent studies have specifically identified cytotoxic CD8+ NKG2D+ T cells as being responsible for the activation of AA.2-4 Two interleukins—IL-2 and IL-15—have been implicated to be cytotoxic sensitizers allowing CD8+ T cells to secrete IFN-γ and recognize autoantigens via major histocompatibility complex class I.5,6 Janus kinases (JAKs) are enzymes that play major roles in many different molecular processes. Specifically, JAK1/3 has been determined to arbitrate IL-15 activation of receptors on CD8+ T cells.7 These cells then interact with CD4 T cells, mast cells, and other inflammatory cells to cause destruction of the hair follicle without damage to the keratinocyte and melanocyte stem cells, allowing for reversible yet relapsing hair loss.8

Treatment of AA is difficult, requiring patience and strict compliance while taking into account duration of disease, age at presentation, site involvement, patient expectations, cost and insurance coverage, prior therapies, and any comorbidities. At the time of this case, no US Food and Drug Administration–approved drug regimen existed for the treatment of AA, and, to date, no treatment is preventative.4 We present a case of a patient with alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that was refractory to intralesional triamcinolone, clobetasol, minoxidil, and UVB brush therapy yet was successfully treated with tofacitinib.

Case Report

A 29-year-old otherwise-healthy woman presented to our clinic for treatment of alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that flared intermittently despite various treatments. Her medical history was unremarkable; however, she had a brother with alopecia universalis. She had no family history of any other autoimmune disorders. At the current presentation, the patient was known to have alopecia universalis with scant evidence of exclamation-point hairs on dermoscopy. Her treatment plan at this point consisted of intralesional triamcinolone to the active areas at 10 mg/mL every 4 weeks, plus clobetasol foam 0.05% at bedtime, minoxidil foam 5% at bedtime, and a UVB brush 3 times a week for 6 months before progressing to universalis type because of hair loss in the eyebrows and eyelashes. This treatment plan continued for 1 year with minimal improvement of the alopecia (Figure 1).

The patient was dissatisfied and wanted to discontinue therapy. Because these treatment options were exhausted with minimal benefit, the patient was then considered for treatment with tofacitinib. Baseline studies were performed, including purified protein derivative, complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid profile, and liver function tests, all of which were within reference range. Insurance initially denied coverage of this therapy; a prior authorization was subsequently submitted and denied. A letter of medical necessity was then proposed, and approval for tofacitinib was finally granted. The patient was started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and was monitored every 2 months with a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panels, and liver function tests. She had a platelet count of 112,000/μL (reference range, 150,000–450,000/μL) at baseline, and continued monitoring revealed a platelet count of 83,000 after 7 months of treatment. This platelet abnormality was evaluated by a hematologist and found to be within reference range; subsequent monitoring did not reveal any abnormalities.

Initial hair growth on the scalp was diffuse with thin, white to light brown hairs in areas of hair loss at months 1 and 2, with progressive hair growth over months 3 to 7. Eyebrow hair growth was noted beginning at month 6. One year later, only hair regrowth occurred without any adverse events (Figure 2). After 5 years of treatment, the patient had a full head of thick hair (Figure 3). The tofacitinib dosage was 5 mg twice daily at initiation, and after 1 year increased to 10 mg twice daily. Her medical insurance subsequently changed and the regimen was adjusted to an 11-mg tablet and 5-mg tablet daily. She remained on this regimen with success.

Comment

Use of JAK Inhibitors—Reports and studies have shed light on the use and efficacy of JAK inhibitors in AA (Table).5-11 Tofacitinib is a selective JAK1/3 inhibitor that predominantly inhibits JAK3 but also inhibits JAK1, albeit to a lesser degree, which interferes with the JAK/STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) cascade responsible for the production, differentiation, and function of various B cells, T cells, and natural killer cells.2 Although it was developed for the management of allograft rejection, tofacitinib has made headway in rheumatology for treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis who are unable to take or are not responding to methotrexate.2 Since 2014, tofacitinib has been introduced to the therapeutic realm for AA but is not yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.3,4

In 2014, Craiglow and King5 reported use of tofacitinib with dosages beginning at 10 mg/d and increasing to 15 mg/d in a patient with alopecia universalis and psoriasis. Total hair regrowth was noted after 8 months of therapy.5 Xing et al6 described 3 patients treated with ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor approved for the treatment of myelofibrosis, at an oral dose of 20 mg twice daily with near-complete hair regrowth after 5 months of treatment.6 Biopsies from lesions at baseline and after 3 months of therapy revealed a reduction in perifollicular T cells and in HLA class I and II expression in follicles.6 A patient in Italy with essential thrombocythemia and concurrent alopecia universalis was enrolled in a clinical trial with ruxolitinib and was treated with 15 mg twice daily. After 10 months of treatment, the patient had progressive hair regrowth that was sustained for more than 50 months of therapy.7 Baricitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor, was used in a 17-year-old adolescent boy to assess efficacy of the drug in

A recent retrospective study assessing response to tofacitinib in adults with AA (>40% hair loss), alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, and stable or progressive diseases for at least 6 months determined a clinical response in 50 of 65 (77%) patients, with 13 patients exhibiting a complete response.10 Patients in this study were started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily with the addition of adjuvant pulsed prednisone (300 mg once monthly for 3 doses) with or without doubled dosing of tofacitinib if they had a halt in hair regrowth. This study demonstrated some benefit when pulsed prednisone was combined with the daily tofacitinib therapy. However, the study emphasized the importance of maintenance therapy, as 8 patients experienced hair loss with discontinuation after previously having hair regrowth; 5 (63%) of these patients experienced regrowth with augmentation of dosing or addition of adjuvant therapy.10

Another group of investigators assessed the efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg in 13 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, most with alopecia universalis (46% [6/13]); 10 of 13 (77%) patients responded to treatment with a mean duration of 6.5 months. The patients who had alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis for more than 10 years were poor responders to tofacitinib, and in fact, 1 of 13 (33%) patients in the study who did not respond to therapy had disease for 12 years.11 Therefore, starting tofacitinib either long-term or intermittently should be considered in children diagnosed early with severe AA, alopecia totalis, or alopecia universalis to prevent irreversible hair loss or progressive disease12,13; however, further data are required to assess efficacy and long-term benefits of this type of regimen.

Safety Profile—Widespread use of a medication is determined not only by its efficacy profile but also its safety profile. With any medication that exhibits immunosuppressive effects, adverse events must be considered and thoroughly discussed with patients and their primary care physicians. A prospective, open-label, single-arm trial examined the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily in the treatment of AA and its more severe forms over 3 months.12 Of the 66 patients who completed the trial, 64% (42/66) exhibited a positive response to tofacitinib. Relapse was noted in 8.5 weeks after discontinuation of tofacitinib, reiterating the potential need for a maintenance regimen. In this study, 25.8% (17/66) of patients experienced infections as adverse events including (in decreasing order) upper respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, herpes zoster, conjunctivitis, bronchitis, mononucleosis, and paronychia. No reports of new or recurrent malignancy were noted. Other more constitutional adverse events were noted including headaches, abdominal pain, acne, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, pruritus, hot flashes, cough, folliculitis, weight gain, dry eyes, and amenorrhea. One patient with a pre-existing liver condition experienced transaminitis that resolved with weight loss. There also were noted increases in low- and high-density lipoprotein levels.12 Our patient with baseline thrombocytopenia had mild drops in platelet count that subsequently stabilized and did not result in any bleeding abnormalities.

Duration of Therapy—Tofacitinib has demonstrated some preliminary success in the management of AA, but the appropriate duration of treatment requires further investigation. Our patient has been on tofacitinib for more than 5 years. She started at a total dosage of 10 mg/d, which increased to 16 mg/d. Initial dosing with maintenance regimens needs to be established for further widespread use to maximize benefit and minimize harm.

At what point do we decide to continue or stop treatment in patients who do not respond as expected or plateau? This is another critical question; our patient had periods of slowed growth and plateauing, but knowing the risks and benefits, she continued the medication and eventually experienced improved regrowth again.

Conclusion

Throughout the literature and in our patient, tofacitinib has demonstrated efficacy in treating AA. When other conventional therapies have failed, use of tofacitinib should be considered.

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease that immunopathogenetically is thought to be due to breakdown of the immune privilege of the proximal hair follicle during the anagen growth phase. Alopecia areata has been reported to have a lifetime prevalence of 1.7%.1 Recent studies have specifically identified cytotoxic CD8+ NKG2D+ T cells as being responsible for the activation of AA.2-4 Two interleukins—IL-2 and IL-15—have been implicated to be cytotoxic sensitizers allowing CD8+ T cells to secrete IFN-γ and recognize autoantigens via major histocompatibility complex class I.5,6 Janus kinases (JAKs) are enzymes that play major roles in many different molecular processes. Specifically, JAK1/3 has been determined to arbitrate IL-15 activation of receptors on CD8+ T cells.7 These cells then interact with CD4 T cells, mast cells, and other inflammatory cells to cause destruction of the hair follicle without damage to the keratinocyte and melanocyte stem cells, allowing for reversible yet relapsing hair loss.8

Treatment of AA is difficult, requiring patience and strict compliance while taking into account duration of disease, age at presentation, site involvement, patient expectations, cost and insurance coverage, prior therapies, and any comorbidities. At the time of this case, no US Food and Drug Administration–approved drug regimen existed for the treatment of AA, and, to date, no treatment is preventative.4 We present a case of a patient with alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that was refractory to intralesional triamcinolone, clobetasol, minoxidil, and UVB brush therapy yet was successfully treated with tofacitinib.

Case Report

A 29-year-old otherwise-healthy woman presented to our clinic for treatment of alopecia universalis of 11 years’ duration that flared intermittently despite various treatments. Her medical history was unremarkable; however, she had a brother with alopecia universalis. She had no family history of any other autoimmune disorders. At the current presentation, the patient was known to have alopecia universalis with scant evidence of exclamation-point hairs on dermoscopy. Her treatment plan at this point consisted of intralesional triamcinolone to the active areas at 10 mg/mL every 4 weeks, plus clobetasol foam 0.05% at bedtime, minoxidil foam 5% at bedtime, and a UVB brush 3 times a week for 6 months before progressing to universalis type because of hair loss in the eyebrows and eyelashes. This treatment plan continued for 1 year with minimal improvement of the alopecia (Figure 1).

The patient was dissatisfied and wanted to discontinue therapy. Because these treatment options were exhausted with minimal benefit, the patient was then considered for treatment with tofacitinib. Baseline studies were performed, including purified protein derivative, complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid profile, and liver function tests, all of which were within reference range. Insurance initially denied coverage of this therapy; a prior authorization was subsequently submitted and denied. A letter of medical necessity was then proposed, and approval for tofacitinib was finally granted. The patient was started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily and was monitored every 2 months with a complete blood cell count, comprehensive metabolic panel, lipid panels, and liver function tests. She had a platelet count of 112,000/μL (reference range, 150,000–450,000/μL) at baseline, and continued monitoring revealed a platelet count of 83,000 after 7 months of treatment. This platelet abnormality was evaluated by a hematologist and found to be within reference range; subsequent monitoring did not reveal any abnormalities.

Initial hair growth on the scalp was diffuse with thin, white to light brown hairs in areas of hair loss at months 1 and 2, with progressive hair growth over months 3 to 7. Eyebrow hair growth was noted beginning at month 6. One year later, only hair regrowth occurred without any adverse events (Figure 2). After 5 years of treatment, the patient had a full head of thick hair (Figure 3). The tofacitinib dosage was 5 mg twice daily at initiation, and after 1 year increased to 10 mg twice daily. Her medical insurance subsequently changed and the regimen was adjusted to an 11-mg tablet and 5-mg tablet daily. She remained on this regimen with success.

Comment

Use of JAK Inhibitors—Reports and studies have shed light on the use and efficacy of JAK inhibitors in AA (Table).5-11 Tofacitinib is a selective JAK1/3 inhibitor that predominantly inhibits JAK3 but also inhibits JAK1, albeit to a lesser degree, which interferes with the JAK/STAT (signal transducer and activator of transcription) cascade responsible for the production, differentiation, and function of various B cells, T cells, and natural killer cells.2 Although it was developed for the management of allograft rejection, tofacitinib has made headway in rheumatology for treatment of patients with moderate to severe rheumatoid arthritis who are unable to take or are not responding to methotrexate.2 Since 2014, tofacitinib has been introduced to the therapeutic realm for AA but is not yet approved by the US Food and Drug Administration.3,4

In 2014, Craiglow and King5 reported use of tofacitinib with dosages beginning at 10 mg/d and increasing to 15 mg/d in a patient with alopecia universalis and psoriasis. Total hair regrowth was noted after 8 months of therapy.5 Xing et al6 described 3 patients treated with ruxolitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor approved for the treatment of myelofibrosis, at an oral dose of 20 mg twice daily with near-complete hair regrowth after 5 months of treatment.6 Biopsies from lesions at baseline and after 3 months of therapy revealed a reduction in perifollicular T cells and in HLA class I and II expression in follicles.6 A patient in Italy with essential thrombocythemia and concurrent alopecia universalis was enrolled in a clinical trial with ruxolitinib and was treated with 15 mg twice daily. After 10 months of treatment, the patient had progressive hair regrowth that was sustained for more than 50 months of therapy.7 Baricitinib, a JAK1/2 inhibitor, was used in a 17-year-old adolescent boy to assess efficacy of the drug in

A recent retrospective study assessing response to tofacitinib in adults with AA (>40% hair loss), alopecia totalis, alopecia universalis, and stable or progressive diseases for at least 6 months determined a clinical response in 50 of 65 (77%) patients, with 13 patients exhibiting a complete response.10 Patients in this study were started on tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily with the addition of adjuvant pulsed prednisone (300 mg once monthly for 3 doses) with or without doubled dosing of tofacitinib if they had a halt in hair regrowth. This study demonstrated some benefit when pulsed prednisone was combined with the daily tofacitinib therapy. However, the study emphasized the importance of maintenance therapy, as 8 patients experienced hair loss with discontinuation after previously having hair regrowth; 5 (63%) of these patients experienced regrowth with augmentation of dosing or addition of adjuvant therapy.10

Another group of investigators assessed the efficacy of tofacitinib 5 mg in 13 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years, most with alopecia universalis (46% [6/13]); 10 of 13 (77%) patients responded to treatment with a mean duration of 6.5 months. The patients who had alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis for more than 10 years were poor responders to tofacitinib, and in fact, 1 of 13 (33%) patients in the study who did not respond to therapy had disease for 12 years.11 Therefore, starting tofacitinib either long-term or intermittently should be considered in children diagnosed early with severe AA, alopecia totalis, or alopecia universalis to prevent irreversible hair loss or progressive disease12,13; however, further data are required to assess efficacy and long-term benefits of this type of regimen.

Safety Profile—Widespread use of a medication is determined not only by its efficacy profile but also its safety profile. With any medication that exhibits immunosuppressive effects, adverse events must be considered and thoroughly discussed with patients and their primary care physicians. A prospective, open-label, single-arm trial examined the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib 5 mg twice daily in the treatment of AA and its more severe forms over 3 months.12 Of the 66 patients who completed the trial, 64% (42/66) exhibited a positive response to tofacitinib. Relapse was noted in 8.5 weeks after discontinuation of tofacitinib, reiterating the potential need for a maintenance regimen. In this study, 25.8% (17/66) of patients experienced infections as adverse events including (in decreasing order) upper respiratory tract infections, urinary tract infections, herpes zoster, conjunctivitis, bronchitis, mononucleosis, and paronychia. No reports of new or recurrent malignancy were noted. Other more constitutional adverse events were noted including headaches, abdominal pain, acne, diarrhea, fatigue, nausea, pruritus, hot flashes, cough, folliculitis, weight gain, dry eyes, and amenorrhea. One patient with a pre-existing liver condition experienced transaminitis that resolved with weight loss. There also were noted increases in low- and high-density lipoprotein levels.12 Our patient with baseline thrombocytopenia had mild drops in platelet count that subsequently stabilized and did not result in any bleeding abnormalities.

Duration of Therapy—Tofacitinib has demonstrated some preliminary success in the management of AA, but the appropriate duration of treatment requires further investigation. Our patient has been on tofacitinib for more than 5 years. She started at a total dosage of 10 mg/d, which increased to 16 mg/d. Initial dosing with maintenance regimens needs to be established for further widespread use to maximize benefit and minimize harm.

At what point do we decide to continue or stop treatment in patients who do not respond as expected or plateau? This is another critical question; our patient had periods of slowed growth and plateauing, but knowing the risks and benefits, she continued the medication and eventually experienced improved regrowth again.

Conclusion

Throughout the literature and in our patient, tofacitinib has demonstrated efficacy in treating AA. When other conventional therapies have failed, use of tofacitinib should be considered.

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, et al. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmstead County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628-633.

- Borazan NH, Furst DE. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, nonopioid analgesics, & drugs used in gout. In: Katzung BG, Trevor AJ, eds. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 13th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2015:618-642.

- Shapiro J. Current treatment of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S42-S44.

- Shapiro J. Dermatologic therapy: alopecia areata update. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:301.

- Craiglow BG, King BA. Killing two birds with one stone: oral tofacitinib reverses alopecia universalis in a patient with plaque psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2988-2990.

- Xing L, Dai Z, Jabbari A, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med. 2014;20:1043-1049.

- Pieri L, Guglielmelli P, Vannucchi AM. Ruxolitinib-induced reversal of alopecia universalis in a patient with essential thrombocythemia. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:82-83.

- Jabbari A, Dai Z, Xing L, et al. Reversal of alopecia areata following treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib. EbioMedicine. 2015;2:351-355.

- Jabbari A, Nguyen N, Cerise JE, et al. Treatment of an alopecia areata patient with tofacitinib results in regrowth of hair and changes in serum and skin biomarkers. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:642-643.

- Liu LY, Craiglow BG, Dai F, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata and variants: a study of 90 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:22-28.

- Craiglow BG, Liu LY, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata and variants in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:29-32.

- Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:E89776.

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Emerging drugs for alopecia areata: JAK inhibitors. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2018;23:77-81.

- Safavi KH, Muller SA, Suman VJ, et al. Incidence of alopecia areata in Olmstead County, Minnesota, 1975 through 1989. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70:628-633.

- Borazan NH, Furst DE. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, nonopioid analgesics, & drugs used in gout. In: Katzung BG, Trevor AJ, eds. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 13th ed. McGraw-Hill; 2015:618-642.

- Shapiro J. Current treatment of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2013;16:S42-S44.

- Shapiro J. Dermatologic therapy: alopecia areata update. Dermatol Ther. 2011;24:301.

- Craiglow BG, King BA. Killing two birds with one stone: oral tofacitinib reverses alopecia universalis in a patient with plaque psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:2988-2990.

- Xing L, Dai Z, Jabbari A, et al. Alopecia areata is driven by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and is reversed by JAK inhibition. Nat Med. 2014;20:1043-1049.

- Pieri L, Guglielmelli P, Vannucchi AM. Ruxolitinib-induced reversal of alopecia universalis in a patient with essential thrombocythemia. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:82-83.

- Jabbari A, Dai Z, Xing L, et al. Reversal of alopecia areata following treatment with the JAK1/2 inhibitor baricitinib. EbioMedicine. 2015;2:351-355.

- Jabbari A, Nguyen N, Cerise JE, et al. Treatment of an alopecia areata patient with tofacitinib results in regrowth of hair and changes in serum and skin biomarkers. Exp Dermatol. 2016;25:642-643.

- Liu LY, Craiglow BG, Dai F, et al. Tofacitinib for the treatment of severe alopecia areata and variants: a study of 90 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:22-28.

- Craiglow BG, Liu LY, King BA. Tofacitinib for the treatment of alopecia areata and variants in adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:29-32.

- Kennedy Crispin M, Ko JM, Craiglow BG, et al. Safety and efficacy of the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib citrate in patients with alopecia areata. JCI Insight. 2016;1:E89776.

- Iorizzo M, Tosti A. Emerging drugs for alopecia areata: JAK inhibitors. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2018;23:77-81.

Practice Points

- Janus kinase inhibitors target one of the cellular pathogeneses of alopecia areata.

- Janus kinase inhibitors may be an option for patients who have exhausted other treatment modalities for alopecia.

Pediatric Primary Cutaneous Marginal Zone Lymphoma Treated With Doxycycline

Case Report

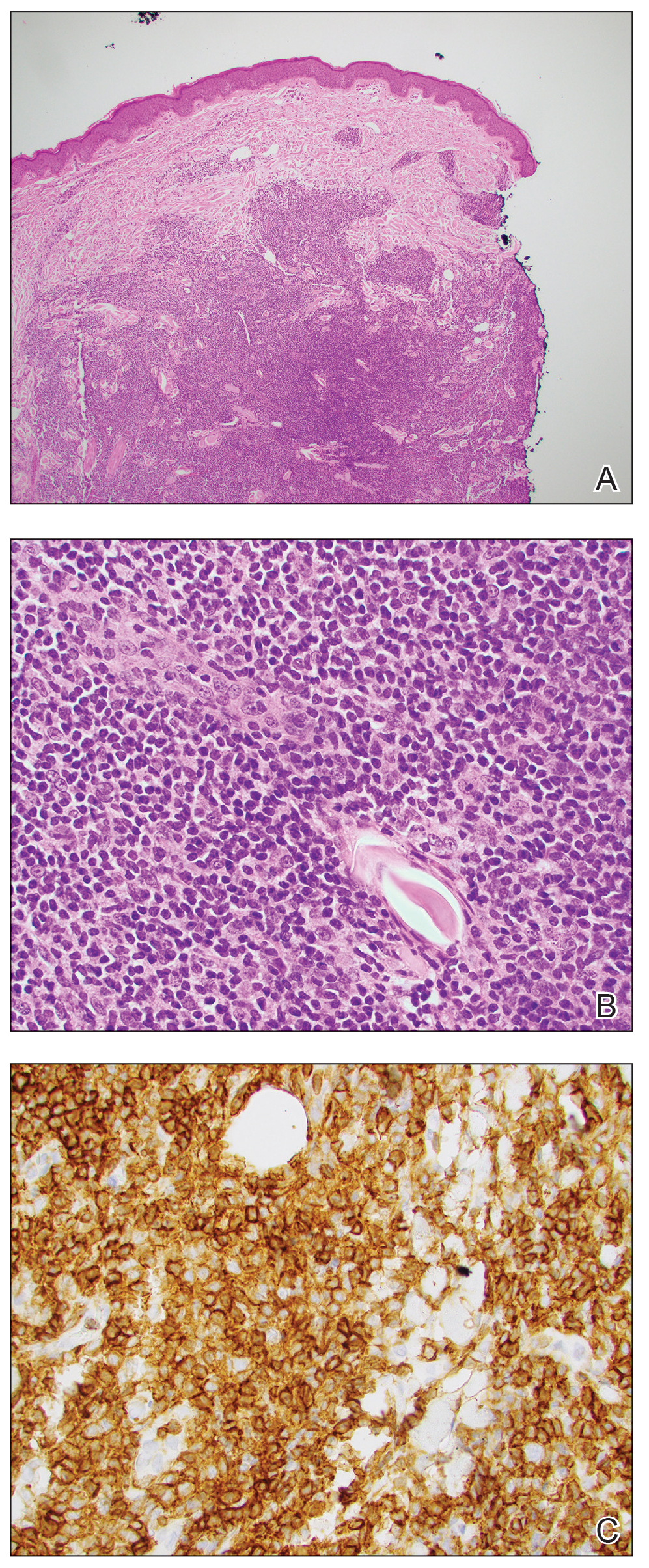

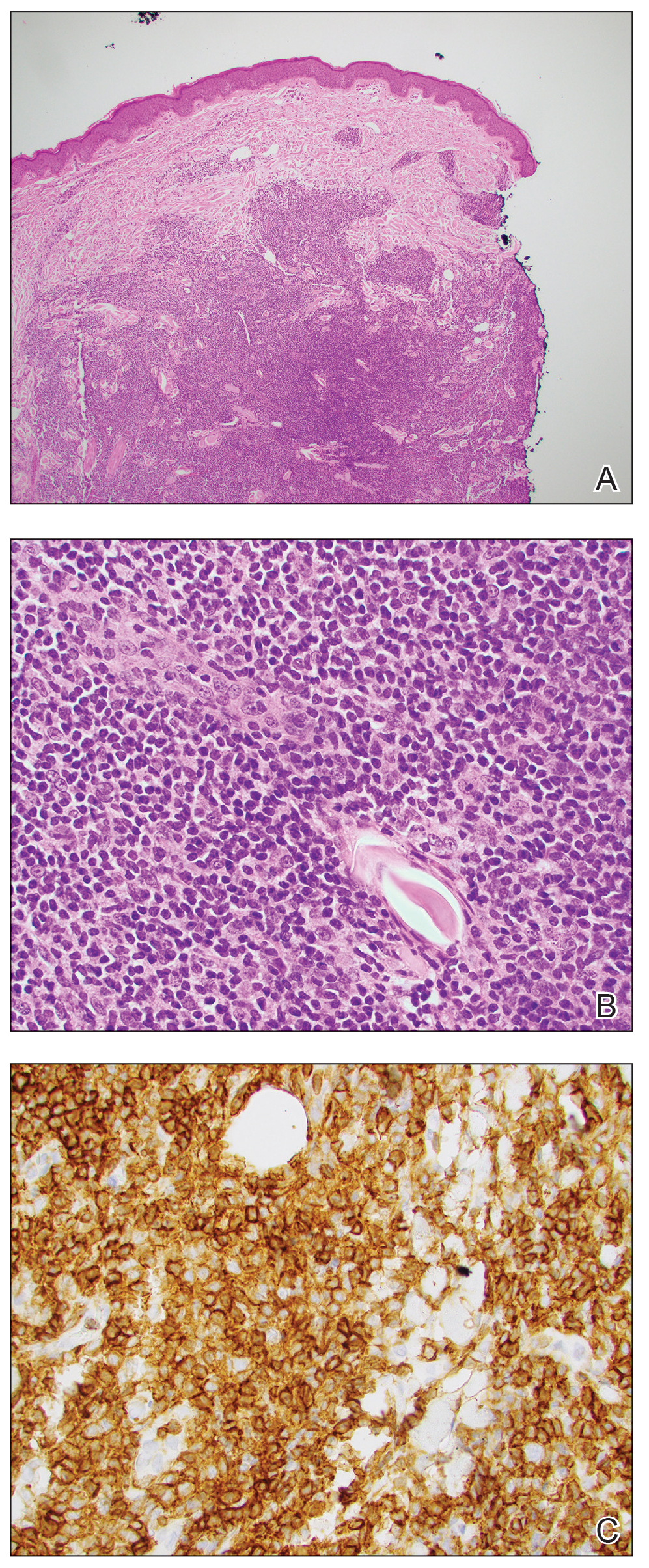

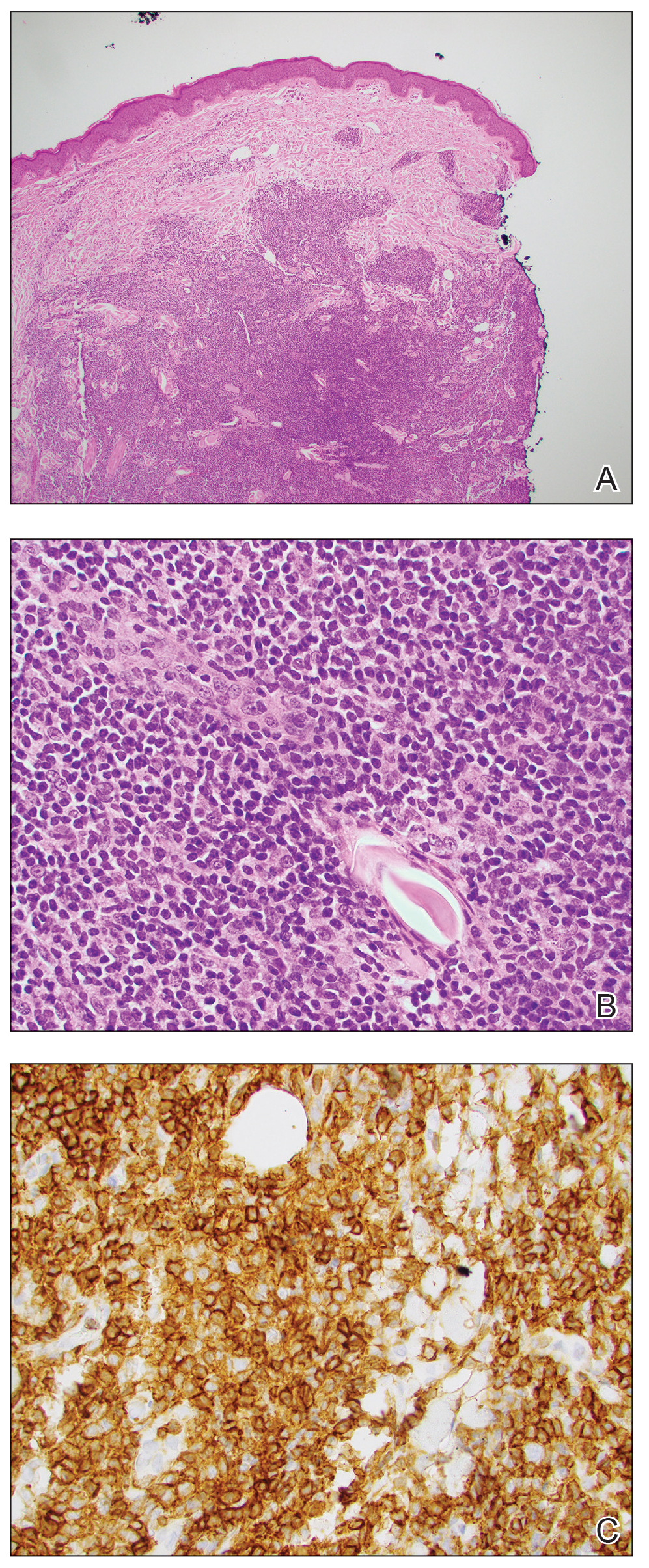

An otherwise healthy 13-year-old boy was referred to pediatric dermatology with multiple asymptomatic erythematous papules throughout the trunk and arms of 6 months’ duration. He denied fevers, night sweats, or weight loss. A punch biopsy revealed a dense atypical lymphoid infiltrate with follicular prominence extending periadnexally and perivascularly, which was most consistent with extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (Figures 1A and 1B). Cells were positive for Bcl-2, CD23, and CD20 (Figure 1C). Polymerase chain reaction analysis of the immunoglobulin heavy and κ chain gene rearrangements were positive, indicating the presence of a clonal B-cell expansion. The patient’s complete blood cell count, complete metabolic profile, serum lactate dehydrogenase, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate were within reference range. Lyme disease antibodies, Helicobacter pylori testing, thyroid function testing, thyroid antibodies, anti–Sjogren syndrome–related antigen A antibody, and anti–Sjogren syndrome–related antigen B were negative. Additionally, positron emission tomography (PET) with computed tomography (CT) revealed no abnormalities. He was diagnosed with stage T3b primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma (PCMZL) due to cutaneous involvement of 3 or more body regions.

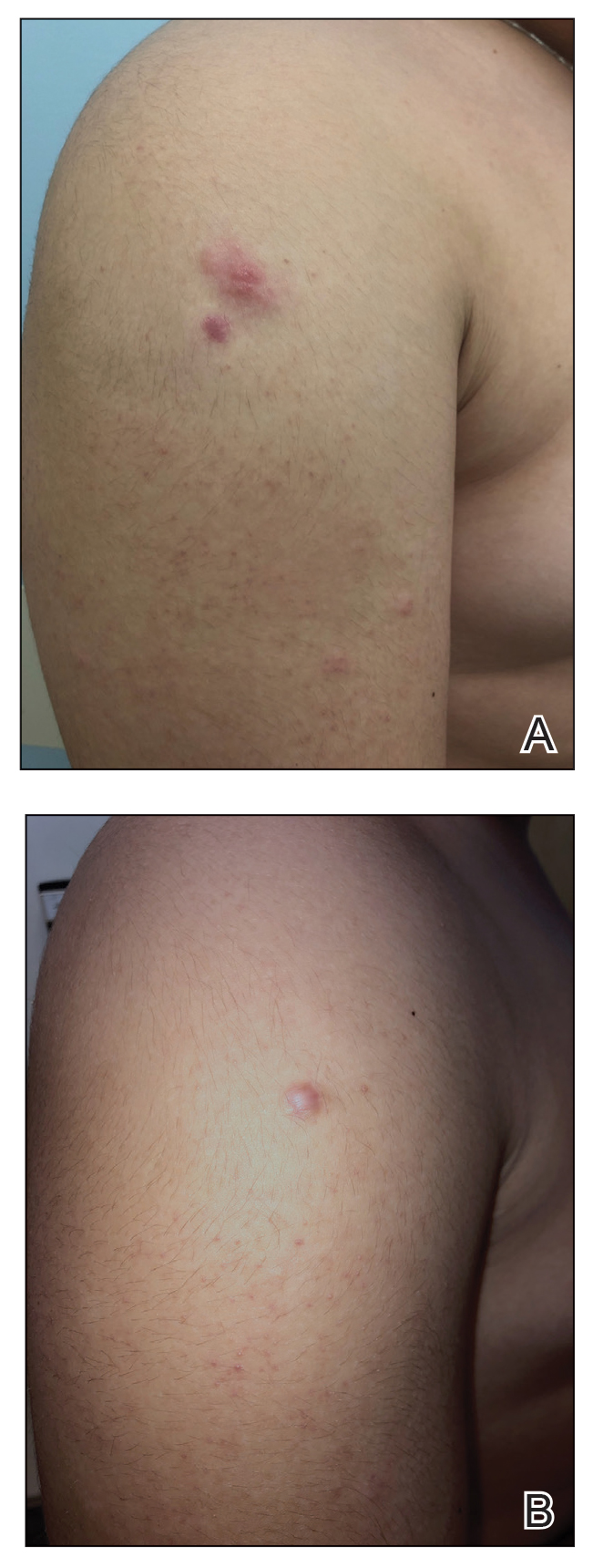

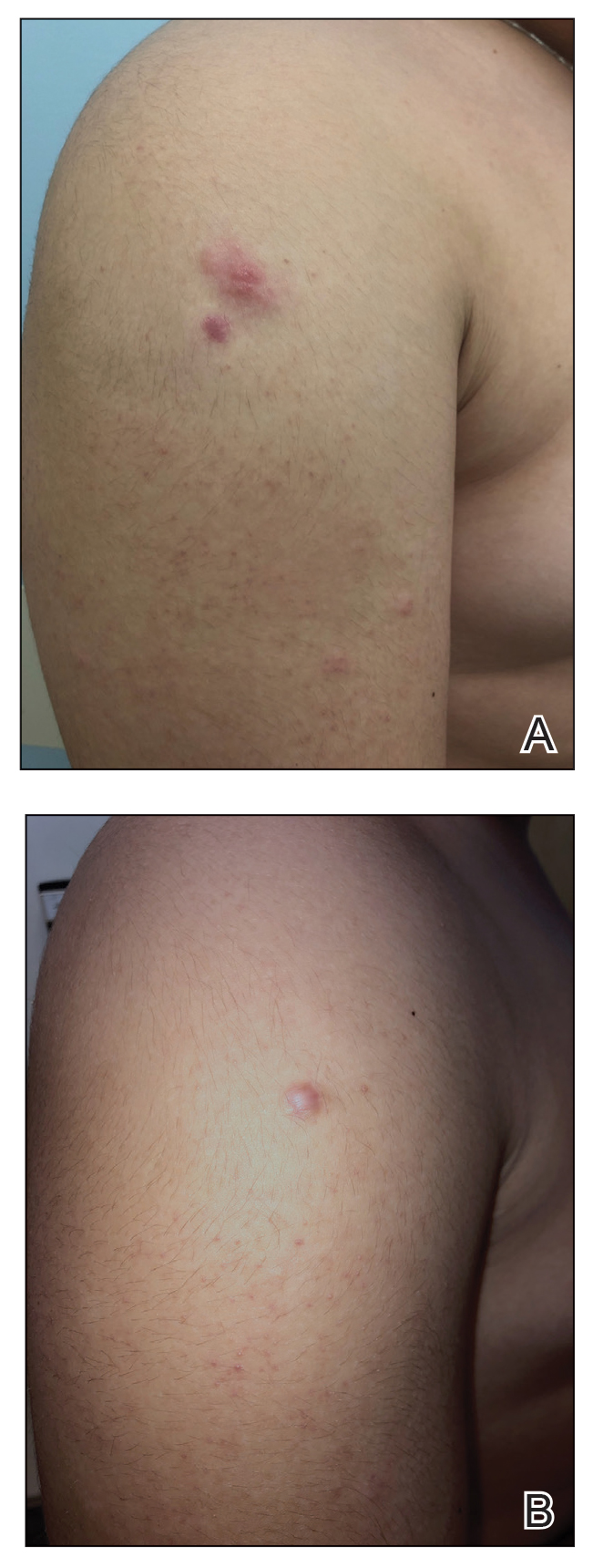

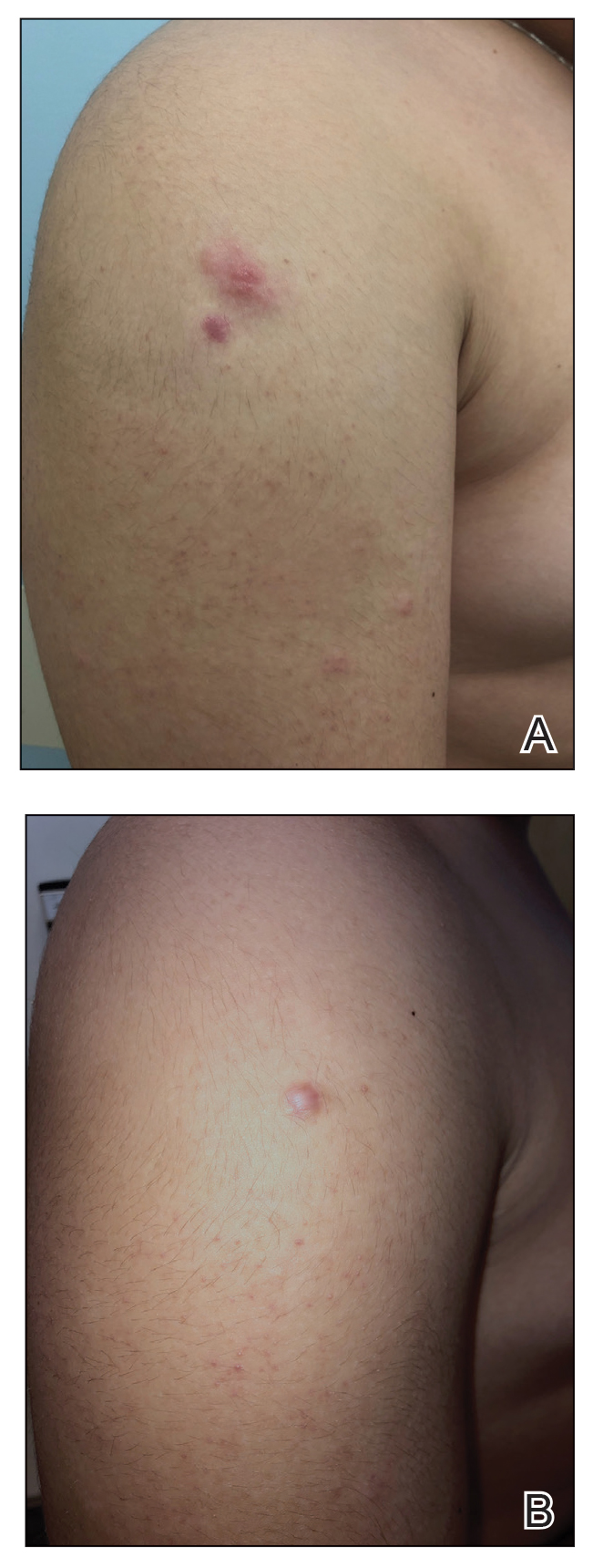

The patient was started on clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily to the affected areas. After 2 months, he had progression of cutaneous disease, including increased number of lesions; erythema; and induration of lesions on the chest, back, and arms (Figure 2A) and was started on oral doxycycline 100 mg twice daily with subsequent notable improvement of the skin lesions at 2-week follow-up, including decreased erythema and induration of all lesions. He then received intralesional triamcinolone 20 mg/mL injections to 4 residual lesions; clobetasol ointment 0.05% twice daily was continued for the remaining lesions as needed for pruritus. He continued doxycycline for 4 months with further improvement of lesions (Figure 2B). Six months after discontinuing doxycycline, 2 small residual lesions remained on the left arm and back, but the patient did not develop any new or recurrent lesions.

Comment

Clinical Presentation—Primary cutaneous B-cell lymphomas include PCMZL, primary cutaneous follicle center lymphoma, and primary cutaneous large B-cell lymphoma. Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma is an indolent extranodal B-cell lymphoma composed of small B cells, marginal zone cells, lymphoplasmacytoid cells, and mature plasma cells.1

Primary cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma typically presents in the fourth to sixth decades of life and is rare in children, with fewer than 40 cases in patients younger than 20 years.2 Amitay-Laish and colleagues2 reported 29 patients with pediatric PCMZL ranging in age from 1 to 19.5 years at diagnosis, with the majority of patients diagnosed after 10 years of age. Clinically, patients present with multifocal, erythematous to brown, dermal papules, plaques, and nodules most commonly distributed on the trunk and arms. A retrospective review of 11 pediatric patients with PCMZL over a median of 5.5 years demonstrated that the clinical presentation, histopathology, molecular findings, and prognosis of pediatric PCMZL appears similar to adult PCMZL.2 Cutaneous relapse is common, but extracutaneous spread is rare. The prognosis is excellent, with a disease-free survival rate of 93%.3

Diagnosis—The diagnosis of PCMZL requires histopathologic analysis of involved skin as well as exclusion of extracutaneous disease at the time of diagnosis during initial staging evaluation. Histologically there are nodular infiltrates of small lymphocytes in interfollicular compartments, reactive germinal centers, and clonality with monotypic immunoglobulin heavy chain genes.4 Laboratory workup should include complete blood cell count with differential, complete metabolic panel, and serum lactate dehydrogenase level. If lymphocytosis is present, flow cytometry of peripheral blood cells should be performed. Radiographic imaging with contrast-enhanced CT or PET/CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis should be performed for routine staging in most patients, with imaging of the neck recommended when cervical lymphadenopathy is detected.5 Patients with multifocal skin lesions should receive PET/CT to exclude systemic disease and assess lymph nodes. Bone marrow studies are not required for diagnosis.5,6

Associated Conditions—Systemic marginal zone lymphoma has been associated with autoimmune conditions, including Hashimoto thyroiditis and Sjögren syndrome; however, this association has not been shown in PCMZL and was not found in our patient.7,8 Borrelia-positive serology has been described in cases of PCMZL in Europe. The pathogenesis has been speculated to be due to chronic antigen stimulation related to the geographic distribution of Borrelia species.9 In endemic areas, Borrelia testing with serology or DNA testing of skin is recommended; however, there has been no strong correlation between Borrelia burgdorferi and PCMZL found in North America or Asia.9,10 Helicobacter pylori has been associated with gastric mucosal-associated lymphatic tissue lymphoma, which responds well to antibiotic therapy. However, an association between PCMZL and H pylori has not been well described.11

Management—Several treatment modalities have been attempted in patients with PCMZL with varying efficacy. Given the rarity of this disease, there is no standard therapy. Treatment options include radiation therapy, excision, topical steroids, intralesional steroids, intralesional rituximab, and antibiotics.2,12-14 Case reports of pediatric patients have demonstrated improvement with excision,15-19 intralesional steroids,20,21 intralesional rituximab,22 and clobetasol cream.23,24 In asymptomatic patients, watchful waiting often is employed given the overall indolent nature of PCMZL. Antibiotic therapy may be favored in Borrelia-positive cases. However, even in B burgdorferi–negative patients, there have been cases where there is response to antibiotics, particularly doxycycline.2,15,25 We elected for a trial of doxycycline in our patient based on these prior reports, along with the overall favorable side-effect profile of doxycycline for adolescents and our patient’s widespread cutaneous involvement.