User login

Practice Makes Perfect?

It is human nature to practice things that we are already good at doing. If you’re a golfer, then you know what I’m talking about. I hit the driver over and over again on the range, but never practice hitting the bad lie in the bunker, or the half-swing wedge from a tight lie. I sink hundreds of 3 footers, but can’t putt into this range from 50 feet. I’ve gotten much better at golf since I started playing, but my scores have hardly gone down.

I think a similar thing happens in our orthopedic practices. I read everything I can on the anterior cruciate ligament, yet I already feel comfortable with my reconstruction technique. I skim, or avoid reading altogether, articles about topics I don’t like to treat, like the hand or spine. Yet, I still see these things every day in my practice and on call. If my depth of knowledge in these areas was as good as it is in sports medicine, I could provide better, more immediate care to my patients, rather than refer them to subspecialists.

A perfect orthopedic example would be the patellofemoral joint. One of the least enjoyable patient encounters for me is the young adult with normal alignment and intractable anterior knee pain that does not respond to nonoperative treatment. I’m concerned any surgical intervention may make them worse and I’m often left without much to offer the patient.

It’s for this reason AJO has partnered with Dr. Jack Farr to produce the patellofemoral issue; to provide a comprehensive guide to the latest thinking in the treatment of patellofemoral disorders (see the March/April 2017 issue). We solicited so much outstanding content, that a single issue could not hold all of the articles. In this issue, our patellofemoral series continues with 3 outstanding articles. Magnussen presents "Patella Alta Sees You, Do You See It?" and Hinckel and colleagues have authored a guide to patellofemoral cartilage restoration. Unal and colleagues follow-up with a review of the lateral retinaculum.

In our "Codes to Know" section, we reexamine diagnostic arthroscopy, a code most of us have billed infrequently. New technologies, however, have made it possible to peer into the joint in the office, and McMillan and colleagues teach us how to make it economically feasible, even for employed physicians.

Finally, we have a number of great articles on difficult problems—the stiff elbow, complex distal radius fractures, and intraoperative acetabular fractures during total hip arthroplasty.

Please enjoy this issue and think about what topics you tend to shy away from. I’m willing to bet you can add the most to your practice by studying up on these topics. As always, please provide your feedback to our editorial team so that we can continue to make improvements to our journal. We envision a change in the way orthopedists utilize a journal in their practice, and are continuously looking for ways to make AJO a more relevant tool for improving your patient care and workflow. We are working hard to give our readers the journal they deserve, but in my spare time, I’ll be brushing up on trochleoplasties and half-swing wedges.

It is human nature to practice things that we are already good at doing. If you’re a golfer, then you know what I’m talking about. I hit the driver over and over again on the range, but never practice hitting the bad lie in the bunker, or the half-swing wedge from a tight lie. I sink hundreds of 3 footers, but can’t putt into this range from 50 feet. I’ve gotten much better at golf since I started playing, but my scores have hardly gone down.

I think a similar thing happens in our orthopedic practices. I read everything I can on the anterior cruciate ligament, yet I already feel comfortable with my reconstruction technique. I skim, or avoid reading altogether, articles about topics I don’t like to treat, like the hand or spine. Yet, I still see these things every day in my practice and on call. If my depth of knowledge in these areas was as good as it is in sports medicine, I could provide better, more immediate care to my patients, rather than refer them to subspecialists.

A perfect orthopedic example would be the patellofemoral joint. One of the least enjoyable patient encounters for me is the young adult with normal alignment and intractable anterior knee pain that does not respond to nonoperative treatment. I’m concerned any surgical intervention may make them worse and I’m often left without much to offer the patient.

It’s for this reason AJO has partnered with Dr. Jack Farr to produce the patellofemoral issue; to provide a comprehensive guide to the latest thinking in the treatment of patellofemoral disorders (see the March/April 2017 issue). We solicited so much outstanding content, that a single issue could not hold all of the articles. In this issue, our patellofemoral series continues with 3 outstanding articles. Magnussen presents "Patella Alta Sees You, Do You See It?" and Hinckel and colleagues have authored a guide to patellofemoral cartilage restoration. Unal and colleagues follow-up with a review of the lateral retinaculum.

In our "Codes to Know" section, we reexamine diagnostic arthroscopy, a code most of us have billed infrequently. New technologies, however, have made it possible to peer into the joint in the office, and McMillan and colleagues teach us how to make it economically feasible, even for employed physicians.

Finally, we have a number of great articles on difficult problems—the stiff elbow, complex distal radius fractures, and intraoperative acetabular fractures during total hip arthroplasty.

Please enjoy this issue and think about what topics you tend to shy away from. I’m willing to bet you can add the most to your practice by studying up on these topics. As always, please provide your feedback to our editorial team so that we can continue to make improvements to our journal. We envision a change in the way orthopedists utilize a journal in their practice, and are continuously looking for ways to make AJO a more relevant tool for improving your patient care and workflow. We are working hard to give our readers the journal they deserve, but in my spare time, I’ll be brushing up on trochleoplasties and half-swing wedges.

It is human nature to practice things that we are already good at doing. If you’re a golfer, then you know what I’m talking about. I hit the driver over and over again on the range, but never practice hitting the bad lie in the bunker, or the half-swing wedge from a tight lie. I sink hundreds of 3 footers, but can’t putt into this range from 50 feet. I’ve gotten much better at golf since I started playing, but my scores have hardly gone down.

I think a similar thing happens in our orthopedic practices. I read everything I can on the anterior cruciate ligament, yet I already feel comfortable with my reconstruction technique. I skim, or avoid reading altogether, articles about topics I don’t like to treat, like the hand or spine. Yet, I still see these things every day in my practice and on call. If my depth of knowledge in these areas was as good as it is in sports medicine, I could provide better, more immediate care to my patients, rather than refer them to subspecialists.

A perfect orthopedic example would be the patellofemoral joint. One of the least enjoyable patient encounters for me is the young adult with normal alignment and intractable anterior knee pain that does not respond to nonoperative treatment. I’m concerned any surgical intervention may make them worse and I’m often left without much to offer the patient.

It’s for this reason AJO has partnered with Dr. Jack Farr to produce the patellofemoral issue; to provide a comprehensive guide to the latest thinking in the treatment of patellofemoral disorders (see the March/April 2017 issue). We solicited so much outstanding content, that a single issue could not hold all of the articles. In this issue, our patellofemoral series continues with 3 outstanding articles. Magnussen presents "Patella Alta Sees You, Do You See It?" and Hinckel and colleagues have authored a guide to patellofemoral cartilage restoration. Unal and colleagues follow-up with a review of the lateral retinaculum.

In our "Codes to Know" section, we reexamine diagnostic arthroscopy, a code most of us have billed infrequently. New technologies, however, have made it possible to peer into the joint in the office, and McMillan and colleagues teach us how to make it economically feasible, even for employed physicians.

Finally, we have a number of great articles on difficult problems—the stiff elbow, complex distal radius fractures, and intraoperative acetabular fractures during total hip arthroplasty.

Please enjoy this issue and think about what topics you tend to shy away from. I’m willing to bet you can add the most to your practice by studying up on these topics. As always, please provide your feedback to our editorial team so that we can continue to make improvements to our journal. We envision a change in the way orthopedists utilize a journal in their practice, and are continuously looking for ways to make AJO a more relevant tool for improving your patient care and workflow. We are working hard to give our readers the journal they deserve, but in my spare time, I’ll be brushing up on trochleoplasties and half-swing wedges.

Prediction tool for mortality after respiratory compromise

Background: Scoring systems exist to predict outcomes following cardiac arrest. There is currently no reliable model to predict outcome of patients who have survived acute respiratory compromise (ARC).

Study Design: A retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Get with the Guidelines Resuscitation (GWTG-R) is an online medical registry that tracks ARC data from more than 300 hospitals.

Synopsis: Using the GWTG-R database of ARC, researchers identified 13,193 cases of ARC to study the variables affecting prognosis. They randomized the group into derivation (75% of patients) and validation (25% of patients) cohorts and used c-statistics to create the prognostic scoring system. The greatest predictors of in-hospital mortality were age greater than 80 years, hypotension in the four hours preceding the ARC event, and the need for intubation.

This scoring system did not take into account any comorbidities (such as organ failure) that occurred shortly after the ARC event, although these likely affect mortality.

Bottom Line: Predicting in-hospital mortality for survivors of ARC events may help clinical prognostication. Such tools could also facilitate comparisons between hospitals and guide quality improvement projects.

Citation: Moskowitz A, Anderson LW, Karlsson M, et. al. Predicting in-hospital mortality for initial survivors of acute respiratory compromise (ARC) events: Development and validation of the ARC score. Resuscitation. 2017 Jun;115:5-10.

Dr. Suman is clinical instructor of medicine in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine.

Background: Scoring systems exist to predict outcomes following cardiac arrest. There is currently no reliable model to predict outcome of patients who have survived acute respiratory compromise (ARC).

Study Design: A retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Get with the Guidelines Resuscitation (GWTG-R) is an online medical registry that tracks ARC data from more than 300 hospitals.

Synopsis: Using the GWTG-R database of ARC, researchers identified 13,193 cases of ARC to study the variables affecting prognosis. They randomized the group into derivation (75% of patients) and validation (25% of patients) cohorts and used c-statistics to create the prognostic scoring system. The greatest predictors of in-hospital mortality were age greater than 80 years, hypotension in the four hours preceding the ARC event, and the need for intubation.

This scoring system did not take into account any comorbidities (such as organ failure) that occurred shortly after the ARC event, although these likely affect mortality.

Bottom Line: Predicting in-hospital mortality for survivors of ARC events may help clinical prognostication. Such tools could also facilitate comparisons between hospitals and guide quality improvement projects.

Citation: Moskowitz A, Anderson LW, Karlsson M, et. al. Predicting in-hospital mortality for initial survivors of acute respiratory compromise (ARC) events: Development and validation of the ARC score. Resuscitation. 2017 Jun;115:5-10.

Dr. Suman is clinical instructor of medicine in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine.

Background: Scoring systems exist to predict outcomes following cardiac arrest. There is currently no reliable model to predict outcome of patients who have survived acute respiratory compromise (ARC).

Study Design: A retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Get with the Guidelines Resuscitation (GWTG-R) is an online medical registry that tracks ARC data from more than 300 hospitals.

Synopsis: Using the GWTG-R database of ARC, researchers identified 13,193 cases of ARC to study the variables affecting prognosis. They randomized the group into derivation (75% of patients) and validation (25% of patients) cohorts and used c-statistics to create the prognostic scoring system. The greatest predictors of in-hospital mortality were age greater than 80 years, hypotension in the four hours preceding the ARC event, and the need for intubation.

This scoring system did not take into account any comorbidities (such as organ failure) that occurred shortly after the ARC event, although these likely affect mortality.

Bottom Line: Predicting in-hospital mortality for survivors of ARC events may help clinical prognostication. Such tools could also facilitate comparisons between hospitals and guide quality improvement projects.

Citation: Moskowitz A, Anderson LW, Karlsson M, et. al. Predicting in-hospital mortality for initial survivors of acute respiratory compromise (ARC) events: Development and validation of the ARC score. Resuscitation. 2017 Jun;115:5-10.

Dr. Suman is clinical instructor of medicine in the University of Kentucky division of hospital medicine.

External cephalic version: How to increase the chances for success

About 3% to 4% of all fetuses at term are in breech presentation. Since 2000, when Hannah and colleagues reported finding that vaginal delivery of breech-presenting babies was riskier than cesarean delivery,1 most breech-presenting neonates in the United States have been delivered abdominally2—despite subsequent questioning of some of that study’s conclusions.

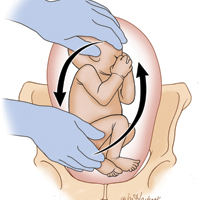

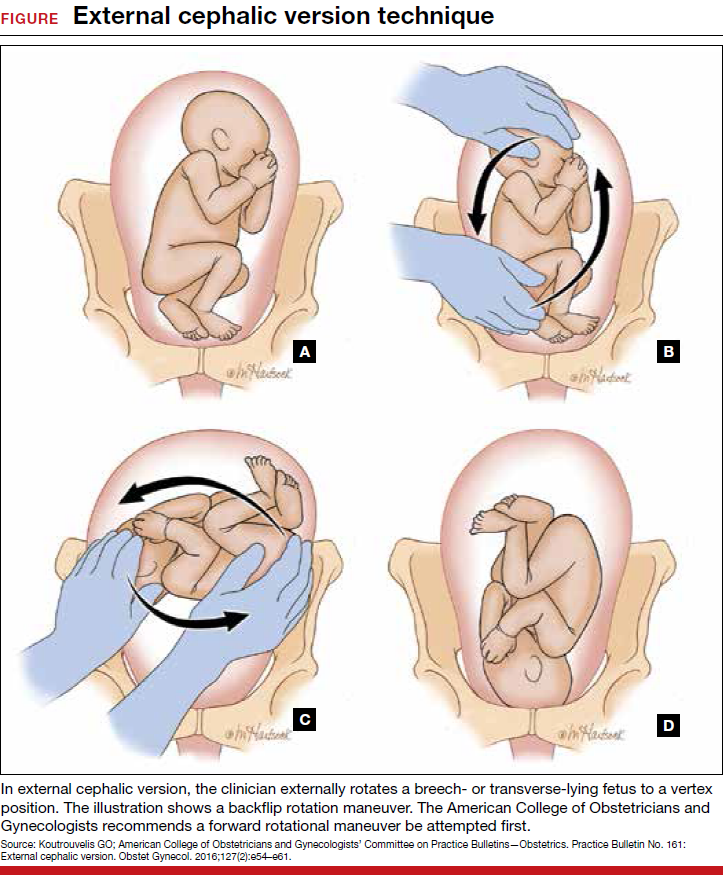

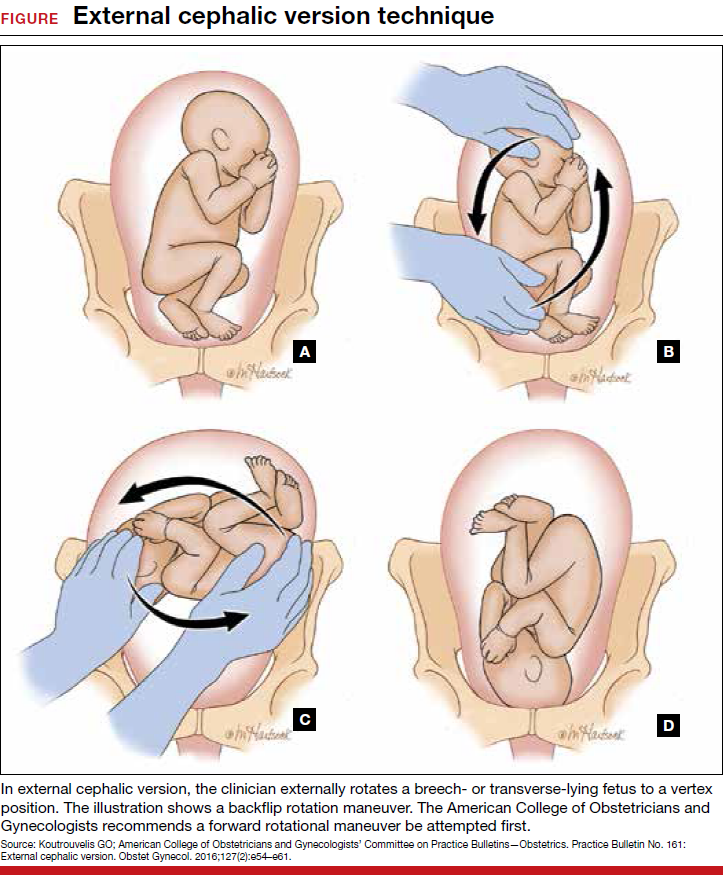

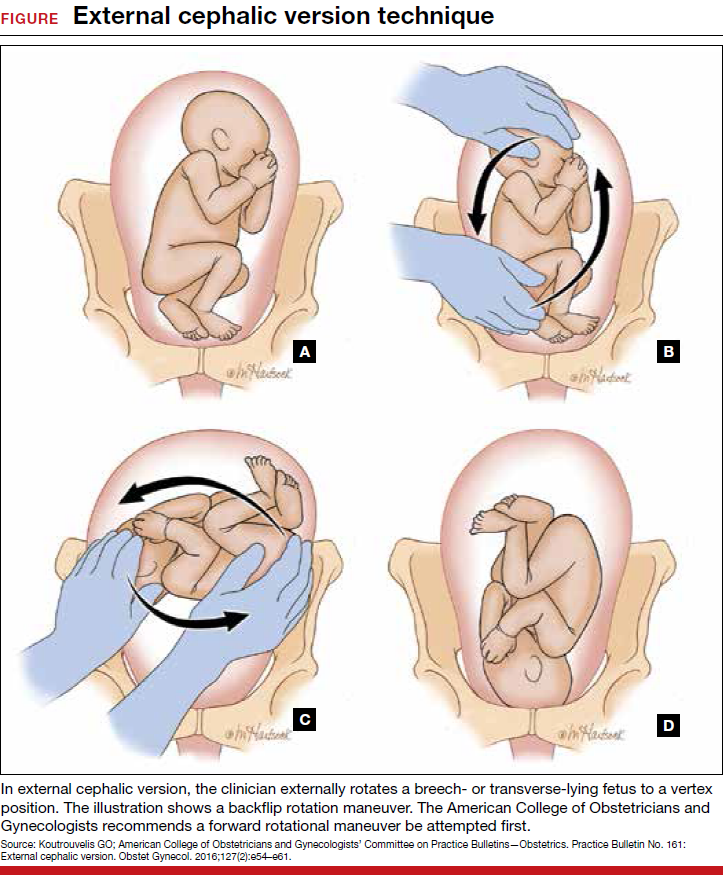

Each year in the United States, approximately 4 million babies are born, and fetal malpresentation accounts for 110,000 to 150,000 cesarean deliveries. In fact, about 15% of all cesarean deliveries in the United States are for breech presentation or transverse lie; in England the percentage is 10%.3 Fortunately, the repopularized technique of external cephalic version (ECV), in which the clinician externally rotates a breech- or transverse-lying fetus to a vertex position (FIGURE), along with the facilitating tools of tocolysis and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, is helping to reduce the number of breech presentations in fetuses at term and thus the number of cesarean deliveries and their sequelae—placenta accreta, prolonged recovery, and cesarean deliveries in subsequent pregnancies.

Reluctance to perform ECV is unfounded

In the United States, the practice of offering ECV to women who present with their fetus in breech presentation at term varies tremendously. It is routine at some institutions but not even offered at others.

Many ObGyns are reluctant to perform ECV. Cited reasons include the potential for injury to the fetus and mother (and related liability concerns), the ease of elective cesarean delivery, the variable success rate of ECV (35% to 86%),4 and the pain that women often have with the procedure. According to the literature, however, these concerns either are unfounded or can be mitigated with use of current techniques. Multiple studies have found that the risk of ECV to the fetus and mother is minimal, and that tocolysis and neuraxial anesthesia can facilitate the success of ECV and relieve the pain associated with the procedure.

Related article:

2017 Update on obstetrics

Indications for ECV

The indications for ECV include breech, oblique, or transverse lie presentation after 36 weeks’ gestation and the mother’s desire to avoid cesarean delivery. A clinician skilled in ECV and a facility where emergency cesarean delivery is possible are essential.

There are several instances in which ECV should not be attempted.

Contraindications include:

- concerns about fetal status, including nonreactive nonstress test, biophysical profile score <6/8, severe intrauterine growth restriction, decreased end-diastolic umbilical blood flow

- placenta previa

- multifetal gestation before delivery of first twin

- severe oligohydramnios

- severe preeclampsia

- significant fetal anomaly

- known malformation of uterus

- breech with hyperextended head or arms above shoulders, as seen on ultrasonography.

More controversial contraindications include prior uterine incision, maternal obesity (body mass index >40 kg/m2), ruptured membranes, and fetal macrosomia.

Read about timing, success rates, risk factors, alternate approaches for ECV

Optimal timing for the ECV procedure

Current practice is to wait until 36 to 37 weeks to perform ECV, as most fetuses spontaneously move into vertex presentation by 36 weeks’ gestation. This time frame has several advantages: Many unnecessary attempts at ECV are avoided; only 8% of fetuses in breech presentation after 36 weeks spontaneously change to vertex5; many fetuses revert to breech if ECV is performed too early; and prematurity generally is not an issue in the rare case that immediate delivery is required during or just after attempted ECV.

ECV during labor. Performing ECV during labor appears to pose no increased risk to mother or fetus if membranes are intact and there are no other contraindications to the procedure. Some clinicians perform ECV only during labor. The advantages are that the fetus has had every chance to move into vertex presentation on its own, the equipment used to continuously monitor the fetus during ECV is in place, and cesarean delivery and anesthesia are immediately available in the event ECV is unsuccessful.

The major disadvantage of waiting until labor is that the increased size of the fetus makes ECV more difficult. In addition, the membranes may have already ruptured, and the breech may have descended deeply into the pelvis.

Related article:

For the management of labor, patience is a virtue

Success rates in breech-to-vertex conversions

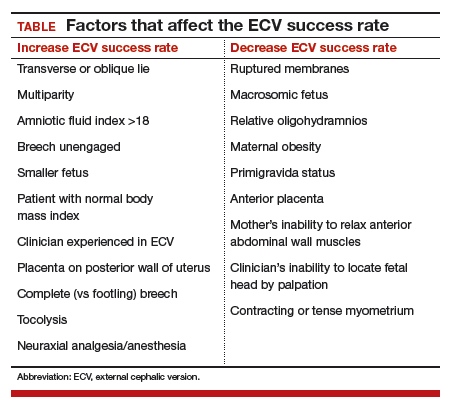

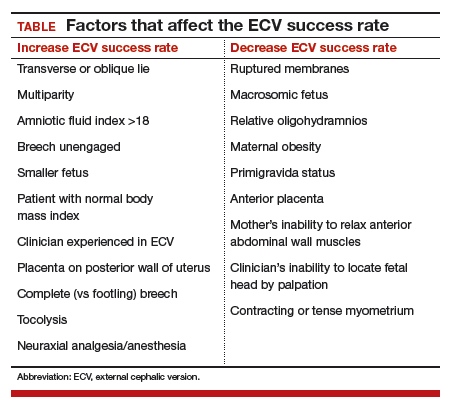

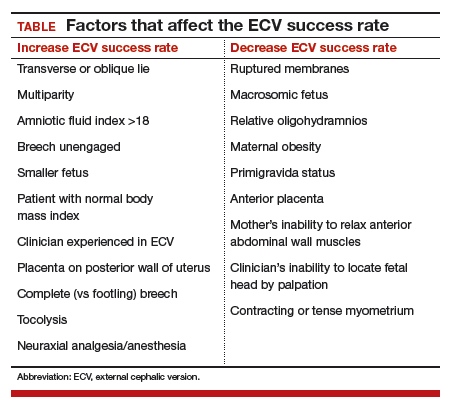

In 2016, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) reported an average ECV success rate of 58% (range, 16% to 100%).6 ACOG noted that, with transverse lie, the success rate was significantly higher. Other studies have found a wide range of rates: 58% in 1,308 patients in a Cochrane review by Hofmeyr and colleagues7; 47% in a study by Beuckens and colleagues8; and 63.1% for primiparas and 82.7% for multiparas in a study by Tong Leung and colleagues.9 These rates were affected by whether ECV was performed with or without tocolysis, with or without intravenous analgesia, and with or without neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia (TABLE).

Likelihood of vaginal delivery after successful ECV

The rate of vaginal delivery after successful ECV is roughly half that of fetuses that were never in breech presentation.10 In successful ECV cases, dystocia and nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns are the major indications for cesarean delivery. Some experts have speculated that the factors leading to near-term breech presentation—such as an unengaged presenting part or a mother’s smaller pelvis—also may be risk factors for dystocia in labor. Despite this, the rate of vaginal delivery of successfully verted babies has been reported to be as high as 80%.10

As might be expected, post-ECV vaginal deliveries are more common in multiparous than in primiparous women.

Although multiple problems may occur with ECV, generally they are rare and reversible. For instance, Grootscholten and colleagues found a stillbirth and placental abruption rate of only 0.25% in a large group of patients who underwent ECV.11 Similarly, the rate of emergency cesarean delivery was 0.35%. In addition, Hofmeyr and Kulier, in their Cochrane Data Review of 2015, found no significant differences in the Apgar scores and pH’s of babies in the ECV group compared with babies in breech presentation whose mothers did not undergo ECV.7 Results of other studies have confirmed the safety of ECV.12,13

One significant risk of ECV attempts is fetal-to-maternal blood transfer. Boucher and colleagues found that 2.4% of 1,244 women who underwent ECV had a positive Kleihauer-Betke test result, and, in one-third of the positive cases, more than 1 mL of fetal blood was found in maternal circulation.14 This risk can be minimized by administering Rho (D) immune globulin to all Rh-negative mothers after the procedure.

Even these small risks, however, should not be considered in isolation. The infrequent complications of ECV must be compared with what can occur with breech-presenting fetuses during labor or cesarean delivery: complications of breech vaginal delivery, cord prolapse, difficulties with cesarean delivery, and maternal operative complications related to present and future cesarean deliveries.

Alternative approaches to converting breech presentation of unproven efficacy

Over the years, attempts have been made to address breech presentations with measures short of ECV. There is little evidence that these measures work, or work consistently.

- Observation. After 36 weeks’ gestation, only 8% of fetuses in breech presentationspontaneously move into vertex presentation.5

- Maternal positioning. There is no good evidence that such maneuvers are effective in changing fetal presentation.15

- Moxibustion and acupuncture. Moxibustion is inhalation of smoke from burning herbal compounds. In formal studies using controls, these techniques did not consistently increase the rate of movement from breech to vertex presentation.16–18 Likewise, studies with the use of acupuncture have not shown consistent success in changing fetal presentation.19

Read about various methods to facilitate ECV success

Methods to facilitate ECV success

Two techniques that can facilitate ECV success are tocolysis, which relaxes the uterus, and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, which relaxes anterior abdominal wall muscles and reduces or relieves ECV-associated pain.

Tocolysis

In tocolysis, a medication is administered to reduce myometrial activity and to relax the uterine muscle so that it stretches more easily around the fetus during repositioning. Tocolytic medications originally were studied for their use in decreasing myometrial tone during preterm labor.

Tocolysis clearly is effective in increasing ECV success rates. Reviewing the results of 4 randomized trials, Cluver showed a 1.38 risk ratio for successful ECV when terbutaline was used versus when there was no tocolysis. The risk ratio for cesarean delivery was 0.82.20 Fernandez, in a study of 103 women divided into terbutaline versus placebo groups, had a 52% success rate for ECV with the terbutaline group versus only a 27% success rate with the placebo group.21

Tocolytic medications include terbutaline, nifedipine, and nitroglycerin.

Tocolysis most often involves the use of β2-adrenergic receptor agonists, particularly terbutaline (despite the boxed safety warning in its prescribing information). A 0.25-mg dose of terbutaline is given subcutaneously 15 to 30 minutes before ECV. Clinicians have successfully used β2-adrenergic receptor agonists in the treatment of patients in preterm labor, and there are more data on this class of medications than on other agents used to facilitate ECV.

Although nifedipine is as effective as terbutaline in the temporary treatment of preterm uterine contractions, several studies have found this calcium channel blocker less effective than terbutaline in facilitating ECV.22,23

The uterus-relaxing effect of nitroglycerin was once thought to make this medication appropriate for facilitating ECV, but multiple studies have found success rates unimproved. In some cases, the drug performed more poorly than placebo.24 Moreover, nitroglycerin is associated with a fairly high rate of adverse effects, such as headaches and blood pressure changes.

Neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia

Over the past 2 decades, there has been a resurgence in the use of neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia in ECV. This technique is more effective than others in improving ECV success rates, it reduces maternal discomfort, and it is very safe. Specifically, it relaxes the maternal abdominal wall muscles and thereby facilitates ECV. Another benefit is that the anesthesia is in place and available for use should emergency cesarean delivery be needed during or after attempted ECV. Neuraxial anesthesia, which includes spinal, epidural, and combined spinal-epidural techniques, is almost always used with tocolysis.

The major complications of neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia are maternal hypotension and fetal bradycardia. Each is dose related and usually transient.

In the past, there was concern that using regional anesthesia to control pain would reduce a patient’s natural warning symptoms and result in a clinician applying excessive force, thus increasing the chances of fetal and maternal injury and even fetal death. However, multiple studies have found that ECV complication rates are not increased with use of neuraxial methods.

Higher doses of neuraxial anesthesia produce higher ECV success rates. This dose-dependent relationship is almost surely attributable to the fact that, although lower dose neuraxial analgesia can relieve the pain associated with ECV, an anesthetic dose is needed to relax the abdominal wall muscles and facilitate fetus repositioning.

The literature is clear: ECV success rates are significantly increased with the use of neuraxial techniques, with anesthesia having higher success rates than analgesia. Reviewing the results of 6 controlled trials in which a total of 508 patients underwent ECV with tocolysis, Goetzinger and colleagues found that the chance of ECV success was almost 60% higher in the 253 patients who received regional anesthesia than in the 255 patients who received intravenous or no analgesia.25 Moreover, only 48.4% of the regional anesthesia patients as compared with 59.3% of patients who did not have regional anesthesia underwent cesarean delivery, roughly a 20% decrease. Pain scores were consistently lower in the regional anesthesia group. Multiple other studies have reported similar results.

Although the use of neuraxial anesthesia increases the ECV success rate, and decreases the cesarean delivery rate for breech presentation by 5% to 15%,25 some groups of obstetrics professionals, noting that the decreased cesarean delivery rate does not meet the formal criterion for statistical significance, have expressed reservations about recommending regional anesthesia for ECV. Thus, despite the positive results obtained with neuraxial anesthesia, neither the literature nor authoritative professional organizations definitively recommend the use of neuraxial anesthesia in facilitating ECV.

This lack of official recommendation, however, overlooks an important point: While the cesarean delivery percentage decrease that occurs with the use of neuraxial anesthesia may not be statistically significant, the promise of a pain-free procedure will encourage more women to undergo ECV. If the procedure population increases, then the average ECV success rate of roughly 60%6 applies to a larger base of patients, reducing the total number of cesarean deliveries for breech presentation. As only a small percentage of the 110,000 to 150,000 women with breech presentation at 36 weeks currently elects to undergo ECV, any increase in the number of women who proceed with attempts at fetal repositioning once procedural pain is no longer an issue will accordingly reduce the number of cesarean deliveries for the indication of malpresentation.

Related article:

Nitrous oxide for labor pain

Overarching goal: Reduce cesarean delivery rate and associated risks

In the United States, increasing the use of ECV in cases of breech-presenting fetuses would reduce the cesarean delivery rate by about 10%, thereby reducing recovery time for cesarean deliveries, minimizing the risks associated with these deliveries (current and future), and providing the health care system with a major cost savings.

Tocolysis and the use of neuraxial anesthesia each increases the ECV success rate and each is remarkably safe within the context of a well-defined protocol. Reducing the pain associated with ECV by administering neuraxial anesthesia will increase the number of women electing to undergo the procedure and ultimately will reduce the number of cesarean deliveries performed for the indication of breech presentation.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned cesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375–1383.

- Weiniger CF, Lyell DJ, Tsen LC, et al. Maternal outcomes of term breech presentation delivery: impact of successful external cephalic version in a nationwide sample of delivery admissions in the United States. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):150.

- Eller DP, Van Dorsten JP. Breech presentation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol.1993;5(5)664–668.

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, et al. Williams Obstetrics. 24th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2014:570.

- Westgren M, Edvall H, Nordstrom L, Svalenius E, Ranstam J. Spontaneous cephalic version of breech presentation in the last trimester. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92(1):19–22.

- External cephalic version. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 161. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2016.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD000083.

- Beuckens A, Rijnders M, Verburgt-Doeleman GH, Rijninks-van Driel GC, Thorpe J, Hutton EK. An observational study of the success and complications of 2546 external cephalic versions in low-risk pregnant women performed by trained midwives. BJOG. 2016;123(3):415–423.

- Tong Leung VK, Suen SS, Singh Sahota D, Lau TK, Yeung Leung T. External cephalic version does not increase the risk of intra-uterine death: a 17-year experience and literature review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(9):1774–1778.

- de Hundt M, Velzel J, de Groot CJ, Mol BW, Kok M. Mode of delivery after successful external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1327–1334.

- Grootscholten K, Kok M, Oei SG, Mol BW, van der Post JA. External cephalic version–related risks: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1143–1151.

- Collaris RJ, Oei SG. External cephalic version: a safe procedure? A systematic review of version-related risk. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(6):511–518.

- Khaw KS, Lee SW, Ngan Kee WD, et al. Randomized trial of anesthetic interventions in external cephalic version for breech presentation. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(6):944–950.

- Boucher M, Marquette GP, Varin J, Champagne J, Bujold E. Fetomaternal hemorrhage during external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):79–84.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. Cephalic version by postural management for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(10):CD00051.

- Coulon C, Poleszczuk M, Paty-Montaigne MH, et al. Version of breech fetuses by moxibustion with acupuncture: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):32–39.

- Bue L, Lauszus FF. Moxibustion did not have an effect in a randomised clinical trial for version of breech position. Dan Med J. 2016;63(2):pii:A5199.

- Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B. Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5):CD003928.

- Sananes N, Roth GE, Aissi GA, et al. Acupuncture version of breech presentation: a randomized sham-controlled single-blinded trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;204:24–30.

- Cluver C, Gyte GM, Sinclair M, Dowswell T, Hofmeyr G. Interventions for helping to turn breech babies to head first presentation when using external cephalic version. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD000184.

- Fernandez CO, Bloom SL, Smulian JC, Ananth CV, Wendel GD Jr. A randomized placebo-controlled evaluation of terbutaline for external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(5):775–779.

- Mohamed Ismail NA, Ibrahim M, Mohd Naim N, Mahdy ZA, Jamil MA, Mohd Razi ZR. Nifedipine versus terbutaline for tocolysis in external cephalic version. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102(3):263–266.

- Kok M, Bais J, van Lith J, et al. Nifedipine as a uterine relaxant for external cephalic version: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):271–276.

- Bujold E, Boucher M, Rinfred D, Berman S, Ferreira E, Marquette GP. Sublingual nitroglycerin versus placebo as a tocolytic for external cephalic version: a randomized controlled trial in parous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):1070–1073.

- Goetzinger KR, Harper LM, Tuuli MG, Macones GA, Colditz GA. Effect of regional anesthesia on the success of external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1137–1144.

About 3% to 4% of all fetuses at term are in breech presentation. Since 2000, when Hannah and colleagues reported finding that vaginal delivery of breech-presenting babies was riskier than cesarean delivery,1 most breech-presenting neonates in the United States have been delivered abdominally2—despite subsequent questioning of some of that study’s conclusions.

Each year in the United States, approximately 4 million babies are born, and fetal malpresentation accounts for 110,000 to 150,000 cesarean deliveries. In fact, about 15% of all cesarean deliveries in the United States are for breech presentation or transverse lie; in England the percentage is 10%.3 Fortunately, the repopularized technique of external cephalic version (ECV), in which the clinician externally rotates a breech- or transverse-lying fetus to a vertex position (FIGURE), along with the facilitating tools of tocolysis and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, is helping to reduce the number of breech presentations in fetuses at term and thus the number of cesarean deliveries and their sequelae—placenta accreta, prolonged recovery, and cesarean deliveries in subsequent pregnancies.

Reluctance to perform ECV is unfounded

In the United States, the practice of offering ECV to women who present with their fetus in breech presentation at term varies tremendously. It is routine at some institutions but not even offered at others.

Many ObGyns are reluctant to perform ECV. Cited reasons include the potential for injury to the fetus and mother (and related liability concerns), the ease of elective cesarean delivery, the variable success rate of ECV (35% to 86%),4 and the pain that women often have with the procedure. According to the literature, however, these concerns either are unfounded or can be mitigated with use of current techniques. Multiple studies have found that the risk of ECV to the fetus and mother is minimal, and that tocolysis and neuraxial anesthesia can facilitate the success of ECV and relieve the pain associated with the procedure.

Related article:

2017 Update on obstetrics

Indications for ECV

The indications for ECV include breech, oblique, or transverse lie presentation after 36 weeks’ gestation and the mother’s desire to avoid cesarean delivery. A clinician skilled in ECV and a facility where emergency cesarean delivery is possible are essential.

There are several instances in which ECV should not be attempted.

Contraindications include:

- concerns about fetal status, including nonreactive nonstress test, biophysical profile score <6/8, severe intrauterine growth restriction, decreased end-diastolic umbilical blood flow

- placenta previa

- multifetal gestation before delivery of first twin

- severe oligohydramnios

- severe preeclampsia

- significant fetal anomaly

- known malformation of uterus

- breech with hyperextended head or arms above shoulders, as seen on ultrasonography.

More controversial contraindications include prior uterine incision, maternal obesity (body mass index >40 kg/m2), ruptured membranes, and fetal macrosomia.

Read about timing, success rates, risk factors, alternate approaches for ECV

Optimal timing for the ECV procedure

Current practice is to wait until 36 to 37 weeks to perform ECV, as most fetuses spontaneously move into vertex presentation by 36 weeks’ gestation. This time frame has several advantages: Many unnecessary attempts at ECV are avoided; only 8% of fetuses in breech presentation after 36 weeks spontaneously change to vertex5; many fetuses revert to breech if ECV is performed too early; and prematurity generally is not an issue in the rare case that immediate delivery is required during or just after attempted ECV.

ECV during labor. Performing ECV during labor appears to pose no increased risk to mother or fetus if membranes are intact and there are no other contraindications to the procedure. Some clinicians perform ECV only during labor. The advantages are that the fetus has had every chance to move into vertex presentation on its own, the equipment used to continuously monitor the fetus during ECV is in place, and cesarean delivery and anesthesia are immediately available in the event ECV is unsuccessful.

The major disadvantage of waiting until labor is that the increased size of the fetus makes ECV more difficult. In addition, the membranes may have already ruptured, and the breech may have descended deeply into the pelvis.

Related article:

For the management of labor, patience is a virtue

Success rates in breech-to-vertex conversions

In 2016, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) reported an average ECV success rate of 58% (range, 16% to 100%).6 ACOG noted that, with transverse lie, the success rate was significantly higher. Other studies have found a wide range of rates: 58% in 1,308 patients in a Cochrane review by Hofmeyr and colleagues7; 47% in a study by Beuckens and colleagues8; and 63.1% for primiparas and 82.7% for multiparas in a study by Tong Leung and colleagues.9 These rates were affected by whether ECV was performed with or without tocolysis, with or without intravenous analgesia, and with or without neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia (TABLE).

Likelihood of vaginal delivery after successful ECV

The rate of vaginal delivery after successful ECV is roughly half that of fetuses that were never in breech presentation.10 In successful ECV cases, dystocia and nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns are the major indications for cesarean delivery. Some experts have speculated that the factors leading to near-term breech presentation—such as an unengaged presenting part or a mother’s smaller pelvis—also may be risk factors for dystocia in labor. Despite this, the rate of vaginal delivery of successfully verted babies has been reported to be as high as 80%.10

As might be expected, post-ECV vaginal deliveries are more common in multiparous than in primiparous women.

Although multiple problems may occur with ECV, generally they are rare and reversible. For instance, Grootscholten and colleagues found a stillbirth and placental abruption rate of only 0.25% in a large group of patients who underwent ECV.11 Similarly, the rate of emergency cesarean delivery was 0.35%. In addition, Hofmeyr and Kulier, in their Cochrane Data Review of 2015, found no significant differences in the Apgar scores and pH’s of babies in the ECV group compared with babies in breech presentation whose mothers did not undergo ECV.7 Results of other studies have confirmed the safety of ECV.12,13

One significant risk of ECV attempts is fetal-to-maternal blood transfer. Boucher and colleagues found that 2.4% of 1,244 women who underwent ECV had a positive Kleihauer-Betke test result, and, in one-third of the positive cases, more than 1 mL of fetal blood was found in maternal circulation.14 This risk can be minimized by administering Rho (D) immune globulin to all Rh-negative mothers after the procedure.

Even these small risks, however, should not be considered in isolation. The infrequent complications of ECV must be compared with what can occur with breech-presenting fetuses during labor or cesarean delivery: complications of breech vaginal delivery, cord prolapse, difficulties with cesarean delivery, and maternal operative complications related to present and future cesarean deliveries.

Alternative approaches to converting breech presentation of unproven efficacy

Over the years, attempts have been made to address breech presentations with measures short of ECV. There is little evidence that these measures work, or work consistently.

- Observation. After 36 weeks’ gestation, only 8% of fetuses in breech presentationspontaneously move into vertex presentation.5

- Maternal positioning. There is no good evidence that such maneuvers are effective in changing fetal presentation.15

- Moxibustion and acupuncture. Moxibustion is inhalation of smoke from burning herbal compounds. In formal studies using controls, these techniques did not consistently increase the rate of movement from breech to vertex presentation.16–18 Likewise, studies with the use of acupuncture have not shown consistent success in changing fetal presentation.19

Read about various methods to facilitate ECV success

Methods to facilitate ECV success

Two techniques that can facilitate ECV success are tocolysis, which relaxes the uterus, and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, which relaxes anterior abdominal wall muscles and reduces or relieves ECV-associated pain.

Tocolysis

In tocolysis, a medication is administered to reduce myometrial activity and to relax the uterine muscle so that it stretches more easily around the fetus during repositioning. Tocolytic medications originally were studied for their use in decreasing myometrial tone during preterm labor.

Tocolysis clearly is effective in increasing ECV success rates. Reviewing the results of 4 randomized trials, Cluver showed a 1.38 risk ratio for successful ECV when terbutaline was used versus when there was no tocolysis. The risk ratio for cesarean delivery was 0.82.20 Fernandez, in a study of 103 women divided into terbutaline versus placebo groups, had a 52% success rate for ECV with the terbutaline group versus only a 27% success rate with the placebo group.21

Tocolytic medications include terbutaline, nifedipine, and nitroglycerin.

Tocolysis most often involves the use of β2-adrenergic receptor agonists, particularly terbutaline (despite the boxed safety warning in its prescribing information). A 0.25-mg dose of terbutaline is given subcutaneously 15 to 30 minutes before ECV. Clinicians have successfully used β2-adrenergic receptor agonists in the treatment of patients in preterm labor, and there are more data on this class of medications than on other agents used to facilitate ECV.

Although nifedipine is as effective as terbutaline in the temporary treatment of preterm uterine contractions, several studies have found this calcium channel blocker less effective than terbutaline in facilitating ECV.22,23

The uterus-relaxing effect of nitroglycerin was once thought to make this medication appropriate for facilitating ECV, but multiple studies have found success rates unimproved. In some cases, the drug performed more poorly than placebo.24 Moreover, nitroglycerin is associated with a fairly high rate of adverse effects, such as headaches and blood pressure changes.

Neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia

Over the past 2 decades, there has been a resurgence in the use of neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia in ECV. This technique is more effective than others in improving ECV success rates, it reduces maternal discomfort, and it is very safe. Specifically, it relaxes the maternal abdominal wall muscles and thereby facilitates ECV. Another benefit is that the anesthesia is in place and available for use should emergency cesarean delivery be needed during or after attempted ECV. Neuraxial anesthesia, which includes spinal, epidural, and combined spinal-epidural techniques, is almost always used with tocolysis.

The major complications of neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia are maternal hypotension and fetal bradycardia. Each is dose related and usually transient.

In the past, there was concern that using regional anesthesia to control pain would reduce a patient’s natural warning symptoms and result in a clinician applying excessive force, thus increasing the chances of fetal and maternal injury and even fetal death. However, multiple studies have found that ECV complication rates are not increased with use of neuraxial methods.

Higher doses of neuraxial anesthesia produce higher ECV success rates. This dose-dependent relationship is almost surely attributable to the fact that, although lower dose neuraxial analgesia can relieve the pain associated with ECV, an anesthetic dose is needed to relax the abdominal wall muscles and facilitate fetus repositioning.

The literature is clear: ECV success rates are significantly increased with the use of neuraxial techniques, with anesthesia having higher success rates than analgesia. Reviewing the results of 6 controlled trials in which a total of 508 patients underwent ECV with tocolysis, Goetzinger and colleagues found that the chance of ECV success was almost 60% higher in the 253 patients who received regional anesthesia than in the 255 patients who received intravenous or no analgesia.25 Moreover, only 48.4% of the regional anesthesia patients as compared with 59.3% of patients who did not have regional anesthesia underwent cesarean delivery, roughly a 20% decrease. Pain scores were consistently lower in the regional anesthesia group. Multiple other studies have reported similar results.

Although the use of neuraxial anesthesia increases the ECV success rate, and decreases the cesarean delivery rate for breech presentation by 5% to 15%,25 some groups of obstetrics professionals, noting that the decreased cesarean delivery rate does not meet the formal criterion for statistical significance, have expressed reservations about recommending regional anesthesia for ECV. Thus, despite the positive results obtained with neuraxial anesthesia, neither the literature nor authoritative professional organizations definitively recommend the use of neuraxial anesthesia in facilitating ECV.

This lack of official recommendation, however, overlooks an important point: While the cesarean delivery percentage decrease that occurs with the use of neuraxial anesthesia may not be statistically significant, the promise of a pain-free procedure will encourage more women to undergo ECV. If the procedure population increases, then the average ECV success rate of roughly 60%6 applies to a larger base of patients, reducing the total number of cesarean deliveries for breech presentation. As only a small percentage of the 110,000 to 150,000 women with breech presentation at 36 weeks currently elects to undergo ECV, any increase in the number of women who proceed with attempts at fetal repositioning once procedural pain is no longer an issue will accordingly reduce the number of cesarean deliveries for the indication of malpresentation.

Related article:

Nitrous oxide for labor pain

Overarching goal: Reduce cesarean delivery rate and associated risks

In the United States, increasing the use of ECV in cases of breech-presenting fetuses would reduce the cesarean delivery rate by about 10%, thereby reducing recovery time for cesarean deliveries, minimizing the risks associated with these deliveries (current and future), and providing the health care system with a major cost savings.

Tocolysis and the use of neuraxial anesthesia each increases the ECV success rate and each is remarkably safe within the context of a well-defined protocol. Reducing the pain associated with ECV by administering neuraxial anesthesia will increase the number of women electing to undergo the procedure and ultimately will reduce the number of cesarean deliveries performed for the indication of breech presentation.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

About 3% to 4% of all fetuses at term are in breech presentation. Since 2000, when Hannah and colleagues reported finding that vaginal delivery of breech-presenting babies was riskier than cesarean delivery,1 most breech-presenting neonates in the United States have been delivered abdominally2—despite subsequent questioning of some of that study’s conclusions.

Each year in the United States, approximately 4 million babies are born, and fetal malpresentation accounts for 110,000 to 150,000 cesarean deliveries. In fact, about 15% of all cesarean deliveries in the United States are for breech presentation or transverse lie; in England the percentage is 10%.3 Fortunately, the repopularized technique of external cephalic version (ECV), in which the clinician externally rotates a breech- or transverse-lying fetus to a vertex position (FIGURE), along with the facilitating tools of tocolysis and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, is helping to reduce the number of breech presentations in fetuses at term and thus the number of cesarean deliveries and their sequelae—placenta accreta, prolonged recovery, and cesarean deliveries in subsequent pregnancies.

Reluctance to perform ECV is unfounded

In the United States, the practice of offering ECV to women who present with their fetus in breech presentation at term varies tremendously. It is routine at some institutions but not even offered at others.

Many ObGyns are reluctant to perform ECV. Cited reasons include the potential for injury to the fetus and mother (and related liability concerns), the ease of elective cesarean delivery, the variable success rate of ECV (35% to 86%),4 and the pain that women often have with the procedure. According to the literature, however, these concerns either are unfounded or can be mitigated with use of current techniques. Multiple studies have found that the risk of ECV to the fetus and mother is minimal, and that tocolysis and neuraxial anesthesia can facilitate the success of ECV and relieve the pain associated with the procedure.

Related article:

2017 Update on obstetrics

Indications for ECV

The indications for ECV include breech, oblique, or transverse lie presentation after 36 weeks’ gestation and the mother’s desire to avoid cesarean delivery. A clinician skilled in ECV and a facility where emergency cesarean delivery is possible are essential.

There are several instances in which ECV should not be attempted.

Contraindications include:

- concerns about fetal status, including nonreactive nonstress test, biophysical profile score <6/8, severe intrauterine growth restriction, decreased end-diastolic umbilical blood flow

- placenta previa

- multifetal gestation before delivery of first twin

- severe oligohydramnios

- severe preeclampsia

- significant fetal anomaly

- known malformation of uterus

- breech with hyperextended head or arms above shoulders, as seen on ultrasonography.

More controversial contraindications include prior uterine incision, maternal obesity (body mass index >40 kg/m2), ruptured membranes, and fetal macrosomia.

Read about timing, success rates, risk factors, alternate approaches for ECV

Optimal timing for the ECV procedure

Current practice is to wait until 36 to 37 weeks to perform ECV, as most fetuses spontaneously move into vertex presentation by 36 weeks’ gestation. This time frame has several advantages: Many unnecessary attempts at ECV are avoided; only 8% of fetuses in breech presentation after 36 weeks spontaneously change to vertex5; many fetuses revert to breech if ECV is performed too early; and prematurity generally is not an issue in the rare case that immediate delivery is required during or just after attempted ECV.

ECV during labor. Performing ECV during labor appears to pose no increased risk to mother or fetus if membranes are intact and there are no other contraindications to the procedure. Some clinicians perform ECV only during labor. The advantages are that the fetus has had every chance to move into vertex presentation on its own, the equipment used to continuously monitor the fetus during ECV is in place, and cesarean delivery and anesthesia are immediately available in the event ECV is unsuccessful.

The major disadvantage of waiting until labor is that the increased size of the fetus makes ECV more difficult. In addition, the membranes may have already ruptured, and the breech may have descended deeply into the pelvis.

Related article:

For the management of labor, patience is a virtue

Success rates in breech-to-vertex conversions

In 2016, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) reported an average ECV success rate of 58% (range, 16% to 100%).6 ACOG noted that, with transverse lie, the success rate was significantly higher. Other studies have found a wide range of rates: 58% in 1,308 patients in a Cochrane review by Hofmeyr and colleagues7; 47% in a study by Beuckens and colleagues8; and 63.1% for primiparas and 82.7% for multiparas in a study by Tong Leung and colleagues.9 These rates were affected by whether ECV was performed with or without tocolysis, with or without intravenous analgesia, and with or without neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia (TABLE).

Likelihood of vaginal delivery after successful ECV

The rate of vaginal delivery after successful ECV is roughly half that of fetuses that were never in breech presentation.10 In successful ECV cases, dystocia and nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns are the major indications for cesarean delivery. Some experts have speculated that the factors leading to near-term breech presentation—such as an unengaged presenting part or a mother’s smaller pelvis—also may be risk factors for dystocia in labor. Despite this, the rate of vaginal delivery of successfully verted babies has been reported to be as high as 80%.10

As might be expected, post-ECV vaginal deliveries are more common in multiparous than in primiparous women.

Although multiple problems may occur with ECV, generally they are rare and reversible. For instance, Grootscholten and colleagues found a stillbirth and placental abruption rate of only 0.25% in a large group of patients who underwent ECV.11 Similarly, the rate of emergency cesarean delivery was 0.35%. In addition, Hofmeyr and Kulier, in their Cochrane Data Review of 2015, found no significant differences in the Apgar scores and pH’s of babies in the ECV group compared with babies in breech presentation whose mothers did not undergo ECV.7 Results of other studies have confirmed the safety of ECV.12,13

One significant risk of ECV attempts is fetal-to-maternal blood transfer. Boucher and colleagues found that 2.4% of 1,244 women who underwent ECV had a positive Kleihauer-Betke test result, and, in one-third of the positive cases, more than 1 mL of fetal blood was found in maternal circulation.14 This risk can be minimized by administering Rho (D) immune globulin to all Rh-negative mothers after the procedure.

Even these small risks, however, should not be considered in isolation. The infrequent complications of ECV must be compared with what can occur with breech-presenting fetuses during labor or cesarean delivery: complications of breech vaginal delivery, cord prolapse, difficulties with cesarean delivery, and maternal operative complications related to present and future cesarean deliveries.

Alternative approaches to converting breech presentation of unproven efficacy

Over the years, attempts have been made to address breech presentations with measures short of ECV. There is little evidence that these measures work, or work consistently.

- Observation. After 36 weeks’ gestation, only 8% of fetuses in breech presentationspontaneously move into vertex presentation.5

- Maternal positioning. There is no good evidence that such maneuvers are effective in changing fetal presentation.15

- Moxibustion and acupuncture. Moxibustion is inhalation of smoke from burning herbal compounds. In formal studies using controls, these techniques did not consistently increase the rate of movement from breech to vertex presentation.16–18 Likewise, studies with the use of acupuncture have not shown consistent success in changing fetal presentation.19

Read about various methods to facilitate ECV success

Methods to facilitate ECV success

Two techniques that can facilitate ECV success are tocolysis, which relaxes the uterus, and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, which relaxes anterior abdominal wall muscles and reduces or relieves ECV-associated pain.

Tocolysis

In tocolysis, a medication is administered to reduce myometrial activity and to relax the uterine muscle so that it stretches more easily around the fetus during repositioning. Tocolytic medications originally were studied for their use in decreasing myometrial tone during preterm labor.

Tocolysis clearly is effective in increasing ECV success rates. Reviewing the results of 4 randomized trials, Cluver showed a 1.38 risk ratio for successful ECV when terbutaline was used versus when there was no tocolysis. The risk ratio for cesarean delivery was 0.82.20 Fernandez, in a study of 103 women divided into terbutaline versus placebo groups, had a 52% success rate for ECV with the terbutaline group versus only a 27% success rate with the placebo group.21

Tocolytic medications include terbutaline, nifedipine, and nitroglycerin.

Tocolysis most often involves the use of β2-adrenergic receptor agonists, particularly terbutaline (despite the boxed safety warning in its prescribing information). A 0.25-mg dose of terbutaline is given subcutaneously 15 to 30 minutes before ECV. Clinicians have successfully used β2-adrenergic receptor agonists in the treatment of patients in preterm labor, and there are more data on this class of medications than on other agents used to facilitate ECV.

Although nifedipine is as effective as terbutaline in the temporary treatment of preterm uterine contractions, several studies have found this calcium channel blocker less effective than terbutaline in facilitating ECV.22,23

The uterus-relaxing effect of nitroglycerin was once thought to make this medication appropriate for facilitating ECV, but multiple studies have found success rates unimproved. In some cases, the drug performed more poorly than placebo.24 Moreover, nitroglycerin is associated with a fairly high rate of adverse effects, such as headaches and blood pressure changes.

Neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia

Over the past 2 decades, there has been a resurgence in the use of neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia in ECV. This technique is more effective than others in improving ECV success rates, it reduces maternal discomfort, and it is very safe. Specifically, it relaxes the maternal abdominal wall muscles and thereby facilitates ECV. Another benefit is that the anesthesia is in place and available for use should emergency cesarean delivery be needed during or after attempted ECV. Neuraxial anesthesia, which includes spinal, epidural, and combined spinal-epidural techniques, is almost always used with tocolysis.

The major complications of neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia are maternal hypotension and fetal bradycardia. Each is dose related and usually transient.

In the past, there was concern that using regional anesthesia to control pain would reduce a patient’s natural warning symptoms and result in a clinician applying excessive force, thus increasing the chances of fetal and maternal injury and even fetal death. However, multiple studies have found that ECV complication rates are not increased with use of neuraxial methods.

Higher doses of neuraxial anesthesia produce higher ECV success rates. This dose-dependent relationship is almost surely attributable to the fact that, although lower dose neuraxial analgesia can relieve the pain associated with ECV, an anesthetic dose is needed to relax the abdominal wall muscles and facilitate fetus repositioning.

The literature is clear: ECV success rates are significantly increased with the use of neuraxial techniques, with anesthesia having higher success rates than analgesia. Reviewing the results of 6 controlled trials in which a total of 508 patients underwent ECV with tocolysis, Goetzinger and colleagues found that the chance of ECV success was almost 60% higher in the 253 patients who received regional anesthesia than in the 255 patients who received intravenous or no analgesia.25 Moreover, only 48.4% of the regional anesthesia patients as compared with 59.3% of patients who did not have regional anesthesia underwent cesarean delivery, roughly a 20% decrease. Pain scores were consistently lower in the regional anesthesia group. Multiple other studies have reported similar results.

Although the use of neuraxial anesthesia increases the ECV success rate, and decreases the cesarean delivery rate for breech presentation by 5% to 15%,25 some groups of obstetrics professionals, noting that the decreased cesarean delivery rate does not meet the formal criterion for statistical significance, have expressed reservations about recommending regional anesthesia for ECV. Thus, despite the positive results obtained with neuraxial anesthesia, neither the literature nor authoritative professional organizations definitively recommend the use of neuraxial anesthesia in facilitating ECV.

This lack of official recommendation, however, overlooks an important point: While the cesarean delivery percentage decrease that occurs with the use of neuraxial anesthesia may not be statistically significant, the promise of a pain-free procedure will encourage more women to undergo ECV. If the procedure population increases, then the average ECV success rate of roughly 60%6 applies to a larger base of patients, reducing the total number of cesarean deliveries for breech presentation. As only a small percentage of the 110,000 to 150,000 women with breech presentation at 36 weeks currently elects to undergo ECV, any increase in the number of women who proceed with attempts at fetal repositioning once procedural pain is no longer an issue will accordingly reduce the number of cesarean deliveries for the indication of malpresentation.

Related article:

Nitrous oxide for labor pain

Overarching goal: Reduce cesarean delivery rate and associated risks

In the United States, increasing the use of ECV in cases of breech-presenting fetuses would reduce the cesarean delivery rate by about 10%, thereby reducing recovery time for cesarean deliveries, minimizing the risks associated with these deliveries (current and future), and providing the health care system with a major cost savings.

Tocolysis and the use of neuraxial anesthesia each increases the ECV success rate and each is remarkably safe within the context of a well-defined protocol. Reducing the pain associated with ECV by administering neuraxial anesthesia will increase the number of women electing to undergo the procedure and ultimately will reduce the number of cesarean deliveries performed for the indication of breech presentation.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned cesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375–1383.

- Weiniger CF, Lyell DJ, Tsen LC, et al. Maternal outcomes of term breech presentation delivery: impact of successful external cephalic version in a nationwide sample of delivery admissions in the United States. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):150.

- Eller DP, Van Dorsten JP. Breech presentation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol.1993;5(5)664–668.

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, et al. Williams Obstetrics. 24th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2014:570.

- Westgren M, Edvall H, Nordstrom L, Svalenius E, Ranstam J. Spontaneous cephalic version of breech presentation in the last trimester. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92(1):19–22.

- External cephalic version. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 161. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2016.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD000083.

- Beuckens A, Rijnders M, Verburgt-Doeleman GH, Rijninks-van Driel GC, Thorpe J, Hutton EK. An observational study of the success and complications of 2546 external cephalic versions in low-risk pregnant women performed by trained midwives. BJOG. 2016;123(3):415–423.

- Tong Leung VK, Suen SS, Singh Sahota D, Lau TK, Yeung Leung T. External cephalic version does not increase the risk of intra-uterine death: a 17-year experience and literature review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(9):1774–1778.

- de Hundt M, Velzel J, de Groot CJ, Mol BW, Kok M. Mode of delivery after successful external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1327–1334.

- Grootscholten K, Kok M, Oei SG, Mol BW, van der Post JA. External cephalic version–related risks: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1143–1151.

- Collaris RJ, Oei SG. External cephalic version: a safe procedure? A systematic review of version-related risk. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(6):511–518.

- Khaw KS, Lee SW, Ngan Kee WD, et al. Randomized trial of anesthetic interventions in external cephalic version for breech presentation. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(6):944–950.

- Boucher M, Marquette GP, Varin J, Champagne J, Bujold E. Fetomaternal hemorrhage during external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):79–84.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. Cephalic version by postural management for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(10):CD00051.

- Coulon C, Poleszczuk M, Paty-Montaigne MH, et al. Version of breech fetuses by moxibustion with acupuncture: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):32–39.

- Bue L, Lauszus FF. Moxibustion did not have an effect in a randomised clinical trial for version of breech position. Dan Med J. 2016;63(2):pii:A5199.

- Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B. Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5):CD003928.

- Sananes N, Roth GE, Aissi GA, et al. Acupuncture version of breech presentation: a randomized sham-controlled single-blinded trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;204:24–30.

- Cluver C, Gyte GM, Sinclair M, Dowswell T, Hofmeyr G. Interventions for helping to turn breech babies to head first presentation when using external cephalic version. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD000184.

- Fernandez CO, Bloom SL, Smulian JC, Ananth CV, Wendel GD Jr. A randomized placebo-controlled evaluation of terbutaline for external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(5):775–779.

- Mohamed Ismail NA, Ibrahim M, Mohd Naim N, Mahdy ZA, Jamil MA, Mohd Razi ZR. Nifedipine versus terbutaline for tocolysis in external cephalic version. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102(3):263–266.

- Kok M, Bais J, van Lith J, et al. Nifedipine as a uterine relaxant for external cephalic version: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):271–276.

- Bujold E, Boucher M, Rinfred D, Berman S, Ferreira E, Marquette GP. Sublingual nitroglycerin versus placebo as a tocolytic for external cephalic version: a randomized controlled trial in parous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):1070–1073.

- Goetzinger KR, Harper LM, Tuuli MG, Macones GA, Colditz GA. Effect of regional anesthesia on the success of external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1137–1144.

- Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned cesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375–1383.

- Weiniger CF, Lyell DJ, Tsen LC, et al. Maternal outcomes of term breech presentation delivery: impact of successful external cephalic version in a nationwide sample of delivery admissions in the United States. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):150.

- Eller DP, Van Dorsten JP. Breech presentation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol.1993;5(5)664–668.

- Cunningham FG, Leveno KJ, Bloom SL, et al. Williams Obstetrics. 24th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2014:570.

- Westgren M, Edvall H, Nordstrom L, Svalenius E, Ranstam J. Spontaneous cephalic version of breech presentation in the last trimester. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92(1):19–22.

- External cephalic version. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 161. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2016.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(4):CD000083.

- Beuckens A, Rijnders M, Verburgt-Doeleman GH, Rijninks-van Driel GC, Thorpe J, Hutton EK. An observational study of the success and complications of 2546 external cephalic versions in low-risk pregnant women performed by trained midwives. BJOG. 2016;123(3):415–423.

- Tong Leung VK, Suen SS, Singh Sahota D, Lau TK, Yeung Leung T. External cephalic version does not increase the risk of intra-uterine death: a 17-year experience and literature review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25(9):1774–1778.

- de Hundt M, Velzel J, de Groot CJ, Mol BW, Kok M. Mode of delivery after successful external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1327–1334.

- Grootscholten K, Kok M, Oei SG, Mol BW, van der Post JA. External cephalic version–related risks: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1143–1151.

- Collaris RJ, Oei SG. External cephalic version: a safe procedure? A systematic review of version-related risk. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2004;83(6):511–518.

- Khaw KS, Lee SW, Ngan Kee WD, et al. Randomized trial of anesthetic interventions in external cephalic version for breech presentation. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114(6):944–950.

- Boucher M, Marquette GP, Varin J, Champagne J, Bujold E. Fetomaternal hemorrhage during external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(1):79–84.

- Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. Cephalic version by postural management for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(10):CD00051.

- Coulon C, Poleszczuk M, Paty-Montaigne MH, et al. Version of breech fetuses by moxibustion with acupuncture: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(1):32–39.

- Bue L, Lauszus FF. Moxibustion did not have an effect in a randomised clinical trial for version of breech position. Dan Med J. 2016;63(2):pii:A5199.

- Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B. Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5):CD003928.

- Sananes N, Roth GE, Aissi GA, et al. Acupuncture version of breech presentation: a randomized sham-controlled single-blinded trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;204:24–30.

- Cluver C, Gyte GM, Sinclair M, Dowswell T, Hofmeyr G. Interventions for helping to turn breech babies to head first presentation when using external cephalic version. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD000184.

- Fernandez CO, Bloom SL, Smulian JC, Ananth CV, Wendel GD Jr. A randomized placebo-controlled evaluation of terbutaline for external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90(5):775–779.

- Mohamed Ismail NA, Ibrahim M, Mohd Naim N, Mahdy ZA, Jamil MA, Mohd Razi ZR. Nifedipine versus terbutaline for tocolysis in external cephalic version. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102(3):263–266.

- Kok M, Bais J, van Lith J, et al. Nifedipine as a uterine relaxant for external cephalic version: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(2 pt 1):271–276.

- Bujold E, Boucher M, Rinfred D, Berman S, Ferreira E, Marquette GP. Sublingual nitroglycerin versus placebo as a tocolytic for external cephalic version: a randomized controlled trial in parous women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(4):1070–1073.

- Goetzinger KR, Harper LM, Tuuli MG, Macones GA, Colditz GA. Effect of regional anesthesia on the success of external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(5):1137–1144.

Fast Tracks

- Current practice is to wait until 36 to 37 weeks of gestation to perform ECV, since most fetuses spontaneously move into vertex presentation by 36 weeks

- Tocolysis, which relaxes the uterus, and neuraxial analgesia/anesthesia, which relaxes anterior abdominal wall muscles and reduces ECV-associated pain, can facilitate ECV success

- Several studies have found that nifedipine is less effective than terbutaline in facilitating ECV

- Higher doses of neuraxial anesthesia produce higher ECV success rates, possibly because the higher anesthetic dose relaxes the abdominal wall muscles and facilitates fetus repositioning

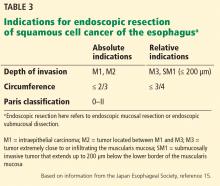

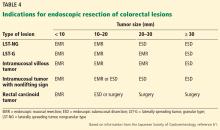

A minimally invasive treatment for early GI cancers

The treatment of early esophageal, gastric, and colorectal cancer is changing.1 For many years, surgery was the mainstay of treatment for early-stage gastrointestinal cancer. Unfortunately, surgery leads to significant loss of function of the organ, resulting in increased morbidity and decreased quality of life.2

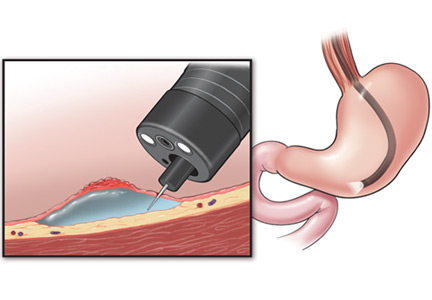

Endoscopic techniques, particularly endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), have been developed and are widely used in Japan, where gastrointestinal cancer is more common than in the West. This article reviews the indications, complications, and outcomes of ESD for early gastrointestinal neoplasms, so that readers will recognize the subset of patients who would benefit from ESD in a Western setting.

ENDOSCOPIC MUCOSAL RESECTION AND SUBMUCOSAL DISSECTION

Since the first therapeutic polypectomy was performed in Japan in 1974, several endoscopic techniques for tumor resection have been developed.3

EMR, one of the most successful and widely used techniques, involves elevating the lesion either with submucosal injection of a solution or with cap suction, and then removing it with a snare.4 Most lesions smaller than 20 mm can be removed in one piece (en bloc).5 Larger lesions are removed in multiple pieces (ie, piecemeal). Unfortunately, some fibrotic lesions, which are usually difficult to lift, cannot be completely removed by EMR.

ESD was first performed in the late 1990s with the aim of overcoming the limitations of EMR in resecting large or fibrotic tumors en bloc.6,7 Since then, ESD technique has been standardized and training centers have been created, especially in Asia, where it is widely used for treatment of early gastric cancer.3,8–10 Since 2012 it has been covered by the Japanese National Health Insurance for treatment of early gastric cancer, and since 2014 for treatment of colorectal malignant tumors measuring 2 to 5 cm.11

Adoption of ESD has been slow in Western countries, where many patients are still referred for surgery or undergo EMR for removal of superficial neoplasms. Reasons for this slow adoption are that gastric cancer is much less common in Western countries, and also that ESD demands a high level of technical skill, is difficult to learn, and is expensive.3,12,13 However, small groups of Western endoscopists have become interested and are advocating it, first studying it on their own and then training in a Japanese center and learning from experts performing the procedure.

Therefore, in a Western setting, ESD should be performed in specialized endoscopy centers and offered to selected patients.1

CANDIDATES SHOULD HAVE EARLY-STAGE, SUPERFICIAL TUMORS

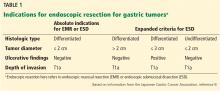

Ideal candidates for endoscopic resection are patients who have early cancer with a negligible risk of lymph node metastasis, such as cancer limited to the mucosa (stage T1a).7 Therefore, to determine the best treatment for a patient with a newly diagnosed gastrointestinal neoplasm, it is mandatory to estimate the depth of invasion.

The depth of invasion is directly correlated with lymph node involvement, which is ultimately the main predictive factor for long-term adverse outcomes of gastrointestinal tumors.4,14–17 Accurate multidisciplinary preprocedure estimations are mandatory, as incorrect evaluations may result in inappropriate therapy and residual cancer.18

Other factors that have been used to predict lymph node involvement include tumor size, macroscopic appearance, histologic differentiation, and lymphatic and vascular involvement.19 Some of these factors can be assessed by special endoscopic techniques (chromoendoscopy and narrow-band imaging with magnifying endoscopy) that allow accurate real-time estimation of the depth of invasion of the lesion.5,17,20–27 Evaluation of microsurface and microvascular arrangements is especially useful for determining the feasibility of ESD in gastric tumors, evaluation of intracapillary loops is useful in esophageal lesions, and assessment of mucosal pit patterns is useful for colorectal lesions.21–29