User login

Advocacy in Action: Meeting Congressman Gene Green

The hospital is often the intersection between a patient’s medical illness and their social and financial issues. As physicians, it is important to recognize that patient care encompasses not only prescribing medications and performing procedures but also practicing systems-based medicine; ensuring social and financial barriers do not impede access to, and delivery of, care. Some of these barriers cannot be eliminated by one individual practitioner; they can only be improved by working with government representatives and policy makers to make systemic changes. For gastroenterologists, advocacy involves educating patients, practitioners, and our government representatives about issues related to GI illnesses and the importance of ensuring access to GI specialty care and treatment for all patients who require it.

As physicians, we are uniquely positioned to represent the needs of our patients. We appreciate the AGA facilitating that voice by providing updates on legislation and coordinating meetings between senators and members of Congress and practicing gastroenterologists and GI fellows. These meetings are an important opportunity to network and share our experiences. Congressman Green was very interested to hear our perspectives as health care providers. It was enlightening to hear about his experiences on the Health Subcommittee and learn about its procedures. We would strongly encourage other AGA members to take advantage of this important program. n

Dr. Natarajan is assistant professor, Dr. Shukla is assistant professor, and Dr. Shapiro is a second-year fellow; all are in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

References

1. Ehrlich E. (2017). NIH’S Role in Sustaining the U.S. Economy. United for Medical Research. Accessed at http://www.unitedformedicalresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NIH-Role-in-the-Economy-FY2016.

2. AGA Position Statement on Research Funding. Accessed at http://www.gastro.org/take-action/top-issues/research-funding.

3. El-Serag H.B., Kanwal F., Davila J.A., Kramer J., Richardson P. A new laboratory-based algorithm to predict development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C and cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;May146(5):1249-55.

4. White D.L., Richardson P., Tayoub N., Davila J.A., Kanwal F., El-Serag H.B. The updated model: An adjusted serum alpha-fetoprotein-based algorithm for hepatocellular carcinoma detection with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2015;Dec 149(7):1986-7.

5. AGA Position Statement on Patient Cost-Sharing for Screening Colonoscopy. Accessed a: http://www.gastro.org/take-action/top-issues/patient-cost-sharing-for-screening-colonoscopy.

The hospital is often the intersection between a patient’s medical illness and their social and financial issues. As physicians, it is important to recognize that patient care encompasses not only prescribing medications and performing procedures but also practicing systems-based medicine; ensuring social and financial barriers do not impede access to, and delivery of, care. Some of these barriers cannot be eliminated by one individual practitioner; they can only be improved by working with government representatives and policy makers to make systemic changes. For gastroenterologists, advocacy involves educating patients, practitioners, and our government representatives about issues related to GI illnesses and the importance of ensuring access to GI specialty care and treatment for all patients who require it.

As physicians, we are uniquely positioned to represent the needs of our patients. We appreciate the AGA facilitating that voice by providing updates on legislation and coordinating meetings between senators and members of Congress and practicing gastroenterologists and GI fellows. These meetings are an important opportunity to network and share our experiences. Congressman Green was very interested to hear our perspectives as health care providers. It was enlightening to hear about his experiences on the Health Subcommittee and learn about its procedures. We would strongly encourage other AGA members to take advantage of this important program. n

Dr. Natarajan is assistant professor, Dr. Shukla is assistant professor, and Dr. Shapiro is a second-year fellow; all are in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

References

1. Ehrlich E. (2017). NIH’S Role in Sustaining the U.S. Economy. United for Medical Research. Accessed at http://www.unitedformedicalresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NIH-Role-in-the-Economy-FY2016.

2. AGA Position Statement on Research Funding. Accessed at http://www.gastro.org/take-action/top-issues/research-funding.

3. El-Serag H.B., Kanwal F., Davila J.A., Kramer J., Richardson P. A new laboratory-based algorithm to predict development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C and cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;May146(5):1249-55.

4. White D.L., Richardson P., Tayoub N., Davila J.A., Kanwal F., El-Serag H.B. The updated model: An adjusted serum alpha-fetoprotein-based algorithm for hepatocellular carcinoma detection with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2015;Dec 149(7):1986-7.

5. AGA Position Statement on Patient Cost-Sharing for Screening Colonoscopy. Accessed a: http://www.gastro.org/take-action/top-issues/patient-cost-sharing-for-screening-colonoscopy.

The hospital is often the intersection between a patient’s medical illness and their social and financial issues. As physicians, it is important to recognize that patient care encompasses not only prescribing medications and performing procedures but also practicing systems-based medicine; ensuring social and financial barriers do not impede access to, and delivery of, care. Some of these barriers cannot be eliminated by one individual practitioner; they can only be improved by working with government representatives and policy makers to make systemic changes. For gastroenterologists, advocacy involves educating patients, practitioners, and our government representatives about issues related to GI illnesses and the importance of ensuring access to GI specialty care and treatment for all patients who require it.

As physicians, we are uniquely positioned to represent the needs of our patients. We appreciate the AGA facilitating that voice by providing updates on legislation and coordinating meetings between senators and members of Congress and practicing gastroenterologists and GI fellows. These meetings are an important opportunity to network and share our experiences. Congressman Green was very interested to hear our perspectives as health care providers. It was enlightening to hear about his experiences on the Health Subcommittee and learn about its procedures. We would strongly encourage other AGA members to take advantage of this important program. n

Dr. Natarajan is assistant professor, Dr. Shukla is assistant professor, and Dr. Shapiro is a second-year fellow; all are in the section of gastroenterology and hepatology, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston.

References

1. Ehrlich E. (2017). NIH’S Role in Sustaining the U.S. Economy. United for Medical Research. Accessed at http://www.unitedformedicalresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NIH-Role-in-the-Economy-FY2016.

2. AGA Position Statement on Research Funding. Accessed at http://www.gastro.org/take-action/top-issues/research-funding.

3. El-Serag H.B., Kanwal F., Davila J.A., Kramer J., Richardson P. A new laboratory-based algorithm to predict development of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with hepatitis C and cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;May146(5):1249-55.

4. White D.L., Richardson P., Tayoub N., Davila J.A., Kanwal F., El-Serag H.B. The updated model: An adjusted serum alpha-fetoprotein-based algorithm for hepatocellular carcinoma detection with hepatitis C virus-related cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2015;Dec 149(7):1986-7.

5. AGA Position Statement on Patient Cost-Sharing for Screening Colonoscopy. Accessed a: http://www.gastro.org/take-action/top-issues/patient-cost-sharing-for-screening-colonoscopy.

Legal Issues for the Gastroenterologist: Part II

In the previous issue of The New Gastroenterologist, we discussed statistics and the basis on which most gastroenterologists are sued as well as what you can do to minimize this risk. In this second article, we discuss steps to assist in your defense in the event you have been sued. The following suggestions are based on our experience as defense attorneys who practice in the arena of medical malpractice.

Do not, under any circumstances, add or alter the plaintiff’s medical records. Although you have continued access to electronic medical records, accessing or altering these documents leaves an electronic trail. Attorneys are now frequently requesting an “audit trail” during discovery, which shows who and when someone accessed or altered relevant medical records. Additionally, it is likely that the plaintiff’s counsel has already obtained and reviewed records for their client. As such, counsel will notice any alterations and will require an explanation as to the same. If you did alter any medical records, it is important that you notify your attorney about the specifics of such.

After you have secured an attorney, it is critical that you arrange a meeting to develop a positive relationship early in the litigation process. This is important for many reasons. A medical malpractice case can be a long and arduous process which requires that you be involved with your attorney during the course of the litigation. For the attorney-client relationship to be successful, it is imperative that you know and feel comfortable with your attorney and develop confidence and trust in her. Without this trust, it will be difficult for you to accept various decisions or suggestions that the attorney believes are in your best interest. Conversely, the attorney should get to know you and understand your background, as this will assist in your representation.

A good relationship with you will also aid your attorney in educating herself on medical concepts relating to your case. Remember, your attorney most likely has not attended medical school and many of the medical concepts will initially be new to her. By the time trial arrives, however, your attorney will be very familiar with the medical issues in your case. This learning process can be expedited with your assistance and research.

Your deposition

At some point during the lawsuit, the plaintiff’s attorney will take your deposition. The plaintiff’s attorney will strive to obtain concessions that establish the standard of care, breach of the standard, causation, and damages. Your deposition is not the time for you to provide explanations. It is the time for you to concisely answer specific questions posed by counsel without volunteering any additional information. Ultimately, trials build on what occurs during depositions. Preparation is key. Be open to advice or criticisms from your lawyer. Try to eliminate any quirks or habits that interfere with the substance of your testimony or perceived credibility. A deposition is not a casual conversation, nor is it a test of your memory. Limit your answers to personal knowledge; never guess or speculate. If you do not know the answer to a question, or do not remember something, it is perfectly acceptable for you to say so. Only answer questions that you understand. You are allowed to ask the plaintiff’s counsel to repeat or rephrase questions.

Finally, and most importantly, always tell the truth. Discuss any anticipated issues or concerns with your lawyer before your deposition.

Preparing for trial

Conclusion

In summary, remember that there are things you can do both before and after you are sued to minimize litigation and its impact. As mentioned previously, before a lawsuit, and as a regular part of your practice, it is important that you stay current with medical advances, that you take the time to create a relationship with your patients involving quality communication, and that you thoroughly and legibly document all aspects of care provided. After a suit is filed against you, make sure you notify your insurer immediately, do not alter any records or discuss the case with anyone other than your lawyer or spouse, and do all you can to create a productive and honest relationship with your lawyer. This relationship will be invaluable as you do the difficult and time-consuming work of preparing for your deposition and trial, and it can help you endure and successfully navigate the litigation process.

The Importance of Follow-Up: Further Advice on How to Decrease the Risk of Being Sued

A common basis for establishing a malpractice liability claim against a physician is the failure to follow-up or track a patient’s test results. In today’s world, there is an increasing number of moving parts involved in any given patient’s care. A particular patient may treat with numerous physicians, all of whom use different record systems. Electronic medical record systems have made records more accessible and easier to track, but they also present a new set of challenges.

Every physician needs to determine how they plan to track test results. The ideal system would allow a physician to quickly get back any lab or diagnostic test that he or she orders. All staff members should know how the physician’s system works. Otherwise, test results might accidentally be filed before the physician reviews them or a miscommunication could prevent test results from being delivered. Whatever choice of system, it is key to follow and effectively use the program every time.

Additionally, it can be beneficial to let the patient know when he or she can expect to hear about their results, as failure to keep the patient reasonably informed can create a new set of patient concerns and anxiety. Ultimately, establishing a well-defined system for record-tracking can help physicians avoid malpractice liability claims because of a failure to follow-up.

In the previous issue of The New Gastroenterologist, we discussed statistics and the basis on which most gastroenterologists are sued as well as what you can do to minimize this risk. In this second article, we discuss steps to assist in your defense in the event you have been sued. The following suggestions are based on our experience as defense attorneys who practice in the arena of medical malpractice.

Do not, under any circumstances, add or alter the plaintiff’s medical records. Although you have continued access to electronic medical records, accessing or altering these documents leaves an electronic trail. Attorneys are now frequently requesting an “audit trail” during discovery, which shows who and when someone accessed or altered relevant medical records. Additionally, it is likely that the plaintiff’s counsel has already obtained and reviewed records for their client. As such, counsel will notice any alterations and will require an explanation as to the same. If you did alter any medical records, it is important that you notify your attorney about the specifics of such.

After you have secured an attorney, it is critical that you arrange a meeting to develop a positive relationship early in the litigation process. This is important for many reasons. A medical malpractice case can be a long and arduous process which requires that you be involved with your attorney during the course of the litigation. For the attorney-client relationship to be successful, it is imperative that you know and feel comfortable with your attorney and develop confidence and trust in her. Without this trust, it will be difficult for you to accept various decisions or suggestions that the attorney believes are in your best interest. Conversely, the attorney should get to know you and understand your background, as this will assist in your representation.

A good relationship with you will also aid your attorney in educating herself on medical concepts relating to your case. Remember, your attorney most likely has not attended medical school and many of the medical concepts will initially be new to her. By the time trial arrives, however, your attorney will be very familiar with the medical issues in your case. This learning process can be expedited with your assistance and research.

Your deposition

At some point during the lawsuit, the plaintiff’s attorney will take your deposition. The plaintiff’s attorney will strive to obtain concessions that establish the standard of care, breach of the standard, causation, and damages. Your deposition is not the time for you to provide explanations. It is the time for you to concisely answer specific questions posed by counsel without volunteering any additional information. Ultimately, trials build on what occurs during depositions. Preparation is key. Be open to advice or criticisms from your lawyer. Try to eliminate any quirks or habits that interfere with the substance of your testimony or perceived credibility. A deposition is not a casual conversation, nor is it a test of your memory. Limit your answers to personal knowledge; never guess or speculate. If you do not know the answer to a question, or do not remember something, it is perfectly acceptable for you to say so. Only answer questions that you understand. You are allowed to ask the plaintiff’s counsel to repeat or rephrase questions.

Finally, and most importantly, always tell the truth. Discuss any anticipated issues or concerns with your lawyer before your deposition.

Preparing for trial

Conclusion

In summary, remember that there are things you can do both before and after you are sued to minimize litigation and its impact. As mentioned previously, before a lawsuit, and as a regular part of your practice, it is important that you stay current with medical advances, that you take the time to create a relationship with your patients involving quality communication, and that you thoroughly and legibly document all aspects of care provided. After a suit is filed against you, make sure you notify your insurer immediately, do not alter any records or discuss the case with anyone other than your lawyer or spouse, and do all you can to create a productive and honest relationship with your lawyer. This relationship will be invaluable as you do the difficult and time-consuming work of preparing for your deposition and trial, and it can help you endure and successfully navigate the litigation process.

The Importance of Follow-Up: Further Advice on How to Decrease the Risk of Being Sued

A common basis for establishing a malpractice liability claim against a physician is the failure to follow-up or track a patient’s test results. In today’s world, there is an increasing number of moving parts involved in any given patient’s care. A particular patient may treat with numerous physicians, all of whom use different record systems. Electronic medical record systems have made records more accessible and easier to track, but they also present a new set of challenges.

Every physician needs to determine how they plan to track test results. The ideal system would allow a physician to quickly get back any lab or diagnostic test that he or she orders. All staff members should know how the physician’s system works. Otherwise, test results might accidentally be filed before the physician reviews them or a miscommunication could prevent test results from being delivered. Whatever choice of system, it is key to follow and effectively use the program every time.

Additionally, it can be beneficial to let the patient know when he or she can expect to hear about their results, as failure to keep the patient reasonably informed can create a new set of patient concerns and anxiety. Ultimately, establishing a well-defined system for record-tracking can help physicians avoid malpractice liability claims because of a failure to follow-up.

In the previous issue of The New Gastroenterologist, we discussed statistics and the basis on which most gastroenterologists are sued as well as what you can do to minimize this risk. In this second article, we discuss steps to assist in your defense in the event you have been sued. The following suggestions are based on our experience as defense attorneys who practice in the arena of medical malpractice.

Do not, under any circumstances, add or alter the plaintiff’s medical records. Although you have continued access to electronic medical records, accessing or altering these documents leaves an electronic trail. Attorneys are now frequently requesting an “audit trail” during discovery, which shows who and when someone accessed or altered relevant medical records. Additionally, it is likely that the plaintiff’s counsel has already obtained and reviewed records for their client. As such, counsel will notice any alterations and will require an explanation as to the same. If you did alter any medical records, it is important that you notify your attorney about the specifics of such.

After you have secured an attorney, it is critical that you arrange a meeting to develop a positive relationship early in the litigation process. This is important for many reasons. A medical malpractice case can be a long and arduous process which requires that you be involved with your attorney during the course of the litigation. For the attorney-client relationship to be successful, it is imperative that you know and feel comfortable with your attorney and develop confidence and trust in her. Without this trust, it will be difficult for you to accept various decisions or suggestions that the attorney believes are in your best interest. Conversely, the attorney should get to know you and understand your background, as this will assist in your representation.

A good relationship with you will also aid your attorney in educating herself on medical concepts relating to your case. Remember, your attorney most likely has not attended medical school and many of the medical concepts will initially be new to her. By the time trial arrives, however, your attorney will be very familiar with the medical issues in your case. This learning process can be expedited with your assistance and research.

Your deposition

At some point during the lawsuit, the plaintiff’s attorney will take your deposition. The plaintiff’s attorney will strive to obtain concessions that establish the standard of care, breach of the standard, causation, and damages. Your deposition is not the time for you to provide explanations. It is the time for you to concisely answer specific questions posed by counsel without volunteering any additional information. Ultimately, trials build on what occurs during depositions. Preparation is key. Be open to advice or criticisms from your lawyer. Try to eliminate any quirks or habits that interfere with the substance of your testimony or perceived credibility. A deposition is not a casual conversation, nor is it a test of your memory. Limit your answers to personal knowledge; never guess or speculate. If you do not know the answer to a question, or do not remember something, it is perfectly acceptable for you to say so. Only answer questions that you understand. You are allowed to ask the plaintiff’s counsel to repeat or rephrase questions.

Finally, and most importantly, always tell the truth. Discuss any anticipated issues or concerns with your lawyer before your deposition.

Preparing for trial

Conclusion

In summary, remember that there are things you can do both before and after you are sued to minimize litigation and its impact. As mentioned previously, before a lawsuit, and as a regular part of your practice, it is important that you stay current with medical advances, that you take the time to create a relationship with your patients involving quality communication, and that you thoroughly and legibly document all aspects of care provided. After a suit is filed against you, make sure you notify your insurer immediately, do not alter any records or discuss the case with anyone other than your lawyer or spouse, and do all you can to create a productive and honest relationship with your lawyer. This relationship will be invaluable as you do the difficult and time-consuming work of preparing for your deposition and trial, and it can help you endure and successfully navigate the litigation process.

The Importance of Follow-Up: Further Advice on How to Decrease the Risk of Being Sued

A common basis for establishing a malpractice liability claim against a physician is the failure to follow-up or track a patient’s test results. In today’s world, there is an increasing number of moving parts involved in any given patient’s care. A particular patient may treat with numerous physicians, all of whom use different record systems. Electronic medical record systems have made records more accessible and easier to track, but they also present a new set of challenges.

Every physician needs to determine how they plan to track test results. The ideal system would allow a physician to quickly get back any lab or diagnostic test that he or she orders. All staff members should know how the physician’s system works. Otherwise, test results might accidentally be filed before the physician reviews them or a miscommunication could prevent test results from being delivered. Whatever choice of system, it is key to follow and effectively use the program every time.

Additionally, it can be beneficial to let the patient know when he or she can expect to hear about their results, as failure to keep the patient reasonably informed can create a new set of patient concerns and anxiety. Ultimately, establishing a well-defined system for record-tracking can help physicians avoid malpractice liability claims because of a failure to follow-up.

The Light at the End of the Tunnel: Recent Advances in Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatograpy

Introduction

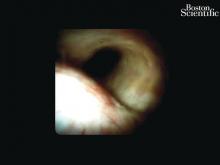

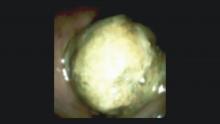

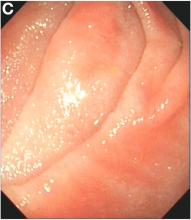

Direct visualization of the biliary ductal system is quickly gaining importance among gastroenterologists. Since the inception of cholangioscopy in the 1970s, the technology has progressed, allowing for ease of use, better visualization, and a growing number of indications. Conventional endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is successful for removal of bile duct stones (with success rates over 90%);1 however, its use in the evaluation of potential biliary neoplasia has been somewhat disappointing. The diagnostic yield of ERCP-guided biliary brushings can range from 30% to 40%.2-4 An alternative to ERCP-guided biliary brushings for biliary strictures is endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-directed fine needle aspiration (FNA), but the reported sensitivity remains poor, ranging from 43% to 77% with negative predictive values of less than 30%.5-7 These results leave much to be desired for diagnostic yield.

Clinical indications

DSOCP appears to have improved accuracy over fiberoptic equipment. In a recent multicenter observational study in patients undergoing digital cholangioscopy, the guided biopsies resulted in adequate tissue for histologic evaluation in 98% of patients. In addition, the sensitivity and specificity of digital cholangioscope-guided biopsies for diagnosis of malignancy was 85% and 100%, respectively.11

Other less common diagnostic indications for DSOCP include evaluation of cystic lesions of the biliary tract, verifying clearance of bile duct stones, bile duct ischemia evaluation after liver transplantation, hemobilia evaluation, removal of a bile duct foreign body, and evaluation of bile duct involvement in the presence of an ampullary adenoma.3,14,15,20,26,27

Risks and complications

Conclusions

Direct visualization of the biliary and pancreatic ductal system with fiber-optic and now digital-based platforms have greatly expanded the diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities available to gastroenterologists in the diagnosis and management of biliary and pancreatic disorders. The digital single-operator cholangiopancreatascope system offers greater diagnostic yield of pancreaticobiliary disorders over conventional diagnostic sampling techniques. In addition, direct visualization has expanded our therapeutic ability in complex stone disease allowing laser-based therapies that are not available with traditional fluoroscopic based techniques. Cholangiopancreatoscopic techniques and indications are rapidly expanding and will continue to expand the diagnostic and therapeutic armamentarium available to gastroenterologists.

Dr. Sonnier is a general gastroenterology fellow, division of gastroenterology, University of South Alabama. Dr. Mizrahi is director of advanced endoscopy, division of gastroenterology, University of South Alabama. Dr. Pleskow, is clinical chief, department of gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and associate professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Sonnier and Dr. Mizrahi have no conflicts of interest. Dr. Pleskow serves as a consultant to Boston Scientific.

References

1. Cohen S., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:803–9

2. Lee J.G., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:722-6.

3. De Bellis M., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:176-82

4. Fritcher E.G., et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2180-6.

5. Rosch T., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:390-6.

6. Byrne M.F., et al. Endoscopy. 2004;36:715-9.

7. DeWitt J., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:325-33.

8. Rosch W., Endoscopy. 1976;8:172-5.

9. Takekoshi T., Takagi K. Gastrointest Endosc. 1975;17:678-83.

10. Chen Y.K. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:303-11.

11. Navaneethan U., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;84:649-55.

12. Navaneethan U., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;82: 608-14.

13. Chen Y.K., Pleskow DK. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832-41.

14. Draganov P.V., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:971-9.

15. Ramchandani M., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:511-9.

16. Chen Y.K., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:805-14.

17. Draganov P.V., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:347-53.

18. Classen M., et al. Endoscopy 1988;20:21-6.

19. Parsi M.A., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;67:AB102.

20. Fishman D.S., et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1353-8.

21. Maydeo A., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1308-14.

22. Yamao K., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57:205-9.

23. Hara T., et al. Gastroenterology 2002;122:34-43.

24. Rösch T., et al. Endoscopy. 2002;34:765–71.

25. Bekkali N.L., et al. Pancreas. 2017;46:528-30.

26. Adwan H., et al. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:199-200.

27. Ransibrahmanakul K., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:e9.

28. Pereira P., et al. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis, June 2017;Vol. 26(No 2):165-70.

29. Kawakubo K., et al. Endoscopy 2011;43:E241-2.

Introduction

Direct visualization of the biliary ductal system is quickly gaining importance among gastroenterologists. Since the inception of cholangioscopy in the 1970s, the technology has progressed, allowing for ease of use, better visualization, and a growing number of indications. Conventional endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is successful for removal of bile duct stones (with success rates over 90%);1 however, its use in the evaluation of potential biliary neoplasia has been somewhat disappointing. The diagnostic yield of ERCP-guided biliary brushings can range from 30% to 40%.2-4 An alternative to ERCP-guided biliary brushings for biliary strictures is endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-directed fine needle aspiration (FNA), but the reported sensitivity remains poor, ranging from 43% to 77% with negative predictive values of less than 30%.5-7 These results leave much to be desired for diagnostic yield.

Clinical indications

DSOCP appears to have improved accuracy over fiberoptic equipment. In a recent multicenter observational study in patients undergoing digital cholangioscopy, the guided biopsies resulted in adequate tissue for histologic evaluation in 98% of patients. In addition, the sensitivity and specificity of digital cholangioscope-guided biopsies for diagnosis of malignancy was 85% and 100%, respectively.11

Other less common diagnostic indications for DSOCP include evaluation of cystic lesions of the biliary tract, verifying clearance of bile duct stones, bile duct ischemia evaluation after liver transplantation, hemobilia evaluation, removal of a bile duct foreign body, and evaluation of bile duct involvement in the presence of an ampullary adenoma.3,14,15,20,26,27

Risks and complications

Conclusions

Direct visualization of the biliary and pancreatic ductal system with fiber-optic and now digital-based platforms have greatly expanded the diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities available to gastroenterologists in the diagnosis and management of biliary and pancreatic disorders. The digital single-operator cholangiopancreatascope system offers greater diagnostic yield of pancreaticobiliary disorders over conventional diagnostic sampling techniques. In addition, direct visualization has expanded our therapeutic ability in complex stone disease allowing laser-based therapies that are not available with traditional fluoroscopic based techniques. Cholangiopancreatoscopic techniques and indications are rapidly expanding and will continue to expand the diagnostic and therapeutic armamentarium available to gastroenterologists.

Dr. Sonnier is a general gastroenterology fellow, division of gastroenterology, University of South Alabama. Dr. Mizrahi is director of advanced endoscopy, division of gastroenterology, University of South Alabama. Dr. Pleskow, is clinical chief, department of gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and associate professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Sonnier and Dr. Mizrahi have no conflicts of interest. Dr. Pleskow serves as a consultant to Boston Scientific.

References

1. Cohen S., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:803–9

2. Lee J.G., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:722-6.

3. De Bellis M., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:176-82

4. Fritcher E.G., et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2180-6.

5. Rosch T., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:390-6.

6. Byrne M.F., et al. Endoscopy. 2004;36:715-9.

7. DeWitt J., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:325-33.

8. Rosch W., Endoscopy. 1976;8:172-5.

9. Takekoshi T., Takagi K. Gastrointest Endosc. 1975;17:678-83.

10. Chen Y.K. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:303-11.

11. Navaneethan U., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;84:649-55.

12. Navaneethan U., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;82: 608-14.

13. Chen Y.K., Pleskow DK. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832-41.

14. Draganov P.V., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:971-9.

15. Ramchandani M., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:511-9.

16. Chen Y.K., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:805-14.

17. Draganov P.V., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:347-53.

18. Classen M., et al. Endoscopy 1988;20:21-6.

19. Parsi M.A., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;67:AB102.

20. Fishman D.S., et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1353-8.

21. Maydeo A., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1308-14.

22. Yamao K., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57:205-9.

23. Hara T., et al. Gastroenterology 2002;122:34-43.

24. Rösch T., et al. Endoscopy. 2002;34:765–71.

25. Bekkali N.L., et al. Pancreas. 2017;46:528-30.

26. Adwan H., et al. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:199-200.

27. Ransibrahmanakul K., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:e9.

28. Pereira P., et al. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis, June 2017;Vol. 26(No 2):165-70.

29. Kawakubo K., et al. Endoscopy 2011;43:E241-2.

Introduction

Direct visualization of the biliary ductal system is quickly gaining importance among gastroenterologists. Since the inception of cholangioscopy in the 1970s, the technology has progressed, allowing for ease of use, better visualization, and a growing number of indications. Conventional endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is successful for removal of bile duct stones (with success rates over 90%);1 however, its use in the evaluation of potential biliary neoplasia has been somewhat disappointing. The diagnostic yield of ERCP-guided biliary brushings can range from 30% to 40%.2-4 An alternative to ERCP-guided biliary brushings for biliary strictures is endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-directed fine needle aspiration (FNA), but the reported sensitivity remains poor, ranging from 43% to 77% with negative predictive values of less than 30%.5-7 These results leave much to be desired for diagnostic yield.

Clinical indications

DSOCP appears to have improved accuracy over fiberoptic equipment. In a recent multicenter observational study in patients undergoing digital cholangioscopy, the guided biopsies resulted in adequate tissue for histologic evaluation in 98% of patients. In addition, the sensitivity and specificity of digital cholangioscope-guided biopsies for diagnosis of malignancy was 85% and 100%, respectively.11

Other less common diagnostic indications for DSOCP include evaluation of cystic lesions of the biliary tract, verifying clearance of bile duct stones, bile duct ischemia evaluation after liver transplantation, hemobilia evaluation, removal of a bile duct foreign body, and evaluation of bile duct involvement in the presence of an ampullary adenoma.3,14,15,20,26,27

Risks and complications

Conclusions

Direct visualization of the biliary and pancreatic ductal system with fiber-optic and now digital-based platforms have greatly expanded the diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities available to gastroenterologists in the diagnosis and management of biliary and pancreatic disorders. The digital single-operator cholangiopancreatascope system offers greater diagnostic yield of pancreaticobiliary disorders over conventional diagnostic sampling techniques. In addition, direct visualization has expanded our therapeutic ability in complex stone disease allowing laser-based therapies that are not available with traditional fluoroscopic based techniques. Cholangiopancreatoscopic techniques and indications are rapidly expanding and will continue to expand the diagnostic and therapeutic armamentarium available to gastroenterologists.

Dr. Sonnier is a general gastroenterology fellow, division of gastroenterology, University of South Alabama. Dr. Mizrahi is director of advanced endoscopy, division of gastroenterology, University of South Alabama. Dr. Pleskow, is clinical chief, department of gastroenterology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and associate professor of medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Dr. Sonnier and Dr. Mizrahi have no conflicts of interest. Dr. Pleskow serves as a consultant to Boston Scientific.

References

1. Cohen S., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:803–9

2. Lee J.G., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:722-6.

3. De Bellis M., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:176-82

4. Fritcher E.G., et al. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2180-6.

5. Rosch T., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:390-6.

6. Byrne M.F., et al. Endoscopy. 2004;36:715-9.

7. DeWitt J., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:325-33.

8. Rosch W., Endoscopy. 1976;8:172-5.

9. Takekoshi T., Takagi K. Gastrointest Endosc. 1975;17:678-83.

10. Chen Y.K. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:303-11.

11. Navaneethan U., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;84:649-55.

12. Navaneethan U., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2015;82: 608-14.

13. Chen Y.K., Pleskow DK. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832-41.

14. Draganov P.V., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:971-9.

15. Ramchandani M., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:511-9.

16. Chen Y.K., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:805-14.

17. Draganov P.V., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:347-53.

18. Classen M., et al. Endoscopy 1988;20:21-6.

19. Parsi M.A., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2008;67:AB102.

20. Fishman D.S., et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1353-8.

21. Maydeo A., et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1308-14.

22. Yamao K., et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2003;57:205-9.

23. Hara T., et al. Gastroenterology 2002;122:34-43.

24. Rösch T., et al. Endoscopy. 2002;34:765–71.

25. Bekkali N.L., et al. Pancreas. 2017;46:528-30.

26. Adwan H., et al. Dig Endosc. 2011;23:199-200.

27. Ransibrahmanakul K., et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:e9.

28. Pereira P., et al. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis, June 2017;Vol. 26(No 2):165-70.

29. Kawakubo K., et al. Endoscopy 2011;43:E241-2.

An Unusual Cause of Recurrent Severe Abdominal Colic

We carefully reviewed the patient’s history and found that he had been using jineijin, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) drug, which is made with dried endothelium corneum gigeriae galli (Figure E), at about 500 g/month and squama mantis (a TCM drug, at less than 5 g/month) as dietary supplements for 3 years.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linshen Xie, MD, department of environmental health and occupational diseases, No. 4 West China Teaching Hospital, Sichuan University, for offering some clinical data. We thank the patient for giving permission to share his information.

References

1. National Research Council (US). Safe Drinking Water Committee. Drinking water and health. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C. 1977;1:309.

2. State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology. New World Press, Beijing. 1995. (vol. 2).

3. Hui Hu, Q.J., Kavan, P. A study of heavy metal pollution in China: Current status, pollution-control policies and countermeasures. Sustainability. 2014;6:5820-38.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit, Learning objective: Upon completion of this examination, successful learners will be able to identify the features of lead poisoning.

We carefully reviewed the patient’s history and found that he had been using jineijin, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) drug, which is made with dried endothelium corneum gigeriae galli (Figure E), at about 500 g/month and squama mantis (a TCM drug, at less than 5 g/month) as dietary supplements for 3 years.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linshen Xie, MD, department of environmental health and occupational diseases, No. 4 West China Teaching Hospital, Sichuan University, for offering some clinical data. We thank the patient for giving permission to share his information.

References

1. National Research Council (US). Safe Drinking Water Committee. Drinking water and health. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C. 1977;1:309.

2. State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology. New World Press, Beijing. 1995. (vol. 2).

3. Hui Hu, Q.J., Kavan, P. A study of heavy metal pollution in China: Current status, pollution-control policies and countermeasures. Sustainability. 2014;6:5820-38.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit, Learning objective: Upon completion of this examination, successful learners will be able to identify the features of lead poisoning.

We carefully reviewed the patient’s history and found that he had been using jineijin, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) drug, which is made with dried endothelium corneum gigeriae galli (Figure E), at about 500 g/month and squama mantis (a TCM drug, at less than 5 g/month) as dietary supplements for 3 years.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linshen Xie, MD, department of environmental health and occupational diseases, No. 4 West China Teaching Hospital, Sichuan University, for offering some clinical data. We thank the patient for giving permission to share his information.

References

1. National Research Council (US). Safe Drinking Water Committee. Drinking water and health. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C. 1977;1:309.

2. State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology. New World Press, Beijing. 1995. (vol. 2).

3. Hui Hu, Q.J., Kavan, P. A study of heavy metal pollution in China: Current status, pollution-control policies and countermeasures. Sustainability. 2014;6:5820-38.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit, Learning objective: Upon completion of this examination, successful learners will be able to identify the features of lead poisoning.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2016;151:819-21)

Dr. Deng, Dr. Hu, and Dr. Zhang are in the department of gastroenterology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Sichuan Province, China.

News from AGA

Advice on Achieving Work-Life Balance

Successfully maintaining a balance between your personal and professional lives is a difficult concept to grasp and practice to enforce. Is this thing called “work-life balance” within reach or just some elusive circumstance people talk about? The AGA Community Early Career Group was the hub for discussions on ways early-career gastroenterologists can modify their day-to-day approach to help prevent burnout.

We consolidated the advice and tips shared into a series of articles and resources to help students, trainees, and early career members get a little closer to balancing their work and professional lives. Here are some highlights:

Choose work-life “integration”

If your career and your personal life were a successful relationship, remember that it’s not always 50/50, and be sure to allow forgiveness and reparation when needed.

Maternity leave

When it comes to starting a family, think about your current training or career climate and how you can make it work. Be transparent with your supervisor so there aren’t any surprises, and plans can be made in advance to cover for your time away. Prepare to be flexible from the beginning.

Learn when to say “no”

Saying “yes” to too many things not only leads to overextending yourself beyond your capabilities, but you could also be losing time on what is important to you. Choose one night a week when you can work late – pack a snack, and give yourself a hard stop the rest of the week. Keep patient documentation as a daytime/work task.

Communication is key

When your partner or spouse is just as busy, it’s important to keep a joint calendar up to date and make plans far in advance. Also, create a routine: Try making time once a month to discuss calendars and anticipated events, face-to-face. When life throws a divot in your path, don’t lose sight of your priorities.

Make time for family and friends

Your career can take over as much of your life as you will allow. Making time for family and friends is rewarding and vacations, staycations, long weekends or even day trips can be great “resets.”

View the tip sheet and other work-life balance resources in the AGA Community Early Career Group library at http://community.gastro.org/WorkLife.

New Clinical Guidelines and Practice Updates

The latest AGA Clinical Practice Guideline, published in Gastroenterology, is on the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the management of IBD. It focuses on the application of TDM for biologic therapy, specifically anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) agents, and for thiopurines, and addresses questions on the risks and benefits of reactive TDM, routine proactive TDM, or no TDM in guiding treatment changes.

View the full guideline, technical review, and patient guide at www.gastro.org/guidelines.

In addition to guidelines, please check out the most recent Clinical Practice Updates (CPU) in Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (CGH), which are often accompanied by a practice quiz from one of the authors, via the AGA Community. Visit http://community.gastro.org/guidelinecpu to test your knowledge. The most recent CPU, published in the September issue of CGH, focuses on GI side effects related to opioid medications.

Be Part of the Meeting to Transform IBD

If you treat patients with inflammatory bowel disease, conduct IBD research, or plan to pursue a career in IBD, join us for the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress™, taking place Jan. 18-20, 2018, in Las Vegas, NV. The Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation (formerly CCFA) and AGA have joined together to develop a must-attend program for the entire IBD care team. Expand your knowledge, network with your peers as well as IBD leaders across multiple disciplines, and get inspired to improve care for patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

You may also be interested in the free precongress workshop – The Lloyd Mayer, MD, Young IBD Investigators Clinical, Basic, and Translational Research Workshop. This half-day precongress workshop is targeted to early-career clinical, basic, and translational researchers as well as senior researchers and will feature a mix of research presentations by young investigator colleagues, keynote presentations, and panel discussion, featuring established IBD researchers. The theme this year is focused around grant proposals and will include two mock grant review sessions.

Learn more about the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress and register: http://crohnscolitiscongress.org.

Advice on Achieving Work-Life Balance

Successfully maintaining a balance between your personal and professional lives is a difficult concept to grasp and practice to enforce. Is this thing called “work-life balance” within reach or just some elusive circumstance people talk about? The AGA Community Early Career Group was the hub for discussions on ways early-career gastroenterologists can modify their day-to-day approach to help prevent burnout.

We consolidated the advice and tips shared into a series of articles and resources to help students, trainees, and early career members get a little closer to balancing their work and professional lives. Here are some highlights:

Choose work-life “integration”

If your career and your personal life were a successful relationship, remember that it’s not always 50/50, and be sure to allow forgiveness and reparation when needed.

Maternity leave

When it comes to starting a family, think about your current training or career climate and how you can make it work. Be transparent with your supervisor so there aren’t any surprises, and plans can be made in advance to cover for your time away. Prepare to be flexible from the beginning.

Learn when to say “no”

Saying “yes” to too many things not only leads to overextending yourself beyond your capabilities, but you could also be losing time on what is important to you. Choose one night a week when you can work late – pack a snack, and give yourself a hard stop the rest of the week. Keep patient documentation as a daytime/work task.

Communication is key

When your partner or spouse is just as busy, it’s important to keep a joint calendar up to date and make plans far in advance. Also, create a routine: Try making time once a month to discuss calendars and anticipated events, face-to-face. When life throws a divot in your path, don’t lose sight of your priorities.

Make time for family and friends

Your career can take over as much of your life as you will allow. Making time for family and friends is rewarding and vacations, staycations, long weekends or even day trips can be great “resets.”

View the tip sheet and other work-life balance resources in the AGA Community Early Career Group library at http://community.gastro.org/WorkLife.

New Clinical Guidelines and Practice Updates

The latest AGA Clinical Practice Guideline, published in Gastroenterology, is on the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the management of IBD. It focuses on the application of TDM for biologic therapy, specifically anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) agents, and for thiopurines, and addresses questions on the risks and benefits of reactive TDM, routine proactive TDM, or no TDM in guiding treatment changes.

View the full guideline, technical review, and patient guide at www.gastro.org/guidelines.

In addition to guidelines, please check out the most recent Clinical Practice Updates (CPU) in Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (CGH), which are often accompanied by a practice quiz from one of the authors, via the AGA Community. Visit http://community.gastro.org/guidelinecpu to test your knowledge. The most recent CPU, published in the September issue of CGH, focuses on GI side effects related to opioid medications.

Be Part of the Meeting to Transform IBD

If you treat patients with inflammatory bowel disease, conduct IBD research, or plan to pursue a career in IBD, join us for the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress™, taking place Jan. 18-20, 2018, in Las Vegas, NV. The Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation (formerly CCFA) and AGA have joined together to develop a must-attend program for the entire IBD care team. Expand your knowledge, network with your peers as well as IBD leaders across multiple disciplines, and get inspired to improve care for patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

You may also be interested in the free precongress workshop – The Lloyd Mayer, MD, Young IBD Investigators Clinical, Basic, and Translational Research Workshop. This half-day precongress workshop is targeted to early-career clinical, basic, and translational researchers as well as senior researchers and will feature a mix of research presentations by young investigator colleagues, keynote presentations, and panel discussion, featuring established IBD researchers. The theme this year is focused around grant proposals and will include two mock grant review sessions.

Learn more about the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress and register: http://crohnscolitiscongress.org.

Advice on Achieving Work-Life Balance

Successfully maintaining a balance between your personal and professional lives is a difficult concept to grasp and practice to enforce. Is this thing called “work-life balance” within reach or just some elusive circumstance people talk about? The AGA Community Early Career Group was the hub for discussions on ways early-career gastroenterologists can modify their day-to-day approach to help prevent burnout.

We consolidated the advice and tips shared into a series of articles and resources to help students, trainees, and early career members get a little closer to balancing their work and professional lives. Here are some highlights:

Choose work-life “integration”

If your career and your personal life were a successful relationship, remember that it’s not always 50/50, and be sure to allow forgiveness and reparation when needed.

Maternity leave

When it comes to starting a family, think about your current training or career climate and how you can make it work. Be transparent with your supervisor so there aren’t any surprises, and plans can be made in advance to cover for your time away. Prepare to be flexible from the beginning.

Learn when to say “no”

Saying “yes” to too many things not only leads to overextending yourself beyond your capabilities, but you could also be losing time on what is important to you. Choose one night a week when you can work late – pack a snack, and give yourself a hard stop the rest of the week. Keep patient documentation as a daytime/work task.

Communication is key

When your partner or spouse is just as busy, it’s important to keep a joint calendar up to date and make plans far in advance. Also, create a routine: Try making time once a month to discuss calendars and anticipated events, face-to-face. When life throws a divot in your path, don’t lose sight of your priorities.

Make time for family and friends

Your career can take over as much of your life as you will allow. Making time for family and friends is rewarding and vacations, staycations, long weekends or even day trips can be great “resets.”

View the tip sheet and other work-life balance resources in the AGA Community Early Career Group library at http://community.gastro.org/WorkLife.

New Clinical Guidelines and Practice Updates

The latest AGA Clinical Practice Guideline, published in Gastroenterology, is on the role of therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) in the management of IBD. It focuses on the application of TDM for biologic therapy, specifically anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) agents, and for thiopurines, and addresses questions on the risks and benefits of reactive TDM, routine proactive TDM, or no TDM in guiding treatment changes.

View the full guideline, technical review, and patient guide at www.gastro.org/guidelines.

In addition to guidelines, please check out the most recent Clinical Practice Updates (CPU) in Gastroenterology and Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (CGH), which are often accompanied by a practice quiz from one of the authors, via the AGA Community. Visit http://community.gastro.org/guidelinecpu to test your knowledge. The most recent CPU, published in the September issue of CGH, focuses on GI side effects related to opioid medications.

Be Part of the Meeting to Transform IBD

If you treat patients with inflammatory bowel disease, conduct IBD research, or plan to pursue a career in IBD, join us for the inaugural Crohn’s & Colitis Congress™, taking place Jan. 18-20, 2018, in Las Vegas, NV. The Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation (formerly CCFA) and AGA have joined together to develop a must-attend program for the entire IBD care team. Expand your knowledge, network with your peers as well as IBD leaders across multiple disciplines, and get inspired to improve care for patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.

You may also be interested in the free precongress workshop – The Lloyd Mayer, MD, Young IBD Investigators Clinical, Basic, and Translational Research Workshop. This half-day precongress workshop is targeted to early-career clinical, basic, and translational researchers as well as senior researchers and will feature a mix of research presentations by young investigator colleagues, keynote presentations, and panel discussion, featuring established IBD researchers. The theme this year is focused around grant proposals and will include two mock grant review sessions.

Learn more about the Crohn’s & Colitis Congress and register: http://crohnscolitiscongress.org.

Cholangiopancreatoscopy

Dear Colleagues,

In this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, the feature article examines recent advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy. In this article, William Sonnier, Meir Mizrahi (University of South Alabama), and Douglas Pleskow (Beth Israel Deaconess) provide a fantastic overview of the technologic advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy as well as the clinical indications for this procedure and the risks involved. Also in this issue, Deborah Fisher (Duke University) and Darrell Gray (Ohio State University) provide advice about how to appropriately and responsibly handle social media. This is an incredibly important topic, given the increasing pervasiveness of social media in many aspects of our personal and professional lives.

Finally, in this issue is the second part in a series on legal issues for gastroenterologists. In this article, which is again authored by a very experienced group of attorneys, many important issues are covered, including what steps should be taken if you are sued, what you should and should not do after being sued, as well as tips on how to best prepare for both deposition and trial.

If there are topics that you would be interested in writing or hearing about in The New Gastroenterologist, please let us know. You can contact me ([email protected]) or the Managing Editor of The New Gastroenterologist, Ryan Farrell ([email protected]).

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Bryson W. Katona is an instructor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dear Colleagues,

In this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, the feature article examines recent advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy. In this article, William Sonnier, Meir Mizrahi (University of South Alabama), and Douglas Pleskow (Beth Israel Deaconess) provide a fantastic overview of the technologic advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy as well as the clinical indications for this procedure and the risks involved. Also in this issue, Deborah Fisher (Duke University) and Darrell Gray (Ohio State University) provide advice about how to appropriately and responsibly handle social media. This is an incredibly important topic, given the increasing pervasiveness of social media in many aspects of our personal and professional lives.

Finally, in this issue is the second part in a series on legal issues for gastroenterologists. In this article, which is again authored by a very experienced group of attorneys, many important issues are covered, including what steps should be taken if you are sued, what you should and should not do after being sued, as well as tips on how to best prepare for both deposition and trial.

If there are topics that you would be interested in writing or hearing about in The New Gastroenterologist, please let us know. You can contact me ([email protected]) or the Managing Editor of The New Gastroenterologist, Ryan Farrell ([email protected]).

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Bryson W. Katona is an instructor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Dear Colleagues,

In this issue of The New Gastroenterologist, the feature article examines recent advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy. In this article, William Sonnier, Meir Mizrahi (University of South Alabama), and Douglas Pleskow (Beth Israel Deaconess) provide a fantastic overview of the technologic advances in the field of cholangiopancreatoscopy as well as the clinical indications for this procedure and the risks involved. Also in this issue, Deborah Fisher (Duke University) and Darrell Gray (Ohio State University) provide advice about how to appropriately and responsibly handle social media. This is an incredibly important topic, given the increasing pervasiveness of social media in many aspects of our personal and professional lives.

Finally, in this issue is the second part in a series on legal issues for gastroenterologists. In this article, which is again authored by a very experienced group of attorneys, many important issues are covered, including what steps should be taken if you are sued, what you should and should not do after being sued, as well as tips on how to best prepare for both deposition and trial.

If there are topics that you would be interested in writing or hearing about in The New Gastroenterologist, please let us know. You can contact me ([email protected]) or the Managing Editor of The New Gastroenterologist, Ryan Farrell ([email protected]).

Sincerely,

Bryson W. Katona, MD, PhD

Editor in Chief

Bryson W. Katona is an instructor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Pennsylvania.

Nanocarriers could treat leukemia, lymphoma and improve HSCT

Researchers say they have created nanoparticles loaded with messenger RNA (mRNA) that can give cells the ability to fight cancers and other diseases.

To use these freeze-dried nanocarriers, the team added water and introduced the resulting mixture to cells.

The nanocarriers were able to target T cells and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), delivering mRNA directly to the cells and triggering short-term gene expression.

The T cells were then able to fight leukemia and lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. And the HSCs demonstrated improvements in growth and regenerative potential.

Matthias Stephan, MD, PhD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

“We developed a nanocarrier that binds and condenses synthetic mRNA and protects it from degradation,” Dr Stephan said.

The researchers surrounded the nanocarrier with a negatively charged envelope with a targeting ligand attached to the surface so the carrier homes and binds to a particular cell type. When this happens, the cell engulfs the carrier, which can be loaded with different types of manmade mRNA.

The researchers mixed the freeze-dried nanocarriers with water and samples of cells. Within 4 hours, cells started showing signs that editing had taken effect.

The team noted that boosters can be given if needed. And the nanocarriers are made from a dissolving biomaterial, so they are removed from the body like other cell waste.

Testing the carriers

Dr Stephan and his colleagues tested their nanocarriers in 3 ways.

First, the researchers tested nanoparticles carrying a gene-editing tool to T cells that snipped out their natural T-cell receptors and was paired with genes encoding a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR).

The resulting CAR T cells maintained their ability to proliferate and successfully eliminated leukemia cells.

Next, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to CAR T cells and containing foxo1 mRNA. This prompted the T cells to develop into a type of memory cell with enhanced antitumor activity.

The team found these CAR T cells induced “substantial disease regression” and prolonged survival in a mouse model of B-cell lymphoma.

Finally, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to HSCs. The carriers were equipped with mRNA that “induced key regulators of self-renewal,” accelerating the growth and regenerative potential of the HSCs in vitro.

Future possibilities

Dr Stephan and his colleagues noted that these nanocarriers are built on existing technology and can be used by individuals without knowledge of nanotechnology. Therefore, the team hopes the nanocarriers will be an off-the-shelf way for cell-therapy engineers to develop new approaches to treat diseases.

The researchers believe the nanocarriers could replace electroporation, a multistep cell-manufacturing technique that requires specialized equipment and clean rooms. The team noted that up to 60 times more cells survive the introduction of the nanocarriers than survive electroporation.

“You can imagine taking the nanoparticles, injecting them into a patient, and then you don’t have to culture cells at all anymore,” Dr Stephan said.

He is now looking for commercial partners to move the technology toward additional applications and into clinical trials. ![]()

Researchers say they have created nanoparticles loaded with messenger RNA (mRNA) that can give cells the ability to fight cancers and other diseases.

To use these freeze-dried nanocarriers, the team added water and introduced the resulting mixture to cells.

The nanocarriers were able to target T cells and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), delivering mRNA directly to the cells and triggering short-term gene expression.

The T cells were then able to fight leukemia and lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. And the HSCs demonstrated improvements in growth and regenerative potential.

Matthias Stephan, MD, PhD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

“We developed a nanocarrier that binds and condenses synthetic mRNA and protects it from degradation,” Dr Stephan said.

The researchers surrounded the nanocarrier with a negatively charged envelope with a targeting ligand attached to the surface so the carrier homes and binds to a particular cell type. When this happens, the cell engulfs the carrier, which can be loaded with different types of manmade mRNA.

The researchers mixed the freeze-dried nanocarriers with water and samples of cells. Within 4 hours, cells started showing signs that editing had taken effect.

The team noted that boosters can be given if needed. And the nanocarriers are made from a dissolving biomaterial, so they are removed from the body like other cell waste.

Testing the carriers

Dr Stephan and his colleagues tested their nanocarriers in 3 ways.

First, the researchers tested nanoparticles carrying a gene-editing tool to T cells that snipped out their natural T-cell receptors and was paired with genes encoding a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR).

The resulting CAR T cells maintained their ability to proliferate and successfully eliminated leukemia cells.

Next, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to CAR T cells and containing foxo1 mRNA. This prompted the T cells to develop into a type of memory cell with enhanced antitumor activity.

The team found these CAR T cells induced “substantial disease regression” and prolonged survival in a mouse model of B-cell lymphoma.

Finally, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to HSCs. The carriers were equipped with mRNA that “induced key regulators of self-renewal,” accelerating the growth and regenerative potential of the HSCs in vitro.

Future possibilities

Dr Stephan and his colleagues noted that these nanocarriers are built on existing technology and can be used by individuals without knowledge of nanotechnology. Therefore, the team hopes the nanocarriers will be an off-the-shelf way for cell-therapy engineers to develop new approaches to treat diseases.

The researchers believe the nanocarriers could replace electroporation, a multistep cell-manufacturing technique that requires specialized equipment and clean rooms. The team noted that up to 60 times more cells survive the introduction of the nanocarriers than survive electroporation.

“You can imagine taking the nanoparticles, injecting them into a patient, and then you don’t have to culture cells at all anymore,” Dr Stephan said.

He is now looking for commercial partners to move the technology toward additional applications and into clinical trials. ![]()

Researchers say they have created nanoparticles loaded with messenger RNA (mRNA) that can give cells the ability to fight cancers and other diseases.

To use these freeze-dried nanocarriers, the team added water and introduced the resulting mixture to cells.

The nanocarriers were able to target T cells and hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), delivering mRNA directly to the cells and triggering short-term gene expression.

The T cells were then able to fight leukemia and lymphoma in vitro and in vivo. And the HSCs demonstrated improvements in growth and regenerative potential.

Matthias Stephan, MD, PhD, of Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues described this research in Nature Communications.

“We developed a nanocarrier that binds and condenses synthetic mRNA and protects it from degradation,” Dr Stephan said.

The researchers surrounded the nanocarrier with a negatively charged envelope with a targeting ligand attached to the surface so the carrier homes and binds to a particular cell type. When this happens, the cell engulfs the carrier, which can be loaded with different types of manmade mRNA.

The researchers mixed the freeze-dried nanocarriers with water and samples of cells. Within 4 hours, cells started showing signs that editing had taken effect.

The team noted that boosters can be given if needed. And the nanocarriers are made from a dissolving biomaterial, so they are removed from the body like other cell waste.

Testing the carriers

Dr Stephan and his colleagues tested their nanocarriers in 3 ways.

First, the researchers tested nanoparticles carrying a gene-editing tool to T cells that snipped out their natural T-cell receptors and was paired with genes encoding a chimeric antigen receptor (CAR).

The resulting CAR T cells maintained their ability to proliferate and successfully eliminated leukemia cells.

Next, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to CAR T cells and containing foxo1 mRNA. This prompted the T cells to develop into a type of memory cell with enhanced antitumor activity.

The team found these CAR T cells induced “substantial disease regression” and prolonged survival in a mouse model of B-cell lymphoma.

Finally, the researchers tested nanocarriers targeted to HSCs. The carriers were equipped with mRNA that “induced key regulators of self-renewal,” accelerating the growth and regenerative potential of the HSCs in vitro.

Future possibilities

Dr Stephan and his colleagues noted that these nanocarriers are built on existing technology and can be used by individuals without knowledge of nanotechnology. Therefore, the team hopes the nanocarriers will be an off-the-shelf way for cell-therapy engineers to develop new approaches to treat diseases.

The researchers believe the nanocarriers could replace electroporation, a multistep cell-manufacturing technique that requires specialized equipment and clean rooms. The team noted that up to 60 times more cells survive the introduction of the nanocarriers than survive electroporation.

“You can imagine taking the nanoparticles, injecting them into a patient, and then you don’t have to culture cells at all anymore,” Dr Stephan said.

He is now looking for commercial partners to move the technology toward additional applications and into clinical trials. ![]()

FDA warns about risk of death with pembrolizumab in MM

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a statement warning about an increased risk of death associated with an unapproved use of pembrolizumab (Keytruda).

Results from 2 clinical trials have shown that combining pembrolizumab with dexamethasone and an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide or pomalidomide) increases the risk of death in patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The FDA issued its statement to remind doctors and patients that pembrolizumab is not approved to treat MM and should not be given in combination with immunomodulatory agents to treat MM.

Pembrolizumab is currently FDA-approved to treat classical Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma, lung cancer, head and neck cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability-high cancer.

The FDA believes the benefits of taking pembrolizumab and other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for their approved uses continue to outweigh the risks, according to Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

However, the FDA is investigating trials of pembrolizumab as well as trials of other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Pembrolizumab in MM

The FDA’s warning is based on a review of data from 2 clinical trials—KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185. The FDA placed a clinical hold on these trials—as well as KEYNOTE-023—in July.

KEYNOTE-183 is a phase 3 study of pomalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, given with or without pembrolizumab, to patients with refractory or relapsed and refractory MM.

KEYNOTE-185 is a phase 3 study of lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone, given with or without pembrolizumab, to patients with newly diagnosed and treatment-naïve MM.

KEYNOTE-023 is a phase 1 trial of pembrolizumab in combination with backbone treatments. Cohort 1 of this trial was designed to evaluate pembrolizumab in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in MM patients who received prior treatment with an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide, pomalidomide, or thalidomide).

Interim results from KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185 revealed an increased risk of death for patients receiving pembrolizumab, when compared to patients receiving the control therapies.

Merck & Co., Inc., the company developing pembrolizumab, was informed of this risk by an external data monitoring committee. The company suspended enrollment in the trials and notified the FDA of the issue in June.

The following month, the FDA announced that all patients enrolled in KEYNOTE-183 and KEYNOTE-185, as well as patients in the pembrolizumab/lenalidomide/dexamethasone cohort of KEYNOTE-023, would discontinue investigational treatment with pembrolizumab.

FDA investigation

The FDA is examining data from the pembrolizumab trials and working with Merck to better understand the cause of the safety concerns, according to Woodcock.

The agency is also working with sponsors of other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to examine other trials in which these drugs are being studied in combination with immunomodulatory agents and trials in which the inhibitors are being studied in combination with other classes of drugs in patients with hematologic malignancies.

Woodcock said the FDA will take appropriate action as warranted to ensure patients enrolled in these trials are protected and that doctors and researchers understand the risks associated with this investigational use.

The agency is also encouraging healthcare professionals and consumers to report any adverse events or side effects related to the use of pembrolizumab and other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors to FDA’s MedWatch Adverse Event Reporting Program. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued a statement warning about an increased risk of death associated with an unapproved use of pembrolizumab (Keytruda).

Results from 2 clinical trials have shown that combining pembrolizumab with dexamethasone and an immunomodulatory agent (lenalidomide or pomalidomide) increases the risk of death in patients with multiple myeloma (MM).

The FDA issued its statement to remind doctors and patients that pembrolizumab is not approved to treat MM and should not be given in combination with immunomodulatory agents to treat MM.

Pembrolizumab is currently FDA-approved to treat classical Hodgkin lymphoma, melanoma, lung cancer, head and neck cancer, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability-high cancer.

The FDA believes the benefits of taking pembrolizumab and other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors for their approved uses continue to outweigh the risks, according to Janet Woodcock, director of the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research.

However, the FDA is investigating trials of pembrolizumab as well as trials of other PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.

Pembrolizumab in MM